User login

Developing essential skills at all career stages

SHM Leadership Academy continues to grow

This fall I attended the 2018 Society of Hospital Medicine Leadership Academy, held in Vancouver. Once again, this conference sold out weeks ahead of time, and 300 hospitalists took time out of their busy schedules for learning and fun. There have been about 18 Leadership Academies over the years, with approximately 3,000 total participants, but this one may have been the best to date.

Why was it so good? Here are my top four reasons that Leadership Academy 2018 was the best ever:

Setting: Vancouver is just beautiful. My family has a strong maritime background, and I am a water person with saltwater in my veins. My inner sailor was overjoyed with the hotel’s views of False Creek and Vancouver Harbor, and I loved the mix of yachts and working boats. I even saw a seaplane! The hotel was a great match for the 300 hospitalists who traveled to the JW Marriott for 4 days of learning and relaxing. It was the perfect blend, whether for work or play; the hotel and city did not disappoint.

Networking: What’s more fun than getting to know 300 like-minded, leadership-oriented hospitalists for a few days? I am always energized by seeing old friends and making new ones. I really enjoy hearing about the professional adventures hospitalists at all career points are going through. Plus, I get really good advice on my own career! I also appreciate that a number of hospital medicine leaders (and even giants) come to SHM’s Leadership Academy. Over half of the SHM Board of Directors were there, as were a number of current and previous SHM presidents (Mark Williams, Jeff Wiese, Burke Kealey, Bob Harrington, Nasim Afsar, Rusty Holman, Ron Greeno, Chris Frost, and John Nelson), as well as Larry Wellikson, the CEO who has led our society through its many successes. All of these hospitalist leaders are there, having fun and networking, alongside everyone else.

Faculty: The faculty for all four courses (yes, Leadership Academy junkies, we’ve added a fourth course!) are absolutely phenomenal. I think the faculty are just the right blend of expert hospitalists (Jeff Glasheen, Rusty Holman, Jeff Wiese, Mark Williams, John Nelson) and national experts outside of hospital medicine. For example, Lenny Marcus of Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, brings his experience coaching the Department of Defense, the White House, the Department of Homeland Security, and many others to the Influential Management and Mastering Teamwork courses. Lenny’s experience working with national leaders through disasters like the Boston Marathon bombing, Hurricane Katrina, and the Ebola outbreak make for more than riveting stories; there are real, tangible lessons for hospitalist leaders trying to improve clinical care. Nancy Spector is a pediatrician, nationally recognized for her work in mentoring, and is the executive director of Drexel University’s Executive Leadership in Academic Medicine. We have been fortunate to have her join the Academies, and Nancy successfully led the first group of hospitalists through the launch of SHM’s fourth leadership course, which I will describe in more detail below.

High energy & continued growth: There continues to be an enormous amount of energy around the Leadership Academy. The Vancouver courses sold out months ahead of the actual meeting! Hospitalists across the country continue to take on leadership roles and have told us that they value the skills they have learned from the courses.

Hospitalist leaders want more

In addition to the current 4-day courses (Strategic Essentials, Influential Management, and Mastering Teamwork), hospitalists are looking for a course that continues skill building once they return home.

That’s why SHM has developed a fourth Leadership Academy course. This course, called the Capstone Course, was launched in Vancouver and consists of 2 days of on-site skill development and team building (during the first 2 days of the traditional Leadership Academy) and 6 months of a longitudinal learning collaborative. The six-month learning collaborative component consists of a learning “pod” of five or six fellow hospitalists and monthly virtual meetings around crucial leadership topics. They are facilitated by an experienced Leadership Academy facilitator.

Dr. Spector is the lead faculty; her expertise made the Capstone launch a huge success. She will work with SHM and the Capstone participants throughout the entire 6 months to ensure the Capstone course is as high-quality as the previous three Academy courses.

If you haven’t been, I invite you to attend our next Leadership Academy. Over the years, despite being course director, I have learned many take-home skills from colleagues and leaders in the field that I use often. Just to name a few:

- Flexing my communications style: Tim Keogh’s lecture opened my eyes to the fact that not everyone is a data-driven introvert. I now know that some people need a social warm up, while others just want the facts, and that there are “huggers and shakers.” (In summary, it’s fine to shake hands with a hugger, but be wary of hugging a shaker.)

- I send birthday emails after I heard Jeff Wiese’s talk.

- Lenny Marcus taught me to be aware when I am “in the basement” emotionally. I now know to wait to send emails or confront others until I can get out of the basement.

And that’s just scratching the surface!

In closing, the Vancouver Leadership Academy was fantastic. Good friends, great professional development, a setting that was amazing, and an Academy that remains relevant and dynamic to our specialty. I can’t wait to see how the 2019 Leadership Academy shapes up for its debut in Nashville. My inner sailor may have to give way to my inner musician! I hope to see you and 300 of my closest friends there.

Learn more about SHM’s Leadership Academy at shmleadershipacademy.org.

Dr. Howell is a professor of medicine at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and chief of the division of hospital medicine at Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center. He is also chief operating officer at the Society of Hospital Medicine and course director of the SHM Leadership Academy.

SHM Leadership Academy continues to grow

SHM Leadership Academy continues to grow

This fall I attended the 2018 Society of Hospital Medicine Leadership Academy, held in Vancouver. Once again, this conference sold out weeks ahead of time, and 300 hospitalists took time out of their busy schedules for learning and fun. There have been about 18 Leadership Academies over the years, with approximately 3,000 total participants, but this one may have been the best to date.

Why was it so good? Here are my top four reasons that Leadership Academy 2018 was the best ever:

Setting: Vancouver is just beautiful. My family has a strong maritime background, and I am a water person with saltwater in my veins. My inner sailor was overjoyed with the hotel’s views of False Creek and Vancouver Harbor, and I loved the mix of yachts and working boats. I even saw a seaplane! The hotel was a great match for the 300 hospitalists who traveled to the JW Marriott for 4 days of learning and relaxing. It was the perfect blend, whether for work or play; the hotel and city did not disappoint.

Networking: What’s more fun than getting to know 300 like-minded, leadership-oriented hospitalists for a few days? I am always energized by seeing old friends and making new ones. I really enjoy hearing about the professional adventures hospitalists at all career points are going through. Plus, I get really good advice on my own career! I also appreciate that a number of hospital medicine leaders (and even giants) come to SHM’s Leadership Academy. Over half of the SHM Board of Directors were there, as were a number of current and previous SHM presidents (Mark Williams, Jeff Wiese, Burke Kealey, Bob Harrington, Nasim Afsar, Rusty Holman, Ron Greeno, Chris Frost, and John Nelson), as well as Larry Wellikson, the CEO who has led our society through its many successes. All of these hospitalist leaders are there, having fun and networking, alongside everyone else.

Faculty: The faculty for all four courses (yes, Leadership Academy junkies, we’ve added a fourth course!) are absolutely phenomenal. I think the faculty are just the right blend of expert hospitalists (Jeff Glasheen, Rusty Holman, Jeff Wiese, Mark Williams, John Nelson) and national experts outside of hospital medicine. For example, Lenny Marcus of Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, brings his experience coaching the Department of Defense, the White House, the Department of Homeland Security, and many others to the Influential Management and Mastering Teamwork courses. Lenny’s experience working with national leaders through disasters like the Boston Marathon bombing, Hurricane Katrina, and the Ebola outbreak make for more than riveting stories; there are real, tangible lessons for hospitalist leaders trying to improve clinical care. Nancy Spector is a pediatrician, nationally recognized for her work in mentoring, and is the executive director of Drexel University’s Executive Leadership in Academic Medicine. We have been fortunate to have her join the Academies, and Nancy successfully led the first group of hospitalists through the launch of SHM’s fourth leadership course, which I will describe in more detail below.

High energy & continued growth: There continues to be an enormous amount of energy around the Leadership Academy. The Vancouver courses sold out months ahead of the actual meeting! Hospitalists across the country continue to take on leadership roles and have told us that they value the skills they have learned from the courses.

Hospitalist leaders want more

In addition to the current 4-day courses (Strategic Essentials, Influential Management, and Mastering Teamwork), hospitalists are looking for a course that continues skill building once they return home.

That’s why SHM has developed a fourth Leadership Academy course. This course, called the Capstone Course, was launched in Vancouver and consists of 2 days of on-site skill development and team building (during the first 2 days of the traditional Leadership Academy) and 6 months of a longitudinal learning collaborative. The six-month learning collaborative component consists of a learning “pod” of five or six fellow hospitalists and monthly virtual meetings around crucial leadership topics. They are facilitated by an experienced Leadership Academy facilitator.

Dr. Spector is the lead faculty; her expertise made the Capstone launch a huge success. She will work with SHM and the Capstone participants throughout the entire 6 months to ensure the Capstone course is as high-quality as the previous three Academy courses.

If you haven’t been, I invite you to attend our next Leadership Academy. Over the years, despite being course director, I have learned many take-home skills from colleagues and leaders in the field that I use often. Just to name a few:

- Flexing my communications style: Tim Keogh’s lecture opened my eyes to the fact that not everyone is a data-driven introvert. I now know that some people need a social warm up, while others just want the facts, and that there are “huggers and shakers.” (In summary, it’s fine to shake hands with a hugger, but be wary of hugging a shaker.)

- I send birthday emails after I heard Jeff Wiese’s talk.

- Lenny Marcus taught me to be aware when I am “in the basement” emotionally. I now know to wait to send emails or confront others until I can get out of the basement.

And that’s just scratching the surface!

In closing, the Vancouver Leadership Academy was fantastic. Good friends, great professional development, a setting that was amazing, and an Academy that remains relevant and dynamic to our specialty. I can’t wait to see how the 2019 Leadership Academy shapes up for its debut in Nashville. My inner sailor may have to give way to my inner musician! I hope to see you and 300 of my closest friends there.

Learn more about SHM’s Leadership Academy at shmleadershipacademy.org.

Dr. Howell is a professor of medicine at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and chief of the division of hospital medicine at Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center. He is also chief operating officer at the Society of Hospital Medicine and course director of the SHM Leadership Academy.

This fall I attended the 2018 Society of Hospital Medicine Leadership Academy, held in Vancouver. Once again, this conference sold out weeks ahead of time, and 300 hospitalists took time out of their busy schedules for learning and fun. There have been about 18 Leadership Academies over the years, with approximately 3,000 total participants, but this one may have been the best to date.

Why was it so good? Here are my top four reasons that Leadership Academy 2018 was the best ever:

Setting: Vancouver is just beautiful. My family has a strong maritime background, and I am a water person with saltwater in my veins. My inner sailor was overjoyed with the hotel’s views of False Creek and Vancouver Harbor, and I loved the mix of yachts and working boats. I even saw a seaplane! The hotel was a great match for the 300 hospitalists who traveled to the JW Marriott for 4 days of learning and relaxing. It was the perfect blend, whether for work or play; the hotel and city did not disappoint.

Networking: What’s more fun than getting to know 300 like-minded, leadership-oriented hospitalists for a few days? I am always energized by seeing old friends and making new ones. I really enjoy hearing about the professional adventures hospitalists at all career points are going through. Plus, I get really good advice on my own career! I also appreciate that a number of hospital medicine leaders (and even giants) come to SHM’s Leadership Academy. Over half of the SHM Board of Directors were there, as were a number of current and previous SHM presidents (Mark Williams, Jeff Wiese, Burke Kealey, Bob Harrington, Nasim Afsar, Rusty Holman, Ron Greeno, Chris Frost, and John Nelson), as well as Larry Wellikson, the CEO who has led our society through its many successes. All of these hospitalist leaders are there, having fun and networking, alongside everyone else.

Faculty: The faculty for all four courses (yes, Leadership Academy junkies, we’ve added a fourth course!) are absolutely phenomenal. I think the faculty are just the right blend of expert hospitalists (Jeff Glasheen, Rusty Holman, Jeff Wiese, Mark Williams, John Nelson) and national experts outside of hospital medicine. For example, Lenny Marcus of Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, brings his experience coaching the Department of Defense, the White House, the Department of Homeland Security, and many others to the Influential Management and Mastering Teamwork courses. Lenny’s experience working with national leaders through disasters like the Boston Marathon bombing, Hurricane Katrina, and the Ebola outbreak make for more than riveting stories; there are real, tangible lessons for hospitalist leaders trying to improve clinical care. Nancy Spector is a pediatrician, nationally recognized for her work in mentoring, and is the executive director of Drexel University’s Executive Leadership in Academic Medicine. We have been fortunate to have her join the Academies, and Nancy successfully led the first group of hospitalists through the launch of SHM’s fourth leadership course, which I will describe in more detail below.

High energy & continued growth: There continues to be an enormous amount of energy around the Leadership Academy. The Vancouver courses sold out months ahead of the actual meeting! Hospitalists across the country continue to take on leadership roles and have told us that they value the skills they have learned from the courses.

Hospitalist leaders want more

In addition to the current 4-day courses (Strategic Essentials, Influential Management, and Mastering Teamwork), hospitalists are looking for a course that continues skill building once they return home.

That’s why SHM has developed a fourth Leadership Academy course. This course, called the Capstone Course, was launched in Vancouver and consists of 2 days of on-site skill development and team building (during the first 2 days of the traditional Leadership Academy) and 6 months of a longitudinal learning collaborative. The six-month learning collaborative component consists of a learning “pod” of five or six fellow hospitalists and monthly virtual meetings around crucial leadership topics. They are facilitated by an experienced Leadership Academy facilitator.

Dr. Spector is the lead faculty; her expertise made the Capstone launch a huge success. She will work with SHM and the Capstone participants throughout the entire 6 months to ensure the Capstone course is as high-quality as the previous three Academy courses.

If you haven’t been, I invite you to attend our next Leadership Academy. Over the years, despite being course director, I have learned many take-home skills from colleagues and leaders in the field that I use often. Just to name a few:

- Flexing my communications style: Tim Keogh’s lecture opened my eyes to the fact that not everyone is a data-driven introvert. I now know that some people need a social warm up, while others just want the facts, and that there are “huggers and shakers.” (In summary, it’s fine to shake hands with a hugger, but be wary of hugging a shaker.)

- I send birthday emails after I heard Jeff Wiese’s talk.

- Lenny Marcus taught me to be aware when I am “in the basement” emotionally. I now know to wait to send emails or confront others until I can get out of the basement.

And that’s just scratching the surface!

In closing, the Vancouver Leadership Academy was fantastic. Good friends, great professional development, a setting that was amazing, and an Academy that remains relevant and dynamic to our specialty. I can’t wait to see how the 2019 Leadership Academy shapes up for its debut in Nashville. My inner sailor may have to give way to my inner musician! I hope to see you and 300 of my closest friends there.

Learn more about SHM’s Leadership Academy at shmleadershipacademy.org.

Dr. Howell is a professor of medicine at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and chief of the division of hospital medicine at Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center. He is also chief operating officer at the Society of Hospital Medicine and course director of the SHM Leadership Academy.

A Concise Tool for Measuring Care Coordination from the Provider’s Perspective in the Hospital Setting

Care Coordination has been defined as “…the deliberate organization of patient care activities between two or more participants (including the patient) involved in a patient’s care to facilitate the appropriate delivery of healthcare services.”1 The Institute of Medicine identified care coordination as a key strategy to improve the American healthcare system,2 and evidence has been building that well-coordinated care improves patient outcomes and reduces healthcare costs associated with chronic conditions.3-5 In 2012, Johns Hopkins Medicine was awarded a Healthcare Innovation Award by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services to improve coordination of care across the continuum of care for adult patients admitted to Johns Hopkins Hospital (JHH) and Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center (JHBMC), and for high-risk low-income Medicare and Medicaid beneficiaries receiving ambulatory care in targeted zip codes. The purpose of this project, known as the Johns Hopkins Community Health Partnership (J-CHiP), was to improve health and healthcare and to reduce healthcare costs. The acute care component of the program consisted of a bundle of interventions focused on improving coordination of care for all patients, including a “bridge to home” discharge process, as they transitioned back to the community from inpatient admission. The bundle included the following: early screening for discharge planning to predict needed postdischarge services; discussion in daily multidisciplinary rounds about goals and priorities of the hospitalization and potential postdischarge needs; patient and family self-care management; education enhanced medication management, including the option of “medications in hand” at the time of discharge; postdischarge telephone follow-up by nurses; and, for patients identified as high-risk, a “transition guide” (a nurse who works with the patient via home visits and by phone to optimize compliance with care for 30 days postdischarge).6 While the primary endpoints of the J-CHiP program were to improve clinical outcomes and reduce healthcare costs, we were also interested in the impact of the program on care coordination processes in the acute care setting. This created the need for an instrument to measure healthcare professionals’ views of care coordination in their immediate work environments.

We began our search for existing measures by reviewing the Coordination Measures Atlas published in 2014.7 Although this report evaluates over 80 different measures of care coordination, most of them focus on the perspective of the patient and/or family members, on specific conditions, and on primary care or outpatient settings.7,8 We were unable to identify an existing measure from the provider perspective, designed for the inpatient setting, that was both brief but comprehensive enough to cover a range of care coordination domains.8

Consequently, our first aim was to develop a brief, comprehensive tool to measure care coordination from the perspective of hospital inpatient staff that could be used to compare different units or types of providers, or to conduct longitudinal assessment. The second aim was to conduct a preliminary evaluation of the tool in our healthcare setting, including to assess its psychometric properties, to describe provider perceptions of care coordination after the implementation of J-CHiP, and to explore potential differences among departments, types of professionals, and between the 2 hospitals.

METHODS

Development of the Care Coordination Questionnaire

The survey was developed in collaboration with leaders of the J-CHiP Acute Care Team. We met at the outset and on multiple subsequent occasions to align survey domains with the main components of the J-CHiP acute care intervention and to assure that the survey would be relevant and understandable to a variety of multidisciplinary professionals, including physicians, nurses, social workers, physical therapists, and other health professionals. Care was taken to avoid redundancy with existing evaluation efforts and to minimize respondent burden. This process helped to ensure the content validity of the items, the usefulness of the results, and the future usability of the tool.

We modeled the Care Coordination Questionnaire (CCQ) after the Safety Attitudes Questionnaire (SAQ),9 a widely used survey that is deployed approximately annually at JHH and JHBMC. While the SAQ focuses on healthcare provider attitudes about issues relevant to patient safety (often referred to as safety climate or safety culture), this new tool was designed to focus on healthcare professionals’ attitudes about care coordination. Similar to the way that the SAQ “elicits a snapshot of the safety climate through surveys of frontline worker perceptions,” we sought to elicit a picture of our care coordination climate through a survey of frontline hospital staff.

The CCQ was built upon the domains and approaches to care coordination described in the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Care Coordination Atlas.3 This report identifies 9 mechanisms for achieving care coordination, including the following: Establish Accountability or Negotiate Responsibility; Communicate; Facilitate Transitions; Assess Needs and Goals; Create a Proactive Plan of Care; Monitor, Follow Up, and Respond to Change; Support Self-Management Goals; Link to Community Resources; and Align Resources with Patient and Population Needs; as well as 5 broad approaches commonly used to improve the delivery of healthcare, including Teamwork Focused on Coordination, Healthcare Home, Care Management, Medication Management, and Health IT-Enabled Coordination.7 We generated at least 1 item to represent 8 of the 9 domains, as well as the broad approach described as Teamwork Focused on Coordination. After developing an initial set of items, we sought input from 3 senior leaders of the J-CHiP Acute Care Team to determine if the items covered the care coordination domains of interest, and to provide feedback on content validity. To test the interpretability of survey items and consistency across professional groups, we sent an initial version of the survey questions to at least 1 person from each of the following professional groups: hospitalist, social worker, case manager, clinical pharmacist, and nurse. We asked them to review all of our survey questions and to provide us with feedback on all aspects of the questions, such as whether they believed the questions were relevant and understandable to the members of their professional discipline, the appropriateness of the wording of the questions, and other comments. Modifications were made to the content and wording of the questions based on the feedback received. The final draft of the questionnaire was reviewed by the leadership team of the J-CHiP Acute Care Team to ensure its usefulness in providing actionable information.

The resulting 12-item questionnaire used a 5-point Likert response scale ranging from 1 = “disagree strongly” to 5 = “agree strongly,” and an additional option of “not applicable (N/A).” To help assess construct validity, a global question was added at the end of the questionnaire asking, “Overall, how would you rate the care coordination at the hospital of your primary work setting?” The response was measured on a 10-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 = “totally uncoordinated care” to 10 = “perfectly coordinated care” (see Appendix). In addition, the questionnaire requested information about the respondents’ gender, position, and their primary unit, department, and hospital affiliation.

Data Collection Procedures

An invitation to complete an anonymous questionnaire was sent to the following inpatient care professionals: all nursing staff working on care coordination units in the departments of medicine, surgery, and neurology/neurosurgery, as well as physicians, pharmacists, acute care therapists (eg, occupational and physical therapists), and other frontline staff. All healthcare staff fitting these criteria was sent an e-mail with a request to fill out the survey online using QualtricsTM (Qualtrics Labs Inc., Provo, UT), as well as multiple follow-up reminders. The participants worked either at the JHH (a 1194-bed tertiary academic medical center in Baltimore, MD) or the JHBMC (a 440-bed academic community hospital located nearby). Data were collected from October 2015 through January 2016.

Analysis

Means and standard deviations were calculated by treating the responses as continuous variables. We tried 3 different methods to handle missing data: (1) without imputation, (2) imputing the mean value of each item, and (3) substituting a neutral score. Because all 3 methods produced very similar results, we treated the N/A responses as missing values without imputation for simplicity of analysis. We used STATA 13.1 (Stata Corporation, College Station, Texas) to analyze the data.

To identify subscales, we performed exploratory factor analysis on responses to the 12 specific items. Promax rotation was selected based on the simple structure. Subscale scores for each respondent were generated by computing the mean of responses to the items in the subscale. Internal consistency reliability of the subscales was estimated using Cronbach’s alpha. We calculated Pearson correlation coefficients for the items in each subscale, and examined Cronbach’s alpha deleting each item in turn. For each of the subscales identified and the global scale, we calculated the mean, standard deviation, median and interquartile range. Although distributions of scores tended to be non-normal, this was done to increase interpretability. We also calculated percent scoring at the ceiling (highest possible score).

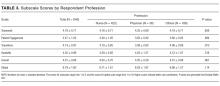

We analyzed the data with 3 research questions in mind: Was there a difference in perceptions of care coordination between (1) staff affiliated with the 2 different hospitals, (2) staff affiliated with different clinical departments, or (3) staff with different professional roles? For comparisons based on hospital and department, and type of professional, nonparametric tests (Wilcoxon rank-sum and Kruskal-Wallis test) were used with a level of statistical significance set at 0.05. The comparison between hospitals and departments was made only among nurses to minimize the confounding effect of different distribution of professionals. We tested the distribution of “years in specialty” between hospitals and departments for this comparison using Pearson’s χ2 test. The difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.167 for hospitals, and P = 0.518 for departments), so we assumed that the potential confounding effect of this variable was negligible in this analysis. The comparison of scores within each professional group used the Friedman test. Pearson’s χ2 test was used to compare the baseline characteristics between 2 hospitals.

RESULTS

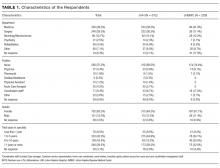

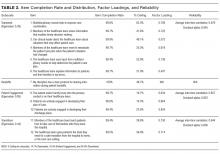

Among the 1486 acute care professionals asked to participate in the survey, 841 completed the questionnaire (response rate 56.6%). Table 1 shows the characteristics of the participants from each hospital. Table 2 summarizes the item response rates, proportion scoring at the ceiling, and weighting from the factor analysis. All items had completion rates of 99.2% or higher, with N/A responses ranging from 0% (item 2) to 3.1% (item 7). The percent scoring at the ceiling was 1.7% for the global item and ranged from 18.3% up to 63.3% for other individual items.

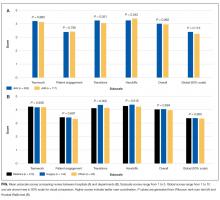

We also examined differences in perceptions of care coordination among nursing units to illustrate the tool’s ability to detect variation in Patient Engagement subscale scores for JHH nurses (see Appendix).

DISCUSSION

This study resulted in one of the first measurement tools to succinctly measure multiple aspects of care coordination in the hospital from the perspective of healthcare professionals. Given the hectic work environment of healthcare professionals, and the increasing emphasis on collecting data for evaluation and improvement, it is important to minimize respondent burden. This effort was catalyzed by a multifaceted initiative to redesign acute care delivery and promote seamless transitions of care, supported by the Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation. In initial testing, this questionnaire has evidence for reliability and validity. It was encouraging to find that the preliminary psychometric performance of the measure was very similar in 2 different settings of a tertiary academic hospital and a community hospital.

Our analysis of the survey data explored potential differences between the 2 hospitals, among different types of healthcare professionals and across different departments. Although we expected differences, we had no specific hypotheses about what those differences might be, and, in fact, did not observe any substantial differences. This could be taken to indicate that the intervention was uniformly and successfully implemented in both hospitals, and engaged various professionals in different departments. The ability to detect differences in care coordination at the nursing unit level could also prove to be beneficial for more precisely targeting where process improvement is needed. Further data collection and analyses should be conducted to more systematically compare units and to help identify those where practice is most advanced and those where improvements may be needed. It would also be informative to link differences in care coordination scores with patient outcomes. In addition, differences identified on specific domains between professional groups could be helpful to identify where greater efforts are needed to improve interdisciplinary practice. Sampling strategies stratified by provider type would need to be targeted to make this kind of analysis informative.

The consistently lower scores observed for patient engagement, from the perspective of care professionals in all groups, suggest that this is an area where improvement is needed. These findings are consistent with published reports on the common failure by hospitals to include patients as a member of their own care team. In addition to measuring care processes from the perspective of frontline healthcare workers, future evaluations within the healthcare system would also benefit from including data collected from the perspective of the patient and family.

This study had some limitations. First, there may be more than 4 domains of care coordination that are important and can be measured in the acute care setting from provider perspective. However, the addition of more domains should be balanced against practicality and respondent burden. It may be possible to further clarify priority domains in hospital settings as opposed to the primary care setting. Future research should be directed to find these areas and to develop a more comprehensive, yet still concise measurement instrument. Second, the tool was developed to measure the impact of a large-scale intervention, and to fit into the specific context of 2 hospitals. Therefore, it should be tested in different settings of hospital care to see how it performs. However, virtually all hospitals in the United States today are adapting to changes in both financing and healthcare delivery. A tool such as the one described in this paper could be helpful to many organizations. Third, the scoring system for the overall scale score is not weighted and therefore reflects teamwork more than other components of care coordination, which are represented by fewer items. In general, we believe that use of the subscale scores may be more informative. Alternative scoring systems might also be proposed, including item weighting based on factor scores.

For the purposes of evaluation in this specific instance, we only collected data at a single point in time, after the intervention had been deployed. Thus, we were not able to evaluate the effectiveness of the J-CHiP intervention. We also did not intend to focus too much on the differences between units, given the limited number of respondents from individual units. It would be useful to collect more data at future time points, both to test the responsiveness of the scales and to evaluate the impact of future interventions at both the hospital and unit level.

The preliminary data from this study have generated insights about gaps in current practice, such as in engaging patients in the inpatient care process. It has also increased awareness by hospital leaders about the need to achieve high reliability in the adoption of new procedures and interdisciplinary practice. This tool might be used to find areas in need of improvement, to evaluate the effect of initiatives to improve care coordination, to monitor the change over time in the perception of care coordination among healthcare professionals, and to develop better intervention strategies for coordination activities in acute care settings. Additional research is needed to provide further evidence for the reliability and validity of this measure in diverse settings.

Disclosure

The project described was supported by Grant Number 1C1CMS331053-01-00 from the US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. The contents of this publication are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the US Department of Health and Human Services or any of its agencies. The research presented was conducted by the awardee. Results may or may not be consistent with or confirmed by the findings of the independent evaluation contractor.

The authors have no other disclosures.

1. McDonald KM, Sundaram V, Bravata DM, et al. Closing the Quality Gap: A Critical Analysis of Quality Improvement Strategies (Vol. 7: Care Coordination). Technical Reviews, No. 9.7. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2007. PubMed

2. Adams K, Corrigan J. Priority areas for national action: transforming health care quality. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2003. PubMed

3. Renders CM, Valk GD, Griffin S, Wagner EH, Eijk JT, Assendelft WJ. Interventions to improve the management of diabetes mellitus in primary care, outpatient and community settings. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2001(1):CD001481. PubMed

4. McAlister FA, Lawson FM, Teo KK, Armstrong PW. A systematic review of randomized trials of disease management programs in heart failure. Am J Med. 2001;110(5):378-384. PubMed

5. Bruce ML, Raue PJ, Reilly CF, et al. Clinical effectiveness of integrating depression care management into medicare home health: the Depression CAREPATH Randomized trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(1):55-64. PubMed

6. Berkowitz SA, Brown P, Brotman DJ, et al. Case Study: Johns Hopkins Community Health Partnership: A model for transformation. Healthc (Amst). 2016;4(4):264-270. PubMed

7. McDonald. KM, Schultz. E, Albin. L, et al. Care Coordination Measures Atlas Version 4. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2014.

8 Schultz EM, Pineda N, Lonhart J, Davies SM, McDonald KM. A systematic review of the care coordination measurement landscape. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13:119. PubMed

9. Sexton JB, Helmreich RL, Neilands TB, et al. The Safety Attitudes Questionnaire: psychometric properties, benchmarking data, and emerging research. BMC Health Serv Res. 2006;6:44. PubMed

Care Coordination has been defined as “…the deliberate organization of patient care activities between two or more participants (including the patient) involved in a patient’s care to facilitate the appropriate delivery of healthcare services.”1 The Institute of Medicine identified care coordination as a key strategy to improve the American healthcare system,2 and evidence has been building that well-coordinated care improves patient outcomes and reduces healthcare costs associated with chronic conditions.3-5 In 2012, Johns Hopkins Medicine was awarded a Healthcare Innovation Award by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services to improve coordination of care across the continuum of care for adult patients admitted to Johns Hopkins Hospital (JHH) and Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center (JHBMC), and for high-risk low-income Medicare and Medicaid beneficiaries receiving ambulatory care in targeted zip codes. The purpose of this project, known as the Johns Hopkins Community Health Partnership (J-CHiP), was to improve health and healthcare and to reduce healthcare costs. The acute care component of the program consisted of a bundle of interventions focused on improving coordination of care for all patients, including a “bridge to home” discharge process, as they transitioned back to the community from inpatient admission. The bundle included the following: early screening for discharge planning to predict needed postdischarge services; discussion in daily multidisciplinary rounds about goals and priorities of the hospitalization and potential postdischarge needs; patient and family self-care management; education enhanced medication management, including the option of “medications in hand” at the time of discharge; postdischarge telephone follow-up by nurses; and, for patients identified as high-risk, a “transition guide” (a nurse who works with the patient via home visits and by phone to optimize compliance with care for 30 days postdischarge).6 While the primary endpoints of the J-CHiP program were to improve clinical outcomes and reduce healthcare costs, we were also interested in the impact of the program on care coordination processes in the acute care setting. This created the need for an instrument to measure healthcare professionals’ views of care coordination in their immediate work environments.

We began our search for existing measures by reviewing the Coordination Measures Atlas published in 2014.7 Although this report evaluates over 80 different measures of care coordination, most of them focus on the perspective of the patient and/or family members, on specific conditions, and on primary care or outpatient settings.7,8 We were unable to identify an existing measure from the provider perspective, designed for the inpatient setting, that was both brief but comprehensive enough to cover a range of care coordination domains.8

Consequently, our first aim was to develop a brief, comprehensive tool to measure care coordination from the perspective of hospital inpatient staff that could be used to compare different units or types of providers, or to conduct longitudinal assessment. The second aim was to conduct a preliminary evaluation of the tool in our healthcare setting, including to assess its psychometric properties, to describe provider perceptions of care coordination after the implementation of J-CHiP, and to explore potential differences among departments, types of professionals, and between the 2 hospitals.

METHODS

Development of the Care Coordination Questionnaire

The survey was developed in collaboration with leaders of the J-CHiP Acute Care Team. We met at the outset and on multiple subsequent occasions to align survey domains with the main components of the J-CHiP acute care intervention and to assure that the survey would be relevant and understandable to a variety of multidisciplinary professionals, including physicians, nurses, social workers, physical therapists, and other health professionals. Care was taken to avoid redundancy with existing evaluation efforts and to minimize respondent burden. This process helped to ensure the content validity of the items, the usefulness of the results, and the future usability of the tool.

We modeled the Care Coordination Questionnaire (CCQ) after the Safety Attitudes Questionnaire (SAQ),9 a widely used survey that is deployed approximately annually at JHH and JHBMC. While the SAQ focuses on healthcare provider attitudes about issues relevant to patient safety (often referred to as safety climate or safety culture), this new tool was designed to focus on healthcare professionals’ attitudes about care coordination. Similar to the way that the SAQ “elicits a snapshot of the safety climate through surveys of frontline worker perceptions,” we sought to elicit a picture of our care coordination climate through a survey of frontline hospital staff.

The CCQ was built upon the domains and approaches to care coordination described in the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Care Coordination Atlas.3 This report identifies 9 mechanisms for achieving care coordination, including the following: Establish Accountability or Negotiate Responsibility; Communicate; Facilitate Transitions; Assess Needs and Goals; Create a Proactive Plan of Care; Monitor, Follow Up, and Respond to Change; Support Self-Management Goals; Link to Community Resources; and Align Resources with Patient and Population Needs; as well as 5 broad approaches commonly used to improve the delivery of healthcare, including Teamwork Focused on Coordination, Healthcare Home, Care Management, Medication Management, and Health IT-Enabled Coordination.7 We generated at least 1 item to represent 8 of the 9 domains, as well as the broad approach described as Teamwork Focused on Coordination. After developing an initial set of items, we sought input from 3 senior leaders of the J-CHiP Acute Care Team to determine if the items covered the care coordination domains of interest, and to provide feedback on content validity. To test the interpretability of survey items and consistency across professional groups, we sent an initial version of the survey questions to at least 1 person from each of the following professional groups: hospitalist, social worker, case manager, clinical pharmacist, and nurse. We asked them to review all of our survey questions and to provide us with feedback on all aspects of the questions, such as whether they believed the questions were relevant and understandable to the members of their professional discipline, the appropriateness of the wording of the questions, and other comments. Modifications were made to the content and wording of the questions based on the feedback received. The final draft of the questionnaire was reviewed by the leadership team of the J-CHiP Acute Care Team to ensure its usefulness in providing actionable information.

The resulting 12-item questionnaire used a 5-point Likert response scale ranging from 1 = “disagree strongly” to 5 = “agree strongly,” and an additional option of “not applicable (N/A).” To help assess construct validity, a global question was added at the end of the questionnaire asking, “Overall, how would you rate the care coordination at the hospital of your primary work setting?” The response was measured on a 10-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 = “totally uncoordinated care” to 10 = “perfectly coordinated care” (see Appendix). In addition, the questionnaire requested information about the respondents’ gender, position, and their primary unit, department, and hospital affiliation.

Data Collection Procedures

An invitation to complete an anonymous questionnaire was sent to the following inpatient care professionals: all nursing staff working on care coordination units in the departments of medicine, surgery, and neurology/neurosurgery, as well as physicians, pharmacists, acute care therapists (eg, occupational and physical therapists), and other frontline staff. All healthcare staff fitting these criteria was sent an e-mail with a request to fill out the survey online using QualtricsTM (Qualtrics Labs Inc., Provo, UT), as well as multiple follow-up reminders. The participants worked either at the JHH (a 1194-bed tertiary academic medical center in Baltimore, MD) or the JHBMC (a 440-bed academic community hospital located nearby). Data were collected from October 2015 through January 2016.

Analysis

Means and standard deviations were calculated by treating the responses as continuous variables. We tried 3 different methods to handle missing data: (1) without imputation, (2) imputing the mean value of each item, and (3) substituting a neutral score. Because all 3 methods produced very similar results, we treated the N/A responses as missing values without imputation for simplicity of analysis. We used STATA 13.1 (Stata Corporation, College Station, Texas) to analyze the data.

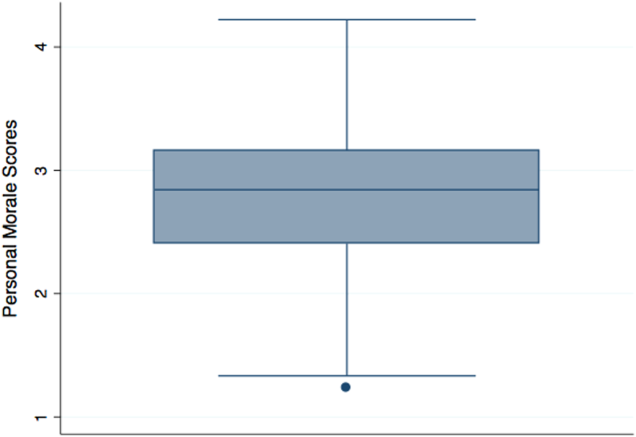

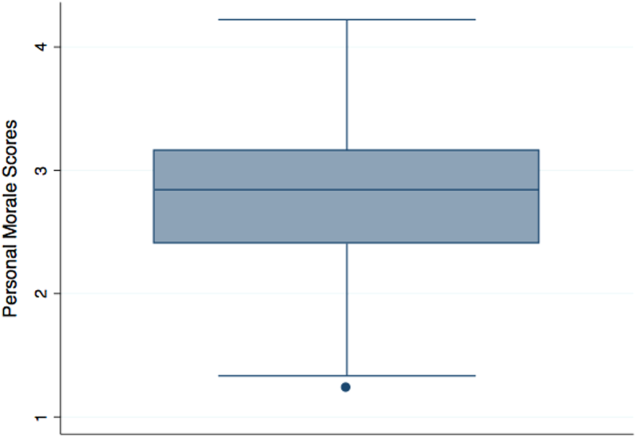

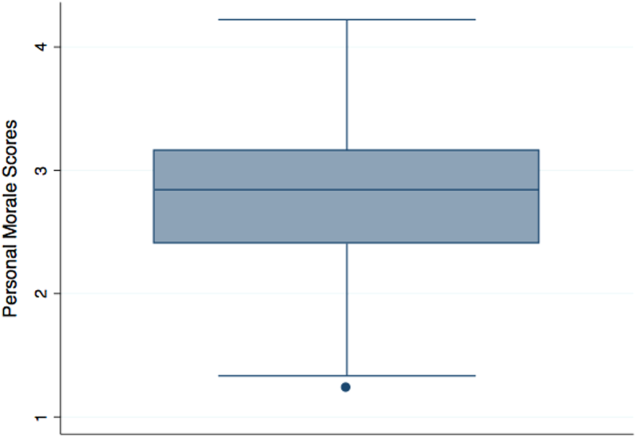

To identify subscales, we performed exploratory factor analysis on responses to the 12 specific items. Promax rotation was selected based on the simple structure. Subscale scores for each respondent were generated by computing the mean of responses to the items in the subscale. Internal consistency reliability of the subscales was estimated using Cronbach’s alpha. We calculated Pearson correlation coefficients for the items in each subscale, and examined Cronbach’s alpha deleting each item in turn. For each of the subscales identified and the global scale, we calculated the mean, standard deviation, median and interquartile range. Although distributions of scores tended to be non-normal, this was done to increase interpretability. We also calculated percent scoring at the ceiling (highest possible score).

We analyzed the data with 3 research questions in mind: Was there a difference in perceptions of care coordination between (1) staff affiliated with the 2 different hospitals, (2) staff affiliated with different clinical departments, or (3) staff with different professional roles? For comparisons based on hospital and department, and type of professional, nonparametric tests (Wilcoxon rank-sum and Kruskal-Wallis test) were used with a level of statistical significance set at 0.05. The comparison between hospitals and departments was made only among nurses to minimize the confounding effect of different distribution of professionals. We tested the distribution of “years in specialty” between hospitals and departments for this comparison using Pearson’s χ2 test. The difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.167 for hospitals, and P = 0.518 for departments), so we assumed that the potential confounding effect of this variable was negligible in this analysis. The comparison of scores within each professional group used the Friedman test. Pearson’s χ2 test was used to compare the baseline characteristics between 2 hospitals.

RESULTS

Among the 1486 acute care professionals asked to participate in the survey, 841 completed the questionnaire (response rate 56.6%). Table 1 shows the characteristics of the participants from each hospital. Table 2 summarizes the item response rates, proportion scoring at the ceiling, and weighting from the factor analysis. All items had completion rates of 99.2% or higher, with N/A responses ranging from 0% (item 2) to 3.1% (item 7). The percent scoring at the ceiling was 1.7% for the global item and ranged from 18.3% up to 63.3% for other individual items.

We also examined differences in perceptions of care coordination among nursing units to illustrate the tool’s ability to detect variation in Patient Engagement subscale scores for JHH nurses (see Appendix).

DISCUSSION

This study resulted in one of the first measurement tools to succinctly measure multiple aspects of care coordination in the hospital from the perspective of healthcare professionals. Given the hectic work environment of healthcare professionals, and the increasing emphasis on collecting data for evaluation and improvement, it is important to minimize respondent burden. This effort was catalyzed by a multifaceted initiative to redesign acute care delivery and promote seamless transitions of care, supported by the Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation. In initial testing, this questionnaire has evidence for reliability and validity. It was encouraging to find that the preliminary psychometric performance of the measure was very similar in 2 different settings of a tertiary academic hospital and a community hospital.

Our analysis of the survey data explored potential differences between the 2 hospitals, among different types of healthcare professionals and across different departments. Although we expected differences, we had no specific hypotheses about what those differences might be, and, in fact, did not observe any substantial differences. This could be taken to indicate that the intervention was uniformly and successfully implemented in both hospitals, and engaged various professionals in different departments. The ability to detect differences in care coordination at the nursing unit level could also prove to be beneficial for more precisely targeting where process improvement is needed. Further data collection and analyses should be conducted to more systematically compare units and to help identify those where practice is most advanced and those where improvements may be needed. It would also be informative to link differences in care coordination scores with patient outcomes. In addition, differences identified on specific domains between professional groups could be helpful to identify where greater efforts are needed to improve interdisciplinary practice. Sampling strategies stratified by provider type would need to be targeted to make this kind of analysis informative.

The consistently lower scores observed for patient engagement, from the perspective of care professionals in all groups, suggest that this is an area where improvement is needed. These findings are consistent with published reports on the common failure by hospitals to include patients as a member of their own care team. In addition to measuring care processes from the perspective of frontline healthcare workers, future evaluations within the healthcare system would also benefit from including data collected from the perspective of the patient and family.

This study had some limitations. First, there may be more than 4 domains of care coordination that are important and can be measured in the acute care setting from provider perspective. However, the addition of more domains should be balanced against practicality and respondent burden. It may be possible to further clarify priority domains in hospital settings as opposed to the primary care setting. Future research should be directed to find these areas and to develop a more comprehensive, yet still concise measurement instrument. Second, the tool was developed to measure the impact of a large-scale intervention, and to fit into the specific context of 2 hospitals. Therefore, it should be tested in different settings of hospital care to see how it performs. However, virtually all hospitals in the United States today are adapting to changes in both financing and healthcare delivery. A tool such as the one described in this paper could be helpful to many organizations. Third, the scoring system for the overall scale score is not weighted and therefore reflects teamwork more than other components of care coordination, which are represented by fewer items. In general, we believe that use of the subscale scores may be more informative. Alternative scoring systems might also be proposed, including item weighting based on factor scores.

For the purposes of evaluation in this specific instance, we only collected data at a single point in time, after the intervention had been deployed. Thus, we were not able to evaluate the effectiveness of the J-CHiP intervention. We also did not intend to focus too much on the differences between units, given the limited number of respondents from individual units. It would be useful to collect more data at future time points, both to test the responsiveness of the scales and to evaluate the impact of future interventions at both the hospital and unit level.

The preliminary data from this study have generated insights about gaps in current practice, such as in engaging patients in the inpatient care process. It has also increased awareness by hospital leaders about the need to achieve high reliability in the adoption of new procedures and interdisciplinary practice. This tool might be used to find areas in need of improvement, to evaluate the effect of initiatives to improve care coordination, to monitor the change over time in the perception of care coordination among healthcare professionals, and to develop better intervention strategies for coordination activities in acute care settings. Additional research is needed to provide further evidence for the reliability and validity of this measure in diverse settings.

Disclosure

The project described was supported by Grant Number 1C1CMS331053-01-00 from the US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. The contents of this publication are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the US Department of Health and Human Services or any of its agencies. The research presented was conducted by the awardee. Results may or may not be consistent with or confirmed by the findings of the independent evaluation contractor.

The authors have no other disclosures.

Care Coordination has been defined as “…the deliberate organization of patient care activities between two or more participants (including the patient) involved in a patient’s care to facilitate the appropriate delivery of healthcare services.”1 The Institute of Medicine identified care coordination as a key strategy to improve the American healthcare system,2 and evidence has been building that well-coordinated care improves patient outcomes and reduces healthcare costs associated with chronic conditions.3-5 In 2012, Johns Hopkins Medicine was awarded a Healthcare Innovation Award by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services to improve coordination of care across the continuum of care for adult patients admitted to Johns Hopkins Hospital (JHH) and Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center (JHBMC), and for high-risk low-income Medicare and Medicaid beneficiaries receiving ambulatory care in targeted zip codes. The purpose of this project, known as the Johns Hopkins Community Health Partnership (J-CHiP), was to improve health and healthcare and to reduce healthcare costs. The acute care component of the program consisted of a bundle of interventions focused on improving coordination of care for all patients, including a “bridge to home” discharge process, as they transitioned back to the community from inpatient admission. The bundle included the following: early screening for discharge planning to predict needed postdischarge services; discussion in daily multidisciplinary rounds about goals and priorities of the hospitalization and potential postdischarge needs; patient and family self-care management; education enhanced medication management, including the option of “medications in hand” at the time of discharge; postdischarge telephone follow-up by nurses; and, for patients identified as high-risk, a “transition guide” (a nurse who works with the patient via home visits and by phone to optimize compliance with care for 30 days postdischarge).6 While the primary endpoints of the J-CHiP program were to improve clinical outcomes and reduce healthcare costs, we were also interested in the impact of the program on care coordination processes in the acute care setting. This created the need for an instrument to measure healthcare professionals’ views of care coordination in their immediate work environments.

We began our search for existing measures by reviewing the Coordination Measures Atlas published in 2014.7 Although this report evaluates over 80 different measures of care coordination, most of them focus on the perspective of the patient and/or family members, on specific conditions, and on primary care or outpatient settings.7,8 We were unable to identify an existing measure from the provider perspective, designed for the inpatient setting, that was both brief but comprehensive enough to cover a range of care coordination domains.8

Consequently, our first aim was to develop a brief, comprehensive tool to measure care coordination from the perspective of hospital inpatient staff that could be used to compare different units or types of providers, or to conduct longitudinal assessment. The second aim was to conduct a preliminary evaluation of the tool in our healthcare setting, including to assess its psychometric properties, to describe provider perceptions of care coordination after the implementation of J-CHiP, and to explore potential differences among departments, types of professionals, and between the 2 hospitals.

METHODS

Development of the Care Coordination Questionnaire

The survey was developed in collaboration with leaders of the J-CHiP Acute Care Team. We met at the outset and on multiple subsequent occasions to align survey domains with the main components of the J-CHiP acute care intervention and to assure that the survey would be relevant and understandable to a variety of multidisciplinary professionals, including physicians, nurses, social workers, physical therapists, and other health professionals. Care was taken to avoid redundancy with existing evaluation efforts and to minimize respondent burden. This process helped to ensure the content validity of the items, the usefulness of the results, and the future usability of the tool.

We modeled the Care Coordination Questionnaire (CCQ) after the Safety Attitudes Questionnaire (SAQ),9 a widely used survey that is deployed approximately annually at JHH and JHBMC. While the SAQ focuses on healthcare provider attitudes about issues relevant to patient safety (often referred to as safety climate or safety culture), this new tool was designed to focus on healthcare professionals’ attitudes about care coordination. Similar to the way that the SAQ “elicits a snapshot of the safety climate through surveys of frontline worker perceptions,” we sought to elicit a picture of our care coordination climate through a survey of frontline hospital staff.

The CCQ was built upon the domains and approaches to care coordination described in the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Care Coordination Atlas.3 This report identifies 9 mechanisms for achieving care coordination, including the following: Establish Accountability or Negotiate Responsibility; Communicate; Facilitate Transitions; Assess Needs and Goals; Create a Proactive Plan of Care; Monitor, Follow Up, and Respond to Change; Support Self-Management Goals; Link to Community Resources; and Align Resources with Patient and Population Needs; as well as 5 broad approaches commonly used to improve the delivery of healthcare, including Teamwork Focused on Coordination, Healthcare Home, Care Management, Medication Management, and Health IT-Enabled Coordination.7 We generated at least 1 item to represent 8 of the 9 domains, as well as the broad approach described as Teamwork Focused on Coordination. After developing an initial set of items, we sought input from 3 senior leaders of the J-CHiP Acute Care Team to determine if the items covered the care coordination domains of interest, and to provide feedback on content validity. To test the interpretability of survey items and consistency across professional groups, we sent an initial version of the survey questions to at least 1 person from each of the following professional groups: hospitalist, social worker, case manager, clinical pharmacist, and nurse. We asked them to review all of our survey questions and to provide us with feedback on all aspects of the questions, such as whether they believed the questions were relevant and understandable to the members of their professional discipline, the appropriateness of the wording of the questions, and other comments. Modifications were made to the content and wording of the questions based on the feedback received. The final draft of the questionnaire was reviewed by the leadership team of the J-CHiP Acute Care Team to ensure its usefulness in providing actionable information.

The resulting 12-item questionnaire used a 5-point Likert response scale ranging from 1 = “disagree strongly” to 5 = “agree strongly,” and an additional option of “not applicable (N/A).” To help assess construct validity, a global question was added at the end of the questionnaire asking, “Overall, how would you rate the care coordination at the hospital of your primary work setting?” The response was measured on a 10-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 = “totally uncoordinated care” to 10 = “perfectly coordinated care” (see Appendix). In addition, the questionnaire requested information about the respondents’ gender, position, and their primary unit, department, and hospital affiliation.

Data Collection Procedures

An invitation to complete an anonymous questionnaire was sent to the following inpatient care professionals: all nursing staff working on care coordination units in the departments of medicine, surgery, and neurology/neurosurgery, as well as physicians, pharmacists, acute care therapists (eg, occupational and physical therapists), and other frontline staff. All healthcare staff fitting these criteria was sent an e-mail with a request to fill out the survey online using QualtricsTM (Qualtrics Labs Inc., Provo, UT), as well as multiple follow-up reminders. The participants worked either at the JHH (a 1194-bed tertiary academic medical center in Baltimore, MD) or the JHBMC (a 440-bed academic community hospital located nearby). Data were collected from October 2015 through January 2016.

Analysis

Means and standard deviations were calculated by treating the responses as continuous variables. We tried 3 different methods to handle missing data: (1) without imputation, (2) imputing the mean value of each item, and (3) substituting a neutral score. Because all 3 methods produced very similar results, we treated the N/A responses as missing values without imputation for simplicity of analysis. We used STATA 13.1 (Stata Corporation, College Station, Texas) to analyze the data.

To identify subscales, we performed exploratory factor analysis on responses to the 12 specific items. Promax rotation was selected based on the simple structure. Subscale scores for each respondent were generated by computing the mean of responses to the items in the subscale. Internal consistency reliability of the subscales was estimated using Cronbach’s alpha. We calculated Pearson correlation coefficients for the items in each subscale, and examined Cronbach’s alpha deleting each item in turn. For each of the subscales identified and the global scale, we calculated the mean, standard deviation, median and interquartile range. Although distributions of scores tended to be non-normal, this was done to increase interpretability. We also calculated percent scoring at the ceiling (highest possible score).

We analyzed the data with 3 research questions in mind: Was there a difference in perceptions of care coordination between (1) staff affiliated with the 2 different hospitals, (2) staff affiliated with different clinical departments, or (3) staff with different professional roles? For comparisons based on hospital and department, and type of professional, nonparametric tests (Wilcoxon rank-sum and Kruskal-Wallis test) were used with a level of statistical significance set at 0.05. The comparison between hospitals and departments was made only among nurses to minimize the confounding effect of different distribution of professionals. We tested the distribution of “years in specialty” between hospitals and departments for this comparison using Pearson’s χ2 test. The difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.167 for hospitals, and P = 0.518 for departments), so we assumed that the potential confounding effect of this variable was negligible in this analysis. The comparison of scores within each professional group used the Friedman test. Pearson’s χ2 test was used to compare the baseline characteristics between 2 hospitals.

RESULTS

Among the 1486 acute care professionals asked to participate in the survey, 841 completed the questionnaire (response rate 56.6%). Table 1 shows the characteristics of the participants from each hospital. Table 2 summarizes the item response rates, proportion scoring at the ceiling, and weighting from the factor analysis. All items had completion rates of 99.2% or higher, with N/A responses ranging from 0% (item 2) to 3.1% (item 7). The percent scoring at the ceiling was 1.7% for the global item and ranged from 18.3% up to 63.3% for other individual items.

We also examined differences in perceptions of care coordination among nursing units to illustrate the tool’s ability to detect variation in Patient Engagement subscale scores for JHH nurses (see Appendix).

DISCUSSION

This study resulted in one of the first measurement tools to succinctly measure multiple aspects of care coordination in the hospital from the perspective of healthcare professionals. Given the hectic work environment of healthcare professionals, and the increasing emphasis on collecting data for evaluation and improvement, it is important to minimize respondent burden. This effort was catalyzed by a multifaceted initiative to redesign acute care delivery and promote seamless transitions of care, supported by the Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation. In initial testing, this questionnaire has evidence for reliability and validity. It was encouraging to find that the preliminary psychometric performance of the measure was very similar in 2 different settings of a tertiary academic hospital and a community hospital.

Our analysis of the survey data explored potential differences between the 2 hospitals, among different types of healthcare professionals and across different departments. Although we expected differences, we had no specific hypotheses about what those differences might be, and, in fact, did not observe any substantial differences. This could be taken to indicate that the intervention was uniformly and successfully implemented in both hospitals, and engaged various professionals in different departments. The ability to detect differences in care coordination at the nursing unit level could also prove to be beneficial for more precisely targeting where process improvement is needed. Further data collection and analyses should be conducted to more systematically compare units and to help identify those where practice is most advanced and those where improvements may be needed. It would also be informative to link differences in care coordination scores with patient outcomes. In addition, differences identified on specific domains between professional groups could be helpful to identify where greater efforts are needed to improve interdisciplinary practice. Sampling strategies stratified by provider type would need to be targeted to make this kind of analysis informative.

The consistently lower scores observed for patient engagement, from the perspective of care professionals in all groups, suggest that this is an area where improvement is needed. These findings are consistent with published reports on the common failure by hospitals to include patients as a member of their own care team. In addition to measuring care processes from the perspective of frontline healthcare workers, future evaluations within the healthcare system would also benefit from including data collected from the perspective of the patient and family.

This study had some limitations. First, there may be more than 4 domains of care coordination that are important and can be measured in the acute care setting from provider perspective. However, the addition of more domains should be balanced against practicality and respondent burden. It may be possible to further clarify priority domains in hospital settings as opposed to the primary care setting. Future research should be directed to find these areas and to develop a more comprehensive, yet still concise measurement instrument. Second, the tool was developed to measure the impact of a large-scale intervention, and to fit into the specific context of 2 hospitals. Therefore, it should be tested in different settings of hospital care to see how it performs. However, virtually all hospitals in the United States today are adapting to changes in both financing and healthcare delivery. A tool such as the one described in this paper could be helpful to many organizations. Third, the scoring system for the overall scale score is not weighted and therefore reflects teamwork more than other components of care coordination, which are represented by fewer items. In general, we believe that use of the subscale scores may be more informative. Alternative scoring systems might also be proposed, including item weighting based on factor scores.

For the purposes of evaluation in this specific instance, we only collected data at a single point in time, after the intervention had been deployed. Thus, we were not able to evaluate the effectiveness of the J-CHiP intervention. We also did not intend to focus too much on the differences between units, given the limited number of respondents from individual units. It would be useful to collect more data at future time points, both to test the responsiveness of the scales and to evaluate the impact of future interventions at both the hospital and unit level.

The preliminary data from this study have generated insights about gaps in current practice, such as in engaging patients in the inpatient care process. It has also increased awareness by hospital leaders about the need to achieve high reliability in the adoption of new procedures and interdisciplinary practice. This tool might be used to find areas in need of improvement, to evaluate the effect of initiatives to improve care coordination, to monitor the change over time in the perception of care coordination among healthcare professionals, and to develop better intervention strategies for coordination activities in acute care settings. Additional research is needed to provide further evidence for the reliability and validity of this measure in diverse settings.

Disclosure

The project described was supported by Grant Number 1C1CMS331053-01-00 from the US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. The contents of this publication are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the US Department of Health and Human Services or any of its agencies. The research presented was conducted by the awardee. Results may or may not be consistent with or confirmed by the findings of the independent evaluation contractor.

The authors have no other disclosures.

1. McDonald KM, Sundaram V, Bravata DM, et al. Closing the Quality Gap: A Critical Analysis of Quality Improvement Strategies (Vol. 7: Care Coordination). Technical Reviews, No. 9.7. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2007. PubMed

2. Adams K, Corrigan J. Priority areas for national action: transforming health care quality. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2003. PubMed

3. Renders CM, Valk GD, Griffin S, Wagner EH, Eijk JT, Assendelft WJ. Interventions to improve the management of diabetes mellitus in primary care, outpatient and community settings. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2001(1):CD001481. PubMed

4. McAlister FA, Lawson FM, Teo KK, Armstrong PW. A systematic review of randomized trials of disease management programs in heart failure. Am J Med. 2001;110(5):378-384. PubMed

5. Bruce ML, Raue PJ, Reilly CF, et al. Clinical effectiveness of integrating depression care management into medicare home health: the Depression CAREPATH Randomized trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(1):55-64. PubMed

6. Berkowitz SA, Brown P, Brotman DJ, et al. Case Study: Johns Hopkins Community Health Partnership: A model for transformation. Healthc (Amst). 2016;4(4):264-270. PubMed

7. McDonald. KM, Schultz. E, Albin. L, et al. Care Coordination Measures Atlas Version 4. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2014.

8 Schultz EM, Pineda N, Lonhart J, Davies SM, McDonald KM. A systematic review of the care coordination measurement landscape. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13:119. PubMed

9. Sexton JB, Helmreich RL, Neilands TB, et al. The Safety Attitudes Questionnaire: psychometric properties, benchmarking data, and emerging research. BMC Health Serv Res. 2006;6:44. PubMed

1. McDonald KM, Sundaram V, Bravata DM, et al. Closing the Quality Gap: A Critical Analysis of Quality Improvement Strategies (Vol. 7: Care Coordination). Technical Reviews, No. 9.7. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2007. PubMed

2. Adams K, Corrigan J. Priority areas for national action: transforming health care quality. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2003. PubMed

3. Renders CM, Valk GD, Griffin S, Wagner EH, Eijk JT, Assendelft WJ. Interventions to improve the management of diabetes mellitus in primary care, outpatient and community settings. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2001(1):CD001481. PubMed

4. McAlister FA, Lawson FM, Teo KK, Armstrong PW. A systematic review of randomized trials of disease management programs in heart failure. Am J Med. 2001;110(5):378-384. PubMed

5. Bruce ML, Raue PJ, Reilly CF, et al. Clinical effectiveness of integrating depression care management into medicare home health: the Depression CAREPATH Randomized trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(1):55-64. PubMed

6. Berkowitz SA, Brown P, Brotman DJ, et al. Case Study: Johns Hopkins Community Health Partnership: A model for transformation. Healthc (Amst). 2016;4(4):264-270. PubMed

7. McDonald. KM, Schultz. E, Albin. L, et al. Care Coordination Measures Atlas Version 4. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2014.

8 Schultz EM, Pineda N, Lonhart J, Davies SM, McDonald KM. A systematic review of the care coordination measurement landscape. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13:119. PubMed

9. Sexton JB, Helmreich RL, Neilands TB, et al. The Safety Attitudes Questionnaire: psychometric properties, benchmarking data, and emerging research. BMC Health Serv Res. 2006;6:44. PubMed

© 2017 Society of Hospital Medicine

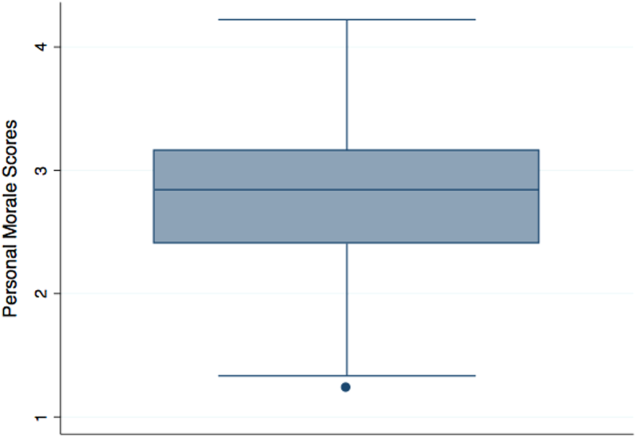

Introducing the Hospitalist Morale Index

Explosive growth in hospital medicine has led to hospitalists having the option to change jobs easily. Annual turnover for all physicians is 6.8%, whereas that of hospitalists exceeds 14.8%.[1] Losing a single physician has significant financial and operational implications, with estimates of $20,000 to $120,000 in recruiting costs, and up to $500,000 in lost revenue that may take years to recoup due to the time required for new physician assimilation.[2, 3] In 2006, the Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) appointed a career task force to develop retention recommendations, 1 of which includes monitoring hospitalists' job satisfaction.[4]

Studies examining physician satisfaction have demonstrated that high physician job satisfaction is associated with lower physician turnover.[5] However, surveys of hospitalists, including SHM's Hospital Medicine Physician Worklife Survey (HMPWS), have reported high job satisfaction among hospitalists,[6, 7, 8, 9, 10] suggesting that high job satisfaction may not be enough to overcome forces that pull hospitalists toward other opportunities.

Morale, a more complex construct related to an individual's contentment and happiness, might provide insight into reducing hospitalist turnover. Morale has been defined as the emotional or mental condition with respect to cheerfulness, confidence, or zeal and is especially relevant in the face of opposition or hardship.[11] Job satisfaction is 1 element that contributes to morale, but alone does not equate morale.[12] Morale, more than satisfaction, relates to how people see themselves within the group and may be closely tied to the concept of esprit de corps. To illustrate, workers may feel satisfied with the content of their job, but frustration with the organization may result in low morale.[13] Efforts focused on assessing provider morale may provide deeper understanding of hospitalists' professional needs and garner insight for retention strategies.