User login

Operational Risk Management in Dermatologic Procedures

Operational Risk Management in Dermatologic Procedures

Operational risk management (ORM) refers to the systematic identification and assessment of daily operational risks within an organization designed to mitigate negative financial, reputational, and safety outcomes while maximizing efficiency and achievement of objectives.1 Operational risk management is indispensable to modern military operations, optimizing mission readiness while minimizing complications and personnel morbidity. Application of ORM in medicine holds considerable promise due to the emphasis on precise and efficient decision-making in high-stakes environments, where the margin for error is minimal. In this article, we propose integrating ORM principles into dermatologic surgery to enhance patient-centered care through improved counseling, risk assessment, and procedural outcomes.

Principles and Processes of ORM

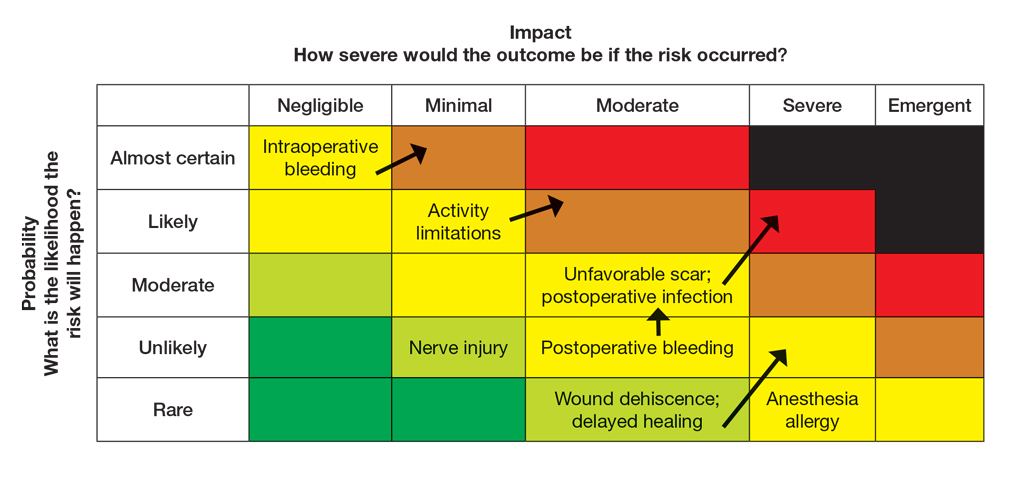

The ORM framework is built on 4 fundamental principles: accept risk when benefits outweigh the cost, accept no unnecessary risk, anticipate and manage risk by planning, and make risk decisions at the right level.2 These principles form the foundation of the ORM’s systematic 5-step approach to identify hazards, assess hazards, make risk decisions, implement controls, and supervise. Key to the ORM process is the use of risk assessment codes and the risk assessment matrix to quantify and prioritize risks. Risk assessment codes are numerical values assigned to hazards based on their assessed severity and probability. The risk assessment matrix is a tool that plots the severity of a hazard against its probability. By locating a hazard on the matrix, users can visualize its risk level in terms of severity and probability. Building and using the risk assessment matrix begins with determining severity by assessing the potential impact of a hazard and categorizing it into levels (catastrophic, critical, moderate, or negligible). Next, probability is determined by evaluating the likelihood of occurrence (frequent, likely, occasional, seldom, or unlikely). Finally, the severity and probability are combined to assign a risk assessment code, which indicates the risk level and helps visualize criticality. Systematically applying these principles and processes enables users to make informed decisions that balance mission objectives with safety.

Proposed Framework for ORM in Dermatology Surgery

Current risk mitigation in dermatologic surgery includes strict medication oversight, sterilization protocols, and photography to prevent wrong-site surgeries. Preoperative risk assessment through conducting a thorough patient history is vital, considering factors such as pregnancy, allergies, bleeding history, cardiac devices, and keloid propensity, all of which impact surgical outcomes.3-5 After gathering the patient’s history, dermatologists determine appropriateness for surgery and its inherent risks, typically via an informed consent process outlining the diagnosis and procedure purpose as well as a list of risks, benefits, and alternatives, including forgoing treatment.

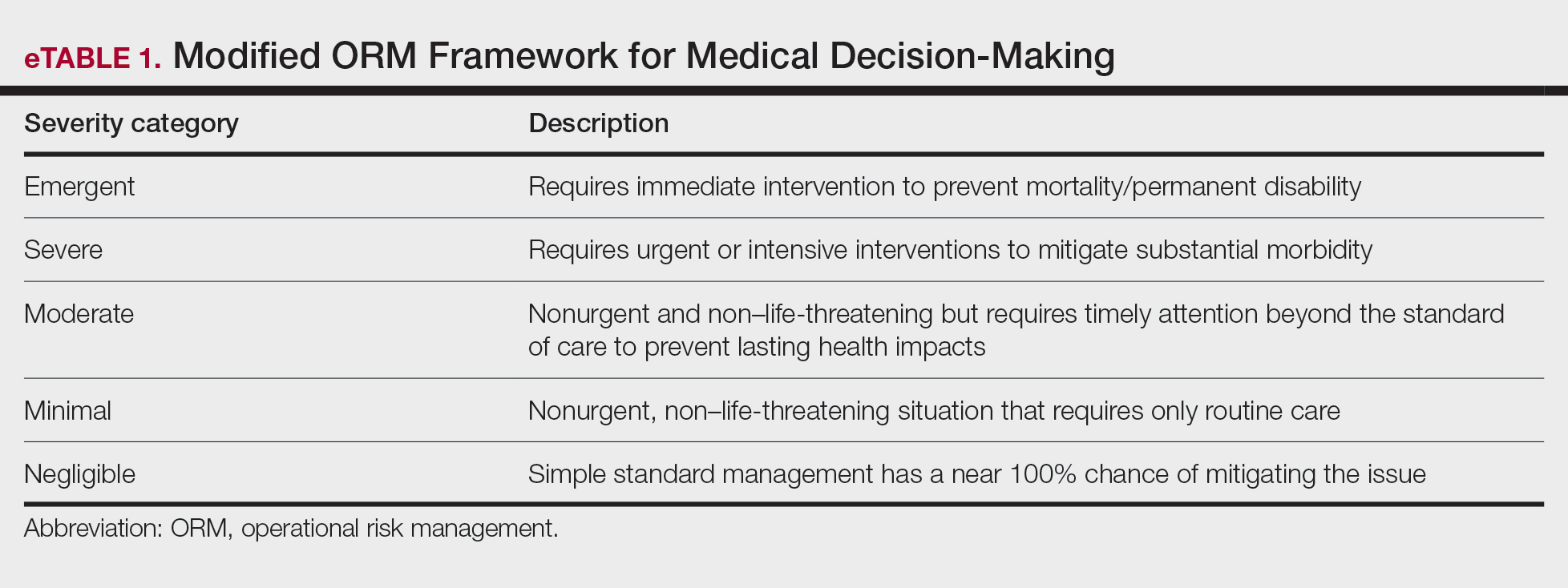

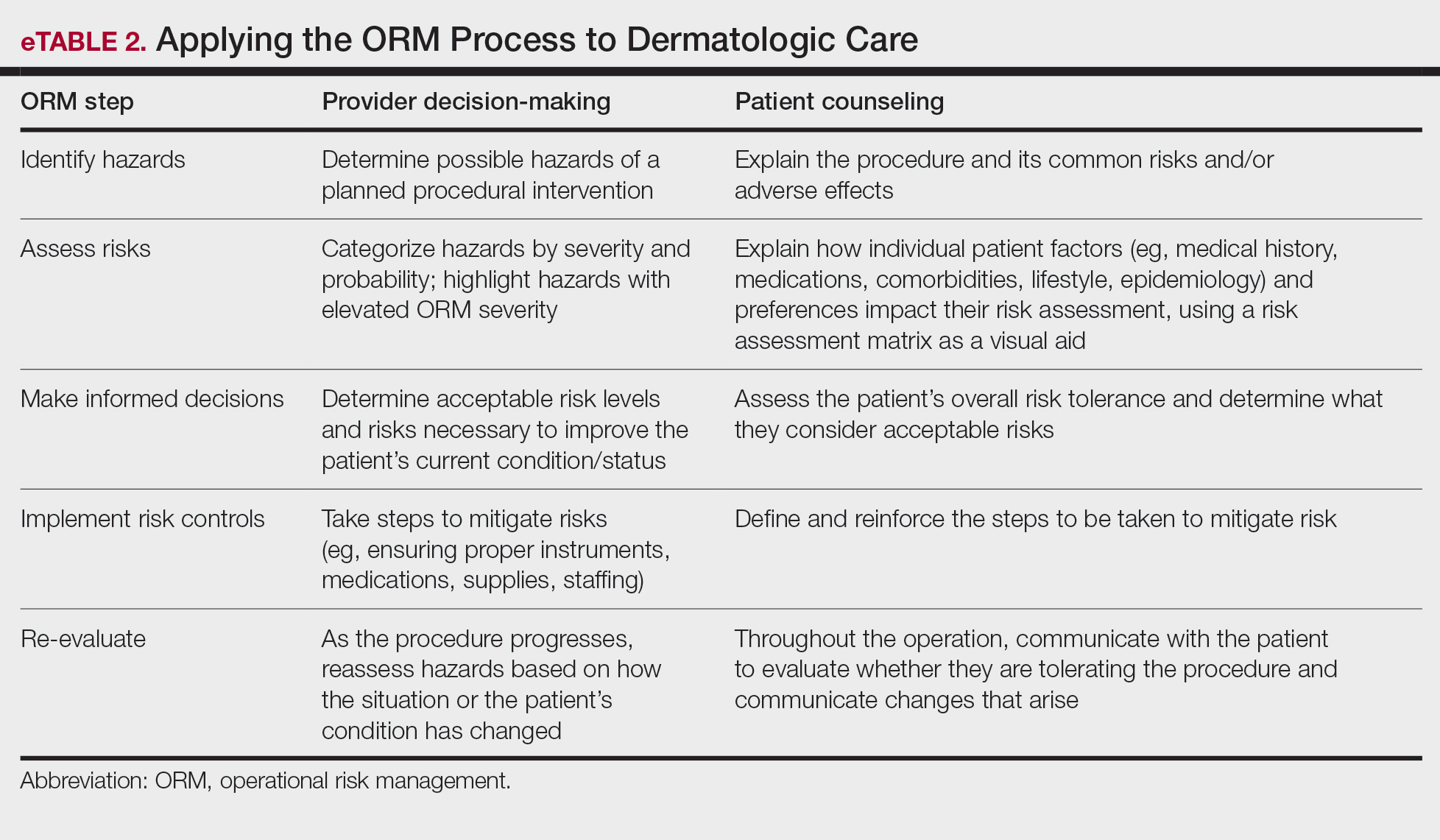

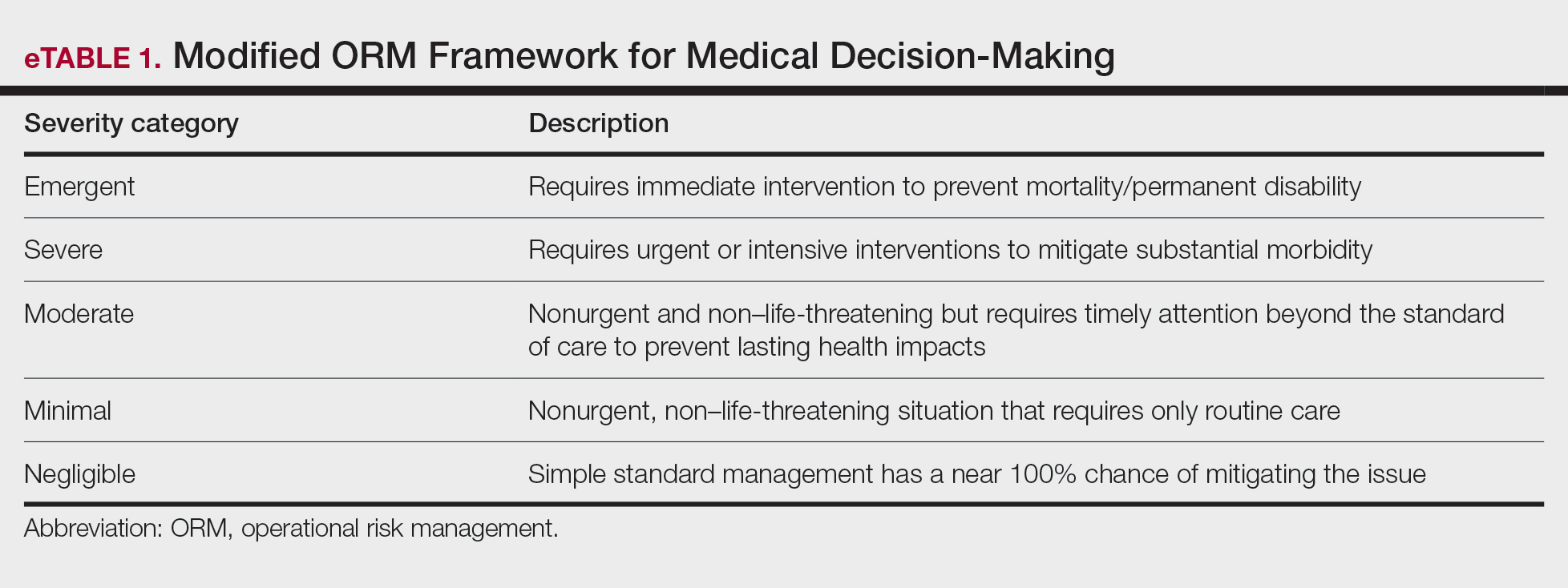

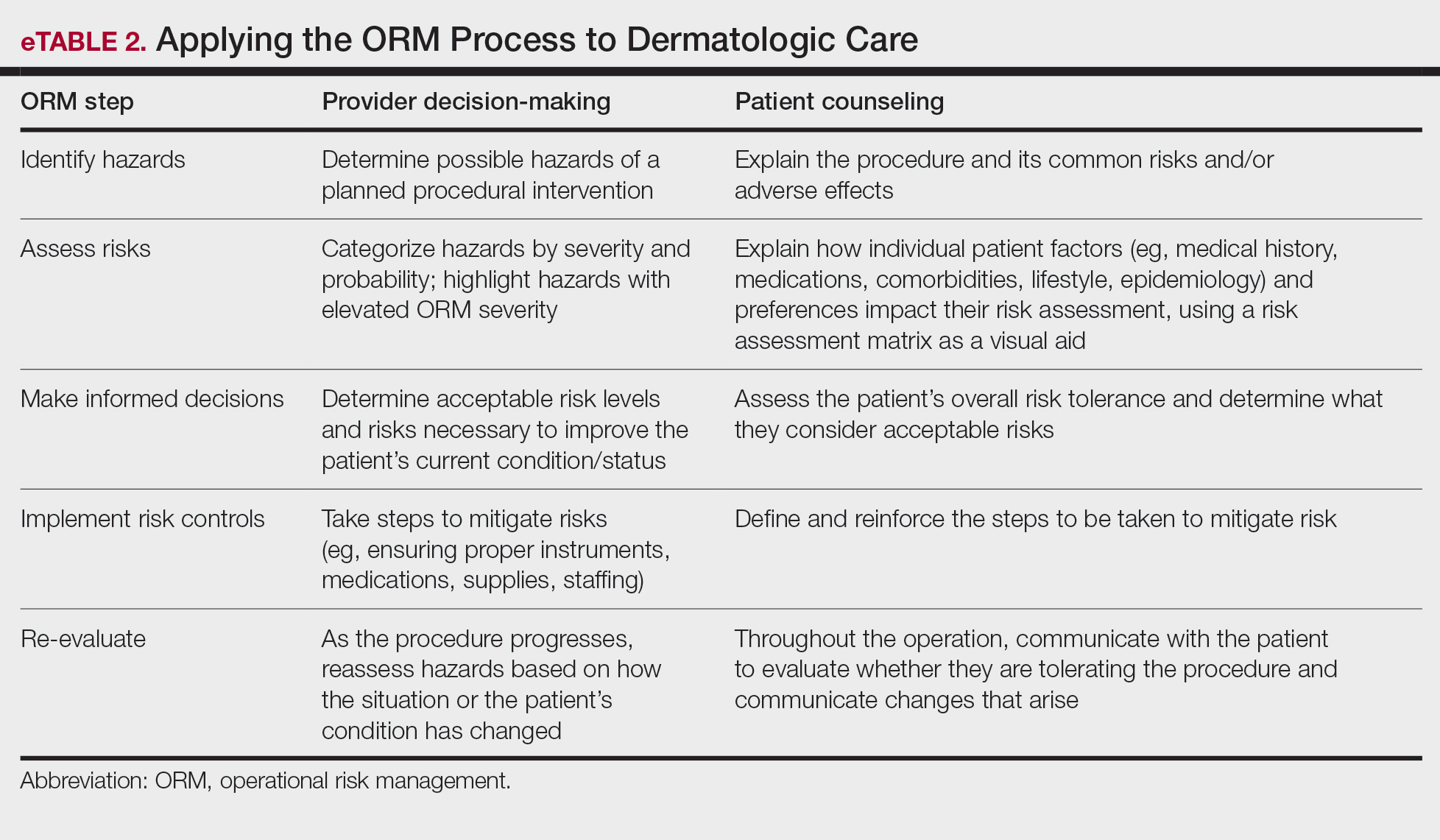

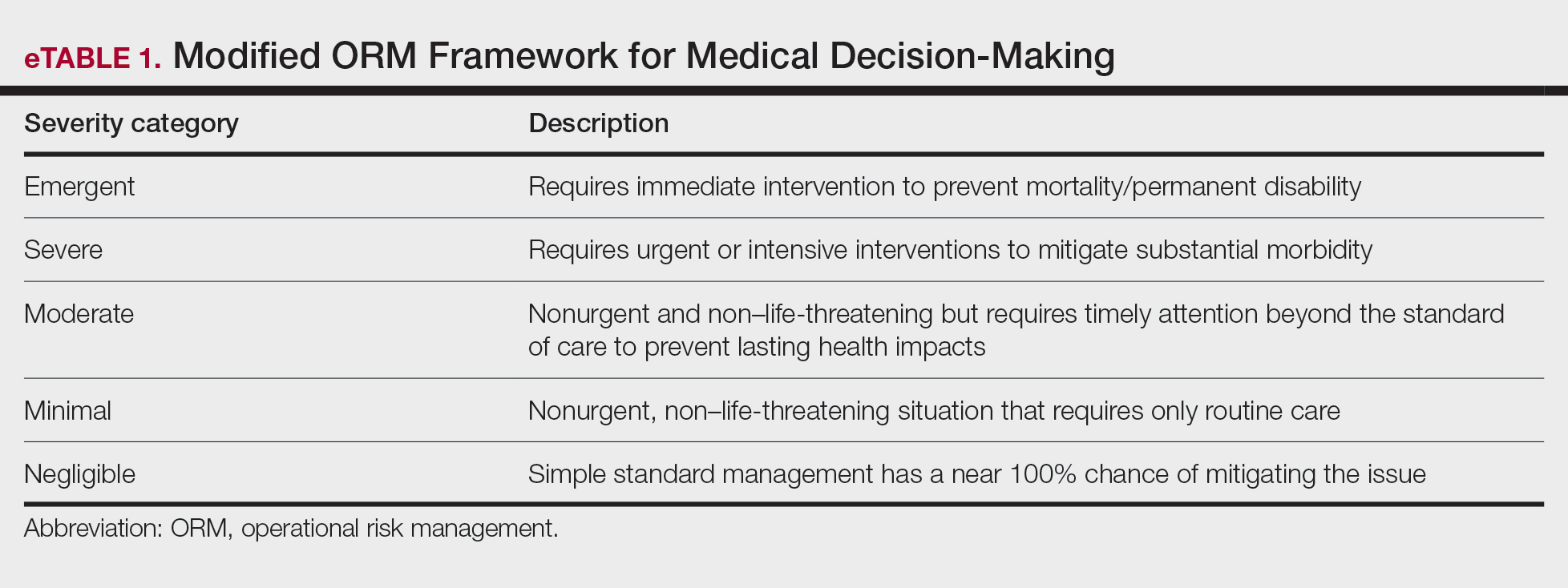

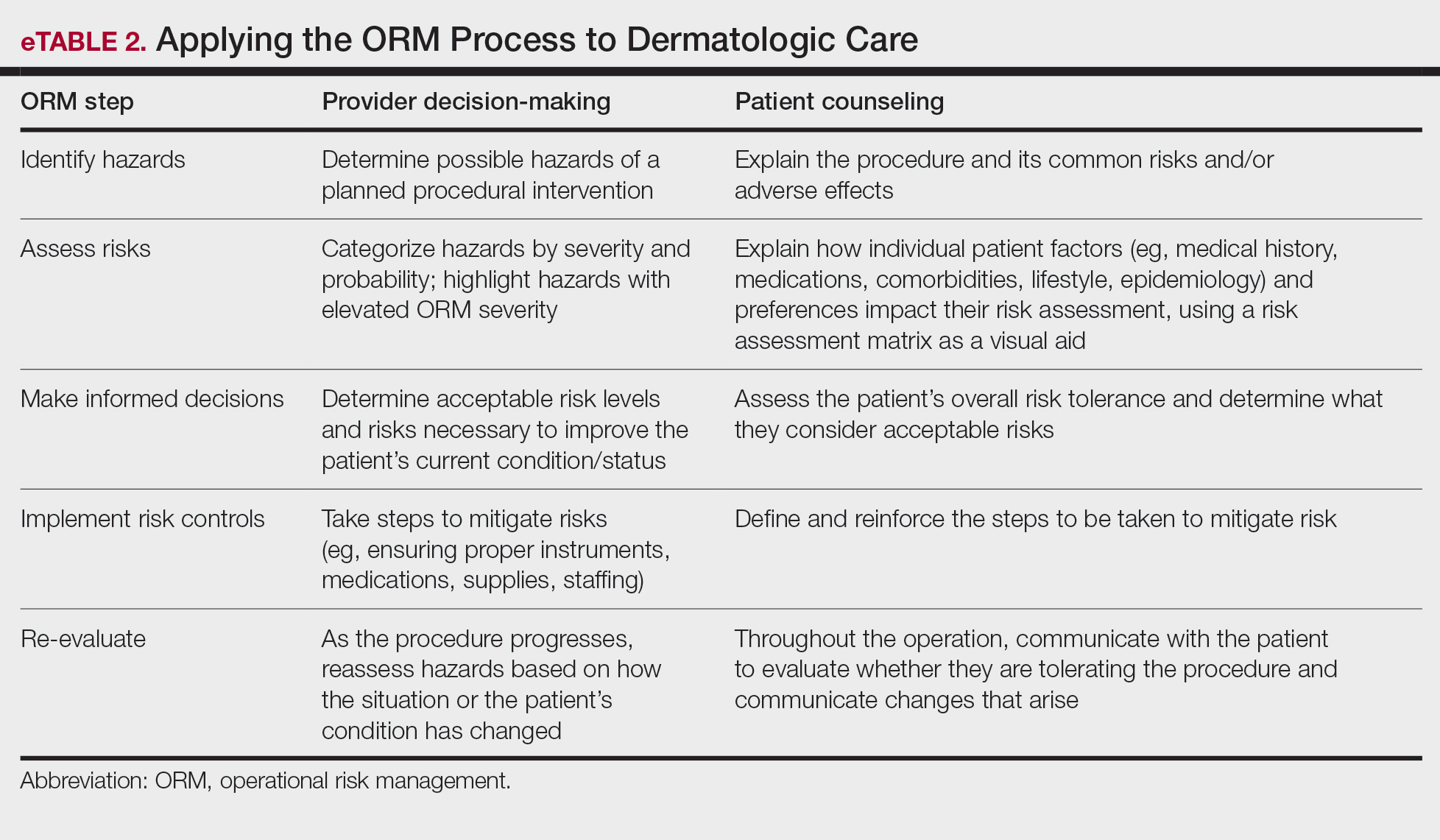

Importantly, the standard process for dermatologic risk evaluation often lacks a comprehensive systematic approach seen in other higher-risk surgical fields. For example, general surgeons frequently utilize risk assessment calculators such as the one developed by the American College of Surgeons’ National Surgical Quality Improvement Program to estimate surgical complications.6 While specific guidelines exist for evaluating factors such as hypertension or anticoagulant use, no single tool synthesizes all patient risk factors for a unified assessment. Therefore, we propose integrating ORM as a structured decision-making process that offers a more consistent means for dermatologists to evaluate, synthesize, categorize, and present risks to patients. Our proposed process includes translating military mishap severity into a framework that helps patients better understand decisions about their health care when using ORM (eTable 1). The proposed process also provides dermatologists with a systematic, proactive, and iterative approach to assessing risks that allows them to consistently qualify medical decisions (eTable 2).

Patients often struggle to understand surgical risk severity, including overestimating the risks of routine minor procedures or underestimating the risks of more intensive procedures.7,8 Incorporating ORM into patient communication mirrors the provider’s process but uses patient-friendly terminology—it is discussion based and integrates patient preferences and tolerances (eTable 2). These steps often occur informally in dermatologic counseling; however, an organized structured approach, especially using a visual aid such as a risk assessment matrix, enhances patient comprehension, recall, and satisfaction.9

Practical Scenarios

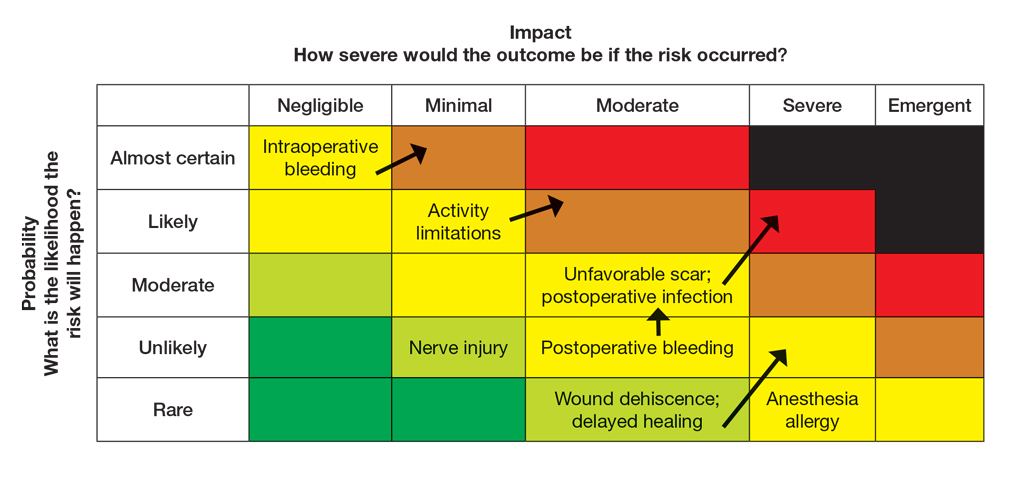

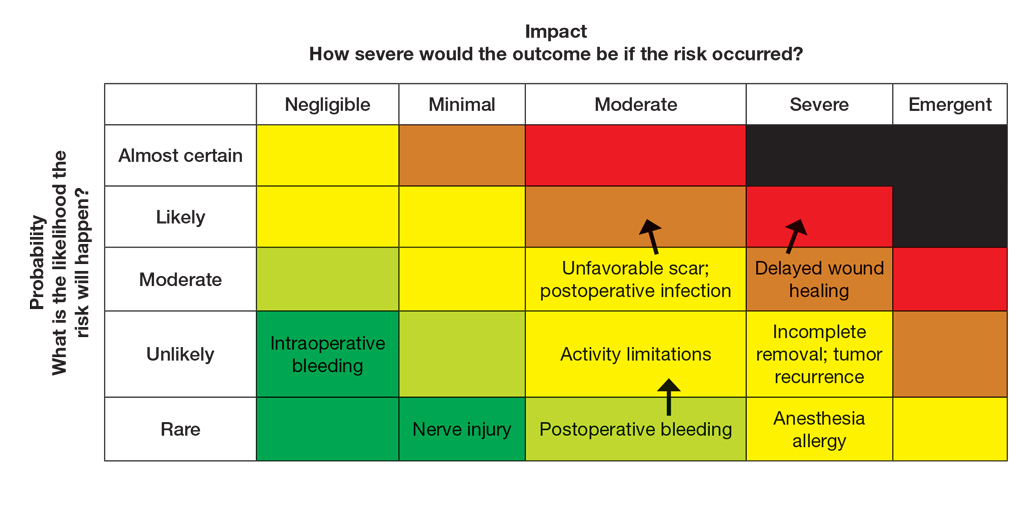

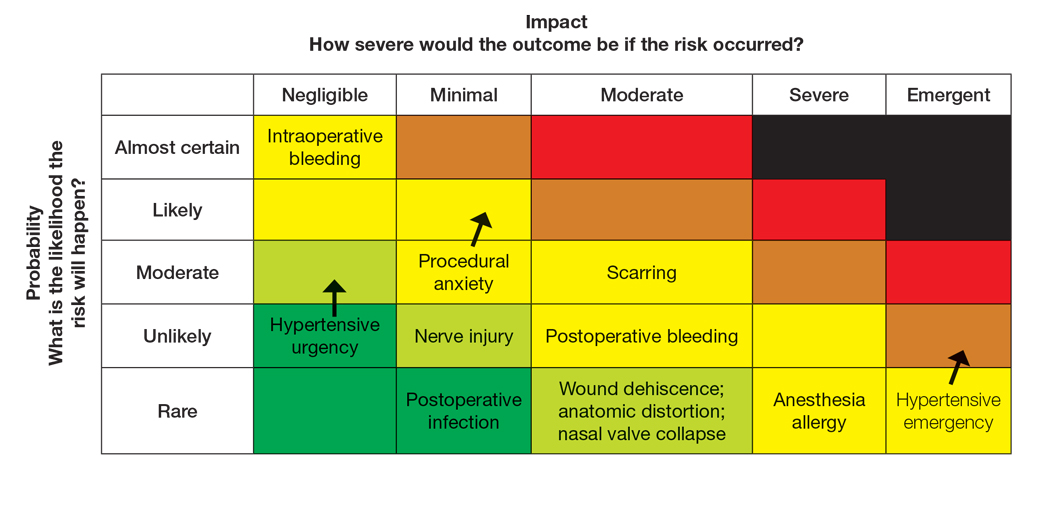

Integrating ORM into dermatologic surgery is a proactive iterative process for both provider decision-making and patient communication. Leveraging a risk assessment matrix as a visual aid allows for clear identification, evaluation, and mitigation of hazards, fostering collaborative choices with regard to the treatment approach. Here we provide 2 case scenarios highlighting how ORM and the risk assessment matrix can be used in the management of a complex patient with a lesion in a high-risk location as well as to address patient anxiety and comorbidities. It is important to note that the way the matrices are completed in the examples provided may differ compared to other providers. The purpose of ORM is not to dictate risk categories but to serve as a tool for providers to take their own experiences and knowledge of the patient to guide their decision-making and counseling processes.

Case Scenario 1—An elderly man with a history of diabetes, cardiovascular accident, coronary artery bypass grafting, and multiple squamous cell carcinoma excisions presents for evaluation of a 1-cm squamous cell carcinoma in situ on the left leg. His current medications include an anticoagulant and antihypertensives.

In this scenario, the provider would apply ORM by identifying and assessing hazards, making risk decisions, implementing controls, and supervising care.

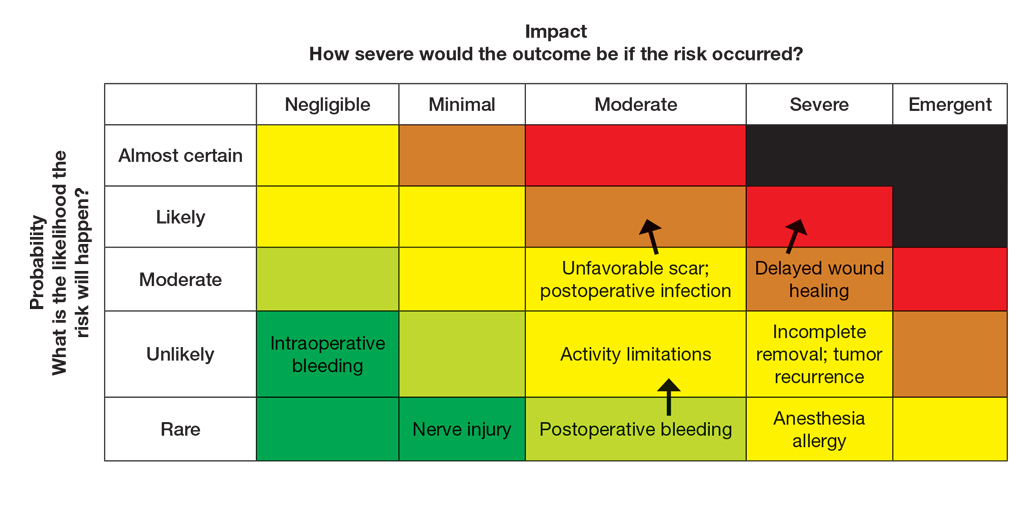

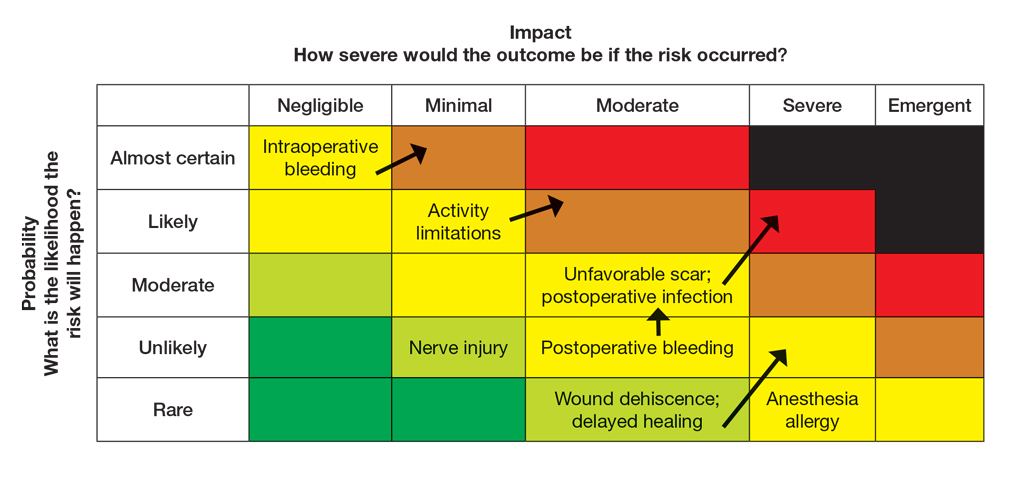

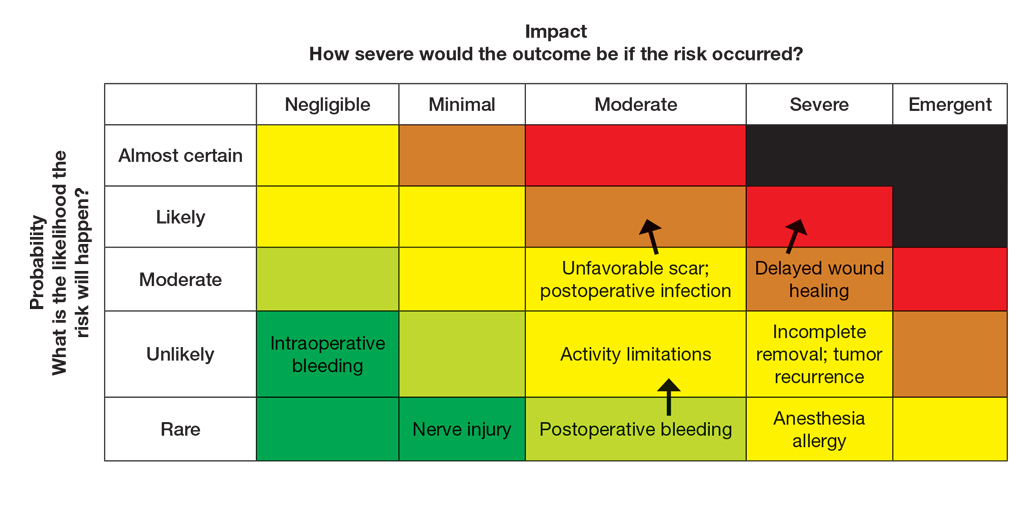

General hazards for excision on the leg include bleeding, infection, scarring, pain, delayed healing, activity limitations, and possible further procedures. Before the visit, the provider should prepare baseline risk matrices for 2 potential treatment options: wide local excision and electrodessication and curettage. For example, surgical bleeding may be assessed as negligible severity and almost certain probability for a general excision.

Next, the provider would incorporate the patient’s unique history in the risk matrices (eFigures 1 and 2). The patient’s use of an anticoagulant indicates a bleeding risk; therefore, the provider may shift the severity to minimal clinical concern, understanding the need for enhanced perioperative management. The history of diabetes also has a considerable impact on wound healing, so the provider might elevate the probability of delayed wound healing from rare to unlikely and the severity from moderate to severe. The prior cardiovascular accident also raises concerns about mobility and activity limitations during recovery, which could be escalated from minimal to moderate clinical concern if postoperative limitations on ambulation increase the risk for new clots. Based on this internal assessment, the provider identifies which risks are elevated and require further attention and discussion with the patient, helping tailor the counseling approach and potential treatment plan. The provider should begin to consider initial control measures such as coordinating anticoagulant management, ensuring diabetes is well controlled, and planning for postoperative ambulation support.

Once the provider has conducted the internal assessment, the ORM matrices become powerful tools for shared decision-making with the patient. The provider can walk the patient through the procedures and their common risks and then explain how their individual situation modifies the risks. The visual and explicit upgrade on the matrices allows the patient to clearly see how unique factors influence their personal risk profile, moving beyond a generic list of complications. The provider then should engage the patient in a discussion about their risk tolerance, which is crucial for mutual agreement on whether to proceed with treatment and, if so, which procedure is most appropriate given the patient’s comfort level with their individualized risk profile. Then the provider should reinforce the proactive steps planned to mitigate the identified risks to provide assurance and reinforce the collaborative approach to safety.

Finally, throughout the preoperative and postoperative phases, the provider should continuously monitor the patient’s condition and the effectiveness of the control measures, adjusting the plan as needed.

In this scenario, both the provider and the patient participated in the risk assessment, with the provider completing the assessment before the visit and presenting it to the patient or performing the assessment in real time with the patient present to explain the reasoning behind assignment of risk based on each procedure and the patient’s unique risk factors.

Case Scenario 2—A 38-year-old woman with a history of hypertension and procedural anxiety presents for evaluation of a biopsy-proven basal cell carcinoma on the nasal ala. The patient is taking diltiazem for hypertension and is compliant with her medication. Her blood pressure at the current visit is 148/96 mm Hg, which she attributes to white coat syndrome. Mohs micrographic surgery generally is the gold standard treatment for this case.

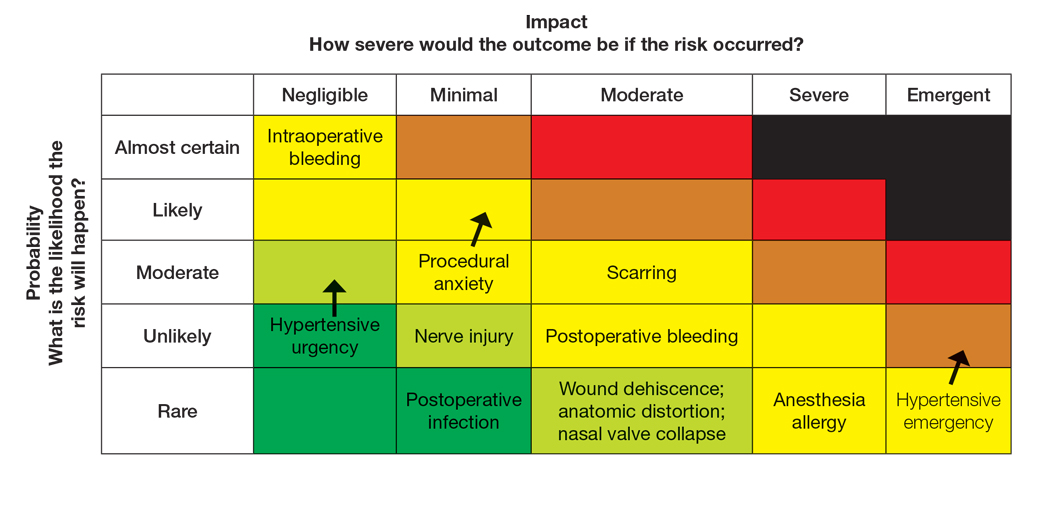

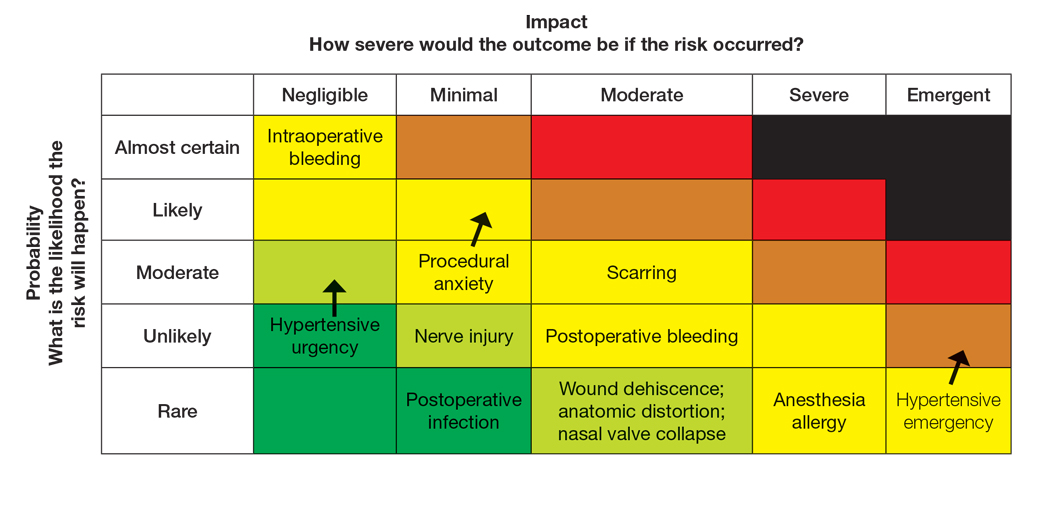

The provider’s ORM process, conducted either before or in real time during the visit, would begin with identification and assessment of the hazards. For Mohs surgery on the nasal ala, common hazards would include scarring, pain, infection, bleeding, and potential cosmetic distortion. Unique to this patient are the procedural anxiety and hypertension.

To populate the risk assessment matrix (eFigure 3), the provider would first map the baseline risks of Mohs surgery, which include considerable scarring as a moderate clinical concern but a seldom probability. Because the patient’s procedural anxiety directly increases the probability of intraoperative distress or elevated blood pressure during the procedure, the provider might assess patient distress/anxiety as a moderate clinical concern with a likely probability. While the patient’s blood pressure is controlled, the white coat syndrome raises the probability of hypertensive urgency/emergency during surgery; this might be elevated from unlikely to occasional or likely probability, and severity might increase from minimal to moderate due to its potential impact on procedural safety. The provider should consider strategies to address these elevated risks during the consultation. Then, as part of preprocedure planning, the provider should consider discussing anxiolytics, emphasizing medication compliance, and ensuring a calm environment for the patient’s surgery.

For this patient, the risk assessment matrix becomes a powerful tool to address fears and proactively manage her unique risk factors. To start the counseling process, the provider should explain the procedure, its benefits, and potential adverse effects. Then, the patient’s individualized risks can be visualized using the matrix, which also is an opportunity for reassurance, as it can alleviate patient fears by contextualizing rare but impactful outcomes.9

Now the provider can assess the patient’s risk tolerance. This discussion ensures that the patient’s comfort level and preferences are central to the treatment decision, even for a gold-standard procedure such as Mohs surgery. By listening and responding to the patient’s input, the provider can build trust and discuss strategies that can help control for some risk factors.

Finally, the provider would re-evaluate throughout the procedure by continuously monitoring the patient’s anxiety and vital signs. The provider should also be ready to adjust pain management or employ anxiety-reduction techniques.

Final Thoughts

Reviewing the risk assessment matrix can be an effective way to nonjudgmentally discuss a patient’s unique risk factors and provide a complete understanding of the planned treatment or procedure. It conveys to the patient that, as the provider, you are taking their health seriously when considering treatment options and can be a means to build patient rapport and trust. This approach mirrors risk communication strategies long employed in military operational planning, where transparency and structured risk evaluation are essential to maintaining mission readiness and unit cohesion.

- The OR Society. The history of OR. The OR Society. Published 2023.

- Naval Postgraduate School. ORM: operational risk management. Accessed September 12, 2025. https://nps.edu/web/safety/orm

- Smith C, Srivastava D, Nijhawan RI. Optimizing patient safety in dermatologic surgery. Dermatol Clin. 2019;37:319-328.

- Minkis K, Whittington A, Alam M. Dermatologic surgery emergencies: complications caused by systemic reactions, high-energy systems, and trauma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:265-284.

- Pomerantz RG, Lee DA, Siegel DM. Risk assessment in surgical patients: balancing iatrogenic risks and benefits. Clin Dermatol. 2011;29:669-677.

- Bilimoria KY, Liu Y, Paruch JL, et al. Development and evaluation of the universal ACS NSQIP surgical risk calculator: a decision aid and informed consent tool for patients and surgeons. J Am Coll Surgeons. 2013;217:833-842.

- Lloyd AJ. The extent of patients’ understanding of the risk of treatments. BMJ Qual Saf. 2001;10:i14-i18.

- Falagas ME, Korbila IP, Giannopoulou KP, et al. Informed consent: how much and what do patients understand? Am J Surg. 2009;198:420-435.

- Cohen SM, Baimas-George M, Ponce C, et al. Is a picture worth a thousand words? a scoping review of the impact of visual aids on patients undergoing surgery. J Surg Educ. 2024;81:1276-1292.

Operational risk management (ORM) refers to the systematic identification and assessment of daily operational risks within an organization designed to mitigate negative financial, reputational, and safety outcomes while maximizing efficiency and achievement of objectives.1 Operational risk management is indispensable to modern military operations, optimizing mission readiness while minimizing complications and personnel morbidity. Application of ORM in medicine holds considerable promise due to the emphasis on precise and efficient decision-making in high-stakes environments, where the margin for error is minimal. In this article, we propose integrating ORM principles into dermatologic surgery to enhance patient-centered care through improved counseling, risk assessment, and procedural outcomes.

Principles and Processes of ORM

The ORM framework is built on 4 fundamental principles: accept risk when benefits outweigh the cost, accept no unnecessary risk, anticipate and manage risk by planning, and make risk decisions at the right level.2 These principles form the foundation of the ORM’s systematic 5-step approach to identify hazards, assess hazards, make risk decisions, implement controls, and supervise. Key to the ORM process is the use of risk assessment codes and the risk assessment matrix to quantify and prioritize risks. Risk assessment codes are numerical values assigned to hazards based on their assessed severity and probability. The risk assessment matrix is a tool that plots the severity of a hazard against its probability. By locating a hazard on the matrix, users can visualize its risk level in terms of severity and probability. Building and using the risk assessment matrix begins with determining severity by assessing the potential impact of a hazard and categorizing it into levels (catastrophic, critical, moderate, or negligible). Next, probability is determined by evaluating the likelihood of occurrence (frequent, likely, occasional, seldom, or unlikely). Finally, the severity and probability are combined to assign a risk assessment code, which indicates the risk level and helps visualize criticality. Systematically applying these principles and processes enables users to make informed decisions that balance mission objectives with safety.

Proposed Framework for ORM in Dermatology Surgery

Current risk mitigation in dermatologic surgery includes strict medication oversight, sterilization protocols, and photography to prevent wrong-site surgeries. Preoperative risk assessment through conducting a thorough patient history is vital, considering factors such as pregnancy, allergies, bleeding history, cardiac devices, and keloid propensity, all of which impact surgical outcomes.3-5 After gathering the patient’s history, dermatologists determine appropriateness for surgery and its inherent risks, typically via an informed consent process outlining the diagnosis and procedure purpose as well as a list of risks, benefits, and alternatives, including forgoing treatment.

Importantly, the standard process for dermatologic risk evaluation often lacks a comprehensive systematic approach seen in other higher-risk surgical fields. For example, general surgeons frequently utilize risk assessment calculators such as the one developed by the American College of Surgeons’ National Surgical Quality Improvement Program to estimate surgical complications.6 While specific guidelines exist for evaluating factors such as hypertension or anticoagulant use, no single tool synthesizes all patient risk factors for a unified assessment. Therefore, we propose integrating ORM as a structured decision-making process that offers a more consistent means for dermatologists to evaluate, synthesize, categorize, and present risks to patients. Our proposed process includes translating military mishap severity into a framework that helps patients better understand decisions about their health care when using ORM (eTable 1). The proposed process also provides dermatologists with a systematic, proactive, and iterative approach to assessing risks that allows them to consistently qualify medical decisions (eTable 2).

Patients often struggle to understand surgical risk severity, including overestimating the risks of routine minor procedures or underestimating the risks of more intensive procedures.7,8 Incorporating ORM into patient communication mirrors the provider’s process but uses patient-friendly terminology—it is discussion based and integrates patient preferences and tolerances (eTable 2). These steps often occur informally in dermatologic counseling; however, an organized structured approach, especially using a visual aid such as a risk assessment matrix, enhances patient comprehension, recall, and satisfaction.9

Practical Scenarios

Integrating ORM into dermatologic surgery is a proactive iterative process for both provider decision-making and patient communication. Leveraging a risk assessment matrix as a visual aid allows for clear identification, evaluation, and mitigation of hazards, fostering collaborative choices with regard to the treatment approach. Here we provide 2 case scenarios highlighting how ORM and the risk assessment matrix can be used in the management of a complex patient with a lesion in a high-risk location as well as to address patient anxiety and comorbidities. It is important to note that the way the matrices are completed in the examples provided may differ compared to other providers. The purpose of ORM is not to dictate risk categories but to serve as a tool for providers to take their own experiences and knowledge of the patient to guide their decision-making and counseling processes.

Case Scenario 1—An elderly man with a history of diabetes, cardiovascular accident, coronary artery bypass grafting, and multiple squamous cell carcinoma excisions presents for evaluation of a 1-cm squamous cell carcinoma in situ on the left leg. His current medications include an anticoagulant and antihypertensives.

In this scenario, the provider would apply ORM by identifying and assessing hazards, making risk decisions, implementing controls, and supervising care.

General hazards for excision on the leg include bleeding, infection, scarring, pain, delayed healing, activity limitations, and possible further procedures. Before the visit, the provider should prepare baseline risk matrices for 2 potential treatment options: wide local excision and electrodessication and curettage. For example, surgical bleeding may be assessed as negligible severity and almost certain probability for a general excision.

Next, the provider would incorporate the patient’s unique history in the risk matrices (eFigures 1 and 2). The patient’s use of an anticoagulant indicates a bleeding risk; therefore, the provider may shift the severity to minimal clinical concern, understanding the need for enhanced perioperative management. The history of diabetes also has a considerable impact on wound healing, so the provider might elevate the probability of delayed wound healing from rare to unlikely and the severity from moderate to severe. The prior cardiovascular accident also raises concerns about mobility and activity limitations during recovery, which could be escalated from minimal to moderate clinical concern if postoperative limitations on ambulation increase the risk for new clots. Based on this internal assessment, the provider identifies which risks are elevated and require further attention and discussion with the patient, helping tailor the counseling approach and potential treatment plan. The provider should begin to consider initial control measures such as coordinating anticoagulant management, ensuring diabetes is well controlled, and planning for postoperative ambulation support.

Once the provider has conducted the internal assessment, the ORM matrices become powerful tools for shared decision-making with the patient. The provider can walk the patient through the procedures and their common risks and then explain how their individual situation modifies the risks. The visual and explicit upgrade on the matrices allows the patient to clearly see how unique factors influence their personal risk profile, moving beyond a generic list of complications. The provider then should engage the patient in a discussion about their risk tolerance, which is crucial for mutual agreement on whether to proceed with treatment and, if so, which procedure is most appropriate given the patient’s comfort level with their individualized risk profile. Then the provider should reinforce the proactive steps planned to mitigate the identified risks to provide assurance and reinforce the collaborative approach to safety.

Finally, throughout the preoperative and postoperative phases, the provider should continuously monitor the patient’s condition and the effectiveness of the control measures, adjusting the plan as needed.

In this scenario, both the provider and the patient participated in the risk assessment, with the provider completing the assessment before the visit and presenting it to the patient or performing the assessment in real time with the patient present to explain the reasoning behind assignment of risk based on each procedure and the patient’s unique risk factors.

Case Scenario 2—A 38-year-old woman with a history of hypertension and procedural anxiety presents for evaluation of a biopsy-proven basal cell carcinoma on the nasal ala. The patient is taking diltiazem for hypertension and is compliant with her medication. Her blood pressure at the current visit is 148/96 mm Hg, which she attributes to white coat syndrome. Mohs micrographic surgery generally is the gold standard treatment for this case.

The provider’s ORM process, conducted either before or in real time during the visit, would begin with identification and assessment of the hazards. For Mohs surgery on the nasal ala, common hazards would include scarring, pain, infection, bleeding, and potential cosmetic distortion. Unique to this patient are the procedural anxiety and hypertension.

To populate the risk assessment matrix (eFigure 3), the provider would first map the baseline risks of Mohs surgery, which include considerable scarring as a moderate clinical concern but a seldom probability. Because the patient’s procedural anxiety directly increases the probability of intraoperative distress or elevated blood pressure during the procedure, the provider might assess patient distress/anxiety as a moderate clinical concern with a likely probability. While the patient’s blood pressure is controlled, the white coat syndrome raises the probability of hypertensive urgency/emergency during surgery; this might be elevated from unlikely to occasional or likely probability, and severity might increase from minimal to moderate due to its potential impact on procedural safety. The provider should consider strategies to address these elevated risks during the consultation. Then, as part of preprocedure planning, the provider should consider discussing anxiolytics, emphasizing medication compliance, and ensuring a calm environment for the patient’s surgery.

For this patient, the risk assessment matrix becomes a powerful tool to address fears and proactively manage her unique risk factors. To start the counseling process, the provider should explain the procedure, its benefits, and potential adverse effects. Then, the patient’s individualized risks can be visualized using the matrix, which also is an opportunity for reassurance, as it can alleviate patient fears by contextualizing rare but impactful outcomes.9

Now the provider can assess the patient’s risk tolerance. This discussion ensures that the patient’s comfort level and preferences are central to the treatment decision, even for a gold-standard procedure such as Mohs surgery. By listening and responding to the patient’s input, the provider can build trust and discuss strategies that can help control for some risk factors.

Finally, the provider would re-evaluate throughout the procedure by continuously monitoring the patient’s anxiety and vital signs. The provider should also be ready to adjust pain management or employ anxiety-reduction techniques.

Final Thoughts

Reviewing the risk assessment matrix can be an effective way to nonjudgmentally discuss a patient’s unique risk factors and provide a complete understanding of the planned treatment or procedure. It conveys to the patient that, as the provider, you are taking their health seriously when considering treatment options and can be a means to build patient rapport and trust. This approach mirrors risk communication strategies long employed in military operational planning, where transparency and structured risk evaluation are essential to maintaining mission readiness and unit cohesion.

Operational risk management (ORM) refers to the systematic identification and assessment of daily operational risks within an organization designed to mitigate negative financial, reputational, and safety outcomes while maximizing efficiency and achievement of objectives.1 Operational risk management is indispensable to modern military operations, optimizing mission readiness while minimizing complications and personnel morbidity. Application of ORM in medicine holds considerable promise due to the emphasis on precise and efficient decision-making in high-stakes environments, where the margin for error is minimal. In this article, we propose integrating ORM principles into dermatologic surgery to enhance patient-centered care through improved counseling, risk assessment, and procedural outcomes.

Principles and Processes of ORM

The ORM framework is built on 4 fundamental principles: accept risk when benefits outweigh the cost, accept no unnecessary risk, anticipate and manage risk by planning, and make risk decisions at the right level.2 These principles form the foundation of the ORM’s systematic 5-step approach to identify hazards, assess hazards, make risk decisions, implement controls, and supervise. Key to the ORM process is the use of risk assessment codes and the risk assessment matrix to quantify and prioritize risks. Risk assessment codes are numerical values assigned to hazards based on their assessed severity and probability. The risk assessment matrix is a tool that plots the severity of a hazard against its probability. By locating a hazard on the matrix, users can visualize its risk level in terms of severity and probability. Building and using the risk assessment matrix begins with determining severity by assessing the potential impact of a hazard and categorizing it into levels (catastrophic, critical, moderate, or negligible). Next, probability is determined by evaluating the likelihood of occurrence (frequent, likely, occasional, seldom, or unlikely). Finally, the severity and probability are combined to assign a risk assessment code, which indicates the risk level and helps visualize criticality. Systematically applying these principles and processes enables users to make informed decisions that balance mission objectives with safety.

Proposed Framework for ORM in Dermatology Surgery

Current risk mitigation in dermatologic surgery includes strict medication oversight, sterilization protocols, and photography to prevent wrong-site surgeries. Preoperative risk assessment through conducting a thorough patient history is vital, considering factors such as pregnancy, allergies, bleeding history, cardiac devices, and keloid propensity, all of which impact surgical outcomes.3-5 After gathering the patient’s history, dermatologists determine appropriateness for surgery and its inherent risks, typically via an informed consent process outlining the diagnosis and procedure purpose as well as a list of risks, benefits, and alternatives, including forgoing treatment.

Importantly, the standard process for dermatologic risk evaluation often lacks a comprehensive systematic approach seen in other higher-risk surgical fields. For example, general surgeons frequently utilize risk assessment calculators such as the one developed by the American College of Surgeons’ National Surgical Quality Improvement Program to estimate surgical complications.6 While specific guidelines exist for evaluating factors such as hypertension or anticoagulant use, no single tool synthesizes all patient risk factors for a unified assessment. Therefore, we propose integrating ORM as a structured decision-making process that offers a more consistent means for dermatologists to evaluate, synthesize, categorize, and present risks to patients. Our proposed process includes translating military mishap severity into a framework that helps patients better understand decisions about their health care when using ORM (eTable 1). The proposed process also provides dermatologists with a systematic, proactive, and iterative approach to assessing risks that allows them to consistently qualify medical decisions (eTable 2).

Patients often struggle to understand surgical risk severity, including overestimating the risks of routine minor procedures or underestimating the risks of more intensive procedures.7,8 Incorporating ORM into patient communication mirrors the provider’s process but uses patient-friendly terminology—it is discussion based and integrates patient preferences and tolerances (eTable 2). These steps often occur informally in dermatologic counseling; however, an organized structured approach, especially using a visual aid such as a risk assessment matrix, enhances patient comprehension, recall, and satisfaction.9

Practical Scenarios

Integrating ORM into dermatologic surgery is a proactive iterative process for both provider decision-making and patient communication. Leveraging a risk assessment matrix as a visual aid allows for clear identification, evaluation, and mitigation of hazards, fostering collaborative choices with regard to the treatment approach. Here we provide 2 case scenarios highlighting how ORM and the risk assessment matrix can be used in the management of a complex patient with a lesion in a high-risk location as well as to address patient anxiety and comorbidities. It is important to note that the way the matrices are completed in the examples provided may differ compared to other providers. The purpose of ORM is not to dictate risk categories but to serve as a tool for providers to take their own experiences and knowledge of the patient to guide their decision-making and counseling processes.

Case Scenario 1—An elderly man with a history of diabetes, cardiovascular accident, coronary artery bypass grafting, and multiple squamous cell carcinoma excisions presents for evaluation of a 1-cm squamous cell carcinoma in situ on the left leg. His current medications include an anticoagulant and antihypertensives.

In this scenario, the provider would apply ORM by identifying and assessing hazards, making risk decisions, implementing controls, and supervising care.

General hazards for excision on the leg include bleeding, infection, scarring, pain, delayed healing, activity limitations, and possible further procedures. Before the visit, the provider should prepare baseline risk matrices for 2 potential treatment options: wide local excision and electrodessication and curettage. For example, surgical bleeding may be assessed as negligible severity and almost certain probability for a general excision.

Next, the provider would incorporate the patient’s unique history in the risk matrices (eFigures 1 and 2). The patient’s use of an anticoagulant indicates a bleeding risk; therefore, the provider may shift the severity to minimal clinical concern, understanding the need for enhanced perioperative management. The history of diabetes also has a considerable impact on wound healing, so the provider might elevate the probability of delayed wound healing from rare to unlikely and the severity from moderate to severe. The prior cardiovascular accident also raises concerns about mobility and activity limitations during recovery, which could be escalated from minimal to moderate clinical concern if postoperative limitations on ambulation increase the risk for new clots. Based on this internal assessment, the provider identifies which risks are elevated and require further attention and discussion with the patient, helping tailor the counseling approach and potential treatment plan. The provider should begin to consider initial control measures such as coordinating anticoagulant management, ensuring diabetes is well controlled, and planning for postoperative ambulation support.

Once the provider has conducted the internal assessment, the ORM matrices become powerful tools for shared decision-making with the patient. The provider can walk the patient through the procedures and their common risks and then explain how their individual situation modifies the risks. The visual and explicit upgrade on the matrices allows the patient to clearly see how unique factors influence their personal risk profile, moving beyond a generic list of complications. The provider then should engage the patient in a discussion about their risk tolerance, which is crucial for mutual agreement on whether to proceed with treatment and, if so, which procedure is most appropriate given the patient’s comfort level with their individualized risk profile. Then the provider should reinforce the proactive steps planned to mitigate the identified risks to provide assurance and reinforce the collaborative approach to safety.

Finally, throughout the preoperative and postoperative phases, the provider should continuously monitor the patient’s condition and the effectiveness of the control measures, adjusting the plan as needed.

In this scenario, both the provider and the patient participated in the risk assessment, with the provider completing the assessment before the visit and presenting it to the patient or performing the assessment in real time with the patient present to explain the reasoning behind assignment of risk based on each procedure and the patient’s unique risk factors.

Case Scenario 2—A 38-year-old woman with a history of hypertension and procedural anxiety presents for evaluation of a biopsy-proven basal cell carcinoma on the nasal ala. The patient is taking diltiazem for hypertension and is compliant with her medication. Her blood pressure at the current visit is 148/96 mm Hg, which she attributes to white coat syndrome. Mohs micrographic surgery generally is the gold standard treatment for this case.

The provider’s ORM process, conducted either before or in real time during the visit, would begin with identification and assessment of the hazards. For Mohs surgery on the nasal ala, common hazards would include scarring, pain, infection, bleeding, and potential cosmetic distortion. Unique to this patient are the procedural anxiety and hypertension.

To populate the risk assessment matrix (eFigure 3), the provider would first map the baseline risks of Mohs surgery, which include considerable scarring as a moderate clinical concern but a seldom probability. Because the patient’s procedural anxiety directly increases the probability of intraoperative distress or elevated blood pressure during the procedure, the provider might assess patient distress/anxiety as a moderate clinical concern with a likely probability. While the patient’s blood pressure is controlled, the white coat syndrome raises the probability of hypertensive urgency/emergency during surgery; this might be elevated from unlikely to occasional or likely probability, and severity might increase from minimal to moderate due to its potential impact on procedural safety. The provider should consider strategies to address these elevated risks during the consultation. Then, as part of preprocedure planning, the provider should consider discussing anxiolytics, emphasizing medication compliance, and ensuring a calm environment for the patient’s surgery.

For this patient, the risk assessment matrix becomes a powerful tool to address fears and proactively manage her unique risk factors. To start the counseling process, the provider should explain the procedure, its benefits, and potential adverse effects. Then, the patient’s individualized risks can be visualized using the matrix, which also is an opportunity for reassurance, as it can alleviate patient fears by contextualizing rare but impactful outcomes.9

Now the provider can assess the patient’s risk tolerance. This discussion ensures that the patient’s comfort level and preferences are central to the treatment decision, even for a gold-standard procedure such as Mohs surgery. By listening and responding to the patient’s input, the provider can build trust and discuss strategies that can help control for some risk factors.

Finally, the provider would re-evaluate throughout the procedure by continuously monitoring the patient’s anxiety and vital signs. The provider should also be ready to adjust pain management or employ anxiety-reduction techniques.

Final Thoughts

Reviewing the risk assessment matrix can be an effective way to nonjudgmentally discuss a patient’s unique risk factors and provide a complete understanding of the planned treatment or procedure. It conveys to the patient that, as the provider, you are taking their health seriously when considering treatment options and can be a means to build patient rapport and trust. This approach mirrors risk communication strategies long employed in military operational planning, where transparency and structured risk evaluation are essential to maintaining mission readiness and unit cohesion.

- The OR Society. The history of OR. The OR Society. Published 2023.

- Naval Postgraduate School. ORM: operational risk management. Accessed September 12, 2025. https://nps.edu/web/safety/orm

- Smith C, Srivastava D, Nijhawan RI. Optimizing patient safety in dermatologic surgery. Dermatol Clin. 2019;37:319-328.

- Minkis K, Whittington A, Alam M. Dermatologic surgery emergencies: complications caused by systemic reactions, high-energy systems, and trauma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:265-284.

- Pomerantz RG, Lee DA, Siegel DM. Risk assessment in surgical patients: balancing iatrogenic risks and benefits. Clin Dermatol. 2011;29:669-677.

- Bilimoria KY, Liu Y, Paruch JL, et al. Development and evaluation of the universal ACS NSQIP surgical risk calculator: a decision aid and informed consent tool for patients and surgeons. J Am Coll Surgeons. 2013;217:833-842.

- Lloyd AJ. The extent of patients’ understanding of the risk of treatments. BMJ Qual Saf. 2001;10:i14-i18.

- Falagas ME, Korbila IP, Giannopoulou KP, et al. Informed consent: how much and what do patients understand? Am J Surg. 2009;198:420-435.

- Cohen SM, Baimas-George M, Ponce C, et al. Is a picture worth a thousand words? a scoping review of the impact of visual aids on patients undergoing surgery. J Surg Educ. 2024;81:1276-1292.

- The OR Society. The history of OR. The OR Society. Published 2023.

- Naval Postgraduate School. ORM: operational risk management. Accessed September 12, 2025. https://nps.edu/web/safety/orm

- Smith C, Srivastava D, Nijhawan RI. Optimizing patient safety in dermatologic surgery. Dermatol Clin. 2019;37:319-328.

- Minkis K, Whittington A, Alam M. Dermatologic surgery emergencies: complications caused by systemic reactions, high-energy systems, and trauma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:265-284.

- Pomerantz RG, Lee DA, Siegel DM. Risk assessment in surgical patients: balancing iatrogenic risks and benefits. Clin Dermatol. 2011;29:669-677.

- Bilimoria KY, Liu Y, Paruch JL, et al. Development and evaluation of the universal ACS NSQIP surgical risk calculator: a decision aid and informed consent tool for patients and surgeons. J Am Coll Surgeons. 2013;217:833-842.

- Lloyd AJ. The extent of patients’ understanding of the risk of treatments. BMJ Qual Saf. 2001;10:i14-i18.

- Falagas ME, Korbila IP, Giannopoulou KP, et al. Informed consent: how much and what do patients understand? Am J Surg. 2009;198:420-435.

- Cohen SM, Baimas-George M, Ponce C, et al. Is a picture worth a thousand words? a scoping review of the impact of visual aids on patients undergoing surgery. J Surg Educ. 2024;81:1276-1292.

Operational Risk Management in Dermatologic Procedures

Operational Risk Management in Dermatologic Procedures

Remarkable Response to Vismodegib in a Locally Advanced Basal Cell Carcinoma on the Nose

Remarkable Response to Vismodegib in a Locally Advanced Basal Cell Carcinoma on the Nose

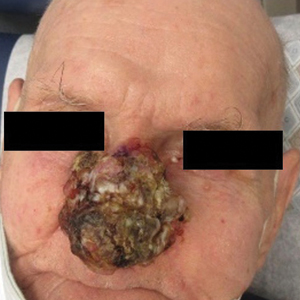

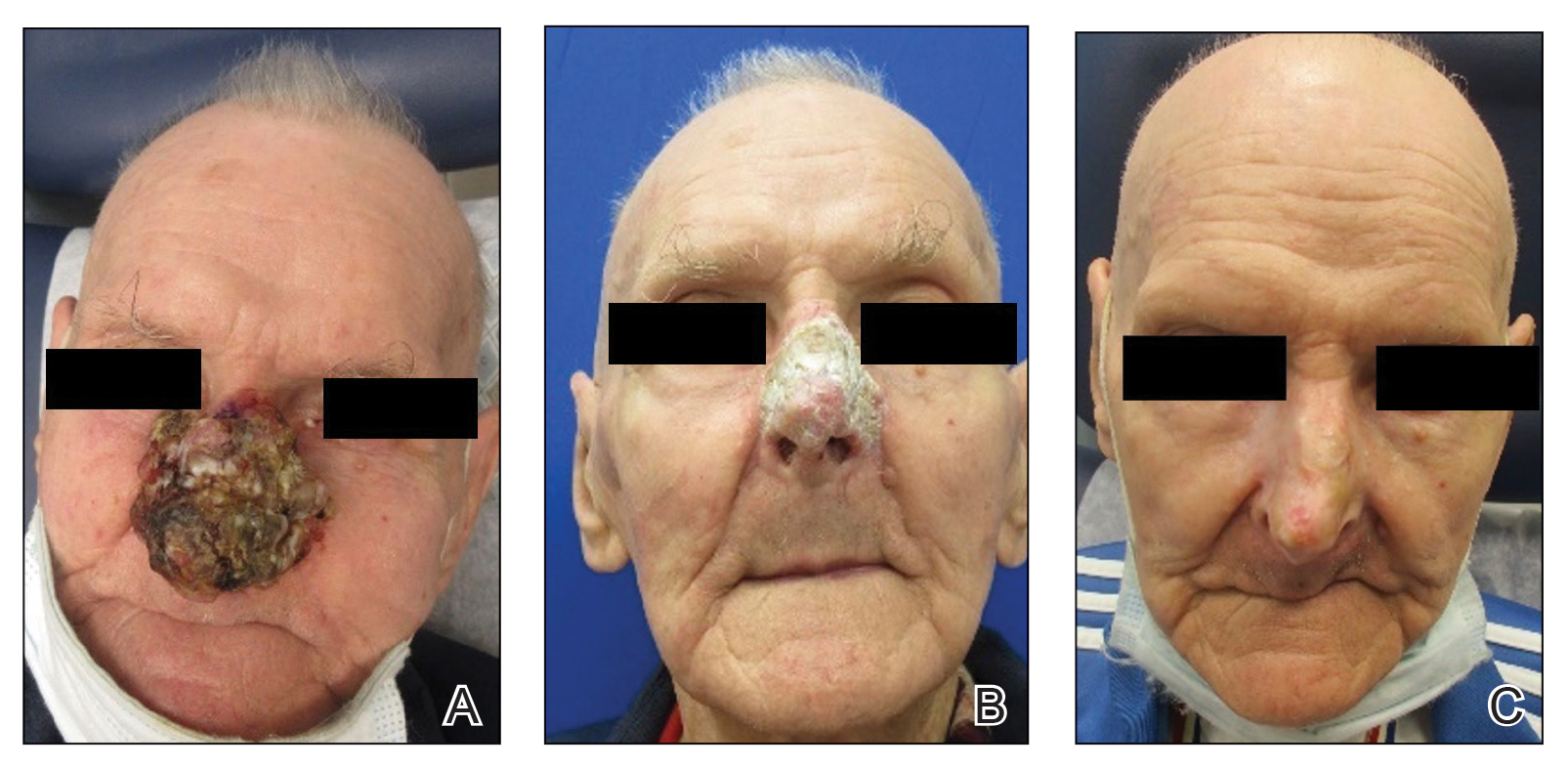

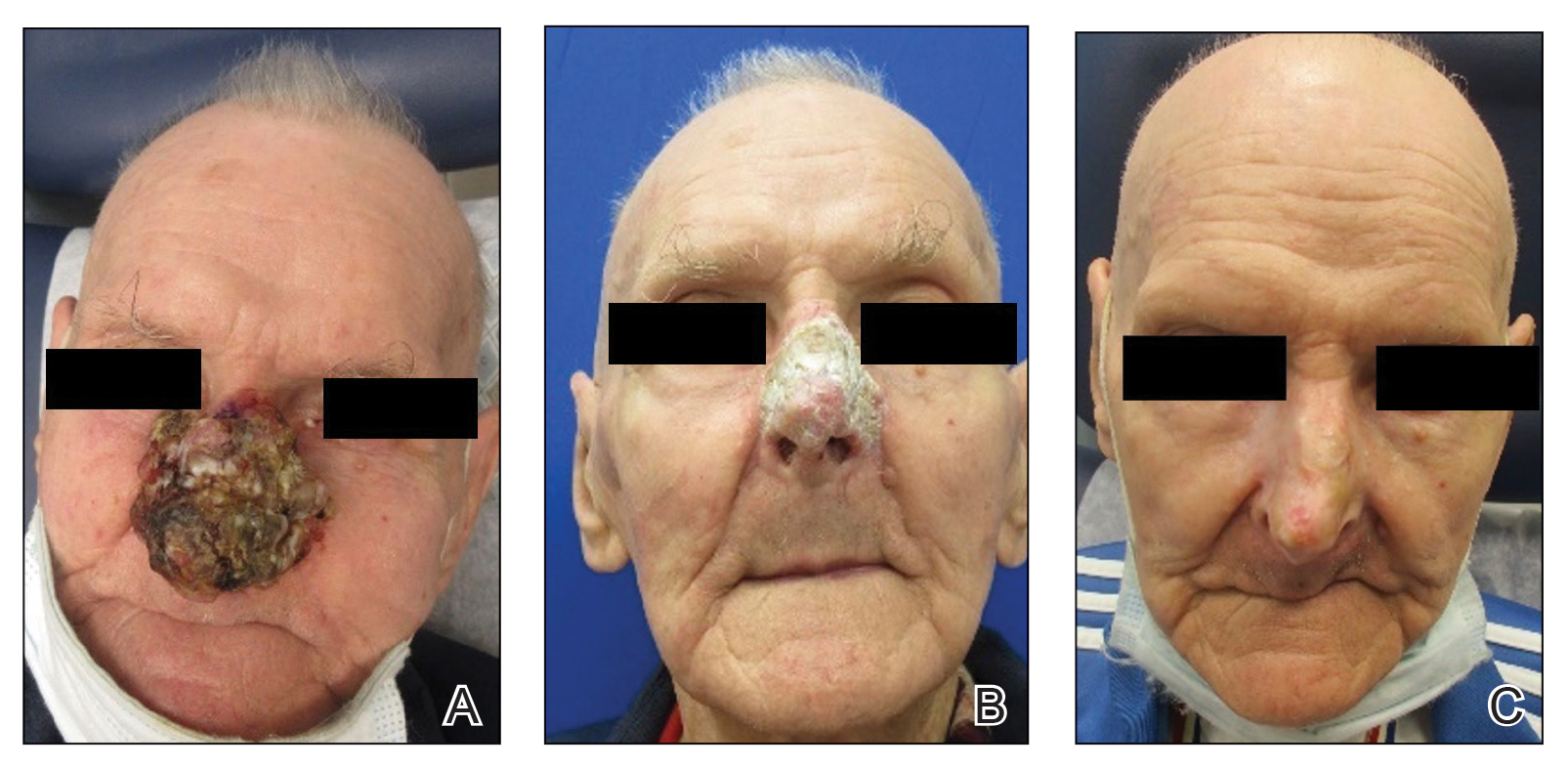

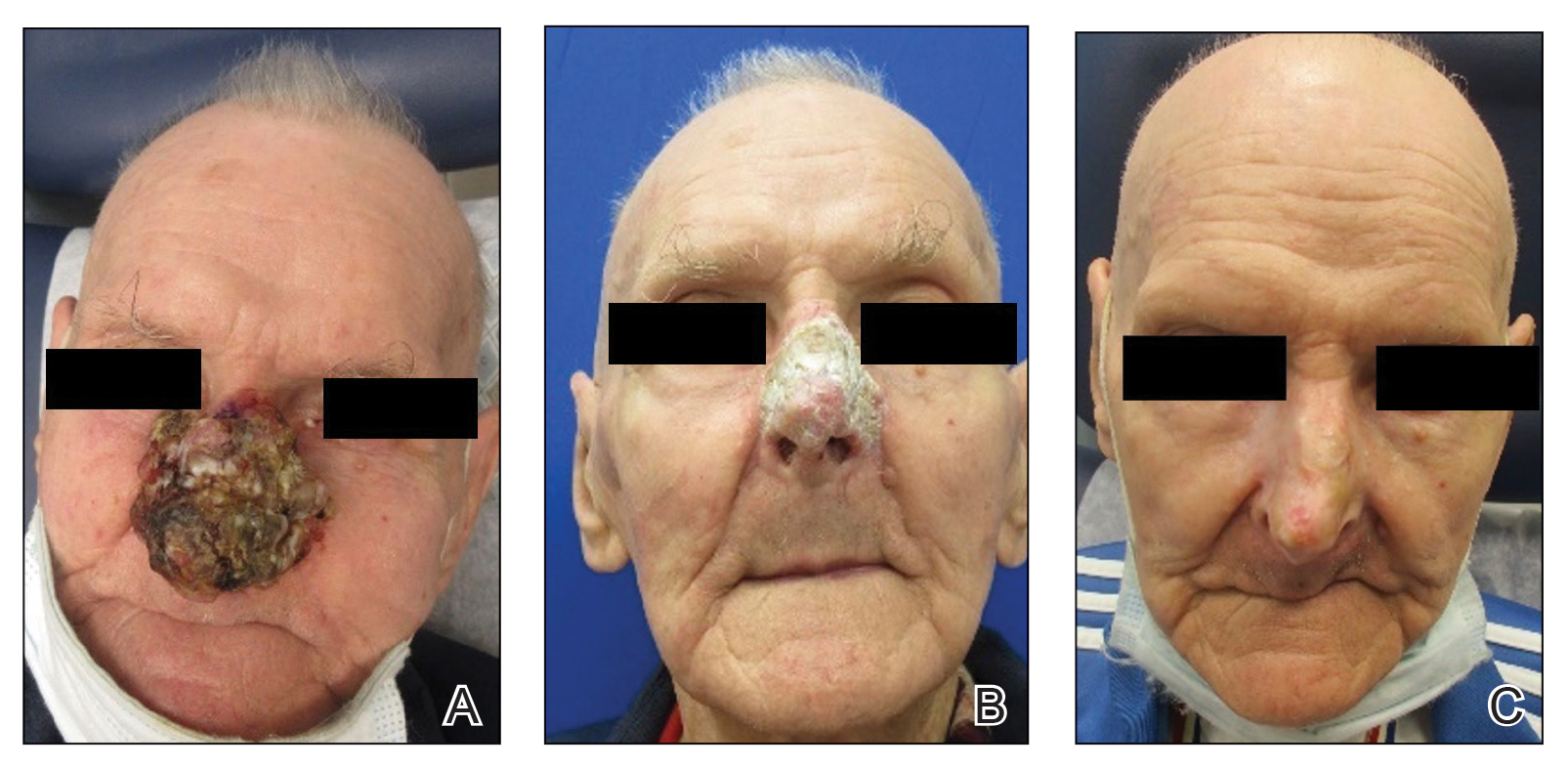

A 90-year-old man presented for evaluation of a large basal cell carcinoma (BCC) involving the nasal region. The lesion was a 7×4-cm pink, crusted, verrucous plaque covering the majority of the nose and extending onto the malar cheeks that originally had been biopsied 26 years prior, and repeat biopsy was performed 3 years prior. Results from both biopsies were consistent with BCC. The patient had avoided treatment for many years due to fear of losing his nose.

Given the size and location of the tumor, surgical intervention posed major challenges for both functional and cosmetic outcomes. After careful consideration and discussion of treatment options, which included Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS), wide local excision, radiation therapy, and systemic therapy, the decision was made to start the patient on vismodegib 150 mg once daily as well as L-carnitine 330 mg twice daily to help with muscle cramps. A baseline complete metabolic panel with an estimated glomerular filtration rate was unremarkable.

By the patient’s first follow-up visit after 2 months of therapy, he had experienced marked clinical improvement with notable regression of the tumor (Figure 1). He reported no adverse effects (eg, muscle cramps, dysgeusia, hair loss, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea). At subsequent follow-up visits, the patient continued to demonstrate clinical improvement. His only adverse effect was a 6-kg weight loss over the prior 6 months of initiating therapy despite no changes in taste or appetite. His dose of vismodegib was decreased to an alternative regimen of 150 mg daily for the first 2 weeks of each month with a drug holiday the rest of the month. Since that time, his weight has stabilized and he has continued with treatment.

Comment

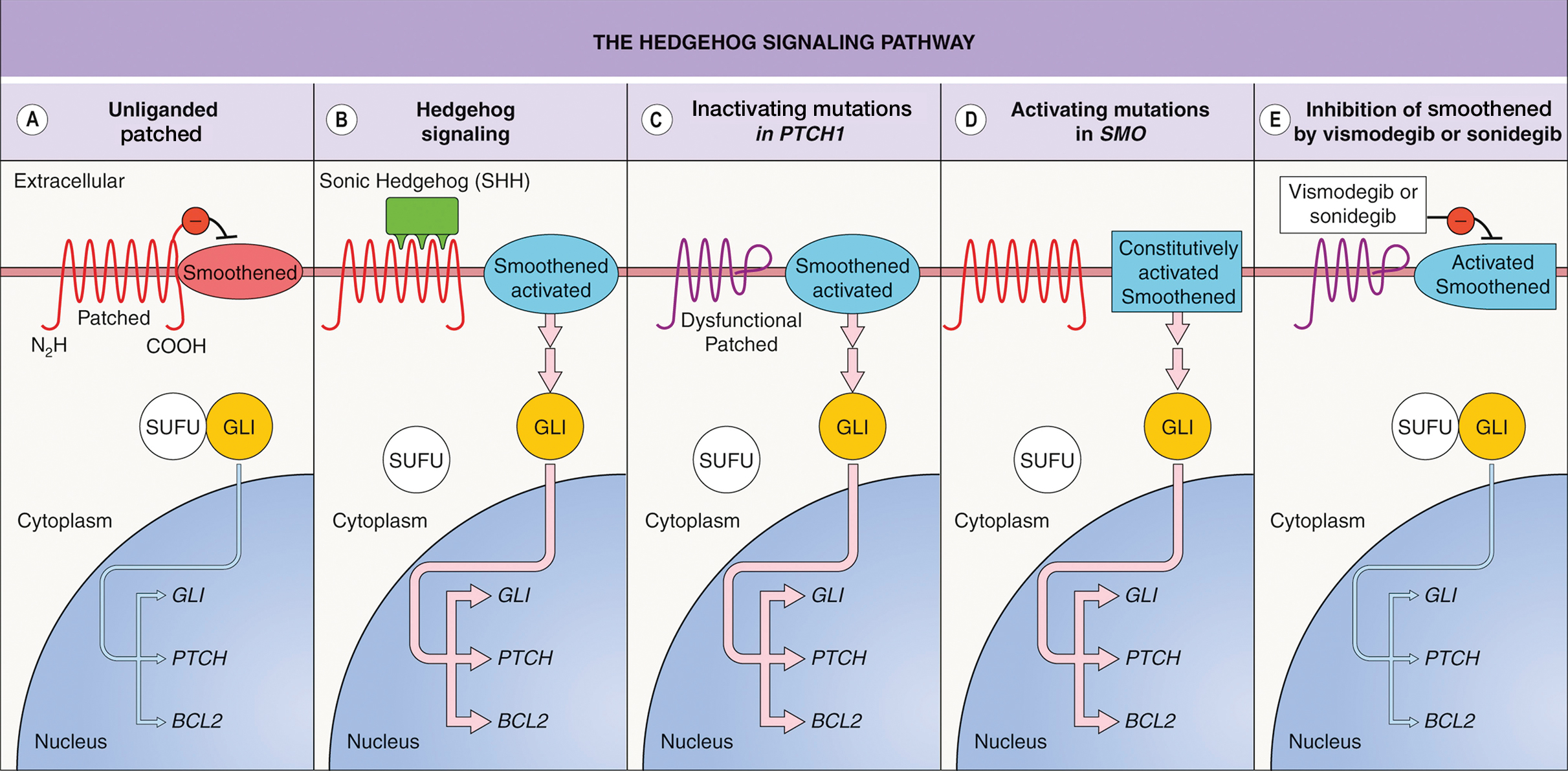

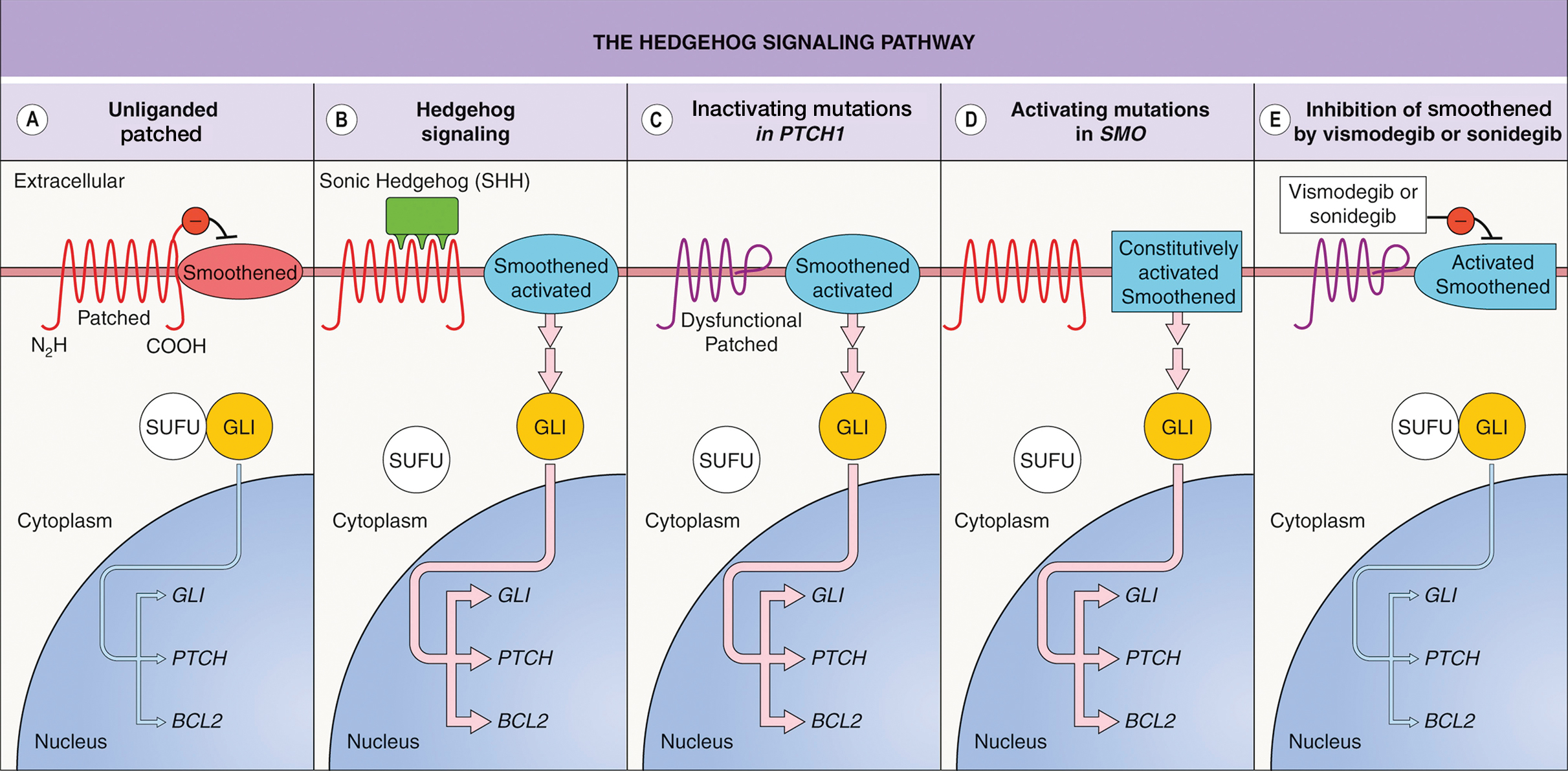

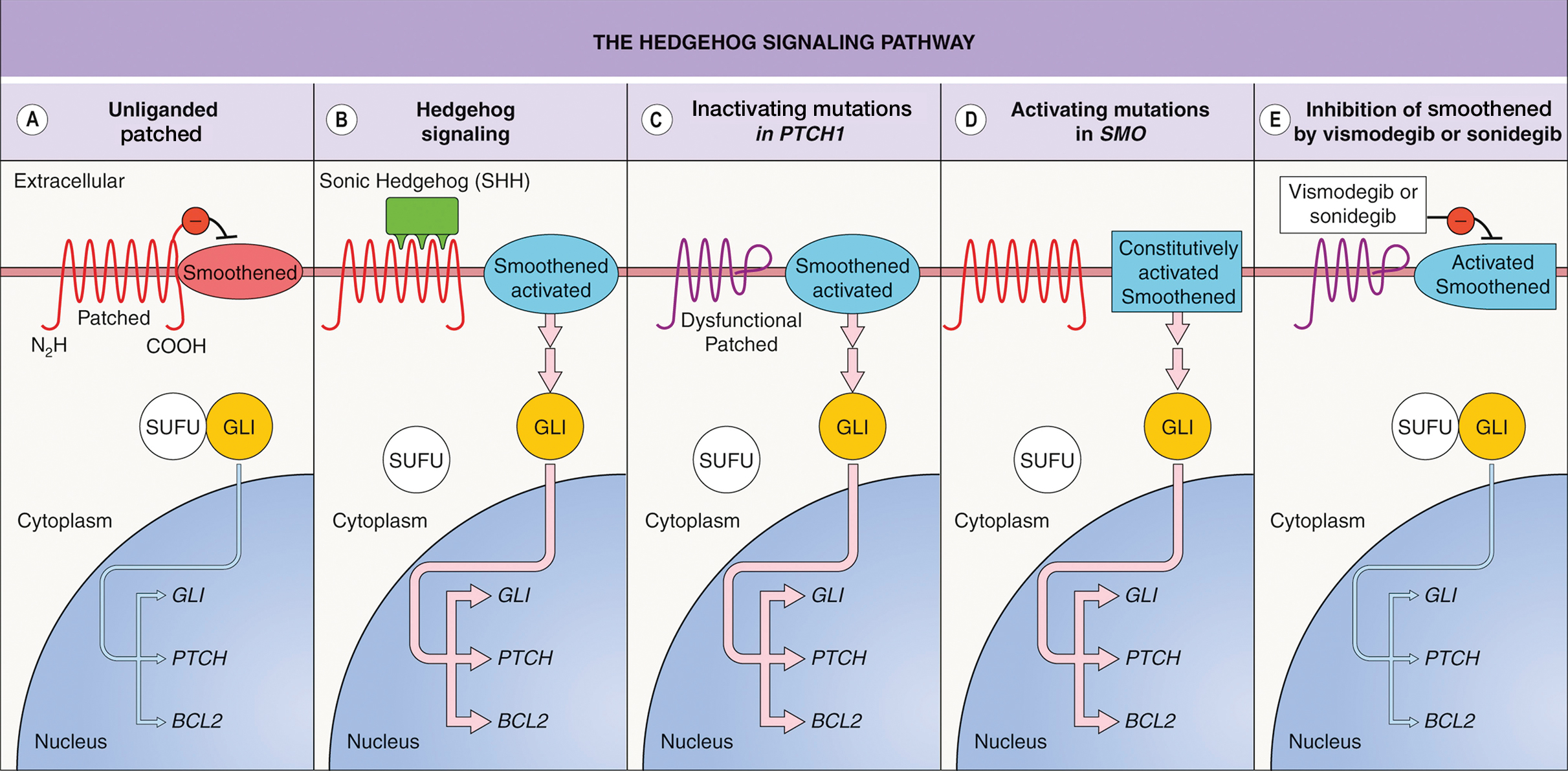

Vismodegib was the first Hedgehog (Hh) inhibitor approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for management of selected locally advanced and metastatic BCC in adults.1,2 Genetic alterations in the Hh signaling pathway resulting in proliferation of basal cells are present in nearly all BCCs.2 In normal function, when the Hh ligand is absent at the patched (PTCH1) receptor, smoothened (SMO) is inhibited. When Hh ligand binds PTCH1, SMO is activated with downstream effects of triggering cell survival and proliferation in the nucleus via GLI. Loss of function mutations at the PTCH1 receptor or SMO-activating mutations lead to the same downstream effects, even when Hh ligand is absent.1 This allows for unregulated tumor growth.

Vismodegib is a small-molecule SMO inhibitor that blocks aberrant activation of the Hh signaling pathway, thereby slowing the growth of BCCs (Figure 2).3,4 Vismodegib and sonidegib have been used to treat patients with basal cell nevus syndrome as well as metastatic or locally advanced BCCs. At least 50% of advanced BCCs develop resistance to vismodegib, commonly via acquiring mutations in SMO.4

Basal cell carcinoma can be classified as low or high risk based on risk for recurrence. First-line treatments for low-risk BCC are surgical excision, electrodessication and curettage, and MMS.4 Second-line treatment includes radiation therapy. High-risk tumors include those involving anatomic locations of Area H near the eyelids, nose, ears, hands, feet, or genitals in addition to tumors with an aggressive histologic subtype.4,5 First-line treatments for high-risk BCC are MMS or surgical excision. Second-line treatments are radiation therapy or systemic therapy, such as vismodegib.4

Although Hh inhibitors are not a first-line treatment, our case highlights vismodegib’s effectiveness in the management of a large unresectable BCC on the nose of an elderly patient. Our patient opted out of surgical first-line options due to functional and cosmetic concerns.4 He also declined radiation treatment due to financial cost and difficulty with transportation. The patient chose to pursue systemic vismodegib therapy through shared decision-making with dermatology. Vismodegib treatment alone granted our patient a highly remarkable result.

There are limited clinical data on the effectiveness and safety profile of vismodegib in elderly patients, even though this is a high-risk population for BCC.6 In a study that categorized responses to vismodegib in 13 patients with canthal BCC, 5 experienced a complete clinical response (defined as complete regression of the tumor), and 8 achieved partial clinical response (defined as regression but not to the extent of a complete response).7 Our patient’s successful response is notable, as it reinforces vismodegib’s effectiveness as a treatment option for BCC in a sensitive facial area. In addition, our patient’s minimal adverse effect profile is evidence in support of establishing visogemib’s role as a viable treatment option in advanced BCC in the elderly.

Alternative dosing regimens of vismodegib involve the use of drug holidays.8 Utilizing a regimen of 1 week with and 3 weeks without vismodegib for 5 to 14 cycles has led to the resolution of BCC with decreased adverse effects.8 Furthermore, the MIKIE study demonstrated the efficacy of 2 dosing regimens: 12 weeks of vismodegib 150 mg followed by 3 cycles of 8 placebo weeks and 12 weeks of vismodegib 150 mg and 24 weeks of vismodegib 150 mg followed by 3 cycles of 8 placebo weeks and 8 weeks of vismodegib 150 mg.9 Both regimens appeared viable to treat BCC in patients who were at risk for treatment discontinuation due to adverse effects.10

One adverse effect associated with vismodegib is muscle cramps, which are a potential cause of treatment discontinuation. The mechanism by which vismodegib causes cramps is not fully understood but is attributed to contractions from Ca2+ influx into muscle cells and a lack of adenosine triphosphate to allow muscle relaxation.11 This is due to vismodegib’s inhibition of the SMO signaling pathway and activation of the SMO–Ca2+/ AMP-related kinase axis.12 L-carnitine can be used as an adjuvant with vismodegib to address this adverse effect. L-carnitine is found in muscle cells, where its role is to produce energy by utilizing fatty acids.13 It is hypothesized that L-carnitine helps prevent cramps through production of adenosine triphosphate via fatty acid Β-oxidation that aids in stabilizing the sarcolemma and promoting muscle relaxation in skeletal muscle.13,14 Evidence suggests that making L-carnitine a common adjuvant to vismodegib can aid in preventing this adverse effect.

Vismodegib can be an effective treatment option for large nasal BCCs that are difficult to resect. Our case demonstrates both clinical efficacy and a favorable safety profile in an elderly patient. Further studies and long-term follow-up are warranted to establish the role of vismodegib in the evolving landscape of BCC management.

- Peris K, Fargnoli MC, Garbe C, et al. European Dermatology Forum (EDF), the European Association of Dermato-Oncology (EADO) and the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC). Diagnosis and treatment of basal cell carcinoma: European consensus-based interdisciplinary guidelines. Eur J Cancer. 2019;118:10-34. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2019.06.003

- Alkeraye SS, Alhammad GA, Binkhonain FK. Vismodegib for basal cell carcinoma and beyond: what dermatologists need to know. Cutis. 2022;110:155-158. doi:10.12788/cutis.0601

- Cameron MC, Lee E, Hibler BP, et al. Basal cell carcinoma: contemporary approaches to diagnosis, treatment, and prevention. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:321-339. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.02.083

- Wolf IH, Soyer P, McMeniman EK, et al. Actinic keratosis, basal cell carcinoma, and squamous cell carcinoma. In: Dermatology. 5th ed. Elsevier; 2024:1888-1910. doi:10.1016/B978-0-7020-8225-2.00108-6

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Guidelines for patients: basal cell carcinoma. 2025. Accessed April 7, 2025. https://www.nccn.org/patients/guidelines/content/PDF/basal-cell-patient-guideline.pdf

- Ad Hoc Task Force; Connolly SM, Baker DR, Coldiron BM, et al. AAD/ACMS/ASDSA/ASMS 2012 appropriate use criteria for Mohs micrographic surgery: a report of the American Academy of Dermatology, American College of Mohs Surgery, American Society for Dermatologic Surgery Association, and the American Society for Mohs Surgery. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:531-550. doi:10.1016/j .jaad.2012.06.009

- Passarelli A, Galdo G, Aieta M, et al. Vismodegib experience in elderly patients with basal cell carcinoma: case reports and review of the literature. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21:8596. doi:10.3390/ijms21228596

- Oliphant H, Laybourne J, Chan K, et al. Vismodegib for periocular basal cell carcinoma: an international multicentre case series. Eye (Lond). 2020;34:2076-2081. doi:10.1038/s41433-020-0778-3

- Becker LR, Aakhus AE, Reich HC, et al. A novel alternate dosing of vismodegib for treatment of patients with advanced basal cell carcinomas. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:321-322. doi:10.1001 /jamadermatol.2016.5058

- Dréno B, Kunstfeld R, Hauschild A, et al. Two intermittent vismodegib dosing regimens in patients with multiple basalcell carcinomas (MIKIE): a randomised, regimen-controlled, double-blind, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18:404-412. doi:10.1016 /S1470-2045(17)30072-4

- Svoboda SA, Johnson NM, Phillips MA. Systemic targeted treatments for basal cell carcinoma. Cutis. 2022;109:E25-E31. doi:10.12788/cutis.0560

- Nakanishi H, Kurosaki M, Tsuchiya K, et al. L-carnitine reduces muscle cramps in patients with cirrhosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13:1540-1543. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2014.12.005

- Teperino R, Amann S, Bayer M, et al. Hedgehog partial agonism drives Warburg-like metabolism in muscle and brown fat. Cell. 2012;151:414-426. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2012.09.021

- Dinehart M, McMurray S, Dinehart SM, et al. L-carnitine reduces muscle cramps in patients taking vismodegib. SKIN J Cutan Med. 2018;2:90-95. doi:10.25251/skin.2.2.1

A 90-year-old man presented for evaluation of a large basal cell carcinoma (BCC) involving the nasal region. The lesion was a 7×4-cm pink, crusted, verrucous plaque covering the majority of the nose and extending onto the malar cheeks that originally had been biopsied 26 years prior, and repeat biopsy was performed 3 years prior. Results from both biopsies were consistent with BCC. The patient had avoided treatment for many years due to fear of losing his nose.

Given the size and location of the tumor, surgical intervention posed major challenges for both functional and cosmetic outcomes. After careful consideration and discussion of treatment options, which included Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS), wide local excision, radiation therapy, and systemic therapy, the decision was made to start the patient on vismodegib 150 mg once daily as well as L-carnitine 330 mg twice daily to help with muscle cramps. A baseline complete metabolic panel with an estimated glomerular filtration rate was unremarkable.

By the patient’s first follow-up visit after 2 months of therapy, he had experienced marked clinical improvement with notable regression of the tumor (Figure 1). He reported no adverse effects (eg, muscle cramps, dysgeusia, hair loss, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea). At subsequent follow-up visits, the patient continued to demonstrate clinical improvement. His only adverse effect was a 6-kg weight loss over the prior 6 months of initiating therapy despite no changes in taste or appetite. His dose of vismodegib was decreased to an alternative regimen of 150 mg daily for the first 2 weeks of each month with a drug holiday the rest of the month. Since that time, his weight has stabilized and he has continued with treatment.

Comment

Vismodegib was the first Hedgehog (Hh) inhibitor approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for management of selected locally advanced and metastatic BCC in adults.1,2 Genetic alterations in the Hh signaling pathway resulting in proliferation of basal cells are present in nearly all BCCs.2 In normal function, when the Hh ligand is absent at the patched (PTCH1) receptor, smoothened (SMO) is inhibited. When Hh ligand binds PTCH1, SMO is activated with downstream effects of triggering cell survival and proliferation in the nucleus via GLI. Loss of function mutations at the PTCH1 receptor or SMO-activating mutations lead to the same downstream effects, even when Hh ligand is absent.1 This allows for unregulated tumor growth.

Vismodegib is a small-molecule SMO inhibitor that blocks aberrant activation of the Hh signaling pathway, thereby slowing the growth of BCCs (Figure 2).3,4 Vismodegib and sonidegib have been used to treat patients with basal cell nevus syndrome as well as metastatic or locally advanced BCCs. At least 50% of advanced BCCs develop resistance to vismodegib, commonly via acquiring mutations in SMO.4

Basal cell carcinoma can be classified as low or high risk based on risk for recurrence. First-line treatments for low-risk BCC are surgical excision, electrodessication and curettage, and MMS.4 Second-line treatment includes radiation therapy. High-risk tumors include those involving anatomic locations of Area H near the eyelids, nose, ears, hands, feet, or genitals in addition to tumors with an aggressive histologic subtype.4,5 First-line treatments for high-risk BCC are MMS or surgical excision. Second-line treatments are radiation therapy or systemic therapy, such as vismodegib.4

Although Hh inhibitors are not a first-line treatment, our case highlights vismodegib’s effectiveness in the management of a large unresectable BCC on the nose of an elderly patient. Our patient opted out of surgical first-line options due to functional and cosmetic concerns.4 He also declined radiation treatment due to financial cost and difficulty with transportation. The patient chose to pursue systemic vismodegib therapy through shared decision-making with dermatology. Vismodegib treatment alone granted our patient a highly remarkable result.

There are limited clinical data on the effectiveness and safety profile of vismodegib in elderly patients, even though this is a high-risk population for BCC.6 In a study that categorized responses to vismodegib in 13 patients with canthal BCC, 5 experienced a complete clinical response (defined as complete regression of the tumor), and 8 achieved partial clinical response (defined as regression but not to the extent of a complete response).7 Our patient’s successful response is notable, as it reinforces vismodegib’s effectiveness as a treatment option for BCC in a sensitive facial area. In addition, our patient’s minimal adverse effect profile is evidence in support of establishing visogemib’s role as a viable treatment option in advanced BCC in the elderly.

Alternative dosing regimens of vismodegib involve the use of drug holidays.8 Utilizing a regimen of 1 week with and 3 weeks without vismodegib for 5 to 14 cycles has led to the resolution of BCC with decreased adverse effects.8 Furthermore, the MIKIE study demonstrated the efficacy of 2 dosing regimens: 12 weeks of vismodegib 150 mg followed by 3 cycles of 8 placebo weeks and 12 weeks of vismodegib 150 mg and 24 weeks of vismodegib 150 mg followed by 3 cycles of 8 placebo weeks and 8 weeks of vismodegib 150 mg.9 Both regimens appeared viable to treat BCC in patients who were at risk for treatment discontinuation due to adverse effects.10

One adverse effect associated with vismodegib is muscle cramps, which are a potential cause of treatment discontinuation. The mechanism by which vismodegib causes cramps is not fully understood but is attributed to contractions from Ca2+ influx into muscle cells and a lack of adenosine triphosphate to allow muscle relaxation.11 This is due to vismodegib’s inhibition of the SMO signaling pathway and activation of the SMO–Ca2+/ AMP-related kinase axis.12 L-carnitine can be used as an adjuvant with vismodegib to address this adverse effect. L-carnitine is found in muscle cells, where its role is to produce energy by utilizing fatty acids.13 It is hypothesized that L-carnitine helps prevent cramps through production of adenosine triphosphate via fatty acid Β-oxidation that aids in stabilizing the sarcolemma and promoting muscle relaxation in skeletal muscle.13,14 Evidence suggests that making L-carnitine a common adjuvant to vismodegib can aid in preventing this adverse effect.

Vismodegib can be an effective treatment option for large nasal BCCs that are difficult to resect. Our case demonstrates both clinical efficacy and a favorable safety profile in an elderly patient. Further studies and long-term follow-up are warranted to establish the role of vismodegib in the evolving landscape of BCC management.

A 90-year-old man presented for evaluation of a large basal cell carcinoma (BCC) involving the nasal region. The lesion was a 7×4-cm pink, crusted, verrucous plaque covering the majority of the nose and extending onto the malar cheeks that originally had been biopsied 26 years prior, and repeat biopsy was performed 3 years prior. Results from both biopsies were consistent with BCC. The patient had avoided treatment for many years due to fear of losing his nose.

Given the size and location of the tumor, surgical intervention posed major challenges for both functional and cosmetic outcomes. After careful consideration and discussion of treatment options, which included Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS), wide local excision, radiation therapy, and systemic therapy, the decision was made to start the patient on vismodegib 150 mg once daily as well as L-carnitine 330 mg twice daily to help with muscle cramps. A baseline complete metabolic panel with an estimated glomerular filtration rate was unremarkable.

By the patient’s first follow-up visit after 2 months of therapy, he had experienced marked clinical improvement with notable regression of the tumor (Figure 1). He reported no adverse effects (eg, muscle cramps, dysgeusia, hair loss, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea). At subsequent follow-up visits, the patient continued to demonstrate clinical improvement. His only adverse effect was a 6-kg weight loss over the prior 6 months of initiating therapy despite no changes in taste or appetite. His dose of vismodegib was decreased to an alternative regimen of 150 mg daily for the first 2 weeks of each month with a drug holiday the rest of the month. Since that time, his weight has stabilized and he has continued with treatment.

Comment

Vismodegib was the first Hedgehog (Hh) inhibitor approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for management of selected locally advanced and metastatic BCC in adults.1,2 Genetic alterations in the Hh signaling pathway resulting in proliferation of basal cells are present in nearly all BCCs.2 In normal function, when the Hh ligand is absent at the patched (PTCH1) receptor, smoothened (SMO) is inhibited. When Hh ligand binds PTCH1, SMO is activated with downstream effects of triggering cell survival and proliferation in the nucleus via GLI. Loss of function mutations at the PTCH1 receptor or SMO-activating mutations lead to the same downstream effects, even when Hh ligand is absent.1 This allows for unregulated tumor growth.

Vismodegib is a small-molecule SMO inhibitor that blocks aberrant activation of the Hh signaling pathway, thereby slowing the growth of BCCs (Figure 2).3,4 Vismodegib and sonidegib have been used to treat patients with basal cell nevus syndrome as well as metastatic or locally advanced BCCs. At least 50% of advanced BCCs develop resistance to vismodegib, commonly via acquiring mutations in SMO.4

Basal cell carcinoma can be classified as low or high risk based on risk for recurrence. First-line treatments for low-risk BCC are surgical excision, electrodessication and curettage, and MMS.4 Second-line treatment includes radiation therapy. High-risk tumors include those involving anatomic locations of Area H near the eyelids, nose, ears, hands, feet, or genitals in addition to tumors with an aggressive histologic subtype.4,5 First-line treatments for high-risk BCC are MMS or surgical excision. Second-line treatments are radiation therapy or systemic therapy, such as vismodegib.4

Although Hh inhibitors are not a first-line treatment, our case highlights vismodegib’s effectiveness in the management of a large unresectable BCC on the nose of an elderly patient. Our patient opted out of surgical first-line options due to functional and cosmetic concerns.4 He also declined radiation treatment due to financial cost and difficulty with transportation. The patient chose to pursue systemic vismodegib therapy through shared decision-making with dermatology. Vismodegib treatment alone granted our patient a highly remarkable result.

There are limited clinical data on the effectiveness and safety profile of vismodegib in elderly patients, even though this is a high-risk population for BCC.6 In a study that categorized responses to vismodegib in 13 patients with canthal BCC, 5 experienced a complete clinical response (defined as complete regression of the tumor), and 8 achieved partial clinical response (defined as regression but not to the extent of a complete response).7 Our patient’s successful response is notable, as it reinforces vismodegib’s effectiveness as a treatment option for BCC in a sensitive facial area. In addition, our patient’s minimal adverse effect profile is evidence in support of establishing visogemib’s role as a viable treatment option in advanced BCC in the elderly.

Alternative dosing regimens of vismodegib involve the use of drug holidays.8 Utilizing a regimen of 1 week with and 3 weeks without vismodegib for 5 to 14 cycles has led to the resolution of BCC with decreased adverse effects.8 Furthermore, the MIKIE study demonstrated the efficacy of 2 dosing regimens: 12 weeks of vismodegib 150 mg followed by 3 cycles of 8 placebo weeks and 12 weeks of vismodegib 150 mg and 24 weeks of vismodegib 150 mg followed by 3 cycles of 8 placebo weeks and 8 weeks of vismodegib 150 mg.9 Both regimens appeared viable to treat BCC in patients who were at risk for treatment discontinuation due to adverse effects.10

One adverse effect associated with vismodegib is muscle cramps, which are a potential cause of treatment discontinuation. The mechanism by which vismodegib causes cramps is not fully understood but is attributed to contractions from Ca2+ influx into muscle cells and a lack of adenosine triphosphate to allow muscle relaxation.11 This is due to vismodegib’s inhibition of the SMO signaling pathway and activation of the SMO–Ca2+/ AMP-related kinase axis.12 L-carnitine can be used as an adjuvant with vismodegib to address this adverse effect. L-carnitine is found in muscle cells, where its role is to produce energy by utilizing fatty acids.13 It is hypothesized that L-carnitine helps prevent cramps through production of adenosine triphosphate via fatty acid Β-oxidation that aids in stabilizing the sarcolemma and promoting muscle relaxation in skeletal muscle.13,14 Evidence suggests that making L-carnitine a common adjuvant to vismodegib can aid in preventing this adverse effect.

Vismodegib can be an effective treatment option for large nasal BCCs that are difficult to resect. Our case demonstrates both clinical efficacy and a favorable safety profile in an elderly patient. Further studies and long-term follow-up are warranted to establish the role of vismodegib in the evolving landscape of BCC management.

- Peris K, Fargnoli MC, Garbe C, et al. European Dermatology Forum (EDF), the European Association of Dermato-Oncology (EADO) and the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC). Diagnosis and treatment of basal cell carcinoma: European consensus-based interdisciplinary guidelines. Eur J Cancer. 2019;118:10-34. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2019.06.003

- Alkeraye SS, Alhammad GA, Binkhonain FK. Vismodegib for basal cell carcinoma and beyond: what dermatologists need to know. Cutis. 2022;110:155-158. doi:10.12788/cutis.0601

- Cameron MC, Lee E, Hibler BP, et al. Basal cell carcinoma: contemporary approaches to diagnosis, treatment, and prevention. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:321-339. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.02.083

- Wolf IH, Soyer P, McMeniman EK, et al. Actinic keratosis, basal cell carcinoma, and squamous cell carcinoma. In: Dermatology. 5th ed. Elsevier; 2024:1888-1910. doi:10.1016/B978-0-7020-8225-2.00108-6

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Guidelines for patients: basal cell carcinoma. 2025. Accessed April 7, 2025. https://www.nccn.org/patients/guidelines/content/PDF/basal-cell-patient-guideline.pdf

- Ad Hoc Task Force; Connolly SM, Baker DR, Coldiron BM, et al. AAD/ACMS/ASDSA/ASMS 2012 appropriate use criteria for Mohs micrographic surgery: a report of the American Academy of Dermatology, American College of Mohs Surgery, American Society for Dermatologic Surgery Association, and the American Society for Mohs Surgery. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:531-550. doi:10.1016/j .jaad.2012.06.009

- Passarelli A, Galdo G, Aieta M, et al. Vismodegib experience in elderly patients with basal cell carcinoma: case reports and review of the literature. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21:8596. doi:10.3390/ijms21228596

- Oliphant H, Laybourne J, Chan K, et al. Vismodegib for periocular basal cell carcinoma: an international multicentre case series. Eye (Lond). 2020;34:2076-2081. doi:10.1038/s41433-020-0778-3

- Becker LR, Aakhus AE, Reich HC, et al. A novel alternate dosing of vismodegib for treatment of patients with advanced basal cell carcinomas. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:321-322. doi:10.1001 /jamadermatol.2016.5058

- Dréno B, Kunstfeld R, Hauschild A, et al. Two intermittent vismodegib dosing regimens in patients with multiple basalcell carcinomas (MIKIE): a randomised, regimen-controlled, double-blind, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18:404-412. doi:10.1016 /S1470-2045(17)30072-4

- Svoboda SA, Johnson NM, Phillips MA. Systemic targeted treatments for basal cell carcinoma. Cutis. 2022;109:E25-E31. doi:10.12788/cutis.0560

- Nakanishi H, Kurosaki M, Tsuchiya K, et al. L-carnitine reduces muscle cramps in patients with cirrhosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13:1540-1543. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2014.12.005

- Teperino R, Amann S, Bayer M, et al. Hedgehog partial agonism drives Warburg-like metabolism in muscle and brown fat. Cell. 2012;151:414-426. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2012.09.021

- Dinehart M, McMurray S, Dinehart SM, et al. L-carnitine reduces muscle cramps in patients taking vismodegib. SKIN J Cutan Med. 2018;2:90-95. doi:10.25251/skin.2.2.1

- Peris K, Fargnoli MC, Garbe C, et al. European Dermatology Forum (EDF), the European Association of Dermato-Oncology (EADO) and the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC). Diagnosis and treatment of basal cell carcinoma: European consensus-based interdisciplinary guidelines. Eur J Cancer. 2019;118:10-34. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2019.06.003

- Alkeraye SS, Alhammad GA, Binkhonain FK. Vismodegib for basal cell carcinoma and beyond: what dermatologists need to know. Cutis. 2022;110:155-158. doi:10.12788/cutis.0601

- Cameron MC, Lee E, Hibler BP, et al. Basal cell carcinoma: contemporary approaches to diagnosis, treatment, and prevention. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:321-339. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.02.083

- Wolf IH, Soyer P, McMeniman EK, et al. Actinic keratosis, basal cell carcinoma, and squamous cell carcinoma. In: Dermatology. 5th ed. Elsevier; 2024:1888-1910. doi:10.1016/B978-0-7020-8225-2.00108-6

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Guidelines for patients: basal cell carcinoma. 2025. Accessed April 7, 2025. https://www.nccn.org/patients/guidelines/content/PDF/basal-cell-patient-guideline.pdf

- Ad Hoc Task Force; Connolly SM, Baker DR, Coldiron BM, et al. AAD/ACMS/ASDSA/ASMS 2012 appropriate use criteria for Mohs micrographic surgery: a report of the American Academy of Dermatology, American College of Mohs Surgery, American Society for Dermatologic Surgery Association, and the American Society for Mohs Surgery. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:531-550. doi:10.1016/j .jaad.2012.06.009

- Passarelli A, Galdo G, Aieta M, et al. Vismodegib experience in elderly patients with basal cell carcinoma: case reports and review of the literature. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21:8596. doi:10.3390/ijms21228596

- Oliphant H, Laybourne J, Chan K, et al. Vismodegib for periocular basal cell carcinoma: an international multicentre case series. Eye (Lond). 2020;34:2076-2081. doi:10.1038/s41433-020-0778-3

- Becker LR, Aakhus AE, Reich HC, et al. A novel alternate dosing of vismodegib for treatment of patients with advanced basal cell carcinomas. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:321-322. doi:10.1001 /jamadermatol.2016.5058

- Dréno B, Kunstfeld R, Hauschild A, et al. Two intermittent vismodegib dosing regimens in patients with multiple basalcell carcinomas (MIKIE): a randomised, regimen-controlled, double-blind, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18:404-412. doi:10.1016 /S1470-2045(17)30072-4

- Svoboda SA, Johnson NM, Phillips MA. Systemic targeted treatments for basal cell carcinoma. Cutis. 2022;109:E25-E31. doi:10.12788/cutis.0560

- Nakanishi H, Kurosaki M, Tsuchiya K, et al. L-carnitine reduces muscle cramps in patients with cirrhosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13:1540-1543. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2014.12.005

- Teperino R, Amann S, Bayer M, et al. Hedgehog partial agonism drives Warburg-like metabolism in muscle and brown fat. Cell. 2012;151:414-426. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2012.09.021

- Dinehart M, McMurray S, Dinehart SM, et al. L-carnitine reduces muscle cramps in patients taking vismodegib. SKIN J Cutan Med. 2018;2:90-95. doi:10.25251/skin.2.2.1

Remarkable Response to Vismodegib in a Locally Advanced Basal Cell Carcinoma on the Nose

Remarkable Response to Vismodegib in a Locally Advanced Basal Cell Carcinoma on the Nose

PRACTICE POINTS

- Dermatologists should consider using vismodegib for treatment of unresectable basal cell carcinoma.

- Vismodegib dosing regimens can vary; drug holidays can be used to mitigate adverse effects while maintaining desirable treatment outcomes.