User login

Louis Johnson: First Cold War SecDef

The VA Medical Center in Clarksburg, West Virginia, is named in honor of Louis Arthur Johnson, the Secretary of Defense under President Truman. Johnson cultivated a diversity of viewpoints and experiences before becoming Secretary of Defense. He was born in Roanoke, Virginia, in 1891, and he earned a law degree from the University of Virginia. Two years later, he began his foray into politics with election to the West Virginia House of Delegates, where he acted as Majority Floor Leader and Chair of the Judiciary Committee.1

Johnson served as an Infantry Captain in France during World War I, fighting in the Meuse-Argonne Offensive and earning the Legion of Honor of France. During his service, he gained insight into the military logistics by presenting a lengthy report on Army management and materiel requisition to the War Department—a foreshadowing of his eventual commitment to military budget restructuring as Secretary of Defense. After returning from the war, he practiced law and focused his efforts on aiding veterans, eventually securing the role of National Commander of the American Legion.1

Johnson was Assistant Secretary of War from 1937 to 1940 under President Franklin D. Roosevelt. Johnson frequently disagreed with the policies of Harry Hines Woodring, the acting Secretary of War who was a committed isolationist. While Johnson was adamant about providing military assistance to Great Britain during World War II, Woodring’s isolationism prevailed. However, in 1940, the fall of France forced the US to re-examine its defenses. Woodring resigned, and an eager Johnson was ready to take his place to re-instill confidence in the nation’s defenses against foreign threats.2

His enthusiasm was short-lived. President Roosevelt instead chose to appoint Henry Stimson as Secretary of Defense. Johnson felt betrayed.2 Johnson served as the personal representative of President Roosevelt in India, where he forged a lasting friendship with Jawaharlal Nehru, the first Prime Minister of India.

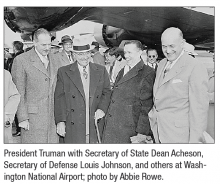

The 1948 presidential campaign was Johnson’s turn of fate. He aggressively raised funds for President Truman’s campaign and explicitly communicated his interest in serving as Secretary of Defense to the President, emphasizing that his goals for the nation’s defense were in line with those of Truman. Both favored aggressive elimination of unnecessary spending as well as unification of the military to minimize redundancies. In 1949, President Truman asked Johnson to replace James V. Forrestal, the acting Secretary of Defense.1

Johnson’s legacy as Defense Secretary was controversial from the beginning. His overarching goal was to cut any military spending that he deemed superfluous, proclaiming that taxpayers would receive “a dollar’s worth of defense for every dollar spent.”1 He and President Truman were confident that the atomic bomb would curtail most foreign aggression.

He faced enormous push back from military leaders in charge of ambitious expansion projects. The animosity amplified abruptly when Johnson canceled construction of the aircraft carrier USS United States, a multiyear construction effort by the US Navy already in progress. Johnson had not consulted with Congress or the Department of the Navy before announcing this cancellation. John L. Sullivan, the Secretary of the Navy, resigned in exasperation amidst the confusion and voiced his concerns about the future of the nation’s defense.1

Other branches of the military also experienced reductions, fueling an atmosphere of competition for limited funds. The “Revolt of the Admirals” that followed the scrapping of the United States was a salient example of this struggle, as leaders of the Navy and Air Force bitterly quarreled to earn Johnson’s approval for their respective expenses. Tensions rose to a peak in June 1949, when the House Committee on Armed Services commissioned a formal investigation of malfeasance against Secretary Johnson and the Air Force Secretary, likely at the behest of the Navy. These hearings challenged the entirety of Johnson’s platform, criticizing him for the United States cancellation, the feasibility of deterring foreign aggression with nuclear deterrence, and his overarching plan for military unification. After a lengthy series of charges, Johnson survived as the Committee found no convincing evidence of malfeasance. They also chose to support his plans for military unification, albeit with an admonition against aggressive, hasty overunification. Although Johnson had originally intended to eliminate waste and promote cohesiveness by establishing a more unified defense, his budget cuts had the unfortunate effect of creating deep rifts between the branches of the military.1

Johnson supported the establishment of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) and the unified efforts of Soviet containment. However, in August 1949 the Soviets shocked the world with a successful atomic bomb test, and the Communists emerged victorious in the Chinese Civil War. In response, President Truman—with Johnson’s support—definitively called for development of the hydrogen bomb. In collaboration with the State Department, Johnson coauthored NSC 68, a top-secret report detailing nuclear expansion, Soviet containment, and aid to allies that laid the groundwork for militarization from the Cold War to the collapse of the Soviet Union in the 1990s.1

Despite the mounting threats, Johnson remained steadfast in his commitment to defense budgeting. The consequences of his economizing were felt at the beginning of the Korean War, as US and South Korean forces lacked adequate supplies to hold back the advance from the North Koreans. The rearguard operations that ensued proved to be extremely costly, and Johnson was forced to acknowledge that, “we have reached the point where the military considerations clearly outweigh the fiscal considerations.”4,5 In response to widespread public outcry over the progress in Korea, Truman asked Johnson to resign as Secretary of Defense, paving the way for George Marshall, General of the Army.

With his resignation, Johnson saw the end of his career in politics. He died in 1966 of a stroke but not before the Louis A. Johnson VA Medical Center, was dedicated in his honor on December 7, 1950.6

Despite the controversies surrounding his tenure, Johnson prioritized the well-being of the US more than anything else. At the end of his term, he solemnly paraphrased Macbeth, “When the hurly burly’s done and the battle is won, I trust the historian will find my record of performance creditable, my services honest and faithful commensurate with the trust that was placed in me and in the best interests of peace and our national defense.”

About this column

This column provides biographical sketches of the namesakes of military and VA health care facilities. To learn more about the individual your facility was named for or to offer a topic suggestion, contact us at fedprac@frontlinemedcom.com or on Facebook.

1. US Department of Defense, Office of the Secretary of Defense, Historical Office. Louis A. Johnson – Harry S. Truman Administration. http://history.defense.gov/Multimedia/Biographies/Article-View/Article/571265/. Accessed June 20, 2018.

2. Master of the Pentagon, Time. 1949;53(23).

3. LaFeber W. America, Russia, and the Cold War, 1945-1992. 7th edition New York: McGraw-Hill; 1993.

4. Zabecki DT. Stand or die—1950 defense of Korea’s Pusan perimeter. http://www.historynet.com/magazines/military_history. Published May 1, 2009. Accessed June 20, 2018.

5. McFarland KD, Roll DL. Louis Johnson and the Arming of America: The Roosevelt And Truman Years. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press; 2005.

6. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Louis A. Johnson Medical Center. https://www.clarksburg.va.gov/about/history.asp. Updated June 9, 2015. Accessed June 20, 2018.

The VA Medical Center in Clarksburg, West Virginia, is named in honor of Louis Arthur Johnson, the Secretary of Defense under President Truman. Johnson cultivated a diversity of viewpoints and experiences before becoming Secretary of Defense. He was born in Roanoke, Virginia, in 1891, and he earned a law degree from the University of Virginia. Two years later, he began his foray into politics with election to the West Virginia House of Delegates, where he acted as Majority Floor Leader and Chair of the Judiciary Committee.1

Johnson served as an Infantry Captain in France during World War I, fighting in the Meuse-Argonne Offensive and earning the Legion of Honor of France. During his service, he gained insight into the military logistics by presenting a lengthy report on Army management and materiel requisition to the War Department—a foreshadowing of his eventual commitment to military budget restructuring as Secretary of Defense. After returning from the war, he practiced law and focused his efforts on aiding veterans, eventually securing the role of National Commander of the American Legion.1

Johnson was Assistant Secretary of War from 1937 to 1940 under President Franklin D. Roosevelt. Johnson frequently disagreed with the policies of Harry Hines Woodring, the acting Secretary of War who was a committed isolationist. While Johnson was adamant about providing military assistance to Great Britain during World War II, Woodring’s isolationism prevailed. However, in 1940, the fall of France forced the US to re-examine its defenses. Woodring resigned, and an eager Johnson was ready to take his place to re-instill confidence in the nation’s defenses against foreign threats.2

His enthusiasm was short-lived. President Roosevelt instead chose to appoint Henry Stimson as Secretary of Defense. Johnson felt betrayed.2 Johnson served as the personal representative of President Roosevelt in India, where he forged a lasting friendship with Jawaharlal Nehru, the first Prime Minister of India.

The 1948 presidential campaign was Johnson’s turn of fate. He aggressively raised funds for President Truman’s campaign and explicitly communicated his interest in serving as Secretary of Defense to the President, emphasizing that his goals for the nation’s defense were in line with those of Truman. Both favored aggressive elimination of unnecessary spending as well as unification of the military to minimize redundancies. In 1949, President Truman asked Johnson to replace James V. Forrestal, the acting Secretary of Defense.1

Johnson’s legacy as Defense Secretary was controversial from the beginning. His overarching goal was to cut any military spending that he deemed superfluous, proclaiming that taxpayers would receive “a dollar’s worth of defense for every dollar spent.”1 He and President Truman were confident that the atomic bomb would curtail most foreign aggression.

He faced enormous push back from military leaders in charge of ambitious expansion projects. The animosity amplified abruptly when Johnson canceled construction of the aircraft carrier USS United States, a multiyear construction effort by the US Navy already in progress. Johnson had not consulted with Congress or the Department of the Navy before announcing this cancellation. John L. Sullivan, the Secretary of the Navy, resigned in exasperation amidst the confusion and voiced his concerns about the future of the nation’s defense.1

Other branches of the military also experienced reductions, fueling an atmosphere of competition for limited funds. The “Revolt of the Admirals” that followed the scrapping of the United States was a salient example of this struggle, as leaders of the Navy and Air Force bitterly quarreled to earn Johnson’s approval for their respective expenses. Tensions rose to a peak in June 1949, when the House Committee on Armed Services commissioned a formal investigation of malfeasance against Secretary Johnson and the Air Force Secretary, likely at the behest of the Navy. These hearings challenged the entirety of Johnson’s platform, criticizing him for the United States cancellation, the feasibility of deterring foreign aggression with nuclear deterrence, and his overarching plan for military unification. After a lengthy series of charges, Johnson survived as the Committee found no convincing evidence of malfeasance. They also chose to support his plans for military unification, albeit with an admonition against aggressive, hasty overunification. Although Johnson had originally intended to eliminate waste and promote cohesiveness by establishing a more unified defense, his budget cuts had the unfortunate effect of creating deep rifts between the branches of the military.1

Johnson supported the establishment of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) and the unified efforts of Soviet containment. However, in August 1949 the Soviets shocked the world with a successful atomic bomb test, and the Communists emerged victorious in the Chinese Civil War. In response, President Truman—with Johnson’s support—definitively called for development of the hydrogen bomb. In collaboration with the State Department, Johnson coauthored NSC 68, a top-secret report detailing nuclear expansion, Soviet containment, and aid to allies that laid the groundwork for militarization from the Cold War to the collapse of the Soviet Union in the 1990s.1

Despite the mounting threats, Johnson remained steadfast in his commitment to defense budgeting. The consequences of his economizing were felt at the beginning of the Korean War, as US and South Korean forces lacked adequate supplies to hold back the advance from the North Koreans. The rearguard operations that ensued proved to be extremely costly, and Johnson was forced to acknowledge that, “we have reached the point where the military considerations clearly outweigh the fiscal considerations.”4,5 In response to widespread public outcry over the progress in Korea, Truman asked Johnson to resign as Secretary of Defense, paving the way for George Marshall, General of the Army.

With his resignation, Johnson saw the end of his career in politics. He died in 1966 of a stroke but not before the Louis A. Johnson VA Medical Center, was dedicated in his honor on December 7, 1950.6

Despite the controversies surrounding his tenure, Johnson prioritized the well-being of the US more than anything else. At the end of his term, he solemnly paraphrased Macbeth, “When the hurly burly’s done and the battle is won, I trust the historian will find my record of performance creditable, my services honest and faithful commensurate with the trust that was placed in me and in the best interests of peace and our national defense.”

About this column

This column provides biographical sketches of the namesakes of military and VA health care facilities. To learn more about the individual your facility was named for or to offer a topic suggestion, contact us at fedprac@frontlinemedcom.com or on Facebook.

The VA Medical Center in Clarksburg, West Virginia, is named in honor of Louis Arthur Johnson, the Secretary of Defense under President Truman. Johnson cultivated a diversity of viewpoints and experiences before becoming Secretary of Defense. He was born in Roanoke, Virginia, in 1891, and he earned a law degree from the University of Virginia. Two years later, he began his foray into politics with election to the West Virginia House of Delegates, where he acted as Majority Floor Leader and Chair of the Judiciary Committee.1

Johnson served as an Infantry Captain in France during World War I, fighting in the Meuse-Argonne Offensive and earning the Legion of Honor of France. During his service, he gained insight into the military logistics by presenting a lengthy report on Army management and materiel requisition to the War Department—a foreshadowing of his eventual commitment to military budget restructuring as Secretary of Defense. After returning from the war, he practiced law and focused his efforts on aiding veterans, eventually securing the role of National Commander of the American Legion.1

Johnson was Assistant Secretary of War from 1937 to 1940 under President Franklin D. Roosevelt. Johnson frequently disagreed with the policies of Harry Hines Woodring, the acting Secretary of War who was a committed isolationist. While Johnson was adamant about providing military assistance to Great Britain during World War II, Woodring’s isolationism prevailed. However, in 1940, the fall of France forced the US to re-examine its defenses. Woodring resigned, and an eager Johnson was ready to take his place to re-instill confidence in the nation’s defenses against foreign threats.2

His enthusiasm was short-lived. President Roosevelt instead chose to appoint Henry Stimson as Secretary of Defense. Johnson felt betrayed.2 Johnson served as the personal representative of President Roosevelt in India, where he forged a lasting friendship with Jawaharlal Nehru, the first Prime Minister of India.

The 1948 presidential campaign was Johnson’s turn of fate. He aggressively raised funds for President Truman’s campaign and explicitly communicated his interest in serving as Secretary of Defense to the President, emphasizing that his goals for the nation’s defense were in line with those of Truman. Both favored aggressive elimination of unnecessary spending as well as unification of the military to minimize redundancies. In 1949, President Truman asked Johnson to replace James V. Forrestal, the acting Secretary of Defense.1

Johnson’s legacy as Defense Secretary was controversial from the beginning. His overarching goal was to cut any military spending that he deemed superfluous, proclaiming that taxpayers would receive “a dollar’s worth of defense for every dollar spent.”1 He and President Truman were confident that the atomic bomb would curtail most foreign aggression.

He faced enormous push back from military leaders in charge of ambitious expansion projects. The animosity amplified abruptly when Johnson canceled construction of the aircraft carrier USS United States, a multiyear construction effort by the US Navy already in progress. Johnson had not consulted with Congress or the Department of the Navy before announcing this cancellation. John L. Sullivan, the Secretary of the Navy, resigned in exasperation amidst the confusion and voiced his concerns about the future of the nation’s defense.1

Other branches of the military also experienced reductions, fueling an atmosphere of competition for limited funds. The “Revolt of the Admirals” that followed the scrapping of the United States was a salient example of this struggle, as leaders of the Navy and Air Force bitterly quarreled to earn Johnson’s approval for their respective expenses. Tensions rose to a peak in June 1949, when the House Committee on Armed Services commissioned a formal investigation of malfeasance against Secretary Johnson and the Air Force Secretary, likely at the behest of the Navy. These hearings challenged the entirety of Johnson’s platform, criticizing him for the United States cancellation, the feasibility of deterring foreign aggression with nuclear deterrence, and his overarching plan for military unification. After a lengthy series of charges, Johnson survived as the Committee found no convincing evidence of malfeasance. They also chose to support his plans for military unification, albeit with an admonition against aggressive, hasty overunification. Although Johnson had originally intended to eliminate waste and promote cohesiveness by establishing a more unified defense, his budget cuts had the unfortunate effect of creating deep rifts between the branches of the military.1

Johnson supported the establishment of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) and the unified efforts of Soviet containment. However, in August 1949 the Soviets shocked the world with a successful atomic bomb test, and the Communists emerged victorious in the Chinese Civil War. In response, President Truman—with Johnson’s support—definitively called for development of the hydrogen bomb. In collaboration with the State Department, Johnson coauthored NSC 68, a top-secret report detailing nuclear expansion, Soviet containment, and aid to allies that laid the groundwork for militarization from the Cold War to the collapse of the Soviet Union in the 1990s.1

Despite the mounting threats, Johnson remained steadfast in his commitment to defense budgeting. The consequences of his economizing were felt at the beginning of the Korean War, as US and South Korean forces lacked adequate supplies to hold back the advance from the North Koreans. The rearguard operations that ensued proved to be extremely costly, and Johnson was forced to acknowledge that, “we have reached the point where the military considerations clearly outweigh the fiscal considerations.”4,5 In response to widespread public outcry over the progress in Korea, Truman asked Johnson to resign as Secretary of Defense, paving the way for George Marshall, General of the Army.

With his resignation, Johnson saw the end of his career in politics. He died in 1966 of a stroke but not before the Louis A. Johnson VA Medical Center, was dedicated in his honor on December 7, 1950.6

Despite the controversies surrounding his tenure, Johnson prioritized the well-being of the US more than anything else. At the end of his term, he solemnly paraphrased Macbeth, “When the hurly burly’s done and the battle is won, I trust the historian will find my record of performance creditable, my services honest and faithful commensurate with the trust that was placed in me and in the best interests of peace and our national defense.”

About this column

This column provides biographical sketches of the namesakes of military and VA health care facilities. To learn more about the individual your facility was named for or to offer a topic suggestion, contact us at fedprac@frontlinemedcom.com or on Facebook.

1. US Department of Defense, Office of the Secretary of Defense, Historical Office. Louis A. Johnson – Harry S. Truman Administration. http://history.defense.gov/Multimedia/Biographies/Article-View/Article/571265/. Accessed June 20, 2018.

2. Master of the Pentagon, Time. 1949;53(23).

3. LaFeber W. America, Russia, and the Cold War, 1945-1992. 7th edition New York: McGraw-Hill; 1993.

4. Zabecki DT. Stand or die—1950 defense of Korea’s Pusan perimeter. http://www.historynet.com/magazines/military_history. Published May 1, 2009. Accessed June 20, 2018.

5. McFarland KD, Roll DL. Louis Johnson and the Arming of America: The Roosevelt And Truman Years. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press; 2005.

6. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Louis A. Johnson Medical Center. https://www.clarksburg.va.gov/about/history.asp. Updated June 9, 2015. Accessed June 20, 2018.

1. US Department of Defense, Office of the Secretary of Defense, Historical Office. Louis A. Johnson – Harry S. Truman Administration. http://history.defense.gov/Multimedia/Biographies/Article-View/Article/571265/. Accessed June 20, 2018.

2. Master of the Pentagon, Time. 1949;53(23).

3. LaFeber W. America, Russia, and the Cold War, 1945-1992. 7th edition New York: McGraw-Hill; 1993.

4. Zabecki DT. Stand or die—1950 defense of Korea’s Pusan perimeter. http://www.historynet.com/magazines/military_history. Published May 1, 2009. Accessed June 20, 2018.

5. McFarland KD, Roll DL. Louis Johnson and the Arming of America: The Roosevelt And Truman Years. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press; 2005.

6. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Louis A. Johnson Medical Center. https://www.clarksburg.va.gov/about/history.asp. Updated June 9, 2015. Accessed June 20, 2018.