User login

Comparing Patient Care Models at a Local Free Clinic vs an Insurance- Based University Medical Center

Comparing Patient Care Models at a Local Free Clinic vs an Insurance- Based University Medical Center

Approximately 25% of Americans have at least one skin condition, and 20% are estimated to develop skin cancer during their lifetime.1,2 However, 40% of the US population lives in areas underserved by dermatologists. 3 The severity and mortality of skin cancers such as melanoma and mycosis fungoides have been positively associated with minoritized race, lack of health insurance, and unstable housing status.4-6 Patients who receive health care at free clinics often are of a racial or ethnic minoritized social group, are uninsured, and/or lack stable housing; this underserved group also includes recent immigrants to the United States who have limited English proficiency (LEP).7 Only 25% of free clinics offer specialty care services such as dermatology.7,8

Of the 42 free clinics and Federally Qualified Health Centers in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, the Birmingham Free Clinic (BFC) is one of the few that offers specialty care services including dermatology.9 Founded in 1994, the BFC serves as a safety net for Pittsburgh’s medically underserved population, offering primary and acute care, medication access, and social services. From January 2020 to May 2022, the BFC offered 27 dermatology clinics that provided approximately 100 people with comprehensive care including full-body skin examinations, dermatologic diagnoses and treatments, minor procedures, and dermatopathology services.

In this study, we compared the BFC dermatology patient care model with that of the dermatology department at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center (UPMC), an insurance-based tertiary referral health care system in western Pennsylvania. By analyzing the demographics, dermatologic diagnoses, and management strategies of both the BFC and UPMC, we gained an understanding of how these patient care models differ and how they can be improved to care for diverse patient populations.

Methods

A retrospective chart review of dermatology patients seen in person at the BFC and UPMC during the period from January 2020 to May 2022 was performed. The UPMC group included patients seen by 3 general dermatologists (including A.J.J.) at matched time points. Data were collected from patients’ first in-person visit during the study period. Variables of interest included patient age, sex, race, ethnicity, primary language, zip code, health insurance status, distance to clinic (estimated using Google Maps to calculate the shortest driving distance from the patient’s zip code to the clinic), history of skin cancer, dermatologic diagnoses, and management strategies. These variables were not collected for patients who cancelled or noshowed their first in-person appointments. All patient charts and notes corresponding to the date and visit of interest were accessed through the electronic medical record (EMR). Patient data were de-identified and stored in a password-protected spreadsheet. Comparisons between the BFC and UPMC patient populations were performed using X2 tests of independence, Fisher exact tests, and Mann-Whitney U tests via SPSS software (IBM). Statistical significance was set at P<.05.

Results

Patient Characteristics—Our analysis included 76 initial appointments at the BFC and 322 at UPMC (Table 1). The mean age for patients at the BFC and UPMC was 39.6 years and 47.8 years, respectively (P=.001). Males accounted for 39 (51.3%) and 112 (34.8%) of BFC and UPMC patients, respectively (P=.008); 2 (0.6%) patients from UPMC were transgender. Of the BFC and UPMC patients, 44.7% (34/76) and 0.9% (3/322) were Hispanic, respectively (P<.001). With regard to race, 52.6% (40/76) of BFC patients were White, 19.7% (15/76) were Black, 6.6% (5/76) were Asian/Pacific Islander (Chinese, 1.3% [1/76]; other Asian, 5.3% [4/76]), and 21.1% (16/76) were American Indian/other/unspecified (American Indian, 1.3% [1/76]; other, 13.2% [10/76]; unspecified, 6.6% [5/76]). At UPMC, 61.2% (197/322) of patients were White, 28.0% (90/322) were Black, 5.3% (17/322) were Asian/Pacific Islander (Chinese, 1.2% [4/322]; Indian [Asian], 1.9% [6/322]; Japanese, 0.3% [1/322]; other Asian, 1.6% [5/322]; other Asian/American Indian, 0.3% [1/322]), and 5.6% (18/322) were American Indian/other/ unspecified (American Indian, 0.3% [1/322]; other, 0.3% [1/322]; unspecified, 5.0% [16/322]). Overall, the BFC patient population was more ethnically and racially diverse than that of UPMC (P<.001).

Forty-six percent (35/76) of BFC patients and 4.3% (14/322) of UPMC patients had LEP (P<.001). Primary languages among BFC patients were 53.9% (41/76) English, 40.8% (31/76) Spanish, and 5.2% (4/76) other/ unspecified (Chinese, 1.3% [1/76]; Indonesian, 2.6% [2/76]; unspecified, 1.3% [1/76]). Primary languages among UPMC patients were 95.7% (308/322) English and 4.3% (14/322) other/unspecified (Chinese, 0.6% [2/322]; Nepali, 0.6% [2/322]; Pali, 0.3% [1/322]; Russian, 0.3% [1/322]; unspecified, 2.5% [8/322]). There were notable differences in insurance status at the BFC vs UPMC (P<.001), with more UPMC patients having private insurance (52.8% [170/322] vs 11.8% [9/76]) and more BFC patients being uninsured (52.8% [51/76] vs 1.9% [6/322]). There was no significant difference in distance to clinic between the 2 groups (P=.183). More UPMC patients had a history of skin cancer (P=.003). More patients at the BFC were no-shows for their appointments (P<.001), and UPMC patients more frequently canceled their appointments (P<.001).

Dermatologic Diagnoses—The most commonly diagnosed dermatologic conditions at the BFC were dermatitis (23.7% [18/76]), neoplasm of uncertain behavior (15.8% [12/76]), alopecia (11.8% [9/76]), and acne (10.5% [8/76]) (Table 2). The most commonly diagnosed conditions at UPMC were nevi (26.4% [85/322]), dermatitis (22.7% [73/322]), seborrheic keratosis (21.7% [70/322]), and skin cancer screening (21.4% [70/322]). Neoplasm of uncertain behavior was more common in BFC vs UPMC patients (P=.040), while UPMC patients were more frequently diagnosed with nevi (P<.001), seborrheic keratosis (P<.001), and skin cancer screening (P<.001). There was no significant difference between the incidence of skin cancer diagnoses in the BFC (1.3% [1/76]) and UPMC (0.6% [2/76]) patient populations (P=.471). Among the biopsied neoplasms, there was also no significant difference in malignant (BFC, 50.0% [5/10]; UPMC, 32.0% [8/25]) and benign (BFC, 50.0% [5/10]; UPMC, 36.0% [9/25]) neoplasms diagnosed at each clinic (P=.444).

Management Strategies—Systemic antibiotics were more frequently prescribed (P<.001) and laboratory testing/ imaging were more frequently ordered (P=.005) at the BFC vs UPMC (Table 3). Patients at the BFC also more frequently required emergency insurance (P=.036). Patients at UPMC were more frequently recommended sunscreen (P=.003) and received education about skin cancer signs by review of the ABCDEs of melanoma (P<.001), sun-protective behaviors (P=.001), and skin examination frequency (P<.001). Notes in the EMR for UPMC patients more frequently specified patient followup instructions (P<.001).

Comment

As of 2020, the city of Pittsburgh had an estimated population of nearly 303,000 based on US Census data.10 Its population is predominantly White (62.7%) followed by Black/African American (22.8%) and Asian (6.5%); 5.9% identify as 2 or more races. Approximately 3.8% identify as Hispanic or Latino. More than 11% of the Pittsburgh population aged 5 years and older speaks a language other than English as their primary language, including Spanish (2.3%), other Indo-European languages (3.9%), and Asian and Pacific Island languages (3.5%).11 More than 5% of the Pittsburgh population does not have health insurance.12

The BFC is located in Pittsburgh’s South Side area, while one of UPMC’s primary dermatology clinics is located in the Oakland district; however, most patients who seek care at these clinics live outside these areas. Our study results indicated that the BFC and UPMC serve distinct groups of people within the Pittsburgh population. The BFC patient population was younger with a higher percentage of patients who were male, Hispanic, racially diverse, and with LEP compared with the UPMC patient population. In this clinical setting, the BFC health care team engages with people from diverse backgrounds and requires greater interpreter and medical support services.

The BFC largely is supported by volunteers, UPMC, grants, and philanthropy. Dermatology clinics are staffed by paid and volunteer team members. Paid team members include 1 nurse and 1 access lead who operates the front desk and registration. Volunteer team members include 1 board-certified dermatologist from UPMC (A.J.J.), or an affiliate clinic and 1 or 2 of each of the following: UPMC dermatology residents, medical or undergraduate students from the University of Pittsburgh, AmeriCorps national service members, and student or community medical interpreters. The onsite pharmacy is run by volunteer faculty, resident, and student pharmacists from the University of Pittsburgh. Dermatology clinics are half-day clinics that occur monthly. Volunteers for each clinic are recruited approximately 1 month in advance.

Dermatology patients at the BFC are referred from the BFC general medicine clinic and nearby Federally Qualified Health Center s for simple to complex medical and surgical dermatologic skin conditions. Each BFC dermatology clinic schedules an average of 7 patients per clinic and places other patients on a wait-list unless more urgent triage is needed. Patients are notified when they are scheduled via phone or text message, and they receive a reminder call or text 1 or 2 days prior to their appointment that also asks them to confirm attendance. Patients with LEP are called with an interpreter and also may receive text reminders that can be translated using Google Translate. Patients are instructed to notify the BFC if they need to cancel or reschedule their appointment. At the end of each visit, patients are given an after-visit summary that lists follow-up instructions, medications prescribed during the visit, and upcoming appointments. The BFC offers bus tickets to help patients get to their appointments. In rare cases, the BFC may pay for a car service to drive patients to and from the clinic.

Dermatology clinics at UPMC use scheduling and self-scheduling systems through which patients can make appointments at a location of their choice with any available board-certified dermatologist or physician assistant. Patients receive a reminder phone call 3 days prior to their appointment instructing them to call the office if they are unable to keep their appointment. Patients signed up for the online portal also receive a reminder message and an option to confirm or cancel their appointment. Patients with cell phone numbers in the UPMC system receive a text message approximately 2 days prior to their appointment that allows them to preregister and pay their copayment in advance. They receive another text 20 minutes prior to their appointment with an option for contactless check-in. At the conclusion of their visit, patients can schedule a follow-up appointment and receive a printed copy of their after-visit summary that provides information about follow-up instructions, prescribed medications, and upcoming visits. They may alternatively access this summary via the online patient portal. Patients are not provided transportation to UPMC clinics, but they are offered parking validation.

Among the most common dermatologic diagnoses for each group, BFC patients presented for treatment of more acute dermatologic conditions, while UPMC patients presented for more benign and preventive-care conditions. This difference may be attributable to the BFC’s referral and triage system, wherein patients with more urgent problems are given scheduling priority. This patient care model contrasts with UPMC’s scheduling process in which no known formal triage system is utilized. Interestingly, there was no difference in skin cancer incidence despite a higher percentage of preventive skin cancer screenings at UPMC.

Patients at the BFC more often required emergency insurance for surgical interventions, which is consistent with the higher percentage of uninsured individuals in this population. Patients at UPMC more frequently were recommended sunscreen and were educated about skin cancer, sun protection, and skin examination, in part due to this group’s more extensive history of skin cancer and frequent presentation for skin cancer screenings. At the same time, educational materials for skin care at both the BFC and UPMC are populated into the EMR in English, whereas materials in other languages are less readily available.

Our retrospective study had several limitations. Demographic information that relied on clinic-dependent intake questionnaires may be limited due to variable intake processes and patients opting out of self-reporting. By comparing patient populations between 2 clinics, confounding variables such as location and hours of operation may impact the patient demographics recorded at the BFC vs UPMC. Resources and staff availability may affect the management strategies and follow-up care offered by each clinic. Our study period also was unique in that COVID-19 may have affected resources, staffing, scheduling, and logistics at both clinics.

Based on the aforementioned differences between the BFC and UPMC patient characteristics, care models should be strategically designed to support the needs of diverse populations. The BFC patient care model appropriately focuses on communication skills with patients with LEP by using interpreter services. Providing more skin care education and follow-up instructions in patients’ primary languages will help them develop a better understanding of their skin conditions. Another key asset of the BFC patient care model is its provision of social services such as transportation and insurance assistance.

To improve the UPMC patient care model, providing patients with bus tickets and car services may potentially reduce appointment cancellations. Using interpreter services to call and text appointment reminders, as well as interpreter resources to facilitate patient visits and patient instructions, also can mitigate language barriers for patients with LEP. Implementing a triage system into the UPMC scheduling system may help patients with more urgent skin conditions to be seen in a timely manner.

Other investigators have analyzed costs of care and proven the value of dermatologic services at free clinics to guide allocation of supplies and resources, demonstrating an area for future investigation at the BFC.13 A cost analysis of care provided at the BFC compared to UPMC could inform us about the value of the BFC’s services.

Conclusion

The dermatology clinics at the BFC and UPMC have distinct demographics, diagnoses, and management strategies to provide an inclusive patient care model. The services provided by both clinics are necessary to ensure that people in Pittsburgh have access to dermatologic care regardless of social barriers (eg, lack of health insurance, LEP). To achieve greater accessibility and health equity, dermatologic care at the BFC and UPMC can be improved by strengthening communication with people with LEP, providing skin care education, and offering social and scheduling services.

- Lim HW, Collins SAB, Resneck JS, et al. The burden of skin disease in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:958-972.e2. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2016.12.043

- American Academy of Dermatology. Skin cancer. Accessed October 7, 2024. https://www.aad.org/media/stats-skin-cancer

- Suneja T, Smith ED, Chen GJ, et al. Waiting times to see a dermatologist are perceived as too long by dermatologists: implications for the dermatology workforce. Arch Dermatol. 2001;137:1303-1307. doi:10.1001/archderm.137.10.1303

- Grossberg AL, Carranza D, Lamp K, et al. Dermatologic care in the homeless and underserved populations: observations from the Venice Family Clinic. Cutis. 2012;89:25-32.

- Amini A, Rusthoven CG, Waxweiler TV, et al. Association of health insurance with outcomes in adults ages 18 to 64 years with melanoma in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:309-316. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.09.054

- Su C, Nguyen KA, Bai HX, et al. Racial disparity in mycosis fungoides: an analysis of 4495 cases from the US National Cancer Database. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:497-502.e2. doi:10.1016/j.jaad .2017.04.1137

- Darnell JS. Free clinics in the United States: a nationwide survey. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170:946-953. doi:10.1001/archinternmed .2010.107

- Madray V, Ginjupalli S, Hashmi O, et al. Access to dermatology services at free medical clinics: a nationwide cross-sectional survey. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:245-246. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.12.011

- Pennsylvania free and income-based clinics. Accessed October 7, 2024. https://www.freeclinics.com/sta/pennsylvania

- United States Census Bureau. Decennial census. P1: race. Accessed October 7, 2024. https://data.census.gov/table/DECENNIALPL2020.P1?g=160XX00US4261000

- United States Census Bureau. American community survey. S1601: language spoken at home. Accessed October 7, 2024. https://data.census.gov/table/ACSST5Y2020S1601?g=160XX00US4261000

- United States Census Bureau. S2701: selected characteristics of health insurance coverage in the United States. Accessed October 7, 2024. https://data.census.gov/table/ACSST5Y2020.S2701?g=160XX00US4261000

- Lin CP, Loy S, Boothe WD, et al. Value of Dermatology Nights at a student-run free clinic. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2020;34:260-261. doi:10.1080/08998280.2020.1834771

Approximately 25% of Americans have at least one skin condition, and 20% are estimated to develop skin cancer during their lifetime.1,2 However, 40% of the US population lives in areas underserved by dermatologists. 3 The severity and mortality of skin cancers such as melanoma and mycosis fungoides have been positively associated with minoritized race, lack of health insurance, and unstable housing status.4-6 Patients who receive health care at free clinics often are of a racial or ethnic minoritized social group, are uninsured, and/or lack stable housing; this underserved group also includes recent immigrants to the United States who have limited English proficiency (LEP).7 Only 25% of free clinics offer specialty care services such as dermatology.7,8

Of the 42 free clinics and Federally Qualified Health Centers in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, the Birmingham Free Clinic (BFC) is one of the few that offers specialty care services including dermatology.9 Founded in 1994, the BFC serves as a safety net for Pittsburgh’s medically underserved population, offering primary and acute care, medication access, and social services. From January 2020 to May 2022, the BFC offered 27 dermatology clinics that provided approximately 100 people with comprehensive care including full-body skin examinations, dermatologic diagnoses and treatments, minor procedures, and dermatopathology services.

In this study, we compared the BFC dermatology patient care model with that of the dermatology department at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center (UPMC), an insurance-based tertiary referral health care system in western Pennsylvania. By analyzing the demographics, dermatologic diagnoses, and management strategies of both the BFC and UPMC, we gained an understanding of how these patient care models differ and how they can be improved to care for diverse patient populations.

Methods

A retrospective chart review of dermatology patients seen in person at the BFC and UPMC during the period from January 2020 to May 2022 was performed. The UPMC group included patients seen by 3 general dermatologists (including A.J.J.) at matched time points. Data were collected from patients’ first in-person visit during the study period. Variables of interest included patient age, sex, race, ethnicity, primary language, zip code, health insurance status, distance to clinic (estimated using Google Maps to calculate the shortest driving distance from the patient’s zip code to the clinic), history of skin cancer, dermatologic diagnoses, and management strategies. These variables were not collected for patients who cancelled or noshowed their first in-person appointments. All patient charts and notes corresponding to the date and visit of interest were accessed through the electronic medical record (EMR). Patient data were de-identified and stored in a password-protected spreadsheet. Comparisons between the BFC and UPMC patient populations were performed using X2 tests of independence, Fisher exact tests, and Mann-Whitney U tests via SPSS software (IBM). Statistical significance was set at P<.05.

Results

Patient Characteristics—Our analysis included 76 initial appointments at the BFC and 322 at UPMC (Table 1). The mean age for patients at the BFC and UPMC was 39.6 years and 47.8 years, respectively (P=.001). Males accounted for 39 (51.3%) and 112 (34.8%) of BFC and UPMC patients, respectively (P=.008); 2 (0.6%) patients from UPMC were transgender. Of the BFC and UPMC patients, 44.7% (34/76) and 0.9% (3/322) were Hispanic, respectively (P<.001). With regard to race, 52.6% (40/76) of BFC patients were White, 19.7% (15/76) were Black, 6.6% (5/76) were Asian/Pacific Islander (Chinese, 1.3% [1/76]; other Asian, 5.3% [4/76]), and 21.1% (16/76) were American Indian/other/unspecified (American Indian, 1.3% [1/76]; other, 13.2% [10/76]; unspecified, 6.6% [5/76]). At UPMC, 61.2% (197/322) of patients were White, 28.0% (90/322) were Black, 5.3% (17/322) were Asian/Pacific Islander (Chinese, 1.2% [4/322]; Indian [Asian], 1.9% [6/322]; Japanese, 0.3% [1/322]; other Asian, 1.6% [5/322]; other Asian/American Indian, 0.3% [1/322]), and 5.6% (18/322) were American Indian/other/ unspecified (American Indian, 0.3% [1/322]; other, 0.3% [1/322]; unspecified, 5.0% [16/322]). Overall, the BFC patient population was more ethnically and racially diverse than that of UPMC (P<.001).

Forty-six percent (35/76) of BFC patients and 4.3% (14/322) of UPMC patients had LEP (P<.001). Primary languages among BFC patients were 53.9% (41/76) English, 40.8% (31/76) Spanish, and 5.2% (4/76) other/ unspecified (Chinese, 1.3% [1/76]; Indonesian, 2.6% [2/76]; unspecified, 1.3% [1/76]). Primary languages among UPMC patients were 95.7% (308/322) English and 4.3% (14/322) other/unspecified (Chinese, 0.6% [2/322]; Nepali, 0.6% [2/322]; Pali, 0.3% [1/322]; Russian, 0.3% [1/322]; unspecified, 2.5% [8/322]). There were notable differences in insurance status at the BFC vs UPMC (P<.001), with more UPMC patients having private insurance (52.8% [170/322] vs 11.8% [9/76]) and more BFC patients being uninsured (52.8% [51/76] vs 1.9% [6/322]). There was no significant difference in distance to clinic between the 2 groups (P=.183). More UPMC patients had a history of skin cancer (P=.003). More patients at the BFC were no-shows for their appointments (P<.001), and UPMC patients more frequently canceled their appointments (P<.001).

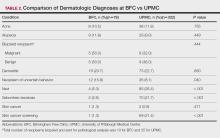

Dermatologic Diagnoses—The most commonly diagnosed dermatologic conditions at the BFC were dermatitis (23.7% [18/76]), neoplasm of uncertain behavior (15.8% [12/76]), alopecia (11.8% [9/76]), and acne (10.5% [8/76]) (Table 2). The most commonly diagnosed conditions at UPMC were nevi (26.4% [85/322]), dermatitis (22.7% [73/322]), seborrheic keratosis (21.7% [70/322]), and skin cancer screening (21.4% [70/322]). Neoplasm of uncertain behavior was more common in BFC vs UPMC patients (P=.040), while UPMC patients were more frequently diagnosed with nevi (P<.001), seborrheic keratosis (P<.001), and skin cancer screening (P<.001). There was no significant difference between the incidence of skin cancer diagnoses in the BFC (1.3% [1/76]) and UPMC (0.6% [2/76]) patient populations (P=.471). Among the biopsied neoplasms, there was also no significant difference in malignant (BFC, 50.0% [5/10]; UPMC, 32.0% [8/25]) and benign (BFC, 50.0% [5/10]; UPMC, 36.0% [9/25]) neoplasms diagnosed at each clinic (P=.444).

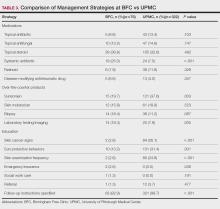

Management Strategies—Systemic antibiotics were more frequently prescribed (P<.001) and laboratory testing/ imaging were more frequently ordered (P=.005) at the BFC vs UPMC (Table 3). Patients at the BFC also more frequently required emergency insurance (P=.036). Patients at UPMC were more frequently recommended sunscreen (P=.003) and received education about skin cancer signs by review of the ABCDEs of melanoma (P<.001), sun-protective behaviors (P=.001), and skin examination frequency (P<.001). Notes in the EMR for UPMC patients more frequently specified patient followup instructions (P<.001).

Comment

As of 2020, the city of Pittsburgh had an estimated population of nearly 303,000 based on US Census data.10 Its population is predominantly White (62.7%) followed by Black/African American (22.8%) and Asian (6.5%); 5.9% identify as 2 or more races. Approximately 3.8% identify as Hispanic or Latino. More than 11% of the Pittsburgh population aged 5 years and older speaks a language other than English as their primary language, including Spanish (2.3%), other Indo-European languages (3.9%), and Asian and Pacific Island languages (3.5%).11 More than 5% of the Pittsburgh population does not have health insurance.12

The BFC is located in Pittsburgh’s South Side area, while one of UPMC’s primary dermatology clinics is located in the Oakland district; however, most patients who seek care at these clinics live outside these areas. Our study results indicated that the BFC and UPMC serve distinct groups of people within the Pittsburgh population. The BFC patient population was younger with a higher percentage of patients who were male, Hispanic, racially diverse, and with LEP compared with the UPMC patient population. In this clinical setting, the BFC health care team engages with people from diverse backgrounds and requires greater interpreter and medical support services.

The BFC largely is supported by volunteers, UPMC, grants, and philanthropy. Dermatology clinics are staffed by paid and volunteer team members. Paid team members include 1 nurse and 1 access lead who operates the front desk and registration. Volunteer team members include 1 board-certified dermatologist from UPMC (A.J.J.), or an affiliate clinic and 1 or 2 of each of the following: UPMC dermatology residents, medical or undergraduate students from the University of Pittsburgh, AmeriCorps national service members, and student or community medical interpreters. The onsite pharmacy is run by volunteer faculty, resident, and student pharmacists from the University of Pittsburgh. Dermatology clinics are half-day clinics that occur monthly. Volunteers for each clinic are recruited approximately 1 month in advance.

Dermatology patients at the BFC are referred from the BFC general medicine clinic and nearby Federally Qualified Health Center s for simple to complex medical and surgical dermatologic skin conditions. Each BFC dermatology clinic schedules an average of 7 patients per clinic and places other patients on a wait-list unless more urgent triage is needed. Patients are notified when they are scheduled via phone or text message, and they receive a reminder call or text 1 or 2 days prior to their appointment that also asks them to confirm attendance. Patients with LEP are called with an interpreter and also may receive text reminders that can be translated using Google Translate. Patients are instructed to notify the BFC if they need to cancel or reschedule their appointment. At the end of each visit, patients are given an after-visit summary that lists follow-up instructions, medications prescribed during the visit, and upcoming appointments. The BFC offers bus tickets to help patients get to their appointments. In rare cases, the BFC may pay for a car service to drive patients to and from the clinic.

Dermatology clinics at UPMC use scheduling and self-scheduling systems through which patients can make appointments at a location of their choice with any available board-certified dermatologist or physician assistant. Patients receive a reminder phone call 3 days prior to their appointment instructing them to call the office if they are unable to keep their appointment. Patients signed up for the online portal also receive a reminder message and an option to confirm or cancel their appointment. Patients with cell phone numbers in the UPMC system receive a text message approximately 2 days prior to their appointment that allows them to preregister and pay their copayment in advance. They receive another text 20 minutes prior to their appointment with an option for contactless check-in. At the conclusion of their visit, patients can schedule a follow-up appointment and receive a printed copy of their after-visit summary that provides information about follow-up instructions, prescribed medications, and upcoming visits. They may alternatively access this summary via the online patient portal. Patients are not provided transportation to UPMC clinics, but they are offered parking validation.

Among the most common dermatologic diagnoses for each group, BFC patients presented for treatment of more acute dermatologic conditions, while UPMC patients presented for more benign and preventive-care conditions. This difference may be attributable to the BFC’s referral and triage system, wherein patients with more urgent problems are given scheduling priority. This patient care model contrasts with UPMC’s scheduling process in which no known formal triage system is utilized. Interestingly, there was no difference in skin cancer incidence despite a higher percentage of preventive skin cancer screenings at UPMC.

Patients at the BFC more often required emergency insurance for surgical interventions, which is consistent with the higher percentage of uninsured individuals in this population. Patients at UPMC more frequently were recommended sunscreen and were educated about skin cancer, sun protection, and skin examination, in part due to this group’s more extensive history of skin cancer and frequent presentation for skin cancer screenings. At the same time, educational materials for skin care at both the BFC and UPMC are populated into the EMR in English, whereas materials in other languages are less readily available.

Our retrospective study had several limitations. Demographic information that relied on clinic-dependent intake questionnaires may be limited due to variable intake processes and patients opting out of self-reporting. By comparing patient populations between 2 clinics, confounding variables such as location and hours of operation may impact the patient demographics recorded at the BFC vs UPMC. Resources and staff availability may affect the management strategies and follow-up care offered by each clinic. Our study period also was unique in that COVID-19 may have affected resources, staffing, scheduling, and logistics at both clinics.

Based on the aforementioned differences between the BFC and UPMC patient characteristics, care models should be strategically designed to support the needs of diverse populations. The BFC patient care model appropriately focuses on communication skills with patients with LEP by using interpreter services. Providing more skin care education and follow-up instructions in patients’ primary languages will help them develop a better understanding of their skin conditions. Another key asset of the BFC patient care model is its provision of social services such as transportation and insurance assistance.

To improve the UPMC patient care model, providing patients with bus tickets and car services may potentially reduce appointment cancellations. Using interpreter services to call and text appointment reminders, as well as interpreter resources to facilitate patient visits and patient instructions, also can mitigate language barriers for patients with LEP. Implementing a triage system into the UPMC scheduling system may help patients with more urgent skin conditions to be seen in a timely manner.

Other investigators have analyzed costs of care and proven the value of dermatologic services at free clinics to guide allocation of supplies and resources, demonstrating an area for future investigation at the BFC.13 A cost analysis of care provided at the BFC compared to UPMC could inform us about the value of the BFC’s services.

Conclusion

The dermatology clinics at the BFC and UPMC have distinct demographics, diagnoses, and management strategies to provide an inclusive patient care model. The services provided by both clinics are necessary to ensure that people in Pittsburgh have access to dermatologic care regardless of social barriers (eg, lack of health insurance, LEP). To achieve greater accessibility and health equity, dermatologic care at the BFC and UPMC can be improved by strengthening communication with people with LEP, providing skin care education, and offering social and scheduling services.

Approximately 25% of Americans have at least one skin condition, and 20% are estimated to develop skin cancer during their lifetime.1,2 However, 40% of the US population lives in areas underserved by dermatologists. 3 The severity and mortality of skin cancers such as melanoma and mycosis fungoides have been positively associated with minoritized race, lack of health insurance, and unstable housing status.4-6 Patients who receive health care at free clinics often are of a racial or ethnic minoritized social group, are uninsured, and/or lack stable housing; this underserved group also includes recent immigrants to the United States who have limited English proficiency (LEP).7 Only 25% of free clinics offer specialty care services such as dermatology.7,8

Of the 42 free clinics and Federally Qualified Health Centers in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, the Birmingham Free Clinic (BFC) is one of the few that offers specialty care services including dermatology.9 Founded in 1994, the BFC serves as a safety net for Pittsburgh’s medically underserved population, offering primary and acute care, medication access, and social services. From January 2020 to May 2022, the BFC offered 27 dermatology clinics that provided approximately 100 people with comprehensive care including full-body skin examinations, dermatologic diagnoses and treatments, minor procedures, and dermatopathology services.

In this study, we compared the BFC dermatology patient care model with that of the dermatology department at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center (UPMC), an insurance-based tertiary referral health care system in western Pennsylvania. By analyzing the demographics, dermatologic diagnoses, and management strategies of both the BFC and UPMC, we gained an understanding of how these patient care models differ and how they can be improved to care for diverse patient populations.

Methods

A retrospective chart review of dermatology patients seen in person at the BFC and UPMC during the period from January 2020 to May 2022 was performed. The UPMC group included patients seen by 3 general dermatologists (including A.J.J.) at matched time points. Data were collected from patients’ first in-person visit during the study period. Variables of interest included patient age, sex, race, ethnicity, primary language, zip code, health insurance status, distance to clinic (estimated using Google Maps to calculate the shortest driving distance from the patient’s zip code to the clinic), history of skin cancer, dermatologic diagnoses, and management strategies. These variables were not collected for patients who cancelled or noshowed their first in-person appointments. All patient charts and notes corresponding to the date and visit of interest were accessed through the electronic medical record (EMR). Patient data were de-identified and stored in a password-protected spreadsheet. Comparisons between the BFC and UPMC patient populations were performed using X2 tests of independence, Fisher exact tests, and Mann-Whitney U tests via SPSS software (IBM). Statistical significance was set at P<.05.

Results

Patient Characteristics—Our analysis included 76 initial appointments at the BFC and 322 at UPMC (Table 1). The mean age for patients at the BFC and UPMC was 39.6 years and 47.8 years, respectively (P=.001). Males accounted for 39 (51.3%) and 112 (34.8%) of BFC and UPMC patients, respectively (P=.008); 2 (0.6%) patients from UPMC were transgender. Of the BFC and UPMC patients, 44.7% (34/76) and 0.9% (3/322) were Hispanic, respectively (P<.001). With regard to race, 52.6% (40/76) of BFC patients were White, 19.7% (15/76) were Black, 6.6% (5/76) were Asian/Pacific Islander (Chinese, 1.3% [1/76]; other Asian, 5.3% [4/76]), and 21.1% (16/76) were American Indian/other/unspecified (American Indian, 1.3% [1/76]; other, 13.2% [10/76]; unspecified, 6.6% [5/76]). At UPMC, 61.2% (197/322) of patients were White, 28.0% (90/322) were Black, 5.3% (17/322) were Asian/Pacific Islander (Chinese, 1.2% [4/322]; Indian [Asian], 1.9% [6/322]; Japanese, 0.3% [1/322]; other Asian, 1.6% [5/322]; other Asian/American Indian, 0.3% [1/322]), and 5.6% (18/322) were American Indian/other/ unspecified (American Indian, 0.3% [1/322]; other, 0.3% [1/322]; unspecified, 5.0% [16/322]). Overall, the BFC patient population was more ethnically and racially diverse than that of UPMC (P<.001).

Forty-six percent (35/76) of BFC patients and 4.3% (14/322) of UPMC patients had LEP (P<.001). Primary languages among BFC patients were 53.9% (41/76) English, 40.8% (31/76) Spanish, and 5.2% (4/76) other/ unspecified (Chinese, 1.3% [1/76]; Indonesian, 2.6% [2/76]; unspecified, 1.3% [1/76]). Primary languages among UPMC patients were 95.7% (308/322) English and 4.3% (14/322) other/unspecified (Chinese, 0.6% [2/322]; Nepali, 0.6% [2/322]; Pali, 0.3% [1/322]; Russian, 0.3% [1/322]; unspecified, 2.5% [8/322]). There were notable differences in insurance status at the BFC vs UPMC (P<.001), with more UPMC patients having private insurance (52.8% [170/322] vs 11.8% [9/76]) and more BFC patients being uninsured (52.8% [51/76] vs 1.9% [6/322]). There was no significant difference in distance to clinic between the 2 groups (P=.183). More UPMC patients had a history of skin cancer (P=.003). More patients at the BFC were no-shows for their appointments (P<.001), and UPMC patients more frequently canceled their appointments (P<.001).

Dermatologic Diagnoses—The most commonly diagnosed dermatologic conditions at the BFC were dermatitis (23.7% [18/76]), neoplasm of uncertain behavior (15.8% [12/76]), alopecia (11.8% [9/76]), and acne (10.5% [8/76]) (Table 2). The most commonly diagnosed conditions at UPMC were nevi (26.4% [85/322]), dermatitis (22.7% [73/322]), seborrheic keratosis (21.7% [70/322]), and skin cancer screening (21.4% [70/322]). Neoplasm of uncertain behavior was more common in BFC vs UPMC patients (P=.040), while UPMC patients were more frequently diagnosed with nevi (P<.001), seborrheic keratosis (P<.001), and skin cancer screening (P<.001). There was no significant difference between the incidence of skin cancer diagnoses in the BFC (1.3% [1/76]) and UPMC (0.6% [2/76]) patient populations (P=.471). Among the biopsied neoplasms, there was also no significant difference in malignant (BFC, 50.0% [5/10]; UPMC, 32.0% [8/25]) and benign (BFC, 50.0% [5/10]; UPMC, 36.0% [9/25]) neoplasms diagnosed at each clinic (P=.444).

Management Strategies—Systemic antibiotics were more frequently prescribed (P<.001) and laboratory testing/ imaging were more frequently ordered (P=.005) at the BFC vs UPMC (Table 3). Patients at the BFC also more frequently required emergency insurance (P=.036). Patients at UPMC were more frequently recommended sunscreen (P=.003) and received education about skin cancer signs by review of the ABCDEs of melanoma (P<.001), sun-protective behaviors (P=.001), and skin examination frequency (P<.001). Notes in the EMR for UPMC patients more frequently specified patient followup instructions (P<.001).

Comment

As of 2020, the city of Pittsburgh had an estimated population of nearly 303,000 based on US Census data.10 Its population is predominantly White (62.7%) followed by Black/African American (22.8%) and Asian (6.5%); 5.9% identify as 2 or more races. Approximately 3.8% identify as Hispanic or Latino. More than 11% of the Pittsburgh population aged 5 years and older speaks a language other than English as their primary language, including Spanish (2.3%), other Indo-European languages (3.9%), and Asian and Pacific Island languages (3.5%).11 More than 5% of the Pittsburgh population does not have health insurance.12

The BFC is located in Pittsburgh’s South Side area, while one of UPMC’s primary dermatology clinics is located in the Oakland district; however, most patients who seek care at these clinics live outside these areas. Our study results indicated that the BFC and UPMC serve distinct groups of people within the Pittsburgh population. The BFC patient population was younger with a higher percentage of patients who were male, Hispanic, racially diverse, and with LEP compared with the UPMC patient population. In this clinical setting, the BFC health care team engages with people from diverse backgrounds and requires greater interpreter and medical support services.

The BFC largely is supported by volunteers, UPMC, grants, and philanthropy. Dermatology clinics are staffed by paid and volunteer team members. Paid team members include 1 nurse and 1 access lead who operates the front desk and registration. Volunteer team members include 1 board-certified dermatologist from UPMC (A.J.J.), or an affiliate clinic and 1 or 2 of each of the following: UPMC dermatology residents, medical or undergraduate students from the University of Pittsburgh, AmeriCorps national service members, and student or community medical interpreters. The onsite pharmacy is run by volunteer faculty, resident, and student pharmacists from the University of Pittsburgh. Dermatology clinics are half-day clinics that occur monthly. Volunteers for each clinic are recruited approximately 1 month in advance.

Dermatology patients at the BFC are referred from the BFC general medicine clinic and nearby Federally Qualified Health Center s for simple to complex medical and surgical dermatologic skin conditions. Each BFC dermatology clinic schedules an average of 7 patients per clinic and places other patients on a wait-list unless more urgent triage is needed. Patients are notified when they are scheduled via phone or text message, and they receive a reminder call or text 1 or 2 days prior to their appointment that also asks them to confirm attendance. Patients with LEP are called with an interpreter and also may receive text reminders that can be translated using Google Translate. Patients are instructed to notify the BFC if they need to cancel or reschedule their appointment. At the end of each visit, patients are given an after-visit summary that lists follow-up instructions, medications prescribed during the visit, and upcoming appointments. The BFC offers bus tickets to help patients get to their appointments. In rare cases, the BFC may pay for a car service to drive patients to and from the clinic.

Dermatology clinics at UPMC use scheduling and self-scheduling systems through which patients can make appointments at a location of their choice with any available board-certified dermatologist or physician assistant. Patients receive a reminder phone call 3 days prior to their appointment instructing them to call the office if they are unable to keep their appointment. Patients signed up for the online portal also receive a reminder message and an option to confirm or cancel their appointment. Patients with cell phone numbers in the UPMC system receive a text message approximately 2 days prior to their appointment that allows them to preregister and pay their copayment in advance. They receive another text 20 minutes prior to their appointment with an option for contactless check-in. At the conclusion of their visit, patients can schedule a follow-up appointment and receive a printed copy of their after-visit summary that provides information about follow-up instructions, prescribed medications, and upcoming visits. They may alternatively access this summary via the online patient portal. Patients are not provided transportation to UPMC clinics, but they are offered parking validation.

Among the most common dermatologic diagnoses for each group, BFC patients presented for treatment of more acute dermatologic conditions, while UPMC patients presented for more benign and preventive-care conditions. This difference may be attributable to the BFC’s referral and triage system, wherein patients with more urgent problems are given scheduling priority. This patient care model contrasts with UPMC’s scheduling process in which no known formal triage system is utilized. Interestingly, there was no difference in skin cancer incidence despite a higher percentage of preventive skin cancer screenings at UPMC.

Patients at the BFC more often required emergency insurance for surgical interventions, which is consistent with the higher percentage of uninsured individuals in this population. Patients at UPMC more frequently were recommended sunscreen and were educated about skin cancer, sun protection, and skin examination, in part due to this group’s more extensive history of skin cancer and frequent presentation for skin cancer screenings. At the same time, educational materials for skin care at both the BFC and UPMC are populated into the EMR in English, whereas materials in other languages are less readily available.

Our retrospective study had several limitations. Demographic information that relied on clinic-dependent intake questionnaires may be limited due to variable intake processes and patients opting out of self-reporting. By comparing patient populations between 2 clinics, confounding variables such as location and hours of operation may impact the patient demographics recorded at the BFC vs UPMC. Resources and staff availability may affect the management strategies and follow-up care offered by each clinic. Our study period also was unique in that COVID-19 may have affected resources, staffing, scheduling, and logistics at both clinics.

Based on the aforementioned differences between the BFC and UPMC patient characteristics, care models should be strategically designed to support the needs of diverse populations. The BFC patient care model appropriately focuses on communication skills with patients with LEP by using interpreter services. Providing more skin care education and follow-up instructions in patients’ primary languages will help them develop a better understanding of their skin conditions. Another key asset of the BFC patient care model is its provision of social services such as transportation and insurance assistance.

To improve the UPMC patient care model, providing patients with bus tickets and car services may potentially reduce appointment cancellations. Using interpreter services to call and text appointment reminders, as well as interpreter resources to facilitate patient visits and patient instructions, also can mitigate language barriers for patients with LEP. Implementing a triage system into the UPMC scheduling system may help patients with more urgent skin conditions to be seen in a timely manner.

Other investigators have analyzed costs of care and proven the value of dermatologic services at free clinics to guide allocation of supplies and resources, demonstrating an area for future investigation at the BFC.13 A cost analysis of care provided at the BFC compared to UPMC could inform us about the value of the BFC’s services.

Conclusion

The dermatology clinics at the BFC and UPMC have distinct demographics, diagnoses, and management strategies to provide an inclusive patient care model. The services provided by both clinics are necessary to ensure that people in Pittsburgh have access to dermatologic care regardless of social barriers (eg, lack of health insurance, LEP). To achieve greater accessibility and health equity, dermatologic care at the BFC and UPMC can be improved by strengthening communication with people with LEP, providing skin care education, and offering social and scheduling services.

- Lim HW, Collins SAB, Resneck JS, et al. The burden of skin disease in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:958-972.e2. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2016.12.043

- American Academy of Dermatology. Skin cancer. Accessed October 7, 2024. https://www.aad.org/media/stats-skin-cancer

- Suneja T, Smith ED, Chen GJ, et al. Waiting times to see a dermatologist are perceived as too long by dermatologists: implications for the dermatology workforce. Arch Dermatol. 2001;137:1303-1307. doi:10.1001/archderm.137.10.1303

- Grossberg AL, Carranza D, Lamp K, et al. Dermatologic care in the homeless and underserved populations: observations from the Venice Family Clinic. Cutis. 2012;89:25-32.

- Amini A, Rusthoven CG, Waxweiler TV, et al. Association of health insurance with outcomes in adults ages 18 to 64 years with melanoma in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:309-316. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.09.054

- Su C, Nguyen KA, Bai HX, et al. Racial disparity in mycosis fungoides: an analysis of 4495 cases from the US National Cancer Database. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:497-502.e2. doi:10.1016/j.jaad .2017.04.1137

- Darnell JS. Free clinics in the United States: a nationwide survey. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170:946-953. doi:10.1001/archinternmed .2010.107

- Madray V, Ginjupalli S, Hashmi O, et al. Access to dermatology services at free medical clinics: a nationwide cross-sectional survey. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:245-246. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.12.011

- Pennsylvania free and income-based clinics. Accessed October 7, 2024. https://www.freeclinics.com/sta/pennsylvania

- United States Census Bureau. Decennial census. P1: race. Accessed October 7, 2024. https://data.census.gov/table/DECENNIALPL2020.P1?g=160XX00US4261000

- United States Census Bureau. American community survey. S1601: language spoken at home. Accessed October 7, 2024. https://data.census.gov/table/ACSST5Y2020S1601?g=160XX00US4261000

- United States Census Bureau. S2701: selected characteristics of health insurance coverage in the United States. Accessed October 7, 2024. https://data.census.gov/table/ACSST5Y2020.S2701?g=160XX00US4261000

- Lin CP, Loy S, Boothe WD, et al. Value of Dermatology Nights at a student-run free clinic. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2020;34:260-261. doi:10.1080/08998280.2020.1834771

- Lim HW, Collins SAB, Resneck JS, et al. The burden of skin disease in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:958-972.e2. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2016.12.043

- American Academy of Dermatology. Skin cancer. Accessed October 7, 2024. https://www.aad.org/media/stats-skin-cancer

- Suneja T, Smith ED, Chen GJ, et al. Waiting times to see a dermatologist are perceived as too long by dermatologists: implications for the dermatology workforce. Arch Dermatol. 2001;137:1303-1307. doi:10.1001/archderm.137.10.1303

- Grossberg AL, Carranza D, Lamp K, et al. Dermatologic care in the homeless and underserved populations: observations from the Venice Family Clinic. Cutis. 2012;89:25-32.

- Amini A, Rusthoven CG, Waxweiler TV, et al. Association of health insurance with outcomes in adults ages 18 to 64 years with melanoma in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:309-316. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.09.054

- Su C, Nguyen KA, Bai HX, et al. Racial disparity in mycosis fungoides: an analysis of 4495 cases from the US National Cancer Database. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:497-502.e2. doi:10.1016/j.jaad .2017.04.1137

- Darnell JS. Free clinics in the United States: a nationwide survey. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170:946-953. doi:10.1001/archinternmed .2010.107

- Madray V, Ginjupalli S, Hashmi O, et al. Access to dermatology services at free medical clinics: a nationwide cross-sectional survey. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:245-246. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.12.011

- Pennsylvania free and income-based clinics. Accessed October 7, 2024. https://www.freeclinics.com/sta/pennsylvania

- United States Census Bureau. Decennial census. P1: race. Accessed October 7, 2024. https://data.census.gov/table/DECENNIALPL2020.P1?g=160XX00US4261000

- United States Census Bureau. American community survey. S1601: language spoken at home. Accessed October 7, 2024. https://data.census.gov/table/ACSST5Y2020S1601?g=160XX00US4261000

- United States Census Bureau. S2701: selected characteristics of health insurance coverage in the United States. Accessed October 7, 2024. https://data.census.gov/table/ACSST5Y2020.S2701?g=160XX00US4261000

- Lin CP, Loy S, Boothe WD, et al. Value of Dermatology Nights at a student-run free clinic. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2020;34:260-261. doi:10.1080/08998280.2020.1834771

Comparing Patient Care Models at a Local Free Clinic vs an Insurance- Based University Medical Center

Comparing Patient Care Models at a Local Free Clinic vs an Insurance- Based University Medical Center

PRACTICE POINTS

- Both free clinics and insurance-based health care systems serve dermatology patients with diverse characteristics, necessitating inclusive health care models.

- Dermatologic care can be improved at both free and insurance-based clinics by strengthening communication with individuals with limited English proficiency, providing skin care education, and offering social and scheduling services such as transportation, insurance assistance, and triage.

Bridging the Digital Divide in Teledermatology Usage: A Retrospective Review of Patient Visits

Teledermatology is an effective patient care model for the delivery of high-quality dermatologic care.1 Teledermatology can occur using synchronous, asynchronous, and hybrid models of care. In asynchronous visits (AVs), patients or health professionals submit photographs and information for dermatologists to review and provide treatment recommendations. With synchronous visits (SVs), patients have a visit with a dermatology health professional in real time via live video conferencing software. Hybrid models incorporate asynchronous strategies for patient intake forms and skin photograph submissions as well as synchronous methods for live video consultation in a single visit.1 However, remarkable inequities in internet access limit telemedicine usage among medically marginalized patient populations, including racialized, elderly, and low socioeconomic status groups.2

Synchronous visits, a relatively newer teledermatology format, allow for communication with dermatology professionals from the convenience of a patient’s selected location. The live interaction of SVs allows dermatology professionals to answer questions, provide treatment recommendations, and build therapeutic relationships with patients. Concerns for dermatologist reimbursement, malpractice/liability, and technological challenges stalled large-scale uptake of teledermatology platforms.3 The COVID-19 pandemic led to a drastic increase in teledermatology usage of approximately 587.2%, largely due to public safety measures and Medicaid reimbursement parity between SV and in-office visits (IVs).3,4

With the implementation of SVs as a patient care model, we investigated the demographics of patients who utilized SVs, AVs, or IVs, and we propose strategies to promote equity in dermatologic care access.

Methods

This study was approved by the University of Pittsburgh institutional review board (STUDY20110043). We performed a retrospective electronic medical record review of deidentified data from the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, a tertiary care center in Allegheny County, Pennsylvania, with an established asynchronous teledermatology program. Hybrid SVs were integrated into the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center patient care visit options in March 2020. Patients were instructed to upload photographs of their skin conditions prior to SV appointments. The study included visits occurring between July and December 2020. Visit types included SVs, AVs, and IVs.

We analyzed the initial dermatology visits of 17,130 patients aged 17.5 years and older. Recorded data included diagnosis, age, sex, race, ethnicity, and insurance type for each visit type. Patients without a reported race (990 patients) or ethnicity (1712 patients) were excluded from analysis of race/ethnicity data. Patient zip codes were compared with the zip codes of Allegheny County municipalities as reported by the Allegheny County Elections Division.

Statistical Analysis—Descriptive statistics were calculated; frequency with percentage was used to report categorical variables, and the mean (SD) was used for normally distributed continuous variables. Univariate analysis was performed using the χ2 test for categorical variables. One-way analysis of variance was used to compare age among visit types. Statistical significance was defined as P<.05. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 24 (IBM Corp) was used for all statistical analyses.

Results

In our study population, 81.2% (13,916) of patients were residents of Allegheny County, where 51.6% of residents are female and 81.4% are older than 18 years according to data from 2020.5 The racial and ethnic demographics of Allegheny County were 13.4% African American/Black, 0.2% American Indian/Alaska Native, 4.2% Asian, 2.3% Hispanic/Latino, and 79.6% White. The percentage of residents who identified as Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander was reported to be greater than 0% but less than 0.5%.5

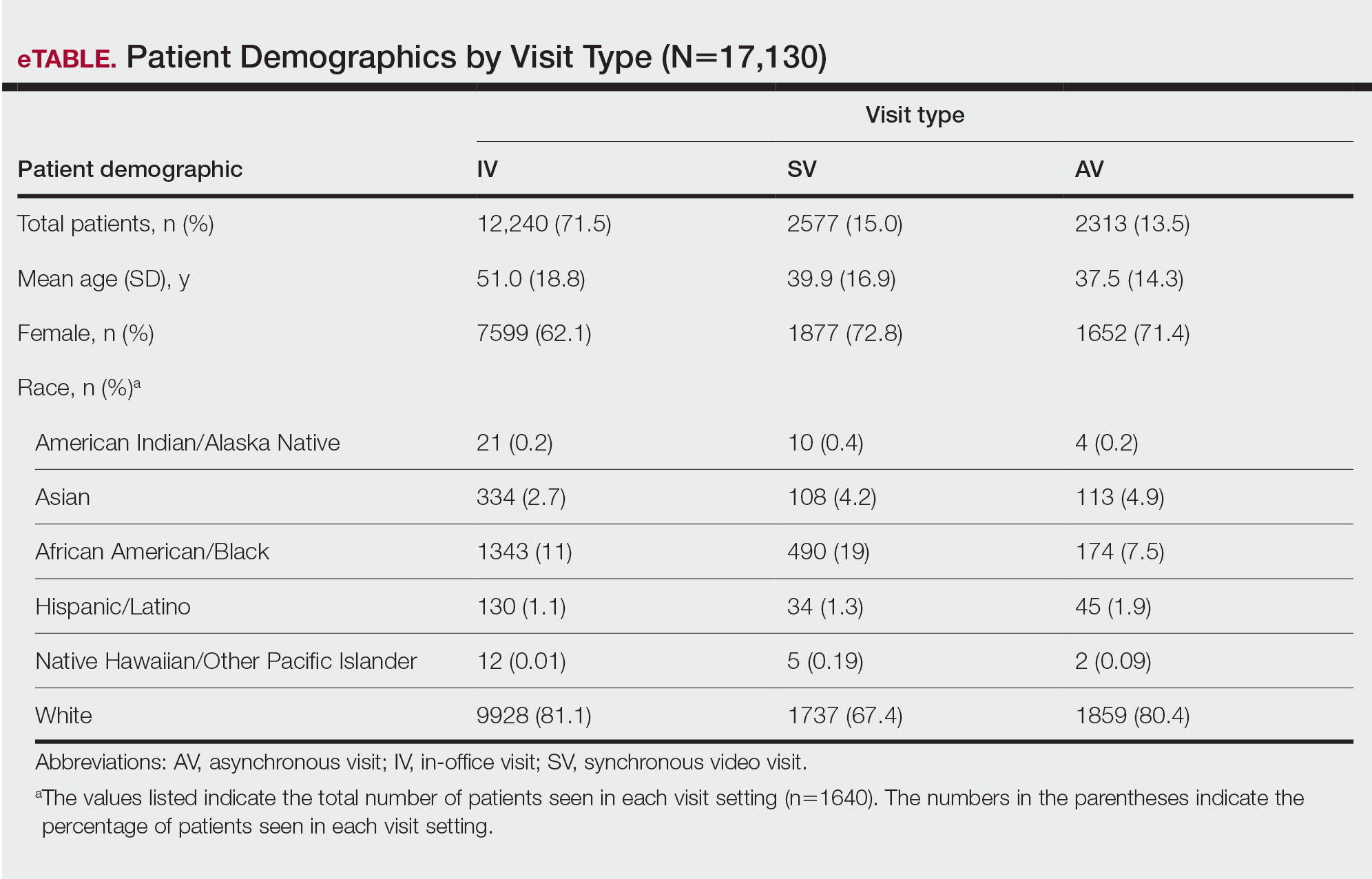

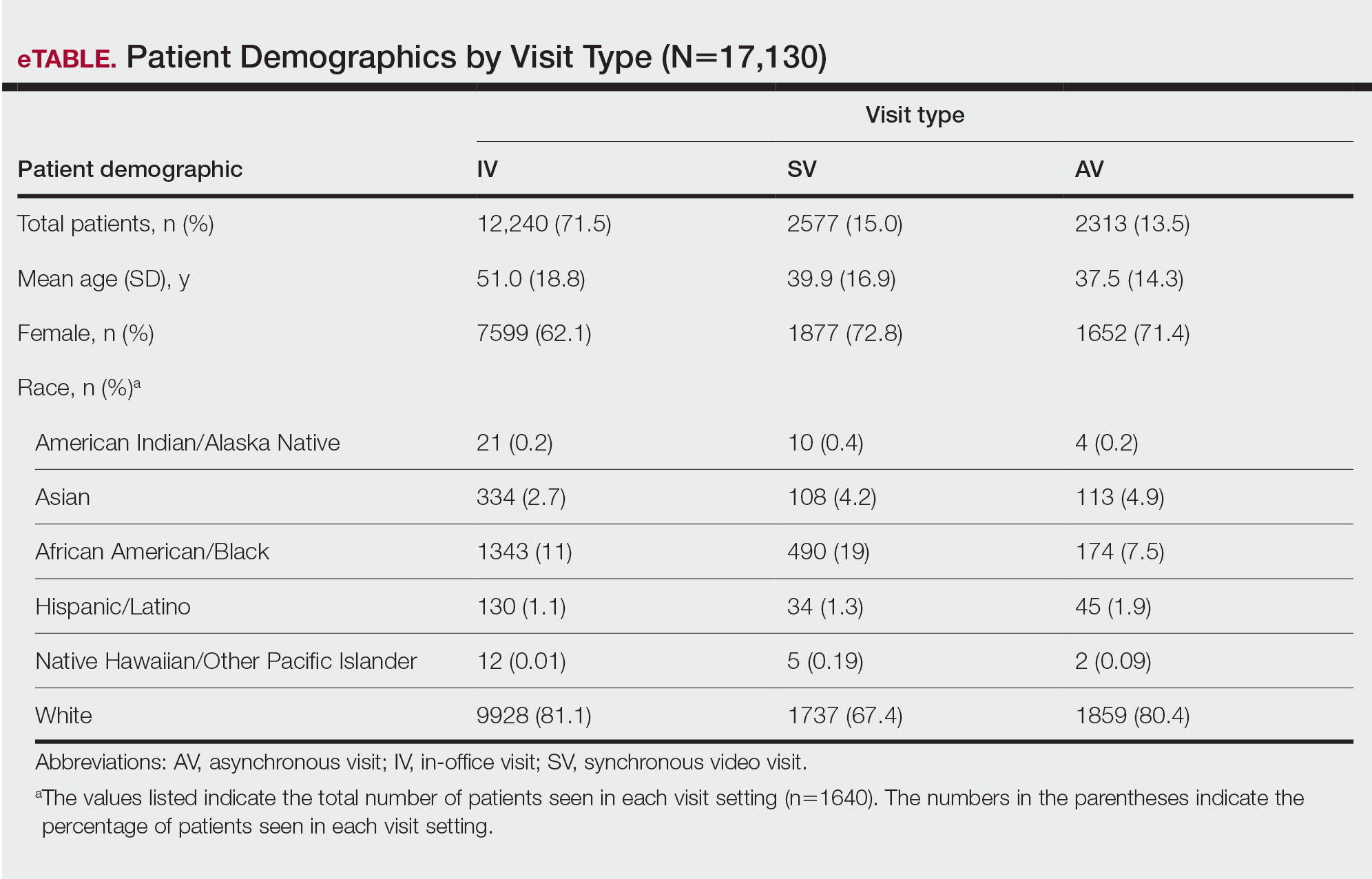

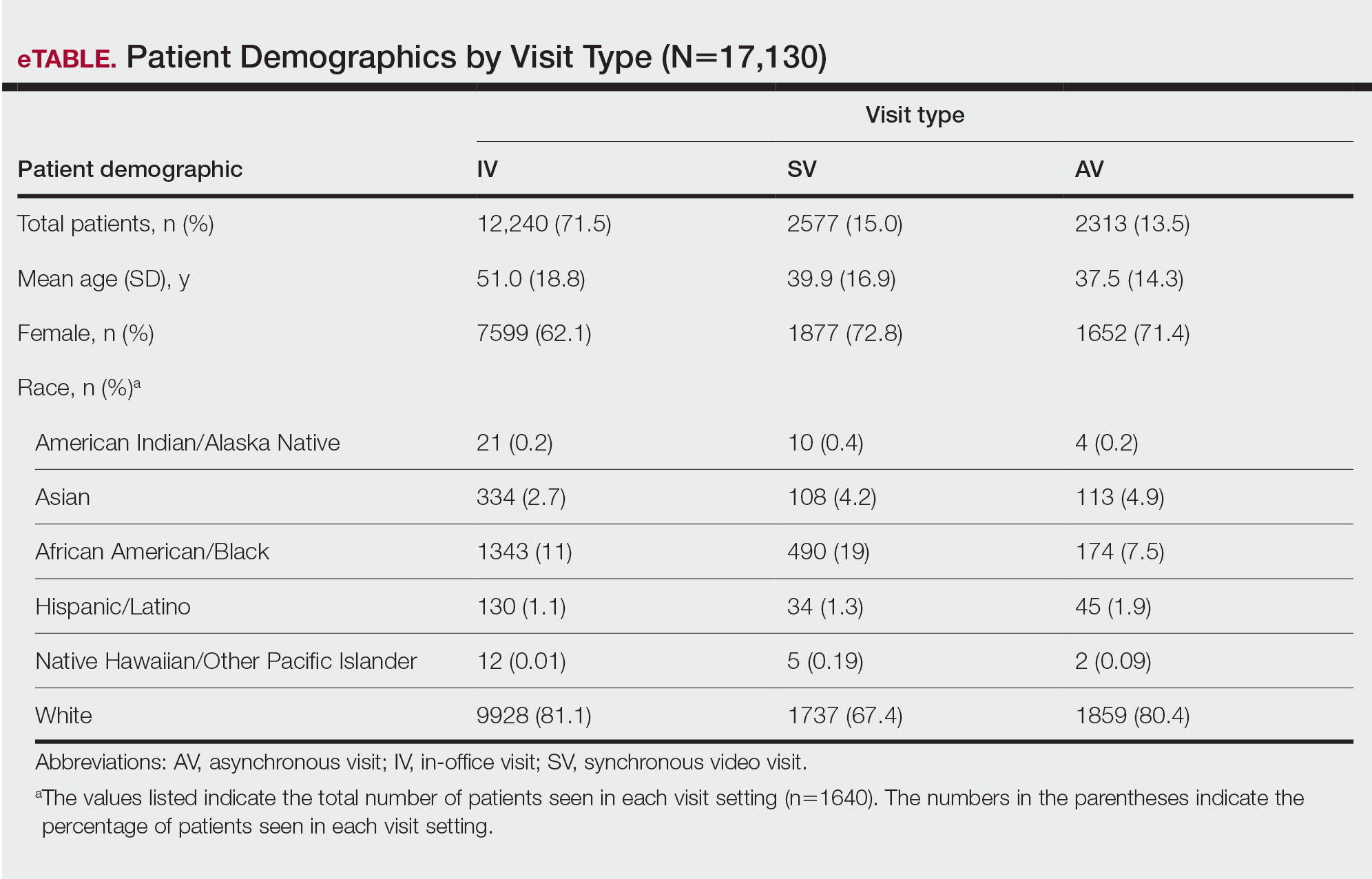

In our analysis, IVs were the most utilized visit type, accounting for 71.5% (12,240) of visits, followed by 15.0% (2577) for SVs and 13.5% (2313) for AVs. The mean age (SD) of IV patients was 51.0 (18.8) years compared with 39.9 (16.9) years for SV patients and 37.5 (14.3) years for AV patients (eTable). The majority of patients for all visits were female: 62.1% (7599) for IVs, 71.4% (1652) for AVs, and 72.8% (1877) for SVs. The largest racial or ethnic group for all visit types included White patients (83.8% [13,524] of all patients), followed by Black (12.4% [2007]), Hispanic/Latino (1.4% [209]), Asian (3.4% [555]), American Indian/Alaska Native (0.2% [35]), and Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific Islander patients (0.1% [19]).

Asian patients, who comprised 4.2% of Allegheny County residents,5 accounted for 2.7% (334) of IVs, 4.9% (113) of AVs, and 4.2% (108) of SVs. Black patients, who were reported as 13.4% of the Allegheny County population,5 were more likely to utilize SVs (19% [490])compared with AVs (7.5% [174]) and IVs (11% [1343]). Hispanic/Latino patients had a disproportionally lower utilization of dermatologic care in all settings, comprising 1.4% (209) of all patients in our study compared with 2.3% of Allegheny County residents.5 White patients, who comprised 79.6% of Allegheny County residents, accounted for 81.1% (9928) of IVs, 67.4% (1737) of SVs, and 80.4% (1859) of AVs. There was no significant difference in the percentage of American Indian/Alaska Native and Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific Islander patients among visit types.

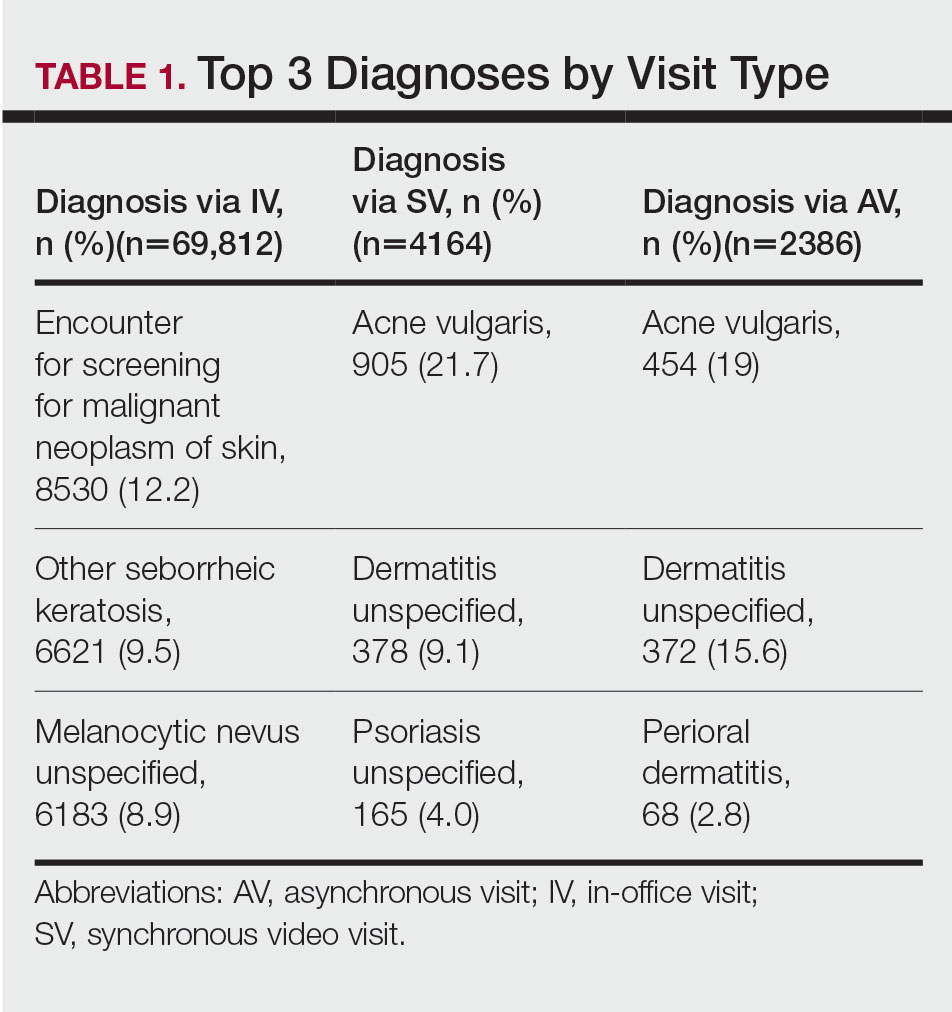

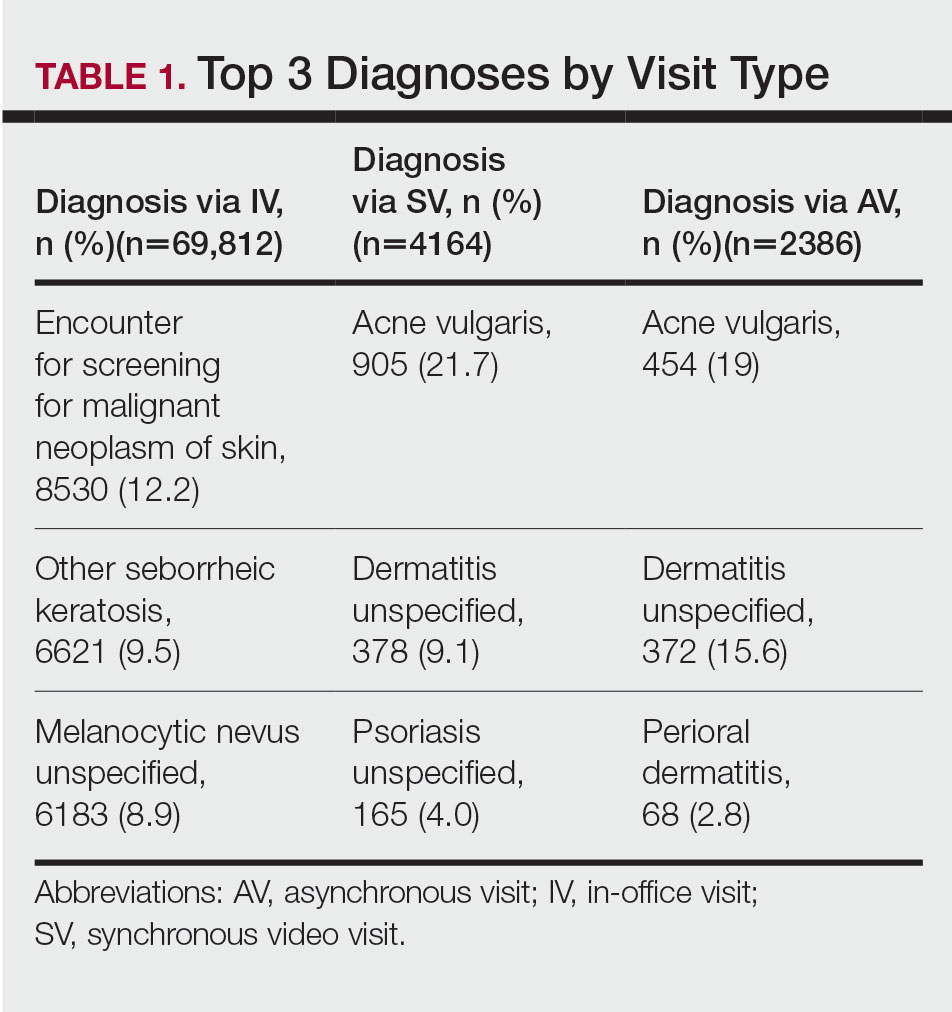

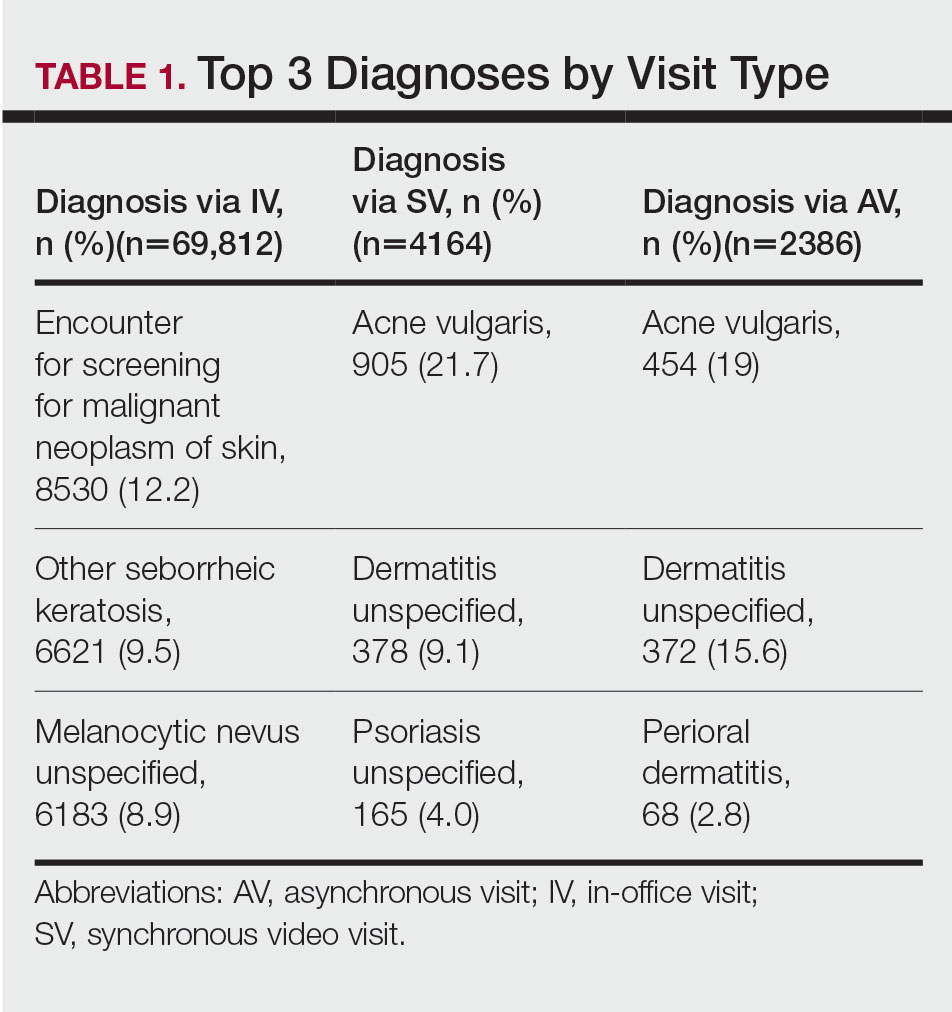

The 3 most common diagnoses for IVs were skin cancer screening, seborrheic keratosis, and melanocytic nevus (Table 1). Skin cancer screening was the most common diagnosis, accounting for 12.2% (8530) of 69,812 IVs. The 3 most common diagnoses for SVs were acne vulgaris, dermatitis, and psoriasis. The 3 most common diagnoses for AVs were acne vulgaris, dermatitis, and perioral dermatitis.

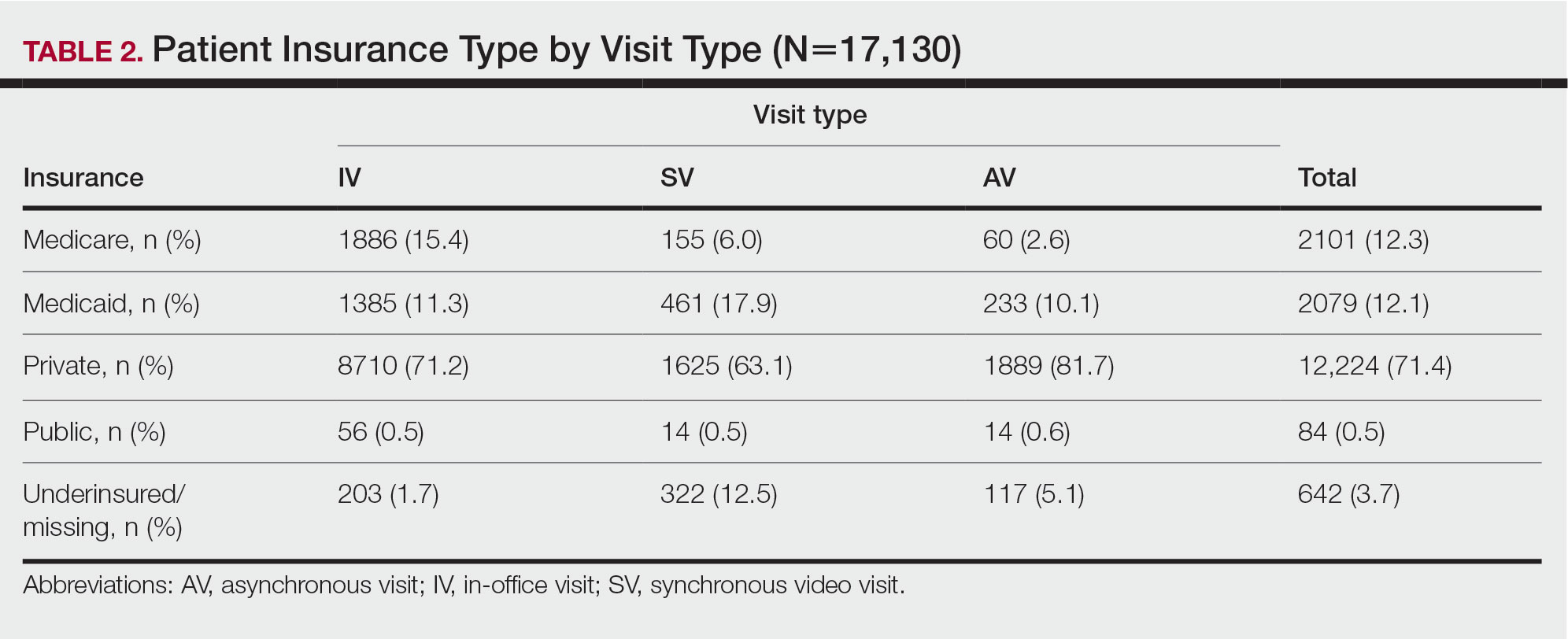

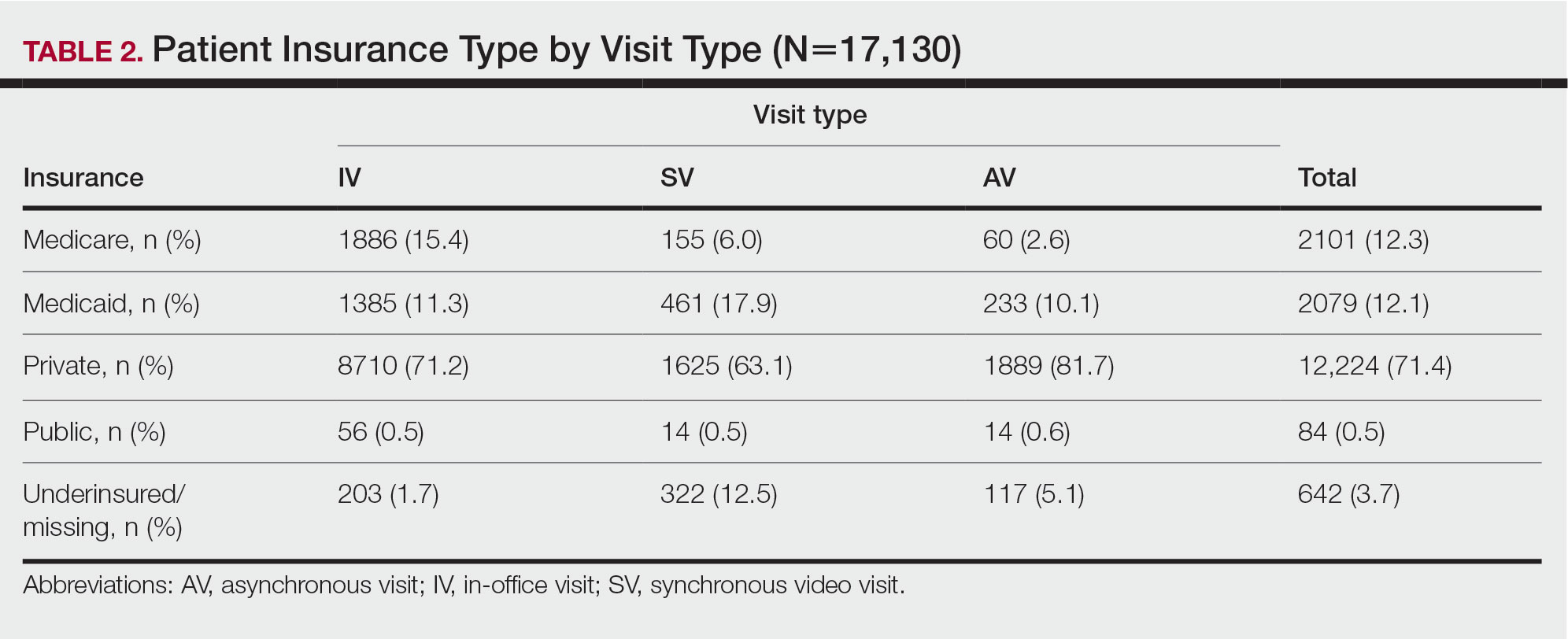

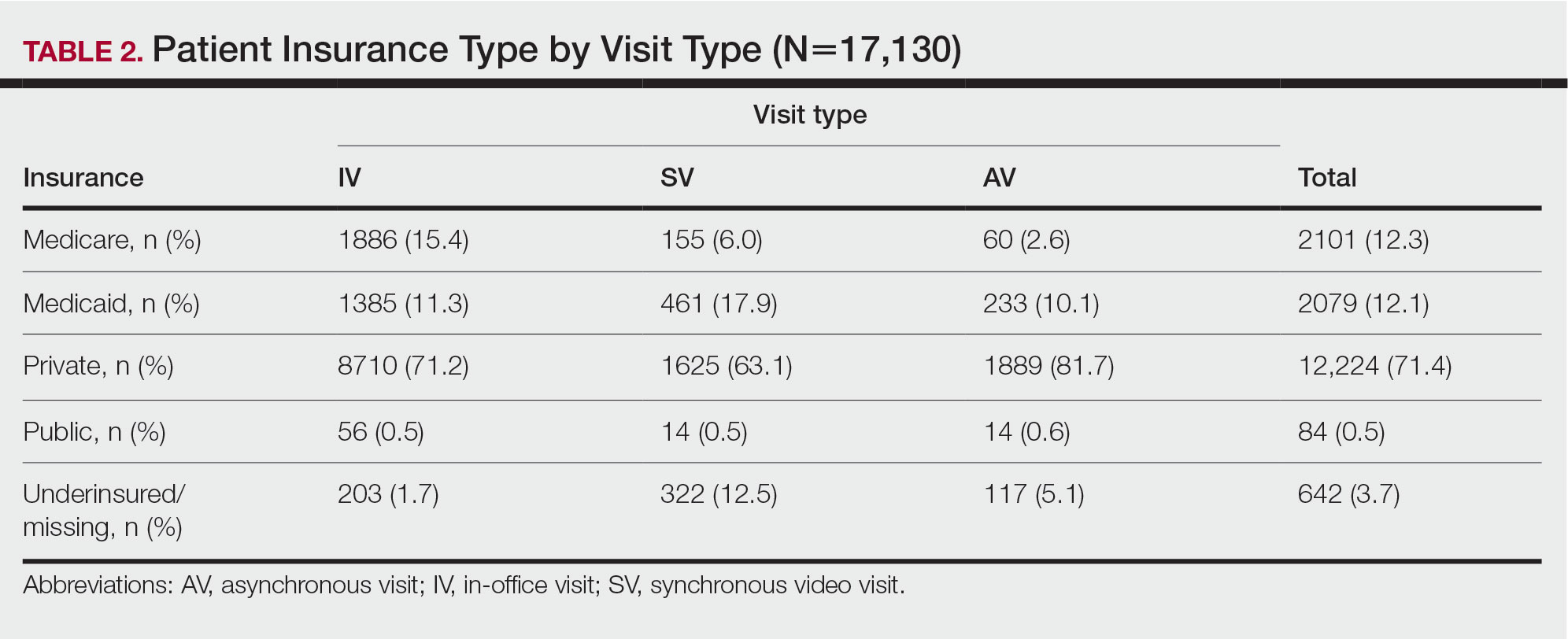

Private insurance was the most common insurance type among all patients (71.4% [12,224])(Table 2). A higher percentage of patients with Medicaid insurance (17.9% [461]) utilized SVs compared with AVs (10.1% [233]) and IVs (11.3% 1385]). Similarly, a higher percentage of patients with no insurance or no insurance listed were seen via SVs (12.5% [322]) compared with AVs (5.1% [117]) and IVs (1.7% [203]). Patients with Medicare insurance used IVs (15.4% [1886]) more than SVs (6.0% [155]) or AVs (2.6% [60]). There was no significant difference among visit type usage for patients with public insurance.

Comment

Teledermatology Benefits—In this retrospective review of medical records of patients who obtained dermatologic care after the implementation of SVs at our institution, we found a proportionally higher use of SVs among Black patients, patients with Medicaid, and patients who are underinsured. Benefits of teledermatology include decreases in patient transportation and associated costs, time away from work or home, and need for childcare.6 The SV format provides the additional advantage of direct live interaction and the development of a patient-physician or patient–physician assistant relationship. Although the prerequisite technology, internet, and broadband connectivity preclude use of teledermatology for many vulnerable patients,2 its convenience ultimately may reduce inequities in access.

Disparities in Dermatologic Care—Hispanic ethnicity and male sex are among described patient demographics associated with decreased rates of outpatient dermatologic care.7 We reported disparities in dermatologic care utilization across all visit types among Hispanic patients and males. Patients identifying as Hispanic/Latino composed only 1.4% (n=209) of our study population compared with 2.3% of Allegheny County residents.5 During our study period, most patients seen were female, accounting for 62.1% to 72.8% of visits, compared with 51.6% of Allegheny County residents.5 These disparities in dermatologic care use may have implications for increased skin-associated morbidity and provide impetus for dermatologists to increase engagement with these patient groups.

Characteristics of Patients Using Teledermatology—Patients using SVs and AVs were significantly younger (mean age [SD], 39.9 [16.9] years and 37.5 [14.3] years, respectively) compared with those using IVs (51.0 [18.8] years). This finding reflects known digital knowledge barriers among older patients.8,9 The synchronous communication format of SVs simulates the traditional visit style of IVs, which may be preferable for some patients. Continued patient education and advocacy for broadband access may increase teledermatology use among older patients and patients with limited technology resources.8

Teledermatology visits were used most frequently for acne and dermatitis, while IVs were used for skin cancer screenings and examination of concerning lesions. This usage pattern is consistent with a previously described consensus among dermatologists on the conditions most amenable to teledermatology evaluation.3

Medicaid reimbursement parity for SVs is in effect nationally until the end of the COVID-19 public health emergency declaration in the United States.10 As of February 2023, the public health emergency declaration has been renewed 12 times since January 2020, with the most recent renewal on January 11, 2023.11 As of January 2023, 21 states have enacted legislation providing permanent reimbursement parity for SV services. Six additional states have some payment parity in place, each with its own qualifying criteria, and 23 states have no payment parity.12 Only 25 Medicaid programs currently provide reimbursement for AV services.13

Study Limitations—Our study was limited by lack of data on patients who are multiracial and those who identify as nonbinary and transgender. Because of the low numbers of Hispanic patients associated with each race category and a high number of patients who did not report an ethnicity or race, race and ethnicity data were analyzed separately. For SVs, patients were instructed to upload photographs prior to their visit; however, the percentage of patients who uploaded photographs was not analyzed.

Conclusion

Expansion of teledermatology services, including SVs and AVs, patient outreach and education, advocacy for broadband access, and Medicaid payment parity, may improve dermatologic care access for medically marginalized groups. Teledermatology has the potential to serve as an effective health care option for patients who are racially minoritized, older, and underinsured. To further assess the effectiveness of teledermatology, we plan to analyze the number of SVs and AVs that were referred to IVs. Future studies also will investigate the impact of implementing patient education and patient-reported outcomes of teledermatology visits.

- Lee JJ, English JC. Teledermatology: a review and update. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2018;19:253-260.

- Bakhtiar M, Elbuluk N, Lipoff JB. The digital divide: how COVID-19’s telemedicine expansion could exacerbate disparities. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:E345-E346.

- Kennedy J, Arey S, Hopkins Z, et al. dermatologist perceptions of teledermatology implementation and future use after COVID-19: demographics, barriers, and insights. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:595-597.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Using telehealth to expand access to essential health services during the COVID-19 pandemic. Updated June 10, 2020. Accessed February 10, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/telehealth.html

- United States Census Bureau. QuickFacts: Allegheny County, Pennsylvania. Accessed August 12, 2021. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/alleghenycountypennsylvania

- Moore HW. Teledermatology—access to specialized care via a different model. Dermatology Advisor. November 12, 2019. Accessed February 10, 2023. https://www.dermatologyadvisor.com/home/topics/practice-management/teledermatology-access-to-specialized-care-via-a-different-model/

- Tripathi R, Knusel KD, Ezaldein HH, et al. Association of demographic and socioeconomic characteristics with differences in use of outpatient dermatology services in the United States. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:1286-1291.

- Nouri S, Khoong EC, Lyles CR, et al. Addressing equity in telemedicine for chronic disease management during the COVID-19 pandemic [published online May 4, 2020]. NEJM Catal Innov Care Deliv. doi:10.1056/CAT.20.0123

- Swenson K, Ghertner R. People in low-income households have less access to internet services—2019 update. Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation; US Department of Health and Human Services. March 2021. Accessed February 10, 2023. https://aspe.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/private/pdf/263601/internet-access-among-low-income-2019.pdf

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. COVID-19 frequently asked questions (FAQs) on Medicare fee-for-service (FFS) billing. Updated August 16, 2022. Accessed February 10, 2023. https://www.cms.gov/files/document/03092020-covid-19-faqs-508.pdf

- US Department of Health and Human Services. Renewal of determination that a public health emergency exists. Updated February 9, 2023. Accessed February 20, 2023. https://aspr.hhs.gov/legal/PHE/Pages/COVID19-9Feb2023.aspx?

- Augenstein J, Smith JM. Executive summary: tracking telehealth changes state-by-state in response to COVID-19. Updated January 27, 2023. Accessed February 10, 2023. https://www.manatt.com/insights/newsletters/covid-19-update/executive-summary-tracking-telehealth-changes-stat

- Center for Connected Health Policy. Policy trend maps: store and forward Medicaid reimbursement. Accessed June 23, 2022. https://www.cchpca.org/policy-trends/

Teledermatology is an effective patient care model for the delivery of high-quality dermatologic care.1 Teledermatology can occur using synchronous, asynchronous, and hybrid models of care. In asynchronous visits (AVs), patients or health professionals submit photographs and information for dermatologists to review and provide treatment recommendations. With synchronous visits (SVs), patients have a visit with a dermatology health professional in real time via live video conferencing software. Hybrid models incorporate asynchronous strategies for patient intake forms and skin photograph submissions as well as synchronous methods for live video consultation in a single visit.1 However, remarkable inequities in internet access limit telemedicine usage among medically marginalized patient populations, including racialized, elderly, and low socioeconomic status groups.2

Synchronous visits, a relatively newer teledermatology format, allow for communication with dermatology professionals from the convenience of a patient’s selected location. The live interaction of SVs allows dermatology professionals to answer questions, provide treatment recommendations, and build therapeutic relationships with patients. Concerns for dermatologist reimbursement, malpractice/liability, and technological challenges stalled large-scale uptake of teledermatology platforms.3 The COVID-19 pandemic led to a drastic increase in teledermatology usage of approximately 587.2%, largely due to public safety measures and Medicaid reimbursement parity between SV and in-office visits (IVs).3,4

With the implementation of SVs as a patient care model, we investigated the demographics of patients who utilized SVs, AVs, or IVs, and we propose strategies to promote equity in dermatologic care access.

Methods

This study was approved by the University of Pittsburgh institutional review board (STUDY20110043). We performed a retrospective electronic medical record review of deidentified data from the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, a tertiary care center in Allegheny County, Pennsylvania, with an established asynchronous teledermatology program. Hybrid SVs were integrated into the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center patient care visit options in March 2020. Patients were instructed to upload photographs of their skin conditions prior to SV appointments. The study included visits occurring between July and December 2020. Visit types included SVs, AVs, and IVs.

We analyzed the initial dermatology visits of 17,130 patients aged 17.5 years and older. Recorded data included diagnosis, age, sex, race, ethnicity, and insurance type for each visit type. Patients without a reported race (990 patients) or ethnicity (1712 patients) were excluded from analysis of race/ethnicity data. Patient zip codes were compared with the zip codes of Allegheny County municipalities as reported by the Allegheny County Elections Division.

Statistical Analysis—Descriptive statistics were calculated; frequency with percentage was used to report categorical variables, and the mean (SD) was used for normally distributed continuous variables. Univariate analysis was performed using the χ2 test for categorical variables. One-way analysis of variance was used to compare age among visit types. Statistical significance was defined as P<.05. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 24 (IBM Corp) was used for all statistical analyses.

Results

In our study population, 81.2% (13,916) of patients were residents of Allegheny County, where 51.6% of residents are female and 81.4% are older than 18 years according to data from 2020.5 The racial and ethnic demographics of Allegheny County were 13.4% African American/Black, 0.2% American Indian/Alaska Native, 4.2% Asian, 2.3% Hispanic/Latino, and 79.6% White. The percentage of residents who identified as Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander was reported to be greater than 0% but less than 0.5%.5

In our analysis, IVs were the most utilized visit type, accounting for 71.5% (12,240) of visits, followed by 15.0% (2577) for SVs and 13.5% (2313) for AVs. The mean age (SD) of IV patients was 51.0 (18.8) years compared with 39.9 (16.9) years for SV patients and 37.5 (14.3) years for AV patients (eTable). The majority of patients for all visits were female: 62.1% (7599) for IVs, 71.4% (1652) for AVs, and 72.8% (1877) for SVs. The largest racial or ethnic group for all visit types included White patients (83.8% [13,524] of all patients), followed by Black (12.4% [2007]), Hispanic/Latino (1.4% [209]), Asian (3.4% [555]), American Indian/Alaska Native (0.2% [35]), and Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific Islander patients (0.1% [19]).

Asian patients, who comprised 4.2% of Allegheny County residents,5 accounted for 2.7% (334) of IVs, 4.9% (113) of AVs, and 4.2% (108) of SVs. Black patients, who were reported as 13.4% of the Allegheny County population,5 were more likely to utilize SVs (19% [490])compared with AVs (7.5% [174]) and IVs (11% [1343]). Hispanic/Latino patients had a disproportionally lower utilization of dermatologic care in all settings, comprising 1.4% (209) of all patients in our study compared with 2.3% of Allegheny County residents.5 White patients, who comprised 79.6% of Allegheny County residents, accounted for 81.1% (9928) of IVs, 67.4% (1737) of SVs, and 80.4% (1859) of AVs. There was no significant difference in the percentage of American Indian/Alaska Native and Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific Islander patients among visit types.

The 3 most common diagnoses for IVs were skin cancer screening, seborrheic keratosis, and melanocytic nevus (Table 1). Skin cancer screening was the most common diagnosis, accounting for 12.2% (8530) of 69,812 IVs. The 3 most common diagnoses for SVs were acne vulgaris, dermatitis, and psoriasis. The 3 most common diagnoses for AVs were acne vulgaris, dermatitis, and perioral dermatitis.

Private insurance was the most common insurance type among all patients (71.4% [12,224])(Table 2). A higher percentage of patients with Medicaid insurance (17.9% [461]) utilized SVs compared with AVs (10.1% [233]) and IVs (11.3% 1385]). Similarly, a higher percentage of patients with no insurance or no insurance listed were seen via SVs (12.5% [322]) compared with AVs (5.1% [117]) and IVs (1.7% [203]). Patients with Medicare insurance used IVs (15.4% [1886]) more than SVs (6.0% [155]) or AVs (2.6% [60]). There was no significant difference among visit type usage for patients with public insurance.

Comment

Teledermatology Benefits—In this retrospective review of medical records of patients who obtained dermatologic care after the implementation of SVs at our institution, we found a proportionally higher use of SVs among Black patients, patients with Medicaid, and patients who are underinsured. Benefits of teledermatology include decreases in patient transportation and associated costs, time away from work or home, and need for childcare.6 The SV format provides the additional advantage of direct live interaction and the development of a patient-physician or patient–physician assistant relationship. Although the prerequisite technology, internet, and broadband connectivity preclude use of teledermatology for many vulnerable patients,2 its convenience ultimately may reduce inequities in access.

Disparities in Dermatologic Care—Hispanic ethnicity and male sex are among described patient demographics associated with decreased rates of outpatient dermatologic care.7 We reported disparities in dermatologic care utilization across all visit types among Hispanic patients and males. Patients identifying as Hispanic/Latino composed only 1.4% (n=209) of our study population compared with 2.3% of Allegheny County residents.5 During our study period, most patients seen were female, accounting for 62.1% to 72.8% of visits, compared with 51.6% of Allegheny County residents.5 These disparities in dermatologic care use may have implications for increased skin-associated morbidity and provide impetus for dermatologists to increase engagement with these patient groups.

Characteristics of Patients Using Teledermatology—Patients using SVs and AVs were significantly younger (mean age [SD], 39.9 [16.9] years and 37.5 [14.3] years, respectively) compared with those using IVs (51.0 [18.8] years). This finding reflects known digital knowledge barriers among older patients.8,9 The synchronous communication format of SVs simulates the traditional visit style of IVs, which may be preferable for some patients. Continued patient education and advocacy for broadband access may increase teledermatology use among older patients and patients with limited technology resources.8

Teledermatology visits were used most frequently for acne and dermatitis, while IVs were used for skin cancer screenings and examination of concerning lesions. This usage pattern is consistent with a previously described consensus among dermatologists on the conditions most amenable to teledermatology evaluation.3

Medicaid reimbursement parity for SVs is in effect nationally until the end of the COVID-19 public health emergency declaration in the United States.10 As of February 2023, the public health emergency declaration has been renewed 12 times since January 2020, with the most recent renewal on January 11, 2023.11 As of January 2023, 21 states have enacted legislation providing permanent reimbursement parity for SV services. Six additional states have some payment parity in place, each with its own qualifying criteria, and 23 states have no payment parity.12 Only 25 Medicaid programs currently provide reimbursement for AV services.13

Study Limitations—Our study was limited by lack of data on patients who are multiracial and those who identify as nonbinary and transgender. Because of the low numbers of Hispanic patients associated with each race category and a high number of patients who did not report an ethnicity or race, race and ethnicity data were analyzed separately. For SVs, patients were instructed to upload photographs prior to their visit; however, the percentage of patients who uploaded photographs was not analyzed.

Conclusion

Expansion of teledermatology services, including SVs and AVs, patient outreach and education, advocacy for broadband access, and Medicaid payment parity, may improve dermatologic care access for medically marginalized groups. Teledermatology has the potential to serve as an effective health care option for patients who are racially minoritized, older, and underinsured. To further assess the effectiveness of teledermatology, we plan to analyze the number of SVs and AVs that were referred to IVs. Future studies also will investigate the impact of implementing patient education and patient-reported outcomes of teledermatology visits.