User login

Pigmented Cystic Masses on the Scalp

THE DIAGNOSIS: Apocrine Hidrocystoma

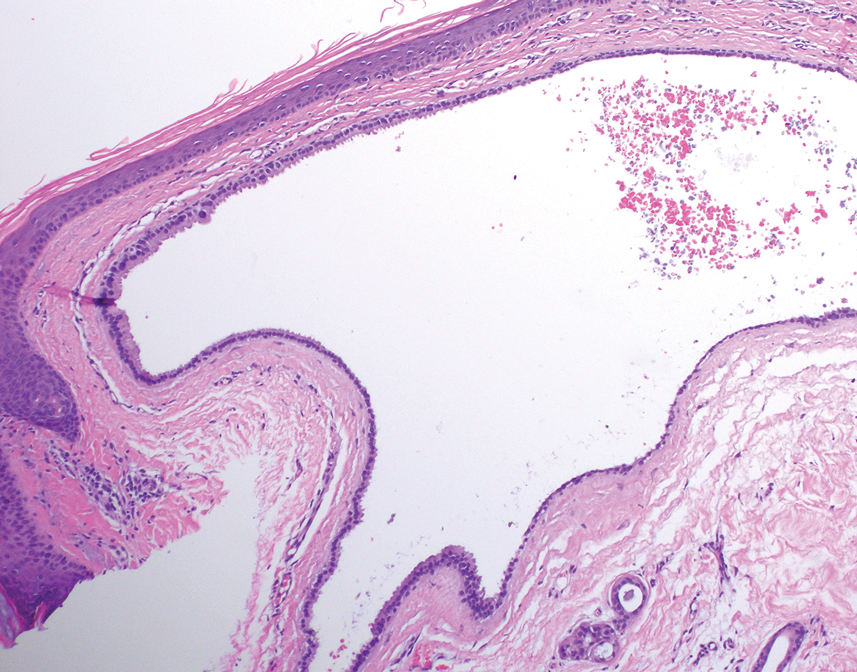

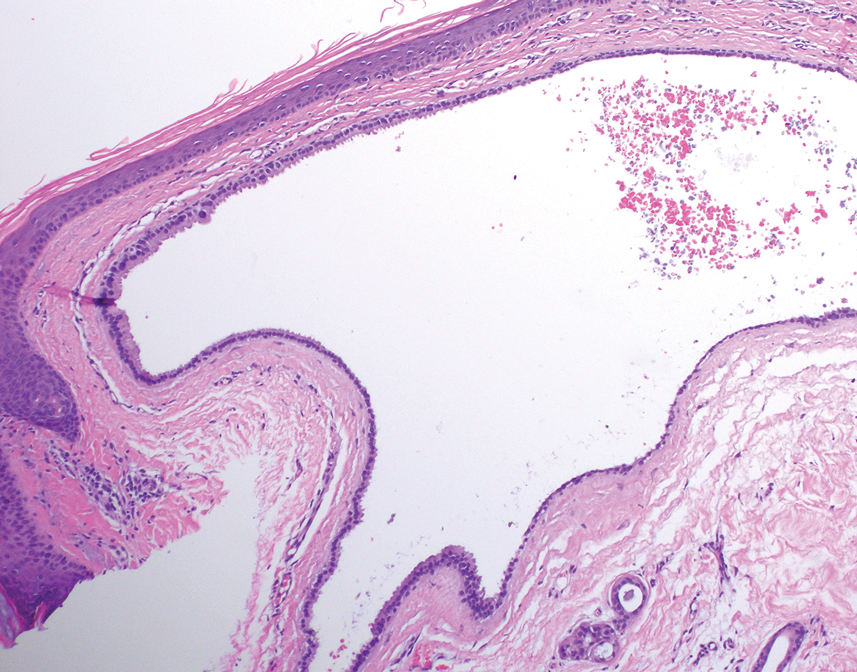

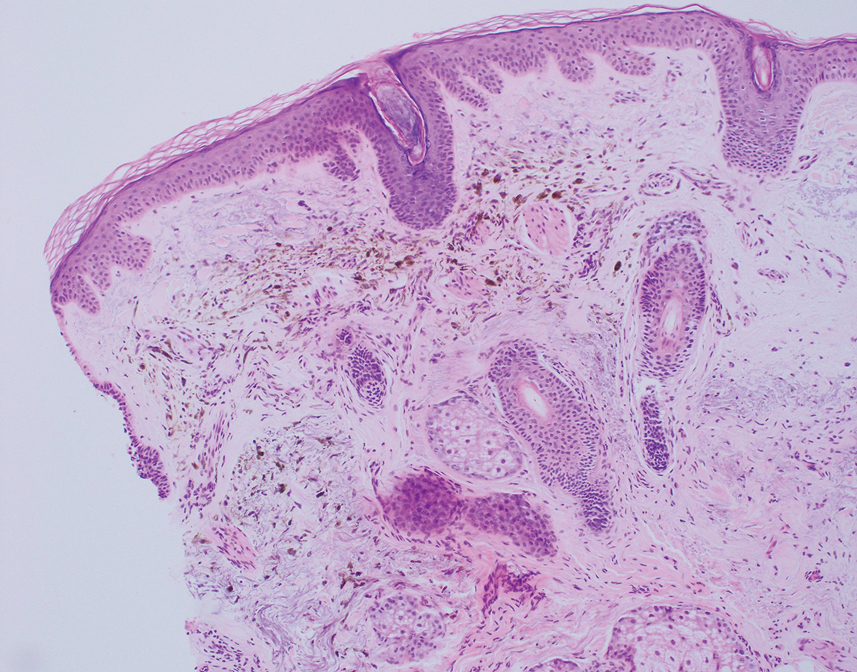

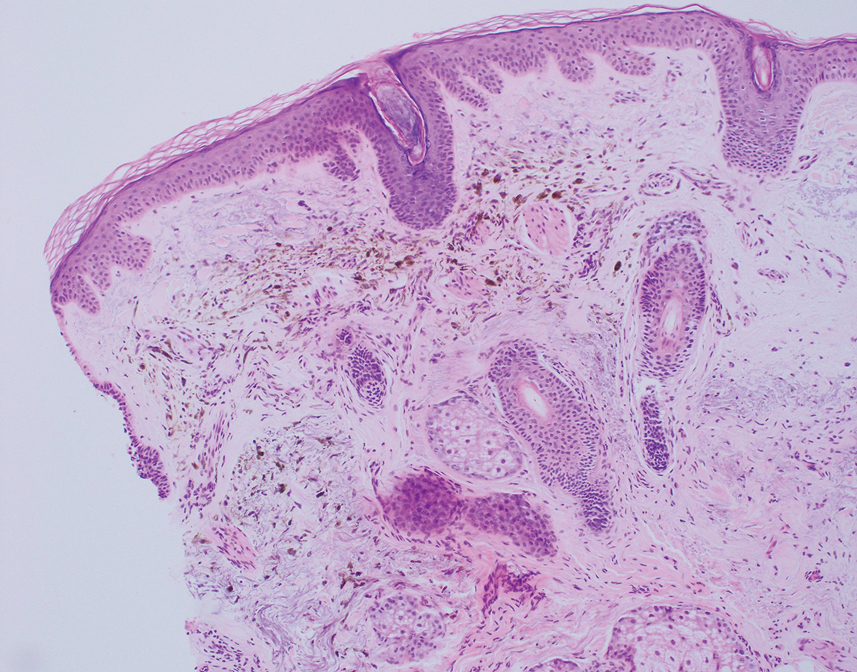

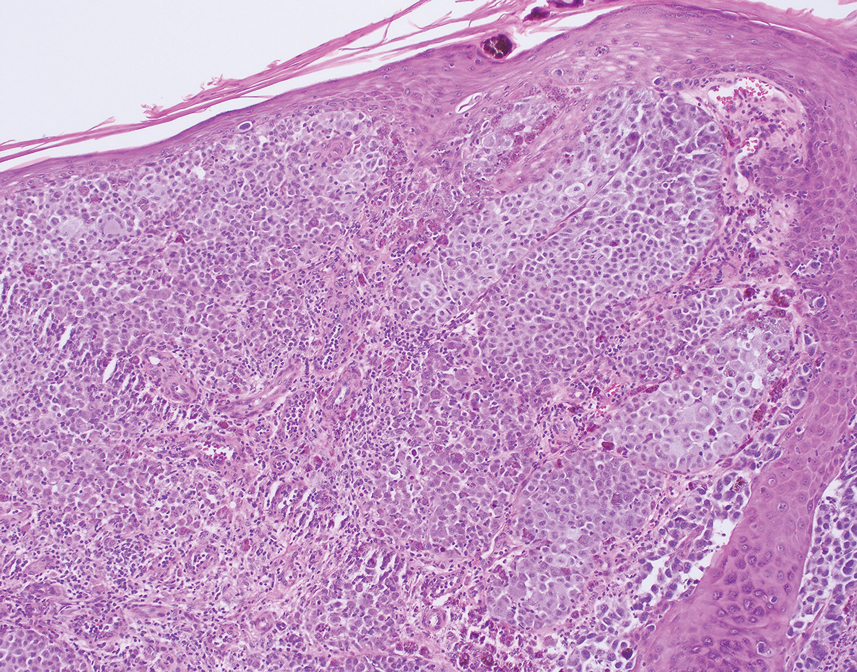

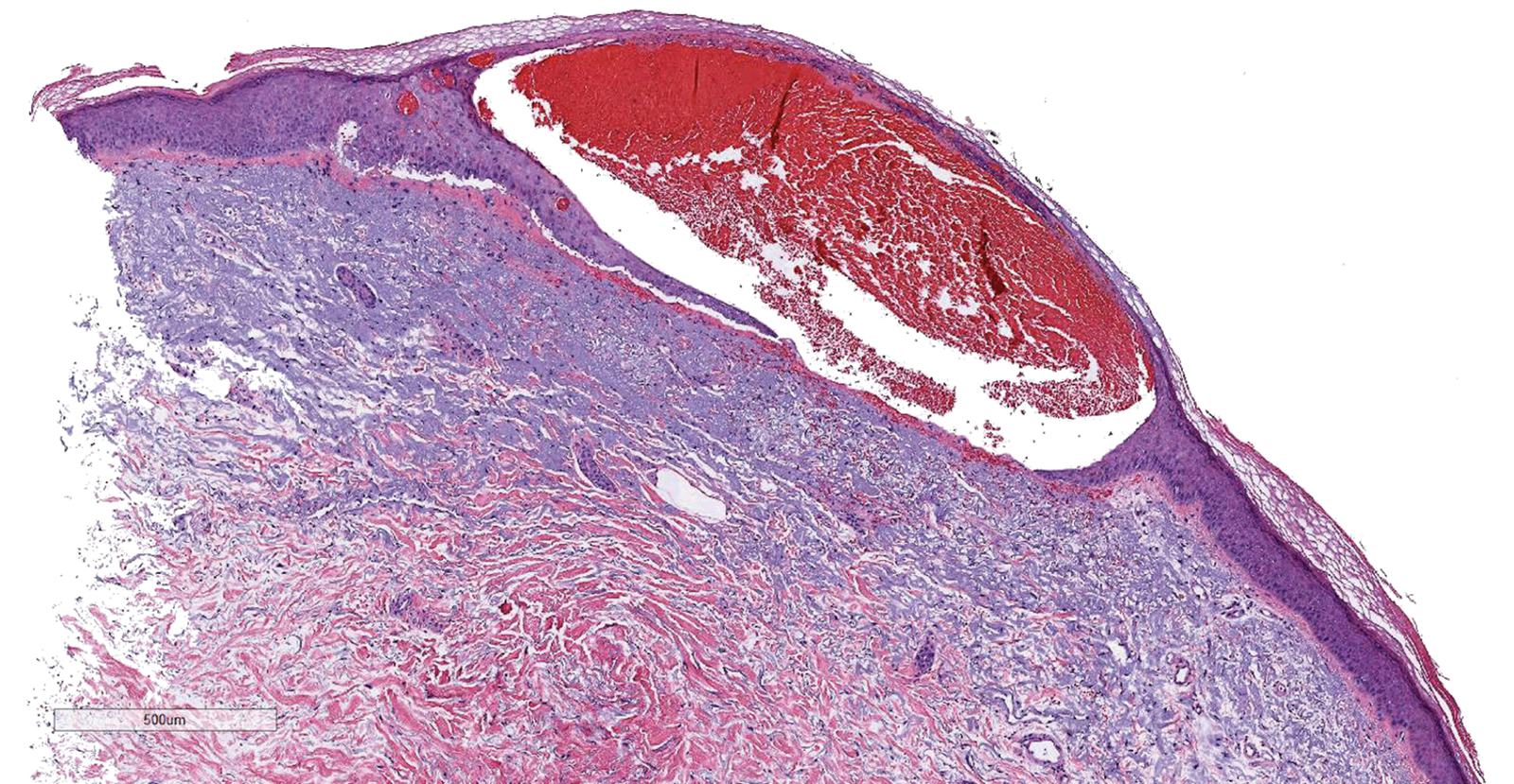

Histology for all 3 lesions demonstrated similar cystic structures lined by a dual layer of epithelial cells, with the outermost layer composed of flattened myoepithelial cells and the inner layer composed of cells with apocrine features (Figure 1). Based on these findings, a diagnosis of apocrine hidrocystoma was made. The patient underwent successful surgical excision shortly thereafter without recurrence at follow-up 1 year later.

Apocrine hidrocystomas are rare benign cystic lesions that are considered to be adenomatous proliferations of apocrine glands. They typically manifest as solitary asymptomatic lesions measuring 3 to 15 mm.1 They tend to appear on the face, usually in the periorbital region, but also have been described on the neck, scalp, trunk, arms, and legs.2-4 Multiple apocrine hidrocystomas can be a marker of 2 rare inherited disorders: Gorlin-Goltz syndrome and Schopf-Schulz-Passarge syndrome.5 Apocrine hidrocystomas may be flesh colored or may have a blue, black, or brown appearance due to the Tyndall effect, in which light with shorter wavelengths is scattered by the contents of the lesions.2 Histologically, apocrine hidrocystomas are cysts lined by a dual layer of epithelial cells. The inner layer is composed of cells with apocrine features, and the outer layer is composed of flattened myoepithelial cells. Due to their range of colors and predilection for sun-exposed surfaces, apocrine hidrocystomas may be mistaken for various malignant neoplasms, including melanoma.6,7

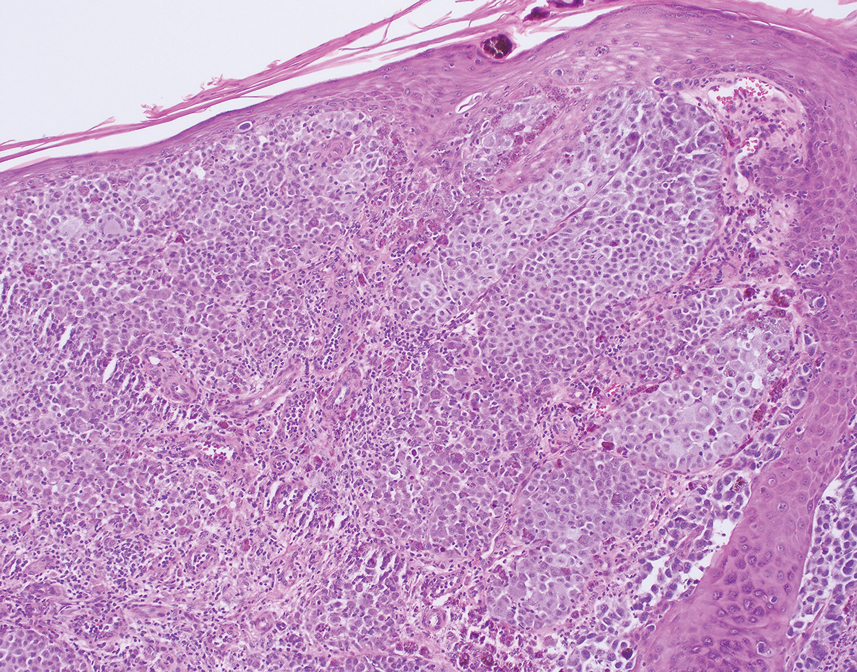

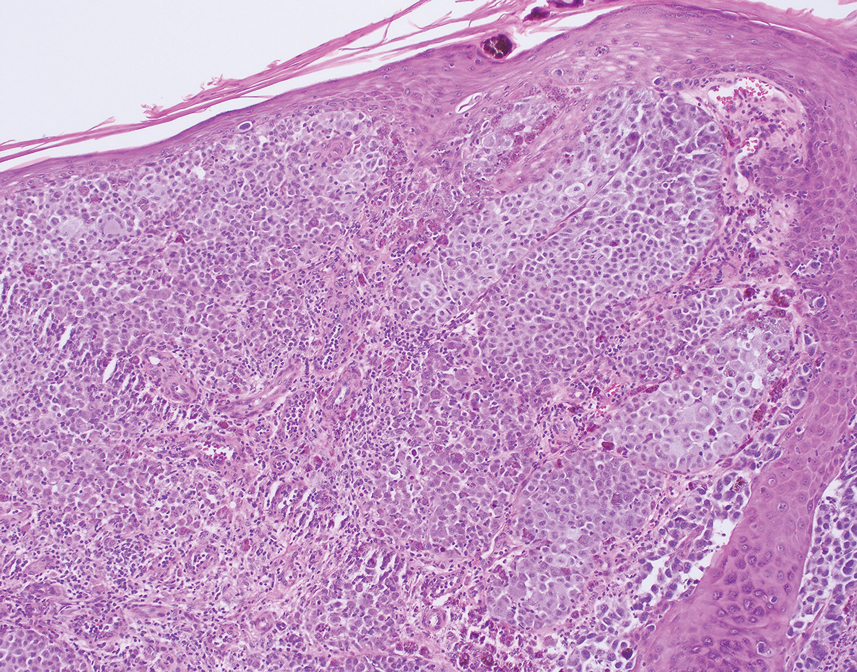

The differential diagnosis for our patient included agminated blue nevi, melanoma, pigmented basal cell carcinoma (BCC), and seborrheic keratosis. A blue nevus is a dermal melanocytic lesion that manifests as a well-demarcated, blue to blue-black papule that typically appears on the face, scalp, arms, legs, lower back, and buttocks. Although there are several histologic subtypes, the common blue nevus usually manifests as a solitary lesion measuring less than 1 cm, often developing during childhood to young adulthood.8 Histologically, common blue nevi are characterized by a dermal proliferation of deeply pigmented bipolar spindled melanocytes embedded in thickened collagen bundles, often with scattered epithelioid melanophages, and no conspicuous mitotic activity (Figure 2).9 There are other types of blue nevi, including cellular blue nevi, which tend to be larger and manifest commonly on the buttocks and sacrococcygeal region in early adulthood.9 Histologically, cellular blue nevi contain oval to spindled melanocytes with scattered melanophages forming a well-demarcated nodule typically in the reticular dermis. There may be bulbous extension into the subcutaneous adipose tissue. Occasional mitoses may be seen.9,10 Melanoma can arise from common or cellular blue nevi, though it more frequently occurs with cellular blue nevi. Other subtypes of blue nevi have been described, including the sclerosing, plaque-type, combined, hypomelanotic/amelanotic, and pigmented epithelioid melanocytoma.11 However, they typically have features of the common blue nevus or cellular blue nevus, such as oval/spindle cell morphology, some degree of melanin, and biphasic architecture, but are classified according to their dominant histologic characteristics.

Given the location of our patient’s lesions on the scalp and his extensive history of sun exposure, malignancy was high in the differential. Multiple synchronous primary melanomas including nodular melanoma, blue nevus–like metastatic melanoma, and metastatic melanoma were considered. The leg and the scalp have the highest reported incidence of cutaneous metastases of melanoma, with many cases presenting as dermal or subcutaneous nodules and eruptive blue nevus–like papules, similar to our patient’s clinical presentation.12,13 Nodular melanoma (NM) is one of 4 major types of melanoma, accounting for approximately 15% to 30% of cases in the United States.14 Nodular melanoma typically manifests as a smooth, raised, symmetric, well-circumscribed lesion with variable pigmentation, from very dark to amelanotic. Histologically, NM is defined as a dermal mass, either in isolation or with an epidermal component, not to exceed 3 rete ridges beyond the dermal component.15 Tumor cells have a high cell density with pleomorphism, usually with atypical epithelioid cells with vesicular nuclei and irregular cytoplasm, and occasionally spindle cells (Figure 2).16 Mitoses and necrosis are frequent. Scalp location independently is responsible for worse survival, both overall and melanoma specific.17 Nodular melanoma tends to have greater Breslow thickness at diagnosis than other melanoma subtypes and often carries a worse prognosis.

Malignant melanomas that develop from or in conjunction with or bear histologic resemblance to blue nevi are termed blue nevus–like melanoma or blue nevus–associated melanoma. These malignancies are exceedingly rare, accounting for only 0.3% of melanomas in one Turkey-based multicenter study.18 The histologic criteria for diagnosing blue nevus–like melanoma are poorly defined, and terminology of these lesions has led to some debate in naming conventions.19 Nevertheless, unlike blue nevus, blue nevus–like melanoma demonstrates histologic features of malignancy, including pleomorphism, prominent nucleoli, mitotic activity, vascular invasion, and potential necrosis.10 The lack of an inflammatory infiltrate, surrounding fibrosis, junctional activity, and pre-existing nevus can help distinguish cutaneous melanoma metastases from primary nodular melanoma. Immunohistochemical stains such as S100, Melan-A/MART1, or SOX-10 can help confirm melanocytic lineage.12

Pigmented BCC is a clinical and histologic variant of BCC characterized by increased melanin pigmentation due to melanocytes admixed with tumor cells. Dermoscopically, the pigment can have a maple leaf–like appearance with spoke-wheel areas, in-focus dots, and concentric structures at the dermoepidermal junction, which is more characteristic of superficial and infiltrating BCC.20 In nodular BCC, the pigment occurs as blue-gray ovoid nests and globules in deeper layers of the dermis.20

Seborrheic keratoses (SKs) can vary widely in clinical appearance, with pigmentation ranging from flesh colored to yellow to brown to black. Melanoacanthomas are acanthotic SKs that are highly pigmented due to intermixed epidermal melanocytes and subepidermal melanophages.21 Dermoscopy can help distinguish cutaneous malignancies from SKs, which often demonstrate fissures and ridges, comedolike openings, and milialike cysts. Biopsy sometimes is required to assess for malignancy, as was the case in our patient. The classic histologic features of SKs include acanthosis, papillomatosis, and hyperkeratosis.22

This case highlights the need to consider apocrine hidrocystoma, along with malignancy, in the differential diagnosis of pigmented cystic masses of the face and scalp. Because apocrine hidrocystomas are benign, they do not need to be treated but often are surgically excised for cosmesis or complete histopathologic examination. Destruction via electrodessication, carbon dioxide ablation, trichloroacetic acid chemical ablation, botulinum toxin injection, and anticholinergic creams sometimes is used, especially for cosmetic treatment of multiple small lesions.5 Our patient was treated with surgical excision with no evidence of recurrence on follow-up 1 year later.

- Ioannidis DG, Drivas EI, Papadakis CE, et al. Hidrocystoma of the external auditory canal: a case report. Cases J. 2009;2:79. doi:10.1186/1757- 1626-2-79

- Nguyen HP, Barker HS, Bloomquist L, et al. Giant pigmented apocrine hidrocystoma of the scalp. Dermatol Online J. 2020;26. doi:10.5070/D3268049895

- Mendoza-Cembranos MD, Haro R, Requena L, et al. Digital apocrine hidrocystoma: the exception confirms the rule. Am J Dermatopathol. 2019;41:79. doi:10.1097/DAD.0000000000001044

- May C, Chang O, Compton N. A giant apocrine hidrocystoma of the trunk. Dermatol Online J. 2017;23. doi:10.5070/D3239036497

- Sarabi K, Khachemoune A. Hidrocystomas—a brief review. Medscape Gen Med. 2006;8:57.

- Kruse ALD, Zwahlen R, Bredell MG, et al. Apocrine hidrocystoma of the cheek. J Craniofac Surg. 2010;21:594-596. doi:10.1097 /SCS.0b013e3181d08c77

- Zaballos P, Bañuls J, Medina C, et al. Dermoscopy of apocrine hidrocystomas: a morphological study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2014;28:378-381. doi:10.1111/jdv.12044

- Rodriguez HA, Ackerman LV. Cellular blue nevus. clinicopathologic study of forty-five cases. Cancer. 1968;21:393-405. doi:10.1002 /1097-0142(196803)21:3<393::aid-cncr2820210309>3.0.co;2-k

- Murali R, McCarthy SW, Scolyer RA. Blue nevi and related lesions: a review highlighting atypical and newly described variants, distinguishing features and diagnostic pitfalls. Adv Anat Pathol. 2009;16:365. doi:10.1097/PAP.0b013e3181bb6b53

- Borgenvik TL, Karlsvik TM, Ray S, et al. Blue nevus-like and blue nevusassociated melanoma: a comprehensive review of the literature. ANZ J Surg. 2017;87:345-349. doi:10.1111/ans.13946

- de la Fouchardiere A. Blue naevi and the blue tumour spectrum. Pathology. 2023;55:187-195. doi:10.1016/j.pathol.2022.12.342

- Lowe L. Metastatic melanoma and rare melanoma variants: a review. Pathology (Phila). 2023;55:236-244. doi:10.1016/j.pathol.2022.11.006

- Plaza JA, Torres-Cabala C, Evans H, et al. Cutaneous metastases of malignant melanoma: a clinicopathologic study of 192 cases with emphasis on the morphologic spectrum. Am J Dermatopathol. 2010;32:129-136. doi:10.1097/DAD.0b013e3181b34a19

- Shaikh WR, Xiong M, Weinstock MA. The contribution of nodular subtype to melanoma mortality in the United States, 1978 to 2007. Archives of Dermatology. 2012;148:30-36. doi:10.1001/archdermatol.2011.264

- Clark WH, From L, Bernardino EA, et al. The histogenesis and biologic behavior of primary human malignant melanomas of the skin. Cancer Res. 1969;29:705-727.

- Bobos M. Histopathologic classification and prognostic factors of melanoma: a 2021 update. Ital J Dermatol Venereol. 2021;156:300-321. doi:10.23736/S2784-8671.21.06958-3

- Ozao-Choy J, Nelson DW, Hiles J, et al. The prognostic importance of scalp location in primary head and neck melanoma. J Surg Oncol. 2017;116:337-343. doi:10.1002/jso.24679

- Gamsizkan M, Yilmaz I, Buyukbabani N, et al. A retrospective multicenter evaluation of cutaneous melanomas in Turkey. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev APJCP. 2014;15:10451-10456. doi:10.7314 /apjcp.2014.15.23.10451

- Mones JM, Ackerman AB. “Atypical” blue nevus, “malignant” blue nevus, and “metastasizing” blue nevus: a critique in historical perspective of three concepts flawed fatally. Am J Dermatopathol. 2004;26:407-430. doi:10.1097/00000372-200410000-00012

- Tanese K. Diagnosis and management of basal cell carcinoma Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2019;20:13. doi:10.1007/s11864 -019-0610-0

- Barthelmann S, Butsch F, Lang BM, et al. Seborrheic keratosis. JDDG J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2023;21:265-277. doi:10.1111/ddg.14984

- Taylor S. Advancing the understanding of seborrheic keratosis. J Drugs Dermatol. 2017;16:419-424.

THE DIAGNOSIS: Apocrine Hidrocystoma

Histology for all 3 lesions demonstrated similar cystic structures lined by a dual layer of epithelial cells, with the outermost layer composed of flattened myoepithelial cells and the inner layer composed of cells with apocrine features (Figure 1). Based on these findings, a diagnosis of apocrine hidrocystoma was made. The patient underwent successful surgical excision shortly thereafter without recurrence at follow-up 1 year later.

Apocrine hidrocystomas are rare benign cystic lesions that are considered to be adenomatous proliferations of apocrine glands. They typically manifest as solitary asymptomatic lesions measuring 3 to 15 mm.1 They tend to appear on the face, usually in the periorbital region, but also have been described on the neck, scalp, trunk, arms, and legs.2-4 Multiple apocrine hidrocystomas can be a marker of 2 rare inherited disorders: Gorlin-Goltz syndrome and Schopf-Schulz-Passarge syndrome.5 Apocrine hidrocystomas may be flesh colored or may have a blue, black, or brown appearance due to the Tyndall effect, in which light with shorter wavelengths is scattered by the contents of the lesions.2 Histologically, apocrine hidrocystomas are cysts lined by a dual layer of epithelial cells. The inner layer is composed of cells with apocrine features, and the outer layer is composed of flattened myoepithelial cells. Due to their range of colors and predilection for sun-exposed surfaces, apocrine hidrocystomas may be mistaken for various malignant neoplasms, including melanoma.6,7

The differential diagnosis for our patient included agminated blue nevi, melanoma, pigmented basal cell carcinoma (BCC), and seborrheic keratosis. A blue nevus is a dermal melanocytic lesion that manifests as a well-demarcated, blue to blue-black papule that typically appears on the face, scalp, arms, legs, lower back, and buttocks. Although there are several histologic subtypes, the common blue nevus usually manifests as a solitary lesion measuring less than 1 cm, often developing during childhood to young adulthood.8 Histologically, common blue nevi are characterized by a dermal proliferation of deeply pigmented bipolar spindled melanocytes embedded in thickened collagen bundles, often with scattered epithelioid melanophages, and no conspicuous mitotic activity (Figure 2).9 There are other types of blue nevi, including cellular blue nevi, which tend to be larger and manifest commonly on the buttocks and sacrococcygeal region in early adulthood.9 Histologically, cellular blue nevi contain oval to spindled melanocytes with scattered melanophages forming a well-demarcated nodule typically in the reticular dermis. There may be bulbous extension into the subcutaneous adipose tissue. Occasional mitoses may be seen.9,10 Melanoma can arise from common or cellular blue nevi, though it more frequently occurs with cellular blue nevi. Other subtypes of blue nevi have been described, including the sclerosing, plaque-type, combined, hypomelanotic/amelanotic, and pigmented epithelioid melanocytoma.11 However, they typically have features of the common blue nevus or cellular blue nevus, such as oval/spindle cell morphology, some degree of melanin, and biphasic architecture, but are classified according to their dominant histologic characteristics.

Given the location of our patient’s lesions on the scalp and his extensive history of sun exposure, malignancy was high in the differential. Multiple synchronous primary melanomas including nodular melanoma, blue nevus–like metastatic melanoma, and metastatic melanoma were considered. The leg and the scalp have the highest reported incidence of cutaneous metastases of melanoma, with many cases presenting as dermal or subcutaneous nodules and eruptive blue nevus–like papules, similar to our patient’s clinical presentation.12,13 Nodular melanoma (NM) is one of 4 major types of melanoma, accounting for approximately 15% to 30% of cases in the United States.14 Nodular melanoma typically manifests as a smooth, raised, symmetric, well-circumscribed lesion with variable pigmentation, from very dark to amelanotic. Histologically, NM is defined as a dermal mass, either in isolation or with an epidermal component, not to exceed 3 rete ridges beyond the dermal component.15 Tumor cells have a high cell density with pleomorphism, usually with atypical epithelioid cells with vesicular nuclei and irregular cytoplasm, and occasionally spindle cells (Figure 2).16 Mitoses and necrosis are frequent. Scalp location independently is responsible for worse survival, both overall and melanoma specific.17 Nodular melanoma tends to have greater Breslow thickness at diagnosis than other melanoma subtypes and often carries a worse prognosis.

Malignant melanomas that develop from or in conjunction with or bear histologic resemblance to blue nevi are termed blue nevus–like melanoma or blue nevus–associated melanoma. These malignancies are exceedingly rare, accounting for only 0.3% of melanomas in one Turkey-based multicenter study.18 The histologic criteria for diagnosing blue nevus–like melanoma are poorly defined, and terminology of these lesions has led to some debate in naming conventions.19 Nevertheless, unlike blue nevus, blue nevus–like melanoma demonstrates histologic features of malignancy, including pleomorphism, prominent nucleoli, mitotic activity, vascular invasion, and potential necrosis.10 The lack of an inflammatory infiltrate, surrounding fibrosis, junctional activity, and pre-existing nevus can help distinguish cutaneous melanoma metastases from primary nodular melanoma. Immunohistochemical stains such as S100, Melan-A/MART1, or SOX-10 can help confirm melanocytic lineage.12

Pigmented BCC is a clinical and histologic variant of BCC characterized by increased melanin pigmentation due to melanocytes admixed with tumor cells. Dermoscopically, the pigment can have a maple leaf–like appearance with spoke-wheel areas, in-focus dots, and concentric structures at the dermoepidermal junction, which is more characteristic of superficial and infiltrating BCC.20 In nodular BCC, the pigment occurs as blue-gray ovoid nests and globules in deeper layers of the dermis.20

Seborrheic keratoses (SKs) can vary widely in clinical appearance, with pigmentation ranging from flesh colored to yellow to brown to black. Melanoacanthomas are acanthotic SKs that are highly pigmented due to intermixed epidermal melanocytes and subepidermal melanophages.21 Dermoscopy can help distinguish cutaneous malignancies from SKs, which often demonstrate fissures and ridges, comedolike openings, and milialike cysts. Biopsy sometimes is required to assess for malignancy, as was the case in our patient. The classic histologic features of SKs include acanthosis, papillomatosis, and hyperkeratosis.22

This case highlights the need to consider apocrine hidrocystoma, along with malignancy, in the differential diagnosis of pigmented cystic masses of the face and scalp. Because apocrine hidrocystomas are benign, they do not need to be treated but often are surgically excised for cosmesis or complete histopathologic examination. Destruction via electrodessication, carbon dioxide ablation, trichloroacetic acid chemical ablation, botulinum toxin injection, and anticholinergic creams sometimes is used, especially for cosmetic treatment of multiple small lesions.5 Our patient was treated with surgical excision with no evidence of recurrence on follow-up 1 year later.

THE DIAGNOSIS: Apocrine Hidrocystoma

Histology for all 3 lesions demonstrated similar cystic structures lined by a dual layer of epithelial cells, with the outermost layer composed of flattened myoepithelial cells and the inner layer composed of cells with apocrine features (Figure 1). Based on these findings, a diagnosis of apocrine hidrocystoma was made. The patient underwent successful surgical excision shortly thereafter without recurrence at follow-up 1 year later.

Apocrine hidrocystomas are rare benign cystic lesions that are considered to be adenomatous proliferations of apocrine glands. They typically manifest as solitary asymptomatic lesions measuring 3 to 15 mm.1 They tend to appear on the face, usually in the periorbital region, but also have been described on the neck, scalp, trunk, arms, and legs.2-4 Multiple apocrine hidrocystomas can be a marker of 2 rare inherited disorders: Gorlin-Goltz syndrome and Schopf-Schulz-Passarge syndrome.5 Apocrine hidrocystomas may be flesh colored or may have a blue, black, or brown appearance due to the Tyndall effect, in which light with shorter wavelengths is scattered by the contents of the lesions.2 Histologically, apocrine hidrocystomas are cysts lined by a dual layer of epithelial cells. The inner layer is composed of cells with apocrine features, and the outer layer is composed of flattened myoepithelial cells. Due to their range of colors and predilection for sun-exposed surfaces, apocrine hidrocystomas may be mistaken for various malignant neoplasms, including melanoma.6,7

The differential diagnosis for our patient included agminated blue nevi, melanoma, pigmented basal cell carcinoma (BCC), and seborrheic keratosis. A blue nevus is a dermal melanocytic lesion that manifests as a well-demarcated, blue to blue-black papule that typically appears on the face, scalp, arms, legs, lower back, and buttocks. Although there are several histologic subtypes, the common blue nevus usually manifests as a solitary lesion measuring less than 1 cm, often developing during childhood to young adulthood.8 Histologically, common blue nevi are characterized by a dermal proliferation of deeply pigmented bipolar spindled melanocytes embedded in thickened collagen bundles, often with scattered epithelioid melanophages, and no conspicuous mitotic activity (Figure 2).9 There are other types of blue nevi, including cellular blue nevi, which tend to be larger and manifest commonly on the buttocks and sacrococcygeal region in early adulthood.9 Histologically, cellular blue nevi contain oval to spindled melanocytes with scattered melanophages forming a well-demarcated nodule typically in the reticular dermis. There may be bulbous extension into the subcutaneous adipose tissue. Occasional mitoses may be seen.9,10 Melanoma can arise from common or cellular blue nevi, though it more frequently occurs with cellular blue nevi. Other subtypes of blue nevi have been described, including the sclerosing, plaque-type, combined, hypomelanotic/amelanotic, and pigmented epithelioid melanocytoma.11 However, they typically have features of the common blue nevus or cellular blue nevus, such as oval/spindle cell morphology, some degree of melanin, and biphasic architecture, but are classified according to their dominant histologic characteristics.

Given the location of our patient’s lesions on the scalp and his extensive history of sun exposure, malignancy was high in the differential. Multiple synchronous primary melanomas including nodular melanoma, blue nevus–like metastatic melanoma, and metastatic melanoma were considered. The leg and the scalp have the highest reported incidence of cutaneous metastases of melanoma, with many cases presenting as dermal or subcutaneous nodules and eruptive blue nevus–like papules, similar to our patient’s clinical presentation.12,13 Nodular melanoma (NM) is one of 4 major types of melanoma, accounting for approximately 15% to 30% of cases in the United States.14 Nodular melanoma typically manifests as a smooth, raised, symmetric, well-circumscribed lesion with variable pigmentation, from very dark to amelanotic. Histologically, NM is defined as a dermal mass, either in isolation or with an epidermal component, not to exceed 3 rete ridges beyond the dermal component.15 Tumor cells have a high cell density with pleomorphism, usually with atypical epithelioid cells with vesicular nuclei and irregular cytoplasm, and occasionally spindle cells (Figure 2).16 Mitoses and necrosis are frequent. Scalp location independently is responsible for worse survival, both overall and melanoma specific.17 Nodular melanoma tends to have greater Breslow thickness at diagnosis than other melanoma subtypes and often carries a worse prognosis.

Malignant melanomas that develop from or in conjunction with or bear histologic resemblance to blue nevi are termed blue nevus–like melanoma or blue nevus–associated melanoma. These malignancies are exceedingly rare, accounting for only 0.3% of melanomas in one Turkey-based multicenter study.18 The histologic criteria for diagnosing blue nevus–like melanoma are poorly defined, and terminology of these lesions has led to some debate in naming conventions.19 Nevertheless, unlike blue nevus, blue nevus–like melanoma demonstrates histologic features of malignancy, including pleomorphism, prominent nucleoli, mitotic activity, vascular invasion, and potential necrosis.10 The lack of an inflammatory infiltrate, surrounding fibrosis, junctional activity, and pre-existing nevus can help distinguish cutaneous melanoma metastases from primary nodular melanoma. Immunohistochemical stains such as S100, Melan-A/MART1, or SOX-10 can help confirm melanocytic lineage.12

Pigmented BCC is a clinical and histologic variant of BCC characterized by increased melanin pigmentation due to melanocytes admixed with tumor cells. Dermoscopically, the pigment can have a maple leaf–like appearance with spoke-wheel areas, in-focus dots, and concentric structures at the dermoepidermal junction, which is more characteristic of superficial and infiltrating BCC.20 In nodular BCC, the pigment occurs as blue-gray ovoid nests and globules in deeper layers of the dermis.20

Seborrheic keratoses (SKs) can vary widely in clinical appearance, with pigmentation ranging from flesh colored to yellow to brown to black. Melanoacanthomas are acanthotic SKs that are highly pigmented due to intermixed epidermal melanocytes and subepidermal melanophages.21 Dermoscopy can help distinguish cutaneous malignancies from SKs, which often demonstrate fissures and ridges, comedolike openings, and milialike cysts. Biopsy sometimes is required to assess for malignancy, as was the case in our patient. The classic histologic features of SKs include acanthosis, papillomatosis, and hyperkeratosis.22

This case highlights the need to consider apocrine hidrocystoma, along with malignancy, in the differential diagnosis of pigmented cystic masses of the face and scalp. Because apocrine hidrocystomas are benign, they do not need to be treated but often are surgically excised for cosmesis or complete histopathologic examination. Destruction via electrodessication, carbon dioxide ablation, trichloroacetic acid chemical ablation, botulinum toxin injection, and anticholinergic creams sometimes is used, especially for cosmetic treatment of multiple small lesions.5 Our patient was treated with surgical excision with no evidence of recurrence on follow-up 1 year later.

- Ioannidis DG, Drivas EI, Papadakis CE, et al. Hidrocystoma of the external auditory canal: a case report. Cases J. 2009;2:79. doi:10.1186/1757- 1626-2-79

- Nguyen HP, Barker HS, Bloomquist L, et al. Giant pigmented apocrine hidrocystoma of the scalp. Dermatol Online J. 2020;26. doi:10.5070/D3268049895

- Mendoza-Cembranos MD, Haro R, Requena L, et al. Digital apocrine hidrocystoma: the exception confirms the rule. Am J Dermatopathol. 2019;41:79. doi:10.1097/DAD.0000000000001044

- May C, Chang O, Compton N. A giant apocrine hidrocystoma of the trunk. Dermatol Online J. 2017;23. doi:10.5070/D3239036497

- Sarabi K, Khachemoune A. Hidrocystomas—a brief review. Medscape Gen Med. 2006;8:57.

- Kruse ALD, Zwahlen R, Bredell MG, et al. Apocrine hidrocystoma of the cheek. J Craniofac Surg. 2010;21:594-596. doi:10.1097 /SCS.0b013e3181d08c77

- Zaballos P, Bañuls J, Medina C, et al. Dermoscopy of apocrine hidrocystomas: a morphological study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2014;28:378-381. doi:10.1111/jdv.12044

- Rodriguez HA, Ackerman LV. Cellular blue nevus. clinicopathologic study of forty-five cases. Cancer. 1968;21:393-405. doi:10.1002 /1097-0142(196803)21:3<393::aid-cncr2820210309>3.0.co;2-k

- Murali R, McCarthy SW, Scolyer RA. Blue nevi and related lesions: a review highlighting atypical and newly described variants, distinguishing features and diagnostic pitfalls. Adv Anat Pathol. 2009;16:365. doi:10.1097/PAP.0b013e3181bb6b53

- Borgenvik TL, Karlsvik TM, Ray S, et al. Blue nevus-like and blue nevusassociated melanoma: a comprehensive review of the literature. ANZ J Surg. 2017;87:345-349. doi:10.1111/ans.13946

- de la Fouchardiere A. Blue naevi and the blue tumour spectrum. Pathology. 2023;55:187-195. doi:10.1016/j.pathol.2022.12.342

- Lowe L. Metastatic melanoma and rare melanoma variants: a review. Pathology (Phila). 2023;55:236-244. doi:10.1016/j.pathol.2022.11.006

- Plaza JA, Torres-Cabala C, Evans H, et al. Cutaneous metastases of malignant melanoma: a clinicopathologic study of 192 cases with emphasis on the morphologic spectrum. Am J Dermatopathol. 2010;32:129-136. doi:10.1097/DAD.0b013e3181b34a19

- Shaikh WR, Xiong M, Weinstock MA. The contribution of nodular subtype to melanoma mortality in the United States, 1978 to 2007. Archives of Dermatology. 2012;148:30-36. doi:10.1001/archdermatol.2011.264

- Clark WH, From L, Bernardino EA, et al. The histogenesis and biologic behavior of primary human malignant melanomas of the skin. Cancer Res. 1969;29:705-727.

- Bobos M. Histopathologic classification and prognostic factors of melanoma: a 2021 update. Ital J Dermatol Venereol. 2021;156:300-321. doi:10.23736/S2784-8671.21.06958-3

- Ozao-Choy J, Nelson DW, Hiles J, et al. The prognostic importance of scalp location in primary head and neck melanoma. J Surg Oncol. 2017;116:337-343. doi:10.1002/jso.24679

- Gamsizkan M, Yilmaz I, Buyukbabani N, et al. A retrospective multicenter evaluation of cutaneous melanomas in Turkey. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev APJCP. 2014;15:10451-10456. doi:10.7314 /apjcp.2014.15.23.10451

- Mones JM, Ackerman AB. “Atypical” blue nevus, “malignant” blue nevus, and “metastasizing” blue nevus: a critique in historical perspective of three concepts flawed fatally. Am J Dermatopathol. 2004;26:407-430. doi:10.1097/00000372-200410000-00012

- Tanese K. Diagnosis and management of basal cell carcinoma Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2019;20:13. doi:10.1007/s11864 -019-0610-0

- Barthelmann S, Butsch F, Lang BM, et al. Seborrheic keratosis. JDDG J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2023;21:265-277. doi:10.1111/ddg.14984

- Taylor S. Advancing the understanding of seborrheic keratosis. J Drugs Dermatol. 2017;16:419-424.

- Ioannidis DG, Drivas EI, Papadakis CE, et al. Hidrocystoma of the external auditory canal: a case report. Cases J. 2009;2:79. doi:10.1186/1757- 1626-2-79

- Nguyen HP, Barker HS, Bloomquist L, et al. Giant pigmented apocrine hidrocystoma of the scalp. Dermatol Online J. 2020;26. doi:10.5070/D3268049895

- Mendoza-Cembranos MD, Haro R, Requena L, et al. Digital apocrine hidrocystoma: the exception confirms the rule. Am J Dermatopathol. 2019;41:79. doi:10.1097/DAD.0000000000001044

- May C, Chang O, Compton N. A giant apocrine hidrocystoma of the trunk. Dermatol Online J. 2017;23. doi:10.5070/D3239036497

- Sarabi K, Khachemoune A. Hidrocystomas—a brief review. Medscape Gen Med. 2006;8:57.

- Kruse ALD, Zwahlen R, Bredell MG, et al. Apocrine hidrocystoma of the cheek. J Craniofac Surg. 2010;21:594-596. doi:10.1097 /SCS.0b013e3181d08c77

- Zaballos P, Bañuls J, Medina C, et al. Dermoscopy of apocrine hidrocystomas: a morphological study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2014;28:378-381. doi:10.1111/jdv.12044

- Rodriguez HA, Ackerman LV. Cellular blue nevus. clinicopathologic study of forty-five cases. Cancer. 1968;21:393-405. doi:10.1002 /1097-0142(196803)21:3<393::aid-cncr2820210309>3.0.co;2-k

- Murali R, McCarthy SW, Scolyer RA. Blue nevi and related lesions: a review highlighting atypical and newly described variants, distinguishing features and diagnostic pitfalls. Adv Anat Pathol. 2009;16:365. doi:10.1097/PAP.0b013e3181bb6b53

- Borgenvik TL, Karlsvik TM, Ray S, et al. Blue nevus-like and blue nevusassociated melanoma: a comprehensive review of the literature. ANZ J Surg. 2017;87:345-349. doi:10.1111/ans.13946

- de la Fouchardiere A. Blue naevi and the blue tumour spectrum. Pathology. 2023;55:187-195. doi:10.1016/j.pathol.2022.12.342

- Lowe L. Metastatic melanoma and rare melanoma variants: a review. Pathology (Phila). 2023;55:236-244. doi:10.1016/j.pathol.2022.11.006

- Plaza JA, Torres-Cabala C, Evans H, et al. Cutaneous metastases of malignant melanoma: a clinicopathologic study of 192 cases with emphasis on the morphologic spectrum. Am J Dermatopathol. 2010;32:129-136. doi:10.1097/DAD.0b013e3181b34a19

- Shaikh WR, Xiong M, Weinstock MA. The contribution of nodular subtype to melanoma mortality in the United States, 1978 to 2007. Archives of Dermatology. 2012;148:30-36. doi:10.1001/archdermatol.2011.264

- Clark WH, From L, Bernardino EA, et al. The histogenesis and biologic behavior of primary human malignant melanomas of the skin. Cancer Res. 1969;29:705-727.

- Bobos M. Histopathologic classification and prognostic factors of melanoma: a 2021 update. Ital J Dermatol Venereol. 2021;156:300-321. doi:10.23736/S2784-8671.21.06958-3

- Ozao-Choy J, Nelson DW, Hiles J, et al. The prognostic importance of scalp location in primary head and neck melanoma. J Surg Oncol. 2017;116:337-343. doi:10.1002/jso.24679

- Gamsizkan M, Yilmaz I, Buyukbabani N, et al. A retrospective multicenter evaluation of cutaneous melanomas in Turkey. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev APJCP. 2014;15:10451-10456. doi:10.7314 /apjcp.2014.15.23.10451

- Mones JM, Ackerman AB. “Atypical” blue nevus, “malignant” blue nevus, and “metastasizing” blue nevus: a critique in historical perspective of three concepts flawed fatally. Am J Dermatopathol. 2004;26:407-430. doi:10.1097/00000372-200410000-00012

- Tanese K. Diagnosis and management of basal cell carcinoma Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2019;20:13. doi:10.1007/s11864 -019-0610-0

- Barthelmann S, Butsch F, Lang BM, et al. Seborrheic keratosis. JDDG J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2023;21:265-277. doi:10.1111/ddg.14984

- Taylor S. Advancing the understanding of seborrheic keratosis. J Drugs Dermatol. 2017;16:419-424.

A 67-year-old man presented to the dermatology clinic with 3 asymptomatic pigmented papules on the scalp. The patient reported that he was unaware of the lesions until they were pointed out weeks earlier by his primary care physician during a routine visit. He then was referred to dermatology for follow-up. Physical examination at the current presentation revealed clustered firm, smooth, well-circumscribed, pigmented papules on the scalp measuring 5 to 8 mm. The patient reported no personal or family history of skin cancer but stated that he spent a lot of time outdoors and had a history of 6 blistering sunburns in his life. A punch biopsy of each lesion was performed.

Dyshidroticlike Contact Dermatitis and Paronychia Resulting From a Dip Powder Manicure

To the Editor:

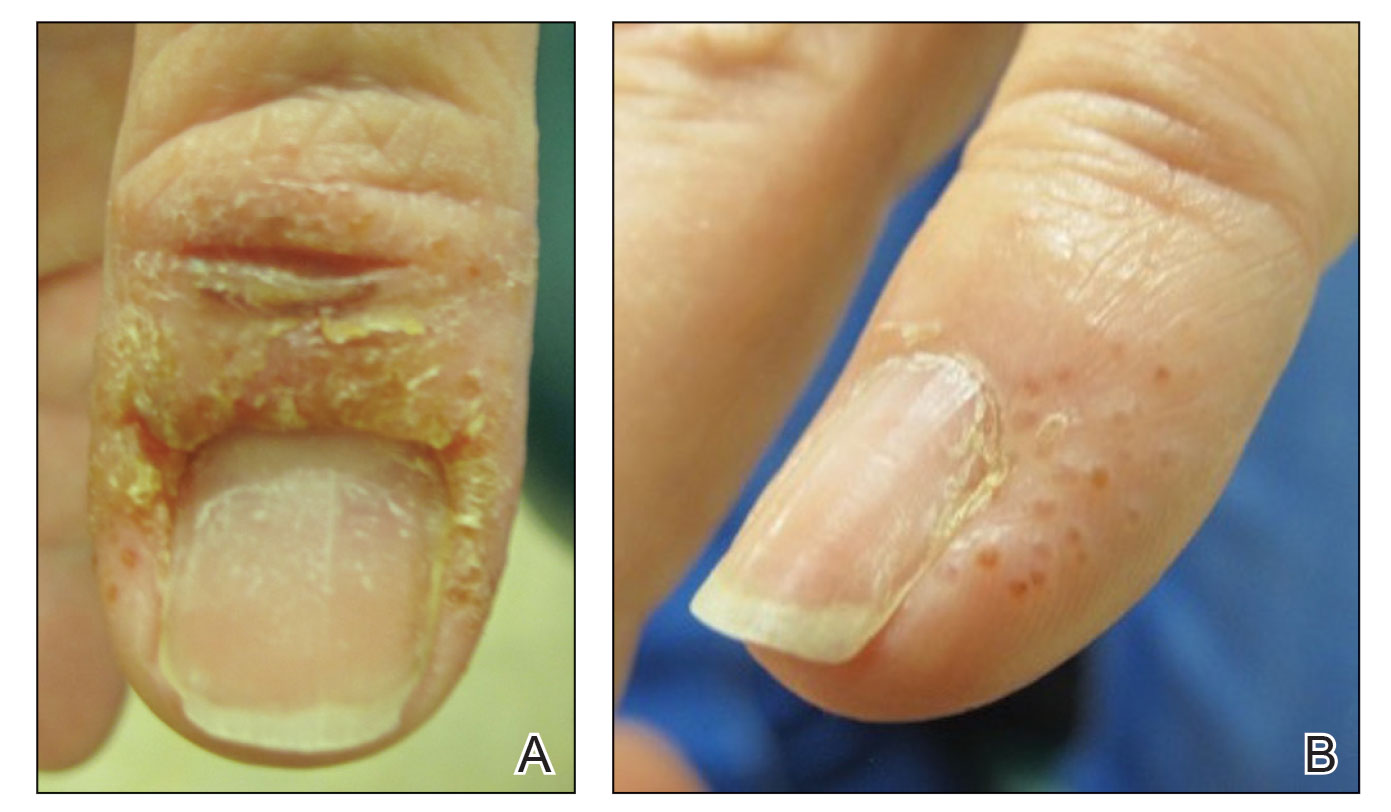

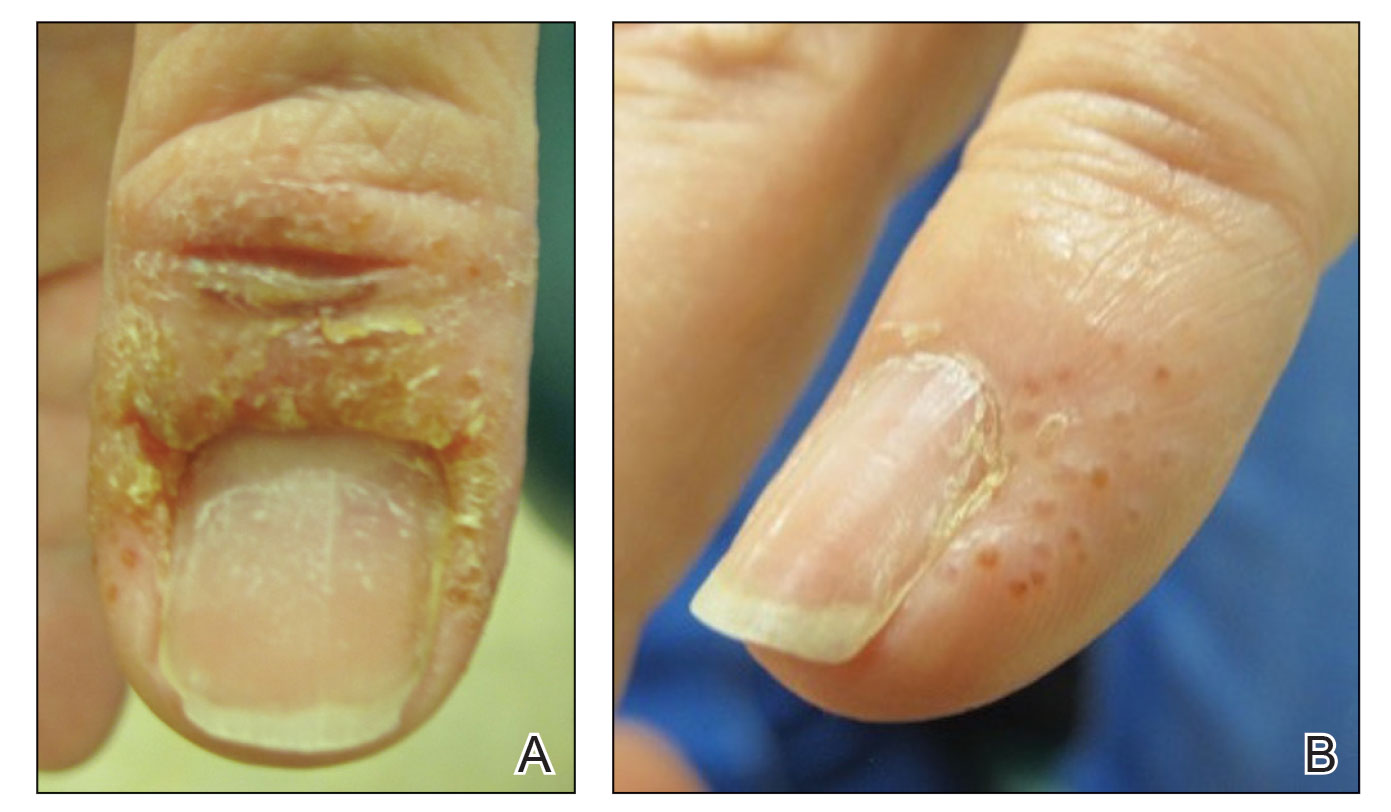

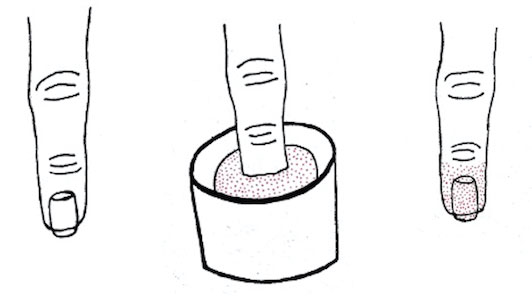

A 58-year-old woman presented to our dermatology clinic with a pruritic weeping eruption circumferentially on the distal digits of both hands of 5 weeks’ duration. The patient disclosed that she had been receiving dip powder manicures at a local nail salon approximately every 2 weeks over the last 3 to 6 months. She had received frequent acrylic nail extensions over the last 8 years prior to starting the dip powder manicures. Physical examination revealed well-demarcated eczematous plaques involving the lateral and proximal nail folds of the right thumb with an overlying serous crust and loss of the cuticle (Figure 1A). Erythematous plaques with firm deep-seated microvesicles also were present on the other digits, distributed distal to the distal interphalangeal joints (Figure 1B). She was diagnosed with dyshidroticlike contact dermatitis and paronychia. Treatment included phenol 1.5% colorless solution and clobetasol ointment 0.05% for twice-daily application to the affected areas. The patient also was advised to stop receiving manicures. At 1-month follow-up, the paronychia had resolved and the dermatitis had nearly resolved.

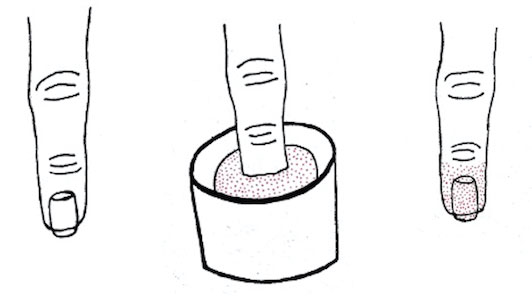

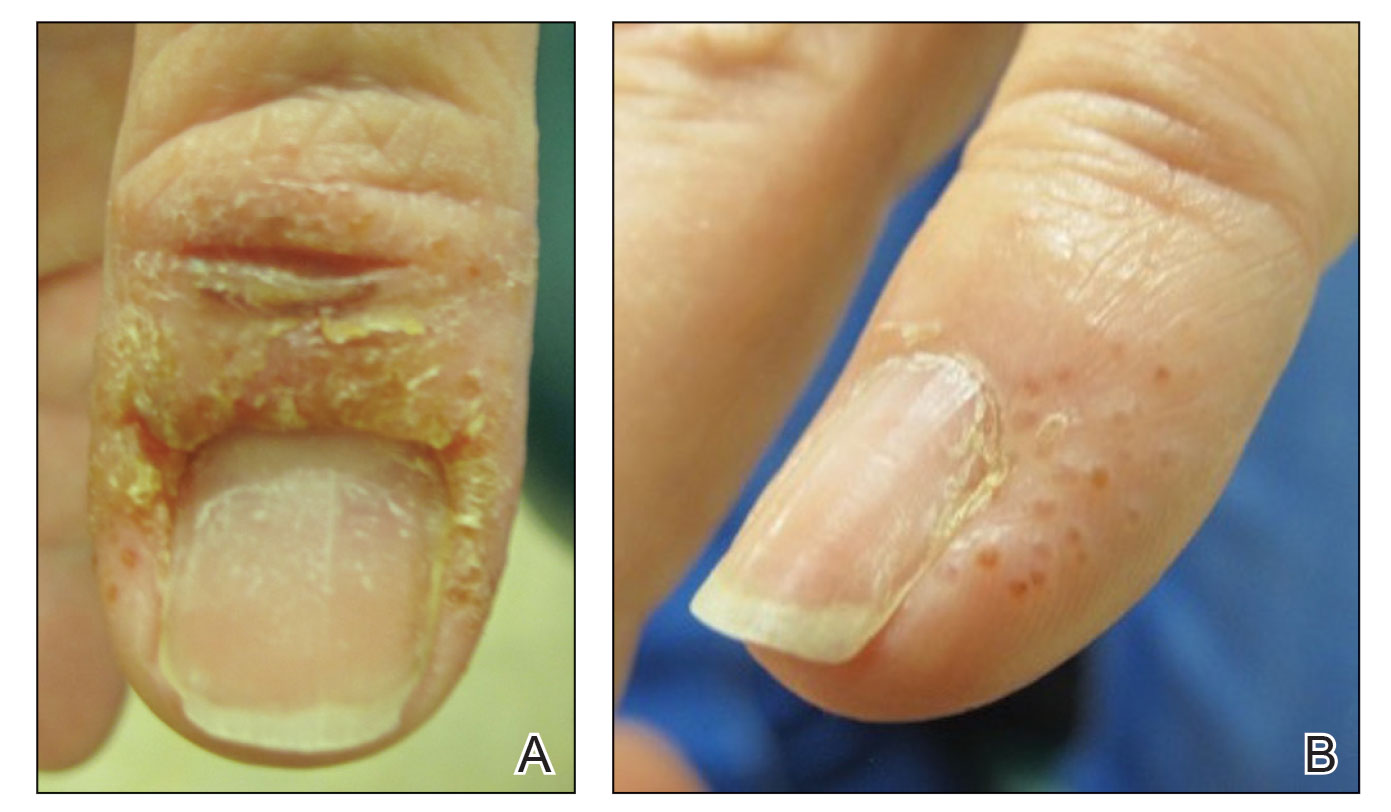

Dip powder manicures use a wet adhesive base coat with acrylic powder and an activator topcoat to initiate a chemical reaction that hardens and sets the nail polish. The colored powder typically is applied by dipping the digit up to the distal interphalangeal joint into a small container of loose powder and then brushing away the excess (Figure 2). Acrylate, a chemical present in dip powders, is a known allergen and has been associated with the development of allergic contact dermatitis and onychodystrophy in patients after receiving acrylic and UV-cured gel polish manicures.1,2 Inadequate sanitation practices at nail salons also have been associated with infection transmission.3,4 Additionally, the news media has covered the potential risk of infection due to contamination from reused dip manicure powder and the use of communal powder containers.5

To increase clinical awareness of the dip manicure technique, we describe the presentation and successful treatment of dyshidroticlike contact dermatitis and paronychia that occurred in a patient after she received a dip powder manicure. Dermatoses and infection limited to the distal phalanges will present in patients more frequently as dip powder manicures continue to increase in popularity and frequency.

- Baran R. Nail cosmetics: allergies and irritations. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2002;3:547-555.

- Chen AF, Chimento SM, Hu S, et al. Nail damage from gel polish manicure. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2012;11:27-29.

- Schmidt AN, Zic JA, Boyd AS. Pedicure-associated Mycobacterium chelonae infection in a hospitalized patient. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:E248-E250.

- Sniezek PJ, Graham BS, Busch HB, et al. Rapidly growing mycobacterial infections after pedicures. Arch Dermatol. 2003;139:629-634.

- Joseph T. You could be risking an infection with nail dipping. NBC Universal Media, LLC. Updated July 11, 2019. Accessed June 7, 2023. https://www.nbcmiami.com/news/local/You-Could-Be-Risking-an-Infection-with-Nail-Dipping-512550372.html

To the Editor:

A 58-year-old woman presented to our dermatology clinic with a pruritic weeping eruption circumferentially on the distal digits of both hands of 5 weeks’ duration. The patient disclosed that she had been receiving dip powder manicures at a local nail salon approximately every 2 weeks over the last 3 to 6 months. She had received frequent acrylic nail extensions over the last 8 years prior to starting the dip powder manicures. Physical examination revealed well-demarcated eczematous plaques involving the lateral and proximal nail folds of the right thumb with an overlying serous crust and loss of the cuticle (Figure 1A). Erythematous plaques with firm deep-seated microvesicles also were present on the other digits, distributed distal to the distal interphalangeal joints (Figure 1B). She was diagnosed with dyshidroticlike contact dermatitis and paronychia. Treatment included phenol 1.5% colorless solution and clobetasol ointment 0.05% for twice-daily application to the affected areas. The patient also was advised to stop receiving manicures. At 1-month follow-up, the paronychia had resolved and the dermatitis had nearly resolved.

Dip powder manicures use a wet adhesive base coat with acrylic powder and an activator topcoat to initiate a chemical reaction that hardens and sets the nail polish. The colored powder typically is applied by dipping the digit up to the distal interphalangeal joint into a small container of loose powder and then brushing away the excess (Figure 2). Acrylate, a chemical present in dip powders, is a known allergen and has been associated with the development of allergic contact dermatitis and onychodystrophy in patients after receiving acrylic and UV-cured gel polish manicures.1,2 Inadequate sanitation practices at nail salons also have been associated with infection transmission.3,4 Additionally, the news media has covered the potential risk of infection due to contamination from reused dip manicure powder and the use of communal powder containers.5

To increase clinical awareness of the dip manicure technique, we describe the presentation and successful treatment of dyshidroticlike contact dermatitis and paronychia that occurred in a patient after she received a dip powder manicure. Dermatoses and infection limited to the distal phalanges will present in patients more frequently as dip powder manicures continue to increase in popularity and frequency.

To the Editor:

A 58-year-old woman presented to our dermatology clinic with a pruritic weeping eruption circumferentially on the distal digits of both hands of 5 weeks’ duration. The patient disclosed that she had been receiving dip powder manicures at a local nail salon approximately every 2 weeks over the last 3 to 6 months. She had received frequent acrylic nail extensions over the last 8 years prior to starting the dip powder manicures. Physical examination revealed well-demarcated eczematous plaques involving the lateral and proximal nail folds of the right thumb with an overlying serous crust and loss of the cuticle (Figure 1A). Erythematous plaques with firm deep-seated microvesicles also were present on the other digits, distributed distal to the distal interphalangeal joints (Figure 1B). She was diagnosed with dyshidroticlike contact dermatitis and paronychia. Treatment included phenol 1.5% colorless solution and clobetasol ointment 0.05% for twice-daily application to the affected areas. The patient also was advised to stop receiving manicures. At 1-month follow-up, the paronychia had resolved and the dermatitis had nearly resolved.

Dip powder manicures use a wet adhesive base coat with acrylic powder and an activator topcoat to initiate a chemical reaction that hardens and sets the nail polish. The colored powder typically is applied by dipping the digit up to the distal interphalangeal joint into a small container of loose powder and then brushing away the excess (Figure 2). Acrylate, a chemical present in dip powders, is a known allergen and has been associated with the development of allergic contact dermatitis and onychodystrophy in patients after receiving acrylic and UV-cured gel polish manicures.1,2 Inadequate sanitation practices at nail salons also have been associated with infection transmission.3,4 Additionally, the news media has covered the potential risk of infection due to contamination from reused dip manicure powder and the use of communal powder containers.5

To increase clinical awareness of the dip manicure technique, we describe the presentation and successful treatment of dyshidroticlike contact dermatitis and paronychia that occurred in a patient after she received a dip powder manicure. Dermatoses and infection limited to the distal phalanges will present in patients more frequently as dip powder manicures continue to increase in popularity and frequency.

- Baran R. Nail cosmetics: allergies and irritations. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2002;3:547-555.

- Chen AF, Chimento SM, Hu S, et al. Nail damage from gel polish manicure. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2012;11:27-29.

- Schmidt AN, Zic JA, Boyd AS. Pedicure-associated Mycobacterium chelonae infection in a hospitalized patient. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:E248-E250.

- Sniezek PJ, Graham BS, Busch HB, et al. Rapidly growing mycobacterial infections after pedicures. Arch Dermatol. 2003;139:629-634.

- Joseph T. You could be risking an infection with nail dipping. NBC Universal Media, LLC. Updated July 11, 2019. Accessed June 7, 2023. https://www.nbcmiami.com/news/local/You-Could-Be-Risking-an-Infection-with-Nail-Dipping-512550372.html

- Baran R. Nail cosmetics: allergies and irritations. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2002;3:547-555.

- Chen AF, Chimento SM, Hu S, et al. Nail damage from gel polish manicure. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2012;11:27-29.

- Schmidt AN, Zic JA, Boyd AS. Pedicure-associated Mycobacterium chelonae infection in a hospitalized patient. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:E248-E250.

- Sniezek PJ, Graham BS, Busch HB, et al. Rapidly growing mycobacterial infections after pedicures. Arch Dermatol. 2003;139:629-634.

- Joseph T. You could be risking an infection with nail dipping. NBC Universal Media, LLC. Updated July 11, 2019. Accessed June 7, 2023. https://www.nbcmiami.com/news/local/You-Could-Be-Risking-an-Infection-with-Nail-Dipping-512550372.html

Practice Points

- Manicures performed at nail salons have been associated with the development of paronychia due to inadequate sanitation practices and contact dermatitis caused by acrylates present in nail polish.

- The dip powder manicure is a relatively new manicure technique. The distribution of dermatoses and infection limited to the distal phalanges will present in patients more frequently as dip powder manicures continue to increase in popularity and are performed more frequently.

Spontaneous ecchymoses

A 65-YEAR-OLD WOMAN was brought into the emergency department by her daughter for spontaneous bruising, fatigue, and weakness of several weeks’ duration. She denied taking any medications or illicit drugs and had not experienced any falls or trauma. On a daily basis, she smoked 5 to 7 cigarettes and drank 6 or 7 beers, as had been her custom for several years. The patient lived alone and was grieving the death of her beloved dog, who had died a month earlier. She reported that since the death of her dog, her diet, which hadn’t been especially good to begin with, had deteriorated; it now consisted of beer and crackers.

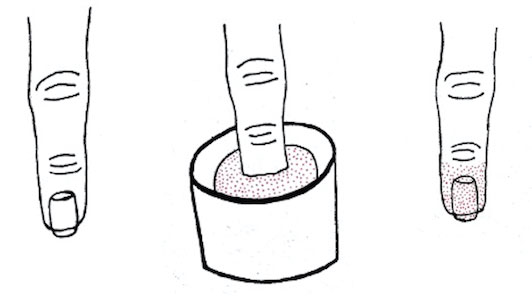

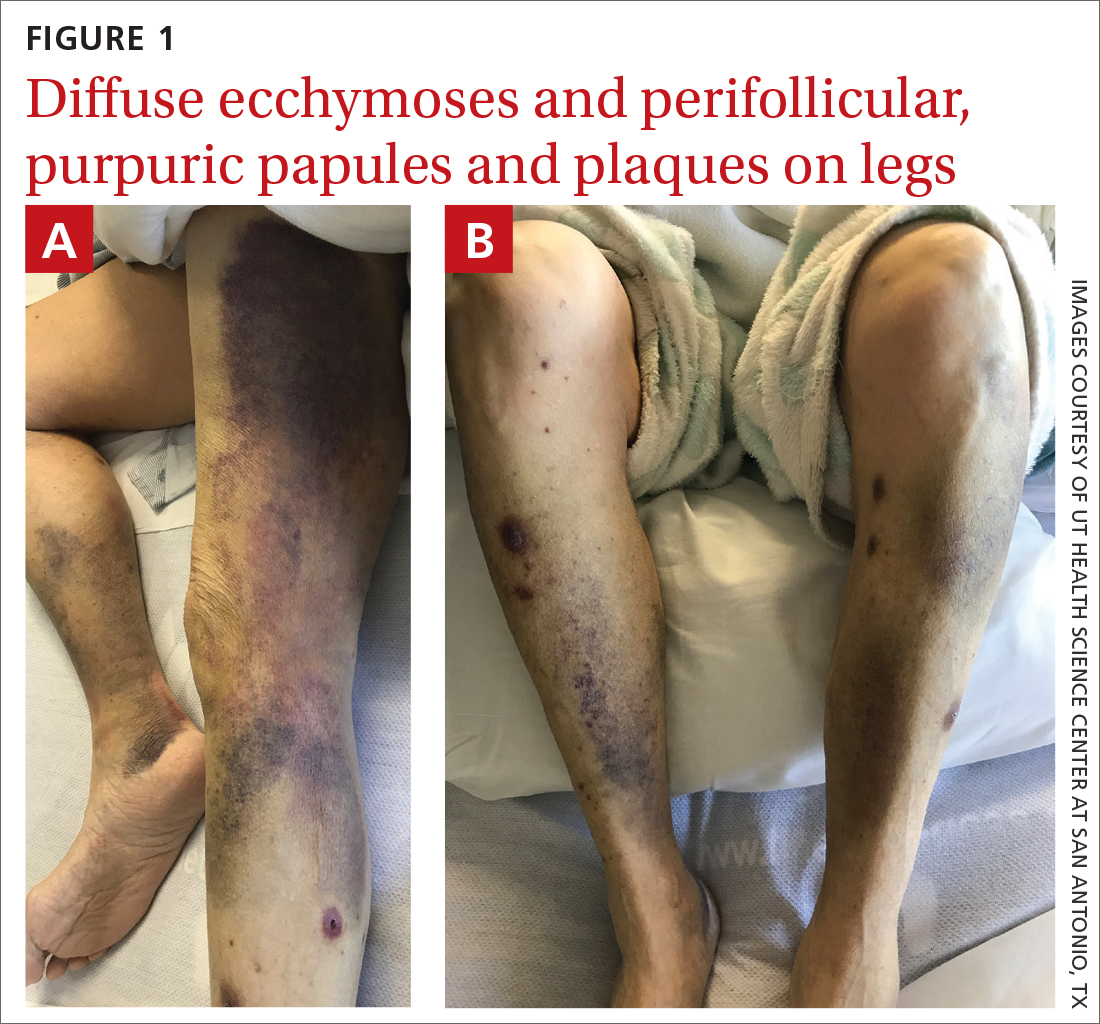

On admission, she was mildly tachycardic (105 beats/min) with a blood pressure of 125/66 mm Hg. Physical examination revealed a frail-appearing woman who was in no acute distress but was unable to stand without assistance. She had diffuse ecchymoses and perifollicular, purpuric, hyperkeratotic papules and plaques on both of her legs (FIGURES 1A and 1B). In addition, she had faint perifollicular purpuric macules on her upper back. An oral examination revealed poor dentition.

A punch biopsy was performed on her leg, and it revealed noninflammatory dermal hemorrhage without evidence of vasculitis or vasculopathy.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Scurvy

Based on the patient’s appearance and her dietary history, we suspected scurvy, so a serum vitamin C level was ordered. The results took several days to return. In the meantime, additional lab work revealed hyponatremia (sodium, 129 mmol/L; normal range, 135-145 mmol/L), hypokalemia (potassium, 3 mmol/L; normal range, 3.5-5.2 mmol/L), hypophosphatemia (phosphorus, 2.3 mg/dL; normal range, 2.8-4.5 mg/dL); low serum vitamin D (6 ng/mL; normal range, 20-40 ng/mL); and macrocytic anemia (hemoglobin, 7.4 g/dL; normal range, 11-18 g/dL) with a mean corpuscular volume of 101.1 fL (normal range, 80-100 fL). Her iron panel showed normal serum iron and total iron binding capacity with a normal ferritin level (294 ng/mL; normal range, 30-300 ng/mL). A peripheral blood smear test uncovered mild anisocytosis and polychromasia, with no schistocytes. A fecal immunochemical test was negative.

Several days after admission, the results of the patient’s vitamin C test came back. Her levels were undetectable (< 5 µmol/L; normal range, 11-23 µmol/L), confirming that the patient had scurvy.

A health hazard to marinersthat is still around today

Scurvy is a condition that arises from a deficiency of vitamin C, or ascorbic acid. The first known case of scurvy was in 1550 BC.1 Hippocrates termed the condition “ileos ematitis” and stated that “the mouth feels bad; the gums are detached from the teeth; blood runs from the nostrils … ulcerations on the legs … skin is thin.”1 Scurvy was a major health hazard of mariners between the 15thand 18th centuries.2 Today, the deficiency is uncommon in industrialized countries because there are many sources of vitamin C available through diet and vitamin supplements.3 In the United States, the prevalence of vitamin C deficiency is approximately 7%.4

An essential nutrient in humans, vitamin C is required as a cofactor in the synthesis of mature collagen.3 Collagen is found in skin, bone, and endothelium. Inadequate collagen levels can result in poor dermal support of vessels and tissue fragility, leading to hemorrhage, which can occur in nearly any organ system.

Vitamin C deficiency occurs when serum concentration falls below 11.4

Continue to: Scurvy manifests after 8 to 12 weeks

Scurvy manifests after 8 to 12 weeks of inadequate vitamin C intake.1 Patients may initially experience malaise and irritability. Anemia is common. Dermatologic findings include hyperkeratotic lesions, ecchymoses, poor wound healing, gingival swelling with loss of teeth, petechiae, and corkscrew hairs. Perifollicular hemorrhage is a characteristic finding of scurvy, generally seen on the lower extremities, where the capillaries are under higher hydrostatic pressure.3 Patients may also have musculoskeletal involvement with osteopenia or hemarthroses, which may be seen on imaging.3,5 Cardiorespiratory, gastrointestinal, ophthalmologic, and neurologic findings have also been reported.3

Differential is broad; zero in on patient’s history

The differential diagnosis for hemorrhagic skin lesions is extensive and includes scurvy, coagulopathies, trauma, vasculitis, and vasculopathies.

The presence of perifollicular hemorrhage with corkscrew hairs and a dietary history of inadequate vitamin C intake can differentiate scurvy from other conditions. Serum testing revealing low plasma vitamin C will support the diagnosis, but this is an insensitive test, as values increase with recent intake. Leukocyte ascorbic acid concentrations are more representative of total body stores, but impractical for routine use.6 Skin biopsy is not necessary but may help to rule out other conditions.

Ascorbic acid will facilitate a speedy recovery

Treatment of scurvy includes vitamin C replacement. Response is rapid, with improvement to lethargy within several days and disappearance of other manifestations within several weeks.3 Recommendations on supplementation doses and forms vary, but adults require 300 to 1000 mg/d of ascorbic acid for at least 1 week or until clinical symptoms resolve and stores are repleted.3,5,7

During our patient’s hospital stay, she remained stable and improved clinically with vitamin supplementation (ascorbic acid 1 g/d for 3 days, 500 mg/d after that) and physical therapy. She was counseled on a healthy diet, which would include citrus fruits, tomatoes, and leafy vegetables. The patient was also advised to refrain from drinking alcohol and was given information on an alcohol abstinence program.

At her 1-month follow-up, her condition had improved with near resolution of the skin lesions. She reported that she had given up cigarettes and alcohol. She said she’d also begun eating more citrus fruits and leafy vegetables.

1. Maxfield L, Crane JS. Vitamin C deficiency (scurvy). In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2020. Accessed on September 13, 2022. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK493187/

2. Worral S. A nightmare disease haunted ships during age of discovery. National Geographic. January 15, 2017. Accessed September 21, 2022. www.nationalgeographic.com/science/article/scurvy-disease-discovery-jonathan-lamb

3. Hirschmann JV, Raugi GJ. Adult Scurvy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41:895-906. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(99)70244-6

4. Schleicher RL, Carroll MD, Ford ES, et al. Serum vitamin C and the prevalence of vitamin C deficiency in the United States: 2003-2004 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES). Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;90:1252-1263. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2008.27016

5. Agarwal A, Shaharyar A, Kumar A, et al. Scurvy in pediatric age group – A disease often forgotten? J Clin Orthop Trauma. 2015;6:101-107. doi: 10.1016/j.jcot.2014.12.003

6. Scurvy and its prevention and control in major emergencies. World Health Organization. February 23, 1999. Accessed September 13, 2022. www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-NHD-99.11

7. Weinstein M, Babyn P, Zlotkin S. An orange a day keeps the doctor away: scurvy in the year 2000. Pediatrics. 2001;108:E55. doi: 10.1542/peds.108.3.e55

A 65-YEAR-OLD WOMAN was brought into the emergency department by her daughter for spontaneous bruising, fatigue, and weakness of several weeks’ duration. She denied taking any medications or illicit drugs and had not experienced any falls or trauma. On a daily basis, she smoked 5 to 7 cigarettes and drank 6 or 7 beers, as had been her custom for several years. The patient lived alone and was grieving the death of her beloved dog, who had died a month earlier. She reported that since the death of her dog, her diet, which hadn’t been especially good to begin with, had deteriorated; it now consisted of beer and crackers.

On admission, she was mildly tachycardic (105 beats/min) with a blood pressure of 125/66 mm Hg. Physical examination revealed a frail-appearing woman who was in no acute distress but was unable to stand without assistance. She had diffuse ecchymoses and perifollicular, purpuric, hyperkeratotic papules and plaques on both of her legs (FIGURES 1A and 1B). In addition, she had faint perifollicular purpuric macules on her upper back. An oral examination revealed poor dentition.

A punch biopsy was performed on her leg, and it revealed noninflammatory dermal hemorrhage without evidence of vasculitis or vasculopathy.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Scurvy

Based on the patient’s appearance and her dietary history, we suspected scurvy, so a serum vitamin C level was ordered. The results took several days to return. In the meantime, additional lab work revealed hyponatremia (sodium, 129 mmol/L; normal range, 135-145 mmol/L), hypokalemia (potassium, 3 mmol/L; normal range, 3.5-5.2 mmol/L), hypophosphatemia (phosphorus, 2.3 mg/dL; normal range, 2.8-4.5 mg/dL); low serum vitamin D (6 ng/mL; normal range, 20-40 ng/mL); and macrocytic anemia (hemoglobin, 7.4 g/dL; normal range, 11-18 g/dL) with a mean corpuscular volume of 101.1 fL (normal range, 80-100 fL). Her iron panel showed normal serum iron and total iron binding capacity with a normal ferritin level (294 ng/mL; normal range, 30-300 ng/mL). A peripheral blood smear test uncovered mild anisocytosis and polychromasia, with no schistocytes. A fecal immunochemical test was negative.

Several days after admission, the results of the patient’s vitamin C test came back. Her levels were undetectable (< 5 µmol/L; normal range, 11-23 µmol/L), confirming that the patient had scurvy.

A health hazard to marinersthat is still around today

Scurvy is a condition that arises from a deficiency of vitamin C, or ascorbic acid. The first known case of scurvy was in 1550 BC.1 Hippocrates termed the condition “ileos ematitis” and stated that “the mouth feels bad; the gums are detached from the teeth; blood runs from the nostrils … ulcerations on the legs … skin is thin.”1 Scurvy was a major health hazard of mariners between the 15thand 18th centuries.2 Today, the deficiency is uncommon in industrialized countries because there are many sources of vitamin C available through diet and vitamin supplements.3 In the United States, the prevalence of vitamin C deficiency is approximately 7%.4

An essential nutrient in humans, vitamin C is required as a cofactor in the synthesis of mature collagen.3 Collagen is found in skin, bone, and endothelium. Inadequate collagen levels can result in poor dermal support of vessels and tissue fragility, leading to hemorrhage, which can occur in nearly any organ system.

Vitamin C deficiency occurs when serum concentration falls below 11.4

Continue to: Scurvy manifests after 8 to 12 weeks

Scurvy manifests after 8 to 12 weeks of inadequate vitamin C intake.1 Patients may initially experience malaise and irritability. Anemia is common. Dermatologic findings include hyperkeratotic lesions, ecchymoses, poor wound healing, gingival swelling with loss of teeth, petechiae, and corkscrew hairs. Perifollicular hemorrhage is a characteristic finding of scurvy, generally seen on the lower extremities, where the capillaries are under higher hydrostatic pressure.3 Patients may also have musculoskeletal involvement with osteopenia or hemarthroses, which may be seen on imaging.3,5 Cardiorespiratory, gastrointestinal, ophthalmologic, and neurologic findings have also been reported.3

Differential is broad; zero in on patient’s history

The differential diagnosis for hemorrhagic skin lesions is extensive and includes scurvy, coagulopathies, trauma, vasculitis, and vasculopathies.

The presence of perifollicular hemorrhage with corkscrew hairs and a dietary history of inadequate vitamin C intake can differentiate scurvy from other conditions. Serum testing revealing low plasma vitamin C will support the diagnosis, but this is an insensitive test, as values increase with recent intake. Leukocyte ascorbic acid concentrations are more representative of total body stores, but impractical for routine use.6 Skin biopsy is not necessary but may help to rule out other conditions.

Ascorbic acid will facilitate a speedy recovery

Treatment of scurvy includes vitamin C replacement. Response is rapid, with improvement to lethargy within several days and disappearance of other manifestations within several weeks.3 Recommendations on supplementation doses and forms vary, but adults require 300 to 1000 mg/d of ascorbic acid for at least 1 week or until clinical symptoms resolve and stores are repleted.3,5,7

During our patient’s hospital stay, she remained stable and improved clinically with vitamin supplementation (ascorbic acid 1 g/d for 3 days, 500 mg/d after that) and physical therapy. She was counseled on a healthy diet, which would include citrus fruits, tomatoes, and leafy vegetables. The patient was also advised to refrain from drinking alcohol and was given information on an alcohol abstinence program.

At her 1-month follow-up, her condition had improved with near resolution of the skin lesions. She reported that she had given up cigarettes and alcohol. She said she’d also begun eating more citrus fruits and leafy vegetables.

A 65-YEAR-OLD WOMAN was brought into the emergency department by her daughter for spontaneous bruising, fatigue, and weakness of several weeks’ duration. She denied taking any medications or illicit drugs and had not experienced any falls or trauma. On a daily basis, she smoked 5 to 7 cigarettes and drank 6 or 7 beers, as had been her custom for several years. The patient lived alone and was grieving the death of her beloved dog, who had died a month earlier. She reported that since the death of her dog, her diet, which hadn’t been especially good to begin with, had deteriorated; it now consisted of beer and crackers.

On admission, she was mildly tachycardic (105 beats/min) with a blood pressure of 125/66 mm Hg. Physical examination revealed a frail-appearing woman who was in no acute distress but was unable to stand without assistance. She had diffuse ecchymoses and perifollicular, purpuric, hyperkeratotic papules and plaques on both of her legs (FIGURES 1A and 1B). In addition, she had faint perifollicular purpuric macules on her upper back. An oral examination revealed poor dentition.

A punch biopsy was performed on her leg, and it revealed noninflammatory dermal hemorrhage without evidence of vasculitis or vasculopathy.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Scurvy

Based on the patient’s appearance and her dietary history, we suspected scurvy, so a serum vitamin C level was ordered. The results took several days to return. In the meantime, additional lab work revealed hyponatremia (sodium, 129 mmol/L; normal range, 135-145 mmol/L), hypokalemia (potassium, 3 mmol/L; normal range, 3.5-5.2 mmol/L), hypophosphatemia (phosphorus, 2.3 mg/dL; normal range, 2.8-4.5 mg/dL); low serum vitamin D (6 ng/mL; normal range, 20-40 ng/mL); and macrocytic anemia (hemoglobin, 7.4 g/dL; normal range, 11-18 g/dL) with a mean corpuscular volume of 101.1 fL (normal range, 80-100 fL). Her iron panel showed normal serum iron and total iron binding capacity with a normal ferritin level (294 ng/mL; normal range, 30-300 ng/mL). A peripheral blood smear test uncovered mild anisocytosis and polychromasia, with no schistocytes. A fecal immunochemical test was negative.

Several days after admission, the results of the patient’s vitamin C test came back. Her levels were undetectable (< 5 µmol/L; normal range, 11-23 µmol/L), confirming that the patient had scurvy.

A health hazard to marinersthat is still around today

Scurvy is a condition that arises from a deficiency of vitamin C, or ascorbic acid. The first known case of scurvy was in 1550 BC.1 Hippocrates termed the condition “ileos ematitis” and stated that “the mouth feels bad; the gums are detached from the teeth; blood runs from the nostrils … ulcerations on the legs … skin is thin.”1 Scurvy was a major health hazard of mariners between the 15thand 18th centuries.2 Today, the deficiency is uncommon in industrialized countries because there are many sources of vitamin C available through diet and vitamin supplements.3 In the United States, the prevalence of vitamin C deficiency is approximately 7%.4

An essential nutrient in humans, vitamin C is required as a cofactor in the synthesis of mature collagen.3 Collagen is found in skin, bone, and endothelium. Inadequate collagen levels can result in poor dermal support of vessels and tissue fragility, leading to hemorrhage, which can occur in nearly any organ system.

Vitamin C deficiency occurs when serum concentration falls below 11.4

Continue to: Scurvy manifests after 8 to 12 weeks

Scurvy manifests after 8 to 12 weeks of inadequate vitamin C intake.1 Patients may initially experience malaise and irritability. Anemia is common. Dermatologic findings include hyperkeratotic lesions, ecchymoses, poor wound healing, gingival swelling with loss of teeth, petechiae, and corkscrew hairs. Perifollicular hemorrhage is a characteristic finding of scurvy, generally seen on the lower extremities, where the capillaries are under higher hydrostatic pressure.3 Patients may also have musculoskeletal involvement with osteopenia or hemarthroses, which may be seen on imaging.3,5 Cardiorespiratory, gastrointestinal, ophthalmologic, and neurologic findings have also been reported.3

Differential is broad; zero in on patient’s history

The differential diagnosis for hemorrhagic skin lesions is extensive and includes scurvy, coagulopathies, trauma, vasculitis, and vasculopathies.

The presence of perifollicular hemorrhage with corkscrew hairs and a dietary history of inadequate vitamin C intake can differentiate scurvy from other conditions. Serum testing revealing low plasma vitamin C will support the diagnosis, but this is an insensitive test, as values increase with recent intake. Leukocyte ascorbic acid concentrations are more representative of total body stores, but impractical for routine use.6 Skin biopsy is not necessary but may help to rule out other conditions.

Ascorbic acid will facilitate a speedy recovery

Treatment of scurvy includes vitamin C replacement. Response is rapid, with improvement to lethargy within several days and disappearance of other manifestations within several weeks.3 Recommendations on supplementation doses and forms vary, but adults require 300 to 1000 mg/d of ascorbic acid for at least 1 week or until clinical symptoms resolve and stores are repleted.3,5,7

During our patient’s hospital stay, she remained stable and improved clinically with vitamin supplementation (ascorbic acid 1 g/d for 3 days, 500 mg/d after that) and physical therapy. She was counseled on a healthy diet, which would include citrus fruits, tomatoes, and leafy vegetables. The patient was also advised to refrain from drinking alcohol and was given information on an alcohol abstinence program.

At her 1-month follow-up, her condition had improved with near resolution of the skin lesions. She reported that she had given up cigarettes and alcohol. She said she’d also begun eating more citrus fruits and leafy vegetables.

1. Maxfield L, Crane JS. Vitamin C deficiency (scurvy). In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2020. Accessed on September 13, 2022. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK493187/

2. Worral S. A nightmare disease haunted ships during age of discovery. National Geographic. January 15, 2017. Accessed September 21, 2022. www.nationalgeographic.com/science/article/scurvy-disease-discovery-jonathan-lamb

3. Hirschmann JV, Raugi GJ. Adult Scurvy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41:895-906. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(99)70244-6

4. Schleicher RL, Carroll MD, Ford ES, et al. Serum vitamin C and the prevalence of vitamin C deficiency in the United States: 2003-2004 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES). Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;90:1252-1263. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2008.27016

5. Agarwal A, Shaharyar A, Kumar A, et al. Scurvy in pediatric age group – A disease often forgotten? J Clin Orthop Trauma. 2015;6:101-107. doi: 10.1016/j.jcot.2014.12.003

6. Scurvy and its prevention and control in major emergencies. World Health Organization. February 23, 1999. Accessed September 13, 2022. www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-NHD-99.11

7. Weinstein M, Babyn P, Zlotkin S. An orange a day keeps the doctor away: scurvy in the year 2000. Pediatrics. 2001;108:E55. doi: 10.1542/peds.108.3.e55

1. Maxfield L, Crane JS. Vitamin C deficiency (scurvy). In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2020. Accessed on September 13, 2022. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK493187/

2. Worral S. A nightmare disease haunted ships during age of discovery. National Geographic. January 15, 2017. Accessed September 21, 2022. www.nationalgeographic.com/science/article/scurvy-disease-discovery-jonathan-lamb

3. Hirschmann JV, Raugi GJ. Adult Scurvy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41:895-906. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(99)70244-6

4. Schleicher RL, Carroll MD, Ford ES, et al. Serum vitamin C and the prevalence of vitamin C deficiency in the United States: 2003-2004 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES). Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;90:1252-1263. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2008.27016

5. Agarwal A, Shaharyar A, Kumar A, et al. Scurvy in pediatric age group – A disease often forgotten? J Clin Orthop Trauma. 2015;6:101-107. doi: 10.1016/j.jcot.2014.12.003

6. Scurvy and its prevention and control in major emergencies. World Health Organization. February 23, 1999. Accessed September 13, 2022. www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-NHD-99.11

7. Weinstein M, Babyn P, Zlotkin S. An orange a day keeps the doctor away: scurvy in the year 2000. Pediatrics. 2001;108:E55. doi: 10.1542/peds.108.3.e55

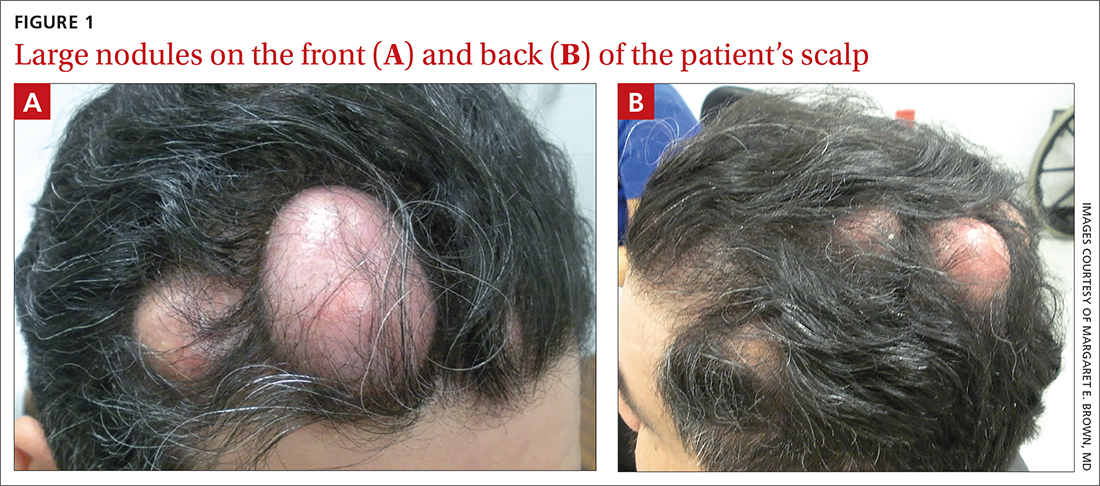

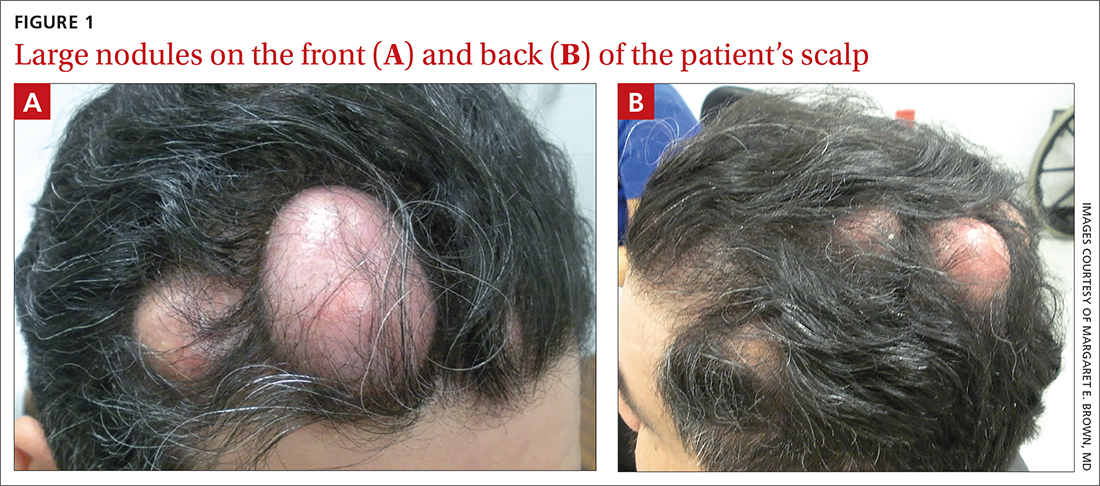

Numerous large nodules on scalp

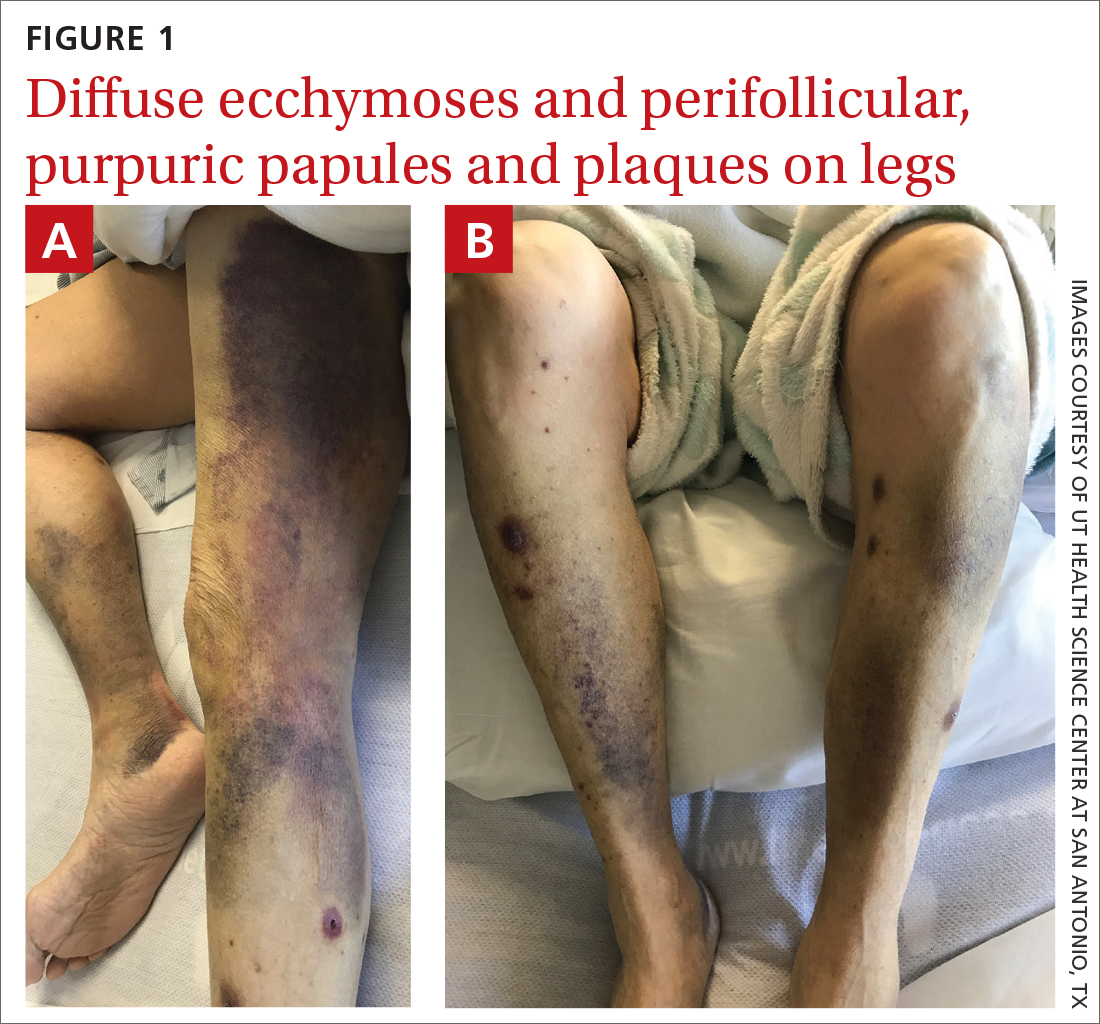

A 31-year-old Hispanic man presented for evaluation of numerous disfiguring growths on his scalp. They first appeared when he was 19 years old. A review of his family history revealed that his father had 2 “cysts” on his body.

The patient had 10 nodules on his scalp and upper back (Figures 1A and 1B). The ones on his scalp lacked puncta and appeared in a “turban tumor” configuration. The lesions were pink, smooth, and semisoft, and ranged in size from 1 to 6 cm.

Six years earlier, the patient had been seen for evaluation of 20 protuberant nodules. At the time, he had been referred to plastic surgery, where 15 lesions were excised. No other treatment was reported by the patient during the 6-year gap between exams.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

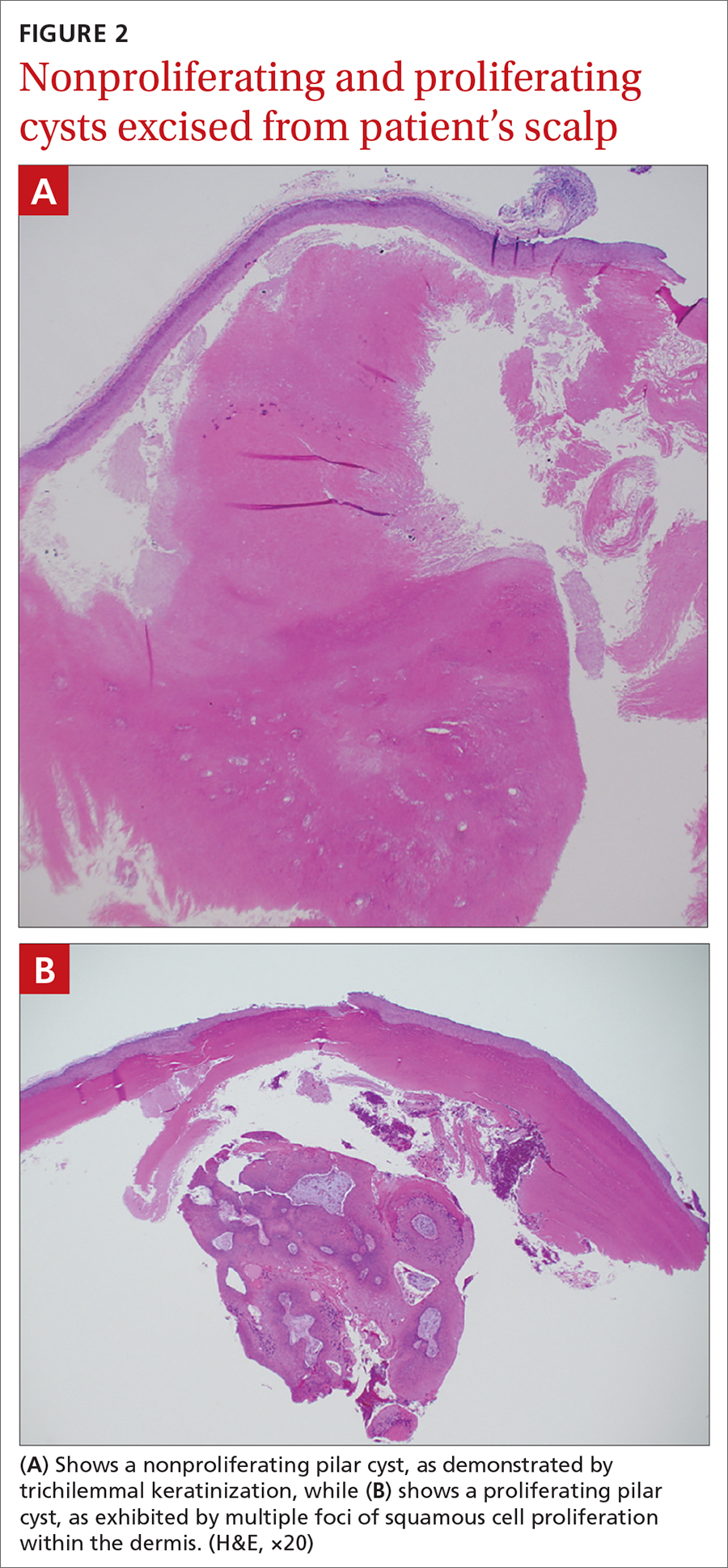

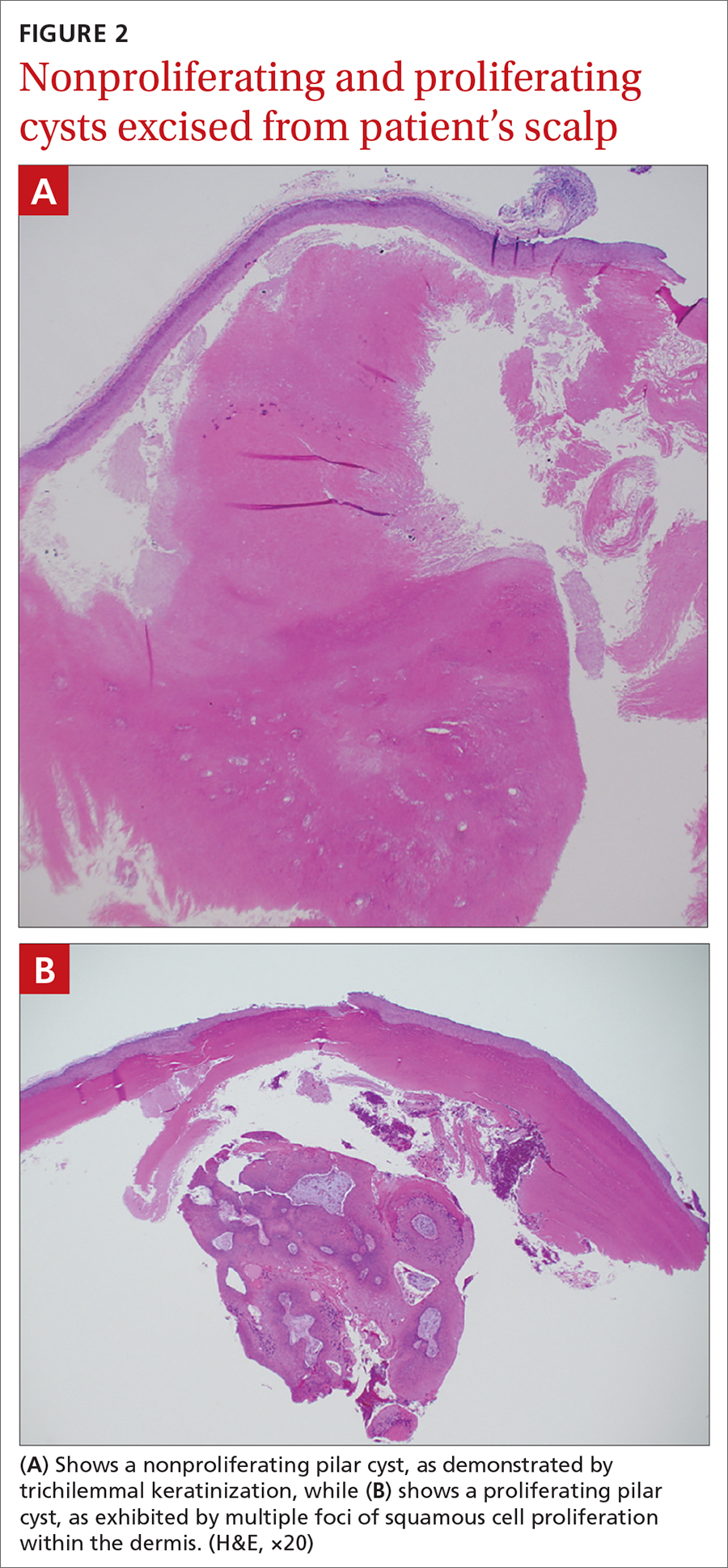

Diagnosis: Pilar cysts

Pilar cysts (PC), also known as trichilemma cysts, wen, or isthmus-catagen cysts, are benign cysts that manifest as smooth, firm, well-circumscribed, pink nodules. PCs originate from the follicular isthmus of the hair’s external root sheath1 and are found in 5% to 10% of the US population.2 Possible sites of appearance include the face, neck, trunk, and extremities, although 90% of PCs develop on the scalp.1 They tend to have an autosomal dominant pattern of inheritance with linkages to the short arm of chromosome 3.3 PCs can occasionally become inflamed following infection or trauma.

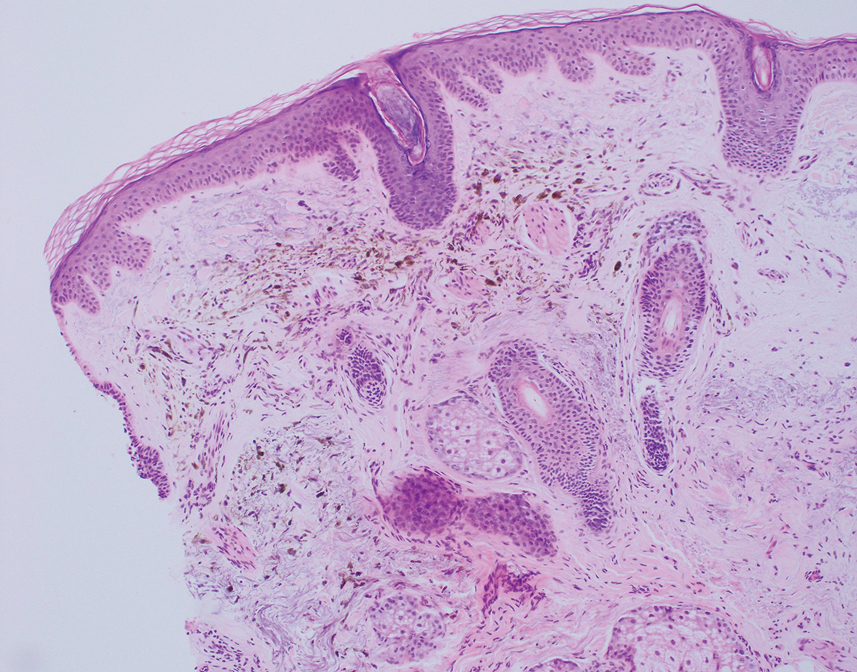

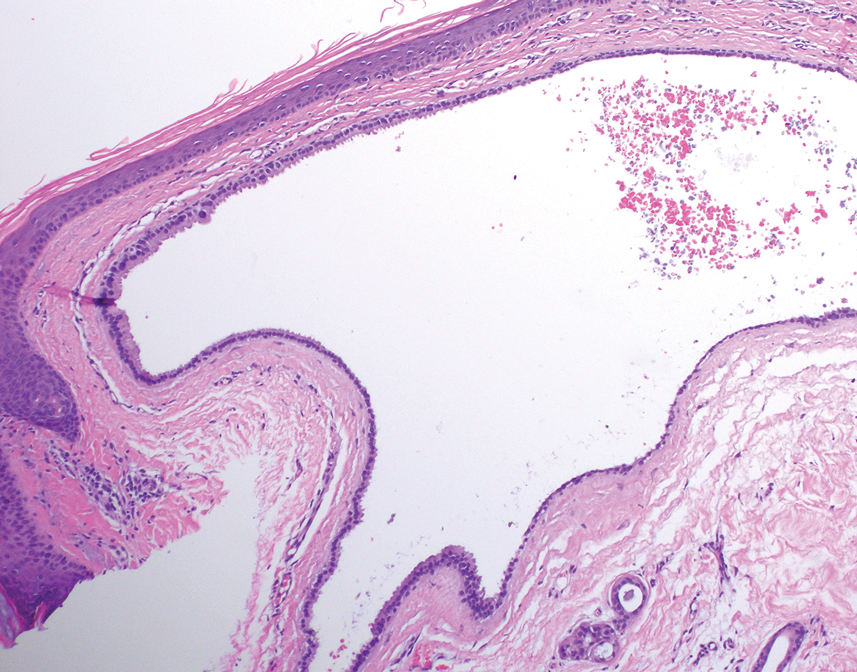

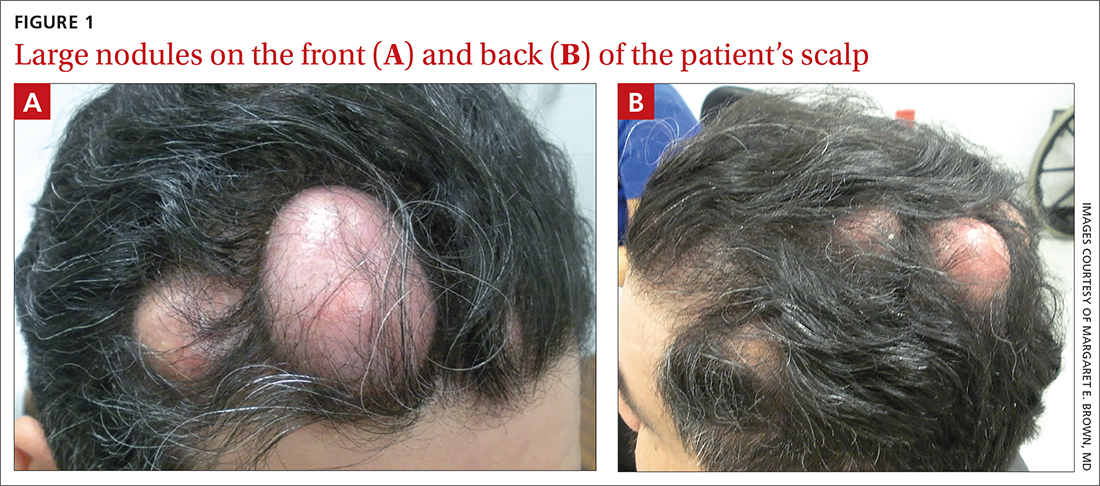

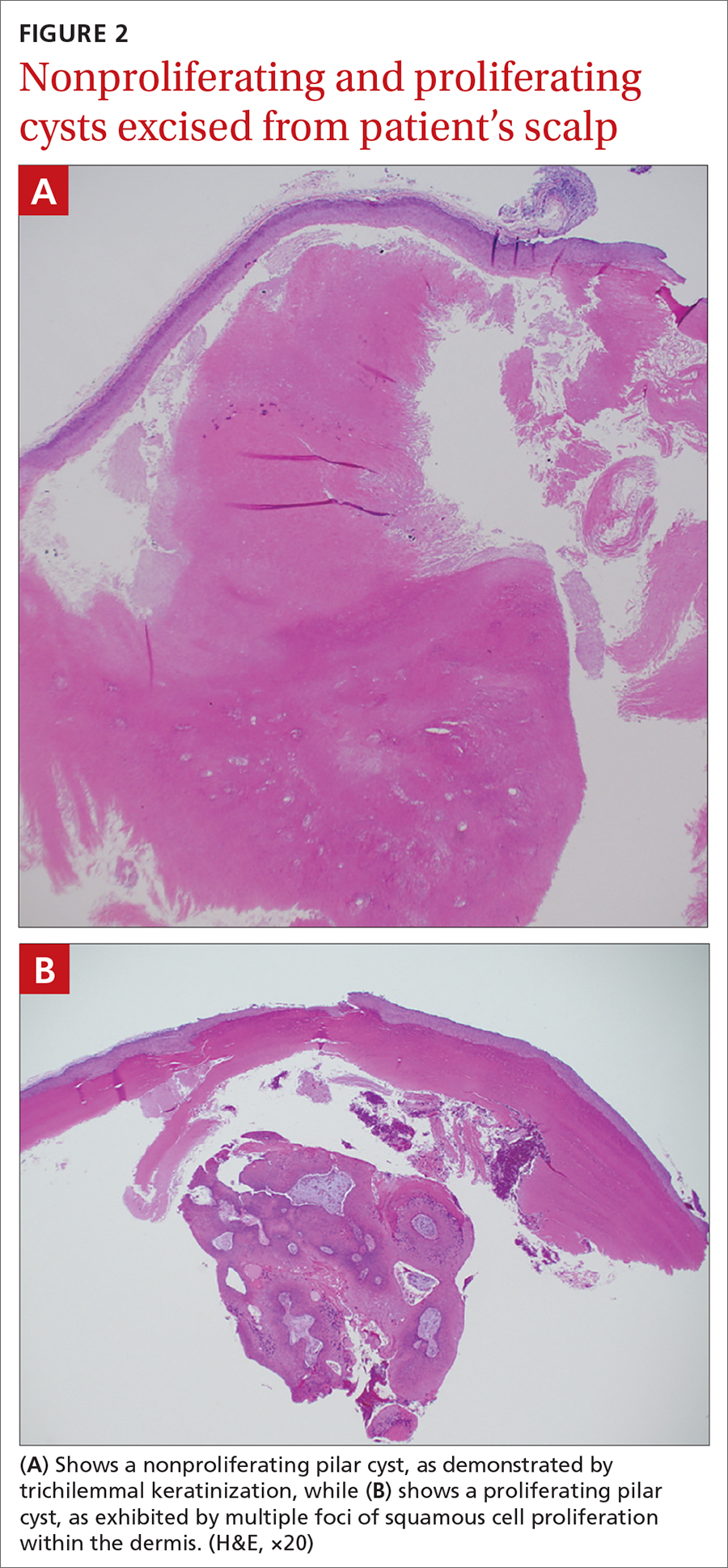

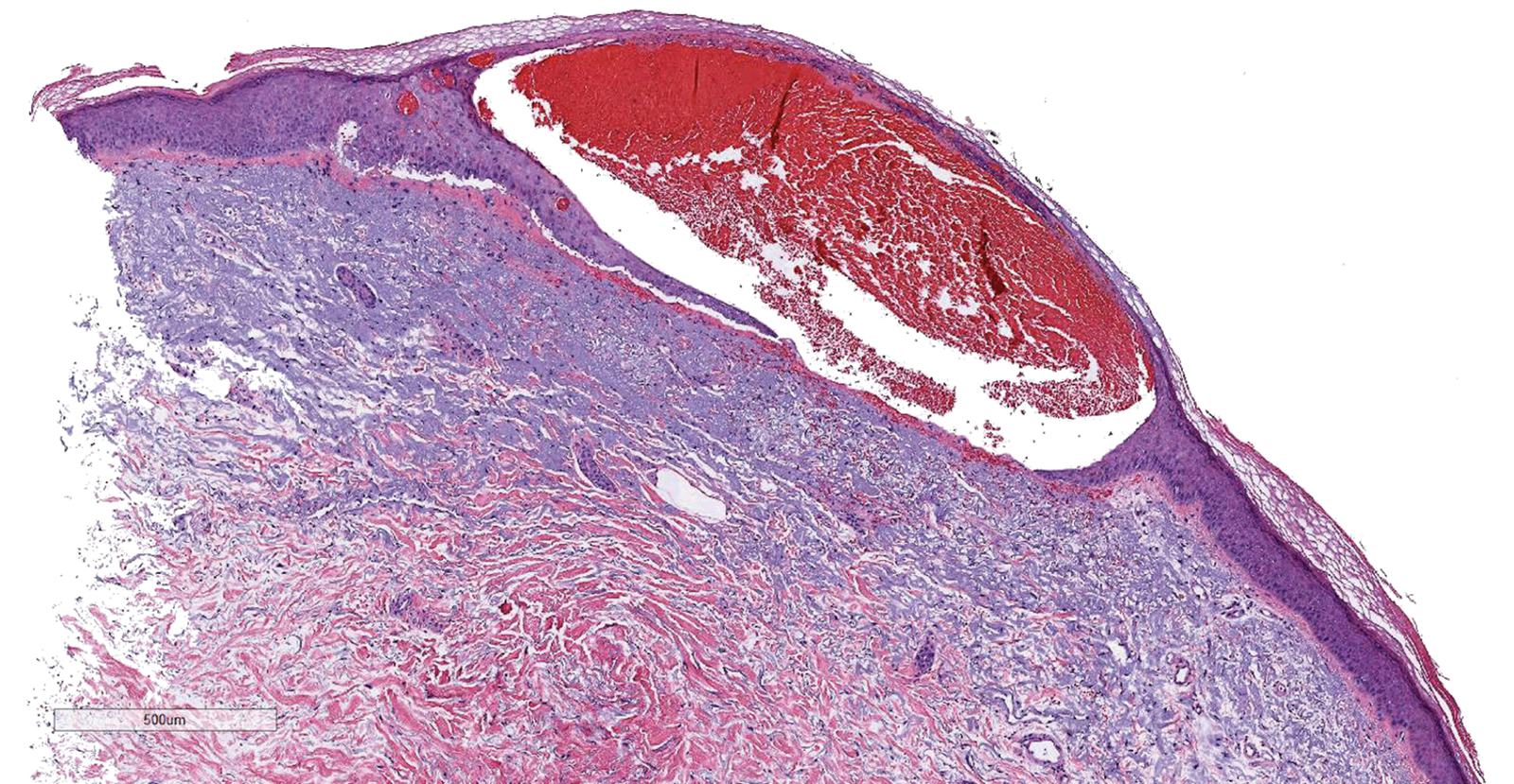

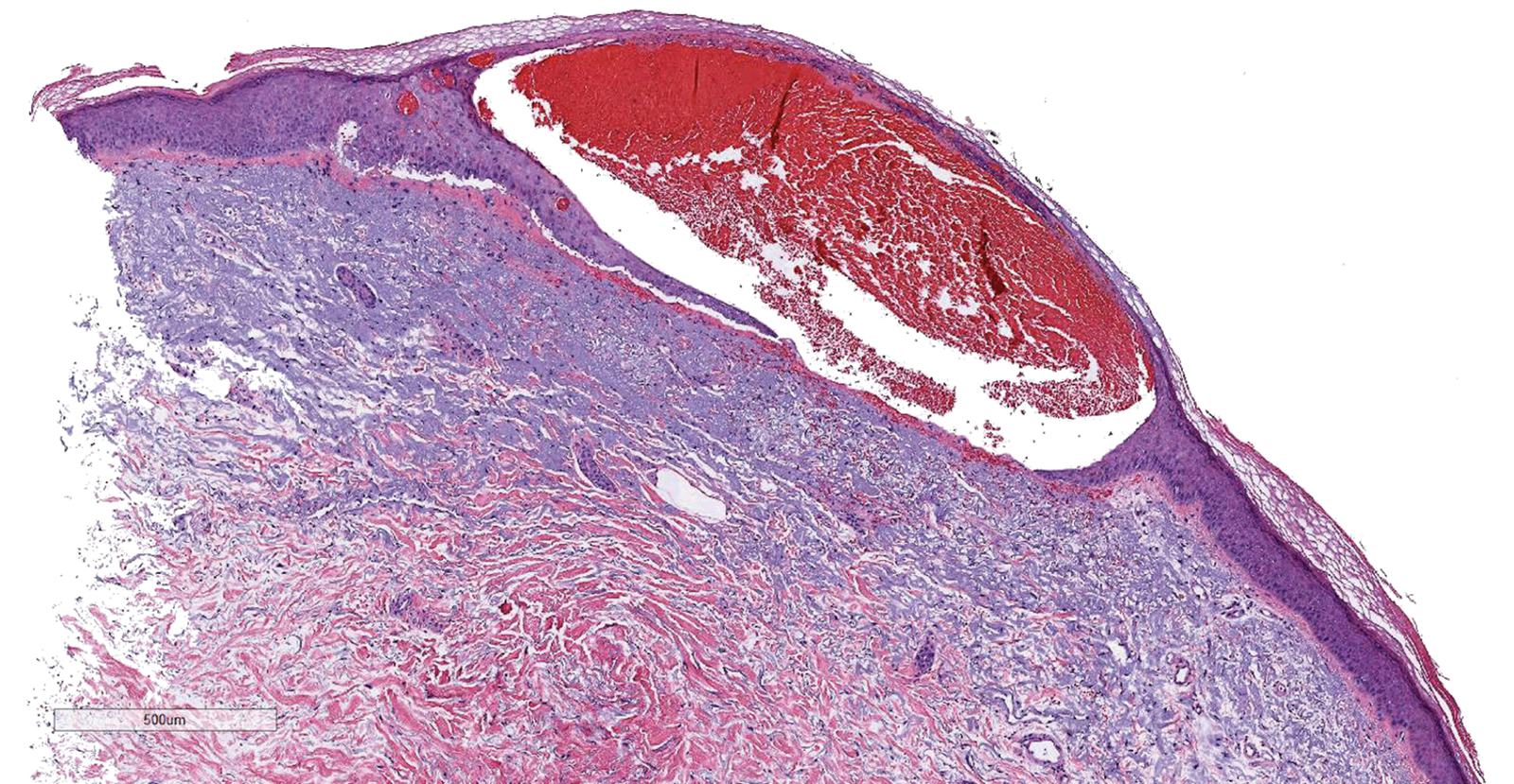

Characteristic histology of PCs demonstrates semisolid, keratin-filled, subepidermal cysts lined by stratified epithelium without a granular layer (trichilemmal keratinization). Lesions excised from this patient’s scalp showed 2 subtypes of PCs: nonproliferating (FIGURE 2A) and proliferating (FIGURE 2B). Subtypes appear similar on exam but can be differentiated on histology.

With gradual growth, proliferating PCs can reach up to 25 cm in diameter.1 Rapid growth, size > 5 cm, infiltration, or a non-scalp location may indicate malignancy.4

Differential diagnosis includes lipomas

The differential diagnosis for a lesion such as this includes epidermal inclusion cysts, dermoid cysts, and lipomas. Epidermal inclusion cysts have a punctum, whereas PCs do not. Dermoid cysts are single congenital lesions that manifest much earlier than PCs. Lipomas are easily movable rubbery bulges that appear more frequently in lipid-dense areas of the body.

For this patient, the striking turban tumor–like presentation, with numerous large cysts on the scalp, initially inspired a differential diagnosis including several genetic tumor syndromes. However, unlike the association between Gardner syndrome and numerous epidermoid cysts or Brooke-Spiegler syndrome and spiradenomas, no syndromes have been linked to numerous trichilemmal cysts.

Continue to: Excision is effective

Excision is effective

Excision is the treatment of choice for both proliferating and nonproliferating PCs.5 The local recurrence rate of proliferating PCs is 3.7% with a rare likelihood of transformation to trichilemmal carcinoma.6

Our patient continues to be followed in clinic for monitoring and periodic excision of bothersome cysts.

1. Ramaswamy AS, Manjunatha HK, Sunilkumar B, et al. Morphological spectrum of pilar cysts. N Am J Med Sci. 2013;5:124-128. http://doi.org/10.4103/1947-2714.107532

2. Ibrahim AE, Barikian A, Janom H, et al. Numerous recurrent trichilemmal cysts of the scalp: differential diagnosis and surgical management. J Craniofac Surg. 2012;23:e164-168. http://doi.org/10.1097/SCS.0b013e31824cdbd2

3. Adya KA, Inamadar AC, Palit A. Multiple firm mobile swellings over the scalp. Int J Trichology. 2012;4:98-99. http://doi.org/10.4103/0974-7753.96906

4. Folpe AL, Reisenauer AK, Mentzel T, et al. Proliferating trichilemmal tumors: clinicopathologic evaluation is a guide to biologic behavior. J Cutan Pathol. 2003;30:492-498. http://doi.org/10.1034/j.1600-0560.2003.00041.x

5. Leppard BJ, Sanderson KV. The natural history of trichilemmal cysts. Br J Dermatol. 1976;94:379-390. http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2133.1976.tb06115.x

6. Kim UG, Kook DB, Kim TH, et al. Trichilemmal carcinoma from proliferating trichilemmal cyst on the posterior neck. Arch Craniofac Surg. 2017;18:50-53. http://doi.org/10.7181/acfs.2017.18.1.50

A 31-year-old Hispanic man presented for evaluation of numerous disfiguring growths on his scalp. They first appeared when he was 19 years old. A review of his family history revealed that his father had 2 “cysts” on his body.

The patient had 10 nodules on his scalp and upper back (Figures 1A and 1B). The ones on his scalp lacked puncta and appeared in a “turban tumor” configuration. The lesions were pink, smooth, and semisoft, and ranged in size from 1 to 6 cm.

Six years earlier, the patient had been seen for evaluation of 20 protuberant nodules. At the time, he had been referred to plastic surgery, where 15 lesions were excised. No other treatment was reported by the patient during the 6-year gap between exams.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Pilar cysts

Pilar cysts (PC), also known as trichilemma cysts, wen, or isthmus-catagen cysts, are benign cysts that manifest as smooth, firm, well-circumscribed, pink nodules. PCs originate from the follicular isthmus of the hair’s external root sheath1 and are found in 5% to 10% of the US population.2 Possible sites of appearance include the face, neck, trunk, and extremities, although 90% of PCs develop on the scalp.1 They tend to have an autosomal dominant pattern of inheritance with linkages to the short arm of chromosome 3.3 PCs can occasionally become inflamed following infection or trauma.

Characteristic histology of PCs demonstrates semisolid, keratin-filled, subepidermal cysts lined by stratified epithelium without a granular layer (trichilemmal keratinization). Lesions excised from this patient’s scalp showed 2 subtypes of PCs: nonproliferating (FIGURE 2A) and proliferating (FIGURE 2B). Subtypes appear similar on exam but can be differentiated on histology.

With gradual growth, proliferating PCs can reach up to 25 cm in diameter.1 Rapid growth, size > 5 cm, infiltration, or a non-scalp location may indicate malignancy.4

Differential diagnosis includes lipomas

The differential diagnosis for a lesion such as this includes epidermal inclusion cysts, dermoid cysts, and lipomas. Epidermal inclusion cysts have a punctum, whereas PCs do not. Dermoid cysts are single congenital lesions that manifest much earlier than PCs. Lipomas are easily movable rubbery bulges that appear more frequently in lipid-dense areas of the body.

For this patient, the striking turban tumor–like presentation, with numerous large cysts on the scalp, initially inspired a differential diagnosis including several genetic tumor syndromes. However, unlike the association between Gardner syndrome and numerous epidermoid cysts or Brooke-Spiegler syndrome and spiradenomas, no syndromes have been linked to numerous trichilemmal cysts.

Continue to: Excision is effective

Excision is effective

Excision is the treatment of choice for both proliferating and nonproliferating PCs.5 The local recurrence rate of proliferating PCs is 3.7% with a rare likelihood of transformation to trichilemmal carcinoma.6

Our patient continues to be followed in clinic for monitoring and periodic excision of bothersome cysts.

A 31-year-old Hispanic man presented for evaluation of numerous disfiguring growths on his scalp. They first appeared when he was 19 years old. A review of his family history revealed that his father had 2 “cysts” on his body.

The patient had 10 nodules on his scalp and upper back (Figures 1A and 1B). The ones on his scalp lacked puncta and appeared in a “turban tumor” configuration. The lesions were pink, smooth, and semisoft, and ranged in size from 1 to 6 cm.

Six years earlier, the patient had been seen for evaluation of 20 protuberant nodules. At the time, he had been referred to plastic surgery, where 15 lesions were excised. No other treatment was reported by the patient during the 6-year gap between exams.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Pilar cysts

Pilar cysts (PC), also known as trichilemma cysts, wen, or isthmus-catagen cysts, are benign cysts that manifest as smooth, firm, well-circumscribed, pink nodules. PCs originate from the follicular isthmus of the hair’s external root sheath1 and are found in 5% to 10% of the US population.2 Possible sites of appearance include the face, neck, trunk, and extremities, although 90% of PCs develop on the scalp.1 They tend to have an autosomal dominant pattern of inheritance with linkages to the short arm of chromosome 3.3 PCs can occasionally become inflamed following infection or trauma.

Characteristic histology of PCs demonstrates semisolid, keratin-filled, subepidermal cysts lined by stratified epithelium without a granular layer (trichilemmal keratinization). Lesions excised from this patient’s scalp showed 2 subtypes of PCs: nonproliferating (FIGURE 2A) and proliferating (FIGURE 2B). Subtypes appear similar on exam but can be differentiated on histology.

With gradual growth, proliferating PCs can reach up to 25 cm in diameter.1 Rapid growth, size > 5 cm, infiltration, or a non-scalp location may indicate malignancy.4

Differential diagnosis includes lipomas

The differential diagnosis for a lesion such as this includes epidermal inclusion cysts, dermoid cysts, and lipomas. Epidermal inclusion cysts have a punctum, whereas PCs do not. Dermoid cysts are single congenital lesions that manifest much earlier than PCs. Lipomas are easily movable rubbery bulges that appear more frequently in lipid-dense areas of the body.

For this patient, the striking turban tumor–like presentation, with numerous large cysts on the scalp, initially inspired a differential diagnosis including several genetic tumor syndromes. However, unlike the association between Gardner syndrome and numerous epidermoid cysts or Brooke-Spiegler syndrome and spiradenomas, no syndromes have been linked to numerous trichilemmal cysts.

Continue to: Excision is effective

Excision is effective

Excision is the treatment of choice for both proliferating and nonproliferating PCs.5 The local recurrence rate of proliferating PCs is 3.7% with a rare likelihood of transformation to trichilemmal carcinoma.6

Our patient continues to be followed in clinic for monitoring and periodic excision of bothersome cysts.

1. Ramaswamy AS, Manjunatha HK, Sunilkumar B, et al. Morphological spectrum of pilar cysts. N Am J Med Sci. 2013;5:124-128. http://doi.org/10.4103/1947-2714.107532

2. Ibrahim AE, Barikian A, Janom H, et al. Numerous recurrent trichilemmal cysts of the scalp: differential diagnosis and surgical management. J Craniofac Surg. 2012;23:e164-168. http://doi.org/10.1097/SCS.0b013e31824cdbd2

3. Adya KA, Inamadar AC, Palit A. Multiple firm mobile swellings over the scalp. Int J Trichology. 2012;4:98-99. http://doi.org/10.4103/0974-7753.96906

4. Folpe AL, Reisenauer AK, Mentzel T, et al. Proliferating trichilemmal tumors: clinicopathologic evaluation is a guide to biologic behavior. J Cutan Pathol. 2003;30:492-498. http://doi.org/10.1034/j.1600-0560.2003.00041.x

5. Leppard BJ, Sanderson KV. The natural history of trichilemmal cysts. Br J Dermatol. 1976;94:379-390. http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2133.1976.tb06115.x

6. Kim UG, Kook DB, Kim TH, et al. Trichilemmal carcinoma from proliferating trichilemmal cyst on the posterior neck. Arch Craniofac Surg. 2017;18:50-53. http://doi.org/10.7181/acfs.2017.18.1.50

1. Ramaswamy AS, Manjunatha HK, Sunilkumar B, et al. Morphological spectrum of pilar cysts. N Am J Med Sci. 2013;5:124-128. http://doi.org/10.4103/1947-2714.107532

2. Ibrahim AE, Barikian A, Janom H, et al. Numerous recurrent trichilemmal cysts of the scalp: differential diagnosis and surgical management. J Craniofac Surg. 2012;23:e164-168. http://doi.org/10.1097/SCS.0b013e31824cdbd2

3. Adya KA, Inamadar AC, Palit A. Multiple firm mobile swellings over the scalp. Int J Trichology. 2012;4:98-99. http://doi.org/10.4103/0974-7753.96906

4. Folpe AL, Reisenauer AK, Mentzel T, et al. Proliferating trichilemmal tumors: clinicopathologic evaluation is a guide to biologic behavior. J Cutan Pathol. 2003;30:492-498. http://doi.org/10.1034/j.1600-0560.2003.00041.x