User login

Beware the Manchineel: A Case of Irritant Contact Dermatitis

What is the world’s most dangerous tree? According to Guinness World Records1 (and one unlucky contestant on the wilderness survival reality show Naked and Afraid,2 who got its sap in his eyes and needed to be evacuated for treatment), the manchineel tree (Hippomane mancinella) has earned this designation.1-3 Manchineel trees are part of the strand vegetation of islands in the West Indies and along the Caribbean coasts of South and Central America, where their copious root systems help reduce coastal erosion. In the United States, this poisonous tree grows along the southern edge of Florida’s Everglades National Park; the Florida Keys; and the US Virgin Islands, especially Virgin Islands National Park. Although the manchineel tree appears on several endangered species lists,4-6 there are places within its distribution where it is locally abundant and thus poses a risk to residents and visitors.

The first European description of manchineel toxicity was by Peter Martyr d’Anghiera, a court historian and geographer of Christopher Columbus’s patroness, Isabella I, Queen of Castile and Léon. In the early 1500s, Peter Martyr wrote that on Columbus’s second New World voyage in 1493, the crew encountered a mysterious tree that burned the skin and eyes of anyone who had contact with it.7 Columbus called the tree’s fruit manzanilla de la muerte (“little apple of death”) after several sailors became severely ill from eating the fruit.8,9 Manchineel lore is rife with tales of agonizing death after eating the applelike fruit, and several contemporaneous accounts describe indigenous Caribbean islanders using manchineel’s toxic sap as an arrow poison.10

Eating manchineel fruit is known to cause abdominal pain, burning sensations in the oropharynx, and esophageal spasms.11 Several case reports mention that consuming the fruit can create an exaggerated

Case Report

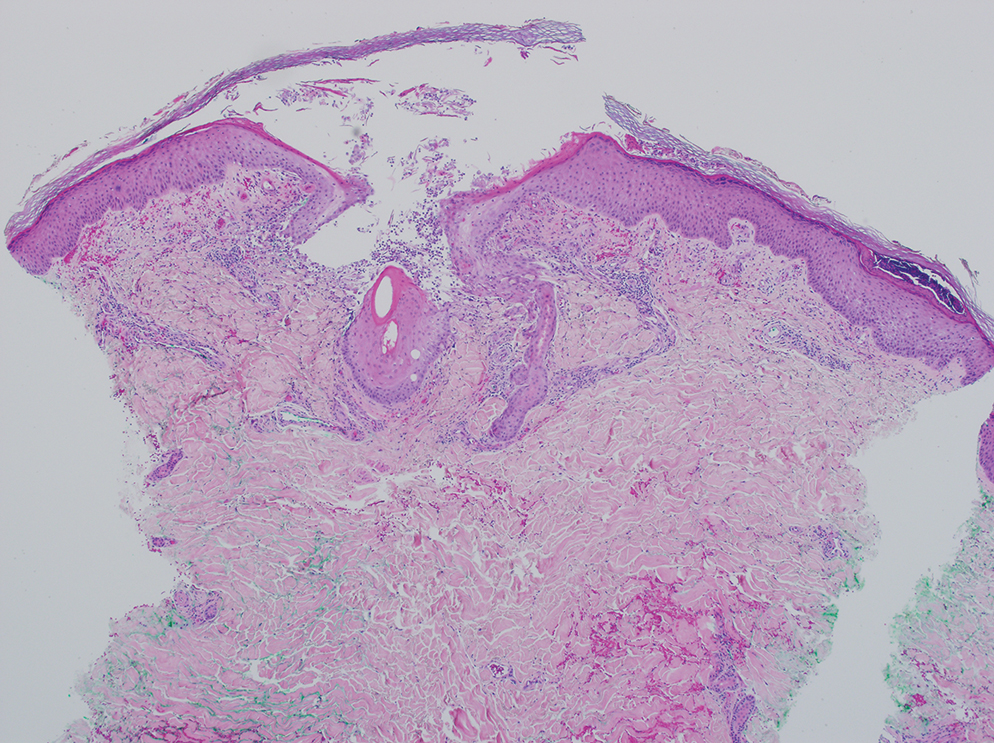

A 64-year-old physician (S.A.N.) came across a stand of manchineel trees while camping in the Virgin Islands National Park on St. John in the US Virgin Islands (Figure 1). The patient—who was knowledgeable about tropical ecology and was familiar with the tree—was curious about its purported cutaneous toxicity and applied the viscous white sap of a broken branchlet (Figure 2) to a patch of skin measuring 4 cm in diameter on the medial left calf. He took serial photographs of the site on days 2, 4 (Figure 3), 6, and 10 (Figure 4), showing the onset of erythema and the subsequent development of follicular pustules. On day 6, a 4-mm punch biopsy specimen was taken of the most prominent pustule. Histopathology showed a subcorneal acantholytic blister and epidermal spongiosis overlying a mixed perivascular infiltrate and follicular necrosis, which was consistent with irritant contact dermatitis (Figure 5). On day 8, the region became indurated and tender to pressure; however, there was no warmth, edema, purulent drainage, lymphangitic streaks, or other signs of infection. The region was never itchy; it was uncomfortable only with firm direct pressure. The patient applied hot compresses to the site for 10 minutes 1 to 2 times daily for roughly 2 weeks, and the affected area healed fully (without any additional intervention) in approximately 6 weeks.

Comment

Manchineel is a member of the Euphorbiaceae (also known as the euphorb or spurge) family, a mainly tropical or subtropical plant family that includes many useful as well as many toxic species. Examples of useful plants include cassava (Manihot esculenta) and the rubber tree (Hevea brasiliensis). Many euphorbs have well-described toxicities, and many (eg, castor bean, Ricinus communis) are useful in some circumstances and toxic in others.6,12-14 Many euphorbs are known to cause skin reactions, usually due to toxins in the milky sap that directly irritate the skin or to latex compounds that can induce IgE-mediated contact dermatitis.9,14

Manchineel contains a complex mix of toxins, though no specific one has been identified as the main cause of the associated irritant contact dermatitis. Manchineel sap (and sap of many other euphorbs) contains phorbol esters that may cause direct pH-induced cytotoxicity leading to keratinocyte necrosis. Diterpenes may augment this cytotoxic effect via induction of proinflammatory cytokines.12 Pitts et al5 pointed to a mixture of oxygenated diterpene esters as the primary cause of toxicity and suggested that their water solubility explained occurrences of keratoconjunctivitis after contact with rainwater or dew from the manchineel tree.

All parts of the manchineel tree—fruit, leaves, wood, and sap—are poisonous. In a retrospective series of 97 cases of manchineel fruit ingestion, the most common symptoms were oropharyngeal pain (68% [66/97]), abdominal pain (42% [41/97]), and diarrhea (37% [36/97]). The same series identified 1 (1%) case of bradycardia and hypotension.3 Contact with the wood, exposure to sawdust, and inhalation of smoke from burning the wood can irritate the skin, conjunctivae, or nasopharynx. Rainwater or dew dripping from the leaves onto the skin can cause dermatitis and ophthalmitis, even without direct contact with the tree.4,5

Management—There is no specific treatment for manchineel dermatitis. Because it is an irritant reaction and not a type IV hypersensitivity reaction, topical corticosteroids have minimal benefit. A regimen consisting of a thorough cleansing, wet compresses, and observation, as most symptoms resolve spontaneously within a few days, has been recommended.4 Our patient used hot compresses, which he believes helped heal the site, although his symptoms lasted for several weeks.

Given that there is no specific treatment for manchineel dermatitis, the wisest approach is strict avoidance. On many Caribbean islands, visitors are warned about the manchineel tree, advised to avoid direct contact, and reminded to avoid standing beneath it during a rainstorm (Figure 6).

Conclusion

This article begins with a question: “What is the world’s most dangerous tree?” Many sources from the indexed medical literature as well as the popular press and social media state that it is the manchineel. Although all parts of the manchineel tree are highly toxic, human exposures are uncommon, and deaths are more apocryphal than actual.

- Most dangerous tree. Guinness World Records. Accessed October 14, 2024. https://www.guinnessworldrecords.com/world-records/most-dangerous-tree

- Naked and Afraid: Garden of Evil (S4E9). Discovery Channel. June 21, 2015. Accessed October 14, 2024. https://go.discovery.com/video/naked-and-afraid-discovery/garden-of-evil

- Boucaud-Maitre D, Cachet X, Bouzidi C, et al. Severity of manchineel fruit (Hippomane mancinella) poisoning: a retrospective case series of 97 patients from French Poison Control Centers. Toxicon. 2019;161:28-32. doi:10.1016/j.toxicon.2019.02.014

- Blue LM, Sailing C, Denapoles C, et al. Manchineel dermatitis in North American students in the Caribbean. J Travel Medicine. 2011;18:422-424. doi:10.1111/j.1708-8305.2011.00568.x

- Pitts JF, Barker NH, Gibbons DC, et al. Manchineel keratoconjunctivitis. Br J Ophthalmol. 1993;77:284-288. doi:10.1136/bjo.77.5.284

- Lauter WM, Fox LE, Ariail WT. Investigation of the toxic principles of Hippomane mancinella, L. I. historical review. J Pharm Sci. 1952;41:199-201. https://doi.org/10.1002/jps.3030410412

- Martyr P. De Orbe Novo: the Eight Decades of Peter Martyr d’Anghera. Vol 1. FA MacNutt (translator). GP Putnam’s Sons; 1912. Accessed October 14, 2024. https://gutenberg.org/cache/epub/12425/pg12425.txt

- Fernandez de Ybarra AM. A forgotten medical worthy, Dr. Diego Alvarex Chanca, of Seville, Spain, and his letter describing the second voyage of Christopher Columbus to America. Med Library Hist J. 1906;4:246-263.

- Muscat MK. Manchineel apple of death. EJIFCC. 2019;30:346-348.

- Handler JS. Aspects of Amerindian ethnography in 17th century Barbados. Caribbean Studies. 1970;9:50-72.

- Howard RA. Three experiences with the manchineel (Hippomane spp., Euphorbiaceae). Biotropica. 1981;13:224-227. https://doi.org/10.2307/2388129

- Rao KV. Toxic principles of Hippomane mancinella. Planta Med. 1974;25:166-171. doi:10.1055/s-0028-1097927

- Lauter WM, Foote PA. Investigation of the toxic principles of Hippomane mancinella L. II. Preliminary isolation of a toxic principle of the fruit. J Am Pharm Assoc. 1955;44:361-363. doi:10.1002/jps.3030440616

- Carroll MN Jr, Fox LE, Ariail WT. Investigation of the toxic principles of Hippomane mancinella L. III. Toxic actions of extracts of Hippomane mancinella L. J Am Pharm Assoc. 1957;46:93-97. doi:10.1002/jps.3030460206

What is the world’s most dangerous tree? According to Guinness World Records1 (and one unlucky contestant on the wilderness survival reality show Naked and Afraid,2 who got its sap in his eyes and needed to be evacuated for treatment), the manchineel tree (Hippomane mancinella) has earned this designation.1-3 Manchineel trees are part of the strand vegetation of islands in the West Indies and along the Caribbean coasts of South and Central America, where their copious root systems help reduce coastal erosion. In the United States, this poisonous tree grows along the southern edge of Florida’s Everglades National Park; the Florida Keys; and the US Virgin Islands, especially Virgin Islands National Park. Although the manchineel tree appears on several endangered species lists,4-6 there are places within its distribution where it is locally abundant and thus poses a risk to residents and visitors.

The first European description of manchineel toxicity was by Peter Martyr d’Anghiera, a court historian and geographer of Christopher Columbus’s patroness, Isabella I, Queen of Castile and Léon. In the early 1500s, Peter Martyr wrote that on Columbus’s second New World voyage in 1493, the crew encountered a mysterious tree that burned the skin and eyes of anyone who had contact with it.7 Columbus called the tree’s fruit manzanilla de la muerte (“little apple of death”) after several sailors became severely ill from eating the fruit.8,9 Manchineel lore is rife with tales of agonizing death after eating the applelike fruit, and several contemporaneous accounts describe indigenous Caribbean islanders using manchineel’s toxic sap as an arrow poison.10

Eating manchineel fruit is known to cause abdominal pain, burning sensations in the oropharynx, and esophageal spasms.11 Several case reports mention that consuming the fruit can create an exaggerated

Case Report

A 64-year-old physician (S.A.N.) came across a stand of manchineel trees while camping in the Virgin Islands National Park on St. John in the US Virgin Islands (Figure 1). The patient—who was knowledgeable about tropical ecology and was familiar with the tree—was curious about its purported cutaneous toxicity and applied the viscous white sap of a broken branchlet (Figure 2) to a patch of skin measuring 4 cm in diameter on the medial left calf. He took serial photographs of the site on days 2, 4 (Figure 3), 6, and 10 (Figure 4), showing the onset of erythema and the subsequent development of follicular pustules. On day 6, a 4-mm punch biopsy specimen was taken of the most prominent pustule. Histopathology showed a subcorneal acantholytic blister and epidermal spongiosis overlying a mixed perivascular infiltrate and follicular necrosis, which was consistent with irritant contact dermatitis (Figure 5). On day 8, the region became indurated and tender to pressure; however, there was no warmth, edema, purulent drainage, lymphangitic streaks, or other signs of infection. The region was never itchy; it was uncomfortable only with firm direct pressure. The patient applied hot compresses to the site for 10 minutes 1 to 2 times daily for roughly 2 weeks, and the affected area healed fully (without any additional intervention) in approximately 6 weeks.

Comment

Manchineel is a member of the Euphorbiaceae (also known as the euphorb or spurge) family, a mainly tropical or subtropical plant family that includes many useful as well as many toxic species. Examples of useful plants include cassava (Manihot esculenta) and the rubber tree (Hevea brasiliensis). Many euphorbs have well-described toxicities, and many (eg, castor bean, Ricinus communis) are useful in some circumstances and toxic in others.6,12-14 Many euphorbs are known to cause skin reactions, usually due to toxins in the milky sap that directly irritate the skin or to latex compounds that can induce IgE-mediated contact dermatitis.9,14

Manchineel contains a complex mix of toxins, though no specific one has been identified as the main cause of the associated irritant contact dermatitis. Manchineel sap (and sap of many other euphorbs) contains phorbol esters that may cause direct pH-induced cytotoxicity leading to keratinocyte necrosis. Diterpenes may augment this cytotoxic effect via induction of proinflammatory cytokines.12 Pitts et al5 pointed to a mixture of oxygenated diterpene esters as the primary cause of toxicity and suggested that their water solubility explained occurrences of keratoconjunctivitis after contact with rainwater or dew from the manchineel tree.

All parts of the manchineel tree—fruit, leaves, wood, and sap—are poisonous. In a retrospective series of 97 cases of manchineel fruit ingestion, the most common symptoms were oropharyngeal pain (68% [66/97]), abdominal pain (42% [41/97]), and diarrhea (37% [36/97]). The same series identified 1 (1%) case of bradycardia and hypotension.3 Contact with the wood, exposure to sawdust, and inhalation of smoke from burning the wood can irritate the skin, conjunctivae, or nasopharynx. Rainwater or dew dripping from the leaves onto the skin can cause dermatitis and ophthalmitis, even without direct contact with the tree.4,5

Management—There is no specific treatment for manchineel dermatitis. Because it is an irritant reaction and not a type IV hypersensitivity reaction, topical corticosteroids have minimal benefit. A regimen consisting of a thorough cleansing, wet compresses, and observation, as most symptoms resolve spontaneously within a few days, has been recommended.4 Our patient used hot compresses, which he believes helped heal the site, although his symptoms lasted for several weeks.

Given that there is no specific treatment for manchineel dermatitis, the wisest approach is strict avoidance. On many Caribbean islands, visitors are warned about the manchineel tree, advised to avoid direct contact, and reminded to avoid standing beneath it during a rainstorm (Figure 6).

Conclusion

This article begins with a question: “What is the world’s most dangerous tree?” Many sources from the indexed medical literature as well as the popular press and social media state that it is the manchineel. Although all parts of the manchineel tree are highly toxic, human exposures are uncommon, and deaths are more apocryphal than actual.

What is the world’s most dangerous tree? According to Guinness World Records1 (and one unlucky contestant on the wilderness survival reality show Naked and Afraid,2 who got its sap in his eyes and needed to be evacuated for treatment), the manchineel tree (Hippomane mancinella) has earned this designation.1-3 Manchineel trees are part of the strand vegetation of islands in the West Indies and along the Caribbean coasts of South and Central America, where their copious root systems help reduce coastal erosion. In the United States, this poisonous tree grows along the southern edge of Florida’s Everglades National Park; the Florida Keys; and the US Virgin Islands, especially Virgin Islands National Park. Although the manchineel tree appears on several endangered species lists,4-6 there are places within its distribution where it is locally abundant and thus poses a risk to residents and visitors.

The first European description of manchineel toxicity was by Peter Martyr d’Anghiera, a court historian and geographer of Christopher Columbus’s patroness, Isabella I, Queen of Castile and Léon. In the early 1500s, Peter Martyr wrote that on Columbus’s second New World voyage in 1493, the crew encountered a mysterious tree that burned the skin and eyes of anyone who had contact with it.7 Columbus called the tree’s fruit manzanilla de la muerte (“little apple of death”) after several sailors became severely ill from eating the fruit.8,9 Manchineel lore is rife with tales of agonizing death after eating the applelike fruit, and several contemporaneous accounts describe indigenous Caribbean islanders using manchineel’s toxic sap as an arrow poison.10

Eating manchineel fruit is known to cause abdominal pain, burning sensations in the oropharynx, and esophageal spasms.11 Several case reports mention that consuming the fruit can create an exaggerated

Case Report

A 64-year-old physician (S.A.N.) came across a stand of manchineel trees while camping in the Virgin Islands National Park on St. John in the US Virgin Islands (Figure 1). The patient—who was knowledgeable about tropical ecology and was familiar with the tree—was curious about its purported cutaneous toxicity and applied the viscous white sap of a broken branchlet (Figure 2) to a patch of skin measuring 4 cm in diameter on the medial left calf. He took serial photographs of the site on days 2, 4 (Figure 3), 6, and 10 (Figure 4), showing the onset of erythema and the subsequent development of follicular pustules. On day 6, a 4-mm punch biopsy specimen was taken of the most prominent pustule. Histopathology showed a subcorneal acantholytic blister and epidermal spongiosis overlying a mixed perivascular infiltrate and follicular necrosis, which was consistent with irritant contact dermatitis (Figure 5). On day 8, the region became indurated and tender to pressure; however, there was no warmth, edema, purulent drainage, lymphangitic streaks, or other signs of infection. The region was never itchy; it was uncomfortable only with firm direct pressure. The patient applied hot compresses to the site for 10 minutes 1 to 2 times daily for roughly 2 weeks, and the affected area healed fully (without any additional intervention) in approximately 6 weeks.

Comment

Manchineel is a member of the Euphorbiaceae (also known as the euphorb or spurge) family, a mainly tropical or subtropical plant family that includes many useful as well as many toxic species. Examples of useful plants include cassava (Manihot esculenta) and the rubber tree (Hevea brasiliensis). Many euphorbs have well-described toxicities, and many (eg, castor bean, Ricinus communis) are useful in some circumstances and toxic in others.6,12-14 Many euphorbs are known to cause skin reactions, usually due to toxins in the milky sap that directly irritate the skin or to latex compounds that can induce IgE-mediated contact dermatitis.9,14

Manchineel contains a complex mix of toxins, though no specific one has been identified as the main cause of the associated irritant contact dermatitis. Manchineel sap (and sap of many other euphorbs) contains phorbol esters that may cause direct pH-induced cytotoxicity leading to keratinocyte necrosis. Diterpenes may augment this cytotoxic effect via induction of proinflammatory cytokines.12 Pitts et al5 pointed to a mixture of oxygenated diterpene esters as the primary cause of toxicity and suggested that their water solubility explained occurrences of keratoconjunctivitis after contact with rainwater or dew from the manchineel tree.

All parts of the manchineel tree—fruit, leaves, wood, and sap—are poisonous. In a retrospective series of 97 cases of manchineel fruit ingestion, the most common symptoms were oropharyngeal pain (68% [66/97]), abdominal pain (42% [41/97]), and diarrhea (37% [36/97]). The same series identified 1 (1%) case of bradycardia and hypotension.3 Contact with the wood, exposure to sawdust, and inhalation of smoke from burning the wood can irritate the skin, conjunctivae, or nasopharynx. Rainwater or dew dripping from the leaves onto the skin can cause dermatitis and ophthalmitis, even without direct contact with the tree.4,5

Management—There is no specific treatment for manchineel dermatitis. Because it is an irritant reaction and not a type IV hypersensitivity reaction, topical corticosteroids have minimal benefit. A regimen consisting of a thorough cleansing, wet compresses, and observation, as most symptoms resolve spontaneously within a few days, has been recommended.4 Our patient used hot compresses, which he believes helped heal the site, although his symptoms lasted for several weeks.

Given that there is no specific treatment for manchineel dermatitis, the wisest approach is strict avoidance. On many Caribbean islands, visitors are warned about the manchineel tree, advised to avoid direct contact, and reminded to avoid standing beneath it during a rainstorm (Figure 6).

Conclusion

This article begins with a question: “What is the world’s most dangerous tree?” Many sources from the indexed medical literature as well as the popular press and social media state that it is the manchineel. Although all parts of the manchineel tree are highly toxic, human exposures are uncommon, and deaths are more apocryphal than actual.

- Most dangerous tree. Guinness World Records. Accessed October 14, 2024. https://www.guinnessworldrecords.com/world-records/most-dangerous-tree

- Naked and Afraid: Garden of Evil (S4E9). Discovery Channel. June 21, 2015. Accessed October 14, 2024. https://go.discovery.com/video/naked-and-afraid-discovery/garden-of-evil

- Boucaud-Maitre D, Cachet X, Bouzidi C, et al. Severity of manchineel fruit (Hippomane mancinella) poisoning: a retrospective case series of 97 patients from French Poison Control Centers. Toxicon. 2019;161:28-32. doi:10.1016/j.toxicon.2019.02.014

- Blue LM, Sailing C, Denapoles C, et al. Manchineel dermatitis in North American students in the Caribbean. J Travel Medicine. 2011;18:422-424. doi:10.1111/j.1708-8305.2011.00568.x

- Pitts JF, Barker NH, Gibbons DC, et al. Manchineel keratoconjunctivitis. Br J Ophthalmol. 1993;77:284-288. doi:10.1136/bjo.77.5.284

- Lauter WM, Fox LE, Ariail WT. Investigation of the toxic principles of Hippomane mancinella, L. I. historical review. J Pharm Sci. 1952;41:199-201. https://doi.org/10.1002/jps.3030410412

- Martyr P. De Orbe Novo: the Eight Decades of Peter Martyr d’Anghera. Vol 1. FA MacNutt (translator). GP Putnam’s Sons; 1912. Accessed October 14, 2024. https://gutenberg.org/cache/epub/12425/pg12425.txt

- Fernandez de Ybarra AM. A forgotten medical worthy, Dr. Diego Alvarex Chanca, of Seville, Spain, and his letter describing the second voyage of Christopher Columbus to America. Med Library Hist J. 1906;4:246-263.

- Muscat MK. Manchineel apple of death. EJIFCC. 2019;30:346-348.

- Handler JS. Aspects of Amerindian ethnography in 17th century Barbados. Caribbean Studies. 1970;9:50-72.

- Howard RA. Three experiences with the manchineel (Hippomane spp., Euphorbiaceae). Biotropica. 1981;13:224-227. https://doi.org/10.2307/2388129

- Rao KV. Toxic principles of Hippomane mancinella. Planta Med. 1974;25:166-171. doi:10.1055/s-0028-1097927

- Lauter WM, Foote PA. Investigation of the toxic principles of Hippomane mancinella L. II. Preliminary isolation of a toxic principle of the fruit. J Am Pharm Assoc. 1955;44:361-363. doi:10.1002/jps.3030440616

- Carroll MN Jr, Fox LE, Ariail WT. Investigation of the toxic principles of Hippomane mancinella L. III. Toxic actions of extracts of Hippomane mancinella L. J Am Pharm Assoc. 1957;46:93-97. doi:10.1002/jps.3030460206

- Most dangerous tree. Guinness World Records. Accessed October 14, 2024. https://www.guinnessworldrecords.com/world-records/most-dangerous-tree

- Naked and Afraid: Garden of Evil (S4E9). Discovery Channel. June 21, 2015. Accessed October 14, 2024. https://go.discovery.com/video/naked-and-afraid-discovery/garden-of-evil

- Boucaud-Maitre D, Cachet X, Bouzidi C, et al. Severity of manchineel fruit (Hippomane mancinella) poisoning: a retrospective case series of 97 patients from French Poison Control Centers. Toxicon. 2019;161:28-32. doi:10.1016/j.toxicon.2019.02.014

- Blue LM, Sailing C, Denapoles C, et al. Manchineel dermatitis in North American students in the Caribbean. J Travel Medicine. 2011;18:422-424. doi:10.1111/j.1708-8305.2011.00568.x

- Pitts JF, Barker NH, Gibbons DC, et al. Manchineel keratoconjunctivitis. Br J Ophthalmol. 1993;77:284-288. doi:10.1136/bjo.77.5.284

- Lauter WM, Fox LE, Ariail WT. Investigation of the toxic principles of Hippomane mancinella, L. I. historical review. J Pharm Sci. 1952;41:199-201. https://doi.org/10.1002/jps.3030410412

- Martyr P. De Orbe Novo: the Eight Decades of Peter Martyr d’Anghera. Vol 1. FA MacNutt (translator). GP Putnam’s Sons; 1912. Accessed October 14, 2024. https://gutenberg.org/cache/epub/12425/pg12425.txt

- Fernandez de Ybarra AM. A forgotten medical worthy, Dr. Diego Alvarex Chanca, of Seville, Spain, and his letter describing the second voyage of Christopher Columbus to America. Med Library Hist J. 1906;4:246-263.

- Muscat MK. Manchineel apple of death. EJIFCC. 2019;30:346-348.

- Handler JS. Aspects of Amerindian ethnography in 17th century Barbados. Caribbean Studies. 1970;9:50-72.

- Howard RA. Three experiences with the manchineel (Hippomane spp., Euphorbiaceae). Biotropica. 1981;13:224-227. https://doi.org/10.2307/2388129

- Rao KV. Toxic principles of Hippomane mancinella. Planta Med. 1974;25:166-171. doi:10.1055/s-0028-1097927

- Lauter WM, Foote PA. Investigation of the toxic principles of Hippomane mancinella L. II. Preliminary isolation of a toxic principle of the fruit. J Am Pharm Assoc. 1955;44:361-363. doi:10.1002/jps.3030440616

- Carroll MN Jr, Fox LE, Ariail WT. Investigation of the toxic principles of Hippomane mancinella L. III. Toxic actions of extracts of Hippomane mancinella L. J Am Pharm Assoc. 1957;46:93-97. doi:10.1002/jps.3030460206

PRACTICE POINTS

- Sap from the manchineel tree—found on the coasts of Caribbean islands, the Atlantic coastline of Central and northern South America, and parts of southernmost Florida—can cause severe dermatologic and ophthalmologic injuries. Eating its fruit can lead to oropharyngeal pain and diarrhea.

- Histopathology of manchineel dermatitis reveals a subcorneal acantholytic blister and epidermal spongiosis overlying a mixed perivascular infiltrate and follicular necrosis, which is consistent with irritant contact dermatitis.

- There is no specific treatment for manchineel dermatitis. Case reports advocate a thorough cleansing, application of wet compresses, and observation.

Abdominal pain in a pregnant woman

<huc>Q</huc> What’s your diagnosis?

A 24-year-old woman at 22 weeks’ gestation came to OB triage with abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting. She said that sharp pain began the night before, starting at the umbilicus and radiating toward her right side. She rated her pain level at 7. She felt no contractions and had no vaginal bleeding, fluid leaking, or dysuria. She had GERD at times and chills the day before, but no fever. Similar pain 1 month before had resolved spontaneously, and no cause was determined. She had no notable personal or family medical history. On examination, she was afebrile, normotensive, and in no apparent distress. Heart and lungs were normal. Her abdomen was soft and gravid with a fundal height of 22 cm. Bowel sounds were present in all 4 quadrants. Fetal heart tones were normal, and there was no indication of contractions. Her abdomen was diffusely tender, with significant tenderness to deep palpation in the right upper quadrant at first. There was no rebound or guarding. The psoas sign was negative. The obturator sign was positive, with increased pain, level 4, in the right lower quadrant. There were no abdominal masses. Digital rectal examination found no masses, and a guaiac stool test was negative. A few hours later, the tenderness seemed to move toward the right lower quadrant (FIGURES 1 AND 2).

FIGURE 1 Ultrasound of RLQ

Ultrasound view of the right lower quadrant with cecum labeled.

FIGURE 2 A second ultrasound of RLQ

A second, graded compression ultrasound was obtained, rather than a CT study, to avoid exposing the fetus to radiation.

<huc>A</huc> The most likely diagnoses are cholecystitis and appendicitis, given the location of the pain and the lack of vaginal bleeding.

Diagnostic imaging and radiation exposure

We performed laboratory analyses, including a complete blood count, chemistry panel including electrolytes and liver function studies, amylase, lipase, and a urinalysis. The test results were all normal. Her white blood cell count was 15,000/mL, which can be normal in pregnancy.

Differential diagnosis of abdominal pain in pregnancy

| Placental abruption |

| Cholecystitis |

| Pancreatitis |

| Appendicitis |

| Intussusception |

| Pyelonephritis |

| Round ligament syndrome |

| Hydronephrosis |

| Ovarian torsion |

| Uterine fibroid degeneration |

| Ovarian cysts or tumors |

| Intra-abdominal and rectus muscle abscess |

| Crohn’s disease with diffuse peritoneal inflammation |

Gallstones ruled out

The initial evaluating physician had obtained a right upper quadrant ultrasound, which showed no gallstones or bilateral hydronephrosis.

Unfortunately, no attempt was made to visualize the right lower quadrant or appendix at that time.

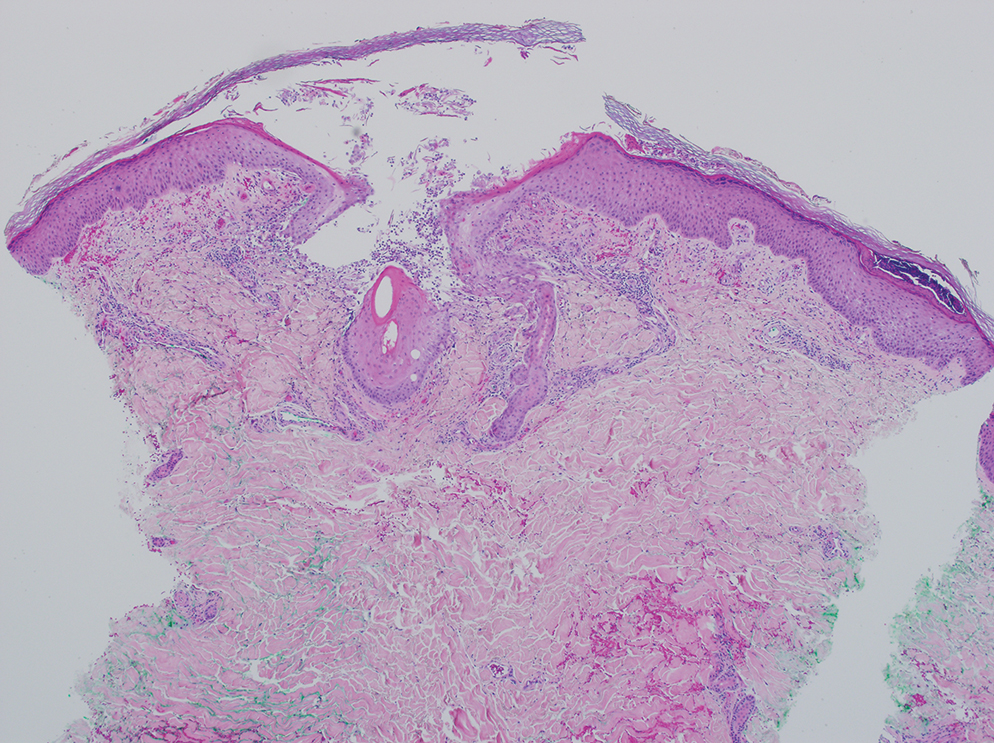

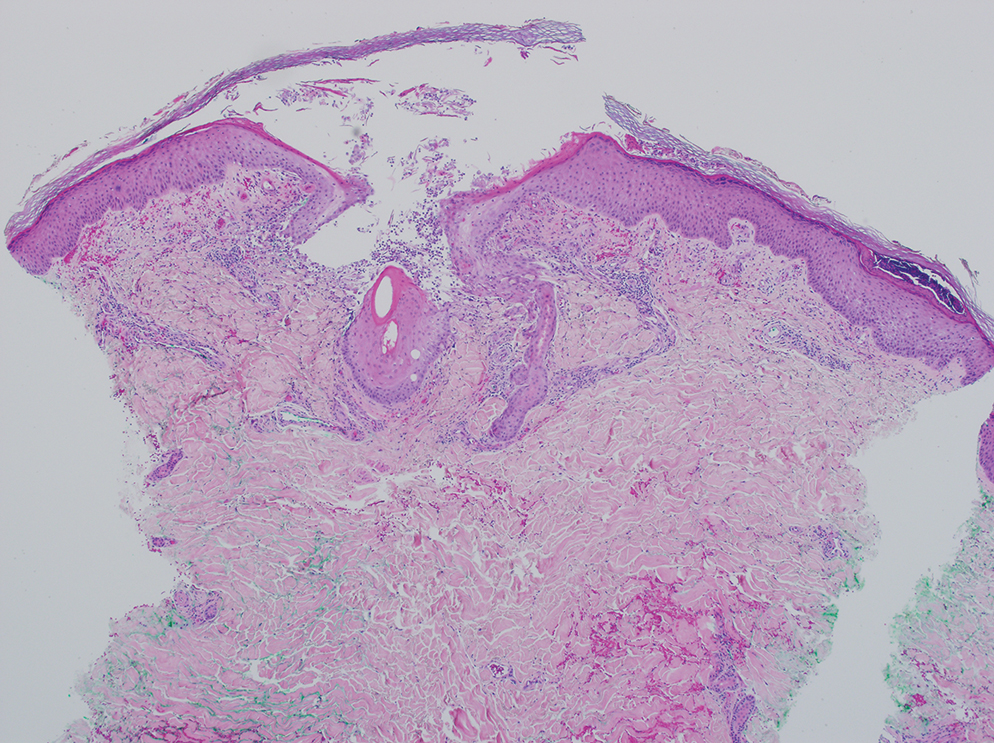

In light of the physical exam findings and the absence of gallstones, the patient was admitted to rule out appendicitis. The surgery team at the university hospital was consulted. They requested a computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen with and without contrast. To avoid the risk of radiation to the fetus, another ultrasound was obtained. The ultrasound showed an enlarged and inflamed appendix with a transverse diameter of 13 mm (normal is <6 mm) (FIGURES 3 AND 4).1

Graded compression was used to assess the appendix. This involves using pressure of the ultrasound probe, starting above the area of tenderness and working toward the tender area while scanning for the appendix. This showed obvious peristalsis in the cecum and no movement within the appendix, indicating obstruction or inflammation.

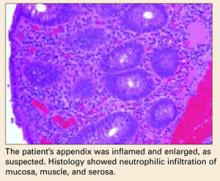

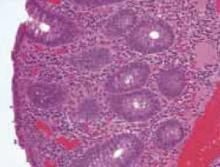

Open appendectomy was performed. The appendix was inflamed and enlarged. Histology showed neutrophilic infiltration of mucosa, muscle, and serosa (BOX).

Postoperatively, the patient recovered in the labor and delivery unit, to monitor for possible preterm labor. She did not develop any signs or symptoms of preterm labor, and was transferred to an antepartum unit after 6 hours of observation.

She did well during hospitalization, and was sent home on post-op day 2. Her abdominal pain had resolved, and she had very little post-op tenderness.

FIGURE 3 Appendix: Longitudinal view

Longitudinal view by ultrasound of enlarged appendix with diameter equal to 13 mm (normal is <6 mm).

FIGURE 4 Appendix: Transverse view

Transverse view of inflamed appendix by ultrasound with wall thickening. Ultrasound showed peristalsis in the cecum and no movement in the appendix, indicating obstruction or inflammation.

Is appendectomy avoidable? The treatment for nonperforated acute appendicitis in pregnancy is appendectomy.

Which approach? In the first trimester, a laparoscopic appendectomy may be performed.2

Antibiotics. Intravenous antibiotics are indicated with perforation, peritonitis, or abscess formation.2,5

Tocolysis. Though unnecessary in uncomplicated appendicitis, tocolysis may be indicated if the patient goes into labor after surgery.

Cesarean. In the late third trimester, with perforation or peritonitis, a cesarean section is indicated.

True danger: Delay

Acute appendicitis is the most common condition requiring surgery during pregnancy.2 Suspected appendicitis is the reason for nearly two thirds of all nonobstetric exploratory laparotomies performed during pregnancy; most cases occur in the second and third trimesters.

The incidence of appendicitis is 0.4 to 1.4 per 1,000 pregnancies.2 Although the incidence of appendicitis is not greater during pregnancy, rupture of the appendix occurs 2 to 3 times more frequently in pregnancy due to delays in diagnosis and operation. Maternal and perinatal mortality and morbidity rates are greatly increased when appendicitis is complicated by peritonitis.

Why diagnosis is not so easy

Many symptoms of appendicitis are considered normal during pregnancy. For example, many times, pain in the right lower quadrant of the abdomen may be attributed to round ligament pain or urinary tract infection.

Anatomy. After the first trimester, the appendix is gradually displaced above McBurney’s point, with horizontal rotation of its base. This upward displacement occurs until the eighth month of gestation, when more than 90% of appendices lie above the iliac crest, and 80% rotate upward and toward the right subcostal area.2,3

Symptoms. The most consistent clinical symptom encountered in pregnant women with appendicitis is vague right-sided abdominal pain.2

- Depending on the gestation, muscle guarding and rebound tenderness may or may not be present.

- Nausea, vomiting, and anorexia are usually present as in the nonpregnant patient.

- Twenty-five percent of pregnant patients with appendicitis are afebrile, as our patient was.2,4

- The leukocytosis of pregnancy makes it difficult to determine if there is an infection. Not all pregnant patients with appendicitis have a white blood cell count of more than 16,000/mL, but approximately 75% have a left shift in the differential.2 Urinalysis may reveal pyuria and hematuria, and can mislead the physician, who may attribute the symptoms to pyelonephritis.2

How likely is fetal loss?

Fetal loss may occur with preterm labor and delivery or with generalized peritonitis and sepsis, but occurs only rarely in uncomplicated appendicitis. Fetal loss appears to be more closely linked to severity of appendicitis than to surgical intervention.2,5,6

Graded compression ultrasonography vs CT

It is imperative that any pregnant patient who comes to the hospital with abdominal pain be evaluated for appendicitis. Ultrasound was a valuable diagnostic tool in this case and saved both the patient and developing fetus the radiation exposure of a CT scan. Ultrasound has a high specificity for diagnosing appendicitis if the appendix is visualized with abnormal findings. However, the sensitivity is not as high as CT (TABLE),7 and failure to visualize the appendix adequately would have required a decision between appendectomy on clinical grounds or going ahead with the CT scan.

A prospective study of patients with signs and symptoms of acute appendicitis found that the graded compression ultrasonography technique was as accurate as focused unenhanced single-detector helical CT. The primary sonographic criterion for the diagnosis was an incompressible appendix with a transverse outer diameter of 6 mm or larger, as seen in this patient. The sensitivity of CT and sonography was 76% and 79%, respectively; the specificity was 83% and 78%; the accuracy was 78% and 78%; the positive predictive value was 90% and 87%; and the negative predictive value was 64% and 65%.8

A rational strategy

It is reasonable to use graded compression ultrasonography in a pregnant woman with suspected appendicitis. If suspicion for appendicitis is high, a negative result may still need further evaluation with a CT or ultimately lead to abdominal surgery despite negative imaging studies.

TABLE

Predictive values of ultrasound and CT in the diagnosis of appendicitis

| TEST | SENSITIVITY | SPECIFICITY | LR+ | LR– |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ultrasound | 0.86 (0.83–0.88) | 0.81 (0.78–0.84) | 5.8 (3.5–9.5) | 0.19 (0.13–0.27) |

| Computed tomography | 0.94 (0.91–0.95) | 0.95 (0.93–0.96) | 13.3 (9.9–17.9) | 0.09 (0.07–0.12) |

| LR+, positive likelihood ratio; LR–, negative likelihood ratio. | ||||

| Source: Terasawa et al.7 | ||||

This article is adapted from Muñoz M, Usatine RP. Abdominal pain in a pregnant woman. J Fam Pract. 2005;54:665-668.

1. Hansen GC, Toot PJ, Lynch CO. Subtle ultrasound signs of appendicitis in pregnancy. A case report. J Reprod Med. 1993;3:223-224.

2. Tamir IL, Bongard FS, Klein SR. Acute appendicitis in the pregnant patient. Am J Surg. 1990;160:571-576.

3. Hodjati H, Kazerooni T. Location of the appendix in the gravid patient: a re-evaluation of the established concept. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2003;81:245-247.

4. Morad JDO, Elliott JP, Lisboa L. Appendicitis in pregnancy: new information that contradicts long-held clinical beliefs. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;182:1027-1029.

5. Andersen B, Nielsen TF. Appendicitis in pregnancy: diagnosis, management and complications. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1999;78:758-762.

6. Thurnau GR, Hales KA. Appendicitis in pregnancy. Female Patient. 1992;17:81.-

7. Terasawa T, Blackmore CC, Bent S, Kohlwes RJ. Systematic review: computed tomography and ultrasonography to detect acute appendicitis in adults and adolescents. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141:537-546.

8. Poortman P, Lohle PN, Schoemaker CM, et al. Comparison of CT and sonography in the diagnosis of acute appendicitis: a blinded prospective study. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2003;181:1355-1359.

<huc>Q</huc> What’s your diagnosis?

A 24-year-old woman at 22 weeks’ gestation came to OB triage with abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting. She said that sharp pain began the night before, starting at the umbilicus and radiating toward her right side. She rated her pain level at 7. She felt no contractions and had no vaginal bleeding, fluid leaking, or dysuria. She had GERD at times and chills the day before, but no fever. Similar pain 1 month before had resolved spontaneously, and no cause was determined. She had no notable personal or family medical history. On examination, she was afebrile, normotensive, and in no apparent distress. Heart and lungs were normal. Her abdomen was soft and gravid with a fundal height of 22 cm. Bowel sounds were present in all 4 quadrants. Fetal heart tones were normal, and there was no indication of contractions. Her abdomen was diffusely tender, with significant tenderness to deep palpation in the right upper quadrant at first. There was no rebound or guarding. The psoas sign was negative. The obturator sign was positive, with increased pain, level 4, in the right lower quadrant. There were no abdominal masses. Digital rectal examination found no masses, and a guaiac stool test was negative. A few hours later, the tenderness seemed to move toward the right lower quadrant (FIGURES 1 AND 2).

FIGURE 1 Ultrasound of RLQ

Ultrasound view of the right lower quadrant with cecum labeled.

FIGURE 2 A second ultrasound of RLQ

A second, graded compression ultrasound was obtained, rather than a CT study, to avoid exposing the fetus to radiation.

<huc>A</huc> The most likely diagnoses are cholecystitis and appendicitis, given the location of the pain and the lack of vaginal bleeding.

Diagnostic imaging and radiation exposure

We performed laboratory analyses, including a complete blood count, chemistry panel including electrolytes and liver function studies, amylase, lipase, and a urinalysis. The test results were all normal. Her white blood cell count was 15,000/mL, which can be normal in pregnancy.

Differential diagnosis of abdominal pain in pregnancy

| Placental abruption |

| Cholecystitis |

| Pancreatitis |

| Appendicitis |

| Intussusception |

| Pyelonephritis |

| Round ligament syndrome |

| Hydronephrosis |

| Ovarian torsion |

| Uterine fibroid degeneration |

| Ovarian cysts or tumors |

| Intra-abdominal and rectus muscle abscess |

| Crohn’s disease with diffuse peritoneal inflammation |

Gallstones ruled out

The initial evaluating physician had obtained a right upper quadrant ultrasound, which showed no gallstones or bilateral hydronephrosis.

Unfortunately, no attempt was made to visualize the right lower quadrant or appendix at that time.

In light of the physical exam findings and the absence of gallstones, the patient was admitted to rule out appendicitis. The surgery team at the university hospital was consulted. They requested a computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen with and without contrast. To avoid the risk of radiation to the fetus, another ultrasound was obtained. The ultrasound showed an enlarged and inflamed appendix with a transverse diameter of 13 mm (normal is <6 mm) (FIGURES 3 AND 4).1

Graded compression was used to assess the appendix. This involves using pressure of the ultrasound probe, starting above the area of tenderness and working toward the tender area while scanning for the appendix. This showed obvious peristalsis in the cecum and no movement within the appendix, indicating obstruction or inflammation.

Open appendectomy was performed. The appendix was inflamed and enlarged. Histology showed neutrophilic infiltration of mucosa, muscle, and serosa (BOX).

Postoperatively, the patient recovered in the labor and delivery unit, to monitor for possible preterm labor. She did not develop any signs or symptoms of preterm labor, and was transferred to an antepartum unit after 6 hours of observation.

She did well during hospitalization, and was sent home on post-op day 2. Her abdominal pain had resolved, and she had very little post-op tenderness.

FIGURE 3 Appendix: Longitudinal view

Longitudinal view by ultrasound of enlarged appendix with diameter equal to 13 mm (normal is <6 mm).

FIGURE 4 Appendix: Transverse view

Transverse view of inflamed appendix by ultrasound with wall thickening. Ultrasound showed peristalsis in the cecum and no movement in the appendix, indicating obstruction or inflammation.

Is appendectomy avoidable? The treatment for nonperforated acute appendicitis in pregnancy is appendectomy.

Which approach? In the first trimester, a laparoscopic appendectomy may be performed.2

Antibiotics. Intravenous antibiotics are indicated with perforation, peritonitis, or abscess formation.2,5

Tocolysis. Though unnecessary in uncomplicated appendicitis, tocolysis may be indicated if the patient goes into labor after surgery.

Cesarean. In the late third trimester, with perforation or peritonitis, a cesarean section is indicated.

True danger: Delay

Acute appendicitis is the most common condition requiring surgery during pregnancy.2 Suspected appendicitis is the reason for nearly two thirds of all nonobstetric exploratory laparotomies performed during pregnancy; most cases occur in the second and third trimesters.

The incidence of appendicitis is 0.4 to 1.4 per 1,000 pregnancies.2 Although the incidence of appendicitis is not greater during pregnancy, rupture of the appendix occurs 2 to 3 times more frequently in pregnancy due to delays in diagnosis and operation. Maternal and perinatal mortality and morbidity rates are greatly increased when appendicitis is complicated by peritonitis.

Why diagnosis is not so easy

Many symptoms of appendicitis are considered normal during pregnancy. For example, many times, pain in the right lower quadrant of the abdomen may be attributed to round ligament pain or urinary tract infection.

Anatomy. After the first trimester, the appendix is gradually displaced above McBurney’s point, with horizontal rotation of its base. This upward displacement occurs until the eighth month of gestation, when more than 90% of appendices lie above the iliac crest, and 80% rotate upward and toward the right subcostal area.2,3

Symptoms. The most consistent clinical symptom encountered in pregnant women with appendicitis is vague right-sided abdominal pain.2

- Depending on the gestation, muscle guarding and rebound tenderness may or may not be present.

- Nausea, vomiting, and anorexia are usually present as in the nonpregnant patient.

- Twenty-five percent of pregnant patients with appendicitis are afebrile, as our patient was.2,4

- The leukocytosis of pregnancy makes it difficult to determine if there is an infection. Not all pregnant patients with appendicitis have a white blood cell count of more than 16,000/mL, but approximately 75% have a left shift in the differential.2 Urinalysis may reveal pyuria and hematuria, and can mislead the physician, who may attribute the symptoms to pyelonephritis.2

How likely is fetal loss?

Fetal loss may occur with preterm labor and delivery or with generalized peritonitis and sepsis, but occurs only rarely in uncomplicated appendicitis. Fetal loss appears to be more closely linked to severity of appendicitis than to surgical intervention.2,5,6

Graded compression ultrasonography vs CT

It is imperative that any pregnant patient who comes to the hospital with abdominal pain be evaluated for appendicitis. Ultrasound was a valuable diagnostic tool in this case and saved both the patient and developing fetus the radiation exposure of a CT scan. Ultrasound has a high specificity for diagnosing appendicitis if the appendix is visualized with abnormal findings. However, the sensitivity is not as high as CT (TABLE),7 and failure to visualize the appendix adequately would have required a decision between appendectomy on clinical grounds or going ahead with the CT scan.

A prospective study of patients with signs and symptoms of acute appendicitis found that the graded compression ultrasonography technique was as accurate as focused unenhanced single-detector helical CT. The primary sonographic criterion for the diagnosis was an incompressible appendix with a transverse outer diameter of 6 mm or larger, as seen in this patient. The sensitivity of CT and sonography was 76% and 79%, respectively; the specificity was 83% and 78%; the accuracy was 78% and 78%; the positive predictive value was 90% and 87%; and the negative predictive value was 64% and 65%.8

A rational strategy

It is reasonable to use graded compression ultrasonography in a pregnant woman with suspected appendicitis. If suspicion for appendicitis is high, a negative result may still need further evaluation with a CT or ultimately lead to abdominal surgery despite negative imaging studies.

TABLE

Predictive values of ultrasound and CT in the diagnosis of appendicitis

| TEST | SENSITIVITY | SPECIFICITY | LR+ | LR– |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ultrasound | 0.86 (0.83–0.88) | 0.81 (0.78–0.84) | 5.8 (3.5–9.5) | 0.19 (0.13–0.27) |

| Computed tomography | 0.94 (0.91–0.95) | 0.95 (0.93–0.96) | 13.3 (9.9–17.9) | 0.09 (0.07–0.12) |

| LR+, positive likelihood ratio; LR–, negative likelihood ratio. | ||||

| Source: Terasawa et al.7 | ||||

This article is adapted from Muñoz M, Usatine RP. Abdominal pain in a pregnant woman. J Fam Pract. 2005;54:665-668.

<huc>Q</huc> What’s your diagnosis?

A 24-year-old woman at 22 weeks’ gestation came to OB triage with abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting. She said that sharp pain began the night before, starting at the umbilicus and radiating toward her right side. She rated her pain level at 7. She felt no contractions and had no vaginal bleeding, fluid leaking, or dysuria. She had GERD at times and chills the day before, but no fever. Similar pain 1 month before had resolved spontaneously, and no cause was determined. She had no notable personal or family medical history. On examination, she was afebrile, normotensive, and in no apparent distress. Heart and lungs were normal. Her abdomen was soft and gravid with a fundal height of 22 cm. Bowel sounds were present in all 4 quadrants. Fetal heart tones were normal, and there was no indication of contractions. Her abdomen was diffusely tender, with significant tenderness to deep palpation in the right upper quadrant at first. There was no rebound or guarding. The psoas sign was negative. The obturator sign was positive, with increased pain, level 4, in the right lower quadrant. There were no abdominal masses. Digital rectal examination found no masses, and a guaiac stool test was negative. A few hours later, the tenderness seemed to move toward the right lower quadrant (FIGURES 1 AND 2).

FIGURE 1 Ultrasound of RLQ

Ultrasound view of the right lower quadrant with cecum labeled.

FIGURE 2 A second ultrasound of RLQ

A second, graded compression ultrasound was obtained, rather than a CT study, to avoid exposing the fetus to radiation.

<huc>A</huc> The most likely diagnoses are cholecystitis and appendicitis, given the location of the pain and the lack of vaginal bleeding.

Diagnostic imaging and radiation exposure

We performed laboratory analyses, including a complete blood count, chemistry panel including electrolytes and liver function studies, amylase, lipase, and a urinalysis. The test results were all normal. Her white blood cell count was 15,000/mL, which can be normal in pregnancy.

Differential diagnosis of abdominal pain in pregnancy

| Placental abruption |

| Cholecystitis |

| Pancreatitis |

| Appendicitis |

| Intussusception |

| Pyelonephritis |

| Round ligament syndrome |

| Hydronephrosis |

| Ovarian torsion |

| Uterine fibroid degeneration |

| Ovarian cysts or tumors |

| Intra-abdominal and rectus muscle abscess |

| Crohn’s disease with diffuse peritoneal inflammation |

Gallstones ruled out

The initial evaluating physician had obtained a right upper quadrant ultrasound, which showed no gallstones or bilateral hydronephrosis.

Unfortunately, no attempt was made to visualize the right lower quadrant or appendix at that time.

In light of the physical exam findings and the absence of gallstones, the patient was admitted to rule out appendicitis. The surgery team at the university hospital was consulted. They requested a computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen with and without contrast. To avoid the risk of radiation to the fetus, another ultrasound was obtained. The ultrasound showed an enlarged and inflamed appendix with a transverse diameter of 13 mm (normal is <6 mm) (FIGURES 3 AND 4).1

Graded compression was used to assess the appendix. This involves using pressure of the ultrasound probe, starting above the area of tenderness and working toward the tender area while scanning for the appendix. This showed obvious peristalsis in the cecum and no movement within the appendix, indicating obstruction or inflammation.

Open appendectomy was performed. The appendix was inflamed and enlarged. Histology showed neutrophilic infiltration of mucosa, muscle, and serosa (BOX).

Postoperatively, the patient recovered in the labor and delivery unit, to monitor for possible preterm labor. She did not develop any signs or symptoms of preterm labor, and was transferred to an antepartum unit after 6 hours of observation.

She did well during hospitalization, and was sent home on post-op day 2. Her abdominal pain had resolved, and she had very little post-op tenderness.

FIGURE 3 Appendix: Longitudinal view

Longitudinal view by ultrasound of enlarged appendix with diameter equal to 13 mm (normal is <6 mm).

FIGURE 4 Appendix: Transverse view

Transverse view of inflamed appendix by ultrasound with wall thickening. Ultrasound showed peristalsis in the cecum and no movement in the appendix, indicating obstruction or inflammation.

Is appendectomy avoidable? The treatment for nonperforated acute appendicitis in pregnancy is appendectomy.

Which approach? In the first trimester, a laparoscopic appendectomy may be performed.2

Antibiotics. Intravenous antibiotics are indicated with perforation, peritonitis, or abscess formation.2,5

Tocolysis. Though unnecessary in uncomplicated appendicitis, tocolysis may be indicated if the patient goes into labor after surgery.

Cesarean. In the late third trimester, with perforation or peritonitis, a cesarean section is indicated.

True danger: Delay

Acute appendicitis is the most common condition requiring surgery during pregnancy.2 Suspected appendicitis is the reason for nearly two thirds of all nonobstetric exploratory laparotomies performed during pregnancy; most cases occur in the second and third trimesters.

The incidence of appendicitis is 0.4 to 1.4 per 1,000 pregnancies.2 Although the incidence of appendicitis is not greater during pregnancy, rupture of the appendix occurs 2 to 3 times more frequently in pregnancy due to delays in diagnosis and operation. Maternal and perinatal mortality and morbidity rates are greatly increased when appendicitis is complicated by peritonitis.

Why diagnosis is not so easy

Many symptoms of appendicitis are considered normal during pregnancy. For example, many times, pain in the right lower quadrant of the abdomen may be attributed to round ligament pain or urinary tract infection.

Anatomy. After the first trimester, the appendix is gradually displaced above McBurney’s point, with horizontal rotation of its base. This upward displacement occurs until the eighth month of gestation, when more than 90% of appendices lie above the iliac crest, and 80% rotate upward and toward the right subcostal area.2,3

Symptoms. The most consistent clinical symptom encountered in pregnant women with appendicitis is vague right-sided abdominal pain.2

- Depending on the gestation, muscle guarding and rebound tenderness may or may not be present.

- Nausea, vomiting, and anorexia are usually present as in the nonpregnant patient.

- Twenty-five percent of pregnant patients with appendicitis are afebrile, as our patient was.2,4

- The leukocytosis of pregnancy makes it difficult to determine if there is an infection. Not all pregnant patients with appendicitis have a white blood cell count of more than 16,000/mL, but approximately 75% have a left shift in the differential.2 Urinalysis may reveal pyuria and hematuria, and can mislead the physician, who may attribute the symptoms to pyelonephritis.2

How likely is fetal loss?

Fetal loss may occur with preterm labor and delivery or with generalized peritonitis and sepsis, but occurs only rarely in uncomplicated appendicitis. Fetal loss appears to be more closely linked to severity of appendicitis than to surgical intervention.2,5,6

Graded compression ultrasonography vs CT

It is imperative that any pregnant patient who comes to the hospital with abdominal pain be evaluated for appendicitis. Ultrasound was a valuable diagnostic tool in this case and saved both the patient and developing fetus the radiation exposure of a CT scan. Ultrasound has a high specificity for diagnosing appendicitis if the appendix is visualized with abnormal findings. However, the sensitivity is not as high as CT (TABLE),7 and failure to visualize the appendix adequately would have required a decision between appendectomy on clinical grounds or going ahead with the CT scan.

A prospective study of patients with signs and symptoms of acute appendicitis found that the graded compression ultrasonography technique was as accurate as focused unenhanced single-detector helical CT. The primary sonographic criterion for the diagnosis was an incompressible appendix with a transverse outer diameter of 6 mm or larger, as seen in this patient. The sensitivity of CT and sonography was 76% and 79%, respectively; the specificity was 83% and 78%; the accuracy was 78% and 78%; the positive predictive value was 90% and 87%; and the negative predictive value was 64% and 65%.8

A rational strategy

It is reasonable to use graded compression ultrasonography in a pregnant woman with suspected appendicitis. If suspicion for appendicitis is high, a negative result may still need further evaluation with a CT or ultimately lead to abdominal surgery despite negative imaging studies.

TABLE

Predictive values of ultrasound and CT in the diagnosis of appendicitis

| TEST | SENSITIVITY | SPECIFICITY | LR+ | LR– |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ultrasound | 0.86 (0.83–0.88) | 0.81 (0.78–0.84) | 5.8 (3.5–9.5) | 0.19 (0.13–0.27) |

| Computed tomography | 0.94 (0.91–0.95) | 0.95 (0.93–0.96) | 13.3 (9.9–17.9) | 0.09 (0.07–0.12) |

| LR+, positive likelihood ratio; LR–, negative likelihood ratio. | ||||

| Source: Terasawa et al.7 | ||||

This article is adapted from Muñoz M, Usatine RP. Abdominal pain in a pregnant woman. J Fam Pract. 2005;54:665-668.

1. Hansen GC, Toot PJ, Lynch CO. Subtle ultrasound signs of appendicitis in pregnancy. A case report. J Reprod Med. 1993;3:223-224.

2. Tamir IL, Bongard FS, Klein SR. Acute appendicitis in the pregnant patient. Am J Surg. 1990;160:571-576.

3. Hodjati H, Kazerooni T. Location of the appendix in the gravid patient: a re-evaluation of the established concept. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2003;81:245-247.

4. Morad JDO, Elliott JP, Lisboa L. Appendicitis in pregnancy: new information that contradicts long-held clinical beliefs. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;182:1027-1029.

5. Andersen B, Nielsen TF. Appendicitis in pregnancy: diagnosis, management and complications. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1999;78:758-762.

6. Thurnau GR, Hales KA. Appendicitis in pregnancy. Female Patient. 1992;17:81.-

7. Terasawa T, Blackmore CC, Bent S, Kohlwes RJ. Systematic review: computed tomography and ultrasonography to detect acute appendicitis in adults and adolescents. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141:537-546.

8. Poortman P, Lohle PN, Schoemaker CM, et al. Comparison of CT and sonography in the diagnosis of acute appendicitis: a blinded prospective study. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2003;181:1355-1359.

1. Hansen GC, Toot PJ, Lynch CO. Subtle ultrasound signs of appendicitis in pregnancy. A case report. J Reprod Med. 1993;3:223-224.

2. Tamir IL, Bongard FS, Klein SR. Acute appendicitis in the pregnant patient. Am J Surg. 1990;160:571-576.

3. Hodjati H, Kazerooni T. Location of the appendix in the gravid patient: a re-evaluation of the established concept. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2003;81:245-247.

4. Morad JDO, Elliott JP, Lisboa L. Appendicitis in pregnancy: new information that contradicts long-held clinical beliefs. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;182:1027-1029.

5. Andersen B, Nielsen TF. Appendicitis in pregnancy: diagnosis, management and complications. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1999;78:758-762.

6. Thurnau GR, Hales KA. Appendicitis in pregnancy. Female Patient. 1992;17:81.-

7. Terasawa T, Blackmore CC, Bent S, Kohlwes RJ. Systematic review: computed tomography and ultrasonography to detect acute appendicitis in adults and adolescents. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141:537-546.

8. Poortman P, Lohle PN, Schoemaker CM, et al. Comparison of CT and sonography in the diagnosis of acute appendicitis: a blinded prospective study. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2003;181:1355-1359.

Abdominal pain in a pregnant woman

A 24-year-old woman, pregnant with a fetus at 22 weeks gestational age, came to the OB triage area with abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting. She described a sharp pain that began the night before, starting at the umbilicus and radiating toward her right side; she rated it 7 out of 10.

The patient said there had been no contractions, vaginal bleeding or fluid leaking, or dysuria. She reported having GERD at times. She experienced chills the day before, but no fever. She had similar pain 1 month before that resolved spontaneously, and for which a cause was never determined. She had nothing significant in her medical history; family history was noncontributory.

On examination, she was afebrile, normotensive, and in no apparent distress. Her heart and lungs were normal. Her abdomen was soft and gravid with a fundal height of 22 cm. Bowel sounds were present in all 4 quadrants. Fetal heart tones were normal, and there was no indication of contractions. Her abdomen was diffusely tender, with significant tenderness to deep palpation in the right upper quadrant at first. There was no rebound or guarding. The psoas sign was negative. The obturator sign was positive, with increased pain 4 out of 10 in the right lower quadrant. There were no abdominal masses. Digital rectal examination revealed no rectal masses, and a guaiac stool test result was negative. A few hours later, the tenderness seemed to move toward the right lower quadrant (FIGURES 1 AND 2).

What is the most likely diagnosis?

How do the ultrasound images help you make the diagnosis?

FIGURE 1

Ultrasound of RLQ

FIGURE 2

A second ultrasound of RLQ

Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of abdominal pain in a gravid patient includes placental abruption, cholecystitis, pancreatitis, appendicitis, intussusception, pyelonephritis, round ligament syndrome, hydronephrosis, ovarian torsion, uterine fibroid degeneration, ovarian cysts or tumors, intra-abdominal and rectus muscle abscesses, and Crohn’s disease with diffuse peritoneal inflammation. Given the location of the pain and the lack of vaginal bleeding, the most likely diagnoses are cholecystitis and appendicitis.

Making the diagnosis

We performed several laboratory analyses, including a complete blood count, chemistry panel (including electrolytes and liver function studies), amylase, lipase, and a urinalysis. The test results were all normal. She had a white blood cell count of 15,000/μL, which can be normal in pregnancy. The initial evaluating physician had obtained a right upper quadrant ultrasound, which showed no gallstones or bilateral hydronephrosis; unfortunately, no attempt was made to visualize the right lower quadrant or appendix at that time.

In light of the physical exam findings and the absence of gallstones, the patient was admitted to rule out appendicitis. The surgery team at the university hospital was consulted. They requested a computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen with and without contrast. To avoid the risk of radiation to the fetus, the family medicine team spoke with Radiology to obtain another ultrasound.

The ultrasound showed an enlarged and inflamed appendix with a transverse diameter of 13 mm (normal is <6 mm) (FIGURES 3 AND 4).1 A graded compression technique was used to assess the appendix. This involves using pressure of the ultrasound probe starting above the area of tenderness and working toward the tender area while scanning for the appendix. This showed obvious peristalsis in the cecum and no movement within the appendix, indicating obstruction or inflammation.

FIGURE 3

Appendix: Longitudinal view

FIGURE 4

Appendix: Transverse view

Patient management and outcome

An open appendectomy was performed. The appendix was inflamed and enlarged as suspected. The histology showed neutrophilic infiltration of mucosa, muscle, and serosa (FIGURE 5). Postoperatively, the patient recovered in Labor and Delivery to monitor for possible preterm labor. She did not develop any signs or symptoms of preterm labor, and was transferred to a regular antepartum floor after being observed for 6 hours.

She did well during her hospitalization, and was sent home on post-op day 2. Her abdominal pain had resolved, and she had very little post-op tenderness.

FIGURE 5

Histology

Discussion: Appendicitis in pregnancy

Acute appendicitis is the most common condition requiring surgery during pregnancy.2 Suspected appendicitis accounts for nearly two thirds of all nonobstetric exploratory laparotomies performed during pregnancy; most cases occur in the second and third trimesters.

The incidence of appendicitis is 0.4 to 1.4 per 1000 pregnancies.2 Although the incidence of appendicitis in not increased during pregnancy, rupture of the appendix occurs 2 to 3 times more frequently in pregnancy secondary to delays in diagnosis and operation. Maternal and perinatal mortality and morbidity rates are greatly increased when appendicitis is complicated by peritonitis.

A difficult diagnosis

Diagnosis is difficult because many symptoms are considered to be normal during pregnancy. Many times, pain in the right lower quadrant of the abdomen may be attributed to round ligament pain or urinary tract infection. After the first trimester, the appendix is gradually displaced above McBurney’s point, with horizontal rotation of its base. This upward displacement occurs until the eighth month of gestation, when more than 90% of appendices lie above the iliac crest, and 80% rotate upward and toward the right subcostal area.2,3

The most consistent clinical symptom encountered in pregnant women with appendicitis is vague right-sided abdominal pain.2 Depending on the gestation, muscle guarding and rebound tenderness may or may not be present. Nausea, vomiting, and anorexia are usually present as in the nonpregnant patient. Twenty five percent of pregnant patients with appendicitis are afebrile, as our patient was.2,4

The leukocytosis of pregnancy makes it difficult to determine if there is an infection. Not all pregnant patients with appendicitis will have a white blood cell count greater than 16,000/μL, but approximately 75% of them will have a left shift in the differential.2 A urinalysis may reveal pyuria and hematuria and can mislead the physician to explain the symptoms as pyelonephritis.2

Treatment: Appendectomy, antibiotics if needed

Treatment of nonperforated acute appendicitis in pregnancy is appendectomy. In the first trimester, a laparoscopic appendectomy may be performed.2 Intravenous antibiotics are indicated with perforation, peritonitis or abscess formation.2,5

Tocolysis is unnecessary in uncomplicated appendicitis, but may be indicated if the patient goes into labor after surgery. In the late third trimester, with perforation or peritonitis, a cesarean section is indicated.

Evaluation is imperative

Fetal loss may occur in association with preterm labor and delivery or with generalized peritonitis and sepsis, and occurs only rarely in uncomplicated appendicitis. Fetal loss appears to be more closely associated with severity of appendicitis than with surgical intervention.2,5,6

Imaging test characteristics: Is sonography enough?

Thus, it is imperative that any pregnant patient that comes in to the hospital or clinic with abdominal pain be evaluated for appendicitis. Ultrasound was a valuable diagnostic tool in this case and saved both the patient and developing fetus the radiation exposure of a CT scan. Ultrasound has a high specificity for diagnosing appendicitis if the appendix is visualized with abnormal findings. However, the sensitivity is not as high as CT, and failure to visualize the appendix adequately would have required a decision between appendectomy on clinical grounds only or going through with the CT scan.

The sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative predictive values for ultrasonography and CT scans in the diagnosis of appendicitis are given in the TABLE (level of evidence [LOE]=1a).7

In a prospective study of patients with clinical signs and symptoms of acute appendicitis using a graded compression technique of ultrasonography, sonographic testing was as accurate as the focused unenhanced single-detector helical CT. The primary sonographic criterion for diagnosing acute appendicitis was an incompressible appendix with a transverse outer diameter of 6 mm or larger, as seen in this patient. The sensitivity of CT and sonography was 76% and 79%, respectively; the specificity was 83% and 78%; the accuracy was 78% and 78%; the positive predictive value was 90% and 87%; and the negative predictive value was 64% and 65% (LOE=2a).8

In conclusion, it is reasonable to use graded compression ultrasonography in a pregnant woman with suspected appendicitis. If the suspicion for appendicitis is high, a negative result may still need further evaluation with a CT or ultimately lead to abdominal surgery despite negative imaging studies.

TABLEUltrasound and CT in the diagnosis of appendicitis

| TEST | SN | SP | LR+ | LR– |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ultrasound | 0.86 (0.83–0.88) | 0.81 (0.78–0.84) | 5.8 (3.5–9.5) | .019 (0.13–0.27) |

| CT | 0.94 (0.91–0.95) | 0.95 (0.93–0.96) | 13.3 (9.9–17.9) | 0.09 (0.07–0.12) |

| Sn, sensitivity; Sp, specificity; LR+, positive likelihood ratio; LR–, negative likelihood ratio; CT, computed tomography. | ||||

| Source: Teresawa et al, Ann Intern Med 2004.7 | ||||

Corresponding Author

Richard P. Usatine, MD, University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, Department of Family and Community Medicine, MC 7794, 7703 Floyd Curl Drive, San Antonio, TX 78229-3900. E-mail: usatine@uthscsa.edu

1. Hansen GC, Toot PJ, Lynch CO. Subtle ultrasound signs of appendicitis in pregnancy. A case report. J Reprod Med 1993;3:223-224.

2. Tamir IL, Bongard FS, Klein SR. Acute appendicitis in the pregnant patient. Am J Surg 1990;160:571-576.

3. Hodjati H, Kazerooni T. Location of the appendix in the gravid patient: a re-evaluation of the established concept. Int J Gynecol Obstet 2003;81:245-247.

4. Morad JDO, Elliott JP, Lisboa L. Appendicitis in pregnancy:new information that contradicts long held clinical beliefs. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2002;182:1027-1029.

5. Andersen B, Nielsen TF. Appendicitis in pregnancy: diagnosis, management and complications. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 1999;78:758-762.

6. Thurnau GR, Hales KA. Appendicitis in pregnancy. Female Patient 1992;17:81.

7. Terasawa T, Blackmore CC, Bent S, Kohlwes RJ. Systematic review: computed tomography and ultrasonography to detect acute appendicitis in adults and adolescents. Ann Intern Med 2004;141:537-546.

8. Poortman P, Lohle PN, Schoemaker CM, et al. Comparison of CT and sonography in the diagnosis of acute appendicitis: a blinded prospective study. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2003;181:1355-1359.

A 24-year-old woman, pregnant with a fetus at 22 weeks gestational age, came to the OB triage area with abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting. She described a sharp pain that began the night before, starting at the umbilicus and radiating toward her right side; she rated it 7 out of 10.

The patient said there had been no contractions, vaginal bleeding or fluid leaking, or dysuria. She reported having GERD at times. She experienced chills the day before, but no fever. She had similar pain 1 month before that resolved spontaneously, and for which a cause was never determined. She had nothing significant in her medical history; family history was noncontributory.

On examination, she was afebrile, normotensive, and in no apparent distress. Her heart and lungs were normal. Her abdomen was soft and gravid with a fundal height of 22 cm. Bowel sounds were present in all 4 quadrants. Fetal heart tones were normal, and there was no indication of contractions. Her abdomen was diffusely tender, with significant tenderness to deep palpation in the right upper quadrant at first. There was no rebound or guarding. The psoas sign was negative. The obturator sign was positive, with increased pain 4 out of 10 in the right lower quadrant. There were no abdominal masses. Digital rectal examination revealed no rectal masses, and a guaiac stool test result was negative. A few hours later, the tenderness seemed to move toward the right lower quadrant (FIGURES 1 AND 2).

What is the most likely diagnosis?

How do the ultrasound images help you make the diagnosis?

FIGURE 1

Ultrasound of RLQ

FIGURE 2

A second ultrasound of RLQ

Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of abdominal pain in a gravid patient includes placental abruption, cholecystitis, pancreatitis, appendicitis, intussusception, pyelonephritis, round ligament syndrome, hydronephrosis, ovarian torsion, uterine fibroid degeneration, ovarian cysts or tumors, intra-abdominal and rectus muscle abscesses, and Crohn’s disease with diffuse peritoneal inflammation. Given the location of the pain and the lack of vaginal bleeding, the most likely diagnoses are cholecystitis and appendicitis.

Making the diagnosis

We performed several laboratory analyses, including a complete blood count, chemistry panel (including electrolytes and liver function studies), amylase, lipase, and a urinalysis. The test results were all normal. She had a white blood cell count of 15,000/μL, which can be normal in pregnancy. The initial evaluating physician had obtained a right upper quadrant ultrasound, which showed no gallstones or bilateral hydronephrosis; unfortunately, no attempt was made to visualize the right lower quadrant or appendix at that time.

In light of the physical exam findings and the absence of gallstones, the patient was admitted to rule out appendicitis. The surgery team at the university hospital was consulted. They requested a computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen with and without contrast. To avoid the risk of radiation to the fetus, the family medicine team spoke with Radiology to obtain another ultrasound.

The ultrasound showed an enlarged and inflamed appendix with a transverse diameter of 13 mm (normal is <6 mm) (FIGURES 3 AND 4).1 A graded compression technique was used to assess the appendix. This involves using pressure of the ultrasound probe starting above the area of tenderness and working toward the tender area while scanning for the appendix. This showed obvious peristalsis in the cecum and no movement within the appendix, indicating obstruction or inflammation.

FIGURE 3

Appendix: Longitudinal view

FIGURE 4

Appendix: Transverse view

Patient management and outcome

An open appendectomy was performed. The appendix was inflamed and enlarged as suspected. The histology showed neutrophilic infiltration of mucosa, muscle, and serosa (FIGURE 5). Postoperatively, the patient recovered in Labor and Delivery to monitor for possible preterm labor. She did not develop any signs or symptoms of preterm labor, and was transferred to a regular antepartum floor after being observed for 6 hours.

She did well during her hospitalization, and was sent home on post-op day 2. Her abdominal pain had resolved, and she had very little post-op tenderness.

FIGURE 5

Histology

Discussion: Appendicitis in pregnancy

Acute appendicitis is the most common condition requiring surgery during pregnancy.2 Suspected appendicitis accounts for nearly two thirds of all nonobstetric exploratory laparotomies performed during pregnancy; most cases occur in the second and third trimesters.

The incidence of appendicitis is 0.4 to 1.4 per 1000 pregnancies.2 Although the incidence of appendicitis in not increased during pregnancy, rupture of the appendix occurs 2 to 3 times more frequently in pregnancy secondary to delays in diagnosis and operation. Maternal and perinatal mortality and morbidity rates are greatly increased when appendicitis is complicated by peritonitis.

A difficult diagnosis

Diagnosis is difficult because many symptoms are considered to be normal during pregnancy. Many times, pain in the right lower quadrant of the abdomen may be attributed to round ligament pain or urinary tract infection. After the first trimester, the appendix is gradually displaced above McBurney’s point, with horizontal rotation of its base. This upward displacement occurs until the eighth month of gestation, when more than 90% of appendices lie above the iliac crest, and 80% rotate upward and toward the right subcostal area.2,3

The most consistent clinical symptom encountered in pregnant women with appendicitis is vague right-sided abdominal pain.2 Depending on the gestation, muscle guarding and rebound tenderness may or may not be present. Nausea, vomiting, and anorexia are usually present as in the nonpregnant patient. Twenty five percent of pregnant patients with appendicitis are afebrile, as our patient was.2,4

The leukocytosis of pregnancy makes it difficult to determine if there is an infection. Not all pregnant patients with appendicitis will have a white blood cell count greater than 16,000/μL, but approximately 75% of them will have a left shift in the differential.2 A urinalysis may reveal pyuria and hematuria and can mislead the physician to explain the symptoms as pyelonephritis.2

Treatment: Appendectomy, antibiotics if needed

Treatment of nonperforated acute appendicitis in pregnancy is appendectomy. In the first trimester, a laparoscopic appendectomy may be performed.2 Intravenous antibiotics are indicated with perforation, peritonitis or abscess formation.2,5

Tocolysis is unnecessary in uncomplicated appendicitis, but may be indicated if the patient goes into labor after surgery. In the late third trimester, with perforation or peritonitis, a cesarean section is indicated.

Evaluation is imperative

Fetal loss may occur in association with preterm labor and delivery or with generalized peritonitis and sepsis, and occurs only rarely in uncomplicated appendicitis. Fetal loss appears to be more closely associated with severity of appendicitis than with surgical intervention.2,5,6

Imaging test characteristics: Is sonography enough?

Thus, it is imperative that any pregnant patient that comes in to the hospital or clinic with abdominal pain be evaluated for appendicitis. Ultrasound was a valuable diagnostic tool in this case and saved both the patient and developing fetus the radiation exposure of a CT scan. Ultrasound has a high specificity for diagnosing appendicitis if the appendix is visualized with abnormal findings. However, the sensitivity is not as high as CT, and failure to visualize the appendix adequately would have required a decision between appendectomy on clinical grounds only or going through with the CT scan.

The sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative predictive values for ultrasonography and CT scans in the diagnosis of appendicitis are given in the TABLE (level of evidence [LOE]=1a).7