User login

Mitchel is a reporter for MDedge based in the Philadelphia area. He started with the company in 1992, when it was International Medical News Group (IMNG), and has since covered a range of medical specialties. Mitchel trained as a virologist at Roswell Park Memorial Institute in Buffalo, and then worked briefly as a researcher at Boston Children's Hospital before pivoting to journalism as a AAAS Mass Media Fellow in 1980. His first reporting job was with Science Digest magazine, and from the mid-1980s to early-1990s he was a reporter with Medical World News. @mitchelzoler

Carotid Artery Interventions Break Three Ways

Optimal management of carotid stenosis to prevent death and strokes is a work in progress right now, with experts groping for the right balance between carotid endarterectomy, carotid artery stenting, and best medical therapy.

The field is bereft of both conclusive, up-to-date data and – more importantly – wide agreement on data interpretation that clearly tips treatment toward one of these options, so much so that in late January an expert panel organized by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services found itself unable to support with high confidence the application of these treatments to any subgroup of carotid disease patients.

Amid this confusion are the following certainties:

- The use of carotid artery stenting (CAS) on U.S. patients grew substantially since its introduction in the late 1990s and since it began receiving limited Medicare coverage in 2004. Data collected through 2007 showed a greater-than-fourfold increase in CAS use among Medicare beneficiaries, compared with 1998 (Circ. Cardiovasc. Qual. Outcomes 2010;3:15-24).

- Other findings documented a shift in CAS use during the 2000s toward patients with asymptomatic carotid stenosis, with a recent estimate that 70%-90% of CAS patients now fall into that category (Arch. Int. Med. 2010;170:1225-7).

- The main results of the landmark CREST (Carotid Revascularization Endarterectomy vs. Stenting) trial, first reported 2 years ago (N. Engl. J. Med. 2010;363:11-23), appeared on the surface to show very similar safety and efficacy for CAS and carotid endarterectomy (CEA), but some experts caution that deeper drilling into the results show that this is an oversimplification of how the two treatments compare.

- And many experts agree that best medical therapy has improved in recent years, to the point where it deserves a new appraisal in a large trial that would compare it against carotid revascularization with CAS or CEA in asymptomatic patients. The leaders of CREST themselves have designed a new trial, CREST II, aimed at making this comparison, and have begun to vigorously lobby the National Institutes of Health to support this study.

In the meantime, vascular surgeons, endovascularists, cardiologists, and the other types of physicians who treat patients with carotid disease try as best they can to strike the right balance in how they apply the three management options.

CREST Provides New Guidance

One surgeon who has perhaps given the most thought to sorting out treatment options is Dr. Brajesh K. Lal, a co–principal investigator on CREST, a vascular surgeon at the University of Maryland in Baltimore, and a researcher who spent the past couple of years sorting through CREST’s voluminous data to find new clues to guide patient triage.

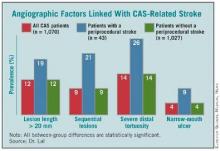

A major, recent guide for matching patients with a specific carotid intervention came from his painstaking analysis of carotid angiograms from 1,070 of the CREST patients who underwent CAS, of whom 43 patients (4%) then went on to have a stroke.

This effort identified the following four anatomical features that appear to mark patients with an increased rate of periprocedural stroke when they are treated with CAS:

- Stenotic lesion more than 20 mm long. The researchers measured lesion length as the distance from the proximal to distal shoulder of the lesion.

- Sequential lesions. This refers to two lesions separated by at least 10 mm of normal vessel.

- Severe distal tortuosity. This was defined as at least two arterial bends of at least 90 degrees that are distal to the lesion.

- Narrow-mouth ulcers. This refers to a small crater or lumen flap that produces a discrete area of contrast extension beyond the normal arterial lumen with a narrow inlet into the ulceration.

Patients with one or more of these carotid anatomical features "should be treated by endarterectomy," Dr. Lal said in an interview. "If I see any one of these in my clinical practice, I will not stent."

The variables assessed in this analysis did not include arterial calcification, as the angiographic imaging routinely collected in the study did not allow calcium quantification, said Dr. Lal. Among the stented patients in the study, the cumulative prevalence of the four significant risk markers was 39%. Patients with none of the four markers had a significantly reduced rate of periprocedural stroke during carotid stenting.

Endovascularists were already routinely assessing carotid anatomy before attempting CAS, but prior to Dr. Lal’s report on these new findings at the International Stroke Conference in New Orleans in February, "I’m not so sure that everyone has been using this [anatomical] information," he said. "When we talk about operator experience in stenting, if we don’t have the facts about what increases the stenting risk, then we won’t improve performance. You’d be surprised at what some interventionalists are willing to do," despite a patient’s challenging carotid anatomy. "These data show that you can work around a single 90-degree bend [of the distal carotid artery], but not around two bends. That is the kind of stuff we’re beginning to find out."

Dr. Lal and his associates plan to further analyze their data and derive a formula that physicians can apply to patients to estimate their periprocedural stroke risk.

Additional, recent CREST analyses that were also reported at the International Stroke Conference revealed other new, important lessons about CAS and CEA.

First, by 2 years after intervention, both CAS and CEA produced roughly comparable low rates of restenosis: a 6.0% rate in the CAS patients who underwent a prespecified, follow-up duplex ultrasound examination of their carotid artery, and 6.3% in the CEA patients (Stroke 2012;43: abstract A3). The rates were also similar regardless of whether patients were symptomatic before their carotid intervention, Dr. Lal reported.

This finding appears to lay to rest the concern about a major restenosis risk using bare-metal stents in carotid arteries, in contrast to what happens in coronary arteries, Dr. Lal said. "To my mind, these data are fairly definitive. We followed more than 2,000 patients, and every ultrasound was reviewed and adjudicated. I’m fairly comfortable with these results."

A third CREST analysis that was also reported in February showed that, after adjustment for baseline differences, patients had no significant changes in their rates of periprocedural events during and after CAS throughout the study, from 2000 to 2008 (Stroke 2012;43: abstract A1). "We hoped to show that CAS was getting better [during the 9 years of CREST], but we saw no evidence it got better with time," said George Howard, Dr.P.H., professor and chairman of the department of biostatistics at the University of Alabama at Birmingham. "It would make sense if CAS got better; it’s a new procedure that people learn." But the CREST results showed no evidence of a learning curve, perhaps because the 224 interventionalists who performed CAS in CREST went through a rigorous credentialing process and also performed their first several CAS procedures in CREST during a lead-in phase that was not included in the main outcomes.

Choosing Among the Options

Dr. Lal said that he draws several other lessons from the CREST results to guide his treatment decisions: Patients who are physiologically elderly, those with a large amount of calcified atheroma in their aortic arch, and patients with significant peripheral arterial disease that impedes endovascular access are all poor CAS candidates, he said, adding that he focuses on a patient’s physiological age rather than chronological age.

Patients who are well suited to CAS are those with a younger physiological age, those with a history of radiation treatment, and patients with restenotic carotid lesions.

Although CREST showed worse performance of CAS in women compared with men, "I don’t know why, so it’s hard for me to exclude or offer a particular treatment" based on the patient’s sex, he said. "I treat women just like men, and work through all the other things that I know about to help me decide."

Then there is a third subgroup, patients with carotid disease who he feels "benefit the most" from medical management only. This category primarily includes asymptomatic patients with moderate stenosis (that is, less than 80% carotid occlusion). His prescription for medical management includes 325 mg of aspirin daily, treatment with a statin, good blood pressure and blood sugar control, smoking cessation, and lifestyle modification. If, despite this, an asymptomatic patient has continued stenotic progression that advances beyond 80%, he will then recommend revascularization.

Dr. Lal said that in his practice today, roughly one-third of carotid-disease patients are on medical management, a third undergo CEA, and a third receive CAS. "We are at a stage of equipoise," for these three options, which is why he helped design and is working to get funding for CREST II.

Dr. Lal personally applies all three treatment options – CAS, CEA, or medical management. Having physicians involved in the decision-making process who are comfortable using each of these options is critical for making a balanced management decision, said Dr. L. Nelson Hopkins, another CREST collaborator and professor and chairman of neurosurgery at the State University of New York at Buffalo.

"The single most important thing we do is have a weekly, multidisciplinary conference to discuss each case, with input from everyone, to decide the best treatment for each [carotid disease] patient," he said when he spoke at ISET 2012, an International Symposium on Endovascular Therapy in Miami Beach in January.

"The most important factors" guiding the decision of whether or not to perform CAS are, does a symptomatic patient has "hot" lesions, what is the arterial tortuosity, and what is the calcification, he said. Other important features include whether the patient has a contralateral carotid occlusion, whether the carotid has a high bifurcation, and whether there are ostial or tandem lesions. "If the anatomy is favorable, CAS is fine even in a 95-year-old," Dr. Hopkins said.

What About Insurance Coverage?

Carotid specialists concede that another, nonmedical issue also plays a big role in deciding how to manage a patient: What will the patient’s health insurance cover?

In its most recent decision on the issue, effective in April 2010, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) said that Medicare covers CAS performed on a routine basis for patients with symptomatic carotid disease who are at high risk for CEA and have at least 70% carotid stenosis. CMS also said that Medicare will cover FDA-approved investigations of CAS in symptomatic patients who are at high risk for CEA and have at least 50% stenosis, as well as CAS investigations in asymptomatic patients at high risk for CEA with at least 80% carotid stenosis.

As a result, patients with other forms of carotid disease often do not have insurance coverage for CAS.

"The issue for us is primarily reimbursement. If we can do [a procedure] and be reimbursed, we often stent the patient," said Dr. Carlos H. Timaran, a vascular surgeon and chief of endovascular surgery at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas.

"For my private practice patients, we assess their risk based on their [anatomical] and medical criteria. If they are high risk, we usually stent. We have a bias toward stenting because it is faster and easier. Some people say they can do endarterectomy in an hour, but I don’t believe that. I do CEA with residents and fellows, and it takes 2 hours. But with stenting, I can do it in 40 minutes, even with a fellow. If I have three patients with carotid disease to treat [and] if I do CEA on all three, it will take all day. If I do CAS, it will take the morning, or less," he said in an interview.

In addition, "CEA is a nice procedure, but you need anesthesia. CAS is easier, I can do it myself, and I don’t need anesthesia. I am in more control of the case," Dr. Timaran said.

For patients who are eligible for both CAS and CEA, "it also comes down to anatomy," he grants. But if the patient has anatomy favorable to either method, "I offer patients both, and they will probably go for a stent," because patients usually prefer the quicker recovery that stenting offers, compared with CEA.

An interesting footnote to the issue of how to best manage patients who are eligible for CAS under CMS rules is that the CREST results offer no direct guidance on the relative safety and efficacy of CAS and CEA in patients with Medicare coverage. That’s because "the CREST cohort was a conventional-risk cohort; most criteria that would make someone a high surgical risk would have been excluded from CREST," Dr. Thomas G. Brott, professor of neurology at the Mayo Clinic in Jacksonville, Fla., and lead investigator for CREST. "The high-surgical-risk patients who are currently covered by Medicare would not have even been enrolled in CREST," Dr. Brott said in an interview.

Where Does Medical Therapy Fit In?

Although Dr. Timaran sees the potential value of medical therapy only for asymptomatic patients, he also urges caution.

"I don’t think [the efficacy of medical treatment] has been proven, and until it’s proven I don’t think physicians should deny revascularization treatment to these patients," he said. "The standard of care for a patient with severe carotid stenosis is revascularization, even if the patient is asymptomatic, unless there is some other consideration." But, he admitted, "there is little downside to medical treatment in asymptomatic patients, even if they have severe stenosis." That’s because their stroke risk is low regardless of which option a patient chooses.

"I tell asymptomatic patients that ‘based on the data, your risk of stroke is 2% per year, and that risk may be even lower with best medical therapy.’ With a carotid intervention, we can lower their risk to 1% per year." In other words, the patient’s stroke risk is low regardless of which option is chosen. Plus, medical therapy only is the best choice for patients with special risk factors, such as radiation-induced stenosis, Dr. Timaran added.

Other experts see medical treatment alone as an excellent option for many carotid-stenosis patients.

"The majority of patients I see don’t get an intervention; we use medical treatment only," said Dr. Jon S. Matsumura in an interview. "I think that’s true for most vascular surgery practices, and in cardiology and neurology practices. A lot of these patients just need reassurance," said Dr. Matsumura, professor and chairman of vascular surgery at the University of Wisconsin in Madison.

"Most asymptomatic patients [with carotid stenosis] should be treated by best medical therapy, with very few – fewer than 5% – treated by CAS or CEA," said Dr. Frank J. Veith at the International Symposium on Endovascular Therapy (ISET 12) in January. He acknowledged that well-controlled trials done during the 1990s showed that CEA led to superior outcomes compared with medical therapy, but since the early 2000s, "best medical therapy to prevent strokes leapt forward," he said, especially with improved statin therapy. He cited findings from a 2010 prospective study that showed asymptomatic Canadian patients managed starting in 2003 with best medical therapy had an annual stroke rate of 0.7% (Arch. Neurol. 2010;67:180-6).

He singled out four small groups of asymptomatic patients who warrant revascularization: patients with CT or MRI evidence for a history of silent strokes, patients with very-high-grade carotid stenosis that leaves just 1% of the carotid lumen open, those with a contralateral occlusion, and patients who serially experience transient occlusions detected by transcranial Doppler ultrasound examination, said Dr. Veith, professor of surgery at New York University. Aside from this small fraction of patients with asymptomatic disease, performing interventions on anyone else will "cause more strokes than you’ll prevent," he warned in an interview.

What Will CMS Do?

Dr. Veith’s take on limiting CAS in asymptomatic patients received substantial support early this year in the days leading up to the Jan. 25 meeting of the Medicare Evidence Development and Coverage Advisory Committee (MEDCAC) that heard evidence and opinions for and against widening of Medicare coverage for CAS. In early January, Dr. Veith joined with 40 other vascular surgeons and stroke specialists to urge CMS not to broaden CAS coverage (Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2012 Jan. 5 [doi:10.1016/j.ejvs.2011.12.006]). But, as MEDCAC heard during this meeting, experts differ on this issue.

"CMS continues to restrict access to CAS to about 10% of patients" with significant carotid stenosis, said Dr. William A. Gray, director of endovascular services at Columbia University in New York, speaking at ISET 2012 in January. "Expanded CAS coverage would allow greater patient access and device development, and therefore create a safer option for patients." Dr. Gray presented his positive views on CAS to MEDCAC in January as well.

At press time, CMS had not announced whether or not the January MEDCAC hearing will result in a change to its CAS coverage policy. But the votes cast by MEDCAC’s membership in January suggested that the issues surrounding management of carotid stenosis remain too unresolved to trigger immediate changes.

Dr. Lal, Dr. Timaran, and Dr. Veith said that they had no disclosures. Dr. Howard said that he has received grant support from Abbott. Dr. Hopkins said that he has financial relationships with Bard, Boston Scientific, Cordis, Abbott Vascular, Toshiba, W.L. Gore, Medtronic, Micrus, St. Jude, Access Closure, Osteal, Vascular Dynamics, Square One, Valor Medical, Claret Medical, and Augmenix. Dr. Brott said that he has been a consultant to Edwards Lifesciences. Dr. Matsumura said that he has received research grants from Abbott, Cook, Covidien, Endologix, and W.L. Gore. Dr. Gray said that he has had financial relationships with Boston Scientific, Coherex, Contego, Cordis, Fiatlux 3D, Nexeon, Quantumcor, Abbott Vascular, and Biocardia.

Optimal management of carotid stenosis to prevent death and strokes is a work in progress right now, with experts groping for the right balance between carotid endarterectomy, carotid artery stenting, and best medical therapy.

The field is bereft of both conclusive, up-to-date data and – more importantly – wide agreement on data interpretation that clearly tips treatment toward one of these options, so much so that in late January an expert panel organized by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services found itself unable to support with high confidence the application of these treatments to any subgroup of carotid disease patients.

Amid this confusion are the following certainties:

- The use of carotid artery stenting (CAS) on U.S. patients grew substantially since its introduction in the late 1990s and since it began receiving limited Medicare coverage in 2004. Data collected through 2007 showed a greater-than-fourfold increase in CAS use among Medicare beneficiaries, compared with 1998 (Circ. Cardiovasc. Qual. Outcomes 2010;3:15-24).

- Other findings documented a shift in CAS use during the 2000s toward patients with asymptomatic carotid stenosis, with a recent estimate that 70%-90% of CAS patients now fall into that category (Arch. Int. Med. 2010;170:1225-7).

- The main results of the landmark CREST (Carotid Revascularization Endarterectomy vs. Stenting) trial, first reported 2 years ago (N. Engl. J. Med. 2010;363:11-23), appeared on the surface to show very similar safety and efficacy for CAS and carotid endarterectomy (CEA), but some experts caution that deeper drilling into the results show that this is an oversimplification of how the two treatments compare.

- And many experts agree that best medical therapy has improved in recent years, to the point where it deserves a new appraisal in a large trial that would compare it against carotid revascularization with CAS or CEA in asymptomatic patients. The leaders of CREST themselves have designed a new trial, CREST II, aimed at making this comparison, and have begun to vigorously lobby the National Institutes of Health to support this study.

In the meantime, vascular surgeons, endovascularists, cardiologists, and the other types of physicians who treat patients with carotid disease try as best they can to strike the right balance in how they apply the three management options.

CREST Provides New Guidance

One surgeon who has perhaps given the most thought to sorting out treatment options is Dr. Brajesh K. Lal, a co–principal investigator on CREST, a vascular surgeon at the University of Maryland in Baltimore, and a researcher who spent the past couple of years sorting through CREST’s voluminous data to find new clues to guide patient triage.

A major, recent guide for matching patients with a specific carotid intervention came from his painstaking analysis of carotid angiograms from 1,070 of the CREST patients who underwent CAS, of whom 43 patients (4%) then went on to have a stroke.

This effort identified the following four anatomical features that appear to mark patients with an increased rate of periprocedural stroke when they are treated with CAS:

- Stenotic lesion more than 20 mm long. The researchers measured lesion length as the distance from the proximal to distal shoulder of the lesion.

- Sequential lesions. This refers to two lesions separated by at least 10 mm of normal vessel.

- Severe distal tortuosity. This was defined as at least two arterial bends of at least 90 degrees that are distal to the lesion.

- Narrow-mouth ulcers. This refers to a small crater or lumen flap that produces a discrete area of contrast extension beyond the normal arterial lumen with a narrow inlet into the ulceration.

Patients with one or more of these carotid anatomical features "should be treated by endarterectomy," Dr. Lal said in an interview. "If I see any one of these in my clinical practice, I will not stent."

The variables assessed in this analysis did not include arterial calcification, as the angiographic imaging routinely collected in the study did not allow calcium quantification, said Dr. Lal. Among the stented patients in the study, the cumulative prevalence of the four significant risk markers was 39%. Patients with none of the four markers had a significantly reduced rate of periprocedural stroke during carotid stenting.

Endovascularists were already routinely assessing carotid anatomy before attempting CAS, but prior to Dr. Lal’s report on these new findings at the International Stroke Conference in New Orleans in February, "I’m not so sure that everyone has been using this [anatomical] information," he said. "When we talk about operator experience in stenting, if we don’t have the facts about what increases the stenting risk, then we won’t improve performance. You’d be surprised at what some interventionalists are willing to do," despite a patient’s challenging carotid anatomy. "These data show that you can work around a single 90-degree bend [of the distal carotid artery], but not around two bends. That is the kind of stuff we’re beginning to find out."

Dr. Lal and his associates plan to further analyze their data and derive a formula that physicians can apply to patients to estimate their periprocedural stroke risk.

Additional, recent CREST analyses that were also reported at the International Stroke Conference revealed other new, important lessons about CAS and CEA.

First, by 2 years after intervention, both CAS and CEA produced roughly comparable low rates of restenosis: a 6.0% rate in the CAS patients who underwent a prespecified, follow-up duplex ultrasound examination of their carotid artery, and 6.3% in the CEA patients (Stroke 2012;43: abstract A3). The rates were also similar regardless of whether patients were symptomatic before their carotid intervention, Dr. Lal reported.

This finding appears to lay to rest the concern about a major restenosis risk using bare-metal stents in carotid arteries, in contrast to what happens in coronary arteries, Dr. Lal said. "To my mind, these data are fairly definitive. We followed more than 2,000 patients, and every ultrasound was reviewed and adjudicated. I’m fairly comfortable with these results."

A third CREST analysis that was also reported in February showed that, after adjustment for baseline differences, patients had no significant changes in their rates of periprocedural events during and after CAS throughout the study, from 2000 to 2008 (Stroke 2012;43: abstract A1). "We hoped to show that CAS was getting better [during the 9 years of CREST], but we saw no evidence it got better with time," said George Howard, Dr.P.H., professor and chairman of the department of biostatistics at the University of Alabama at Birmingham. "It would make sense if CAS got better; it’s a new procedure that people learn." But the CREST results showed no evidence of a learning curve, perhaps because the 224 interventionalists who performed CAS in CREST went through a rigorous credentialing process and also performed their first several CAS procedures in CREST during a lead-in phase that was not included in the main outcomes.

Choosing Among the Options

Dr. Lal said that he draws several other lessons from the CREST results to guide his treatment decisions: Patients who are physiologically elderly, those with a large amount of calcified atheroma in their aortic arch, and patients with significant peripheral arterial disease that impedes endovascular access are all poor CAS candidates, he said, adding that he focuses on a patient’s physiological age rather than chronological age.

Patients who are well suited to CAS are those with a younger physiological age, those with a history of radiation treatment, and patients with restenotic carotid lesions.

Although CREST showed worse performance of CAS in women compared with men, "I don’t know why, so it’s hard for me to exclude or offer a particular treatment" based on the patient’s sex, he said. "I treat women just like men, and work through all the other things that I know about to help me decide."

Then there is a third subgroup, patients with carotid disease who he feels "benefit the most" from medical management only. This category primarily includes asymptomatic patients with moderate stenosis (that is, less than 80% carotid occlusion). His prescription for medical management includes 325 mg of aspirin daily, treatment with a statin, good blood pressure and blood sugar control, smoking cessation, and lifestyle modification. If, despite this, an asymptomatic patient has continued stenotic progression that advances beyond 80%, he will then recommend revascularization.

Dr. Lal said that in his practice today, roughly one-third of carotid-disease patients are on medical management, a third undergo CEA, and a third receive CAS. "We are at a stage of equipoise," for these three options, which is why he helped design and is working to get funding for CREST II.

Dr. Lal personally applies all three treatment options – CAS, CEA, or medical management. Having physicians involved in the decision-making process who are comfortable using each of these options is critical for making a balanced management decision, said Dr. L. Nelson Hopkins, another CREST collaborator and professor and chairman of neurosurgery at the State University of New York at Buffalo.

"The single most important thing we do is have a weekly, multidisciplinary conference to discuss each case, with input from everyone, to decide the best treatment for each [carotid disease] patient," he said when he spoke at ISET 2012, an International Symposium on Endovascular Therapy in Miami Beach in January.

"The most important factors" guiding the decision of whether or not to perform CAS are, does a symptomatic patient has "hot" lesions, what is the arterial tortuosity, and what is the calcification, he said. Other important features include whether the patient has a contralateral carotid occlusion, whether the carotid has a high bifurcation, and whether there are ostial or tandem lesions. "If the anatomy is favorable, CAS is fine even in a 95-year-old," Dr. Hopkins said.

What About Insurance Coverage?

Carotid specialists concede that another, nonmedical issue also plays a big role in deciding how to manage a patient: What will the patient’s health insurance cover?

In its most recent decision on the issue, effective in April 2010, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) said that Medicare covers CAS performed on a routine basis for patients with symptomatic carotid disease who are at high risk for CEA and have at least 70% carotid stenosis. CMS also said that Medicare will cover FDA-approved investigations of CAS in symptomatic patients who are at high risk for CEA and have at least 50% stenosis, as well as CAS investigations in asymptomatic patients at high risk for CEA with at least 80% carotid stenosis.

As a result, patients with other forms of carotid disease often do not have insurance coverage for CAS.

"The issue for us is primarily reimbursement. If we can do [a procedure] and be reimbursed, we often stent the patient," said Dr. Carlos H. Timaran, a vascular surgeon and chief of endovascular surgery at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas.

"For my private practice patients, we assess their risk based on their [anatomical] and medical criteria. If they are high risk, we usually stent. We have a bias toward stenting because it is faster and easier. Some people say they can do endarterectomy in an hour, but I don’t believe that. I do CEA with residents and fellows, and it takes 2 hours. But with stenting, I can do it in 40 minutes, even with a fellow. If I have three patients with carotid disease to treat [and] if I do CEA on all three, it will take all day. If I do CAS, it will take the morning, or less," he said in an interview.

In addition, "CEA is a nice procedure, but you need anesthesia. CAS is easier, I can do it myself, and I don’t need anesthesia. I am in more control of the case," Dr. Timaran said.

For patients who are eligible for both CAS and CEA, "it also comes down to anatomy," he grants. But if the patient has anatomy favorable to either method, "I offer patients both, and they will probably go for a stent," because patients usually prefer the quicker recovery that stenting offers, compared with CEA.

An interesting footnote to the issue of how to best manage patients who are eligible for CAS under CMS rules is that the CREST results offer no direct guidance on the relative safety and efficacy of CAS and CEA in patients with Medicare coverage. That’s because "the CREST cohort was a conventional-risk cohort; most criteria that would make someone a high surgical risk would have been excluded from CREST," Dr. Thomas G. Brott, professor of neurology at the Mayo Clinic in Jacksonville, Fla., and lead investigator for CREST. "The high-surgical-risk patients who are currently covered by Medicare would not have even been enrolled in CREST," Dr. Brott said in an interview.

Where Does Medical Therapy Fit In?

Although Dr. Timaran sees the potential value of medical therapy only for asymptomatic patients, he also urges caution.

"I don’t think [the efficacy of medical treatment] has been proven, and until it’s proven I don’t think physicians should deny revascularization treatment to these patients," he said. "The standard of care for a patient with severe carotid stenosis is revascularization, even if the patient is asymptomatic, unless there is some other consideration." But, he admitted, "there is little downside to medical treatment in asymptomatic patients, even if they have severe stenosis." That’s because their stroke risk is low regardless of which option a patient chooses.

"I tell asymptomatic patients that ‘based on the data, your risk of stroke is 2% per year, and that risk may be even lower with best medical therapy.’ With a carotid intervention, we can lower their risk to 1% per year." In other words, the patient’s stroke risk is low regardless of which option is chosen. Plus, medical therapy only is the best choice for patients with special risk factors, such as radiation-induced stenosis, Dr. Timaran added.

Other experts see medical treatment alone as an excellent option for many carotid-stenosis patients.

"The majority of patients I see don’t get an intervention; we use medical treatment only," said Dr. Jon S. Matsumura in an interview. "I think that’s true for most vascular surgery practices, and in cardiology and neurology practices. A lot of these patients just need reassurance," said Dr. Matsumura, professor and chairman of vascular surgery at the University of Wisconsin in Madison.

"Most asymptomatic patients [with carotid stenosis] should be treated by best medical therapy, with very few – fewer than 5% – treated by CAS or CEA," said Dr. Frank J. Veith at the International Symposium on Endovascular Therapy (ISET 12) in January. He acknowledged that well-controlled trials done during the 1990s showed that CEA led to superior outcomes compared with medical therapy, but since the early 2000s, "best medical therapy to prevent strokes leapt forward," he said, especially with improved statin therapy. He cited findings from a 2010 prospective study that showed asymptomatic Canadian patients managed starting in 2003 with best medical therapy had an annual stroke rate of 0.7% (Arch. Neurol. 2010;67:180-6).

He singled out four small groups of asymptomatic patients who warrant revascularization: patients with CT or MRI evidence for a history of silent strokes, patients with very-high-grade carotid stenosis that leaves just 1% of the carotid lumen open, those with a contralateral occlusion, and patients who serially experience transient occlusions detected by transcranial Doppler ultrasound examination, said Dr. Veith, professor of surgery at New York University. Aside from this small fraction of patients with asymptomatic disease, performing interventions on anyone else will "cause more strokes than you’ll prevent," he warned in an interview.

What Will CMS Do?

Dr. Veith’s take on limiting CAS in asymptomatic patients received substantial support early this year in the days leading up to the Jan. 25 meeting of the Medicare Evidence Development and Coverage Advisory Committee (MEDCAC) that heard evidence and opinions for and against widening of Medicare coverage for CAS. In early January, Dr. Veith joined with 40 other vascular surgeons and stroke specialists to urge CMS not to broaden CAS coverage (Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2012 Jan. 5 [doi:10.1016/j.ejvs.2011.12.006]). But, as MEDCAC heard during this meeting, experts differ on this issue.

"CMS continues to restrict access to CAS to about 10% of patients" with significant carotid stenosis, said Dr. William A. Gray, director of endovascular services at Columbia University in New York, speaking at ISET 2012 in January. "Expanded CAS coverage would allow greater patient access and device development, and therefore create a safer option for patients." Dr. Gray presented his positive views on CAS to MEDCAC in January as well.

At press time, CMS had not announced whether or not the January MEDCAC hearing will result in a change to its CAS coverage policy. But the votes cast by MEDCAC’s membership in January suggested that the issues surrounding management of carotid stenosis remain too unresolved to trigger immediate changes.

Dr. Lal, Dr. Timaran, and Dr. Veith said that they had no disclosures. Dr. Howard said that he has received grant support from Abbott. Dr. Hopkins said that he has financial relationships with Bard, Boston Scientific, Cordis, Abbott Vascular, Toshiba, W.L. Gore, Medtronic, Micrus, St. Jude, Access Closure, Osteal, Vascular Dynamics, Square One, Valor Medical, Claret Medical, and Augmenix. Dr. Brott said that he has been a consultant to Edwards Lifesciences. Dr. Matsumura said that he has received research grants from Abbott, Cook, Covidien, Endologix, and W.L. Gore. Dr. Gray said that he has had financial relationships with Boston Scientific, Coherex, Contego, Cordis, Fiatlux 3D, Nexeon, Quantumcor, Abbott Vascular, and Biocardia.

Optimal management of carotid stenosis to prevent death and strokes is a work in progress right now, with experts groping for the right balance between carotid endarterectomy, carotid artery stenting, and best medical therapy.

The field is bereft of both conclusive, up-to-date data and – more importantly – wide agreement on data interpretation that clearly tips treatment toward one of these options, so much so that in late January an expert panel organized by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services found itself unable to support with high confidence the application of these treatments to any subgroup of carotid disease patients.

Amid this confusion are the following certainties:

- The use of carotid artery stenting (CAS) on U.S. patients grew substantially since its introduction in the late 1990s and since it began receiving limited Medicare coverage in 2004. Data collected through 2007 showed a greater-than-fourfold increase in CAS use among Medicare beneficiaries, compared with 1998 (Circ. Cardiovasc. Qual. Outcomes 2010;3:15-24).

- Other findings documented a shift in CAS use during the 2000s toward patients with asymptomatic carotid stenosis, with a recent estimate that 70%-90% of CAS patients now fall into that category (Arch. Int. Med. 2010;170:1225-7).

- The main results of the landmark CREST (Carotid Revascularization Endarterectomy vs. Stenting) trial, first reported 2 years ago (N. Engl. J. Med. 2010;363:11-23), appeared on the surface to show very similar safety and efficacy for CAS and carotid endarterectomy (CEA), but some experts caution that deeper drilling into the results show that this is an oversimplification of how the two treatments compare.

- And many experts agree that best medical therapy has improved in recent years, to the point where it deserves a new appraisal in a large trial that would compare it against carotid revascularization with CAS or CEA in asymptomatic patients. The leaders of CREST themselves have designed a new trial, CREST II, aimed at making this comparison, and have begun to vigorously lobby the National Institutes of Health to support this study.

In the meantime, vascular surgeons, endovascularists, cardiologists, and the other types of physicians who treat patients with carotid disease try as best they can to strike the right balance in how they apply the three management options.

CREST Provides New Guidance

One surgeon who has perhaps given the most thought to sorting out treatment options is Dr. Brajesh K. Lal, a co–principal investigator on CREST, a vascular surgeon at the University of Maryland in Baltimore, and a researcher who spent the past couple of years sorting through CREST’s voluminous data to find new clues to guide patient triage.

A major, recent guide for matching patients with a specific carotid intervention came from his painstaking analysis of carotid angiograms from 1,070 of the CREST patients who underwent CAS, of whom 43 patients (4%) then went on to have a stroke.

This effort identified the following four anatomical features that appear to mark patients with an increased rate of periprocedural stroke when they are treated with CAS:

- Stenotic lesion more than 20 mm long. The researchers measured lesion length as the distance from the proximal to distal shoulder of the lesion.

- Sequential lesions. This refers to two lesions separated by at least 10 mm of normal vessel.

- Severe distal tortuosity. This was defined as at least two arterial bends of at least 90 degrees that are distal to the lesion.

- Narrow-mouth ulcers. This refers to a small crater or lumen flap that produces a discrete area of contrast extension beyond the normal arterial lumen with a narrow inlet into the ulceration.

Patients with one or more of these carotid anatomical features "should be treated by endarterectomy," Dr. Lal said in an interview. "If I see any one of these in my clinical practice, I will not stent."

The variables assessed in this analysis did not include arterial calcification, as the angiographic imaging routinely collected in the study did not allow calcium quantification, said Dr. Lal. Among the stented patients in the study, the cumulative prevalence of the four significant risk markers was 39%. Patients with none of the four markers had a significantly reduced rate of periprocedural stroke during carotid stenting.

Endovascularists were already routinely assessing carotid anatomy before attempting CAS, but prior to Dr. Lal’s report on these new findings at the International Stroke Conference in New Orleans in February, "I’m not so sure that everyone has been using this [anatomical] information," he said. "When we talk about operator experience in stenting, if we don’t have the facts about what increases the stenting risk, then we won’t improve performance. You’d be surprised at what some interventionalists are willing to do," despite a patient’s challenging carotid anatomy. "These data show that you can work around a single 90-degree bend [of the distal carotid artery], but not around two bends. That is the kind of stuff we’re beginning to find out."

Dr. Lal and his associates plan to further analyze their data and derive a formula that physicians can apply to patients to estimate their periprocedural stroke risk.

Additional, recent CREST analyses that were also reported at the International Stroke Conference revealed other new, important lessons about CAS and CEA.

First, by 2 years after intervention, both CAS and CEA produced roughly comparable low rates of restenosis: a 6.0% rate in the CAS patients who underwent a prespecified, follow-up duplex ultrasound examination of their carotid artery, and 6.3% in the CEA patients (Stroke 2012;43: abstract A3). The rates were also similar regardless of whether patients were symptomatic before their carotid intervention, Dr. Lal reported.

This finding appears to lay to rest the concern about a major restenosis risk using bare-metal stents in carotid arteries, in contrast to what happens in coronary arteries, Dr. Lal said. "To my mind, these data are fairly definitive. We followed more than 2,000 patients, and every ultrasound was reviewed and adjudicated. I’m fairly comfortable with these results."

A third CREST analysis that was also reported in February showed that, after adjustment for baseline differences, patients had no significant changes in their rates of periprocedural events during and after CAS throughout the study, from 2000 to 2008 (Stroke 2012;43: abstract A1). "We hoped to show that CAS was getting better [during the 9 years of CREST], but we saw no evidence it got better with time," said George Howard, Dr.P.H., professor and chairman of the department of biostatistics at the University of Alabama at Birmingham. "It would make sense if CAS got better; it’s a new procedure that people learn." But the CREST results showed no evidence of a learning curve, perhaps because the 224 interventionalists who performed CAS in CREST went through a rigorous credentialing process and also performed their first several CAS procedures in CREST during a lead-in phase that was not included in the main outcomes.

Choosing Among the Options

Dr. Lal said that he draws several other lessons from the CREST results to guide his treatment decisions: Patients who are physiologically elderly, those with a large amount of calcified atheroma in their aortic arch, and patients with significant peripheral arterial disease that impedes endovascular access are all poor CAS candidates, he said, adding that he focuses on a patient’s physiological age rather than chronological age.

Patients who are well suited to CAS are those with a younger physiological age, those with a history of radiation treatment, and patients with restenotic carotid lesions.

Although CREST showed worse performance of CAS in women compared with men, "I don’t know why, so it’s hard for me to exclude or offer a particular treatment" based on the patient’s sex, he said. "I treat women just like men, and work through all the other things that I know about to help me decide."

Then there is a third subgroup, patients with carotid disease who he feels "benefit the most" from medical management only. This category primarily includes asymptomatic patients with moderate stenosis (that is, less than 80% carotid occlusion). His prescription for medical management includes 325 mg of aspirin daily, treatment with a statin, good blood pressure and blood sugar control, smoking cessation, and lifestyle modification. If, despite this, an asymptomatic patient has continued stenotic progression that advances beyond 80%, he will then recommend revascularization.

Dr. Lal said that in his practice today, roughly one-third of carotid-disease patients are on medical management, a third undergo CEA, and a third receive CAS. "We are at a stage of equipoise," for these three options, which is why he helped design and is working to get funding for CREST II.

Dr. Lal personally applies all three treatment options – CAS, CEA, or medical management. Having physicians involved in the decision-making process who are comfortable using each of these options is critical for making a balanced management decision, said Dr. L. Nelson Hopkins, another CREST collaborator and professor and chairman of neurosurgery at the State University of New York at Buffalo.

"The single most important thing we do is have a weekly, multidisciplinary conference to discuss each case, with input from everyone, to decide the best treatment for each [carotid disease] patient," he said when he spoke at ISET 2012, an International Symposium on Endovascular Therapy in Miami Beach in January.

"The most important factors" guiding the decision of whether or not to perform CAS are, does a symptomatic patient has "hot" lesions, what is the arterial tortuosity, and what is the calcification, he said. Other important features include whether the patient has a contralateral carotid occlusion, whether the carotid has a high bifurcation, and whether there are ostial or tandem lesions. "If the anatomy is favorable, CAS is fine even in a 95-year-old," Dr. Hopkins said.

What About Insurance Coverage?

Carotid specialists concede that another, nonmedical issue also plays a big role in deciding how to manage a patient: What will the patient’s health insurance cover?

In its most recent decision on the issue, effective in April 2010, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) said that Medicare covers CAS performed on a routine basis for patients with symptomatic carotid disease who are at high risk for CEA and have at least 70% carotid stenosis. CMS also said that Medicare will cover FDA-approved investigations of CAS in symptomatic patients who are at high risk for CEA and have at least 50% stenosis, as well as CAS investigations in asymptomatic patients at high risk for CEA with at least 80% carotid stenosis.

As a result, patients with other forms of carotid disease often do not have insurance coverage for CAS.

"The issue for us is primarily reimbursement. If we can do [a procedure] and be reimbursed, we often stent the patient," said Dr. Carlos H. Timaran, a vascular surgeon and chief of endovascular surgery at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas.

"For my private practice patients, we assess their risk based on their [anatomical] and medical criteria. If they are high risk, we usually stent. We have a bias toward stenting because it is faster and easier. Some people say they can do endarterectomy in an hour, but I don’t believe that. I do CEA with residents and fellows, and it takes 2 hours. But with stenting, I can do it in 40 minutes, even with a fellow. If I have three patients with carotid disease to treat [and] if I do CEA on all three, it will take all day. If I do CAS, it will take the morning, or less," he said in an interview.

In addition, "CEA is a nice procedure, but you need anesthesia. CAS is easier, I can do it myself, and I don’t need anesthesia. I am in more control of the case," Dr. Timaran said.

For patients who are eligible for both CAS and CEA, "it also comes down to anatomy," he grants. But if the patient has anatomy favorable to either method, "I offer patients both, and they will probably go for a stent," because patients usually prefer the quicker recovery that stenting offers, compared with CEA.

An interesting footnote to the issue of how to best manage patients who are eligible for CAS under CMS rules is that the CREST results offer no direct guidance on the relative safety and efficacy of CAS and CEA in patients with Medicare coverage. That’s because "the CREST cohort was a conventional-risk cohort; most criteria that would make someone a high surgical risk would have been excluded from CREST," Dr. Thomas G. Brott, professor of neurology at the Mayo Clinic in Jacksonville, Fla., and lead investigator for CREST. "The high-surgical-risk patients who are currently covered by Medicare would not have even been enrolled in CREST," Dr. Brott said in an interview.

Where Does Medical Therapy Fit In?

Although Dr. Timaran sees the potential value of medical therapy only for asymptomatic patients, he also urges caution.

"I don’t think [the efficacy of medical treatment] has been proven, and until it’s proven I don’t think physicians should deny revascularization treatment to these patients," he said. "The standard of care for a patient with severe carotid stenosis is revascularization, even if the patient is asymptomatic, unless there is some other consideration." But, he admitted, "there is little downside to medical treatment in asymptomatic patients, even if they have severe stenosis." That’s because their stroke risk is low regardless of which option a patient chooses.

"I tell asymptomatic patients that ‘based on the data, your risk of stroke is 2% per year, and that risk may be even lower with best medical therapy.’ With a carotid intervention, we can lower their risk to 1% per year." In other words, the patient’s stroke risk is low regardless of which option is chosen. Plus, medical therapy only is the best choice for patients with special risk factors, such as radiation-induced stenosis, Dr. Timaran added.

Other experts see medical treatment alone as an excellent option for many carotid-stenosis patients.

"The majority of patients I see don’t get an intervention; we use medical treatment only," said Dr. Jon S. Matsumura in an interview. "I think that’s true for most vascular surgery practices, and in cardiology and neurology practices. A lot of these patients just need reassurance," said Dr. Matsumura, professor and chairman of vascular surgery at the University of Wisconsin in Madison.

"Most asymptomatic patients [with carotid stenosis] should be treated by best medical therapy, with very few – fewer than 5% – treated by CAS or CEA," said Dr. Frank J. Veith at the International Symposium on Endovascular Therapy (ISET 12) in January. He acknowledged that well-controlled trials done during the 1990s showed that CEA led to superior outcomes compared with medical therapy, but since the early 2000s, "best medical therapy to prevent strokes leapt forward," he said, especially with improved statin therapy. He cited findings from a 2010 prospective study that showed asymptomatic Canadian patients managed starting in 2003 with best medical therapy had an annual stroke rate of 0.7% (Arch. Neurol. 2010;67:180-6).

He singled out four small groups of asymptomatic patients who warrant revascularization: patients with CT or MRI evidence for a history of silent strokes, patients with very-high-grade carotid stenosis that leaves just 1% of the carotid lumen open, those with a contralateral occlusion, and patients who serially experience transient occlusions detected by transcranial Doppler ultrasound examination, said Dr. Veith, professor of surgery at New York University. Aside from this small fraction of patients with asymptomatic disease, performing interventions on anyone else will "cause more strokes than you’ll prevent," he warned in an interview.

What Will CMS Do?

Dr. Veith’s take on limiting CAS in asymptomatic patients received substantial support early this year in the days leading up to the Jan. 25 meeting of the Medicare Evidence Development and Coverage Advisory Committee (MEDCAC) that heard evidence and opinions for and against widening of Medicare coverage for CAS. In early January, Dr. Veith joined with 40 other vascular surgeons and stroke specialists to urge CMS not to broaden CAS coverage (Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2012 Jan. 5 [doi:10.1016/j.ejvs.2011.12.006]). But, as MEDCAC heard during this meeting, experts differ on this issue.

"CMS continues to restrict access to CAS to about 10% of patients" with significant carotid stenosis, said Dr. William A. Gray, director of endovascular services at Columbia University in New York, speaking at ISET 2012 in January. "Expanded CAS coverage would allow greater patient access and device development, and therefore create a safer option for patients." Dr. Gray presented his positive views on CAS to MEDCAC in January as well.

At press time, CMS had not announced whether or not the January MEDCAC hearing will result in a change to its CAS coverage policy. But the votes cast by MEDCAC’s membership in January suggested that the issues surrounding management of carotid stenosis remain too unresolved to trigger immediate changes.

Dr. Lal, Dr. Timaran, and Dr. Veith said that they had no disclosures. Dr. Howard said that he has received grant support from Abbott. Dr. Hopkins said that he has financial relationships with Bard, Boston Scientific, Cordis, Abbott Vascular, Toshiba, W.L. Gore, Medtronic, Micrus, St. Jude, Access Closure, Osteal, Vascular Dynamics, Square One, Valor Medical, Claret Medical, and Augmenix. Dr. Brott said that he has been a consultant to Edwards Lifesciences. Dr. Matsumura said that he has received research grants from Abbott, Cook, Covidien, Endologix, and W.L. Gore. Dr. Gray said that he has had financial relationships with Boston Scientific, Coherex, Contego, Cordis, Fiatlux 3D, Nexeon, Quantumcor, Abbott Vascular, and Biocardia.

Epilepsy Incidence High Following Pediatric Stroke

NEW ORLEANS – Pediatric stroke survivors had an absolute risk of 39% for developing epilepsy in the 10 years following their stroke in a review of 371 patients in Northern California.

Two factors significantly boosted a child’s risk of developing epilepsy following a stroke: A seizure at the time of stroke, and a neurologic deficit at the time of hospital discharge following the index stroke, Dr. Christine Fox said at the International Stroke Conference (Stroke 2012;43:A41).

Although these findings have no immediate management implications, the information could help parents know what to expect when their child has a stroke.

Epilepsy "is not always one of the first outcomes we think about when we speak with parents," said Dr. Fox, a neurologist at the University of California, San Francisco. "If there is such a high incidence of epilepsy after stroke, maybe it’s something to talk about with parents," she said in an interview.

The study reviewed used data collected in the Kaiser Pediatric Stroke Study, run by Kaiser Permanente of Northern California, and included children who ranged from neonates to 19 years old and had a clinical presentation and brain imaging results consistent with a stroke. The group included hemorrhagic and ischemic strokes occurring during 1993-2003, and arterial ischemic strokes during 2003-2007. This cohort consisted of 371 children who survived a stroke to hospital discharge, including 110 neonates and 261 older children who had 226 ischemic strokes and 145 hemorrhagic strokes.

During a median follow-up of 4.5 years, 89 of these children developed epilepsy, defined as a confirmed, unprovoked seizure occurring more than 30 days following the index stroke. The researchers excluded 7 of the 89 incident epilepsy cases because they had a history of seizures prior to their stroke. Survivor analysis of the 82 new-onset cases showed an average annual incidence of 6%, with a cumulative 5-year incidence of 23% and a cumulative 10-year rate of 39%, Dr. Fox said.

A multivariate adjusted analysis that controlled for factors such as age, sex, race, and type of stroke identified two parameters linked with a significantly higher risk for developing epilepsy following stroke: a seizure concurrent with the stroke ictus, which boosted the risk of subsequent epilepsy 3.6-fold, and a neurologic deficit at discharge, which increased the risk for later epilepsy twofold.

In contrast to these findings, previous reports documented a much lower incidence of epilepsy in adults following a stroke, with a 3% rate after 1 year, and an 8% rate after 5 years, Dr. Fox said.

Dr. Fox said that she had no disclosures. The conference was sponsored by the American Heart Association.

NEW ORLEANS – Pediatric stroke survivors had an absolute risk of 39% for developing epilepsy in the 10 years following their stroke in a review of 371 patients in Northern California.

Two factors significantly boosted a child’s risk of developing epilepsy following a stroke: A seizure at the time of stroke, and a neurologic deficit at the time of hospital discharge following the index stroke, Dr. Christine Fox said at the International Stroke Conference (Stroke 2012;43:A41).

Although these findings have no immediate management implications, the information could help parents know what to expect when their child has a stroke.

Epilepsy "is not always one of the first outcomes we think about when we speak with parents," said Dr. Fox, a neurologist at the University of California, San Francisco. "If there is such a high incidence of epilepsy after stroke, maybe it’s something to talk about with parents," she said in an interview.

The study reviewed used data collected in the Kaiser Pediatric Stroke Study, run by Kaiser Permanente of Northern California, and included children who ranged from neonates to 19 years old and had a clinical presentation and brain imaging results consistent with a stroke. The group included hemorrhagic and ischemic strokes occurring during 1993-2003, and arterial ischemic strokes during 2003-2007. This cohort consisted of 371 children who survived a stroke to hospital discharge, including 110 neonates and 261 older children who had 226 ischemic strokes and 145 hemorrhagic strokes.

During a median follow-up of 4.5 years, 89 of these children developed epilepsy, defined as a confirmed, unprovoked seizure occurring more than 30 days following the index stroke. The researchers excluded 7 of the 89 incident epilepsy cases because they had a history of seizures prior to their stroke. Survivor analysis of the 82 new-onset cases showed an average annual incidence of 6%, with a cumulative 5-year incidence of 23% and a cumulative 10-year rate of 39%, Dr. Fox said.

A multivariate adjusted analysis that controlled for factors such as age, sex, race, and type of stroke identified two parameters linked with a significantly higher risk for developing epilepsy following stroke: a seizure concurrent with the stroke ictus, which boosted the risk of subsequent epilepsy 3.6-fold, and a neurologic deficit at discharge, which increased the risk for later epilepsy twofold.

In contrast to these findings, previous reports documented a much lower incidence of epilepsy in adults following a stroke, with a 3% rate after 1 year, and an 8% rate after 5 years, Dr. Fox said.

Dr. Fox said that she had no disclosures. The conference was sponsored by the American Heart Association.

NEW ORLEANS – Pediatric stroke survivors had an absolute risk of 39% for developing epilepsy in the 10 years following their stroke in a review of 371 patients in Northern California.

Two factors significantly boosted a child’s risk of developing epilepsy following a stroke: A seizure at the time of stroke, and a neurologic deficit at the time of hospital discharge following the index stroke, Dr. Christine Fox said at the International Stroke Conference (Stroke 2012;43:A41).

Although these findings have no immediate management implications, the information could help parents know what to expect when their child has a stroke.

Epilepsy "is not always one of the first outcomes we think about when we speak with parents," said Dr. Fox, a neurologist at the University of California, San Francisco. "If there is such a high incidence of epilepsy after stroke, maybe it’s something to talk about with parents," she said in an interview.

The study reviewed used data collected in the Kaiser Pediatric Stroke Study, run by Kaiser Permanente of Northern California, and included children who ranged from neonates to 19 years old and had a clinical presentation and brain imaging results consistent with a stroke. The group included hemorrhagic and ischemic strokes occurring during 1993-2003, and arterial ischemic strokes during 2003-2007. This cohort consisted of 371 children who survived a stroke to hospital discharge, including 110 neonates and 261 older children who had 226 ischemic strokes and 145 hemorrhagic strokes.

During a median follow-up of 4.5 years, 89 of these children developed epilepsy, defined as a confirmed, unprovoked seizure occurring more than 30 days following the index stroke. The researchers excluded 7 of the 89 incident epilepsy cases because they had a history of seizures prior to their stroke. Survivor analysis of the 82 new-onset cases showed an average annual incidence of 6%, with a cumulative 5-year incidence of 23% and a cumulative 10-year rate of 39%, Dr. Fox said.

A multivariate adjusted analysis that controlled for factors such as age, sex, race, and type of stroke identified two parameters linked with a significantly higher risk for developing epilepsy following stroke: a seizure concurrent with the stroke ictus, which boosted the risk of subsequent epilepsy 3.6-fold, and a neurologic deficit at discharge, which increased the risk for later epilepsy twofold.

In contrast to these findings, previous reports documented a much lower incidence of epilepsy in adults following a stroke, with a 3% rate after 1 year, and an 8% rate after 5 years, Dr. Fox said.

Dr. Fox said that she had no disclosures. The conference was sponsored by the American Heart Association.

FROM THE INTERNATIONAL STROKE CONFERENCE

Major Finding: During the 10 years following a stroke, the cumulative incidence of epilepsy in children aged 19 years and younger was 39%.

Data Source: The review included 371 pediatric strokes included in the Kaiser Pediatric Stroke Study.

Disclosures: Dr. Fox said that she had no disclosures.

Tenecteplase Edges TPA in Acute Stroke

NEW ORLEANS – The potential advantages of tenecteplase, a modified form of tissue plasminogen activator engineered to outperform the native molecule, finally shone through for treating patients with acute ischemic stroke.

A head-to-head comparison of tenecteplase against recombinant tissue plasminogen activator (TPA; alteplase) showed that the modified molecule produced better reperfusion and better clinical recovery 24 hours after treatment in a randomized trial of 75 Australian patients whose treatment was guided by CT brain imaging, Dr. Bill O’Brien reported at the International Stroke Conference.

Although Dr. O’Brien cautioned that this pilot study did not produce definitive results, the superiority of tenecteplase eclipsed its failure to surpass TPA in a randomized comparison of 112 patients reported in 2010.

The results "support using advanced imaging to identify the patients who are most likely to benefit" from tenecteplase, he said. The use of systematic CT brain imaging to select patients appeared to be the main factor that distinguished this study from the previous trial where tenecteplase failed to show an advantage, said Dr. O’Brien, a stroke physician at John Hunter Hospital in Newcastle, Australia.

Targeted patient selection may also explain why the tenecteplase treatment was so safe, resulting in a trend toward a reduced rate of type 2 parenchymal hemorrhages, compared with TPA, despite the superior thrombolytic activity shown by tenecteplase, he said.

Although the current trial had "compelling results," another study will follow to compare the two drugs by several 3-month outcomes, Dr. O’Brien said in an interview. The successful dosages of tenecteplase tested also have the advantage of being cheaper than the standard TPA dosage, he added.

Developed in the 1990s, tenecteplase resulted from three targeted amino acid substitutions in conventional TPA. This produced a molecule with increased fibrin specificity, and longer plasma half-life due to increased resistance to enzymatic degradation, which meant that it could be administered by an intravenous bolus instead of requiring continuous infusion like TPA. When used to treat myocardial infarctions, tenecteplase has also resulted in fewer bleeding complications than TPA.

The study enrolled 75 patients within 6 hours of onset of an ischemic stroke at any of three Australian hospitals, following selection by CT imaging to identify patients with a small infarct core and a large penumbra of salvageable brain. Researchers randomized patients to receive 0.1 mg/kg tenecteplase or 0.25 mg/kg tenecteplase by an intravenous bolus injection, or standard infusion with 0.9 mg/kg TPA. The patients averaged 70 years old, their average NIHSS (National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale) score at entry was about 14, and patients received treatment an average of about 3 hours after symptom onset.

The reperfusion rate after 24 hours was 78% among all 50 patients treated with tenecteplase, and 55% among the TPA treated patients, a statistically significant difference for one of the study’s two primary end points, Dr. O’Brien said. The second primary end point, change in NIHSS score after 24 hours, improved by an average of 8 points in all 50 tenecteplase patients, and by an average of 3 points in the TPA patients, also a significant difference.

The results appeared to show a dose-response relationship for tenecteplase, with the 25 patients who received the 0.25-mg/kg dosage having better reperfusion rates and reductions in their NIHSS scores than the 25 patients who received a 0.1-mg/kg dosage as well as the patients treated with TPA, but Dr. O’Brien did not report specific numbers from this analysis.

Of the 50 tenecteplase patients, 2 (4%) developed a type 2 parenchymal hemorrhage within 24 hours, compared with 4 (16%) of the 25 TPA-treated patients, a difference that trended toward significance. The rates of symptomatic intracerebral hemorrhages and death at 24 hours were similar with both drugs. But at 90 days after treatment, the combined rate of death or severe disability was 10% in the 50 tenecteplase patients and 25% in the TPA patients, a difference that also trended toward significance.

These findings contrast with a 2010 report from a randomized trial that compared three different tenecteplase dosages with TPA in a multicenter U.S. study of 112 patients (Stroke 2010;41:707-11). The results showed no significant differences between any of the tenecteplase dosages and TPA for any of the outcomes measured out to 90 days after treatment.

The major difference between the U.S. study and the new Australian study was in patient selection, Dr. O’Brien said. "We used imaging to balance the groups," and to select patients who stood to benefit most from effective reperfusion, he said.

Dr. O’Brien said that he and his associates had no disclosures.

NEW ORLEANS – The potential advantages of tenecteplase, a modified form of tissue plasminogen activator engineered to outperform the native molecule, finally shone through for treating patients with acute ischemic stroke.

A head-to-head comparison of tenecteplase against recombinant tissue plasminogen activator (TPA; alteplase) showed that the modified molecule produced better reperfusion and better clinical recovery 24 hours after treatment in a randomized trial of 75 Australian patients whose treatment was guided by CT brain imaging, Dr. Bill O’Brien reported at the International Stroke Conference.

Although Dr. O’Brien cautioned that this pilot study did not produce definitive results, the superiority of tenecteplase eclipsed its failure to surpass TPA in a randomized comparison of 112 patients reported in 2010.

The results "support using advanced imaging to identify the patients who are most likely to benefit" from tenecteplase, he said. The use of systematic CT brain imaging to select patients appeared to be the main factor that distinguished this study from the previous trial where tenecteplase failed to show an advantage, said Dr. O’Brien, a stroke physician at John Hunter Hospital in Newcastle, Australia.

Targeted patient selection may also explain why the tenecteplase treatment was so safe, resulting in a trend toward a reduced rate of type 2 parenchymal hemorrhages, compared with TPA, despite the superior thrombolytic activity shown by tenecteplase, he said.

Although the current trial had "compelling results," another study will follow to compare the two drugs by several 3-month outcomes, Dr. O’Brien said in an interview. The successful dosages of tenecteplase tested also have the advantage of being cheaper than the standard TPA dosage, he added.

Developed in the 1990s, tenecteplase resulted from three targeted amino acid substitutions in conventional TPA. This produced a molecule with increased fibrin specificity, and longer plasma half-life due to increased resistance to enzymatic degradation, which meant that it could be administered by an intravenous bolus instead of requiring continuous infusion like TPA. When used to treat myocardial infarctions, tenecteplase has also resulted in fewer bleeding complications than TPA.

The study enrolled 75 patients within 6 hours of onset of an ischemic stroke at any of three Australian hospitals, following selection by CT imaging to identify patients with a small infarct core and a large penumbra of salvageable brain. Researchers randomized patients to receive 0.1 mg/kg tenecteplase or 0.25 mg/kg tenecteplase by an intravenous bolus injection, or standard infusion with 0.9 mg/kg TPA. The patients averaged 70 years old, their average NIHSS (National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale) score at entry was about 14, and patients received treatment an average of about 3 hours after symptom onset.

The reperfusion rate after 24 hours was 78% among all 50 patients treated with tenecteplase, and 55% among the TPA treated patients, a statistically significant difference for one of the study’s two primary end points, Dr. O’Brien said. The second primary end point, change in NIHSS score after 24 hours, improved by an average of 8 points in all 50 tenecteplase patients, and by an average of 3 points in the TPA patients, also a significant difference.

The results appeared to show a dose-response relationship for tenecteplase, with the 25 patients who received the 0.25-mg/kg dosage having better reperfusion rates and reductions in their NIHSS scores than the 25 patients who received a 0.1-mg/kg dosage as well as the patients treated with TPA, but Dr. O’Brien did not report specific numbers from this analysis.

Of the 50 tenecteplase patients, 2 (4%) developed a type 2 parenchymal hemorrhage within 24 hours, compared with 4 (16%) of the 25 TPA-treated patients, a difference that trended toward significance. The rates of symptomatic intracerebral hemorrhages and death at 24 hours were similar with both drugs. But at 90 days after treatment, the combined rate of death or severe disability was 10% in the 50 tenecteplase patients and 25% in the TPA patients, a difference that also trended toward significance.

These findings contrast with a 2010 report from a randomized trial that compared three different tenecteplase dosages with TPA in a multicenter U.S. study of 112 patients (Stroke 2010;41:707-11). The results showed no significant differences between any of the tenecteplase dosages and TPA for any of the outcomes measured out to 90 days after treatment.

The major difference between the U.S. study and the new Australian study was in patient selection, Dr. O’Brien said. "We used imaging to balance the groups," and to select patients who stood to benefit most from effective reperfusion, he said.

Dr. O’Brien said that he and his associates had no disclosures.

NEW ORLEANS – The potential advantages of tenecteplase, a modified form of tissue plasminogen activator engineered to outperform the native molecule, finally shone through for treating patients with acute ischemic stroke.

A head-to-head comparison of tenecteplase against recombinant tissue plasminogen activator (TPA; alteplase) showed that the modified molecule produced better reperfusion and better clinical recovery 24 hours after treatment in a randomized trial of 75 Australian patients whose treatment was guided by CT brain imaging, Dr. Bill O’Brien reported at the International Stroke Conference.

Although Dr. O’Brien cautioned that this pilot study did not produce definitive results, the superiority of tenecteplase eclipsed its failure to surpass TPA in a randomized comparison of 112 patients reported in 2010.

The results "support using advanced imaging to identify the patients who are most likely to benefit" from tenecteplase, he said. The use of systematic CT brain imaging to select patients appeared to be the main factor that distinguished this study from the previous trial where tenecteplase failed to show an advantage, said Dr. O’Brien, a stroke physician at John Hunter Hospital in Newcastle, Australia.

Targeted patient selection may also explain why the tenecteplase treatment was so safe, resulting in a trend toward a reduced rate of type 2 parenchymal hemorrhages, compared with TPA, despite the superior thrombolytic activity shown by tenecteplase, he said.

Although the current trial had "compelling results," another study will follow to compare the two drugs by several 3-month outcomes, Dr. O’Brien said in an interview. The successful dosages of tenecteplase tested also have the advantage of being cheaper than the standard TPA dosage, he added.

Developed in the 1990s, tenecteplase resulted from three targeted amino acid substitutions in conventional TPA. This produced a molecule with increased fibrin specificity, and longer plasma half-life due to increased resistance to enzymatic degradation, which meant that it could be administered by an intravenous bolus instead of requiring continuous infusion like TPA. When used to treat myocardial infarctions, tenecteplase has also resulted in fewer bleeding complications than TPA.

The study enrolled 75 patients within 6 hours of onset of an ischemic stroke at any of three Australian hospitals, following selection by CT imaging to identify patients with a small infarct core and a large penumbra of salvageable brain. Researchers randomized patients to receive 0.1 mg/kg tenecteplase or 0.25 mg/kg tenecteplase by an intravenous bolus injection, or standard infusion with 0.9 mg/kg TPA. The patients averaged 70 years old, their average NIHSS (National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale) score at entry was about 14, and patients received treatment an average of about 3 hours after symptom onset.

The reperfusion rate after 24 hours was 78% among all 50 patients treated with tenecteplase, and 55% among the TPA treated patients, a statistically significant difference for one of the study’s two primary end points, Dr. O’Brien said. The second primary end point, change in NIHSS score after 24 hours, improved by an average of 8 points in all 50 tenecteplase patients, and by an average of 3 points in the TPA patients, also a significant difference.

The results appeared to show a dose-response relationship for tenecteplase, with the 25 patients who received the 0.25-mg/kg dosage having better reperfusion rates and reductions in their NIHSS scores than the 25 patients who received a 0.1-mg/kg dosage as well as the patients treated with TPA, but Dr. O’Brien did not report specific numbers from this analysis.

Of the 50 tenecteplase patients, 2 (4%) developed a type 2 parenchymal hemorrhage within 24 hours, compared with 4 (16%) of the 25 TPA-treated patients, a difference that trended toward significance. The rates of symptomatic intracerebral hemorrhages and death at 24 hours were similar with both drugs. But at 90 days after treatment, the combined rate of death or severe disability was 10% in the 50 tenecteplase patients and 25% in the TPA patients, a difference that also trended toward significance.

These findings contrast with a 2010 report from a randomized trial that compared three different tenecteplase dosages with TPA in a multicenter U.S. study of 112 patients (Stroke 2010;41:707-11). The results showed no significant differences between any of the tenecteplase dosages and TPA for any of the outcomes measured out to 90 days after treatment.

The major difference between the U.S. study and the new Australian study was in patient selection, Dr. O’Brien said. "We used imaging to balance the groups," and to select patients who stood to benefit most from effective reperfusion, he said.

Dr. O’Brien said that he and his associates had no disclosures.

FROM THE INTERNATIONAL STROKE CONFERENCE

Desensitization Succeeds for Aspirin-Allergic Heart Patients