User login

Mitchel is a reporter for MDedge based in the Philadelphia area. He started with the company in 1992, when it was International Medical News Group (IMNG), and has since covered a range of medical specialties. Mitchel trained as a virologist at Roswell Park Memorial Institute in Buffalo, and then worked briefly as a researcher at Boston Children's Hospital before pivoting to journalism as a AAAS Mass Media Fellow in 1980. His first reporting job was with Science Digest magazine, and from the mid-1980s to early-1990s he was a reporter with Medical World News. @mitchelzoler

After 2006 Recommendation, More Autism Diagnoses Made at Earlier Age

BALTIMORE – The American Academy of Pediatrics’ 2006 recommendation to screen all children for autism spectrum disorder at age 18 months appears to have resulted in a substantially earlier age of diagnosis among children seen in at least one U.S. center.

Among children diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and referred to the Children’s Evaluation and Rehabilitation Center of Montefiore Medical Center in the Bronx, N.Y., the average age of initial ASD diagnosis fell from 45 months among 295 diagnosed children born in 2003 or 2004 to 31 months among 217 diagnosed children born during or after 2005, Dr. Maria D. Valicenti-McDermott said at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies.

Expressed another way, the percentage of children first diagnosed with ASD at age 4 years or older fell from 67% of children born during 2003 and 2004 to 26% of those born during or after 2005, said Dr. Valicenti-McDermott, a developmental pediatrician at Montefiore.

Although the review did not examine the outcomes of those children, she said that earlier age at diagnosis has been proven in previously reported studies to make a “big difference” for prognosis.

“The earlier you start treatment, the better the outcomes,” Dr. Valicenti-McDermott said in an interview. “More and more literature shows that the age of diagnosis of ASD is very important.”

Interventions that seem to make a difference when begun earlier include applied behavioral analysis and intensive speech and language therapy. A recent study by Dr. Valicenti-McDermott and her associates at Montefiore documented that those early interventions reversed the ASD diagnosis in at least some children, although she noted that many of these children continue to have problems, such as academic difficulties. She also acknowledged that some of this “reversal” may result from “instability” of the ASD diagnosis when made at a relatively early age.

The findings she reported came from a review of all children diagnosed with ASD and seen at Montefiore during 2003-2012. The analysis also showed that the earlier age of diagnosis after 2006 occurred across racial and ethnic groups, with similar reductions seen among Hispanic, African American, and white children.

In a multivariate analysis, the odds ratio for a first diagnosis of ASD at age 4 years or older was fourfold greater among children born during 2003 or 2004, compared with those born during 2005 or after.

Dr. Valicenti-McDermott conceded it was impossible to fully credit the 2006 screening recommendation from the American Academy of Pediatrics for that shift, based on her observational study. Another possible factor was increased awareness among parents about ASD over the time frame studied. In addition, community physicians also may have helped drive earlier diagnosis.

BALTIMORE – The American Academy of Pediatrics’ 2006 recommendation to screen all children for autism spectrum disorder at age 18 months appears to have resulted in a substantially earlier age of diagnosis among children seen in at least one U.S. center.

Among children diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and referred to the Children’s Evaluation and Rehabilitation Center of Montefiore Medical Center in the Bronx, N.Y., the average age of initial ASD diagnosis fell from 45 months among 295 diagnosed children born in 2003 or 2004 to 31 months among 217 diagnosed children born during or after 2005, Dr. Maria D. Valicenti-McDermott said at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies.

Expressed another way, the percentage of children first diagnosed with ASD at age 4 years or older fell from 67% of children born during 2003 and 2004 to 26% of those born during or after 2005, said Dr. Valicenti-McDermott, a developmental pediatrician at Montefiore.

Although the review did not examine the outcomes of those children, she said that earlier age at diagnosis has been proven in previously reported studies to make a “big difference” for prognosis.

“The earlier you start treatment, the better the outcomes,” Dr. Valicenti-McDermott said in an interview. “More and more literature shows that the age of diagnosis of ASD is very important.”

Interventions that seem to make a difference when begun earlier include applied behavioral analysis and intensive speech and language therapy. A recent study by Dr. Valicenti-McDermott and her associates at Montefiore documented that those early interventions reversed the ASD diagnosis in at least some children, although she noted that many of these children continue to have problems, such as academic difficulties. She also acknowledged that some of this “reversal” may result from “instability” of the ASD diagnosis when made at a relatively early age.

The findings she reported came from a review of all children diagnosed with ASD and seen at Montefiore during 2003-2012. The analysis also showed that the earlier age of diagnosis after 2006 occurred across racial and ethnic groups, with similar reductions seen among Hispanic, African American, and white children.

In a multivariate analysis, the odds ratio for a first diagnosis of ASD at age 4 years or older was fourfold greater among children born during 2003 or 2004, compared with those born during 2005 or after.

Dr. Valicenti-McDermott conceded it was impossible to fully credit the 2006 screening recommendation from the American Academy of Pediatrics for that shift, based on her observational study. Another possible factor was increased awareness among parents about ASD over the time frame studied. In addition, community physicians also may have helped drive earlier diagnosis.

BALTIMORE – The American Academy of Pediatrics’ 2006 recommendation to screen all children for autism spectrum disorder at age 18 months appears to have resulted in a substantially earlier age of diagnosis among children seen in at least one U.S. center.

Among children diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and referred to the Children’s Evaluation and Rehabilitation Center of Montefiore Medical Center in the Bronx, N.Y., the average age of initial ASD diagnosis fell from 45 months among 295 diagnosed children born in 2003 or 2004 to 31 months among 217 diagnosed children born during or after 2005, Dr. Maria D. Valicenti-McDermott said at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies.

Expressed another way, the percentage of children first diagnosed with ASD at age 4 years or older fell from 67% of children born during 2003 and 2004 to 26% of those born during or after 2005, said Dr. Valicenti-McDermott, a developmental pediatrician at Montefiore.

Although the review did not examine the outcomes of those children, she said that earlier age at diagnosis has been proven in previously reported studies to make a “big difference” for prognosis.

“The earlier you start treatment, the better the outcomes,” Dr. Valicenti-McDermott said in an interview. “More and more literature shows that the age of diagnosis of ASD is very important.”

Interventions that seem to make a difference when begun earlier include applied behavioral analysis and intensive speech and language therapy. A recent study by Dr. Valicenti-McDermott and her associates at Montefiore documented that those early interventions reversed the ASD diagnosis in at least some children, although she noted that many of these children continue to have problems, such as academic difficulties. She also acknowledged that some of this “reversal” may result from “instability” of the ASD diagnosis when made at a relatively early age.

The findings she reported came from a review of all children diagnosed with ASD and seen at Montefiore during 2003-2012. The analysis also showed that the earlier age of diagnosis after 2006 occurred across racial and ethnic groups, with similar reductions seen among Hispanic, African American, and white children.

In a multivariate analysis, the odds ratio for a first diagnosis of ASD at age 4 years or older was fourfold greater among children born during 2003 or 2004, compared with those born during 2005 or after.

Dr. Valicenti-McDermott conceded it was impossible to fully credit the 2006 screening recommendation from the American Academy of Pediatrics for that shift, based on her observational study. Another possible factor was increased awareness among parents about ASD over the time frame studied. In addition, community physicians also may have helped drive earlier diagnosis.

AT THE PAS ANNUAL MEETING

After 2006 recommendation, more autism diagnoses made at earlier age

BALTIMORE – The American Academy of Pediatrics’ 2006 recommendation to screen all children for autism spectrum disorder at age 18 months appears to have resulted in a substantially earlier age of diagnosis among children seen in at least one U.S. center.

Among children diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and referred to the Children’s Evaluation and Rehabilitation Center of Montefiore Medical Center in the Bronx, N.Y., the average age of initial ASD diagnosis fell from 45 months among 295 diagnosed children born in 2003 or 2004 to 31 months among 217 diagnosed children born during or after 2005, Dr. Maria D. Valicenti-McDermott said at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies.

Expressed another way, the percentage of children first diagnosed with ASD at age 4 years or older fell from 67% of children born during 2003 and 2004 to 26% of those born during or after 2005, said Dr. Valicenti-McDermott, a developmental pediatrician at Montefiore.

Although the review did not examine the outcomes of those children, she said that earlier age at diagnosis has been proven in previously reported studies to make a “big difference” for prognosis.

“The earlier you start treatment, the better the outcomes,” Dr. Valicenti-McDermott said in an interview. “More and more literature shows that the age of diagnosis of ASD is very important.”

Interventions that seem to make a difference when begun earlier include applied behavioral analysis and intensive speech and language therapy. A recent study by Dr. Valicenti-McDermott and her associates at Montefiore documented that those early interventions reversed the ASD diagnosis in at least some children, although she noted that many of these children continue to have problems, such as academic difficulties. She also acknowledged that some of this “reversal” may result from “instability” of the ASD diagnosis when made at a relatively early age.

The findings she reported came from a review of all children diagnosed with ASD and seen at Montefiore during 2003-2012. The analysis also showed that the earlier age of diagnosis after 2006 occurred across racial and ethnic groups, with similar reductions seen among Hispanic, African American, and white children.

In a multivariate analysis, the odds ratio for a first diagnosis of ASD at age 4 years or older was fourfold greater among children born during 2003 or 2004, compared with those born during 2005 or after.

Dr. Valicenti-McDermott conceded it was impossible to fully credit the 2006 screening recommendation from the American Academy of Pediatrics for that shift, based on her observational study. Another possible factor was increased awareness among parents about ASD over the time frame studied. In addition, community physicians also may have helped drive earlier diagnosis.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

BALTIMORE – The American Academy of Pediatrics’ 2006 recommendation to screen all children for autism spectrum disorder at age 18 months appears to have resulted in a substantially earlier age of diagnosis among children seen in at least one U.S. center.

Among children diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and referred to the Children’s Evaluation and Rehabilitation Center of Montefiore Medical Center in the Bronx, N.Y., the average age of initial ASD diagnosis fell from 45 months among 295 diagnosed children born in 2003 or 2004 to 31 months among 217 diagnosed children born during or after 2005, Dr. Maria D. Valicenti-McDermott said at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies.

Expressed another way, the percentage of children first diagnosed with ASD at age 4 years or older fell from 67% of children born during 2003 and 2004 to 26% of those born during or after 2005, said Dr. Valicenti-McDermott, a developmental pediatrician at Montefiore.

Although the review did not examine the outcomes of those children, she said that earlier age at diagnosis has been proven in previously reported studies to make a “big difference” for prognosis.

“The earlier you start treatment, the better the outcomes,” Dr. Valicenti-McDermott said in an interview. “More and more literature shows that the age of diagnosis of ASD is very important.”

Interventions that seem to make a difference when begun earlier include applied behavioral analysis and intensive speech and language therapy. A recent study by Dr. Valicenti-McDermott and her associates at Montefiore documented that those early interventions reversed the ASD diagnosis in at least some children, although she noted that many of these children continue to have problems, such as academic difficulties. She also acknowledged that some of this “reversal” may result from “instability” of the ASD diagnosis when made at a relatively early age.

The findings she reported came from a review of all children diagnosed with ASD and seen at Montefiore during 2003-2012. The analysis also showed that the earlier age of diagnosis after 2006 occurred across racial and ethnic groups, with similar reductions seen among Hispanic, African American, and white children.

In a multivariate analysis, the odds ratio for a first diagnosis of ASD at age 4 years or older was fourfold greater among children born during 2003 or 2004, compared with those born during 2005 or after.

Dr. Valicenti-McDermott conceded it was impossible to fully credit the 2006 screening recommendation from the American Academy of Pediatrics for that shift, based on her observational study. Another possible factor was increased awareness among parents about ASD over the time frame studied. In addition, community physicians also may have helped drive earlier diagnosis.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

BALTIMORE – The American Academy of Pediatrics’ 2006 recommendation to screen all children for autism spectrum disorder at age 18 months appears to have resulted in a substantially earlier age of diagnosis among children seen in at least one U.S. center.

Among children diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and referred to the Children’s Evaluation and Rehabilitation Center of Montefiore Medical Center in the Bronx, N.Y., the average age of initial ASD diagnosis fell from 45 months among 295 diagnosed children born in 2003 or 2004 to 31 months among 217 diagnosed children born during or after 2005, Dr. Maria D. Valicenti-McDermott said at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies.

Expressed another way, the percentage of children first diagnosed with ASD at age 4 years or older fell from 67% of children born during 2003 and 2004 to 26% of those born during or after 2005, said Dr. Valicenti-McDermott, a developmental pediatrician at Montefiore.

Although the review did not examine the outcomes of those children, she said that earlier age at diagnosis has been proven in previously reported studies to make a “big difference” for prognosis.

“The earlier you start treatment, the better the outcomes,” Dr. Valicenti-McDermott said in an interview. “More and more literature shows that the age of diagnosis of ASD is very important.”

Interventions that seem to make a difference when begun earlier include applied behavioral analysis and intensive speech and language therapy. A recent study by Dr. Valicenti-McDermott and her associates at Montefiore documented that those early interventions reversed the ASD diagnosis in at least some children, although she noted that many of these children continue to have problems, such as academic difficulties. She also acknowledged that some of this “reversal” may result from “instability” of the ASD diagnosis when made at a relatively early age.

The findings she reported came from a review of all children diagnosed with ASD and seen at Montefiore during 2003-2012. The analysis also showed that the earlier age of diagnosis after 2006 occurred across racial and ethnic groups, with similar reductions seen among Hispanic, African American, and white children.

In a multivariate analysis, the odds ratio for a first diagnosis of ASD at age 4 years or older was fourfold greater among children born during 2003 or 2004, compared with those born during 2005 or after.

Dr. Valicenti-McDermott conceded it was impossible to fully credit the 2006 screening recommendation from the American Academy of Pediatrics for that shift, based on her observational study. Another possible factor was increased awareness among parents about ASD over the time frame studied. In addition, community physicians also may have helped drive earlier diagnosis.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

AT THE PAS ANNUAL MEETING

Key clinical point: Diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder occurred significantly earlier for children born in 2005 or later, compared with children born in prior years, suggesting an impact from the 2006 U.S. recommendation for universal screening at age 18 months.

Major finding: Age at autism diagnosis fell from 45 months in children born in 2003 or 2004 to 31 months in those born later.

Data source: Review of 512 children diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder at one U.S. center during 2003-2012.

Disclosures: Dr. Valicenti-McDermott had no disclosures.

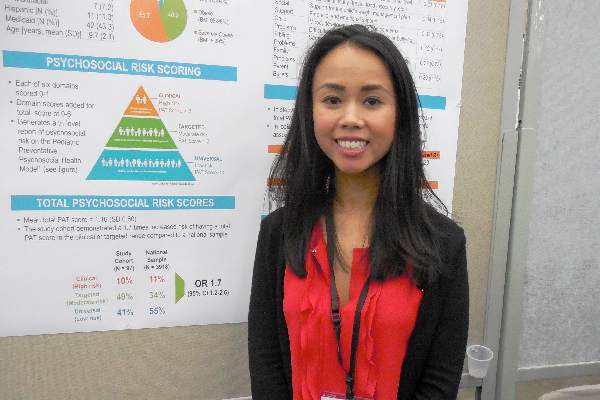

Family’s Psychosocial Problems Complicate Pediatric Obesity

BALTIMORE – Childhood obesity can result from more than just poor diet, not enough exercise, and too much screen time; it also often occurs in families with parents who have a significantly increased prevalence of psychosocial problems, judging from findings from a pilot, single-center study involving 97 parents who brought their child to a tertiary-care pediatric obesity center.

This preliminary finding “supports the need for universal psychosocial screening in this population, with particular attention to families whose children have comorbid behavioral health problems,” Dr. Thao-Ly T. Phan said while presenting a poster at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies.

“You might think that when a child is brought to an obesity clinic, you just need to ask what foods the child eats, how often the child exercises and how much television they watch, but we also need to ask about problems in the families and address those problems,” said Dr. Phan, a pediatrician and weight management specialist at the Alfred I. duPont Hospital for Children in Wilmington, Del.

Dr. Phan said although a key next step in this research is to assess how interventions aimed at family psychosocial problems affect a child’s obesity and well-being, her experience so far suggests that the psychosocial setting where a child lives can play a significant role in the etiology and maintenance of obesity.

“We find that families at higher psychosocial risk don’t come back for treatment, and when that happens the children don’t do well. That’s a reason to screen [for such problems] and intervene with psychological and social work support,” she said in an interview.

“A lot of our messages to families focus on things like screen time and eating more fruits and vegetables, but if the family can’t implement that, then we’re missing the boat,” Dr. Phan said.

She and her associates used the Psychosocial Assessment Tool (PAT), a screening tool for parents that takes about 5-10 minutes to complete and that was developed by researchers at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (ACTA Oncologica. 2015 May;54[5]:574-80). The PAT poses a series of questions that deal with a spectrum of potential psychosocial issues including financial status, a child’s problems at school, parents’ mood and substance abuse, and parental views of weight and health issues.

The investigators administered the PAT to 97 parents of children aged 4-12 years old who had their first visit to the tertiary-care pediatric obesity clinic at Alfred I. duPont. The children had body mass index levels that averaged close to the 99th percentile, with 56% of the children classified as severely obese with a BMI at or above the 99th percentile, 40% classified as obese with a BMI in the 95th-98th percentile, and 4% classified as overweight with a BMI at the 85th-94th percentile.

The PAT scores in these 97 parents identified 41% with a low risk for having psychosocial problems, 49% with a moderate risk, and 10% with a higher risk. In contrast, a historical control group of 3,918 representative U.S. parents who took the PAT showed 55% at low risk, 34% at moderate risk, and 11% at high risk, which meant that the parents of the children at the clinic had a statistically significant 70% increased prevalence of being in a high- or moderate-risk group for psychosocial problems, compared with parents in the general U.S. population, Dr. Phan reported.

A stepwise linear regression analysis of the PAT results identified two factors that significantly linked with higher PAT scores in these parents: attention- deficit/hyperactivity disorder in the child, and mood disorder in a parent. Logistic regression analysis further narrowed this down to just the child’s attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder as the only significant correlate with higher PAT scores. The analysis showed that the severity of obesity had no significant correlation with psychosocial risk scores.

The next steps are to assess more parents of obese children this way, see whether the questions posed in the PAT can be better focused for this setting to make the screening simpler and easier to administer, and determine how interventions aimed at the identified risks improve child outcomes, Dr. Phan said.

Another goal of this research is to raise the profile of family psychosocial problems as an important factor in the development and maintenance of obesity in children, she said. “I think that people who work at pediatric weight management clinics have recognized the role of family psychosocial problems, but it is less recognized by the general pediatric community.”

Dr. Phan had no relevant financial disclosures.

BALTIMORE – Childhood obesity can result from more than just poor diet, not enough exercise, and too much screen time; it also often occurs in families with parents who have a significantly increased prevalence of psychosocial problems, judging from findings from a pilot, single-center study involving 97 parents who brought their child to a tertiary-care pediatric obesity center.

This preliminary finding “supports the need for universal psychosocial screening in this population, with particular attention to families whose children have comorbid behavioral health problems,” Dr. Thao-Ly T. Phan said while presenting a poster at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies.

“You might think that when a child is brought to an obesity clinic, you just need to ask what foods the child eats, how often the child exercises and how much television they watch, but we also need to ask about problems in the families and address those problems,” said Dr. Phan, a pediatrician and weight management specialist at the Alfred I. duPont Hospital for Children in Wilmington, Del.

Dr. Phan said although a key next step in this research is to assess how interventions aimed at family psychosocial problems affect a child’s obesity and well-being, her experience so far suggests that the psychosocial setting where a child lives can play a significant role in the etiology and maintenance of obesity.

“We find that families at higher psychosocial risk don’t come back for treatment, and when that happens the children don’t do well. That’s a reason to screen [for such problems] and intervene with psychological and social work support,” she said in an interview.

“A lot of our messages to families focus on things like screen time and eating more fruits and vegetables, but if the family can’t implement that, then we’re missing the boat,” Dr. Phan said.

She and her associates used the Psychosocial Assessment Tool (PAT), a screening tool for parents that takes about 5-10 minutes to complete and that was developed by researchers at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (ACTA Oncologica. 2015 May;54[5]:574-80). The PAT poses a series of questions that deal with a spectrum of potential psychosocial issues including financial status, a child’s problems at school, parents’ mood and substance abuse, and parental views of weight and health issues.

The investigators administered the PAT to 97 parents of children aged 4-12 years old who had their first visit to the tertiary-care pediatric obesity clinic at Alfred I. duPont. The children had body mass index levels that averaged close to the 99th percentile, with 56% of the children classified as severely obese with a BMI at or above the 99th percentile, 40% classified as obese with a BMI in the 95th-98th percentile, and 4% classified as overweight with a BMI at the 85th-94th percentile.

The PAT scores in these 97 parents identified 41% with a low risk for having psychosocial problems, 49% with a moderate risk, and 10% with a higher risk. In contrast, a historical control group of 3,918 representative U.S. parents who took the PAT showed 55% at low risk, 34% at moderate risk, and 11% at high risk, which meant that the parents of the children at the clinic had a statistically significant 70% increased prevalence of being in a high- or moderate-risk group for psychosocial problems, compared with parents in the general U.S. population, Dr. Phan reported.

A stepwise linear regression analysis of the PAT results identified two factors that significantly linked with higher PAT scores in these parents: attention- deficit/hyperactivity disorder in the child, and mood disorder in a parent. Logistic regression analysis further narrowed this down to just the child’s attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder as the only significant correlate with higher PAT scores. The analysis showed that the severity of obesity had no significant correlation with psychosocial risk scores.

The next steps are to assess more parents of obese children this way, see whether the questions posed in the PAT can be better focused for this setting to make the screening simpler and easier to administer, and determine how interventions aimed at the identified risks improve child outcomes, Dr. Phan said.

Another goal of this research is to raise the profile of family psychosocial problems as an important factor in the development and maintenance of obesity in children, she said. “I think that people who work at pediatric weight management clinics have recognized the role of family psychosocial problems, but it is less recognized by the general pediatric community.”

Dr. Phan had no relevant financial disclosures.

BALTIMORE – Childhood obesity can result from more than just poor diet, not enough exercise, and too much screen time; it also often occurs in families with parents who have a significantly increased prevalence of psychosocial problems, judging from findings from a pilot, single-center study involving 97 parents who brought their child to a tertiary-care pediatric obesity center.

This preliminary finding “supports the need for universal psychosocial screening in this population, with particular attention to families whose children have comorbid behavioral health problems,” Dr. Thao-Ly T. Phan said while presenting a poster at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies.

“You might think that when a child is brought to an obesity clinic, you just need to ask what foods the child eats, how often the child exercises and how much television they watch, but we also need to ask about problems in the families and address those problems,” said Dr. Phan, a pediatrician and weight management specialist at the Alfred I. duPont Hospital for Children in Wilmington, Del.

Dr. Phan said although a key next step in this research is to assess how interventions aimed at family psychosocial problems affect a child’s obesity and well-being, her experience so far suggests that the psychosocial setting where a child lives can play a significant role in the etiology and maintenance of obesity.

“We find that families at higher psychosocial risk don’t come back for treatment, and when that happens the children don’t do well. That’s a reason to screen [for such problems] and intervene with psychological and social work support,” she said in an interview.

“A lot of our messages to families focus on things like screen time and eating more fruits and vegetables, but if the family can’t implement that, then we’re missing the boat,” Dr. Phan said.

She and her associates used the Psychosocial Assessment Tool (PAT), a screening tool for parents that takes about 5-10 minutes to complete and that was developed by researchers at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (ACTA Oncologica. 2015 May;54[5]:574-80). The PAT poses a series of questions that deal with a spectrum of potential psychosocial issues including financial status, a child’s problems at school, parents’ mood and substance abuse, and parental views of weight and health issues.

The investigators administered the PAT to 97 parents of children aged 4-12 years old who had their first visit to the tertiary-care pediatric obesity clinic at Alfred I. duPont. The children had body mass index levels that averaged close to the 99th percentile, with 56% of the children classified as severely obese with a BMI at or above the 99th percentile, 40% classified as obese with a BMI in the 95th-98th percentile, and 4% classified as overweight with a BMI at the 85th-94th percentile.

The PAT scores in these 97 parents identified 41% with a low risk for having psychosocial problems, 49% with a moderate risk, and 10% with a higher risk. In contrast, a historical control group of 3,918 representative U.S. parents who took the PAT showed 55% at low risk, 34% at moderate risk, and 11% at high risk, which meant that the parents of the children at the clinic had a statistically significant 70% increased prevalence of being in a high- or moderate-risk group for psychosocial problems, compared with parents in the general U.S. population, Dr. Phan reported.

A stepwise linear regression analysis of the PAT results identified two factors that significantly linked with higher PAT scores in these parents: attention- deficit/hyperactivity disorder in the child, and mood disorder in a parent. Logistic regression analysis further narrowed this down to just the child’s attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder as the only significant correlate with higher PAT scores. The analysis showed that the severity of obesity had no significant correlation with psychosocial risk scores.

The next steps are to assess more parents of obese children this way, see whether the questions posed in the PAT can be better focused for this setting to make the screening simpler and easier to administer, and determine how interventions aimed at the identified risks improve child outcomes, Dr. Phan said.

Another goal of this research is to raise the profile of family psychosocial problems as an important factor in the development and maintenance of obesity in children, she said. “I think that people who work at pediatric weight management clinics have recognized the role of family psychosocial problems, but it is less recognized by the general pediatric community.”

Dr. Phan had no relevant financial disclosures.

AT THE PAS ANNUAL MEETING

Family’s psychosocial problems complicate pediatric obesity

BALTIMORE – Childhood obesity can result from more than just poor diet, not enough exercise, and too much screen time; it also often occurs in families with parents who have a significantly increased prevalence of psychosocial problems, judging from findings from a pilot, single-center study involving 97 parents who brought their child to a tertiary-care pediatric obesity center.

This preliminary finding “supports the need for universal psychosocial screening in this population, with particular attention to families whose children have comorbid behavioral health problems,” Dr. Thao-Ly T. Phan said while presenting a poster at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies.

“You might think that when a child is brought to an obesity clinic, you just need to ask what foods the child eats, how often the child exercises and how much television they watch, but we also need to ask about problems in the families and address those problems,” said Dr. Phan, a pediatrician and weight management specialist at the Alfred I. duPont Hospital for Children in Wilmington, Del.

Dr. Phan said although a key next step in this research is to assess how interventions aimed at family psychosocial problems affect a child’s obesity and well-being, her experience so far suggests that the psychosocial setting where a child lives can play a significant role in the etiology and maintenance of obesity.

“We find that families at higher psychosocial risk don’t come back for treatment, and when that happens the children don’t do well. That’s a reason to screen [for such problems] and intervene with psychological and social work support,” she said in an interview.

“A lot of our messages to families focus on things like screen time and eating more fruits and vegetables, but if the family can’t implement that, then we’re missing the boat,” Dr. Phan said.

She and her associates used the Psychosocial Assessment Tool (PAT), a screening tool for parents that takes about 5-10 minutes to complete and that was developed by researchers at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (ACTA Oncologica. 2015 May;54[5]:574-80). The PAT poses a series of questions that deal with a spectrum of potential psychosocial issues including financial status, a child’s problems at school, parents’ mood and substance abuse, and parental views of weight and health issues.

The investigators administered the PAT to 97 parents of children aged 4-12 years old who had their first visit to the tertiary-care pediatric obesity clinic at Alfred I. duPont. The children had body mass index levels that averaged close to the 99th percentile, with 56% of the children classified as severely obese with a BMI at or above the 99th percentile, 40% classified as obese with a BMI in the 95th-98th percentile, and 4% classified as overweight with a BMI at the 85th-94th percentile.

The PAT scores in these 97 parents identified 41% with a low risk for having psychosocial problems, 49% with a moderate risk, and 10% with a higher risk. In contrast, a historical control group of 3,918 representative U.S. parents who took the PAT showed 55% at low risk, 34% at moderate risk, and 11% at high risk, which meant that the parents of the children at the clinic had a statistically significant 70% increased prevalence of being in a high- or moderate-risk group for psychosocial problems, compared with parents in the general U.S. population, Dr. Phan reported.

A stepwise linear regression analysis of the PAT results identified two factors that significantly linked with higher PAT scores in these parents: attention- deficit/hyperactivity disorder in the child, and mood disorder in a parent. Logistic regression analysis further narrowed this down to just the child’s attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder as the only significant correlate with higher PAT scores. The analysis showed that the severity of obesity had no significant correlation with psychosocial risk scores.

The next steps are to assess more parents of obese children this way, see whether the questions posed in the PAT can be better focused for this setting to make the screening simpler and easier to administer, and determine how interventions aimed at the identified risks improve child outcomes, Dr. Phan said.

Another goal of this research is to raise the profile of family psychosocial problems as an important factor in the development and maintenance of obesity in children, she said. “I think that people who work at pediatric weight management clinics have recognized the role of family psychosocial problems, but it is less recognized by the general pediatric community.”

Dr. Phan had no relevant financial disclosures.

mzoler@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

BALTIMORE – Childhood obesity can result from more than just poor diet, not enough exercise, and too much screen time; it also often occurs in families with parents who have a significantly increased prevalence of psychosocial problems, judging from findings from a pilot, single-center study involving 97 parents who brought their child to a tertiary-care pediatric obesity center.

This preliminary finding “supports the need for universal psychosocial screening in this population, with particular attention to families whose children have comorbid behavioral health problems,” Dr. Thao-Ly T. Phan said while presenting a poster at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies.

“You might think that when a child is brought to an obesity clinic, you just need to ask what foods the child eats, how often the child exercises and how much television they watch, but we also need to ask about problems in the families and address those problems,” said Dr. Phan, a pediatrician and weight management specialist at the Alfred I. duPont Hospital for Children in Wilmington, Del.

Dr. Phan said although a key next step in this research is to assess how interventions aimed at family psychosocial problems affect a child’s obesity and well-being, her experience so far suggests that the psychosocial setting where a child lives can play a significant role in the etiology and maintenance of obesity.

“We find that families at higher psychosocial risk don’t come back for treatment, and when that happens the children don’t do well. That’s a reason to screen [for such problems] and intervene with psychological and social work support,” she said in an interview.

“A lot of our messages to families focus on things like screen time and eating more fruits and vegetables, but if the family can’t implement that, then we’re missing the boat,” Dr. Phan said.

She and her associates used the Psychosocial Assessment Tool (PAT), a screening tool for parents that takes about 5-10 minutes to complete and that was developed by researchers at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (ACTA Oncologica. 2015 May;54[5]:574-80). The PAT poses a series of questions that deal with a spectrum of potential psychosocial issues including financial status, a child’s problems at school, parents’ mood and substance abuse, and parental views of weight and health issues.

The investigators administered the PAT to 97 parents of children aged 4-12 years old who had their first visit to the tertiary-care pediatric obesity clinic at Alfred I. duPont. The children had body mass index levels that averaged close to the 99th percentile, with 56% of the children classified as severely obese with a BMI at or above the 99th percentile, 40% classified as obese with a BMI in the 95th-98th percentile, and 4% classified as overweight with a BMI at the 85th-94th percentile.

The PAT scores in these 97 parents identified 41% with a low risk for having psychosocial problems, 49% with a moderate risk, and 10% with a higher risk. In contrast, a historical control group of 3,918 representative U.S. parents who took the PAT showed 55% at low risk, 34% at moderate risk, and 11% at high risk, which meant that the parents of the children at the clinic had a statistically significant 70% increased prevalence of being in a high- or moderate-risk group for psychosocial problems, compared with parents in the general U.S. population, Dr. Phan reported.

A stepwise linear regression analysis of the PAT results identified two factors that significantly linked with higher PAT scores in these parents: attention- deficit/hyperactivity disorder in the child, and mood disorder in a parent. Logistic regression analysis further narrowed this down to just the child’s attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder as the only significant correlate with higher PAT scores. The analysis showed that the severity of obesity had no significant correlation with psychosocial risk scores.

The next steps are to assess more parents of obese children this way, see whether the questions posed in the PAT can be better focused for this setting to make the screening simpler and easier to administer, and determine how interventions aimed at the identified risks improve child outcomes, Dr. Phan said.

Another goal of this research is to raise the profile of family psychosocial problems as an important factor in the development and maintenance of obesity in children, she said. “I think that people who work at pediatric weight management clinics have recognized the role of family psychosocial problems, but it is less recognized by the general pediatric community.”

Dr. Phan had no relevant financial disclosures.

mzoler@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

BALTIMORE – Childhood obesity can result from more than just poor diet, not enough exercise, and too much screen time; it also often occurs in families with parents who have a significantly increased prevalence of psychosocial problems, judging from findings from a pilot, single-center study involving 97 parents who brought their child to a tertiary-care pediatric obesity center.

This preliminary finding “supports the need for universal psychosocial screening in this population, with particular attention to families whose children have comorbid behavioral health problems,” Dr. Thao-Ly T. Phan said while presenting a poster at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies.

“You might think that when a child is brought to an obesity clinic, you just need to ask what foods the child eats, how often the child exercises and how much television they watch, but we also need to ask about problems in the families and address those problems,” said Dr. Phan, a pediatrician and weight management specialist at the Alfred I. duPont Hospital for Children in Wilmington, Del.

Dr. Phan said although a key next step in this research is to assess how interventions aimed at family psychosocial problems affect a child’s obesity and well-being, her experience so far suggests that the psychosocial setting where a child lives can play a significant role in the etiology and maintenance of obesity.

“We find that families at higher psychosocial risk don’t come back for treatment, and when that happens the children don’t do well. That’s a reason to screen [for such problems] and intervene with psychological and social work support,” she said in an interview.

“A lot of our messages to families focus on things like screen time and eating more fruits and vegetables, but if the family can’t implement that, then we’re missing the boat,” Dr. Phan said.

She and her associates used the Psychosocial Assessment Tool (PAT), a screening tool for parents that takes about 5-10 minutes to complete and that was developed by researchers at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (ACTA Oncologica. 2015 May;54[5]:574-80). The PAT poses a series of questions that deal with a spectrum of potential psychosocial issues including financial status, a child’s problems at school, parents’ mood and substance abuse, and parental views of weight and health issues.

The investigators administered the PAT to 97 parents of children aged 4-12 years old who had their first visit to the tertiary-care pediatric obesity clinic at Alfred I. duPont. The children had body mass index levels that averaged close to the 99th percentile, with 56% of the children classified as severely obese with a BMI at or above the 99th percentile, 40% classified as obese with a BMI in the 95th-98th percentile, and 4% classified as overweight with a BMI at the 85th-94th percentile.

The PAT scores in these 97 parents identified 41% with a low risk for having psychosocial problems, 49% with a moderate risk, and 10% with a higher risk. In contrast, a historical control group of 3,918 representative U.S. parents who took the PAT showed 55% at low risk, 34% at moderate risk, and 11% at high risk, which meant that the parents of the children at the clinic had a statistically significant 70% increased prevalence of being in a high- or moderate-risk group for psychosocial problems, compared with parents in the general U.S. population, Dr. Phan reported.

A stepwise linear regression analysis of the PAT results identified two factors that significantly linked with higher PAT scores in these parents: attention- deficit/hyperactivity disorder in the child, and mood disorder in a parent. Logistic regression analysis further narrowed this down to just the child’s attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder as the only significant correlate with higher PAT scores. The analysis showed that the severity of obesity had no significant correlation with psychosocial risk scores.

The next steps are to assess more parents of obese children this way, see whether the questions posed in the PAT can be better focused for this setting to make the screening simpler and easier to administer, and determine how interventions aimed at the identified risks improve child outcomes, Dr. Phan said.

Another goal of this research is to raise the profile of family psychosocial problems as an important factor in the development and maintenance of obesity in children, she said. “I think that people who work at pediatric weight management clinics have recognized the role of family psychosocial problems, but it is less recognized by the general pediatric community.”

Dr. Phan had no relevant financial disclosures.

mzoler@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

AT THE PAS ANNUAL MEETING

Key clinical point: Parents of children who came to a tertiary-care pediatric obesity clinic showed a relatively high prevalence of psychosocial problems, suggesting a new intervention target for refractory childhood obesity.

Major finding: Parents of children presenting to a referral obesity clinic had a psychosocial risk score 70% higher than the U.S. average.

Data source: A single-center study of 97 parents of children initially presenting to a tertiary-care pediatric obesity clinic.

Disclosures: Dr. Phan had no relevant financial disclosures.

NSAIDs work best in selected systemic JIA kids

BALTIMORE – Children with systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis have the best odds for responding to initial treatment with a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug if they are no older than 6 years old, have five or fewer involved joints, and have a serum level of C-reactive protein that is at or below 13 mg/dL, based on a review of 57 children with systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis treated with these drugs at a single U.S. center during 2000-2014.

“We recommend a trial of NSAID [nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug] monotherapy for these patients with systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis [JIA],” Dr. Anjali S. Sura said at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies. A reasonable trial of NSAID monotherapy would last 6 weeks; if patients failed to adequately respond at the end of 6 weeks, it would be reasonable to switch to another of the first-line drugs recommended for children starting treatment for JIA, either a glucocorticoid or the biological agent anakinra (Kineret), said Dr. Sura, a pediatrician at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor.

Initial treatment with a NSAID is preferred, even though it will probably work in only about a quarter of patients, because it generally has the best safety profile among these three options, Dr. Sura said in an interview. “If we can risk-stratify children with systemic JIA for NSAID therapy” using these three criteria, “then NSAID monotherapy may be more effective,” she explained.

The NSAIDs most commonly used to treat systemic JIA are naproxen or indomethacin, at anti-inflammatory dosages, which for naproxen is 15-20 mg/kg per day, and for indomethacin 3-4 mg/kg per day, she said.

But Dr. Sura also cautioned that the analysis she presented focused on a relatively small and selected group of children with systemic JIA who received initial NSAID monotherapy. The series she and her associates reviewed included 99 patients, of whom 57 received NSAID monotherapy; 35 of these patients were 6 years old or younger.

The researchers compared the 15 NSAID responders (26%), defined as patients who had clinically inactive disease, with the 42 nonresponders and identified the three clinical and demographic characteristics that occurred much more often among responders. The ideal candidates for initial NSAID monotherapy should fulfill all three criteria: age, number of affected joints, and serum level of C-reactive protein, Dr. Sura said in her report.

Dr. Sura noted that a panel of the American College of Rheumatology said that NSAIDs, glucocorticoids, and anakinra were equally good options for initial treatment of JIA in their 2013 update of JIA recommendations (Arthritis Rheum. 2013 Oct;65[10]:2499-512). This 2013 update excepted patients with no actively affected joints, whom the panel said should specifically receive an NSAID, and excepted patients with a high global severity score as rated by their physicians, whom the panel said should receive either a glucocorticoid or anakinra but not NSAID monotherapy. The European League Against Rheumatism has not issued recommendations for managing systemic JIA.

Dr. Sura had no disclosures.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

BALTIMORE – Children with systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis have the best odds for responding to initial treatment with a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug if they are no older than 6 years old, have five or fewer involved joints, and have a serum level of C-reactive protein that is at or below 13 mg/dL, based on a review of 57 children with systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis treated with these drugs at a single U.S. center during 2000-2014.

“We recommend a trial of NSAID [nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug] monotherapy for these patients with systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis [JIA],” Dr. Anjali S. Sura said at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies. A reasonable trial of NSAID monotherapy would last 6 weeks; if patients failed to adequately respond at the end of 6 weeks, it would be reasonable to switch to another of the first-line drugs recommended for children starting treatment for JIA, either a glucocorticoid or the biological agent anakinra (Kineret), said Dr. Sura, a pediatrician at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor.

Initial treatment with a NSAID is preferred, even though it will probably work in only about a quarter of patients, because it generally has the best safety profile among these three options, Dr. Sura said in an interview. “If we can risk-stratify children with systemic JIA for NSAID therapy” using these three criteria, “then NSAID monotherapy may be more effective,” she explained.

The NSAIDs most commonly used to treat systemic JIA are naproxen or indomethacin, at anti-inflammatory dosages, which for naproxen is 15-20 mg/kg per day, and for indomethacin 3-4 mg/kg per day, she said.

But Dr. Sura also cautioned that the analysis she presented focused on a relatively small and selected group of children with systemic JIA who received initial NSAID monotherapy. The series she and her associates reviewed included 99 patients, of whom 57 received NSAID monotherapy; 35 of these patients were 6 years old or younger.

The researchers compared the 15 NSAID responders (26%), defined as patients who had clinically inactive disease, with the 42 nonresponders and identified the three clinical and demographic characteristics that occurred much more often among responders. The ideal candidates for initial NSAID monotherapy should fulfill all three criteria: age, number of affected joints, and serum level of C-reactive protein, Dr. Sura said in her report.

Dr. Sura noted that a panel of the American College of Rheumatology said that NSAIDs, glucocorticoids, and anakinra were equally good options for initial treatment of JIA in their 2013 update of JIA recommendations (Arthritis Rheum. 2013 Oct;65[10]:2499-512). This 2013 update excepted patients with no actively affected joints, whom the panel said should specifically receive an NSAID, and excepted patients with a high global severity score as rated by their physicians, whom the panel said should receive either a glucocorticoid or anakinra but not NSAID monotherapy. The European League Against Rheumatism has not issued recommendations for managing systemic JIA.

Dr. Sura had no disclosures.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

BALTIMORE – Children with systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis have the best odds for responding to initial treatment with a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug if they are no older than 6 years old, have five or fewer involved joints, and have a serum level of C-reactive protein that is at or below 13 mg/dL, based on a review of 57 children with systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis treated with these drugs at a single U.S. center during 2000-2014.

“We recommend a trial of NSAID [nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug] monotherapy for these patients with systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis [JIA],” Dr. Anjali S. Sura said at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies. A reasonable trial of NSAID monotherapy would last 6 weeks; if patients failed to adequately respond at the end of 6 weeks, it would be reasonable to switch to another of the first-line drugs recommended for children starting treatment for JIA, either a glucocorticoid or the biological agent anakinra (Kineret), said Dr. Sura, a pediatrician at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor.

Initial treatment with a NSAID is preferred, even though it will probably work in only about a quarter of patients, because it generally has the best safety profile among these three options, Dr. Sura said in an interview. “If we can risk-stratify children with systemic JIA for NSAID therapy” using these three criteria, “then NSAID monotherapy may be more effective,” she explained.

The NSAIDs most commonly used to treat systemic JIA are naproxen or indomethacin, at anti-inflammatory dosages, which for naproxen is 15-20 mg/kg per day, and for indomethacin 3-4 mg/kg per day, she said.

But Dr. Sura also cautioned that the analysis she presented focused on a relatively small and selected group of children with systemic JIA who received initial NSAID monotherapy. The series she and her associates reviewed included 99 patients, of whom 57 received NSAID monotherapy; 35 of these patients were 6 years old or younger.

The researchers compared the 15 NSAID responders (26%), defined as patients who had clinically inactive disease, with the 42 nonresponders and identified the three clinical and demographic characteristics that occurred much more often among responders. The ideal candidates for initial NSAID monotherapy should fulfill all three criteria: age, number of affected joints, and serum level of C-reactive protein, Dr. Sura said in her report.

Dr. Sura noted that a panel of the American College of Rheumatology said that NSAIDs, glucocorticoids, and anakinra were equally good options for initial treatment of JIA in their 2013 update of JIA recommendations (Arthritis Rheum. 2013 Oct;65[10]:2499-512). This 2013 update excepted patients with no actively affected joints, whom the panel said should specifically receive an NSAID, and excepted patients with a high global severity score as rated by their physicians, whom the panel said should receive either a glucocorticoid or anakinra but not NSAID monotherapy. The European League Against Rheumatism has not issued recommendations for managing systemic JIA.

Dr. Sura had no disclosures.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

AT THE PAS ANNUAL MEETING

Key clinical point: Three clinical parameters identified the children with systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis who historically responded best to initial treatment with a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug.

Major finding: Five or fewer involved joints, 6 years old or younger, and C-reactive protein of 13 mg/dL or less identified the best NSAID responders.

Data source: Review of 57 children with systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis treated initially with NSAID monotherapy at one U.S. center.

Disclosures: Dr. Sura had no disclosures.

Ambulatory blood pressure rules hypertension diagnosis and follow-up

Evidence is becoming overwhelming that ambulatory blood pressure monitoring is the only reliable way to measure blood pressure for both diagnosing hypertension and following patients once they are diagnosed.

Office-based blood pressure measurement is out, be it a one-off reading or a cluster of sequential readings during a single office visit. Ambulatory blood pressure monitoring (ABPM) increasingly is the standard of care.

One recent nail in the coffin of office-based measurement came in a modestly-sized but revealing study reported by Dr. Joyce P. Samuel, a pediatric hypertension specialist at the University of Texas in Houston. She reported her experience directly comparing ambulatory and carefully-done office-based blood pressure measurement in a presentation at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies in Baltimore.

Dr. Samuel followed 40 patients age 9-21 years whom she had previously diagnosed with essential hypertension (children with a systolic blood pressure at or above the 95th percentile for sex, age, and height), and repeatedly measured their blood pressures by both ambulatory and office-based readings at 2-week intervals as she searched for the best combination of antihypertensive drugs for each patient. She sent patients home for 24 hours of blood-pressure monitoring with an ambulatory device, and when they returned to her office the next day, she performed an office-based measurement using meticulous technique: Each child was seated and calm, measured on the right arm, with four measurements taken sequentially at about 1 minute intervals with the first reading discarded and the remaining three averaged.

Over the course of several months, she collected 173 paired ambulatory and office-based systolic blood pressure readings from individual patients. Substantial differences between the two forms of measurement were remarkably common. In 20% of the pairs, the ambulatory systolic reading was at least 10 mm Hg higher than the office-based reading, and for some pairs the differences ran as high as 30 mm Hg. In an additional 32% of the paired readings, office-based systolic pressure ran at least 10 mm Hg higher and in some cases as much as 35 mm Hg higher than the ambulatory reading.

Dr. Samuel also analyzed her findings a different way to assess the clinical consequences of these differences based on whether a child’s systolic pressure identified the patient as normotensive, hypertensive, or prehypertensive (a systolic pressure at the 90-94th percentile for the child’s age, sex and height). She found that the diagnoses matched for only 49% of the paired measurements. In 24% of the paired readings, ABPM identified children with hypertension that was not seen with concurrent office-based measurement, cases of masked hypertension. In 17% of the pairs, office-based measurement diagnosed hypertension that was not confirmed by ABPM, cases of white-coat hypertension. The remaining 10% of pairs were mismatched by showing normotensive with one method and prehypertensive with the other method. Dr. Samuel searched for any consistent patterns in these differences and found none. The disparate results with ambulatory and office-based measurements seemed almost random, with no correlation with age, sex, race, the medications patients received, or how many times a patient had already undergone dual blood-pressure monitoring. Individual patients had no meaningful differences between some of their paired measurements but had a meaningful disparity for others.

“We were unable to predict discrepancies,” said Dr. Samuels.

“You can’t get around it, you need ambulatory blood pressure monitoring to make the best diagnosis” of hypertension, she told me. “We need to push to make ambulatory monitoring more available. I am moving toward believing that ambulatory blood pressure monitoring must be routinely done on everyone. This is what the data suggest.”

It’s also where medicine is headed. In 2015, the U.S. Preventative Services Task Force (USPSTF) issued new recommendations for hypertension screening in adults aged 18 years or older, indicating that there was “convincing evidence that ABPM is the best method for diagnosing hypertension,” and the agency further recommended that ABPM is “the reference standard for confirming the diagnosis of hypertension.” Another endorsement of ambulatory blood pressure monitoring came out last year from the International Society for Chronobiology.

Recommendations are not yet as evolved for children. The USPSTF last weighed in on screening kids for hypertension in 2013, and said the evidence as of then was “insufficient” to assess the benefits and harms of screening for hypertension in children and adolescents. That document endorsed careful office-based blood pressure measurement, which highlights how recently expert sentiment has shifted on the issue of measurement. In response to the USPSTF 2013 statement, the American Academy of Pediatrics noted that it continued to back recommendations that are more than a decade old from the National High Blood Pressure Education Program that called for hypertension screening in children starting when they are 3 years old. Neither of these two groups has made any recent statement about the preferred method to measure blood pressure.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

Evidence is becoming overwhelming that ambulatory blood pressure monitoring is the only reliable way to measure blood pressure for both diagnosing hypertension and following patients once they are diagnosed.

Office-based blood pressure measurement is out, be it a one-off reading or a cluster of sequential readings during a single office visit. Ambulatory blood pressure monitoring (ABPM) increasingly is the standard of care.

One recent nail in the coffin of office-based measurement came in a modestly-sized but revealing study reported by Dr. Joyce P. Samuel, a pediatric hypertension specialist at the University of Texas in Houston. She reported her experience directly comparing ambulatory and carefully-done office-based blood pressure measurement in a presentation at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies in Baltimore.

Dr. Samuel followed 40 patients age 9-21 years whom she had previously diagnosed with essential hypertension (children with a systolic blood pressure at or above the 95th percentile for sex, age, and height), and repeatedly measured their blood pressures by both ambulatory and office-based readings at 2-week intervals as she searched for the best combination of antihypertensive drugs for each patient. She sent patients home for 24 hours of blood-pressure monitoring with an ambulatory device, and when they returned to her office the next day, she performed an office-based measurement using meticulous technique: Each child was seated and calm, measured on the right arm, with four measurements taken sequentially at about 1 minute intervals with the first reading discarded and the remaining three averaged.

Over the course of several months, she collected 173 paired ambulatory and office-based systolic blood pressure readings from individual patients. Substantial differences between the two forms of measurement were remarkably common. In 20% of the pairs, the ambulatory systolic reading was at least 10 mm Hg higher than the office-based reading, and for some pairs the differences ran as high as 30 mm Hg. In an additional 32% of the paired readings, office-based systolic pressure ran at least 10 mm Hg higher and in some cases as much as 35 mm Hg higher than the ambulatory reading.

Dr. Samuel also analyzed her findings a different way to assess the clinical consequences of these differences based on whether a child’s systolic pressure identified the patient as normotensive, hypertensive, or prehypertensive (a systolic pressure at the 90-94th percentile for the child’s age, sex and height). She found that the diagnoses matched for only 49% of the paired measurements. In 24% of the paired readings, ABPM identified children with hypertension that was not seen with concurrent office-based measurement, cases of masked hypertension. In 17% of the pairs, office-based measurement diagnosed hypertension that was not confirmed by ABPM, cases of white-coat hypertension. The remaining 10% of pairs were mismatched by showing normotensive with one method and prehypertensive with the other method. Dr. Samuel searched for any consistent patterns in these differences and found none. The disparate results with ambulatory and office-based measurements seemed almost random, with no correlation with age, sex, race, the medications patients received, or how many times a patient had already undergone dual blood-pressure monitoring. Individual patients had no meaningful differences between some of their paired measurements but had a meaningful disparity for others.

“We were unable to predict discrepancies,” said Dr. Samuels.

“You can’t get around it, you need ambulatory blood pressure monitoring to make the best diagnosis” of hypertension, she told me. “We need to push to make ambulatory monitoring more available. I am moving toward believing that ambulatory blood pressure monitoring must be routinely done on everyone. This is what the data suggest.”

It’s also where medicine is headed. In 2015, the U.S. Preventative Services Task Force (USPSTF) issued new recommendations for hypertension screening in adults aged 18 years or older, indicating that there was “convincing evidence that ABPM is the best method for diagnosing hypertension,” and the agency further recommended that ABPM is “the reference standard for confirming the diagnosis of hypertension.” Another endorsement of ambulatory blood pressure monitoring came out last year from the International Society for Chronobiology.

Recommendations are not yet as evolved for children. The USPSTF last weighed in on screening kids for hypertension in 2013, and said the evidence as of then was “insufficient” to assess the benefits and harms of screening for hypertension in children and adolescents. That document endorsed careful office-based blood pressure measurement, which highlights how recently expert sentiment has shifted on the issue of measurement. In response to the USPSTF 2013 statement, the American Academy of Pediatrics noted that it continued to back recommendations that are more than a decade old from the National High Blood Pressure Education Program that called for hypertension screening in children starting when they are 3 years old. Neither of these two groups has made any recent statement about the preferred method to measure blood pressure.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

Evidence is becoming overwhelming that ambulatory blood pressure monitoring is the only reliable way to measure blood pressure for both diagnosing hypertension and following patients once they are diagnosed.

Office-based blood pressure measurement is out, be it a one-off reading or a cluster of sequential readings during a single office visit. Ambulatory blood pressure monitoring (ABPM) increasingly is the standard of care.

One recent nail in the coffin of office-based measurement came in a modestly-sized but revealing study reported by Dr. Joyce P. Samuel, a pediatric hypertension specialist at the University of Texas in Houston. She reported her experience directly comparing ambulatory and carefully-done office-based blood pressure measurement in a presentation at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies in Baltimore.

Dr. Samuel followed 40 patients age 9-21 years whom she had previously diagnosed with essential hypertension (children with a systolic blood pressure at or above the 95th percentile for sex, age, and height), and repeatedly measured their blood pressures by both ambulatory and office-based readings at 2-week intervals as she searched for the best combination of antihypertensive drugs for each patient. She sent patients home for 24 hours of blood-pressure monitoring with an ambulatory device, and when they returned to her office the next day, she performed an office-based measurement using meticulous technique: Each child was seated and calm, measured on the right arm, with four measurements taken sequentially at about 1 minute intervals with the first reading discarded and the remaining three averaged.

Over the course of several months, she collected 173 paired ambulatory and office-based systolic blood pressure readings from individual patients. Substantial differences between the two forms of measurement were remarkably common. In 20% of the pairs, the ambulatory systolic reading was at least 10 mm Hg higher than the office-based reading, and for some pairs the differences ran as high as 30 mm Hg. In an additional 32% of the paired readings, office-based systolic pressure ran at least 10 mm Hg higher and in some cases as much as 35 mm Hg higher than the ambulatory reading.

Dr. Samuel also analyzed her findings a different way to assess the clinical consequences of these differences based on whether a child’s systolic pressure identified the patient as normotensive, hypertensive, or prehypertensive (a systolic pressure at the 90-94th percentile for the child’s age, sex and height). She found that the diagnoses matched for only 49% of the paired measurements. In 24% of the paired readings, ABPM identified children with hypertension that was not seen with concurrent office-based measurement, cases of masked hypertension. In 17% of the pairs, office-based measurement diagnosed hypertension that was not confirmed by ABPM, cases of white-coat hypertension. The remaining 10% of pairs were mismatched by showing normotensive with one method and prehypertensive with the other method. Dr. Samuel searched for any consistent patterns in these differences and found none. The disparate results with ambulatory and office-based measurements seemed almost random, with no correlation with age, sex, race, the medications patients received, or how many times a patient had already undergone dual blood-pressure monitoring. Individual patients had no meaningful differences between some of their paired measurements but had a meaningful disparity for others.

“We were unable to predict discrepancies,” said Dr. Samuels.

“You can’t get around it, you need ambulatory blood pressure monitoring to make the best diagnosis” of hypertension, she told me. “We need to push to make ambulatory monitoring more available. I am moving toward believing that ambulatory blood pressure monitoring must be routinely done on everyone. This is what the data suggest.”

It’s also where medicine is headed. In 2015, the U.S. Preventative Services Task Force (USPSTF) issued new recommendations for hypertension screening in adults aged 18 years or older, indicating that there was “convincing evidence that ABPM is the best method for diagnosing hypertension,” and the agency further recommended that ABPM is “the reference standard for confirming the diagnosis of hypertension.” Another endorsement of ambulatory blood pressure monitoring came out last year from the International Society for Chronobiology.

Recommendations are not yet as evolved for children. The USPSTF last weighed in on screening kids for hypertension in 2013, and said the evidence as of then was “insufficient” to assess the benefits and harms of screening for hypertension in children and adolescents. That document endorsed careful office-based blood pressure measurement, which highlights how recently expert sentiment has shifted on the issue of measurement. In response to the USPSTF 2013 statement, the American Academy of Pediatrics noted that it continued to back recommendations that are more than a decade old from the National High Blood Pressure Education Program that called for hypertension screening in children starting when they are 3 years old. Neither of these two groups has made any recent statement about the preferred method to measure blood pressure.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

TAVR enters a new risk-scoring era

In the 14 years since the first transcatheter aortic valve replacement in 2002, devices and delivery methods have undergone several generations of improvement, but one facet of the procedure remained largely unchanged: When prospective patients underwent preprocedural assessment to gauge their risk level, the long-standing approach to quantify their disease severity and 30-day mortality risk was to run their clinical and demographic numbers through the risk calculator developed by the Society of Thoracic Surgeons.

Although determining a patient’s Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS) risk score using a formula based on extensive experience performing surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR) by open surgery made a lot of sense during an era when the preeminent question was how transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) compared with SAVR, it also carried the inherent limitation of estimating a patient’s risk when undergoing TAVR based on SAVR’s track record.

That limitation is now gone.

In December 2015, a team of cardiothoracic surgeons and interventional cardiologists assembled by the STS and the American College of Cardiology placed a new risk calculator online to estimate a prospective TAVR patient’s risk for dying in hospital following a TAVR procedure. The panel developed this risk calculator with data from nearly 14,000 U.S. TAVR patients enrolled in the STS/ACC Transcatheter Valve Replacement Registry during November 2011–February 2014 and then validated it with data from another nearly 7,000 U.S. TAVR patients who underwent their procedure during March-October 2014. This created the first mortality-risk calculator for TAVR patients based entirely on experience with such patients (JAMA Cardiology. 2016 Apr;1[1]:46-52).

In May 2016, a second, independent risk calculator will go live, also based exclusively on experience in TAVR patients, that estimates a patient’s risk for either dying or having a worsened or unimproved and poor quality of life during the 6 months following TAVR. This risk calculator, developed by a team led by researchers based at Saint Luke’s Mid America Heart Institute in Kansas City, Mo., used data collected from more than 2,000 TAVR patients enrolled in the PARTNER trial or in the continued-access PARTNER registry (Circulation. 2014 June 24;129[25]:2682-90), and is offered to users by Health Outcomes Sciences, a Kansas City–based company that’s affiliated with Saint Luke’s.

Although use of these two TAVR-specific risk calculators during their early days of availability remains relatively light, TAVR experts see them as marking a new era in the workup of TAVR candidates.

“There is universal agreement that risk models must be developed based on the history of patients who actually received the treatment,” said Dr. Fred H. Edwards, the cardiothoracic surgeon at the University of Florida, Jacksonville, who led the team that developed the transcatheter valve therapy (TVT)-derived in-hospital mortality risk calculator. “Everyone realized that the STS score and the EuroScore [another operative-risk calculator historically used for prospective TAVR patients] were inadequate to extrapolate to TAVR patients.” But development had to wait until an adequately-sized experience with TAVR had accumulated. “We started the process [to develop the TVT risk calculator] when we reached about 10,000 patients” enrolled in the registry, after which it took “close to 2 years” to produce the finished product, Dr. Edwards said in an interview.

The TVT in-hospital mortality predictor gradually goes mainstream

“There is consensus that the new TVT calculator will be more reliable than the STS operative-risk model” for assessing patients being considered for TAVR, but it has not yet gained widespread use “because it is so new,” noted Dr. Edwards.

“It will take a while to incorporate it into routine practice, but I think it will be used quite a bit,” especially for “trickier and harder cases,” commented Dr. George Dangas, a professor of medicine at the Mount Sinai School of Medicine in New York and an interventional cardiologist who performs TAVR.

He also predicted that prospective patients and their families will become frequent users of the TVT in-hospital risk calculator. He sees the new risk tool as a complement to the STS risk score rather than something to replace it.

“Patients find it useful to receive an estimate of their surgical risk, and they’ll want to compare that” with their TAVR risk. “It helps to know both,” Dr. Dangas said in an interview. “Patients will likely compute it themselves.”

He foresees fairly quick integration of the new TVT score into heart team discussions as well. “The STS score will always be part of the discussion, but over time as people grow accustomed to the TVT score they will incorporate it as well. The [TAVR] community has to figure out how to use the two scores in combination.”