User login

Mitchel is a reporter for MDedge based in the Philadelphia area. He started with the company in 1992, when it was International Medical News Group (IMNG), and has since covered a range of medical specialties. Mitchel trained as a virologist at Roswell Park Memorial Institute in Buffalo, and then worked briefly as a researcher at Boston Children's Hospital before pivoting to journalism as a AAAS Mass Media Fellow in 1980. His first reporting job was with Science Digest magazine, and from the mid-1980s to early-1990s he was a reporter with Medical World News. @mitchelzoler

VIDEO: Monitoring helps only adherent heart failure patients

ORLANDO – A multipronged approach to following and managing heart failure patients closely after they are hospitalized for acute decompensation led to significant reductions in subsequent rehospitalization or death in a randomized trial, but only in the subgroup of patients who actually adhered to the program.

The main message from the study was “this type of telemonitoring should not get used on everyone,” said Dr. Michael K. Ong in an interview at the American Heart Association scientific sessions. “A key issue is who are the people who would benefit” from an intensified at-home monitoring program following hospitalization for an acute heart failure episode.

Another issue is that new monitoring technologies introduced after launch of the BEAT-HF (Better Effectiveness After Transition–Heart Failure) trial more than 4 years ago have produced unobtrusive and implantable monitoring devices that could help boost monitoring compliance, said Dr. Ong, an internist at the University of California, Los Angeles.

“We all monitor our patients remotely on a variety of ways,” commented Dr. Mariell Jessup, professor of medicine and heart failure specialist and at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia. “Depending on our resources and technology, we might use implantable monitors or have nurses call patients, and have patients send us emails. There is a wide range of telemonitoring available. But we need to find out what works. An enormous effort has been made to enhance patients’ ability to monitor themselves, so they can take charge of their disease,” Dr. Jessup said.

BEAT-HF randomized 1,437 patients with confirmed heart failure and an index hospitalization to an intensive monitoring and education program or usual care during 2011-2013 at six academic health centers in California. Patients averaged 73 years old, and most patients had class III New York Heart Association heart failure, with three quarters having either class III or IV.

The intensive program included three elements:

• An in-hospital education program.

• A schedule of nine follow-up telephone calls by a registered nurse starting 2-3 days post discharge and continuing out to 6 months. Patients in the intervention arm completed a median of six of these calls.

• Telemonitoring of daily measurement of weight, blood pressure, and heart rate using electronically linked monitoring devices supplied to each patient. The monitoring equipment actually was used by 83% of the 715 patients randomized to this arm, and at 180 days, 52% of the patients in this arm had transmitted more than half of their daily measurement updates.

The study showed no significant benefit from the intensive monitoring arm compared with usual care for the primary endpoint of all-cause hospitalizations after 180 days, Dr. Ong reported. However, in a post hoc analysis that divided the intervention arm patients into those with more than 50% days with monitoring information sent and those with 50% or less, the rehospitalization rate was 61% among the patients who complied 50% or less of the time with daily home monitoring, and 41% in patients with greater than 50% compliance, a one-third relative drop. The more-compliant patients also substantially and significantly reduced their mortality rates at both 30 and 180 days, compared with the less-adherent patients in the intervention arm.

Additional studies must now examine how to optimize adherence and better match patients with various monitoring techniques. “If patients won’t use a treatment, they won’t benefit,” said Dr. Ong. Finding out what makes people adherent and encourage them to participate is the next research issue, he added.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

We are now in the second decade of research aimed at finding the most effective ways to monitor patients following a hospitalization for acute heart failure decompensation. Interest runs high to find the best ways to monitor these patients and treat them with interventions intended to cut the rate of future decompensation events and hospitalizations and mortality.

Despite all this, research and interest studies have not yet clearly identified monitoring and intervention strategies that are consistently effective. In fact, sometimes so many monitoring strategies are begun by both health systems and by payers that it can become can become confusing.

|

Dr. Mary Norine Walsh |

A key issue is, who receives the monitoring data and what do they do with it? The way that physicians and nurses act on monitoring data really matters, and ideally, patients should also know their monitoring data and be an active part of maintaining their stability.

At the center where I work, we routinely educate patients during their hospitalization on the importance of maintaining a low-sodium diet and daily weight monitoring. Daily weights as a way to track the fluid-balance status of patients has been unfairly criticized, as new technology has made implantable monitors routinely available. Although they are routinely available, implanted technologies are not yet for the masses. I am a firm believer in the value of daily weights.

At my center, we put a paper weight chart in each patient’s room, recorded in pounds, so that patients can track their weight fluctuations themselves. We try to educate and indoctrinate our heart failure patients to the importance of tracking their weight, and tell them to bring the charts they maintain at home to their clinic visits. We even instruct selected patients who have taken good, personal control of their heart failure to adjust their daily furosemide dosage themselves – within specified limits and while keeping us informed – when they see their weight tracking up or down.

The better patients with heart failure understand the tight relationship between their lifestyle choices and their status, the better it is for their long-term success.

Dr. Mary Norine Walsh is medical director of the Heart Failure and Cardiac Transplantation program at the St. Vincent Heart Center in Indianapolis. She had no disclosures. She made these comments in an interview.

We are now in the second decade of research aimed at finding the most effective ways to monitor patients following a hospitalization for acute heart failure decompensation. Interest runs high to find the best ways to monitor these patients and treat them with interventions intended to cut the rate of future decompensation events and hospitalizations and mortality.

Despite all this, research and interest studies have not yet clearly identified monitoring and intervention strategies that are consistently effective. In fact, sometimes so many monitoring strategies are begun by both health systems and by payers that it can become can become confusing.

|

Dr. Mary Norine Walsh |

A key issue is, who receives the monitoring data and what do they do with it? The way that physicians and nurses act on monitoring data really matters, and ideally, patients should also know their monitoring data and be an active part of maintaining their stability.

At the center where I work, we routinely educate patients during their hospitalization on the importance of maintaining a low-sodium diet and daily weight monitoring. Daily weights as a way to track the fluid-balance status of patients has been unfairly criticized, as new technology has made implantable monitors routinely available. Although they are routinely available, implanted technologies are not yet for the masses. I am a firm believer in the value of daily weights.

At my center, we put a paper weight chart in each patient’s room, recorded in pounds, so that patients can track their weight fluctuations themselves. We try to educate and indoctrinate our heart failure patients to the importance of tracking their weight, and tell them to bring the charts they maintain at home to their clinic visits. We even instruct selected patients who have taken good, personal control of their heart failure to adjust their daily furosemide dosage themselves – within specified limits and while keeping us informed – when they see their weight tracking up or down.

The better patients with heart failure understand the tight relationship between their lifestyle choices and their status, the better it is for their long-term success.

Dr. Mary Norine Walsh is medical director of the Heart Failure and Cardiac Transplantation program at the St. Vincent Heart Center in Indianapolis. She had no disclosures. She made these comments in an interview.

We are now in the second decade of research aimed at finding the most effective ways to monitor patients following a hospitalization for acute heart failure decompensation. Interest runs high to find the best ways to monitor these patients and treat them with interventions intended to cut the rate of future decompensation events and hospitalizations and mortality.

Despite all this, research and interest studies have not yet clearly identified monitoring and intervention strategies that are consistently effective. In fact, sometimes so many monitoring strategies are begun by both health systems and by payers that it can become can become confusing.

|

Dr. Mary Norine Walsh |

A key issue is, who receives the monitoring data and what do they do with it? The way that physicians and nurses act on monitoring data really matters, and ideally, patients should also know their monitoring data and be an active part of maintaining their stability.

At the center where I work, we routinely educate patients during their hospitalization on the importance of maintaining a low-sodium diet and daily weight monitoring. Daily weights as a way to track the fluid-balance status of patients has been unfairly criticized, as new technology has made implantable monitors routinely available. Although they are routinely available, implanted technologies are not yet for the masses. I am a firm believer in the value of daily weights.

At my center, we put a paper weight chart in each patient’s room, recorded in pounds, so that patients can track their weight fluctuations themselves. We try to educate and indoctrinate our heart failure patients to the importance of tracking their weight, and tell them to bring the charts they maintain at home to their clinic visits. We even instruct selected patients who have taken good, personal control of their heart failure to adjust their daily furosemide dosage themselves – within specified limits and while keeping us informed – when they see their weight tracking up or down.

The better patients with heart failure understand the tight relationship between their lifestyle choices and their status, the better it is for their long-term success.

Dr. Mary Norine Walsh is medical director of the Heart Failure and Cardiac Transplantation program at the St. Vincent Heart Center in Indianapolis. She had no disclosures. She made these comments in an interview.

ORLANDO – A multipronged approach to following and managing heart failure patients closely after they are hospitalized for acute decompensation led to significant reductions in subsequent rehospitalization or death in a randomized trial, but only in the subgroup of patients who actually adhered to the program.

The main message from the study was “this type of telemonitoring should not get used on everyone,” said Dr. Michael K. Ong in an interview at the American Heart Association scientific sessions. “A key issue is who are the people who would benefit” from an intensified at-home monitoring program following hospitalization for an acute heart failure episode.

Another issue is that new monitoring technologies introduced after launch of the BEAT-HF (Better Effectiveness After Transition–Heart Failure) trial more than 4 years ago have produced unobtrusive and implantable monitoring devices that could help boost monitoring compliance, said Dr. Ong, an internist at the University of California, Los Angeles.

“We all monitor our patients remotely on a variety of ways,” commented Dr. Mariell Jessup, professor of medicine and heart failure specialist and at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia. “Depending on our resources and technology, we might use implantable monitors or have nurses call patients, and have patients send us emails. There is a wide range of telemonitoring available. But we need to find out what works. An enormous effort has been made to enhance patients’ ability to monitor themselves, so they can take charge of their disease,” Dr. Jessup said.

BEAT-HF randomized 1,437 patients with confirmed heart failure and an index hospitalization to an intensive monitoring and education program or usual care during 2011-2013 at six academic health centers in California. Patients averaged 73 years old, and most patients had class III New York Heart Association heart failure, with three quarters having either class III or IV.

The intensive program included three elements:

• An in-hospital education program.

• A schedule of nine follow-up telephone calls by a registered nurse starting 2-3 days post discharge and continuing out to 6 months. Patients in the intervention arm completed a median of six of these calls.

• Telemonitoring of daily measurement of weight, blood pressure, and heart rate using electronically linked monitoring devices supplied to each patient. The monitoring equipment actually was used by 83% of the 715 patients randomized to this arm, and at 180 days, 52% of the patients in this arm had transmitted more than half of their daily measurement updates.

The study showed no significant benefit from the intensive monitoring arm compared with usual care for the primary endpoint of all-cause hospitalizations after 180 days, Dr. Ong reported. However, in a post hoc analysis that divided the intervention arm patients into those with more than 50% days with monitoring information sent and those with 50% or less, the rehospitalization rate was 61% among the patients who complied 50% or less of the time with daily home monitoring, and 41% in patients with greater than 50% compliance, a one-third relative drop. The more-compliant patients also substantially and significantly reduced their mortality rates at both 30 and 180 days, compared with the less-adherent patients in the intervention arm.

Additional studies must now examine how to optimize adherence and better match patients with various monitoring techniques. “If patients won’t use a treatment, they won’t benefit,” said Dr. Ong. Finding out what makes people adherent and encourage them to participate is the next research issue, he added.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

ORLANDO – A multipronged approach to following and managing heart failure patients closely after they are hospitalized for acute decompensation led to significant reductions in subsequent rehospitalization or death in a randomized trial, but only in the subgroup of patients who actually adhered to the program.

The main message from the study was “this type of telemonitoring should not get used on everyone,” said Dr. Michael K. Ong in an interview at the American Heart Association scientific sessions. “A key issue is who are the people who would benefit” from an intensified at-home monitoring program following hospitalization for an acute heart failure episode.

Another issue is that new monitoring technologies introduced after launch of the BEAT-HF (Better Effectiveness After Transition–Heart Failure) trial more than 4 years ago have produced unobtrusive and implantable monitoring devices that could help boost monitoring compliance, said Dr. Ong, an internist at the University of California, Los Angeles.

“We all monitor our patients remotely on a variety of ways,” commented Dr. Mariell Jessup, professor of medicine and heart failure specialist and at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia. “Depending on our resources and technology, we might use implantable monitors or have nurses call patients, and have patients send us emails. There is a wide range of telemonitoring available. But we need to find out what works. An enormous effort has been made to enhance patients’ ability to monitor themselves, so they can take charge of their disease,” Dr. Jessup said.

BEAT-HF randomized 1,437 patients with confirmed heart failure and an index hospitalization to an intensive monitoring and education program or usual care during 2011-2013 at six academic health centers in California. Patients averaged 73 years old, and most patients had class III New York Heart Association heart failure, with three quarters having either class III or IV.

The intensive program included three elements:

• An in-hospital education program.

• A schedule of nine follow-up telephone calls by a registered nurse starting 2-3 days post discharge and continuing out to 6 months. Patients in the intervention arm completed a median of six of these calls.

• Telemonitoring of daily measurement of weight, blood pressure, and heart rate using electronically linked monitoring devices supplied to each patient. The monitoring equipment actually was used by 83% of the 715 patients randomized to this arm, and at 180 days, 52% of the patients in this arm had transmitted more than half of their daily measurement updates.

The study showed no significant benefit from the intensive monitoring arm compared with usual care for the primary endpoint of all-cause hospitalizations after 180 days, Dr. Ong reported. However, in a post hoc analysis that divided the intervention arm patients into those with more than 50% days with monitoring information sent and those with 50% or less, the rehospitalization rate was 61% among the patients who complied 50% or less of the time with daily home monitoring, and 41% in patients with greater than 50% compliance, a one-third relative drop. The more-compliant patients also substantially and significantly reduced their mortality rates at both 30 and 180 days, compared with the less-adherent patients in the intervention arm.

Additional studies must now examine how to optimize adherence and better match patients with various monitoring techniques. “If patients won’t use a treatment, they won’t benefit,” said Dr. Ong. Finding out what makes people adherent and encourage them to participate is the next research issue, he added.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

AT THE AHA SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS

Key clinical point: Remote monitoring failed to reduce mortality or hospitalizations for all patients during the 180 days following heart failure hospitalization, but was effective for patients who adhered to the program.

Major finding: Telemonitoring more than half the time cut 180-day readmissions by a third relative to usual care.

Data source: The BEAT-HF study, which enrolled 1,437 patients hospitalized for acute heart failure at six California centers.

Disclosures: BEAT-HF had no commercial sponsors. Dr. Ong had no disclosures. Dr. Jessup had no disclosures.

AHA: DAPT score helps decide whether DAPT continues

ORLANDO – The common challenge faced by clinicians in deciding whether or not to continue dual antiplatelet therapy beyond a year in a patient who underwent percutaneous coronary intervention has gotten easier.

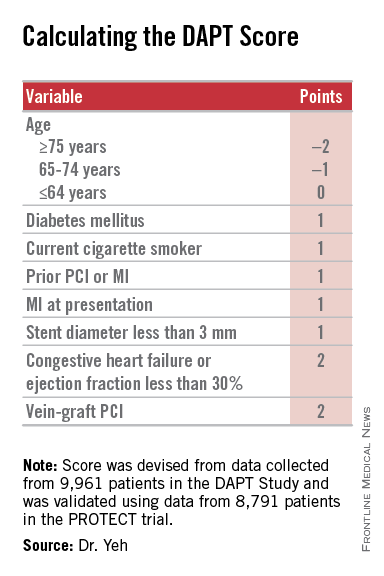

Researchers have devised a simple, eight-element scoring system using information already available in a patient’s records to help determine whether an individual patient will be more likely to benefit from continuing or stopping dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT).

“The DAPT score may help clinicians decide who should and who should not be treated with extended DAPT,” Dr. Robert W. Yeh said at the American Heart Association Scientific Sessions.

“This is a step forward for an issue we deal with daily, balancing an individual patient’s risk from ischemia and bleeding,” commented Dr. Alice Jacobs, professor of medicine at Boston University and director of the cardiac catheterization laboratory and interventional cardiology at Boston Medical Center.

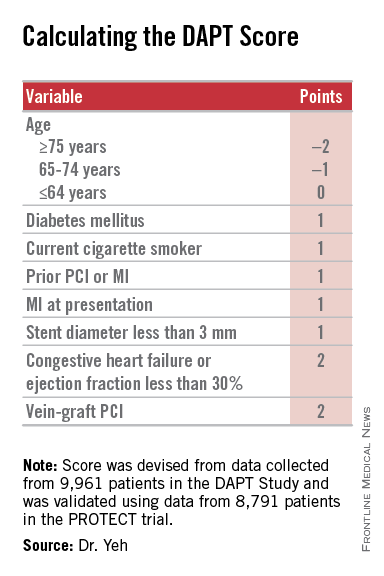

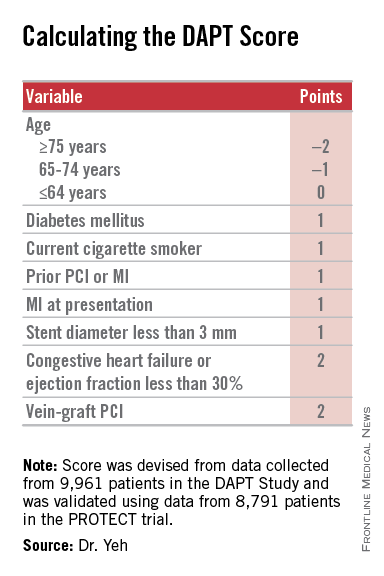

Dr. Yeh and his associates devised the DAPT score from the data collected in the DAPT study, which enrolled more than 25,000 patients and randomized about 10,000 to test whether patients fared better by stopping or continuing DAPT after completing their initial year of DAPT following percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). The DAPT study results showed that after 18 additional months, continuing DAPT cut the rate of definite or probable stent thrombosis by 1 percentage point and the combined rate of death, MI, or stroke by 1.6 percentage points, both statistically significant differences, compared with patients randomized to treatment with aspirin plus placebo. The results also showed that continued DAPT increased GUSTO moderate or severe bleeding events by 1 percentage point, compared with the control patients (N Engl J Med. 2014 Dec 4;371[23]:2155-66).

The researchers used data collected in the DAPT study to build risk models using patient- and procedure-specific variables that predicted the ischemic and bleeding outcomes, and then combined the two into a single model. That meant abandoning some variables that had significant impact on both outcomes.

The result was a scoring system that includes eight variables that result in a score that ranges from –2 to 9. The analysis showed that a score of 1 or less identified patients for whom the risk for bleeding outweighs their potential gain by avoiding an ischemic event by about 2.5-fold, and hence likely would fare better by stopping DAPT. A score of 2 or higher flagged patients who benefited about eightfold more from avoided ischemic events, compared with their risk for a moderate or severe bleed.

Patient scores showed a classic bell-shaped curve, with roughly a quarter of the DAPT study patients having a score of 1 and about a quarter with a score of 2, about 16% had a score of 0 and about 16% had a score of 3, and about 8% had a score of –1 or –2, while about 9% had a score of 4 or more.

The investigators validated the scoring system using data collected in the PROTECT trial, which included 8,791 patients who underwent PCI during 2007-2008. Dr. Yeh acknowledged that the discrimination strength of the models he and his associated developed was “modest,” but added that its efficacy was greater than what has been shown in validation cohorts for the commonly used CH2ADS2-VASc and HAS-BLED scoring systems.

Dr. Yeh stressed that using the DAPT score “cannot trump clinical judgment.” He suggested that a clinician use the score to help facilitate a conversation with a PCI patient when the time comes to decide whether or not to continue DAPT beyond 1 year.

Other factors that could influence the decision include the length of the stented coronary lesions or prior radiation exposure to the patient’s coronary arteries, said Dr. Laura Mauri, who led the DAPT study and collaborated on developing the DAPT score. “It requires judgment to decide [on whether to continue DAPT] for patients who are on the borderline” for risk and benefit. “This gives patients a way to better understand what they might gain or lose” by continuing treatment. Without the quantification that the DAPT score provides, the balance of risk and benefit “is somewhat nebulous,” said Dr. Mauri, an interventional cardiologist and director of the Center for Clinical Biometrics in the division of cardiovascular medicine at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

The investigators who ran the DAPT study realized several years before the study finished that development of the DAPT score was a critical part of applying the findings from the study into clinical practice, she said in an interview.

Dr. Yeh cautioned that the score is only appropriate for patients who match those enrolled into the DAPT study: patients who went through their first year post PCI on DAPT without having any ischemic or bleeding complications. For these patients, “we feel the DAPT score is incredibly valuable,” said Dr. Yeh, an interventional cardiologist and director of the Center for Outcomes Research in Cardiology at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston. He and his associates are now using data from the DAPT study to model bleeding and ischemia risks during the first year following PCI to try to come up with risk models that can address DAPT use during this period.

Dr. Yeh and Dr. Mauri have placed a link to the electronic DAPT score calculator on the website for the DAPT study (www.daptstudy.org), and Dr. Yeh said that an app version will soon become available. Interventionalists in the programs that Dr. Yeh and Mauri are affiliated with have recently begun using the DAPT score calculator in their routine practice, Dr. Yeh said.

The DAPT study received funding from Abbott, Boston Scientific, Cordis, Medtronic, Bristol-Myers Squib-Sanofi, Eli Lilly, and Daiichi Sankyo. Derivation of the DAPT score was funded by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Yeh has received honoraria from Abbott, Boston Scientific, and Merck. Dr. Jacobs had no disclosures. Dr. Mauri has been a consultant to Biotronik, Medtronic, and St. Jude and has received research funding from several companies.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

The DAPT score is a clever and innovative idea. It is a major step forward in helping clinicians decide which patients should continue dual antiplatelet therapy after safely completing a year on this therapy following percutaneous coronary intervention. The DAPT score was data driven and provides a tool to help personalize decision making with a simple, practical solution to a common clinical dilemma. It’s a welcome addition to our decision-making process.

The competing risks from bleeding events caused by continued dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) beyond 1 year and ischemic events caused by stopping DAPT creates difficulty in determining whether or not to continue or stop DAPT for an individual patient. The DAPT score helps make that decision.

|

| Mitchel L. Zoler/Frontline Medical News Dr. James de Lemos |

The analysis performed by Dr. Yeh and his associates produced a clear and convincing result. The primary caveat is that it is only applicable to patients who entered the randomized phase of the DAPT study, specifically patients who underwent a full first year of DAPT treatment following PCI without an ischemic or major bleeding event. I would like to see replication of the score’s validation in an additional data set, although few data sets exist that are suitable for such replication. Although the discrimination produced by the DAPT score is moderate, it compares favorably with other widely used clinical decision scores such as the CHA2ADS2-VASc.

The added decision-making ability facilitated by this score revises my interpretation of the results from the DAPT study. When the results of the trial appeared in 2014, I considered the outcome null because of the problem it highlighted in balancing the competing risks of ischemic and bleeding events when deciding about continuing DAPT beyond 1 year. The DAPT score helps produce a much clearer risk versus benefit decision for a sizable subset of patients who undergo percutaneous coronary intervention.

Dr. James de Lemos is a professor of medicine at UT Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, and chief of the cardiology service at Parkland Memorial Hospital in Dallas. He has received honoraria from Novo Nordisk and St. Jude and research funding from Roche Diagnostics and Abbott Diagnostics. He made these comments as the designated discussant for Dr. Yeh’s report.

The DAPT score is a clever and innovative idea. It is a major step forward in helping clinicians decide which patients should continue dual antiplatelet therapy after safely completing a year on this therapy following percutaneous coronary intervention. The DAPT score was data driven and provides a tool to help personalize decision making with a simple, practical solution to a common clinical dilemma. It’s a welcome addition to our decision-making process.

The competing risks from bleeding events caused by continued dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) beyond 1 year and ischemic events caused by stopping DAPT creates difficulty in determining whether or not to continue or stop DAPT for an individual patient. The DAPT score helps make that decision.

|

| Mitchel L. Zoler/Frontline Medical News Dr. James de Lemos |

The analysis performed by Dr. Yeh and his associates produced a clear and convincing result. The primary caveat is that it is only applicable to patients who entered the randomized phase of the DAPT study, specifically patients who underwent a full first year of DAPT treatment following PCI without an ischemic or major bleeding event. I would like to see replication of the score’s validation in an additional data set, although few data sets exist that are suitable for such replication. Although the discrimination produced by the DAPT score is moderate, it compares favorably with other widely used clinical decision scores such as the CHA2ADS2-VASc.

The added decision-making ability facilitated by this score revises my interpretation of the results from the DAPT study. When the results of the trial appeared in 2014, I considered the outcome null because of the problem it highlighted in balancing the competing risks of ischemic and bleeding events when deciding about continuing DAPT beyond 1 year. The DAPT score helps produce a much clearer risk versus benefit decision for a sizable subset of patients who undergo percutaneous coronary intervention.

Dr. James de Lemos is a professor of medicine at UT Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, and chief of the cardiology service at Parkland Memorial Hospital in Dallas. He has received honoraria from Novo Nordisk and St. Jude and research funding from Roche Diagnostics and Abbott Diagnostics. He made these comments as the designated discussant for Dr. Yeh’s report.

The DAPT score is a clever and innovative idea. It is a major step forward in helping clinicians decide which patients should continue dual antiplatelet therapy after safely completing a year on this therapy following percutaneous coronary intervention. The DAPT score was data driven and provides a tool to help personalize decision making with a simple, practical solution to a common clinical dilemma. It’s a welcome addition to our decision-making process.

The competing risks from bleeding events caused by continued dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) beyond 1 year and ischemic events caused by stopping DAPT creates difficulty in determining whether or not to continue or stop DAPT for an individual patient. The DAPT score helps make that decision.

|

| Mitchel L. Zoler/Frontline Medical News Dr. James de Lemos |

The analysis performed by Dr. Yeh and his associates produced a clear and convincing result. The primary caveat is that it is only applicable to patients who entered the randomized phase of the DAPT study, specifically patients who underwent a full first year of DAPT treatment following PCI without an ischemic or major bleeding event. I would like to see replication of the score’s validation in an additional data set, although few data sets exist that are suitable for such replication. Although the discrimination produced by the DAPT score is moderate, it compares favorably with other widely used clinical decision scores such as the CHA2ADS2-VASc.

The added decision-making ability facilitated by this score revises my interpretation of the results from the DAPT study. When the results of the trial appeared in 2014, I considered the outcome null because of the problem it highlighted in balancing the competing risks of ischemic and bleeding events when deciding about continuing DAPT beyond 1 year. The DAPT score helps produce a much clearer risk versus benefit decision for a sizable subset of patients who undergo percutaneous coronary intervention.

Dr. James de Lemos is a professor of medicine at UT Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, and chief of the cardiology service at Parkland Memorial Hospital in Dallas. He has received honoraria from Novo Nordisk and St. Jude and research funding from Roche Diagnostics and Abbott Diagnostics. He made these comments as the designated discussant for Dr. Yeh’s report.

ORLANDO – The common challenge faced by clinicians in deciding whether or not to continue dual antiplatelet therapy beyond a year in a patient who underwent percutaneous coronary intervention has gotten easier.

Researchers have devised a simple, eight-element scoring system using information already available in a patient’s records to help determine whether an individual patient will be more likely to benefit from continuing or stopping dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT).

“The DAPT score may help clinicians decide who should and who should not be treated with extended DAPT,” Dr. Robert W. Yeh said at the American Heart Association Scientific Sessions.

“This is a step forward for an issue we deal with daily, balancing an individual patient’s risk from ischemia and bleeding,” commented Dr. Alice Jacobs, professor of medicine at Boston University and director of the cardiac catheterization laboratory and interventional cardiology at Boston Medical Center.

Dr. Yeh and his associates devised the DAPT score from the data collected in the DAPT study, which enrolled more than 25,000 patients and randomized about 10,000 to test whether patients fared better by stopping or continuing DAPT after completing their initial year of DAPT following percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). The DAPT study results showed that after 18 additional months, continuing DAPT cut the rate of definite or probable stent thrombosis by 1 percentage point and the combined rate of death, MI, or stroke by 1.6 percentage points, both statistically significant differences, compared with patients randomized to treatment with aspirin plus placebo. The results also showed that continued DAPT increased GUSTO moderate or severe bleeding events by 1 percentage point, compared with the control patients (N Engl J Med. 2014 Dec 4;371[23]:2155-66).

The researchers used data collected in the DAPT study to build risk models using patient- and procedure-specific variables that predicted the ischemic and bleeding outcomes, and then combined the two into a single model. That meant abandoning some variables that had significant impact on both outcomes.

The result was a scoring system that includes eight variables that result in a score that ranges from –2 to 9. The analysis showed that a score of 1 or less identified patients for whom the risk for bleeding outweighs their potential gain by avoiding an ischemic event by about 2.5-fold, and hence likely would fare better by stopping DAPT. A score of 2 or higher flagged patients who benefited about eightfold more from avoided ischemic events, compared with their risk for a moderate or severe bleed.

Patient scores showed a classic bell-shaped curve, with roughly a quarter of the DAPT study patients having a score of 1 and about a quarter with a score of 2, about 16% had a score of 0 and about 16% had a score of 3, and about 8% had a score of –1 or –2, while about 9% had a score of 4 or more.

The investigators validated the scoring system using data collected in the PROTECT trial, which included 8,791 patients who underwent PCI during 2007-2008. Dr. Yeh acknowledged that the discrimination strength of the models he and his associated developed was “modest,” but added that its efficacy was greater than what has been shown in validation cohorts for the commonly used CH2ADS2-VASc and HAS-BLED scoring systems.

Dr. Yeh stressed that using the DAPT score “cannot trump clinical judgment.” He suggested that a clinician use the score to help facilitate a conversation with a PCI patient when the time comes to decide whether or not to continue DAPT beyond 1 year.

Other factors that could influence the decision include the length of the stented coronary lesions or prior radiation exposure to the patient’s coronary arteries, said Dr. Laura Mauri, who led the DAPT study and collaborated on developing the DAPT score. “It requires judgment to decide [on whether to continue DAPT] for patients who are on the borderline” for risk and benefit. “This gives patients a way to better understand what they might gain or lose” by continuing treatment. Without the quantification that the DAPT score provides, the balance of risk and benefit “is somewhat nebulous,” said Dr. Mauri, an interventional cardiologist and director of the Center for Clinical Biometrics in the division of cardiovascular medicine at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

The investigators who ran the DAPT study realized several years before the study finished that development of the DAPT score was a critical part of applying the findings from the study into clinical practice, she said in an interview.

Dr. Yeh cautioned that the score is only appropriate for patients who match those enrolled into the DAPT study: patients who went through their first year post PCI on DAPT without having any ischemic or bleeding complications. For these patients, “we feel the DAPT score is incredibly valuable,” said Dr. Yeh, an interventional cardiologist and director of the Center for Outcomes Research in Cardiology at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston. He and his associates are now using data from the DAPT study to model bleeding and ischemia risks during the first year following PCI to try to come up with risk models that can address DAPT use during this period.

Dr. Yeh and Dr. Mauri have placed a link to the electronic DAPT score calculator on the website for the DAPT study (www.daptstudy.org), and Dr. Yeh said that an app version will soon become available. Interventionalists in the programs that Dr. Yeh and Mauri are affiliated with have recently begun using the DAPT score calculator in their routine practice, Dr. Yeh said.

The DAPT study received funding from Abbott, Boston Scientific, Cordis, Medtronic, Bristol-Myers Squib-Sanofi, Eli Lilly, and Daiichi Sankyo. Derivation of the DAPT score was funded by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Yeh has received honoraria from Abbott, Boston Scientific, and Merck. Dr. Jacobs had no disclosures. Dr. Mauri has been a consultant to Biotronik, Medtronic, and St. Jude and has received research funding from several companies.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

ORLANDO – The common challenge faced by clinicians in deciding whether or not to continue dual antiplatelet therapy beyond a year in a patient who underwent percutaneous coronary intervention has gotten easier.

Researchers have devised a simple, eight-element scoring system using information already available in a patient’s records to help determine whether an individual patient will be more likely to benefit from continuing or stopping dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT).

“The DAPT score may help clinicians decide who should and who should not be treated with extended DAPT,” Dr. Robert W. Yeh said at the American Heart Association Scientific Sessions.

“This is a step forward for an issue we deal with daily, balancing an individual patient’s risk from ischemia and bleeding,” commented Dr. Alice Jacobs, professor of medicine at Boston University and director of the cardiac catheterization laboratory and interventional cardiology at Boston Medical Center.

Dr. Yeh and his associates devised the DAPT score from the data collected in the DAPT study, which enrolled more than 25,000 patients and randomized about 10,000 to test whether patients fared better by stopping or continuing DAPT after completing their initial year of DAPT following percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). The DAPT study results showed that after 18 additional months, continuing DAPT cut the rate of definite or probable stent thrombosis by 1 percentage point and the combined rate of death, MI, or stroke by 1.6 percentage points, both statistically significant differences, compared with patients randomized to treatment with aspirin plus placebo. The results also showed that continued DAPT increased GUSTO moderate or severe bleeding events by 1 percentage point, compared with the control patients (N Engl J Med. 2014 Dec 4;371[23]:2155-66).

The researchers used data collected in the DAPT study to build risk models using patient- and procedure-specific variables that predicted the ischemic and bleeding outcomes, and then combined the two into a single model. That meant abandoning some variables that had significant impact on both outcomes.

The result was a scoring system that includes eight variables that result in a score that ranges from –2 to 9. The analysis showed that a score of 1 or less identified patients for whom the risk for bleeding outweighs their potential gain by avoiding an ischemic event by about 2.5-fold, and hence likely would fare better by stopping DAPT. A score of 2 or higher flagged patients who benefited about eightfold more from avoided ischemic events, compared with their risk for a moderate or severe bleed.

Patient scores showed a classic bell-shaped curve, with roughly a quarter of the DAPT study patients having a score of 1 and about a quarter with a score of 2, about 16% had a score of 0 and about 16% had a score of 3, and about 8% had a score of –1 or –2, while about 9% had a score of 4 or more.

The investigators validated the scoring system using data collected in the PROTECT trial, which included 8,791 patients who underwent PCI during 2007-2008. Dr. Yeh acknowledged that the discrimination strength of the models he and his associated developed was “modest,” but added that its efficacy was greater than what has been shown in validation cohorts for the commonly used CH2ADS2-VASc and HAS-BLED scoring systems.

Dr. Yeh stressed that using the DAPT score “cannot trump clinical judgment.” He suggested that a clinician use the score to help facilitate a conversation with a PCI patient when the time comes to decide whether or not to continue DAPT beyond 1 year.

Other factors that could influence the decision include the length of the stented coronary lesions or prior radiation exposure to the patient’s coronary arteries, said Dr. Laura Mauri, who led the DAPT study and collaborated on developing the DAPT score. “It requires judgment to decide [on whether to continue DAPT] for patients who are on the borderline” for risk and benefit. “This gives patients a way to better understand what they might gain or lose” by continuing treatment. Without the quantification that the DAPT score provides, the balance of risk and benefit “is somewhat nebulous,” said Dr. Mauri, an interventional cardiologist and director of the Center for Clinical Biometrics in the division of cardiovascular medicine at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

The investigators who ran the DAPT study realized several years before the study finished that development of the DAPT score was a critical part of applying the findings from the study into clinical practice, she said in an interview.

Dr. Yeh cautioned that the score is only appropriate for patients who match those enrolled into the DAPT study: patients who went through their first year post PCI on DAPT without having any ischemic or bleeding complications. For these patients, “we feel the DAPT score is incredibly valuable,” said Dr. Yeh, an interventional cardiologist and director of the Center for Outcomes Research in Cardiology at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston. He and his associates are now using data from the DAPT study to model bleeding and ischemia risks during the first year following PCI to try to come up with risk models that can address DAPT use during this period.

Dr. Yeh and Dr. Mauri have placed a link to the electronic DAPT score calculator on the website for the DAPT study (www.daptstudy.org), and Dr. Yeh said that an app version will soon become available. Interventionalists in the programs that Dr. Yeh and Mauri are affiliated with have recently begun using the DAPT score calculator in their routine practice, Dr. Yeh said.

The DAPT study received funding from Abbott, Boston Scientific, Cordis, Medtronic, Bristol-Myers Squib-Sanofi, Eli Lilly, and Daiichi Sankyo. Derivation of the DAPT score was funded by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Yeh has received honoraria from Abbott, Boston Scientific, and Merck. Dr. Jacobs had no disclosures. Dr. Mauri has been a consultant to Biotronik, Medtronic, and St. Jude and has received research funding from several companies.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

AT THE AHA SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS

Key clinical point: A year after percutaneous coronary intervention, the DAPT score helps clinicians decide whether to continue dual antiplatelet therapy.

Major finding: DAPT scores of 1 or less were linked with a 2.5-fold higher risk of bleeding than ischemic events prevented by continued DAPT; scores of 2 or more were linked with an eightfold increased rate of ischemic events prevented, compared with bleeding events triggered.

Data source: The DAPT study, a multicenter, international, randomized trial that enrolled 25,682 patients.

Disclosures: The DAPT study received funding from Abbott, Boston Scientific, Cordis, Medtronic, Bristol-Myers Squibb-Sanofi, Eli Lilly, and Daiichi Sankyo. Derivation of the DAPT score was funded by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Yeh has received honoraria from Abbott, Boston Scientific, and Merck.

ACC/AHA guidelines upgrade multivessel PCI, downgrade thrombectomy

ORLANDO – Two guideline panels jointly upgraded percutaneous coronary interventions in noninfarct coronary arteries in patients with a recent MI, and downgraded manual aspiration thrombectomy in acute MI patients.

The panels, organized by the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association, cover, respectively, percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) and ST-elevation MI (STEMI).

The revised guidance on percutaneous coronary intervention for multivessel coronary disease affects roughly half the patients with an acute ST-elevation MI, those who have significant stenoses in noninfarct coronaries. The 2011 guidelines from the PCI panel (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011 Dec;58[24]:e44-122) and the 2013 guidelines from the STEMI committee (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013 Jan;61[4]:e78-140) only endorsed revascularization of stenotic, noninfarct arteries in patients with cardiogenic shock or severe heart failure. Multivessel PCI for patients without hemodynamic compromise at the time of primary PCI was deemed a class III indication, “thought to confer harm,” based on the results of several observational studies, Dr. Patrick T. O’Gara said at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

After the 2013 STEMI guidelines came out, results from four studies showed either benefit or no harm from multivessel PCI in patients with appropriate anatomy performed either at the time of primary PCI or as a scheduled, staged procedure soon after primary PCI, said Dr. O’Gara, professor and director of clinical cardiology at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. Three of the four studies, PRAMI (N Engl J Med. 2013 Sept 19;369[12]:1115-23), CvLPRIT (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015 March;65[10]:963-72), and DANAMI-3–PRIMULTI (Lancet. 2015 Aug 15;386[9994]:665-71), are published, while results from the fourth, PRAGUE-13, came out in a meeting report this year but as of mid-November had not been published.

Based on these data the two committees reset PCI of noninfarct arteries as a class IIb recommendation that “could be considered” in selected STEMI patients with multivessel disease who are hemodynamically stable.

The guidelines further said that “insufficient data exist to inform a recommendation” about the optimal time for this multivessel PCI, which could be coincident with primary PCI or 2 days, 3 days, a week, or even later after initial PCI, said Dr. O’Gara. “The writing committees do not advocate for routine use of multivessel PCI; clinical judgment is obviously needed,” he cautioned.

The two committees also reassessed manual aspiration thrombectomy during primary PCI for STEMI, which until now has been a class IIa recommendation, “reasonable” for STEMI patients undergoing primary PCI. But based on the neutral results for thrombectomy in the recent findings from the two largest randomized trials of thrombectomy, TOTAL (N Engl J Med. 2015 April 9;372[15]:1389-98) and TASTE (N Engl J Med. 2013 Oct 24;369[17]:1587-97), as well as a recent, 17-trial meta-analysis, the revised guidelines rate routine aspiration thrombectomy as class III, with “no benefit” and “not useful,” and selective and bailout thrombectomy as a class IIb recommendation, with usefulness that is “not well established.”

Selective use of thrombectomy will require good judgment, noted Dr. O’Gara, who added “it will be important to see what effect, if any, these observations, this evidence, and this distillation of the recommendations from the writing committees have on a change in practice” – using thrombectomy to treat STEMI patients.

Dr. O’Gara chairs the STEMI writing panel of the American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

ORLANDO – Two guideline panels jointly upgraded percutaneous coronary interventions in noninfarct coronary arteries in patients with a recent MI, and downgraded manual aspiration thrombectomy in acute MI patients.

The panels, organized by the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association, cover, respectively, percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) and ST-elevation MI (STEMI).

The revised guidance on percutaneous coronary intervention for multivessel coronary disease affects roughly half the patients with an acute ST-elevation MI, those who have significant stenoses in noninfarct coronaries. The 2011 guidelines from the PCI panel (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011 Dec;58[24]:e44-122) and the 2013 guidelines from the STEMI committee (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013 Jan;61[4]:e78-140) only endorsed revascularization of stenotic, noninfarct arteries in patients with cardiogenic shock or severe heart failure. Multivessel PCI for patients without hemodynamic compromise at the time of primary PCI was deemed a class III indication, “thought to confer harm,” based on the results of several observational studies, Dr. Patrick T. O’Gara said at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

After the 2013 STEMI guidelines came out, results from four studies showed either benefit or no harm from multivessel PCI in patients with appropriate anatomy performed either at the time of primary PCI or as a scheduled, staged procedure soon after primary PCI, said Dr. O’Gara, professor and director of clinical cardiology at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. Three of the four studies, PRAMI (N Engl J Med. 2013 Sept 19;369[12]:1115-23), CvLPRIT (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015 March;65[10]:963-72), and DANAMI-3–PRIMULTI (Lancet. 2015 Aug 15;386[9994]:665-71), are published, while results from the fourth, PRAGUE-13, came out in a meeting report this year but as of mid-November had not been published.

Based on these data the two committees reset PCI of noninfarct arteries as a class IIb recommendation that “could be considered” in selected STEMI patients with multivessel disease who are hemodynamically stable.

The guidelines further said that “insufficient data exist to inform a recommendation” about the optimal time for this multivessel PCI, which could be coincident with primary PCI or 2 days, 3 days, a week, or even later after initial PCI, said Dr. O’Gara. “The writing committees do not advocate for routine use of multivessel PCI; clinical judgment is obviously needed,” he cautioned.

The two committees also reassessed manual aspiration thrombectomy during primary PCI for STEMI, which until now has been a class IIa recommendation, “reasonable” for STEMI patients undergoing primary PCI. But based on the neutral results for thrombectomy in the recent findings from the two largest randomized trials of thrombectomy, TOTAL (N Engl J Med. 2015 April 9;372[15]:1389-98) and TASTE (N Engl J Med. 2013 Oct 24;369[17]:1587-97), as well as a recent, 17-trial meta-analysis, the revised guidelines rate routine aspiration thrombectomy as class III, with “no benefit” and “not useful,” and selective and bailout thrombectomy as a class IIb recommendation, with usefulness that is “not well established.”

Selective use of thrombectomy will require good judgment, noted Dr. O’Gara, who added “it will be important to see what effect, if any, these observations, this evidence, and this distillation of the recommendations from the writing committees have on a change in practice” – using thrombectomy to treat STEMI patients.

Dr. O’Gara chairs the STEMI writing panel of the American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

ORLANDO – Two guideline panels jointly upgraded percutaneous coronary interventions in noninfarct coronary arteries in patients with a recent MI, and downgraded manual aspiration thrombectomy in acute MI patients.

The panels, organized by the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association, cover, respectively, percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) and ST-elevation MI (STEMI).

The revised guidance on percutaneous coronary intervention for multivessel coronary disease affects roughly half the patients with an acute ST-elevation MI, those who have significant stenoses in noninfarct coronaries. The 2011 guidelines from the PCI panel (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011 Dec;58[24]:e44-122) and the 2013 guidelines from the STEMI committee (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013 Jan;61[4]:e78-140) only endorsed revascularization of stenotic, noninfarct arteries in patients with cardiogenic shock or severe heart failure. Multivessel PCI for patients without hemodynamic compromise at the time of primary PCI was deemed a class III indication, “thought to confer harm,” based on the results of several observational studies, Dr. Patrick T. O’Gara said at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

After the 2013 STEMI guidelines came out, results from four studies showed either benefit or no harm from multivessel PCI in patients with appropriate anatomy performed either at the time of primary PCI or as a scheduled, staged procedure soon after primary PCI, said Dr. O’Gara, professor and director of clinical cardiology at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. Three of the four studies, PRAMI (N Engl J Med. 2013 Sept 19;369[12]:1115-23), CvLPRIT (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015 March;65[10]:963-72), and DANAMI-3–PRIMULTI (Lancet. 2015 Aug 15;386[9994]:665-71), are published, while results from the fourth, PRAGUE-13, came out in a meeting report this year but as of mid-November had not been published.

Based on these data the two committees reset PCI of noninfarct arteries as a class IIb recommendation that “could be considered” in selected STEMI patients with multivessel disease who are hemodynamically stable.

The guidelines further said that “insufficient data exist to inform a recommendation” about the optimal time for this multivessel PCI, which could be coincident with primary PCI or 2 days, 3 days, a week, or even later after initial PCI, said Dr. O’Gara. “The writing committees do not advocate for routine use of multivessel PCI; clinical judgment is obviously needed,” he cautioned.

The two committees also reassessed manual aspiration thrombectomy during primary PCI for STEMI, which until now has been a class IIa recommendation, “reasonable” for STEMI patients undergoing primary PCI. But based on the neutral results for thrombectomy in the recent findings from the two largest randomized trials of thrombectomy, TOTAL (N Engl J Med. 2015 April 9;372[15]:1389-98) and TASTE (N Engl J Med. 2013 Oct 24;369[17]:1587-97), as well as a recent, 17-trial meta-analysis, the revised guidelines rate routine aspiration thrombectomy as class III, with “no benefit” and “not useful,” and selective and bailout thrombectomy as a class IIb recommendation, with usefulness that is “not well established.”

Selective use of thrombectomy will require good judgment, noted Dr. O’Gara, who added “it will be important to see what effect, if any, these observations, this evidence, and this distillation of the recommendations from the writing committees have on a change in practice” – using thrombectomy to treat STEMI patients.

Dr. O’Gara chairs the STEMI writing panel of the American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

AT THE AHA SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS

VIDEO: SPRINT Results Rebut JNC 8’s Blood Pressure Targets

ORLANDO – SPRINT’s hypertension-treatment results serve as a rebuttal to the systolic blood pressure target of less than 150 mm Hg for older patients set less than 2 years ago by the panel originally constituted as JNC 8, Dr. Prakash Deedwania said in an interview at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

“We were all concerned” by the high target systolic blood pressure for patients aged 60 years or older set by the panel initially organized as JNC 8, said Dr. Deedwania, professor of medicine at the University of California, San Francisco, in Fresno. The SPRINT results, which showed incremental value for a systolic blood pressure target of less than 120 mm Hg for selected patients at risk for cardiovascular disease, will influence the new hypertension-treatment guidelines now in development by a panel formed by the American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association, he said.

While applauding SPRINT (Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial) and its clear outcome, Dr. Deedwania cited several cautions to keep in mind when applying the results to practice. One of his concerns centered on driving diastolic pressure low with aggressive antihypertensive treatment, especially in elderly patients with underlying coronary artery disease who could have inadequate coronary perfusion if their diastolic pressure drops too low.

Another caution was the need to reconcile the SPRINT results with those from the ACCORD blood pressure trial results, which failed to show that a systolic blood pressure target of less than 120 mm Hg led to better outcomes than did a target of less than 140 mm Hg in patients with diabetes. Although SPRINT specifically excluded patients with diabetes, a helpful analysis that the SPRINT data should allow is assessment of outcomes in patients who were obese and had hyperlipidemia as well as hypertension, defining a subgroup of patients with metabolic syndrome that is considered a prediabetes state.

Dr. Deedwania also warned that so far researchers have not reported the SPRINT results in patients with preexisting renal dysfunction compared with patients with more normal kidney function. Patients with impaired renal function can be in jeopardy if their blood pressure gets too low, he noted.

Dr. Deedwania had no disclosures.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

ORLANDO – SPRINT’s hypertension-treatment results serve as a rebuttal to the systolic blood pressure target of less than 150 mm Hg for older patients set less than 2 years ago by the panel originally constituted as JNC 8, Dr. Prakash Deedwania said in an interview at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

“We were all concerned” by the high target systolic blood pressure for patients aged 60 years or older set by the panel initially organized as JNC 8, said Dr. Deedwania, professor of medicine at the University of California, San Francisco, in Fresno. The SPRINT results, which showed incremental value for a systolic blood pressure target of less than 120 mm Hg for selected patients at risk for cardiovascular disease, will influence the new hypertension-treatment guidelines now in development by a panel formed by the American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association, he said.

While applauding SPRINT (Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial) and its clear outcome, Dr. Deedwania cited several cautions to keep in mind when applying the results to practice. One of his concerns centered on driving diastolic pressure low with aggressive antihypertensive treatment, especially in elderly patients with underlying coronary artery disease who could have inadequate coronary perfusion if their diastolic pressure drops too low.

Another caution was the need to reconcile the SPRINT results with those from the ACCORD blood pressure trial results, which failed to show that a systolic blood pressure target of less than 120 mm Hg led to better outcomes than did a target of less than 140 mm Hg in patients with diabetes. Although SPRINT specifically excluded patients with diabetes, a helpful analysis that the SPRINT data should allow is assessment of outcomes in patients who were obese and had hyperlipidemia as well as hypertension, defining a subgroup of patients with metabolic syndrome that is considered a prediabetes state.

Dr. Deedwania also warned that so far researchers have not reported the SPRINT results in patients with preexisting renal dysfunction compared with patients with more normal kidney function. Patients with impaired renal function can be in jeopardy if their blood pressure gets too low, he noted.

Dr. Deedwania had no disclosures.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

ORLANDO – SPRINT’s hypertension-treatment results serve as a rebuttal to the systolic blood pressure target of less than 150 mm Hg for older patients set less than 2 years ago by the panel originally constituted as JNC 8, Dr. Prakash Deedwania said in an interview at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

“We were all concerned” by the high target systolic blood pressure for patients aged 60 years or older set by the panel initially organized as JNC 8, said Dr. Deedwania, professor of medicine at the University of California, San Francisco, in Fresno. The SPRINT results, which showed incremental value for a systolic blood pressure target of less than 120 mm Hg for selected patients at risk for cardiovascular disease, will influence the new hypertension-treatment guidelines now in development by a panel formed by the American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association, he said.

While applauding SPRINT (Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial) and its clear outcome, Dr. Deedwania cited several cautions to keep in mind when applying the results to practice. One of his concerns centered on driving diastolic pressure low with aggressive antihypertensive treatment, especially in elderly patients with underlying coronary artery disease who could have inadequate coronary perfusion if their diastolic pressure drops too low.

Another caution was the need to reconcile the SPRINT results with those from the ACCORD blood pressure trial results, which failed to show that a systolic blood pressure target of less than 120 mm Hg led to better outcomes than did a target of less than 140 mm Hg in patients with diabetes. Although SPRINT specifically excluded patients with diabetes, a helpful analysis that the SPRINT data should allow is assessment of outcomes in patients who were obese and had hyperlipidemia as well as hypertension, defining a subgroup of patients with metabolic syndrome that is considered a prediabetes state.

Dr. Deedwania also warned that so far researchers have not reported the SPRINT results in patients with preexisting renal dysfunction compared with patients with more normal kidney function. Patients with impaired renal function can be in jeopardy if their blood pressure gets too low, he noted.

Dr. Deedwania had no disclosures.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE AHA SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS

VIDEO: SPRINT results rebut JNC 8’s blood pressure targets

ORLANDO – SPRINT’s hypertension-treatment results serve as a rebuttal to the systolic blood pressure target of less than 150 mm Hg for older patients set less than 2 years ago by the panel originally constituted as JNC 8, Dr. Prakash Deedwania said in an interview at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

“We were all concerned” by the high target systolic blood pressure for patients aged 60 years or older set by the panel initially organized as JNC 8, said Dr. Deedwania, professor of medicine at the University of California, San Francisco, in Fresno. The SPRINT results, which showed incremental value for a systolic blood pressure target of less than 120 mm Hg for selected patients at risk for cardiovascular disease, will influence the new hypertension-treatment guidelines now in development by a panel formed by the American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association, he said.

While applauding SPRINT (Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial) and its clear outcome, Dr. Deedwania cited several cautions to keep in mind when applying the results to practice. One of his concerns centered on driving diastolic pressure low with aggressive antihypertensive treatment, especially in elderly patients with underlying coronary artery disease who could have inadequate coronary perfusion if their diastolic pressure drops too low.

Another caution was the need to reconcile the SPRINT results with those from the ACCORD blood pressure trial results, which failed to show that a systolic blood pressure target of less than 120 mm Hg led to better outcomes than did a target of less than 140 mm Hg in patients with diabetes. Although SPRINT specifically excluded patients with diabetes, a helpful analysis that the SPRINT data should allow is assessment of outcomes in patients who were obese and had hyperlipidemia as well as hypertension, defining a subgroup of patients with metabolic syndrome that is considered a prediabetes state.

Dr. Deedwania also warned that so far researchers have not reported the SPRINT results in patients with preexisting renal dysfunction compared with patients with more normal kidney function. Patients with impaired renal function can be in jeopardy if their blood pressure gets too low, he noted.

Dr. Deedwania had no disclosures.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

ORLANDO – SPRINT’s hypertension-treatment results serve as a rebuttal to the systolic blood pressure target of less than 150 mm Hg for older patients set less than 2 years ago by the panel originally constituted as JNC 8, Dr. Prakash Deedwania said in an interview at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

“We were all concerned” by the high target systolic blood pressure for patients aged 60 years or older set by the panel initially organized as JNC 8, said Dr. Deedwania, professor of medicine at the University of California, San Francisco, in Fresno. The SPRINT results, which showed incremental value for a systolic blood pressure target of less than 120 mm Hg for selected patients at risk for cardiovascular disease, will influence the new hypertension-treatment guidelines now in development by a panel formed by the American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association, he said.

While applauding SPRINT (Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial) and its clear outcome, Dr. Deedwania cited several cautions to keep in mind when applying the results to practice. One of his concerns centered on driving diastolic pressure low with aggressive antihypertensive treatment, especially in elderly patients with underlying coronary artery disease who could have inadequate coronary perfusion if their diastolic pressure drops too low.

Another caution was the need to reconcile the SPRINT results with those from the ACCORD blood pressure trial results, which failed to show that a systolic blood pressure target of less than 120 mm Hg led to better outcomes than did a target of less than 140 mm Hg in patients with diabetes. Although SPRINT specifically excluded patients with diabetes, a helpful analysis that the SPRINT data should allow is assessment of outcomes in patients who were obese and had hyperlipidemia as well as hypertension, defining a subgroup of patients with metabolic syndrome that is considered a prediabetes state.

Dr. Deedwania also warned that so far researchers have not reported the SPRINT results in patients with preexisting renal dysfunction compared with patients with more normal kidney function. Patients with impaired renal function can be in jeopardy if their blood pressure gets too low, he noted.

Dr. Deedwania had no disclosures.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

ORLANDO – SPRINT’s hypertension-treatment results serve as a rebuttal to the systolic blood pressure target of less than 150 mm Hg for older patients set less than 2 years ago by the panel originally constituted as JNC 8, Dr. Prakash Deedwania said in an interview at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

“We were all concerned” by the high target systolic blood pressure for patients aged 60 years or older set by the panel initially organized as JNC 8, said Dr. Deedwania, professor of medicine at the University of California, San Francisco, in Fresno. The SPRINT results, which showed incremental value for a systolic blood pressure target of less than 120 mm Hg for selected patients at risk for cardiovascular disease, will influence the new hypertension-treatment guidelines now in development by a panel formed by the American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association, he said.

While applauding SPRINT (Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial) and its clear outcome, Dr. Deedwania cited several cautions to keep in mind when applying the results to practice. One of his concerns centered on driving diastolic pressure low with aggressive antihypertensive treatment, especially in elderly patients with underlying coronary artery disease who could have inadequate coronary perfusion if their diastolic pressure drops too low.

Another caution was the need to reconcile the SPRINT results with those from the ACCORD blood pressure trial results, which failed to show that a systolic blood pressure target of less than 120 mm Hg led to better outcomes than did a target of less than 140 mm Hg in patients with diabetes. Although SPRINT specifically excluded patients with diabetes, a helpful analysis that the SPRINT data should allow is assessment of outcomes in patients who were obese and had hyperlipidemia as well as hypertension, defining a subgroup of patients with metabolic syndrome that is considered a prediabetes state.

Dr. Deedwania also warned that so far researchers have not reported the SPRINT results in patients with preexisting renal dysfunction compared with patients with more normal kidney function. Patients with impaired renal function can be in jeopardy if their blood pressure gets too low, he noted.

Dr. Deedwania had no disclosures.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE AHA SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS

AHA: Sacubitril/valsartan cuts heart failure hospital readmissions

ORLANDO – The combined formulation of sacubitril and valsartan substantially cut the rate of 30-day heart failure rehospitalizations, trimming the control rate by 38% in an analysis of data from the PARADIGM-HF trial, Dr. Scott D. Solomon reported at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

This is an especially meaningful additional benefit for heart failure patients who take sacubitril/valsartan (Entresto) in place of enalapril or similar drugs because heart failure rehospitalizations have become a closely tracked metric for U.S. hospitals.

The sacubitril/valsartan combination received Food and Drug Administration approval last summer for treating chronic heart failure with reduced ejection fraction on the strength of results from PARADIGM-HF, which showed the two-drug combination substantially cut the rate of cardiovascular death and heart failure hospitalizations, compared with enalapril (N Engl J Med. 2014 Sep 11;371:993-1004).

“The data suggest that chronic heart failure patients treated with sacubitril/valsartan relative to enalapril are less likely to be initially hospitalized, and subsequent to discharge are less likely to return to the hospital within 30 days, thereby reducing the risk to patients and the potential financial burden to the health care system,” said Dr. Solomon, professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and director of noninvasive cardiology at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

This finding may help spur faster adoption of sacubitril/valsartan as the top drug for treating the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system in heart failure patients, commented Dr. Adrian F. Hernandez, professor and heart failure specialist at Duke University in Durham, N.C. “The fact that you can derive an early clinical benefit” that becomes an early financial benefit should help counter the higher cost for sacubitril/valsartan, compared with generic ACE inhibitors and angiotensin-receptor blockers, he said in an interview. Health system administrators “face an issue when they can only look at long-term horizons. But data like these, with the early benefit of reduced readmissions” make it easier to justify paying a higher drug cost. Health care systems increasingly focus on treatments that can produce rapid benefits, both clinically and financially, said Dr. Hernandez, director of health services and outcomes research at Duke.

In fact, a cost-effectiveness analysis of sacubitril/valsartan treatment in PARADIGM-HF that included the hospital readmissions data showed that the combined formulation was “highly cost effective,” compared with enalapril, said Dr. Solomon, who added that he and his associates will have a full report on this in 2016.

“Not only does sacubitril/valsartan reduce mortality and hospital admissions, but it also reduced readmissions. That is very exciting. This is one of the few treatments to have this effect”, commented Dr. Jennifer Thibodeau, medical director of the heart failure disease management program at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas. The 38% reduction in total heart failure readmissions, compared with enalapril, and the 44% reduction in number of patients with a 30-day readmission was “pretty good,” she said in an interview. “Anything that could reduce readmissions that much is pretty good.” Plus, clinicians have already been quite excited about sacubitril/valsartan based on the primary-endpoint benefits it showed in PARADIGM-HF, “although there is always caution when a drug is brand new,” she added.

Since U.S. marketing for sacubitril/valsartan began last summer, “there has not been a big rush to adopt it,” primarily out of the usual concerns about new agents. “As we continue to see findings like these [reduced readmissions], there will be [substantial] adoption of this drug. The new findings definitely add to its attraction.” Dr. Thibodeau said.

The two subgroups of patients who had heart failure hospitalizations in PARADIGM-HF, the 675 patients in the sacubitril/valsartan arm and the 775 in the enalapril arm, closely matched each other for virtually all demographic and clinical parameters aside from history of atrial fibrillation, which was significantly more common in the enalapril patients. Even though these two subgroups had not been randomized, the near uniform consistency of their profiles made this “a valid analysis,” Dr. Solomon said. Overall, 20% of the PARADIGM-HF patients who had a heart failure hospitalization had a rehospitalization for any cause within 30 days.

The 30-day heart failure readmission rate was 10% among patients on sacubitril/valsartan and 13% among those on enalapril, a 38% relative risk reduction that was statistically significant. The number of patients with a heart failure readmission was 44% lower in the group on the combined formulation. After 60 days, readmissions for any cause were 23% lower in the sacubitril/valsartan arm, compared with enalapril, and the combined formulation dropped the number with any 60-day readmission by 30%, he reported.

Sacubitril/valsartan patients also had significantly fewer 30-day rehospitalizations of any kind, compared with the enalapril patients, whether based on investigator-reported rehospitalizations, first rehospitalizations only, or rehospitalizations confirmed by a clinical evaluation committee. Adjustments for baseline characteristics also did not affect the findings.

PARADIGM-HF was sponsored by Novartis, the company marketing sacubitril/valsartan (Entresto). Dr. Solomon has been a consultant to and has received research support from Novartis. Dr. Hernandez has received honoraria and research support from Novartis and from several other companies. Dr. Thibodeau had no financial disclosures.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

ORLANDO – The combined formulation of sacubitril and valsartan substantially cut the rate of 30-day heart failure rehospitalizations, trimming the control rate by 38% in an analysis of data from the PARADIGM-HF trial, Dr. Scott D. Solomon reported at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.