User login

Mitchel is a reporter for MDedge based in the Philadelphia area. He started with the company in 1992, when it was International Medical News Group (IMNG), and has since covered a range of medical specialties. Mitchel trained as a virologist at Roswell Park Memorial Institute in Buffalo, and then worked briefly as a researcher at Boston Children's Hospital before pivoting to journalism as a AAAS Mass Media Fellow in 1980. His first reporting job was with Science Digest magazine, and from the mid-1980s to early-1990s he was a reporter with Medical World News. @mitchelzoler

Yoga Performs Like Pulmonary Rehab for COPD Patients

MONTREAL – A structured regimen of regular yoga exercises was as effective as a standard pulmonary rehabilitation program in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease for improving lung function, exercise tolerance, dyspnea severity, and quality of life in a single-center, randomized comparison of the two strategies with 60 patients.

In addition, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) patients had a higher level of acceptance of yoga and were more comfortable doing it, compared with standard pulmonary rehabilitation, and it is a cost-effective approach given the minimal equipment required, Dr. Randeep Guleria said at the annual meeting of the American College of Chest Physicians.

“Patients with difficulty walking, osteoarthritis, knee problems, or unable to do exercises like cycling or treadmill found yoga to be much more acceptable,” said Dr. Guleria in an interview. Acceptance of yoga was also higher than standard rehabilitation among patients with more severe COPD, said Dr. Guleria, professor and head of the department of pulmonary medicine and sleep disorders at the All India Institute of Medical Sciences in New Delhi.

“I think that yoga could be a very valuable adjunct” to pulmonary rehabilitation in COPD patients, commented Dr. Roger S. Goldstein, director of the divisional program in respiratory rehabilitation at the University of Toronto. Dr. Goldstein speculated that even better than comparing yoga against conventional pulmonary rehabilitation would be a study that compared a combined yoga plus rehabilitation program against standard rehabilitation alone. Yoga is “a tremendous opportunity,” he said.

The 12-week study enrolled 60 patients who averaged 56 years old who had been diagnosed with COPD for an average of 8 years. Just under a third of the patients had moderate COPD, 42% had severe COPD, and 28% had very severe COPD.

Dr. Guleria and his associates randomized 30 patients into a yoga program that included 4 weeks of biweekly 1-hour sessions that instructed patients in a series of specially designed yoga exercises. That was followed by 8 weeks during which patients were mostly left to perform their learned exercises on their own, but with a supervised session once every 2 weeks. The other 30 patients participated in a standard pulmonary rehabilitation program for 12 weeks.

The researchers measured several parameters at baseline and after 12 weeks, including two measures of dyspnea severity, 6-minute walk distance, a quality of life assessment, and two serum markers of inflammation, C-reactive protein and interleukin 6.

Both interventions resulted in modest but statistically significant improvements, such as increases in 6-minute walk distance and a reduced modified Borg scale assessment. The Borg scale score fell from an average of 1.5 at baseline to 1.0 after 12 weeks in the yoga patients, and from an average 3.0 at baseline to 0.5 after 12 weeks in the rehabilitation patients.

A score that measured total quality of life improved by an average of 32% in the yoga patients and by an average of 21% in the rehabilitation patients, changes that approached statistical significance in both subgroups.

Comparing the assessment measures after 12 weeks in both arms of the study showed no statistically significant between-group differences, Dr. Guleria reported.

The researchers commissioned a specially designed yoga program from a professional yoga instructor who had been briefed about COPD. The yoga exercises included physical postures, breathing technique, and meditation and relaxation. The pulmonary rehabilitation program included patient education, upper and lower limb exercises, and breathing exercises.

Dr. Guleria said he believed the opportunity exists to further modify the yoga program to better optimize its potential to benefit COPD patients.

Dr. Guleria had no relevant disclosures. Dr. Goldstein had no relevant disclosures.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

On Twitter@mitchelzoler

MONTREAL – A structured regimen of regular yoga exercises was as effective as a standard pulmonary rehabilitation program in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease for improving lung function, exercise tolerance, dyspnea severity, and quality of life in a single-center, randomized comparison of the two strategies with 60 patients.

In addition, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) patients had a higher level of acceptance of yoga and were more comfortable doing it, compared with standard pulmonary rehabilitation, and it is a cost-effective approach given the minimal equipment required, Dr. Randeep Guleria said at the annual meeting of the American College of Chest Physicians.

“Patients with difficulty walking, osteoarthritis, knee problems, or unable to do exercises like cycling or treadmill found yoga to be much more acceptable,” said Dr. Guleria in an interview. Acceptance of yoga was also higher than standard rehabilitation among patients with more severe COPD, said Dr. Guleria, professor and head of the department of pulmonary medicine and sleep disorders at the All India Institute of Medical Sciences in New Delhi.

“I think that yoga could be a very valuable adjunct” to pulmonary rehabilitation in COPD patients, commented Dr. Roger S. Goldstein, director of the divisional program in respiratory rehabilitation at the University of Toronto. Dr. Goldstein speculated that even better than comparing yoga against conventional pulmonary rehabilitation would be a study that compared a combined yoga plus rehabilitation program against standard rehabilitation alone. Yoga is “a tremendous opportunity,” he said.

The 12-week study enrolled 60 patients who averaged 56 years old who had been diagnosed with COPD for an average of 8 years. Just under a third of the patients had moderate COPD, 42% had severe COPD, and 28% had very severe COPD.

Dr. Guleria and his associates randomized 30 patients into a yoga program that included 4 weeks of biweekly 1-hour sessions that instructed patients in a series of specially designed yoga exercises. That was followed by 8 weeks during which patients were mostly left to perform their learned exercises on their own, but with a supervised session once every 2 weeks. The other 30 patients participated in a standard pulmonary rehabilitation program for 12 weeks.

The researchers measured several parameters at baseline and after 12 weeks, including two measures of dyspnea severity, 6-minute walk distance, a quality of life assessment, and two serum markers of inflammation, C-reactive protein and interleukin 6.

Both interventions resulted in modest but statistically significant improvements, such as increases in 6-minute walk distance and a reduced modified Borg scale assessment. The Borg scale score fell from an average of 1.5 at baseline to 1.0 after 12 weeks in the yoga patients, and from an average 3.0 at baseline to 0.5 after 12 weeks in the rehabilitation patients.

A score that measured total quality of life improved by an average of 32% in the yoga patients and by an average of 21% in the rehabilitation patients, changes that approached statistical significance in both subgroups.

Comparing the assessment measures after 12 weeks in both arms of the study showed no statistically significant between-group differences, Dr. Guleria reported.

The researchers commissioned a specially designed yoga program from a professional yoga instructor who had been briefed about COPD. The yoga exercises included physical postures, breathing technique, and meditation and relaxation. The pulmonary rehabilitation program included patient education, upper and lower limb exercises, and breathing exercises.

Dr. Guleria said he believed the opportunity exists to further modify the yoga program to better optimize its potential to benefit COPD patients.

Dr. Guleria had no relevant disclosures. Dr. Goldstein had no relevant disclosures.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

On Twitter@mitchelzoler

MONTREAL – A structured regimen of regular yoga exercises was as effective as a standard pulmonary rehabilitation program in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease for improving lung function, exercise tolerance, dyspnea severity, and quality of life in a single-center, randomized comparison of the two strategies with 60 patients.

In addition, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) patients had a higher level of acceptance of yoga and were more comfortable doing it, compared with standard pulmonary rehabilitation, and it is a cost-effective approach given the minimal equipment required, Dr. Randeep Guleria said at the annual meeting of the American College of Chest Physicians.

“Patients with difficulty walking, osteoarthritis, knee problems, or unable to do exercises like cycling or treadmill found yoga to be much more acceptable,” said Dr. Guleria in an interview. Acceptance of yoga was also higher than standard rehabilitation among patients with more severe COPD, said Dr. Guleria, professor and head of the department of pulmonary medicine and sleep disorders at the All India Institute of Medical Sciences in New Delhi.

“I think that yoga could be a very valuable adjunct” to pulmonary rehabilitation in COPD patients, commented Dr. Roger S. Goldstein, director of the divisional program in respiratory rehabilitation at the University of Toronto. Dr. Goldstein speculated that even better than comparing yoga against conventional pulmonary rehabilitation would be a study that compared a combined yoga plus rehabilitation program against standard rehabilitation alone. Yoga is “a tremendous opportunity,” he said.

The 12-week study enrolled 60 patients who averaged 56 years old who had been diagnosed with COPD for an average of 8 years. Just under a third of the patients had moderate COPD, 42% had severe COPD, and 28% had very severe COPD.

Dr. Guleria and his associates randomized 30 patients into a yoga program that included 4 weeks of biweekly 1-hour sessions that instructed patients in a series of specially designed yoga exercises. That was followed by 8 weeks during which patients were mostly left to perform their learned exercises on their own, but with a supervised session once every 2 weeks. The other 30 patients participated in a standard pulmonary rehabilitation program for 12 weeks.

The researchers measured several parameters at baseline and after 12 weeks, including two measures of dyspnea severity, 6-minute walk distance, a quality of life assessment, and two serum markers of inflammation, C-reactive protein and interleukin 6.

Both interventions resulted in modest but statistically significant improvements, such as increases in 6-minute walk distance and a reduced modified Borg scale assessment. The Borg scale score fell from an average of 1.5 at baseline to 1.0 after 12 weeks in the yoga patients, and from an average 3.0 at baseline to 0.5 after 12 weeks in the rehabilitation patients.

A score that measured total quality of life improved by an average of 32% in the yoga patients and by an average of 21% in the rehabilitation patients, changes that approached statistical significance in both subgroups.

Comparing the assessment measures after 12 weeks in both arms of the study showed no statistically significant between-group differences, Dr. Guleria reported.

The researchers commissioned a specially designed yoga program from a professional yoga instructor who had been briefed about COPD. The yoga exercises included physical postures, breathing technique, and meditation and relaxation. The pulmonary rehabilitation program included patient education, upper and lower limb exercises, and breathing exercises.

Dr. Guleria said he believed the opportunity exists to further modify the yoga program to better optimize its potential to benefit COPD patients.

Dr. Guleria had no relevant disclosures. Dr. Goldstein had no relevant disclosures.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

On Twitter@mitchelzoler

AT CHEST 2015

AES: Many U.S. epilepsy patients receive suboptimal treatment

PHILADELPHIA – Roughly half of U.S. patients newly diagnosed with epilepsy fail to receive a stable and effective treatment that keeps them seizure free during the first year following their diagnosis, according to an analysis of more than 17,000 incident epilepsy cases who received documented treatment with antiepileptic drugs and had at least 1 year of follow-up.

“Under the best health care circumstances, we can achieve full seizure control in two-thirds to 70% of patients, but the fact that we fall way short points to a treatment gap,” said Dr. David J. Thurman, a neurologist and epilepsy specialist who practices in Atlanta and is affiliated with Emory University. “We’re doing a lousy job,” he said in an interview while presenting a poster at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society.

Dr. Thurman suggested that several factors likely contribute to epilepsy patients receiving less than ideal care, including their access to neurologists and epilepsy subspecialists, patients’ ability to afford the drugs they need to control their seizures, and social limitations, such as the ability to travel to see specialists.

He cited a recent study he and his associates published that documented these barriers. They analyzed data collected from U.S. adults in 2010 and 2013 by the National Health Interview Survey run by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. That analysis showed that, when compared with the general U.S. adult population, people diagnosed with epilepsy were significantly less likely to be employed and more likely to be disabled. The epilepsy patients also reported relatively higher rates of inability to afford their medications, mental health care, eyeglasses, and dental care, and the patients also reported a relatively high rate of having transportation to health care as a barrier to receiving their care (Epilepsy Behav. 2015 Nov 25. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2015.10.028). CDC data also showed that in 2010, 42% of U.S. adults with epilepsy and uncontrolled seizures had not been seen by a neurologist or epilepsy specialist during the preceding year.

The new report presented by Dr, Thurman at the meeting used U.S. claims data from patients of any age with private insurance or coverage through Medicare or Medicaid contained in the Truven Health Marketscan database during January 2011–June 2013. They identified 36,035 patients who appeared to have newly diagnosed epilepsy, of whom 17,106 received documented treatment for epilepsy during at least 1 year following their diagnosis. About a quarter of these patients had focal epilepsy, about a quarter generalized epilepsy, and about half had undefined epilepsy.

Among these 17,106 patients, 8,835 (52%) appeared to attain “treatment stability,” which the researchers defined as no changes in their antiepileptic drug regimen and no epilepsy-related hospitalizations in either the emergency department or as inpatients. About 42% of the patients reached stability with their first antiepileptic drug, another 6% reached stability with their second drug, and about 3% with their third drug, the researchers reported. The vast majority of patients who attained stability maintained it with monotherapy. Variables that linked with a greater likelihood of achieving treatment stability included older age, male sex, a history of a childhood psychiatric disorder, and having identified focal or generalized epilepsy rather than undefined epilepsy.

The study was funded by UCB. Dr. Thurman has been a consultant to and has received research funding from UCB.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

PHILADELPHIA – Roughly half of U.S. patients newly diagnosed with epilepsy fail to receive a stable and effective treatment that keeps them seizure free during the first year following their diagnosis, according to an analysis of more than 17,000 incident epilepsy cases who received documented treatment with antiepileptic drugs and had at least 1 year of follow-up.

“Under the best health care circumstances, we can achieve full seizure control in two-thirds to 70% of patients, but the fact that we fall way short points to a treatment gap,” said Dr. David J. Thurman, a neurologist and epilepsy specialist who practices in Atlanta and is affiliated with Emory University. “We’re doing a lousy job,” he said in an interview while presenting a poster at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society.

Dr. Thurman suggested that several factors likely contribute to epilepsy patients receiving less than ideal care, including their access to neurologists and epilepsy subspecialists, patients’ ability to afford the drugs they need to control their seizures, and social limitations, such as the ability to travel to see specialists.

He cited a recent study he and his associates published that documented these barriers. They analyzed data collected from U.S. adults in 2010 and 2013 by the National Health Interview Survey run by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. That analysis showed that, when compared with the general U.S. adult population, people diagnosed with epilepsy were significantly less likely to be employed and more likely to be disabled. The epilepsy patients also reported relatively higher rates of inability to afford their medications, mental health care, eyeglasses, and dental care, and the patients also reported a relatively high rate of having transportation to health care as a barrier to receiving their care (Epilepsy Behav. 2015 Nov 25. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2015.10.028). CDC data also showed that in 2010, 42% of U.S. adults with epilepsy and uncontrolled seizures had not been seen by a neurologist or epilepsy specialist during the preceding year.

The new report presented by Dr, Thurman at the meeting used U.S. claims data from patients of any age with private insurance or coverage through Medicare or Medicaid contained in the Truven Health Marketscan database during January 2011–June 2013. They identified 36,035 patients who appeared to have newly diagnosed epilepsy, of whom 17,106 received documented treatment for epilepsy during at least 1 year following their diagnosis. About a quarter of these patients had focal epilepsy, about a quarter generalized epilepsy, and about half had undefined epilepsy.

Among these 17,106 patients, 8,835 (52%) appeared to attain “treatment stability,” which the researchers defined as no changes in their antiepileptic drug regimen and no epilepsy-related hospitalizations in either the emergency department or as inpatients. About 42% of the patients reached stability with their first antiepileptic drug, another 6% reached stability with their second drug, and about 3% with their third drug, the researchers reported. The vast majority of patients who attained stability maintained it with monotherapy. Variables that linked with a greater likelihood of achieving treatment stability included older age, male sex, a history of a childhood psychiatric disorder, and having identified focal or generalized epilepsy rather than undefined epilepsy.

The study was funded by UCB. Dr. Thurman has been a consultant to and has received research funding from UCB.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

PHILADELPHIA – Roughly half of U.S. patients newly diagnosed with epilepsy fail to receive a stable and effective treatment that keeps them seizure free during the first year following their diagnosis, according to an analysis of more than 17,000 incident epilepsy cases who received documented treatment with antiepileptic drugs and had at least 1 year of follow-up.

“Under the best health care circumstances, we can achieve full seizure control in two-thirds to 70% of patients, but the fact that we fall way short points to a treatment gap,” said Dr. David J. Thurman, a neurologist and epilepsy specialist who practices in Atlanta and is affiliated with Emory University. “We’re doing a lousy job,” he said in an interview while presenting a poster at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society.

Dr. Thurman suggested that several factors likely contribute to epilepsy patients receiving less than ideal care, including their access to neurologists and epilepsy subspecialists, patients’ ability to afford the drugs they need to control their seizures, and social limitations, such as the ability to travel to see specialists.

He cited a recent study he and his associates published that documented these barriers. They analyzed data collected from U.S. adults in 2010 and 2013 by the National Health Interview Survey run by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. That analysis showed that, when compared with the general U.S. adult population, people diagnosed with epilepsy were significantly less likely to be employed and more likely to be disabled. The epilepsy patients also reported relatively higher rates of inability to afford their medications, mental health care, eyeglasses, and dental care, and the patients also reported a relatively high rate of having transportation to health care as a barrier to receiving their care (Epilepsy Behav. 2015 Nov 25. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2015.10.028). CDC data also showed that in 2010, 42% of U.S. adults with epilepsy and uncontrolled seizures had not been seen by a neurologist or epilepsy specialist during the preceding year.

The new report presented by Dr, Thurman at the meeting used U.S. claims data from patients of any age with private insurance or coverage through Medicare or Medicaid contained in the Truven Health Marketscan database during January 2011–June 2013. They identified 36,035 patients who appeared to have newly diagnosed epilepsy, of whom 17,106 received documented treatment for epilepsy during at least 1 year following their diagnosis. About a quarter of these patients had focal epilepsy, about a quarter generalized epilepsy, and about half had undefined epilepsy.

Among these 17,106 patients, 8,835 (52%) appeared to attain “treatment stability,” which the researchers defined as no changes in their antiepileptic drug regimen and no epilepsy-related hospitalizations in either the emergency department or as inpatients. About 42% of the patients reached stability with their first antiepileptic drug, another 6% reached stability with their second drug, and about 3% with their third drug, the researchers reported. The vast majority of patients who attained stability maintained it with monotherapy. Variables that linked with a greater likelihood of achieving treatment stability included older age, male sex, a history of a childhood psychiatric disorder, and having identified focal or generalized epilepsy rather than undefined epilepsy.

The study was funded by UCB. Dr. Thurman has been a consultant to and has received research funding from UCB.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

AT AES 2015

Key clinical point: A sample of newly diagnosed U.S. epilepsy patients showed about half failed to have first-year treatment stability, an indicator that many patients receive suboptimal care.

Major finding: During 2011-2013, about 52% of Americans newly diagnosed with epilepsy achieved treatment “stability.”

Data source: Retrospective review of 17,106 newly diagnosed U.S. epilepsy patients contained in the Truven Health Marketscan database.

Disclosures: The study was funded by UCB. Dr. Thurman has been a consultant to and has received research funding from UCB.

AES: Cannabidiol shows promising epilepsy safety and efficacy

PHILADELPHIA – A pharmaceutical-grade formulation of orally administered cannabidiol, a cannabis derivative, showed “very positive and promising” safety and efficacy during in an open-label, multicenter, compassionate-use U.S. program that has so far enrolled 313 children and young adults with severe and “extremely” treatment-refractory epilepsy.

In the 261 patients followed on treatment for at least 12 weeks at a total of 16 U.S. centers, patients had a median 49% reduction in their baseline number of monthly convulsant seizures, Dr. Orrin Devinsky said while presenting in a late-breaker poster at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society.

In addition, 47% of these patients had at least a 50% cut in their baseline number of monthly convulsant seizures. And during the final 4 weeks on treatment (weeks 9-12 on treatment), 9% of all patients and 13% of the 44 patients with Dravet syndrome were completely seizure free, reported Dr. Devinsky, professor of neurology and director of the Comprehensive Epilepsy Center at New York University.

“In these extremely treatment-refractory patients, these numbers [of seizure-free patients] were much greater than I would have predicted,” Dr. Devinsky said during a press conference. Although he cautioned that a more definitive assessment of the drug’s safety and efficacy will need to await reports of results from four phase III, randomized, placebo-controlled trials that are expected in 2016, “this drug will likely be effective for some patients,” he predicted. “I’m very encouraged by these results.”

The safety analysis, done using data from all 313 patients including those who had not yet received the drug for 12 weeks, showed a “generally well-tolerated” profile, with 4% of patients stopping treatment because of adverse events, 5% experiencing a serious adverse event considered treatment related, and 12% of patients withdrawing because of lack of efficacy.

In a second poster presented at the meeting, investigators at the University of California, San Francisco, one of the other centers involved in this series, reported results for 25 of these patients who they followed on continuous treatment for up to 12 months. In this subgroup, 10 patients (40%) had at least a 50% reduction in their baseline number of convulsant seizures at 12 months, and 1 patient, with Dravet syndrome, was seizure free. During 12 months of follow-up, 12 of the 25 patients discontinued treatment because of lack of efficacy, reported Dr. Michael S. Oldham, a member of the San Francisco group who is now a pediatric neurologist at the University of Louisville (Ky.).

Speaking at the same press conference, Dr. Oldham echoed Dr. Devinsky’s assessment of these uncontrolled findings using this cannabidiol formulation. “This was a significantly drug-resistant population, so the fact that we saw at least 50% seizure reductions [in about a third of patients] was remarkable,” he said. “It was exciting to see the results sustained to 12 months with no added adverse events” beyond those seen after 3 months on treatment, Dr. Oldham said in an interview.

Cannabidiol is the most abundant nonpsychoactive cannabinoid contained in cannabis, and the formulation tested in this series contains 99% cannabidiol dissolved in oil. It is being developed by GW Pharmaceuticals under the brand name Epidiolex.

The reported series enrolled patients with various types of juvenile-onset epilepsies, the most common of which was Dravet syndrome. The series also included 40 patients (15%) with Lennox-Gastaut syndrome, and 19% had epilepsy of unknown cause. The enrolled patients averaged 12 years old, ranging from 4 months to 41 years old. At entry enrolled patients averaged 139 convulsant seizures and a median of 31 convulsant seizures every 28 days. The seizure tally focused on convulsant seizures because they are the easiest to reliably identify, Dr. Devinsky noted. The enrolled patients were concurrently on an average of three other antiepileptic drugs. Patients received a gradually escalated dosage until they reached their maximally tolerated dosage or a maximum of 50 mg/kg/day.

The four phase III trials expected to have results reported in 2016 include two that have enrolled patients with Dravet syndrome and two that have enrolled patients with Lennox-Gastaut syndrome. If the tested cannabidiol formulation continues to show good safety and efficacy in those studies and enters the U.S. market, its use will likely gradually expand, first to patients with other severe and drug-refractory forms of epilepsy and then, as experience further grows, to use in less drug-refractory patients, Dr. Devinsky predicted. Both Dr. Devinsky and Dr. Oldham noted that they have heard from several parents who are eager to put their children with milder forms of epilepsy on this formulation, but Dr. Devinsky cautioned that it is much too soon in the drug’s development to consider taking that step.

Other posters presented at the meeting reported promising efficacy and safety results from small series of pediatric patients with specific, refractory epilepsy syndromes, including 10 children and adolescents with epilepsy in tuberous sclerosis complex, and 9 children and adolescents with refractory epileptic spasms. Both of these studies were run at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston.

The study received research funding from GW Pharmaceuticals, the company developing the tested formulation of cannabidiol (Epidiolex). Dr. Devinsky and Dr. Oldham had no personal disclosures.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

PHILADELPHIA – A pharmaceutical-grade formulation of orally administered cannabidiol, a cannabis derivative, showed “very positive and promising” safety and efficacy during in an open-label, multicenter, compassionate-use U.S. program that has so far enrolled 313 children and young adults with severe and “extremely” treatment-refractory epilepsy.

In the 261 patients followed on treatment for at least 12 weeks at a total of 16 U.S. centers, patients had a median 49% reduction in their baseline number of monthly convulsant seizures, Dr. Orrin Devinsky said while presenting in a late-breaker poster at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society.

In addition, 47% of these patients had at least a 50% cut in their baseline number of monthly convulsant seizures. And during the final 4 weeks on treatment (weeks 9-12 on treatment), 9% of all patients and 13% of the 44 patients with Dravet syndrome were completely seizure free, reported Dr. Devinsky, professor of neurology and director of the Comprehensive Epilepsy Center at New York University.

“In these extremely treatment-refractory patients, these numbers [of seizure-free patients] were much greater than I would have predicted,” Dr. Devinsky said during a press conference. Although he cautioned that a more definitive assessment of the drug’s safety and efficacy will need to await reports of results from four phase III, randomized, placebo-controlled trials that are expected in 2016, “this drug will likely be effective for some patients,” he predicted. “I’m very encouraged by these results.”

The safety analysis, done using data from all 313 patients including those who had not yet received the drug for 12 weeks, showed a “generally well-tolerated” profile, with 4% of patients stopping treatment because of adverse events, 5% experiencing a serious adverse event considered treatment related, and 12% of patients withdrawing because of lack of efficacy.

In a second poster presented at the meeting, investigators at the University of California, San Francisco, one of the other centers involved in this series, reported results for 25 of these patients who they followed on continuous treatment for up to 12 months. In this subgroup, 10 patients (40%) had at least a 50% reduction in their baseline number of convulsant seizures at 12 months, and 1 patient, with Dravet syndrome, was seizure free. During 12 months of follow-up, 12 of the 25 patients discontinued treatment because of lack of efficacy, reported Dr. Michael S. Oldham, a member of the San Francisco group who is now a pediatric neurologist at the University of Louisville (Ky.).

Speaking at the same press conference, Dr. Oldham echoed Dr. Devinsky’s assessment of these uncontrolled findings using this cannabidiol formulation. “This was a significantly drug-resistant population, so the fact that we saw at least 50% seizure reductions [in about a third of patients] was remarkable,” he said. “It was exciting to see the results sustained to 12 months with no added adverse events” beyond those seen after 3 months on treatment, Dr. Oldham said in an interview.

Cannabidiol is the most abundant nonpsychoactive cannabinoid contained in cannabis, and the formulation tested in this series contains 99% cannabidiol dissolved in oil. It is being developed by GW Pharmaceuticals under the brand name Epidiolex.

The reported series enrolled patients with various types of juvenile-onset epilepsies, the most common of which was Dravet syndrome. The series also included 40 patients (15%) with Lennox-Gastaut syndrome, and 19% had epilepsy of unknown cause. The enrolled patients averaged 12 years old, ranging from 4 months to 41 years old. At entry enrolled patients averaged 139 convulsant seizures and a median of 31 convulsant seizures every 28 days. The seizure tally focused on convulsant seizures because they are the easiest to reliably identify, Dr. Devinsky noted. The enrolled patients were concurrently on an average of three other antiepileptic drugs. Patients received a gradually escalated dosage until they reached their maximally tolerated dosage or a maximum of 50 mg/kg/day.

The four phase III trials expected to have results reported in 2016 include two that have enrolled patients with Dravet syndrome and two that have enrolled patients with Lennox-Gastaut syndrome. If the tested cannabidiol formulation continues to show good safety and efficacy in those studies and enters the U.S. market, its use will likely gradually expand, first to patients with other severe and drug-refractory forms of epilepsy and then, as experience further grows, to use in less drug-refractory patients, Dr. Devinsky predicted. Both Dr. Devinsky and Dr. Oldham noted that they have heard from several parents who are eager to put their children with milder forms of epilepsy on this formulation, but Dr. Devinsky cautioned that it is much too soon in the drug’s development to consider taking that step.

Other posters presented at the meeting reported promising efficacy and safety results from small series of pediatric patients with specific, refractory epilepsy syndromes, including 10 children and adolescents with epilepsy in tuberous sclerosis complex, and 9 children and adolescents with refractory epileptic spasms. Both of these studies were run at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston.

The study received research funding from GW Pharmaceuticals, the company developing the tested formulation of cannabidiol (Epidiolex). Dr. Devinsky and Dr. Oldham had no personal disclosures.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

PHILADELPHIA – A pharmaceutical-grade formulation of orally administered cannabidiol, a cannabis derivative, showed “very positive and promising” safety and efficacy during in an open-label, multicenter, compassionate-use U.S. program that has so far enrolled 313 children and young adults with severe and “extremely” treatment-refractory epilepsy.

In the 261 patients followed on treatment for at least 12 weeks at a total of 16 U.S. centers, patients had a median 49% reduction in their baseline number of monthly convulsant seizures, Dr. Orrin Devinsky said while presenting in a late-breaker poster at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society.

In addition, 47% of these patients had at least a 50% cut in their baseline number of monthly convulsant seizures. And during the final 4 weeks on treatment (weeks 9-12 on treatment), 9% of all patients and 13% of the 44 patients with Dravet syndrome were completely seizure free, reported Dr. Devinsky, professor of neurology and director of the Comprehensive Epilepsy Center at New York University.

“In these extremely treatment-refractory patients, these numbers [of seizure-free patients] were much greater than I would have predicted,” Dr. Devinsky said during a press conference. Although he cautioned that a more definitive assessment of the drug’s safety and efficacy will need to await reports of results from four phase III, randomized, placebo-controlled trials that are expected in 2016, “this drug will likely be effective for some patients,” he predicted. “I’m very encouraged by these results.”

The safety analysis, done using data from all 313 patients including those who had not yet received the drug for 12 weeks, showed a “generally well-tolerated” profile, with 4% of patients stopping treatment because of adverse events, 5% experiencing a serious adverse event considered treatment related, and 12% of patients withdrawing because of lack of efficacy.

In a second poster presented at the meeting, investigators at the University of California, San Francisco, one of the other centers involved in this series, reported results for 25 of these patients who they followed on continuous treatment for up to 12 months. In this subgroup, 10 patients (40%) had at least a 50% reduction in their baseline number of convulsant seizures at 12 months, and 1 patient, with Dravet syndrome, was seizure free. During 12 months of follow-up, 12 of the 25 patients discontinued treatment because of lack of efficacy, reported Dr. Michael S. Oldham, a member of the San Francisco group who is now a pediatric neurologist at the University of Louisville (Ky.).

Speaking at the same press conference, Dr. Oldham echoed Dr. Devinsky’s assessment of these uncontrolled findings using this cannabidiol formulation. “This was a significantly drug-resistant population, so the fact that we saw at least 50% seizure reductions [in about a third of patients] was remarkable,” he said. “It was exciting to see the results sustained to 12 months with no added adverse events” beyond those seen after 3 months on treatment, Dr. Oldham said in an interview.

Cannabidiol is the most abundant nonpsychoactive cannabinoid contained in cannabis, and the formulation tested in this series contains 99% cannabidiol dissolved in oil. It is being developed by GW Pharmaceuticals under the brand name Epidiolex.

The reported series enrolled patients with various types of juvenile-onset epilepsies, the most common of which was Dravet syndrome. The series also included 40 patients (15%) with Lennox-Gastaut syndrome, and 19% had epilepsy of unknown cause. The enrolled patients averaged 12 years old, ranging from 4 months to 41 years old. At entry enrolled patients averaged 139 convulsant seizures and a median of 31 convulsant seizures every 28 days. The seizure tally focused on convulsant seizures because they are the easiest to reliably identify, Dr. Devinsky noted. The enrolled patients were concurrently on an average of three other antiepileptic drugs. Patients received a gradually escalated dosage until they reached their maximally tolerated dosage or a maximum of 50 mg/kg/day.

The four phase III trials expected to have results reported in 2016 include two that have enrolled patients with Dravet syndrome and two that have enrolled patients with Lennox-Gastaut syndrome. If the tested cannabidiol formulation continues to show good safety and efficacy in those studies and enters the U.S. market, its use will likely gradually expand, first to patients with other severe and drug-refractory forms of epilepsy and then, as experience further grows, to use in less drug-refractory patients, Dr. Devinsky predicted. Both Dr. Devinsky and Dr. Oldham noted that they have heard from several parents who are eager to put their children with milder forms of epilepsy on this formulation, but Dr. Devinsky cautioned that it is much too soon in the drug’s development to consider taking that step.

Other posters presented at the meeting reported promising efficacy and safety results from small series of pediatric patients with specific, refractory epilepsy syndromes, including 10 children and adolescents with epilepsy in tuberous sclerosis complex, and 9 children and adolescents with refractory epileptic spasms. Both of these studies were run at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston.

The study received research funding from GW Pharmaceuticals, the company developing the tested formulation of cannabidiol (Epidiolex). Dr. Devinsky and Dr. Oldham had no personal disclosures.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

AT AES 2015

Key clinical point: Children and young adults with various severe and treatment-refractory forms of epilepsy who received a pharmaceutical-grade oral cannabidiol formulation showed promising safety and efficacy outcomes during 12 weeks of open-label treatment.

Major finding: After 12 weeks, convulsant seizures dropped from baseline numbers by a median of 49%.

Data source: An open-label series of 313 patients enrolled at any of 16 U.S. centers.

Disclosures: The study received research funding from GW Pharmaceuticals, the company developing the tested formulation of cannabidiol (Epidiolex). Dr. Devinsky and Dr. Oldham had no personal disclosures.

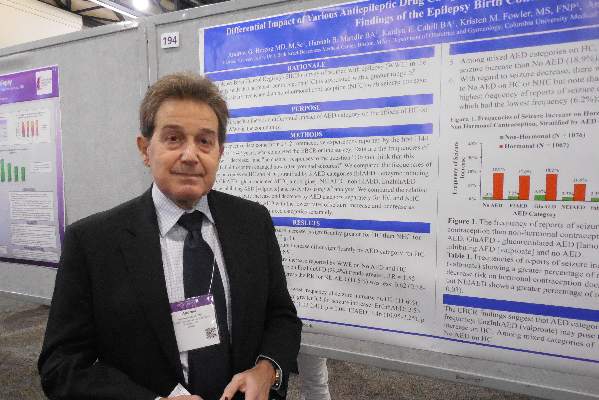

AES: Hormonal contraceptives can boost seizures in epileptics

PHILADELPHIA – Women with epilepsy often reported having an increased number of seizures when taking a hormonal contraceptive, according to data collected from 1,144 women with epilepsy who completed an online survey.

The data showed that women who used hormonal contraception reported having an increased number of seizures while on the contraceptive about 4.5-fold more often than did women who used nonhormonal contraception. The risk for an increased number of seizures with hormonal contraception seemed greatest for women treated with valproate.

Until now, “valproate was generally accepted as okay to use” by women also taking a hormonal contraceptive, but the new findings suggest that if a woman of childbearing age with epilepsy needs valproate for seizure control she would be better off using a nonhormonal form of contraception such as an intrauterine device, Dr. Andrew G. Herzog said while presenting a poster at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society.

Dr. Herzog highlighted the need for some form of contraception for most younger women on valproate because of the drug’s potential teratogenic effects, but he also stressed that the risk for increased seizures does not appear to affect a majority of women. The survey results showed that overall only 28% of women with epilepsy reported an increased seizure frequency when using a hormonal contraceptive.

“The first goal of a neurologist is to get seizures under control, and you go with the [antiepileptic drugs] that work,” Dr. Herzog said in an interview. Once an effective regimen is found, the physician can then deal with other issues, such as adverse effects as well as the potential for an adverse interaction with a hormonal contraceptive. Valproate can be the antiepileptic drug of choice as it is one of the most effective agents for controlling seizures in patients with primary generalized epilepsy, said Dr. Herzog, professor of neurology at Harvard Medical School, Boston, and director of the neuroendocrine unit of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Wellesley, Mass.

The new data come from an Internet-based survey, which is subject to biases and appeared to attract a preponderance of responses from women who were better educated and had higher incomes than did the general population. In addition, the researchers collected the data retrospectively. Despite these limitations, the results are notable because they represent the only data set yet reported from a community-based source large enough to allow analysis of the many clinical variables that play into the potential interactions between various contraceptive types, various antiepileptic drug classes, and the diverse number of epilepsy subtypes, he said. Dr. Herzog and his associates are planning a study to collect similar data prospectively, but the results would likely not be available for at least about 5 years, he noted.

The Epilepsy Birth Control Registry enrolled women with epilepsy aged 18-47 years who had a history of using at least one form of contraception while on antiepileptic treatment, and the 1,144 women who completed the survey reported a total of 2,712 contraceptive experiences. The survey asked women, “Do you think this method of birth control changed how often you had seizures?” with the option to reply that their contraceptive method seemed to increase, decrease, or not change their seizure number.

One of the analyses done by Dr. Herzog and his associates compared the responses by women on any form of hormonal contraceptive (combined or progestin pill, hormonal patch, vaginal ring, depot medroxyprogesterone acetate, or implanted hormone) with women on any form of nonhormonal contraception (withdrawal, male or female condom, copper or progestin intrauterine device, or tubal ligation).

The results showed that 72% of women on any hormonal contraceptive and 91% of women on any form of nonhormonal contraceptive reported no change in their seizure frequency. The rates of reporting an increased number of seizures were 19% with hormonal contraceptives and 4% with nonhormonal contraceptives, which computed to a relative risk of about 4.5-fold for an increased number of seizures while on hormonal contraception, compared with nonhormonal contraception, the researchers reported.

Barrier contraception (male or female condoms) had the lowest rate of seizure increase among any of the nonhormonal methods. The risk for greater seizure frequency on hormonal contraceptives of all types was 6.75-fold higher when compared specifically with barrier contraception.

In analyses of specific types of hormonal contraceptives, women using a hormonal patch reported a 68% greater incidence of seizure increases, compared with women using combined oral contraceptive pills (the hormonal method that produced the fewest episodes of seizure increases). Those using a progestin-only pill had a 62% higher rate of seizure increases.

More women on hormonal contraceptives also reported having a decrease in seizures after starting contraception, compared with those starting on a nonhormonal method (9.5% vs. 5.2%, respectively), which calculated to a 85% relative rate increase for decreased seizures. Depot medroxyprogesterone acetate was the only specific hormonal contraceptive that linked with a higher rate of seizure decreases, compared with combined oral pills, a 95% higher rate.

A second analysis of the results by Dr. Herzog and his associates examined the frequencies of seizure outcomes on hormonal and nonhormonal contraceptives stratifying by type of antiepileptic drug women used when starting a particular contraceptive method. This analysis broke down antiepileptic drugs into four types: enzyme inducing (29%), glucuronidated (such as lamotrigine; 27%), nonenzyme inducing (such as levetiracetam; 22%), enzyme inhibiting (valproate; 8%), and a fifth category that included women who were not on any antiepileptic drug (14%).

This analysis showed that the frequency of seizure increases was significantly greater with hormonal contraceptive use, compared with nonhormonal methods, across all five subgroups of antiepileptic drug type. In addition, the frequency of seizure increases with hormonal contraceptives differed significantly, depending on which antiepileptic drug type women used, but these significant differences among the antiepileptic drug types also occurred among women using nonhormonal contraception.

Women receiving a nonenzyme-inducing drug when starting a hormonal contraceptive reported the lowest frequency of seizure increases, a 12% rate. In contrast, women on an enzyme-inhibiting drug, valproate, had the highest rate of increased seizures when starting a hormonal contraceptive, 29%. This calculated out to about a 2.5-fold relative risk increase for having more seizures when starting hormonal contraception while on valproate, compared with women on a nonenzyme-inducing drug, Dr. Herzog reported.

Physicians “need to be on the lookout for the possibility that seizures could increase when women start a hormonal contraceptive,” he concluded.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

PHILADELPHIA – Women with epilepsy often reported having an increased number of seizures when taking a hormonal contraceptive, according to data collected from 1,144 women with epilepsy who completed an online survey.

The data showed that women who used hormonal contraception reported having an increased number of seizures while on the contraceptive about 4.5-fold more often than did women who used nonhormonal contraception. The risk for an increased number of seizures with hormonal contraception seemed greatest for women treated with valproate.

Until now, “valproate was generally accepted as okay to use” by women also taking a hormonal contraceptive, but the new findings suggest that if a woman of childbearing age with epilepsy needs valproate for seizure control she would be better off using a nonhormonal form of contraception such as an intrauterine device, Dr. Andrew G. Herzog said while presenting a poster at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society.

Dr. Herzog highlighted the need for some form of contraception for most younger women on valproate because of the drug’s potential teratogenic effects, but he also stressed that the risk for increased seizures does not appear to affect a majority of women. The survey results showed that overall only 28% of women with epilepsy reported an increased seizure frequency when using a hormonal contraceptive.

“The first goal of a neurologist is to get seizures under control, and you go with the [antiepileptic drugs] that work,” Dr. Herzog said in an interview. Once an effective regimen is found, the physician can then deal with other issues, such as adverse effects as well as the potential for an adverse interaction with a hormonal contraceptive. Valproate can be the antiepileptic drug of choice as it is one of the most effective agents for controlling seizures in patients with primary generalized epilepsy, said Dr. Herzog, professor of neurology at Harvard Medical School, Boston, and director of the neuroendocrine unit of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Wellesley, Mass.

The new data come from an Internet-based survey, which is subject to biases and appeared to attract a preponderance of responses from women who were better educated and had higher incomes than did the general population. In addition, the researchers collected the data retrospectively. Despite these limitations, the results are notable because they represent the only data set yet reported from a community-based source large enough to allow analysis of the many clinical variables that play into the potential interactions between various contraceptive types, various antiepileptic drug classes, and the diverse number of epilepsy subtypes, he said. Dr. Herzog and his associates are planning a study to collect similar data prospectively, but the results would likely not be available for at least about 5 years, he noted.

The Epilepsy Birth Control Registry enrolled women with epilepsy aged 18-47 years who had a history of using at least one form of contraception while on antiepileptic treatment, and the 1,144 women who completed the survey reported a total of 2,712 contraceptive experiences. The survey asked women, “Do you think this method of birth control changed how often you had seizures?” with the option to reply that their contraceptive method seemed to increase, decrease, or not change their seizure number.

One of the analyses done by Dr. Herzog and his associates compared the responses by women on any form of hormonal contraceptive (combined or progestin pill, hormonal patch, vaginal ring, depot medroxyprogesterone acetate, or implanted hormone) with women on any form of nonhormonal contraception (withdrawal, male or female condom, copper or progestin intrauterine device, or tubal ligation).

The results showed that 72% of women on any hormonal contraceptive and 91% of women on any form of nonhormonal contraceptive reported no change in their seizure frequency. The rates of reporting an increased number of seizures were 19% with hormonal contraceptives and 4% with nonhormonal contraceptives, which computed to a relative risk of about 4.5-fold for an increased number of seizures while on hormonal contraception, compared with nonhormonal contraception, the researchers reported.

Barrier contraception (male or female condoms) had the lowest rate of seizure increase among any of the nonhormonal methods. The risk for greater seizure frequency on hormonal contraceptives of all types was 6.75-fold higher when compared specifically with barrier contraception.

In analyses of specific types of hormonal contraceptives, women using a hormonal patch reported a 68% greater incidence of seizure increases, compared with women using combined oral contraceptive pills (the hormonal method that produced the fewest episodes of seizure increases). Those using a progestin-only pill had a 62% higher rate of seizure increases.

More women on hormonal contraceptives also reported having a decrease in seizures after starting contraception, compared with those starting on a nonhormonal method (9.5% vs. 5.2%, respectively), which calculated to a 85% relative rate increase for decreased seizures. Depot medroxyprogesterone acetate was the only specific hormonal contraceptive that linked with a higher rate of seizure decreases, compared with combined oral pills, a 95% higher rate.

A second analysis of the results by Dr. Herzog and his associates examined the frequencies of seizure outcomes on hormonal and nonhormonal contraceptives stratifying by type of antiepileptic drug women used when starting a particular contraceptive method. This analysis broke down antiepileptic drugs into four types: enzyme inducing (29%), glucuronidated (such as lamotrigine; 27%), nonenzyme inducing (such as levetiracetam; 22%), enzyme inhibiting (valproate; 8%), and a fifth category that included women who were not on any antiepileptic drug (14%).

This analysis showed that the frequency of seizure increases was significantly greater with hormonal contraceptive use, compared with nonhormonal methods, across all five subgroups of antiepileptic drug type. In addition, the frequency of seizure increases with hormonal contraceptives differed significantly, depending on which antiepileptic drug type women used, but these significant differences among the antiepileptic drug types also occurred among women using nonhormonal contraception.

Women receiving a nonenzyme-inducing drug when starting a hormonal contraceptive reported the lowest frequency of seizure increases, a 12% rate. In contrast, women on an enzyme-inhibiting drug, valproate, had the highest rate of increased seizures when starting a hormonal contraceptive, 29%. This calculated out to about a 2.5-fold relative risk increase for having more seizures when starting hormonal contraception while on valproate, compared with women on a nonenzyme-inducing drug, Dr. Herzog reported.

Physicians “need to be on the lookout for the possibility that seizures could increase when women start a hormonal contraceptive,” he concluded.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

PHILADELPHIA – Women with epilepsy often reported having an increased number of seizures when taking a hormonal contraceptive, according to data collected from 1,144 women with epilepsy who completed an online survey.

The data showed that women who used hormonal contraception reported having an increased number of seizures while on the contraceptive about 4.5-fold more often than did women who used nonhormonal contraception. The risk for an increased number of seizures with hormonal contraception seemed greatest for women treated with valproate.

Until now, “valproate was generally accepted as okay to use” by women also taking a hormonal contraceptive, but the new findings suggest that if a woman of childbearing age with epilepsy needs valproate for seizure control she would be better off using a nonhormonal form of contraception such as an intrauterine device, Dr. Andrew G. Herzog said while presenting a poster at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society.

Dr. Herzog highlighted the need for some form of contraception for most younger women on valproate because of the drug’s potential teratogenic effects, but he also stressed that the risk for increased seizures does not appear to affect a majority of women. The survey results showed that overall only 28% of women with epilepsy reported an increased seizure frequency when using a hormonal contraceptive.

“The first goal of a neurologist is to get seizures under control, and you go with the [antiepileptic drugs] that work,” Dr. Herzog said in an interview. Once an effective regimen is found, the physician can then deal with other issues, such as adverse effects as well as the potential for an adverse interaction with a hormonal contraceptive. Valproate can be the antiepileptic drug of choice as it is one of the most effective agents for controlling seizures in patients with primary generalized epilepsy, said Dr. Herzog, professor of neurology at Harvard Medical School, Boston, and director of the neuroendocrine unit of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Wellesley, Mass.

The new data come from an Internet-based survey, which is subject to biases and appeared to attract a preponderance of responses from women who were better educated and had higher incomes than did the general population. In addition, the researchers collected the data retrospectively. Despite these limitations, the results are notable because they represent the only data set yet reported from a community-based source large enough to allow analysis of the many clinical variables that play into the potential interactions between various contraceptive types, various antiepileptic drug classes, and the diverse number of epilepsy subtypes, he said. Dr. Herzog and his associates are planning a study to collect similar data prospectively, but the results would likely not be available for at least about 5 years, he noted.

The Epilepsy Birth Control Registry enrolled women with epilepsy aged 18-47 years who had a history of using at least one form of contraception while on antiepileptic treatment, and the 1,144 women who completed the survey reported a total of 2,712 contraceptive experiences. The survey asked women, “Do you think this method of birth control changed how often you had seizures?” with the option to reply that their contraceptive method seemed to increase, decrease, or not change their seizure number.

One of the analyses done by Dr. Herzog and his associates compared the responses by women on any form of hormonal contraceptive (combined or progestin pill, hormonal patch, vaginal ring, depot medroxyprogesterone acetate, or implanted hormone) with women on any form of nonhormonal contraception (withdrawal, male or female condom, copper or progestin intrauterine device, or tubal ligation).

The results showed that 72% of women on any hormonal contraceptive and 91% of women on any form of nonhormonal contraceptive reported no change in their seizure frequency. The rates of reporting an increased number of seizures were 19% with hormonal contraceptives and 4% with nonhormonal contraceptives, which computed to a relative risk of about 4.5-fold for an increased number of seizures while on hormonal contraception, compared with nonhormonal contraception, the researchers reported.

Barrier contraception (male or female condoms) had the lowest rate of seizure increase among any of the nonhormonal methods. The risk for greater seizure frequency on hormonal contraceptives of all types was 6.75-fold higher when compared specifically with barrier contraception.

In analyses of specific types of hormonal contraceptives, women using a hormonal patch reported a 68% greater incidence of seizure increases, compared with women using combined oral contraceptive pills (the hormonal method that produced the fewest episodes of seizure increases). Those using a progestin-only pill had a 62% higher rate of seizure increases.

More women on hormonal contraceptives also reported having a decrease in seizures after starting contraception, compared with those starting on a nonhormonal method (9.5% vs. 5.2%, respectively), which calculated to a 85% relative rate increase for decreased seizures. Depot medroxyprogesterone acetate was the only specific hormonal contraceptive that linked with a higher rate of seizure decreases, compared with combined oral pills, a 95% higher rate.

A second analysis of the results by Dr. Herzog and his associates examined the frequencies of seizure outcomes on hormonal and nonhormonal contraceptives stratifying by type of antiepileptic drug women used when starting a particular contraceptive method. This analysis broke down antiepileptic drugs into four types: enzyme inducing (29%), glucuronidated (such as lamotrigine; 27%), nonenzyme inducing (such as levetiracetam; 22%), enzyme inhibiting (valproate; 8%), and a fifth category that included women who were not on any antiepileptic drug (14%).

This analysis showed that the frequency of seizure increases was significantly greater with hormonal contraceptive use, compared with nonhormonal methods, across all five subgroups of antiepileptic drug type. In addition, the frequency of seizure increases with hormonal contraceptives differed significantly, depending on which antiepileptic drug type women used, but these significant differences among the antiepileptic drug types also occurred among women using nonhormonal contraception.

Women receiving a nonenzyme-inducing drug when starting a hormonal contraceptive reported the lowest frequency of seizure increases, a 12% rate. In contrast, women on an enzyme-inhibiting drug, valproate, had the highest rate of increased seizures when starting a hormonal contraceptive, 29%. This calculated out to about a 2.5-fold relative risk increase for having more seizures when starting hormonal contraception while on valproate, compared with women on a nonenzyme-inducing drug, Dr. Herzog reported.

Physicians “need to be on the lookout for the possibility that seizures could increase when women start a hormonal contraceptive,” he concluded.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

AT AES 2015

Key clinical point: Women with epilepsy often reported having more seizures while taking a hormonal contraceptive, compared with women using nonhormonal contraception.

Major finding: Epileptic women reported a 4.5-fold higher rate of increased seizures when using hormonal contraception, compared with nonhormonal contraception.

Data source: Internet-based survey completed by 1,144 women with epilepsy.

Disclosures: The study received partial support from Lundbeck. Dr. Herzog had no personal disclosures.

AES: Neurologists ignore low driving risk from epilepsy-drug withdrawal

PHILADELPHIA – Many U.S. epilepsy specialists take a conservative stance and advise their patients not to drive when they have been seizure free for more than 2 years and taper off of anti-seizure medications or have just stopped medications altogether, based on survey replies from more than 400 U.S. neurologists.

Roughly two-thirds of these physicians said they advise their tapering-down epilepsy patients not to drive even though these patients face about a 0.3% annual risk for a seizure while driving if they drive for 30 minutes a day, Dr. Joon-Yi Kang said in a poster she presented at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society. And more than half the surveyed neurologists advised abstaining from all driving during the 3-6 months after taper down completes and patients are completely off anti-seizure therapy.

Neurologists who advise their epilepsy patients who are tapering down or recently stopped anti-seizure medications “need to think more carefully” about the actual risk patients face when driving, suggested Dr. Kang, a neurologist at Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore. Typically neurologists advise patients to taper down medications after they have been seizure free for at least 2 years, she said in an interview. No U.S. guidelines cover driving once seizure-free epilepsy patients start to withdraw from treatment and no states have laws that cover this situation, she noted.

Once tapering-down of treatment begins, the immediate risk for a seizure runs from 12%-30%, based on published reports, with the risk dropping below 20% once a patient has been seizure free for at least 3 months on gradually reduced treatment or completely stopped treatment, she noted. Based on this Dr. Kang estimated that during the first year of taper down and then full withdrawal the average U.S. epilepsy patient has an overall seizure risk of 15%. If this patient drove 30 minutes each day their average seizure rate while driving would be about 0.3% for the entire year, she reported in her poster.

“This sort of calculation is usually not done” but estimating the risk faced by each patient and discussing that risk with each patient is important, she said. “Some patients stay on their medications just so that they can continue to drive. We need to carefully think about what is an acceptable level of risk.” The restrictions many neurologists recommend to patients “unnecessarily limit patient function,” Dr. Kang said.

She and her co-author sent their survey to 2,028 neurologist members of the American Epilepsy Society and received replies from 411 (20%) in 42 states. About 80% of respondents said that more than half of their practice involved patients with epilepsy, and about 70% said that they had at least 5 years of clinical experience.

During the taper-down period, 65% of respondents said they advise patients to not drive and an additional 24% said they advise patients to minimize their driving. Once patients totally withdrew from treatment, 53% advised continuing to restrict all driving, usually for an additional 3-6 months, and 26% said they advise patients to minimize driving. In addition, 89% of respondents said that their recommendations to restrict or minimize driving often prompted patients to remain on treatment. “I think these findings reflect usual practice” among U.S. neurologists, Dr. Kang said.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

PHILADELPHIA – Many U.S. epilepsy specialists take a conservative stance and advise their patients not to drive when they have been seizure free for more than 2 years and taper off of anti-seizure medications or have just stopped medications altogether, based on survey replies from more than 400 U.S. neurologists.

Roughly two-thirds of these physicians said they advise their tapering-down epilepsy patients not to drive even though these patients face about a 0.3% annual risk for a seizure while driving if they drive for 30 minutes a day, Dr. Joon-Yi Kang said in a poster she presented at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society. And more than half the surveyed neurologists advised abstaining from all driving during the 3-6 months after taper down completes and patients are completely off anti-seizure therapy.

Neurologists who advise their epilepsy patients who are tapering down or recently stopped anti-seizure medications “need to think more carefully” about the actual risk patients face when driving, suggested Dr. Kang, a neurologist at Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore. Typically neurologists advise patients to taper down medications after they have been seizure free for at least 2 years, she said in an interview. No U.S. guidelines cover driving once seizure-free epilepsy patients start to withdraw from treatment and no states have laws that cover this situation, she noted.

Once tapering-down of treatment begins, the immediate risk for a seizure runs from 12%-30%, based on published reports, with the risk dropping below 20% once a patient has been seizure free for at least 3 months on gradually reduced treatment or completely stopped treatment, she noted. Based on this Dr. Kang estimated that during the first year of taper down and then full withdrawal the average U.S. epilepsy patient has an overall seizure risk of 15%. If this patient drove 30 minutes each day their average seizure rate while driving would be about 0.3% for the entire year, she reported in her poster.

“This sort of calculation is usually not done” but estimating the risk faced by each patient and discussing that risk with each patient is important, she said. “Some patients stay on their medications just so that they can continue to drive. We need to carefully think about what is an acceptable level of risk.” The restrictions many neurologists recommend to patients “unnecessarily limit patient function,” Dr. Kang said.

She and her co-author sent their survey to 2,028 neurologist members of the American Epilepsy Society and received replies from 411 (20%) in 42 states. About 80% of respondents said that more than half of their practice involved patients with epilepsy, and about 70% said that they had at least 5 years of clinical experience.

During the taper-down period, 65% of respondents said they advise patients to not drive and an additional 24% said they advise patients to minimize their driving. Once patients totally withdrew from treatment, 53% advised continuing to restrict all driving, usually for an additional 3-6 months, and 26% said they advise patients to minimize driving. In addition, 89% of respondents said that their recommendations to restrict or minimize driving often prompted patients to remain on treatment. “I think these findings reflect usual practice” among U.S. neurologists, Dr. Kang said.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

PHILADELPHIA – Many U.S. epilepsy specialists take a conservative stance and advise their patients not to drive when they have been seizure free for more than 2 years and taper off of anti-seizure medications or have just stopped medications altogether, based on survey replies from more than 400 U.S. neurologists.

Roughly two-thirds of these physicians said they advise their tapering-down epilepsy patients not to drive even though these patients face about a 0.3% annual risk for a seizure while driving if they drive for 30 minutes a day, Dr. Joon-Yi Kang said in a poster she presented at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society. And more than half the surveyed neurologists advised abstaining from all driving during the 3-6 months after taper down completes and patients are completely off anti-seizure therapy.

Neurologists who advise their epilepsy patients who are tapering down or recently stopped anti-seizure medications “need to think more carefully” about the actual risk patients face when driving, suggested Dr. Kang, a neurologist at Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore. Typically neurologists advise patients to taper down medications after they have been seizure free for at least 2 years, she said in an interview. No U.S. guidelines cover driving once seizure-free epilepsy patients start to withdraw from treatment and no states have laws that cover this situation, she noted.

Once tapering-down of treatment begins, the immediate risk for a seizure runs from 12%-30%, based on published reports, with the risk dropping below 20% once a patient has been seizure free for at least 3 months on gradually reduced treatment or completely stopped treatment, she noted. Based on this Dr. Kang estimated that during the first year of taper down and then full withdrawal the average U.S. epilepsy patient has an overall seizure risk of 15%. If this patient drove 30 minutes each day their average seizure rate while driving would be about 0.3% for the entire year, she reported in her poster.

“This sort of calculation is usually not done” but estimating the risk faced by each patient and discussing that risk with each patient is important, she said. “Some patients stay on their medications just so that they can continue to drive. We need to carefully think about what is an acceptable level of risk.” The restrictions many neurologists recommend to patients “unnecessarily limit patient function,” Dr. Kang said.

She and her co-author sent their survey to 2,028 neurologist members of the American Epilepsy Society and received replies from 411 (20%) in 42 states. About 80% of respondents said that more than half of their practice involved patients with epilepsy, and about 70% said that they had at least 5 years of clinical experience.

During the taper-down period, 65% of respondents said they advise patients to not drive and an additional 24% said they advise patients to minimize their driving. Once patients totally withdrew from treatment, 53% advised continuing to restrict all driving, usually for an additional 3-6 months, and 26% said they advise patients to minimize driving. In addition, 89% of respondents said that their recommendations to restrict or minimize driving often prompted patients to remain on treatment. “I think these findings reflect usual practice” among U.S. neurologists, Dr. Kang said.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

AT AES 2015

Key clinical point: Although epilepsy patients tapering off anti-seizure medication face a less than 1% seizure risk when driving neurologists usually advise them not to drive.

Major finding: Nearly two-thirds of surveyed U.S. neurologists advised patients withdrawing from anti-seizure medications not to drive.

Data source: Survey responses from 411 U.S. neurologists who specialize in epilepsy treatment.

Disclosures: Dr. Kang had no disclosures.

AHA: Three measures risk stratify acute heart failure

ORLANDO – Three simple, routinely collected measurements together provide a lot of insight into the risk faced by community-dwelling patients hospitalized for acute decompensated heart failure, according to data collected from 3,628 patients at one U.S. center.

The three measures are blood urea nitrogen (BUN), systolic blood pressure, and serum creatinine. Using dichotomous cutoffs first calculated a decade ago, these three parameters distinguish up to an eightfold range of postdischarge mortality during the 30 or 90 days following an index hospitalization, and up to a fourfold range of risk for rehospitalization for heart failure during the ensuing 30 or 90 days, Dr. Sithu Win said at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

Applying this three-measure assessment to patients hospitalized with acute decompensated heart failure “may guide care-transition planning and promote efficient allocation of limited resources,” said Dr. Win, a cardiologist at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn. The next step is to try to figure out the best way to use this risk prognostication in routine practice, he added.

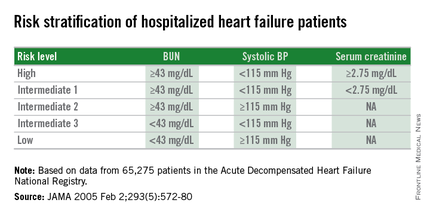

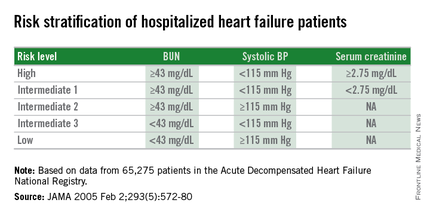

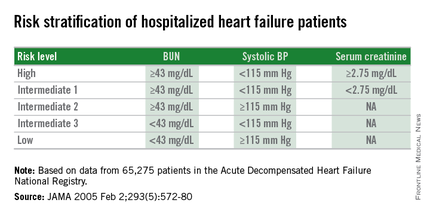

Researchers published the original analysis that identified BUN, systolic BP, and serum creatinine as key prognostic measures in 2005 using data taken from more than 65,000 U.S. heart failure patients enrolled in ADHERE (Acute Decompensated Heart Failure National Registry) (JAMA. 2005 Feb 2;293[5]:572-80). Using a classification and regression tree analysis, the 2005 study verified dichotomous cutoffs for these three parameters that identified patients at highest risk for in-hospital mortality.

The 2005 study prioritized the application of these cutoffs to define in-hospital mortality risk: first BUN, then the systolic BP criterion, and lastly the serum creatinine criterion. This resulted in five risk levels: Highest-risk patients had a BUN of at least 43 mg/dL, a systolic BP of less than 115 mm Hg, and a serum creatinine of at least 2.75 mg/dL. Lowest-risk patients had a BUN of less than 43 mg/dL and a systolic BP of more than 115 mm Hg. (In lower-risk patients, serum-creatinine level dropped out as a risk determinant.) The analysis also created three categories of patients with intermediate risk based on various combinations of the three measures.

The new study run by Dr. Win and his associates evaluated how this risk-assessment tool developed to predict in-hospital mortality performed for predicting event rates among community-based heart failure patients who had a total of 5,918 hospitalizations for acute decompensated heart failure at the Mayo Clinic during 2000-2013. They averaged 78 years old, half were women, and 48% had heart failure with preserved ejection fraction.

The risk-level distribution of the 3,628 Mayo patients closely matched the pattern seen in the original ADHERE registry: 63% were low risk, 17% were at intermediate level 3 (the lowest risk level in the intermediate range), 13% were at intermediate level 2, 5% at intermediate level 1, and 2% were categorized as high risk.

For 30-day mortality post hospitalization, patients at the highest risk level had a mortality rate eightfold higher than did the lowest-risk patients, those rated intermediate level 1 had a fivefold higher mortality rate, intermediate level 2 patients had a threefold higher rate, and those at intermediate 3 had a 50% higher rate, Dr. Win reported. During the 90 days after discharge, mortality rates relative to the lowest risk level ranged from a sixfold higher rate among the highest-risk patients to a 50% higher rate among patients with an intermediate 3 designation.

Analysis of rehospitalizations for heart failure showed that, by 30 days after hospitalization, the readmission rate ran threefold higher in the highest-risk patients, compared with those at the lowest risk and fourfold higher among those at intermediate risk level 1. Heart failure readmissions by 90 days following the index hospitalization ran threefold higher for both the highest-risk patients as well as those at intermediate level 1, compared with the patients at lowest risk.