User login

Cross-Sectional Analysis of Biologic Use in the Treatment of Veterans With Hidradenitis Suppurativa

Cross-Sectional Analysis of Biologic Use in the Treatment of Veterans With Hidradenitis Suppurativa

Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is a chronic, inflammatory skin disorder characterized by painful nodules, abscesses, and tunnels predominantly affecting intertriginous areas of the body.1,2 The condition poses significant challenges in terms of diagnosis, treatment, and quality of life for affected individuals. Various systemic therapies have been explored to manage this debilitating condition, with the emergence of biologic agents offering hope for improved outcomes. In 2015, adalimumab (ADA) was the first biologic approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of HS, followed by secukinumab in 2023 and bimekizumab in 2024. However, the off-label use of other biologics and/or tumor necrosis factor inhibitors such as infliximab (IFX) has become common practice.3

Although these therapies have demonstrated promising results in the treatment of HS, their widespread use may be hindered by accessibility and cost barriers. Orenstein et al analyzed data from the IBM Explorys platform from 2015 to 2020 and found that only 1.8% of patients diagnosed with HS had been prescribed ADA or IFX.4 More recently, Garg et al examined IBM MarketScan and IBM US Medicaid data from 2015 to 2018 to evaluate trends in clinical care and treatment. The prevalence of ADA and IFX prescriptions among patients with HS ranged from 2.3% to 8.0% (ADA) and 0.7% to 0.9% (IFX) for patients with commercial insurance, and 1.4% to 4.8% (ADA) and 0.5% to 0.7% (IFX) for patients with Medicaid.5 Biologics are often expensive, and the high cost associated with these therapies has been identified as a significant barrier to access for patients with HS, particularly those who lack adequate insurance coverage or face financial constraints.6

Furthermore, these barriers, particularly the financial barriers, are potentially compounded by the demographics of patients most notably affected by HS. In the US, a disproportionate incidence of HS has been noted in specific groups and age ranges, including women, individuals aged 18 to 29 years, and Black individuals.4 Orenstein et al found a statistically significant difference in use of ADA and IFX biologics based on age, sex, and race.4

The aim of this study was to examine the use of 2 biologics (ADA and IFX) in the Veterans Health Administration (VHA), a unique population in which financial barriers are reduced due to the single-payer government health care system structure. This design allowed for improved isolation and evaluation of variation in ADA and/or IFX prescription rates by demographics and health-related factors among patients with HS. To our knowledge, no studies have analyzed these metrics within the VHA.

Methods

This retrospective, cross-sectional analysis of VHA patients used data from the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Corporate Data Warehouse, a data repository that provides access to longitudinal national electronic health record data for all veterans receiving care through VHA facilities. This study received ethical approval from institutional review boards at the Minneapolis Veterans Affairs Health Care System and VA Salt Lake City Healthcare System. Patient information was deidentified, and patient consent was not required.

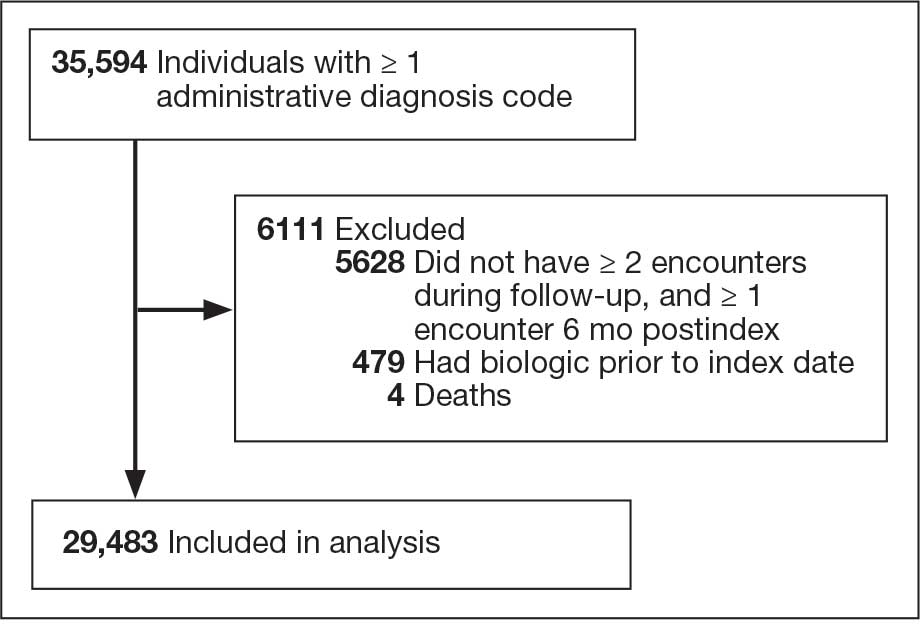

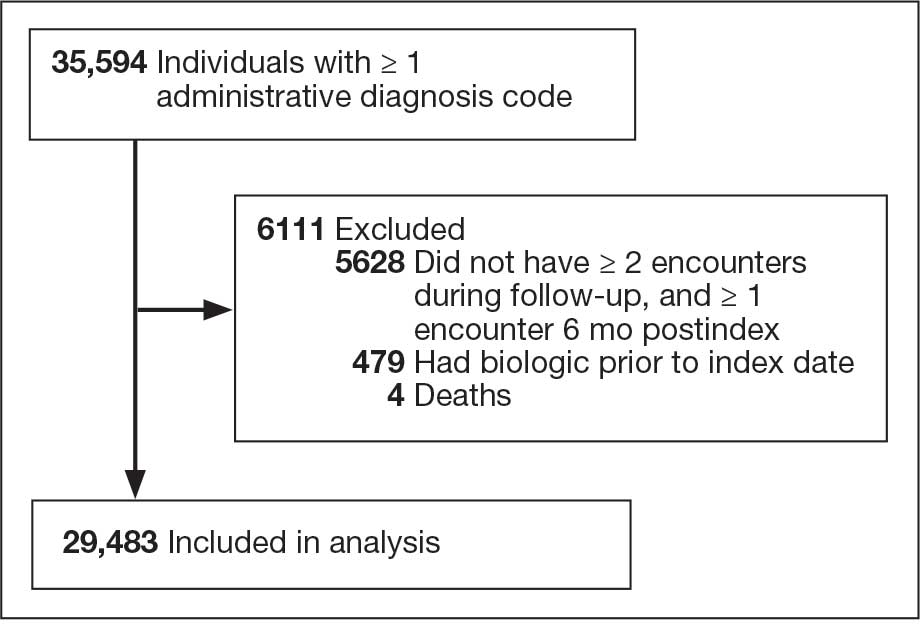

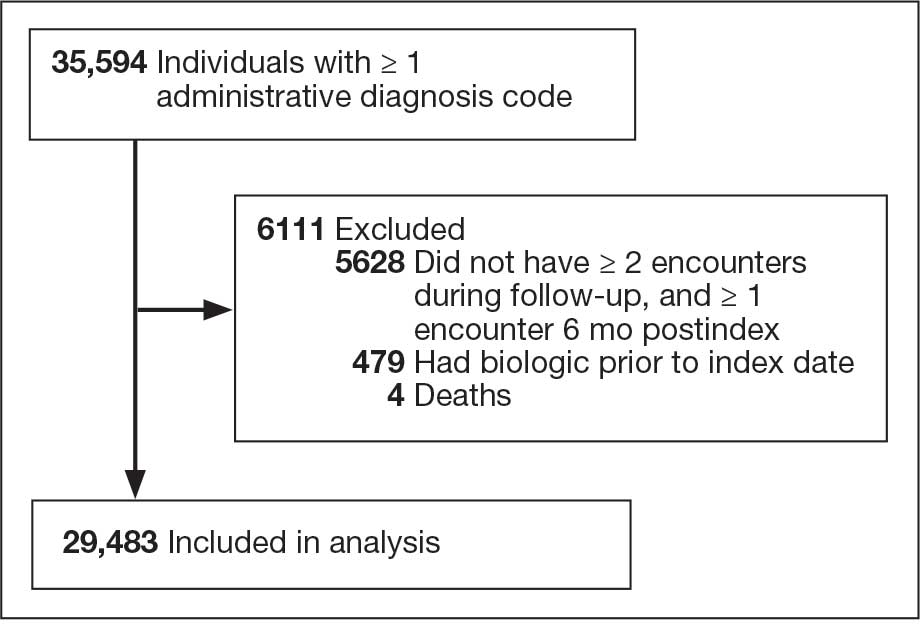

Patients with HS were identified using ≥ 1 International Classification of Diseases (ICD) diagnostic code: (ICD-9 [705.83] or ICD-10 [L73.2]) between January 1, 2011, and December 31, 2021. The study included patients aged ≥ 18 years as of January 1, 2011, with ≥ 2 patient encounters during the postdiagnosis follow-up period, and with ≥ 1 encounter 6 months postindex. Patients with a biologic prescription prior to HS diagnosis were excluded. For this study, the term biologics refers to ADA and/or IFX prescriptions, unless otherwise specified. Only ADA and IFX were included in this analysis because ADA, a tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-á inhibitor, was the only FDA-approved medication at the time of the search, and IFX is another common TNF-α inhibitor used for the treatment of HS.

Statistical Analysis

We calculated logistic regression using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). For each variable, the univariate relationship with biologic prescriptions was examined first, followed by the multivariate relationship controlling for all other variables. The following variables were controlled for in the multivariate models and were chosen a priori: sex, age, race, ethnicity, US region, hospital setting, current or previous tobacco use, obesity (defined as body mass index [BMI] ≥ 30), and Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI).7

Results

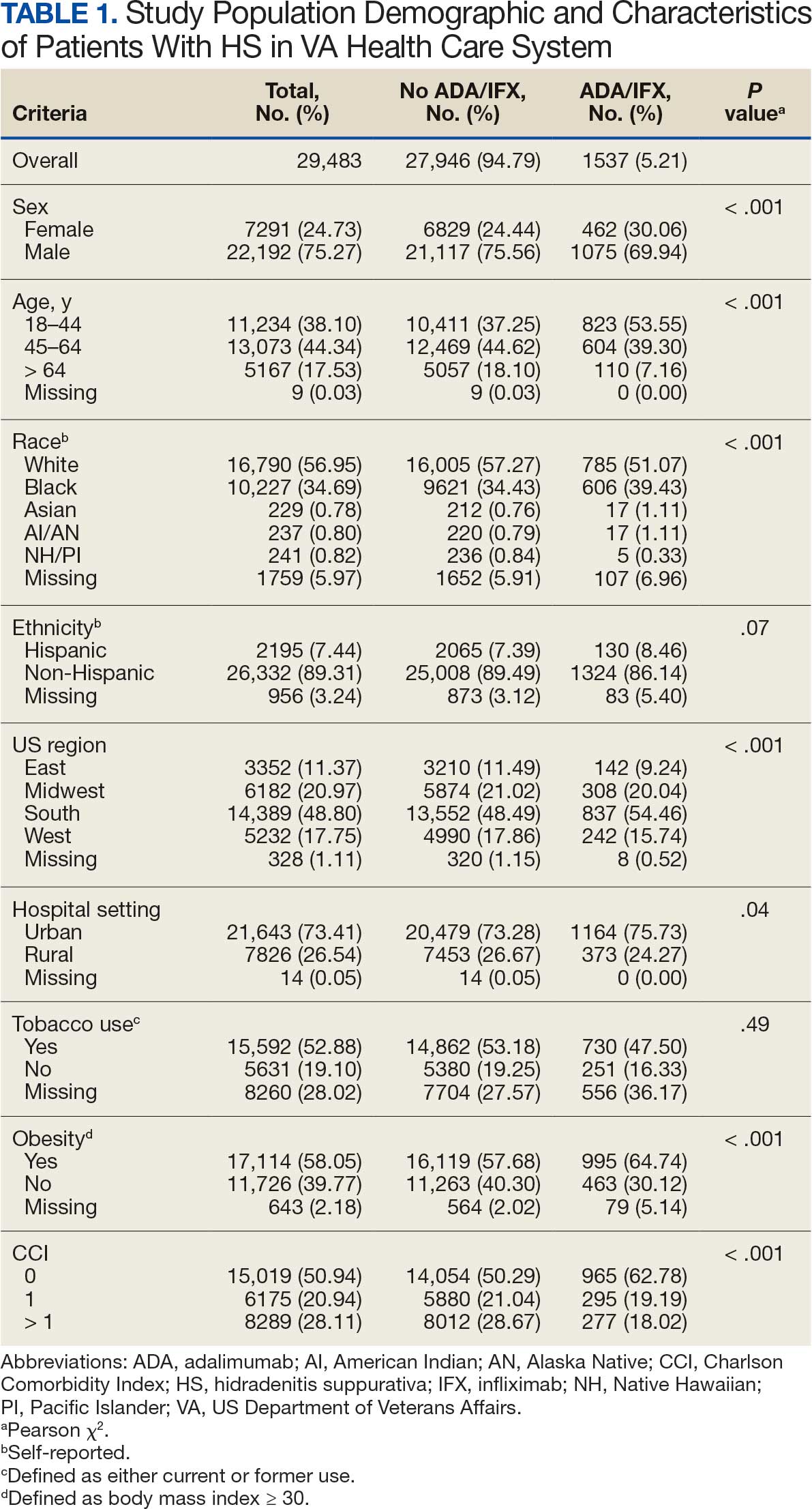

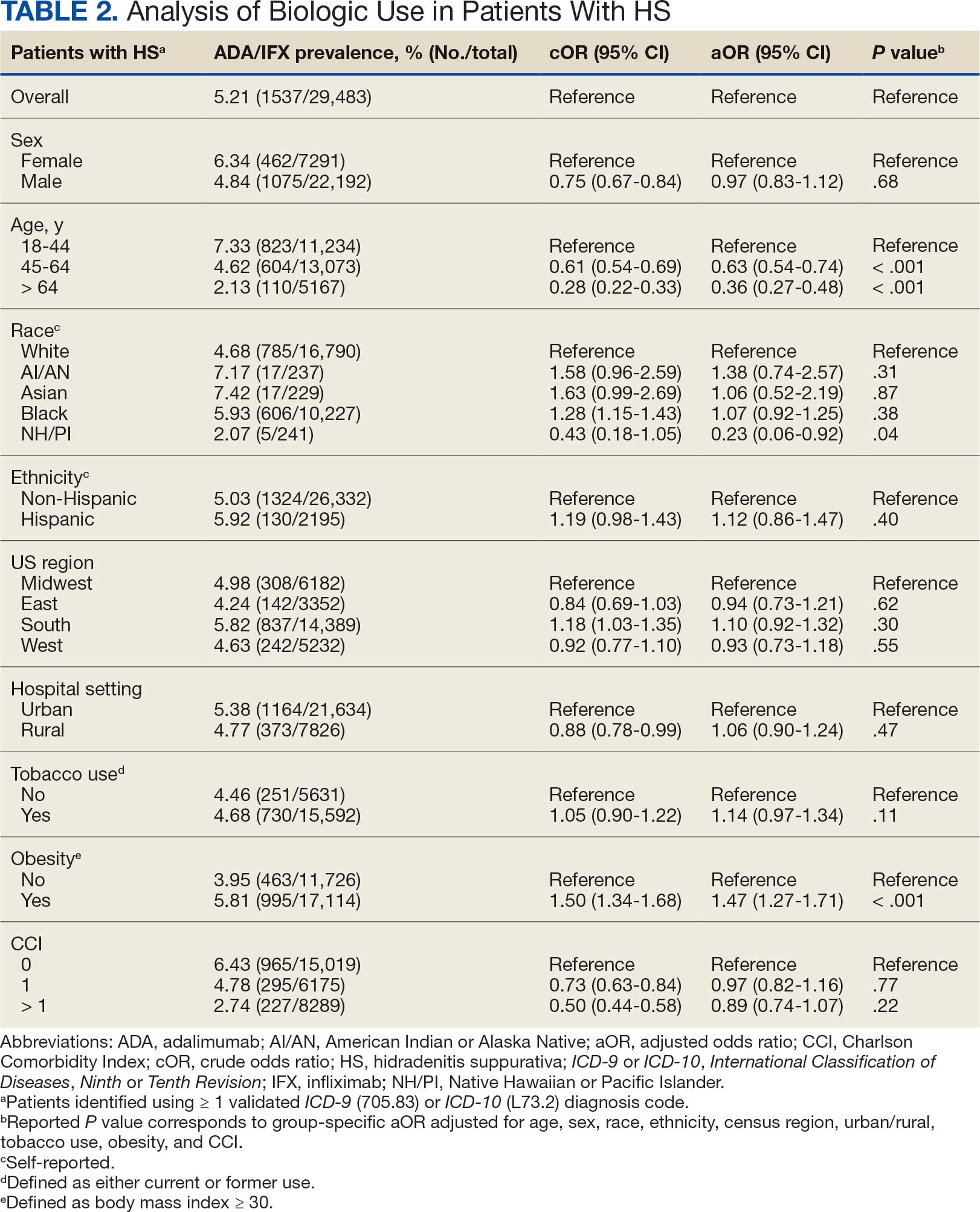

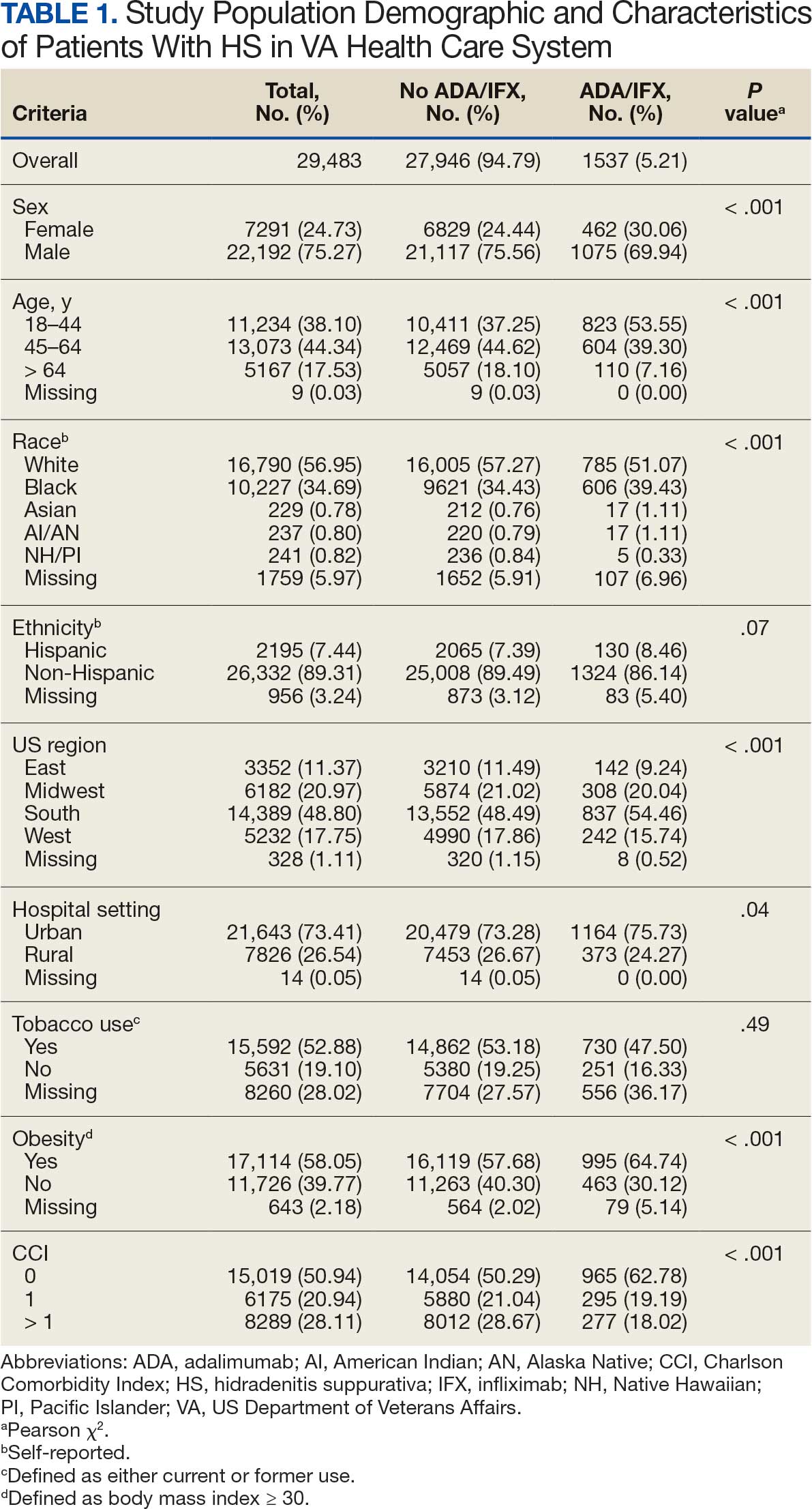

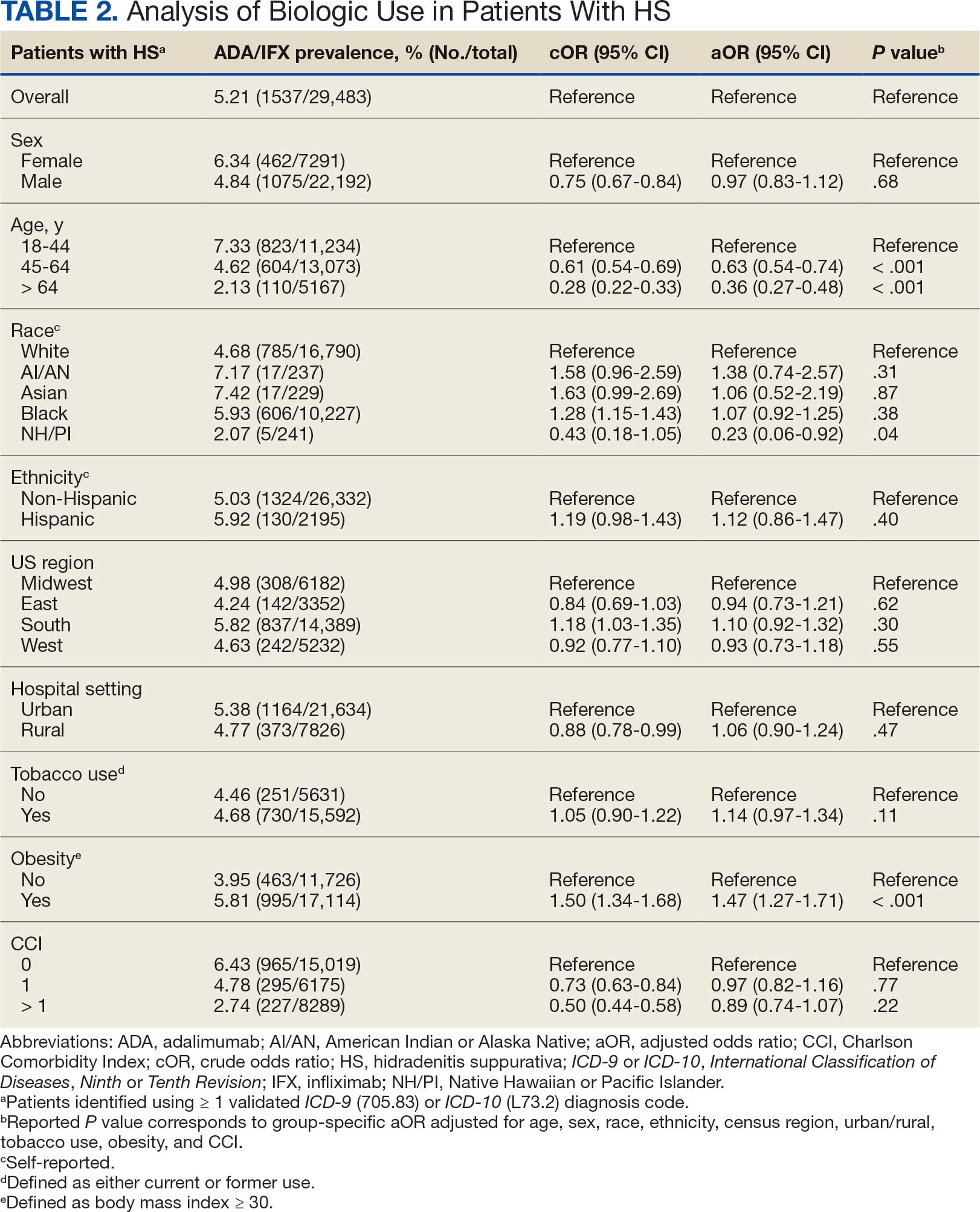

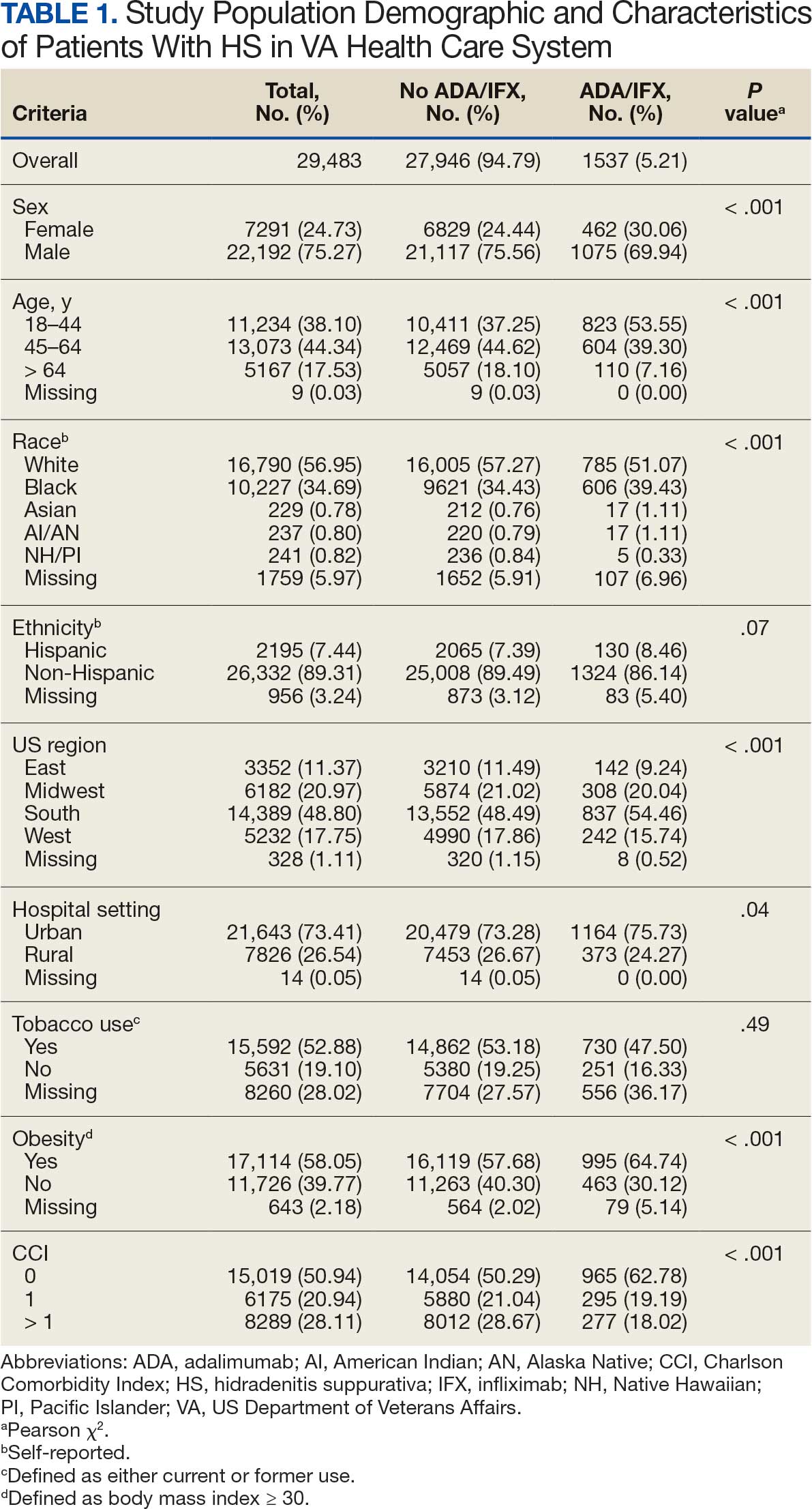

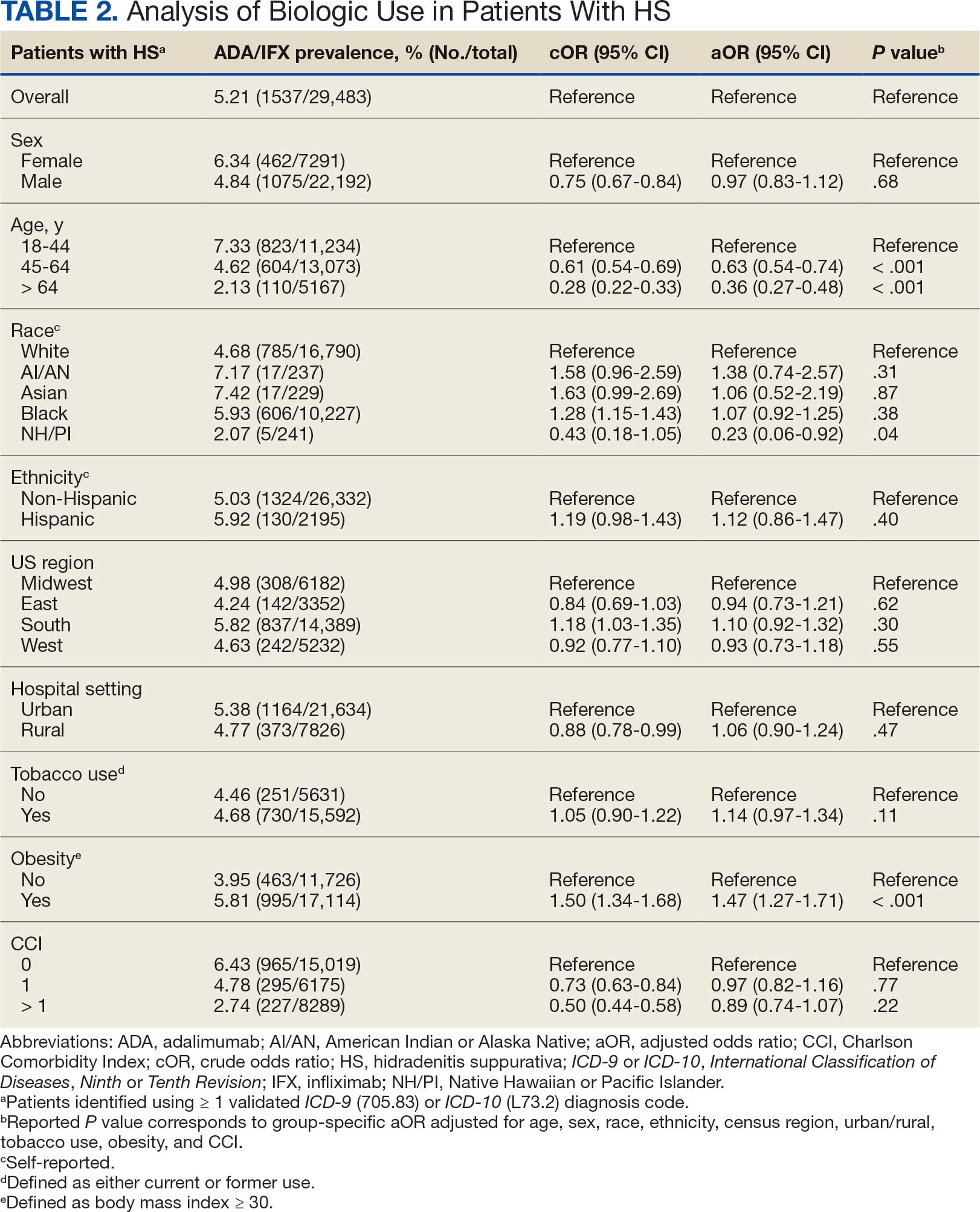

Using ICD codes, we identified 29,483 individuals with ≥ 1 HS diagnosis (Figure 1). Of those identified, 1537 patients (5.21%) had been prescribed ≥ 1 biologic. The cohort was predominantly White (60.56%), male (75.27%), obese (59.34%), and had a history of current or previous tobacco use (73.47%) (Table 1). There were significant adjusted differences in prescription rates among veterans with HS based on age, race, and BMI. Notably, there was an age-dependent reduction in the odds of being prescribed a biologic in patients with HS. Compared with patients aged 18 to 44 years, patients aged 45 to 64 years (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 0.63; 95% CI, 0.54–0.74; P < .001) and patients aged ≥ 65 years (aOR, 0.36; 95% CI, 0.27–0.48; P < .001) had significantly lower odds of receiving a biologic prescription (Table 2). Compared with White patients with HS, Native Hawaiian (NH) or Pacific Islander (PI) patients were less likely to be prescribed a biologic (aOR, 0.23; 95% CI, 0.06–0.92; P = .04). Patients with obesity had significantly higher odds of receiving a biologic prescription compared with patients without obesity (aOR, 1.47; 95% CI, 1.27– 1.71; P < .001).

Included in Analysis.

After adjusting for the variables listed in Table 1, there were no significant differences in biologic prescription rates for men compared with women (aOR, 0.97; 95% CI, 0.83-1.12; P = .68). We observed slight variations in biologic prescriptions between US regions (Midwest 5.0%, East 4.2%, South 5.8%, West 4.6%), none of which were significantly different in the fully adjusted model. No statistically significant differences were found in biologic prescriptions between urban and rural VA settings (5.4% vs 4.8%; aOR, 1.06; 95% CI, 0.90–1.24; P = .47). Tobacco use was not associated with the rate of biologic prescription receipt (aOR, 1.14; 95% CI, 0.97–1.34; P = .11). After adjusting for other variables (as outlined in Table 2), no significant differences were found between CCI of 0 and 1 (aOR, 0.97; 95% CI, 0.82–1.16; P = .77) or between CCI of 0 and 2 (aOR, 0.89; 95% CI, 0.74–1.07; P = .22).7

Discussion

The aim of the study was to ascertain potential discrepancies in biologic prescription patterns among patients with HS in the VHA by demographic and lifestyle behavior modifiers. Veteran cohorts are unique in composition, consisting predominantly of older White men within a single-payer health care system. The prevalence of biologic prescriptions in this population was low (5.2%), consistent with prior studies (1.8%–8.9%).4,5

We found a significant difference in ADA/IFX prescription patterns between White patients and NH/PI patients (aOR, 0.23; 95% CI, 0.06-0.92; P = .04). Further replication of this result is needed due to the small number of NH/PI patients included in the study (n = 241). Notably, we did not find a significant difference in the odds of Black patients being prescribed a biologic compared with White patients (aOR, 1.07; 95% CI, 0.92–1.25; P = .38), consistent with prior studies.4

In line with prior studies, age was associated with the likelihood of receiving a biologic prescription.4 Using the multivariate model adjusting for variables listed in Table 1, including CCI, patients aged 45 to 64 years and > 64 years were less likely to be prescribed a biologic than patients aged 18 to 44 years. HS disease activity could be a potential confounding variable, as HS severity may subside in some people with increasing age or menopause.8

Because different regions in the US have different sociopolitical ideologies and governing legislation, we hypothesized that there may be dissimilarities in the prevalence rates of biologic prescribing across various US regions. However, no significant differences were found in prescription patterns among US regions or between rural and urban settings. Previous research has demonstrated discernible disparities in both dermatologic care and clinical outcomes based on hospital setting (ie, urban vs rural).9-11

Tobacco use has been demonstrated to be associated with the development of HS.12 In a large retrospective analysis, Garg et al reported increased odds of receiving a new HS diagnosis in known tobacco users (aOR, 1.9; 95% CI, 1.8–2.0).13 The extent to which tobacco use affects HS severity is less understood. While some studies have found an association between smoking and HS severity, other analyses have failed to find this association.14,15 The effects of smoking cessation on the disease course of HS are unknown.16 This analysis, found no significant difference in prescriptions for biologics among patients with HS comparing current or previous tobacco users with nonusers.

There is a known positive correlation between increasing BMI and HS prevalence and severity that may be explained by the downstream effects of adipose tissue secretion of proinflammatory mediators and insulin resistance in the setting of chronic inflammation.12 This analysis found that patients with HS and obesity were 1.47 times more likely to be prescribed a biologic than patients with HS without obesity, which may be confounded by increased HS severity among patients with obesity. The initial concern when analyzing tobacco use and obesity was that clinician bias may result in a decrease in the prevalence of biologic use in these demographics, which was not supported in this study.

Although we identified few disparities, the results demonstrated a substantial underutilization of biologic therapies (5.2%), similar to the other US civilian studies (1.8-8.9%).4,5 While there is no current universal, standardized severity scoring system to evaluate HS (it is difficult to objectively define moderate to severe HS), estimates have shown that 40.3% to 65.8% of patients with HS have Hurley stage II or III.17-19 Therefore, only a small percentage of patients with moderate to severe disease were prescribed the only FDA-approved medication during this time period. The persistence of this underutilization within a medical system that reduces financial barriers suggests that nonfinancial barriers have a notable role in the underutilization of biologics.

For instance, risk of adverse events, particularly lymphoma and infection, has been cited by patients as a reason to avoid biologics. Additionally, treatment fatigue reduced some patients’ willingness to try new treatments, as did lack of knowledge about treatment options.6,20 Other reported barriers included the frequency of injections and fear of needles.6 Additionally, within the VA, ADA may require prior authorization at the local facility level.21 An established relationship with a dermatologist has been shown to significantly increase the odds of being prescribed a biologic medication in the face of these barriers.4 Future system-wide quality improvement initiatives could be implemented to identify patients with HS not followed by dermatology, with the goal of establishing care with a dermatologist.

Limitations

Limitations to this study include an inability to categorize HS disease severity and assess the degree to which disease severity confounded study findings, particularly in relation to tobacco use and obesity. The generalizability of this study is also limited because of the demographic characteristics of the veteran patient population, which is predominantly older, White, and male, whereas HS disproportionately affects younger, Black, and female individuals in the US.22 Despite these limitations, this study contributes valuable insights into the use of biologic therapies for veteran populations with HS using a national dataset.

Conclusions

This study was performed within a single-payer government medical system, likely reducing or removing the financial barriers that some patient populations may face when pursuing biologics for HS treatment. However, the prevalence of biologic use in this population was low overall (5.2%), suggesting that other factors play a role in the underutilization of biologics in HS. Consistent with previous studies, younger individuals were more likely to be prescribed a biologic, and no difference in prescription rates between Black and White patients was observed. Unlike previous studies, no significant difference in prescription rates between men and women was observed.

- Goldburg SR, Strober BE, Payette MJ. Hidradenitis suppurativa: epidemiology, clinical presentation, and pathogenesis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:1045-1058. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.08.090

- Tchero H, Herlin C, Bekara F, et al. Hidradenitis suppurativa: a systematic review and meta-analysis of therapeutic interventions. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2019;85:248-257. doi:10.4103/ijdvl.IJDVL_69_18

- Shih T, Lee K, Grogan T, et al. Infliximab in hidradenitis suppurativa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Dermatol Ther. 2022;35:e15691. doi:10.1111/dth.15691

- Orenstein LAV, Wright S, Strunk A, et al. Low prescription of tumor necrosis alpha inhibitors in hidradenitis suppurativa: a cross-sectional analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:1399-1401. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.07.108

- Garg A, Naik HB, Alavi A, et al. Real-world findings on the characteristics and treatment exposures of patients with hidradenitis suppurativa from US claims data. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2023;13:581-594. doi:10.1007/s13555-022-00872-1

- De DR, Shih T, Fixsen D, et al. Biologic use in hidradenitis suppurativa: patient perspectives and barriers. J Dermatolog Treat. 2022;33:3060-3062. doi:10.1080/09546634.2022.2089336

- Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, et al. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373- 383. doi:10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8

- von der Werth JM, Williams HC. The natural history of hidradenitis suppurativa. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2000;14:389-392. doi:10.1046/j.1468-3083.2000.00087.x

- Silverberg JI, Barbarot S, Gadkari A, et al. Atopic dermatitis in the pediatric population: a cross-sectional, international epidemiologic study. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2021;126:417-428.e2. doi:10.1016/j.anai.2020.12.020

- Wu YP, Parsons B, Jo Y, et al. Outdoor activities and sunburn among urban and rural families in a Western region of the US: implications for skin cancer prevention. Prev Med Rep. 2022;29:101914. doi:10.1016/j.pmedr.2022.101914

- Mannschreck DB, Li X, Okoye G. Rural melanoma patients in Maryland do not present with more advanced disease than urban patients. Dermatol Online J. 2021;27. doi:10.5070/D327553607

- Garg A, Malviya N, Strunk A, et al. Comorbidity screening in hidradenitis suppurativa: evidence-based recommendations from the US and Canadian Hidradenitis Suppurativa Foundations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86:1092-1101. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.01.059

- Garg A, Papagermanos V, Midura M, et al. Incidence of hidradenitis suppurativa among tobacco smokers: a population- based retrospective analysis in the U.S.A. Br J Dermatol. 2018;178:709-714. doi:10.1111/bjd.15939

- Sartorius K, Emtestam L, Jemec GBE, et al. Objective scoring of hidradenitis suppurativa reflecting the role of tobacco smoking and obesity. Br J Dermatol. 2009;161:831- 839. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2009.09198.x

- Canoui-Poitrine F, Revuz JE, Wolkenstein P, et al. Clinical characteristics of a series of 302 French patients with hidradenitis suppurativa, with an analysis of factors associated with disease severity. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:51-57. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2009.02.013

- Dufour DN, Emtestam L, Jemec GB. Hidradenitis suppurativa: a common and burdensome, yet under-recognised, inflammatory skin disease. Postgrad Med J. 2014;90:216- 221. doi:10.1136/postgradmedj-2013-131994

- Vazquez BG, Alikhan A, Weaver AL, et al. Incidence of hidradenitis suppurativa and associated factors: a population- based study of Olmsted County, Minnesota. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133:97-103. doi:10.1038/jid.2012.255

- Vanlaerhoven AMJD, Ardon CB, van Straalen KR, et al. Hurley III hidradenitis suppurativa has an aggressive disease course. Dermatology. 2018;234:232-233. doi:10.1159/000491547

- Shahi V, Alikhan A, Vazquez BG, et al. Prevalence of hidradenitis suppurativa: a population-based study in Olmsted County, Minnesota. Dermatology. 2014;229:154-158. doi:10.1159/000363381

- Salame N, Sow YN, Siira MR, et al. Factors affecting treatment selection among patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. JAMA Dermatol. 2024;160:179. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2023.5425

- VA Formulary Advisor: ADALIMUMAB-BWWD INJ,SOLN. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Updated December 17, 2025. Accessed January 15, 2026. https://www.va.gov/formularyadvisor/drugs/4042383-ADALIMUMAB-BWWD-INJ-SOLN

- Garg A, Lavian J, Lin G, et al. Incidence of hidradenitis suppurativa in the United States: a sex- and age-adjusted population analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:118- 122. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.02.005

Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is a chronic, inflammatory skin disorder characterized by painful nodules, abscesses, and tunnels predominantly affecting intertriginous areas of the body.1,2 The condition poses significant challenges in terms of diagnosis, treatment, and quality of life for affected individuals. Various systemic therapies have been explored to manage this debilitating condition, with the emergence of biologic agents offering hope for improved outcomes. In 2015, adalimumab (ADA) was the first biologic approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of HS, followed by secukinumab in 2023 and bimekizumab in 2024. However, the off-label use of other biologics and/or tumor necrosis factor inhibitors such as infliximab (IFX) has become common practice.3

Although these therapies have demonstrated promising results in the treatment of HS, their widespread use may be hindered by accessibility and cost barriers. Orenstein et al analyzed data from the IBM Explorys platform from 2015 to 2020 and found that only 1.8% of patients diagnosed with HS had been prescribed ADA or IFX.4 More recently, Garg et al examined IBM MarketScan and IBM US Medicaid data from 2015 to 2018 to evaluate trends in clinical care and treatment. The prevalence of ADA and IFX prescriptions among patients with HS ranged from 2.3% to 8.0% (ADA) and 0.7% to 0.9% (IFX) for patients with commercial insurance, and 1.4% to 4.8% (ADA) and 0.5% to 0.7% (IFX) for patients with Medicaid.5 Biologics are often expensive, and the high cost associated with these therapies has been identified as a significant barrier to access for patients with HS, particularly those who lack adequate insurance coverage or face financial constraints.6

Furthermore, these barriers, particularly the financial barriers, are potentially compounded by the demographics of patients most notably affected by HS. In the US, a disproportionate incidence of HS has been noted in specific groups and age ranges, including women, individuals aged 18 to 29 years, and Black individuals.4 Orenstein et al found a statistically significant difference in use of ADA and IFX biologics based on age, sex, and race.4

The aim of this study was to examine the use of 2 biologics (ADA and IFX) in the Veterans Health Administration (VHA), a unique population in which financial barriers are reduced due to the single-payer government health care system structure. This design allowed for improved isolation and evaluation of variation in ADA and/or IFX prescription rates by demographics and health-related factors among patients with HS. To our knowledge, no studies have analyzed these metrics within the VHA.

Methods

This retrospective, cross-sectional analysis of VHA patients used data from the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Corporate Data Warehouse, a data repository that provides access to longitudinal national electronic health record data for all veterans receiving care through VHA facilities. This study received ethical approval from institutional review boards at the Minneapolis Veterans Affairs Health Care System and VA Salt Lake City Healthcare System. Patient information was deidentified, and patient consent was not required.

Patients with HS were identified using ≥ 1 International Classification of Diseases (ICD) diagnostic code: (ICD-9 [705.83] or ICD-10 [L73.2]) between January 1, 2011, and December 31, 2021. The study included patients aged ≥ 18 years as of January 1, 2011, with ≥ 2 patient encounters during the postdiagnosis follow-up period, and with ≥ 1 encounter 6 months postindex. Patients with a biologic prescription prior to HS diagnosis were excluded. For this study, the term biologics refers to ADA and/or IFX prescriptions, unless otherwise specified. Only ADA and IFX were included in this analysis because ADA, a tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-á inhibitor, was the only FDA-approved medication at the time of the search, and IFX is another common TNF-α inhibitor used for the treatment of HS.

Statistical Analysis

We calculated logistic regression using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). For each variable, the univariate relationship with biologic prescriptions was examined first, followed by the multivariate relationship controlling for all other variables. The following variables were controlled for in the multivariate models and were chosen a priori: sex, age, race, ethnicity, US region, hospital setting, current or previous tobacco use, obesity (defined as body mass index [BMI] ≥ 30), and Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI).7

Results

Using ICD codes, we identified 29,483 individuals with ≥ 1 HS diagnosis (Figure 1). Of those identified, 1537 patients (5.21%) had been prescribed ≥ 1 biologic. The cohort was predominantly White (60.56%), male (75.27%), obese (59.34%), and had a history of current or previous tobacco use (73.47%) (Table 1). There were significant adjusted differences in prescription rates among veterans with HS based on age, race, and BMI. Notably, there was an age-dependent reduction in the odds of being prescribed a biologic in patients with HS. Compared with patients aged 18 to 44 years, patients aged 45 to 64 years (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 0.63; 95% CI, 0.54–0.74; P < .001) and patients aged ≥ 65 years (aOR, 0.36; 95% CI, 0.27–0.48; P < .001) had significantly lower odds of receiving a biologic prescription (Table 2). Compared with White patients with HS, Native Hawaiian (NH) or Pacific Islander (PI) patients were less likely to be prescribed a biologic (aOR, 0.23; 95% CI, 0.06–0.92; P = .04). Patients with obesity had significantly higher odds of receiving a biologic prescription compared with patients without obesity (aOR, 1.47; 95% CI, 1.27– 1.71; P < .001).

Included in Analysis.

After adjusting for the variables listed in Table 1, there were no significant differences in biologic prescription rates for men compared with women (aOR, 0.97; 95% CI, 0.83-1.12; P = .68). We observed slight variations in biologic prescriptions between US regions (Midwest 5.0%, East 4.2%, South 5.8%, West 4.6%), none of which were significantly different in the fully adjusted model. No statistically significant differences were found in biologic prescriptions between urban and rural VA settings (5.4% vs 4.8%; aOR, 1.06; 95% CI, 0.90–1.24; P = .47). Tobacco use was not associated with the rate of biologic prescription receipt (aOR, 1.14; 95% CI, 0.97–1.34; P = .11). After adjusting for other variables (as outlined in Table 2), no significant differences were found between CCI of 0 and 1 (aOR, 0.97; 95% CI, 0.82–1.16; P = .77) or between CCI of 0 and 2 (aOR, 0.89; 95% CI, 0.74–1.07; P = .22).7

Discussion

The aim of the study was to ascertain potential discrepancies in biologic prescription patterns among patients with HS in the VHA by demographic and lifestyle behavior modifiers. Veteran cohorts are unique in composition, consisting predominantly of older White men within a single-payer health care system. The prevalence of biologic prescriptions in this population was low (5.2%), consistent with prior studies (1.8%–8.9%).4,5

We found a significant difference in ADA/IFX prescription patterns between White patients and NH/PI patients (aOR, 0.23; 95% CI, 0.06-0.92; P = .04). Further replication of this result is needed due to the small number of NH/PI patients included in the study (n = 241). Notably, we did not find a significant difference in the odds of Black patients being prescribed a biologic compared with White patients (aOR, 1.07; 95% CI, 0.92–1.25; P = .38), consistent with prior studies.4

In line with prior studies, age was associated with the likelihood of receiving a biologic prescription.4 Using the multivariate model adjusting for variables listed in Table 1, including CCI, patients aged 45 to 64 years and > 64 years were less likely to be prescribed a biologic than patients aged 18 to 44 years. HS disease activity could be a potential confounding variable, as HS severity may subside in some people with increasing age or menopause.8

Because different regions in the US have different sociopolitical ideologies and governing legislation, we hypothesized that there may be dissimilarities in the prevalence rates of biologic prescribing across various US regions. However, no significant differences were found in prescription patterns among US regions or between rural and urban settings. Previous research has demonstrated discernible disparities in both dermatologic care and clinical outcomes based on hospital setting (ie, urban vs rural).9-11

Tobacco use has been demonstrated to be associated with the development of HS.12 In a large retrospective analysis, Garg et al reported increased odds of receiving a new HS diagnosis in known tobacco users (aOR, 1.9; 95% CI, 1.8–2.0).13 The extent to which tobacco use affects HS severity is less understood. While some studies have found an association between smoking and HS severity, other analyses have failed to find this association.14,15 The effects of smoking cessation on the disease course of HS are unknown.16 This analysis, found no significant difference in prescriptions for biologics among patients with HS comparing current or previous tobacco users with nonusers.

There is a known positive correlation between increasing BMI and HS prevalence and severity that may be explained by the downstream effects of adipose tissue secretion of proinflammatory mediators and insulin resistance in the setting of chronic inflammation.12 This analysis found that patients with HS and obesity were 1.47 times more likely to be prescribed a biologic than patients with HS without obesity, which may be confounded by increased HS severity among patients with obesity. The initial concern when analyzing tobacco use and obesity was that clinician bias may result in a decrease in the prevalence of biologic use in these demographics, which was not supported in this study.

Although we identified few disparities, the results demonstrated a substantial underutilization of biologic therapies (5.2%), similar to the other US civilian studies (1.8-8.9%).4,5 While there is no current universal, standardized severity scoring system to evaluate HS (it is difficult to objectively define moderate to severe HS), estimates have shown that 40.3% to 65.8% of patients with HS have Hurley stage II or III.17-19 Therefore, only a small percentage of patients with moderate to severe disease were prescribed the only FDA-approved medication during this time period. The persistence of this underutilization within a medical system that reduces financial barriers suggests that nonfinancial barriers have a notable role in the underutilization of biologics.

For instance, risk of adverse events, particularly lymphoma and infection, has been cited by patients as a reason to avoid biologics. Additionally, treatment fatigue reduced some patients’ willingness to try new treatments, as did lack of knowledge about treatment options.6,20 Other reported barriers included the frequency of injections and fear of needles.6 Additionally, within the VA, ADA may require prior authorization at the local facility level.21 An established relationship with a dermatologist has been shown to significantly increase the odds of being prescribed a biologic medication in the face of these barriers.4 Future system-wide quality improvement initiatives could be implemented to identify patients with HS not followed by dermatology, with the goal of establishing care with a dermatologist.

Limitations

Limitations to this study include an inability to categorize HS disease severity and assess the degree to which disease severity confounded study findings, particularly in relation to tobacco use and obesity. The generalizability of this study is also limited because of the demographic characteristics of the veteran patient population, which is predominantly older, White, and male, whereas HS disproportionately affects younger, Black, and female individuals in the US.22 Despite these limitations, this study contributes valuable insights into the use of biologic therapies for veteran populations with HS using a national dataset.

Conclusions

This study was performed within a single-payer government medical system, likely reducing or removing the financial barriers that some patient populations may face when pursuing biologics for HS treatment. However, the prevalence of biologic use in this population was low overall (5.2%), suggesting that other factors play a role in the underutilization of biologics in HS. Consistent with previous studies, younger individuals were more likely to be prescribed a biologic, and no difference in prescription rates between Black and White patients was observed. Unlike previous studies, no significant difference in prescription rates between men and women was observed.

Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is a chronic, inflammatory skin disorder characterized by painful nodules, abscesses, and tunnels predominantly affecting intertriginous areas of the body.1,2 The condition poses significant challenges in terms of diagnosis, treatment, and quality of life for affected individuals. Various systemic therapies have been explored to manage this debilitating condition, with the emergence of biologic agents offering hope for improved outcomes. In 2015, adalimumab (ADA) was the first biologic approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of HS, followed by secukinumab in 2023 and bimekizumab in 2024. However, the off-label use of other biologics and/or tumor necrosis factor inhibitors such as infliximab (IFX) has become common practice.3

Although these therapies have demonstrated promising results in the treatment of HS, their widespread use may be hindered by accessibility and cost barriers. Orenstein et al analyzed data from the IBM Explorys platform from 2015 to 2020 and found that only 1.8% of patients diagnosed with HS had been prescribed ADA or IFX.4 More recently, Garg et al examined IBM MarketScan and IBM US Medicaid data from 2015 to 2018 to evaluate trends in clinical care and treatment. The prevalence of ADA and IFX prescriptions among patients with HS ranged from 2.3% to 8.0% (ADA) and 0.7% to 0.9% (IFX) for patients with commercial insurance, and 1.4% to 4.8% (ADA) and 0.5% to 0.7% (IFX) for patients with Medicaid.5 Biologics are often expensive, and the high cost associated with these therapies has been identified as a significant barrier to access for patients with HS, particularly those who lack adequate insurance coverage or face financial constraints.6

Furthermore, these barriers, particularly the financial barriers, are potentially compounded by the demographics of patients most notably affected by HS. In the US, a disproportionate incidence of HS has been noted in specific groups and age ranges, including women, individuals aged 18 to 29 years, and Black individuals.4 Orenstein et al found a statistically significant difference in use of ADA and IFX biologics based on age, sex, and race.4

The aim of this study was to examine the use of 2 biologics (ADA and IFX) in the Veterans Health Administration (VHA), a unique population in which financial barriers are reduced due to the single-payer government health care system structure. This design allowed for improved isolation and evaluation of variation in ADA and/or IFX prescription rates by demographics and health-related factors among patients with HS. To our knowledge, no studies have analyzed these metrics within the VHA.

Methods

This retrospective, cross-sectional analysis of VHA patients used data from the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Corporate Data Warehouse, a data repository that provides access to longitudinal national electronic health record data for all veterans receiving care through VHA facilities. This study received ethical approval from institutional review boards at the Minneapolis Veterans Affairs Health Care System and VA Salt Lake City Healthcare System. Patient information was deidentified, and patient consent was not required.

Patients with HS were identified using ≥ 1 International Classification of Diseases (ICD) diagnostic code: (ICD-9 [705.83] or ICD-10 [L73.2]) between January 1, 2011, and December 31, 2021. The study included patients aged ≥ 18 years as of January 1, 2011, with ≥ 2 patient encounters during the postdiagnosis follow-up period, and with ≥ 1 encounter 6 months postindex. Patients with a biologic prescription prior to HS diagnosis were excluded. For this study, the term biologics refers to ADA and/or IFX prescriptions, unless otherwise specified. Only ADA and IFX were included in this analysis because ADA, a tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-á inhibitor, was the only FDA-approved medication at the time of the search, and IFX is another common TNF-α inhibitor used for the treatment of HS.

Statistical Analysis

We calculated logistic regression using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). For each variable, the univariate relationship with biologic prescriptions was examined first, followed by the multivariate relationship controlling for all other variables. The following variables were controlled for in the multivariate models and were chosen a priori: sex, age, race, ethnicity, US region, hospital setting, current or previous tobacco use, obesity (defined as body mass index [BMI] ≥ 30), and Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI).7

Results

Using ICD codes, we identified 29,483 individuals with ≥ 1 HS diagnosis (Figure 1). Of those identified, 1537 patients (5.21%) had been prescribed ≥ 1 biologic. The cohort was predominantly White (60.56%), male (75.27%), obese (59.34%), and had a history of current or previous tobacco use (73.47%) (Table 1). There were significant adjusted differences in prescription rates among veterans with HS based on age, race, and BMI. Notably, there was an age-dependent reduction in the odds of being prescribed a biologic in patients with HS. Compared with patients aged 18 to 44 years, patients aged 45 to 64 years (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 0.63; 95% CI, 0.54–0.74; P < .001) and patients aged ≥ 65 years (aOR, 0.36; 95% CI, 0.27–0.48; P < .001) had significantly lower odds of receiving a biologic prescription (Table 2). Compared with White patients with HS, Native Hawaiian (NH) or Pacific Islander (PI) patients were less likely to be prescribed a biologic (aOR, 0.23; 95% CI, 0.06–0.92; P = .04). Patients with obesity had significantly higher odds of receiving a biologic prescription compared with patients without obesity (aOR, 1.47; 95% CI, 1.27– 1.71; P < .001).

Included in Analysis.

After adjusting for the variables listed in Table 1, there were no significant differences in biologic prescription rates for men compared with women (aOR, 0.97; 95% CI, 0.83-1.12; P = .68). We observed slight variations in biologic prescriptions between US regions (Midwest 5.0%, East 4.2%, South 5.8%, West 4.6%), none of which were significantly different in the fully adjusted model. No statistically significant differences were found in biologic prescriptions between urban and rural VA settings (5.4% vs 4.8%; aOR, 1.06; 95% CI, 0.90–1.24; P = .47). Tobacco use was not associated with the rate of biologic prescription receipt (aOR, 1.14; 95% CI, 0.97–1.34; P = .11). After adjusting for other variables (as outlined in Table 2), no significant differences were found between CCI of 0 and 1 (aOR, 0.97; 95% CI, 0.82–1.16; P = .77) or between CCI of 0 and 2 (aOR, 0.89; 95% CI, 0.74–1.07; P = .22).7

Discussion

The aim of the study was to ascertain potential discrepancies in biologic prescription patterns among patients with HS in the VHA by demographic and lifestyle behavior modifiers. Veteran cohorts are unique in composition, consisting predominantly of older White men within a single-payer health care system. The prevalence of biologic prescriptions in this population was low (5.2%), consistent with prior studies (1.8%–8.9%).4,5

We found a significant difference in ADA/IFX prescription patterns between White patients and NH/PI patients (aOR, 0.23; 95% CI, 0.06-0.92; P = .04). Further replication of this result is needed due to the small number of NH/PI patients included in the study (n = 241). Notably, we did not find a significant difference in the odds of Black patients being prescribed a biologic compared with White patients (aOR, 1.07; 95% CI, 0.92–1.25; P = .38), consistent with prior studies.4

In line with prior studies, age was associated with the likelihood of receiving a biologic prescription.4 Using the multivariate model adjusting for variables listed in Table 1, including CCI, patients aged 45 to 64 years and > 64 years were less likely to be prescribed a biologic than patients aged 18 to 44 years. HS disease activity could be a potential confounding variable, as HS severity may subside in some people with increasing age or menopause.8

Because different regions in the US have different sociopolitical ideologies and governing legislation, we hypothesized that there may be dissimilarities in the prevalence rates of biologic prescribing across various US regions. However, no significant differences were found in prescription patterns among US regions or between rural and urban settings. Previous research has demonstrated discernible disparities in both dermatologic care and clinical outcomes based on hospital setting (ie, urban vs rural).9-11

Tobacco use has been demonstrated to be associated with the development of HS.12 In a large retrospective analysis, Garg et al reported increased odds of receiving a new HS diagnosis in known tobacco users (aOR, 1.9; 95% CI, 1.8–2.0).13 The extent to which tobacco use affects HS severity is less understood. While some studies have found an association between smoking and HS severity, other analyses have failed to find this association.14,15 The effects of smoking cessation on the disease course of HS are unknown.16 This analysis, found no significant difference in prescriptions for biologics among patients with HS comparing current or previous tobacco users with nonusers.

There is a known positive correlation between increasing BMI and HS prevalence and severity that may be explained by the downstream effects of adipose tissue secretion of proinflammatory mediators and insulin resistance in the setting of chronic inflammation.12 This analysis found that patients with HS and obesity were 1.47 times more likely to be prescribed a biologic than patients with HS without obesity, which may be confounded by increased HS severity among patients with obesity. The initial concern when analyzing tobacco use and obesity was that clinician bias may result in a decrease in the prevalence of biologic use in these demographics, which was not supported in this study.

Although we identified few disparities, the results demonstrated a substantial underutilization of biologic therapies (5.2%), similar to the other US civilian studies (1.8-8.9%).4,5 While there is no current universal, standardized severity scoring system to evaluate HS (it is difficult to objectively define moderate to severe HS), estimates have shown that 40.3% to 65.8% of patients with HS have Hurley stage II or III.17-19 Therefore, only a small percentage of patients with moderate to severe disease were prescribed the only FDA-approved medication during this time period. The persistence of this underutilization within a medical system that reduces financial barriers suggests that nonfinancial barriers have a notable role in the underutilization of biologics.

For instance, risk of adverse events, particularly lymphoma and infection, has been cited by patients as a reason to avoid biologics. Additionally, treatment fatigue reduced some patients’ willingness to try new treatments, as did lack of knowledge about treatment options.6,20 Other reported barriers included the frequency of injections and fear of needles.6 Additionally, within the VA, ADA may require prior authorization at the local facility level.21 An established relationship with a dermatologist has been shown to significantly increase the odds of being prescribed a biologic medication in the face of these barriers.4 Future system-wide quality improvement initiatives could be implemented to identify patients with HS not followed by dermatology, with the goal of establishing care with a dermatologist.

Limitations

Limitations to this study include an inability to categorize HS disease severity and assess the degree to which disease severity confounded study findings, particularly in relation to tobacco use and obesity. The generalizability of this study is also limited because of the demographic characteristics of the veteran patient population, which is predominantly older, White, and male, whereas HS disproportionately affects younger, Black, and female individuals in the US.22 Despite these limitations, this study contributes valuable insights into the use of biologic therapies for veteran populations with HS using a national dataset.

Conclusions

This study was performed within a single-payer government medical system, likely reducing or removing the financial barriers that some patient populations may face when pursuing biologics for HS treatment. However, the prevalence of biologic use in this population was low overall (5.2%), suggesting that other factors play a role in the underutilization of biologics in HS. Consistent with previous studies, younger individuals were more likely to be prescribed a biologic, and no difference in prescription rates between Black and White patients was observed. Unlike previous studies, no significant difference in prescription rates between men and women was observed.

- Goldburg SR, Strober BE, Payette MJ. Hidradenitis suppurativa: epidemiology, clinical presentation, and pathogenesis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:1045-1058. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.08.090

- Tchero H, Herlin C, Bekara F, et al. Hidradenitis suppurativa: a systematic review and meta-analysis of therapeutic interventions. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2019;85:248-257. doi:10.4103/ijdvl.IJDVL_69_18

- Shih T, Lee K, Grogan T, et al. Infliximab in hidradenitis suppurativa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Dermatol Ther. 2022;35:e15691. doi:10.1111/dth.15691

- Orenstein LAV, Wright S, Strunk A, et al. Low prescription of tumor necrosis alpha inhibitors in hidradenitis suppurativa: a cross-sectional analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:1399-1401. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.07.108

- Garg A, Naik HB, Alavi A, et al. Real-world findings on the characteristics and treatment exposures of patients with hidradenitis suppurativa from US claims data. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2023;13:581-594. doi:10.1007/s13555-022-00872-1

- De DR, Shih T, Fixsen D, et al. Biologic use in hidradenitis suppurativa: patient perspectives and barriers. J Dermatolog Treat. 2022;33:3060-3062. doi:10.1080/09546634.2022.2089336

- Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, et al. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373- 383. doi:10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8

- von der Werth JM, Williams HC. The natural history of hidradenitis suppurativa. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2000;14:389-392. doi:10.1046/j.1468-3083.2000.00087.x

- Silverberg JI, Barbarot S, Gadkari A, et al. Atopic dermatitis in the pediatric population: a cross-sectional, international epidemiologic study. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2021;126:417-428.e2. doi:10.1016/j.anai.2020.12.020

- Wu YP, Parsons B, Jo Y, et al. Outdoor activities and sunburn among urban and rural families in a Western region of the US: implications for skin cancer prevention. Prev Med Rep. 2022;29:101914. doi:10.1016/j.pmedr.2022.101914

- Mannschreck DB, Li X, Okoye G. Rural melanoma patients in Maryland do not present with more advanced disease than urban patients. Dermatol Online J. 2021;27. doi:10.5070/D327553607

- Garg A, Malviya N, Strunk A, et al. Comorbidity screening in hidradenitis suppurativa: evidence-based recommendations from the US and Canadian Hidradenitis Suppurativa Foundations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86:1092-1101. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.01.059

- Garg A, Papagermanos V, Midura M, et al. Incidence of hidradenitis suppurativa among tobacco smokers: a population- based retrospective analysis in the U.S.A. Br J Dermatol. 2018;178:709-714. doi:10.1111/bjd.15939

- Sartorius K, Emtestam L, Jemec GBE, et al. Objective scoring of hidradenitis suppurativa reflecting the role of tobacco smoking and obesity. Br J Dermatol. 2009;161:831- 839. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2009.09198.x

- Canoui-Poitrine F, Revuz JE, Wolkenstein P, et al. Clinical characteristics of a series of 302 French patients with hidradenitis suppurativa, with an analysis of factors associated with disease severity. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:51-57. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2009.02.013

- Dufour DN, Emtestam L, Jemec GB. Hidradenitis suppurativa: a common and burdensome, yet under-recognised, inflammatory skin disease. Postgrad Med J. 2014;90:216- 221. doi:10.1136/postgradmedj-2013-131994

- Vazquez BG, Alikhan A, Weaver AL, et al. Incidence of hidradenitis suppurativa and associated factors: a population- based study of Olmsted County, Minnesota. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133:97-103. doi:10.1038/jid.2012.255

- Vanlaerhoven AMJD, Ardon CB, van Straalen KR, et al. Hurley III hidradenitis suppurativa has an aggressive disease course. Dermatology. 2018;234:232-233. doi:10.1159/000491547

- Shahi V, Alikhan A, Vazquez BG, et al. Prevalence of hidradenitis suppurativa: a population-based study in Olmsted County, Minnesota. Dermatology. 2014;229:154-158. doi:10.1159/000363381

- Salame N, Sow YN, Siira MR, et al. Factors affecting treatment selection among patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. JAMA Dermatol. 2024;160:179. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2023.5425

- VA Formulary Advisor: ADALIMUMAB-BWWD INJ,SOLN. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Updated December 17, 2025. Accessed January 15, 2026. https://www.va.gov/formularyadvisor/drugs/4042383-ADALIMUMAB-BWWD-INJ-SOLN

- Garg A, Lavian J, Lin G, et al. Incidence of hidradenitis suppurativa in the United States: a sex- and age-adjusted population analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:118- 122. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.02.005

- Goldburg SR, Strober BE, Payette MJ. Hidradenitis suppurativa: epidemiology, clinical presentation, and pathogenesis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:1045-1058. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.08.090

- Tchero H, Herlin C, Bekara F, et al. Hidradenitis suppurativa: a systematic review and meta-analysis of therapeutic interventions. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2019;85:248-257. doi:10.4103/ijdvl.IJDVL_69_18

- Shih T, Lee K, Grogan T, et al. Infliximab in hidradenitis suppurativa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Dermatol Ther. 2022;35:e15691. doi:10.1111/dth.15691

- Orenstein LAV, Wright S, Strunk A, et al. Low prescription of tumor necrosis alpha inhibitors in hidradenitis suppurativa: a cross-sectional analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:1399-1401. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.07.108

- Garg A, Naik HB, Alavi A, et al. Real-world findings on the characteristics and treatment exposures of patients with hidradenitis suppurativa from US claims data. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2023;13:581-594. doi:10.1007/s13555-022-00872-1

- De DR, Shih T, Fixsen D, et al. Biologic use in hidradenitis suppurativa: patient perspectives and barriers. J Dermatolog Treat. 2022;33:3060-3062. doi:10.1080/09546634.2022.2089336

- Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, et al. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373- 383. doi:10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8

- von der Werth JM, Williams HC. The natural history of hidradenitis suppurativa. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2000;14:389-392. doi:10.1046/j.1468-3083.2000.00087.x

- Silverberg JI, Barbarot S, Gadkari A, et al. Atopic dermatitis in the pediatric population: a cross-sectional, international epidemiologic study. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2021;126:417-428.e2. doi:10.1016/j.anai.2020.12.020

- Wu YP, Parsons B, Jo Y, et al. Outdoor activities and sunburn among urban and rural families in a Western region of the US: implications for skin cancer prevention. Prev Med Rep. 2022;29:101914. doi:10.1016/j.pmedr.2022.101914

- Mannschreck DB, Li X, Okoye G. Rural melanoma patients in Maryland do not present with more advanced disease than urban patients. Dermatol Online J. 2021;27. doi:10.5070/D327553607

- Garg A, Malviya N, Strunk A, et al. Comorbidity screening in hidradenitis suppurativa: evidence-based recommendations from the US and Canadian Hidradenitis Suppurativa Foundations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86:1092-1101. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.01.059

- Garg A, Papagermanos V, Midura M, et al. Incidence of hidradenitis suppurativa among tobacco smokers: a population- based retrospective analysis in the U.S.A. Br J Dermatol. 2018;178:709-714. doi:10.1111/bjd.15939

- Sartorius K, Emtestam L, Jemec GBE, et al. Objective scoring of hidradenitis suppurativa reflecting the role of tobacco smoking and obesity. Br J Dermatol. 2009;161:831- 839. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2009.09198.x

- Canoui-Poitrine F, Revuz JE, Wolkenstein P, et al. Clinical characteristics of a series of 302 French patients with hidradenitis suppurativa, with an analysis of factors associated with disease severity. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:51-57. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2009.02.013

- Dufour DN, Emtestam L, Jemec GB. Hidradenitis suppurativa: a common and burdensome, yet under-recognised, inflammatory skin disease. Postgrad Med J. 2014;90:216- 221. doi:10.1136/postgradmedj-2013-131994

- Vazquez BG, Alikhan A, Weaver AL, et al. Incidence of hidradenitis suppurativa and associated factors: a population- based study of Olmsted County, Minnesota. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133:97-103. doi:10.1038/jid.2012.255

- Vanlaerhoven AMJD, Ardon CB, van Straalen KR, et al. Hurley III hidradenitis suppurativa has an aggressive disease course. Dermatology. 2018;234:232-233. doi:10.1159/000491547

- Shahi V, Alikhan A, Vazquez BG, et al. Prevalence of hidradenitis suppurativa: a population-based study in Olmsted County, Minnesota. Dermatology. 2014;229:154-158. doi:10.1159/000363381

- Salame N, Sow YN, Siira MR, et al. Factors affecting treatment selection among patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. JAMA Dermatol. 2024;160:179. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2023.5425

- VA Formulary Advisor: ADALIMUMAB-BWWD INJ,SOLN. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Updated December 17, 2025. Accessed January 15, 2026. https://www.va.gov/formularyadvisor/drugs/4042383-ADALIMUMAB-BWWD-INJ-SOLN

- Garg A, Lavian J, Lin G, et al. Incidence of hidradenitis suppurativa in the United States: a sex- and age-adjusted population analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:118- 122. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.02.005

Cross-Sectional Analysis of Biologic Use in the Treatment of Veterans With Hidradenitis Suppurativa

Cross-Sectional Analysis of Biologic Use in the Treatment of Veterans With Hidradenitis Suppurativa

Coronary Artery Bypass Graft Saphenous Vein Harvest Site Hyperpigmentation

A 59-year-old man with a history of coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG), ischemic cardiomyopathy (ejection fraction, 15%-20%) with implantable cardioverter-defibrillator, recurrent paroxysmal ventricular tachycardia on amiodarone and mexiletine, and heart failure requiring left ventricular assist device (LVAD) placement presented for recurrent cellulitis and infection of the LVAD driveline exit site. He was initiated on minocycline 100 mg twice daily in combination with cefadroxil 500 mg twice daily. At his 8-week follow-up, the driveline site appeared improved with minimal erythema and no drainage. However, the patient developed a well-demarcated, linear, hyperpigmented patch along the length of the saphenous vein CABG harvest site and a few hyperpigmented macules medial to the harvest site (Figure).

Discussion

Hyperpigmentation presenting within scar tissue, as seen in this patient undergoing minocycline therapy, is a classic presentation of minocycline-induced hyperpigmentation (MIH) type I.

MIH is an uncommon, potentially cosmetically disfiguring adverse effect associated with systemic minocycline use. MIH can affect skin, teeth, nails, oral mucosa, sclera, and internal organs. The cumulative incidence of MIH in patients receiving minocycline over prolonged periods of time has been estimated from 2% to 15% in patients with acne and rosacea, to approximately 50% over 5 years in orthopedic patient populations.1-3 The risk for developing MIH increases with vitamin D deficiency, liver disease, concurrent use with other medications that can induce hyperpigmentation, and higher cumulative doses (> 70-100 g; more important for MIH types II and III).3,4

There are 3 distinct types of MIH. Type I MIH is characterized by blue-black macules and patches at sites of inflammation or prior scarring, most commonly described in facial acne scars.1,2,4 Type II is typified by blue-grey pigmentation on normal-appearing skin, most commonly on the shins, but also on sun-exposed sites.3 Biopsies of type I and II MIH demonstrate pigmented granules within macrophages or within the dermis.4,5 Both Perls iron stain and Fontana-Masson melanin stain are positive in type I and II MIH.5 Type III MIH presents as diffuse brownish hyperpigmentation on normal skin in chronically sun-exposed sites.3 Histopathology of type III MIH can be distinguished by increased melanin noted inside basal keratinocytes as well as dermal melanophages that stain positive for only Fontana-Masson.5 The current case exemplifies a unique presentation of type I MIH along the length of the saphenous vein CABG harvest site. The concomitant use of amiodarone with minocycline may have contributed to the presentation.

The differential diagnosis for MIH depends on the type of MIH. Blue-grey pigmentation within scars is fairly unique to minocycline but has been reported with other medications, including vandetanib.6 The differential diagnosis for diffuse blue-grey or brown hyperpigmentation in predominately sun-exposed sites is broader, including endocrine disorders (ie, Addison disease), heavy metal poisoning (ie, argyria), inherited conditions (ie, alkaptonuria, Wilson disease, and hemochromatosis), medication-induced hyperpigmentation (ie, antipsychotics, anticonvulsant, antimalarials, amiodarone, and cytotoxic drugs), as well as inflammatory dermatoses, such as erythema dyschromicum perstans.7

MIH typically fades over months to years following minocycline discontinuation, so prompt recognition and discontinuation is recommended. Unfortunately, some cases persist or only partially fade over time. While MIH is benign, it can be of aesthetic concern, cause anxiety, and impact patients’ quality of life.3,8 Persistent MIH is typically recalcitrant to topical hydroquinone.9 However, persistent MIH has been shown to improve with Q-switched, nanosecond lasers such as the 694 nm ruby, 755 nm alexandrite, and 1064 nm neodymium-doped yttrium aluminum garnet neodymium (Nd:YAG) lasers, as well as the 755 nm picosecond alexandrite laser.4,9,10

In our patient, minocycline therapy was discontinued and replaced with doxycycline 100 mg twice daily monotherapy. At a subsequent visit 12 weeks later, the hyperpigmentation remained unchanged.

Conclusions

Though uncommon, we hope to encourage clinician awareness of MIH through our case, as prompt diagnosis and the discontinuation of minocycline are preferred to improve patient outcomes.

1. Goulden V, Glass D, Cunliffe WJ. Safety of long-term high-dose minocycline in the treatment of acne. Br J Dermatol. 1996;134(4):693-695. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.1996.tb06972.x

2. Dwyer CM, Cuddihy AM, Kerr RE, Chapman RS, Allam BF. Skin pigmentation due to minocycline treatment of facial dermatoses. Br J Dermatol. 1993;129(2):158-162. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.1993.tb03519.x

3. Hanada Y, Berbari EF, Steckelberg JM. Minocycline-induced cutaneous hyperpigmentation in an orthopedic patient population. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2016;3(1):ofv107. doi:10.1093/ofid/ofv107

4. Eisen D, Hakim MD. Minocycline-induced pigmentation. Incidence, prevention and management. Drug Saf. 1998;18(6):431-440. doi:10.2165/00002018-199818060-00004

5. Bowen AR, McCalmont TH. The histopathology of subcutaneous minocycline pigmentation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57(5):836-839. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2007.04.028

6. Perlmutter JW, Cogan RC, Wiseman MC. Blue-grey hyperpigmentation in acne after vandetanib therapy and doxycycline use: a case report. SAGE Open Med Case Rep. 2022;10:2050313X221086316. doi:10.1177/2050313X221086316

7. Judson T, Mihara K. Minocycline-induced hyperpigmentation. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(1):133. doi:10.1007/s11606-016-3735-x

8. Li Y, Zhen X, Yao X, Lu J. Successful treatment of minocycline-induced facial hyperpigmentation with a combination of chemical peels and intense pulsed light. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2023;16:253-256. doi:10.2147/CCID.S394754

9. Sasaki K, Ohshiro T, Ohshiro T, et al. Type 2 Minocycline-induced hyperpigmentation successfully treated with the novel 755 nm picosecond alexandrite laser – a case report. Laser Ther. 2017;26(2):137-144. doi:10.5978/islsm.17-CR-03

10. Nisar MS, Iyer K, Brodell RT, Lloyd JR, Shin TM, Ahmad A. Minocycline-induced hyperpigmentation: comparison of 3 Q-switched lasers to reverse its effects. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2013;6:159-162. doi:10.2147/CCID.S42166

A 59-year-old man with a history of coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG), ischemic cardiomyopathy (ejection fraction, 15%-20%) with implantable cardioverter-defibrillator, recurrent paroxysmal ventricular tachycardia on amiodarone and mexiletine, and heart failure requiring left ventricular assist device (LVAD) placement presented for recurrent cellulitis and infection of the LVAD driveline exit site. He was initiated on minocycline 100 mg twice daily in combination with cefadroxil 500 mg twice daily. At his 8-week follow-up, the driveline site appeared improved with minimal erythema and no drainage. However, the patient developed a well-demarcated, linear, hyperpigmented patch along the length of the saphenous vein CABG harvest site and a few hyperpigmented macules medial to the harvest site (Figure).

Discussion

Hyperpigmentation presenting within scar tissue, as seen in this patient undergoing minocycline therapy, is a classic presentation of minocycline-induced hyperpigmentation (MIH) type I.

MIH is an uncommon, potentially cosmetically disfiguring adverse effect associated with systemic minocycline use. MIH can affect skin, teeth, nails, oral mucosa, sclera, and internal organs. The cumulative incidence of MIH in patients receiving minocycline over prolonged periods of time has been estimated from 2% to 15% in patients with acne and rosacea, to approximately 50% over 5 years in orthopedic patient populations.1-3 The risk for developing MIH increases with vitamin D deficiency, liver disease, concurrent use with other medications that can induce hyperpigmentation, and higher cumulative doses (> 70-100 g; more important for MIH types II and III).3,4

There are 3 distinct types of MIH. Type I MIH is characterized by blue-black macules and patches at sites of inflammation or prior scarring, most commonly described in facial acne scars.1,2,4 Type II is typified by blue-grey pigmentation on normal-appearing skin, most commonly on the shins, but also on sun-exposed sites.3 Biopsies of type I and II MIH demonstrate pigmented granules within macrophages or within the dermis.4,5 Both Perls iron stain and Fontana-Masson melanin stain are positive in type I and II MIH.5 Type III MIH presents as diffuse brownish hyperpigmentation on normal skin in chronically sun-exposed sites.3 Histopathology of type III MIH can be distinguished by increased melanin noted inside basal keratinocytes as well as dermal melanophages that stain positive for only Fontana-Masson.5 The current case exemplifies a unique presentation of type I MIH along the length of the saphenous vein CABG harvest site. The concomitant use of amiodarone with minocycline may have contributed to the presentation.

The differential diagnosis for MIH depends on the type of MIH. Blue-grey pigmentation within scars is fairly unique to minocycline but has been reported with other medications, including vandetanib.6 The differential diagnosis for diffuse blue-grey or brown hyperpigmentation in predominately sun-exposed sites is broader, including endocrine disorders (ie, Addison disease), heavy metal poisoning (ie, argyria), inherited conditions (ie, alkaptonuria, Wilson disease, and hemochromatosis), medication-induced hyperpigmentation (ie, antipsychotics, anticonvulsant, antimalarials, amiodarone, and cytotoxic drugs), as well as inflammatory dermatoses, such as erythema dyschromicum perstans.7

MIH typically fades over months to years following minocycline discontinuation, so prompt recognition and discontinuation is recommended. Unfortunately, some cases persist or only partially fade over time. While MIH is benign, it can be of aesthetic concern, cause anxiety, and impact patients’ quality of life.3,8 Persistent MIH is typically recalcitrant to topical hydroquinone.9 However, persistent MIH has been shown to improve with Q-switched, nanosecond lasers such as the 694 nm ruby, 755 nm alexandrite, and 1064 nm neodymium-doped yttrium aluminum garnet neodymium (Nd:YAG) lasers, as well as the 755 nm picosecond alexandrite laser.4,9,10

In our patient, minocycline therapy was discontinued and replaced with doxycycline 100 mg twice daily monotherapy. At a subsequent visit 12 weeks later, the hyperpigmentation remained unchanged.

Conclusions

Though uncommon, we hope to encourage clinician awareness of MIH through our case, as prompt diagnosis and the discontinuation of minocycline are preferred to improve patient outcomes.

A 59-year-old man with a history of coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG), ischemic cardiomyopathy (ejection fraction, 15%-20%) with implantable cardioverter-defibrillator, recurrent paroxysmal ventricular tachycardia on amiodarone and mexiletine, and heart failure requiring left ventricular assist device (LVAD) placement presented for recurrent cellulitis and infection of the LVAD driveline exit site. He was initiated on minocycline 100 mg twice daily in combination with cefadroxil 500 mg twice daily. At his 8-week follow-up, the driveline site appeared improved with minimal erythema and no drainage. However, the patient developed a well-demarcated, linear, hyperpigmented patch along the length of the saphenous vein CABG harvest site and a few hyperpigmented macules medial to the harvest site (Figure).

Discussion

Hyperpigmentation presenting within scar tissue, as seen in this patient undergoing minocycline therapy, is a classic presentation of minocycline-induced hyperpigmentation (MIH) type I.

MIH is an uncommon, potentially cosmetically disfiguring adverse effect associated with systemic minocycline use. MIH can affect skin, teeth, nails, oral mucosa, sclera, and internal organs. The cumulative incidence of MIH in patients receiving minocycline over prolonged periods of time has been estimated from 2% to 15% in patients with acne and rosacea, to approximately 50% over 5 years in orthopedic patient populations.1-3 The risk for developing MIH increases with vitamin D deficiency, liver disease, concurrent use with other medications that can induce hyperpigmentation, and higher cumulative doses (> 70-100 g; more important for MIH types II and III).3,4

There are 3 distinct types of MIH. Type I MIH is characterized by blue-black macules and patches at sites of inflammation or prior scarring, most commonly described in facial acne scars.1,2,4 Type II is typified by blue-grey pigmentation on normal-appearing skin, most commonly on the shins, but also on sun-exposed sites.3 Biopsies of type I and II MIH demonstrate pigmented granules within macrophages or within the dermis.4,5 Both Perls iron stain and Fontana-Masson melanin stain are positive in type I and II MIH.5 Type III MIH presents as diffuse brownish hyperpigmentation on normal skin in chronically sun-exposed sites.3 Histopathology of type III MIH can be distinguished by increased melanin noted inside basal keratinocytes as well as dermal melanophages that stain positive for only Fontana-Masson.5 The current case exemplifies a unique presentation of type I MIH along the length of the saphenous vein CABG harvest site. The concomitant use of amiodarone with minocycline may have contributed to the presentation.

The differential diagnosis for MIH depends on the type of MIH. Blue-grey pigmentation within scars is fairly unique to minocycline but has been reported with other medications, including vandetanib.6 The differential diagnosis for diffuse blue-grey or brown hyperpigmentation in predominately sun-exposed sites is broader, including endocrine disorders (ie, Addison disease), heavy metal poisoning (ie, argyria), inherited conditions (ie, alkaptonuria, Wilson disease, and hemochromatosis), medication-induced hyperpigmentation (ie, antipsychotics, anticonvulsant, antimalarials, amiodarone, and cytotoxic drugs), as well as inflammatory dermatoses, such as erythema dyschromicum perstans.7

MIH typically fades over months to years following minocycline discontinuation, so prompt recognition and discontinuation is recommended. Unfortunately, some cases persist or only partially fade over time. While MIH is benign, it can be of aesthetic concern, cause anxiety, and impact patients’ quality of life.3,8 Persistent MIH is typically recalcitrant to topical hydroquinone.9 However, persistent MIH has been shown to improve with Q-switched, nanosecond lasers such as the 694 nm ruby, 755 nm alexandrite, and 1064 nm neodymium-doped yttrium aluminum garnet neodymium (Nd:YAG) lasers, as well as the 755 nm picosecond alexandrite laser.4,9,10

In our patient, minocycline therapy was discontinued and replaced with doxycycline 100 mg twice daily monotherapy. At a subsequent visit 12 weeks later, the hyperpigmentation remained unchanged.

Conclusions

Though uncommon, we hope to encourage clinician awareness of MIH through our case, as prompt diagnosis and the discontinuation of minocycline are preferred to improve patient outcomes.

1. Goulden V, Glass D, Cunliffe WJ. Safety of long-term high-dose minocycline in the treatment of acne. Br J Dermatol. 1996;134(4):693-695. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.1996.tb06972.x

2. Dwyer CM, Cuddihy AM, Kerr RE, Chapman RS, Allam BF. Skin pigmentation due to minocycline treatment of facial dermatoses. Br J Dermatol. 1993;129(2):158-162. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.1993.tb03519.x

3. Hanada Y, Berbari EF, Steckelberg JM. Minocycline-induced cutaneous hyperpigmentation in an orthopedic patient population. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2016;3(1):ofv107. doi:10.1093/ofid/ofv107

4. Eisen D, Hakim MD. Minocycline-induced pigmentation. Incidence, prevention and management. Drug Saf. 1998;18(6):431-440. doi:10.2165/00002018-199818060-00004

5. Bowen AR, McCalmont TH. The histopathology of subcutaneous minocycline pigmentation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57(5):836-839. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2007.04.028

6. Perlmutter JW, Cogan RC, Wiseman MC. Blue-grey hyperpigmentation in acne after vandetanib therapy and doxycycline use: a case report. SAGE Open Med Case Rep. 2022;10:2050313X221086316. doi:10.1177/2050313X221086316

7. Judson T, Mihara K. Minocycline-induced hyperpigmentation. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(1):133. doi:10.1007/s11606-016-3735-x

8. Li Y, Zhen X, Yao X, Lu J. Successful treatment of minocycline-induced facial hyperpigmentation with a combination of chemical peels and intense pulsed light. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2023;16:253-256. doi:10.2147/CCID.S394754

9. Sasaki K, Ohshiro T, Ohshiro T, et al. Type 2 Minocycline-induced hyperpigmentation successfully treated with the novel 755 nm picosecond alexandrite laser – a case report. Laser Ther. 2017;26(2):137-144. doi:10.5978/islsm.17-CR-03

10. Nisar MS, Iyer K, Brodell RT, Lloyd JR, Shin TM, Ahmad A. Minocycline-induced hyperpigmentation: comparison of 3 Q-switched lasers to reverse its effects. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2013;6:159-162. doi:10.2147/CCID.S42166

1. Goulden V, Glass D, Cunliffe WJ. Safety of long-term high-dose minocycline in the treatment of acne. Br J Dermatol. 1996;134(4):693-695. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.1996.tb06972.x

2. Dwyer CM, Cuddihy AM, Kerr RE, Chapman RS, Allam BF. Skin pigmentation due to minocycline treatment of facial dermatoses. Br J Dermatol. 1993;129(2):158-162. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.1993.tb03519.x

3. Hanada Y, Berbari EF, Steckelberg JM. Minocycline-induced cutaneous hyperpigmentation in an orthopedic patient population. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2016;3(1):ofv107. doi:10.1093/ofid/ofv107

4. Eisen D, Hakim MD. Minocycline-induced pigmentation. Incidence, prevention and management. Drug Saf. 1998;18(6):431-440. doi:10.2165/00002018-199818060-00004

5. Bowen AR, McCalmont TH. The histopathology of subcutaneous minocycline pigmentation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57(5):836-839. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2007.04.028

6. Perlmutter JW, Cogan RC, Wiseman MC. Blue-grey hyperpigmentation in acne after vandetanib therapy and doxycycline use: a case report. SAGE Open Med Case Rep. 2022;10:2050313X221086316. doi:10.1177/2050313X221086316

7. Judson T, Mihara K. Minocycline-induced hyperpigmentation. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(1):133. doi:10.1007/s11606-016-3735-x

8. Li Y, Zhen X, Yao X, Lu J. Successful treatment of minocycline-induced facial hyperpigmentation with a combination of chemical peels and intense pulsed light. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2023;16:253-256. doi:10.2147/CCID.S394754

9. Sasaki K, Ohshiro T, Ohshiro T, et al. Type 2 Minocycline-induced hyperpigmentation successfully treated with the novel 755 nm picosecond alexandrite laser – a case report. Laser Ther. 2017;26(2):137-144. doi:10.5978/islsm.17-CR-03

10. Nisar MS, Iyer K, Brodell RT, Lloyd JR, Shin TM, Ahmad A. Minocycline-induced hyperpigmentation: comparison of 3 Q-switched lasers to reverse its effects. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2013;6:159-162. doi:10.2147/CCID.S42166