User login

Analysis of Predictors and Outcomes of Allogeneic Blood Transfusion After Shoulder Arthroplasty

In shoulder arthroplasty, it is not uncommon for patients to receive postoperative blood transfusions; rates range from 7% to 43%.1-6 Allogeneic blood transfusions (ABTs) are costly and not entirely free of risks.7 The risk for infection has decreased because of improved screening and risk reduction strategies, but there are still significant risks associated with ABTs, such as clerical errors, acute and delayed hemolytic reactions, graft-versus-host reactions, transfusion-related acute lung injury, and anaphylaxis.8-10 As use of shoulder arthroplasty continues to increase, the importance of minimizing unnecessary transfusions is growing as well.7

Predictive factors for ABT have been explored in other orthopedic settings, yet little has been done in shoulder arthroplasty.1-6,11-15 Previous shoulder arthroplasty studies have shown that low preoperative hemoglobin (Hb) levels are independent risk factors for postoperative blood transfusion. However, there is debate over the significance of other variables, such as procedure type, age, sex, and medical comorbidities. Further, prior studies were limited by relatively small samples from single institutions; the largest series included fewer than 600 patients.1-6

We conducted a study to determine predictors of ABT in a large cohort of patients admitted to US hospitals for shoulder arthroplasty. We also wanted to evaluate the effect of ABT on postoperative outcomes, including inpatient mortality, adverse events, prolonged hospital stay, and nonroutine discharge. According to the null hypothesis, in shoulder arthroplasty there will be no difference in risk factors between patients who require ABT and those who did not, after accounting for confounding variables.

Materials and Methods

This study was exempt from institutional review board approval, as all data were appropriately deidentified before use in this project. We used the Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS) to retrospectively study the period 2002–2011, from which all demographic, clinical, and resource use data were derived.16 NIS, an annual survey conducted by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) since 1988, has generated a huge amount of data, forming the largest all-payer inpatient care database in the United States. Yearly samples contain discharge data from about 8 million hospital stays at more than 1000 hospitals across 46 states, approximating a 20% random sample of all hospital discharges at participating institutions.17 These data are then weighted to generate statistically valid national estimates.

The NIS database uses International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Edition, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) codes to identify 15 medical diagnoses up to the year 2008 and a maximum of 25 medical diagnoses and 15 procedures thereafter. In addition, the database includes information on patient and hospital characteristics as well as inpatient outcomes such as length of stay, total hospitalization charges, and discharge disposition.18,19 Given its large sample size and data volume, NIS is a powerful tool in the analysis of data associated with a multitude of medical diagnoses and procedures.20

We used the NIS database to study a population of 422,371 patients (age, >18 years) who underwent total shoulder arthroplasty (TSA) or hemiarthroplasty (HSA) between 2002 and 2011. ICD-9-CM procedure codes for TSA (81.80, 81.88) and HSA (81.81) were used to identify this population. We also analyzed data for reverse TSA for the year 2011. Then we divided our target population into 2 different cohorts: patients who did not receive any blood transfusion products and patients who received a transfusion of allogeneic packed cells (ICD-9-CM code 99.04 was used to identify the latter cohort).

In this study, normal distribution of the dataset was assumed, given the large sample size. The 2 cohorts were evaluated through bivariate analysis using the Pearson χ2 test for categorical data and the independent-samples t test for continuous data. The extent to which diagnosis, age, race, sex, and medical comorbidities were predictive of blood transfusion after TSA or HSA was evaluated through multivariate binary logistic regression analysis. Statistical significance was set at P < .05. All statistical analyses and data modeling were performed with SPSS Version 22.0.

Results

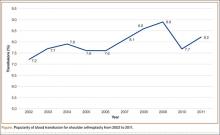

Using the NIS database, we stratified an estimated 422,371 patients who presented for shoulder arthroplasty between January 1, 2002, and December 31, 2011, into a TSA cohort (59.3%) and an HSA cohort (40.7%). Eight percent (33,889) of all patients received an ABT; the proportion of patients who received ABT was higher (P < .001) for the HSA cohort (55.6%) than the TSA cohort (39.4%). Further, the rate of ABT after shoulder arthroplasty showed an upward inclination (Figure).

Demographically, patients who received ABT tended (P < .001) to be older (74±11 years vs 68±11 years) and of a minority race (black or Hispanic) and to fall in either the lowest range of median household income (21.5% vs 20.7%; ≤$38,999) or the highest (27.3% vs 25.4%; ≥$63,000). Shoulder arthroplasty with ABT occurred more often (P < .001) at hospitals that were urban (13.3% vs 11.3%), medium in size (27.3% vs 23.4%), and nonteaching (56.2% vs 54.3%). In addition, ABT was used more often (P < .001) in patients with a primary diagnosis of fracture (43.1% vs 14.3%) or fracture nonunion (4.4% vs 2.1%). These groups also had a longer (P < .001) hospital stay (5.0±4.3 days vs 2.5±2.2 days). Table 1 summarizes these findings.

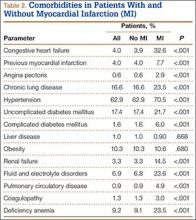

The 2 cohorts were then analyzed for presence of medical comorbidities (Table 2). Patients who required ABT during shoulder arthroplasty had a significantly (P < .001) higher prevalence of congestive heart failure, chronic lung disease, hypertension, uncomplicated and complicated diabetes mellitus, liver disease, renal failure, fluid and electrolyte disorders, pulmonary circulatory disease, weight loss, coagulopathy, and deficiency anemia.

In multivariate regression modeling (Table 3), demographic predictors of ABT (P < .001) included increasing age (odds ratio [OR], 1.03 per year; 95% confidence interval [95% CI], 1.03-1.03), female sex (OR, 1.55; 95% CI, 1.51-1.60), and minority race (black or Hispanic). Odds of requiring ABT were higher for patients with Medicare (OR, 1.25; 95% CI, 1.20-1.30) and patients with Medicaid (OR, 1.63; 95% CI, 1.51-1.77) than for patients with private insurance.

ABT was more likely to be required (P < .001) in patients with a primary diagnosis of fracture (OR, 4.49; 95% CI, 4.34-4.65), avascular necrosis (OR, 2.06; 95% CI, 1.91-2.22), rheumatoid arthritis (OR, 1.91; 95% CI, 1.72-2.12), fracture nonunion (OR, 3.55; 95% CI, 3.33-3.79), or rotator cuff arthropathy (OR, 1.47; 95% CI, 1.41-1.54) than for patients with osteoarthritis. Moreover, compared with patients having HSA, patients having TSA were more likely to require ABT (OR, 1.20; 95% CI, 1.17-1.24). According to the analysis restricted to the year 2011, compared with patients having anatomical TSAs, patients having reverse TSAs were 1.6 times more likely (P < .001) to require ABT (OR, 1.63; 95% CI, 1.50-1.79).

With the exception of obesity, all comorbidities were significant (P < .001) independent predictors of ABT after shoulder arthroplasty: deficiency anemia (OR, 3.42; 95% CI, 3.32-3.52), coagulopathy (OR, 2.54; 95% CI, 2.36-2.73), fluid and electrolyte disorders (OR, 1.91; 95% CI, 1.84-1.97), and weight loss (OR, 1.78; 95% CI, 1.58-2.00).

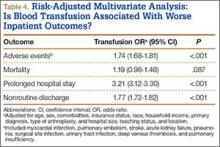

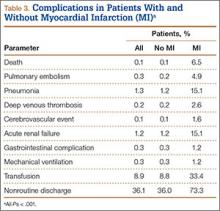

Patients who received ABT were more likely to experience adverse events (OR, 1.74; 95% CI, 1.68-1.81), prolonged hospital stay (OR, 3.21; 95% CI, 3.12-3.30), and nonroutine discharge (OR, 1.77; 95% CI, 1.72-1.82) (Table 4). There was no difference in mortality between the 2 cohorts.

Discussion

There is an abundance of literature on blood transfusions in hip and knee arthroplasty, but there are few articles on ABT in shoulder arthroplasty, and they all report data from single institutions with relatively low caseloads.1,2,11-13,15,21 In the present study, we investigated ABT in shoulder arthroplasty from the perspective of a multi-institutional database with a caseload of more than 400,000. Given the rapidly increasing rates of shoulder arthroplasty, it is important to further examine this issue to minimize unnecessary blood transfusion and its associated risks and costs.7

We found that 8% of patients who had shoulder arthroplasty received ABT, which is consistent with previously reported transfusion rates (range, 7%-43%).1-6 Rates of ABT after shoulder arthroplasty have continued to rise. The exception, a decrease during the year 2010, can be explained by increased efforts to more rigidly follow transfusion indication guidelines to reduce the number of potentially unnecessary ABTs.21-24 Our study also identified numerous significant independent predictors of ABT in shoulder arthroplasty: age, sex, race, insurance status, procedure type, primary diagnoses, and multiple medical comorbidities.

Demographics

According to our analysis, more than 80% of patients who received ABT were over age 65 years, which aligns with what several other studies have demonstrated: Increasing age is a predictor of ABT, despite higher rates of comorbidities and lower preoperative Hb levels in this population.1,2,4,5,25-27 Consistent with previous work, female sex was predictive of ABT.2,5 It has been suggested that females are more likely predisposed to ABT because of lower preoperative Hb and smaller blood mass.2,5,28 Interestingly, our study showed a higher likelihood of ABT in both black and Hispanic populations. Further, patients with Medicare or Medicaid were more likely to receive ABT.

Primary Diagnosis

Although patients with a primary diagnosis of osteoarthritis constitute the majority of patients who undergo shoulder arthroplasty, our analysis showed that patients with a diagnosis of proximal humerus fracture were more likely to receive ABT. This finding is reasonable given studies showing the high prevalence of proximal humerus fractures in elderly women.29,30 Similarly, patients with a humerus fracture nonunion were more likely to receive a blood transfusion, which is unsurprising given the increased complexity associated with arthroplasty in this predominately elderly population.31 Interestingly, compared with patients with osteoarthritis, patients with any one of the other primary diagnoses were more likely to require a transfusion—proximal humerus fracture being the most significant, followed by humerus fracture nonunion, avascular necrosis, rheumatoid arthritis, and rotator cuff arthropathy.

Type of Arthroplasty

Bivariate analysis revealed that 55.6% of the patients who received ABT underwent HSA; the other 44.4% underwent TSA. The effect of primary diagnosis on procedure choice likely played a role in this finding. HSA indications include humerus fracture, which has been associated with increased ABT, whereas patients with osteoarthritis requiring TSA are significantly less likely to require ABT, as reflected in this analysis.7,32-34 Previous studies have failed to show a difference in blood transfusion rates between TSA and HSA.2,4-6,35 Conversely, with confounding factors controlled for, multivariate logistic regression analysis showed that TSA was 1.2 times more likely than HSA to require ABT, which could be explained by the increased operative time, case complexity, and blood loss that may be associated with the glenoid exposure.36,37 With analysis restricted to the year 2011, patients with reverse TSAs were 1.6 times more likely than patients with anatomical TSAs to receive a blood transfusion (OR, 1.63; 95% CI, 1.50-1.79). Although this finding differs from what was previously reported, it fits given that patients having reverse TSAs are often older and may present with a more significant comorbidity profile.3 In addition, there are the increased technical surgical aspects associated with “salvage surgery” for challenging indications such as cuff arthropathy and failed previous arthroplasty.38-41

Medical Comorbidities

Patients who received ABT were more likely to present with numerous medical comorbidities. Previous studies have indicated that the presence of multiple medical comorbidities significantly increased blood transfusion rates, possibly by working synergistically.42 All studies of blood transfusion in shoulder arthroplasty concluded that lower preoperative Hb was an independent predictor.1-6 Schumer and colleagues4 reported a 4-fold increase in likelihood of blood transfusion in patients with a preoperative Hb level less than 12.5 g/dL. In addition, Millett and colleagues6 showed a 20-fold increase in likelihood of transfusion in patients with a preoperative Hb level less than 11.0 g/dL compared with patients with a level higher than 13.0 g/dL. Patients with a Hb level between 11.0 and 13.0 g/dL showed a 5-fold increase in likelihood of transfusion.6 We should note that correction of preoperative anemia through various pharmacologic methods (eg, erythropoietin, intravenous iron supplementation) has been shown to decrease postoperative transfusion rates.43,44 Although we could not include preoperative Hb levels in the present study, given inherent limitations in using NIS, our multivariate analysis showed that preoperative deficiency anemia and coagulopathy were the most significant predictors of ABT.

In addition, the multivariate logistic regression model showed that both cardiac disease and diabetes were independent predictors of ABT, confirming data reported by Ahmadi and colleagues.1 Although not as well characterized in other studies, in the current analysis multiple other medical comorbidities, including fluid and electrolyte abnormalities, weight loss, liver disease, renal failure, and chronic lung disease, had significant predictive value. Contrarily, obesity significantly decreased the odds of ABT, likely because of higher baseline blood volume in obese patients.

Patient Outcomes

Patients who undergo shoulder arthroplasty with ABT are more likely to experience adverse events or a prolonged hospital stay and are more often discharged to a nursing home or an extended-care facility. In this population, however, deaths did not occur at a significantly higher rate—similar to what was found for patients who underwent hip or knee arthroplasty with blood transfusions.45

Little has been done to investigate the effect of pharmacologic agents on the need for perioperative ABT for orthopedic shoulder procedures. Aprotinin, tranexamic acid, epoetin-α, and aminocaproic acid have all been effective in limiting ABT during the perioperative period in various orthopedic hip, knee, and spine procedures.9,46-53 Given the increased morbidity associated with ABT, it may be beneficial to use similar methods to limit blood loss in high-risk patients undergoing shoulder arthroplasty.

Study Limitations

NIS has intrinsic limitations. Given its massive volume, it is subject to errors in both data entry and clinical coding. Moreover, the database lacks data that would have been useful in our study: preoperative Hb levels, intraoperative course, number of units transfused, total blood loss, use of blood conservation techniques, transfusion protocols, and severity of comorbidities. Reverse TSA was given a unique ICD-9-CM code in October 2010, so 2011 was the only year we were able to examine the relationship between reverse TSA and transfusions. Further, our analysis was unable to identify any medications, including chronic anticoagulants or postoperative prophylaxis, that have been shown to significantly affect blood transfusion rates.54 Yet, there are obvious advantages to using the NIS database, as previously outlined across the medical landscape.

Conclusion

Our results confirmed previous findings and identified new predictors of ABT in shoulder arthroplasty in a large cohort. We examined demographics and perioperative complications while identifying predictors of ABT use. Patients who received ABT were older, female, and nonwhite and were covered by Medicare or Medicaid insurance, and many had a primary diagnosis of proximal humerus fracture. The ABT cohort had numerous medical comorbidities, including deficiency anemia and coagulopathy. Identifying this patient population is a prerequisite to educating patients while minimizing unnecessary risks and costs.

Using NIS data on a population of 422,371 patients who underwent shoulder arthroplasty, we identified the 5 likeliest predictors of ABT: fracture, fracture nonunion, deficiency anemia, coagulopathy, and avascular necrosis. Of the identified variables associated with ABT, deficiency anemia may be the most amenable to treatment; therefore, there may be benefit in delaying elective shoulder arthroplasty in this cohort. Given these findings, it is important to identify at-risk patients before surgery, with the intent to provide education and minimize risk.

1. Ahmadi S, Lawrence TM, Sahota S, et al. The incidence and risk factors for blood transfusion in revision shoulder arthroplasty: our institution’s experience and review of the literature. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2014;23(1):43-48.

2. Sperling JW, Duncan SF, Cofield RH, Schleck CD, Harmsen WS. Incidence and risk factors for blood transfusion in shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2005;14(6):599-601.

3. Hardy JC, Hung M, Snow BJ, et al. Blood transfusion associated with shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2013;22(2):233-239.

4. Schumer RA, Chae JS, Markert RJ, Sprott D, Crosby LA. Predicting transfusion in shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2010;19(1):91-96.

5. Gruson KI, Accousti KJ, Parsons BO, Pillai G, Flatow EL. Transfusion after shoulder arthroplasty: an analysis of rates and risk factors. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2009;18(2):225-230.

6. Millett PJ, Porramatikul M, Chen N, Zurakowski D, Warner JJ. Analysis of transfusion predictors in shoulder arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88(6):1223-1230.

7. Kim SH, Wise BL, Zhang Y, Szabo RM. Increasing incidence of shoulder arthroplasty in the United States. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011;93(24):2249-2254.

8. Ceccherini-Nelli L, Filipponi F, Mosca F, Campa M. The risk of contracting an infectious disease from blood transfusion. Transplantation Proc. 2004;36(3):680-682.

9. Friedman R, Homering M, Holberg G, Berkowitz SD. Allogeneic blood transfusions and postoperative infections after total hip or knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96(4):272-278.

10. Hatzidakis AM, Mendlick RM, McKillip T, Reddy RL, Garvin KL. Preoperative autologous donation for total joint arthroplasty. An analysis of risk factors for allogenic transfusion. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2000;82(1):89-100.

11. Park JH, Rasouli MR, Mortazavi SM, Tokarski AT, Maltenfort MG, Parvizi J. Predictors of perioperative blood loss in total joint arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95(19):1777-1783.

12. Aderinto J, Brenkel IJ. Pre-operative predictors of the requirement for blood transfusion following total hip replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2004;86(7):970-973.

13. Browne JA, Adib F, Brown TE, Novicoff WM. Transfusion rates are increasing following total hip arthroplasty: risk factors and outcomes. J Arthroplasty. 2013;28(8 suppl):34-37.

14. Yoshihara H, Yoneoka D. Predictors of allogeneic blood transfusion in spinal fusion in the United States, 2004–2009. Spine. 2014;39(4):304-310.

15. Noticewala MS, Nyce JD, Wang W, Geller JA, Macaulay W. Predicting need for allogeneic transfusion after total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2012;27(6):961-967.

16. Griffin JW, Novicoff WM, Browne JA, Brockmeier SF. Obstructive sleep apnea as a risk factor after shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2013;22(12):e6-e9.

17. Maynard C, Sales AE. Changes in the use of coronary artery revascularization procedures in the Department of Veterans Affairs, the National Hospital Discharge Survey, and the Nationwide Inpatient Sample, 1991–1999. BMC Health Serv Res. 2003;3(1):12.

18. Pereira BM, Chan PH, Weinstein PR, Fishman RA. Cerebral protection during reperfusion with superoxide dismutase in focal cerebral ischemia. Adv Neurol. 1990;52:97-103.

19. Hambright D, Henderson RA, Cook C, Worrell T, Moorman CT, Bolognesi MP. A comparison of perioperative outcomes in patients with and without rheumatoid arthritis after receiving a total shoulder replacement arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2011;20(1):77-85.

20. Ponce BA, Menendez ME, Oladeji LO, Soldado F. Diabetes as a risk factor for poorer early postoperative outcomes after shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2014;23(5):671-678.

21. Pierson JL, Hannon TJ, Earles DR. A blood-conservation algorithm to reduce blood transfusions after total hip and knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86(7):1512-1518.

22. Martinez V, Monsaingeon-Lion A, Cherif K, Judet T, Chauvin M, Fletcher D. Transfusion strategy for primary knee and hip arthroplasty: impact of an algorithm to lower transfusion rates and hospital costs. Br J Anaesth. 2007;99(6):794-800.

23. Helm AT, Karski MT, Parsons SJ, Sampath JS, Bale RS. A strategy for reducing blood-transfusion requirements in elective orthopaedic surgery. Audit of an algorithm for arthroplasty of the lower limb. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2003;85(4):484-489.

24. Watts CD, Pagnano MW. Minimising blood loss and transfusion in contemporary hip and knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2012;94(11 suppl A):8-10.

25. Guralnik JM, Eisenstaedt RS, Ferrucci L, Klein HG, Woodman RC. Prevalence of anemia in persons 65 years and older in the United States: evidence for a high rate of unexplained anemia. Blood. 2004;104(8):2263-2268.

26. Rogers MA, Blumberg N, Heal JM, Langa KM. Utilization of blood transfusion among older adults in the United States. Transfusion. 2011;51(4):710-718.

27. Cobain TJ, Vamvakas EC, Wells A, Titlestad K. A survey of the demographics of blood use. Transfusion Med. 2007;17(1):1-15.

28. Fosco M, Di Fiore M. Factors predicting blood transfusion in different surgical procedures for degenerative spine disease. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2012;16(13):1853-1858.

29. Handoll HH, Ollivere BJ, Rollins KE. Interventions for treating proximal humeral fractures in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;12:CD000434.

30. Neuhaus V, Swellengrebel CH, Bossen JK, Ring D. What are the factors influencing outcome among patients admitted to a hospital with a proximal humeral fracture? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2013;471(5):1698-1706.

31. Volgas DA, Stannard JP, Alonso JE. Nonunions of the humerus. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2004;(419):46-50.

32. Chambers L, Dines JS, Lorich DG, Dines DM. Hemiarthroplasty for proximal humerus fractures. Curr Rev Musculoskeletal Med. 2013;6(1):57-62.

33. Jain NB, Hocker S, Pietrobon R, Guller U, Bathia N, Higgins LD. Total arthroplasty versus hemiarthroplasty for glenohumeral osteoarthritis: role of provider volume. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2005;14(4):361-367.

34. Izquierdo R, Voloshin I, Edwards S, et al. Treatment of glenohumeral osteoarthritis. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2010;18(6):375-382.

35. Shields E, Iannuzzi JC, Thorsness R, Noyes K, Voloshin I. Perioperative complications after hemiarthroplasty and total shoulder arthroplasty are equivalent. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2014;23(10):1449-1453.

36. Gartsman GM, Roddey TS, Hammerman SM. Shoulder arthroplasty with or without resurfacing of the glenoid in patients who have osteoarthritis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2000;82(1):26-34.

37. Singh A, Yian EH, Dillon MT, Takayanagi M, Burke MF, Navarro RA. The effect of surgeon and hospital volume on shoulder arthroplasty perioperative quality metrics. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2014;23(8):1187-1194.

38. Groh GI, Groh GM. Complications rates, reoperation rates, and the learning curve in reverse shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2014;23(3):388-394.

39. Boileau P, Gonzalez JF, Chuinard C, Bicknell R, Walch G. Reverse total shoulder arthroplasty after failed rotator cuff surgery. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2009;18(4):600-606.

40. Boileau P, Watkinson D, Hatzidakis AM, Hovorka I. Neer Award 2005: the Grammont reverse shoulder prosthesis: results in cuff tear arthritis, fracture sequelae, and revision arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2006;15(5):527-540.

41. Boileau P, Watkinson DJ, Hatzidakis AM, Balg F. Grammont reverse prosthesis: design, rationale, and biomechanics. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2005;14(1 suppl S):147S-161S.

42. Pola E, Papaleo P, Santoliquido A, Gasparini G, Aulisa L, De Santis E. Clinical factors associated with an increased risk of perioperative blood transfusion in nonanemic patients undergoing total hip arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86(1):57-61.

43. Lin DM, Lin ES, Tran MH. Efficacy and safety of erythropoietin and intravenous iron in perioperative blood management: a systematic review. Transfusion Med Rev. 2013;27(4):221-234.

44. Muñoz M, Gómez-Ramírez S, Cuenca J, et al. Very-short-term perioperative intravenous iron administration and postoperative outcome in major orthopedic surgery: a pooled analysis of observational data from 2547 patients. Transfusion. 2014;54(2):289-299.

45. Danninger T, Rasul R, Poeran J, et al. Blood transfusions in total hip and knee arthroplasty: an analysis of outcomes. ScientificWorldJournal. 2014;2014:623460.

46. Baldus CR, Bridwell KH, Lenke LG, Okubadejo GO. Can we safely reduce blood loss during lumbar pedicle subtraction osteotomy procedures using tranexamic acid or aprotinin? A comparative study with controls. Spine. 2010;35(2):235-239.

47. Chang CH, Chang Y, Chen DW, Ueng SW, Lee MS. Topical tranexamic acid reduces blood loss and transfusion rates associated with primary total hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014;472(5):1552-1557.

48. Delasotta LA, Orozco F, Jafari SM, Blair JL, Ong A. Should we use preoperative epoetin-alpha in the mildly anemic patient undergoing simultaneous total knee arthroplasty? Open Orthop J. 2013;7:47-50.

49. Delasotta LA, Rangavajjula A, Frank ML, Blair J, Orozco F, Ong A. The use of preoperative epoetin-alpha in revision hip arthroplasty. Open Orthop J. 2012;6:179-183.

50. Kelley TC, Tucker KK, Adams MJ, Dalury DF. Use of tranexamic acid results in decreased blood loss and decreased transfusions in patients undergoing staged bilateral total knee arthroplasty. Transfusion. 2014;54(1):26-30.

51. Martin JG, Cassatt KB, Kincaid-Cinnamon KA, Westendorf DS, Garton AS, Lemke JH. Topical administration of tranexamic acid in primary total hip and total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2014;29(5):889-894.

52. Tzortzopoulou A, Cepeda MS, Schumann R, Carr DB. Antifibrinolytic agents for reducing blood loss in scoliosis surgery in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008(3):CD006883.

53. Zhang H, Chen J, Chen F, Que W. The effect of tranexamic acid on blood loss and use of blood products in total knee arthroplasty: a meta-analysis. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2012;20(9):1742-1752.

54. Bong MR, Patel V, Chang E, Issack PS, Hebert R, Di Cesare PE. Risks associated with blood transfusion after total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2004;19(3):281-287.

In shoulder arthroplasty, it is not uncommon for patients to receive postoperative blood transfusions; rates range from 7% to 43%.1-6 Allogeneic blood transfusions (ABTs) are costly and not entirely free of risks.7 The risk for infection has decreased because of improved screening and risk reduction strategies, but there are still significant risks associated with ABTs, such as clerical errors, acute and delayed hemolytic reactions, graft-versus-host reactions, transfusion-related acute lung injury, and anaphylaxis.8-10 As use of shoulder arthroplasty continues to increase, the importance of minimizing unnecessary transfusions is growing as well.7

Predictive factors for ABT have been explored in other orthopedic settings, yet little has been done in shoulder arthroplasty.1-6,11-15 Previous shoulder arthroplasty studies have shown that low preoperative hemoglobin (Hb) levels are independent risk factors for postoperative blood transfusion. However, there is debate over the significance of other variables, such as procedure type, age, sex, and medical comorbidities. Further, prior studies were limited by relatively small samples from single institutions; the largest series included fewer than 600 patients.1-6

We conducted a study to determine predictors of ABT in a large cohort of patients admitted to US hospitals for shoulder arthroplasty. We also wanted to evaluate the effect of ABT on postoperative outcomes, including inpatient mortality, adverse events, prolonged hospital stay, and nonroutine discharge. According to the null hypothesis, in shoulder arthroplasty there will be no difference in risk factors between patients who require ABT and those who did not, after accounting for confounding variables.

Materials and Methods

This study was exempt from institutional review board approval, as all data were appropriately deidentified before use in this project. We used the Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS) to retrospectively study the period 2002–2011, from which all demographic, clinical, and resource use data were derived.16 NIS, an annual survey conducted by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) since 1988, has generated a huge amount of data, forming the largest all-payer inpatient care database in the United States. Yearly samples contain discharge data from about 8 million hospital stays at more than 1000 hospitals across 46 states, approximating a 20% random sample of all hospital discharges at participating institutions.17 These data are then weighted to generate statistically valid national estimates.

The NIS database uses International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Edition, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) codes to identify 15 medical diagnoses up to the year 2008 and a maximum of 25 medical diagnoses and 15 procedures thereafter. In addition, the database includes information on patient and hospital characteristics as well as inpatient outcomes such as length of stay, total hospitalization charges, and discharge disposition.18,19 Given its large sample size and data volume, NIS is a powerful tool in the analysis of data associated with a multitude of medical diagnoses and procedures.20

We used the NIS database to study a population of 422,371 patients (age, >18 years) who underwent total shoulder arthroplasty (TSA) or hemiarthroplasty (HSA) between 2002 and 2011. ICD-9-CM procedure codes for TSA (81.80, 81.88) and HSA (81.81) were used to identify this population. We also analyzed data for reverse TSA for the year 2011. Then we divided our target population into 2 different cohorts: patients who did not receive any blood transfusion products and patients who received a transfusion of allogeneic packed cells (ICD-9-CM code 99.04 was used to identify the latter cohort).

In this study, normal distribution of the dataset was assumed, given the large sample size. The 2 cohorts were evaluated through bivariate analysis using the Pearson χ2 test for categorical data and the independent-samples t test for continuous data. The extent to which diagnosis, age, race, sex, and medical comorbidities were predictive of blood transfusion after TSA or HSA was evaluated through multivariate binary logistic regression analysis. Statistical significance was set at P < .05. All statistical analyses and data modeling were performed with SPSS Version 22.0.

Results

Using the NIS database, we stratified an estimated 422,371 patients who presented for shoulder arthroplasty between January 1, 2002, and December 31, 2011, into a TSA cohort (59.3%) and an HSA cohort (40.7%). Eight percent (33,889) of all patients received an ABT; the proportion of patients who received ABT was higher (P < .001) for the HSA cohort (55.6%) than the TSA cohort (39.4%). Further, the rate of ABT after shoulder arthroplasty showed an upward inclination (Figure).

Demographically, patients who received ABT tended (P < .001) to be older (74±11 years vs 68±11 years) and of a minority race (black or Hispanic) and to fall in either the lowest range of median household income (21.5% vs 20.7%; ≤$38,999) or the highest (27.3% vs 25.4%; ≥$63,000). Shoulder arthroplasty with ABT occurred more often (P < .001) at hospitals that were urban (13.3% vs 11.3%), medium in size (27.3% vs 23.4%), and nonteaching (56.2% vs 54.3%). In addition, ABT was used more often (P < .001) in patients with a primary diagnosis of fracture (43.1% vs 14.3%) or fracture nonunion (4.4% vs 2.1%). These groups also had a longer (P < .001) hospital stay (5.0±4.3 days vs 2.5±2.2 days). Table 1 summarizes these findings.

The 2 cohorts were then analyzed for presence of medical comorbidities (Table 2). Patients who required ABT during shoulder arthroplasty had a significantly (P < .001) higher prevalence of congestive heart failure, chronic lung disease, hypertension, uncomplicated and complicated diabetes mellitus, liver disease, renal failure, fluid and electrolyte disorders, pulmonary circulatory disease, weight loss, coagulopathy, and deficiency anemia.

In multivariate regression modeling (Table 3), demographic predictors of ABT (P < .001) included increasing age (odds ratio [OR], 1.03 per year; 95% confidence interval [95% CI], 1.03-1.03), female sex (OR, 1.55; 95% CI, 1.51-1.60), and minority race (black or Hispanic). Odds of requiring ABT were higher for patients with Medicare (OR, 1.25; 95% CI, 1.20-1.30) and patients with Medicaid (OR, 1.63; 95% CI, 1.51-1.77) than for patients with private insurance.

ABT was more likely to be required (P < .001) in patients with a primary diagnosis of fracture (OR, 4.49; 95% CI, 4.34-4.65), avascular necrosis (OR, 2.06; 95% CI, 1.91-2.22), rheumatoid arthritis (OR, 1.91; 95% CI, 1.72-2.12), fracture nonunion (OR, 3.55; 95% CI, 3.33-3.79), or rotator cuff arthropathy (OR, 1.47; 95% CI, 1.41-1.54) than for patients with osteoarthritis. Moreover, compared with patients having HSA, patients having TSA were more likely to require ABT (OR, 1.20; 95% CI, 1.17-1.24). According to the analysis restricted to the year 2011, compared with patients having anatomical TSAs, patients having reverse TSAs were 1.6 times more likely (P < .001) to require ABT (OR, 1.63; 95% CI, 1.50-1.79).

With the exception of obesity, all comorbidities were significant (P < .001) independent predictors of ABT after shoulder arthroplasty: deficiency anemia (OR, 3.42; 95% CI, 3.32-3.52), coagulopathy (OR, 2.54; 95% CI, 2.36-2.73), fluid and electrolyte disorders (OR, 1.91; 95% CI, 1.84-1.97), and weight loss (OR, 1.78; 95% CI, 1.58-2.00).

Patients who received ABT were more likely to experience adverse events (OR, 1.74; 95% CI, 1.68-1.81), prolonged hospital stay (OR, 3.21; 95% CI, 3.12-3.30), and nonroutine discharge (OR, 1.77; 95% CI, 1.72-1.82) (Table 4). There was no difference in mortality between the 2 cohorts.

Discussion

There is an abundance of literature on blood transfusions in hip and knee arthroplasty, but there are few articles on ABT in shoulder arthroplasty, and they all report data from single institutions with relatively low caseloads.1,2,11-13,15,21 In the present study, we investigated ABT in shoulder arthroplasty from the perspective of a multi-institutional database with a caseload of more than 400,000. Given the rapidly increasing rates of shoulder arthroplasty, it is important to further examine this issue to minimize unnecessary blood transfusion and its associated risks and costs.7

We found that 8% of patients who had shoulder arthroplasty received ABT, which is consistent with previously reported transfusion rates (range, 7%-43%).1-6 Rates of ABT after shoulder arthroplasty have continued to rise. The exception, a decrease during the year 2010, can be explained by increased efforts to more rigidly follow transfusion indication guidelines to reduce the number of potentially unnecessary ABTs.21-24 Our study also identified numerous significant independent predictors of ABT in shoulder arthroplasty: age, sex, race, insurance status, procedure type, primary diagnoses, and multiple medical comorbidities.

Demographics

According to our analysis, more than 80% of patients who received ABT were over age 65 years, which aligns with what several other studies have demonstrated: Increasing age is a predictor of ABT, despite higher rates of comorbidities and lower preoperative Hb levels in this population.1,2,4,5,25-27 Consistent with previous work, female sex was predictive of ABT.2,5 It has been suggested that females are more likely predisposed to ABT because of lower preoperative Hb and smaller blood mass.2,5,28 Interestingly, our study showed a higher likelihood of ABT in both black and Hispanic populations. Further, patients with Medicare or Medicaid were more likely to receive ABT.

Primary Diagnosis

Although patients with a primary diagnosis of osteoarthritis constitute the majority of patients who undergo shoulder arthroplasty, our analysis showed that patients with a diagnosis of proximal humerus fracture were more likely to receive ABT. This finding is reasonable given studies showing the high prevalence of proximal humerus fractures in elderly women.29,30 Similarly, patients with a humerus fracture nonunion were more likely to receive a blood transfusion, which is unsurprising given the increased complexity associated with arthroplasty in this predominately elderly population.31 Interestingly, compared with patients with osteoarthritis, patients with any one of the other primary diagnoses were more likely to require a transfusion—proximal humerus fracture being the most significant, followed by humerus fracture nonunion, avascular necrosis, rheumatoid arthritis, and rotator cuff arthropathy.

Type of Arthroplasty

Bivariate analysis revealed that 55.6% of the patients who received ABT underwent HSA; the other 44.4% underwent TSA. The effect of primary diagnosis on procedure choice likely played a role in this finding. HSA indications include humerus fracture, which has been associated with increased ABT, whereas patients with osteoarthritis requiring TSA are significantly less likely to require ABT, as reflected in this analysis.7,32-34 Previous studies have failed to show a difference in blood transfusion rates between TSA and HSA.2,4-6,35 Conversely, with confounding factors controlled for, multivariate logistic regression analysis showed that TSA was 1.2 times more likely than HSA to require ABT, which could be explained by the increased operative time, case complexity, and blood loss that may be associated with the glenoid exposure.36,37 With analysis restricted to the year 2011, patients with reverse TSAs were 1.6 times more likely than patients with anatomical TSAs to receive a blood transfusion (OR, 1.63; 95% CI, 1.50-1.79). Although this finding differs from what was previously reported, it fits given that patients having reverse TSAs are often older and may present with a more significant comorbidity profile.3 In addition, there are the increased technical surgical aspects associated with “salvage surgery” for challenging indications such as cuff arthropathy and failed previous arthroplasty.38-41

Medical Comorbidities

Patients who received ABT were more likely to present with numerous medical comorbidities. Previous studies have indicated that the presence of multiple medical comorbidities significantly increased blood transfusion rates, possibly by working synergistically.42 All studies of blood transfusion in shoulder arthroplasty concluded that lower preoperative Hb was an independent predictor.1-6 Schumer and colleagues4 reported a 4-fold increase in likelihood of blood transfusion in patients with a preoperative Hb level less than 12.5 g/dL. In addition, Millett and colleagues6 showed a 20-fold increase in likelihood of transfusion in patients with a preoperative Hb level less than 11.0 g/dL compared with patients with a level higher than 13.0 g/dL. Patients with a Hb level between 11.0 and 13.0 g/dL showed a 5-fold increase in likelihood of transfusion.6 We should note that correction of preoperative anemia through various pharmacologic methods (eg, erythropoietin, intravenous iron supplementation) has been shown to decrease postoperative transfusion rates.43,44 Although we could not include preoperative Hb levels in the present study, given inherent limitations in using NIS, our multivariate analysis showed that preoperative deficiency anemia and coagulopathy were the most significant predictors of ABT.

In addition, the multivariate logistic regression model showed that both cardiac disease and diabetes were independent predictors of ABT, confirming data reported by Ahmadi and colleagues.1 Although not as well characterized in other studies, in the current analysis multiple other medical comorbidities, including fluid and electrolyte abnormalities, weight loss, liver disease, renal failure, and chronic lung disease, had significant predictive value. Contrarily, obesity significantly decreased the odds of ABT, likely because of higher baseline blood volume in obese patients.

Patient Outcomes

Patients who undergo shoulder arthroplasty with ABT are more likely to experience adverse events or a prolonged hospital stay and are more often discharged to a nursing home or an extended-care facility. In this population, however, deaths did not occur at a significantly higher rate—similar to what was found for patients who underwent hip or knee arthroplasty with blood transfusions.45

Little has been done to investigate the effect of pharmacologic agents on the need for perioperative ABT for orthopedic shoulder procedures. Aprotinin, tranexamic acid, epoetin-α, and aminocaproic acid have all been effective in limiting ABT during the perioperative period in various orthopedic hip, knee, and spine procedures.9,46-53 Given the increased morbidity associated with ABT, it may be beneficial to use similar methods to limit blood loss in high-risk patients undergoing shoulder arthroplasty.

Study Limitations

NIS has intrinsic limitations. Given its massive volume, it is subject to errors in both data entry and clinical coding. Moreover, the database lacks data that would have been useful in our study: preoperative Hb levels, intraoperative course, number of units transfused, total blood loss, use of blood conservation techniques, transfusion protocols, and severity of comorbidities. Reverse TSA was given a unique ICD-9-CM code in October 2010, so 2011 was the only year we were able to examine the relationship between reverse TSA and transfusions. Further, our analysis was unable to identify any medications, including chronic anticoagulants or postoperative prophylaxis, that have been shown to significantly affect blood transfusion rates.54 Yet, there are obvious advantages to using the NIS database, as previously outlined across the medical landscape.

Conclusion

Our results confirmed previous findings and identified new predictors of ABT in shoulder arthroplasty in a large cohort. We examined demographics and perioperative complications while identifying predictors of ABT use. Patients who received ABT were older, female, and nonwhite and were covered by Medicare or Medicaid insurance, and many had a primary diagnosis of proximal humerus fracture. The ABT cohort had numerous medical comorbidities, including deficiency anemia and coagulopathy. Identifying this patient population is a prerequisite to educating patients while minimizing unnecessary risks and costs.

Using NIS data on a population of 422,371 patients who underwent shoulder arthroplasty, we identified the 5 likeliest predictors of ABT: fracture, fracture nonunion, deficiency anemia, coagulopathy, and avascular necrosis. Of the identified variables associated with ABT, deficiency anemia may be the most amenable to treatment; therefore, there may be benefit in delaying elective shoulder arthroplasty in this cohort. Given these findings, it is important to identify at-risk patients before surgery, with the intent to provide education and minimize risk.

In shoulder arthroplasty, it is not uncommon for patients to receive postoperative blood transfusions; rates range from 7% to 43%.1-6 Allogeneic blood transfusions (ABTs) are costly and not entirely free of risks.7 The risk for infection has decreased because of improved screening and risk reduction strategies, but there are still significant risks associated with ABTs, such as clerical errors, acute and delayed hemolytic reactions, graft-versus-host reactions, transfusion-related acute lung injury, and anaphylaxis.8-10 As use of shoulder arthroplasty continues to increase, the importance of minimizing unnecessary transfusions is growing as well.7

Predictive factors for ABT have been explored in other orthopedic settings, yet little has been done in shoulder arthroplasty.1-6,11-15 Previous shoulder arthroplasty studies have shown that low preoperative hemoglobin (Hb) levels are independent risk factors for postoperative blood transfusion. However, there is debate over the significance of other variables, such as procedure type, age, sex, and medical comorbidities. Further, prior studies were limited by relatively small samples from single institutions; the largest series included fewer than 600 patients.1-6

We conducted a study to determine predictors of ABT in a large cohort of patients admitted to US hospitals for shoulder arthroplasty. We also wanted to evaluate the effect of ABT on postoperative outcomes, including inpatient mortality, adverse events, prolonged hospital stay, and nonroutine discharge. According to the null hypothesis, in shoulder arthroplasty there will be no difference in risk factors between patients who require ABT and those who did not, after accounting for confounding variables.

Materials and Methods

This study was exempt from institutional review board approval, as all data were appropriately deidentified before use in this project. We used the Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS) to retrospectively study the period 2002–2011, from which all demographic, clinical, and resource use data were derived.16 NIS, an annual survey conducted by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) since 1988, has generated a huge amount of data, forming the largest all-payer inpatient care database in the United States. Yearly samples contain discharge data from about 8 million hospital stays at more than 1000 hospitals across 46 states, approximating a 20% random sample of all hospital discharges at participating institutions.17 These data are then weighted to generate statistically valid national estimates.

The NIS database uses International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Edition, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) codes to identify 15 medical diagnoses up to the year 2008 and a maximum of 25 medical diagnoses and 15 procedures thereafter. In addition, the database includes information on patient and hospital characteristics as well as inpatient outcomes such as length of stay, total hospitalization charges, and discharge disposition.18,19 Given its large sample size and data volume, NIS is a powerful tool in the analysis of data associated with a multitude of medical diagnoses and procedures.20

We used the NIS database to study a population of 422,371 patients (age, >18 years) who underwent total shoulder arthroplasty (TSA) or hemiarthroplasty (HSA) between 2002 and 2011. ICD-9-CM procedure codes for TSA (81.80, 81.88) and HSA (81.81) were used to identify this population. We also analyzed data for reverse TSA for the year 2011. Then we divided our target population into 2 different cohorts: patients who did not receive any blood transfusion products and patients who received a transfusion of allogeneic packed cells (ICD-9-CM code 99.04 was used to identify the latter cohort).

In this study, normal distribution of the dataset was assumed, given the large sample size. The 2 cohorts were evaluated through bivariate analysis using the Pearson χ2 test for categorical data and the independent-samples t test for continuous data. The extent to which diagnosis, age, race, sex, and medical comorbidities were predictive of blood transfusion after TSA or HSA was evaluated through multivariate binary logistic regression analysis. Statistical significance was set at P < .05. All statistical analyses and data modeling were performed with SPSS Version 22.0.

Results

Using the NIS database, we stratified an estimated 422,371 patients who presented for shoulder arthroplasty between January 1, 2002, and December 31, 2011, into a TSA cohort (59.3%) and an HSA cohort (40.7%). Eight percent (33,889) of all patients received an ABT; the proportion of patients who received ABT was higher (P < .001) for the HSA cohort (55.6%) than the TSA cohort (39.4%). Further, the rate of ABT after shoulder arthroplasty showed an upward inclination (Figure).

Demographically, patients who received ABT tended (P < .001) to be older (74±11 years vs 68±11 years) and of a minority race (black or Hispanic) and to fall in either the lowest range of median household income (21.5% vs 20.7%; ≤$38,999) or the highest (27.3% vs 25.4%; ≥$63,000). Shoulder arthroplasty with ABT occurred more often (P < .001) at hospitals that were urban (13.3% vs 11.3%), medium in size (27.3% vs 23.4%), and nonteaching (56.2% vs 54.3%). In addition, ABT was used more often (P < .001) in patients with a primary diagnosis of fracture (43.1% vs 14.3%) or fracture nonunion (4.4% vs 2.1%). These groups also had a longer (P < .001) hospital stay (5.0±4.3 days vs 2.5±2.2 days). Table 1 summarizes these findings.

The 2 cohorts were then analyzed for presence of medical comorbidities (Table 2). Patients who required ABT during shoulder arthroplasty had a significantly (P < .001) higher prevalence of congestive heart failure, chronic lung disease, hypertension, uncomplicated and complicated diabetes mellitus, liver disease, renal failure, fluid and electrolyte disorders, pulmonary circulatory disease, weight loss, coagulopathy, and deficiency anemia.

In multivariate regression modeling (Table 3), demographic predictors of ABT (P < .001) included increasing age (odds ratio [OR], 1.03 per year; 95% confidence interval [95% CI], 1.03-1.03), female sex (OR, 1.55; 95% CI, 1.51-1.60), and minority race (black or Hispanic). Odds of requiring ABT were higher for patients with Medicare (OR, 1.25; 95% CI, 1.20-1.30) and patients with Medicaid (OR, 1.63; 95% CI, 1.51-1.77) than for patients with private insurance.

ABT was more likely to be required (P < .001) in patients with a primary diagnosis of fracture (OR, 4.49; 95% CI, 4.34-4.65), avascular necrosis (OR, 2.06; 95% CI, 1.91-2.22), rheumatoid arthritis (OR, 1.91; 95% CI, 1.72-2.12), fracture nonunion (OR, 3.55; 95% CI, 3.33-3.79), or rotator cuff arthropathy (OR, 1.47; 95% CI, 1.41-1.54) than for patients with osteoarthritis. Moreover, compared with patients having HSA, patients having TSA were more likely to require ABT (OR, 1.20; 95% CI, 1.17-1.24). According to the analysis restricted to the year 2011, compared with patients having anatomical TSAs, patients having reverse TSAs were 1.6 times more likely (P < .001) to require ABT (OR, 1.63; 95% CI, 1.50-1.79).

With the exception of obesity, all comorbidities were significant (P < .001) independent predictors of ABT after shoulder arthroplasty: deficiency anemia (OR, 3.42; 95% CI, 3.32-3.52), coagulopathy (OR, 2.54; 95% CI, 2.36-2.73), fluid and electrolyte disorders (OR, 1.91; 95% CI, 1.84-1.97), and weight loss (OR, 1.78; 95% CI, 1.58-2.00).

Patients who received ABT were more likely to experience adverse events (OR, 1.74; 95% CI, 1.68-1.81), prolonged hospital stay (OR, 3.21; 95% CI, 3.12-3.30), and nonroutine discharge (OR, 1.77; 95% CI, 1.72-1.82) (Table 4). There was no difference in mortality between the 2 cohorts.

Discussion

There is an abundance of literature on blood transfusions in hip and knee arthroplasty, but there are few articles on ABT in shoulder arthroplasty, and they all report data from single institutions with relatively low caseloads.1,2,11-13,15,21 In the present study, we investigated ABT in shoulder arthroplasty from the perspective of a multi-institutional database with a caseload of more than 400,000. Given the rapidly increasing rates of shoulder arthroplasty, it is important to further examine this issue to minimize unnecessary blood transfusion and its associated risks and costs.7

We found that 8% of patients who had shoulder arthroplasty received ABT, which is consistent with previously reported transfusion rates (range, 7%-43%).1-6 Rates of ABT after shoulder arthroplasty have continued to rise. The exception, a decrease during the year 2010, can be explained by increased efforts to more rigidly follow transfusion indication guidelines to reduce the number of potentially unnecessary ABTs.21-24 Our study also identified numerous significant independent predictors of ABT in shoulder arthroplasty: age, sex, race, insurance status, procedure type, primary diagnoses, and multiple medical comorbidities.

Demographics

According to our analysis, more than 80% of patients who received ABT were over age 65 years, which aligns with what several other studies have demonstrated: Increasing age is a predictor of ABT, despite higher rates of comorbidities and lower preoperative Hb levels in this population.1,2,4,5,25-27 Consistent with previous work, female sex was predictive of ABT.2,5 It has been suggested that females are more likely predisposed to ABT because of lower preoperative Hb and smaller blood mass.2,5,28 Interestingly, our study showed a higher likelihood of ABT in both black and Hispanic populations. Further, patients with Medicare or Medicaid were more likely to receive ABT.

Primary Diagnosis

Although patients with a primary diagnosis of osteoarthritis constitute the majority of patients who undergo shoulder arthroplasty, our analysis showed that patients with a diagnosis of proximal humerus fracture were more likely to receive ABT. This finding is reasonable given studies showing the high prevalence of proximal humerus fractures in elderly women.29,30 Similarly, patients with a humerus fracture nonunion were more likely to receive a blood transfusion, which is unsurprising given the increased complexity associated with arthroplasty in this predominately elderly population.31 Interestingly, compared with patients with osteoarthritis, patients with any one of the other primary diagnoses were more likely to require a transfusion—proximal humerus fracture being the most significant, followed by humerus fracture nonunion, avascular necrosis, rheumatoid arthritis, and rotator cuff arthropathy.

Type of Arthroplasty

Bivariate analysis revealed that 55.6% of the patients who received ABT underwent HSA; the other 44.4% underwent TSA. The effect of primary diagnosis on procedure choice likely played a role in this finding. HSA indications include humerus fracture, which has been associated with increased ABT, whereas patients with osteoarthritis requiring TSA are significantly less likely to require ABT, as reflected in this analysis.7,32-34 Previous studies have failed to show a difference in blood transfusion rates between TSA and HSA.2,4-6,35 Conversely, with confounding factors controlled for, multivariate logistic regression analysis showed that TSA was 1.2 times more likely than HSA to require ABT, which could be explained by the increased operative time, case complexity, and blood loss that may be associated with the glenoid exposure.36,37 With analysis restricted to the year 2011, patients with reverse TSAs were 1.6 times more likely than patients with anatomical TSAs to receive a blood transfusion (OR, 1.63; 95% CI, 1.50-1.79). Although this finding differs from what was previously reported, it fits given that patients having reverse TSAs are often older and may present with a more significant comorbidity profile.3 In addition, there are the increased technical surgical aspects associated with “salvage surgery” for challenging indications such as cuff arthropathy and failed previous arthroplasty.38-41

Medical Comorbidities

Patients who received ABT were more likely to present with numerous medical comorbidities. Previous studies have indicated that the presence of multiple medical comorbidities significantly increased blood transfusion rates, possibly by working synergistically.42 All studies of blood transfusion in shoulder arthroplasty concluded that lower preoperative Hb was an independent predictor.1-6 Schumer and colleagues4 reported a 4-fold increase in likelihood of blood transfusion in patients with a preoperative Hb level less than 12.5 g/dL. In addition, Millett and colleagues6 showed a 20-fold increase in likelihood of transfusion in patients with a preoperative Hb level less than 11.0 g/dL compared with patients with a level higher than 13.0 g/dL. Patients with a Hb level between 11.0 and 13.0 g/dL showed a 5-fold increase in likelihood of transfusion.6 We should note that correction of preoperative anemia through various pharmacologic methods (eg, erythropoietin, intravenous iron supplementation) has been shown to decrease postoperative transfusion rates.43,44 Although we could not include preoperative Hb levels in the present study, given inherent limitations in using NIS, our multivariate analysis showed that preoperative deficiency anemia and coagulopathy were the most significant predictors of ABT.

In addition, the multivariate logistic regression model showed that both cardiac disease and diabetes were independent predictors of ABT, confirming data reported by Ahmadi and colleagues.1 Although not as well characterized in other studies, in the current analysis multiple other medical comorbidities, including fluid and electrolyte abnormalities, weight loss, liver disease, renal failure, and chronic lung disease, had significant predictive value. Contrarily, obesity significantly decreased the odds of ABT, likely because of higher baseline blood volume in obese patients.

Patient Outcomes

Patients who undergo shoulder arthroplasty with ABT are more likely to experience adverse events or a prolonged hospital stay and are more often discharged to a nursing home or an extended-care facility. In this population, however, deaths did not occur at a significantly higher rate—similar to what was found for patients who underwent hip or knee arthroplasty with blood transfusions.45

Little has been done to investigate the effect of pharmacologic agents on the need for perioperative ABT for orthopedic shoulder procedures. Aprotinin, tranexamic acid, epoetin-α, and aminocaproic acid have all been effective in limiting ABT during the perioperative period in various orthopedic hip, knee, and spine procedures.9,46-53 Given the increased morbidity associated with ABT, it may be beneficial to use similar methods to limit blood loss in high-risk patients undergoing shoulder arthroplasty.

Study Limitations

NIS has intrinsic limitations. Given its massive volume, it is subject to errors in both data entry and clinical coding. Moreover, the database lacks data that would have been useful in our study: preoperative Hb levels, intraoperative course, number of units transfused, total blood loss, use of blood conservation techniques, transfusion protocols, and severity of comorbidities. Reverse TSA was given a unique ICD-9-CM code in October 2010, so 2011 was the only year we were able to examine the relationship between reverse TSA and transfusions. Further, our analysis was unable to identify any medications, including chronic anticoagulants or postoperative prophylaxis, that have been shown to significantly affect blood transfusion rates.54 Yet, there are obvious advantages to using the NIS database, as previously outlined across the medical landscape.

Conclusion

Our results confirmed previous findings and identified new predictors of ABT in shoulder arthroplasty in a large cohort. We examined demographics and perioperative complications while identifying predictors of ABT use. Patients who received ABT were older, female, and nonwhite and were covered by Medicare or Medicaid insurance, and many had a primary diagnosis of proximal humerus fracture. The ABT cohort had numerous medical comorbidities, including deficiency anemia and coagulopathy. Identifying this patient population is a prerequisite to educating patients while minimizing unnecessary risks and costs.

Using NIS data on a population of 422,371 patients who underwent shoulder arthroplasty, we identified the 5 likeliest predictors of ABT: fracture, fracture nonunion, deficiency anemia, coagulopathy, and avascular necrosis. Of the identified variables associated with ABT, deficiency anemia may be the most amenable to treatment; therefore, there may be benefit in delaying elective shoulder arthroplasty in this cohort. Given these findings, it is important to identify at-risk patients before surgery, with the intent to provide education and minimize risk.

1. Ahmadi S, Lawrence TM, Sahota S, et al. The incidence and risk factors for blood transfusion in revision shoulder arthroplasty: our institution’s experience and review of the literature. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2014;23(1):43-48.

2. Sperling JW, Duncan SF, Cofield RH, Schleck CD, Harmsen WS. Incidence and risk factors for blood transfusion in shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2005;14(6):599-601.

3. Hardy JC, Hung M, Snow BJ, et al. Blood transfusion associated with shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2013;22(2):233-239.

4. Schumer RA, Chae JS, Markert RJ, Sprott D, Crosby LA. Predicting transfusion in shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2010;19(1):91-96.

5. Gruson KI, Accousti KJ, Parsons BO, Pillai G, Flatow EL. Transfusion after shoulder arthroplasty: an analysis of rates and risk factors. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2009;18(2):225-230.

6. Millett PJ, Porramatikul M, Chen N, Zurakowski D, Warner JJ. Analysis of transfusion predictors in shoulder arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88(6):1223-1230.

7. Kim SH, Wise BL, Zhang Y, Szabo RM. Increasing incidence of shoulder arthroplasty in the United States. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011;93(24):2249-2254.

8. Ceccherini-Nelli L, Filipponi F, Mosca F, Campa M. The risk of contracting an infectious disease from blood transfusion. Transplantation Proc. 2004;36(3):680-682.

9. Friedman R, Homering M, Holberg G, Berkowitz SD. Allogeneic blood transfusions and postoperative infections after total hip or knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96(4):272-278.

10. Hatzidakis AM, Mendlick RM, McKillip T, Reddy RL, Garvin KL. Preoperative autologous donation for total joint arthroplasty. An analysis of risk factors for allogenic transfusion. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2000;82(1):89-100.

11. Park JH, Rasouli MR, Mortazavi SM, Tokarski AT, Maltenfort MG, Parvizi J. Predictors of perioperative blood loss in total joint arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95(19):1777-1783.

12. Aderinto J, Brenkel IJ. Pre-operative predictors of the requirement for blood transfusion following total hip replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2004;86(7):970-973.

13. Browne JA, Adib F, Brown TE, Novicoff WM. Transfusion rates are increasing following total hip arthroplasty: risk factors and outcomes. J Arthroplasty. 2013;28(8 suppl):34-37.

14. Yoshihara H, Yoneoka D. Predictors of allogeneic blood transfusion in spinal fusion in the United States, 2004–2009. Spine. 2014;39(4):304-310.

15. Noticewala MS, Nyce JD, Wang W, Geller JA, Macaulay W. Predicting need for allogeneic transfusion after total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2012;27(6):961-967.

16. Griffin JW, Novicoff WM, Browne JA, Brockmeier SF. Obstructive sleep apnea as a risk factor after shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2013;22(12):e6-e9.

17. Maynard C, Sales AE. Changes in the use of coronary artery revascularization procedures in the Department of Veterans Affairs, the National Hospital Discharge Survey, and the Nationwide Inpatient Sample, 1991–1999. BMC Health Serv Res. 2003;3(1):12.

18. Pereira BM, Chan PH, Weinstein PR, Fishman RA. Cerebral protection during reperfusion with superoxide dismutase in focal cerebral ischemia. Adv Neurol. 1990;52:97-103.

19. Hambright D, Henderson RA, Cook C, Worrell T, Moorman CT, Bolognesi MP. A comparison of perioperative outcomes in patients with and without rheumatoid arthritis after receiving a total shoulder replacement arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2011;20(1):77-85.

20. Ponce BA, Menendez ME, Oladeji LO, Soldado F. Diabetes as a risk factor for poorer early postoperative outcomes after shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2014;23(5):671-678.

21. Pierson JL, Hannon TJ, Earles DR. A blood-conservation algorithm to reduce blood transfusions after total hip and knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86(7):1512-1518.

22. Martinez V, Monsaingeon-Lion A, Cherif K, Judet T, Chauvin M, Fletcher D. Transfusion strategy for primary knee and hip arthroplasty: impact of an algorithm to lower transfusion rates and hospital costs. Br J Anaesth. 2007;99(6):794-800.

23. Helm AT, Karski MT, Parsons SJ, Sampath JS, Bale RS. A strategy for reducing blood-transfusion requirements in elective orthopaedic surgery. Audit of an algorithm for arthroplasty of the lower limb. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2003;85(4):484-489.

24. Watts CD, Pagnano MW. Minimising blood loss and transfusion in contemporary hip and knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2012;94(11 suppl A):8-10.

25. Guralnik JM, Eisenstaedt RS, Ferrucci L, Klein HG, Woodman RC. Prevalence of anemia in persons 65 years and older in the United States: evidence for a high rate of unexplained anemia. Blood. 2004;104(8):2263-2268.

26. Rogers MA, Blumberg N, Heal JM, Langa KM. Utilization of blood transfusion among older adults in the United States. Transfusion. 2011;51(4):710-718.

27. Cobain TJ, Vamvakas EC, Wells A, Titlestad K. A survey of the demographics of blood use. Transfusion Med. 2007;17(1):1-15.

28. Fosco M, Di Fiore M. Factors predicting blood transfusion in different surgical procedures for degenerative spine disease. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2012;16(13):1853-1858.

29. Handoll HH, Ollivere BJ, Rollins KE. Interventions for treating proximal humeral fractures in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;12:CD000434.

30. Neuhaus V, Swellengrebel CH, Bossen JK, Ring D. What are the factors influencing outcome among patients admitted to a hospital with a proximal humeral fracture? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2013;471(5):1698-1706.

31. Volgas DA, Stannard JP, Alonso JE. Nonunions of the humerus. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2004;(419):46-50.

32. Chambers L, Dines JS, Lorich DG, Dines DM. Hemiarthroplasty for proximal humerus fractures. Curr Rev Musculoskeletal Med. 2013;6(1):57-62.

33. Jain NB, Hocker S, Pietrobon R, Guller U, Bathia N, Higgins LD. Total arthroplasty versus hemiarthroplasty for glenohumeral osteoarthritis: role of provider volume. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2005;14(4):361-367.

34. Izquierdo R, Voloshin I, Edwards S, et al. Treatment of glenohumeral osteoarthritis. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2010;18(6):375-382.

35. Shields E, Iannuzzi JC, Thorsness R, Noyes K, Voloshin I. Perioperative complications after hemiarthroplasty and total shoulder arthroplasty are equivalent. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2014;23(10):1449-1453.

36. Gartsman GM, Roddey TS, Hammerman SM. Shoulder arthroplasty with or without resurfacing of the glenoid in patients who have osteoarthritis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2000;82(1):26-34.

37. Singh A, Yian EH, Dillon MT, Takayanagi M, Burke MF, Navarro RA. The effect of surgeon and hospital volume on shoulder arthroplasty perioperative quality metrics. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2014;23(8):1187-1194.

38. Groh GI, Groh GM. Complications rates, reoperation rates, and the learning curve in reverse shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2014;23(3):388-394.

39. Boileau P, Gonzalez JF, Chuinard C, Bicknell R, Walch G. Reverse total shoulder arthroplasty after failed rotator cuff surgery. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2009;18(4):600-606.

40. Boileau P, Watkinson D, Hatzidakis AM, Hovorka I. Neer Award 2005: the Grammont reverse shoulder prosthesis: results in cuff tear arthritis, fracture sequelae, and revision arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2006;15(5):527-540.

41. Boileau P, Watkinson DJ, Hatzidakis AM, Balg F. Grammont reverse prosthesis: design, rationale, and biomechanics. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2005;14(1 suppl S):147S-161S.

42. Pola E, Papaleo P, Santoliquido A, Gasparini G, Aulisa L, De Santis E. Clinical factors associated with an increased risk of perioperative blood transfusion in nonanemic patients undergoing total hip arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86(1):57-61.

43. Lin DM, Lin ES, Tran MH. Efficacy and safety of erythropoietin and intravenous iron in perioperative blood management: a systematic review. Transfusion Med Rev. 2013;27(4):221-234.

44. Muñoz M, Gómez-Ramírez S, Cuenca J, et al. Very-short-term perioperative intravenous iron administration and postoperative outcome in major orthopedic surgery: a pooled analysis of observational data from 2547 patients. Transfusion. 2014;54(2):289-299.

45. Danninger T, Rasul R, Poeran J, et al. Blood transfusions in total hip and knee arthroplasty: an analysis of outcomes. ScientificWorldJournal. 2014;2014:623460.

46. Baldus CR, Bridwell KH, Lenke LG, Okubadejo GO. Can we safely reduce blood loss during lumbar pedicle subtraction osteotomy procedures using tranexamic acid or aprotinin? A comparative study with controls. Spine. 2010;35(2):235-239.

47. Chang CH, Chang Y, Chen DW, Ueng SW, Lee MS. Topical tranexamic acid reduces blood loss and transfusion rates associated with primary total hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014;472(5):1552-1557.

48. Delasotta LA, Orozco F, Jafari SM, Blair JL, Ong A. Should we use preoperative epoetin-alpha in the mildly anemic patient undergoing simultaneous total knee arthroplasty? Open Orthop J. 2013;7:47-50.

49. Delasotta LA, Rangavajjula A, Frank ML, Blair J, Orozco F, Ong A. The use of preoperative epoetin-alpha in revision hip arthroplasty. Open Orthop J. 2012;6:179-183.

50. Kelley TC, Tucker KK, Adams MJ, Dalury DF. Use of tranexamic acid results in decreased blood loss and decreased transfusions in patients undergoing staged bilateral total knee arthroplasty. Transfusion. 2014;54(1):26-30.

51. Martin JG, Cassatt KB, Kincaid-Cinnamon KA, Westendorf DS, Garton AS, Lemke JH. Topical administration of tranexamic acid in primary total hip and total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2014;29(5):889-894.

52. Tzortzopoulou A, Cepeda MS, Schumann R, Carr DB. Antifibrinolytic agents for reducing blood loss in scoliosis surgery in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008(3):CD006883.

53. Zhang H, Chen J, Chen F, Que W. The effect of tranexamic acid on blood loss and use of blood products in total knee arthroplasty: a meta-analysis. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2012;20(9):1742-1752.

54. Bong MR, Patel V, Chang E, Issack PS, Hebert R, Di Cesare PE. Risks associated with blood transfusion after total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2004;19(3):281-287.

1. Ahmadi S, Lawrence TM, Sahota S, et al. The incidence and risk factors for blood transfusion in revision shoulder arthroplasty: our institution’s experience and review of the literature. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2014;23(1):43-48.

2. Sperling JW, Duncan SF, Cofield RH, Schleck CD, Harmsen WS. Incidence and risk factors for blood transfusion in shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2005;14(6):599-601.

3. Hardy JC, Hung M, Snow BJ, et al. Blood transfusion associated with shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2013;22(2):233-239.

4. Schumer RA, Chae JS, Markert RJ, Sprott D, Crosby LA. Predicting transfusion in shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2010;19(1):91-96.

5. Gruson KI, Accousti KJ, Parsons BO, Pillai G, Flatow EL. Transfusion after shoulder arthroplasty: an analysis of rates and risk factors. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2009;18(2):225-230.

6. Millett PJ, Porramatikul M, Chen N, Zurakowski D, Warner JJ. Analysis of transfusion predictors in shoulder arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88(6):1223-1230.

7. Kim SH, Wise BL, Zhang Y, Szabo RM. Increasing incidence of shoulder arthroplasty in the United States. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011;93(24):2249-2254.

8. Ceccherini-Nelli L, Filipponi F, Mosca F, Campa M. The risk of contracting an infectious disease from blood transfusion. Transplantation Proc. 2004;36(3):680-682.

9. Friedman R, Homering M, Holberg G, Berkowitz SD. Allogeneic blood transfusions and postoperative infections after total hip or knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96(4):272-278.

10. Hatzidakis AM, Mendlick RM, McKillip T, Reddy RL, Garvin KL. Preoperative autologous donation for total joint arthroplasty. An analysis of risk factors for allogenic transfusion. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2000;82(1):89-100.

11. Park JH, Rasouli MR, Mortazavi SM, Tokarski AT, Maltenfort MG, Parvizi J. Predictors of perioperative blood loss in total joint arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95(19):1777-1783.

12. Aderinto J, Brenkel IJ. Pre-operative predictors of the requirement for blood transfusion following total hip replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2004;86(7):970-973.

13. Browne JA, Adib F, Brown TE, Novicoff WM. Transfusion rates are increasing following total hip arthroplasty: risk factors and outcomes. J Arthroplasty. 2013;28(8 suppl):34-37.

14. Yoshihara H, Yoneoka D. Predictors of allogeneic blood transfusion in spinal fusion in the United States, 2004–2009. Spine. 2014;39(4):304-310.

15. Noticewala MS, Nyce JD, Wang W, Geller JA, Macaulay W. Predicting need for allogeneic transfusion after total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2012;27(6):961-967.

16. Griffin JW, Novicoff WM, Browne JA, Brockmeier SF. Obstructive sleep apnea as a risk factor after shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2013;22(12):e6-e9.

17. Maynard C, Sales AE. Changes in the use of coronary artery revascularization procedures in the Department of Veterans Affairs, the National Hospital Discharge Survey, and the Nationwide Inpatient Sample, 1991–1999. BMC Health Serv Res. 2003;3(1):12.

18. Pereira BM, Chan PH, Weinstein PR, Fishman RA. Cerebral protection during reperfusion with superoxide dismutase in focal cerebral ischemia. Adv Neurol. 1990;52:97-103.

19. Hambright D, Henderson RA, Cook C, Worrell T, Moorman CT, Bolognesi MP. A comparison of perioperative outcomes in patients with and without rheumatoid arthritis after receiving a total shoulder replacement arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2011;20(1):77-85.

20. Ponce BA, Menendez ME, Oladeji LO, Soldado F. Diabetes as a risk factor for poorer early postoperative outcomes after shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2014;23(5):671-678.

21. Pierson JL, Hannon TJ, Earles DR. A blood-conservation algorithm to reduce blood transfusions after total hip and knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86(7):1512-1518.

22. Martinez V, Monsaingeon-Lion A, Cherif K, Judet T, Chauvin M, Fletcher D. Transfusion strategy for primary knee and hip arthroplasty: impact of an algorithm to lower transfusion rates and hospital costs. Br J Anaesth. 2007;99(6):794-800.

23. Helm AT, Karski MT, Parsons SJ, Sampath JS, Bale RS. A strategy for reducing blood-transfusion requirements in elective orthopaedic surgery. Audit of an algorithm for arthroplasty of the lower limb. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2003;85(4):484-489.

24. Watts CD, Pagnano MW. Minimising blood loss and transfusion in contemporary hip and knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2012;94(11 suppl A):8-10.

25. Guralnik JM, Eisenstaedt RS, Ferrucci L, Klein HG, Woodman RC. Prevalence of anemia in persons 65 years and older in the United States: evidence for a high rate of unexplained anemia. Blood. 2004;104(8):2263-2268.

26. Rogers MA, Blumberg N, Heal JM, Langa KM. Utilization of blood transfusion among older adults in the United States. Transfusion. 2011;51(4):710-718.

27. Cobain TJ, Vamvakas EC, Wells A, Titlestad K. A survey of the demographics of blood use. Transfusion Med. 2007;17(1):1-15.

28. Fosco M, Di Fiore M. Factors predicting blood transfusion in different surgical procedures for degenerative spine disease. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2012;16(13):1853-1858.

29. Handoll HH, Ollivere BJ, Rollins KE. Interventions for treating proximal humeral fractures in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;12:CD000434.

30. Neuhaus V, Swellengrebel CH, Bossen JK, Ring D. What are the factors influencing outcome among patients admitted to a hospital with a proximal humeral fracture? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2013;471(5):1698-1706.

31. Volgas DA, Stannard JP, Alonso JE. Nonunions of the humerus. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2004;(419):46-50.

32. Chambers L, Dines JS, Lorich DG, Dines DM. Hemiarthroplasty for proximal humerus fractures. Curr Rev Musculoskeletal Med. 2013;6(1):57-62.

33. Jain NB, Hocker S, Pietrobon R, Guller U, Bathia N, Higgins LD. Total arthroplasty versus hemiarthroplasty for glenohumeral osteoarthritis: role of provider volume. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2005;14(4):361-367.

34. Izquierdo R, Voloshin I, Edwards S, et al. Treatment of glenohumeral osteoarthritis. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2010;18(6):375-382.

35. Shields E, Iannuzzi JC, Thorsness R, Noyes K, Voloshin I. Perioperative complications after hemiarthroplasty and total shoulder arthroplasty are equivalent. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2014;23(10):1449-1453.

36. Gartsman GM, Roddey TS, Hammerman SM. Shoulder arthroplasty with or without resurfacing of the glenoid in patients who have osteoarthritis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2000;82(1):26-34.

37. Singh A, Yian EH, Dillon MT, Takayanagi M, Burke MF, Navarro RA. The effect of surgeon and hospital volume on shoulder arthroplasty perioperative quality metrics. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2014;23(8):1187-1194.

38. Groh GI, Groh GM. Complications rates, reoperation rates, and the learning curve in reverse shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2014;23(3):388-394.

39. Boileau P, Gonzalez JF, Chuinard C, Bicknell R, Walch G. Reverse total shoulder arthroplasty after failed rotator cuff surgery. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2009;18(4):600-606.