User login

Is the Orthopedic Fellowship Interview Process Broken? A Survey of Program Directors and Residents

Over the past several decades, an increasing number of orthopedic surgery residents have pursued fellowship training.1 This inclination parallels market trends toward subspecialization.2-5 In 1984, 83% of orthopedics job announcements were for general orthopedists. Twenty-five years later, almost 70% of orthopedic opportunities were for fellowship-trained surgeons.6 Further, between 1990 and 2006, the proportion of practicing orthopedic generalists decreased from 44% to 29%.3 In 2007, the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgery (AAOS) reported 90% of graduating residents were planning to pursue fellowship training.7 Reasons for the explosion in subspecialty training are plentiful and well documented.2-5 Subspecialty positions now dominate the job market, further reinforcing incentives for residents to pursue fellowship training.

The past several decades have seen numerous changes in the orthopedic fellowship interview process. Early on, it was largely unregulated, dependent on personal and professional connections, and flush with the classic “exploding offer” (residents were given a fellowship offer that expired within hours or days). In the 1980s, as the number of fellowship applications surged, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) pushed for a more regulated process.8 To further standardize the system, the American Orthopaedic Association (AOA), the AAOS, and several other specialty organizations created the Orthopaedic Fellowship Match Program Initiative in 2008.9 Currently, all orthopedic specialties are represented in either the San Francisco Match Program or National Residency Match Program.

As the system currently stands, postgraduate year 4 (PGY-4) residents are required to interview across the country to secure postgraduate training. This process necessitates residents’ absence from their program, reducing educational opportunities and placing potential continuity-of-care constraints on the residency program. Despite the growing competitiveness for fellowship positions, the increasing number of fellowships available, the rising educational debt of residents, and the limitations of the 80-hour work week, the impact of the interview process on both residents and residency programs has received minimal attention.

We conducted a study to elucidate the impact of the fellowship interview process on residents and residency programs. We hypothesized the time and financial costs for fellowship interviews would be substantial.

Materials and Methods

We obtained institutional review board (IRB) approval for this study. Then, in April 2014, we sent 2 mixed-response questionnaires to orthopedic surgery residency directors and residents. There were 8 items on the director questionnaire and 11 on the resident questionnaire. The surveys were designed to determine the impact of the fellowship interview process on residents and residency programs with respect to finances, time, education, and continuity of care. Each survey had at least 1 free-response question, providing the opportunity to recommend changes to the interview process. The surveys were reviewed and approved by our IRB.

An email was sent to 155 orthopedic surgery program directors or their secretaries. The email asked that the director complete the director questionnaire and that the resident questionnaire be forwarded to senior-level residents, PGY-4s and PGY-5s, who had completed the fellowship interview process. Forty-five (29%) of the 155 directors responded, as did 129 (estimated 9.5%) of an estimated 1354 potential PGY-4s and PGY-5s.10

The Survey Monkey surveys could be completed over a 3-week period. All responses were anonymous. Using Survey Monkey, we aggregated individual responses into predefined clusters before performing statistical analysis. Descriptive statistics were generated with Microsoft Excel.

Results

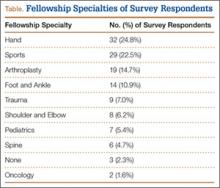

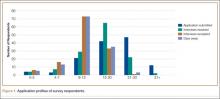

Survey respondents represented all the orthopedic subspecialties (Table). Seventy-eight percent of residents applied to at least 13 programs (average, 19) (Figure 1). Ninety-two percent received at least 8 interview offers (average, 14). Eighty-three percent attended 8 or more interviews (average, 11). Seventy-one percent of all interviews were granted when requested, and 79% of all interviews were attended when offered.

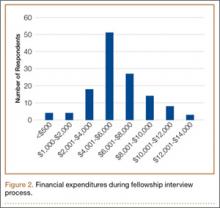

Residents spent an average of $5875 (range, $500-$12,000+) on the fellowship interview process (Figure 2). The highest percentage of respondents, 39.5%, selected an average expense between $4000 and $6000. Forty-nine percent of residents borrowed money (from credit cards, additional loans, family members) to pay their expenses.

Average number of days away from residency programs was 11, with 86% of residents missing more than 8 days (Figure 1). About one-third of residents reported being away from their home program for almost 2 weeks during the interview season. Further, 74% of residents wanted changes made to the fellowship application process.

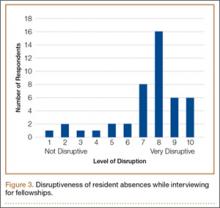

Thirty-seven (82%) of the 45 program directors were from academic programs, the other 8 from community-based programs. Average number of residents in programs per year was 4 (73% of the programs had 4-6 residents per year). Respondents rated the disruption caused by residents’ interview absences from 1 (least disruptive) to 10 (most disruptive) (Figure 3); the average rating was over 7 (high level of disruption). Although 9% of directors thought the process caused little or no disruption (rating, 1-3), 62% thought it extremely disruptive (rating, 8-10).

Thirty-one (69%) of the 45 directors agreed that the fellowship interview process should undergo fundamental change. Asked about possible solutions to current complaints, 60% of the directors agreed that interviews should be conducted in a central location. Of the directors who thought fundamental change was needed, 59% indicated AAOS and other specialty societies together should lead the change in the fellowship interview process.

Both residents and program directors were given the opportunity to write in suggestions regarding how to improve the fellowship interview process. Suggestions were made by 85 (66%) of the 129 residents and 24 (53%) of the 45 directors (Appendix).

Discussion

Graduating residents are entering a health care environment in which they must be financially conscious because of increasing education debt and decreasing reimbursement prospects.3 Nevertheless, an overwhelming majority of residents delay entering practice to pursue fellowship training—an estimated opportunity cost of $350,000.3 Minimal attention has been given to the potential costs of the fellowship interview process.

Our study results highlight that time away from residency training, financial costs associated with the fellowship interview process, and disruption of the residency program are substantial. On average, residents applied to 19 programs, received 14 interview offers, attended 11 interviews, were away from residency training 11 days, and spent $5875 on travel. The great majority of both residents and program directors wanted changes in the current paradigm governing the orthopedic fellowship interview process.

It is reasonable to think that the number of days residents spend away on interviews would reduce the time available for education and patient care. Although unknown, it is plausible that residents of programs outside major metropolitan centers and residents who apply to more competitive fellowships may be forced to spend even more time away from training. Outside the focus of this study are the impact that residents’ absence might have on their education and the impact of this absence on the people who do the residents’ work while they are away.

Mean fellowship expense was similar to that reported by residents pursuing a pediatric general surgery fellowship ($6974) or a plastic surgery fellowship ($6100).11,12 Unfortunately, we were unable to determine if average cost is influenced by choice of fellowship specialty or location of residency program. Regardless, fellowship cost may impose an additional financial burden on residents. According to the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC), the median salary for PGY-4 residents was $56,380 in 2013. Therefore, on average, the fellowship process consumes more than 10% of a resident’s pretax salary. For perspective, this equates to more than $40,000 for a practicing orthopedic surgeon with a median salary of $413,000.13 With an average medical student graduate debt of $175,000 and continuing decreases in reimbursement, further financial hardships to newly graduating residents cannot be understated.5,11,12

Almost 70% of program directors thought the fellowship process significantly disrupted their program. Reasons given for this disruption mainly involved residents’ time away from the program and the resulting strains placed on maintaining adequate coverage for patient care. The overall disruption score of 7.4 out of 10 was consistent with the great majority thinking that the fellowship process negatively affects their residency program. Altering the fellowship interview process may provide unintended benefits to programs and program directors.

Both program directors and residents communicated that change is needed, but there was little consensus regarding how to effect change and who should lead. This lack of consensus highlights how important it is for the various orthopedic leadership committees to actively and collectively participate in discussions about redefining the system. It has been proposed that it would be ideal for the AOA to lead the change, as the AOA consists of a representative cohort of academic orthopedists and leaders across the spectrum of all fellowship specialties.14 Given the abundant concern of both residents and program directors, we find it prudent to issue a call to arms of sorts to the AAOS and the individual orthopedic subspecialty societies to work together on a common goal that would benefit residents, programs, and subspecialties within orthopedics.

In trying to understand the challenges that residents, program directors, and programs face, as well as the inherent complexity of the current system, we incorporated respondents’ write-in comments into suggested ways of improving the fellowship interview process. These comments had broad perspectives but overall were consistent with the survey results (Appendix).

Technology

Health care is continually finding new ways to take advantage of technological advances. This is occurring with the fellowship interview schema. Numerous disciplines are using videoconferencing platforms (eg, Skype) to conduct interviews. This practice is becoming more commonplace in the business sector. In a recent survey, more than 60% of human resource managers reported conducting video interviews.15 Two independent residency programs have used video interviews with mixed success.16,17

Another technological change requested by residents is the creation and updating of fellowship web pages with standardized information. Such a service may prove useful to residents researching a program and may even lead to limiting the number of programs residents apply to, as they may be able to dial in on exactly what distinguishes one program from another before traveling for an interview. A recent study of orthopedic sports medicine fellowship programs found that most of these programs lacked pertinent information on their websites.18 Important information regarding case logs from current and former fellows; number of faculty, residents, and fellows; and schedules and facilities of interview sites are a few of the online data points that may help residents differentiate particular programs.19,20 Questions like these are often asked at interviews and site visits. Having accurate information easily available online may reduce or eliminate the need to travel to a site for such information. Standardizing information would also increase transparency among available fellowships. Although not specifically mentioned, organizational software that improves the productivity of the process may help limit the large number of programs applied to, the interviews offered and attended, the days away, and the financial costs without reducing the match rate.

Timing and Location

The issue of timing—with respect to geographical or meteorological concerns—was another recurring theme among respondents. Numerous respondents indicated that certain programs located in geographic proximity tried to minimize travel by offering interviews around the same time. This coordination potentially minimizes travel expenses and time away from the residency program by allowing residents to interview at multiple locations during a single trip per region. The sports medicine fellowship process was identified as a good example of aligning interviews based on geography. Several respondents suggested an option that also reflects the practice of nonsurgical fellowships—delaying the interview season to bypass potential weather concerns. Winter 2013–2014 saw the most flight delays or cancellations in more than a decade; about 50% of all flights scheduled between December and February were delayed or canceled.21 Beyond the additional factor of more time away or missing an interview because of the weather are safety concerns related to the weather. One resident reported having a motor vehicle accident while traveling to an interview in poor weather conditions (Appendix).

National Meetings

Each orthopedic subspecialty has numerous national meetings. Many programs offer applicants the opportunity to interview at these meetings. One respondent mentioned that the annual meeting of the Orthopaedic Trauma Association offers trauma applicants the opportunity to interview with multiple programs. It might be beneficial to endorse this practice on a larger scale to help reduce travel and time away. We recognize that visiting individual programs is an important aspect of the match process, but doing so on a targeted level may make more sense, increasing financial efficiency and reducing time away from programs.

Proposed Solution

A combined proposed solution that can be implemented without a radical overhaul or significant investments might involve moving the interview season to early spring, switching to a 2-tiered system with a centralized first round of interview screening coinciding with subspecialty national meetings or the AAOS annual meeting, and standardizing online information for all orthopedic fellowship programs. A 2-tiered interview process would allow programs and candidates to obtain exposure to a significant number of programs in the first round without incurring significant costs and then would impose a cap on the number of programs to visit. This would level the playing field between candidates with more time and money and candidates who are more constrained in their training environment and finances. A stopgap or adjunct to residents or fellowship programs unable to attend a centralized meeting would be to combine technological tools, such as Internet-based videoconferencing (Skype), before site visits by residents. After this first round of introductions and interviews, residents could then decide on a limited number of programs to formally visit, attend, and ultimately rank. This proposed system would still be able to function within the confines of the match, and it would benefit from the protections offered to residents and programs. Although capping the number of interviews attended by residents clearly can lower costs across the board, we recognize the difficulty of enforcing such a requirement. These potential changes to the system are not exhaustive, and we hope this work will serve as a springboard to further discussion.

Our study had several inherent weaknesses. Our data came from survey responses, which reflect the perspectives only of the responding residents and program directors. Unfortunately, a small number of orthopedic residents responded to this survey, so there was a potential for bias. However, we think the central themes discovered in this survey are only echoes of the concerns of the larger population of residents and program directors. Our hope in designing such a study was to bring to light some of the discrepancies in the fellowship interview process, the goal being to stimulate interest among the orthopedic leadership representing future orthopedic surgeons. More study is needed to clarify if these issues are reflective of a larger segment of residents and program directors. In addition, action may be needed to fully elucidate the intricate interworking of the fellowship process in order to maximize the interest of the orthopedic surgeons who are seeking fellowship training. Another study limitation was the potential for recall bias in the more senior PGY-5 residents, who were further from the interview process than PGY-4 respondents were. Because of the need for anonymity with the surveys, we could not link some findings (eg, program impact, cost, time away) to individual programs or different specialty fellowships. Although it appears there is a desire for a more cost-effective system, given the financial pressures on medical students and residents, the desire to match increases costs because students are likely to attend more interviews than actually needed. Our proposed solution does not take into account residents’ behavior with respect to the current match system. For example, the prevailing thought is that interviewing at more programs increases the likelihood of matching into a desired subspecialty. Despite these study limitations, we think our results identified important points for discussion, investigation, and potential action by orthopedic leadership.

Conclusion

The challenge of critiquing and improving the orthopedic fellowship process requires the same courageous leadership that was recommended almost a decade ago.14 In this study, we tried to elucidate the impact of the PGY-4 fellowship interview process with respect to residents and residency programs. Our results highlight that time away from residency training, financial costs associated with the fellowship interview process, and disruption of the residency program are substantial and that both residents and program directors want changes made. Leadership needs to further investigate alternatives to the current process to lessen the impact on all parties in this important process.

1. Simon MA. Evolution of the present status of orthopaedic surgery fellowships. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1998;80(12):1826-1829.

2. Brunworth LS, Chintalapani SR, Gray RR, Cardoso R, Owens PW. Resident selection of hand surgery fellowships: a survey of the 2011, 2012, and 2013 hand fellowship graduates. Hand. 2013;8(2):164-171.

3. Gaskill T, Cook C, Nunley J, Mather RC. The financial impact of orthopaedic fellowship training. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91(7):1814-1821.

4. Sarmiento A. Additional thoughts on orthopedic residency and fellowships. Orthopedics. 2010;33(10):712-713.

5. Griffin SM, Stoneback JW. Navigating the Orthopaedic Trauma Fellowship Match from a candidate’s perspective. J Orthop Trauma. 2011;25(suppl 3):S101-S103.

6. Morrell NT, Mercer DM, Moneim MS. Trends in the orthopedic job market and the importance of fellowship subspecialty training. Orthopedics. 2012;35(4):e555-e560.

7. Iorio R, Robb WJ, Healy WL, et al. Orthopaedic surgeon workforce and volume assessment for total hip and knee replacement in the United States: preparing for an epidemic. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90(7):1598-1605.

8. Emery SE, Guss D, Kuremsky MA, Hamlin BR, Herndon JH, Rubash HE. Resident education versus fellowship training—conflict or synergy? AOA critical issues. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94(21):e159.

9. Harner CD, Ranawat AS, Niederle M, et al. AOA symposium. Current state of fellowship hiring: is a universal match necessary? Is it possible? J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90(6):1375-1384.

10. Ranawat A, Nunley RM, Genuario JW, Sharan AD, Mehta S; Washington Health Policy Fellows. Current state of the fellowship hiring process: Are we in 1957 or 2007? AAOS Now. 2007;1(8).

11. Little DC, Yoder SM, Grikscheit TC, et al. Cost considerations and applicant characteristics for the Pediatric Surgery Match. J Pediatr Surg. 2005;40(1):69-73.

12. Claiborne JR, Crantford JC, Swett KR, David LR. The Plastic Surgery Match: predicting success and improving the process. Ann Plast Surg. 2013;70(6):698-703.

13. Kane L, Peckham C. Medscape Physician Compensation Report 2014. http://www.medscape.com/features/slideshow/compensation/2014/public/overview. Published April 15, 2014. Accessed September 26, 2015.

14. Swiontkowski MF. A simple formula for continued improvement in orthopaedic surgery postgraduate training: courageous leadership. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90(6):1175.

15. Survey: six in 10 companies conduct video job interviews [news release]. http://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/survey-six-in-10-companies-conduct-video-job-interviews-167973406.html. Published August 30, 2012. Accessed September 26, 2015.

16. Kerfoot BP, Asher KP, McCullough DL. Financial and educational costs of the residency interview process for urology applicants. Urology. 2008;71(6):990-994.

17. Edje L, Miller C, Kiefer J, Oram D. Using Skype as an alternative for residency selection interviews. J Grad Med Educ. 2013;5(3):503-505.

18. Mulcahey MK, Gosselin MM, Fadale PD. Evaluation of the content and accessibility of web sites for accredited orthopaedic sports medicine fellowships. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95(12):e85.

19. Gaeta TJ, Birkhahn RH, Lamont D, Banga N, Bove JJ. Aspects of residency programs’ web sites important to student applicants. Acad Emerg Med. 2005;12(1):89-92.

20. Mahler SA, Wagner MJ, Church A, Sokolosky M, Cline DM. Importance of residency program web sites to emergency medicine applicants. J Emerg Med. 2009;36(1):83-88.

21. Davies A. Winter’s toll: 1 million flights cancelled or delayed, costing travelers $5.3 billion. Business Insider. http://www.businessinsider.com/winter-flights-cancelled-delayed-cost-2014-3. Published March 3, 2014. Accessed September 26, 2015.

Over the past several decades, an increasing number of orthopedic surgery residents have pursued fellowship training.1 This inclination parallels market trends toward subspecialization.2-5 In 1984, 83% of orthopedics job announcements were for general orthopedists. Twenty-five years later, almost 70% of orthopedic opportunities were for fellowship-trained surgeons.6 Further, between 1990 and 2006, the proportion of practicing orthopedic generalists decreased from 44% to 29%.3 In 2007, the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgery (AAOS) reported 90% of graduating residents were planning to pursue fellowship training.7 Reasons for the explosion in subspecialty training are plentiful and well documented.2-5 Subspecialty positions now dominate the job market, further reinforcing incentives for residents to pursue fellowship training.

The past several decades have seen numerous changes in the orthopedic fellowship interview process. Early on, it was largely unregulated, dependent on personal and professional connections, and flush with the classic “exploding offer” (residents were given a fellowship offer that expired within hours or days). In the 1980s, as the number of fellowship applications surged, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) pushed for a more regulated process.8 To further standardize the system, the American Orthopaedic Association (AOA), the AAOS, and several other specialty organizations created the Orthopaedic Fellowship Match Program Initiative in 2008.9 Currently, all orthopedic specialties are represented in either the San Francisco Match Program or National Residency Match Program.

As the system currently stands, postgraduate year 4 (PGY-4) residents are required to interview across the country to secure postgraduate training. This process necessitates residents’ absence from their program, reducing educational opportunities and placing potential continuity-of-care constraints on the residency program. Despite the growing competitiveness for fellowship positions, the increasing number of fellowships available, the rising educational debt of residents, and the limitations of the 80-hour work week, the impact of the interview process on both residents and residency programs has received minimal attention.

We conducted a study to elucidate the impact of the fellowship interview process on residents and residency programs. We hypothesized the time and financial costs for fellowship interviews would be substantial.

Materials and Methods

We obtained institutional review board (IRB) approval for this study. Then, in April 2014, we sent 2 mixed-response questionnaires to orthopedic surgery residency directors and residents. There were 8 items on the director questionnaire and 11 on the resident questionnaire. The surveys were designed to determine the impact of the fellowship interview process on residents and residency programs with respect to finances, time, education, and continuity of care. Each survey had at least 1 free-response question, providing the opportunity to recommend changes to the interview process. The surveys were reviewed and approved by our IRB.

An email was sent to 155 orthopedic surgery program directors or their secretaries. The email asked that the director complete the director questionnaire and that the resident questionnaire be forwarded to senior-level residents, PGY-4s and PGY-5s, who had completed the fellowship interview process. Forty-five (29%) of the 155 directors responded, as did 129 (estimated 9.5%) of an estimated 1354 potential PGY-4s and PGY-5s.10

The Survey Monkey surveys could be completed over a 3-week period. All responses were anonymous. Using Survey Monkey, we aggregated individual responses into predefined clusters before performing statistical analysis. Descriptive statistics were generated with Microsoft Excel.

Results

Survey respondents represented all the orthopedic subspecialties (Table). Seventy-eight percent of residents applied to at least 13 programs (average, 19) (Figure 1). Ninety-two percent received at least 8 interview offers (average, 14). Eighty-three percent attended 8 or more interviews (average, 11). Seventy-one percent of all interviews were granted when requested, and 79% of all interviews were attended when offered.

Residents spent an average of $5875 (range, $500-$12,000+) on the fellowship interview process (Figure 2). The highest percentage of respondents, 39.5%, selected an average expense between $4000 and $6000. Forty-nine percent of residents borrowed money (from credit cards, additional loans, family members) to pay their expenses.

Average number of days away from residency programs was 11, with 86% of residents missing more than 8 days (Figure 1). About one-third of residents reported being away from their home program for almost 2 weeks during the interview season. Further, 74% of residents wanted changes made to the fellowship application process.

Thirty-seven (82%) of the 45 program directors were from academic programs, the other 8 from community-based programs. Average number of residents in programs per year was 4 (73% of the programs had 4-6 residents per year). Respondents rated the disruption caused by residents’ interview absences from 1 (least disruptive) to 10 (most disruptive) (Figure 3); the average rating was over 7 (high level of disruption). Although 9% of directors thought the process caused little or no disruption (rating, 1-3), 62% thought it extremely disruptive (rating, 8-10).

Thirty-one (69%) of the 45 directors agreed that the fellowship interview process should undergo fundamental change. Asked about possible solutions to current complaints, 60% of the directors agreed that interviews should be conducted in a central location. Of the directors who thought fundamental change was needed, 59% indicated AAOS and other specialty societies together should lead the change in the fellowship interview process.

Both residents and program directors were given the opportunity to write in suggestions regarding how to improve the fellowship interview process. Suggestions were made by 85 (66%) of the 129 residents and 24 (53%) of the 45 directors (Appendix).

Discussion

Graduating residents are entering a health care environment in which they must be financially conscious because of increasing education debt and decreasing reimbursement prospects.3 Nevertheless, an overwhelming majority of residents delay entering practice to pursue fellowship training—an estimated opportunity cost of $350,000.3 Minimal attention has been given to the potential costs of the fellowship interview process.

Our study results highlight that time away from residency training, financial costs associated with the fellowship interview process, and disruption of the residency program are substantial. On average, residents applied to 19 programs, received 14 interview offers, attended 11 interviews, were away from residency training 11 days, and spent $5875 on travel. The great majority of both residents and program directors wanted changes in the current paradigm governing the orthopedic fellowship interview process.

It is reasonable to think that the number of days residents spend away on interviews would reduce the time available for education and patient care. Although unknown, it is plausible that residents of programs outside major metropolitan centers and residents who apply to more competitive fellowships may be forced to spend even more time away from training. Outside the focus of this study are the impact that residents’ absence might have on their education and the impact of this absence on the people who do the residents’ work while they are away.

Mean fellowship expense was similar to that reported by residents pursuing a pediatric general surgery fellowship ($6974) or a plastic surgery fellowship ($6100).11,12 Unfortunately, we were unable to determine if average cost is influenced by choice of fellowship specialty or location of residency program. Regardless, fellowship cost may impose an additional financial burden on residents. According to the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC), the median salary for PGY-4 residents was $56,380 in 2013. Therefore, on average, the fellowship process consumes more than 10% of a resident’s pretax salary. For perspective, this equates to more than $40,000 for a practicing orthopedic surgeon with a median salary of $413,000.13 With an average medical student graduate debt of $175,000 and continuing decreases in reimbursement, further financial hardships to newly graduating residents cannot be understated.5,11,12

Almost 70% of program directors thought the fellowship process significantly disrupted their program. Reasons given for this disruption mainly involved residents’ time away from the program and the resulting strains placed on maintaining adequate coverage for patient care. The overall disruption score of 7.4 out of 10 was consistent with the great majority thinking that the fellowship process negatively affects their residency program. Altering the fellowship interview process may provide unintended benefits to programs and program directors.

Both program directors and residents communicated that change is needed, but there was little consensus regarding how to effect change and who should lead. This lack of consensus highlights how important it is for the various orthopedic leadership committees to actively and collectively participate in discussions about redefining the system. It has been proposed that it would be ideal for the AOA to lead the change, as the AOA consists of a representative cohort of academic orthopedists and leaders across the spectrum of all fellowship specialties.14 Given the abundant concern of both residents and program directors, we find it prudent to issue a call to arms of sorts to the AAOS and the individual orthopedic subspecialty societies to work together on a common goal that would benefit residents, programs, and subspecialties within orthopedics.

In trying to understand the challenges that residents, program directors, and programs face, as well as the inherent complexity of the current system, we incorporated respondents’ write-in comments into suggested ways of improving the fellowship interview process. These comments had broad perspectives but overall were consistent with the survey results (Appendix).

Technology

Health care is continually finding new ways to take advantage of technological advances. This is occurring with the fellowship interview schema. Numerous disciplines are using videoconferencing platforms (eg, Skype) to conduct interviews. This practice is becoming more commonplace in the business sector. In a recent survey, more than 60% of human resource managers reported conducting video interviews.15 Two independent residency programs have used video interviews with mixed success.16,17

Another technological change requested by residents is the creation and updating of fellowship web pages with standardized information. Such a service may prove useful to residents researching a program and may even lead to limiting the number of programs residents apply to, as they may be able to dial in on exactly what distinguishes one program from another before traveling for an interview. A recent study of orthopedic sports medicine fellowship programs found that most of these programs lacked pertinent information on their websites.18 Important information regarding case logs from current and former fellows; number of faculty, residents, and fellows; and schedules and facilities of interview sites are a few of the online data points that may help residents differentiate particular programs.19,20 Questions like these are often asked at interviews and site visits. Having accurate information easily available online may reduce or eliminate the need to travel to a site for such information. Standardizing information would also increase transparency among available fellowships. Although not specifically mentioned, organizational software that improves the productivity of the process may help limit the large number of programs applied to, the interviews offered and attended, the days away, and the financial costs without reducing the match rate.

Timing and Location

The issue of timing—with respect to geographical or meteorological concerns—was another recurring theme among respondents. Numerous respondents indicated that certain programs located in geographic proximity tried to minimize travel by offering interviews around the same time. This coordination potentially minimizes travel expenses and time away from the residency program by allowing residents to interview at multiple locations during a single trip per region. The sports medicine fellowship process was identified as a good example of aligning interviews based on geography. Several respondents suggested an option that also reflects the practice of nonsurgical fellowships—delaying the interview season to bypass potential weather concerns. Winter 2013–2014 saw the most flight delays or cancellations in more than a decade; about 50% of all flights scheduled between December and February were delayed or canceled.21 Beyond the additional factor of more time away or missing an interview because of the weather are safety concerns related to the weather. One resident reported having a motor vehicle accident while traveling to an interview in poor weather conditions (Appendix).

National Meetings

Each orthopedic subspecialty has numerous national meetings. Many programs offer applicants the opportunity to interview at these meetings. One respondent mentioned that the annual meeting of the Orthopaedic Trauma Association offers trauma applicants the opportunity to interview with multiple programs. It might be beneficial to endorse this practice on a larger scale to help reduce travel and time away. We recognize that visiting individual programs is an important aspect of the match process, but doing so on a targeted level may make more sense, increasing financial efficiency and reducing time away from programs.

Proposed Solution

A combined proposed solution that can be implemented without a radical overhaul or significant investments might involve moving the interview season to early spring, switching to a 2-tiered system with a centralized first round of interview screening coinciding with subspecialty national meetings or the AAOS annual meeting, and standardizing online information for all orthopedic fellowship programs. A 2-tiered interview process would allow programs and candidates to obtain exposure to a significant number of programs in the first round without incurring significant costs and then would impose a cap on the number of programs to visit. This would level the playing field between candidates with more time and money and candidates who are more constrained in their training environment and finances. A stopgap or adjunct to residents or fellowship programs unable to attend a centralized meeting would be to combine technological tools, such as Internet-based videoconferencing (Skype), before site visits by residents. After this first round of introductions and interviews, residents could then decide on a limited number of programs to formally visit, attend, and ultimately rank. This proposed system would still be able to function within the confines of the match, and it would benefit from the protections offered to residents and programs. Although capping the number of interviews attended by residents clearly can lower costs across the board, we recognize the difficulty of enforcing such a requirement. These potential changes to the system are not exhaustive, and we hope this work will serve as a springboard to further discussion.

Our study had several inherent weaknesses. Our data came from survey responses, which reflect the perspectives only of the responding residents and program directors. Unfortunately, a small number of orthopedic residents responded to this survey, so there was a potential for bias. However, we think the central themes discovered in this survey are only echoes of the concerns of the larger population of residents and program directors. Our hope in designing such a study was to bring to light some of the discrepancies in the fellowship interview process, the goal being to stimulate interest among the orthopedic leadership representing future orthopedic surgeons. More study is needed to clarify if these issues are reflective of a larger segment of residents and program directors. In addition, action may be needed to fully elucidate the intricate interworking of the fellowship process in order to maximize the interest of the orthopedic surgeons who are seeking fellowship training. Another study limitation was the potential for recall bias in the more senior PGY-5 residents, who were further from the interview process than PGY-4 respondents were. Because of the need for anonymity with the surveys, we could not link some findings (eg, program impact, cost, time away) to individual programs or different specialty fellowships. Although it appears there is a desire for a more cost-effective system, given the financial pressures on medical students and residents, the desire to match increases costs because students are likely to attend more interviews than actually needed. Our proposed solution does not take into account residents’ behavior with respect to the current match system. For example, the prevailing thought is that interviewing at more programs increases the likelihood of matching into a desired subspecialty. Despite these study limitations, we think our results identified important points for discussion, investigation, and potential action by orthopedic leadership.

Conclusion

The challenge of critiquing and improving the orthopedic fellowship process requires the same courageous leadership that was recommended almost a decade ago.14 In this study, we tried to elucidate the impact of the PGY-4 fellowship interview process with respect to residents and residency programs. Our results highlight that time away from residency training, financial costs associated with the fellowship interview process, and disruption of the residency program are substantial and that both residents and program directors want changes made. Leadership needs to further investigate alternatives to the current process to lessen the impact on all parties in this important process.

Over the past several decades, an increasing number of orthopedic surgery residents have pursued fellowship training.1 This inclination parallels market trends toward subspecialization.2-5 In 1984, 83% of orthopedics job announcements were for general orthopedists. Twenty-five years later, almost 70% of orthopedic opportunities were for fellowship-trained surgeons.6 Further, between 1990 and 2006, the proportion of practicing orthopedic generalists decreased from 44% to 29%.3 In 2007, the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgery (AAOS) reported 90% of graduating residents were planning to pursue fellowship training.7 Reasons for the explosion in subspecialty training are plentiful and well documented.2-5 Subspecialty positions now dominate the job market, further reinforcing incentives for residents to pursue fellowship training.

The past several decades have seen numerous changes in the orthopedic fellowship interview process. Early on, it was largely unregulated, dependent on personal and professional connections, and flush with the classic “exploding offer” (residents were given a fellowship offer that expired within hours or days). In the 1980s, as the number of fellowship applications surged, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) pushed for a more regulated process.8 To further standardize the system, the American Orthopaedic Association (AOA), the AAOS, and several other specialty organizations created the Orthopaedic Fellowship Match Program Initiative in 2008.9 Currently, all orthopedic specialties are represented in either the San Francisco Match Program or National Residency Match Program.

As the system currently stands, postgraduate year 4 (PGY-4) residents are required to interview across the country to secure postgraduate training. This process necessitates residents’ absence from their program, reducing educational opportunities and placing potential continuity-of-care constraints on the residency program. Despite the growing competitiveness for fellowship positions, the increasing number of fellowships available, the rising educational debt of residents, and the limitations of the 80-hour work week, the impact of the interview process on both residents and residency programs has received minimal attention.

We conducted a study to elucidate the impact of the fellowship interview process on residents and residency programs. We hypothesized the time and financial costs for fellowship interviews would be substantial.

Materials and Methods

We obtained institutional review board (IRB) approval for this study. Then, in April 2014, we sent 2 mixed-response questionnaires to orthopedic surgery residency directors and residents. There were 8 items on the director questionnaire and 11 on the resident questionnaire. The surveys were designed to determine the impact of the fellowship interview process on residents and residency programs with respect to finances, time, education, and continuity of care. Each survey had at least 1 free-response question, providing the opportunity to recommend changes to the interview process. The surveys were reviewed and approved by our IRB.

An email was sent to 155 orthopedic surgery program directors or their secretaries. The email asked that the director complete the director questionnaire and that the resident questionnaire be forwarded to senior-level residents, PGY-4s and PGY-5s, who had completed the fellowship interview process. Forty-five (29%) of the 155 directors responded, as did 129 (estimated 9.5%) of an estimated 1354 potential PGY-4s and PGY-5s.10

The Survey Monkey surveys could be completed over a 3-week period. All responses were anonymous. Using Survey Monkey, we aggregated individual responses into predefined clusters before performing statistical analysis. Descriptive statistics were generated with Microsoft Excel.

Results

Survey respondents represented all the orthopedic subspecialties (Table). Seventy-eight percent of residents applied to at least 13 programs (average, 19) (Figure 1). Ninety-two percent received at least 8 interview offers (average, 14). Eighty-three percent attended 8 or more interviews (average, 11). Seventy-one percent of all interviews were granted when requested, and 79% of all interviews were attended when offered.

Residents spent an average of $5875 (range, $500-$12,000+) on the fellowship interview process (Figure 2). The highest percentage of respondents, 39.5%, selected an average expense between $4000 and $6000. Forty-nine percent of residents borrowed money (from credit cards, additional loans, family members) to pay their expenses.

Average number of days away from residency programs was 11, with 86% of residents missing more than 8 days (Figure 1). About one-third of residents reported being away from their home program for almost 2 weeks during the interview season. Further, 74% of residents wanted changes made to the fellowship application process.

Thirty-seven (82%) of the 45 program directors were from academic programs, the other 8 from community-based programs. Average number of residents in programs per year was 4 (73% of the programs had 4-6 residents per year). Respondents rated the disruption caused by residents’ interview absences from 1 (least disruptive) to 10 (most disruptive) (Figure 3); the average rating was over 7 (high level of disruption). Although 9% of directors thought the process caused little or no disruption (rating, 1-3), 62% thought it extremely disruptive (rating, 8-10).

Thirty-one (69%) of the 45 directors agreed that the fellowship interview process should undergo fundamental change. Asked about possible solutions to current complaints, 60% of the directors agreed that interviews should be conducted in a central location. Of the directors who thought fundamental change was needed, 59% indicated AAOS and other specialty societies together should lead the change in the fellowship interview process.

Both residents and program directors were given the opportunity to write in suggestions regarding how to improve the fellowship interview process. Suggestions were made by 85 (66%) of the 129 residents and 24 (53%) of the 45 directors (Appendix).

Discussion

Graduating residents are entering a health care environment in which they must be financially conscious because of increasing education debt and decreasing reimbursement prospects.3 Nevertheless, an overwhelming majority of residents delay entering practice to pursue fellowship training—an estimated opportunity cost of $350,000.3 Minimal attention has been given to the potential costs of the fellowship interview process.

Our study results highlight that time away from residency training, financial costs associated with the fellowship interview process, and disruption of the residency program are substantial. On average, residents applied to 19 programs, received 14 interview offers, attended 11 interviews, were away from residency training 11 days, and spent $5875 on travel. The great majority of both residents and program directors wanted changes in the current paradigm governing the orthopedic fellowship interview process.

It is reasonable to think that the number of days residents spend away on interviews would reduce the time available for education and patient care. Although unknown, it is plausible that residents of programs outside major metropolitan centers and residents who apply to more competitive fellowships may be forced to spend even more time away from training. Outside the focus of this study are the impact that residents’ absence might have on their education and the impact of this absence on the people who do the residents’ work while they are away.

Mean fellowship expense was similar to that reported by residents pursuing a pediatric general surgery fellowship ($6974) or a plastic surgery fellowship ($6100).11,12 Unfortunately, we were unable to determine if average cost is influenced by choice of fellowship specialty or location of residency program. Regardless, fellowship cost may impose an additional financial burden on residents. According to the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC), the median salary for PGY-4 residents was $56,380 in 2013. Therefore, on average, the fellowship process consumes more than 10% of a resident’s pretax salary. For perspective, this equates to more than $40,000 for a practicing orthopedic surgeon with a median salary of $413,000.13 With an average medical student graduate debt of $175,000 and continuing decreases in reimbursement, further financial hardships to newly graduating residents cannot be understated.5,11,12

Almost 70% of program directors thought the fellowship process significantly disrupted their program. Reasons given for this disruption mainly involved residents’ time away from the program and the resulting strains placed on maintaining adequate coverage for patient care. The overall disruption score of 7.4 out of 10 was consistent with the great majority thinking that the fellowship process negatively affects their residency program. Altering the fellowship interview process may provide unintended benefits to programs and program directors.

Both program directors and residents communicated that change is needed, but there was little consensus regarding how to effect change and who should lead. This lack of consensus highlights how important it is for the various orthopedic leadership committees to actively and collectively participate in discussions about redefining the system. It has been proposed that it would be ideal for the AOA to lead the change, as the AOA consists of a representative cohort of academic orthopedists and leaders across the spectrum of all fellowship specialties.14 Given the abundant concern of both residents and program directors, we find it prudent to issue a call to arms of sorts to the AAOS and the individual orthopedic subspecialty societies to work together on a common goal that would benefit residents, programs, and subspecialties within orthopedics.

In trying to understand the challenges that residents, program directors, and programs face, as well as the inherent complexity of the current system, we incorporated respondents’ write-in comments into suggested ways of improving the fellowship interview process. These comments had broad perspectives but overall were consistent with the survey results (Appendix).

Technology

Health care is continually finding new ways to take advantage of technological advances. This is occurring with the fellowship interview schema. Numerous disciplines are using videoconferencing platforms (eg, Skype) to conduct interviews. This practice is becoming more commonplace in the business sector. In a recent survey, more than 60% of human resource managers reported conducting video interviews.15 Two independent residency programs have used video interviews with mixed success.16,17

Another technological change requested by residents is the creation and updating of fellowship web pages with standardized information. Such a service may prove useful to residents researching a program and may even lead to limiting the number of programs residents apply to, as they may be able to dial in on exactly what distinguishes one program from another before traveling for an interview. A recent study of orthopedic sports medicine fellowship programs found that most of these programs lacked pertinent information on their websites.18 Important information regarding case logs from current and former fellows; number of faculty, residents, and fellows; and schedules and facilities of interview sites are a few of the online data points that may help residents differentiate particular programs.19,20 Questions like these are often asked at interviews and site visits. Having accurate information easily available online may reduce or eliminate the need to travel to a site for such information. Standardizing information would also increase transparency among available fellowships. Although not specifically mentioned, organizational software that improves the productivity of the process may help limit the large number of programs applied to, the interviews offered and attended, the days away, and the financial costs without reducing the match rate.

Timing and Location

The issue of timing—with respect to geographical or meteorological concerns—was another recurring theme among respondents. Numerous respondents indicated that certain programs located in geographic proximity tried to minimize travel by offering interviews around the same time. This coordination potentially minimizes travel expenses and time away from the residency program by allowing residents to interview at multiple locations during a single trip per region. The sports medicine fellowship process was identified as a good example of aligning interviews based on geography. Several respondents suggested an option that also reflects the practice of nonsurgical fellowships—delaying the interview season to bypass potential weather concerns. Winter 2013–2014 saw the most flight delays or cancellations in more than a decade; about 50% of all flights scheduled between December and February were delayed or canceled.21 Beyond the additional factor of more time away or missing an interview because of the weather are safety concerns related to the weather. One resident reported having a motor vehicle accident while traveling to an interview in poor weather conditions (Appendix).

National Meetings

Each orthopedic subspecialty has numerous national meetings. Many programs offer applicants the opportunity to interview at these meetings. One respondent mentioned that the annual meeting of the Orthopaedic Trauma Association offers trauma applicants the opportunity to interview with multiple programs. It might be beneficial to endorse this practice on a larger scale to help reduce travel and time away. We recognize that visiting individual programs is an important aspect of the match process, but doing so on a targeted level may make more sense, increasing financial efficiency and reducing time away from programs.

Proposed Solution

A combined proposed solution that can be implemented without a radical overhaul or significant investments might involve moving the interview season to early spring, switching to a 2-tiered system with a centralized first round of interview screening coinciding with subspecialty national meetings or the AAOS annual meeting, and standardizing online information for all orthopedic fellowship programs. A 2-tiered interview process would allow programs and candidates to obtain exposure to a significant number of programs in the first round without incurring significant costs and then would impose a cap on the number of programs to visit. This would level the playing field between candidates with more time and money and candidates who are more constrained in their training environment and finances. A stopgap or adjunct to residents or fellowship programs unable to attend a centralized meeting would be to combine technological tools, such as Internet-based videoconferencing (Skype), before site visits by residents. After this first round of introductions and interviews, residents could then decide on a limited number of programs to formally visit, attend, and ultimately rank. This proposed system would still be able to function within the confines of the match, and it would benefit from the protections offered to residents and programs. Although capping the number of interviews attended by residents clearly can lower costs across the board, we recognize the difficulty of enforcing such a requirement. These potential changes to the system are not exhaustive, and we hope this work will serve as a springboard to further discussion.

Our study had several inherent weaknesses. Our data came from survey responses, which reflect the perspectives only of the responding residents and program directors. Unfortunately, a small number of orthopedic residents responded to this survey, so there was a potential for bias. However, we think the central themes discovered in this survey are only echoes of the concerns of the larger population of residents and program directors. Our hope in designing such a study was to bring to light some of the discrepancies in the fellowship interview process, the goal being to stimulate interest among the orthopedic leadership representing future orthopedic surgeons. More study is needed to clarify if these issues are reflective of a larger segment of residents and program directors. In addition, action may be needed to fully elucidate the intricate interworking of the fellowship process in order to maximize the interest of the orthopedic surgeons who are seeking fellowship training. Another study limitation was the potential for recall bias in the more senior PGY-5 residents, who were further from the interview process than PGY-4 respondents were. Because of the need for anonymity with the surveys, we could not link some findings (eg, program impact, cost, time away) to individual programs or different specialty fellowships. Although it appears there is a desire for a more cost-effective system, given the financial pressures on medical students and residents, the desire to match increases costs because students are likely to attend more interviews than actually needed. Our proposed solution does not take into account residents’ behavior with respect to the current match system. For example, the prevailing thought is that interviewing at more programs increases the likelihood of matching into a desired subspecialty. Despite these study limitations, we think our results identified important points for discussion, investigation, and potential action by orthopedic leadership.

Conclusion

The challenge of critiquing and improving the orthopedic fellowship process requires the same courageous leadership that was recommended almost a decade ago.14 In this study, we tried to elucidate the impact of the PGY-4 fellowship interview process with respect to residents and residency programs. Our results highlight that time away from residency training, financial costs associated with the fellowship interview process, and disruption of the residency program are substantial and that both residents and program directors want changes made. Leadership needs to further investigate alternatives to the current process to lessen the impact on all parties in this important process.

1. Simon MA. Evolution of the present status of orthopaedic surgery fellowships. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1998;80(12):1826-1829.

2. Brunworth LS, Chintalapani SR, Gray RR, Cardoso R, Owens PW. Resident selection of hand surgery fellowships: a survey of the 2011, 2012, and 2013 hand fellowship graduates. Hand. 2013;8(2):164-171.

3. Gaskill T, Cook C, Nunley J, Mather RC. The financial impact of orthopaedic fellowship training. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91(7):1814-1821.

4. Sarmiento A. Additional thoughts on orthopedic residency and fellowships. Orthopedics. 2010;33(10):712-713.

5. Griffin SM, Stoneback JW. Navigating the Orthopaedic Trauma Fellowship Match from a candidate’s perspective. J Orthop Trauma. 2011;25(suppl 3):S101-S103.

6. Morrell NT, Mercer DM, Moneim MS. Trends in the orthopedic job market and the importance of fellowship subspecialty training. Orthopedics. 2012;35(4):e555-e560.

7. Iorio R, Robb WJ, Healy WL, et al. Orthopaedic surgeon workforce and volume assessment for total hip and knee replacement in the United States: preparing for an epidemic. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90(7):1598-1605.

8. Emery SE, Guss D, Kuremsky MA, Hamlin BR, Herndon JH, Rubash HE. Resident education versus fellowship training—conflict or synergy? AOA critical issues. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94(21):e159.

9. Harner CD, Ranawat AS, Niederle M, et al. AOA symposium. Current state of fellowship hiring: is a universal match necessary? Is it possible? J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90(6):1375-1384.

10. Ranawat A, Nunley RM, Genuario JW, Sharan AD, Mehta S; Washington Health Policy Fellows. Current state of the fellowship hiring process: Are we in 1957 or 2007? AAOS Now. 2007;1(8).

11. Little DC, Yoder SM, Grikscheit TC, et al. Cost considerations and applicant characteristics for the Pediatric Surgery Match. J Pediatr Surg. 2005;40(1):69-73.

12. Claiborne JR, Crantford JC, Swett KR, David LR. The Plastic Surgery Match: predicting success and improving the process. Ann Plast Surg. 2013;70(6):698-703.

13. Kane L, Peckham C. Medscape Physician Compensation Report 2014. http://www.medscape.com/features/slideshow/compensation/2014/public/overview. Published April 15, 2014. Accessed September 26, 2015.

14. Swiontkowski MF. A simple formula for continued improvement in orthopaedic surgery postgraduate training: courageous leadership. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90(6):1175.

15. Survey: six in 10 companies conduct video job interviews [news release]. http://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/survey-six-in-10-companies-conduct-video-job-interviews-167973406.html. Published August 30, 2012. Accessed September 26, 2015.

16. Kerfoot BP, Asher KP, McCullough DL. Financial and educational costs of the residency interview process for urology applicants. Urology. 2008;71(6):990-994.

17. Edje L, Miller C, Kiefer J, Oram D. Using Skype as an alternative for residency selection interviews. J Grad Med Educ. 2013;5(3):503-505.

18. Mulcahey MK, Gosselin MM, Fadale PD. Evaluation of the content and accessibility of web sites for accredited orthopaedic sports medicine fellowships. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95(12):e85.

19. Gaeta TJ, Birkhahn RH, Lamont D, Banga N, Bove JJ. Aspects of residency programs’ web sites important to student applicants. Acad Emerg Med. 2005;12(1):89-92.

20. Mahler SA, Wagner MJ, Church A, Sokolosky M, Cline DM. Importance of residency program web sites to emergency medicine applicants. J Emerg Med. 2009;36(1):83-88.

21. Davies A. Winter’s toll: 1 million flights cancelled or delayed, costing travelers $5.3 billion. Business Insider. http://www.businessinsider.com/winter-flights-cancelled-delayed-cost-2014-3. Published March 3, 2014. Accessed September 26, 2015.

1. Simon MA. Evolution of the present status of orthopaedic surgery fellowships. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1998;80(12):1826-1829.

2. Brunworth LS, Chintalapani SR, Gray RR, Cardoso R, Owens PW. Resident selection of hand surgery fellowships: a survey of the 2011, 2012, and 2013 hand fellowship graduates. Hand. 2013;8(2):164-171.

3. Gaskill T, Cook C, Nunley J, Mather RC. The financial impact of orthopaedic fellowship training. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91(7):1814-1821.

4. Sarmiento A. Additional thoughts on orthopedic residency and fellowships. Orthopedics. 2010;33(10):712-713.

5. Griffin SM, Stoneback JW. Navigating the Orthopaedic Trauma Fellowship Match from a candidate’s perspective. J Orthop Trauma. 2011;25(suppl 3):S101-S103.

6. Morrell NT, Mercer DM, Moneim MS. Trends in the orthopedic job market and the importance of fellowship subspecialty training. Orthopedics. 2012;35(4):e555-e560.

7. Iorio R, Robb WJ, Healy WL, et al. Orthopaedic surgeon workforce and volume assessment for total hip and knee replacement in the United States: preparing for an epidemic. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90(7):1598-1605.

8. Emery SE, Guss D, Kuremsky MA, Hamlin BR, Herndon JH, Rubash HE. Resident education versus fellowship training—conflict or synergy? AOA critical issues. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94(21):e159.

9. Harner CD, Ranawat AS, Niederle M, et al. AOA symposium. Current state of fellowship hiring: is a universal match necessary? Is it possible? J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90(6):1375-1384.

10. Ranawat A, Nunley RM, Genuario JW, Sharan AD, Mehta S; Washington Health Policy Fellows. Current state of the fellowship hiring process: Are we in 1957 or 2007? AAOS Now. 2007;1(8).

11. Little DC, Yoder SM, Grikscheit TC, et al. Cost considerations and applicant characteristics for the Pediatric Surgery Match. J Pediatr Surg. 2005;40(1):69-73.

12. Claiborne JR, Crantford JC, Swett KR, David LR. The Plastic Surgery Match: predicting success and improving the process. Ann Plast Surg. 2013;70(6):698-703.

13. Kane L, Peckham C. Medscape Physician Compensation Report 2014. http://www.medscape.com/features/slideshow/compensation/2014/public/overview. Published April 15, 2014. Accessed September 26, 2015.

14. Swiontkowski MF. A simple formula for continued improvement in orthopaedic surgery postgraduate training: courageous leadership. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90(6):1175.

15. Survey: six in 10 companies conduct video job interviews [news release]. http://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/survey-six-in-10-companies-conduct-video-job-interviews-167973406.html. Published August 30, 2012. Accessed September 26, 2015.

16. Kerfoot BP, Asher KP, McCullough DL. Financial and educational costs of the residency interview process for urology applicants. Urology. 2008;71(6):990-994.

17. Edje L, Miller C, Kiefer J, Oram D. Using Skype as an alternative for residency selection interviews. J Grad Med Educ. 2013;5(3):503-505.

18. Mulcahey MK, Gosselin MM, Fadale PD. Evaluation of the content and accessibility of web sites for accredited orthopaedic sports medicine fellowships. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95(12):e85.

19. Gaeta TJ, Birkhahn RH, Lamont D, Banga N, Bove JJ. Aspects of residency programs’ web sites important to student applicants. Acad Emerg Med. 2005;12(1):89-92.

20. Mahler SA, Wagner MJ, Church A, Sokolosky M, Cline DM. Importance of residency program web sites to emergency medicine applicants. J Emerg Med. 2009;36(1):83-88.

21. Davies A. Winter’s toll: 1 million flights cancelled or delayed, costing travelers $5.3 billion. Business Insider. http://www.businessinsider.com/winter-flights-cancelled-delayed-cost-2014-3. Published March 3, 2014. Accessed September 26, 2015.