User login

Mycosis Fungoides Manifesting as a Morbilliform Eruption Mimicking a Viral Exanthem

To the Editor:

Mycosis fungoides (MF) is the most common type of primary cutaneous lymphoma, occurring in approximately 4 of 1 million individuals per year in the United States.1 It classically occurs in patch, plaque, and tumor stages with lesions preferentially occurring on regions of the body spared from sun exposure2; however, MF is known to have variable presentations and has been reported to imitate at least 25 other dermatoses.3 This case describes MF as a morbilliform eruption mimicking a viral exanthem.

A 30-year-old man with a 12-year history of nodular sclerosing Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) presented with a widespread rash of 2 weeks’ duration. At the time of diagnosis of HL, the patient had several slightly enlarged, hyperdense, bilateral inguinal lymph nodes seen on positron emission tomography–computed tomography. He achieved complete remission 11 years prior after 6 cycles of ABVD (doxorubicin-bleomycin-vinblastine-dacarbazine) chemotherapy. He initially presented to us prior to starting chemotherapy for evaluation of what he described as eczema on the bilateral arms and legs that had been present for 10 years. Findings from a skin biopsy of an erythematous scaling patch on the left lateral thigh were consistent with MF. One year later, new lesions on the left lateral thigh were clinically and histologically consistent with lymphomatoid papulosis (LyP).

At the current presentation, the patient denied any changes in medications, which consisted of topical clobetasol, triamcinolone, and mupirocin; however, he reported that his young child had recently been diagnosed with bronchitis and impetigo. Physical examination revealed pink-orange macules and papules on the anterior and posterior trunk, medial upper arms, and bilateral legs involving 18% of the body surface area. A complete blood cell count showed no leukocytosis or left shift. A respiratory viral panel was positive for human metapneumovirus. Two weeks later, the patient noted improvement of the rash with use of topical triamcinolone.

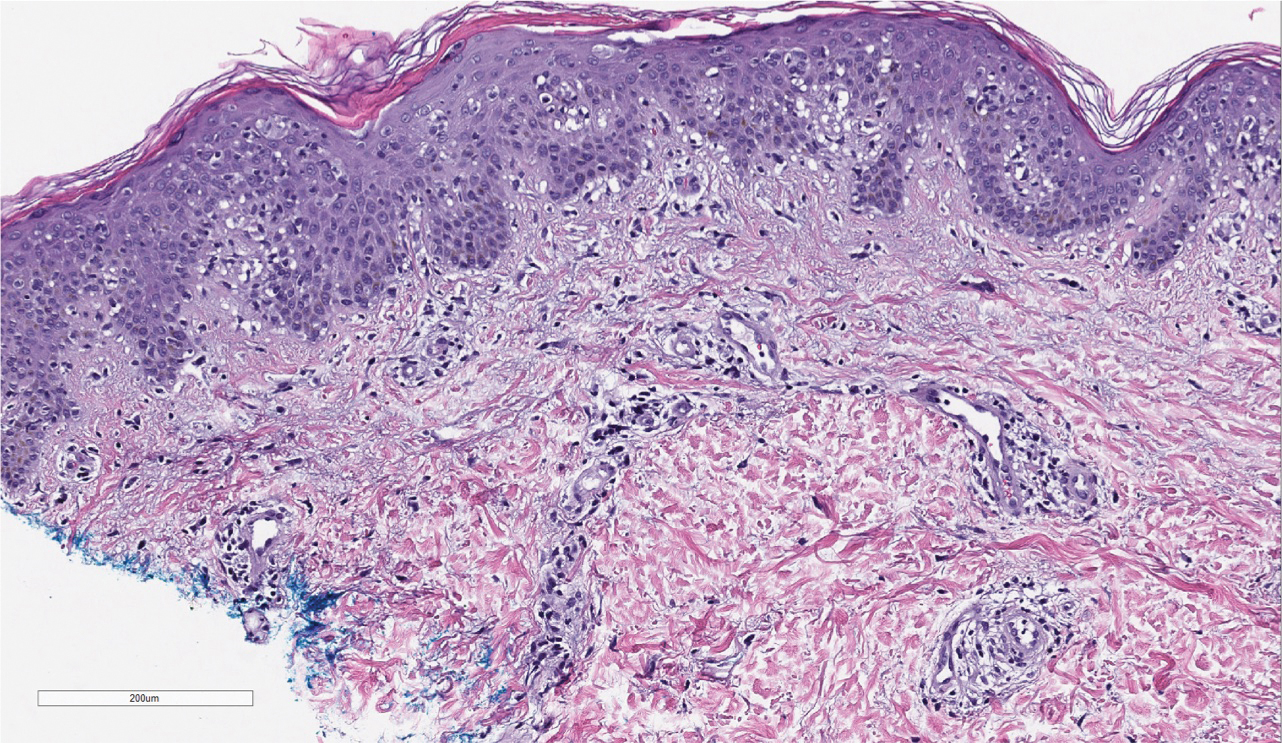

Four months later, the rash still had not completely resolved and now involved 50% of the body surface area. A punch biopsy of the left lower abdomen demonstrated an atypical lymphoid infiltrate with focal epidermotropism and predominance of CD4 over CD8 cells (approximately 4:1 ratio), and CD30 labeled rare cells. Polymerase chain reaction analysis of the biopsy revealed monoclonal T-cell receptor gamma chain gene rearrangement. Taken together, the findings were consistent with MF. The patient started narrowband UVB phototherapy and completed a total of 25 treatments, reaching a maximum 4-minute dose, with minimal improvement.

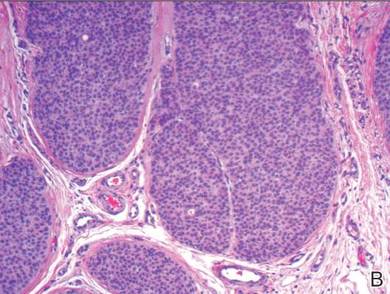

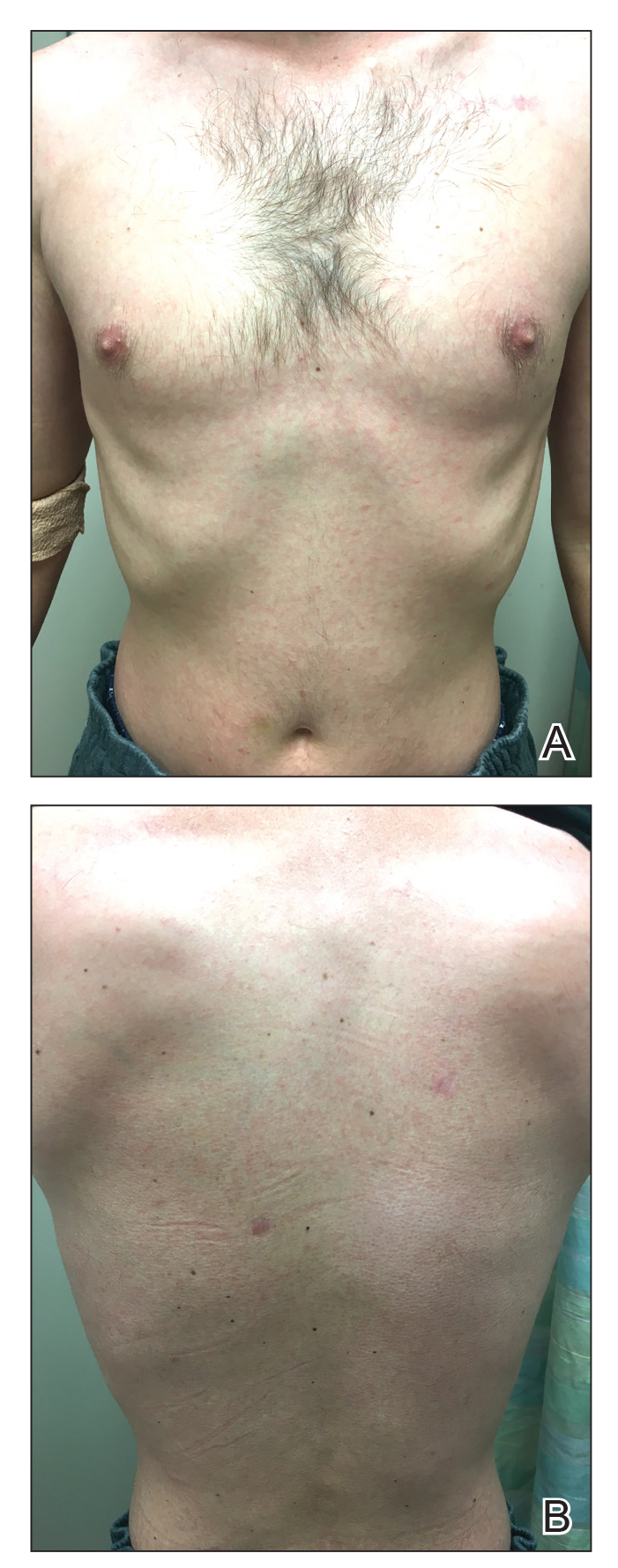

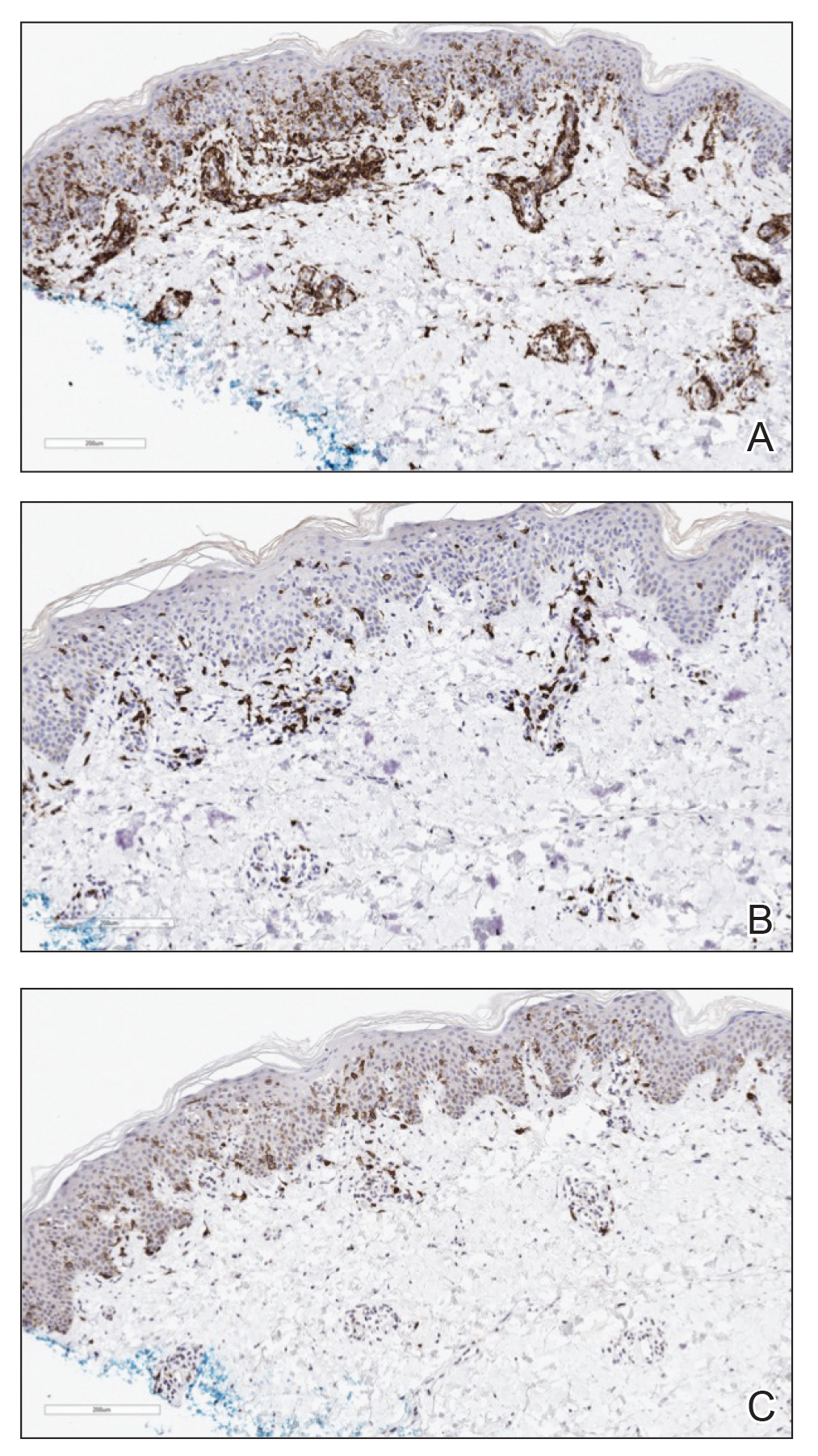

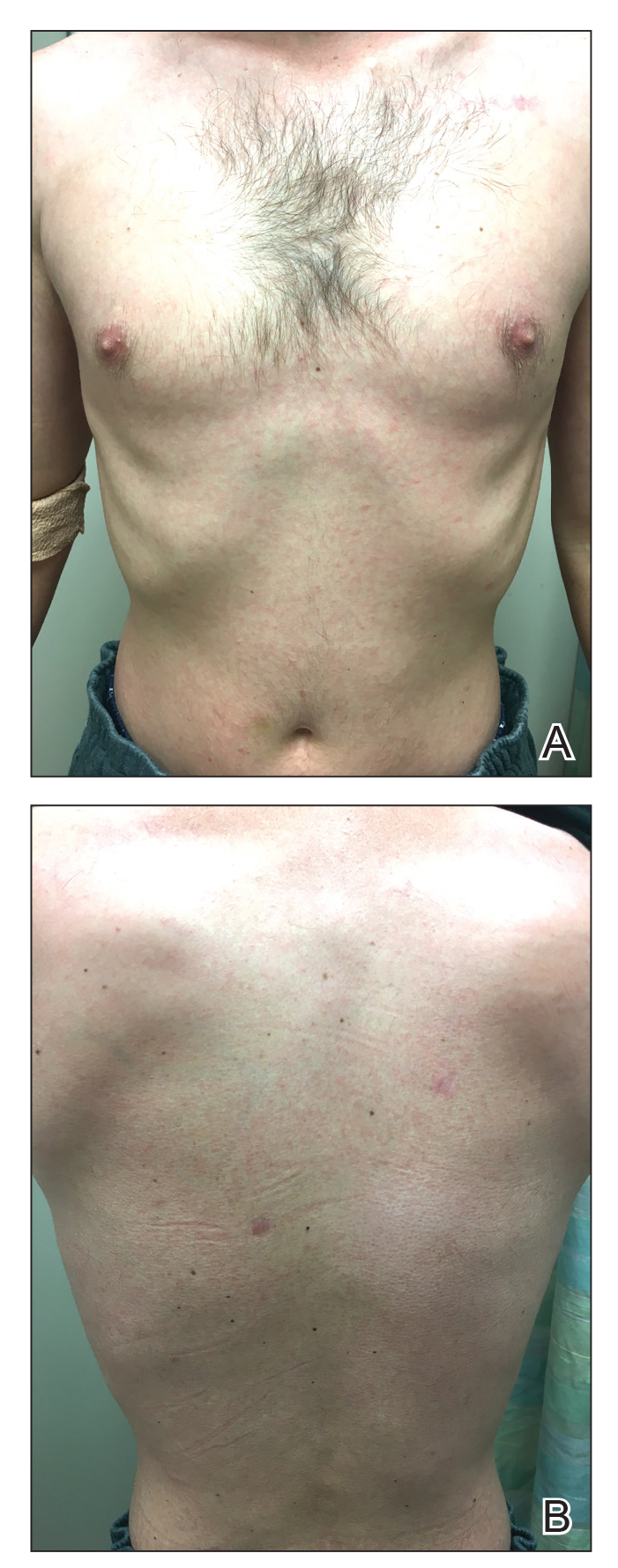

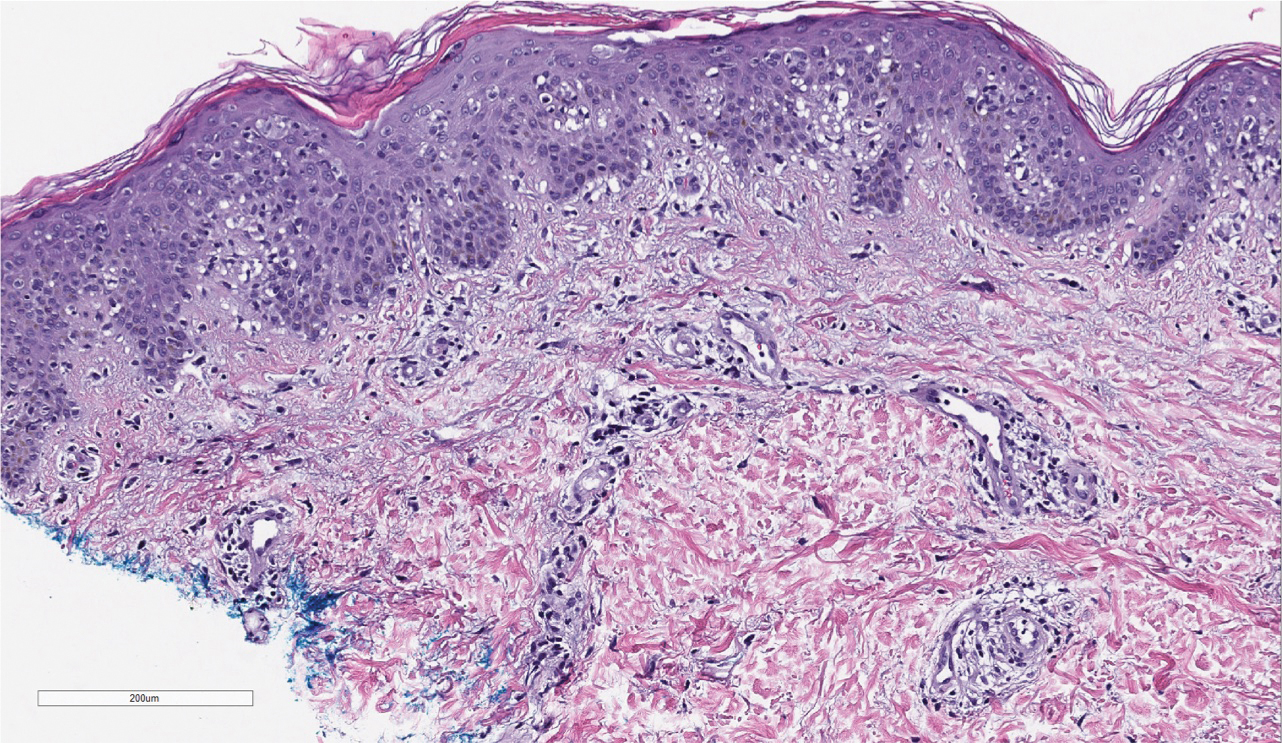

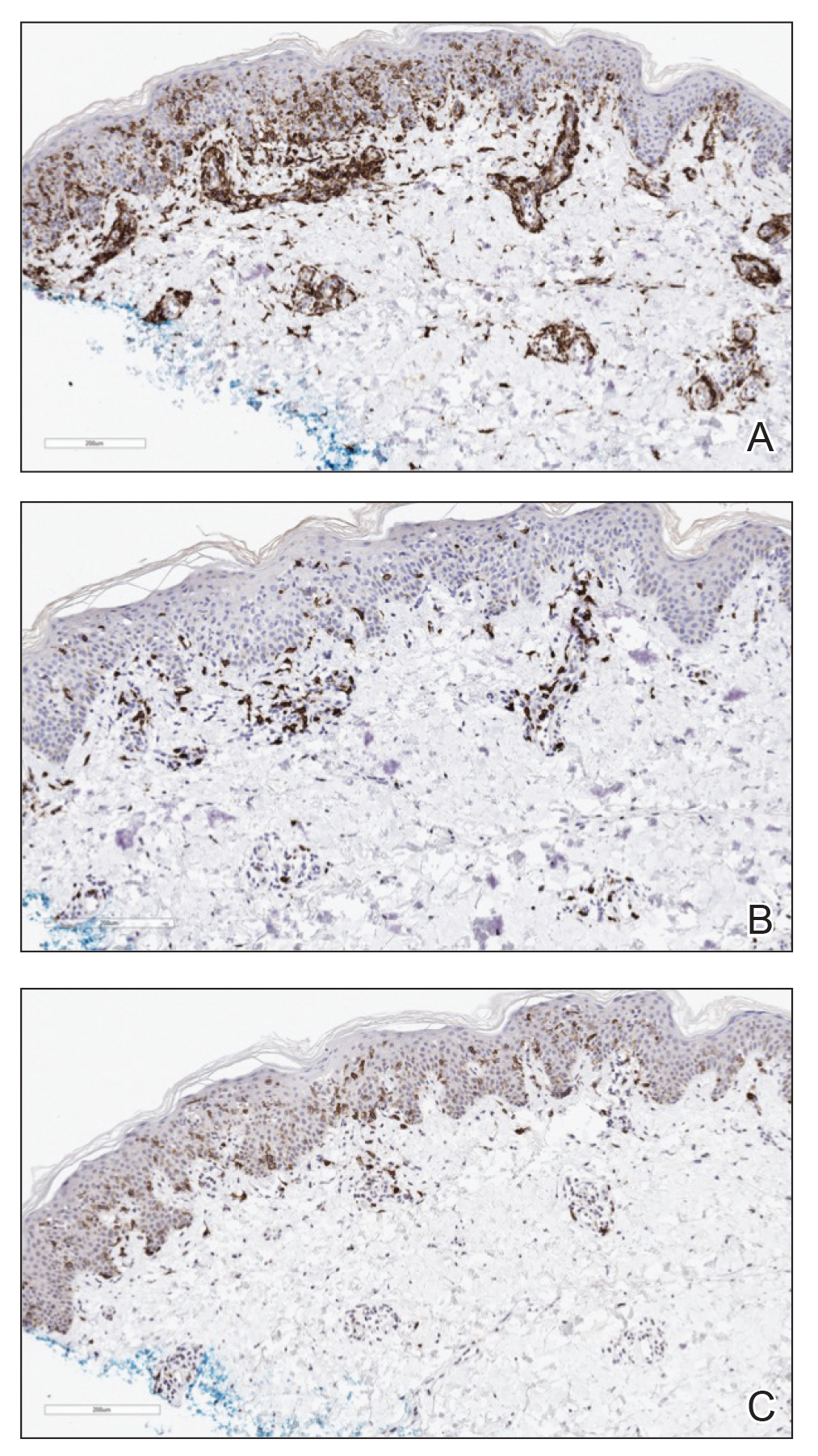

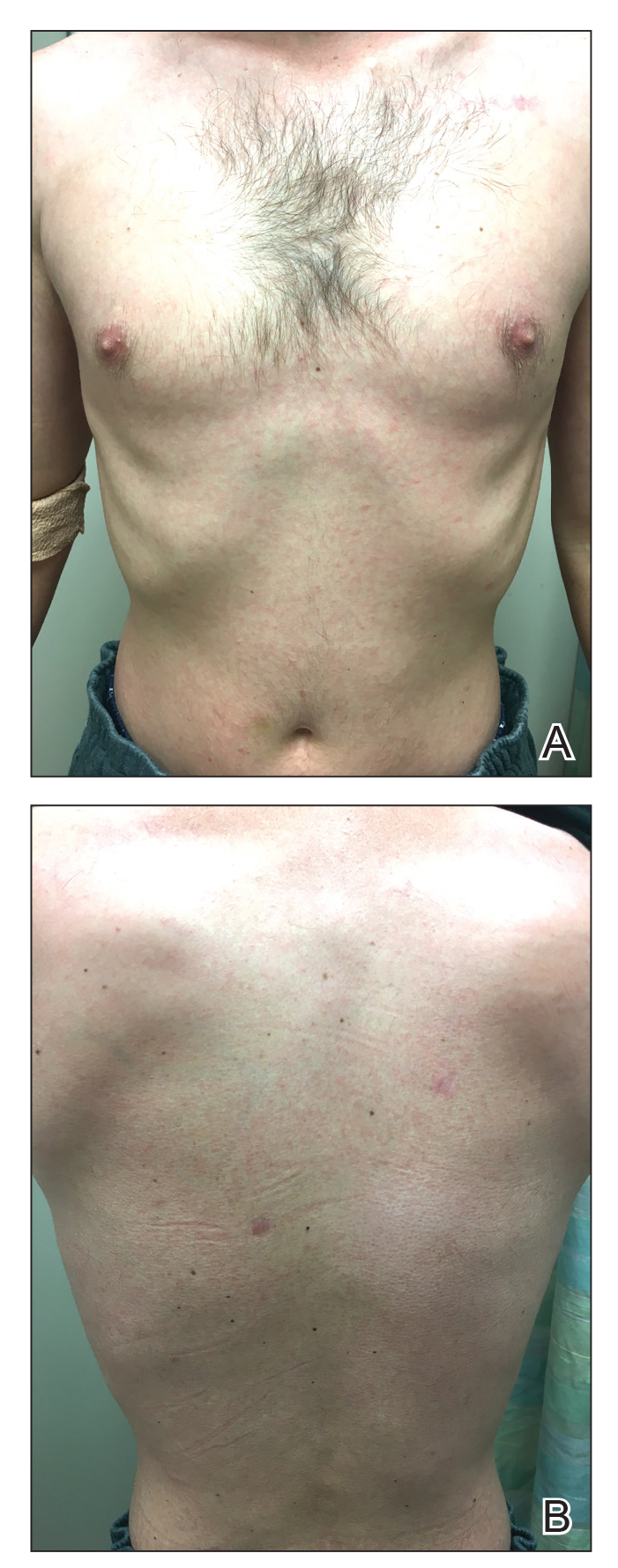

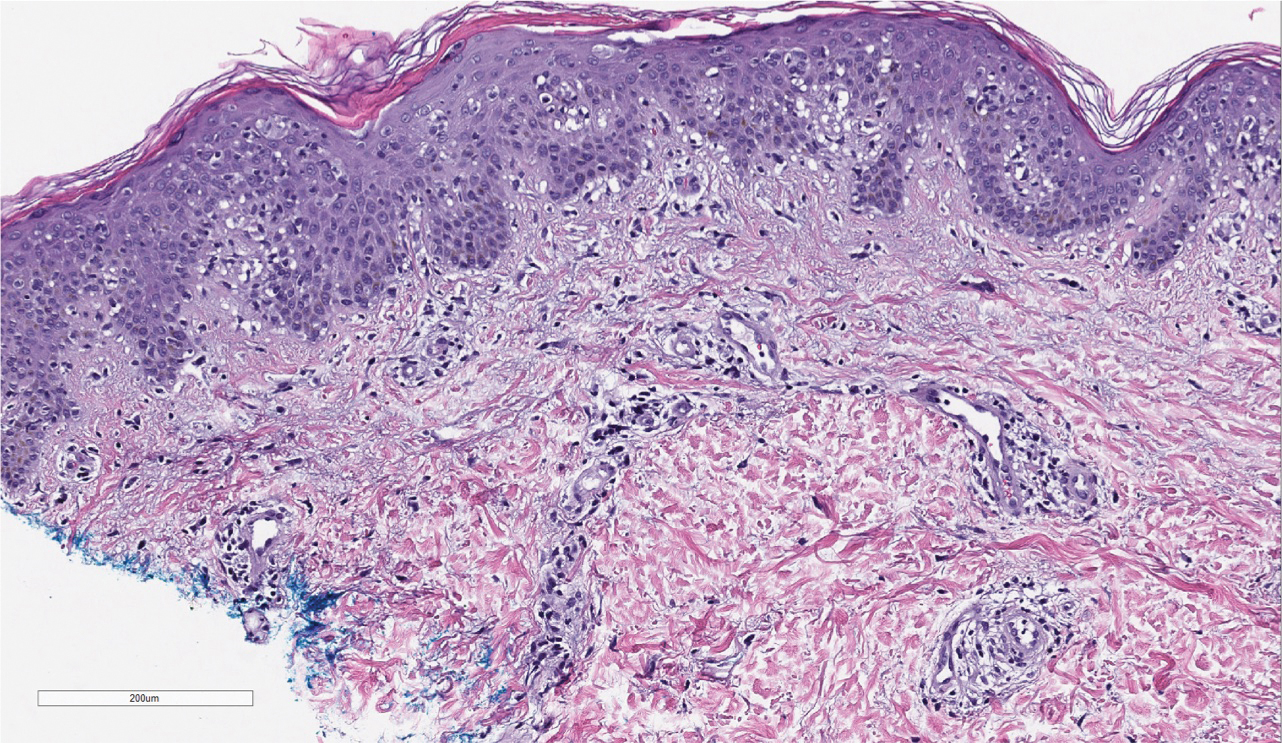

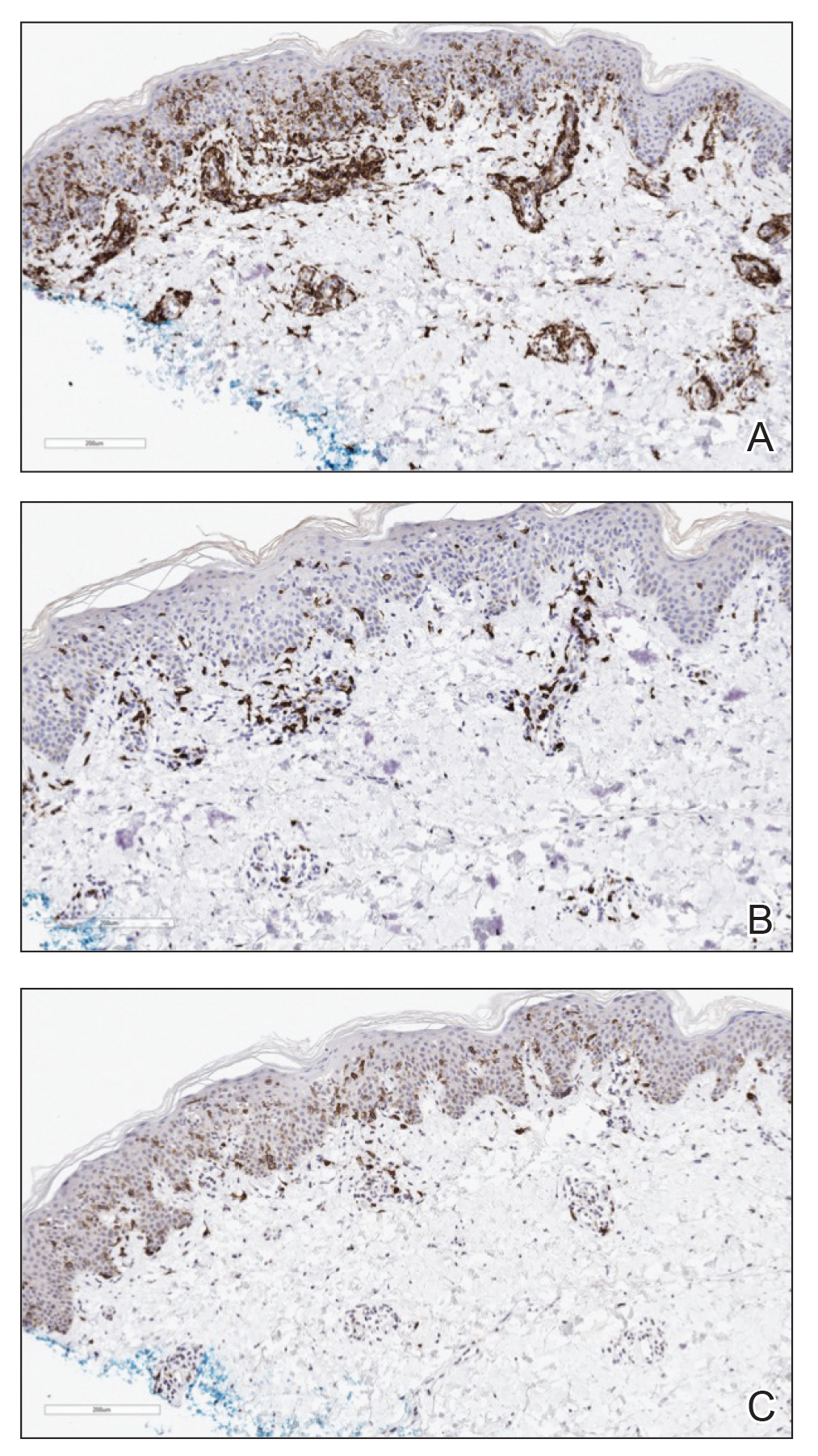

Three months later, the patient had 90% body surface area involvement and started treatment with intramuscular interferon alfa-2b at 1 million units 3 times weekly. He noticed improvement within the first week of treatment and reported that his skin was clear until 5 months later when he woke up one morning with a morbilliform eruption on the anterior trunk, thighs, and upper arms (Figure 1). Biopsy from the right thigh showed an infiltrate of CD3+ lymphocytes with a predominance of CD4 over CD8 cells (approximately 6:1 ratio), both in the dermis and epidermis (Figure 2). CD30 highlighted approximately 10% of cells (Figure 3). Findings again were consistent with MF. Flow cytometry was negative for peripheral blood involvement.

Three months later, the patient reported enlargement of several left inguinal nodes. Fine needle aspiration of 1 node demonstrated an atypical lymphoid proliferation consistent with MF. Positron emission tomography–computed tomography showed several mildly enlarged inguinal lymph nodes, which were unchanged from the initial diagnosis of HL. There were no hypermetabolic lesions. One month later, the patient started extracorporeal electrophoresis in addition to interferon alfa-2b with notable improvement of the rash. The rash later recurred after completion of these treatments and continues to have a waxing and waning course. It is currently managed with triamcinolone cream only.

At the time of the initial diagnosis of MF, the patient’s lesions appeared as eczematous patches on the face, abdomen, buttocks, and legs. Based on the history of a sick child at home, viral panel positive for human metapneumovirus, and clinical appearance, a viral exanthem was considered to be a likely explanation for the patient’s new-onset morbilliform eruption rash occurring 12 years later. A drug reaction also was considered in the differential based on the appearance of the rash; however, it was deemed less likely because the patient reported no changes in his medications at the time of rash onset. Persistence of the eruption for many months was less consistent with a reactive condition. A biopsy demonstrated the rash to be histologically consistent with MF. This patient was a rare case of MF manifesting as a morbilliform eruption mimicking a viral exanthem.

Various inflammatory conditions, including drug eruptions and lichen sclerosus et atrophicus, may mimic MF, not only based on their histophenotypic findings but also occasionally clonal proliferation by molecular study.4,5 In our patient, one consideration was the possibility of a viral infection mimicking MF; however, biopsies showed both definite histophenotypic features of MF and clonality. More importantly, subsequent biopsy also revealed similar findings by morphology, immunohistochemical study, and T-cell gene rearrangement study, confirming the diagnosis of MF.

Another interesting feature of our case was the occurrence of HL, LyP, and MF in the same patient. Lymphomatoid papulosis is a chronic condition characterized by self-healing lesions and histologic features suggestive of malignancy that lies within a spectrum of primary cutaneous CD30+ lymphoproliferative disorders. There is a known association between LyP and an increased incidence of lymphomas, including MF and HL.1 In a 2016 study, lymphomas occurred in 52% of patients with LyP (N=180), with MF being the most frequently associated lymphoma.6 Notably, biopsies consistent with both HL and MF, respectively, in our patient were positive for the CD30 marker. Patients with HL also are at increased risk for developing other malignancies, with the risk of leukemias and non-HLs greater than that of solid tumors.5 There have been multiple reported cases of HL and MF occurring in the same patient and at least one prior reported case of LyP, HL, and MF occurring in the same patient.6,7

This case highlights the myriad presentations of MF and describes an unusual case of MF manifesting as a morbilliform eruption mimicking a viral exanthem.

- de la Garza Bravo MM, Patel KP, Loghavi S, et al. Shared clonality in distinctive lesions of lymphomatoid papulosis and mycosis fungoides occurring in the same patients suggests a common origin [published online December 31, 2014]. Hum Pathol. 2015;46:558-569.

- Howard MS, Smoller BR. Mycosis fungoides: classic disease and variant presentations. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2000;19:91-99.

- Zackheim HS, Mccalmont TH. Mycosis fungoides: the great imitator. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:914-918.

- Suchak R, Verdolini R, Robson A, et al. Extragenital lichen sclerosus et atrophicus mimicking cutaneous T-cell lymphoma: report of a case. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:982-986.

- Sarantopoulos GP, Palla B, Said J, et al. Mimics of cutaneous lymphoma: report of the 2011 Society for Hematopathology/European Association for Haematopathology workshop. Am J Clin Pathol. 2013;139:536-551.

- Wieser I, Oh CW, Talpur R, et al. Lymphomatoid papulosis: treatment response and associated lymphomas in a study of 180 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:59-67.

- Sont JK, van Stiphout WA, Noordijk EM, et al. Increased risk of second cancers in managing Hodgkins disease: the 20-year Leiden experience. Ann Hematol. 1992;65:213-218.

To the Editor:

Mycosis fungoides (MF) is the most common type of primary cutaneous lymphoma, occurring in approximately 4 of 1 million individuals per year in the United States.1 It classically occurs in patch, plaque, and tumor stages with lesions preferentially occurring on regions of the body spared from sun exposure2; however, MF is known to have variable presentations and has been reported to imitate at least 25 other dermatoses.3 This case describes MF as a morbilliform eruption mimicking a viral exanthem.

A 30-year-old man with a 12-year history of nodular sclerosing Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) presented with a widespread rash of 2 weeks’ duration. At the time of diagnosis of HL, the patient had several slightly enlarged, hyperdense, bilateral inguinal lymph nodes seen on positron emission tomography–computed tomography. He achieved complete remission 11 years prior after 6 cycles of ABVD (doxorubicin-bleomycin-vinblastine-dacarbazine) chemotherapy. He initially presented to us prior to starting chemotherapy for evaluation of what he described as eczema on the bilateral arms and legs that had been present for 10 years. Findings from a skin biopsy of an erythematous scaling patch on the left lateral thigh were consistent with MF. One year later, new lesions on the left lateral thigh were clinically and histologically consistent with lymphomatoid papulosis (LyP).

At the current presentation, the patient denied any changes in medications, which consisted of topical clobetasol, triamcinolone, and mupirocin; however, he reported that his young child had recently been diagnosed with bronchitis and impetigo. Physical examination revealed pink-orange macules and papules on the anterior and posterior trunk, medial upper arms, and bilateral legs involving 18% of the body surface area. A complete blood cell count showed no leukocytosis or left shift. A respiratory viral panel was positive for human metapneumovirus. Two weeks later, the patient noted improvement of the rash with use of topical triamcinolone.

Four months later, the rash still had not completely resolved and now involved 50% of the body surface area. A punch biopsy of the left lower abdomen demonstrated an atypical lymphoid infiltrate with focal epidermotropism and predominance of CD4 over CD8 cells (approximately 4:1 ratio), and CD30 labeled rare cells. Polymerase chain reaction analysis of the biopsy revealed monoclonal T-cell receptor gamma chain gene rearrangement. Taken together, the findings were consistent with MF. The patient started narrowband UVB phototherapy and completed a total of 25 treatments, reaching a maximum 4-minute dose, with minimal improvement.

Three months later, the patient had 90% body surface area involvement and started treatment with intramuscular interferon alfa-2b at 1 million units 3 times weekly. He noticed improvement within the first week of treatment and reported that his skin was clear until 5 months later when he woke up one morning with a morbilliform eruption on the anterior trunk, thighs, and upper arms (Figure 1). Biopsy from the right thigh showed an infiltrate of CD3+ lymphocytes with a predominance of CD4 over CD8 cells (approximately 6:1 ratio), both in the dermis and epidermis (Figure 2). CD30 highlighted approximately 10% of cells (Figure 3). Findings again were consistent with MF. Flow cytometry was negative for peripheral blood involvement.

Three months later, the patient reported enlargement of several left inguinal nodes. Fine needle aspiration of 1 node demonstrated an atypical lymphoid proliferation consistent with MF. Positron emission tomography–computed tomography showed several mildly enlarged inguinal lymph nodes, which were unchanged from the initial diagnosis of HL. There were no hypermetabolic lesions. One month later, the patient started extracorporeal electrophoresis in addition to interferon alfa-2b with notable improvement of the rash. The rash later recurred after completion of these treatments and continues to have a waxing and waning course. It is currently managed with triamcinolone cream only.

At the time of the initial diagnosis of MF, the patient’s lesions appeared as eczematous patches on the face, abdomen, buttocks, and legs. Based on the history of a sick child at home, viral panel positive for human metapneumovirus, and clinical appearance, a viral exanthem was considered to be a likely explanation for the patient’s new-onset morbilliform eruption rash occurring 12 years later. A drug reaction also was considered in the differential based on the appearance of the rash; however, it was deemed less likely because the patient reported no changes in his medications at the time of rash onset. Persistence of the eruption for many months was less consistent with a reactive condition. A biopsy demonstrated the rash to be histologically consistent with MF. This patient was a rare case of MF manifesting as a morbilliform eruption mimicking a viral exanthem.

Various inflammatory conditions, including drug eruptions and lichen sclerosus et atrophicus, may mimic MF, not only based on their histophenotypic findings but also occasionally clonal proliferation by molecular study.4,5 In our patient, one consideration was the possibility of a viral infection mimicking MF; however, biopsies showed both definite histophenotypic features of MF and clonality. More importantly, subsequent biopsy also revealed similar findings by morphology, immunohistochemical study, and T-cell gene rearrangement study, confirming the diagnosis of MF.

Another interesting feature of our case was the occurrence of HL, LyP, and MF in the same patient. Lymphomatoid papulosis is a chronic condition characterized by self-healing lesions and histologic features suggestive of malignancy that lies within a spectrum of primary cutaneous CD30+ lymphoproliferative disorders. There is a known association between LyP and an increased incidence of lymphomas, including MF and HL.1 In a 2016 study, lymphomas occurred in 52% of patients with LyP (N=180), with MF being the most frequently associated lymphoma.6 Notably, biopsies consistent with both HL and MF, respectively, in our patient were positive for the CD30 marker. Patients with HL also are at increased risk for developing other malignancies, with the risk of leukemias and non-HLs greater than that of solid tumors.5 There have been multiple reported cases of HL and MF occurring in the same patient and at least one prior reported case of LyP, HL, and MF occurring in the same patient.6,7

This case highlights the myriad presentations of MF and describes an unusual case of MF manifesting as a morbilliform eruption mimicking a viral exanthem.

To the Editor:

Mycosis fungoides (MF) is the most common type of primary cutaneous lymphoma, occurring in approximately 4 of 1 million individuals per year in the United States.1 It classically occurs in patch, plaque, and tumor stages with lesions preferentially occurring on regions of the body spared from sun exposure2; however, MF is known to have variable presentations and has been reported to imitate at least 25 other dermatoses.3 This case describes MF as a morbilliform eruption mimicking a viral exanthem.

A 30-year-old man with a 12-year history of nodular sclerosing Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) presented with a widespread rash of 2 weeks’ duration. At the time of diagnosis of HL, the patient had several slightly enlarged, hyperdense, bilateral inguinal lymph nodes seen on positron emission tomography–computed tomography. He achieved complete remission 11 years prior after 6 cycles of ABVD (doxorubicin-bleomycin-vinblastine-dacarbazine) chemotherapy. He initially presented to us prior to starting chemotherapy for evaluation of what he described as eczema on the bilateral arms and legs that had been present for 10 years. Findings from a skin biopsy of an erythematous scaling patch on the left lateral thigh were consistent with MF. One year later, new lesions on the left lateral thigh were clinically and histologically consistent with lymphomatoid papulosis (LyP).

At the current presentation, the patient denied any changes in medications, which consisted of topical clobetasol, triamcinolone, and mupirocin; however, he reported that his young child had recently been diagnosed with bronchitis and impetigo. Physical examination revealed pink-orange macules and papules on the anterior and posterior trunk, medial upper arms, and bilateral legs involving 18% of the body surface area. A complete blood cell count showed no leukocytosis or left shift. A respiratory viral panel was positive for human metapneumovirus. Two weeks later, the patient noted improvement of the rash with use of topical triamcinolone.

Four months later, the rash still had not completely resolved and now involved 50% of the body surface area. A punch biopsy of the left lower abdomen demonstrated an atypical lymphoid infiltrate with focal epidermotropism and predominance of CD4 over CD8 cells (approximately 4:1 ratio), and CD30 labeled rare cells. Polymerase chain reaction analysis of the biopsy revealed monoclonal T-cell receptor gamma chain gene rearrangement. Taken together, the findings were consistent with MF. The patient started narrowband UVB phototherapy and completed a total of 25 treatments, reaching a maximum 4-minute dose, with minimal improvement.

Three months later, the patient had 90% body surface area involvement and started treatment with intramuscular interferon alfa-2b at 1 million units 3 times weekly. He noticed improvement within the first week of treatment and reported that his skin was clear until 5 months later when he woke up one morning with a morbilliform eruption on the anterior trunk, thighs, and upper arms (Figure 1). Biopsy from the right thigh showed an infiltrate of CD3+ lymphocytes with a predominance of CD4 over CD8 cells (approximately 6:1 ratio), both in the dermis and epidermis (Figure 2). CD30 highlighted approximately 10% of cells (Figure 3). Findings again were consistent with MF. Flow cytometry was negative for peripheral blood involvement.

Three months later, the patient reported enlargement of several left inguinal nodes. Fine needle aspiration of 1 node demonstrated an atypical lymphoid proliferation consistent with MF. Positron emission tomography–computed tomography showed several mildly enlarged inguinal lymph nodes, which were unchanged from the initial diagnosis of HL. There were no hypermetabolic lesions. One month later, the patient started extracorporeal electrophoresis in addition to interferon alfa-2b with notable improvement of the rash. The rash later recurred after completion of these treatments and continues to have a waxing and waning course. It is currently managed with triamcinolone cream only.

At the time of the initial diagnosis of MF, the patient’s lesions appeared as eczematous patches on the face, abdomen, buttocks, and legs. Based on the history of a sick child at home, viral panel positive for human metapneumovirus, and clinical appearance, a viral exanthem was considered to be a likely explanation for the patient’s new-onset morbilliform eruption rash occurring 12 years later. A drug reaction also was considered in the differential based on the appearance of the rash; however, it was deemed less likely because the patient reported no changes in his medications at the time of rash onset. Persistence of the eruption for many months was less consistent with a reactive condition. A biopsy demonstrated the rash to be histologically consistent with MF. This patient was a rare case of MF manifesting as a morbilliform eruption mimicking a viral exanthem.

Various inflammatory conditions, including drug eruptions and lichen sclerosus et atrophicus, may mimic MF, not only based on their histophenotypic findings but also occasionally clonal proliferation by molecular study.4,5 In our patient, one consideration was the possibility of a viral infection mimicking MF; however, biopsies showed both definite histophenotypic features of MF and clonality. More importantly, subsequent biopsy also revealed similar findings by morphology, immunohistochemical study, and T-cell gene rearrangement study, confirming the diagnosis of MF.

Another interesting feature of our case was the occurrence of HL, LyP, and MF in the same patient. Lymphomatoid papulosis is a chronic condition characterized by self-healing lesions and histologic features suggestive of malignancy that lies within a spectrum of primary cutaneous CD30+ lymphoproliferative disorders. There is a known association between LyP and an increased incidence of lymphomas, including MF and HL.1 In a 2016 study, lymphomas occurred in 52% of patients with LyP (N=180), with MF being the most frequently associated lymphoma.6 Notably, biopsies consistent with both HL and MF, respectively, in our patient were positive for the CD30 marker. Patients with HL also are at increased risk for developing other malignancies, with the risk of leukemias and non-HLs greater than that of solid tumors.5 There have been multiple reported cases of HL and MF occurring in the same patient and at least one prior reported case of LyP, HL, and MF occurring in the same patient.6,7

This case highlights the myriad presentations of MF and describes an unusual case of MF manifesting as a morbilliform eruption mimicking a viral exanthem.

- de la Garza Bravo MM, Patel KP, Loghavi S, et al. Shared clonality in distinctive lesions of lymphomatoid papulosis and mycosis fungoides occurring in the same patients suggests a common origin [published online December 31, 2014]. Hum Pathol. 2015;46:558-569.

- Howard MS, Smoller BR. Mycosis fungoides: classic disease and variant presentations. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2000;19:91-99.

- Zackheim HS, Mccalmont TH. Mycosis fungoides: the great imitator. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:914-918.

- Suchak R, Verdolini R, Robson A, et al. Extragenital lichen sclerosus et atrophicus mimicking cutaneous T-cell lymphoma: report of a case. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:982-986.

- Sarantopoulos GP, Palla B, Said J, et al. Mimics of cutaneous lymphoma: report of the 2011 Society for Hematopathology/European Association for Haematopathology workshop. Am J Clin Pathol. 2013;139:536-551.

- Wieser I, Oh CW, Talpur R, et al. Lymphomatoid papulosis: treatment response and associated lymphomas in a study of 180 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:59-67.

- Sont JK, van Stiphout WA, Noordijk EM, et al. Increased risk of second cancers in managing Hodgkins disease: the 20-year Leiden experience. Ann Hematol. 1992;65:213-218.

- de la Garza Bravo MM, Patel KP, Loghavi S, et al. Shared clonality in distinctive lesions of lymphomatoid papulosis and mycosis fungoides occurring in the same patients suggests a common origin [published online December 31, 2014]. Hum Pathol. 2015;46:558-569.

- Howard MS, Smoller BR. Mycosis fungoides: classic disease and variant presentations. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2000;19:91-99.

- Zackheim HS, Mccalmont TH. Mycosis fungoides: the great imitator. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:914-918.

- Suchak R, Verdolini R, Robson A, et al. Extragenital lichen sclerosus et atrophicus mimicking cutaneous T-cell lymphoma: report of a case. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:982-986.

- Sarantopoulos GP, Palla B, Said J, et al. Mimics of cutaneous lymphoma: report of the 2011 Society for Hematopathology/European Association for Haematopathology workshop. Am J Clin Pathol. 2013;139:536-551.

- Wieser I, Oh CW, Talpur R, et al. Lymphomatoid papulosis: treatment response and associated lymphomas in a study of 180 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:59-67.

- Sont JK, van Stiphout WA, Noordijk EM, et al. Increased risk of second cancers in managing Hodgkins disease: the 20-year Leiden experience. Ann Hematol. 1992;65:213-218.

Practice Points

- Mycosis fungoides classically occurs in patch, plaque, and tumor stages, with lesions preferentially occurring on regions of the body spared from sun exposure; however, the condition may present atypically, mimicking a variety of other conditions.

- Lymphomatoid papulosis exists within a spectrum of primary cutaneous CD30+ lymphoproliferative disorders and is associated with increased incidence of lymphomas.

Sessile Pink Plaque on the Lower Back

The Diagnosis: Eccrine Poroma

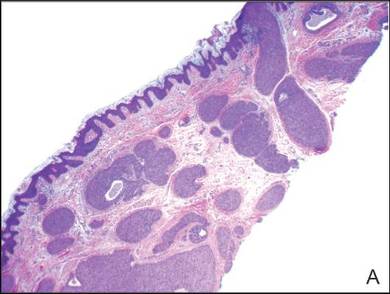

A shave biopsy of the lesion was performed for definitive diagnosis and demonstrated a well-circumscribed tumor with cords and broad columns composed of uniform basaloid cells extending into the dermis and in areas connecting to the overlying epidermis (Figure). There also were small ducts and cysts admixed in the tumor columns that were embedded in a tumor stroma rich in blood vessels. A diagnosis of eccrine poroma was made based on these characteristic histologic features.

|

Biopsy revealed a basaloid tumor originating from the epidermis and extending into the dermis (A)(H&E, original magnification ×4). On higher magnification, ducts were evident amongst the tumor cells and a vascular rich stroma was revealed (B)(H&E, original magnification ×10). |

First described by Pinkus et al1 in 1956, eccrine poroma is a benign neoplasm of cells from the intraepidermal ductal portion of the eccrine sweat gland. Eccrine poroma (along with hidroacanthoma simplex, dermal duct tumor, and poroid hidradenoma) is one of the poroid neoplasms, which account for approximately 10% of all primary sweat gland tumors.2 Eccrine poroma usually is seen in patients over 40 years of age without any predilection for race or sex.

Characteristically, eccrine poromas clinically manifest as solitary, firm, sharply demarcated papules or nodules that may be sessile or pedunculated and rarely exceed 2 cm in diameter. This entity classically presents on acral, non–hair-bearing areas (eg, palms and soles). Eccrine poromas have a wide range of clinical appearances that can lead to broad differential diagnoses3 and have been described as flesh-colored,3 pink to red,4 purple,5 and pigmented3,4 papules or nodules depending on features such as blood vessel proliferation and pigment deposition.

Eccrine poromas also have been reported on hair-bearing areas of the body, including the head,3 neck,3,6 chest,4,6 hip,7 and pubic area,8 despite the paucity of eccrine glands in these areas on the body. These findings suggest that these neoplasms may not be purely eccrine in origin. The wide range of clinical presentations of eccrine poromas has prompted investigation into further classification and delineation of this neoplasm.3 The occurrence of eccrine poromas on areas of the skin known to have few eccrine glands suggests that eccrine poromas may not be purely comprised of eccrine ducts and instead may be of apocrine origin.3,9,10 Histologic features of eccrine poromas that suggest apocrine origination include sebaceous and follicular differentiation (eg, folliculocentric distribution), the association with the follicular infundibulum, and the presence of follicular germ cells.3,9,10 Thus, apocrine gland involvement in eccrine poromas may account for their appearance in anatomic areas that do not have high concentrations of eccrine glands, such as the trunk and pubic area.

Based on these findings, eccrine poromas may therefore be of eccrine and/or apocrine origin; however, the nomenclature of this neoplasm remains confusing and possibly misleading, as the term eccrine poroma continues to be accepted even in instances in which the differentiation appears to be largely apocrine. The terms poroma and eccrine poroma often are used interchangeably, which contributes to the confusion by failing to acknowledge the possibility of apocrine influence and possibly causing the clinician to exclude eccrine poromas from the differential diagnosis in areas that do not have high concentrations of eccrine glands.

Because of their high degree of clinical variability, characteristic acral location, and misleading nomenclature, eccrine poromas often are mistakenly confused with a long list of other cutaneous neoplasms, including hemangiomas, pyogenic granulomas, melanocytic nevi, warts, cysts, and other adnexal neoplasms.3 In our case, the lesion was abnormally large and was clinically concerning for an unusual sebaceous nevus. Its location on the lower back is not commonly noted and should remind the clinician of the possibility of apocrine differentiation. Clinicians should be aware of the wide phenotypic diversity of eccrine poromas, and therefore they should consider this diagnosis in their differential diagnosis for solitary papules or nodules occurring in any anatomic area.

- Pinkus H, Rogin JR, Goldman P. Eccrine poroma: tumors exhibiting features of the epidermal sweat duct unit. Arch Dermatol. 1956;74:511-521.

- Pylyser K, Dewolf-Peeters C, Marlen K. The histology of eccrine poromas: a study of 14 cases. Dermatologica. 1983;167:243-249.

- Moore TO, Orman HL, Orman SK, et al. Poromas of the head and neck. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;44:48-52.

- Agarwal S, Kumar B, Sharma N. Nodule on the chest. eccrine poroma. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2009;75:639.

- Ackerman AB, Abenoza P. Neoplasms With Eccrine Differentiation. Philadelphia, PA: Lea & Febinger; 1990:113-185.

- Okun M, Ansell H. Eccrine poroma. report of three cases, two with an unusual location. Arch Dermatol. 1963;88:561-566.

- Sarma DP, Zaman SU, Santos EE, et al. Poroma of the hip and buttock. Dermatol Online J. 2009;15:10.

- Altamura D, Piccolo D, Lozzi GP, et al. Eccrine poroma in an unusual site: a clinical and dermoscopic simulator of amelanotic melanoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:539-541.

- Groben PA, Hitchcock MG, Leshin B, et al. Apocrine poroma, a distinctive case in a patient with nevoid BCC. Am J Dermatopathol. 1992;21:31-33.

- Harvell JD, Kerschmann RL, LeBoit PE. Eccrine or apocrine poroma? six poromas with divergent adnexal differentiation. Am J Dermatopathol. 1996;18:1-9.

The Diagnosis: Eccrine Poroma

A shave biopsy of the lesion was performed for definitive diagnosis and demonstrated a well-circumscribed tumor with cords and broad columns composed of uniform basaloid cells extending into the dermis and in areas connecting to the overlying epidermis (Figure). There also were small ducts and cysts admixed in the tumor columns that were embedded in a tumor stroma rich in blood vessels. A diagnosis of eccrine poroma was made based on these characteristic histologic features.

|

Biopsy revealed a basaloid tumor originating from the epidermis and extending into the dermis (A)(H&E, original magnification ×4). On higher magnification, ducts were evident amongst the tumor cells and a vascular rich stroma was revealed (B)(H&E, original magnification ×10). |

First described by Pinkus et al1 in 1956, eccrine poroma is a benign neoplasm of cells from the intraepidermal ductal portion of the eccrine sweat gland. Eccrine poroma (along with hidroacanthoma simplex, dermal duct tumor, and poroid hidradenoma) is one of the poroid neoplasms, which account for approximately 10% of all primary sweat gland tumors.2 Eccrine poroma usually is seen in patients over 40 years of age without any predilection for race or sex.

Characteristically, eccrine poromas clinically manifest as solitary, firm, sharply demarcated papules or nodules that may be sessile or pedunculated and rarely exceed 2 cm in diameter. This entity classically presents on acral, non–hair-bearing areas (eg, palms and soles). Eccrine poromas have a wide range of clinical appearances that can lead to broad differential diagnoses3 and have been described as flesh-colored,3 pink to red,4 purple,5 and pigmented3,4 papules or nodules depending on features such as blood vessel proliferation and pigment deposition.

Eccrine poromas also have been reported on hair-bearing areas of the body, including the head,3 neck,3,6 chest,4,6 hip,7 and pubic area,8 despite the paucity of eccrine glands in these areas on the body. These findings suggest that these neoplasms may not be purely eccrine in origin. The wide range of clinical presentations of eccrine poromas has prompted investigation into further classification and delineation of this neoplasm.3 The occurrence of eccrine poromas on areas of the skin known to have few eccrine glands suggests that eccrine poromas may not be purely comprised of eccrine ducts and instead may be of apocrine origin.3,9,10 Histologic features of eccrine poromas that suggest apocrine origination include sebaceous and follicular differentiation (eg, folliculocentric distribution), the association with the follicular infundibulum, and the presence of follicular germ cells.3,9,10 Thus, apocrine gland involvement in eccrine poromas may account for their appearance in anatomic areas that do not have high concentrations of eccrine glands, such as the trunk and pubic area.

Based on these findings, eccrine poromas may therefore be of eccrine and/or apocrine origin; however, the nomenclature of this neoplasm remains confusing and possibly misleading, as the term eccrine poroma continues to be accepted even in instances in which the differentiation appears to be largely apocrine. The terms poroma and eccrine poroma often are used interchangeably, which contributes to the confusion by failing to acknowledge the possibility of apocrine influence and possibly causing the clinician to exclude eccrine poromas from the differential diagnosis in areas that do not have high concentrations of eccrine glands.

Because of their high degree of clinical variability, characteristic acral location, and misleading nomenclature, eccrine poromas often are mistakenly confused with a long list of other cutaneous neoplasms, including hemangiomas, pyogenic granulomas, melanocytic nevi, warts, cysts, and other adnexal neoplasms.3 In our case, the lesion was abnormally large and was clinically concerning for an unusual sebaceous nevus. Its location on the lower back is not commonly noted and should remind the clinician of the possibility of apocrine differentiation. Clinicians should be aware of the wide phenotypic diversity of eccrine poromas, and therefore they should consider this diagnosis in their differential diagnosis for solitary papules or nodules occurring in any anatomic area.

The Diagnosis: Eccrine Poroma

A shave biopsy of the lesion was performed for definitive diagnosis and demonstrated a well-circumscribed tumor with cords and broad columns composed of uniform basaloid cells extending into the dermis and in areas connecting to the overlying epidermis (Figure). There also were small ducts and cysts admixed in the tumor columns that were embedded in a tumor stroma rich in blood vessels. A diagnosis of eccrine poroma was made based on these characteristic histologic features.

|

Biopsy revealed a basaloid tumor originating from the epidermis and extending into the dermis (A)(H&E, original magnification ×4). On higher magnification, ducts were evident amongst the tumor cells and a vascular rich stroma was revealed (B)(H&E, original magnification ×10). |

First described by Pinkus et al1 in 1956, eccrine poroma is a benign neoplasm of cells from the intraepidermal ductal portion of the eccrine sweat gland. Eccrine poroma (along with hidroacanthoma simplex, dermal duct tumor, and poroid hidradenoma) is one of the poroid neoplasms, which account for approximately 10% of all primary sweat gland tumors.2 Eccrine poroma usually is seen in patients over 40 years of age without any predilection for race or sex.

Characteristically, eccrine poromas clinically manifest as solitary, firm, sharply demarcated papules or nodules that may be sessile or pedunculated and rarely exceed 2 cm in diameter. This entity classically presents on acral, non–hair-bearing areas (eg, palms and soles). Eccrine poromas have a wide range of clinical appearances that can lead to broad differential diagnoses3 and have been described as flesh-colored,3 pink to red,4 purple,5 and pigmented3,4 papules or nodules depending on features such as blood vessel proliferation and pigment deposition.

Eccrine poromas also have been reported on hair-bearing areas of the body, including the head,3 neck,3,6 chest,4,6 hip,7 and pubic area,8 despite the paucity of eccrine glands in these areas on the body. These findings suggest that these neoplasms may not be purely eccrine in origin. The wide range of clinical presentations of eccrine poromas has prompted investigation into further classification and delineation of this neoplasm.3 The occurrence of eccrine poromas on areas of the skin known to have few eccrine glands suggests that eccrine poromas may not be purely comprised of eccrine ducts and instead may be of apocrine origin.3,9,10 Histologic features of eccrine poromas that suggest apocrine origination include sebaceous and follicular differentiation (eg, folliculocentric distribution), the association with the follicular infundibulum, and the presence of follicular germ cells.3,9,10 Thus, apocrine gland involvement in eccrine poromas may account for their appearance in anatomic areas that do not have high concentrations of eccrine glands, such as the trunk and pubic area.

Based on these findings, eccrine poromas may therefore be of eccrine and/or apocrine origin; however, the nomenclature of this neoplasm remains confusing and possibly misleading, as the term eccrine poroma continues to be accepted even in instances in which the differentiation appears to be largely apocrine. The terms poroma and eccrine poroma often are used interchangeably, which contributes to the confusion by failing to acknowledge the possibility of apocrine influence and possibly causing the clinician to exclude eccrine poromas from the differential diagnosis in areas that do not have high concentrations of eccrine glands.

Because of their high degree of clinical variability, characteristic acral location, and misleading nomenclature, eccrine poromas often are mistakenly confused with a long list of other cutaneous neoplasms, including hemangiomas, pyogenic granulomas, melanocytic nevi, warts, cysts, and other adnexal neoplasms.3 In our case, the lesion was abnormally large and was clinically concerning for an unusual sebaceous nevus. Its location on the lower back is not commonly noted and should remind the clinician of the possibility of apocrine differentiation. Clinicians should be aware of the wide phenotypic diversity of eccrine poromas, and therefore they should consider this diagnosis in their differential diagnosis for solitary papules or nodules occurring in any anatomic area.

- Pinkus H, Rogin JR, Goldman P. Eccrine poroma: tumors exhibiting features of the epidermal sweat duct unit. Arch Dermatol. 1956;74:511-521.

- Pylyser K, Dewolf-Peeters C, Marlen K. The histology of eccrine poromas: a study of 14 cases. Dermatologica. 1983;167:243-249.

- Moore TO, Orman HL, Orman SK, et al. Poromas of the head and neck. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;44:48-52.

- Agarwal S, Kumar B, Sharma N. Nodule on the chest. eccrine poroma. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2009;75:639.

- Ackerman AB, Abenoza P. Neoplasms With Eccrine Differentiation. Philadelphia, PA: Lea & Febinger; 1990:113-185.

- Okun M, Ansell H. Eccrine poroma. report of three cases, two with an unusual location. Arch Dermatol. 1963;88:561-566.

- Sarma DP, Zaman SU, Santos EE, et al. Poroma of the hip and buttock. Dermatol Online J. 2009;15:10.

- Altamura D, Piccolo D, Lozzi GP, et al. Eccrine poroma in an unusual site: a clinical and dermoscopic simulator of amelanotic melanoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:539-541.

- Groben PA, Hitchcock MG, Leshin B, et al. Apocrine poroma, a distinctive case in a patient with nevoid BCC. Am J Dermatopathol. 1992;21:31-33.

- Harvell JD, Kerschmann RL, LeBoit PE. Eccrine or apocrine poroma? six poromas with divergent adnexal differentiation. Am J Dermatopathol. 1996;18:1-9.

- Pinkus H, Rogin JR, Goldman P. Eccrine poroma: tumors exhibiting features of the epidermal sweat duct unit. Arch Dermatol. 1956;74:511-521.

- Pylyser K, Dewolf-Peeters C, Marlen K. The histology of eccrine poromas: a study of 14 cases. Dermatologica. 1983;167:243-249.

- Moore TO, Orman HL, Orman SK, et al. Poromas of the head and neck. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;44:48-52.

- Agarwal S, Kumar B, Sharma N. Nodule on the chest. eccrine poroma. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2009;75:639.

- Ackerman AB, Abenoza P. Neoplasms With Eccrine Differentiation. Philadelphia, PA: Lea & Febinger; 1990:113-185.

- Okun M, Ansell H. Eccrine poroma. report of three cases, two with an unusual location. Arch Dermatol. 1963;88:561-566.

- Sarma DP, Zaman SU, Santos EE, et al. Poroma of the hip and buttock. Dermatol Online J. 2009;15:10.

- Altamura D, Piccolo D, Lozzi GP, et al. Eccrine poroma in an unusual site: a clinical and dermoscopic simulator of amelanotic melanoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:539-541.

- Groben PA, Hitchcock MG, Leshin B, et al. Apocrine poroma, a distinctive case in a patient with nevoid BCC. Am J Dermatopathol. 1992;21:31-33.

- Harvell JD, Kerschmann RL, LeBoit PE. Eccrine or apocrine poroma? six poromas with divergent adnexal differentiation. Am J Dermatopathol. 1996;18:1-9.

A 47-year-old man presented with an asymptomatic, 2.5×1.5-cm, sessile pink plaque with a coalescing papular texture on the lower back of 30 years’ duration. The patient reported that 2 papillated papules with peripheral rims of dark crust had developed in the center of the lesion over the past 6 months. His personal and family histories were unremarkable.