User login

Adverse pregnancy outcomes and later cardiovascular disease

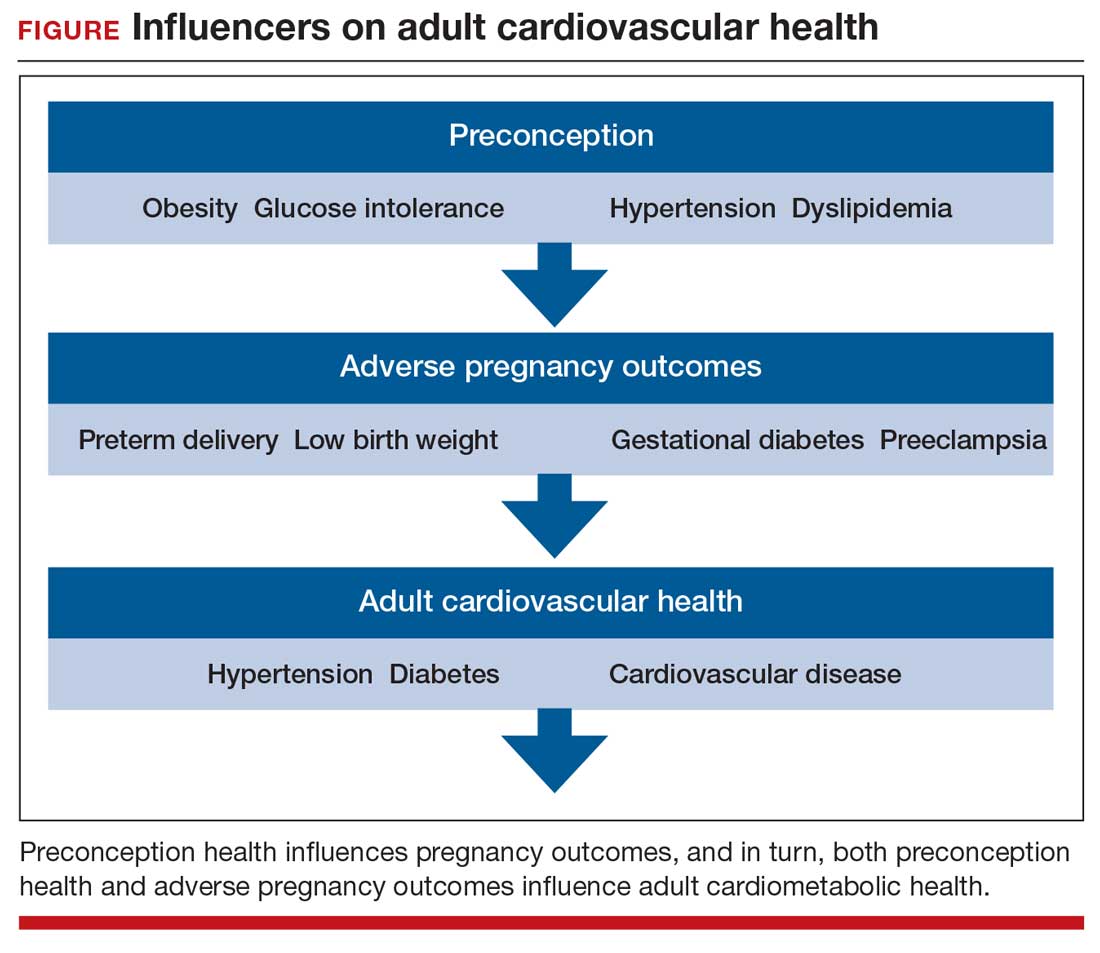

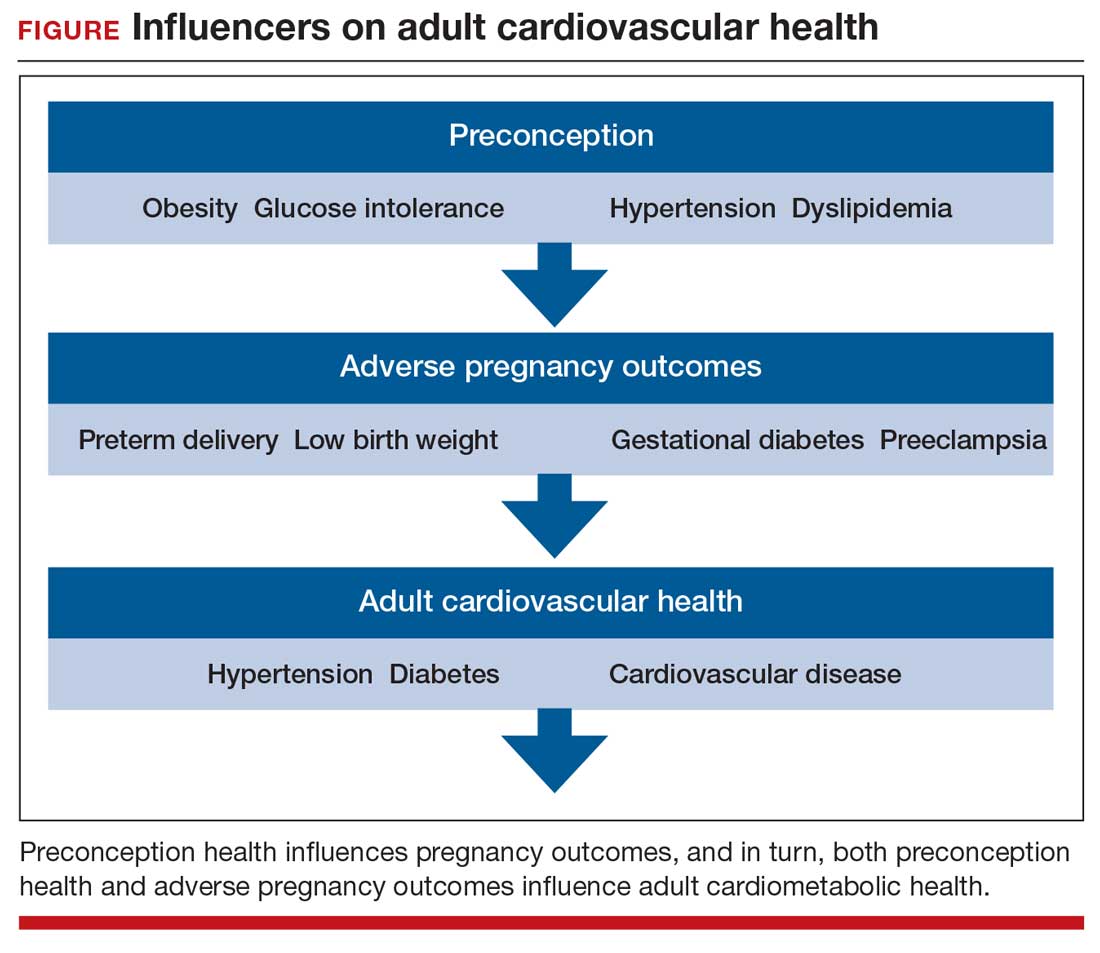

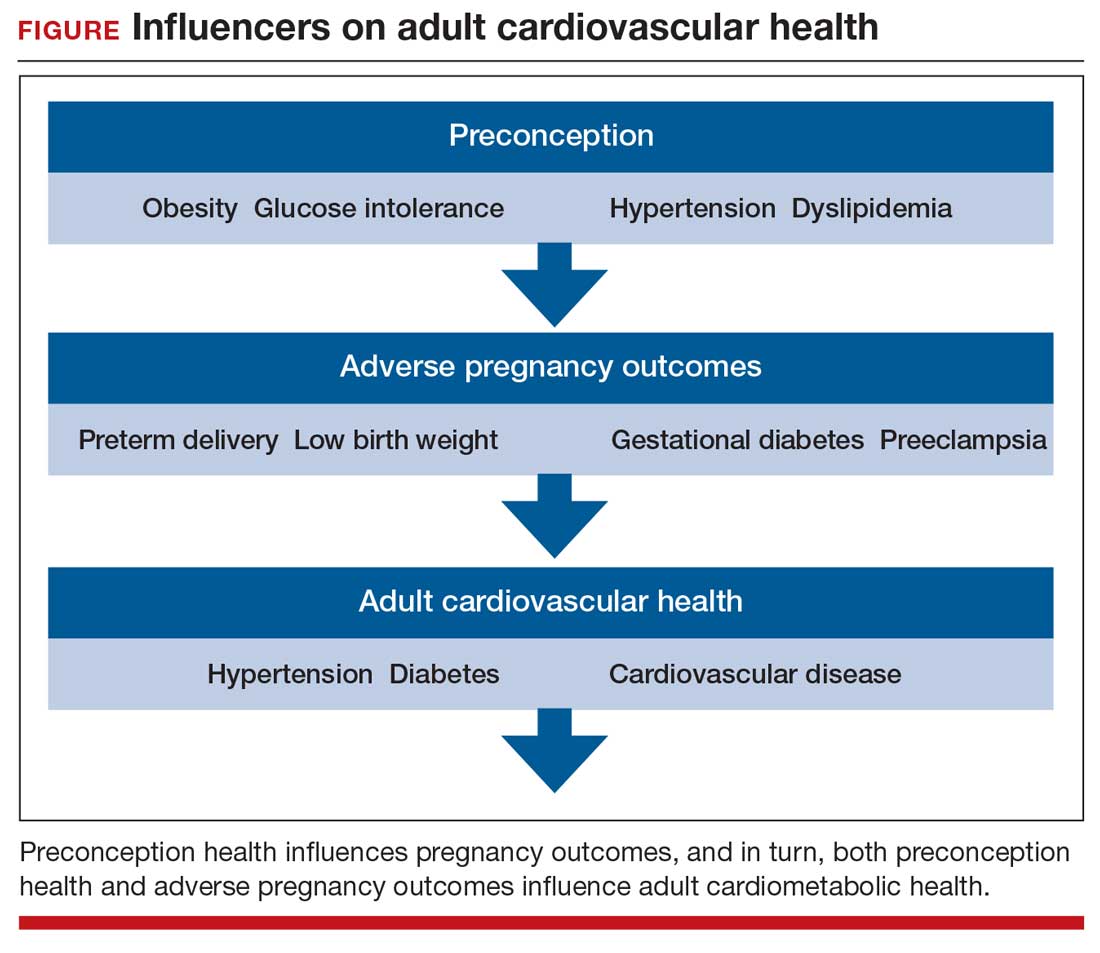

Preconception health influences pregnancy outcomes, and in turn, both preconception health and an APO influence adult cardiometabolic health (FIGURE). This editorial is focused on the link between APOs and later cardiometabolic morbidity and mortality, recognizing that preconception health greatly influences the risk of an APO and lifetime cardiometabolic disease.

Adverse pregnancy outcomes

Major APOs include miscarriage, preterm birth (birth <37 weeks’ gestation), low birth weight (birth weight ≤2,500 g; 5.5 lb), gestational diabetes (GDM), preeclampsia, and placental abruption. In the United States, among all births, reported rates of the following APOs are:1-3

- preterm birth, 10.2%

- low birth weight, 8.3%

- GDM, 6%

- preeclampsia, 5%

- placental abruption, 1%.

Miscarriage occurs in approximately 10% to 15% of pregnancies, influenced by both the age of the woman and the method used to diagnose pregnancy.4 Miscarriage, preterm birth, low birth weight, GDM, preeclampsia, and placental abruption have been reported to be associated with an increased risk of later cardiovascular morbidity and mortality.

APOs and cardiovascular disease

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) affects the majority of people past the age of 60 years and includes 4 major subcategories:

- coronary heart disease, including myocardial infarction, angina, and heart failure

- CVD, stroke, and transient ischemic attack

- peripheral artery disease

- atherosclerosis of the aorta leading to aortic aneurysm.

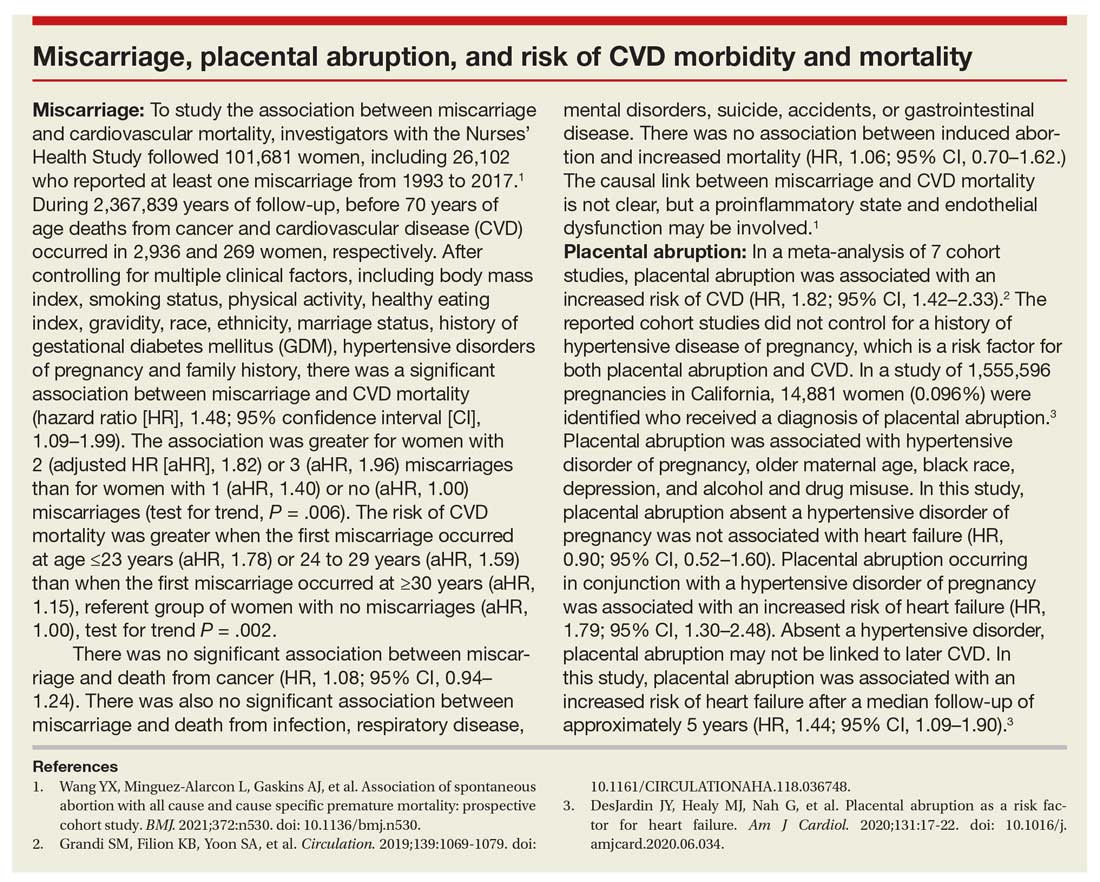

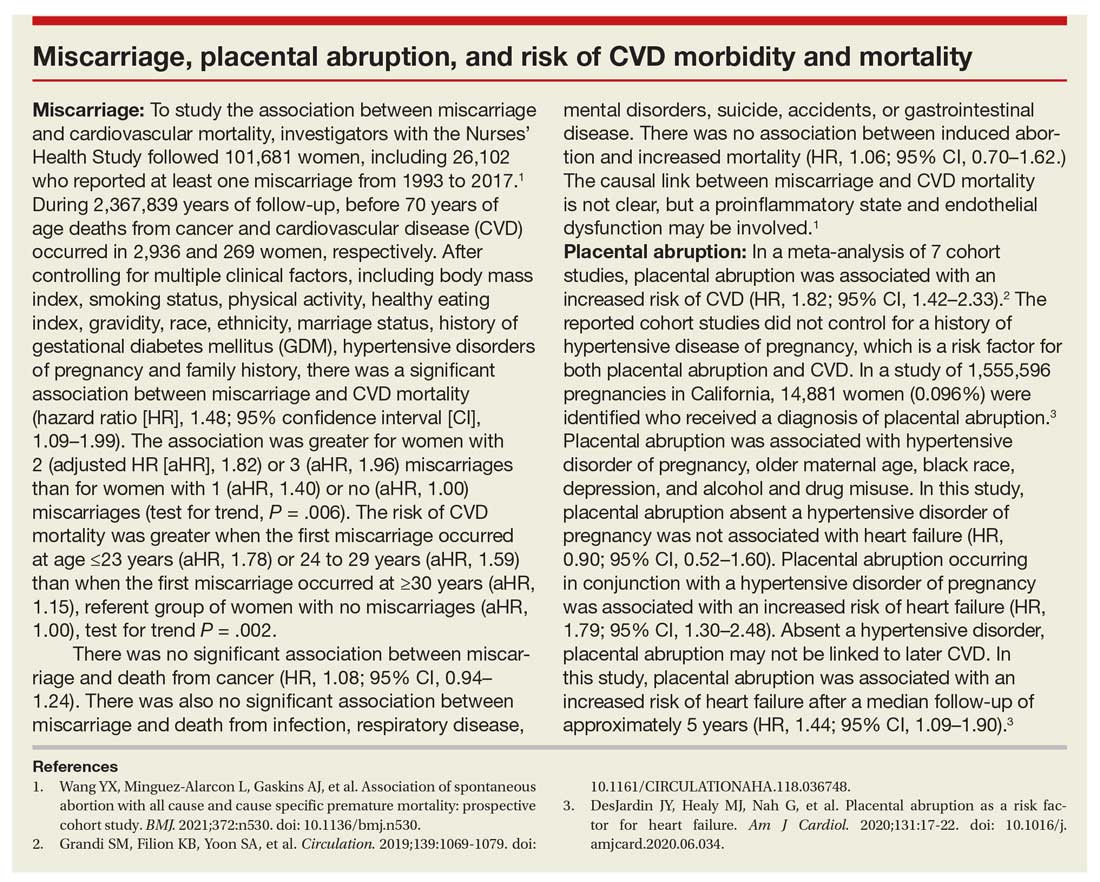

Multiple meta-analyses report that APOs are associated with CVD in later life. A comprehensive review reported that the risk of CVD was increased following a pregnancy with one of these APOs: severe preeclampsia (odds ratio [OR], 2.74), GDM (OR, 1.68), preterm birth (OR, 1.93), low birth weight (OR, 1.29), and placental abruption (OR, 1.82).5

The link between APOs and CVD may be explained in part by the association of APOs with multiple risk factors for CVD, including chronic hypertension, type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), and dyslipidemia. A meta-analysis of 43 studies reported that, compared with controls, women with a history of preeclampsia have a 3.13 times greater risk of developing chronic hypertension.6 Among women with preeclampsia, approximately 20% will develop hypertension within 15 years.7 A meta-analysis of 20 studies reported that women with a history of GDM had a 9.51-times greater risk of developing T2DM than women without GDM.8 Among women with a history of GDM, over 16 years of follow-up, T2DM was diagnosed in 16.2%, compared with 1.9% of control women.8

CVD prevention—Breastfeeding: An antidote for APOs

Pregnancy stresses both the cardiovascular and metabolic systems. Breastfeeding is an antidote to the stresses imposed by pregnancy. Breastfeeding women have lower blood glucose9 and blood pressure.10

Breastfeeding reduces the risk of CVD. In a study of 100,864 parous Australian women, with a mean age of 60 years, ever breastfeeding was associated a lower risk of CVD hospitalization (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR], 0.86; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.78–0.96; P = .005) and CVD mortality (aHR, 0.66; 95% CI, 0.49–0.89; P = .006).11

Continue to: CVD prevention—American Heart Association recommendations...

CVD prevention—American Heart Association recommendations

The American Heart Association12 recommends lifestyle interventions to reduce the risk of CVD, including:

- Eat a high-quality diet that includes vegetables, fruit, whole grains, beans, legumes, nuts, plant-based protein, lean animal protein, and fish.

- Limit intake of sugary drinks and foods, fatty or processed meats, full-fat dairy products, eggs, highly processed foods, and tropical oils.

- Exercise at least 150 minutes weekly at a moderate activity level, including muscle-strengthening activity.

- Reduce prolonged intervals of sitting.

- Live a tobacco- and nicotine-free life.

- Strive to maintain a normal body mass index.

- Consider using an activity tracker to monitor activity level.

- After 40 years of age calculate CVD risk using a validated calculator such as the American Cardiology Association risk calculator.13 This calculator uses age, gender, and lipid and blood pressure measurements to calculate the 10-year risk of atherosclerotic CVD, including coronary death, myocardial infarction, and stroke.

Medications to reduce CVD risk

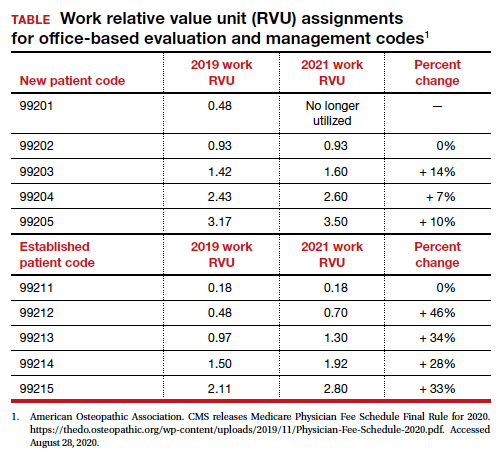

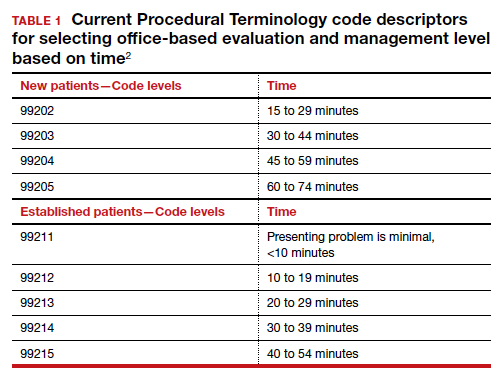

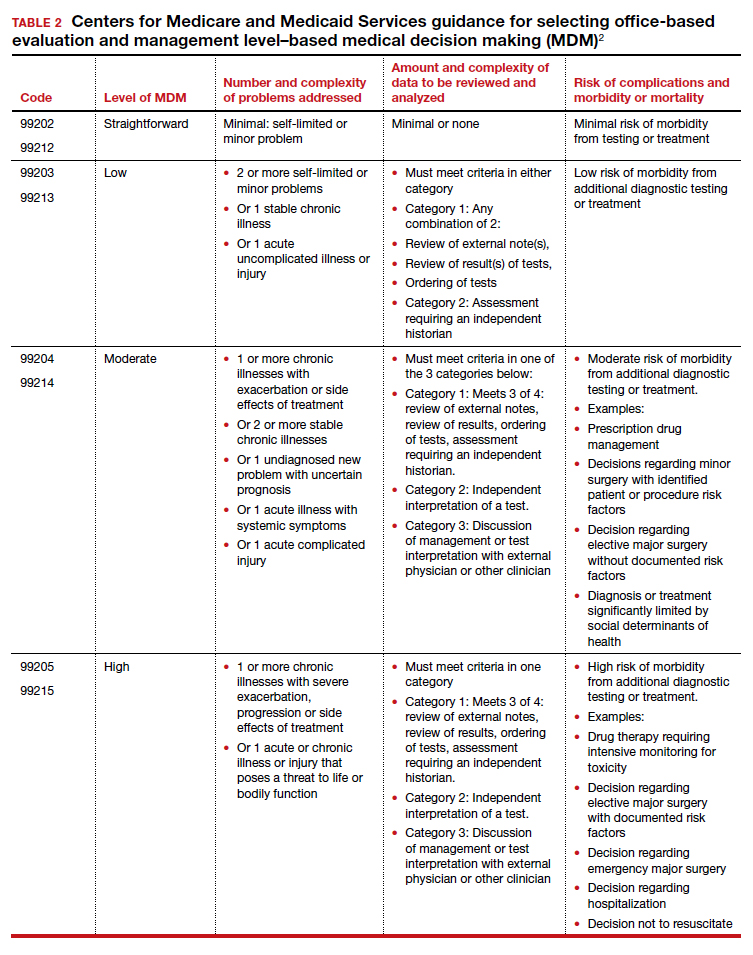

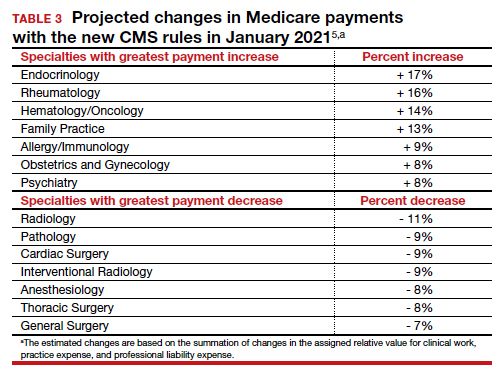

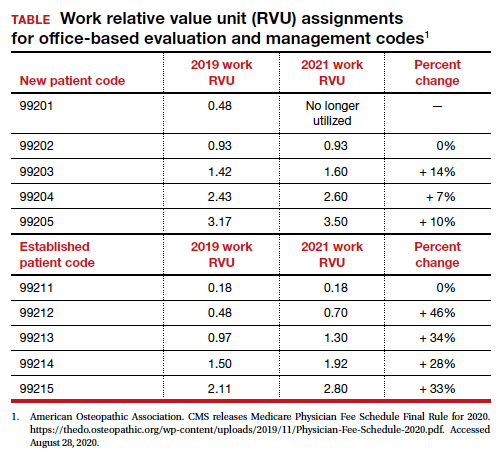

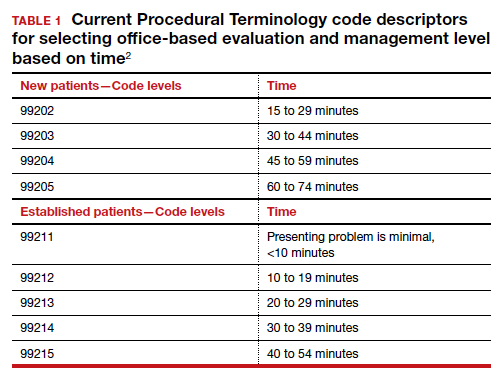

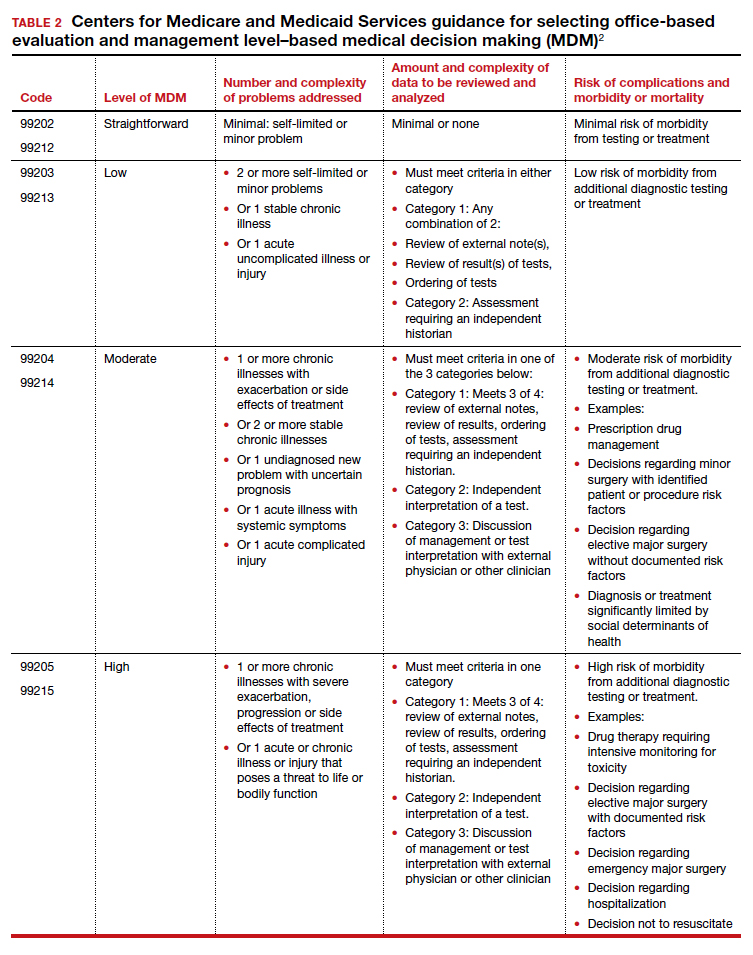

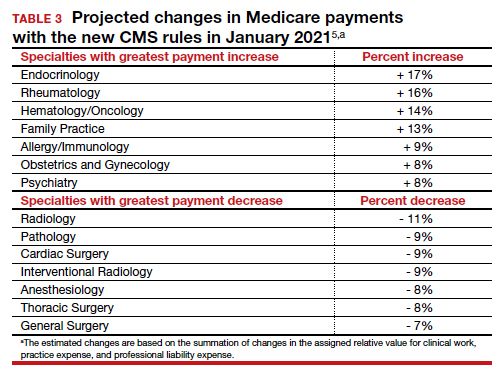

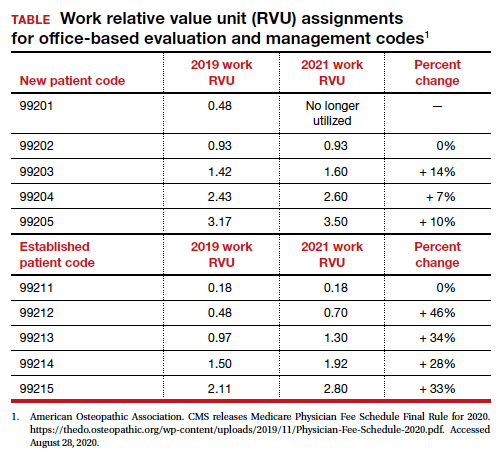

Historically, ObGyns have not routinely prescribed medications to treat hypertension, dyslipidemia, or to prevent diabetes. The recent increase in the valuation of return ambulatory visits and a reduction in the valuation assigned to procedural care may provide ObGyn practices the additional resources needed to manage some chronic diseases. Physician assistants and nurse practitioners may help ObGyn practices to manage hypertension, dyslipidemia, and prediabetes.

Prior to initiating a medicine, counseling about healthy living, including smoking cessation, exercise, heart-healthy diet, and achieving an optimal body mass index is warranted.

For treatment of stage II hypertension, defined as blood pressure (BP) measurements with systolic BP ≥140 mm Hg and diastolic BP ≥90 mm Hg, therapeutic lifestyle interventions include: optimizing weight, following the DASH diet, restricting dietary sodium, physical activity, and reducing alcohol consumption. Medication treatment for essential hypertension is guided by the magnitude of BP reduction needed to achieve normotension. For women with hypertension needing antihypertensive medication and planning another pregnancy in the near future, labetalol or extended-release nifedipine may be first-line medications. For women who have completed their families or who have no immediate plans for pregnancy, an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor, angiotensin receptor blocker, calcium channel blocker, or thiazide diuretic are commonly prescribed.14

For the treatment of elevated low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol in women who have not had a cardiovascular event, statin therapy is often warranted when both the LDL cholesterol is >100 mg/dL and the woman has a calculated 10-year risk of >10% for a cardiovascular event using the American Heart Association or American College of Cardiology calculator. Most women who meet these criteria will be older than age 40 years and many will be under the care of an internal medicine or family medicine specialist, limiting the role of the ObGyn.15-17

For prevention of diabetes in women with a history of GDM, both weight loss and metformin (1,750 mg daily) have been shown in clinical trials to reduce the risk of developing T2DM.18 Among 350 women with a history of GDM who were followed for 10 years, metformin 850 mg twice daily reduced the risk of developing T2DM by 40% compared with placebo.19 In the same study, lifestyle changes without metformin, including loss of 7% of body weight plus 150 minutes of exercise weekly was associated with a 35% reduction in the risk of developing T2DM.19 Metformin is one of the least expensive prescription medications and is cost-effective for the prevention of T2DM.18

Low-dose aspirin treatment for the prevention of CVD in women who have not had a cardiovascular event must balance a modest reduction in cardiovascular events with a small increased risk of bleeding events. The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends low-dose aspirin for a limited group of women, those aged 50 to 59 years of age with a 10-year risk of a cardiovascular event >10% who are willing to take aspirin for 10 years. The USPSTF concluded that there is insufficient evidence to recommend low-dose aspirin prevention of CVD in women aged <50 years.20

Continue to: Beyond the fourth trimester...

Beyond the fourth trimester

The fourth trimester is the 12-week period following birth. At the comprehensive postpartum visit, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recommends that women with APOs be counseled about their increased lifetime risk of maternal cardiometabolic disease.21 In addition, ACOG recommends that at this visit the clinician who will assume primary responsibility for the woman’s ongoing medical care in her primary medical home be clarified. One option is to ensure a high-quality hand-off to an internal medicine or family medicine clinician. Another option is for a clinician in the ObGyn’s office practice, including a physician assistant, nurse practitioner, or office-based ObGyn, to assume some role in the primary care of the woman.

An APO is not only a pregnancy problem

An APO reverberates across a woman’s lifetime, increasing the risk of CVD and diabetes. In the United States the mean age at first birth is 27 years.1 The mean life expectancy of US women is 81 years.22 Following a birth complicated by an APO there are 5 decades of opportunity to improve health through lifestyle changes and medication treatment of obesity, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and hyperglycemia, thereby reducing the risk of CVD.

- Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Osterman MJ, et al. Births: final data for 2019. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2021;70:1-51.

- Deputy NP, Kim SY, Conrey EJ, et al. Prevalence and changes in preexisting diabetes and gestational diabetes among women who had a live birth—United States, 2012-2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67:1201-1207. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6743a2.

- Fingar KR, Mabry-Hernandez I, Ngo-Metzger Q, et al. Delivery hospitalizations involving preeclampsia and eclampsia, 2005–2014. Statistical brief #222. In: Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Statistical Briefs [Internet]. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality: Rockville, MD; April 2017.

- Magnus MC, Wilcox AJ, Morken NH, et al. Role of maternal age and pregnancy history in risk of miscarriage: prospective register-based study. BMJ. 2019;364:869.

- Parikh NI, Gonzalez JM, Anderson CAM, et al. Adverse pregnancy outcomes and cardiovascular disease risk: unique opportunities for cardiovascular disease prevention in women. Circulation. 2021;143:e902-e916. doi: 10.1161 /CIR.0000000000000961.

- Brown MC, Best KE, Pearce MS, et al. Cardiovascular disease risk in women with pre-eclampsia: systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Epidemiol. 2013;28:1-19. doi: 10.1007/s10654-013- 9762-6.

- Groenfol TK, Zoet GA, Franx A, et al; on behalf of the PREVENT Group. Trajectory of cardiovascular risk factors after hypertensive disorders of pregnancy. Hypertension. 2019;73:171-178. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.118.11726.

- Vounzoulaki E, Khunti K, Abner SC, et al. Progression to type 2 diabetes in women with a known history of gestational diabetes: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2020;369:m1361. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1361.

- Tarrant M, Chooniedass R, Fan HSL, et al. Breastfeeding and postpartum glucose regulation among women with prior gestational diabetes: a systematic review. J Hum Lact. 2020;36:723-738. doi: 10.1177/0890334420950259.

- Park S, Choi NK. Breastfeeding and maternal hypertension. Am J Hypertens. 2018;31:615-621. doi: 10.1093/ajh/hpx219.

- Nguyen B, Gale J, Nassar N, et al. Breastfeeding and cardiovascular disease hospitalization and mortality in parous women: evidence from a large Australian cohort study. J Am Heart Assoc. 2019;8:e011056. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.118.011056.

- Eight things you can do to prevent heart disease and stroke. American Heart Association website. https://www.heart.org/en/healthy-living /healthy-lifestyle/prevent-heart-disease-andstroke. Last Reviewed March 14, 2019. Accessed May 19, 2021.

- ASCVD risk estimator plus. American College of Cardiology website. https://tools.acc.org /ascvd-risk-estimator-plus/#!/calculate /estimate/. Accessed May 19, 2021.

- Ferdinand KC, Nasser SA. Management of essential hypertension. Cardiol Clin. 2017;35:231-246. doi: 10.1016/j.ccl.2016.12.005.

- Packard CJ. LDL cholesterol: how low to go? Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2018;28:348-354. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2017.12.011.

- Simons L. An updated review of lipid-modifying therapy. Med J Aust. 2019;211:87-92. doi: 10.5694 /mja2.50142.

- Chou R, Dana T, Blazina I, et al. Statins for the prevention of cardiovascular disease in adults: evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2016;316:2008. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.15629.

- Moin T, Schmittdiel JA, Flory JH, et al. Review of metformin use for type 2 diabetes mellitus prevention. Am J Prev Med. 2018;55:565-574. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2018.04.038.

- Aorda VR, Christophi CA, Edelstein SL, et al, for the Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group. The effect of lifestyle intervention and metformin on preventing or delaying diabetes among women with and without gestational diabetes: the Diabetes Prevention Program outcomes study 10-year follow-up. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;100:1646- 1653. doi: 10.1210/jc.2014-3761.

- Bibbins-Domingo K, U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Aspirin use of the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease and colorectal cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. Ann Int Med. 2016; 164: 836-845. doi: 10.7326/M16-0577.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 736: optimizing postpartum care. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;131:e140-e150. doi: 10.1097 /AOG.0000000000002633.

- National Center for Health Statistics. Health, United States, 2017: Table 015. Hyattsville, MD; 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data /hus/2017/015.pdf. Accessed May 18, 2021.

Preconception health influences pregnancy outcomes, and in turn, both preconception health and an APO influence adult cardiometabolic health (FIGURE). This editorial is focused on the link between APOs and later cardiometabolic morbidity and mortality, recognizing that preconception health greatly influences the risk of an APO and lifetime cardiometabolic disease.

Adverse pregnancy outcomes

Major APOs include miscarriage, preterm birth (birth <37 weeks’ gestation), low birth weight (birth weight ≤2,500 g; 5.5 lb), gestational diabetes (GDM), preeclampsia, and placental abruption. In the United States, among all births, reported rates of the following APOs are:1-3

- preterm birth, 10.2%

- low birth weight, 8.3%

- GDM, 6%

- preeclampsia, 5%

- placental abruption, 1%.

Miscarriage occurs in approximately 10% to 15% of pregnancies, influenced by both the age of the woman and the method used to diagnose pregnancy.4 Miscarriage, preterm birth, low birth weight, GDM, preeclampsia, and placental abruption have been reported to be associated with an increased risk of later cardiovascular morbidity and mortality.

APOs and cardiovascular disease

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) affects the majority of people past the age of 60 years and includes 4 major subcategories:

- coronary heart disease, including myocardial infarction, angina, and heart failure

- CVD, stroke, and transient ischemic attack

- peripheral artery disease

- atherosclerosis of the aorta leading to aortic aneurysm.

Multiple meta-analyses report that APOs are associated with CVD in later life. A comprehensive review reported that the risk of CVD was increased following a pregnancy with one of these APOs: severe preeclampsia (odds ratio [OR], 2.74), GDM (OR, 1.68), preterm birth (OR, 1.93), low birth weight (OR, 1.29), and placental abruption (OR, 1.82).5

The link between APOs and CVD may be explained in part by the association of APOs with multiple risk factors for CVD, including chronic hypertension, type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), and dyslipidemia. A meta-analysis of 43 studies reported that, compared with controls, women with a history of preeclampsia have a 3.13 times greater risk of developing chronic hypertension.6 Among women with preeclampsia, approximately 20% will develop hypertension within 15 years.7 A meta-analysis of 20 studies reported that women with a history of GDM had a 9.51-times greater risk of developing T2DM than women without GDM.8 Among women with a history of GDM, over 16 years of follow-up, T2DM was diagnosed in 16.2%, compared with 1.9% of control women.8

CVD prevention—Breastfeeding: An antidote for APOs

Pregnancy stresses both the cardiovascular and metabolic systems. Breastfeeding is an antidote to the stresses imposed by pregnancy. Breastfeeding women have lower blood glucose9 and blood pressure.10

Breastfeeding reduces the risk of CVD. In a study of 100,864 parous Australian women, with a mean age of 60 years, ever breastfeeding was associated a lower risk of CVD hospitalization (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR], 0.86; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.78–0.96; P = .005) and CVD mortality (aHR, 0.66; 95% CI, 0.49–0.89; P = .006).11

Continue to: CVD prevention—American Heart Association recommendations...

CVD prevention—American Heart Association recommendations

The American Heart Association12 recommends lifestyle interventions to reduce the risk of CVD, including:

- Eat a high-quality diet that includes vegetables, fruit, whole grains, beans, legumes, nuts, plant-based protein, lean animal protein, and fish.

- Limit intake of sugary drinks and foods, fatty or processed meats, full-fat dairy products, eggs, highly processed foods, and tropical oils.

- Exercise at least 150 minutes weekly at a moderate activity level, including muscle-strengthening activity.

- Reduce prolonged intervals of sitting.

- Live a tobacco- and nicotine-free life.

- Strive to maintain a normal body mass index.

- Consider using an activity tracker to monitor activity level.

- After 40 years of age calculate CVD risk using a validated calculator such as the American Cardiology Association risk calculator.13 This calculator uses age, gender, and lipid and blood pressure measurements to calculate the 10-year risk of atherosclerotic CVD, including coronary death, myocardial infarction, and stroke.

Medications to reduce CVD risk

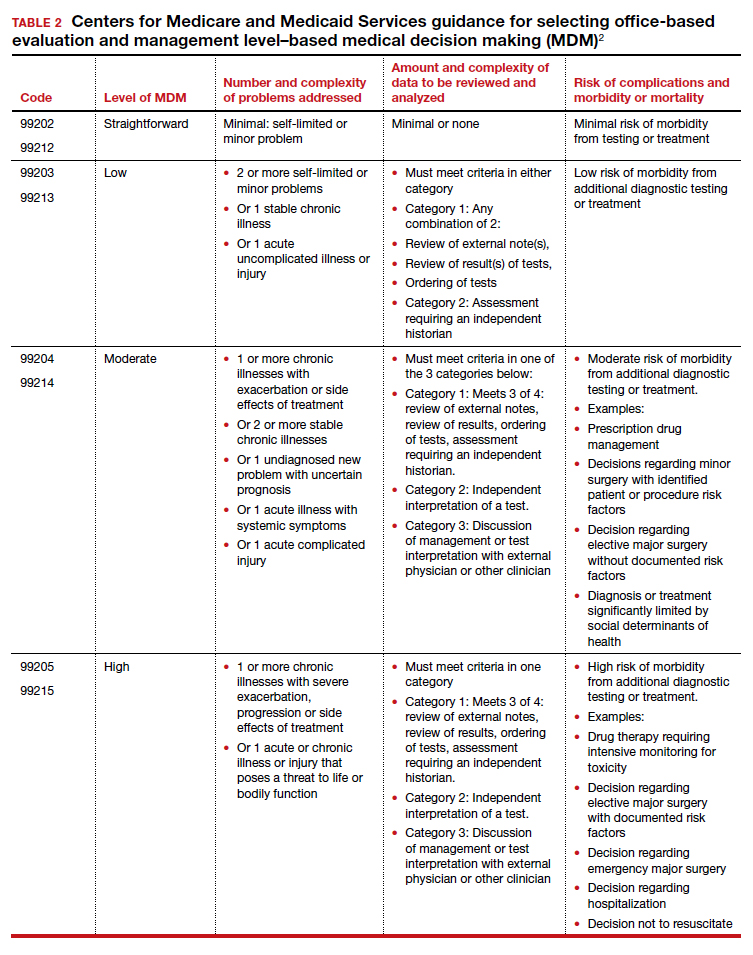

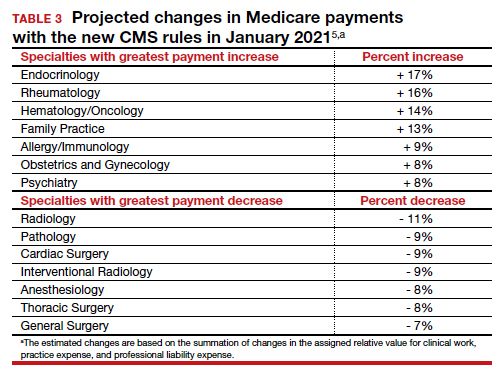

Historically, ObGyns have not routinely prescribed medications to treat hypertension, dyslipidemia, or to prevent diabetes. The recent increase in the valuation of return ambulatory visits and a reduction in the valuation assigned to procedural care may provide ObGyn practices the additional resources needed to manage some chronic diseases. Physician assistants and nurse practitioners may help ObGyn practices to manage hypertension, dyslipidemia, and prediabetes.

Prior to initiating a medicine, counseling about healthy living, including smoking cessation, exercise, heart-healthy diet, and achieving an optimal body mass index is warranted.

For treatment of stage II hypertension, defined as blood pressure (BP) measurements with systolic BP ≥140 mm Hg and diastolic BP ≥90 mm Hg, therapeutic lifestyle interventions include: optimizing weight, following the DASH diet, restricting dietary sodium, physical activity, and reducing alcohol consumption. Medication treatment for essential hypertension is guided by the magnitude of BP reduction needed to achieve normotension. For women with hypertension needing antihypertensive medication and planning another pregnancy in the near future, labetalol or extended-release nifedipine may be first-line medications. For women who have completed their families or who have no immediate plans for pregnancy, an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor, angiotensin receptor blocker, calcium channel blocker, or thiazide diuretic are commonly prescribed.14

For the treatment of elevated low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol in women who have not had a cardiovascular event, statin therapy is often warranted when both the LDL cholesterol is >100 mg/dL and the woman has a calculated 10-year risk of >10% for a cardiovascular event using the American Heart Association or American College of Cardiology calculator. Most women who meet these criteria will be older than age 40 years and many will be under the care of an internal medicine or family medicine specialist, limiting the role of the ObGyn.15-17

For prevention of diabetes in women with a history of GDM, both weight loss and metformin (1,750 mg daily) have been shown in clinical trials to reduce the risk of developing T2DM.18 Among 350 women with a history of GDM who were followed for 10 years, metformin 850 mg twice daily reduced the risk of developing T2DM by 40% compared with placebo.19 In the same study, lifestyle changes without metformin, including loss of 7% of body weight plus 150 minutes of exercise weekly was associated with a 35% reduction in the risk of developing T2DM.19 Metformin is one of the least expensive prescription medications and is cost-effective for the prevention of T2DM.18

Low-dose aspirin treatment for the prevention of CVD in women who have not had a cardiovascular event must balance a modest reduction in cardiovascular events with a small increased risk of bleeding events. The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends low-dose aspirin for a limited group of women, those aged 50 to 59 years of age with a 10-year risk of a cardiovascular event >10% who are willing to take aspirin for 10 years. The USPSTF concluded that there is insufficient evidence to recommend low-dose aspirin prevention of CVD in women aged <50 years.20

Continue to: Beyond the fourth trimester...

Beyond the fourth trimester

The fourth trimester is the 12-week period following birth. At the comprehensive postpartum visit, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recommends that women with APOs be counseled about their increased lifetime risk of maternal cardiometabolic disease.21 In addition, ACOG recommends that at this visit the clinician who will assume primary responsibility for the woman’s ongoing medical care in her primary medical home be clarified. One option is to ensure a high-quality hand-off to an internal medicine or family medicine clinician. Another option is for a clinician in the ObGyn’s office practice, including a physician assistant, nurse practitioner, or office-based ObGyn, to assume some role in the primary care of the woman.

An APO is not only a pregnancy problem

An APO reverberates across a woman’s lifetime, increasing the risk of CVD and diabetes. In the United States the mean age at first birth is 27 years.1 The mean life expectancy of US women is 81 years.22 Following a birth complicated by an APO there are 5 decades of opportunity to improve health through lifestyle changes and medication treatment of obesity, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and hyperglycemia, thereby reducing the risk of CVD.

Preconception health influences pregnancy outcomes, and in turn, both preconception health and an APO influence adult cardiometabolic health (FIGURE). This editorial is focused on the link between APOs and later cardiometabolic morbidity and mortality, recognizing that preconception health greatly influences the risk of an APO and lifetime cardiometabolic disease.

Adverse pregnancy outcomes

Major APOs include miscarriage, preterm birth (birth <37 weeks’ gestation), low birth weight (birth weight ≤2,500 g; 5.5 lb), gestational diabetes (GDM), preeclampsia, and placental abruption. In the United States, among all births, reported rates of the following APOs are:1-3

- preterm birth, 10.2%

- low birth weight, 8.3%

- GDM, 6%

- preeclampsia, 5%

- placental abruption, 1%.

Miscarriage occurs in approximately 10% to 15% of pregnancies, influenced by both the age of the woman and the method used to diagnose pregnancy.4 Miscarriage, preterm birth, low birth weight, GDM, preeclampsia, and placental abruption have been reported to be associated with an increased risk of later cardiovascular morbidity and mortality.

APOs and cardiovascular disease

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) affects the majority of people past the age of 60 years and includes 4 major subcategories:

- coronary heart disease, including myocardial infarction, angina, and heart failure

- CVD, stroke, and transient ischemic attack

- peripheral artery disease

- atherosclerosis of the aorta leading to aortic aneurysm.

Multiple meta-analyses report that APOs are associated with CVD in later life. A comprehensive review reported that the risk of CVD was increased following a pregnancy with one of these APOs: severe preeclampsia (odds ratio [OR], 2.74), GDM (OR, 1.68), preterm birth (OR, 1.93), low birth weight (OR, 1.29), and placental abruption (OR, 1.82).5

The link between APOs and CVD may be explained in part by the association of APOs with multiple risk factors for CVD, including chronic hypertension, type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), and dyslipidemia. A meta-analysis of 43 studies reported that, compared with controls, women with a history of preeclampsia have a 3.13 times greater risk of developing chronic hypertension.6 Among women with preeclampsia, approximately 20% will develop hypertension within 15 years.7 A meta-analysis of 20 studies reported that women with a history of GDM had a 9.51-times greater risk of developing T2DM than women without GDM.8 Among women with a history of GDM, over 16 years of follow-up, T2DM was diagnosed in 16.2%, compared with 1.9% of control women.8

CVD prevention—Breastfeeding: An antidote for APOs

Pregnancy stresses both the cardiovascular and metabolic systems. Breastfeeding is an antidote to the stresses imposed by pregnancy. Breastfeeding women have lower blood glucose9 and blood pressure.10

Breastfeeding reduces the risk of CVD. In a study of 100,864 parous Australian women, with a mean age of 60 years, ever breastfeeding was associated a lower risk of CVD hospitalization (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR], 0.86; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.78–0.96; P = .005) and CVD mortality (aHR, 0.66; 95% CI, 0.49–0.89; P = .006).11

Continue to: CVD prevention—American Heart Association recommendations...

CVD prevention—American Heart Association recommendations

The American Heart Association12 recommends lifestyle interventions to reduce the risk of CVD, including:

- Eat a high-quality diet that includes vegetables, fruit, whole grains, beans, legumes, nuts, plant-based protein, lean animal protein, and fish.

- Limit intake of sugary drinks and foods, fatty or processed meats, full-fat dairy products, eggs, highly processed foods, and tropical oils.

- Exercise at least 150 minutes weekly at a moderate activity level, including muscle-strengthening activity.

- Reduce prolonged intervals of sitting.

- Live a tobacco- and nicotine-free life.

- Strive to maintain a normal body mass index.

- Consider using an activity tracker to monitor activity level.

- After 40 years of age calculate CVD risk using a validated calculator such as the American Cardiology Association risk calculator.13 This calculator uses age, gender, and lipid and blood pressure measurements to calculate the 10-year risk of atherosclerotic CVD, including coronary death, myocardial infarction, and stroke.

Medications to reduce CVD risk

Historically, ObGyns have not routinely prescribed medications to treat hypertension, dyslipidemia, or to prevent diabetes. The recent increase in the valuation of return ambulatory visits and a reduction in the valuation assigned to procedural care may provide ObGyn practices the additional resources needed to manage some chronic diseases. Physician assistants and nurse practitioners may help ObGyn practices to manage hypertension, dyslipidemia, and prediabetes.

Prior to initiating a medicine, counseling about healthy living, including smoking cessation, exercise, heart-healthy diet, and achieving an optimal body mass index is warranted.

For treatment of stage II hypertension, defined as blood pressure (BP) measurements with systolic BP ≥140 mm Hg and diastolic BP ≥90 mm Hg, therapeutic lifestyle interventions include: optimizing weight, following the DASH diet, restricting dietary sodium, physical activity, and reducing alcohol consumption. Medication treatment for essential hypertension is guided by the magnitude of BP reduction needed to achieve normotension. For women with hypertension needing antihypertensive medication and planning another pregnancy in the near future, labetalol or extended-release nifedipine may be first-line medications. For women who have completed their families or who have no immediate plans for pregnancy, an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor, angiotensin receptor blocker, calcium channel blocker, or thiazide diuretic are commonly prescribed.14

For the treatment of elevated low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol in women who have not had a cardiovascular event, statin therapy is often warranted when both the LDL cholesterol is >100 mg/dL and the woman has a calculated 10-year risk of >10% for a cardiovascular event using the American Heart Association or American College of Cardiology calculator. Most women who meet these criteria will be older than age 40 years and many will be under the care of an internal medicine or family medicine specialist, limiting the role of the ObGyn.15-17

For prevention of diabetes in women with a history of GDM, both weight loss and metformin (1,750 mg daily) have been shown in clinical trials to reduce the risk of developing T2DM.18 Among 350 women with a history of GDM who were followed for 10 years, metformin 850 mg twice daily reduced the risk of developing T2DM by 40% compared with placebo.19 In the same study, lifestyle changes without metformin, including loss of 7% of body weight plus 150 minutes of exercise weekly was associated with a 35% reduction in the risk of developing T2DM.19 Metformin is one of the least expensive prescription medications and is cost-effective for the prevention of T2DM.18

Low-dose aspirin treatment for the prevention of CVD in women who have not had a cardiovascular event must balance a modest reduction in cardiovascular events with a small increased risk of bleeding events. The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends low-dose aspirin for a limited group of women, those aged 50 to 59 years of age with a 10-year risk of a cardiovascular event >10% who are willing to take aspirin for 10 years. The USPSTF concluded that there is insufficient evidence to recommend low-dose aspirin prevention of CVD in women aged <50 years.20

Continue to: Beyond the fourth trimester...

Beyond the fourth trimester

The fourth trimester is the 12-week period following birth. At the comprehensive postpartum visit, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recommends that women with APOs be counseled about their increased lifetime risk of maternal cardiometabolic disease.21 In addition, ACOG recommends that at this visit the clinician who will assume primary responsibility for the woman’s ongoing medical care in her primary medical home be clarified. One option is to ensure a high-quality hand-off to an internal medicine or family medicine clinician. Another option is for a clinician in the ObGyn’s office practice, including a physician assistant, nurse practitioner, or office-based ObGyn, to assume some role in the primary care of the woman.

An APO is not only a pregnancy problem

An APO reverberates across a woman’s lifetime, increasing the risk of CVD and diabetes. In the United States the mean age at first birth is 27 years.1 The mean life expectancy of US women is 81 years.22 Following a birth complicated by an APO there are 5 decades of opportunity to improve health through lifestyle changes and medication treatment of obesity, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and hyperglycemia, thereby reducing the risk of CVD.

- Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Osterman MJ, et al. Births: final data for 2019. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2021;70:1-51.

- Deputy NP, Kim SY, Conrey EJ, et al. Prevalence and changes in preexisting diabetes and gestational diabetes among women who had a live birth—United States, 2012-2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67:1201-1207. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6743a2.

- Fingar KR, Mabry-Hernandez I, Ngo-Metzger Q, et al. Delivery hospitalizations involving preeclampsia and eclampsia, 2005–2014. Statistical brief #222. In: Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Statistical Briefs [Internet]. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality: Rockville, MD; April 2017.

- Magnus MC, Wilcox AJ, Morken NH, et al. Role of maternal age and pregnancy history in risk of miscarriage: prospective register-based study. BMJ. 2019;364:869.

- Parikh NI, Gonzalez JM, Anderson CAM, et al. Adverse pregnancy outcomes and cardiovascular disease risk: unique opportunities for cardiovascular disease prevention in women. Circulation. 2021;143:e902-e916. doi: 10.1161 /CIR.0000000000000961.

- Brown MC, Best KE, Pearce MS, et al. Cardiovascular disease risk in women with pre-eclampsia: systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Epidemiol. 2013;28:1-19. doi: 10.1007/s10654-013- 9762-6.

- Groenfol TK, Zoet GA, Franx A, et al; on behalf of the PREVENT Group. Trajectory of cardiovascular risk factors after hypertensive disorders of pregnancy. Hypertension. 2019;73:171-178. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.118.11726.

- Vounzoulaki E, Khunti K, Abner SC, et al. Progression to type 2 diabetes in women with a known history of gestational diabetes: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2020;369:m1361. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1361.

- Tarrant M, Chooniedass R, Fan HSL, et al. Breastfeeding and postpartum glucose regulation among women with prior gestational diabetes: a systematic review. J Hum Lact. 2020;36:723-738. doi: 10.1177/0890334420950259.

- Park S, Choi NK. Breastfeeding and maternal hypertension. Am J Hypertens. 2018;31:615-621. doi: 10.1093/ajh/hpx219.

- Nguyen B, Gale J, Nassar N, et al. Breastfeeding and cardiovascular disease hospitalization and mortality in parous women: evidence from a large Australian cohort study. J Am Heart Assoc. 2019;8:e011056. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.118.011056.

- Eight things you can do to prevent heart disease and stroke. American Heart Association website. https://www.heart.org/en/healthy-living /healthy-lifestyle/prevent-heart-disease-andstroke. Last Reviewed March 14, 2019. Accessed May 19, 2021.

- ASCVD risk estimator plus. American College of Cardiology website. https://tools.acc.org /ascvd-risk-estimator-plus/#!/calculate /estimate/. Accessed May 19, 2021.

- Ferdinand KC, Nasser SA. Management of essential hypertension. Cardiol Clin. 2017;35:231-246. doi: 10.1016/j.ccl.2016.12.005.

- Packard CJ. LDL cholesterol: how low to go? Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2018;28:348-354. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2017.12.011.

- Simons L. An updated review of lipid-modifying therapy. Med J Aust. 2019;211:87-92. doi: 10.5694 /mja2.50142.

- Chou R, Dana T, Blazina I, et al. Statins for the prevention of cardiovascular disease in adults: evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2016;316:2008. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.15629.

- Moin T, Schmittdiel JA, Flory JH, et al. Review of metformin use for type 2 diabetes mellitus prevention. Am J Prev Med. 2018;55:565-574. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2018.04.038.

- Aorda VR, Christophi CA, Edelstein SL, et al, for the Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group. The effect of lifestyle intervention and metformin on preventing or delaying diabetes among women with and without gestational diabetes: the Diabetes Prevention Program outcomes study 10-year follow-up. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;100:1646- 1653. doi: 10.1210/jc.2014-3761.

- Bibbins-Domingo K, U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Aspirin use of the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease and colorectal cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. Ann Int Med. 2016; 164: 836-845. doi: 10.7326/M16-0577.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 736: optimizing postpartum care. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;131:e140-e150. doi: 10.1097 /AOG.0000000000002633.

- National Center for Health Statistics. Health, United States, 2017: Table 015. Hyattsville, MD; 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data /hus/2017/015.pdf. Accessed May 18, 2021.

- Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Osterman MJ, et al. Births: final data for 2019. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2021;70:1-51.

- Deputy NP, Kim SY, Conrey EJ, et al. Prevalence and changes in preexisting diabetes and gestational diabetes among women who had a live birth—United States, 2012-2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67:1201-1207. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6743a2.

- Fingar KR, Mabry-Hernandez I, Ngo-Metzger Q, et al. Delivery hospitalizations involving preeclampsia and eclampsia, 2005–2014. Statistical brief #222. In: Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Statistical Briefs [Internet]. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality: Rockville, MD; April 2017.

- Magnus MC, Wilcox AJ, Morken NH, et al. Role of maternal age and pregnancy history in risk of miscarriage: prospective register-based study. BMJ. 2019;364:869.

- Parikh NI, Gonzalez JM, Anderson CAM, et al. Adverse pregnancy outcomes and cardiovascular disease risk: unique opportunities for cardiovascular disease prevention in women. Circulation. 2021;143:e902-e916. doi: 10.1161 /CIR.0000000000000961.

- Brown MC, Best KE, Pearce MS, et al. Cardiovascular disease risk in women with pre-eclampsia: systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Epidemiol. 2013;28:1-19. doi: 10.1007/s10654-013- 9762-6.

- Groenfol TK, Zoet GA, Franx A, et al; on behalf of the PREVENT Group. Trajectory of cardiovascular risk factors after hypertensive disorders of pregnancy. Hypertension. 2019;73:171-178. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.118.11726.

- Vounzoulaki E, Khunti K, Abner SC, et al. Progression to type 2 diabetes in women with a known history of gestational diabetes: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2020;369:m1361. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1361.

- Tarrant M, Chooniedass R, Fan HSL, et al. Breastfeeding and postpartum glucose regulation among women with prior gestational diabetes: a systematic review. J Hum Lact. 2020;36:723-738. doi: 10.1177/0890334420950259.

- Park S, Choi NK. Breastfeeding and maternal hypertension. Am J Hypertens. 2018;31:615-621. doi: 10.1093/ajh/hpx219.

- Nguyen B, Gale J, Nassar N, et al. Breastfeeding and cardiovascular disease hospitalization and mortality in parous women: evidence from a large Australian cohort study. J Am Heart Assoc. 2019;8:e011056. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.118.011056.

- Eight things you can do to prevent heart disease and stroke. American Heart Association website. https://www.heart.org/en/healthy-living /healthy-lifestyle/prevent-heart-disease-andstroke. Last Reviewed March 14, 2019. Accessed May 19, 2021.

- ASCVD risk estimator plus. American College of Cardiology website. https://tools.acc.org /ascvd-risk-estimator-plus/#!/calculate /estimate/. Accessed May 19, 2021.

- Ferdinand KC, Nasser SA. Management of essential hypertension. Cardiol Clin. 2017;35:231-246. doi: 10.1016/j.ccl.2016.12.005.

- Packard CJ. LDL cholesterol: how low to go? Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2018;28:348-354. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2017.12.011.

- Simons L. An updated review of lipid-modifying therapy. Med J Aust. 2019;211:87-92. doi: 10.5694 /mja2.50142.

- Chou R, Dana T, Blazina I, et al. Statins for the prevention of cardiovascular disease in adults: evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2016;316:2008. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.15629.

- Moin T, Schmittdiel JA, Flory JH, et al. Review of metformin use for type 2 diabetes mellitus prevention. Am J Prev Med. 2018;55:565-574. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2018.04.038.

- Aorda VR, Christophi CA, Edelstein SL, et al, for the Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group. The effect of lifestyle intervention and metformin on preventing or delaying diabetes among women with and without gestational diabetes: the Diabetes Prevention Program outcomes study 10-year follow-up. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;100:1646- 1653. doi: 10.1210/jc.2014-3761.

- Bibbins-Domingo K, U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Aspirin use of the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease and colorectal cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. Ann Int Med. 2016; 164: 836-845. doi: 10.7326/M16-0577.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 736: optimizing postpartum care. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;131:e140-e150. doi: 10.1097 /AOG.0000000000002633.

- National Center for Health Statistics. Health, United States, 2017: Table 015. Hyattsville, MD; 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data /hus/2017/015.pdf. Accessed May 18, 2021.

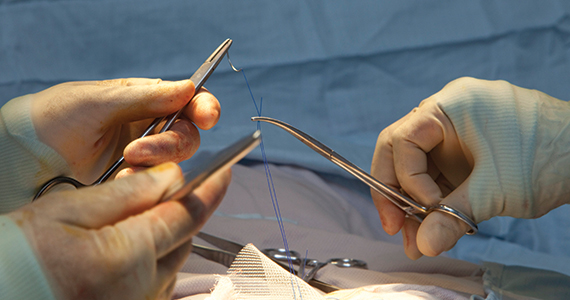

Obstetric anal sphincter injury: Prevention and repair

The rate of obstetric anal sphincter injury (OASIS) is approximately 4.4% of vaginal deliveries, with 3.3% 3rd-degree tears and 1.1% 4th-degree tears.1 In the United States in 2019 there were 3,745,540 births—a 31.7% rate of cesarean delivery (CD) and a 68.3% rate of vaginal delivery—resulting in approximately 112,600 births with OASIS.2 A meta-analysis reported that, among 716,031 vaginal births, the risk factors for OASIS included: forceps delivery (relative risk [RR], 3.15), midline episiotomy (RR, 2.88), occiput posterior fetal position (RR, 2.73), vacuum delivery (RR, 2.60), Asian race (RR, 1.87), primiparity (RR, 1.59), mediolateral episiotomy (RR, 1.55), augmentation of labor (RR, 1.46), and epidural anesthesia (RR, 1.21).3 OASIS is associated with an increased risk for developing postpartum perineal pain, anal incontinence, dyspareunia, and wound breakdown.4 Complications following OASIS repair can trigger many follow-up appointments to assess wound healing and provide physical therapy.

This editorial review focuses on evolving recommendations for preventing and repairing OASIS.

The optimal cutting angle for a mediolateral episiotomy is 60 degrees from the midline

For spontaneous vaginal delivery, a policy of restricted episiotomy reduces the risk of OASIS by approximately 30%.5 With an operative vaginal delivery, especially forceps delivery of a large fetus in the occiput posterior position, a mediolateral episiotomy may help to reduce the risk of OASIS, although there are minimal data from clinical trials to support this practice. In one clinical trial, 407 women were randomly assigned to either a mediolateral or midline episiotomy.6 Approximately 25% of the births in both groups were operative deliveries. The mediolateral episiotomy began in the posterior midline of the vaginal introitus and was carried to the right side of the anal sphincter for 3 cm to 4 cm. The midline episiotomy began in the posterior midline of the vagina and was carried 2 cm to 3 cm into the midline perineal tissue. In the women having a midline or mediolateral episiotomy, a 4th-degree tear occurred in 5.5% and 0.4% of births, respectively. For the midline or mediolateral episiotomy, a third-degree tear occurred in 18.4% and 8.6%, respectively. In a prospective cohort study of 1,302 women with an episiotomy and vaginal birth, the rate of OASIS associated with midline or mediolateral episiotomy was 14.8% and 7%, respectively (P<.05).7 In this study, the operative vaginal delivery rate was 11.6% and 15.2% for the women in the midline and mediolateral groups, respectively.

The angle of the mediolateral episiotomy may influence the rate of OASIS and persistent postpartum perineal pain. In one study, 330 nulliparous women who were assessed to need a mediolateral episiotomy at delivery were randomized to an incision with a 40- or 60-degree angle from the midline.8 Prior to incision, a line was drawn on the skin to mark the course of the incision and then infiltrated with 10 mL of lignocaine. The fetal head was delivered with a Ritgen maneuver. The length of the episiotomy averaged 4 cm in both groups. After delivery, the angle of the episiotomy incision was reassessed. The episiotomy incision cut 60 degrees from the midline was measured on average to be 44 degrees from the midline after delivery of the newborn. Similarly, the incision cut at a 40-degree angle was measured to be 24 degrees from the midline after delivery. The rates of OASIS in the women who had a 40- and 60-degree angle incision were 5.5% and 2.4%, respectively (P = .16).

Continue to: Use a prophylactic antibiotic with extended coverage for anaerobes prior to or during your anal sphincter repair...

Use a prophylactic antibiotic with extended coverage for anaerobes prior to or during your anal sphincter repair

Many experts recommend one dose of a prophylactic antibiotic prior to, or during, OASIS repair in order to reduce the risk of wound complications. In a trial 147 women with OASIS were randomly assigned to receive one dose of a second-generation cephalosporin (cefotetan or cefoxitin) with extended anaerobic coverage or a placebo just before repair of the laceration.9 At 2 weeks postpartum, perineal wound complications were significantly lower in women receiving one dose of prophylactic antibiotic with extended anaerobe coverage compared with placebo—8.2% and 24.1%, respectively (P = .037). Additionally, at 2 weeks postpartum, purulent wound discharge was significantly lower in women receiving antibiotic versus placebo, 4% and 17%, respectively (P = .036). Experts writing for the Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada also recommend one dose of cefotetan or cefoxitin.10 Extended anaerobic coverage also can be achieved by administering a single dose of BOTH cefazolin 2 g by intravenous (IV) infusion PLUS metronidazole 500 mg by IV infusion or oral medication.11 For women with severe penicillin allergy, a recommended regimen is gentamicin 5 mg/kg plus clindamycin 900 mg by IV infusion.11 There is evidence that for colorectal or hysterectomy surgery, expanding prophylactic antibiotic coverage of anaerobes with cefazolin PLUS metronidazole significantly reduces postoperative surgical site infection.12,13 Following an OASIS repair, wound breakdown is a catastrophic problem that may take many months to resolve. Administration of a prophylactic antibiotic with extended coverage of anaerobes may help to prevent wound breakdown.

Prioritize identifying and separately repairing the internal anal sphincter

The internal anal sphincter is a smooth muscle that runs along the outside of the rectal wall and thickens into a sphincter toward the anal canal. The internal anal sphincter is thin and grey-white in appearance, like a veil. By contrast, the external anal sphincter is a thick band of red striated muscle tissue. In one study of 3,333 primiparous women with OASIS, an internal anal sphincter injury was detected in 33% of cases.14 In this large cohort, the rate of internal anal sphincter injury with a 3A tear, a 3B tear, a complete tear of the external sphincter and a 4th-degree perineal tear was 22%, 23%, 42%, and 71%, respectively. The internal anal sphincter is important for maintaining rectal continence and is estimated to contribute 50% to 85% of resting anal tone.15 If injury to the internal anal sphincter is detected at a birth with an OASIS, it is important to separately repair the internal anal sphincter to reduce the risk of postpartum rectal incontinence.16

Polyglactin 910 vs Polydioxanone (PDS) Suture—Is PDS the winner?

Polyglactin 910 (Vicryl) is a braided suture that is absorbed within 56 to 70 days. Polydioxanone suture is a long-lasting monofilament suture that is absorbed within 200 days. Many colorectal surgeons and urogynecologists prefer PDS suture for the repair of both the internal and external anal sphincters.16 Authors of one randomized trial of OASIS repair with Vicryl or PDS suture did not report significant differences in most clinical outcomes.17 However, in this study, anal endosonographic imaging of the internal and external anal sphincter demonstrated more internal sphincter defects but not external sphincter defects when the repair was performed with Vicryl rather than PDS. The investigators concluded that comprehensive training of the surgeon, not choice of suture, is probably the most important factor in achieving a good OASIS repair. However, because many subspecialists favor PDS suture for sphincter repair, specialists in obstetrics and gynecology should consider this option.

Continue to: Can your patient access early secondary repair if they develop a perineal laceration wound breakdown?

Can your patient access early secondary repair if they develop a perineal laceration wound breakdown?

The breakdown of an OASIS repair is an obstetric catastrophe with complications that can last many months and sometimes stretch into years. The best approach to a perineal laceration wound breakdown remains controversial. It is optimal if all patients with a wound breakdown can be offered an early secondary repair or healing by secondary intention, permitting the patient to select the best approach for their specific situation.

As noted by the pioneers of early repair of episiotomy dehiscence, Drs. Hankins, Haugh, Gilstrap, Ramin, and others,18-20 conventional doctrine is that an episiotomy repair dehiscence should be managed expectantly, allowing healing by secondary intention and delaying repair of the sphincters for a minimum of 3 to 4 months.21 However, many small case-series report that early secondary repair of a perineal laceration wound breakdown is possible following multiple days of wound preparation prior to the repair, good surgical technique and diligent postoperative follow-up care. One large case series reported on 72 women with complete perineal wound dehiscence who had early secondary repair.22 The median time to complete wound healing following early repair was 28 days. About 36% of the patients had one or more complications, including skin dehiscence, granuloma formation, perineal pain, and sinus formation. A pilot randomized trial reported that, compared with expectant management of a wound breakdown, early repair resulted in a shorter time to wound healing.23

Early repair of perineal wound dehiscence often involves a course of care that extends over multiple weeks. As an example, following a vaginal birth with OASIS and immediate repair, the patient is often discharged from the hospital to home on postpartum day 3. The wound breakdown often is detected between postpartum days 6 to 10. If early secondary repair is selected as the best treatment, 1 to 6 days of daily debridement of the wound is needed to prepare the wound for early secondary repair. The daily debridement required to prepare the wound for early repair is often performed in the hospital, potentially disrupting early mother-newborn bonding. Following the repair, the patient is observed in the hospital for 1 to 3 days and then discharged home with daily wound care and multiple follow-up visits to monitor wound healing. Pelvic floor physical therapy may be initiated when the wound is healed. The prolonged process required for early secondary repair may be best undertaken by a subspecialty practice.24

The surgical repair and postpartum care of OASIS continues to evolve. In your practice you should consider:

- performing a mediolateral episiotomy at a 60-degree angle to reduce the risk of OASIS in situations where there is a high risk of anal sphincter injury, such as in forceps delivery

- using one dose of a prophylactic antibiotic with extended anaerobic coverage, such as cefotetan or cefoxitin

- focus on identifying and separately repairing an internal anal sphincter injury

- using a long-lasting absorbable suture, such as PDS, to repair the internal and external anal sphincters

- ensuring that the patient with a dehiscence following an episiotomy or anal sphincter injury has access to early secondary repair. Standardizing your approach to the prevention and repair of anal sphincter injury will benefit the approximately 112,600 US women who experience OASIS each year. ●

A Cochrane Database Systematic Review reported that moderate-quality evidence showed a decrease in OASIS with the use of intrapartum warm compresses to the perineum and perineal massage.1 Compared with control, intrapartum warm compresses to the perineum did not result in a reduction in first- or second-degree tears, suturing of perineal tears, or use of episiotomy. However, compared with control, intrapartum warm compresses to the perineum was associated with a reduction in OASIS (relative risk [RR], 0.46; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.27–0.79; 1,799 women; 4 studies; moderate quality evidence; substantial heterogeneity among studies). In addition to a possible reduction in OASIS, warm compresses also may provide the laboring woman, especially those having a natural childbirth, a positive sensory experience and reinforce her perception of the thoughtfulness and caring of her clinicians.

Compared with control, perineal massage was associated with an increase in the rate of an intact perineum (RR, 1.74; 95% CI, 1.11–2.73; 6 studies; 2,618 women; low-quality evidence; substantial heterogeneity among studies) and a decrease in OASIS (RR, 0.49; 95% CI, 0.25–0.94; 5 studies; 2,477 women; moderate quality evidence). Compared with control, perineal massage did not significantly reduce first- or second-degree tears, perineal tears requiring suturing, or the use of episiotomy (very low-quality evidence). Although perineal massage may have benefit, excessive perineal massage likely can contribute to tissue edema and epithelial trauma.

Reference

1. Aasheim V, Nilsen ABC, Reinar LM, et al. Perineal techniques during the second stage of labour for reducing perineal trauma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;CD006672.

- Friedman AM, Ananth CV, Prendergast E, et al. Evaluation of third-degree and fourth-degree laceration rates as quality indicators. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125:927-937.

- Hamilton BE, Martin JA, Osterman MK. Births: Provisional data for 2019. Vital Statistics Rapid Release; No. 8. Hyattsville MD: National Center for Health Statistics; May 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/vsrr/vsrr-8-508.pdf

- Pergialitotis V, Bellos I, Fanaki M, et al. Risk factors for severe perineal trauma during childbirth: an updated meta-analysis. European J Obstet Gynecol Repro Biol. 2020;247:94-100.

- Sultan AH, Kettle C. Diagnosis of perineal trauma. In: Sultan AH, Thakar R, Fenner DE, eds. Perineal and anal sphincter trauma. 1st ed. London, England: Springer-Verlag; 2009:33-51.

- Jiang H, Qian X, Carroli G, et al. Selective versus routine use of episiotomy for vaginal birth. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;CD000081.

- Coats PM, Chan KK, Wilkins M, et al. A comparison between midline and mediolateral episiotomies. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1980;87:408-412.

- Sooklim R, Thinkhamrop J, Lumbiganon P, et al. The outcomes of midline versus medio-lateral episiotomy. Reprod Health. 2007;4:10.

- El-Din AS, Kamal MM, Amin MA. Comparison between two incision angles of mediolateral episiotomy in primiparous women: a randomized controlled trial. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2014;40:1877-1882.

- Duggal N, Mercado C, Daniels K, et al. Antibiotic prophylaxis for prevention of postpartum perineal wound complications: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;111:1268-1273.

- Harvey MA, Pierce M. Obstetrical anal sphincter injuries (OASIS): prevention, recognition and repair. J Obstet Gynecol Can. 2015;37:1131-1148.

- Cox CK, Bugosh MD, Fenner DE, et al. Antibiotic use during repair of obstetrical anal sphincter injury: a qualitative improvement initiative. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2021; Epub January 28.

- Deierhoi RJ, Dawes LG, Vick C, et al. Choice of intravenous antibiotic prophylaxis for colorectal surgery does matter. J Am Coll Surg. 2013;217:763-769.

- Till Sr, Morgan DM, Bazzi AA, et al. Reducing surgical site infections after hysterectomy: metronidazole plus cefazolin compared with cephalosporin alone. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;217:187.e1-e11.

- Pihl S, Blomberg M, Uustal E. Internal anal sphincter injury in the immediate postpartum period: prevalence, risk factors and diagnostic methods in the Swedish perineal laceration registry. European J Obst Gynecol Repro Biol. 2020;245:1-6.

- Fornell EU, Matthiesen L, Sjodahl R, et al. Obstetric anal sphincter injury ten years after: subjective and objective long-term effects. BJOG. 2005;112:312-316.

- Sultan AH, Monga AK, Kumar D, et al. Primary repair of obstetric anal sphincter rupture using the overlap technique. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1999;106:318-323.

- Williams A, Adams EJ, Tincello DG, et al. How to repair an anal sphincter injury after vaginal delivery: results of a randomised controlled trial. BJOG. 2006;113:201-207.

- Hauth JC, Gilstrap LC, Ward SC, et al. Early repair of an external sphincter ani muscle and rectal mucosal dehiscence. Obstet Gynecol. 1986;67:806-809.

- Hankins GD, Hauth JC, Gilstrap LC, et al. Early repair of episiotomy dehiscence. Obstet Gynecol. 1990;75:48-51.

- Ramin SR, Ramus RM, Little BB, et al. Early repair of episiotomy dehiscence associated with infection. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1992;167:1104-1107.

- Pritchard JA, MacDonald PC, Gant NF. Williams Obstetrics, 17th ed. Norwalk Connecticut: Appleton-Century-Crofts; 1985:349-350.

- Okeahialam NA, Thakar R, Kleprlikova H, et al. Early re-suturing of dehisced obstetric perineal woulds: a 13-year experience. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Repro Biol. 2020;254:69-73.

- Dudley L, Kettle C, Thomas PW, et al. Perineal resuturing versus expectant management following vaginal delivery complicated by a dehisced wound (PREVIEW): a pilot and feasibility randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open. 2017;7:e012766.

- Lewicky-Gaupp C, Leader-Cramer A, Johnson LL, et al. Wound complications after obstetrical anal sphincter injuries. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125:1088-1093.

The rate of obstetric anal sphincter injury (OASIS) is approximately 4.4% of vaginal deliveries, with 3.3% 3rd-degree tears and 1.1% 4th-degree tears.1 In the United States in 2019 there were 3,745,540 births—a 31.7% rate of cesarean delivery (CD) and a 68.3% rate of vaginal delivery—resulting in approximately 112,600 births with OASIS.2 A meta-analysis reported that, among 716,031 vaginal births, the risk factors for OASIS included: forceps delivery (relative risk [RR], 3.15), midline episiotomy (RR, 2.88), occiput posterior fetal position (RR, 2.73), vacuum delivery (RR, 2.60), Asian race (RR, 1.87), primiparity (RR, 1.59), mediolateral episiotomy (RR, 1.55), augmentation of labor (RR, 1.46), and epidural anesthesia (RR, 1.21).3 OASIS is associated with an increased risk for developing postpartum perineal pain, anal incontinence, dyspareunia, and wound breakdown.4 Complications following OASIS repair can trigger many follow-up appointments to assess wound healing and provide physical therapy.

This editorial review focuses on evolving recommendations for preventing and repairing OASIS.

The optimal cutting angle for a mediolateral episiotomy is 60 degrees from the midline

For spontaneous vaginal delivery, a policy of restricted episiotomy reduces the risk of OASIS by approximately 30%.5 With an operative vaginal delivery, especially forceps delivery of a large fetus in the occiput posterior position, a mediolateral episiotomy may help to reduce the risk of OASIS, although there are minimal data from clinical trials to support this practice. In one clinical trial, 407 women were randomly assigned to either a mediolateral or midline episiotomy.6 Approximately 25% of the births in both groups were operative deliveries. The mediolateral episiotomy began in the posterior midline of the vaginal introitus and was carried to the right side of the anal sphincter for 3 cm to 4 cm. The midline episiotomy began in the posterior midline of the vagina and was carried 2 cm to 3 cm into the midline perineal tissue. In the women having a midline or mediolateral episiotomy, a 4th-degree tear occurred in 5.5% and 0.4% of births, respectively. For the midline or mediolateral episiotomy, a third-degree tear occurred in 18.4% and 8.6%, respectively. In a prospective cohort study of 1,302 women with an episiotomy and vaginal birth, the rate of OASIS associated with midline or mediolateral episiotomy was 14.8% and 7%, respectively (P<.05).7 In this study, the operative vaginal delivery rate was 11.6% and 15.2% for the women in the midline and mediolateral groups, respectively.

The angle of the mediolateral episiotomy may influence the rate of OASIS and persistent postpartum perineal pain. In one study, 330 nulliparous women who were assessed to need a mediolateral episiotomy at delivery were randomized to an incision with a 40- or 60-degree angle from the midline.8 Prior to incision, a line was drawn on the skin to mark the course of the incision and then infiltrated with 10 mL of lignocaine. The fetal head was delivered with a Ritgen maneuver. The length of the episiotomy averaged 4 cm in both groups. After delivery, the angle of the episiotomy incision was reassessed. The episiotomy incision cut 60 degrees from the midline was measured on average to be 44 degrees from the midline after delivery of the newborn. Similarly, the incision cut at a 40-degree angle was measured to be 24 degrees from the midline after delivery. The rates of OASIS in the women who had a 40- and 60-degree angle incision were 5.5% and 2.4%, respectively (P = .16).

Continue to: Use a prophylactic antibiotic with extended coverage for anaerobes prior to or during your anal sphincter repair...

Use a prophylactic antibiotic with extended coverage for anaerobes prior to or during your anal sphincter repair

Many experts recommend one dose of a prophylactic antibiotic prior to, or during, OASIS repair in order to reduce the risk of wound complications. In a trial 147 women with OASIS were randomly assigned to receive one dose of a second-generation cephalosporin (cefotetan or cefoxitin) with extended anaerobic coverage or a placebo just before repair of the laceration.9 At 2 weeks postpartum, perineal wound complications were significantly lower in women receiving one dose of prophylactic antibiotic with extended anaerobe coverage compared with placebo—8.2% and 24.1%, respectively (P = .037). Additionally, at 2 weeks postpartum, purulent wound discharge was significantly lower in women receiving antibiotic versus placebo, 4% and 17%, respectively (P = .036). Experts writing for the Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada also recommend one dose of cefotetan or cefoxitin.10 Extended anaerobic coverage also can be achieved by administering a single dose of BOTH cefazolin 2 g by intravenous (IV) infusion PLUS metronidazole 500 mg by IV infusion or oral medication.11 For women with severe penicillin allergy, a recommended regimen is gentamicin 5 mg/kg plus clindamycin 900 mg by IV infusion.11 There is evidence that for colorectal or hysterectomy surgery, expanding prophylactic antibiotic coverage of anaerobes with cefazolin PLUS metronidazole significantly reduces postoperative surgical site infection.12,13 Following an OASIS repair, wound breakdown is a catastrophic problem that may take many months to resolve. Administration of a prophylactic antibiotic with extended coverage of anaerobes may help to prevent wound breakdown.

Prioritize identifying and separately repairing the internal anal sphincter

The internal anal sphincter is a smooth muscle that runs along the outside of the rectal wall and thickens into a sphincter toward the anal canal. The internal anal sphincter is thin and grey-white in appearance, like a veil. By contrast, the external anal sphincter is a thick band of red striated muscle tissue. In one study of 3,333 primiparous women with OASIS, an internal anal sphincter injury was detected in 33% of cases.14 In this large cohort, the rate of internal anal sphincter injury with a 3A tear, a 3B tear, a complete tear of the external sphincter and a 4th-degree perineal tear was 22%, 23%, 42%, and 71%, respectively. The internal anal sphincter is important for maintaining rectal continence and is estimated to contribute 50% to 85% of resting anal tone.15 If injury to the internal anal sphincter is detected at a birth with an OASIS, it is important to separately repair the internal anal sphincter to reduce the risk of postpartum rectal incontinence.16

Polyglactin 910 vs Polydioxanone (PDS) Suture—Is PDS the winner?

Polyglactin 910 (Vicryl) is a braided suture that is absorbed within 56 to 70 days. Polydioxanone suture is a long-lasting monofilament suture that is absorbed within 200 days. Many colorectal surgeons and urogynecologists prefer PDS suture for the repair of both the internal and external anal sphincters.16 Authors of one randomized trial of OASIS repair with Vicryl or PDS suture did not report significant differences in most clinical outcomes.17 However, in this study, anal endosonographic imaging of the internal and external anal sphincter demonstrated more internal sphincter defects but not external sphincter defects when the repair was performed with Vicryl rather than PDS. The investigators concluded that comprehensive training of the surgeon, not choice of suture, is probably the most important factor in achieving a good OASIS repair. However, because many subspecialists favor PDS suture for sphincter repair, specialists in obstetrics and gynecology should consider this option.

Continue to: Can your patient access early secondary repair if they develop a perineal laceration wound breakdown?

Can your patient access early secondary repair if they develop a perineal laceration wound breakdown?

The breakdown of an OASIS repair is an obstetric catastrophe with complications that can last many months and sometimes stretch into years. The best approach to a perineal laceration wound breakdown remains controversial. It is optimal if all patients with a wound breakdown can be offered an early secondary repair or healing by secondary intention, permitting the patient to select the best approach for their specific situation.

As noted by the pioneers of early repair of episiotomy dehiscence, Drs. Hankins, Haugh, Gilstrap, Ramin, and others,18-20 conventional doctrine is that an episiotomy repair dehiscence should be managed expectantly, allowing healing by secondary intention and delaying repair of the sphincters for a minimum of 3 to 4 months.21 However, many small case-series report that early secondary repair of a perineal laceration wound breakdown is possible following multiple days of wound preparation prior to the repair, good surgical technique and diligent postoperative follow-up care. One large case series reported on 72 women with complete perineal wound dehiscence who had early secondary repair.22 The median time to complete wound healing following early repair was 28 days. About 36% of the patients had one or more complications, including skin dehiscence, granuloma formation, perineal pain, and sinus formation. A pilot randomized trial reported that, compared with expectant management of a wound breakdown, early repair resulted in a shorter time to wound healing.23

Early repair of perineal wound dehiscence often involves a course of care that extends over multiple weeks. As an example, following a vaginal birth with OASIS and immediate repair, the patient is often discharged from the hospital to home on postpartum day 3. The wound breakdown often is detected between postpartum days 6 to 10. If early secondary repair is selected as the best treatment, 1 to 6 days of daily debridement of the wound is needed to prepare the wound for early secondary repair. The daily debridement required to prepare the wound for early repair is often performed in the hospital, potentially disrupting early mother-newborn bonding. Following the repair, the patient is observed in the hospital for 1 to 3 days and then discharged home with daily wound care and multiple follow-up visits to monitor wound healing. Pelvic floor physical therapy may be initiated when the wound is healed. The prolonged process required for early secondary repair may be best undertaken by a subspecialty practice.24

The surgical repair and postpartum care of OASIS continues to evolve. In your practice you should consider:

- performing a mediolateral episiotomy at a 60-degree angle to reduce the risk of OASIS in situations where there is a high risk of anal sphincter injury, such as in forceps delivery

- using one dose of a prophylactic antibiotic with extended anaerobic coverage, such as cefotetan or cefoxitin

- focus on identifying and separately repairing an internal anal sphincter injury

- using a long-lasting absorbable suture, such as PDS, to repair the internal and external anal sphincters

- ensuring that the patient with a dehiscence following an episiotomy or anal sphincter injury has access to early secondary repair. Standardizing your approach to the prevention and repair of anal sphincter injury will benefit the approximately 112,600 US women who experience OASIS each year. ●

A Cochrane Database Systematic Review reported that moderate-quality evidence showed a decrease in OASIS with the use of intrapartum warm compresses to the perineum and perineal massage.1 Compared with control, intrapartum warm compresses to the perineum did not result in a reduction in first- or second-degree tears, suturing of perineal tears, or use of episiotomy. However, compared with control, intrapartum warm compresses to the perineum was associated with a reduction in OASIS (relative risk [RR], 0.46; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.27–0.79; 1,799 women; 4 studies; moderate quality evidence; substantial heterogeneity among studies). In addition to a possible reduction in OASIS, warm compresses also may provide the laboring woman, especially those having a natural childbirth, a positive sensory experience and reinforce her perception of the thoughtfulness and caring of her clinicians.

Compared with control, perineal massage was associated with an increase in the rate of an intact perineum (RR, 1.74; 95% CI, 1.11–2.73; 6 studies; 2,618 women; low-quality evidence; substantial heterogeneity among studies) and a decrease in OASIS (RR, 0.49; 95% CI, 0.25–0.94; 5 studies; 2,477 women; moderate quality evidence). Compared with control, perineal massage did not significantly reduce first- or second-degree tears, perineal tears requiring suturing, or the use of episiotomy (very low-quality evidence). Although perineal massage may have benefit, excessive perineal massage likely can contribute to tissue edema and epithelial trauma.

Reference

1. Aasheim V, Nilsen ABC, Reinar LM, et al. Perineal techniques during the second stage of labour for reducing perineal trauma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;CD006672.

The rate of obstetric anal sphincter injury (OASIS) is approximately 4.4% of vaginal deliveries, with 3.3% 3rd-degree tears and 1.1% 4th-degree tears.1 In the United States in 2019 there were 3,745,540 births—a 31.7% rate of cesarean delivery (CD) and a 68.3% rate of vaginal delivery—resulting in approximately 112,600 births with OASIS.2 A meta-analysis reported that, among 716,031 vaginal births, the risk factors for OASIS included: forceps delivery (relative risk [RR], 3.15), midline episiotomy (RR, 2.88), occiput posterior fetal position (RR, 2.73), vacuum delivery (RR, 2.60), Asian race (RR, 1.87), primiparity (RR, 1.59), mediolateral episiotomy (RR, 1.55), augmentation of labor (RR, 1.46), and epidural anesthesia (RR, 1.21).3 OASIS is associated with an increased risk for developing postpartum perineal pain, anal incontinence, dyspareunia, and wound breakdown.4 Complications following OASIS repair can trigger many follow-up appointments to assess wound healing and provide physical therapy.

This editorial review focuses on evolving recommendations for preventing and repairing OASIS.

The optimal cutting angle for a mediolateral episiotomy is 60 degrees from the midline

For spontaneous vaginal delivery, a policy of restricted episiotomy reduces the risk of OASIS by approximately 30%.5 With an operative vaginal delivery, especially forceps delivery of a large fetus in the occiput posterior position, a mediolateral episiotomy may help to reduce the risk of OASIS, although there are minimal data from clinical trials to support this practice. In one clinical trial, 407 women were randomly assigned to either a mediolateral or midline episiotomy.6 Approximately 25% of the births in both groups were operative deliveries. The mediolateral episiotomy began in the posterior midline of the vaginal introitus and was carried to the right side of the anal sphincter for 3 cm to 4 cm. The midline episiotomy began in the posterior midline of the vagina and was carried 2 cm to 3 cm into the midline perineal tissue. In the women having a midline or mediolateral episiotomy, a 4th-degree tear occurred in 5.5% and 0.4% of births, respectively. For the midline or mediolateral episiotomy, a third-degree tear occurred in 18.4% and 8.6%, respectively. In a prospective cohort study of 1,302 women with an episiotomy and vaginal birth, the rate of OASIS associated with midline or mediolateral episiotomy was 14.8% and 7%, respectively (P<.05).7 In this study, the operative vaginal delivery rate was 11.6% and 15.2% for the women in the midline and mediolateral groups, respectively.

The angle of the mediolateral episiotomy may influence the rate of OASIS and persistent postpartum perineal pain. In one study, 330 nulliparous women who were assessed to need a mediolateral episiotomy at delivery were randomized to an incision with a 40- or 60-degree angle from the midline.8 Prior to incision, a line was drawn on the skin to mark the course of the incision and then infiltrated with 10 mL of lignocaine. The fetal head was delivered with a Ritgen maneuver. The length of the episiotomy averaged 4 cm in both groups. After delivery, the angle of the episiotomy incision was reassessed. The episiotomy incision cut 60 degrees from the midline was measured on average to be 44 degrees from the midline after delivery of the newborn. Similarly, the incision cut at a 40-degree angle was measured to be 24 degrees from the midline after delivery. The rates of OASIS in the women who had a 40- and 60-degree angle incision were 5.5% and 2.4%, respectively (P = .16).

Continue to: Use a prophylactic antibiotic with extended coverage for anaerobes prior to or during your anal sphincter repair...

Use a prophylactic antibiotic with extended coverage for anaerobes prior to or during your anal sphincter repair

Many experts recommend one dose of a prophylactic antibiotic prior to, or during, OASIS repair in order to reduce the risk of wound complications. In a trial 147 women with OASIS were randomly assigned to receive one dose of a second-generation cephalosporin (cefotetan or cefoxitin) with extended anaerobic coverage or a placebo just before repair of the laceration.9 At 2 weeks postpartum, perineal wound complications were significantly lower in women receiving one dose of prophylactic antibiotic with extended anaerobe coverage compared with placebo—8.2% and 24.1%, respectively (P = .037). Additionally, at 2 weeks postpartum, purulent wound discharge was significantly lower in women receiving antibiotic versus placebo, 4% and 17%, respectively (P = .036). Experts writing for the Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada also recommend one dose of cefotetan or cefoxitin.10 Extended anaerobic coverage also can be achieved by administering a single dose of BOTH cefazolin 2 g by intravenous (IV) infusion PLUS metronidazole 500 mg by IV infusion or oral medication.11 For women with severe penicillin allergy, a recommended regimen is gentamicin 5 mg/kg plus clindamycin 900 mg by IV infusion.11 There is evidence that for colorectal or hysterectomy surgery, expanding prophylactic antibiotic coverage of anaerobes with cefazolin PLUS metronidazole significantly reduces postoperative surgical site infection.12,13 Following an OASIS repair, wound breakdown is a catastrophic problem that may take many months to resolve. Administration of a prophylactic antibiotic with extended coverage of anaerobes may help to prevent wound breakdown.

Prioritize identifying and separately repairing the internal anal sphincter

The internal anal sphincter is a smooth muscle that runs along the outside of the rectal wall and thickens into a sphincter toward the anal canal. The internal anal sphincter is thin and grey-white in appearance, like a veil. By contrast, the external anal sphincter is a thick band of red striated muscle tissue. In one study of 3,333 primiparous women with OASIS, an internal anal sphincter injury was detected in 33% of cases.14 In this large cohort, the rate of internal anal sphincter injury with a 3A tear, a 3B tear, a complete tear of the external sphincter and a 4th-degree perineal tear was 22%, 23%, 42%, and 71%, respectively. The internal anal sphincter is important for maintaining rectal continence and is estimated to contribute 50% to 85% of resting anal tone.15 If injury to the internal anal sphincter is detected at a birth with an OASIS, it is important to separately repair the internal anal sphincter to reduce the risk of postpartum rectal incontinence.16

Polyglactin 910 vs Polydioxanone (PDS) Suture—Is PDS the winner?

Polyglactin 910 (Vicryl) is a braided suture that is absorbed within 56 to 70 days. Polydioxanone suture is a long-lasting monofilament suture that is absorbed within 200 days. Many colorectal surgeons and urogynecologists prefer PDS suture for the repair of both the internal and external anal sphincters.16 Authors of one randomized trial of OASIS repair with Vicryl or PDS suture did not report significant differences in most clinical outcomes.17 However, in this study, anal endosonographic imaging of the internal and external anal sphincter demonstrated more internal sphincter defects but not external sphincter defects when the repair was performed with Vicryl rather than PDS. The investigators concluded that comprehensive training of the surgeon, not choice of suture, is probably the most important factor in achieving a good OASIS repair. However, because many subspecialists favor PDS suture for sphincter repair, specialists in obstetrics and gynecology should consider this option.

Continue to: Can your patient access early secondary repair if they develop a perineal laceration wound breakdown?

Can your patient access early secondary repair if they develop a perineal laceration wound breakdown?