User login

Painful Purple Toes

The Diagnosis: Blue Toe Syndrome

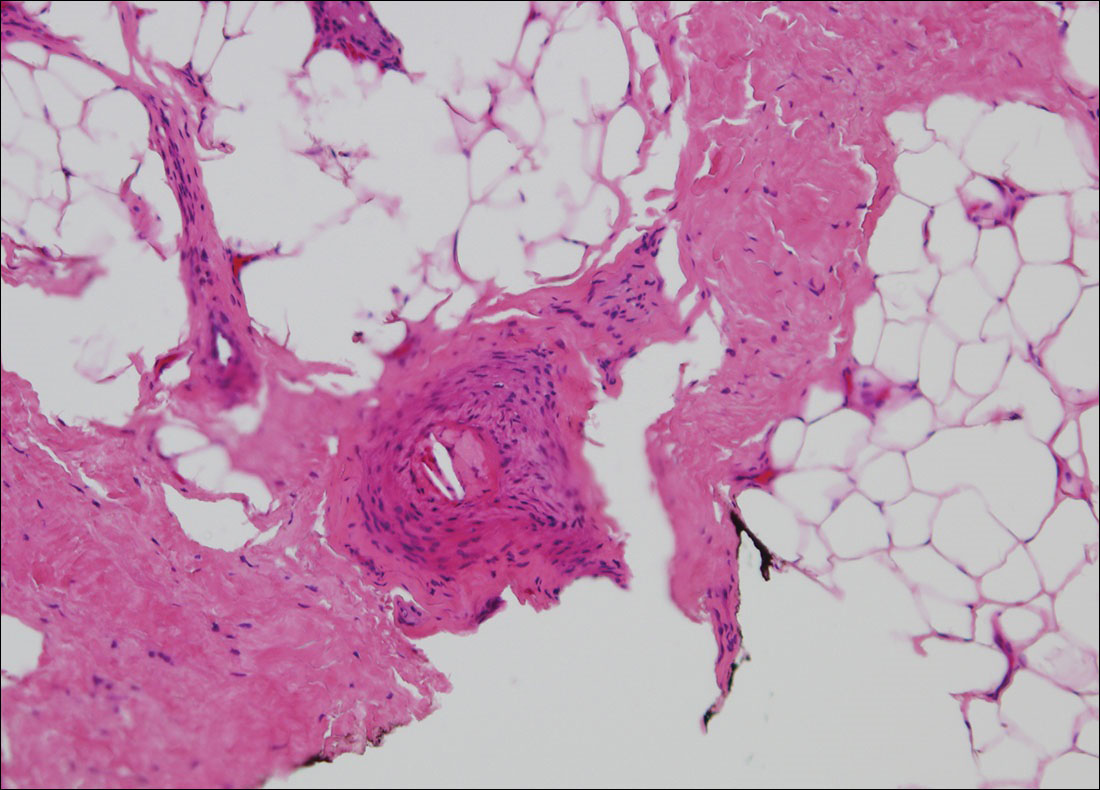

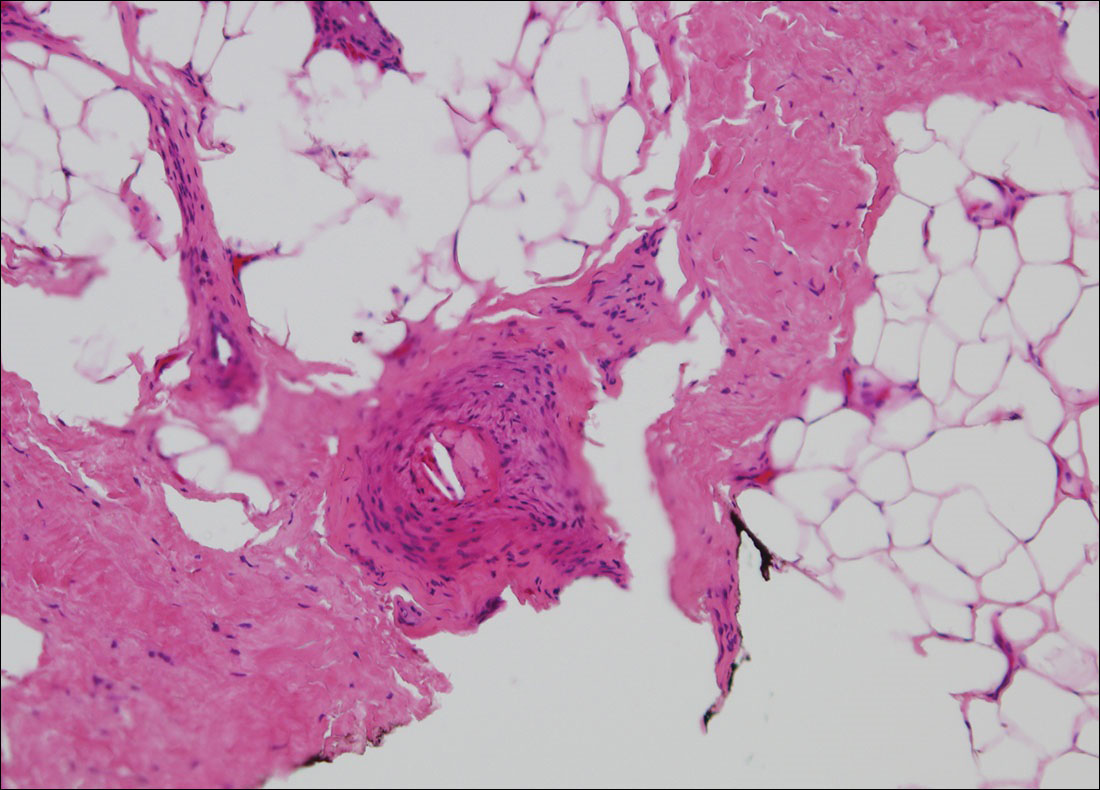

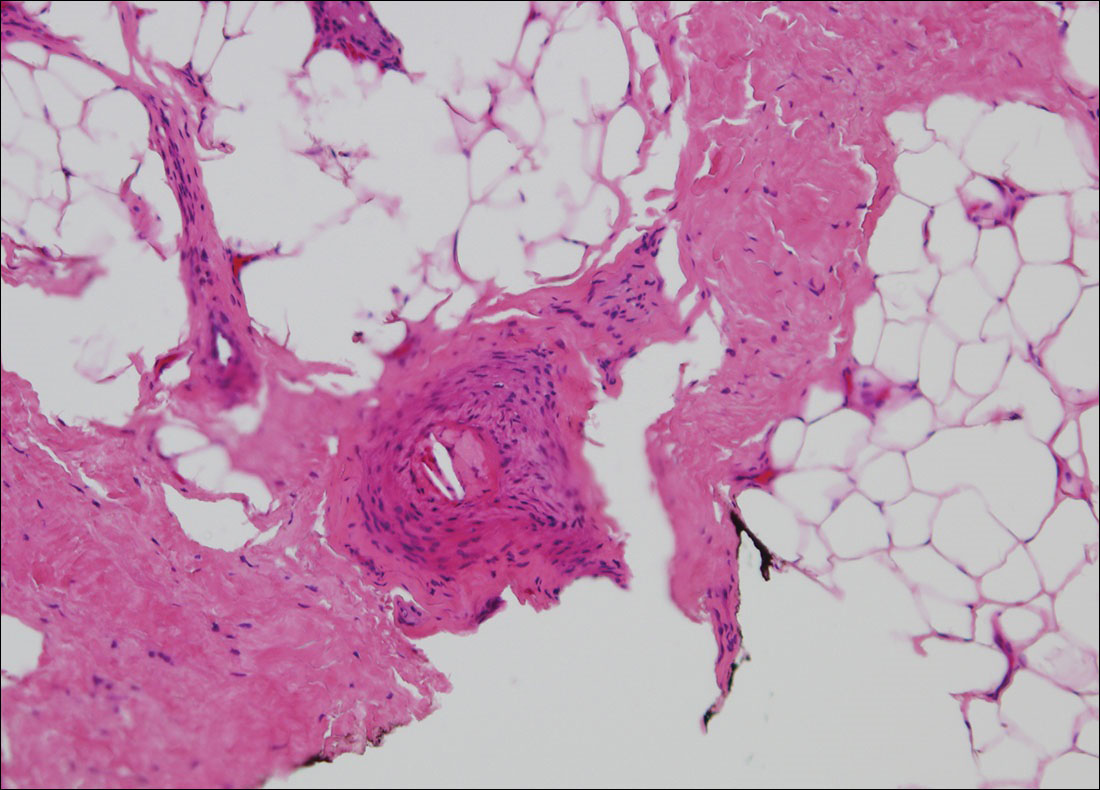

The clinical manifestation suggested blue toe syndrome. A variety of causes for blue toe syndrome are known such as embolism, thrombosis, vasoconstrictive disorders, infectious and noninfectious inflammation, extensive venous thrombosis, and abnormal circulating blood.1 Among them, only emboli from atherosclerotic plaques give rise to typical cholesterol clefts on skin biopsy (Figure 1). Such atheroemboli often are an iatrogenic complication, especially those caused by invasive percutaneous procedures or damage to the arterial walls from vascular surgery. However, spontaneous plaque hemorrhage or shearing forces of the circulating blood can disrupt atheromatous plaques and cause embolization of the cholesterol crystals, which was likely to be the case in our patient because no preceding trigger events were noted.

Other clinical features also are seen in atheroembolism. Approximately half of patients with atheroembolism develop clinical kidney disease.2 Almost all iatrogenic cases have acute or subacute reduction in glomerular filtration rate of at least to 50% level, whereas the spontaneous cases present as stable chronic renal failure.3 Approximately 20% of patients with atheroembolism also have involvement of digestive organs.4,5 Abdominal pain, diarrhea, and gastrointestinal blood loss are common features; bowel infarction and perforation occasionally occur.5 Pancreatitis is another common complication, and serum amylase levels are raised in approximately 50% of patients.6 Atheroemboli may reach the eyes and brain. They occasionally can cause loss of vision,7 as well as transient ischemic attacks, strokes, and gradual deterioration in cerebral function.3 Blood eosinophilia, which occurs in approximately 60% of patients, is an important finding.3,8

Although there is no specific therapy for atheroembolism, the use of antiplatelet agents is considered reasonable because they are beneficial in preventing myocardial infarction in patients with atherosclerosis.9 In our case, the livedo reticularis cleared, as did the coldness on the affected toes after 2 weeks of sarpogrelate hydrochloride administration; however, development of necrotic change was noted (Figure 2). Necrotic change on the hallux disappeared after 2 weeks.

- Hirschmann JV, Raugi GJ. Blue (or purple) toe syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:1-20; quiz 21-22.

- Scolari F, Ravani P, Gaggi R, et al. The challenge of diagnosing atheroembolic renal disease: clinical features and prognostic factors. Circulation. 2007;116:298-304.

- Scolari F, Tardanico R, Zani R, et al. Cholesterol crystal embolism: a recognizable cause of renal disease. Am J Kidney Dis. 2000;36:1089-1109.

- Moolenaar W, Lamers CB. Cholesterol crystal embolization in the Netherlands. Arch Intern Med. 1996;156:653-657.

- Ben-Horin S, Bardan E, Barshack I, et al. Cholesterol crystal embolization to the digestive system: characterization of a common, yet overlooked presentation of atheroembolism. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:1471-1479.

- Mayo RR, Swartz RD. Redefining the incidence of clinically detectable atheroembolism. Am J Med. 1996;100:524-529.

- Gittinger JW Jr, Kershaw GR. Retinal cholesterol emboli in the diagnosis of renal atheroembolism. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158:1265-1267.

- Kasinath BS, Corwin HL, Bidani AK, et al. Eosinophilia in the diagnosis of atheroembolic renal disease. Am J Nephrol. 1987;7:173-177.

- Quinones A, Saric M. The cholesterol emboli syndrome in atherosclerosis. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2013;15:315.

The Diagnosis: Blue Toe Syndrome

The clinical manifestation suggested blue toe syndrome. A variety of causes for blue toe syndrome are known such as embolism, thrombosis, vasoconstrictive disorders, infectious and noninfectious inflammation, extensive venous thrombosis, and abnormal circulating blood.1 Among them, only emboli from atherosclerotic plaques give rise to typical cholesterol clefts on skin biopsy (Figure 1). Such atheroemboli often are an iatrogenic complication, especially those caused by invasive percutaneous procedures or damage to the arterial walls from vascular surgery. However, spontaneous plaque hemorrhage or shearing forces of the circulating blood can disrupt atheromatous plaques and cause embolization of the cholesterol crystals, which was likely to be the case in our patient because no preceding trigger events were noted.

Other clinical features also are seen in atheroembolism. Approximately half of patients with atheroembolism develop clinical kidney disease.2 Almost all iatrogenic cases have acute or subacute reduction in glomerular filtration rate of at least to 50% level, whereas the spontaneous cases present as stable chronic renal failure.3 Approximately 20% of patients with atheroembolism also have involvement of digestive organs.4,5 Abdominal pain, diarrhea, and gastrointestinal blood loss are common features; bowel infarction and perforation occasionally occur.5 Pancreatitis is another common complication, and serum amylase levels are raised in approximately 50% of patients.6 Atheroemboli may reach the eyes and brain. They occasionally can cause loss of vision,7 as well as transient ischemic attacks, strokes, and gradual deterioration in cerebral function.3 Blood eosinophilia, which occurs in approximately 60% of patients, is an important finding.3,8

Although there is no specific therapy for atheroembolism, the use of antiplatelet agents is considered reasonable because they are beneficial in preventing myocardial infarction in patients with atherosclerosis.9 In our case, the livedo reticularis cleared, as did the coldness on the affected toes after 2 weeks of sarpogrelate hydrochloride administration; however, development of necrotic change was noted (Figure 2). Necrotic change on the hallux disappeared after 2 weeks.

The Diagnosis: Blue Toe Syndrome

The clinical manifestation suggested blue toe syndrome. A variety of causes for blue toe syndrome are known such as embolism, thrombosis, vasoconstrictive disorders, infectious and noninfectious inflammation, extensive venous thrombosis, and abnormal circulating blood.1 Among them, only emboli from atherosclerotic plaques give rise to typical cholesterol clefts on skin biopsy (Figure 1). Such atheroemboli often are an iatrogenic complication, especially those caused by invasive percutaneous procedures or damage to the arterial walls from vascular surgery. However, spontaneous plaque hemorrhage or shearing forces of the circulating blood can disrupt atheromatous plaques and cause embolization of the cholesterol crystals, which was likely to be the case in our patient because no preceding trigger events were noted.

Other clinical features also are seen in atheroembolism. Approximately half of patients with atheroembolism develop clinical kidney disease.2 Almost all iatrogenic cases have acute or subacute reduction in glomerular filtration rate of at least to 50% level, whereas the spontaneous cases present as stable chronic renal failure.3 Approximately 20% of patients with atheroembolism also have involvement of digestive organs.4,5 Abdominal pain, diarrhea, and gastrointestinal blood loss are common features; bowel infarction and perforation occasionally occur.5 Pancreatitis is another common complication, and serum amylase levels are raised in approximately 50% of patients.6 Atheroemboli may reach the eyes and brain. They occasionally can cause loss of vision,7 as well as transient ischemic attacks, strokes, and gradual deterioration in cerebral function.3 Blood eosinophilia, which occurs in approximately 60% of patients, is an important finding.3,8

Although there is no specific therapy for atheroembolism, the use of antiplatelet agents is considered reasonable because they are beneficial in preventing myocardial infarction in patients with atherosclerosis.9 In our case, the livedo reticularis cleared, as did the coldness on the affected toes after 2 weeks of sarpogrelate hydrochloride administration; however, development of necrotic change was noted (Figure 2). Necrotic change on the hallux disappeared after 2 weeks.

- Hirschmann JV, Raugi GJ. Blue (or purple) toe syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:1-20; quiz 21-22.

- Scolari F, Ravani P, Gaggi R, et al. The challenge of diagnosing atheroembolic renal disease: clinical features and prognostic factors. Circulation. 2007;116:298-304.

- Scolari F, Tardanico R, Zani R, et al. Cholesterol crystal embolism: a recognizable cause of renal disease. Am J Kidney Dis. 2000;36:1089-1109.

- Moolenaar W, Lamers CB. Cholesterol crystal embolization in the Netherlands. Arch Intern Med. 1996;156:653-657.

- Ben-Horin S, Bardan E, Barshack I, et al. Cholesterol crystal embolization to the digestive system: characterization of a common, yet overlooked presentation of atheroembolism. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:1471-1479.

- Mayo RR, Swartz RD. Redefining the incidence of clinically detectable atheroembolism. Am J Med. 1996;100:524-529.

- Gittinger JW Jr, Kershaw GR. Retinal cholesterol emboli in the diagnosis of renal atheroembolism. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158:1265-1267.

- Kasinath BS, Corwin HL, Bidani AK, et al. Eosinophilia in the diagnosis of atheroembolic renal disease. Am J Nephrol. 1987;7:173-177.

- Quinones A, Saric M. The cholesterol emboli syndrome in atherosclerosis. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2013;15:315.

- Hirschmann JV, Raugi GJ. Blue (or purple) toe syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:1-20; quiz 21-22.

- Scolari F, Ravani P, Gaggi R, et al. The challenge of diagnosing atheroembolic renal disease: clinical features and prognostic factors. Circulation. 2007;116:298-304.

- Scolari F, Tardanico R, Zani R, et al. Cholesterol crystal embolism: a recognizable cause of renal disease. Am J Kidney Dis. 2000;36:1089-1109.

- Moolenaar W, Lamers CB. Cholesterol crystal embolization in the Netherlands. Arch Intern Med. 1996;156:653-657.

- Ben-Horin S, Bardan E, Barshack I, et al. Cholesterol crystal embolization to the digestive system: characterization of a common, yet overlooked presentation of atheroembolism. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:1471-1479.

- Mayo RR, Swartz RD. Redefining the incidence of clinically detectable atheroembolism. Am J Med. 1996;100:524-529.

- Gittinger JW Jr, Kershaw GR. Retinal cholesterol emboli in the diagnosis of renal atheroembolism. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158:1265-1267.

- Kasinath BS, Corwin HL, Bidani AK, et al. Eosinophilia in the diagnosis of atheroembolic renal disease. Am J Nephrol. 1987;7:173-177.

- Quinones A, Saric M. The cholesterol emboli syndrome in atherosclerosis. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2013;15:315.

A 63-year-old man presented with sudden onset of severe pain in the right hallux and fifth toe of 3 days' duration. The patient had hypertension and hyperlipidemia with a 45-year history of smoking and had not undergone any vascular procedures. Physical examination revealed relatively well-defined cyanotic change with remarkable coldness on the affected toes as well as livedo reticularis on the underside of the toes. All peripheral pulses were present. Laboratory investigation revealed no remarkable changes with eosinophil counts within reference range and normal renal function. A biopsy taken from the fifth toe revealed thrombotic arterioles with cholesterol clefts.