User login

Palmoplantar exanthema and liver dysfunction

A 51-year-old man with type 2 diabetes was referred to our hospital because of liver dysfunction and nonpruritic exanthema, with papulosquamous, scaly, papular and macular lesions on his trunk and extremities, including his palms (Figure 1) and soles. Also noted were tiny grayish mucus patches on the oral mucosa. Axillary and inguinal superficial lymph nodes were palpable.

Laboratory testing revealed elevated serum levels of markers of liver disease, ie:

- Total bilirubin 9.8 mg/dL (reference range 0.2–1.3)

- Direct bilirubin 8.0 mg/dL (< 0.2)

- Aspartate aminotransferase 57 IU/L (13–35)

- Alanine aminotransferase 90 IU/L (10–54)

- Alkaline phosphatase 4,446 IU/L (36–108).

Possible causes of liver dysfunction such as legal and illicit drugs, alcohol abuse, obstructive biliary tract or liver disease, viral hepatitis, and primary biliary cirrhosis were ruled out by history, serologic testing, abdominal ultrasonography, and computed tomography.

Secondary syphilis was suspected in view of the characteristic distribution of exanthema involving the trunk and extremities, especially the palms and soles. On questioning, the patient admitted to having had unprotected sex with a female sex worker, which also raised the probability of syphilis infection.

The rapid plasma reagin test was positive at a titer of 1:16, and the Treponema pallidum agglutination test was positive at a signal-to-cutoff ratio of 27.02. Antibody testing for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) was negative.

The patient was started on penicillin G, but 4 hours later, he developed a fever with a temperature of 100.2°F (37.9°C), which was assumed to be a Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction. The fever resolved by the next morning without further treatment.

His course was otherwise uneventful. The exanthema resolved within 3 months, and his liver function returned to normal. Five months later, the rapid plasma reagin test was repeated on an outpatient basis, and the result was normal.

SYPHILIS IS NOT A DISEASE OF THE PAST

Syphilis is caused by T pallidum and is mainly transmitted by sexual contact.1

The incidence of syphilis has substantially increased in recent years in Japan2,3 and worldwide.4 The typical patient is a young man who has sex with men, is infected with HIV, and has a history of syphilis infection.3 However, the rapid increase in syphilis infections in Japan in recent years is largely because of an increase in heterosexual transmission.3

Infectious in its early stages

Syphilis is potentially infectious in its early (primary, secondary, and early latent) stages.1,5 The secondary stage generally begins 6 to 8 weeks after the primary infection1 and presents with diverse symptoms, including arthralgia, condylomata lata, generalized lymphadenopathy, maculopapular and papulosquamous exanthema, myalgia, and pharyngitis.1

Liver dysfunction in secondary syphilis

Liver dysfunction is common in secondary syphilis, occurring in 25% to 50% of cases.5 The liver enzyme pattern in most cases is a disproportionate increase in the alkaline phosphatase level compared with modest elevations of aminotransferases and bilirubin.2,5 However, some cases may show predominant hepatocellular damage (with prominent elevations in aminotransferase levels), and others may present with severe cholestasis (with prominent elevations in alkaline phosphatase and bilirubin) or even fulminant hepatic failure.2,5

The diagnostic criteria for syphilitic hepatitis are abnormal liver enzyme levels, serologic evidence of syphilis in conjunction with acute clinical presentation of secondary syphilis, exclusion of alternative causes of liver dysfunction, and prompt recovery of liver function after antimicrobial therapy.2,5

Pathogenic mechanisms in syphilitic hepatitis include direct portal venous inoculation and immune complex-mediated disease.2 However, direct hepatotoxicity of the microorganism seems unlikely, as spirochetes are rarely detected in liver specimens.2,5

Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction

The Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction is an acute febrile illness during the first 24 hours of antimicrobial treatment.1,6 It is assumed to be due to lysis of large numbers of spirochetes, releasing lipopolysaccharides (endotoxins) that further incite the release of a range of cytokines, resulting in symptoms such as fever, chills, myalgias, headache, tachycardia, hyperventilation, vasodilation with flushing, and mild hypotension.6,7

The frequency of Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction in syphilis and other spirochetal infections has varied widely in different reports.8 It is common in primary and secondary syphilis but usually does not occur in latent syphilis.6

Consider the diagnosis

Physicians should consider secondary syphilis in patients who present with characteristic generalized reddish macules and papules with papulosquamous lesions, including on the palms and soles as in our patient, and also in patients who have had unprotected sexual contact. Syphilis is not a disease of the past.

Acknowledgment: The authors thank Dr. Joel Branch, Shonan Kamakura General Hospital, Japan, for his editorial assistance.

- Mattei PL, Beachkofsky TM, Gilson RT, Wisco OJ. Syphilis: a reemerging infection. Am Fam Physician 2012; 86(5):433–440. pmid:22963062

- Miura H, Nakano M, Ryu T, Kitamura S, Suzaki A. A case of syphilis presenting with initial syphilitic hepatitis and serological recurrence with cerebrospinal abnormality. Intern Med 2010; 49(14):1377–1381. pmid:20647651

- Nishijima T, Teruya K, Shibata S, et al. Incidence and risk factors for incident syphilis among HIV-1-infected men who have sex with men in a large urban HIV clinic in Tokyo, 2008-2015. PLoS One 2016; 11(12):e0168642. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0168642

- US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF), Bibbins-Domingo K, Grossman DC, Curry SJ, et al. Screening for syphilis infection in nonpregnant adults and adolescents: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA 2016; 315(21):2321–2327. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.5824

- Aggarwal A, Sharma V, Vaiphei K, Duseja A, Chawla YK. An unusual cause of cholestatic hepatitis: syphilis. Dig Dis Sci 2013; 58(10):3049–3051. doi:10.1007/s10620-013-2581-5

- Belum GR, Belum VR, Chaitanya Arudra SK, Reddy BS. The Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction: revisited. Travel Med Infect Dis 2013; 11(4):231–237. doi:10.1016/j.tmaid.2013.04.001

- Nau R, Eiffert H. Modulation of release of proinflammatory bacterial compounds by antibacterials: potential impact on course of inflammation and outcome in sepsis and meningitis. Clin Microbiol Rev 2002; 15(1):95–110. pmid:11781269

- Butler T. The Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction after antibiotic treatment of spirochetal infections: a review of recent cases and our understanding of pathogenesis. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2017; 96(1):46–52. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.16-0434

A 51-year-old man with type 2 diabetes was referred to our hospital because of liver dysfunction and nonpruritic exanthema, with papulosquamous, scaly, papular and macular lesions on his trunk and extremities, including his palms (Figure 1) and soles. Also noted were tiny grayish mucus patches on the oral mucosa. Axillary and inguinal superficial lymph nodes were palpable.

Laboratory testing revealed elevated serum levels of markers of liver disease, ie:

- Total bilirubin 9.8 mg/dL (reference range 0.2–1.3)

- Direct bilirubin 8.0 mg/dL (< 0.2)

- Aspartate aminotransferase 57 IU/L (13–35)

- Alanine aminotransferase 90 IU/L (10–54)

- Alkaline phosphatase 4,446 IU/L (36–108).

Possible causes of liver dysfunction such as legal and illicit drugs, alcohol abuse, obstructive biliary tract or liver disease, viral hepatitis, and primary biliary cirrhosis were ruled out by history, serologic testing, abdominal ultrasonography, and computed tomography.

Secondary syphilis was suspected in view of the characteristic distribution of exanthema involving the trunk and extremities, especially the palms and soles. On questioning, the patient admitted to having had unprotected sex with a female sex worker, which also raised the probability of syphilis infection.

The rapid plasma reagin test was positive at a titer of 1:16, and the Treponema pallidum agglutination test was positive at a signal-to-cutoff ratio of 27.02. Antibody testing for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) was negative.

The patient was started on penicillin G, but 4 hours later, he developed a fever with a temperature of 100.2°F (37.9°C), which was assumed to be a Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction. The fever resolved by the next morning without further treatment.

His course was otherwise uneventful. The exanthema resolved within 3 months, and his liver function returned to normal. Five months later, the rapid plasma reagin test was repeated on an outpatient basis, and the result was normal.

SYPHILIS IS NOT A DISEASE OF THE PAST

Syphilis is caused by T pallidum and is mainly transmitted by sexual contact.1

The incidence of syphilis has substantially increased in recent years in Japan2,3 and worldwide.4 The typical patient is a young man who has sex with men, is infected with HIV, and has a history of syphilis infection.3 However, the rapid increase in syphilis infections in Japan in recent years is largely because of an increase in heterosexual transmission.3

Infectious in its early stages

Syphilis is potentially infectious in its early (primary, secondary, and early latent) stages.1,5 The secondary stage generally begins 6 to 8 weeks after the primary infection1 and presents with diverse symptoms, including arthralgia, condylomata lata, generalized lymphadenopathy, maculopapular and papulosquamous exanthema, myalgia, and pharyngitis.1

Liver dysfunction in secondary syphilis

Liver dysfunction is common in secondary syphilis, occurring in 25% to 50% of cases.5 The liver enzyme pattern in most cases is a disproportionate increase in the alkaline phosphatase level compared with modest elevations of aminotransferases and bilirubin.2,5 However, some cases may show predominant hepatocellular damage (with prominent elevations in aminotransferase levels), and others may present with severe cholestasis (with prominent elevations in alkaline phosphatase and bilirubin) or even fulminant hepatic failure.2,5

The diagnostic criteria for syphilitic hepatitis are abnormal liver enzyme levels, serologic evidence of syphilis in conjunction with acute clinical presentation of secondary syphilis, exclusion of alternative causes of liver dysfunction, and prompt recovery of liver function after antimicrobial therapy.2,5

Pathogenic mechanisms in syphilitic hepatitis include direct portal venous inoculation and immune complex-mediated disease.2 However, direct hepatotoxicity of the microorganism seems unlikely, as spirochetes are rarely detected in liver specimens.2,5

Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction

The Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction is an acute febrile illness during the first 24 hours of antimicrobial treatment.1,6 It is assumed to be due to lysis of large numbers of spirochetes, releasing lipopolysaccharides (endotoxins) that further incite the release of a range of cytokines, resulting in symptoms such as fever, chills, myalgias, headache, tachycardia, hyperventilation, vasodilation with flushing, and mild hypotension.6,7

The frequency of Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction in syphilis and other spirochetal infections has varied widely in different reports.8 It is common in primary and secondary syphilis but usually does not occur in latent syphilis.6

Consider the diagnosis

Physicians should consider secondary syphilis in patients who present with characteristic generalized reddish macules and papules with papulosquamous lesions, including on the palms and soles as in our patient, and also in patients who have had unprotected sexual contact. Syphilis is not a disease of the past.

Acknowledgment: The authors thank Dr. Joel Branch, Shonan Kamakura General Hospital, Japan, for his editorial assistance.

A 51-year-old man with type 2 diabetes was referred to our hospital because of liver dysfunction and nonpruritic exanthema, with papulosquamous, scaly, papular and macular lesions on his trunk and extremities, including his palms (Figure 1) and soles. Also noted were tiny grayish mucus patches on the oral mucosa. Axillary and inguinal superficial lymph nodes were palpable.

Laboratory testing revealed elevated serum levels of markers of liver disease, ie:

- Total bilirubin 9.8 mg/dL (reference range 0.2–1.3)

- Direct bilirubin 8.0 mg/dL (< 0.2)

- Aspartate aminotransferase 57 IU/L (13–35)

- Alanine aminotransferase 90 IU/L (10–54)

- Alkaline phosphatase 4,446 IU/L (36–108).

Possible causes of liver dysfunction such as legal and illicit drugs, alcohol abuse, obstructive biliary tract or liver disease, viral hepatitis, and primary biliary cirrhosis were ruled out by history, serologic testing, abdominal ultrasonography, and computed tomography.

Secondary syphilis was suspected in view of the characteristic distribution of exanthema involving the trunk and extremities, especially the palms and soles. On questioning, the patient admitted to having had unprotected sex with a female sex worker, which also raised the probability of syphilis infection.

The rapid plasma reagin test was positive at a titer of 1:16, and the Treponema pallidum agglutination test was positive at a signal-to-cutoff ratio of 27.02. Antibody testing for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) was negative.

The patient was started on penicillin G, but 4 hours later, he developed a fever with a temperature of 100.2°F (37.9°C), which was assumed to be a Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction. The fever resolved by the next morning without further treatment.

His course was otherwise uneventful. The exanthema resolved within 3 months, and his liver function returned to normal. Five months later, the rapid plasma reagin test was repeated on an outpatient basis, and the result was normal.

SYPHILIS IS NOT A DISEASE OF THE PAST

Syphilis is caused by T pallidum and is mainly transmitted by sexual contact.1

The incidence of syphilis has substantially increased in recent years in Japan2,3 and worldwide.4 The typical patient is a young man who has sex with men, is infected with HIV, and has a history of syphilis infection.3 However, the rapid increase in syphilis infections in Japan in recent years is largely because of an increase in heterosexual transmission.3

Infectious in its early stages

Syphilis is potentially infectious in its early (primary, secondary, and early latent) stages.1,5 The secondary stage generally begins 6 to 8 weeks after the primary infection1 and presents with diverse symptoms, including arthralgia, condylomata lata, generalized lymphadenopathy, maculopapular and papulosquamous exanthema, myalgia, and pharyngitis.1

Liver dysfunction in secondary syphilis

Liver dysfunction is common in secondary syphilis, occurring in 25% to 50% of cases.5 The liver enzyme pattern in most cases is a disproportionate increase in the alkaline phosphatase level compared with modest elevations of aminotransferases and bilirubin.2,5 However, some cases may show predominant hepatocellular damage (with prominent elevations in aminotransferase levels), and others may present with severe cholestasis (with prominent elevations in alkaline phosphatase and bilirubin) or even fulminant hepatic failure.2,5

The diagnostic criteria for syphilitic hepatitis are abnormal liver enzyme levels, serologic evidence of syphilis in conjunction with acute clinical presentation of secondary syphilis, exclusion of alternative causes of liver dysfunction, and prompt recovery of liver function after antimicrobial therapy.2,5

Pathogenic mechanisms in syphilitic hepatitis include direct portal venous inoculation and immune complex-mediated disease.2 However, direct hepatotoxicity of the microorganism seems unlikely, as spirochetes are rarely detected in liver specimens.2,5

Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction

The Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction is an acute febrile illness during the first 24 hours of antimicrobial treatment.1,6 It is assumed to be due to lysis of large numbers of spirochetes, releasing lipopolysaccharides (endotoxins) that further incite the release of a range of cytokines, resulting in symptoms such as fever, chills, myalgias, headache, tachycardia, hyperventilation, vasodilation with flushing, and mild hypotension.6,7

The frequency of Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction in syphilis and other spirochetal infections has varied widely in different reports.8 It is common in primary and secondary syphilis but usually does not occur in latent syphilis.6

Consider the diagnosis

Physicians should consider secondary syphilis in patients who present with characteristic generalized reddish macules and papules with papulosquamous lesions, including on the palms and soles as in our patient, and also in patients who have had unprotected sexual contact. Syphilis is not a disease of the past.

Acknowledgment: The authors thank Dr. Joel Branch, Shonan Kamakura General Hospital, Japan, for his editorial assistance.

- Mattei PL, Beachkofsky TM, Gilson RT, Wisco OJ. Syphilis: a reemerging infection. Am Fam Physician 2012; 86(5):433–440. pmid:22963062

- Miura H, Nakano M, Ryu T, Kitamura S, Suzaki A. A case of syphilis presenting with initial syphilitic hepatitis and serological recurrence with cerebrospinal abnormality. Intern Med 2010; 49(14):1377–1381. pmid:20647651

- Nishijima T, Teruya K, Shibata S, et al. Incidence and risk factors for incident syphilis among HIV-1-infected men who have sex with men in a large urban HIV clinic in Tokyo, 2008-2015. PLoS One 2016; 11(12):e0168642. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0168642

- US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF), Bibbins-Domingo K, Grossman DC, Curry SJ, et al. Screening for syphilis infection in nonpregnant adults and adolescents: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA 2016; 315(21):2321–2327. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.5824

- Aggarwal A, Sharma V, Vaiphei K, Duseja A, Chawla YK. An unusual cause of cholestatic hepatitis: syphilis. Dig Dis Sci 2013; 58(10):3049–3051. doi:10.1007/s10620-013-2581-5

- Belum GR, Belum VR, Chaitanya Arudra SK, Reddy BS. The Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction: revisited. Travel Med Infect Dis 2013; 11(4):231–237. doi:10.1016/j.tmaid.2013.04.001

- Nau R, Eiffert H. Modulation of release of proinflammatory bacterial compounds by antibacterials: potential impact on course of inflammation and outcome in sepsis and meningitis. Clin Microbiol Rev 2002; 15(1):95–110. pmid:11781269

- Butler T. The Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction after antibiotic treatment of spirochetal infections: a review of recent cases and our understanding of pathogenesis. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2017; 96(1):46–52. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.16-0434

- Mattei PL, Beachkofsky TM, Gilson RT, Wisco OJ. Syphilis: a reemerging infection. Am Fam Physician 2012; 86(5):433–440. pmid:22963062

- Miura H, Nakano M, Ryu T, Kitamura S, Suzaki A. A case of syphilis presenting with initial syphilitic hepatitis and serological recurrence with cerebrospinal abnormality. Intern Med 2010; 49(14):1377–1381. pmid:20647651

- Nishijima T, Teruya K, Shibata S, et al. Incidence and risk factors for incident syphilis among HIV-1-infected men who have sex with men in a large urban HIV clinic in Tokyo, 2008-2015. PLoS One 2016; 11(12):e0168642. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0168642

- US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF), Bibbins-Domingo K, Grossman DC, Curry SJ, et al. Screening for syphilis infection in nonpregnant adults and adolescents: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA 2016; 315(21):2321–2327. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.5824

- Aggarwal A, Sharma V, Vaiphei K, Duseja A, Chawla YK. An unusual cause of cholestatic hepatitis: syphilis. Dig Dis Sci 2013; 58(10):3049–3051. doi:10.1007/s10620-013-2581-5

- Belum GR, Belum VR, Chaitanya Arudra SK, Reddy BS. The Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction: revisited. Travel Med Infect Dis 2013; 11(4):231–237. doi:10.1016/j.tmaid.2013.04.001

- Nau R, Eiffert H. Modulation of release of proinflammatory bacterial compounds by antibacterials: potential impact on course of inflammation and outcome in sepsis and meningitis. Clin Microbiol Rev 2002; 15(1):95–110. pmid:11781269

- Butler T. The Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction after antibiotic treatment of spirochetal infections: a review of recent cases and our understanding of pathogenesis. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2017; 96(1):46–52. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.16-0434

Ascites from intraperitoneal urine leakage after pelvic radiation

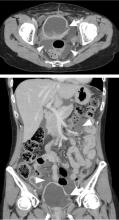

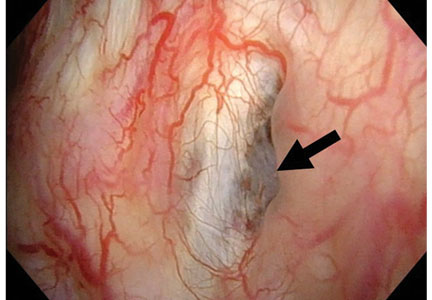

A 44-year-old woman was admitted to the hospital for the second time in 2 months with acute onset of severe abdominal pain. She had a history of cervical cancer treated with total hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy at age 38.

LONG-TERM EFFECTS OF RADIATION ON THE BLADDER

Urinary ascites from intraperitoneal urine leakage is a rare but clinically important sequel to bladder fistula or bladder wall rupture. Fistula or rupture can be caused by pelvic irradiation, blunt trauma, or surgical procedures, but may also be spontaneous.2

When the total radiation dose to the bladder exceeds 60 Gy, radiation cystitis may occur, leading to bladder fistula.3 Effects of radiation on the bladder are usually seen within 2 to 4 years3 but may occur long after the completion of radiation therapy—10 years2 or even 30 to 40 years later.4 Therefore, ascites of unknown origin in a patient with a history of pelvic radiation therapy should lead to an evaluation for late radiation cystitis and urinary ascites from bladder rupture.

- Ramcharan K, Poon-King TM, Indar R. Spontaneous intraperitoneal rupture of a neurogenic bladder; the importance of ascitic fluid urea and electrolytes in diagnosis. Postgrad Med J 1987; 63:999–1000.

- Matsumura M, Ando N, Kumabe A, Dhaliwal G. Pseudo-renal failure: bladder rupture with urinary ascites. BMJ Case Rep 2015; pii:bcr2015212671.

- Shi F, Wang T, Wang J, et al. Peritoneal bladder fistula following radiotherapy for cervical cancer: a case report. Oncol Lett 2016; 12:2008–2010.

- Hayashi W, Nishino T, Namie S, Obata Y, Furukawa M, Kohno S. Spontaneous bladder rupture diagnosis based on urinary appearance of mesothelial cells: a case report. J Med Case Rep 2014; 8:46.

A 44-year-old woman was admitted to the hospital for the second time in 2 months with acute onset of severe abdominal pain. She had a history of cervical cancer treated with total hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy at age 38.

LONG-TERM EFFECTS OF RADIATION ON THE BLADDER

Urinary ascites from intraperitoneal urine leakage is a rare but clinically important sequel to bladder fistula or bladder wall rupture. Fistula or rupture can be caused by pelvic irradiation, blunt trauma, or surgical procedures, but may also be spontaneous.2

When the total radiation dose to the bladder exceeds 60 Gy, radiation cystitis may occur, leading to bladder fistula.3 Effects of radiation on the bladder are usually seen within 2 to 4 years3 but may occur long after the completion of radiation therapy—10 years2 or even 30 to 40 years later.4 Therefore, ascites of unknown origin in a patient with a history of pelvic radiation therapy should lead to an evaluation for late radiation cystitis and urinary ascites from bladder rupture.

A 44-year-old woman was admitted to the hospital for the second time in 2 months with acute onset of severe abdominal pain. She had a history of cervical cancer treated with total hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy at age 38.

LONG-TERM EFFECTS OF RADIATION ON THE BLADDER

Urinary ascites from intraperitoneal urine leakage is a rare but clinically important sequel to bladder fistula or bladder wall rupture. Fistula or rupture can be caused by pelvic irradiation, blunt trauma, or surgical procedures, but may also be spontaneous.2

When the total radiation dose to the bladder exceeds 60 Gy, radiation cystitis may occur, leading to bladder fistula.3 Effects of radiation on the bladder are usually seen within 2 to 4 years3 but may occur long after the completion of radiation therapy—10 years2 or even 30 to 40 years later.4 Therefore, ascites of unknown origin in a patient with a history of pelvic radiation therapy should lead to an evaluation for late radiation cystitis and urinary ascites from bladder rupture.

- Ramcharan K, Poon-King TM, Indar R. Spontaneous intraperitoneal rupture of a neurogenic bladder; the importance of ascitic fluid urea and electrolytes in diagnosis. Postgrad Med J 1987; 63:999–1000.

- Matsumura M, Ando N, Kumabe A, Dhaliwal G. Pseudo-renal failure: bladder rupture with urinary ascites. BMJ Case Rep 2015; pii:bcr2015212671.

- Shi F, Wang T, Wang J, et al. Peritoneal bladder fistula following radiotherapy for cervical cancer: a case report. Oncol Lett 2016; 12:2008–2010.

- Hayashi W, Nishino T, Namie S, Obata Y, Furukawa M, Kohno S. Spontaneous bladder rupture diagnosis based on urinary appearance of mesothelial cells: a case report. J Med Case Rep 2014; 8:46.

- Ramcharan K, Poon-King TM, Indar R. Spontaneous intraperitoneal rupture of a neurogenic bladder; the importance of ascitic fluid urea and electrolytes in diagnosis. Postgrad Med J 1987; 63:999–1000.

- Matsumura M, Ando N, Kumabe A, Dhaliwal G. Pseudo-renal failure: bladder rupture with urinary ascites. BMJ Case Rep 2015; pii:bcr2015212671.

- Shi F, Wang T, Wang J, et al. Peritoneal bladder fistula following radiotherapy for cervical cancer: a case report. Oncol Lett 2016; 12:2008–2010.

- Hayashi W, Nishino T, Namie S, Obata Y, Furukawa M, Kohno S. Spontaneous bladder rupture diagnosis based on urinary appearance of mesothelial cells: a case report. J Med Case Rep 2014; 8:46.