User login

Nonblanching Rash on the Legs and Chest

The Diagnosis: Leukemia Cutis

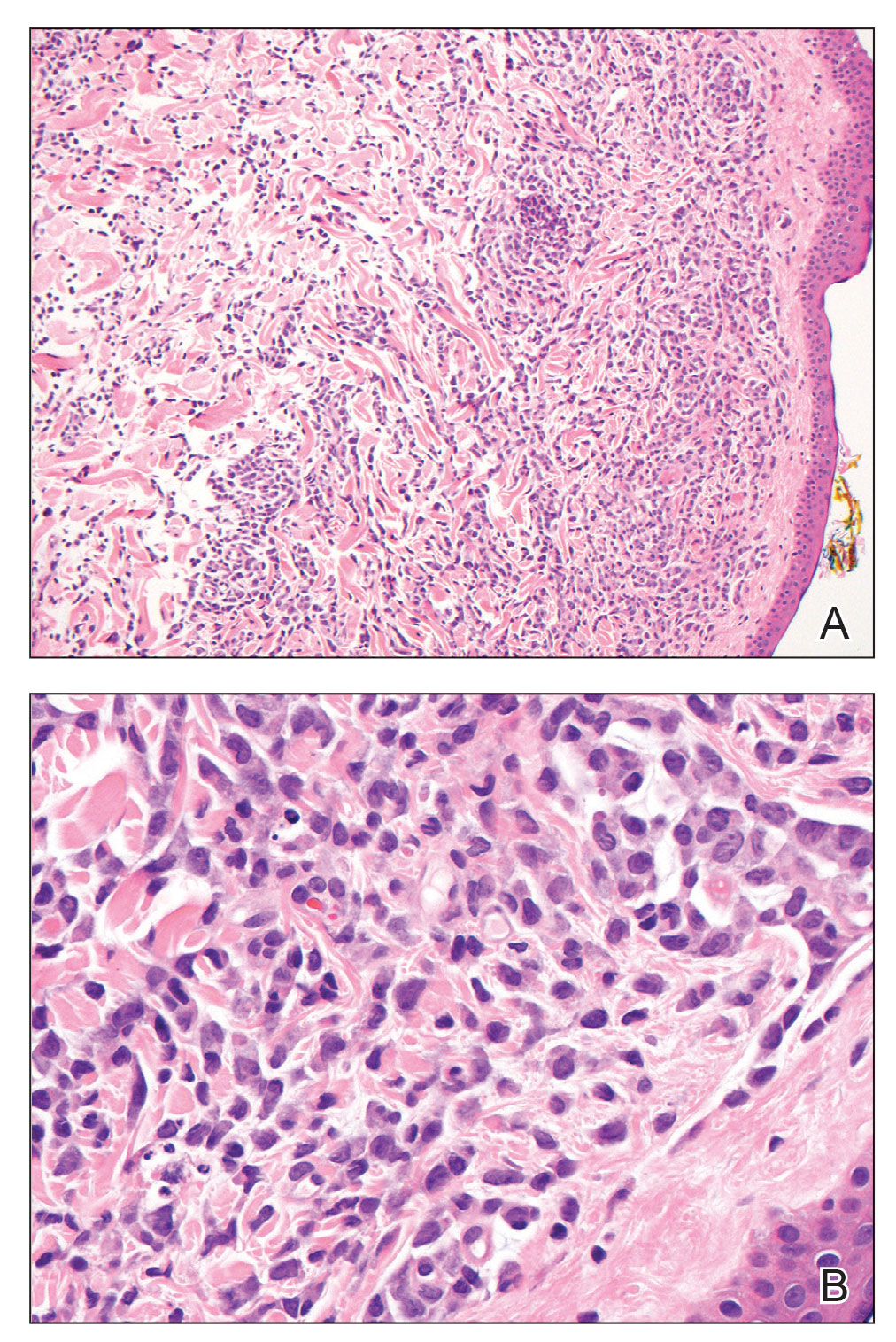

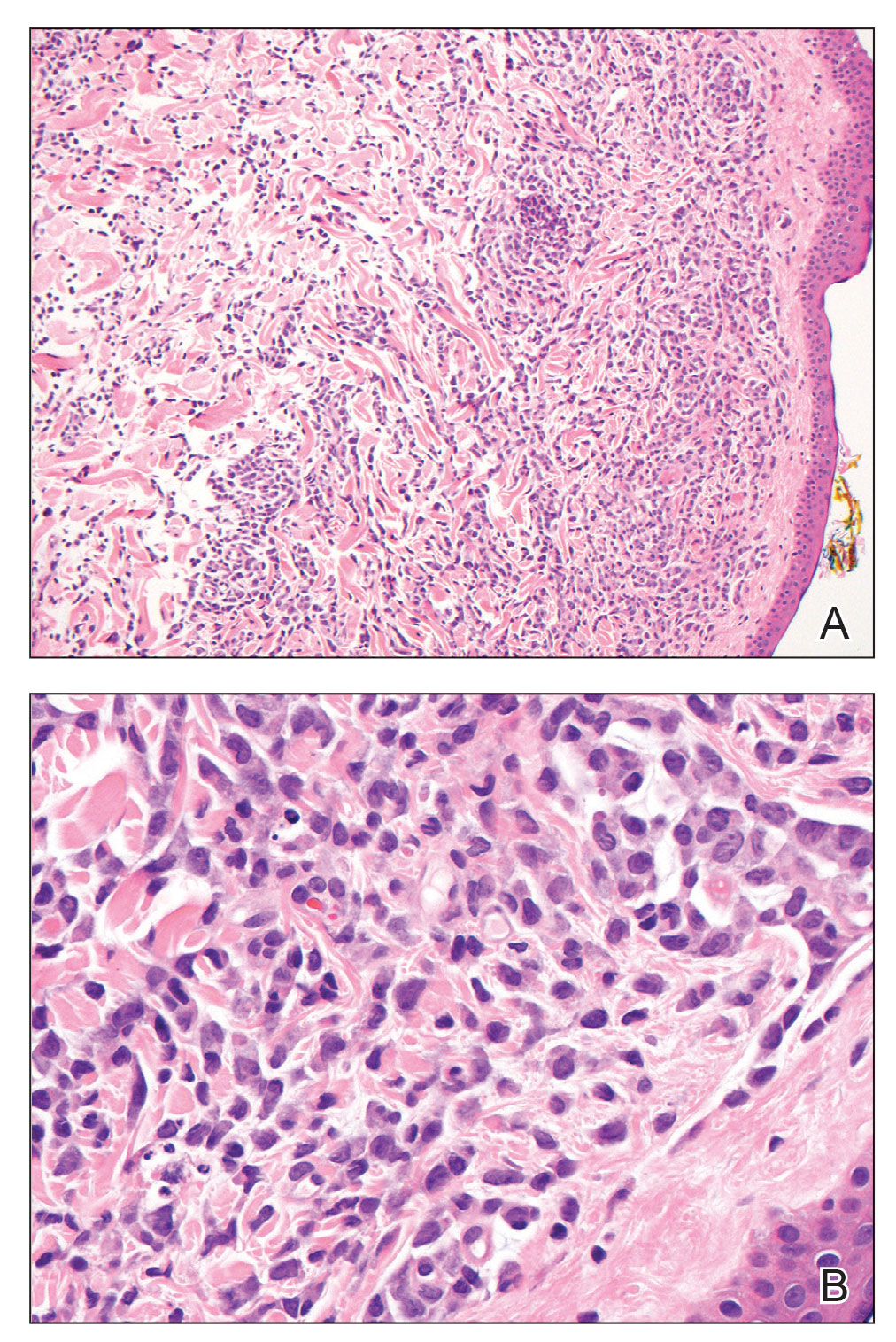

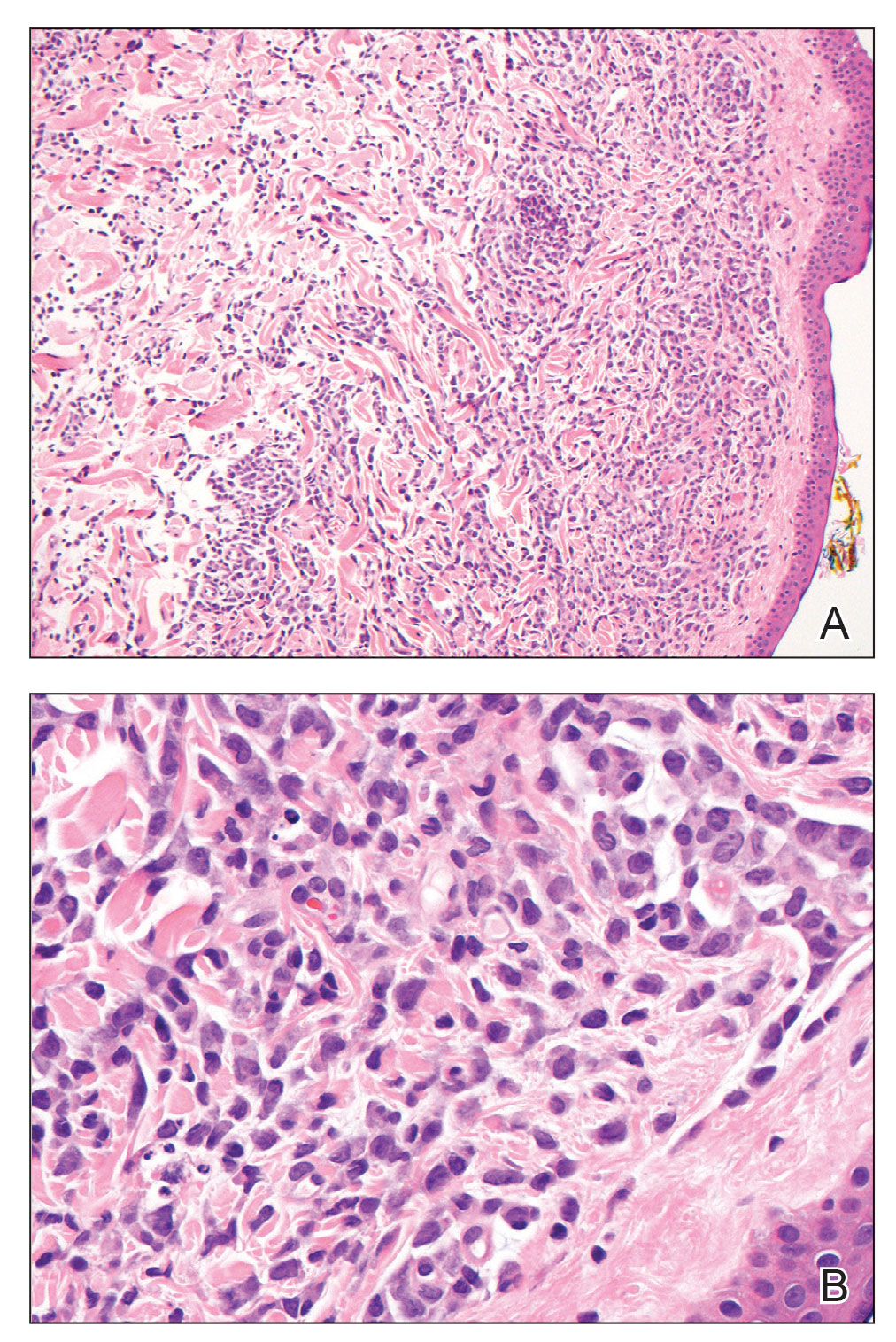

Hematoxylin and eosin staining revealed an infiltration of monomorphic atypical myeloid cells with cleaved nuclei within the dermis, with a relatively uninvolved epidermis (Figure, A). The cells formed aggregates in single-file lines along dermal collagen bundles. Occasional Auer rods, which are crystal aggregates of the enzyme myeloperoxidase, a marker unique to cells of the myeloid lineage (Figure, B) were appreciated.

Immunohistochemical staining for myeloperoxidase was weakly positive; however, flow cytometric evaluation of the bone marrow aspirate revealed that approximately 20% of all CD45+ cells were myeloid blasts. These findings confirmed the diagnosis of recurrent acute myeloid leukemia (AML). The diagnosis of AML can be confirmed with a bone marrow biopsy demonstrating more than 20% of the total cells in blast form as well as evidence that the cells are of myeloid origin, which can be inferred by the presence of Auer rods, positive myeloperoxidase staining, or immunophenotyping. In our patient, the Auer rods, myeloperoxidase staining, and atypical myeloid cells on skin biopsy, in conjunction with the bone marrow biopsy results, confirmed leukemia cutis.

Leukemia cutis is the infiltration of neoplastic proliferating leukocytes in the epidermis, dermis, or subcutis from a primary or more commonly metastatic malignancy. Leukemic cutaneous involvement is seen in up to 13% of leukemia patients and most commonly is seen in monocytic or myelomonocytic forms of AML.1 It may present anywhere on the body but mostly is found on the back, trunk, and head. It also may have a predilection for areas with a history of trauma or inflammation. The lesions most often are firm, erythematous to violaceous papules and nodules, though leukemia cutis can present with hemorrhagic ulcers, purpura, or other cutaneous manifestations of concomitant thrombocytopenia such as petechiae and ecchymoses.2 Involvement of the lower extremities mimicking venous stasis dermatitis has been described.3,4

Treatment of leukemia cutis requires targeting the underlying leukemia2 under the guidance of hematology and oncology as well as the use of chemotherapeutic agents.5 The presence of leukemia cutis is a poor prognostic sign, and a discussion regarding goals of care often is appropriate. Our patient initially responded to FLAG (fludarabine, cytarabine, filgrastim) chemotherapy induction and consolidation, which was followed by midostaurin maintenance. However, she ultimately regressed, requiring decitabine and gilteritinib treatment, and died 9 months later from the course of the disease.

Although typically asymptomatic and presenting on the lower limbs, capillaritis (also known as the pigmented purpuric dermatoses) consists of a set of cutaneous conditions that often are chronic and relapsing in nature, as opposed to our patient’s subacute presentation. These benign conditions have several distinct morphologies; some are characterized by pigmented macules or pinpoint red-brown petechiae that most often are found on the legs but also are seen on the trunk and upper extremities.6 Of the various clinical presentations of capillaritis, our patient’s skin findings may be most consistent with pigmented purpuric lichenoid dermatitis of Gougerot and Blum, in which purpuric red-brown papules coalesce into plaques, though her lesions were not raised. The other pigmented purpuric dermatoses can present with cayenne pepper–colored petechiae, golden-brown macules, pruritic purpuric patches, or red-brown annular patches,6 which were not seen in our patient.

Venous stasis dermatitis also favors the lower extremities7; however, it classically includes the medial malleolus and often presents with scaling and hyperpigmentation from hemosiderin deposition.8 It often is associated with pruritus, as opposed to the nonpruritic nonpainful lesions in leukemia cutis. Other signs of venous insufficiency also may be appreciated, including edema or varicose veins,7 which were not evident in our patient.

Leukocytoclastic vasculitis, a small vessel vasculitis, also appears as palpable or macular purpura, which classically is asymptomatic and erupts on the shins approximately 1 week after an inciting exposure,9 such as medications, pathogens, or autoimmune diseases. One of the least distinctive vasculitides is polyarteritis nodosa, a form of medium vessel vasculitis, which presents most often with palpable purpura or painful nodules on the lower extremities and may be accompanied by livedo reticularis or digital necrosis.9 Acute leukemia may be accompanied by inflammatory paraneoplastic conditions including vasculitis, which is thought to be due to leukemic cells infiltrating and damaging blood vessels.10

Pretibial myxedema is closely associated with Graves disease and shares some features seen in the presentation of our patient’s leukemia cutis. It is asymptomatic, classically affects the pretibial regions, and most commonly affects older adults and women.11,12 Pretibial myxedema presents with thick indurated plaques rather than patches. Our patient did not demonstrate ophthalmopathy, which nearly always precedes pretibial myxedema.12 The most common form of pretibial myxedema is nonpitting, though nodular, plaquelike, polypoid, and elephantiasic forms also exist.11 Pretibial myxedema classically favors the shins; however, it also can affect the ankles, dorsal aspects of the feet, and toes. The characteristic induration of the skin is believed to be the result of excess fibroblast production of glycosaminoglycans in the dermis and subcutis likely triggered by stimulation of fibroblast thyroid stimulating hormone receptors.11

- Bakst RL, Tallman MS, Douer D, et al. How I treat extramedullary acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2011;118:3785-3793.

- Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Duncan KO, et al. Other lymphoproliferative and myeloproliferative diseases. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Duncan KO, et al, eds. Dermatology Essentials. 2nd ed. Elsevier; 2014:973-977.

- Papadavid E, Panayiotides I, Katoulis A, et al. Stasis dermatitis-like leukaemic infiltration in a patient with myelodysplastic syndrome. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2008;33:298-300.

- Chang HY, Wong KM, Bosenberg M, et al. Myelogenous leukemia cutis resembling stasis dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:128-129.

- Aguilera SB, Zarraga M, Rosen L. Leukemia cutis in a patient with acute myelogenous leukemia: a case report and review of the literature. Cutis. 2010;85:31-36.

- Kim DH, Seo SH, Ahn HH, et al. Characteristics and clinical manifestations of pigmented purpuric dermatosis. Ann Dermatol. 2015;27:404-410.

- Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Duncan KO, et al. Other eczematous eruptions. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Duncan KO, et al, eds. Dermatology Essentials. 2nd ed. Elsevier; 2014:103-108.

- Krooks JA, Weatherall AG. Leukemia cutis in acute myeloid leukemia signifies a poor prognosis. Cutis. 2018;102:266, 271-272.

- Wetter DA, Dutz JP, Shinkai K, et al. Cutaneous vasculitis. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Lorenzo C, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2018:409-439.

- Jones D, Dorfman DM, Barnhill RL, et al. Leukemic vasculitis: a feature of leukemia cutis in some patients. Am J Clin Pathol. 1997;107:637-642.

- Fatourechi V. Pretibial myxedema: pathophysiology and treatment options. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2005;6:295-309.

- Fatourechi V, Pajouhi M, Fransway AF. Dermopathy of Graves disease (pretibial myxedema). review of 150 cases. Medicine (Baltimore). 1994;73:1-7.

The Diagnosis: Leukemia Cutis

Hematoxylin and eosin staining revealed an infiltration of monomorphic atypical myeloid cells with cleaved nuclei within the dermis, with a relatively uninvolved epidermis (Figure, A). The cells formed aggregates in single-file lines along dermal collagen bundles. Occasional Auer rods, which are crystal aggregates of the enzyme myeloperoxidase, a marker unique to cells of the myeloid lineage (Figure, B) were appreciated.

Immunohistochemical staining for myeloperoxidase was weakly positive; however, flow cytometric evaluation of the bone marrow aspirate revealed that approximately 20% of all CD45+ cells were myeloid blasts. These findings confirmed the diagnosis of recurrent acute myeloid leukemia (AML). The diagnosis of AML can be confirmed with a bone marrow biopsy demonstrating more than 20% of the total cells in blast form as well as evidence that the cells are of myeloid origin, which can be inferred by the presence of Auer rods, positive myeloperoxidase staining, or immunophenotyping. In our patient, the Auer rods, myeloperoxidase staining, and atypical myeloid cells on skin biopsy, in conjunction with the bone marrow biopsy results, confirmed leukemia cutis.

Leukemia cutis is the infiltration of neoplastic proliferating leukocytes in the epidermis, dermis, or subcutis from a primary or more commonly metastatic malignancy. Leukemic cutaneous involvement is seen in up to 13% of leukemia patients and most commonly is seen in monocytic or myelomonocytic forms of AML.1 It may present anywhere on the body but mostly is found on the back, trunk, and head. It also may have a predilection for areas with a history of trauma or inflammation. The lesions most often are firm, erythematous to violaceous papules and nodules, though leukemia cutis can present with hemorrhagic ulcers, purpura, or other cutaneous manifestations of concomitant thrombocytopenia such as petechiae and ecchymoses.2 Involvement of the lower extremities mimicking venous stasis dermatitis has been described.3,4

Treatment of leukemia cutis requires targeting the underlying leukemia2 under the guidance of hematology and oncology as well as the use of chemotherapeutic agents.5 The presence of leukemia cutis is a poor prognostic sign, and a discussion regarding goals of care often is appropriate. Our patient initially responded to FLAG (fludarabine, cytarabine, filgrastim) chemotherapy induction and consolidation, which was followed by midostaurin maintenance. However, she ultimately regressed, requiring decitabine and gilteritinib treatment, and died 9 months later from the course of the disease.

Although typically asymptomatic and presenting on the lower limbs, capillaritis (also known as the pigmented purpuric dermatoses) consists of a set of cutaneous conditions that often are chronic and relapsing in nature, as opposed to our patient’s subacute presentation. These benign conditions have several distinct morphologies; some are characterized by pigmented macules or pinpoint red-brown petechiae that most often are found on the legs but also are seen on the trunk and upper extremities.6 Of the various clinical presentations of capillaritis, our patient’s skin findings may be most consistent with pigmented purpuric lichenoid dermatitis of Gougerot and Blum, in which purpuric red-brown papules coalesce into plaques, though her lesions were not raised. The other pigmented purpuric dermatoses can present with cayenne pepper–colored petechiae, golden-brown macules, pruritic purpuric patches, or red-brown annular patches,6 which were not seen in our patient.

Venous stasis dermatitis also favors the lower extremities7; however, it classically includes the medial malleolus and often presents with scaling and hyperpigmentation from hemosiderin deposition.8 It often is associated with pruritus, as opposed to the nonpruritic nonpainful lesions in leukemia cutis. Other signs of venous insufficiency also may be appreciated, including edema or varicose veins,7 which were not evident in our patient.

Leukocytoclastic vasculitis, a small vessel vasculitis, also appears as palpable or macular purpura, which classically is asymptomatic and erupts on the shins approximately 1 week after an inciting exposure,9 such as medications, pathogens, or autoimmune diseases. One of the least distinctive vasculitides is polyarteritis nodosa, a form of medium vessel vasculitis, which presents most often with palpable purpura or painful nodules on the lower extremities and may be accompanied by livedo reticularis or digital necrosis.9 Acute leukemia may be accompanied by inflammatory paraneoplastic conditions including vasculitis, which is thought to be due to leukemic cells infiltrating and damaging blood vessels.10

Pretibial myxedema is closely associated with Graves disease and shares some features seen in the presentation of our patient’s leukemia cutis. It is asymptomatic, classically affects the pretibial regions, and most commonly affects older adults and women.11,12 Pretibial myxedema presents with thick indurated plaques rather than patches. Our patient did not demonstrate ophthalmopathy, which nearly always precedes pretibial myxedema.12 The most common form of pretibial myxedema is nonpitting, though nodular, plaquelike, polypoid, and elephantiasic forms also exist.11 Pretibial myxedema classically favors the shins; however, it also can affect the ankles, dorsal aspects of the feet, and toes. The characteristic induration of the skin is believed to be the result of excess fibroblast production of glycosaminoglycans in the dermis and subcutis likely triggered by stimulation of fibroblast thyroid stimulating hormone receptors.11

The Diagnosis: Leukemia Cutis

Hematoxylin and eosin staining revealed an infiltration of monomorphic atypical myeloid cells with cleaved nuclei within the dermis, with a relatively uninvolved epidermis (Figure, A). The cells formed aggregates in single-file lines along dermal collagen bundles. Occasional Auer rods, which are crystal aggregates of the enzyme myeloperoxidase, a marker unique to cells of the myeloid lineage (Figure, B) were appreciated.

Immunohistochemical staining for myeloperoxidase was weakly positive; however, flow cytometric evaluation of the bone marrow aspirate revealed that approximately 20% of all CD45+ cells were myeloid blasts. These findings confirmed the diagnosis of recurrent acute myeloid leukemia (AML). The diagnosis of AML can be confirmed with a bone marrow biopsy demonstrating more than 20% of the total cells in blast form as well as evidence that the cells are of myeloid origin, which can be inferred by the presence of Auer rods, positive myeloperoxidase staining, or immunophenotyping. In our patient, the Auer rods, myeloperoxidase staining, and atypical myeloid cells on skin biopsy, in conjunction with the bone marrow biopsy results, confirmed leukemia cutis.

Leukemia cutis is the infiltration of neoplastic proliferating leukocytes in the epidermis, dermis, or subcutis from a primary or more commonly metastatic malignancy. Leukemic cutaneous involvement is seen in up to 13% of leukemia patients and most commonly is seen in monocytic or myelomonocytic forms of AML.1 It may present anywhere on the body but mostly is found on the back, trunk, and head. It also may have a predilection for areas with a history of trauma or inflammation. The lesions most often are firm, erythematous to violaceous papules and nodules, though leukemia cutis can present with hemorrhagic ulcers, purpura, or other cutaneous manifestations of concomitant thrombocytopenia such as petechiae and ecchymoses.2 Involvement of the lower extremities mimicking venous stasis dermatitis has been described.3,4

Treatment of leukemia cutis requires targeting the underlying leukemia2 under the guidance of hematology and oncology as well as the use of chemotherapeutic agents.5 The presence of leukemia cutis is a poor prognostic sign, and a discussion regarding goals of care often is appropriate. Our patient initially responded to FLAG (fludarabine, cytarabine, filgrastim) chemotherapy induction and consolidation, which was followed by midostaurin maintenance. However, she ultimately regressed, requiring decitabine and gilteritinib treatment, and died 9 months later from the course of the disease.

Although typically asymptomatic and presenting on the lower limbs, capillaritis (also known as the pigmented purpuric dermatoses) consists of a set of cutaneous conditions that often are chronic and relapsing in nature, as opposed to our patient’s subacute presentation. These benign conditions have several distinct morphologies; some are characterized by pigmented macules or pinpoint red-brown petechiae that most often are found on the legs but also are seen on the trunk and upper extremities.6 Of the various clinical presentations of capillaritis, our patient’s skin findings may be most consistent with pigmented purpuric lichenoid dermatitis of Gougerot and Blum, in which purpuric red-brown papules coalesce into plaques, though her lesions were not raised. The other pigmented purpuric dermatoses can present with cayenne pepper–colored petechiae, golden-brown macules, pruritic purpuric patches, or red-brown annular patches,6 which were not seen in our patient.

Venous stasis dermatitis also favors the lower extremities7; however, it classically includes the medial malleolus and often presents with scaling and hyperpigmentation from hemosiderin deposition.8 It often is associated with pruritus, as opposed to the nonpruritic nonpainful lesions in leukemia cutis. Other signs of venous insufficiency also may be appreciated, including edema or varicose veins,7 which were not evident in our patient.

Leukocytoclastic vasculitis, a small vessel vasculitis, also appears as palpable or macular purpura, which classically is asymptomatic and erupts on the shins approximately 1 week after an inciting exposure,9 such as medications, pathogens, or autoimmune diseases. One of the least distinctive vasculitides is polyarteritis nodosa, a form of medium vessel vasculitis, which presents most often with palpable purpura or painful nodules on the lower extremities and may be accompanied by livedo reticularis or digital necrosis.9 Acute leukemia may be accompanied by inflammatory paraneoplastic conditions including vasculitis, which is thought to be due to leukemic cells infiltrating and damaging blood vessels.10

Pretibial myxedema is closely associated with Graves disease and shares some features seen in the presentation of our patient’s leukemia cutis. It is asymptomatic, classically affects the pretibial regions, and most commonly affects older adults and women.11,12 Pretibial myxedema presents with thick indurated plaques rather than patches. Our patient did not demonstrate ophthalmopathy, which nearly always precedes pretibial myxedema.12 The most common form of pretibial myxedema is nonpitting, though nodular, plaquelike, polypoid, and elephantiasic forms also exist.11 Pretibial myxedema classically favors the shins; however, it also can affect the ankles, dorsal aspects of the feet, and toes. The characteristic induration of the skin is believed to be the result of excess fibroblast production of glycosaminoglycans in the dermis and subcutis likely triggered by stimulation of fibroblast thyroid stimulating hormone receptors.11

- Bakst RL, Tallman MS, Douer D, et al. How I treat extramedullary acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2011;118:3785-3793.

- Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Duncan KO, et al. Other lymphoproliferative and myeloproliferative diseases. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Duncan KO, et al, eds. Dermatology Essentials. 2nd ed. Elsevier; 2014:973-977.

- Papadavid E, Panayiotides I, Katoulis A, et al. Stasis dermatitis-like leukaemic infiltration in a patient with myelodysplastic syndrome. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2008;33:298-300.

- Chang HY, Wong KM, Bosenberg M, et al. Myelogenous leukemia cutis resembling stasis dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:128-129.

- Aguilera SB, Zarraga M, Rosen L. Leukemia cutis in a patient with acute myelogenous leukemia: a case report and review of the literature. Cutis. 2010;85:31-36.

- Kim DH, Seo SH, Ahn HH, et al. Characteristics and clinical manifestations of pigmented purpuric dermatosis. Ann Dermatol. 2015;27:404-410.

- Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Duncan KO, et al. Other eczematous eruptions. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Duncan KO, et al, eds. Dermatology Essentials. 2nd ed. Elsevier; 2014:103-108.

- Krooks JA, Weatherall AG. Leukemia cutis in acute myeloid leukemia signifies a poor prognosis. Cutis. 2018;102:266, 271-272.

- Wetter DA, Dutz JP, Shinkai K, et al. Cutaneous vasculitis. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Lorenzo C, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2018:409-439.

- Jones D, Dorfman DM, Barnhill RL, et al. Leukemic vasculitis: a feature of leukemia cutis in some patients. Am J Clin Pathol. 1997;107:637-642.

- Fatourechi V. Pretibial myxedema: pathophysiology and treatment options. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2005;6:295-309.

- Fatourechi V, Pajouhi M, Fransway AF. Dermopathy of Graves disease (pretibial myxedema). review of 150 cases. Medicine (Baltimore). 1994;73:1-7.

- Bakst RL, Tallman MS, Douer D, et al. How I treat extramedullary acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2011;118:3785-3793.

- Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Duncan KO, et al. Other lymphoproliferative and myeloproliferative diseases. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Duncan KO, et al, eds. Dermatology Essentials. 2nd ed. Elsevier; 2014:973-977.

- Papadavid E, Panayiotides I, Katoulis A, et al. Stasis dermatitis-like leukaemic infiltration in a patient with myelodysplastic syndrome. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2008;33:298-300.

- Chang HY, Wong KM, Bosenberg M, et al. Myelogenous leukemia cutis resembling stasis dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:128-129.

- Aguilera SB, Zarraga M, Rosen L. Leukemia cutis in a patient with acute myelogenous leukemia: a case report and review of the literature. Cutis. 2010;85:31-36.

- Kim DH, Seo SH, Ahn HH, et al. Characteristics and clinical manifestations of pigmented purpuric dermatosis. Ann Dermatol. 2015;27:404-410.

- Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Duncan KO, et al. Other eczematous eruptions. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Duncan KO, et al, eds. Dermatology Essentials. 2nd ed. Elsevier; 2014:103-108.

- Krooks JA, Weatherall AG. Leukemia cutis in acute myeloid leukemia signifies a poor prognosis. Cutis. 2018;102:266, 271-272.

- Wetter DA, Dutz JP, Shinkai K, et al. Cutaneous vasculitis. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Lorenzo C, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2018:409-439.

- Jones D, Dorfman DM, Barnhill RL, et al. Leukemic vasculitis: a feature of leukemia cutis in some patients. Am J Clin Pathol. 1997;107:637-642.

- Fatourechi V. Pretibial myxedema: pathophysiology and treatment options. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2005;6:295-309.

- Fatourechi V, Pajouhi M, Fransway AF. Dermopathy of Graves disease (pretibial myxedema). review of 150 cases. Medicine (Baltimore). 1994;73:1-7.

A 67-year-old woman with history of atrial fibrillation and leukemia presented with a nonpruritic nonpainful rash of 10 days' duration that began on the distal lower extremities (top) and then spread superiorly. She reported having a sore throat and mouth, cough, night sweats, unintentional weight loss, and lymphadenopathy. Physical examination revealed pink-purple nonblanching macules and patches on the lower extremities extending from the ankles to the knees. She also had firm pink papules on the chest (bottom) and back. Punch biopsies of the skin on the chest and leg were obtained for histologic examination and immunohistochemical staining.

Teledermatology During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Lessons Learned and Future Directions

Although teledermatology utilization in the United States traditionally has lagged behind other countries,1,2 the COVID-19 pandemic upended this trend by creating the need for a massive teledermatology experiment. Recently reported survey results from a large representative sample of US dermatologists (5000 participants) on perceptions of teledermatology during COVID-19 indicated that only 14.1% of participants used teledermatology prior to the COVID-19 pandemic vs 54.1% of dermatologists in Europe.2,3 Since the pandemic started, 97% of US dermatologists reported teledermatology use,3 demonstrating a huge shift in utilization. This trend is notable, as teledermatology has been shown to increase access to dermatology in underserved areas, reduce patient travel times, improve patient triage, and even reduce carbon footprints.1,4 Thus, to sustain the momentum, insights from the recent teledermatology experience during the pandemic should inform future development.

Notably, the COVID-19 pandemic led to a rapid shift in focus from store-and-forward teledermatology to live video–based models.1,2 Logistically, live video visits are challenging, require more time and resources, and often are diagnostically limited, with concerns regarding technology, connectivity, reimbursement, and appropriate use.3 Prior to COVID-19, formal Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act–compliant teledermatology platforms often were costly to establish and maintain, largely relegating use to academic centers and Veterans Affairs hospitals. Thus, many fewer private practice dermatologists had used teledermatology compared to academic dermatologists in the United States (11.4% vs 27.6%).3 Government regulations—a key barrier to the adoption of teledermatology in private practice before COVID-19—were greatly relaxed during the pandemic. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services removed restrictions on where patients could be seen, improved reimbursement for video visits, and allowed the use of platforms that are not Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act compliant. Many states also relaxed medical licensing rules.

Overall, the general outlook on telehealth seems positive. Reimbursement has been found to be a primary factor in dermatologists’ willingness to use teledermatology.3 Thus, sustainable use of teledermatology likely will depend on continued reimbursement parity for live video as well as store-and-forward consultations, which have several advantages but currently are de-incentivized by low reimbursement. The survey also found that 70% of respondents felt that teledermatology use will continue after COVID-19, while 58% intended to continue use—nearly 5-fold more than before the pandemic.3 We suspect the discrepancy between participants’ predictions regarding future use of teledermatology and their personal intent to use it highlights perceived barriers and limitations of the long-term success of teledermatology. Aside from reimbursement, connectivity and functionality were common concerns, emphasizing the need for innovative technological solutions.3 Moving forward, we anticipate that dermatologists will need to establish consistent workflows to establish consistent triage for the most appropriate visit—in-person visits vs teledermatology, which may include augmented, intelligence-enhanced solutions. Similar to prior clinician perspectives about which types of visits are conducive to teledermatology,2 most survey participants believed virtual visits were effective for acne, routine follow-ups, medication monitoring, and some inflammatory conditions.3

Importantly, we must be mindful of patients who may be left behind by the digital divide, such as those with lack of access to a smartphone or the internet, language barriers, or limited telehealth experience.5 Systems should be designed to provide these patients with technologic and health literacy aid or alternate modalities to access care. For example, structured methods could be introduced to provide training and instructions on how to access phone applications, computer-based programs, and more. Likewise, for those with hearing or vision deficits, it will be important to improve sound amplification and accessibility for headphones or hearing aid connectivity, as well as appropriate font size, button size, and application navigation. In remote areas, existing clinics may be used to help field specialty consultation teleconferences. Certainly, applications and platforms devised for teledermatology must be designed to serve diverse patient groups, with special consideration for the elderly, those who speak languages other than English, and those with disabilities that may make telehealth use more challenging.

Large-scale regulatory changes and reimbursement parity can have a substantial impact on future teledermatology use. Advocacy efforts continue to push for fair valuation of telemedicine, coverage of store-and-forward teledermatology codes, and coverage for all models of care. It is imperative for the dermatology community to continue discussions on implementation and methodology to best leverage this technology for the most patient benefit.

- Tensen E, van der Heijden JP, Jaspers MWM, et al. Two decades of teledermatology: current status and integration in national healthcare systems. Curr Dermatol Rep. 2016;5:96-104.

- Moscarella E, Pasquali P, Cinotti E, et al. A survey on teledermatology use and doctors’ perception in times of COVID-19 [published online August 17, 2020]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34:E772-E773.

- Kennedy J, Arey S, Hopkins Z, et al. Dermatologist perceptions of teledermatology implementation and future use after COVID-19: demographics, barriers, and insights. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:595-597.

- Bonsall A. Unleashing carbon emissions savings with regular teledermatology clinics. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2021;46:574-575.

- Bakhtiar M, Elbuluk N, Lipoff JB. The digital divide: how COVID-19’s telemedicine expansion could exacerbate disparities. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:E345-E346.

Although teledermatology utilization in the United States traditionally has lagged behind other countries,1,2 the COVID-19 pandemic upended this trend by creating the need for a massive teledermatology experiment. Recently reported survey results from a large representative sample of US dermatologists (5000 participants) on perceptions of teledermatology during COVID-19 indicated that only 14.1% of participants used teledermatology prior to the COVID-19 pandemic vs 54.1% of dermatologists in Europe.2,3 Since the pandemic started, 97% of US dermatologists reported teledermatology use,3 demonstrating a huge shift in utilization. This trend is notable, as teledermatology has been shown to increase access to dermatology in underserved areas, reduce patient travel times, improve patient triage, and even reduce carbon footprints.1,4 Thus, to sustain the momentum, insights from the recent teledermatology experience during the pandemic should inform future development.

Notably, the COVID-19 pandemic led to a rapid shift in focus from store-and-forward teledermatology to live video–based models.1,2 Logistically, live video visits are challenging, require more time and resources, and often are diagnostically limited, with concerns regarding technology, connectivity, reimbursement, and appropriate use.3 Prior to COVID-19, formal Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act–compliant teledermatology platforms often were costly to establish and maintain, largely relegating use to academic centers and Veterans Affairs hospitals. Thus, many fewer private practice dermatologists had used teledermatology compared to academic dermatologists in the United States (11.4% vs 27.6%).3 Government regulations—a key barrier to the adoption of teledermatology in private practice before COVID-19—were greatly relaxed during the pandemic. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services removed restrictions on where patients could be seen, improved reimbursement for video visits, and allowed the use of platforms that are not Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act compliant. Many states also relaxed medical licensing rules.

Overall, the general outlook on telehealth seems positive. Reimbursement has been found to be a primary factor in dermatologists’ willingness to use teledermatology.3 Thus, sustainable use of teledermatology likely will depend on continued reimbursement parity for live video as well as store-and-forward consultations, which have several advantages but currently are de-incentivized by low reimbursement. The survey also found that 70% of respondents felt that teledermatology use will continue after COVID-19, while 58% intended to continue use—nearly 5-fold more than before the pandemic.3 We suspect the discrepancy between participants’ predictions regarding future use of teledermatology and their personal intent to use it highlights perceived barriers and limitations of the long-term success of teledermatology. Aside from reimbursement, connectivity and functionality were common concerns, emphasizing the need for innovative technological solutions.3 Moving forward, we anticipate that dermatologists will need to establish consistent workflows to establish consistent triage for the most appropriate visit—in-person visits vs teledermatology, which may include augmented, intelligence-enhanced solutions. Similar to prior clinician perspectives about which types of visits are conducive to teledermatology,2 most survey participants believed virtual visits were effective for acne, routine follow-ups, medication monitoring, and some inflammatory conditions.3

Importantly, we must be mindful of patients who may be left behind by the digital divide, such as those with lack of access to a smartphone or the internet, language barriers, or limited telehealth experience.5 Systems should be designed to provide these patients with technologic and health literacy aid or alternate modalities to access care. For example, structured methods could be introduced to provide training and instructions on how to access phone applications, computer-based programs, and more. Likewise, for those with hearing or vision deficits, it will be important to improve sound amplification and accessibility for headphones or hearing aid connectivity, as well as appropriate font size, button size, and application navigation. In remote areas, existing clinics may be used to help field specialty consultation teleconferences. Certainly, applications and platforms devised for teledermatology must be designed to serve diverse patient groups, with special consideration for the elderly, those who speak languages other than English, and those with disabilities that may make telehealth use more challenging.

Large-scale regulatory changes and reimbursement parity can have a substantial impact on future teledermatology use. Advocacy efforts continue to push for fair valuation of telemedicine, coverage of store-and-forward teledermatology codes, and coverage for all models of care. It is imperative for the dermatology community to continue discussions on implementation and methodology to best leverage this technology for the most patient benefit.

Although teledermatology utilization in the United States traditionally has lagged behind other countries,1,2 the COVID-19 pandemic upended this trend by creating the need for a massive teledermatology experiment. Recently reported survey results from a large representative sample of US dermatologists (5000 participants) on perceptions of teledermatology during COVID-19 indicated that only 14.1% of participants used teledermatology prior to the COVID-19 pandemic vs 54.1% of dermatologists in Europe.2,3 Since the pandemic started, 97% of US dermatologists reported teledermatology use,3 demonstrating a huge shift in utilization. This trend is notable, as teledermatology has been shown to increase access to dermatology in underserved areas, reduce patient travel times, improve patient triage, and even reduce carbon footprints.1,4 Thus, to sustain the momentum, insights from the recent teledermatology experience during the pandemic should inform future development.

Notably, the COVID-19 pandemic led to a rapid shift in focus from store-and-forward teledermatology to live video–based models.1,2 Logistically, live video visits are challenging, require more time and resources, and often are diagnostically limited, with concerns regarding technology, connectivity, reimbursement, and appropriate use.3 Prior to COVID-19, formal Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act–compliant teledermatology platforms often were costly to establish and maintain, largely relegating use to academic centers and Veterans Affairs hospitals. Thus, many fewer private practice dermatologists had used teledermatology compared to academic dermatologists in the United States (11.4% vs 27.6%).3 Government regulations—a key barrier to the adoption of teledermatology in private practice before COVID-19—were greatly relaxed during the pandemic. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services removed restrictions on where patients could be seen, improved reimbursement for video visits, and allowed the use of platforms that are not Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act compliant. Many states also relaxed medical licensing rules.

Overall, the general outlook on telehealth seems positive. Reimbursement has been found to be a primary factor in dermatologists’ willingness to use teledermatology.3 Thus, sustainable use of teledermatology likely will depend on continued reimbursement parity for live video as well as store-and-forward consultations, which have several advantages but currently are de-incentivized by low reimbursement. The survey also found that 70% of respondents felt that teledermatology use will continue after COVID-19, while 58% intended to continue use—nearly 5-fold more than before the pandemic.3 We suspect the discrepancy between participants’ predictions regarding future use of teledermatology and their personal intent to use it highlights perceived barriers and limitations of the long-term success of teledermatology. Aside from reimbursement, connectivity and functionality were common concerns, emphasizing the need for innovative technological solutions.3 Moving forward, we anticipate that dermatologists will need to establish consistent workflows to establish consistent triage for the most appropriate visit—in-person visits vs teledermatology, which may include augmented, intelligence-enhanced solutions. Similar to prior clinician perspectives about which types of visits are conducive to teledermatology,2 most survey participants believed virtual visits were effective for acne, routine follow-ups, medication monitoring, and some inflammatory conditions.3

Importantly, we must be mindful of patients who may be left behind by the digital divide, such as those with lack of access to a smartphone or the internet, language barriers, or limited telehealth experience.5 Systems should be designed to provide these patients with technologic and health literacy aid or alternate modalities to access care. For example, structured methods could be introduced to provide training and instructions on how to access phone applications, computer-based programs, and more. Likewise, for those with hearing or vision deficits, it will be important to improve sound amplification and accessibility for headphones or hearing aid connectivity, as well as appropriate font size, button size, and application navigation. In remote areas, existing clinics may be used to help field specialty consultation teleconferences. Certainly, applications and platforms devised for teledermatology must be designed to serve diverse patient groups, with special consideration for the elderly, those who speak languages other than English, and those with disabilities that may make telehealth use more challenging.

Large-scale regulatory changes and reimbursement parity can have a substantial impact on future teledermatology use. Advocacy efforts continue to push for fair valuation of telemedicine, coverage of store-and-forward teledermatology codes, and coverage for all models of care. It is imperative for the dermatology community to continue discussions on implementation and methodology to best leverage this technology for the most patient benefit.

- Tensen E, van der Heijden JP, Jaspers MWM, et al. Two decades of teledermatology: current status and integration in national healthcare systems. Curr Dermatol Rep. 2016;5:96-104.

- Moscarella E, Pasquali P, Cinotti E, et al. A survey on teledermatology use and doctors’ perception in times of COVID-19 [published online August 17, 2020]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34:E772-E773.

- Kennedy J, Arey S, Hopkins Z, et al. Dermatologist perceptions of teledermatology implementation and future use after COVID-19: demographics, barriers, and insights. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:595-597.

- Bonsall A. Unleashing carbon emissions savings with regular teledermatology clinics. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2021;46:574-575.

- Bakhtiar M, Elbuluk N, Lipoff JB. The digital divide: how COVID-19’s telemedicine expansion could exacerbate disparities. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:E345-E346.

- Tensen E, van der Heijden JP, Jaspers MWM, et al. Two decades of teledermatology: current status and integration in national healthcare systems. Curr Dermatol Rep. 2016;5:96-104.

- Moscarella E, Pasquali P, Cinotti E, et al. A survey on teledermatology use and doctors’ perception in times of COVID-19 [published online August 17, 2020]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34:E772-E773.

- Kennedy J, Arey S, Hopkins Z, et al. Dermatologist perceptions of teledermatology implementation and future use after COVID-19: demographics, barriers, and insights. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:595-597.

- Bonsall A. Unleashing carbon emissions savings with regular teledermatology clinics. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2021;46:574-575.

- Bakhtiar M, Elbuluk N, Lipoff JB. The digital divide: how COVID-19’s telemedicine expansion could exacerbate disparities. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:E345-E346.