User login

The dramatic reduction in cardiovascular death and heart failure hospitalization seen during treatment with empagliflozin (Jardiance) in the EMPA-REG OUTCOME (Empagliflozin Cardiovascular Outcome Event Trial in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Patients) trial, for example, has prompted some cardiologists in the year since the first EMPA-REG report to become active prescribers of the drug to their patients who have type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease. The same evidence has driven other cardiologists who may not feel fully comfortable prescribing an antidiabetic drug on their own to enter into active partnerships with endocrinologists to work as a team to put diabetes patients with cardiovascular disease on empagliflozin.

In Dr. Fitchett’s practice, “if a patient with type 2 diabetes has an endocrinologist, then I will send a letter to that physician saying I think the patient should be on one of these drugs,” empagliflozin or liraglutide, he said. “If the patient is being treated by a primary care physician, then I will prescribe empagliflozin myself because most primary care physicians are not willing to prescribe it. I think more and more cardiologists are doing this. The great thing about empagliflozin and liraglutide is that they do not cause hypoglycemia and the adverse effect profiles are relatively good. As long as drug cost is not an issue, then as cardiologists we need to adjust glycemia control with cardiovascular benefit as we did years ago with statin treatment,” explained Dr. Fitchett, a cardiologist at St. Michael’s Hospital in Toronto and a senior collaborator and coauthor on the EMPA-REG study.

When results from the 4S [Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study] came out in 1994, proving that long-term statin treatment was both safe and increased survival in patients with coronary heart disease, “cardiologists took over lipid management from endocrinologists,” he recalled. “We now have a safe and simple treatment for glucose lowering that also cuts cardiovascular disease events, so cardiologists have to also be involved, at least to some extent. Their degree of involvement depends on their practice and who provides a patient’s primary diabetes care,” he said.

Cardiologists vary on empagliflozin

Other cardiologists are mixed in their take on personally prescribing antidiabetic drugs to high-risk patients with type 2 diabetes. Greg C. Fonarow, MD, has also aggressively taken to empagliflozin over the past year, especially for his patients with heart failure or at high risk for developing heart failure. The EMPA-REG results showed that empagliflozin’s potent impact on reducing cardiovascular death in patients linked closely with a reduction in heart failure hospitalizations. In his recent experience, endocrinologists as well as other physicians who care for patients with type 2 diabetes “are often reluctant to make any changes [in a patient’s hypoglycemic regimen], and in general they have not gravitated toward the treatments that have been shown to improve cardiovascular outcomes and instead focus solely on a patient’s hemoglobin A1c,” Dr. Fonarow said in an interview at the recent annual meeting of the Heart Failure Society of America.

He said he prescribes empagliflozin to patients with type 2 diabetes if they are hospitalized for heart failure or as outpatients, and he targets it to patients diagnosed with heart failure – including heart failure with preserved ejection fraction – as well as to patients with other forms of cardiovascular disease, closely following the EMPA-REG enrollment criteria. It’s too early in the experience with empagliflozin to use it preferentially in diabetes patients without cardiovascular disease or patients who in any other way fall outside the enrollment criteria for EMPA-REG, he said.

“I am happy to consult with their endocrinologist, or I tell patients to discuss this treatment with their endocrinologist. If the endocrinologist prescribes empagliflozin, great; if not, I feel an obligation to provide the best care I can to my patients. This is not a hard medication to use. The safety profile is good. Treatment with empagliflozin obviously has renal-function considerations, but that’s true for many drugs. The biggest challenge is what is covered by the patient’s insurance. We often need preauthorization.

“So far I have seen excellent responses in patients for both metabolic control and clinical responses in patients with heart failure. Their symptoms seem to improve,” said Dr. Fonarow, professor of medicine and co-chief of cardiology at the University of Southern California , Los Angeles.

While Dr. Fonarow cautioned that he also would not start empagliflozin in a patient with a HbA1c below 7%, he would seriously consider swapping out a patient’s drug for empagliflozin if it were a sulfonylurea or a dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor. He stopped short of suggesting a substitution of empagliflozin for metformin. In Dr. Fonarow’s opinion, the evidence for empagliflozin is also “more robust” than it has been for liraglutide or semaglutide. With what’s now known about the clinical impact of these drugs, he foresees a time when a combination between a SGLT-2 inhibitor, with its effect on heart failure, and a GLP-1 analogue, with its effect on atherosclerotic disease, may seem an ideal initial drug pairing for patients with type 2 diabetes and significant cardiovascular disease risk, with metformin relegated to a second-line role.

Other cardiologists endorsed a more collaborative approach to prescribing empagliflozin and liraglutide.

Another team-approach advocate is Robert O. Bonow, MD, cardiologist and professor of medicine at Northwestern University in Chicago. “Cardiologists are comfortable prescribing metformin and telling patients about lifestyle, but when it comes to newer antidiabetic drugs, that’s a new field, and a team approach may be best,” he said in an interview. “If possible, a cardiologist should have a friendly partnership with a diabetologist or endocrinologist who is expert in treating diabetes.” Many cardiologists now work in and for hospitals, and easy access to an endocrinologist is probably available, he noted.

But new analyses of the EMPA-REG data reported by Dr. Fitchett at the ESC congress showed that empagliflozin treatment exerted a similar benefit of reduced cardiovascular death regardless of whether patients had prevalent heart failure at entry into the study, incident heart failure during follow-up, or no heart failure of any sort.

Impact of heart failure in EMPA-REG

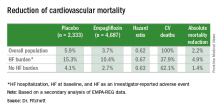

Roughly 10% of the 7,020 patients enrolled in EMPA-REG had heart failure at the time they entered the trial. During a median follow-up of just over 3 years, the incidence of new-onset heart failure – tallied as either a new heart failure hospitalization or a clinical episode deemed to be heart failure by an investigator – occurred in 4.6% of patients on empagliflozin and in 6.5% of patients in the placebo arm, a 1.9-percentage-point difference and a 30% relative risk reduction linked with empagliflozin use, Dr. Fitchett reported.

The main EMPA-REG outcome was a composite of cardiovascular death, nonfatal MI, and nonfatal stroke. This positive outcome in favor of empagliflozin treatment was primarily driven by a difference in the rate of cardiovascular death. In the new analysis, the relative reduction in cardiovascular deaths with empagliflozin compared with placebo was 29% among patients with prevalent heart failure at baseline, 35% among those who had an incident heart failure hospitalization during follow-up, 27% among patients with an incident heart failure episode diagnosed by an investigator during follow-up, 33% among the combined group of trial patients with any form of heart failure at trial entry or during the trial (those with prevalent heart failure at baseline plus those with an incident event), and 37% among the large number of patients in the trial who remained free from any indication of heart failure during follow-up.

In short, treatment with empagliflozin “reduced cardiovascular mortality by the same relative amount” regardless of whether patients did or did not have heart failure during the trial,” Dr. Fitchett concluded.

Additional secondary analyses from EMPA-REG reported at the ESC congress in August also documented that the benefit from empagliflozin treatment was roughly the same regardless of the age of patients enrolled in the trial and regardless of patients’ blood level of LDL cholesterol at entry into the study. These findings provide “confidence in the consistency of the effect” by empagliflozin, Dr. Fitchett said.

The endocrinologists’ view

“Most cardiologists are not thoroughly familiar with the full palette of medications for hyperglycemia. Selection of medication should not be made solely on the basis of results from a cardiovascular outcomes trial,” said Helena W. Rodbard, MD, a clinical endocrinologist in Rockville, Md.

“The EMPA-REG OUTCOMES and LEADER results are very exciting and encouraging. When all other factors are equal, the cardiovascular results could sway the decision about which medication to use. But an endocrinologist is in the best position to balance the many factors when choosing combination therapy and to set a target level for HbA1c, fasting blood glucose, and postprandial glucose, and to adjust therapy to minimize the risk of hypoglycemia,” Dr. Rodbard said in an interview.

He called empagliflozin a drug with “interesting promise,” especially for patients with incipient heart failure. The extra cardiovascular benefit from the GLP-1 analogues is “less settled,” although the liraglutide and semaglutide trial results are important and mean these drugs need more consideration and study. The EMPA-REG results were more clearly positive, he said.

“Metformin is still the initial drug” for most patients with type 2 diabetes, echoed Dr. Levy. Drugs like empagliflozin and liraglutide are usually used in combination with metformin.

“Like many endocrinologists, I have for some time used the oral SGLT-2 inhibitors and GLP-1 analogues in combination with metformin. It made sense before the recent cardiovascular data appeared, and it makes even more sense now,” said Dr. Jellinger, professor of clinical medicine and an endocrinologist at the University of Miami.

“Endocrinologists and diabetologists are aware that cardiologists have been taking a larger role in the care of patients with diabetes,” noted Dr. Rodbard. “I favor cardiologists and endocrinologists working in concert to improve the care of patients with diabetes.”

“Over the next few years, we will need to decide whether to treat patients with type 2 diabetes with an agent with proven benefits,” said Dr. Fitchett. “Until the results from EMPA-REG and the LEADER trial came out, there was no specific glucose-lowering agent that also reduced cardiovascular events. Some cardiologists might ask when they should get involved in managing patients with type 2 diabetes. What I would do for patients with a history of cardiovascular disease who develop new type 2 diabetes is start empagliflozin as their first drug,” Dr. Fitchett said, though he admitted that no evidence yet exists to back that approach.

The EMPA-REG trial was sponsored by Boehringer Ingelheim and by Eli Lilly, the companies that market empagliflozin. The LEADER trial was sponsored in part by Novo Nordisk, the company that markets liraglutide. Dr. Fitchett and Dr. Mentz were both researchers for EMPA-REG. Dr. Fitchett has been a consultant to AstraZeneca, Merck, and Amgen. Dr. Mentz has been an adviser to Boehringer Ingelheim. Dr. Fonarow has been an adviser to Amgen, Janssen, Novartis, and ZS Pharma. Dr. Bozkurt had no disclosures. Dr. Bonow has been a consultant to Gilead. Dr. Jellinger has been a speaker on behalf of Boehringer-Ingelheim, Novo Nordisk, Merck, and Janssen. Dr. Rodbard has been a consultant to or speaker for several drug companies including Boehringer-Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, and Novo Nordisk. Dr. Levy has been a speaker on behalf of Boehringer-Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, Novo Nordisk, and AstraZeneca. Dr. Hellman had no disclosures.

mzoler@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

The dramatic reduction in cardiovascular death and heart failure hospitalization seen during treatment with empagliflozin (Jardiance) in the EMPA-REG OUTCOME (Empagliflozin Cardiovascular Outcome Event Trial in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Patients) trial, for example, has prompted some cardiologists in the year since the first EMPA-REG report to become active prescribers of the drug to their patients who have type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease. The same evidence has driven other cardiologists who may not feel fully comfortable prescribing an antidiabetic drug on their own to enter into active partnerships with endocrinologists to work as a team to put diabetes patients with cardiovascular disease on empagliflozin.

In Dr. Fitchett’s practice, “if a patient with type 2 diabetes has an endocrinologist, then I will send a letter to that physician saying I think the patient should be on one of these drugs,” empagliflozin or liraglutide, he said. “If the patient is being treated by a primary care physician, then I will prescribe empagliflozin myself because most primary care physicians are not willing to prescribe it. I think more and more cardiologists are doing this. The great thing about empagliflozin and liraglutide is that they do not cause hypoglycemia and the adverse effect profiles are relatively good. As long as drug cost is not an issue, then as cardiologists we need to adjust glycemia control with cardiovascular benefit as we did years ago with statin treatment,” explained Dr. Fitchett, a cardiologist at St. Michael’s Hospital in Toronto and a senior collaborator and coauthor on the EMPA-REG study.

When results from the 4S [Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study] came out in 1994, proving that long-term statin treatment was both safe and increased survival in patients with coronary heart disease, “cardiologists took over lipid management from endocrinologists,” he recalled. “We now have a safe and simple treatment for glucose lowering that also cuts cardiovascular disease events, so cardiologists have to also be involved, at least to some extent. Their degree of involvement depends on their practice and who provides a patient’s primary diabetes care,” he said.

Cardiologists vary on empagliflozin

Other cardiologists are mixed in their take on personally prescribing antidiabetic drugs to high-risk patients with type 2 diabetes. Greg C. Fonarow, MD, has also aggressively taken to empagliflozin over the past year, especially for his patients with heart failure or at high risk for developing heart failure. The EMPA-REG results showed that empagliflozin’s potent impact on reducing cardiovascular death in patients linked closely with a reduction in heart failure hospitalizations. In his recent experience, endocrinologists as well as other physicians who care for patients with type 2 diabetes “are often reluctant to make any changes [in a patient’s hypoglycemic regimen], and in general they have not gravitated toward the treatments that have been shown to improve cardiovascular outcomes and instead focus solely on a patient’s hemoglobin A1c,” Dr. Fonarow said in an interview at the recent annual meeting of the Heart Failure Society of America.

He said he prescribes empagliflozin to patients with type 2 diabetes if they are hospitalized for heart failure or as outpatients, and he targets it to patients diagnosed with heart failure – including heart failure with preserved ejection fraction – as well as to patients with other forms of cardiovascular disease, closely following the EMPA-REG enrollment criteria. It’s too early in the experience with empagliflozin to use it preferentially in diabetes patients without cardiovascular disease or patients who in any other way fall outside the enrollment criteria for EMPA-REG, he said.

“I am happy to consult with their endocrinologist, or I tell patients to discuss this treatment with their endocrinologist. If the endocrinologist prescribes empagliflozin, great; if not, I feel an obligation to provide the best care I can to my patients. This is not a hard medication to use. The safety profile is good. Treatment with empagliflozin obviously has renal-function considerations, but that’s true for many drugs. The biggest challenge is what is covered by the patient’s insurance. We often need preauthorization.

“So far I have seen excellent responses in patients for both metabolic control and clinical responses in patients with heart failure. Their symptoms seem to improve,” said Dr. Fonarow, professor of medicine and co-chief of cardiology at the University of Southern California , Los Angeles.

While Dr. Fonarow cautioned that he also would not start empagliflozin in a patient with a HbA1c below 7%, he would seriously consider swapping out a patient’s drug for empagliflozin if it were a sulfonylurea or a dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor. He stopped short of suggesting a substitution of empagliflozin for metformin. In Dr. Fonarow’s opinion, the evidence for empagliflozin is also “more robust” than it has been for liraglutide or semaglutide. With what’s now known about the clinical impact of these drugs, he foresees a time when a combination between a SGLT-2 inhibitor, with its effect on heart failure, and a GLP-1 analogue, with its effect on atherosclerotic disease, may seem an ideal initial drug pairing for patients with type 2 diabetes and significant cardiovascular disease risk, with metformin relegated to a second-line role.

Other cardiologists endorsed a more collaborative approach to prescribing empagliflozin and liraglutide.

Another team-approach advocate is Robert O. Bonow, MD, cardiologist and professor of medicine at Northwestern University in Chicago. “Cardiologists are comfortable prescribing metformin and telling patients about lifestyle, but when it comes to newer antidiabetic drugs, that’s a new field, and a team approach may be best,” he said in an interview. “If possible, a cardiologist should have a friendly partnership with a diabetologist or endocrinologist who is expert in treating diabetes.” Many cardiologists now work in and for hospitals, and easy access to an endocrinologist is probably available, he noted.

But new analyses of the EMPA-REG data reported by Dr. Fitchett at the ESC congress showed that empagliflozin treatment exerted a similar benefit of reduced cardiovascular death regardless of whether patients had prevalent heart failure at entry into the study, incident heart failure during follow-up, or no heart failure of any sort.

Impact of heart failure in EMPA-REG

Roughly 10% of the 7,020 patients enrolled in EMPA-REG had heart failure at the time they entered the trial. During a median follow-up of just over 3 years, the incidence of new-onset heart failure – tallied as either a new heart failure hospitalization or a clinical episode deemed to be heart failure by an investigator – occurred in 4.6% of patients on empagliflozin and in 6.5% of patients in the placebo arm, a 1.9-percentage-point difference and a 30% relative risk reduction linked with empagliflozin use, Dr. Fitchett reported.

The main EMPA-REG outcome was a composite of cardiovascular death, nonfatal MI, and nonfatal stroke. This positive outcome in favor of empagliflozin treatment was primarily driven by a difference in the rate of cardiovascular death. In the new analysis, the relative reduction in cardiovascular deaths with empagliflozin compared with placebo was 29% among patients with prevalent heart failure at baseline, 35% among those who had an incident heart failure hospitalization during follow-up, 27% among patients with an incident heart failure episode diagnosed by an investigator during follow-up, 33% among the combined group of trial patients with any form of heart failure at trial entry or during the trial (those with prevalent heart failure at baseline plus those with an incident event), and 37% among the large number of patients in the trial who remained free from any indication of heart failure during follow-up.

In short, treatment with empagliflozin “reduced cardiovascular mortality by the same relative amount” regardless of whether patients did or did not have heart failure during the trial,” Dr. Fitchett concluded.

Additional secondary analyses from EMPA-REG reported at the ESC congress in August also documented that the benefit from empagliflozin treatment was roughly the same regardless of the age of patients enrolled in the trial and regardless of patients’ blood level of LDL cholesterol at entry into the study. These findings provide “confidence in the consistency of the effect” by empagliflozin, Dr. Fitchett said.

The endocrinologists’ view

“Most cardiologists are not thoroughly familiar with the full palette of medications for hyperglycemia. Selection of medication should not be made solely on the basis of results from a cardiovascular outcomes trial,” said Helena W. Rodbard, MD, a clinical endocrinologist in Rockville, Md.

“The EMPA-REG OUTCOMES and LEADER results are very exciting and encouraging. When all other factors are equal, the cardiovascular results could sway the decision about which medication to use. But an endocrinologist is in the best position to balance the many factors when choosing combination therapy and to set a target level for HbA1c, fasting blood glucose, and postprandial glucose, and to adjust therapy to minimize the risk of hypoglycemia,” Dr. Rodbard said in an interview.

He called empagliflozin a drug with “interesting promise,” especially for patients with incipient heart failure. The extra cardiovascular benefit from the GLP-1 analogues is “less settled,” although the liraglutide and semaglutide trial results are important and mean these drugs need more consideration and study. The EMPA-REG results were more clearly positive, he said.

“Metformin is still the initial drug” for most patients with type 2 diabetes, echoed Dr. Levy. Drugs like empagliflozin and liraglutide are usually used in combination with metformin.

“Like many endocrinologists, I have for some time used the oral SGLT-2 inhibitors and GLP-1 analogues in combination with metformin. It made sense before the recent cardiovascular data appeared, and it makes even more sense now,” said Dr. Jellinger, professor of clinical medicine and an endocrinologist at the University of Miami.

“Endocrinologists and diabetologists are aware that cardiologists have been taking a larger role in the care of patients with diabetes,” noted Dr. Rodbard. “I favor cardiologists and endocrinologists working in concert to improve the care of patients with diabetes.”

“Over the next few years, we will need to decide whether to treat patients with type 2 diabetes with an agent with proven benefits,” said Dr. Fitchett. “Until the results from EMPA-REG and the LEADER trial came out, there was no specific glucose-lowering agent that also reduced cardiovascular events. Some cardiologists might ask when they should get involved in managing patients with type 2 diabetes. What I would do for patients with a history of cardiovascular disease who develop new type 2 diabetes is start empagliflozin as their first drug,” Dr. Fitchett said, though he admitted that no evidence yet exists to back that approach.

The EMPA-REG trial was sponsored by Boehringer Ingelheim and by Eli Lilly, the companies that market empagliflozin. The LEADER trial was sponsored in part by Novo Nordisk, the company that markets liraglutide. Dr. Fitchett and Dr. Mentz were both researchers for EMPA-REG. Dr. Fitchett has been a consultant to AstraZeneca, Merck, and Amgen. Dr. Mentz has been an adviser to Boehringer Ingelheim. Dr. Fonarow has been an adviser to Amgen, Janssen, Novartis, and ZS Pharma. Dr. Bozkurt had no disclosures. Dr. Bonow has been a consultant to Gilead. Dr. Jellinger has been a speaker on behalf of Boehringer-Ingelheim, Novo Nordisk, Merck, and Janssen. Dr. Rodbard has been a consultant to or speaker for several drug companies including Boehringer-Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, and Novo Nordisk. Dr. Levy has been a speaker on behalf of Boehringer-Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, Novo Nordisk, and AstraZeneca. Dr. Hellman had no disclosures.

mzoler@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

The dramatic reduction in cardiovascular death and heart failure hospitalization seen during treatment with empagliflozin (Jardiance) in the EMPA-REG OUTCOME (Empagliflozin Cardiovascular Outcome Event Trial in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Patients) trial, for example, has prompted some cardiologists in the year since the first EMPA-REG report to become active prescribers of the drug to their patients who have type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease. The same evidence has driven other cardiologists who may not feel fully comfortable prescribing an antidiabetic drug on their own to enter into active partnerships with endocrinologists to work as a team to put diabetes patients with cardiovascular disease on empagliflozin.

In Dr. Fitchett’s practice, “if a patient with type 2 diabetes has an endocrinologist, then I will send a letter to that physician saying I think the patient should be on one of these drugs,” empagliflozin or liraglutide, he said. “If the patient is being treated by a primary care physician, then I will prescribe empagliflozin myself because most primary care physicians are not willing to prescribe it. I think more and more cardiologists are doing this. The great thing about empagliflozin and liraglutide is that they do not cause hypoglycemia and the adverse effect profiles are relatively good. As long as drug cost is not an issue, then as cardiologists we need to adjust glycemia control with cardiovascular benefit as we did years ago with statin treatment,” explained Dr. Fitchett, a cardiologist at St. Michael’s Hospital in Toronto and a senior collaborator and coauthor on the EMPA-REG study.

When results from the 4S [Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study] came out in 1994, proving that long-term statin treatment was both safe and increased survival in patients with coronary heart disease, “cardiologists took over lipid management from endocrinologists,” he recalled. “We now have a safe and simple treatment for glucose lowering that also cuts cardiovascular disease events, so cardiologists have to also be involved, at least to some extent. Their degree of involvement depends on their practice and who provides a patient’s primary diabetes care,” he said.

Cardiologists vary on empagliflozin

Other cardiologists are mixed in their take on personally prescribing antidiabetic drugs to high-risk patients with type 2 diabetes. Greg C. Fonarow, MD, has also aggressively taken to empagliflozin over the past year, especially for his patients with heart failure or at high risk for developing heart failure. The EMPA-REG results showed that empagliflozin’s potent impact on reducing cardiovascular death in patients linked closely with a reduction in heart failure hospitalizations. In his recent experience, endocrinologists as well as other physicians who care for patients with type 2 diabetes “are often reluctant to make any changes [in a patient’s hypoglycemic regimen], and in general they have not gravitated toward the treatments that have been shown to improve cardiovascular outcomes and instead focus solely on a patient’s hemoglobin A1c,” Dr. Fonarow said in an interview at the recent annual meeting of the Heart Failure Society of America.

He said he prescribes empagliflozin to patients with type 2 diabetes if they are hospitalized for heart failure or as outpatients, and he targets it to patients diagnosed with heart failure – including heart failure with preserved ejection fraction – as well as to patients with other forms of cardiovascular disease, closely following the EMPA-REG enrollment criteria. It’s too early in the experience with empagliflozin to use it preferentially in diabetes patients without cardiovascular disease or patients who in any other way fall outside the enrollment criteria for EMPA-REG, he said.

“I am happy to consult with their endocrinologist, or I tell patients to discuss this treatment with their endocrinologist. If the endocrinologist prescribes empagliflozin, great; if not, I feel an obligation to provide the best care I can to my patients. This is not a hard medication to use. The safety profile is good. Treatment with empagliflozin obviously has renal-function considerations, but that’s true for many drugs. The biggest challenge is what is covered by the patient’s insurance. We often need preauthorization.

“So far I have seen excellent responses in patients for both metabolic control and clinical responses in patients with heart failure. Their symptoms seem to improve,” said Dr. Fonarow, professor of medicine and co-chief of cardiology at the University of Southern California , Los Angeles.

While Dr. Fonarow cautioned that he also would not start empagliflozin in a patient with a HbA1c below 7%, he would seriously consider swapping out a patient’s drug for empagliflozin if it were a sulfonylurea or a dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor. He stopped short of suggesting a substitution of empagliflozin for metformin. In Dr. Fonarow’s opinion, the evidence for empagliflozin is also “more robust” than it has been for liraglutide or semaglutide. With what’s now known about the clinical impact of these drugs, he foresees a time when a combination between a SGLT-2 inhibitor, with its effect on heart failure, and a GLP-1 analogue, with its effect on atherosclerotic disease, may seem an ideal initial drug pairing for patients with type 2 diabetes and significant cardiovascular disease risk, with metformin relegated to a second-line role.

Other cardiologists endorsed a more collaborative approach to prescribing empagliflozin and liraglutide.

Another team-approach advocate is Robert O. Bonow, MD, cardiologist and professor of medicine at Northwestern University in Chicago. “Cardiologists are comfortable prescribing metformin and telling patients about lifestyle, but when it comes to newer antidiabetic drugs, that’s a new field, and a team approach may be best,” he said in an interview. “If possible, a cardiologist should have a friendly partnership with a diabetologist or endocrinologist who is expert in treating diabetes.” Many cardiologists now work in and for hospitals, and easy access to an endocrinologist is probably available, he noted.

But new analyses of the EMPA-REG data reported by Dr. Fitchett at the ESC congress showed that empagliflozin treatment exerted a similar benefit of reduced cardiovascular death regardless of whether patients had prevalent heart failure at entry into the study, incident heart failure during follow-up, or no heart failure of any sort.

Impact of heart failure in EMPA-REG

Roughly 10% of the 7,020 patients enrolled in EMPA-REG had heart failure at the time they entered the trial. During a median follow-up of just over 3 years, the incidence of new-onset heart failure – tallied as either a new heart failure hospitalization or a clinical episode deemed to be heart failure by an investigator – occurred in 4.6% of patients on empagliflozin and in 6.5% of patients in the placebo arm, a 1.9-percentage-point difference and a 30% relative risk reduction linked with empagliflozin use, Dr. Fitchett reported.

The main EMPA-REG outcome was a composite of cardiovascular death, nonfatal MI, and nonfatal stroke. This positive outcome in favor of empagliflozin treatment was primarily driven by a difference in the rate of cardiovascular death. In the new analysis, the relative reduction in cardiovascular deaths with empagliflozin compared with placebo was 29% among patients with prevalent heart failure at baseline, 35% among those who had an incident heart failure hospitalization during follow-up, 27% among patients with an incident heart failure episode diagnosed by an investigator during follow-up, 33% among the combined group of trial patients with any form of heart failure at trial entry or during the trial (those with prevalent heart failure at baseline plus those with an incident event), and 37% among the large number of patients in the trial who remained free from any indication of heart failure during follow-up.

In short, treatment with empagliflozin “reduced cardiovascular mortality by the same relative amount” regardless of whether patients did or did not have heart failure during the trial,” Dr. Fitchett concluded.

Additional secondary analyses from EMPA-REG reported at the ESC congress in August also documented that the benefit from empagliflozin treatment was roughly the same regardless of the age of patients enrolled in the trial and regardless of patients’ blood level of LDL cholesterol at entry into the study. These findings provide “confidence in the consistency of the effect” by empagliflozin, Dr. Fitchett said.

The endocrinologists’ view

“Most cardiologists are not thoroughly familiar with the full palette of medications for hyperglycemia. Selection of medication should not be made solely on the basis of results from a cardiovascular outcomes trial,” said Helena W. Rodbard, MD, a clinical endocrinologist in Rockville, Md.

“The EMPA-REG OUTCOMES and LEADER results are very exciting and encouraging. When all other factors are equal, the cardiovascular results could sway the decision about which medication to use. But an endocrinologist is in the best position to balance the many factors when choosing combination therapy and to set a target level for HbA1c, fasting blood glucose, and postprandial glucose, and to adjust therapy to minimize the risk of hypoglycemia,” Dr. Rodbard said in an interview.

He called empagliflozin a drug with “interesting promise,” especially for patients with incipient heart failure. The extra cardiovascular benefit from the GLP-1 analogues is “less settled,” although the liraglutide and semaglutide trial results are important and mean these drugs need more consideration and study. The EMPA-REG results were more clearly positive, he said.

“Metformin is still the initial drug” for most patients with type 2 diabetes, echoed Dr. Levy. Drugs like empagliflozin and liraglutide are usually used in combination with metformin.

“Like many endocrinologists, I have for some time used the oral SGLT-2 inhibitors and GLP-1 analogues in combination with metformin. It made sense before the recent cardiovascular data appeared, and it makes even more sense now,” said Dr. Jellinger, professor of clinical medicine and an endocrinologist at the University of Miami.

“Endocrinologists and diabetologists are aware that cardiologists have been taking a larger role in the care of patients with diabetes,” noted Dr. Rodbard. “I favor cardiologists and endocrinologists working in concert to improve the care of patients with diabetes.”

“Over the next few years, we will need to decide whether to treat patients with type 2 diabetes with an agent with proven benefits,” said Dr. Fitchett. “Until the results from EMPA-REG and the LEADER trial came out, there was no specific glucose-lowering agent that also reduced cardiovascular events. Some cardiologists might ask when they should get involved in managing patients with type 2 diabetes. What I would do for patients with a history of cardiovascular disease who develop new type 2 diabetes is start empagliflozin as their first drug,” Dr. Fitchett said, though he admitted that no evidence yet exists to back that approach.

The EMPA-REG trial was sponsored by Boehringer Ingelheim and by Eli Lilly, the companies that market empagliflozin. The LEADER trial was sponsored in part by Novo Nordisk, the company that markets liraglutide. Dr. Fitchett and Dr. Mentz were both researchers for EMPA-REG. Dr. Fitchett has been a consultant to AstraZeneca, Merck, and Amgen. Dr. Mentz has been an adviser to Boehringer Ingelheim. Dr. Fonarow has been an adviser to Amgen, Janssen, Novartis, and ZS Pharma. Dr. Bozkurt had no disclosures. Dr. Bonow has been a consultant to Gilead. Dr. Jellinger has been a speaker on behalf of Boehringer-Ingelheim, Novo Nordisk, Merck, and Janssen. Dr. Rodbard has been a consultant to or speaker for several drug companies including Boehringer-Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, and Novo Nordisk. Dr. Levy has been a speaker on behalf of Boehringer-Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, Novo Nordisk, and AstraZeneca. Dr. Hellman had no disclosures.

mzoler@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @mitchelzoler