User login

A shot of relief. A shot of hope. Those are the words used to describe COVID-19 vaccines on a television commercial running in prime time in Kentucky.

“We all can’t get the vaccine at once,” the announcer says solemnly, “but we’ll all get a turn.”

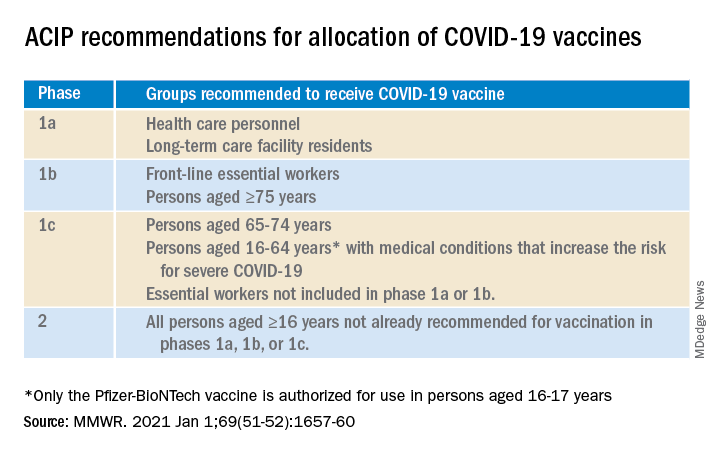

For some of us, that turn came quickly. In December, the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices recommended that health care personnel (HCP) and long-term care facility residents be the first to be immunized with COVID-19 vaccines (see table).

On Dec. 14, 2020, Sandra Lindsay, a nurse and director of patient care services in the intensive care unit at Long Island Jewish Medical Center, was the first person in the United States to receive a COVID-19 vaccine outside a clinical trial.

In subsequent days, social media sites were quickly flooded with photos of HCP rolling up their sleeves or flashing their immunization cards. There was jubilation ... and perhaps a little bit of jealousy. There were tears of joy and some tears of frustration.

There are more than 21 million HCP in the United States and to date, there have not been enough vaccines nor adequate infrastructure to immunize all of them. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Data Tracker, as of Jan. 7, 2021, 21,419,800 doses of vaccine had been distributed to states to immunize everyone identified in phase 1a, but only 5,919,418 people had received a first dose. Limited supply has necessitated prioritization of subgroups of HCP; those in the front of the line have varied by state, and even by hospital or health care systems within states. Both the American Academy of Pediatrics and the American Academy of Family Physicians have noted that primary care providers not employed by a hospital may have more difficulty accessing vaccine.

The mismatch between supply and demand has created an intense focus on improving supply and distribution. Soon though, we’re going to shift our attention to how we increase demand. We don’t have good data on those who being are offered COVID-19 vaccine and declining, but several studies that predate the Emergency Use Authorization for the Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna vaccines suggest significant COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among adults in the United States.

One large, longitudinal Internet-based study of U.S. adults found that the proportion who reported they were “somewhat or very likely” to receive COVID-19 vaccine declined from 74% in early April to 56% in early December.

In the Understanding America Study, self-reported likelihood of being vaccinated with COVID-19 vaccine was lower among Black compared to White respondents (38% vs. 59%; aRR, 0.7 [95% confidence interval, 0.6-0.8]), and lower among women compared to men (51% vs. 62%; aRR, 0.9 [95% CI, 0.8-0.9]). Those 65 years of age and older were more likely to report a willingness to be vaccinated than were those 18-49 years of age, as were those with at least a bachelor’s degree compared to those with a high school education or less.

A study conducted by the Pew Research Center in November – before any COVID-19 vaccines were available – found that only 60% of American adults said they would “definitely or probably get a vaccine for coronavirus” if one were available. That was an increase from 51% in September, but and overall decrease of 72% in May. Of the remaining 40%, just over half said they did not intend to get vaccinated and were “pretty certain” that more information would not change their minds.

Concern about acquiring a serious case of COVID-19 and trust in the vaccine development process were associated with an intent to receive vaccine, as was a personal history of receiving a flu shot annually. Willingness to be vaccinated varied by age, race, and family income, with Black respondents, women, and those with a lower family incomes less likely to accept a vaccine.

To date, few data are available about HCP and willingness to receive COVID-19 vaccine. A preprint posted at medrxiv.org reports on a cross-sectional study of more than 3,400 HCP surveyed between Oct. 7 and Nov. 9, 2020. In that study, only 36% of respondents voiced a willingness to be immunized as soon as vaccine is available. Vaccine acceptance increased with increasing age, income level, and education. As in other studies, self-reported willingness to accept vaccine was lower in women and Black individuals. While vaccine acceptance was higher in direct medical care providers than others, it was still only 49%.

So here’s the paradox: Even as limited supplies of vaccine are available and many are frustrated about lack of access, we need to promote the value of immunization to those who are hesitant. Pediatricians are trusted sources of vaccine information and we are in a good position to educate our colleagues, our staff, the parents of our patients and the community at-large.

A useful resource for those ready to take that step it is the CDC’s COVID-19 Vaccination Communication Toolkit. While this collection is designed to build vaccine confidence and promote immunization among health care providers, many of the strategies will be easily adapted for use with patients.

It’s not clear when we might have a COVID 19 vaccine for most children. The Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine emergency use authorization includes those as young as 16 years of age, and 16- and 17-year-olds with high risk medical conditions are included in phase 1c of vaccine allocation. Pfizer is currently enrolling children as young as 12 years of age in clinical trials, and Moderna and Janssen are poised to do the same. It is conceivable but far from certain that we could have a vaccine for children late this year. Are parents going to be ready to vaccinate their children?

Limited data about parental acceptance of vaccine for their children mirrors what was seen in the Understanding America Study and the Pew Research Study. In December 2020, the National Parents Union surveyed 1,008 parents of public school students enrolled in kindergarten through 12th grade. Sixty percent of parents said they would allow their children to receive a COVID-19 vaccine, while 25% would not and 15% were unsure. This suggests that now is the time to begin building vaccine confidence with parents. One conversation starter might be, “I am going to be vaccinated as soon as the vaccine is available.” Ideally, many of you will soon be able to say what I do: “I am excited to tell you that I have been immunized with the COVID-19 vaccine. I did this to protect myself, my family, and our community. I’m hopeful that vaccine will soon be available for all of us.”

Dr. Bryant is a pediatrician specializing in infectious diseases at the University of Louisville (Ky.) and Norton Children’s Hospital, also in Louisville. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at pdnews@mdedge.com.

A shot of relief. A shot of hope. Those are the words used to describe COVID-19 vaccines on a television commercial running in prime time in Kentucky.

“We all can’t get the vaccine at once,” the announcer says solemnly, “but we’ll all get a turn.”

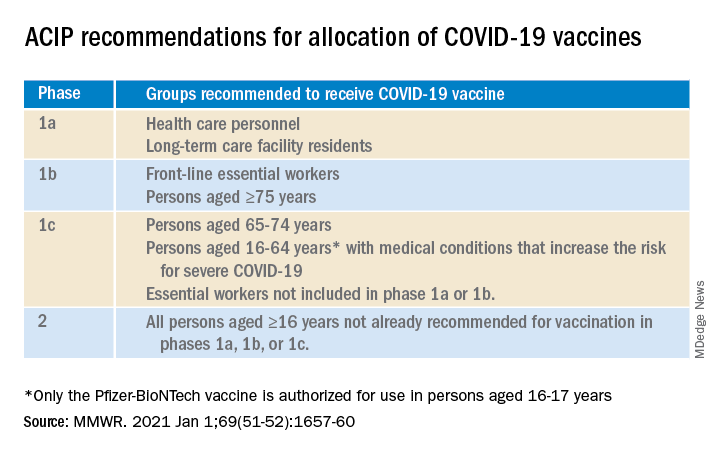

For some of us, that turn came quickly. In December, the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices recommended that health care personnel (HCP) and long-term care facility residents be the first to be immunized with COVID-19 vaccines (see table).

On Dec. 14, 2020, Sandra Lindsay, a nurse and director of patient care services in the intensive care unit at Long Island Jewish Medical Center, was the first person in the United States to receive a COVID-19 vaccine outside a clinical trial.

In subsequent days, social media sites were quickly flooded with photos of HCP rolling up their sleeves or flashing their immunization cards. There was jubilation ... and perhaps a little bit of jealousy. There were tears of joy and some tears of frustration.

There are more than 21 million HCP in the United States and to date, there have not been enough vaccines nor adequate infrastructure to immunize all of them. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Data Tracker, as of Jan. 7, 2021, 21,419,800 doses of vaccine had been distributed to states to immunize everyone identified in phase 1a, but only 5,919,418 people had received a first dose. Limited supply has necessitated prioritization of subgroups of HCP; those in the front of the line have varied by state, and even by hospital or health care systems within states. Both the American Academy of Pediatrics and the American Academy of Family Physicians have noted that primary care providers not employed by a hospital may have more difficulty accessing vaccine.

The mismatch between supply and demand has created an intense focus on improving supply and distribution. Soon though, we’re going to shift our attention to how we increase demand. We don’t have good data on those who being are offered COVID-19 vaccine and declining, but several studies that predate the Emergency Use Authorization for the Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna vaccines suggest significant COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among adults in the United States.

One large, longitudinal Internet-based study of U.S. adults found that the proportion who reported they were “somewhat or very likely” to receive COVID-19 vaccine declined from 74% in early April to 56% in early December.

In the Understanding America Study, self-reported likelihood of being vaccinated with COVID-19 vaccine was lower among Black compared to White respondents (38% vs. 59%; aRR, 0.7 [95% confidence interval, 0.6-0.8]), and lower among women compared to men (51% vs. 62%; aRR, 0.9 [95% CI, 0.8-0.9]). Those 65 years of age and older were more likely to report a willingness to be vaccinated than were those 18-49 years of age, as were those with at least a bachelor’s degree compared to those with a high school education or less.

A study conducted by the Pew Research Center in November – before any COVID-19 vaccines were available – found that only 60% of American adults said they would “definitely or probably get a vaccine for coronavirus” if one were available. That was an increase from 51% in September, but and overall decrease of 72% in May. Of the remaining 40%, just over half said they did not intend to get vaccinated and were “pretty certain” that more information would not change their minds.

Concern about acquiring a serious case of COVID-19 and trust in the vaccine development process were associated with an intent to receive vaccine, as was a personal history of receiving a flu shot annually. Willingness to be vaccinated varied by age, race, and family income, with Black respondents, women, and those with a lower family incomes less likely to accept a vaccine.

To date, few data are available about HCP and willingness to receive COVID-19 vaccine. A preprint posted at medrxiv.org reports on a cross-sectional study of more than 3,400 HCP surveyed between Oct. 7 and Nov. 9, 2020. In that study, only 36% of respondents voiced a willingness to be immunized as soon as vaccine is available. Vaccine acceptance increased with increasing age, income level, and education. As in other studies, self-reported willingness to accept vaccine was lower in women and Black individuals. While vaccine acceptance was higher in direct medical care providers than others, it was still only 49%.

So here’s the paradox: Even as limited supplies of vaccine are available and many are frustrated about lack of access, we need to promote the value of immunization to those who are hesitant. Pediatricians are trusted sources of vaccine information and we are in a good position to educate our colleagues, our staff, the parents of our patients and the community at-large.

A useful resource for those ready to take that step it is the CDC’s COVID-19 Vaccination Communication Toolkit. While this collection is designed to build vaccine confidence and promote immunization among health care providers, many of the strategies will be easily adapted for use with patients.

It’s not clear when we might have a COVID 19 vaccine for most children. The Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine emergency use authorization includes those as young as 16 years of age, and 16- and 17-year-olds with high risk medical conditions are included in phase 1c of vaccine allocation. Pfizer is currently enrolling children as young as 12 years of age in clinical trials, and Moderna and Janssen are poised to do the same. It is conceivable but far from certain that we could have a vaccine for children late this year. Are parents going to be ready to vaccinate their children?

Limited data about parental acceptance of vaccine for their children mirrors what was seen in the Understanding America Study and the Pew Research Study. In December 2020, the National Parents Union surveyed 1,008 parents of public school students enrolled in kindergarten through 12th grade. Sixty percent of parents said they would allow their children to receive a COVID-19 vaccine, while 25% would not and 15% were unsure. This suggests that now is the time to begin building vaccine confidence with parents. One conversation starter might be, “I am going to be vaccinated as soon as the vaccine is available.” Ideally, many of you will soon be able to say what I do: “I am excited to tell you that I have been immunized with the COVID-19 vaccine. I did this to protect myself, my family, and our community. I’m hopeful that vaccine will soon be available for all of us.”

Dr. Bryant is a pediatrician specializing in infectious diseases at the University of Louisville (Ky.) and Norton Children’s Hospital, also in Louisville. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at pdnews@mdedge.com.

A shot of relief. A shot of hope. Those are the words used to describe COVID-19 vaccines on a television commercial running in prime time in Kentucky.

“We all can’t get the vaccine at once,” the announcer says solemnly, “but we’ll all get a turn.”

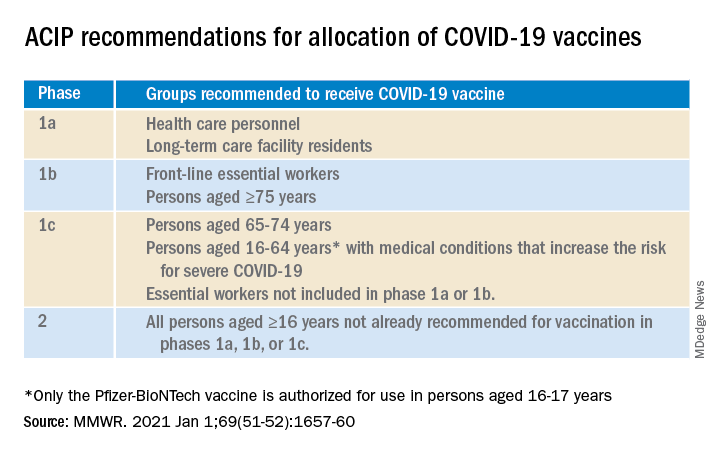

For some of us, that turn came quickly. In December, the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices recommended that health care personnel (HCP) and long-term care facility residents be the first to be immunized with COVID-19 vaccines (see table).

On Dec. 14, 2020, Sandra Lindsay, a nurse and director of patient care services in the intensive care unit at Long Island Jewish Medical Center, was the first person in the United States to receive a COVID-19 vaccine outside a clinical trial.

In subsequent days, social media sites were quickly flooded with photos of HCP rolling up their sleeves or flashing their immunization cards. There was jubilation ... and perhaps a little bit of jealousy. There were tears of joy and some tears of frustration.

There are more than 21 million HCP in the United States and to date, there have not been enough vaccines nor adequate infrastructure to immunize all of them. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Data Tracker, as of Jan. 7, 2021, 21,419,800 doses of vaccine had been distributed to states to immunize everyone identified in phase 1a, but only 5,919,418 people had received a first dose. Limited supply has necessitated prioritization of subgroups of HCP; those in the front of the line have varied by state, and even by hospital or health care systems within states. Both the American Academy of Pediatrics and the American Academy of Family Physicians have noted that primary care providers not employed by a hospital may have more difficulty accessing vaccine.

The mismatch between supply and demand has created an intense focus on improving supply and distribution. Soon though, we’re going to shift our attention to how we increase demand. We don’t have good data on those who being are offered COVID-19 vaccine and declining, but several studies that predate the Emergency Use Authorization for the Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna vaccines suggest significant COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among adults in the United States.

One large, longitudinal Internet-based study of U.S. adults found that the proportion who reported they were “somewhat or very likely” to receive COVID-19 vaccine declined from 74% in early April to 56% in early December.

In the Understanding America Study, self-reported likelihood of being vaccinated with COVID-19 vaccine was lower among Black compared to White respondents (38% vs. 59%; aRR, 0.7 [95% confidence interval, 0.6-0.8]), and lower among women compared to men (51% vs. 62%; aRR, 0.9 [95% CI, 0.8-0.9]). Those 65 years of age and older were more likely to report a willingness to be vaccinated than were those 18-49 years of age, as were those with at least a bachelor’s degree compared to those with a high school education or less.

A study conducted by the Pew Research Center in November – before any COVID-19 vaccines were available – found that only 60% of American adults said they would “definitely or probably get a vaccine for coronavirus” if one were available. That was an increase from 51% in September, but and overall decrease of 72% in May. Of the remaining 40%, just over half said they did not intend to get vaccinated and were “pretty certain” that more information would not change their minds.

Concern about acquiring a serious case of COVID-19 and trust in the vaccine development process were associated with an intent to receive vaccine, as was a personal history of receiving a flu shot annually. Willingness to be vaccinated varied by age, race, and family income, with Black respondents, women, and those with a lower family incomes less likely to accept a vaccine.

To date, few data are available about HCP and willingness to receive COVID-19 vaccine. A preprint posted at medrxiv.org reports on a cross-sectional study of more than 3,400 HCP surveyed between Oct. 7 and Nov. 9, 2020. In that study, only 36% of respondents voiced a willingness to be immunized as soon as vaccine is available. Vaccine acceptance increased with increasing age, income level, and education. As in other studies, self-reported willingness to accept vaccine was lower in women and Black individuals. While vaccine acceptance was higher in direct medical care providers than others, it was still only 49%.

So here’s the paradox: Even as limited supplies of vaccine are available and many are frustrated about lack of access, we need to promote the value of immunization to those who are hesitant. Pediatricians are trusted sources of vaccine information and we are in a good position to educate our colleagues, our staff, the parents of our patients and the community at-large.

A useful resource for those ready to take that step it is the CDC’s COVID-19 Vaccination Communication Toolkit. While this collection is designed to build vaccine confidence and promote immunization among health care providers, many of the strategies will be easily adapted for use with patients.

It’s not clear when we might have a COVID 19 vaccine for most children. The Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine emergency use authorization includes those as young as 16 years of age, and 16- and 17-year-olds with high risk medical conditions are included in phase 1c of vaccine allocation. Pfizer is currently enrolling children as young as 12 years of age in clinical trials, and Moderna and Janssen are poised to do the same. It is conceivable but far from certain that we could have a vaccine for children late this year. Are parents going to be ready to vaccinate their children?

Limited data about parental acceptance of vaccine for their children mirrors what was seen in the Understanding America Study and the Pew Research Study. In December 2020, the National Parents Union surveyed 1,008 parents of public school students enrolled in kindergarten through 12th grade. Sixty percent of parents said they would allow their children to receive a COVID-19 vaccine, while 25% would not and 15% were unsure. This suggests that now is the time to begin building vaccine confidence with parents. One conversation starter might be, “I am going to be vaccinated as soon as the vaccine is available.” Ideally, many of you will soon be able to say what I do: “I am excited to tell you that I have been immunized with the COVID-19 vaccine. I did this to protect myself, my family, and our community. I’m hopeful that vaccine will soon be available for all of us.”

Dr. Bryant is a pediatrician specializing in infectious diseases at the University of Louisville (Ky.) and Norton Children’s Hospital, also in Louisville. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at pdnews@mdedge.com.