User login

A Group Approach to Clinical Research Mentorship at a Veterans Affairs Medical Center

Supporting meaningful research that has a positive impact on the health and quality of life of veterans is a priority of the US Department of Veterans Affairs Office of Research and Development.1 For nearly a century, VA researchers have been conducting high quality studies. To continue this trajectory, it is imperative to attract, train, and retain exceptional investigators while nurturing their development throughout their careers.2

Mentorship is defined as guidance provided by an experienced and trusted party to another (usually junior) individual with the intent of helping the person succeed. It benefits the mentee, mentor, and their institutions.3 Mentorship is crucial for personal and professional development as well as productivity, which may help reduce clinician burnout.4-7 Conversely, a lack of mentorship could have negative effects on work satisfaction and stagnate career progression.8

Mentorship is vital for developing and advancing a VA investigator’s research agenda. Funding, grant writing, and research design were among the most discussed topics in a large comprehensive mentorship program for academic faculty.9 However, there are several known barriers to effective research mentorship; among them include a lack of resources, time constraints, and competing clinical priorities.10,11

Finding time for effective one-on-one research mentoring is difficult within the time constraints of clinical duties; a group mentorship model may help overcome this barrier. Group mentorship can aid in personal and professional development because no single mentor can effectively meet every mentoring need of an individual.12 Group mentorship also allows for the exchange of ideas among individuals with different backgrounds and the ability to utilize the strengths of each member of the group. For example, a member may have methodological expertise, while another may be skilled in grantsmanship. A team of mentors may be more beneficial for both the mentors (eg, establish a more manageable workload) and the mentee (eg, gains a broader perspective of expertise) when compared to having a single mentor.3

Peer mentorship within the group setting may also yield additional benefits. For example, having a supportive peer group may help reduce stress levels and burnout, while also improving overall well-being.3,13 Formal mentorship programs do not frequently discuss concerns such as work-life balance, so including peers as mentors may help fill this void.9 Peer mentorship has also been found to be beneficial in providing mentees with pooled resources and shared learning.12,13 This article describes the components, benefits, impacts, and challenges of a group research mentorship program for VA clinicians interested in conducting VArelevant research.

Program Description

The VA Clinical Research Mentorship Program was initiated at the VA Ann Arbor Healthcare System (VAAAHS) in October 2015 by the Chief of Medicine to assist VA clinician investigators with developing and submitting VA clinical science and health services research grant applications. The program offers group and one-on-one consultation services through the expertise of 2 experienced investigators/faculty mentors who also serve as program directors, each of whom devote about 3 to 5 hours per month to activities associated with the mentorship program (eg, attending the meeting, reviewing materials sent by mentees, and one-on-one discussions with mentees).

The program also fostered peer-led mentorship. This encourages all attendees to provide feedback during group sessions and communication by mentees outside the group sessions. An experienced project manager serves as program coordinator and contributes about 4 hours per month for activities such as attending, scheduling, and sending reminders for each meeting, distributing handouts, reviewing materials, and answering mentee’s questions via email. A statistician and additional research staff (ie, an epidemiologist and research assistant) do not attend the recurring meetings, but are available for offline consultation as needed. The program runs on a 12-month cycle with regular meetings occurring twice monthly during the 9-month academic period. Resources to support the program, primarily program director(s) and project coordinator effort, are provided by the Chief of Medicine and through the VAAAHS affiliated VA Health Systems Research (formerly Health Services Research & Development) Center of Innovation.

Invitations for new mentees are sent annually. Mentees expressing interest in the program outside of its annual recruitment period are evaluated for inclusion on a rolling basis. Recruitment begins with the program coordinator sending email notifications to all VAAAHS Medicine Service faculty, section chiefs, and division chiefs at the VAAAHS academic affiliate. Recipients are encouraged to distribute the announcement to eligible applicants and refer them to the application materials for entry consideration into the program. The application consists of the applicant’s curriculum vitae and a 1-page summary that includes a description of their research area of interest, how it is relevant to the VA, in addition to an idea for a research study, its potential significance, and proposed methodology. Applicant materials are reviewed by the program coordinator and program directors. The applicants are evaluated using a simple scoring approach that focuses on the applicant’s research area and agenda, past research training, past research productivity, potential for obtaining VA funding, and whether they have sufficient research time.

Program eligibility initially required being a physician with ≥ 1/8 VA appointment from the Medicine Service. However, clinicians with clinical appointments from other VA services are also accepted for participation as needed. Applicants must have previous research experience and have a career goal to obtain external funding for conducting and publishing original research. Those who have previously served as a principal investigator on a funded VA grant proposal are not eligible as new applicants but can remain in the program as peer mentors. The number of annual applicants varies and ranges from 1 to 11; on average, about 90% of applicants receive invitations to join the program.

Sessions

The program holds recurring meetings twice monthly for 1 hour during the 9-month academic year. However, program directors are available year-round, and mentees are encouraged to communicate questions or concerns via email during nonacademic months. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, all meetings were held in-person. However, the group pivoted to virtual meetings and continues to utilize this format. The dedicated program coordinator is responsible for coordinating meetings and distributing meeting materials.

Each session is informal, flexible, and supportive. Attendance is not enforced, and mentees are allowed to join meetings as their schedules permit; however, program directors and program coordinator attend each meeting. In advance of each session, the program coordinator sends out a call for agenda items to all active members invited to discuss any research related items. Each mentee presents their ideas to lead the discussion for their portion of the meeting with no defined format required.

A variety of topics are covered including, but not limited to: (1) grant-specific concerns (eg, questions related to specific aim pages, grantsmanship, postsubmission comments from reviewers, or postaward logistics); (2) research procedures (eg, questions related to methodological practices or institutional review board concerns); (3) manuscript or presentation preparation; and (4) careerrelated issues. The program coordinator distributes handouts prior to meetings and mentees may record their presentations. These handouts may include, but are not limited to, specific aims pages, analytical plans, grant solicitations, and PowerPoint presentations. If a resource that can benefit the entire group is mentioned during the meeting, the program coordinator is responsible for distribution.

The program follows a group facilitated discussion format. Program directors facilitate each meeting, but input is encouraged from all attendees. This model allows for mentees to learn from the faculty mentors as well as peer mentees in a simultaneous and efficient fashion. Group discussions foster collective problem solving, peer support, and resource sharing that would not be possible through individualized mentorship. Participants have access to varied expertise during each session which reduces the need to seek specialized help elsewhere. Participants are also encouraged to contact the program directors or research staff for consultation as needed. Some one-on-one consultations have transitioned to a more sustained and ongoing mentorship relationship between a program director and mentee, but most are often brief email exchanges or a single meeting.

Participants

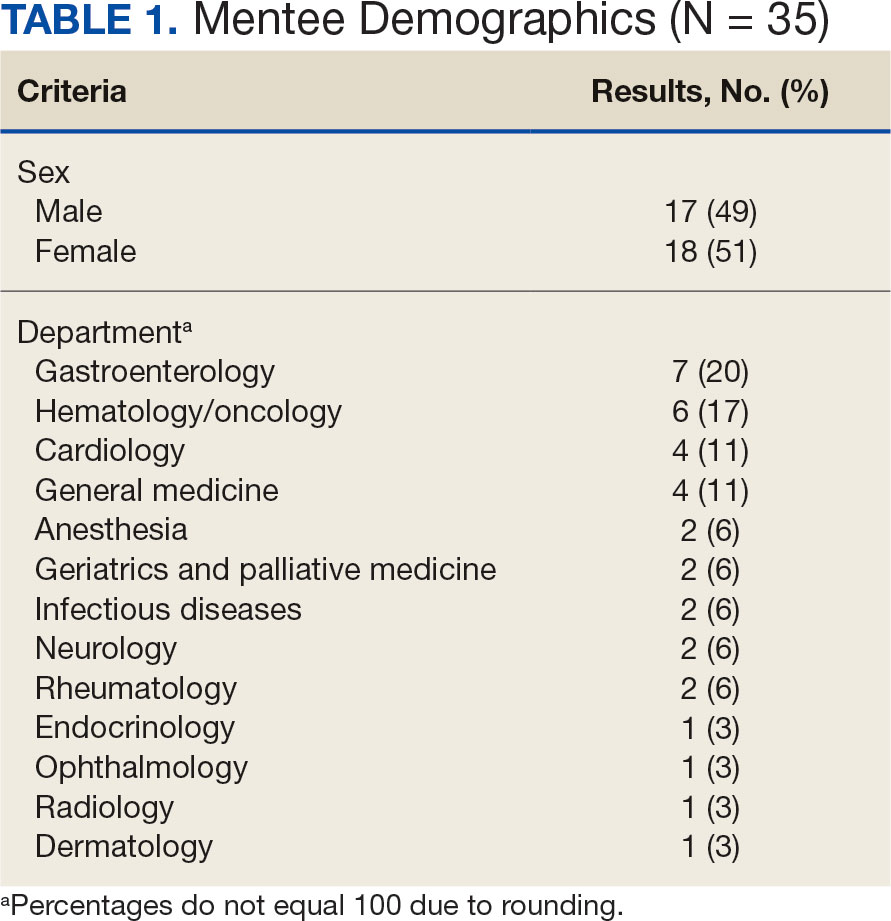

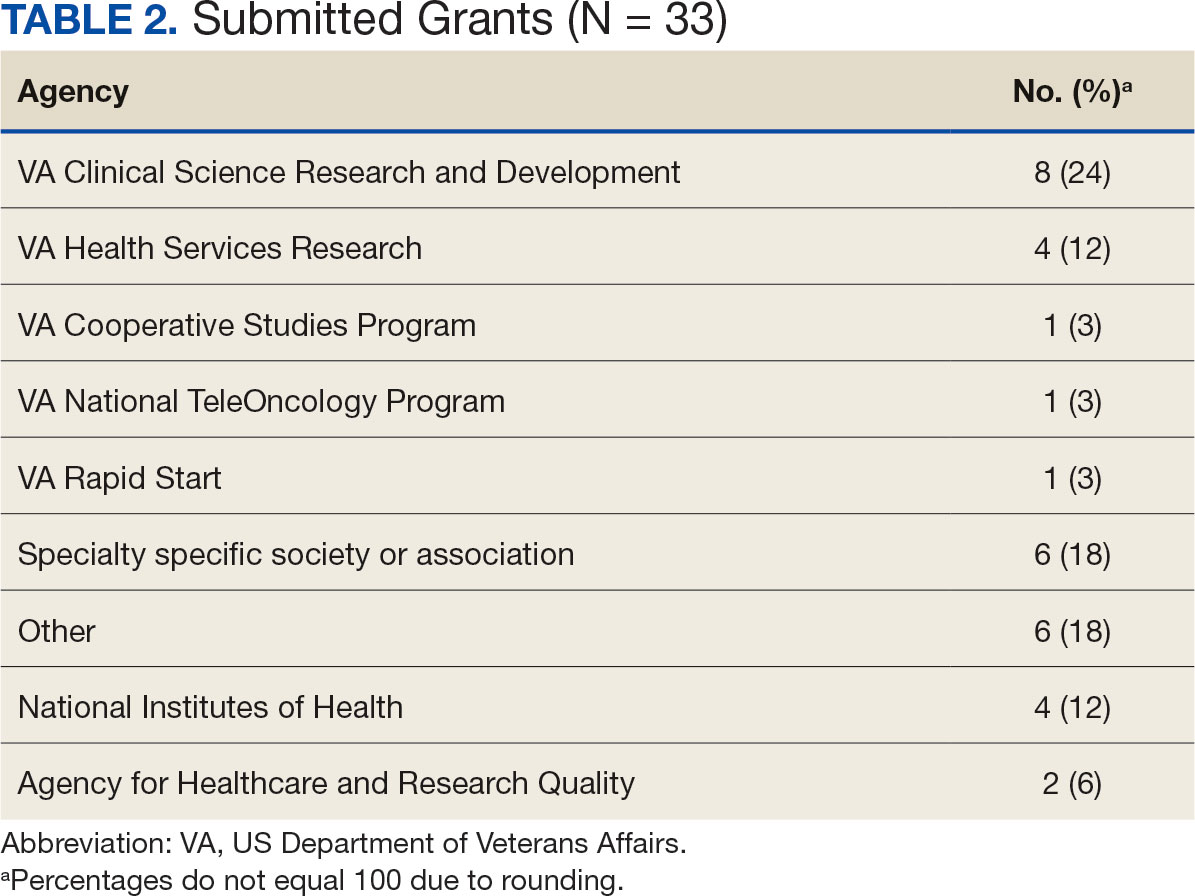

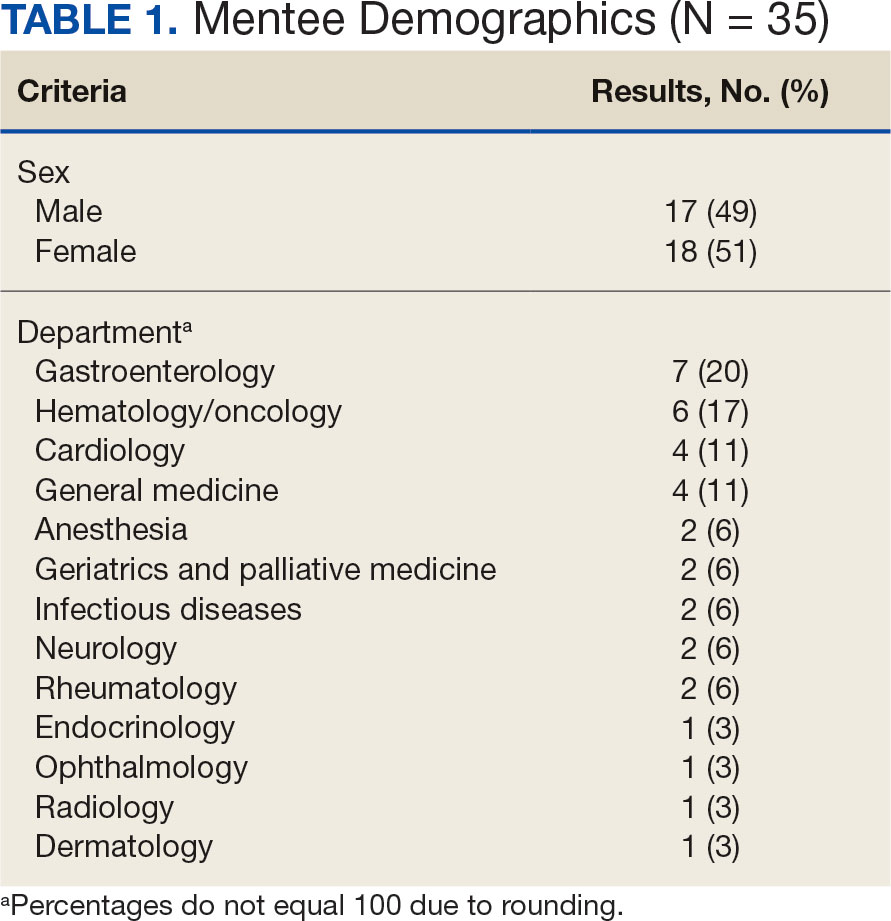

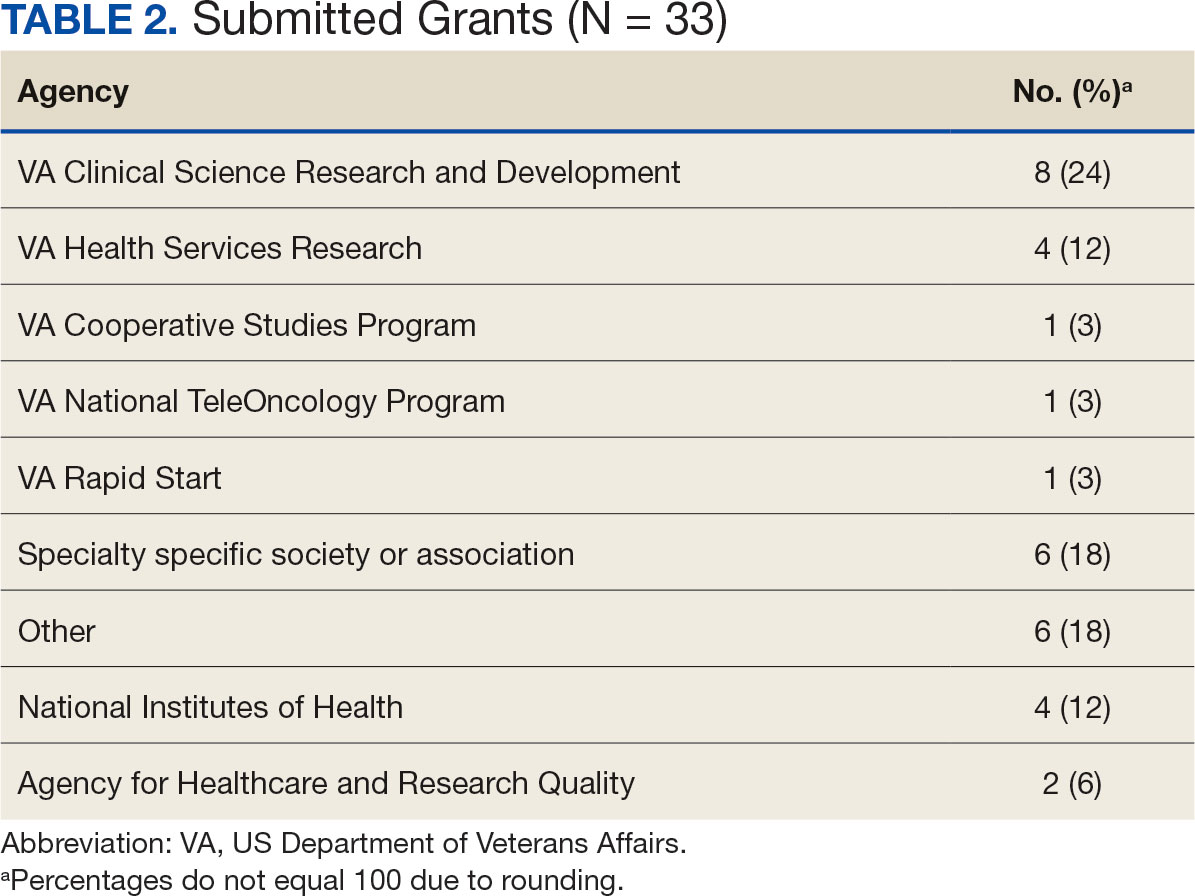

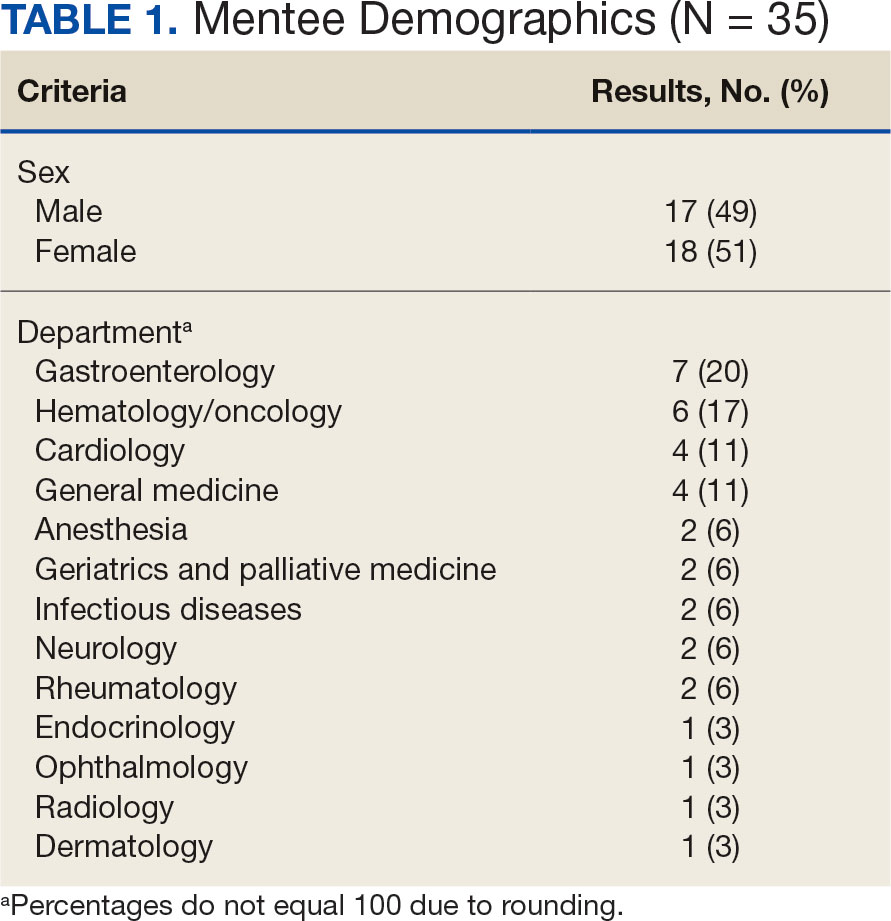

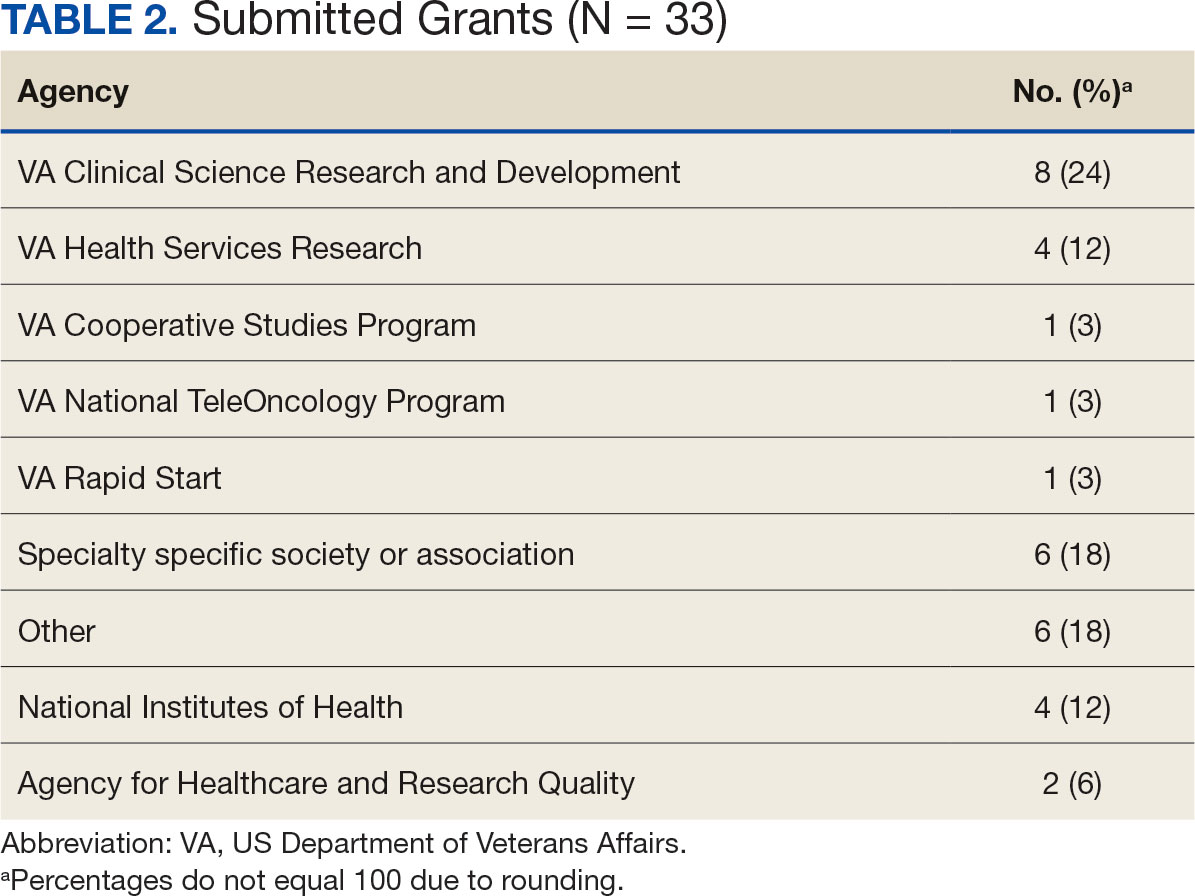

Since its inception in 2015, 35 clinicians have enrolled in the program. The mentees are equally distributed by sex and practice in a variety of disciplines including gastroenterology, hematology/oncology, cardiology, and general medicine (Table 1). Mentees have submitted 33 grant proposals addressing a variety of health care issues to a diverse group of federal and nonfederal funding agencies (Table 2). As of May 15, 2024, 19 (58%) of the submitted applications have been funded.

Many factors contribute to a successfully funded grant application, and several mentees report that participating in the mentorship program was helpful. For example, a mentee became the first lead investigator for a VA Cooperative Studies Program funded at VAAAHS. The VA Cooperative Studies Program, a division of the Office of Research and Development, plans and conducts large multicenter clinical trials and epidemiological studies within the VA via a vast network of clinician investigators, statisticians, and other key research experts.14

Several program mentees have also received VA Clinical Science Research and Development Career Development Awards. The VA Career Development program supports investigators during their early research careers with a goal of retaining talented researchers committed to improving the health and care of veterans.15

Survey Responses

Mentee productivity and updates are tracked through direct mentee input, as requested by the program coordinator. Since 2022, participants could complete an end-of-year survey based on an assessment tool used in a VAAAHS nonresearch mentorship program.16 The survey, distributed to mentees and program directors, requests feedback on logistics (eg, if the meeting was a good use of time and barriers to attendance); perceptions of effectiveness (eg, ability to discuss agenda items, helpfulness with setting and reaching research goals, and quality of mentors’ feedback); and the impact of the mentoring program on work satisfaction and clinician burnout. Respondents are also encouraged to leave open-ended qualitative feedback.

To date the survey has elicited 19 responses. Seventeen (89%) indicated that they agree or strongly agree the meetings were an effective use of their time and 11 (58%) indicated that they were able to discuss all or most of the items they wanted to during the meeting. Sixteen respondents (84%) agreed the program helped them set and achieve their research goals and 14 respondents (74%) agreed the feedback they received during the meeting was specific, actionable, and focused on how to improve their research agenda. Seventeen respondents (89%) agreed the program increased their work satisfaction, while 13 respondents (68%) felt the program reduced levels of clinician burnout.

As attendance was not mandatory, the survey asked participants how often they attended meetings during the past year. Responses were mixed: 4 (21%) respondents attended regularly (12 to 16 times per year) and 8 (42%) attended most sessions (8 to 11 times per year). Noted barriers to attendance included conflicts with patient care activities and conflicts with other high priority meetings.

Mentees also provided qualitive feedback regarding the program. They highlighted the supportive environment, valuable expertise of the mentors, and usefulness of obtaining tailored feedback from the group. “This group is an amazing resource to anyone developing a research career,” a mentee noted, adding that the program directors “fostered an incredibly supportive group where research ideas and methodology can be explored in a nonthreatening and creative environment.”

Conclusions

This mentorship program aims to help aspiring VA clinician investigators develop and submit competitive research grant applications. The addition of the program to the existing robust research environments at VAAAHS and its academic affiliate appears to have contributed to this success, with 58% of applications submitted by program mentees receiving funding.

In addition to funding success, we also found that most participants have a favorable impression of the program. Of the participants who responded to the program evaluation survey, nearly all indicated the program was an effective use of their time. The program also appeared to increase work satisfaction and reduce levels of clinician burnout. Barriers to attendance were also noted, with the most frequent being scheduling conflicts.

This program’s format includes facilitated group discussion as well as peer mentorship. This collaborative structure allows for an efficient and rich learning experience. Feedback from multiple perspectives encourages natural networking and relationship building. Incorporating the collective wisdom of the faculty mentors and peer mentees is beneficial; it not only empowers the mentees but also enriches the experience for the mentors. This program can serve as a model for other VA facilities—or non-VA academic medical centers—to enhance their research programs.

- US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Research and Development. Strategic priorities for VA research. Published March 10, 2021. Accessed September 17, 2024. https://www.research.va.gov/about/strategic_priorities.cfm

- . US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Research and Development. About the Office of Research & Development. Published November 11, 2023. Accessed September 17, 2024. https://www.research.va.gov/about/default.cfm

- Chopra V, Vaughn V, Saint S. The Mentoring Guide: Helping Mentors and Mentees Succeed. Michigan Publishing Services; 2019.

- Gilster SD, Accorinti KL. Mentoring program yields staff satisfaction. Mentoring through the exchange of information across all organizational levels can help administrators retain valuable staff. Provider. 1999;25(10):99-100.

- Ramanan RA, Phillips RS, Davis RB, Silen W, Reede JY. Mentoring in medicine: keys to satisfaction. Am J Med. 2002;112(4):336-341. doi:10.1016/s0002-9343(02)01032-x

- Sambunjak D, Straus SE, Marusi' A. Mentoring in academic medicine: a systematic review. JAMA. 2006;296(9):1103-1115. doi:10.1001/jama.296.9.1103

- Sambunjak D, Straus SE, Marusi' A. A systematic review of qualitative research on the meaning and characteristics of mentoring in academic medicine. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(1):72-78. doi:10.1007/s11606-009-1165-8

- Jackson VA, Palepu A, Szalacha L, Caswell C, Carr PL, Inui T. “Having the right chemistry”: a qualitative study of mentoring in academic medicine. Acad Med. 2003;78(3):328-334. doi:10.1097/00001888-200303000-00020

- Feldman MD, Arean PA, Marshall SJ, Lovett M, O’Sullivan P. Does mentoring matter: results from a survey of faculty mentees at a large health sciences university. Med Educ Online. 2010;15:10.3402/meo.v15i0.5063. doi:10.3402/meo.v15i0.5063

- Leary JC, Schainker EG, Leyenaar JK. The unwritten rules of mentorship: facilitators of and barriers to effective mentorship in pediatric hospital medicine. Hosp Pediatr. 2016;6(4):219-225. doi:10.1542/hpeds.2015-0108

- Rustgi AK, Hecht GA. Mentorship in academic medicine. Gastroenterology. 2011;141(3):789-792. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2011.07.024

- DeCastro R, Sambuco D, Ubel PA, Stewart A, Jagsi R. Mentor networks in academic medicine: moving beyond a dyadic conception of mentoring for junior faculty researchers. Acad Med. 2013;88(4):488-496. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e318285d302

- McDaugall M, Beattie RS. Peer mentoring at work: the nature and outcomes of non-hierarchical developmental relationships. Management Learning. 2016;28(4):423-437. doi:10.1177/1350507697284003

- US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Rsearch and Development. VA Cooperative Studies Program (CSP). Updated July 2019. Accessed September 17, 2024. https://www.vacsp.research.va.gov

- US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Research and Development. Career development program for biomedical laboratory and clinical science R&D services. Published April 17, 2023. Accessed September 17, 2024. https://www.research.va.gov/services/shared_docs/career_dev.cfm

- Houchens N, Kuhn L, Ratz D, Su G, Saint S. Committed to success: a structured mentoring program for clinically-oriented physicians. Mayo Clin Pro Innov Qual Outcomes. 2024;8(4):356-363. doi:10.1016/j.mayocpiqo.2024.05.002

Supporting meaningful research that has a positive impact on the health and quality of life of veterans is a priority of the US Department of Veterans Affairs Office of Research and Development.1 For nearly a century, VA researchers have been conducting high quality studies. To continue this trajectory, it is imperative to attract, train, and retain exceptional investigators while nurturing their development throughout their careers.2

Mentorship is defined as guidance provided by an experienced and trusted party to another (usually junior) individual with the intent of helping the person succeed. It benefits the mentee, mentor, and their institutions.3 Mentorship is crucial for personal and professional development as well as productivity, which may help reduce clinician burnout.4-7 Conversely, a lack of mentorship could have negative effects on work satisfaction and stagnate career progression.8

Mentorship is vital for developing and advancing a VA investigator’s research agenda. Funding, grant writing, and research design were among the most discussed topics in a large comprehensive mentorship program for academic faculty.9 However, there are several known barriers to effective research mentorship; among them include a lack of resources, time constraints, and competing clinical priorities.10,11

Finding time for effective one-on-one research mentoring is difficult within the time constraints of clinical duties; a group mentorship model may help overcome this barrier. Group mentorship can aid in personal and professional development because no single mentor can effectively meet every mentoring need of an individual.12 Group mentorship also allows for the exchange of ideas among individuals with different backgrounds and the ability to utilize the strengths of each member of the group. For example, a member may have methodological expertise, while another may be skilled in grantsmanship. A team of mentors may be more beneficial for both the mentors (eg, establish a more manageable workload) and the mentee (eg, gains a broader perspective of expertise) when compared to having a single mentor.3

Peer mentorship within the group setting may also yield additional benefits. For example, having a supportive peer group may help reduce stress levels and burnout, while also improving overall well-being.3,13 Formal mentorship programs do not frequently discuss concerns such as work-life balance, so including peers as mentors may help fill this void.9 Peer mentorship has also been found to be beneficial in providing mentees with pooled resources and shared learning.12,13 This article describes the components, benefits, impacts, and challenges of a group research mentorship program for VA clinicians interested in conducting VArelevant research.

Program Description

The VA Clinical Research Mentorship Program was initiated at the VA Ann Arbor Healthcare System (VAAAHS) in October 2015 by the Chief of Medicine to assist VA clinician investigators with developing and submitting VA clinical science and health services research grant applications. The program offers group and one-on-one consultation services through the expertise of 2 experienced investigators/faculty mentors who also serve as program directors, each of whom devote about 3 to 5 hours per month to activities associated with the mentorship program (eg, attending the meeting, reviewing materials sent by mentees, and one-on-one discussions with mentees).

The program also fostered peer-led mentorship. This encourages all attendees to provide feedback during group sessions and communication by mentees outside the group sessions. An experienced project manager serves as program coordinator and contributes about 4 hours per month for activities such as attending, scheduling, and sending reminders for each meeting, distributing handouts, reviewing materials, and answering mentee’s questions via email. A statistician and additional research staff (ie, an epidemiologist and research assistant) do not attend the recurring meetings, but are available for offline consultation as needed. The program runs on a 12-month cycle with regular meetings occurring twice monthly during the 9-month academic period. Resources to support the program, primarily program director(s) and project coordinator effort, are provided by the Chief of Medicine and through the VAAAHS affiliated VA Health Systems Research (formerly Health Services Research & Development) Center of Innovation.

Invitations for new mentees are sent annually. Mentees expressing interest in the program outside of its annual recruitment period are evaluated for inclusion on a rolling basis. Recruitment begins with the program coordinator sending email notifications to all VAAAHS Medicine Service faculty, section chiefs, and division chiefs at the VAAAHS academic affiliate. Recipients are encouraged to distribute the announcement to eligible applicants and refer them to the application materials for entry consideration into the program. The application consists of the applicant’s curriculum vitae and a 1-page summary that includes a description of their research area of interest, how it is relevant to the VA, in addition to an idea for a research study, its potential significance, and proposed methodology. Applicant materials are reviewed by the program coordinator and program directors. The applicants are evaluated using a simple scoring approach that focuses on the applicant’s research area and agenda, past research training, past research productivity, potential for obtaining VA funding, and whether they have sufficient research time.

Program eligibility initially required being a physician with ≥ 1/8 VA appointment from the Medicine Service. However, clinicians with clinical appointments from other VA services are also accepted for participation as needed. Applicants must have previous research experience and have a career goal to obtain external funding for conducting and publishing original research. Those who have previously served as a principal investigator on a funded VA grant proposal are not eligible as new applicants but can remain in the program as peer mentors. The number of annual applicants varies and ranges from 1 to 11; on average, about 90% of applicants receive invitations to join the program.

Sessions

The program holds recurring meetings twice monthly for 1 hour during the 9-month academic year. However, program directors are available year-round, and mentees are encouraged to communicate questions or concerns via email during nonacademic months. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, all meetings were held in-person. However, the group pivoted to virtual meetings and continues to utilize this format. The dedicated program coordinator is responsible for coordinating meetings and distributing meeting materials.

Each session is informal, flexible, and supportive. Attendance is not enforced, and mentees are allowed to join meetings as their schedules permit; however, program directors and program coordinator attend each meeting. In advance of each session, the program coordinator sends out a call for agenda items to all active members invited to discuss any research related items. Each mentee presents their ideas to lead the discussion for their portion of the meeting with no defined format required.

A variety of topics are covered including, but not limited to: (1) grant-specific concerns (eg, questions related to specific aim pages, grantsmanship, postsubmission comments from reviewers, or postaward logistics); (2) research procedures (eg, questions related to methodological practices or institutional review board concerns); (3) manuscript or presentation preparation; and (4) careerrelated issues. The program coordinator distributes handouts prior to meetings and mentees may record their presentations. These handouts may include, but are not limited to, specific aims pages, analytical plans, grant solicitations, and PowerPoint presentations. If a resource that can benefit the entire group is mentioned during the meeting, the program coordinator is responsible for distribution.

The program follows a group facilitated discussion format. Program directors facilitate each meeting, but input is encouraged from all attendees. This model allows for mentees to learn from the faculty mentors as well as peer mentees in a simultaneous and efficient fashion. Group discussions foster collective problem solving, peer support, and resource sharing that would not be possible through individualized mentorship. Participants have access to varied expertise during each session which reduces the need to seek specialized help elsewhere. Participants are also encouraged to contact the program directors or research staff for consultation as needed. Some one-on-one consultations have transitioned to a more sustained and ongoing mentorship relationship between a program director and mentee, but most are often brief email exchanges or a single meeting.

Participants

Since its inception in 2015, 35 clinicians have enrolled in the program. The mentees are equally distributed by sex and practice in a variety of disciplines including gastroenterology, hematology/oncology, cardiology, and general medicine (Table 1). Mentees have submitted 33 grant proposals addressing a variety of health care issues to a diverse group of federal and nonfederal funding agencies (Table 2). As of May 15, 2024, 19 (58%) of the submitted applications have been funded.

Many factors contribute to a successfully funded grant application, and several mentees report that participating in the mentorship program was helpful. For example, a mentee became the first lead investigator for a VA Cooperative Studies Program funded at VAAAHS. The VA Cooperative Studies Program, a division of the Office of Research and Development, plans and conducts large multicenter clinical trials and epidemiological studies within the VA via a vast network of clinician investigators, statisticians, and other key research experts.14

Several program mentees have also received VA Clinical Science Research and Development Career Development Awards. The VA Career Development program supports investigators during their early research careers with a goal of retaining talented researchers committed to improving the health and care of veterans.15

Survey Responses

Mentee productivity and updates are tracked through direct mentee input, as requested by the program coordinator. Since 2022, participants could complete an end-of-year survey based on an assessment tool used in a VAAAHS nonresearch mentorship program.16 The survey, distributed to mentees and program directors, requests feedback on logistics (eg, if the meeting was a good use of time and barriers to attendance); perceptions of effectiveness (eg, ability to discuss agenda items, helpfulness with setting and reaching research goals, and quality of mentors’ feedback); and the impact of the mentoring program on work satisfaction and clinician burnout. Respondents are also encouraged to leave open-ended qualitative feedback.

To date the survey has elicited 19 responses. Seventeen (89%) indicated that they agree or strongly agree the meetings were an effective use of their time and 11 (58%) indicated that they were able to discuss all or most of the items they wanted to during the meeting. Sixteen respondents (84%) agreed the program helped them set and achieve their research goals and 14 respondents (74%) agreed the feedback they received during the meeting was specific, actionable, and focused on how to improve their research agenda. Seventeen respondents (89%) agreed the program increased their work satisfaction, while 13 respondents (68%) felt the program reduced levels of clinician burnout.

As attendance was not mandatory, the survey asked participants how often they attended meetings during the past year. Responses were mixed: 4 (21%) respondents attended regularly (12 to 16 times per year) and 8 (42%) attended most sessions (8 to 11 times per year). Noted barriers to attendance included conflicts with patient care activities and conflicts with other high priority meetings.

Mentees also provided qualitive feedback regarding the program. They highlighted the supportive environment, valuable expertise of the mentors, and usefulness of obtaining tailored feedback from the group. “This group is an amazing resource to anyone developing a research career,” a mentee noted, adding that the program directors “fostered an incredibly supportive group where research ideas and methodology can be explored in a nonthreatening and creative environment.”

Conclusions

This mentorship program aims to help aspiring VA clinician investigators develop and submit competitive research grant applications. The addition of the program to the existing robust research environments at VAAAHS and its academic affiliate appears to have contributed to this success, with 58% of applications submitted by program mentees receiving funding.

In addition to funding success, we also found that most participants have a favorable impression of the program. Of the participants who responded to the program evaluation survey, nearly all indicated the program was an effective use of their time. The program also appeared to increase work satisfaction and reduce levels of clinician burnout. Barriers to attendance were also noted, with the most frequent being scheduling conflicts.

This program’s format includes facilitated group discussion as well as peer mentorship. This collaborative structure allows for an efficient and rich learning experience. Feedback from multiple perspectives encourages natural networking and relationship building. Incorporating the collective wisdom of the faculty mentors and peer mentees is beneficial; it not only empowers the mentees but also enriches the experience for the mentors. This program can serve as a model for other VA facilities—or non-VA academic medical centers—to enhance their research programs.

Supporting meaningful research that has a positive impact on the health and quality of life of veterans is a priority of the US Department of Veterans Affairs Office of Research and Development.1 For nearly a century, VA researchers have been conducting high quality studies. To continue this trajectory, it is imperative to attract, train, and retain exceptional investigators while nurturing their development throughout their careers.2

Mentorship is defined as guidance provided by an experienced and trusted party to another (usually junior) individual with the intent of helping the person succeed. It benefits the mentee, mentor, and their institutions.3 Mentorship is crucial for personal and professional development as well as productivity, which may help reduce clinician burnout.4-7 Conversely, a lack of mentorship could have negative effects on work satisfaction and stagnate career progression.8

Mentorship is vital for developing and advancing a VA investigator’s research agenda. Funding, grant writing, and research design were among the most discussed topics in a large comprehensive mentorship program for academic faculty.9 However, there are several known barriers to effective research mentorship; among them include a lack of resources, time constraints, and competing clinical priorities.10,11

Finding time for effective one-on-one research mentoring is difficult within the time constraints of clinical duties; a group mentorship model may help overcome this barrier. Group mentorship can aid in personal and professional development because no single mentor can effectively meet every mentoring need of an individual.12 Group mentorship also allows for the exchange of ideas among individuals with different backgrounds and the ability to utilize the strengths of each member of the group. For example, a member may have methodological expertise, while another may be skilled in grantsmanship. A team of mentors may be more beneficial for both the mentors (eg, establish a more manageable workload) and the mentee (eg, gains a broader perspective of expertise) when compared to having a single mentor.3

Peer mentorship within the group setting may also yield additional benefits. For example, having a supportive peer group may help reduce stress levels and burnout, while also improving overall well-being.3,13 Formal mentorship programs do not frequently discuss concerns such as work-life balance, so including peers as mentors may help fill this void.9 Peer mentorship has also been found to be beneficial in providing mentees with pooled resources and shared learning.12,13 This article describes the components, benefits, impacts, and challenges of a group research mentorship program for VA clinicians interested in conducting VArelevant research.

Program Description

The VA Clinical Research Mentorship Program was initiated at the VA Ann Arbor Healthcare System (VAAAHS) in October 2015 by the Chief of Medicine to assist VA clinician investigators with developing and submitting VA clinical science and health services research grant applications. The program offers group and one-on-one consultation services through the expertise of 2 experienced investigators/faculty mentors who also serve as program directors, each of whom devote about 3 to 5 hours per month to activities associated with the mentorship program (eg, attending the meeting, reviewing materials sent by mentees, and one-on-one discussions with mentees).

The program also fostered peer-led mentorship. This encourages all attendees to provide feedback during group sessions and communication by mentees outside the group sessions. An experienced project manager serves as program coordinator and contributes about 4 hours per month for activities such as attending, scheduling, and sending reminders for each meeting, distributing handouts, reviewing materials, and answering mentee’s questions via email. A statistician and additional research staff (ie, an epidemiologist and research assistant) do not attend the recurring meetings, but are available for offline consultation as needed. The program runs on a 12-month cycle with regular meetings occurring twice monthly during the 9-month academic period. Resources to support the program, primarily program director(s) and project coordinator effort, are provided by the Chief of Medicine and through the VAAAHS affiliated VA Health Systems Research (formerly Health Services Research & Development) Center of Innovation.

Invitations for new mentees are sent annually. Mentees expressing interest in the program outside of its annual recruitment period are evaluated for inclusion on a rolling basis. Recruitment begins with the program coordinator sending email notifications to all VAAAHS Medicine Service faculty, section chiefs, and division chiefs at the VAAAHS academic affiliate. Recipients are encouraged to distribute the announcement to eligible applicants and refer them to the application materials for entry consideration into the program. The application consists of the applicant’s curriculum vitae and a 1-page summary that includes a description of their research area of interest, how it is relevant to the VA, in addition to an idea for a research study, its potential significance, and proposed methodology. Applicant materials are reviewed by the program coordinator and program directors. The applicants are evaluated using a simple scoring approach that focuses on the applicant’s research area and agenda, past research training, past research productivity, potential for obtaining VA funding, and whether they have sufficient research time.

Program eligibility initially required being a physician with ≥ 1/8 VA appointment from the Medicine Service. However, clinicians with clinical appointments from other VA services are also accepted for participation as needed. Applicants must have previous research experience and have a career goal to obtain external funding for conducting and publishing original research. Those who have previously served as a principal investigator on a funded VA grant proposal are not eligible as new applicants but can remain in the program as peer mentors. The number of annual applicants varies and ranges from 1 to 11; on average, about 90% of applicants receive invitations to join the program.

Sessions

The program holds recurring meetings twice monthly for 1 hour during the 9-month academic year. However, program directors are available year-round, and mentees are encouraged to communicate questions or concerns via email during nonacademic months. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, all meetings were held in-person. However, the group pivoted to virtual meetings and continues to utilize this format. The dedicated program coordinator is responsible for coordinating meetings and distributing meeting materials.

Each session is informal, flexible, and supportive. Attendance is not enforced, and mentees are allowed to join meetings as their schedules permit; however, program directors and program coordinator attend each meeting. In advance of each session, the program coordinator sends out a call for agenda items to all active members invited to discuss any research related items. Each mentee presents their ideas to lead the discussion for their portion of the meeting with no defined format required.

A variety of topics are covered including, but not limited to: (1) grant-specific concerns (eg, questions related to specific aim pages, grantsmanship, postsubmission comments from reviewers, or postaward logistics); (2) research procedures (eg, questions related to methodological practices or institutional review board concerns); (3) manuscript or presentation preparation; and (4) careerrelated issues. The program coordinator distributes handouts prior to meetings and mentees may record their presentations. These handouts may include, but are not limited to, specific aims pages, analytical plans, grant solicitations, and PowerPoint presentations. If a resource that can benefit the entire group is mentioned during the meeting, the program coordinator is responsible for distribution.

The program follows a group facilitated discussion format. Program directors facilitate each meeting, but input is encouraged from all attendees. This model allows for mentees to learn from the faculty mentors as well as peer mentees in a simultaneous and efficient fashion. Group discussions foster collective problem solving, peer support, and resource sharing that would not be possible through individualized mentorship. Participants have access to varied expertise during each session which reduces the need to seek specialized help elsewhere. Participants are also encouraged to contact the program directors or research staff for consultation as needed. Some one-on-one consultations have transitioned to a more sustained and ongoing mentorship relationship between a program director and mentee, but most are often brief email exchanges or a single meeting.

Participants

Since its inception in 2015, 35 clinicians have enrolled in the program. The mentees are equally distributed by sex and practice in a variety of disciplines including gastroenterology, hematology/oncology, cardiology, and general medicine (Table 1). Mentees have submitted 33 grant proposals addressing a variety of health care issues to a diverse group of federal and nonfederal funding agencies (Table 2). As of May 15, 2024, 19 (58%) of the submitted applications have been funded.

Many factors contribute to a successfully funded grant application, and several mentees report that participating in the mentorship program was helpful. For example, a mentee became the first lead investigator for a VA Cooperative Studies Program funded at VAAAHS. The VA Cooperative Studies Program, a division of the Office of Research and Development, plans and conducts large multicenter clinical trials and epidemiological studies within the VA via a vast network of clinician investigators, statisticians, and other key research experts.14

Several program mentees have also received VA Clinical Science Research and Development Career Development Awards. The VA Career Development program supports investigators during their early research careers with a goal of retaining talented researchers committed to improving the health and care of veterans.15

Survey Responses

Mentee productivity and updates are tracked through direct mentee input, as requested by the program coordinator. Since 2022, participants could complete an end-of-year survey based on an assessment tool used in a VAAAHS nonresearch mentorship program.16 The survey, distributed to mentees and program directors, requests feedback on logistics (eg, if the meeting was a good use of time and barriers to attendance); perceptions of effectiveness (eg, ability to discuss agenda items, helpfulness with setting and reaching research goals, and quality of mentors’ feedback); and the impact of the mentoring program on work satisfaction and clinician burnout. Respondents are also encouraged to leave open-ended qualitative feedback.

To date the survey has elicited 19 responses. Seventeen (89%) indicated that they agree or strongly agree the meetings were an effective use of their time and 11 (58%) indicated that they were able to discuss all or most of the items they wanted to during the meeting. Sixteen respondents (84%) agreed the program helped them set and achieve their research goals and 14 respondents (74%) agreed the feedback they received during the meeting was specific, actionable, and focused on how to improve their research agenda. Seventeen respondents (89%) agreed the program increased their work satisfaction, while 13 respondents (68%) felt the program reduced levels of clinician burnout.

As attendance was not mandatory, the survey asked participants how often they attended meetings during the past year. Responses were mixed: 4 (21%) respondents attended regularly (12 to 16 times per year) and 8 (42%) attended most sessions (8 to 11 times per year). Noted barriers to attendance included conflicts with patient care activities and conflicts with other high priority meetings.

Mentees also provided qualitive feedback regarding the program. They highlighted the supportive environment, valuable expertise of the mentors, and usefulness of obtaining tailored feedback from the group. “This group is an amazing resource to anyone developing a research career,” a mentee noted, adding that the program directors “fostered an incredibly supportive group where research ideas and methodology can be explored in a nonthreatening and creative environment.”

Conclusions

This mentorship program aims to help aspiring VA clinician investigators develop and submit competitive research grant applications. The addition of the program to the existing robust research environments at VAAAHS and its academic affiliate appears to have contributed to this success, with 58% of applications submitted by program mentees receiving funding.

In addition to funding success, we also found that most participants have a favorable impression of the program. Of the participants who responded to the program evaluation survey, nearly all indicated the program was an effective use of their time. The program also appeared to increase work satisfaction and reduce levels of clinician burnout. Barriers to attendance were also noted, with the most frequent being scheduling conflicts.

This program’s format includes facilitated group discussion as well as peer mentorship. This collaborative structure allows for an efficient and rich learning experience. Feedback from multiple perspectives encourages natural networking and relationship building. Incorporating the collective wisdom of the faculty mentors and peer mentees is beneficial; it not only empowers the mentees but also enriches the experience for the mentors. This program can serve as a model for other VA facilities—or non-VA academic medical centers—to enhance their research programs.

- US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Research and Development. Strategic priorities for VA research. Published March 10, 2021. Accessed September 17, 2024. https://www.research.va.gov/about/strategic_priorities.cfm

- . US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Research and Development. About the Office of Research & Development. Published November 11, 2023. Accessed September 17, 2024. https://www.research.va.gov/about/default.cfm

- Chopra V, Vaughn V, Saint S. The Mentoring Guide: Helping Mentors and Mentees Succeed. Michigan Publishing Services; 2019.

- Gilster SD, Accorinti KL. Mentoring program yields staff satisfaction. Mentoring through the exchange of information across all organizational levels can help administrators retain valuable staff. Provider. 1999;25(10):99-100.

- Ramanan RA, Phillips RS, Davis RB, Silen W, Reede JY. Mentoring in medicine: keys to satisfaction. Am J Med. 2002;112(4):336-341. doi:10.1016/s0002-9343(02)01032-x

- Sambunjak D, Straus SE, Marusi' A. Mentoring in academic medicine: a systematic review. JAMA. 2006;296(9):1103-1115. doi:10.1001/jama.296.9.1103

- Sambunjak D, Straus SE, Marusi' A. A systematic review of qualitative research on the meaning and characteristics of mentoring in academic medicine. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(1):72-78. doi:10.1007/s11606-009-1165-8

- Jackson VA, Palepu A, Szalacha L, Caswell C, Carr PL, Inui T. “Having the right chemistry”: a qualitative study of mentoring in academic medicine. Acad Med. 2003;78(3):328-334. doi:10.1097/00001888-200303000-00020

- Feldman MD, Arean PA, Marshall SJ, Lovett M, O’Sullivan P. Does mentoring matter: results from a survey of faculty mentees at a large health sciences university. Med Educ Online. 2010;15:10.3402/meo.v15i0.5063. doi:10.3402/meo.v15i0.5063

- Leary JC, Schainker EG, Leyenaar JK. The unwritten rules of mentorship: facilitators of and barriers to effective mentorship in pediatric hospital medicine. Hosp Pediatr. 2016;6(4):219-225. doi:10.1542/hpeds.2015-0108

- Rustgi AK, Hecht GA. Mentorship in academic medicine. Gastroenterology. 2011;141(3):789-792. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2011.07.024

- DeCastro R, Sambuco D, Ubel PA, Stewart A, Jagsi R. Mentor networks in academic medicine: moving beyond a dyadic conception of mentoring for junior faculty researchers. Acad Med. 2013;88(4):488-496. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e318285d302

- McDaugall M, Beattie RS. Peer mentoring at work: the nature and outcomes of non-hierarchical developmental relationships. Management Learning. 2016;28(4):423-437. doi:10.1177/1350507697284003

- US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Rsearch and Development. VA Cooperative Studies Program (CSP). Updated July 2019. Accessed September 17, 2024. https://www.vacsp.research.va.gov

- US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Research and Development. Career development program for biomedical laboratory and clinical science R&D services. Published April 17, 2023. Accessed September 17, 2024. https://www.research.va.gov/services/shared_docs/career_dev.cfm

- Houchens N, Kuhn L, Ratz D, Su G, Saint S. Committed to success: a structured mentoring program for clinically-oriented physicians. Mayo Clin Pro Innov Qual Outcomes. 2024;8(4):356-363. doi:10.1016/j.mayocpiqo.2024.05.002

- US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Research and Development. Strategic priorities for VA research. Published March 10, 2021. Accessed September 17, 2024. https://www.research.va.gov/about/strategic_priorities.cfm

- . US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Research and Development. About the Office of Research & Development. Published November 11, 2023. Accessed September 17, 2024. https://www.research.va.gov/about/default.cfm

- Chopra V, Vaughn V, Saint S. The Mentoring Guide: Helping Mentors and Mentees Succeed. Michigan Publishing Services; 2019.

- Gilster SD, Accorinti KL. Mentoring program yields staff satisfaction. Mentoring through the exchange of information across all organizational levels can help administrators retain valuable staff. Provider. 1999;25(10):99-100.

- Ramanan RA, Phillips RS, Davis RB, Silen W, Reede JY. Mentoring in medicine: keys to satisfaction. Am J Med. 2002;112(4):336-341. doi:10.1016/s0002-9343(02)01032-x

- Sambunjak D, Straus SE, Marusi' A. Mentoring in academic medicine: a systematic review. JAMA. 2006;296(9):1103-1115. doi:10.1001/jama.296.9.1103

- Sambunjak D, Straus SE, Marusi' A. A systematic review of qualitative research on the meaning and characteristics of mentoring in academic medicine. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(1):72-78. doi:10.1007/s11606-009-1165-8

- Jackson VA, Palepu A, Szalacha L, Caswell C, Carr PL, Inui T. “Having the right chemistry”: a qualitative study of mentoring in academic medicine. Acad Med. 2003;78(3):328-334. doi:10.1097/00001888-200303000-00020

- Feldman MD, Arean PA, Marshall SJ, Lovett M, O’Sullivan P. Does mentoring matter: results from a survey of faculty mentees at a large health sciences university. Med Educ Online. 2010;15:10.3402/meo.v15i0.5063. doi:10.3402/meo.v15i0.5063

- Leary JC, Schainker EG, Leyenaar JK. The unwritten rules of mentorship: facilitators of and barriers to effective mentorship in pediatric hospital medicine. Hosp Pediatr. 2016;6(4):219-225. doi:10.1542/hpeds.2015-0108

- Rustgi AK, Hecht GA. Mentorship in academic medicine. Gastroenterology. 2011;141(3):789-792. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2011.07.024

- DeCastro R, Sambuco D, Ubel PA, Stewart A, Jagsi R. Mentor networks in academic medicine: moving beyond a dyadic conception of mentoring for junior faculty researchers. Acad Med. 2013;88(4):488-496. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e318285d302

- McDaugall M, Beattie RS. Peer mentoring at work: the nature and outcomes of non-hierarchical developmental relationships. Management Learning. 2016;28(4):423-437. doi:10.1177/1350507697284003

- US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Rsearch and Development. VA Cooperative Studies Program (CSP). Updated July 2019. Accessed September 17, 2024. https://www.vacsp.research.va.gov

- US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Research and Development. Career development program for biomedical laboratory and clinical science R&D services. Published April 17, 2023. Accessed September 17, 2024. https://www.research.va.gov/services/shared_docs/career_dev.cfm

- Houchens N, Kuhn L, Ratz D, Su G, Saint S. Committed to success: a structured mentoring program for clinically-oriented physicians. Mayo Clin Pro Innov Qual Outcomes. 2024;8(4):356-363. doi:10.1016/j.mayocpiqo.2024.05.002

A Group Approach to Clinical Research Mentorship at a Veterans Affairs Medical Center

A Group Approach to Clinical Research Mentorship at a Veterans Affairs Medical Center