User login

Primary Care Clinician and Patient Knowledge, Interest, and Use of Integrative Treatment Options for Chronic Low Back Pain Management

Primary Care Clinician and Patient Knowledge, Interest, and Use of Integrative Treatment Options for Chronic Low Back Pain Management

More than 50 million US adults report experiencing chronic pain, with nearly 7% experiencing high-impact chronic pain.1-3 Chronic pain negatively affects daily function, results in lost productivity, is a leading cause of disability, and is more prevalent among veterans compared with the general population.1,2,4-6 Estimates from 2021 suggest the prevalence of chronic pain among veterans exceeds 30%; > 11% experienced high-impact chronic pain.1

Primary care practitioners (PCPs) have a prominent role in chronic pain management. Pharmacologic options for treating pain, once a mainstay of therapy, present several challenges for patients and PCPs, including drug-drug interactions and adverse effects.7 The US opioid epidemic and shift to a biopsychosocial model of chronic pain care have increased emphasis on nonpharmacologic treatment options.8,9 These include integrative modalities, which incorporate conventional approaches with an array of complementary health approaches.10-12

Integrative therapy is a prominent feature in whole person care, which may be best exemplified by the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Whole Health System of care.13-14 Whole health empowers an individual to take charge of their health and well-being so they can “live their life to the fullest.”14 As implemented in the Veterans Health Administration (VHA), whole health includes the use of evidence-based

METHODS

Using a cross-sectional survey design, PCPs and patients with chronic back pain affiliated with the VA Ann Arbor Healthcare System were invited to participate in separate but similar surveys to assess knowledge, interest, and use of nonpharmacologic integrative modalities for the treatment of chronic pain. In May, June, and July 2023, 78 PCPs received 3 email

Both survey instruments are available upon request, were developed by the study team, and included a mix of yes/no questions, “select all that apply” items, Likert scale response items, and open-ended questions. For one question about which modalities they would like available, the respondent was instructed to select up to 5 modalities. The instruments were extensively pretested by members of the study team, which included 2 PCPs and a nonveteran with chronic back pain.

The list of integrative modalities included in the survey was derived from the tier 1 and tier 2 complementary and integrative health modalities identified in a VHA Directive on complementary and integrative health.15,16 Tier 1 approaches are considered to have sufficient evidence and must be made available to veterans either within a VA medical facility or in the community. Tier 2 approaches are generally considered safe and may be made available but do not have sufficient evidence to mandate their provision. For participant ease, the integrative modalities were divided into 5 subgroups: manual therapies, energy/biofield therapies, mental health therapies, nutrition counseling, and movement therapies. The clinician survey assessed clinicians’ training and interest, clinical and personal use, and perceived barriers to providing integrative modalities for chronic pain. Professional and personal demographic data were also collected. Similarly, the patient survey assessed use of integrative therapies, perceptions of and interest in integrative modalities, and potential barriers to use. Demographic and health-related information was also collected.

Data analysis included descriptive statistics (eg, frequency counts, means, medians) and visual graphic displays. Separate analyses were conducted for clinicians and patients in addition to a comparative analysis of the use and potential interest in integrative modalities. Analysis were conducted using R software. This study was deemed nonresearch quality improvement by the VA Ann Arbor Healthcare System facility research oversight board and institutional review board approval was not solicited.

RESULTS

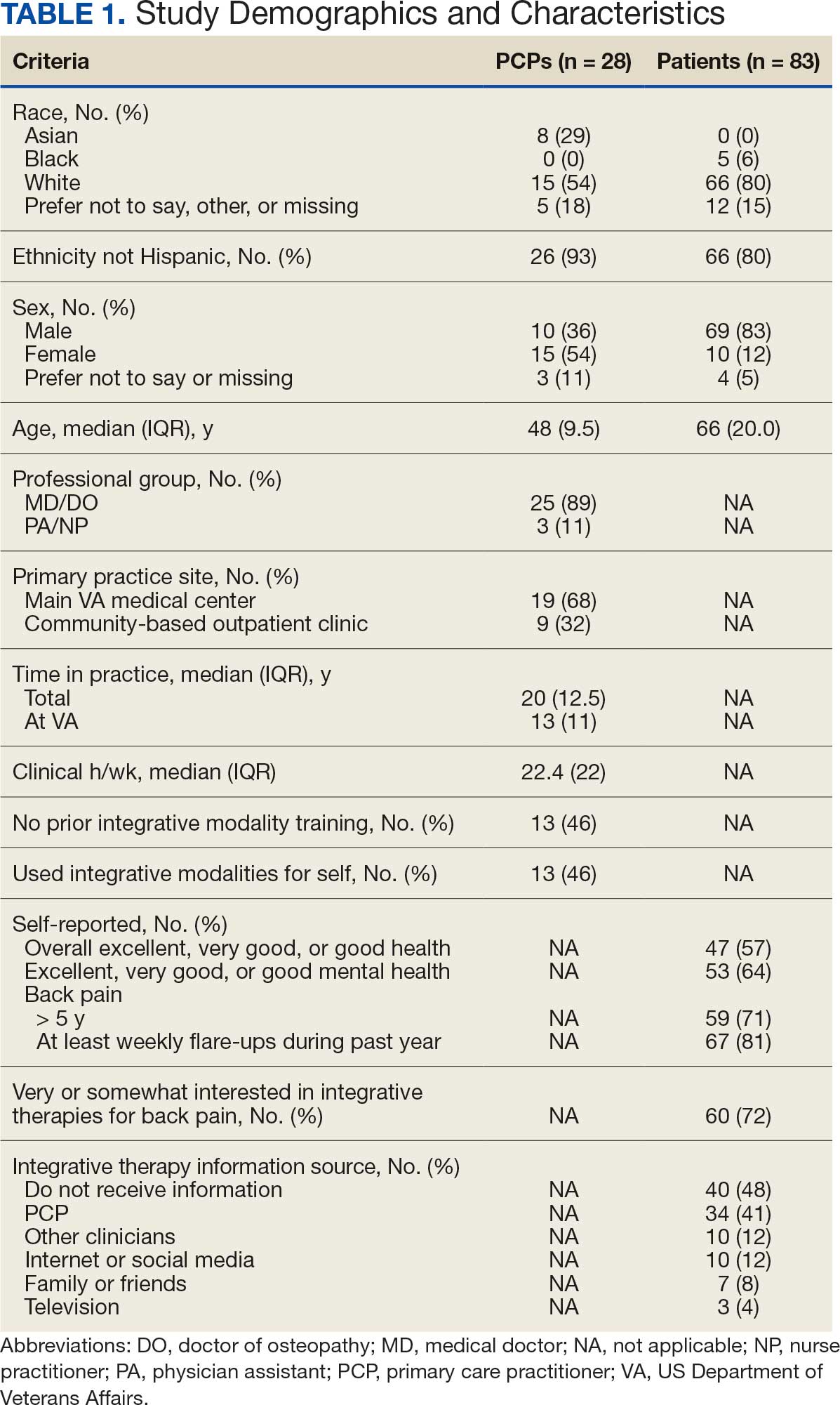

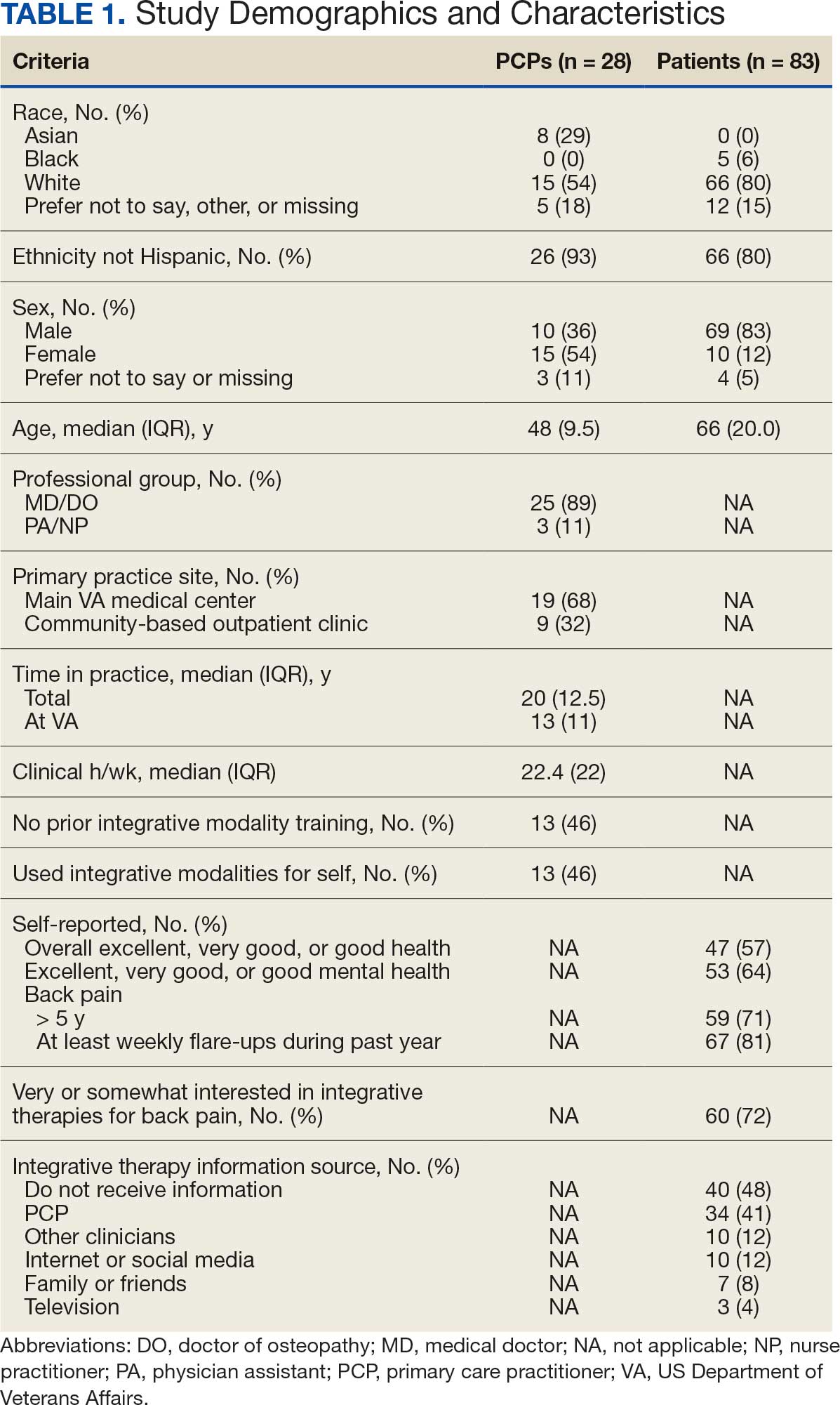

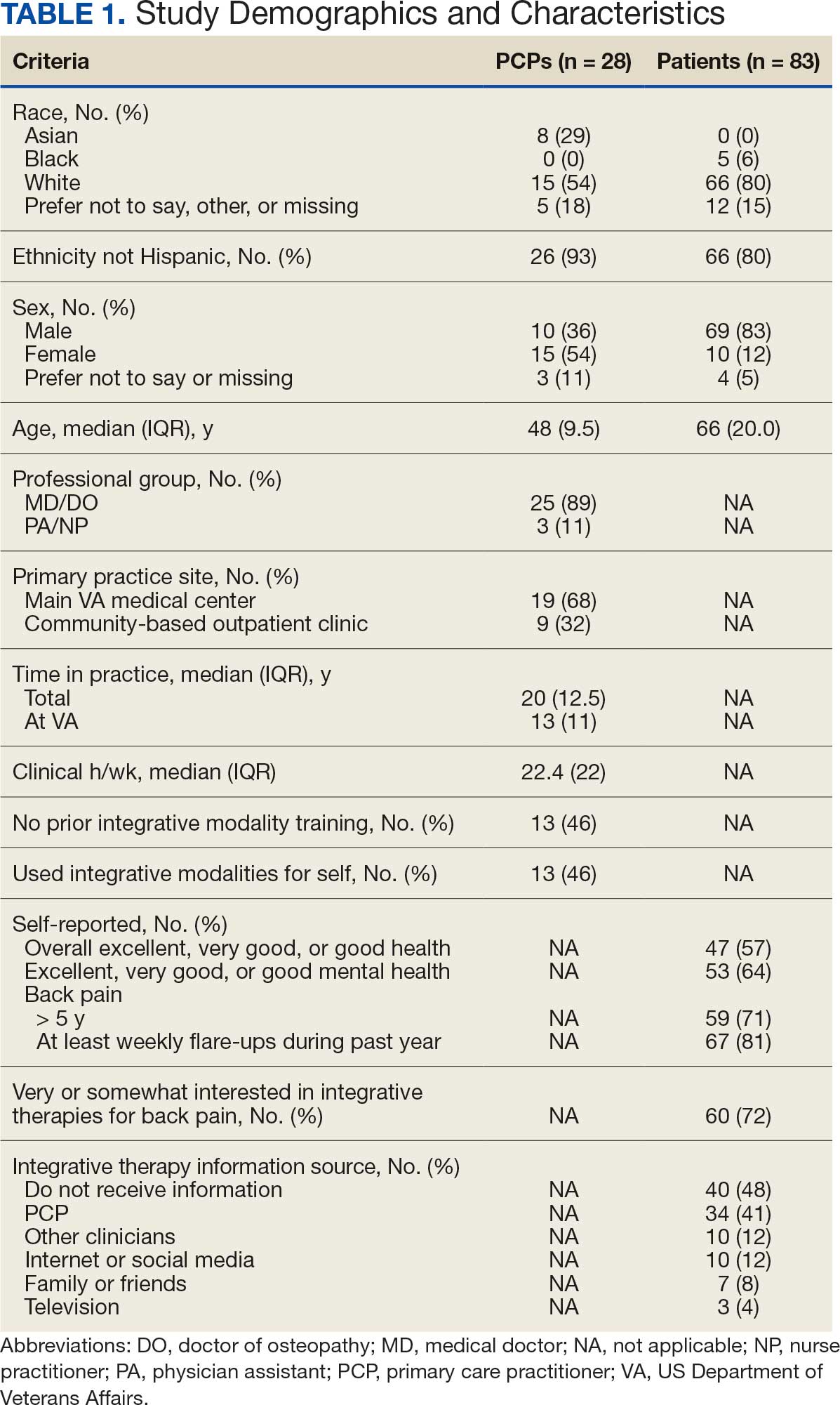

Twenty-eight clinicians completed the survey, yielding a participation rate of 36%. Participating clinicians had a median (IQR) age of 48 years (9.5), 15 self-identified as White (54%), 8 as Asian (29%), 15 as female (54%), 26 as non-Hispanic (93%), and 25 were medical doctors or doctors of osteopathy (89%). Nineteen (68%) worked at the main hospital outpatient clinic, and 9 practiced at community-based outpatient clinics (CBOCs). Thirteen respondents (46%) reported having no formal education or training in integrative approaches. Among those with prior training, 8 clinicians had nutrition counseling (29%) and 7 had psychologic therapy training (25%). Thirteen respondents (46%) also reported using integrative modalities for personal health needs: 8 used psychological therapies, 8 used movement therapies, 10 used integrative modalities for stress management or relaxation, and 8 used them for physical symptoms (Table 1).

Overall, 85 of 200 patients (43%) responded to the study survey. Two patients indicated they did not have chronic back pain and were excluded. Patients had a median (IQR) age of 66 (20) years, with 66 self-identifying as White (80%), 69 as male (83%), and 66 as non-Hispanic (80%). Forty-four patients (53%) received care at CBOCs. Forty-seven patients reported excellent, very good, or good overall health (57%), while 53 reported excellent, very good, or good mental health (64%). Fifty-nine patients reported back pain duration > 5 years (71%), and 67 (81%) indicated experiencing back pain flare-ups at least once per week over the previous 12 months. Sixty patients (72%) indicated they were somewhat or very interested in using integrative therapies as a back pain treatment; however, 40 patients (48%) indicated they had not received information about these therapies. Among those who indicated they had received information, the most frequently reported source was their PCP (41%). Most patients (72%) also reported feeling somewhat to very comfortable discussing integrative medicine therapies with their PCP.

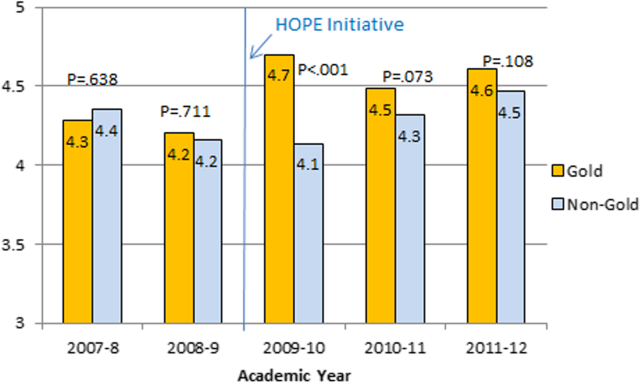

Integrative Therapy Recommendations and Use

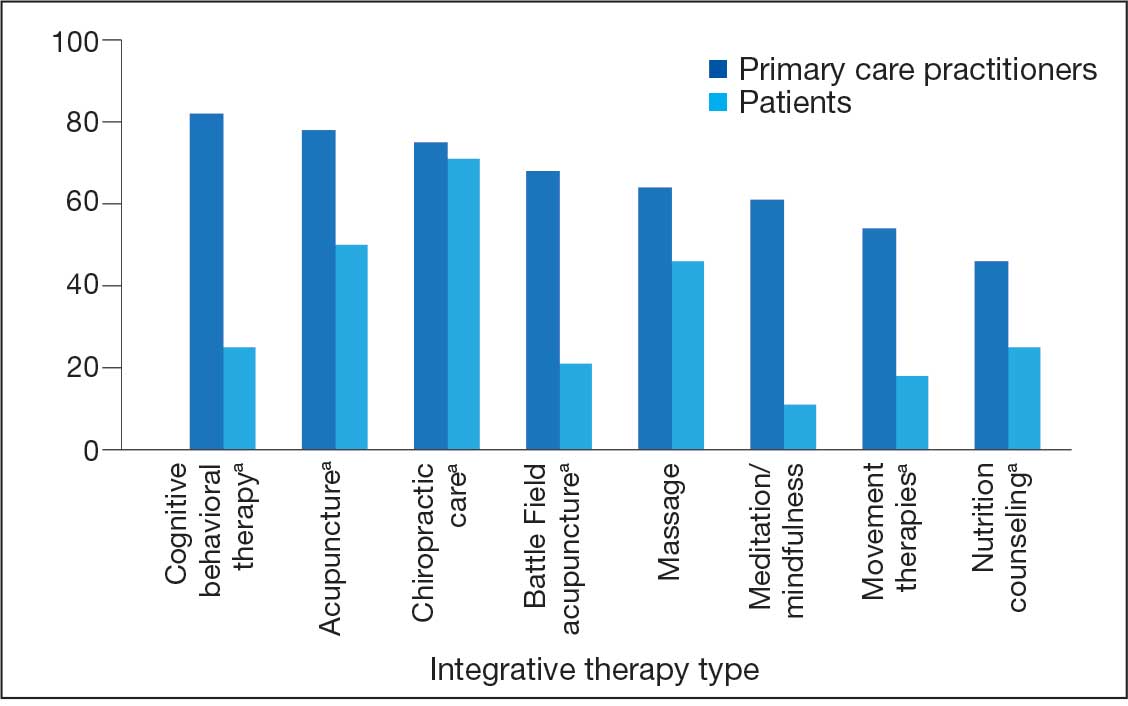

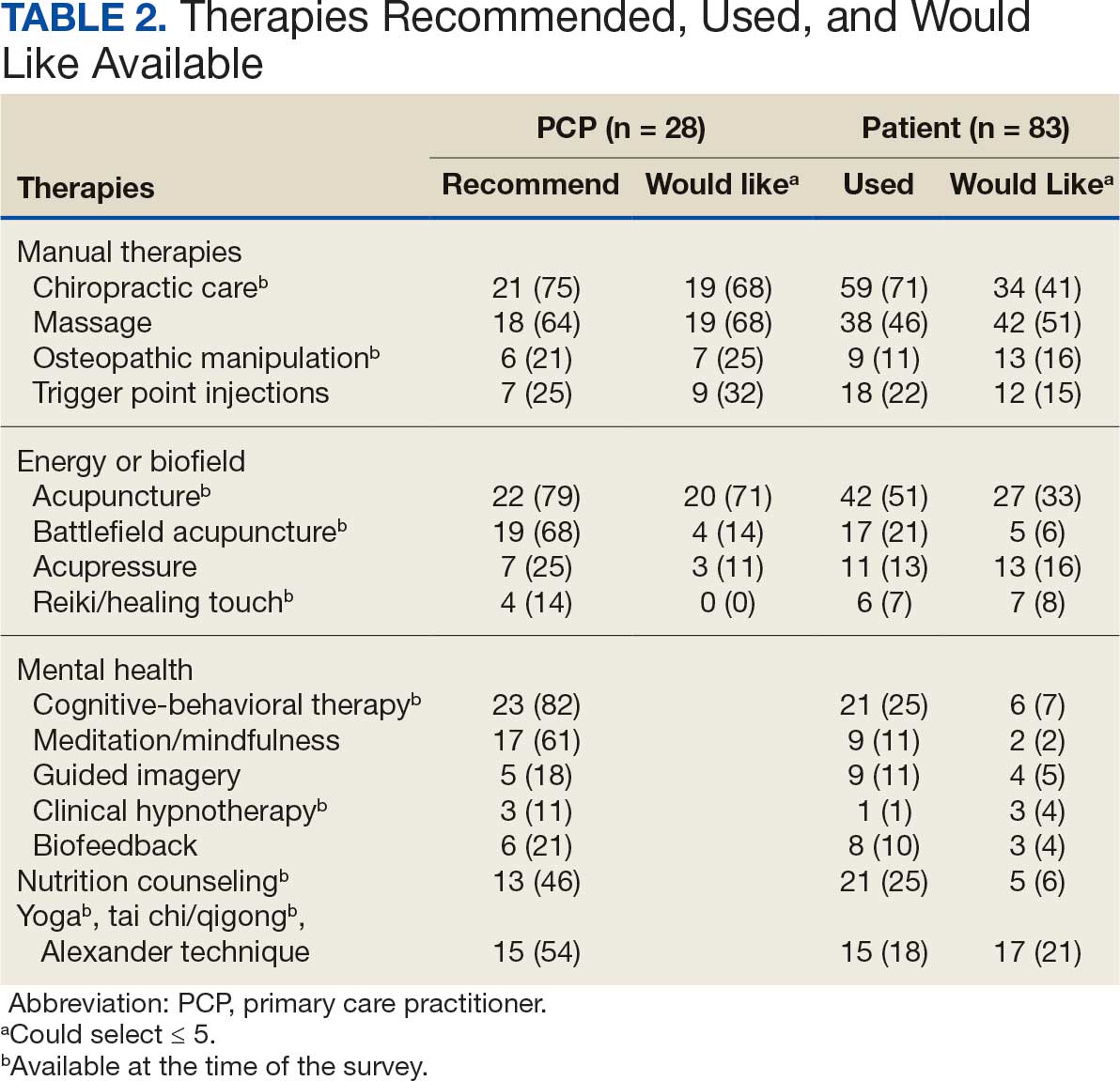

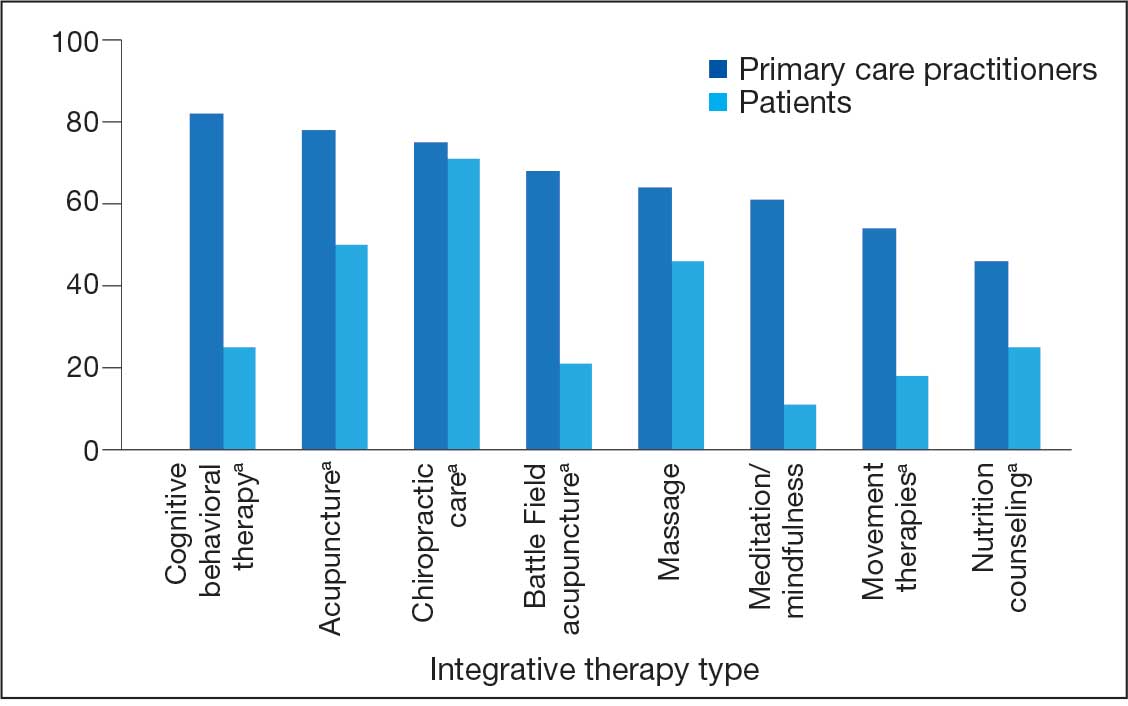

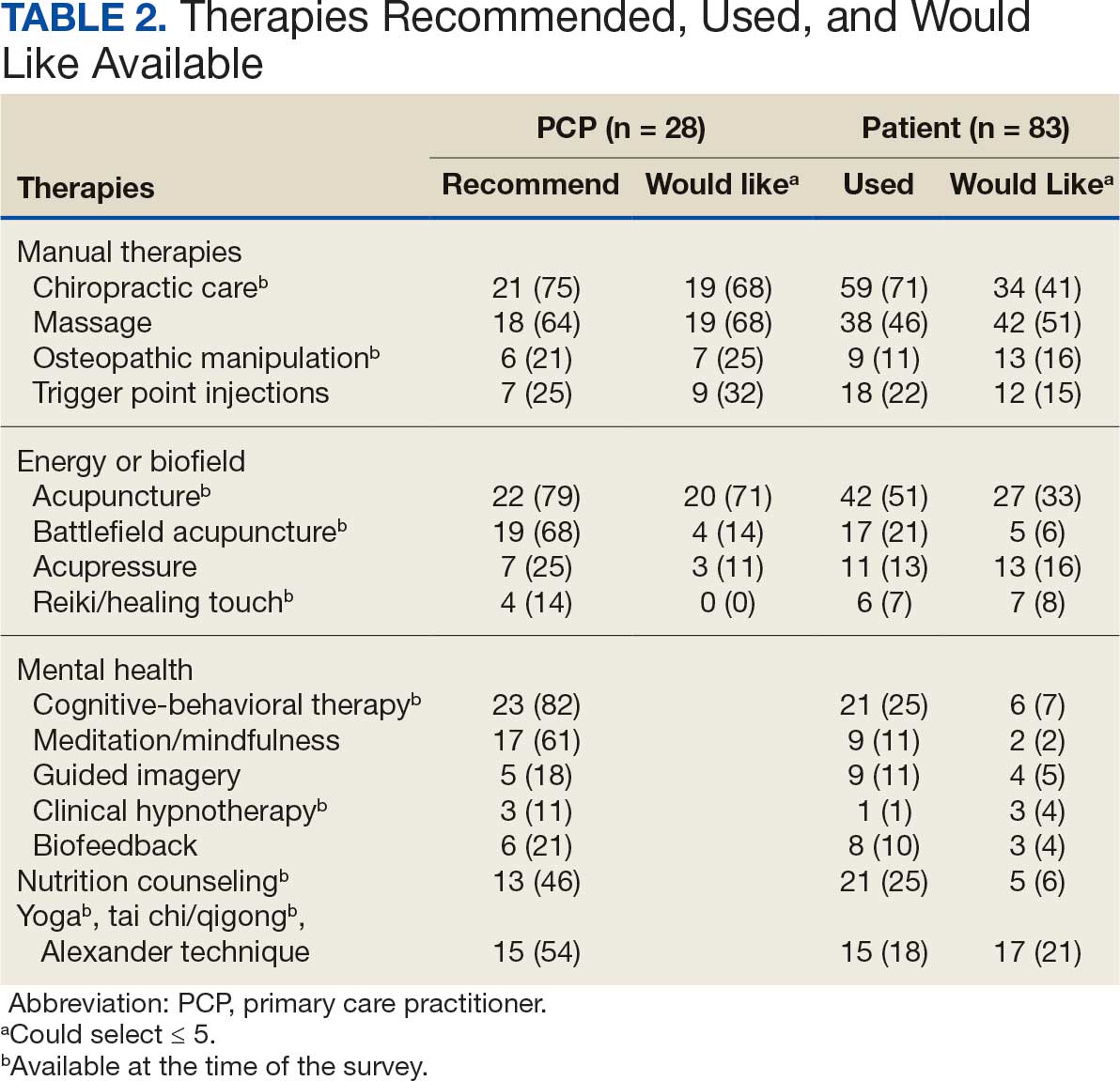

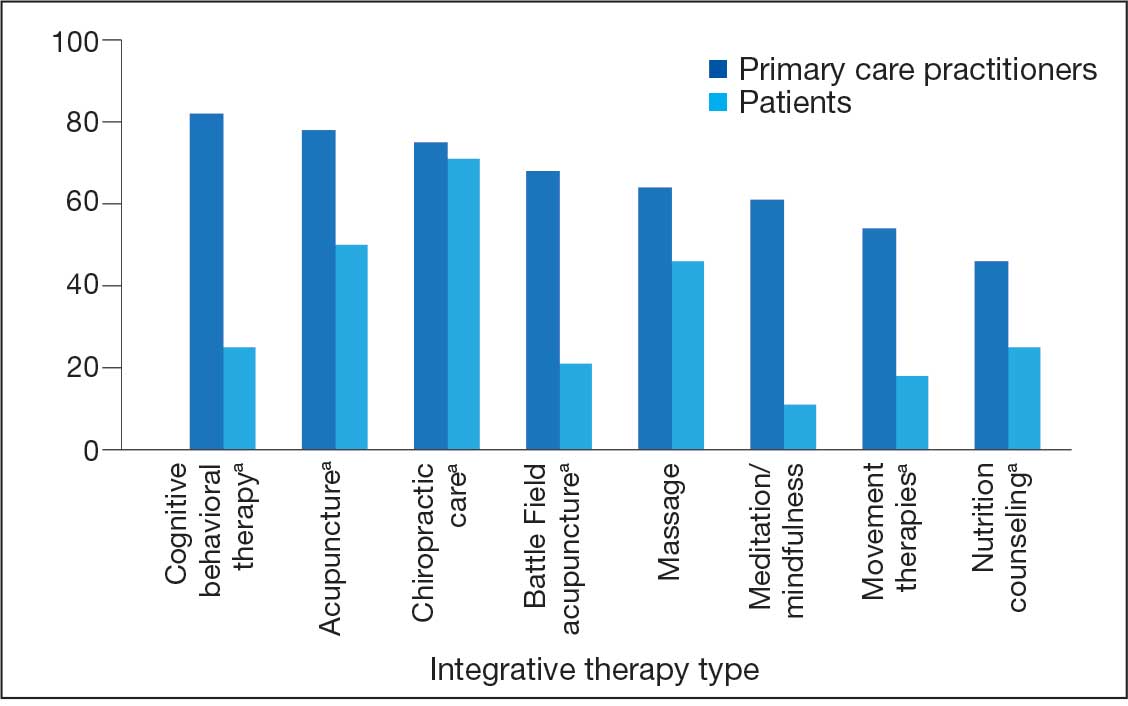

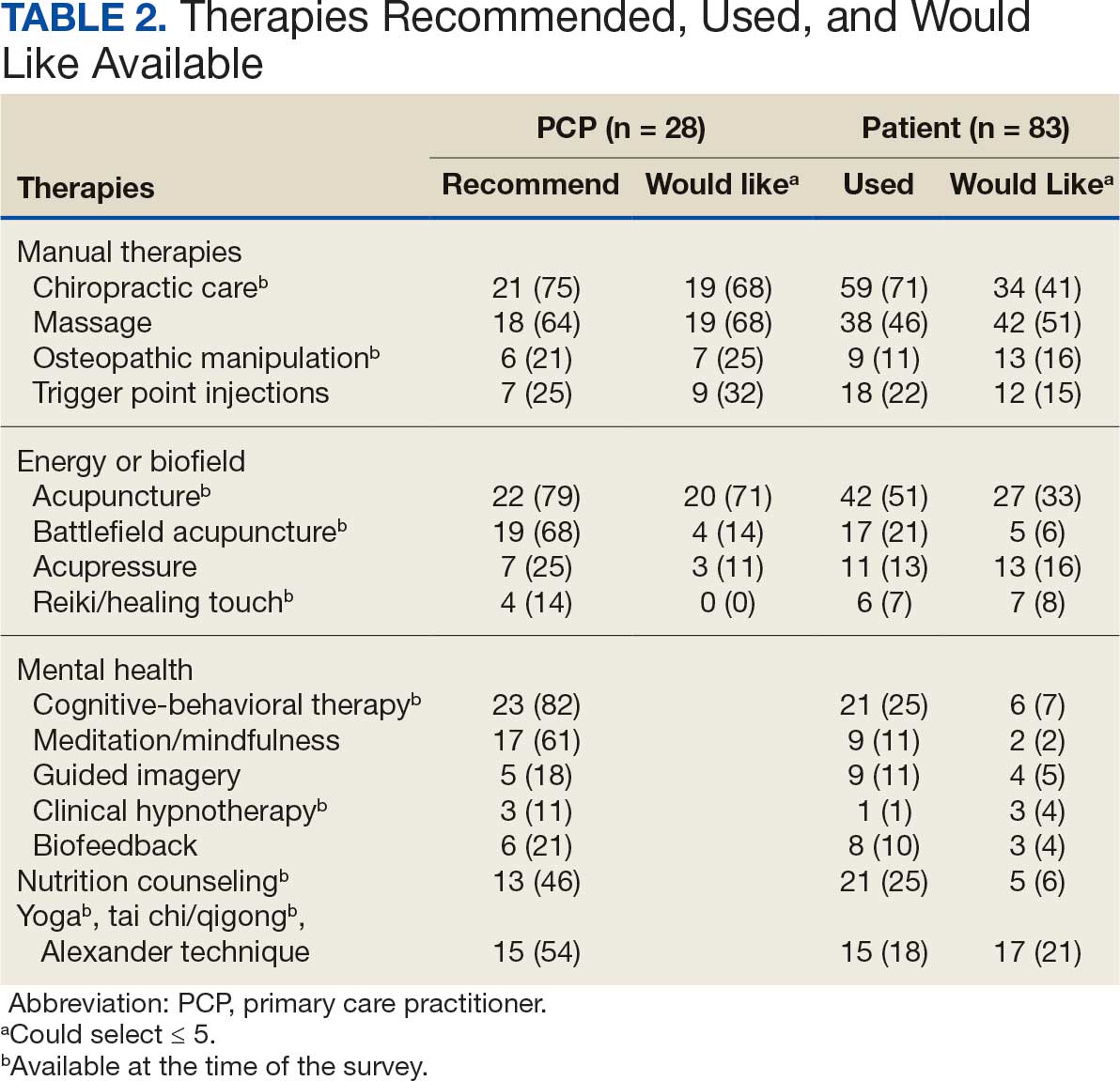

PCPs reported recommending multiple integrative modalities: 23 (82%) recommended cognitive-behavioral therapy, 22 (79%) recommended acupuncture, 21 (75%) recommended chiropractic, 19 (68%) recommended battlefield acupuncture, recommended massage 18 (64%), 17 (61%) recommended meditation or mindfulness, and 15 (54%) recommended movement therapies such as yoga or tai chi/qigong (Figure 1). The only therapies used by at least half of the patients were chiropractic used by 59 patients (71%) and acupuncture by 42 patients (51%). Thirty-eight patients (46%) reported massage use and 21 patients (25%) used cognitive-behavioral therapy (Table 2).

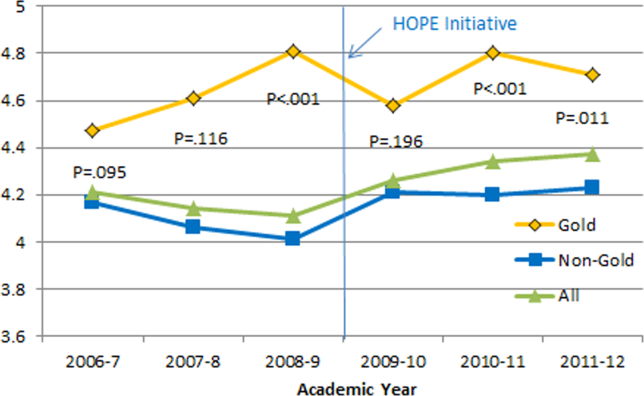

Integrative Therapies Desired

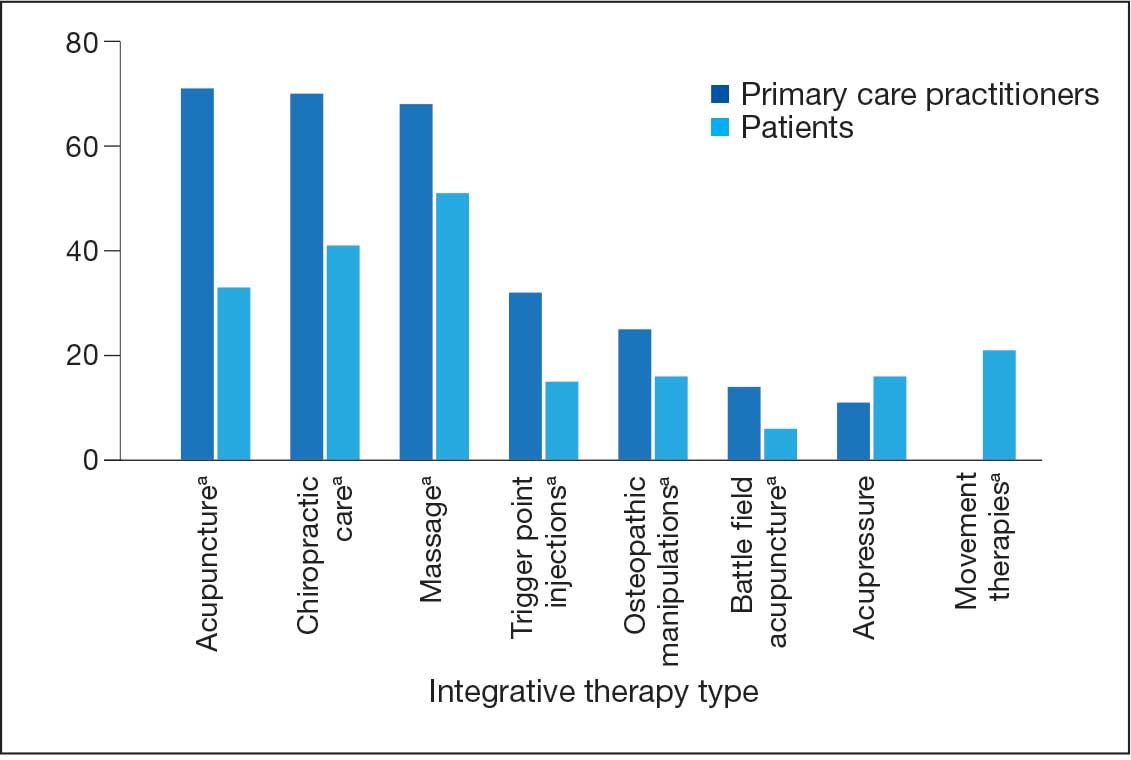

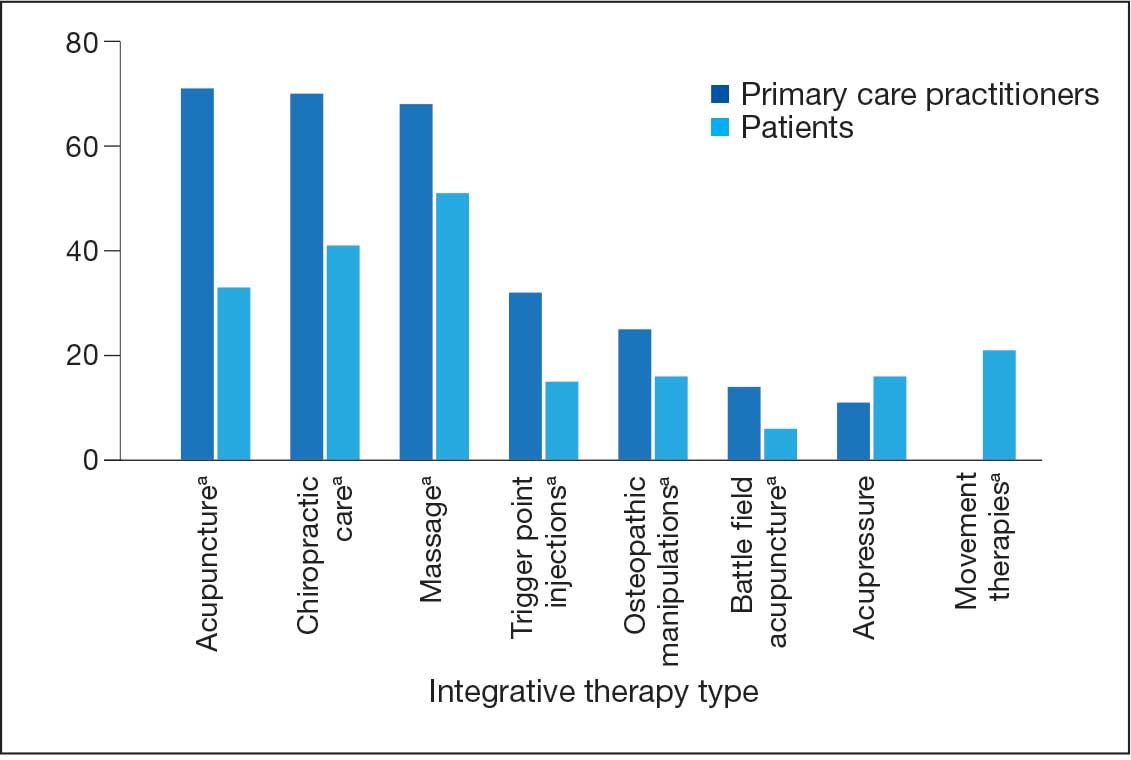

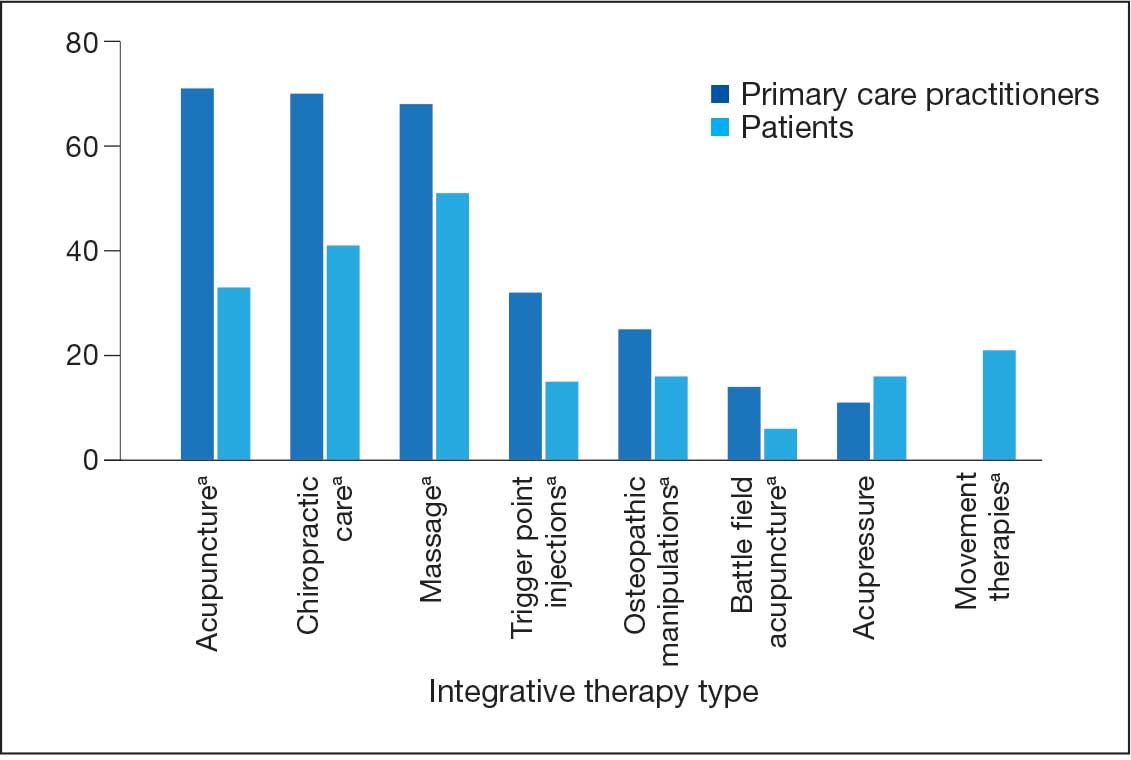

A majority of PCPs identified acupuncture (n = 20, 71%), chiropractic (n = 19, 68%), and massage (n = 19, 68%) as therapies they would most like to have available for patients with chronic pain (Figure 2). Similarly, patients identified massage (n = 42, 51%), chiropractic (n = 34, 41%), and acupuncture (n = 27, 33%) as most desired. Seventeen patients (21%) expressed interest in movement therapies.

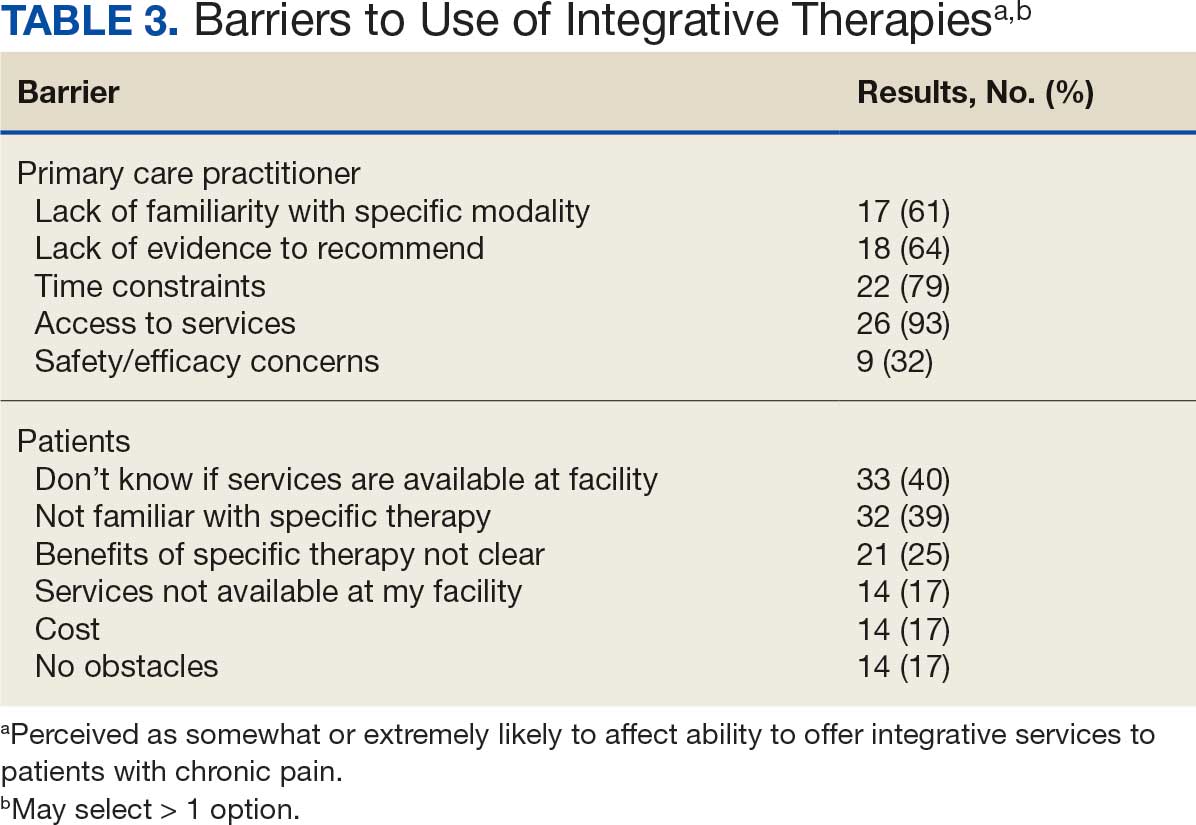

Barriers to Integrative Therapies Use

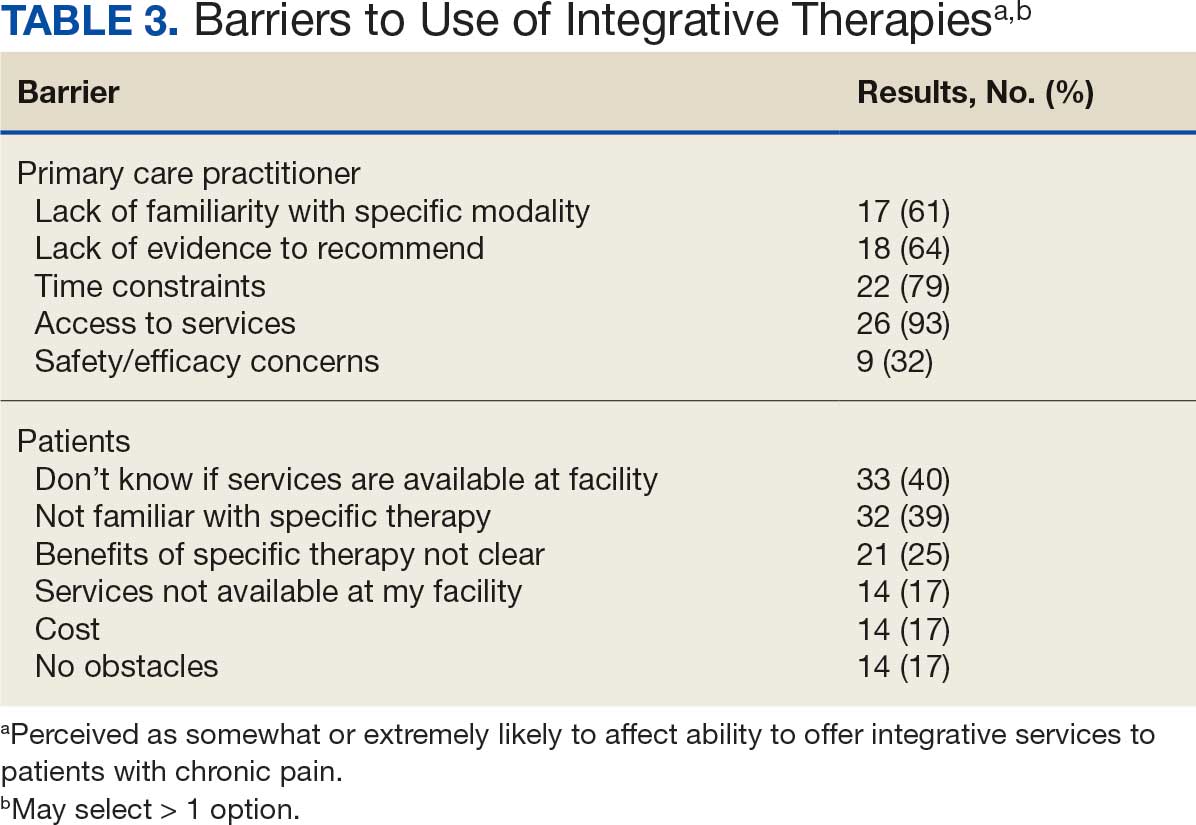

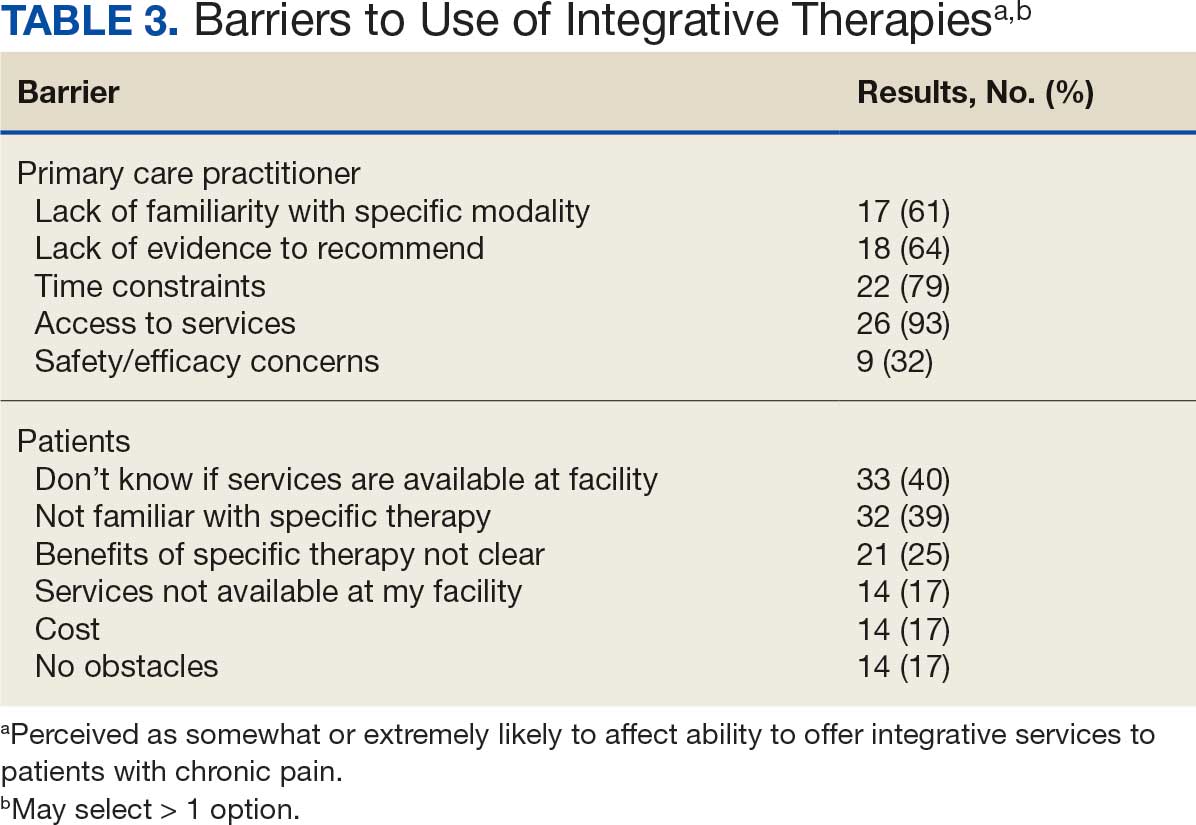

When asked about barriers to use, 26 PCPs (93%) identified access to services as a somewhat or extremely likely barrier, and 22 identified time constraints (79%) (Table 3). However, 17 PCPs (61%) noted lack of familiarity, and 18 (64%) noted a lack of scientific evidence as barriers to recommending integrative modalities. Among patients, 33 (40%) indicated not knowing what services were available at their facility as a barrier, 32 (39%) were not familiar with specific therapies, and 21 (25%) indicated a lack of clarity about the benefits of a specific therapy. Only 14 patients (17%) indicated that there were no obstacles to use.

DISCUSSION

Use of integrative therapies, including complementary treatments, is an increasingly important part of chronic pain management. This survey study suggests VA PCPs are willing to recommend integrative therapies and patients with chronic back pain both desire and use several therapies. Moreover, both groups expressed interest in greater availability of similar therapies. The results also highlight key barriers, such as knowledge gaps, that should be addressed to increase the uptake of integrative modalities for managing chronic pain.

An increasing number of US adults are using complementary health approaches, an important component of integrative therapy.12 This trend includes an increase in use for pain management, from 42.3% in 2002 to 49.2% in 2022; chiropractic care, acupuncture, and massage were most frequently used.12 Similarly, chiropractic, acupuncture and massage were most often used by this sample of veterans with chronic back pain and were identified by the highest percentages of PCPs and patients as the therapies they would most like available.

There were areas where the opinions of patients and clinicians differed. As has been seen previously reported, clinicians largely recommended cognitive-behavioral therapy while patients showed less interest.17 Additionally, while patients expressed interest in the availability of movement therapies, such as yoga, PCPs expressed more interest in other strategies, such as trigger point injections. These differences may reflect true preference or a tendency for clinicians and patients to select therapies with which they are more familiar. Additional research is needed to better understand the acceptability and potential use of integrative health treatments across a broad array of therapeutic options.

Despite VHA policy requiring facilities to provide certain complementary and integrative health modalities, almost all PCPs identified access to services as a major obstacle.15 Based on evidence and a rigorous vetting process, services currently required on-site, via telehealth, or through community partners include acupuncture and battlefield acupuncture (battlefield auricular acupuncture), biofeedback, clinical hypnosis, guided imagery, medical massage therapy, medication, tai chi/qigong, and yoga. Optional approaches, which may be made available to veterans, include chiropractic and healing touch. Outside the VHA, some states have introduced or enacted legislation mandating insurance coverage of nonpharmacological pain treatments.18 However, these requirements and mandates do not help address challenges such as the availability of trained/qualified practitioners.19,20 Ensuring access to complementary and integrative health treatments requires a more concerted effort to ensure that supply meets demand. It is also important to acknowledge the budgetary and physical space constraints that further limit access to services. Although expansion and integration of integrative medicine services remain a priority within the VA Whole Health program, implementation is contingent on available financial and infrastructure resources.

Time was also identified by PCPs as a barrier to recommending integrative therapies to patients. Developing and implementing time-efficient communication strategies for patient education such as concise talking points and informational handouts could help address this barrier. Furthermore, leveraging existing programs and engaging the entire health care team in patient education and referral could help increase integrative and complementary therapy uptake and use.

Although access and time were identified as major barriers, these findings also suggest that PCP and patient knowledge are another target area for enhancing the use of complementary and integrative therapies. Like prior research, most clinicians identified a lack of familiarity with certain services and a lack of scientific evidence as extremely or somewhat likely to affect their ability to offer integrative services to patients with chronic pain.21 Likewise, about 40% of patients identified being unfamiliar with a specific therapy as one of the major obstacles to receiving integrative therapies, with a similar number identifying PCPs as a source of information. The lack of familiarity may be due in part to the evolving nomenclature, with terms such as alternative, complementary, and integrative used to describe approaches outside what is often considered conventional medicine.10 On the other hand, there has also been considerable expansion in the number of therapies within this domain, along with an expanding evidence base. This suggests a need for targeted educational strategies for clinicians and patients, which can be rapidly deployed and continuously adapted as new therapies and evidence emerge.

Limitations

There are some inherent limitations with a survey-based approach, including sampling, non-response, and social desirability biases. In addition, this study only included PCPs and patients affiliated with a single VA medical center. Steps to mitigate these limitations included maintaining survey anonymity and reporting information about respondent characteristics to enhance transparency about the representativeness of the study findings.

CONCLUSIONS

Expanding the use of nonpharmacological pain treatments, including integrative modalities, is essential for safe and effective chronic pain management and reducing opioid use. Our findings show that VA PCPs and patients with chronic back pain are interested in and have some experience with certain integrative therapies. However, even within the context of a health care system that supports the use of integrative therapies for chronic pain as part of whole person care, increasing uptake will require addressing access and time-related constraints as well as ongoing clinician and patient education.

- Rikard SM, Strahan AE, Schmit KM, et al. Chronic pain among adults — United States, 2018-2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2023;72:379-385. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm7215a1

- Yong RJ, Mullins PM, Bhattacharyya N. Prevalence of chronic pain among adults in the United States. Pain. 2022;163:E328-E332. doi:10.1097/j.pain.0000000000002291

- Nahin RL, Feinberg T, Kapos FP, Terman GW. Estimated rates of incident and persistent chronic pain among US adults, 2019-2020. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6:e2313563. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.13563

- Ferrari AJ, Santomauro DF, Aali A, et al. Global incidence, prevalence, years lived with disability (YLDs), disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs), and healthy life expectancy (HALE) for 371 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories and 811 subnational locations, 1990–2021: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. The Lancet. 2024;403:2133-2161. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(24)00757-8 5.

- Qureshi AR, Patel M, Neumark S, et al. Prevalence of chronic non-cancer pain among military veterans: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. BMJ Mil Health. 2025;171:310-314. doi:10.1136/military-2023-002554

- Feldman DE, Nahin RL. Disability among persons with chronic severe back pain: results from a nationally representative population-based sample. J Pain. 2022;23:2144-2154. doi:10.1016/j.jpain.2022.07.016

- Qaseem A, Wilt TJ, McLean RM, Forciea MA. Noninvasive treatments for acute, subacute, and chronic low back pain: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166:514-530. doi:10.7326/M16-2367

- van Erp RMA, Huijnen IPJ, Jakobs MLG, Kleijnen J, Smeets RJEM. Effectiveness of primary care interventions using a biopsychosocial approach in chronic low back pain: a systematic review. Pain Practice. 2019;19:224-241. doi:10.1111/papr.12735

- Chou R, Deyo R, Friedly J, et al. Nonpharmacologic therapies for low back pain: a systematic review for an American College of physicians clinical practice guideline. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166:493-505. doi:10.7326/M16-2459

- Complementary, alternative, or integrative health: what’s in a name? National Institutes of Health, National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health. Updated April 2021. Accessed December 15, 2025. https://www.nccih.nih.gov/health/complementary-alternative-or-integrative-health-whats-in-a-name.

- Taylor SL, Elwy AR. Complementary and alternative medicine for US veterans and active duty military personnel promising steps to improve their health. Med Care. 2014;52:S1-S4. doi:10.1097/MLR.0000000000000270.

- Nahin RL, Rhee A, Stussman B. Use of complementary health approaches overall and for pain management by US adults. JAMA. 2024;331:613-615. doi:10.1001/jama.2023.26775

- Gantt CJ, Donovan N, Khung M. Veterans Affairs’ Whole Health System of Care for transitioning service members and veterans. Mil Med. 2023;188:28-32. doi:10.1093/milmed/usad047

- Bokhour BG, Hyde J, Kligler B, et al. From patient outcomes to system change: evaluating the impact of VHA’s implementation of the Whole Health System of Care. Health Serv Res. 2022;57:53-65. doi:10.1111/1475-6773.13938

- Department of Veterans Affairs VHA. VHA Policy Directive 1137: Provision of Complementary and Integrative Health. December 2022. Accessed December 15, 2025. https://www.va.gov/VHApublications/ViewPublication.asp?pub_ID=10072

- Giannitrapani KF, Holliday JR, Miake-Lye IM, Hempel S, Taylor SL. Synthesizing the strength of the evidence of complementary and integrative health therapies for pain. Pain Med. 2019;20:1831-1840. doi:10.1093/pm/pnz068

- Belitskaya-Levy I, David Clark J, Shih MC, Bair MJ. Treatment preferences for chronic low back pain: views of veterans and their providers. J Pain Res. 2021;14:161-171. doi:10.2147/JPR.S290400

- Onstott TN, Hurst S, Kronick R, Tsou AC, Groessl E, McMenamin SB. Health insurance mandates for nonpharmacological pain treatments in 7 US states. JAMA Netw Open. 2024;7:E245737. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.5737

- Sullivan M, Leach M, Snow J, Moonaz S. The North American yoga therapy workforce survey. Complement Ther Med. 2017;31:39-48. doi:10.1016/j.ctim.2017.01.006

- Bolton R, Ritter G, Highland K, Larson MJ. The relationship between capacity and utilization of nonpharmacologic therapies in the US Military Health System. BMC Health Serv Res. 2022;22. doi:10.1186/s12913-022-07700-4

- Stussman BJ, Nahin RL, Barnes PM, Scott R, Feinberg T, Ward BW. Reasons office-based physicians in the United States recommend common complementary health approaches to patients: an exploratory study using a national survey. J Integr Complement Med. 2022;28:651-663. doi:10.1089/jicm.2022.0493

More than 50 million US adults report experiencing chronic pain, with nearly 7% experiencing high-impact chronic pain.1-3 Chronic pain negatively affects daily function, results in lost productivity, is a leading cause of disability, and is more prevalent among veterans compared with the general population.1,2,4-6 Estimates from 2021 suggest the prevalence of chronic pain among veterans exceeds 30%; > 11% experienced high-impact chronic pain.1

Primary care practitioners (PCPs) have a prominent role in chronic pain management. Pharmacologic options for treating pain, once a mainstay of therapy, present several challenges for patients and PCPs, including drug-drug interactions and adverse effects.7 The US opioid epidemic and shift to a biopsychosocial model of chronic pain care have increased emphasis on nonpharmacologic treatment options.8,9 These include integrative modalities, which incorporate conventional approaches with an array of complementary health approaches.10-12

Integrative therapy is a prominent feature in whole person care, which may be best exemplified by the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Whole Health System of care.13-14 Whole health empowers an individual to take charge of their health and well-being so they can “live their life to the fullest.”14 As implemented in the Veterans Health Administration (VHA), whole health includes the use of evidence-based

METHODS

Using a cross-sectional survey design, PCPs and patients with chronic back pain affiliated with the VA Ann Arbor Healthcare System were invited to participate in separate but similar surveys to assess knowledge, interest, and use of nonpharmacologic integrative modalities for the treatment of chronic pain. In May, June, and July 2023, 78 PCPs received 3 email

Both survey instruments are available upon request, were developed by the study team, and included a mix of yes/no questions, “select all that apply” items, Likert scale response items, and open-ended questions. For one question about which modalities they would like available, the respondent was instructed to select up to 5 modalities. The instruments were extensively pretested by members of the study team, which included 2 PCPs and a nonveteran with chronic back pain.

The list of integrative modalities included in the survey was derived from the tier 1 and tier 2 complementary and integrative health modalities identified in a VHA Directive on complementary and integrative health.15,16 Tier 1 approaches are considered to have sufficient evidence and must be made available to veterans either within a VA medical facility or in the community. Tier 2 approaches are generally considered safe and may be made available but do not have sufficient evidence to mandate their provision. For participant ease, the integrative modalities were divided into 5 subgroups: manual therapies, energy/biofield therapies, mental health therapies, nutrition counseling, and movement therapies. The clinician survey assessed clinicians’ training and interest, clinical and personal use, and perceived barriers to providing integrative modalities for chronic pain. Professional and personal demographic data were also collected. Similarly, the patient survey assessed use of integrative therapies, perceptions of and interest in integrative modalities, and potential barriers to use. Demographic and health-related information was also collected.

Data analysis included descriptive statistics (eg, frequency counts, means, medians) and visual graphic displays. Separate analyses were conducted for clinicians and patients in addition to a comparative analysis of the use and potential interest in integrative modalities. Analysis were conducted using R software. This study was deemed nonresearch quality improvement by the VA Ann Arbor Healthcare System facility research oversight board and institutional review board approval was not solicited.

RESULTS

Twenty-eight clinicians completed the survey, yielding a participation rate of 36%. Participating clinicians had a median (IQR) age of 48 years (9.5), 15 self-identified as White (54%), 8 as Asian (29%), 15 as female (54%), 26 as non-Hispanic (93%), and 25 were medical doctors or doctors of osteopathy (89%). Nineteen (68%) worked at the main hospital outpatient clinic, and 9 practiced at community-based outpatient clinics (CBOCs). Thirteen respondents (46%) reported having no formal education or training in integrative approaches. Among those with prior training, 8 clinicians had nutrition counseling (29%) and 7 had psychologic therapy training (25%). Thirteen respondents (46%) also reported using integrative modalities for personal health needs: 8 used psychological therapies, 8 used movement therapies, 10 used integrative modalities for stress management or relaxation, and 8 used them for physical symptoms (Table 1).

Overall, 85 of 200 patients (43%) responded to the study survey. Two patients indicated they did not have chronic back pain and were excluded. Patients had a median (IQR) age of 66 (20) years, with 66 self-identifying as White (80%), 69 as male (83%), and 66 as non-Hispanic (80%). Forty-four patients (53%) received care at CBOCs. Forty-seven patients reported excellent, very good, or good overall health (57%), while 53 reported excellent, very good, or good mental health (64%). Fifty-nine patients reported back pain duration > 5 years (71%), and 67 (81%) indicated experiencing back pain flare-ups at least once per week over the previous 12 months. Sixty patients (72%) indicated they were somewhat or very interested in using integrative therapies as a back pain treatment; however, 40 patients (48%) indicated they had not received information about these therapies. Among those who indicated they had received information, the most frequently reported source was their PCP (41%). Most patients (72%) also reported feeling somewhat to very comfortable discussing integrative medicine therapies with their PCP.

Integrative Therapy Recommendations and Use

PCPs reported recommending multiple integrative modalities: 23 (82%) recommended cognitive-behavioral therapy, 22 (79%) recommended acupuncture, 21 (75%) recommended chiropractic, 19 (68%) recommended battlefield acupuncture, recommended massage 18 (64%), 17 (61%) recommended meditation or mindfulness, and 15 (54%) recommended movement therapies such as yoga or tai chi/qigong (Figure 1). The only therapies used by at least half of the patients were chiropractic used by 59 patients (71%) and acupuncture by 42 patients (51%). Thirty-eight patients (46%) reported massage use and 21 patients (25%) used cognitive-behavioral therapy (Table 2).

Integrative Therapies Desired

A majority of PCPs identified acupuncture (n = 20, 71%), chiropractic (n = 19, 68%), and massage (n = 19, 68%) as therapies they would most like to have available for patients with chronic pain (Figure 2). Similarly, patients identified massage (n = 42, 51%), chiropractic (n = 34, 41%), and acupuncture (n = 27, 33%) as most desired. Seventeen patients (21%) expressed interest in movement therapies.

Barriers to Integrative Therapies Use

When asked about barriers to use, 26 PCPs (93%) identified access to services as a somewhat or extremely likely barrier, and 22 identified time constraints (79%) (Table 3). However, 17 PCPs (61%) noted lack of familiarity, and 18 (64%) noted a lack of scientific evidence as barriers to recommending integrative modalities. Among patients, 33 (40%) indicated not knowing what services were available at their facility as a barrier, 32 (39%) were not familiar with specific therapies, and 21 (25%) indicated a lack of clarity about the benefits of a specific therapy. Only 14 patients (17%) indicated that there were no obstacles to use.

DISCUSSION

Use of integrative therapies, including complementary treatments, is an increasingly important part of chronic pain management. This survey study suggests VA PCPs are willing to recommend integrative therapies and patients with chronic back pain both desire and use several therapies. Moreover, both groups expressed interest in greater availability of similar therapies. The results also highlight key barriers, such as knowledge gaps, that should be addressed to increase the uptake of integrative modalities for managing chronic pain.

An increasing number of US adults are using complementary health approaches, an important component of integrative therapy.12 This trend includes an increase in use for pain management, from 42.3% in 2002 to 49.2% in 2022; chiropractic care, acupuncture, and massage were most frequently used.12 Similarly, chiropractic, acupuncture and massage were most often used by this sample of veterans with chronic back pain and were identified by the highest percentages of PCPs and patients as the therapies they would most like available.

There were areas where the opinions of patients and clinicians differed. As has been seen previously reported, clinicians largely recommended cognitive-behavioral therapy while patients showed less interest.17 Additionally, while patients expressed interest in the availability of movement therapies, such as yoga, PCPs expressed more interest in other strategies, such as trigger point injections. These differences may reflect true preference or a tendency for clinicians and patients to select therapies with which they are more familiar. Additional research is needed to better understand the acceptability and potential use of integrative health treatments across a broad array of therapeutic options.

Despite VHA policy requiring facilities to provide certain complementary and integrative health modalities, almost all PCPs identified access to services as a major obstacle.15 Based on evidence and a rigorous vetting process, services currently required on-site, via telehealth, or through community partners include acupuncture and battlefield acupuncture (battlefield auricular acupuncture), biofeedback, clinical hypnosis, guided imagery, medical massage therapy, medication, tai chi/qigong, and yoga. Optional approaches, which may be made available to veterans, include chiropractic and healing touch. Outside the VHA, some states have introduced or enacted legislation mandating insurance coverage of nonpharmacological pain treatments.18 However, these requirements and mandates do not help address challenges such as the availability of trained/qualified practitioners.19,20 Ensuring access to complementary and integrative health treatments requires a more concerted effort to ensure that supply meets demand. It is also important to acknowledge the budgetary and physical space constraints that further limit access to services. Although expansion and integration of integrative medicine services remain a priority within the VA Whole Health program, implementation is contingent on available financial and infrastructure resources.

Time was also identified by PCPs as a barrier to recommending integrative therapies to patients. Developing and implementing time-efficient communication strategies for patient education such as concise talking points and informational handouts could help address this barrier. Furthermore, leveraging existing programs and engaging the entire health care team in patient education and referral could help increase integrative and complementary therapy uptake and use.

Although access and time were identified as major barriers, these findings also suggest that PCP and patient knowledge are another target area for enhancing the use of complementary and integrative therapies. Like prior research, most clinicians identified a lack of familiarity with certain services and a lack of scientific evidence as extremely or somewhat likely to affect their ability to offer integrative services to patients with chronic pain.21 Likewise, about 40% of patients identified being unfamiliar with a specific therapy as one of the major obstacles to receiving integrative therapies, with a similar number identifying PCPs as a source of information. The lack of familiarity may be due in part to the evolving nomenclature, with terms such as alternative, complementary, and integrative used to describe approaches outside what is often considered conventional medicine.10 On the other hand, there has also been considerable expansion in the number of therapies within this domain, along with an expanding evidence base. This suggests a need for targeted educational strategies for clinicians and patients, which can be rapidly deployed and continuously adapted as new therapies and evidence emerge.

Limitations

There are some inherent limitations with a survey-based approach, including sampling, non-response, and social desirability biases. In addition, this study only included PCPs and patients affiliated with a single VA medical center. Steps to mitigate these limitations included maintaining survey anonymity and reporting information about respondent characteristics to enhance transparency about the representativeness of the study findings.

CONCLUSIONS

Expanding the use of nonpharmacological pain treatments, including integrative modalities, is essential for safe and effective chronic pain management and reducing opioid use. Our findings show that VA PCPs and patients with chronic back pain are interested in and have some experience with certain integrative therapies. However, even within the context of a health care system that supports the use of integrative therapies for chronic pain as part of whole person care, increasing uptake will require addressing access and time-related constraints as well as ongoing clinician and patient education.

More than 50 million US adults report experiencing chronic pain, with nearly 7% experiencing high-impact chronic pain.1-3 Chronic pain negatively affects daily function, results in lost productivity, is a leading cause of disability, and is more prevalent among veterans compared with the general population.1,2,4-6 Estimates from 2021 suggest the prevalence of chronic pain among veterans exceeds 30%; > 11% experienced high-impact chronic pain.1

Primary care practitioners (PCPs) have a prominent role in chronic pain management. Pharmacologic options for treating pain, once a mainstay of therapy, present several challenges for patients and PCPs, including drug-drug interactions and adverse effects.7 The US opioid epidemic and shift to a biopsychosocial model of chronic pain care have increased emphasis on nonpharmacologic treatment options.8,9 These include integrative modalities, which incorporate conventional approaches with an array of complementary health approaches.10-12

Integrative therapy is a prominent feature in whole person care, which may be best exemplified by the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Whole Health System of care.13-14 Whole health empowers an individual to take charge of their health and well-being so they can “live their life to the fullest.”14 As implemented in the Veterans Health Administration (VHA), whole health includes the use of evidence-based

METHODS

Using a cross-sectional survey design, PCPs and patients with chronic back pain affiliated with the VA Ann Arbor Healthcare System were invited to participate in separate but similar surveys to assess knowledge, interest, and use of nonpharmacologic integrative modalities for the treatment of chronic pain. In May, June, and July 2023, 78 PCPs received 3 email

Both survey instruments are available upon request, were developed by the study team, and included a mix of yes/no questions, “select all that apply” items, Likert scale response items, and open-ended questions. For one question about which modalities they would like available, the respondent was instructed to select up to 5 modalities. The instruments were extensively pretested by members of the study team, which included 2 PCPs and a nonveteran with chronic back pain.

The list of integrative modalities included in the survey was derived from the tier 1 and tier 2 complementary and integrative health modalities identified in a VHA Directive on complementary and integrative health.15,16 Tier 1 approaches are considered to have sufficient evidence and must be made available to veterans either within a VA medical facility or in the community. Tier 2 approaches are generally considered safe and may be made available but do not have sufficient evidence to mandate their provision. For participant ease, the integrative modalities were divided into 5 subgroups: manual therapies, energy/biofield therapies, mental health therapies, nutrition counseling, and movement therapies. The clinician survey assessed clinicians’ training and interest, clinical and personal use, and perceived barriers to providing integrative modalities for chronic pain. Professional and personal demographic data were also collected. Similarly, the patient survey assessed use of integrative therapies, perceptions of and interest in integrative modalities, and potential barriers to use. Demographic and health-related information was also collected.

Data analysis included descriptive statistics (eg, frequency counts, means, medians) and visual graphic displays. Separate analyses were conducted for clinicians and patients in addition to a comparative analysis of the use and potential interest in integrative modalities. Analysis were conducted using R software. This study was deemed nonresearch quality improvement by the VA Ann Arbor Healthcare System facility research oversight board and institutional review board approval was not solicited.

RESULTS

Twenty-eight clinicians completed the survey, yielding a participation rate of 36%. Participating clinicians had a median (IQR) age of 48 years (9.5), 15 self-identified as White (54%), 8 as Asian (29%), 15 as female (54%), 26 as non-Hispanic (93%), and 25 were medical doctors or doctors of osteopathy (89%). Nineteen (68%) worked at the main hospital outpatient clinic, and 9 practiced at community-based outpatient clinics (CBOCs). Thirteen respondents (46%) reported having no formal education or training in integrative approaches. Among those with prior training, 8 clinicians had nutrition counseling (29%) and 7 had psychologic therapy training (25%). Thirteen respondents (46%) also reported using integrative modalities for personal health needs: 8 used psychological therapies, 8 used movement therapies, 10 used integrative modalities for stress management or relaxation, and 8 used them for physical symptoms (Table 1).

Overall, 85 of 200 patients (43%) responded to the study survey. Two patients indicated they did not have chronic back pain and were excluded. Patients had a median (IQR) age of 66 (20) years, with 66 self-identifying as White (80%), 69 as male (83%), and 66 as non-Hispanic (80%). Forty-four patients (53%) received care at CBOCs. Forty-seven patients reported excellent, very good, or good overall health (57%), while 53 reported excellent, very good, or good mental health (64%). Fifty-nine patients reported back pain duration > 5 years (71%), and 67 (81%) indicated experiencing back pain flare-ups at least once per week over the previous 12 months. Sixty patients (72%) indicated they were somewhat or very interested in using integrative therapies as a back pain treatment; however, 40 patients (48%) indicated they had not received information about these therapies. Among those who indicated they had received information, the most frequently reported source was their PCP (41%). Most patients (72%) also reported feeling somewhat to very comfortable discussing integrative medicine therapies with their PCP.

Integrative Therapy Recommendations and Use

PCPs reported recommending multiple integrative modalities: 23 (82%) recommended cognitive-behavioral therapy, 22 (79%) recommended acupuncture, 21 (75%) recommended chiropractic, 19 (68%) recommended battlefield acupuncture, recommended massage 18 (64%), 17 (61%) recommended meditation or mindfulness, and 15 (54%) recommended movement therapies such as yoga or tai chi/qigong (Figure 1). The only therapies used by at least half of the patients were chiropractic used by 59 patients (71%) and acupuncture by 42 patients (51%). Thirty-eight patients (46%) reported massage use and 21 patients (25%) used cognitive-behavioral therapy (Table 2).

Integrative Therapies Desired

A majority of PCPs identified acupuncture (n = 20, 71%), chiropractic (n = 19, 68%), and massage (n = 19, 68%) as therapies they would most like to have available for patients with chronic pain (Figure 2). Similarly, patients identified massage (n = 42, 51%), chiropractic (n = 34, 41%), and acupuncture (n = 27, 33%) as most desired. Seventeen patients (21%) expressed interest in movement therapies.

Barriers to Integrative Therapies Use

When asked about barriers to use, 26 PCPs (93%) identified access to services as a somewhat or extremely likely barrier, and 22 identified time constraints (79%) (Table 3). However, 17 PCPs (61%) noted lack of familiarity, and 18 (64%) noted a lack of scientific evidence as barriers to recommending integrative modalities. Among patients, 33 (40%) indicated not knowing what services were available at their facility as a barrier, 32 (39%) were not familiar with specific therapies, and 21 (25%) indicated a lack of clarity about the benefits of a specific therapy. Only 14 patients (17%) indicated that there were no obstacles to use.

DISCUSSION

Use of integrative therapies, including complementary treatments, is an increasingly important part of chronic pain management. This survey study suggests VA PCPs are willing to recommend integrative therapies and patients with chronic back pain both desire and use several therapies. Moreover, both groups expressed interest in greater availability of similar therapies. The results also highlight key barriers, such as knowledge gaps, that should be addressed to increase the uptake of integrative modalities for managing chronic pain.

An increasing number of US adults are using complementary health approaches, an important component of integrative therapy.12 This trend includes an increase in use for pain management, from 42.3% in 2002 to 49.2% in 2022; chiropractic care, acupuncture, and massage were most frequently used.12 Similarly, chiropractic, acupuncture and massage were most often used by this sample of veterans with chronic back pain and were identified by the highest percentages of PCPs and patients as the therapies they would most like available.

There were areas where the opinions of patients and clinicians differed. As has been seen previously reported, clinicians largely recommended cognitive-behavioral therapy while patients showed less interest.17 Additionally, while patients expressed interest in the availability of movement therapies, such as yoga, PCPs expressed more interest in other strategies, such as trigger point injections. These differences may reflect true preference or a tendency for clinicians and patients to select therapies with which they are more familiar. Additional research is needed to better understand the acceptability and potential use of integrative health treatments across a broad array of therapeutic options.

Despite VHA policy requiring facilities to provide certain complementary and integrative health modalities, almost all PCPs identified access to services as a major obstacle.15 Based on evidence and a rigorous vetting process, services currently required on-site, via telehealth, or through community partners include acupuncture and battlefield acupuncture (battlefield auricular acupuncture), biofeedback, clinical hypnosis, guided imagery, medical massage therapy, medication, tai chi/qigong, and yoga. Optional approaches, which may be made available to veterans, include chiropractic and healing touch. Outside the VHA, some states have introduced or enacted legislation mandating insurance coverage of nonpharmacological pain treatments.18 However, these requirements and mandates do not help address challenges such as the availability of trained/qualified practitioners.19,20 Ensuring access to complementary and integrative health treatments requires a more concerted effort to ensure that supply meets demand. It is also important to acknowledge the budgetary and physical space constraints that further limit access to services. Although expansion and integration of integrative medicine services remain a priority within the VA Whole Health program, implementation is contingent on available financial and infrastructure resources.

Time was also identified by PCPs as a barrier to recommending integrative therapies to patients. Developing and implementing time-efficient communication strategies for patient education such as concise talking points and informational handouts could help address this barrier. Furthermore, leveraging existing programs and engaging the entire health care team in patient education and referral could help increase integrative and complementary therapy uptake and use.

Although access and time were identified as major barriers, these findings also suggest that PCP and patient knowledge are another target area for enhancing the use of complementary and integrative therapies. Like prior research, most clinicians identified a lack of familiarity with certain services and a lack of scientific evidence as extremely or somewhat likely to affect their ability to offer integrative services to patients with chronic pain.21 Likewise, about 40% of patients identified being unfamiliar with a specific therapy as one of the major obstacles to receiving integrative therapies, with a similar number identifying PCPs as a source of information. The lack of familiarity may be due in part to the evolving nomenclature, with terms such as alternative, complementary, and integrative used to describe approaches outside what is often considered conventional medicine.10 On the other hand, there has also been considerable expansion in the number of therapies within this domain, along with an expanding evidence base. This suggests a need for targeted educational strategies for clinicians and patients, which can be rapidly deployed and continuously adapted as new therapies and evidence emerge.

Limitations

There are some inherent limitations with a survey-based approach, including sampling, non-response, and social desirability biases. In addition, this study only included PCPs and patients affiliated with a single VA medical center. Steps to mitigate these limitations included maintaining survey anonymity and reporting information about respondent characteristics to enhance transparency about the representativeness of the study findings.

CONCLUSIONS

Expanding the use of nonpharmacological pain treatments, including integrative modalities, is essential for safe and effective chronic pain management and reducing opioid use. Our findings show that VA PCPs and patients with chronic back pain are interested in and have some experience with certain integrative therapies. However, even within the context of a health care system that supports the use of integrative therapies for chronic pain as part of whole person care, increasing uptake will require addressing access and time-related constraints as well as ongoing clinician and patient education.

- Rikard SM, Strahan AE, Schmit KM, et al. Chronic pain among adults — United States, 2018-2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2023;72:379-385. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm7215a1

- Yong RJ, Mullins PM, Bhattacharyya N. Prevalence of chronic pain among adults in the United States. Pain. 2022;163:E328-E332. doi:10.1097/j.pain.0000000000002291

- Nahin RL, Feinberg T, Kapos FP, Terman GW. Estimated rates of incident and persistent chronic pain among US adults, 2019-2020. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6:e2313563. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.13563

- Ferrari AJ, Santomauro DF, Aali A, et al. Global incidence, prevalence, years lived with disability (YLDs), disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs), and healthy life expectancy (HALE) for 371 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories and 811 subnational locations, 1990–2021: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. The Lancet. 2024;403:2133-2161. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(24)00757-8 5.

- Qureshi AR, Patel M, Neumark S, et al. Prevalence of chronic non-cancer pain among military veterans: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. BMJ Mil Health. 2025;171:310-314. doi:10.1136/military-2023-002554

- Feldman DE, Nahin RL. Disability among persons with chronic severe back pain: results from a nationally representative population-based sample. J Pain. 2022;23:2144-2154. doi:10.1016/j.jpain.2022.07.016

- Qaseem A, Wilt TJ, McLean RM, Forciea MA. Noninvasive treatments for acute, subacute, and chronic low back pain: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166:514-530. doi:10.7326/M16-2367

- van Erp RMA, Huijnen IPJ, Jakobs MLG, Kleijnen J, Smeets RJEM. Effectiveness of primary care interventions using a biopsychosocial approach in chronic low back pain: a systematic review. Pain Practice. 2019;19:224-241. doi:10.1111/papr.12735

- Chou R, Deyo R, Friedly J, et al. Nonpharmacologic therapies for low back pain: a systematic review for an American College of physicians clinical practice guideline. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166:493-505. doi:10.7326/M16-2459

- Complementary, alternative, or integrative health: what’s in a name? National Institutes of Health, National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health. Updated April 2021. Accessed December 15, 2025. https://www.nccih.nih.gov/health/complementary-alternative-or-integrative-health-whats-in-a-name.

- Taylor SL, Elwy AR. Complementary and alternative medicine for US veterans and active duty military personnel promising steps to improve their health. Med Care. 2014;52:S1-S4. doi:10.1097/MLR.0000000000000270.

- Nahin RL, Rhee A, Stussman B. Use of complementary health approaches overall and for pain management by US adults. JAMA. 2024;331:613-615. doi:10.1001/jama.2023.26775

- Gantt CJ, Donovan N, Khung M. Veterans Affairs’ Whole Health System of Care for transitioning service members and veterans. Mil Med. 2023;188:28-32. doi:10.1093/milmed/usad047

- Bokhour BG, Hyde J, Kligler B, et al. From patient outcomes to system change: evaluating the impact of VHA’s implementation of the Whole Health System of Care. Health Serv Res. 2022;57:53-65. doi:10.1111/1475-6773.13938

- Department of Veterans Affairs VHA. VHA Policy Directive 1137: Provision of Complementary and Integrative Health. December 2022. Accessed December 15, 2025. https://www.va.gov/VHApublications/ViewPublication.asp?pub_ID=10072

- Giannitrapani KF, Holliday JR, Miake-Lye IM, Hempel S, Taylor SL. Synthesizing the strength of the evidence of complementary and integrative health therapies for pain. Pain Med. 2019;20:1831-1840. doi:10.1093/pm/pnz068

- Belitskaya-Levy I, David Clark J, Shih MC, Bair MJ. Treatment preferences for chronic low back pain: views of veterans and their providers. J Pain Res. 2021;14:161-171. doi:10.2147/JPR.S290400

- Onstott TN, Hurst S, Kronick R, Tsou AC, Groessl E, McMenamin SB. Health insurance mandates for nonpharmacological pain treatments in 7 US states. JAMA Netw Open. 2024;7:E245737. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.5737

- Sullivan M, Leach M, Snow J, Moonaz S. The North American yoga therapy workforce survey. Complement Ther Med. 2017;31:39-48. doi:10.1016/j.ctim.2017.01.006

- Bolton R, Ritter G, Highland K, Larson MJ. The relationship between capacity and utilization of nonpharmacologic therapies in the US Military Health System. BMC Health Serv Res. 2022;22. doi:10.1186/s12913-022-07700-4

- Stussman BJ, Nahin RL, Barnes PM, Scott R, Feinberg T, Ward BW. Reasons office-based physicians in the United States recommend common complementary health approaches to patients: an exploratory study using a national survey. J Integr Complement Med. 2022;28:651-663. doi:10.1089/jicm.2022.0493

- Rikard SM, Strahan AE, Schmit KM, et al. Chronic pain among adults — United States, 2018-2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2023;72:379-385. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm7215a1

- Yong RJ, Mullins PM, Bhattacharyya N. Prevalence of chronic pain among adults in the United States. Pain. 2022;163:E328-E332. doi:10.1097/j.pain.0000000000002291

- Nahin RL, Feinberg T, Kapos FP, Terman GW. Estimated rates of incident and persistent chronic pain among US adults, 2019-2020. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6:e2313563. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.13563

- Ferrari AJ, Santomauro DF, Aali A, et al. Global incidence, prevalence, years lived with disability (YLDs), disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs), and healthy life expectancy (HALE) for 371 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories and 811 subnational locations, 1990–2021: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. The Lancet. 2024;403:2133-2161. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(24)00757-8 5.

- Qureshi AR, Patel M, Neumark S, et al. Prevalence of chronic non-cancer pain among military veterans: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. BMJ Mil Health. 2025;171:310-314. doi:10.1136/military-2023-002554

- Feldman DE, Nahin RL. Disability among persons with chronic severe back pain: results from a nationally representative population-based sample. J Pain. 2022;23:2144-2154. doi:10.1016/j.jpain.2022.07.016

- Qaseem A, Wilt TJ, McLean RM, Forciea MA. Noninvasive treatments for acute, subacute, and chronic low back pain: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166:514-530. doi:10.7326/M16-2367

- van Erp RMA, Huijnen IPJ, Jakobs MLG, Kleijnen J, Smeets RJEM. Effectiveness of primary care interventions using a biopsychosocial approach in chronic low back pain: a systematic review. Pain Practice. 2019;19:224-241. doi:10.1111/papr.12735

- Chou R, Deyo R, Friedly J, et al. Nonpharmacologic therapies for low back pain: a systematic review for an American College of physicians clinical practice guideline. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166:493-505. doi:10.7326/M16-2459

- Complementary, alternative, or integrative health: what’s in a name? National Institutes of Health, National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health. Updated April 2021. Accessed December 15, 2025. https://www.nccih.nih.gov/health/complementary-alternative-or-integrative-health-whats-in-a-name.

- Taylor SL, Elwy AR. Complementary and alternative medicine for US veterans and active duty military personnel promising steps to improve their health. Med Care. 2014;52:S1-S4. doi:10.1097/MLR.0000000000000270.

- Nahin RL, Rhee A, Stussman B. Use of complementary health approaches overall and for pain management by US adults. JAMA. 2024;331:613-615. doi:10.1001/jama.2023.26775

- Gantt CJ, Donovan N, Khung M. Veterans Affairs’ Whole Health System of Care for transitioning service members and veterans. Mil Med. 2023;188:28-32. doi:10.1093/milmed/usad047

- Bokhour BG, Hyde J, Kligler B, et al. From patient outcomes to system change: evaluating the impact of VHA’s implementation of the Whole Health System of Care. Health Serv Res. 2022;57:53-65. doi:10.1111/1475-6773.13938

- Department of Veterans Affairs VHA. VHA Policy Directive 1137: Provision of Complementary and Integrative Health. December 2022. Accessed December 15, 2025. https://www.va.gov/VHApublications/ViewPublication.asp?pub_ID=10072

- Giannitrapani KF, Holliday JR, Miake-Lye IM, Hempel S, Taylor SL. Synthesizing the strength of the evidence of complementary and integrative health therapies for pain. Pain Med. 2019;20:1831-1840. doi:10.1093/pm/pnz068

- Belitskaya-Levy I, David Clark J, Shih MC, Bair MJ. Treatment preferences for chronic low back pain: views of veterans and their providers. J Pain Res. 2021;14:161-171. doi:10.2147/JPR.S290400

- Onstott TN, Hurst S, Kronick R, Tsou AC, Groessl E, McMenamin SB. Health insurance mandates for nonpharmacological pain treatments in 7 US states. JAMA Netw Open. 2024;7:E245737. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.5737

- Sullivan M, Leach M, Snow J, Moonaz S. The North American yoga therapy workforce survey. Complement Ther Med. 2017;31:39-48. doi:10.1016/j.ctim.2017.01.006

- Bolton R, Ritter G, Highland K, Larson MJ. The relationship between capacity and utilization of nonpharmacologic therapies in the US Military Health System. BMC Health Serv Res. 2022;22. doi:10.1186/s12913-022-07700-4

- Stussman BJ, Nahin RL, Barnes PM, Scott R, Feinberg T, Ward BW. Reasons office-based physicians in the United States recommend common complementary health approaches to patients: an exploratory study using a national survey. J Integr Complement Med. 2022;28:651-663. doi:10.1089/jicm.2022.0493

Primary Care Clinician and Patient Knowledge, Interest, and Use of Integrative Treatment Options for Chronic Low Back Pain Management

Primary Care Clinician and Patient Knowledge, Interest, and Use of Integrative Treatment Options for Chronic Low Back Pain Management

A Group Approach to Clinical Research Mentorship at a Veterans Affairs Medical Center

A Group Approach to Clinical Research Mentorship at a Veterans Affairs Medical Center

Supporting meaningful research that has a positive impact on the health and quality of life of veterans is a priority of the US Department of Veterans Affairs Office of Research and Development.1 For nearly a century, VA researchers have been conducting high quality studies. To continue this trajectory, it is imperative to attract, train, and retain exceptional investigators while nurturing their development throughout their careers.2

Mentorship is defined as guidance provided by an experienced and trusted party to another (usually junior) individual with the intent of helping the person succeed. It benefits the mentee, mentor, and their institutions.3 Mentorship is crucial for personal and professional development as well as productivity, which may help reduce clinician burnout.4-7 Conversely, a lack of mentorship could have negative effects on work satisfaction and stagnate career progression.8

Mentorship is vital for developing and advancing a VA investigator’s research agenda. Funding, grant writing, and research design were among the most discussed topics in a large comprehensive mentorship program for academic faculty.9 However, there are several known barriers to effective research mentorship; among them include a lack of resources, time constraints, and competing clinical priorities.10,11

Finding time for effective one-on-one research mentoring is difficult within the time constraints of clinical duties; a group mentorship model may help overcome this barrier. Group mentorship can aid in personal and professional development because no single mentor can effectively meet every mentoring need of an individual.12 Group mentorship also allows for the exchange of ideas among individuals with different backgrounds and the ability to utilize the strengths of each member of the group. For example, a member may have methodological expertise, while another may be skilled in grantsmanship. A team of mentors may be more beneficial for both the mentors (eg, establish a more manageable workload) and the mentee (eg, gains a broader perspective of expertise) when compared to having a single mentor.3

Peer mentorship within the group setting may also yield additional benefits. For example, having a supportive peer group may help reduce stress levels and burnout, while also improving overall well-being.3,13 Formal mentorship programs do not frequently discuss concerns such as work-life balance, so including peers as mentors may help fill this void.9 Peer mentorship has also been found to be beneficial in providing mentees with pooled resources and shared learning.12,13 This article describes the components, benefits, impacts, and challenges of a group research mentorship program for VA clinicians interested in conducting VA-relevant research.

Program Description

The VA Clinical Research Mentorship Program was initiated at the VA Ann Arbor Healthcare System (VAAAHS) in October 2015 by the Chief of Medicine to assist VA clinician investigators with developing and submitting VA clinical science and health services research grant applications. The program offers group and one-on-one consultation services through the expertise of 2 experienced investigators/faculty mentors who also serve as program directors, each of whom devote about 3 to 5 hours per month to activities associated with the mentorship program (eg, attending the meeting, reviewing materials sent by mentees, and one-on-one discussions with mentees).

The program also fostered peer-led mentorship. This encourages all attendees to provide feedback during group sessions and communication by mentees outside the group sessions. An experienced project manager serves as program coordinator and contributes about 4 hours per month for activities such as attending, scheduling, and sending reminders for each meeting, distributing handouts, reviewing materials, and answering mentee’s questions via email. A statistician and additional research staff (ie, an epidemiologist and research assistant) do not attend the recurring meetings, but are available for offline consultation as needed. The program runs on a 12-month cycle with regular meetings occurring twice monthly during the 9-month academic period. Resources to support the program, primarily program director(s) and project coordinator effort, are provided by the Chief of Medicine and through the VAAAHS affiliated VA Health Systems Research (formerly Health Services Research & Development) Center of Innovation.

Invitations for new mentees are sent annually. Mentees expressing interest in the program outside of its annual recruitment period are evaluated for inclusion on a rolling basis. Recruitment begins with the program coordinator sending email notifications to all VAAAHS Medicine Service faculty, section chiefs, and division chiefs at the VAAAHS academic affiliate. Recipients are encouraged to distribute the announcement to eligible applicants and refer them to the application materials for entry consideration into the program. The application consists of the applicant’s curriculum vitae and a 1-page summary that includes a description of their research area of interest, how it is relevant to the VA, in addition to an idea for a research study, its potential significance, and proposed methodology. Applicant materials are reviewed by the program coordinator and program directors. The applicants are evaluated using a simple scoring approach that focuses on the applicant’s research area and agenda, past research training, past research productivity, potential for obtaining VA funding, and whether they have sufficient research time.

Program eligibility initially required being a physician with ≥ 1/8 VA appointment from the Medicine Service. However, clinicians with clinical appointments from other VA services are also accepted for participation as needed. Applicants must have previous research experience and have a career goal to obtain external funding for conducting and publishing original research. Those who have previously served as a principal investigator on a funded VA grant proposal are not eligible as new applicants but can remain in the program as peer mentors. The number of annual applicants varies and ranges from 1 to 11; on average, about 90% of applicants receive invitations to join the program.

Sessions

The program holds recurring meetings twice monthly for 1 hour during the 9-month academic year. However, program directors are available year-round, and mentees are encouraged to communicate questions or concerns via email during nonacademic months. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, all meetings were held in-person. However, the group pivoted to virtual meetings and continues to utilize this format. The dedicated program coordinator is responsible for coordinating meetings and distributing meeting materials.

Each session is informal, flexible, and supportive. Attendance is not enforced, and mentees are allowed to join meetings as their schedules permit; however, program directors and program coordinator attend each meeting. In advance of each session, the program coordinator sends out a call for agenda items to all active members invited to discuss any research related items. Each mentee presents their ideas to lead the discussion for their portion of the meeting with no defined format required.

A variety of topics are covered including, but not limited to: (1) grant-specific concerns (eg, questions related to specific aim pages, grantsmanship, postsubmission comments from reviewers, or postaward logistics); (2) research procedures (eg, questions related to methodological practices or institutional review board concerns); (3) manuscript or presentation preparation; and (4) careerrelated issues. The program coordinator distributes handouts prior to meetings and mentees may record their presentations. These handouts may include, but are not limited to, specific aims pages, analytical plans, grant solicitations, and PowerPoint presentations. If a resource that can benefit the entire group is mentioned during the meeting, the program coordinator is responsible for distribution.

The program follows a group facilitated discussion format. Program directors facilitate each meeting, but input is encouraged from all attendees. This model allows for mentees to learn from the faculty mentors as well as peer mentees in a simultaneous and efficient fashion. Group discussions foster collective problem solving, peer support, and resource sharing that would not be possible through individualized mentorship. Participants have access to varied expertise during each session which reduces the need to seek specialized help elsewhere. Participants are also encouraged to contact the program directors or research staff for consultation as needed. Some one-on-one consultations have transitioned to a more sustained and ongoing mentorship relationship between a program director and mentee, but most are often brief email exchanges or a single meeting.

Participants

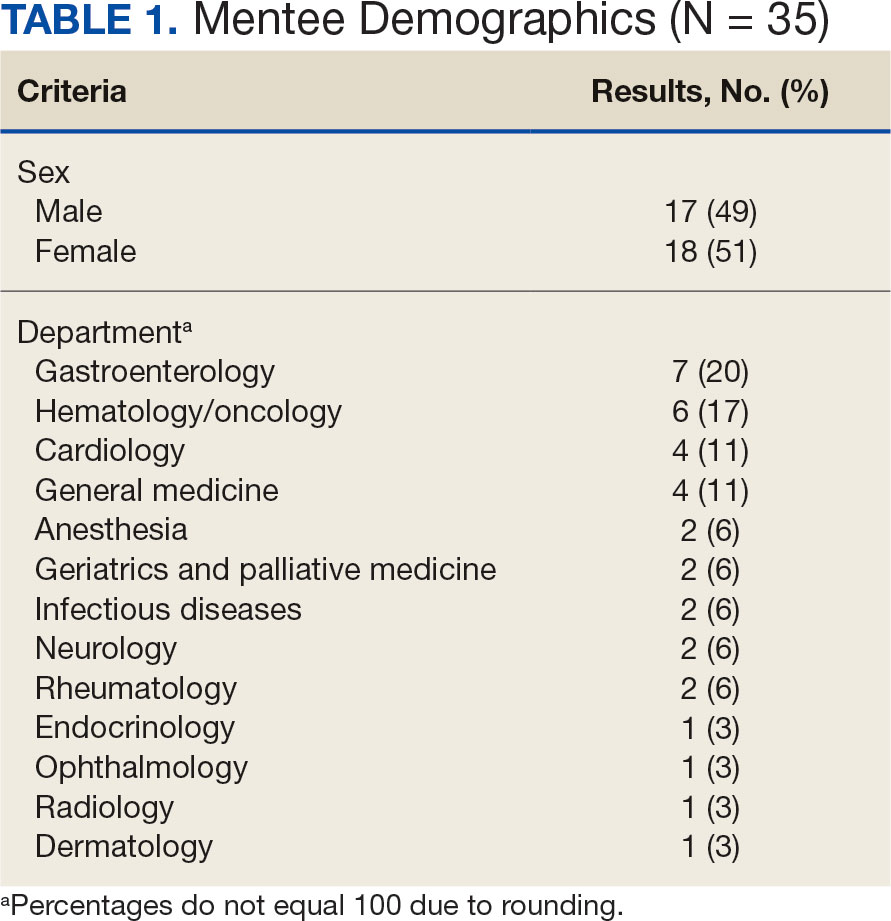

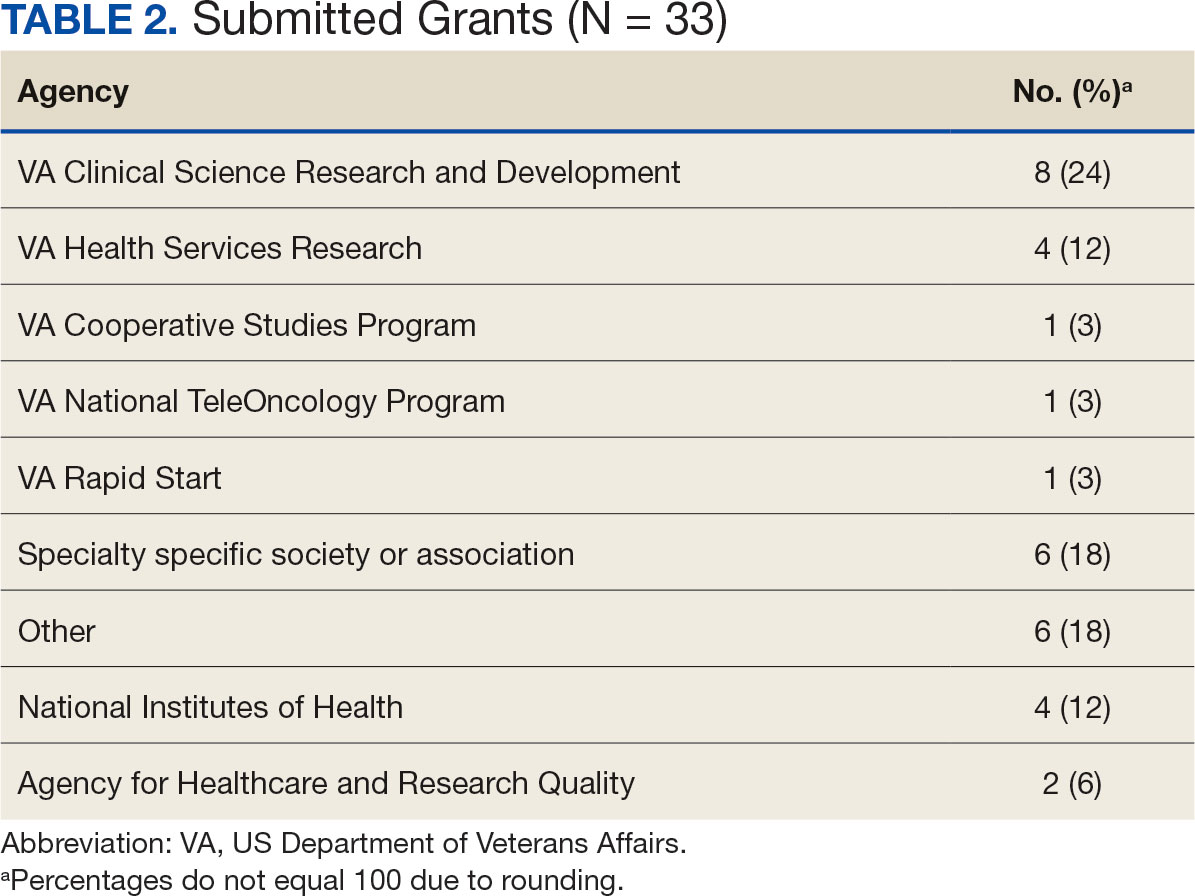

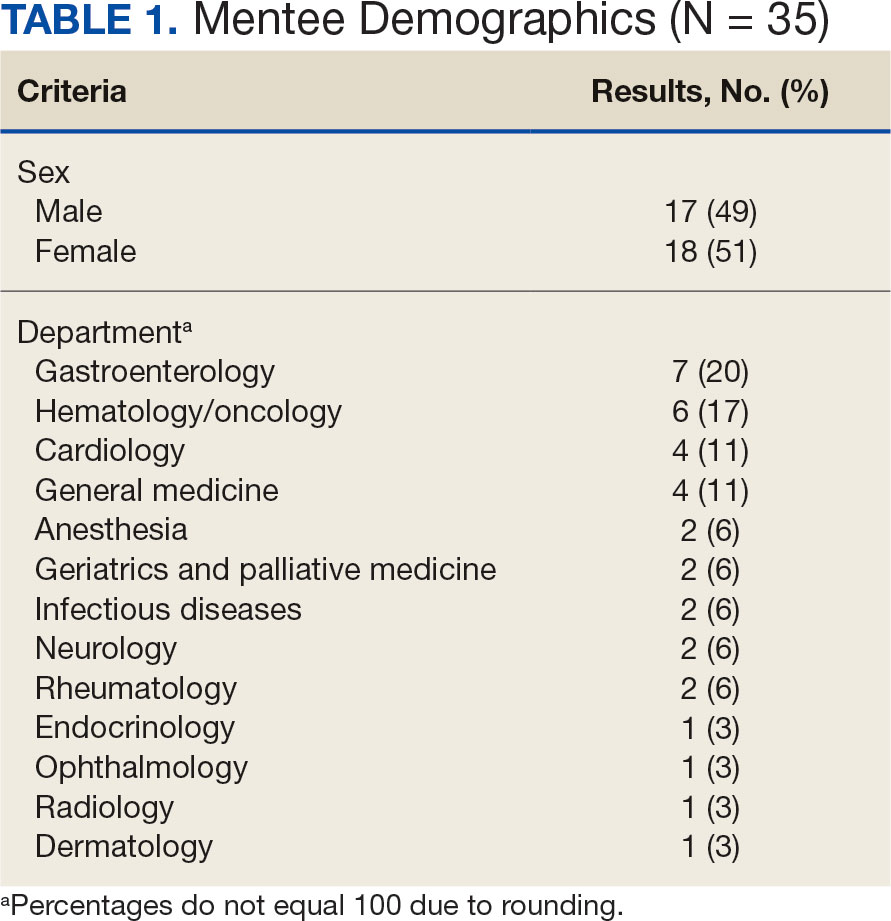

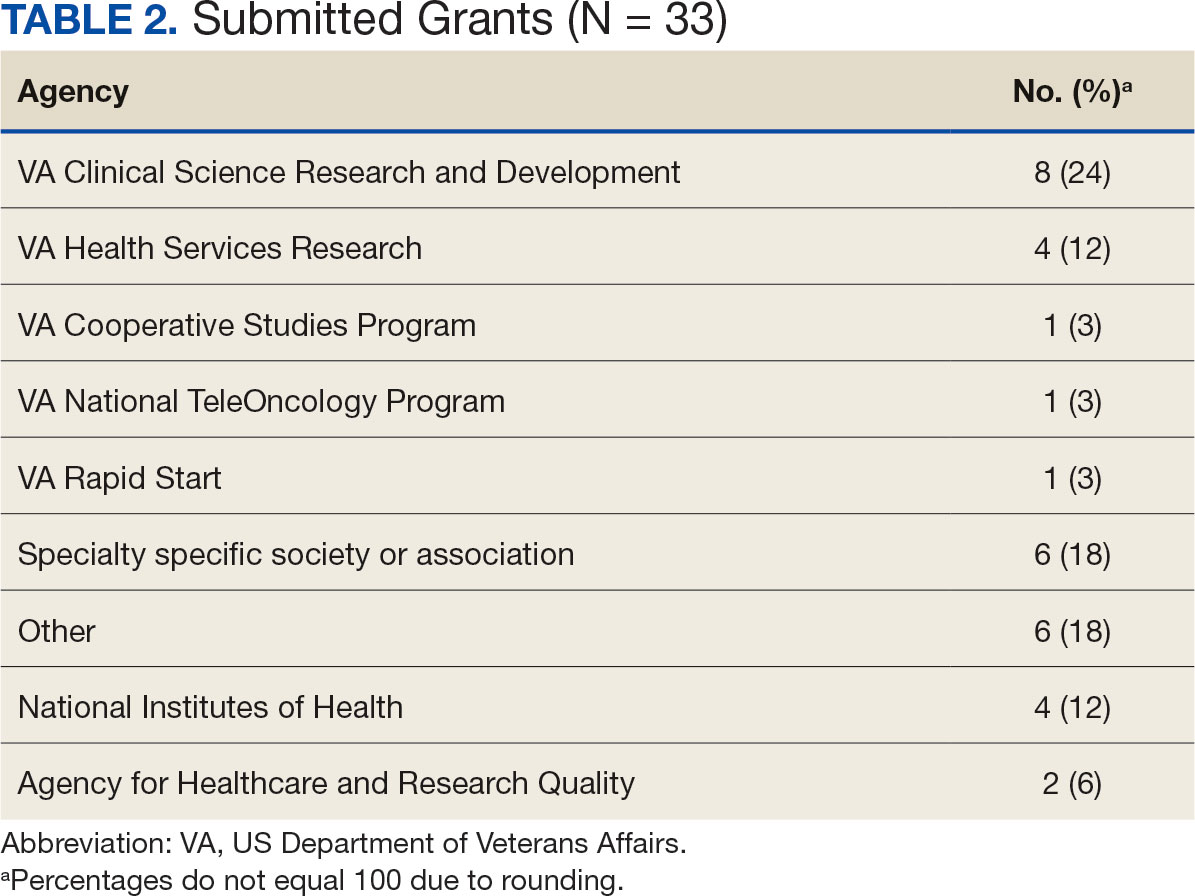

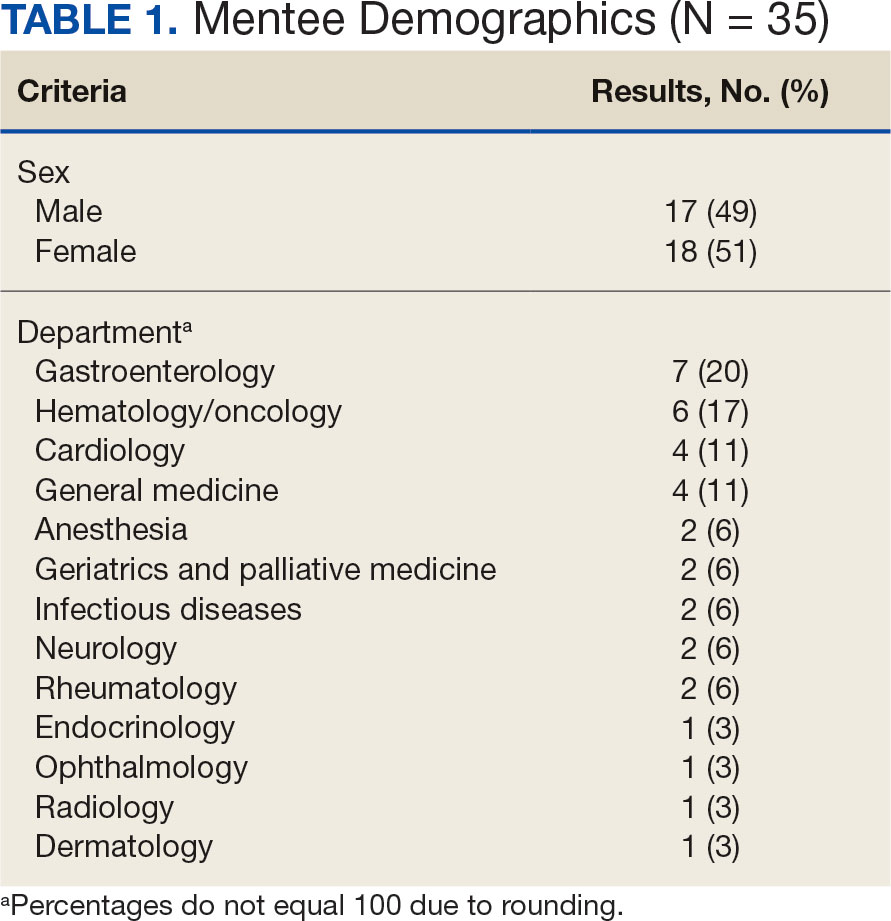

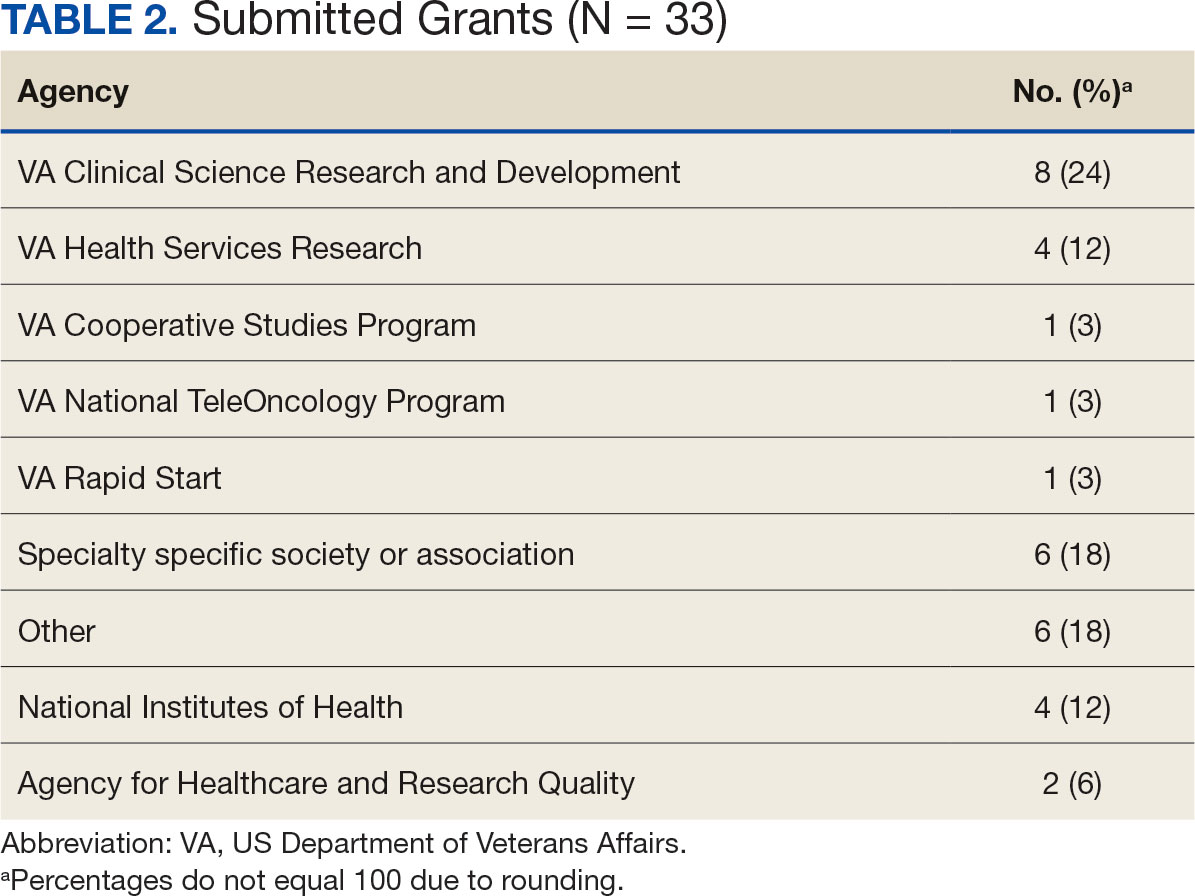

Since its inception in 2015, 35 clinicians have enrolled in the program. The mentees are equally distributed by sex and practice in a variety of disciplines including gastroenterology, hematology/oncology, cardiology, and general medicine (Table 1). Mentees have submitted 33 grant proposals addressing a variety of health care issues to a diverse group of federal and nonfederal funding agencies (Table 2). As of May 15, 2024, 19 (58%) of the submitted applications have been funded.

Many factors contribute to a successfully funded grant application, and several mentees report that participating in the mentorship program was helpful. For example, a mentee became the first lead investigator for a VA Cooperative Studies Program funded at VAAAHS. The VA Cooperative Studies Program, a division of the Office of Research and Development, plans and conducts large multicenter clinical trials and epidemiological studies within the VA via a vast network of clinician investigators, statisticians, and other key research experts.14

Several program mentees have also received VA Clinical Science Research and Development Career Development Awards. The VA Career Development program supports investigators during their early research careers with a goal of retaining talented researchers committed to improving the health and care of veterans.15

Survey Responses

Mentee productivity and updates are tracked through direct mentee input, as requested by the program coordinator. Since 2022, participants could complete an end-of-year survey based on an assessment tool used in a VAAAHS nonresearch mentorship program.16 The survey, distributed to mentees and program directors, requests feedback on logistics (eg, if the meeting was a good use of time and barriers to attendance); perceptions of effectiveness (eg, ability to discuss agenda items, helpfulness with setting and reaching research goals, and quality of mentors’ feedback); and the impact of the mentoring program on work satisfaction and clinician burnout. Respondents are also encouraged to leave open-ended qualitative feedback.

To date the survey has elicited 19 responses. Seventeen (89%) indicated that they agree or strongly agree the meetings were an effective use of their time and 11 (58%) indicated that they were able to discuss all or most of the items they wanted to during the meeting. Sixteen respondents (84%) agreed the program helped them set and achieve their research goals and 14 respondents (74%) agreed the feedback they received during the meeting was specific, actionable, and focused on how to improve their research agenda. Seventeen respondents (89%) agreed the program increased their work satisfaction, while 13 respondents (68%) felt the program reduced levels of clinician burnout.

As attendance was not mandatory, the survey asked participants how often they attended meetings during the past year. Responses were mixed: 4 (21%) respondents attended regularly (12 to 16 times per year) and 8 (42%) attended most sessions (8 to 11 times per year). Noted barriers to attendance included conflicts with patient care activities and conflicts with other high priority meetings.

Mentees also provided qualitive feedback regarding the program. They highlighted the supportive environment, valuable expertise of the mentors, and usefulness of obtaining tailored feedback from the group. “This group is an amazing resource to anyone developing a research career,” a mentee noted, adding that the program directors “fostered an incredibly supportive group where research ideas and methodology can be explored in a nonthreatening and creative environment.”

Conclusions

This mentorship program aims to help aspiring VA clinician investigators develop and submit competitive research grant applications. The addition of the program to the existing robust research environments at VAAAHS and its academic affiliate appears to have contributed to this success, with 58% of applications submitted by program mentees receiving funding.

In addition to funding success, we also found that most participants have a favorable impression of the program. Of the participants who responded to the program evaluation survey, nearly all indicated the program was an effective use of their time. The program also appeared to increase work satisfaction and reduce levels of clinician burnout. Barriers to attendance were also noted, with the most frequent being scheduling conflicts.

This program’s format includes facilitated group discussion as well as peer mentorship. This collaborative structure allows for an efficient and rich learning experience. Feedback from multiple perspectives encourages natural networking and relationship building. Incorporating the collective wisdom of the faculty mentors and peer mentees is beneficial; it not only empowers the mentees but also enriches the experience for the mentors. This program can serve as a model for other VA facilities—or non-VA academic medical centers—to enhance their research programs.

- US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Research and Development. Strategic priorities for VA research. Published March 10, 2021. Accessed September 17, 2024. https://www.research.va.gov/about/strategic_priorities.cfm

- US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Research and Development. About the Office of Research & Development. Published November 11, 2023. Accessed September 17, 2024. https://www.research.va.gov/about/default.cfm

- Chopra V, Vaughn V, Saint S. The Mentoring Guide: Helping Mentors and Mentees Succeed. Michigan Publishing Services; 2019.

- Gilster SD, Accorinti KL. Mentoring program yields staff satisfaction. Mentoring through the exchange of information across all organizational levels can help administrators retain valuable staff. Provider. 1999;25(10):99-100.

- Ramanan RA, Phillips RS, Davis RB, Silen W, Reede JY. Mentoring in medicine: keys to satisfaction. Am J Med. 2002;112(4):336-341. doi:10.1016/s0002-9343(02)01032-x

- Sambunjak D, Straus SE, Marusi' A. Mentoring in academic medicine: a systematic review. JAMA. 2006;296(9):1103-1115. doi:10.1001/jama.296.9.1103

- Sambunjak D, Straus SE, Marusi' A. A systematic review of qualitative research on the meaning and characteristics of mentoring in academic medicine. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(1):72-78. doi:10.1007/s11606-009-1165-8

- Jackson VA, Palepu A, Szalacha L, Caswell C, Carr PL, Inui T. “Having the right chemistry”: a qualitative study of mentoring in academic medicine. Acad Med. 2003;78(3):328-334. doi:10.1097/00001888-200303000-00020

- Feldman MD, Arean PA, Marshall SJ, Lovett M, O’Sullivan P. Does mentoring matter: results from a survey of faculty mentees at a large health sciences university. Med Educ Online. 2010;15:10.3402/meo.v15i0.5063. doi:10.3402/meo.v15i0.5063

- Leary JC, Schainker EG, Leyenaar JK. The unwritten rules of mentorship: facilitators of and barriers to effective mentorship in pediatric hospital medicine. Hosp Pediatr. 2016;6(4):219-225. doi:10.1542/hpeds.2015-0108

- Rustgi AK, Hecht GA. Mentorship in academic medicine. Gastroenterology. 2011;141(3):789-792. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2011.07.024

- DeCastro R, Sambuco D, Ubel PA, Stewart A, Jagsi R. Mentor networks in academic medicine: moving beyond a dyadic conception of mentoring for junior faculty researchers. Acad Med. 2013;88(4):488-496. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e318285d302

- McDaugall M, Beattie RS. Peer mentoring at work: the nature and outcomes of non-hierarchical developmental relationships. Management Learning. 2016;28(4):423-437. doi:10.1177/1350507697284003

- US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Rsearch and Development. VA Cooperative Studies Program (CSP). Updated July 2019. Accessed September 17, 2024. https://www.vacsp.research.va.gov

- US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Research and Development. Career development program for biomedical laboratory and clinical science R&D services. Published April 17, 2023. Accessed September 17, 2024. https://www.research.va.gov/services/shared_docs/career_dev.cfm

- Houchens N, Kuhn L, Ratz D, Su G, Saint S. Committed to success: a structured mentoring program for clinically-oriented physicians. Mayo Clin Pro Innov Qual Outcomes. 2024;8(4):356-363. doi:10.1016/j.mayocpiqo.2024.05.002

Supporting meaningful research that has a positive impact on the health and quality of life of veterans is a priority of the US Department of Veterans Affairs Office of Research and Development.1 For nearly a century, VA researchers have been conducting high quality studies. To continue this trajectory, it is imperative to attract, train, and retain exceptional investigators while nurturing their development throughout their careers.2

Mentorship is defined as guidance provided by an experienced and trusted party to another (usually junior) individual with the intent of helping the person succeed. It benefits the mentee, mentor, and their institutions.3 Mentorship is crucial for personal and professional development as well as productivity, which may help reduce clinician burnout.4-7 Conversely, a lack of mentorship could have negative effects on work satisfaction and stagnate career progression.8

Mentorship is vital for developing and advancing a VA investigator’s research agenda. Funding, grant writing, and research design were among the most discussed topics in a large comprehensive mentorship program for academic faculty.9 However, there are several known barriers to effective research mentorship; among them include a lack of resources, time constraints, and competing clinical priorities.10,11

Finding time for effective one-on-one research mentoring is difficult within the time constraints of clinical duties; a group mentorship model may help overcome this barrier. Group mentorship can aid in personal and professional development because no single mentor can effectively meet every mentoring need of an individual.12 Group mentorship also allows for the exchange of ideas among individuals with different backgrounds and the ability to utilize the strengths of each member of the group. For example, a member may have methodological expertise, while another may be skilled in grantsmanship. A team of mentors may be more beneficial for both the mentors (eg, establish a more manageable workload) and the mentee (eg, gains a broader perspective of expertise) when compared to having a single mentor.3

Peer mentorship within the group setting may also yield additional benefits. For example, having a supportive peer group may help reduce stress levels and burnout, while also improving overall well-being.3,13 Formal mentorship programs do not frequently discuss concerns such as work-life balance, so including peers as mentors may help fill this void.9 Peer mentorship has also been found to be beneficial in providing mentees with pooled resources and shared learning.12,13 This article describes the components, benefits, impacts, and challenges of a group research mentorship program for VA clinicians interested in conducting VA-relevant research.

Program Description

The VA Clinical Research Mentorship Program was initiated at the VA Ann Arbor Healthcare System (VAAAHS) in October 2015 by the Chief of Medicine to assist VA clinician investigators with developing and submitting VA clinical science and health services research grant applications. The program offers group and one-on-one consultation services through the expertise of 2 experienced investigators/faculty mentors who also serve as program directors, each of whom devote about 3 to 5 hours per month to activities associated with the mentorship program (eg, attending the meeting, reviewing materials sent by mentees, and one-on-one discussions with mentees).

The program also fostered peer-led mentorship. This encourages all attendees to provide feedback during group sessions and communication by mentees outside the group sessions. An experienced project manager serves as program coordinator and contributes about 4 hours per month for activities such as attending, scheduling, and sending reminders for each meeting, distributing handouts, reviewing materials, and answering mentee’s questions via email. A statistician and additional research staff (ie, an epidemiologist and research assistant) do not attend the recurring meetings, but are available for offline consultation as needed. The program runs on a 12-month cycle with regular meetings occurring twice monthly during the 9-month academic period. Resources to support the program, primarily program director(s) and project coordinator effort, are provided by the Chief of Medicine and through the VAAAHS affiliated VA Health Systems Research (formerly Health Services Research & Development) Center of Innovation.

Invitations for new mentees are sent annually. Mentees expressing interest in the program outside of its annual recruitment period are evaluated for inclusion on a rolling basis. Recruitment begins with the program coordinator sending email notifications to all VAAAHS Medicine Service faculty, section chiefs, and division chiefs at the VAAAHS academic affiliate. Recipients are encouraged to distribute the announcement to eligible applicants and refer them to the application materials for entry consideration into the program. The application consists of the applicant’s curriculum vitae and a 1-page summary that includes a description of their research area of interest, how it is relevant to the VA, in addition to an idea for a research study, its potential significance, and proposed methodology. Applicant materials are reviewed by the program coordinator and program directors. The applicants are evaluated using a simple scoring approach that focuses on the applicant’s research area and agenda, past research training, past research productivity, potential for obtaining VA funding, and whether they have sufficient research time.