User login

An Unusual Cause of Recurrent Severe Abdominal Colic

We carefully reviewed the patient’s history and found that he had been using jineijin, a traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) drug, which is made with dried endothelium corneum gigeriae galli (Figure E), at about 500 g/month and squama mantis (a TCM drug, at less than 5 g/month) as dietary supplements for 3 years.

Acknowledgments

We thank Linshen Xie, MD, department of environmental health and occupational diseases, No. 4 West China Teaching Hospital, Sichuan University, for offering some clinical data. We thank the patient for giving permission to share his information.

References

1. National Research Council (US). Safe Drinking Water Committee. Drinking water and health. National Academy Press. Washington, D.C. 1977;1:309.

2. State Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine. Advanced Textbook on Traditional Chinese Medicine and Pharmacology. New World Press, Beijing. 1995. (vol. 2).

3. Hui Hu, Q.J., Kavan, P. A study of heavy metal pollution in China: Current status, pollution-control policies and countermeasures. Sustainability. 2014;6:5820-38.

This article has an accompanying continuing medical education activity, also eligible for MOC credit, Learning objective: Upon completion of this examination, successful learners will be able to identify the features of lead poisoning.

We carefully reviewed the patient’s history and found that he had been using jineijin, a traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) drug, which is made with dried endothelium corneum gigeriae galli (Figure E), at about 500 g/month and squama mantis (a TCM drug, at less than 5 g/month) as dietary supplements for 3 years.

Acknowledgments

We thank Linshen Xie, MD, department of environmental health and occupational diseases, No. 4 West China Teaching Hospital, Sichuan University, for offering some clinical data. We thank the patient for giving permission to share his information.

References

1. National Research Council (US). Safe Drinking Water Committee. Drinking water and health. National Academy Press. Washington, D.C. 1977;1:309.

2. State Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine. Advanced Textbook on Traditional Chinese Medicine and Pharmacology. New World Press, Beijing. 1995. (vol. 2).

3. Hui Hu, Q.J., Kavan, P. A study of heavy metal pollution in China: Current status, pollution-control policies and countermeasures. Sustainability. 2014;6:5820-38.

This article has an accompanying continuing medical education activity, also eligible for MOC credit, Learning objective: Upon completion of this examination, successful learners will be able to identify the features of lead poisoning.

We carefully reviewed the patient’s history and found that he had been using jineijin, a traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) drug, which is made with dried endothelium corneum gigeriae galli (Figure E), at about 500 g/month and squama mantis (a TCM drug, at less than 5 g/month) as dietary supplements for 3 years.

Acknowledgments

We thank Linshen Xie, MD, department of environmental health and occupational diseases, No. 4 West China Teaching Hospital, Sichuan University, for offering some clinical data. We thank the patient for giving permission to share his information.

References

1. National Research Council (US). Safe Drinking Water Committee. Drinking water and health. National Academy Press. Washington, D.C. 1977;1:309.

2. State Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine. Advanced Textbook on Traditional Chinese Medicine and Pharmacology. New World Press, Beijing. 1995. (vol. 2).

3. Hui Hu, Q.J., Kavan, P. A study of heavy metal pollution in China: Current status, pollution-control policies and countermeasures. Sustainability. 2014;6:5820-38.

This article has an accompanying continuing medical education activity, also eligible for MOC credit, Learning objective: Upon completion of this examination, successful learners will be able to identify the features of lead poisoning.

Published previously in Gastroenterology (2016;151:819-21)

Dr. Deng, Dr. Hu, and Dr. Zhang are in the department of gastroenterology, West China Hospital, Sichuan University, Sichuan Province, China.

News from AGA

Advice on Achieving Work-Life Balance

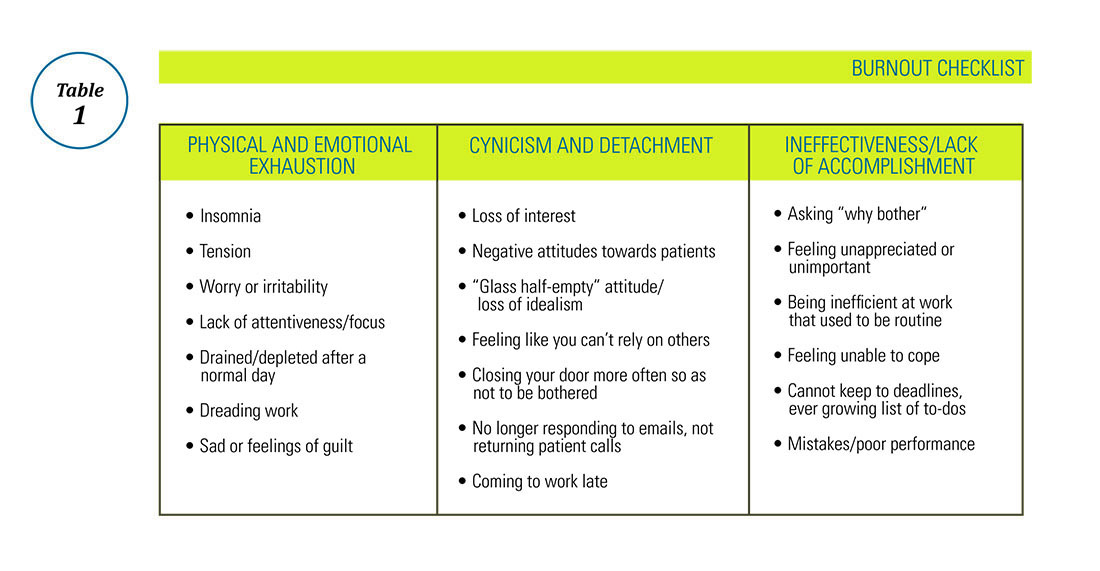

Successfully maintaining a balance between your personal and professional lives is a difficult concept to grasp and practice to enforce. Is this thing called “work-life balance” within reach or just some elusive circumstance people talk about? The AGA Community Early Career Group was the hub for discussions on ways early-career gastroenterologists can modify their day-to-day approach to help prevent burnout.

We consolidated the advice and tips shared into a series of articles and resources to help students, trainees, and early career members get a little closer to balancing their work and professional lives. Here are some highlights:

Choose work-life “integration”

If your career and your personal life were a successful relationship, remember that it’s not always 50/50, and be sure to allow forgiveness and reparation when needed.

Maternity leave

When it comes to starting a family, think about your current training or career climate and how you can make it work. Be transparent with your supervisor so there aren’t any surprises, and plans can be made in advance to cover for your time away. Prepare to be flexible from the beginning.

Learn when to say “no”

Saying “yes” to too many things not only leads to overextending yourself beyond your capabilities, but you could also be losing time on what is important to you. Choose one night a week when you can work late – pack a snack, and give yourself a hard stop the rest of the week. Keep patient documentation as a daytime/work task.

Communication is key

When your partner or spouse is just as busy, it’s important to keep a joint calendar up to date and make plans far in advance. Also, create a routine: Try making time once a month to discuss calendars and anticipated events, face-to-face. When life throws a divot in your path, don’t lose sight of your priorities.

Make time for family and friends

Your career can take over as much of your life as you will allow. Making time for family and friends is rewarding and vacations, staycations, long weekends or even day trips can be great “resets.”

View the tip sheet and other work-life balance resources in the AGA Community Early Career Group library at http://community.gastro.org/WorkLife.

New Clinical Guidelines and Practice Updates

The latest AGA Clinical Practice Guideline, published in Gastroenterology, is on the role of therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM) in the management of IBD. It focuses on the application of TDM for biologic therapy, specifically anti-tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF) agents, and for thiopurines, and addresses questions on the risks and benefits of reactive TDM, routine proactive TDM, or no TDM in guiding treatment changes.

View the full guideline, technical review, and patient guide at www.gastro.org/guidelines.

In addition to guidelines, please check out the most recent Clinical Practice Updates (CPU) in Gastroenterology and Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology (CGH), which are often accompanied by a practice quiz from one of the authors, via the AGA Community. Visit http://community.gastro.org/guidelinecpu to test your knowledge. The most recent CPU, published in the September issue of CGH, focuses on GI side effects related to opioid medications.

Be Part of the Meeting to Transform IBD

If you treat patients with inflammatory bowel disease, conduct IBD research, or plan to pursue a career in IBD, join us for the inaugural Crohn’s & Colitis Congress™, taking place Jan. 18-20, 2018, in Las Vegas, NV. The Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation (formerly CCFA) and AGA have joined together to develop a must-attend program for the entire IBD care team. Expand your knowledge, network with your peers as well as IBD leaders across multiple disciplines, and get inspired to improve care for patients with Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis.

You may also be interested in the free precongress workshop – The Lloyd Mayer, MD, Young IBD Investigators Clinical, Basic, and Translational Research Workshop. This half-day precongress workshop is targeted to early-career clinical, basic, and translational researchers as well as senior researchers and will feature a mix of research presentations by young investigator colleagues, keynote presentations, and panel discussion, featuring established IBD researchers. The theme this year is focused around grant proposals and will include two mock grant review sessions.

Learn more about the Crohn’s & Colitis Congress and register: http://crohnscolitiscongress.org.

Advice on Achieving Work-Life Balance

Successfully maintaining a balance between your personal and professional lives is a difficult concept to grasp and practice to enforce. Is this thing called “work-life balance” within reach or just some elusive circumstance people talk about? The AGA Community Early Career Group was the hub for discussions on ways early-career gastroenterologists can modify their day-to-day approach to help prevent burnout.

We consolidated the advice and tips shared into a series of articles and resources to help students, trainees, and early career members get a little closer to balancing their work and professional lives. Here are some highlights:

Choose work-life “integration”

If your career and your personal life were a successful relationship, remember that it’s not always 50/50, and be sure to allow forgiveness and reparation when needed.

Maternity leave

When it comes to starting a family, think about your current training or career climate and how you can make it work. Be transparent with your supervisor so there aren’t any surprises, and plans can be made in advance to cover for your time away. Prepare to be flexible from the beginning.

Learn when to say “no”

Saying “yes” to too many things not only leads to overextending yourself beyond your capabilities, but you could also be losing time on what is important to you. Choose one night a week when you can work late – pack a snack, and give yourself a hard stop the rest of the week. Keep patient documentation as a daytime/work task.

Communication is key

When your partner or spouse is just as busy, it’s important to keep a joint calendar up to date and make plans far in advance. Also, create a routine: Try making time once a month to discuss calendars and anticipated events, face-to-face. When life throws a divot in your path, don’t lose sight of your priorities.

Make time for family and friends

Your career can take over as much of your life as you will allow. Making time for family and friends is rewarding and vacations, staycations, long weekends or even day trips can be great “resets.”

View the tip sheet and other work-life balance resources in the AGA Community Early Career Group library at http://community.gastro.org/WorkLife.

New Clinical Guidelines and Practice Updates

The latest AGA Clinical Practice Guideline, published in Gastroenterology, is on the role of therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM) in the management of IBD. It focuses on the application of TDM for biologic therapy, specifically anti-tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF) agents, and for thiopurines, and addresses questions on the risks and benefits of reactive TDM, routine proactive TDM, or no TDM in guiding treatment changes.

View the full guideline, technical review, and patient guide at www.gastro.org/guidelines.

In addition to guidelines, please check out the most recent Clinical Practice Updates (CPU) in Gastroenterology and Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology (CGH), which are often accompanied by a practice quiz from one of the authors, via the AGA Community. Visit http://community.gastro.org/guidelinecpu to test your knowledge. The most recent CPU, published in the September issue of CGH, focuses on GI side effects related to opioid medications.

Be Part of the Meeting to Transform IBD

If you treat patients with inflammatory bowel disease, conduct IBD research, or plan to pursue a career in IBD, join us for the inaugural Crohn’s & Colitis Congress™, taking place Jan. 18-20, 2018, in Las Vegas, NV. The Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation (formerly CCFA) and AGA have joined together to develop a must-attend program for the entire IBD care team. Expand your knowledge, network with your peers as well as IBD leaders across multiple disciplines, and get inspired to improve care for patients with Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis.

You may also be interested in the free precongress workshop – The Lloyd Mayer, MD, Young IBD Investigators Clinical, Basic, and Translational Research Workshop. This half-day precongress workshop is targeted to early-career clinical, basic, and translational researchers as well as senior researchers and will feature a mix of research presentations by young investigator colleagues, keynote presentations, and panel discussion, featuring established IBD researchers. The theme this year is focused around grant proposals and will include two mock grant review sessions.

Learn more about the Crohn’s & Colitis Congress and register: http://crohnscolitiscongress.org.

Advice on Achieving Work-Life Balance

Successfully maintaining a balance between your personal and professional lives is a difficult concept to grasp and practice to enforce. Is this thing called “work-life balance” within reach or just some elusive circumstance people talk about? The AGA Community Early Career Group was the hub for discussions on ways early-career gastroenterologists can modify their day-to-day approach to help prevent burnout.

We consolidated the advice and tips shared into a series of articles and resources to help students, trainees, and early career members get a little closer to balancing their work and professional lives. Here are some highlights:

Choose work-life “integration”

If your career and your personal life were a successful relationship, remember that it’s not always 50/50, and be sure to allow forgiveness and reparation when needed.

Maternity leave

When it comes to starting a family, think about your current training or career climate and how you can make it work. Be transparent with your supervisor so there aren’t any surprises, and plans can be made in advance to cover for your time away. Prepare to be flexible from the beginning.

Learn when to say “no”

Saying “yes” to too many things not only leads to overextending yourself beyond your capabilities, but you could also be losing time on what is important to you. Choose one night a week when you can work late – pack a snack, and give yourself a hard stop the rest of the week. Keep patient documentation as a daytime/work task.

Communication is key

When your partner or spouse is just as busy, it’s important to keep a joint calendar up to date and make plans far in advance. Also, create a routine: Try making time once a month to discuss calendars and anticipated events, face-to-face. When life throws a divot in your path, don’t lose sight of your priorities.

Make time for family and friends

Your career can take over as much of your life as you will allow. Making time for family and friends is rewarding and vacations, staycations, long weekends or even day trips can be great “resets.”

View the tip sheet and other work-life balance resources in the AGA Community Early Career Group library at http://community.gastro.org/WorkLife.

New Clinical Guidelines and Practice Updates

The latest AGA Clinical Practice Guideline, published in Gastroenterology, is on the role of therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM) in the management of IBD. It focuses on the application of TDM for biologic therapy, specifically anti-tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF) agents, and for thiopurines, and addresses questions on the risks and benefits of reactive TDM, routine proactive TDM, or no TDM in guiding treatment changes.

View the full guideline, technical review, and patient guide at www.gastro.org/guidelines.

In addition to guidelines, please check out the most recent Clinical Practice Updates (CPU) in Gastroenterology and Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology (CGH), which are often accompanied by a practice quiz from one of the authors, via the AGA Community. Visit http://community.gastro.org/guidelinecpu to test your knowledge. The most recent CPU, published in the September issue of CGH, focuses on GI side effects related to opioid medications.

Be Part of the Meeting to Transform IBD

If you treat patients with inflammatory bowel disease, conduct IBD research, or plan to pursue a career in IBD, join us for the inaugural Crohn’s & Colitis Congress™, taking place Jan. 18-20, 2018, in Las Vegas, NV. The Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation (formerly CCFA) and AGA have joined together to develop a must-attend program for the entire IBD care team. Expand your knowledge, network with your peers as well as IBD leaders across multiple disciplines, and get inspired to improve care for patients with Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis.

You may also be interested in the free precongress workshop – The Lloyd Mayer, MD, Young IBD Investigators Clinical, Basic, and Translational Research Workshop. This half-day precongress workshop is targeted to early-career clinical, basic, and translational researchers as well as senior researchers and will feature a mix of research presentations by young investigator colleagues, keynote presentations, and panel discussion, featuring established IBD researchers. The theme this year is focused around grant proposals and will include two mock grant review sessions.

Learn more about the Crohn’s & Colitis Congress and register: http://crohnscolitiscongress.org.

Cholangiopancreatoscopy

Dear Colleagues,

In this issue of The New Gastroenterologist, the feature article examines recent advances in the field of cholangiopancreatoscopy. In this article, William Sonnier, Meir Mizrahi (University of South Alabama), and Douglas Pleskow (Beth Israel Deaconess) provide a fantastic overview of the technologic advances in the field of cholangiopancreatoscopy as well as the clinical indications for this procedure and the risks involved. Also in this issue, Deborah Fisher (Duke University) and Darrell Gray (Ohio State University) provide advice about how to appropriately and responsibly handle social media. This is an incredibly important topic, given the increasing pervasiveness of social media in many aspects of our personal and professional lives.

Finally, in this issue is the second part in a series on legal issues for gastroenterologists. In this article, which is again authored by a very experienced group of attorneys, many important issues are covered, including what steps should be taken if you are sued, what you should and should not do after being sued, as well as tips on how to best prepare for both deposition and trial.

If there are topics that you would be interested in writing or hearing about in The New Gastroenterologist, please let us know. You can contact me (bryson.katona@uphs.upenn.edu) or the Managing Editor of The New Gastroenterologist, Ryan Farrell (rfarrell@gastro.org).

Sincerely,

Bryson W. Katona, MD, PhD

Editor in Chief

Bryson W. Katona is an instructor of medicine in the division of gastroenterology at the University of Pennsylvania.

Dear Colleagues,

In this issue of The New Gastroenterologist, the feature article examines recent advances in the field of cholangiopancreatoscopy. In this article, William Sonnier, Meir Mizrahi (University of South Alabama), and Douglas Pleskow (Beth Israel Deaconess) provide a fantastic overview of the technologic advances in the field of cholangiopancreatoscopy as well as the clinical indications for this procedure and the risks involved. Also in this issue, Deborah Fisher (Duke University) and Darrell Gray (Ohio State University) provide advice about how to appropriately and responsibly handle social media. This is an incredibly important topic, given the increasing pervasiveness of social media in many aspects of our personal and professional lives.

Finally, in this issue is the second part in a series on legal issues for gastroenterologists. In this article, which is again authored by a very experienced group of attorneys, many important issues are covered, including what steps should be taken if you are sued, what you should and should not do after being sued, as well as tips on how to best prepare for both deposition and trial.

If there are topics that you would be interested in writing or hearing about in The New Gastroenterologist, please let us know. You can contact me (bryson.katona@uphs.upenn.edu) or the Managing Editor of The New Gastroenterologist, Ryan Farrell (rfarrell@gastro.org).

Sincerely,

Bryson W. Katona, MD, PhD

Editor in Chief

Bryson W. Katona is an instructor of medicine in the division of gastroenterology at the University of Pennsylvania.

Dear Colleagues,

In this issue of The New Gastroenterologist, the feature article examines recent advances in the field of cholangiopancreatoscopy. In this article, William Sonnier, Meir Mizrahi (University of South Alabama), and Douglas Pleskow (Beth Israel Deaconess) provide a fantastic overview of the technologic advances in the field of cholangiopancreatoscopy as well as the clinical indications for this procedure and the risks involved. Also in this issue, Deborah Fisher (Duke University) and Darrell Gray (Ohio State University) provide advice about how to appropriately and responsibly handle social media. This is an incredibly important topic, given the increasing pervasiveness of social media in many aspects of our personal and professional lives.

Finally, in this issue is the second part in a series on legal issues for gastroenterologists. In this article, which is again authored by a very experienced group of attorneys, many important issues are covered, including what steps should be taken if you are sued, what you should and should not do after being sued, as well as tips on how to best prepare for both deposition and trial.

If there are topics that you would be interested in writing or hearing about in The New Gastroenterologist, please let us know. You can contact me (bryson.katona@uphs.upenn.edu) or the Managing Editor of The New Gastroenterologist, Ryan Farrell (rfarrell@gastro.org).

Sincerely,

Bryson W. Katona, MD, PhD

Editor in Chief

Bryson W. Katona is an instructor of medicine in the division of gastroenterology at the University of Pennsylvania.

Nanocarriers could treat leukemia, lymphoma and improve HSCT

Researchers say they have created nanoparticles loaded with messenger RNA (mRNA) that can give cells the ability to fight cancers and other diseases.

To use these freeze-dried nanocarriers, the team added water and introduced the resulting mixture to cells.

The nanocarriers were able to target T cells and hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs), delivering mRNA directly to the cells and triggering short-term gene expression.

The T cells were then able to fight leukemia and lymphoma in vitro and in vivo. And the HSCs demonstrated improvements in growth and regenerative potential.

Matthias Stephan, MD, PhD, of Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle, Washington, and his colleagues described this research in Nature Communications.

“We developed a nanocarrier that binds and condenses synthetic mRNA and protects it from degradation,” Dr Stephan said.

The researchers surrounded the nanocarrier with a negatively charged envelope with a targeting ligand attached to the surface so the carrier homes and binds to a particular cell type. When this happens, the cell engulfs the carrier, which can be loaded with different types of manmade mRNA.

The researchers mixed the freeze-dried nanocarriers with water and samples of cells. Within 4 hours, cells started showing signs that editing had taken effect.

The team noted that boosters can be given if needed. And the nanocarriers are made from a dissolving biomaterial, so they are removed from the body like other cell waste.

Testing the carriers

Dr Stephan and his colleagues tested their nanocarriers in 3 ways.

First, the researchers tested nanoparticles carrying a gene-editing tool to T cells that snipped out their natural T-cell receptors and was paired with genes encoding a chimeric antigen receptor (CAR).

The resulting CAR T cells maintained their ability to proliferate and successfully eliminated leukemia cells.

Next, the researchers tested nanocarriers targeted to CAR T cells and containing foxo1 mRNA. This prompted the T cells to develop into a type of memory cell with enhanced antitumor activity.

The team found these CAR T cells induced “substantial disease regression” and prolonged survival in a mouse model of B-cell lymphoma.

Finally, the researchers tested nanocarriers targeted to HSCs. The carriers were equipped with mRNA that “induced key regulators of self-renewal,” accelerating the growth and regenerative potential of the HSCs in vitro.

Future possibilities

Dr Stephan and his colleagues noted that these nanocarriers are built on existing technology and can be used by individuals without knowledge of nanotechnology. Therefore, the team hopes the nanocarriers will be an off-the-shelf way for cell-therapy engineers to develop new approaches to treat diseases.

The researchers believe the nanocarriers could replace electroporation, a multistep cell-manufacturing technique that requires specialized equipment and clean rooms. The team noted that up to 60 times more cells survive the introduction of the nanocarriers than survive electroporation.

“You can imagine taking the nanoparticles, injecting them into a patient, and then you don’t have to culture cells at all anymore,” Dr Stephan said.

He is now looking for commercial partners to move the technology toward additional applications and into clinical trials. ![]()

Researchers say they have created nanoparticles loaded with messenger RNA (mRNA) that can give cells the ability to fight cancers and other diseases.

To use these freeze-dried nanocarriers, the team added water and introduced the resulting mixture to cells.

The nanocarriers were able to target T cells and hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs), delivering mRNA directly to the cells and triggering short-term gene expression.

The T cells were then able to fight leukemia and lymphoma in vitro and in vivo. And the HSCs demonstrated improvements in growth and regenerative potential.

Matthias Stephan, MD, PhD, of Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle, Washington, and his colleagues described this research in Nature Communications.

“We developed a nanocarrier that binds and condenses synthetic mRNA and protects it from degradation,” Dr Stephan said.

The researchers surrounded the nanocarrier with a negatively charged envelope with a targeting ligand attached to the surface so the carrier homes and binds to a particular cell type. When this happens, the cell engulfs the carrier, which can be loaded with different types of manmade mRNA.

The researchers mixed the freeze-dried nanocarriers with water and samples of cells. Within 4 hours, cells started showing signs that editing had taken effect.

The team noted that boosters can be given if needed. And the nanocarriers are made from a dissolving biomaterial, so they are removed from the body like other cell waste.

Testing the carriers

Dr Stephan and his colleagues tested their nanocarriers in 3 ways.

First, the researchers tested nanoparticles carrying a gene-editing tool to T cells that snipped out their natural T-cell receptors and was paired with genes encoding a chimeric antigen receptor (CAR).

The resulting CAR T cells maintained their ability to proliferate and successfully eliminated leukemia cells.

Next, the researchers tested nanocarriers targeted to CAR T cells and containing foxo1 mRNA. This prompted the T cells to develop into a type of memory cell with enhanced antitumor activity.

The team found these CAR T cells induced “substantial disease regression” and prolonged survival in a mouse model of B-cell lymphoma.

Finally, the researchers tested nanocarriers targeted to HSCs. The carriers were equipped with mRNA that “induced key regulators of self-renewal,” accelerating the growth and regenerative potential of the HSCs in vitro.

Future possibilities

Dr Stephan and his colleagues noted that these nanocarriers are built on existing technology and can be used by individuals without knowledge of nanotechnology. Therefore, the team hopes the nanocarriers will be an off-the-shelf way for cell-therapy engineers to develop new approaches to treat diseases.

The researchers believe the nanocarriers could replace electroporation, a multistep cell-manufacturing technique that requires specialized equipment and clean rooms. The team noted that up to 60 times more cells survive the introduction of the nanocarriers than survive electroporation.

“You can imagine taking the nanoparticles, injecting them into a patient, and then you don’t have to culture cells at all anymore,” Dr Stephan said.

He is now looking for commercial partners to move the technology toward additional applications and into clinical trials. ![]()

Researchers say they have created nanoparticles loaded with messenger RNA (mRNA) that can give cells the ability to fight cancers and other diseases.

To use these freeze-dried nanocarriers, the team added water and introduced the resulting mixture to cells.

The nanocarriers were able to target T cells and hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs), delivering mRNA directly to the cells and triggering short-term gene expression.

The T cells were then able to fight leukemia and lymphoma in vitro and in vivo. And the HSCs demonstrated improvements in growth and regenerative potential.

Matthias Stephan, MD, PhD, of Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle, Washington, and his colleagues described this research in Nature Communications.

“We developed a nanocarrier that binds and condenses synthetic mRNA and protects it from degradation,” Dr Stephan said.

The researchers surrounded the nanocarrier with a negatively charged envelope with a targeting ligand attached to the surface so the carrier homes and binds to a particular cell type. When this happens, the cell engulfs the carrier, which can be loaded with different types of manmade mRNA.

The researchers mixed the freeze-dried nanocarriers with water and samples of cells. Within 4 hours, cells started showing signs that editing had taken effect.

The team noted that boosters can be given if needed. And the nanocarriers are made from a dissolving biomaterial, so they are removed from the body like other cell waste.

Testing the carriers

Dr Stephan and his colleagues tested their nanocarriers in 3 ways.

First, the researchers tested nanoparticles carrying a gene-editing tool to T cells that snipped out their natural T-cell receptors and was paired with genes encoding a chimeric antigen receptor (CAR).

The resulting CAR T cells maintained their ability to proliferate and successfully eliminated leukemia cells.

Next, the researchers tested nanocarriers targeted to CAR T cells and containing foxo1 mRNA. This prompted the T cells to develop into a type of memory cell with enhanced antitumor activity.

The team found these CAR T cells induced “substantial disease regression” and prolonged survival in a mouse model of B-cell lymphoma.

Finally, the researchers tested nanocarriers targeted to HSCs. The carriers were equipped with mRNA that “induced key regulators of self-renewal,” accelerating the growth and regenerative potential of the HSCs in vitro.

Future possibilities

Dr Stephan and his colleagues noted that these nanocarriers are built on existing technology and can be used by individuals without knowledge of nanotechnology. Therefore, the team hopes the nanocarriers will be an off-the-shelf way for cell-therapy engineers to develop new approaches to treat diseases.

The researchers believe the nanocarriers could replace electroporation, a multistep cell-manufacturing technique that requires specialized equipment and clean rooms. The team noted that up to 60 times more cells survive the introduction of the nanocarriers than survive electroporation.

“You can imagine taking the nanoparticles, injecting them into a patient, and then you don’t have to culture cells at all anymore,” Dr Stephan said.

He is now looking for commercial partners to move the technology toward additional applications and into clinical trials. ![]()

FDA warns about risk of death with pembrolizumab in MM

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has issued a statement warning about an increased risk of death associated with an unapproved use of pembrolizumab (Keytruda).

Results from 2 clinical trials have shown that combining pembrolizumab with dexamethasone and an immunomodulatory agent (lenalidomide or pomalidomide) increases the risk of death in patients with multiple myeloma (MM).

The FDA issued its statement to remind doctors and patients that pembrolizumab is not approved to treat MM and should not be given in combination with immunomodulatory agents to treat MM.

Pembrolizumab is currently FDA-approved to treat classical Hodgkin lymphoma, melanoma, lung cancer, head and neck cancer, urothelial carcinoma, and microsatellite instability-high cancer.

The FDA believes the benefits of taking pembrolizumab and other PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors for their approved uses continue to outweigh the risks, according to Janet Woodcock, director of the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research.

However, the FDA is investigating trials of pembrolizumab as well as trials of other PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors.

Pembrolizumab in MM

The FDA’s warning is based on a review of data from 2 clinical trials—KEYNOTE-183 and KEYNOTE-185. The FDA placed a clinical hold on these trials—as well as KEYNOTE-023—in July.

KEYNOTE-183 is a phase 3 study of pomalidomide and low-dose dexamethasone, given with or without pembrolizumab, to patients with refractory or relapsed and refractory MM.

KEYNOTE-185 is a phase 3 study of lenalidomide and low-dose dexamethasone, given with or without pembrolizumab, to patients with newly diagnosed and treatment-naïve MM.

KEYNOTE-023 is a phase 1 trial of pembrolizumab in combination with backbone treatments. Cohort 1 of this trial was designed to evaluate pembrolizumab in combination with lenalidomide and dexamethasone in MM patients who received prior treatment with an immunomodulatory agent (lenalidomide, pomalidomide, or thalidomide).

Interim results from KEYNOTE-183 and KEYNOTE-185 revealed an increased risk of death for patients receiving pembrolizumab, when compared to patients receiving the control therapies.

Merck & Co., Inc., the company developing pembrolizumab, was informed of this risk by an external data monitoring committee. The company suspended enrollment in the trials and notified the FDA of the issue in June.

The following month, the FDA announced that all patients enrolled in KEYNOTE-183 and KEYNOTE-185, as well as patients in the pembrolizumab/lenalidomide/dexamethasone cohort of KEYNOTE-023, would discontinue investigational treatment with pembrolizumab.

FDA investigation

The FDA is examining data from the pembrolizumab trials and working with Merck to better understand the cause of the safety concerns, according to Woodcock.

The agency is also working with sponsors of other PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors to examine other trials in which these drugs are being studied in combination with immunomodulatory agents and trials in which the inhibitors are being studied in combination with other classes of drugs in patients with hematologic malignancies.

Woodcock said the FDA will take appropriate action as warranted to ensure patients enrolled in these trials are protected and that doctors and researchers understand the risks associated with this investigational use.

The agency is also encouraging healthcare professionals and consumers to report any adverse events or side effects related to the use of pembrolizumab and other PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors to FDA’s MedWatch Adverse Event Reporting Program. ![]()

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has issued a statement warning about an increased risk of death associated with an unapproved use of pembrolizumab (Keytruda).

Results from 2 clinical trials have shown that combining pembrolizumab with dexamethasone and an immunomodulatory agent (lenalidomide or pomalidomide) increases the risk of death in patients with multiple myeloma (MM).

The FDA issued its statement to remind doctors and patients that pembrolizumab is not approved to treat MM and should not be given in combination with immunomodulatory agents to treat MM.

Pembrolizumab is currently FDA-approved to treat classical Hodgkin lymphoma, melanoma, lung cancer, head and neck cancer, urothelial carcinoma, and microsatellite instability-high cancer.

The FDA believes the benefits of taking pembrolizumab and other PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors for their approved uses continue to outweigh the risks, according to Janet Woodcock, director of the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research.

However, the FDA is investigating trials of pembrolizumab as well as trials of other PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors.

Pembrolizumab in MM

The FDA’s warning is based on a review of data from 2 clinical trials—KEYNOTE-183 and KEYNOTE-185. The FDA placed a clinical hold on these trials—as well as KEYNOTE-023—in July.

KEYNOTE-183 is a phase 3 study of pomalidomide and low-dose dexamethasone, given with or without pembrolizumab, to patients with refractory or relapsed and refractory MM.

KEYNOTE-185 is a phase 3 study of lenalidomide and low-dose dexamethasone, given with or without pembrolizumab, to patients with newly diagnosed and treatment-naïve MM.

KEYNOTE-023 is a phase 1 trial of pembrolizumab in combination with backbone treatments. Cohort 1 of this trial was designed to evaluate pembrolizumab in combination with lenalidomide and dexamethasone in MM patients who received prior treatment with an immunomodulatory agent (lenalidomide, pomalidomide, or thalidomide).

Interim results from KEYNOTE-183 and KEYNOTE-185 revealed an increased risk of death for patients receiving pembrolizumab, when compared to patients receiving the control therapies.

Merck & Co., Inc., the company developing pembrolizumab, was informed of this risk by an external data monitoring committee. The company suspended enrollment in the trials and notified the FDA of the issue in June.

The following month, the FDA announced that all patients enrolled in KEYNOTE-183 and KEYNOTE-185, as well as patients in the pembrolizumab/lenalidomide/dexamethasone cohort of KEYNOTE-023, would discontinue investigational treatment with pembrolizumab.

FDA investigation

The FDA is examining data from the pembrolizumab trials and working with Merck to better understand the cause of the safety concerns, according to Woodcock.

The agency is also working with sponsors of other PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors to examine other trials in which these drugs are being studied in combination with immunomodulatory agents and trials in which the inhibitors are being studied in combination with other classes of drugs in patients with hematologic malignancies.

Woodcock said the FDA will take appropriate action as warranted to ensure patients enrolled in these trials are protected and that doctors and researchers understand the risks associated with this investigational use.

The agency is also encouraging healthcare professionals and consumers to report any adverse events or side effects related to the use of pembrolizumab and other PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors to FDA’s MedWatch Adverse Event Reporting Program. ![]()

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has issued a statement warning about an increased risk of death associated with an unapproved use of pembrolizumab (Keytruda).

Results from 2 clinical trials have shown that combining pembrolizumab with dexamethasone and an immunomodulatory agent (lenalidomide or pomalidomide) increases the risk of death in patients with multiple myeloma (MM).

The FDA issued its statement to remind doctors and patients that pembrolizumab is not approved to treat MM and should not be given in combination with immunomodulatory agents to treat MM.

Pembrolizumab is currently FDA-approved to treat classical Hodgkin lymphoma, melanoma, lung cancer, head and neck cancer, urothelial carcinoma, and microsatellite instability-high cancer.

The FDA believes the benefits of taking pembrolizumab and other PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors for their approved uses continue to outweigh the risks, according to Janet Woodcock, director of the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research.

However, the FDA is investigating trials of pembrolizumab as well as trials of other PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors.

Pembrolizumab in MM

The FDA’s warning is based on a review of data from 2 clinical trials—KEYNOTE-183 and KEYNOTE-185. The FDA placed a clinical hold on these trials—as well as KEYNOTE-023—in July.

KEYNOTE-183 is a phase 3 study of pomalidomide and low-dose dexamethasone, given with or without pembrolizumab, to patients with refractory or relapsed and refractory MM.

KEYNOTE-185 is a phase 3 study of lenalidomide and low-dose dexamethasone, given with or without pembrolizumab, to patients with newly diagnosed and treatment-naïve MM.

KEYNOTE-023 is a phase 1 trial of pembrolizumab in combination with backbone treatments. Cohort 1 of this trial was designed to evaluate pembrolizumab in combination with lenalidomide and dexamethasone in MM patients who received prior treatment with an immunomodulatory agent (lenalidomide, pomalidomide, or thalidomide).

Interim results from KEYNOTE-183 and KEYNOTE-185 revealed an increased risk of death for patients receiving pembrolizumab, when compared to patients receiving the control therapies.

Merck & Co., Inc., the company developing pembrolizumab, was informed of this risk by an external data monitoring committee. The company suspended enrollment in the trials and notified the FDA of the issue in June.

The following month, the FDA announced that all patients enrolled in KEYNOTE-183 and KEYNOTE-185, as well as patients in the pembrolizumab/lenalidomide/dexamethasone cohort of KEYNOTE-023, would discontinue investigational treatment with pembrolizumab.

FDA investigation

The FDA is examining data from the pembrolizumab trials and working with Merck to better understand the cause of the safety concerns, according to Woodcock.

The agency is also working with sponsors of other PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors to examine other trials in which these drugs are being studied in combination with immunomodulatory agents and trials in which the inhibitors are being studied in combination with other classes of drugs in patients with hematologic malignancies.

Woodcock said the FDA will take appropriate action as warranted to ensure patients enrolled in these trials are protected and that doctors and researchers understand the risks associated with this investigational use.

The agency is also encouraging healthcare professionals and consumers to report any adverse events or side effects related to the use of pembrolizumab and other PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors to FDA’s MedWatch Adverse Event Reporting Program. ![]()

Young cancer patients want more digital support, survey says

A recent survey of young cancer patients in the UK revealed their desire for additional digital oncology resources.

The survey showed that many of the patients already used digital resources to access information about their cancer.

However, many also expressed a need for additional resources such as online counseling or psychological support.

Esha Abrol, of Camden and Islington NHS Foundation Trust in London, UK, and her colleagues reported these findings in the Journal of Cancer Survivorship.

The researchers surveyed 102 cancer patients, ages 13 to 24, about digital media use.

The patients reported having active digital lives, with 41.6% of them rating digital resources as “essential” to their lives.

The patients reported using a variety of healthcare-related digital resources to access information about their disease, including independent sources and ones recommended to them by the professional team treating them.

Half (51%) of respondents said they kept in contact through digital means with other patients they had met during treatment. Twelve percent contacted others or started new digital relationships with people they had never met in person.

However, most of the patients were still most likely to get information about their treatment from professionals in a face-to-face environment, such as when visiting their doctor.

“This is a reassuring and appropriate finding, as this is the conventional means by which teenage and young adult oncology care is delivered by the multidisciplinary team, whether the young people choose to engage or not,” Abrol said.

At the same time, many survey respondents expressed a desire for virtual online groups (54.3%), online counseling or psychological support (43.5%), and the ability to receive (66.3%) and share (48.9%) clinical information online.

Young adults (ages 19 to 24) were more interested than adolescents (ages 13 to 18) in online counseling options and preferred receiving clinical information online.

The researchers said this may reflect young adults’ greater independence, resilience, breadth of experience in the digital world, and confidence in discussing clinical matters online.

Abrol believes these preliminary results can help inform the development of local, national, and global services to teenagers and young adults with cancer to address their unmet needs.

“These digital support resources have the potential to improve patient experience and engagement for an important subsection of teenagers and young people treated for cancer,” Abrol said. ![]()

A recent survey of young cancer patients in the UK revealed their desire for additional digital oncology resources.

The survey showed that many of the patients already used digital resources to access information about their cancer.

However, many also expressed a need for additional resources such as online counseling or psychological support.

Esha Abrol, of Camden and Islington NHS Foundation Trust in London, UK, and her colleagues reported these findings in the Journal of Cancer Survivorship.

The researchers surveyed 102 cancer patients, ages 13 to 24, about digital media use.

The patients reported having active digital lives, with 41.6% of them rating digital resources as “essential” to their lives.

The patients reported using a variety of healthcare-related digital resources to access information about their disease, including independent sources and ones recommended to them by the professional team treating them.

Half (51%) of respondents said they kept in contact through digital means with other patients they had met during treatment. Twelve percent contacted others or started new digital relationships with people they had never met in person.

However, most of the patients were still most likely to get information about their treatment from professionals in a face-to-face environment, such as when visiting their doctor.

“This is a reassuring and appropriate finding, as this is the conventional means by which teenage and young adult oncology care is delivered by the multidisciplinary team, whether the young people choose to engage or not,” Abrol said.

At the same time, many survey respondents expressed a desire for virtual online groups (54.3%), online counseling or psychological support (43.5%), and the ability to receive (66.3%) and share (48.9%) clinical information online.

Young adults (ages 19 to 24) were more interested than adolescents (ages 13 to 18) in online counseling options and preferred receiving clinical information online.

The researchers said this may reflect young adults’ greater independence, resilience, breadth of experience in the digital world, and confidence in discussing clinical matters online.

Abrol believes these preliminary results can help inform the development of local, national, and global services to teenagers and young adults with cancer to address their unmet needs.

“These digital support resources have the potential to improve patient experience and engagement for an important subsection of teenagers and young people treated for cancer,” Abrol said. ![]()

A recent survey of young cancer patients in the UK revealed their desire for additional digital oncology resources.

The survey showed that many of the patients already used digital resources to access information about their cancer.

However, many also expressed a need for additional resources such as online counseling or psychological support.

Esha Abrol, of Camden and Islington NHS Foundation Trust in London, UK, and her colleagues reported these findings in the Journal of Cancer Survivorship.

The researchers surveyed 102 cancer patients, ages 13 to 24, about digital media use.

The patients reported having active digital lives, with 41.6% of them rating digital resources as “essential” to their lives.

The patients reported using a variety of healthcare-related digital resources to access information about their disease, including independent sources and ones recommended to them by the professional team treating them.

Half (51%) of respondents said they kept in contact through digital means with other patients they had met during treatment. Twelve percent contacted others or started new digital relationships with people they had never met in person.

However, most of the patients were still most likely to get information about their treatment from professionals in a face-to-face environment, such as when visiting their doctor.

“This is a reassuring and appropriate finding, as this is the conventional means by which teenage and young adult oncology care is delivered by the multidisciplinary team, whether the young people choose to engage or not,” Abrol said.

At the same time, many survey respondents expressed a desire for virtual online groups (54.3%), online counseling or psychological support (43.5%), and the ability to receive (66.3%) and share (48.9%) clinical information online.

Young adults (ages 19 to 24) were more interested than adolescents (ages 13 to 18) in online counseling options and preferred receiving clinical information online.

The researchers said this may reflect young adults’ greater independence, resilience, breadth of experience in the digital world, and confidence in discussing clinical matters online.

Abrol believes these preliminary results can help inform the development of local, national, and global services to teenagers and young adults with cancer to address their unmet needs.

“These digital support resources have the potential to improve patient experience and engagement for an important subsection of teenagers and young people treated for cancer,” Abrol said. ![]()

How to Increase HPV Vaccination Rates

CE/CME No: CR-1709

PROGRAM OVERVIEW

Earn credit by reading this article and successfully completing the posttest and evaluation. Successful completion is defined as a cumulative score of at least 70% correct.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

• Understand and identify the low- and high-risk human papillomavirus (HPV) types that can lead to benign and malignant manifestations.

• Know the recommended age range and dosing schedule for individuals who can and should receive the vaccination.

• Recognize important barriers to HPV vaccination in the health care setting.

• Understand how to promote HPV vaccination to parents/caregivers and patients.

• Find resources and educational material from national organizations that recommend and support HPV vaccination.

FACULTY

Tyler Cole practices at Coastal Community Health Services in Brunswick, Georgia, and is a clinical instructor in the DNP-APRN program at the Medical University of South Carolina (MUSC). Marie C. Thomas is a registered nurse on a surgical oncology unit at MUSC and will receive her DNP-FNP from MUSC in December 2017. Katlyn Straup practices at Roper St. Francis Healthcare and Southern Care Hospice in Charleston, South Carolina; she is also a clinical associate faculty member in the MUSC College of Nursing. Ashlyn Savage is an Associate Professor of Obstetrics and Gynecology at MUSC College of Nursing and is certified by the American Board of Obstetrics and Gynecology.

ACCREDITATION STATEMENT

This program has been reviewed and is approved for a maximum of 1.0 hour of American Academy of Physician Assistants (AAPA) Category 1 CME credit by the Physician Assistant Review Panel. [NPs: Both ANCC and the AANP Certification Program recognize AAPA as an approved provider of Category 1 credit.] Approval is valid through August 31, 2018.

Article begins on next page >>

Although human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine is a safe and effective means of preventing most HPV-related cancers, HPV vaccination rates lag well behind those of other vaccines recommended for children and adolescents. Understanding the barriers to HPV vaccine acceptance and effective strategies for overcoming them will improve vaccine uptake and completion in adolescents.

Human papillomavirus (HPV) infection is the most common sexually transmitted infection in the United States.1,2 HPV causes approximately 30,700 new cancer cases in the US annually.3 It is the primary cause of cervical cancer, which resulted in more than 4,000 deaths in the US in 2016.4 HPV is also associated with some vaginal, vulvar, penile, anal, and oropharyngeal cancers and causes anogenital warts.3

Although HPV vaccines are available to protect against infection with the HPV types that lead to these sequelae, HPV vaccination rates remain low compared with other routinely administered vaccines.5 Reasons for these lower rates include vaccine cost, lack of patient and provider education, providers’ failure to recommend, stigmas related to sexual behavior, and misconceptions about the vaccine, such as concerns about harm.5 This article discusses these barriers to better educate providers about the HPV vaccine and encourage them to assist in increasing vaccination rates.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Approximately 79 million Americans are currently infected with HPV, and 14 million new cases are reported each year.2 In the US, the prevalence of HPV is highest among sexually active adolescents and young adults, especially those ages 20 to 24.2 Of the more than 150 types of HPV that have been identified, 40 infect the genital area. HPV genital infections are mainly spread through sexual intercourse but can also be spread through oral-to-genital contact.2

The genital HPV types are categorized as low-risk and high-risk based on their association with cervical cancer.2 High-risk types 16 and 18 are the most troublesome, accounting for 63% of all HPV-associated cancers, with HPV 16 posing the highest risk for cancer.3 High-risk types HPV 31, 33, 45, 52, and 58 account for another 10% of these cancers.3 Low-risk types, such as HPV 6 and 11, can cause low-grade cervical intraepithelial lesions, and HPV 6 and 11 account for more than 90% of genital warts.2

Most HPV infections, whether with high- or low-risk types, do not cause symptoms and resolve spontaneously in about two years.2 Persistent high-risk HPV infection is necessary for the development of cervical cancer precursor lesions—and therefore, once the infection has cleared, the risk for cancer declines.2

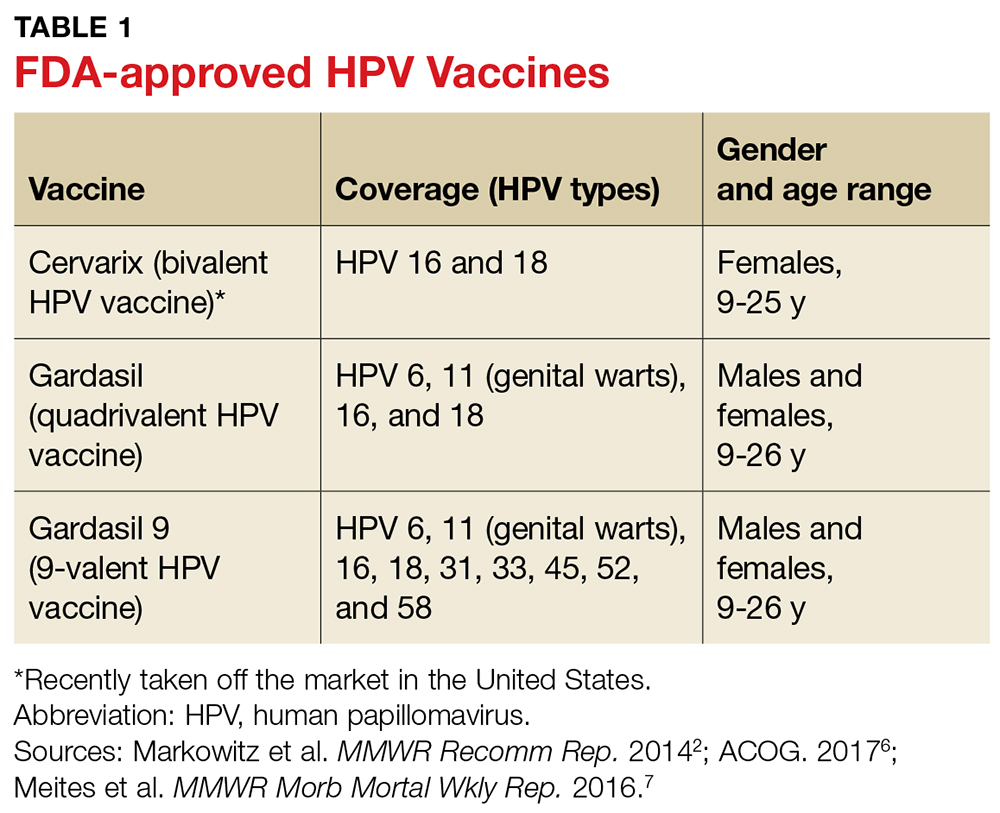

HPV VACCINES

Three HPV vaccines are licensed for use in the US: bivalent (Cervarix), quadrivalent (Gardasil), and 9-valent (Gardasil 9) vaccines (see Table 1).2,6,7 The bivalent, Cervarix, has recently been removed from the US market due to a decrease in product demand.6,8

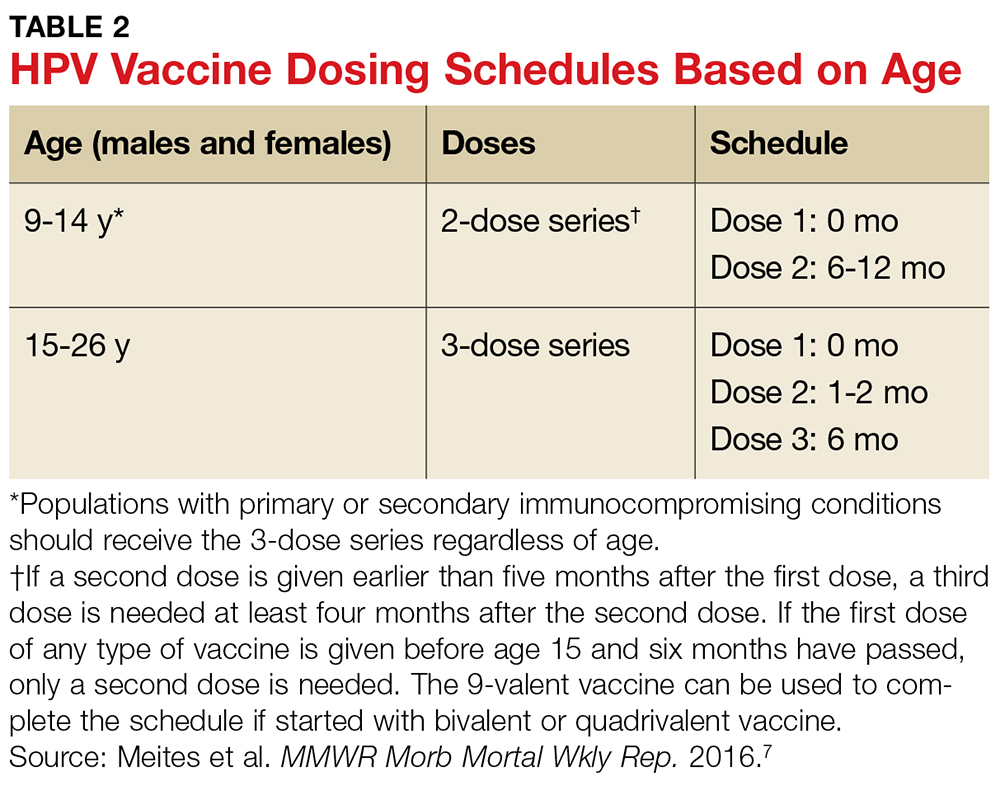

To ensure optimal protection, the vaccines must be administered in a series of scheduled doses over six to 12 months. The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) recently updated their recommendations to include a two- or three-dose series based on age (see Table 2).7

HPV vaccines are recommended for males and females between the ages of 9 and 26 years, but the ACIP and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) strongly promote a targeted age range for vaccination between 11 and 12 years for both genders.6,7 Earlier vaccination is preferred because clinical data show a more rapid antibody response at a younger age, and because the vaccines are more effective if administered before an individual is exposed to or infected with HPV (ie, before the start of sexual activity).6,7

LOW VACCINATION RATES

HPV vaccination rates in the US are significantly lower than rates for other regularly administered vaccines; furthermore, they do not meet the Healthy People 2020 national goal of 80% for all vaccines.9 Immunization rates for most childhood vaccines range from 80% to 90%, but in 2015 only 28.1% of males and 41.9% of females ages 13 to 17 had completed the entire HPV vaccine series.9-11

The total HPV vaccination rates for male and female adolescents combined were 56.1% for one dose or more, 45.4% for two or more doses, and 34.9% for all three doses.9 In comparison, coverage rates for the meningococcal and Tdap (tetanus, diphtheria, and pertussis) immunizations, also recommended at the same age range as the HPV vaccine, were 81.3% and 86.4%, respectively.9

In addition to variation by gender and age, factors such as race, insurance coverage, and socioeconomic status influence vaccination rates.11 For the HPV vaccine specifically, Hispanic, non-Hispanic black, and American Indian/Alaska Native adolescents have higher rates of receiving each of the vaccine doses and higher rates of completing the vaccine series, compared to non-Hispanic white adolescents.9 Adolescents with Medicaid insurance and those living below the federal poverty level have better HPV vaccination coverage compared with adolescents with commercial insurance plans or those living at or above the poverty level.9,11

The HPV vaccine series completion rates in 2015 for males and females ages 13 to 17 living below the poverty level were 31.0% and 44.4%, respectively, compared to 27.4% and 41.3% for those living at or above the poverty level.9 One reason for increased rates among those living in lower-income households may be their eligibility for vaccinations at no cost through the Vaccines for Children (VFC) program, a federal program that provides vaccines to children who might otherwise forgo vaccination because of inability to pay.9

BARRIERS TO VACCINATION

Impediments that prevent adolescents and young adults from receiving the HPV vaccine exist throughout the vaccination process, with providers, parents, and the medical system itself contributing to low rates. Barriers to vaccination include fear and misconceptions, costs and socioeconomic status, lack of understanding and education, and logistic obstacles to completing the full series.5 Understanding these barriers, as well as discussing methods to overcome them, is key to increasing HPV vaccination rates and preventing the spread of this cancer-causing infection.

Health care provider barriers

Even though accredited national institutions and committees such as the CDC, ACIP, and ACOG strongly recommend vaccination based on current evidence, some health care providers still do not recommend the HPV vaccine to parents and patients.2,6,7,11 Lack of provider recommendation and the resulting lack of parental awareness of the vaccine account for many adolescents not receiving the vaccination.10,12

Providers do not recommend the vaccine for a number of reasons. Some have limited knowledge or conflicting ideas about the specific disease protection of the HPV vaccine, while others are hesitant to administer the vaccine before the onset of sexual activity, because they feel the suggested age for vaccination (11 to 12 years) is too young.10,11 Still other providers report difficulty approaching parents who they perceive as having concerns about the vaccine’s association with a sexually transmitted infection or believing that it might promote sexual activity.10

Some professionals simply claim that they forget to address the HPV vaccine at health visits, or that they propose it as optional and up to the parent’s discretion.5,10 Many providers do recommend and administer the initial dose of the vaccine, but have difficulties ensuring that patients complete the full multidose series.13 Evidence has shown that a strong provider recommendation is one of the most important incentives for parents and patients to accept vaccination.14

Parental and caregiver barriers

Lack of knowledge about the HPV vaccine and lack of recommendation from providers are two top reasons parents and caregivers cite for not vaccinating their children.5,10,14,15 In a national survey, almost all parents whose daughters completed the full vaccination series reported being counseled by their provider on the appropriate age for vaccination and the timeline of the series.14

Fears and apprehensions about side effects, especially with newer vaccines, can prevent some parents from having their children vaccinated.15 Although there is some stigma related to the vaccine’s association with the sexually transmitted HPV, this is a much less significant barrier than lack of provider recommendation or knowledge about the vaccine.5,11

Health care system barriers

Both providers and parents agree that system-level issues such as access, follow-up, and cost are barriers to initiating or completing the vaccination series.11,13 Many adolescents have few opportunities to receive the vaccine because they do not have a primary care provider.11 For those with access to primary care, visits are often problem-focused and frequently do not include a review of immunization history.13 Health care professionals also report challenges with scheduling follow-up visits for the second and third doses to complete the series within the recommended timeframe.13

Cost, insurance coverage, and reimbursement pose additional hurdles for both providers and patients, with some providers citing concerns about the cost of stocking the vaccine.16 Providers, both family practice providers and gynecologists, agree that reimbursement for administering the HPV vaccine in office poses a barrier when recommending the vaccine to patients.17 Lack of insurance coverage and type of insurance also pose barriers, with Medicaid patients more often completing the full series compared to those with private or no insurance, because Medicaid covers the cost of vaccination for men up to age 19.9,18 A national survey of males ages 9 to 17 found that the percentage of HPV vaccine initiation was double for those with public insurance compared to those with private insurance.19 Changes at the system-level, such as participation in the VFC program, in coordination with better provider recommendation should help increase HPV vaccination rates.9,11

STRATEGIES TO IMPROVE VACCINATION RATES

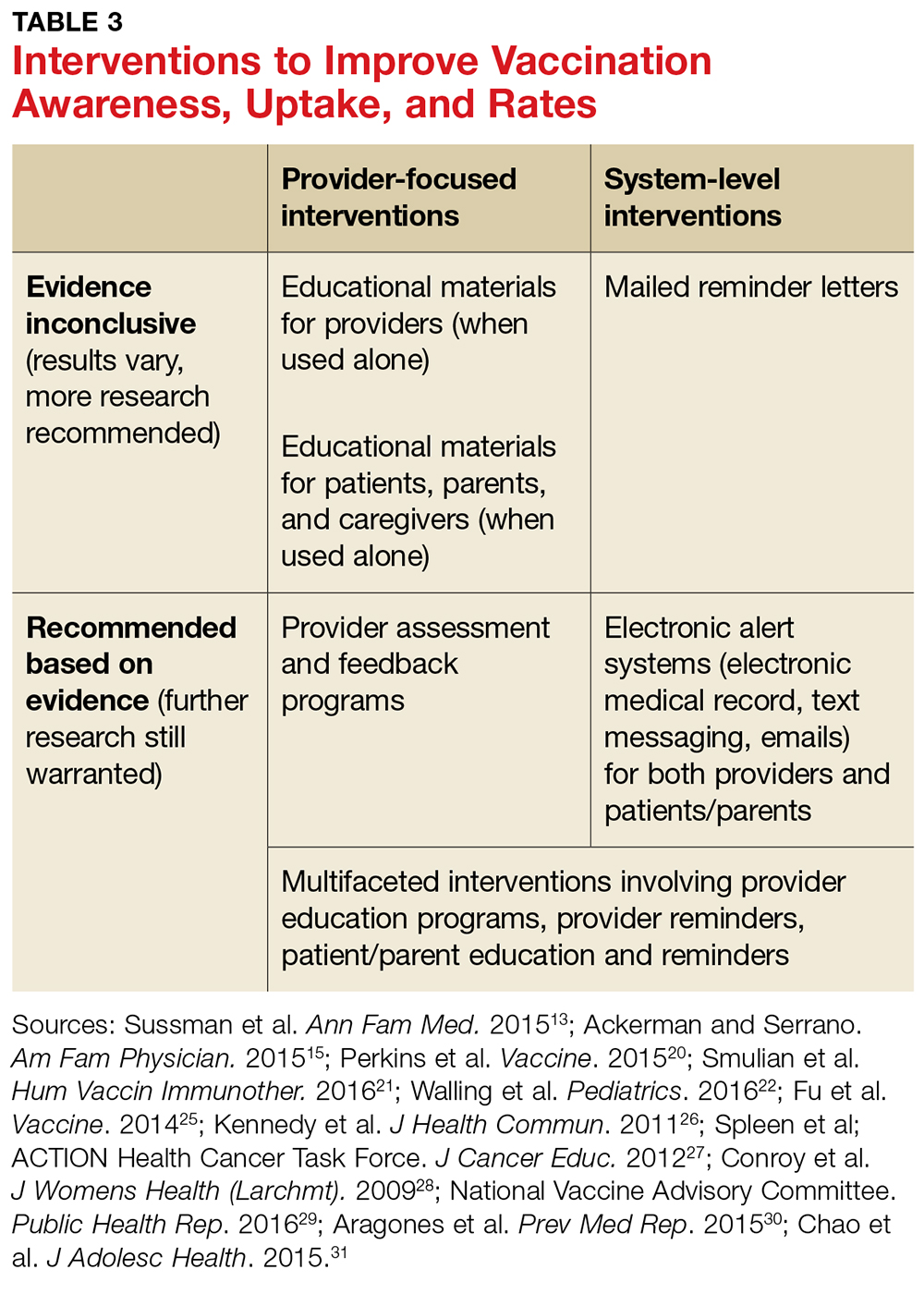

Many strategies for increasing HPV vaccination acceptance, decreasing barriers to access, and improving compliance with vaccine completion have been reported in the literature, with some strategies achieving more success than others. This section discusses interventions and strategies designed to help overcome provider-, parent-, and system-related barriers that have been shown to be effective (see Table 3).

Health care provider interventions

Evidence supports a number of provider-level strategies to increase HPV vaccination rates (see Table 3). An improvement in vaccination acceptance was observed when providers promoted the vaccine as a safe, effective way to prevent cancer, rather than as a means to prevent a sexually transmitted infection.10,11,20

Some primary care providers found that encouraging the HPV vaccine at the same time as the meningococcal and Tdap vaccinations, which are also recommended at age 11 to 12 years, increased vaccination rates as well.13,20 Another successful strategy is reviewing vaccination history at every visit, whether the visit is for an acute event or an annual well exam.10,13,20 These tactics are most useful when providers practice them consistently, which may require them to change or adapt their way of practice.

Provider-based trainings that educate and prepare them to consistently recommend the vaccine have demonstrated success in increasing HPV vaccination uptake.21,22 The CDC’s Assessment/Feedback/Incentive/eXchange (AFIX) quality improvement program to increase vaccination rates, which includes Web-based or in-person consults, has been shown to increase HPV vaccination rates.20-23 The Assessment phase of the AFIX program determines a practice’s current immunization practices and rates, while the Feedback portion provides strategies for increasing vaccination rates.23 A study by Perkins and colleagues utilized AFIX strategies, specifically for the HPV vaccine, such as focusing provider education on HPV-related cancers and vaccine efficacy, as well as preparing providers to discuss and answer questions through basic motivational interviewing tactics.20

The CDC also offers PowerPoint presentations, flyers, posters, videos, and other informational resources to guide and educate providers, parents, and patients about the HPV vaccine.24 Educational resources, such as pamphlets, flyers, or fact sheets given to parents and patients, have been shown to improve intent to vaccinate as well as awareness of the vaccine.25-27

Although Fu and colleagues in a systematic review concluded that there was insufficient data to support a specific educational intervention for widespread use, the authors did recommend utilizing educational pieces and adapting them to specific populations.25 These simple interventions help increase awareness and can be implemented with other interventions in health care offices by providers and other staff.

System-level interventions

The use of systems that track patients for necessary vaccines and remind providers, parents, and patients about vaccine appointments have increased vaccination rates.13,28 Facility-based interventions, such as electronic medical records (EMR) that track patients for scheduled vaccines and remind providers when patients are due for vaccinations, will help increase provider recommendations and completion of the entire vaccination series.13

The National Vaccine Advisory Committee (NVAC) suggests that provider offices implement reminder-recall systems and provide educational material for parents and patients to increase vaccination rates.29 One specific study using both educational material and text-message reminders for parents found that these interventions significantly increased vaccination rates.30 Health care facilities could also incorporate reminder letters mailed to patients and parents to promote vaccine initiation and completion.31 The evidence supports the use of reminder alerts and EMR tracking systems to increase rates, but more research is warranted to determine the most cost-effective approach.

National programs, committees, and organizations have provided recommendations for overcoming system-related barriers to HPV vaccination, such as access and cost.29,32 The NVAC recommends incorporating alternative venues for vaccination delivery, such as pharmacies, schools, and health clinics, to increase availability to the adolescent population, especially to those who do not have primary care providers.29 One study that addressed parental opinions of vaccination administration in schools found that the majority of parents were in favor of this type of program.33 Although these recommendations seem promising and are accepted by parents, logistical barriers such as reimbursement to the pharmacies, schools, and clinics and accurate documentation of the doses received need to be addressed.29 The NVAC recommends continued evaluation and efforts to develop these programs in the future.29

In addition to school-based interventions, providing home visits for vaccination and implementing standing orders are other suggestions to overcome access and cost barriers for vaccinations, including HPV.32 Standing orders allow for individuals to receive a vaccine by a health care professional in an approved institution, where allowed by state law.32 This provides easier access to vaccinations, especially for those who do not see a primary care provider.

Although some of the system-level interventions mentioned in this article are outside the realm of what providers can do in the office, understanding and advocating for these advancements will promote vaccine uptake.

CONCLUSION

Lack of provider recommendation, coupled with poor or no parental knowledge about the HPV vaccine, are significant factors affecting vaccination uptake. Evidence supports the use of multifaceted interventions that promote and support provider recommendation and parent/patient education. Studies of interventions that incorporated educational resources and alert systems for both providers and patients or their caregivers have shown these strategies to be effective in increasing vaccination uptake and completion.

In addition to recommending the HPV vaccine, providers must educate parents/caregivers and patients about it, particularly by presenting the vaccine as a means of cancer prevention. Primary care facilities should implement reminder plans and provide educational literature to promote vaccine uptake. Although the interventions highlighted here have increased HPV vaccination rates, further research is warranted to evaluate more effective strategies for overcoming barriers and to determine which strategies are most cost-effective.

1. Juckett G, Hartsman-Adams H. Human papillomavirus: clinical manifestations and prevention. Am Fam Physician. 2010;82(10):1209-1213.

2. Markowitz LE, Dunne EF, Saraiya M, et al. Human papillomavirus vaccination: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep. 2014;63(RR-05):1-30.

3. Viens LJ, Henley SJ, Watson M, et al. Human papillomavirus-associated cancers—United States, 2008-2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65(26):661-666.

4. American Cancer Society. Cancer facts and figures 2016. Atlanta: American Cancer Society; 2016.

5. Holman DM, Benard V, Roland KB, et al. Barriers to the human papillomavirus vaccination among US adolescents: a systematic review of the literature. JAMA Pediatr. 2014;168(1):76-82.

6. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Human papillomavirus vaccination. Committee Opinion. Number 704. June 2017. www.acog.org/Resources-And-Publications/Committee-Opinions/Committee-on-Adolescent-Health-Care/Human-Papillomavirus-Vaccination. Accessed August 17, 2017.

7. Meites E, Kempe A, Markowitz LE. Use of a 2-dose schedule for human papillomavirus vaccination—updated recommendation of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65(49):1405-1408.

8. Mulcahy N. GSK’s HPV vaccine, Cervarix, no longer available in the US. Medscape Medical News. October 26, 2016. www.medscape.com/viewarticle/870853. Accessed June 11, 2017.

9. Reagan-Steiner S, Yankey D, Jeyarajah J, et al. National, regional, state, and selected local area vaccination coverage among adolescents aged 13–17 years—United States, 2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64(29):784-792.

10. Muncie HL, Lebato AL. HPV vaccination: overcoming parental and physician impediments. Am Fam Physician. 2015;92(6):449-454.

11. Bratic JS, Seyferth ER, Bocchini JA Jr. Update on barriers to human papillomavirus vaccination and effective strategies to promote vaccine acceptance. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2016;28(3):407-412.

12. Rahman M, Laz TH, McGrath CJ, Berenson AB. Provider recommendation mediates the relationship between parental human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine awareness and HPV vaccine initiation and completion among 13- to 17-year-old US adolescent children. Clin Pediatr. 2015;54(4):371-375.

13. Sussman AL, Helitzer D, Bennett A, et al. Catching up with the HPV vaccine: challenges and opportunities in primary care. Ann Fam Med. 2015;13(4):354-360.

14. Clark SJ, Cowan AE, Filipp SL, et al. Parent perception of provider interactions influences HPV vaccination status of adolescent females. Clin Pediatr. 2016;55(8):701-706.

15. Ackerman LK, Serrano JL. Update on routine childhood and adolescent immunizations. Am Fam Physician. 2015;92(6):460-468.

16. Tom A, Robinett H, Buenconsejo-Lum L, et al. Promoting and providing the HPV vaccination in Hawaii: barriers faced by health providers. J Community Health. 2016;41(5):1069-1077.

17. Young JL, Bernheim RG, Korte JE, et al. Human papillomavirus vaccination recommendation may be linked to reimbursement: A survey of Virginia family practitioners and gynecologists. J Pediat Adolesc Gynecol. 2011;24(6):380-385.

18. Thomas R, Higgins L, Ding L, et al. Factors associated with HPV vaccine initiation, vaccine completion, and accuracy of self-reported vaccination status among 13- to 26-year-old men. Am J Mens Health. 2016;1-9.

19. Laz TH, Rahman M, Berenson AB. Human papillomavirus vaccine uptake among 9-17 year old males in the United States: the National Health Interview Survey, 2010. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2013;9(4):874-878.

20. Perkins RB, Zisblatt L, Legler A, et al. Effectiveness of a provider-focused intervention to improve HPV vaccination rates in boys and girls. Vaccine. 2015;33:1223-1229.

21. Smulian EA, Mitchell KR, Stokley S. Interventions to increase HPV vaccination coverage: a systematic review. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2016;12:1566-1588.

22. Walling EB, Benzoni N, Dornfeld J, et al. Interventions to improve HPV vaccine uptake: a systematic review. Pediatrics. 2016;138(1).

23. CDC. Overview of AFIX. www.cdc.gov/vaccines/programs/afix/index.html. Accessed August 17, 2017.

24. CDC. Human papillomavirus (HPV). www.cdc.gov/hpv/. Accessed August 17, 2017.

25. Fu LY, Bonhomme LA, Cooper SC, et al. Educational interventions to increase HPV vaccination acceptance: a systematic review. Vaccine. 2014;32(17):1901-1920.

26. Kennedy A, Sapsis KF, Stokley S, et al. Parental attitudes toward human papillomavirus vaccination: evaluation of an educational intervention, 2008. J Health Commun. 2011;16(3):300-313.

27. Spleen AM, Kluhsman BC, Clark AD, et al; ACTION Health Cancer Task Force. An increase in HPV-related knowledge and vaccination intent among parental and non-parental caregivers of adolescent girls, ages 9-17 years, in Appalachian Pennsylvania. J Cancer Educ. 2012;27(2):312-319.

28. Conroy K, Rosenthal SL, Zimet GD, et al. Human papillomavirus vaccine uptake, predictors of vaccination, and self-reported barriers to vaccination. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2009;18(10):1679-1686.

29. National Vaccine Advisory Committee. Overcoming barriers to low HPV vaccine uptake in the United States: recommendations from the National Vaccine Advisory Committee. Public Health Rep. 2016;131(1):17-25.

30. Aragones A, Bruno DM, Ehrenberg M, et al. Parental education and text messaging reminders as effective community based tools to increase HPV vaccination rates among Mexican American children. Prev Med Rep. 2015;2:554-558.

31. Chao C, Preciado M, Slezak J, Xu L. A randomized intervention of reminder letter for human papillomavirus vaccine series completion. J Adolesc Health. 2015;56(1):85-90.

32. Community Preventive Services Task Force. The community guide—guide to community preventive services: increasing appropriate vaccinations. Atlanta, GA: Community Preventive Services Task Force; 2016

33. Kelminson K, Saville A, Seewald L, et al. Parental views of school-located delivery of adolescent vaccines. J Adolesc Health. 2012;51(2):190-196.

CE/CME No: CR-1709

PROGRAM OVERVIEW

Earn credit by reading this article and successfully completing the posttest and evaluation. Successful completion is defined as a cumulative score of at least 70% correct.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

• Understand and identify the low- and high-risk human papillomavirus (HPV) types that can lead to benign and malignant manifestations.

• Know the recommended age range and dosing schedule for individuals who can and should receive the vaccination.

• Recognize important barriers to HPV vaccination in the health care setting.

• Understand how to promote HPV vaccination to parents/caregivers and patients.

• Find resources and educational material from national organizations that recommend and support HPV vaccination.

FACULTY

Tyler Cole practices at Coastal Community Health Services in Brunswick, Georgia, and is a clinical instructor in the DNP-APRN program at the Medical University of South Carolina (MUSC). Marie C. Thomas is a registered nurse on a surgical oncology unit at MUSC and will receive her DNP-FNP from MUSC in December 2017. Katlyn Straup practices at Roper St. Francis Healthcare and Southern Care Hospice in Charleston, South Carolina; she is also a clinical associate faculty member in the MUSC College of Nursing. Ashlyn Savage is an Associate Professor of Obstetrics and Gynecology at MUSC College of Nursing and is certified by the American Board of Obstetrics and Gynecology.

ACCREDITATION STATEMENT

This program has been reviewed and is approved for a maximum of 1.0 hour of American Academy of Physician Assistants (AAPA) Category 1 CME credit by the Physician Assistant Review Panel. [NPs: Both ANCC and the AANP Certification Program recognize AAPA as an approved provider of Category 1 credit.] Approval is valid through August 31, 2018.

Article begins on next page >>