User login

Two new tests can detect CJD

Credit: Elise Amendola

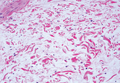

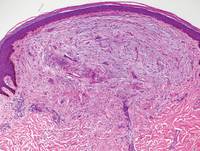

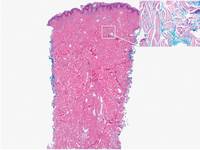

Two groups of scientists have developed new tests to diagnose Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD).

One test uses samples collected from nasal passages to detect sporadic CJD, and the other uses urine samples to identify variant CJD.

The researchers said these tests provide simple methods for differentiating CJD from other diseases and could help prevent the transmission of CJD via blood

transfusions, transplants, or contaminated surgical instruments.

Both tests are described in The New England Journal of Medicine.

Nasal test for sporadic CJD

In one NEJM article, Byron Caughey, PhD, of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases in Rockville, Maryland, and his colleagues detailed their results with the nasal test.

The researchers collected 31 nasal samples from patients with sporadic CJD and 43 samples from patients who had other neurologic diseases or no neurologic disease. The team brushed the inside of a subject’s nose to collect olfactory neurons connected to the brain.

Testing these samples allowed the researchers to correctly identify 30 of the 31 sporadic CJD patients (97% sensitivity). The tests also correctly showed negative results for all 43 of the non-CJD patients (100% specificity).

By comparison, tests using cerebral spinal fluid, which is currently used to detect sporadic CJD, were 77% sensitive and 100% specific. And these results took twice as long to obtain.

While continuing to validate the new testing method in CJD patients, the scientists are looking to expand their research to diagnose forms of prion diseases in sheep, cattle, and wildlife. The team also hopes to replace the nasal brush with an even simpler swabbing approach.

Urine test for variant CJD

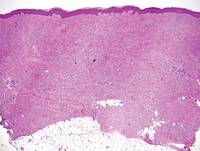

In another NEJM article, Fabio Moda, PhD, of the University of Texas Medical School at Houston, and his colleagues described results observed with their urine test.

The team noted that the infectious agent in transmissible spongiform encephalopathies appears to be composed exclusively of the misfolded form of the prion protein, PrPSc. So they set out to determine if they could detect PrPSc in the urine of patients with CJD.

The researchers analyzed urine samples from healthy individuals (n=52) and patients with variant CJD (n=68), sporadic CJD (n=14), genetic forms of prion disease (n=4), other neurodegenerative disorders (n=50), and nondegenerative neurologic disorders (n=50).

The group found they could only detect PrPSc in samples from patients with variant CJD. They found “minute quantities” of PrPSc in 13 of the 14 urine samples from variant CJD patients, but PrPSc was not present in any of the samples from the other patients or the healthy individuals.

This suggests the test has a sensitivity of 92.9% and a specificity of 100%. ![]()

Credit: Elise Amendola

Two groups of scientists have developed new tests to diagnose Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD).

One test uses samples collected from nasal passages to detect sporadic CJD, and the other uses urine samples to identify variant CJD.

The researchers said these tests provide simple methods for differentiating CJD from other diseases and could help prevent the transmission of CJD via blood

transfusions, transplants, or contaminated surgical instruments.

Both tests are described in The New England Journal of Medicine.

Nasal test for sporadic CJD

In one NEJM article, Byron Caughey, PhD, of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases in Rockville, Maryland, and his colleagues detailed their results with the nasal test.

The researchers collected 31 nasal samples from patients with sporadic CJD and 43 samples from patients who had other neurologic diseases or no neurologic disease. The team brushed the inside of a subject’s nose to collect olfactory neurons connected to the brain.

Testing these samples allowed the researchers to correctly identify 30 of the 31 sporadic CJD patients (97% sensitivity). The tests also correctly showed negative results for all 43 of the non-CJD patients (100% specificity).

By comparison, tests using cerebral spinal fluid, which is currently used to detect sporadic CJD, were 77% sensitive and 100% specific. And these results took twice as long to obtain.

While continuing to validate the new testing method in CJD patients, the scientists are looking to expand their research to diagnose forms of prion diseases in sheep, cattle, and wildlife. The team also hopes to replace the nasal brush with an even simpler swabbing approach.

Urine test for variant CJD

In another NEJM article, Fabio Moda, PhD, of the University of Texas Medical School at Houston, and his colleagues described results observed with their urine test.

The team noted that the infectious agent in transmissible spongiform encephalopathies appears to be composed exclusively of the misfolded form of the prion protein, PrPSc. So they set out to determine if they could detect PrPSc in the urine of patients with CJD.

The researchers analyzed urine samples from healthy individuals (n=52) and patients with variant CJD (n=68), sporadic CJD (n=14), genetic forms of prion disease (n=4), other neurodegenerative disorders (n=50), and nondegenerative neurologic disorders (n=50).

The group found they could only detect PrPSc in samples from patients with variant CJD. They found “minute quantities” of PrPSc in 13 of the 14 urine samples from variant CJD patients, but PrPSc was not present in any of the samples from the other patients or the healthy individuals.

This suggests the test has a sensitivity of 92.9% and a specificity of 100%. ![]()

Credit: Elise Amendola

Two groups of scientists have developed new tests to diagnose Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD).

One test uses samples collected from nasal passages to detect sporadic CJD, and the other uses urine samples to identify variant CJD.

The researchers said these tests provide simple methods for differentiating CJD from other diseases and could help prevent the transmission of CJD via blood

transfusions, transplants, or contaminated surgical instruments.

Both tests are described in The New England Journal of Medicine.

Nasal test for sporadic CJD

In one NEJM article, Byron Caughey, PhD, of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases in Rockville, Maryland, and his colleagues detailed their results with the nasal test.

The researchers collected 31 nasal samples from patients with sporadic CJD and 43 samples from patients who had other neurologic diseases or no neurologic disease. The team brushed the inside of a subject’s nose to collect olfactory neurons connected to the brain.

Testing these samples allowed the researchers to correctly identify 30 of the 31 sporadic CJD patients (97% sensitivity). The tests also correctly showed negative results for all 43 of the non-CJD patients (100% specificity).

By comparison, tests using cerebral spinal fluid, which is currently used to detect sporadic CJD, were 77% sensitive and 100% specific. And these results took twice as long to obtain.

While continuing to validate the new testing method in CJD patients, the scientists are looking to expand their research to diagnose forms of prion diseases in sheep, cattle, and wildlife. The team also hopes to replace the nasal brush with an even simpler swabbing approach.

Urine test for variant CJD

In another NEJM article, Fabio Moda, PhD, of the University of Texas Medical School at Houston, and his colleagues described results observed with their urine test.

The team noted that the infectious agent in transmissible spongiform encephalopathies appears to be composed exclusively of the misfolded form of the prion protein, PrPSc. So they set out to determine if they could detect PrPSc in the urine of patients with CJD.

The researchers analyzed urine samples from healthy individuals (n=52) and patients with variant CJD (n=68), sporadic CJD (n=14), genetic forms of prion disease (n=4), other neurodegenerative disorders (n=50), and nondegenerative neurologic disorders (n=50).

The group found they could only detect PrPSc in samples from patients with variant CJD. They found “minute quantities” of PrPSc in 13 of the 14 urine samples from variant CJD patients, but PrPSc was not present in any of the samples from the other patients or the healthy individuals.

This suggests the test has a sensitivity of 92.9% and a specificity of 100%. ![]()

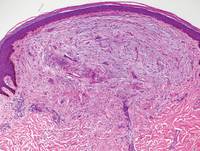

Gene plays crucial role in cancer development, team says

Credit: Beth A. Sullivan

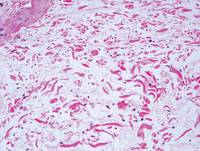

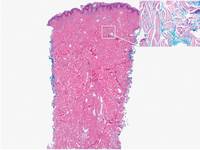

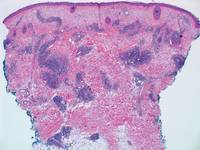

New research suggests DNA ligase 3 is crucial for the evolutionary processes that drive cancer.

“We have identified a gene that, as cells age, seems to regulate whether the cells become cancerous or not,” said Eric A. Hendrickson, PhD, of the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis.

“This gene has never been identified before in this role, so this makes it a potentially very important therapeutic target.”

Dr Hendrickson and his colleagues recounted this discovery in Cell Reports.

The researchers noted that short, dysfunctional telomeres can fuse, thereby generating dicentric chromosomes and initiating breakage-fusion-bridge cycles. The cells that manage to escape the subsequent crisis have genomic rearrangements that drive clonal evolution and malignant progression.

The team wanted to determine exactly what allows these malignant cells to escape telomere-driven crisis and avoid death.

To find out, the group disabled certain genes in human cells and then studied the impact this had on telomere fusion.

They found that cells escaped death when ligase 3 was active but not when its action, which appears to promote fusion within like chromosomes rather than between different chromosomes, was inhibited.

“Telomere dysfunction has been identified in many human cancers,” said study author Duncan Baird, PhD, of Cardiff University in the UK.

“And, as we have shown previously, short telomeres can predict the outcome of patients with [chronic lymphocytic leukemia] and probably many other tumor types. Thus, the discovery that ligase 3 is required for this process is fundamentally important.”

This research was made possible by a chance meeting between Dr Baird and Dr Hendrickson at an international conference. The pair discovered they were both looking at the role of ligase 3 in cancer and decided to collaborate.

“The collaboration paid off, as we were able to uncover something that neither one of us could have done on our own,” Dr Hendrickson said.

Additional studies are already underway. The researchers are investigating the discovery that the reliance on ligase 3 appears to be dependent upon the activity of another key DNA repair gene, p53.

“Since p53 is the most commonly mutated gene in human cancer, it now behooves us to discover how these two genes are interacting and to see if we can’t use that information to develop synergistic treatment modalities,” Dr Hendrickson concluded. ![]()

Credit: Beth A. Sullivan

New research suggests DNA ligase 3 is crucial for the evolutionary processes that drive cancer.

“We have identified a gene that, as cells age, seems to regulate whether the cells become cancerous or not,” said Eric A. Hendrickson, PhD, of the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis.

“This gene has never been identified before in this role, so this makes it a potentially very important therapeutic target.”

Dr Hendrickson and his colleagues recounted this discovery in Cell Reports.

The researchers noted that short, dysfunctional telomeres can fuse, thereby generating dicentric chromosomes and initiating breakage-fusion-bridge cycles. The cells that manage to escape the subsequent crisis have genomic rearrangements that drive clonal evolution and malignant progression.

The team wanted to determine exactly what allows these malignant cells to escape telomere-driven crisis and avoid death.

To find out, the group disabled certain genes in human cells and then studied the impact this had on telomere fusion.

They found that cells escaped death when ligase 3 was active but not when its action, which appears to promote fusion within like chromosomes rather than between different chromosomes, was inhibited.

“Telomere dysfunction has been identified in many human cancers,” said study author Duncan Baird, PhD, of Cardiff University in the UK.

“And, as we have shown previously, short telomeres can predict the outcome of patients with [chronic lymphocytic leukemia] and probably many other tumor types. Thus, the discovery that ligase 3 is required for this process is fundamentally important.”

This research was made possible by a chance meeting between Dr Baird and Dr Hendrickson at an international conference. The pair discovered they were both looking at the role of ligase 3 in cancer and decided to collaborate.

“The collaboration paid off, as we were able to uncover something that neither one of us could have done on our own,” Dr Hendrickson said.

Additional studies are already underway. The researchers are investigating the discovery that the reliance on ligase 3 appears to be dependent upon the activity of another key DNA repair gene, p53.

“Since p53 is the most commonly mutated gene in human cancer, it now behooves us to discover how these two genes are interacting and to see if we can’t use that information to develop synergistic treatment modalities,” Dr Hendrickson concluded. ![]()

Credit: Beth A. Sullivan

New research suggests DNA ligase 3 is crucial for the evolutionary processes that drive cancer.

“We have identified a gene that, as cells age, seems to regulate whether the cells become cancerous or not,” said Eric A. Hendrickson, PhD, of the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis.

“This gene has never been identified before in this role, so this makes it a potentially very important therapeutic target.”

Dr Hendrickson and his colleagues recounted this discovery in Cell Reports.

The researchers noted that short, dysfunctional telomeres can fuse, thereby generating dicentric chromosomes and initiating breakage-fusion-bridge cycles. The cells that manage to escape the subsequent crisis have genomic rearrangements that drive clonal evolution and malignant progression.

The team wanted to determine exactly what allows these malignant cells to escape telomere-driven crisis and avoid death.

To find out, the group disabled certain genes in human cells and then studied the impact this had on telomere fusion.

They found that cells escaped death when ligase 3 was active but not when its action, which appears to promote fusion within like chromosomes rather than between different chromosomes, was inhibited.

“Telomere dysfunction has been identified in many human cancers,” said study author Duncan Baird, PhD, of Cardiff University in the UK.

“And, as we have shown previously, short telomeres can predict the outcome of patients with [chronic lymphocytic leukemia] and probably many other tumor types. Thus, the discovery that ligase 3 is required for this process is fundamentally important.”

This research was made possible by a chance meeting between Dr Baird and Dr Hendrickson at an international conference. The pair discovered they were both looking at the role of ligase 3 in cancer and decided to collaborate.

“The collaboration paid off, as we were able to uncover something that neither one of us could have done on our own,” Dr Hendrickson said.

Additional studies are already underway. The researchers are investigating the discovery that the reliance on ligase 3 appears to be dependent upon the activity of another key DNA repair gene, p53.

“Since p53 is the most commonly mutated gene in human cancer, it now behooves us to discover how these two genes are interacting and to see if we can’t use that information to develop synergistic treatment modalities,” Dr Hendrickson concluded. ![]()

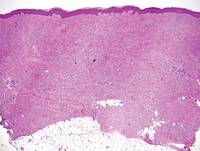

Interim data appear positive for MM drug

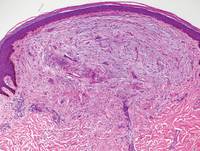

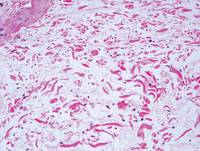

Interim results of the phase 3 ASPIRE trial suggest carfilzomib can improve progression-free survival (PFS) in patients with relapsed multiple myeloma (MM).

Patients who received carfilzomib, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone lived 8.7 months longer without progression than patients who received only lenalidomide and dexamethasone.

The companies developing carfilzomib, Amgen and its subsidiary, Onyx Pharmaceuticals, Inc., recently shared these results.

They said additional results will be submitted for presentation at the 56th Annual ASH Meeting in December.

The companies also said data from the ASPIRE trial will form the basis for regulatory submissions for carfilzomib throughout the world.

In the US, the data may support the conversion of accelerated approval to full approval and expand the current indication for carfilzomib.

The ASPIRE trial includes 792 patients with relapsed MM who were randomized to treatment at sites in North America, Europe, and Israel. Prior to study treatment, the patients had received 1 to 3 therapeutic regimens.

The patients were randomized to receive carfilzomib (20 mg/m2 on days 1 and 2 of cycle 1 only, then 27 mg/m2), in addition to a standard dosing schedule of lenalidomide (25 mg per day for 21 days on, 7 days off) and low-dose dexamethasone (40 mg per week in 4-week cycles), or lenalidomide and low-dose dexamethasone alone.

The primary endpoint was PFS, and secondary endpoints included overall survival, overall response rate, duration of response, disease control rate, health-related quality of life, and safety.

At a planned interim analysis, patients in the carfilzomib arm had a significantly longer median PFS than patients in the other arm—26.3 months and 17.6 months, respectively (P<0.0001).

The data for overall survival are not yet mature, but the analysis showed a trend in favor of carfilzomib that did not reach statistical significance, according to Amgen and Onyx.

The companies said the safety profile in this study is consistent with previous studies, including the rate of cardiac events.

Treatment discontinuation due to adverse events and on-study deaths were comparable between the 2 arms, and researchers did not identify any new safety signals. ![]()

Interim results of the phase 3 ASPIRE trial suggest carfilzomib can improve progression-free survival (PFS) in patients with relapsed multiple myeloma (MM).

Patients who received carfilzomib, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone lived 8.7 months longer without progression than patients who received only lenalidomide and dexamethasone.

The companies developing carfilzomib, Amgen and its subsidiary, Onyx Pharmaceuticals, Inc., recently shared these results.

They said additional results will be submitted for presentation at the 56th Annual ASH Meeting in December.

The companies also said data from the ASPIRE trial will form the basis for regulatory submissions for carfilzomib throughout the world.

In the US, the data may support the conversion of accelerated approval to full approval and expand the current indication for carfilzomib.

The ASPIRE trial includes 792 patients with relapsed MM who were randomized to treatment at sites in North America, Europe, and Israel. Prior to study treatment, the patients had received 1 to 3 therapeutic regimens.

The patients were randomized to receive carfilzomib (20 mg/m2 on days 1 and 2 of cycle 1 only, then 27 mg/m2), in addition to a standard dosing schedule of lenalidomide (25 mg per day for 21 days on, 7 days off) and low-dose dexamethasone (40 mg per week in 4-week cycles), or lenalidomide and low-dose dexamethasone alone.

The primary endpoint was PFS, and secondary endpoints included overall survival, overall response rate, duration of response, disease control rate, health-related quality of life, and safety.

At a planned interim analysis, patients in the carfilzomib arm had a significantly longer median PFS than patients in the other arm—26.3 months and 17.6 months, respectively (P<0.0001).

The data for overall survival are not yet mature, but the analysis showed a trend in favor of carfilzomib that did not reach statistical significance, according to Amgen and Onyx.

The companies said the safety profile in this study is consistent with previous studies, including the rate of cardiac events.

Treatment discontinuation due to adverse events and on-study deaths were comparable between the 2 arms, and researchers did not identify any new safety signals. ![]()

Interim results of the phase 3 ASPIRE trial suggest carfilzomib can improve progression-free survival (PFS) in patients with relapsed multiple myeloma (MM).

Patients who received carfilzomib, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone lived 8.7 months longer without progression than patients who received only lenalidomide and dexamethasone.

The companies developing carfilzomib, Amgen and its subsidiary, Onyx Pharmaceuticals, Inc., recently shared these results.

They said additional results will be submitted for presentation at the 56th Annual ASH Meeting in December.

The companies also said data from the ASPIRE trial will form the basis for regulatory submissions for carfilzomib throughout the world.

In the US, the data may support the conversion of accelerated approval to full approval and expand the current indication for carfilzomib.

The ASPIRE trial includes 792 patients with relapsed MM who were randomized to treatment at sites in North America, Europe, and Israel. Prior to study treatment, the patients had received 1 to 3 therapeutic regimens.

The patients were randomized to receive carfilzomib (20 mg/m2 on days 1 and 2 of cycle 1 only, then 27 mg/m2), in addition to a standard dosing schedule of lenalidomide (25 mg per day for 21 days on, 7 days off) and low-dose dexamethasone (40 mg per week in 4-week cycles), or lenalidomide and low-dose dexamethasone alone.

The primary endpoint was PFS, and secondary endpoints included overall survival, overall response rate, duration of response, disease control rate, health-related quality of life, and safety.

At a planned interim analysis, patients in the carfilzomib arm had a significantly longer median PFS than patients in the other arm—26.3 months and 17.6 months, respectively (P<0.0001).

The data for overall survival are not yet mature, but the analysis showed a trend in favor of carfilzomib that did not reach statistical significance, according to Amgen and Onyx.

The companies said the safety profile in this study is consistent with previous studies, including the rate of cardiac events.

Treatment discontinuation due to adverse events and on-study deaths were comparable between the 2 arms, and researchers did not identify any new safety signals. ![]()

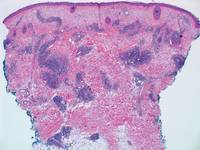

Combative Behavior and Delirium

Delirium affects up to 82% of critical‐care patients and 29% to 64% of general medical patients, resulting in medical morbidity, decreased function, and mortality.[1, 2, 3, 4, 5] Delirium is associated with specific, adverse hospital outcomes, including falls, aspiration pneumonia, pressure ulcers, and restraint use.[6, 7] As a consequence of delirium, individuals may be transformed from independent and active at the time of admission to requiring skilled nursing supervision at discharge, in some cases resulting in permanent cognitive disability for the remainder of the person's life.[4, 8]

Combative behavior in hospitalized patients can be a threat to self or others, including other patients and staff. An emergency alert to staff regarding the presence of a combative patient requiring intervention is known as a behavioral code or Code Gray.[9] Guidelines addressing this particular hospital emergency typically refer to de‐escalation methods and implementation of security measures. Ideally, however, at‐risk patients would be identified prior to development into a full behavioral code. Unfortunately, the medical literature on the causes, prevention, and interventions for combative behavior requiring intervention is limited. Interventions published to date focus on patients living with severe and persistent mental illness, such as schizophrenia or bipolar disorder.[9, 10, 11, 12]

We hypothesized that delirium contributes to combative behavior in hospitalized patients, leading to the adverse outcome of behavioral codes. Delirium identification would therefore provide an opportunity for prevention and early identification of patients at risk, thereby improving safety for patients and staff. However, no studies published to date address the impact of delirium on the likelihood of a patient hospitalized in a general medical/surgical setting becoming combative and requiring intervention such as a behavioral code. The purpose of this article is to determine the strength of the association between delirium and combative behavior requiring intervention.

METHODS

This study was conducted as part of a quality improvement project, resulting in a waiver by the institutional review board of the hospital. All data with patient‐specific information were securely handled and deidentified prior to analysis. The setting is a 336‐bed, nonuniversity, teaching hospital serving adults in the Pacific Northwest, with approximately 16,000 admissions per year, and 31 critical‐care beds. Delirium prevention has been identified as an institutional priority, and we have been screening for delirium on admission and with twice‐daily Confusion Assessment Method (CAM) scores since 2010.

The study design was a retrospective case control study of hospital inpatients. Consecutive patients experiencing combative behavior requiring a specific behavioral code intervention (n=125) between January 1, 2011 to December 31, 2011 were identified using security reports and operator code logs. Five patients were excluded because the combative behavior requiring intervention occurred prior to hospital admission, in the emergency department or short‐stay observation unit. Interventions for combative behavior are institution specific. At our institution, a behavioral code is called when a patient or visitor is disruptive and exhibiting behavior that, if not controlled immediately, may result in serious injury to self or others, in line with the approach recommended by the Washington State Hospital Association.[9] When this situation arises, a staff member calls the hospital operator and an alert is paged overhead. Security staff then comes to the area to assist the clinical staff in determining the proper response.

The sample of 120 patients with behavioral codes was compared to a control group of 159 inpatients from the same year, randomly selected from all hospital discharges. For both groups, patients under the age of 18 and patients who were cared for only in the emergency department or short stay observation unit were excluded.

The presence or absence of delirium, the primary exposure of interest, was determined using a combined reference standard. First, by institutional protocol, all inpatients underwent nursing administration of the CAM[13] or the CAM for the Intensive Care Unit[14] on admission and every 12 hours thereafter. Patients with a positive CAM score within the 48 hours preceding the behavioral code event in cases, or anytime during the hospitalization in controls, were considered to have delirium. The CAM was performed as part of routine care at our institution by clinical nurses. However, when used outside of the research setting, untrained nurses using the CAM may substantially underestimate the incidence of delirium.[15, 16] Therefore, as a second reference standard, among patients who did not have delirium by the CAM criteria above, chart review was performed to identify delirium. Though chart review is also imperfect for the determination of both delirium and potential confounders, given the limitations of CAM scores in clinical rather than research settings, the use of this combined reference standard improves detection of delirium. Our chart review method is based on the previously reported work by Lakatos et al. and Inouye et al., identifying delirium from key words in the medical record demonstrating the diagnostic criteria for delirium.[6, 16] The Lakatos et al. study provided the specific key words used in our chart review.[6]

For each case and control subject, 1 of 2 experienced chart reviewers abstracted data from the electronic medical record retrospectively. The abstractors were not informed as to whether or not the patients were cases or controls, but could not be blinded as this information may be clear from the medical record. (The chart abstraction tool, with the key words mapped to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition criteria for delirium and the CAM is included in the Supporting Information, Appendix, in the online version of this article). We assessed interobserver agreement for delirium diagnosis through double review of 20% of charts. The presence or absence of potential confounders, including dementia, substance use or other psychiatric illness, and use of drugs associated with delirium specific (opiates, sedatives, anticholinergics, and antihistamines), and demographic information, including time of admission; hospital length of stay; any intensive care unit (ICU) visit; and discharge disposition was also determined from the electronic medical record.

Bivariate statistics were completed comparing patients with a behavioral code to the control group. Categorical variables were compared using 2, and continuous variables were compared using the t test. Logistic regression using stepwise regression, threshold of 0.1, dependent variable of behavioral code, and independent variable of delirium was performed to determine the association of delirium with behavioral codes after adjustment for confounders. In the multivariate model, use of any medication associated with delirium (Table 1) was considered as a single binary variable, regardless of drug type or class. Agreement was assessed through the kappa statistic. All statistics were performed using Stata MP v.12 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

| Patients With Behavioral Code, N=120 | Patients Without Behavioral Code, N=159 | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Narcotic analgesics (%) | 78 (65) | 111 (70) | 0.40 |

| Fentanyl (%) | 47 (39) | 84 (53) | 0.024 |

| Hydromorphone (%) | 51 (43) | 78 (49) | 0.28 |

| Oxycodone (%) | 34 (28) | 46 (29) | 0.91 |

| Sedative hypnotics (%) | 76 (63) | 84 (53) | 0.08 |

| Midazolam (%) | 35 (29) | 70 (44) | 0.011 |

| Lorazepam (%) | 58 (48) | 15 (9) | <0.001 |

| No. of different drugs/person, mean (SD), range 010 | 2.6 (2.2) | 2.3 (1.9) | 0.27 |

RESULTS

Patients experiencing combative behavior requiring intervention through a behavioral code were significantly more likely to be male, admitted overnight, require an ICU stay during their hospitalization, and have a diagnosis of dementia or substance‐use disorder (Table 2). Patients with a behavioral code demonstrated an increased hospital length of stay (9.4 vs 4.5 days) and were significantly more likely to be discharged to a skilled nursing facility (31/120, 26% vs 16/159, 10%), or leave against medical advice (10% 12/120 vs 0%, P<0.001). Of the patients leaving against medical advice, none had evidence of delirium or dementia in the record; 92% (11/12) had International Classification of Disease9th Revision codes reflecting alcohol and/or drug abuse or dependence. Exposure to medications commonly associated with delirium was common in both groups, with differences in usage patterns for different drugs (Table 1).

| Characteristic | Patients With Behavioral Code, N=120 | Patients Without Behavioral Code, N=159 | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Age, y, mean (SD) | 64.8 (19.5) | 63.9 (16.7) | 0.66 |

| Female (%) | 39 (33) | 78 (49) | 0.006 |

| Race/ethnicity (%) | 0.68 | ||

| White non‐Hispanic | 95 (79) | 129 (81) | |

| Other or unknown | 25 (21) | 30 (19) | |

| Patient Diagnosis Related Group (%) | 0.017 | ||

| Medical | 69 (57) | 69 (43) | |

| Gynecological or surgical | 51 (43) | 90 (57) | |

| Hospital admit between 6 pm and 6 am (%) | 63 (53) | 54 (34) | 0.002 |

| Any intensive care unit visit (%) | 43 (36) | 26 (16) | <0.001 |

| Any positive Confusion Assessment Method score | 70 (58) | 16 (10) | 0.002 |

| Delirium (%)a | 87 (73) | 26 (16) | <0.001 |

| Mental disorders as any discharge diagnosis code (%) | 110 (92) | 58 (36) | <0.001 |

| Dementia and other persistent (%) | 29 (24) | 9 (6) | <0.001 |

| Alcohol/drugs (%) | 61 (51) | 23 (14) | <0.001 |

Although combative behavior requiring intervention occurred throughout the stay, the majority (84/120, 70%) of behavioral codes occurred during the first 72 hours of hospital admission. Behavioral codes occurred throughout all nursing shifts, with 27% (32/120) between 7:00 am and 3:00 pm, 32% (39/120) between 3:00 pm and 11:00 pm, and 41% (49/120) between 11:00 pm and 7:00 am. Psychiatric consultation occurred in only 17% (20/120) of patients prior to the behavioral code.

Delirium was evident in the 48 hours preceding the behavioral code event in 50% (60/120) of cases, and was present overall in 16% of the comparison group. In the cases, delirium prior to behavioral code was identified by positive CAM scores in 23% (28/120) and by chart review in 27% (32/120). In the control subjects, delirium was identified by CAM scores in 10% (16/159) and by chart review in 10% (16/159). The chart review delirium assessment demonstrated high interobserver reliability (kappa=0.71). Among patients with behavioral codes, only 28/60 (46.7%) of delirium cases were identified by the CAM score.

The unadjusted odds ratio (OR) for having a behavioral code in the setting of delirium (within 48 hours prior to the code) was 5.1 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 2.9‐8.9, P<0.001), with the combined reference standard of positive CAM or delirium by chart review. Because each reference standard (chart review or CAM) only identified some of the delirium, the OR with only a single reference standard was lower. The risk of behavioral code in the setting of delirium when only CAM scores are considered for the diagnosis of delirium, the OR for behavioral code was 2.7 (95% CI: 1.4‐ 5.3, P=0.003), and when only chart review was used for delirium diagnosis, the OR was 2.7 (95% CI: 1.5‐5.0, P=0.001).

In the stepwise logistic regression model (using the composite reference standard of positive CAM score or delirium on chart review), the odds of having a behavioral code was 3.8 times greater in the setting of delirium (OR: 3.8, 95% CI: 2.07.3, P<0.001), after adjustment for substance abuse (OR: 5.3, 95% CI: 2.810.2, P<0.001), dementia (OR: 6.5, 95% CI: 2.616.1, P<0.001), other mental health diagnosis (OR: 3.2, 95% CI: 1.7‐6.1, P<0.001), and gender (OR male gender: 2.4, 95% CI: 1.34.5, P=0.006). Other potential confounders (age, use of delirium‐associated medications, ICU stay, time of admission) were not significant and so were not included in the final multivariate model.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we identify a 3.8‐fold increased odds of combative behavior requiring a behavioral code intervention in hospitalized patients with delirium. Although a previous association between delirium and restraint use among mechanically ventilated patients in the ICU has been published,[6] this is the first article to describe the strong, statistically significant association between combative patient behavior and delirium in the general medical/surgical acute‐care setting. This association raises the possibility that prevention, early identification, and treatment of delirium in hospitalized patients can decrease the incidence of such combative behavior, and may lead to shorter length of stay and less institutionalization after discharge.

In the multivariate model, we did identify other predictors of combative behavior requiring intervention, including substance abuse, dementia, and other psychiatric diagnoses. Our results do not support age as predictive of combative behavior after adjustment for other predictors. However, our hospital population is relatively old (mean age in controls, 63.9 years). In populations different from ours, age may still be an important predictor. We also did not identify use of medications potentially associated with delirium as a predictor of combative behavior requiring intervention, after adjustment for other predictors. We did, however, consider all medications together, and are not able to differentiate the potential predictive ability of any single drug or class. Finally, we report relatively high rates of opiate and sedative use in our sample, likely because we included short‐acting agents (ie, midazolam, fentanyl) that are commonly used for procedures and perioperative care.

Our study also highlights the challenges of accurately identifying delirium for quality improvement interventions. The CAM is a validated and widely accepted method of prospective screening for delirium, but in relatively untrained hands outside of research settings (as in our institution) does underestimate the true incidence of delirium.[15, 16, 17] Further, both CAM assessment and chart review may underestimate the incidence of hypoactive delirium. In our study, we note that the CAM scores only identified 46.7% of the behavioral code patients with delirium. Chart review also has limitations, identified by Inouye et al.,[16] particularly in the setting of comorbid dementia, high baseline delirium risk, and other comorbid conditions. Comorbidities as defined by APACHE II (Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II) score may contribute to false positives, and poor documentation may result in false negatives. Our use of a combined reference standard of CAM assessment and chart review for delirium is supported by the fact that the incidence of delirium we report in the control group is similar to the published literature.[5]

Combative behavior in the hospital setting may be a threat to patients, staff, and visitors, and multiple state hospital associations have called for standardized responses, including the calling of behavioral codes when such circumstances arise.[9] In general, de‐escalation techniques and security measures are sufficient for patients exhibiting combative behavior. However, in cases of delirium‐associated combative behavior, clinical evaluation of root causes and both pharmacological and nonpharmacological interventions, including proactive psychiatric consultation, may also be beneficial.[18, 19, 20, 21] Many nonpharmacological interventions may need to be multicomponent in nature, as has been described previously.[18, 19, 20, 21]

We acknowledge the limitations of this article. First, we identify a strong association between combative behavior requiring intervention and delirium, but cannot prove causality. Second, though the chart reviewers where not told if reviewing cases or controls, we were not able to blind them to information on combative behavior that might have been present in the medical record. The use of unblinded reviewers could lead to overestimation of the presence of delirium in cases, and overestimation of the association between delirium and combative behavior requiring intervention. Third, chart review methods may underestimate the prevalence of dementia, which can confound the diagnosis of delirium. Finally, we defined delirium in the behavioral code cases as occurring in the 48 hours prior to the code event. However, as no such event occurred in the controls, we considered delirium as present if identified any time during the hospitalization. This could potentially lead to underestimation of the true association of delirium with combative behavior requiring intervention. It is also worth noting that many of the identified predictors for combative behavior are also predictors for delirium and may be identifying a subset of combative behavior related to agitated delirium. Overall, however, the strength of the association we report does strongly support identification and treatment of delirium in the context of combative behavior.

In this article, we identify a strong association between delirium and combative behavior requiring intervention, even after adjustment for other predictors. Understanding this association can help providers consider delirium as a potential cause of combative behavior in a medical/surgical setting, beyond behavioral issues associated with community violence, serious mental illness, progressive dementia, or substance use. Overall, therefore, delirium risk assessment, screening, prevention, and early intervention may potentially decrease combative behavior, and contribute to improving patient and staff safety in hospital settings.

Disclosures: C. Craig Blackmore, MD, reports royalties from the Springer Verlag publishing company for a textbook series on evidence‐based imaging, which is not relevant to this article. None of the authors report any conflicts of interest.

- Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition, Text Revision. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

- , , , et al. Delirium as a predictor of mortality in mechanically ventilated patients in the ICU. JAMA. 2004;291:1753–1762.

- , , . Delirium: a symptom of how hospital care is failing older persons and a window to improve quality of hospital care. Am J Med. 1999;106:565–573.

- , , , et al. Delirium in elderly patients and the risk of postdischarge mortality, institutionalization and dementia. JAMA. 2010;304:443–451.

- , , . Delirium in elderly people. Lancet. 2014;383(9920):911–922.

- , , , et al. Falls in the general hospital: association with delirium, advanced age, and specific surgical procedures. Psychosomatics. 2009;50:218–226.

- , , , , . Delirium as detected by the CAM‐ICU predicts restraint use among mechanically ventilated patients. Crit Care Med. 2005;33:226–229.

- , , . Delirium: prevention, treatment and outcome studies. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 1998;11:126–137.

- Washington State Hospital Association. Standardization of emergency code calls in Washington: implementation toolkit. Available at: http://www.wsha.org/files/82/EmergencyCodesExceutiveSummary.pdf. Accessed October 23, 2013.

- . Words for the wise: defusing combative patient behavior through verbal intervention. J Healthc Prot Manage. 2005;21:81–88.

- , , , . Rapid response team for behavioral emergencies. J Am Psychiatric Nurses Assoc. 2010;16:93–100.

- , . Physical and chemical restraints. Emerg Med Clin N Am. 2009;27:655–667.

- , , , , , . Clarifying confusion: the Confusion Assessment Method. Ann Int Med. 1990;113:941–948.

- , , , et al. Delirium in mechanically ventilated patients: validity and reliability of the Confusion Assessment Method for the Intensive Care Unit (CAM‐ICU). JAMA. 2001;286:2703–2710.

- , , , , , . A researchh algorithm to improve detection of delirium in the intensive care unit. Crit Care. 2006;10:R121.

- , , , , , . A chart‐based method for identification of delirium: validation compared with interviewer ratings using the Confusion Assessment Method. J Am Geriatic Soc. 2005;53:312–318.

- , , , , . Nurses' recognition of delirium and its symptoms. Arch Int Med. 2001;161:2467–2473.

- , , , et al. A multi‐component intervention to prevent delirium in hospitalized older patients. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:669–676.

- , , . Delirium: screening, prevention and diagnosis—a systematic review of the evidence. Evidence‐based Synthesis Program (ESP). Washington, DC: Department of Veterans Affairs; 2011.

- , , , , , . A longitudinal study of motor subtypes in delirium: frequency and stability during episodes. J Psychsom Res. 2012;72:236–241.

- , , , et al. Pharmacologic management of delirium in hospitalized adults—a systematic evidence review. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24:848–853.

Delirium affects up to 82% of critical‐care patients and 29% to 64% of general medical patients, resulting in medical morbidity, decreased function, and mortality.[1, 2, 3, 4, 5] Delirium is associated with specific, adverse hospital outcomes, including falls, aspiration pneumonia, pressure ulcers, and restraint use.[6, 7] As a consequence of delirium, individuals may be transformed from independent and active at the time of admission to requiring skilled nursing supervision at discharge, in some cases resulting in permanent cognitive disability for the remainder of the person's life.[4, 8]

Combative behavior in hospitalized patients can be a threat to self or others, including other patients and staff. An emergency alert to staff regarding the presence of a combative patient requiring intervention is known as a behavioral code or Code Gray.[9] Guidelines addressing this particular hospital emergency typically refer to de‐escalation methods and implementation of security measures. Ideally, however, at‐risk patients would be identified prior to development into a full behavioral code. Unfortunately, the medical literature on the causes, prevention, and interventions for combative behavior requiring intervention is limited. Interventions published to date focus on patients living with severe and persistent mental illness, such as schizophrenia or bipolar disorder.[9, 10, 11, 12]

We hypothesized that delirium contributes to combative behavior in hospitalized patients, leading to the adverse outcome of behavioral codes. Delirium identification would therefore provide an opportunity for prevention and early identification of patients at risk, thereby improving safety for patients and staff. However, no studies published to date address the impact of delirium on the likelihood of a patient hospitalized in a general medical/surgical setting becoming combative and requiring intervention such as a behavioral code. The purpose of this article is to determine the strength of the association between delirium and combative behavior requiring intervention.

METHODS

This study was conducted as part of a quality improvement project, resulting in a waiver by the institutional review board of the hospital. All data with patient‐specific information were securely handled and deidentified prior to analysis. The setting is a 336‐bed, nonuniversity, teaching hospital serving adults in the Pacific Northwest, with approximately 16,000 admissions per year, and 31 critical‐care beds. Delirium prevention has been identified as an institutional priority, and we have been screening for delirium on admission and with twice‐daily Confusion Assessment Method (CAM) scores since 2010.

The study design was a retrospective case control study of hospital inpatients. Consecutive patients experiencing combative behavior requiring a specific behavioral code intervention (n=125) between January 1, 2011 to December 31, 2011 were identified using security reports and operator code logs. Five patients were excluded because the combative behavior requiring intervention occurred prior to hospital admission, in the emergency department or short‐stay observation unit. Interventions for combative behavior are institution specific. At our institution, a behavioral code is called when a patient or visitor is disruptive and exhibiting behavior that, if not controlled immediately, may result in serious injury to self or others, in line with the approach recommended by the Washington State Hospital Association.[9] When this situation arises, a staff member calls the hospital operator and an alert is paged overhead. Security staff then comes to the area to assist the clinical staff in determining the proper response.

The sample of 120 patients with behavioral codes was compared to a control group of 159 inpatients from the same year, randomly selected from all hospital discharges. For both groups, patients under the age of 18 and patients who were cared for only in the emergency department or short stay observation unit were excluded.

The presence or absence of delirium, the primary exposure of interest, was determined using a combined reference standard. First, by institutional protocol, all inpatients underwent nursing administration of the CAM[13] or the CAM for the Intensive Care Unit[14] on admission and every 12 hours thereafter. Patients with a positive CAM score within the 48 hours preceding the behavioral code event in cases, or anytime during the hospitalization in controls, were considered to have delirium. The CAM was performed as part of routine care at our institution by clinical nurses. However, when used outside of the research setting, untrained nurses using the CAM may substantially underestimate the incidence of delirium.[15, 16] Therefore, as a second reference standard, among patients who did not have delirium by the CAM criteria above, chart review was performed to identify delirium. Though chart review is also imperfect for the determination of both delirium and potential confounders, given the limitations of CAM scores in clinical rather than research settings, the use of this combined reference standard improves detection of delirium. Our chart review method is based on the previously reported work by Lakatos et al. and Inouye et al., identifying delirium from key words in the medical record demonstrating the diagnostic criteria for delirium.[6, 16] The Lakatos et al. study provided the specific key words used in our chart review.[6]

For each case and control subject, 1 of 2 experienced chart reviewers abstracted data from the electronic medical record retrospectively. The abstractors were not informed as to whether or not the patients were cases or controls, but could not be blinded as this information may be clear from the medical record. (The chart abstraction tool, with the key words mapped to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition criteria for delirium and the CAM is included in the Supporting Information, Appendix, in the online version of this article). We assessed interobserver agreement for delirium diagnosis through double review of 20% of charts. The presence or absence of potential confounders, including dementia, substance use or other psychiatric illness, and use of drugs associated with delirium specific (opiates, sedatives, anticholinergics, and antihistamines), and demographic information, including time of admission; hospital length of stay; any intensive care unit (ICU) visit; and discharge disposition was also determined from the electronic medical record.

Bivariate statistics were completed comparing patients with a behavioral code to the control group. Categorical variables were compared using 2, and continuous variables were compared using the t test. Logistic regression using stepwise regression, threshold of 0.1, dependent variable of behavioral code, and independent variable of delirium was performed to determine the association of delirium with behavioral codes after adjustment for confounders. In the multivariate model, use of any medication associated with delirium (Table 1) was considered as a single binary variable, regardless of drug type or class. Agreement was assessed through the kappa statistic. All statistics were performed using Stata MP v.12 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

| Patients With Behavioral Code, N=120 | Patients Without Behavioral Code, N=159 | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Narcotic analgesics (%) | 78 (65) | 111 (70) | 0.40 |

| Fentanyl (%) | 47 (39) | 84 (53) | 0.024 |

| Hydromorphone (%) | 51 (43) | 78 (49) | 0.28 |

| Oxycodone (%) | 34 (28) | 46 (29) | 0.91 |

| Sedative hypnotics (%) | 76 (63) | 84 (53) | 0.08 |

| Midazolam (%) | 35 (29) | 70 (44) | 0.011 |

| Lorazepam (%) | 58 (48) | 15 (9) | <0.001 |

| No. of different drugs/person, mean (SD), range 010 | 2.6 (2.2) | 2.3 (1.9) | 0.27 |

RESULTS

Patients experiencing combative behavior requiring intervention through a behavioral code were significantly more likely to be male, admitted overnight, require an ICU stay during their hospitalization, and have a diagnosis of dementia or substance‐use disorder (Table 2). Patients with a behavioral code demonstrated an increased hospital length of stay (9.4 vs 4.5 days) and were significantly more likely to be discharged to a skilled nursing facility (31/120, 26% vs 16/159, 10%), or leave against medical advice (10% 12/120 vs 0%, P<0.001). Of the patients leaving against medical advice, none had evidence of delirium or dementia in the record; 92% (11/12) had International Classification of Disease9th Revision codes reflecting alcohol and/or drug abuse or dependence. Exposure to medications commonly associated with delirium was common in both groups, with differences in usage patterns for different drugs (Table 1).

| Characteristic | Patients With Behavioral Code, N=120 | Patients Without Behavioral Code, N=159 | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Age, y, mean (SD) | 64.8 (19.5) | 63.9 (16.7) | 0.66 |

| Female (%) | 39 (33) | 78 (49) | 0.006 |

| Race/ethnicity (%) | 0.68 | ||

| White non‐Hispanic | 95 (79) | 129 (81) | |

| Other or unknown | 25 (21) | 30 (19) | |

| Patient Diagnosis Related Group (%) | 0.017 | ||

| Medical | 69 (57) | 69 (43) | |

| Gynecological or surgical | 51 (43) | 90 (57) | |

| Hospital admit between 6 pm and 6 am (%) | 63 (53) | 54 (34) | 0.002 |

| Any intensive care unit visit (%) | 43 (36) | 26 (16) | <0.001 |

| Any positive Confusion Assessment Method score | 70 (58) | 16 (10) | 0.002 |

| Delirium (%)a | 87 (73) | 26 (16) | <0.001 |

| Mental disorders as any discharge diagnosis code (%) | 110 (92) | 58 (36) | <0.001 |

| Dementia and other persistent (%) | 29 (24) | 9 (6) | <0.001 |

| Alcohol/drugs (%) | 61 (51) | 23 (14) | <0.001 |

Although combative behavior requiring intervention occurred throughout the stay, the majority (84/120, 70%) of behavioral codes occurred during the first 72 hours of hospital admission. Behavioral codes occurred throughout all nursing shifts, with 27% (32/120) between 7:00 am and 3:00 pm, 32% (39/120) between 3:00 pm and 11:00 pm, and 41% (49/120) between 11:00 pm and 7:00 am. Psychiatric consultation occurred in only 17% (20/120) of patients prior to the behavioral code.

Delirium was evident in the 48 hours preceding the behavioral code event in 50% (60/120) of cases, and was present overall in 16% of the comparison group. In the cases, delirium prior to behavioral code was identified by positive CAM scores in 23% (28/120) and by chart review in 27% (32/120). In the control subjects, delirium was identified by CAM scores in 10% (16/159) and by chart review in 10% (16/159). The chart review delirium assessment demonstrated high interobserver reliability (kappa=0.71). Among patients with behavioral codes, only 28/60 (46.7%) of delirium cases were identified by the CAM score.

The unadjusted odds ratio (OR) for having a behavioral code in the setting of delirium (within 48 hours prior to the code) was 5.1 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 2.9‐8.9, P<0.001), with the combined reference standard of positive CAM or delirium by chart review. Because each reference standard (chart review or CAM) only identified some of the delirium, the OR with only a single reference standard was lower. The risk of behavioral code in the setting of delirium when only CAM scores are considered for the diagnosis of delirium, the OR for behavioral code was 2.7 (95% CI: 1.4‐ 5.3, P=0.003), and when only chart review was used for delirium diagnosis, the OR was 2.7 (95% CI: 1.5‐5.0, P=0.001).

In the stepwise logistic regression model (using the composite reference standard of positive CAM score or delirium on chart review), the odds of having a behavioral code was 3.8 times greater in the setting of delirium (OR: 3.8, 95% CI: 2.07.3, P<0.001), after adjustment for substance abuse (OR: 5.3, 95% CI: 2.810.2, P<0.001), dementia (OR: 6.5, 95% CI: 2.616.1, P<0.001), other mental health diagnosis (OR: 3.2, 95% CI: 1.7‐6.1, P<0.001), and gender (OR male gender: 2.4, 95% CI: 1.34.5, P=0.006). Other potential confounders (age, use of delirium‐associated medications, ICU stay, time of admission) were not significant and so were not included in the final multivariate model.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we identify a 3.8‐fold increased odds of combative behavior requiring a behavioral code intervention in hospitalized patients with delirium. Although a previous association between delirium and restraint use among mechanically ventilated patients in the ICU has been published,[6] this is the first article to describe the strong, statistically significant association between combative patient behavior and delirium in the general medical/surgical acute‐care setting. This association raises the possibility that prevention, early identification, and treatment of delirium in hospitalized patients can decrease the incidence of such combative behavior, and may lead to shorter length of stay and less institutionalization after discharge.

In the multivariate model, we did identify other predictors of combative behavior requiring intervention, including substance abuse, dementia, and other psychiatric diagnoses. Our results do not support age as predictive of combative behavior after adjustment for other predictors. However, our hospital population is relatively old (mean age in controls, 63.9 years). In populations different from ours, age may still be an important predictor. We also did not identify use of medications potentially associated with delirium as a predictor of combative behavior requiring intervention, after adjustment for other predictors. We did, however, consider all medications together, and are not able to differentiate the potential predictive ability of any single drug or class. Finally, we report relatively high rates of opiate and sedative use in our sample, likely because we included short‐acting agents (ie, midazolam, fentanyl) that are commonly used for procedures and perioperative care.

Our study also highlights the challenges of accurately identifying delirium for quality improvement interventions. The CAM is a validated and widely accepted method of prospective screening for delirium, but in relatively untrained hands outside of research settings (as in our institution) does underestimate the true incidence of delirium.[15, 16, 17] Further, both CAM assessment and chart review may underestimate the incidence of hypoactive delirium. In our study, we note that the CAM scores only identified 46.7% of the behavioral code patients with delirium. Chart review also has limitations, identified by Inouye et al.,[16] particularly in the setting of comorbid dementia, high baseline delirium risk, and other comorbid conditions. Comorbidities as defined by APACHE II (Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II) score may contribute to false positives, and poor documentation may result in false negatives. Our use of a combined reference standard of CAM assessment and chart review for delirium is supported by the fact that the incidence of delirium we report in the control group is similar to the published literature.[5]

Combative behavior in the hospital setting may be a threat to patients, staff, and visitors, and multiple state hospital associations have called for standardized responses, including the calling of behavioral codes when such circumstances arise.[9] In general, de‐escalation techniques and security measures are sufficient for patients exhibiting combative behavior. However, in cases of delirium‐associated combative behavior, clinical evaluation of root causes and both pharmacological and nonpharmacological interventions, including proactive psychiatric consultation, may also be beneficial.[18, 19, 20, 21] Many nonpharmacological interventions may need to be multicomponent in nature, as has been described previously.[18, 19, 20, 21]

We acknowledge the limitations of this article. First, we identify a strong association between combative behavior requiring intervention and delirium, but cannot prove causality. Second, though the chart reviewers where not told if reviewing cases or controls, we were not able to blind them to information on combative behavior that might have been present in the medical record. The use of unblinded reviewers could lead to overestimation of the presence of delirium in cases, and overestimation of the association between delirium and combative behavior requiring intervention. Third, chart review methods may underestimate the prevalence of dementia, which can confound the diagnosis of delirium. Finally, we defined delirium in the behavioral code cases as occurring in the 48 hours prior to the code event. However, as no such event occurred in the controls, we considered delirium as present if identified any time during the hospitalization. This could potentially lead to underestimation of the true association of delirium with combative behavior requiring intervention. It is also worth noting that many of the identified predictors for combative behavior are also predictors for delirium and may be identifying a subset of combative behavior related to agitated delirium. Overall, however, the strength of the association we report does strongly support identification and treatment of delirium in the context of combative behavior.

In this article, we identify a strong association between delirium and combative behavior requiring intervention, even after adjustment for other predictors. Understanding this association can help providers consider delirium as a potential cause of combative behavior in a medical/surgical setting, beyond behavioral issues associated with community violence, serious mental illness, progressive dementia, or substance use. Overall, therefore, delirium risk assessment, screening, prevention, and early intervention may potentially decrease combative behavior, and contribute to improving patient and staff safety in hospital settings.

Disclosures: C. Craig Blackmore, MD, reports royalties from the Springer Verlag publishing company for a textbook series on evidence‐based imaging, which is not relevant to this article. None of the authors report any conflicts of interest.

Delirium affects up to 82% of critical‐care patients and 29% to 64% of general medical patients, resulting in medical morbidity, decreased function, and mortality.[1, 2, 3, 4, 5] Delirium is associated with specific, adverse hospital outcomes, including falls, aspiration pneumonia, pressure ulcers, and restraint use.[6, 7] As a consequence of delirium, individuals may be transformed from independent and active at the time of admission to requiring skilled nursing supervision at discharge, in some cases resulting in permanent cognitive disability for the remainder of the person's life.[4, 8]

Combative behavior in hospitalized patients can be a threat to self or others, including other patients and staff. An emergency alert to staff regarding the presence of a combative patient requiring intervention is known as a behavioral code or Code Gray.[9] Guidelines addressing this particular hospital emergency typically refer to de‐escalation methods and implementation of security measures. Ideally, however, at‐risk patients would be identified prior to development into a full behavioral code. Unfortunately, the medical literature on the causes, prevention, and interventions for combative behavior requiring intervention is limited. Interventions published to date focus on patients living with severe and persistent mental illness, such as schizophrenia or bipolar disorder.[9, 10, 11, 12]

We hypothesized that delirium contributes to combative behavior in hospitalized patients, leading to the adverse outcome of behavioral codes. Delirium identification would therefore provide an opportunity for prevention and early identification of patients at risk, thereby improving safety for patients and staff. However, no studies published to date address the impact of delirium on the likelihood of a patient hospitalized in a general medical/surgical setting becoming combative and requiring intervention such as a behavioral code. The purpose of this article is to determine the strength of the association between delirium and combative behavior requiring intervention.

METHODS

This study was conducted as part of a quality improvement project, resulting in a waiver by the institutional review board of the hospital. All data with patient‐specific information were securely handled and deidentified prior to analysis. The setting is a 336‐bed, nonuniversity, teaching hospital serving adults in the Pacific Northwest, with approximately 16,000 admissions per year, and 31 critical‐care beds. Delirium prevention has been identified as an institutional priority, and we have been screening for delirium on admission and with twice‐daily Confusion Assessment Method (CAM) scores since 2010.

The study design was a retrospective case control study of hospital inpatients. Consecutive patients experiencing combative behavior requiring a specific behavioral code intervention (n=125) between January 1, 2011 to December 31, 2011 were identified using security reports and operator code logs. Five patients were excluded because the combative behavior requiring intervention occurred prior to hospital admission, in the emergency department or short‐stay observation unit. Interventions for combative behavior are institution specific. At our institution, a behavioral code is called when a patient or visitor is disruptive and exhibiting behavior that, if not controlled immediately, may result in serious injury to self or others, in line with the approach recommended by the Washington State Hospital Association.[9] When this situation arises, a staff member calls the hospital operator and an alert is paged overhead. Security staff then comes to the area to assist the clinical staff in determining the proper response.

The sample of 120 patients with behavioral codes was compared to a control group of 159 inpatients from the same year, randomly selected from all hospital discharges. For both groups, patients under the age of 18 and patients who were cared for only in the emergency department or short stay observation unit were excluded.

The presence or absence of delirium, the primary exposure of interest, was determined using a combined reference standard. First, by institutional protocol, all inpatients underwent nursing administration of the CAM[13] or the CAM for the Intensive Care Unit[14] on admission and every 12 hours thereafter. Patients with a positive CAM score within the 48 hours preceding the behavioral code event in cases, or anytime during the hospitalization in controls, were considered to have delirium. The CAM was performed as part of routine care at our institution by clinical nurses. However, when used outside of the research setting, untrained nurses using the CAM may substantially underestimate the incidence of delirium.[15, 16] Therefore, as a second reference standard, among patients who did not have delirium by the CAM criteria above, chart review was performed to identify delirium. Though chart review is also imperfect for the determination of both delirium and potential confounders, given the limitations of CAM scores in clinical rather than research settings, the use of this combined reference standard improves detection of delirium. Our chart review method is based on the previously reported work by Lakatos et al. and Inouye et al., identifying delirium from key words in the medical record demonstrating the diagnostic criteria for delirium.[6, 16] The Lakatos et al. study provided the specific key words used in our chart review.[6]

For each case and control subject, 1 of 2 experienced chart reviewers abstracted data from the electronic medical record retrospectively. The abstractors were not informed as to whether or not the patients were cases or controls, but could not be blinded as this information may be clear from the medical record. (The chart abstraction tool, with the key words mapped to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition criteria for delirium and the CAM is included in the Supporting Information, Appendix, in the online version of this article). We assessed interobserver agreement for delirium diagnosis through double review of 20% of charts. The presence or absence of potential confounders, including dementia, substance use or other psychiatric illness, and use of drugs associated with delirium specific (opiates, sedatives, anticholinergics, and antihistamines), and demographic information, including time of admission; hospital length of stay; any intensive care unit (ICU) visit; and discharge disposition was also determined from the electronic medical record.

Bivariate statistics were completed comparing patients with a behavioral code to the control group. Categorical variables were compared using 2, and continuous variables were compared using the t test. Logistic regression using stepwise regression, threshold of 0.1, dependent variable of behavioral code, and independent variable of delirium was performed to determine the association of delirium with behavioral codes after adjustment for confounders. In the multivariate model, use of any medication associated with delirium (Table 1) was considered as a single binary variable, regardless of drug type or class. Agreement was assessed through the kappa statistic. All statistics were performed using Stata MP v.12 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

| Patients With Behavioral Code, N=120 | Patients Without Behavioral Code, N=159 | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Narcotic analgesics (%) | 78 (65) | 111 (70) | 0.40 |

| Fentanyl (%) | 47 (39) | 84 (53) | 0.024 |

| Hydromorphone (%) | 51 (43) | 78 (49) | 0.28 |

| Oxycodone (%) | 34 (28) | 46 (29) | 0.91 |

| Sedative hypnotics (%) | 76 (63) | 84 (53) | 0.08 |

| Midazolam (%) | 35 (29) | 70 (44) | 0.011 |

| Lorazepam (%) | 58 (48) | 15 (9) | <0.001 |

| No. of different drugs/person, mean (SD), range 010 | 2.6 (2.2) | 2.3 (1.9) | 0.27 |

RESULTS

Patients experiencing combative behavior requiring intervention through a behavioral code were significantly more likely to be male, admitted overnight, require an ICU stay during their hospitalization, and have a diagnosis of dementia or substance‐use disorder (Table 2). Patients with a behavioral code demonstrated an increased hospital length of stay (9.4 vs 4.5 days) and were significantly more likely to be discharged to a skilled nursing facility (31/120, 26% vs 16/159, 10%), or leave against medical advice (10% 12/120 vs 0%, P<0.001). Of the patients leaving against medical advice, none had evidence of delirium or dementia in the record; 92% (11/12) had International Classification of Disease9th Revision codes reflecting alcohol and/or drug abuse or dependence. Exposure to medications commonly associated with delirium was common in both groups, with differences in usage patterns for different drugs (Table 1).

| Characteristic | Patients With Behavioral Code, N=120 | Patients Without Behavioral Code, N=159 | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Age, y, mean (SD) | 64.8 (19.5) | 63.9 (16.7) | 0.66 |

| Female (%) | 39 (33) | 78 (49) | 0.006 |

| Race/ethnicity (%) | 0.68 | ||

| White non‐Hispanic | 95 (79) | 129 (81) | |

| Other or unknown | 25 (21) | 30 (19) | |

| Patient Diagnosis Related Group (%) | 0.017 | ||

| Medical | 69 (57) | 69 (43) | |

| Gynecological or surgical | 51 (43) | 90 (57) | |

| Hospital admit between 6 pm and 6 am (%) | 63 (53) | 54 (34) | 0.002 |

| Any intensive care unit visit (%) | 43 (36) | 26 (16) | <0.001 |

| Any positive Confusion Assessment Method score | 70 (58) | 16 (10) | 0.002 |

| Delirium (%)a | 87 (73) | 26 (16) | <0.001 |

| Mental disorders as any discharge diagnosis code (%) | 110 (92) | 58 (36) | <0.001 |

| Dementia and other persistent (%) | 29 (24) | 9 (6) | <0.001 |

| Alcohol/drugs (%) | 61 (51) | 23 (14) | <0.001 |

Although combative behavior requiring intervention occurred throughout the stay, the majority (84/120, 70%) of behavioral codes occurred during the first 72 hours of hospital admission. Behavioral codes occurred throughout all nursing shifts, with 27% (32/120) between 7:00 am and 3:00 pm, 32% (39/120) between 3:00 pm and 11:00 pm, and 41% (49/120) between 11:00 pm and 7:00 am. Psychiatric consultation occurred in only 17% (20/120) of patients prior to the behavioral code.

Delirium was evident in the 48 hours preceding the behavioral code event in 50% (60/120) of cases, and was present overall in 16% of the comparison group. In the cases, delirium prior to behavioral code was identified by positive CAM scores in 23% (28/120) and by chart review in 27% (32/120). In the control subjects, delirium was identified by CAM scores in 10% (16/159) and by chart review in 10% (16/159). The chart review delirium assessment demonstrated high interobserver reliability (kappa=0.71). Among patients with behavioral codes, only 28/60 (46.7%) of delirium cases were identified by the CAM score.

The unadjusted odds ratio (OR) for having a behavioral code in the setting of delirium (within 48 hours prior to the code) was 5.1 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 2.9‐8.9, P<0.001), with the combined reference standard of positive CAM or delirium by chart review. Because each reference standard (chart review or CAM) only identified some of the delirium, the OR with only a single reference standard was lower. The risk of behavioral code in the setting of delirium when only CAM scores are considered for the diagnosis of delirium, the OR for behavioral code was 2.7 (95% CI: 1.4‐ 5.3, P=0.003), and when only chart review was used for delirium diagnosis, the OR was 2.7 (95% CI: 1.5‐5.0, P=0.001).

In the stepwise logistic regression model (using the composite reference standard of positive CAM score or delirium on chart review), the odds of having a behavioral code was 3.8 times greater in the setting of delirium (OR: 3.8, 95% CI: 2.07.3, P<0.001), after adjustment for substance abuse (OR: 5.3, 95% CI: 2.810.2, P<0.001), dementia (OR: 6.5, 95% CI: 2.616.1, P<0.001), other mental health diagnosis (OR: 3.2, 95% CI: 1.7‐6.1, P<0.001), and gender (OR male gender: 2.4, 95% CI: 1.34.5, P=0.006). Other potential confounders (age, use of delirium‐associated medications, ICU stay, time of admission) were not significant and so were not included in the final multivariate model.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we identify a 3.8‐fold increased odds of combative behavior requiring a behavioral code intervention in hospitalized patients with delirium. Although a previous association between delirium and restraint use among mechanically ventilated patients in the ICU has been published,[6] this is the first article to describe the strong, statistically significant association between combative patient behavior and delirium in the general medical/surgical acute‐care setting. This association raises the possibility that prevention, early identification, and treatment of delirium in hospitalized patients can decrease the incidence of such combative behavior, and may lead to shorter length of stay and less institutionalization after discharge.

In the multivariate model, we did identify other predictors of combative behavior requiring intervention, including substance abuse, dementia, and other psychiatric diagnoses. Our results do not support age as predictive of combative behavior after adjustment for other predictors. However, our hospital population is relatively old (mean age in controls, 63.9 years). In populations different from ours, age may still be an important predictor. We also did not identify use of medications potentially associated with delirium as a predictor of combative behavior requiring intervention, after adjustment for other predictors. We did, however, consider all medications together, and are not able to differentiate the potential predictive ability of any single drug or class. Finally, we report relatively high rates of opiate and sedative use in our sample, likely because we included short‐acting agents (ie, midazolam, fentanyl) that are commonly used for procedures and perioperative care.

Our study also highlights the challenges of accurately identifying delirium for quality improvement interventions. The CAM is a validated and widely accepted method of prospective screening for delirium, but in relatively untrained hands outside of research settings (as in our institution) does underestimate the true incidence of delirium.[15, 16, 17] Further, both CAM assessment and chart review may underestimate the incidence of hypoactive delirium. In our study, we note that the CAM scores only identified 46.7% of the behavioral code patients with delirium. Chart review also has limitations, identified by Inouye et al.,[16] particularly in the setting of comorbid dementia, high baseline delirium risk, and other comorbid conditions. Comorbidities as defined by APACHE II (Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II) score may contribute to false positives, and poor documentation may result in false negatives. Our use of a combined reference standard of CAM assessment and chart review for delirium is supported by the fact that the incidence of delirium we report in the control group is similar to the published literature.[5]

Combative behavior in the hospital setting may be a threat to patients, staff, and visitors, and multiple state hospital associations have called for standardized responses, including the calling of behavioral codes when such circumstances arise.[9] In general, de‐escalation techniques and security measures are sufficient for patients exhibiting combative behavior. However, in cases of delirium‐associated combative behavior, clinical evaluation of root causes and both pharmacological and nonpharmacological interventions, including proactive psychiatric consultation, may also be beneficial.[18, 19, 20, 21] Many nonpharmacological interventions may need to be multicomponent in nature, as has been described previously.[18, 19, 20, 21]