User login

What to Know About NOSE

Traditionally, a laparoscopic approach to bowel resection secondary to endometriosis means enlargement of the port site or more commonly, a Pfannenstiel incision to introduce an anvil. Both incisions raise the risk of postoperative complications including pain and incisional hernia. Moreover, recovery time is prolonged.

Natural orifice specimen extraction (NOSE) makes use of a natural orifice, the vagina or anus, to extract the specimen and introduce the anvil. Transanal extraction for the management of endometriosis-related bowel disease was first described by the late David Redwine, MD, in his 1996 publication in Fertility and Sterility.1

The concern with use of vaginal NOSE surgery is rectovaginal fistula secondary to two incision lines in close opposition. Both transvaginal NOSE and transanal NOSE have been criticized for longer dissection of the mesorectum and thus longer resected specimen. Despite these concerns, over the past 10 years, articles have been published showing not only the feasibility of the NOSE technique, but excellent comparative outcomes, as well.2-4

A recent systematic review and meta-analysis by Kar et al. comparing NOSE extraction to minilaparotomy in bowel resection due to endometriosis revealed no significant difference in complication rate, but significantly shorter operation duration, reduced length of stay, and less blood loss in the NOSE surgical arm.5

The most recent study to be published in the Journal of Minimally Invasive Gynecology involving total laparoscopic segmental resection with transanal NOSE for the treatment of colorectal endometriosis was written by the guest author of this edition of the Master Class in Gynecologic Surgery, Professor Mario Malzoni, Scientific Director of the Malzoni Research Hospital, the Center for Advanced Pelvic Surgery, in Avellino, Italy. In the JMIG article, and in this Master Class, Professor Malzoni, a world-renowned endometriosis specialist recognized for his extraordinary skill and multi-organ surgical work, discusses the difference between the standard bowel resection technique with that of NOSE, and reports on his experience with NOSE.6

It is a pleasure and honor to welcome my friend and colleague, Professor Mario Malzoni, to this edition of the Master Class in Gynecologic Surgery.

Dr. Charles E. Miller is Professor, Obstetrics & Gynecology, Department of Clinical Sciences, Rosalind Franklin University of Medicine and Science, North Chicago, and Director, Minimally Invasive Gynecologic Surgery, Advocate Lutheran General Hospital, Park Ridge, both in Illinois. Email him at obnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. Redwine DB et al. Laparoscopically assisted transvaginal segmental resection of the rectosigmoid colon for endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 1996 Jan;65(1):193-7.

2. Akladios C et al. Totally laparoscopic intracorporeal anastomosis with natural orifice specimen extraction (NOSE) techniques, particularly suitable for bowel endometriosis. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2014 Nov-Dec;21(6):1095-102.

3. Bokor A et al. Natural orifice specimen extraction during laparoscopic bowel resection for colorectal endometriosis: technique and outcome. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2018 Sep-Oct;25(6):1065-74.

4. Grigoriadis G et al. Natural orifice specimen extraction colorectal resection for deep endometriosis: A 50 case series. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2022 Sep;29(9):1054-62.

5. Kar E et al. Natural orifice specimen extraction as a promising alternative for minilaparotomy in bowel resection due to endometriosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2024 Jul;31(7):574-83.e1.

6. Malzoni M et al. Total laparoscopic segmental resection with transanal natural orifice specimen extraction for treatment of colorectal endometriosis: Descriptive analysis from the TrEnd study database. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2024 Oct;18:S1553-4650(24)01453-5.

Laparoscopic Resection With Transanal NOSE for Deep Colorectal Endometriosis

When segmental sigmoid colon/rectal resection is indicated for treatment of deep infiltrating bowel endometriosis, a totally laparoscopic resection with intracorporeal anastomosis and transanal natural orifice specimen extraction (NOSE) can be safe, effective, and advantageous compared with an abdominal mini-laparotomy for extracorporeal anastomosis and specimen retrieval.

With advanced laparoscopic surgical skills, accurate preoperative ultrasound evaluation, and a high-quality perioperative care protocol (including high-quality bowel preparation), segmental resection with NOSE can offer better preservation of vascularization, smaller resection sizes, lower rates of postoperative pain, a shorter time for gas passage after surgery, decreased hospital stays, and lower rates of wound infection and incisional hernia.

We have seen such improved results in our high-volume center since shifting in April 2021 from our classical technique for segmental rectosigmoid resection1 to a totally laparoscopic approach with NOSE. We first reported on this new technique in 2022 in a video article in the Journal of Minimally Invasive Gynecology,2and in October 2024, outcomes of 81 patients who underwent segmental sigmoid colon/rectal resection with intracorporeal anastomosis and transanal NOSE at our institution from April 2021 through March 2024 were reported in Journal of Minimally Invasive Gynecology.3Given our experience with this approach for deep endometriosis, I am convinced that NOSE should be preferred to transabdominal specimen extraction for segmental rectosigmoid resection. This is where the future lies for deep infiltrating endometriosis. Here, I share our outcomes and describe our technique.

Our Prior Approach With A Mini-Laparotomy

Our traditional laparoscopic approach for segmental colon/rectal resection of deep infiltrating endometriosis involved an abdominal mini-laparotomy (no more than 4 cm in length) for specimen retrieval, resection of the proximal rectum, and positioning of the head of a circular stapler for end-to-end anastomosis. (Connection of the two parts of the circular stapler for anastomosis was achieved via laparoscopy.)1

Several factors allowed us to minimize potential complications, including standardization of our technique, the use of three-dimensional endoscopes, and indocyanine green fluorescence angiography to assess the perfusion of the bowel after the completion of anastomosis. Still, an unpublished analysis of 1050 segmental bowel resections performed over more than 17 years using our traditional technique showed that hospital stays averaged 8 days, time to first defecation averaged 7 days, and time to first passage of flatus averaged 1 day.

Per the Clavien-Dindo classification system for surgical complications that was used at the time, 1.9% of these 1050 patients had grade 1 (minor) or grade 2 complications and 6% had grade 3 complications. Grade 2 complications were defined as needing intervention or a hospital stay more than twice the median for the procedure. Grade 3 complications were defined as leading to lasting disability or organ resection.

In the meantime, in colorectal cancer surgery, published studies on NOSE versus conventional laparoscopy with transabdominal specimen extraction have consistently pointed to the benefits of NOSE. A 2022 review 4 of 19 studies involving over 3400 patients and a 2022 meta-analysis 5 of 21 randomized controlled trials involving more than 2000 patients both showed significantly reduced postoperative morbidity and no differences in oncologic outcomes. Among the notable differences in the 2022 meta-analysis was a relative risk of postoperative infection of 0.34 for patients treated with NOSE compared with conventional laparoscopic techniques.

Among patients with deep rectal endometriosis, reported experience with intracorporeal anastomosis and NOSE for segmental resection is limited, with a few studies published between 2014 and 2022. Excluding anecdotal reports, only about 140 patients have been reported in the literature as having intracorporeal anastomosis and transanal NOSE for deep infiltrating bowel endometriosis. 3

Our Outcomes With A Totally Laparoscopic Approach

Our approach to evaluating our experience with totally laparoscopic resection with transanal NOSE has been to systematically collect data from consecutive patients and to analyze 1) complications of the technique, 2) conversion to the traditional technique/open surgery, and 3) endometriosis-free bowel resection margins and recurrence. Secondarily, we look at intraoperative blood loss, operative time, recovery of gastrointestinal function, hospital stay length, and reproductive outcomes.

Across 81 patients from our TrEnd study database (Surgical TReatment of women with deep ENDometriosis infiltrating the sigmoid colon and/or rectum) who received a totally laparoscopic standardized procedure involving intracorporeal anastomosis and transanal NOSE, we had no conversions even to mini-laparotomy, and no cases of protective colostomy or ileostomy.

Complete endometriosis removal was achieved in 100% of cases, with final pathology showing endometriosis-free resection margins, and patients remained free of bowel endometriosis at a median follow-up of 21 months.3Our analysis also shows improved gastrointestinal function recovery (median time to first defecation of 4 days, compared to 7 days previously, with the same 1-day median time to first passage of flatus) and a significantly improved hospital length of stay to a median of 3 days (interquartile range, 3-4.5 days); the latter reflects in part the absence of infection.3There were no intra-operative complications. Postoperative Clavien-Dindo grade 3 complications occurred in three patients (3.7%), two of whom required reoperation (one for hemoperitoneum and one for ureteral injury) and one who experienced rectal anastomotic bleeding on postoperative day 1. (The two requiring reoperation had significant right lateral parametrial involvement and underwent nerve-sparing parametrectomy at the time of bowel resection).3Notably, 7 of the 81 patients had totally laparoscopic double segmental colorectal resection — 6 with simultaneous ileocecal valve and rectal resection, and 1 with simultaneous ileal and rectal resection. None of these seven patients had postoperative complications. (A report on the six surgeries for deep endometriosis infiltrating the ileocecal valve and rectum was also published this year in the journal Colorectal Disease.6)

Median blood loss in the 81-patient cohort was 20 mL (IQR, 20-30 mL), and the median length of surgery was 160 minutes (IQR, 130-210 minutes).

Bowel endometriotic nodules had a mean maximum diameter of 4.3 cm (3.5-5.5 cm), a mean depth of invasion of 9 mm (7-9 mm), a mean estimated stenosis of 40% (35%-50%), and a mean distance from the anal verge of 13 cm (10-15 cm).3 (The cohort in this analysis did not include patients who received concomitant hysterectomy and transvaginal NOSE.)

Specifics of the New Technique, Including Totally Intracorporeal Anastomosis

As in our previous technique, the surgical procedure starts with left and dorsal rectal mobilization. The left pelvic sidewall dissection begins with incision of the parietal peritoneum along the pelvic portions of the psoas muscle. The retroperitoneal connective tissue is dissected in order to identify the ureter, the hypogastric nerve, and the presacral parietal pelvic fascia (PPPF). Dissection is carried downward in front of the PPPF and medially to the left hypogastric nerve.

Right and ventral rectal mobilization begins with incision of the peritoneum along the gray avascular line, which is seen with upward retraction of the rectum.

Again, for preservation of bowel and bladder function, the hypogastric nerve must be identified and preserved through dissection that displaces the nerve dorsally and laterally.

Dissection proceeds to sharply divide the nodule into two parts (rectal and rectocervical components). The caudal boundary of ventral dissection is reached by incising the septum and opening the rectovaginal space. The lymphovascular fatty tissue surrounding the rectum is then excised and the rectal tube is denuded at the level of the distal resection margin.

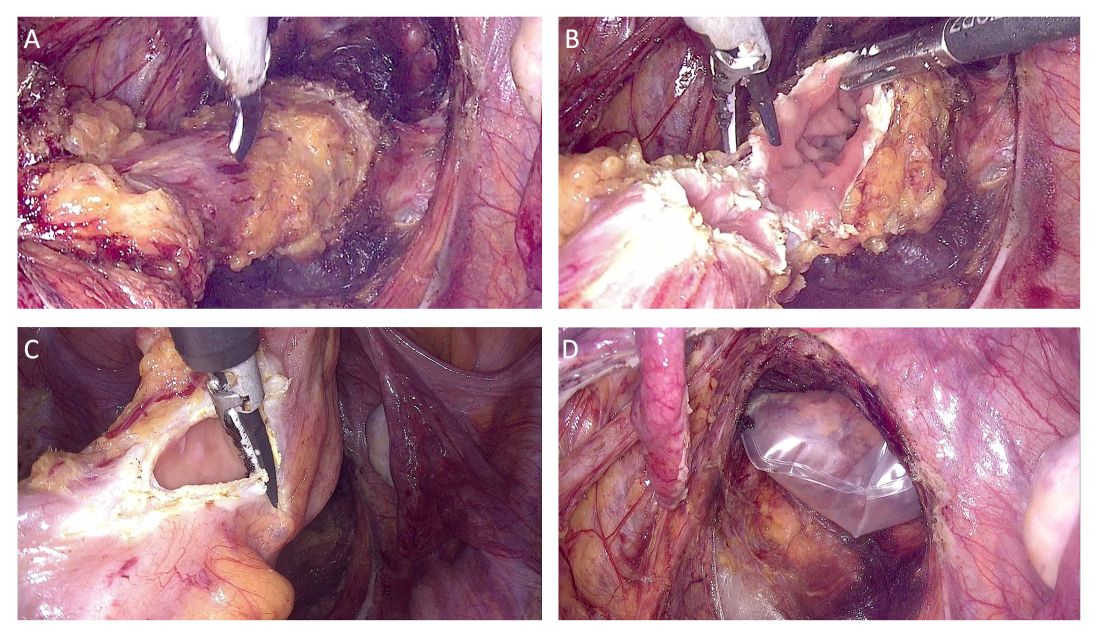

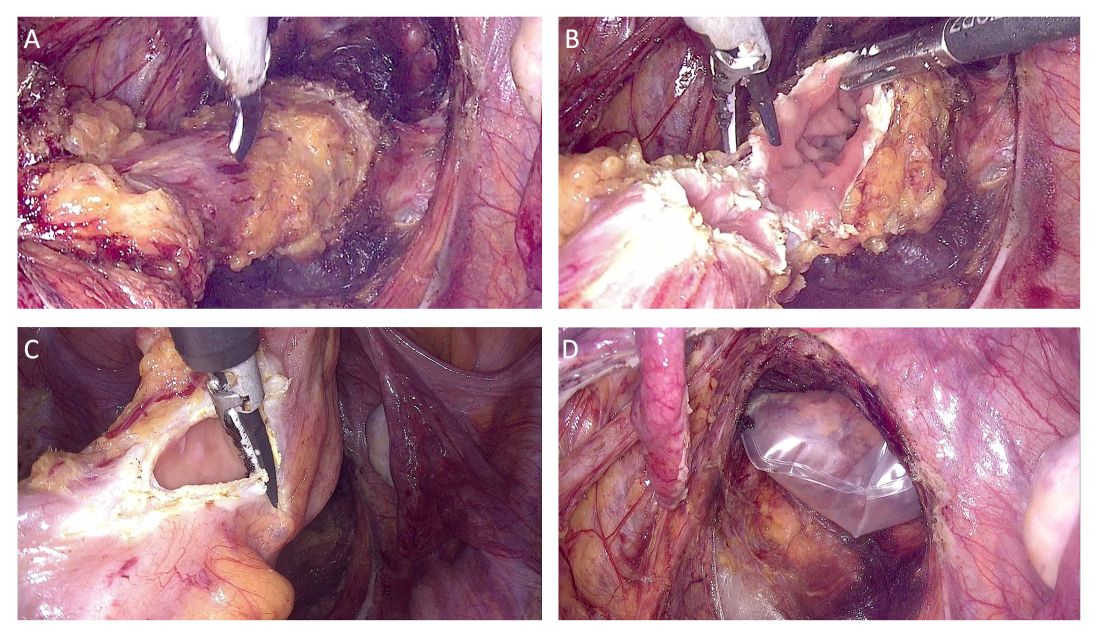

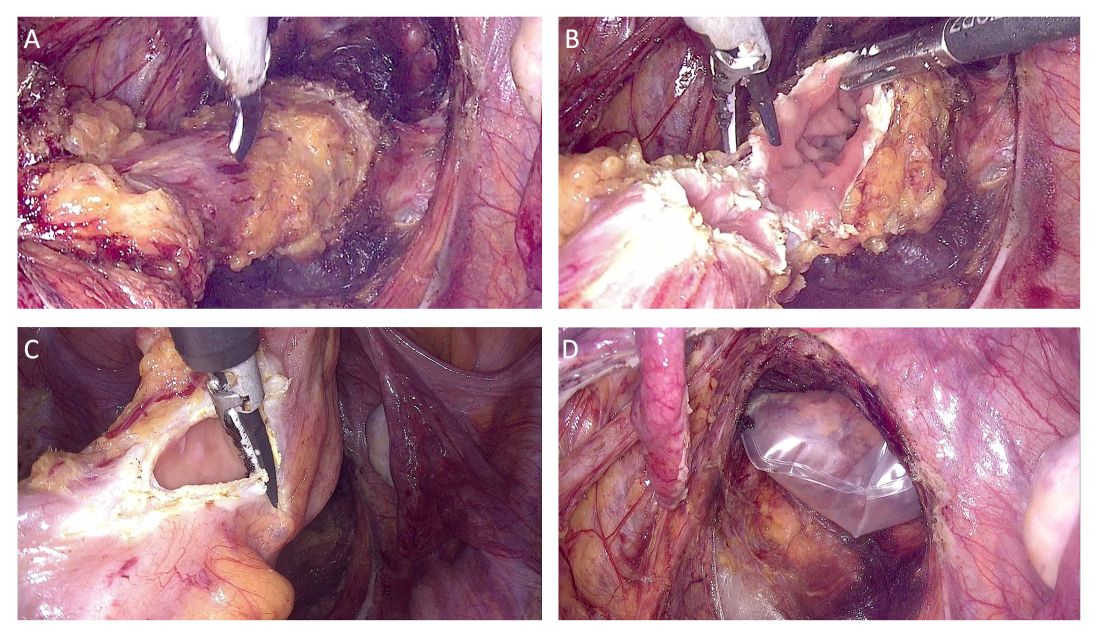

The distal and proximal resection margins are prepared and transected using a tissue-sealing device, and the resected rectal specimen is placed into a retrieval bag and pulled out through the anus (Figure 1).

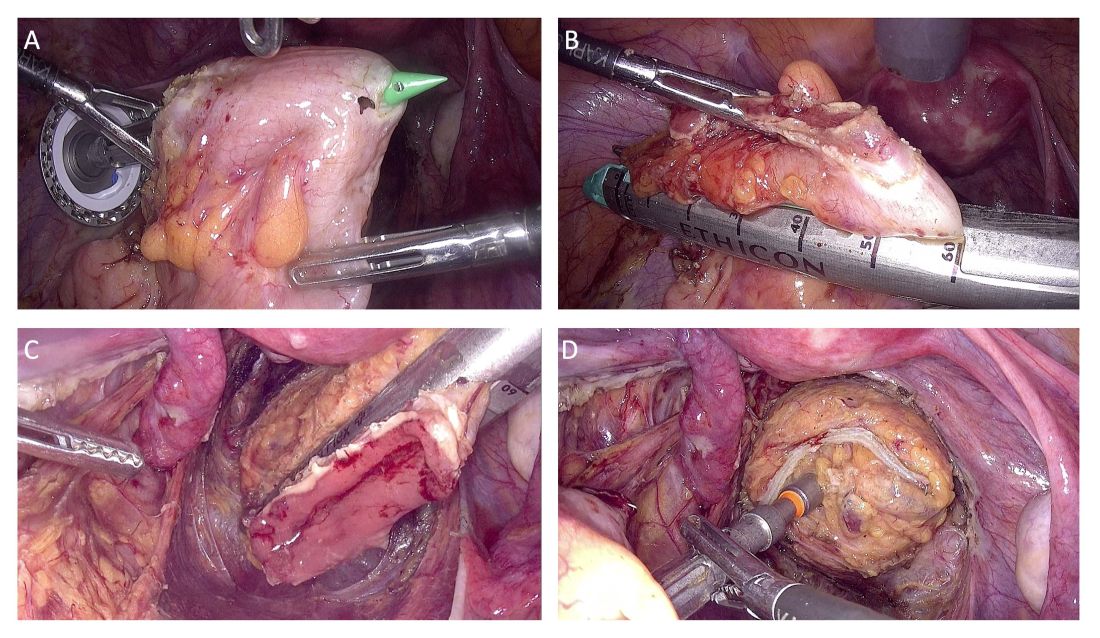

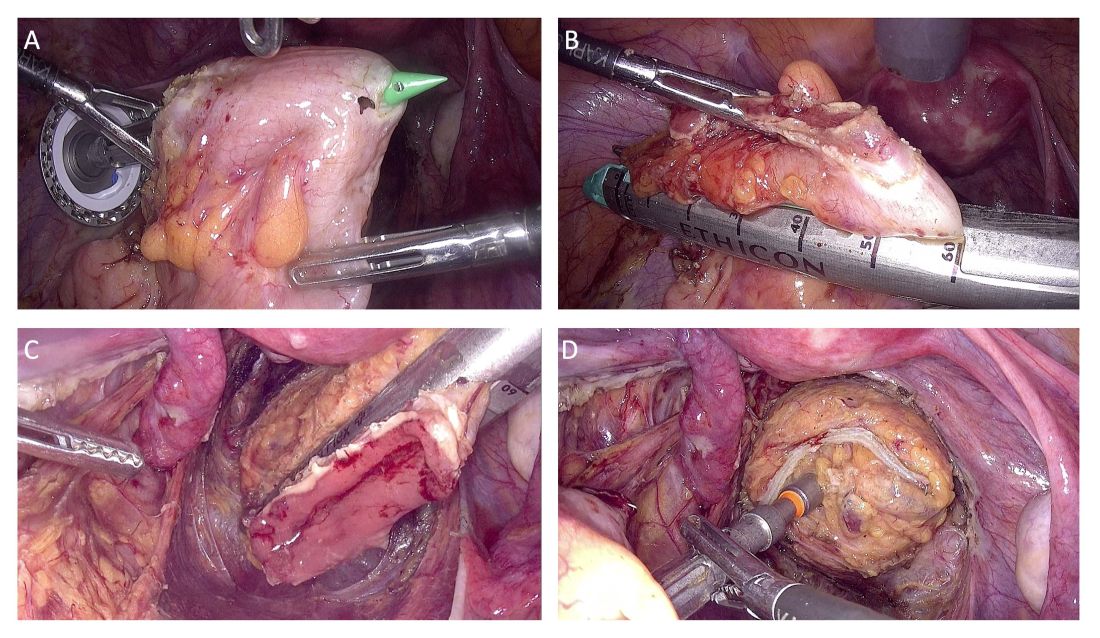

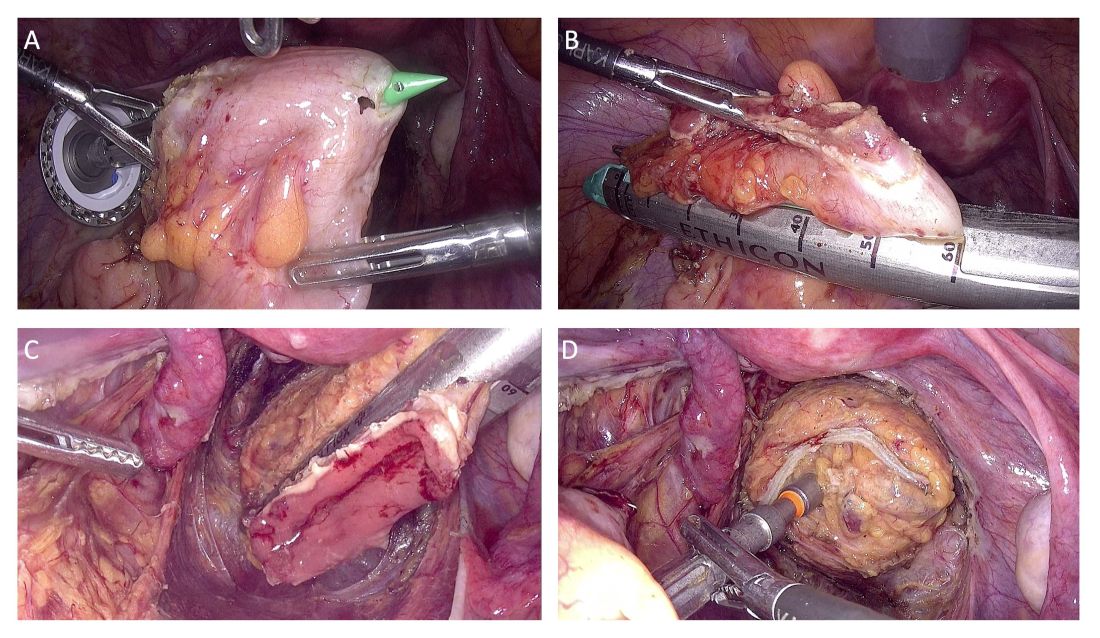

The totally intracorporeal side-to-end anastomosis is performed using a traditional circular stapler. Its anvil is inserted through the proximal resection line and exteriorized forward on the antimesenteric side of the sigmoid colon/rectum. The proximal and distal resection lines are closed with a 60-mm linear endo-stapler, and finally, the shaft of the circular stapler is inserted into the rectum, and the two parts of the stapler are joined. The stapler is then closed and fired (Figure 2).

An air leak test is performed to check the quality of the rectal sutures. However, regardless of the results, we routinely apply interrupted stitches to the so-called “dog ears” in order to reduce tension along the anastomotic line.

We also evaluate the microvascularization of the two parts of the bowel at the level of the reanastomosis using indocyanine green fluorescence angiography. Doing so allows us to avoid complications caused by anastomotic leakage.

Patient Selection And Peri-Surgical Care

The decision to perform segmental resection as opposed to other more conservative laparoscopic excision techniques is made after skilled preoperative imaging reveals the number of lesions, the largest nodule diameter, the infiltration depth, and the circumference of bowel involvement.

A recently published international consensus statement7 on noninvasive imaging techniques for diagnosis of pelvic deep endometriosis and endometriosis classification systems concludes there is Level 1a evidence that preoperative imaging with transvaginal ultrasound (TVUS) can predict with good precision the size and degree of infiltration of deep endometriosis of the rectum (a Grade A statement, per the Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine levels of evidence).

The consensus document was published across seven different journals by international and European societies, and the American Association of Gynecologic Laparoscopists (AAGL), each of which contributed to a multidisciplinary panel of gynecological surgeons, sonographers, and radiologists.

At our center, we achieve precise preoperative evaluations with TVUS (other centers also employ MRI) and have long set clear preoperative indications for segmental resection. Based on our experience,8 a nodule ≥ 3 cm and infiltration of the tunica muscularis of the sigmoid colon/rectum ≥ 7 mm indicate the need for segmental resection. It is impossible to achieve surgical goals in such cases through shaving or discoid resection.

Our perioperative care protocol for total laparoscopic segmental resection with transanal NOSE, described in our new paper,3 includes several components: antibiotic therapy (metronidazole 500 mg 12 hours before surgery; cefazolin 2 g plus metronidazole 500 mg 1 hour before skin incision; and cefazolin 1 g plus metronidazole 500 mg 12 hours after surgery); good intraoperative bowel preparation (mechanical with oral polyethylene glycol solution preoperatively, and rectal irrigation with a mixed solution of povidine-iodine and normal saline intraoperatively); and venous thromboembolism prophylaxis postoperatively for 28 days.

Moving Forward, A Word On Classification

Multicenter trials and research with longer follow-up times will be helpful in advancing the use of totally laparoscopic segmental colorectal resection for deep endometriosis. To enable better sharing of diagnostic and therapeutic results — and to advance the credibility of research — my hope is that the field will reach further agreement on endometriosis classification systems. This would also help with the development of standards for postgraduate education.

We have made significant strides in recognizing imaging as a standard for diagnosis and treatment, and I believe we currently have two very good endometriosis classification systems — the #Enzian classification system issued in 2021 and the AAGL 2021 Endometriosis Classification — that can be used in combination with imaging to reliably and consistently describe deep endometriosis.

Mario Malzoni, MD, is scientific director of the Malzoni Research Hospital, the Center for Advanced Pelvic Surgery, in Avellino, Italy. He reported having no disclosures relevant to this Master Class.

References

1. Malzoni M et al. Surgical principles of segmental rectosigmoid resection and reanastomosis for deep infiltrating endometriosis. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2020;27(2):258.

2. Malzoni M et al. Totally laparoscopic resection with transanal natural orifice specimen extraction for deep endometriosis infiltrating the rectum. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2022;29(1):19.

3. Malzoni M et al. Total laparoscopic segmental resection with transanal natural orifice specimen extraction for treatment of colorectal endometriosis: Descriptive analysis from the TrEnd study database. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2024. (in press). 4. Brincat SD et al. Natural orifice versus transabdominal specimen extraction in laparoscopic surgery for colorectal cancer: meta-analysis. BJS Open 2022;6(3):zrac074.

5. Zhou Z et al. Laparoscopic natural orifice specimen extraction surgery versus conventional surgery in colorectal cancer: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2022 Jan 18;2022:6661651.

6. Malzoni M et al. Simultaneous total laparoscopic double segmental resection with transanal natural orifice specimen extraction for deep endometriosis infiltrating the ileocaecal valve and rectum—A video vignette. Colorectal Dis 2024 Jul 25.

7. Condous G et al. Noninvasive imaging techniques for diagnosis of pelvic deep endometriosis and endometriosis classification systems: An international consensus. J. Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2024;31(7):557-73.

8. Malzoni M et al. Preoperative ultrasound indications determine excision technique for bowel surgery for deep infiltrating endometriosis: A single, high-volume center. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2020;27(5):1141-7.

What to Know About NOSE

Traditionally, a laparoscopic approach to bowel resection secondary to endometriosis means enlargement of the port site or more commonly, a Pfannenstiel incision to introduce an anvil. Both incisions raise the risk of postoperative complications including pain and incisional hernia. Moreover, recovery time is prolonged.

Natural orifice specimen extraction (NOSE) makes use of a natural orifice, the vagina or anus, to extract the specimen and introduce the anvil. Transanal extraction for the management of endometriosis-related bowel disease was first described by the late David Redwine, MD, in his 1996 publication in Fertility and Sterility.1

The concern with use of vaginal NOSE surgery is rectovaginal fistula secondary to two incision lines in close opposition. Both transvaginal NOSE and transanal NOSE have been criticized for longer dissection of the mesorectum and thus longer resected specimen. Despite these concerns, over the past 10 years, articles have been published showing not only the feasibility of the NOSE technique, but excellent comparative outcomes, as well.2-4

A recent systematic review and meta-analysis by Kar et al. comparing NOSE extraction to minilaparotomy in bowel resection due to endometriosis revealed no significant difference in complication rate, but significantly shorter operation duration, reduced length of stay, and less blood loss in the NOSE surgical arm.5

The most recent study to be published in the Journal of Minimally Invasive Gynecology involving total laparoscopic segmental resection with transanal NOSE for the treatment of colorectal endometriosis was written by the guest author of this edition of the Master Class in Gynecologic Surgery, Professor Mario Malzoni, Scientific Director of the Malzoni Research Hospital, the Center for Advanced Pelvic Surgery, in Avellino, Italy. In the JMIG article, and in this Master Class, Professor Malzoni, a world-renowned endometriosis specialist recognized for his extraordinary skill and multi-organ surgical work, discusses the difference between the standard bowel resection technique with that of NOSE, and reports on his experience with NOSE.6

It is a pleasure and honor to welcome my friend and colleague, Professor Mario Malzoni, to this edition of the Master Class in Gynecologic Surgery.

Dr. Charles E. Miller is Professor, Obstetrics & Gynecology, Department of Clinical Sciences, Rosalind Franklin University of Medicine and Science, North Chicago, and Director, Minimally Invasive Gynecologic Surgery, Advocate Lutheran General Hospital, Park Ridge, both in Illinois. Email him at obnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. Redwine DB et al. Laparoscopically assisted transvaginal segmental resection of the rectosigmoid colon for endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 1996 Jan;65(1):193-7.

2. Akladios C et al. Totally laparoscopic intracorporeal anastomosis with natural orifice specimen extraction (NOSE) techniques, particularly suitable for bowel endometriosis. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2014 Nov-Dec;21(6):1095-102.

3. Bokor A et al. Natural orifice specimen extraction during laparoscopic bowel resection for colorectal endometriosis: technique and outcome. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2018 Sep-Oct;25(6):1065-74.

4. Grigoriadis G et al. Natural orifice specimen extraction colorectal resection for deep endometriosis: A 50 case series. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2022 Sep;29(9):1054-62.

5. Kar E et al. Natural orifice specimen extraction as a promising alternative for minilaparotomy in bowel resection due to endometriosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2024 Jul;31(7):574-83.e1.

6. Malzoni M et al. Total laparoscopic segmental resection with transanal natural orifice specimen extraction for treatment of colorectal endometriosis: Descriptive analysis from the TrEnd study database. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2024 Oct;18:S1553-4650(24)01453-5.

Laparoscopic Resection With Transanal NOSE for Deep Colorectal Endometriosis

When segmental sigmoid colon/rectal resection is indicated for treatment of deep infiltrating bowel endometriosis, a totally laparoscopic resection with intracorporeal anastomosis and transanal natural orifice specimen extraction (NOSE) can be safe, effective, and advantageous compared with an abdominal mini-laparotomy for extracorporeal anastomosis and specimen retrieval.

With advanced laparoscopic surgical skills, accurate preoperative ultrasound evaluation, and a high-quality perioperative care protocol (including high-quality bowel preparation), segmental resection with NOSE can offer better preservation of vascularization, smaller resection sizes, lower rates of postoperative pain, a shorter time for gas passage after surgery, decreased hospital stays, and lower rates of wound infection and incisional hernia.

We have seen such improved results in our high-volume center since shifting in April 2021 from our classical technique for segmental rectosigmoid resection1 to a totally laparoscopic approach with NOSE. We first reported on this new technique in 2022 in a video article in the Journal of Minimally Invasive Gynecology,2and in October 2024, outcomes of 81 patients who underwent segmental sigmoid colon/rectal resection with intracorporeal anastomosis and transanal NOSE at our institution from April 2021 through March 2024 were reported in Journal of Minimally Invasive Gynecology.3Given our experience with this approach for deep endometriosis, I am convinced that NOSE should be preferred to transabdominal specimen extraction for segmental rectosigmoid resection. This is where the future lies for deep infiltrating endometriosis. Here, I share our outcomes and describe our technique.

Our Prior Approach With A Mini-Laparotomy

Our traditional laparoscopic approach for segmental colon/rectal resection of deep infiltrating endometriosis involved an abdominal mini-laparotomy (no more than 4 cm in length) for specimen retrieval, resection of the proximal rectum, and positioning of the head of a circular stapler for end-to-end anastomosis. (Connection of the two parts of the circular stapler for anastomosis was achieved via laparoscopy.)1

Several factors allowed us to minimize potential complications, including standardization of our technique, the use of three-dimensional endoscopes, and indocyanine green fluorescence angiography to assess the perfusion of the bowel after the completion of anastomosis. Still, an unpublished analysis of 1050 segmental bowel resections performed over more than 17 years using our traditional technique showed that hospital stays averaged 8 days, time to first defecation averaged 7 days, and time to first passage of flatus averaged 1 day.

Per the Clavien-Dindo classification system for surgical complications that was used at the time, 1.9% of these 1050 patients had grade 1 (minor) or grade 2 complications and 6% had grade 3 complications. Grade 2 complications were defined as needing intervention or a hospital stay more than twice the median for the procedure. Grade 3 complications were defined as leading to lasting disability or organ resection.

In the meantime, in colorectal cancer surgery, published studies on NOSE versus conventional laparoscopy with transabdominal specimen extraction have consistently pointed to the benefits of NOSE. A 2022 review 4 of 19 studies involving over 3400 patients and a 2022 meta-analysis 5 of 21 randomized controlled trials involving more than 2000 patients both showed significantly reduced postoperative morbidity and no differences in oncologic outcomes. Among the notable differences in the 2022 meta-analysis was a relative risk of postoperative infection of 0.34 for patients treated with NOSE compared with conventional laparoscopic techniques.

Among patients with deep rectal endometriosis, reported experience with intracorporeal anastomosis and NOSE for segmental resection is limited, with a few studies published between 2014 and 2022. Excluding anecdotal reports, only about 140 patients have been reported in the literature as having intracorporeal anastomosis and transanal NOSE for deep infiltrating bowel endometriosis. 3

Our Outcomes With A Totally Laparoscopic Approach

Our approach to evaluating our experience with totally laparoscopic resection with transanal NOSE has been to systematically collect data from consecutive patients and to analyze 1) complications of the technique, 2) conversion to the traditional technique/open surgery, and 3) endometriosis-free bowel resection margins and recurrence. Secondarily, we look at intraoperative blood loss, operative time, recovery of gastrointestinal function, hospital stay length, and reproductive outcomes.

Across 81 patients from our TrEnd study database (Surgical TReatment of women with deep ENDometriosis infiltrating the sigmoid colon and/or rectum) who received a totally laparoscopic standardized procedure involving intracorporeal anastomosis and transanal NOSE, we had no conversions even to mini-laparotomy, and no cases of protective colostomy or ileostomy.

Complete endometriosis removal was achieved in 100% of cases, with final pathology showing endometriosis-free resection margins, and patients remained free of bowel endometriosis at a median follow-up of 21 months.3Our analysis also shows improved gastrointestinal function recovery (median time to first defecation of 4 days, compared to 7 days previously, with the same 1-day median time to first passage of flatus) and a significantly improved hospital length of stay to a median of 3 days (interquartile range, 3-4.5 days); the latter reflects in part the absence of infection.3There were no intra-operative complications. Postoperative Clavien-Dindo grade 3 complications occurred in three patients (3.7%), two of whom required reoperation (one for hemoperitoneum and one for ureteral injury) and one who experienced rectal anastomotic bleeding on postoperative day 1. (The two requiring reoperation had significant right lateral parametrial involvement and underwent nerve-sparing parametrectomy at the time of bowel resection).3Notably, 7 of the 81 patients had totally laparoscopic double segmental colorectal resection — 6 with simultaneous ileocecal valve and rectal resection, and 1 with simultaneous ileal and rectal resection. None of these seven patients had postoperative complications. (A report on the six surgeries for deep endometriosis infiltrating the ileocecal valve and rectum was also published this year in the journal Colorectal Disease.6)

Median blood loss in the 81-patient cohort was 20 mL (IQR, 20-30 mL), and the median length of surgery was 160 minutes (IQR, 130-210 minutes).

Bowel endometriotic nodules had a mean maximum diameter of 4.3 cm (3.5-5.5 cm), a mean depth of invasion of 9 mm (7-9 mm), a mean estimated stenosis of 40% (35%-50%), and a mean distance from the anal verge of 13 cm (10-15 cm).3 (The cohort in this analysis did not include patients who received concomitant hysterectomy and transvaginal NOSE.)

Specifics of the New Technique, Including Totally Intracorporeal Anastomosis

As in our previous technique, the surgical procedure starts with left and dorsal rectal mobilization. The left pelvic sidewall dissection begins with incision of the parietal peritoneum along the pelvic portions of the psoas muscle. The retroperitoneal connective tissue is dissected in order to identify the ureter, the hypogastric nerve, and the presacral parietal pelvic fascia (PPPF). Dissection is carried downward in front of the PPPF and medially to the left hypogastric nerve.

Right and ventral rectal mobilization begins with incision of the peritoneum along the gray avascular line, which is seen with upward retraction of the rectum.

Again, for preservation of bowel and bladder function, the hypogastric nerve must be identified and preserved through dissection that displaces the nerve dorsally and laterally.

Dissection proceeds to sharply divide the nodule into two parts (rectal and rectocervical components). The caudal boundary of ventral dissection is reached by incising the septum and opening the rectovaginal space. The lymphovascular fatty tissue surrounding the rectum is then excised and the rectal tube is denuded at the level of the distal resection margin.

The distal and proximal resection margins are prepared and transected using a tissue-sealing device, and the resected rectal specimen is placed into a retrieval bag and pulled out through the anus (Figure 1).

The totally intracorporeal side-to-end anastomosis is performed using a traditional circular stapler. Its anvil is inserted through the proximal resection line and exteriorized forward on the antimesenteric side of the sigmoid colon/rectum. The proximal and distal resection lines are closed with a 60-mm linear endo-stapler, and finally, the shaft of the circular stapler is inserted into the rectum, and the two parts of the stapler are joined. The stapler is then closed and fired (Figure 2).

An air leak test is performed to check the quality of the rectal sutures. However, regardless of the results, we routinely apply interrupted stitches to the so-called “dog ears” in order to reduce tension along the anastomotic line.

We also evaluate the microvascularization of the two parts of the bowel at the level of the reanastomosis using indocyanine green fluorescence angiography. Doing so allows us to avoid complications caused by anastomotic leakage.

Patient Selection And Peri-Surgical Care

The decision to perform segmental resection as opposed to other more conservative laparoscopic excision techniques is made after skilled preoperative imaging reveals the number of lesions, the largest nodule diameter, the infiltration depth, and the circumference of bowel involvement.

A recently published international consensus statement7 on noninvasive imaging techniques for diagnosis of pelvic deep endometriosis and endometriosis classification systems concludes there is Level 1a evidence that preoperative imaging with transvaginal ultrasound (TVUS) can predict with good precision the size and degree of infiltration of deep endometriosis of the rectum (a Grade A statement, per the Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine levels of evidence).

The consensus document was published across seven different journals by international and European societies, and the American Association of Gynecologic Laparoscopists (AAGL), each of which contributed to a multidisciplinary panel of gynecological surgeons, sonographers, and radiologists.

At our center, we achieve precise preoperative evaluations with TVUS (other centers also employ MRI) and have long set clear preoperative indications for segmental resection. Based on our experience,8 a nodule ≥ 3 cm and infiltration of the tunica muscularis of the sigmoid colon/rectum ≥ 7 mm indicate the need for segmental resection. It is impossible to achieve surgical goals in such cases through shaving or discoid resection.

Our perioperative care protocol for total laparoscopic segmental resection with transanal NOSE, described in our new paper,3 includes several components: antibiotic therapy (metronidazole 500 mg 12 hours before surgery; cefazolin 2 g plus metronidazole 500 mg 1 hour before skin incision; and cefazolin 1 g plus metronidazole 500 mg 12 hours after surgery); good intraoperative bowel preparation (mechanical with oral polyethylene glycol solution preoperatively, and rectal irrigation with a mixed solution of povidine-iodine and normal saline intraoperatively); and venous thromboembolism prophylaxis postoperatively for 28 days.

Moving Forward, A Word On Classification

Multicenter trials and research with longer follow-up times will be helpful in advancing the use of totally laparoscopic segmental colorectal resection for deep endometriosis. To enable better sharing of diagnostic and therapeutic results — and to advance the credibility of research — my hope is that the field will reach further agreement on endometriosis classification systems. This would also help with the development of standards for postgraduate education.

We have made significant strides in recognizing imaging as a standard for diagnosis and treatment, and I believe we currently have two very good endometriosis classification systems — the #Enzian classification system issued in 2021 and the AAGL 2021 Endometriosis Classification — that can be used in combination with imaging to reliably and consistently describe deep endometriosis.

Mario Malzoni, MD, is scientific director of the Malzoni Research Hospital, the Center for Advanced Pelvic Surgery, in Avellino, Italy. He reported having no disclosures relevant to this Master Class.

References

1. Malzoni M et al. Surgical principles of segmental rectosigmoid resection and reanastomosis for deep infiltrating endometriosis. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2020;27(2):258.

2. Malzoni M et al. Totally laparoscopic resection with transanal natural orifice specimen extraction for deep endometriosis infiltrating the rectum. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2022;29(1):19.

3. Malzoni M et al. Total laparoscopic segmental resection with transanal natural orifice specimen extraction for treatment of colorectal endometriosis: Descriptive analysis from the TrEnd study database. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2024. (in press). 4. Brincat SD et al. Natural orifice versus transabdominal specimen extraction in laparoscopic surgery for colorectal cancer: meta-analysis. BJS Open 2022;6(3):zrac074.

5. Zhou Z et al. Laparoscopic natural orifice specimen extraction surgery versus conventional surgery in colorectal cancer: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2022 Jan 18;2022:6661651.

6. Malzoni M et al. Simultaneous total laparoscopic double segmental resection with transanal natural orifice specimen extraction for deep endometriosis infiltrating the ileocaecal valve and rectum—A video vignette. Colorectal Dis 2024 Jul 25.

7. Condous G et al. Noninvasive imaging techniques for diagnosis of pelvic deep endometriosis and endometriosis classification systems: An international consensus. J. Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2024;31(7):557-73.

8. Malzoni M et al. Preoperative ultrasound indications determine excision technique for bowel surgery for deep infiltrating endometriosis: A single, high-volume center. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2020;27(5):1141-7.

What to Know About NOSE

Traditionally, a laparoscopic approach to bowel resection secondary to endometriosis means enlargement of the port site or more commonly, a Pfannenstiel incision to introduce an anvil. Both incisions raise the risk of postoperative complications including pain and incisional hernia. Moreover, recovery time is prolonged.

Natural orifice specimen extraction (NOSE) makes use of a natural orifice, the vagina or anus, to extract the specimen and introduce the anvil. Transanal extraction for the management of endometriosis-related bowel disease was first described by the late David Redwine, MD, in his 1996 publication in Fertility and Sterility.1

The concern with use of vaginal NOSE surgery is rectovaginal fistula secondary to two incision lines in close opposition. Both transvaginal NOSE and transanal NOSE have been criticized for longer dissection of the mesorectum and thus longer resected specimen. Despite these concerns, over the past 10 years, articles have been published showing not only the feasibility of the NOSE technique, but excellent comparative outcomes, as well.2-4

A recent systematic review and meta-analysis by Kar et al. comparing NOSE extraction to minilaparotomy in bowel resection due to endometriosis revealed no significant difference in complication rate, but significantly shorter operation duration, reduced length of stay, and less blood loss in the NOSE surgical arm.5

The most recent study to be published in the Journal of Minimally Invasive Gynecology involving total laparoscopic segmental resection with transanal NOSE for the treatment of colorectal endometriosis was written by the guest author of this edition of the Master Class in Gynecologic Surgery, Professor Mario Malzoni, Scientific Director of the Malzoni Research Hospital, the Center for Advanced Pelvic Surgery, in Avellino, Italy. In the JMIG article, and in this Master Class, Professor Malzoni, a world-renowned endometriosis specialist recognized for his extraordinary skill and multi-organ surgical work, discusses the difference between the standard bowel resection technique with that of NOSE, and reports on his experience with NOSE.6

It is a pleasure and honor to welcome my friend and colleague, Professor Mario Malzoni, to this edition of the Master Class in Gynecologic Surgery.

Dr. Charles E. Miller is Professor, Obstetrics & Gynecology, Department of Clinical Sciences, Rosalind Franklin University of Medicine and Science, North Chicago, and Director, Minimally Invasive Gynecologic Surgery, Advocate Lutheran General Hospital, Park Ridge, both in Illinois. Email him at obnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. Redwine DB et al. Laparoscopically assisted transvaginal segmental resection of the rectosigmoid colon for endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 1996 Jan;65(1):193-7.

2. Akladios C et al. Totally laparoscopic intracorporeal anastomosis with natural orifice specimen extraction (NOSE) techniques, particularly suitable for bowel endometriosis. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2014 Nov-Dec;21(6):1095-102.

3. Bokor A et al. Natural orifice specimen extraction during laparoscopic bowel resection for colorectal endometriosis: technique and outcome. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2018 Sep-Oct;25(6):1065-74.

4. Grigoriadis G et al. Natural orifice specimen extraction colorectal resection for deep endometriosis: A 50 case series. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2022 Sep;29(9):1054-62.

5. Kar E et al. Natural orifice specimen extraction as a promising alternative for minilaparotomy in bowel resection due to endometriosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2024 Jul;31(7):574-83.e1.

6. Malzoni M et al. Total laparoscopic segmental resection with transanal natural orifice specimen extraction for treatment of colorectal endometriosis: Descriptive analysis from the TrEnd study database. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2024 Oct;18:S1553-4650(24)01453-5.

Laparoscopic Resection With Transanal NOSE for Deep Colorectal Endometriosis

When segmental sigmoid colon/rectal resection is indicated for treatment of deep infiltrating bowel endometriosis, a totally laparoscopic resection with intracorporeal anastomosis and transanal natural orifice specimen extraction (NOSE) can be safe, effective, and advantageous compared with an abdominal mini-laparotomy for extracorporeal anastomosis and specimen retrieval.

With advanced laparoscopic surgical skills, accurate preoperative ultrasound evaluation, and a high-quality perioperative care protocol (including high-quality bowel preparation), segmental resection with NOSE can offer better preservation of vascularization, smaller resection sizes, lower rates of postoperative pain, a shorter time for gas passage after surgery, decreased hospital stays, and lower rates of wound infection and incisional hernia.

We have seen such improved results in our high-volume center since shifting in April 2021 from our classical technique for segmental rectosigmoid resection1 to a totally laparoscopic approach with NOSE. We first reported on this new technique in 2022 in a video article in the Journal of Minimally Invasive Gynecology,2and in October 2024, outcomes of 81 patients who underwent segmental sigmoid colon/rectal resection with intracorporeal anastomosis and transanal NOSE at our institution from April 2021 through March 2024 were reported in Journal of Minimally Invasive Gynecology.3Given our experience with this approach for deep endometriosis, I am convinced that NOSE should be preferred to transabdominal specimen extraction for segmental rectosigmoid resection. This is where the future lies for deep infiltrating endometriosis. Here, I share our outcomes and describe our technique.

Our Prior Approach With A Mini-Laparotomy

Our traditional laparoscopic approach for segmental colon/rectal resection of deep infiltrating endometriosis involved an abdominal mini-laparotomy (no more than 4 cm in length) for specimen retrieval, resection of the proximal rectum, and positioning of the head of a circular stapler for end-to-end anastomosis. (Connection of the two parts of the circular stapler for anastomosis was achieved via laparoscopy.)1

Several factors allowed us to minimize potential complications, including standardization of our technique, the use of three-dimensional endoscopes, and indocyanine green fluorescence angiography to assess the perfusion of the bowel after the completion of anastomosis. Still, an unpublished analysis of 1050 segmental bowel resections performed over more than 17 years using our traditional technique showed that hospital stays averaged 8 days, time to first defecation averaged 7 days, and time to first passage of flatus averaged 1 day.

Per the Clavien-Dindo classification system for surgical complications that was used at the time, 1.9% of these 1050 patients had grade 1 (minor) or grade 2 complications and 6% had grade 3 complications. Grade 2 complications were defined as needing intervention or a hospital stay more than twice the median for the procedure. Grade 3 complications were defined as leading to lasting disability or organ resection.

In the meantime, in colorectal cancer surgery, published studies on NOSE versus conventional laparoscopy with transabdominal specimen extraction have consistently pointed to the benefits of NOSE. A 2022 review 4 of 19 studies involving over 3400 patients and a 2022 meta-analysis 5 of 21 randomized controlled trials involving more than 2000 patients both showed significantly reduced postoperative morbidity and no differences in oncologic outcomes. Among the notable differences in the 2022 meta-analysis was a relative risk of postoperative infection of 0.34 for patients treated with NOSE compared with conventional laparoscopic techniques.

Among patients with deep rectal endometriosis, reported experience with intracorporeal anastomosis and NOSE for segmental resection is limited, with a few studies published between 2014 and 2022. Excluding anecdotal reports, only about 140 patients have been reported in the literature as having intracorporeal anastomosis and transanal NOSE for deep infiltrating bowel endometriosis. 3

Our Outcomes With A Totally Laparoscopic Approach

Our approach to evaluating our experience with totally laparoscopic resection with transanal NOSE has been to systematically collect data from consecutive patients and to analyze 1) complications of the technique, 2) conversion to the traditional technique/open surgery, and 3) endometriosis-free bowel resection margins and recurrence. Secondarily, we look at intraoperative blood loss, operative time, recovery of gastrointestinal function, hospital stay length, and reproductive outcomes.

Across 81 patients from our TrEnd study database (Surgical TReatment of women with deep ENDometriosis infiltrating the sigmoid colon and/or rectum) who received a totally laparoscopic standardized procedure involving intracorporeal anastomosis and transanal NOSE, we had no conversions even to mini-laparotomy, and no cases of protective colostomy or ileostomy.

Complete endometriosis removal was achieved in 100% of cases, with final pathology showing endometriosis-free resection margins, and patients remained free of bowel endometriosis at a median follow-up of 21 months.3Our analysis also shows improved gastrointestinal function recovery (median time to first defecation of 4 days, compared to 7 days previously, with the same 1-day median time to first passage of flatus) and a significantly improved hospital length of stay to a median of 3 days (interquartile range, 3-4.5 days); the latter reflects in part the absence of infection.3There were no intra-operative complications. Postoperative Clavien-Dindo grade 3 complications occurred in three patients (3.7%), two of whom required reoperation (one for hemoperitoneum and one for ureteral injury) and one who experienced rectal anastomotic bleeding on postoperative day 1. (The two requiring reoperation had significant right lateral parametrial involvement and underwent nerve-sparing parametrectomy at the time of bowel resection).3Notably, 7 of the 81 patients had totally laparoscopic double segmental colorectal resection — 6 with simultaneous ileocecal valve and rectal resection, and 1 with simultaneous ileal and rectal resection. None of these seven patients had postoperative complications. (A report on the six surgeries for deep endometriosis infiltrating the ileocecal valve and rectum was also published this year in the journal Colorectal Disease.6)

Median blood loss in the 81-patient cohort was 20 mL (IQR, 20-30 mL), and the median length of surgery was 160 minutes (IQR, 130-210 minutes).

Bowel endometriotic nodules had a mean maximum diameter of 4.3 cm (3.5-5.5 cm), a mean depth of invasion of 9 mm (7-9 mm), a mean estimated stenosis of 40% (35%-50%), and a mean distance from the anal verge of 13 cm (10-15 cm).3 (The cohort in this analysis did not include patients who received concomitant hysterectomy and transvaginal NOSE.)

Specifics of the New Technique, Including Totally Intracorporeal Anastomosis

As in our previous technique, the surgical procedure starts with left and dorsal rectal mobilization. The left pelvic sidewall dissection begins with incision of the parietal peritoneum along the pelvic portions of the psoas muscle. The retroperitoneal connective tissue is dissected in order to identify the ureter, the hypogastric nerve, and the presacral parietal pelvic fascia (PPPF). Dissection is carried downward in front of the PPPF and medially to the left hypogastric nerve.

Right and ventral rectal mobilization begins with incision of the peritoneum along the gray avascular line, which is seen with upward retraction of the rectum.

Again, for preservation of bowel and bladder function, the hypogastric nerve must be identified and preserved through dissection that displaces the nerve dorsally and laterally.

Dissection proceeds to sharply divide the nodule into two parts (rectal and rectocervical components). The caudal boundary of ventral dissection is reached by incising the septum and opening the rectovaginal space. The lymphovascular fatty tissue surrounding the rectum is then excised and the rectal tube is denuded at the level of the distal resection margin.

The distal and proximal resection margins are prepared and transected using a tissue-sealing device, and the resected rectal specimen is placed into a retrieval bag and pulled out through the anus (Figure 1).

The totally intracorporeal side-to-end anastomosis is performed using a traditional circular stapler. Its anvil is inserted through the proximal resection line and exteriorized forward on the antimesenteric side of the sigmoid colon/rectum. The proximal and distal resection lines are closed with a 60-mm linear endo-stapler, and finally, the shaft of the circular stapler is inserted into the rectum, and the two parts of the stapler are joined. The stapler is then closed and fired (Figure 2).

An air leak test is performed to check the quality of the rectal sutures. However, regardless of the results, we routinely apply interrupted stitches to the so-called “dog ears” in order to reduce tension along the anastomotic line.

We also evaluate the microvascularization of the two parts of the bowel at the level of the reanastomosis using indocyanine green fluorescence angiography. Doing so allows us to avoid complications caused by anastomotic leakage.

Patient Selection And Peri-Surgical Care

The decision to perform segmental resection as opposed to other more conservative laparoscopic excision techniques is made after skilled preoperative imaging reveals the number of lesions, the largest nodule diameter, the infiltration depth, and the circumference of bowel involvement.

A recently published international consensus statement7 on noninvasive imaging techniques for diagnosis of pelvic deep endometriosis and endometriosis classification systems concludes there is Level 1a evidence that preoperative imaging with transvaginal ultrasound (TVUS) can predict with good precision the size and degree of infiltration of deep endometriosis of the rectum (a Grade A statement, per the Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine levels of evidence).

The consensus document was published across seven different journals by international and European societies, and the American Association of Gynecologic Laparoscopists (AAGL), each of which contributed to a multidisciplinary panel of gynecological surgeons, sonographers, and radiologists.

At our center, we achieve precise preoperative evaluations with TVUS (other centers also employ MRI) and have long set clear preoperative indications for segmental resection. Based on our experience,8 a nodule ≥ 3 cm and infiltration of the tunica muscularis of the sigmoid colon/rectum ≥ 7 mm indicate the need for segmental resection. It is impossible to achieve surgical goals in such cases through shaving or discoid resection.

Our perioperative care protocol for total laparoscopic segmental resection with transanal NOSE, described in our new paper,3 includes several components: antibiotic therapy (metronidazole 500 mg 12 hours before surgery; cefazolin 2 g plus metronidazole 500 mg 1 hour before skin incision; and cefazolin 1 g plus metronidazole 500 mg 12 hours after surgery); good intraoperative bowel preparation (mechanical with oral polyethylene glycol solution preoperatively, and rectal irrigation with a mixed solution of povidine-iodine and normal saline intraoperatively); and venous thromboembolism prophylaxis postoperatively for 28 days.

Moving Forward, A Word On Classification

Multicenter trials and research with longer follow-up times will be helpful in advancing the use of totally laparoscopic segmental colorectal resection for deep endometriosis. To enable better sharing of diagnostic and therapeutic results — and to advance the credibility of research — my hope is that the field will reach further agreement on endometriosis classification systems. This would also help with the development of standards for postgraduate education.

We have made significant strides in recognizing imaging as a standard for diagnosis and treatment, and I believe we currently have two very good endometriosis classification systems — the #Enzian classification system issued in 2021 and the AAGL 2021 Endometriosis Classification — that can be used in combination with imaging to reliably and consistently describe deep endometriosis.

Mario Malzoni, MD, is scientific director of the Malzoni Research Hospital, the Center for Advanced Pelvic Surgery, in Avellino, Italy. He reported having no disclosures relevant to this Master Class.

References

1. Malzoni M et al. Surgical principles of segmental rectosigmoid resection and reanastomosis for deep infiltrating endometriosis. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2020;27(2):258.

2. Malzoni M et al. Totally laparoscopic resection with transanal natural orifice specimen extraction for deep endometriosis infiltrating the rectum. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2022;29(1):19.

3. Malzoni M et al. Total laparoscopic segmental resection with transanal natural orifice specimen extraction for treatment of colorectal endometriosis: Descriptive analysis from the TrEnd study database. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2024. (in press). 4. Brincat SD et al. Natural orifice versus transabdominal specimen extraction in laparoscopic surgery for colorectal cancer: meta-analysis. BJS Open 2022;6(3):zrac074.

5. Zhou Z et al. Laparoscopic natural orifice specimen extraction surgery versus conventional surgery in colorectal cancer: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2022 Jan 18;2022:6661651.

6. Malzoni M et al. Simultaneous total laparoscopic double segmental resection with transanal natural orifice specimen extraction for deep endometriosis infiltrating the ileocaecal valve and rectum—A video vignette. Colorectal Dis 2024 Jul 25.

7. Condous G et al. Noninvasive imaging techniques for diagnosis of pelvic deep endometriosis and endometriosis classification systems: An international consensus. J. Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2024;31(7):557-73.

8. Malzoni M et al. Preoperative ultrasound indications determine excision technique for bowel surgery for deep infiltrating endometriosis: A single, high-volume center. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2020;27(5):1141-7.