User login

Point of Care Ultrasound (POCUS) for Small Bowel Obstruction in the ED

Small bowel obstruction (SBO) accounts for 2% of all cases of abdominal pain presenting to the ED and 15% of abdominal pain admissions to surgical units from the ED.1,2 SBO can be a difficult diagnosis; the most common symptoms include nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, obstipation, and constipation. The symptomatology depends on multiple factors: the area of the blockage, length of obstruction, and degree of the obstruction (either partial or complete).3 An upper gastrointestinal (GI) blockage classically presents with nausea and vomiting, while a lower GI blockage often presents with abdominal pain, constipation, and obstipation. Complications of obstruction range from significant morbidity—such as bowel strangulation (23%) and sepsis (31%)—to mortality (9%).4 ED POCUS allows for rapid and accurate diagnosis of SBO.

CASE

A 60-year-old female with a past medical history of peptic ulcer disease and multiple abdominal surgeries, including umbilical hernia repair, appendectomy, and total abdominal hysterectomy, presented to the ED with an 8-hour history of nausea and vomiting. She reported that her abdomen felt bloated. She had experienced non-bloody, watery stools for the prior 3 weeks. She also reported three to four weeks of epigastric abdominal pain similar to her previous “ulcer pain.” Of note, she was evaluated in GI clinic one day prior to her ED visit for dysphagia, abdominal distention, and diarrhea and was scheduled for an outpatient upper endoscopy. Initial vitals were significant for a heart rate of 100 beats/min. Physical exam was significant for a mildly distended abdomen, tender to palpation at epigastrium without rebound or guarding. Labs showed a white blood cell count of 11.8 K/uL and otherwise unremarkable complete blood count, basic metabolic panel, liver function tests, and lactate measurement. Given the patient’s history of multiple abdominal surgeries and clinical presentation, POCUS was performed to evaluate for SBO. Dilated loops of small bowel were visualized in the lower abdomen gas, suggestive of SBO.

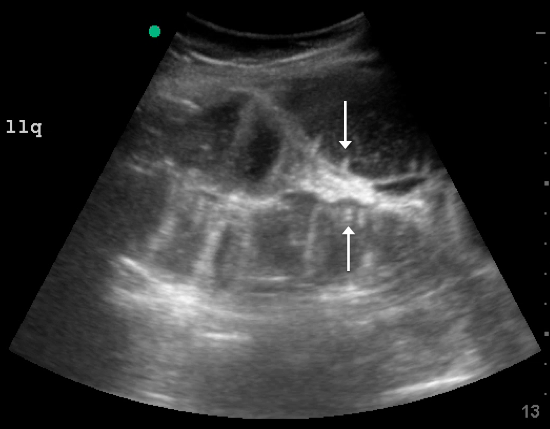

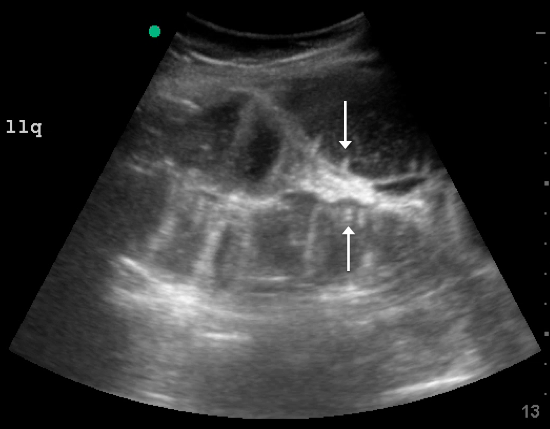

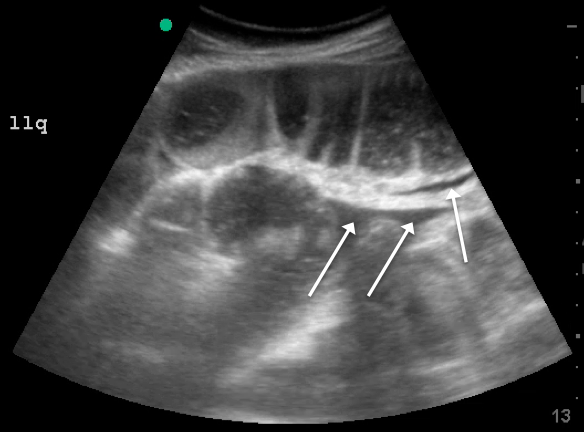

Since the small bowel encompasses a large portion of the abdomen, to fully evaluate for SBO, multiple views are necessary. These include the epigastrium, bilateral colic gutters, and suprapubic regions.5 Use the low-frequency curvilinear transducer to obtain these views, scanning in the transverse and sagittal planes (see Figures 1 and 2). Scan while moving the transducer in columns (ie, “mowing the lawn”), making sure to cover the entire abdomen. To assure that you are evaluating the small bowel, and not the large bowel, look for the characteristic plicae circularis of the small bowel (shown in Figure 3). In children and very slender adults, the high-frequency linear probe may provide enough depth to obtain adequate views.

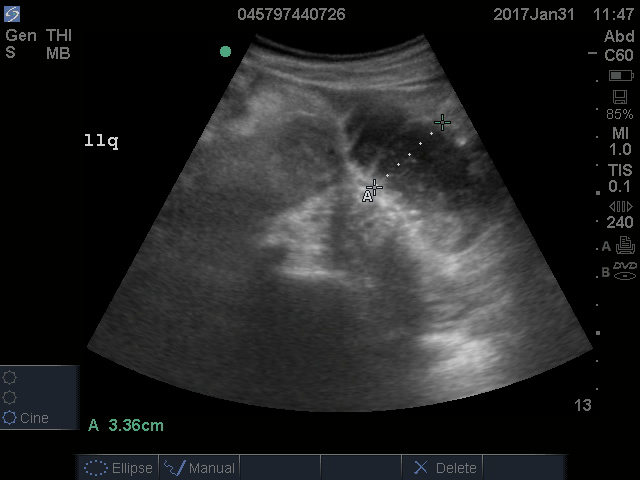

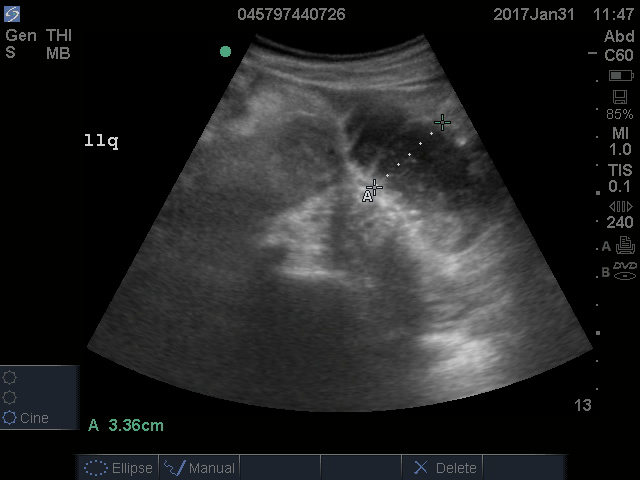

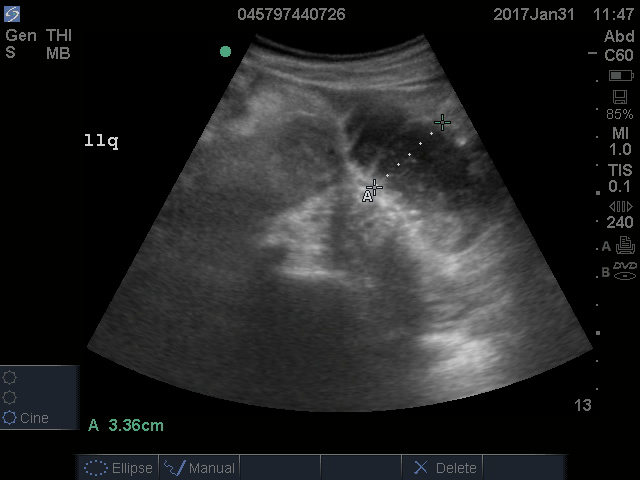

A fluid-filled small intestinal segment >2.5 cm is consistent with a diagnosis of SBO. Measuring the diameter of the small bowel is both the most sensitive and specific sign; a measurement of greater than 2.5 cm is diagnostic, with a sensitivity of 97% and specificity of 91% (see Figure 4).6 This can be somewhat difficult to visualize, as bowel loops are multidirectional and diameters can mistakenly be taken on an indirect cut; to avoid over- or underestimation of bowel diameter, you may want to measure in the short axis using a transverse cross-sectional view of the bowel.

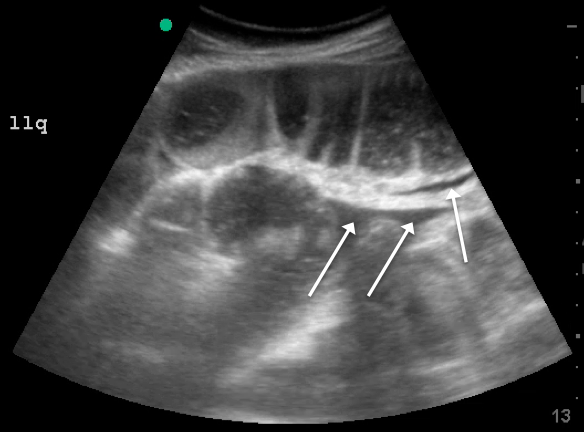

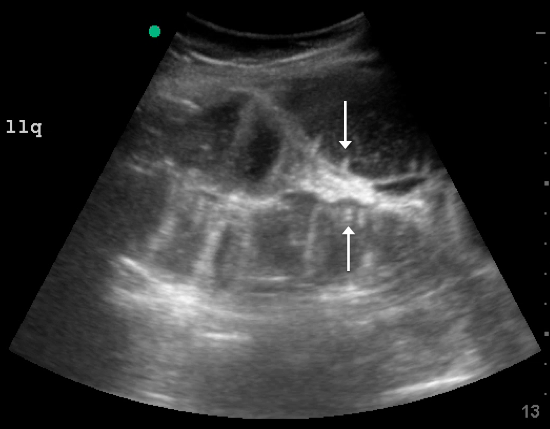

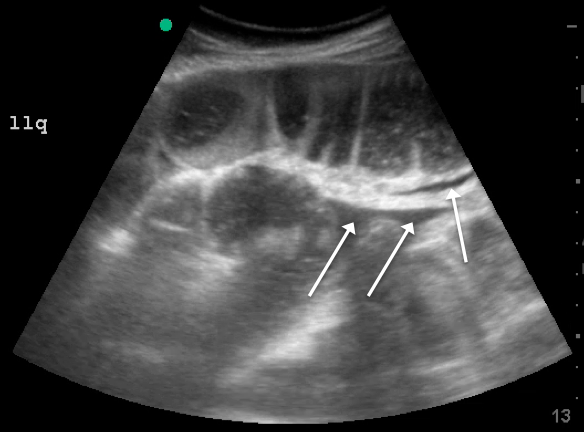

Lack of peristalsis is suggestive of a closed-loop obstruction. However, this finding may be more difficult to visualize, as it requires several continuous minutes of scanning or repeated exams to truly establish absent peristalsis. In prolonged courses of SBO, the bowel wall can measure >3 mm, which suggests necrosis, warranting accelerated surgical intervention. In addition, the detection of extraluminal peritoneal fluid can help determine the severity of the SBO, and small versus large fluid amounts can help determine whether medical or surgical management is warranted (see Figure 5).7

DISCUSSION

Increased time to diagnosis of SBO can lead to prolonged patient suffering and greater complication rates. The gold standard for diagnosing SBO—CT with intravenous and oral contrast—can take hours, requiring patients, who are often nauseated, to ingest and tolerate oral contrast. In the past, an “obstructive series” of x-rays would have been used early in the work-up of possible SBO.6

Recent literature suggests that POCUS is not only faster, more cost effective, and advantageous (involving no ionizing radiation), but also more accurate than x-rays. Specifically, a meta-analysis by Taylor et al showed pooled estimates for obstructive series x-rays have a sensitivity (Sn) of 75%, a specificity (Sp) of 66%, a positive likelihood ratio (+LR) of 1.6, and a negative likelihood ratio (-LR) of 0.43.1 On the other hand, pooled results from ED studies of emergency medicine (EM) residents performing POCUS in patients with signs and symptoms suspicious for SBO showed POCUS had a Sn of 97%, Sp of 90%, +LR of 9.5, and a -LR of 0.04.1,5,8 While detractors point to the operator-dependent nature of POCUS, literature suggests that with EM residents novice to POCUS for SBO (defined as less than 5 previous scans for SBO) were given a 10-minute didactic session and yielded Sn 94%, Sp 81%, +LR 5.0, -LR 0.07.5 Unluer et al trained novice EM residents for 6 hours and found them to yield Sn 98%, Sp 95%, +LR 19.5, and -LR 0.02.8 Thus, while it is no surprise that those with more training attain better results, both studies show it does not take much time for EM providers to surpass the accuracy of x-rays with POCUS.

CASE CONCLUSION

The findings on POCUS highly suggested the diagnosis of an SBO. A CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis with intravenous and oral contrast was ordered to further evaluate obstruction, transition point, and possible complications, including signs of ischemia per surgical request. CT demonstrated dilated loops of small bowel with transition point in the right lower quadrant, with a small amount of mesenteric fluid consistent with SBO with possible early bowel compromise due to ischemia. General surgery admitted the patient; conservative treatment with serial abdominal exams, nasogastric tube, NPO and bowel rest was ordered. The patient’s diet was gradually advanced, and she was discharged on the eleventh day of hospitalization.

SUMMARY

POCUS is a useful non-invasive tool that can accurately diagnose SBO. POCUS has increased sensitivity and specificity when compared to abdominal X-rays. This bedside imaging will not only give the ED provider rapid diagnostic information but also lead to expedited surgical intervention.

- Taylor MR, Lalani N. Adult small bowel obstruction. Acad Emerg Med. 2013;20(6):528-544.

- Hastings RS, Powers RD. Abdominal pain in the ED: a 35-year retrospective. Am J Emerg Med.2011;29:711-716.

- Markogiannakis H, Messaris E, Dardamanis D, et al. Acute mechanical bowel obstruction: clinical presentation, etiology, management and outcome. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:432.

- Bickell N, Federman A, Aufses A. Influence of time on risk of bowel resection in complete small bowel obstruction. J Am Coll Surg. 2005;201(6):847-854.

- Jang TB, Chandler D, Kaji AH. Bedside ultrasonography for the detection of small bowel obstruction in the emergency department. Emerg Med J. 2011;28:676-678.

- Carpenter CR, Pines JM. The end of X-rays for suspected small bowel obstruction? Using evidence-based diagnostics to inform best practices in emergency medicine. Acad Emerg Med. 2013;20:618-20.

- Grassi R, Romano S, D’Amario F, et al. The relevance of free fluid between intestinal loops detected by sonography in the clinical assessment of small bowel obstruction in adults. Eur J Radiol. 2004;50(1):5-14.

- Unlüer E, Yavaşi O, Eroğlu O, Yilmaz C, Akarca F. Ultrasonography by emergency medicine and radiology residents for the diagnosis of small bowel obstruction. Eur J Emerg Med. 2010;17(5):260-264.

Small bowel obstruction (SBO) accounts for 2% of all cases of abdominal pain presenting to the ED and 15% of abdominal pain admissions to surgical units from the ED.1,2 SBO can be a difficult diagnosis; the most common symptoms include nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, obstipation, and constipation. The symptomatology depends on multiple factors: the area of the blockage, length of obstruction, and degree of the obstruction (either partial or complete).3 An upper gastrointestinal (GI) blockage classically presents with nausea and vomiting, while a lower GI blockage often presents with abdominal pain, constipation, and obstipation. Complications of obstruction range from significant morbidity—such as bowel strangulation (23%) and sepsis (31%)—to mortality (9%).4 ED POCUS allows for rapid and accurate diagnosis of SBO.

CASE

A 60-year-old female with a past medical history of peptic ulcer disease and multiple abdominal surgeries, including umbilical hernia repair, appendectomy, and total abdominal hysterectomy, presented to the ED with an 8-hour history of nausea and vomiting. She reported that her abdomen felt bloated. She had experienced non-bloody, watery stools for the prior 3 weeks. She also reported three to four weeks of epigastric abdominal pain similar to her previous “ulcer pain.” Of note, she was evaluated in GI clinic one day prior to her ED visit for dysphagia, abdominal distention, and diarrhea and was scheduled for an outpatient upper endoscopy. Initial vitals were significant for a heart rate of 100 beats/min. Physical exam was significant for a mildly distended abdomen, tender to palpation at epigastrium without rebound or guarding. Labs showed a white blood cell count of 11.8 K/uL and otherwise unremarkable complete blood count, basic metabolic panel, liver function tests, and lactate measurement. Given the patient’s history of multiple abdominal surgeries and clinical presentation, POCUS was performed to evaluate for SBO. Dilated loops of small bowel were visualized in the lower abdomen gas, suggestive of SBO.

Since the small bowel encompasses a large portion of the abdomen, to fully evaluate for SBO, multiple views are necessary. These include the epigastrium, bilateral colic gutters, and suprapubic regions.5 Use the low-frequency curvilinear transducer to obtain these views, scanning in the transverse and sagittal planes (see Figures 1 and 2). Scan while moving the transducer in columns (ie, “mowing the lawn”), making sure to cover the entire abdomen. To assure that you are evaluating the small bowel, and not the large bowel, look for the characteristic plicae circularis of the small bowel (shown in Figure 3). In children and very slender adults, the high-frequency linear probe may provide enough depth to obtain adequate views.

A fluid-filled small intestinal segment >2.5 cm is consistent with a diagnosis of SBO. Measuring the diameter of the small bowel is both the most sensitive and specific sign; a measurement of greater than 2.5 cm is diagnostic, with a sensitivity of 97% and specificity of 91% (see Figure 4).6 This can be somewhat difficult to visualize, as bowel loops are multidirectional and diameters can mistakenly be taken on an indirect cut; to avoid over- or underestimation of bowel diameter, you may want to measure in the short axis using a transverse cross-sectional view of the bowel.

Lack of peristalsis is suggestive of a closed-loop obstruction. However, this finding may be more difficult to visualize, as it requires several continuous minutes of scanning or repeated exams to truly establish absent peristalsis. In prolonged courses of SBO, the bowel wall can measure >3 mm, which suggests necrosis, warranting accelerated surgical intervention. In addition, the detection of extraluminal peritoneal fluid can help determine the severity of the SBO, and small versus large fluid amounts can help determine whether medical or surgical management is warranted (see Figure 5).7

DISCUSSION

Increased time to diagnosis of SBO can lead to prolonged patient suffering and greater complication rates. The gold standard for diagnosing SBO—CT with intravenous and oral contrast—can take hours, requiring patients, who are often nauseated, to ingest and tolerate oral contrast. In the past, an “obstructive series” of x-rays would have been used early in the work-up of possible SBO.6

Recent literature suggests that POCUS is not only faster, more cost effective, and advantageous (involving no ionizing radiation), but also more accurate than x-rays. Specifically, a meta-analysis by Taylor et al showed pooled estimates for obstructive series x-rays have a sensitivity (Sn) of 75%, a specificity (Sp) of 66%, a positive likelihood ratio (+LR) of 1.6, and a negative likelihood ratio (-LR) of 0.43.1 On the other hand, pooled results from ED studies of emergency medicine (EM) residents performing POCUS in patients with signs and symptoms suspicious for SBO showed POCUS had a Sn of 97%, Sp of 90%, +LR of 9.5, and a -LR of 0.04.1,5,8 While detractors point to the operator-dependent nature of POCUS, literature suggests that with EM residents novice to POCUS for SBO (defined as less than 5 previous scans for SBO) were given a 10-minute didactic session and yielded Sn 94%, Sp 81%, +LR 5.0, -LR 0.07.5 Unluer et al trained novice EM residents for 6 hours and found them to yield Sn 98%, Sp 95%, +LR 19.5, and -LR 0.02.8 Thus, while it is no surprise that those with more training attain better results, both studies show it does not take much time for EM providers to surpass the accuracy of x-rays with POCUS.

CASE CONCLUSION

The findings on POCUS highly suggested the diagnosis of an SBO. A CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis with intravenous and oral contrast was ordered to further evaluate obstruction, transition point, and possible complications, including signs of ischemia per surgical request. CT demonstrated dilated loops of small bowel with transition point in the right lower quadrant, with a small amount of mesenteric fluid consistent with SBO with possible early bowel compromise due to ischemia. General surgery admitted the patient; conservative treatment with serial abdominal exams, nasogastric tube, NPO and bowel rest was ordered. The patient’s diet was gradually advanced, and she was discharged on the eleventh day of hospitalization.

SUMMARY

POCUS is a useful non-invasive tool that can accurately diagnose SBO. POCUS has increased sensitivity and specificity when compared to abdominal X-rays. This bedside imaging will not only give the ED provider rapid diagnostic information but also lead to expedited surgical intervention.

Small bowel obstruction (SBO) accounts for 2% of all cases of abdominal pain presenting to the ED and 15% of abdominal pain admissions to surgical units from the ED.1,2 SBO can be a difficult diagnosis; the most common symptoms include nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, obstipation, and constipation. The symptomatology depends on multiple factors: the area of the blockage, length of obstruction, and degree of the obstruction (either partial or complete).3 An upper gastrointestinal (GI) blockage classically presents with nausea and vomiting, while a lower GI blockage often presents with abdominal pain, constipation, and obstipation. Complications of obstruction range from significant morbidity—such as bowel strangulation (23%) and sepsis (31%)—to mortality (9%).4 ED POCUS allows for rapid and accurate diagnosis of SBO.

CASE

A 60-year-old female with a past medical history of peptic ulcer disease and multiple abdominal surgeries, including umbilical hernia repair, appendectomy, and total abdominal hysterectomy, presented to the ED with an 8-hour history of nausea and vomiting. She reported that her abdomen felt bloated. She had experienced non-bloody, watery stools for the prior 3 weeks. She also reported three to four weeks of epigastric abdominal pain similar to her previous “ulcer pain.” Of note, she was evaluated in GI clinic one day prior to her ED visit for dysphagia, abdominal distention, and diarrhea and was scheduled for an outpatient upper endoscopy. Initial vitals were significant for a heart rate of 100 beats/min. Physical exam was significant for a mildly distended abdomen, tender to palpation at epigastrium without rebound or guarding. Labs showed a white blood cell count of 11.8 K/uL and otherwise unremarkable complete blood count, basic metabolic panel, liver function tests, and lactate measurement. Given the patient’s history of multiple abdominal surgeries and clinical presentation, POCUS was performed to evaluate for SBO. Dilated loops of small bowel were visualized in the lower abdomen gas, suggestive of SBO.

Since the small bowel encompasses a large portion of the abdomen, to fully evaluate for SBO, multiple views are necessary. These include the epigastrium, bilateral colic gutters, and suprapubic regions.5 Use the low-frequency curvilinear transducer to obtain these views, scanning in the transverse and sagittal planes (see Figures 1 and 2). Scan while moving the transducer in columns (ie, “mowing the lawn”), making sure to cover the entire abdomen. To assure that you are evaluating the small bowel, and not the large bowel, look for the characteristic plicae circularis of the small bowel (shown in Figure 3). In children and very slender adults, the high-frequency linear probe may provide enough depth to obtain adequate views.

A fluid-filled small intestinal segment >2.5 cm is consistent with a diagnosis of SBO. Measuring the diameter of the small bowel is both the most sensitive and specific sign; a measurement of greater than 2.5 cm is diagnostic, with a sensitivity of 97% and specificity of 91% (see Figure 4).6 This can be somewhat difficult to visualize, as bowel loops are multidirectional and diameters can mistakenly be taken on an indirect cut; to avoid over- or underestimation of bowel diameter, you may want to measure in the short axis using a transverse cross-sectional view of the bowel.

Lack of peristalsis is suggestive of a closed-loop obstruction. However, this finding may be more difficult to visualize, as it requires several continuous minutes of scanning or repeated exams to truly establish absent peristalsis. In prolonged courses of SBO, the bowel wall can measure >3 mm, which suggests necrosis, warranting accelerated surgical intervention. In addition, the detection of extraluminal peritoneal fluid can help determine the severity of the SBO, and small versus large fluid amounts can help determine whether medical or surgical management is warranted (see Figure 5).7

DISCUSSION

Increased time to diagnosis of SBO can lead to prolonged patient suffering and greater complication rates. The gold standard for diagnosing SBO—CT with intravenous and oral contrast—can take hours, requiring patients, who are often nauseated, to ingest and tolerate oral contrast. In the past, an “obstructive series” of x-rays would have been used early in the work-up of possible SBO.6

Recent literature suggests that POCUS is not only faster, more cost effective, and advantageous (involving no ionizing radiation), but also more accurate than x-rays. Specifically, a meta-analysis by Taylor et al showed pooled estimates for obstructive series x-rays have a sensitivity (Sn) of 75%, a specificity (Sp) of 66%, a positive likelihood ratio (+LR) of 1.6, and a negative likelihood ratio (-LR) of 0.43.1 On the other hand, pooled results from ED studies of emergency medicine (EM) residents performing POCUS in patients with signs and symptoms suspicious for SBO showed POCUS had a Sn of 97%, Sp of 90%, +LR of 9.5, and a -LR of 0.04.1,5,8 While detractors point to the operator-dependent nature of POCUS, literature suggests that with EM residents novice to POCUS for SBO (defined as less than 5 previous scans for SBO) were given a 10-minute didactic session and yielded Sn 94%, Sp 81%, +LR 5.0, -LR 0.07.5 Unluer et al trained novice EM residents for 6 hours and found them to yield Sn 98%, Sp 95%, +LR 19.5, and -LR 0.02.8 Thus, while it is no surprise that those with more training attain better results, both studies show it does not take much time for EM providers to surpass the accuracy of x-rays with POCUS.

CASE CONCLUSION

The findings on POCUS highly suggested the diagnosis of an SBO. A CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis with intravenous and oral contrast was ordered to further evaluate obstruction, transition point, and possible complications, including signs of ischemia per surgical request. CT demonstrated dilated loops of small bowel with transition point in the right lower quadrant, with a small amount of mesenteric fluid consistent with SBO with possible early bowel compromise due to ischemia. General surgery admitted the patient; conservative treatment with serial abdominal exams, nasogastric tube, NPO and bowel rest was ordered. The patient’s diet was gradually advanced, and she was discharged on the eleventh day of hospitalization.

SUMMARY

POCUS is a useful non-invasive tool that can accurately diagnose SBO. POCUS has increased sensitivity and specificity when compared to abdominal X-rays. This bedside imaging will not only give the ED provider rapid diagnostic information but also lead to expedited surgical intervention.

- Taylor MR, Lalani N. Adult small bowel obstruction. Acad Emerg Med. 2013;20(6):528-544.

- Hastings RS, Powers RD. Abdominal pain in the ED: a 35-year retrospective. Am J Emerg Med.2011;29:711-716.

- Markogiannakis H, Messaris E, Dardamanis D, et al. Acute mechanical bowel obstruction: clinical presentation, etiology, management and outcome. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:432.

- Bickell N, Federman A, Aufses A. Influence of time on risk of bowel resection in complete small bowel obstruction. J Am Coll Surg. 2005;201(6):847-854.

- Jang TB, Chandler D, Kaji AH. Bedside ultrasonography for the detection of small bowel obstruction in the emergency department. Emerg Med J. 2011;28:676-678.

- Carpenter CR, Pines JM. The end of X-rays for suspected small bowel obstruction? Using evidence-based diagnostics to inform best practices in emergency medicine. Acad Emerg Med. 2013;20:618-20.

- Grassi R, Romano S, D’Amario F, et al. The relevance of free fluid between intestinal loops detected by sonography in the clinical assessment of small bowel obstruction in adults. Eur J Radiol. 2004;50(1):5-14.

- Unlüer E, Yavaşi O, Eroğlu O, Yilmaz C, Akarca F. Ultrasonography by emergency medicine and radiology residents for the diagnosis of small bowel obstruction. Eur J Emerg Med. 2010;17(5):260-264.

- Taylor MR, Lalani N. Adult small bowel obstruction. Acad Emerg Med. 2013;20(6):528-544.

- Hastings RS, Powers RD. Abdominal pain in the ED: a 35-year retrospective. Am J Emerg Med.2011;29:711-716.

- Markogiannakis H, Messaris E, Dardamanis D, et al. Acute mechanical bowel obstruction: clinical presentation, etiology, management and outcome. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:432.

- Bickell N, Federman A, Aufses A. Influence of time on risk of bowel resection in complete small bowel obstruction. J Am Coll Surg. 2005;201(6):847-854.

- Jang TB, Chandler D, Kaji AH. Bedside ultrasonography for the detection of small bowel obstruction in the emergency department. Emerg Med J. 2011;28:676-678.

- Carpenter CR, Pines JM. The end of X-rays for suspected small bowel obstruction? Using evidence-based diagnostics to inform best practices in emergency medicine. Acad Emerg Med. 2013;20:618-20.

- Grassi R, Romano S, D’Amario F, et al. The relevance of free fluid between intestinal loops detected by sonography in the clinical assessment of small bowel obstruction in adults. Eur J Radiol. 2004;50(1):5-14.

- Unlüer E, Yavaşi O, Eroğlu O, Yilmaz C, Akarca F. Ultrasonography by emergency medicine and radiology residents for the diagnosis of small bowel obstruction. Eur J Emerg Med. 2010;17(5):260-264.

Malignant olecranon bursitis in the setting of multiple myeloma relapse

Multiple myeloma is the most common plasma cell neoplasm, with an estimated 24,000 cases occurring annually.1 Symptomatic multiple myeloma most commonly presents with one or more of the cardinal CRAB phenomena of hypercalcemia, renal dysfunction, anemia, or lytic bone lesions.2 Less commonly, patients may present with plasmacytomas (focal lesions of malignant plasma cells), which may involve bony or soft tissues.1

Plasma cell neoplasms occasionally involve the joints, including the elbows, typically as plasmacytomas. The elbow is an unusual but reported location of plasmacytomas.3,4 A case of multiple myeloma and amyloid light-chain (AL) amyloidosis has been reported, with manifestations including pseudomyopathy, bone marrow plasmacytosis, and bilateral trochanteric bursitis.5Bursitis is defined as inflammation of the synovial-fluid–containing sacs that lubricate joints. The olecranon bursa is commonly affected. Etiologies include infection, inflammatory disease, trauma, and malignancy. Furthermore, there is an association between bursitis and immunosuppression.6,7 The most common modes of therapy used to treat bursitis are nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, corticosteroid injections, and surgical management.

Trochanteric bursitis has been attributed to multiple myeloma in one previous case report, but we are not aware of any previous cases of olecranon bursitis caused by multiple myeloma. Here, we present the case of a 46-year-old man with heavily pretreated multiple myeloma and amyloidosis who developed left olecranon bursitis contemporaneously with disease relapse; flow cytometric analysis of the bursal fluid demonstrated an abnormal plasma cell population, establishing the etiology.

Case presentation and summary

A 46-year-old man with a longstanding history of multiple myeloma developed swelling of the left elbow that was initially painless in September 2016. He had been diagnosed with IgA kappa multiple myeloma and AL deposition in 2011. Over the course of his disease, he was treated with the following sequence of therapies: cyclophosphamide, bortezomib, and dexamethasone, followed by melphalan-conditioned autologous peripheral blood stem cell transplant; lenalidomide and dexamethasone; carfilzomib and dexamethasone; pomalidomide, bortezomib, and dexamethasone; and bortezomib, lenalidomide, dexamethasone, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, and etoposide, followed by second melphalan-conditioned autologous peripheral blood stem cell transplant. In addition to treatment with numerous novel and chemotherapeutic agents, his disease course was notable for amyloid deposition in the liver, bone marrow, and kidneys, which resulted in dialysis dependence.

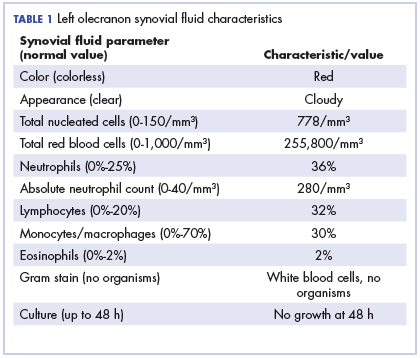

After the second autologous transplant, he achieved a very good partial response and experienced about 9 months of remission, after which laboratory evaluation indicated recurrence of IgA kappa monoclonal protein and free kappa light-chains, which increased slowly over several months without focal symptoms, cytopenias, or decline in organ function (Figure 1).

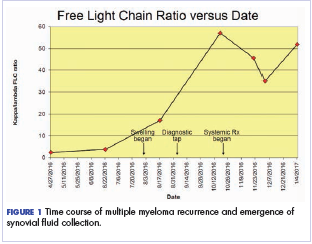

Twelve months after his second transplant, he presented in September 2016 with 4 weeks of left elbow swelling, with the appearance suggesting a fluid collection over the left olecranon process (Figure 2). The fluid collection was not painful unless bumped or pushed. The maximum pain level was 1-2 on a scale of 0-10. His daughter drained the fluid collection on 2 occasions, but it reaccumulated over 2 to 3 days. He reported no fevers, chills, or sweats. He did not have any redness at the site. He did not report any systemic symptoms.

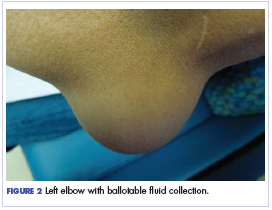

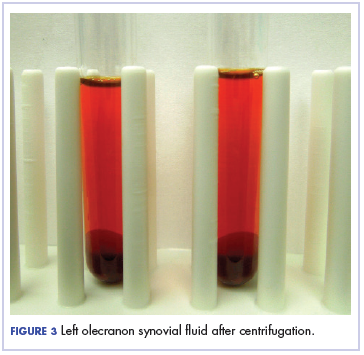

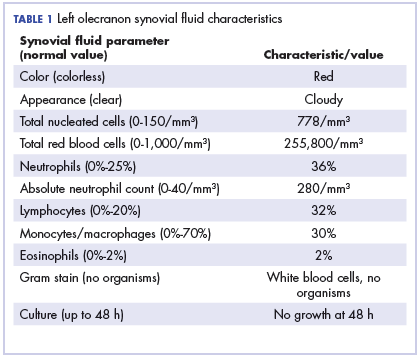

Physical examination of the left elbow demonstrated a ballotable fluid collection associated with the olecranon, with no associated warmth, tenderness, or erythema. Bursal fluid was sampled, yielding orange-colored serous fluid with bland characteristics (Figure 3). Microbiologic studies were negative (Table 1). We did not suspect a malignant cause initially.

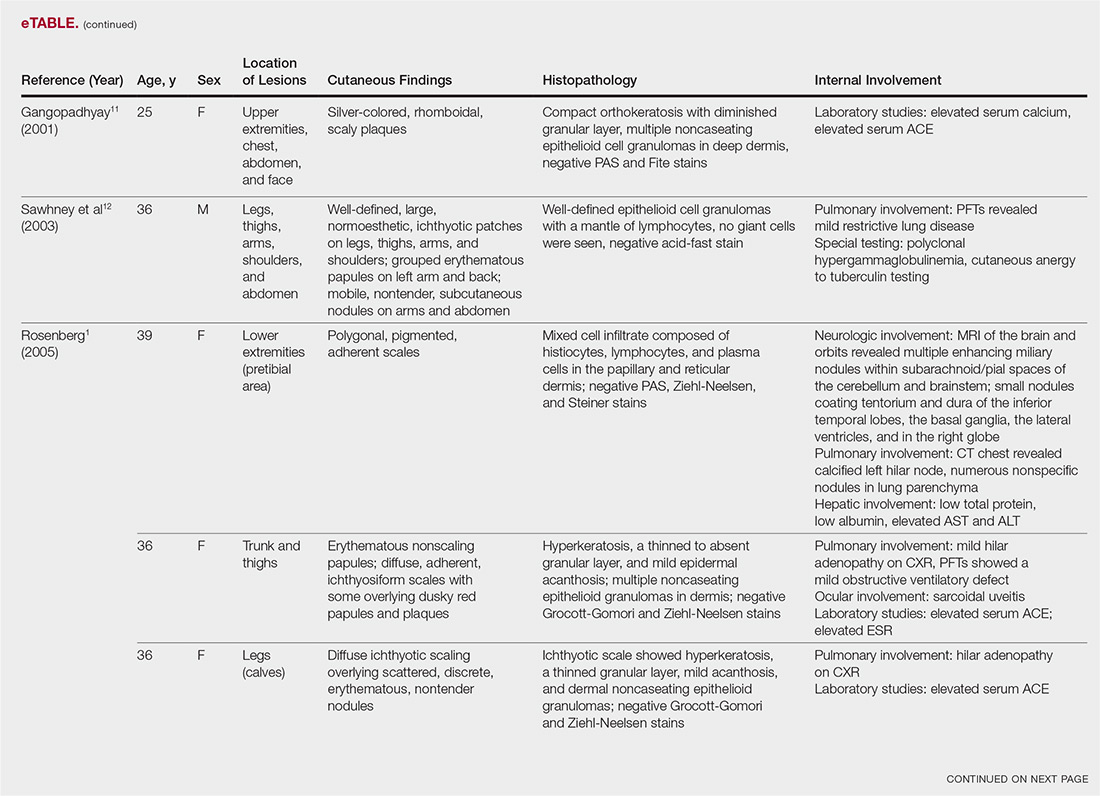

The fluid collection persisted despite treatment with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and serial drainage procedures approximately twice per week. It became more erythematous and uncomfortable. We repeated diagnostic sampling at 13 months post-transplant. Cytospin revealed scant plasma cells. A multiparametric 8-color flow cytometric analysis was performed on the bursal fluid. It demonstrated the presence of a small abnormal population of plasma cells (0.04%). The abnormal plasma cells showed expression of CD138 and bright CD38 with aberrant expression of CD56, dim CD45, and loss of CD19, CD81 and CD27. They did not express CD117 or CD20 (Figure 4).

Because of the patient’s discomfort and his history of multidrug-refractory multiple myeloma, we obtained computed tomography imaging of the axial and appendicular skeleton, which demonstrated diffuse small lytic lesions, none larger than 3 mm, including the left elbow joint. The patient began systemic treatment with ixazomib, pomalidomide, and dexamethasone and then received radiation therapy of 20 Gy in 4 fractions to the left olecranon area. The bursal fluid collection remained stable in size but required periodic, though less frequent, drainage procedures. Unfortunately, the patient only tolerated 2 cycles of systemic therapy before experiencing hypercalcemia, exacerbation of hepatic amyloidosis, and a decline in performance status. He died 17 months after the transplant.

Discussion

Our patient experienced left olecranon bursitis simultaneously with relapse of multiple myeloma and AL amyloidosis. Evaluation for infectious causes was negative, and the bursal fluid did not have strongly inflammatory characteristics. Furthermore, a small plasma cell population was isolated from the fluid. Imaging did not reveal an underlying dominant lytic lesion. Although we do not have direct pathologic confirmation, the clinical scenario and flow cytometry findings support our interpretation that the patient’s bursitis was caused by or at least related to underlying multiple myeloma. While reactive plasma cells are also CD38 positive and CD138 positive, they maintain the expression of CD19 and CD45 without aberrant expression of CD56 or CD117 and do not show loss of expression of CD81 or CD27. In this situation, we suspect that either a plasmacytoma involving the soft tissue of the bursa or amyloid infiltration of the synovium may have occurred. Anti-myeloma therapies and radiation therapy did not result in control of the bursitis, though it should be noted that the patient’s highly refractory disease progressed despite treatment with a combination of later-generation immunomodulatory imide and proteasome inhibitor therapies.

Cases of malignant bursitis have been reported several times in the literature, though nearly all of the instances involved connective tissue or metastatic tumors. Tumor histologies include osteochondroma,8,9 malignant fibrous histiocytoma,10 synovial sarcoma,11 and metastatic breast cancer.12

Hematologic malignancies are more rare causes of bursitis; our literature search identified a report of 2 cases of non-Hodgkin lymphoma mimicking rheumatoid arthritis. The joints were the knee and elbow. Synovial fluid from one case was clear and yellow, with leukocytosis with a neutrophilic predominance (similar to our case). In both cases, pathology confirmed lymphomatous infiltration of the synovium.13 Notably, we identified a case of a previously healthy 35-year-old woman with bilateral trochanteric bursitis. Biopsy of tissue from the right trochanteric bursa demonstrated positive birefringence, diagnostic of AL amyloidosis. The patient also had a biclonal paraprotein accompanied by calvarial lytic lesions. She was treated with a corticosteroid pulse and bisphosphonates, followed by autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplant. 5 Our case shares features with the above case, including the relatively young age of the patient and the presence of AL amyloidosis.

Our patient wished to avoid a surgical biopsy procedure, and therefore we utilized flow cytometry of the bursal fluid to establish that the etiology of fluid collection was consistent with his concurrent relapse of multiple myeloma. We believe that we are reporting the second case of multiple myeloma-associated bursitis and the first case associated with multiple myeloma relapse; to our knowledge, it is the first to be diagnosed with the aid of flow cytometry.

Because of our patient’s reliance on hemodialysis beginning one year prior to his presentation with olecranon bursitis, we entertain “dialysis elbow” within the differential diagnosis. Dialysis elbow is a relatively uncommon complication of dialysis, in which patients develop olecranon bursitis on the same side as the hemodialysis access after a prolonged (months to years) duration of hemodialysis. Serositis and mechanical forces are the hypothesized etiologies14; infectious and rheumatologic causes were excluded from the reported cases. Nevertheless, we favor a malignant cause based upon the flow cytometry findings indicating involvement by immunophenotypically abnormal plasma cells.

Our patient was treated initially with serial drainage and nonsteroidals, which had little impact. After diagnosis of a plasma cell population in the fluid, we offered local treatment with radiation and systemic treatment of multiple myeloma, which offered better but suboptimal control. Possible treatments for olecranon bursitis include surgery, corticosteroid injections, anti-inflammatories, and serial drainage. Nonsurgical management may be more effective than surgical management, and corticosteroid injection carries significant risks. On the other hand, serial drainage does not confer additional infection risk in cases with aseptic etiology.15 We combined conservative measures as well as treatment of the underlying disease, but we believe that our patient did not derive significant benefit because of the refractory nature of his disease; he also expressed a preference to avoid surgical intervention.

Conclusion

Bursitis is a rare but thought-provoking potential manifestation of multiple myeloma and AL amyloidosis; we believe that our patient’s bursitis was related to plasma cell neoplasia based upon co-occurrence with disease relapse. His bursitis turned out to be an early indicator of impending systemic relapse. In this particular case, in which the patient wished to avoid surgical intervention, flow cytometry was of great value, and we believe that our case is the first report of malignant bursitis being diagnosed by flow cytometry. Our patient’s case shares similarities with other biopsy-confirmed cases of malignant bursitis, but we were able to avoid the need for surgical biopsy or bursal stripping.

The authors thank Jennifer Wilham MT (ASCP), Pat Byrd MT (ASCP), and Darlene Mann MT (ASCP) for their technical support.

1. Teras LR, DeSantis CE, Cerhan JR, Morton LM, Jemal A, Flowers CR. 2016 US lymphoid malignancy statistics by World Health Organization subtypes. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66(6):443-459.

2. Rajkumar SV, Dimopoulos MA, Palumbo A, et al. International Myeloma Working Group updated criteria for the diagnosis of multiple myeloma. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15(12):e538–e548.

3. Gozzetti A, Coviello G, Fabbri A, et al. Unusual localizations of plasmacytoma. Leuk Res. 2011;35(7):e104-e105.

4. Kivioja AH, Karaharju EO, Elomaa I, Böhling TO. Surgical treatment of myeloma of bone. Eur J Cancer. 1992;28(11):1865-1869.

5. Santos MS, Soares B, Mendes O, Carvalho CM, Casimiro RF. Multiple myeloma-amyloidosis presenting as pseudomyopathy. Rev Bras Reumatol. 2011;51(6):651-654. 6. Blackwell JR, Hay BA, Bolt AM, May SM. Olecranon bursitis: a systematic overview. Shoulder Elbow. 2014;6(3):182-190.

7. Reilly D, Kamineni S. Olecranon bursitis. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2016;25(1):158-167.

8. De Groote J, Geerts B, Mermuys K, Verstraete K. Osteochondroma of the proximal humerus with frictional bursitis and secondary synovial osteochondromatosis. JBR-BTR. 2015;98(1):45-47. 9. Kumar R, Anjana, Kundan M. Retrocalcaneal bursitis due to rare calcaneal osteochrondroma in adult male: excision and outcome. J Orthop Case Rep. 2016;6(2):16-19.

10. Yoon PW, Jang WY, Yoo JJ, Yoon KS, Kim HJ. Malignant fibrous histiocytoma at the site of an alumina-on-alumina-bearing total hip arthroplasty mimicking infected trochanteric bursitis. J Arthroplasty. 2012;27(2):324.e9-324.e12.

11. Hutchison CW, Kling DH. Malignant synovioma. Am J Cancer. 1940;40(1):8-84.

12. Hutchings C, Hull R. Metastatic bone disease presenting as trochanteric bursitis. J R Soc Med. 1997;90(12):685-686.

13. Dorfman HD, Siegel HL, Perry MC, Oxenhandler R. Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma of the synovium simulating rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1987;30(2):155-161.

14. Chao CT, Wu MS. Dialysis elbow. QJM. 2012;105(5):485-486.

15. Sayegh ET, Strauch RJ. Treatment of olecranon bursitis: a systematic review. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2014;134(11):1517-1536.

Multiple myeloma is the most common plasma cell neoplasm, with an estimated 24,000 cases occurring annually.1 Symptomatic multiple myeloma most commonly presents with one or more of the cardinal CRAB phenomena of hypercalcemia, renal dysfunction, anemia, or lytic bone lesions.2 Less commonly, patients may present with plasmacytomas (focal lesions of malignant plasma cells), which may involve bony or soft tissues.1

Plasma cell neoplasms occasionally involve the joints, including the elbows, typically as plasmacytomas. The elbow is an unusual but reported location of plasmacytomas.3,4 A case of multiple myeloma and amyloid light-chain (AL) amyloidosis has been reported, with manifestations including pseudomyopathy, bone marrow plasmacytosis, and bilateral trochanteric bursitis.5Bursitis is defined as inflammation of the synovial-fluid–containing sacs that lubricate joints. The olecranon bursa is commonly affected. Etiologies include infection, inflammatory disease, trauma, and malignancy. Furthermore, there is an association between bursitis and immunosuppression.6,7 The most common modes of therapy used to treat bursitis are nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, corticosteroid injections, and surgical management.

Trochanteric bursitis has been attributed to multiple myeloma in one previous case report, but we are not aware of any previous cases of olecranon bursitis caused by multiple myeloma. Here, we present the case of a 46-year-old man with heavily pretreated multiple myeloma and amyloidosis who developed left olecranon bursitis contemporaneously with disease relapse; flow cytometric analysis of the bursal fluid demonstrated an abnormal plasma cell population, establishing the etiology.

Case presentation and summary

A 46-year-old man with a longstanding history of multiple myeloma developed swelling of the left elbow that was initially painless in September 2016. He had been diagnosed with IgA kappa multiple myeloma and AL deposition in 2011. Over the course of his disease, he was treated with the following sequence of therapies: cyclophosphamide, bortezomib, and dexamethasone, followed by melphalan-conditioned autologous peripheral blood stem cell transplant; lenalidomide and dexamethasone; carfilzomib and dexamethasone; pomalidomide, bortezomib, and dexamethasone; and bortezomib, lenalidomide, dexamethasone, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, and etoposide, followed by second melphalan-conditioned autologous peripheral blood stem cell transplant. In addition to treatment with numerous novel and chemotherapeutic agents, his disease course was notable for amyloid deposition in the liver, bone marrow, and kidneys, which resulted in dialysis dependence.

After the second autologous transplant, he achieved a very good partial response and experienced about 9 months of remission, after which laboratory evaluation indicated recurrence of IgA kappa monoclonal protein and free kappa light-chains, which increased slowly over several months without focal symptoms, cytopenias, or decline in organ function (Figure 1).

Twelve months after his second transplant, he presented in September 2016 with 4 weeks of left elbow swelling, with the appearance suggesting a fluid collection over the left olecranon process (Figure 2). The fluid collection was not painful unless bumped or pushed. The maximum pain level was 1-2 on a scale of 0-10. His daughter drained the fluid collection on 2 occasions, but it reaccumulated over 2 to 3 days. He reported no fevers, chills, or sweats. He did not have any redness at the site. He did not report any systemic symptoms.

Physical examination of the left elbow demonstrated a ballotable fluid collection associated with the olecranon, with no associated warmth, tenderness, or erythema. Bursal fluid was sampled, yielding orange-colored serous fluid with bland characteristics (Figure 3). Microbiologic studies were negative (Table 1). We did not suspect a malignant cause initially.

The fluid collection persisted despite treatment with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and serial drainage procedures approximately twice per week. It became more erythematous and uncomfortable. We repeated diagnostic sampling at 13 months post-transplant. Cytospin revealed scant plasma cells. A multiparametric 8-color flow cytometric analysis was performed on the bursal fluid. It demonstrated the presence of a small abnormal population of plasma cells (0.04%). The abnormal plasma cells showed expression of CD138 and bright CD38 with aberrant expression of CD56, dim CD45, and loss of CD19, CD81 and CD27. They did not express CD117 or CD20 (Figure 4).

Because of the patient’s discomfort and his history of multidrug-refractory multiple myeloma, we obtained computed tomography imaging of the axial and appendicular skeleton, which demonstrated diffuse small lytic lesions, none larger than 3 mm, including the left elbow joint. The patient began systemic treatment with ixazomib, pomalidomide, and dexamethasone and then received radiation therapy of 20 Gy in 4 fractions to the left olecranon area. The bursal fluid collection remained stable in size but required periodic, though less frequent, drainage procedures. Unfortunately, the patient only tolerated 2 cycles of systemic therapy before experiencing hypercalcemia, exacerbation of hepatic amyloidosis, and a decline in performance status. He died 17 months after the transplant.

Discussion

Our patient experienced left olecranon bursitis simultaneously with relapse of multiple myeloma and AL amyloidosis. Evaluation for infectious causes was negative, and the bursal fluid did not have strongly inflammatory characteristics. Furthermore, a small plasma cell population was isolated from the fluid. Imaging did not reveal an underlying dominant lytic lesion. Although we do not have direct pathologic confirmation, the clinical scenario and flow cytometry findings support our interpretation that the patient’s bursitis was caused by or at least related to underlying multiple myeloma. While reactive plasma cells are also CD38 positive and CD138 positive, they maintain the expression of CD19 and CD45 without aberrant expression of CD56 or CD117 and do not show loss of expression of CD81 or CD27. In this situation, we suspect that either a plasmacytoma involving the soft tissue of the bursa or amyloid infiltration of the synovium may have occurred. Anti-myeloma therapies and radiation therapy did not result in control of the bursitis, though it should be noted that the patient’s highly refractory disease progressed despite treatment with a combination of later-generation immunomodulatory imide and proteasome inhibitor therapies.

Cases of malignant bursitis have been reported several times in the literature, though nearly all of the instances involved connective tissue or metastatic tumors. Tumor histologies include osteochondroma,8,9 malignant fibrous histiocytoma,10 synovial sarcoma,11 and metastatic breast cancer.12

Hematologic malignancies are more rare causes of bursitis; our literature search identified a report of 2 cases of non-Hodgkin lymphoma mimicking rheumatoid arthritis. The joints were the knee and elbow. Synovial fluid from one case was clear and yellow, with leukocytosis with a neutrophilic predominance (similar to our case). In both cases, pathology confirmed lymphomatous infiltration of the synovium.13 Notably, we identified a case of a previously healthy 35-year-old woman with bilateral trochanteric bursitis. Biopsy of tissue from the right trochanteric bursa demonstrated positive birefringence, diagnostic of AL amyloidosis. The patient also had a biclonal paraprotein accompanied by calvarial lytic lesions. She was treated with a corticosteroid pulse and bisphosphonates, followed by autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplant. 5 Our case shares features with the above case, including the relatively young age of the patient and the presence of AL amyloidosis.

Our patient wished to avoid a surgical biopsy procedure, and therefore we utilized flow cytometry of the bursal fluid to establish that the etiology of fluid collection was consistent with his concurrent relapse of multiple myeloma. We believe that we are reporting the second case of multiple myeloma-associated bursitis and the first case associated with multiple myeloma relapse; to our knowledge, it is the first to be diagnosed with the aid of flow cytometry.

Because of our patient’s reliance on hemodialysis beginning one year prior to his presentation with olecranon bursitis, we entertain “dialysis elbow” within the differential diagnosis. Dialysis elbow is a relatively uncommon complication of dialysis, in which patients develop olecranon bursitis on the same side as the hemodialysis access after a prolonged (months to years) duration of hemodialysis. Serositis and mechanical forces are the hypothesized etiologies14; infectious and rheumatologic causes were excluded from the reported cases. Nevertheless, we favor a malignant cause based upon the flow cytometry findings indicating involvement by immunophenotypically abnormal plasma cells.

Our patient was treated initially with serial drainage and nonsteroidals, which had little impact. After diagnosis of a plasma cell population in the fluid, we offered local treatment with radiation and systemic treatment of multiple myeloma, which offered better but suboptimal control. Possible treatments for olecranon bursitis include surgery, corticosteroid injections, anti-inflammatories, and serial drainage. Nonsurgical management may be more effective than surgical management, and corticosteroid injection carries significant risks. On the other hand, serial drainage does not confer additional infection risk in cases with aseptic etiology.15 We combined conservative measures as well as treatment of the underlying disease, but we believe that our patient did not derive significant benefit because of the refractory nature of his disease; he also expressed a preference to avoid surgical intervention.

Conclusion

Bursitis is a rare but thought-provoking potential manifestation of multiple myeloma and AL amyloidosis; we believe that our patient’s bursitis was related to plasma cell neoplasia based upon co-occurrence with disease relapse. His bursitis turned out to be an early indicator of impending systemic relapse. In this particular case, in which the patient wished to avoid surgical intervention, flow cytometry was of great value, and we believe that our case is the first report of malignant bursitis being diagnosed by flow cytometry. Our patient’s case shares similarities with other biopsy-confirmed cases of malignant bursitis, but we were able to avoid the need for surgical biopsy or bursal stripping.

The authors thank Jennifer Wilham MT (ASCP), Pat Byrd MT (ASCP), and Darlene Mann MT (ASCP) for their technical support.

Multiple myeloma is the most common plasma cell neoplasm, with an estimated 24,000 cases occurring annually.1 Symptomatic multiple myeloma most commonly presents with one or more of the cardinal CRAB phenomena of hypercalcemia, renal dysfunction, anemia, or lytic bone lesions.2 Less commonly, patients may present with plasmacytomas (focal lesions of malignant plasma cells), which may involve bony or soft tissues.1

Plasma cell neoplasms occasionally involve the joints, including the elbows, typically as plasmacytomas. The elbow is an unusual but reported location of plasmacytomas.3,4 A case of multiple myeloma and amyloid light-chain (AL) amyloidosis has been reported, with manifestations including pseudomyopathy, bone marrow plasmacytosis, and bilateral trochanteric bursitis.5Bursitis is defined as inflammation of the synovial-fluid–containing sacs that lubricate joints. The olecranon bursa is commonly affected. Etiologies include infection, inflammatory disease, trauma, and malignancy. Furthermore, there is an association between bursitis and immunosuppression.6,7 The most common modes of therapy used to treat bursitis are nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, corticosteroid injections, and surgical management.

Trochanteric bursitis has been attributed to multiple myeloma in one previous case report, but we are not aware of any previous cases of olecranon bursitis caused by multiple myeloma. Here, we present the case of a 46-year-old man with heavily pretreated multiple myeloma and amyloidosis who developed left olecranon bursitis contemporaneously with disease relapse; flow cytometric analysis of the bursal fluid demonstrated an abnormal plasma cell population, establishing the etiology.

Case presentation and summary

A 46-year-old man with a longstanding history of multiple myeloma developed swelling of the left elbow that was initially painless in September 2016. He had been diagnosed with IgA kappa multiple myeloma and AL deposition in 2011. Over the course of his disease, he was treated with the following sequence of therapies: cyclophosphamide, bortezomib, and dexamethasone, followed by melphalan-conditioned autologous peripheral blood stem cell transplant; lenalidomide and dexamethasone; carfilzomib and dexamethasone; pomalidomide, bortezomib, and dexamethasone; and bortezomib, lenalidomide, dexamethasone, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, and etoposide, followed by second melphalan-conditioned autologous peripheral blood stem cell transplant. In addition to treatment with numerous novel and chemotherapeutic agents, his disease course was notable for amyloid deposition in the liver, bone marrow, and kidneys, which resulted in dialysis dependence.

After the second autologous transplant, he achieved a very good partial response and experienced about 9 months of remission, after which laboratory evaluation indicated recurrence of IgA kappa monoclonal protein and free kappa light-chains, which increased slowly over several months without focal symptoms, cytopenias, or decline in organ function (Figure 1).

Twelve months after his second transplant, he presented in September 2016 with 4 weeks of left elbow swelling, with the appearance suggesting a fluid collection over the left olecranon process (Figure 2). The fluid collection was not painful unless bumped or pushed. The maximum pain level was 1-2 on a scale of 0-10. His daughter drained the fluid collection on 2 occasions, but it reaccumulated over 2 to 3 days. He reported no fevers, chills, or sweats. He did not have any redness at the site. He did not report any systemic symptoms.

Physical examination of the left elbow demonstrated a ballotable fluid collection associated with the olecranon, with no associated warmth, tenderness, or erythema. Bursal fluid was sampled, yielding orange-colored serous fluid with bland characteristics (Figure 3). Microbiologic studies were negative (Table 1). We did not suspect a malignant cause initially.

The fluid collection persisted despite treatment with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and serial drainage procedures approximately twice per week. It became more erythematous and uncomfortable. We repeated diagnostic sampling at 13 months post-transplant. Cytospin revealed scant plasma cells. A multiparametric 8-color flow cytometric analysis was performed on the bursal fluid. It demonstrated the presence of a small abnormal population of plasma cells (0.04%). The abnormal plasma cells showed expression of CD138 and bright CD38 with aberrant expression of CD56, dim CD45, and loss of CD19, CD81 and CD27. They did not express CD117 or CD20 (Figure 4).

Because of the patient’s discomfort and his history of multidrug-refractory multiple myeloma, we obtained computed tomography imaging of the axial and appendicular skeleton, which demonstrated diffuse small lytic lesions, none larger than 3 mm, including the left elbow joint. The patient began systemic treatment with ixazomib, pomalidomide, and dexamethasone and then received radiation therapy of 20 Gy in 4 fractions to the left olecranon area. The bursal fluid collection remained stable in size but required periodic, though less frequent, drainage procedures. Unfortunately, the patient only tolerated 2 cycles of systemic therapy before experiencing hypercalcemia, exacerbation of hepatic amyloidosis, and a decline in performance status. He died 17 months after the transplant.

Discussion

Our patient experienced left olecranon bursitis simultaneously with relapse of multiple myeloma and AL amyloidosis. Evaluation for infectious causes was negative, and the bursal fluid did not have strongly inflammatory characteristics. Furthermore, a small plasma cell population was isolated from the fluid. Imaging did not reveal an underlying dominant lytic lesion. Although we do not have direct pathologic confirmation, the clinical scenario and flow cytometry findings support our interpretation that the patient’s bursitis was caused by or at least related to underlying multiple myeloma. While reactive plasma cells are also CD38 positive and CD138 positive, they maintain the expression of CD19 and CD45 without aberrant expression of CD56 or CD117 and do not show loss of expression of CD81 or CD27. In this situation, we suspect that either a plasmacytoma involving the soft tissue of the bursa or amyloid infiltration of the synovium may have occurred. Anti-myeloma therapies and radiation therapy did not result in control of the bursitis, though it should be noted that the patient’s highly refractory disease progressed despite treatment with a combination of later-generation immunomodulatory imide and proteasome inhibitor therapies.

Cases of malignant bursitis have been reported several times in the literature, though nearly all of the instances involved connective tissue or metastatic tumors. Tumor histologies include osteochondroma,8,9 malignant fibrous histiocytoma,10 synovial sarcoma,11 and metastatic breast cancer.12

Hematologic malignancies are more rare causes of bursitis; our literature search identified a report of 2 cases of non-Hodgkin lymphoma mimicking rheumatoid arthritis. The joints were the knee and elbow. Synovial fluid from one case was clear and yellow, with leukocytosis with a neutrophilic predominance (similar to our case). In both cases, pathology confirmed lymphomatous infiltration of the synovium.13 Notably, we identified a case of a previously healthy 35-year-old woman with bilateral trochanteric bursitis. Biopsy of tissue from the right trochanteric bursa demonstrated positive birefringence, diagnostic of AL amyloidosis. The patient also had a biclonal paraprotein accompanied by calvarial lytic lesions. She was treated with a corticosteroid pulse and bisphosphonates, followed by autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplant. 5 Our case shares features with the above case, including the relatively young age of the patient and the presence of AL amyloidosis.

Our patient wished to avoid a surgical biopsy procedure, and therefore we utilized flow cytometry of the bursal fluid to establish that the etiology of fluid collection was consistent with his concurrent relapse of multiple myeloma. We believe that we are reporting the second case of multiple myeloma-associated bursitis and the first case associated with multiple myeloma relapse; to our knowledge, it is the first to be diagnosed with the aid of flow cytometry.

Because of our patient’s reliance on hemodialysis beginning one year prior to his presentation with olecranon bursitis, we entertain “dialysis elbow” within the differential diagnosis. Dialysis elbow is a relatively uncommon complication of dialysis, in which patients develop olecranon bursitis on the same side as the hemodialysis access after a prolonged (months to years) duration of hemodialysis. Serositis and mechanical forces are the hypothesized etiologies14; infectious and rheumatologic causes were excluded from the reported cases. Nevertheless, we favor a malignant cause based upon the flow cytometry findings indicating involvement by immunophenotypically abnormal plasma cells.

Our patient was treated initially with serial drainage and nonsteroidals, which had little impact. After diagnosis of a plasma cell population in the fluid, we offered local treatment with radiation and systemic treatment of multiple myeloma, which offered better but suboptimal control. Possible treatments for olecranon bursitis include surgery, corticosteroid injections, anti-inflammatories, and serial drainage. Nonsurgical management may be more effective than surgical management, and corticosteroid injection carries significant risks. On the other hand, serial drainage does not confer additional infection risk in cases with aseptic etiology.15 We combined conservative measures as well as treatment of the underlying disease, but we believe that our patient did not derive significant benefit because of the refractory nature of his disease; he also expressed a preference to avoid surgical intervention.

Conclusion

Bursitis is a rare but thought-provoking potential manifestation of multiple myeloma and AL amyloidosis; we believe that our patient’s bursitis was related to plasma cell neoplasia based upon co-occurrence with disease relapse. His bursitis turned out to be an early indicator of impending systemic relapse. In this particular case, in which the patient wished to avoid surgical intervention, flow cytometry was of great value, and we believe that our case is the first report of malignant bursitis being diagnosed by flow cytometry. Our patient’s case shares similarities with other biopsy-confirmed cases of malignant bursitis, but we were able to avoid the need for surgical biopsy or bursal stripping.

The authors thank Jennifer Wilham MT (ASCP), Pat Byrd MT (ASCP), and Darlene Mann MT (ASCP) for their technical support.

1. Teras LR, DeSantis CE, Cerhan JR, Morton LM, Jemal A, Flowers CR. 2016 US lymphoid malignancy statistics by World Health Organization subtypes. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66(6):443-459.

2. Rajkumar SV, Dimopoulos MA, Palumbo A, et al. International Myeloma Working Group updated criteria for the diagnosis of multiple myeloma. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15(12):e538–e548.

3. Gozzetti A, Coviello G, Fabbri A, et al. Unusual localizations of plasmacytoma. Leuk Res. 2011;35(7):e104-e105.

4. Kivioja AH, Karaharju EO, Elomaa I, Böhling TO. Surgical treatment of myeloma of bone. Eur J Cancer. 1992;28(11):1865-1869.

5. Santos MS, Soares B, Mendes O, Carvalho CM, Casimiro RF. Multiple myeloma-amyloidosis presenting as pseudomyopathy. Rev Bras Reumatol. 2011;51(6):651-654. 6. Blackwell JR, Hay BA, Bolt AM, May SM. Olecranon bursitis: a systematic overview. Shoulder Elbow. 2014;6(3):182-190.

7. Reilly D, Kamineni S. Olecranon bursitis. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2016;25(1):158-167.

8. De Groote J, Geerts B, Mermuys K, Verstraete K. Osteochondroma of the proximal humerus with frictional bursitis and secondary synovial osteochondromatosis. JBR-BTR. 2015;98(1):45-47. 9. Kumar R, Anjana, Kundan M. Retrocalcaneal bursitis due to rare calcaneal osteochrondroma in adult male: excision and outcome. J Orthop Case Rep. 2016;6(2):16-19.

10. Yoon PW, Jang WY, Yoo JJ, Yoon KS, Kim HJ. Malignant fibrous histiocytoma at the site of an alumina-on-alumina-bearing total hip arthroplasty mimicking infected trochanteric bursitis. J Arthroplasty. 2012;27(2):324.e9-324.e12.

11. Hutchison CW, Kling DH. Malignant synovioma. Am J Cancer. 1940;40(1):8-84.

12. Hutchings C, Hull R. Metastatic bone disease presenting as trochanteric bursitis. J R Soc Med. 1997;90(12):685-686.

13. Dorfman HD, Siegel HL, Perry MC, Oxenhandler R. Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma of the synovium simulating rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1987;30(2):155-161.

14. Chao CT, Wu MS. Dialysis elbow. QJM. 2012;105(5):485-486.

15. Sayegh ET, Strauch RJ. Treatment of olecranon bursitis: a systematic review. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2014;134(11):1517-1536.

1. Teras LR, DeSantis CE, Cerhan JR, Morton LM, Jemal A, Flowers CR. 2016 US lymphoid malignancy statistics by World Health Organization subtypes. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66(6):443-459.

2. Rajkumar SV, Dimopoulos MA, Palumbo A, et al. International Myeloma Working Group updated criteria for the diagnosis of multiple myeloma. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15(12):e538–e548.

3. Gozzetti A, Coviello G, Fabbri A, et al. Unusual localizations of plasmacytoma. Leuk Res. 2011;35(7):e104-e105.

4. Kivioja AH, Karaharju EO, Elomaa I, Böhling TO. Surgical treatment of myeloma of bone. Eur J Cancer. 1992;28(11):1865-1869.

5. Santos MS, Soares B, Mendes O, Carvalho CM, Casimiro RF. Multiple myeloma-amyloidosis presenting as pseudomyopathy. Rev Bras Reumatol. 2011;51(6):651-654. 6. Blackwell JR, Hay BA, Bolt AM, May SM. Olecranon bursitis: a systematic overview. Shoulder Elbow. 2014;6(3):182-190.

7. Reilly D, Kamineni S. Olecranon bursitis. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2016;25(1):158-167.

8. De Groote J, Geerts B, Mermuys K, Verstraete K. Osteochondroma of the proximal humerus with frictional bursitis and secondary synovial osteochondromatosis. JBR-BTR. 2015;98(1):45-47. 9. Kumar R, Anjana, Kundan M. Retrocalcaneal bursitis due to rare calcaneal osteochrondroma in adult male: excision and outcome. J Orthop Case Rep. 2016;6(2):16-19.

10. Yoon PW, Jang WY, Yoo JJ, Yoon KS, Kim HJ. Malignant fibrous histiocytoma at the site of an alumina-on-alumina-bearing total hip arthroplasty mimicking infected trochanteric bursitis. J Arthroplasty. 2012;27(2):324.e9-324.e12.

11. Hutchison CW, Kling DH. Malignant synovioma. Am J Cancer. 1940;40(1):8-84.

12. Hutchings C, Hull R. Metastatic bone disease presenting as trochanteric bursitis. J R Soc Med. 1997;90(12):685-686.

13. Dorfman HD, Siegel HL, Perry MC, Oxenhandler R. Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma of the synovium simulating rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1987;30(2):155-161.

14. Chao CT, Wu MS. Dialysis elbow. QJM. 2012;105(5):485-486.

15. Sayegh ET, Strauch RJ. Treatment of olecranon bursitis: a systematic review. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2014;134(11):1517-1536.

Primary Cutaneous Epstein-Barr Virus–Positive Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma: A Rare and Aggressive Cutaneous Lymphoma

Cutaneous B-cell lymphomas represent a group of lymphomas derived from B lymphocytes in various stages of differentiation. The skin can be the site of primary or secondary involvement of any of the B-cell lymphomas. Primary cutaneous B-cell lymphomas present in the skin without evidence of extracutaneous disease at the time of diagnosis.1 The World Health Organization Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues recognizes 5 distinct primary cutaneous B-cell lymphoma subtypes: primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma; primary cutaneous marginal zone lymphoma; primary cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), leg type; DLBCL, not otherwise specified; and intravascular DLBCL.1-3 The DLBCL, not otherwise specified, category includes less common provisional entities with insufficient evidence to be recognized as distinct diseases. Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)–positive DLBCL is a rare subtype in this group.4

This article reviews the different clinicopathologic subtypes of primary cutaneous B-cell lymphoma. It also serves to help dermatologists recognize primary cutaneous EBV-positive DLBCL as a rare and aggressive form of this disease.

Case Report

An 84-year-old white man presented with a pruritic eruption on the arms, legs, back, neck, and face of 5 months’ duration. His medical history was notable for prostate cancer that was successfully treated with radiation therapy 6 years prior. The patient denied any constitutional symptoms such as fever, chills, night sweats, or weight loss, and review of systems was negative. The patient was taking prednisone, which alleviated the pruritus, but the lesions persisted.

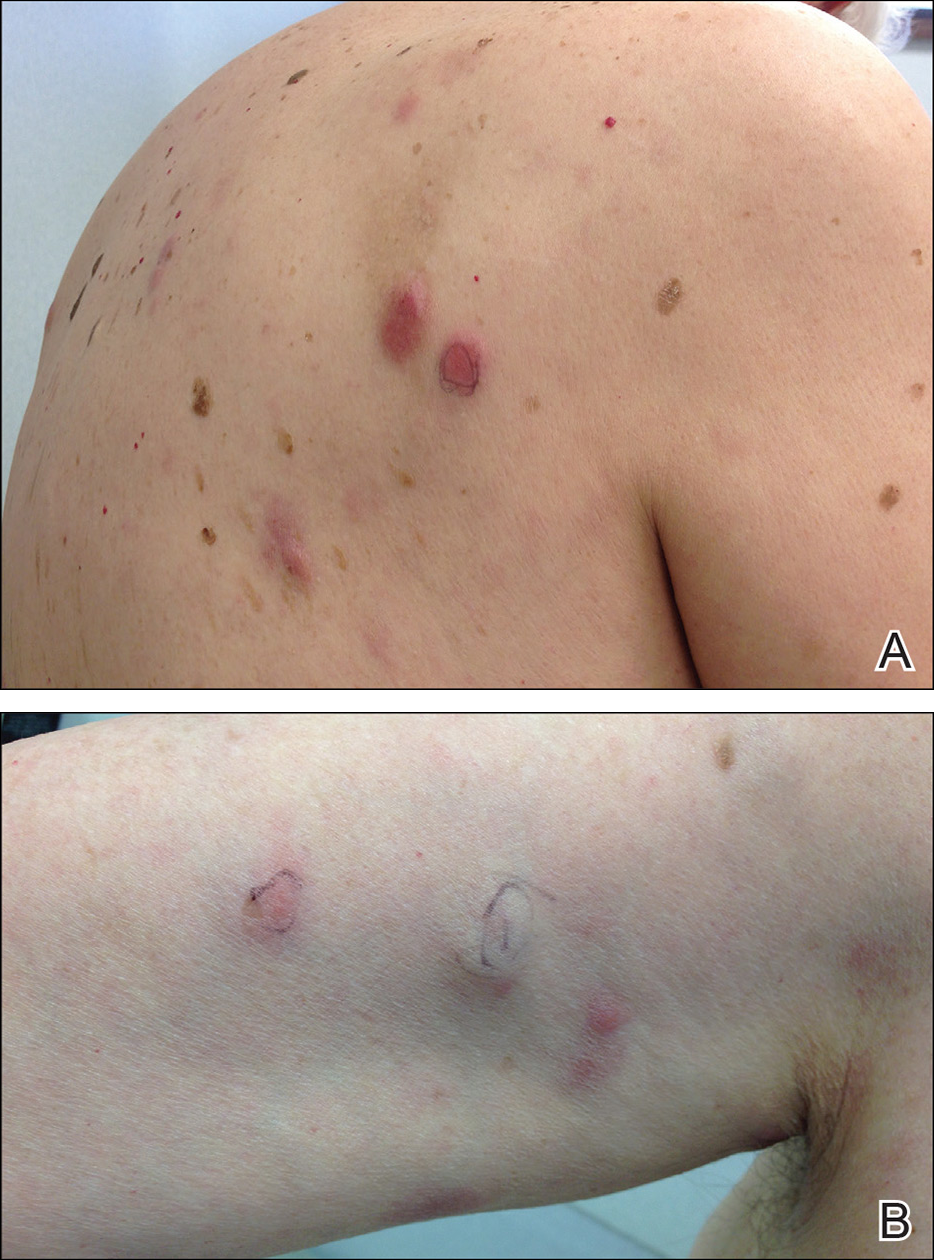

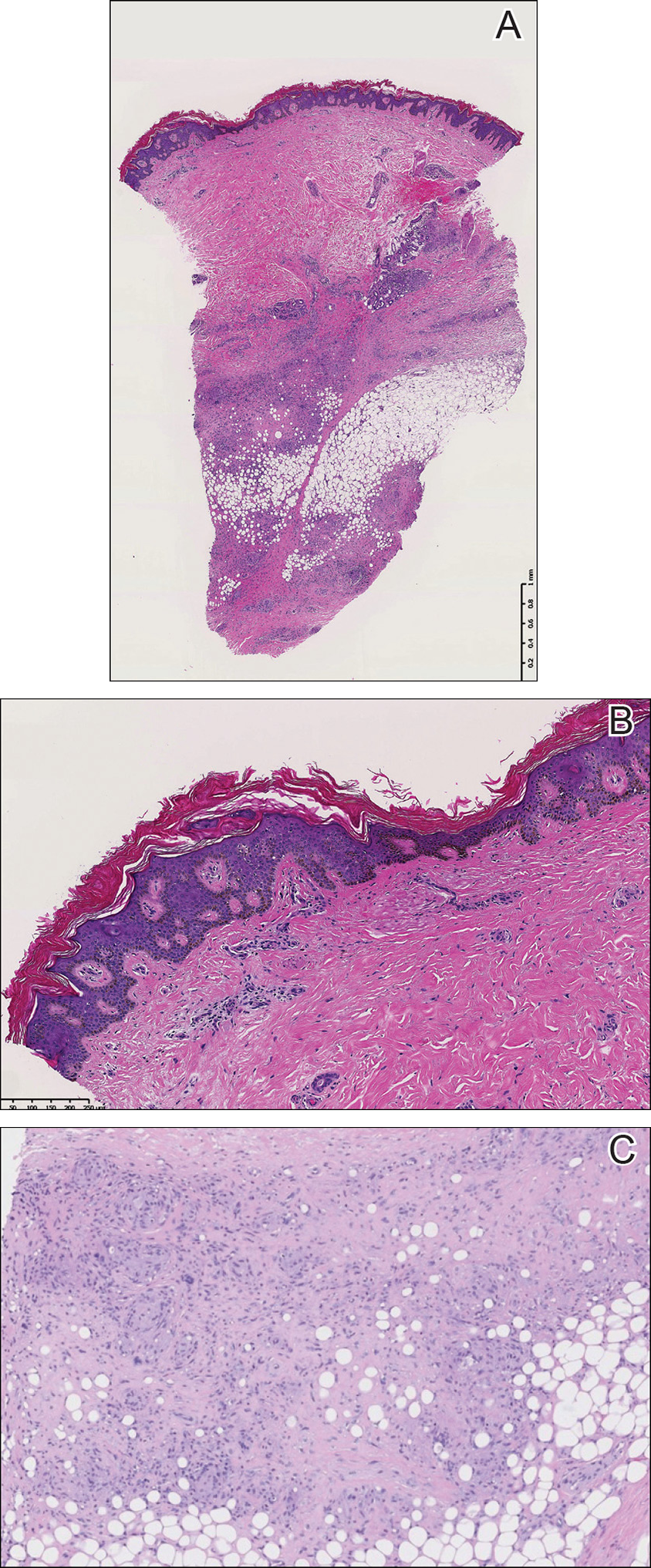

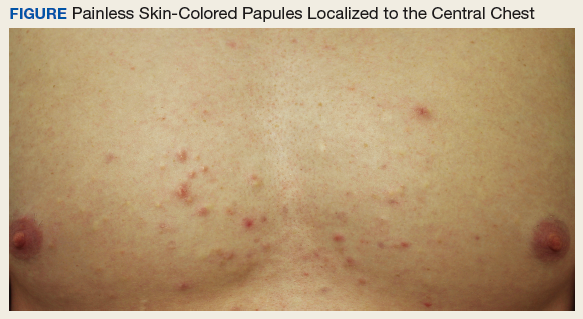

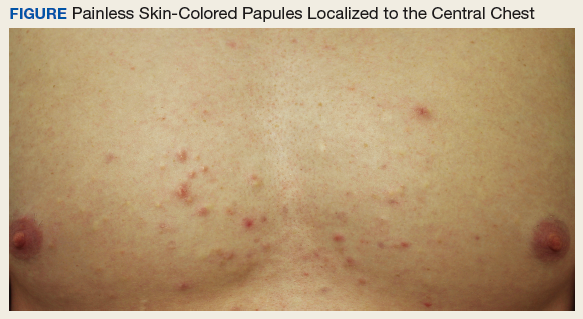

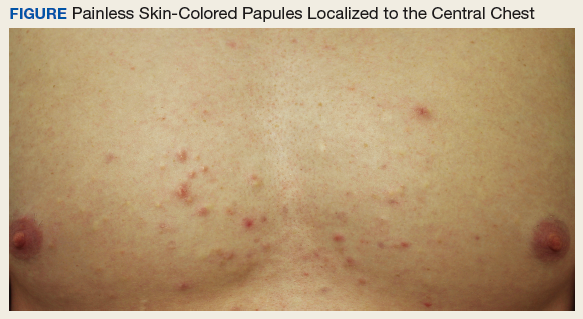

Physical examination revealed multiple pink to erythematous papules and subcutaneous nodules involving the face, neck, back, arms, and legs (Figure 1). No scale, crust, or ulceration was present. Palpation of the cervical, supraclavicular, axillary, and inguinal lymph nodes was negative for lymphadenopathy.

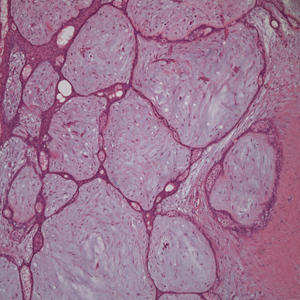

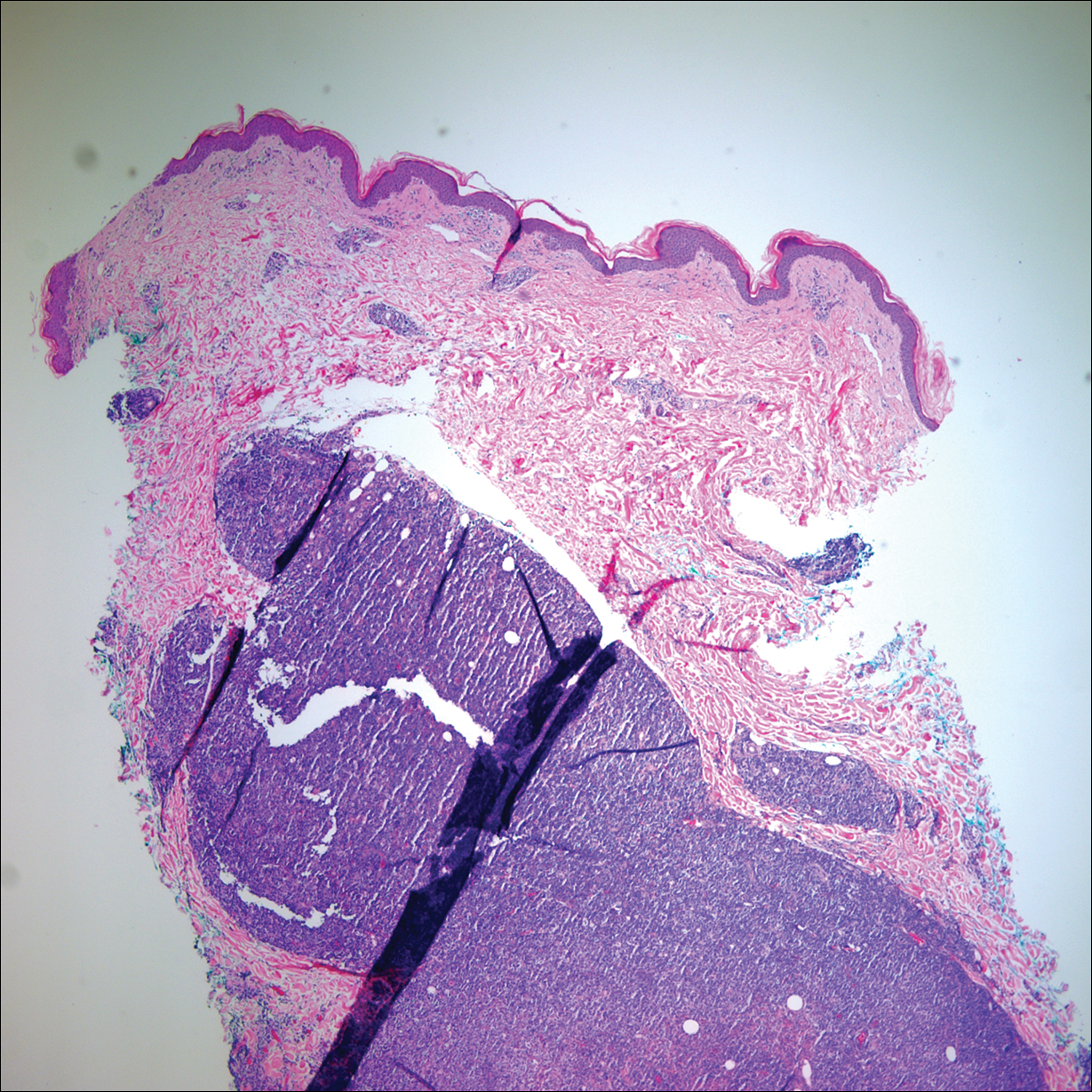

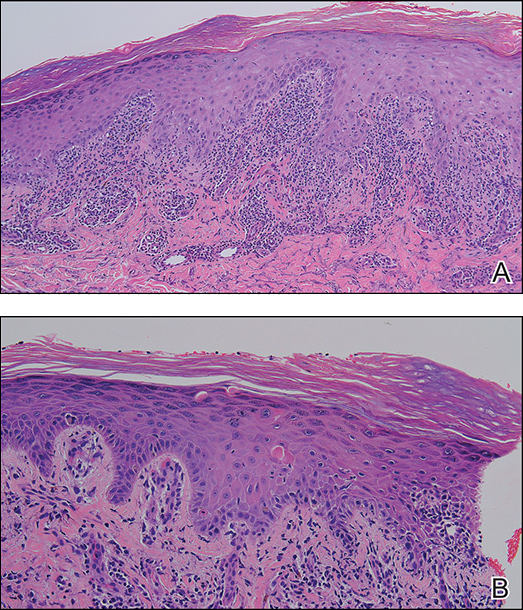

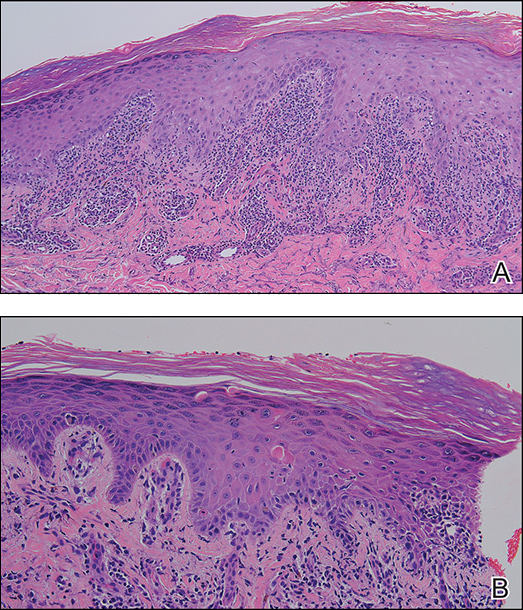

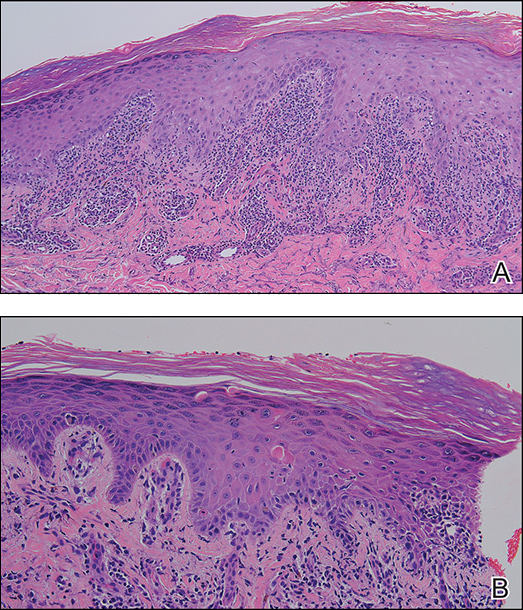

Punch biopsies of representative lesions on the upper back and right arm revealed diffuse and nodular infiltrates of large atypical lymphoid cells with scattered centroblasts and immunoblasts (Figures 2 and 3). Immunohistochemical staining demonstrated CD79, MUM-1, and EBV-encoded RNA positivity among the neoplastic cells. The Ki-67 proliferative index was greater than 90%. The neoplastic cells were negative for CD5, CD10, CD20, CD21, CD30, CD56, CD123, CD138, PAX5, C-MYC, BCL-2, BCL-6, cyclin D1, TCL-1A, and terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase

A peripheral blood smear did not show evidence of a B-cell lymphoproliferative process. A bone marrow biopsy was performed and did not show evidence of B-cell lymphoid neoplasia but did show reactive lymphoid aggregates composed of CD4+ and CD10+ T cells. Peripheral blood T-cell rearrangement and JAK2 were negative.

Based on clinical and histologic findings, the patient was diagnosed with primary cutaneous EBV-positive DLBCL. The patient was started on CHOP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone) chemotherapy for treatment of this aggressive cutaneous lymphoma, which initially resulted in clinical improvement of the lesions and complete involution of the subcutaneous nodules. After the sixth cycle of CHOP, he developed faintly erythematous indurated papules on the upper arms, chest, and back. Biopsy confirmed recurrence of the EBV-positive cutaneous lymphoma, and he started salvage chemotherapy with gemcitabine, oxaliplatin, and rituximab every 2 weeks; however, 4 months later (9 months after the initial presentation) he died from complications of the disease.

Comment

Etiology

Epstein-Barr virus–positive DLBCL, also called EBV-positive DLBCL of the elderly, was initially described in 2003 by Oyama et al5 and was included as a provisional entity in the 2008 World Health Organization classification system as a rare subtype of the DLBCL, not otherwise specified, category.2 It is defined as an EBV-positive monoclonal large B-cell proliferation that occurs in immunocompetent patients older than 50 years.6 Epstein-Barr virus is a human herpesvirus that demonstrates tropism for lymphocytes and survives in human hosts by establishing latency in B cells. Under normal immune conditions, the proliferation of EBV-infected B cells is prevented by cytotoxic T cells.7 It is important to recognize that patients with EBV-positive DLBCL do not have a known immunodeficiency state; therefore, it has been postulated that EBV-positive DLBCL might be caused by age-related senescence of the immune system.4,8

Epidemiology and Clinical Features

Epstein-Barr virus–positive DLBCL is more common in Asian countries than in Western countries, and there is a slight male predominance.6 A majority of patients present with extranodal disease at the time of diagnosis, and the skin is the most common extranodal site of involvement.6,9 Rare cases of primary cutaneous involvement also have been described.7,9,10 Cutaneous manifestations include erythematous papules and subcutaneous nodules. Other sites of extranodal involvement include the lungs, oral cavity, pharynx, gastrointestinal tract, and bone marrow.8,9 However, EBV-positive DLBCL is an aggressive lymphoma and prognosis is poor irrespective of the primary site of involvement.

Histopathology

Two morphologic subtypes can be seen on histology. The polymorphic pattern is characterized by a broad range of B-cell maturation with admixed reactive cells (eg, lymphocytes, histiocytes, plasma cells). The monomorphic or large-cell pattern is characterized by monotonous sheets of large transformed B cells.4,11 Many cases show both histologic patterns, and these morphologic variants do not impart any clinical or prognostic significance. Regardless of the histologic subtype, the neoplastic cells express pan B-cell antigens (eg, CD19, CD20, CD79a, PAX5), as well as MUM-1, BCL-2, and EBV-encoded RNA.4 Cases with plasmablastic features, as in our patient, may show weak or absent CD20 staining.12 Detection of EBV by in situ hybridization is required for the diagnosis.

Diagnosis

Workup for a suspected cutaneous lymphoma should include a complete history and physical examination; laboratory studies; and relevant imaging evaluation such as computed tomography of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis with or without whole-body positron emission tomography. A bone marrow biopsy and aspirate also should be performed in all cutaneous lymphomas with intermediate to aggressive clinical behavior. Accurate staging evaluation is integral to confirm the absence of extracutaneous involvement and to provide prognostic and anatomic information for the appropriate selection of treatment.13

Prognosis and Management

Primary cutaneous lymphomas tend to have different clinical behaviors and prognoses compared to histologically similar systemic lymphomas; therefore, different therapeutic strategies are warranted.14 Epstein-Barr virus–positive DLBCL has an aggressive clinical course with a median survival of 2 years.8 Patients with EBV-positive DLBCL have a poorer overall survival and treatment response when compared to patients with EBV-negative DLBCLs.4 Primary cutaneous B-cell lymphomas with indolent behavior, such as primary cutaneous marginal zone lymphoma and primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma, can be treated with surgical excision, radiation therapy, or observation.15 No standard treatment exists for EBV-positive DLBCL, but R-CHOP (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone), which is the standard treatment of primary cutaneous DLBCL, leg type, may provide a survival benefit.13,15 Further studies are required to determine optimal treatment strategies.

Conclusion

Although rare, EBV-positive DLBCL is an important entity to consider when evaluating a patient with a suspected primary cutaneous lymphoma. Workup to rule out an underlying systemic lymphoma with relevant laboratory evaluation, imaging studies, and bone marrow biopsy is critical. Prognosis is poor and treatment is difficult, as standard treatment protocols have yet to be determined.

- Willemze R, Jaffe ES, Burg G, et al. WHO-EORTC classification for cutaneous lymphomas. Blood. 2005;105:3768-3785.

- Nakmura S, Jaffe ES, Swerdlow SH. EBV positive diffuse large B-cell lymphoma of the elderly. In: Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Harris NL, et al, eds. WHO Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues. 4th ed. Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC); 2008:243-244.

- Kempf W, Sander CA. Classification of cutaneous lymphomas—an update. Histopathology. 2010;56:57-70.

- Castillo JJ, Beltran BE, Miranda RN, et al. Epstein-Barr virus-positive diffuse large B-cell lymphoma of the elderly: what we know so far. Oncologist. 2011;16:87-96.

- Oyama T, Ichimura K, Suzuki R, et al. Senile EBV+ B-cell lymphoproliferative disorders: a clinicopathologic study of 22 patients. Am J Surg Pathol. 2003;27:16-26.

- Ok CY, Papathomas TG, Medeiros LJ, et al. EBV-positive diffuse large B-cell lymphoma of the elderly. Blood. 2013;122:328-340.

- Tokuda Y, Fukushima M, Nakazawa K, et al. A case of primary Epstein-Barr virus-associated cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma unassociated with iatrogenic or endogenous immune dysregulation. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:666-671.

- Oyama T, Yamamoto K, Asano N, et al. Age-related EBV-associated B-cell lymphoproliferative disorders constitute a distinct clinicopathologic group: a study of 96 patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:5124-5132.

- Eminger LA, Hall LD, Hesterman KS, et al. Epstein-Barr virus: dermatologic associations and implications. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:21-34.

- Martin B, Whittaker S, Morris S, et al. A case of primary cutaneous senile EBV-related diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2010;32:190-193.

- Gibson SE, Hsi ED. Epstein-Barr virus-positive B-cell lymphoma of the elderly at a United States tertiary medical center: an uncommon aggressive lymphoma with a nongerminal center B-cell phenotype. Hum Pathol. 2009;40:653-661.

- Castillo JJ, Bibas M, Miranda RN. The biology and treatment of plasmablastic lymphoma. Blood. 2015;125:2323-2330.

- Kim YH, Willemze R, Pimpinelli N, et al. TNM classification system for primary cutaneous lymphomas other than mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome: a proposal of the International Society for Cutaneous Lymphomas (ISCL) and the Cutaneous Lymphoma Task Force of the European Organization of Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC). Blood. 2007;110:479-484.

- Suárez AL, Pulitzer M, Horwitz S, et al. Primary cutaneous B-cell lymphomas: part I. clinical features, diagnosis, and classification. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:329.e1-329.e13; quiz 341-342.

- Suárez AL, Querfeld C, Horwitz S, et al. Primary cutaneous B-cell lymphomas: part II. therapy and future directions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:343.e1-343.e11; quiz 355-356.

Cutaneous B-cell lymphomas represent a group of lymphomas derived from B lymphocytes in various stages of differentiation. The skin can be the site of primary or secondary involvement of any of the B-cell lymphomas. Primary cutaneous B-cell lymphomas present in the skin without evidence of extracutaneous disease at the time of diagnosis.1 The World Health Organization Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues recognizes 5 distinct primary cutaneous B-cell lymphoma subtypes: primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma; primary cutaneous marginal zone lymphoma; primary cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), leg type; DLBCL, not otherwise specified; and intravascular DLBCL.1-3 The DLBCL, not otherwise specified, category includes less common provisional entities with insufficient evidence to be recognized as distinct diseases. Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)–positive DLBCL is a rare subtype in this group.4

This article reviews the different clinicopathologic subtypes of primary cutaneous B-cell lymphoma. It also serves to help dermatologists recognize primary cutaneous EBV-positive DLBCL as a rare and aggressive form of this disease.

Case Report

An 84-year-old white man presented with a pruritic eruption on the arms, legs, back, neck, and face of 5 months’ duration. His medical history was notable for prostate cancer that was successfully treated with radiation therapy 6 years prior. The patient denied any constitutional symptoms such as fever, chills, night sweats, or weight loss, and review of systems was negative. The patient was taking prednisone, which alleviated the pruritus, but the lesions persisted.

Physical examination revealed multiple pink to erythematous papules and subcutaneous nodules involving the face, neck, back, arms, and legs (Figure 1). No scale, crust, or ulceration was present. Palpation of the cervical, supraclavicular, axillary, and inguinal lymph nodes was negative for lymphadenopathy.

Punch biopsies of representative lesions on the upper back and right arm revealed diffuse and nodular infiltrates of large atypical lymphoid cells with scattered centroblasts and immunoblasts (Figures 2 and 3). Immunohistochemical staining demonstrated CD79, MUM-1, and EBV-encoded RNA positivity among the neoplastic cells. The Ki-67 proliferative index was greater than 90%. The neoplastic cells were negative for CD5, CD10, CD20, CD21, CD30, CD56, CD123, CD138, PAX5, C-MYC, BCL-2, BCL-6, cyclin D1, TCL-1A, and terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase

A peripheral blood smear did not show evidence of a B-cell lymphoproliferative process. A bone marrow biopsy was performed and did not show evidence of B-cell lymphoid neoplasia but did show reactive lymphoid aggregates composed of CD4+ and CD10+ T cells. Peripheral blood T-cell rearrangement and JAK2 were negative.

Based on clinical and histologic findings, the patient was diagnosed with primary cutaneous EBV-positive DLBCL. The patient was started on CHOP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone) chemotherapy for treatment of this aggressive cutaneous lymphoma, which initially resulted in clinical improvement of the lesions and complete involution of the subcutaneous nodules. After the sixth cycle of CHOP, he developed faintly erythematous indurated papules on the upper arms, chest, and back. Biopsy confirmed recurrence of the EBV-positive cutaneous lymphoma, and he started salvage chemotherapy with gemcitabine, oxaliplatin, and rituximab every 2 weeks; however, 4 months later (9 months after the initial presentation) he died from complications of the disease.

Comment

Etiology

Epstein-Barr virus–positive DLBCL, also called EBV-positive DLBCL of the elderly, was initially described in 2003 by Oyama et al5 and was included as a provisional entity in the 2008 World Health Organization classification system as a rare subtype of the DLBCL, not otherwise specified, category.2 It is defined as an EBV-positive monoclonal large B-cell proliferation that occurs in immunocompetent patients older than 50 years.6 Epstein-Barr virus is a human herpesvirus that demonstrates tropism for lymphocytes and survives in human hosts by establishing latency in B cells. Under normal immune conditions, the proliferation of EBV-infected B cells is prevented by cytotoxic T cells.7 It is important to recognize that patients with EBV-positive DLBCL do not have a known immunodeficiency state; therefore, it has been postulated that EBV-positive DLBCL might be caused by age-related senescence of the immune system.4,8

Epidemiology and Clinical Features