User login

Roundtable Discussion: Anticoagulation Management

Case 1

Tracy Minichiello, MD. The first case we’ll discuss is a 75-year-old man with mild chronic kidney disease (CKD). His calculated creatinine clearance (CrCl) is about 52 mL/min, and he has a remote history of a gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding 3 years previously from a peptic ulcer. He presents with new onset nonvalvular atrial fibrillation (AF), and he’s already on aspirin for his stable coronary artery disease (CAD).

How do we think about anticoagulant selection in this patient? We have a number of new oral anticoagulants and we have warfarin. How do we decide between warfarin vs one of the direct-acting oral anticoagulants (DOACs)? If we choose a DOAC, which one would we select?

David Parra, PharmD. The first step for anticoagulation is to assess a patient’s thromboembolic risk utilizing the CHA2DS2-VASc and bleeding risk using a HAS-BLED score, or something similar. The next question is which oral anticoagulant to use. We have widespread experience with warfarin and can measure the anticoagulant effect easily. Warfarin has a long duration of action, so perhaps it’s more forgiving if you miss a dose. It also has an antidote. Lastly, organ dysfunction doesn’t preclude use of warfarin as you can still monitor the anticoagulant effect. So there still may be patients that may benefit significantly from warfarin vs a DOAC.

On the flip side, DOACs are easier to use and perform quite acceptably in comparison with warfarin in nonvalvular AF. There are some scenarios where a specific DOAC may be preferred over another, such as recent GI bleeding.

Dr. Minichiello. Do you consider renal function, bleeding history, or concomitant antiplatelet therapy?

Geoffrey Barnes, MD, MSc. A couple of factors are relevant. I think we should consider renal function for this gentleman. However, I look at some of the other features as Dr. Parra suggested. What’s the likelihood that this patient is going to take the medicine as prescribed? Is a twice-a-day regimen going to be something that’s particularly challenging? I also look at the real-world vs randomized trial experience.

This patient has a remote GI bleeding history. Some of the real-world data suggest there might be some more GI bleeding with rivaroxaban, but across the board, apixaban (in both the randomized trials and much of the real-world data) seem to have a favorable bleeding risk profile. For a patient who is open and reliable for taking medicine twice a day, apixaban might be a good option as long as we make sure that the dose is appropriate.

Arthur L. Allen, PharmD, CACP. In pivotal trial experience, dabigatran and rivaroxaban demonstrated an increased incidence of GI bleeding compared with warfarin. In some of the real-world studies, rivaroxaban mirrors warfarin with regard to bleeding, whereas dabigatran and apixaban have a lower incidence. In the pivotal trials, apixaban did not have a trigger of increased GI bleeding, but I would let the details of this patient’s GI bleeding history help me determine how important an issue this is at this point.

The other thing that is important to understand when considering choice of agents: As Dr. Parra mentioned, we do have quite a bit of experience with warfarin. But comparing the quality of evidence, the DOACs have been investigated in a far more rigorous fashion and in far more patients than warfarin ever was in its more than 60 years on the market. For example, the RE-LY trial alone enrolled more than 18,000 patients. Each of the DOACs have been studied in tens of thousands of patients for their approved indications. Further, we shouldn’t forget that the risk of intracranial hemorrhage is reduced by roughly 50% by choosing a DOAC over warfarin, which should be a consideration in this elderly gentleman.

Dr. Minichiello. In the veteran population, there is a sense of comfort with warfarin, and some concerns have been raised over a lack of reversibility for the newer agents. We have patients who have trepidation about starting one of the new anticoagulants. However, there is a marked reduction in the risk of the most devastating bleeding complication, namely intracranial hemorrhage, making the use of these agents most compelling. And when they did have bleeding complications, at least in the trials, their outcomes were no worse than they were with warfarin, where there is a reversal agent. In most cases the outcomes were actually better.

Dr. Barnes. You often have to remind patients that there was no reversal agent in these huge trials where the DOACs showed similar or safer bleeding risk profiles, especially for the most serious bleeding, such as intracranial hemorrhage. I find patients often are reassured by knowing that.

Dr. Allen. I agree that there is concern about the lack of reversibility, but I think it has been completely overplayed. In the pivotal trials, patients who bled on DOAC therapy actually had better outcomes than those that bled on warfarin. This includes intracranial hemorrhage. There was a paper published in Stroke in 2012 that evaluated the subgroup of patients in the RE-LY trial that suffered intracranial hemorrhage. Patients on dabigatran actually fared better despite a lack of a specific reversal agent. When evaluating the available data about reversal of the DOACs, I’m not 100% convinced that we’re significantly impacting outcomes by reversing these agents. We’re certainly running up the bill, but are we treating the patient or treating the providers? As long as the renal function remains intact, the DOACs clear quickly, perhaps more quickly than warfarin can typically be reversed with standard reversal agents.

Dr. Minichiello. Remember that this patient has a history of a GI bleed. We are going to start him on full-dose anticoagulation for stroke prevention for his nonvalvular AF. He’s also on aspirin, and he has stable coronary disease. He does not have any stents in place but he did have a remote non-ST elevation myocardial infarction (MI) a number of years ago. Do we feel that the risk of dual therapy—anticoagulation combined with antiplatelet therapy—outweighs the risks? And how do we approach that risk?

Dr. Barnes. This is an important point to discuss. There has been a lot of discussion in the literature recently. When I start this type of patient on an oral anticoagulant, I try to discontinue the antiplatelet agent because I know how much bleeding risk that brings. The European guidelines (for example, Eur Heart J. 2014;35[45]:3155-3179) have been forward thinking with this for the last couple of years and have highlighted that if there’s an indication for anticoagulation for patients with stable coronary disease, meaning no MI and no stent within the past year, then we should stop the antiplatelet agents after a year in order to reduce the risk of MI. This is based on a lot of older literature where warfarin was compared with aspirin and shown to be protective in coronary patients, but at the risk of bleeding.

It’s important because there have been recent studies that have raised questions, including a recent Swedish article in (Circulation. 2017;136:1183-1192) that suggested discontinuing aspirin led to increased mortality. But it’s important to look at the details. While that was true for most patients, it was not true for the group of patients who were on an oral anticoagulant. Many colleagues ask me questions about that particular paper and its media coverage. I tell them that for our patients on chronic oral anticoagulants, the paper supports the notion that there is not increased mortality when aspirin use is stopped. We know that aspirin plus an anticoagulant leads to increased bleeding, so I try to stop it for patients who have stable CAD but are on long-term anticoagulation.

Dr. Allen. This isn’t a new thought. Back in early 2012, the 9th edition of the American College of Chest Physicians (CHEST) Antithrombotic Guidelines probably gave us the best guidance that we had ever seen to help us address this issue. Since that time the cardiology guidelines have caught up to recommend that we do not need additional antiplatelet therapy for stable CAD, and, in fact, it should be limited even in the setting of acute coronary syndromes and percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI).

Dr. Minichiello. That’s a good point because people are not necessarily clear about when there would be an indication to continue dual therapy and when it is safe to go to monotherapy. Scenarios where benefit of dual therapy may outweigh risk suggested in the CHEST 2012 guidelines include acute coronary syndrome or a recent stent, high-risk mechanical valves, and history of coronary artery bypass surgery.

I think the important thing is to consider each case individually and not to reflexively continue aspirin therapy. Often what we see is once on aspirin—always on aspirin. Being thoughtful about it, we should acknowledge that it likely results in a 2-fold increased risk of bleeding and make sure that we believe that the benefit outweighs the risk.

Dr. Allen. I agree. We probably have better evidence in the CAD population, but what do we do for patients with significant peripheral vascular disease, or those patients with symptomatic carotid stenosis or history of strokes? Some of the European guidance suggests taking a similar approach to CAD, but these are the patients for whom stopping aspirin makes me more nervous.

Dr. Parra. This is a perfect example of where less is more. All too often the reflex is to continue aspirin treatment indefinitely because the patient has a history of acute coronary syndrome or even peripheral arterial disease, when the best thing to do would be to drop the aspirin. It involves an individualized risk assessment and underscores the need to periodically do a risk/benefit assessment in all patients on anticoagulants, whether it’s warfarin or a DOAC.

I’d like to take a moment and step back to the case in the context of the GI bleeding. When we look at patients with a history of GI bleeding, it is important to understand the circumstances that surround it. This individual had a GI bleed 3 years previously and peptic ulcer disease. In these situations I ask whether the patient was taking over-the-counter nonsteroidal anti-inflamitory drugs at the time, had excessive alcohol use, or was successfully treated for Helicobacter pylori. All of these may influence whether or not I think the GI bleed is significant to influence the DOAC choice.

The other thing I consider is that the overall risk of major GI bleeding in those pivotal DOAC trials was quite small, < 1.5% per year with dabigatran 150 mg twice daily and < 1% per year with apixaban. The numbers needed to harm were quite high, over 200 patients per year with dabigatran 150 mg twice daily vs warfarin and over 350 patients per year with edoxaban 60 mg daily vs warfarin. There are no head-to-head comparisons with DOACs, but this small increased risk vs warfarin may still be an important consideration in some patients. In addition, it is important to remember that intracranial hemorrhage and fatal bleeding was less in all the pivotal NVAF trials with the DOACs when compared with warfarin. So that is something we need to reinforce with patients when we discuss treatment regardless of the DOAC selected.

Case 2

Dr. Minichiello. The next case is a 63-year-old man with hypertension, diabetes mellitus, nonvalvular AF, and he is taking dabigatran for stroke prevention. He presents in the emergency department with chest pain, and he is found to have a non-ST elevation MI. He goes to the cath lab and he is found to have a lesion in his left circumflex. The patient receives a newer generation drug-eluting stent. What are we going to do with his anticoagulation? We know he’s going to get some antiplatelet therapy, but what are our thoughts on this?

Dr. Parra. This is something that we run into all too often. I think the estimates are about 20% to 30% of patients who have indications for anticoagulation also end up having ischemic heart disease that requires PCI. The second thing is that we know combining an anticoagulant with antiplatelet therapy is associated with a 4% to 16% risk of fatal and nonfatal bleeding, and we have found out in patients with ischemic heart disease that when they bleed, they also have a higher mortality rate.

We’re trying to find the optimal balance between ischemic and thrombotic risk and bleeding risk. This is where some of the risk assessment tools that we have come into play. First, we need to establish the thrombotic risk by considering the CHA2DS2-VASc score, and the factors associated with increasing bleeding risk and stent thrombosis. You have time to work this out because, initially, all patients that are at sufficiently high thrombotic risk will receive dual antiplatelet therapy and anticoagulation therapy for a given period. This gives providers time to use some of those resources and figure out a long-term plan for the patient.

Dr. Allen. The fear and loathing that this brings up comes back to some historic things that should be considered. What we did for drug-eluting stents or bare-metal stents comes from older data where different stent technology was used. The stents used today are safer with a lower risk of in-stent thrombosis. Historically, we knew what to do for ACS and PCI and we knew what to do for AF, but we didn’t know what to do when the 2 crossed paths. We would put patients on warfarin and say, “Well, for now, target the INR between 2 and 2.5 and good luck with that.” That was all we had. The good news is now we have some evidence to move away from the use of dual antiplatelet plus anticoagulant therapies.

There were 2 DOAC studies recently published: The PIONEER-AF trial used rivaroxaban and more recently the RE-DUAL PCI trial used dabigatran. Each of the studies had some issues, but they were both studied in AF populations and aimed to address this issue of triple therapy. The PIONEER-AF trial looked at a number of different scenarios on different doses of rivaroxaban with either single or dual antiplatelet therapy compared to triple therapy with warfarin. The RE-DUAL PCI trial with dabigatran was less complex. Both studies were powered to look at safety, and they did show that with single antiplatelet plus oral anticoagulation regimens, the incidence of major bleeding complications was reduced.

However, that brings up some issues about how the studies were conducted. Both studied AF populations and in some cases did not study doses approved for AF. Yet at the same time, the studies were not powered to look at stroke outcomes, which raises the question: Are we running the risk of giving up stroke efficacy for reduced bleeding? I don’t think that we’ve fully answered that, certainly not with the PIONEER AF trial.

Dr. Parra. I agree. When we look at those trials, 2 things come to mind. First, the doses of dabigatran used in the RE-DUAL PCI trial were doses that have been shown to be beneficial in the nonvalvular AF population. Second, a take-home point from those trials is the P2Y12 inhibitor that was utilized—close to 90% or more used clopidogrel in the PIONEER-AF trial. Clopidogrel remains the P2Y12 inhibitor of choice. One of the other findings is that the aspirin dosing should be low, < 100 mg daily, and that we need to consider routine use of proton pump inhibitors to protect against the bleeding that can be found with the antiplatelet agents.

Also of interest, the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) recently released a focused update with some excellent recommendations on dual antiplatelet therapy in coronary artery disease in which they incorporated the results from the PIONEER-AF-PCI trial. The RE-DUAL PCI trial had not been published when these came out. If you’re concerned about ischemic risk prevailing, ESC recommendations based upon risk stratification are triple therapy with aspirin, clopidogrel, and an oral anticoagulant for longer than 1 month and up to 6 months and then dual therapy with 1 antiplatelet agent and an oral anticoagulant to complete the 12 months; afterward just oral anticoagulation alone. If the concerns about bleeding prevail, then we have 2 different pathways: one limiting triple therapy to 1 month and then dual therapy with 1 antiplatelet agent and an oral anticoagulant to complete the 12 months. But the ESC also has a second recommendation for patients at high risk of bleeding, which is dual therapy with clopidogrel and an oral anticoagulant at the offset for up to 12 months. I found these guidelines to be particularly helpful in terms of how to put this into practice.

Dr. Allen. There’s still so much concern about in-stent thrombosis. Although a smaller trial, we knew from the WOEST trial that single antiplatelet therapy with warfarin was reasonable. We know from the PIONEER-AF and RE-DUAL PCI trials that we didn’t get significantly more in-stent thrombosis by giving up the second antiplatelet. Whether or not we answered the stroke question is another issue, but the cardiology societies are still hanging on to dual antiplatelet therapy. I question if that’s based on the older data and the older stent technologies.

Dr. Minichiello. This highlights again that often we have to consider these patients’ case-by-case analysis, and that these decisions require multidisciplinary input. It involves coming together and figuring out in this particular patient, which of those 3 options would be best. We have a lot more options than we did just a short year or year and a half ago with at least some data providing comfort that DOACs at effective doses for stroke prevention in nonvalvular AF look like they can be combined with single antiplatelet therapy for post-PCI patients.

Dr. Barnes. Speaking as a cardiologist, this is a question I encounter all the time. I think everything said here is really well taken. I’ll just summarize to say for patients who have acute coronary syndromes and AF. First, I’m okay with using warfarin and now I’m okay using the DOACs, but the anticoagulant needs to continue for stroke prevention. Second, the patient has to be on clopidogrel as a P2Y12 inhibitor because it has the lowest bleeding risk profile. Third, the patient doesn’t always need 1 year of dual antiplatelet therapy the way we used to think of it. With newer generation stents and ongoing anticoagulation, you can get away with shorter courses of your antiplatelets, albeit 3 or 6 months. Providers should have a conversation with patients and think hard about how to balance clotting vs that bleeding profile.

Case 3

Dr. Minichiello. This case involves a 66-year-old man who has nonvalvular AF and is on warfarin. He has CKD, and his CrCl is about 30. He has hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and he is going to go for a colonoscopy. The proceduralist lets you know about the date and wants to know whether he needs to be bridged. He also has a remote history of a transient ischemic attack.

Dr. Allen. Historically, we’ve had detailed guidance on how to risk assess patients with AF, venous thromboembolism (VT), and mechanical heart valves in the periprocedural period. From that risk assessment the guidance helped us determine whether or not we should offer periprocedural bridging with heparin or low-molecularweight heparin.

The issue is that the detailed guidance was always based on expert opinion not hard science and there was no great evidence that we were preventing thrombotic events or that there was a net clinical benefit to bridging. Some retrospective cohort studies started coming out around 2012 that demonstrated an increased incidence of major bleeding events associated with bridging with no reduction in thrombotic complications. Some might argue that this is because thrombotic complications are so rare that you would have to have tens of thousands of patients for adequate power. Nonetheless, these studies were adequately powered to show a significant increase in major bleeding.

The best prospective trial data we have for this population comes from the BRIDGE trial, which randomized AF patients to receive dalteparin bridge therapy vs placebo during periprocedural interruptions in warfarin therapy. It too demonstrated a significant increase in the risk of bleeding complications associated with bridging with no significant reduction in the risk of thromboembolic events. Critics point out that some of the higher risk patients were underrepresented, and the same could be said about some of the other retrospective studies in the VT and mechanical valve populations.

We have waited for quite a while for guidances to catch up with these data. The most recent guidance published would apply to this patient. It was guidance for the AF population published by the American College of Cardiology (ACC) in early 2017

To make a decision to bridge, you not only have to make an assumption that your patient is at such extraordinary thrombotic risk that you would find some reduction in thrombotic events associated with bridging, but also that the benefit is going to be so great that it would overcome this very clear increased risk of bleeding, resulting in a net clinical benefit. Only then would it make sense to bridge. Based on the available data, it is quite possible that no such patient population exists.

Dr. Parra. I agree. We found from the BRIDGE trial, with the caveat that you pointed out, that high or moderately high thrombotic risk individuals weren’t as well represented, that there is at least a 2.5-fold increase in major bleeding. We also know that higher thrombotic-risk patients tend to also have higher bleeding risk. So in high thrombotic-risk patients, while there is uncertainty about whether or not there’s going to be a thrombotic benefit from bridging, we can be confident there will be an increased risk of major bleeding perhaps even more than that seen in the BRIDGE trial.

One thing that really illustrates this is the 2017 American Heart Association/ACC-focused update on the 2014 guideline for the management of patients with valvular heart disease. The guideline has a section on bridging therapy for prosthetic valves. And that was recently downgraded from a Class I recommendation to Class IIA, recognizing that the data are limited in terms of even when to bridge prosthetic valves.

Dr. Allen. Bridging is an area where we continue to do something that we know causes harm because we hope it has some benefit. Despite what some societal guidance still says, I very rarely bridge patients. If I do, it’s because the patient and/or caregivers have heard the facts and have opted to do it.

Dr. Minichiello. Practically speaking, the data—the retrospective data, the observational data, the BRIDGE trial, etc—definitely make us step back and think about bridging and realize that it’s a HIGH RISK of intervention. We really need to be informing patients about that risk. We know that bridging increases the risk of bleeding. We do not have data showing a reduction in the risk of thromboembolic disease with bridge therapy. That’s all based on what we think would happen, what we hope would be the result of bridge therapy, but in truth we do not know if this is the case. The risks of bridge therapy must be weighed heavily each time we consider using it.

In my practice I reserve bridge therapy, which we know is associated with increased harm for patients in whom we think there is the very highest risk of thromboembolism, ie, those with very recent arterial or venous thrombosis, and by recently, I mean within the past 1 to 3 months; patients who have very severe thrombophilia like antitphospholipid antibody syndrome, some cancer patients, and those with mechanical valves in the mitral position or those with high-risk mechanical aortic valves.

I don’t bridge most AF patients. In fact, I can’t remember the last time I bridged an AF patient. I do know that this is somewhat discordant with the ACC recommendations, but absent the data to support bridge therapy, I’m really concerned that the risk outweighs the benefit. This is particularly true in our VA population where the bleeding risk is high because of CKD or a history of bleeding or thrombocytopenia or concomitant aspirin or something else.

Dr. Barnes. We know from some studies that have been published that the biggest driver of a clinician deciding whether or not a patient should bridge is actually whether or not they’ve had a stroke. The truth is that the BRIDGE trial enrolled a sizeable population; it was about 15% of patients with a prior TIA or stroke. So it gave us some insight. Despite that, our event rates for thromboembolism, arterial thromboembolism, including stroke, were quite low.

I tend to look far more at the collection of risk factors and not just at a history of stroke. Now as you mentioned, Dr. Minichiello, a stroke within the past 1 to 3 months, I ask, “does this procedure even need to happen?” But outside of that, it’s not a history of stroke that’s going to make the decision for me: It’s all the risk factors together.

There’s an ongoing study, the PERIOP 2 study, that is enrolling patients at higher risk for stroke and patients with mechanical valves. This study may give us more insight into exactly what kind of risks these patients are at and whether they get benefit from bridging. But in the meantime, I’m really reserving bridging for my highest risk patients, those with multiple risk factors, CHADS2 scores of 5 and 6 or CHA2DS2-VASc of 7, 8, 9, and those with a recent VT or mechanical mitral valves.

Click here to read the digital edition.

Case 1

Tracy Minichiello, MD. The first case we’ll discuss is a 75-year-old man with mild chronic kidney disease (CKD). His calculated creatinine clearance (CrCl) is about 52 mL/min, and he has a remote history of a gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding 3 years previously from a peptic ulcer. He presents with new onset nonvalvular atrial fibrillation (AF), and he’s already on aspirin for his stable coronary artery disease (CAD).

How do we think about anticoagulant selection in this patient? We have a number of new oral anticoagulants and we have warfarin. How do we decide between warfarin vs one of the direct-acting oral anticoagulants (DOACs)? If we choose a DOAC, which one would we select?

David Parra, PharmD. The first step for anticoagulation is to assess a patient’s thromboembolic risk utilizing the CHA2DS2-VASc and bleeding risk using a HAS-BLED score, or something similar. The next question is which oral anticoagulant to use. We have widespread experience with warfarin and can measure the anticoagulant effect easily. Warfarin has a long duration of action, so perhaps it’s more forgiving if you miss a dose. It also has an antidote. Lastly, organ dysfunction doesn’t preclude use of warfarin as you can still monitor the anticoagulant effect. So there still may be patients that may benefit significantly from warfarin vs a DOAC.

On the flip side, DOACs are easier to use and perform quite acceptably in comparison with warfarin in nonvalvular AF. There are some scenarios where a specific DOAC may be preferred over another, such as recent GI bleeding.

Dr. Minichiello. Do you consider renal function, bleeding history, or concomitant antiplatelet therapy?

Geoffrey Barnes, MD, MSc. A couple of factors are relevant. I think we should consider renal function for this gentleman. However, I look at some of the other features as Dr. Parra suggested. What’s the likelihood that this patient is going to take the medicine as prescribed? Is a twice-a-day regimen going to be something that’s particularly challenging? I also look at the real-world vs randomized trial experience.

This patient has a remote GI bleeding history. Some of the real-world data suggest there might be some more GI bleeding with rivaroxaban, but across the board, apixaban (in both the randomized trials and much of the real-world data) seem to have a favorable bleeding risk profile. For a patient who is open and reliable for taking medicine twice a day, apixaban might be a good option as long as we make sure that the dose is appropriate.

Arthur L. Allen, PharmD, CACP. In pivotal trial experience, dabigatran and rivaroxaban demonstrated an increased incidence of GI bleeding compared with warfarin. In some of the real-world studies, rivaroxaban mirrors warfarin with regard to bleeding, whereas dabigatran and apixaban have a lower incidence. In the pivotal trials, apixaban did not have a trigger of increased GI bleeding, but I would let the details of this patient’s GI bleeding history help me determine how important an issue this is at this point.

The other thing that is important to understand when considering choice of agents: As Dr. Parra mentioned, we do have quite a bit of experience with warfarin. But comparing the quality of evidence, the DOACs have been investigated in a far more rigorous fashion and in far more patients than warfarin ever was in its more than 60 years on the market. For example, the RE-LY trial alone enrolled more than 18,000 patients. Each of the DOACs have been studied in tens of thousands of patients for their approved indications. Further, we shouldn’t forget that the risk of intracranial hemorrhage is reduced by roughly 50% by choosing a DOAC over warfarin, which should be a consideration in this elderly gentleman.

Dr. Minichiello. In the veteran population, there is a sense of comfort with warfarin, and some concerns have been raised over a lack of reversibility for the newer agents. We have patients who have trepidation about starting one of the new anticoagulants. However, there is a marked reduction in the risk of the most devastating bleeding complication, namely intracranial hemorrhage, making the use of these agents most compelling. And when they did have bleeding complications, at least in the trials, their outcomes were no worse than they were with warfarin, where there is a reversal agent. In most cases the outcomes were actually better.

Dr. Barnes. You often have to remind patients that there was no reversal agent in these huge trials where the DOACs showed similar or safer bleeding risk profiles, especially for the most serious bleeding, such as intracranial hemorrhage. I find patients often are reassured by knowing that.

Dr. Allen. I agree that there is concern about the lack of reversibility, but I think it has been completely overplayed. In the pivotal trials, patients who bled on DOAC therapy actually had better outcomes than those that bled on warfarin. This includes intracranial hemorrhage. There was a paper published in Stroke in 2012 that evaluated the subgroup of patients in the RE-LY trial that suffered intracranial hemorrhage. Patients on dabigatran actually fared better despite a lack of a specific reversal agent. When evaluating the available data about reversal of the DOACs, I’m not 100% convinced that we’re significantly impacting outcomes by reversing these agents. We’re certainly running up the bill, but are we treating the patient or treating the providers? As long as the renal function remains intact, the DOACs clear quickly, perhaps more quickly than warfarin can typically be reversed with standard reversal agents.

Dr. Minichiello. Remember that this patient has a history of a GI bleed. We are going to start him on full-dose anticoagulation for stroke prevention for his nonvalvular AF. He’s also on aspirin, and he has stable coronary disease. He does not have any stents in place but he did have a remote non-ST elevation myocardial infarction (MI) a number of years ago. Do we feel that the risk of dual therapy—anticoagulation combined with antiplatelet therapy—outweighs the risks? And how do we approach that risk?

Dr. Barnes. This is an important point to discuss. There has been a lot of discussion in the literature recently. When I start this type of patient on an oral anticoagulant, I try to discontinue the antiplatelet agent because I know how much bleeding risk that brings. The European guidelines (for example, Eur Heart J. 2014;35[45]:3155-3179) have been forward thinking with this for the last couple of years and have highlighted that if there’s an indication for anticoagulation for patients with stable coronary disease, meaning no MI and no stent within the past year, then we should stop the antiplatelet agents after a year in order to reduce the risk of MI. This is based on a lot of older literature where warfarin was compared with aspirin and shown to be protective in coronary patients, but at the risk of bleeding.

It’s important because there have been recent studies that have raised questions, including a recent Swedish article in (Circulation. 2017;136:1183-1192) that suggested discontinuing aspirin led to increased mortality. But it’s important to look at the details. While that was true for most patients, it was not true for the group of patients who were on an oral anticoagulant. Many colleagues ask me questions about that particular paper and its media coverage. I tell them that for our patients on chronic oral anticoagulants, the paper supports the notion that there is not increased mortality when aspirin use is stopped. We know that aspirin plus an anticoagulant leads to increased bleeding, so I try to stop it for patients who have stable CAD but are on long-term anticoagulation.

Dr. Allen. This isn’t a new thought. Back in early 2012, the 9th edition of the American College of Chest Physicians (CHEST) Antithrombotic Guidelines probably gave us the best guidance that we had ever seen to help us address this issue. Since that time the cardiology guidelines have caught up to recommend that we do not need additional antiplatelet therapy for stable CAD, and, in fact, it should be limited even in the setting of acute coronary syndromes and percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI).

Dr. Minichiello. That’s a good point because people are not necessarily clear about when there would be an indication to continue dual therapy and when it is safe to go to monotherapy. Scenarios where benefit of dual therapy may outweigh risk suggested in the CHEST 2012 guidelines include acute coronary syndrome or a recent stent, high-risk mechanical valves, and history of coronary artery bypass surgery.

I think the important thing is to consider each case individually and not to reflexively continue aspirin therapy. Often what we see is once on aspirin—always on aspirin. Being thoughtful about it, we should acknowledge that it likely results in a 2-fold increased risk of bleeding and make sure that we believe that the benefit outweighs the risk.

Dr. Allen. I agree. We probably have better evidence in the CAD population, but what do we do for patients with significant peripheral vascular disease, or those patients with symptomatic carotid stenosis or history of strokes? Some of the European guidance suggests taking a similar approach to CAD, but these are the patients for whom stopping aspirin makes me more nervous.

Dr. Parra. This is a perfect example of where less is more. All too often the reflex is to continue aspirin treatment indefinitely because the patient has a history of acute coronary syndrome or even peripheral arterial disease, when the best thing to do would be to drop the aspirin. It involves an individualized risk assessment and underscores the need to periodically do a risk/benefit assessment in all patients on anticoagulants, whether it’s warfarin or a DOAC.

I’d like to take a moment and step back to the case in the context of the GI bleeding. When we look at patients with a history of GI bleeding, it is important to understand the circumstances that surround it. This individual had a GI bleed 3 years previously and peptic ulcer disease. In these situations I ask whether the patient was taking over-the-counter nonsteroidal anti-inflamitory drugs at the time, had excessive alcohol use, or was successfully treated for Helicobacter pylori. All of these may influence whether or not I think the GI bleed is significant to influence the DOAC choice.

The other thing I consider is that the overall risk of major GI bleeding in those pivotal DOAC trials was quite small, < 1.5% per year with dabigatran 150 mg twice daily and < 1% per year with apixaban. The numbers needed to harm were quite high, over 200 patients per year with dabigatran 150 mg twice daily vs warfarin and over 350 patients per year with edoxaban 60 mg daily vs warfarin. There are no head-to-head comparisons with DOACs, but this small increased risk vs warfarin may still be an important consideration in some patients. In addition, it is important to remember that intracranial hemorrhage and fatal bleeding was less in all the pivotal NVAF trials with the DOACs when compared with warfarin. So that is something we need to reinforce with patients when we discuss treatment regardless of the DOAC selected.

Case 2

Dr. Minichiello. The next case is a 63-year-old man with hypertension, diabetes mellitus, nonvalvular AF, and he is taking dabigatran for stroke prevention. He presents in the emergency department with chest pain, and he is found to have a non-ST elevation MI. He goes to the cath lab and he is found to have a lesion in his left circumflex. The patient receives a newer generation drug-eluting stent. What are we going to do with his anticoagulation? We know he’s going to get some antiplatelet therapy, but what are our thoughts on this?

Dr. Parra. This is something that we run into all too often. I think the estimates are about 20% to 30% of patients who have indications for anticoagulation also end up having ischemic heart disease that requires PCI. The second thing is that we know combining an anticoagulant with antiplatelet therapy is associated with a 4% to 16% risk of fatal and nonfatal bleeding, and we have found out in patients with ischemic heart disease that when they bleed, they also have a higher mortality rate.

We’re trying to find the optimal balance between ischemic and thrombotic risk and bleeding risk. This is where some of the risk assessment tools that we have come into play. First, we need to establish the thrombotic risk by considering the CHA2DS2-VASc score, and the factors associated with increasing bleeding risk and stent thrombosis. You have time to work this out because, initially, all patients that are at sufficiently high thrombotic risk will receive dual antiplatelet therapy and anticoagulation therapy for a given period. This gives providers time to use some of those resources and figure out a long-term plan for the patient.

Dr. Allen. The fear and loathing that this brings up comes back to some historic things that should be considered. What we did for drug-eluting stents or bare-metal stents comes from older data where different stent technology was used. The stents used today are safer with a lower risk of in-stent thrombosis. Historically, we knew what to do for ACS and PCI and we knew what to do for AF, but we didn’t know what to do when the 2 crossed paths. We would put patients on warfarin and say, “Well, for now, target the INR between 2 and 2.5 and good luck with that.” That was all we had. The good news is now we have some evidence to move away from the use of dual antiplatelet plus anticoagulant therapies.

There were 2 DOAC studies recently published: The PIONEER-AF trial used rivaroxaban and more recently the RE-DUAL PCI trial used dabigatran. Each of the studies had some issues, but they were both studied in AF populations and aimed to address this issue of triple therapy. The PIONEER-AF trial looked at a number of different scenarios on different doses of rivaroxaban with either single or dual antiplatelet therapy compared to triple therapy with warfarin. The RE-DUAL PCI trial with dabigatran was less complex. Both studies were powered to look at safety, and they did show that with single antiplatelet plus oral anticoagulation regimens, the incidence of major bleeding complications was reduced.

However, that brings up some issues about how the studies were conducted. Both studied AF populations and in some cases did not study doses approved for AF. Yet at the same time, the studies were not powered to look at stroke outcomes, which raises the question: Are we running the risk of giving up stroke efficacy for reduced bleeding? I don’t think that we’ve fully answered that, certainly not with the PIONEER AF trial.

Dr. Parra. I agree. When we look at those trials, 2 things come to mind. First, the doses of dabigatran used in the RE-DUAL PCI trial were doses that have been shown to be beneficial in the nonvalvular AF population. Second, a take-home point from those trials is the P2Y12 inhibitor that was utilized—close to 90% or more used clopidogrel in the PIONEER-AF trial. Clopidogrel remains the P2Y12 inhibitor of choice. One of the other findings is that the aspirin dosing should be low, < 100 mg daily, and that we need to consider routine use of proton pump inhibitors to protect against the bleeding that can be found with the antiplatelet agents.

Also of interest, the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) recently released a focused update with some excellent recommendations on dual antiplatelet therapy in coronary artery disease in which they incorporated the results from the PIONEER-AF-PCI trial. The RE-DUAL PCI trial had not been published when these came out. If you’re concerned about ischemic risk prevailing, ESC recommendations based upon risk stratification are triple therapy with aspirin, clopidogrel, and an oral anticoagulant for longer than 1 month and up to 6 months and then dual therapy with 1 antiplatelet agent and an oral anticoagulant to complete the 12 months; afterward just oral anticoagulation alone. If the concerns about bleeding prevail, then we have 2 different pathways: one limiting triple therapy to 1 month and then dual therapy with 1 antiplatelet agent and an oral anticoagulant to complete the 12 months. But the ESC also has a second recommendation for patients at high risk of bleeding, which is dual therapy with clopidogrel and an oral anticoagulant at the offset for up to 12 months. I found these guidelines to be particularly helpful in terms of how to put this into practice.

Dr. Allen. There’s still so much concern about in-stent thrombosis. Although a smaller trial, we knew from the WOEST trial that single antiplatelet therapy with warfarin was reasonable. We know from the PIONEER-AF and RE-DUAL PCI trials that we didn’t get significantly more in-stent thrombosis by giving up the second antiplatelet. Whether or not we answered the stroke question is another issue, but the cardiology societies are still hanging on to dual antiplatelet therapy. I question if that’s based on the older data and the older stent technologies.

Dr. Minichiello. This highlights again that often we have to consider these patients’ case-by-case analysis, and that these decisions require multidisciplinary input. It involves coming together and figuring out in this particular patient, which of those 3 options would be best. We have a lot more options than we did just a short year or year and a half ago with at least some data providing comfort that DOACs at effective doses for stroke prevention in nonvalvular AF look like they can be combined with single antiplatelet therapy for post-PCI patients.

Dr. Barnes. Speaking as a cardiologist, this is a question I encounter all the time. I think everything said here is really well taken. I’ll just summarize to say for patients who have acute coronary syndromes and AF. First, I’m okay with using warfarin and now I’m okay using the DOACs, but the anticoagulant needs to continue for stroke prevention. Second, the patient has to be on clopidogrel as a P2Y12 inhibitor because it has the lowest bleeding risk profile. Third, the patient doesn’t always need 1 year of dual antiplatelet therapy the way we used to think of it. With newer generation stents and ongoing anticoagulation, you can get away with shorter courses of your antiplatelets, albeit 3 or 6 months. Providers should have a conversation with patients and think hard about how to balance clotting vs that bleeding profile.

Case 3

Dr. Minichiello. This case involves a 66-year-old man who has nonvalvular AF and is on warfarin. He has CKD, and his CrCl is about 30. He has hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and he is going to go for a colonoscopy. The proceduralist lets you know about the date and wants to know whether he needs to be bridged. He also has a remote history of a transient ischemic attack.

Dr. Allen. Historically, we’ve had detailed guidance on how to risk assess patients with AF, venous thromboembolism (VT), and mechanical heart valves in the periprocedural period. From that risk assessment the guidance helped us determine whether or not we should offer periprocedural bridging with heparin or low-molecularweight heparin.

The issue is that the detailed guidance was always based on expert opinion not hard science and there was no great evidence that we were preventing thrombotic events or that there was a net clinical benefit to bridging. Some retrospective cohort studies started coming out around 2012 that demonstrated an increased incidence of major bleeding events associated with bridging with no reduction in thrombotic complications. Some might argue that this is because thrombotic complications are so rare that you would have to have tens of thousands of patients for adequate power. Nonetheless, these studies were adequately powered to show a significant increase in major bleeding.

The best prospective trial data we have for this population comes from the BRIDGE trial, which randomized AF patients to receive dalteparin bridge therapy vs placebo during periprocedural interruptions in warfarin therapy. It too demonstrated a significant increase in the risk of bleeding complications associated with bridging with no significant reduction in the risk of thromboembolic events. Critics point out that some of the higher risk patients were underrepresented, and the same could be said about some of the other retrospective studies in the VT and mechanical valve populations.

We have waited for quite a while for guidances to catch up with these data. The most recent guidance published would apply to this patient. It was guidance for the AF population published by the American College of Cardiology (ACC) in early 2017

To make a decision to bridge, you not only have to make an assumption that your patient is at such extraordinary thrombotic risk that you would find some reduction in thrombotic events associated with bridging, but also that the benefit is going to be so great that it would overcome this very clear increased risk of bleeding, resulting in a net clinical benefit. Only then would it make sense to bridge. Based on the available data, it is quite possible that no such patient population exists.

Dr. Parra. I agree. We found from the BRIDGE trial, with the caveat that you pointed out, that high or moderately high thrombotic risk individuals weren’t as well represented, that there is at least a 2.5-fold increase in major bleeding. We also know that higher thrombotic-risk patients tend to also have higher bleeding risk. So in high thrombotic-risk patients, while there is uncertainty about whether or not there’s going to be a thrombotic benefit from bridging, we can be confident there will be an increased risk of major bleeding perhaps even more than that seen in the BRIDGE trial.

One thing that really illustrates this is the 2017 American Heart Association/ACC-focused update on the 2014 guideline for the management of patients with valvular heart disease. The guideline has a section on bridging therapy for prosthetic valves. And that was recently downgraded from a Class I recommendation to Class IIA, recognizing that the data are limited in terms of even when to bridge prosthetic valves.

Dr. Allen. Bridging is an area where we continue to do something that we know causes harm because we hope it has some benefit. Despite what some societal guidance still says, I very rarely bridge patients. If I do, it’s because the patient and/or caregivers have heard the facts and have opted to do it.

Dr. Minichiello. Practically speaking, the data—the retrospective data, the observational data, the BRIDGE trial, etc—definitely make us step back and think about bridging and realize that it’s a HIGH RISK of intervention. We really need to be informing patients about that risk. We know that bridging increases the risk of bleeding. We do not have data showing a reduction in the risk of thromboembolic disease with bridge therapy. That’s all based on what we think would happen, what we hope would be the result of bridge therapy, but in truth we do not know if this is the case. The risks of bridge therapy must be weighed heavily each time we consider using it.

In my practice I reserve bridge therapy, which we know is associated with increased harm for patients in whom we think there is the very highest risk of thromboembolism, ie, those with very recent arterial or venous thrombosis, and by recently, I mean within the past 1 to 3 months; patients who have very severe thrombophilia like antitphospholipid antibody syndrome, some cancer patients, and those with mechanical valves in the mitral position or those with high-risk mechanical aortic valves.

I don’t bridge most AF patients. In fact, I can’t remember the last time I bridged an AF patient. I do know that this is somewhat discordant with the ACC recommendations, but absent the data to support bridge therapy, I’m really concerned that the risk outweighs the benefit. This is particularly true in our VA population where the bleeding risk is high because of CKD or a history of bleeding or thrombocytopenia or concomitant aspirin or something else.

Dr. Barnes. We know from some studies that have been published that the biggest driver of a clinician deciding whether or not a patient should bridge is actually whether or not they’ve had a stroke. The truth is that the BRIDGE trial enrolled a sizeable population; it was about 15% of patients with a prior TIA or stroke. So it gave us some insight. Despite that, our event rates for thromboembolism, arterial thromboembolism, including stroke, were quite low.

I tend to look far more at the collection of risk factors and not just at a history of stroke. Now as you mentioned, Dr. Minichiello, a stroke within the past 1 to 3 months, I ask, “does this procedure even need to happen?” But outside of that, it’s not a history of stroke that’s going to make the decision for me: It’s all the risk factors together.

There’s an ongoing study, the PERIOP 2 study, that is enrolling patients at higher risk for stroke and patients with mechanical valves. This study may give us more insight into exactly what kind of risks these patients are at and whether they get benefit from bridging. But in the meantime, I’m really reserving bridging for my highest risk patients, those with multiple risk factors, CHADS2 scores of 5 and 6 or CHA2DS2-VASc of 7, 8, 9, and those with a recent VT or mechanical mitral valves.

Click here to read the digital edition.

Case 1

Tracy Minichiello, MD. The first case we’ll discuss is a 75-year-old man with mild chronic kidney disease (CKD). His calculated creatinine clearance (CrCl) is about 52 mL/min, and he has a remote history of a gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding 3 years previously from a peptic ulcer. He presents with new onset nonvalvular atrial fibrillation (AF), and he’s already on aspirin for his stable coronary artery disease (CAD).

How do we think about anticoagulant selection in this patient? We have a number of new oral anticoagulants and we have warfarin. How do we decide between warfarin vs one of the direct-acting oral anticoagulants (DOACs)? If we choose a DOAC, which one would we select?

David Parra, PharmD. The first step for anticoagulation is to assess a patient’s thromboembolic risk utilizing the CHA2DS2-VASc and bleeding risk using a HAS-BLED score, or something similar. The next question is which oral anticoagulant to use. We have widespread experience with warfarin and can measure the anticoagulant effect easily. Warfarin has a long duration of action, so perhaps it’s more forgiving if you miss a dose. It also has an antidote. Lastly, organ dysfunction doesn’t preclude use of warfarin as you can still monitor the anticoagulant effect. So there still may be patients that may benefit significantly from warfarin vs a DOAC.

On the flip side, DOACs are easier to use and perform quite acceptably in comparison with warfarin in nonvalvular AF. There are some scenarios where a specific DOAC may be preferred over another, such as recent GI bleeding.

Dr. Minichiello. Do you consider renal function, bleeding history, or concomitant antiplatelet therapy?

Geoffrey Barnes, MD, MSc. A couple of factors are relevant. I think we should consider renal function for this gentleman. However, I look at some of the other features as Dr. Parra suggested. What’s the likelihood that this patient is going to take the medicine as prescribed? Is a twice-a-day regimen going to be something that’s particularly challenging? I also look at the real-world vs randomized trial experience.

This patient has a remote GI bleeding history. Some of the real-world data suggest there might be some more GI bleeding with rivaroxaban, but across the board, apixaban (in both the randomized trials and much of the real-world data) seem to have a favorable bleeding risk profile. For a patient who is open and reliable for taking medicine twice a day, apixaban might be a good option as long as we make sure that the dose is appropriate.

Arthur L. Allen, PharmD, CACP. In pivotal trial experience, dabigatran and rivaroxaban demonstrated an increased incidence of GI bleeding compared with warfarin. In some of the real-world studies, rivaroxaban mirrors warfarin with regard to bleeding, whereas dabigatran and apixaban have a lower incidence. In the pivotal trials, apixaban did not have a trigger of increased GI bleeding, but I would let the details of this patient’s GI bleeding history help me determine how important an issue this is at this point.

The other thing that is important to understand when considering choice of agents: As Dr. Parra mentioned, we do have quite a bit of experience with warfarin. But comparing the quality of evidence, the DOACs have been investigated in a far more rigorous fashion and in far more patients than warfarin ever was in its more than 60 years on the market. For example, the RE-LY trial alone enrolled more than 18,000 patients. Each of the DOACs have been studied in tens of thousands of patients for their approved indications. Further, we shouldn’t forget that the risk of intracranial hemorrhage is reduced by roughly 50% by choosing a DOAC over warfarin, which should be a consideration in this elderly gentleman.

Dr. Minichiello. In the veteran population, there is a sense of comfort with warfarin, and some concerns have been raised over a lack of reversibility for the newer agents. We have patients who have trepidation about starting one of the new anticoagulants. However, there is a marked reduction in the risk of the most devastating bleeding complication, namely intracranial hemorrhage, making the use of these agents most compelling. And when they did have bleeding complications, at least in the trials, their outcomes were no worse than they were with warfarin, where there is a reversal agent. In most cases the outcomes were actually better.

Dr. Barnes. You often have to remind patients that there was no reversal agent in these huge trials where the DOACs showed similar or safer bleeding risk profiles, especially for the most serious bleeding, such as intracranial hemorrhage. I find patients often are reassured by knowing that.

Dr. Allen. I agree that there is concern about the lack of reversibility, but I think it has been completely overplayed. In the pivotal trials, patients who bled on DOAC therapy actually had better outcomes than those that bled on warfarin. This includes intracranial hemorrhage. There was a paper published in Stroke in 2012 that evaluated the subgroup of patients in the RE-LY trial that suffered intracranial hemorrhage. Patients on dabigatran actually fared better despite a lack of a specific reversal agent. When evaluating the available data about reversal of the DOACs, I’m not 100% convinced that we’re significantly impacting outcomes by reversing these agents. We’re certainly running up the bill, but are we treating the patient or treating the providers? As long as the renal function remains intact, the DOACs clear quickly, perhaps more quickly than warfarin can typically be reversed with standard reversal agents.

Dr. Minichiello. Remember that this patient has a history of a GI bleed. We are going to start him on full-dose anticoagulation for stroke prevention for his nonvalvular AF. He’s also on aspirin, and he has stable coronary disease. He does not have any stents in place but he did have a remote non-ST elevation myocardial infarction (MI) a number of years ago. Do we feel that the risk of dual therapy—anticoagulation combined with antiplatelet therapy—outweighs the risks? And how do we approach that risk?

Dr. Barnes. This is an important point to discuss. There has been a lot of discussion in the literature recently. When I start this type of patient on an oral anticoagulant, I try to discontinue the antiplatelet agent because I know how much bleeding risk that brings. The European guidelines (for example, Eur Heart J. 2014;35[45]:3155-3179) have been forward thinking with this for the last couple of years and have highlighted that if there’s an indication for anticoagulation for patients with stable coronary disease, meaning no MI and no stent within the past year, then we should stop the antiplatelet agents after a year in order to reduce the risk of MI. This is based on a lot of older literature where warfarin was compared with aspirin and shown to be protective in coronary patients, but at the risk of bleeding.

It’s important because there have been recent studies that have raised questions, including a recent Swedish article in (Circulation. 2017;136:1183-1192) that suggested discontinuing aspirin led to increased mortality. But it’s important to look at the details. While that was true for most patients, it was not true for the group of patients who were on an oral anticoagulant. Many colleagues ask me questions about that particular paper and its media coverage. I tell them that for our patients on chronic oral anticoagulants, the paper supports the notion that there is not increased mortality when aspirin use is stopped. We know that aspirin plus an anticoagulant leads to increased bleeding, so I try to stop it for patients who have stable CAD but are on long-term anticoagulation.

Dr. Allen. This isn’t a new thought. Back in early 2012, the 9th edition of the American College of Chest Physicians (CHEST) Antithrombotic Guidelines probably gave us the best guidance that we had ever seen to help us address this issue. Since that time the cardiology guidelines have caught up to recommend that we do not need additional antiplatelet therapy for stable CAD, and, in fact, it should be limited even in the setting of acute coronary syndromes and percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI).

Dr. Minichiello. That’s a good point because people are not necessarily clear about when there would be an indication to continue dual therapy and when it is safe to go to monotherapy. Scenarios where benefit of dual therapy may outweigh risk suggested in the CHEST 2012 guidelines include acute coronary syndrome or a recent stent, high-risk mechanical valves, and history of coronary artery bypass surgery.

I think the important thing is to consider each case individually and not to reflexively continue aspirin therapy. Often what we see is once on aspirin—always on aspirin. Being thoughtful about it, we should acknowledge that it likely results in a 2-fold increased risk of bleeding and make sure that we believe that the benefit outweighs the risk.

Dr. Allen. I agree. We probably have better evidence in the CAD population, but what do we do for patients with significant peripheral vascular disease, or those patients with symptomatic carotid stenosis or history of strokes? Some of the European guidance suggests taking a similar approach to CAD, but these are the patients for whom stopping aspirin makes me more nervous.

Dr. Parra. This is a perfect example of where less is more. All too often the reflex is to continue aspirin treatment indefinitely because the patient has a history of acute coronary syndrome or even peripheral arterial disease, when the best thing to do would be to drop the aspirin. It involves an individualized risk assessment and underscores the need to periodically do a risk/benefit assessment in all patients on anticoagulants, whether it’s warfarin or a DOAC.

I’d like to take a moment and step back to the case in the context of the GI bleeding. When we look at patients with a history of GI bleeding, it is important to understand the circumstances that surround it. This individual had a GI bleed 3 years previously and peptic ulcer disease. In these situations I ask whether the patient was taking over-the-counter nonsteroidal anti-inflamitory drugs at the time, had excessive alcohol use, or was successfully treated for Helicobacter pylori. All of these may influence whether or not I think the GI bleed is significant to influence the DOAC choice.

The other thing I consider is that the overall risk of major GI bleeding in those pivotal DOAC trials was quite small, < 1.5% per year with dabigatran 150 mg twice daily and < 1% per year with apixaban. The numbers needed to harm were quite high, over 200 patients per year with dabigatran 150 mg twice daily vs warfarin and over 350 patients per year with edoxaban 60 mg daily vs warfarin. There are no head-to-head comparisons with DOACs, but this small increased risk vs warfarin may still be an important consideration in some patients. In addition, it is important to remember that intracranial hemorrhage and fatal bleeding was less in all the pivotal NVAF trials with the DOACs when compared with warfarin. So that is something we need to reinforce with patients when we discuss treatment regardless of the DOAC selected.

Case 2

Dr. Minichiello. The next case is a 63-year-old man with hypertension, diabetes mellitus, nonvalvular AF, and he is taking dabigatran for stroke prevention. He presents in the emergency department with chest pain, and he is found to have a non-ST elevation MI. He goes to the cath lab and he is found to have a lesion in his left circumflex. The patient receives a newer generation drug-eluting stent. What are we going to do with his anticoagulation? We know he’s going to get some antiplatelet therapy, but what are our thoughts on this?

Dr. Parra. This is something that we run into all too often. I think the estimates are about 20% to 30% of patients who have indications for anticoagulation also end up having ischemic heart disease that requires PCI. The second thing is that we know combining an anticoagulant with antiplatelet therapy is associated with a 4% to 16% risk of fatal and nonfatal bleeding, and we have found out in patients with ischemic heart disease that when they bleed, they also have a higher mortality rate.

We’re trying to find the optimal balance between ischemic and thrombotic risk and bleeding risk. This is where some of the risk assessment tools that we have come into play. First, we need to establish the thrombotic risk by considering the CHA2DS2-VASc score, and the factors associated with increasing bleeding risk and stent thrombosis. You have time to work this out because, initially, all patients that are at sufficiently high thrombotic risk will receive dual antiplatelet therapy and anticoagulation therapy for a given period. This gives providers time to use some of those resources and figure out a long-term plan for the patient.

Dr. Allen. The fear and loathing that this brings up comes back to some historic things that should be considered. What we did for drug-eluting stents or bare-metal stents comes from older data where different stent technology was used. The stents used today are safer with a lower risk of in-stent thrombosis. Historically, we knew what to do for ACS and PCI and we knew what to do for AF, but we didn’t know what to do when the 2 crossed paths. We would put patients on warfarin and say, “Well, for now, target the INR between 2 and 2.5 and good luck with that.” That was all we had. The good news is now we have some evidence to move away from the use of dual antiplatelet plus anticoagulant therapies.

There were 2 DOAC studies recently published: The PIONEER-AF trial used rivaroxaban and more recently the RE-DUAL PCI trial used dabigatran. Each of the studies had some issues, but they were both studied in AF populations and aimed to address this issue of triple therapy. The PIONEER-AF trial looked at a number of different scenarios on different doses of rivaroxaban with either single or dual antiplatelet therapy compared to triple therapy with warfarin. The RE-DUAL PCI trial with dabigatran was less complex. Both studies were powered to look at safety, and they did show that with single antiplatelet plus oral anticoagulation regimens, the incidence of major bleeding complications was reduced.

However, that brings up some issues about how the studies were conducted. Both studied AF populations and in some cases did not study doses approved for AF. Yet at the same time, the studies were not powered to look at stroke outcomes, which raises the question: Are we running the risk of giving up stroke efficacy for reduced bleeding? I don’t think that we’ve fully answered that, certainly not with the PIONEER AF trial.

Dr. Parra. I agree. When we look at those trials, 2 things come to mind. First, the doses of dabigatran used in the RE-DUAL PCI trial were doses that have been shown to be beneficial in the nonvalvular AF population. Second, a take-home point from those trials is the P2Y12 inhibitor that was utilized—close to 90% or more used clopidogrel in the PIONEER-AF trial. Clopidogrel remains the P2Y12 inhibitor of choice. One of the other findings is that the aspirin dosing should be low, < 100 mg daily, and that we need to consider routine use of proton pump inhibitors to protect against the bleeding that can be found with the antiplatelet agents.

Also of interest, the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) recently released a focused update with some excellent recommendations on dual antiplatelet therapy in coronary artery disease in which they incorporated the results from the PIONEER-AF-PCI trial. The RE-DUAL PCI trial had not been published when these came out. If you’re concerned about ischemic risk prevailing, ESC recommendations based upon risk stratification are triple therapy with aspirin, clopidogrel, and an oral anticoagulant for longer than 1 month and up to 6 months and then dual therapy with 1 antiplatelet agent and an oral anticoagulant to complete the 12 months; afterward just oral anticoagulation alone. If the concerns about bleeding prevail, then we have 2 different pathways: one limiting triple therapy to 1 month and then dual therapy with 1 antiplatelet agent and an oral anticoagulant to complete the 12 months. But the ESC also has a second recommendation for patients at high risk of bleeding, which is dual therapy with clopidogrel and an oral anticoagulant at the offset for up to 12 months. I found these guidelines to be particularly helpful in terms of how to put this into practice.

Dr. Allen. There’s still so much concern about in-stent thrombosis. Although a smaller trial, we knew from the WOEST trial that single antiplatelet therapy with warfarin was reasonable. We know from the PIONEER-AF and RE-DUAL PCI trials that we didn’t get significantly more in-stent thrombosis by giving up the second antiplatelet. Whether or not we answered the stroke question is another issue, but the cardiology societies are still hanging on to dual antiplatelet therapy. I question if that’s based on the older data and the older stent technologies.

Dr. Minichiello. This highlights again that often we have to consider these patients’ case-by-case analysis, and that these decisions require multidisciplinary input. It involves coming together and figuring out in this particular patient, which of those 3 options would be best. We have a lot more options than we did just a short year or year and a half ago with at least some data providing comfort that DOACs at effective doses for stroke prevention in nonvalvular AF look like they can be combined with single antiplatelet therapy for post-PCI patients.

Dr. Barnes. Speaking as a cardiologist, this is a question I encounter all the time. I think everything said here is really well taken. I’ll just summarize to say for patients who have acute coronary syndromes and AF. First, I’m okay with using warfarin and now I’m okay using the DOACs, but the anticoagulant needs to continue for stroke prevention. Second, the patient has to be on clopidogrel as a P2Y12 inhibitor because it has the lowest bleeding risk profile. Third, the patient doesn’t always need 1 year of dual antiplatelet therapy the way we used to think of it. With newer generation stents and ongoing anticoagulation, you can get away with shorter courses of your antiplatelets, albeit 3 or 6 months. Providers should have a conversation with patients and think hard about how to balance clotting vs that bleeding profile.

Case 3

Dr. Minichiello. This case involves a 66-year-old man who has nonvalvular AF and is on warfarin. He has CKD, and his CrCl is about 30. He has hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and he is going to go for a colonoscopy. The proceduralist lets you know about the date and wants to know whether he needs to be bridged. He also has a remote history of a transient ischemic attack.

Dr. Allen. Historically, we’ve had detailed guidance on how to risk assess patients with AF, venous thromboembolism (VT), and mechanical heart valves in the periprocedural period. From that risk assessment the guidance helped us determine whether or not we should offer periprocedural bridging with heparin or low-molecularweight heparin.

The issue is that the detailed guidance was always based on expert opinion not hard science and there was no great evidence that we were preventing thrombotic events or that there was a net clinical benefit to bridging. Some retrospective cohort studies started coming out around 2012 that demonstrated an increased incidence of major bleeding events associated with bridging with no reduction in thrombotic complications. Some might argue that this is because thrombotic complications are so rare that you would have to have tens of thousands of patients for adequate power. Nonetheless, these studies were adequately powered to show a significant increase in major bleeding.

The best prospective trial data we have for this population comes from the BRIDGE trial, which randomized AF patients to receive dalteparin bridge therapy vs placebo during periprocedural interruptions in warfarin therapy. It too demonstrated a significant increase in the risk of bleeding complications associated with bridging with no significant reduction in the risk of thromboembolic events. Critics point out that some of the higher risk patients were underrepresented, and the same could be said about some of the other retrospective studies in the VT and mechanical valve populations.

We have waited for quite a while for guidances to catch up with these data. The most recent guidance published would apply to this patient. It was guidance for the AF population published by the American College of Cardiology (ACC) in early 2017

To make a decision to bridge, you not only have to make an assumption that your patient is at such extraordinary thrombotic risk that you would find some reduction in thrombotic events associated with bridging, but also that the benefit is going to be so great that it would overcome this very clear increased risk of bleeding, resulting in a net clinical benefit. Only then would it make sense to bridge. Based on the available data, it is quite possible that no such patient population exists.

Dr. Parra. I agree. We found from the BRIDGE trial, with the caveat that you pointed out, that high or moderately high thrombotic risk individuals weren’t as well represented, that there is at least a 2.5-fold increase in major bleeding. We also know that higher thrombotic-risk patients tend to also have higher bleeding risk. So in high thrombotic-risk patients, while there is uncertainty about whether or not there’s going to be a thrombotic benefit from bridging, we can be confident there will be an increased risk of major bleeding perhaps even more than that seen in the BRIDGE trial.

One thing that really illustrates this is the 2017 American Heart Association/ACC-focused update on the 2014 guideline for the management of patients with valvular heart disease. The guideline has a section on bridging therapy for prosthetic valves. And that was recently downgraded from a Class I recommendation to Class IIA, recognizing that the data are limited in terms of even when to bridge prosthetic valves.

Dr. Allen. Bridging is an area where we continue to do something that we know causes harm because we hope it has some benefit. Despite what some societal guidance still says, I very rarely bridge patients. If I do, it’s because the patient and/or caregivers have heard the facts and have opted to do it.

Dr. Minichiello. Practically speaking, the data—the retrospective data, the observational data, the BRIDGE trial, etc—definitely make us step back and think about bridging and realize that it’s a HIGH RISK of intervention. We really need to be informing patients about that risk. We know that bridging increases the risk of bleeding. We do not have data showing a reduction in the risk of thromboembolic disease with bridge therapy. That’s all based on what we think would happen, what we hope would be the result of bridge therapy, but in truth we do not know if this is the case. The risks of bridge therapy must be weighed heavily each time we consider using it.

In my practice I reserve bridge therapy, which we know is associated with increased harm for patients in whom we think there is the very highest risk of thromboembolism, ie, those with very recent arterial or venous thrombosis, and by recently, I mean within the past 1 to 3 months; patients who have very severe thrombophilia like antitphospholipid antibody syndrome, some cancer patients, and those with mechanical valves in the mitral position or those with high-risk mechanical aortic valves.

I don’t bridge most AF patients. In fact, I can’t remember the last time I bridged an AF patient. I do know that this is somewhat discordant with the ACC recommendations, but absent the data to support bridge therapy, I’m really concerned that the risk outweighs the benefit. This is particularly true in our VA population where the bleeding risk is high because of CKD or a history of bleeding or thrombocytopenia or concomitant aspirin or something else.

Dr. Barnes. We know from some studies that have been published that the biggest driver of a clinician deciding whether or not a patient should bridge is actually whether or not they’ve had a stroke. The truth is that the BRIDGE trial enrolled a sizeable population; it was about 15% of patients with a prior TIA or stroke. So it gave us some insight. Despite that, our event rates for thromboembolism, arterial thromboembolism, including stroke, were quite low.

I tend to look far more at the collection of risk factors and not just at a history of stroke. Now as you mentioned, Dr. Minichiello, a stroke within the past 1 to 3 months, I ask, “does this procedure even need to happen?” But outside of that, it’s not a history of stroke that’s going to make the decision for me: It’s all the risk factors together.

There’s an ongoing study, the PERIOP 2 study, that is enrolling patients at higher risk for stroke and patients with mechanical valves. This study may give us more insight into exactly what kind of risks these patients are at and whether they get benefit from bridging. But in the meantime, I’m really reserving bridging for my highest risk patients, those with multiple risk factors, CHADS2 scores of 5 and 6 or CHA2DS2-VASc of 7, 8, 9, and those with a recent VT or mechanical mitral valves.

Click here to read the digital edition.

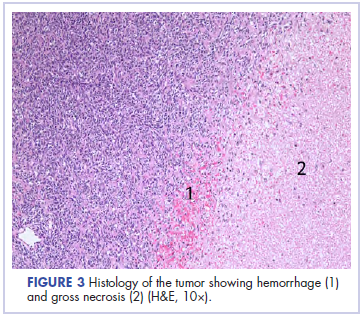

Eruptive Vellus Hair Cysts in Identical Triplets With Dermoscopic Findings

Case Report

Four-year-old identical triplet girls with numerous asymptomatic scattered papules on the chest of 4 months’ duration were referred to a dermatologist by their pediatrician for molluscum contagiosum. The patients’ father reported that there was no history of trauma, irritation, or manipulation to the affected area. Their medical history was notable for prematurity at 32 weeks’ gestation and congenital dermal melanocytosis. Family history was notable for their father having acne and similar papules on the chest during adolescence that resolved with isotretinoin therapy.

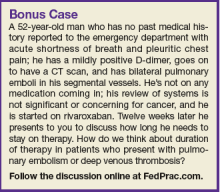

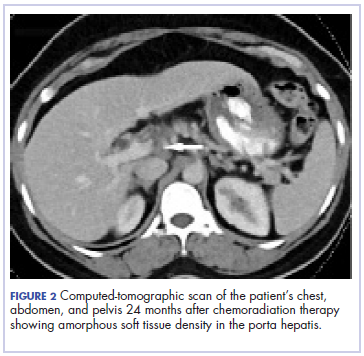

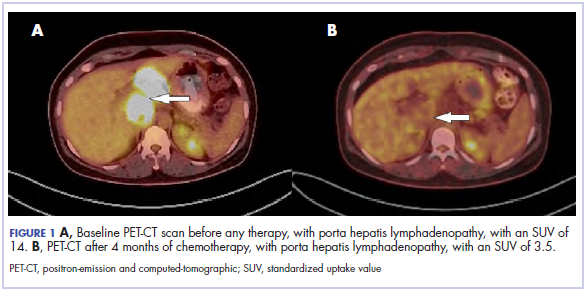

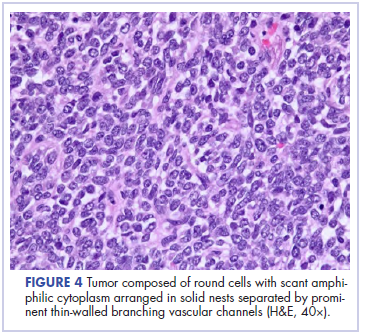

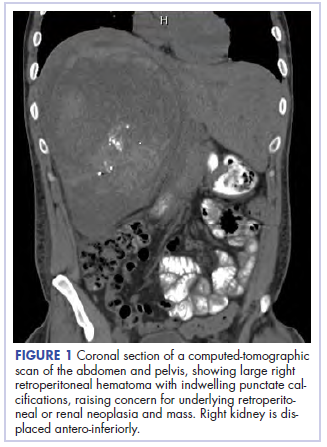

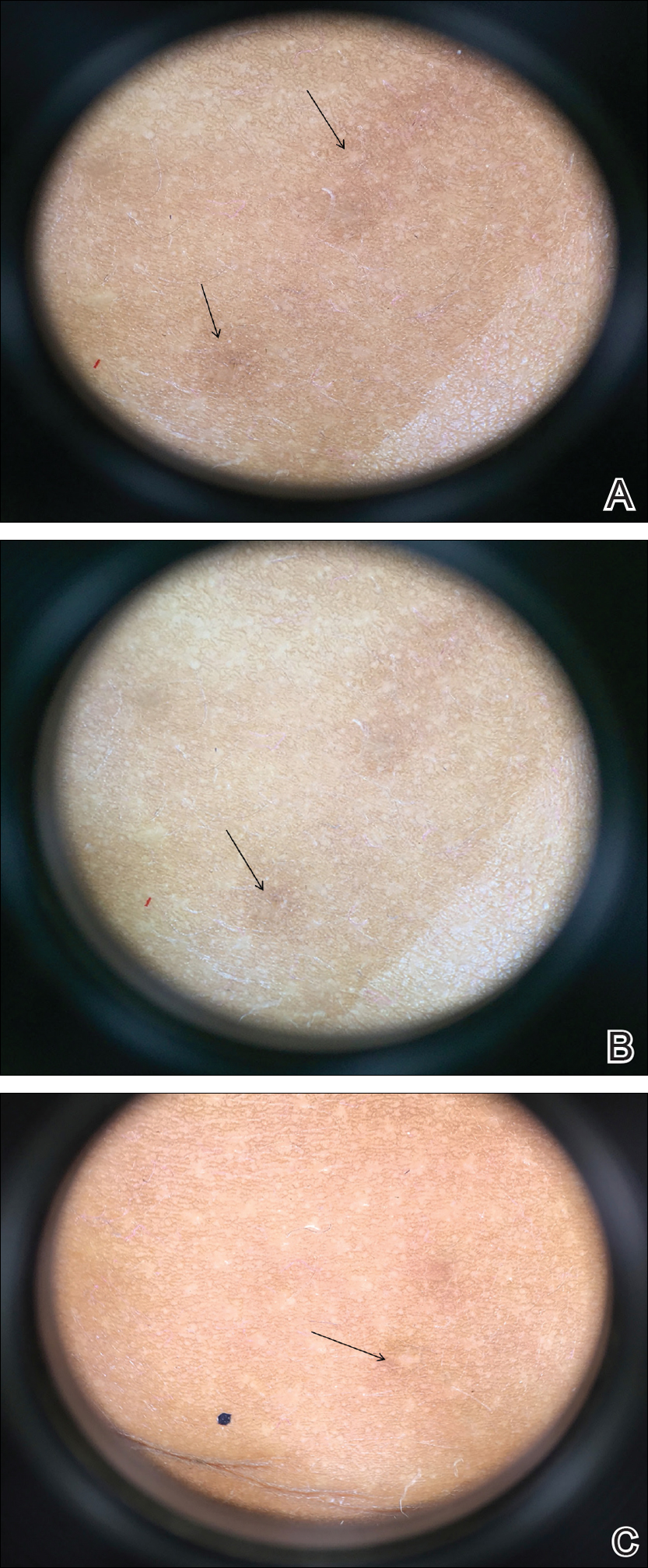

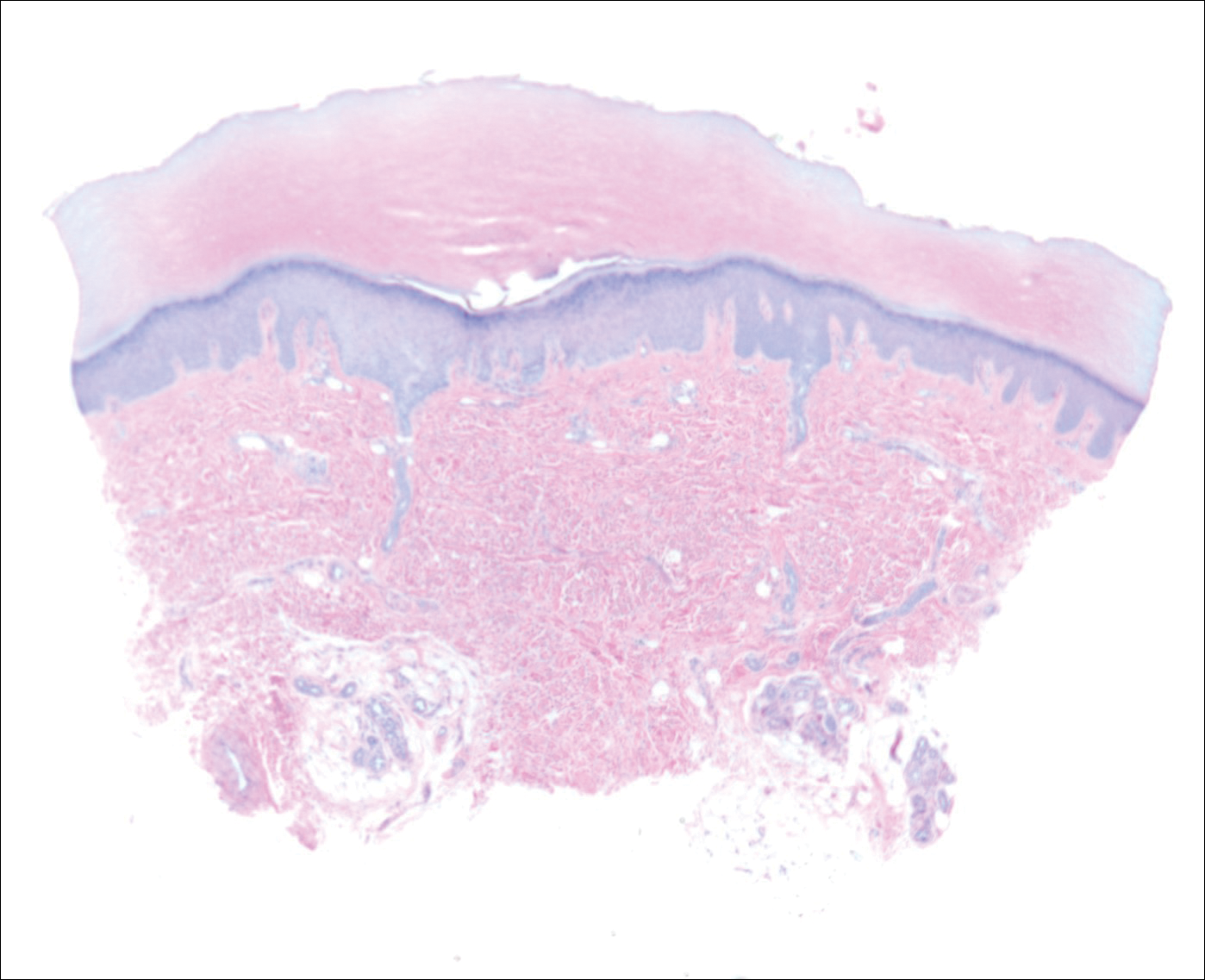

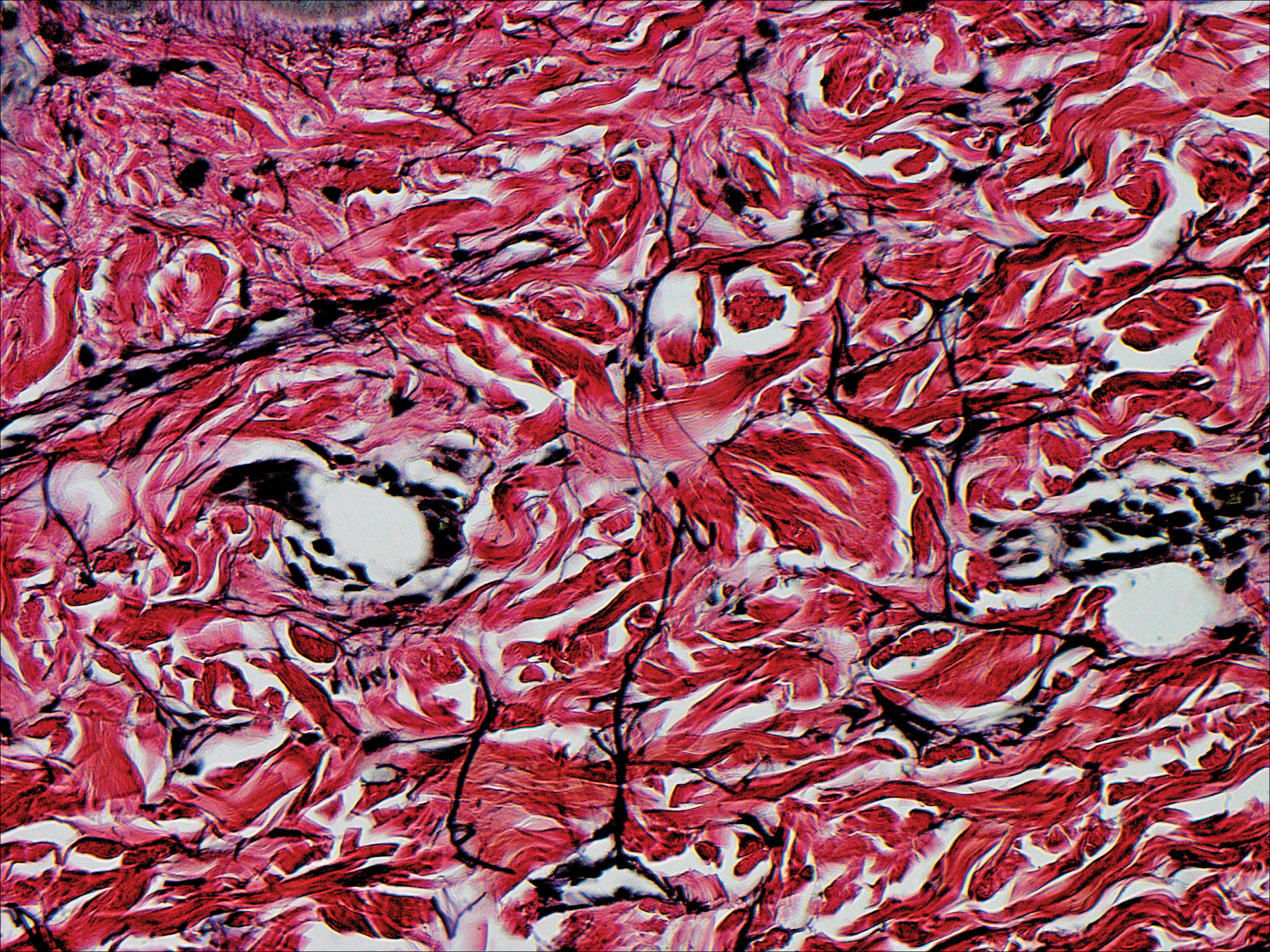

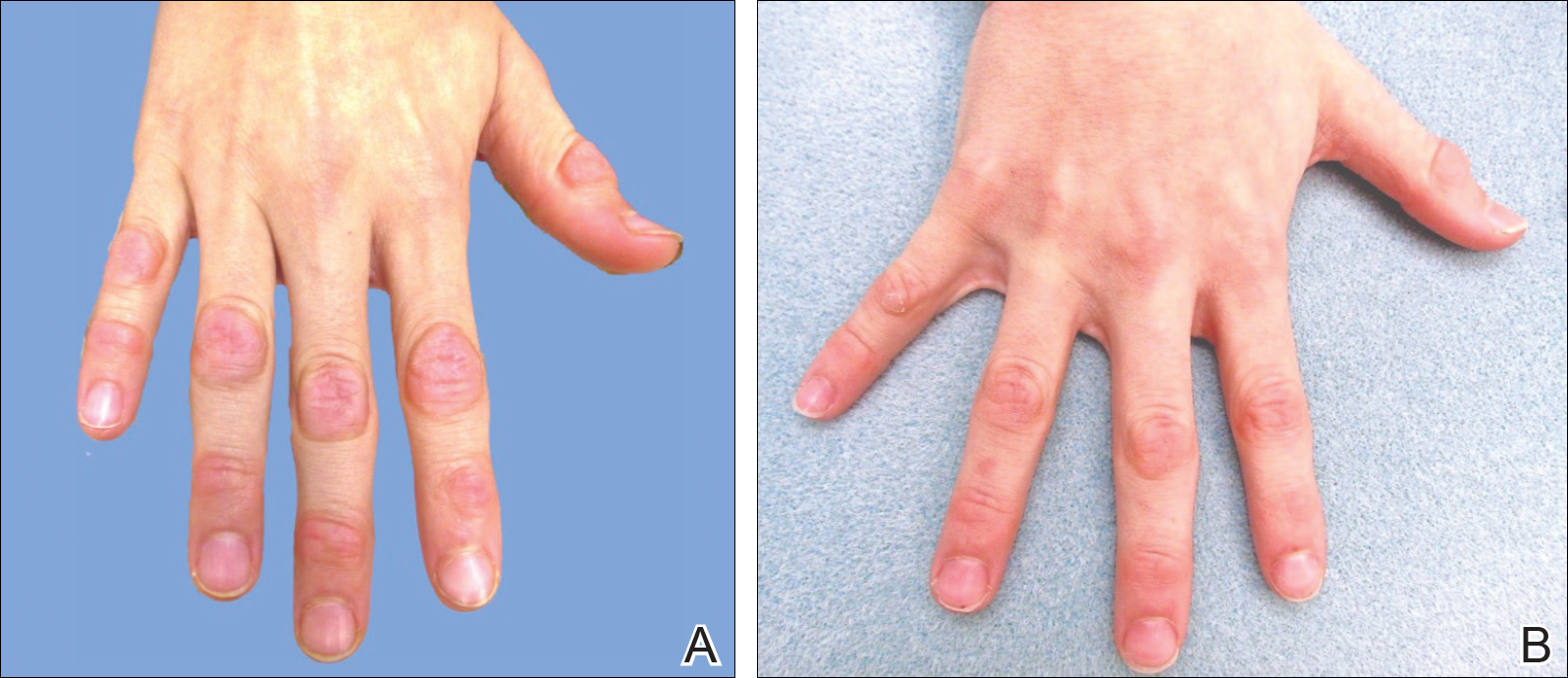

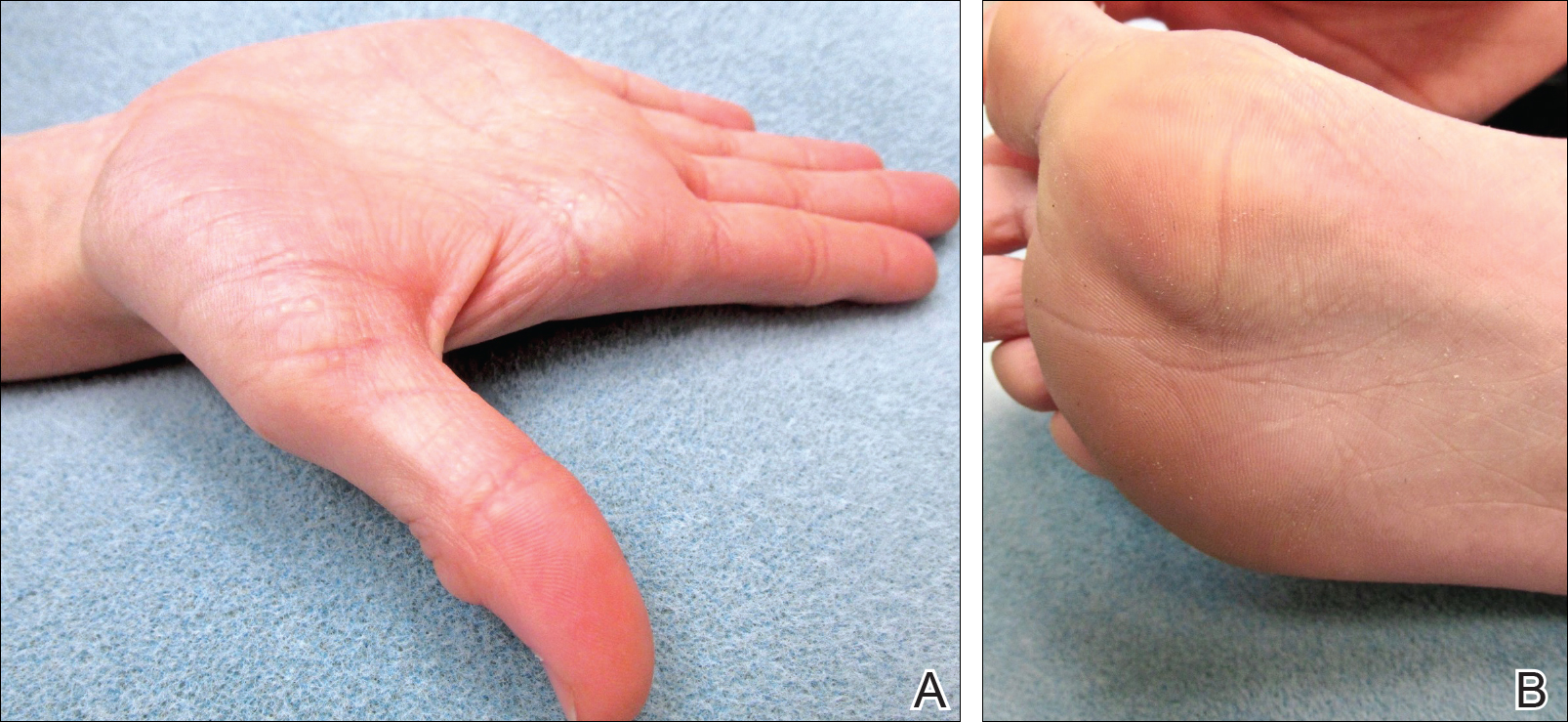

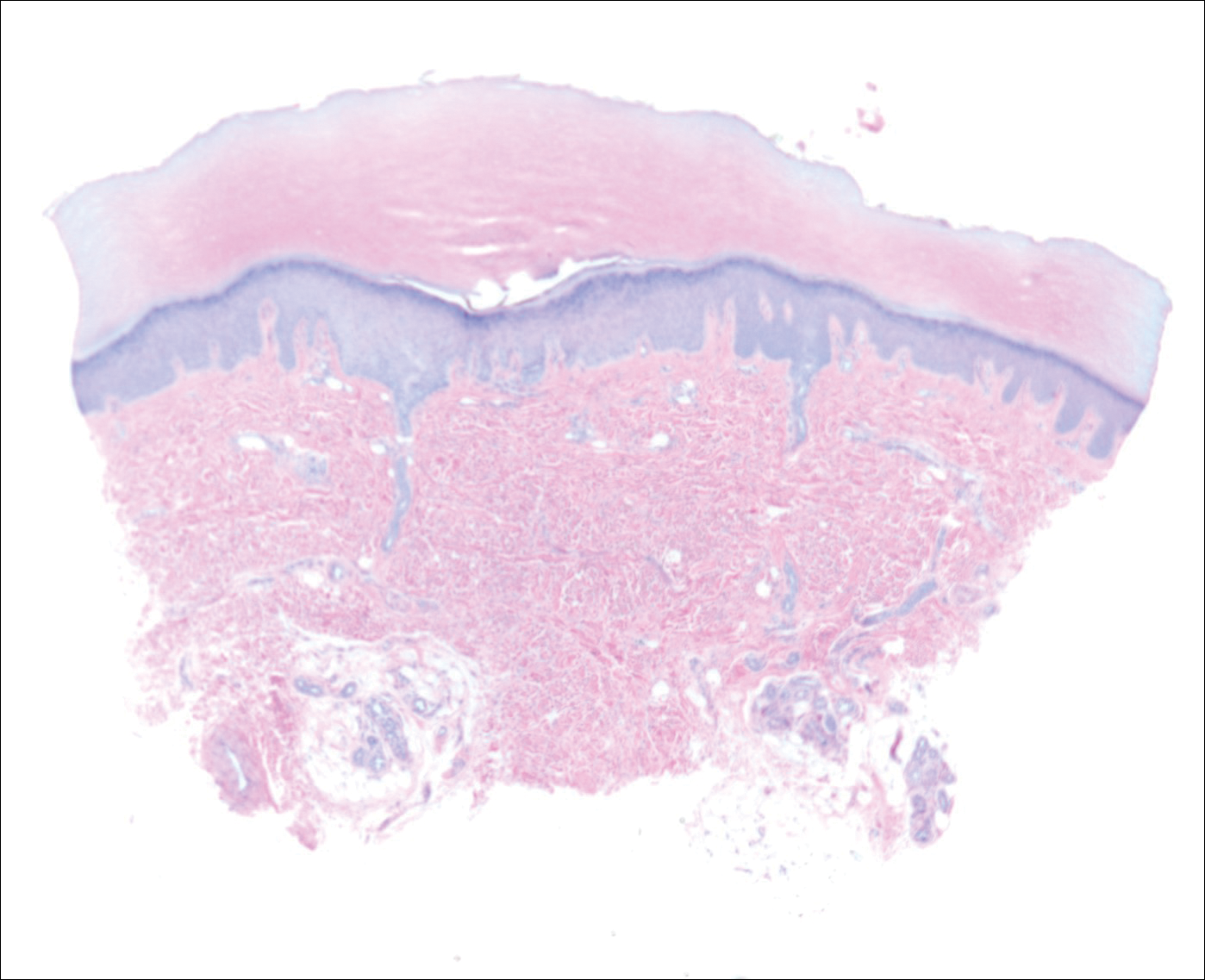

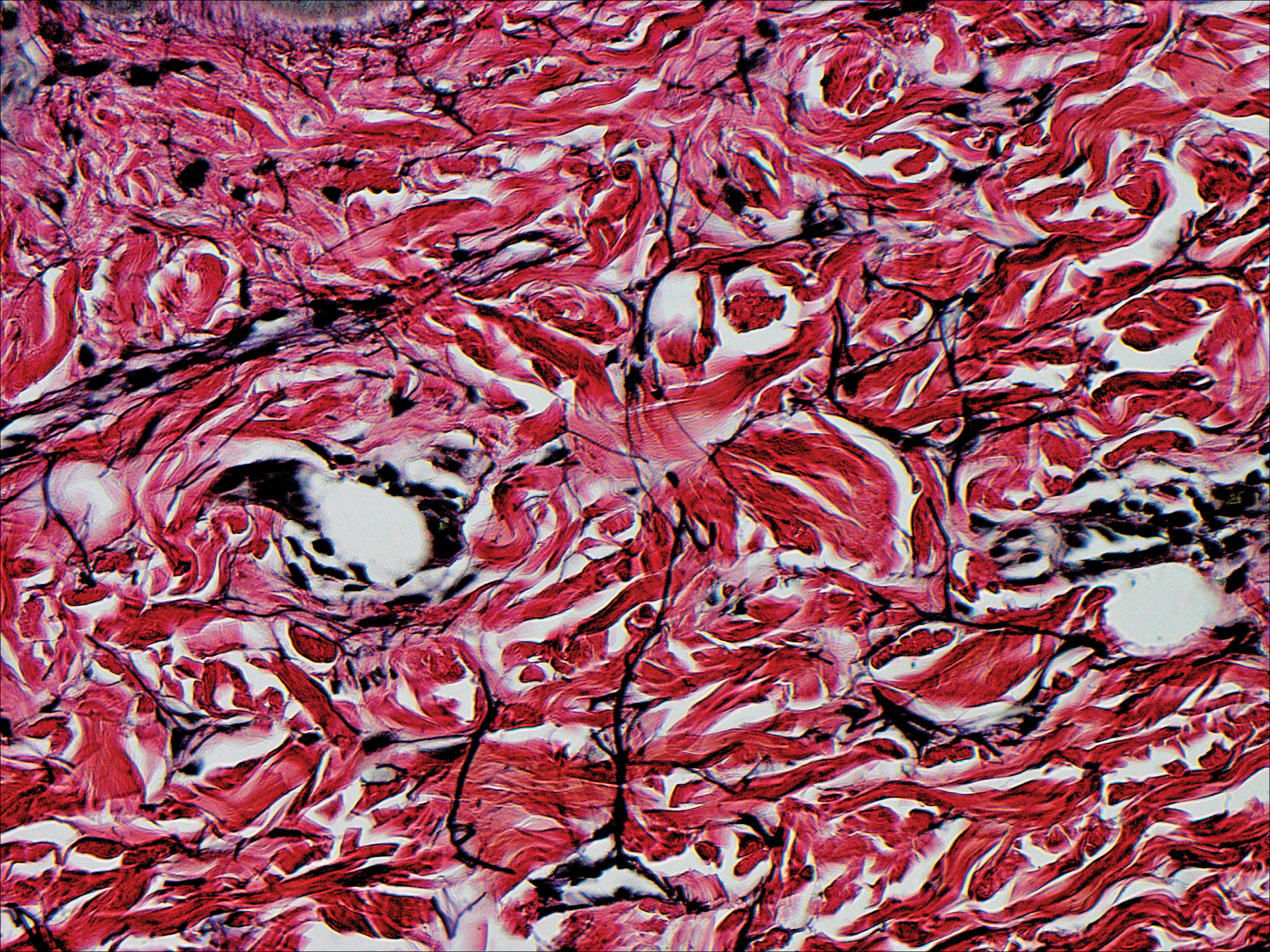

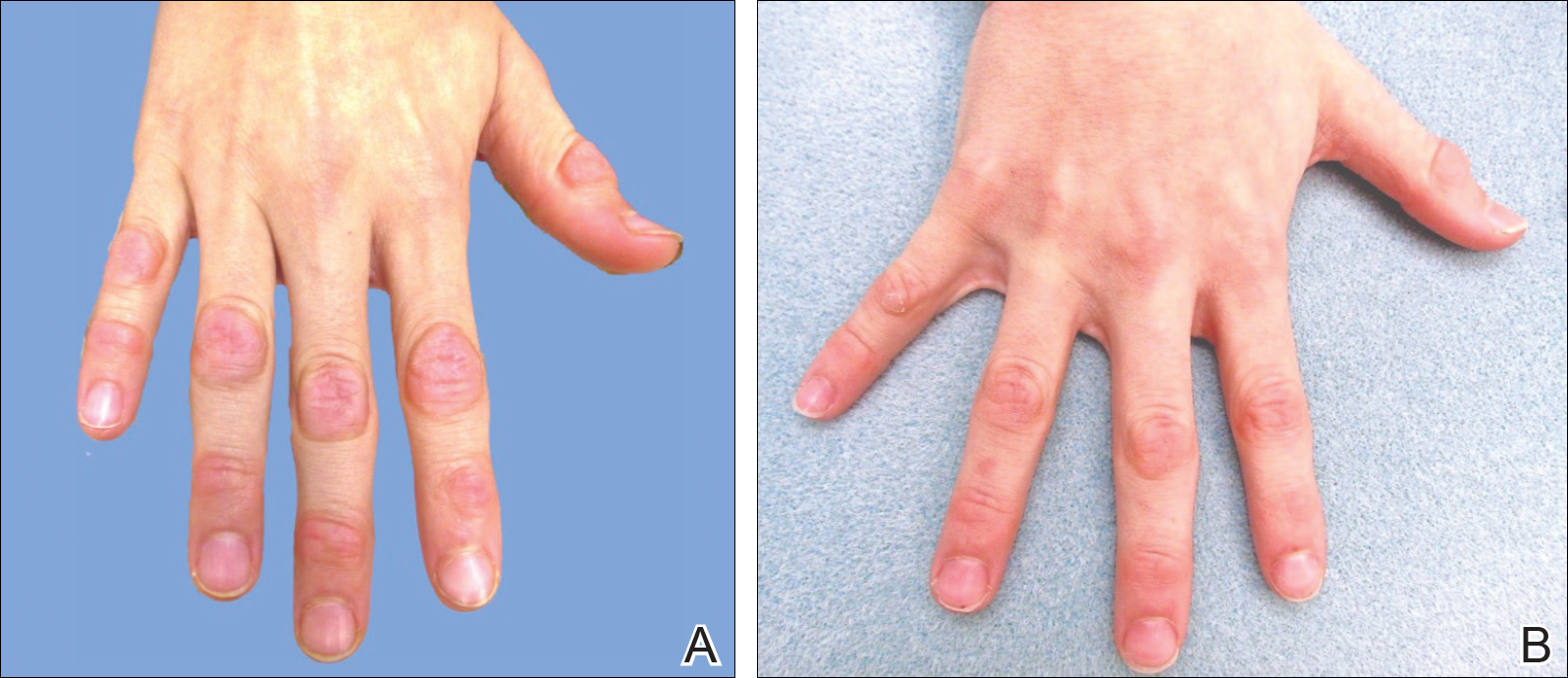

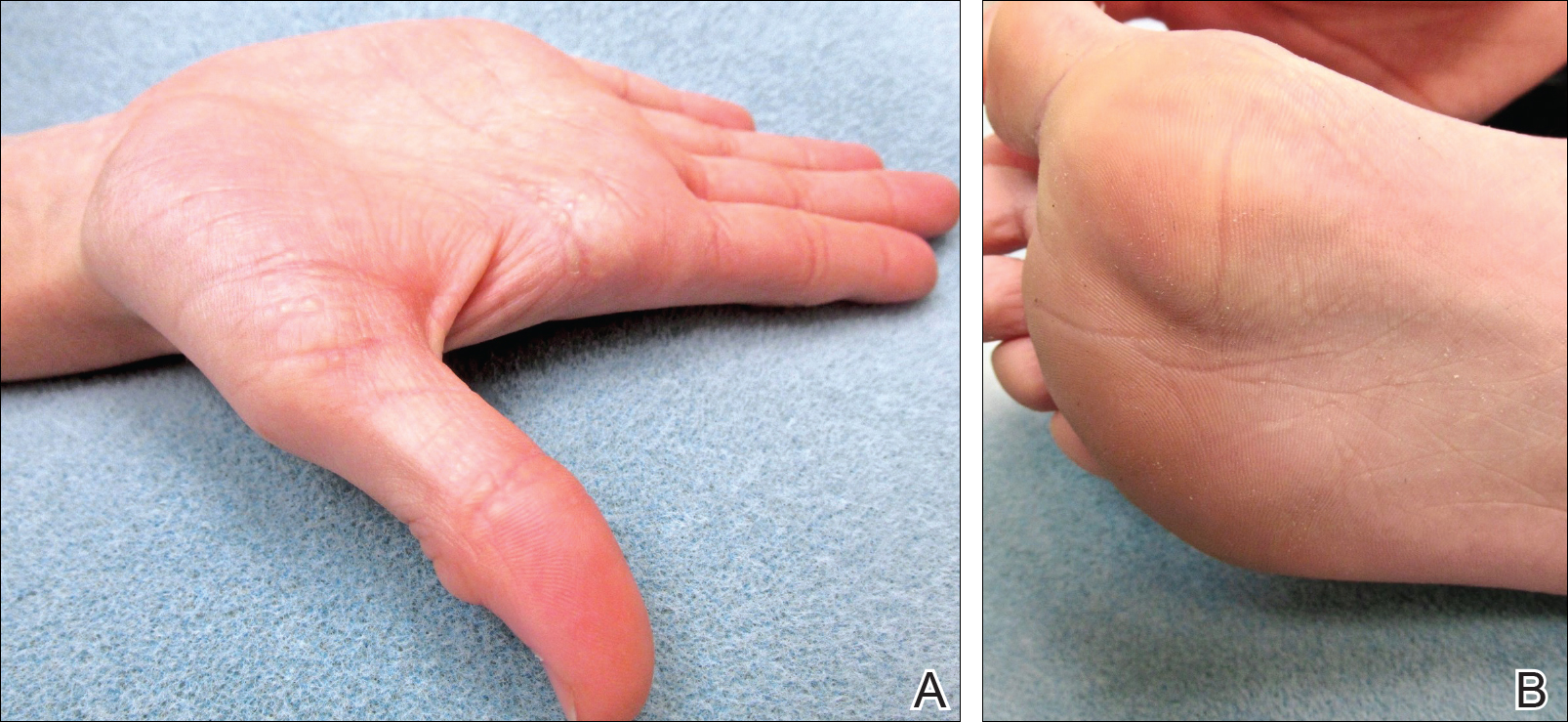

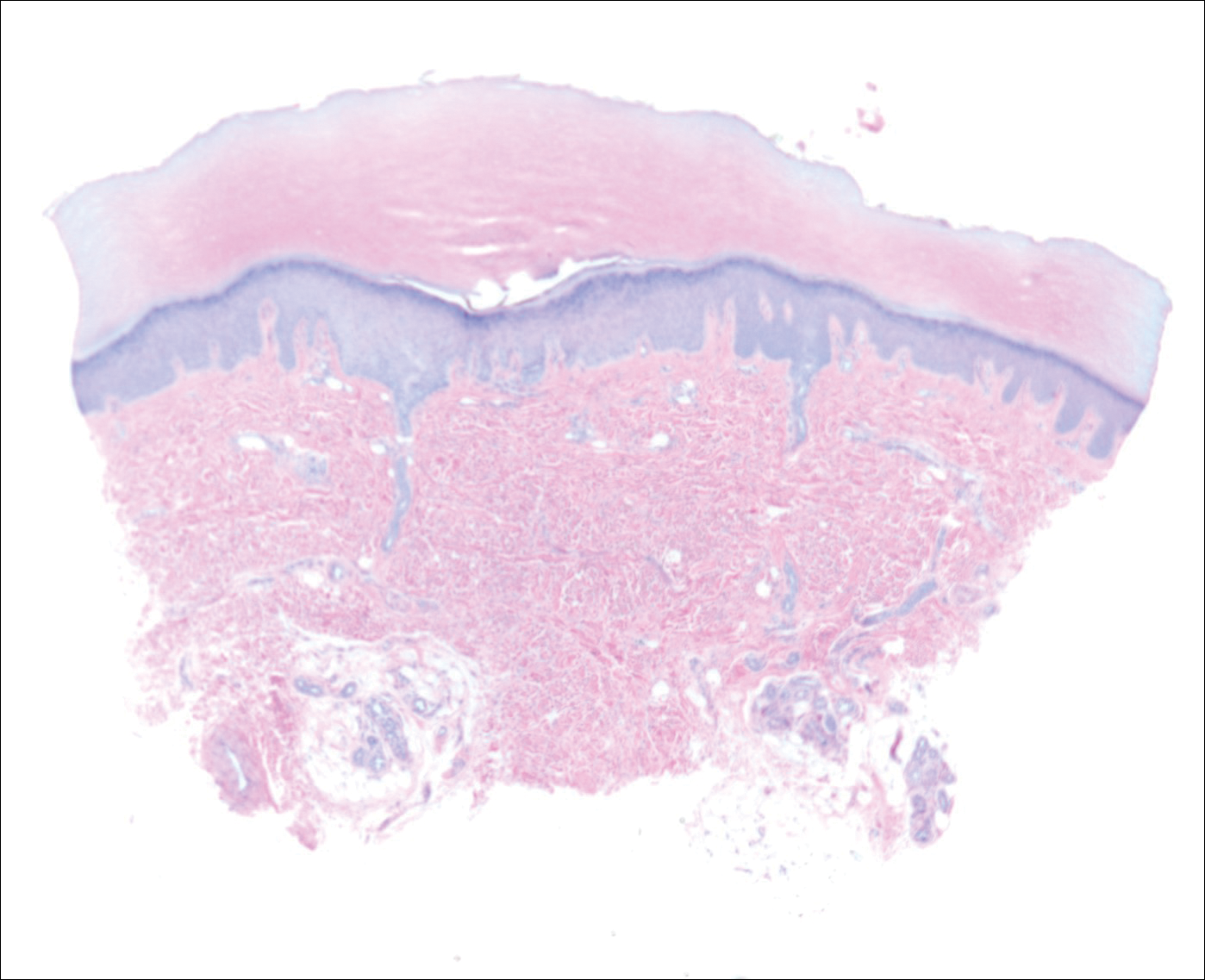

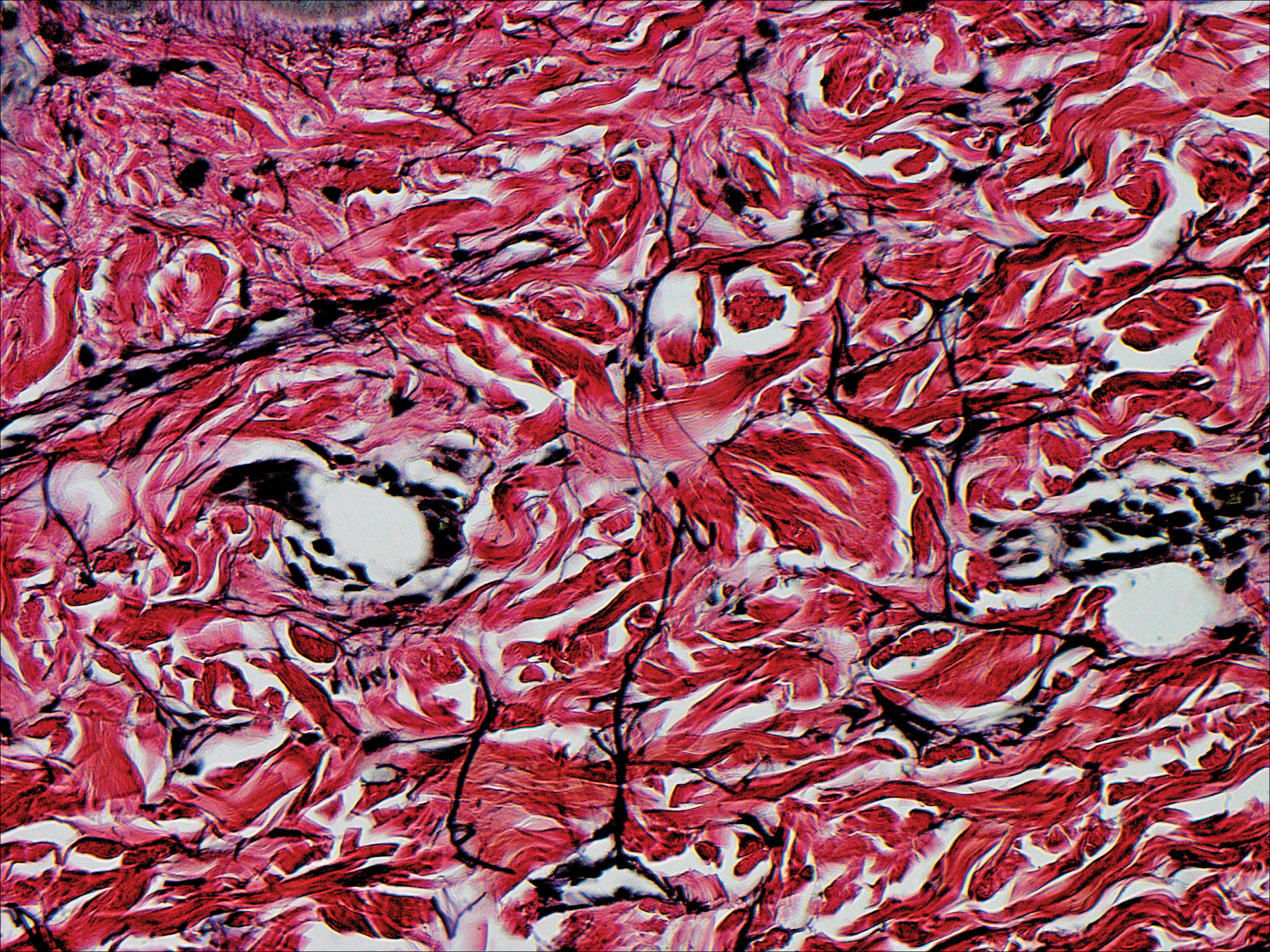

On physical examination there were multiple smooth, hyperpigmented to erythematous, comedonal, 1- to 2-mm papules dispersed on the anterior central chest of all 3 patients (Figure 1). Clinically, these lesions were fairly indistinguishable from other common dermatologic conditions such as acne or milia. Dermoscopic examination revealed homogenous yellow-white areas surrounded by light brown to erythematous halos (Figure 2). Histopathologic examination was not performed given the benign clinical diagnosis and avoidance of biopsy in pediatric populations. Based on dermoscopic features and history, a diagnosis of eruptive vellus hair cysts (EVHCs) in identical triplets was made.

Comment

Pathogenesis