User login

Coding Changes for 2016

New Codes for 2016

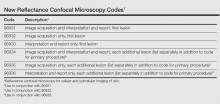

In 2016, noninvasive imaging in dermatology finally received recognition at the Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) level with the publication of 6 new Category I codes for reflectance confocal microscopy.1 These new codes are classified under the “Special Dermatological Procedures” section of CPT where codes do not have technical and professional payment splits, unlike pathology codes (Table). Currently, the new codes for reflectance confocal microscopy can only be implemented when using the VivaScope 1500 (Caliber I.D.) reflectance confocal imaging system and not with any other devices. At present, these codes are priced by each insurer and should be payable, as they are Category I codes that meet all criteria for widely used procedures that are well supported by strong evidence.

Additionally, MelaFind (MELA Sciences) has received 2 Category III CPT codes in 2016: 0400T, multispectral digital skin lesion analysis of clinically atypical cutaneous pigmented lesions for detection of melanomas and high-risk melanocytic atypia [1–5 lesions]; 0401T, multispectral digital skin lesion analysis of clinically atypical cutaneous pigmented lesions for detection of melanomas and high-risk melanocytic atypia [≥6 lesions]).

The CPT Professional Edition notes that Category III codes are a set of temporary codes for emerging technology, services, and procedures that allow data collection for these services and procedures.1 Inclusion implies nothing about safety, efficacy, frequency of use, or payment. These codes are used to differentiate emerging technology from the widely accepted Category I codes and use of alphanumeric characters instead of 5-digit codes. If reading this paragraph makes you giddy all over, pay a visit to the American Medical Association website to learn more about the process by which CPT codes come to life.2

Policy and Coding Changes

Last year saw much sturm and drang with the passage of the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015 (MACRA).3 The MACRA repealed the Sustainable Growth Rate formula and established annual positive or flat-fee updates for 10 years. A 2-tracked fee update was instituted afterward. It also established the Merit-Based Incentive Payment System, which consolidates existing Medicare fee-for-service physician incentive programs, establishes a pathway for physicians to participate in alternative payment models including the patient-centered medical home, and makes a bunch of other changes to existing Medicare physician payment statutes. It is too early to say if and how it will work and if it will change dermatology. It could fail miserably or it could be a brave new world; stay tuned.3

On the coding front, MACRA prohibits across-the-board elimination of global periods that the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) had previously announced.4 Instead, the CMS must develop and implement a process to gather data on services furnished during global periods based on a representative sample of physician data. The CMS can delay up to 5% of payments if it does not get the data it asks for and must work through the rulemaking process, which will impact medicine in 2019. Among our codes with nonzero global periods, the premalignant destruction codes 17000 and 17004, each of which contains the value of a 99212 established patient visit, are at the very apex of the hit list. It is not clear if the CMS will retrospectively pull medical records to evaluate the occurrence of the global visit or will prospectively have us use 99024, the code for a “[p]ostoperative follow-up visit, normally included in the surgical package, to indicate that an evaluation and management service was performed during a postoperative period for a reason(s) related to the original procedure.”1 This code is not used unless your practice needs a “filler” code for nonreportable visits but that may change. Is this another unfunded mandate? Yes.

Clarifications also have been made for reporting superficial radiation therapy.1 Treatment delivery using energies below 1 MV are to be reported with CPT code 77401 and cannot be combined with radiation treatment delivery codes (77402, 77407, 77412), clinical treatment planning codes (77261–77263), treatment device development codes (77332–77334), isodose planning codes (77306, 77307, 77316–77318), radiation treatment management codes (77427, 77431, 77432, 77435, 77469, 77470, 77499), continuing medical physics consultation code (77336), and special physics consultation code (77370). Evaluation and management services may still be reported separately, when appropriate, in cases in which only superficial radiation therapy services (ie, 77401) are provided.1

Electronic brachytherapy for skin cancer has a new Category III tracking code (0394T [high-dose-rate electronic brachytherapy, skin surface application, per fraction, includes basic dosimetry, when performed]) that is priced by the insurer. Noridian Healthcare Solutions pulled the plug on what many perceived as astronomical payments, but changes may be afoot, as its URL for their new policy was down at the time of publication, and there is still great variability in how payment is being made for these codes. For those interested in learning about perception, a visit to http://forums.studentdoctor.net/threads/electronic-brachy.1132531/ is in order, as the economic drivers to the utilization of this therapy are discussed in detail from the perspective of students and young physicians.

Although there are new telehealth codes for inpatient services and end-stage renal disease management, there are still none that are relevant to dermatology.

Place of service codes have been updated. Place of service code 19 refers to “off campus outpatient hospital” settings while place of service code 22 has been revised to “on campus outpatient hospital.” If your practice is a facility, consult the Medicare Claims Processing Manual (20.4.2) on the site of service payment differential for further enlightenment.5 Do note that CMS is increasingly interested in physicians who use wrong place of service codes.

Incident to billing rules are somewhat clearer. The physician or other practitioner who bills must be the supervising physician or practitioner. Services cannot be provided by individuals who have been excluded from Medicare, Medicaid, or other federal programs, nor can they be provided by an individual who has had Medicare enrollment revoked. State laws that are more restrictive take precedence.

Of course, the Relative Value Scale Update Committee (RUC) process moves on as always and you likely will receive 1 or more surveys in the near future. If you get one of these surveys, do not delete it. The surveys are the currency of the RUC, and if you give your RUC team bad or no data, the specialty will suffer cuts in valuation of what we do. If you have questions about the survey, contact the American Academy of Dermatology staff as listed in the survey. If you want to learn more about RUC, visit the American Medical Association website.6 To see the current relative value units for what dermatologists do and the typical time for these procedures, visit the CMS website, which provides resources that supply tremendous amounts of data on code valuation including documents detailing relative value units for every CPT code.7 You also can access current time values for preservice work, intraservice work, and postservice work times for all CPT codes in the entire CPT Professional Edition. They are based on typical times and are the major determinants of what you get paid. Happy reading.

1. Current Procedural Terminology 2016, Professional Edition. Chicago, IL: American Medical Association; 2015.

2. CPT–Current Procedural Terminology. American Medical Association website. http://www.ama-assn.org/ama/pub/physician-resources/solutions-managing-your-practice/coding-billing-insurance/cpt/cpt-editorial-panel.page. Accessed March 23, 2016.

3. The Merit-Based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) & Alternative Payment Models (APMs). Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services website. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/Value-Based-Programs/MACRA-MIPS-and-APMs/MACRA-MIPS-and-APMs.html. Accessed March 23, 2016.

4. Text of the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015. GovTrack website. https://www.govtrack.us/congress/bills/114/hr2/text. Accessed March 23, 2016.

5. Physicians/Nonphysician Practitioners. Medicare Claims Processing Manual. https://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Guidance/Manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed March 23, 2016.

6. American Medical Association. The RVS update committee. http://www.ama-assn.org/ama/pub/physician-resources/solutions-managing-your-practice/coding-billing-insurance/medicare/the-resource-based-relative-value-scale/the-rvs-update-committee.page?. Accessed March 23, 2016.

7. Details for title: CMS-1631-FC. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services website. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/Physician FeeSched/PFS-Federal-Regulation-Notices-Items/CMS-1631-FC.html. Published November 16, 2015. Accessed March 23, 2016.

New Codes for 2016

In 2016, noninvasive imaging in dermatology finally received recognition at the Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) level with the publication of 6 new Category I codes for reflectance confocal microscopy.1 These new codes are classified under the “Special Dermatological Procedures” section of CPT where codes do not have technical and professional payment splits, unlike pathology codes (Table). Currently, the new codes for reflectance confocal microscopy can only be implemented when using the VivaScope 1500 (Caliber I.D.) reflectance confocal imaging system and not with any other devices. At present, these codes are priced by each insurer and should be payable, as they are Category I codes that meet all criteria for widely used procedures that are well supported by strong evidence.

Additionally, MelaFind (MELA Sciences) has received 2 Category III CPT codes in 2016: 0400T, multispectral digital skin lesion analysis of clinically atypical cutaneous pigmented lesions for detection of melanomas and high-risk melanocytic atypia [1–5 lesions]; 0401T, multispectral digital skin lesion analysis of clinically atypical cutaneous pigmented lesions for detection of melanomas and high-risk melanocytic atypia [≥6 lesions]).

The CPT Professional Edition notes that Category III codes are a set of temporary codes for emerging technology, services, and procedures that allow data collection for these services and procedures.1 Inclusion implies nothing about safety, efficacy, frequency of use, or payment. These codes are used to differentiate emerging technology from the widely accepted Category I codes and use of alphanumeric characters instead of 5-digit codes. If reading this paragraph makes you giddy all over, pay a visit to the American Medical Association website to learn more about the process by which CPT codes come to life.2

Policy and Coding Changes

Last year saw much sturm and drang with the passage of the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015 (MACRA).3 The MACRA repealed the Sustainable Growth Rate formula and established annual positive or flat-fee updates for 10 years. A 2-tracked fee update was instituted afterward. It also established the Merit-Based Incentive Payment System, which consolidates existing Medicare fee-for-service physician incentive programs, establishes a pathway for physicians to participate in alternative payment models including the patient-centered medical home, and makes a bunch of other changes to existing Medicare physician payment statutes. It is too early to say if and how it will work and if it will change dermatology. It could fail miserably or it could be a brave new world; stay tuned.3

On the coding front, MACRA prohibits across-the-board elimination of global periods that the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) had previously announced.4 Instead, the CMS must develop and implement a process to gather data on services furnished during global periods based on a representative sample of physician data. The CMS can delay up to 5% of payments if it does not get the data it asks for and must work through the rulemaking process, which will impact medicine in 2019. Among our codes with nonzero global periods, the premalignant destruction codes 17000 and 17004, each of which contains the value of a 99212 established patient visit, are at the very apex of the hit list. It is not clear if the CMS will retrospectively pull medical records to evaluate the occurrence of the global visit or will prospectively have us use 99024, the code for a “[p]ostoperative follow-up visit, normally included in the surgical package, to indicate that an evaluation and management service was performed during a postoperative period for a reason(s) related to the original procedure.”1 This code is not used unless your practice needs a “filler” code for nonreportable visits but that may change. Is this another unfunded mandate? Yes.

Clarifications also have been made for reporting superficial radiation therapy.1 Treatment delivery using energies below 1 MV are to be reported with CPT code 77401 and cannot be combined with radiation treatment delivery codes (77402, 77407, 77412), clinical treatment planning codes (77261–77263), treatment device development codes (77332–77334), isodose planning codes (77306, 77307, 77316–77318), radiation treatment management codes (77427, 77431, 77432, 77435, 77469, 77470, 77499), continuing medical physics consultation code (77336), and special physics consultation code (77370). Evaluation and management services may still be reported separately, when appropriate, in cases in which only superficial radiation therapy services (ie, 77401) are provided.1

Electronic brachytherapy for skin cancer has a new Category III tracking code (0394T [high-dose-rate electronic brachytherapy, skin surface application, per fraction, includes basic dosimetry, when performed]) that is priced by the insurer. Noridian Healthcare Solutions pulled the plug on what many perceived as astronomical payments, but changes may be afoot, as its URL for their new policy was down at the time of publication, and there is still great variability in how payment is being made for these codes. For those interested in learning about perception, a visit to http://forums.studentdoctor.net/threads/electronic-brachy.1132531/ is in order, as the economic drivers to the utilization of this therapy are discussed in detail from the perspective of students and young physicians.

Although there are new telehealth codes for inpatient services and end-stage renal disease management, there are still none that are relevant to dermatology.

Place of service codes have been updated. Place of service code 19 refers to “off campus outpatient hospital” settings while place of service code 22 has been revised to “on campus outpatient hospital.” If your practice is a facility, consult the Medicare Claims Processing Manual (20.4.2) on the site of service payment differential for further enlightenment.5 Do note that CMS is increasingly interested in physicians who use wrong place of service codes.

Incident to billing rules are somewhat clearer. The physician or other practitioner who bills must be the supervising physician or practitioner. Services cannot be provided by individuals who have been excluded from Medicare, Medicaid, or other federal programs, nor can they be provided by an individual who has had Medicare enrollment revoked. State laws that are more restrictive take precedence.

Of course, the Relative Value Scale Update Committee (RUC) process moves on as always and you likely will receive 1 or more surveys in the near future. If you get one of these surveys, do not delete it. The surveys are the currency of the RUC, and if you give your RUC team bad or no data, the specialty will suffer cuts in valuation of what we do. If you have questions about the survey, contact the American Academy of Dermatology staff as listed in the survey. If you want to learn more about RUC, visit the American Medical Association website.6 To see the current relative value units for what dermatologists do and the typical time for these procedures, visit the CMS website, which provides resources that supply tremendous amounts of data on code valuation including documents detailing relative value units for every CPT code.7 You also can access current time values for preservice work, intraservice work, and postservice work times for all CPT codes in the entire CPT Professional Edition. They are based on typical times and are the major determinants of what you get paid. Happy reading.

New Codes for 2016

In 2016, noninvasive imaging in dermatology finally received recognition at the Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) level with the publication of 6 new Category I codes for reflectance confocal microscopy.1 These new codes are classified under the “Special Dermatological Procedures” section of CPT where codes do not have technical and professional payment splits, unlike pathology codes (Table). Currently, the new codes for reflectance confocal microscopy can only be implemented when using the VivaScope 1500 (Caliber I.D.) reflectance confocal imaging system and not with any other devices. At present, these codes are priced by each insurer and should be payable, as they are Category I codes that meet all criteria for widely used procedures that are well supported by strong evidence.

Additionally, MelaFind (MELA Sciences) has received 2 Category III CPT codes in 2016: 0400T, multispectral digital skin lesion analysis of clinically atypical cutaneous pigmented lesions for detection of melanomas and high-risk melanocytic atypia [1–5 lesions]; 0401T, multispectral digital skin lesion analysis of clinically atypical cutaneous pigmented lesions for detection of melanomas and high-risk melanocytic atypia [≥6 lesions]).

The CPT Professional Edition notes that Category III codes are a set of temporary codes for emerging technology, services, and procedures that allow data collection for these services and procedures.1 Inclusion implies nothing about safety, efficacy, frequency of use, or payment. These codes are used to differentiate emerging technology from the widely accepted Category I codes and use of alphanumeric characters instead of 5-digit codes. If reading this paragraph makes you giddy all over, pay a visit to the American Medical Association website to learn more about the process by which CPT codes come to life.2

Policy and Coding Changes

Last year saw much sturm and drang with the passage of the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015 (MACRA).3 The MACRA repealed the Sustainable Growth Rate formula and established annual positive or flat-fee updates for 10 years. A 2-tracked fee update was instituted afterward. It also established the Merit-Based Incentive Payment System, which consolidates existing Medicare fee-for-service physician incentive programs, establishes a pathway for physicians to participate in alternative payment models including the patient-centered medical home, and makes a bunch of other changes to existing Medicare physician payment statutes. It is too early to say if and how it will work and if it will change dermatology. It could fail miserably or it could be a brave new world; stay tuned.3

On the coding front, MACRA prohibits across-the-board elimination of global periods that the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) had previously announced.4 Instead, the CMS must develop and implement a process to gather data on services furnished during global periods based on a representative sample of physician data. The CMS can delay up to 5% of payments if it does not get the data it asks for and must work through the rulemaking process, which will impact medicine in 2019. Among our codes with nonzero global periods, the premalignant destruction codes 17000 and 17004, each of which contains the value of a 99212 established patient visit, are at the very apex of the hit list. It is not clear if the CMS will retrospectively pull medical records to evaluate the occurrence of the global visit or will prospectively have us use 99024, the code for a “[p]ostoperative follow-up visit, normally included in the surgical package, to indicate that an evaluation and management service was performed during a postoperative period for a reason(s) related to the original procedure.”1 This code is not used unless your practice needs a “filler” code for nonreportable visits but that may change. Is this another unfunded mandate? Yes.

Clarifications also have been made for reporting superficial radiation therapy.1 Treatment delivery using energies below 1 MV are to be reported with CPT code 77401 and cannot be combined with radiation treatment delivery codes (77402, 77407, 77412), clinical treatment planning codes (77261–77263), treatment device development codes (77332–77334), isodose planning codes (77306, 77307, 77316–77318), radiation treatment management codes (77427, 77431, 77432, 77435, 77469, 77470, 77499), continuing medical physics consultation code (77336), and special physics consultation code (77370). Evaluation and management services may still be reported separately, when appropriate, in cases in which only superficial radiation therapy services (ie, 77401) are provided.1

Electronic brachytherapy for skin cancer has a new Category III tracking code (0394T [high-dose-rate electronic brachytherapy, skin surface application, per fraction, includes basic dosimetry, when performed]) that is priced by the insurer. Noridian Healthcare Solutions pulled the plug on what many perceived as astronomical payments, but changes may be afoot, as its URL for their new policy was down at the time of publication, and there is still great variability in how payment is being made for these codes. For those interested in learning about perception, a visit to http://forums.studentdoctor.net/threads/electronic-brachy.1132531/ is in order, as the economic drivers to the utilization of this therapy are discussed in detail from the perspective of students and young physicians.

Although there are new telehealth codes for inpatient services and end-stage renal disease management, there are still none that are relevant to dermatology.

Place of service codes have been updated. Place of service code 19 refers to “off campus outpatient hospital” settings while place of service code 22 has been revised to “on campus outpatient hospital.” If your practice is a facility, consult the Medicare Claims Processing Manual (20.4.2) on the site of service payment differential for further enlightenment.5 Do note that CMS is increasingly interested in physicians who use wrong place of service codes.

Incident to billing rules are somewhat clearer. The physician or other practitioner who bills must be the supervising physician or practitioner. Services cannot be provided by individuals who have been excluded from Medicare, Medicaid, or other federal programs, nor can they be provided by an individual who has had Medicare enrollment revoked. State laws that are more restrictive take precedence.

Of course, the Relative Value Scale Update Committee (RUC) process moves on as always and you likely will receive 1 or more surveys in the near future. If you get one of these surveys, do not delete it. The surveys are the currency of the RUC, and if you give your RUC team bad or no data, the specialty will suffer cuts in valuation of what we do. If you have questions about the survey, contact the American Academy of Dermatology staff as listed in the survey. If you want to learn more about RUC, visit the American Medical Association website.6 To see the current relative value units for what dermatologists do and the typical time for these procedures, visit the CMS website, which provides resources that supply tremendous amounts of data on code valuation including documents detailing relative value units for every CPT code.7 You also can access current time values for preservice work, intraservice work, and postservice work times for all CPT codes in the entire CPT Professional Edition. They are based on typical times and are the major determinants of what you get paid. Happy reading.

1. Current Procedural Terminology 2016, Professional Edition. Chicago, IL: American Medical Association; 2015.

2. CPT–Current Procedural Terminology. American Medical Association website. http://www.ama-assn.org/ama/pub/physician-resources/solutions-managing-your-practice/coding-billing-insurance/cpt/cpt-editorial-panel.page. Accessed March 23, 2016.

3. The Merit-Based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) & Alternative Payment Models (APMs). Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services website. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/Value-Based-Programs/MACRA-MIPS-and-APMs/MACRA-MIPS-and-APMs.html. Accessed March 23, 2016.

4. Text of the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015. GovTrack website. https://www.govtrack.us/congress/bills/114/hr2/text. Accessed March 23, 2016.

5. Physicians/Nonphysician Practitioners. Medicare Claims Processing Manual. https://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Guidance/Manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed March 23, 2016.

6. American Medical Association. The RVS update committee. http://www.ama-assn.org/ama/pub/physician-resources/solutions-managing-your-practice/coding-billing-insurance/medicare/the-resource-based-relative-value-scale/the-rvs-update-committee.page?. Accessed March 23, 2016.

7. Details for title: CMS-1631-FC. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services website. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/Physician FeeSched/PFS-Federal-Regulation-Notices-Items/CMS-1631-FC.html. Published November 16, 2015. Accessed March 23, 2016.

1. Current Procedural Terminology 2016, Professional Edition. Chicago, IL: American Medical Association; 2015.

2. CPT–Current Procedural Terminology. American Medical Association website. http://www.ama-assn.org/ama/pub/physician-resources/solutions-managing-your-practice/coding-billing-insurance/cpt/cpt-editorial-panel.page. Accessed March 23, 2016.

3. The Merit-Based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) & Alternative Payment Models (APMs). Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services website. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/Value-Based-Programs/MACRA-MIPS-and-APMs/MACRA-MIPS-and-APMs.html. Accessed March 23, 2016.

4. Text of the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015. GovTrack website. https://www.govtrack.us/congress/bills/114/hr2/text. Accessed March 23, 2016.

5. Physicians/Nonphysician Practitioners. Medicare Claims Processing Manual. https://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Guidance/Manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed March 23, 2016.

6. American Medical Association. The RVS update committee. http://www.ama-assn.org/ama/pub/physician-resources/solutions-managing-your-practice/coding-billing-insurance/medicare/the-resource-based-relative-value-scale/the-rvs-update-committee.page?. Accessed March 23, 2016.

7. Details for title: CMS-1631-FC. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services website. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/Physician FeeSched/PFS-Federal-Regulation-Notices-Items/CMS-1631-FC.html. Published November 16, 2015. Accessed March 23, 2016.

Practice Points

- Many dermatology codes are in the “Special Dermatological Procedures” section of the Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) manual.

- Physicians should purchase a new CPT manual every year, as accurate coding is critical for accurate reimbursement.

HM16 Session Analysis: Maximizing Collaboration With PAs & NPs: Rules, Realities, Reimbursement

Presenter: Tricia Marriott, PA-C, MPAS, MJ Health Law

Summary: Ms. Marriott brought humor to a detailed #HospMed16 presentation on the rules of reimbursement and Medicare requirements for physician assistants (PAs) and nurse practitioners (NPs). The session was packed with information regarding the Medicare regulations relating to PAs and NPs, as well as information from state Medicaid programs and commercial payors. The presentation continued with focusing on myth busters and misperceptions about PAs and NPs. These topics were reviewed in depth:

- PAs and NPs have been recognized as providers by Medicare since 1998, as demonstrated by Medicare citations provided to the audience.

- Supervision/collaboration, as defined by Medicare requirements.

- Medicare payment policy: “incident to” vs. “split/shared visit,” reviewing unacceptable shared visit documentation and unintended consequences of fewer shared visits.

The discussion provided detailed insight into how to address the question, “What about the 15% reduced Medicare reimbursement for PAs and NPs?” An analytical approach to answering this question was provided as it relates to inpatient services, observation services, critical care services, and consultations. At the end of the talk, the audience was very engaged, and a lively Q&A ensued past the scheduled time. TH

Presenter: Tricia Marriott, PA-C, MPAS, MJ Health Law

Summary: Ms. Marriott brought humor to a detailed #HospMed16 presentation on the rules of reimbursement and Medicare requirements for physician assistants (PAs) and nurse practitioners (NPs). The session was packed with information regarding the Medicare regulations relating to PAs and NPs, as well as information from state Medicaid programs and commercial payors. The presentation continued with focusing on myth busters and misperceptions about PAs and NPs. These topics were reviewed in depth:

- PAs and NPs have been recognized as providers by Medicare since 1998, as demonstrated by Medicare citations provided to the audience.

- Supervision/collaboration, as defined by Medicare requirements.

- Medicare payment policy: “incident to” vs. “split/shared visit,” reviewing unacceptable shared visit documentation and unintended consequences of fewer shared visits.

The discussion provided detailed insight into how to address the question, “What about the 15% reduced Medicare reimbursement for PAs and NPs?” An analytical approach to answering this question was provided as it relates to inpatient services, observation services, critical care services, and consultations. At the end of the talk, the audience was very engaged, and a lively Q&A ensued past the scheduled time. TH

Presenter: Tricia Marriott, PA-C, MPAS, MJ Health Law

Summary: Ms. Marriott brought humor to a detailed #HospMed16 presentation on the rules of reimbursement and Medicare requirements for physician assistants (PAs) and nurse practitioners (NPs). The session was packed with information regarding the Medicare regulations relating to PAs and NPs, as well as information from state Medicaid programs and commercial payors. The presentation continued with focusing on myth busters and misperceptions about PAs and NPs. These topics were reviewed in depth:

- PAs and NPs have been recognized as providers by Medicare since 1998, as demonstrated by Medicare citations provided to the audience.

- Supervision/collaboration, as defined by Medicare requirements.

- Medicare payment policy: “incident to” vs. “split/shared visit,” reviewing unacceptable shared visit documentation and unintended consequences of fewer shared visits.

The discussion provided detailed insight into how to address the question, “What about the 15% reduced Medicare reimbursement for PAs and NPs?” An analytical approach to answering this question was provided as it relates to inpatient services, observation services, critical care services, and consultations. At the end of the talk, the audience was very engaged, and a lively Q&A ensued past the scheduled time. TH

HM16 Session Analysis: ICD-10 Coding Tips

Presenter: Aziz Ansari, DO, FHM

Summary: With the implementation of ICD-10, correct and specific documentation to ensure proper patient diagnosis categorization has become increasingly important. Hospitalists are urged to understand the impact CDI has on quality and reimbursement.

Quality Impact: Documentation has a direct impact on quality reporting for mortality and complication rates, risk of mortality, as well as severity of illness. Documenting present on admission (POA) also directly impacts the hospital-acquired condition (HAC) classifications.

Reimbursement Impact: Documentation has a direct impact on expected length of stay, case mix index (CMI), cost reporting, and appropriate hospital reimbursement.

HM Takeaways:

- Be clear and specific.

- Document principle diagnosis and secondary diagnoses, and their associated interactions, are critically important.

- Ensure all diagnoses are a part of the discharge summary.

- Avoid saying “History of.”

- It’s OK to document “possible,” “probably,” “likely,” or “suspected.”

- Document “why” the patient has the diagnosis.

- List all differentials, and identify if ruled in or ruled out.

- Indicate acuity, even if obvious.

This presenter also reviewed common CDI opportunities in hospital medicine.

Note: This discussion was specific to the needs of the hospital patient diagnosis and billing, and not related to physician billing and CPT codes.

Presenter: Aziz Ansari, DO, FHM

Summary: With the implementation of ICD-10, correct and specific documentation to ensure proper patient diagnosis categorization has become increasingly important. Hospitalists are urged to understand the impact CDI has on quality and reimbursement.

Quality Impact: Documentation has a direct impact on quality reporting for mortality and complication rates, risk of mortality, as well as severity of illness. Documenting present on admission (POA) also directly impacts the hospital-acquired condition (HAC) classifications.

Reimbursement Impact: Documentation has a direct impact on expected length of stay, case mix index (CMI), cost reporting, and appropriate hospital reimbursement.

HM Takeaways:

- Be clear and specific.

- Document principle diagnosis and secondary diagnoses, and their associated interactions, are critically important.

- Ensure all diagnoses are a part of the discharge summary.

- Avoid saying “History of.”

- It’s OK to document “possible,” “probably,” “likely,” or “suspected.”

- Document “why” the patient has the diagnosis.

- List all differentials, and identify if ruled in or ruled out.

- Indicate acuity, even if obvious.

This presenter also reviewed common CDI opportunities in hospital medicine.

Note: This discussion was specific to the needs of the hospital patient diagnosis and billing, and not related to physician billing and CPT codes.

Presenter: Aziz Ansari, DO, FHM

Summary: With the implementation of ICD-10, correct and specific documentation to ensure proper patient diagnosis categorization has become increasingly important. Hospitalists are urged to understand the impact CDI has on quality and reimbursement.

Quality Impact: Documentation has a direct impact on quality reporting for mortality and complication rates, risk of mortality, as well as severity of illness. Documenting present on admission (POA) also directly impacts the hospital-acquired condition (HAC) classifications.

Reimbursement Impact: Documentation has a direct impact on expected length of stay, case mix index (CMI), cost reporting, and appropriate hospital reimbursement.

HM Takeaways:

- Be clear and specific.

- Document principle diagnosis and secondary diagnoses, and their associated interactions, are critically important.

- Ensure all diagnoses are a part of the discharge summary.

- Avoid saying “History of.”

- It’s OK to document “possible,” “probably,” “likely,” or “suspected.”

- Document “why” the patient has the diagnosis.

- List all differentials, and identify if ruled in or ruled out.

- Indicate acuity, even if obvious.

This presenter also reviewed common CDI opportunities in hospital medicine.

Note: This discussion was specific to the needs of the hospital patient diagnosis and billing, and not related to physician billing and CPT codes.

Key Elements of Critical Care

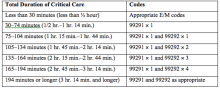

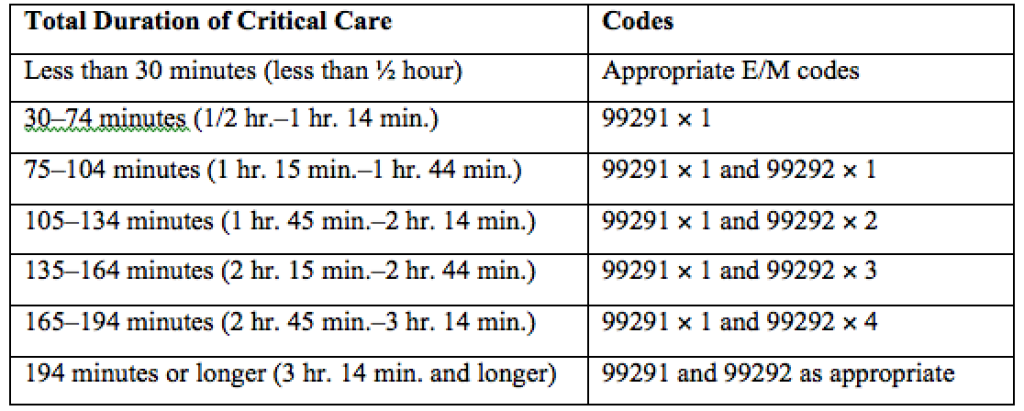

Code 99291 is used for critical care, evaluation, and management of the critically ill or critically injured patient, first 30–74 minutes.1 It is to be reported only once per day per physician or group member of the same specialty.

Code 99292 is for critical care, evaluation, and management of the critically ill or critically injured patient, each additional 30 minutes. It is to be listed separately in addition to the code for primary service.1 Code 99292 is categorized as an add-on code. It must be reported on the same invoice as its primary code, 99291. Multiple units of code 99292 can be reported per day per physician/group.

Despite the increased resources and references for critical care billing, critical care reporting issues persist. Medicare data analysis continues to identify 99291 as high risk for claim payment errors, perpetuating prepayment claim edits for outlier utilization and location discrepancies (i.e., settings other than inpatient hospital, outpatient hospital, or the emergency department). 2,3,4

Bolster your documentation with these three key elements.

Critical Illness, Injury Management

Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) define “critical illness or injury” as a condition that acutely impairs one or more vital organ systems such that there is a high probability of imminent or life-threatening deterioration in the patient’s condition (e.g., central nervous system failure; circulatory failure; shock; renal, hepatic, metabolic, and/or respiratory failure).5

Hospitalists providing care to the critically ill patient must perform highly complex decision making and interventions of high intensity that are required to prevent the patient’s inevitable decline. CMS further elaborates that “the patient shall be critically ill or injured at the time of the physician’s visit.”6 This is to ensure that hospitalists and other specialists support the medical necessity of the service and do not continue to report critical care codes on days after the patient has become stable and improved.

Consider the following scenarios:

CMS examples of patients whose medical condition may warrant critical care services (99291, 99292):6

- An 81-year-old male patient is admitted to the ICU following abdominal aortic aneurysm resection. Two days after surgery, he requires fluids and pressors to maintain adequate perfusion and arterial pressures. He remains ventilator dependent.

- A 67-year-old female patient is three days post mitral valve repair. She develops petechiae, hypotension, and hypoxia requiring respiratory and circulatory support.

- A 70-year-old admitted for right lower lobe pneumococcal pneumonia with a history of COPD becomes hypoxic and hypotensive two days after admission.

- A 68-year-old admitted for an acute anterior wall myocardial infarction continues to have symptomatic ventricular tachycardia that is marginally responsive to antiarrhythmic therapy.

CMS examples of patients who may not satisfy Medicare medical necessity criteria, or do not meet critical care criteria, or who do not have a critical care illness or injury and, therefore, are not eligible for critical care payment but may be reported using another appropriate hospital care code, such as subsequent hospital care codes (99231–99233), initial hospital care codes (99221–99223), or hospital consultation codes (99251–99255) when applicable:1,6

- Patients admitted to a critical care unit because no other hospital beds were available;

- Patients admitted to a critical care unit for close nursing observation and/or frequent monitoring of vital signs (e.g., drug toxicity or overdose);

- Patients admitted to a critical care unit because hospital rules require certain treatments (e.g., insulin infusions) to be administered in the critical care unit; and

- Patients receiving only care of a chronic illness in absence of care for a critical illness (e.g., daily management of a chronic ventilator patient, management of or care related to dialysis for end-stage renal disease). Services considered palliative in nature as this type of care do not meet the definition of critical care services.7

Concurrent Care

Critically ill patients often require the care of hospitalists and other specialists throughout the course of treatment. Payors are sensitive to the multiple hours billed by multiple providers for a single patient on a given day. Claim logic provides an automated response to only allow reimbursement for 99291 once per day when reported by physicians of the same group and specialty.8 Physicians of different specialties can separately report critical care hours as long as they are caring for a condition that meets the definition of critical care.

The CMS example of this: A dermatologist evaluates and treats a rash on an ICU patient who is maintained on a ventilator and nitroglycerine infusion that are being managed by an intensivist. The dermatologist should not report a service for critical care.6

Similarly for hospitalists, if an intensivist is taking care of the critical condition and there is nothing more for the hospitalist to add to the plan of care for the critical condition, critical care services may not be justified.

When different specialists are reporting critical care on the same day, it is imperative for the documentation to demonstrate that care is not duplicative of any other provider’s care (i.e., identify management of different conditions or revising elements of the plan). The care cannot overlap the same time period of any other physician reporting critical care services.

Calculating Time

Critical care time constitutes bedside time and time spent on the patient’s unit/floor where the physician is immediately available to the patient (see Table 1). Certain labs, diagnostic studies, and procedures are considered inherent to critical care services and are not reported separately on the claim form: cardiac output measurements (93561, 93562); chest X-rays (71010, 71015, 71020); pulse oximetry (94760, 94761, 94762); blood gases and interpretation of data stored in computers, such as ECGs, blood pressures, and hematologic data (99090); gastric intubation (43752, 43753); temporary transcutaneous pacing (92953); ventilation management (94002–94004, 94660, 94662); and vascular access procedures (36000, 36410, 36415, 36591, 36600).1

Instead, physician time associated with the performance and/or interpretation of these services is toward the cumulative critical care time of the day. Services or procedures that are considered separately billable (e.g., central line placement, intubation, CPR) cannot contribute to critical care time.

When separately billable procedures are performed by the same provider/specialty group on the same day as critical care, physicians should make a notation in the medical record indicating the non-overlapping service times (e.g., “central line insertion is not included as critical care time”). This may assist with securing reimbursement when the payor requests the documentation for each reported claim item.

Activities on the floor/unit that do not directly contribute to patient care or management (e.g., review of literature, teaching rounds) cannot be counted toward critical care time. Do not count time associated with indirect care provided outside of the patient’s unit/floor (e.g., reviewing data or calling the family from the office) toward critical care time.

Family discussions can be counted toward critical care time but must take place at bedside or on the patient’s unit/floor. The patient must participate in the discussion unless medically unable or clinically incompetent to participate. If unable to participate, a notation in the chart must delineate the patient’s inability to participate and the reason.

Credited time can only involve obtaining a medical history and/or discussing treatment options or limitation(s) of treatment. The conversation must bear directly on patient management.1,7 Do not count time associated with providing periodic condition updates to the family, answering questions about the patient’s condition that are unrelated to decision making, or counseling the family during their grief process. If the conversation must take place via phone, it may be counted toward critical care time if the physician is calling from the patient’s unit/floor and the conversation involves the same criterion identified for face-to-face family meetings.10

Physicians should keep track of their critical care time throughout the day. Since critical care time is a cumulative service, each entry should include the total time that critical care services were provided (e.g., 45 minutes).10 Some payors may still impose the notation of “start-and-stop time” per encounter (e.g., 2–2:50 a.m.).

Same-specialty physicians (i.e., two hospitalists from the same group practice) may require separate claims. The initial critical care hour (99291) must be met by a single physician. Medically necessary critical care time beyond the first hour (99292) may be met individually by the same physician or collectively with another physician from the same group. The physician performing the additional time, beyond the first hour, reports the appropriate units of 99292 (see Table 1) under the corresponding NPI.11

CMS has issued instructions for contractors to recognize this atypical reporting method. However, non-Medicare payors may not recognize this newer reporting method and maintain that the cumulative service (by the same-specialty physician in the same provider group) should be reported under one physician name. Be sure to query the payors for appropriate reporting methods. TH

References

- Abraham M, Ahlman J, Boudreau A, Connelly J, Crosslin, R. Current Procedural Terminology 2015 Professional Edition. Chicago: American Medical Association Press; 2014. 23-25.

- Widespread prepayment targeted review notification—CPT 99291. Cahaba website. Available at: www.cahabagba.com/news/widespread-prepayment-targeted-review-notification-part-b/. Accessed December 17, 2015.

- Critical care CPT 99291 widespread prepayment targeted review results. Cahaba website. Available at: https://www.cahabagba.com/news/critical-care-cpt-99291-widespread-prepayment-targeted-review-results-2/. Accessed December 17, 2015.

- Prepayment edit of evaluation and management (E/M) code 99291. First Coast Service Options, Inc. website. Available at: medicare.fcso.com/Publications_B/2013/251608.pdf. Accessed December 17, 2015.

- Medicare claims processing manual: chapter 12, section 30.6.12A. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services website. Available at: www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Guidance/Manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed December 17, 2015.

- Medicare claims processing manual: chapter 12, section 30.6.12B. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services website. Available at: www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Guidance/Manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed December 17, 2015.

- Critical care fact sheet. CGS Administrators, LLC website. Available at: www.cgsmedicare.com/partb/mr/pdf/critical_care_fact_sheet.pdf. Accessed December 17, 2015.

- Same day same service policy. United Healthcare website. Available at: www.unitedhealthcareonline.com/ccmcontent/ProviderII/UHC/en-US/Main%20Menu/Tools%20&%20Resources/Policies%20and%20Protocols/Medicare%20Advantage%20Reimbursement%20Policies/S/SameDaySameService.pdf. Accessed December 17, 2015.

- Medicare claims processing manual: chapter 12, section 30.6.12G. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services website. Available at: www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Guidance/Manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed December 17, 2015.

- Medicare claims processing manual: chapter 12, section 30.6.12E. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services website. Available at: www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Guidance/Manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed December 17, 2015.

- Medicare claims processing manual: chapter 12, section 30.6.12I. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services website. Available at: www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Guidance/Manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed December 17, 2015.

Code 99291 is used for critical care, evaluation, and management of the critically ill or critically injured patient, first 30–74 minutes.1 It is to be reported only once per day per physician or group member of the same specialty.

Code 99292 is for critical care, evaluation, and management of the critically ill or critically injured patient, each additional 30 minutes. It is to be listed separately in addition to the code for primary service.1 Code 99292 is categorized as an add-on code. It must be reported on the same invoice as its primary code, 99291. Multiple units of code 99292 can be reported per day per physician/group.

Despite the increased resources and references for critical care billing, critical care reporting issues persist. Medicare data analysis continues to identify 99291 as high risk for claim payment errors, perpetuating prepayment claim edits for outlier utilization and location discrepancies (i.e., settings other than inpatient hospital, outpatient hospital, or the emergency department). 2,3,4

Bolster your documentation with these three key elements.

Critical Illness, Injury Management

Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) define “critical illness or injury” as a condition that acutely impairs one or more vital organ systems such that there is a high probability of imminent or life-threatening deterioration in the patient’s condition (e.g., central nervous system failure; circulatory failure; shock; renal, hepatic, metabolic, and/or respiratory failure).5

Hospitalists providing care to the critically ill patient must perform highly complex decision making and interventions of high intensity that are required to prevent the patient’s inevitable decline. CMS further elaborates that “the patient shall be critically ill or injured at the time of the physician’s visit.”6 This is to ensure that hospitalists and other specialists support the medical necessity of the service and do not continue to report critical care codes on days after the patient has become stable and improved.

Consider the following scenarios:

CMS examples of patients whose medical condition may warrant critical care services (99291, 99292):6

- An 81-year-old male patient is admitted to the ICU following abdominal aortic aneurysm resection. Two days after surgery, he requires fluids and pressors to maintain adequate perfusion and arterial pressures. He remains ventilator dependent.

- A 67-year-old female patient is three days post mitral valve repair. She develops petechiae, hypotension, and hypoxia requiring respiratory and circulatory support.

- A 70-year-old admitted for right lower lobe pneumococcal pneumonia with a history of COPD becomes hypoxic and hypotensive two days after admission.

- A 68-year-old admitted for an acute anterior wall myocardial infarction continues to have symptomatic ventricular tachycardia that is marginally responsive to antiarrhythmic therapy.

CMS examples of patients who may not satisfy Medicare medical necessity criteria, or do not meet critical care criteria, or who do not have a critical care illness or injury and, therefore, are not eligible for critical care payment but may be reported using another appropriate hospital care code, such as subsequent hospital care codes (99231–99233), initial hospital care codes (99221–99223), or hospital consultation codes (99251–99255) when applicable:1,6

- Patients admitted to a critical care unit because no other hospital beds were available;

- Patients admitted to a critical care unit for close nursing observation and/or frequent monitoring of vital signs (e.g., drug toxicity or overdose);

- Patients admitted to a critical care unit because hospital rules require certain treatments (e.g., insulin infusions) to be administered in the critical care unit; and

- Patients receiving only care of a chronic illness in absence of care for a critical illness (e.g., daily management of a chronic ventilator patient, management of or care related to dialysis for end-stage renal disease). Services considered palliative in nature as this type of care do not meet the definition of critical care services.7

Concurrent Care

Critically ill patients often require the care of hospitalists and other specialists throughout the course of treatment. Payors are sensitive to the multiple hours billed by multiple providers for a single patient on a given day. Claim logic provides an automated response to only allow reimbursement for 99291 once per day when reported by physicians of the same group and specialty.8 Physicians of different specialties can separately report critical care hours as long as they are caring for a condition that meets the definition of critical care.

The CMS example of this: A dermatologist evaluates and treats a rash on an ICU patient who is maintained on a ventilator and nitroglycerine infusion that are being managed by an intensivist. The dermatologist should not report a service for critical care.6

Similarly for hospitalists, if an intensivist is taking care of the critical condition and there is nothing more for the hospitalist to add to the plan of care for the critical condition, critical care services may not be justified.

When different specialists are reporting critical care on the same day, it is imperative for the documentation to demonstrate that care is not duplicative of any other provider’s care (i.e., identify management of different conditions or revising elements of the plan). The care cannot overlap the same time period of any other physician reporting critical care services.

Calculating Time

Critical care time constitutes bedside time and time spent on the patient’s unit/floor where the physician is immediately available to the patient (see Table 1). Certain labs, diagnostic studies, and procedures are considered inherent to critical care services and are not reported separately on the claim form: cardiac output measurements (93561, 93562); chest X-rays (71010, 71015, 71020); pulse oximetry (94760, 94761, 94762); blood gases and interpretation of data stored in computers, such as ECGs, blood pressures, and hematologic data (99090); gastric intubation (43752, 43753); temporary transcutaneous pacing (92953); ventilation management (94002–94004, 94660, 94662); and vascular access procedures (36000, 36410, 36415, 36591, 36600).1

Instead, physician time associated with the performance and/or interpretation of these services is toward the cumulative critical care time of the day. Services or procedures that are considered separately billable (e.g., central line placement, intubation, CPR) cannot contribute to critical care time.

When separately billable procedures are performed by the same provider/specialty group on the same day as critical care, physicians should make a notation in the medical record indicating the non-overlapping service times (e.g., “central line insertion is not included as critical care time”). This may assist with securing reimbursement when the payor requests the documentation for each reported claim item.

Activities on the floor/unit that do not directly contribute to patient care or management (e.g., review of literature, teaching rounds) cannot be counted toward critical care time. Do not count time associated with indirect care provided outside of the patient’s unit/floor (e.g., reviewing data or calling the family from the office) toward critical care time.

Family discussions can be counted toward critical care time but must take place at bedside or on the patient’s unit/floor. The patient must participate in the discussion unless medically unable or clinically incompetent to participate. If unable to participate, a notation in the chart must delineate the patient’s inability to participate and the reason.

Credited time can only involve obtaining a medical history and/or discussing treatment options or limitation(s) of treatment. The conversation must bear directly on patient management.1,7 Do not count time associated with providing periodic condition updates to the family, answering questions about the patient’s condition that are unrelated to decision making, or counseling the family during their grief process. If the conversation must take place via phone, it may be counted toward critical care time if the physician is calling from the patient’s unit/floor and the conversation involves the same criterion identified for face-to-face family meetings.10

Physicians should keep track of their critical care time throughout the day. Since critical care time is a cumulative service, each entry should include the total time that critical care services were provided (e.g., 45 minutes).10 Some payors may still impose the notation of “start-and-stop time” per encounter (e.g., 2–2:50 a.m.).

Same-specialty physicians (i.e., two hospitalists from the same group practice) may require separate claims. The initial critical care hour (99291) must be met by a single physician. Medically necessary critical care time beyond the first hour (99292) may be met individually by the same physician or collectively with another physician from the same group. The physician performing the additional time, beyond the first hour, reports the appropriate units of 99292 (see Table 1) under the corresponding NPI.11

CMS has issued instructions for contractors to recognize this atypical reporting method. However, non-Medicare payors may not recognize this newer reporting method and maintain that the cumulative service (by the same-specialty physician in the same provider group) should be reported under one physician name. Be sure to query the payors for appropriate reporting methods. TH

References

- Abraham M, Ahlman J, Boudreau A, Connelly J, Crosslin, R. Current Procedural Terminology 2015 Professional Edition. Chicago: American Medical Association Press; 2014. 23-25.

- Widespread prepayment targeted review notification—CPT 99291. Cahaba website. Available at: www.cahabagba.com/news/widespread-prepayment-targeted-review-notification-part-b/. Accessed December 17, 2015.

- Critical care CPT 99291 widespread prepayment targeted review results. Cahaba website. Available at: https://www.cahabagba.com/news/critical-care-cpt-99291-widespread-prepayment-targeted-review-results-2/. Accessed December 17, 2015.

- Prepayment edit of evaluation and management (E/M) code 99291. First Coast Service Options, Inc. website. Available at: medicare.fcso.com/Publications_B/2013/251608.pdf. Accessed December 17, 2015.

- Medicare claims processing manual: chapter 12, section 30.6.12A. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services website. Available at: www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Guidance/Manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed December 17, 2015.

- Medicare claims processing manual: chapter 12, section 30.6.12B. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services website. Available at: www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Guidance/Manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed December 17, 2015.

- Critical care fact sheet. CGS Administrators, LLC website. Available at: www.cgsmedicare.com/partb/mr/pdf/critical_care_fact_sheet.pdf. Accessed December 17, 2015.

- Same day same service policy. United Healthcare website. Available at: www.unitedhealthcareonline.com/ccmcontent/ProviderII/UHC/en-US/Main%20Menu/Tools%20&%20Resources/Policies%20and%20Protocols/Medicare%20Advantage%20Reimbursement%20Policies/S/SameDaySameService.pdf. Accessed December 17, 2015.

- Medicare claims processing manual: chapter 12, section 30.6.12G. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services website. Available at: www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Guidance/Manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed December 17, 2015.

- Medicare claims processing manual: chapter 12, section 30.6.12E. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services website. Available at: www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Guidance/Manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed December 17, 2015.

- Medicare claims processing manual: chapter 12, section 30.6.12I. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services website. Available at: www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Guidance/Manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed December 17, 2015.

Code 99291 is used for critical care, evaluation, and management of the critically ill or critically injured patient, first 30–74 minutes.1 It is to be reported only once per day per physician or group member of the same specialty.

Code 99292 is for critical care, evaluation, and management of the critically ill or critically injured patient, each additional 30 minutes. It is to be listed separately in addition to the code for primary service.1 Code 99292 is categorized as an add-on code. It must be reported on the same invoice as its primary code, 99291. Multiple units of code 99292 can be reported per day per physician/group.

Despite the increased resources and references for critical care billing, critical care reporting issues persist. Medicare data analysis continues to identify 99291 as high risk for claim payment errors, perpetuating prepayment claim edits for outlier utilization and location discrepancies (i.e., settings other than inpatient hospital, outpatient hospital, or the emergency department). 2,3,4

Bolster your documentation with these three key elements.

Critical Illness, Injury Management

Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) define “critical illness or injury” as a condition that acutely impairs one or more vital organ systems such that there is a high probability of imminent or life-threatening deterioration in the patient’s condition (e.g., central nervous system failure; circulatory failure; shock; renal, hepatic, metabolic, and/or respiratory failure).5

Hospitalists providing care to the critically ill patient must perform highly complex decision making and interventions of high intensity that are required to prevent the patient’s inevitable decline. CMS further elaborates that “the patient shall be critically ill or injured at the time of the physician’s visit.”6 This is to ensure that hospitalists and other specialists support the medical necessity of the service and do not continue to report critical care codes on days after the patient has become stable and improved.

Consider the following scenarios:

CMS examples of patients whose medical condition may warrant critical care services (99291, 99292):6

- An 81-year-old male patient is admitted to the ICU following abdominal aortic aneurysm resection. Two days after surgery, he requires fluids and pressors to maintain adequate perfusion and arterial pressures. He remains ventilator dependent.

- A 67-year-old female patient is three days post mitral valve repair. She develops petechiae, hypotension, and hypoxia requiring respiratory and circulatory support.

- A 70-year-old admitted for right lower lobe pneumococcal pneumonia with a history of COPD becomes hypoxic and hypotensive two days after admission.

- A 68-year-old admitted for an acute anterior wall myocardial infarction continues to have symptomatic ventricular tachycardia that is marginally responsive to antiarrhythmic therapy.

CMS examples of patients who may not satisfy Medicare medical necessity criteria, or do not meet critical care criteria, or who do not have a critical care illness or injury and, therefore, are not eligible for critical care payment but may be reported using another appropriate hospital care code, such as subsequent hospital care codes (99231–99233), initial hospital care codes (99221–99223), or hospital consultation codes (99251–99255) when applicable:1,6

- Patients admitted to a critical care unit because no other hospital beds were available;

- Patients admitted to a critical care unit for close nursing observation and/or frequent monitoring of vital signs (e.g., drug toxicity or overdose);

- Patients admitted to a critical care unit because hospital rules require certain treatments (e.g., insulin infusions) to be administered in the critical care unit; and

- Patients receiving only care of a chronic illness in absence of care for a critical illness (e.g., daily management of a chronic ventilator patient, management of or care related to dialysis for end-stage renal disease). Services considered palliative in nature as this type of care do not meet the definition of critical care services.7

Concurrent Care

Critically ill patients often require the care of hospitalists and other specialists throughout the course of treatment. Payors are sensitive to the multiple hours billed by multiple providers for a single patient on a given day. Claim logic provides an automated response to only allow reimbursement for 99291 once per day when reported by physicians of the same group and specialty.8 Physicians of different specialties can separately report critical care hours as long as they are caring for a condition that meets the definition of critical care.

The CMS example of this: A dermatologist evaluates and treats a rash on an ICU patient who is maintained on a ventilator and nitroglycerine infusion that are being managed by an intensivist. The dermatologist should not report a service for critical care.6

Similarly for hospitalists, if an intensivist is taking care of the critical condition and there is nothing more for the hospitalist to add to the plan of care for the critical condition, critical care services may not be justified.

When different specialists are reporting critical care on the same day, it is imperative for the documentation to demonstrate that care is not duplicative of any other provider’s care (i.e., identify management of different conditions or revising elements of the plan). The care cannot overlap the same time period of any other physician reporting critical care services.

Calculating Time

Critical care time constitutes bedside time and time spent on the patient’s unit/floor where the physician is immediately available to the patient (see Table 1). Certain labs, diagnostic studies, and procedures are considered inherent to critical care services and are not reported separately on the claim form: cardiac output measurements (93561, 93562); chest X-rays (71010, 71015, 71020); pulse oximetry (94760, 94761, 94762); blood gases and interpretation of data stored in computers, such as ECGs, blood pressures, and hematologic data (99090); gastric intubation (43752, 43753); temporary transcutaneous pacing (92953); ventilation management (94002–94004, 94660, 94662); and vascular access procedures (36000, 36410, 36415, 36591, 36600).1

Instead, physician time associated with the performance and/or interpretation of these services is toward the cumulative critical care time of the day. Services or procedures that are considered separately billable (e.g., central line placement, intubation, CPR) cannot contribute to critical care time.

When separately billable procedures are performed by the same provider/specialty group on the same day as critical care, physicians should make a notation in the medical record indicating the non-overlapping service times (e.g., “central line insertion is not included as critical care time”). This may assist with securing reimbursement when the payor requests the documentation for each reported claim item.

Activities on the floor/unit that do not directly contribute to patient care or management (e.g., review of literature, teaching rounds) cannot be counted toward critical care time. Do not count time associated with indirect care provided outside of the patient’s unit/floor (e.g., reviewing data or calling the family from the office) toward critical care time.

Family discussions can be counted toward critical care time but must take place at bedside or on the patient’s unit/floor. The patient must participate in the discussion unless medically unable or clinically incompetent to participate. If unable to participate, a notation in the chart must delineate the patient’s inability to participate and the reason.

Credited time can only involve obtaining a medical history and/or discussing treatment options or limitation(s) of treatment. The conversation must bear directly on patient management.1,7 Do not count time associated with providing periodic condition updates to the family, answering questions about the patient’s condition that are unrelated to decision making, or counseling the family during their grief process. If the conversation must take place via phone, it may be counted toward critical care time if the physician is calling from the patient’s unit/floor and the conversation involves the same criterion identified for face-to-face family meetings.10

Physicians should keep track of their critical care time throughout the day. Since critical care time is a cumulative service, each entry should include the total time that critical care services were provided (e.g., 45 minutes).10 Some payors may still impose the notation of “start-and-stop time” per encounter (e.g., 2–2:50 a.m.).

Same-specialty physicians (i.e., two hospitalists from the same group practice) may require separate claims. The initial critical care hour (99291) must be met by a single physician. Medically necessary critical care time beyond the first hour (99292) may be met individually by the same physician or collectively with another physician from the same group. The physician performing the additional time, beyond the first hour, reports the appropriate units of 99292 (see Table 1) under the corresponding NPI.11

CMS has issued instructions for contractors to recognize this atypical reporting method. However, non-Medicare payors may not recognize this newer reporting method and maintain that the cumulative service (by the same-specialty physician in the same provider group) should be reported under one physician name. Be sure to query the payors for appropriate reporting methods. TH

References

- Abraham M, Ahlman J, Boudreau A, Connelly J, Crosslin, R. Current Procedural Terminology 2015 Professional Edition. Chicago: American Medical Association Press; 2014. 23-25.

- Widespread prepayment targeted review notification—CPT 99291. Cahaba website. Available at: www.cahabagba.com/news/widespread-prepayment-targeted-review-notification-part-b/. Accessed December 17, 2015.

- Critical care CPT 99291 widespread prepayment targeted review results. Cahaba website. Available at: https://www.cahabagba.com/news/critical-care-cpt-99291-widespread-prepayment-targeted-review-results-2/. Accessed December 17, 2015.

- Prepayment edit of evaluation and management (E/M) code 99291. First Coast Service Options, Inc. website. Available at: medicare.fcso.com/Publications_B/2013/251608.pdf. Accessed December 17, 2015.

- Medicare claims processing manual: chapter 12, section 30.6.12A. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services website. Available at: www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Guidance/Manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed December 17, 2015.

- Medicare claims processing manual: chapter 12, section 30.6.12B. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services website. Available at: www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Guidance/Manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed December 17, 2015.

- Critical care fact sheet. CGS Administrators, LLC website. Available at: www.cgsmedicare.com/partb/mr/pdf/critical_care_fact_sheet.pdf. Accessed December 17, 2015.

- Same day same service policy. United Healthcare website. Available at: www.unitedhealthcareonline.com/ccmcontent/ProviderII/UHC/en-US/Main%20Menu/Tools%20&%20Resources/Policies%20and%20Protocols/Medicare%20Advantage%20Reimbursement%20Policies/S/SameDaySameService.pdf. Accessed December 17, 2015.

- Medicare claims processing manual: chapter 12, section 30.6.12G. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services website. Available at: www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Guidance/Manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed December 17, 2015.

- Medicare claims processing manual: chapter 12, section 30.6.12E. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services website. Available at: www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Guidance/Manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed December 17, 2015.

- Medicare claims processing manual: chapter 12, section 30.6.12I. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services website. Available at: www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Guidance/Manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed December 17, 2015.

Medicare Grants Billing Code for Hospitalists

PHILADELPHIA—The Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) is pleased to announce the introduction of a dedicated billing code for hospitalists by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). This decision comes in response to concerted advocacy efforts from SHM for CMS to recognize the specialty. This is a monumental step for hospital medicine, which continues to be the fastest growing medical specialty in the United States with over 48,000 practitioners identifying as hospitalists, growing from approximately 1,000 in the mid-1990s.

“We see each day that hospitalists are driving positive change in healthcare, and this recognition by CMS affirms that hospital medicine is growing both in scope and impact,” notes Laurence Wellikson, MD, MHM, CEO of SHM. “The ability for hospital medicine practitioners to differentiate themselves from providers in other specialties will have a huge impact, particularly for upcoming value-based or pay-for-performance programs.”

Until now, hospitalists could only compare performance to that of practitioners in internal medicine or another related specialty. This new billing code will allow hospitalists to appropriately benchmark and focus improvement efforts with others in the hospital medicine specialty, facilitating more accurate comparisons and fairer assessments of hospitalist performance.

Despite varied training backgrounds, hospitalists have become focused within their own unique specialty, dedicated to providing care to hospitalized patients and working toward high-quality, patient-centered care in the hospital. They have developed institutional-based skills that differentiate them from practitioners in other specialties, such as internal and family medicine. Their specialized expertise includes improving both the efficiency and safety of care for hospitalized patients and the ability to manage and innovate in a hospital’s team-based environment.

This momentous decision coincides with the twenty-year anniversary of the coining of the term ‘hospitalist’ by Robert Wachter, MD, MHM, and Lee Goldman, MD in the New England Journal of Medicine. In recognition of this anniversary, SHM introduced a year-long celebration, the “Year of the Hospitalist,” to commemorate the specialty’s continued success and bright future.

“We have known who we are for years, and the special role that hospitalists play in the well-being of our patients, communities and health systems,” explains Brian Harte, MD, SFHM, president-elect of SHM. “The hospitalist provider code will provide Medicare and other players in the healthcare system an important new tool to better understand and acknowledge the critical role we play in the care of hospitalized patients nationwide.”

Lisa Zoks is SHM's Vice-President of Communications.

ABOUT SHM

Representing the fastest growing specialty in modern healthcare, SHM is the leading medical society for more than 48,000 hospitalists and their patients. SHM is dedicated to promoting the highest quality care for all hospitalized patients and overall excellence in the practice of hospital medicine through quality improvement, education, advocacy and research. Over the past decade, studies have shown that hospitalists can contribute to decreased patient lengths of stay, reductions in hospital costs and readmission rates, and increased patient satisfaction.

PHILADELPHIA—The Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) is pleased to announce the introduction of a dedicated billing code for hospitalists by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). This decision comes in response to concerted advocacy efforts from SHM for CMS to recognize the specialty. This is a monumental step for hospital medicine, which continues to be the fastest growing medical specialty in the United States with over 48,000 practitioners identifying as hospitalists, growing from approximately 1,000 in the mid-1990s.

“We see each day that hospitalists are driving positive change in healthcare, and this recognition by CMS affirms that hospital medicine is growing both in scope and impact,” notes Laurence Wellikson, MD, MHM, CEO of SHM. “The ability for hospital medicine practitioners to differentiate themselves from providers in other specialties will have a huge impact, particularly for upcoming value-based or pay-for-performance programs.”

Until now, hospitalists could only compare performance to that of practitioners in internal medicine or another related specialty. This new billing code will allow hospitalists to appropriately benchmark and focus improvement efforts with others in the hospital medicine specialty, facilitating more accurate comparisons and fairer assessments of hospitalist performance.

Despite varied training backgrounds, hospitalists have become focused within their own unique specialty, dedicated to providing care to hospitalized patients and working toward high-quality, patient-centered care in the hospital. They have developed institutional-based skills that differentiate them from practitioners in other specialties, such as internal and family medicine. Their specialized expertise includes improving both the efficiency and safety of care for hospitalized patients and the ability to manage and innovate in a hospital’s team-based environment.