User login

Solitary Papule on the Nose

The Diagnosis: Sclerosing Perineurioma

Sclerosing perineurioma, first described in 1997 by Fetsch and Miettinen,1 is a subtype of perineurioma with a strong predilection for the fingers and palms of young adults. Rare cases involving extra-acral sites including the forearm, elbow, axilla, back, neck, lower leg, thigh, knee, lips, nose, and mouth have been reported.2-4 Perineurioma is a relatively uncommon and benign peripheral nerve sheath tumor with exclusive perineurial differentiation.5 Perineurioma is divided into intraneural and extraneural types; the latter are further subclassified into soft tissue, sclerosing, reticular, and plexiform types. Other rare forms include the sclerosing, Pacinian corpuscle-like perineurioma, lipomatous perineurioma, perineurioma with xanthomatous areas, and perineurioma with granular cells.6,7

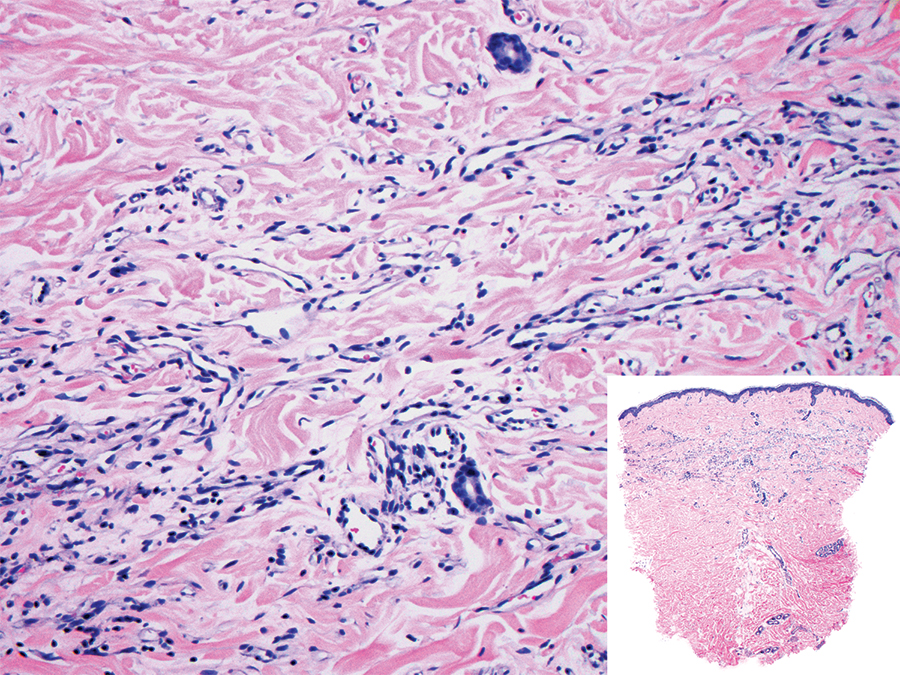

Clinically, sclerosing perineurioma usually presents as a solitary lesion; however, rare cases of multiple lesions have been reported.8 Our patient presented with a solitary papule on the nose. Histopathologically, sclerosing perineurioma demonstrates slender spindle cells in a whorled growth pattern (onion skin) embedded in a hyalinized, lamellar, and dense collagenous stroma with intervening cleftlike spaces. Immunohistochemically, the spindle cells of our case stained positive for epithelial membrane antigen (quiz images). Other positive immunostains for perineurioma include claudin-1 and glucose transporter 1 (GLUT1). Perineurioma lacks expression of S-100 but can express CD34.2 As a benign tumor, the prognosis of sclerosing perineurioma is excellent. Complete local excision is considered curative.1

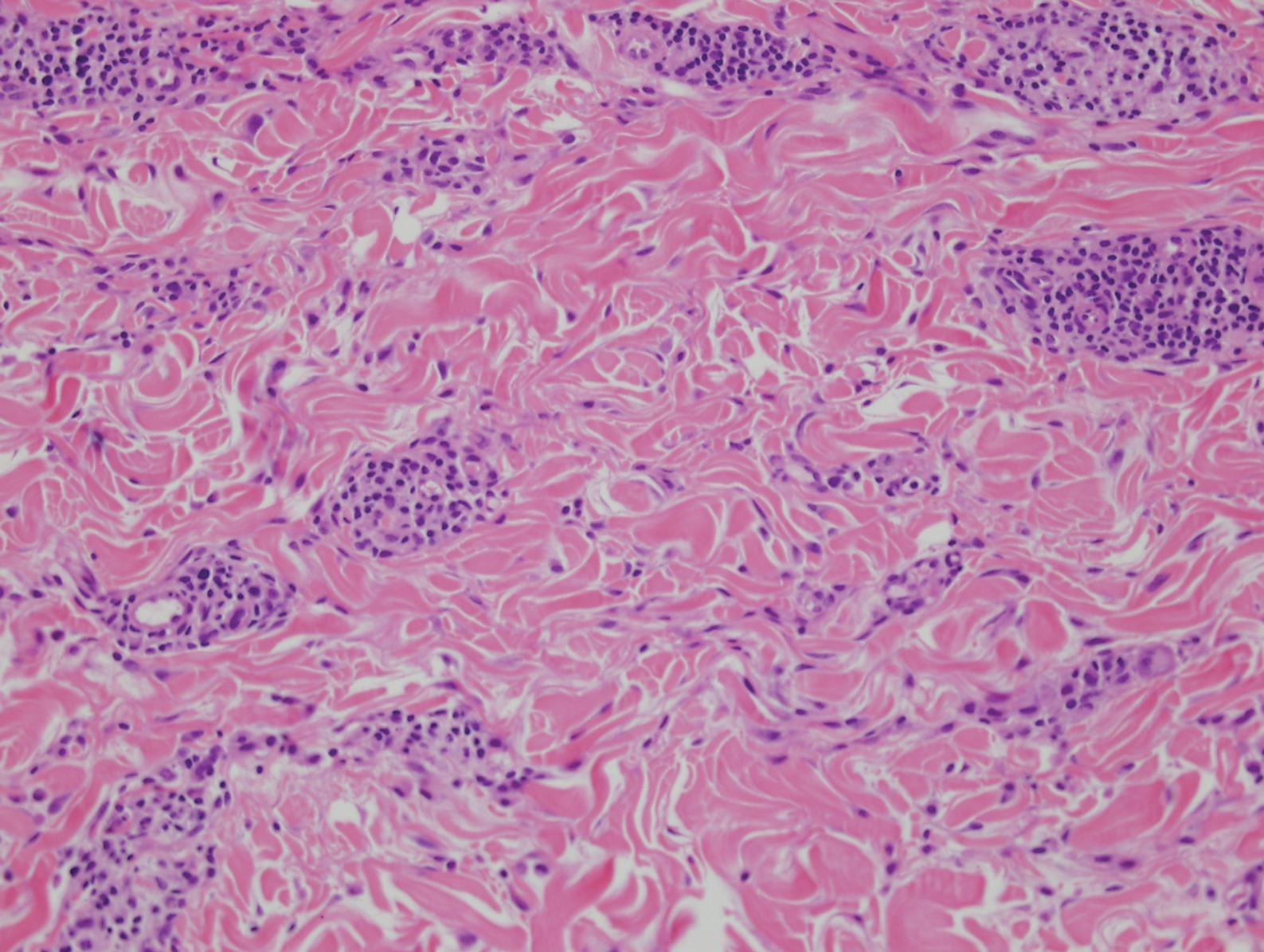

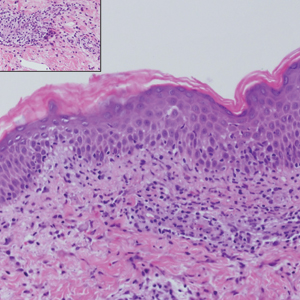

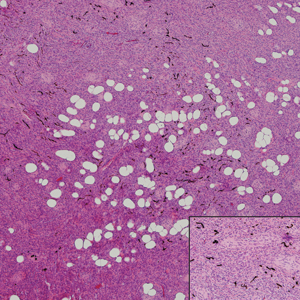

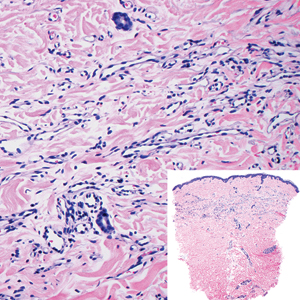

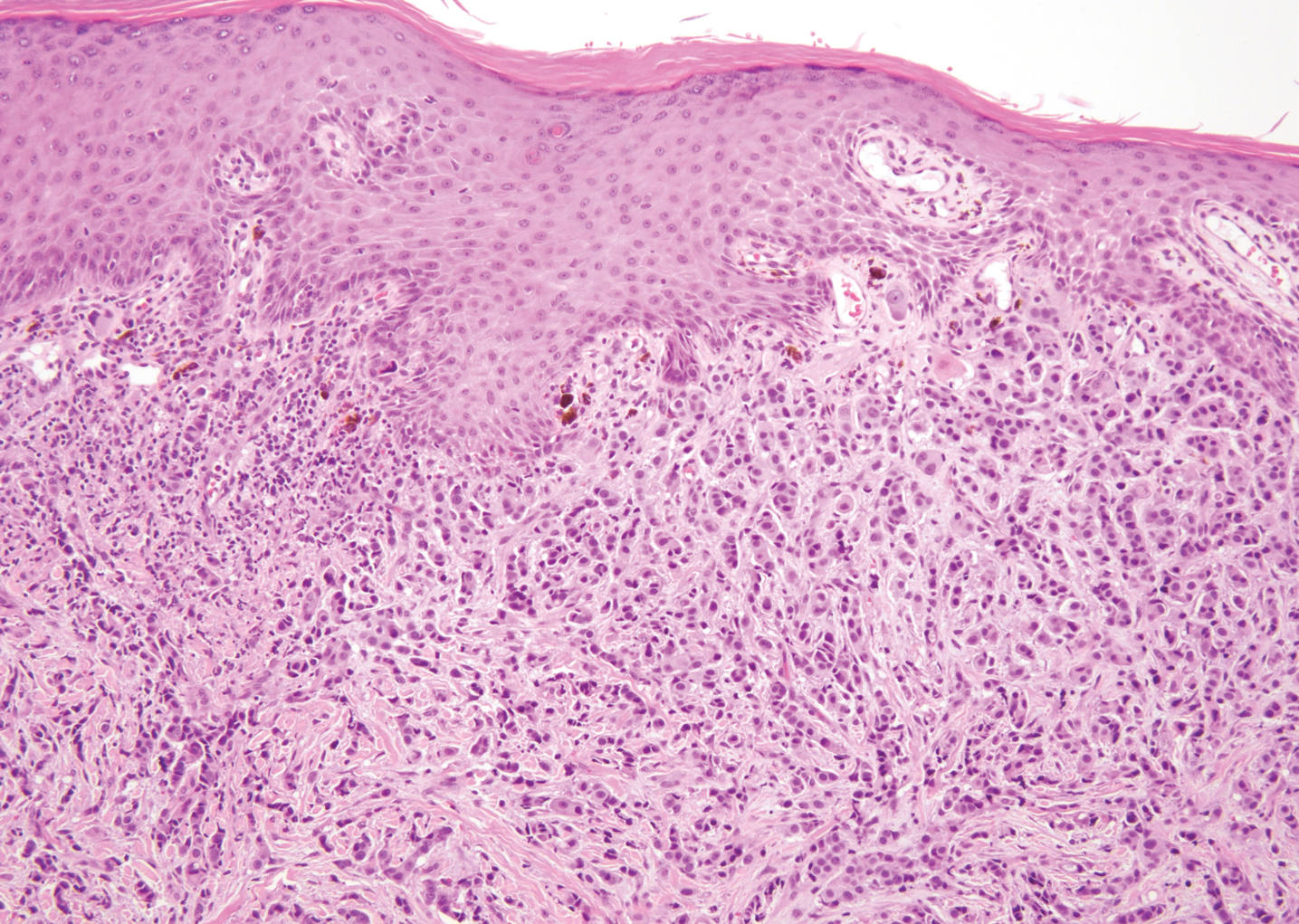

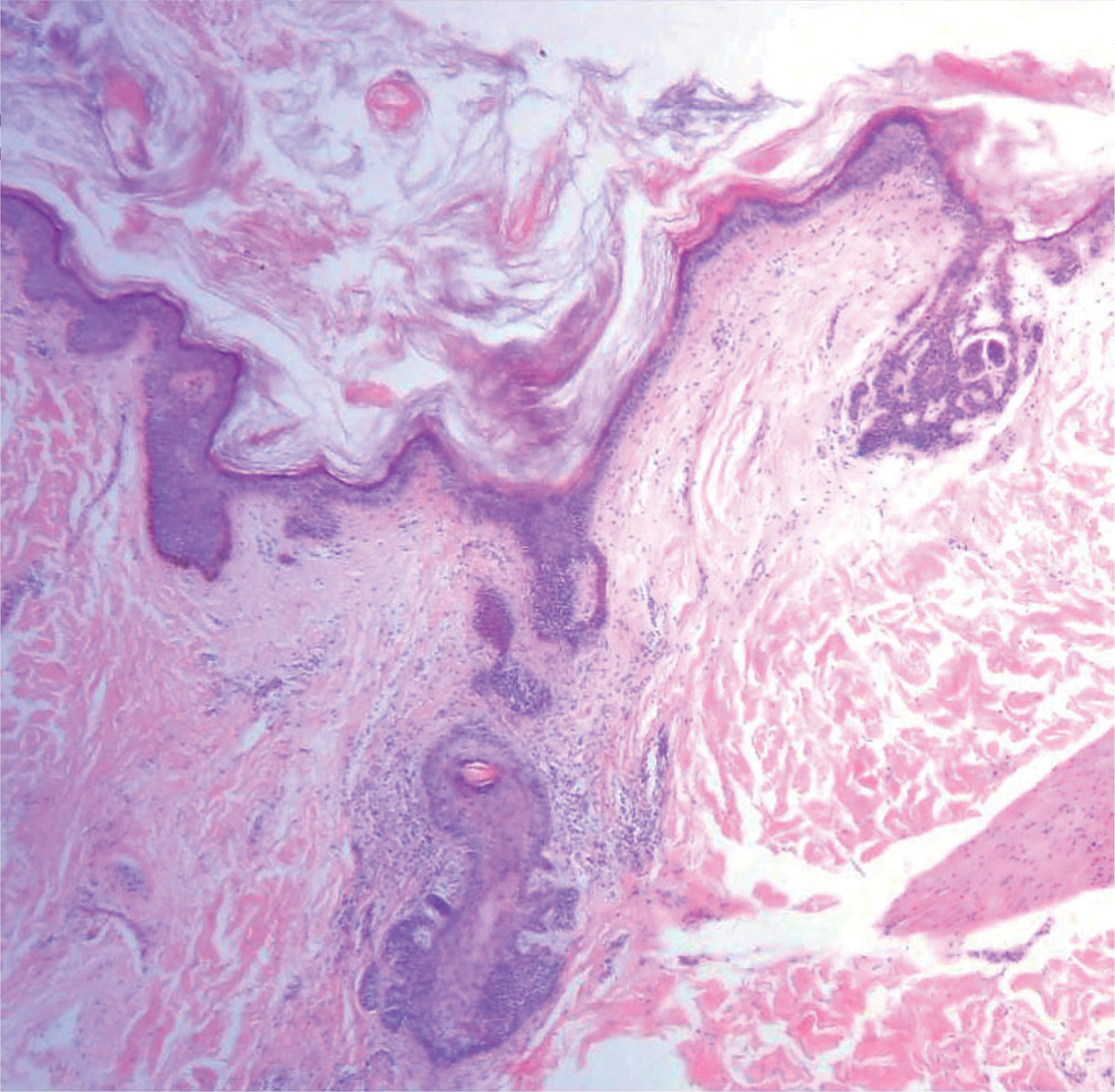

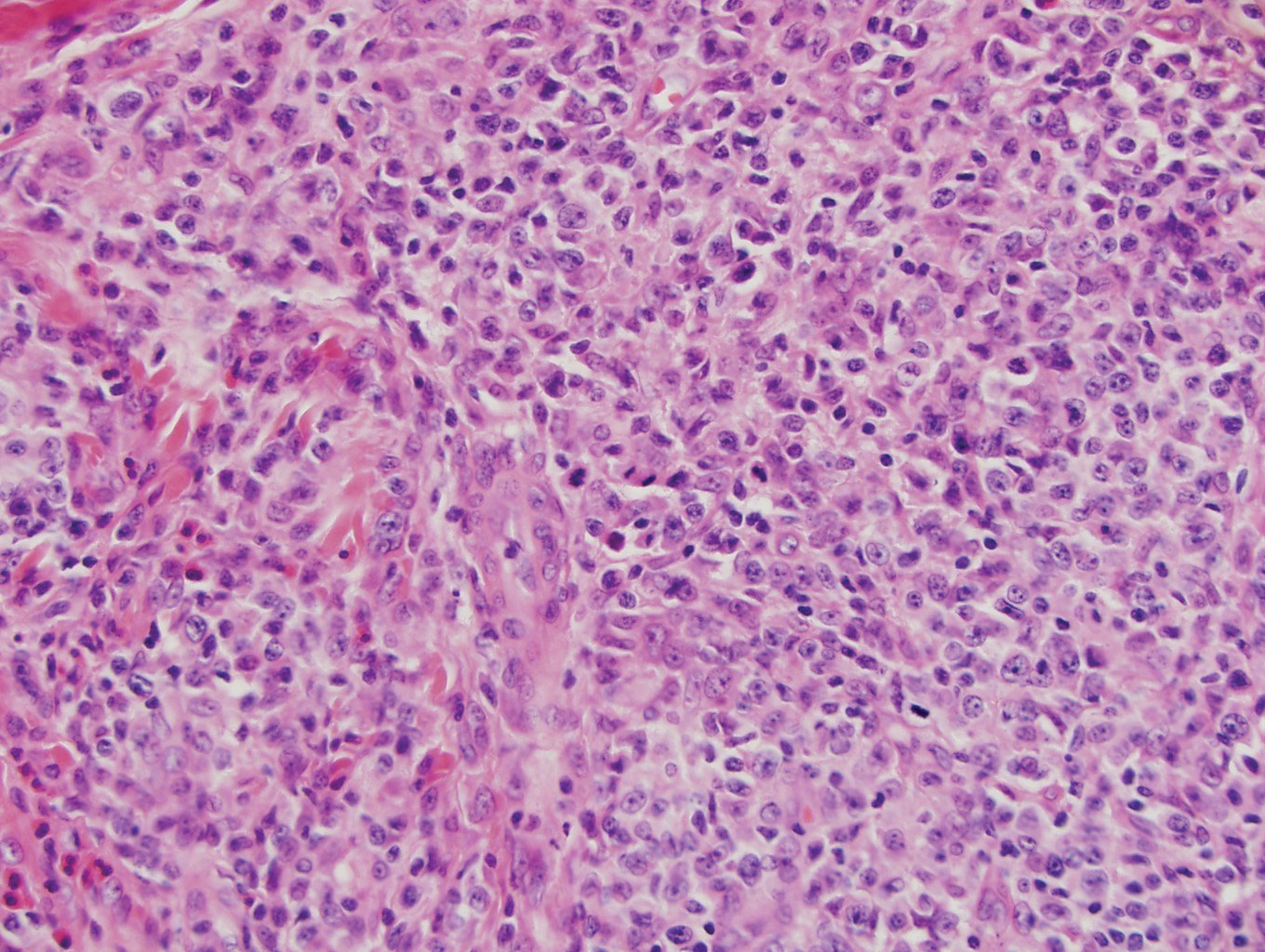

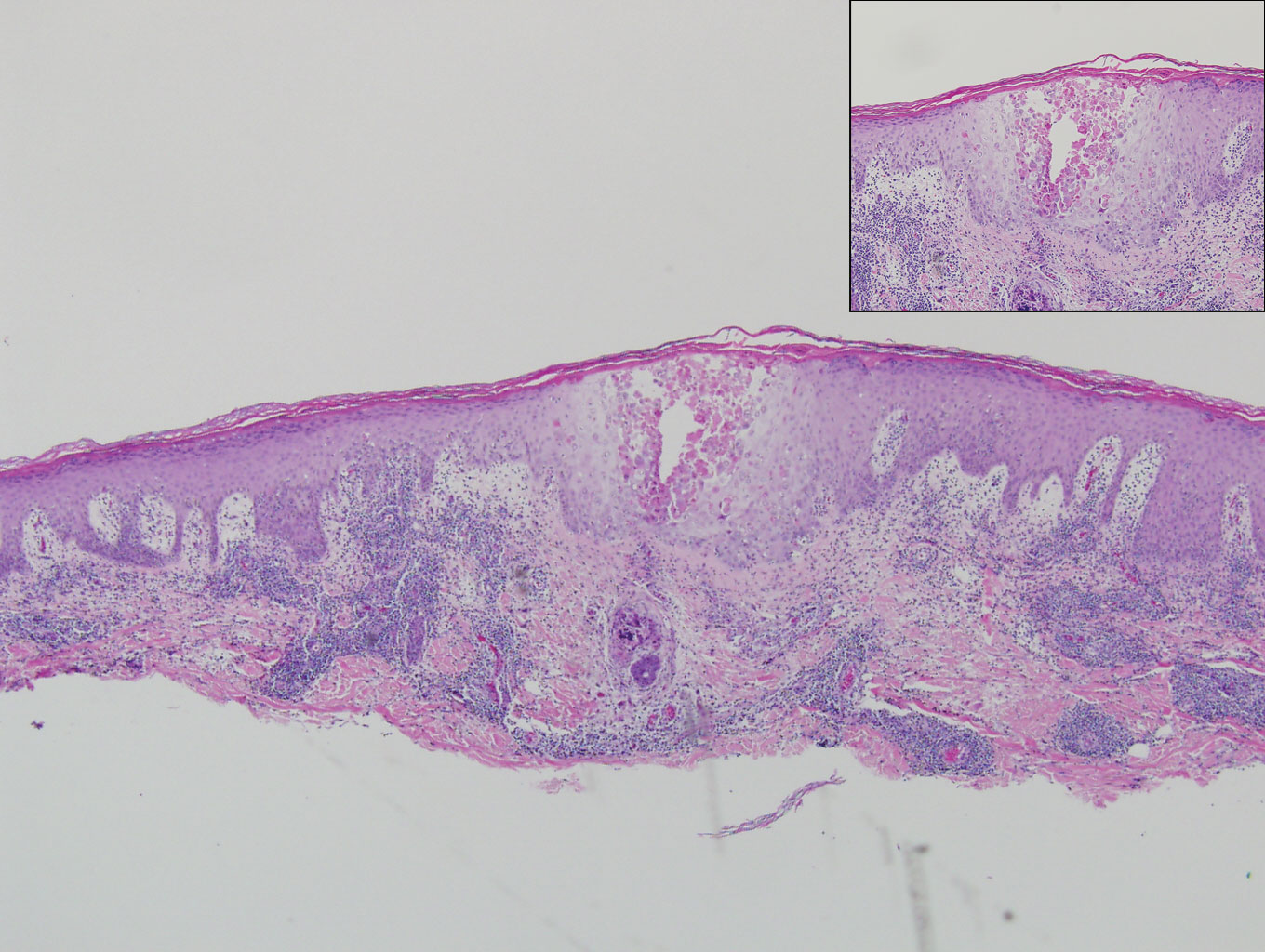

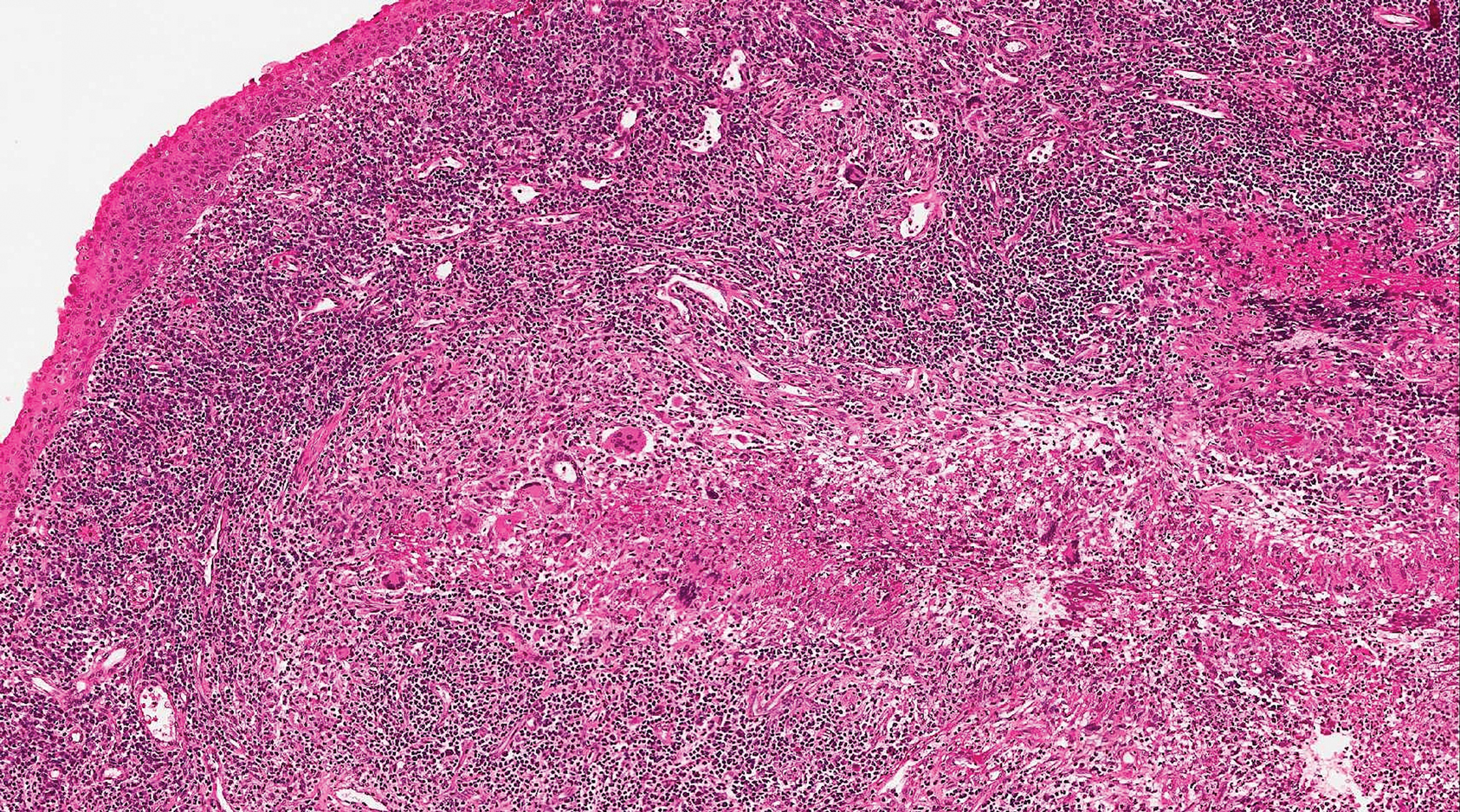

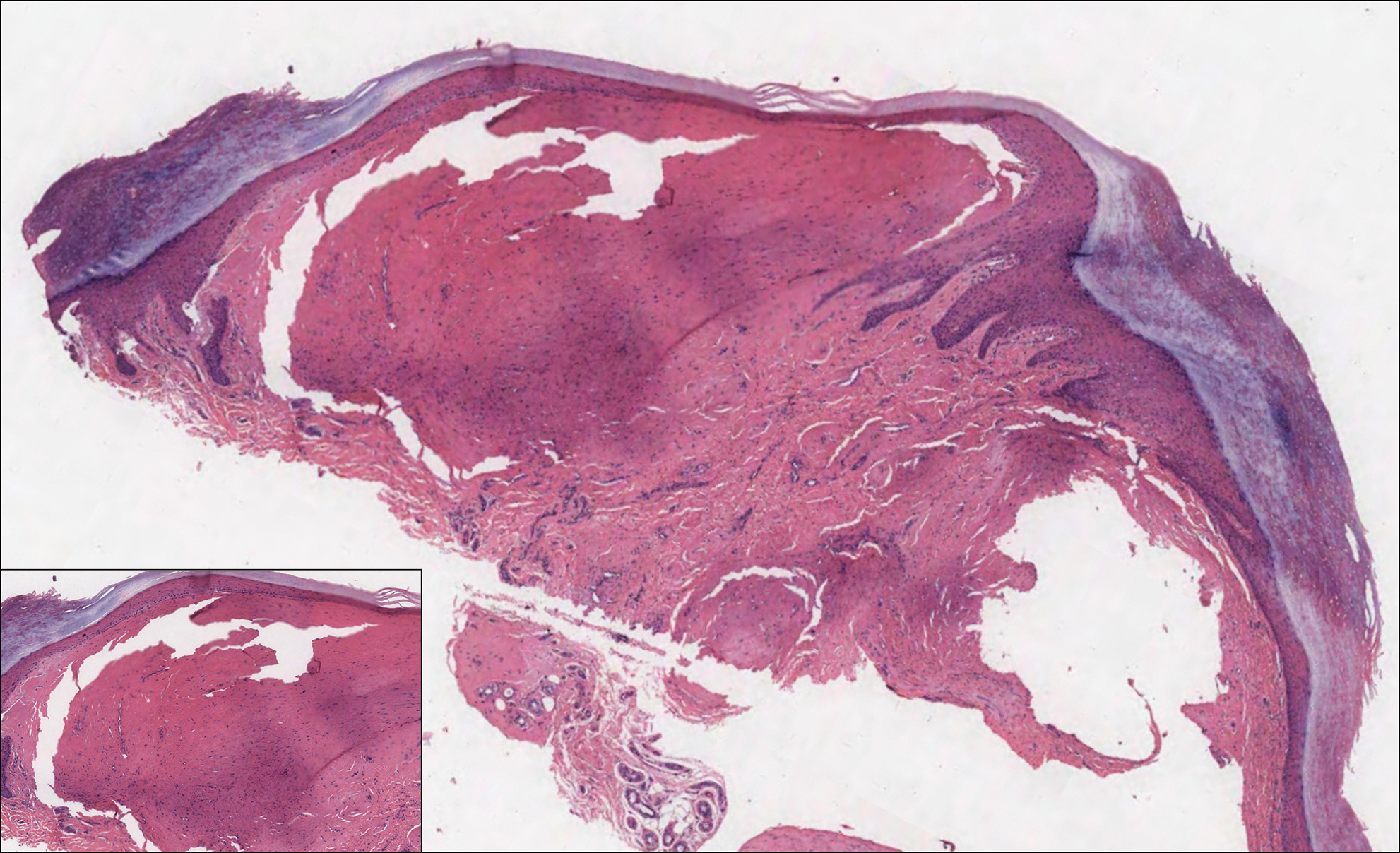

Angiofibroma, also known as fibrous papule, is a common and benign lesion located primarily on or in close proximity to the nose.9 Angiofibromas can be associated with genodermatoses such as tuberous sclerosis, multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1, or Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome. When angiofibromas involve the penis, they are called pearly penile papules. Ungual angiofibroma, also known as Koenen tumor, occurs underneath the nail.10-12 Both facial angiofibromas (>3) and ungual angiofibromas (>2) are independent major criteria for tuberous sclerosis.13 Clinically, angiofibroma presents as a small, dome-shaped, pink papule arising on the lower portion of the nose or nearby area of the central face. Histopathologically, angiofibromas classically demonstrate increased dilated vessels and fibrosis in the dermis. Stellate, plump, spindle-shaped, and multinucleated cells can be seen in the collagenous stroma. The collagen fibers around hair follicles are arranged concentrically, resulting in an onion skin-like appearance. The epidermal rete ridges can be effaced (Figure 1). Increased numbers of single-unit melanocytes along the dermoepidermal junction can be seen in some cases. Immunohistochemically, a variable number of spindled and multinucleated cells in the dermis stain with factor XIIIa. There are at least 7 histologic variants of angiofibroma including hypercellular, pigmented, inflammatory, pleomorphic, clear cell, granular cell, and epithelioid.9,14

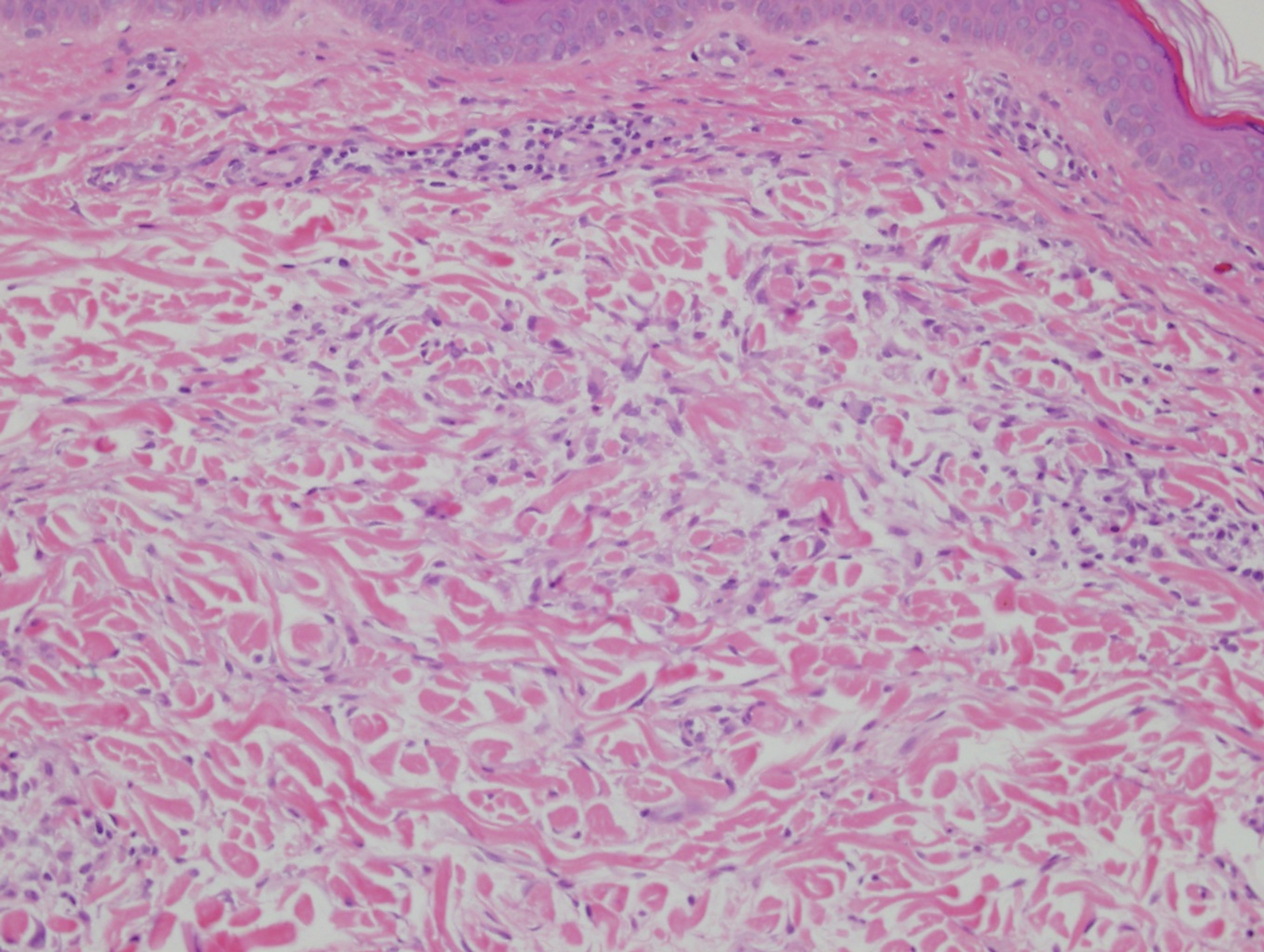

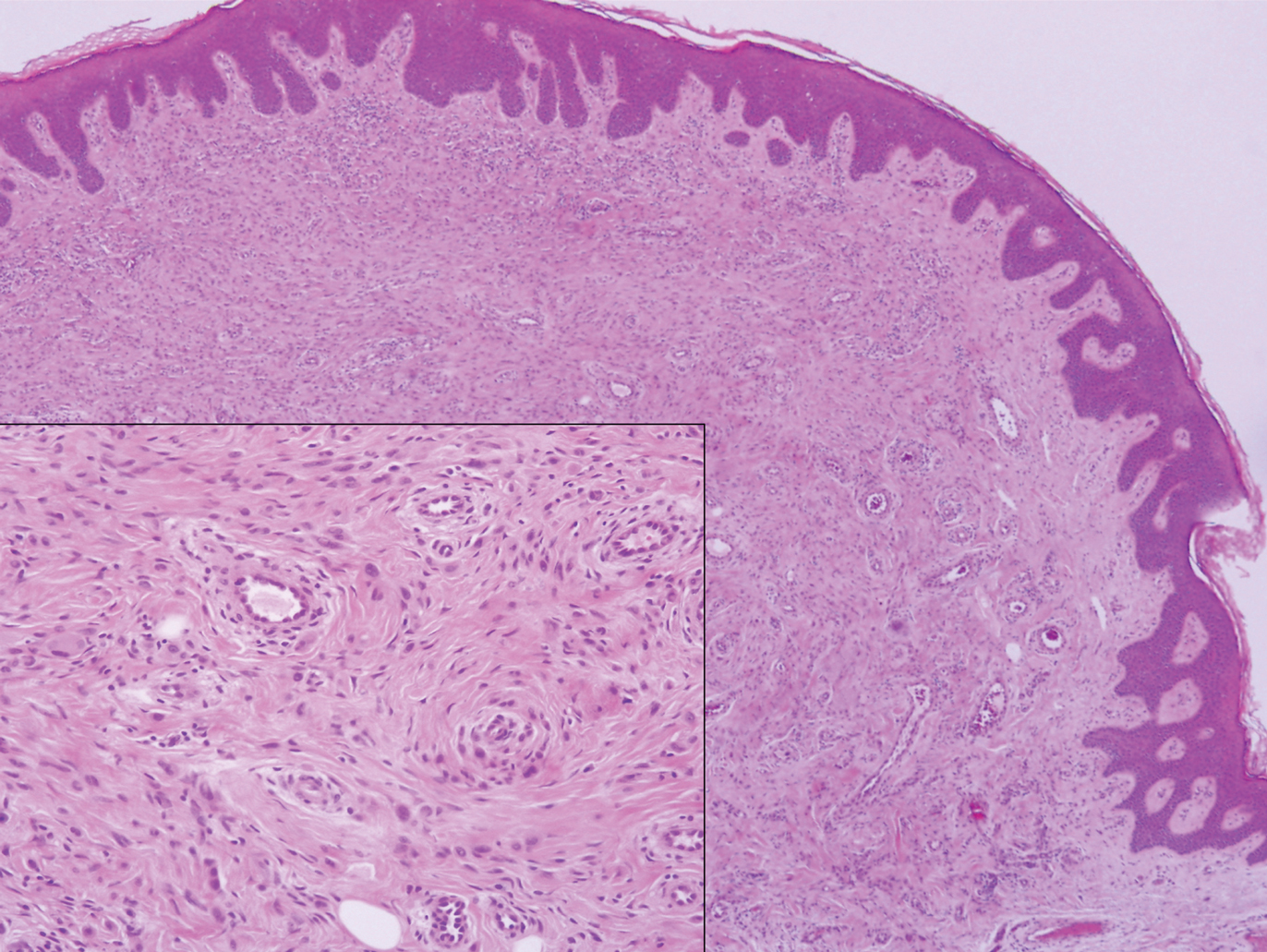

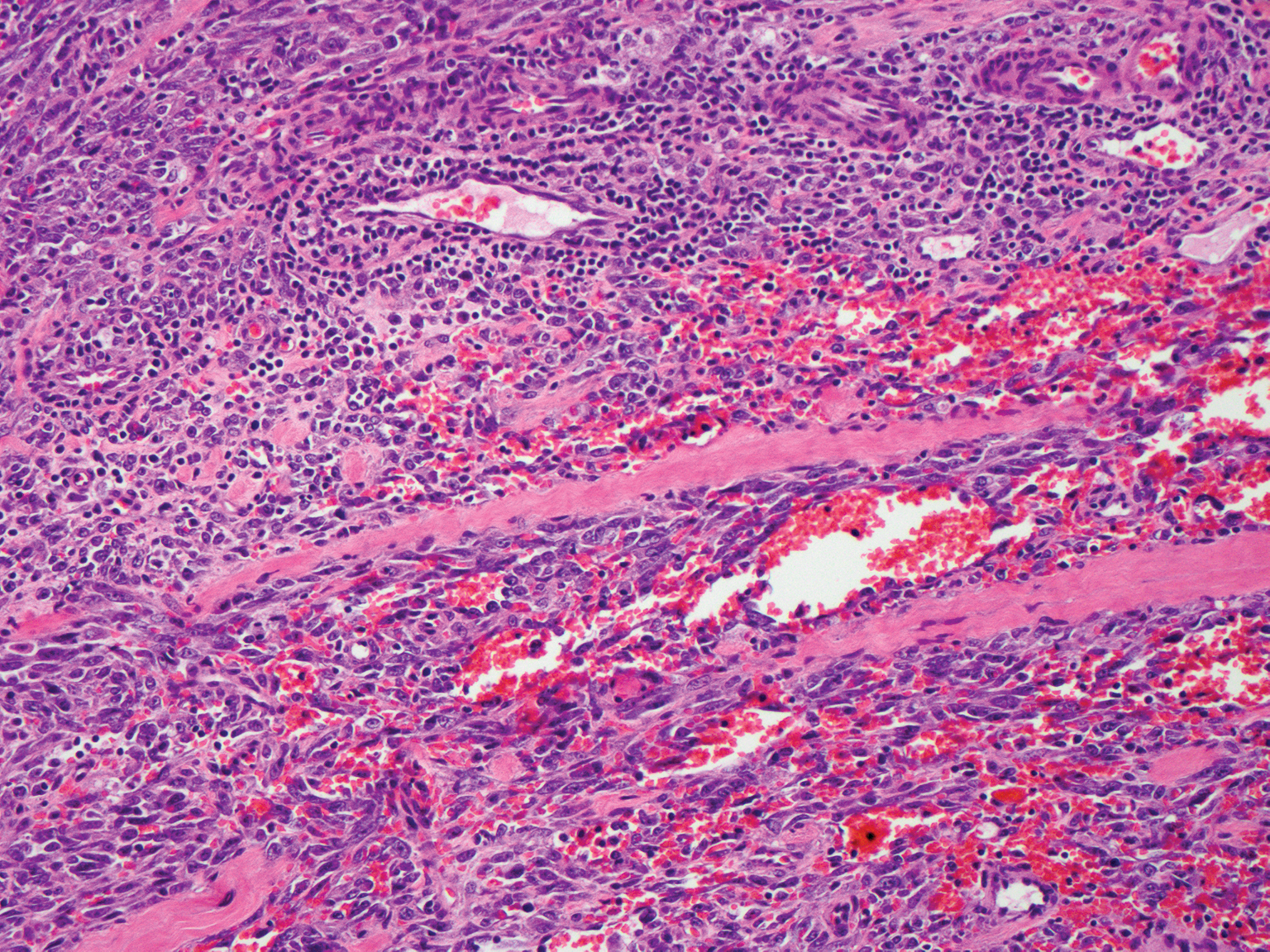

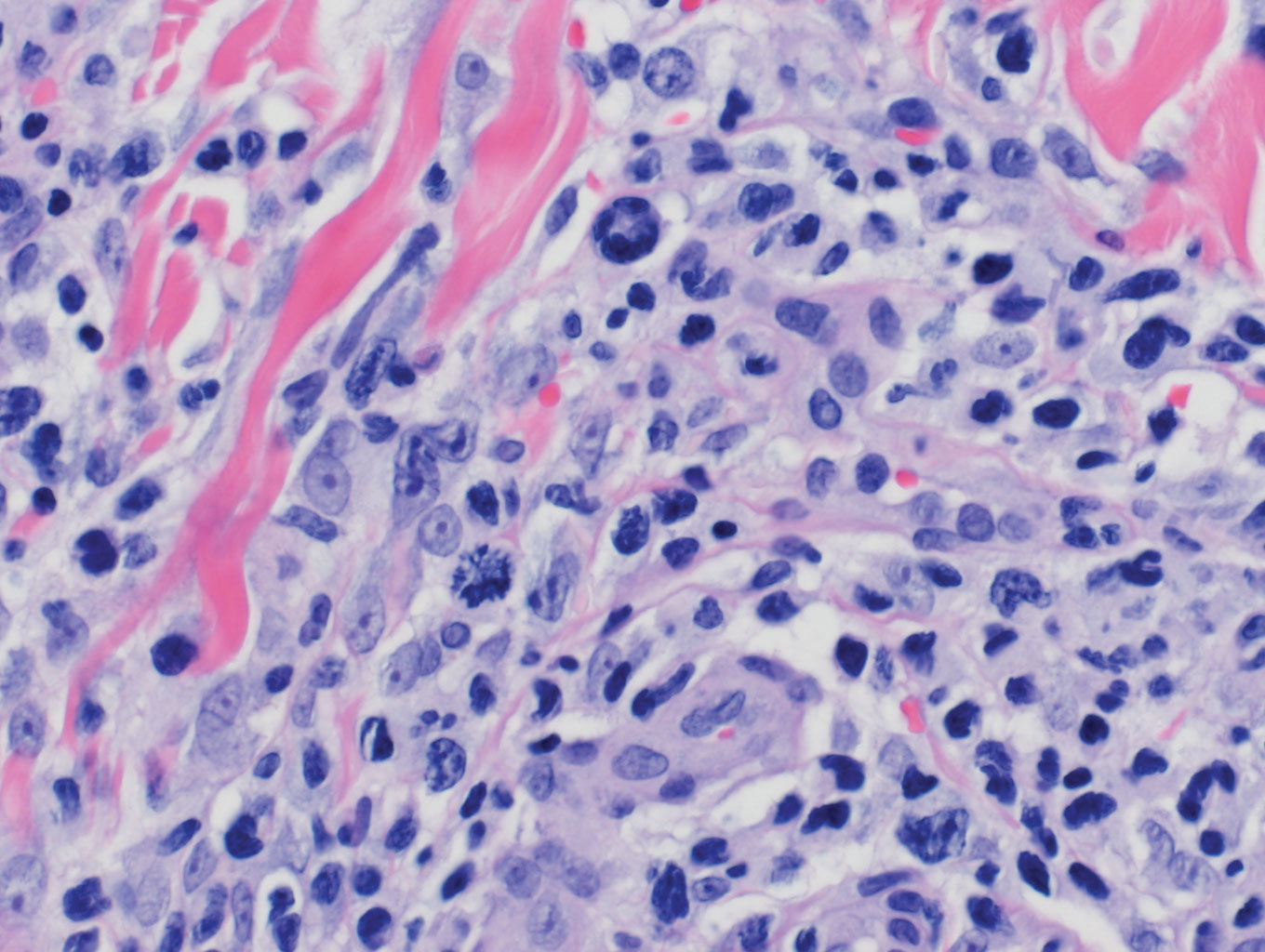

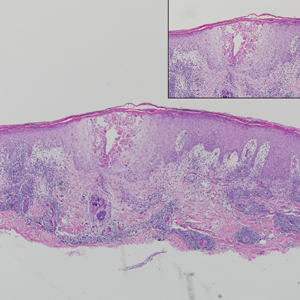

Desmoplastic nevus (DN) is a benign melanocytic neoplasm characterized by predominantly spindle-shaped nevus cells embedded within a fibrotic stroma. Although it can resemble a Spitz nevus, it is recognized as a distinct entity.15-17 Clinically, DN presents as a small and flesh-colored, erythematous or slightly pigmented papule or nodule that usually occurs on the arms and legs of young adults. Histopathologically, DN demonstrates a dermal-based proliferation of spindled melanocytes embedded in a dense collagenous stroma with sparse or absent melanin deposition. The collagen bundles often show artifactual clefts and onion skin-like accentuation around vessels. Melanocytes may be epithelioid (Figure 2).16 Immunohistochemically, DN expresses melanocytic markers such as S-100, Melan-A, and human melanoma black 45, but epithelial membrane antigen is negative. Human melanoma black 45 demonstrates maturation with stronger staining in superficial portions of the lesion and diminution of staining with increasing dermal depth.18 Many other melanocytic tumors share histologic similarities to DN including blue nevus and desmoplastic melanoma.17,19,20

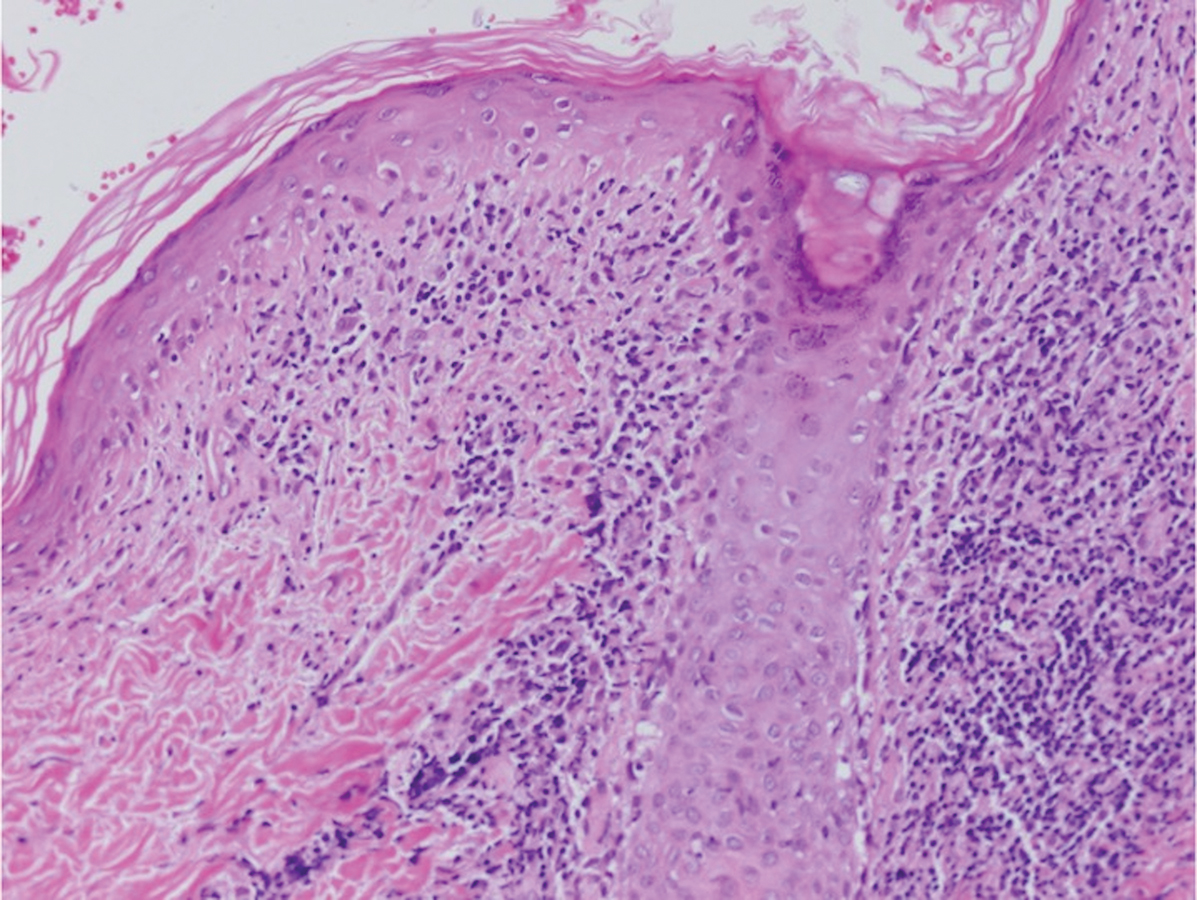

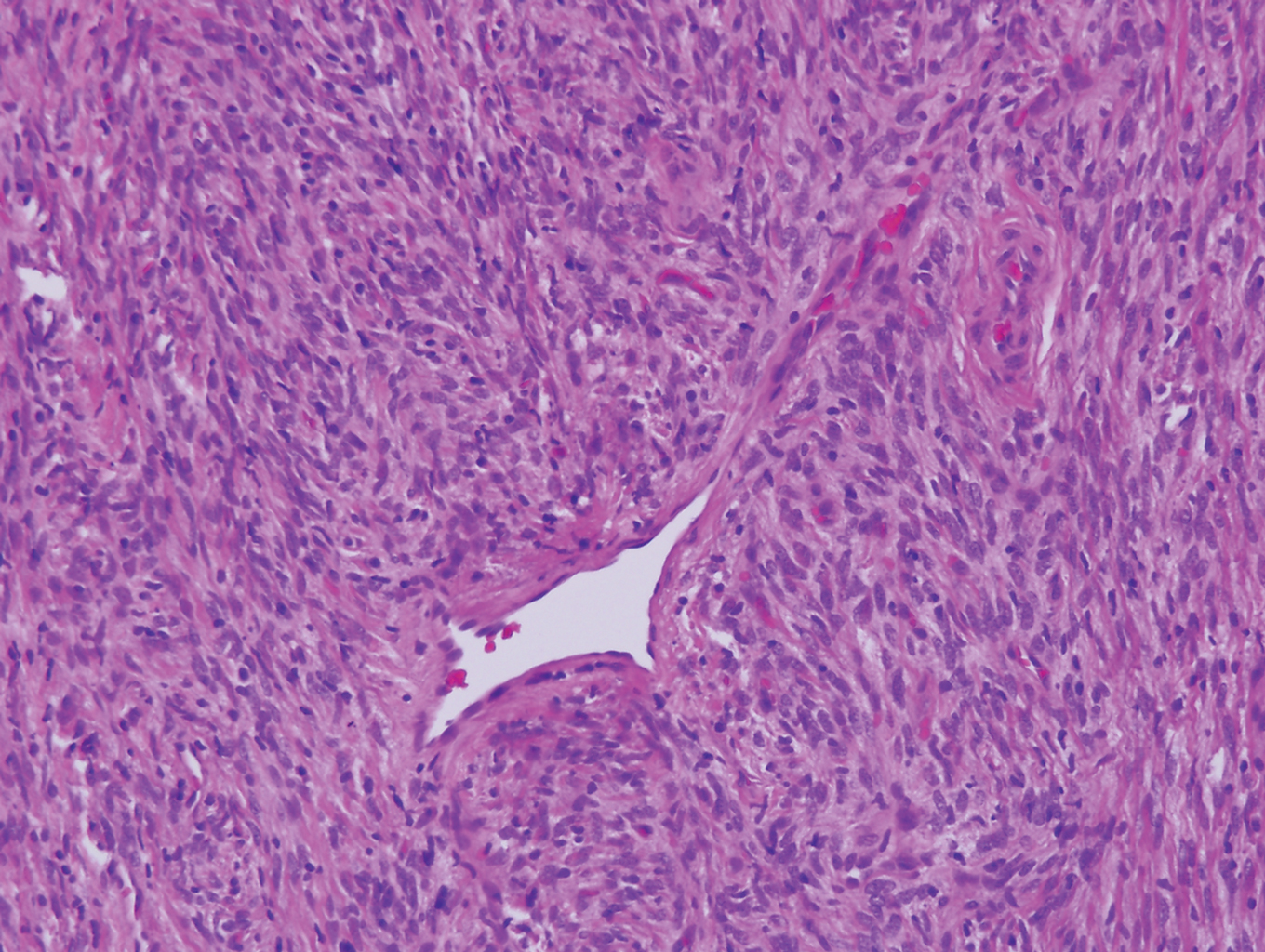

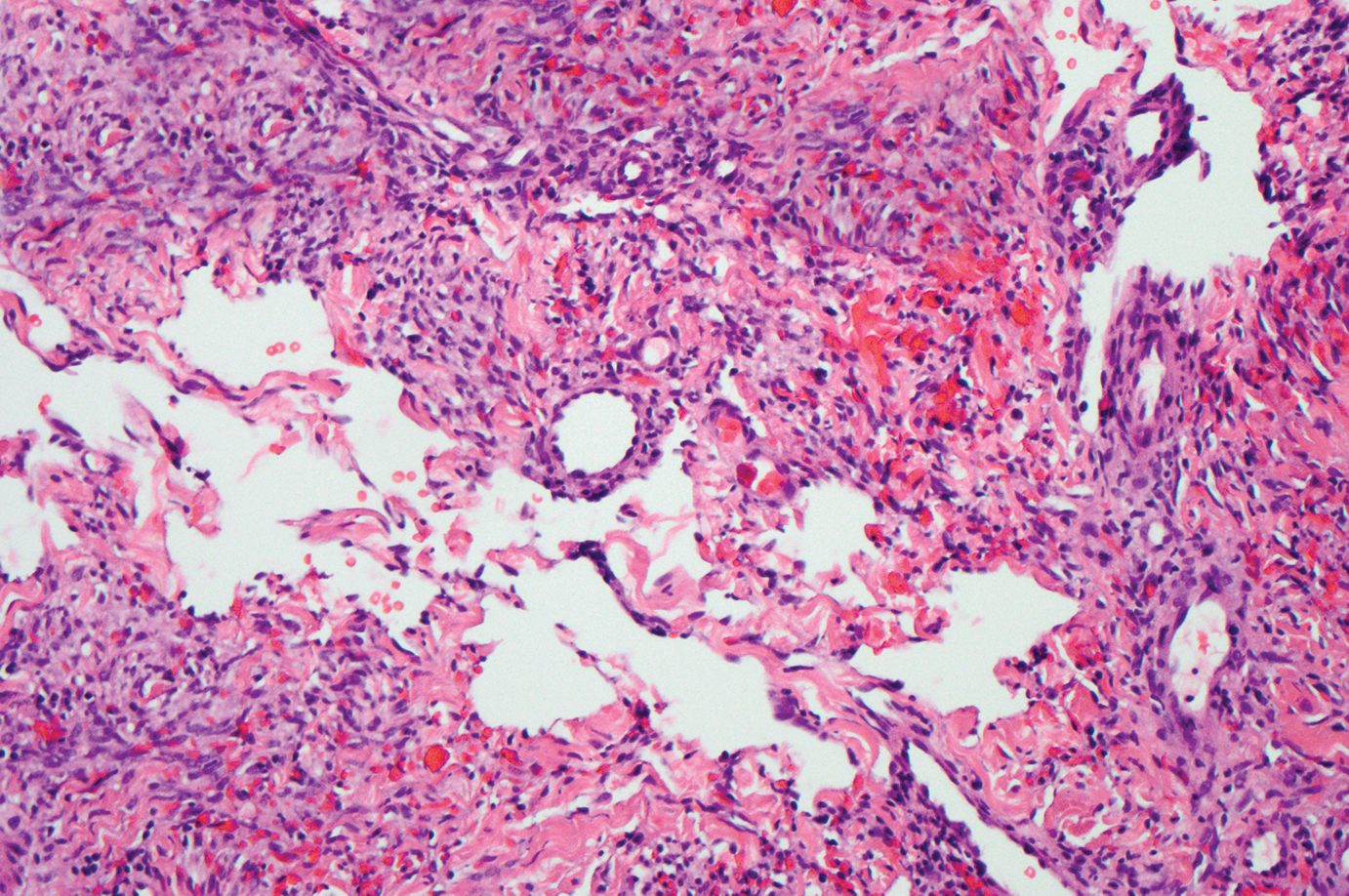

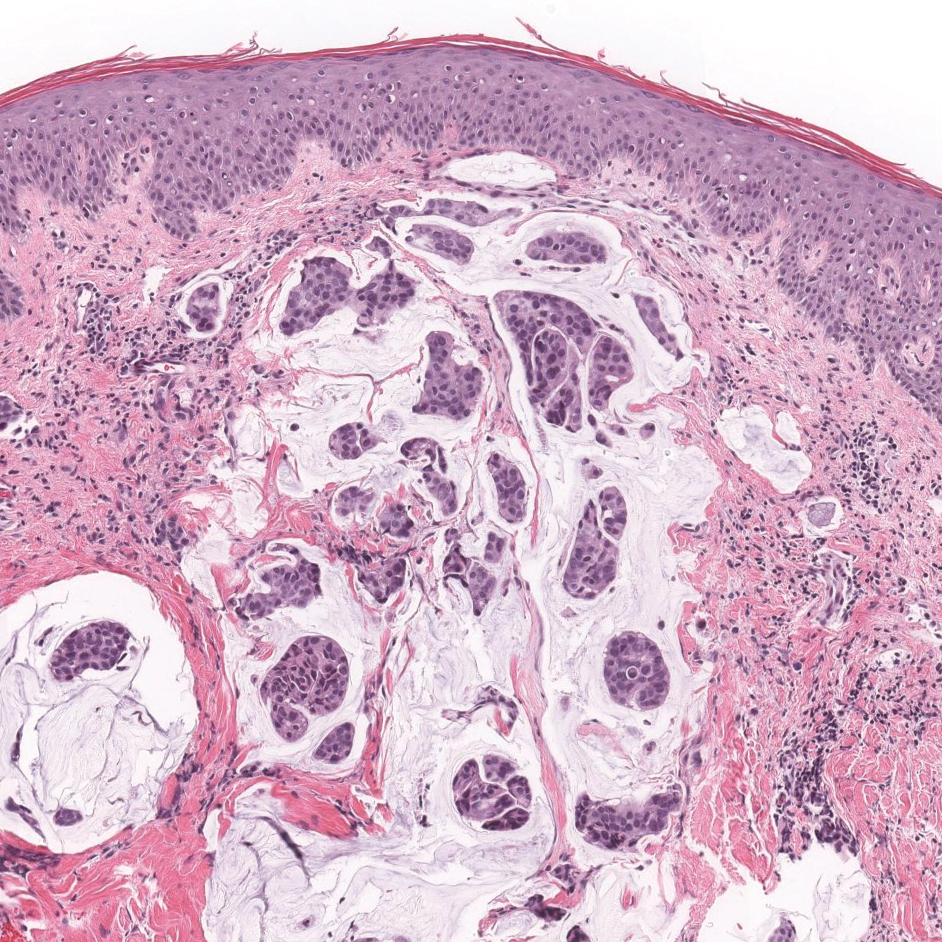

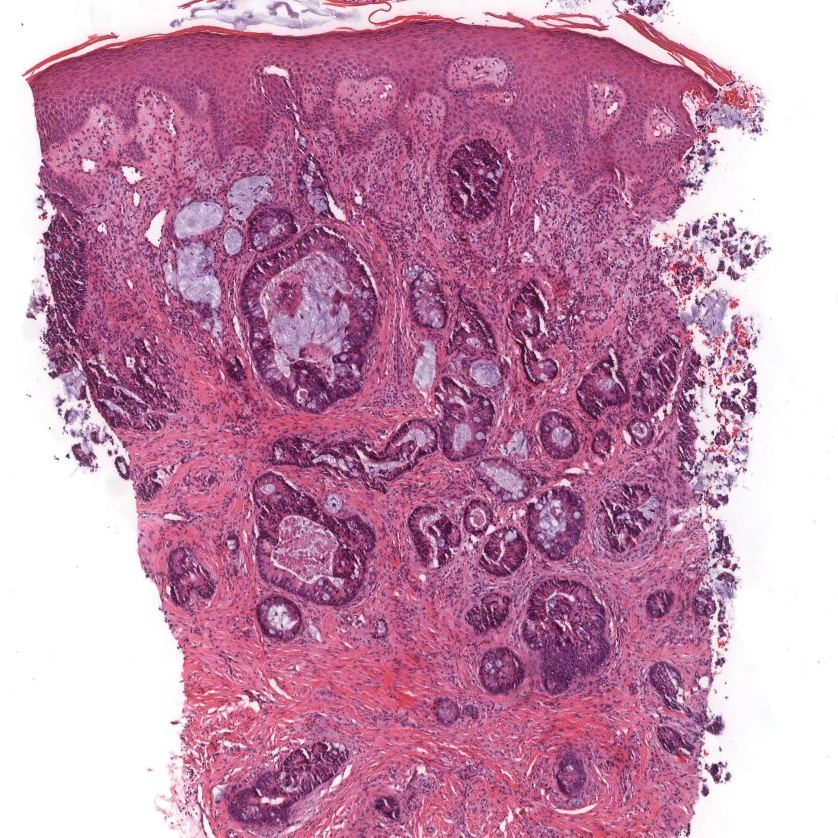

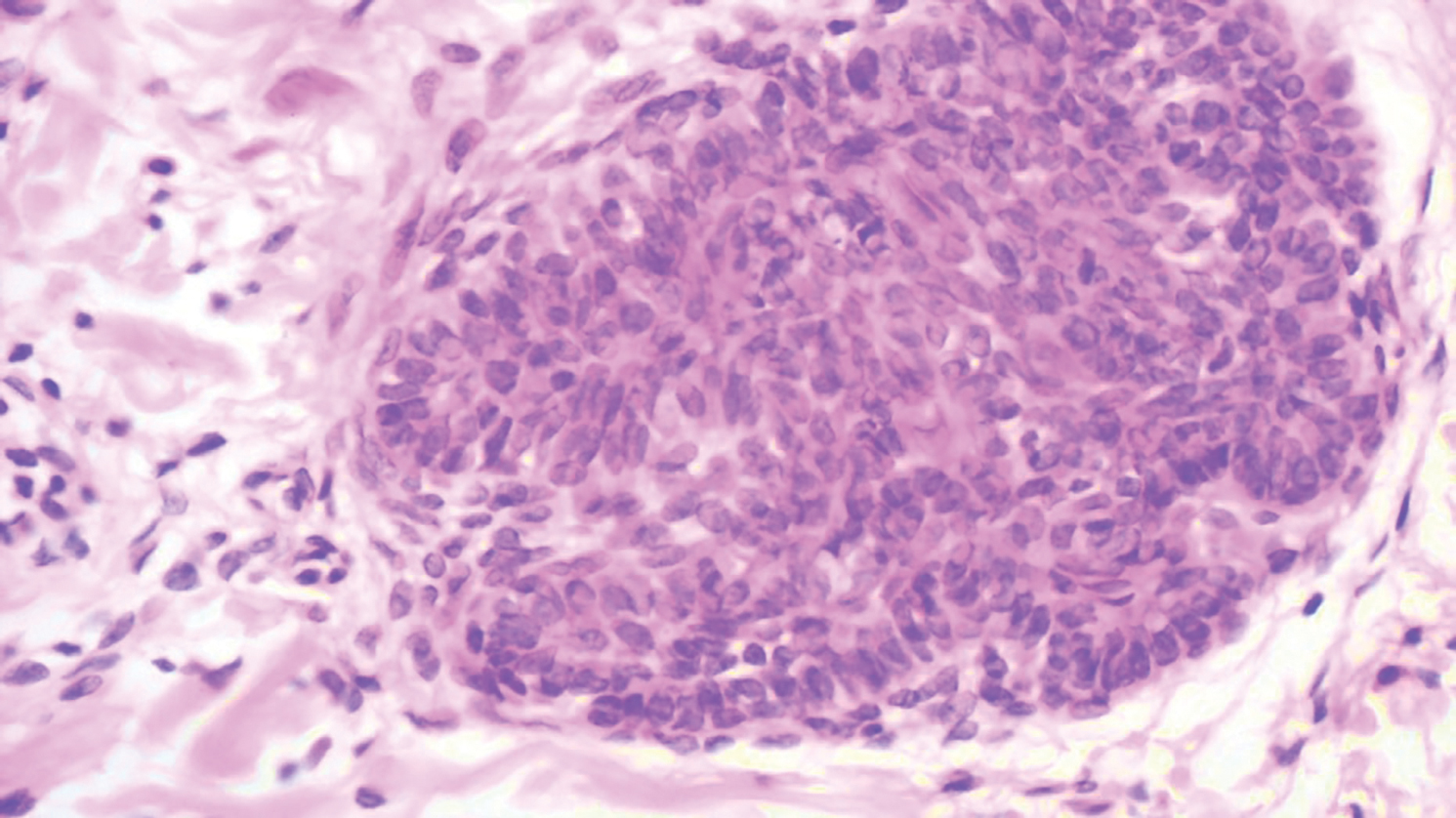

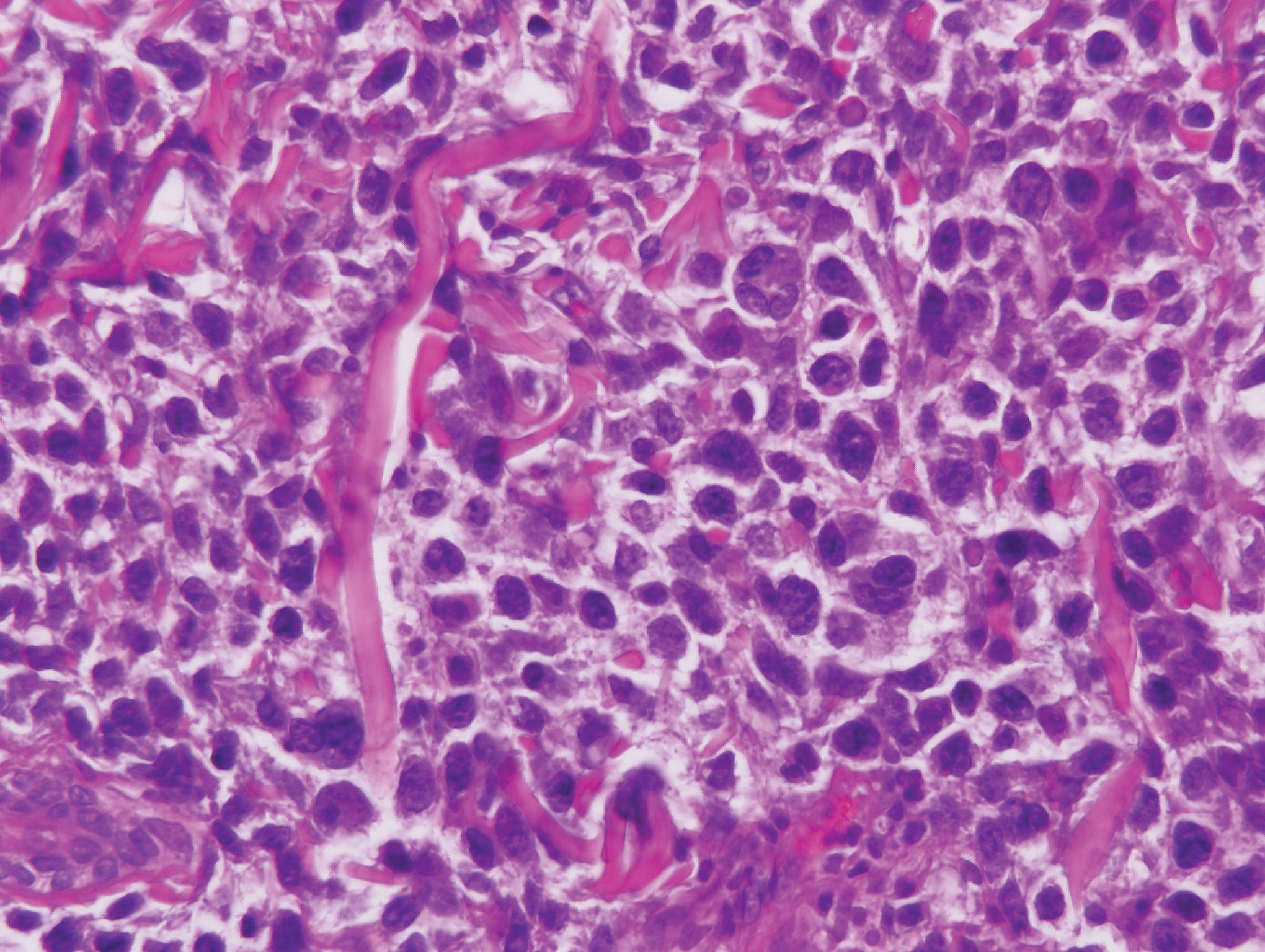

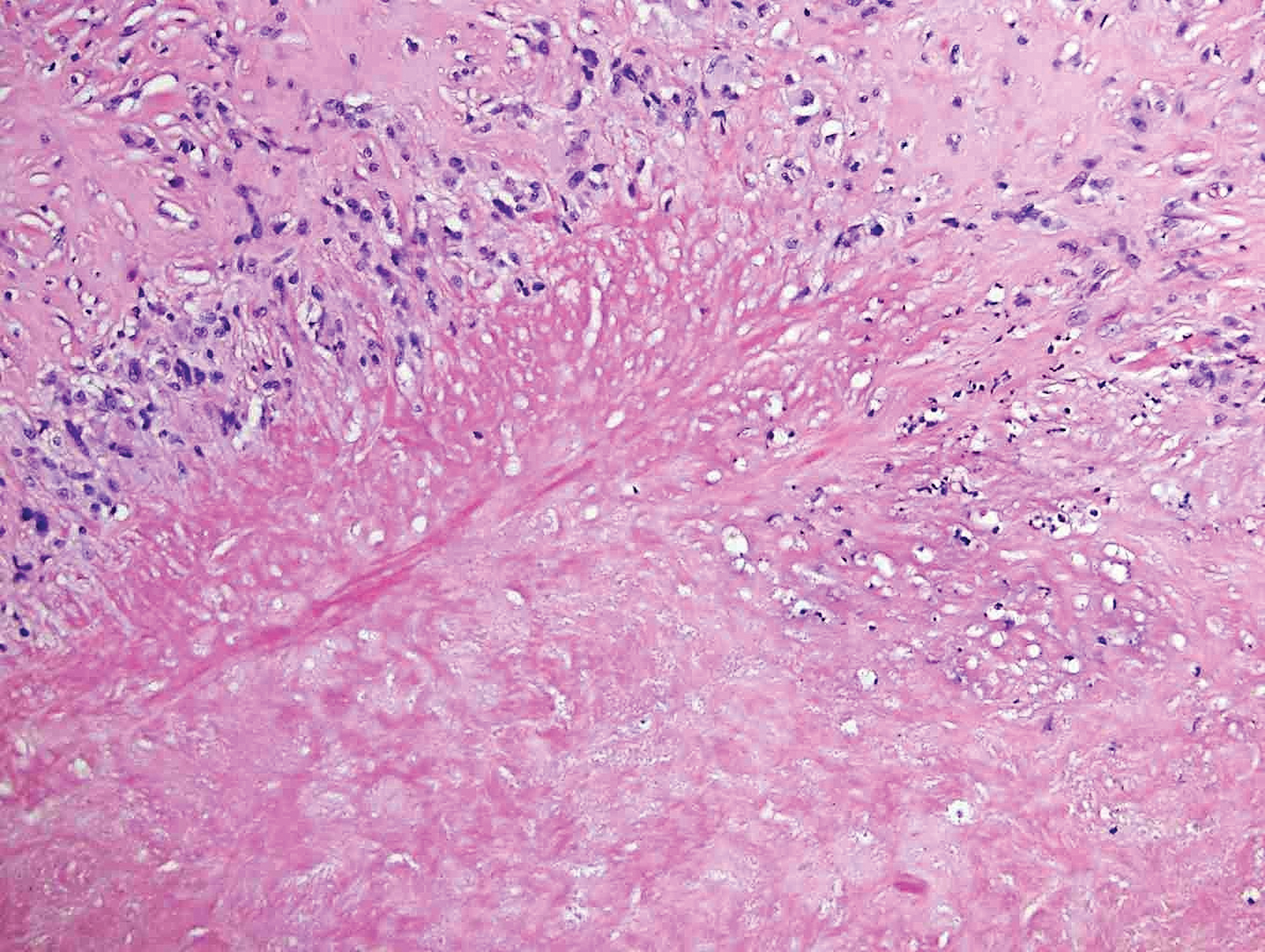

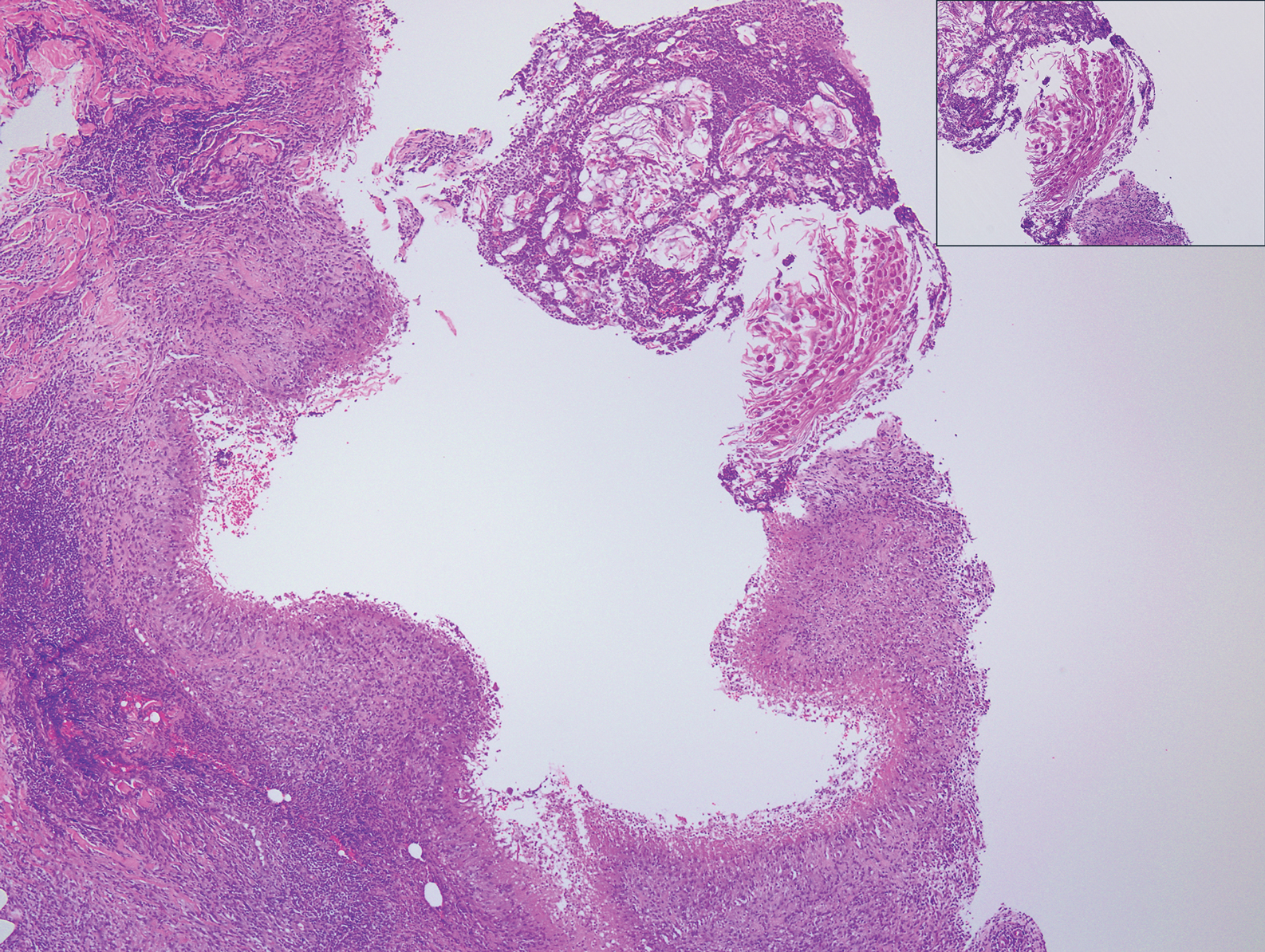

Palisaded encapsulated neuroma, also referred to as solitary circumscribed neuroma, was first described by Reed et al21 in 1972. It is a benign and solitary, firm, dome-shaped, flesh-colored papule that occurs in middle-aged adults, predominately near mucocutaneous junctions of the face. Other locations include the oral mucosa, eyelid, nasal fossa, shoulder, arm, hand, foot, and glans penis.22,23 Histopathologically, palisaded encapsulated neuroma demonstrates a solitary, well-circumscribed, partially encapsulated, intradermal nodule composed of interweaving fascicles of spindle cells with prominent clefts (Figure 3). Rarely, palisaded encapsulated neuroma may have a plexiform or multinodular architecture.24 Immunohistochemically, tumor cells stain positively for S-100 protein, type IV collagen, and vimentin. The capsule, composed of perineural cells, stains positive for epithelial membrane antigen. A neurofilament stain will highlight axons within the tumor.24,25 Currently, palisaded encapsulated neuroma does not have a well-established link to known neurocutaneous or inherited syndromes. Excision is curative with a low risk of recurrence.26

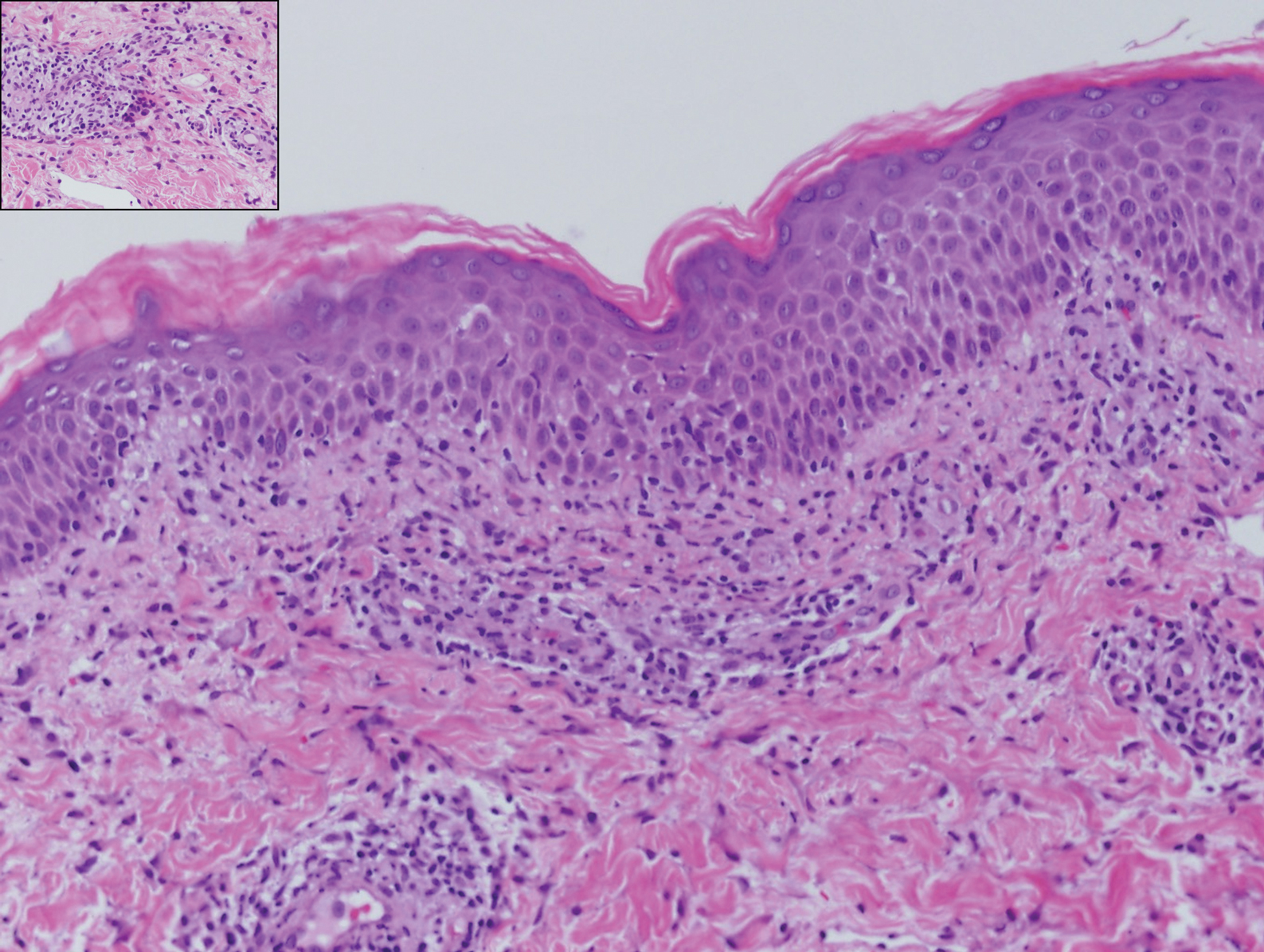

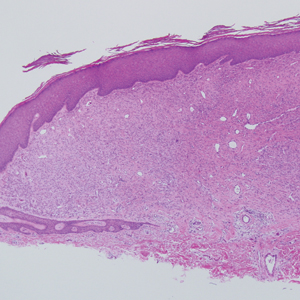

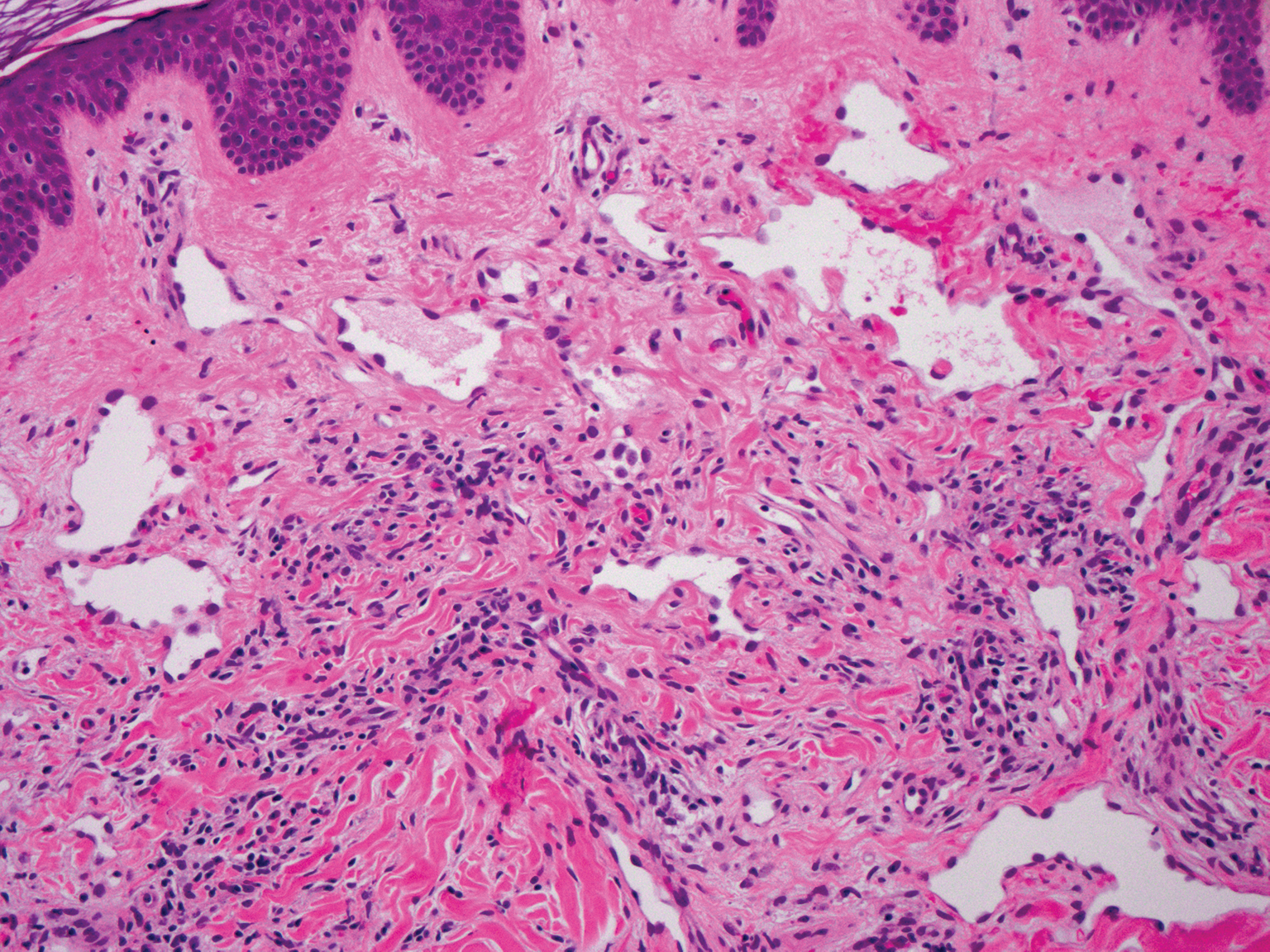

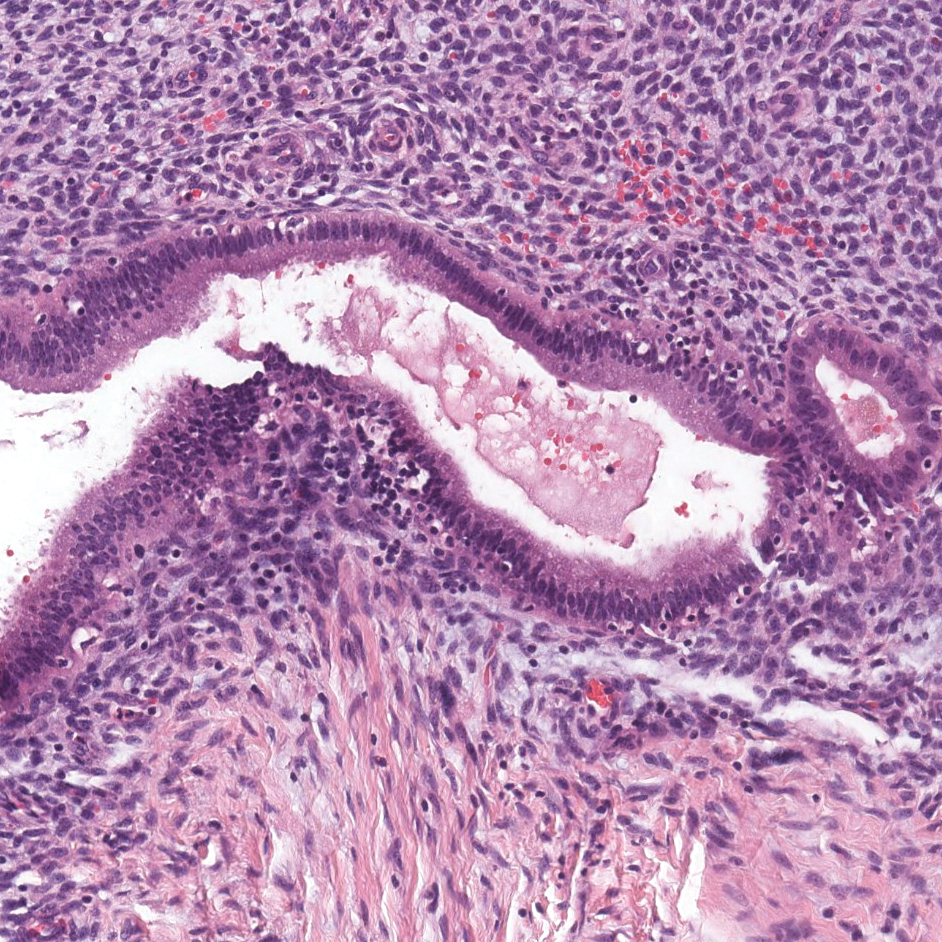

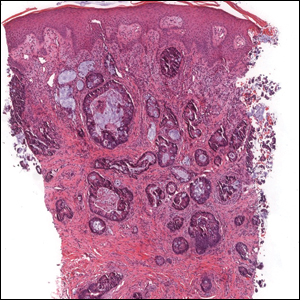

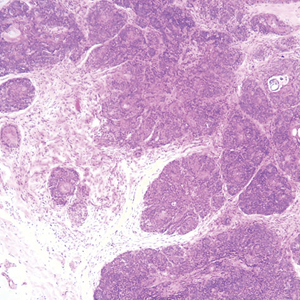

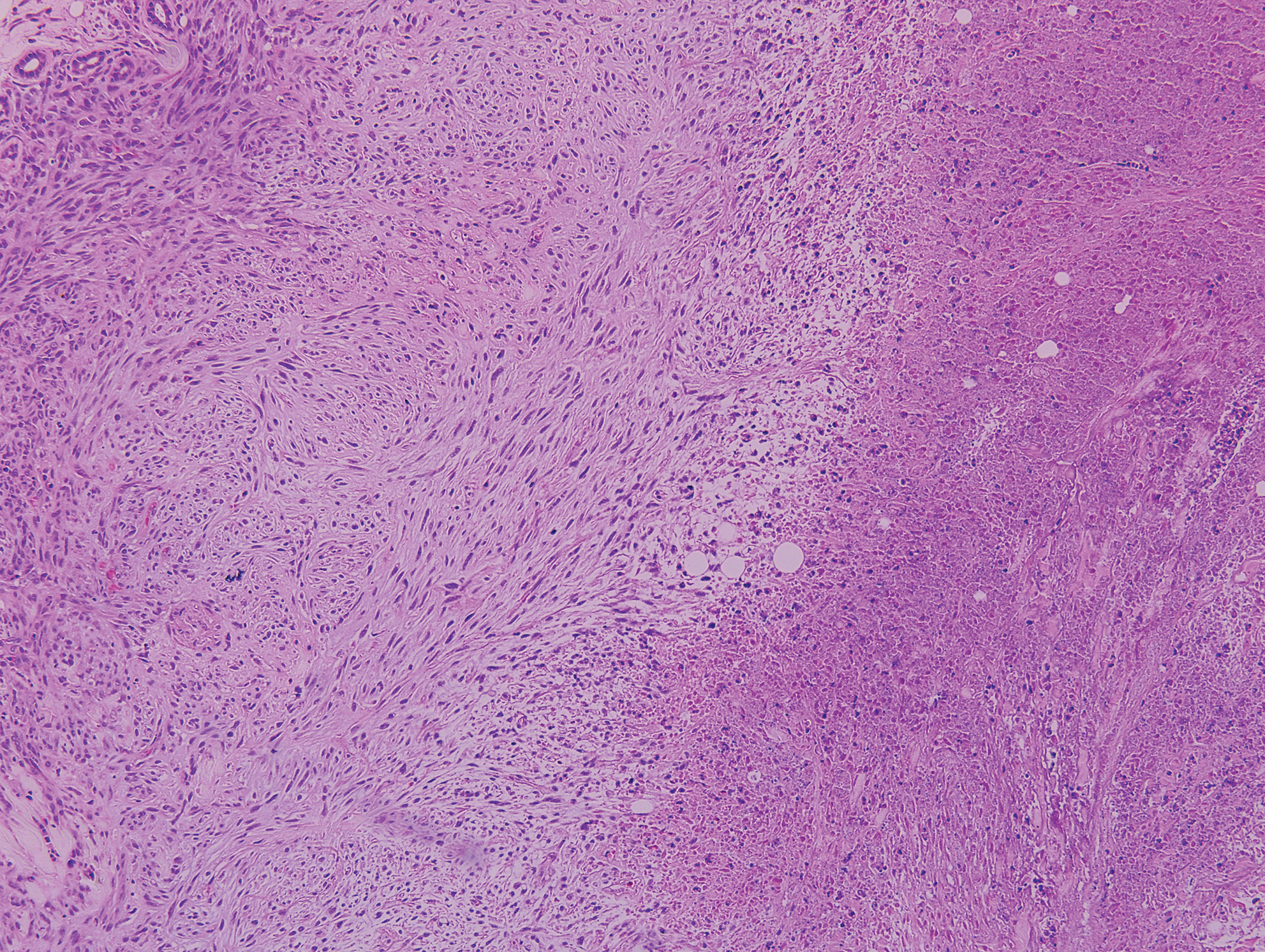

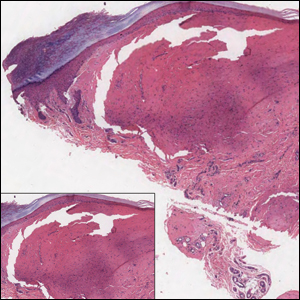

Sclerotic fibromas (SFs) were first reported by Weary et al27 as multiple tumors involving the tongues of patients with Cowden syndrome. Sporadic or solitary SFs of the skin in patients without Cowden syndrome have been reported, and both multiple and solitary SFs present with similar pathologic changes.28-30 Clinically, the solitary variant manifests as a well-demarcated, flesh-colored to erythematous, waxy papule or nodule with no site or sex predilection.30,31 Histologically, SF demonstrates a well-demarcated, nonencapsulated dermal nodule composed of hypocellular and sclerotic collagen bundles with scattered spindled cells and prominent clefts resembling Vincent van Gogh's Starry Night or plywood (Figure 4). Immunohistochemically, the spindled cells strongly express CD34. Factor XIIIa and markers of melanocytic, neural, and muscular differentiation are negative. When rendering a diagnosis in a patient with multiple SFs, a comment regarding the possibility of Cowden syndrome should be mentioned.32

- Fetsch JF, Miettinen M. Sclerosing perineurioma: a clinicopathologic study of 19 cases of a distinctive soft tissue lesion with a predilection for the fingers and palms of young adults. Am J Surg Pathol. 1997;21:1433-1442.

- Fox MD, Gleason BC, Thomas AB, et al. Extra-acral cutaneous/soft tissue sclerosing perineurioma: an under-recognized entity in the differential of CD34-positive cutaneous neoplasms. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:1053-1056.

- Erstine EM, Ko JS, Rubin BP, et al. Broadening the anatomic landscape of sclerosing perineurioma: a series of 5 cases in nonacral sites. Am J Dermatopathol. 2017;39:679-681.

- Senghore N, Cunliffe D, Watt-Smith S, et al. Extraneural perineurioma of the face: an unusual cutaneous presentation of an uncommon tumour. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2001;39:315-319.

- Lazarus SS, Trombetta LD. Ultrastructural identification of a benign perineurial cell tumor. Cancer. 1978;41:1823-1829.

- Macarenco RS, Cury-Martins J. Extra-acral cutaneous sclerosing perineurioma with CD34 fingerprint pattern. J Cutan Pathol. 2017;44:388-392.

- Santos-Briz A, Godoy E, Canueto J, et al. Cutaneous intraneural perineurioma: a case report. Am J Dermatopathol. 2013;35:E45-E48.

- Rubin AI, Yassaee M, Johnson W, et al. Multiple cutaneous sclerosing perineuriomas: an extensive presentation with involvement of the bilateral upper extremities. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36(suppl 1):60-65.

- Damman J, Biswas A. Fibrous papule: a histopathologic review. Am J Dermatopathol. 2018;40:551-560.

- Macri A, Tanner LS. Cutaneous angiofibroma. StatPearls. https://www.statpearls.com/kb/viewarticle/17566/. Updated January 24, 2019. Accessed October 21, 2019.

- Darling TN, Skarulis MC, Steinberg SM, et al. Multiple facial angiofibromas and collagenomas in patients with multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1. Arch Dermatol. 1997;133:853-857.

- Schaffer JV, Gohara MA, McNiff JM, et al. Multiple facial angiofibromas: a cutaneous manifestation of Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:S108-S111.

- Northrup H, Krueger DA; International Tuberous Sclerosis Complex Consensus Group. Tuberous sclerosis complex diagnostic criteria update: recommendations of the 2012 International Tuberous Sclerosis Complex Consensus Conference. Pediatr Neurol. 2013;49:243-254.

- Bansal C, Stewart D, Li A, et al. Histologic variants of fibrous papule. J Cutan Pathol. 2005;32:424-428.

- Harris GR, Shea CR, Horenstein MG, et al. Desmoplastic (sclerotic) nevus: an underrecognized entity that resembles dermatofibroma and desmoplastic melanoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 1999;23:786-794.

- Ferrara G, Brasiello M, Annese P, et al. Desmoplastic nevus: clinicopathologic keynotes. Am J Dermatopathol. 2009;31:718-722.

- Sherrill AM, Crespo G, Prakash AV, et al. Desmoplastic nevus: an entity distinct from Spitz nevus and blue nevus. Am J Dermatopathol. 2011;33:35-39.

- Kucher C, Zhang PJ, Pasha T, et al. Expression of Melan-A and Ki-67 in desmoplastic melanoma and desmoplastic nevi. Am J Dermatopathol. 2004;26:452-457.

- Sidiropoulos M, Sholl LM, Obregon R, et al. Desmoplastic nevus of chronically sun-damaged skin: an entity to be distinguished from desmoplastic melanoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2014;36:629-634.

- Kiuru M, Patel RM, Busam KJ. Desmoplastic melanocytic nevi with lymphocytic aggregates. J Cutan Pathol. 2012;39:940-944.

- Reed RJ, Fine RM, Meltzer HD. Palisaded, encapsulated neuromas of the skin. Arch Dermatol. 1972;106:865-870.

- Newman MD, Milgraum S. Palisaded encapsulated neuroma (PEN): an often misdiagnosed neural tumor. Dermatol Online J. 2008;14:12.

- Beutler B, Cohen PR. Palisaded encapsulated neuroma of the trunk: a case report and review of palisaded encapsulated neuroma. Cureus. 2016;8:E726.

- Jokinen CH, Ragsdale BD, Argenyi ZB. Expanding the clinicopathologic spectrum of palisaded encapsulated neuroma. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:43-48.

- Argenyi ZB. Immunohistochemical characterization of palisaded, encapsulated neuroma. J Cutan Pathol. 1990;17:329-335.

- Batra J, Ramesh V, Molpariya A, et al. Palisaded encapsulated neuroma: an unusual presentation. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2018;9:262-264.

- Weary PE, Gorlin RJ, Gentry WC Jr, et al. Multiple hamartoma syndrome (Cowden's disease). Arch Dermatol. 1972;106:682-690.

- Mahmood MN, Salama ME, Chaffins M, et al. Solitary sclerotic fibroma of skin: a possible link with pleomorphic fibroma with immunophenotypic expression for O13 (CD99) and CD34. J Cutan Pathol. 2003;30:631-636.

- Nakashima K, Yamada N, Adachi K, et al. Solitary sclerotic fibroma of the skin: morphological characterization of the 'plywood-like pattern'. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35(suppl 1):74-79.

- Rapini RP, Golitz LE. Sclerotic fibromas of the skin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;20:266-271.

- Abbas O, Ghosn S, Bahhady R, et al. Solitary sclerotic fibroma on the scalp of a young girl: reactive sclerosis pattern? J Dermatol. 2010;37:575-577.

- Hanft VN, Shea CR, McNutt NS, et al. Expression of CD34 in sclerotic ("plywood") fibromas. Am J Dermatopathol. 2000;22:17-21.

The Diagnosis: Sclerosing Perineurioma

Sclerosing perineurioma, first described in 1997 by Fetsch and Miettinen,1 is a subtype of perineurioma with a strong predilection for the fingers and palms of young adults. Rare cases involving extra-acral sites including the forearm, elbow, axilla, back, neck, lower leg, thigh, knee, lips, nose, and mouth have been reported.2-4 Perineurioma is a relatively uncommon and benign peripheral nerve sheath tumor with exclusive perineurial differentiation.5 Perineurioma is divided into intraneural and extraneural types; the latter are further subclassified into soft tissue, sclerosing, reticular, and plexiform types. Other rare forms include the sclerosing, Pacinian corpuscle-like perineurioma, lipomatous perineurioma, perineurioma with xanthomatous areas, and perineurioma with granular cells.6,7

Clinically, sclerosing perineurioma usually presents as a solitary lesion; however, rare cases of multiple lesions have been reported.8 Our patient presented with a solitary papule on the nose. Histopathologically, sclerosing perineurioma demonstrates slender spindle cells in a whorled growth pattern (onion skin) embedded in a hyalinized, lamellar, and dense collagenous stroma with intervening cleftlike spaces. Immunohistochemically, the spindle cells of our case stained positive for epithelial membrane antigen (quiz images). Other positive immunostains for perineurioma include claudin-1 and glucose transporter 1 (GLUT1). Perineurioma lacks expression of S-100 but can express CD34.2 As a benign tumor, the prognosis of sclerosing perineurioma is excellent. Complete local excision is considered curative.1

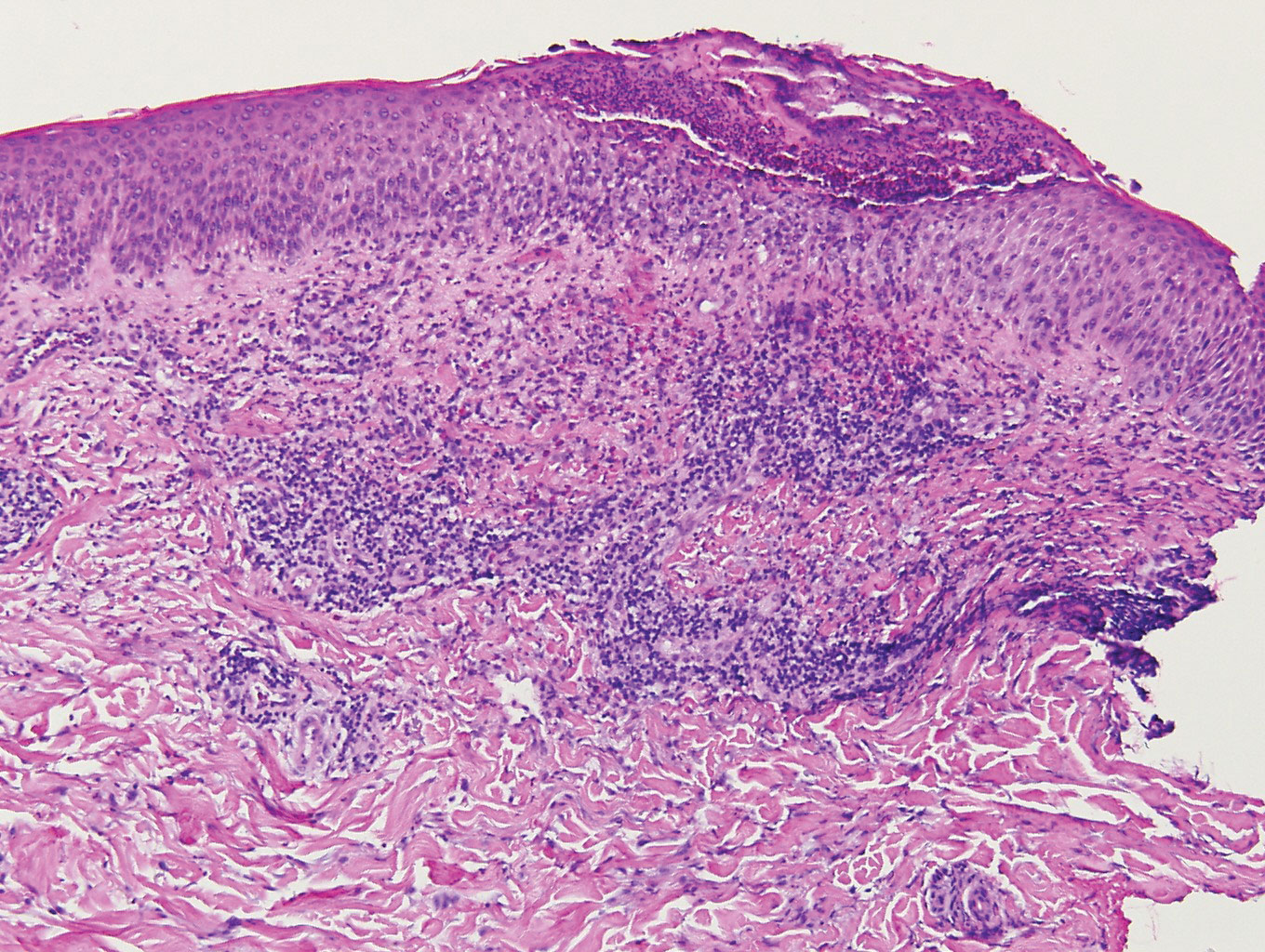

Angiofibroma, also known as fibrous papule, is a common and benign lesion located primarily on or in close proximity to the nose.9 Angiofibromas can be associated with genodermatoses such as tuberous sclerosis, multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1, or Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome. When angiofibromas involve the penis, they are called pearly penile papules. Ungual angiofibroma, also known as Koenen tumor, occurs underneath the nail.10-12 Both facial angiofibromas (>3) and ungual angiofibromas (>2) are independent major criteria for tuberous sclerosis.13 Clinically, angiofibroma presents as a small, dome-shaped, pink papule arising on the lower portion of the nose or nearby area of the central face. Histopathologically, angiofibromas classically demonstrate increased dilated vessels and fibrosis in the dermis. Stellate, plump, spindle-shaped, and multinucleated cells can be seen in the collagenous stroma. The collagen fibers around hair follicles are arranged concentrically, resulting in an onion skin-like appearance. The epidermal rete ridges can be effaced (Figure 1). Increased numbers of single-unit melanocytes along the dermoepidermal junction can be seen in some cases. Immunohistochemically, a variable number of spindled and multinucleated cells in the dermis stain with factor XIIIa. There are at least 7 histologic variants of angiofibroma including hypercellular, pigmented, inflammatory, pleomorphic, clear cell, granular cell, and epithelioid.9,14

Desmoplastic nevus (DN) is a benign melanocytic neoplasm characterized by predominantly spindle-shaped nevus cells embedded within a fibrotic stroma. Although it can resemble a Spitz nevus, it is recognized as a distinct entity.15-17 Clinically, DN presents as a small and flesh-colored, erythematous or slightly pigmented papule or nodule that usually occurs on the arms and legs of young adults. Histopathologically, DN demonstrates a dermal-based proliferation of spindled melanocytes embedded in a dense collagenous stroma with sparse or absent melanin deposition. The collagen bundles often show artifactual clefts and onion skin-like accentuation around vessels. Melanocytes may be epithelioid (Figure 2).16 Immunohistochemically, DN expresses melanocytic markers such as S-100, Melan-A, and human melanoma black 45, but epithelial membrane antigen is negative. Human melanoma black 45 demonstrates maturation with stronger staining in superficial portions of the lesion and diminution of staining with increasing dermal depth.18 Many other melanocytic tumors share histologic similarities to DN including blue nevus and desmoplastic melanoma.17,19,20

Palisaded encapsulated neuroma, also referred to as solitary circumscribed neuroma, was first described by Reed et al21 in 1972. It is a benign and solitary, firm, dome-shaped, flesh-colored papule that occurs in middle-aged adults, predominately near mucocutaneous junctions of the face. Other locations include the oral mucosa, eyelid, nasal fossa, shoulder, arm, hand, foot, and glans penis.22,23 Histopathologically, palisaded encapsulated neuroma demonstrates a solitary, well-circumscribed, partially encapsulated, intradermal nodule composed of interweaving fascicles of spindle cells with prominent clefts (Figure 3). Rarely, palisaded encapsulated neuroma may have a plexiform or multinodular architecture.24 Immunohistochemically, tumor cells stain positively for S-100 protein, type IV collagen, and vimentin. The capsule, composed of perineural cells, stains positive for epithelial membrane antigen. A neurofilament stain will highlight axons within the tumor.24,25 Currently, palisaded encapsulated neuroma does not have a well-established link to known neurocutaneous or inherited syndromes. Excision is curative with a low risk of recurrence.26

Sclerotic fibromas (SFs) were first reported by Weary et al27 as multiple tumors involving the tongues of patients with Cowden syndrome. Sporadic or solitary SFs of the skin in patients without Cowden syndrome have been reported, and both multiple and solitary SFs present with similar pathologic changes.28-30 Clinically, the solitary variant manifests as a well-demarcated, flesh-colored to erythematous, waxy papule or nodule with no site or sex predilection.30,31 Histologically, SF demonstrates a well-demarcated, nonencapsulated dermal nodule composed of hypocellular and sclerotic collagen bundles with scattered spindled cells and prominent clefts resembling Vincent van Gogh's Starry Night or plywood (Figure 4). Immunohistochemically, the spindled cells strongly express CD34. Factor XIIIa and markers of melanocytic, neural, and muscular differentiation are negative. When rendering a diagnosis in a patient with multiple SFs, a comment regarding the possibility of Cowden syndrome should be mentioned.32

The Diagnosis: Sclerosing Perineurioma

Sclerosing perineurioma, first described in 1997 by Fetsch and Miettinen,1 is a subtype of perineurioma with a strong predilection for the fingers and palms of young adults. Rare cases involving extra-acral sites including the forearm, elbow, axilla, back, neck, lower leg, thigh, knee, lips, nose, and mouth have been reported.2-4 Perineurioma is a relatively uncommon and benign peripheral nerve sheath tumor with exclusive perineurial differentiation.5 Perineurioma is divided into intraneural and extraneural types; the latter are further subclassified into soft tissue, sclerosing, reticular, and plexiform types. Other rare forms include the sclerosing, Pacinian corpuscle-like perineurioma, lipomatous perineurioma, perineurioma with xanthomatous areas, and perineurioma with granular cells.6,7

Clinically, sclerosing perineurioma usually presents as a solitary lesion; however, rare cases of multiple lesions have been reported.8 Our patient presented with a solitary papule on the nose. Histopathologically, sclerosing perineurioma demonstrates slender spindle cells in a whorled growth pattern (onion skin) embedded in a hyalinized, lamellar, and dense collagenous stroma with intervening cleftlike spaces. Immunohistochemically, the spindle cells of our case stained positive for epithelial membrane antigen (quiz images). Other positive immunostains for perineurioma include claudin-1 and glucose transporter 1 (GLUT1). Perineurioma lacks expression of S-100 but can express CD34.2 As a benign tumor, the prognosis of sclerosing perineurioma is excellent. Complete local excision is considered curative.1

Angiofibroma, also known as fibrous papule, is a common and benign lesion located primarily on or in close proximity to the nose.9 Angiofibromas can be associated with genodermatoses such as tuberous sclerosis, multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1, or Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome. When angiofibromas involve the penis, they are called pearly penile papules. Ungual angiofibroma, also known as Koenen tumor, occurs underneath the nail.10-12 Both facial angiofibromas (>3) and ungual angiofibromas (>2) are independent major criteria for tuberous sclerosis.13 Clinically, angiofibroma presents as a small, dome-shaped, pink papule arising on the lower portion of the nose or nearby area of the central face. Histopathologically, angiofibromas classically demonstrate increased dilated vessels and fibrosis in the dermis. Stellate, plump, spindle-shaped, and multinucleated cells can be seen in the collagenous stroma. The collagen fibers around hair follicles are arranged concentrically, resulting in an onion skin-like appearance. The epidermal rete ridges can be effaced (Figure 1). Increased numbers of single-unit melanocytes along the dermoepidermal junction can be seen in some cases. Immunohistochemically, a variable number of spindled and multinucleated cells in the dermis stain with factor XIIIa. There are at least 7 histologic variants of angiofibroma including hypercellular, pigmented, inflammatory, pleomorphic, clear cell, granular cell, and epithelioid.9,14

Desmoplastic nevus (DN) is a benign melanocytic neoplasm characterized by predominantly spindle-shaped nevus cells embedded within a fibrotic stroma. Although it can resemble a Spitz nevus, it is recognized as a distinct entity.15-17 Clinically, DN presents as a small and flesh-colored, erythematous or slightly pigmented papule or nodule that usually occurs on the arms and legs of young adults. Histopathologically, DN demonstrates a dermal-based proliferation of spindled melanocytes embedded in a dense collagenous stroma with sparse or absent melanin deposition. The collagen bundles often show artifactual clefts and onion skin-like accentuation around vessels. Melanocytes may be epithelioid (Figure 2).16 Immunohistochemically, DN expresses melanocytic markers such as S-100, Melan-A, and human melanoma black 45, but epithelial membrane antigen is negative. Human melanoma black 45 demonstrates maturation with stronger staining in superficial portions of the lesion and diminution of staining with increasing dermal depth.18 Many other melanocytic tumors share histologic similarities to DN including blue nevus and desmoplastic melanoma.17,19,20

Palisaded encapsulated neuroma, also referred to as solitary circumscribed neuroma, was first described by Reed et al21 in 1972. It is a benign and solitary, firm, dome-shaped, flesh-colored papule that occurs in middle-aged adults, predominately near mucocutaneous junctions of the face. Other locations include the oral mucosa, eyelid, nasal fossa, shoulder, arm, hand, foot, and glans penis.22,23 Histopathologically, palisaded encapsulated neuroma demonstrates a solitary, well-circumscribed, partially encapsulated, intradermal nodule composed of interweaving fascicles of spindle cells with prominent clefts (Figure 3). Rarely, palisaded encapsulated neuroma may have a plexiform or multinodular architecture.24 Immunohistochemically, tumor cells stain positively for S-100 protein, type IV collagen, and vimentin. The capsule, composed of perineural cells, stains positive for epithelial membrane antigen. A neurofilament stain will highlight axons within the tumor.24,25 Currently, palisaded encapsulated neuroma does not have a well-established link to known neurocutaneous or inherited syndromes. Excision is curative with a low risk of recurrence.26

Sclerotic fibromas (SFs) were first reported by Weary et al27 as multiple tumors involving the tongues of patients with Cowden syndrome. Sporadic or solitary SFs of the skin in patients without Cowden syndrome have been reported, and both multiple and solitary SFs present with similar pathologic changes.28-30 Clinically, the solitary variant manifests as a well-demarcated, flesh-colored to erythematous, waxy papule or nodule with no site or sex predilection.30,31 Histologically, SF demonstrates a well-demarcated, nonencapsulated dermal nodule composed of hypocellular and sclerotic collagen bundles with scattered spindled cells and prominent clefts resembling Vincent van Gogh's Starry Night or plywood (Figure 4). Immunohistochemically, the spindled cells strongly express CD34. Factor XIIIa and markers of melanocytic, neural, and muscular differentiation are negative. When rendering a diagnosis in a patient with multiple SFs, a comment regarding the possibility of Cowden syndrome should be mentioned.32

- Fetsch JF, Miettinen M. Sclerosing perineurioma: a clinicopathologic study of 19 cases of a distinctive soft tissue lesion with a predilection for the fingers and palms of young adults. Am J Surg Pathol. 1997;21:1433-1442.

- Fox MD, Gleason BC, Thomas AB, et al. Extra-acral cutaneous/soft tissue sclerosing perineurioma: an under-recognized entity in the differential of CD34-positive cutaneous neoplasms. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:1053-1056.

- Erstine EM, Ko JS, Rubin BP, et al. Broadening the anatomic landscape of sclerosing perineurioma: a series of 5 cases in nonacral sites. Am J Dermatopathol. 2017;39:679-681.

- Senghore N, Cunliffe D, Watt-Smith S, et al. Extraneural perineurioma of the face: an unusual cutaneous presentation of an uncommon tumour. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2001;39:315-319.

- Lazarus SS, Trombetta LD. Ultrastructural identification of a benign perineurial cell tumor. Cancer. 1978;41:1823-1829.

- Macarenco RS, Cury-Martins J. Extra-acral cutaneous sclerosing perineurioma with CD34 fingerprint pattern. J Cutan Pathol. 2017;44:388-392.

- Santos-Briz A, Godoy E, Canueto J, et al. Cutaneous intraneural perineurioma: a case report. Am J Dermatopathol. 2013;35:E45-E48.

- Rubin AI, Yassaee M, Johnson W, et al. Multiple cutaneous sclerosing perineuriomas: an extensive presentation with involvement of the bilateral upper extremities. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36(suppl 1):60-65.

- Damman J, Biswas A. Fibrous papule: a histopathologic review. Am J Dermatopathol. 2018;40:551-560.

- Macri A, Tanner LS. Cutaneous angiofibroma. StatPearls. https://www.statpearls.com/kb/viewarticle/17566/. Updated January 24, 2019. Accessed October 21, 2019.

- Darling TN, Skarulis MC, Steinberg SM, et al. Multiple facial angiofibromas and collagenomas in patients with multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1. Arch Dermatol. 1997;133:853-857.

- Schaffer JV, Gohara MA, McNiff JM, et al. Multiple facial angiofibromas: a cutaneous manifestation of Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:S108-S111.

- Northrup H, Krueger DA; International Tuberous Sclerosis Complex Consensus Group. Tuberous sclerosis complex diagnostic criteria update: recommendations of the 2012 International Tuberous Sclerosis Complex Consensus Conference. Pediatr Neurol. 2013;49:243-254.

- Bansal C, Stewart D, Li A, et al. Histologic variants of fibrous papule. J Cutan Pathol. 2005;32:424-428.

- Harris GR, Shea CR, Horenstein MG, et al. Desmoplastic (sclerotic) nevus: an underrecognized entity that resembles dermatofibroma and desmoplastic melanoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 1999;23:786-794.

- Ferrara G, Brasiello M, Annese P, et al. Desmoplastic nevus: clinicopathologic keynotes. Am J Dermatopathol. 2009;31:718-722.

- Sherrill AM, Crespo G, Prakash AV, et al. Desmoplastic nevus: an entity distinct from Spitz nevus and blue nevus. Am J Dermatopathol. 2011;33:35-39.

- Kucher C, Zhang PJ, Pasha T, et al. Expression of Melan-A and Ki-67 in desmoplastic melanoma and desmoplastic nevi. Am J Dermatopathol. 2004;26:452-457.

- Sidiropoulos M, Sholl LM, Obregon R, et al. Desmoplastic nevus of chronically sun-damaged skin: an entity to be distinguished from desmoplastic melanoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2014;36:629-634.

- Kiuru M, Patel RM, Busam KJ. Desmoplastic melanocytic nevi with lymphocytic aggregates. J Cutan Pathol. 2012;39:940-944.

- Reed RJ, Fine RM, Meltzer HD. Palisaded, encapsulated neuromas of the skin. Arch Dermatol. 1972;106:865-870.

- Newman MD, Milgraum S. Palisaded encapsulated neuroma (PEN): an often misdiagnosed neural tumor. Dermatol Online J. 2008;14:12.

- Beutler B, Cohen PR. Palisaded encapsulated neuroma of the trunk: a case report and review of palisaded encapsulated neuroma. Cureus. 2016;8:E726.

- Jokinen CH, Ragsdale BD, Argenyi ZB. Expanding the clinicopathologic spectrum of palisaded encapsulated neuroma. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:43-48.

- Argenyi ZB. Immunohistochemical characterization of palisaded, encapsulated neuroma. J Cutan Pathol. 1990;17:329-335.

- Batra J, Ramesh V, Molpariya A, et al. Palisaded encapsulated neuroma: an unusual presentation. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2018;9:262-264.

- Weary PE, Gorlin RJ, Gentry WC Jr, et al. Multiple hamartoma syndrome (Cowden's disease). Arch Dermatol. 1972;106:682-690.

- Mahmood MN, Salama ME, Chaffins M, et al. Solitary sclerotic fibroma of skin: a possible link with pleomorphic fibroma with immunophenotypic expression for O13 (CD99) and CD34. J Cutan Pathol. 2003;30:631-636.

- Nakashima K, Yamada N, Adachi K, et al. Solitary sclerotic fibroma of the skin: morphological characterization of the 'plywood-like pattern'. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35(suppl 1):74-79.

- Rapini RP, Golitz LE. Sclerotic fibromas of the skin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;20:266-271.

- Abbas O, Ghosn S, Bahhady R, et al. Solitary sclerotic fibroma on the scalp of a young girl: reactive sclerosis pattern? J Dermatol. 2010;37:575-577.

- Hanft VN, Shea CR, McNutt NS, et al. Expression of CD34 in sclerotic ("plywood") fibromas. Am J Dermatopathol. 2000;22:17-21.

- Fetsch JF, Miettinen M. Sclerosing perineurioma: a clinicopathologic study of 19 cases of a distinctive soft tissue lesion with a predilection for the fingers and palms of young adults. Am J Surg Pathol. 1997;21:1433-1442.

- Fox MD, Gleason BC, Thomas AB, et al. Extra-acral cutaneous/soft tissue sclerosing perineurioma: an under-recognized entity in the differential of CD34-positive cutaneous neoplasms. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:1053-1056.

- Erstine EM, Ko JS, Rubin BP, et al. Broadening the anatomic landscape of sclerosing perineurioma: a series of 5 cases in nonacral sites. Am J Dermatopathol. 2017;39:679-681.

- Senghore N, Cunliffe D, Watt-Smith S, et al. Extraneural perineurioma of the face: an unusual cutaneous presentation of an uncommon tumour. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2001;39:315-319.

- Lazarus SS, Trombetta LD. Ultrastructural identification of a benign perineurial cell tumor. Cancer. 1978;41:1823-1829.

- Macarenco RS, Cury-Martins J. Extra-acral cutaneous sclerosing perineurioma with CD34 fingerprint pattern. J Cutan Pathol. 2017;44:388-392.

- Santos-Briz A, Godoy E, Canueto J, et al. Cutaneous intraneural perineurioma: a case report. Am J Dermatopathol. 2013;35:E45-E48.

- Rubin AI, Yassaee M, Johnson W, et al. Multiple cutaneous sclerosing perineuriomas: an extensive presentation with involvement of the bilateral upper extremities. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36(suppl 1):60-65.

- Damman J, Biswas A. Fibrous papule: a histopathologic review. Am J Dermatopathol. 2018;40:551-560.

- Macri A, Tanner LS. Cutaneous angiofibroma. StatPearls. https://www.statpearls.com/kb/viewarticle/17566/. Updated January 24, 2019. Accessed October 21, 2019.

- Darling TN, Skarulis MC, Steinberg SM, et al. Multiple facial angiofibromas and collagenomas in patients with multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1. Arch Dermatol. 1997;133:853-857.

- Schaffer JV, Gohara MA, McNiff JM, et al. Multiple facial angiofibromas: a cutaneous manifestation of Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:S108-S111.

- Northrup H, Krueger DA; International Tuberous Sclerosis Complex Consensus Group. Tuberous sclerosis complex diagnostic criteria update: recommendations of the 2012 International Tuberous Sclerosis Complex Consensus Conference. Pediatr Neurol. 2013;49:243-254.

- Bansal C, Stewart D, Li A, et al. Histologic variants of fibrous papule. J Cutan Pathol. 2005;32:424-428.

- Harris GR, Shea CR, Horenstein MG, et al. Desmoplastic (sclerotic) nevus: an underrecognized entity that resembles dermatofibroma and desmoplastic melanoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 1999;23:786-794.

- Ferrara G, Brasiello M, Annese P, et al. Desmoplastic nevus: clinicopathologic keynotes. Am J Dermatopathol. 2009;31:718-722.

- Sherrill AM, Crespo G, Prakash AV, et al. Desmoplastic nevus: an entity distinct from Spitz nevus and blue nevus. Am J Dermatopathol. 2011;33:35-39.

- Kucher C, Zhang PJ, Pasha T, et al. Expression of Melan-A and Ki-67 in desmoplastic melanoma and desmoplastic nevi. Am J Dermatopathol. 2004;26:452-457.

- Sidiropoulos M, Sholl LM, Obregon R, et al. Desmoplastic nevus of chronically sun-damaged skin: an entity to be distinguished from desmoplastic melanoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2014;36:629-634.

- Kiuru M, Patel RM, Busam KJ. Desmoplastic melanocytic nevi with lymphocytic aggregates. J Cutan Pathol. 2012;39:940-944.

- Reed RJ, Fine RM, Meltzer HD. Palisaded, encapsulated neuromas of the skin. Arch Dermatol. 1972;106:865-870.

- Newman MD, Milgraum S. Palisaded encapsulated neuroma (PEN): an often misdiagnosed neural tumor. Dermatol Online J. 2008;14:12.

- Beutler B, Cohen PR. Palisaded encapsulated neuroma of the trunk: a case report and review of palisaded encapsulated neuroma. Cureus. 2016;8:E726.

- Jokinen CH, Ragsdale BD, Argenyi ZB. Expanding the clinicopathologic spectrum of palisaded encapsulated neuroma. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:43-48.

- Argenyi ZB. Immunohistochemical characterization of palisaded, encapsulated neuroma. J Cutan Pathol. 1990;17:329-335.

- Batra J, Ramesh V, Molpariya A, et al. Palisaded encapsulated neuroma: an unusual presentation. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2018;9:262-264.

- Weary PE, Gorlin RJ, Gentry WC Jr, et al. Multiple hamartoma syndrome (Cowden's disease). Arch Dermatol. 1972;106:682-690.

- Mahmood MN, Salama ME, Chaffins M, et al. Solitary sclerotic fibroma of skin: a possible link with pleomorphic fibroma with immunophenotypic expression for O13 (CD99) and CD34. J Cutan Pathol. 2003;30:631-636.

- Nakashima K, Yamada N, Adachi K, et al. Solitary sclerotic fibroma of the skin: morphological characterization of the 'plywood-like pattern'. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35(suppl 1):74-79.

- Rapini RP, Golitz LE. Sclerotic fibromas of the skin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;20:266-271.

- Abbas O, Ghosn S, Bahhady R, et al. Solitary sclerotic fibroma on the scalp of a young girl: reactive sclerosis pattern? J Dermatol. 2010;37:575-577.

- Hanft VN, Shea CR, McNutt NS, et al. Expression of CD34 in sclerotic ("plywood") fibromas. Am J Dermatopathol. 2000;22:17-21.

A 25-year-old man presented with a flesh-colored papule on the left side of the nose of 2 years' duration.

Erythematous Papules on the Scrotum, Trunk, and Extremities

The Diagnosis: Lichenoid and Granulomatous Dermatitis in the Setting of Secondary Syphilis

Syphilis, an infectious disease that has risen in incidence and is most commonly reported in men who have sex with men, involves a vast array of clinical and histologic presentations.1 Clinically, secondary syphilis involves an erythematous maculopapular eruption on the face, trunk, palms, soles, or genital area.2 The characteristic histologic features for secondary syphilis include endothelial swelling, interstitial inflammatory array, irregular acanthosis, elongated rete ridges, and vacuolar interface dermatitis with lymphocytes and plasma cells.1 Syphilitic infection has been associated with lichenoid and granulomatous dermatitis, which is an inflammatory skin disease described by Magro and Crowson.3 Lichenoid and granulomatous dermatitis has been linked to various systemic disorders, including chronic hepatitis C, Crohn disease, rheumatoid arthritis, endocrinopathy, subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus, secondary syphilis, prior herpes infection, tuberculoid leprosy, mycobacterial infection, and human immunodeficiency virus infection.3-7 For this patient, given histopathology findings, clinical presentation, and positive rapid plasma reagin serologies, a diagnosis of lichenoid and granulomatous dermatitis in the setting of a secondary syphilis infection was established. A comprehensive investigation should be conducted to consider secondary syphilis or other systemic diseases in patients with a histologic finding of lichenoid and granulomatous dermatitis.

Histologically, lichenoid and granulomatous dermatitis cases show a bandlike infiltrate of lymphocytes with neighboring histiocytes along the dermoepidermal junction, accompanied by epithelial changes of dyskeratosis, vasculopathy, and colloid body formation, in addition to a dermal histiocytic component.3 Our patient's biopsy showed a lichenoid reaction pattern with vacuolar interface changes, dyskeratosis, plump endothelial cells, and small collections of plasma cells. Additionally, there was a granulomatous component in the dermis with histiocytes admixed with lymphocytes and plasma cells. The presence of spirochetes was confirmed with antitreponemal immunohistochemical stain (Figure 1). Quantitative rapid plasma reagin was 1:64 (reference range, <1:1) and Treponema pallidum antibody was reactive.

Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis has a variable clinical presentation, often with red-purple annular plaques, hyperpigmented papules, and nodules frequently in a linear arrangement and predominantly on the trunk, thighs, groin, or buttocks.8,9 On histopathology, there are histiocytes in the reticular dermis and/or a macrophage infiltrate in the mid to deep dermis with collections of degenerated collagen (Figure 2).8,10 An interstitial infiltrate of eosinophils and neutrophils also may be appreciated, but mucin generally is absent.8,11 This condition often coexists with rheumatic and systemic autoimmune diseases.8-10

Interstitial granuloma annulare is a noninfectious granulomatous skin condition that often presents clinically as asymptomatic annular red-brown patches, usually on the extremities.11-13 On histopathology, an interstitial or palisaded inflammatory infiltrate with histiocytes and multinucleated giant cells may be seen along with collagen degeneration or collagen bundles without necrosis (Figure 3).9 Mucin often is associated with the histiocytes.11 Of note, our patient's skin biopsy shows interface dermatitis, differentiating it from both interstitial granuloma annulare and interstitial granulomatous dermatitis.

Postviral granulomatous reactions are the most frequently reported types of reactions to occur at the location of herpes zoster infection up to years after the initial disease. Wolf isotopic reaction encompasses skin reactions in the body region of formerly resolved skin disease, commonly herpesvirus infection.14,15 This manifestation may occur due to a hypersensitivity reaction from enduring viral proteins, resident memory T cells, or local neuroimmune imbalance from herpesvirus-induced injury to dermal sensory nerve fibers.14-17 Clinically, patients present with red-purple pruritic papules and plaques in a bandlike unilateral pattern, usually in the same region as the prior herpes infection and often accompanied by postherpetic neuralgia.16-19 Of note, our patient's clinical findings were more diffuse than the frequently localized and often linear distribution seen in postherpetic granulomatous reaction. On histopathology, granulomatous or lichenoid tissue reaction most commonly is appreciated.15 Specifically, interstitial granulomatous dermatitis with histiocytes, lymphocytes, and multinucleated giant cells showing elastophagocytosis and an inflammatory infiltrate with lymphocytes and plasma cells around vasculature, eccrine glands, and nerves can be noted (Figure 4).19

Lupus erythematosus is an autoimmune condition with a wide array of clinical features, including skin manifestations and systemic symptoms. Specifically, discoid lupus erythematosus presents with clearly outlined, red-pink macules or papules with scaling. Histologic features include keratotic follicular plugging, acanthosis, dermal mucin, thickening of the basement membrane zone, and dense lymphocytic infiltrate (Figure 5).20

- Flamm A, Parikh K, Xie Q, et al. Histologic features of secondary syphilis: a multicenter retrospective review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:325-330.

- Zeltser R, Kurban AK. Syphilis. Clin Dermatol. 2004;22:461-468.

- Magro CM, Crowson AN. Lichenoid and granulomatous dermatitis. Int J Dermatol. 2000;39:12-33.

- S Breza T Jr, Magro CM. Lichenoid and granulomatous dermatitis associated with atypical mycobacterium infections. J Cutan Pathol. 2006;33:512-515.

- Granel B, Serratrice J, Rey J, et al. Chronic hepatitis C virus infection associated with a generalized granuloma annulare. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43(5, pt 2):918-919.

- Jorizzo JL, Gonzalez EB, Apisarnthanarax P, et al. Pigmented purpuric eruption in a patient with rheumatoid arthritis. Arch Intern Med. 1982;142:2184-2185.

- Magro CM, Crowson AN, Regauer S. Granuloma annulare and necrobiosis lipoidica tissue reactions as a manifestation of systemic disease. Hum Pathol. 1996;27:50-56.

- Błażewicz I, Szczerkowska-Dobosz A, Pęksa R, et al. Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis: a characteristic histological pattern with variable clinical manifestations. Postepy Dermatol Alergol. 2015;32:475-477.

- Sezer E, Luzar B, Calonje E. Secondary syphilis with an interstitial granuloma annulare-like histopathologic pattern. J Cutan Pathol. 2011;38:439-442.

- Peroni A, Colato C, Schena D, et al. Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis: a distinct entity with characteristic histological and clinical pattern. Br J Dermatol. 2012;166:775-783.

- Sakiyama T, Hirai I, Konohana A, et al. Interstitial-type granuloma annulare associated with Sjögren syndrome. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2014;12:415-416.

- Spring P, Vernez M, Maniu CM, et al. Localized interstitial granuloma annulare induced by subcutaneous injections for desensitization. Dermatol Online J. 2013;19:18572.

- Kluger N, Moguelet P, Chaslin-Ferbus D, et al. Generalized interstitial granuloma annulare induced by pegylated interferon-alpha. Dermatology. 2006;213:248-249.

- Ruocco E, Baroni A, Cutrì FT, et al. Granuloma annulare in a site of healed herpes zoster: Wolf's isotopic response. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2003;17:686-688.

- Ise M, Tanese K, Adachi T, et al. Postherpetic Wolf's isotopic response: possible contribution of resident memory T cells to the pathogenesis of lichenoid reaction. Br J Dermatol. 2015;173:1331-1334.

- Lora V, Cota C, Kanitakis J. Zosteriform lichen planus after herpes zoster: report of a new case of Wolf's isotopic phenomenon and literature review. Dermatol Online J. 2014;20. pii:13030/qt5vf99178.

- Lin CH, Chen HC, Gao HW, et al. Wolf's post-herpetic isotopic response to tocilizumab for rheumatoid arthritis. Australas J Dermatol. 2018;59:E135-E137.

- Melgar E, Henry J, Valois A, et al. Extra-facial Lever granuloma on a herpes zoster scar: Wolf's isotopic response. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2018;145:354-358.

- Ferenczi K, Rosenberg AS, McCalmont TH, et al. Herpes zoster granulomatous dermatitis: histopathologic findings in a case series. J Cutan Pathol. 2015;42:739-745.

- Li Q, Wu H, Liao W, et al. A comprehensive review of immune-mediated dermatopathology in systemic lupus erythematosus. J Autoimmun. 2018;93:1-15.

The Diagnosis: Lichenoid and Granulomatous Dermatitis in the Setting of Secondary Syphilis

Syphilis, an infectious disease that has risen in incidence and is most commonly reported in men who have sex with men, involves a vast array of clinical and histologic presentations.1 Clinically, secondary syphilis involves an erythematous maculopapular eruption on the face, trunk, palms, soles, or genital area.2 The characteristic histologic features for secondary syphilis include endothelial swelling, interstitial inflammatory array, irregular acanthosis, elongated rete ridges, and vacuolar interface dermatitis with lymphocytes and plasma cells.1 Syphilitic infection has been associated with lichenoid and granulomatous dermatitis, which is an inflammatory skin disease described by Magro and Crowson.3 Lichenoid and granulomatous dermatitis has been linked to various systemic disorders, including chronic hepatitis C, Crohn disease, rheumatoid arthritis, endocrinopathy, subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus, secondary syphilis, prior herpes infection, tuberculoid leprosy, mycobacterial infection, and human immunodeficiency virus infection.3-7 For this patient, given histopathology findings, clinical presentation, and positive rapid plasma reagin serologies, a diagnosis of lichenoid and granulomatous dermatitis in the setting of a secondary syphilis infection was established. A comprehensive investigation should be conducted to consider secondary syphilis or other systemic diseases in patients with a histologic finding of lichenoid and granulomatous dermatitis.

Histologically, lichenoid and granulomatous dermatitis cases show a bandlike infiltrate of lymphocytes with neighboring histiocytes along the dermoepidermal junction, accompanied by epithelial changes of dyskeratosis, vasculopathy, and colloid body formation, in addition to a dermal histiocytic component.3 Our patient's biopsy showed a lichenoid reaction pattern with vacuolar interface changes, dyskeratosis, plump endothelial cells, and small collections of plasma cells. Additionally, there was a granulomatous component in the dermis with histiocytes admixed with lymphocytes and plasma cells. The presence of spirochetes was confirmed with antitreponemal immunohistochemical stain (Figure 1). Quantitative rapid plasma reagin was 1:64 (reference range, <1:1) and Treponema pallidum antibody was reactive.

Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis has a variable clinical presentation, often with red-purple annular plaques, hyperpigmented papules, and nodules frequently in a linear arrangement and predominantly on the trunk, thighs, groin, or buttocks.8,9 On histopathology, there are histiocytes in the reticular dermis and/or a macrophage infiltrate in the mid to deep dermis with collections of degenerated collagen (Figure 2).8,10 An interstitial infiltrate of eosinophils and neutrophils also may be appreciated, but mucin generally is absent.8,11 This condition often coexists with rheumatic and systemic autoimmune diseases.8-10

Interstitial granuloma annulare is a noninfectious granulomatous skin condition that often presents clinically as asymptomatic annular red-brown patches, usually on the extremities.11-13 On histopathology, an interstitial or palisaded inflammatory infiltrate with histiocytes and multinucleated giant cells may be seen along with collagen degeneration or collagen bundles without necrosis (Figure 3).9 Mucin often is associated with the histiocytes.11 Of note, our patient's skin biopsy shows interface dermatitis, differentiating it from both interstitial granuloma annulare and interstitial granulomatous dermatitis.

Postviral granulomatous reactions are the most frequently reported types of reactions to occur at the location of herpes zoster infection up to years after the initial disease. Wolf isotopic reaction encompasses skin reactions in the body region of formerly resolved skin disease, commonly herpesvirus infection.14,15 This manifestation may occur due to a hypersensitivity reaction from enduring viral proteins, resident memory T cells, or local neuroimmune imbalance from herpesvirus-induced injury to dermal sensory nerve fibers.14-17 Clinically, patients present with red-purple pruritic papules and plaques in a bandlike unilateral pattern, usually in the same region as the prior herpes infection and often accompanied by postherpetic neuralgia.16-19 Of note, our patient's clinical findings were more diffuse than the frequently localized and often linear distribution seen in postherpetic granulomatous reaction. On histopathology, granulomatous or lichenoid tissue reaction most commonly is appreciated.15 Specifically, interstitial granulomatous dermatitis with histiocytes, lymphocytes, and multinucleated giant cells showing elastophagocytosis and an inflammatory infiltrate with lymphocytes and plasma cells around vasculature, eccrine glands, and nerves can be noted (Figure 4).19

Lupus erythematosus is an autoimmune condition with a wide array of clinical features, including skin manifestations and systemic symptoms. Specifically, discoid lupus erythematosus presents with clearly outlined, red-pink macules or papules with scaling. Histologic features include keratotic follicular plugging, acanthosis, dermal mucin, thickening of the basement membrane zone, and dense lymphocytic infiltrate (Figure 5).20

The Diagnosis: Lichenoid and Granulomatous Dermatitis in the Setting of Secondary Syphilis

Syphilis, an infectious disease that has risen in incidence and is most commonly reported in men who have sex with men, involves a vast array of clinical and histologic presentations.1 Clinically, secondary syphilis involves an erythematous maculopapular eruption on the face, trunk, palms, soles, or genital area.2 The characteristic histologic features for secondary syphilis include endothelial swelling, interstitial inflammatory array, irregular acanthosis, elongated rete ridges, and vacuolar interface dermatitis with lymphocytes and plasma cells.1 Syphilitic infection has been associated with lichenoid and granulomatous dermatitis, which is an inflammatory skin disease described by Magro and Crowson.3 Lichenoid and granulomatous dermatitis has been linked to various systemic disorders, including chronic hepatitis C, Crohn disease, rheumatoid arthritis, endocrinopathy, subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus, secondary syphilis, prior herpes infection, tuberculoid leprosy, mycobacterial infection, and human immunodeficiency virus infection.3-7 For this patient, given histopathology findings, clinical presentation, and positive rapid plasma reagin serologies, a diagnosis of lichenoid and granulomatous dermatitis in the setting of a secondary syphilis infection was established. A comprehensive investigation should be conducted to consider secondary syphilis or other systemic diseases in patients with a histologic finding of lichenoid and granulomatous dermatitis.

Histologically, lichenoid and granulomatous dermatitis cases show a bandlike infiltrate of lymphocytes with neighboring histiocytes along the dermoepidermal junction, accompanied by epithelial changes of dyskeratosis, vasculopathy, and colloid body formation, in addition to a dermal histiocytic component.3 Our patient's biopsy showed a lichenoid reaction pattern with vacuolar interface changes, dyskeratosis, plump endothelial cells, and small collections of plasma cells. Additionally, there was a granulomatous component in the dermis with histiocytes admixed with lymphocytes and plasma cells. The presence of spirochetes was confirmed with antitreponemal immunohistochemical stain (Figure 1). Quantitative rapid plasma reagin was 1:64 (reference range, <1:1) and Treponema pallidum antibody was reactive.

Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis has a variable clinical presentation, often with red-purple annular plaques, hyperpigmented papules, and nodules frequently in a linear arrangement and predominantly on the trunk, thighs, groin, or buttocks.8,9 On histopathology, there are histiocytes in the reticular dermis and/or a macrophage infiltrate in the mid to deep dermis with collections of degenerated collagen (Figure 2).8,10 An interstitial infiltrate of eosinophils and neutrophils also may be appreciated, but mucin generally is absent.8,11 This condition often coexists with rheumatic and systemic autoimmune diseases.8-10

Interstitial granuloma annulare is a noninfectious granulomatous skin condition that often presents clinically as asymptomatic annular red-brown patches, usually on the extremities.11-13 On histopathology, an interstitial or palisaded inflammatory infiltrate with histiocytes and multinucleated giant cells may be seen along with collagen degeneration or collagen bundles without necrosis (Figure 3).9 Mucin often is associated with the histiocytes.11 Of note, our patient's skin biopsy shows interface dermatitis, differentiating it from both interstitial granuloma annulare and interstitial granulomatous dermatitis.

Postviral granulomatous reactions are the most frequently reported types of reactions to occur at the location of herpes zoster infection up to years after the initial disease. Wolf isotopic reaction encompasses skin reactions in the body region of formerly resolved skin disease, commonly herpesvirus infection.14,15 This manifestation may occur due to a hypersensitivity reaction from enduring viral proteins, resident memory T cells, or local neuroimmune imbalance from herpesvirus-induced injury to dermal sensory nerve fibers.14-17 Clinically, patients present with red-purple pruritic papules and plaques in a bandlike unilateral pattern, usually in the same region as the prior herpes infection and often accompanied by postherpetic neuralgia.16-19 Of note, our patient's clinical findings were more diffuse than the frequently localized and often linear distribution seen in postherpetic granulomatous reaction. On histopathology, granulomatous or lichenoid tissue reaction most commonly is appreciated.15 Specifically, interstitial granulomatous dermatitis with histiocytes, lymphocytes, and multinucleated giant cells showing elastophagocytosis and an inflammatory infiltrate with lymphocytes and plasma cells around vasculature, eccrine glands, and nerves can be noted (Figure 4).19

Lupus erythematosus is an autoimmune condition with a wide array of clinical features, including skin manifestations and systemic symptoms. Specifically, discoid lupus erythematosus presents with clearly outlined, red-pink macules or papules with scaling. Histologic features include keratotic follicular plugging, acanthosis, dermal mucin, thickening of the basement membrane zone, and dense lymphocytic infiltrate (Figure 5).20

- Flamm A, Parikh K, Xie Q, et al. Histologic features of secondary syphilis: a multicenter retrospective review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:325-330.

- Zeltser R, Kurban AK. Syphilis. Clin Dermatol. 2004;22:461-468.

- Magro CM, Crowson AN. Lichenoid and granulomatous dermatitis. Int J Dermatol. 2000;39:12-33.

- S Breza T Jr, Magro CM. Lichenoid and granulomatous dermatitis associated with atypical mycobacterium infections. J Cutan Pathol. 2006;33:512-515.

- Granel B, Serratrice J, Rey J, et al. Chronic hepatitis C virus infection associated with a generalized granuloma annulare. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43(5, pt 2):918-919.

- Jorizzo JL, Gonzalez EB, Apisarnthanarax P, et al. Pigmented purpuric eruption in a patient with rheumatoid arthritis. Arch Intern Med. 1982;142:2184-2185.

- Magro CM, Crowson AN, Regauer S. Granuloma annulare and necrobiosis lipoidica tissue reactions as a manifestation of systemic disease. Hum Pathol. 1996;27:50-56.

- Błażewicz I, Szczerkowska-Dobosz A, Pęksa R, et al. Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis: a characteristic histological pattern with variable clinical manifestations. Postepy Dermatol Alergol. 2015;32:475-477.

- Sezer E, Luzar B, Calonje E. Secondary syphilis with an interstitial granuloma annulare-like histopathologic pattern. J Cutan Pathol. 2011;38:439-442.

- Peroni A, Colato C, Schena D, et al. Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis: a distinct entity with characteristic histological and clinical pattern. Br J Dermatol. 2012;166:775-783.

- Sakiyama T, Hirai I, Konohana A, et al. Interstitial-type granuloma annulare associated with Sjögren syndrome. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2014;12:415-416.

- Spring P, Vernez M, Maniu CM, et al. Localized interstitial granuloma annulare induced by subcutaneous injections for desensitization. Dermatol Online J. 2013;19:18572.

- Kluger N, Moguelet P, Chaslin-Ferbus D, et al. Generalized interstitial granuloma annulare induced by pegylated interferon-alpha. Dermatology. 2006;213:248-249.

- Ruocco E, Baroni A, Cutrì FT, et al. Granuloma annulare in a site of healed herpes zoster: Wolf's isotopic response. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2003;17:686-688.

- Ise M, Tanese K, Adachi T, et al. Postherpetic Wolf's isotopic response: possible contribution of resident memory T cells to the pathogenesis of lichenoid reaction. Br J Dermatol. 2015;173:1331-1334.

- Lora V, Cota C, Kanitakis J. Zosteriform lichen planus after herpes zoster: report of a new case of Wolf's isotopic phenomenon and literature review. Dermatol Online J. 2014;20. pii:13030/qt5vf99178.

- Lin CH, Chen HC, Gao HW, et al. Wolf's post-herpetic isotopic response to tocilizumab for rheumatoid arthritis. Australas J Dermatol. 2018;59:E135-E137.

- Melgar E, Henry J, Valois A, et al. Extra-facial Lever granuloma on a herpes zoster scar: Wolf's isotopic response. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2018;145:354-358.

- Ferenczi K, Rosenberg AS, McCalmont TH, et al. Herpes zoster granulomatous dermatitis: histopathologic findings in a case series. J Cutan Pathol. 2015;42:739-745.

- Li Q, Wu H, Liao W, et al. A comprehensive review of immune-mediated dermatopathology in systemic lupus erythematosus. J Autoimmun. 2018;93:1-15.

- Flamm A, Parikh K, Xie Q, et al. Histologic features of secondary syphilis: a multicenter retrospective review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:325-330.

- Zeltser R, Kurban AK. Syphilis. Clin Dermatol. 2004;22:461-468.

- Magro CM, Crowson AN. Lichenoid and granulomatous dermatitis. Int J Dermatol. 2000;39:12-33.

- S Breza T Jr, Magro CM. Lichenoid and granulomatous dermatitis associated with atypical mycobacterium infections. J Cutan Pathol. 2006;33:512-515.

- Granel B, Serratrice J, Rey J, et al. Chronic hepatitis C virus infection associated with a generalized granuloma annulare. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43(5, pt 2):918-919.

- Jorizzo JL, Gonzalez EB, Apisarnthanarax P, et al. Pigmented purpuric eruption in a patient with rheumatoid arthritis. Arch Intern Med. 1982;142:2184-2185.

- Magro CM, Crowson AN, Regauer S. Granuloma annulare and necrobiosis lipoidica tissue reactions as a manifestation of systemic disease. Hum Pathol. 1996;27:50-56.

- Błażewicz I, Szczerkowska-Dobosz A, Pęksa R, et al. Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis: a characteristic histological pattern with variable clinical manifestations. Postepy Dermatol Alergol. 2015;32:475-477.

- Sezer E, Luzar B, Calonje E. Secondary syphilis with an interstitial granuloma annulare-like histopathologic pattern. J Cutan Pathol. 2011;38:439-442.

- Peroni A, Colato C, Schena D, et al. Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis: a distinct entity with characteristic histological and clinical pattern. Br J Dermatol. 2012;166:775-783.

- Sakiyama T, Hirai I, Konohana A, et al. Interstitial-type granuloma annulare associated with Sjögren syndrome. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2014;12:415-416.

- Spring P, Vernez M, Maniu CM, et al. Localized interstitial granuloma annulare induced by subcutaneous injections for desensitization. Dermatol Online J. 2013;19:18572.

- Kluger N, Moguelet P, Chaslin-Ferbus D, et al. Generalized interstitial granuloma annulare induced by pegylated interferon-alpha. Dermatology. 2006;213:248-249.

- Ruocco E, Baroni A, Cutrì FT, et al. Granuloma annulare in a site of healed herpes zoster: Wolf's isotopic response. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2003;17:686-688.

- Ise M, Tanese K, Adachi T, et al. Postherpetic Wolf's isotopic response: possible contribution of resident memory T cells to the pathogenesis of lichenoid reaction. Br J Dermatol. 2015;173:1331-1334.

- Lora V, Cota C, Kanitakis J. Zosteriform lichen planus after herpes zoster: report of a new case of Wolf's isotopic phenomenon and literature review. Dermatol Online J. 2014;20. pii:13030/qt5vf99178.

- Lin CH, Chen HC, Gao HW, et al. Wolf's post-herpetic isotopic response to tocilizumab for rheumatoid arthritis. Australas J Dermatol. 2018;59:E135-E137.

- Melgar E, Henry J, Valois A, et al. Extra-facial Lever granuloma on a herpes zoster scar: Wolf's isotopic response. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2018;145:354-358.

- Ferenczi K, Rosenberg AS, McCalmont TH, et al. Herpes zoster granulomatous dermatitis: histopathologic findings in a case series. J Cutan Pathol. 2015;42:739-745.

- Li Q, Wu H, Liao W, et al. A comprehensive review of immune-mediated dermatopathology in systemic lupus erythematosus. J Autoimmun. 2018;93:1-15.

A 54-year-old man presented with painful, nonpruritic, erythematous papules that began on the scrotum. The eruption progressed to involve the trunk, arms, and legs.

Solitary Papule on the Leg

The Diagnosis: Epithelioid Histiocytoma

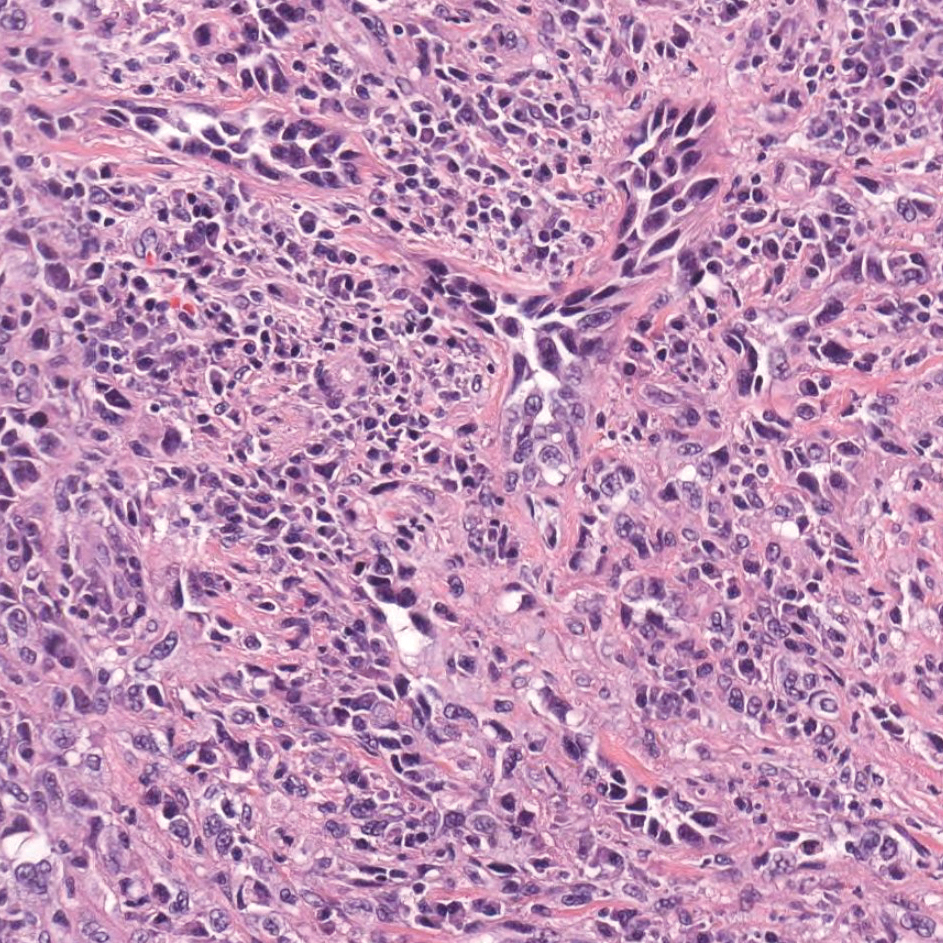

Epithelioid histiocytoma (EH), also known as epithelioid cell histiocytoma or epithelioid fibrous histiocytoma, is a rare benign fibrohistiocytic tumor first described in 1989.1 Epithelioid histiocytoma commonly presents in middle-aged adults with a slight predilection for males.2 The most frequently affected site is the lower extremity. The arms, trunk, head and neck, groin, and tongue also can be involved.3,4 It usually presents as a solitary asymptomatic papule or nodule, though cases with multiple lesions have been reported.5 Anaplastic lymphoma kinase rearrangement and overexpression have been confirmed and suggest that EH is distinct from conventional cutaneous fibrous histiocytoma.5

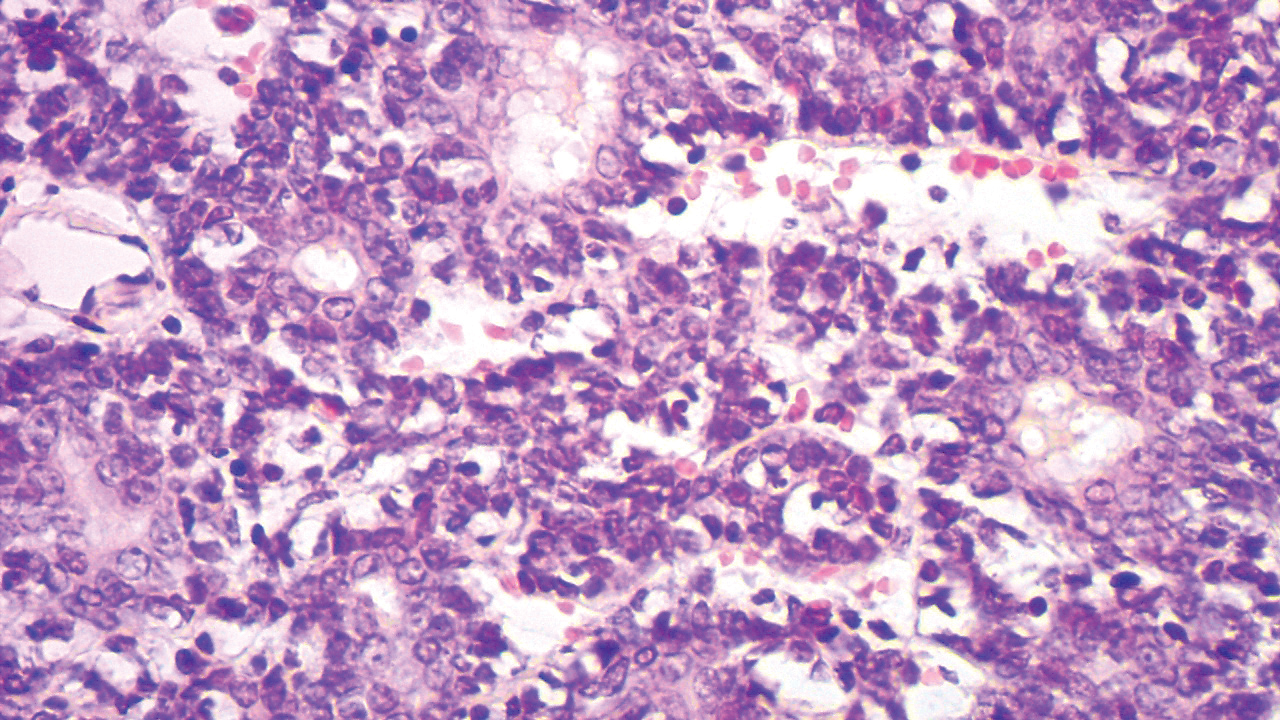

Histologically, EH appears as an exophytic, symmetric, and well-demarcated dermal nodule with a classic epidermal collarette. Prominent vascularity with perivascular accentuation of the epithelioid tumor cells is common. Older lesions may be hyalinized and sclerotic. Epithelioid cells commonly account for more than 50% of the tumor and are characterized by eosinophilic cytoplasm, vesicular nuclei, and small eosinophilic nucleoli. A small population of lymphocytes and mast cells are variably present (quiz image, bottom).1-3,7 A predominantly spindle cell variant has been reported.8 Other histopathologic variants include granular cell,9 cellular,10 and EH with perineuriomalike growth.11 Immunohistochemical staining shows anaplastic lymphoma kinase positivity in most cases, and more than half of cases stain positive for factor XIIIa and epithelial membrane antigen. Tumor cells consistently are negative for desmin and cytokeratins.6,10,12 Excision is curative.8

Polypoid Spitz nevus (PSN) is a benign nevus with a conspicuous polypoid or papillary exophytic architecture. The term was coined in 2000 by Fabrizi and Massi.13 Spitz nevus is a benign acquired melanocytic tumor that typically presents in children and adolescents and has a wide histologic spectrum.14 There is some debate on this entity, as some authors do not regard PSN as a distinct histologic variant; thus, it seems underreported in the literature.15 In a review of 349 cases of Spitz nevi, the authors found 7 cases of PSN.16 In another review of 74 cases of intradermal Spitz nevi, 14 cases of PSN were identified.14 This polypoid variant is easily mistaken for a polypoid melanoma because it can show cytologic atypia with large nuclei. Polypoid Spitz nevus usually lacks mitoses, notable pleomorphism, and sheetlike growth, unlike melanoma (Figure 1).13,14

Myopericytoma is an uncommon benign mesenchymal neoplasm that typically presents as a solitary, slowly enlarging and painless nodule with a predilection for the lower extremities, usually in adult males.17-20 Histologically, it consists of a well-circumscribed nodule with numerous thin-walled vessels and a proliferation of ovoid to spindled myopericytes exhibiting a concentric perivascular growth pattern (Figure 2). Myopericytoma usually is positive for smooth muscle actin and h-caldesmon but is negative or only focally positive for desmin. The prognosis is good with rare recurrence, despite incomplete excision.17,18

Solitary reticulohistiocytoma is a rare benign form of non-Langerhans cell histiocytosis.21,22 Unlike its multicentric counterpart, solitary reticulohistiocytoma rarely is associated with systemic disease. It presents as a small, dome-shaped, painless papule or nodule that can affect any part of the body.22,23 Solitary reticulohistiocytoma characteristically demonstrates cells with a ground glass-like appearance and 2-toned cytoplasm. A mixed inflammatory infiltrate including neutrophils, eosinophils, and lymphocytes commonly is present (Figure 3). The epithelioid histiocytes are positive for vimentin and histiocytic markers including CD68 and CD163.22

Solitary fibrous tumor (SFT) is an uncommon mesenchymal fibroblastic neoplasm that can arise at almost any anatomic site.24 Cutaneous SFTs are more common in women, most often involve the head, and appear to behave in an indolent manner.25 Solitary fibrous tumors are translocation-associated neoplasms with a NAB2-STAT6 gene fusion.26 The classic histology of SFT is a spindled fibroblastic proliferation arranged in a "patternless pattern" with interspersed stag horn-like, thin-walled blood vessels (Figure 4). Tumor cells usually are positive for CD34, CD99, and Bcl-2.27 In addition, STAT6 immunoreactivity is useful in diagnosis of SFT.25

- Jones EW, Cerio R, Smith NP. Epithelioid cell histiocytoma: a new entity. Br J Dermatol. 1989;120:185-195.

- Singh Gomez C, Calonje E, Fletcher CD. Epithelioid benign fibrous histiocytoma of skin: clinico-pathological analysis of 20 cases of a poorly known variant. Histopathology. 1994;24:123-129.

- Felty CC, Linos K. Epithelioid fibrous histiocytoma: a concise review [published online October 4, 2018]. Am J Dermatopathol. doi:10.1097/DAD.0000000000001272.

- Rawal YB, Kalmar JR, Shumway B, et al. Presentation of an epithelioid cell histiocytoma on the ventral tongue. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2005;100:75-83.

- Cangelosi JJ, Prieto VG, Baker GF, et al. Unusual presentation of multiple epithelioid cell histiocytomas. Am J Dermatopathol. 2008;30:373-376.

- Doyle LA, Marino-Enriquez A, Fletcher CD, et al. ALK rearrangement and overexpression in epithelioid fibrous histiocytoma. Mod Pathol. 2015;28:904-912.

- Silverman JS, Glusac EJ. Epithelioid cell histiocytoma--histogenetic and kinetics analysis of dermal microvascular unit dendritic cell subpopulations. J Cutan Pathol. 2003;30:415-422.

- Murigu T, Bhatt N, Miller K, et al. Spindle cell-predominant epithelioid fibrous histiocytoma. Histopathology. 2018;72:1233-1236.

- Rabkin MS, Vukmer T. Granular cell variant of epithelioid cell histiocytoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2012;34:766-769.

- Glusac EJ, Barr RJ, Everett MA, et al. Epithelioid cell histiocytoma. a report of 10 cases including a new cellular variant. Am J Surg Pathol. 1994;18:583-590.

- Creytens D, Ferdinande L, Van Dorpe J. ALK Rearrangement and overexpression in an unusual cutaneous epithelioid tumor with a peculiar whorled "perineurioma-like" growth pattern: epithelioid fibrous histiocytoma. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol. 2017;25:E46-E48.

- Doyle LA, Fletcher CD. EMA positivity in epithelioid fibrous histiocytoma: a potential diagnostic pitfall. J Cutan Pathol. 2011;38:697-703.

- Fabrizi G, Massi G. Polypoid Spitz naevus: the benign counterpart of polypoid malignant melanoma. Br J Dermatol. 2000;142:128-132.

- Plaza JA, De Stefano D, Suster S, et al. Intradermal Spitz nevi: a rare subtype of Spitz nevi analyzed in a clinicopathologic study of 74 cases. Am J Dermatopathol. 2014;36:283-294; quiz 295-287.

- Menezes FD, Mooi WJ. Spitz tumors of the skin. Surg Pathol Clin. 2017;10:281-298.

- Requena C, Requena L, Kutzner H, et al. Spitz nevus: a clinicopathological study of 349 cases. Am J Dermatopathol. 2009;31:107-116.

- Mentzel T, Dei Tos AP, Sapi Z, et al. Myopericytoma of skin and soft tissues: clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of 54 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2006;30:104-113.

- Aung PP, Goldberg LJ, Mahalingam M, et al. Cutaneous myopericytoma: a report of 3 cases and review of the literature. Dermatopathology (Basel). 2015;2:9-14.

- Morzycki A, Joukhadar N, Murphy A, et al. Digital myopericytoma: a case report and systematic literature review. J Hand Microsurg. 2017;9:32-36.

- LeBlanc RE, Taube J. Myofibroma, myopericytoma, myoepithelioma, and myofibroblastoma of skin and soft tissue. Surg Pathol Clin. 2011;4:745-759.

- Chisolm SS, Schulman JM, Fox LP. Adult xanthogranuloma, reticulohistiocytosis, and Rosai-Dorfman disease. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:465-472; discussion 473.

- Miettinen M, Fetsch JF. Reticulohistiocytoma (solitary epithelioid histiocytoma): a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of 44 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2006;30:521-528.

- Cohen PR, Lee RA. Adult-onset reticulohistiocytoma presenting as a solitary asymptomatic red knee nodule: report and review of clinical presentations and immunohistochemistry staining features of reticulohistiocytosis. Dermatol Online J. 2014. pii:doj_21725.

- Soldano AC, Meehan SA. Cutaneous solitary fibrous tumor: a report of 2 cases and review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2008;30:54-58.

- Feasel P, Al-Ibraheemi A, Fritchie K, et al. Superficial solitary fibrous tumor: a series of 26 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2018;42:778-785.

- Thway K, Ng W, Noujaim J, et al. The current status of solitary fibrous tumor: diagnostic features, variants, and genetics. Int J Surg Pathol. 2016;24:281-292.

- Erdag G, Qureshi HS, Patterson JW, et al. Solitary fibrous tumors of the skin: a clinicopathologic study of 10 cases and review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2007;34:844-850.

The Diagnosis: Epithelioid Histiocytoma

Epithelioid histiocytoma (EH), also known as epithelioid cell histiocytoma or epithelioid fibrous histiocytoma, is a rare benign fibrohistiocytic tumor first described in 1989.1 Epithelioid histiocytoma commonly presents in middle-aged adults with a slight predilection for males.2 The most frequently affected site is the lower extremity. The arms, trunk, head and neck, groin, and tongue also can be involved.3,4 It usually presents as a solitary asymptomatic papule or nodule, though cases with multiple lesions have been reported.5 Anaplastic lymphoma kinase rearrangement and overexpression have been confirmed and suggest that EH is distinct from conventional cutaneous fibrous histiocytoma.5

Histologically, EH appears as an exophytic, symmetric, and well-demarcated dermal nodule with a classic epidermal collarette. Prominent vascularity with perivascular accentuation of the epithelioid tumor cells is common. Older lesions may be hyalinized and sclerotic. Epithelioid cells commonly account for more than 50% of the tumor and are characterized by eosinophilic cytoplasm, vesicular nuclei, and small eosinophilic nucleoli. A small population of lymphocytes and mast cells are variably present (quiz image, bottom).1-3,7 A predominantly spindle cell variant has been reported.8 Other histopathologic variants include granular cell,9 cellular,10 and EH with perineuriomalike growth.11 Immunohistochemical staining shows anaplastic lymphoma kinase positivity in most cases, and more than half of cases stain positive for factor XIIIa and epithelial membrane antigen. Tumor cells consistently are negative for desmin and cytokeratins.6,10,12 Excision is curative.8

Polypoid Spitz nevus (PSN) is a benign nevus with a conspicuous polypoid or papillary exophytic architecture. The term was coined in 2000 by Fabrizi and Massi.13 Spitz nevus is a benign acquired melanocytic tumor that typically presents in children and adolescents and has a wide histologic spectrum.14 There is some debate on this entity, as some authors do not regard PSN as a distinct histologic variant; thus, it seems underreported in the literature.15 In a review of 349 cases of Spitz nevi, the authors found 7 cases of PSN.16 In another review of 74 cases of intradermal Spitz nevi, 14 cases of PSN were identified.14 This polypoid variant is easily mistaken for a polypoid melanoma because it can show cytologic atypia with large nuclei. Polypoid Spitz nevus usually lacks mitoses, notable pleomorphism, and sheetlike growth, unlike melanoma (Figure 1).13,14

Myopericytoma is an uncommon benign mesenchymal neoplasm that typically presents as a solitary, slowly enlarging and painless nodule with a predilection for the lower extremities, usually in adult males.17-20 Histologically, it consists of a well-circumscribed nodule with numerous thin-walled vessels and a proliferation of ovoid to spindled myopericytes exhibiting a concentric perivascular growth pattern (Figure 2). Myopericytoma usually is positive for smooth muscle actin and h-caldesmon but is negative or only focally positive for desmin. The prognosis is good with rare recurrence, despite incomplete excision.17,18

Solitary reticulohistiocytoma is a rare benign form of non-Langerhans cell histiocytosis.21,22 Unlike its multicentric counterpart, solitary reticulohistiocytoma rarely is associated with systemic disease. It presents as a small, dome-shaped, painless papule or nodule that can affect any part of the body.22,23 Solitary reticulohistiocytoma characteristically demonstrates cells with a ground glass-like appearance and 2-toned cytoplasm. A mixed inflammatory infiltrate including neutrophils, eosinophils, and lymphocytes commonly is present (Figure 3). The epithelioid histiocytes are positive for vimentin and histiocytic markers including CD68 and CD163.22

Solitary fibrous tumor (SFT) is an uncommon mesenchymal fibroblastic neoplasm that can arise at almost any anatomic site.24 Cutaneous SFTs are more common in women, most often involve the head, and appear to behave in an indolent manner.25 Solitary fibrous tumors are translocation-associated neoplasms with a NAB2-STAT6 gene fusion.26 The classic histology of SFT is a spindled fibroblastic proliferation arranged in a "patternless pattern" with interspersed stag horn-like, thin-walled blood vessels (Figure 4). Tumor cells usually are positive for CD34, CD99, and Bcl-2.27 In addition, STAT6 immunoreactivity is useful in diagnosis of SFT.25

The Diagnosis: Epithelioid Histiocytoma

Epithelioid histiocytoma (EH), also known as epithelioid cell histiocytoma or epithelioid fibrous histiocytoma, is a rare benign fibrohistiocytic tumor first described in 1989.1 Epithelioid histiocytoma commonly presents in middle-aged adults with a slight predilection for males.2 The most frequently affected site is the lower extremity. The arms, trunk, head and neck, groin, and tongue also can be involved.3,4 It usually presents as a solitary asymptomatic papule or nodule, though cases with multiple lesions have been reported.5 Anaplastic lymphoma kinase rearrangement and overexpression have been confirmed and suggest that EH is distinct from conventional cutaneous fibrous histiocytoma.5

Histologically, EH appears as an exophytic, symmetric, and well-demarcated dermal nodule with a classic epidermal collarette. Prominent vascularity with perivascular accentuation of the epithelioid tumor cells is common. Older lesions may be hyalinized and sclerotic. Epithelioid cells commonly account for more than 50% of the tumor and are characterized by eosinophilic cytoplasm, vesicular nuclei, and small eosinophilic nucleoli. A small population of lymphocytes and mast cells are variably present (quiz image, bottom).1-3,7 A predominantly spindle cell variant has been reported.8 Other histopathologic variants include granular cell,9 cellular,10 and EH with perineuriomalike growth.11 Immunohistochemical staining shows anaplastic lymphoma kinase positivity in most cases, and more than half of cases stain positive for factor XIIIa and epithelial membrane antigen. Tumor cells consistently are negative for desmin and cytokeratins.6,10,12 Excision is curative.8

Polypoid Spitz nevus (PSN) is a benign nevus with a conspicuous polypoid or papillary exophytic architecture. The term was coined in 2000 by Fabrizi and Massi.13 Spitz nevus is a benign acquired melanocytic tumor that typically presents in children and adolescents and has a wide histologic spectrum.14 There is some debate on this entity, as some authors do not regard PSN as a distinct histologic variant; thus, it seems underreported in the literature.15 In a review of 349 cases of Spitz nevi, the authors found 7 cases of PSN.16 In another review of 74 cases of intradermal Spitz nevi, 14 cases of PSN were identified.14 This polypoid variant is easily mistaken for a polypoid melanoma because it can show cytologic atypia with large nuclei. Polypoid Spitz nevus usually lacks mitoses, notable pleomorphism, and sheetlike growth, unlike melanoma (Figure 1).13,14

Myopericytoma is an uncommon benign mesenchymal neoplasm that typically presents as a solitary, slowly enlarging and painless nodule with a predilection for the lower extremities, usually in adult males.17-20 Histologically, it consists of a well-circumscribed nodule with numerous thin-walled vessels and a proliferation of ovoid to spindled myopericytes exhibiting a concentric perivascular growth pattern (Figure 2). Myopericytoma usually is positive for smooth muscle actin and h-caldesmon but is negative or only focally positive for desmin. The prognosis is good with rare recurrence, despite incomplete excision.17,18

Solitary reticulohistiocytoma is a rare benign form of non-Langerhans cell histiocytosis.21,22 Unlike its multicentric counterpart, solitary reticulohistiocytoma rarely is associated with systemic disease. It presents as a small, dome-shaped, painless papule or nodule that can affect any part of the body.22,23 Solitary reticulohistiocytoma characteristically demonstrates cells with a ground glass-like appearance and 2-toned cytoplasm. A mixed inflammatory infiltrate including neutrophils, eosinophils, and lymphocytes commonly is present (Figure 3). The epithelioid histiocytes are positive for vimentin and histiocytic markers including CD68 and CD163.22

Solitary fibrous tumor (SFT) is an uncommon mesenchymal fibroblastic neoplasm that can arise at almost any anatomic site.24 Cutaneous SFTs are more common in women, most often involve the head, and appear to behave in an indolent manner.25 Solitary fibrous tumors are translocation-associated neoplasms with a NAB2-STAT6 gene fusion.26 The classic histology of SFT is a spindled fibroblastic proliferation arranged in a "patternless pattern" with interspersed stag horn-like, thin-walled blood vessels (Figure 4). Tumor cells usually are positive for CD34, CD99, and Bcl-2.27 In addition, STAT6 immunoreactivity is useful in diagnosis of SFT.25

- Jones EW, Cerio R, Smith NP. Epithelioid cell histiocytoma: a new entity. Br J Dermatol. 1989;120:185-195.