User login

Multiple Pink Papules on the Chest and Upper Abdomen

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Metastases

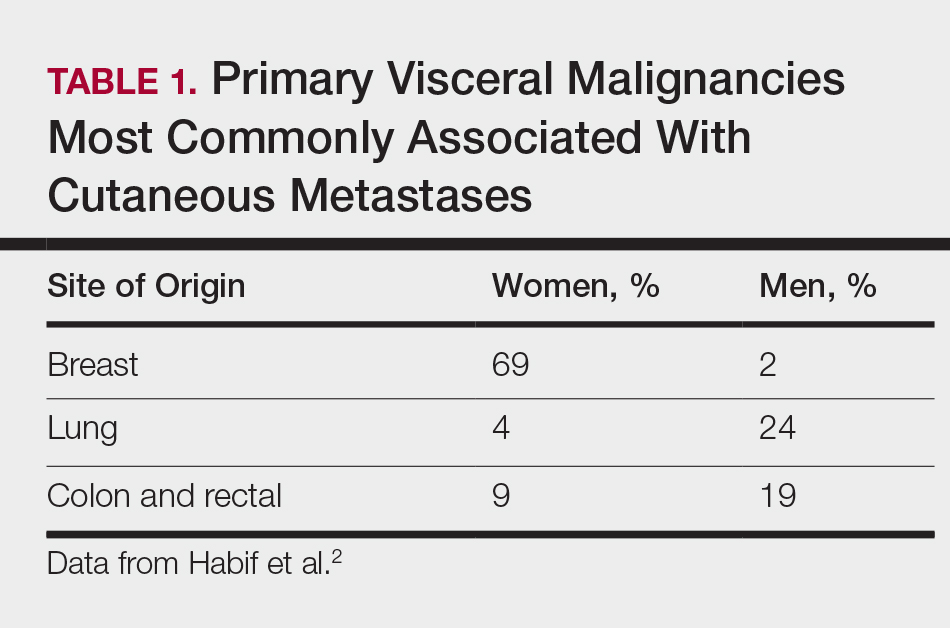

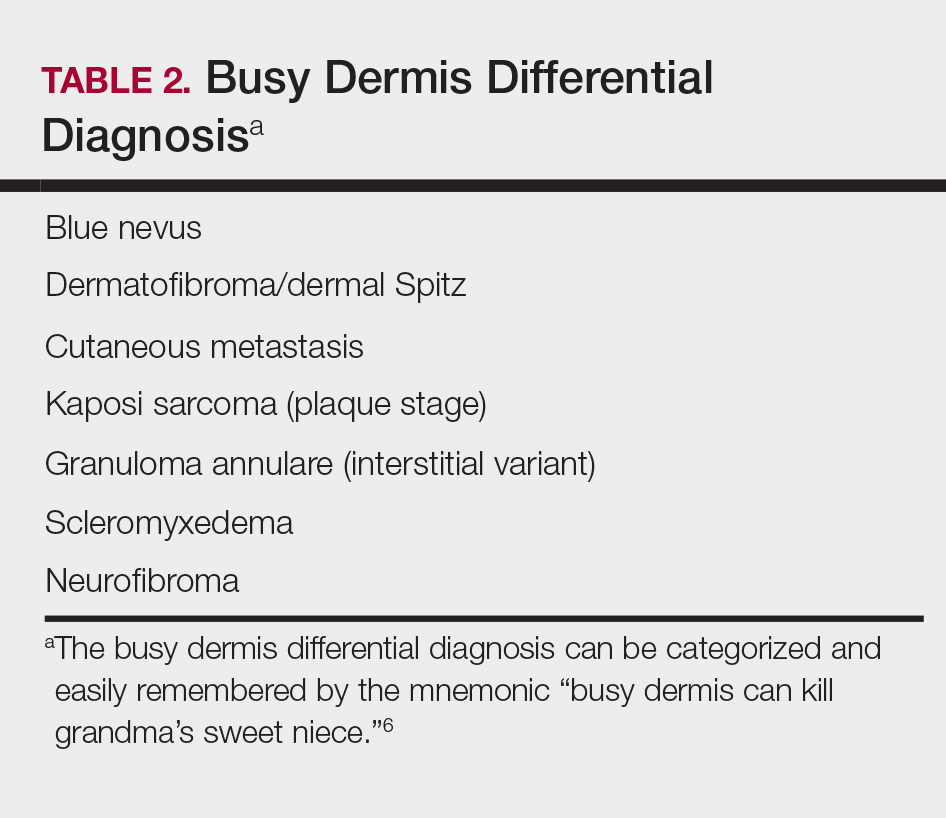

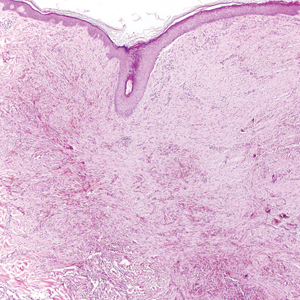

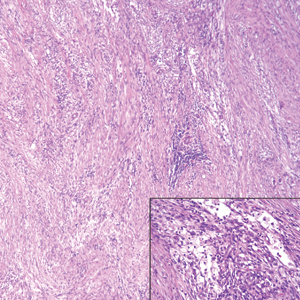

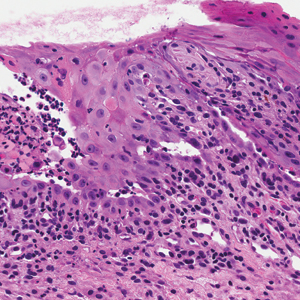

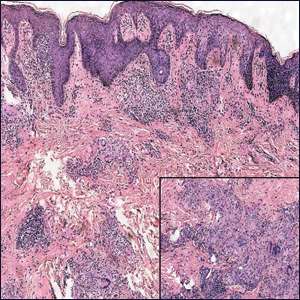

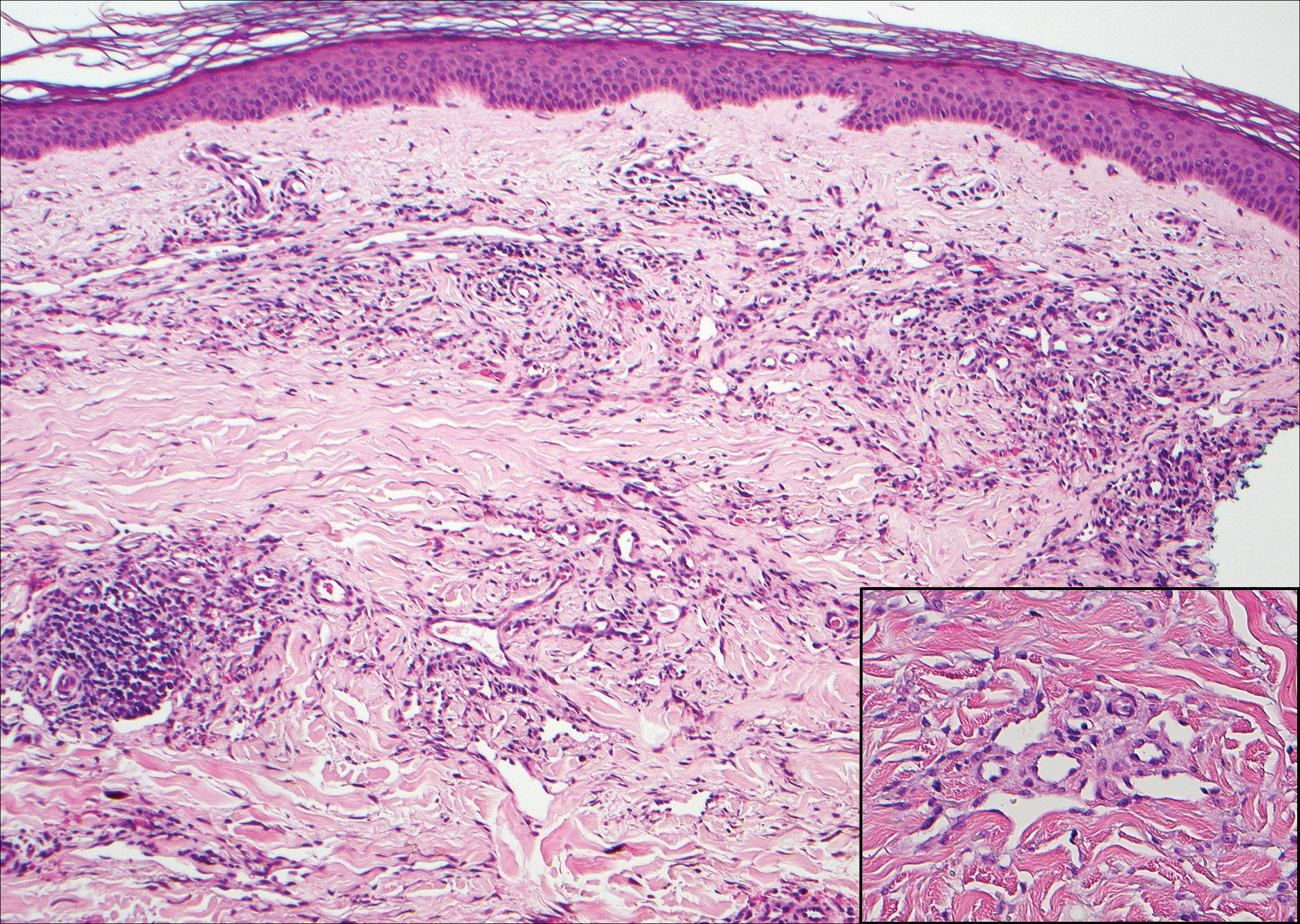

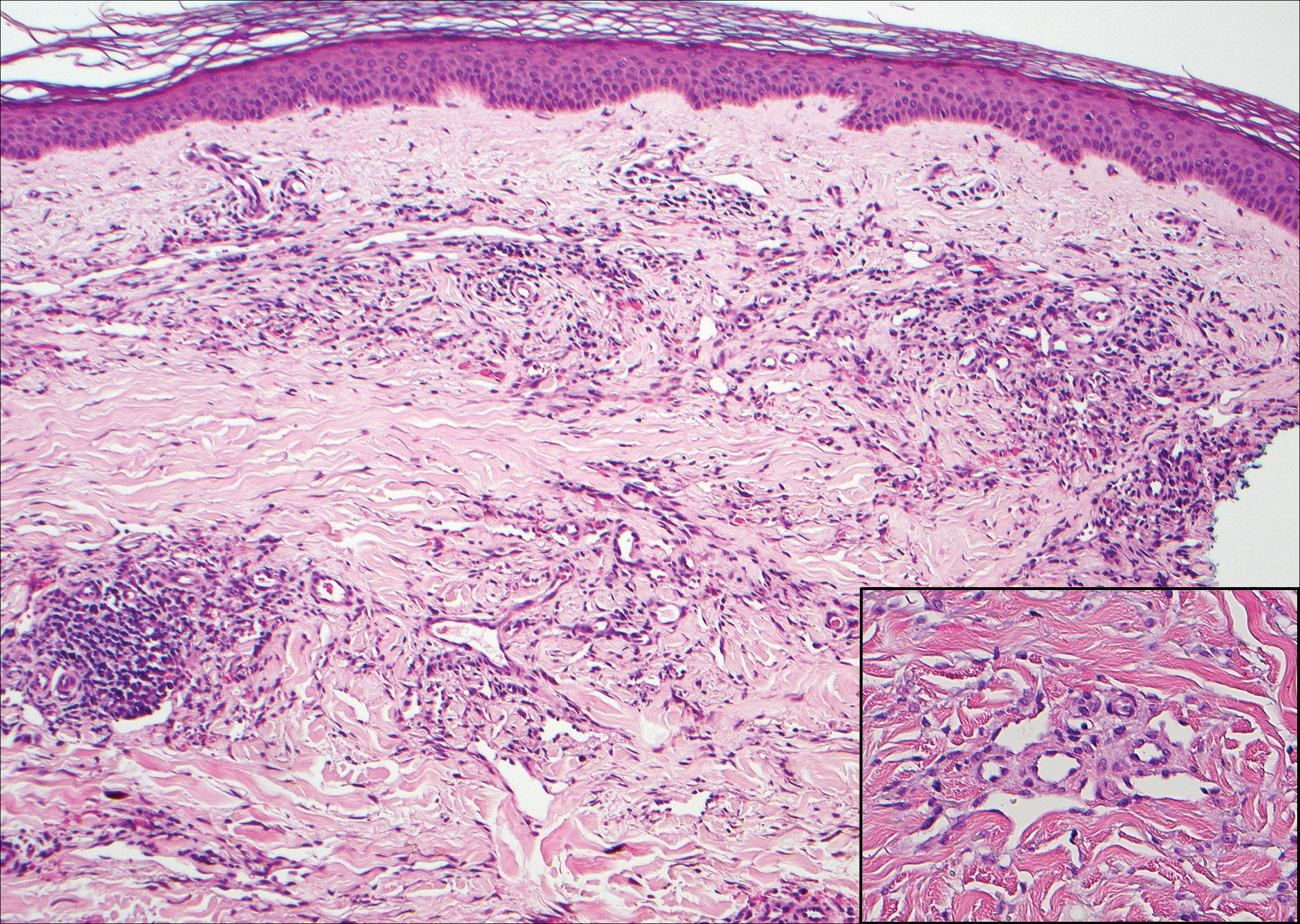

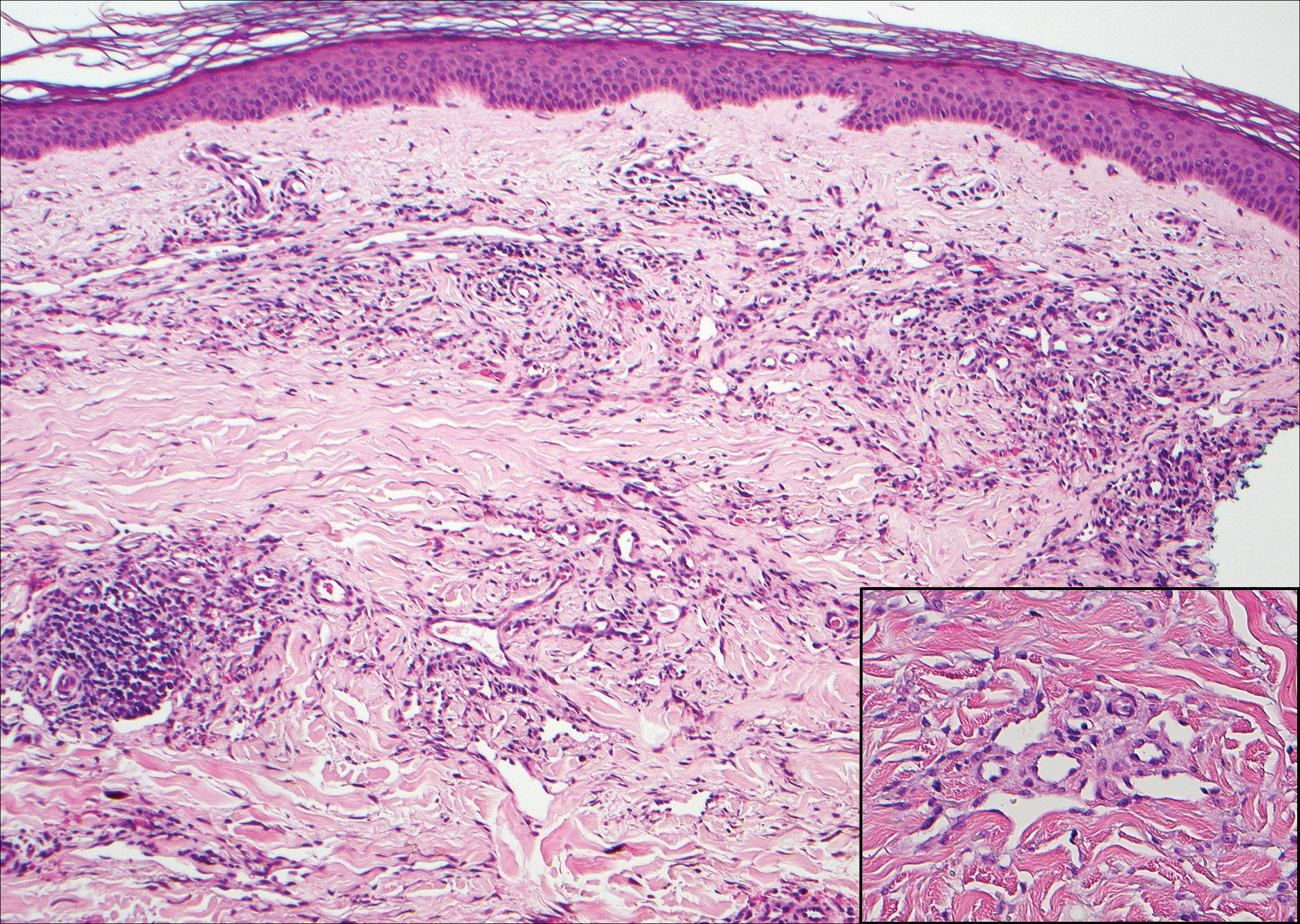

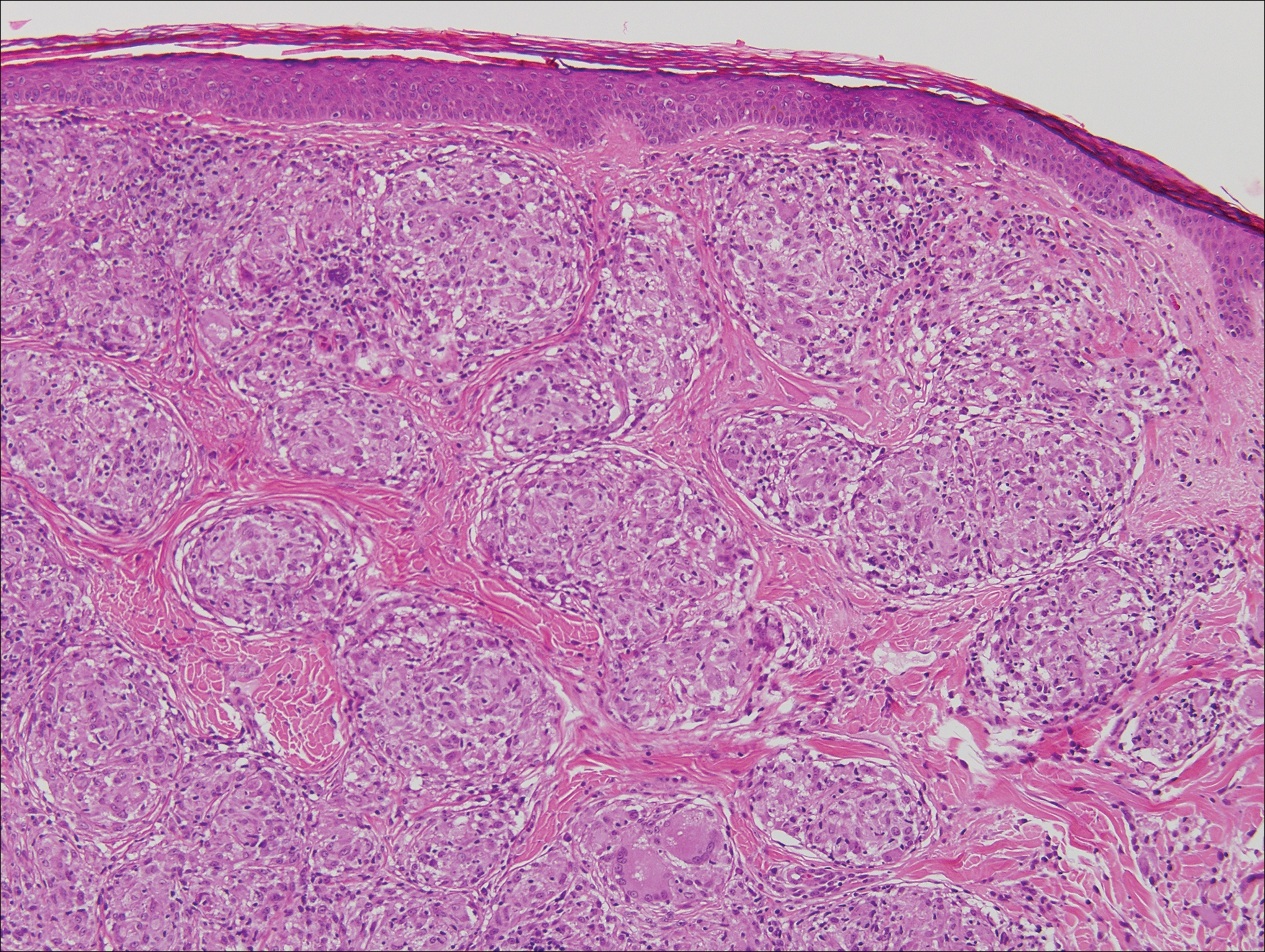

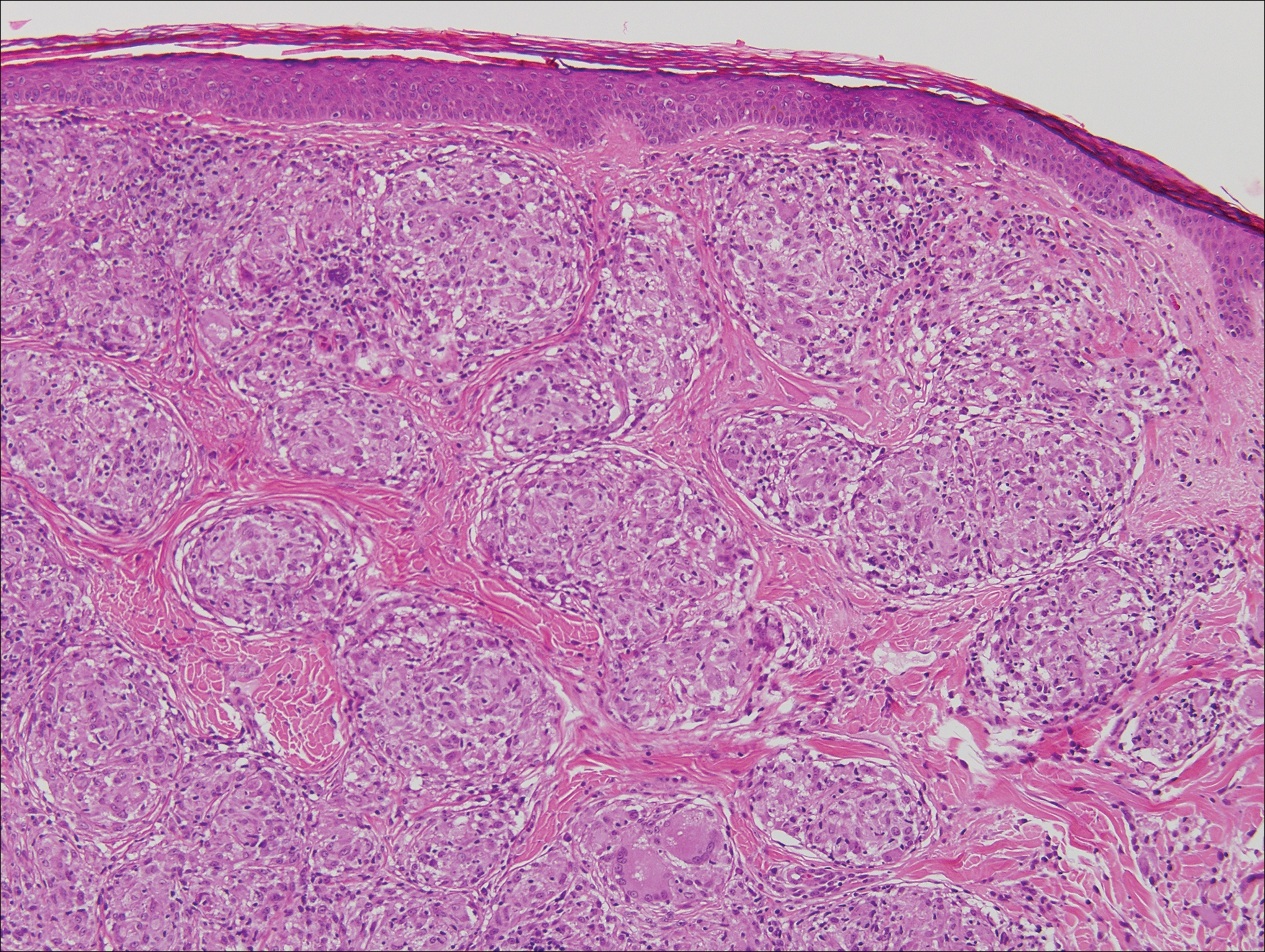

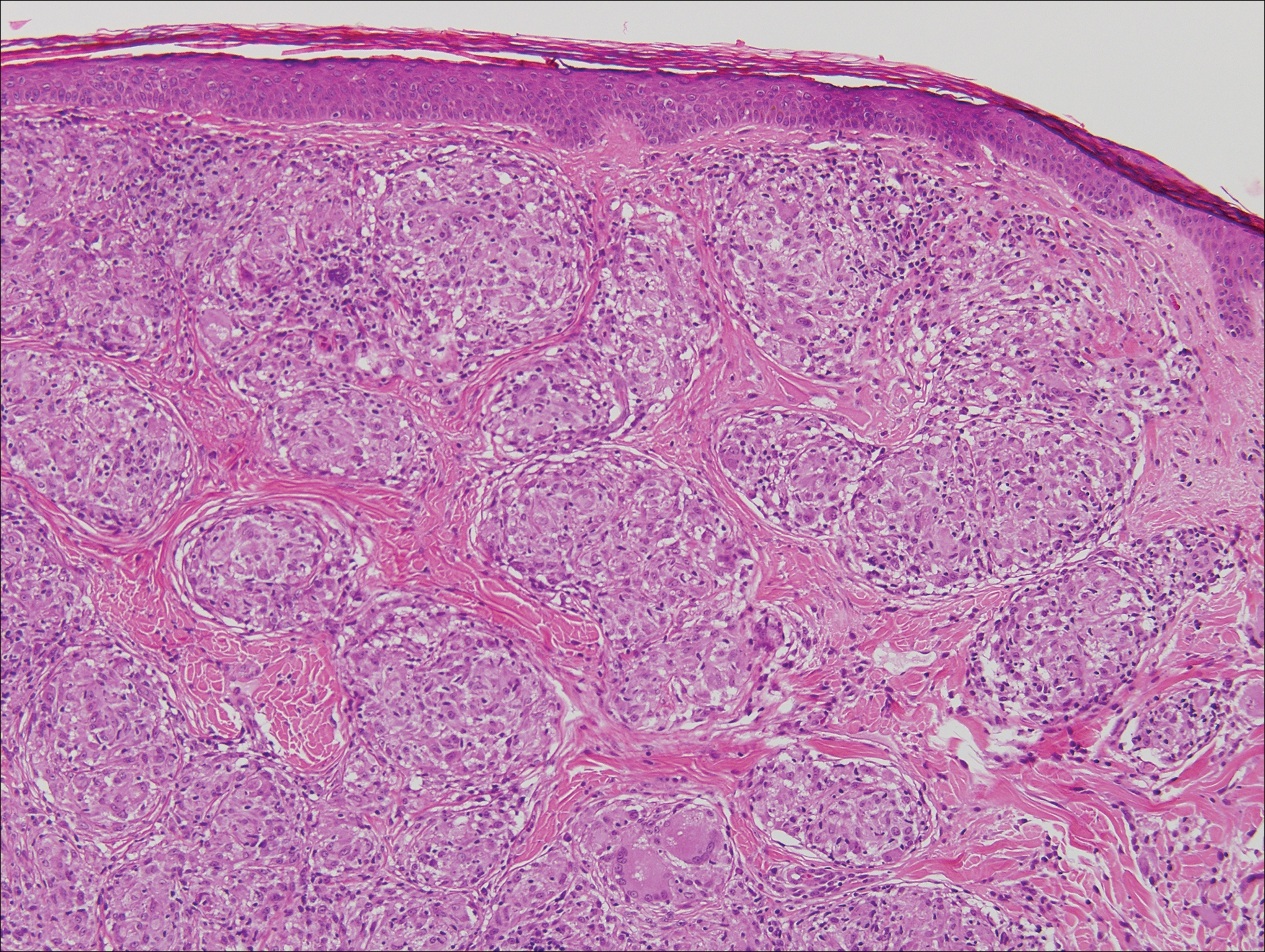

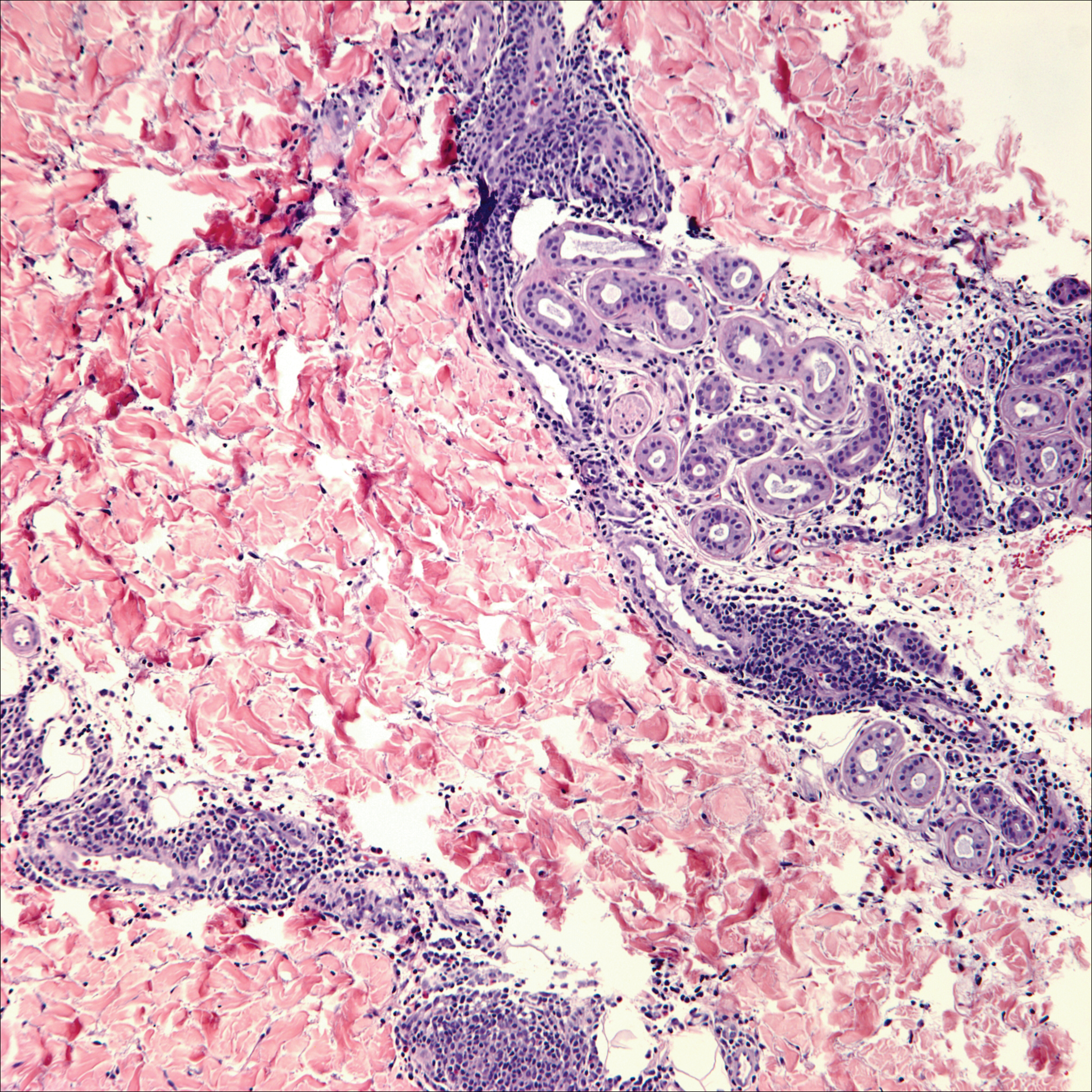

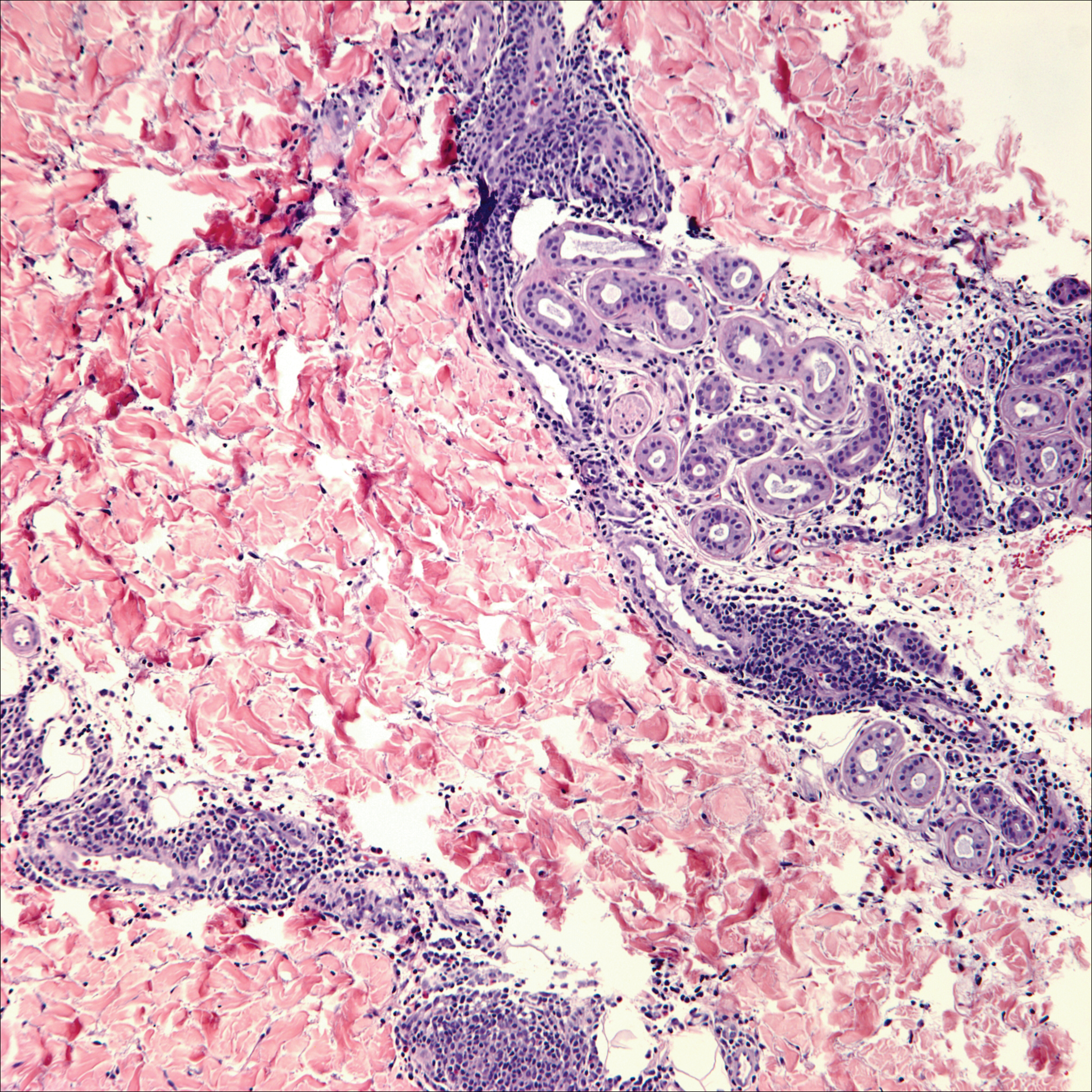

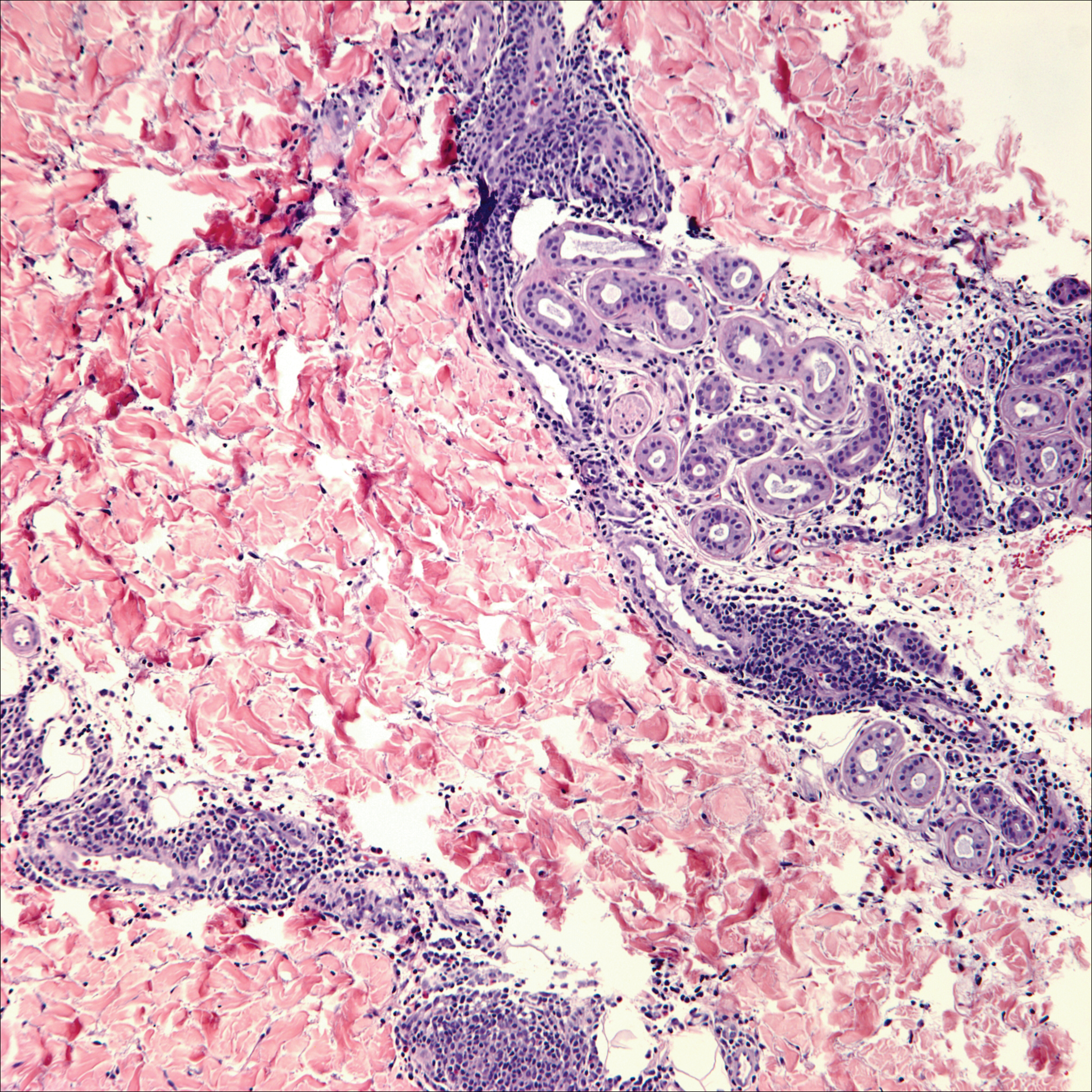

Cutaneous metastases (CMs) can present in an otherwise asymptomatic patient as the only sign of an underlying disease process. In women, the most common cause of CM is breast carcinoma.1-3 Cutaneous metastases are found in approximately 25% of all patients with breast carcinoma,1 and breast carcinomas represent approximately 69% of all CMs found in women (Table 1).2 Cutaneous metastatic breast carcinoma (CMBC) is associated with a poor prognosis with a mean survival of approximately 6 months at the time of diagnosis.1,3 It commonly presents as a collection of flesh-colored, firm, asymptomatic, and rapidly appearing papules and nodules that can resemble cysts or fibrous tumors.1,3,4 They typically are located on the chest wall or abdomen near the site of the underlying malignancy.1-3 The histologic features of CMBC can include hyperchromatic tumor cells infiltrating between the collagen fibers in a characteristic single file manner,3,5 giving the appearance of a busy dermis, a nonspecific term to describe a focally hypercellular dermis at low-power magnification (Table 2).5,6 Cords and clusters of atypical cells with intracytoplasmic vacuoles or well-developed ducts also can be seen (quiz image [inset]). The carcinoma en cuirasse subtype of CMBC is characterized by a fibrotic scarlike plaque on the chest wall.1,3 If a punch biopsy is obtained, the specimen typically appears rectangular rather than tapered because of the sclerotic dermal collagen.6 In contrast, inflammatory carcinoma (carcinoma erysipelatoides) presents as an erythematous plaque resembling cellulitis due to the lymphatics being congested by tumor cells.3 Immunohistochemistry is a valuable tool in diagnosis. Positive staining is seen with cytokeratin 7, gross cystic disease fluid protein-15, mammaglobin, and GATA-3.1,3,6

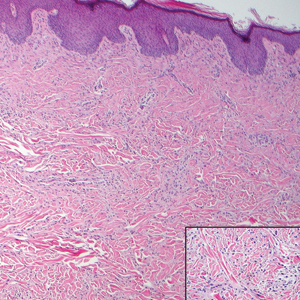

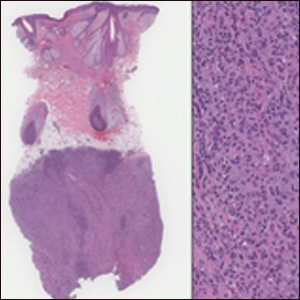

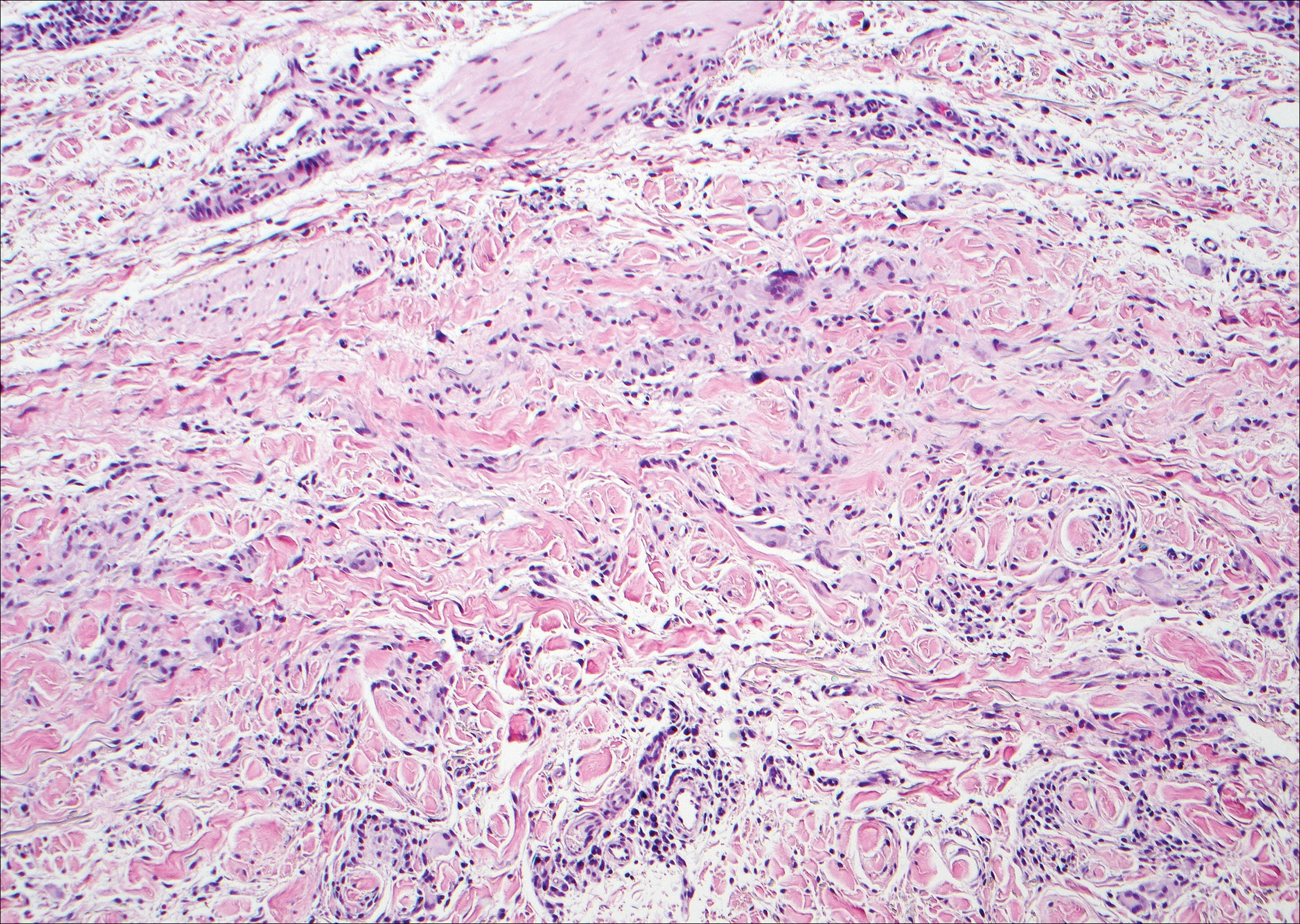

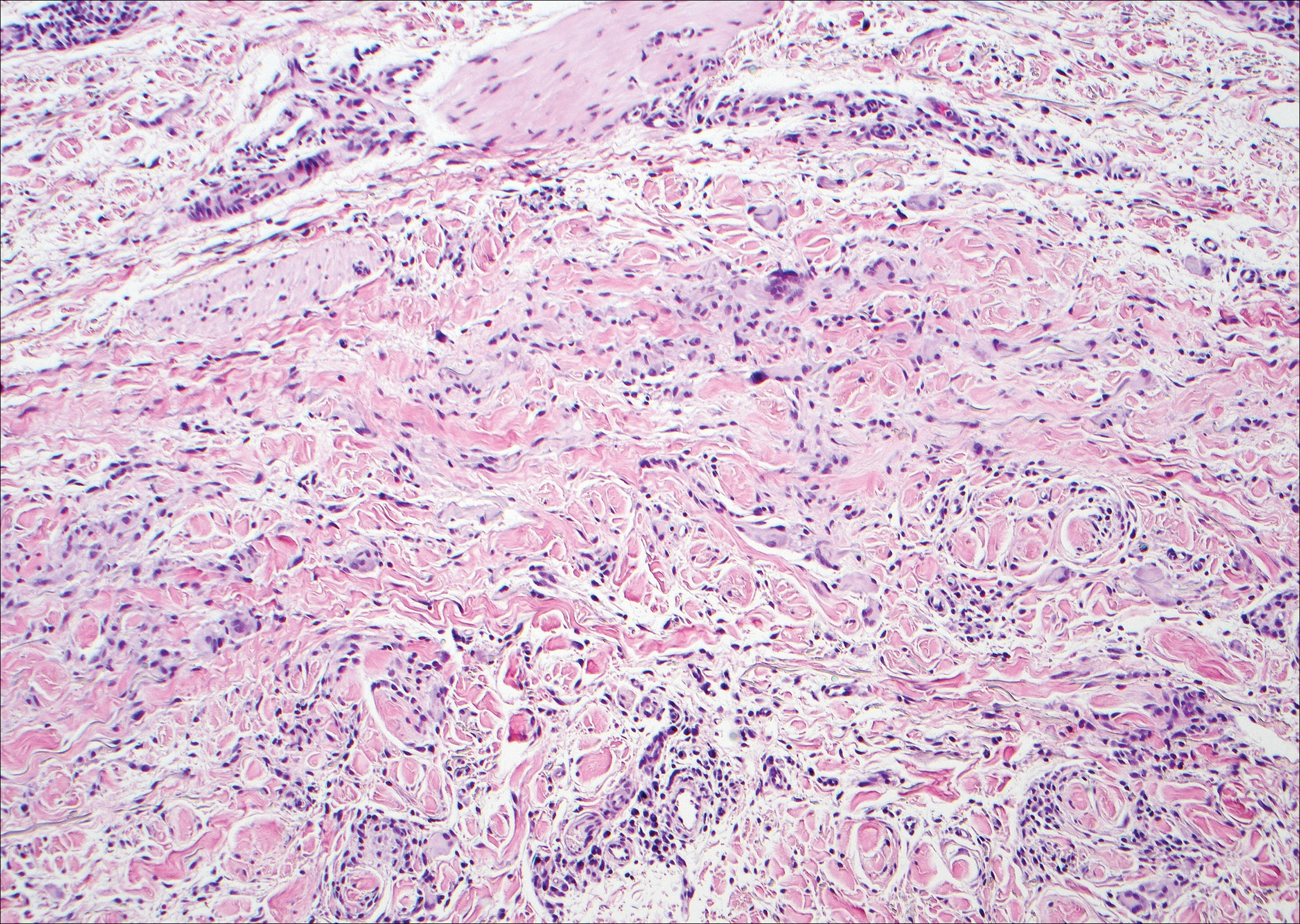

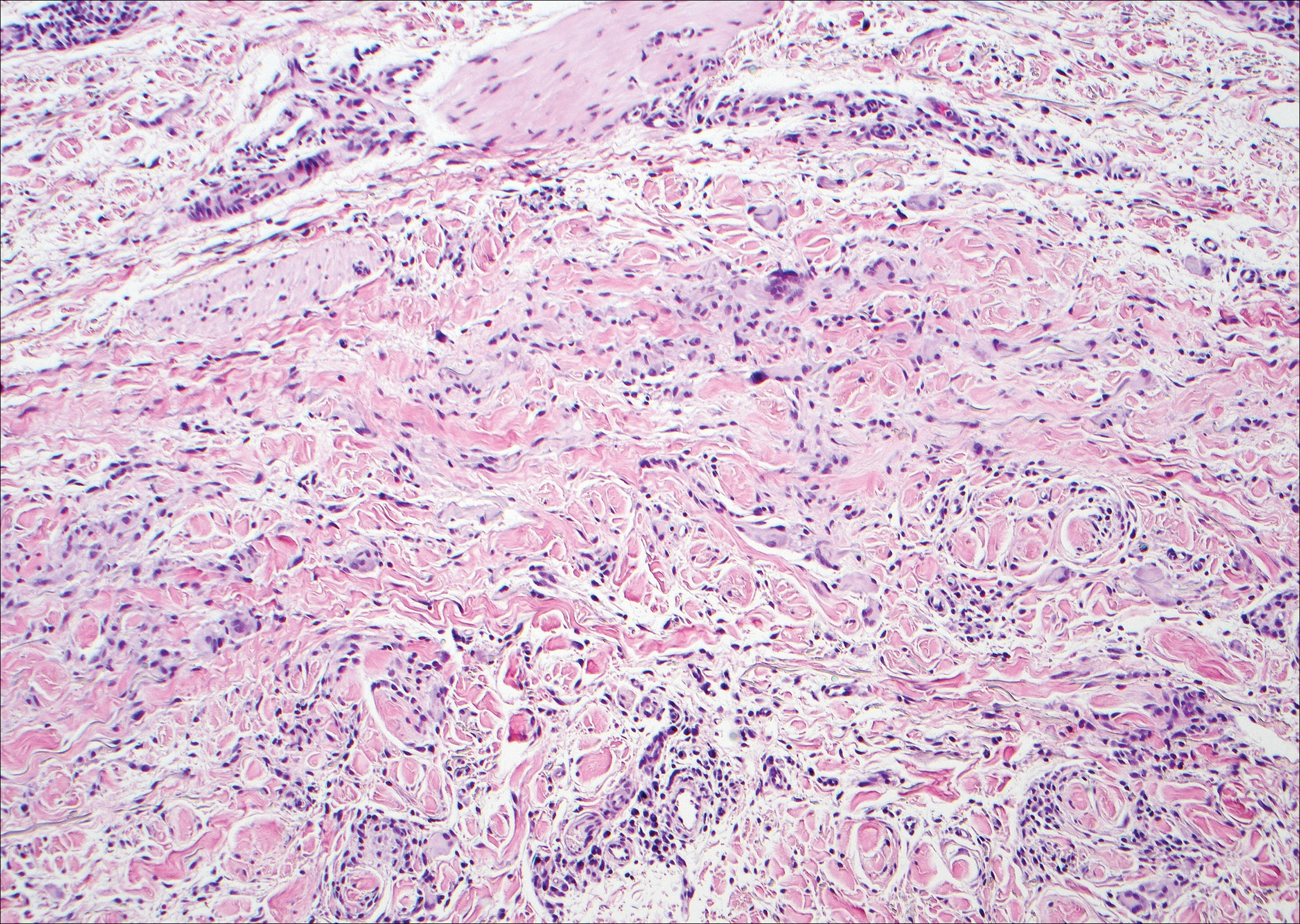

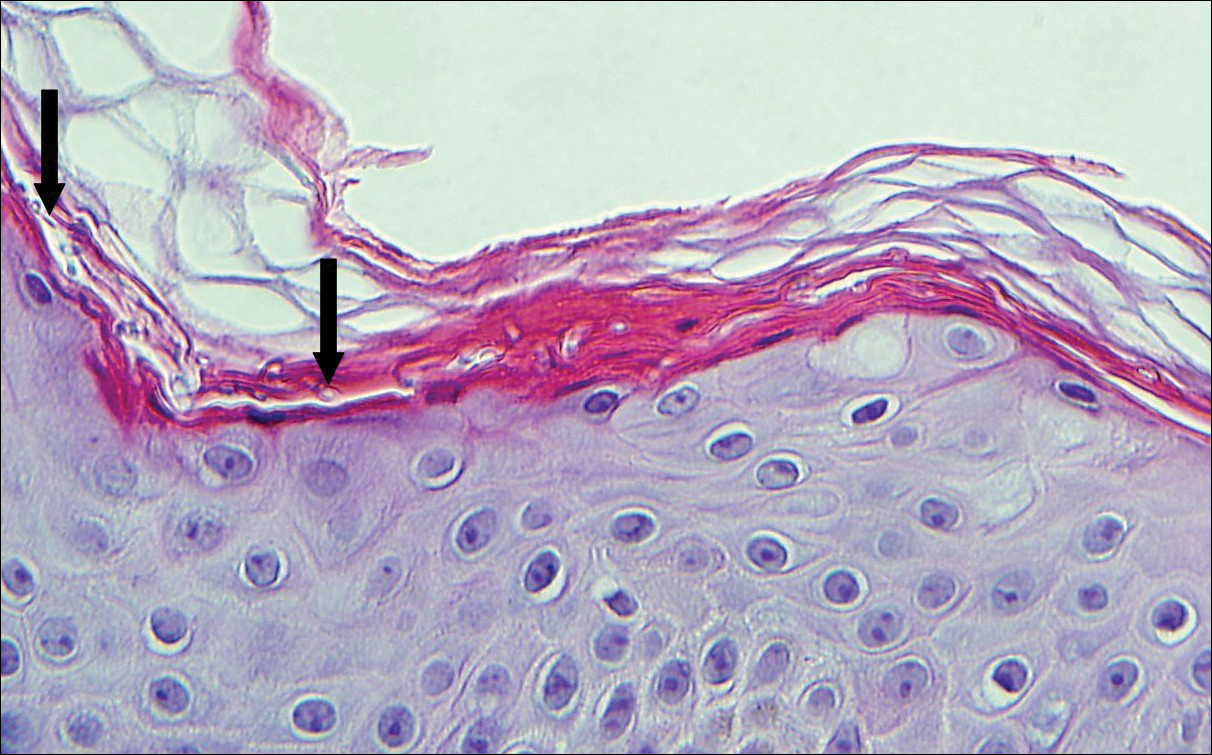

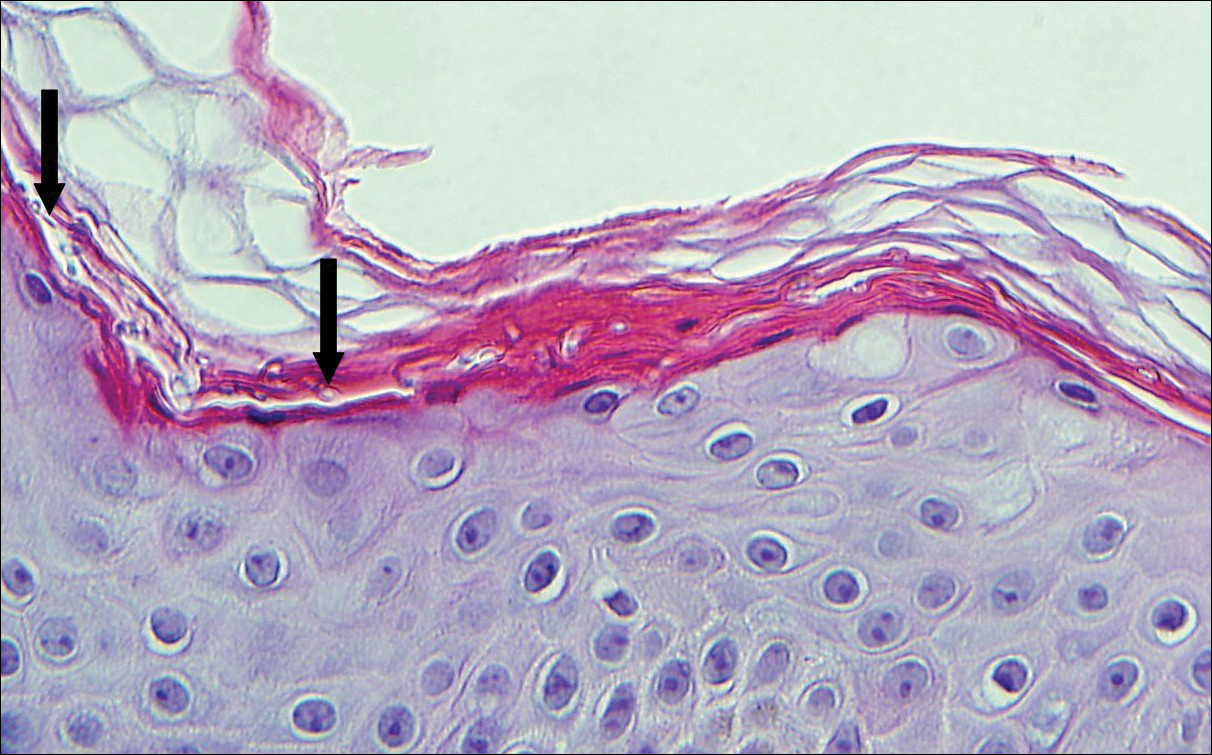

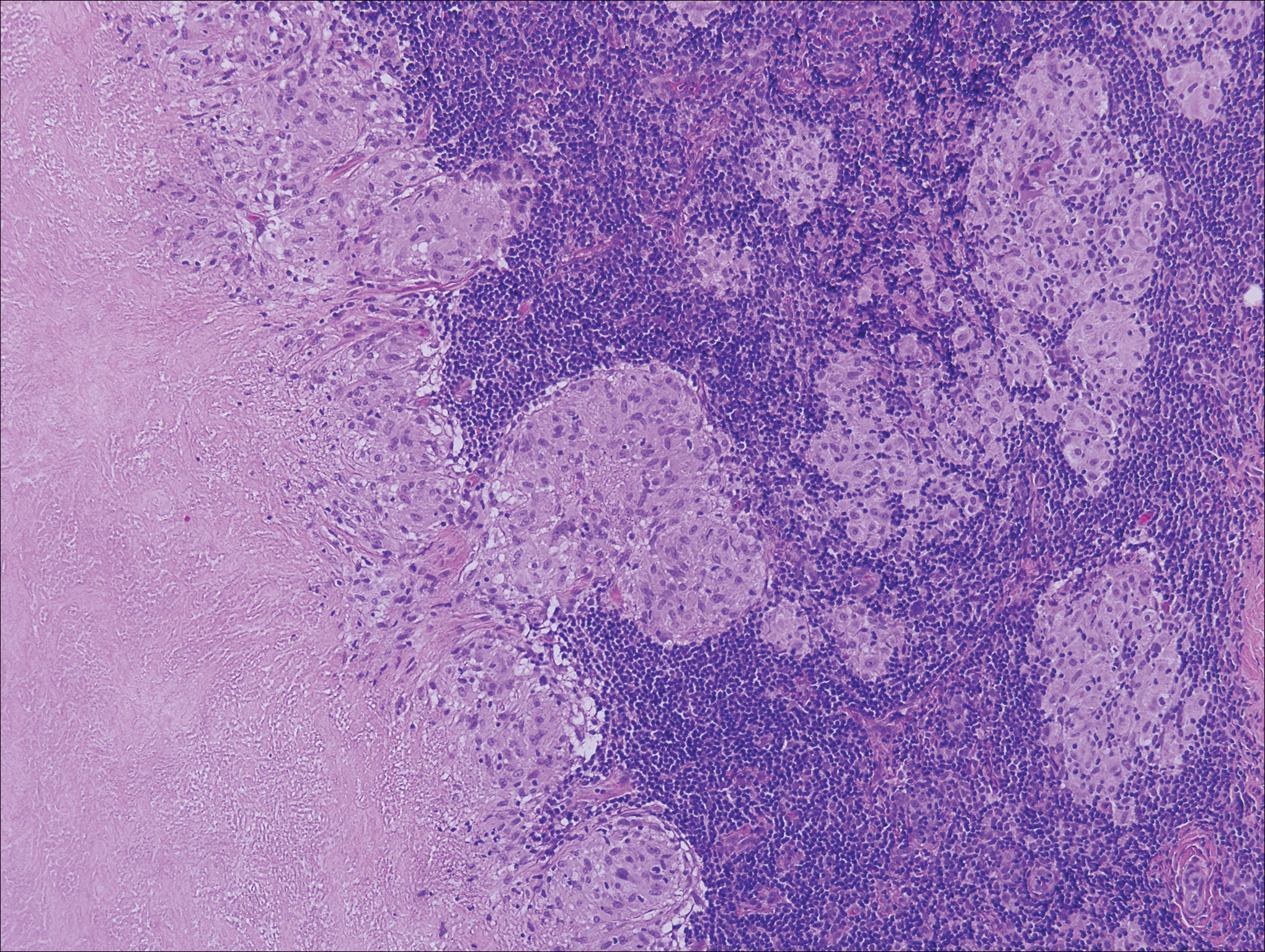

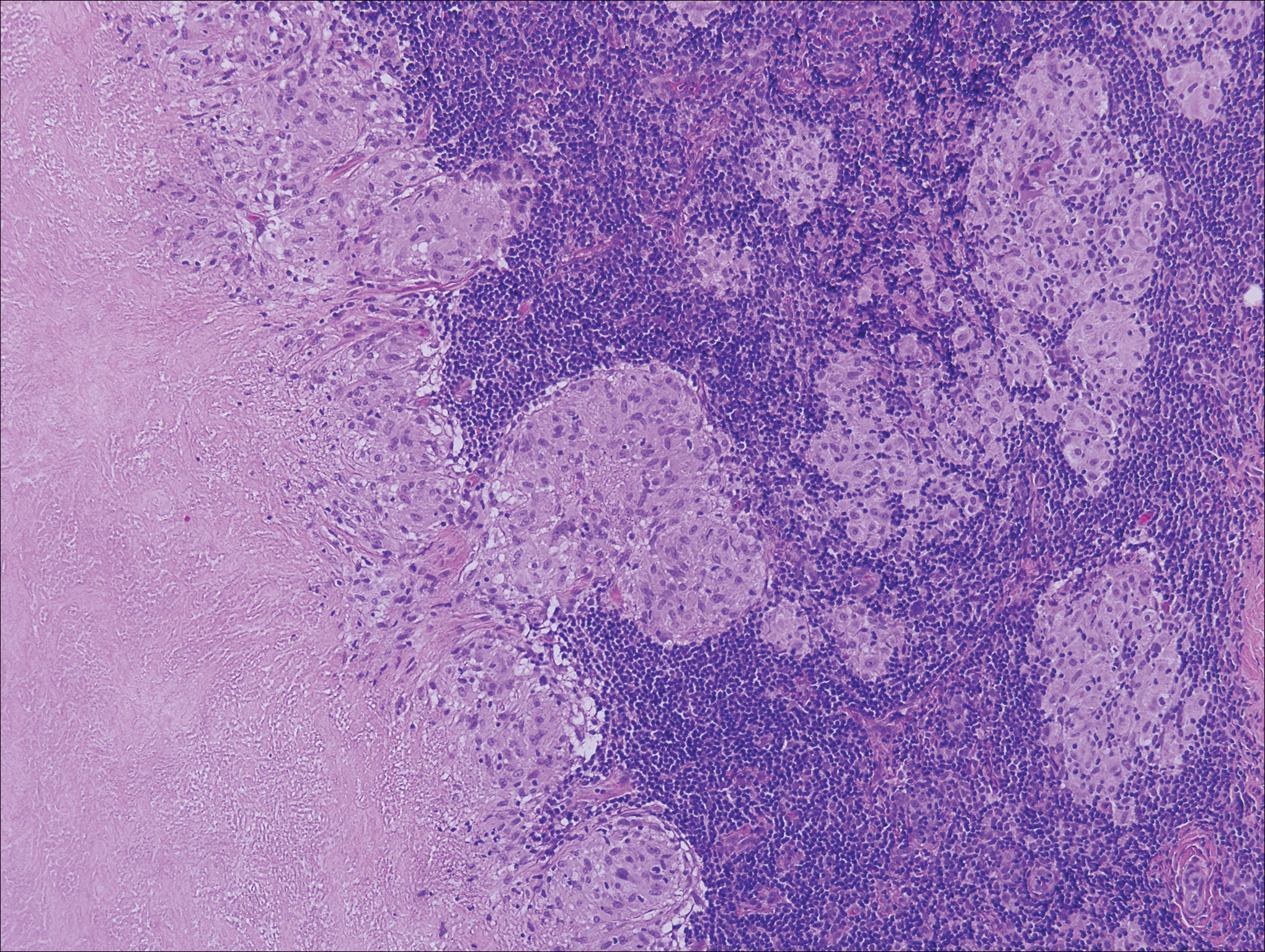

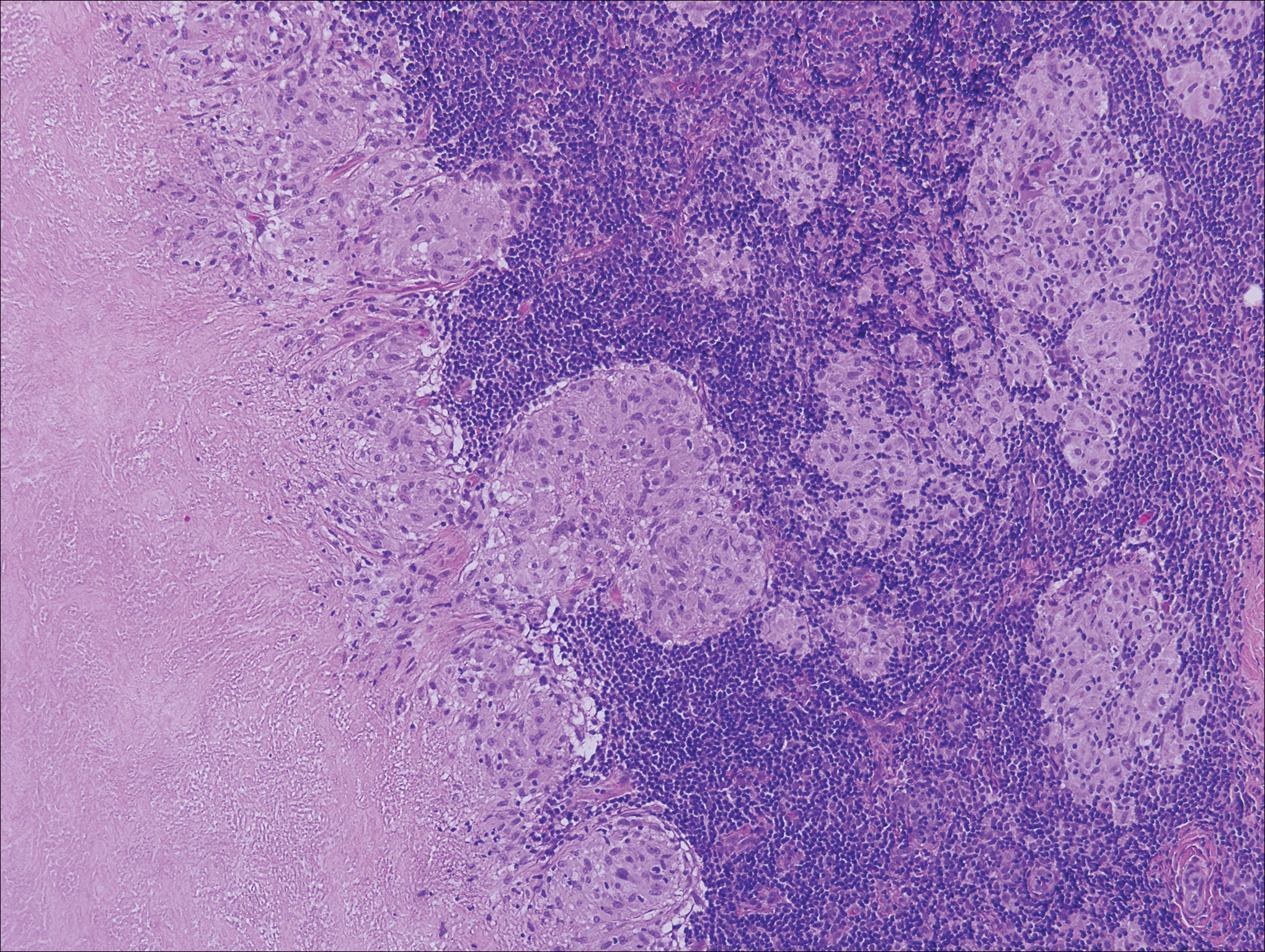

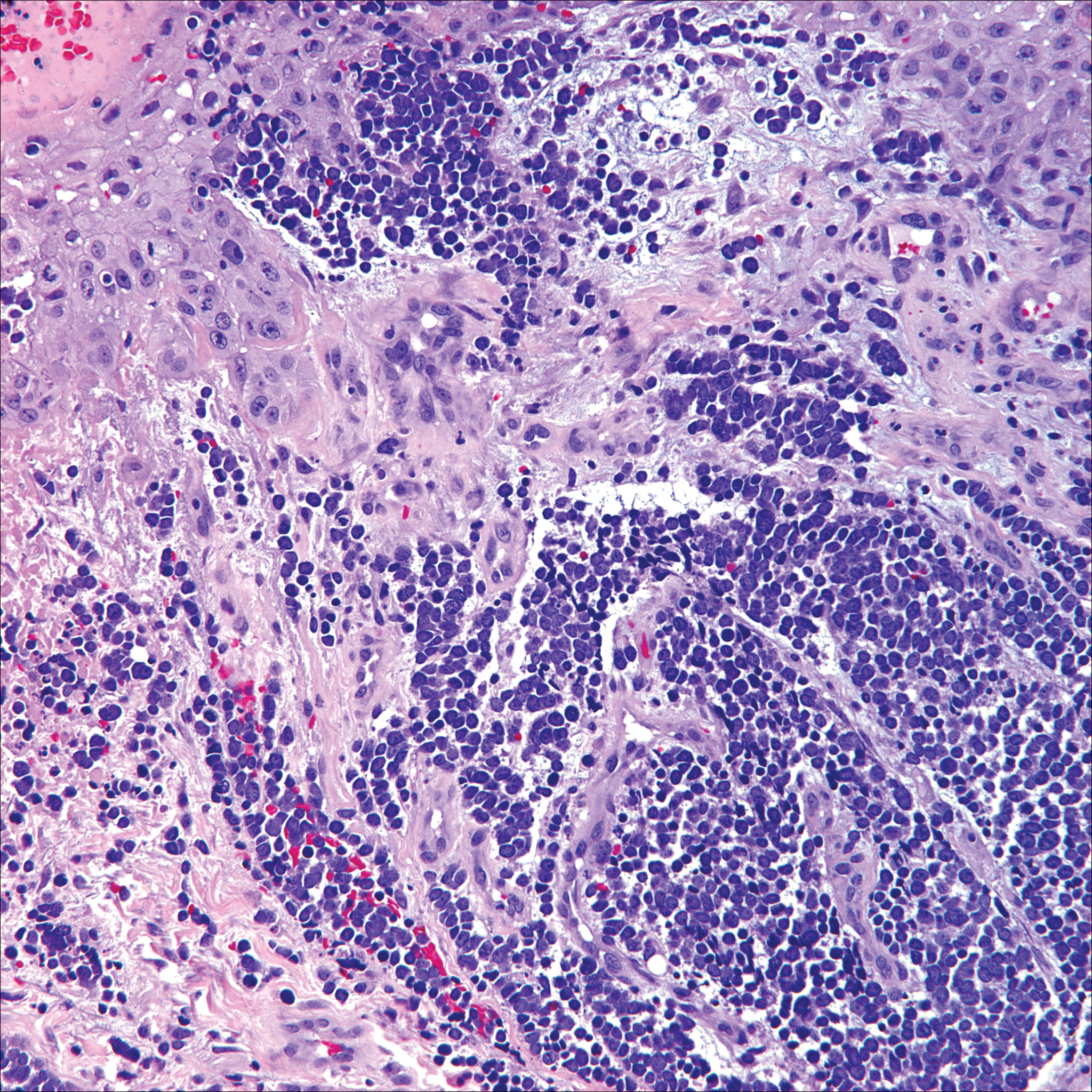

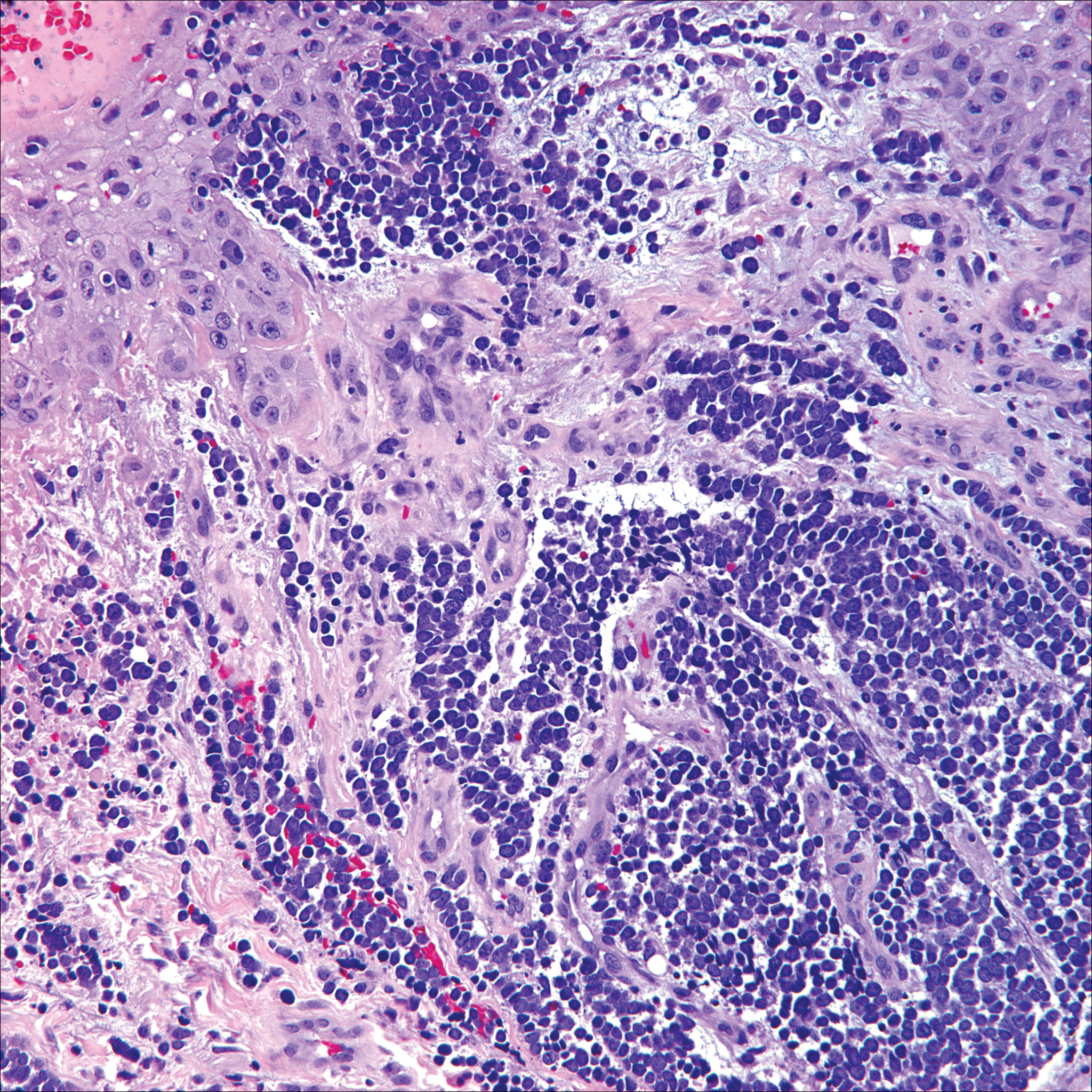

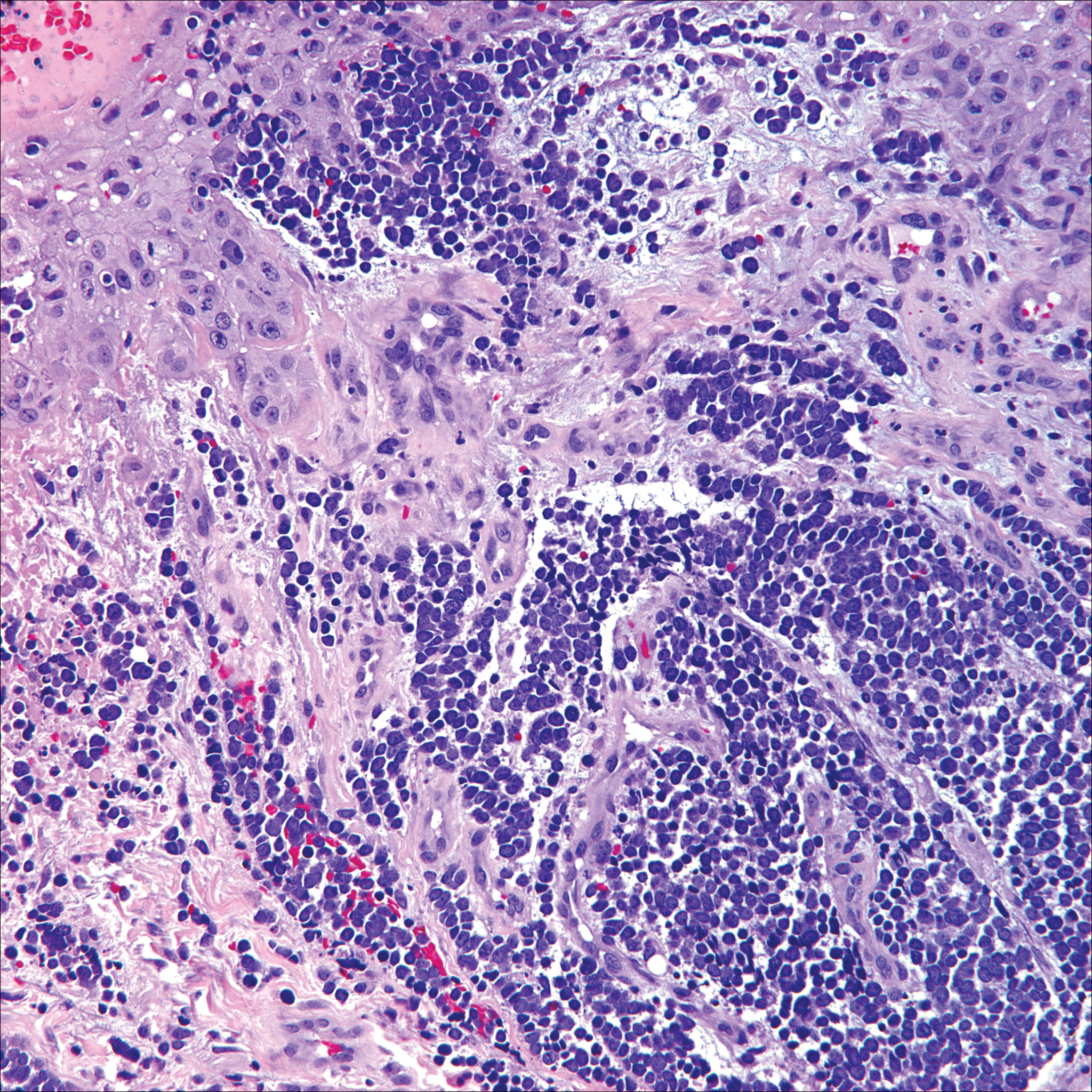

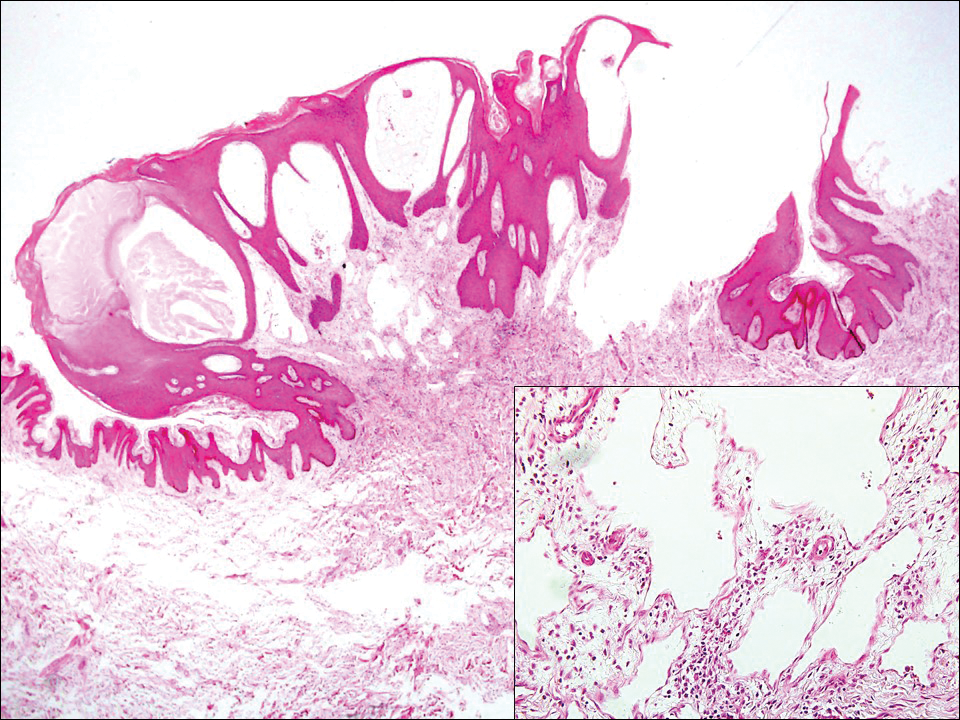

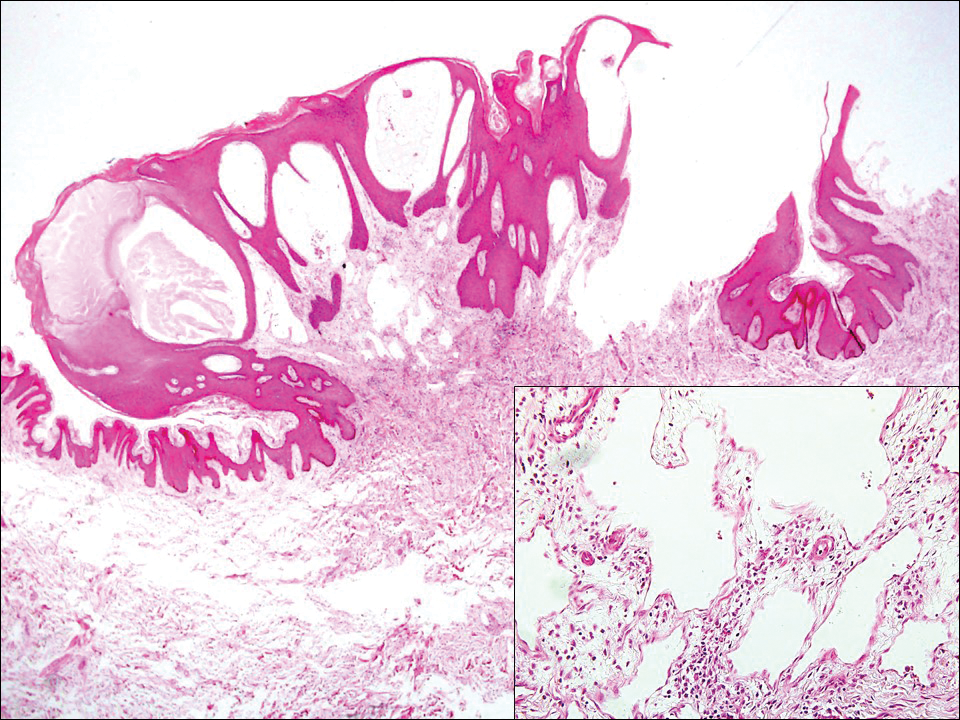

Kaposi sarcoma (KS) is a low-grade endothelial malignancy associated with human herpesvirus 8.3,4 Kaposi sarcoma can be divided into 4 main subtypes: classic KS, African KS, AIDS-related KS, and immunosuppression-associated KS that occurs in patients with diseases such as human immunodeficiency virus. The cutaneous lesions are similar between subtypes and present as dark reddish purple macules that may enlarge or become nodular lesions.3,4 Histologically, 3 distinct stages of progression are described: patch, plaque, and tumor. The plaque stage has the appearance of a busy dermis due to the rapid proliferation of vascular structures within the dermis.3,6 A useful histologic feature known as the promontory sign can be seen as the proliferating tumor causes preexisting structures to project into vascular spaces (Figure 1).6 Immunohistochemistry for the endothelial and lymphatic markers CD31 and D2-40, respectively, are positive and may aid in the diagnosis.3 Staining for the latent nuclear antigen-1 of human herpesvirus 8 is a highly specific marker used to diagnose KS and can further distinguish it from the other busy dermis lesions.3

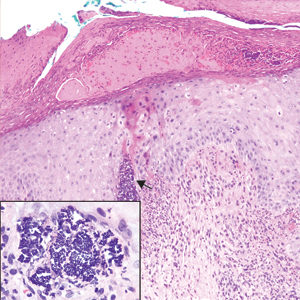

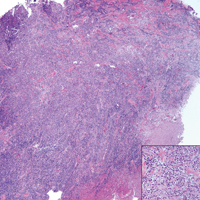

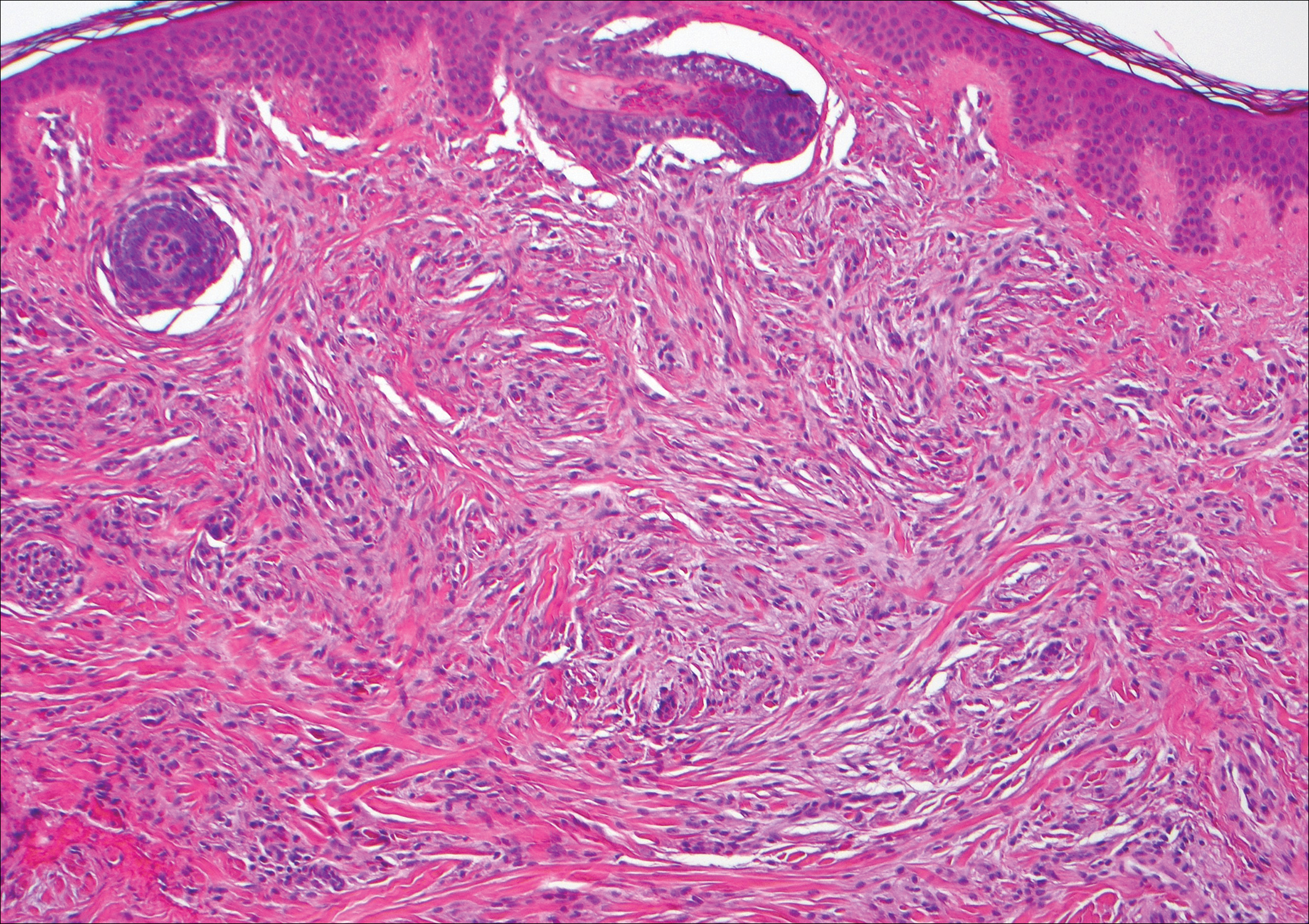

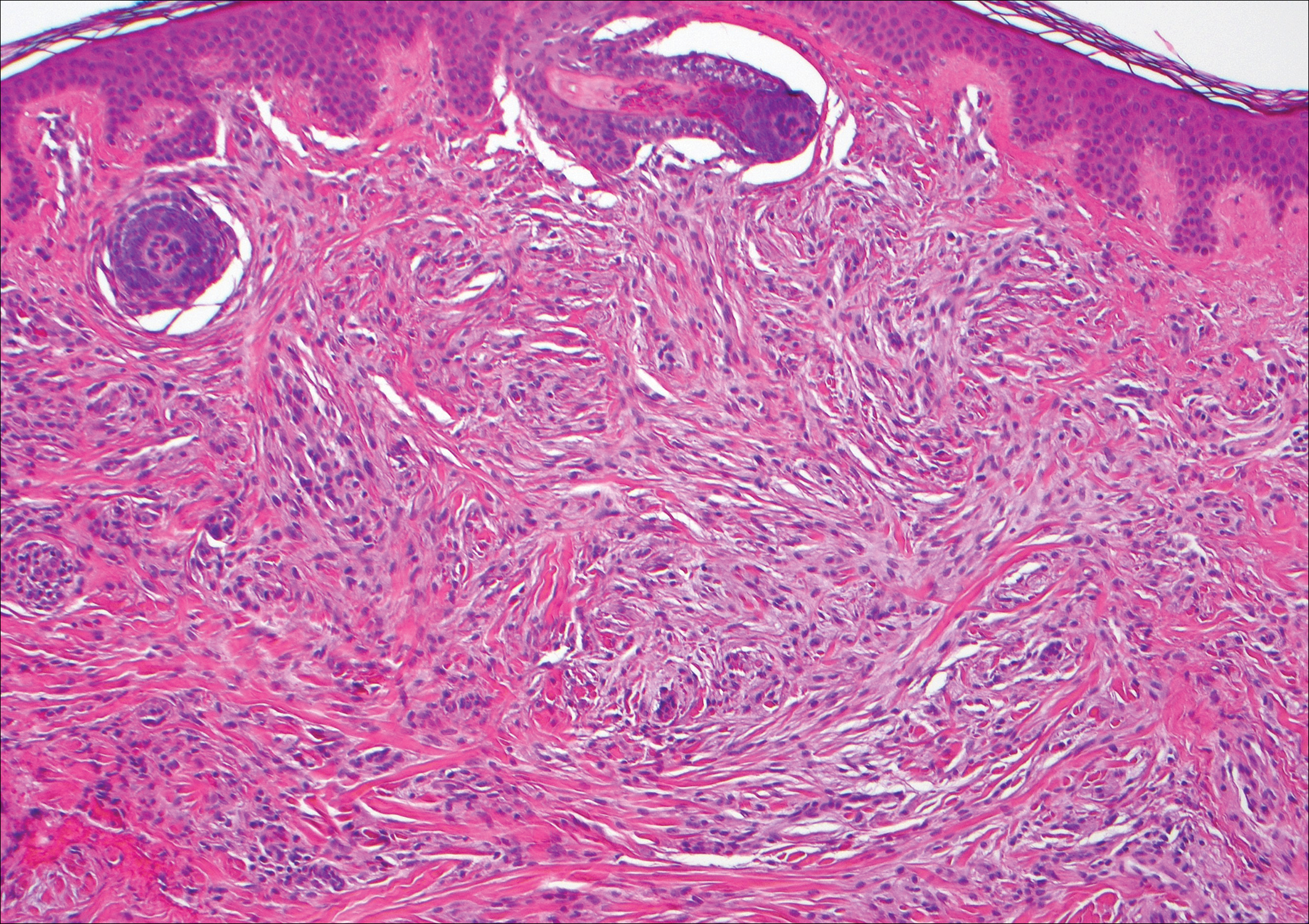

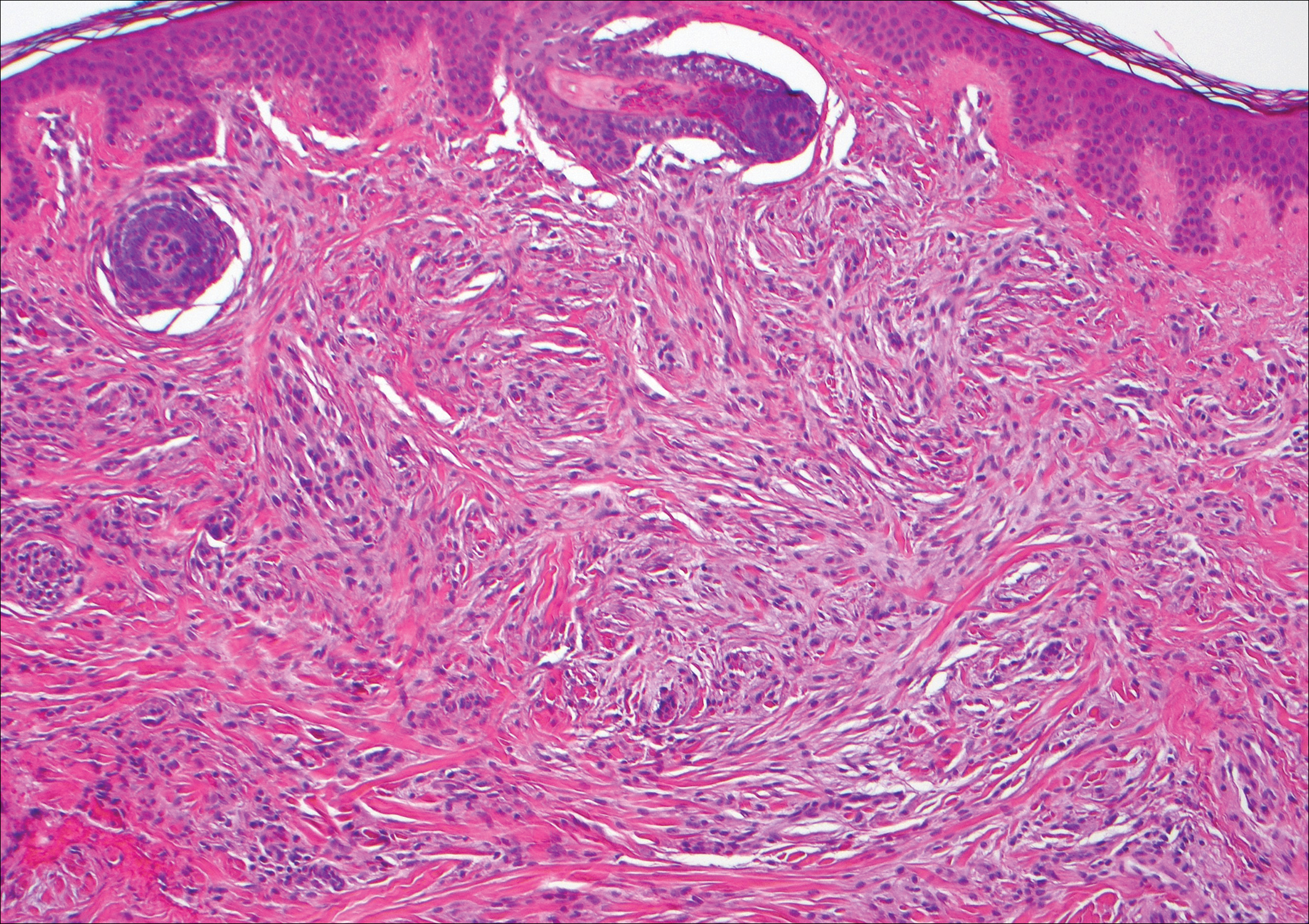

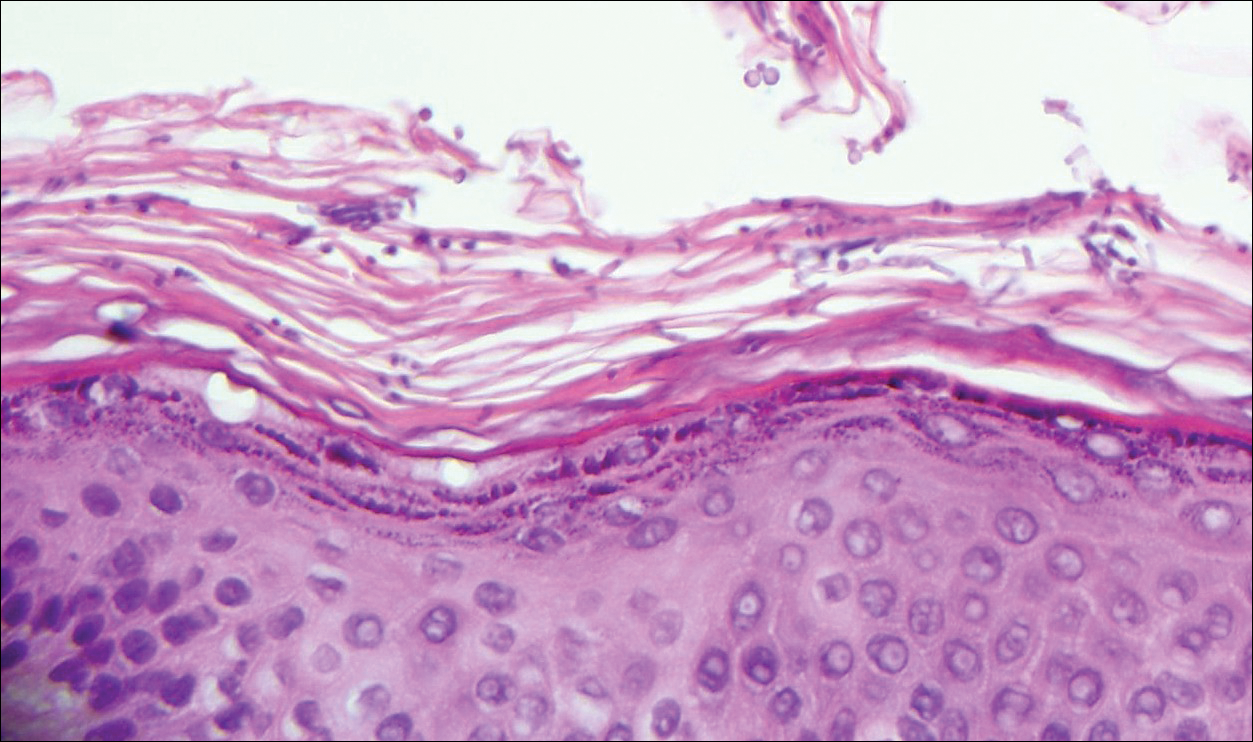

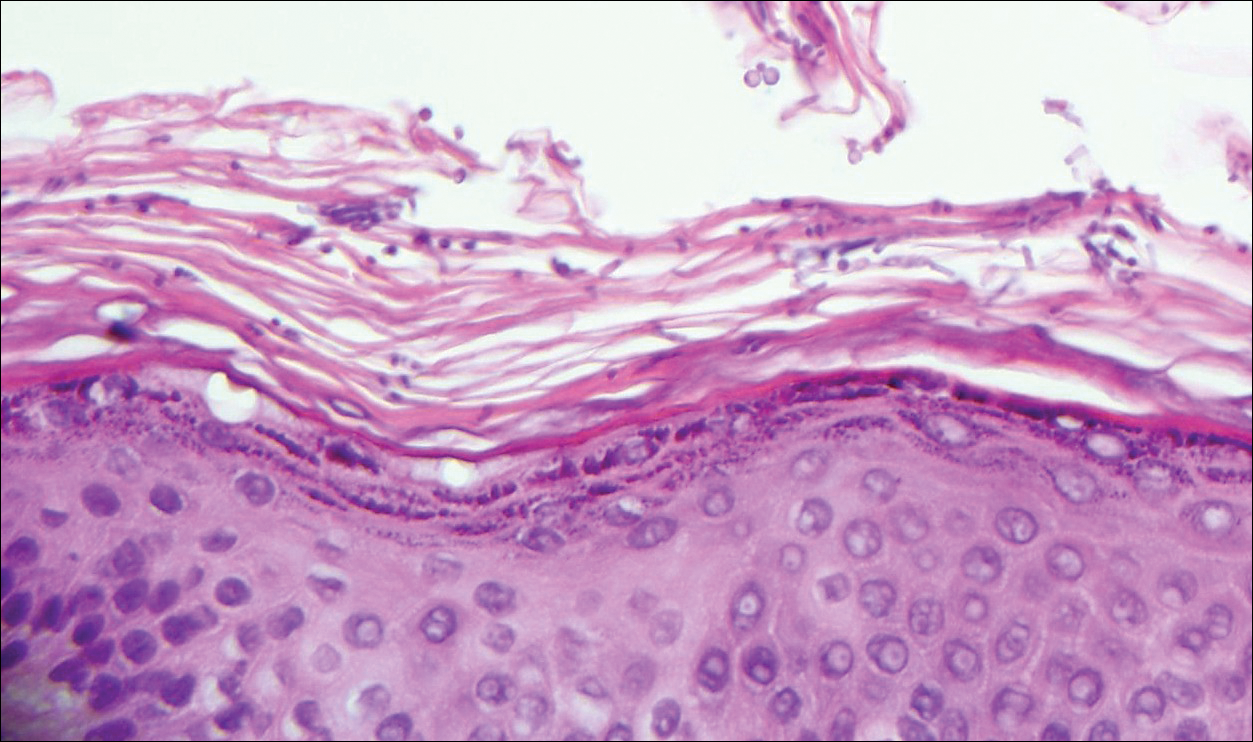

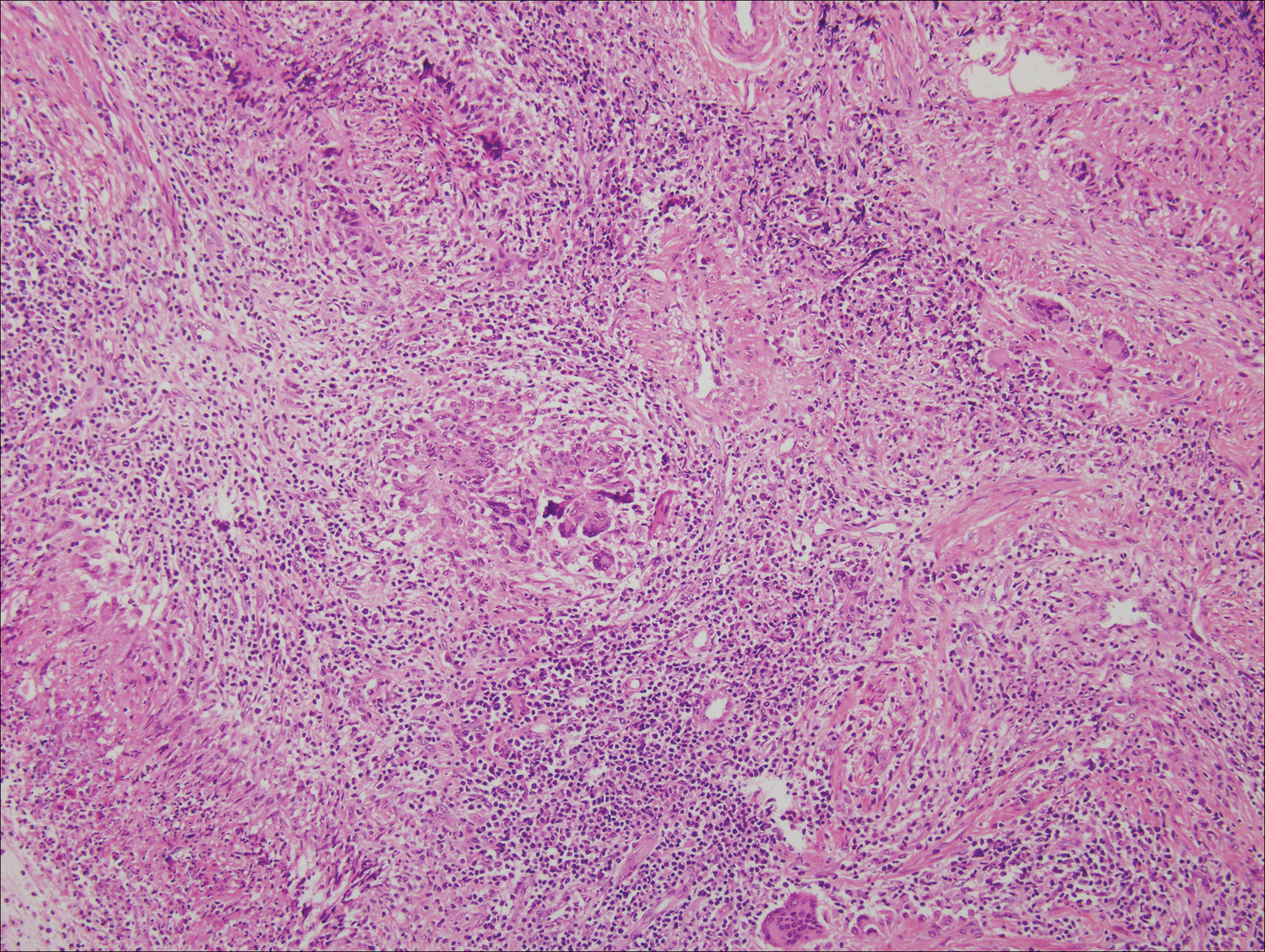

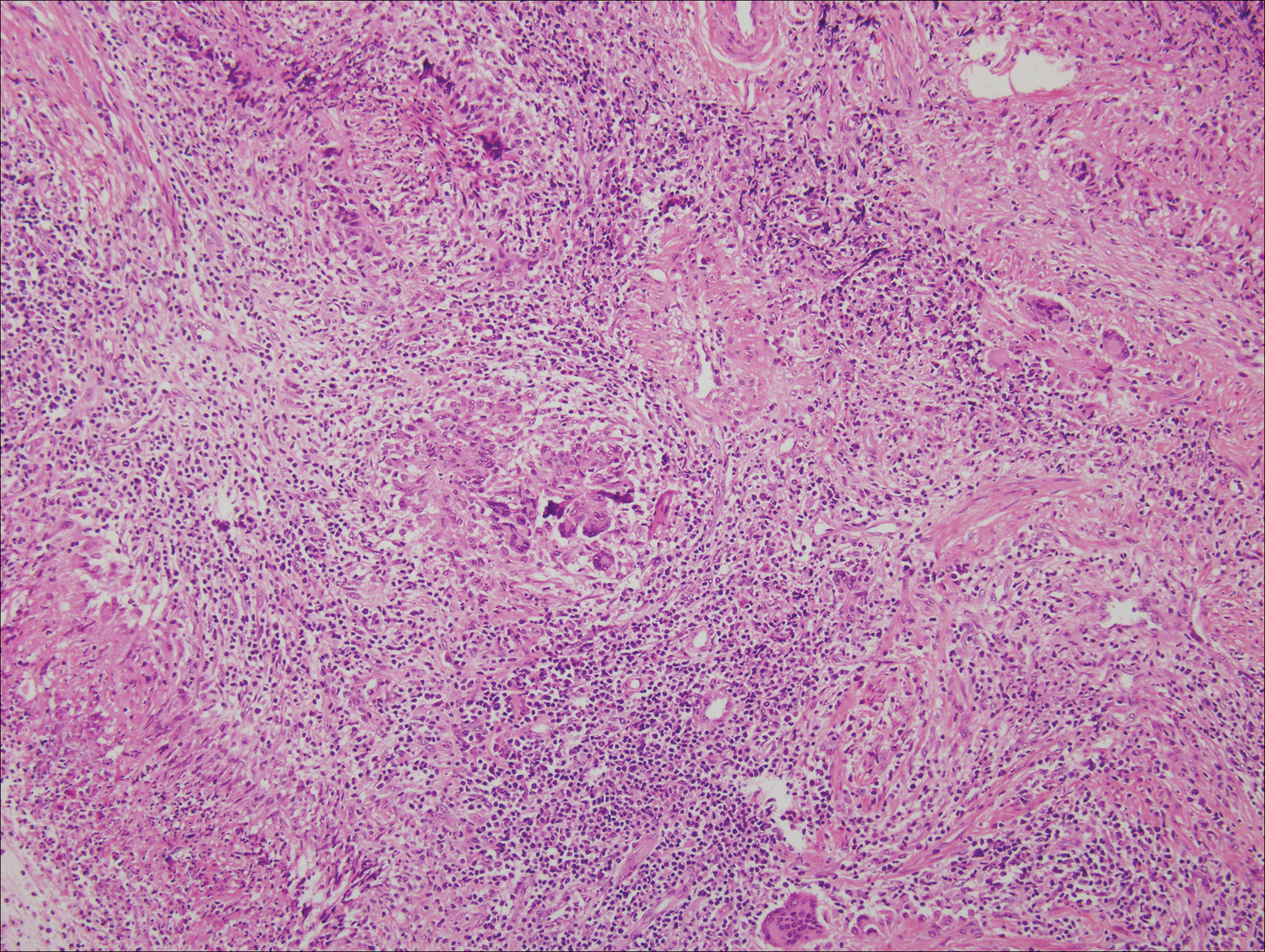

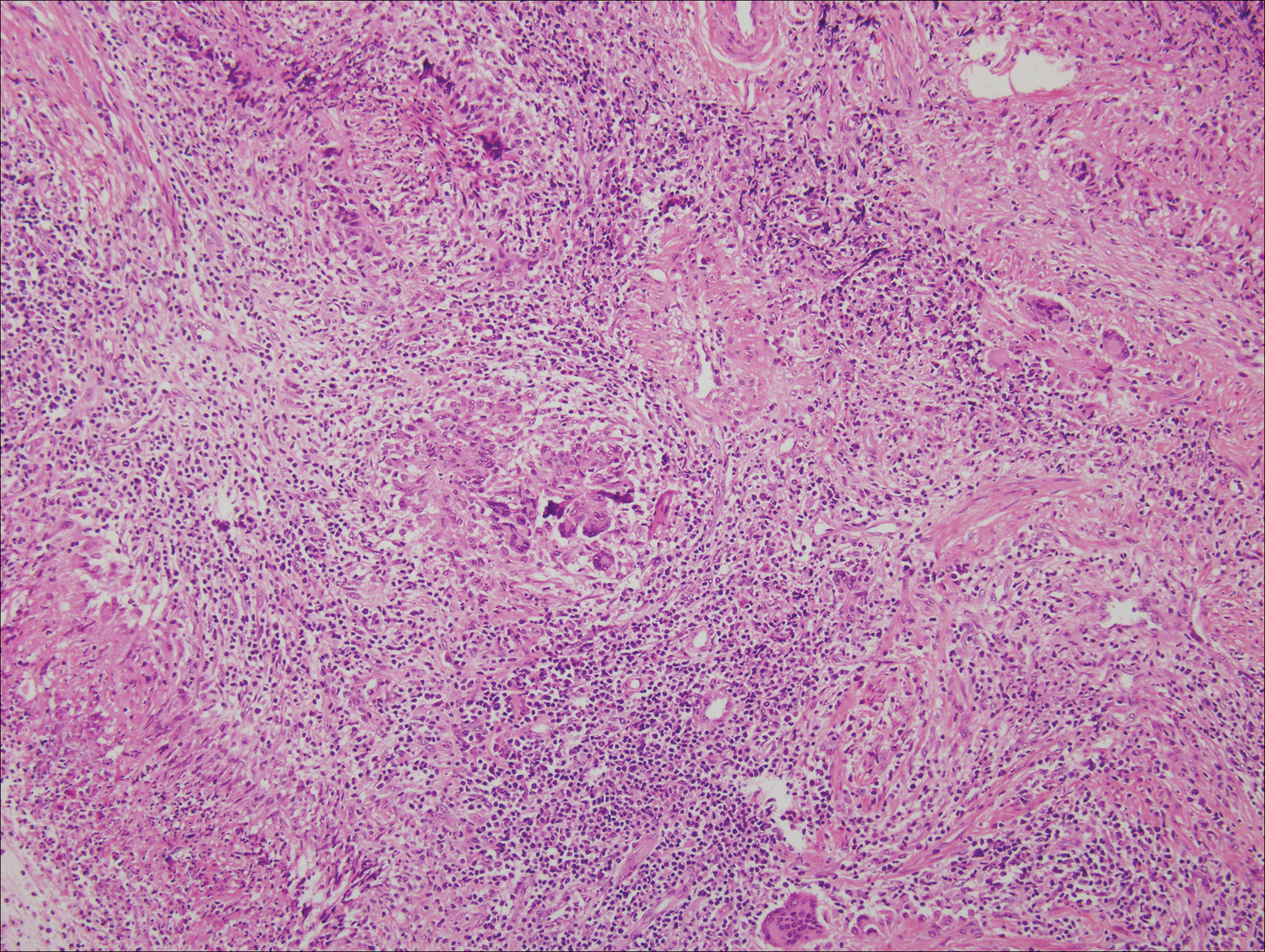

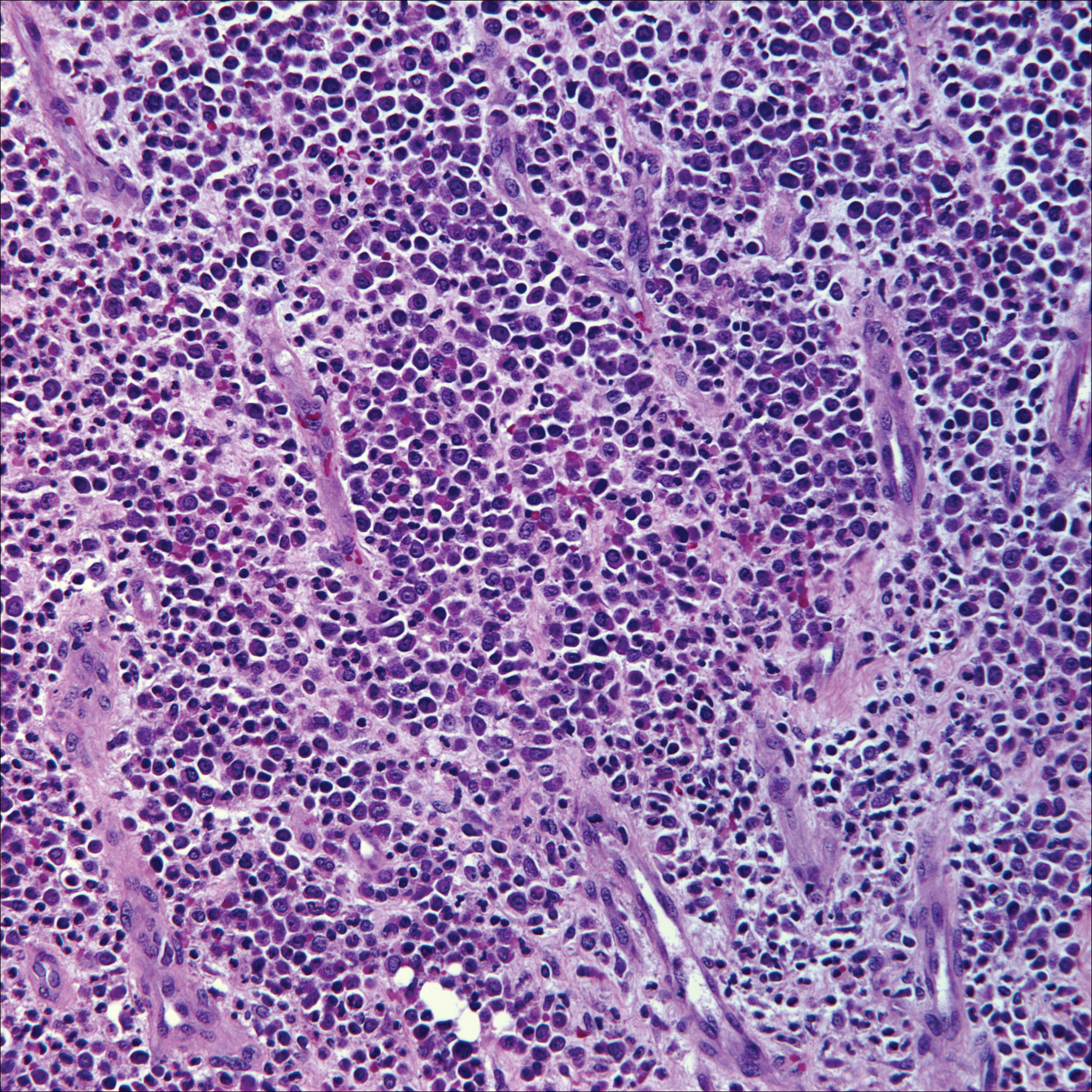

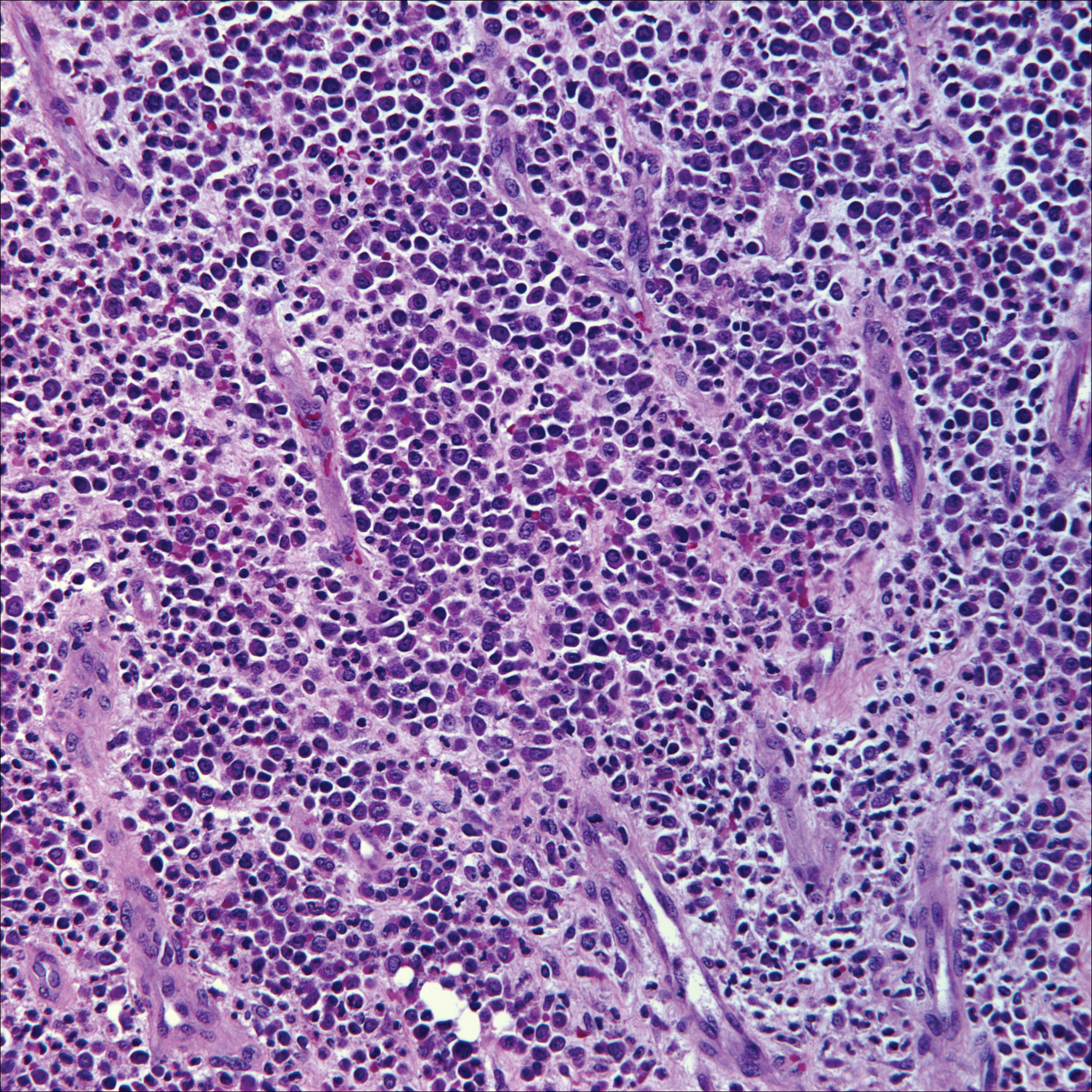

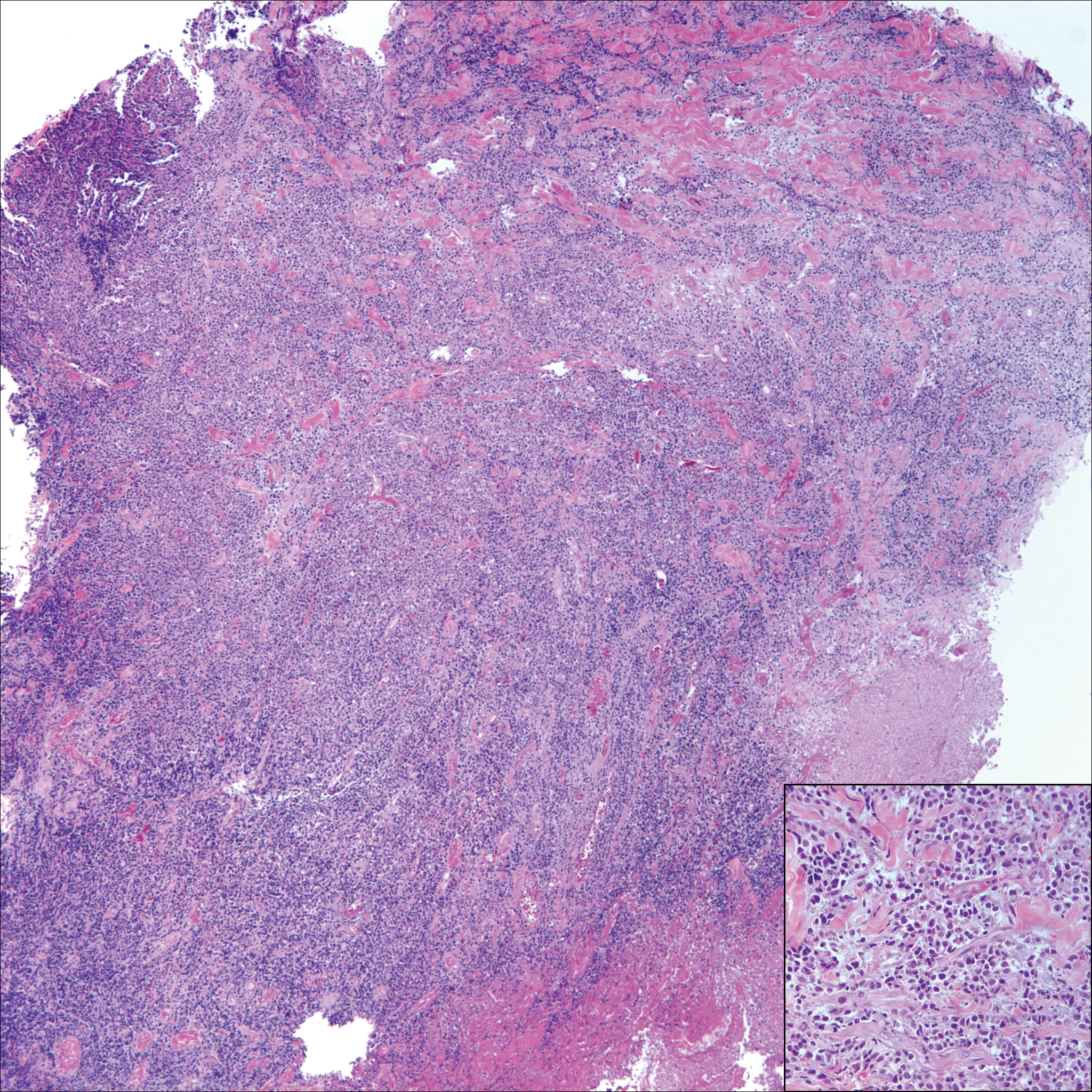

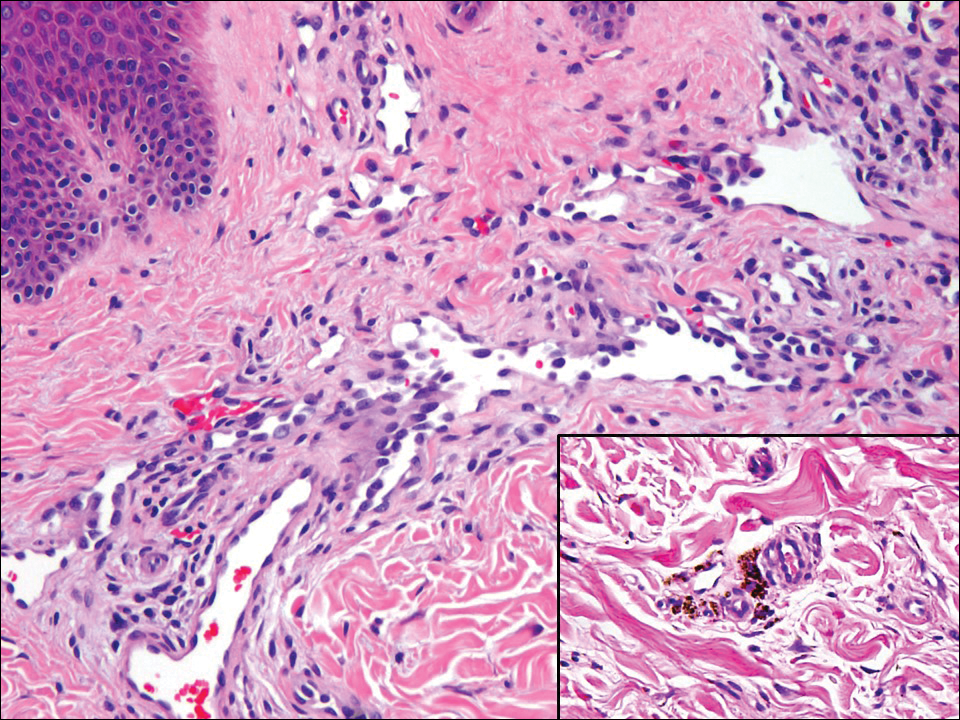

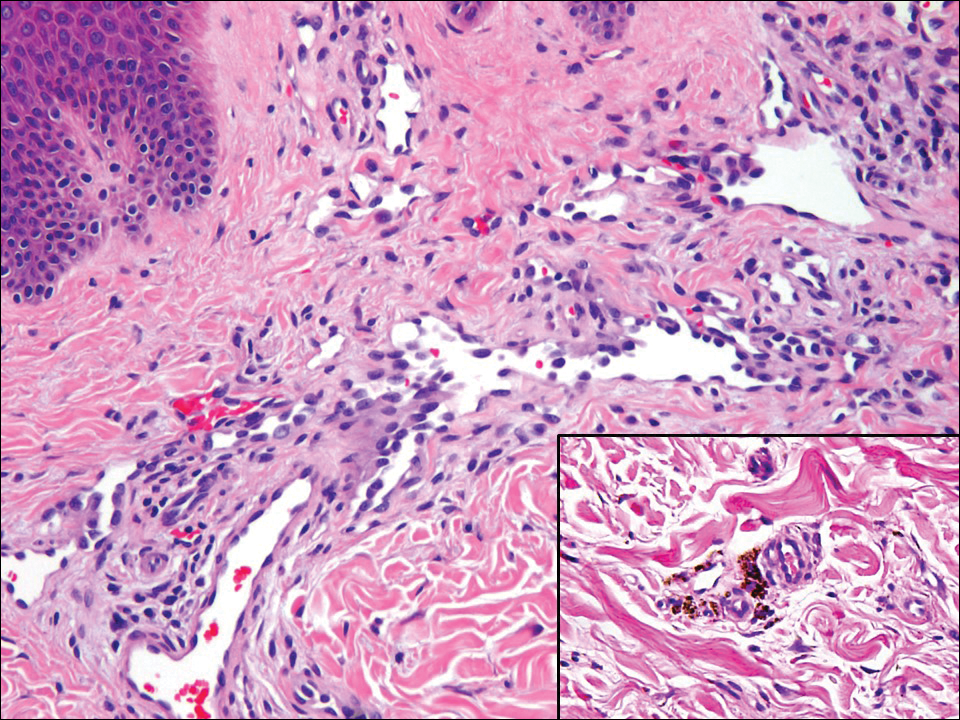

Granuloma annulare (GA) is characterized by rings of small, firm, pink to flesh-colored papules with a variable disease duration.4 Histologically, the interstitial variant of GA is characterized by a scattered inflammatory infiltrate consisting of histiocytes and lymphocytes located between altered collagen fibers in the superficial to mid dermis (Figure 2).3,6 Occasional eosinophils and increased dermal mucin are useful features to distinguish interstitial GA from other entities in the busy dermis differential.7

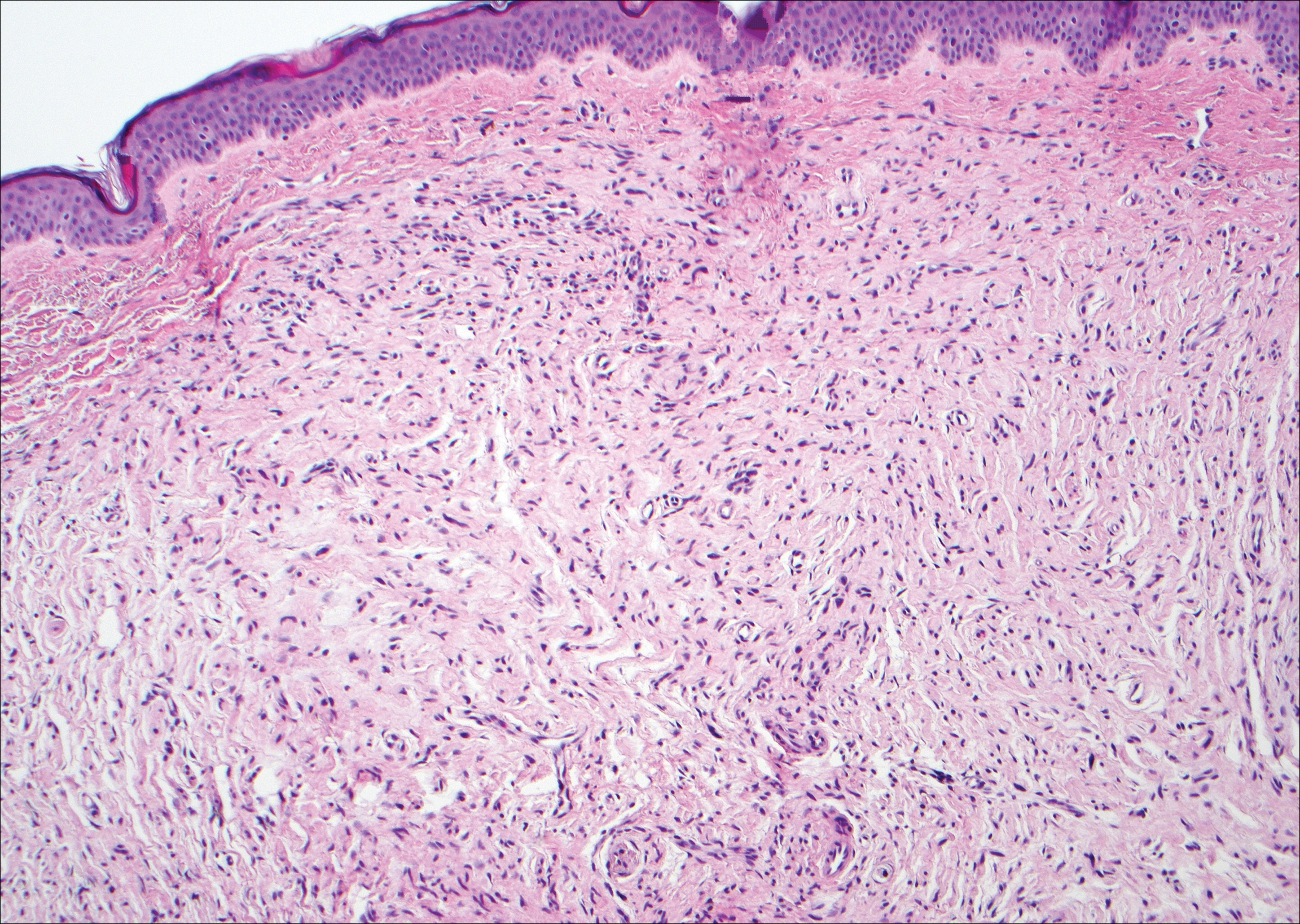

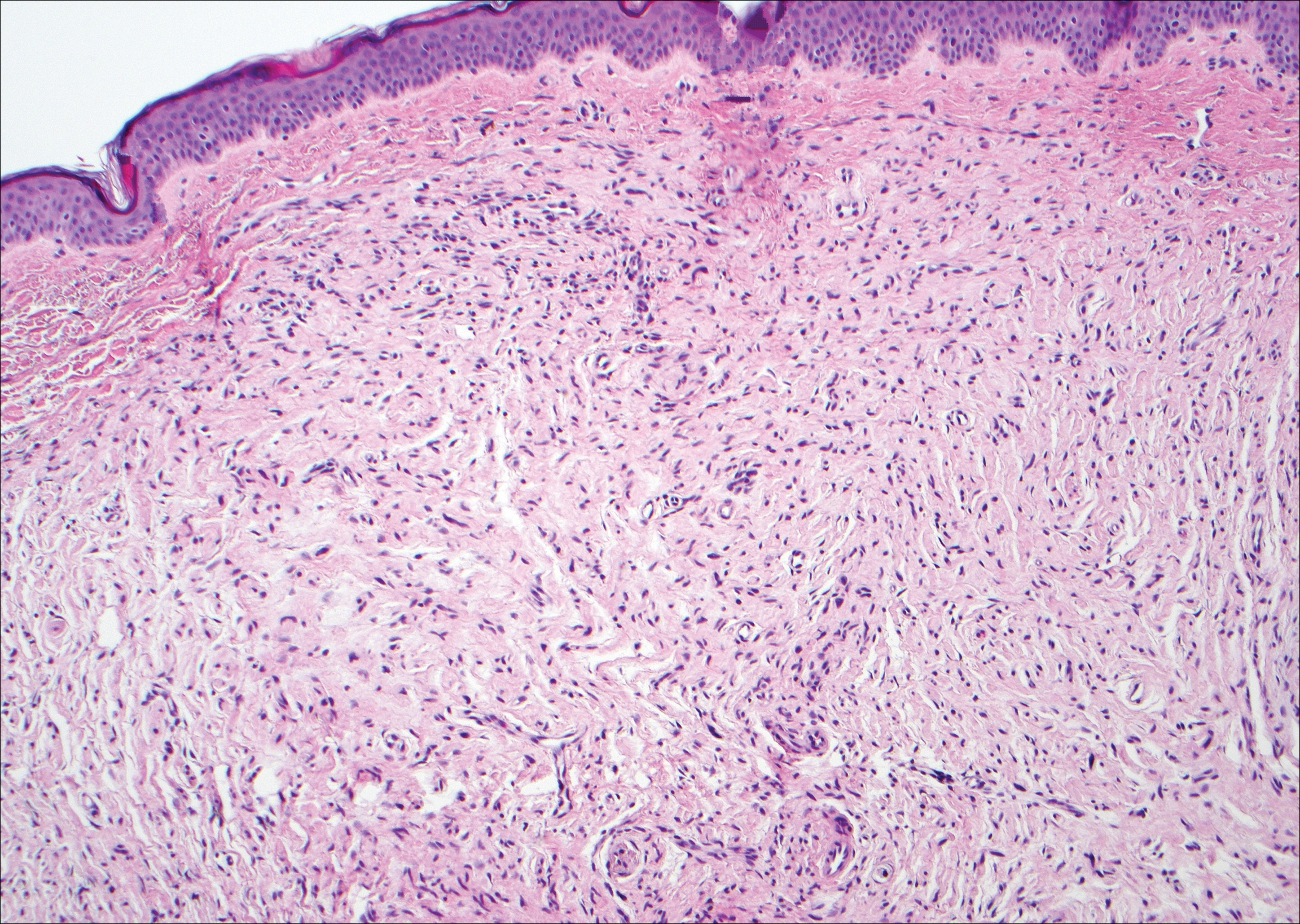

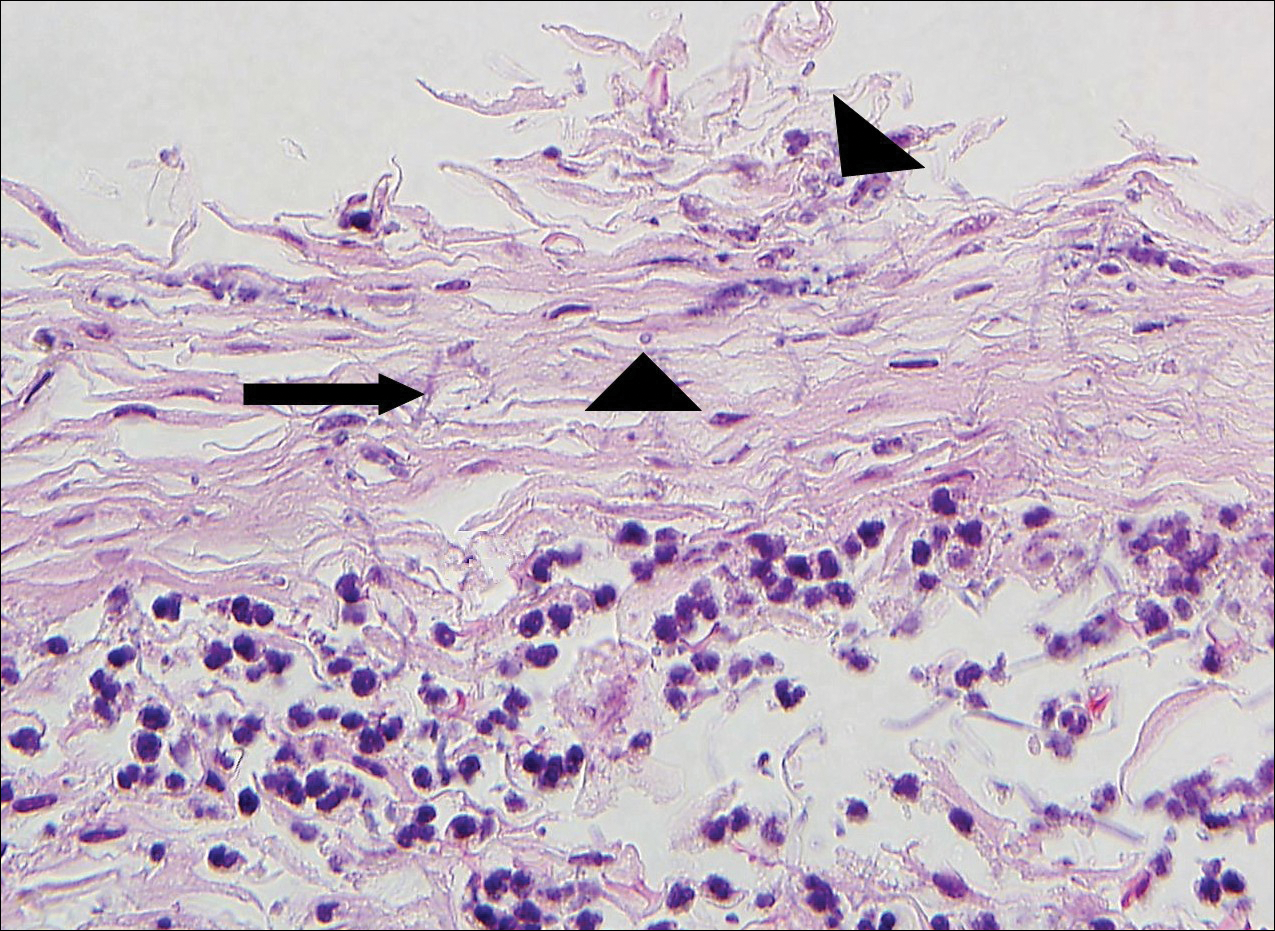

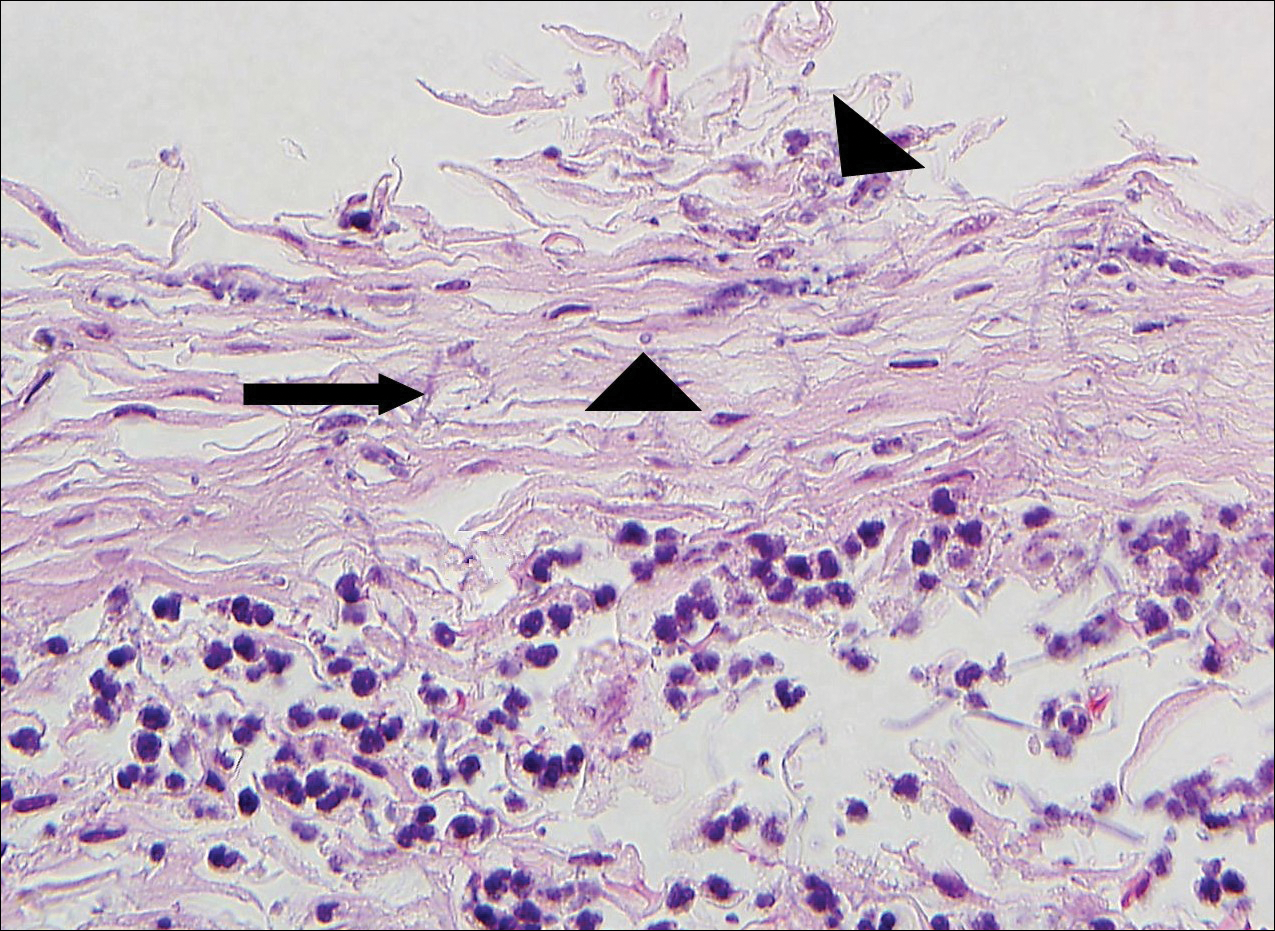

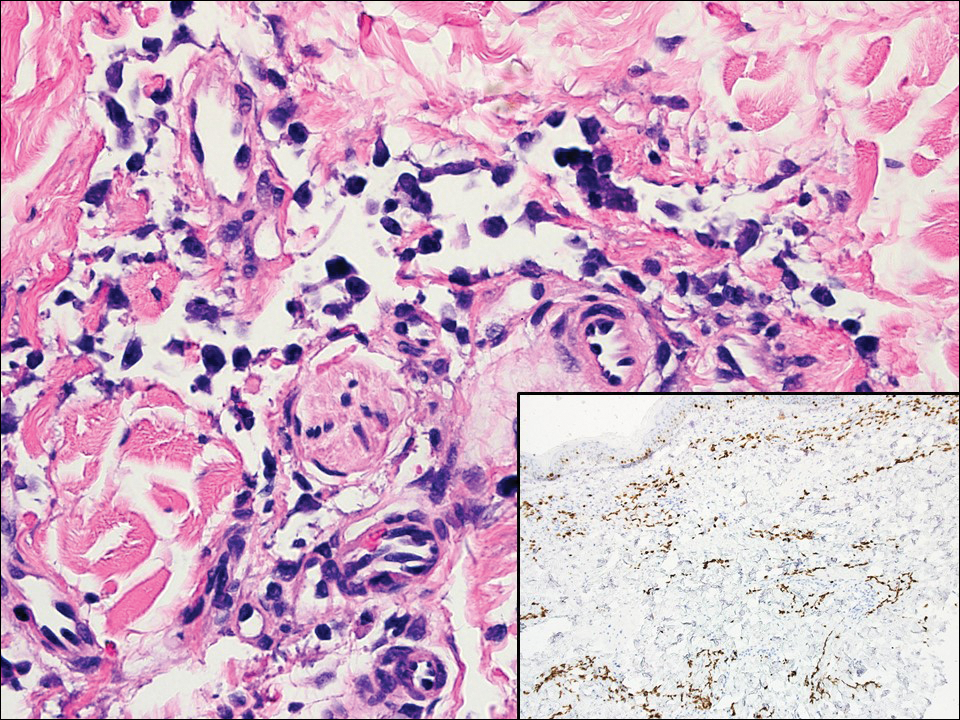

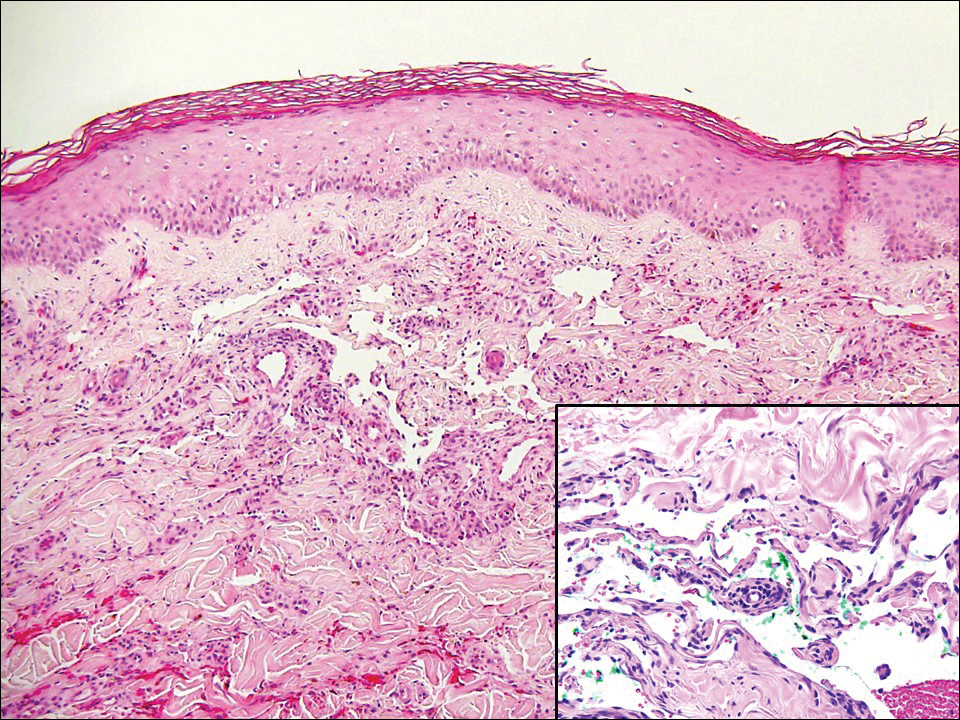

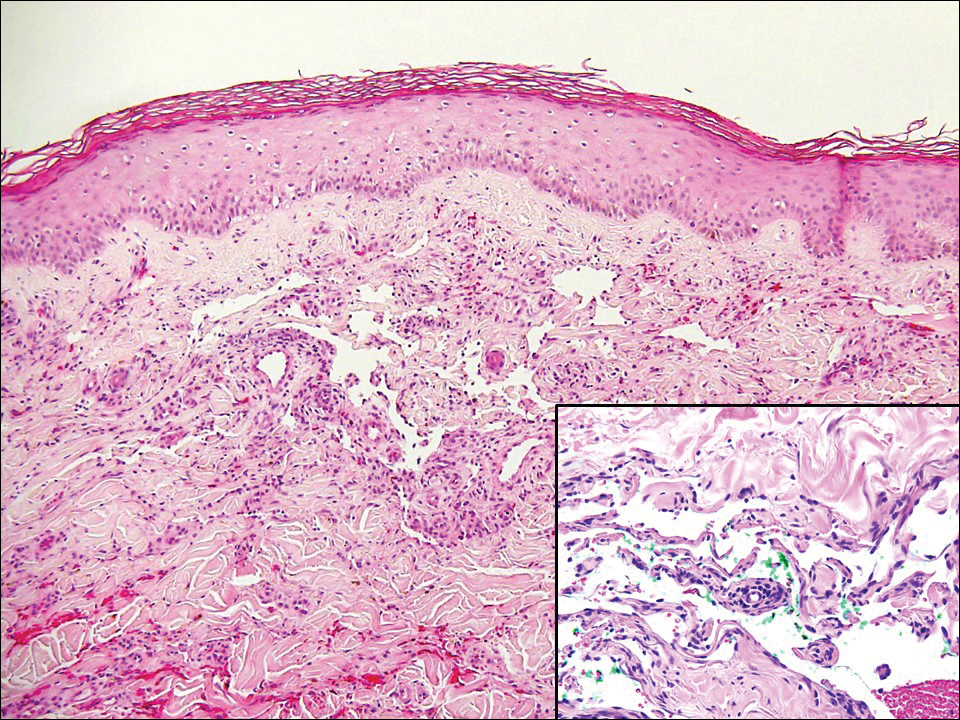

Scleromyxedema, also known as generalized lichen myxedematosus, is a rare mucinosis.3,8 Although its pathogenesis is unknown, it has been suggested that paraproteins related to the underlying gammopathy act to stimulate fibroblast proliferation and mucin overproduction.8 Clinically, characteristic widespread firm, waxy, dome-shaped papules are present over the head, upper trunk, and extremities.3,8 Histologically, scleromyxedema is characterized by increased dermal fibroblasts, mucin, and fibrosis, leading to the appearance of a busy dermis (Figure 3).3,6

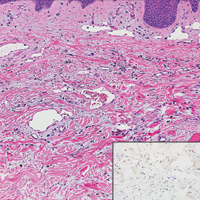

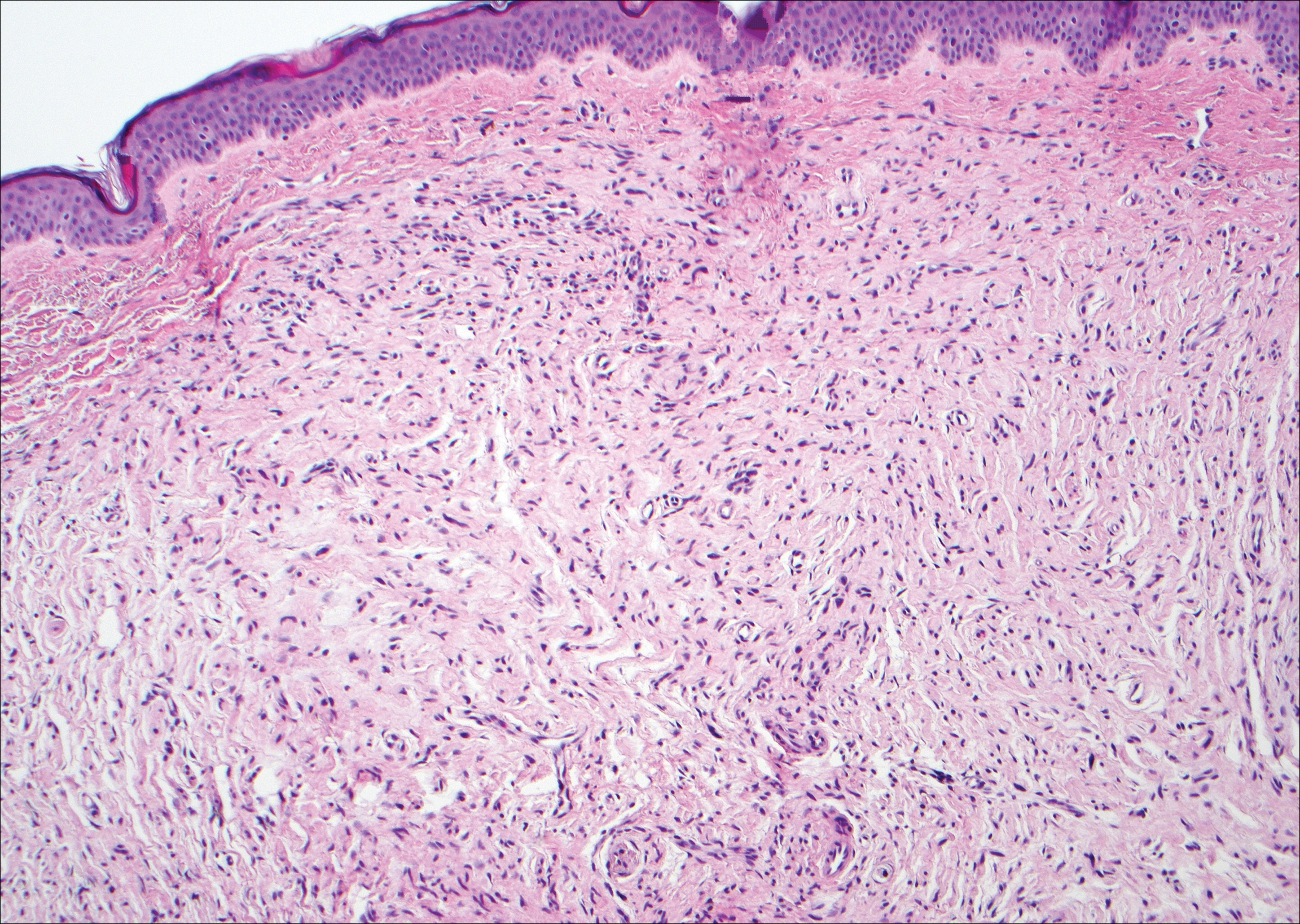

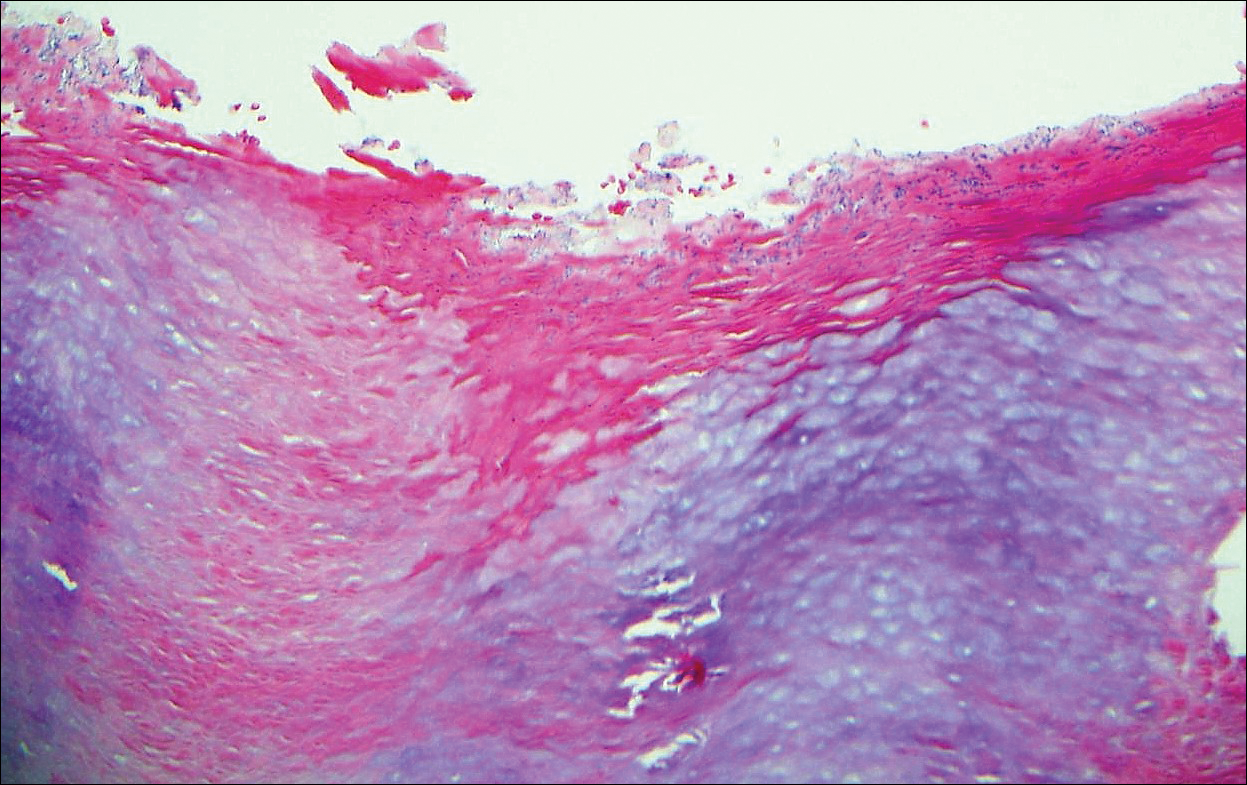

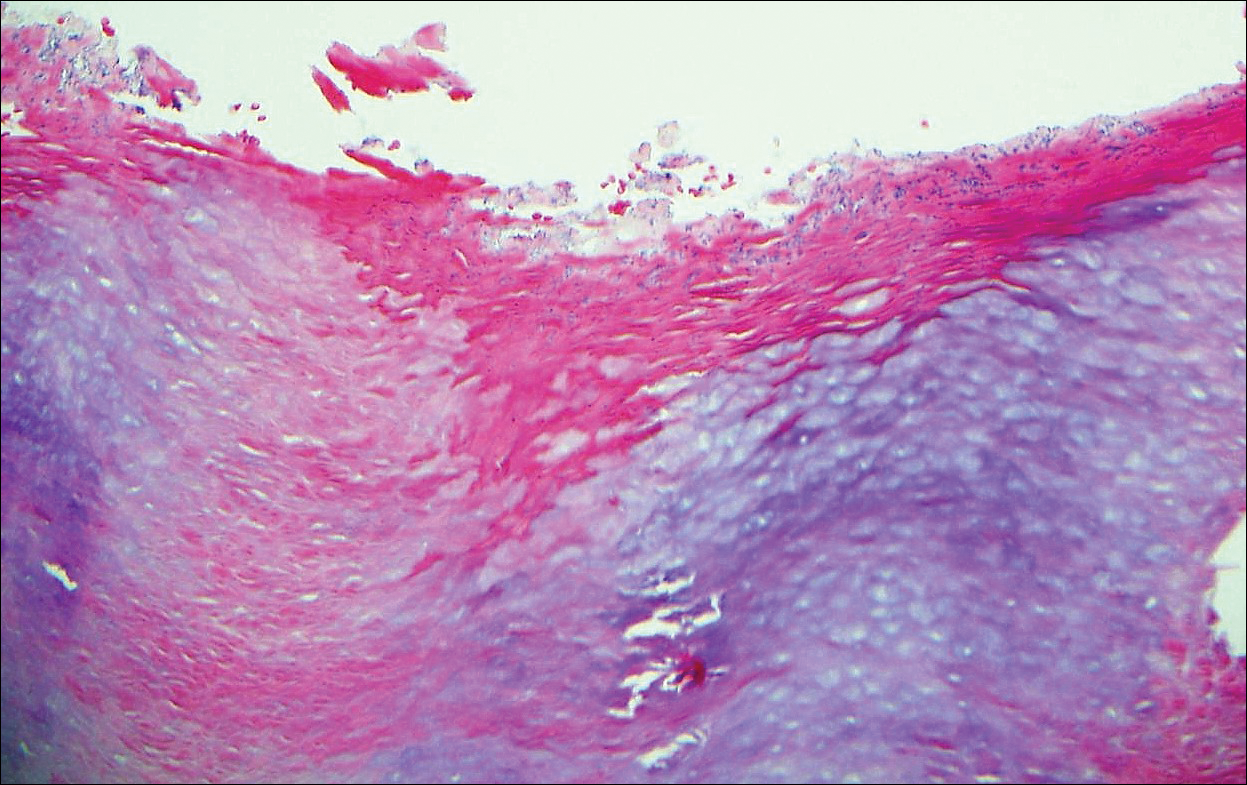

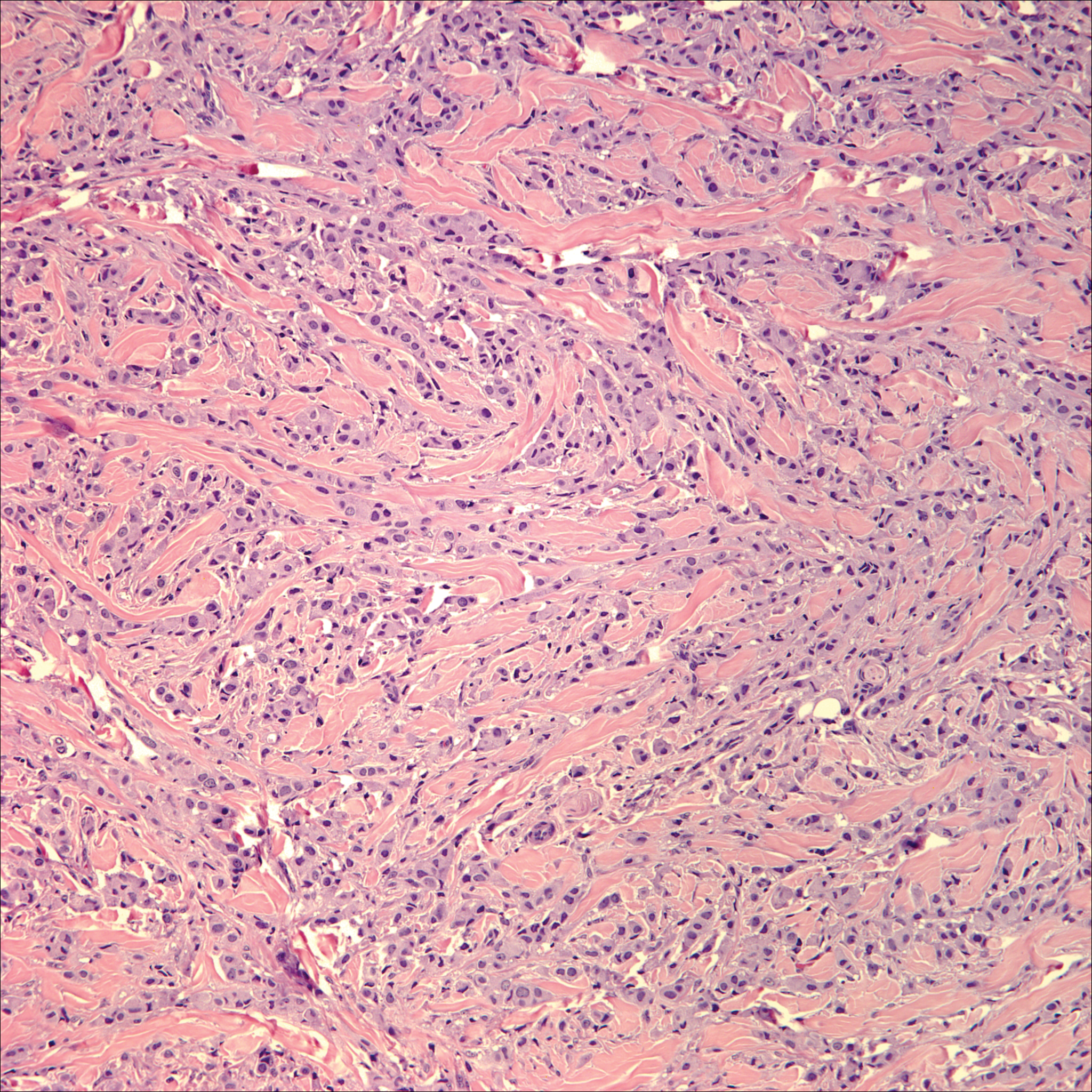

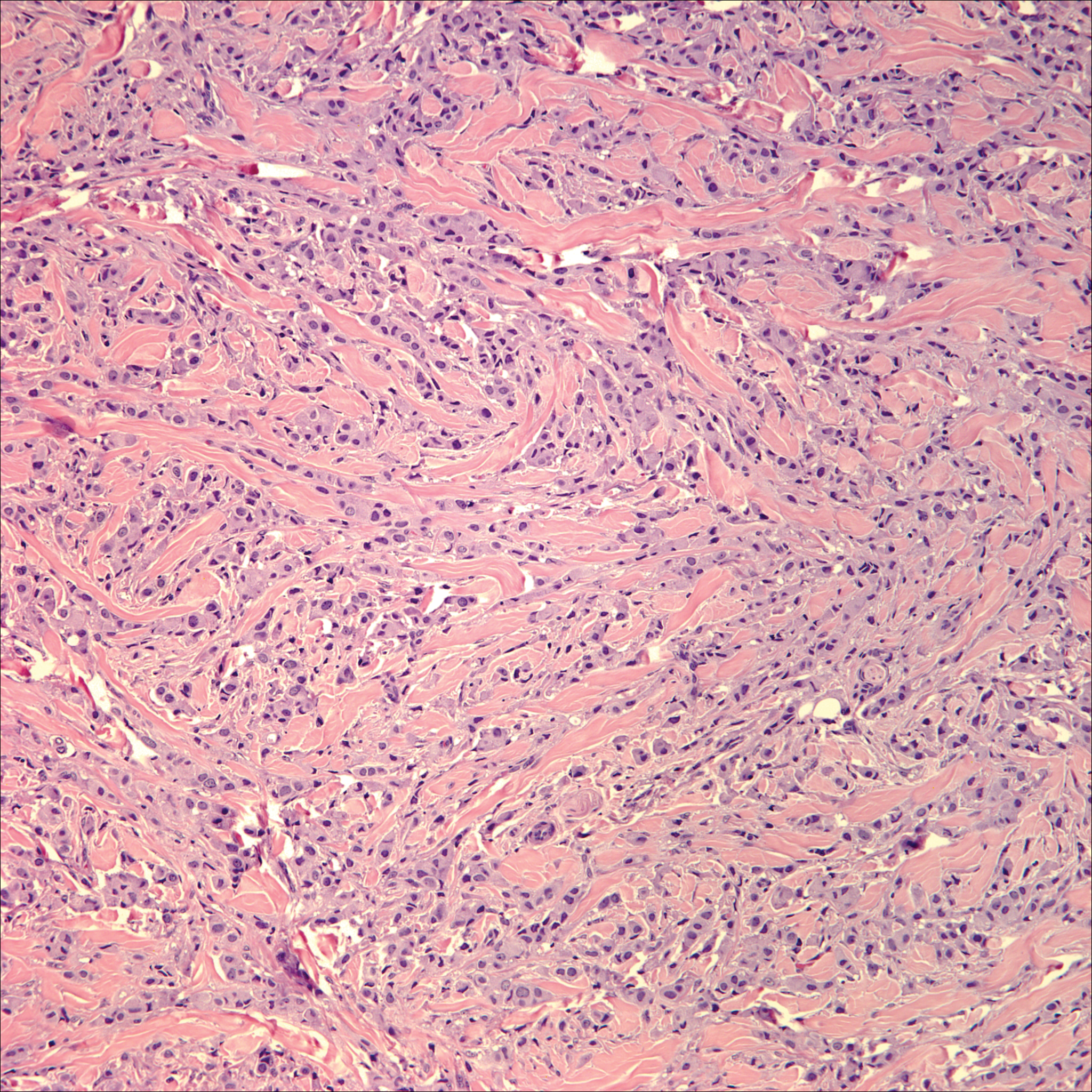

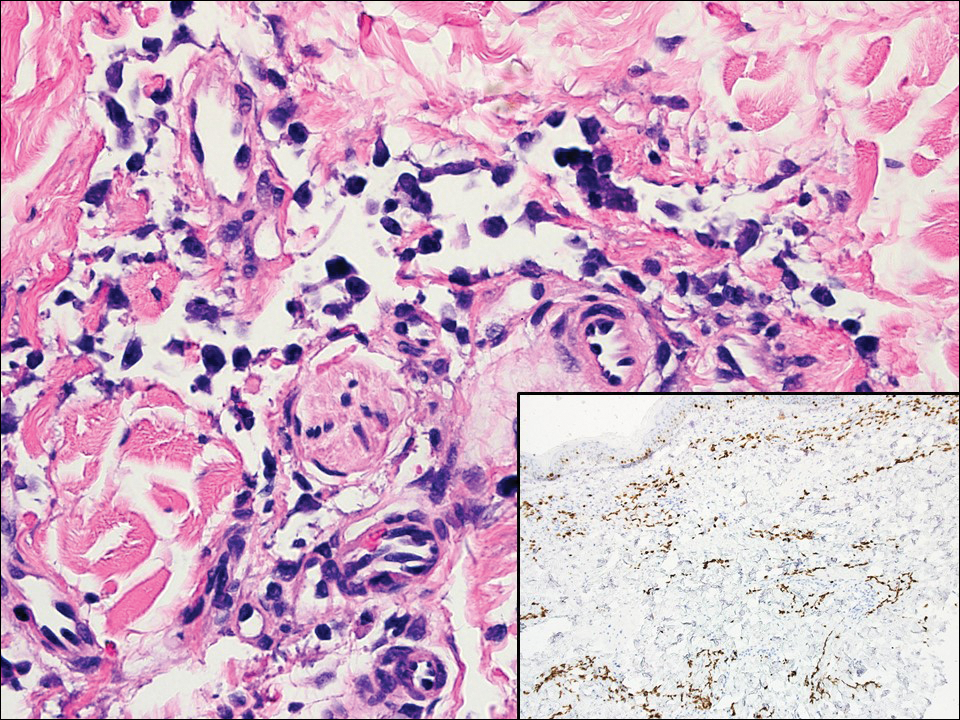

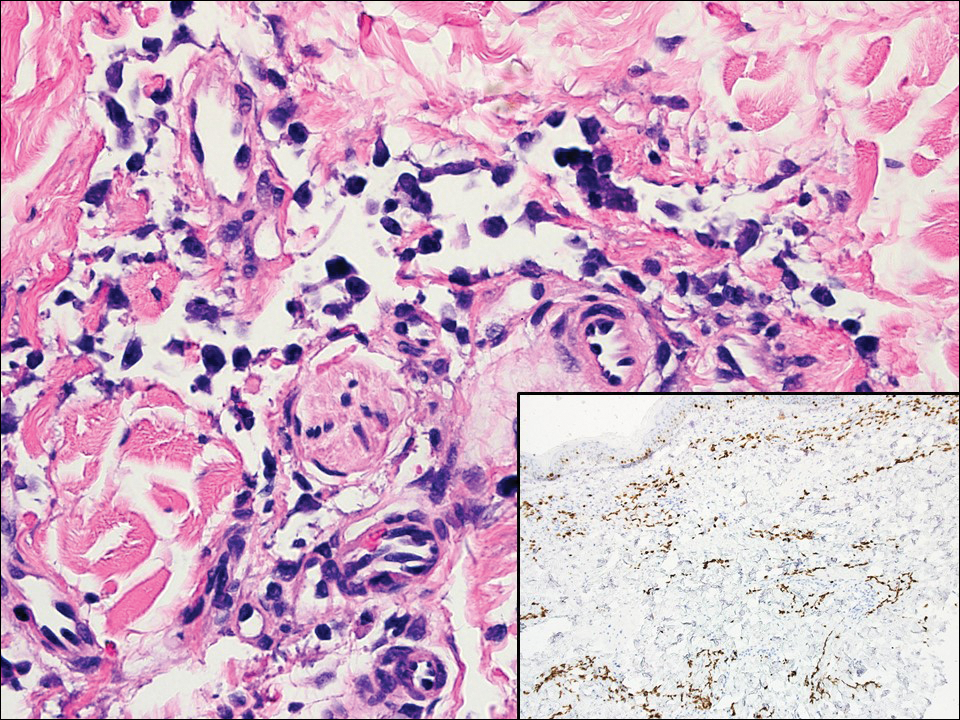

Neurofibromas are common benign peripheral nerve sheath tumors that can occur sporadically or in the setting of neurofibromatosis.3-5 They present as soft, flesh-colored papules or nodules most commonly located on the trunk and limbs.4 Histologically, neurofibromas are nonencapsulated tumors composed of abundant spindle cells with comma-shaped nuclei diffusely arranged in a pale myxoid stroma (Figure 4). Scattered mast cells can be visualized at higher magnification.3,6

- Alcaraz I, Cerroni L, Rutten A, et al. Cutaneous metastases from internal malignancies: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical review. Am J Dermatopathol. 2012;34:347-393.

- Habif TP, Dinulos JGH, Chapman MS, et al. Skin Disease: Diagnosis and Treatment. 4th ed. Edinburgh, Scotland: Elsevier; 2017.

- Calonje JE, Brenn T, Lazar AJ, et al, eds. McKee's Pathology of the Skin. 4th ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier Saunders; 2012.

- Habif TP. Clinical Dermatology: A Color Guide to Diagnosis and Therapy. 6th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2015.

- Patterson JW, Hosler GA. Weedon's Skin Pathology. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier; 2016.

- Elston DM, Ferringer T, eds. Dermatopathology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders Elsevier; 2014.

- Silverman RA, Rabinowitz AD. Eosinophils in the cellular infiltrate of granuloma annulare. J Cutan Pathol. 1985;12:13-17.

- Rongioletti F, Merlo G, Cinotti E, et al. Scleromyxedema: a multicenter study of characteristics, comorbidities, course, and therapy in 30 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:66-72.

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Metastases

Cutaneous metastases (CMs) can present in an otherwise asymptomatic patient as the only sign of an underlying disease process. In women, the most common cause of CM is breast carcinoma.1-3 Cutaneous metastases are found in approximately 25% of all patients with breast carcinoma,1 and breast carcinomas represent approximately 69% of all CMs found in women (Table 1).2 Cutaneous metastatic breast carcinoma (CMBC) is associated with a poor prognosis with a mean survival of approximately 6 months at the time of diagnosis.1,3 It commonly presents as a collection of flesh-colored, firm, asymptomatic, and rapidly appearing papules and nodules that can resemble cysts or fibrous tumors.1,3,4 They typically are located on the chest wall or abdomen near the site of the underlying malignancy.1-3 The histologic features of CMBC can include hyperchromatic tumor cells infiltrating between the collagen fibers in a characteristic single file manner,3,5 giving the appearance of a busy dermis, a nonspecific term to describe a focally hypercellular dermis at low-power magnification (Table 2).5,6 Cords and clusters of atypical cells with intracytoplasmic vacuoles or well-developed ducts also can be seen (quiz image [inset]). The carcinoma en cuirasse subtype of CMBC is characterized by a fibrotic scarlike plaque on the chest wall.1,3 If a punch biopsy is obtained, the specimen typically appears rectangular rather than tapered because of the sclerotic dermal collagen.6 In contrast, inflammatory carcinoma (carcinoma erysipelatoides) presents as an erythematous plaque resembling cellulitis due to the lymphatics being congested by tumor cells.3 Immunohistochemistry is a valuable tool in diagnosis. Positive staining is seen with cytokeratin 7, gross cystic disease fluid protein-15, mammaglobin, and GATA-3.1,3,6

Kaposi sarcoma (KS) is a low-grade endothelial malignancy associated with human herpesvirus 8.3,4 Kaposi sarcoma can be divided into 4 main subtypes: classic KS, African KS, AIDS-related KS, and immunosuppression-associated KS that occurs in patients with diseases such as human immunodeficiency virus. The cutaneous lesions are similar between subtypes and present as dark reddish purple macules that may enlarge or become nodular lesions.3,4 Histologically, 3 distinct stages of progression are described: patch, plaque, and tumor. The plaque stage has the appearance of a busy dermis due to the rapid proliferation of vascular structures within the dermis.3,6 A useful histologic feature known as the promontory sign can be seen as the proliferating tumor causes preexisting structures to project into vascular spaces (Figure 1).6 Immunohistochemistry for the endothelial and lymphatic markers CD31 and D2-40, respectively, are positive and may aid in the diagnosis.3 Staining for the latent nuclear antigen-1 of human herpesvirus 8 is a highly specific marker used to diagnose KS and can further distinguish it from the other busy dermis lesions.3

Granuloma annulare (GA) is characterized by rings of small, firm, pink to flesh-colored papules with a variable disease duration.4 Histologically, the interstitial variant of GA is characterized by a scattered inflammatory infiltrate consisting of histiocytes and lymphocytes located between altered collagen fibers in the superficial to mid dermis (Figure 2).3,6 Occasional eosinophils and increased dermal mucin are useful features to distinguish interstitial GA from other entities in the busy dermis differential.7

Scleromyxedema, also known as generalized lichen myxedematosus, is a rare mucinosis.3,8 Although its pathogenesis is unknown, it has been suggested that paraproteins related to the underlying gammopathy act to stimulate fibroblast proliferation and mucin overproduction.8 Clinically, characteristic widespread firm, waxy, dome-shaped papules are present over the head, upper trunk, and extremities.3,8 Histologically, scleromyxedema is characterized by increased dermal fibroblasts, mucin, and fibrosis, leading to the appearance of a busy dermis (Figure 3).3,6

Neurofibromas are common benign peripheral nerve sheath tumors that can occur sporadically or in the setting of neurofibromatosis.3-5 They present as soft, flesh-colored papules or nodules most commonly located on the trunk and limbs.4 Histologically, neurofibromas are nonencapsulated tumors composed of abundant spindle cells with comma-shaped nuclei diffusely arranged in a pale myxoid stroma (Figure 4). Scattered mast cells can be visualized at higher magnification.3,6

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Metastases

Cutaneous metastases (CMs) can present in an otherwise asymptomatic patient as the only sign of an underlying disease process. In women, the most common cause of CM is breast carcinoma.1-3 Cutaneous metastases are found in approximately 25% of all patients with breast carcinoma,1 and breast carcinomas represent approximately 69% of all CMs found in women (Table 1).2 Cutaneous metastatic breast carcinoma (CMBC) is associated with a poor prognosis with a mean survival of approximately 6 months at the time of diagnosis.1,3 It commonly presents as a collection of flesh-colored, firm, asymptomatic, and rapidly appearing papules and nodules that can resemble cysts or fibrous tumors.1,3,4 They typically are located on the chest wall or abdomen near the site of the underlying malignancy.1-3 The histologic features of CMBC can include hyperchromatic tumor cells infiltrating between the collagen fibers in a characteristic single file manner,3,5 giving the appearance of a busy dermis, a nonspecific term to describe a focally hypercellular dermis at low-power magnification (Table 2).5,6 Cords and clusters of atypical cells with intracytoplasmic vacuoles or well-developed ducts also can be seen (quiz image [inset]). The carcinoma en cuirasse subtype of CMBC is characterized by a fibrotic scarlike plaque on the chest wall.1,3 If a punch biopsy is obtained, the specimen typically appears rectangular rather than tapered because of the sclerotic dermal collagen.6 In contrast, inflammatory carcinoma (carcinoma erysipelatoides) presents as an erythematous plaque resembling cellulitis due to the lymphatics being congested by tumor cells.3 Immunohistochemistry is a valuable tool in diagnosis. Positive staining is seen with cytokeratin 7, gross cystic disease fluid protein-15, mammaglobin, and GATA-3.1,3,6

Kaposi sarcoma (KS) is a low-grade endothelial malignancy associated with human herpesvirus 8.3,4 Kaposi sarcoma can be divided into 4 main subtypes: classic KS, African KS, AIDS-related KS, and immunosuppression-associated KS that occurs in patients with diseases such as human immunodeficiency virus. The cutaneous lesions are similar between subtypes and present as dark reddish purple macules that may enlarge or become nodular lesions.3,4 Histologically, 3 distinct stages of progression are described: patch, plaque, and tumor. The plaque stage has the appearance of a busy dermis due to the rapid proliferation of vascular structures within the dermis.3,6 A useful histologic feature known as the promontory sign can be seen as the proliferating tumor causes preexisting structures to project into vascular spaces (Figure 1).6 Immunohistochemistry for the endothelial and lymphatic markers CD31 and D2-40, respectively, are positive and may aid in the diagnosis.3 Staining for the latent nuclear antigen-1 of human herpesvirus 8 is a highly specific marker used to diagnose KS and can further distinguish it from the other busy dermis lesions.3

Granuloma annulare (GA) is characterized by rings of small, firm, pink to flesh-colored papules with a variable disease duration.4 Histologically, the interstitial variant of GA is characterized by a scattered inflammatory infiltrate consisting of histiocytes and lymphocytes located between altered collagen fibers in the superficial to mid dermis (Figure 2).3,6 Occasional eosinophils and increased dermal mucin are useful features to distinguish interstitial GA from other entities in the busy dermis differential.7

Scleromyxedema, also known as generalized lichen myxedematosus, is a rare mucinosis.3,8 Although its pathogenesis is unknown, it has been suggested that paraproteins related to the underlying gammopathy act to stimulate fibroblast proliferation and mucin overproduction.8 Clinically, characteristic widespread firm, waxy, dome-shaped papules are present over the head, upper trunk, and extremities.3,8 Histologically, scleromyxedema is characterized by increased dermal fibroblasts, mucin, and fibrosis, leading to the appearance of a busy dermis (Figure 3).3,6

Neurofibromas are common benign peripheral nerve sheath tumors that can occur sporadically or in the setting of neurofibromatosis.3-5 They present as soft, flesh-colored papules or nodules most commonly located on the trunk and limbs.4 Histologically, neurofibromas are nonencapsulated tumors composed of abundant spindle cells with comma-shaped nuclei diffusely arranged in a pale myxoid stroma (Figure 4). Scattered mast cells can be visualized at higher magnification.3,6

- Alcaraz I, Cerroni L, Rutten A, et al. Cutaneous metastases from internal malignancies: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical review. Am J Dermatopathol. 2012;34:347-393.

- Habif TP, Dinulos JGH, Chapman MS, et al. Skin Disease: Diagnosis and Treatment. 4th ed. Edinburgh, Scotland: Elsevier; 2017.

- Calonje JE, Brenn T, Lazar AJ, et al, eds. McKee's Pathology of the Skin. 4th ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier Saunders; 2012.

- Habif TP. Clinical Dermatology: A Color Guide to Diagnosis and Therapy. 6th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2015.

- Patterson JW, Hosler GA. Weedon's Skin Pathology. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier; 2016.

- Elston DM, Ferringer T, eds. Dermatopathology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders Elsevier; 2014.

- Silverman RA, Rabinowitz AD. Eosinophils in the cellular infiltrate of granuloma annulare. J Cutan Pathol. 1985;12:13-17.

- Rongioletti F, Merlo G, Cinotti E, et al. Scleromyxedema: a multicenter study of characteristics, comorbidities, course, and therapy in 30 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:66-72.

- Alcaraz I, Cerroni L, Rutten A, et al. Cutaneous metastases from internal malignancies: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical review. Am J Dermatopathol. 2012;34:347-393.

- Habif TP, Dinulos JGH, Chapman MS, et al. Skin Disease: Diagnosis and Treatment. 4th ed. Edinburgh, Scotland: Elsevier; 2017.

- Calonje JE, Brenn T, Lazar AJ, et al, eds. McKee's Pathology of the Skin. 4th ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier Saunders; 2012.

- Habif TP. Clinical Dermatology: A Color Guide to Diagnosis and Therapy. 6th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2015.

- Patterson JW, Hosler GA. Weedon's Skin Pathology. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier; 2016.

- Elston DM, Ferringer T, eds. Dermatopathology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders Elsevier; 2014.

- Silverman RA, Rabinowitz AD. Eosinophils in the cellular infiltrate of granuloma annulare. J Cutan Pathol. 1985;12:13-17.

- Rongioletti F, Merlo G, Cinotti E, et al. Scleromyxedema: a multicenter study of characteristics, comorbidities, course, and therapy in 30 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:66-72.

A 56-year-old woman presented with multiple asymptomatic lesions of 2 months' duration. On physical examination firm pink papules were noted dispersed across the upper abdomen, chest, and back. A 5-mm punch biopsy was obtained.

Tetrad Bodies in Skin

The Diagnosis: Bacterial Infection

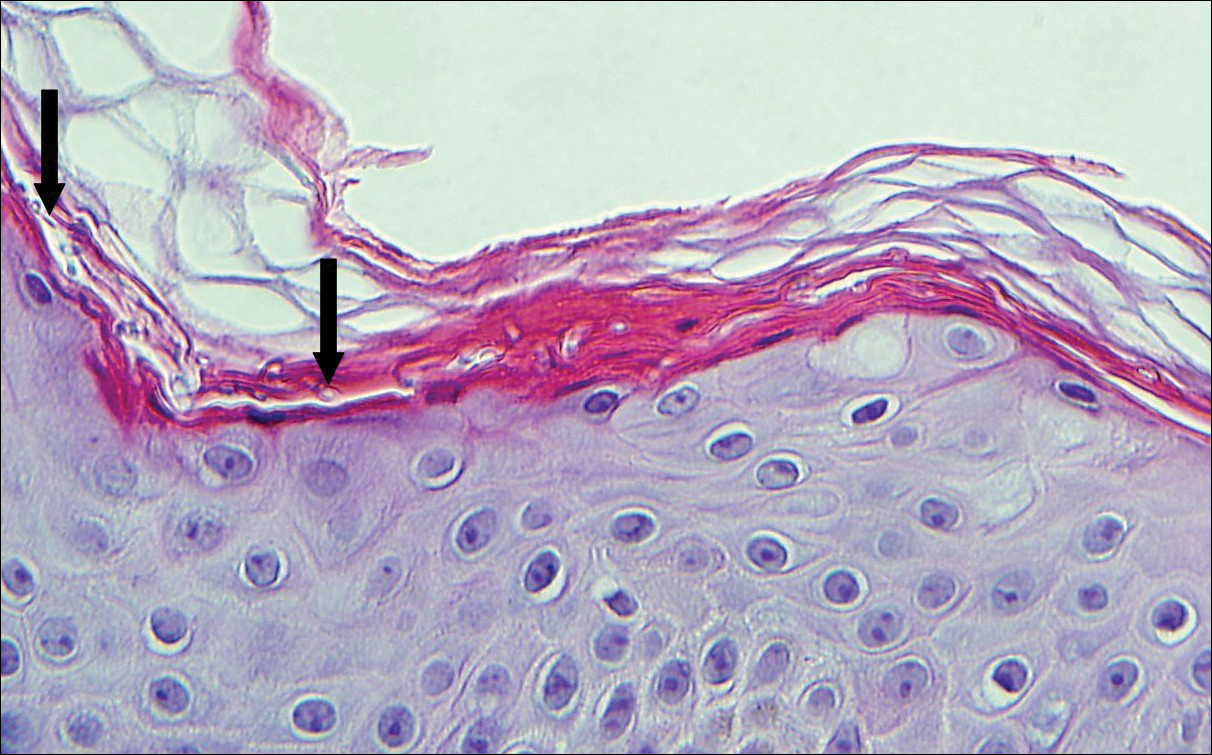

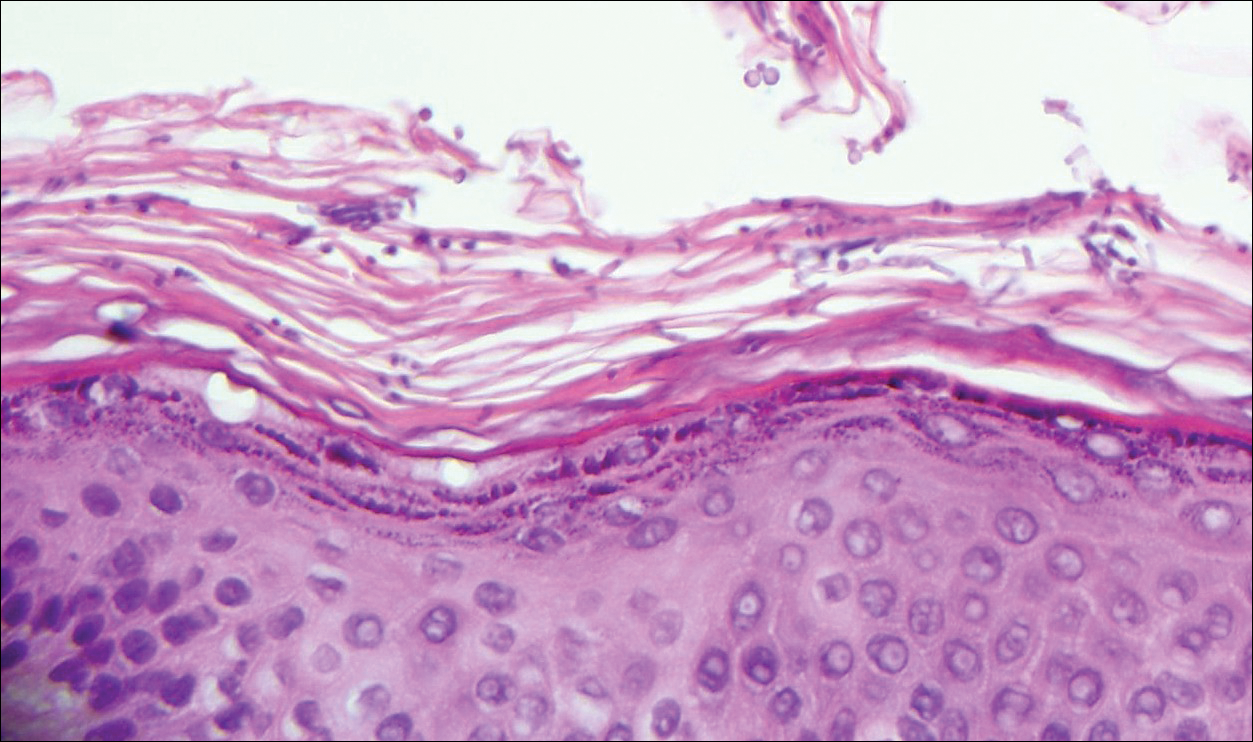

The tetrad arrangement of organisms seen in this case was classic for Micrococcus and Sarcina species. Both are gram-positive cocci that occur in tetrads, but Micrococcus is aerobic and catalase positive, whereas Sarcina species are anaerobic, catalase negative, acidophilic, and form spores in alkaline pH.1 Although difficult to definitively differentiate on light microscopy, micrococci are smaller in size, ranging from 0.5 to 2.0 μm, and occur in tight clusters, as seen in this case (quiz images), in contrast to Sarcina species, which are relatively larger (1.8-3.0 μm).2 Sarcinae typically are found in soil and air, are considered pathogenic, and are associated with gastric symptoms (Sarcina ventriculi).1Sarcina species also are reported to colonize the skin of patients with diabetes mellitus, but no pathogenic activity is known in the skin.3Micrococcus species, with the majority being Micrococcus luteus, are part of the normal flora of the human skin as well as the oral and nasal cavities. Occasional reports of pneumonia, endocarditis, meningitis, arthritis, endophthalmitis, and sepsis have been reported in immunocompromised individuals.4 In the skin, Micrococcus is a commensal organism; however, Micrococcus sedentarius has been associated with pitted keratolysis, and reports of Micrococcus folliculitis in human immunodeficiency virus patients also are described in the literature.5,6 Micrococci are considered opportunistic bacteria and may worsen and prolong a localized cutaneous infection caused by other organisms under favorable conditions.7Micrococcus luteus is one of the most common bacteria cultured from skin and soft tissue infections caused by fungal organisms.8 Depending on the immune status of an individual, use of broad-spectrum antibiotic and/or elimination of favorable milieu (ie, primary pathogen, breaks in skin) usually treats the infection.

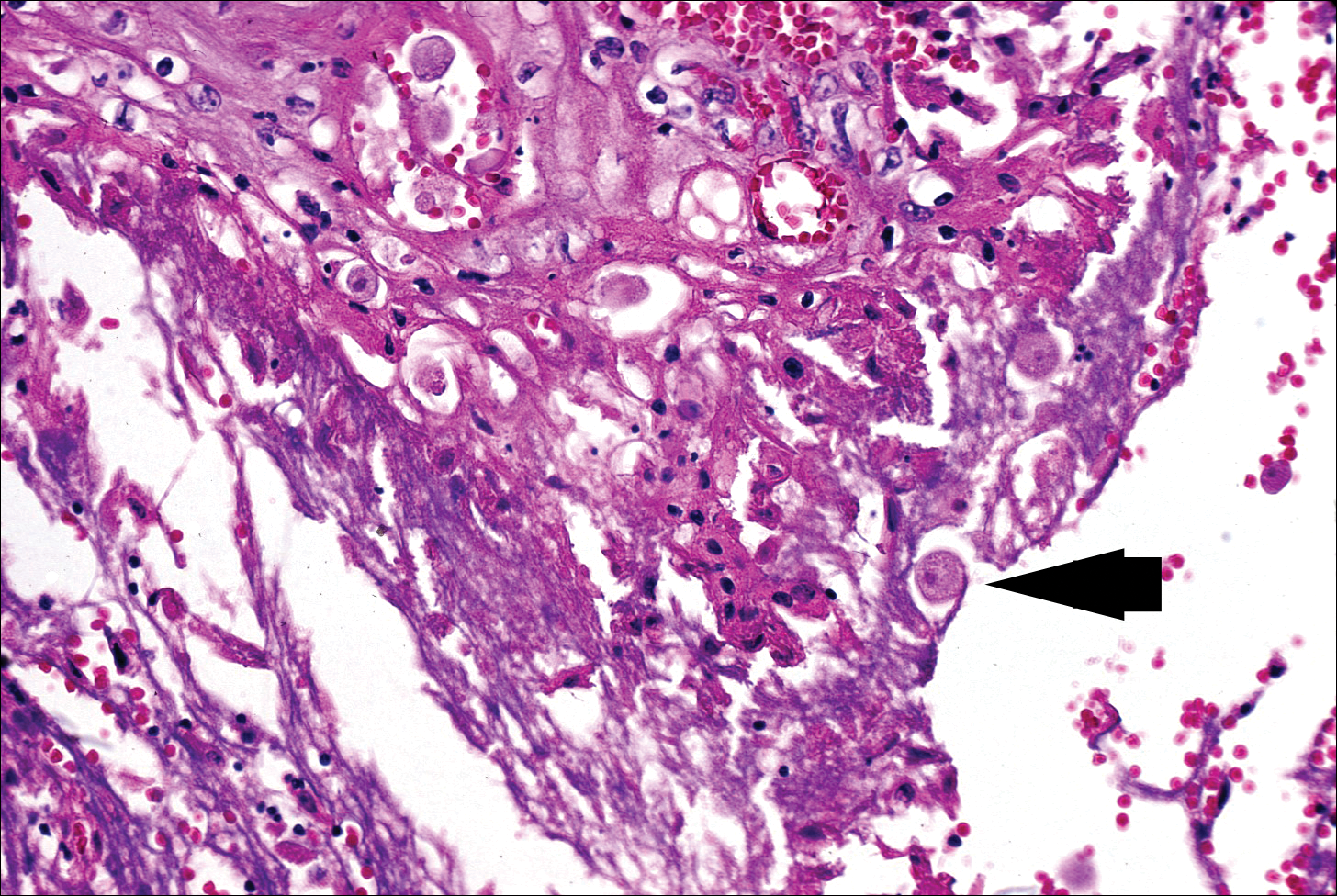

Because of the rarity of infections caused and being part of the normal flora, the clinical implications of subtyping and sensitivity studies via culture or molecular studies may not be important; however, incidental presence of these organisms with unfamiliar morphology may cause confusion for the dermatopathologist. An extremely small size (0.5-2.0 μm) compared to red blood cells (7-8 μm) and white blood cells (10-12 μm) in a tight tetrad arrangement should raise the suspicion for Micrococcus.1 The refractive nature of these organisms from a thick extracellular layer can mimic fungus or plant matter; a negative Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver stain in this case helped in not only differentiating but also ruling out secondary fungal infection. Finally, a Gram stain with violet staining of these organisms reaffirmed the diagnosis of gram-positive bacterial organisms, most consistent with Micrococcus species (Figure 1). Culture studies were not performed because of contamination of the tissue specimen and resolution of the patient's symptoms.

The presence of foreign material in the skin may be traumatic, occupational, cosmetic, iatrogenic, or self-inflicted, including a wide variety of substances that appear in different morphological forms on hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)-stained sections, depending on their structure and physiochemical properties.9 Although not all foreign bodies may polarize, examining the sample under polarized light is considered an important step to narrow down the differential diagnosis. The tissue reaction is primarily dependent on the nature of the substance and duration, consisting of histiocytes, macrophages, plasma cells, lymphocytes, and fibrosis.9 Activated histiocytes, multinucleated giant cells, and granulomas are classic findings that generally are seen surrounding and engulfing the foreign material (Figure 2). In addition to foreign material, substances such as calcium salts, urate crystals, extruded keratin, ruptured cysts, and hair follicles may act as foreign materials and can incite a tissue response.9 Absence of histiocytic response, granuloma formation, and fibrosis in a lesion of 1 month's duration made the tetrad bodies unlikely to be foreign material.

Demodex mites are superficial inhabitants of human skin that are acquired shortly after birth, live in or near pilosebaceous units, and obtain nourishment from skin cells and sebum.10,11 The mites can be recovered on 10% of skin biopsies, most commonly on the face due to high sebum production.10 Adult mites range from 0.1 to 0.4 mm in length and are round to oval in shape. Females lay eggs inside the hair follicle or sebaceous glands.11 They usually are asymptomatic, but their infestation may become pathogenic, especially in immunocompromised individuals.10 The clinical picture may resemble bacterial folliculitis, rosacea, and perioral dermatitis, while histology typically is characterized by spongiosis, lymphohistiocytic inflammation around infested follicles, and mite(s) in follicular infundibula (Figure 3). Sometimes the protrusion of mites and keratin from the follicles is seen as follicular spines on histology and referred to as pityriasis folliculorum.

Deposits of urate crystals in skin occur from the elevated serum uric acid levels in gout. The cutaneous deposits are mainly in the dermis and subcutaneous tissue and are extremely painful.12 Urate crystals get dissolved during formalin fixation and leave needlelike clefts in a homogenous, lightly basophilic material on H&E slide (Figure 4). For the same reason, polarized microscopy also is not helpful despite the birefringent nature of urate crystals.12

Fungal yeast forms appear round to oval under light microscopy, ranging from 2 to 100 μm in size.13 The common superficial forms involving the epidermis or hair follicles similar to the current case of bacterial infection include Malassezia and dermatophyte infections. Malassezia is part of the normal flora of sebum-rich areas of skin and is associated with superficial infections such as folliculitis, atopic dermatitis, psoriasis, seborrheic dermatitis, and dandruff.14Malassezia appear as clusters of yeast cells that are pleomorphic and round to oval in shape, ranging from 2 to 6 μm in size. It forms hyphae in its pathogenic form and gives rise to the classic spaghetti and meatball-like appearance that can be highlighted by periodic acid-Schiff (Figure 5) and Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver special stains. Dermatophytes include 3 genera--Trichophyton, Microsporum, and Epidermophyton--with at least 40 species that causes skin infections in humans.14 Fungal spores and hyphae forms are restricted to the stratum corneum. The hyphae forms may not be apparent on H&E stain, and periodic acid-Schiff staining is helpful in visualizing the fungal elements. The presence of neutrophils in the corneal layer, basket weave hyperkeratosis, and presence of fungal hyphae within the corneal layer fissures (sandwich sign) are clues to the dermatophyte infection.15 Other smaller fungi such as Histoplasma capsulatum (2-4 μm), Candida (3-5 μm), and Pneumocystis (2-5 μm) species can be found in skin in disseminated infections, usually affecting immunocompromised individuals.13Histoplasma is a basophilic yeast that exhibits narrow-based budding and appears clustered within or outside of macrophages. Candida species generally are dimorphic, and yeasts are found intermingled with filamentous forms. Pneumocystis infection in skin is extremely rare, and the fungi appear as spherical or crescent-shaped bodies in a foamy amorphous material.16

- Al Rasheed MR, Senseng CG. Sarcina ventriculi: review of the literature. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2016;140:1441-1445.

- Lam-Himlin D, Tsiatis AC, Montgomery E, et al. Sarcina organisms in the gastrointestinal tract: a clinicopathologic and molecular study. Am J Surg Pathol. 2011;35:1700-1705.

- Somerville DA, Lancaster-Smith M. The aerobic cutaneous microflora of diabetic subjects. Br J Dermatol. 1973;89:395-400.

- Hetem DJ, Rooijakkers S, Ekkelenkamp MB. Staphylococci and Micrococci. In: Cohen J, Powderly WG, Opal SM, eds. Infectious Diseases. 4th ed. Vol 2. New York, NY: Elsevier; 2017:1509-1522.

- Nordstrom KM, McGinley KJ, Cappiello L, et al. Pitted keratolysis. the role of Micrococcus sedentarius. Arch Dermatol. 1987;123:1320-1325.

- Smith KJ, Neafie R, Yeager J, et al. Micrococcus folliculitis in HIV-1 disease. Br J Dermatol. 1999;141:558-561.

- van Rensburg JJ, Lin H, Gao X, et al. The human skin microbiome associates with the outcome of and is influenced by bacterial infection. mBio. 2015;6:E01315-15. doi:10.1128/mBio.01315-15.

- Chuku A, Nwankiti OO. Association of bacteria with fungal infection of skin and soft tissue lesions in plateau state, Nigeria. Br Microbiol Res J. 2013;3:470-477.

- Molina-Ruiz AM, Requena L. Foreign body granulomas. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:497-523.

- Elston CA, Elston DM. Demodex mites. Clin Dermatol. 2014;32:739-743.

- Rather PA, Hassan I. Human Demodex mite: the versatile mite of dermatological importance. Indian J Dermatol. 2014;59:60-66.

- Gaviria JL, Ortega VG, Gaona J, et al. Unusual dermatological manifestations of gout: review of literature and a case report. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2015;3:E445.

- Guarner J, Brandt ME. Histopathologic diagnosis of fungal infections in the 21st century. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2011;24:247-280.

- White TC, Findley K, Dawson TL Jr, et al. Fungi on the skin: dermatophytes and Malassezia. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2014;4. pii:a019802. doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a019802.

- Gottlieb GJ, Ackerman AB. The "sandwich sign" of dermatophytosis. Am J Dermatopathol. 1986;8:347.

- Hennessey NP, Parro EL, Cockerell CJ. Cutaneous Pneumocystis carinii infection in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Arch Dermatol. 1991;127:1699-1701.

The Diagnosis: Bacterial Infection

The tetrad arrangement of organisms seen in this case was classic for Micrococcus and Sarcina species. Both are gram-positive cocci that occur in tetrads, but Micrococcus is aerobic and catalase positive, whereas Sarcina species are anaerobic, catalase negative, acidophilic, and form spores in alkaline pH.1 Although difficult to definitively differentiate on light microscopy, micrococci are smaller in size, ranging from 0.5 to 2.0 μm, and occur in tight clusters, as seen in this case (quiz images), in contrast to Sarcina species, which are relatively larger (1.8-3.0 μm).2 Sarcinae typically are found in soil and air, are considered pathogenic, and are associated with gastric symptoms (Sarcina ventriculi).1Sarcina species also are reported to colonize the skin of patients with diabetes mellitus, but no pathogenic activity is known in the skin.3Micrococcus species, with the majority being Micrococcus luteus, are part of the normal flora of the human skin as well as the oral and nasal cavities. Occasional reports of pneumonia, endocarditis, meningitis, arthritis, endophthalmitis, and sepsis have been reported in immunocompromised individuals.4 In the skin, Micrococcus is a commensal organism; however, Micrococcus sedentarius has been associated with pitted keratolysis, and reports of Micrococcus folliculitis in human immunodeficiency virus patients also are described in the literature.5,6 Micrococci are considered opportunistic bacteria and may worsen and prolong a localized cutaneous infection caused by other organisms under favorable conditions.7Micrococcus luteus is one of the most common bacteria cultured from skin and soft tissue infections caused by fungal organisms.8 Depending on the immune status of an individual, use of broad-spectrum antibiotic and/or elimination of favorable milieu (ie, primary pathogen, breaks in skin) usually treats the infection.

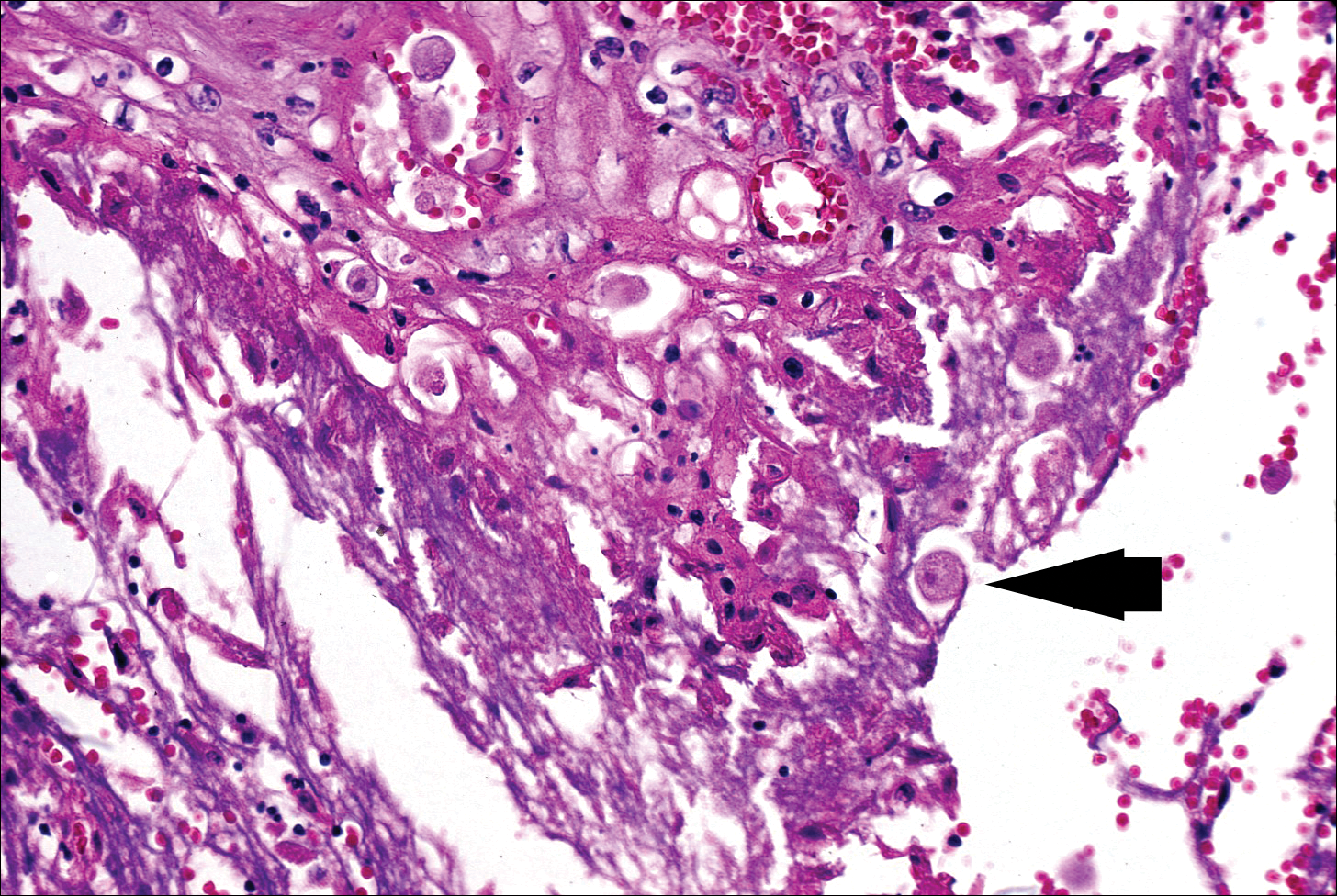

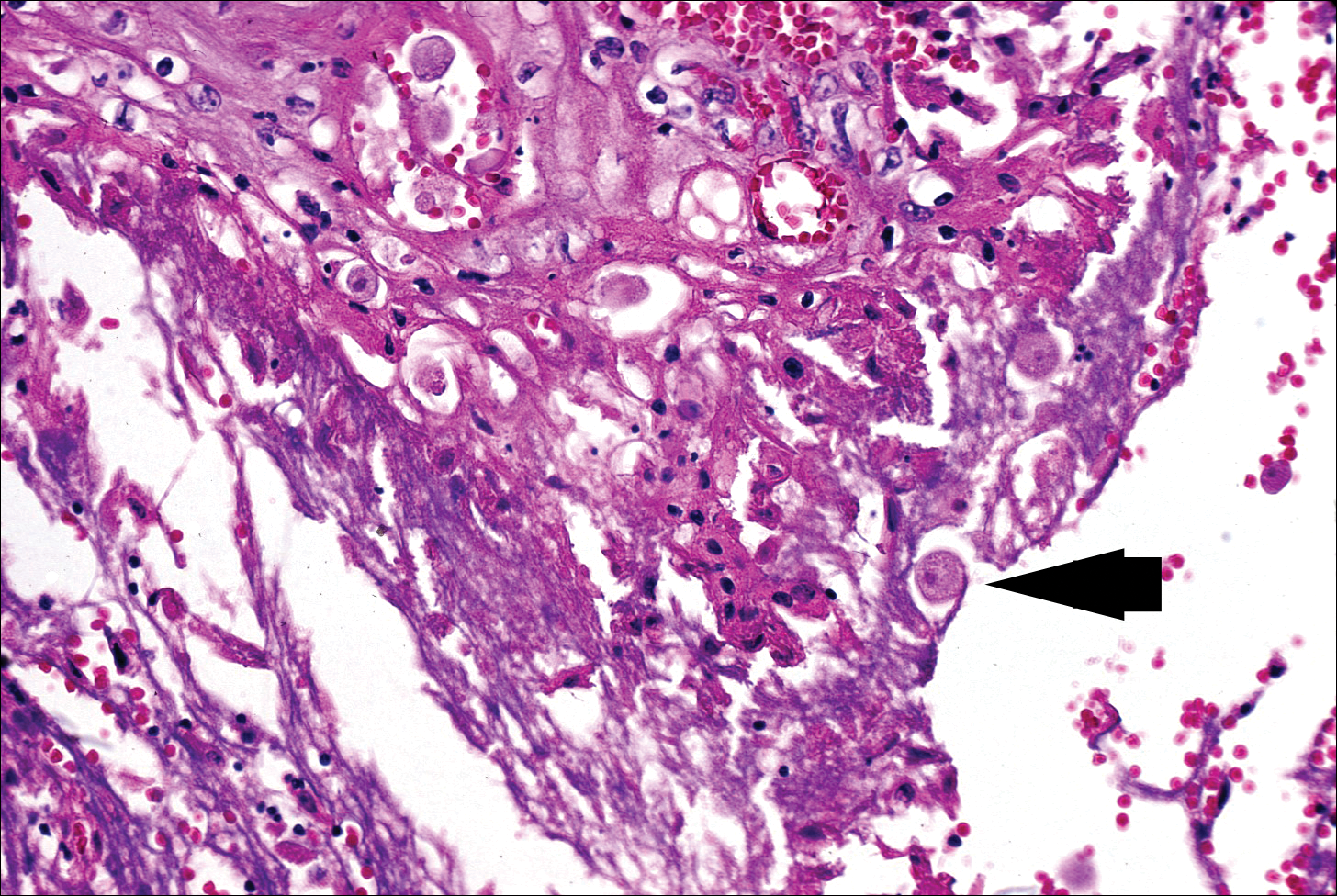

Because of the rarity of infections caused and being part of the normal flora, the clinical implications of subtyping and sensitivity studies via culture or molecular studies may not be important; however, incidental presence of these organisms with unfamiliar morphology may cause confusion for the dermatopathologist. An extremely small size (0.5-2.0 μm) compared to red blood cells (7-8 μm) and white blood cells (10-12 μm) in a tight tetrad arrangement should raise the suspicion for Micrococcus.1 The refractive nature of these organisms from a thick extracellular layer can mimic fungus or plant matter; a negative Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver stain in this case helped in not only differentiating but also ruling out secondary fungal infection. Finally, a Gram stain with violet staining of these organisms reaffirmed the diagnosis of gram-positive bacterial organisms, most consistent with Micrococcus species (Figure 1). Culture studies were not performed because of contamination of the tissue specimen and resolution of the patient's symptoms.

The presence of foreign material in the skin may be traumatic, occupational, cosmetic, iatrogenic, or self-inflicted, including a wide variety of substances that appear in different morphological forms on hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)-stained sections, depending on their structure and physiochemical properties.9 Although not all foreign bodies may polarize, examining the sample under polarized light is considered an important step to narrow down the differential diagnosis. The tissue reaction is primarily dependent on the nature of the substance and duration, consisting of histiocytes, macrophages, plasma cells, lymphocytes, and fibrosis.9 Activated histiocytes, multinucleated giant cells, and granulomas are classic findings that generally are seen surrounding and engulfing the foreign material (Figure 2). In addition to foreign material, substances such as calcium salts, urate crystals, extruded keratin, ruptured cysts, and hair follicles may act as foreign materials and can incite a tissue response.9 Absence of histiocytic response, granuloma formation, and fibrosis in a lesion of 1 month's duration made the tetrad bodies unlikely to be foreign material.

Demodex mites are superficial inhabitants of human skin that are acquired shortly after birth, live in or near pilosebaceous units, and obtain nourishment from skin cells and sebum.10,11 The mites can be recovered on 10% of skin biopsies, most commonly on the face due to high sebum production.10 Adult mites range from 0.1 to 0.4 mm in length and are round to oval in shape. Females lay eggs inside the hair follicle or sebaceous glands.11 They usually are asymptomatic, but their infestation may become pathogenic, especially in immunocompromised individuals.10 The clinical picture may resemble bacterial folliculitis, rosacea, and perioral dermatitis, while histology typically is characterized by spongiosis, lymphohistiocytic inflammation around infested follicles, and mite(s) in follicular infundibula (Figure 3). Sometimes the protrusion of mites and keratin from the follicles is seen as follicular spines on histology and referred to as pityriasis folliculorum.

Deposits of urate crystals in skin occur from the elevated serum uric acid levels in gout. The cutaneous deposits are mainly in the dermis and subcutaneous tissue and are extremely painful.12 Urate crystals get dissolved during formalin fixation and leave needlelike clefts in a homogenous, lightly basophilic material on H&E slide (Figure 4). For the same reason, polarized microscopy also is not helpful despite the birefringent nature of urate crystals.12

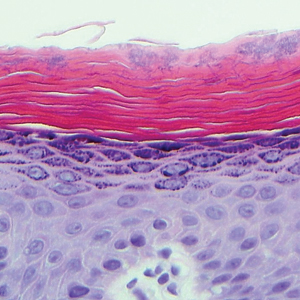

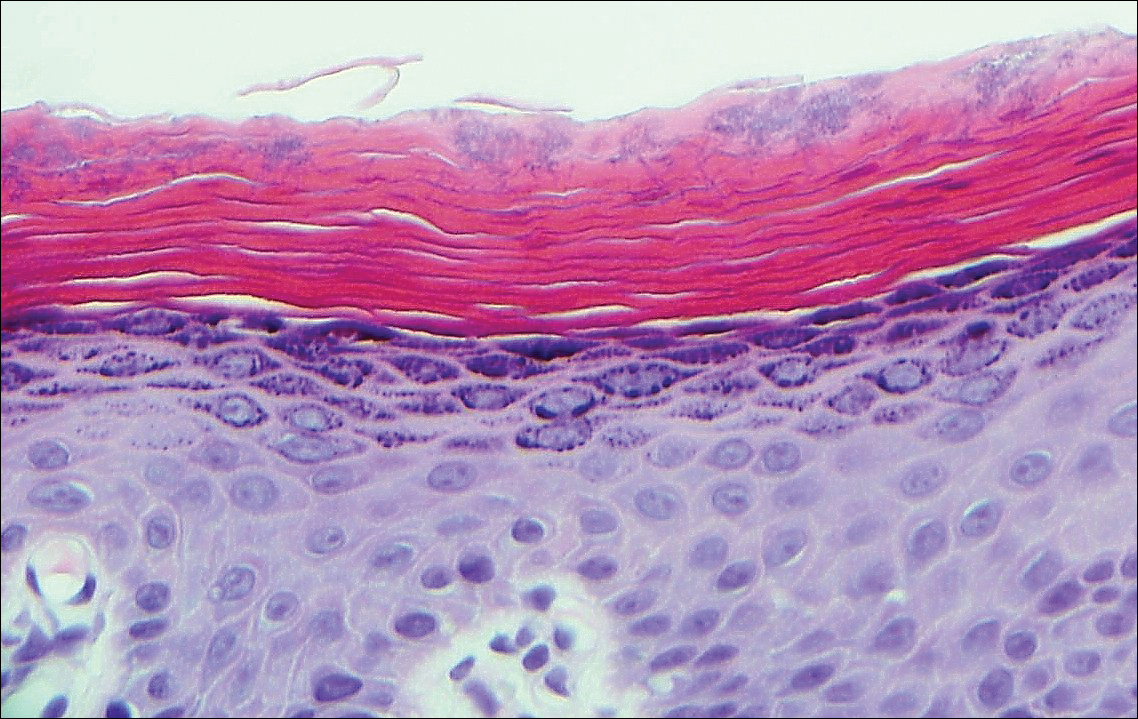

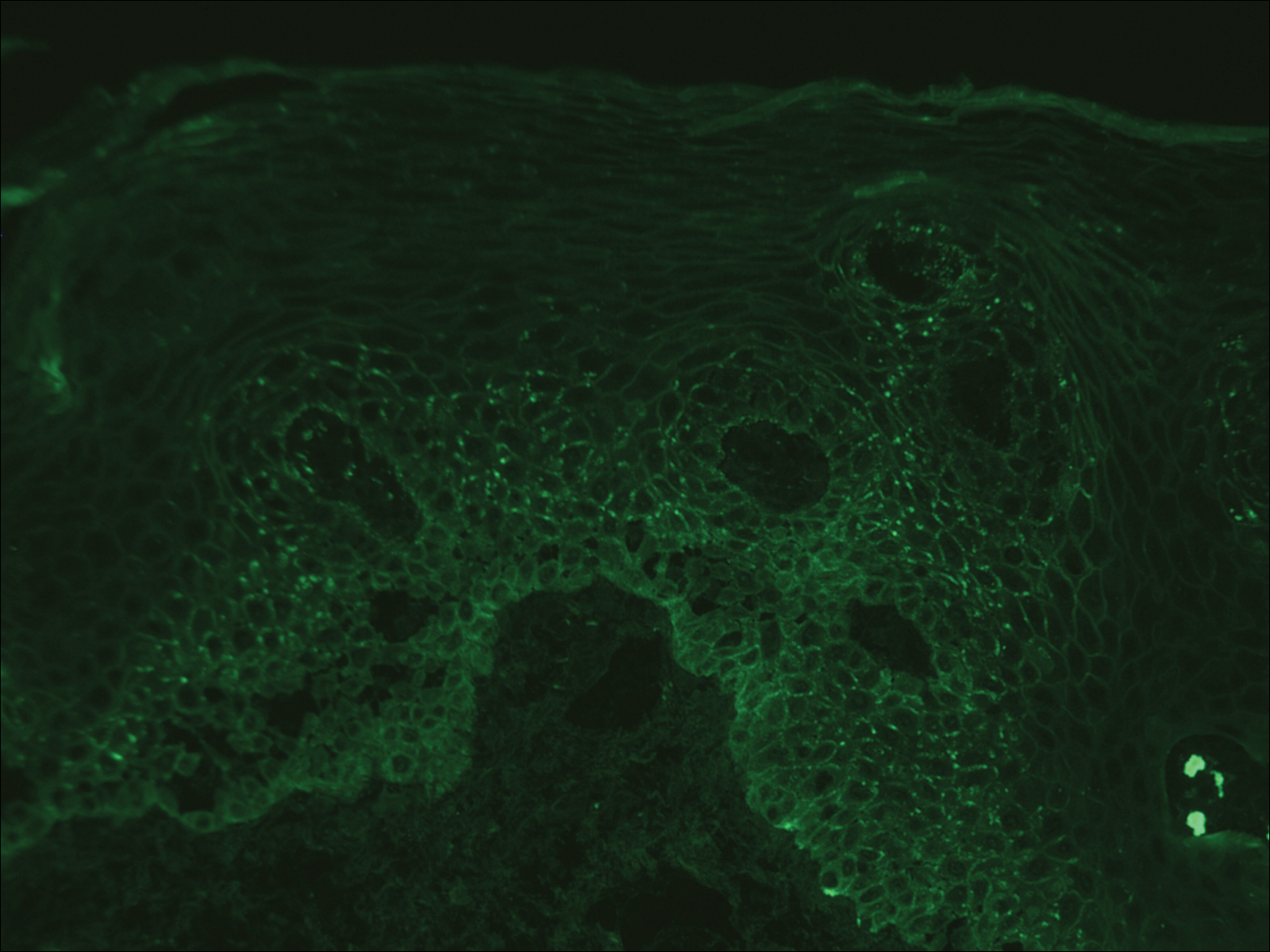

Fungal yeast forms appear round to oval under light microscopy, ranging from 2 to 100 μm in size.13 The common superficial forms involving the epidermis or hair follicles similar to the current case of bacterial infection include Malassezia and dermatophyte infections. Malassezia is part of the normal flora of sebum-rich areas of skin and is associated with superficial infections such as folliculitis, atopic dermatitis, psoriasis, seborrheic dermatitis, and dandruff.14Malassezia appear as clusters of yeast cells that are pleomorphic and round to oval in shape, ranging from 2 to 6 μm in size. It forms hyphae in its pathogenic form and gives rise to the classic spaghetti and meatball-like appearance that can be highlighted by periodic acid-Schiff (Figure 5) and Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver special stains. Dermatophytes include 3 genera--Trichophyton, Microsporum, and Epidermophyton--with at least 40 species that causes skin infections in humans.14 Fungal spores and hyphae forms are restricted to the stratum corneum. The hyphae forms may not be apparent on H&E stain, and periodic acid-Schiff staining is helpful in visualizing the fungal elements. The presence of neutrophils in the corneal layer, basket weave hyperkeratosis, and presence of fungal hyphae within the corneal layer fissures (sandwich sign) are clues to the dermatophyte infection.15 Other smaller fungi such as Histoplasma capsulatum (2-4 μm), Candida (3-5 μm), and Pneumocystis (2-5 μm) species can be found in skin in disseminated infections, usually affecting immunocompromised individuals.13Histoplasma is a basophilic yeast that exhibits narrow-based budding and appears clustered within or outside of macrophages. Candida species generally are dimorphic, and yeasts are found intermingled with filamentous forms. Pneumocystis infection in skin is extremely rare, and the fungi appear as spherical or crescent-shaped bodies in a foamy amorphous material.16

The Diagnosis: Bacterial Infection

The tetrad arrangement of organisms seen in this case was classic for Micrococcus and Sarcina species. Both are gram-positive cocci that occur in tetrads, but Micrococcus is aerobic and catalase positive, whereas Sarcina species are anaerobic, catalase negative, acidophilic, and form spores in alkaline pH.1 Although difficult to definitively differentiate on light microscopy, micrococci are smaller in size, ranging from 0.5 to 2.0 μm, and occur in tight clusters, as seen in this case (quiz images), in contrast to Sarcina species, which are relatively larger (1.8-3.0 μm).2 Sarcinae typically are found in soil and air, are considered pathogenic, and are associated with gastric symptoms (Sarcina ventriculi).1Sarcina species also are reported to colonize the skin of patients with diabetes mellitus, but no pathogenic activity is known in the skin.3Micrococcus species, with the majority being Micrococcus luteus, are part of the normal flora of the human skin as well as the oral and nasal cavities. Occasional reports of pneumonia, endocarditis, meningitis, arthritis, endophthalmitis, and sepsis have been reported in immunocompromised individuals.4 In the skin, Micrococcus is a commensal organism; however, Micrococcus sedentarius has been associated with pitted keratolysis, and reports of Micrococcus folliculitis in human immunodeficiency virus patients also are described in the literature.5,6 Micrococci are considered opportunistic bacteria and may worsen and prolong a localized cutaneous infection caused by other organisms under favorable conditions.7Micrococcus luteus is one of the most common bacteria cultured from skin and soft tissue infections caused by fungal organisms.8 Depending on the immune status of an individual, use of broad-spectrum antibiotic and/or elimination of favorable milieu (ie, primary pathogen, breaks in skin) usually treats the infection.

Because of the rarity of infections caused and being part of the normal flora, the clinical implications of subtyping and sensitivity studies via culture or molecular studies may not be important; however, incidental presence of these organisms with unfamiliar morphology may cause confusion for the dermatopathologist. An extremely small size (0.5-2.0 μm) compared to red blood cells (7-8 μm) and white blood cells (10-12 μm) in a tight tetrad arrangement should raise the suspicion for Micrococcus.1 The refractive nature of these organisms from a thick extracellular layer can mimic fungus or plant matter; a negative Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver stain in this case helped in not only differentiating but also ruling out secondary fungal infection. Finally, a Gram stain with violet staining of these organisms reaffirmed the diagnosis of gram-positive bacterial organisms, most consistent with Micrococcus species (Figure 1). Culture studies were not performed because of contamination of the tissue specimen and resolution of the patient's symptoms.

The presence of foreign material in the skin may be traumatic, occupational, cosmetic, iatrogenic, or self-inflicted, including a wide variety of substances that appear in different morphological forms on hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)-stained sections, depending on their structure and physiochemical properties.9 Although not all foreign bodies may polarize, examining the sample under polarized light is considered an important step to narrow down the differential diagnosis. The tissue reaction is primarily dependent on the nature of the substance and duration, consisting of histiocytes, macrophages, plasma cells, lymphocytes, and fibrosis.9 Activated histiocytes, multinucleated giant cells, and granulomas are classic findings that generally are seen surrounding and engulfing the foreign material (Figure 2). In addition to foreign material, substances such as calcium salts, urate crystals, extruded keratin, ruptured cysts, and hair follicles may act as foreign materials and can incite a tissue response.9 Absence of histiocytic response, granuloma formation, and fibrosis in a lesion of 1 month's duration made the tetrad bodies unlikely to be foreign material.

Demodex mites are superficial inhabitants of human skin that are acquired shortly after birth, live in or near pilosebaceous units, and obtain nourishment from skin cells and sebum.10,11 The mites can be recovered on 10% of skin biopsies, most commonly on the face due to high sebum production.10 Adult mites range from 0.1 to 0.4 mm in length and are round to oval in shape. Females lay eggs inside the hair follicle or sebaceous glands.11 They usually are asymptomatic, but their infestation may become pathogenic, especially in immunocompromised individuals.10 The clinical picture may resemble bacterial folliculitis, rosacea, and perioral dermatitis, while histology typically is characterized by spongiosis, lymphohistiocytic inflammation around infested follicles, and mite(s) in follicular infundibula (Figure 3). Sometimes the protrusion of mites and keratin from the follicles is seen as follicular spines on histology and referred to as pityriasis folliculorum.

Deposits of urate crystals in skin occur from the elevated serum uric acid levels in gout. The cutaneous deposits are mainly in the dermis and subcutaneous tissue and are extremely painful.12 Urate crystals get dissolved during formalin fixation and leave needlelike clefts in a homogenous, lightly basophilic material on H&E slide (Figure 4). For the same reason, polarized microscopy also is not helpful despite the birefringent nature of urate crystals.12

Fungal yeast forms appear round to oval under light microscopy, ranging from 2 to 100 μm in size.13 The common superficial forms involving the epidermis or hair follicles similar to the current case of bacterial infection include Malassezia and dermatophyte infections. Malassezia is part of the normal flora of sebum-rich areas of skin and is associated with superficial infections such as folliculitis, atopic dermatitis, psoriasis, seborrheic dermatitis, and dandruff.14Malassezia appear as clusters of yeast cells that are pleomorphic and round to oval in shape, ranging from 2 to 6 μm in size. It forms hyphae in its pathogenic form and gives rise to the classic spaghetti and meatball-like appearance that can be highlighted by periodic acid-Schiff (Figure 5) and Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver special stains. Dermatophytes include 3 genera--Trichophyton, Microsporum, and Epidermophyton--with at least 40 species that causes skin infections in humans.14 Fungal spores and hyphae forms are restricted to the stratum corneum. The hyphae forms may not be apparent on H&E stain, and periodic acid-Schiff staining is helpful in visualizing the fungal elements. The presence of neutrophils in the corneal layer, basket weave hyperkeratosis, and presence of fungal hyphae within the corneal layer fissures (sandwich sign) are clues to the dermatophyte infection.15 Other smaller fungi such as Histoplasma capsulatum (2-4 μm), Candida (3-5 μm), and Pneumocystis (2-5 μm) species can be found in skin in disseminated infections, usually affecting immunocompromised individuals.13Histoplasma is a basophilic yeast that exhibits narrow-based budding and appears clustered within or outside of macrophages. Candida species generally are dimorphic, and yeasts are found intermingled with filamentous forms. Pneumocystis infection in skin is extremely rare, and the fungi appear as spherical or crescent-shaped bodies in a foamy amorphous material.16

- Al Rasheed MR, Senseng CG. Sarcina ventriculi: review of the literature. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2016;140:1441-1445.

- Lam-Himlin D, Tsiatis AC, Montgomery E, et al. Sarcina organisms in the gastrointestinal tract: a clinicopathologic and molecular study. Am J Surg Pathol. 2011;35:1700-1705.

- Somerville DA, Lancaster-Smith M. The aerobic cutaneous microflora of diabetic subjects. Br J Dermatol. 1973;89:395-400.

- Hetem DJ, Rooijakkers S, Ekkelenkamp MB. Staphylococci and Micrococci. In: Cohen J, Powderly WG, Opal SM, eds. Infectious Diseases. 4th ed. Vol 2. New York, NY: Elsevier; 2017:1509-1522.

- Nordstrom KM, McGinley KJ, Cappiello L, et al. Pitted keratolysis. the role of Micrococcus sedentarius. Arch Dermatol. 1987;123:1320-1325.

- Smith KJ, Neafie R, Yeager J, et al. Micrococcus folliculitis in HIV-1 disease. Br J Dermatol. 1999;141:558-561.

- van Rensburg JJ, Lin H, Gao X, et al. The human skin microbiome associates with the outcome of and is influenced by bacterial infection. mBio. 2015;6:E01315-15. doi:10.1128/mBio.01315-15.

- Chuku A, Nwankiti OO. Association of bacteria with fungal infection of skin and soft tissue lesions in plateau state, Nigeria. Br Microbiol Res J. 2013;3:470-477.

- Molina-Ruiz AM, Requena L. Foreign body granulomas. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:497-523.

- Elston CA, Elston DM. Demodex mites. Clin Dermatol. 2014;32:739-743.

- Rather PA, Hassan I. Human Demodex mite: the versatile mite of dermatological importance. Indian J Dermatol. 2014;59:60-66.

- Gaviria JL, Ortega VG, Gaona J, et al. Unusual dermatological manifestations of gout: review of literature and a case report. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2015;3:E445.

- Guarner J, Brandt ME. Histopathologic diagnosis of fungal infections in the 21st century. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2011;24:247-280.

- White TC, Findley K, Dawson TL Jr, et al. Fungi on the skin: dermatophytes and Malassezia. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2014;4. pii:a019802. doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a019802.

- Gottlieb GJ, Ackerman AB. The "sandwich sign" of dermatophytosis. Am J Dermatopathol. 1986;8:347.

- Hennessey NP, Parro EL, Cockerell CJ. Cutaneous Pneumocystis carinii infection in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Arch Dermatol. 1991;127:1699-1701.

- Al Rasheed MR, Senseng CG. Sarcina ventriculi: review of the literature. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2016;140:1441-1445.

- Lam-Himlin D, Tsiatis AC, Montgomery E, et al. Sarcina organisms in the gastrointestinal tract: a clinicopathologic and molecular study. Am J Surg Pathol. 2011;35:1700-1705.

- Somerville DA, Lancaster-Smith M. The aerobic cutaneous microflora of diabetic subjects. Br J Dermatol. 1973;89:395-400.

- Hetem DJ, Rooijakkers S, Ekkelenkamp MB. Staphylococci and Micrococci. In: Cohen J, Powderly WG, Opal SM, eds. Infectious Diseases. 4th ed. Vol 2. New York, NY: Elsevier; 2017:1509-1522.

- Nordstrom KM, McGinley KJ, Cappiello L, et al. Pitted keratolysis. the role of Micrococcus sedentarius. Arch Dermatol. 1987;123:1320-1325.

- Smith KJ, Neafie R, Yeager J, et al. Micrococcus folliculitis in HIV-1 disease. Br J Dermatol. 1999;141:558-561.

- van Rensburg JJ, Lin H, Gao X, et al. The human skin microbiome associates with the outcome of and is influenced by bacterial infection. mBio. 2015;6:E01315-15. doi:10.1128/mBio.01315-15.

- Chuku A, Nwankiti OO. Association of bacteria with fungal infection of skin and soft tissue lesions in plateau state, Nigeria. Br Microbiol Res J. 2013;3:470-477.

- Molina-Ruiz AM, Requena L. Foreign body granulomas. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:497-523.

- Elston CA, Elston DM. Demodex mites. Clin Dermatol. 2014;32:739-743.

- Rather PA, Hassan I. Human Demodex mite: the versatile mite of dermatological importance. Indian J Dermatol. 2014;59:60-66.

- Gaviria JL, Ortega VG, Gaona J, et al. Unusual dermatological manifestations of gout: review of literature and a case report. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2015;3:E445.

- Guarner J, Brandt ME. Histopathologic diagnosis of fungal infections in the 21st century. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2011;24:247-280.

- White TC, Findley K, Dawson TL Jr, et al. Fungi on the skin: dermatophytes and Malassezia. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2014;4. pii:a019802. doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a019802.

- Gottlieb GJ, Ackerman AB. The "sandwich sign" of dermatophytosis. Am J Dermatopathol. 1986;8:347.

- Hennessey NP, Parro EL, Cockerell CJ. Cutaneous Pneumocystis carinii infection in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Arch Dermatol. 1991;127:1699-1701.

A 72-year-old woman with a medical history notable for multiple sclerosis and intravenous drug abuse presented to the dermatology clinic with a 0.6×0.5-cm, pruritic, wartlike, inflamed, keratotic papule on the palmar aspect of the right finger of more than 1 month's duration. A shave biopsy was performed that showed excoriation with serum crust, parakeratosis, and neutrophilic infiltrate in the papillary dermis. Within the serum crust and at the dermoepidermal junction, clusters of refractive basophilic bodies (arrows) in tetrad arrangement also were noted (inset). The papule resolved after the biopsy without any additional treatment.

Pigmented Lesion on the Forearm

The Diagnosis: Monsel Solution Reaction

Exogenous substances can cause interesting incongruities in cutaneous biopsies of which pathologists and dermatologists should be cognizant. Exogenous lesions are caused by externally introduced foreign bodies, substances, or materials, such as sterile compressed sponges, aluminum chloride hexahydrate and anhydrous ethyl alcohol, silica, paraffin, and Monsel solution. Monsel solution reaction is a florid fibrohistiocytic proliferation stimulated by the application of Monsel solution. Monsel solution is a ferric subsulfate that often is used to achieve hemostasis after shave biopsies. Hemostasis is thought to result from the ability of ferric ions to denature and agglutinate proteins such as fibrinogen.1,2 Application of Monsel solution likely causes ferrugination of fibrin, dermal collagen, and striated muscle fibers. Some ferruginated collagen fibers are eliminated through the epidermis as the epidermis regenerates, while some fibers become calcified. Siderophages (iron-containing macrophages) are present in these areas. The ferrugination of collagen fibers becomes less pronounced as the biopsy sites heal and the iron pigment subsequently is absorbed by macrophages. Ferruginated skeletal muscles can act as foreign bodies and may elicit granulomatous reactions.2

It is currently unclear why fibrohistiocytic responses occur in some instances but not others. Iron stains (eg, Perls Prussian blue stain) make interpretation clear, provided the pathologist is familiar with Monsel solution. The primary differential diagnosis of these lesions centers on heavily pigmented melanocytic proliferations. It is critical to review prior biopsy sections or to have definite knowledge of the prior biopsy diagnosis. Histologically, the epidermis may demonstrate nonspecific reactive changes such as hyperkeratosis with foci of irregular acanthosis. The prominent features are present in the dermis where there is a proliferation of spindle- and polyhedral-shaped cells that may show cytologic atypia and occasional mitotic figures. The cells contain refractile brown pigment scattered in the dermis and deposited on collagen fibers (quiz images). Occasional large black or brown encrustations may be identified. Monsel-containing cells may indiscernibly blend with foci of more blatantly fibrohistiocytic differentiation, in which case iron stains are strongly positive (Figure 1). If the clinician uses Monsel solution for hemostasis during the removal of a nevomelanocytic neoplasm, it might be necessary to use melanin stains or immunohistochemistry on the reexcision specimen to distinguish between residual nevomelanocytic and fibrohistiocytic cells.3

Common blue nevus is a benign, typically intradermal melanocytic lesion. It most frequently occurs in young adults and has a predilection for females. Clinically, it can be found anywhere on the body as a single, asymptomatic, well-circumscribed, blue-black, dome-shaped papule measuring less than 1 cm in diameter. Histologically, it is characterized by pigmented, dendritic, spindle-shaped melanocytes that typically are separated by thick collagen bundles (Figure 2). The melanocytes typically have small nuclei with occasional basophilic nucleolus. Melanocytes typically are diffusely positive for melanocytic markers including human melanoma black (HMB) 45, S-100, Melan-A, and microphthalmia transcription factor 1. In contrast to most other benign melanocytic nevi, HMB-45 strongly stains the entire lesion in blue nevi.4

Desmoplastic melanoma accounts for 1% to 4% of all melanomas. The median age at diagnosis is 62 years and, as in other types of melanoma, men are more commonly affected.5 Clinically, desmoplastic melanoma typically presents on the head and neck as a painless indurated plaque, though it can present as a small papule or nodule. Nearly half of desmoplastic melanomas lack obvious pigmentation, which may lead to the misdiagnosis of basal cell carcinoma or a scar. Histologically, desmoplastic melanomas are composed of spindled melanocytes separated by collagen fibers or fibrous stroma (Figure 3). Histology displays variable cytologic atypia and stromal fibrosis. Characteristically there are small islands of lymphocytes and plasma cells within or at the edge of the tumor. The spindle cells stain positive with S-100 and Sry-related HMg-box gene 10, SOX10. Type IV collagen and laminin often are expressed in desmoplastic melanoma. In contrast to many other subtypes of melanoma, HMB-45 and Melan-A usually are negative.6

Animal-type melanoma is a rare neoplasm that differs from other subtypes of melanoma both clinically and histologically. Most frequently, animal-type melanoma affects younger adults (median age, 27 years) and arises on the arms and legs, head and neck, or trunk; men and women are affected equally.7 It most commonly presents with a blue or blue-black nodule with a blue-white veil or irregular white areas. Histologically, animal-type melanoma is a predominantly dermal-based melanocytic proliferation with heavily pigmented epithelioid and spindled melanocytes (Figure 4). The pigmentation pattern ranges widely from fine, granular, light brown deposits to coarse dark brown deposits with malignant cells often arranged in fascicles or sheets. Frequently, there is periadnexal and perieccrine spread. Often, there is epidermal hyperplasia above the dermis. As with conventional melanoma, the immunohistochemistry of animal-type melanoma is positive for S-100 protein, HMB-45, SOX10, and Melan-A.7

Recurrent nevi typically arise within 6 months of a previously biopsied melanocytic nevus. Most recurrent nevi originate from common banal nevi (most often a compound nevus). Recurrent nevi also may arise from congenital, atypical/dysplastic, and Spitz nevi. Most often they are found on the back of women aged 20 to 30 years.8 Clinically, they manifest as a macular area of scar with variegated hyperpigmentation and hypopigmentation as well as linear streaking. They may demonstrate variable diffuse, stippled, and halo pigmentation patterns. Classically, recurrent nevi present with a trizonal histologic pattern. Within the epidermis there is a proliferation of melanocytes along the dermoepidermal junction, which may show varying degrees of atypia and pagetoid migration. The melanocytes often are described as epithelioid with round nuclei and even chromatin (Figure 5). The atypical features should be confined to the epidermis overlying the prior biopsy site. Within the dermis there is dense dermal collagen and fibrosis with vertically oriented blood vessels. Finally, features of the original nevus may be seen at the base of the lesion. Although immunohistochemistry may be helpful in some cases, an appropriate clinical history and comparison to the prior biopsy can be invaluable.8

Host tissue reactions resulting in artefactual changes caused by foreign bodies or substances may confound the untrained eye. Monsel solution reaction may be confused for a blue nevus, desmoplastic melanoma, animal-type melanoma, and a residual/recurrent nevus. This confusion could lead to serious diagnostic errors that could cause an unfavorable outcome for the patient. It is critical to know the salient points in the patient's clinical history. Knowledge of the Monsel solution reaction and other exogenous lesions as well as the subsequent unique tissue reaction patterns can aid in facilitating an accurate and prompt pathologic diagnosis.

- Olmstead PM, Lund HZ, Leonard DD. Monsel's solution: a histologic nuisance. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1980;3:492-498.

- Amazon K, Robinson MJ, Rywlin AM. Ferrugination caused by Monsel's solution. clinical observations and experimentations. Am J Dermatopathol. 1980;2:197-205.

- Del Rosario RN, Barr RJ, Graham BS, et al. Exogenous and endogenous cutaneous anomalies and curiosities. Am J Dermatopathol. 2005;27:259-267.

- Calonje E, Blessing K, Glusac E, et al. Blue naevi. In: LeBoit PE, Burg G, Weedon D, et al, eds. World Health Organization Classification of Tumours, Pathology and Genetics of Skin Tumours. Lyon, France: IARC Press; 2006:95-99.

- Jain S, Allen PW. Desmoplastic malignant melanoma and its variants. a study of 45 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1989;13:358-373.

- McCarthy SW, Crotty KA, Scolyer RA. Desmoplastic melanoma and desmoplastic neurotropic melanoma. In: LeBoit PE, Burg G, Weedon D, et al, eds. World Health Organization Classification of Tumours, Pathology and Genetics of Skin Tumours. Lyon, France: IARC Press; 2006:76-78.

- Vyas R, Keller JJ, Honda K, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of animal-type melanoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:1031-1039.

- Fox JC, Reed JA, Shea CR. The recurrent nevus phenomenon: a history of challenge, controversy, and discovery. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2011;135:842-846.

The Diagnosis: Monsel Solution Reaction

Exogenous substances can cause interesting incongruities in cutaneous biopsies of which pathologists and dermatologists should be cognizant. Exogenous lesions are caused by externally introduced foreign bodies, substances, or materials, such as sterile compressed sponges, aluminum chloride hexahydrate and anhydrous ethyl alcohol, silica, paraffin, and Monsel solution. Monsel solution reaction is a florid fibrohistiocytic proliferation stimulated by the application of Monsel solution. Monsel solution is a ferric subsulfate that often is used to achieve hemostasis after shave biopsies. Hemostasis is thought to result from the ability of ferric ions to denature and agglutinate proteins such as fibrinogen.1,2 Application of Monsel solution likely causes ferrugination of fibrin, dermal collagen, and striated muscle fibers. Some ferruginated collagen fibers are eliminated through the epidermis as the epidermis regenerates, while some fibers become calcified. Siderophages (iron-containing macrophages) are present in these areas. The ferrugination of collagen fibers becomes less pronounced as the biopsy sites heal and the iron pigment subsequently is absorbed by macrophages. Ferruginated skeletal muscles can act as foreign bodies and may elicit granulomatous reactions.2

It is currently unclear why fibrohistiocytic responses occur in some instances but not others. Iron stains (eg, Perls Prussian blue stain) make interpretation clear, provided the pathologist is familiar with Monsel solution. The primary differential diagnosis of these lesions centers on heavily pigmented melanocytic proliferations. It is critical to review prior biopsy sections or to have definite knowledge of the prior biopsy diagnosis. Histologically, the epidermis may demonstrate nonspecific reactive changes such as hyperkeratosis with foci of irregular acanthosis. The prominent features are present in the dermis where there is a proliferation of spindle- and polyhedral-shaped cells that may show cytologic atypia and occasional mitotic figures. The cells contain refractile brown pigment scattered in the dermis and deposited on collagen fibers (quiz images). Occasional large black or brown encrustations may be identified. Monsel-containing cells may indiscernibly blend with foci of more blatantly fibrohistiocytic differentiation, in which case iron stains are strongly positive (Figure 1). If the clinician uses Monsel solution for hemostasis during the removal of a nevomelanocytic neoplasm, it might be necessary to use melanin stains or immunohistochemistry on the reexcision specimen to distinguish between residual nevomelanocytic and fibrohistiocytic cells.3

Common blue nevus is a benign, typically intradermal melanocytic lesion. It most frequently occurs in young adults and has a predilection for females. Clinically, it can be found anywhere on the body as a single, asymptomatic, well-circumscribed, blue-black, dome-shaped papule measuring less than 1 cm in diameter. Histologically, it is characterized by pigmented, dendritic, spindle-shaped melanocytes that typically are separated by thick collagen bundles (Figure 2). The melanocytes typically have small nuclei with occasional basophilic nucleolus. Melanocytes typically are diffusely positive for melanocytic markers including human melanoma black (HMB) 45, S-100, Melan-A, and microphthalmia transcription factor 1. In contrast to most other benign melanocytic nevi, HMB-45 strongly stains the entire lesion in blue nevi.4

Desmoplastic melanoma accounts for 1% to 4% of all melanomas. The median age at diagnosis is 62 years and, as in other types of melanoma, men are more commonly affected.5 Clinically, desmoplastic melanoma typically presents on the head and neck as a painless indurated plaque, though it can present as a small papule or nodule. Nearly half of desmoplastic melanomas lack obvious pigmentation, which may lead to the misdiagnosis of basal cell carcinoma or a scar. Histologically, desmoplastic melanomas are composed of spindled melanocytes separated by collagen fibers or fibrous stroma (Figure 3). Histology displays variable cytologic atypia and stromal fibrosis. Characteristically there are small islands of lymphocytes and plasma cells within or at the edge of the tumor. The spindle cells stain positive with S-100 and Sry-related HMg-box gene 10, SOX10. Type IV collagen and laminin often are expressed in desmoplastic melanoma. In contrast to many other subtypes of melanoma, HMB-45 and Melan-A usually are negative.6

Animal-type melanoma is a rare neoplasm that differs from other subtypes of melanoma both clinically and histologically. Most frequently, animal-type melanoma affects younger adults (median age, 27 years) and arises on the arms and legs, head and neck, or trunk; men and women are affected equally.7 It most commonly presents with a blue or blue-black nodule with a blue-white veil or irregular white areas. Histologically, animal-type melanoma is a predominantly dermal-based melanocytic proliferation with heavily pigmented epithelioid and spindled melanocytes (Figure 4). The pigmentation pattern ranges widely from fine, granular, light brown deposits to coarse dark brown deposits with malignant cells often arranged in fascicles or sheets. Frequently, there is periadnexal and perieccrine spread. Often, there is epidermal hyperplasia above the dermis. As with conventional melanoma, the immunohistochemistry of animal-type melanoma is positive for S-100 protein, HMB-45, SOX10, and Melan-A.7

Recurrent nevi typically arise within 6 months of a previously biopsied melanocytic nevus. Most recurrent nevi originate from common banal nevi (most often a compound nevus). Recurrent nevi also may arise from congenital, atypical/dysplastic, and Spitz nevi. Most often they are found on the back of women aged 20 to 30 years.8 Clinically, they manifest as a macular area of scar with variegated hyperpigmentation and hypopigmentation as well as linear streaking. They may demonstrate variable diffuse, stippled, and halo pigmentation patterns. Classically, recurrent nevi present with a trizonal histologic pattern. Within the epidermis there is a proliferation of melanocytes along the dermoepidermal junction, which may show varying degrees of atypia and pagetoid migration. The melanocytes often are described as epithelioid with round nuclei and even chromatin (Figure 5). The atypical features should be confined to the epidermis overlying the prior biopsy site. Within the dermis there is dense dermal collagen and fibrosis with vertically oriented blood vessels. Finally, features of the original nevus may be seen at the base of the lesion. Although immunohistochemistry may be helpful in some cases, an appropriate clinical history and comparison to the prior biopsy can be invaluable.8

Host tissue reactions resulting in artefactual changes caused by foreign bodies or substances may confound the untrained eye. Monsel solution reaction may be confused for a blue nevus, desmoplastic melanoma, animal-type melanoma, and a residual/recurrent nevus. This confusion could lead to serious diagnostic errors that could cause an unfavorable outcome for the patient. It is critical to know the salient points in the patient's clinical history. Knowledge of the Monsel solution reaction and other exogenous lesions as well as the subsequent unique tissue reaction patterns can aid in facilitating an accurate and prompt pathologic diagnosis.

The Diagnosis: Monsel Solution Reaction

Exogenous substances can cause interesting incongruities in cutaneous biopsies of which pathologists and dermatologists should be cognizant. Exogenous lesions are caused by externally introduced foreign bodies, substances, or materials, such as sterile compressed sponges, aluminum chloride hexahydrate and anhydrous ethyl alcohol, silica, paraffin, and Monsel solution. Monsel solution reaction is a florid fibrohistiocytic proliferation stimulated by the application of Monsel solution. Monsel solution is a ferric subsulfate that often is used to achieve hemostasis after shave biopsies. Hemostasis is thought to result from the ability of ferric ions to denature and agglutinate proteins such as fibrinogen.1,2 Application of Monsel solution likely causes ferrugination of fibrin, dermal collagen, and striated muscle fibers. Some ferruginated collagen fibers are eliminated through the epidermis as the epidermis regenerates, while some fibers become calcified. Siderophages (iron-containing macrophages) are present in these areas. The ferrugination of collagen fibers becomes less pronounced as the biopsy sites heal and the iron pigment subsequently is absorbed by macrophages. Ferruginated skeletal muscles can act as foreign bodies and may elicit granulomatous reactions.2

It is currently unclear why fibrohistiocytic responses occur in some instances but not others. Iron stains (eg, Perls Prussian blue stain) make interpretation clear, provided the pathologist is familiar with Monsel solution. The primary differential diagnosis of these lesions centers on heavily pigmented melanocytic proliferations. It is critical to review prior biopsy sections or to have definite knowledge of the prior biopsy diagnosis. Histologically, the epidermis may demonstrate nonspecific reactive changes such as hyperkeratosis with foci of irregular acanthosis. The prominent features are present in the dermis where there is a proliferation of spindle- and polyhedral-shaped cells that may show cytologic atypia and occasional mitotic figures. The cells contain refractile brown pigment scattered in the dermis and deposited on collagen fibers (quiz images). Occasional large black or brown encrustations may be identified. Monsel-containing cells may indiscernibly blend with foci of more blatantly fibrohistiocytic differentiation, in which case iron stains are strongly positive (Figure 1). If the clinician uses Monsel solution for hemostasis during the removal of a nevomelanocytic neoplasm, it might be necessary to use melanin stains or immunohistochemistry on the reexcision specimen to distinguish between residual nevomelanocytic and fibrohistiocytic cells.3

Common blue nevus is a benign, typically intradermal melanocytic lesion. It most frequently occurs in young adults and has a predilection for females. Clinically, it can be found anywhere on the body as a single, asymptomatic, well-circumscribed, blue-black, dome-shaped papule measuring less than 1 cm in diameter. Histologically, it is characterized by pigmented, dendritic, spindle-shaped melanocytes that typically are separated by thick collagen bundles (Figure 2). The melanocytes typically have small nuclei with occasional basophilic nucleolus. Melanocytes typically are diffusely positive for melanocytic markers including human melanoma black (HMB) 45, S-100, Melan-A, and microphthalmia transcription factor 1. In contrast to most other benign melanocytic nevi, HMB-45 strongly stains the entire lesion in blue nevi.4

Desmoplastic melanoma accounts for 1% to 4% of all melanomas. The median age at diagnosis is 62 years and, as in other types of melanoma, men are more commonly affected.5 Clinically, desmoplastic melanoma typically presents on the head and neck as a painless indurated plaque, though it can present as a small papule or nodule. Nearly half of desmoplastic melanomas lack obvious pigmentation, which may lead to the misdiagnosis of basal cell carcinoma or a scar. Histologically, desmoplastic melanomas are composed of spindled melanocytes separated by collagen fibers or fibrous stroma (Figure 3). Histology displays variable cytologic atypia and stromal fibrosis. Characteristically there are small islands of lymphocytes and plasma cells within or at the edge of the tumor. The spindle cells stain positive with S-100 and Sry-related HMg-box gene 10, SOX10. Type IV collagen and laminin often are expressed in desmoplastic melanoma. In contrast to many other subtypes of melanoma, HMB-45 and Melan-A usually are negative.6

Animal-type melanoma is a rare neoplasm that differs from other subtypes of melanoma both clinically and histologically. Most frequently, animal-type melanoma affects younger adults (median age, 27 years) and arises on the arms and legs, head and neck, or trunk; men and women are affected equally.7 It most commonly presents with a blue or blue-black nodule with a blue-white veil or irregular white areas. Histologically, animal-type melanoma is a predominantly dermal-based melanocytic proliferation with heavily pigmented epithelioid and spindled melanocytes (Figure 4). The pigmentation pattern ranges widely from fine, granular, light brown deposits to coarse dark brown deposits with malignant cells often arranged in fascicles or sheets. Frequently, there is periadnexal and perieccrine spread. Often, there is epidermal hyperplasia above the dermis. As with conventional melanoma, the immunohistochemistry of animal-type melanoma is positive for S-100 protein, HMB-45, SOX10, and Melan-A.7

Recurrent nevi typically arise within 6 months of a previously biopsied melanocytic nevus. Most recurrent nevi originate from common banal nevi (most often a compound nevus). Recurrent nevi also may arise from congenital, atypical/dysplastic, and Spitz nevi. Most often they are found on the back of women aged 20 to 30 years.8 Clinically, they manifest as a macular area of scar with variegated hyperpigmentation and hypopigmentation as well as linear streaking. They may demonstrate variable diffuse, stippled, and halo pigmentation patterns. Classically, recurrent nevi present with a trizonal histologic pattern. Within the epidermis there is a proliferation of melanocytes along the dermoepidermal junction, which may show varying degrees of atypia and pagetoid migration. The melanocytes often are described as epithelioid with round nuclei and even chromatin (Figure 5). The atypical features should be confined to the epidermis overlying the prior biopsy site. Within the dermis there is dense dermal collagen and fibrosis with vertically oriented blood vessels. Finally, features of the original nevus may be seen at the base of the lesion. Although immunohistochemistry may be helpful in some cases, an appropriate clinical history and comparison to the prior biopsy can be invaluable.8

Host tissue reactions resulting in artefactual changes caused by foreign bodies or substances may confound the untrained eye. Monsel solution reaction may be confused for a blue nevus, desmoplastic melanoma, animal-type melanoma, and a residual/recurrent nevus. This confusion could lead to serious diagnostic errors that could cause an unfavorable outcome for the patient. It is critical to know the salient points in the patient's clinical history. Knowledge of the Monsel solution reaction and other exogenous lesions as well as the subsequent unique tissue reaction patterns can aid in facilitating an accurate and prompt pathologic diagnosis.

- Olmstead PM, Lund HZ, Leonard DD. Monsel's solution: a histologic nuisance. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1980;3:492-498.

- Amazon K, Robinson MJ, Rywlin AM. Ferrugination caused by Monsel's solution. clinical observations and experimentations. Am J Dermatopathol. 1980;2:197-205.

- Del Rosario RN, Barr RJ, Graham BS, et al. Exogenous and endogenous cutaneous anomalies and curiosities. Am J Dermatopathol. 2005;27:259-267.

- Calonje E, Blessing K, Glusac E, et al. Blue naevi. In: LeBoit PE, Burg G, Weedon D, et al, eds. World Health Organization Classification of Tumours, Pathology and Genetics of Skin Tumours. Lyon, France: IARC Press; 2006:95-99.

- Jain S, Allen PW. Desmoplastic malignant melanoma and its variants. a study of 45 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1989;13:358-373.

- McCarthy SW, Crotty KA, Scolyer RA. Desmoplastic melanoma and desmoplastic neurotropic melanoma. In: LeBoit PE, Burg G, Weedon D, et al, eds. World Health Organization Classification of Tumours, Pathology and Genetics of Skin Tumours. Lyon, France: IARC Press; 2006:76-78.

- Vyas R, Keller JJ, Honda K, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of animal-type melanoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:1031-1039.

- Fox JC, Reed JA, Shea CR. The recurrent nevus phenomenon: a history of challenge, controversy, and discovery. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2011;135:842-846.

- Olmstead PM, Lund HZ, Leonard DD. Monsel's solution: a histologic nuisance. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1980;3:492-498.

- Amazon K, Robinson MJ, Rywlin AM. Ferrugination caused by Monsel's solution. clinical observations and experimentations. Am J Dermatopathol. 1980;2:197-205.

- Del Rosario RN, Barr RJ, Graham BS, et al. Exogenous and endogenous cutaneous anomalies and curiosities. Am J Dermatopathol. 2005;27:259-267.

- Calonje E, Blessing K, Glusac E, et al. Blue naevi. In: LeBoit PE, Burg G, Weedon D, et al, eds. World Health Organization Classification of Tumours, Pathology and Genetics of Skin Tumours. Lyon, France: IARC Press; 2006:95-99.

- Jain S, Allen PW. Desmoplastic malignant melanoma and its variants. a study of 45 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1989;13:358-373.

- McCarthy SW, Crotty KA, Scolyer RA. Desmoplastic melanoma and desmoplastic neurotropic melanoma. In: LeBoit PE, Burg G, Weedon D, et al, eds. World Health Organization Classification of Tumours, Pathology and Genetics of Skin Tumours. Lyon, France: IARC Press; 2006:76-78.

- Vyas R, Keller JJ, Honda K, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of animal-type melanoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:1031-1039.

- Fox JC, Reed JA, Shea CR. The recurrent nevus phenomenon: a history of challenge, controversy, and discovery. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2011;135:842-846.

A 67-year-old man presented to the dermatology clinic with a 2-cm pigmented lesion on the forearm. An excisional biopsy was obtained.

Deep Soft Tissue Mass of the Knee

The Diagnosis: Nodular Fasciitis

The diagnosis of spindle cell tumors can be challenging; however, by using a variety of immunoperoxidase stains and fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) testing in conjunction with histology, it often is possible to arrive at a definitive diagnosis. For this case, the histologic features in conjunction with the immunoperoxidase stains and FISH were consistent with a diagnosis of nodular fasciitis.

Nodular fasciitis is a benign, self-limiting, myofibroblastic, soft-tissue proliferation typically found in the subcutaneous tissue.1 It can be found anywhere on the body but most commonly on the upper arms and trunk. It most often is seen in young adults, and many cases have been reported in association with a history of trauma to the area.1,2 It typically measures less than 2 cm in diameter.3 The diagnosis of nodular fasciitis is particularly challenging because it mimics sarcoma, both in presentation and in histologic findings with rapid growth, high mitotic activity, and increased cellularity.1,4-7 In contrast to malignancy, nodular fasciitis has no atypical mitoses and little cytologic atypia.8,9 Rather, it contains plump myofibroblasts loosely arranged in a myxoid or fibrous stroma that also may contain lymphocytes, extravasated erythrocytes, and osteoclastlike giant cells distributed throughout.5,10,11 In this case, lymphocytes, extravasated red blood cells, and myxoid change are present, suggesting the diagnosis of nodular fasciitis. In other cases, however, these features may be much more limited, making the diagnosis more challenging. The spindle cells are arranged in poorly defined short fascicles. The tumor cells do not infiltrate between individual adipocytes. There is no notable cytologic atypia.

Because of the difficulty in making the diagnosis, overtreatment of this benign condition can be a problem, causing increased morbidity.1 Erickson-Johnson et al12 identified the role of an ubiquitin-specific peptidase 6, USP6, gene rearrangement on chromosome 17p13 in 92% (44/48) of cases of nodular fasciitis. The USP6 gene most often is rearranged with the myosin heavy chain 9 gene, MYH9, on chromosome 22q12.3. With this rearrangement, the MYH9 promoter leads to the overexpression of USP6, causing tumor formation.2,13 The use of multiple immunoperoxidase stains can be important in the identification of nodular fasciitis. Nodular fasciitis stains negative for S-100, epithelial membrane antigen, CD34, β-catenin, and cytokeratin, but typically stains positive for smooth muscle actin.9

Although dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (DFSP) was in the differential diagnosis, these tumors tend to have greater cellularity than nodular fasciitis. In addition, the spindle cells of DFSP typically are arranged in a storiform pattern. Another characteristic feature of DFSP is that the tumor cells will infiltrate between adipose cells creating a lacelike or honeycomblike appearance within the subcutaneous tissue (Figure 1). Immunohistochemistry staining and FISH testing may be useful in making a diagnosis of DFSP. These tumors typically are positive for CD34 by immunoperoxidase staining and demonstrate a translocation t(17;22)(q21;q13) between platelet-derived growth factor subunit B gene, PDGFB, and collagen type I alpha 1 chain gene, COL1A1, by FISH.

The distinction between the fibrous phase of nodular fasciitis and fibromatosis can be challenging. The size of the lesion may be helpful, with most lesions of nodular fasciitis being less than 3 cm, while lesions of fibromatosis have a mean diameter of 7 cm.5,14 Microscopically, both tumors demonstrate a fascicular growth pattern; however, the fascicles in nodular fasciitis tend to be short and irregular compared to the longer fascicles seen in fibromatosis (Figure 2). Immunohistochemistry staining has limited utility with only 56% (14/25) of superficial fibromatoses having positive nuclear staining for β-catenin.15

Low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma (LGFMS) would be unusual in this clinical scenario. Only 13% to 19% of cases present in patients younger than 18 years (mean age, 33 years).16 In LGFMS there are cytologically bland spindle cells that are typically arranged in a patternless or whorled pattern (Figure 3), though fascicular architecture may be seen. There are alternating areas of fibrous and myxoid stroma. A curvilinear vasculature network and lack of lymphocytes and extravasated red blood cells are histologic features favoring LGFMS over nodular fasciitis. Immunohistochemistry staining and FISH testing can be useful in making the diagnosis of LGFMS. These tumors are characterized by a translocation t(7;16)(q34;p11) involving the fusion in sarcoma, FUS, and cAMP responsive element binding protein 3 like 2, CREB3L2, genes.16 Positive immunohistochemistry staining for MUC4 can be seen in up to 100% of LGFMS and is absent in many other spindle cell tumors.16