User login

STOP performing dilation and curettage for the evaluation of abnormal uterine bleeding

CASE: In-office hysteroscopy spies previously missed polyp

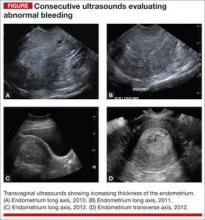

A 51-year-old woman with a history of breast cancer completed 5 years of tamoxifen. During her treatment she had a 3-year history of abnormal vaginal bleeding. Results from consecutive pelvic ultrasounds indicated that the patient had progressively thickening endometrium (from 1.4 cm to 2.5 cm to 4.7 cm). In-office biopsy was negative for endometrial pathology. An ultimate dilation and curettage (D&C) was performed with negative histologic diagnosis. The patient is seen in consultation, and the ultrasound images are reviewed (FIGURE).

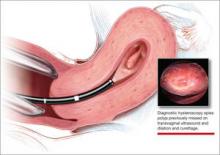

These images show an increasing thickness of the ednometrium with definitive intracavitary pathology that was missed with the prevous clinical evaluation with enodmetrial biopsy and D&C. An in-office hysteroscopy is performed, and a large 5 x 4 x 7 cm cystic and fibrous polyp is identified with normal endometrium (VIDEO 1).

Hysteroscopy reveals massive polyp extending into a dilated lower uterine segment

Abnormal uterine bleeding

The evaluation of abnormal uterine bleeding. (AUB), as described in this clinical scenario, is quite common. As a consequence, many patients have a missed or inaccurate diagnosis and undergo unnecessary invasive procedures under general anesthesia.

AUB is one of the primary indications for a gynecologic consultation, accounting for approximately 33% of all gynecology visits, and for 69% of visits among postmenopausal women.1 Confirming the etiology and planning appropriate intervention is important in the clinical management of AUB because accurate diagnosis may result in avoiding major gynecologic surgery in favor of minimally invasive hysteroscopic management.

Diagnostic hysteroscopy is proven in AUB evaluation

Drawbacks of other diagnostic tools. It is generally accepted that the initial evaluation of women with AUB is performed with noninvasive transvaginal ultrasound (TVUS).1-3 As illustrated by the opening case, however, the accuracy of TVUS is limited in the diagnosis of focal endometrial lesions, and further investigation of the uterine cavity is warranted.

Evaluation of the uterine cavity with sonohysterography (SH)—vaginal ultrasound with the instillation of saline into the uterine cavity—is more accurate than TVUS alone. Yet, diagnostic hysteroscopy (DH) has proven to be superior to either modality for the accurate evaluation of intracavitary pathology.1-3

Evidence of DH superiority. Farquhar and colleagues reported results of a systematic review of studies published from 1980 to July 2001 that examined TVUS versus SH and DH for the investigation of AUB in premenopausal women. The researchers found that TVUS had a higher rate of false negatives for detecting intrauterine pathology, compared with SH and DH. They also found that DH was superior to SH in diagnosing submucous myomas.2

In 2010, results of a prospective comparison of TVUS, SH, and DH for detecting endometrial pathology, showed that DH had a significantly better diagnostic performance than SH and TVUS and that hysteroscopy was significantly more precise in the diagnosis of intracavitary masses.3

Again, in 2012, a prospective comparison of TVUS, SH, and DH in the diagnosis of AUB revealed that hysteroscopy provided the most accurate diagnosis.1

In a systematic review and meta-analysis, van Dongen found the accuracy of DH to be estimated at 96.9%.4

Hysteroscopy is also considered to be more comfortable for patients than SH.2

blinded sampling missed intracavitary lesions such as polyps and myomas that accounted for bleeding abnormalities.5

A procedure performed “blind” limits its usefulness in AUB evaluation

This statement is not a new realization. As far back as 1989, Loffer showed that blind D&C was less accurate for diagnosing AUB than was hysteroscopy with visually directed biopsy. The sensitivity of diagnosing the etiology of AUB with D&C was 65%, compared to a sensitivity of 98% with hysteroscopy with directed biopsy. Hysteroscopy was shown to be better because blinded sampling missed intracavitary lesions such as polyps and myomas that accounted for bleeding abnormalities.5

The limitations of D&C are evident in the opening case, as the D&C performed in the operating room under general anesthesia, without visualization of the uterine cavity, failed to identify the patient’s intrauterine pathology. D&C is seldom necessary to evaluate AUB and has significant surgical risks beyond general anesthesia, including cervical or uterine trauma that can occur with cervical dilation and instrumentation of the uterus.

As with D&C, endometrial biopsy has limitations in diagnosing abnormalities within the uterine cavity. In a 2008 prospective comparative study of hysteroscopy versus blind biopsy with a suction biopsy curette, Angioni and colleagues showed a significant difference in the capability of these two procedures to accurately diagnose the etiology of bleeding for menopausal women. Blinded biopsy had a sensitivity for diagnosing polyps, myomas, and hyperplasia of 11%, 13%, and 25%, respectively. The sensitivity of hysteroscopy to diagnose the same intracavitary pathology was 89%, 100%, and 74%, respectively.6

This does not mean, however, that the endometrial biopsy is not beneficial in the evaluation of AUB. Several authors recommend that in a clinically relevant situation, endometrial biopsy with a small suction curette should be performed concomitantly with hysteroscopy to improve the sensitivity of the overall evaluation with histology.7,8 And, as Loffer showed, the hysteroscopic evaluation with a visually directed biopsy is extremely accurate (VIDEO 2, VIDEO 3).5

The bottom line for D&C use in AUB evaluation

Sometimes a D&C is needed. For instance, when more tissue is needed for histologic evaluation than can be obtained with small suction curette at endometrial biopsy. However, there are several shortcomings of D&C for the evaluation of AUB:

- Most clinicians perform D&C in the operating room under general anesthesia.

- It is often done without concomitant hysteroscopy.

- There is significant potential to miss pathology, such as polyps or myomas.

- There is risk of uterine perforation with cervical dilation and uterine instrumentation.

- Hysteroscopy with visually directed biopsy provides a method that offers a more accurate diagnosis, and the procedure can be performed in the office.

In-office AUB evaluation using hysteroscopy is possible and advantageous

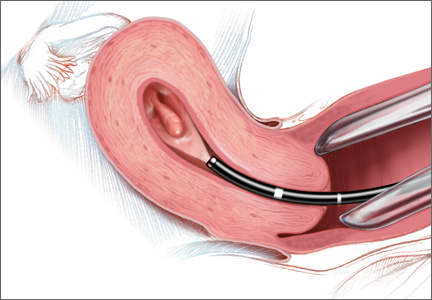

Hysteroscopy not only has increased accuracy for identifying the etiology of AUB, compared with D&C, but also offers the possibility of in-office use. Newer hysteroscopes with small diameters and decreasing costs of hysteroscopic equipment allow gynecologists to perform hysteroscopy economically and safely in the office.

Office evaluation of the uterine cavity and preoperative decision-making before a patient is taken to the operating room (OR) improve the likelihood that the appropriate procedure will be performed. They also provide an opportunity for the patient to see inside her own uterine cavity and for the surgeon to discuss management options with her (VIDEO 4: Diagnostic hysteroscopy with fundal myoma, VIDEO 5: Diagnostic hysteroscopy in a menopausal patient with atypical hyperplasia, VIDEO 6: Diagnostic hysteroscopy in a menopausal patient with polyps). If pathology is noted, there is a potential to treat abnormalities such as endometrial polyps at the same time, thus avoiding the OR altogether (VIDEO 7).

The small diameter of the hysteroscope allows evaluation in most menopausal and nulliparous patients comfortably without first having to dilate or soften the cervix. Paracervical placement of local anesthetic can be used as needed for patient comfort (VIDEO 8).9 A vaginoscopic approach will eliminate the discomfort of having to place a speculum (VIDEO 9).

It offers:

- a familiar and comfortable environment for the procedure

- saved time for patient and physician

- saved money for the patient with a large deductible or coinsurance

- no requirement for general anesthesia

- local anesthesia can be used but is not necessary

- immediate visual affirmation for the patient and physician

- a see and treat possibility

- possibility of preoperative decision-making

- saved trip to the OR if significant precancer or cancer is identified

- use in menopausal and nulliparous patients with no cervical preparation necessary when a small-diameter hysteroscope or flexible hysteroscope is used

- minimized discomfort from a speculum with the vaginoscopic approach for awake patients

- possibility of cervical access when needed (VIDEO 10).

My clinical recommendation

Use office hysteroscopy with endometrial biopsy as needed with the opportunity to perform a directed biopsy.

Coding for in-office hysteroscopy

Some procedures now can be performed in the office setting. Among these is operative hysteroscopy, for things such as abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB), foreign body removal, and tubal occlusion. When performing hysteroscopic evaluation of AUB, the Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) code 58558 (Hysteroscopy, surgical; with sampling (biopsy) of endometrium and/or polypectomy, with or without D&C) should be reported. This code is reported whether polyp(s) are removed or a sampling of the uterine lining or a full D&C is performed.

Under the Resource-Based Relative Value System (RBRVS), used by the majority of payers for reimbursement, there is a payment differential for site of service. In other words, when performed in the office setting, reimbursement will be higher than in the hospital setting to offset the increased practice expenses incurred. In the office setting, 58558 has 11.93 relative value units. In comparison, a D&C performed without hysteroscopy has 7.75 relative value units in the office setting. Keep in mind, however, that all supplies used in performing this procedure are included in the reimbursement amount.

Some payers will reimburse separately for administering a regional anesthetic, but a local anesthetic is considered integral to the procedure. Under CPT rules, you may bill separately for regional anesthesia. When performing office hysteroscopy, the most common regional anesthesia would be a paracervical nerve block (CPT code 66435—Injection, anesthetic agent; paracervical [uterine] nerve). Under CPT rules, coding should go in as 58558-47, 64435-51. The modifier -47 lets the payer know that the physician performed the regional block, and the modifier -51 identifies the regional block as a multiple procedure.

Medicare, however, will never reimburse separately for regional anesthesia performed by the operating physician, and because of this, Medicare’s Correct Coding Initiative (CCI) permanently bundles 64435 when billed with 58558. Medicare will not permit a modifier to be used to bypass this bundling edit, and separate payment is never allowed. If your payer has adopted this Medicare policy, separate payment will also not be made.

—Melanie Witt, RN, CPC, COBGC, MA

Ms. Witt is an independent coding and documentation consultant and former program manager, department of coding and nomenclature, American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists

- Soguktas S, Cogendez E, Kayatas SE, Asoglu MR, Selcuk S, Ertekin A. Comparison of saline infusion sonohysterography and hysteroscopy in diagnosis of premenopausal women with abnormal uterine bleeding. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Repro Biol. 2012;161(1):66−70.

- Farquhar C, Ekeroma A, Furness S, Arroll B. A systematic review of transvaginal ultrasonography, sonohysterography and hysteroscopy for the investigation of abnormal uterine bleeding in premenopausal bleeding. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2003;82(6):493–504.

- Grimbizis GF, Tsolakidis D, Mikos T, et al. A prospective comparison of transvaginal ultrasound, saline infusion sonohysterography, and diagnostic hysteroscopy in the evaluation of endometrial pathology. Fertil Steril. 2010;94(7):2721−2725.

- van Dongen H, de Kroon CD, Jacobi CE, Trimbos JB, Jansen FW. Diagnostic hysteroscopy in abnormal uterine bleeding: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BJOG. 2007;114(6):664–75.

- Loffer FD. Hysteroscopy with selective endometrial sampling compared with D & C for abnormal uterine bleeding: the value of a negative hysteroscopic view. Obstet Gynecol. 1989;73(1):16–20.

- Angioni S, Loddo A, Milano F, Piras B, Minerba L, Melis GB. Detection of benign intracavitary lesions in postmenopausal women with abnormal uterine bleeding: a prospective comparative study on outpatient hysteroscopy and blind biopsy. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2008;15(1):87–91.

- Lo KY, Yuen PM. The role of outpatient diagnostic hysteroscopy in identifying anatomic pathology and histopathology in the endometrial cavity. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 2000;7(3):381–385.

- Garuti G, Sambruni I, Colonneli M, Luerti M. Accuracy of hysteroscopy in predicting histopathology of endometrium in 1500 women. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 2001;8(2):207–213.

- Munro MG, Brooks PG. Use of local anesthesia for office diagnostic and operative hysteroscopy. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2010;17(6):709–718.

CASE: In-office hysteroscopy spies previously missed polyp

A 51-year-old woman with a history of breast cancer completed 5 years of tamoxifen. During her treatment she had a 3-year history of abnormal vaginal bleeding. Results from consecutive pelvic ultrasounds indicated that the patient had progressively thickening endometrium (from 1.4 cm to 2.5 cm to 4.7 cm). In-office biopsy was negative for endometrial pathology. An ultimate dilation and curettage (D&C) was performed with negative histologic diagnosis. The patient is seen in consultation, and the ultrasound images are reviewed (FIGURE).

These images show an increasing thickness of the ednometrium with definitive intracavitary pathology that was missed with the prevous clinical evaluation with enodmetrial biopsy and D&C. An in-office hysteroscopy is performed, and a large 5 x 4 x 7 cm cystic and fibrous polyp is identified with normal endometrium (VIDEO 1).

Hysteroscopy reveals massive polyp extending into a dilated lower uterine segment

Abnormal uterine bleeding

The evaluation of abnormal uterine bleeding. (AUB), as described in this clinical scenario, is quite common. As a consequence, many patients have a missed or inaccurate diagnosis and undergo unnecessary invasive procedures under general anesthesia.

AUB is one of the primary indications for a gynecologic consultation, accounting for approximately 33% of all gynecology visits, and for 69% of visits among postmenopausal women.1 Confirming the etiology and planning appropriate intervention is important in the clinical management of AUB because accurate diagnosis may result in avoiding major gynecologic surgery in favor of minimally invasive hysteroscopic management.

Diagnostic hysteroscopy is proven in AUB evaluation

Drawbacks of other diagnostic tools. It is generally accepted that the initial evaluation of women with AUB is performed with noninvasive transvaginal ultrasound (TVUS).1-3 As illustrated by the opening case, however, the accuracy of TVUS is limited in the diagnosis of focal endometrial lesions, and further investigation of the uterine cavity is warranted.

Evaluation of the uterine cavity with sonohysterography (SH)—vaginal ultrasound with the instillation of saline into the uterine cavity—is more accurate than TVUS alone. Yet, diagnostic hysteroscopy (DH) has proven to be superior to either modality for the accurate evaluation of intracavitary pathology.1-3

Evidence of DH superiority. Farquhar and colleagues reported results of a systematic review of studies published from 1980 to July 2001 that examined TVUS versus SH and DH for the investigation of AUB in premenopausal women. The researchers found that TVUS had a higher rate of false negatives for detecting intrauterine pathology, compared with SH and DH. They also found that DH was superior to SH in diagnosing submucous myomas.2

In 2010, results of a prospective comparison of TVUS, SH, and DH for detecting endometrial pathology, showed that DH had a significantly better diagnostic performance than SH and TVUS and that hysteroscopy was significantly more precise in the diagnosis of intracavitary masses.3

Again, in 2012, a prospective comparison of TVUS, SH, and DH in the diagnosis of AUB revealed that hysteroscopy provided the most accurate diagnosis.1

In a systematic review and meta-analysis, van Dongen found the accuracy of DH to be estimated at 96.9%.4

Hysteroscopy is also considered to be more comfortable for patients than SH.2

blinded sampling missed intracavitary lesions such as polyps and myomas that accounted for bleeding abnormalities.5

A procedure performed “blind” limits its usefulness in AUB evaluation

This statement is not a new realization. As far back as 1989, Loffer showed that blind D&C was less accurate for diagnosing AUB than was hysteroscopy with visually directed biopsy. The sensitivity of diagnosing the etiology of AUB with D&C was 65%, compared to a sensitivity of 98% with hysteroscopy with directed biopsy. Hysteroscopy was shown to be better because blinded sampling missed intracavitary lesions such as polyps and myomas that accounted for bleeding abnormalities.5

The limitations of D&C are evident in the opening case, as the D&C performed in the operating room under general anesthesia, without visualization of the uterine cavity, failed to identify the patient’s intrauterine pathology. D&C is seldom necessary to evaluate AUB and has significant surgical risks beyond general anesthesia, including cervical or uterine trauma that can occur with cervical dilation and instrumentation of the uterus.

As with D&C, endometrial biopsy has limitations in diagnosing abnormalities within the uterine cavity. In a 2008 prospective comparative study of hysteroscopy versus blind biopsy with a suction biopsy curette, Angioni and colleagues showed a significant difference in the capability of these two procedures to accurately diagnose the etiology of bleeding for menopausal women. Blinded biopsy had a sensitivity for diagnosing polyps, myomas, and hyperplasia of 11%, 13%, and 25%, respectively. The sensitivity of hysteroscopy to diagnose the same intracavitary pathology was 89%, 100%, and 74%, respectively.6

This does not mean, however, that the endometrial biopsy is not beneficial in the evaluation of AUB. Several authors recommend that in a clinically relevant situation, endometrial biopsy with a small suction curette should be performed concomitantly with hysteroscopy to improve the sensitivity of the overall evaluation with histology.7,8 And, as Loffer showed, the hysteroscopic evaluation with a visually directed biopsy is extremely accurate (VIDEO 2, VIDEO 3).5

The bottom line for D&C use in AUB evaluation

Sometimes a D&C is needed. For instance, when more tissue is needed for histologic evaluation than can be obtained with small suction curette at endometrial biopsy. However, there are several shortcomings of D&C for the evaluation of AUB:

- Most clinicians perform D&C in the operating room under general anesthesia.

- It is often done without concomitant hysteroscopy.

- There is significant potential to miss pathology, such as polyps or myomas.

- There is risk of uterine perforation with cervical dilation and uterine instrumentation.

- Hysteroscopy with visually directed biopsy provides a method that offers a more accurate diagnosis, and the procedure can be performed in the office.

In-office AUB evaluation using hysteroscopy is possible and advantageous

Hysteroscopy not only has increased accuracy for identifying the etiology of AUB, compared with D&C, but also offers the possibility of in-office use. Newer hysteroscopes with small diameters and decreasing costs of hysteroscopic equipment allow gynecologists to perform hysteroscopy economically and safely in the office.

Office evaluation of the uterine cavity and preoperative decision-making before a patient is taken to the operating room (OR) improve the likelihood that the appropriate procedure will be performed. They also provide an opportunity for the patient to see inside her own uterine cavity and for the surgeon to discuss management options with her (VIDEO 4: Diagnostic hysteroscopy with fundal myoma, VIDEO 5: Diagnostic hysteroscopy in a menopausal patient with atypical hyperplasia, VIDEO 6: Diagnostic hysteroscopy in a menopausal patient with polyps). If pathology is noted, there is a potential to treat abnormalities such as endometrial polyps at the same time, thus avoiding the OR altogether (VIDEO 7).

The small diameter of the hysteroscope allows evaluation in most menopausal and nulliparous patients comfortably without first having to dilate or soften the cervix. Paracervical placement of local anesthetic can be used as needed for patient comfort (VIDEO 8).9 A vaginoscopic approach will eliminate the discomfort of having to place a speculum (VIDEO 9).

It offers:

- a familiar and comfortable environment for the procedure

- saved time for patient and physician

- saved money for the patient with a large deductible or coinsurance

- no requirement for general anesthesia

- local anesthesia can be used but is not necessary

- immediate visual affirmation for the patient and physician

- a see and treat possibility

- possibility of preoperative decision-making

- saved trip to the OR if significant precancer or cancer is identified

- use in menopausal and nulliparous patients with no cervical preparation necessary when a small-diameter hysteroscope or flexible hysteroscope is used

- minimized discomfort from a speculum with the vaginoscopic approach for awake patients

- possibility of cervical access when needed (VIDEO 10).

My clinical recommendation

Use office hysteroscopy with endometrial biopsy as needed with the opportunity to perform a directed biopsy.

Coding for in-office hysteroscopy

Some procedures now can be performed in the office setting. Among these is operative hysteroscopy, for things such as abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB), foreign body removal, and tubal occlusion. When performing hysteroscopic evaluation of AUB, the Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) code 58558 (Hysteroscopy, surgical; with sampling (biopsy) of endometrium and/or polypectomy, with or without D&C) should be reported. This code is reported whether polyp(s) are removed or a sampling of the uterine lining or a full D&C is performed.

Under the Resource-Based Relative Value System (RBRVS), used by the majority of payers for reimbursement, there is a payment differential for site of service. In other words, when performed in the office setting, reimbursement will be higher than in the hospital setting to offset the increased practice expenses incurred. In the office setting, 58558 has 11.93 relative value units. In comparison, a D&C performed without hysteroscopy has 7.75 relative value units in the office setting. Keep in mind, however, that all supplies used in performing this procedure are included in the reimbursement amount.

Some payers will reimburse separately for administering a regional anesthetic, but a local anesthetic is considered integral to the procedure. Under CPT rules, you may bill separately for regional anesthesia. When performing office hysteroscopy, the most common regional anesthesia would be a paracervical nerve block (CPT code 66435—Injection, anesthetic agent; paracervical [uterine] nerve). Under CPT rules, coding should go in as 58558-47, 64435-51. The modifier -47 lets the payer know that the physician performed the regional block, and the modifier -51 identifies the regional block as a multiple procedure.

Medicare, however, will never reimburse separately for regional anesthesia performed by the operating physician, and because of this, Medicare’s Correct Coding Initiative (CCI) permanently bundles 64435 when billed with 58558. Medicare will not permit a modifier to be used to bypass this bundling edit, and separate payment is never allowed. If your payer has adopted this Medicare policy, separate payment will also not be made.

—Melanie Witt, RN, CPC, COBGC, MA

Ms. Witt is an independent coding and documentation consultant and former program manager, department of coding and nomenclature, American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists

CASE: In-office hysteroscopy spies previously missed polyp

A 51-year-old woman with a history of breast cancer completed 5 years of tamoxifen. During her treatment she had a 3-year history of abnormal vaginal bleeding. Results from consecutive pelvic ultrasounds indicated that the patient had progressively thickening endometrium (from 1.4 cm to 2.5 cm to 4.7 cm). In-office biopsy was negative for endometrial pathology. An ultimate dilation and curettage (D&C) was performed with negative histologic diagnosis. The patient is seen in consultation, and the ultrasound images are reviewed (FIGURE).

These images show an increasing thickness of the ednometrium with definitive intracavitary pathology that was missed with the prevous clinical evaluation with enodmetrial biopsy and D&C. An in-office hysteroscopy is performed, and a large 5 x 4 x 7 cm cystic and fibrous polyp is identified with normal endometrium (VIDEO 1).

Hysteroscopy reveals massive polyp extending into a dilated lower uterine segment

Abnormal uterine bleeding

The evaluation of abnormal uterine bleeding. (AUB), as described in this clinical scenario, is quite common. As a consequence, many patients have a missed or inaccurate diagnosis and undergo unnecessary invasive procedures under general anesthesia.

AUB is one of the primary indications for a gynecologic consultation, accounting for approximately 33% of all gynecology visits, and for 69% of visits among postmenopausal women.1 Confirming the etiology and planning appropriate intervention is important in the clinical management of AUB because accurate diagnosis may result in avoiding major gynecologic surgery in favor of minimally invasive hysteroscopic management.

Diagnostic hysteroscopy is proven in AUB evaluation

Drawbacks of other diagnostic tools. It is generally accepted that the initial evaluation of women with AUB is performed with noninvasive transvaginal ultrasound (TVUS).1-3 As illustrated by the opening case, however, the accuracy of TVUS is limited in the diagnosis of focal endometrial lesions, and further investigation of the uterine cavity is warranted.

Evaluation of the uterine cavity with sonohysterography (SH)—vaginal ultrasound with the instillation of saline into the uterine cavity—is more accurate than TVUS alone. Yet, diagnostic hysteroscopy (DH) has proven to be superior to either modality for the accurate evaluation of intracavitary pathology.1-3

Evidence of DH superiority. Farquhar and colleagues reported results of a systematic review of studies published from 1980 to July 2001 that examined TVUS versus SH and DH for the investigation of AUB in premenopausal women. The researchers found that TVUS had a higher rate of false negatives for detecting intrauterine pathology, compared with SH and DH. They also found that DH was superior to SH in diagnosing submucous myomas.2

In 2010, results of a prospective comparison of TVUS, SH, and DH for detecting endometrial pathology, showed that DH had a significantly better diagnostic performance than SH and TVUS and that hysteroscopy was significantly more precise in the diagnosis of intracavitary masses.3

Again, in 2012, a prospective comparison of TVUS, SH, and DH in the diagnosis of AUB revealed that hysteroscopy provided the most accurate diagnosis.1

In a systematic review and meta-analysis, van Dongen found the accuracy of DH to be estimated at 96.9%.4

Hysteroscopy is also considered to be more comfortable for patients than SH.2

blinded sampling missed intracavitary lesions such as polyps and myomas that accounted for bleeding abnormalities.5

A procedure performed “blind” limits its usefulness in AUB evaluation

This statement is not a new realization. As far back as 1989, Loffer showed that blind D&C was less accurate for diagnosing AUB than was hysteroscopy with visually directed biopsy. The sensitivity of diagnosing the etiology of AUB with D&C was 65%, compared to a sensitivity of 98% with hysteroscopy with directed biopsy. Hysteroscopy was shown to be better because blinded sampling missed intracavitary lesions such as polyps and myomas that accounted for bleeding abnormalities.5

The limitations of D&C are evident in the opening case, as the D&C performed in the operating room under general anesthesia, without visualization of the uterine cavity, failed to identify the patient’s intrauterine pathology. D&C is seldom necessary to evaluate AUB and has significant surgical risks beyond general anesthesia, including cervical or uterine trauma that can occur with cervical dilation and instrumentation of the uterus.

As with D&C, endometrial biopsy has limitations in diagnosing abnormalities within the uterine cavity. In a 2008 prospective comparative study of hysteroscopy versus blind biopsy with a suction biopsy curette, Angioni and colleagues showed a significant difference in the capability of these two procedures to accurately diagnose the etiology of bleeding for menopausal women. Blinded biopsy had a sensitivity for diagnosing polyps, myomas, and hyperplasia of 11%, 13%, and 25%, respectively. The sensitivity of hysteroscopy to diagnose the same intracavitary pathology was 89%, 100%, and 74%, respectively.6

This does not mean, however, that the endometrial biopsy is not beneficial in the evaluation of AUB. Several authors recommend that in a clinically relevant situation, endometrial biopsy with a small suction curette should be performed concomitantly with hysteroscopy to improve the sensitivity of the overall evaluation with histology.7,8 And, as Loffer showed, the hysteroscopic evaluation with a visually directed biopsy is extremely accurate (VIDEO 2, VIDEO 3).5

The bottom line for D&C use in AUB evaluation

Sometimes a D&C is needed. For instance, when more tissue is needed for histologic evaluation than can be obtained with small suction curette at endometrial biopsy. However, there are several shortcomings of D&C for the evaluation of AUB:

- Most clinicians perform D&C in the operating room under general anesthesia.

- It is often done without concomitant hysteroscopy.

- There is significant potential to miss pathology, such as polyps or myomas.

- There is risk of uterine perforation with cervical dilation and uterine instrumentation.

- Hysteroscopy with visually directed biopsy provides a method that offers a more accurate diagnosis, and the procedure can be performed in the office.

In-office AUB evaluation using hysteroscopy is possible and advantageous

Hysteroscopy not only has increased accuracy for identifying the etiology of AUB, compared with D&C, but also offers the possibility of in-office use. Newer hysteroscopes with small diameters and decreasing costs of hysteroscopic equipment allow gynecologists to perform hysteroscopy economically and safely in the office.

Office evaluation of the uterine cavity and preoperative decision-making before a patient is taken to the operating room (OR) improve the likelihood that the appropriate procedure will be performed. They also provide an opportunity for the patient to see inside her own uterine cavity and for the surgeon to discuss management options with her (VIDEO 4: Diagnostic hysteroscopy with fundal myoma, VIDEO 5: Diagnostic hysteroscopy in a menopausal patient with atypical hyperplasia, VIDEO 6: Diagnostic hysteroscopy in a menopausal patient with polyps). If pathology is noted, there is a potential to treat abnormalities such as endometrial polyps at the same time, thus avoiding the OR altogether (VIDEO 7).

The small diameter of the hysteroscope allows evaluation in most menopausal and nulliparous patients comfortably without first having to dilate or soften the cervix. Paracervical placement of local anesthetic can be used as needed for patient comfort (VIDEO 8).9 A vaginoscopic approach will eliminate the discomfort of having to place a speculum (VIDEO 9).

It offers:

- a familiar and comfortable environment for the procedure

- saved time for patient and physician

- saved money for the patient with a large deductible or coinsurance

- no requirement for general anesthesia

- local anesthesia can be used but is not necessary

- immediate visual affirmation for the patient and physician

- a see and treat possibility

- possibility of preoperative decision-making

- saved trip to the OR if significant precancer or cancer is identified

- use in menopausal and nulliparous patients with no cervical preparation necessary when a small-diameter hysteroscope or flexible hysteroscope is used

- minimized discomfort from a speculum with the vaginoscopic approach for awake patients

- possibility of cervical access when needed (VIDEO 10).

My clinical recommendation

Use office hysteroscopy with endometrial biopsy as needed with the opportunity to perform a directed biopsy.

Coding for in-office hysteroscopy

Some procedures now can be performed in the office setting. Among these is operative hysteroscopy, for things such as abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB), foreign body removal, and tubal occlusion. When performing hysteroscopic evaluation of AUB, the Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) code 58558 (Hysteroscopy, surgical; with sampling (biopsy) of endometrium and/or polypectomy, with or without D&C) should be reported. This code is reported whether polyp(s) are removed or a sampling of the uterine lining or a full D&C is performed.

Under the Resource-Based Relative Value System (RBRVS), used by the majority of payers for reimbursement, there is a payment differential for site of service. In other words, when performed in the office setting, reimbursement will be higher than in the hospital setting to offset the increased practice expenses incurred. In the office setting, 58558 has 11.93 relative value units. In comparison, a D&C performed without hysteroscopy has 7.75 relative value units in the office setting. Keep in mind, however, that all supplies used in performing this procedure are included in the reimbursement amount.

Some payers will reimburse separately for administering a regional anesthetic, but a local anesthetic is considered integral to the procedure. Under CPT rules, you may bill separately for regional anesthesia. When performing office hysteroscopy, the most common regional anesthesia would be a paracervical nerve block (CPT code 66435—Injection, anesthetic agent; paracervical [uterine] nerve). Under CPT rules, coding should go in as 58558-47, 64435-51. The modifier -47 lets the payer know that the physician performed the regional block, and the modifier -51 identifies the regional block as a multiple procedure.

Medicare, however, will never reimburse separately for regional anesthesia performed by the operating physician, and because of this, Medicare’s Correct Coding Initiative (CCI) permanently bundles 64435 when billed with 58558. Medicare will not permit a modifier to be used to bypass this bundling edit, and separate payment is never allowed. If your payer has adopted this Medicare policy, separate payment will also not be made.

—Melanie Witt, RN, CPC, COBGC, MA

Ms. Witt is an independent coding and documentation consultant and former program manager, department of coding and nomenclature, American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists

- Soguktas S, Cogendez E, Kayatas SE, Asoglu MR, Selcuk S, Ertekin A. Comparison of saline infusion sonohysterography and hysteroscopy in diagnosis of premenopausal women with abnormal uterine bleeding. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Repro Biol. 2012;161(1):66−70.

- Farquhar C, Ekeroma A, Furness S, Arroll B. A systematic review of transvaginal ultrasonography, sonohysterography and hysteroscopy for the investigation of abnormal uterine bleeding in premenopausal bleeding. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2003;82(6):493–504.

- Grimbizis GF, Tsolakidis D, Mikos T, et al. A prospective comparison of transvaginal ultrasound, saline infusion sonohysterography, and diagnostic hysteroscopy in the evaluation of endometrial pathology. Fertil Steril. 2010;94(7):2721−2725.

- van Dongen H, de Kroon CD, Jacobi CE, Trimbos JB, Jansen FW. Diagnostic hysteroscopy in abnormal uterine bleeding: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BJOG. 2007;114(6):664–75.

- Loffer FD. Hysteroscopy with selective endometrial sampling compared with D & C for abnormal uterine bleeding: the value of a negative hysteroscopic view. Obstet Gynecol. 1989;73(1):16–20.

- Angioni S, Loddo A, Milano F, Piras B, Minerba L, Melis GB. Detection of benign intracavitary lesions in postmenopausal women with abnormal uterine bleeding: a prospective comparative study on outpatient hysteroscopy and blind biopsy. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2008;15(1):87–91.

- Lo KY, Yuen PM. The role of outpatient diagnostic hysteroscopy in identifying anatomic pathology and histopathology in the endometrial cavity. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 2000;7(3):381–385.

- Garuti G, Sambruni I, Colonneli M, Luerti M. Accuracy of hysteroscopy in predicting histopathology of endometrium in 1500 women. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 2001;8(2):207–213.

- Munro MG, Brooks PG. Use of local anesthesia for office diagnostic and operative hysteroscopy. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2010;17(6):709–718.

- Soguktas S, Cogendez E, Kayatas SE, Asoglu MR, Selcuk S, Ertekin A. Comparison of saline infusion sonohysterography and hysteroscopy in diagnosis of premenopausal women with abnormal uterine bleeding. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Repro Biol. 2012;161(1):66−70.

- Farquhar C, Ekeroma A, Furness S, Arroll B. A systematic review of transvaginal ultrasonography, sonohysterography and hysteroscopy for the investigation of abnormal uterine bleeding in premenopausal bleeding. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2003;82(6):493–504.

- Grimbizis GF, Tsolakidis D, Mikos T, et al. A prospective comparison of transvaginal ultrasound, saline infusion sonohysterography, and diagnostic hysteroscopy in the evaluation of endometrial pathology. Fertil Steril. 2010;94(7):2721−2725.

- van Dongen H, de Kroon CD, Jacobi CE, Trimbos JB, Jansen FW. Diagnostic hysteroscopy in abnormal uterine bleeding: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BJOG. 2007;114(6):664–75.

- Loffer FD. Hysteroscopy with selective endometrial sampling compared with D & C for abnormal uterine bleeding: the value of a negative hysteroscopic view. Obstet Gynecol. 1989;73(1):16–20.

- Angioni S, Loddo A, Milano F, Piras B, Minerba L, Melis GB. Detection of benign intracavitary lesions in postmenopausal women with abnormal uterine bleeding: a prospective comparative study on outpatient hysteroscopy and blind biopsy. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2008;15(1):87–91.

- Lo KY, Yuen PM. The role of outpatient diagnostic hysteroscopy in identifying anatomic pathology and histopathology in the endometrial cavity. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 2000;7(3):381–385.

- Garuti G, Sambruni I, Colonneli M, Luerti M. Accuracy of hysteroscopy in predicting histopathology of endometrium in 1500 women. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 2001;8(2):207–213.

- Munro MG, Brooks PG. Use of local anesthesia for office diagnostic and operative hysteroscopy. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2010;17(6):709–718.

Effective Clinical Documentation Can Influence Medicare Reimbursement

Back in the 1980s, I would go by medical records every day or two and find, on the front of the charts of my recently discharged patients, a form listing the diagnoses the hospital was billing to Medicare. Before the hospital could submit a patient’s bill, the attending physician was required to review the form and, by signing it, indicate agreement.

The requirement for this signature by the physician went away a long time ago and in my memory is one of the very few examples of reducing a doctor’s paperwork.

For my first few months in practice, I regularly would seek out the people who completed the form and explain they had misunderstood the patient’s clinical situation. “The main issue was a urinary tract infection,” I would say, “but you listed diabetes as the principal diagnosis.”

I don’t ever remember them changing anything based on my feedback. Instead, they explained to me that, for billing purposes, it was legitimate to list diabetes as the principal diagnosis because it had the additional benefit of resulting in a higher payment to the hospital than having “urinary tract infection” listed first.

Such was my introduction to the world of documentation and coding for hospital billing purposes and how it can sometimes differ significantly from the way a doctor sees the clinical picture. Things have evolved a lot since then, but the way doctors document medical conditions still has a huge influence on hospital reimbursement.

Hospital CDI Programs

About 80% of hospitals have formal clinical documentation improvement (CDI) programs to help ensure all clinical conditions are captured and described in the medical record in ways that are valuable for billing and other recordkeeping purposes. These programs might lead to you receive queries about your documentation. For example, you might be asked to clarify whether your patient’s pneumonia might be on the basis of aspiration.

Within SHM’s Code-H program, Dr. Richard Pinson, a former ED physician who now works with Houston-based HCQ Consulting, has a good presentation explaining these documentation issues. In it, he makes the point that, in addition to influencing how hospitals are paid, the way various conditions are documented also influences quality ratings.

Novel Approach

The most common approach to engaging hospitalists in CDI initiatives is to have them attend a presentation on the topic, then put in place documentation specialists who generate queries asking the doctor to clarify diagnoses when it might influence payment, severity of illness determination, etc. Dr. Kenji Asakura, a Seattle hospitalist, and Erik Ordal, MBA, have a company called ClinIntell that analyzes each hospitalist (or other specialty) group’s historical patient mix and trains them on the documentation issues that they see most often. The idea of this focused approach is to make “documentation queries” unnecessary, or at least much less necessary. The benefits of this approach are many, including reducing or eliminating the risk of “leading queries”—that is, queries that seem to encourage the doctor to document a diagnosis because it is an advantage to the hospital rather than a well-considered medical opinion. Leading queries can be regarded as fraudulent and can get a lot of people in trouble.

I asked Kenji and Erik if they could provide me with a list of common documentation issues that most hospitalists need to know more about. Table 1 is what they came up with. I hope it helps you and your practice.

Dr. Nelson has been a practicing hospitalist since 1988. He is co-founder and past president of SHM, and principal in Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants. He is co-director for SHM's "Best Practices in Managing a Hospital Medicine Program" course. Write to him at john.nelson@nelsonflores.com.

Back in the 1980s, I would go by medical records every day or two and find, on the front of the charts of my recently discharged patients, a form listing the diagnoses the hospital was billing to Medicare. Before the hospital could submit a patient’s bill, the attending physician was required to review the form and, by signing it, indicate agreement.

The requirement for this signature by the physician went away a long time ago and in my memory is one of the very few examples of reducing a doctor’s paperwork.

For my first few months in practice, I regularly would seek out the people who completed the form and explain they had misunderstood the patient’s clinical situation. “The main issue was a urinary tract infection,” I would say, “but you listed diabetes as the principal diagnosis.”

I don’t ever remember them changing anything based on my feedback. Instead, they explained to me that, for billing purposes, it was legitimate to list diabetes as the principal diagnosis because it had the additional benefit of resulting in a higher payment to the hospital than having “urinary tract infection” listed first.

Such was my introduction to the world of documentation and coding for hospital billing purposes and how it can sometimes differ significantly from the way a doctor sees the clinical picture. Things have evolved a lot since then, but the way doctors document medical conditions still has a huge influence on hospital reimbursement.

Hospital CDI Programs

About 80% of hospitals have formal clinical documentation improvement (CDI) programs to help ensure all clinical conditions are captured and described in the medical record in ways that are valuable for billing and other recordkeeping purposes. These programs might lead to you receive queries about your documentation. For example, you might be asked to clarify whether your patient’s pneumonia might be on the basis of aspiration.

Within SHM’s Code-H program, Dr. Richard Pinson, a former ED physician who now works with Houston-based HCQ Consulting, has a good presentation explaining these documentation issues. In it, he makes the point that, in addition to influencing how hospitals are paid, the way various conditions are documented also influences quality ratings.

Novel Approach

The most common approach to engaging hospitalists in CDI initiatives is to have them attend a presentation on the topic, then put in place documentation specialists who generate queries asking the doctor to clarify diagnoses when it might influence payment, severity of illness determination, etc. Dr. Kenji Asakura, a Seattle hospitalist, and Erik Ordal, MBA, have a company called ClinIntell that analyzes each hospitalist (or other specialty) group’s historical patient mix and trains them on the documentation issues that they see most often. The idea of this focused approach is to make “documentation queries” unnecessary, or at least much less necessary. The benefits of this approach are many, including reducing or eliminating the risk of “leading queries”—that is, queries that seem to encourage the doctor to document a diagnosis because it is an advantage to the hospital rather than a well-considered medical opinion. Leading queries can be regarded as fraudulent and can get a lot of people in trouble.

I asked Kenji and Erik if they could provide me with a list of common documentation issues that most hospitalists need to know more about. Table 1 is what they came up with. I hope it helps you and your practice.

Dr. Nelson has been a practicing hospitalist since 1988. He is co-founder and past president of SHM, and principal in Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants. He is co-director for SHM's "Best Practices in Managing a Hospital Medicine Program" course. Write to him at john.nelson@nelsonflores.com.

Back in the 1980s, I would go by medical records every day or two and find, on the front of the charts of my recently discharged patients, a form listing the diagnoses the hospital was billing to Medicare. Before the hospital could submit a patient’s bill, the attending physician was required to review the form and, by signing it, indicate agreement.

The requirement for this signature by the physician went away a long time ago and in my memory is one of the very few examples of reducing a doctor’s paperwork.

For my first few months in practice, I regularly would seek out the people who completed the form and explain they had misunderstood the patient’s clinical situation. “The main issue was a urinary tract infection,” I would say, “but you listed diabetes as the principal diagnosis.”

I don’t ever remember them changing anything based on my feedback. Instead, they explained to me that, for billing purposes, it was legitimate to list diabetes as the principal diagnosis because it had the additional benefit of resulting in a higher payment to the hospital than having “urinary tract infection” listed first.

Such was my introduction to the world of documentation and coding for hospital billing purposes and how it can sometimes differ significantly from the way a doctor sees the clinical picture. Things have evolved a lot since then, but the way doctors document medical conditions still has a huge influence on hospital reimbursement.

Hospital CDI Programs

About 80% of hospitals have formal clinical documentation improvement (CDI) programs to help ensure all clinical conditions are captured and described in the medical record in ways that are valuable for billing and other recordkeeping purposes. These programs might lead to you receive queries about your documentation. For example, you might be asked to clarify whether your patient’s pneumonia might be on the basis of aspiration.

Within SHM’s Code-H program, Dr. Richard Pinson, a former ED physician who now works with Houston-based HCQ Consulting, has a good presentation explaining these documentation issues. In it, he makes the point that, in addition to influencing how hospitals are paid, the way various conditions are documented also influences quality ratings.

Novel Approach

The most common approach to engaging hospitalists in CDI initiatives is to have them attend a presentation on the topic, then put in place documentation specialists who generate queries asking the doctor to clarify diagnoses when it might influence payment, severity of illness determination, etc. Dr. Kenji Asakura, a Seattle hospitalist, and Erik Ordal, MBA, have a company called ClinIntell that analyzes each hospitalist (or other specialty) group’s historical patient mix and trains them on the documentation issues that they see most often. The idea of this focused approach is to make “documentation queries” unnecessary, or at least much less necessary. The benefits of this approach are many, including reducing or eliminating the risk of “leading queries”—that is, queries that seem to encourage the doctor to document a diagnosis because it is an advantage to the hospital rather than a well-considered medical opinion. Leading queries can be regarded as fraudulent and can get a lot of people in trouble.

I asked Kenji and Erik if they could provide me with a list of common documentation issues that most hospitalists need to know more about. Table 1 is what they came up with. I hope it helps you and your practice.

Dr. Nelson has been a practicing hospitalist since 1988. He is co-founder and past president of SHM, and principal in Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants. He is co-director for SHM's "Best Practices in Managing a Hospital Medicine Program" course. Write to him at john.nelson@nelsonflores.com.

Coordinated Approach May Help in Caring for Hospitals’ Neediest Patients

To my way of thinking, a person’s diagnosis or pathophysiology is not as strong a predictor of needing inpatient hospital care as it might have been 10 or 20 years ago. Rather than the clinical diagnosis (e.g. pneumonia), it seems to me that frailty or social complexity often are the principal determinants of which patients are admitted to a hospital for medical conditions.

Some of these patients are admitted frequently but appear to realize little or no benefit from hospitalization. These patients typically have little or no social support, and they often have either significant mental health disorders or substance abuse, or both. Much has been written about these patients, and I recommend an article by Dr. Atul Gawande in the Jan. 24, 2011, issue of The New Yorker titled “The Hot Spotters: Can We Lower Medical Costs by Giving the Neediest Patients Better Care?”

The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s “Statistical Brief 354” on how health-care expenditures are allocated across the population reported that 1% of the population accounted for more than 22% of health-care spending in 2008. One in 5 of those were in that category again in 2009. Some of these patients would benefit from care plans.

The Role of Care Plans

It seems that there may be few effective inpatient interventions that will benefit these patients. After all, they have chronic issues that require ongoing relationships with outpatient providers, something that many of these patients lack. But for some (most?) of these patients, it seems clear that frequent hospitalizations don’t help and sometimes just perpetuate or worsen the patient’s dependence on the hospital at a high financial cost to society—and significant frustration and burnout on the part of hospital caregivers, including hospitalists.

For most hospitals, this problem is significant enough to require some sort of coordinated approach to the care of the dozens of types of patients in this category. Implementing whatever plan of care seems appropriate to the caregivers during each admission is frustrating, ensures lots of variation in care, and makes it easier for manipulative patients to abuse the hospital resources and personnel.

A better approach is to follow the same plan of care from one hospital visit to the next. You already knew that. But developing a care plan to follow during each ED visit and admission is time-consuming and often fraught with uncertainty about where boundaries should be set. So if you’re like me, you might just try to guide the patient to discharge this time and hope that whoever sees the patient on the next admission will take the initiative to develop the care plan. The result is that few such plans are developed.

Your Hospital Needs a Care Plan

Relying on individual doctors or nurses to take the initiative to develop care plans will almost always mean few plans are developed, they will vary in their effectiveness, and other providers may not be aware a plan exists. This was the case at the hospital where I practice until I heard Dr. Rick Hilger, MD, SFHM, a hospitalist at Regions Hospital in Minneapolis, present on this topic at HM12 in San Diego.

Dr. Hilger led a multidisciplinary team to develop care plans (they call them “restriction care plans”) and found that they dramatically reduced the rate of hospital admissions and ED visits for these patients. Hearing about this experience served as a kick in the pants for me, so I did much the same thing at “my” hospital. We have now developed plans for more than 20 patients and found that they visit our ED and are admitted less often. And, anecdotally at least, hospitalists and other hospital staff find that the care plans reduce, at least a little, the stress of caring for these patients.

Unanswered Questions

Although it seems clear that care plans reduce visits to the hospital that develops them, I suspect that some of these patients aren’t consuming any fewer health-care resources. They may just seek care from a different hospital.

My home state of Washington is working to develop individual patient care plans available to all hospitals in the state. A system called the Emergency Department Information Exchange (EDIE) has been adopted by nearly all the hospitals in the state. It allows them to share information on ED visits and such things as care plans with one another. For example, through EDIE, each hospital could see the opiate dosing schedule and admission criteria agreed to by patient and primary-care physician.

So it seems that care plans and the technology to share them can make it more difficult for patients to harm themselves by visiting many hospitals to get excessive opiate prescriptions, for example. This should benefit the patient and lower ED and hospital expenditures for these patients. But we don’t know what portion of costs simply is shifted to other settings, so there is no easy way to know the net effect on health-care costs.

An important unanswered question is whether these care plans improve patient well-being. It seems clear they do in some cases, but it is hard to know whether some patients may be worse off because of the plan.

Conclusion

I think nearly every hospital would benefit from a care plan committee composed of at least one hospitalist, ED physician, a nursing representative, and potentially other disciplines (see “Care Plan Attributes,” above). Our committee includes our inpatient psychiatrist, a really valuable contributor.

Dr. Nelson has been a practicing hospitalist since 1988. He is co-founder and past president of SHM, and principal in Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants. He is co-director for SHM’s “Best Practices in Managing a Hospital Medicine Program” course. Write to him at john.nelson@nelsonflores.com.

To my way of thinking, a person’s diagnosis or pathophysiology is not as strong a predictor of needing inpatient hospital care as it might have been 10 or 20 years ago. Rather than the clinical diagnosis (e.g. pneumonia), it seems to me that frailty or social complexity often are the principal determinants of which patients are admitted to a hospital for medical conditions.

Some of these patients are admitted frequently but appear to realize little or no benefit from hospitalization. These patients typically have little or no social support, and they often have either significant mental health disorders or substance abuse, or both. Much has been written about these patients, and I recommend an article by Dr. Atul Gawande in the Jan. 24, 2011, issue of The New Yorker titled “The Hot Spotters: Can We Lower Medical Costs by Giving the Neediest Patients Better Care?”

The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s “Statistical Brief 354” on how health-care expenditures are allocated across the population reported that 1% of the population accounted for more than 22% of health-care spending in 2008. One in 5 of those were in that category again in 2009. Some of these patients would benefit from care plans.

The Role of Care Plans

It seems that there may be few effective inpatient interventions that will benefit these patients. After all, they have chronic issues that require ongoing relationships with outpatient providers, something that many of these patients lack. But for some (most?) of these patients, it seems clear that frequent hospitalizations don’t help and sometimes just perpetuate or worsen the patient’s dependence on the hospital at a high financial cost to society—and significant frustration and burnout on the part of hospital caregivers, including hospitalists.

For most hospitals, this problem is significant enough to require some sort of coordinated approach to the care of the dozens of types of patients in this category. Implementing whatever plan of care seems appropriate to the caregivers during each admission is frustrating, ensures lots of variation in care, and makes it easier for manipulative patients to abuse the hospital resources and personnel.

A better approach is to follow the same plan of care from one hospital visit to the next. You already knew that. But developing a care plan to follow during each ED visit and admission is time-consuming and often fraught with uncertainty about where boundaries should be set. So if you’re like me, you might just try to guide the patient to discharge this time and hope that whoever sees the patient on the next admission will take the initiative to develop the care plan. The result is that few such plans are developed.

Your Hospital Needs a Care Plan

Relying on individual doctors or nurses to take the initiative to develop care plans will almost always mean few plans are developed, they will vary in their effectiveness, and other providers may not be aware a plan exists. This was the case at the hospital where I practice until I heard Dr. Rick Hilger, MD, SFHM, a hospitalist at Regions Hospital in Minneapolis, present on this topic at HM12 in San Diego.

Dr. Hilger led a multidisciplinary team to develop care plans (they call them “restriction care plans”) and found that they dramatically reduced the rate of hospital admissions and ED visits for these patients. Hearing about this experience served as a kick in the pants for me, so I did much the same thing at “my” hospital. We have now developed plans for more than 20 patients and found that they visit our ED and are admitted less often. And, anecdotally at least, hospitalists and other hospital staff find that the care plans reduce, at least a little, the stress of caring for these patients.

Unanswered Questions

Although it seems clear that care plans reduce visits to the hospital that develops them, I suspect that some of these patients aren’t consuming any fewer health-care resources. They may just seek care from a different hospital.

My home state of Washington is working to develop individual patient care plans available to all hospitals in the state. A system called the Emergency Department Information Exchange (EDIE) has been adopted by nearly all the hospitals in the state. It allows them to share information on ED visits and such things as care plans with one another. For example, through EDIE, each hospital could see the opiate dosing schedule and admission criteria agreed to by patient and primary-care physician.

So it seems that care plans and the technology to share them can make it more difficult for patients to harm themselves by visiting many hospitals to get excessive opiate prescriptions, for example. This should benefit the patient and lower ED and hospital expenditures for these patients. But we don’t know what portion of costs simply is shifted to other settings, so there is no easy way to know the net effect on health-care costs.

An important unanswered question is whether these care plans improve patient well-being. It seems clear they do in some cases, but it is hard to know whether some patients may be worse off because of the plan.

Conclusion

I think nearly every hospital would benefit from a care plan committee composed of at least one hospitalist, ED physician, a nursing representative, and potentially other disciplines (see “Care Plan Attributes,” above). Our committee includes our inpatient psychiatrist, a really valuable contributor.

Dr. Nelson has been a practicing hospitalist since 1988. He is co-founder and past president of SHM, and principal in Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants. He is co-director for SHM’s “Best Practices in Managing a Hospital Medicine Program” course. Write to him at john.nelson@nelsonflores.com.

To my way of thinking, a person’s diagnosis or pathophysiology is not as strong a predictor of needing inpatient hospital care as it might have been 10 or 20 years ago. Rather than the clinical diagnosis (e.g. pneumonia), it seems to me that frailty or social complexity often are the principal determinants of which patients are admitted to a hospital for medical conditions.

Some of these patients are admitted frequently but appear to realize little or no benefit from hospitalization. These patients typically have little or no social support, and they often have either significant mental health disorders or substance abuse, or both. Much has been written about these patients, and I recommend an article by Dr. Atul Gawande in the Jan. 24, 2011, issue of The New Yorker titled “The Hot Spotters: Can We Lower Medical Costs by Giving the Neediest Patients Better Care?”

The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s “Statistical Brief 354” on how health-care expenditures are allocated across the population reported that 1% of the population accounted for more than 22% of health-care spending in 2008. One in 5 of those were in that category again in 2009. Some of these patients would benefit from care plans.

The Role of Care Plans

It seems that there may be few effective inpatient interventions that will benefit these patients. After all, they have chronic issues that require ongoing relationships with outpatient providers, something that many of these patients lack. But for some (most?) of these patients, it seems clear that frequent hospitalizations don’t help and sometimes just perpetuate or worsen the patient’s dependence on the hospital at a high financial cost to society—and significant frustration and burnout on the part of hospital caregivers, including hospitalists.

For most hospitals, this problem is significant enough to require some sort of coordinated approach to the care of the dozens of types of patients in this category. Implementing whatever plan of care seems appropriate to the caregivers during each admission is frustrating, ensures lots of variation in care, and makes it easier for manipulative patients to abuse the hospital resources and personnel.

A better approach is to follow the same plan of care from one hospital visit to the next. You already knew that. But developing a care plan to follow during each ED visit and admission is time-consuming and often fraught with uncertainty about where boundaries should be set. So if you’re like me, you might just try to guide the patient to discharge this time and hope that whoever sees the patient on the next admission will take the initiative to develop the care plan. The result is that few such plans are developed.

Your Hospital Needs a Care Plan

Relying on individual doctors or nurses to take the initiative to develop care plans will almost always mean few plans are developed, they will vary in their effectiveness, and other providers may not be aware a plan exists. This was the case at the hospital where I practice until I heard Dr. Rick Hilger, MD, SFHM, a hospitalist at Regions Hospital in Minneapolis, present on this topic at HM12 in San Diego.

Dr. Hilger led a multidisciplinary team to develop care plans (they call them “restriction care plans”) and found that they dramatically reduced the rate of hospital admissions and ED visits for these patients. Hearing about this experience served as a kick in the pants for me, so I did much the same thing at “my” hospital. We have now developed plans for more than 20 patients and found that they visit our ED and are admitted less often. And, anecdotally at least, hospitalists and other hospital staff find that the care plans reduce, at least a little, the stress of caring for these patients.

Unanswered Questions

Although it seems clear that care plans reduce visits to the hospital that develops them, I suspect that some of these patients aren’t consuming any fewer health-care resources. They may just seek care from a different hospital.

My home state of Washington is working to develop individual patient care plans available to all hospitals in the state. A system called the Emergency Department Information Exchange (EDIE) has been adopted by nearly all the hospitals in the state. It allows them to share information on ED visits and such things as care plans with one another. For example, through EDIE, each hospital could see the opiate dosing schedule and admission criteria agreed to by patient and primary-care physician.

So it seems that care plans and the technology to share them can make it more difficult for patients to harm themselves by visiting many hospitals to get excessive opiate prescriptions, for example. This should benefit the patient and lower ED and hospital expenditures for these patients. But we don’t know what portion of costs simply is shifted to other settings, so there is no easy way to know the net effect on health-care costs.

An important unanswered question is whether these care plans improve patient well-being. It seems clear they do in some cases, but it is hard to know whether some patients may be worse off because of the plan.

Conclusion

I think nearly every hospital would benefit from a care plan committee composed of at least one hospitalist, ED physician, a nursing representative, and potentially other disciplines (see “Care Plan Attributes,” above). Our committee includes our inpatient psychiatrist, a really valuable contributor.

Dr. Nelson has been a practicing hospitalist since 1988. He is co-founder and past president of SHM, and principal in Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants. He is co-director for SHM’s “Best Practices in Managing a Hospital Medicine Program” course. Write to him at john.nelson@nelsonflores.com.

Communication Key to Peaceful Coexistence for Competing Hospital Medicine Groups

Experienced hospitalists and medical directors agree that the key to multiple hospitalist groups coexisting effectively under one roof—whether directly competing or not—is good communication. Effective communication can take time to build.

“Start by working together on something—anything, [such as] a hospital committee of some sort where there’s not likely to be much tension,” says hospitalist pioneer and practice consultant John Nelson, MD, MHM.

Dr. Nelson practices at Overlake Hospital in Bellevue, Wash., which has a hospitalist group employed by the hospital and another employed by Group Health Cooperative, a nonprofit health system in Washington state. It is important to put some trust in the trust bank, he says, “and that’s hard if you have no social connections at all. At my hospital, we enjoy each other’s company, we visit each other at lunch, and we even tried to have a journal club.” The two hospitalist groups work together on developing care protocols. Dr. Nelson says it also makes sense for the groups’ leaders to sit down together on a regular basis and have a venue for discussing important issues and solving problems that may arise.

Other suggestions for hospitalist groups working together under one roof include:

- Clearly define each group’s territory. The groups’ representatives can go out and try to persuade health plans or physician groups to shift their hospitalist allegiances, but there should be no “trolling” or “poaching” of patients going on inside the hospital’s walls. That will only confuse patients and disrupt the hospital’s larger service goals.

- Inform the ED and other key staff of your schedules. It’s important that everyone know exactly who is supposed to get which patients, and how these referrals get made. But recognize that mistakes happen and, hopefully, these will even out between the groups over time.

- Transparency, honesty, and even-handed treatment of all hospitalists can prevent resentment. Clearly defined guidelines and expectations are helpful. If the policy spells out transfers for an incorrectly referred patient, both sides should be accessible and cooperative with that process.

- Identify areas of common interest and agree to work together on these areas (i.e. competition-free zones). It might be possible, for example, for competing groups to take each others’ after-hours call on a rotating basis, with a firm commitment not to steal patients along the way.

- Spell out responsibilities in a way that everyone can agree is fair, such as alternating referrals or taking call on alternating days. For example, if subsidies are paid to more than one hospitalist group, is this done equitably, such as based on the number of hospitalist FTEs or shifts?

- Restrictive covenants and contractual noncompete clauses could become an issue in areas where multiple groups practice. Rather than using overly broad, blanket language, it could be clarified that such pacts apply only to the hospital where the physician currently works, and within a reasonable time frame. But everyone involved should be aware of what these covenants contain and, if they appear unreasonable, don’t sign them.

—Larry Beresford

Experienced hospitalists and medical directors agree that the key to multiple hospitalist groups coexisting effectively under one roof—whether directly competing or not—is good communication. Effective communication can take time to build.

“Start by working together on something—anything, [such as] a hospital committee of some sort where there’s not likely to be much tension,” says hospitalist pioneer and practice consultant John Nelson, MD, MHM.

Dr. Nelson practices at Overlake Hospital in Bellevue, Wash., which has a hospitalist group employed by the hospital and another employed by Group Health Cooperative, a nonprofit health system in Washington state. It is important to put some trust in the trust bank, he says, “and that’s hard if you have no social connections at all. At my hospital, we enjoy each other’s company, we visit each other at lunch, and we even tried to have a journal club.” The two hospitalist groups work together on developing care protocols. Dr. Nelson says it also makes sense for the groups’ leaders to sit down together on a regular basis and have a venue for discussing important issues and solving problems that may arise.

Other suggestions for hospitalist groups working together under one roof include:

- Clearly define each group’s territory. The groups’ representatives can go out and try to persuade health plans or physician groups to shift their hospitalist allegiances, but there should be no “trolling” or “poaching” of patients going on inside the hospital’s walls. That will only confuse patients and disrupt the hospital’s larger service goals.

- Inform the ED and other key staff of your schedules. It’s important that everyone know exactly who is supposed to get which patients, and how these referrals get made. But recognize that mistakes happen and, hopefully, these will even out between the groups over time.

- Transparency, honesty, and even-handed treatment of all hospitalists can prevent resentment. Clearly defined guidelines and expectations are helpful. If the policy spells out transfers for an incorrectly referred patient, both sides should be accessible and cooperative with that process.

- Identify areas of common interest and agree to work together on these areas (i.e. competition-free zones). It might be possible, for example, for competing groups to take each others’ after-hours call on a rotating basis, with a firm commitment not to steal patients along the way.

- Spell out responsibilities in a way that everyone can agree is fair, such as alternating referrals or taking call on alternating days. For example, if subsidies are paid to more than one hospitalist group, is this done equitably, such as based on the number of hospitalist FTEs or shifts?

- Restrictive covenants and contractual noncompete clauses could become an issue in areas where multiple groups practice. Rather than using overly broad, blanket language, it could be clarified that such pacts apply only to the hospital where the physician currently works, and within a reasonable time frame. But everyone involved should be aware of what these covenants contain and, if they appear unreasonable, don’t sign them.

—Larry Beresford

Experienced hospitalists and medical directors agree that the key to multiple hospitalist groups coexisting effectively under one roof—whether directly competing or not—is good communication. Effective communication can take time to build.

“Start by working together on something—anything, [such as] a hospital committee of some sort where there’s not likely to be much tension,” says hospitalist pioneer and practice consultant John Nelson, MD, MHM.

Dr. Nelson practices at Overlake Hospital in Bellevue, Wash., which has a hospitalist group employed by the hospital and another employed by Group Health Cooperative, a nonprofit health system in Washington state. It is important to put some trust in the trust bank, he says, “and that’s hard if you have no social connections at all. At my hospital, we enjoy each other’s company, we visit each other at lunch, and we even tried to have a journal club.” The two hospitalist groups work together on developing care protocols. Dr. Nelson says it also makes sense for the groups’ leaders to sit down together on a regular basis and have a venue for discussing important issues and solving problems that may arise.

Other suggestions for hospitalist groups working together under one roof include:

- Clearly define each group’s territory. The groups’ representatives can go out and try to persuade health plans or physician groups to shift their hospitalist allegiances, but there should be no “trolling” or “poaching” of patients going on inside the hospital’s walls. That will only confuse patients and disrupt the hospital’s larger service goals.

- Inform the ED and other key staff of your schedules. It’s important that everyone know exactly who is supposed to get which patients, and how these referrals get made. But recognize that mistakes happen and, hopefully, these will even out between the groups over time.

- Transparency, honesty, and even-handed treatment of all hospitalists can prevent resentment. Clearly defined guidelines and expectations are helpful. If the policy spells out transfers for an incorrectly referred patient, both sides should be accessible and cooperative with that process.

- Identify areas of common interest and agree to work together on these areas (i.e. competition-free zones). It might be possible, for example, for competing groups to take each others’ after-hours call on a rotating basis, with a firm commitment not to steal patients along the way.

- Spell out responsibilities in a way that everyone can agree is fair, such as alternating referrals or taking call on alternating days. For example, if subsidies are paid to more than one hospitalist group, is this done equitably, such as based on the number of hospitalist FTEs or shifts?

- Restrictive covenants and contractual noncompete clauses could become an issue in areas where multiple groups practice. Rather than using overly broad, blanket language, it could be clarified that such pacts apply only to the hospital where the physician currently works, and within a reasonable time frame. But everyone involved should be aware of what these covenants contain and, if they appear unreasonable, don’t sign them.

—Larry Beresford

A lifetime of service to women and their health—the career of Barbara S. Levy, MD