User login

John Nelson: Peformance Key to Federal Value-Based Payment Modifier Plan

For years, your hospital was paid additional money by Medicare to report its performance on such things as core measures. Medicare then shared that information with the public via www.hospitalcompare.hhs.gov. Even if the hospital never gave Pneumovax when indicated, it was paid more simply for reporting that fact. (Fortunately, there were lots of reasons hospitals wanted to perform well.)

The days of hospitals being paid more simply for reporting ended a long time ago. Now performance, e.g., how often Pneumovax was given when indicated, influences payment. That is, things have transitioned from pay-for-reporting to a pay-for-performance program called hospital value-based purchasing (VBP).

I hope that at least one member of your hospitalist group is keeping up with hospital VBP. It got a lot of attention in the fall because it was the first time Medicare Part A payments to hospitals were adjusted based on performance on some core measures and patient satisfaction domains, as well as readmission rates for congestive heart failure (CHF), acute myocardial infarction (AMI), and pneumonia patients. The dollars at stake and performance metrics change will change every year, so plan to pay attention to hospital VBP on an ongoing basis.

Physicians’ Turn

Medicare payment to physicians is evolving along the same trajectory as hospitals. For several years, doctors have had the option to voluntarily participate in the Physician Quality Reporting System (PQRS). As long as a doctor reported quality performance on a sufficient portion of certain patient types, Medicare would provide a “bonus” at the end of the year. From 2012 through 2014, the “bonus” is 0.5% of that doctor’s total allowable Medicare charges. For example, if that doctor generated $150,000 of Medicare allowable charges over the calendar year, the additional payment for successful reporting PQRS would be $750 (0.5% of $150,000).

Although $750 is only a tiny fraction of collections, the right charge-capture system can make it pretty easy to achieve. And an extra payment of $750 sure is better than the 1.5% penalty for not participating; that program starts in 2015 and increases to a 2% penalty in 2016. If you are still not participating successfully in PQRS in 2015, the reimbursement for that $150,000 in charges will be reduced by $2,250 (1.5% of $150,000). So I strongly recommend that you begin reporting in 2013 so that you have time to work out the kinks well ahead of 2015. Don’t delay, but don’t panic, either, because you can still succeed in 2013 even if you don’t start capturing or reporting PQRS data until late winter or early spring.

At some point in the next year or so, data from as early as January 2013 for doctors reporting through PQRS will be made public on the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid’s (CMS) physician compare website: www.medicare.gov/find-a-doctor/provider-search.aspx. For example, should you choose to report the portion of stroke patients for whom you prescribed DVT prophylaxis, the public will be able to see your data.

The Next Wave of Physician Pay for Performance

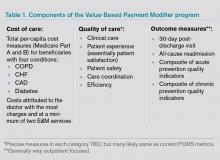

As the name implies, PQRS is a program based on reporting. Now CMS is adding the Value-Based Payment Modifier (VBPM) program, in which performance determines payments (see Table 1). It incorporates quality measures from PQRS, but is for now a separate program. It is very similar in name and structure to the hospital VBP program mentioned above, but incorporates cost of care data as well as quality performance. So it is really about value and not just quality performance (hence the name).

For providers in groups of more than 100 that bill under the same tax ID number (they don’t have to be in the same specialty), VBPM will first influence Part B Medicare reimbursement for physician services in 2015. It will expand to include all providers in 2017.

But don’t think you have until 2015 or 2017 to learn about all of this. There is a two-year lag, so payments in 2015 are based on performance in 2013 and 2017 payments presumably will be based on 2015 performance. In the fall of 2013, CMS plans to provide group-level (not individual) performance reports to all doctors in groups of 100 or more under the same tax ID number. These performance reports are known as quality resource use reports (QRURs). QRURs were trialed on physicians in a few states who received reports in 2012 based on 2011 performance, but in 2013, reports based on 2012 performance will be distributed to all doctors who practice in groups of 100 or more.

The calculation to determine whether a doctor is due additional payment for good performance (more accurately, good value) is awfully complicated. But providers have a choice to make. They can choose to:

- Not report data and accept a 1% penalty (likely to increase in successive years and in addition to the penalty for not reporting PQRS data, for a total penalty of 2.5%);

- Report data but not compete for financial upside or downside; or

- Compete for additional payments (amount to be determined) and risk a penalty of 0.5% or 1% for poor performance.

Look for more details about the VBPM program in future columns and other articles in The Hospitalist. There are a number of good online resources, including a CMS presentation titled “CMS Proposals for the Physician Value-Based Payment Modifier under the Medicare Physician Fee Schedule.” Type “Value-Based Payment Modifier” and “CMS” into any search engine to locate the video.

Parting Recommendations

Just about every hospitalist group should:

- Designate someone in your group to keep up with evolving pay-for-performance programs. It doesn’t have to be an MD, but you do need someone local that can guide your group through it. Consider becoming the most expert physician at your hospital on this topic.

- Start reporting through PQRS in 2013 if you haven’t already.

- Support SHM’s efforts to provide feedback to CMS to ensure that the metrics are meaningful for the type of care we provide.

Dr. Nelson has been a practicing hospitalist since 1988. He is co-founder and past president of SHM, and principal in Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants. He is course co-director for SHM’s “Best Practices in Managing a Hospital Medicine Program” course. Write to him at john.nelson@nelsonflores.com.

Author’s note: For helping to explain all this pay-for-performance stuff, I once again owe thanks to Dr. Pat Torcson, a hospitalist in Covington, La., and member of SHM’s Public Policy Committee. He does an amazing job of keeping up with the evolving pay-for-performance programs, advocating on behalf of hospitalists and the patients we serve, and graciously answers my tedious questions with thoughtful and informative replies. He is a really pleasant guy and a terrific asset to SHM and hospital medicine.

For years, your hospital was paid additional money by Medicare to report its performance on such things as core measures. Medicare then shared that information with the public via www.hospitalcompare.hhs.gov. Even if the hospital never gave Pneumovax when indicated, it was paid more simply for reporting that fact. (Fortunately, there were lots of reasons hospitals wanted to perform well.)

The days of hospitals being paid more simply for reporting ended a long time ago. Now performance, e.g., how often Pneumovax was given when indicated, influences payment. That is, things have transitioned from pay-for-reporting to a pay-for-performance program called hospital value-based purchasing (VBP).

I hope that at least one member of your hospitalist group is keeping up with hospital VBP. It got a lot of attention in the fall because it was the first time Medicare Part A payments to hospitals were adjusted based on performance on some core measures and patient satisfaction domains, as well as readmission rates for congestive heart failure (CHF), acute myocardial infarction (AMI), and pneumonia patients. The dollars at stake and performance metrics change will change every year, so plan to pay attention to hospital VBP on an ongoing basis.

Physicians’ Turn

Medicare payment to physicians is evolving along the same trajectory as hospitals. For several years, doctors have had the option to voluntarily participate in the Physician Quality Reporting System (PQRS). As long as a doctor reported quality performance on a sufficient portion of certain patient types, Medicare would provide a “bonus” at the end of the year. From 2012 through 2014, the “bonus” is 0.5% of that doctor’s total allowable Medicare charges. For example, if that doctor generated $150,000 of Medicare allowable charges over the calendar year, the additional payment for successful reporting PQRS would be $750 (0.5% of $150,000).

Although $750 is only a tiny fraction of collections, the right charge-capture system can make it pretty easy to achieve. And an extra payment of $750 sure is better than the 1.5% penalty for not participating; that program starts in 2015 and increases to a 2% penalty in 2016. If you are still not participating successfully in PQRS in 2015, the reimbursement for that $150,000 in charges will be reduced by $2,250 (1.5% of $150,000). So I strongly recommend that you begin reporting in 2013 so that you have time to work out the kinks well ahead of 2015. Don’t delay, but don’t panic, either, because you can still succeed in 2013 even if you don’t start capturing or reporting PQRS data until late winter or early spring.

At some point in the next year or so, data from as early as January 2013 for doctors reporting through PQRS will be made public on the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid’s (CMS) physician compare website: www.medicare.gov/find-a-doctor/provider-search.aspx. For example, should you choose to report the portion of stroke patients for whom you prescribed DVT prophylaxis, the public will be able to see your data.

The Next Wave of Physician Pay for Performance

As the name implies, PQRS is a program based on reporting. Now CMS is adding the Value-Based Payment Modifier (VBPM) program, in which performance determines payments (see Table 1). It incorporates quality measures from PQRS, but is for now a separate program. It is very similar in name and structure to the hospital VBP program mentioned above, but incorporates cost of care data as well as quality performance. So it is really about value and not just quality performance (hence the name).

For providers in groups of more than 100 that bill under the same tax ID number (they don’t have to be in the same specialty), VBPM will first influence Part B Medicare reimbursement for physician services in 2015. It will expand to include all providers in 2017.

But don’t think you have until 2015 or 2017 to learn about all of this. There is a two-year lag, so payments in 2015 are based on performance in 2013 and 2017 payments presumably will be based on 2015 performance. In the fall of 2013, CMS plans to provide group-level (not individual) performance reports to all doctors in groups of 100 or more under the same tax ID number. These performance reports are known as quality resource use reports (QRURs). QRURs were trialed on physicians in a few states who received reports in 2012 based on 2011 performance, but in 2013, reports based on 2012 performance will be distributed to all doctors who practice in groups of 100 or more.

The calculation to determine whether a doctor is due additional payment for good performance (more accurately, good value) is awfully complicated. But providers have a choice to make. They can choose to:

- Not report data and accept a 1% penalty (likely to increase in successive years and in addition to the penalty for not reporting PQRS data, for a total penalty of 2.5%);

- Report data but not compete for financial upside or downside; or

- Compete for additional payments (amount to be determined) and risk a penalty of 0.5% or 1% for poor performance.

Look for more details about the VBPM program in future columns and other articles in The Hospitalist. There are a number of good online resources, including a CMS presentation titled “CMS Proposals for the Physician Value-Based Payment Modifier under the Medicare Physician Fee Schedule.” Type “Value-Based Payment Modifier” and “CMS” into any search engine to locate the video.

Parting Recommendations

Just about every hospitalist group should:

- Designate someone in your group to keep up with evolving pay-for-performance programs. It doesn’t have to be an MD, but you do need someone local that can guide your group through it. Consider becoming the most expert physician at your hospital on this topic.

- Start reporting through PQRS in 2013 if you haven’t already.

- Support SHM’s efforts to provide feedback to CMS to ensure that the metrics are meaningful for the type of care we provide.

Dr. Nelson has been a practicing hospitalist since 1988. He is co-founder and past president of SHM, and principal in Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants. He is course co-director for SHM’s “Best Practices in Managing a Hospital Medicine Program” course. Write to him at john.nelson@nelsonflores.com.

Author’s note: For helping to explain all this pay-for-performance stuff, I once again owe thanks to Dr. Pat Torcson, a hospitalist in Covington, La., and member of SHM’s Public Policy Committee. He does an amazing job of keeping up with the evolving pay-for-performance programs, advocating on behalf of hospitalists and the patients we serve, and graciously answers my tedious questions with thoughtful and informative replies. He is a really pleasant guy and a terrific asset to SHM and hospital medicine.

For years, your hospital was paid additional money by Medicare to report its performance on such things as core measures. Medicare then shared that information with the public via www.hospitalcompare.hhs.gov. Even if the hospital never gave Pneumovax when indicated, it was paid more simply for reporting that fact. (Fortunately, there were lots of reasons hospitals wanted to perform well.)

The days of hospitals being paid more simply for reporting ended a long time ago. Now performance, e.g., how often Pneumovax was given when indicated, influences payment. That is, things have transitioned from pay-for-reporting to a pay-for-performance program called hospital value-based purchasing (VBP).

I hope that at least one member of your hospitalist group is keeping up with hospital VBP. It got a lot of attention in the fall because it was the first time Medicare Part A payments to hospitals were adjusted based on performance on some core measures and patient satisfaction domains, as well as readmission rates for congestive heart failure (CHF), acute myocardial infarction (AMI), and pneumonia patients. The dollars at stake and performance metrics change will change every year, so plan to pay attention to hospital VBP on an ongoing basis.

Physicians’ Turn

Medicare payment to physicians is evolving along the same trajectory as hospitals. For several years, doctors have had the option to voluntarily participate in the Physician Quality Reporting System (PQRS). As long as a doctor reported quality performance on a sufficient portion of certain patient types, Medicare would provide a “bonus” at the end of the year. From 2012 through 2014, the “bonus” is 0.5% of that doctor’s total allowable Medicare charges. For example, if that doctor generated $150,000 of Medicare allowable charges over the calendar year, the additional payment for successful reporting PQRS would be $750 (0.5% of $150,000).

Although $750 is only a tiny fraction of collections, the right charge-capture system can make it pretty easy to achieve. And an extra payment of $750 sure is better than the 1.5% penalty for not participating; that program starts in 2015 and increases to a 2% penalty in 2016. If you are still not participating successfully in PQRS in 2015, the reimbursement for that $150,000 in charges will be reduced by $2,250 (1.5% of $150,000). So I strongly recommend that you begin reporting in 2013 so that you have time to work out the kinks well ahead of 2015. Don’t delay, but don’t panic, either, because you can still succeed in 2013 even if you don’t start capturing or reporting PQRS data until late winter or early spring.

At some point in the next year or so, data from as early as January 2013 for doctors reporting through PQRS will be made public on the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid’s (CMS) physician compare website: www.medicare.gov/find-a-doctor/provider-search.aspx. For example, should you choose to report the portion of stroke patients for whom you prescribed DVT prophylaxis, the public will be able to see your data.

The Next Wave of Physician Pay for Performance

As the name implies, PQRS is a program based on reporting. Now CMS is adding the Value-Based Payment Modifier (VBPM) program, in which performance determines payments (see Table 1). It incorporates quality measures from PQRS, but is for now a separate program. It is very similar in name and structure to the hospital VBP program mentioned above, but incorporates cost of care data as well as quality performance. So it is really about value and not just quality performance (hence the name).

For providers in groups of more than 100 that bill under the same tax ID number (they don’t have to be in the same specialty), VBPM will first influence Part B Medicare reimbursement for physician services in 2015. It will expand to include all providers in 2017.

But don’t think you have until 2015 or 2017 to learn about all of this. There is a two-year lag, so payments in 2015 are based on performance in 2013 and 2017 payments presumably will be based on 2015 performance. In the fall of 2013, CMS plans to provide group-level (not individual) performance reports to all doctors in groups of 100 or more under the same tax ID number. These performance reports are known as quality resource use reports (QRURs). QRURs were trialed on physicians in a few states who received reports in 2012 based on 2011 performance, but in 2013, reports based on 2012 performance will be distributed to all doctors who practice in groups of 100 or more.

The calculation to determine whether a doctor is due additional payment for good performance (more accurately, good value) is awfully complicated. But providers have a choice to make. They can choose to:

- Not report data and accept a 1% penalty (likely to increase in successive years and in addition to the penalty for not reporting PQRS data, for a total penalty of 2.5%);

- Report data but not compete for financial upside or downside; or

- Compete for additional payments (amount to be determined) and risk a penalty of 0.5% or 1% for poor performance.

Look for more details about the VBPM program in future columns and other articles in The Hospitalist. There are a number of good online resources, including a CMS presentation titled “CMS Proposals for the Physician Value-Based Payment Modifier under the Medicare Physician Fee Schedule.” Type “Value-Based Payment Modifier” and “CMS” into any search engine to locate the video.

Parting Recommendations

Just about every hospitalist group should:

- Designate someone in your group to keep up with evolving pay-for-performance programs. It doesn’t have to be an MD, but you do need someone local that can guide your group through it. Consider becoming the most expert physician at your hospital on this topic.

- Start reporting through PQRS in 2013 if you haven’t already.

- Support SHM’s efforts to provide feedback to CMS to ensure that the metrics are meaningful for the type of care we provide.

Dr. Nelson has been a practicing hospitalist since 1988. He is co-founder and past president of SHM, and principal in Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants. He is course co-director for SHM’s “Best Practices in Managing a Hospital Medicine Program” course. Write to him at john.nelson@nelsonflores.com.

Author’s note: For helping to explain all this pay-for-performance stuff, I once again owe thanks to Dr. Pat Torcson, a hospitalist in Covington, La., and member of SHM’s Public Policy Committee. He does an amazing job of keeping up with the evolving pay-for-performance programs, advocating on behalf of hospitalists and the patients we serve, and graciously answers my tedious questions with thoughtful and informative replies. He is a really pleasant guy and a terrific asset to SHM and hospital medicine.

Consider Patient Safety, Outcomes Risk before Prescribing Off-Label Drugs

Consider Patient Safety, Outcomes Risk before Prescribing “Off-Label”

What is the story with off-label drug use? I have seen some other physicians in my group use dabigatran for VTE prophylaxis, which I know it is not an approved indication. Am I taking on risk by continuing this treatment?

—Fabian Harris, Tuscaloosa, Ala.

Dr. Hospitalist responds:

Our friends at the FDA are in the business of approving drugs for use, but they do not regulate medical practice. So the short answer to your question is that off-label drug use is perfectly acceptable. Once a drug has been approved for use, if, in your clinical judgment, there are other indications for which it could be beneficial, then you are well within your rights to prescribe it. The FDA does not dictate how you practice medicine.

However, you will still be held to the community standard when it comes to your medical practice. As an example, gabapentin is used all the time for neuropathic pain syndromes, though technically it is only approved for seizures and post-herpetic neuralgia. Although the FDA won’t restrict your prescribing, it does prohibit pharmaceutical companies from marketing their drugs for anything other than their approved indications. In fact, Pfizer settled a case in 2004 on this very drug due to the promotion of prescribing it for nonapproved indications. I think at this point it’s fairly well accepted that lots of physicians use gabapentin for neuropathic pain, so you would not be too far out on a limb in prescribing it yourself in this manner.

For newer drugs, I might proceed with a little more caution. Anyone out there remember trovofloxacin (Trovan)? It was a new antibiotic approved in the late 1990s, with a coverage spectrum similar to levofloxacin, but with even more weight toward the gram positives. A wonder drug! Oral! As a result, it got prescribed like water, but not for the serious infections it was designed for: It got prescribed “off label” for common URIs and sinusitis. Unfortunately, it also caused a fair amount of liver failure and was summarily pulled from the market.

Does this mean dabigatran is a bad drug? No, but we don’t have much history with it, either. So while it might seem to be an innocuous extension to prescribe it for VTE prevention when it has already been approved for stroke prevention in afib, I think you carry some risk by doing this. In addition, some insurers will not cover a drug being prescribed in this manner, so you might be exposing your patient to added costs as well. Additionally, there’s nothing about off-label prescribing that says you have to tell the patient that’s what you’re doing. However, if you put together the factors of not informing a patient about an off-label use, and a patient having to pay out of pocket for that medicine, with an adverse outcome ... well, let’s just say that might not end too well.

Ultimately, I think you will need to consider the safety profile of the drug, the risk for an adverse outcome, your own risk tolerance, and the current state of medical practice before you consistently agree to use a drug “off label.” Given the slow-moving jungle of FDA approval, I can understand the desire to use a newer drug in an off-label manner, but it’s probably best to stop and think about the alternatives before proceeding. If you’re practicing in a group, then it’s just as important to come to a consensus with your partners about which drugs you will comfortably use off-label and which ones you won’t, especially as newer drugs come into the marketplace.

Consider Patient Safety, Outcomes Risk before Prescribing “Off-Label”

What is the story with off-label drug use? I have seen some other physicians in my group use dabigatran for VTE prophylaxis, which I know it is not an approved indication. Am I taking on risk by continuing this treatment?

—Fabian Harris, Tuscaloosa, Ala.

Dr. Hospitalist responds:

Our friends at the FDA are in the business of approving drugs for use, but they do not regulate medical practice. So the short answer to your question is that off-label drug use is perfectly acceptable. Once a drug has been approved for use, if, in your clinical judgment, there are other indications for which it could be beneficial, then you are well within your rights to prescribe it. The FDA does not dictate how you practice medicine.

However, you will still be held to the community standard when it comes to your medical practice. As an example, gabapentin is used all the time for neuropathic pain syndromes, though technically it is only approved for seizures and post-herpetic neuralgia. Although the FDA won’t restrict your prescribing, it does prohibit pharmaceutical companies from marketing their drugs for anything other than their approved indications. In fact, Pfizer settled a case in 2004 on this very drug due to the promotion of prescribing it for nonapproved indications. I think at this point it’s fairly well accepted that lots of physicians use gabapentin for neuropathic pain, so you would not be too far out on a limb in prescribing it yourself in this manner.

For newer drugs, I might proceed with a little more caution. Anyone out there remember trovofloxacin (Trovan)? It was a new antibiotic approved in the late 1990s, with a coverage spectrum similar to levofloxacin, but with even more weight toward the gram positives. A wonder drug! Oral! As a result, it got prescribed like water, but not for the serious infections it was designed for: It got prescribed “off label” for common URIs and sinusitis. Unfortunately, it also caused a fair amount of liver failure and was summarily pulled from the market.

Does this mean dabigatran is a bad drug? No, but we don’t have much history with it, either. So while it might seem to be an innocuous extension to prescribe it for VTE prevention when it has already been approved for stroke prevention in afib, I think you carry some risk by doing this. In addition, some insurers will not cover a drug being prescribed in this manner, so you might be exposing your patient to added costs as well. Additionally, there’s nothing about off-label prescribing that says you have to tell the patient that’s what you’re doing. However, if you put together the factors of not informing a patient about an off-label use, and a patient having to pay out of pocket for that medicine, with an adverse outcome ... well, let’s just say that might not end too well.

Ultimately, I think you will need to consider the safety profile of the drug, the risk for an adverse outcome, your own risk tolerance, and the current state of medical practice before you consistently agree to use a drug “off label.” Given the slow-moving jungle of FDA approval, I can understand the desire to use a newer drug in an off-label manner, but it’s probably best to stop and think about the alternatives before proceeding. If you’re practicing in a group, then it’s just as important to come to a consensus with your partners about which drugs you will comfortably use off-label and which ones you won’t, especially as newer drugs come into the marketplace.

Consider Patient Safety, Outcomes Risk before Prescribing “Off-Label”

What is the story with off-label drug use? I have seen some other physicians in my group use dabigatran for VTE prophylaxis, which I know it is not an approved indication. Am I taking on risk by continuing this treatment?

—Fabian Harris, Tuscaloosa, Ala.

Dr. Hospitalist responds:

Our friends at the FDA are in the business of approving drugs for use, but they do not regulate medical practice. So the short answer to your question is that off-label drug use is perfectly acceptable. Once a drug has been approved for use, if, in your clinical judgment, there are other indications for which it could be beneficial, then you are well within your rights to prescribe it. The FDA does not dictate how you practice medicine.

However, you will still be held to the community standard when it comes to your medical practice. As an example, gabapentin is used all the time for neuropathic pain syndromes, though technically it is only approved for seizures and post-herpetic neuralgia. Although the FDA won’t restrict your prescribing, it does prohibit pharmaceutical companies from marketing their drugs for anything other than their approved indications. In fact, Pfizer settled a case in 2004 on this very drug due to the promotion of prescribing it for nonapproved indications. I think at this point it’s fairly well accepted that lots of physicians use gabapentin for neuropathic pain, so you would not be too far out on a limb in prescribing it yourself in this manner.

For newer drugs, I might proceed with a little more caution. Anyone out there remember trovofloxacin (Trovan)? It was a new antibiotic approved in the late 1990s, with a coverage spectrum similar to levofloxacin, but with even more weight toward the gram positives. A wonder drug! Oral! As a result, it got prescribed like water, but not for the serious infections it was designed for: It got prescribed “off label” for common URIs and sinusitis. Unfortunately, it also caused a fair amount of liver failure and was summarily pulled from the market.

Does this mean dabigatran is a bad drug? No, but we don’t have much history with it, either. So while it might seem to be an innocuous extension to prescribe it for VTE prevention when it has already been approved for stroke prevention in afib, I think you carry some risk by doing this. In addition, some insurers will not cover a drug being prescribed in this manner, so you might be exposing your patient to added costs as well. Additionally, there’s nothing about off-label prescribing that says you have to tell the patient that’s what you’re doing. However, if you put together the factors of not informing a patient about an off-label use, and a patient having to pay out of pocket for that medicine, with an adverse outcome ... well, let’s just say that might not end too well.

Ultimately, I think you will need to consider the safety profile of the drug, the risk for an adverse outcome, your own risk tolerance, and the current state of medical practice before you consistently agree to use a drug “off label.” Given the slow-moving jungle of FDA approval, I can understand the desire to use a newer drug in an off-label manner, but it’s probably best to stop and think about the alternatives before proceeding. If you’re practicing in a group, then it’s just as important to come to a consensus with your partners about which drugs you will comfortably use off-label and which ones you won’t, especially as newer drugs come into the marketplace.

Defining a Safe Workload for Pediatric Hospitalists

As I write this column, I am on the second leg of an overnight flight back home to Austin, Texas. I think it actually went pretty well, considering my 2-year-old daughter was wide awake after sleeping for the first three hours of this 14-hour odyssey. The remainder of the trip is a blur of awkward sleep positions interspersed with brief periods of semilucidity. Those of you with first-hand knowledge of what this experience is like might be feeling sorry for me, but you shouldn’t. I am returning from a “why don’t I live here” kind of vacation week in Hawaii. The rest of you are probably wondering how anyone could write a coherent column at this point, which is fair, but to which I would reply: Aren’t all hospitalists expected to function at high levels during periods of sleep deprivation?

While the issue of resident duty-hours has been discussed endlessly and studied increasingly, in terms of effects on outcomes, I am surprised there has not been more discussion surrounding the concept of attending duty-hours. The subject might not always be phrased to include the term “duty-hours,” but it seems that when it comes to scheduling, strong opinions come out in my group when the duration of, frequency of, or time off between night shifts are brought up. And when it comes to safety, I am certain sleep deprivation and sleep inertia (that period of haziness immediately after being awakened in the middle of the night) have led to questionable decisions on my part.

Why? Well...

So why do pediatric hospitalists avoid the issue of sleep hygiene, work schedules, and clinical impact? I think the reasons are multifactorial.

First, there are definitely individual variations in how all of us tolerate this work, and I suspect some of this is based on such traits as age and general ability to adapt to uncomfortable circadian flip-flops. I will admit that every time I wake up achy after a call night, I begin to wonder if I will be able to handle this in 10 to 15 years.

Second, I think pediatric HM as a field has not yet explored this topic fully because we are young both in terms of chronological age as well as nocturnal work-years. The work has not yet aged us to the point of making this a critical issue. We’re also somewhat behind our adult-hospitalist colleagues in terms of the volume of nocturnal work. Adult HM groups have long explored different shift schedules (seven-on/seven-off, day/evening/overnight distribution, etc.) because they routinely cover large services of more than 100 patients in large hospitals with more than 500 beds. In pediatrics, most of us operate in small community hospital settings or large academic centers where the nightly in-house quantity of work is relatively low, mitigated by the smaller size of most community programs and the presence of residents in most large children’s hospitals.

But I see this as an important issue for us to define: the imperative to define safe, round-the-clock clinical care and sustainable careers. Although we will need to learn from other fields, HM is somewhat different from other types of 24/7 medicine in that we require more continuity in our daytime work, which also carries over to night shifts both in terms of how the schedule is made as well as the benefit on the clinical side. The need for continuity adds an extra degree of difficulty in creating and studying different schedules that try to optimize nocturnal functioning.

Clarity, Please

Unfortunately, those looking for evidence-based, or even consensus-based, solutions might have to wait. A recent article in the Journal of Hospital Medicine does a nice job of synthesizing the literature and highlights the lack of clear answers for what kind of shift schedules work best.1

In the absence of scientific solutions, it might be too easy to say that we need “more research,” because what doesn’t need more research? (OK, we don’t need more research on interventions for bronchiolitis.) But in the same manner in which pediatric hospitalists have taken the lead in defining a night curriculum for residents (congratulations, Becky Blankenburg, on winning the Ray E. Helfer award in pediatric education), I believe there is an opportunity to improve circadian functioning for all hospital-based physicians, but more specifically attendings. This is even more important as residents work less and a 24/7 attending presence becomes the norm in teaching facilities. While the link between safety and fatigue may have been seen as a nonissue in past decades, I think that in our current era, this is something that we own and/or will be asked to define in the near future.

In the meantime, I think we’re left to our own schedules. And in defense of all schedulers like me out there, I will say that there are no proven solutions, so local culture will predominate. Different groups with different personalities and family makeups will have varying preferences. Smaller groups will tend to have longer shift times with less flexibility in “swing”-type midday or evening shifts, while larger groups might have increased flexibility in defining different shifts at the expense of added complexity in terms of creating a schedule with no gaps.

As we come up with more rules about night shifts, such as “clockwise” scheduling of day-evening-overnight shifts, single versus clustered nights based on frequency, and days off after night shifts, the more complex and awkward our Tetris-like schedule will become. I predict that this is something hospitalists will begin to think about more, with a necessary push for safe and sustainable schedules. In the short-term, allowing for financial and structural wiggle room in the scheduling process (i.e. adjusting shift patterns and differential pay for night work) might be the most balanced approach for the immediate future.

Dr. Shen is pediatric editor of The Hospitalist. Write to him at mshen@seton.edu.

Reference

As I write this column, I am on the second leg of an overnight flight back home to Austin, Texas. I think it actually went pretty well, considering my 2-year-old daughter was wide awake after sleeping for the first three hours of this 14-hour odyssey. The remainder of the trip is a blur of awkward sleep positions interspersed with brief periods of semilucidity. Those of you with first-hand knowledge of what this experience is like might be feeling sorry for me, but you shouldn’t. I am returning from a “why don’t I live here” kind of vacation week in Hawaii. The rest of you are probably wondering how anyone could write a coherent column at this point, which is fair, but to which I would reply: Aren’t all hospitalists expected to function at high levels during periods of sleep deprivation?

While the issue of resident duty-hours has been discussed endlessly and studied increasingly, in terms of effects on outcomes, I am surprised there has not been more discussion surrounding the concept of attending duty-hours. The subject might not always be phrased to include the term “duty-hours,” but it seems that when it comes to scheduling, strong opinions come out in my group when the duration of, frequency of, or time off between night shifts are brought up. And when it comes to safety, I am certain sleep deprivation and sleep inertia (that period of haziness immediately after being awakened in the middle of the night) have led to questionable decisions on my part.

Why? Well...

So why do pediatric hospitalists avoid the issue of sleep hygiene, work schedules, and clinical impact? I think the reasons are multifactorial.

First, there are definitely individual variations in how all of us tolerate this work, and I suspect some of this is based on such traits as age and general ability to adapt to uncomfortable circadian flip-flops. I will admit that every time I wake up achy after a call night, I begin to wonder if I will be able to handle this in 10 to 15 years.

Second, I think pediatric HM as a field has not yet explored this topic fully because we are young both in terms of chronological age as well as nocturnal work-years. The work has not yet aged us to the point of making this a critical issue. We’re also somewhat behind our adult-hospitalist colleagues in terms of the volume of nocturnal work. Adult HM groups have long explored different shift schedules (seven-on/seven-off, day/evening/overnight distribution, etc.) because they routinely cover large services of more than 100 patients in large hospitals with more than 500 beds. In pediatrics, most of us operate in small community hospital settings or large academic centers where the nightly in-house quantity of work is relatively low, mitigated by the smaller size of most community programs and the presence of residents in most large children’s hospitals.

But I see this as an important issue for us to define: the imperative to define safe, round-the-clock clinical care and sustainable careers. Although we will need to learn from other fields, HM is somewhat different from other types of 24/7 medicine in that we require more continuity in our daytime work, which also carries over to night shifts both in terms of how the schedule is made as well as the benefit on the clinical side. The need for continuity adds an extra degree of difficulty in creating and studying different schedules that try to optimize nocturnal functioning.

Clarity, Please

Unfortunately, those looking for evidence-based, or even consensus-based, solutions might have to wait. A recent article in the Journal of Hospital Medicine does a nice job of synthesizing the literature and highlights the lack of clear answers for what kind of shift schedules work best.1

In the absence of scientific solutions, it might be too easy to say that we need “more research,” because what doesn’t need more research? (OK, we don’t need more research on interventions for bronchiolitis.) But in the same manner in which pediatric hospitalists have taken the lead in defining a night curriculum for residents (congratulations, Becky Blankenburg, on winning the Ray E. Helfer award in pediatric education), I believe there is an opportunity to improve circadian functioning for all hospital-based physicians, but more specifically attendings. This is even more important as residents work less and a 24/7 attending presence becomes the norm in teaching facilities. While the link between safety and fatigue may have been seen as a nonissue in past decades, I think that in our current era, this is something that we own and/or will be asked to define in the near future.

In the meantime, I think we’re left to our own schedules. And in defense of all schedulers like me out there, I will say that there are no proven solutions, so local culture will predominate. Different groups with different personalities and family makeups will have varying preferences. Smaller groups will tend to have longer shift times with less flexibility in “swing”-type midday or evening shifts, while larger groups might have increased flexibility in defining different shifts at the expense of added complexity in terms of creating a schedule with no gaps.

As we come up with more rules about night shifts, such as “clockwise” scheduling of day-evening-overnight shifts, single versus clustered nights based on frequency, and days off after night shifts, the more complex and awkward our Tetris-like schedule will become. I predict that this is something hospitalists will begin to think about more, with a necessary push for safe and sustainable schedules. In the short-term, allowing for financial and structural wiggle room in the scheduling process (i.e. adjusting shift patterns and differential pay for night work) might be the most balanced approach for the immediate future.

Dr. Shen is pediatric editor of The Hospitalist. Write to him at mshen@seton.edu.

Reference

As I write this column, I am on the second leg of an overnight flight back home to Austin, Texas. I think it actually went pretty well, considering my 2-year-old daughter was wide awake after sleeping for the first three hours of this 14-hour odyssey. The remainder of the trip is a blur of awkward sleep positions interspersed with brief periods of semilucidity. Those of you with first-hand knowledge of what this experience is like might be feeling sorry for me, but you shouldn’t. I am returning from a “why don’t I live here” kind of vacation week in Hawaii. The rest of you are probably wondering how anyone could write a coherent column at this point, which is fair, but to which I would reply: Aren’t all hospitalists expected to function at high levels during periods of sleep deprivation?

While the issue of resident duty-hours has been discussed endlessly and studied increasingly, in terms of effects on outcomes, I am surprised there has not been more discussion surrounding the concept of attending duty-hours. The subject might not always be phrased to include the term “duty-hours,” but it seems that when it comes to scheduling, strong opinions come out in my group when the duration of, frequency of, or time off between night shifts are brought up. And when it comes to safety, I am certain sleep deprivation and sleep inertia (that period of haziness immediately after being awakened in the middle of the night) have led to questionable decisions on my part.

Why? Well...

So why do pediatric hospitalists avoid the issue of sleep hygiene, work schedules, and clinical impact? I think the reasons are multifactorial.

First, there are definitely individual variations in how all of us tolerate this work, and I suspect some of this is based on such traits as age and general ability to adapt to uncomfortable circadian flip-flops. I will admit that every time I wake up achy after a call night, I begin to wonder if I will be able to handle this in 10 to 15 years.

Second, I think pediatric HM as a field has not yet explored this topic fully because we are young both in terms of chronological age as well as nocturnal work-years. The work has not yet aged us to the point of making this a critical issue. We’re also somewhat behind our adult-hospitalist colleagues in terms of the volume of nocturnal work. Adult HM groups have long explored different shift schedules (seven-on/seven-off, day/evening/overnight distribution, etc.) because they routinely cover large services of more than 100 patients in large hospitals with more than 500 beds. In pediatrics, most of us operate in small community hospital settings or large academic centers where the nightly in-house quantity of work is relatively low, mitigated by the smaller size of most community programs and the presence of residents in most large children’s hospitals.

But I see this as an important issue for us to define: the imperative to define safe, round-the-clock clinical care and sustainable careers. Although we will need to learn from other fields, HM is somewhat different from other types of 24/7 medicine in that we require more continuity in our daytime work, which also carries over to night shifts both in terms of how the schedule is made as well as the benefit on the clinical side. The need for continuity adds an extra degree of difficulty in creating and studying different schedules that try to optimize nocturnal functioning.

Clarity, Please

Unfortunately, those looking for evidence-based, or even consensus-based, solutions might have to wait. A recent article in the Journal of Hospital Medicine does a nice job of synthesizing the literature and highlights the lack of clear answers for what kind of shift schedules work best.1

In the absence of scientific solutions, it might be too easy to say that we need “more research,” because what doesn’t need more research? (OK, we don’t need more research on interventions for bronchiolitis.) But in the same manner in which pediatric hospitalists have taken the lead in defining a night curriculum for residents (congratulations, Becky Blankenburg, on winning the Ray E. Helfer award in pediatric education), I believe there is an opportunity to improve circadian functioning for all hospital-based physicians, but more specifically attendings. This is even more important as residents work less and a 24/7 attending presence becomes the norm in teaching facilities. While the link between safety and fatigue may have been seen as a nonissue in past decades, I think that in our current era, this is something that we own and/or will be asked to define in the near future.

In the meantime, I think we’re left to our own schedules. And in defense of all schedulers like me out there, I will say that there are no proven solutions, so local culture will predominate. Different groups with different personalities and family makeups will have varying preferences. Smaller groups will tend to have longer shift times with less flexibility in “swing”-type midday or evening shifts, while larger groups might have increased flexibility in defining different shifts at the expense of added complexity in terms of creating a schedule with no gaps.

As we come up with more rules about night shifts, such as “clockwise” scheduling of day-evening-overnight shifts, single versus clustered nights based on frequency, and days off after night shifts, the more complex and awkward our Tetris-like schedule will become. I predict that this is something hospitalists will begin to think about more, with a necessary push for safe and sustainable schedules. In the short-term, allowing for financial and structural wiggle room in the scheduling process (i.e. adjusting shift patterns and differential pay for night work) might be the most balanced approach for the immediate future.

Dr. Shen is pediatric editor of The Hospitalist. Write to him at mshen@seton.edu.

Reference

VA Study Shows Yoga Improves Balance After Stroke, Service Members Encouraged to Get a Mental Health Checkup From Home, Electronic Payments Required for Some TRICARE Beneficiaries, and more

Pay-for-Performance Challenged as Best Model for Healthcare

Pushing healthcare toward pay-for-performance models that provide financial rewards for patient outcomes might not be the best direction for healthcare, according to an article published by a duo of doctors and a behavioral economist.

“Will Pay for Performance Backfire? Insights from Behavioral Economics” posted at Healthaffairs.org, questions the validity of paying for outcomes, particularly as there is no evidence yet that the model improves patient outcomes.

“You’re not actually paying for quality,” says David Himmelstein, MD, a professor at City University of New York School of Public Health at Hunter College, New York. “What you’re paying for is some very gameable measurement that doctors will find a way to cheat.”

The blog post notes that monetary rewards can actually undermine motivation for tasks that are intrinsically interesting or rewarding, a phenomenon known as “motivational crowd-out.” Dr. Himmelstein says it could focus attention on coding, rather than patients, or encourage providers to avoid noncompliant patients who will make their measured performances look bad.

“Injecting different monetary incentives into healthcare can certainly change it,” according to the article, “but not necessarily in the ways that policy makers would plan, much less hope for.”

Dr. Himmelstein says that without evidence for, or against, pay for performance, it’s difficult to say whether it will improve outcomes over the long term. Given the government push toward pay-for-performance programs—such as value-based purchasing (VBP)—he suggests physicians prepare themselves to comply. Accordingly, SHM supports policies that link "quality measurement to performance-based payment” and has created a toolkit to help hospitalists prepare for VBP, one of the most targeted pay-for-performance programs.

Even as HM moves toward adopting pay for performance as a mantra, Dr. Himmelstein believes hospitalists are in a good position to lead discussions on whether pay for performance is the only way to move forward.

“It can feel like a fait d’accompli, but things can change, and they can change rapidly,” Dr. Himmelstein adds. “The first step is to have real discussions about it. Up to now, much of the medical literature is saying, ‘It’s not working. We must have the wrong incentives.’ What if there are no right incentives?”

Visit our website for more information about pay-for-performance programs.

Pushing healthcare toward pay-for-performance models that provide financial rewards for patient outcomes might not be the best direction for healthcare, according to an article published by a duo of doctors and a behavioral economist.

“Will Pay for Performance Backfire? Insights from Behavioral Economics” posted at Healthaffairs.org, questions the validity of paying for outcomes, particularly as there is no evidence yet that the model improves patient outcomes.

“You’re not actually paying for quality,” says David Himmelstein, MD, a professor at City University of New York School of Public Health at Hunter College, New York. “What you’re paying for is some very gameable measurement that doctors will find a way to cheat.”

The blog post notes that monetary rewards can actually undermine motivation for tasks that are intrinsically interesting or rewarding, a phenomenon known as “motivational crowd-out.” Dr. Himmelstein says it could focus attention on coding, rather than patients, or encourage providers to avoid noncompliant patients who will make their measured performances look bad.

“Injecting different monetary incentives into healthcare can certainly change it,” according to the article, “but not necessarily in the ways that policy makers would plan, much less hope for.”

Dr. Himmelstein says that without evidence for, or against, pay for performance, it’s difficult to say whether it will improve outcomes over the long term. Given the government push toward pay-for-performance programs—such as value-based purchasing (VBP)—he suggests physicians prepare themselves to comply. Accordingly, SHM supports policies that link "quality measurement to performance-based payment” and has created a toolkit to help hospitalists prepare for VBP, one of the most targeted pay-for-performance programs.

Even as HM moves toward adopting pay for performance as a mantra, Dr. Himmelstein believes hospitalists are in a good position to lead discussions on whether pay for performance is the only way to move forward.

“It can feel like a fait d’accompli, but things can change, and they can change rapidly,” Dr. Himmelstein adds. “The first step is to have real discussions about it. Up to now, much of the medical literature is saying, ‘It’s not working. We must have the wrong incentives.’ What if there are no right incentives?”

Visit our website for more information about pay-for-performance programs.

Pushing healthcare toward pay-for-performance models that provide financial rewards for patient outcomes might not be the best direction for healthcare, according to an article published by a duo of doctors and a behavioral economist.

“Will Pay for Performance Backfire? Insights from Behavioral Economics” posted at Healthaffairs.org, questions the validity of paying for outcomes, particularly as there is no evidence yet that the model improves patient outcomes.

“You’re not actually paying for quality,” says David Himmelstein, MD, a professor at City University of New York School of Public Health at Hunter College, New York. “What you’re paying for is some very gameable measurement that doctors will find a way to cheat.”

The blog post notes that monetary rewards can actually undermine motivation for tasks that are intrinsically interesting or rewarding, a phenomenon known as “motivational crowd-out.” Dr. Himmelstein says it could focus attention on coding, rather than patients, or encourage providers to avoid noncompliant patients who will make their measured performances look bad.

“Injecting different monetary incentives into healthcare can certainly change it,” according to the article, “but not necessarily in the ways that policy makers would plan, much less hope for.”

Dr. Himmelstein says that without evidence for, or against, pay for performance, it’s difficult to say whether it will improve outcomes over the long term. Given the government push toward pay-for-performance programs—such as value-based purchasing (VBP)—he suggests physicians prepare themselves to comply. Accordingly, SHM supports policies that link "quality measurement to performance-based payment” and has created a toolkit to help hospitalists prepare for VBP, one of the most targeted pay-for-performance programs.

Even as HM moves toward adopting pay for performance as a mantra, Dr. Himmelstein believes hospitalists are in a good position to lead discussions on whether pay for performance is the only way to move forward.

“It can feel like a fait d’accompli, but things can change, and they can change rapidly,” Dr. Himmelstein adds. “The first step is to have real discussions about it. Up to now, much of the medical literature is saying, ‘It’s not working. We must have the wrong incentives.’ What if there are no right incentives?”

Visit our website for more information about pay-for-performance programs.

Accountable-Care Organizations on the Horizon for Hospitalists

Every HM group should look into transitioning from a fee-for-service model to an accountable-care organization (ACO), a leading hospitalist told conference attendees recently at the Third National Accountable Care Organization Congress.

"You need to be tackling it now, but that doesn't mean you need to be aggressively doing it now," Edward Murphy, MD, chairman of Sound Physicians, told eWire days before he spoke at the ACO Congress on Oct. 31 in Los Angeles. "By tackling it, you need to be doing a hard-nosed assessment of what's best for your group and your patients."

Question: Why is the ACO model so difficult in some instances?

Answer: The problem with the healthcare system today is we’ve spent 100 years building up a system that is designed around, and competent at, delivering services for fees. We're really not set up to manage care.

Q: What is the No. 1 thing you want hospitalists to know about ACOs today?

A: Figure out every single day how to improve the care of your patients at a lower cost. And then, how you can demonstrate it in a quantitative and clear way. ACO-style payments are really only a value proposition centered on providing superior outcomes for patients at higher satisfaction for lower cost. That’s a fundamental value that will always be noteworthy.

Q: Is a hospitalist's job to lead the charge toward ACOs, or support those who do?

A: That's the sort of thing that people on the ground don't have to be told. They just know. If I were the leader of a hospitalist group someplace and really thought the smart thing to do was to think about how to move to an accountable-care model … I would know from my discussions with my colleagues, my discussions with hospital executives where everybody was.

Visit our website for more information about ACOs.

Every HM group should look into transitioning from a fee-for-service model to an accountable-care organization (ACO), a leading hospitalist told conference attendees recently at the Third National Accountable Care Organization Congress.

"You need to be tackling it now, but that doesn't mean you need to be aggressively doing it now," Edward Murphy, MD, chairman of Sound Physicians, told eWire days before he spoke at the ACO Congress on Oct. 31 in Los Angeles. "By tackling it, you need to be doing a hard-nosed assessment of what's best for your group and your patients."

Question: Why is the ACO model so difficult in some instances?

Answer: The problem with the healthcare system today is we’ve spent 100 years building up a system that is designed around, and competent at, delivering services for fees. We're really not set up to manage care.

Q: What is the No. 1 thing you want hospitalists to know about ACOs today?

A: Figure out every single day how to improve the care of your patients at a lower cost. And then, how you can demonstrate it in a quantitative and clear way. ACO-style payments are really only a value proposition centered on providing superior outcomes for patients at higher satisfaction for lower cost. That’s a fundamental value that will always be noteworthy.

Q: Is a hospitalist's job to lead the charge toward ACOs, or support those who do?

A: That's the sort of thing that people on the ground don't have to be told. They just know. If I were the leader of a hospitalist group someplace and really thought the smart thing to do was to think about how to move to an accountable-care model … I would know from my discussions with my colleagues, my discussions with hospital executives where everybody was.

Visit our website for more information about ACOs.

Every HM group should look into transitioning from a fee-for-service model to an accountable-care organization (ACO), a leading hospitalist told conference attendees recently at the Third National Accountable Care Organization Congress.

"You need to be tackling it now, but that doesn't mean you need to be aggressively doing it now," Edward Murphy, MD, chairman of Sound Physicians, told eWire days before he spoke at the ACO Congress on Oct. 31 in Los Angeles. "By tackling it, you need to be doing a hard-nosed assessment of what's best for your group and your patients."

Question: Why is the ACO model so difficult in some instances?

Answer: The problem with the healthcare system today is we’ve spent 100 years building up a system that is designed around, and competent at, delivering services for fees. We're really not set up to manage care.

Q: What is the No. 1 thing you want hospitalists to know about ACOs today?

A: Figure out every single day how to improve the care of your patients at a lower cost. And then, how you can demonstrate it in a quantitative and clear way. ACO-style payments are really only a value proposition centered on providing superior outcomes for patients at higher satisfaction for lower cost. That’s a fundamental value that will always be noteworthy.

Q: Is a hospitalist's job to lead the charge toward ACOs, or support those who do?

A: That's the sort of thing that people on the ground don't have to be told. They just know. If I were the leader of a hospitalist group someplace and really thought the smart thing to do was to think about how to move to an accountable-care model … I would know from my discussions with my colleagues, my discussions with hospital executives where everybody was.

Visit our website for more information about ACOs.

Nonpayment Fails to Help Infection Rates

The 2008 Medicare policy to withhold payment for treating certain hospital-acquired infections failed to decrease infection rates in U.S. hospitals, according to a report published online in the New England Journal of Medicine.

In a study involving a total of 398 hospitals or medical systems across the country, implementing a Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services policy of nonpayment for the treatment of preventable catheter-associated bloodstream infections and catheter-associated urinary tract infections appeared to have no impact at all on the acquisition of those infections, according to Dr. Ashish K. Jha of the department of health policy and management, Harvard School of Public Health, Boston, and his associates.

"As CMS continues to expand this policy to cover Medicaid through the Affordable Care Act, require public reporting of National Healthcare Safety Network [NHSN] data through the Hospital Compare website, and impose greater financial penalties on hospitals that perform poorly on these measures, careful evaluation is needed to determine when these programs work, when they have unintended consequences, and what might be done to improve patient outcomes," Dr. Jha noted.

Dr. Jha and his colleagues assessed data from the NHSN, a public health surveillance program for monitoring health care-associated infections across the country. A total of 1,166 nonfederal acute-care hospitals report their infection rates to this Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's sponsored network every month.

Dr. Jha and his colleagues assessed NHSN data on three different types of infection at 398 of those hospitals in 41 states. They examined central catheter-associated bloodstream and catheter-associated urinary tract infections because these are the two hospital-acquired infections for which CMS currently does not pay. They also looked at ventilator-associated pneumonia, which is not targeted by the CMS policy, as a control.

Rates of central catheter-associated bloodstream infections were already decreasing at the time the CMS policy was implemented, likely because the federal government, national organizations, and accrediting agencies had already focused attention on preventing these nosocomial infections. The rate of these infections was 4.8% per quarter before the policy was implemented and 4.7% afterward, a nonsignificant difference, the investigators said (N. Engl. J. Med. 2012 [doi:10.1056/NEJMsa1202419]).

This pattern also was seen with catheter-associated UTIs, in which there was a small, nonsignificant increase in the infection rate after implementation of the CMS policy. For the control condition of ventilator-associated pneumonia, the infection rate was 7.3% before implementation and 8.2% after implementation of the policy, also showing no significant impact on infection rates.

These findings were consistent across all hospital types, regardless of size, regional location, type of ownership, or teaching status.

To assess whether any benefit of the nonpayment policy may have been offset by strategies to lower infection rates, such as mandatory reporting, the researchers performed a separate analysis involving only the hospital units located in states that didn't have mandatory reporting. Again, no demonstrable effect on infection rates was seen.

To allow more time for hospitals to adapt to the policy change, the investigators performed a sensitivity analysis comparing infection rates 2 years after implementation with those before implementation. Again, they found no further decreases in the rates of any infections.

A possible explanation for these findings is that the amount of this financial disincentive was quite small. "Reductions in payment may have been equivalent to as little as 0.6% of Medicare revenue for the average hospital," Dr. Jha and his associates said.

"Greater financial penalties might induce a greater change in hospital responsiveness to the CMS policy."

The study results are particularly important given the increasing use of financial disincentives to improve the quality of health care. There is very little evidence that this strategy, or other pay-for-performance strategies, actually improves patient outcomes, the authors noted.

This study was supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

None of the authors reported having any financial conflicts of interest regarding this study.

The 2008 Medicare policy to withhold payment for treating certain hospital-acquired infections failed to decrease infection rates in U.S. hospitals, according to a report published online in the New England Journal of Medicine.

In a study involving a total of 398 hospitals or medical systems across the country, implementing a Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services policy of nonpayment for the treatment of preventable catheter-associated bloodstream infections and catheter-associated urinary tract infections appeared to have no impact at all on the acquisition of those infections, according to Dr. Ashish K. Jha of the department of health policy and management, Harvard School of Public Health, Boston, and his associates.

"As CMS continues to expand this policy to cover Medicaid through the Affordable Care Act, require public reporting of National Healthcare Safety Network [NHSN] data through the Hospital Compare website, and impose greater financial penalties on hospitals that perform poorly on these measures, careful evaluation is needed to determine when these programs work, when they have unintended consequences, and what might be done to improve patient outcomes," Dr. Jha noted.

Dr. Jha and his colleagues assessed data from the NHSN, a public health surveillance program for monitoring health care-associated infections across the country. A total of 1,166 nonfederal acute-care hospitals report their infection rates to this Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's sponsored network every month.

Dr. Jha and his colleagues assessed NHSN data on three different types of infection at 398 of those hospitals in 41 states. They examined central catheter-associated bloodstream and catheter-associated urinary tract infections because these are the two hospital-acquired infections for which CMS currently does not pay. They also looked at ventilator-associated pneumonia, which is not targeted by the CMS policy, as a control.

Rates of central catheter-associated bloodstream infections were already decreasing at the time the CMS policy was implemented, likely because the federal government, national organizations, and accrediting agencies had already focused attention on preventing these nosocomial infections. The rate of these infections was 4.8% per quarter before the policy was implemented and 4.7% afterward, a nonsignificant difference, the investigators said (N. Engl. J. Med. 2012 [doi:10.1056/NEJMsa1202419]).

This pattern also was seen with catheter-associated UTIs, in which there was a small, nonsignificant increase in the infection rate after implementation of the CMS policy. For the control condition of ventilator-associated pneumonia, the infection rate was 7.3% before implementation and 8.2% after implementation of the policy, also showing no significant impact on infection rates.

These findings were consistent across all hospital types, regardless of size, regional location, type of ownership, or teaching status.

To assess whether any benefit of the nonpayment policy may have been offset by strategies to lower infection rates, such as mandatory reporting, the researchers performed a separate analysis involving only the hospital units located in states that didn't have mandatory reporting. Again, no demonstrable effect on infection rates was seen.

To allow more time for hospitals to adapt to the policy change, the investigators performed a sensitivity analysis comparing infection rates 2 years after implementation with those before implementation. Again, they found no further decreases in the rates of any infections.

A possible explanation for these findings is that the amount of this financial disincentive was quite small. "Reductions in payment may have been equivalent to as little as 0.6% of Medicare revenue for the average hospital," Dr. Jha and his associates said.

"Greater financial penalties might induce a greater change in hospital responsiveness to the CMS policy."

The study results are particularly important given the increasing use of financial disincentives to improve the quality of health care. There is very little evidence that this strategy, or other pay-for-performance strategies, actually improves patient outcomes, the authors noted.

This study was supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

None of the authors reported having any financial conflicts of interest regarding this study.

The 2008 Medicare policy to withhold payment for treating certain hospital-acquired infections failed to decrease infection rates in U.S. hospitals, according to a report published online in the New England Journal of Medicine.

In a study involving a total of 398 hospitals or medical systems across the country, implementing a Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services policy of nonpayment for the treatment of preventable catheter-associated bloodstream infections and catheter-associated urinary tract infections appeared to have no impact at all on the acquisition of those infections, according to Dr. Ashish K. Jha of the department of health policy and management, Harvard School of Public Health, Boston, and his associates.

"As CMS continues to expand this policy to cover Medicaid through the Affordable Care Act, require public reporting of National Healthcare Safety Network [NHSN] data through the Hospital Compare website, and impose greater financial penalties on hospitals that perform poorly on these measures, careful evaluation is needed to determine when these programs work, when they have unintended consequences, and what might be done to improve patient outcomes," Dr. Jha noted.

Dr. Jha and his colleagues assessed data from the NHSN, a public health surveillance program for monitoring health care-associated infections across the country. A total of 1,166 nonfederal acute-care hospitals report their infection rates to this Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's sponsored network every month.

Dr. Jha and his colleagues assessed NHSN data on three different types of infection at 398 of those hospitals in 41 states. They examined central catheter-associated bloodstream and catheter-associated urinary tract infections because these are the two hospital-acquired infections for which CMS currently does not pay. They also looked at ventilator-associated pneumonia, which is not targeted by the CMS policy, as a control.

Rates of central catheter-associated bloodstream infections were already decreasing at the time the CMS policy was implemented, likely because the federal government, national organizations, and accrediting agencies had already focused attention on preventing these nosocomial infections. The rate of these infections was 4.8% per quarter before the policy was implemented and 4.7% afterward, a nonsignificant difference, the investigators said (N. Engl. J. Med. 2012 [doi:10.1056/NEJMsa1202419]).

This pattern also was seen with catheter-associated UTIs, in which there was a small, nonsignificant increase in the infection rate after implementation of the CMS policy. For the control condition of ventilator-associated pneumonia, the infection rate was 7.3% before implementation and 8.2% after implementation of the policy, also showing no significant impact on infection rates.

These findings were consistent across all hospital types, regardless of size, regional location, type of ownership, or teaching status.

To assess whether any benefit of the nonpayment policy may have been offset by strategies to lower infection rates, such as mandatory reporting, the researchers performed a separate analysis involving only the hospital units located in states that didn't have mandatory reporting. Again, no demonstrable effect on infection rates was seen.

To allow more time for hospitals to adapt to the policy change, the investigators performed a sensitivity analysis comparing infection rates 2 years after implementation with those before implementation. Again, they found no further decreases in the rates of any infections.

A possible explanation for these findings is that the amount of this financial disincentive was quite small. "Reductions in payment may have been equivalent to as little as 0.6% of Medicare revenue for the average hospital," Dr. Jha and his associates said.

"Greater financial penalties might induce a greater change in hospital responsiveness to the CMS policy."

The study results are particularly important given the increasing use of financial disincentives to improve the quality of health care. There is very little evidence that this strategy, or other pay-for-performance strategies, actually improves patient outcomes, the authors noted.

This study was supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

None of the authors reported having any financial conflicts of interest regarding this study.

Major Finding: The rate of central catheter–associated bloodstream infections was 4.8% before the nonpayment policy was implemented and 4.7% afterward, showing that the policy failed to decrease the infection rate.

Data Source: The data come from an analysis of trends in hospital-acquired infection rates before and after implementation of a federal policy to withhold payment for treating those infections, involving 398 hospitals in 41 states.

Disclosures: This study was supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. No financial conflicts of interest were reported.

ONLINE EXCLUSIVE: Anticoagulant's Receives FDA Approval to Treat Deep Vein Thrombosis, Pulmonary Embolism

Rivaroxaban (Xarelto) has won another approval from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Already green-lighted for use to reduce the risk of DVT and pulmonary embolism (PE) after knee or hip replacement surgery—and reduce the risk of stroke in non-valvular atrial fibrillation patients—the anticoagulant therapy has been approved for use in the treatment of acute DVT and PE, and to reduce the risk of recurrent DVT and PE after initial treatment. It’s a landmark step that will likely have big implications for hospitalists.

“Xarelto is the first oral anti-clotting drug approved to treat and reduce the recurrence of blood clots since the approval of warfarin nearly 60 years ago,” Richard Pazdur, MD, director of the Office of Hematology and Oncology Products in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, said in a news release.

—Hiren Shah, MD, assistant professor of medicine, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, medical director, hospital medicine, Northwestern Memorial Hospital, Chicago

“Single-drug therapy without the need for parental bridging treatment, or drug-level monitoring, is a breakthrough in the treatment of VTE, and represents a paradigm shift that we have not seen in a long time for a very common emergency room and hospital-based medical condition,” says Hiren Shah, MD, assistant professor of medicine at Northwestern University’s Feinberg School of Medicine and medical director of hospital medicine at Northwestern Memorial Hospital in Chicago.

Ian Jenkins, assistant professor in the Division of Hospital Medicine at the University of California at San Diego, says factors that will help determine whether a patient is a candidate for rivaroxaban include the ability to pay for it; compliance, because the duration of effect is shorter than it is for warfarin; and good and stable renal function.

“We now have the first approved oral warfarin alternative for VTE, and for appropriate candidates, it's a more convenient if not better treatment,” Dr. Jenkins says. “The main downside is that warfarin remains reversible, and the new drugs are minimally so.”

Dr. Shah predicts a more efficient discharge process, which, for rivaroxaban patients, will no longer include arranging for international normalized ratio (INR) monitoring or time-consuming counseling on taking injections and drug interactions with vitamin-K antagonists.

“That’s a very complex, 30-minute process,” says Dr. Shah, who also who runs Northwestern’s VTE-prevention program. “With a single agent, I think the value here is you don’t need that complex care coordination anymore, and that’s time-saving for a hospitalist.”