User login

AHA Program Chair on Election, ACA, and NIH Funding

One day after President Obama's reelection, we caught up with Dr. Elliott Antman, American Heart Association's 2012 Program Chair, for comments on how the results of the election could impact physicians' practices and patient care.

One day after President Obama's reelection, we caught up with Dr. Elliott Antman, American Heart Association's 2012 Program Chair, for comments on how the results of the election could impact physicians' practices and patient care.

One day after President Obama's reelection, we caught up with Dr. Elliott Antman, American Heart Association's 2012 Program Chair, for comments on how the results of the election could impact physicians' practices and patient care.

Win Whitcomb: Hospitalists Must Grin and Bear the Hospital-Acquired Conditions Program

The Inpatient Prospective Payment System FY2013 Final Rule charts a different future: By fiscal-year 2015 (October 2014), it will morph into a set of measures that are vetted by the National Quality Forum. Hopefully, this will be an improvement.

In recent years, hospitalists have been deluged with rules about documentation, being asked to use medical vocabulary in ways that were foreign to many of us during our training years. Much of the focus on documentation has been propelled by hospitals’ quest to optimize (“maximize” is a forbidden term) reimbursement, which is purely a function of what is written by “licensed providers” (doctors, physician assistants, and nurse practitioners) in the medical chart.

But another powerful driver of documentation practices of late is the hospital-acquired conditions (HAC) program developed by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) and enacted in 2009.

Origins of the HAC List

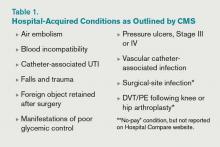

CMS disliked the fact that they were paying for conditions acquired in the hospital that were “reasonably preventable” if evidence-based—or at least “best”—practice was applied. After all, who likes to pay for a punctured gas tank when you brought the minivan in for an oil change? CMS worked with stakeholder groups, including SHM, to create a list of conditions known as hospital-acquired conditions (see Table 1, right).

(As an aside, SHM was supportive of CMS. In fact, we provided direct input into the final rule, recognizing some of the drawbacks of the CMS approach but understanding the larger objective of reengineering a flawed incentive system.)

The idea was that if a hospital submitted a bill to CMS that contained one of these conditions, the hospital would not be paid the amount by which that condition increased total reimbursement for that hospitalization. Note that if you’ve been told your hospital isn’t getting paid at all for patients with one of these conditions, that is not quite correct. Instead, your hospital may not get paid the added amount that is derived from having one of the diagnoses on the list submitted in your hospital’s bill to CMS for a given patient. At the end of the day, this might be a few hundred dollars each time one of these is documented—or $0, if your hospital biller can add another diagnosis in its place to capture the higher payment.

How big a hit to a hospital’s bottom line is this? Meddings and colleagues recently reported that a measly 0.003% of all hospitalizations in Michigan in 2009 saw payments lowered as a result of hospital-acquired catheter-associated UTI, one of the list’s HACs (Ann Int Med. 2012;157:305-312). When all the HACs are added together, one can extrapolate that they haven’t exactly had a big impact on hospital payments.

If the specter of nonpayment for one of these is not enough of a motivator (and it shouldn’t be, given the paltry financial stakes), the rate of HACs are now reported for all hospitals on the Hospital Compare website (www.hospitalcompare.hhs.gov). If a small poke to the pocketbook doesn’t work, maybe public humiliation will.

The Problem with HACs

Although CMS’ intent in creating the HAC program—to eliminate payment for “reasonably preventable” hospital-acquired conditions, thereby improving patient safety—was good, in practice, the program has turned out to be as much about documentation as it is about providing good care. For example, if I forget to write that a Stage III pressure ulcer was present on admission, it gets coded as hospital-acquired and my hospital gets dinged.

It’s important to note that HACs as quality measures were never endorsed by the National Quality Forum (NQF), and without such an endorsement, a quality measure suffers from Rodney Dangerfield syndrome: It don’t get no respect.

Finally, it is disquieting that Meddings et al showed that hospital-acquired catheter-associated UTI rates derived from chart documentation for HACs were but a small fraction of rates determined from rigorous epidemiologic studies, demonstrating that using claims data for determining rates for that specific HAC is flawed. We can only wonder how divergent reported vs. actual rates for the other HACs are.

The Future of the HAC Program

The Affordable Care Act specifies that the lowest-performing quartile of U.S. hospitals for HAC rates will see a 1% Medicare reimbursement reduction beginning in fiscal-year 2015. That’s right: Hospitals facing possible readmissions penalties and losses under value-based purchasing also will face a HAC penalty.

Thankfully, the recently released Inpatient Prospective Payment System FY2013 Final Rule, CMS’ annual update of how hospitals are paid, specifies that the HAC measures are to be removed from public reporting on the Hospital Compare website effective Oct. 1, 2014. They will be replaced by a new set of measures that will (hopefully) be more methodologically sound, because they will require the scrutiny required for endorsement by the NQF. Exactly how these measures will look is not certain, as the rule-making has not yet occurred.

We do know that the three infection measures—catheter-associated UTI, surgical-site infection, and vascular catheter infection—will be generated from clinical data and, therefore, more methodologically sound under the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) National Healthcare Safety Network. The derivation of the other measures will have to wait until the rule is written next year.

So, until further notice, pay attention to the queries of your hospital’s documentation experts when they approach you about a potential HAC!

Dr. Whitcomb is medical director of healthcare quality at Baystate Medical Center in Springfield, Mass. He is a co-founder and past president of SHM. Email him at wfwhit@comcast.net.

The Inpatient Prospective Payment System FY2013 Final Rule charts a different future: By fiscal-year 2015 (October 2014), it will morph into a set of measures that are vetted by the National Quality Forum. Hopefully, this will be an improvement.

In recent years, hospitalists have been deluged with rules about documentation, being asked to use medical vocabulary in ways that were foreign to many of us during our training years. Much of the focus on documentation has been propelled by hospitals’ quest to optimize (“maximize” is a forbidden term) reimbursement, which is purely a function of what is written by “licensed providers” (doctors, physician assistants, and nurse practitioners) in the medical chart.

But another powerful driver of documentation practices of late is the hospital-acquired conditions (HAC) program developed by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) and enacted in 2009.

Origins of the HAC List

CMS disliked the fact that they were paying for conditions acquired in the hospital that were “reasonably preventable” if evidence-based—or at least “best”—practice was applied. After all, who likes to pay for a punctured gas tank when you brought the minivan in for an oil change? CMS worked with stakeholder groups, including SHM, to create a list of conditions known as hospital-acquired conditions (see Table 1, right).

(As an aside, SHM was supportive of CMS. In fact, we provided direct input into the final rule, recognizing some of the drawbacks of the CMS approach but understanding the larger objective of reengineering a flawed incentive system.)

The idea was that if a hospital submitted a bill to CMS that contained one of these conditions, the hospital would not be paid the amount by which that condition increased total reimbursement for that hospitalization. Note that if you’ve been told your hospital isn’t getting paid at all for patients with one of these conditions, that is not quite correct. Instead, your hospital may not get paid the added amount that is derived from having one of the diagnoses on the list submitted in your hospital’s bill to CMS for a given patient. At the end of the day, this might be a few hundred dollars each time one of these is documented—or $0, if your hospital biller can add another diagnosis in its place to capture the higher payment.

How big a hit to a hospital’s bottom line is this? Meddings and colleagues recently reported that a measly 0.003% of all hospitalizations in Michigan in 2009 saw payments lowered as a result of hospital-acquired catheter-associated UTI, one of the list’s HACs (Ann Int Med. 2012;157:305-312). When all the HACs are added together, one can extrapolate that they haven’t exactly had a big impact on hospital payments.

If the specter of nonpayment for one of these is not enough of a motivator (and it shouldn’t be, given the paltry financial stakes), the rate of HACs are now reported for all hospitals on the Hospital Compare website (www.hospitalcompare.hhs.gov). If a small poke to the pocketbook doesn’t work, maybe public humiliation will.

The Problem with HACs

Although CMS’ intent in creating the HAC program—to eliminate payment for “reasonably preventable” hospital-acquired conditions, thereby improving patient safety—was good, in practice, the program has turned out to be as much about documentation as it is about providing good care. For example, if I forget to write that a Stage III pressure ulcer was present on admission, it gets coded as hospital-acquired and my hospital gets dinged.

It’s important to note that HACs as quality measures were never endorsed by the National Quality Forum (NQF), and without such an endorsement, a quality measure suffers from Rodney Dangerfield syndrome: It don’t get no respect.

Finally, it is disquieting that Meddings et al showed that hospital-acquired catheter-associated UTI rates derived from chart documentation for HACs were but a small fraction of rates determined from rigorous epidemiologic studies, demonstrating that using claims data for determining rates for that specific HAC is flawed. We can only wonder how divergent reported vs. actual rates for the other HACs are.

The Future of the HAC Program

The Affordable Care Act specifies that the lowest-performing quartile of U.S. hospitals for HAC rates will see a 1% Medicare reimbursement reduction beginning in fiscal-year 2015. That’s right: Hospitals facing possible readmissions penalties and losses under value-based purchasing also will face a HAC penalty.

Thankfully, the recently released Inpatient Prospective Payment System FY2013 Final Rule, CMS’ annual update of how hospitals are paid, specifies that the HAC measures are to be removed from public reporting on the Hospital Compare website effective Oct. 1, 2014. They will be replaced by a new set of measures that will (hopefully) be more methodologically sound, because they will require the scrutiny required for endorsement by the NQF. Exactly how these measures will look is not certain, as the rule-making has not yet occurred.

We do know that the three infection measures—catheter-associated UTI, surgical-site infection, and vascular catheter infection—will be generated from clinical data and, therefore, more methodologically sound under the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) National Healthcare Safety Network. The derivation of the other measures will have to wait until the rule is written next year.

So, until further notice, pay attention to the queries of your hospital’s documentation experts when they approach you about a potential HAC!

Dr. Whitcomb is medical director of healthcare quality at Baystate Medical Center in Springfield, Mass. He is a co-founder and past president of SHM. Email him at wfwhit@comcast.net.

The Inpatient Prospective Payment System FY2013 Final Rule charts a different future: By fiscal-year 2015 (October 2014), it will morph into a set of measures that are vetted by the National Quality Forum. Hopefully, this will be an improvement.

In recent years, hospitalists have been deluged with rules about documentation, being asked to use medical vocabulary in ways that were foreign to many of us during our training years. Much of the focus on documentation has been propelled by hospitals’ quest to optimize (“maximize” is a forbidden term) reimbursement, which is purely a function of what is written by “licensed providers” (doctors, physician assistants, and nurse practitioners) in the medical chart.

But another powerful driver of documentation practices of late is the hospital-acquired conditions (HAC) program developed by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) and enacted in 2009.

Origins of the HAC List

CMS disliked the fact that they were paying for conditions acquired in the hospital that were “reasonably preventable” if evidence-based—or at least “best”—practice was applied. After all, who likes to pay for a punctured gas tank when you brought the minivan in for an oil change? CMS worked with stakeholder groups, including SHM, to create a list of conditions known as hospital-acquired conditions (see Table 1, right).

(As an aside, SHM was supportive of CMS. In fact, we provided direct input into the final rule, recognizing some of the drawbacks of the CMS approach but understanding the larger objective of reengineering a flawed incentive system.)

The idea was that if a hospital submitted a bill to CMS that contained one of these conditions, the hospital would not be paid the amount by which that condition increased total reimbursement for that hospitalization. Note that if you’ve been told your hospital isn’t getting paid at all for patients with one of these conditions, that is not quite correct. Instead, your hospital may not get paid the added amount that is derived from having one of the diagnoses on the list submitted in your hospital’s bill to CMS for a given patient. At the end of the day, this might be a few hundred dollars each time one of these is documented—or $0, if your hospital biller can add another diagnosis in its place to capture the higher payment.

How big a hit to a hospital’s bottom line is this? Meddings and colleagues recently reported that a measly 0.003% of all hospitalizations in Michigan in 2009 saw payments lowered as a result of hospital-acquired catheter-associated UTI, one of the list’s HACs (Ann Int Med. 2012;157:305-312). When all the HACs are added together, one can extrapolate that they haven’t exactly had a big impact on hospital payments.

If the specter of nonpayment for one of these is not enough of a motivator (and it shouldn’t be, given the paltry financial stakes), the rate of HACs are now reported for all hospitals on the Hospital Compare website (www.hospitalcompare.hhs.gov). If a small poke to the pocketbook doesn’t work, maybe public humiliation will.

The Problem with HACs

Although CMS’ intent in creating the HAC program—to eliminate payment for “reasonably preventable” hospital-acquired conditions, thereby improving patient safety—was good, in practice, the program has turned out to be as much about documentation as it is about providing good care. For example, if I forget to write that a Stage III pressure ulcer was present on admission, it gets coded as hospital-acquired and my hospital gets dinged.

It’s important to note that HACs as quality measures were never endorsed by the National Quality Forum (NQF), and without such an endorsement, a quality measure suffers from Rodney Dangerfield syndrome: It don’t get no respect.

Finally, it is disquieting that Meddings et al showed that hospital-acquired catheter-associated UTI rates derived from chart documentation for HACs were but a small fraction of rates determined from rigorous epidemiologic studies, demonstrating that using claims data for determining rates for that specific HAC is flawed. We can only wonder how divergent reported vs. actual rates for the other HACs are.

The Future of the HAC Program

The Affordable Care Act specifies that the lowest-performing quartile of U.S. hospitals for HAC rates will see a 1% Medicare reimbursement reduction beginning in fiscal-year 2015. That’s right: Hospitals facing possible readmissions penalties and losses under value-based purchasing also will face a HAC penalty.

Thankfully, the recently released Inpatient Prospective Payment System FY2013 Final Rule, CMS’ annual update of how hospitals are paid, specifies that the HAC measures are to be removed from public reporting on the Hospital Compare website effective Oct. 1, 2014. They will be replaced by a new set of measures that will (hopefully) be more methodologically sound, because they will require the scrutiny required for endorsement by the NQF. Exactly how these measures will look is not certain, as the rule-making has not yet occurred.

We do know that the three infection measures—catheter-associated UTI, surgical-site infection, and vascular catheter infection—will be generated from clinical data and, therefore, more methodologically sound under the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) National Healthcare Safety Network. The derivation of the other measures will have to wait until the rule is written next year.

So, until further notice, pay attention to the queries of your hospital’s documentation experts when they approach you about a potential HAC!

Dr. Whitcomb is medical director of healthcare quality at Baystate Medical Center in Springfield, Mass. He is a co-founder and past president of SHM. Email him at wfwhit@comcast.net.

Off-Label Use of Antipsychotics for Dementia Patients Discouraged

Hospitalists can play a major role in reducing deaths that come as a result of off-label prescriptions for antipsychotic drugs being given to dementia patients, according to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) and SHM.

In a letter to hospitalist leaders, SHM encouraged hospitalists to “partner with others in your clinical work environment to reduce the use of antipsychotics for treating behavioral problems in patients with dementia. We believe that hospitalists have an important role to play in this initiative; hospital-based clinicians frequently care for patients with dementia and are responsible for medications prescribed during a patient’s hospitalization and at discharge.”

The joint education effort by CMS and SHM is based on an April 2011 report from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ Office of Inspector General (OIG) that found that antipsychotic medications sometimes are used to treat patients with dementia for off-label reasons (e.g. “behaviors”) or against black-box warnings despite potential dangers to patients’ health.

An earlier warning from the FDA in 2008 outlined the potential dangers as:

- Increased risk (60% to 70%) of death in older adults with dementia;

- Prolongation of the QT interval on electrocardiogram, particularly with intravenous haloperidol use;

- Increased risk of stroke and TIAs; and

- Worsening cognitive function.

The letter to hospitalists noted the necessary changes and the need for collaboration between SHM, its members, and hospital leaders. “Increased prescriber training and system practice changes will help reduce unnecessary antipsychotic drug prescribing,” the letter stated. “SHM looks forward to an ongoing collaboration with members and hospital leaders on this important patient safety concern.”

Hospitalists can play a major role in reducing deaths that come as a result of off-label prescriptions for antipsychotic drugs being given to dementia patients, according to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) and SHM.

In a letter to hospitalist leaders, SHM encouraged hospitalists to “partner with others in your clinical work environment to reduce the use of antipsychotics for treating behavioral problems in patients with dementia. We believe that hospitalists have an important role to play in this initiative; hospital-based clinicians frequently care for patients with dementia and are responsible for medications prescribed during a patient’s hospitalization and at discharge.”

The joint education effort by CMS and SHM is based on an April 2011 report from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ Office of Inspector General (OIG) that found that antipsychotic medications sometimes are used to treat patients with dementia for off-label reasons (e.g. “behaviors”) or against black-box warnings despite potential dangers to patients’ health.

An earlier warning from the FDA in 2008 outlined the potential dangers as:

- Increased risk (60% to 70%) of death in older adults with dementia;

- Prolongation of the QT interval on electrocardiogram, particularly with intravenous haloperidol use;

- Increased risk of stroke and TIAs; and

- Worsening cognitive function.

The letter to hospitalists noted the necessary changes and the need for collaboration between SHM, its members, and hospital leaders. “Increased prescriber training and system practice changes will help reduce unnecessary antipsychotic drug prescribing,” the letter stated. “SHM looks forward to an ongoing collaboration with members and hospital leaders on this important patient safety concern.”

Hospitalists can play a major role in reducing deaths that come as a result of off-label prescriptions for antipsychotic drugs being given to dementia patients, according to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) and SHM.

In a letter to hospitalist leaders, SHM encouraged hospitalists to “partner with others in your clinical work environment to reduce the use of antipsychotics for treating behavioral problems in patients with dementia. We believe that hospitalists have an important role to play in this initiative; hospital-based clinicians frequently care for patients with dementia and are responsible for medications prescribed during a patient’s hospitalization and at discharge.”

The joint education effort by CMS and SHM is based on an April 2011 report from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ Office of Inspector General (OIG) that found that antipsychotic medications sometimes are used to treat patients with dementia for off-label reasons (e.g. “behaviors”) or against black-box warnings despite potential dangers to patients’ health.

An earlier warning from the FDA in 2008 outlined the potential dangers as:

- Increased risk (60% to 70%) of death in older adults with dementia;

- Prolongation of the QT interval on electrocardiogram, particularly with intravenous haloperidol use;

- Increased risk of stroke and TIAs; and

- Worsening cognitive function.

The letter to hospitalists noted the necessary changes and the need for collaboration between SHM, its members, and hospital leaders. “Increased prescriber training and system practice changes will help reduce unnecessary antipsychotic drug prescribing,” the letter stated. “SHM looks forward to an ongoing collaboration with members and hospital leaders on this important patient safety concern.”

How is Acute Pericarditis Diagnosed and Treated?

Case

A 32-year-old female with no significant past medical history is evaluated for sharp, left-sided chest pain for five days. Her pain is intermittent, worse with deep inspiration and in the supine position. She denies any shortness of breath. Her temperature is 100.8ºF, but otherwise her vital signs are normal. The physical exam and chest radiograph are unremarkable, but an electrocardiogram shows diffuse ST-segment elevations. The initial troponin is mildly elevated at 0.35 ng/ml.

Could this patient have acute pericarditis? If so, how should she be managed?

Background

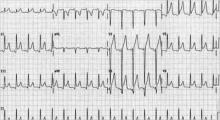

Pericarditis is the most common pericardial disease encountered by hospitalists. As many as 5% of chest pain cases unattributable to myocardial infarction (MI) are diagnosed with pericarditis.1 In immunocompetent individuals, as many as 90% of acute pericarditis cases are viral or idiopathic in etiology.1,2 Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and tuberculosis are common culprits in developing countries and immunocompromised hosts.3 Other specific etiologies of acute pericarditis include autoimmune diseases, neoplasms, chest irradiation, trauma, and metabolic disturbances (e.g. uremia). An etiologic classification of acute pericarditis is shown in Table 2 (p. 16).

Pericarditis primarily is a clinical diagnosis. Most patients present with chest pain.4 A pericardial friction rub may or may not be heard (sensitivity 16% to 85%), but when present is nearly 100% specific for pericarditis.2,5 Diffuse ST-segment elevation on electrocardiogram (EKG) is present in 60% to 90% of cases, but it can be difficult to differentiate from ST-segment elevations in acute MI.4,6

Uncomplicated acute pericarditis often is treated successfully as an outpatient.4 However, patients with high-risk features (see Table 1, right) should be hospitalized for identification and treatment of specific underlying etiology and for monitoring of complications, such as tamponade.7

Our patient has features consistent with pericarditis. In the following sections, we will review the diagnosis and treatment of acute pericarditis.

Review of the Data

How is acute pericarditis diagnosed?

Acute pericarditis is a clinical diagnosis supported by EKG and echocardiogram. At least two of the following four criteria must be present for the diagnosis: pleuritic chest pain, pericardial rub, diffuse ST-segment elevation on EKG, and pericardial effusion.8

History. Patients may report fever (46% in one small study of 69 patients) or a recent history of respiratory or gastrointestinal infection (40%).5 Most patients will report pleuritic chest pain. Typically, the pain is improved when sitting up and leaning forward, and gets worse when lying supine.4 Pain might radiate to the trapezius muscle ridge due to the common phrenic nerve innervation of pericardium and trapezius.9 However, pain might be minimal or absent in patients with uremic, neoplastic, tuberculous, or post-irradiation pericarditis.

Physical exam. A pericardial friction rub is nearly 100% specific for a pericarditis diagnosis, but sensitivity can vary (16% to 85%) depending on the frequency of auscultation and underlying etiology.2,5 It is thought to be caused by friction between the parietal and visceral layers of inflamed pericardium. A pericardial rub classically is described as a superficial, high-pitched, scratchy, or squeaking sound best heard with the diaphragm of the stethoscope at the lower left sternal border with the patient leaning forward.

Laboratory data. A complete blood count, metabolic panel, and cardiac enzymes should be checked in all patients with suspected acute pericarditis. Troponin values are elevated in up to one-third of patients, indicating cardiac muscle injury or myopericarditis, but have not been shown to adversely impact hospital length of stay, readmission, or complication rates.5,10 Markers of inflammation (e.g. erythrocyte sedimentation rate or C-reactive protein) are frequently elevated but do not point to a specific underlying etiology. Routine viral cultures and antibody titers are not useful.11

Most cases of pericarditis are presumed idiopathic (viral); however, finding a specific etiology should be considered in patients who do not respond after one week of therapy. Anti-nuclear antibody, complement levels, and rheumatoid factor can serve as screening tests for autoimmune disease. Purified protein derivative or quantiferon testing and HIV testing might be indicated in patients with appropriate risk factors. In cases of suspected tuberculous or neoplastic pericarditis, pericardial fluid analysis and biopsy could be warranted.

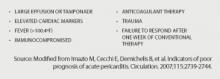

Electrocardiography. The EKG is the most useful test in diagnosing acute pericarditis. EKG changes in acute pericarditis can progress over four stages:

- Stage 1: diffuse ST elevations with or without PR depressions, initially;

- Stage 2: normalization of ST and PR segments, typically after several days;

- Stage 3: diffuse T-wave inversions; and

- Stage 4: normalization of T-waves, typically after weeks or months.

While all four stages are unlikely to be present in a given case, 80% of patients with pericarditis will demonstrate diffuse ST-segment elevations and PR-segment depression (see Figure 2, above).12

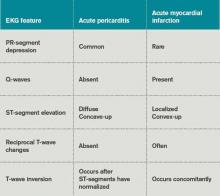

Table 3 lists EKG features helpful in differentiating acute pericarditis from acute myocardial infarction.

Chest radiography. Because a pericardial effusion often accompanies pericarditis, a chest radiograph (CXR) should be performed in all suspected cases. The CXR might show enlargement of the cardiac silhouette if more than 250 ml of pericardial fluid is present.3 A CXR also is helpful to diagnose concomitant pulmonary infection, pleural effusion, or mediastinal mass—all findings that could point to an underlying specific etiology of pericarditis and/or pericardial effusion.

Echocardiography. An echocardiogram should be performed in all patients with suspected pericarditis to detect effusion, associated myocardial, or paracardial disease.13 The echocardiogram frequently is normal but could show an effusion in 60%, and tamponade (see Figure 1, p. 15) in 5%, of cases.4

Computed tomography (CT) and cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (CMR).CT or CMR are the imaging modalities of choice when an echocardiogram is inconclusive or in cases of pericarditis complicated by a hemorrhagic or localized effusion, pericardial thickening, or pericardial mass.14 They also help in precise imaging of neighboring structures, such as lungs or mediastinum.

Pericardial fluid analysis and pericardial biopsy. In cases of refractory pericarditis with effusion, pericardial fluid analysis might provide clues to the underlying etiology. Routine chemistry, cell count, gram and acid fast staining, culture, and cytology should be sent. In addition, acid-fast bacillus staining and culture, adenosine deaminase, and interferon-gamma testing should be ordered when tuberculous pericarditis is suspected. A pericardial biopsy may show granulomas or neoplastic cells. Overall, pericardial fluid analysis and biopsy reveal a diagnosis in roughly 20% of cases.11

How is acute pericarditis treated?

Most cases of uncomplicated acute pericarditis are viral and respond well to NSAID plus colchicine therapy.2,4 Failure to respond to NSAIDs plus colchicine—evidenced by persistent fever, pericardial chest pain, new pericardial effusion, or worsening of general illness—within a week of treatment should prompt a search for an underlying systemic illness. If found, treatment should be aimed at the causative illness.

Bacterial pericarditis usually requires surgical drainage in addition to treatment with appropriate antibiotics.11 Tuberculous pericarditis is treated with multidrug therapy; when underlying HIV is present, patients should receive highly active anti-retroviral therapy as well. Steroids and immunosuppressants should be considered in addition to NSAIDs and colchicine in autoimmune pericarditis.10 Neoplastic pericarditis may resolve with chemotherapy but it has a high recurrence rate.13 Uremic pericarditis requires intensified dialysis.

Treatment options for uncomplicated idiopathic or viral pericarditis include:

NSAIDs. It is important to adequately dose NSAIDs when treating acute pericarditis. Initial treatment options include ibuprofen (1,600 to 3,200 mg daily), indomethacin (75 to 150 mg daily) or aspirin (2 to 4 gm daily) for one week.11,15 Aspirin is preferred in patients with ischemic heart disease. For patients with symptoms that persist longer than a week, NSAIDS may be continued, but investigation for an underlying etiology is indicated. Concomitant proton-pump-inhibitor therapy should be considered in patients at high risk for peptic ulcer disease to minimize gastric side effects.

Colchicine. Colchicine has a favorable risk-benefit profile as an adjunct treatment for acute and recurrent pericarditis. Patients experience better symptom relief when treated with both colchicine and an NSAID, compared with NSAIDs alone (88% versus 63%). Recurrence rates are lower with combined therapy (11% versus 32%).16 Colchicine treatment (0.6 mg twice daily after a loading dose of up to 2 mg) is recommended for several months to greater than one year.13,16,17

Glucocorticoids. Routine glucocorticoid use should be avoided in the treatment of acute pericarditis, as it has been associated with an increased risk for recurrence (OR 4.3).16,18 Glucocorticoid use should be considered in cases of pericarditis refractory to NSAIDs and colchicine, cases in which NSAIDs and or colchicine are contraindicated, and in autoimmune or connective-tissue-disease-related pericarditis. Prednisone should be dosed up to 1 mg/kg/day for at least one month, depending on symptom resolution, then tapered after either NSAIDs or colchicine have been started.13 Smaller prednisone doses of up to 0.5 mg/kg/day could be as effective, with the added benefit of reduced side effects and recurrences.19

Invasive treatment. Pericardiocentesis and/or pericardiectomy should be considered when pericarditis is complicated by a large effusion or tamponade, constrictive physiology, or recurrent effusion.11 Pericardiocentesis is the least invasive option and helps provide immediate relief in cases of tamponade or large symptomatic effusions. It is the preferred modality for obtaining pericardial fluid for diagnostic analysis. However, effusions can recur and in those cases pericardial window is preferred, as it provides continued outflow of pericardial fluid. Pericardiectomy is recommended in cases of symptomatic constrictive pericarditis unresponsive to medical therapy.15

Back to the Case

The patient’s presentation—prodrome followed by fever and pleuritic chest pain—is characteristic of acute idiopathic pericarditis. No pericardial rub was heard, but EKG findings were typical. Troponin I elevation suggested underlying myopericarditis. An echocardiogram was unremarkable. Given the likely viral or idiopathic etiology, no further diagnostic tests were ordered to explore the possibility of an underlying systemic illness.

The patient was started on ibuprofen 600 mg every eight hours. She had significant relief of her symptoms within two days. A routine fever workup was negative. She was discharged the following day.

The patient was readmitted three months later with recurrent pleuritic chest pain, which did not improve with resumption of NSAID therapy. Initial troponin I was 0.22 ng/ml, electrocardiogram was unchanged, and an echocardiogram showed small effusion. She was started on ibuprofen 800 mg every eight hours, as well as colchicine 0.6 mg twice daily. Her symptoms resolved the next day and she was discharged with prescriptions for ibuprofen and colchicine. She was instructed to follow up with a primary-care doctor in one week.

At the clinic visit, ibuprofen was tapered but colchicine was continued for another six months. She remained asymptomatic at her six-month clinic follow-up.

Bottom Line

Acute pericarditis is a clinical diagnosis supported by EKG findings. Most cases are idiopathic or viral, and can be treated successfully with NSAIDs and colchicine. For cases that do not respond to initial therapy, or cases that present with high-risk features, a specific etiology should be sought.

Dr. Southern is chief of the division of hospital medicine at Montefiore Medical Center in Bronx, N.Y. Dr. Galhorta is an instructor and Drs. Martin, Korcak, and Stehlihova are assistant professors in the department of medicine at Albert Einstein.

References

- Lange RA, Hillis LD. Clinical practice. Acute pericarditis. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:2195-2202.

- Zayas R, Anguita M, Torres F, et al. Incidence of specific etiology and role of methods for specific etiologic diagnosis of primary acute pericarditis. Am J Cardiol. 1995;75:378-382.

- Troughton RW, Asher CR, Klein AL. Pericarditis. Lancet. 2004;363:717-727.

- Imazio M, Demichelis B, Parrini I, et al. Day-hospital treatment of acute pericarditis: a management program for outpatient therapy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43:1042-1046.

- Bonnefoy E, Godon P, Kirkorian G, et al. Serum cardiac troponin I and ST-segment elevation in patients with acute pericarditis. Eur Heart J. 2000;21:832-836.

- Salisbury AC, Olalla-Gomez C, Rihal CS, et al. Frequency and predictors of urgent coronary angiography in patients with acute pericarditis. Mayo Clin Proc. 2009;84(1):11-15.

- Imazio M, Cecchi E, Demichelis B, et al. Indicators of poor prognosis of acute pericarditis. Circulation. 2007;115:2739-2744.

- Imazio M, Spodick DH, Brucato A, et al. Diagnostic issues in the clinical management of pericarditis. Int J Clin Pract. 2010;64(10):1384-1392.

- Spodick DH. Acute pericarditis: current concepts and practice. JAMA. 2003;289:1150-1153.

- Imazio M, Demichelis B, Cecchi E. Cardiac troponin I in acute pericarditis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;42(12):2144-2148.

- Sagristà Sauleda J, Permanyer Miralda G, Soler Soler J. Diagnosis and management of pericardial syndromes. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2005;58(7):830-841.

- Bruce MA, Spodick DH. Atypical electrocardiogram in acute pericarditis: characteristics and prevalence. J Electrocardiol. 1980;13:61-66.

- Maisch B, Seferovic PM, Ristic AD, et al. Guidelines on the diagnosis and management of pericardial diseases executive summary; the task force on the diagnosis and management of pericardial diseases of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J. 2004; 25(7):587-610.

- Verhaert D, Gabriel RS, Johnston D, et al. The role of multimodality imaging in the management of pericardial disease. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2010;3:333-343.

- Imazio M, Spodick DH, Brucato A, et al. Controversial issues in the management of pericardial diseases. Circulation. 2010;121:916-928.

- Imazio M, Bobbio M, Cecchi E, et al. Colchicine in addition to conventional therapy for acute pericarditis: results of the colchicine for acute pericarditis (COPE) trial. Circulation. 2005;112(13):2012-2016.

- Adler Y, Finkelstein Y, Guindo J, et al. Colchicine treatment for recurrent pericarditis: a decade of experience. Circulation. 1998;97:2183-185.

- Imazio M, Bobbio M, Cecchi E, et al. Colchicine as first-choice therapy for recurrent pericarditis: results of the colchicine for recurrent pericarditis (CORE) trial. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:1987-1991.

- Imazio M, Brucato A, Cumetti D, et al. Corticosteroids for recurrent pericarditis: high versus low doses: a nonrandomized observation. Circulation. 2008;118:667-771.

Case

A 32-year-old female with no significant past medical history is evaluated for sharp, left-sided chest pain for five days. Her pain is intermittent, worse with deep inspiration and in the supine position. She denies any shortness of breath. Her temperature is 100.8ºF, but otherwise her vital signs are normal. The physical exam and chest radiograph are unremarkable, but an electrocardiogram shows diffuse ST-segment elevations. The initial troponin is mildly elevated at 0.35 ng/ml.

Could this patient have acute pericarditis? If so, how should she be managed?

Background

Pericarditis is the most common pericardial disease encountered by hospitalists. As many as 5% of chest pain cases unattributable to myocardial infarction (MI) are diagnosed with pericarditis.1 In immunocompetent individuals, as many as 90% of acute pericarditis cases are viral or idiopathic in etiology.1,2 Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and tuberculosis are common culprits in developing countries and immunocompromised hosts.3 Other specific etiologies of acute pericarditis include autoimmune diseases, neoplasms, chest irradiation, trauma, and metabolic disturbances (e.g. uremia). An etiologic classification of acute pericarditis is shown in Table 2 (p. 16).

Pericarditis primarily is a clinical diagnosis. Most patients present with chest pain.4 A pericardial friction rub may or may not be heard (sensitivity 16% to 85%), but when present is nearly 100% specific for pericarditis.2,5 Diffuse ST-segment elevation on electrocardiogram (EKG) is present in 60% to 90% of cases, but it can be difficult to differentiate from ST-segment elevations in acute MI.4,6

Uncomplicated acute pericarditis often is treated successfully as an outpatient.4 However, patients with high-risk features (see Table 1, right) should be hospitalized for identification and treatment of specific underlying etiology and for monitoring of complications, such as tamponade.7

Our patient has features consistent with pericarditis. In the following sections, we will review the diagnosis and treatment of acute pericarditis.

Review of the Data

How is acute pericarditis diagnosed?

Acute pericarditis is a clinical diagnosis supported by EKG and echocardiogram. At least two of the following four criteria must be present for the diagnosis: pleuritic chest pain, pericardial rub, diffuse ST-segment elevation on EKG, and pericardial effusion.8

History. Patients may report fever (46% in one small study of 69 patients) or a recent history of respiratory or gastrointestinal infection (40%).5 Most patients will report pleuritic chest pain. Typically, the pain is improved when sitting up and leaning forward, and gets worse when lying supine.4 Pain might radiate to the trapezius muscle ridge due to the common phrenic nerve innervation of pericardium and trapezius.9 However, pain might be minimal or absent in patients with uremic, neoplastic, tuberculous, or post-irradiation pericarditis.

Physical exam. A pericardial friction rub is nearly 100% specific for a pericarditis diagnosis, but sensitivity can vary (16% to 85%) depending on the frequency of auscultation and underlying etiology.2,5 It is thought to be caused by friction between the parietal and visceral layers of inflamed pericardium. A pericardial rub classically is described as a superficial, high-pitched, scratchy, or squeaking sound best heard with the diaphragm of the stethoscope at the lower left sternal border with the patient leaning forward.

Laboratory data. A complete blood count, metabolic panel, and cardiac enzymes should be checked in all patients with suspected acute pericarditis. Troponin values are elevated in up to one-third of patients, indicating cardiac muscle injury or myopericarditis, but have not been shown to adversely impact hospital length of stay, readmission, or complication rates.5,10 Markers of inflammation (e.g. erythrocyte sedimentation rate or C-reactive protein) are frequently elevated but do not point to a specific underlying etiology. Routine viral cultures and antibody titers are not useful.11

Most cases of pericarditis are presumed idiopathic (viral); however, finding a specific etiology should be considered in patients who do not respond after one week of therapy. Anti-nuclear antibody, complement levels, and rheumatoid factor can serve as screening tests for autoimmune disease. Purified protein derivative or quantiferon testing and HIV testing might be indicated in patients with appropriate risk factors. In cases of suspected tuberculous or neoplastic pericarditis, pericardial fluid analysis and biopsy could be warranted.

Electrocardiography. The EKG is the most useful test in diagnosing acute pericarditis. EKG changes in acute pericarditis can progress over four stages:

- Stage 1: diffuse ST elevations with or without PR depressions, initially;

- Stage 2: normalization of ST and PR segments, typically after several days;

- Stage 3: diffuse T-wave inversions; and

- Stage 4: normalization of T-waves, typically after weeks or months.

While all four stages are unlikely to be present in a given case, 80% of patients with pericarditis will demonstrate diffuse ST-segment elevations and PR-segment depression (see Figure 2, above).12

Table 3 lists EKG features helpful in differentiating acute pericarditis from acute myocardial infarction.

Chest radiography. Because a pericardial effusion often accompanies pericarditis, a chest radiograph (CXR) should be performed in all suspected cases. The CXR might show enlargement of the cardiac silhouette if more than 250 ml of pericardial fluid is present.3 A CXR also is helpful to diagnose concomitant pulmonary infection, pleural effusion, or mediastinal mass—all findings that could point to an underlying specific etiology of pericarditis and/or pericardial effusion.

Echocardiography. An echocardiogram should be performed in all patients with suspected pericarditis to detect effusion, associated myocardial, or paracardial disease.13 The echocardiogram frequently is normal but could show an effusion in 60%, and tamponade (see Figure 1, p. 15) in 5%, of cases.4

Computed tomography (CT) and cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (CMR).CT or CMR are the imaging modalities of choice when an echocardiogram is inconclusive or in cases of pericarditis complicated by a hemorrhagic or localized effusion, pericardial thickening, or pericardial mass.14 They also help in precise imaging of neighboring structures, such as lungs or mediastinum.

Pericardial fluid analysis and pericardial biopsy. In cases of refractory pericarditis with effusion, pericardial fluid analysis might provide clues to the underlying etiology. Routine chemistry, cell count, gram and acid fast staining, culture, and cytology should be sent. In addition, acid-fast bacillus staining and culture, adenosine deaminase, and interferon-gamma testing should be ordered when tuberculous pericarditis is suspected. A pericardial biopsy may show granulomas or neoplastic cells. Overall, pericardial fluid analysis and biopsy reveal a diagnosis in roughly 20% of cases.11

How is acute pericarditis treated?

Most cases of uncomplicated acute pericarditis are viral and respond well to NSAID plus colchicine therapy.2,4 Failure to respond to NSAIDs plus colchicine—evidenced by persistent fever, pericardial chest pain, new pericardial effusion, or worsening of general illness—within a week of treatment should prompt a search for an underlying systemic illness. If found, treatment should be aimed at the causative illness.

Bacterial pericarditis usually requires surgical drainage in addition to treatment with appropriate antibiotics.11 Tuberculous pericarditis is treated with multidrug therapy; when underlying HIV is present, patients should receive highly active anti-retroviral therapy as well. Steroids and immunosuppressants should be considered in addition to NSAIDs and colchicine in autoimmune pericarditis.10 Neoplastic pericarditis may resolve with chemotherapy but it has a high recurrence rate.13 Uremic pericarditis requires intensified dialysis.

Treatment options for uncomplicated idiopathic or viral pericarditis include:

NSAIDs. It is important to adequately dose NSAIDs when treating acute pericarditis. Initial treatment options include ibuprofen (1,600 to 3,200 mg daily), indomethacin (75 to 150 mg daily) or aspirin (2 to 4 gm daily) for one week.11,15 Aspirin is preferred in patients with ischemic heart disease. For patients with symptoms that persist longer than a week, NSAIDS may be continued, but investigation for an underlying etiology is indicated. Concomitant proton-pump-inhibitor therapy should be considered in patients at high risk for peptic ulcer disease to minimize gastric side effects.

Colchicine. Colchicine has a favorable risk-benefit profile as an adjunct treatment for acute and recurrent pericarditis. Patients experience better symptom relief when treated with both colchicine and an NSAID, compared with NSAIDs alone (88% versus 63%). Recurrence rates are lower with combined therapy (11% versus 32%).16 Colchicine treatment (0.6 mg twice daily after a loading dose of up to 2 mg) is recommended for several months to greater than one year.13,16,17

Glucocorticoids. Routine glucocorticoid use should be avoided in the treatment of acute pericarditis, as it has been associated with an increased risk for recurrence (OR 4.3).16,18 Glucocorticoid use should be considered in cases of pericarditis refractory to NSAIDs and colchicine, cases in which NSAIDs and or colchicine are contraindicated, and in autoimmune or connective-tissue-disease-related pericarditis. Prednisone should be dosed up to 1 mg/kg/day for at least one month, depending on symptom resolution, then tapered after either NSAIDs or colchicine have been started.13 Smaller prednisone doses of up to 0.5 mg/kg/day could be as effective, with the added benefit of reduced side effects and recurrences.19

Invasive treatment. Pericardiocentesis and/or pericardiectomy should be considered when pericarditis is complicated by a large effusion or tamponade, constrictive physiology, or recurrent effusion.11 Pericardiocentesis is the least invasive option and helps provide immediate relief in cases of tamponade or large symptomatic effusions. It is the preferred modality for obtaining pericardial fluid for diagnostic analysis. However, effusions can recur and in those cases pericardial window is preferred, as it provides continued outflow of pericardial fluid. Pericardiectomy is recommended in cases of symptomatic constrictive pericarditis unresponsive to medical therapy.15

Back to the Case

The patient’s presentation—prodrome followed by fever and pleuritic chest pain—is characteristic of acute idiopathic pericarditis. No pericardial rub was heard, but EKG findings were typical. Troponin I elevation suggested underlying myopericarditis. An echocardiogram was unremarkable. Given the likely viral or idiopathic etiology, no further diagnostic tests were ordered to explore the possibility of an underlying systemic illness.

The patient was started on ibuprofen 600 mg every eight hours. She had significant relief of her symptoms within two days. A routine fever workup was negative. She was discharged the following day.

The patient was readmitted three months later with recurrent pleuritic chest pain, which did not improve with resumption of NSAID therapy. Initial troponin I was 0.22 ng/ml, electrocardiogram was unchanged, and an echocardiogram showed small effusion. She was started on ibuprofen 800 mg every eight hours, as well as colchicine 0.6 mg twice daily. Her symptoms resolved the next day and she was discharged with prescriptions for ibuprofen and colchicine. She was instructed to follow up with a primary-care doctor in one week.

At the clinic visit, ibuprofen was tapered but colchicine was continued for another six months. She remained asymptomatic at her six-month clinic follow-up.

Bottom Line

Acute pericarditis is a clinical diagnosis supported by EKG findings. Most cases are idiopathic or viral, and can be treated successfully with NSAIDs and colchicine. For cases that do not respond to initial therapy, or cases that present with high-risk features, a specific etiology should be sought.

Dr. Southern is chief of the division of hospital medicine at Montefiore Medical Center in Bronx, N.Y. Dr. Galhorta is an instructor and Drs. Martin, Korcak, and Stehlihova are assistant professors in the department of medicine at Albert Einstein.

References

- Lange RA, Hillis LD. Clinical practice. Acute pericarditis. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:2195-2202.

- Zayas R, Anguita M, Torres F, et al. Incidence of specific etiology and role of methods for specific etiologic diagnosis of primary acute pericarditis. Am J Cardiol. 1995;75:378-382.

- Troughton RW, Asher CR, Klein AL. Pericarditis. Lancet. 2004;363:717-727.

- Imazio M, Demichelis B, Parrini I, et al. Day-hospital treatment of acute pericarditis: a management program for outpatient therapy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43:1042-1046.

- Bonnefoy E, Godon P, Kirkorian G, et al. Serum cardiac troponin I and ST-segment elevation in patients with acute pericarditis. Eur Heart J. 2000;21:832-836.

- Salisbury AC, Olalla-Gomez C, Rihal CS, et al. Frequency and predictors of urgent coronary angiography in patients with acute pericarditis. Mayo Clin Proc. 2009;84(1):11-15.

- Imazio M, Cecchi E, Demichelis B, et al. Indicators of poor prognosis of acute pericarditis. Circulation. 2007;115:2739-2744.

- Imazio M, Spodick DH, Brucato A, et al. Diagnostic issues in the clinical management of pericarditis. Int J Clin Pract. 2010;64(10):1384-1392.

- Spodick DH. Acute pericarditis: current concepts and practice. JAMA. 2003;289:1150-1153.

- Imazio M, Demichelis B, Cecchi E. Cardiac troponin I in acute pericarditis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;42(12):2144-2148.

- Sagristà Sauleda J, Permanyer Miralda G, Soler Soler J. Diagnosis and management of pericardial syndromes. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2005;58(7):830-841.

- Bruce MA, Spodick DH. Atypical electrocardiogram in acute pericarditis: characteristics and prevalence. J Electrocardiol. 1980;13:61-66.

- Maisch B, Seferovic PM, Ristic AD, et al. Guidelines on the diagnosis and management of pericardial diseases executive summary; the task force on the diagnosis and management of pericardial diseases of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J. 2004; 25(7):587-610.

- Verhaert D, Gabriel RS, Johnston D, et al. The role of multimodality imaging in the management of pericardial disease. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2010;3:333-343.

- Imazio M, Spodick DH, Brucato A, et al. Controversial issues in the management of pericardial diseases. Circulation. 2010;121:916-928.

- Imazio M, Bobbio M, Cecchi E, et al. Colchicine in addition to conventional therapy for acute pericarditis: results of the colchicine for acute pericarditis (COPE) trial. Circulation. 2005;112(13):2012-2016.

- Adler Y, Finkelstein Y, Guindo J, et al. Colchicine treatment for recurrent pericarditis: a decade of experience. Circulation. 1998;97:2183-185.

- Imazio M, Bobbio M, Cecchi E, et al. Colchicine as first-choice therapy for recurrent pericarditis: results of the colchicine for recurrent pericarditis (CORE) trial. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:1987-1991.

- Imazio M, Brucato A, Cumetti D, et al. Corticosteroids for recurrent pericarditis: high versus low doses: a nonrandomized observation. Circulation. 2008;118:667-771.

Case

A 32-year-old female with no significant past medical history is evaluated for sharp, left-sided chest pain for five days. Her pain is intermittent, worse with deep inspiration and in the supine position. She denies any shortness of breath. Her temperature is 100.8ºF, but otherwise her vital signs are normal. The physical exam and chest radiograph are unremarkable, but an electrocardiogram shows diffuse ST-segment elevations. The initial troponin is mildly elevated at 0.35 ng/ml.

Could this patient have acute pericarditis? If so, how should she be managed?

Background

Pericarditis is the most common pericardial disease encountered by hospitalists. As many as 5% of chest pain cases unattributable to myocardial infarction (MI) are diagnosed with pericarditis.1 In immunocompetent individuals, as many as 90% of acute pericarditis cases are viral or idiopathic in etiology.1,2 Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and tuberculosis are common culprits in developing countries and immunocompromised hosts.3 Other specific etiologies of acute pericarditis include autoimmune diseases, neoplasms, chest irradiation, trauma, and metabolic disturbances (e.g. uremia). An etiologic classification of acute pericarditis is shown in Table 2 (p. 16).

Pericarditis primarily is a clinical diagnosis. Most patients present with chest pain.4 A pericardial friction rub may or may not be heard (sensitivity 16% to 85%), but when present is nearly 100% specific for pericarditis.2,5 Diffuse ST-segment elevation on electrocardiogram (EKG) is present in 60% to 90% of cases, but it can be difficult to differentiate from ST-segment elevations in acute MI.4,6

Uncomplicated acute pericarditis often is treated successfully as an outpatient.4 However, patients with high-risk features (see Table 1, right) should be hospitalized for identification and treatment of specific underlying etiology and for monitoring of complications, such as tamponade.7

Our patient has features consistent with pericarditis. In the following sections, we will review the diagnosis and treatment of acute pericarditis.

Review of the Data

How is acute pericarditis diagnosed?

Acute pericarditis is a clinical diagnosis supported by EKG and echocardiogram. At least two of the following four criteria must be present for the diagnosis: pleuritic chest pain, pericardial rub, diffuse ST-segment elevation on EKG, and pericardial effusion.8

History. Patients may report fever (46% in one small study of 69 patients) or a recent history of respiratory or gastrointestinal infection (40%).5 Most patients will report pleuritic chest pain. Typically, the pain is improved when sitting up and leaning forward, and gets worse when lying supine.4 Pain might radiate to the trapezius muscle ridge due to the common phrenic nerve innervation of pericardium and trapezius.9 However, pain might be minimal or absent in patients with uremic, neoplastic, tuberculous, or post-irradiation pericarditis.

Physical exam. A pericardial friction rub is nearly 100% specific for a pericarditis diagnosis, but sensitivity can vary (16% to 85%) depending on the frequency of auscultation and underlying etiology.2,5 It is thought to be caused by friction between the parietal and visceral layers of inflamed pericardium. A pericardial rub classically is described as a superficial, high-pitched, scratchy, or squeaking sound best heard with the diaphragm of the stethoscope at the lower left sternal border with the patient leaning forward.

Laboratory data. A complete blood count, metabolic panel, and cardiac enzymes should be checked in all patients with suspected acute pericarditis. Troponin values are elevated in up to one-third of patients, indicating cardiac muscle injury or myopericarditis, but have not been shown to adversely impact hospital length of stay, readmission, or complication rates.5,10 Markers of inflammation (e.g. erythrocyte sedimentation rate or C-reactive protein) are frequently elevated but do not point to a specific underlying etiology. Routine viral cultures and antibody titers are not useful.11

Most cases of pericarditis are presumed idiopathic (viral); however, finding a specific etiology should be considered in patients who do not respond after one week of therapy. Anti-nuclear antibody, complement levels, and rheumatoid factor can serve as screening tests for autoimmune disease. Purified protein derivative or quantiferon testing and HIV testing might be indicated in patients with appropriate risk factors. In cases of suspected tuberculous or neoplastic pericarditis, pericardial fluid analysis and biopsy could be warranted.

Electrocardiography. The EKG is the most useful test in diagnosing acute pericarditis. EKG changes in acute pericarditis can progress over four stages:

- Stage 1: diffuse ST elevations with or without PR depressions, initially;

- Stage 2: normalization of ST and PR segments, typically after several days;

- Stage 3: diffuse T-wave inversions; and

- Stage 4: normalization of T-waves, typically after weeks or months.

While all four stages are unlikely to be present in a given case, 80% of patients with pericarditis will demonstrate diffuse ST-segment elevations and PR-segment depression (see Figure 2, above).12

Table 3 lists EKG features helpful in differentiating acute pericarditis from acute myocardial infarction.

Chest radiography. Because a pericardial effusion often accompanies pericarditis, a chest radiograph (CXR) should be performed in all suspected cases. The CXR might show enlargement of the cardiac silhouette if more than 250 ml of pericardial fluid is present.3 A CXR also is helpful to diagnose concomitant pulmonary infection, pleural effusion, or mediastinal mass—all findings that could point to an underlying specific etiology of pericarditis and/or pericardial effusion.

Echocardiography. An echocardiogram should be performed in all patients with suspected pericarditis to detect effusion, associated myocardial, or paracardial disease.13 The echocardiogram frequently is normal but could show an effusion in 60%, and tamponade (see Figure 1, p. 15) in 5%, of cases.4

Computed tomography (CT) and cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (CMR).CT or CMR are the imaging modalities of choice when an echocardiogram is inconclusive or in cases of pericarditis complicated by a hemorrhagic or localized effusion, pericardial thickening, or pericardial mass.14 They also help in precise imaging of neighboring structures, such as lungs or mediastinum.

Pericardial fluid analysis and pericardial biopsy. In cases of refractory pericarditis with effusion, pericardial fluid analysis might provide clues to the underlying etiology. Routine chemistry, cell count, gram and acid fast staining, culture, and cytology should be sent. In addition, acid-fast bacillus staining and culture, adenosine deaminase, and interferon-gamma testing should be ordered when tuberculous pericarditis is suspected. A pericardial biopsy may show granulomas or neoplastic cells. Overall, pericardial fluid analysis and biopsy reveal a diagnosis in roughly 20% of cases.11

How is acute pericarditis treated?

Most cases of uncomplicated acute pericarditis are viral and respond well to NSAID plus colchicine therapy.2,4 Failure to respond to NSAIDs plus colchicine—evidenced by persistent fever, pericardial chest pain, new pericardial effusion, or worsening of general illness—within a week of treatment should prompt a search for an underlying systemic illness. If found, treatment should be aimed at the causative illness.

Bacterial pericarditis usually requires surgical drainage in addition to treatment with appropriate antibiotics.11 Tuberculous pericarditis is treated with multidrug therapy; when underlying HIV is present, patients should receive highly active anti-retroviral therapy as well. Steroids and immunosuppressants should be considered in addition to NSAIDs and colchicine in autoimmune pericarditis.10 Neoplastic pericarditis may resolve with chemotherapy but it has a high recurrence rate.13 Uremic pericarditis requires intensified dialysis.

Treatment options for uncomplicated idiopathic or viral pericarditis include:

NSAIDs. It is important to adequately dose NSAIDs when treating acute pericarditis. Initial treatment options include ibuprofen (1,600 to 3,200 mg daily), indomethacin (75 to 150 mg daily) or aspirin (2 to 4 gm daily) for one week.11,15 Aspirin is preferred in patients with ischemic heart disease. For patients with symptoms that persist longer than a week, NSAIDS may be continued, but investigation for an underlying etiology is indicated. Concomitant proton-pump-inhibitor therapy should be considered in patients at high risk for peptic ulcer disease to minimize gastric side effects.

Colchicine. Colchicine has a favorable risk-benefit profile as an adjunct treatment for acute and recurrent pericarditis. Patients experience better symptom relief when treated with both colchicine and an NSAID, compared with NSAIDs alone (88% versus 63%). Recurrence rates are lower with combined therapy (11% versus 32%).16 Colchicine treatment (0.6 mg twice daily after a loading dose of up to 2 mg) is recommended for several months to greater than one year.13,16,17

Glucocorticoids. Routine glucocorticoid use should be avoided in the treatment of acute pericarditis, as it has been associated with an increased risk for recurrence (OR 4.3).16,18 Glucocorticoid use should be considered in cases of pericarditis refractory to NSAIDs and colchicine, cases in which NSAIDs and or colchicine are contraindicated, and in autoimmune or connective-tissue-disease-related pericarditis. Prednisone should be dosed up to 1 mg/kg/day for at least one month, depending on symptom resolution, then tapered after either NSAIDs or colchicine have been started.13 Smaller prednisone doses of up to 0.5 mg/kg/day could be as effective, with the added benefit of reduced side effects and recurrences.19

Invasive treatment. Pericardiocentesis and/or pericardiectomy should be considered when pericarditis is complicated by a large effusion or tamponade, constrictive physiology, or recurrent effusion.11 Pericardiocentesis is the least invasive option and helps provide immediate relief in cases of tamponade or large symptomatic effusions. It is the preferred modality for obtaining pericardial fluid for diagnostic analysis. However, effusions can recur and in those cases pericardial window is preferred, as it provides continued outflow of pericardial fluid. Pericardiectomy is recommended in cases of symptomatic constrictive pericarditis unresponsive to medical therapy.15

Back to the Case

The patient’s presentation—prodrome followed by fever and pleuritic chest pain—is characteristic of acute idiopathic pericarditis. No pericardial rub was heard, but EKG findings were typical. Troponin I elevation suggested underlying myopericarditis. An echocardiogram was unremarkable. Given the likely viral or idiopathic etiology, no further diagnostic tests were ordered to explore the possibility of an underlying systemic illness.

The patient was started on ibuprofen 600 mg every eight hours. She had significant relief of her symptoms within two days. A routine fever workup was negative. She was discharged the following day.

The patient was readmitted three months later with recurrent pleuritic chest pain, which did not improve with resumption of NSAID therapy. Initial troponin I was 0.22 ng/ml, electrocardiogram was unchanged, and an echocardiogram showed small effusion. She was started on ibuprofen 800 mg every eight hours, as well as colchicine 0.6 mg twice daily. Her symptoms resolved the next day and she was discharged with prescriptions for ibuprofen and colchicine. She was instructed to follow up with a primary-care doctor in one week.

At the clinic visit, ibuprofen was tapered but colchicine was continued for another six months. She remained asymptomatic at her six-month clinic follow-up.

Bottom Line

Acute pericarditis is a clinical diagnosis supported by EKG findings. Most cases are idiopathic or viral, and can be treated successfully with NSAIDs and colchicine. For cases that do not respond to initial therapy, or cases that present with high-risk features, a specific etiology should be sought.

Dr. Southern is chief of the division of hospital medicine at Montefiore Medical Center in Bronx, N.Y. Dr. Galhorta is an instructor and Drs. Martin, Korcak, and Stehlihova are assistant professors in the department of medicine at Albert Einstein.

References

- Lange RA, Hillis LD. Clinical practice. Acute pericarditis. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:2195-2202.

- Zayas R, Anguita M, Torres F, et al. Incidence of specific etiology and role of methods for specific etiologic diagnosis of primary acute pericarditis. Am J Cardiol. 1995;75:378-382.

- Troughton RW, Asher CR, Klein AL. Pericarditis. Lancet. 2004;363:717-727.

- Imazio M, Demichelis B, Parrini I, et al. Day-hospital treatment of acute pericarditis: a management program for outpatient therapy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43:1042-1046.

- Bonnefoy E, Godon P, Kirkorian G, et al. Serum cardiac troponin I and ST-segment elevation in patients with acute pericarditis. Eur Heart J. 2000;21:832-836.

- Salisbury AC, Olalla-Gomez C, Rihal CS, et al. Frequency and predictors of urgent coronary angiography in patients with acute pericarditis. Mayo Clin Proc. 2009;84(1):11-15.

- Imazio M, Cecchi E, Demichelis B, et al. Indicators of poor prognosis of acute pericarditis. Circulation. 2007;115:2739-2744.

- Imazio M, Spodick DH, Brucato A, et al. Diagnostic issues in the clinical management of pericarditis. Int J Clin Pract. 2010;64(10):1384-1392.

- Spodick DH. Acute pericarditis: current concepts and practice. JAMA. 2003;289:1150-1153.

- Imazio M, Demichelis B, Cecchi E. Cardiac troponin I in acute pericarditis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;42(12):2144-2148.

- Sagristà Sauleda J, Permanyer Miralda G, Soler Soler J. Diagnosis and management of pericardial syndromes. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2005;58(7):830-841.

- Bruce MA, Spodick DH. Atypical electrocardiogram in acute pericarditis: characteristics and prevalence. J Electrocardiol. 1980;13:61-66.

- Maisch B, Seferovic PM, Ristic AD, et al. Guidelines on the diagnosis and management of pericardial diseases executive summary; the task force on the diagnosis and management of pericardial diseases of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J. 2004; 25(7):587-610.

- Verhaert D, Gabriel RS, Johnston D, et al. The role of multimodality imaging in the management of pericardial disease. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2010;3:333-343.

- Imazio M, Spodick DH, Brucato A, et al. Controversial issues in the management of pericardial diseases. Circulation. 2010;121:916-928.

- Imazio M, Bobbio M, Cecchi E, et al. Colchicine in addition to conventional therapy for acute pericarditis: results of the colchicine for acute pericarditis (COPE) trial. Circulation. 2005;112(13):2012-2016.

- Adler Y, Finkelstein Y, Guindo J, et al. Colchicine treatment for recurrent pericarditis: a decade of experience. Circulation. 1998;97:2183-185.

- Imazio M, Bobbio M, Cecchi E, et al. Colchicine as first-choice therapy for recurrent pericarditis: results of the colchicine for recurrent pericarditis (CORE) trial. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:1987-1991.

- Imazio M, Brucato A, Cumetti D, et al. Corticosteroids for recurrent pericarditis: high versus low doses: a nonrandomized observation. Circulation. 2008;118:667-771.

$100M PTSD and TBI Study; VA, EIC Introduce Tool for Veteran Mental Health; Study Links Combat Stress to Brain Changes; and more

Guidelines Help Slash CLABSI Rate by 40% in the ICU

The largest effort to date to tackle central-line-associated bloodstream infections (CLABSIs) has reduced infection rates in ICUs nationwide by 40%, according to preliminary findings from the federal Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ).

AHRQ attributes the decrease to a CLABSI safety checklist from the Comprehensive Unit-Based Safety Program (CUSP) that encourages hospital staff to wash their hands prior to inserting central lines, avoid the femoral site, remove lines when they are no longer needed, and use the antimicrobial agent chlorhexidine to clean the patient's insertion site.

The checklist was developed by Peter Pronovost, MD, PhD, FCCM, and colleagues at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, and originally implemented in ICUs statewide in Michigan as the Keystone Project. Since 2009, CUSP has recruited more than 1,000 participating hospitals in 44 states. CUSP collectively reported a decrease to 1.25 from 1.87 CLABSIs per 1,000 central-line days 10-12 months after implementing the program, according to AHRQ [PDF].

The real game-changer for CLABSIs has been the widespread adoption of chlorhexidine as an insertion site disinfectant, says Sanjay Saint, MD, MPH, director of the Veterans Administration at the University of Michigan Patient Safety Enhancement Program in Ann Arbor and professor of medicine at the University of Michigan. Dr. Saint is on the national leadership team of On the CUSP: Stop CAUTI (Catheter-Associated Urinary Tract Infections), an initiative that aims to reduce mean rates of CAUTI infections by 25% in hospitals nationwide.

Although hospitalists don't routinely place central lines, their role in this procedure is growing, both in nonacademic hospitals that lack intensivists and on hospitals' general medicine floors.

"My take-home message for hospitalists: if you are putting in central lines, if you only make one change in practice, is to use chlorhexidine as the site disinfectant," Dr. Saint says.

Visit our website for more information about central-line-associated bloodstream infections.

The largest effort to date to tackle central-line-associated bloodstream infections (CLABSIs) has reduced infection rates in ICUs nationwide by 40%, according to preliminary findings from the federal Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ).

AHRQ attributes the decrease to a CLABSI safety checklist from the Comprehensive Unit-Based Safety Program (CUSP) that encourages hospital staff to wash their hands prior to inserting central lines, avoid the femoral site, remove lines when they are no longer needed, and use the antimicrobial agent chlorhexidine to clean the patient's insertion site.

The checklist was developed by Peter Pronovost, MD, PhD, FCCM, and colleagues at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, and originally implemented in ICUs statewide in Michigan as the Keystone Project. Since 2009, CUSP has recruited more than 1,000 participating hospitals in 44 states. CUSP collectively reported a decrease to 1.25 from 1.87 CLABSIs per 1,000 central-line days 10-12 months after implementing the program, according to AHRQ [PDF].

The real game-changer for CLABSIs has been the widespread adoption of chlorhexidine as an insertion site disinfectant, says Sanjay Saint, MD, MPH, director of the Veterans Administration at the University of Michigan Patient Safety Enhancement Program in Ann Arbor and professor of medicine at the University of Michigan. Dr. Saint is on the national leadership team of On the CUSP: Stop CAUTI (Catheter-Associated Urinary Tract Infections), an initiative that aims to reduce mean rates of CAUTI infections by 25% in hospitals nationwide.

Although hospitalists don't routinely place central lines, their role in this procedure is growing, both in nonacademic hospitals that lack intensivists and on hospitals' general medicine floors.

"My take-home message for hospitalists: if you are putting in central lines, if you only make one change in practice, is to use chlorhexidine as the site disinfectant," Dr. Saint says.

Visit our website for more information about central-line-associated bloodstream infections.

The largest effort to date to tackle central-line-associated bloodstream infections (CLABSIs) has reduced infection rates in ICUs nationwide by 40%, according to preliminary findings from the federal Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ).

AHRQ attributes the decrease to a CLABSI safety checklist from the Comprehensive Unit-Based Safety Program (CUSP) that encourages hospital staff to wash their hands prior to inserting central lines, avoid the femoral site, remove lines when they are no longer needed, and use the antimicrobial agent chlorhexidine to clean the patient's insertion site.

The checklist was developed by Peter Pronovost, MD, PhD, FCCM, and colleagues at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, and originally implemented in ICUs statewide in Michigan as the Keystone Project. Since 2009, CUSP has recruited more than 1,000 participating hospitals in 44 states. CUSP collectively reported a decrease to 1.25 from 1.87 CLABSIs per 1,000 central-line days 10-12 months after implementing the program, according to AHRQ [PDF].

The real game-changer for CLABSIs has been the widespread adoption of chlorhexidine as an insertion site disinfectant, says Sanjay Saint, MD, MPH, director of the Veterans Administration at the University of Michigan Patient Safety Enhancement Program in Ann Arbor and professor of medicine at the University of Michigan. Dr. Saint is on the national leadership team of On the CUSP: Stop CAUTI (Catheter-Associated Urinary Tract Infections), an initiative that aims to reduce mean rates of CAUTI infections by 25% in hospitals nationwide.

Although hospitalists don't routinely place central lines, their role in this procedure is growing, both in nonacademic hospitals that lack intensivists and on hospitals' general medicine floors.

"My take-home message for hospitalists: if you are putting in central lines, if you only make one change in practice, is to use chlorhexidine as the site disinfectant," Dr. Saint says.

Visit our website for more information about central-line-associated bloodstream infections.

Male Gender and Length of Stay Raise Readmission Risk

CHICAGO – Approximately half of hospital readmissions are surgery related and one-third of these are due to infections, data from nearly 3,000 Medicare patients indicated.

Risk factors for readmission included male gender, higher ASA (American Society of Anesthesiologists) class, and longer hospital stay, Dr. Shanu N. Kothari said at the annual clinical congress of the American College of Surgeons.

Recent health care reform initiatives include a proposal to reduce reimbursement for certain 30-day hospital readmissions among Medicare patients, he noted.

Dr. Kothari of Gundersen Lutheran Health System in La Crosse, Wis., and his colleagues reviewed data from 2,865 Medicare patients who had surgery at their institution between Jan. 1, 2010, and May 16, 2011. A readmission was defined as any patient who was readmitted within 30 days of initial surgery. Patients with incomplete follow-up data and those who died within 30 days were excluded.

The overall 30-day readmission rate was 7%. Readmitted patients were significantly more likely to be male compared with nonreadmitted patients (54% vs. 44%) and significantly more likely to have an ASA class of 3 or greater (84% vs. 66%). There were no significant differences in age or body mass index between readmitted and nonreadmitted patients.

In addition, the average length of stay and operative times were significantly longer for readmitted patients vs. nonreadmitted patients (4.8 days vs. 2.8 days and 123 minutes vs. 98 minutes).

A majority of the procedures were general and orthopedic, and 77% were elective.

Of the readmitted patients, "84% had at least one chronic condition, and patients with cardiac disease, renal disease, and diabetes had higher readmission rates," Dr. Kothari said.