User login

Early career considerations for gastroenterologists interested in diversity, equity, and inclusion roles

Highlighting the importance of DEI across all aspects of medicine is long overdue, and the field of gastroenterology is no exception. Diversity in the gastroenterology workforce still has significant room for improvement with only 12% of all gastroenterology fellows in 2018 identifying as Black, Latino/a/x, American Indian or Alaskan Native, or Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander.1 Moreover, only 4.4% of practicing gastroenterologists identify as Black, 6.7% identify as Latino/a/x, 0.1% as American Indian or Alaskan Native, and 0.003% as Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander.2

The intensified focus on diversity in GI is welcomed, but increasing physician workforce diversity is only one of the necessary steps. If our ultimate goal is to improve health outcomes and achieve health equity for historically marginalized racial, ethnic, and socioeconomically disadvantaged communities, we must critically evaluate the path beyond just enhancing workforce diversity.

Black and Latino/a/x physicians are more likely to care for historically marginalized communities,3 which has been shown to improve all-cause mortality and reduce racial disparities.4 Additionally, diverse work teams are more innovative and productive.5 Therefore, expanding diversity must include 1) providing equitable policies and access to opportunities and promotions; 2) building inclusive environments in our institutions and practices; and 3) providing space for all people to feel like they can belong, feel respected at work, and genuinely have their opinions and ideas valued. What diversity, equity, inclusion, and belonging provide for us and our patients are avenues to thrive, solve complex problems, and tackle prominent issues within our institutions, workplaces, and communities.

To this end, many academic centers, hospitals, and private practice entities have produced a flurry of new DEI initiatives coupled with titles and roles. Some of these roles have thankfully brought recognition and economic compensation to the people doing this work. Still, as an early career gastroenterologist, you may be offered or are considering taking on a DEI role during your early career. As two underrepresented minority women in medicine who took on DEI roles with their first jobs, we wanted to highlight a few aspects to think about during your early career:

Does the DEI role come with resources?

Historically, DEI efforts were treated as “extra work,” or an activity that was done using one’s own personal time. In addition, this work called upon the small number of physicians underrepresented in medicine, largely uncompensated and with an exorbitant minority tax during a critical moment in establishing their early careers. DEI should no longer be seen as an extracurricular activity but as a vital component of an institution’s success.

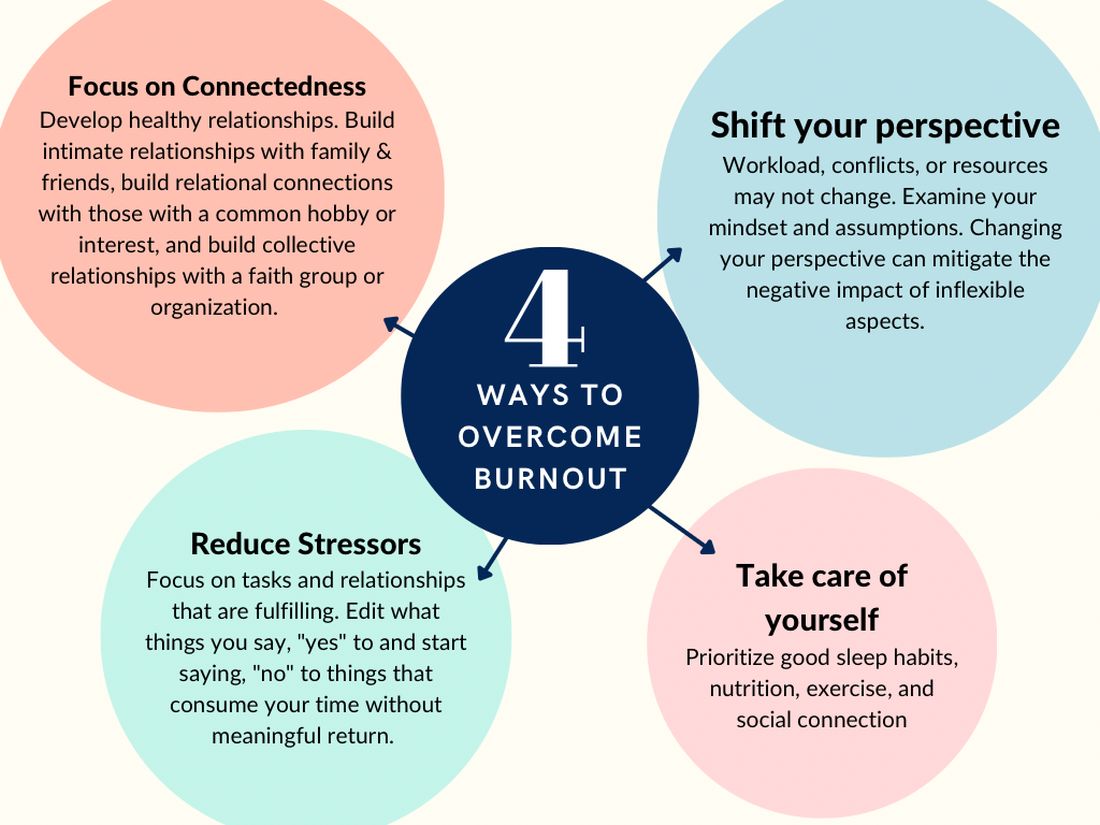

If you are considering a DEI role, the first question to ask is, “Does this role come with extra compensation or protected time?” We highly recommend not taking on the role if the answer is no. If your institution or employer is only offering increased minority tax, you are being set up to either fail, burn out, or both. Your employer or institution does not appear to value your time or effort in DEI, and you should interpret their lack of compensation or protected time as such.

If the answer is yes, then here are a few other things to consider: Is there institutional support for you to be successful in your new role? As DEI work challenges you to come up with solutions to combat years of historic marginalization for racial and ethnic minorities, this work can sometimes feel overwhelming and isolating. The importance of the DEI community and mentorship within and outside your institution is critical. You should consider joining DEI working groups or committees through GI national societies, the Association of American Medical Colleges, or the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. You can also connect with a fantastic network of people engaged in this work via social media and lean on friends and colleagues leading similar initiatives across the country.

Other critical logistical questions are if your role will come with administrative support, whether there is a budget for programs or events, and whether your institution/employer will support you in seeking continued professional development for your DEI role.6

Make sure to understand the “ask” from your division, department, or company.

Before confirming you are willing to take on this role, get a clear vision of what you are being asked to accomplish. There are so many opportunities to improve the DEI landscape. Therefore, knowing what you are specifically being asked to do will be critical to your success.

Are you being asked to work on diversity?

Does your institution want you to focus on and improve the recruitment and retention of trainees, physicians, or staff underrepresented in medicine? If so, you will need to have access to all the prior work and statistics. Capture the landscape before your interventions (% underrepresented in medicine [URiM] trainees, % URiM faculty at each level, % of URiM trainees retained as faculty, % of URiM faculty being promoted each year, etc.) This will allow you to determine the outcomes of your proposed improvements or programs.

Is your employer focused on equity?

Are you being asked to think about ways to operationalize improved patient health equity, or are you being asked to build equitable opportunities/programs for career advancement for URiMs at your institution? For either equity issue, you first need to understand the scope of the problem to ask for the necessary resources for a potential solution. Discuss timeline expectations, as equity work is a marathon and may take years to move the needle on any particular issue. This timeline is also critical for your employer to be aware of and support, as unrealistic timelines and expectations will also set you up for failure.

Or, are you being asked to concentrate on inclusion?

Does your institution need an assessment of how inclusive the climate is for trainees, staff, or physicians? Does this assessment align with your division or department’s impression, and how do you plan to work toward potential solutions for improvement?

Although diversity, equity, and inclusion are interconnected entities, they all have distinct objectives and solutions. It is essential to understand your vision and your employer’s vision for this role. If they are not aligned, having early and in-depth conversations about aligning your visions will set you on a path to success in your early career.

Know your why or more importantly, your who?

Early career physicians who are considering taking on DEI work do so for a reason. Being passionate about this type of work is usually born from a personal experience or your deep-rooted values. For us, experiencing and witnessing health disparities for our family members and people who look like us are what initially fueled our passion for this work. Additional experiences with trainees and patients keep us invigorated to continue highlighting the importance of DEI and encourage others to be passionate about DEI’s huge value added. As DEI work can come with challenges, remembering and re-centering on why you are passionate about this work or who you are engaging in this work for can keep you going.

There are several aspects to consider before taking on a DEI role, but overall, the work is rewarding and can be a great addition to the building blocks of your early career. In the short term, you build a DEI community network of peers, mentors, colleagues, and friends beyond your immediate institution and specialty. You also can demonstrate your leadership skills and potential early on in your career. In the long-term, engaging in these types of roles helps build a climate and culture that is conducive to enacting change for our patients and communities, including advancing healthcare equity and working toward recruitment, retention, and expansion efforts for our trainees and faculty. Overall, we think this type of work in your early career can be an integral part of your personal and professional development, while also having an impact that ripples beyond the walls of the endoscopy suite.

Dr. Fritz is an assistant professor of medicine in the division of gastroenterology at Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis. Dr. Rodriguez is a gastroenterologist with Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. Neither Dr. Rodriguez nor Dr. Fritz disclosed no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Santhosh L,Babik JM. Trends in racial and ethnic diversity in internal medicine subspecialty fellowships from 2006 to 2018. JAMA Network Open 2020;3:e1920482-e1920482.

2. Colleges AoAM. Physician Specialty Data Report/Active physicians who identified as Black or African-American, 2021. 2022.

3. Komaromy M et al. The role of black and Hispanic physicians in providing health care for underserved populations. New England Journal of Medicine 1996;334:1305-10.

4. Snyder JE et al. Black representation in the primary care physician workforce and its association with population life expectancy and mortality rates in the US. JAMA Network Open 2023;6:e236687-e236687.

5. Page S. Diversity bonuses and the business case. The Diversity Bonus: Princeton University Press, 2017:184-208.

6. Vela MB et al. Diversity, equity, and inclusion officer position available: Proceed with caution. Journal of Graduate Medical Education 2021;13:771-3.

Helpful resources

Diversity and Inclusion Toolkit Resources, AAMC

Blackinggastro.org, The Association of Black Gastroenterologists and Hepatologists (ABGH)

Podcast: Clinical Problem Solvers: Anti-Racism in Medicine

Highlighting the importance of DEI across all aspects of medicine is long overdue, and the field of gastroenterology is no exception. Diversity in the gastroenterology workforce still has significant room for improvement with only 12% of all gastroenterology fellows in 2018 identifying as Black, Latino/a/x, American Indian or Alaskan Native, or Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander.1 Moreover, only 4.4% of practicing gastroenterologists identify as Black, 6.7% identify as Latino/a/x, 0.1% as American Indian or Alaskan Native, and 0.003% as Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander.2

The intensified focus on diversity in GI is welcomed, but increasing physician workforce diversity is only one of the necessary steps. If our ultimate goal is to improve health outcomes and achieve health equity for historically marginalized racial, ethnic, and socioeconomically disadvantaged communities, we must critically evaluate the path beyond just enhancing workforce diversity.

Black and Latino/a/x physicians are more likely to care for historically marginalized communities,3 which has been shown to improve all-cause mortality and reduce racial disparities.4 Additionally, diverse work teams are more innovative and productive.5 Therefore, expanding diversity must include 1) providing equitable policies and access to opportunities and promotions; 2) building inclusive environments in our institutions and practices; and 3) providing space for all people to feel like they can belong, feel respected at work, and genuinely have their opinions and ideas valued. What diversity, equity, inclusion, and belonging provide for us and our patients are avenues to thrive, solve complex problems, and tackle prominent issues within our institutions, workplaces, and communities.

To this end, many academic centers, hospitals, and private practice entities have produced a flurry of new DEI initiatives coupled with titles and roles. Some of these roles have thankfully brought recognition and economic compensation to the people doing this work. Still, as an early career gastroenterologist, you may be offered or are considering taking on a DEI role during your early career. As two underrepresented minority women in medicine who took on DEI roles with their first jobs, we wanted to highlight a few aspects to think about during your early career:

Does the DEI role come with resources?

Historically, DEI efforts were treated as “extra work,” or an activity that was done using one’s own personal time. In addition, this work called upon the small number of physicians underrepresented in medicine, largely uncompensated and with an exorbitant minority tax during a critical moment in establishing their early careers. DEI should no longer be seen as an extracurricular activity but as a vital component of an institution’s success.

If you are considering a DEI role, the first question to ask is, “Does this role come with extra compensation or protected time?” We highly recommend not taking on the role if the answer is no. If your institution or employer is only offering increased minority tax, you are being set up to either fail, burn out, or both. Your employer or institution does not appear to value your time or effort in DEI, and you should interpret their lack of compensation or protected time as such.

If the answer is yes, then here are a few other things to consider: Is there institutional support for you to be successful in your new role? As DEI work challenges you to come up with solutions to combat years of historic marginalization for racial and ethnic minorities, this work can sometimes feel overwhelming and isolating. The importance of the DEI community and mentorship within and outside your institution is critical. You should consider joining DEI working groups or committees through GI national societies, the Association of American Medical Colleges, or the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. You can also connect with a fantastic network of people engaged in this work via social media and lean on friends and colleagues leading similar initiatives across the country.

Other critical logistical questions are if your role will come with administrative support, whether there is a budget for programs or events, and whether your institution/employer will support you in seeking continued professional development for your DEI role.6

Make sure to understand the “ask” from your division, department, or company.

Before confirming you are willing to take on this role, get a clear vision of what you are being asked to accomplish. There are so many opportunities to improve the DEI landscape. Therefore, knowing what you are specifically being asked to do will be critical to your success.

Are you being asked to work on diversity?

Does your institution want you to focus on and improve the recruitment and retention of trainees, physicians, or staff underrepresented in medicine? If so, you will need to have access to all the prior work and statistics. Capture the landscape before your interventions (% underrepresented in medicine [URiM] trainees, % URiM faculty at each level, % of URiM trainees retained as faculty, % of URiM faculty being promoted each year, etc.) This will allow you to determine the outcomes of your proposed improvements or programs.

Is your employer focused on equity?

Are you being asked to think about ways to operationalize improved patient health equity, or are you being asked to build equitable opportunities/programs for career advancement for URiMs at your institution? For either equity issue, you first need to understand the scope of the problem to ask for the necessary resources for a potential solution. Discuss timeline expectations, as equity work is a marathon and may take years to move the needle on any particular issue. This timeline is also critical for your employer to be aware of and support, as unrealistic timelines and expectations will also set you up for failure.

Or, are you being asked to concentrate on inclusion?

Does your institution need an assessment of how inclusive the climate is for trainees, staff, or physicians? Does this assessment align with your division or department’s impression, and how do you plan to work toward potential solutions for improvement?

Although diversity, equity, and inclusion are interconnected entities, they all have distinct objectives and solutions. It is essential to understand your vision and your employer’s vision for this role. If they are not aligned, having early and in-depth conversations about aligning your visions will set you on a path to success in your early career.

Know your why or more importantly, your who?

Early career physicians who are considering taking on DEI work do so for a reason. Being passionate about this type of work is usually born from a personal experience or your deep-rooted values. For us, experiencing and witnessing health disparities for our family members and people who look like us are what initially fueled our passion for this work. Additional experiences with trainees and patients keep us invigorated to continue highlighting the importance of DEI and encourage others to be passionate about DEI’s huge value added. As DEI work can come with challenges, remembering and re-centering on why you are passionate about this work or who you are engaging in this work for can keep you going.

There are several aspects to consider before taking on a DEI role, but overall, the work is rewarding and can be a great addition to the building blocks of your early career. In the short term, you build a DEI community network of peers, mentors, colleagues, and friends beyond your immediate institution and specialty. You also can demonstrate your leadership skills and potential early on in your career. In the long-term, engaging in these types of roles helps build a climate and culture that is conducive to enacting change for our patients and communities, including advancing healthcare equity and working toward recruitment, retention, and expansion efforts for our trainees and faculty. Overall, we think this type of work in your early career can be an integral part of your personal and professional development, while also having an impact that ripples beyond the walls of the endoscopy suite.

Dr. Fritz is an assistant professor of medicine in the division of gastroenterology at Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis. Dr. Rodriguez is a gastroenterologist with Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. Neither Dr. Rodriguez nor Dr. Fritz disclosed no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Santhosh L,Babik JM. Trends in racial and ethnic diversity in internal medicine subspecialty fellowships from 2006 to 2018. JAMA Network Open 2020;3:e1920482-e1920482.

2. Colleges AoAM. Physician Specialty Data Report/Active physicians who identified as Black or African-American, 2021. 2022.

3. Komaromy M et al. The role of black and Hispanic physicians in providing health care for underserved populations. New England Journal of Medicine 1996;334:1305-10.

4. Snyder JE et al. Black representation in the primary care physician workforce and its association with population life expectancy and mortality rates in the US. JAMA Network Open 2023;6:e236687-e236687.

5. Page S. Diversity bonuses and the business case. The Diversity Bonus: Princeton University Press, 2017:184-208.

6. Vela MB et al. Diversity, equity, and inclusion officer position available: Proceed with caution. Journal of Graduate Medical Education 2021;13:771-3.

Helpful resources

Diversity and Inclusion Toolkit Resources, AAMC

Blackinggastro.org, The Association of Black Gastroenterologists and Hepatologists (ABGH)

Podcast: Clinical Problem Solvers: Anti-Racism in Medicine

Highlighting the importance of DEI across all aspects of medicine is long overdue, and the field of gastroenterology is no exception. Diversity in the gastroenterology workforce still has significant room for improvement with only 12% of all gastroenterology fellows in 2018 identifying as Black, Latino/a/x, American Indian or Alaskan Native, or Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander.1 Moreover, only 4.4% of practicing gastroenterologists identify as Black, 6.7% identify as Latino/a/x, 0.1% as American Indian or Alaskan Native, and 0.003% as Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander.2

The intensified focus on diversity in GI is welcomed, but increasing physician workforce diversity is only one of the necessary steps. If our ultimate goal is to improve health outcomes and achieve health equity for historically marginalized racial, ethnic, and socioeconomically disadvantaged communities, we must critically evaluate the path beyond just enhancing workforce diversity.

Black and Latino/a/x physicians are more likely to care for historically marginalized communities,3 which has been shown to improve all-cause mortality and reduce racial disparities.4 Additionally, diverse work teams are more innovative and productive.5 Therefore, expanding diversity must include 1) providing equitable policies and access to opportunities and promotions; 2) building inclusive environments in our institutions and practices; and 3) providing space for all people to feel like they can belong, feel respected at work, and genuinely have their opinions and ideas valued. What diversity, equity, inclusion, and belonging provide for us and our patients are avenues to thrive, solve complex problems, and tackle prominent issues within our institutions, workplaces, and communities.

To this end, many academic centers, hospitals, and private practice entities have produced a flurry of new DEI initiatives coupled with titles and roles. Some of these roles have thankfully brought recognition and economic compensation to the people doing this work. Still, as an early career gastroenterologist, you may be offered or are considering taking on a DEI role during your early career. As two underrepresented minority women in medicine who took on DEI roles with their first jobs, we wanted to highlight a few aspects to think about during your early career:

Does the DEI role come with resources?

Historically, DEI efforts were treated as “extra work,” or an activity that was done using one’s own personal time. In addition, this work called upon the small number of physicians underrepresented in medicine, largely uncompensated and with an exorbitant minority tax during a critical moment in establishing their early careers. DEI should no longer be seen as an extracurricular activity but as a vital component of an institution’s success.

If you are considering a DEI role, the first question to ask is, “Does this role come with extra compensation or protected time?” We highly recommend not taking on the role if the answer is no. If your institution or employer is only offering increased minority tax, you are being set up to either fail, burn out, or both. Your employer or institution does not appear to value your time or effort in DEI, and you should interpret their lack of compensation or protected time as such.

If the answer is yes, then here are a few other things to consider: Is there institutional support for you to be successful in your new role? As DEI work challenges you to come up with solutions to combat years of historic marginalization for racial and ethnic minorities, this work can sometimes feel overwhelming and isolating. The importance of the DEI community and mentorship within and outside your institution is critical. You should consider joining DEI working groups or committees through GI national societies, the Association of American Medical Colleges, or the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. You can also connect with a fantastic network of people engaged in this work via social media and lean on friends and colleagues leading similar initiatives across the country.

Other critical logistical questions are if your role will come with administrative support, whether there is a budget for programs or events, and whether your institution/employer will support you in seeking continued professional development for your DEI role.6

Make sure to understand the “ask” from your division, department, or company.

Before confirming you are willing to take on this role, get a clear vision of what you are being asked to accomplish. There are so many opportunities to improve the DEI landscape. Therefore, knowing what you are specifically being asked to do will be critical to your success.

Are you being asked to work on diversity?

Does your institution want you to focus on and improve the recruitment and retention of trainees, physicians, or staff underrepresented in medicine? If so, you will need to have access to all the prior work and statistics. Capture the landscape before your interventions (% underrepresented in medicine [URiM] trainees, % URiM faculty at each level, % of URiM trainees retained as faculty, % of URiM faculty being promoted each year, etc.) This will allow you to determine the outcomes of your proposed improvements or programs.

Is your employer focused on equity?

Are you being asked to think about ways to operationalize improved patient health equity, or are you being asked to build equitable opportunities/programs for career advancement for URiMs at your institution? For either equity issue, you first need to understand the scope of the problem to ask for the necessary resources for a potential solution. Discuss timeline expectations, as equity work is a marathon and may take years to move the needle on any particular issue. This timeline is also critical for your employer to be aware of and support, as unrealistic timelines and expectations will also set you up for failure.

Or, are you being asked to concentrate on inclusion?

Does your institution need an assessment of how inclusive the climate is for trainees, staff, or physicians? Does this assessment align with your division or department’s impression, and how do you plan to work toward potential solutions for improvement?

Although diversity, equity, and inclusion are interconnected entities, they all have distinct objectives and solutions. It is essential to understand your vision and your employer’s vision for this role. If they are not aligned, having early and in-depth conversations about aligning your visions will set you on a path to success in your early career.

Know your why or more importantly, your who?

Early career physicians who are considering taking on DEI work do so for a reason. Being passionate about this type of work is usually born from a personal experience or your deep-rooted values. For us, experiencing and witnessing health disparities for our family members and people who look like us are what initially fueled our passion for this work. Additional experiences with trainees and patients keep us invigorated to continue highlighting the importance of DEI and encourage others to be passionate about DEI’s huge value added. As DEI work can come with challenges, remembering and re-centering on why you are passionate about this work or who you are engaging in this work for can keep you going.

There are several aspects to consider before taking on a DEI role, but overall, the work is rewarding and can be a great addition to the building blocks of your early career. In the short term, you build a DEI community network of peers, mentors, colleagues, and friends beyond your immediate institution and specialty. You also can demonstrate your leadership skills and potential early on in your career. In the long-term, engaging in these types of roles helps build a climate and culture that is conducive to enacting change for our patients and communities, including advancing healthcare equity and working toward recruitment, retention, and expansion efforts for our trainees and faculty. Overall, we think this type of work in your early career can be an integral part of your personal and professional development, while also having an impact that ripples beyond the walls of the endoscopy suite.

Dr. Fritz is an assistant professor of medicine in the division of gastroenterology at Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis. Dr. Rodriguez is a gastroenterologist with Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. Neither Dr. Rodriguez nor Dr. Fritz disclosed no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Santhosh L,Babik JM. Trends in racial and ethnic diversity in internal medicine subspecialty fellowships from 2006 to 2018. JAMA Network Open 2020;3:e1920482-e1920482.

2. Colleges AoAM. Physician Specialty Data Report/Active physicians who identified as Black or African-American, 2021. 2022.

3. Komaromy M et al. The role of black and Hispanic physicians in providing health care for underserved populations. New England Journal of Medicine 1996;334:1305-10.

4. Snyder JE et al. Black representation in the primary care physician workforce and its association with population life expectancy and mortality rates in the US. JAMA Network Open 2023;6:e236687-e236687.

5. Page S. Diversity bonuses and the business case. The Diversity Bonus: Princeton University Press, 2017:184-208.

6. Vela MB et al. Diversity, equity, and inclusion officer position available: Proceed with caution. Journal of Graduate Medical Education 2021;13:771-3.

Helpful resources

Diversity and Inclusion Toolkit Resources, AAMC

Blackinggastro.org, The Association of Black Gastroenterologists and Hepatologists (ABGH)

Podcast: Clinical Problem Solvers: Anti-Racism in Medicine

Selecting therapies in moderate to severe inflammatory bowel disease: Key factors in decision making

Despite new advances in treatment, head to head clinical trials, which are considered the gold standard when comparing therapies, remain limited. Other comparative effectiveness studies and network meta-analyses are the currently available substitutes to guide decision making.1

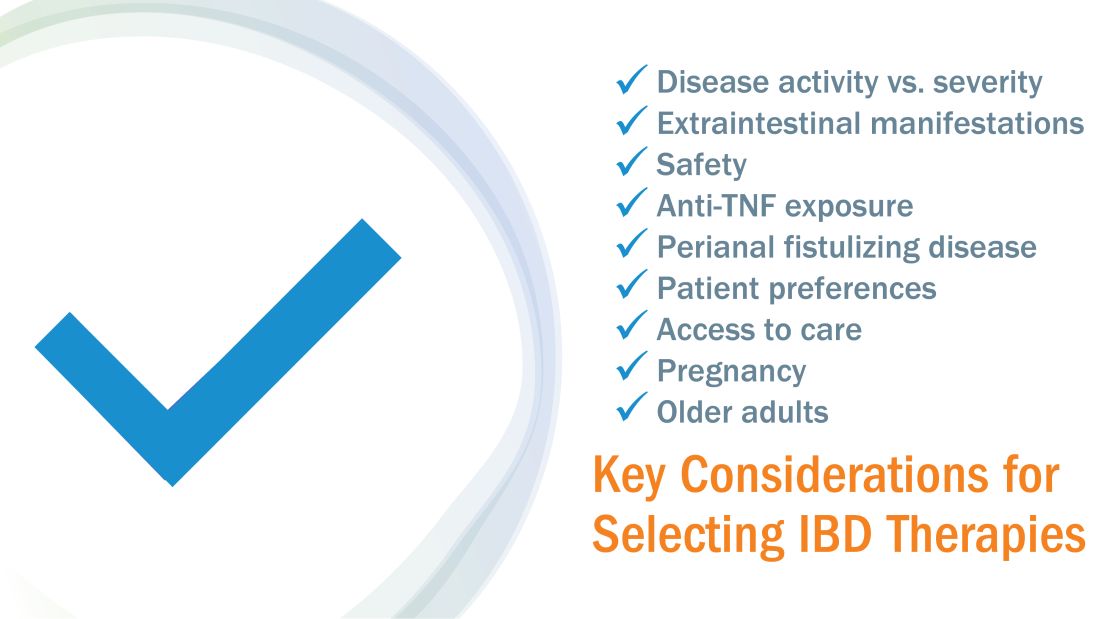

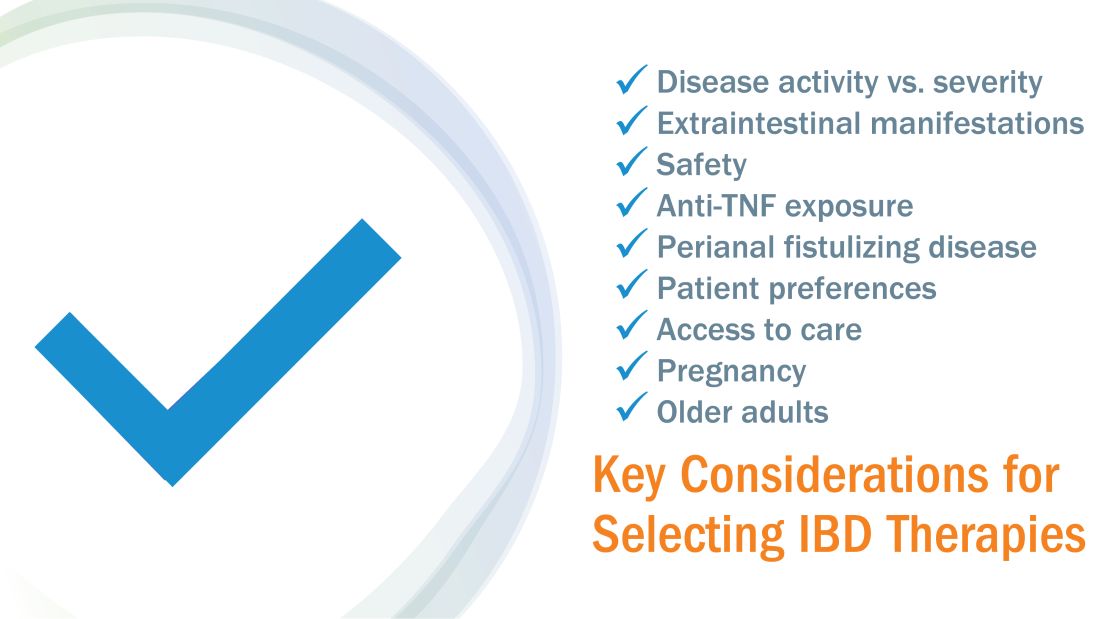

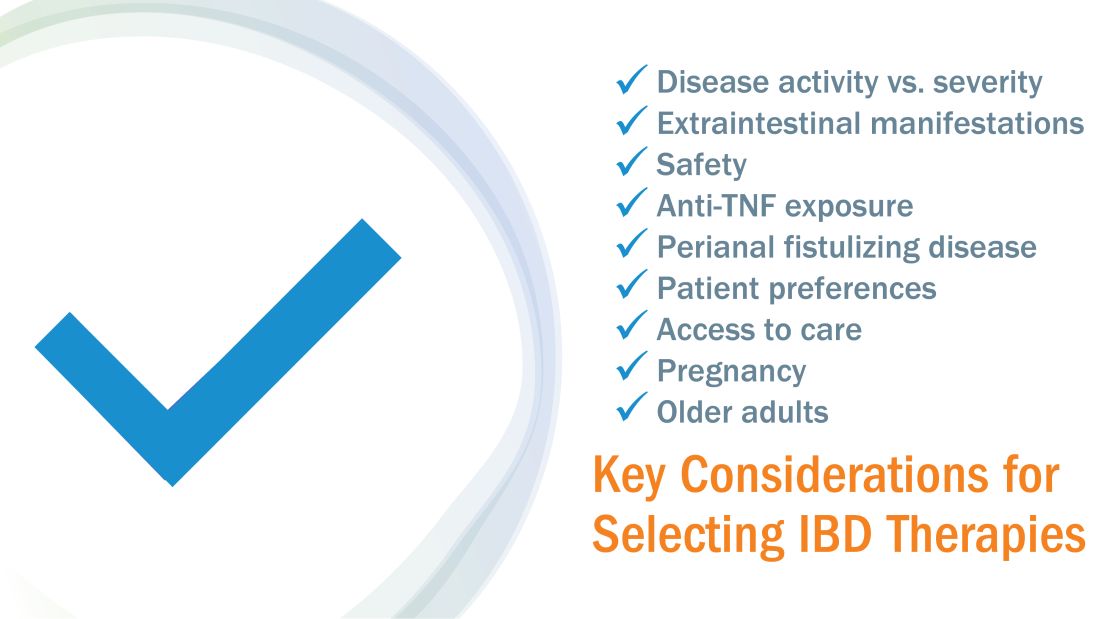

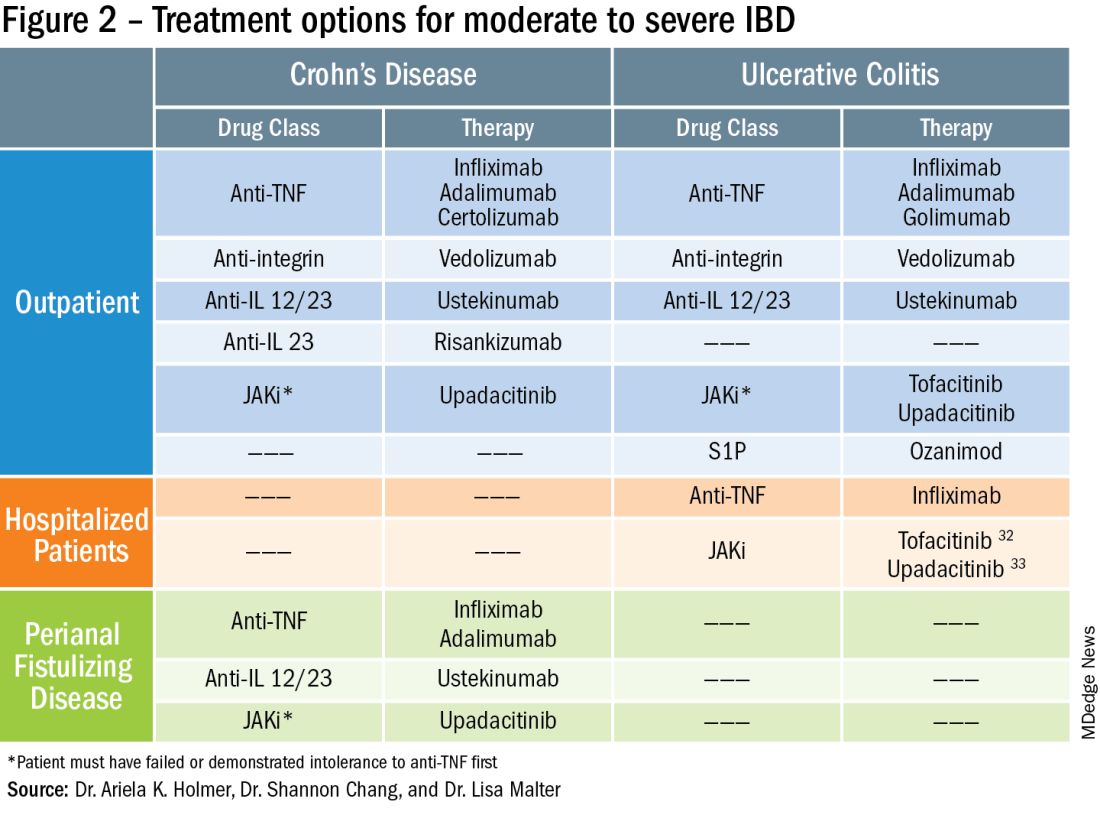

While efficacy is often considered first when choosing a drug, other critical factors play a role in tailoring a treatment plan. This article focuses on key considerations to help guide clinical decision making when treating patients with moderate to severe IBD (Figure 1).

Disease activity versus severity

Both disease activity and disease severity should be considered when evaluating a patient for treatment. Disease activity is a cross-sectional view of one’s signs and symptoms which can vary visit to visit. Standardized indices measure disease activity in both Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC).2,3 Disease severity encompasses the overall prognosis of disease over time and includes factors such as the presence or absence of high risk features, prior medication exposure, history of surgery, hospitalizations and the impact on quality of life.4

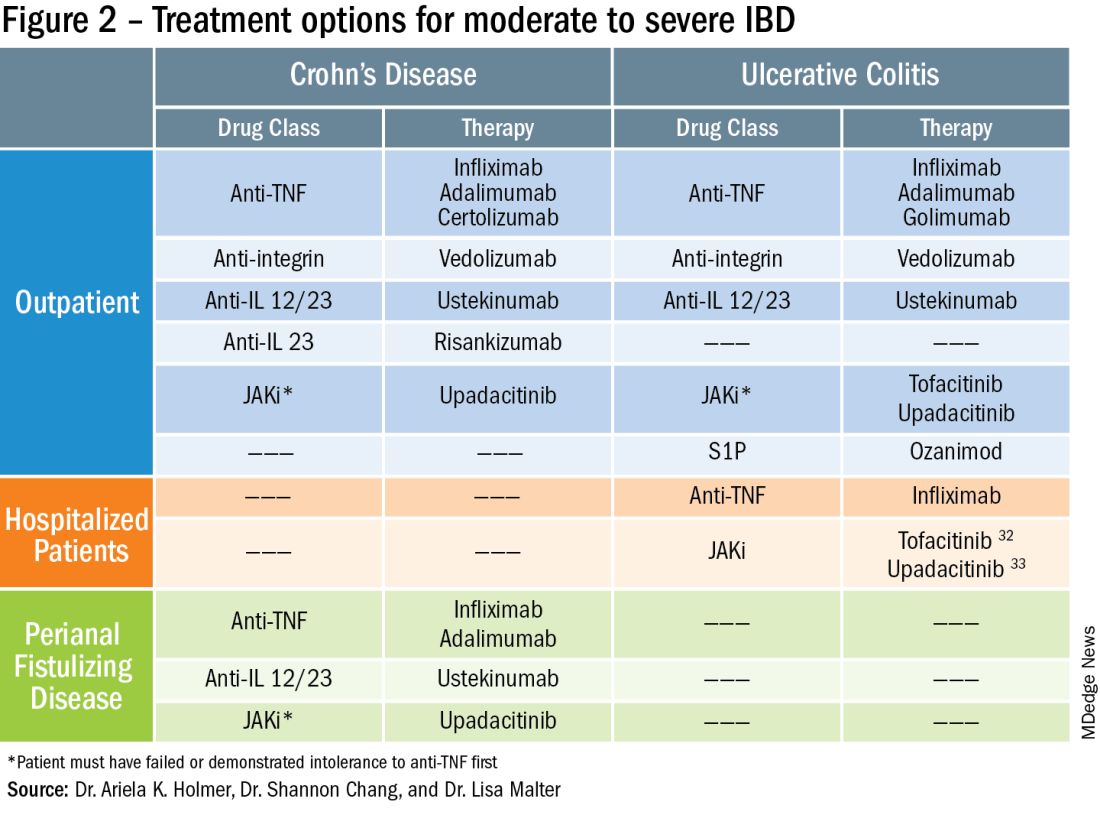

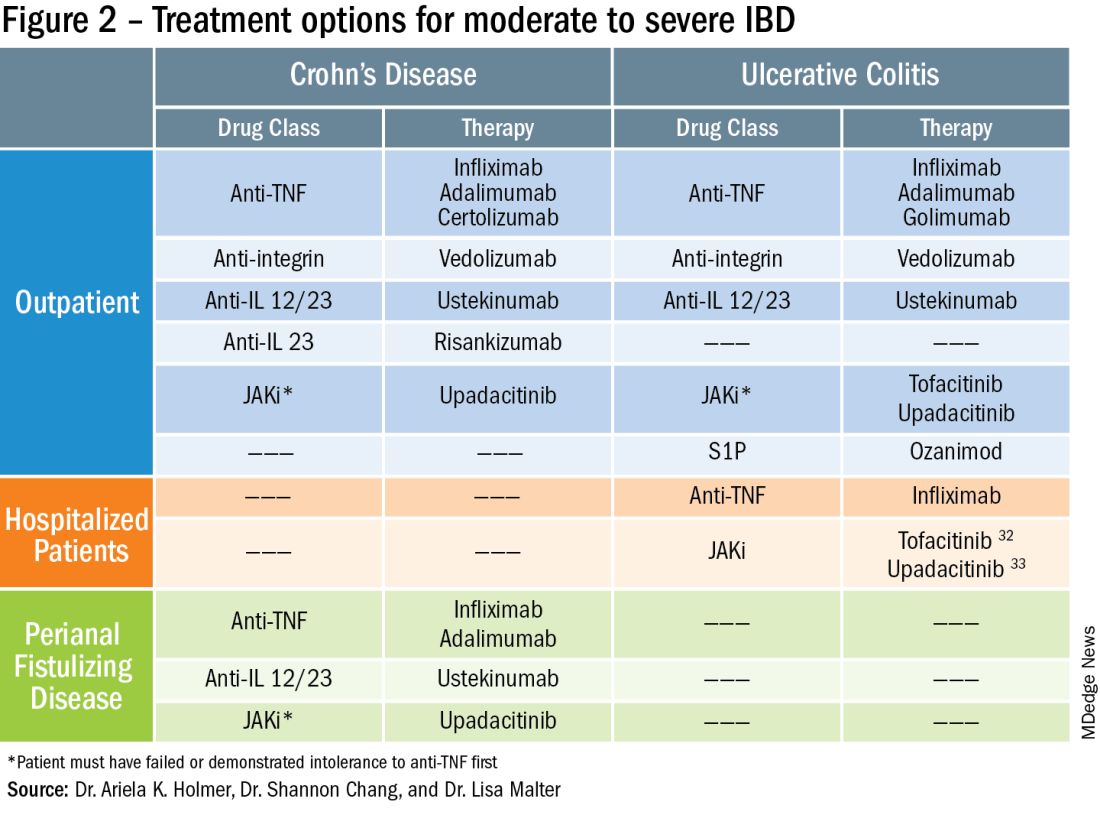

To prevent disease complications, the goals of treatment should be aimed at both reducing active symptoms (disease activity) but also healing mucosal inflammation, preventing disease progression (disease severity) and downstream sequelae including cancer, hospitalization or surgery.5 Determining the best treatment option takes disease activity and severity into account, in addition to the other key factors listed below (Figure 2).

Extraintestinal manifestations

Inflammation of organs outside of the gastrointestinal tract is common and can occur in up to 50% of patients with IBD.6 The most prevalent extraintestinal manifestations (EIMs) involve the skin and joints, which will be the primary focus in this article. We will also focus on treatment options with the most evidence supporting their use. Peripheral arthritis is often associated with intestinal inflammation, and treatment of underlying IBD can simultaneously improve joint symptoms. Conversely, axial spondyloarthritis does not commonly parallel intestinal inflammation. Anti–tumor necrosis factor (TNF) agents including infliximab and adalimumab are effective for the treatment of both peripheral and axial disease.6

Ustekinumab, an interleukin (IL)-12/23 inhibitor, may be effective for peripheral arthritis, however is ineffective for the treatment of axial spondyloarthritis.6 Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors which include tofacitinib and upadacitinib are oral small molecules used to treat peripheral and axial spondyloarthritis and have more recently been approved for moderate to severe IBD.6,7

Erythema nodosum (EN) and pyoderma gangrenosum (PG) are skin manifestations seen in patients with IBD. EN appears as subcutaneous nodules and parallels intestinal inflammation, while PG consists of violaceous, ulcerated plaques, and presents with more significant pain. Anti-TNFs are effective for both EN and PG, with infliximab being the only biologic studied in a randomized control trial of patients with PG.8 In addition, small case reports have described some benefit from ustekinumab and upadacitinib in the treatment of PG.9,10

Safety

The safety of IBD therapies is a key consideration and often the most important factor to patients when choosing a treatment option. It is important to note that untreated disease is associated with significant morbidity, and should be weighed when discussing risks of medications with patients. In general, anti-TNFs and JAK inhibitors may be associated with an increased risk of infection and malignancy, while ustekinumab, vedolizumab, risankizumab and ozanimod offer a more favorable safety profile.11 In large registries and observational studies, infliximab was associated with up to a two times greater risk of serious infection as compared to nonbiologic medications, with the most common infections being pneumonia, sepsis and herpes zoster.12 JAK inhibitors are associated with an increased risk of herpes zoster infection, with a dose dependent effect seen in the maintenance clinical trials with tofacitinib.7

Ozanimod may be associated with atrioventricular conduction delays and bradycardia, however long-term safety data has reported a low incidence of serious cardiac related adverse events.13 Overall, though risks of infection may vary with different therapies, other consistent risk factors associated with greater rates of serious infection include prolonged corticosteroid use, combination therapy with thiopurines, and disease severity. Anti-TNFs have also been associated with a somewhat increased risk of lymphoma, increased when used in combination with thiopurines. Reassuringly, however, in patients with a prior history of cancer, anti-TNFs and non-TNF biologics have not been found to increase the risk of new or recurrent cancer.14

Ultimately, in patients with a prior history of cancer, the choice of biologic or small molecule should be made in collaboration with a patient’s oncologist.

Anti-TNF exposure

Anti-TNFs were the first available biologics for the treatment of IBD. After the approval of vedolizumab in 2014, the first non-TNF biologic, many patients enrolled in clinical trials thereafter had already tried and failed anti-TNFs. In general, exposure to anti-TNFs may reduce the efficacy of a future biologic. In patients treated with vedolizumab, endoscopic and clinical outcomes were negatively impacted by prior anti-TNF exposure.15 However, in VARSITY, a head-to-head clinical trial where 20% of patients with UC were previously exposed to anti-TNFs other than adalimumab, vedolizumab had significantly higher rates of clinical remission and endoscopic improvement compared to adalimumab.16 Clinical remission rates with tofacitinib were not impacted by exposure to anti-TNF treatment, and similar findings were observed with ustekinumab.7,17 Risankizumab, a newly approved selective anti-IL23, also does not appear to be impacted by prior anti-TNF exposure by demonstrating similar rates of clinical remission regardless of biologic exposure status.18 Therefore, in patients with prior history of anti-TNF use, consideration of ustekinumab, risankizumab or JAK inhibitors as second line agents may be more favorable as compared to vedolizumab.

Perianal fistulizing disease

Perianal fistulizing disease can affect up to one-third of patients with CD and significantly impact a patient’s quality of life.19 The most robust data for the treatment of perianal fistulizing disease includes the use of infliximab with up to one-third of patients on maintenance therapy achieving complete resolution of fistula drainage. While no head-to-head trials compare combination therapy with infliximab plus immunomodulators versus infliximab alone for this indication specifically, one observational study demonstrated higher rates of fistula closure with combination therapy as compared to infliximab mono-therapy.19 In a post hoc analysis, higher infliximab concentrations at week 14 were associated with greater fistula response and remission rates.20 In patients with perianal disease, ustekinumab and vedolizumab may also be an effective treatment option by promoting resolution of fistula drainage.21

More recently, emerging data demonstrate that upadacitinib may be an excellent option as a second-line treatment for perianal disease in patients who have failed anti-TNF therapy. Use of upadacitinib was associated with greater rates of complete resolution of fistula drainage and higher rates of external fistula closure (Figure 2).22 Lastly, as an alternative to medical therapy, mesenchymal stem cell therapy has also shown to improve fistula drainage and improve external fistula openings in patients with CD.23 Stem cell therapy is only available through clinical trials at this time.

Patient preferences

Overall, data are lacking for evaluating patient preferences in treatment options for IBD especially with the recent increase in therapeutic options. One survey demonstrated that patient preferences were most impacted by the possibility of improving abdominal pain, with patients accepting additional risk of treatment side effects in order to reduce their abdominal pain.24 An oral route of administration and improving fatigue and bowel urgency were similarly important to patients. Patient preferences can also be highly variable with some valuing avoidance of corticosteroid use while others valuing avoidance of symptoms or risks of medication side effects and surgery. It is important to tailor the discussion on treatment strategies to each individual patient and inquire about the patient’s lifestyle, medical history, and value system, which may impact their treatment preferences utilizing shared decision making.

Access to treatment including the role of social determinants of health

The expanded therapeutic armamentarium has the potential to help patients achieve the current goals of care in IBD. However, these medications are not available to all patients due to numerous barriers including step therapy payer policies, prohibitive costs, insurance prior authorizations, and the role of social determinants of health and proximity to IBD expertise.25 While clinicians work with patients to determine the best treatment option, more often than not, the decision lies with the insurance payer. Step therapy is the protocol used by insurance companies that requires patients to try a lower-cost medication and fail to respond before they approve the originally requested treatment. This can lead to treatment delays, progression of disease, and disease complications. The option to incorporate the use of biosimilars, currently available for anti-TNFs, and other biologics in the near future, will reduce cost and potentially increase access.26 Additionally, working with a clinical pharmacist to navigate access and utilize patient assistance programs may help overcome cost related barriers to treatment and prevent delays in care.

Socioeconomic status has been shown to impact IBD disease outcomes, and compliance rates in treatment vary depending on race and ethnicity.27 Certain racial and ethnic groups remain vulnerable and may require additional support to achieve treatment goals. For example, disparities in health literacy in patients with IBD have been demonstrated with older black men at risk.28 Additionally, the patient’s proximity to their health care facility may impact treatment options. Most IBD centers are located in metropolitan areas and numerous “IBD deserts” exist, potentially limiting therapies for patients from more remote/rural settings.29 Access to treatment and the interplay of social determinants of health can have a large role in therapy selection.

Special considerations: Pregnancy and older adults

Certain patient populations warrant special consideration when approaching treatment strategies. Pregnancy in IBD will not be addressed in full depth in this article, however a key takeaway is that planning is critical and providers should emphasize the importance of steroid-free clinical remission for at least 3 months before conception.30 Additionally, biologic use during pregnancy has not been shown to increase adverse fetal outcomes, thus should be continued to minimize disease flare. Newer novel small molecules are generally avoided during pregnancy due to limited available safety data.

Older adults are the largest growing patient population with IBD. Frailty, or a state of decreased reserve, is more commonly observed in older patients and has been shown to increase adverse events including hospitalization and mortaility.31 Ultimately reducing polypharmacy, ensuring adequate nutrition, minimizing corticosteroid exposure and avoiding undertreatment of active IBD are all key in optimizing outcomes in an older patient with IBD.

Conclusion

When discussing treatment options with patients with IBD, it is important to individualize care and share the decision-making process with patients. Goals include improving symptoms and quality of life while working to achieve the goal of healing intestinal inflammation. In summary, this article can serve as a guide to clinicians for key factors in decision making when selecting therapies in moderate to severe IBD.

Dr. Holmer is a gastroenterologist with NYU Langone Health specializing in inflammatory bowel disease. Dr. Chang is director of clinical operations for the NYU Langone Health Inflammatory Bowel Disease Center. Dr. Malter is director of education for the Inflammatory Bowel Disease Center at NYU Langone Health and director of the inflammatory bowel disease program at Bellevue Hospital Center. Follow Dr. Holmer on X (formerly Twitter) at @HolmerMd and Dr. Chang @shannonchangmd. Dr. Holmer disclosed affiliations with Pfizer, Bristol Myers Squibb, and AvevoRx. Dr. Chang disclosed affiliations with Pfizer and Bristol Myers Squibb. Dr. Malter disclosed receiving educational grants form Abbvie, Janssen, Pfizer and Takeda, and serving on the advisory boards of AbbVie, Bristol Myers Squibb, Celltrion, Janssen, Merck, and Takeda.

References

1. Chang S et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2023 Aug 24. doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000002485.

2. Harvey RF et al. The Lancet. 1980;1:514.

3. Lewis JD et al. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. 2008;14:1660-1666.

4. Siegel CA et al. Gut. 2018;67(2):244-54.

5. Peyrin-Biroulet L et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110:1324-38

6. Rogler G et al. Gastroenterology. 2021;161:1118-32.

7. Sandborn WJ et al. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:1723-36.

8. Brooklyn TN et al. Gut. 2006;55:505-9.

9. Fahmy M et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:794-5.

10. Van Eycken L et al. JAAD Case Rep. 2023;37:89-91.

11. Lasa JS et al. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;7:161-70.

12. Lichtenstein GR et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2018;24:490-501.

13. Long MD et al. Gastroenterology. 2022;162:S-5-S-6.

14. Holmer AK et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol.2023;21:1598-1606.e5.

15. Sands BE et al. Gastroenterology. 2014;147:618-27.e3.

16. Sands BE et al. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:1215-26.

17. Sands BE et al. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:1201-14.

18. D’Haens G et al. Lancet. 2022;399:2015-30.

19. Bouguen G et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11:975-81.e1-4.

20. Papamichael K et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2021;116:1007-14.

21. Shehab M et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2023;29:367-75.

22. Colombel JF et al. J Crohns Colitis. 2023;17:i620-i623.

23. Garcia-Olmo D et al. Dis Colon Rectum. 2022;65:713-20.

24. Louis E et al. J Crohns Colitis. 2023;17:231-9.

25. Rubin DT et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2017;23:224-32.

26. Gulacsi L et al. Curr Med Chem. 2019;26:259-69.

27. Cai Q et al. BMC Gastroenterol. 2022;22:545.

28. Dos Santos Marques IC et al. Crohns Colitis 360. 2020 Oct;2(4):otaa076.

29. Deepak P et al. Gastroenterology. 2023;165:11-15.

30. Mahadevan U et al. Gastroenterology. 2019;156:1508-24.

31. Faye AS et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2022;28:126-32.

32. Berinstein JA et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;19:2112-20.e1.

33. Levine J et al. Gastroenterology. 2023;164:S103-S104.

Despite new advances in treatment, head to head clinical trials, which are considered the gold standard when comparing therapies, remain limited. Other comparative effectiveness studies and network meta-analyses are the currently available substitutes to guide decision making.1

While efficacy is often considered first when choosing a drug, other critical factors play a role in tailoring a treatment plan. This article focuses on key considerations to help guide clinical decision making when treating patients with moderate to severe IBD (Figure 1).

Disease activity versus severity

Both disease activity and disease severity should be considered when evaluating a patient for treatment. Disease activity is a cross-sectional view of one’s signs and symptoms which can vary visit to visit. Standardized indices measure disease activity in both Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC).2,3 Disease severity encompasses the overall prognosis of disease over time and includes factors such as the presence or absence of high risk features, prior medication exposure, history of surgery, hospitalizations and the impact on quality of life.4

To prevent disease complications, the goals of treatment should be aimed at both reducing active symptoms (disease activity) but also healing mucosal inflammation, preventing disease progression (disease severity) and downstream sequelae including cancer, hospitalization or surgery.5 Determining the best treatment option takes disease activity and severity into account, in addition to the other key factors listed below (Figure 2).

Extraintestinal manifestations

Inflammation of organs outside of the gastrointestinal tract is common and can occur in up to 50% of patients with IBD.6 The most prevalent extraintestinal manifestations (EIMs) involve the skin and joints, which will be the primary focus in this article. We will also focus on treatment options with the most evidence supporting their use. Peripheral arthritis is often associated with intestinal inflammation, and treatment of underlying IBD can simultaneously improve joint symptoms. Conversely, axial spondyloarthritis does not commonly parallel intestinal inflammation. Anti–tumor necrosis factor (TNF) agents including infliximab and adalimumab are effective for the treatment of both peripheral and axial disease.6

Ustekinumab, an interleukin (IL)-12/23 inhibitor, may be effective for peripheral arthritis, however is ineffective for the treatment of axial spondyloarthritis.6 Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors which include tofacitinib and upadacitinib are oral small molecules used to treat peripheral and axial spondyloarthritis and have more recently been approved for moderate to severe IBD.6,7

Erythema nodosum (EN) and pyoderma gangrenosum (PG) are skin manifestations seen in patients with IBD. EN appears as subcutaneous nodules and parallels intestinal inflammation, while PG consists of violaceous, ulcerated plaques, and presents with more significant pain. Anti-TNFs are effective for both EN and PG, with infliximab being the only biologic studied in a randomized control trial of patients with PG.8 In addition, small case reports have described some benefit from ustekinumab and upadacitinib in the treatment of PG.9,10

Safety

The safety of IBD therapies is a key consideration and often the most important factor to patients when choosing a treatment option. It is important to note that untreated disease is associated with significant morbidity, and should be weighed when discussing risks of medications with patients. In general, anti-TNFs and JAK inhibitors may be associated with an increased risk of infection and malignancy, while ustekinumab, vedolizumab, risankizumab and ozanimod offer a more favorable safety profile.11 In large registries and observational studies, infliximab was associated with up to a two times greater risk of serious infection as compared to nonbiologic medications, with the most common infections being pneumonia, sepsis and herpes zoster.12 JAK inhibitors are associated with an increased risk of herpes zoster infection, with a dose dependent effect seen in the maintenance clinical trials with tofacitinib.7

Ozanimod may be associated with atrioventricular conduction delays and bradycardia, however long-term safety data has reported a low incidence of serious cardiac related adverse events.13 Overall, though risks of infection may vary with different therapies, other consistent risk factors associated with greater rates of serious infection include prolonged corticosteroid use, combination therapy with thiopurines, and disease severity. Anti-TNFs have also been associated with a somewhat increased risk of lymphoma, increased when used in combination with thiopurines. Reassuringly, however, in patients with a prior history of cancer, anti-TNFs and non-TNF biologics have not been found to increase the risk of new or recurrent cancer.14

Ultimately, in patients with a prior history of cancer, the choice of biologic or small molecule should be made in collaboration with a patient’s oncologist.

Anti-TNF exposure

Anti-TNFs were the first available biologics for the treatment of IBD. After the approval of vedolizumab in 2014, the first non-TNF biologic, many patients enrolled in clinical trials thereafter had already tried and failed anti-TNFs. In general, exposure to anti-TNFs may reduce the efficacy of a future biologic. In patients treated with vedolizumab, endoscopic and clinical outcomes were negatively impacted by prior anti-TNF exposure.15 However, in VARSITY, a head-to-head clinical trial where 20% of patients with UC were previously exposed to anti-TNFs other than adalimumab, vedolizumab had significantly higher rates of clinical remission and endoscopic improvement compared to adalimumab.16 Clinical remission rates with tofacitinib were not impacted by exposure to anti-TNF treatment, and similar findings were observed with ustekinumab.7,17 Risankizumab, a newly approved selective anti-IL23, also does not appear to be impacted by prior anti-TNF exposure by demonstrating similar rates of clinical remission regardless of biologic exposure status.18 Therefore, in patients with prior history of anti-TNF use, consideration of ustekinumab, risankizumab or JAK inhibitors as second line agents may be more favorable as compared to vedolizumab.

Perianal fistulizing disease

Perianal fistulizing disease can affect up to one-third of patients with CD and significantly impact a patient’s quality of life.19 The most robust data for the treatment of perianal fistulizing disease includes the use of infliximab with up to one-third of patients on maintenance therapy achieving complete resolution of fistula drainage. While no head-to-head trials compare combination therapy with infliximab plus immunomodulators versus infliximab alone for this indication specifically, one observational study demonstrated higher rates of fistula closure with combination therapy as compared to infliximab mono-therapy.19 In a post hoc analysis, higher infliximab concentrations at week 14 were associated with greater fistula response and remission rates.20 In patients with perianal disease, ustekinumab and vedolizumab may also be an effective treatment option by promoting resolution of fistula drainage.21

More recently, emerging data demonstrate that upadacitinib may be an excellent option as a second-line treatment for perianal disease in patients who have failed anti-TNF therapy. Use of upadacitinib was associated with greater rates of complete resolution of fistula drainage and higher rates of external fistula closure (Figure 2).22 Lastly, as an alternative to medical therapy, mesenchymal stem cell therapy has also shown to improve fistula drainage and improve external fistula openings in patients with CD.23 Stem cell therapy is only available through clinical trials at this time.

Patient preferences

Overall, data are lacking for evaluating patient preferences in treatment options for IBD especially with the recent increase in therapeutic options. One survey demonstrated that patient preferences were most impacted by the possibility of improving abdominal pain, with patients accepting additional risk of treatment side effects in order to reduce their abdominal pain.24 An oral route of administration and improving fatigue and bowel urgency were similarly important to patients. Patient preferences can also be highly variable with some valuing avoidance of corticosteroid use while others valuing avoidance of symptoms or risks of medication side effects and surgery. It is important to tailor the discussion on treatment strategies to each individual patient and inquire about the patient’s lifestyle, medical history, and value system, which may impact their treatment preferences utilizing shared decision making.

Access to treatment including the role of social determinants of health

The expanded therapeutic armamentarium has the potential to help patients achieve the current goals of care in IBD. However, these medications are not available to all patients due to numerous barriers including step therapy payer policies, prohibitive costs, insurance prior authorizations, and the role of social determinants of health and proximity to IBD expertise.25 While clinicians work with patients to determine the best treatment option, more often than not, the decision lies with the insurance payer. Step therapy is the protocol used by insurance companies that requires patients to try a lower-cost medication and fail to respond before they approve the originally requested treatment. This can lead to treatment delays, progression of disease, and disease complications. The option to incorporate the use of biosimilars, currently available for anti-TNFs, and other biologics in the near future, will reduce cost and potentially increase access.26 Additionally, working with a clinical pharmacist to navigate access and utilize patient assistance programs may help overcome cost related barriers to treatment and prevent delays in care.

Socioeconomic status has been shown to impact IBD disease outcomes, and compliance rates in treatment vary depending on race and ethnicity.27 Certain racial and ethnic groups remain vulnerable and may require additional support to achieve treatment goals. For example, disparities in health literacy in patients with IBD have been demonstrated with older black men at risk.28 Additionally, the patient’s proximity to their health care facility may impact treatment options. Most IBD centers are located in metropolitan areas and numerous “IBD deserts” exist, potentially limiting therapies for patients from more remote/rural settings.29 Access to treatment and the interplay of social determinants of health can have a large role in therapy selection.

Special considerations: Pregnancy and older adults

Certain patient populations warrant special consideration when approaching treatment strategies. Pregnancy in IBD will not be addressed in full depth in this article, however a key takeaway is that planning is critical and providers should emphasize the importance of steroid-free clinical remission for at least 3 months before conception.30 Additionally, biologic use during pregnancy has not been shown to increase adverse fetal outcomes, thus should be continued to minimize disease flare. Newer novel small molecules are generally avoided during pregnancy due to limited available safety data.

Older adults are the largest growing patient population with IBD. Frailty, or a state of decreased reserve, is more commonly observed in older patients and has been shown to increase adverse events including hospitalization and mortaility.31 Ultimately reducing polypharmacy, ensuring adequate nutrition, minimizing corticosteroid exposure and avoiding undertreatment of active IBD are all key in optimizing outcomes in an older patient with IBD.

Conclusion

When discussing treatment options with patients with IBD, it is important to individualize care and share the decision-making process with patients. Goals include improving symptoms and quality of life while working to achieve the goal of healing intestinal inflammation. In summary, this article can serve as a guide to clinicians for key factors in decision making when selecting therapies in moderate to severe IBD.

Dr. Holmer is a gastroenterologist with NYU Langone Health specializing in inflammatory bowel disease. Dr. Chang is director of clinical operations for the NYU Langone Health Inflammatory Bowel Disease Center. Dr. Malter is director of education for the Inflammatory Bowel Disease Center at NYU Langone Health and director of the inflammatory bowel disease program at Bellevue Hospital Center. Follow Dr. Holmer on X (formerly Twitter) at @HolmerMd and Dr. Chang @shannonchangmd. Dr. Holmer disclosed affiliations with Pfizer, Bristol Myers Squibb, and AvevoRx. Dr. Chang disclosed affiliations with Pfizer and Bristol Myers Squibb. Dr. Malter disclosed receiving educational grants form Abbvie, Janssen, Pfizer and Takeda, and serving on the advisory boards of AbbVie, Bristol Myers Squibb, Celltrion, Janssen, Merck, and Takeda.

References

1. Chang S et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2023 Aug 24. doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000002485.

2. Harvey RF et al. The Lancet. 1980;1:514.

3. Lewis JD et al. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. 2008;14:1660-1666.

4. Siegel CA et al. Gut. 2018;67(2):244-54.

5. Peyrin-Biroulet L et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110:1324-38

6. Rogler G et al. Gastroenterology. 2021;161:1118-32.

7. Sandborn WJ et al. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:1723-36.

8. Brooklyn TN et al. Gut. 2006;55:505-9.

9. Fahmy M et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:794-5.

10. Van Eycken L et al. JAAD Case Rep. 2023;37:89-91.

11. Lasa JS et al. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;7:161-70.

12. Lichtenstein GR et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2018;24:490-501.

13. Long MD et al. Gastroenterology. 2022;162:S-5-S-6.

14. Holmer AK et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol.2023;21:1598-1606.e5.

15. Sands BE et al. Gastroenterology. 2014;147:618-27.e3.

16. Sands BE et al. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:1215-26.

17. Sands BE et al. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:1201-14.

18. D’Haens G et al. Lancet. 2022;399:2015-30.

19. Bouguen G et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11:975-81.e1-4.

20. Papamichael K et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2021;116:1007-14.

21. Shehab M et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2023;29:367-75.

22. Colombel JF et al. J Crohns Colitis. 2023;17:i620-i623.

23. Garcia-Olmo D et al. Dis Colon Rectum. 2022;65:713-20.

24. Louis E et al. J Crohns Colitis. 2023;17:231-9.

25. Rubin DT et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2017;23:224-32.

26. Gulacsi L et al. Curr Med Chem. 2019;26:259-69.

27. Cai Q et al. BMC Gastroenterol. 2022;22:545.

28. Dos Santos Marques IC et al. Crohns Colitis 360. 2020 Oct;2(4):otaa076.

29. Deepak P et al. Gastroenterology. 2023;165:11-15.

30. Mahadevan U et al. Gastroenterology. 2019;156:1508-24.

31. Faye AS et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2022;28:126-32.

32. Berinstein JA et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;19:2112-20.e1.

33. Levine J et al. Gastroenterology. 2023;164:S103-S104.

Despite new advances in treatment, head to head clinical trials, which are considered the gold standard when comparing therapies, remain limited. Other comparative effectiveness studies and network meta-analyses are the currently available substitutes to guide decision making.1

While efficacy is often considered first when choosing a drug, other critical factors play a role in tailoring a treatment plan. This article focuses on key considerations to help guide clinical decision making when treating patients with moderate to severe IBD (Figure 1).

Disease activity versus severity

Both disease activity and disease severity should be considered when evaluating a patient for treatment. Disease activity is a cross-sectional view of one’s signs and symptoms which can vary visit to visit. Standardized indices measure disease activity in both Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC).2,3 Disease severity encompasses the overall prognosis of disease over time and includes factors such as the presence or absence of high risk features, prior medication exposure, history of surgery, hospitalizations and the impact on quality of life.4

To prevent disease complications, the goals of treatment should be aimed at both reducing active symptoms (disease activity) but also healing mucosal inflammation, preventing disease progression (disease severity) and downstream sequelae including cancer, hospitalization or surgery.5 Determining the best treatment option takes disease activity and severity into account, in addition to the other key factors listed below (Figure 2).

Extraintestinal manifestations

Inflammation of organs outside of the gastrointestinal tract is common and can occur in up to 50% of patients with IBD.6 The most prevalent extraintestinal manifestations (EIMs) involve the skin and joints, which will be the primary focus in this article. We will also focus on treatment options with the most evidence supporting their use. Peripheral arthritis is often associated with intestinal inflammation, and treatment of underlying IBD can simultaneously improve joint symptoms. Conversely, axial spondyloarthritis does not commonly parallel intestinal inflammation. Anti–tumor necrosis factor (TNF) agents including infliximab and adalimumab are effective for the treatment of both peripheral and axial disease.6

Ustekinumab, an interleukin (IL)-12/23 inhibitor, may be effective for peripheral arthritis, however is ineffective for the treatment of axial spondyloarthritis.6 Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors which include tofacitinib and upadacitinib are oral small molecules used to treat peripheral and axial spondyloarthritis and have more recently been approved for moderate to severe IBD.6,7

Erythema nodosum (EN) and pyoderma gangrenosum (PG) are skin manifestations seen in patients with IBD. EN appears as subcutaneous nodules and parallels intestinal inflammation, while PG consists of violaceous, ulcerated plaques, and presents with more significant pain. Anti-TNFs are effective for both EN and PG, with infliximab being the only biologic studied in a randomized control trial of patients with PG.8 In addition, small case reports have described some benefit from ustekinumab and upadacitinib in the treatment of PG.9,10

Safety

The safety of IBD therapies is a key consideration and often the most important factor to patients when choosing a treatment option. It is important to note that untreated disease is associated with significant morbidity, and should be weighed when discussing risks of medications with patients. In general, anti-TNFs and JAK inhibitors may be associated with an increased risk of infection and malignancy, while ustekinumab, vedolizumab, risankizumab and ozanimod offer a more favorable safety profile.11 In large registries and observational studies, infliximab was associated with up to a two times greater risk of serious infection as compared to nonbiologic medications, with the most common infections being pneumonia, sepsis and herpes zoster.12 JAK inhibitors are associated with an increased risk of herpes zoster infection, with a dose dependent effect seen in the maintenance clinical trials with tofacitinib.7

Ozanimod may be associated with atrioventricular conduction delays and bradycardia, however long-term safety data has reported a low incidence of serious cardiac related adverse events.13 Overall, though risks of infection may vary with different therapies, other consistent risk factors associated with greater rates of serious infection include prolonged corticosteroid use, combination therapy with thiopurines, and disease severity. Anti-TNFs have also been associated with a somewhat increased risk of lymphoma, increased when used in combination with thiopurines. Reassuringly, however, in patients with a prior history of cancer, anti-TNFs and non-TNF biologics have not been found to increase the risk of new or recurrent cancer.14

Ultimately, in patients with a prior history of cancer, the choice of biologic or small molecule should be made in collaboration with a patient’s oncologist.

Anti-TNF exposure

Anti-TNFs were the first available biologics for the treatment of IBD. After the approval of vedolizumab in 2014, the first non-TNF biologic, many patients enrolled in clinical trials thereafter had already tried and failed anti-TNFs. In general, exposure to anti-TNFs may reduce the efficacy of a future biologic. In patients treated with vedolizumab, endoscopic and clinical outcomes were negatively impacted by prior anti-TNF exposure.15 However, in VARSITY, a head-to-head clinical trial where 20% of patients with UC were previously exposed to anti-TNFs other than adalimumab, vedolizumab had significantly higher rates of clinical remission and endoscopic improvement compared to adalimumab.16 Clinical remission rates with tofacitinib were not impacted by exposure to anti-TNF treatment, and similar findings were observed with ustekinumab.7,17 Risankizumab, a newly approved selective anti-IL23, also does not appear to be impacted by prior anti-TNF exposure by demonstrating similar rates of clinical remission regardless of biologic exposure status.18 Therefore, in patients with prior history of anti-TNF use, consideration of ustekinumab, risankizumab or JAK inhibitors as second line agents may be more favorable as compared to vedolizumab.

Perianal fistulizing disease

Perianal fistulizing disease can affect up to one-third of patients with CD and significantly impact a patient’s quality of life.19 The most robust data for the treatment of perianal fistulizing disease includes the use of infliximab with up to one-third of patients on maintenance therapy achieving complete resolution of fistula drainage. While no head-to-head trials compare combination therapy with infliximab plus immunomodulators versus infliximab alone for this indication specifically, one observational study demonstrated higher rates of fistula closure with combination therapy as compared to infliximab mono-therapy.19 In a post hoc analysis, higher infliximab concentrations at week 14 were associated with greater fistula response and remission rates.20 In patients with perianal disease, ustekinumab and vedolizumab may also be an effective treatment option by promoting resolution of fistula drainage.21

More recently, emerging data demonstrate that upadacitinib may be an excellent option as a second-line treatment for perianal disease in patients who have failed anti-TNF therapy. Use of upadacitinib was associated with greater rates of complete resolution of fistula drainage and higher rates of external fistula closure (Figure 2).22 Lastly, as an alternative to medical therapy, mesenchymal stem cell therapy has also shown to improve fistula drainage and improve external fistula openings in patients with CD.23 Stem cell therapy is only available through clinical trials at this time.

Patient preferences

Overall, data are lacking for evaluating patient preferences in treatment options for IBD especially with the recent increase in therapeutic options. One survey demonstrated that patient preferences were most impacted by the possibility of improving abdominal pain, with patients accepting additional risk of treatment side effects in order to reduce their abdominal pain.24 An oral route of administration and improving fatigue and bowel urgency were similarly important to patients. Patient preferences can also be highly variable with some valuing avoidance of corticosteroid use while others valuing avoidance of symptoms or risks of medication side effects and surgery. It is important to tailor the discussion on treatment strategies to each individual patient and inquire about the patient’s lifestyle, medical history, and value system, which may impact their treatment preferences utilizing shared decision making.

Access to treatment including the role of social determinants of health

The expanded therapeutic armamentarium has the potential to help patients achieve the current goals of care in IBD. However, these medications are not available to all patients due to numerous barriers including step therapy payer policies, prohibitive costs, insurance prior authorizations, and the role of social determinants of health and proximity to IBD expertise.25 While clinicians work with patients to determine the best treatment option, more often than not, the decision lies with the insurance payer. Step therapy is the protocol used by insurance companies that requires patients to try a lower-cost medication and fail to respond before they approve the originally requested treatment. This can lead to treatment delays, progression of disease, and disease complications. The option to incorporate the use of biosimilars, currently available for anti-TNFs, and other biologics in the near future, will reduce cost and potentially increase access.26 Additionally, working with a clinical pharmacist to navigate access and utilize patient assistance programs may help overcome cost related barriers to treatment and prevent delays in care.

Socioeconomic status has been shown to impact IBD disease outcomes, and compliance rates in treatment vary depending on race and ethnicity.27 Certain racial and ethnic groups remain vulnerable and may require additional support to achieve treatment goals. For example, disparities in health literacy in patients with IBD have been demonstrated with older black men at risk.28 Additionally, the patient’s proximity to their health care facility may impact treatment options. Most IBD centers are located in metropolitan areas and numerous “IBD deserts” exist, potentially limiting therapies for patients from more remote/rural settings.29 Access to treatment and the interplay of social determinants of health can have a large role in therapy selection.

Special considerations: Pregnancy and older adults

Certain patient populations warrant special consideration when approaching treatment strategies. Pregnancy in IBD will not be addressed in full depth in this article, however a key takeaway is that planning is critical and providers should emphasize the importance of steroid-free clinical remission for at least 3 months before conception.30 Additionally, biologic use during pregnancy has not been shown to increase adverse fetal outcomes, thus should be continued to minimize disease flare. Newer novel small molecules are generally avoided during pregnancy due to limited available safety data.

Older adults are the largest growing patient population with IBD. Frailty, or a state of decreased reserve, is more commonly observed in older patients and has been shown to increase adverse events including hospitalization and mortaility.31 Ultimately reducing polypharmacy, ensuring adequate nutrition, minimizing corticosteroid exposure and avoiding undertreatment of active IBD are all key in optimizing outcomes in an older patient with IBD.

Conclusion

When discussing treatment options with patients with IBD, it is important to individualize care and share the decision-making process with patients. Goals include improving symptoms and quality of life while working to achieve the goal of healing intestinal inflammation. In summary, this article can serve as a guide to clinicians for key factors in decision making when selecting therapies in moderate to severe IBD.

Dr. Holmer is a gastroenterologist with NYU Langone Health specializing in inflammatory bowel disease. Dr. Chang is director of clinical operations for the NYU Langone Health Inflammatory Bowel Disease Center. Dr. Malter is director of education for the Inflammatory Bowel Disease Center at NYU Langone Health and director of the inflammatory bowel disease program at Bellevue Hospital Center. Follow Dr. Holmer on X (formerly Twitter) at @HolmerMd and Dr. Chang @shannonchangmd. Dr. Holmer disclosed affiliations with Pfizer, Bristol Myers Squibb, and AvevoRx. Dr. Chang disclosed affiliations with Pfizer and Bristol Myers Squibb. Dr. Malter disclosed receiving educational grants form Abbvie, Janssen, Pfizer and Takeda, and serving on the advisory boards of AbbVie, Bristol Myers Squibb, Celltrion, Janssen, Merck, and Takeda.

References

1. Chang S et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2023 Aug 24. doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000002485.

2. Harvey RF et al. The Lancet. 1980;1:514.

3. Lewis JD et al. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. 2008;14:1660-1666.

4. Siegel CA et al. Gut. 2018;67(2):244-54.

5. Peyrin-Biroulet L et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110:1324-38

6. Rogler G et al. Gastroenterology. 2021;161:1118-32.

7. Sandborn WJ et al. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:1723-36.

8. Brooklyn TN et al. Gut. 2006;55:505-9.

9. Fahmy M et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:794-5.

10. Van Eycken L et al. JAAD Case Rep. 2023;37:89-91.

11. Lasa JS et al. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;7:161-70.

12. Lichtenstein GR et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2018;24:490-501.

13. Long MD et al. Gastroenterology. 2022;162:S-5-S-6.

14. Holmer AK et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol.2023;21:1598-1606.e5.

15. Sands BE et al. Gastroenterology. 2014;147:618-27.e3.

16. Sands BE et al. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:1215-26.

17. Sands BE et al. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:1201-14.

18. D’Haens G et al. Lancet. 2022;399:2015-30.

19. Bouguen G et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11:975-81.e1-4.

20. Papamichael K et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2021;116:1007-14.

21. Shehab M et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2023;29:367-75.

22. Colombel JF et al. J Crohns Colitis. 2023;17:i620-i623.

23. Garcia-Olmo D et al. Dis Colon Rectum. 2022;65:713-20.

24. Louis E et al. J Crohns Colitis. 2023;17:231-9.

25. Rubin DT et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2017;23:224-32.

26. Gulacsi L et al. Curr Med Chem. 2019;26:259-69.

27. Cai Q et al. BMC Gastroenterol. 2022;22:545.

28. Dos Santos Marques IC et al. Crohns Colitis 360. 2020 Oct;2(4):otaa076.

29. Deepak P et al. Gastroenterology. 2023;165:11-15.

30. Mahadevan U et al. Gastroenterology. 2019;156:1508-24.

31. Faye AS et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2022;28:126-32.

32. Berinstein JA et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;19:2112-20.e1.

33. Levine J et al. Gastroenterology. 2023;164:S103-S104.

Working with industry in private practice gastroenterology

In this video, Dr. Nadeem Baig of Allied Digestive Health in West Long Branck, N.J., discusses why he chose private practice gastroenterology and how his organization works with industry to support its mission of providing the best care for patients.

He has no financial conflicts relative to the topics in this video.

In this video, Dr. Nadeem Baig of Allied Digestive Health in West Long Branck, N.J., discusses why he chose private practice gastroenterology and how his organization works with industry to support its mission of providing the best care for patients.

He has no financial conflicts relative to the topics in this video.

In this video, Dr. Nadeem Baig of Allied Digestive Health in West Long Branck, N.J., discusses why he chose private practice gastroenterology and how his organization works with industry to support its mission of providing the best care for patients.

He has no financial conflicts relative to the topics in this video.

AGA patient and physician advocates visit Capitol Hill to push for prior authorization reform

In our first in-person Advocacy Day on Capitol Hill since 2019, AGA leaders and patient advocates from 22 total states met with House and Senate offices to educate members of Congress and their staff about policies affecting GI patient care such as prior authorization and step therapy. Federal research funding and Medicare reimbursement were also on the agenda.

In the meetings, the patient shared their stories of living with various gastrointestinal diseases, including ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease, and the struggles they’ve gone through to get treatments approved by their insurers. AGA physicians shared the provider perspective of how policies like prior authorization negatively impact practices. According to a 2023 AGA member survey, 95% of respondents say that prior authorization restrictions have impacted patient access to clinically appropriate treatments and patient clinical outcomes and 84% described that the burden associated with prior authorization policies have increased “significantly” or “somewhat” over the last 5 years. AGA’s advocacy day came not long after UnitedHealthcare’s announcement of a new “Gold Card” prior authorization policy to be implemented in 2024, which will impact most colonoscopies and endoscopies for its 27 million commercial beneficiaries. The group expressed serious concerns about the proposed policy to lawmakers.

“It was a wonderful and empowering experience to share my personal story with my Representative/Senator and know that they were really listening to my concerns about insurer overreach,” said Aaron Blocker, a Crohn’s disease patient and advocate. “I hope Congress acts swiftly on passing prior authorization reform, so no more patients are forced to live in pain while they wait for treatments to be approved.” As gastroenterologists, too much administrative time is spent submitting onerous prior authorization requests on a near daily basis. We hope Congress takes our concerns seriously and comes together to rein in prior authorization.

AGA thanks the patient and physician advocates who participated in this year’s Advocacy Day and looks forward to continuing our work to ensure timely access to care.