User login

Imaging Evaluation of Superior Labral Anteroposterior (SLAP) Tears

Superior labral anteroposterior (SLAP) tears are common labral injuries. They occur at the attachment of the long head of the biceps tendon on the superior glenoid and extend anterior and/or posterior to the biceps anchor. The mechanism of action for SLAP tears is traction on the superior labrum by the long head of the biceps tendon, resulting in “peeling” of the labrum off the glenoid. Such forces may result from repetitive overhead arm motion (pitching) or from direct trauma.

Clinical diagnosis is challenging with SLAP tears, as they often present with nonspecific shoulder pain and may not be associated with an acute injury. A further complication is that they are often associated with other shoulder pathology, such as rotator cuff tears.1 As physical examination is typically nonspecific, proper diagnostic imaging is essential for diagnosis.

We prefer to assess potential SLAP tears with magnetic resonance arthrography (MRA).2 Dilute (1:200) gadolinium contrast material (12-15 mL) is introduced into the glenohumeral joint under sonographic or fluoroscopic guidance. Capsular distention by dilute intra-articular contrast enables superior imaging resolution of the labroligamentous complex. We think the increase in diagnostic confidence enabled by direct arthrography outweighs the additional invasiveness and cost associated with MRA relative to noncontrast magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

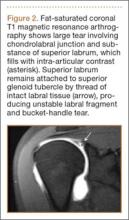

The MRA protocol differs from our routine noncontrast shoulder imaging. We perform a fat-saturated coronal oblique T1 sequence that maximizes the conspicuity of intra-articular contrast in the plane that optimally visualizes the superior labrum. Three planes of intermediate-weighted fast spin echo not only contrast the high-signal intra-articular fluid with the low-signal fibrocartilaginous labrum and the stratified intermediate signal of glenoid articular cartilage, but they also allow optimal assessment of the rotator cuff. In addition, we perform a fat-saturated coronal T2 sequence that highlights all fluid signal structures as well as edema.

SLAP tears appear on MRA as the insinuation of intra-articular contrast between the articular cartilage and the attachment of the superior labrum,3 within the substance of the labrum, or as detachment of the labrum from the glenoid rim4 (Figure 1). Findings can range from labral fraying to complete detachment with displacement. Tears can extend into other quadrants of the labrum, extend from a Bankart lesion, or involve the biceps tendon and/or the glenohumeral ligaments (Figures 2–4). Up to 10 types of SLAP tears have been described on arthroscopy. This classification scheme, however, is seldom helpful in the interpretation of SLAP tears on MRI. More important in guiding treatment is having a detailed description of the tear, including location, extent, and morphology, along with associated abnormalities.

Several findings can aid in the diagnosis of SLAP tears. Normal anatomical variants of the anterior-superior labrum do not extend posterior to the biceps anchor—an important finding for discerning normal morphologic variants from tears. Therefore, high signal within the posterior third of the superior labrum or extension of high signal laterally within the labrum and away from the glenoid suggests a SLAP tear.5 A paralabral cyst is almost always associated with a labral tear,1 so signal abnormality of the superior labrum with a paralabral cyst suggests a SLAP tear (Figure 5).

MRA is not the only method for diagnosing SLAP tears. Standard 3-Tesla MRI had 83% sensitivity and 99% specificity for diagnosing SLAP tears in a recent study, though MRA had 98% sensitivity and 99% specificity—a statistically significant sensitivity difference.6 In another study, computed tomography arthrography (CTA) had 95% sensitivity and 88% specificity for diagnosing recurrent SLAP tears after surgery.7 CTA is associated with ionizing radiation and is limited in its assessment of other structures that may show concomitant abnormalities, such as the articular cartilage and the rotator cuff. Indirect MRA, wherein magnetic resonance sequences are obtained after intravenous injection of gadolinium contrast and exercise of the affected shoulder, had a high sensitivity of detection of labral tears of all types.8

MRA is most sensitive and specific for diagnosing SLAP tears; 3-Tesla MRI, indirect MRA, and CTA are useful alternative modalities for cases in which MRA cannot be performed.

1. Chang D, Mohana-Borges A, Borso M, Chung CB. SLAP lesions: anatomy, clinical presentation, MR imaging diagnosis and characterization. Eur J Radiol. 2008;68(1):72-87.

2. Jee WH, McCauley TR, Katz LD, Matheny JM, Ruwe PA, Daigneault JP. Superior labral anterior posterior (SLAP) lesions of the glenoid labrum: reliability and accuracy of MR arthrography for diagnosis. Radiology. 2001;218(1):127-132.

3. Fitzpatrick D, Walz DM. Shoulder MR imaging normal variants and imaging artifacts. Magn Reson Imaging Clin N Am. 2010;18(4):615-632.

4. Bencardino JT, Beltran J, Rosenberg ZS, et al. Superior labrum anterior-posterior lesions: diagnosis with MR arthrography of the shoulder. Radiology. 2000;214(1):267-271.

5. Tuite MJ, Cirillo RL, De Smet AA, Orwin JF. Superior labrum anterior-posterior (SLAP) tears: evaluation of three MR signs on T2-weighted images. Radiology. 2000;215(3):841-845.

6. Magee T. 3-T MRI of the shoulder: is MR arthrography necessary? AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009;192(1):86-92.

7. De Filippo M, Araoz PA, Pogliacomi F, et al. Recurrent superior labral anterior-to-posterior tears after surgery: detection and grading with CT arthrography. Radiology. 2009;252(3):781-788.

8. Fallahi F, Green N, Gadde S, Jeavons L, Armstrong P, Jonker L. Indirect magnetic resonance arthrography of the shoulder; a reliable diagnostic tool for investigation of suspected labral pathology. Skeletal Radiol. 2013;42(9):1225-1233.

Superior labral anteroposterior (SLAP) tears are common labral injuries. They occur at the attachment of the long head of the biceps tendon on the superior glenoid and extend anterior and/or posterior to the biceps anchor. The mechanism of action for SLAP tears is traction on the superior labrum by the long head of the biceps tendon, resulting in “peeling” of the labrum off the glenoid. Such forces may result from repetitive overhead arm motion (pitching) or from direct trauma.

Clinical diagnosis is challenging with SLAP tears, as they often present with nonspecific shoulder pain and may not be associated with an acute injury. A further complication is that they are often associated with other shoulder pathology, such as rotator cuff tears.1 As physical examination is typically nonspecific, proper diagnostic imaging is essential for diagnosis.

We prefer to assess potential SLAP tears with magnetic resonance arthrography (MRA).2 Dilute (1:200) gadolinium contrast material (12-15 mL) is introduced into the glenohumeral joint under sonographic or fluoroscopic guidance. Capsular distention by dilute intra-articular contrast enables superior imaging resolution of the labroligamentous complex. We think the increase in diagnostic confidence enabled by direct arthrography outweighs the additional invasiveness and cost associated with MRA relative to noncontrast magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

The MRA protocol differs from our routine noncontrast shoulder imaging. We perform a fat-saturated coronal oblique T1 sequence that maximizes the conspicuity of intra-articular contrast in the plane that optimally visualizes the superior labrum. Three planes of intermediate-weighted fast spin echo not only contrast the high-signal intra-articular fluid with the low-signal fibrocartilaginous labrum and the stratified intermediate signal of glenoid articular cartilage, but they also allow optimal assessment of the rotator cuff. In addition, we perform a fat-saturated coronal T2 sequence that highlights all fluid signal structures as well as edema.

SLAP tears appear on MRA as the insinuation of intra-articular contrast between the articular cartilage and the attachment of the superior labrum,3 within the substance of the labrum, or as detachment of the labrum from the glenoid rim4 (Figure 1). Findings can range from labral fraying to complete detachment with displacement. Tears can extend into other quadrants of the labrum, extend from a Bankart lesion, or involve the biceps tendon and/or the glenohumeral ligaments (Figures 2–4). Up to 10 types of SLAP tears have been described on arthroscopy. This classification scheme, however, is seldom helpful in the interpretation of SLAP tears on MRI. More important in guiding treatment is having a detailed description of the tear, including location, extent, and morphology, along with associated abnormalities.

Several findings can aid in the diagnosis of SLAP tears. Normal anatomical variants of the anterior-superior labrum do not extend posterior to the biceps anchor—an important finding for discerning normal morphologic variants from tears. Therefore, high signal within the posterior third of the superior labrum or extension of high signal laterally within the labrum and away from the glenoid suggests a SLAP tear.5 A paralabral cyst is almost always associated with a labral tear,1 so signal abnormality of the superior labrum with a paralabral cyst suggests a SLAP tear (Figure 5).

MRA is not the only method for diagnosing SLAP tears. Standard 3-Tesla MRI had 83% sensitivity and 99% specificity for diagnosing SLAP tears in a recent study, though MRA had 98% sensitivity and 99% specificity—a statistically significant sensitivity difference.6 In another study, computed tomography arthrography (CTA) had 95% sensitivity and 88% specificity for diagnosing recurrent SLAP tears after surgery.7 CTA is associated with ionizing radiation and is limited in its assessment of other structures that may show concomitant abnormalities, such as the articular cartilage and the rotator cuff. Indirect MRA, wherein magnetic resonance sequences are obtained after intravenous injection of gadolinium contrast and exercise of the affected shoulder, had a high sensitivity of detection of labral tears of all types.8

MRA is most sensitive and specific for diagnosing SLAP tears; 3-Tesla MRI, indirect MRA, and CTA are useful alternative modalities for cases in which MRA cannot be performed.

Superior labral anteroposterior (SLAP) tears are common labral injuries. They occur at the attachment of the long head of the biceps tendon on the superior glenoid and extend anterior and/or posterior to the biceps anchor. The mechanism of action for SLAP tears is traction on the superior labrum by the long head of the biceps tendon, resulting in “peeling” of the labrum off the glenoid. Such forces may result from repetitive overhead arm motion (pitching) or from direct trauma.

Clinical diagnosis is challenging with SLAP tears, as they often present with nonspecific shoulder pain and may not be associated with an acute injury. A further complication is that they are often associated with other shoulder pathology, such as rotator cuff tears.1 As physical examination is typically nonspecific, proper diagnostic imaging is essential for diagnosis.

We prefer to assess potential SLAP tears with magnetic resonance arthrography (MRA).2 Dilute (1:200) gadolinium contrast material (12-15 mL) is introduced into the glenohumeral joint under sonographic or fluoroscopic guidance. Capsular distention by dilute intra-articular contrast enables superior imaging resolution of the labroligamentous complex. We think the increase in diagnostic confidence enabled by direct arthrography outweighs the additional invasiveness and cost associated with MRA relative to noncontrast magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

The MRA protocol differs from our routine noncontrast shoulder imaging. We perform a fat-saturated coronal oblique T1 sequence that maximizes the conspicuity of intra-articular contrast in the plane that optimally visualizes the superior labrum. Three planes of intermediate-weighted fast spin echo not only contrast the high-signal intra-articular fluid with the low-signal fibrocartilaginous labrum and the stratified intermediate signal of glenoid articular cartilage, but they also allow optimal assessment of the rotator cuff. In addition, we perform a fat-saturated coronal T2 sequence that highlights all fluid signal structures as well as edema.

SLAP tears appear on MRA as the insinuation of intra-articular contrast between the articular cartilage and the attachment of the superior labrum,3 within the substance of the labrum, or as detachment of the labrum from the glenoid rim4 (Figure 1). Findings can range from labral fraying to complete detachment with displacement. Tears can extend into other quadrants of the labrum, extend from a Bankart lesion, or involve the biceps tendon and/or the glenohumeral ligaments (Figures 2–4). Up to 10 types of SLAP tears have been described on arthroscopy. This classification scheme, however, is seldom helpful in the interpretation of SLAP tears on MRI. More important in guiding treatment is having a detailed description of the tear, including location, extent, and morphology, along with associated abnormalities.

Several findings can aid in the diagnosis of SLAP tears. Normal anatomical variants of the anterior-superior labrum do not extend posterior to the biceps anchor—an important finding for discerning normal morphologic variants from tears. Therefore, high signal within the posterior third of the superior labrum or extension of high signal laterally within the labrum and away from the glenoid suggests a SLAP tear.5 A paralabral cyst is almost always associated with a labral tear,1 so signal abnormality of the superior labrum with a paralabral cyst suggests a SLAP tear (Figure 5).

MRA is not the only method for diagnosing SLAP tears. Standard 3-Tesla MRI had 83% sensitivity and 99% specificity for diagnosing SLAP tears in a recent study, though MRA had 98% sensitivity and 99% specificity—a statistically significant sensitivity difference.6 In another study, computed tomography arthrography (CTA) had 95% sensitivity and 88% specificity for diagnosing recurrent SLAP tears after surgery.7 CTA is associated with ionizing radiation and is limited in its assessment of other structures that may show concomitant abnormalities, such as the articular cartilage and the rotator cuff. Indirect MRA, wherein magnetic resonance sequences are obtained after intravenous injection of gadolinium contrast and exercise of the affected shoulder, had a high sensitivity of detection of labral tears of all types.8

MRA is most sensitive and specific for diagnosing SLAP tears; 3-Tesla MRI, indirect MRA, and CTA are useful alternative modalities for cases in which MRA cannot be performed.

1. Chang D, Mohana-Borges A, Borso M, Chung CB. SLAP lesions: anatomy, clinical presentation, MR imaging diagnosis and characterization. Eur J Radiol. 2008;68(1):72-87.

2. Jee WH, McCauley TR, Katz LD, Matheny JM, Ruwe PA, Daigneault JP. Superior labral anterior posterior (SLAP) lesions of the glenoid labrum: reliability and accuracy of MR arthrography for diagnosis. Radiology. 2001;218(1):127-132.

3. Fitzpatrick D, Walz DM. Shoulder MR imaging normal variants and imaging artifacts. Magn Reson Imaging Clin N Am. 2010;18(4):615-632.

4. Bencardino JT, Beltran J, Rosenberg ZS, et al. Superior labrum anterior-posterior lesions: diagnosis with MR arthrography of the shoulder. Radiology. 2000;214(1):267-271.

5. Tuite MJ, Cirillo RL, De Smet AA, Orwin JF. Superior labrum anterior-posterior (SLAP) tears: evaluation of three MR signs on T2-weighted images. Radiology. 2000;215(3):841-845.

6. Magee T. 3-T MRI of the shoulder: is MR arthrography necessary? AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009;192(1):86-92.

7. De Filippo M, Araoz PA, Pogliacomi F, et al. Recurrent superior labral anterior-to-posterior tears after surgery: detection and grading with CT arthrography. Radiology. 2009;252(3):781-788.

8. Fallahi F, Green N, Gadde S, Jeavons L, Armstrong P, Jonker L. Indirect magnetic resonance arthrography of the shoulder; a reliable diagnostic tool for investigation of suspected labral pathology. Skeletal Radiol. 2013;42(9):1225-1233.

1. Chang D, Mohana-Borges A, Borso M, Chung CB. SLAP lesions: anatomy, clinical presentation, MR imaging diagnosis and characterization. Eur J Radiol. 2008;68(1):72-87.

2. Jee WH, McCauley TR, Katz LD, Matheny JM, Ruwe PA, Daigneault JP. Superior labral anterior posterior (SLAP) lesions of the glenoid labrum: reliability and accuracy of MR arthrography for diagnosis. Radiology. 2001;218(1):127-132.

3. Fitzpatrick D, Walz DM. Shoulder MR imaging normal variants and imaging artifacts. Magn Reson Imaging Clin N Am. 2010;18(4):615-632.

4. Bencardino JT, Beltran J, Rosenberg ZS, et al. Superior labrum anterior-posterior lesions: diagnosis with MR arthrography of the shoulder. Radiology. 2000;214(1):267-271.

5. Tuite MJ, Cirillo RL, De Smet AA, Orwin JF. Superior labrum anterior-posterior (SLAP) tears: evaluation of three MR signs on T2-weighted images. Radiology. 2000;215(3):841-845.

6. Magee T. 3-T MRI of the shoulder: is MR arthrography necessary? AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009;192(1):86-92.

7. De Filippo M, Araoz PA, Pogliacomi F, et al. Recurrent superior labral anterior-to-posterior tears after surgery: detection and grading with CT arthrography. Radiology. 2009;252(3):781-788.

8. Fallahi F, Green N, Gadde S, Jeavons L, Armstrong P, Jonker L. Indirect magnetic resonance arthrography of the shoulder; a reliable diagnostic tool for investigation of suspected labral pathology. Skeletal Radiol. 2013;42(9):1225-1233.

Measurement of Resource Utilization for Total and Reverse Shoulder Arthroplasty

As total health care costs reach almost $3 trillion per year—capturing more than 17% of the total US gross domestic product—payers are searching for more effective ways to limit health care spending.1,2 One increasingly discussed plan is payment bundling.3 This one-lump-sum payment model arose as a result of rapid year-on-year increases in total reimbursements under the current, fee-for-service model. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services hypothesized that a single all-inclusive payment for a procedure or set of services would incentivize improvements in patient-centered care and disincentivize cost-shifting behaviors.4 Bundled reimbursement is becoming increasingly common in orthopedic practice. With the recent introduction of the Bundled Payment for Care Improvement Initiative, several orthopedic practices around the United States are already actively engaged in creating models for bundled payment for common elective procedures and for associated services provided up to 90 days after surgery.3,5

Bundled payment increases the burden on the provider to understand the cost of care provided during a care cycle. However, not only has the current system blinded physicians to the cost of care, but current antitrust legislation has made discussions of pricing with colleagues (so-called price collusion) illegal and subject to fines of up to $1 million per person and $100 million per organization,6 therefore limiting orthopedic physician involvement.

Given these legal constraints, instead of measuring direct costs of goods, we developed a “grocery list” approach in which direct comparisons are made of resources (goods and services) used and delivered during the entire 90-day cycle of care for patients who undergo anatomical total shoulder arthroplasty (TSA) or reverse shoulder arthroplasty (RSA). We used one surgeon’s practice experience as a model for measuring other orthopedic surgeons’ resource utilization, based on their electronic medical records (EMR) system data. By capturing the costs of the components of resource utilization rather than just the final cost of care, we can assess, compare, understand, endorse, and address these driving factors.

1. The significance of resource utilization

To maximize the efficiency of their practices, high-volume shoulder surgeons have introduced standardization to health care delivery.7 Identifying specific efficiencies makes uniform acceptance of beneficial practice patterns possible.

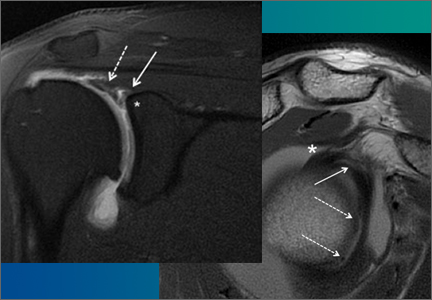

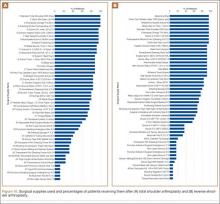

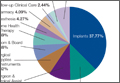

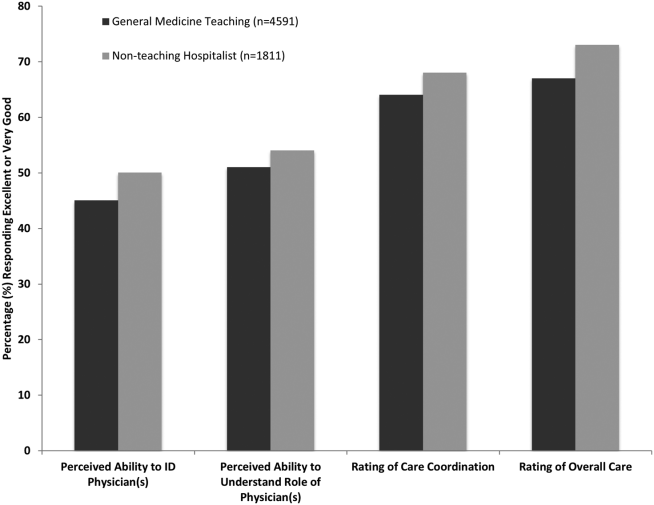

To facilitate comparison of goods and services used during an episode of surgical care, Virani and colleagues8,9 studied the costs of TSA and RSA and calculated the top 10 driving cost factors for these procedures (Figure 1). Their systematic analysis provided a framework for a common method of communication, allowing an orthopedic surgeon to gain a more complete understanding of the resources used during a particular operative procedure in his or her practice, and allowing several physicians to compare and contrast the resources collectively used for a single procedure, facilitating an understanding of different practice patterns within a local community. At a societal level, these data can be collected to help guide overall recommendations.

2. How we defined utilization

To define the resources used, we had to decide which procedure components cost the most. Virani and colleagues8,9 found that the top 10 cost drivers accounted for 93.11% and 94.77% of the total cost of the TSA and RSA care cycles, respectively (Figure 1). For each cost driver, information on resources used (goods, services, overhead) was collected on 2 forms, the Hospital Utilization Form (7 hospital-based items) and the Clinical Utilization Form (3 non-hospital-based items). To make hospital data easy to compile, we piloted use of a “smart form” in the EpicCare EMR system to isolate and auto-populate specific data fields.

3. EMR data collection

With EMR becoming mandatory for all public and private health care providers starting in 2014, utilization data are now included in a single unified system. Working with our in-house information technology department, we developed an algorithm to populate this information in a separate, easy-to-follow hospital utilization form. This form can be adopted by other institutions. Although EpicCare EMR is used by 52% of hospitals and at our institution, the data points required to make the same measurements are generalizable and exist in other EMRs.

Smartlinks, a tool in this EMR, allows utilization data to be quickly retrieved from different locations in a medical record and allows a form to be electronically completed in seconds. Data can be retrieved for any patient in the EMR system, regardless of when that patient’s hospital stay occurred. We populated data from surgeries performed 2 years before the start of this project.

4. What we can learn from these data

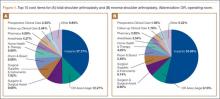

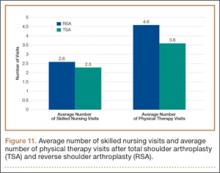

Data from a pilot study of 25 patients who underwent primary anatomical TSA for osteoarthritis and 25 patients who underwent primary RSA for massive rotator cuff tear allowed us to generate graphical representations of a single surgeon’s practice patterns that most affected the cost of care. Time in holding, time in the operating room, time in the postanesthesia care unit, and percentage of patients receiving different medications were recorded for each procedure (Figures 2–11). The study did not capture the wide variances in practice patterns in shoulder arthroplasty, and therefore other surgeons’ resource utilization may differ from ours. However, replicating this methodology at other institutions will produce a more robust data set from which conclusions about resource utilization and, indirectly, cost of care can be made.

5. Future possibilities

By using existing EMR tools to better understand resource utilization, orthopedic surgeons can play a constructive role in the dialogue on health care costs and new reimbursement models. The data presented here are not meant to be interpreted as hard and fast numbers on global resource utilization, but instead we intend to establish a model for collecting data on resource utilization. Resource utilization begins the dialogue that allows orthopedic surgeons and specialty societies to speak a common language without discussing actual cost numbers, which is discouraged under antitrust regulation. The data presented will allow comparisons to be made between surgeons in all practice settings to highlight areas of inconsistency in order to further improve patient care. Although this work involved only 50 patients undergoing only 2 types of surgeries, the resource-capturing methodology can be expanded to include more procedures and orthopedic practices. As all hospitals are now required to have EMRs, the metrics tracked in this work can be found on any patient medical record and auto-populated using our open-source utilization forms. Starting this data collection at your hospital may require no more than a conversation with the informatics department, as the metrics can for the most part be populated into a database on surgeon request.

As orthopedic surgeons return to the economic health care discussion, this information could prove essential in helping the individual surgeon and the orthopedic community justify the cost of care as well as fully understand the cost drivers for musculoskeletal care.

Click here to read the commentary on this article by Peter D. McCann, MD

1. National health expenditures 2013 highlights. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services website. http://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/NationalHealthExpendData/downloads/highlights.pdf. Accessed September 14, 2015.

2. Wilson KB. Health care costs 101: slow growth persists. California HealthCare Foundation website. http://www.chcf.org/publications/2014/07/health-care-costs-101. Published July 2014. Accessed August 24, 2015.

3. Froimson MI, Rana A, White RE Jr, et al. Bundled Payments for Care Improvement Initiative: the next evolution of payment formulations: AAHKS Bundled Payment Task Force. J Arthroplasty. 2013;28(8 suppl):157-165.

4. Morley M, Bogasky S, Gage B, Flood S, Ingber MJ. Medicare post-acute care episodes and payment bundling. Medicare Medicaid Res Rev. 2014;4(1).

5. Teusink MJ, Virani NA, Polikandriotis JA, Frankle MA. Cost analysis in shoulder arthroplasty surgery. Adv Orthop. 2012;2012:692869.

6. Fassbender E, Pandya S. Legislation focuses on AAOS priorities. American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons website. http://www.aaos.org/news/aaosnow/may14/advocacy2.asp. AAOS Now. Published May 2014. Accessed August 24, 2015.

7. Porter ME, Teisberg EO. Redefining Health Care: Creating Value-Based Competition on Results. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press; 2006.

8. Virani NA, Williams CD, Clark R, Polikandriotis J, Downes KL, Frankle MA. Preparing for the bundled-payment initiative: the cost and clinical outcomes of reverse shoulder arthroplasty for the surgical treatment of advanced rotator cuff deficiency at an average 4-year follow-up. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2013;22(12):1612-1622.

9. Virani NA, Williams CD, Clark R, Polikandriotis J, Downes KL, Frankle MA. Preparing for the bundled-payment initiative: the cost and clinical outcomes of total shoulder arthroplasty for the surgical treatment of glenohumeral arthritis at an average 4-year follow-up. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2013;22(12):1601-1611.

As total health care costs reach almost $3 trillion per year—capturing more than 17% of the total US gross domestic product—payers are searching for more effective ways to limit health care spending.1,2 One increasingly discussed plan is payment bundling.3 This one-lump-sum payment model arose as a result of rapid year-on-year increases in total reimbursements under the current, fee-for-service model. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services hypothesized that a single all-inclusive payment for a procedure or set of services would incentivize improvements in patient-centered care and disincentivize cost-shifting behaviors.4 Bundled reimbursement is becoming increasingly common in orthopedic practice. With the recent introduction of the Bundled Payment for Care Improvement Initiative, several orthopedic practices around the United States are already actively engaged in creating models for bundled payment for common elective procedures and for associated services provided up to 90 days after surgery.3,5

Bundled payment increases the burden on the provider to understand the cost of care provided during a care cycle. However, not only has the current system blinded physicians to the cost of care, but current antitrust legislation has made discussions of pricing with colleagues (so-called price collusion) illegal and subject to fines of up to $1 million per person and $100 million per organization,6 therefore limiting orthopedic physician involvement.

Given these legal constraints, instead of measuring direct costs of goods, we developed a “grocery list” approach in which direct comparisons are made of resources (goods and services) used and delivered during the entire 90-day cycle of care for patients who undergo anatomical total shoulder arthroplasty (TSA) or reverse shoulder arthroplasty (RSA). We used one surgeon’s practice experience as a model for measuring other orthopedic surgeons’ resource utilization, based on their electronic medical records (EMR) system data. By capturing the costs of the components of resource utilization rather than just the final cost of care, we can assess, compare, understand, endorse, and address these driving factors.

1. The significance of resource utilization

To maximize the efficiency of their practices, high-volume shoulder surgeons have introduced standardization to health care delivery.7 Identifying specific efficiencies makes uniform acceptance of beneficial practice patterns possible.

To facilitate comparison of goods and services used during an episode of surgical care, Virani and colleagues8,9 studied the costs of TSA and RSA and calculated the top 10 driving cost factors for these procedures (Figure 1). Their systematic analysis provided a framework for a common method of communication, allowing an orthopedic surgeon to gain a more complete understanding of the resources used during a particular operative procedure in his or her practice, and allowing several physicians to compare and contrast the resources collectively used for a single procedure, facilitating an understanding of different practice patterns within a local community. At a societal level, these data can be collected to help guide overall recommendations.

2. How we defined utilization

To define the resources used, we had to decide which procedure components cost the most. Virani and colleagues8,9 found that the top 10 cost drivers accounted for 93.11% and 94.77% of the total cost of the TSA and RSA care cycles, respectively (Figure 1). For each cost driver, information on resources used (goods, services, overhead) was collected on 2 forms, the Hospital Utilization Form (7 hospital-based items) and the Clinical Utilization Form (3 non-hospital-based items). To make hospital data easy to compile, we piloted use of a “smart form” in the EpicCare EMR system to isolate and auto-populate specific data fields.

3. EMR data collection

With EMR becoming mandatory for all public and private health care providers starting in 2014, utilization data are now included in a single unified system. Working with our in-house information technology department, we developed an algorithm to populate this information in a separate, easy-to-follow hospital utilization form. This form can be adopted by other institutions. Although EpicCare EMR is used by 52% of hospitals and at our institution, the data points required to make the same measurements are generalizable and exist in other EMRs.

Smartlinks, a tool in this EMR, allows utilization data to be quickly retrieved from different locations in a medical record and allows a form to be electronically completed in seconds. Data can be retrieved for any patient in the EMR system, regardless of when that patient’s hospital stay occurred. We populated data from surgeries performed 2 years before the start of this project.

4. What we can learn from these data

Data from a pilot study of 25 patients who underwent primary anatomical TSA for osteoarthritis and 25 patients who underwent primary RSA for massive rotator cuff tear allowed us to generate graphical representations of a single surgeon’s practice patterns that most affected the cost of care. Time in holding, time in the operating room, time in the postanesthesia care unit, and percentage of patients receiving different medications were recorded for each procedure (Figures 2–11). The study did not capture the wide variances in practice patterns in shoulder arthroplasty, and therefore other surgeons’ resource utilization may differ from ours. However, replicating this methodology at other institutions will produce a more robust data set from which conclusions about resource utilization and, indirectly, cost of care can be made.

5. Future possibilities

By using existing EMR tools to better understand resource utilization, orthopedic surgeons can play a constructive role in the dialogue on health care costs and new reimbursement models. The data presented here are not meant to be interpreted as hard and fast numbers on global resource utilization, but instead we intend to establish a model for collecting data on resource utilization. Resource utilization begins the dialogue that allows orthopedic surgeons and specialty societies to speak a common language without discussing actual cost numbers, which is discouraged under antitrust regulation. The data presented will allow comparisons to be made between surgeons in all practice settings to highlight areas of inconsistency in order to further improve patient care. Although this work involved only 50 patients undergoing only 2 types of surgeries, the resource-capturing methodology can be expanded to include more procedures and orthopedic practices. As all hospitals are now required to have EMRs, the metrics tracked in this work can be found on any patient medical record and auto-populated using our open-source utilization forms. Starting this data collection at your hospital may require no more than a conversation with the informatics department, as the metrics can for the most part be populated into a database on surgeon request.

As orthopedic surgeons return to the economic health care discussion, this information could prove essential in helping the individual surgeon and the orthopedic community justify the cost of care as well as fully understand the cost drivers for musculoskeletal care.

Click here to read the commentary on this article by Peter D. McCann, MD

As total health care costs reach almost $3 trillion per year—capturing more than 17% of the total US gross domestic product—payers are searching for more effective ways to limit health care spending.1,2 One increasingly discussed plan is payment bundling.3 This one-lump-sum payment model arose as a result of rapid year-on-year increases in total reimbursements under the current, fee-for-service model. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services hypothesized that a single all-inclusive payment for a procedure or set of services would incentivize improvements in patient-centered care and disincentivize cost-shifting behaviors.4 Bundled reimbursement is becoming increasingly common in orthopedic practice. With the recent introduction of the Bundled Payment for Care Improvement Initiative, several orthopedic practices around the United States are already actively engaged in creating models for bundled payment for common elective procedures and for associated services provided up to 90 days after surgery.3,5

Bundled payment increases the burden on the provider to understand the cost of care provided during a care cycle. However, not only has the current system blinded physicians to the cost of care, but current antitrust legislation has made discussions of pricing with colleagues (so-called price collusion) illegal and subject to fines of up to $1 million per person and $100 million per organization,6 therefore limiting orthopedic physician involvement.

Given these legal constraints, instead of measuring direct costs of goods, we developed a “grocery list” approach in which direct comparisons are made of resources (goods and services) used and delivered during the entire 90-day cycle of care for patients who undergo anatomical total shoulder arthroplasty (TSA) or reverse shoulder arthroplasty (RSA). We used one surgeon’s practice experience as a model for measuring other orthopedic surgeons’ resource utilization, based on their electronic medical records (EMR) system data. By capturing the costs of the components of resource utilization rather than just the final cost of care, we can assess, compare, understand, endorse, and address these driving factors.

1. The significance of resource utilization

To maximize the efficiency of their practices, high-volume shoulder surgeons have introduced standardization to health care delivery.7 Identifying specific efficiencies makes uniform acceptance of beneficial practice patterns possible.

To facilitate comparison of goods and services used during an episode of surgical care, Virani and colleagues8,9 studied the costs of TSA and RSA and calculated the top 10 driving cost factors for these procedures (Figure 1). Their systematic analysis provided a framework for a common method of communication, allowing an orthopedic surgeon to gain a more complete understanding of the resources used during a particular operative procedure in his or her practice, and allowing several physicians to compare and contrast the resources collectively used for a single procedure, facilitating an understanding of different practice patterns within a local community. At a societal level, these data can be collected to help guide overall recommendations.

2. How we defined utilization

To define the resources used, we had to decide which procedure components cost the most. Virani and colleagues8,9 found that the top 10 cost drivers accounted for 93.11% and 94.77% of the total cost of the TSA and RSA care cycles, respectively (Figure 1). For each cost driver, information on resources used (goods, services, overhead) was collected on 2 forms, the Hospital Utilization Form (7 hospital-based items) and the Clinical Utilization Form (3 non-hospital-based items). To make hospital data easy to compile, we piloted use of a “smart form” in the EpicCare EMR system to isolate and auto-populate specific data fields.

3. EMR data collection

With EMR becoming mandatory for all public and private health care providers starting in 2014, utilization data are now included in a single unified system. Working with our in-house information technology department, we developed an algorithm to populate this information in a separate, easy-to-follow hospital utilization form. This form can be adopted by other institutions. Although EpicCare EMR is used by 52% of hospitals and at our institution, the data points required to make the same measurements are generalizable and exist in other EMRs.

Smartlinks, a tool in this EMR, allows utilization data to be quickly retrieved from different locations in a medical record and allows a form to be electronically completed in seconds. Data can be retrieved for any patient in the EMR system, regardless of when that patient’s hospital stay occurred. We populated data from surgeries performed 2 years before the start of this project.

4. What we can learn from these data

Data from a pilot study of 25 patients who underwent primary anatomical TSA for osteoarthritis and 25 patients who underwent primary RSA for massive rotator cuff tear allowed us to generate graphical representations of a single surgeon’s practice patterns that most affected the cost of care. Time in holding, time in the operating room, time in the postanesthesia care unit, and percentage of patients receiving different medications were recorded for each procedure (Figures 2–11). The study did not capture the wide variances in practice patterns in shoulder arthroplasty, and therefore other surgeons’ resource utilization may differ from ours. However, replicating this methodology at other institutions will produce a more robust data set from which conclusions about resource utilization and, indirectly, cost of care can be made.

5. Future possibilities

By using existing EMR tools to better understand resource utilization, orthopedic surgeons can play a constructive role in the dialogue on health care costs and new reimbursement models. The data presented here are not meant to be interpreted as hard and fast numbers on global resource utilization, but instead we intend to establish a model for collecting data on resource utilization. Resource utilization begins the dialogue that allows orthopedic surgeons and specialty societies to speak a common language without discussing actual cost numbers, which is discouraged under antitrust regulation. The data presented will allow comparisons to be made between surgeons in all practice settings to highlight areas of inconsistency in order to further improve patient care. Although this work involved only 50 patients undergoing only 2 types of surgeries, the resource-capturing methodology can be expanded to include more procedures and orthopedic practices. As all hospitals are now required to have EMRs, the metrics tracked in this work can be found on any patient medical record and auto-populated using our open-source utilization forms. Starting this data collection at your hospital may require no more than a conversation with the informatics department, as the metrics can for the most part be populated into a database on surgeon request.

As orthopedic surgeons return to the economic health care discussion, this information could prove essential in helping the individual surgeon and the orthopedic community justify the cost of care as well as fully understand the cost drivers for musculoskeletal care.

Click here to read the commentary on this article by Peter D. McCann, MD

1. National health expenditures 2013 highlights. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services website. http://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/NationalHealthExpendData/downloads/highlights.pdf. Accessed September 14, 2015.

2. Wilson KB. Health care costs 101: slow growth persists. California HealthCare Foundation website. http://www.chcf.org/publications/2014/07/health-care-costs-101. Published July 2014. Accessed August 24, 2015.

3. Froimson MI, Rana A, White RE Jr, et al. Bundled Payments for Care Improvement Initiative: the next evolution of payment formulations: AAHKS Bundled Payment Task Force. J Arthroplasty. 2013;28(8 suppl):157-165.

4. Morley M, Bogasky S, Gage B, Flood S, Ingber MJ. Medicare post-acute care episodes and payment bundling. Medicare Medicaid Res Rev. 2014;4(1).

5. Teusink MJ, Virani NA, Polikandriotis JA, Frankle MA. Cost analysis in shoulder arthroplasty surgery. Adv Orthop. 2012;2012:692869.

6. Fassbender E, Pandya S. Legislation focuses on AAOS priorities. American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons website. http://www.aaos.org/news/aaosnow/may14/advocacy2.asp. AAOS Now. Published May 2014. Accessed August 24, 2015.

7. Porter ME, Teisberg EO. Redefining Health Care: Creating Value-Based Competition on Results. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press; 2006.

8. Virani NA, Williams CD, Clark R, Polikandriotis J, Downes KL, Frankle MA. Preparing for the bundled-payment initiative: the cost and clinical outcomes of reverse shoulder arthroplasty for the surgical treatment of advanced rotator cuff deficiency at an average 4-year follow-up. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2013;22(12):1612-1622.

9. Virani NA, Williams CD, Clark R, Polikandriotis J, Downes KL, Frankle MA. Preparing for the bundled-payment initiative: the cost and clinical outcomes of total shoulder arthroplasty for the surgical treatment of glenohumeral arthritis at an average 4-year follow-up. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2013;22(12):1601-1611.

1. National health expenditures 2013 highlights. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services website. http://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/NationalHealthExpendData/downloads/highlights.pdf. Accessed September 14, 2015.

2. Wilson KB. Health care costs 101: slow growth persists. California HealthCare Foundation website. http://www.chcf.org/publications/2014/07/health-care-costs-101. Published July 2014. Accessed August 24, 2015.

3. Froimson MI, Rana A, White RE Jr, et al. Bundled Payments for Care Improvement Initiative: the next evolution of payment formulations: AAHKS Bundled Payment Task Force. J Arthroplasty. 2013;28(8 suppl):157-165.

4. Morley M, Bogasky S, Gage B, Flood S, Ingber MJ. Medicare post-acute care episodes and payment bundling. Medicare Medicaid Res Rev. 2014;4(1).

5. Teusink MJ, Virani NA, Polikandriotis JA, Frankle MA. Cost analysis in shoulder arthroplasty surgery. Adv Orthop. 2012;2012:692869.

6. Fassbender E, Pandya S. Legislation focuses on AAOS priorities. American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons website. http://www.aaos.org/news/aaosnow/may14/advocacy2.asp. AAOS Now. Published May 2014. Accessed August 24, 2015.

7. Porter ME, Teisberg EO. Redefining Health Care: Creating Value-Based Competition on Results. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press; 2006.

8. Virani NA, Williams CD, Clark R, Polikandriotis J, Downes KL, Frankle MA. Preparing for the bundled-payment initiative: the cost and clinical outcomes of reverse shoulder arthroplasty for the surgical treatment of advanced rotator cuff deficiency at an average 4-year follow-up. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2013;22(12):1612-1622.

9. Virani NA, Williams CD, Clark R, Polikandriotis J, Downes KL, Frankle MA. Preparing for the bundled-payment initiative: the cost and clinical outcomes of total shoulder arthroplasty for the surgical treatment of glenohumeral arthritis at an average 4-year follow-up. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2013;22(12):1601-1611.

Technique of Open Reduction and Internal Fixation of Comminuted Proximal Humerus Fractures With Allograft Femoral Head Metaphyseal Reconstruction

Proximal humerus fractures are exceedingly common and account for almost 5% of all fractures. As osteoporosis is a risk factor for these fractures, their incidence rises with patient age.1

In 1970, Neer2 described these type of fractures and classified them as having 2, 3, or 4 parts based on the amount of angulation and displacement of the humeral head and the greater and lesser tuberosities with respect to the shaft.

Three- and 4-part proximal humerus fractures can be treated either nonoperatively, or surgically with closed reduction and percutaneous fixation, intramedullary fixation, open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF), or arthroplasty. There remains controversy over the best treatment, but a key component of any surgical treatment is anatomical reduction, stable fixation, and then healing of the tuberosities. A current common form of treatment is augmentation with an allograft fibula placed in the medullary canal. Although not formally reported, anecdotal evidence demonstrates that revision to arthroplasty is very difficult in the setting of an ingrown graft in the medullary canal of the humerus.

In this article, we present a novel technique of using allograft femoral head to reconstruct the metaphysis in ORIF of comminuted proximal humerus fractures.

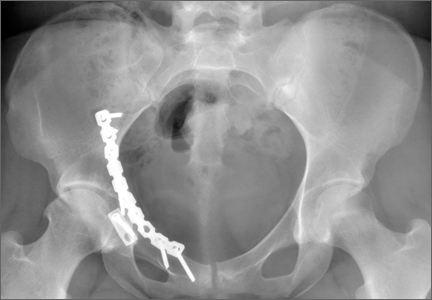

Technique

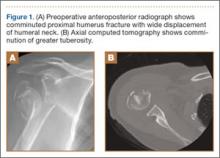

Presented in Figure 1 are preoperative images of a representative displaced 4-part proximal humerus fracture treated surgically using the technique described here. General anesthesia is used. After intubation on the operating table, the patient is placed in the beach-chair position with about 75° of hip flexion. All bony prominences are padded, and the head and trunk are well secured. A pneumatic arm positioner is used to alleviate the need for an assistant to manipulate the arm. An image intensifier is used before preparing to verify that appropriate images of the proximal humerus can be obtained. Once adequate images are confirmed, the floor can be marked at the position of the fluoroscopic unit’s wheels to allow easy reproduction of images once the arm is prepared and draped. The intensifier is then removed from the field, the shoulder is prepared and draped in usual fashion, and prophylactic antibiotics are administered.

A deltopectoral incision is used, and sharp dissection is made through the subcutaneous tissue to raise full-thickness subcutaneous flaps on each side. The deltopectoral interval is sharply dissected while protecting the cephalic vein. Subdeltoid adhesions are then released. Palpation of the axillary nerve in the quadrilateral space to identify its location is helpful to avoid injury during the procedure.

The fracture is then identified, and No. 5 permanent suture is placed through the posterior and superior rotator cuff and through the subscapularis insertion (Figure 2). The tuberosities are freed from the humeral head sharply. A blunt elevator is then used to gently elevate the humeral head upward, with care taken to avoid comminuting the metaphyseal bone while levering. Reduction is achieved by manipulating the sutures and levering the head with the elevator while placing the arm in extension and posterior translation. Fluoroscopic images are used to verify correct anatomical alignment. Generally, the metaphysis demonstrates comminution and impaction, with poor bone quality necessitating use of bone graft.

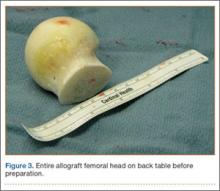

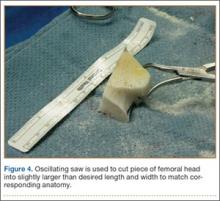

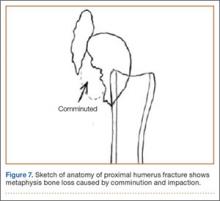

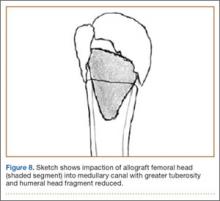

A frozen allograft femoral head is then obtained and split into 2 equal pieces using a saw (Figures 3–5). One piece is fashioned with a saw and a burr into a trapezoid such that the proximal portion is wider, and the distal, tapered portion is sized to fit the canal. The broad, proximal portion of the graft will serve as a pedestal to reduce the head to the shaft. Measuring the internal diameter of the humeral canal can be useful in estimating the necessary dimensions of the distal portion of the allograft. The graft often needs several small adjustments that necessitate attempting to place it in the intramedullary canal and then trimming as necessary to ensure proper fit distally within the shaft. For this reason, it is beneficial to perform the graft preparation near the surgical field. Once completed, the distal portion is then impacted into the humeral canal (Figure 6). Because of this impaction, there is no possibility for subsidence or pistoning of the graft within the canal, which can occur with a fibular graft. The humeral head is reduced onto the shaft with the already placed sutures; this is achieved by abducting the shoulder. The image intensifier is then used to confirm appropriate alignment and positioning of the fragments, making sure that both neck–shaft angle and medial calcar alignment have been restored (Figures 7, 8).

An appropriately sized proximal humerus plate is then selected based on the location of the fracture line. We have used standard lateral proximal humerus locking plates as well as laterality-specific anterolateral proximal humerus plates and found that both are suitable for incorporation of the screws through the graft and into the head. The plate is positioned on the humerus, and a guide pin is placed by hand through the proximal-most hole so that the appropriate height of the plate can be verified on fluoroscopy. The first screw is then a nonlocking bicortical screw placed through the oval hole in the shaft of the plate to allow further fine manipulation of the plate more proximally or distally as needed. The final height is confirmed, and the screw is firmly tightened (Figure 9). The locking-screw guide is fixed to the proximal portion of the plate, and 2 locking screws are then placed into the head. The arm is then rotated to an anteroposterior view by placing the arm in external rotation and neutral flexion and is then abducted and internally rotated to recreate a lateral view to perform final verification of the position of the plate on orthogonal images. If the surgeon is satisfied with the position of the plate, another nonlocking screw is placed distally, and then the proximal holes are used to place locking screws as needed. If the surgeon is not satisfied, the 2 proximal screws can be removed and the plate repositioned.

After each screw is placed, fluoroscopy is used to ensure there has been no breach of the articular surface. The number of proximal screws placed depends on fracture configuration and surgeon preference.

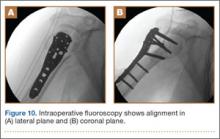

The sutures through the rotator cuff are then fixed to the plate, securing the tuberosities. Final intraoperative radiographs are used to confirm reduction, alignment, and final position of hardware (Figure 10). After copious irrigation, a surgical drain is placed as needed, and the wound is closed in layered fashion. Three years after surgery, follow-up examination revealed no radiographic change in alignment, no necrosis, and no varus collapse (Figure 11), and the patient was pain-free during activities.

Discussion

Surgical treatment of comminuted proximal humerus fractures usually consists of some type of plate fixation with screw fixation of the shaft, screws or smooth pegs to support the chondral surfaces, and screw fixation or suture cerclage of the tuberosities.

Fixed-angle locking-plate-and-screw constructs increased the biomechanical stability and pullout strength of proximal humerus plates.3,4 Nevertheless, avascular necrosis, malunion, and nonunion are still known complications of proximal humerus fractures, especially those with comminution, with up to 14% of patients still experiencing loss of fixation.5

For this reason, several authors have proposed using allograft bone and/or augmentation with calcium-containing cement to supplement fixation and provide an endosteal form of support for the head and tuberosities to decrease the risk for varus collapse. Osteobiologics (eg, calcium phosphate or sulfate cement) have been shown to decrease the risk for loss of reduction of proximal humerus fractures and decrease the risk for intra-articular screw penetration.6,7 Many calcium phosphate cements are commercially available. Cost and availability are 2 reasons that these supplements are not more widely used. Cancellous chips have also been used to aid in the reduction of proximal humerus fractures.8 No randomized study has been conducted to show a clinical advantage of this technique, though retrospective studies have shown that it is not as advantageous as using calcium phosphate cement with respect to loss of reduction or screw penetration.6 Certainly, cancellous chips are easily available in most hospitals and are less expensive than some alternatives. A recent review of these techniques in osteoporotic proximal humerus fractures found no clear indication for using one of these supplements over another.9

However, some fracture patterns require a structural graft to reduce the tuberosities and head component. Although described more than 30 years ago as a treatment for nonunions with an intramedullary “peg” of iliac crest graft,10 the graft most commonly reported today is allograft fibula.11-15 This technique consists of preparing the humeral shaft and often the fractured head segment with reaming to create a channel to receive the graft. Even with use of a small fibula, it is often time-consuming to use a saw, rasp, or burr to size the fibular segment to fit the medullary canal of the humerus. Once in place, the graft provides a strut on which the head fragment can be reduced and around which the tuberosities can be reduced. Although this technique is successful clinically and is biomechanically superior to plate-only constructs,16,17 concerns remain.

One such concern is keeping this graft in routine supply at most hospitals. Supply and pricing from vendors can differ significantly between hospitals, and a surgeon may need to request grafts in advance, which makes their use nonviable in a trauma case. Certain grafts are often kept in routine supply based on their overall utilization. At our institution, allograft femoral heads meet this criterion and are routinely stocked.

Of more importance are the ramifications of these procedures for future revision surgeries. The need for arthroplasty revision is common after ORIF of a proximal humerus fracture.18

Arthroplasty revision is an already challenging procedure that becomes more complex with the need to remove 6 to 8 cm of ingrown endosteal bone from a shell of outer osteoporotic cortical bone. Our experience with these complex revisions provided the impetus to search for an alternate graft type that still provides a strut for reducing the head and tuberosities but limits the amount of endosteal bone that would need to be removed in arthroplasty revision in order to place a stemmed component into the humeral canal.

Some currently available arthroplasty fracture systems modify the previous anatomy of the stem to provide a more anatomical platform to reduce the tuberosities to a broader metaphyseal construct that incorporates bone grafting to assist with healing.

Because of these concerns and factors, we adapted our technique to create an individual-specific pedestal with allograft femoral head that can be anatomically matched to each patient. This provides a strut to reduce the head and tuberosity fragments but still limits the amount of allograft bone needed to seat into the existing canal. The geometry of the allograft can also be customized to the fracture, with most 3- and 4-part fractures needing a trapezoidal strut that resembles the metaphyseal portion of a fracture-specific shoulder arthroplasty implant.

We have used this technique for comminuted 3- and 4-part fractures of the proximal humerus in 14 cases with at least 2-year follow-up and in several more cases that have not reached 2-year follow-up. All cases have gone on to radiographic union; none have had to be revised either with revision ORIF or to an arthroplasty. Formal measurements of final postoperative range of motion have not been tabulated in all cases, as some cases have been lost to follow-up after radiographic union was achieved. Medium- and long-term results are not yet available, but no short-term complications have been noted.

Disadvantages of this technique are that, while an individualized graft is created, proper shaping still takes time, and a moderate amount of the femoral head is not used. However, we have found that, if a graft is inadvertently undersized, there is still ample femoral head remaining to create another sized graft. Other disadvantages are the added cost and the (rare) risk of disease transmission, which come with use of any allograft, but the technique is used instead of another type of allograft, so these disadvantages are largely equivalent. At our hospital, differences in cost and availability between femoral head or fibular allografts are negligible.

This procedure, which is easily performed in a short amount of time, allows a stable base of bone graft to be used as an aid in the anatomical reduction of proximal humerus fractures, without the need for reaming and preparation of the medullary canal and without further increasing the difficulty associated with a future revision procedure.

1. Barrett JA, Baron JA, Karagas MR, Beach ML. Fracture risk in the U.S. Medicare population. J Clin Epidemiol. 1999;52(3):243-249.

2. Neer CS 2nd. Displaced proximal humeral fractures. I. Classification and evaluation. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1970;52(6):1077-1089.

3. Liew AS, Johnson JA, Patterson SD, King GJ, Chess DG. Effect of screw placement on fixation in the humeral head. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2000;9(5):423-426.

4. Weinstein DM, Bratton DR, Ciccone WJ 2nd, Elias JJ. Locking plates improve torsional resistance in the stabilization of three-part proximal humeral fractures. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2006;15(2):239-243.

5. Agudelo J, Schurmann M, Stahel P, et al. Analysis of efficacy and failure in proximal humerus fractures treated with locking plates. J Orthop Trauma. 2007;21(10):676-681.

6. Egol KA, Sugi MT, Ong CC, Montero N, Davidovitch R, Zuckerman JD. Fracture site augmentation with calcium phosphate cement reduces screw penetration after open reduction-internal fixation of proximal humeral fractures. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012;21(6):741-748.

7. Gradl G, Knobe M, Stoffel M, Prescher A, Dirrichs T, Pape HC. Biomechanical evaluation of locking plate fixation of proximal humeral fractures augmented with calcium phosphate cement. J Orthop Trauma. 2013;27(7):399-404.

8. Ong CC, Kwon YW, Walsh M, Davidovitch R, Zuckerman JD, Egol KA. Outcomes of open reduction and internal fixation of proximal humerus fractures managed with locking plates. Am J Orthop. 2012;41(9):407-412.

9. Namdari S, Voleti PB, Mehta S. Evaluation of the osteoporotic proximal humeral fracture and strategies for structural augmentation during surgical treatment. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012;21(12):1787-1795.

10. Scheck M. Surgical treatment of nonunions of the surgical neck of the humerus. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1982;(167):255-259.

11. Hettrich CM, Neviaser A, Beamer BS, Paul O, Helfet DL, Lorich DG. Locked plating of the proximal humerus using an endosteal implant. J Orthop Trauma. 2012;26(4):212-215.

12. Neviaser AS, Hettrich CM, Beamer BS, Dines JS, Lorich DG. Endosteal strut augment reduces complications associated with proximal humeral locking plates. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011;469(12):3300-3306.

13. Gardner MJ, Boraiah S, Helfet DL, Lorich DG. Indirect medial reduction and strut support of proximal humerus fractures using an endosteal implant. J Orthop Trauma. 2008;22(3):195-200.

14. Matassi F, Angeloni R, Carulli C, et al. Locking plate and fibular allograft augmentation in unstable fractures of proximal humerus. Injury. 2012;43(11):1939-1942.

15. Little MT, Berkes MB, Schottel PC, et al. The impact of preoperative coronal plane deformity on proximal humerus fixation with endosteal augmentation. J Orthop Trauma. 2014;28(6):338-347.

16. Mathison C, Chaudhary R, Beaupre L, Reynolds M, Adeeb S, Bouliane M. Biomechanical analysis of proximal humeral fixation using locking plate fixation with an intramedullary fibular allograft. Clin Biomech. 2010;25(7):642-646.

17. Chow RM, Begum F, Beaupre LA, Carey JP, Adeeb S, Bouliane MJ. Proximal humeral fracture fixation: locking plate construct +/- intramedullary fibular allograft. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012;21(7):894-901.

18. Jost B, Spross C, Grehn H, Gerber C. Locking plate fixation of fractures of the proximal humerus: analysis of complications, revision strategies and outcome. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2013;22(4):542-549.

Proximal humerus fractures are exceedingly common and account for almost 5% of all fractures. As osteoporosis is a risk factor for these fractures, their incidence rises with patient age.1

In 1970, Neer2 described these type of fractures and classified them as having 2, 3, or 4 parts based on the amount of angulation and displacement of the humeral head and the greater and lesser tuberosities with respect to the shaft.

Three- and 4-part proximal humerus fractures can be treated either nonoperatively, or surgically with closed reduction and percutaneous fixation, intramedullary fixation, open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF), or arthroplasty. There remains controversy over the best treatment, but a key component of any surgical treatment is anatomical reduction, stable fixation, and then healing of the tuberosities. A current common form of treatment is augmentation with an allograft fibula placed in the medullary canal. Although not formally reported, anecdotal evidence demonstrates that revision to arthroplasty is very difficult in the setting of an ingrown graft in the medullary canal of the humerus.

In this article, we present a novel technique of using allograft femoral head to reconstruct the metaphysis in ORIF of comminuted proximal humerus fractures.

Technique

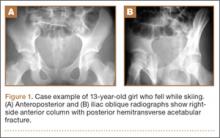

Presented in Figure 1 are preoperative images of a representative displaced 4-part proximal humerus fracture treated surgically using the technique described here. General anesthesia is used. After intubation on the operating table, the patient is placed in the beach-chair position with about 75° of hip flexion. All bony prominences are padded, and the head and trunk are well secured. A pneumatic arm positioner is used to alleviate the need for an assistant to manipulate the arm. An image intensifier is used before preparing to verify that appropriate images of the proximal humerus can be obtained. Once adequate images are confirmed, the floor can be marked at the position of the fluoroscopic unit’s wheels to allow easy reproduction of images once the arm is prepared and draped. The intensifier is then removed from the field, the shoulder is prepared and draped in usual fashion, and prophylactic antibiotics are administered.

A deltopectoral incision is used, and sharp dissection is made through the subcutaneous tissue to raise full-thickness subcutaneous flaps on each side. The deltopectoral interval is sharply dissected while protecting the cephalic vein. Subdeltoid adhesions are then released. Palpation of the axillary nerve in the quadrilateral space to identify its location is helpful to avoid injury during the procedure.

The fracture is then identified, and No. 5 permanent suture is placed through the posterior and superior rotator cuff and through the subscapularis insertion (Figure 2). The tuberosities are freed from the humeral head sharply. A blunt elevator is then used to gently elevate the humeral head upward, with care taken to avoid comminuting the metaphyseal bone while levering. Reduction is achieved by manipulating the sutures and levering the head with the elevator while placing the arm in extension and posterior translation. Fluoroscopic images are used to verify correct anatomical alignment. Generally, the metaphysis demonstrates comminution and impaction, with poor bone quality necessitating use of bone graft.

A frozen allograft femoral head is then obtained and split into 2 equal pieces using a saw (Figures 3–5). One piece is fashioned with a saw and a burr into a trapezoid such that the proximal portion is wider, and the distal, tapered portion is sized to fit the canal. The broad, proximal portion of the graft will serve as a pedestal to reduce the head to the shaft. Measuring the internal diameter of the humeral canal can be useful in estimating the necessary dimensions of the distal portion of the allograft. The graft often needs several small adjustments that necessitate attempting to place it in the intramedullary canal and then trimming as necessary to ensure proper fit distally within the shaft. For this reason, it is beneficial to perform the graft preparation near the surgical field. Once completed, the distal portion is then impacted into the humeral canal (Figure 6). Because of this impaction, there is no possibility for subsidence or pistoning of the graft within the canal, which can occur with a fibular graft. The humeral head is reduced onto the shaft with the already placed sutures; this is achieved by abducting the shoulder. The image intensifier is then used to confirm appropriate alignment and positioning of the fragments, making sure that both neck–shaft angle and medial calcar alignment have been restored (Figures 7, 8).

An appropriately sized proximal humerus plate is then selected based on the location of the fracture line. We have used standard lateral proximal humerus locking plates as well as laterality-specific anterolateral proximal humerus plates and found that both are suitable for incorporation of the screws through the graft and into the head. The plate is positioned on the humerus, and a guide pin is placed by hand through the proximal-most hole so that the appropriate height of the plate can be verified on fluoroscopy. The first screw is then a nonlocking bicortical screw placed through the oval hole in the shaft of the plate to allow further fine manipulation of the plate more proximally or distally as needed. The final height is confirmed, and the screw is firmly tightened (Figure 9). The locking-screw guide is fixed to the proximal portion of the plate, and 2 locking screws are then placed into the head. The arm is then rotated to an anteroposterior view by placing the arm in external rotation and neutral flexion and is then abducted and internally rotated to recreate a lateral view to perform final verification of the position of the plate on orthogonal images. If the surgeon is satisfied with the position of the plate, another nonlocking screw is placed distally, and then the proximal holes are used to place locking screws as needed. If the surgeon is not satisfied, the 2 proximal screws can be removed and the plate repositioned.

After each screw is placed, fluoroscopy is used to ensure there has been no breach of the articular surface. The number of proximal screws placed depends on fracture configuration and surgeon preference.

The sutures through the rotator cuff are then fixed to the plate, securing the tuberosities. Final intraoperative radiographs are used to confirm reduction, alignment, and final position of hardware (Figure 10). After copious irrigation, a surgical drain is placed as needed, and the wound is closed in layered fashion. Three years after surgery, follow-up examination revealed no radiographic change in alignment, no necrosis, and no varus collapse (Figure 11), and the patient was pain-free during activities.

Discussion

Surgical treatment of comminuted proximal humerus fractures usually consists of some type of plate fixation with screw fixation of the shaft, screws or smooth pegs to support the chondral surfaces, and screw fixation or suture cerclage of the tuberosities.

Fixed-angle locking-plate-and-screw constructs increased the biomechanical stability and pullout strength of proximal humerus plates.3,4 Nevertheless, avascular necrosis, malunion, and nonunion are still known complications of proximal humerus fractures, especially those with comminution, with up to 14% of patients still experiencing loss of fixation.5

For this reason, several authors have proposed using allograft bone and/or augmentation with calcium-containing cement to supplement fixation and provide an endosteal form of support for the head and tuberosities to decrease the risk for varus collapse. Osteobiologics (eg, calcium phosphate or sulfate cement) have been shown to decrease the risk for loss of reduction of proximal humerus fractures and decrease the risk for intra-articular screw penetration.6,7 Many calcium phosphate cements are commercially available. Cost and availability are 2 reasons that these supplements are not more widely used. Cancellous chips have also been used to aid in the reduction of proximal humerus fractures.8 No randomized study has been conducted to show a clinical advantage of this technique, though retrospective studies have shown that it is not as advantageous as using calcium phosphate cement with respect to loss of reduction or screw penetration.6 Certainly, cancellous chips are easily available in most hospitals and are less expensive than some alternatives. A recent review of these techniques in osteoporotic proximal humerus fractures found no clear indication for using one of these supplements over another.9

However, some fracture patterns require a structural graft to reduce the tuberosities and head component. Although described more than 30 years ago as a treatment for nonunions with an intramedullary “peg” of iliac crest graft,10 the graft most commonly reported today is allograft fibula.11-15 This technique consists of preparing the humeral shaft and often the fractured head segment with reaming to create a channel to receive the graft. Even with use of a small fibula, it is often time-consuming to use a saw, rasp, or burr to size the fibular segment to fit the medullary canal of the humerus. Once in place, the graft provides a strut on which the head fragment can be reduced and around which the tuberosities can be reduced. Although this technique is successful clinically and is biomechanically superior to plate-only constructs,16,17 concerns remain.

One such concern is keeping this graft in routine supply at most hospitals. Supply and pricing from vendors can differ significantly between hospitals, and a surgeon may need to request grafts in advance, which makes their use nonviable in a trauma case. Certain grafts are often kept in routine supply based on their overall utilization. At our institution, allograft femoral heads meet this criterion and are routinely stocked.

Of more importance are the ramifications of these procedures for future revision surgeries. The need for arthroplasty revision is common after ORIF of a proximal humerus fracture.18

Arthroplasty revision is an already challenging procedure that becomes more complex with the need to remove 6 to 8 cm of ingrown endosteal bone from a shell of outer osteoporotic cortical bone. Our experience with these complex revisions provided the impetus to search for an alternate graft type that still provides a strut for reducing the head and tuberosities but limits the amount of endosteal bone that would need to be removed in arthroplasty revision in order to place a stemmed component into the humeral canal.

Some currently available arthroplasty fracture systems modify the previous anatomy of the stem to provide a more anatomical platform to reduce the tuberosities to a broader metaphyseal construct that incorporates bone grafting to assist with healing.

Because of these concerns and factors, we adapted our technique to create an individual-specific pedestal with allograft femoral head that can be anatomically matched to each patient. This provides a strut to reduce the head and tuberosity fragments but still limits the amount of allograft bone needed to seat into the existing canal. The geometry of the allograft can also be customized to the fracture, with most 3- and 4-part fractures needing a trapezoidal strut that resembles the metaphyseal portion of a fracture-specific shoulder arthroplasty implant.

We have used this technique for comminuted 3- and 4-part fractures of the proximal humerus in 14 cases with at least 2-year follow-up and in several more cases that have not reached 2-year follow-up. All cases have gone on to radiographic union; none have had to be revised either with revision ORIF or to an arthroplasty. Formal measurements of final postoperative range of motion have not been tabulated in all cases, as some cases have been lost to follow-up after radiographic union was achieved. Medium- and long-term results are not yet available, but no short-term complications have been noted.

Disadvantages of this technique are that, while an individualized graft is created, proper shaping still takes time, and a moderate amount of the femoral head is not used. However, we have found that, if a graft is inadvertently undersized, there is still ample femoral head remaining to create another sized graft. Other disadvantages are the added cost and the (rare) risk of disease transmission, which come with use of any allograft, but the technique is used instead of another type of allograft, so these disadvantages are largely equivalent. At our hospital, differences in cost and availability between femoral head or fibular allografts are negligible.

This procedure, which is easily performed in a short amount of time, allows a stable base of bone graft to be used as an aid in the anatomical reduction of proximal humerus fractures, without the need for reaming and preparation of the medullary canal and without further increasing the difficulty associated with a future revision procedure.

Proximal humerus fractures are exceedingly common and account for almost 5% of all fractures. As osteoporosis is a risk factor for these fractures, their incidence rises with patient age.1

In 1970, Neer2 described these type of fractures and classified them as having 2, 3, or 4 parts based on the amount of angulation and displacement of the humeral head and the greater and lesser tuberosities with respect to the shaft.

Three- and 4-part proximal humerus fractures can be treated either nonoperatively, or surgically with closed reduction and percutaneous fixation, intramedullary fixation, open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF), or arthroplasty. There remains controversy over the best treatment, but a key component of any surgical treatment is anatomical reduction, stable fixation, and then healing of the tuberosities. A current common form of treatment is augmentation with an allograft fibula placed in the medullary canal. Although not formally reported, anecdotal evidence demonstrates that revision to arthroplasty is very difficult in the setting of an ingrown graft in the medullary canal of the humerus.

In this article, we present a novel technique of using allograft femoral head to reconstruct the metaphysis in ORIF of comminuted proximal humerus fractures.

Technique

Presented in Figure 1 are preoperative images of a representative displaced 4-part proximal humerus fracture treated surgically using the technique described here. General anesthesia is used. After intubation on the operating table, the patient is placed in the beach-chair position with about 75° of hip flexion. All bony prominences are padded, and the head and trunk are well secured. A pneumatic arm positioner is used to alleviate the need for an assistant to manipulate the arm. An image intensifier is used before preparing to verify that appropriate images of the proximal humerus can be obtained. Once adequate images are confirmed, the floor can be marked at the position of the fluoroscopic unit’s wheels to allow easy reproduction of images once the arm is prepared and draped. The intensifier is then removed from the field, the shoulder is prepared and draped in usual fashion, and prophylactic antibiotics are administered.

A deltopectoral incision is used, and sharp dissection is made through the subcutaneous tissue to raise full-thickness subcutaneous flaps on each side. The deltopectoral interval is sharply dissected while protecting the cephalic vein. Subdeltoid adhesions are then released. Palpation of the axillary nerve in the quadrilateral space to identify its location is helpful to avoid injury during the procedure.