User login

Education Pitfalls of Insulin Administration in Patients With Diabetes

Diabetes mellitus is a growing problem in the U.S., with the number of disease-related complications on the rise. It affects 29.1 million people of all ages; however, only 21 million people are diagnosed, leaving 8.1 million people undiagnosed.1 Heart disease death rates among adults with diabetes are 2 to 4 times higher than the rates for adults without diabetes.2 At least 68% of patients with diabetes aged > 65 years die of some form of heart disease; 16% die of stroke.2

Type 2 diabetes remains the leading cause for cardiovascular disorders, blindness, end-stage renal disease, amputations, and hospitalizations.3 Due to the long-term complications of diabetes, it is important to help patients control their disease. However, diabetes control in patients can be difficult because of the broad disease education needed and its medication administration.

Insulin requires the most extensive instruction when educating patients with diabetes. Specifically, patient counseling needs to incorporate the importance of proper insulin administration. If patients are not properly administering their insulin, controlling their diabetes will be very difficult. Many clinicians know to educate the patient about drawing insulin into a syringe and how to inject insulin properly. However, clinicians do not always think about other aspects of insulin administration education, such as the mixing of different insulins in 1 syringe. Patients and family members need to be taught about the types of insulins that can and cannot be mixed. The American Diabetes Association (ADA) provides recommendations on the appropriate time to mix insulin and the types of insulin that can and cannot be mixed (Table 1).4

CASE REPORT

A white male, aged 69 years, presented to a pharmacist-run pharmacotherapy clinic for a follow-up appointment for uncontrolled diabetes. The patient’s wife, who managed his medications, accompanied him. Significant past medical history included diabetes, nephropathy, retinopathy, degenerative joint disease, migraines, gastroesophageal reflux disease, depression, posttraumatic stress disorder, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, lumbago, panic attacks, medication noncompliance, status post cerebral vascular accident, and renal insufficiency.

The patient had a long history of type 2 diabetes, and his insulin had been titrated multiple times since he was established in this clinic in 2009. At his establishing visit, he was taken off his insulin pump due to noncompliance with blood glucose checks and placed on basal-bolus therapy with insulin glargine and insulin aspart. The patient then titrated his basal-bolus insulin for 6 weeks but stated his blood sugars were consistently elevated (reaching 600 mg/dL); therefore, he self-reinitiated the insulin pump. After restarting the insulin pump, the clinic made several attempts to follow-up with the patient, but none were successful. He was subsequently dismissed from the clinic following his admission to a local nursing home.

The patient was reestablished at the clinic in 2010 (about 1 year after dismissal). He reported discontinuing the insulin pump and using insulin glargine and insulin aspart injections but was self-adjusting insulin glargine based on readings. He was told not to self-adjust insulin glargine dose and was given a sliding scale for self-adjustment of his insulin aspart dose based on blood glucose readings. Since the reestablished visit, both insulin therapies were titrated without much success in controlling his blood glucose levels. He was also advised to check his fasting blood glucose (FBG) more often and was demonstrated correct insulin drawing technique.

At a follow-up visit in August 2012, the patient’s A1c was 10.7%, and FBG readings ranged from 108 mg/dL to 555 mg/dL. Goal A1c was between 8% and 8.5% per VA/DoD diabetes guidelines.5 After a discussion with the patient’s wife, it was discovered that the patient was improperly administrating his insulin. The patient had been administrating the insulin glargine and insulin aspart in the same syringe. Since the combined dose of insulin was greater than his syringe would allow, he adjusted the insulin glargine dose downward if more insulin aspart was needed per the sliding scale. He did this to avoid more injections than he thought were necessary. Based on his A1c and home blood glucose readings, it was also suspected that insulin doses were being missed. The patient and wife were instructed about the importance of adherence and not mixing these insulins in the same syringe.

At the most recent visit, the patient’s FBG readings (200 mg/dL-500 mg/dL) and A1c (10.7%) were still greatly elevated. He reported taking 40 units insulin glargine in the morning and 60 units at bedtime, along with 40 units insulin aspart plus sliding scale insulin (1:20 > 120 mg/dL) at breakfast and 40 to 70 units at lunch and supper. The patient reported compliance with insulin therapy; however, it was likely he was not dosing accurately, according to his sliding scale. He stated he was eating less and was worried about hypoglycemia. Due to the patient’s FBG and A1c still being elevated, insulin aspart was titrated again, which was closer to a 50% basal and 50% bolus regimen, and he was again educated about proper dosing.

DISCUSSION

Patients have many obstacles to managing their diseases. This is especially prevalent in patients with diabetes. These patients both experience the emotional stress of being diagnosed with diabetes and are given a wealth of information on diabetes, nutrition, therapy, and insulin-dosing technique at the same time. The information can be overwhelming for patients to hear and for the educator to present. Sometimes health care professionals (HCPs) overlook a patient’s hindrances due to the amount of information they have to give to the patient. For example, in this case, the patient was mixing insulin inappropriately, and it was overlooked by the HCP.

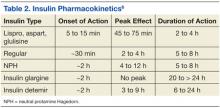

Insulin therapy has been used for several decades. It is obtained from either a pork pancreas or is chemically manufactured to be identical to human insulin. This can be achieved by recombinant DNA technology or chemical modification of pork insulin.4 Insulin is available as short-, intermediate-, or long-acting duration. The pharmacokinetics of available insulins is listed in Table 2.6

Some insulin can be mixed in the same syringe, but these mainly consist of the short- and intermediate-acting insulin. Insulin glargine, a long-acting formulation, should not be mixed with any other insulin due to its pharmacokinetic properties.7 Insulin glargine has been designed to have a low solubility at a neutral pH. After injection, the pH rises and leads to the formation of microprecipitates, causing a slow release of the insulin over 24 hours with no peak. If insulin glargine is mixed, it is likely the pH would be altered before entering the body. In addition, mixing insulin in the same syringe could likely contaminate the dose.

The maker of insulin glargine advises against mixing it with any other insulin.7 Several different studies have been done with admixtures of insulin glargine with short- or rapid-acting insulin. The studies revealed no differences in glycemic control, blunted and delayed rapid-acting insulin peak, the need for larger doses, or worsened glycemic control.8-12

Other education points about insulin administration that are often overlooked or sometimes ignored by patients and that require follow-up for compliance include the following:

• Manufacturers recommend discarding an open bottle of insulin at room temperature after 28 days.7

• Insulin should be kept in a temperature-controlled environment between 36°F and 86°F.4,7

• Rotation of injection sites is necessary to prevent lipodystrophy.4,7

• It is recommended that patients stick with 1 approved anatomical site for all insulin injections, such as the abdomen or leg, to maintain consistent pharmacokinetics.4,13,14

It is also important to know the constitution of the different insulins and whether they have been compromised. For example, if a clear solution insulin turns cloudy, it is considered compromised and should be thrown away.

CONCLUSION

Patients are diagnosed every day with diabetes, and many treatment regimens include insulin therapy. With the diagnosis of diabetes, patients are given extensive information on therapy, nutrition, preventative measures, and technique. Since controlling diabetes can call for intensive insulin therapy, medication administration instruction by HCPs is important. It is important to discuss in detail how the patient manages their insulin therapy at each visit so that issues will not be overlooked. Long-term, inappropriate use of insulin may lead to uncontrolled diabetes.

Diabetes is a complex disease to manage and takes a joint effort by both the HCP and patient to control. Patients need to understand the importance of compliance in all aspects of the disease, and the HCP needs to understand the importance of extensive counseling, including diet, exercise, and medication therapy.

Author disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review the complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Diabetes Statistics Report: Estimates of Diabetes and Its Burden in the United States, 2014. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2014. http://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/pubs/statsreport14.htm. Updated July 28, 2014. Accessed August 12, 2014.

2. Roger VL, Go AS, Lloyd-Jones DM. et al; American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2012 update: A report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2012;125(1):e2-e220.

3. Inzucchi SE, Bergenstal RM, Buse JB, et al; American Diabetes Association (ADA); European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Management of hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes: A patient-centered approach: Position statement of the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Diabetes Care. 2012;35(6):1364-1379.

4. American Diabetes Association. Insulin administration. Diabetes Care. 2004;27(suppl 1): S106-S109.

5. VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guidelines: Management of Diabetes Mellitus (DM). Version 4.0. Website: http://www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/CD/diabetes/DM2010_FUL-v4e.pdf. Updated August 2010. Accessed August 12, 2014.

6. McCulloch DK. General principles of isulin therapy in diabetes mellitus. UpToDate Website. http://www .uptodate.com /contents/general-principles-of-insulin-therapy-in-diabetes-mellitus. Accessed August 5, 2014.

7. Lantus [package insert]. Bridgewater, NJ: sanofi-aventis US; 2013.

8. Cengiz E, Tamborlane WV, Martin-Fredericksen M, Dziura J, Weinzimer SA. Early pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic effects of mixing lispro with glargine insulin: Results of glucose clamp studies in youth with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2010;33(5):1009-1012.

9. Lucchesi MB, Komatsu WR, Gabbay MA, Dib SA. A 12-wk follow-up study to evaluate the effects of mixing insulin lispro and insulin glargine in young individuals with type 1 diabetes. Pediatr Diabetes. 2012;13(7):519-524.

10. Kaplan W, Rodriguez LM, Smith OE, Haymond MW, Heptulla RA. Effects of mixing glargine and short-acting insulin analogs on glucose control. Diabetes Care. 2004;27(11):2739-2740.

11. Fiallo-Scharer R, Horner B, McFann K, Walravens P, Chase HP. Mixing rapid-acting insulin analogs with insulin glargine in children with type 1 diabetes mellitus. J Pediatr. 2006;148(4):481-484.

12. Hassan K, Rodriguez LM, Johnson SE, Tadlock S, Heptulla RA. A randomized, controlled trial comparing twice-a-day insulin glargine mixed with rapid-acting insulin analogs versus standard neutral protamine Hagedorn (NPH) therapy in newly diagnosed type 1 diabetes. Pediatrics. 2008;121(3):e466 -e472.

13. Koivisto VA, Felig P. Alterations in insulin absorption and in blood glucose control associated with varying insulin injection sites in diabetic patients. Ann Intern Med. 1980;92(1):59-61.

14. Berger M, Cüppers HJ, Hegner H, Jörgens V, Berchtold P. Absorption kinetics and biologic effects of subcutaneously injected insulin preparations. Diabetes Care. 1982;5(2):77-91.

Diabetes mellitus is a growing problem in the U.S., with the number of disease-related complications on the rise. It affects 29.1 million people of all ages; however, only 21 million people are diagnosed, leaving 8.1 million people undiagnosed.1 Heart disease death rates among adults with diabetes are 2 to 4 times higher than the rates for adults without diabetes.2 At least 68% of patients with diabetes aged > 65 years die of some form of heart disease; 16% die of stroke.2

Type 2 diabetes remains the leading cause for cardiovascular disorders, blindness, end-stage renal disease, amputations, and hospitalizations.3 Due to the long-term complications of diabetes, it is important to help patients control their disease. However, diabetes control in patients can be difficult because of the broad disease education needed and its medication administration.

Insulin requires the most extensive instruction when educating patients with diabetes. Specifically, patient counseling needs to incorporate the importance of proper insulin administration. If patients are not properly administering their insulin, controlling their diabetes will be very difficult. Many clinicians know to educate the patient about drawing insulin into a syringe and how to inject insulin properly. However, clinicians do not always think about other aspects of insulin administration education, such as the mixing of different insulins in 1 syringe. Patients and family members need to be taught about the types of insulins that can and cannot be mixed. The American Diabetes Association (ADA) provides recommendations on the appropriate time to mix insulin and the types of insulin that can and cannot be mixed (Table 1).4

CASE REPORT

A white male, aged 69 years, presented to a pharmacist-run pharmacotherapy clinic for a follow-up appointment for uncontrolled diabetes. The patient’s wife, who managed his medications, accompanied him. Significant past medical history included diabetes, nephropathy, retinopathy, degenerative joint disease, migraines, gastroesophageal reflux disease, depression, posttraumatic stress disorder, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, lumbago, panic attacks, medication noncompliance, status post cerebral vascular accident, and renal insufficiency.

The patient had a long history of type 2 diabetes, and his insulin had been titrated multiple times since he was established in this clinic in 2009. At his establishing visit, he was taken off his insulin pump due to noncompliance with blood glucose checks and placed on basal-bolus therapy with insulin glargine and insulin aspart. The patient then titrated his basal-bolus insulin for 6 weeks but stated his blood sugars were consistently elevated (reaching 600 mg/dL); therefore, he self-reinitiated the insulin pump. After restarting the insulin pump, the clinic made several attempts to follow-up with the patient, but none were successful. He was subsequently dismissed from the clinic following his admission to a local nursing home.

The patient was reestablished at the clinic in 2010 (about 1 year after dismissal). He reported discontinuing the insulin pump and using insulin glargine and insulin aspart injections but was self-adjusting insulin glargine based on readings. He was told not to self-adjust insulin glargine dose and was given a sliding scale for self-adjustment of his insulin aspart dose based on blood glucose readings. Since the reestablished visit, both insulin therapies were titrated without much success in controlling his blood glucose levels. He was also advised to check his fasting blood glucose (FBG) more often and was demonstrated correct insulin drawing technique.

At a follow-up visit in August 2012, the patient’s A1c was 10.7%, and FBG readings ranged from 108 mg/dL to 555 mg/dL. Goal A1c was between 8% and 8.5% per VA/DoD diabetes guidelines.5 After a discussion with the patient’s wife, it was discovered that the patient was improperly administrating his insulin. The patient had been administrating the insulin glargine and insulin aspart in the same syringe. Since the combined dose of insulin was greater than his syringe would allow, he adjusted the insulin glargine dose downward if more insulin aspart was needed per the sliding scale. He did this to avoid more injections than he thought were necessary. Based on his A1c and home blood glucose readings, it was also suspected that insulin doses were being missed. The patient and wife were instructed about the importance of adherence and not mixing these insulins in the same syringe.

At the most recent visit, the patient’s FBG readings (200 mg/dL-500 mg/dL) and A1c (10.7%) were still greatly elevated. He reported taking 40 units insulin glargine in the morning and 60 units at bedtime, along with 40 units insulin aspart plus sliding scale insulin (1:20 > 120 mg/dL) at breakfast and 40 to 70 units at lunch and supper. The patient reported compliance with insulin therapy; however, it was likely he was not dosing accurately, according to his sliding scale. He stated he was eating less and was worried about hypoglycemia. Due to the patient’s FBG and A1c still being elevated, insulin aspart was titrated again, which was closer to a 50% basal and 50% bolus regimen, and he was again educated about proper dosing.

DISCUSSION

Patients have many obstacles to managing their diseases. This is especially prevalent in patients with diabetes. These patients both experience the emotional stress of being diagnosed with diabetes and are given a wealth of information on diabetes, nutrition, therapy, and insulin-dosing technique at the same time. The information can be overwhelming for patients to hear and for the educator to present. Sometimes health care professionals (HCPs) overlook a patient’s hindrances due to the amount of information they have to give to the patient. For example, in this case, the patient was mixing insulin inappropriately, and it was overlooked by the HCP.

Insulin therapy has been used for several decades. It is obtained from either a pork pancreas or is chemically manufactured to be identical to human insulin. This can be achieved by recombinant DNA technology or chemical modification of pork insulin.4 Insulin is available as short-, intermediate-, or long-acting duration. The pharmacokinetics of available insulins is listed in Table 2.6

Some insulin can be mixed in the same syringe, but these mainly consist of the short- and intermediate-acting insulin. Insulin glargine, a long-acting formulation, should not be mixed with any other insulin due to its pharmacokinetic properties.7 Insulin glargine has been designed to have a low solubility at a neutral pH. After injection, the pH rises and leads to the formation of microprecipitates, causing a slow release of the insulin over 24 hours with no peak. If insulin glargine is mixed, it is likely the pH would be altered before entering the body. In addition, mixing insulin in the same syringe could likely contaminate the dose.

The maker of insulin glargine advises against mixing it with any other insulin.7 Several different studies have been done with admixtures of insulin glargine with short- or rapid-acting insulin. The studies revealed no differences in glycemic control, blunted and delayed rapid-acting insulin peak, the need for larger doses, or worsened glycemic control.8-12

Other education points about insulin administration that are often overlooked or sometimes ignored by patients and that require follow-up for compliance include the following:

• Manufacturers recommend discarding an open bottle of insulin at room temperature after 28 days.7

• Insulin should be kept in a temperature-controlled environment between 36°F and 86°F.4,7

• Rotation of injection sites is necessary to prevent lipodystrophy.4,7

• It is recommended that patients stick with 1 approved anatomical site for all insulin injections, such as the abdomen or leg, to maintain consistent pharmacokinetics.4,13,14

It is also important to know the constitution of the different insulins and whether they have been compromised. For example, if a clear solution insulin turns cloudy, it is considered compromised and should be thrown away.

CONCLUSION

Patients are diagnosed every day with diabetes, and many treatment regimens include insulin therapy. With the diagnosis of diabetes, patients are given extensive information on therapy, nutrition, preventative measures, and technique. Since controlling diabetes can call for intensive insulin therapy, medication administration instruction by HCPs is important. It is important to discuss in detail how the patient manages their insulin therapy at each visit so that issues will not be overlooked. Long-term, inappropriate use of insulin may lead to uncontrolled diabetes.

Diabetes is a complex disease to manage and takes a joint effort by both the HCP and patient to control. Patients need to understand the importance of compliance in all aspects of the disease, and the HCP needs to understand the importance of extensive counseling, including diet, exercise, and medication therapy.

Author disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review the complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

Diabetes mellitus is a growing problem in the U.S., with the number of disease-related complications on the rise. It affects 29.1 million people of all ages; however, only 21 million people are diagnosed, leaving 8.1 million people undiagnosed.1 Heart disease death rates among adults with diabetes are 2 to 4 times higher than the rates for adults without diabetes.2 At least 68% of patients with diabetes aged > 65 years die of some form of heart disease; 16% die of stroke.2

Type 2 diabetes remains the leading cause for cardiovascular disorders, blindness, end-stage renal disease, amputations, and hospitalizations.3 Due to the long-term complications of diabetes, it is important to help patients control their disease. However, diabetes control in patients can be difficult because of the broad disease education needed and its medication administration.

Insulin requires the most extensive instruction when educating patients with diabetes. Specifically, patient counseling needs to incorporate the importance of proper insulin administration. If patients are not properly administering their insulin, controlling their diabetes will be very difficult. Many clinicians know to educate the patient about drawing insulin into a syringe and how to inject insulin properly. However, clinicians do not always think about other aspects of insulin administration education, such as the mixing of different insulins in 1 syringe. Patients and family members need to be taught about the types of insulins that can and cannot be mixed. The American Diabetes Association (ADA) provides recommendations on the appropriate time to mix insulin and the types of insulin that can and cannot be mixed (Table 1).4

CASE REPORT

A white male, aged 69 years, presented to a pharmacist-run pharmacotherapy clinic for a follow-up appointment for uncontrolled diabetes. The patient’s wife, who managed his medications, accompanied him. Significant past medical history included diabetes, nephropathy, retinopathy, degenerative joint disease, migraines, gastroesophageal reflux disease, depression, posttraumatic stress disorder, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, lumbago, panic attacks, medication noncompliance, status post cerebral vascular accident, and renal insufficiency.

The patient had a long history of type 2 diabetes, and his insulin had been titrated multiple times since he was established in this clinic in 2009. At his establishing visit, he was taken off his insulin pump due to noncompliance with blood glucose checks and placed on basal-bolus therapy with insulin glargine and insulin aspart. The patient then titrated his basal-bolus insulin for 6 weeks but stated his blood sugars were consistently elevated (reaching 600 mg/dL); therefore, he self-reinitiated the insulin pump. After restarting the insulin pump, the clinic made several attempts to follow-up with the patient, but none were successful. He was subsequently dismissed from the clinic following his admission to a local nursing home.

The patient was reestablished at the clinic in 2010 (about 1 year after dismissal). He reported discontinuing the insulin pump and using insulin glargine and insulin aspart injections but was self-adjusting insulin glargine based on readings. He was told not to self-adjust insulin glargine dose and was given a sliding scale for self-adjustment of his insulin aspart dose based on blood glucose readings. Since the reestablished visit, both insulin therapies were titrated without much success in controlling his blood glucose levels. He was also advised to check his fasting blood glucose (FBG) more often and was demonstrated correct insulin drawing technique.

At a follow-up visit in August 2012, the patient’s A1c was 10.7%, and FBG readings ranged from 108 mg/dL to 555 mg/dL. Goal A1c was between 8% and 8.5% per VA/DoD diabetes guidelines.5 After a discussion with the patient’s wife, it was discovered that the patient was improperly administrating his insulin. The patient had been administrating the insulin glargine and insulin aspart in the same syringe. Since the combined dose of insulin was greater than his syringe would allow, he adjusted the insulin glargine dose downward if more insulin aspart was needed per the sliding scale. He did this to avoid more injections than he thought were necessary. Based on his A1c and home blood glucose readings, it was also suspected that insulin doses were being missed. The patient and wife were instructed about the importance of adherence and not mixing these insulins in the same syringe.

At the most recent visit, the patient’s FBG readings (200 mg/dL-500 mg/dL) and A1c (10.7%) were still greatly elevated. He reported taking 40 units insulin glargine in the morning and 60 units at bedtime, along with 40 units insulin aspart plus sliding scale insulin (1:20 > 120 mg/dL) at breakfast and 40 to 70 units at lunch and supper. The patient reported compliance with insulin therapy; however, it was likely he was not dosing accurately, according to his sliding scale. He stated he was eating less and was worried about hypoglycemia. Due to the patient’s FBG and A1c still being elevated, insulin aspart was titrated again, which was closer to a 50% basal and 50% bolus regimen, and he was again educated about proper dosing.

DISCUSSION

Patients have many obstacles to managing their diseases. This is especially prevalent in patients with diabetes. These patients both experience the emotional stress of being diagnosed with diabetes and are given a wealth of information on diabetes, nutrition, therapy, and insulin-dosing technique at the same time. The information can be overwhelming for patients to hear and for the educator to present. Sometimes health care professionals (HCPs) overlook a patient’s hindrances due to the amount of information they have to give to the patient. For example, in this case, the patient was mixing insulin inappropriately, and it was overlooked by the HCP.

Insulin therapy has been used for several decades. It is obtained from either a pork pancreas or is chemically manufactured to be identical to human insulin. This can be achieved by recombinant DNA technology or chemical modification of pork insulin.4 Insulin is available as short-, intermediate-, or long-acting duration. The pharmacokinetics of available insulins is listed in Table 2.6

Some insulin can be mixed in the same syringe, but these mainly consist of the short- and intermediate-acting insulin. Insulin glargine, a long-acting formulation, should not be mixed with any other insulin due to its pharmacokinetic properties.7 Insulin glargine has been designed to have a low solubility at a neutral pH. After injection, the pH rises and leads to the formation of microprecipitates, causing a slow release of the insulin over 24 hours with no peak. If insulin glargine is mixed, it is likely the pH would be altered before entering the body. In addition, mixing insulin in the same syringe could likely contaminate the dose.

The maker of insulin glargine advises against mixing it with any other insulin.7 Several different studies have been done with admixtures of insulin glargine with short- or rapid-acting insulin. The studies revealed no differences in glycemic control, blunted and delayed rapid-acting insulin peak, the need for larger doses, or worsened glycemic control.8-12

Other education points about insulin administration that are often overlooked or sometimes ignored by patients and that require follow-up for compliance include the following:

• Manufacturers recommend discarding an open bottle of insulin at room temperature after 28 days.7

• Insulin should be kept in a temperature-controlled environment between 36°F and 86°F.4,7

• Rotation of injection sites is necessary to prevent lipodystrophy.4,7

• It is recommended that patients stick with 1 approved anatomical site for all insulin injections, such as the abdomen or leg, to maintain consistent pharmacokinetics.4,13,14

It is also important to know the constitution of the different insulins and whether they have been compromised. For example, if a clear solution insulin turns cloudy, it is considered compromised and should be thrown away.

CONCLUSION

Patients are diagnosed every day with diabetes, and many treatment regimens include insulin therapy. With the diagnosis of diabetes, patients are given extensive information on therapy, nutrition, preventative measures, and technique. Since controlling diabetes can call for intensive insulin therapy, medication administration instruction by HCPs is important. It is important to discuss in detail how the patient manages their insulin therapy at each visit so that issues will not be overlooked. Long-term, inappropriate use of insulin may lead to uncontrolled diabetes.

Diabetes is a complex disease to manage and takes a joint effort by both the HCP and patient to control. Patients need to understand the importance of compliance in all aspects of the disease, and the HCP needs to understand the importance of extensive counseling, including diet, exercise, and medication therapy.

Author disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review the complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Diabetes Statistics Report: Estimates of Diabetes and Its Burden in the United States, 2014. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2014. http://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/pubs/statsreport14.htm. Updated July 28, 2014. Accessed August 12, 2014.

2. Roger VL, Go AS, Lloyd-Jones DM. et al; American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2012 update: A report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2012;125(1):e2-e220.

3. Inzucchi SE, Bergenstal RM, Buse JB, et al; American Diabetes Association (ADA); European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Management of hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes: A patient-centered approach: Position statement of the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Diabetes Care. 2012;35(6):1364-1379.

4. American Diabetes Association. Insulin administration. Diabetes Care. 2004;27(suppl 1): S106-S109.

5. VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guidelines: Management of Diabetes Mellitus (DM). Version 4.0. Website: http://www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/CD/diabetes/DM2010_FUL-v4e.pdf. Updated August 2010. Accessed August 12, 2014.

6. McCulloch DK. General principles of isulin therapy in diabetes mellitus. UpToDate Website. http://www .uptodate.com /contents/general-principles-of-insulin-therapy-in-diabetes-mellitus. Accessed August 5, 2014.

7. Lantus [package insert]. Bridgewater, NJ: sanofi-aventis US; 2013.

8. Cengiz E, Tamborlane WV, Martin-Fredericksen M, Dziura J, Weinzimer SA. Early pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic effects of mixing lispro with glargine insulin: Results of glucose clamp studies in youth with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2010;33(5):1009-1012.

9. Lucchesi MB, Komatsu WR, Gabbay MA, Dib SA. A 12-wk follow-up study to evaluate the effects of mixing insulin lispro and insulin glargine in young individuals with type 1 diabetes. Pediatr Diabetes. 2012;13(7):519-524.

10. Kaplan W, Rodriguez LM, Smith OE, Haymond MW, Heptulla RA. Effects of mixing glargine and short-acting insulin analogs on glucose control. Diabetes Care. 2004;27(11):2739-2740.

11. Fiallo-Scharer R, Horner B, McFann K, Walravens P, Chase HP. Mixing rapid-acting insulin analogs with insulin glargine in children with type 1 diabetes mellitus. J Pediatr. 2006;148(4):481-484.

12. Hassan K, Rodriguez LM, Johnson SE, Tadlock S, Heptulla RA. A randomized, controlled trial comparing twice-a-day insulin glargine mixed with rapid-acting insulin analogs versus standard neutral protamine Hagedorn (NPH) therapy in newly diagnosed type 1 diabetes. Pediatrics. 2008;121(3):e466 -e472.

13. Koivisto VA, Felig P. Alterations in insulin absorption and in blood glucose control associated with varying insulin injection sites in diabetic patients. Ann Intern Med. 1980;92(1):59-61.

14. Berger M, Cüppers HJ, Hegner H, Jörgens V, Berchtold P. Absorption kinetics and biologic effects of subcutaneously injected insulin preparations. Diabetes Care. 1982;5(2):77-91.

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Diabetes Statistics Report: Estimates of Diabetes and Its Burden in the United States, 2014. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2014. http://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/pubs/statsreport14.htm. Updated July 28, 2014. Accessed August 12, 2014.

2. Roger VL, Go AS, Lloyd-Jones DM. et al; American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2012 update: A report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2012;125(1):e2-e220.

3. Inzucchi SE, Bergenstal RM, Buse JB, et al; American Diabetes Association (ADA); European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Management of hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes: A patient-centered approach: Position statement of the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Diabetes Care. 2012;35(6):1364-1379.

4. American Diabetes Association. Insulin administration. Diabetes Care. 2004;27(suppl 1): S106-S109.

5. VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guidelines: Management of Diabetes Mellitus (DM). Version 4.0. Website: http://www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/CD/diabetes/DM2010_FUL-v4e.pdf. Updated August 2010. Accessed August 12, 2014.

6. McCulloch DK. General principles of isulin therapy in diabetes mellitus. UpToDate Website. http://www .uptodate.com /contents/general-principles-of-insulin-therapy-in-diabetes-mellitus. Accessed August 5, 2014.

7. Lantus [package insert]. Bridgewater, NJ: sanofi-aventis US; 2013.

8. Cengiz E, Tamborlane WV, Martin-Fredericksen M, Dziura J, Weinzimer SA. Early pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic effects of mixing lispro with glargine insulin: Results of glucose clamp studies in youth with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2010;33(5):1009-1012.

9. Lucchesi MB, Komatsu WR, Gabbay MA, Dib SA. A 12-wk follow-up study to evaluate the effects of mixing insulin lispro and insulin glargine in young individuals with type 1 diabetes. Pediatr Diabetes. 2012;13(7):519-524.

10. Kaplan W, Rodriguez LM, Smith OE, Haymond MW, Heptulla RA. Effects of mixing glargine and short-acting insulin analogs on glucose control. Diabetes Care. 2004;27(11):2739-2740.

11. Fiallo-Scharer R, Horner B, McFann K, Walravens P, Chase HP. Mixing rapid-acting insulin analogs with insulin glargine in children with type 1 diabetes mellitus. J Pediatr. 2006;148(4):481-484.

12. Hassan K, Rodriguez LM, Johnson SE, Tadlock S, Heptulla RA. A randomized, controlled trial comparing twice-a-day insulin glargine mixed with rapid-acting insulin analogs versus standard neutral protamine Hagedorn (NPH) therapy in newly diagnosed type 1 diabetes. Pediatrics. 2008;121(3):e466 -e472.

13. Koivisto VA, Felig P. Alterations in insulin absorption and in blood glucose control associated with varying insulin injection sites in diabetic patients. Ann Intern Med. 1980;92(1):59-61.

14. Berger M, Cüppers HJ, Hegner H, Jörgens V, Berchtold P. Absorption kinetics and biologic effects of subcutaneously injected insulin preparations. Diabetes Care. 1982;5(2):77-91.

The VALOR Program: Preparing Nursing Students to Care for Our Veterans

The VA Learning Opportunity Residency (VALOR) program is a prelicensure experience with a nurse preceptor for rising senior students enrolled in a bachelor of science in nursing program. Students must have a minimum 3.0 grade-point average to apply. The program provides 800 hours of paid learning experiences in diverse didactic and hands-on clinical situations. The first 400 hours of the program (10 weeks) occur over the summer, and the second 400 hours take place during the fall and spring semesters of the student’s last year of school.1 During the last 400 hours, students are placed in the areas they are interested in working as new graduate nurses.

The aim of the Salem VALOR program is to develop the next generation of VAMC nurses by recruiting new graduate nurses. The Salem VAMC structures the VALOR program to meet the needs of both the students and the facility. According to Glenda Fuller, the student programs manager for the VA, national VALOR retention rates from 2007 to 2011 have averaged 38%. However, more applicants apply for new graduate nurse positions than are available. Included in the VHA Directive 2011-039, facilities that hire a nurse with ≤ 1 year of experience must enroll them in a yearlong transition-to-practice program.2 Therefore, facilities may limit the number of new graduate nurse positions.

On entry into the VALOR program, participants write a journal entry regarding their fears and concerns about becoming a new graduate nurse. In addition, each student turns in a written reflection about their experiences each week and participates in daily group discussions with the program coordinator. The last day of the summer portion of the program, students again write about their fears and concerns about becoming a new graduate nurse. After reviewing the VALOR journals, conducting focus groups, and taking notes during the daily meetings, the authors describe the following VALOR experience from the summer of 2013 at the Salem VAMC.

Preparing New Graduates

Hospitals are under pressure to provide high-quality nursing care despite hiring new graduate nurses who are unfamiliar and inexperienced in caring for patients’ complex health care needs. New graduate nurses currently make up more than 10% of hospital nursing staff, and that number is expected to grow as baby boomers retire.3 Boswell and colleagues suggest that those new graduate nurses are unprepared for the registered nurse role.4 Identifying strategies to facilitate the transition from student to the new graduate nurse role will likely decrease attrition rates and increase the effectiveness and the quality of patient care. Nursing programs, such as the VALOR, can ease the transition from the classroom to the working environment.5

This result is evident when observing how VALOR students enhance their nursing skills after the 10-week summer program. VALOR participant Andrea King published her summer experience at the Salem VAMC in The Torch, the Virginia Nursing Students’ Association newsletter.6 “I had so much practice and eventually confidence in my nursing skills,” she wrote, “that I had the autonomy and independence to feel like I was working as an actual nurse.”6

The VALOR Experience

During the summer months, senior nursing students have the opportunity to go on rounds with the chaplain, work with nurse practitioners, attend outings with mental health patients, participate in home health visits, interact with patients in groups, and rotate to different hospital units. Students attend FranklinCovey classes (which specialize in employee performance improvement), participate in an evidence-based practice (EBP) project (which helps them to learn about teamwork), and collaborate with interdisciplinary health care professionals. At the end of the summer, students present their team EBP project to the nurse executive committee. Presentation experience assists students in acquiring public speaking skills. Students are nervous about presenting to a room full of executives. However, they learn to depend on one another and to strengthen weaknesses and build on strengths.

When high-performing students come together as one cohort, this dynamic poses challenges for the VALOR participants. One student described her vulnerability in relation to her VALOR peers as “the hardest hit to my self-confidence has been working with such intelligent and accomplished cohorts.” Another student found that even though she was at the top of her class, working with the other VALORs “challenged her self-confidence” because all the program participants were high-performing students. She found it pushed her to perform better. One person reflected, “I feel the VALOR experience has really given all of us the opportunity to unleash our full potential. I have no doubt that these students will become future health care leaders.”

Building Skills

Learning new skills and interacting with physicians are stressful experiences for new graduate nurses.7 A study by Casey and colleagues suggests that new graduate nurses feel inadequate and lack self-confidence.8 VALOR participants share these concerns. The initial journal entries revealed fears of making a mistake, harming patients, fitting in to the work culture, working with doctors, feeling anxious about patient interactions, and performing clinical skills competently.

Initially, students focused on needing extensive practice with nursing skills as evidenced by one student’s comments, “I’m honestly concerned about some of the procedures; I’ve only put in 3 IVs during nursing school, I am not confident walking in to a room and performing a procedure on my own. I would be overwhelmed.” When considering RN-to-MD communication, one student commented, “I’m nervous, doctors can be very hard on new nurses, I’ve witnessed this over and over.”

During the first weeks, the participants discussed the fear of being “on their own” without the benefit of their instructor once they graduate. One person noted this feeling as “The seed of fear grows as graduation approaches.” This lack of self-confidence and feeling scared is a consistent issue with all the VALOR students the first day of the program.

During the program, VALOR students developed nursing skills and became certified in advanced cardiac life support (ACLS). One student suggested that the ACLS class was a great team builder and instilled confidence among the VALOR participants. Another student shared, “We all agreed that attaining this certification was a culmination of our overall VA experience.” A student who was working in an acute care area applied the newly learned ACLS skills the following week when a patient coded. The student’s journal reflected how preparation makes a difference and described his experience and knowing how to react as “powerful.”

The Reality of Nursing

The VALOR program helps connect the academic environment with the realities of the workplace. Wilson found bridging the theory-practice gap between school and workplace improves learning opportunities for students.9 Wilson also suggests that having peers to identify with helps to bridge the theory-practice gap.9 Journal entries reflected “the perfect hospital” of textbooks was different from working every day and “almost being a nurse.” During the VALOR program, students immerse themselves in the realistic nursing environment of staff shortages, equipment unavailability, disgruntled patients, and peer-to-peer communication that is not always civil. The 40-hour workweek provides a realistic hands-on view of nursing and introduces students to socializing as a nurse and the nursing work culture.

After the 2013 summer portion of the program, students were able to differentiate between the realities of the world of health care and the academic view of the health care environment. As students progressed over the summer, a noticeable transformation took place. The student who wrote about needing more skills practice on day 1 found that she was comfortable with injections, hanging IVs, and providing patient care at the end of week 3. Students grew more comfortable collaborating with doctors and other interdisciplinary professionals. They also became competent with basic nursing skills and had a realistic view of the nursing world.

In addition, students became aware of the emotional aspects of nursing. One student discussed making a difference in a veteran’s life after participating in a substance abuse group. “While I was on my way home I started thinking about those vets and their stories, and I started getting emotional. I just felt bad that after doing the great deed of fighting for our country that they became victims of substance abuse,” the student explained. “That afternoon, as I departed the vets, I left hopeful and realized I could make a difference in the life of a veteran.” Another student perceived that doctors were discussing a veteran’s terminal lung cancer “nonchalantly” and reflected, “though I do recognize that a certain degree of disconnection must take place, a certain measure of empathy must remain at all times to effect positive outcomes in the patient’s health.”

VALOR students noted that the program gave them exposure to different areas of nursing. This experience assisted them in deciding on an area of nursing interest. One student who always wanted to be an emergency department nurse found that after that rotation, she was not “cut out to be an emergency department nurse.” Some students came into the program thinking they knew precisely what they wanted to do following graduation, but found a new interest.

Daily Debriefings

Through daily debriefing discussions, students learn about best practices, patient advocacy, nursing leadership, and communication skills. Some have said that it has helped them “get through the day” knowing they had an outlet to review their experiences with VALOR peers. Discussions focus on both the positive and negative aspects of their day.

Students found that group discussions bonded them as a team and allowed them to share their feelings openly. One student found, “What really impacted me was just the amount of learning I received from my VALOR friends.” The group discussions and projects allow students who may typically work in isolation to come together as a team, providing a safe outlet for reflection and self-expression. Meeting daily with peers to share personal experiences increases team cohesion. Research suggests that students learn from their peers.10,11 Working closely with these students, the benefit of peer-to-peer learning was obvious. Students support and teach one another in a nonthreatening environment, which enhances their learning process.

End of the Summer Journey

For the students’ final journal entry, they are asked to identify their greatest fear from week 1 and describe how that has changed by week 10. Journal entries indicated that the students were no longer afraid of being a new nurse, and doctors were “not so scary anymore.” Students already know that nursing is not “going to be peachy,” but participating in the VALOR program allayed their worst fears. One student wrote, “When I had the experiences of doctors, dieticians, and physical therapists asking me questions about my patient and taking what I said seriously, it really boosted my confidence.”

Students seemed less nervous taking on the new graduate nurse role, because they practiced skills and experienced the real life of a nurse. The student who was worried about starting IVs stated, “It is second nature now.” The student who was worried about talking to doctors is now paging and communicating with them in teams. “I feel that I’m more likely to converse with other members of the health care team because of this experience,” one student reported. Another student experienced being afraid of practicing clinical skills because of her lack of experience. “I had put in only 3 IVs previously. I had never seen a cardiac catheterization,” she related. “I had never run an electrocardiography (EKG), and I had never had an opportunity to see many of the things I have seen. I was afraid of taking a full patient load, and I was apprehensive about simple things such as hanging IV medications. I was unsure of myself, and desperately needed practice. I lacked confidence, and needed to gain experience. Now, looking back, those things seem silly.”

Coming out of this program, one student suggested, “I have found that my expectations were blown away.” The 2013 cohort walked away from the summer portion of the program with ACLS training, EKG classes, interdisciplinary team experiences, FranklinCovey personal development seminars, and most of all, hands-on experience that provided these future nurses with confidence in their abilities. Participants felt that after this summer they would be “a step ahead” of their peers when they returned to school in the fall. One student related, after returning to school, “My professor asked me to help teach an EKG class since I was ACLS certified.”

Conclusion

The goal of sharing the VALOR program and students’ experiences at the Salem VAMC is to highlight how students grow clinically and professionally. The program is not a single-person endeavor. The chief nurse executive, managers, interdisciplinary health care professionals, and nursing preceptors support the program. Gaining stakeholder buy-in for the program results in positive experiences for both students and veterans.

Taking top-performing students and grouping them as a cohort creates a learning experience for students and benefits the facility. Students develop essential nursing skills, which assist their transition to the new graduate nurse role. In the words of one student, “As this experience comes to a close, I find myself increasingly apprehensive of finishing. The VALOR position has been like a dream come true for me. I have developed as a person and a future nurse.” As the new generation of nurses, the VALORs provide the institution with fresh eyes and new ideas on how to improve the system and to care for our nation’s veterans.

Author disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review the complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

1. Shipman D, Garrison M, Hooten J. VALOR: A win-win for VA medical centers and BSN students. Fed Pract. 2010;27(7):31-33.

2. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. VHA registered nurses (RN) transition-to-practice program. Veterans Health Administration Website.

http://www1.va.gov/vhapublications/ViewPublication.asp?pub_ID=2469. Published November 23, 2011. Accessed July 1, 2014.

3. Nursing Executive Center. Bridging the Preparation-Practice Gap. Vol. 1: Quantifying new graduate nurse improvement needs. Washington, DC: The Advisory Board Company; 2008. https://hci-portal.hci.utah.edu/sites/hch-nursing/staff-development/Shared%20Documents/Manager%20Tools/Published%20Articles/Bridging%20the%20Preparation%20Practice%20Gap.10.10.pdf. Published 2008. Accessed July 1, 2014.

4. Boswell S, Lowry LW, Wilhoit K. New nurses’ perceptions of nursing practice and quality patient care. J Nurs Care Qual. 2004;19(1):76-81.

5. Rhoads J, Sensenig K, Ruth-Sahd L, Thompson E. Nursing externship: A collaborative endeavor between nursing education and nursing administration. Dimens Crit Care Nurs. 2003;22(6):255-258.

6. King A. My summer externship experience. The Torch. Virginia Nursing Students’ Association Newsletter. Fall 2013. VNSA Website. http://www.vnsa.us/uploads/1/9/0/2/19025131/fall2013torch-final-1.pdf. Accessed July 1, 2014.

7. Oermann MH, Moffitt-Wolf A. New graduates’ perceptions of clinical practice. J Contin Educ Nurs. 1997;28(1):20-25.

8. Casey K, Fink R, Krugman M, Propst J. The graduate nurse experience. J Nurs Adm. 2004;34(6):303-311.

9. Wilson J. Bridging the theory practice gap. Aust Nurs J. 2008;16(4):25.

10. Etheridge SA. Learning to think like a nurse: Stories from new nurse graduates. J Contin Educ Nurs. 2007;38(1):24-30.

11. Roberts D. Friendship fosters learning: The importance of friendship in clinical practice. Nurse Educ Pract. 2009;9(6):367-371.

The VA Learning Opportunity Residency (VALOR) program is a prelicensure experience with a nurse preceptor for rising senior students enrolled in a bachelor of science in nursing program. Students must have a minimum 3.0 grade-point average to apply. The program provides 800 hours of paid learning experiences in diverse didactic and hands-on clinical situations. The first 400 hours of the program (10 weeks) occur over the summer, and the second 400 hours take place during the fall and spring semesters of the student’s last year of school.1 During the last 400 hours, students are placed in the areas they are interested in working as new graduate nurses.

The aim of the Salem VALOR program is to develop the next generation of VAMC nurses by recruiting new graduate nurses. The Salem VAMC structures the VALOR program to meet the needs of both the students and the facility. According to Glenda Fuller, the student programs manager for the VA, national VALOR retention rates from 2007 to 2011 have averaged 38%. However, more applicants apply for new graduate nurse positions than are available. Included in the VHA Directive 2011-039, facilities that hire a nurse with ≤ 1 year of experience must enroll them in a yearlong transition-to-practice program.2 Therefore, facilities may limit the number of new graduate nurse positions.

On entry into the VALOR program, participants write a journal entry regarding their fears and concerns about becoming a new graduate nurse. In addition, each student turns in a written reflection about their experiences each week and participates in daily group discussions with the program coordinator. The last day of the summer portion of the program, students again write about their fears and concerns about becoming a new graduate nurse. After reviewing the VALOR journals, conducting focus groups, and taking notes during the daily meetings, the authors describe the following VALOR experience from the summer of 2013 at the Salem VAMC.

Preparing New Graduates

Hospitals are under pressure to provide high-quality nursing care despite hiring new graduate nurses who are unfamiliar and inexperienced in caring for patients’ complex health care needs. New graduate nurses currently make up more than 10% of hospital nursing staff, and that number is expected to grow as baby boomers retire.3 Boswell and colleagues suggest that those new graduate nurses are unprepared for the registered nurse role.4 Identifying strategies to facilitate the transition from student to the new graduate nurse role will likely decrease attrition rates and increase the effectiveness and the quality of patient care. Nursing programs, such as the VALOR, can ease the transition from the classroom to the working environment.5

This result is evident when observing how VALOR students enhance their nursing skills after the 10-week summer program. VALOR participant Andrea King published her summer experience at the Salem VAMC in The Torch, the Virginia Nursing Students’ Association newsletter.6 “I had so much practice and eventually confidence in my nursing skills,” she wrote, “that I had the autonomy and independence to feel like I was working as an actual nurse.”6

The VALOR Experience

During the summer months, senior nursing students have the opportunity to go on rounds with the chaplain, work with nurse practitioners, attend outings with mental health patients, participate in home health visits, interact with patients in groups, and rotate to different hospital units. Students attend FranklinCovey classes (which specialize in employee performance improvement), participate in an evidence-based practice (EBP) project (which helps them to learn about teamwork), and collaborate with interdisciplinary health care professionals. At the end of the summer, students present their team EBP project to the nurse executive committee. Presentation experience assists students in acquiring public speaking skills. Students are nervous about presenting to a room full of executives. However, they learn to depend on one another and to strengthen weaknesses and build on strengths.

When high-performing students come together as one cohort, this dynamic poses challenges for the VALOR participants. One student described her vulnerability in relation to her VALOR peers as “the hardest hit to my self-confidence has been working with such intelligent and accomplished cohorts.” Another student found that even though she was at the top of her class, working with the other VALORs “challenged her self-confidence” because all the program participants were high-performing students. She found it pushed her to perform better. One person reflected, “I feel the VALOR experience has really given all of us the opportunity to unleash our full potential. I have no doubt that these students will become future health care leaders.”

Building Skills

Learning new skills and interacting with physicians are stressful experiences for new graduate nurses.7 A study by Casey and colleagues suggests that new graduate nurses feel inadequate and lack self-confidence.8 VALOR participants share these concerns. The initial journal entries revealed fears of making a mistake, harming patients, fitting in to the work culture, working with doctors, feeling anxious about patient interactions, and performing clinical skills competently.

Initially, students focused on needing extensive practice with nursing skills as evidenced by one student’s comments, “I’m honestly concerned about some of the procedures; I’ve only put in 3 IVs during nursing school, I am not confident walking in to a room and performing a procedure on my own. I would be overwhelmed.” When considering RN-to-MD communication, one student commented, “I’m nervous, doctors can be very hard on new nurses, I’ve witnessed this over and over.”

During the first weeks, the participants discussed the fear of being “on their own” without the benefit of their instructor once they graduate. One person noted this feeling as “The seed of fear grows as graduation approaches.” This lack of self-confidence and feeling scared is a consistent issue with all the VALOR students the first day of the program.

During the program, VALOR students developed nursing skills and became certified in advanced cardiac life support (ACLS). One student suggested that the ACLS class was a great team builder and instilled confidence among the VALOR participants. Another student shared, “We all agreed that attaining this certification was a culmination of our overall VA experience.” A student who was working in an acute care area applied the newly learned ACLS skills the following week when a patient coded. The student’s journal reflected how preparation makes a difference and described his experience and knowing how to react as “powerful.”

The Reality of Nursing

The VALOR program helps connect the academic environment with the realities of the workplace. Wilson found bridging the theory-practice gap between school and workplace improves learning opportunities for students.9 Wilson also suggests that having peers to identify with helps to bridge the theory-practice gap.9 Journal entries reflected “the perfect hospital” of textbooks was different from working every day and “almost being a nurse.” During the VALOR program, students immerse themselves in the realistic nursing environment of staff shortages, equipment unavailability, disgruntled patients, and peer-to-peer communication that is not always civil. The 40-hour workweek provides a realistic hands-on view of nursing and introduces students to socializing as a nurse and the nursing work culture.

After the 2013 summer portion of the program, students were able to differentiate between the realities of the world of health care and the academic view of the health care environment. As students progressed over the summer, a noticeable transformation took place. The student who wrote about needing more skills practice on day 1 found that she was comfortable with injections, hanging IVs, and providing patient care at the end of week 3. Students grew more comfortable collaborating with doctors and other interdisciplinary professionals. They also became competent with basic nursing skills and had a realistic view of the nursing world.

In addition, students became aware of the emotional aspects of nursing. One student discussed making a difference in a veteran’s life after participating in a substance abuse group. “While I was on my way home I started thinking about those vets and their stories, and I started getting emotional. I just felt bad that after doing the great deed of fighting for our country that they became victims of substance abuse,” the student explained. “That afternoon, as I departed the vets, I left hopeful and realized I could make a difference in the life of a veteran.” Another student perceived that doctors were discussing a veteran’s terminal lung cancer “nonchalantly” and reflected, “though I do recognize that a certain degree of disconnection must take place, a certain measure of empathy must remain at all times to effect positive outcomes in the patient’s health.”

VALOR students noted that the program gave them exposure to different areas of nursing. This experience assisted them in deciding on an area of nursing interest. One student who always wanted to be an emergency department nurse found that after that rotation, she was not “cut out to be an emergency department nurse.” Some students came into the program thinking they knew precisely what they wanted to do following graduation, but found a new interest.

Daily Debriefings

Through daily debriefing discussions, students learn about best practices, patient advocacy, nursing leadership, and communication skills. Some have said that it has helped them “get through the day” knowing they had an outlet to review their experiences with VALOR peers. Discussions focus on both the positive and negative aspects of their day.

Students found that group discussions bonded them as a team and allowed them to share their feelings openly. One student found, “What really impacted me was just the amount of learning I received from my VALOR friends.” The group discussions and projects allow students who may typically work in isolation to come together as a team, providing a safe outlet for reflection and self-expression. Meeting daily with peers to share personal experiences increases team cohesion. Research suggests that students learn from their peers.10,11 Working closely with these students, the benefit of peer-to-peer learning was obvious. Students support and teach one another in a nonthreatening environment, which enhances their learning process.

End of the Summer Journey

For the students’ final journal entry, they are asked to identify their greatest fear from week 1 and describe how that has changed by week 10. Journal entries indicated that the students were no longer afraid of being a new nurse, and doctors were “not so scary anymore.” Students already know that nursing is not “going to be peachy,” but participating in the VALOR program allayed their worst fears. One student wrote, “When I had the experiences of doctors, dieticians, and physical therapists asking me questions about my patient and taking what I said seriously, it really boosted my confidence.”

Students seemed less nervous taking on the new graduate nurse role, because they practiced skills and experienced the real life of a nurse. The student who was worried about starting IVs stated, “It is second nature now.” The student who was worried about talking to doctors is now paging and communicating with them in teams. “I feel that I’m more likely to converse with other members of the health care team because of this experience,” one student reported. Another student experienced being afraid of practicing clinical skills because of her lack of experience. “I had put in only 3 IVs previously. I had never seen a cardiac catheterization,” she related. “I had never run an electrocardiography (EKG), and I had never had an opportunity to see many of the things I have seen. I was afraid of taking a full patient load, and I was apprehensive about simple things such as hanging IV medications. I was unsure of myself, and desperately needed practice. I lacked confidence, and needed to gain experience. Now, looking back, those things seem silly.”

Coming out of this program, one student suggested, “I have found that my expectations were blown away.” The 2013 cohort walked away from the summer portion of the program with ACLS training, EKG classes, interdisciplinary team experiences, FranklinCovey personal development seminars, and most of all, hands-on experience that provided these future nurses with confidence in their abilities. Participants felt that after this summer they would be “a step ahead” of their peers when they returned to school in the fall. One student related, after returning to school, “My professor asked me to help teach an EKG class since I was ACLS certified.”

Conclusion

The goal of sharing the VALOR program and students’ experiences at the Salem VAMC is to highlight how students grow clinically and professionally. The program is not a single-person endeavor. The chief nurse executive, managers, interdisciplinary health care professionals, and nursing preceptors support the program. Gaining stakeholder buy-in for the program results in positive experiences for both students and veterans.

Taking top-performing students and grouping them as a cohort creates a learning experience for students and benefits the facility. Students develop essential nursing skills, which assist their transition to the new graduate nurse role. In the words of one student, “As this experience comes to a close, I find myself increasingly apprehensive of finishing. The VALOR position has been like a dream come true for me. I have developed as a person and a future nurse.” As the new generation of nurses, the VALORs provide the institution with fresh eyes and new ideas on how to improve the system and to care for our nation’s veterans.

Author disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review the complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

The VA Learning Opportunity Residency (VALOR) program is a prelicensure experience with a nurse preceptor for rising senior students enrolled in a bachelor of science in nursing program. Students must have a minimum 3.0 grade-point average to apply. The program provides 800 hours of paid learning experiences in diverse didactic and hands-on clinical situations. The first 400 hours of the program (10 weeks) occur over the summer, and the second 400 hours take place during the fall and spring semesters of the student’s last year of school.1 During the last 400 hours, students are placed in the areas they are interested in working as new graduate nurses.

The aim of the Salem VALOR program is to develop the next generation of VAMC nurses by recruiting new graduate nurses. The Salem VAMC structures the VALOR program to meet the needs of both the students and the facility. According to Glenda Fuller, the student programs manager for the VA, national VALOR retention rates from 2007 to 2011 have averaged 38%. However, more applicants apply for new graduate nurse positions than are available. Included in the VHA Directive 2011-039, facilities that hire a nurse with ≤ 1 year of experience must enroll them in a yearlong transition-to-practice program.2 Therefore, facilities may limit the number of new graduate nurse positions.

On entry into the VALOR program, participants write a journal entry regarding their fears and concerns about becoming a new graduate nurse. In addition, each student turns in a written reflection about their experiences each week and participates in daily group discussions with the program coordinator. The last day of the summer portion of the program, students again write about their fears and concerns about becoming a new graduate nurse. After reviewing the VALOR journals, conducting focus groups, and taking notes during the daily meetings, the authors describe the following VALOR experience from the summer of 2013 at the Salem VAMC.

Preparing New Graduates

Hospitals are under pressure to provide high-quality nursing care despite hiring new graduate nurses who are unfamiliar and inexperienced in caring for patients’ complex health care needs. New graduate nurses currently make up more than 10% of hospital nursing staff, and that number is expected to grow as baby boomers retire.3 Boswell and colleagues suggest that those new graduate nurses are unprepared for the registered nurse role.4 Identifying strategies to facilitate the transition from student to the new graduate nurse role will likely decrease attrition rates and increase the effectiveness and the quality of patient care. Nursing programs, such as the VALOR, can ease the transition from the classroom to the working environment.5

This result is evident when observing how VALOR students enhance their nursing skills after the 10-week summer program. VALOR participant Andrea King published her summer experience at the Salem VAMC in The Torch, the Virginia Nursing Students’ Association newsletter.6 “I had so much practice and eventually confidence in my nursing skills,” she wrote, “that I had the autonomy and independence to feel like I was working as an actual nurse.”6

The VALOR Experience

During the summer months, senior nursing students have the opportunity to go on rounds with the chaplain, work with nurse practitioners, attend outings with mental health patients, participate in home health visits, interact with patients in groups, and rotate to different hospital units. Students attend FranklinCovey classes (which specialize in employee performance improvement), participate in an evidence-based practice (EBP) project (which helps them to learn about teamwork), and collaborate with interdisciplinary health care professionals. At the end of the summer, students present their team EBP project to the nurse executive committee. Presentation experience assists students in acquiring public speaking skills. Students are nervous about presenting to a room full of executives. However, they learn to depend on one another and to strengthen weaknesses and build on strengths.

When high-performing students come together as one cohort, this dynamic poses challenges for the VALOR participants. One student described her vulnerability in relation to her VALOR peers as “the hardest hit to my self-confidence has been working with such intelligent and accomplished cohorts.” Another student found that even though she was at the top of her class, working with the other VALORs “challenged her self-confidence” because all the program participants were high-performing students. She found it pushed her to perform better. One person reflected, “I feel the VALOR experience has really given all of us the opportunity to unleash our full potential. I have no doubt that these students will become future health care leaders.”

Building Skills

Learning new skills and interacting with physicians are stressful experiences for new graduate nurses.7 A study by Casey and colleagues suggests that new graduate nurses feel inadequate and lack self-confidence.8 VALOR participants share these concerns. The initial journal entries revealed fears of making a mistake, harming patients, fitting in to the work culture, working with doctors, feeling anxious about patient interactions, and performing clinical skills competently.

Initially, students focused on needing extensive practice with nursing skills as evidenced by one student’s comments, “I’m honestly concerned about some of the procedures; I’ve only put in 3 IVs during nursing school, I am not confident walking in to a room and performing a procedure on my own. I would be overwhelmed.” When considering RN-to-MD communication, one student commented, “I’m nervous, doctors can be very hard on new nurses, I’ve witnessed this over and over.”

During the first weeks, the participants discussed the fear of being “on their own” without the benefit of their instructor once they graduate. One person noted this feeling as “The seed of fear grows as graduation approaches.” This lack of self-confidence and feeling scared is a consistent issue with all the VALOR students the first day of the program.

During the program, VALOR students developed nursing skills and became certified in advanced cardiac life support (ACLS). One student suggested that the ACLS class was a great team builder and instilled confidence among the VALOR participants. Another student shared, “We all agreed that attaining this certification was a culmination of our overall VA experience.” A student who was working in an acute care area applied the newly learned ACLS skills the following week when a patient coded. The student’s journal reflected how preparation makes a difference and described his experience and knowing how to react as “powerful.”

The Reality of Nursing

The VALOR program helps connect the academic environment with the realities of the workplace. Wilson found bridging the theory-practice gap between school and workplace improves learning opportunities for students.9 Wilson also suggests that having peers to identify with helps to bridge the theory-practice gap.9 Journal entries reflected “the perfect hospital” of textbooks was different from working every day and “almost being a nurse.” During the VALOR program, students immerse themselves in the realistic nursing environment of staff shortages, equipment unavailability, disgruntled patients, and peer-to-peer communication that is not always civil. The 40-hour workweek provides a realistic hands-on view of nursing and introduces students to socializing as a nurse and the nursing work culture.

After the 2013 summer portion of the program, students were able to differentiate between the realities of the world of health care and the academic view of the health care environment. As students progressed over the summer, a noticeable transformation took place. The student who wrote about needing more skills practice on day 1 found that she was comfortable with injections, hanging IVs, and providing patient care at the end of week 3. Students grew more comfortable collaborating with doctors and other interdisciplinary professionals. They also became competent with basic nursing skills and had a realistic view of the nursing world.