User login

Cost Analysis of Use of Tranexamic Acid to Prevent Major Bleeding Complications in Hip and Knee Arthroplasty Surgery

Diabetes Mellitus and Skin Infections

Diabetes mellitus is one of the most common comorbid conditions among patients hospitalized for acute bacterial skin infections.[1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6] Acute bacterial skin infections in diabetics represent a spectrum of conditions ranging from cellulitis or cutaneous abscess to more complicated infections such as infected ulcers or deep tissue infections. Although most skin infections in diabetics are caused by gram‐positive pathogens (Staphylococcus aureus and streptococci), the risk of gram‐negative pathogens is increased in certain complicated infections such as diabetic foot infections.[7] For such complicated infections, national guidelines therefore recommend broad‐spectrum empiric antibiotic therapy.[7]

The role of gram‐negative pathogens has not been clearly established in diabetics with cellulitis or cutaneous abscess not associated with an infected ulcer or diabetic foot infection. National guidelines for the treatment of cellulitis and abscess recommend antibiotic therapy targeted toward S aureus and streptococcal species irrespective of the presence of diabetes mellitus.[8, 9] However, in a recent multicenter study of patients hospitalized with acute bacterial skin infections in which cases involving infected ulcers or deep tissue infection were excluded, diabetes mellitus was an independent predictor of use of antibiotics with broad gram‐negative activity.[2] This suggests that either gram‐negative pathogens are more common or providers perceive gram‐negative pathogens to be more common among diabetics with otherwise uncomplicated cellulitis or abscess.

A better understanding of the relationship between the microbiology and antibiotic prescribing practices for diabetics with cellulitis or abscess is therefore necessary to promote the most appropriate spectrum of therapy for these patients. We evaluated a large cohort of patients hospitalized with acute bacterial skin infections in order to: (1) compare the microbiology of diabetics and nondiabetics with cellulitis or cutaneous abscess not associated with an ulcer or deep tissue infection; and (2) compare antibiotic prescribing practices among diabetics and nondiabetics. We hypothesized that diabetics would have a similar spectrum of microorganisms as nondiabetics but would be more frequently treated with antibiotics with broad gram‐negative activity.

METHODS

Study Design

This was a secondary analysis of 2 published retrospective studies of patients hospitalized for cellulitis or cutaneous abscess between January 1, 2007 and May 31, 2012.[2, 10] For the purposes of this study, the terms cellulitis and abscess will refer to infections not involving an infected ulcer, osteomyelitis, or other deep tissue infection.

Study Setting and Population

The first of the 2 cohorts analyzed for the present study included patients hospitalized with cellulitis, abscess, or wound infection at 7 academic or community hospitals in Colorado.[2] The second cohort included patients hospitalized with cellulitis or abscess at a single academic medical center (1 of the 7 hospitals above) in Denver, Colorado.[10] The methods of these studies have been reported in detail elsewhere.[2, 10, 11] Briefly, potential cases were identified using International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification codes. The main inclusion and exclusion criteria of the 2 studies were similar. In both studies, cases were excluded that involved infected ulcers or suspected or confirmed deep tissue involvement (eg, osteomyelitis, myositis, fasciitis). Cases were also excluded that involved other infections where empiric antibiotic therapy with gram‐negative activity is standard including infected human or animal bites, periorbital or orbital infections, and perineal infections. The combined cohort in the present study therefore represented a group of patients hospitalized with relatively uncomplicated cellulitis or cutaneous abscess.

Definitions and Study Outcomes

Only 1 of the 2 studies from which the current cohort was derived distinguished between nonpurulent cellulitis, purulent cellulitis, and wound infection.[2] In the other study, cases were more broadly defined as either cellulitis or cutaneous abscess.[10] Infected ulcers and deep tissue infections were excluded from both studies. In combining the data into the current cohort, all nondrainable infections (purulent or nonpurulent cellulitis and wound infection) were categorized generally as cellulitis. All cases with documentation of an abscess in the medical record were categorized as cutaneous abscess. Presence of diabetes mellitus was based on provider documentation of the condition during the hospitalization. Microbiological cultures were obtained at the discretion of treating providers. Exposure to antibiotics with a broad spectrum of gram‐negative activity was defined as receipt of 2 or more calendar days of ‐lactam/‐lactamase inhibitor combinations, second‐ through fifth‐generation cephalosporins, fluoroquinolones, carbapenems, tigecycline, aminoglycosides, or colistin.[2]

The follow‐up periods differed slightly between the 2 studies used to derive the current cohort. In 1 study, all clinical encounters within 30 days of hospital discharge were reviewed to assess clinical outcomes.[10] In the other, clinical encounters within 45 days from the date of hospitalization were reviewed.[2] Clinical failure was defined as any of the following within the 30‐ or 45‐day follow‐up periods, respectively: (1) treatment failure, defined as a change in antibiotic therapy or unplanned drainage procedure due to inadequate clinical response more than 5 days[2] or 7 days[10] after hospital admission; (2) recurrence, defined as reinitiation of antibiotics for skin infection after completion of the initial treatment course; or (3) rehospitalization due to skin infection.[11]

Statistical Analysis

Because the clinical factors, microbiology, and treatment of cellulitis and cutaneous abscesses differ, analyses were performed for the total cohort and stratified by type of infection. Microorganisms cultured, antibiotic selection, and treatment duration were compared between diabetics and nondiabetics using the Wilcoxon rank sum test, 2, or Fisher exact test, as appropriate.

Because we hypothesized that the presence of diabetes mellitus in patients with cellulitis or abscess leads to use of broad gram‐negative therapy, we developed a multivariable logistic regression model to identify factors independently associated with exposure to antibiotics with broad gram‐negative activity. We also developed a linear regression model to explore the relationship between diabetes mellitus and duration of antibiotic therapy after adjusting for covariates. To develop these models, we first performed bivariate analyses and retained variables with a P value 0.25 in the regression models. Variables that did not meet the P value threshold but were considered to be clinically relevant covariates were also included in the model. We assessed for effect modification, multicollinearity, and goodness of fit when developing the models. We used SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) for data analysis.

RESULTS

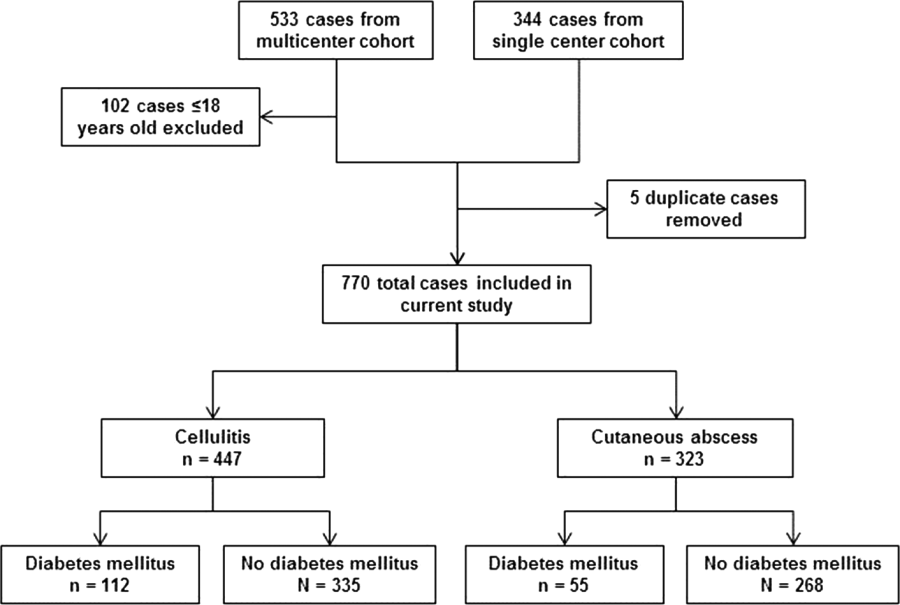

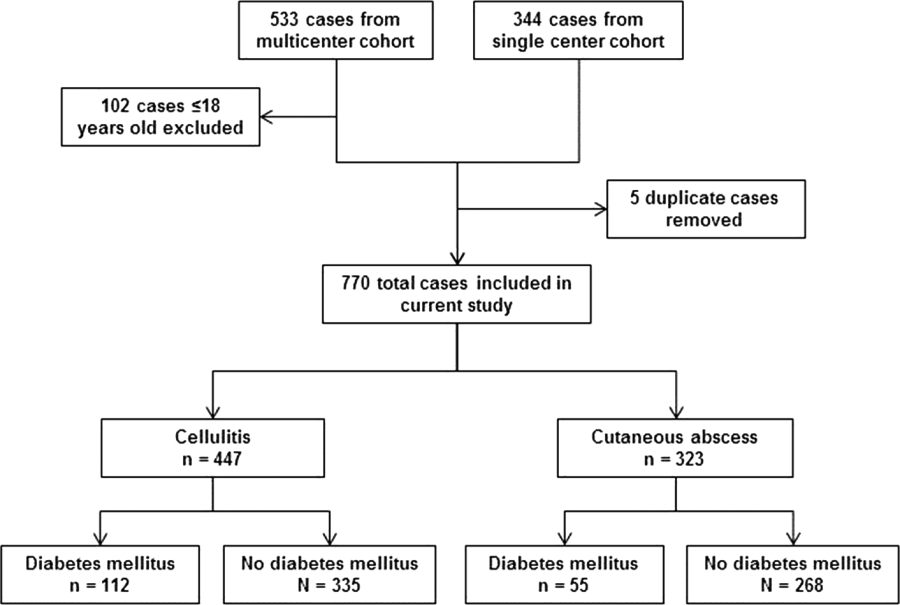

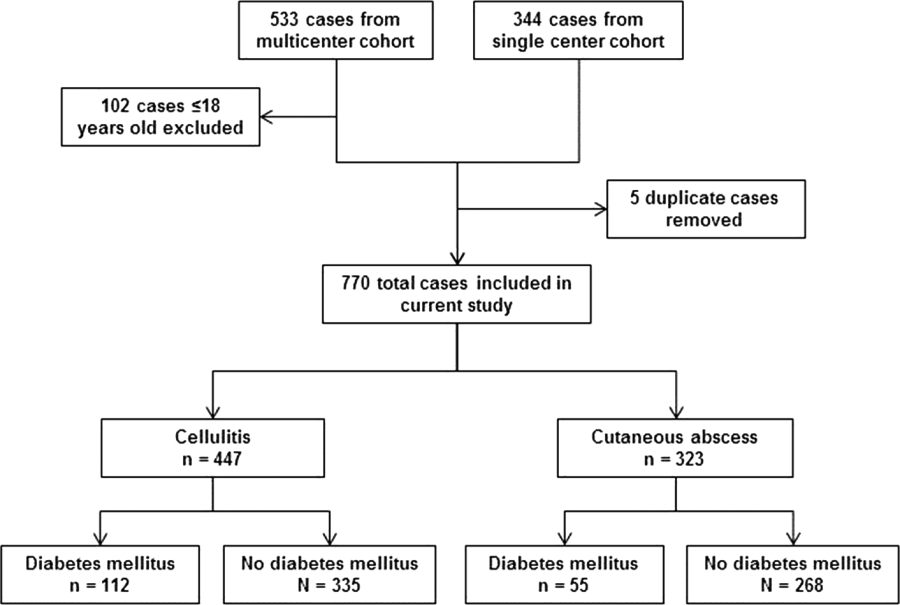

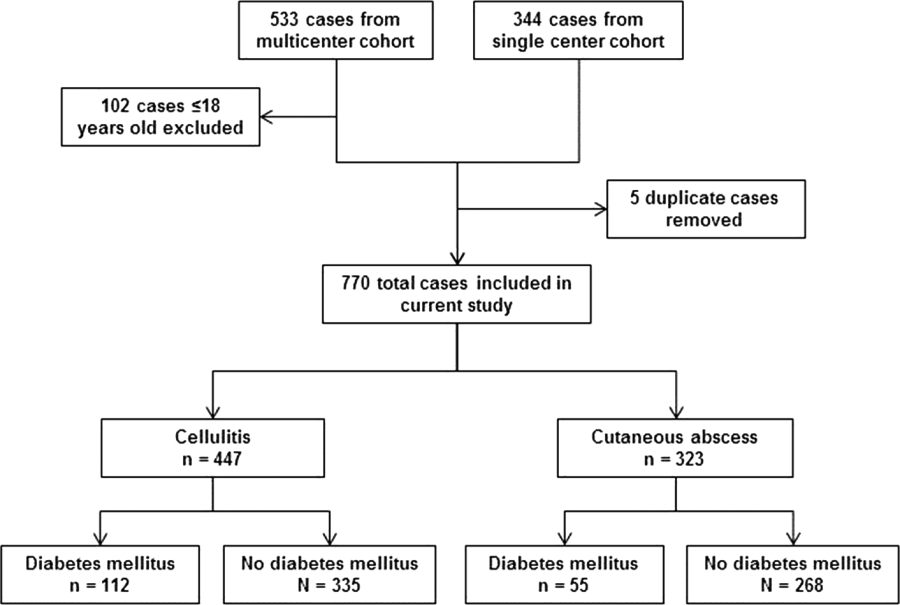

After excluding 102 pediatric cases and removing 5 duplicate cases, 770 total cases were included for analysis: 447 involved cellulitis and 323 involved cutaneous abscess (Figure 1). Overall, 167 (22%) patients had diabetes mellitus. Diabetics were significantly more likely than nondiabetics to have cellulitis as the presenting infection (67% of cases vs 56%, P=0.008) and to have lower extremity involvement (48% vs 33%, P<0.001) (Table 1). Diabetics were also older (median age 55 years vs 48 years, P<0.001), more likely to have cirrhosis or prior skin infection, and less likely to be injection‐drug users or human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infected. Demographic and clinical characteristics among diabetics and nondiabetics stratified by the categorizations of cellulitis and cutaneous abscess are presented in the Supporting Information, Appendix Table 1, in the online version of this article.

| Diabetes Mellitus, N=167 | No Diabetes Mellitus, N=603 | |

|---|---|---|

| ||

| Type of infection | ||

| Cellulitis | 112 (67) | 335 (56)a |

| Cutaneous abscess | 55 (33) | 268 (44) |

| Age, y, median (IQR) | 55 (4763) | 48 (3658)a |

| Male | 102 (61) | 405 (67) |

| Injection drug use | 9 (5) | 117 (19)a |

| Alcohol abuse or dependence | 15 (9) | 86 (14) |

| Cirrhosis | 11 (7) | 17 (3)a |

| HIV infection | 0 | 29 (5)a |

| Dialysis dependence | 4 (2) | 5 (1) |

| Peripheral arterial disease | 4 (2) | 5 (1) |

| Saphenous vein harvest | 7 (4) | 11 (2) |

| Prior skin infection | 56 (34) | 125 (21)a |

| Prior MRSA infection or colonization | 20 (12) | 50 (8) |

| Anatomical location | ||

| Lower extremity | 80 (48) | 200 (33)a |

| Upper extremity | 6 (4) | 79 (13)a |

| Head and neck | 14 (8) | 38 (6) |

| Buttock or inguinal | 8 (5) | 35 (6) |

| Chest, abdomen, back, or axilla | 9 (5) | 25 (4) |

| Multiple distinct sites | 7 (4) | 34 (6) |

| Medical primary service | 139 (83) | 395 (66)a |

| Consultation requested | 99 (59) | 294 (49)a |

| Surgery | 58 (35) | 152 (25)a |

| Internal medicine | 18 (11) | 47 (8) |

| Infectious diseases | 41 (25) | 149 (25) |

| Failed initial outpatient antibiotic therapy | 52 (31) | 186 (31) |

| Fever (temperature 38.0C) | 20 (12) | 102 (17) |

| Leukocytosis (WBC >10,000 cells/mm3) | 78 (47) | 311 (52) |

The frequency of use of microbiological cultures was similar among diabetics and nondiabetics (Table 2). In cases of cellulitis, a microorganism was identified in 18% of diabetics and 12% of nondiabetics (P=0.09). In cases of cutaneous abscess, a microorganism was identified more commonly (69% and 74%, respectively, P=0.50). Among cases where a microorganism was identified, aerobic gram‐positive organisms were isolated in 90% of diabetics and 92% of nondiabetics (P=0.59). Aerobic gram‐negative organisms were isolated in 7% of diabetics and 12% of nondiabetics (P=0.28). Specific gram‐negative organisms isolated are shown in the Supporting Information, Appendix Table 2, in the online version of this article; no cases in diabetics involved Pseudomonas aeruginosa. The comparison of microbiological data among diabetics and nondiabetics was similar when stratified by cellulitis versus cutaneous abscess (Table 2).

| Cellulitis | Cutaneous Abscess | All Cases | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diabetes Mellitus, N=112 | No Diabetes Mellitus, N=335 | P | Diabetes Mellitus, N=55 | No Diabetes Mellitus, N=268 | P | Diabetes Mellitus, N=167 | No Diabetes Mellitus, N=603 | P | |

| |||||||||

| Any microbiological culture obtaineda | 82 (73) | 234 (70) | 46 (84) | 239 (89) | 128 (77) | 473 (78) | |||

| Wound drainage or swab | 19 (17) | 36 (11) | 1 (2) | 8 (3) | 20 (12) | 44 (7) | |||

| Abscess material | 1 (1) | 3 (1) | 39 (71) | 205 (76) | 40 (24) | 208 (34) | |||

| Tissueb | 2 (2) | 17 (5) | 1 (2) | 8 (3) | 3 (2) | 25 (4) | |||

| Blood | 73 (65) | 212 (63) | 26 (47) | 121 (45) | 99 (59) | 333 (55) | |||

| Any microorganism identifiedc | 20 (18) | 39 (12) | 0.09 | 38 (69) | 197 (74) | 0.50 | 58 (35) | 236 (39) | 0.30 |

| Aerobic gram‐positive | 15 (75) | 36 (92) | 0.11 | 37 (97) | 182 (92) | 0.48 | 52 (90) | 218 (92) | 0.59 |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 11 (55) | 26 (67) | 0.38 | 28 (74) | 132 (67) | 0.42 | 39 (67) | 158 (67) | 0.97 |

| Methicillin‐susceptible | 4 (20) | 15 (38) | 0.15 | 12 (32) | 42 (21) | 0.17 | 16 (28) | 57 (24) | 0.59 |

| Methicillin‐resistant | 5 (25) | 11 (28) | 1.00 | 14 (37) | 85 (43) | 0.47 | 19 (33) | 96 (41) | 0.27 |

| Susceptibility not performed | 2 (10) | 0 | 0.11 | 2 (5) | 5 (3) | 0.32 | 4 (7) | 5 (2) | 0.08 |

| Streptococcal species | 6 (30) | 15 (38) | 0.52 | 12 (32) | 69 (35) | 0.68 | 18 (31) | 84 (36) | 0.51 |

| ‐hemolytic streptococcus | 3 (15) | 13 (33) | 0.13 | 6 (16) | 32 (16) | 0.94 | 9 (16) | 45 (19) | 0.53 |

| Streptococcus anginosus/Streptococcus milleri group | 1 (5) | 0 | 0.34 | 2 (5) | 29 (15) | 0.11 | 3 (5) | 29 (12) | 0.12 |

| Other ‐hemolytic streptococcus | 2 (10) | 2 (5) | 0.60 | 4 (11) | 12 (6) | 0.30 | 6 (10) | 14 (6) | 0.25 |

| Other streptococcus | 0 | 0 | 1 (3) | 3 (2) | 0.51 | 1 (2) | 3 (1) | 0.59 | |

| Staphylococcus aureus or streptococci | 15 (75) | 35 (90) | 0.25 | 37 (97) | 182 (92) | 0.48 | 52 (90) | 217 (92) | 0.60 |

| Enterococcus species | 0 | 2 (5) | 0.54 | 0 | 4 (2) | 1.00 | 0 | 6 (3) | 0.60 |

| Aerobic gram‐negative | 2 (10) | 7 (18) | 0.70 | 2 (5) | 21 (11) | 0.39 | 4 (7) | 28 (12) | 0.28 |

| Anaerobic organism(s) | 2 (10) | 3 (8) | 1.00 | 8 (21) | 30 (15) | 0.37 | 10 (17) | 33 (14) | 0.53 |

| Mixed skin or oral flora | 1 (5) | 1 (3) | 1.00 | 0 | 1 (1) | 1.00 | 1 (2) | 2 (1) | 0.48 |

| Other | 1 (5) | 3 (8) | 1.00 | 2 (5) | 3 (2) | 0.19 | 3 (5) | 6 (3) | 0.39 |

| Polymicrobial | 3 (15) | 17 (45) | 0.03 | 11 (29) | 47 (24) | 0.51 | 14 (24) | 64 (27) | 0.65 |

| Positive blood cultured | 4 (5) | 8 (4) | 0.51 | 2 (8) | 3 (2) | 0.21 | 6 (6) | 11 (3) | 0.24 |

Antibiotic utilization is summarized in Table 3. Among patients who were started on antibiotic therapy in the emergency department or urgent care, the initial regimen included an agent with broad gram‐negative activity in 31% of both diabetics and nondiabetics (P=0.97). During the entire hospital stay (including the emergency department or urgent care), diabetics were significantly more likely to be treated with ‐lactam/‐lactamase inhibitor combinations (42% vs 33%, P=0.04). At the time of hospital discharge, diabetics were more likely to be prescribed fluoroquinolones (11% vs 5%, P=0.01) (Table 3) particularly for cases of cellulitis (13% vs 6%, P=0.008) (see Supporting Information, Appendix Table 3, in the online version of this article). Diabetics were somewhat more likely to be prescribed parenteral antibiotics (10% vs 6%, P=0.07) after discharge. When considering both inpatient and discharge therapy, more diabetics than nondiabetics were exposed to at least 2 calendar days of broad gram‐negative therapy (54% vs 44%, P=0.02) and more were prescribed an antipseudomonal agent (38% vs 25%, P=0.002). In the group of patients who received at least 1 dose of an antibiotic with broad gram‐negative activity, broad gram‐negative agents accounted for 33% of the total days of therapy prescribed for diabetics and 32% for nondiabetics. Overall prescribing patterns were similar when stratified by cellulitis versus cutaneous abscess (see Supporting Information, Appendix Table 3, in the online version of this article).

| Diabetes Mellitus, N=167 | No Diabetes Mellitus, N=603 | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Individual antibiotics prescribed during the inpatient stayab | |||

| Vancomycin | 142 (85) | 504 (84) | 0.65 |

| Clindamycin | 27 (16) | 131 (22) | 0.12 |

| Parenteral ‐lactam/‐lactamase inhibitor | 70 (42) | 200 (33) | 0.04 |

| Second‐generation or higher cephalosporin | 13 (8) | 51 (8) | 0.78 |

| Cefazolin | 17 (10) | 91 (15) | 0.11 |

| Carbapenem | 9 (5) | 34 (6) | 0.90 |

| Fluoroquinolone | 20 (12) | 53 (9) | 0.21 |

| Daptomycin | 8 (5) | 24 (4) | 0.64 |

| Linezolid | 2 (1) | 8 (1) | 1.00 |

| Other ‐lactam | 6 (4) | 30 (5) | 0.45 |

| Trimethoprim‐sulfamethoxazole | 12 (7) | 30 (5) | 0.27 |

| Doxycycline | 15 (9) | 44 (7) | 0.47 |

| Cephalexin | 7 (4) | 22 (4) | 0.74 |

| Amoxicillin‐clavulanate | 11 (7) | 24 (4) | 0.15 |

| Antibiotics prescribed at hospital dischargeb | 163 (98) | 580 (96) | 0.38 |

| Clindamycin | 20 (12) | 95 (16) | 0.23 |

| Trimethoprim‐sulfamethoxazole | 52 (31) | 215 (36) | 0.28 |

| Doxycycline | 32 (19) | 91 (15) | 0.20 |

| Cephalexin | 12 (7) | 46 (8) | 0.85 |

| Amoxicillin‐clavulanate | 24 (14) | 82 (14) | 0.80 |

| Fluoroquinolone | 18 (11) | 32 (5) | 0.01 |

| Linezolid | 8 (5) | 19 (3) | 0.31 |

| Other oral ‐lactam | 3 (2) | 28 (5) | 0.10 |

| Other oral antibiotic | 1 (1) | 2 (0.3) | 0.52 |

| Vancomycin | 8 (5) | 15 (2) | 0.13 |

| Daptomycin | 5 (3) | 10 (2) | 0.34 |

| Other parenteral antibiotic | 4 (2) | 11 (2) | 0.75 |

| Antibiotic with broad gram‐negative activity initiated in emergency department or urgent care | 46/149 (31) | 174/561 (31) | 0.97 |

| Exposed to any antibiotic with broad gram‐negative activityc | 101 (62) | 311 (53) | 0.048 |

| Exposed to any antibiotic with antipseudomonal activity | 62 (38) | 149 (25) | 0.002 |

| Exposed to at least 2 calendar days of antibiotics with broad gram‐negative activityc | 89 (54) | 259 (44) | 0.02 |

| Treatment durationd | |||

| Total duration of therapy, d, median (IQR) | 13 (1015) | 12 (1015) | 0.09 |

| Duration of inpatient therapy, d, median (IQR) | 4 (36) | 4 (35) | 0.03 |

| Duration of therapy after discharge, d, median (IQR) | 8 (710) | 8 (710) | 0.58 |

After adjusting for covariates in the logistic regression model, diabetes mellitus was an independent predictor of exposure to broad gram‐negative therapy (see Supporting Information, Appendix Table 4, in the online version of this article). In addition to diabetes mellitus, culture of an aerobic gram‐negative microorganism, infectious diseases service consultation, presence of fever, and nonmedical admitting services were significantly associated with exposure to broad gram‐negative therapy. Prior methicillin‐resistant S aureus infection or colonization and HIV infection were inversely associated. Compared with nondiabetics, the total duration of antibiotic therapy in diabetics was somewhat longer (median 13 days vs 12 days, P=0.09) (Table 3). After adjusting for covariates in the linear regression model, there was a significant association between diabetes mellitus and treatment duration. On average, diabetics were treated 1 day (95% confidence interval: 0.2‐1.7 days) longer than nondiabetics.

Compared with nondiabetics, diabetics were more likely to have an outpatient follow‐up visit (73% vs 61%, P=0.002) and to be rehospitalized for any reason after discharge (16% vs 9%, P=0.02) (Table 4). Diabetics were overall more likely to be classified as clinical failure (15% vs 9%, P=0.02); this difference was driven by the cellulitis subgroup (19% vs 10%, P=0.01).

| Cellulitis | Cutaneous Abscess | All Cases | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diabetes Mellitus, N=112 | No Diabetes Mellitus, N=335 | P | Diabetes Mellitus, N=55 | No Diabetes Mellitus, N=268 | P | Diabetes Mellitus, N=167 | No Diabetes Mellitus, N=603 | P | |

| |||||||||

| Survived to discharge | 111 (99) | 335 (100) | 0.25 | 55 (100) | 268 (100) | 166 (99) | 603 (100) | 0.22 | |

| Outpatient follow‐up documented | 82 (74) | 204 (61) | 0.01 | 40 (73) | 161 (60) | 0.08 | 122 (73) | 365 (61) | 0.002 |

| Rehospitalized | 22 (20) | 34 (10) | 0.008 | 4 (7) | 21 (8) | 1.00 | 26 (16) | 55 (9) | 0.02 |

| Clinical failure | 21 (19) | 34 (10) | 0.01 | 4 (7) | 20 (7) | 1.00 | 25 (15) | 54 (9) | 0.02 |

| Treatment failure | 7 (6) | 17 (5) | 0.62 | 2 (4) | 7 (3) | 0.65 | 9 (5) | 24 (4) | 0.42 |

| Recurrence | 10 (9) | 16 (5) | 0.10 | 1 (2) | 11 (4) | 0.70 | 11 (7) | 27 (4) | 0.26 |

| Rehospitalization due to skin infection | 14 (13) | 17 (5) | 0.01 | 3 (5) | 11 (4) | 0.71 | 17 (10) | 28 (5) | 0.01 |

| Length of stay, d, median (IQR) | 4 (36) | 4 (35) | 0.03 | 4 (36) | 4 (35) | 0.28 | 4 (36) | 4 (35) | 0.02 |

DISCUSSION

Diabetes mellitus is a common comorbidity in patients with acute bacterial skin infections. In this large cohort of patients hospitalized for cellulitis or cutaneous abscess, where those with infected ulcers or deep tissue infections were excluded, microbiological findings in cases associated with positive cultures were similar among diabetics and nondiabetics. Although aerobic gram‐negative microorganisms were not more likely to be identified in diabetics, diabetics were significantly more likely to be exposed to at least 2 calendar days of antibiotics with broad gram‐negative activity. After adjusting for covariates, diabetes mellitus was independently associated with exposure to broad gram‐negative therapy.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to compare the microbiology of cellulitis and cutaneous abscess among diabetics and nondiabetics. Lipsky and colleagues previously described the microbiology of a cohort of diabetic patients hospitalized with a broader range of skin infections including cellulitis, infected ulcers, and surgical site infections.[12] Similar to our findings, gram‐negative pathogens were uncommonly isolated in that study; however, in the absence of a comparator group, whether diabetics were at higher risk for gram‐negative involvement than nondiabetics was not known. Similar to the study by Lipsky and colleagues, most studies of skin infections in diabetics have included a relatively heterogeneous group of infections.[12, 13, 14, 15] The present study therefore contributes to the literature by providing a focused comparison of the microbiology of inpatient cellulitis and abscess in the absence of complicating factors such as an infected ulcer or deep tissue involvement. We found that among cases with a positive culture (13% of cases in the cellulitis group and 73% in the abscess group), the microbiology was similar among diabetics and nondiabetics. Although a microorganism was identified in only a minority of cases of cellulitis, our findings do not support the need for broad gram‐negative therapy in diabetics with cellulitis not associated with an ulcer or deep tissue infection. In diabetics with an abscess, antibiotics with broad gram‐negative activity do not appear to be indicated.

The present study also adds to the literature by providing a detailed comparison of antibiotic utilization patterns among diabetics and nondiabetics. We demonstrated that diabetics were more likely to have significant exposure to antibiotics with broad gram‐negative activity, particularly antipseudomonal agents (the broadest‐spectrum antibiotics). Because initiation of broad gram‐negative therapy in the emergency department or urgent care was not more common among diabetics, the increased use of these agents among diabetics appeared to be driven by inpatient providers. It is also notable that of patients who received any antibiotic with broad gram‐negative activity, these agents accounted for similar proportions of the total days of therapy in both diabetics and nondiabetics. In aggregate, our findings demonstrate that diabetics are more likely to be started on antibiotics with broad gram‐negative activity by inpatient providers, diabetics are not necessarily continued on longer durations of broad gram‐negative therapy once started, and the total amount of exposure to broad gram‐negative agents is substantial.

Overall, our findings suggest that inpatient providers perceive diabetics with cellulitis or abscess to be at increased risk for gram‐negative pathogens. This perhaps reflects an extrapolation of recommendations to use broad‐spectrum empiric therapy in diabetics with certain complicated skin infections.[7] However, for patients with cellulitis or cutaneous abscess, Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) guidelines recommend antibiotic therapy targeted toward S aureus and streptococcal species; there is no suggestion to use a broader spectrum of therapy in diabetics.[8, 9] Our findings therefore highlight an important opportunity to improve antibiotic selection for all patients hospitalized with cellulitis and abscess, but particularly diabetics. It is also noteworthy that by linear regression, diabetes mellitus was independently associated with longer treatment durations. Although the average increase in treatment duration was small (1 day), this finding adds to the evidence that the presence of diabetes mellitus alters providers' treatment approach to cellulitis or abscess.

We found that despite more frequent treatment with broad gram‐negative therapy, diabetics were more likely than nondiabetics to be classified as clinical failures. It is important to point out that diabetics were also more likely than nondiabetics to have postdischarge outpatient follow‐up visits, raising the possibility of biased ascertainment of clinical failure events in this group. However, we also demonstrated that diabetics with cellulitis were more likely to be rehospitalized than nondiabetics. This is similar to a finding by Suaya and colleagues who showed that diabetics with skin infections were about twice as likely to be rehospitalized as nondiabetics.[13] One could hypothesize that the increased frequency of clinical failure events among diabetics was due to their older age, hyperglycemia, or vascular insufficiency; however, other factors may have contributed. For example, providers may have mistaken residual erythema for ongoing or recurrent cellulitis, or the diagnosis of cellulitis could have been incorrect to begin with. Additionally, there may have been uncertainty about the microbiology of cellulitis because the infecting pathogen was not usually identified. These factors may have led to alterations in treatment that would have resulted in a classification of clinical failure, and it is possible that providers had a lower threshold to alter treatment in diabetics. It is therefore not clear whether our findings represent a true difference in clinical outcomes between diabetics or nondiabetics. Regardless, in cases associated with a positive culture, our microbiological results do not support that the difference in clinical failure between diabetics and nondiabetics with cellulitis was related to a different spectrum of microorganisms.

In addition to the limitations outlined previously[2, 10] and above, the present study has at least 5 additional limitations. First, this was a secondary analysis of studies that were not designed to evaluate the effect of diabetes mellitus on the microbiology and treatment of skin infections. For example, hemoglobin A1C values were not collected; therefore, we could not examine whether the microbiology and antibiotic prescribing practices differed based on control of diabetes mellitus. Second, there were minor differences in inclusion and exclusion criteria between the 2 cohorts included in this study. Because the proportion of patients with diabetes mellitus was similar among both cohorts, and comparisons were not made between the cohorts, this should not have impacted our results. Third, the broad categorization of cellulitis used when combining the 2 cohorts raised the possibility of differences in infection characteristics between diabetics and nondiabetics (eg, presence of a wound) that could have confounded our findings regarding use of gram‐negative therapy. In the larger of the 2 cohorts from which the combined cohort was derived, only 17 (3%) of 533 patients had wound infections, whereas those with infected ulcers or suspected deep‐tissue infection were excluded from both cohorts. Furthermore, in the combined cohort, the increased frequency of broad gram‐negative therapy among diabetics was also observed in the cutaneous abscess group. It is therefore unlikely that the categorization of cellulitis had a significant impact on our results. Fourth, given the observational nature of the study, the microbiological data were subject to limitations. Importantly, because the infecting pathogen was identified in only 13% of cases of cellulitis, firm conclusions regarding the microbiology of cellulitis cannot be drawn. Finally, the small number of gram‐negative organisms isolated precluded comparisons of specific pathogens among diabetics and nondiabetics. In addition, because a number of gram‐negative organisms were isolated from wound cultures, it is not known whether they were clinically relevant or simply represented colonization.

In conclusion, in cases of cellulitis or abscess associated with a positive culture, gram‐negative microorganisms were not isolated more commonly among diabetics compared with nondiabetics. However, in general, diabetics were more likely to be treated with broad gram‐negative therapy suggesting that, particularly for cutaneous abscesses, this prescribing practice may not be warranted. These findings support current IDSA guidelines that recommend antibiotic therapy targeted toward gram‐positive pathogens for cellulitis or abscess, irrespective of the presence of diabetes mellitus.[8, 9] Because nearly one‐fourth of patients hospitalized with cellulitis or abscess are diabetic, these findings have relevance for national antimicrobial stewardship efforts aimed at curbing antimicrobial resistance through reducing use of antibiotics with broad gram‐negative activity in hospitals.[16]

Disclosures: This work was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institute of Health (TCJ: K23 AI099082). D.M.P. reports potential conflicts of interests with Optimer, Cubist, and Forest Pharmaceuticals. The authors report no other conflicts of interest.

- , , , et al. Increased risk of common infections in patients with type 1 and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41(3):281–288.

- , , , et al. Antibiotic prescribing practices in a multicenter cohort of patients hospitalized for acute bacterial skin and skin structure infection. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2014;35(10):1241–1250.

- , , , . The role of beta‐hemolytic streptococci in causing diffuse, nonculturable cellulitis: a prospective investigation. Medicine. 2010;89(4):217–226.

- , , , et al. Factors associated with complications and mortality in adult patients hospitalized for infectious cellulitis. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2003;22(3):151–157.

- , , , et al. Epidemiology and outcomes of complicated skin and soft tissue infections in hospitalized patients. J Clin Microbiol. 2012;50(2):238–245.

- , , , , , . Current management of patients hospitalized with complicated skin and soft tissue infections across Europe (2010–2011): assessment of clinical practice patterns and real‐life effectiveness of antibiotics from the REACH study. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2013;19(9):E377–E385.

- , , , et al. 2012 Infectious Diseases Society of America clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of diabetic foot infections. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54(12):e132–e173.

- , , , et al. Clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society Of America for the treatment of methicillin‐resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections in adults and children: executive summary. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52(3):285–292.

- , , , et al. Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of skin and soft tissue infections: 2014 update by the Infectious Diseases Society Of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59(2):e10–e52.

- , , , et al. Decreased antibiotic utilization after implementation of a guideline for inpatient cellulitis and cutaneous abscess. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(12):1072–1079.

- , , , , , . Skin and soft‐tissue infections requiring hospitalization at an academic medical center: opportunities for antimicrobial stewardship. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;51(8):895–903.

- , , , , , . Skin and soft tissue infections in hospitalised patients with diabetes: culture isolates and risk factors associated with mortality, length of stay and cost. Diabetologia. 2010;53(5):914–923.

- , , , . Skin and soft tissue infections and associated complications among commercially insured patients aged 0–64 years with and without diabetes in the U.S. PLoS One. 2013;8(4):e60057.

- , , . A post hoc subgroup analysis of meropenem versus imipenem/cilastatin in a multicenter, double‐blind, randomized study of complicated skin and skin‐structure infections in patients with diabetes mellitus. Clin Ther. 2006;28(8):1164–1174.

- , , , . Treating diabetic foot infections with sequential intravenous to oral moxifloxacin compared with piperacillin‐tazobactam/amoxicillin‐clavulanate. J Antimicr Chemo. 2007;60(2):370–376.

- , , , et al. Vital signs: improving antibiotic use among hospitalized patients. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63(9):194–200.

Diabetes mellitus is one of the most common comorbid conditions among patients hospitalized for acute bacterial skin infections.[1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6] Acute bacterial skin infections in diabetics represent a spectrum of conditions ranging from cellulitis or cutaneous abscess to more complicated infections such as infected ulcers or deep tissue infections. Although most skin infections in diabetics are caused by gram‐positive pathogens (Staphylococcus aureus and streptococci), the risk of gram‐negative pathogens is increased in certain complicated infections such as diabetic foot infections.[7] For such complicated infections, national guidelines therefore recommend broad‐spectrum empiric antibiotic therapy.[7]

The role of gram‐negative pathogens has not been clearly established in diabetics with cellulitis or cutaneous abscess not associated with an infected ulcer or diabetic foot infection. National guidelines for the treatment of cellulitis and abscess recommend antibiotic therapy targeted toward S aureus and streptococcal species irrespective of the presence of diabetes mellitus.[8, 9] However, in a recent multicenter study of patients hospitalized with acute bacterial skin infections in which cases involving infected ulcers or deep tissue infection were excluded, diabetes mellitus was an independent predictor of use of antibiotics with broad gram‐negative activity.[2] This suggests that either gram‐negative pathogens are more common or providers perceive gram‐negative pathogens to be more common among diabetics with otherwise uncomplicated cellulitis or abscess.

A better understanding of the relationship between the microbiology and antibiotic prescribing practices for diabetics with cellulitis or abscess is therefore necessary to promote the most appropriate spectrum of therapy for these patients. We evaluated a large cohort of patients hospitalized with acute bacterial skin infections in order to: (1) compare the microbiology of diabetics and nondiabetics with cellulitis or cutaneous abscess not associated with an ulcer or deep tissue infection; and (2) compare antibiotic prescribing practices among diabetics and nondiabetics. We hypothesized that diabetics would have a similar spectrum of microorganisms as nondiabetics but would be more frequently treated with antibiotics with broad gram‐negative activity.

METHODS

Study Design

This was a secondary analysis of 2 published retrospective studies of patients hospitalized for cellulitis or cutaneous abscess between January 1, 2007 and May 31, 2012.[2, 10] For the purposes of this study, the terms cellulitis and abscess will refer to infections not involving an infected ulcer, osteomyelitis, or other deep tissue infection.

Study Setting and Population

The first of the 2 cohorts analyzed for the present study included patients hospitalized with cellulitis, abscess, or wound infection at 7 academic or community hospitals in Colorado.[2] The second cohort included patients hospitalized with cellulitis or abscess at a single academic medical center (1 of the 7 hospitals above) in Denver, Colorado.[10] The methods of these studies have been reported in detail elsewhere.[2, 10, 11] Briefly, potential cases were identified using International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification codes. The main inclusion and exclusion criteria of the 2 studies were similar. In both studies, cases were excluded that involved infected ulcers or suspected or confirmed deep tissue involvement (eg, osteomyelitis, myositis, fasciitis). Cases were also excluded that involved other infections where empiric antibiotic therapy with gram‐negative activity is standard including infected human or animal bites, periorbital or orbital infections, and perineal infections. The combined cohort in the present study therefore represented a group of patients hospitalized with relatively uncomplicated cellulitis or cutaneous abscess.

Definitions and Study Outcomes

Only 1 of the 2 studies from which the current cohort was derived distinguished between nonpurulent cellulitis, purulent cellulitis, and wound infection.[2] In the other study, cases were more broadly defined as either cellulitis or cutaneous abscess.[10] Infected ulcers and deep tissue infections were excluded from both studies. In combining the data into the current cohort, all nondrainable infections (purulent or nonpurulent cellulitis and wound infection) were categorized generally as cellulitis. All cases with documentation of an abscess in the medical record were categorized as cutaneous abscess. Presence of diabetes mellitus was based on provider documentation of the condition during the hospitalization. Microbiological cultures were obtained at the discretion of treating providers. Exposure to antibiotics with a broad spectrum of gram‐negative activity was defined as receipt of 2 or more calendar days of ‐lactam/‐lactamase inhibitor combinations, second‐ through fifth‐generation cephalosporins, fluoroquinolones, carbapenems, tigecycline, aminoglycosides, or colistin.[2]

The follow‐up periods differed slightly between the 2 studies used to derive the current cohort. In 1 study, all clinical encounters within 30 days of hospital discharge were reviewed to assess clinical outcomes.[10] In the other, clinical encounters within 45 days from the date of hospitalization were reviewed.[2] Clinical failure was defined as any of the following within the 30‐ or 45‐day follow‐up periods, respectively: (1) treatment failure, defined as a change in antibiotic therapy or unplanned drainage procedure due to inadequate clinical response more than 5 days[2] or 7 days[10] after hospital admission; (2) recurrence, defined as reinitiation of antibiotics for skin infection after completion of the initial treatment course; or (3) rehospitalization due to skin infection.[11]

Statistical Analysis

Because the clinical factors, microbiology, and treatment of cellulitis and cutaneous abscesses differ, analyses were performed for the total cohort and stratified by type of infection. Microorganisms cultured, antibiotic selection, and treatment duration were compared between diabetics and nondiabetics using the Wilcoxon rank sum test, 2, or Fisher exact test, as appropriate.

Because we hypothesized that the presence of diabetes mellitus in patients with cellulitis or abscess leads to use of broad gram‐negative therapy, we developed a multivariable logistic regression model to identify factors independently associated with exposure to antibiotics with broad gram‐negative activity. We also developed a linear regression model to explore the relationship between diabetes mellitus and duration of antibiotic therapy after adjusting for covariates. To develop these models, we first performed bivariate analyses and retained variables with a P value 0.25 in the regression models. Variables that did not meet the P value threshold but were considered to be clinically relevant covariates were also included in the model. We assessed for effect modification, multicollinearity, and goodness of fit when developing the models. We used SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) for data analysis.

RESULTS

After excluding 102 pediatric cases and removing 5 duplicate cases, 770 total cases were included for analysis: 447 involved cellulitis and 323 involved cutaneous abscess (Figure 1). Overall, 167 (22%) patients had diabetes mellitus. Diabetics were significantly more likely than nondiabetics to have cellulitis as the presenting infection (67% of cases vs 56%, P=0.008) and to have lower extremity involvement (48% vs 33%, P<0.001) (Table 1). Diabetics were also older (median age 55 years vs 48 years, P<0.001), more likely to have cirrhosis or prior skin infection, and less likely to be injection‐drug users or human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infected. Demographic and clinical characteristics among diabetics and nondiabetics stratified by the categorizations of cellulitis and cutaneous abscess are presented in the Supporting Information, Appendix Table 1, in the online version of this article.

| Diabetes Mellitus, N=167 | No Diabetes Mellitus, N=603 | |

|---|---|---|

| ||

| Type of infection | ||

| Cellulitis | 112 (67) | 335 (56)a |

| Cutaneous abscess | 55 (33) | 268 (44) |

| Age, y, median (IQR) | 55 (4763) | 48 (3658)a |

| Male | 102 (61) | 405 (67) |

| Injection drug use | 9 (5) | 117 (19)a |

| Alcohol abuse or dependence | 15 (9) | 86 (14) |

| Cirrhosis | 11 (7) | 17 (3)a |

| HIV infection | 0 | 29 (5)a |

| Dialysis dependence | 4 (2) | 5 (1) |

| Peripheral arterial disease | 4 (2) | 5 (1) |

| Saphenous vein harvest | 7 (4) | 11 (2) |

| Prior skin infection | 56 (34) | 125 (21)a |

| Prior MRSA infection or colonization | 20 (12) | 50 (8) |

| Anatomical location | ||

| Lower extremity | 80 (48) | 200 (33)a |

| Upper extremity | 6 (4) | 79 (13)a |

| Head and neck | 14 (8) | 38 (6) |

| Buttock or inguinal | 8 (5) | 35 (6) |

| Chest, abdomen, back, or axilla | 9 (5) | 25 (4) |

| Multiple distinct sites | 7 (4) | 34 (6) |

| Medical primary service | 139 (83) | 395 (66)a |

| Consultation requested | 99 (59) | 294 (49)a |

| Surgery | 58 (35) | 152 (25)a |

| Internal medicine | 18 (11) | 47 (8) |

| Infectious diseases | 41 (25) | 149 (25) |

| Failed initial outpatient antibiotic therapy | 52 (31) | 186 (31) |

| Fever (temperature 38.0C) | 20 (12) | 102 (17) |

| Leukocytosis (WBC >10,000 cells/mm3) | 78 (47) | 311 (52) |

The frequency of use of microbiological cultures was similar among diabetics and nondiabetics (Table 2). In cases of cellulitis, a microorganism was identified in 18% of diabetics and 12% of nondiabetics (P=0.09). In cases of cutaneous abscess, a microorganism was identified more commonly (69% and 74%, respectively, P=0.50). Among cases where a microorganism was identified, aerobic gram‐positive organisms were isolated in 90% of diabetics and 92% of nondiabetics (P=0.59). Aerobic gram‐negative organisms were isolated in 7% of diabetics and 12% of nondiabetics (P=0.28). Specific gram‐negative organisms isolated are shown in the Supporting Information, Appendix Table 2, in the online version of this article; no cases in diabetics involved Pseudomonas aeruginosa. The comparison of microbiological data among diabetics and nondiabetics was similar when stratified by cellulitis versus cutaneous abscess (Table 2).

| Cellulitis | Cutaneous Abscess | All Cases | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diabetes Mellitus, N=112 | No Diabetes Mellitus, N=335 | P | Diabetes Mellitus, N=55 | No Diabetes Mellitus, N=268 | P | Diabetes Mellitus, N=167 | No Diabetes Mellitus, N=603 | P | |

| |||||||||

| Any microbiological culture obtaineda | 82 (73) | 234 (70) | 46 (84) | 239 (89) | 128 (77) | 473 (78) | |||

| Wound drainage or swab | 19 (17) | 36 (11) | 1 (2) | 8 (3) | 20 (12) | 44 (7) | |||

| Abscess material | 1 (1) | 3 (1) | 39 (71) | 205 (76) | 40 (24) | 208 (34) | |||

| Tissueb | 2 (2) | 17 (5) | 1 (2) | 8 (3) | 3 (2) | 25 (4) | |||

| Blood | 73 (65) | 212 (63) | 26 (47) | 121 (45) | 99 (59) | 333 (55) | |||

| Any microorganism identifiedc | 20 (18) | 39 (12) | 0.09 | 38 (69) | 197 (74) | 0.50 | 58 (35) | 236 (39) | 0.30 |

| Aerobic gram‐positive | 15 (75) | 36 (92) | 0.11 | 37 (97) | 182 (92) | 0.48 | 52 (90) | 218 (92) | 0.59 |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 11 (55) | 26 (67) | 0.38 | 28 (74) | 132 (67) | 0.42 | 39 (67) | 158 (67) | 0.97 |

| Methicillin‐susceptible | 4 (20) | 15 (38) | 0.15 | 12 (32) | 42 (21) | 0.17 | 16 (28) | 57 (24) | 0.59 |

| Methicillin‐resistant | 5 (25) | 11 (28) | 1.00 | 14 (37) | 85 (43) | 0.47 | 19 (33) | 96 (41) | 0.27 |

| Susceptibility not performed | 2 (10) | 0 | 0.11 | 2 (5) | 5 (3) | 0.32 | 4 (7) | 5 (2) | 0.08 |

| Streptococcal species | 6 (30) | 15 (38) | 0.52 | 12 (32) | 69 (35) | 0.68 | 18 (31) | 84 (36) | 0.51 |

| ‐hemolytic streptococcus | 3 (15) | 13 (33) | 0.13 | 6 (16) | 32 (16) | 0.94 | 9 (16) | 45 (19) | 0.53 |

| Streptococcus anginosus/Streptococcus milleri group | 1 (5) | 0 | 0.34 | 2 (5) | 29 (15) | 0.11 | 3 (5) | 29 (12) | 0.12 |

| Other ‐hemolytic streptococcus | 2 (10) | 2 (5) | 0.60 | 4 (11) | 12 (6) | 0.30 | 6 (10) | 14 (6) | 0.25 |

| Other streptococcus | 0 | 0 | 1 (3) | 3 (2) | 0.51 | 1 (2) | 3 (1) | 0.59 | |

| Staphylococcus aureus or streptococci | 15 (75) | 35 (90) | 0.25 | 37 (97) | 182 (92) | 0.48 | 52 (90) | 217 (92) | 0.60 |

| Enterococcus species | 0 | 2 (5) | 0.54 | 0 | 4 (2) | 1.00 | 0 | 6 (3) | 0.60 |

| Aerobic gram‐negative | 2 (10) | 7 (18) | 0.70 | 2 (5) | 21 (11) | 0.39 | 4 (7) | 28 (12) | 0.28 |

| Anaerobic organism(s) | 2 (10) | 3 (8) | 1.00 | 8 (21) | 30 (15) | 0.37 | 10 (17) | 33 (14) | 0.53 |

| Mixed skin or oral flora | 1 (5) | 1 (3) | 1.00 | 0 | 1 (1) | 1.00 | 1 (2) | 2 (1) | 0.48 |

| Other | 1 (5) | 3 (8) | 1.00 | 2 (5) | 3 (2) | 0.19 | 3 (5) | 6 (3) | 0.39 |

| Polymicrobial | 3 (15) | 17 (45) | 0.03 | 11 (29) | 47 (24) | 0.51 | 14 (24) | 64 (27) | 0.65 |

| Positive blood cultured | 4 (5) | 8 (4) | 0.51 | 2 (8) | 3 (2) | 0.21 | 6 (6) | 11 (3) | 0.24 |

Antibiotic utilization is summarized in Table 3. Among patients who were started on antibiotic therapy in the emergency department or urgent care, the initial regimen included an agent with broad gram‐negative activity in 31% of both diabetics and nondiabetics (P=0.97). During the entire hospital stay (including the emergency department or urgent care), diabetics were significantly more likely to be treated with ‐lactam/‐lactamase inhibitor combinations (42% vs 33%, P=0.04). At the time of hospital discharge, diabetics were more likely to be prescribed fluoroquinolones (11% vs 5%, P=0.01) (Table 3) particularly for cases of cellulitis (13% vs 6%, P=0.008) (see Supporting Information, Appendix Table 3, in the online version of this article). Diabetics were somewhat more likely to be prescribed parenteral antibiotics (10% vs 6%, P=0.07) after discharge. When considering both inpatient and discharge therapy, more diabetics than nondiabetics were exposed to at least 2 calendar days of broad gram‐negative therapy (54% vs 44%, P=0.02) and more were prescribed an antipseudomonal agent (38% vs 25%, P=0.002). In the group of patients who received at least 1 dose of an antibiotic with broad gram‐negative activity, broad gram‐negative agents accounted for 33% of the total days of therapy prescribed for diabetics and 32% for nondiabetics. Overall prescribing patterns were similar when stratified by cellulitis versus cutaneous abscess (see Supporting Information, Appendix Table 3, in the online version of this article).

| Diabetes Mellitus, N=167 | No Diabetes Mellitus, N=603 | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Individual antibiotics prescribed during the inpatient stayab | |||

| Vancomycin | 142 (85) | 504 (84) | 0.65 |

| Clindamycin | 27 (16) | 131 (22) | 0.12 |

| Parenteral ‐lactam/‐lactamase inhibitor | 70 (42) | 200 (33) | 0.04 |

| Second‐generation or higher cephalosporin | 13 (8) | 51 (8) | 0.78 |

| Cefazolin | 17 (10) | 91 (15) | 0.11 |

| Carbapenem | 9 (5) | 34 (6) | 0.90 |

| Fluoroquinolone | 20 (12) | 53 (9) | 0.21 |

| Daptomycin | 8 (5) | 24 (4) | 0.64 |

| Linezolid | 2 (1) | 8 (1) | 1.00 |

| Other ‐lactam | 6 (4) | 30 (5) | 0.45 |

| Trimethoprim‐sulfamethoxazole | 12 (7) | 30 (5) | 0.27 |

| Doxycycline | 15 (9) | 44 (7) | 0.47 |

| Cephalexin | 7 (4) | 22 (4) | 0.74 |

| Amoxicillin‐clavulanate | 11 (7) | 24 (4) | 0.15 |

| Antibiotics prescribed at hospital dischargeb | 163 (98) | 580 (96) | 0.38 |

| Clindamycin | 20 (12) | 95 (16) | 0.23 |

| Trimethoprim‐sulfamethoxazole | 52 (31) | 215 (36) | 0.28 |

| Doxycycline | 32 (19) | 91 (15) | 0.20 |

| Cephalexin | 12 (7) | 46 (8) | 0.85 |

| Amoxicillin‐clavulanate | 24 (14) | 82 (14) | 0.80 |

| Fluoroquinolone | 18 (11) | 32 (5) | 0.01 |

| Linezolid | 8 (5) | 19 (3) | 0.31 |

| Other oral ‐lactam | 3 (2) | 28 (5) | 0.10 |

| Other oral antibiotic | 1 (1) | 2 (0.3) | 0.52 |

| Vancomycin | 8 (5) | 15 (2) | 0.13 |

| Daptomycin | 5 (3) | 10 (2) | 0.34 |

| Other parenteral antibiotic | 4 (2) | 11 (2) | 0.75 |

| Antibiotic with broad gram‐negative activity initiated in emergency department or urgent care | 46/149 (31) | 174/561 (31) | 0.97 |

| Exposed to any antibiotic with broad gram‐negative activityc | 101 (62) | 311 (53) | 0.048 |

| Exposed to any antibiotic with antipseudomonal activity | 62 (38) | 149 (25) | 0.002 |

| Exposed to at least 2 calendar days of antibiotics with broad gram‐negative activityc | 89 (54) | 259 (44) | 0.02 |

| Treatment durationd | |||

| Total duration of therapy, d, median (IQR) | 13 (1015) | 12 (1015) | 0.09 |

| Duration of inpatient therapy, d, median (IQR) | 4 (36) | 4 (35) | 0.03 |

| Duration of therapy after discharge, d, median (IQR) | 8 (710) | 8 (710) | 0.58 |

After adjusting for covariates in the logistic regression model, diabetes mellitus was an independent predictor of exposure to broad gram‐negative therapy (see Supporting Information, Appendix Table 4, in the online version of this article). In addition to diabetes mellitus, culture of an aerobic gram‐negative microorganism, infectious diseases service consultation, presence of fever, and nonmedical admitting services were significantly associated with exposure to broad gram‐negative therapy. Prior methicillin‐resistant S aureus infection or colonization and HIV infection were inversely associated. Compared with nondiabetics, the total duration of antibiotic therapy in diabetics was somewhat longer (median 13 days vs 12 days, P=0.09) (Table 3). After adjusting for covariates in the linear regression model, there was a significant association between diabetes mellitus and treatment duration. On average, diabetics were treated 1 day (95% confidence interval: 0.2‐1.7 days) longer than nondiabetics.

Compared with nondiabetics, diabetics were more likely to have an outpatient follow‐up visit (73% vs 61%, P=0.002) and to be rehospitalized for any reason after discharge (16% vs 9%, P=0.02) (Table 4). Diabetics were overall more likely to be classified as clinical failure (15% vs 9%, P=0.02); this difference was driven by the cellulitis subgroup (19% vs 10%, P=0.01).

| Cellulitis | Cutaneous Abscess | All Cases | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diabetes Mellitus, N=112 | No Diabetes Mellitus, N=335 | P | Diabetes Mellitus, N=55 | No Diabetes Mellitus, N=268 | P | Diabetes Mellitus, N=167 | No Diabetes Mellitus, N=603 | P | |

| |||||||||

| Survived to discharge | 111 (99) | 335 (100) | 0.25 | 55 (100) | 268 (100) | 166 (99) | 603 (100) | 0.22 | |

| Outpatient follow‐up documented | 82 (74) | 204 (61) | 0.01 | 40 (73) | 161 (60) | 0.08 | 122 (73) | 365 (61) | 0.002 |

| Rehospitalized | 22 (20) | 34 (10) | 0.008 | 4 (7) | 21 (8) | 1.00 | 26 (16) | 55 (9) | 0.02 |

| Clinical failure | 21 (19) | 34 (10) | 0.01 | 4 (7) | 20 (7) | 1.00 | 25 (15) | 54 (9) | 0.02 |

| Treatment failure | 7 (6) | 17 (5) | 0.62 | 2 (4) | 7 (3) | 0.65 | 9 (5) | 24 (4) | 0.42 |

| Recurrence | 10 (9) | 16 (5) | 0.10 | 1 (2) | 11 (4) | 0.70 | 11 (7) | 27 (4) | 0.26 |

| Rehospitalization due to skin infection | 14 (13) | 17 (5) | 0.01 | 3 (5) | 11 (4) | 0.71 | 17 (10) | 28 (5) | 0.01 |

| Length of stay, d, median (IQR) | 4 (36) | 4 (35) | 0.03 | 4 (36) | 4 (35) | 0.28 | 4 (36) | 4 (35) | 0.02 |

DISCUSSION

Diabetes mellitus is a common comorbidity in patients with acute bacterial skin infections. In this large cohort of patients hospitalized for cellulitis or cutaneous abscess, where those with infected ulcers or deep tissue infections were excluded, microbiological findings in cases associated with positive cultures were similar among diabetics and nondiabetics. Although aerobic gram‐negative microorganisms were not more likely to be identified in diabetics, diabetics were significantly more likely to be exposed to at least 2 calendar days of antibiotics with broad gram‐negative activity. After adjusting for covariates, diabetes mellitus was independently associated with exposure to broad gram‐negative therapy.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to compare the microbiology of cellulitis and cutaneous abscess among diabetics and nondiabetics. Lipsky and colleagues previously described the microbiology of a cohort of diabetic patients hospitalized with a broader range of skin infections including cellulitis, infected ulcers, and surgical site infections.[12] Similar to our findings, gram‐negative pathogens were uncommonly isolated in that study; however, in the absence of a comparator group, whether diabetics were at higher risk for gram‐negative involvement than nondiabetics was not known. Similar to the study by Lipsky and colleagues, most studies of skin infections in diabetics have included a relatively heterogeneous group of infections.[12, 13, 14, 15] The present study therefore contributes to the literature by providing a focused comparison of the microbiology of inpatient cellulitis and abscess in the absence of complicating factors such as an infected ulcer or deep tissue involvement. We found that among cases with a positive culture (13% of cases in the cellulitis group and 73% in the abscess group), the microbiology was similar among diabetics and nondiabetics. Although a microorganism was identified in only a minority of cases of cellulitis, our findings do not support the need for broad gram‐negative therapy in diabetics with cellulitis not associated with an ulcer or deep tissue infection. In diabetics with an abscess, antibiotics with broad gram‐negative activity do not appear to be indicated.

The present study also adds to the literature by providing a detailed comparison of antibiotic utilization patterns among diabetics and nondiabetics. We demonstrated that diabetics were more likely to have significant exposure to antibiotics with broad gram‐negative activity, particularly antipseudomonal agents (the broadest‐spectrum antibiotics). Because initiation of broad gram‐negative therapy in the emergency department or urgent care was not more common among diabetics, the increased use of these agents among diabetics appeared to be driven by inpatient providers. It is also notable that of patients who received any antibiotic with broad gram‐negative activity, these agents accounted for similar proportions of the total days of therapy in both diabetics and nondiabetics. In aggregate, our findings demonstrate that diabetics are more likely to be started on antibiotics with broad gram‐negative activity by inpatient providers, diabetics are not necessarily continued on longer durations of broad gram‐negative therapy once started, and the total amount of exposure to broad gram‐negative agents is substantial.

Overall, our findings suggest that inpatient providers perceive diabetics with cellulitis or abscess to be at increased risk for gram‐negative pathogens. This perhaps reflects an extrapolation of recommendations to use broad‐spectrum empiric therapy in diabetics with certain complicated skin infections.[7] However, for patients with cellulitis or cutaneous abscess, Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) guidelines recommend antibiotic therapy targeted toward S aureus and streptococcal species; there is no suggestion to use a broader spectrum of therapy in diabetics.[8, 9] Our findings therefore highlight an important opportunity to improve antibiotic selection for all patients hospitalized with cellulitis and abscess, but particularly diabetics. It is also noteworthy that by linear regression, diabetes mellitus was independently associated with longer treatment durations. Although the average increase in treatment duration was small (1 day), this finding adds to the evidence that the presence of diabetes mellitus alters providers' treatment approach to cellulitis or abscess.

We found that despite more frequent treatment with broad gram‐negative therapy, diabetics were more likely than nondiabetics to be classified as clinical failures. It is important to point out that diabetics were also more likely than nondiabetics to have postdischarge outpatient follow‐up visits, raising the possibility of biased ascertainment of clinical failure events in this group. However, we also demonstrated that diabetics with cellulitis were more likely to be rehospitalized than nondiabetics. This is similar to a finding by Suaya and colleagues who showed that diabetics with skin infections were about twice as likely to be rehospitalized as nondiabetics.[13] One could hypothesize that the increased frequency of clinical failure events among diabetics was due to their older age, hyperglycemia, or vascular insufficiency; however, other factors may have contributed. For example, providers may have mistaken residual erythema for ongoing or recurrent cellulitis, or the diagnosis of cellulitis could have been incorrect to begin with. Additionally, there may have been uncertainty about the microbiology of cellulitis because the infecting pathogen was not usually identified. These factors may have led to alterations in treatment that would have resulted in a classification of clinical failure, and it is possible that providers had a lower threshold to alter treatment in diabetics. It is therefore not clear whether our findings represent a true difference in clinical outcomes between diabetics or nondiabetics. Regardless, in cases associated with a positive culture, our microbiological results do not support that the difference in clinical failure between diabetics and nondiabetics with cellulitis was related to a different spectrum of microorganisms.

In addition to the limitations outlined previously[2, 10] and above, the present study has at least 5 additional limitations. First, this was a secondary analysis of studies that were not designed to evaluate the effect of diabetes mellitus on the microbiology and treatment of skin infections. For example, hemoglobin A1C values were not collected; therefore, we could not examine whether the microbiology and antibiotic prescribing practices differed based on control of diabetes mellitus. Second, there were minor differences in inclusion and exclusion criteria between the 2 cohorts included in this study. Because the proportion of patients with diabetes mellitus was similar among both cohorts, and comparisons were not made between the cohorts, this should not have impacted our results. Third, the broad categorization of cellulitis used when combining the 2 cohorts raised the possibility of differences in infection characteristics between diabetics and nondiabetics (eg, presence of a wound) that could have confounded our findings regarding use of gram‐negative therapy. In the larger of the 2 cohorts from which the combined cohort was derived, only 17 (3%) of 533 patients had wound infections, whereas those with infected ulcers or suspected deep‐tissue infection were excluded from both cohorts. Furthermore, in the combined cohort, the increased frequency of broad gram‐negative therapy among diabetics was also observed in the cutaneous abscess group. It is therefore unlikely that the categorization of cellulitis had a significant impact on our results. Fourth, given the observational nature of the study, the microbiological data were subject to limitations. Importantly, because the infecting pathogen was identified in only 13% of cases of cellulitis, firm conclusions regarding the microbiology of cellulitis cannot be drawn. Finally, the small number of gram‐negative organisms isolated precluded comparisons of specific pathogens among diabetics and nondiabetics. In addition, because a number of gram‐negative organisms were isolated from wound cultures, it is not known whether they were clinically relevant or simply represented colonization.

In conclusion, in cases of cellulitis or abscess associated with a positive culture, gram‐negative microorganisms were not isolated more commonly among diabetics compared with nondiabetics. However, in general, diabetics were more likely to be treated with broad gram‐negative therapy suggesting that, particularly for cutaneous abscesses, this prescribing practice may not be warranted. These findings support current IDSA guidelines that recommend antibiotic therapy targeted toward gram‐positive pathogens for cellulitis or abscess, irrespective of the presence of diabetes mellitus.[8, 9] Because nearly one‐fourth of patients hospitalized with cellulitis or abscess are diabetic, these findings have relevance for national antimicrobial stewardship efforts aimed at curbing antimicrobial resistance through reducing use of antibiotics with broad gram‐negative activity in hospitals.[16]

Disclosures: This work was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institute of Health (TCJ: K23 AI099082). D.M.P. reports potential conflicts of interests with Optimer, Cubist, and Forest Pharmaceuticals. The authors report no other conflicts of interest.

Diabetes mellitus is one of the most common comorbid conditions among patients hospitalized for acute bacterial skin infections.[1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6] Acute bacterial skin infections in diabetics represent a spectrum of conditions ranging from cellulitis or cutaneous abscess to more complicated infections such as infected ulcers or deep tissue infections. Although most skin infections in diabetics are caused by gram‐positive pathogens (Staphylococcus aureus and streptococci), the risk of gram‐negative pathogens is increased in certain complicated infections such as diabetic foot infections.[7] For such complicated infections, national guidelines therefore recommend broad‐spectrum empiric antibiotic therapy.[7]

The role of gram‐negative pathogens has not been clearly established in diabetics with cellulitis or cutaneous abscess not associated with an infected ulcer or diabetic foot infection. National guidelines for the treatment of cellulitis and abscess recommend antibiotic therapy targeted toward S aureus and streptococcal species irrespective of the presence of diabetes mellitus.[8, 9] However, in a recent multicenter study of patients hospitalized with acute bacterial skin infections in which cases involving infected ulcers or deep tissue infection were excluded, diabetes mellitus was an independent predictor of use of antibiotics with broad gram‐negative activity.[2] This suggests that either gram‐negative pathogens are more common or providers perceive gram‐negative pathogens to be more common among diabetics with otherwise uncomplicated cellulitis or abscess.

A better understanding of the relationship between the microbiology and antibiotic prescribing practices for diabetics with cellulitis or abscess is therefore necessary to promote the most appropriate spectrum of therapy for these patients. We evaluated a large cohort of patients hospitalized with acute bacterial skin infections in order to: (1) compare the microbiology of diabetics and nondiabetics with cellulitis or cutaneous abscess not associated with an ulcer or deep tissue infection; and (2) compare antibiotic prescribing practices among diabetics and nondiabetics. We hypothesized that diabetics would have a similar spectrum of microorganisms as nondiabetics but would be more frequently treated with antibiotics with broad gram‐negative activity.

METHODS

Study Design

This was a secondary analysis of 2 published retrospective studies of patients hospitalized for cellulitis or cutaneous abscess between January 1, 2007 and May 31, 2012.[2, 10] For the purposes of this study, the terms cellulitis and abscess will refer to infections not involving an infected ulcer, osteomyelitis, or other deep tissue infection.

Study Setting and Population

The first of the 2 cohorts analyzed for the present study included patients hospitalized with cellulitis, abscess, or wound infection at 7 academic or community hospitals in Colorado.[2] The second cohort included patients hospitalized with cellulitis or abscess at a single academic medical center (1 of the 7 hospitals above) in Denver, Colorado.[10] The methods of these studies have been reported in detail elsewhere.[2, 10, 11] Briefly, potential cases were identified using International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification codes. The main inclusion and exclusion criteria of the 2 studies were similar. In both studies, cases were excluded that involved infected ulcers or suspected or confirmed deep tissue involvement (eg, osteomyelitis, myositis, fasciitis). Cases were also excluded that involved other infections where empiric antibiotic therapy with gram‐negative activity is standard including infected human or animal bites, periorbital or orbital infections, and perineal infections. The combined cohort in the present study therefore represented a group of patients hospitalized with relatively uncomplicated cellulitis or cutaneous abscess.

Definitions and Study Outcomes

Only 1 of the 2 studies from which the current cohort was derived distinguished between nonpurulent cellulitis, purulent cellulitis, and wound infection.[2] In the other study, cases were more broadly defined as either cellulitis or cutaneous abscess.[10] Infected ulcers and deep tissue infections were excluded from both studies. In combining the data into the current cohort, all nondrainable infections (purulent or nonpurulent cellulitis and wound infection) were categorized generally as cellulitis. All cases with documentation of an abscess in the medical record were categorized as cutaneous abscess. Presence of diabetes mellitus was based on provider documentation of the condition during the hospitalization. Microbiological cultures were obtained at the discretion of treating providers. Exposure to antibiotics with a broad spectrum of gram‐negative activity was defined as receipt of 2 or more calendar days of ‐lactam/‐lactamase inhibitor combinations, second‐ through fifth‐generation cephalosporins, fluoroquinolones, carbapenems, tigecycline, aminoglycosides, or colistin.[2]

The follow‐up periods differed slightly between the 2 studies used to derive the current cohort. In 1 study, all clinical encounters within 30 days of hospital discharge were reviewed to assess clinical outcomes.[10] In the other, clinical encounters within 45 days from the date of hospitalization were reviewed.[2] Clinical failure was defined as any of the following within the 30‐ or 45‐day follow‐up periods, respectively: (1) treatment failure, defined as a change in antibiotic therapy or unplanned drainage procedure due to inadequate clinical response more than 5 days[2] or 7 days[10] after hospital admission; (2) recurrence, defined as reinitiation of antibiotics for skin infection after completion of the initial treatment course; or (3) rehospitalization due to skin infection.[11]

Statistical Analysis

Because the clinical factors, microbiology, and treatment of cellulitis and cutaneous abscesses differ, analyses were performed for the total cohort and stratified by type of infection. Microorganisms cultured, antibiotic selection, and treatment duration were compared between diabetics and nondiabetics using the Wilcoxon rank sum test, 2, or Fisher exact test, as appropriate.

Because we hypothesized that the presence of diabetes mellitus in patients with cellulitis or abscess leads to use of broad gram‐negative therapy, we developed a multivariable logistic regression model to identify factors independently associated with exposure to antibiotics with broad gram‐negative activity. We also developed a linear regression model to explore the relationship between diabetes mellitus and duration of antibiotic therapy after adjusting for covariates. To develop these models, we first performed bivariate analyses and retained variables with a P value 0.25 in the regression models. Variables that did not meet the P value threshold but were considered to be clinically relevant covariates were also included in the model. We assessed for effect modification, multicollinearity, and goodness of fit when developing the models. We used SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) for data analysis.

RESULTS

After excluding 102 pediatric cases and removing 5 duplicate cases, 770 total cases were included for analysis: 447 involved cellulitis and 323 involved cutaneous abscess (Figure 1). Overall, 167 (22%) patients had diabetes mellitus. Diabetics were significantly more likely than nondiabetics to have cellulitis as the presenting infection (67% of cases vs 56%, P=0.008) and to have lower extremity involvement (48% vs 33%, P<0.001) (Table 1). Diabetics were also older (median age 55 years vs 48 years, P<0.001), more likely to have cirrhosis or prior skin infection, and less likely to be injection‐drug users or human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infected. Demographic and clinical characteristics among diabetics and nondiabetics stratified by the categorizations of cellulitis and cutaneous abscess are presented in the Supporting Information, Appendix Table 1, in the online version of this article.

| Diabetes Mellitus, N=167 | No Diabetes Mellitus, N=603 | |

|---|---|---|

| ||

| Type of infection | ||

| Cellulitis | 112 (67) | 335 (56)a |

| Cutaneous abscess | 55 (33) | 268 (44) |

| Age, y, median (IQR) | 55 (4763) | 48 (3658)a |

| Male | 102 (61) | 405 (67) |

| Injection drug use | 9 (5) | 117 (19)a |

| Alcohol abuse or dependence | 15 (9) | 86 (14) |

| Cirrhosis | 11 (7) | 17 (3)a |

| HIV infection | 0 | 29 (5)a |

| Dialysis dependence | 4 (2) | 5 (1) |

| Peripheral arterial disease | 4 (2) | 5 (1) |

| Saphenous vein harvest | 7 (4) | 11 (2) |

| Prior skin infection | 56 (34) | 125 (21)a |

| Prior MRSA infection or colonization | 20 (12) | 50 (8) |

| Anatomical location | ||

| Lower extremity | 80 (48) | 200 (33)a |

| Upper extremity | 6 (4) | 79 (13)a |

| Head and neck | 14 (8) | 38 (6) |

| Buttock or inguinal | 8 (5) | 35 (6) |

| Chest, abdomen, back, or axilla | 9 (5) | 25 (4) |

| Multiple distinct sites | 7 (4) | 34 (6) |

| Medical primary service | 139 (83) | 395 (66)a |

| Consultation requested | 99 (59) | 294 (49)a |

| Surgery | 58 (35) | 152 (25)a |

| Internal medicine | 18 (11) | 47 (8) |

| Infectious diseases | 41 (25) | 149 (25) |

| Failed initial outpatient antibiotic therapy | 52 (31) | 186 (31) |

| Fever (temperature 38.0C) | 20 (12) | 102 (17) |

| Leukocytosis (WBC >10,000 cells/mm3) | 78 (47) | 311 (52) |

The frequency of use of microbiological cultures was similar among diabetics and nondiabetics (Table 2). In cases of cellulitis, a microorganism was identified in 18% of diabetics and 12% of nondiabetics (P=0.09). In cases of cutaneous abscess, a microorganism was identified more commonly (69% and 74%, respectively, P=0.50). Among cases where a microorganism was identified, aerobic gram‐positive organisms were isolated in 90% of diabetics and 92% of nondiabetics (P=0.59). Aerobic gram‐negative organisms were isolated in 7% of diabetics and 12% of nondiabetics (P=0.28). Specific gram‐negative organisms isolated are shown in the Supporting Information, Appendix Table 2, in the online version of this article; no cases in diabetics involved Pseudomonas aeruginosa. The comparison of microbiological data among diabetics and nondiabetics was similar when stratified by cellulitis versus cutaneous abscess (Table 2).

| Cellulitis | Cutaneous Abscess | All Cases | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diabetes Mellitus, N=112 | No Diabetes Mellitus, N=335 | P | Diabetes Mellitus, N=55 | No Diabetes Mellitus, N=268 | P | Diabetes Mellitus, N=167 | No Diabetes Mellitus, N=603 | P | |

| |||||||||

| Any microbiological culture obtaineda | 82 (73) | 234 (70) | 46 (84) | 239 (89) | 128 (77) | 473 (78) | |||

| Wound drainage or swab | 19 (17) | 36 (11) | 1 (2) | 8 (3) | 20 (12) | 44 (7) | |||

| Abscess material | 1 (1) | 3 (1) | 39 (71) | 205 (76) | 40 (24) | 208 (34) | |||

| Tissueb | 2 (2) | 17 (5) | 1 (2) | 8 (3) | 3 (2) | 25 (4) | |||

| Blood | 73 (65) | 212 (63) | 26 (47) | 121 (45) | 99 (59) | 333 (55) | |||

| Any microorganism identifiedc | 20 (18) | 39 (12) | 0.09 | 38 (69) | 197 (74) | 0.50 | 58 (35) | 236 (39) | 0.30 |

| Aerobic gram‐positive | 15 (75) | 36 (92) | 0.11 | 37 (97) | 182 (92) | 0.48 | 52 (90) | 218 (92) | 0.59 |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 11 (55) | 26 (67) | 0.38 | 28 (74) | 132 (67) | 0.42 | 39 (67) | 158 (67) | 0.97 |

| Methicillin‐susceptible | 4 (20) | 15 (38) | 0.15 | 12 (32) | 42 (21) | 0.17 | 16 (28) | 57 (24) | 0.59 |

| Methicillin‐resistant | 5 (25) | 11 (28) | 1.00 | 14 (37) | 85 (43) | 0.47 | 19 (33) | 96 (41) | 0.27 |

| Susceptibility not performed | 2 (10) | 0 | 0.11 | 2 (5) | 5 (3) | 0.32 | 4 (7) | 5 (2) | 0.08 |

| Streptococcal species | 6 (30) | 15 (38) | 0.52 | 12 (32) | 69 (35) | 0.68 | 18 (31) | 84 (36) | 0.51 |

| ‐hemolytic streptococcus | 3 (15) | 13 (33) | 0.13 | 6 (16) | 32 (16) | 0.94 | 9 (16) | 45 (19) | 0.53 |

| Streptococcus anginosus/Streptococcus milleri group | 1 (5) | 0 | 0.34 | 2 (5) | 29 (15) | 0.11 | 3 (5) | 29 (12) | 0.12 |

| Other ‐hemolytic streptococcus | 2 (10) | 2 (5) | 0.60 | 4 (11) | 12 (6) | 0.30 | 6 (10) | 14 (6) | 0.25 |

| Other streptococcus | 0 | 0 | 1 (3) | 3 (2) | 0.51 | 1 (2) | 3 (1) | 0.59 | |

| Staphylococcus aureus or streptococci | 15 (75) | 35 (90) | 0.25 | 37 (97) | 182 (92) | 0.48 | 52 (90) | 217 (92) | 0.60 |

| Enterococcus species | 0 | 2 (5) | 0.54 | 0 | 4 (2) | 1.00 | 0 | 6 (3) | 0.60 |

| Aerobic gram‐negative | 2 (10) | 7 (18) | 0.70 | 2 (5) | 21 (11) | 0.39 | 4 (7) | 28 (12) | 0.28 |

| Anaerobic organism(s) | 2 (10) | 3 (8) | 1.00 | 8 (21) | 30 (15) | 0.37 | 10 (17) | 33 (14) | 0.53 |

| Mixed skin or oral flora | 1 (5) | 1 (3) | 1.00 | 0 | 1 (1) | 1.00 | 1 (2) | 2 (1) | 0.48 |

| Other | 1 (5) | 3 (8) | 1.00 | 2 (5) | 3 (2) | 0.19 | 3 (5) | 6 (3) | 0.39 |

| Polymicrobial | 3 (15) | 17 (45) | 0.03 | 11 (29) | 47 (24) | 0.51 | 14 (24) | 64 (27) | 0.65 |

| Positive blood cultured | 4 (5) | 8 (4) | 0.51 | 2 (8) | 3 (2) | 0.21 | 6 (6) | 11 (3) | 0.24 |

Antibiotic utilization is summarized in Table 3. Among patients who were started on antibiotic therapy in the emergency department or urgent care, the initial regimen included an agent with broad gram‐negative activity in 31% of both diabetics and nondiabetics (P=0.97). During the entire hospital stay (including the emergency department or urgent care), diabetics were significantly more likely to be treated with ‐lactam/‐lactamase inhibitor combinations (42% vs 33%, P=0.04). At the time of hospital discharge, diabetics were more likely to be prescribed fluoroquinolones (11% vs 5%, P=0.01) (Table 3) particularly for cases of cellulitis (13% vs 6%, P=0.008) (see Supporting Information, Appendix Table 3, in the online version of this article). Diabetics were somewhat more likely to be prescribed parenteral antibiotics (10% vs 6%, P=0.07) after discharge. When considering both inpatient and discharge therapy, more diabetics than nondiabetics were exposed to at least 2 calendar days of broad gram‐negative therapy (54% vs 44%, P=0.02) and more were prescribed an antipseudomonal agent (38% vs 25%, P=0.002). In the group of patients who received at least 1 dose of an antibiotic with broad gram‐negative activity, broad gram‐negative agents accounted for 33% of the total days of therapy prescribed for diabetics and 32% for nondiabetics. Overall prescribing patterns were similar when stratified by cellulitis versus cutaneous abscess (see Supporting Information, Appendix Table 3, in the online version of this article).

| Diabetes Mellitus, N=167 | No Diabetes Mellitus, N=603 | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Individual antibiotics prescribed during the inpatient stayab | |||

| Vancomycin | 142 (85) | 504 (84) | 0.65 |

| Clindamycin | 27 (16) | 131 (22) | 0.12 |

| Parenteral ‐lactam/‐lactamase inhibitor | 70 (42) | 200 (33) | 0.04 |

| Second‐generation or higher cephalosporin | 13 (8) | 51 (8) | 0.78 |

| Cefazolin | 17 (10) | 91 (15) | 0.11 |

| Carbapenem | 9 (5) | 34 (6) | 0.90 |

| Fluoroquinolone | 20 (12) | 53 (9) | 0.21 |

| Daptomycin | 8 (5) | 24 (4) | 0.64 |

| Linezolid | 2 (1) | 8 (1) | 1.00 |

| Other ‐lactam | 6 (4) | 30 (5) | 0.45 |

| Trimethoprim‐sulfamethoxazole | 12 (7) | 30 (5) | 0.27 |

| Doxycycline | 15 (9) | 44 (7) | 0.47 |

| Cephalexin | 7 (4) | 22 (4) | 0.74 |

| Amoxicillin‐clavulanate | 11 (7) | 24 (4) | 0.15 |

| Antibiotics prescribed at hospital dischargeb | 163 (98) | 580 (96) | 0.38 |

| Clindamycin | 20 (12) | 95 (16) | 0.23 |

| Trimethoprim‐sulfamethoxazole | 52 (31) | 215 (36) | 0.28 |

| Doxycycline | 32 (19) | 91 (15) | 0.20 |

| Cephalexin | 12 (7) | 46 (8) | 0.85 |

| Amoxicillin‐clavulanate | 24 (14) | 82 (14) | 0.80 |

| Fluoroquinolone | 18 (11) | 32 (5) | 0.01 |

| Linezolid | 8 (5) | 19 (3) | 0.31 |

| Other oral ‐lactam | 3 (2) | 28 (5) | 0.10 |

| Other oral antibiotic | 1 (1) | 2 (0.3) | 0.52 |

| Vancomycin | 8 (5) | 15 (2) | 0.13 |

| Daptomycin | 5 (3) | 10 (2) | 0.34 |

| Other parenteral antibiotic | 4 (2) | 11 (2) | 0.75 |

| Antibiotic with broad gram‐negative activity initiated in emergency department or urgent care | 46/149 (31) | 174/561 (31) | 0.97 |

| Exposed to any antibiotic with broad gram‐negative activityc | 101 (62) | 311 (53) | 0.048 |

| Exposed to any antibiotic with antipseudomonal activity | 62 (38) | 149 (25) | 0.002 |

| Exposed to at least 2 calendar days of antibiotics with broad gram‐negative activityc | 89 (54) | 259 (44) | 0.02 |

| Treatment durationd | |||

| Total duration of therapy, d, median (IQR) | 13 (1015) | 12 (1015) | 0.09 |