User login

Treatment Trends and Outcomes in Healthcare-Associated Pneumonia

Bacterial pneumonia remains an important cause of morbidity and mortality in the United States, and is the 8th leading cause of death with 55,227 deaths among adults annually.1 In 2005, the American Thoracic Society (ATS) and the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) collaborated to update guidelines for hospital-acquired pneumonia (HAP), ventilator-associated pneumonia, and healthcare-associated pneumonia (HCAP).2 This broad document outlines an evidence-based approach to diagnostic testing and antibiotic management based on the epidemiology and risk factors for these conditions. The guideline specifies the following criteria for HCAP: hospitalization in the past 90 days, residence in a skilled nursing facility (SNF), home infusion therapy, hemodialysis, home wound care, family members with multidrug resistant organisms (MDRO), and immunosuppressive diseases or medications, with the presumption that these patients are more likely to be harboring MDRO and should thus be treated empirically with broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy. Prior studies have shown that patients with HCAP have a more severe illness, are more likely to have MDRO, are more likely to be inadequately treated, and are at a higher risk for mortality than patients with community-acquired pneumonia (CAP).3,4

These guidelines are controversial, especially in regard to the recommendations to empirically treat broadly with 2 antibiotics targeting Pseudomonas species, whether patients with HCAP merit broader spectrum coverage than patients with CAP, and whether the criteria for defining HCAP are adequate to predict which patients are harboring MDRO. It has subsequently been proposed that HCAP is more related to CAP than to HAP, and a recent update to the guideline removed recommendations for treatment of HCAP and will be placing HCAP into the guidelines for CAP instead.5 We sought to investigate the degree of uptake of the ATS and IDSA guideline recommendations by physicians over time, and whether this led to a change in outcomes among patients who met the criteria for HCAP.

METHODS

Setting and Patients

We identified patients discharged between July 1, 2007, and November 30, 2011, from 488 US hospitals that participated in the Premier database (Premier Inc., Charlotte, North Carolina), an inpatient database developed for measuring quality and healthcare utilization. The database is frequently used for healthcare research and has been described previously.6 Member hospitals are in all regions of the US and are generally reflective of US hospitals. This database contains multiple data elements, including sociodemographic information, International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision-Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) diagnosis and procedure codes, hospital and physician information, source of admission, and discharge status. It also includes a date-stamped log of all billed items and services, including diagnostic tests, medications, and other treatments. Because the data do not contain identifiable information, the institutional review board at our medical center determined that this study did not constitute human subjects research.

We included all patients aged ≥18 years with a principal diagnosis of pneumonia or with a secondary diagnosis of pneumonia paired with a principal diagnosis of respiratory failure, acute respiratory distress syndrome, respiratory arrest, sepsis, or influenza. Patients were excluded if they were transferred to or from another acute care institution, had a length of stay of 1 day or less, had cystic fibrosis, did not have a chest radiograph, or did not receive antibiotics within 48 hours of admission.

For each patient, we extracted age, gender, principal diagnosis, comorbidities, and the specialty of the attending physician. Comorbidities were identified from ICD-9-CM secondary diagnosis codes and Diagnosis Related Groups by using Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project Comorbidity Software, version 3.1, based on the work of Elixhauser (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, Maryland).7 In order to ensure that patients had HCAP, we required the presence of ≥1 HCAP criteria, including hospitalization in the past 90 days, hemodialysis, admission from an SNF, or immune suppression (which was derived from either a secondary diagnosis for neutropenia, hematological malignancy, organ transplant, acquired immunodeficiency virus, or receiving immunosuppressant drugs or corticosteroids [equivalent to ≥20 mg/day of prednisone]).

Definitions of Guideline-Concordant and Discordant Antibiotic Therapy

The ATS and IDSA guidelines recommended the following antibiotic combinations for HCAP: an antipseudomonal cephalosporin or carbapenem or a beta-lactam/lactamase inhibitor, plus an antipseudomonal quinolone or aminoglycoside, plus an antibiotic with activity versus methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), such as vancomycin or linezolid. Based on these guidelines, we defined the receipt of fully guideline-concordant antibiotics as 2 recommended antibiotics for Pseudomonas species plus 1 for MRSA administered by the second day of admission. Partially guideline-concordant antibiotics were defined as 1 recommended antibiotic for Pseudomonas species plus 1 for MRSA by the second day of hospitalization. Guideline-discordant antibiotics were defined as all other combinations.

Statistical Analysis

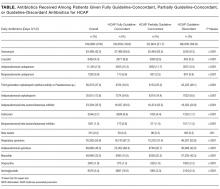

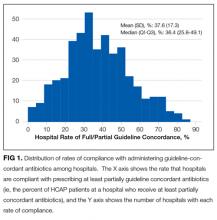

Descriptive statistics on patient characteristics are presented as frequency, proportions for categorical factors, and median with interquartile range (IQR) for continuous variables for the full cohort and by treatment group, defined as fully or partially guideline-concordant antibiotic therapy or discordant therapy. Hospital rates of fully guideline-concordant treatment are presented overall and by hospital characteristics. The association of hospital characteristics with rates of fully guideline-concordant therapy were assessed by using 1-way analysis of variance tests.

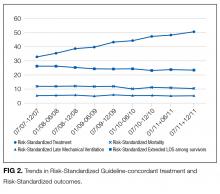

To assess trends across hospitals for the association between the use of guideline-concordant therapy and mortality, progression to respiratory failure as measured by the late initiation of invasive mechanical ventilation (day 3 or later), and the length of stay among survivors, we divided the 4.5-year study period into 9 intervals of 6 months each; 292 hospitals that submitted data for all 9 time points were examined in this analysis. Based on the distribution of length of stay in the first time period, we created an indicator variable for extended length of stay with length of stay at or above the 75th percentile, defined as extended. For each hospital at each 6-month interval, we then computed risk-standardized guideline-concordant treatment (RS-treatment) rates and risk-standardized in-hospital outcome rates similar to methods used by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services for public reporting.8 For each hospital at each time interval, we estimated a predicted rate of guideline-concordant treatment as the sum of predicted probabilities of guideline-concordant treatment from patient factors and the random intercept for the hospital in which they were admitted. We then calculated the expected rate of guideline-concordant treatment as the sum of expected probabilities of treatment received from patient factors only. RS-treatment was then calculated as the ratio of predicted to expected rates multiplied by the overall unadjusted mean treatment rate from all patients.9 We repeated the same modeling strategy to calculate risk-standardized outcome (RS-outcome) rates for each hospital across all time points. All models were adjusted for patient demographics and comorbidities. Similar models using administrative data have moderate discrimination for mortality.10

We then fit mixed-effects linear models with random hospital intercept and slope across time for the RS-treatment and outcome rates, respectively. From these models, we estimated the mean slope for RS-treatment and for RS-outcome over time. In addition, we estimated a slope or trend over time for each hospital for treatment and for outcome and evaluated the correlation between the treatment and outcome trends.

All analyses were performed using the Statistical Analysis System version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC) and STATA release 13 (StataCorp, LLC, College Station, Texas).

RESULTS

DISCUSSION

In this large, retrospective cohort study, we found that there was a substantial gap between the empiric antibiotics recommended by the ATS and IDSA guidelines and the empiric antibiotics that patients actually received. Over the study period, we saw an increased adherence to guidelines, in spite of growing evidence that HCAP risk factors do not adequately predict which patients are at risk for infection with an MDRO.11 We used this change in antibiotic prescribing behavior over time to determine if there was a clinical impact on patient outcomes and found that at the hospital level, there were no improvements in mortality, excess length of stay, or progression to respiratory failure despite a doubling in guideline-concordant antibiotic use.

At least 2 other large studies have assessed the association between guideline-concordant therapy and outcomes in HCAP.12,13 Both found that guideline-concordant therapy was associated with increased mortality, despite propensity matching. Both were conducted at the individual patient level by using administrative data, and results were likely affected by unmeasured clinical confounders, with sicker patients being more likely to receive guideline-concordant therapy. Our focus on the outcomes at the hospital level avoids this selection bias because the overall severity of illness of patients at any given hospital would not be expected to change over the study period, while physician uptake of antibiotic prescribing guidelines would be expected to increase over time. Determining the correlation between increases in guideline adherence and changes in patient outcome may offer a better assessment of the impact of guideline adherence. In this regard, our results are similar to those achieved by 1 quality improvement collaborative that was aimed at increasing guideline concordant therapy in ICUs. Despite an increase in guideline concordance from 33% to 47% of patients, they found no change in overall mortality.14

There were several limitations to our study. We did not have access to microbiologic data, so we were unable to determine which patients had MDRO infection or determine antibiotic-pathogen matching. However, the treating physicians in our study population presumably did not have access to this data at the time of treatment either because the time period we examined was within the first 48 hours of hospitalization, the interval during which cultures are incubating and the patients are being treated empirically. In addition, there may have been HCAP patients that we failed to identify, such as patients who were admitted in the past 90 days to a hospital that does not submit data to Premier. However, it is unlikely that prescribing for such patients should differ systematically from what we observed. While the database draws from 488 hospitals nationwide, it is possible that practices may be different at facilities that are not contained within the Premier database, such as Veterans Administration Hospitals. Similarly, we did not have readings for chest x-rays; hence, there could be some patients in the dataset who did not have pneumonia. However, we tried to overcome this by including only those patients with a principal diagnosis of pneumonia or sepsis with a secondary pneumonia diagnosis, a chest x-ray, and antibiotics administered within the first 48 hours of admission.

There are likely several reasons why so few HCAP patients in our study received guideline-concordant antibiotics. A lack of knowledge about the ATS and IDSA guidelines may have impacted the physicians in our study population. El-Solh et al.15 surveyed physicians about the ATS-IDSA guidelines 4 years after publication and found that only 45% were familiar with the document. We found that the rate of prescribing at least partially guideline-concordant antibiotics rose steadily over time, supporting the idea that the newness of the guidelines was 1 barrier. Additionally, prior studies have shown that many physicians may not agree with or choose to follow guidelines, with only 20% of physicians indicating that guidelines have a major impact on their clinical decision making,16 and the majority do not choose HCAP guideline-concordant antibiotics when tested.17 Alternatively, clinicians may not follow the guidelines because of a belief that the HCAP criteria do not adequately indicate patients who are at risk for MDRO. Previous studies have demonstrated the relative inability of HCAP risk factors to predict patients who harbor MDRO18 and suggest that better tools such as clinical scoring systems, which include not only the traditional HCAP risk factors but also prior exposure to antibiotics, prior culture data, and a cumulative assessment of both intrinsic and extrinsic factors, could more accurately predict MDRO and lead to a more judicious use of broad-spectrum antimicrobial agents.19-25 Indeed, these collective findings have led the authors of the recently updated guidelines to remove HCAP as a clinical entity from the hospital-acquired or ventilator-associated pneumonia guidelines and place them instead in the upcoming updated guidelines on the management of CAP.5 Of these 3 explanations, the lack of familiarity fits best with our observation that guideline-concordant therapy increased steadily over time with no evidence of reaching a plateau. Ironically, as consensus was building that HCAP is a poor marker for MDROs, routine empiric treatment with vancomycin and piperacillin-tazobactam (“vanco and zosyn”) have become routine in many hospitals. Additional studies are needed to know if this trend has stabilized or reversed.

CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, clinicians in our large, nationally representative sample treated the majority of HCAP patients as though they had CAP. Although there was an increase in the administration of guideline-concordant therapy over time, this increase was not associated with improved outcomes. This study supports the growing consensus that HCAP criteria do not accurately predict which patients benefit from broad-spectrum antibiotics for pneumonia, and most patients fare well with antibiotics targeting common community-acquired organisms.

Disclosure

This work was supported by grant # R01HS018723 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Dr. Lagu is also supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health under award number K01HL114745. Dr. Lindenauer is supported by grant K24HL132008 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. The funding agency had no role in the data acquisition, analysis, or manuscript preparation for this study. Drs. Haessler and Rothberg had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Drs. Haessler, Lagu, Lindenauer, Skiest, Zilberberg, Higgins, and Rothberg conceived of the study and analyzed and interpreted the data. Dr. Lindenauer acquired the data. Dr. Pekow and Ms. Priya carried out the statistical analyses. Dr. Haessler drafted the manuscript. All authors critically reviewed the manuscript for accuracy and integrity. All authors certify no potential conflicts of interest. Preliminary results from this study were presented in oral and poster format at IDWeek in 2012 and 2013.

1. Kochanek KD, Murphy SL, Xu JQ, Tejada-Vera B. Deaths: Final data for 2014. National vital statistics reports; vol 65 no 4. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. 2016. PubMed

2. American Thoracic Society, Infectious Diseases Society of America. Guidelines for the Management of Adults with Hospital-acquired, Ventilator-associated, and Healthcare-associated Pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171(4):388-416. PubMed

3. Zilberberg MD, Shorr A. Healthcare-associated pneumonia: the state of the evidence to date. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2011;17(3):142-147. PubMed

4. Kollef MK, Shorr A, Tabak YP, Gupta V, Liu LZ, Johannes RS. Epidemiology and Outcomes of Health-care-associated pneumonia. Chest. 2005;128(6):3854-3862. PubMed

5. Kalil AC, Metersky ML, Klompas M, et al. Management of Adults With Hospital-acquired and Ventilator-associated Pneumonia: 2016 Clinical Practice Guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the American Thoracic Society. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63(5):575-582. PubMed

6. Lindenauer PK, Pekow PS, Lahti MC, Lee Y, Benjamin EM, Rothberg MB. Association of corticosteroid dose and route of administration with risk of treatment failure in acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. JAMA. 2010;303(23):2359-2367. PubMed

7. Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Harris DR, Coffey RM. Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Med Care. 1998;36(1):8-27. PubMed

8. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Frequently asked questions (FAQs): Implementation and maintenance of CMS mortality measures for AMI & HF. 2007. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/HospitalQualityInits/downloads/HospitalMortalityAboutAMI_HF.pdf. Accessed November 1, 2016.

9. Normand SL, Shahian DM. Statistical and Clinical Aspects of Hospital Outcomes Profiling. Stat Sci. 2007;22(2):206-226.

10. Rothberg MB, Pekow PS, Priya A, et al. Using highly detailed administrative data to predict pneumonia mortality. PLoS One. 2014;9(1):e87382. PubMed

11. Jones BE, Jones MM, Huttner B, et al. Trends in antibiotic use and nosocomial pathogens in hospitalized veterans with pneumonia at 128 medical centers, 2006-2010. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61(9):1403-1410. PubMed

12. Attridge RT, Frei CR, Restrepo MI, et al. Guideline-concordant therapy and outcomes in healthcare-associated pneumonia. Eur Respir J. 2011;38(4):878-887. PubMed

13. Rothberg MB, Zilberberg MD, Pekow PS, et al. Association of Guideline-based Antimicrobial Therapy and Outcomes in Healthcare-Associated Pneumonia. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2015;70(5):1573-1579. PubMed

14. Kett DH, Cano E, Quartin AA, et al. Improving Medicine through Pathway Assessment of Critical Therapy of Hospital-Acquired Pneumonia (IMPACT-HAP) Investigators. Implementation of guidelines for management of possible multidrug-resistant pneumonia in intensive care: an observational, multicentre cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2011;11(3):181-189. PubMed

15. El-Solh AA, Alhajhusain A, Saliba RG, Drinka P. Physicians’ Attitudes Toward Guidelines for the Treatment of Hospitalized Nursing-Home -Acquired Pneumonia. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2011;12(4):270-276. PubMed

16. Tunis S, Hayward R, Wilson M, et al. Internists’ Attitudes about Clinical Practice Guidelines. Ann Intern Med. 1994;120(11):956-963. PubMed

17. Seymann GB, Di Francesco L, Sharpe B, et al. The HCAP Gap: Differences between Self-Reported Practice Patterns and Published Guidelines for Health Care-Associated Pneumonia. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49(12):1868-1874. PubMed

18. Chalmers JD, Rother C, Salih W, Ewig S. Healthcare associated pneumonia does not accurately identify potentially resistant pathogens: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;58(3):330-339. PubMed

19. Shorr A, Zilberberg MD, Reichley R, et al. Validation of a Clinical Score for Assessing the Risk of Resistant Pathogens in Patients with Pneumonia Presenting to the Emergency Department. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54(2):193-198. PubMed

20. Aliberti S, Pasquale MD, Zanaboni AM, et al. Stratifying Risk Factors for Multidrug-Resistant Pathogens in Hospitalized Patients Coming from the Community with Pneumonia. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54(4):470-478. PubMed

21. Schreiber MP, Chan CM, Shorr AF. Resistant Pathogens in Nonnosocomial Pneumonia and Respiratory Failure: Is it Time to Refine the Definition of Health-care-Associated Pneumonia? Chest. 2010;137(6):1283-1288. PubMed

22. Madaras-Kelly KJ, Remington RE, Fan VS, Sloan KL. Predicting antibiotic resistance to community-acquired pneumonia antibiotics in culture-positive patients with healthcare-associated pneumonia. J Hosp Med. 2012;7(3):195-202. PubMed

23. Shindo Y, Ito R, Kobayashi D, et al. Risk factors for drug-resistant pathogens in community-acquired and healthcare-associated pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;188(8):985-995. PubMed

24. Metersky ML, Frei CR, Mortensen EM. Predictors of Pseudomonas and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in hospitalized patients with healthcare-associated pneumonia. Respirology. 2016;21(1):157-163. PubMed

25. Webb BJ, Dascomb K, Stenehjem E, Dean N. Predicting risk of drug-resistant organisms in pneumonia: moving beyond the HCAP model. Respir Med. 2015;109(1):1-10. PubMed

Bacterial pneumonia remains an important cause of morbidity and mortality in the United States, and is the 8th leading cause of death with 55,227 deaths among adults annually.1 In 2005, the American Thoracic Society (ATS) and the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) collaborated to update guidelines for hospital-acquired pneumonia (HAP), ventilator-associated pneumonia, and healthcare-associated pneumonia (HCAP).2 This broad document outlines an evidence-based approach to diagnostic testing and antibiotic management based on the epidemiology and risk factors for these conditions. The guideline specifies the following criteria for HCAP: hospitalization in the past 90 days, residence in a skilled nursing facility (SNF), home infusion therapy, hemodialysis, home wound care, family members with multidrug resistant organisms (MDRO), and immunosuppressive diseases or medications, with the presumption that these patients are more likely to be harboring MDRO and should thus be treated empirically with broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy. Prior studies have shown that patients with HCAP have a more severe illness, are more likely to have MDRO, are more likely to be inadequately treated, and are at a higher risk for mortality than patients with community-acquired pneumonia (CAP).3,4

These guidelines are controversial, especially in regard to the recommendations to empirically treat broadly with 2 antibiotics targeting Pseudomonas species, whether patients with HCAP merit broader spectrum coverage than patients with CAP, and whether the criteria for defining HCAP are adequate to predict which patients are harboring MDRO. It has subsequently been proposed that HCAP is more related to CAP than to HAP, and a recent update to the guideline removed recommendations for treatment of HCAP and will be placing HCAP into the guidelines for CAP instead.5 We sought to investigate the degree of uptake of the ATS and IDSA guideline recommendations by physicians over time, and whether this led to a change in outcomes among patients who met the criteria for HCAP.

METHODS

Setting and Patients

We identified patients discharged between July 1, 2007, and November 30, 2011, from 488 US hospitals that participated in the Premier database (Premier Inc., Charlotte, North Carolina), an inpatient database developed for measuring quality and healthcare utilization. The database is frequently used for healthcare research and has been described previously.6 Member hospitals are in all regions of the US and are generally reflective of US hospitals. This database contains multiple data elements, including sociodemographic information, International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision-Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) diagnosis and procedure codes, hospital and physician information, source of admission, and discharge status. It also includes a date-stamped log of all billed items and services, including diagnostic tests, medications, and other treatments. Because the data do not contain identifiable information, the institutional review board at our medical center determined that this study did not constitute human subjects research.

We included all patients aged ≥18 years with a principal diagnosis of pneumonia or with a secondary diagnosis of pneumonia paired with a principal diagnosis of respiratory failure, acute respiratory distress syndrome, respiratory arrest, sepsis, or influenza. Patients were excluded if they were transferred to or from another acute care institution, had a length of stay of 1 day or less, had cystic fibrosis, did not have a chest radiograph, or did not receive antibiotics within 48 hours of admission.

For each patient, we extracted age, gender, principal diagnosis, comorbidities, and the specialty of the attending physician. Comorbidities were identified from ICD-9-CM secondary diagnosis codes and Diagnosis Related Groups by using Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project Comorbidity Software, version 3.1, based on the work of Elixhauser (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, Maryland).7 In order to ensure that patients had HCAP, we required the presence of ≥1 HCAP criteria, including hospitalization in the past 90 days, hemodialysis, admission from an SNF, or immune suppression (which was derived from either a secondary diagnosis for neutropenia, hematological malignancy, organ transplant, acquired immunodeficiency virus, or receiving immunosuppressant drugs or corticosteroids [equivalent to ≥20 mg/day of prednisone]).

Definitions of Guideline-Concordant and Discordant Antibiotic Therapy

The ATS and IDSA guidelines recommended the following antibiotic combinations for HCAP: an antipseudomonal cephalosporin or carbapenem or a beta-lactam/lactamase inhibitor, plus an antipseudomonal quinolone or aminoglycoside, plus an antibiotic with activity versus methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), such as vancomycin or linezolid. Based on these guidelines, we defined the receipt of fully guideline-concordant antibiotics as 2 recommended antibiotics for Pseudomonas species plus 1 for MRSA administered by the second day of admission. Partially guideline-concordant antibiotics were defined as 1 recommended antibiotic for Pseudomonas species plus 1 for MRSA by the second day of hospitalization. Guideline-discordant antibiotics were defined as all other combinations.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics on patient characteristics are presented as frequency, proportions for categorical factors, and median with interquartile range (IQR) for continuous variables for the full cohort and by treatment group, defined as fully or partially guideline-concordant antibiotic therapy or discordant therapy. Hospital rates of fully guideline-concordant treatment are presented overall and by hospital characteristics. The association of hospital characteristics with rates of fully guideline-concordant therapy were assessed by using 1-way analysis of variance tests.

To assess trends across hospitals for the association between the use of guideline-concordant therapy and mortality, progression to respiratory failure as measured by the late initiation of invasive mechanical ventilation (day 3 or later), and the length of stay among survivors, we divided the 4.5-year study period into 9 intervals of 6 months each; 292 hospitals that submitted data for all 9 time points were examined in this analysis. Based on the distribution of length of stay in the first time period, we created an indicator variable for extended length of stay with length of stay at or above the 75th percentile, defined as extended. For each hospital at each 6-month interval, we then computed risk-standardized guideline-concordant treatment (RS-treatment) rates and risk-standardized in-hospital outcome rates similar to methods used by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services for public reporting.8 For each hospital at each time interval, we estimated a predicted rate of guideline-concordant treatment as the sum of predicted probabilities of guideline-concordant treatment from patient factors and the random intercept for the hospital in which they were admitted. We then calculated the expected rate of guideline-concordant treatment as the sum of expected probabilities of treatment received from patient factors only. RS-treatment was then calculated as the ratio of predicted to expected rates multiplied by the overall unadjusted mean treatment rate from all patients.9 We repeated the same modeling strategy to calculate risk-standardized outcome (RS-outcome) rates for each hospital across all time points. All models were adjusted for patient demographics and comorbidities. Similar models using administrative data have moderate discrimination for mortality.10

We then fit mixed-effects linear models with random hospital intercept and slope across time for the RS-treatment and outcome rates, respectively. From these models, we estimated the mean slope for RS-treatment and for RS-outcome over time. In addition, we estimated a slope or trend over time for each hospital for treatment and for outcome and evaluated the correlation between the treatment and outcome trends.

All analyses were performed using the Statistical Analysis System version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC) and STATA release 13 (StataCorp, LLC, College Station, Texas).

RESULTS

DISCUSSION

In this large, retrospective cohort study, we found that there was a substantial gap between the empiric antibiotics recommended by the ATS and IDSA guidelines and the empiric antibiotics that patients actually received. Over the study period, we saw an increased adherence to guidelines, in spite of growing evidence that HCAP risk factors do not adequately predict which patients are at risk for infection with an MDRO.11 We used this change in antibiotic prescribing behavior over time to determine if there was a clinical impact on patient outcomes and found that at the hospital level, there were no improvements in mortality, excess length of stay, or progression to respiratory failure despite a doubling in guideline-concordant antibiotic use.

At least 2 other large studies have assessed the association between guideline-concordant therapy and outcomes in HCAP.12,13 Both found that guideline-concordant therapy was associated with increased mortality, despite propensity matching. Both were conducted at the individual patient level by using administrative data, and results were likely affected by unmeasured clinical confounders, with sicker patients being more likely to receive guideline-concordant therapy. Our focus on the outcomes at the hospital level avoids this selection bias because the overall severity of illness of patients at any given hospital would not be expected to change over the study period, while physician uptake of antibiotic prescribing guidelines would be expected to increase over time. Determining the correlation between increases in guideline adherence and changes in patient outcome may offer a better assessment of the impact of guideline adherence. In this regard, our results are similar to those achieved by 1 quality improvement collaborative that was aimed at increasing guideline concordant therapy in ICUs. Despite an increase in guideline concordance from 33% to 47% of patients, they found no change in overall mortality.14

There were several limitations to our study. We did not have access to microbiologic data, so we were unable to determine which patients had MDRO infection or determine antibiotic-pathogen matching. However, the treating physicians in our study population presumably did not have access to this data at the time of treatment either because the time period we examined was within the first 48 hours of hospitalization, the interval during which cultures are incubating and the patients are being treated empirically. In addition, there may have been HCAP patients that we failed to identify, such as patients who were admitted in the past 90 days to a hospital that does not submit data to Premier. However, it is unlikely that prescribing for such patients should differ systematically from what we observed. While the database draws from 488 hospitals nationwide, it is possible that practices may be different at facilities that are not contained within the Premier database, such as Veterans Administration Hospitals. Similarly, we did not have readings for chest x-rays; hence, there could be some patients in the dataset who did not have pneumonia. However, we tried to overcome this by including only those patients with a principal diagnosis of pneumonia or sepsis with a secondary pneumonia diagnosis, a chest x-ray, and antibiotics administered within the first 48 hours of admission.

There are likely several reasons why so few HCAP patients in our study received guideline-concordant antibiotics. A lack of knowledge about the ATS and IDSA guidelines may have impacted the physicians in our study population. El-Solh et al.15 surveyed physicians about the ATS-IDSA guidelines 4 years after publication and found that only 45% were familiar with the document. We found that the rate of prescribing at least partially guideline-concordant antibiotics rose steadily over time, supporting the idea that the newness of the guidelines was 1 barrier. Additionally, prior studies have shown that many physicians may not agree with or choose to follow guidelines, with only 20% of physicians indicating that guidelines have a major impact on their clinical decision making,16 and the majority do not choose HCAP guideline-concordant antibiotics when tested.17 Alternatively, clinicians may not follow the guidelines because of a belief that the HCAP criteria do not adequately indicate patients who are at risk for MDRO. Previous studies have demonstrated the relative inability of HCAP risk factors to predict patients who harbor MDRO18 and suggest that better tools such as clinical scoring systems, which include not only the traditional HCAP risk factors but also prior exposure to antibiotics, prior culture data, and a cumulative assessment of both intrinsic and extrinsic factors, could more accurately predict MDRO and lead to a more judicious use of broad-spectrum antimicrobial agents.19-25 Indeed, these collective findings have led the authors of the recently updated guidelines to remove HCAP as a clinical entity from the hospital-acquired or ventilator-associated pneumonia guidelines and place them instead in the upcoming updated guidelines on the management of CAP.5 Of these 3 explanations, the lack of familiarity fits best with our observation that guideline-concordant therapy increased steadily over time with no evidence of reaching a plateau. Ironically, as consensus was building that HCAP is a poor marker for MDROs, routine empiric treatment with vancomycin and piperacillin-tazobactam (“vanco and zosyn”) have become routine in many hospitals. Additional studies are needed to know if this trend has stabilized or reversed.

CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, clinicians in our large, nationally representative sample treated the majority of HCAP patients as though they had CAP. Although there was an increase in the administration of guideline-concordant therapy over time, this increase was not associated with improved outcomes. This study supports the growing consensus that HCAP criteria do not accurately predict which patients benefit from broad-spectrum antibiotics for pneumonia, and most patients fare well with antibiotics targeting common community-acquired organisms.

Disclosure

This work was supported by grant # R01HS018723 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Dr. Lagu is also supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health under award number K01HL114745. Dr. Lindenauer is supported by grant K24HL132008 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. The funding agency had no role in the data acquisition, analysis, or manuscript preparation for this study. Drs. Haessler and Rothberg had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Drs. Haessler, Lagu, Lindenauer, Skiest, Zilberberg, Higgins, and Rothberg conceived of the study and analyzed and interpreted the data. Dr. Lindenauer acquired the data. Dr. Pekow and Ms. Priya carried out the statistical analyses. Dr. Haessler drafted the manuscript. All authors critically reviewed the manuscript for accuracy and integrity. All authors certify no potential conflicts of interest. Preliminary results from this study were presented in oral and poster format at IDWeek in 2012 and 2013.

Bacterial pneumonia remains an important cause of morbidity and mortality in the United States, and is the 8th leading cause of death with 55,227 deaths among adults annually.1 In 2005, the American Thoracic Society (ATS) and the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) collaborated to update guidelines for hospital-acquired pneumonia (HAP), ventilator-associated pneumonia, and healthcare-associated pneumonia (HCAP).2 This broad document outlines an evidence-based approach to diagnostic testing and antibiotic management based on the epidemiology and risk factors for these conditions. The guideline specifies the following criteria for HCAP: hospitalization in the past 90 days, residence in a skilled nursing facility (SNF), home infusion therapy, hemodialysis, home wound care, family members with multidrug resistant organisms (MDRO), and immunosuppressive diseases or medications, with the presumption that these patients are more likely to be harboring MDRO and should thus be treated empirically with broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy. Prior studies have shown that patients with HCAP have a more severe illness, are more likely to have MDRO, are more likely to be inadequately treated, and are at a higher risk for mortality than patients with community-acquired pneumonia (CAP).3,4

These guidelines are controversial, especially in regard to the recommendations to empirically treat broadly with 2 antibiotics targeting Pseudomonas species, whether patients with HCAP merit broader spectrum coverage than patients with CAP, and whether the criteria for defining HCAP are adequate to predict which patients are harboring MDRO. It has subsequently been proposed that HCAP is more related to CAP than to HAP, and a recent update to the guideline removed recommendations for treatment of HCAP and will be placing HCAP into the guidelines for CAP instead.5 We sought to investigate the degree of uptake of the ATS and IDSA guideline recommendations by physicians over time, and whether this led to a change in outcomes among patients who met the criteria for HCAP.

METHODS

Setting and Patients

We identified patients discharged between July 1, 2007, and November 30, 2011, from 488 US hospitals that participated in the Premier database (Premier Inc., Charlotte, North Carolina), an inpatient database developed for measuring quality and healthcare utilization. The database is frequently used for healthcare research and has been described previously.6 Member hospitals are in all regions of the US and are generally reflective of US hospitals. This database contains multiple data elements, including sociodemographic information, International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision-Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) diagnosis and procedure codes, hospital and physician information, source of admission, and discharge status. It also includes a date-stamped log of all billed items and services, including diagnostic tests, medications, and other treatments. Because the data do not contain identifiable information, the institutional review board at our medical center determined that this study did not constitute human subjects research.

We included all patients aged ≥18 years with a principal diagnosis of pneumonia or with a secondary diagnosis of pneumonia paired with a principal diagnosis of respiratory failure, acute respiratory distress syndrome, respiratory arrest, sepsis, or influenza. Patients were excluded if they were transferred to or from another acute care institution, had a length of stay of 1 day or less, had cystic fibrosis, did not have a chest radiograph, or did not receive antibiotics within 48 hours of admission.

For each patient, we extracted age, gender, principal diagnosis, comorbidities, and the specialty of the attending physician. Comorbidities were identified from ICD-9-CM secondary diagnosis codes and Diagnosis Related Groups by using Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project Comorbidity Software, version 3.1, based on the work of Elixhauser (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, Maryland).7 In order to ensure that patients had HCAP, we required the presence of ≥1 HCAP criteria, including hospitalization in the past 90 days, hemodialysis, admission from an SNF, or immune suppression (which was derived from either a secondary diagnosis for neutropenia, hematological malignancy, organ transplant, acquired immunodeficiency virus, or receiving immunosuppressant drugs or corticosteroids [equivalent to ≥20 mg/day of prednisone]).

Definitions of Guideline-Concordant and Discordant Antibiotic Therapy

The ATS and IDSA guidelines recommended the following antibiotic combinations for HCAP: an antipseudomonal cephalosporin or carbapenem or a beta-lactam/lactamase inhibitor, plus an antipseudomonal quinolone or aminoglycoside, plus an antibiotic with activity versus methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), such as vancomycin or linezolid. Based on these guidelines, we defined the receipt of fully guideline-concordant antibiotics as 2 recommended antibiotics for Pseudomonas species plus 1 for MRSA administered by the second day of admission. Partially guideline-concordant antibiotics were defined as 1 recommended antibiotic for Pseudomonas species plus 1 for MRSA by the second day of hospitalization. Guideline-discordant antibiotics were defined as all other combinations.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics on patient characteristics are presented as frequency, proportions for categorical factors, and median with interquartile range (IQR) for continuous variables for the full cohort and by treatment group, defined as fully or partially guideline-concordant antibiotic therapy or discordant therapy. Hospital rates of fully guideline-concordant treatment are presented overall and by hospital characteristics. The association of hospital characteristics with rates of fully guideline-concordant therapy were assessed by using 1-way analysis of variance tests.

To assess trends across hospitals for the association between the use of guideline-concordant therapy and mortality, progression to respiratory failure as measured by the late initiation of invasive mechanical ventilation (day 3 or later), and the length of stay among survivors, we divided the 4.5-year study period into 9 intervals of 6 months each; 292 hospitals that submitted data for all 9 time points were examined in this analysis. Based on the distribution of length of stay in the first time period, we created an indicator variable for extended length of stay with length of stay at or above the 75th percentile, defined as extended. For each hospital at each 6-month interval, we then computed risk-standardized guideline-concordant treatment (RS-treatment) rates and risk-standardized in-hospital outcome rates similar to methods used by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services for public reporting.8 For each hospital at each time interval, we estimated a predicted rate of guideline-concordant treatment as the sum of predicted probabilities of guideline-concordant treatment from patient factors and the random intercept for the hospital in which they were admitted. We then calculated the expected rate of guideline-concordant treatment as the sum of expected probabilities of treatment received from patient factors only. RS-treatment was then calculated as the ratio of predicted to expected rates multiplied by the overall unadjusted mean treatment rate from all patients.9 We repeated the same modeling strategy to calculate risk-standardized outcome (RS-outcome) rates for each hospital across all time points. All models were adjusted for patient demographics and comorbidities. Similar models using administrative data have moderate discrimination for mortality.10

We then fit mixed-effects linear models with random hospital intercept and slope across time for the RS-treatment and outcome rates, respectively. From these models, we estimated the mean slope for RS-treatment and for RS-outcome over time. In addition, we estimated a slope or trend over time for each hospital for treatment and for outcome and evaluated the correlation between the treatment and outcome trends.

All analyses were performed using the Statistical Analysis System version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC) and STATA release 13 (StataCorp, LLC, College Station, Texas).

RESULTS

DISCUSSION

In this large, retrospective cohort study, we found that there was a substantial gap between the empiric antibiotics recommended by the ATS and IDSA guidelines and the empiric antibiotics that patients actually received. Over the study period, we saw an increased adherence to guidelines, in spite of growing evidence that HCAP risk factors do not adequately predict which patients are at risk for infection with an MDRO.11 We used this change in antibiotic prescribing behavior over time to determine if there was a clinical impact on patient outcomes and found that at the hospital level, there were no improvements in mortality, excess length of stay, or progression to respiratory failure despite a doubling in guideline-concordant antibiotic use.

At least 2 other large studies have assessed the association between guideline-concordant therapy and outcomes in HCAP.12,13 Both found that guideline-concordant therapy was associated with increased mortality, despite propensity matching. Both were conducted at the individual patient level by using administrative data, and results were likely affected by unmeasured clinical confounders, with sicker patients being more likely to receive guideline-concordant therapy. Our focus on the outcomes at the hospital level avoids this selection bias because the overall severity of illness of patients at any given hospital would not be expected to change over the study period, while physician uptake of antibiotic prescribing guidelines would be expected to increase over time. Determining the correlation between increases in guideline adherence and changes in patient outcome may offer a better assessment of the impact of guideline adherence. In this regard, our results are similar to those achieved by 1 quality improvement collaborative that was aimed at increasing guideline concordant therapy in ICUs. Despite an increase in guideline concordance from 33% to 47% of patients, they found no change in overall mortality.14

There were several limitations to our study. We did not have access to microbiologic data, so we were unable to determine which patients had MDRO infection or determine antibiotic-pathogen matching. However, the treating physicians in our study population presumably did not have access to this data at the time of treatment either because the time period we examined was within the first 48 hours of hospitalization, the interval during which cultures are incubating and the patients are being treated empirically. In addition, there may have been HCAP patients that we failed to identify, such as patients who were admitted in the past 90 days to a hospital that does not submit data to Premier. However, it is unlikely that prescribing for such patients should differ systematically from what we observed. While the database draws from 488 hospitals nationwide, it is possible that practices may be different at facilities that are not contained within the Premier database, such as Veterans Administration Hospitals. Similarly, we did not have readings for chest x-rays; hence, there could be some patients in the dataset who did not have pneumonia. However, we tried to overcome this by including only those patients with a principal diagnosis of pneumonia or sepsis with a secondary pneumonia diagnosis, a chest x-ray, and antibiotics administered within the first 48 hours of admission.

There are likely several reasons why so few HCAP patients in our study received guideline-concordant antibiotics. A lack of knowledge about the ATS and IDSA guidelines may have impacted the physicians in our study population. El-Solh et al.15 surveyed physicians about the ATS-IDSA guidelines 4 years after publication and found that only 45% were familiar with the document. We found that the rate of prescribing at least partially guideline-concordant antibiotics rose steadily over time, supporting the idea that the newness of the guidelines was 1 barrier. Additionally, prior studies have shown that many physicians may not agree with or choose to follow guidelines, with only 20% of physicians indicating that guidelines have a major impact on their clinical decision making,16 and the majority do not choose HCAP guideline-concordant antibiotics when tested.17 Alternatively, clinicians may not follow the guidelines because of a belief that the HCAP criteria do not adequately indicate patients who are at risk for MDRO. Previous studies have demonstrated the relative inability of HCAP risk factors to predict patients who harbor MDRO18 and suggest that better tools such as clinical scoring systems, which include not only the traditional HCAP risk factors but also prior exposure to antibiotics, prior culture data, and a cumulative assessment of both intrinsic and extrinsic factors, could more accurately predict MDRO and lead to a more judicious use of broad-spectrum antimicrobial agents.19-25 Indeed, these collective findings have led the authors of the recently updated guidelines to remove HCAP as a clinical entity from the hospital-acquired or ventilator-associated pneumonia guidelines and place them instead in the upcoming updated guidelines on the management of CAP.5 Of these 3 explanations, the lack of familiarity fits best with our observation that guideline-concordant therapy increased steadily over time with no evidence of reaching a plateau. Ironically, as consensus was building that HCAP is a poor marker for MDROs, routine empiric treatment with vancomycin and piperacillin-tazobactam (“vanco and zosyn”) have become routine in many hospitals. Additional studies are needed to know if this trend has stabilized or reversed.

CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, clinicians in our large, nationally representative sample treated the majority of HCAP patients as though they had CAP. Although there was an increase in the administration of guideline-concordant therapy over time, this increase was not associated with improved outcomes. This study supports the growing consensus that HCAP criteria do not accurately predict which patients benefit from broad-spectrum antibiotics for pneumonia, and most patients fare well with antibiotics targeting common community-acquired organisms.

Disclosure

This work was supported by grant # R01HS018723 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Dr. Lagu is also supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health under award number K01HL114745. Dr. Lindenauer is supported by grant K24HL132008 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. The funding agency had no role in the data acquisition, analysis, or manuscript preparation for this study. Drs. Haessler and Rothberg had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Drs. Haessler, Lagu, Lindenauer, Skiest, Zilberberg, Higgins, and Rothberg conceived of the study and analyzed and interpreted the data. Dr. Lindenauer acquired the data. Dr. Pekow and Ms. Priya carried out the statistical analyses. Dr. Haessler drafted the manuscript. All authors critically reviewed the manuscript for accuracy and integrity. All authors certify no potential conflicts of interest. Preliminary results from this study were presented in oral and poster format at IDWeek in 2012 and 2013.

1. Kochanek KD, Murphy SL, Xu JQ, Tejada-Vera B. Deaths: Final data for 2014. National vital statistics reports; vol 65 no 4. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. 2016. PubMed

2. American Thoracic Society, Infectious Diseases Society of America. Guidelines for the Management of Adults with Hospital-acquired, Ventilator-associated, and Healthcare-associated Pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171(4):388-416. PubMed

3. Zilberberg MD, Shorr A. Healthcare-associated pneumonia: the state of the evidence to date. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2011;17(3):142-147. PubMed

4. Kollef MK, Shorr A, Tabak YP, Gupta V, Liu LZ, Johannes RS. Epidemiology and Outcomes of Health-care-associated pneumonia. Chest. 2005;128(6):3854-3862. PubMed

5. Kalil AC, Metersky ML, Klompas M, et al. Management of Adults With Hospital-acquired and Ventilator-associated Pneumonia: 2016 Clinical Practice Guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the American Thoracic Society. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63(5):575-582. PubMed

6. Lindenauer PK, Pekow PS, Lahti MC, Lee Y, Benjamin EM, Rothberg MB. Association of corticosteroid dose and route of administration with risk of treatment failure in acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. JAMA. 2010;303(23):2359-2367. PubMed

7. Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Harris DR, Coffey RM. Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Med Care. 1998;36(1):8-27. PubMed

8. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Frequently asked questions (FAQs): Implementation and maintenance of CMS mortality measures for AMI & HF. 2007. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/HospitalQualityInits/downloads/HospitalMortalityAboutAMI_HF.pdf. Accessed November 1, 2016.

9. Normand SL, Shahian DM. Statistical and Clinical Aspects of Hospital Outcomes Profiling. Stat Sci. 2007;22(2):206-226.

10. Rothberg MB, Pekow PS, Priya A, et al. Using highly detailed administrative data to predict pneumonia mortality. PLoS One. 2014;9(1):e87382. PubMed

11. Jones BE, Jones MM, Huttner B, et al. Trends in antibiotic use and nosocomial pathogens in hospitalized veterans with pneumonia at 128 medical centers, 2006-2010. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61(9):1403-1410. PubMed

12. Attridge RT, Frei CR, Restrepo MI, et al. Guideline-concordant therapy and outcomes in healthcare-associated pneumonia. Eur Respir J. 2011;38(4):878-887. PubMed

13. Rothberg MB, Zilberberg MD, Pekow PS, et al. Association of Guideline-based Antimicrobial Therapy and Outcomes in Healthcare-Associated Pneumonia. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2015;70(5):1573-1579. PubMed

14. Kett DH, Cano E, Quartin AA, et al. Improving Medicine through Pathway Assessment of Critical Therapy of Hospital-Acquired Pneumonia (IMPACT-HAP) Investigators. Implementation of guidelines for management of possible multidrug-resistant pneumonia in intensive care: an observational, multicentre cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2011;11(3):181-189. PubMed

15. El-Solh AA, Alhajhusain A, Saliba RG, Drinka P. Physicians’ Attitudes Toward Guidelines for the Treatment of Hospitalized Nursing-Home -Acquired Pneumonia. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2011;12(4):270-276. PubMed

16. Tunis S, Hayward R, Wilson M, et al. Internists’ Attitudes about Clinical Practice Guidelines. Ann Intern Med. 1994;120(11):956-963. PubMed

17. Seymann GB, Di Francesco L, Sharpe B, et al. The HCAP Gap: Differences between Self-Reported Practice Patterns and Published Guidelines for Health Care-Associated Pneumonia. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49(12):1868-1874. PubMed

18. Chalmers JD, Rother C, Salih W, Ewig S. Healthcare associated pneumonia does not accurately identify potentially resistant pathogens: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;58(3):330-339. PubMed

19. Shorr A, Zilberberg MD, Reichley R, et al. Validation of a Clinical Score for Assessing the Risk of Resistant Pathogens in Patients with Pneumonia Presenting to the Emergency Department. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54(2):193-198. PubMed

20. Aliberti S, Pasquale MD, Zanaboni AM, et al. Stratifying Risk Factors for Multidrug-Resistant Pathogens in Hospitalized Patients Coming from the Community with Pneumonia. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54(4):470-478. PubMed

21. Schreiber MP, Chan CM, Shorr AF. Resistant Pathogens in Nonnosocomial Pneumonia and Respiratory Failure: Is it Time to Refine the Definition of Health-care-Associated Pneumonia? Chest. 2010;137(6):1283-1288. PubMed

22. Madaras-Kelly KJ, Remington RE, Fan VS, Sloan KL. Predicting antibiotic resistance to community-acquired pneumonia antibiotics in culture-positive patients with healthcare-associated pneumonia. J Hosp Med. 2012;7(3):195-202. PubMed

23. Shindo Y, Ito R, Kobayashi D, et al. Risk factors for drug-resistant pathogens in community-acquired and healthcare-associated pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;188(8):985-995. PubMed

24. Metersky ML, Frei CR, Mortensen EM. Predictors of Pseudomonas and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in hospitalized patients with healthcare-associated pneumonia. Respirology. 2016;21(1):157-163. PubMed

25. Webb BJ, Dascomb K, Stenehjem E, Dean N. Predicting risk of drug-resistant organisms in pneumonia: moving beyond the HCAP model. Respir Med. 2015;109(1):1-10. PubMed

1. Kochanek KD, Murphy SL, Xu JQ, Tejada-Vera B. Deaths: Final data for 2014. National vital statistics reports; vol 65 no 4. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. 2016. PubMed

2. American Thoracic Society, Infectious Diseases Society of America. Guidelines for the Management of Adults with Hospital-acquired, Ventilator-associated, and Healthcare-associated Pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171(4):388-416. PubMed

3. Zilberberg MD, Shorr A. Healthcare-associated pneumonia: the state of the evidence to date. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2011;17(3):142-147. PubMed

4. Kollef MK, Shorr A, Tabak YP, Gupta V, Liu LZ, Johannes RS. Epidemiology and Outcomes of Health-care-associated pneumonia. Chest. 2005;128(6):3854-3862. PubMed

5. Kalil AC, Metersky ML, Klompas M, et al. Management of Adults With Hospital-acquired and Ventilator-associated Pneumonia: 2016 Clinical Practice Guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the American Thoracic Society. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63(5):575-582. PubMed

6. Lindenauer PK, Pekow PS, Lahti MC, Lee Y, Benjamin EM, Rothberg MB. Association of corticosteroid dose and route of administration with risk of treatment failure in acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. JAMA. 2010;303(23):2359-2367. PubMed

7. Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Harris DR, Coffey RM. Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Med Care. 1998;36(1):8-27. PubMed

8. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Frequently asked questions (FAQs): Implementation and maintenance of CMS mortality measures for AMI & HF. 2007. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/HospitalQualityInits/downloads/HospitalMortalityAboutAMI_HF.pdf. Accessed November 1, 2016.

9. Normand SL, Shahian DM. Statistical and Clinical Aspects of Hospital Outcomes Profiling. Stat Sci. 2007;22(2):206-226.

10. Rothberg MB, Pekow PS, Priya A, et al. Using highly detailed administrative data to predict pneumonia mortality. PLoS One. 2014;9(1):e87382. PubMed

11. Jones BE, Jones MM, Huttner B, et al. Trends in antibiotic use and nosocomial pathogens in hospitalized veterans with pneumonia at 128 medical centers, 2006-2010. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61(9):1403-1410. PubMed

12. Attridge RT, Frei CR, Restrepo MI, et al. Guideline-concordant therapy and outcomes in healthcare-associated pneumonia. Eur Respir J. 2011;38(4):878-887. PubMed

13. Rothberg MB, Zilberberg MD, Pekow PS, et al. Association of Guideline-based Antimicrobial Therapy and Outcomes in Healthcare-Associated Pneumonia. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2015;70(5):1573-1579. PubMed

14. Kett DH, Cano E, Quartin AA, et al. Improving Medicine through Pathway Assessment of Critical Therapy of Hospital-Acquired Pneumonia (IMPACT-HAP) Investigators. Implementation of guidelines for management of possible multidrug-resistant pneumonia in intensive care: an observational, multicentre cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2011;11(3):181-189. PubMed

15. El-Solh AA, Alhajhusain A, Saliba RG, Drinka P. Physicians’ Attitudes Toward Guidelines for the Treatment of Hospitalized Nursing-Home -Acquired Pneumonia. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2011;12(4):270-276. PubMed

16. Tunis S, Hayward R, Wilson M, et al. Internists’ Attitudes about Clinical Practice Guidelines. Ann Intern Med. 1994;120(11):956-963. PubMed

17. Seymann GB, Di Francesco L, Sharpe B, et al. The HCAP Gap: Differences between Self-Reported Practice Patterns and Published Guidelines for Health Care-Associated Pneumonia. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49(12):1868-1874. PubMed

18. Chalmers JD, Rother C, Salih W, Ewig S. Healthcare associated pneumonia does not accurately identify potentially resistant pathogens: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;58(3):330-339. PubMed

19. Shorr A, Zilberberg MD, Reichley R, et al. Validation of a Clinical Score for Assessing the Risk of Resistant Pathogens in Patients with Pneumonia Presenting to the Emergency Department. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54(2):193-198. PubMed

20. Aliberti S, Pasquale MD, Zanaboni AM, et al. Stratifying Risk Factors for Multidrug-Resistant Pathogens in Hospitalized Patients Coming from the Community with Pneumonia. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54(4):470-478. PubMed

21. Schreiber MP, Chan CM, Shorr AF. Resistant Pathogens in Nonnosocomial Pneumonia and Respiratory Failure: Is it Time to Refine the Definition of Health-care-Associated Pneumonia? Chest. 2010;137(6):1283-1288. PubMed

22. Madaras-Kelly KJ, Remington RE, Fan VS, Sloan KL. Predicting antibiotic resistance to community-acquired pneumonia antibiotics in culture-positive patients with healthcare-associated pneumonia. J Hosp Med. 2012;7(3):195-202. PubMed

23. Shindo Y, Ito R, Kobayashi D, et al. Risk factors for drug-resistant pathogens in community-acquired and healthcare-associated pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;188(8):985-995. PubMed

24. Metersky ML, Frei CR, Mortensen EM. Predictors of Pseudomonas and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in hospitalized patients with healthcare-associated pneumonia. Respirology. 2016;21(1):157-163. PubMed

25. Webb BJ, Dascomb K, Stenehjem E, Dean N. Predicting risk of drug-resistant organisms in pneumonia: moving beyond the HCAP model. Respir Med. 2015;109(1):1-10. PubMed

© 2017 Society of Hospital Medicine

Observational Study of Peripheral Intravenous Catheter Outcomes in Adult Hospitalized Patients: A Multivariable Analysis of Peripheral Intravenous Catheter Failure

INTRODUCTION

Peripheral intravenous catheter (PIV) insertion is the fastest, simplest, and most cost-effective method to gain vascular access, and it is used for short-term intravenous (IV) fluids, medications, blood products, and contrast media.1 It is the most common invasive device in hospitalized patients,2 with up to 70% of hospital patients receiving a PIV.3 Unacceptable PIV failure rates have been reported as high as 69%.4-7 Failure is most frequently due to phlebitis (vein wall irritation/inflammation), occlusion (blockage), infiltration or extravasation (IV fluids/vesicant therapy entering surrounding tissue), partial dislodgement or accidental removal, leakage, and infection.4,6,8 These failures have important implications for patients, who endure the discomfort of PIV complications and catheter replacements, and healthcare staff and budgets.

To reduce the incidence of catheter failure and avoid preventable PIV replacements, a clear understanding of why catheters fail is required. Previous research has identified that catheter gauge,9-11 insertion site,12-14 and inserter skill10,15 have an impact on PIV failure. Limitations of existing research are small study sizes,16-18 retrospective design,19 or secondary analysis of an existing data set; all potentially introduce sampling bias.10,20

To overcome these potential biases, we developed a data collection instrument based on the catheter-associated risk factors described in the literature,9-11,13 and other potential insertion and maintenance risks for PIV failure (eg, multiple insertion attempts, medications administered), with data collected prospectively. The study aim was to improve patient outcomes by identifying PIV insertion and maintenance risk factors amenable to modification through education or alternative clinical interventions, such as catheter gauge selection or insertion site.

METHODS

Study Design and Participants

We conducted this prospective cohort study in a large tertiary hospital in Queensland, Australia. Ethics committee approval was obtained from the hospital (HREC/14/QRBW/76) and Griffith University (NRS/26/14/HREC). The study was registered with the Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry (ACTRN12615000738527). Patients in medical and surgical wards were screened Monday, Wednesday, and Friday between October 2014 and December 2015. Patients over 18 years with a PIV (BD InsyteTM AutoguardTM BC; Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ) inserted within 24 hours, and who were able to provide written informed consent, were eligible and recruited sequentially. Patients classified as palliative by the treating clinical team were excluded.

Sample Size Calculation

The “10 events per variable” rule was used to determine the sample size required to study 50 potential risk factors.21,22 This determined that 1000 patients, with an average of 1.5 PIVs each and an expected PIV failure of 30% (500 events), were required.

Data Collection

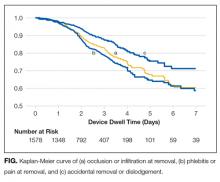

At recruitment, baseline patient information was collected by a research nurse (ReNs) (demographics, admitting diagnosis, comorbidities, skin type,23 and vein condition) and entered into an electronic data platform supported by Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap).24 Baseline data also included catheter variables (eg, gauge, insertion site, catheterized vein) and insertion details (eg, department of insertion, inserting clinician, number of insertion attempts). We included every PIV the participant had during their admission until hospital discharge or insertion of a central venous access device. PIV sites were reviewed Monday, Wednesday, and Friday by ReNs for site complications (eg, redness, pain, swelling, palpable cord). Potential risk factors for failure were also recorded (eg, infusates and additives, antibiotic type and dosage, flushing regimen, number of times the PIV was accessed each day for administration of IV medications or fluids, dressing type and condition, securement method for the catheter and tubing, presence of extension tubing or 3-way taps, patient mobility status, and delirium). A project manager trained and supervised ReNs for protocol compliance and audited study data quality. We considered PIV failure to have occurred if the catheter had complications at removal identified by the ReNs assessment, from medical charts, or by speaking to the patient and beside nurse. We grouped the failures in 1 of 3 types: (1) occlusion or infiltration, defined as blockage, IV fluids moving into surrounding tissue, induration, or swelling greater than 1 cm from the insertion site at or within 24 hours of removal; (2) phlebitis, defined as per clinicians’ definitions or one or more of the following signs and symptoms: pain or tenderness scored at 2 or more on a 1 to 10 increasing severity pain scale, or redness or a palpable cord (either extending greater than 1 cm from the insertion site) at or within 24 hours of PIV removal; and (3) dislodgement (partial or complete). If multiple complications were present, all were recorded.

Statistical Analysis

Data were downloaded from REDcap to Stata 14.2 (StataCorp., College Station, TX) for data management and analysis. Missing data were not imputed. Nominal data observations were collapsed into a single observation per device. Patient and device variables were described as frequencies and proportions, means and standard deviations, or medians and interquartile ranges. Failure incidence rates were calculated, and a Kaplan-Meier survival curve was plotted. In general, Cox proportional hazards models were fitted (Efron method) to handle tied failures (clustering by patient). Variables significant at P < 0.20 on univariable analyses were subjected to multivariable regression. Generally, the largest category was set as referent. Correlations between variables were checked (Spearman’s rank for binary variables, R-squared value of linear regressions for continuous/categorical or continuous/continuous variables). Correlations were considered significant if r > 0.5 and the lower bound of the 95% confidence interval (CI) was >0.5 (where calculated). Covariate interactions were explored, and effects at P < 0.05 noted. The 4 steps of multivariable model building were (1) baseline covariates only with manual stepwise removal of covariates at P ≥ 0.05, (2) treatment covariates only with manual stepwise removal of covariates at P ≥ 0.05, (3) a combination of the derived models from (1) and (2) and manual stepwise removal of covariates at P ≥ 0.05, and (4) manual stepwise addition and removal (at P ≥ 0.05) of variables dropped during the previous steps and interaction testing. Final models were checked as follows: global proportional-hazards assumption test, concordance probability (that predictions and outcomes were in agreement), and Nelson-Aalen cumulative hazard function plotted against the Cox-Snell residuals.

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

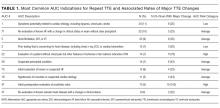

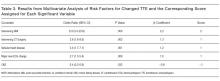

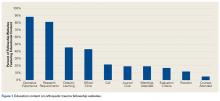

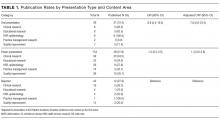

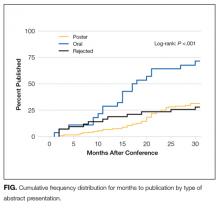

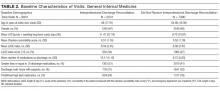

In total, 1000 patients with 1578 PIVs were recruited. The average age was 54 years and the majority were surgical patients (673; 67%). Almost half of patients (455; 46%) had 2 or more comorbidities, and 334 (33%) were obese (body mass index greater than 30). Sample characteristics are shown by the type of catheter failure in Table 1.

PIV Characteristics

All 1578 PIVs were followed until removal, with only 7 PIVs (0.44%) having missing data for the 3 outcomes of interest (these were coded as nonfailures for analysis). Sixty percent of participants had more than 1 PIV followed in the study. Doctors and physicians inserted 1278 (83%) catheters. A total of 550 (35%) were placed in the ward, with 428 (28%) inserted in the emergency department or ambulance. A third of the catheters (540; 34%) were 18-gauge or larger in diameter, and 1000 (64%) were located in the cubital fossa or hand. Multiple insertion attempts were required to place 315 (23%) PIVs. No PIVs were inserted with ultrasound, as this is rarely used in this hospital. The flushing policy was for the administration of 9% sodium chloride every 8 hours if no IV medications or fluids were ordered. Table 2 contains further details of device-related characteristics. Although the hospital policy was for catheter removal by 72 hours, dwell time ranged from <1 to 14 days, with an average of 2.4 days.

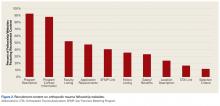

PIV Complications

Catheter failure (any cause) occurred in 512 (32%) catheters, which is a failure rate of 136 per 1000 catheter days (95% CI, 125-148). A total of 346 patients out of 1000 (35%) had at least 1 failed PIV during the study. Failures were 267 phlebitis (17%), 228 occlusion/infiltration (14%), and/or 154 dislodgement (10%; Figure), with some PIVs exhibiting multiple concurrent complications (Table 2).

Multivariable AnalysisOcclusion/Infiltration

The multivariable analysis (Table 3) showed occlusion or infiltration was statistically significantly associated with female patients (hazard ratio [HR], 1.48; 95% CI, 1.10-2.00), with a 22-gauge catheter (HR, 1.43; 95% CI, 1.02-2.00), IV flucloxacillin (HR, 1.98; 95% CI, 1.19-3.31), and with frequent PIV access (HR, 1.12; 95% CI, 1.04-1.21; ie, with each increase of 1 in the mean medications/fluids administrations per day, relative PIV failure increased 112%). Less occlusion and infiltration were statistically significantly associated with securement by using additional nonsterile tape (HR, 0.46; 95% CI, 0.33-0.63), elasticized tubular bandages (HR, 0.49; 95% CI, 0.35-0.70 ), or other types of additional securement for the PIV (HR, 0.35; 95% CI, 0.26-0.47).

Phlebitis

Phlebitis was statistically significantly associated with female patients (HR, 1.81; 95% CI, 1.40-2.35), bruising at the insertion site (HR, 2.16; 95% CI, 1.26-3.71), insertion in patients’ dominant side (HR, 1.39; 95% CI, 1.09-1.77), IV flucloxicillin (HR, 2.01; 95% CI, 1.26-3.21), or with frequent PIV access (HR, 1.14; 95% CI, 1.08-1.21). Older age, (HR, 0.99; 95% CI, 0.98-0.99; ie, each year older was associated with 1% less phlebitis), securement with additional nonsterile tape (HR, 0.63; 95% CI, 0.48-0.82) or with any other additional securement (HR, 0.53; 95% CI, 0.39-0.70), or the administration of IV cephazolin (HR, 0.63; 95% CI, 0.44-0.89) were associated with lower phlebitis risk.

Dislodgement

Statistically significant predictors associated with an increased risk of PIV dislodgement included paramedic insertion (HR, 1.78; 95% CI, 1.03-3.06) and frequent PIV access (HR, 1.11; 95% CI, 1.03-1.20). A decreased risk was associated with the additional securement of the PIV, including nonsterile tape (HR, 0.44; 95% CI, 0.31-0.63) or other forms of additional securement (HR, 0.32; 95% CI, 0.22-0.46).

DISCUSSION

One in 3 PIVs failed in this study, with phlebitis as the most common cause of PIV failure. The 17% phlebitis rate reflected clinician-reported phlebitis or phlebitis observed by research staff using a 1-criteria definition because any sign or symptom can trigger PIV removal (eg, pain), even if other signs or symptoms are not present. Reported phlebitis rates are lower if definitions require 2 signs or symptoms.4,6 With over 71 different phlebitis assessment scales in use, and none well validated, the best method for diagnosing phlebitis remains unclear and explains the variation in reported rates.25 Occlusion/infiltration and dislodgement were also highly prevalent forms of PIV failure at 14% and 10%, respectively. Occlusion and infiltration were combined because clinical staff use these terms interchangeably, and differential diagnostic tools are not used in practice. Both result in the same outcome (therapy interruption and PIV removal), and this combination of outcomes has been used previously.23 No PIV-associated bloodstream infections occurred, despite the heightened awareness of these infections in the literature.3

Females had significantly more occlusion/infiltration and phlebitis than males, in keeping with previous studies.7,9,10 This could be because of females’ smaller vein caliber, although the effect remained after adjustment for PIV gauge.7,26 The effect of aging on vascular endothelium and structural integrity may explain the observed decrease in phlebitis of 1% with each older year of age.27 However, gender and age effects could be explained by psychosocial factors (eg, older people may be less likely to admit pain, or we may question them less sympathetically), but, regardless, women and younger patients should be monitored more closely.

We found 22-gauge catheters were more likely to fail from occlusion/infiltration than other sizes. This confirms similar findings from Abolfotouh et al.9 PIV gauge selection for this study was made at the inserter’s discretion and may be confounded by smaller vein size, which was not measured. In addition, risk may be because of smaller gauge alone or also more influenced by the shorter length of the studied 22-gauge (25 mm) than the <20-gauge catheters (30 mm). These results question international guidelines, which currently recommend the smallest gauge peripheral catheter possible,28,29 and randomized trials are needed. Although practice varies between inserters, some preferentially cannulate the nondominant limb. We are not aware of previous studies on this practice; however, our results support this approach.

Flucloxacillin was associated with a 2-fold increase in occlusion/infiltration and phlebitis. Although multiple studies have reported IV medications9,11 and IV antibiotics10,30,31 as risk factors for PIV failure, none have identified flucloxacillin as an independent risk factor. IV flucloxacillin is recommended for reconstitution as 1 g in 15 mL to 20 mL of sterile water, and injection over 3 to 4 minutes, although this may not be adhered to in practice. Alternative administration regimes or improved adherence to current policy may be needed. An exception to the relationship between IV antibiotics and catheter failure was IV cephazolin, associated with 40% relatively less phlebitis. This may be a spurious finding because the administration, pH, and osmolality of cephazolin are similar to other IV antibiotics.

The more PIVs that were accessed per day, whether for infusions or medications, the more failure occurred from occlusion/infiltration, phlebitis, and dislodgement. This suggests that peripheral veins are easily damaged and/or inflamed by the influx of fluids or medications. Lower injection pressures or the timely transfer to oral medications may limit this problem. Flushing regimens may also assist because practice varies greatly, and questions on whether slow continuous flush infusion or intermittent manual flushing are more vein-protective, and the optimal flush volume, frequency, and technique (eg, pulsatile) remain.32,33 Manual handling for frequent access may loosen dressings and securement, thus explaining the observed association between frequent access and catheter dislodgement. Finally, the association between use and failure may indicate that many of these patients were not suitable for a PIV, and different approaches (eg, ultrasound-guided insertion) or a midline may have been a superior option. There is growing emphasis on the need for better preinsertion assessment and selection of the most appropriate device for the patient and the IV treatment required.34