User login

The Hospitalist only

Geographic Rounding of Hospital Nurses Challenges Unit-Based Theory

Nurses, of course, have always been assigned by unit—that is, geographically. So it should come as no surprise that searching “unit-based” at the-hospitalist.org returns many articles about assigning hospitalists geographically, but not nurses, partly because few would consider it a new idea. But this article is about a new wrinkle in assigning nurses.

Although there likely are a number of hospitals doing something similar, I’ll describe a place I was lucky enough to see up close.

Bassett Medical Center

On a cold day last December, I was part of a team that spent a few days in Cooperstown, N.Y. This is a place that is so pretty that I didn’t immediately recognize we had arrived at the Bassett Medical Center Campus, since the entrance we used looked more like a library topped by a pretty cupola and warmly decorated for the holidays. We met so many nice people, including Kai Mebust, MD, FHM, who I’m convinced works full-time for the local Chamber of Commerce and tourism industry. If he doesn’t, then they should put him on their payroll.

Not long after our arrival, Dr. Mebust led us outside in the winter air without our coats to see the very beautiful view from the patio adjacent to the hospital cafeteria. And before we left for home he climbed in our car to direct us on a tour of the town. I’m sold. What a beautiful place. So much more than the Baseball Hall of Fame for which Cooperstown is known.

When not promoting his town’s tourism or enthusiastically describing his eighth-grade son playing with the Preservation Hall Jazz Band in New Orleans, he seems to find time to serve as the chief of this academic hospital’s hospital medicine practice. He was the principal engineer of the geographic assignment of nurses and describes it with an enthusiasm that matches his service as tour guide.

Geographic Care: Single RN Caring for Five Adjacent Patients

The idea is simple and best described using an illustration. A single nurse cares for five patients in adjacent rooms referred to as a “pod.” A second nurse is responsible for the next pod of five consecutive patients, and a single hospitalist cares for all 10 in both pods. There are currently four pods on a single floor of 36 beds; however, they hope to expand this system to most of the medical-surgical beds in the hospital.

The nurses eligible to care for patients in these pods are all trained to be able to provide “step down” level of care, meaning patients don’t need to transfer to a different location for more frequent monitoring and such therapies as vasopressors, mask ventilation, and the like.

Each hospitalist caring for two pods of 10 adjacent patients will typically have additional patients in other locations. This is the hospital’s way of finding the sweet spot between the competing interests of “load leveling” patient volume across hospitalists and rigidly assigning each doctor to a single location, though if they succeed in expanding the model through most of the hospital, the hospitalists will likely need to figure out how to assign themselves more rigidly to three or four pods.

Additional Components

Each morning, the hospitalist meets with the two pod nurses. They briefly discuss overnight events and plans for the day.

Much later in the morning, they also conduct daily multidisciplinary rounds involving nurse, case manager, pharmacist, dietician, social worker, respiratory therapist, and hospitalist. These follow a standard format, which is posted on the wall, and are done in a workroom that allows most participants to be in front of a computer, so they can enter notes and orders into the electronic health record (EHR) as they discuss patients.

What Is the Big Deal Here?

A lot of smart people have developed and written about systems that assign hospitalists geographically, but in most cases this has not been accompanied by adjustments in the way nurses are assigned. On nursing units at most hospitals, this means that even if a hospitalist has all of her patients on the same floor, she is still interacting with five to seven nurses caring for her patients. That usually means the hospitalist and nurse have less awareness of each other’s thinking and doing than if the ratio is reduced to no more than three or four nurses for a single hospitalist.

Dr. Mebust provided a document enumerating the goals for the program:

- Improve communication;

- Reduce patient bed moves;

- Improve patient and staff satisfaction; and

- Provide more efficient care as measured in time-of-discharge, decreased physician time-per-patient, and possibly length of stay.

Because of a number of problems teasing out the effects of this program and its limited duration to this point, Dr. Mebust and staff can’t provide robust statistics to document success in these goals. But anecdotal information is very encouraging, and clearly the nurses love it.

A major barrier to assigning nurses based rigidly on patients in adjacent rooms is the inability to ensure that each nurse has a workload of roughly equivalent complexity, but they’ve found this is a much less significant problem than feared. The nurse I spoke with said any risk of ending up with unusually complex and time-consuming patients is essentially offset by the efficiency gained by having the same attending hospitalist for all of her patients.

In fact, the nurses love it so much that they much prefer being assigned to a pod rather than a traditional assortment of patients with different attending physicians, even if the latter offers a chance to address uneven acuity.

The Big Picture

I’ve often wished that I could incorporate into hospitalist work some of the efficient ways a doctor and nurse can work together seeing scheduled patients in an outpatient setting. Surely assigning hospitalists geographically does this to some degree and has a number of advantages that others have written about. But it comes at the cost of difficult tradeoffs for hospitalists, and I know of many groups that have abandoned it after concluding that the challenges of the system exceeded its benefits.

But when it is coupled with assigning nurses geographically, I think the benefits are even greater, not only for the hospitalists, but also for patients, nurses, and other hospital staff.

Next time you’re in Cooperstown, be sure you don’t just visit the Baseball Hall of Fame. Look up Dr. Mebust, Komron Ostovar, MD, and their colleagues at Bassett Medical Center. I betcha you’ll be persuaded to see the value of their geographic model.

And maybe you’ll even fall so far under the spell of how they all talk about where they work and live that you’ll be ready to move there and join them.

Nurses, of course, have always been assigned by unit—that is, geographically. So it should come as no surprise that searching “unit-based” at the-hospitalist.org returns many articles about assigning hospitalists geographically, but not nurses, partly because few would consider it a new idea. But this article is about a new wrinkle in assigning nurses.

Although there likely are a number of hospitals doing something similar, I’ll describe a place I was lucky enough to see up close.

Bassett Medical Center

On a cold day last December, I was part of a team that spent a few days in Cooperstown, N.Y. This is a place that is so pretty that I didn’t immediately recognize we had arrived at the Bassett Medical Center Campus, since the entrance we used looked more like a library topped by a pretty cupola and warmly decorated for the holidays. We met so many nice people, including Kai Mebust, MD, FHM, who I’m convinced works full-time for the local Chamber of Commerce and tourism industry. If he doesn’t, then they should put him on their payroll.

Not long after our arrival, Dr. Mebust led us outside in the winter air without our coats to see the very beautiful view from the patio adjacent to the hospital cafeteria. And before we left for home he climbed in our car to direct us on a tour of the town. I’m sold. What a beautiful place. So much more than the Baseball Hall of Fame for which Cooperstown is known.

When not promoting his town’s tourism or enthusiastically describing his eighth-grade son playing with the Preservation Hall Jazz Band in New Orleans, he seems to find time to serve as the chief of this academic hospital’s hospital medicine practice. He was the principal engineer of the geographic assignment of nurses and describes it with an enthusiasm that matches his service as tour guide.

Geographic Care: Single RN Caring for Five Adjacent Patients

The idea is simple and best described using an illustration. A single nurse cares for five patients in adjacent rooms referred to as a “pod.” A second nurse is responsible for the next pod of five consecutive patients, and a single hospitalist cares for all 10 in both pods. There are currently four pods on a single floor of 36 beds; however, they hope to expand this system to most of the medical-surgical beds in the hospital.

The nurses eligible to care for patients in these pods are all trained to be able to provide “step down” level of care, meaning patients don’t need to transfer to a different location for more frequent monitoring and such therapies as vasopressors, mask ventilation, and the like.

Each hospitalist caring for two pods of 10 adjacent patients will typically have additional patients in other locations. This is the hospital’s way of finding the sweet spot between the competing interests of “load leveling” patient volume across hospitalists and rigidly assigning each doctor to a single location, though if they succeed in expanding the model through most of the hospital, the hospitalists will likely need to figure out how to assign themselves more rigidly to three or four pods.

Additional Components

Each morning, the hospitalist meets with the two pod nurses. They briefly discuss overnight events and plans for the day.

Much later in the morning, they also conduct daily multidisciplinary rounds involving nurse, case manager, pharmacist, dietician, social worker, respiratory therapist, and hospitalist. These follow a standard format, which is posted on the wall, and are done in a workroom that allows most participants to be in front of a computer, so they can enter notes and orders into the electronic health record (EHR) as they discuss patients.

What Is the Big Deal Here?

A lot of smart people have developed and written about systems that assign hospitalists geographically, but in most cases this has not been accompanied by adjustments in the way nurses are assigned. On nursing units at most hospitals, this means that even if a hospitalist has all of her patients on the same floor, she is still interacting with five to seven nurses caring for her patients. That usually means the hospitalist and nurse have less awareness of each other’s thinking and doing than if the ratio is reduced to no more than three or four nurses for a single hospitalist.

Dr. Mebust provided a document enumerating the goals for the program:

- Improve communication;

- Reduce patient bed moves;

- Improve patient and staff satisfaction; and

- Provide more efficient care as measured in time-of-discharge, decreased physician time-per-patient, and possibly length of stay.

Because of a number of problems teasing out the effects of this program and its limited duration to this point, Dr. Mebust and staff can’t provide robust statistics to document success in these goals. But anecdotal information is very encouraging, and clearly the nurses love it.

A major barrier to assigning nurses based rigidly on patients in adjacent rooms is the inability to ensure that each nurse has a workload of roughly equivalent complexity, but they’ve found this is a much less significant problem than feared. The nurse I spoke with said any risk of ending up with unusually complex and time-consuming patients is essentially offset by the efficiency gained by having the same attending hospitalist for all of her patients.

In fact, the nurses love it so much that they much prefer being assigned to a pod rather than a traditional assortment of patients with different attending physicians, even if the latter offers a chance to address uneven acuity.

The Big Picture

I’ve often wished that I could incorporate into hospitalist work some of the efficient ways a doctor and nurse can work together seeing scheduled patients in an outpatient setting. Surely assigning hospitalists geographically does this to some degree and has a number of advantages that others have written about. But it comes at the cost of difficult tradeoffs for hospitalists, and I know of many groups that have abandoned it after concluding that the challenges of the system exceeded its benefits.

But when it is coupled with assigning nurses geographically, I think the benefits are even greater, not only for the hospitalists, but also for patients, nurses, and other hospital staff.

Next time you’re in Cooperstown, be sure you don’t just visit the Baseball Hall of Fame. Look up Dr. Mebust, Komron Ostovar, MD, and their colleagues at Bassett Medical Center. I betcha you’ll be persuaded to see the value of their geographic model.

And maybe you’ll even fall so far under the spell of how they all talk about where they work and live that you’ll be ready to move there and join them.

Nurses, of course, have always been assigned by unit—that is, geographically. So it should come as no surprise that searching “unit-based” at the-hospitalist.org returns many articles about assigning hospitalists geographically, but not nurses, partly because few would consider it a new idea. But this article is about a new wrinkle in assigning nurses.

Although there likely are a number of hospitals doing something similar, I’ll describe a place I was lucky enough to see up close.

Bassett Medical Center

On a cold day last December, I was part of a team that spent a few days in Cooperstown, N.Y. This is a place that is so pretty that I didn’t immediately recognize we had arrived at the Bassett Medical Center Campus, since the entrance we used looked more like a library topped by a pretty cupola and warmly decorated for the holidays. We met so many nice people, including Kai Mebust, MD, FHM, who I’m convinced works full-time for the local Chamber of Commerce and tourism industry. If he doesn’t, then they should put him on their payroll.

Not long after our arrival, Dr. Mebust led us outside in the winter air without our coats to see the very beautiful view from the patio adjacent to the hospital cafeteria. And before we left for home he climbed in our car to direct us on a tour of the town. I’m sold. What a beautiful place. So much more than the Baseball Hall of Fame for which Cooperstown is known.

When not promoting his town’s tourism or enthusiastically describing his eighth-grade son playing with the Preservation Hall Jazz Band in New Orleans, he seems to find time to serve as the chief of this academic hospital’s hospital medicine practice. He was the principal engineer of the geographic assignment of nurses and describes it with an enthusiasm that matches his service as tour guide.

Geographic Care: Single RN Caring for Five Adjacent Patients

The idea is simple and best described using an illustration. A single nurse cares for five patients in adjacent rooms referred to as a “pod.” A second nurse is responsible for the next pod of five consecutive patients, and a single hospitalist cares for all 10 in both pods. There are currently four pods on a single floor of 36 beds; however, they hope to expand this system to most of the medical-surgical beds in the hospital.

The nurses eligible to care for patients in these pods are all trained to be able to provide “step down” level of care, meaning patients don’t need to transfer to a different location for more frequent monitoring and such therapies as vasopressors, mask ventilation, and the like.

Each hospitalist caring for two pods of 10 adjacent patients will typically have additional patients in other locations. This is the hospital’s way of finding the sweet spot between the competing interests of “load leveling” patient volume across hospitalists and rigidly assigning each doctor to a single location, though if they succeed in expanding the model through most of the hospital, the hospitalists will likely need to figure out how to assign themselves more rigidly to three or four pods.

Additional Components

Each morning, the hospitalist meets with the two pod nurses. They briefly discuss overnight events and plans for the day.

Much later in the morning, they also conduct daily multidisciplinary rounds involving nurse, case manager, pharmacist, dietician, social worker, respiratory therapist, and hospitalist. These follow a standard format, which is posted on the wall, and are done in a workroom that allows most participants to be in front of a computer, so they can enter notes and orders into the electronic health record (EHR) as they discuss patients.

What Is the Big Deal Here?

A lot of smart people have developed and written about systems that assign hospitalists geographically, but in most cases this has not been accompanied by adjustments in the way nurses are assigned. On nursing units at most hospitals, this means that even if a hospitalist has all of her patients on the same floor, she is still interacting with five to seven nurses caring for her patients. That usually means the hospitalist and nurse have less awareness of each other’s thinking and doing than if the ratio is reduced to no more than three or four nurses for a single hospitalist.

Dr. Mebust provided a document enumerating the goals for the program:

- Improve communication;

- Reduce patient bed moves;

- Improve patient and staff satisfaction; and

- Provide more efficient care as measured in time-of-discharge, decreased physician time-per-patient, and possibly length of stay.

Because of a number of problems teasing out the effects of this program and its limited duration to this point, Dr. Mebust and staff can’t provide robust statistics to document success in these goals. But anecdotal information is very encouraging, and clearly the nurses love it.

A major barrier to assigning nurses based rigidly on patients in adjacent rooms is the inability to ensure that each nurse has a workload of roughly equivalent complexity, but they’ve found this is a much less significant problem than feared. The nurse I spoke with said any risk of ending up with unusually complex and time-consuming patients is essentially offset by the efficiency gained by having the same attending hospitalist for all of her patients.

In fact, the nurses love it so much that they much prefer being assigned to a pod rather than a traditional assortment of patients with different attending physicians, even if the latter offers a chance to address uneven acuity.

The Big Picture

I’ve often wished that I could incorporate into hospitalist work some of the efficient ways a doctor and nurse can work together seeing scheduled patients in an outpatient setting. Surely assigning hospitalists geographically does this to some degree and has a number of advantages that others have written about. But it comes at the cost of difficult tradeoffs for hospitalists, and I know of many groups that have abandoned it after concluding that the challenges of the system exceeded its benefits.

But when it is coupled with assigning nurses geographically, I think the benefits are even greater, not only for the hospitalists, but also for patients, nurses, and other hospital staff.

Next time you’re in Cooperstown, be sure you don’t just visit the Baseball Hall of Fame. Look up Dr. Mebust, Komron Ostovar, MD, and their colleagues at Bassett Medical Center. I betcha you’ll be persuaded to see the value of their geographic model.

And maybe you’ll even fall so far under the spell of how they all talk about where they work and live that you’ll be ready to move there and join them.

Little Progress Made Training Hospitalists to Stem Shortage of Intensivists

What would the status be for a hospitalist who could train for one year to become a critical care intensivist to address the shortage of intensivists? I’m one of the hospitalists who love critical care but cannot do two more years out for critical care training.

—Amadeo Rivera, MD

Has there been any progress in the 2012 SCCM/SHM proposal to train hospitalists as intensivists?

—Stephen M. Pastores, MD, Memorial

Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, New York, N.Y.

Dr. Hospitalist responds:

As you may recall, SHM and the Society of Critical Care Medicine (SCCM) published a joint position paper in the Journal of Hospital Medicine in June 2012 in which they proposed a one-year critical care fellowship for hospitalists with at least three years of experience.

Since only one year of clinical rotations is required for critical care board eligibility, and there already exists a one-year track for other medical subspecialists (e.g. nephrology, infectious disease), most of us in hospital medicine thought the recommendation would have been much better received. Well, you guessed it. The following month, the leadership of the American College of Chest Physicians and the American Association of Critical-Care Nurses wrote in an editorial that a one-year fellowship was inadequate for hospitalists to gain competence in critical care medicine. Since then, there has not been much progress, at least not publicly, toward a standardized, streamlined, and accredited process for hospitalists to achieve critical care certification in one year.

Nevertheless, employing a standard search engine (Google) and terminology, I was able to locate one U.S.-based training program offering a one-year critical care medicine fellowship program recognized by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education for candidates with a background in anesthesiology, surgery, or internal medicine.

What would the status be for a hospitalist who could train for one year to become a critical care intensivist to address the shortage of intensivists? I’m one of the hospitalists who love critical care but cannot do two more years out for critical care training.

—Amadeo Rivera, MD

Has there been any progress in the 2012 SCCM/SHM proposal to train hospitalists as intensivists?

—Stephen M. Pastores, MD, Memorial

Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, New York, N.Y.

Dr. Hospitalist responds:

As you may recall, SHM and the Society of Critical Care Medicine (SCCM) published a joint position paper in the Journal of Hospital Medicine in June 2012 in which they proposed a one-year critical care fellowship for hospitalists with at least three years of experience.

Since only one year of clinical rotations is required for critical care board eligibility, and there already exists a one-year track for other medical subspecialists (e.g. nephrology, infectious disease), most of us in hospital medicine thought the recommendation would have been much better received. Well, you guessed it. The following month, the leadership of the American College of Chest Physicians and the American Association of Critical-Care Nurses wrote in an editorial that a one-year fellowship was inadequate for hospitalists to gain competence in critical care medicine. Since then, there has not been much progress, at least not publicly, toward a standardized, streamlined, and accredited process for hospitalists to achieve critical care certification in one year.

Nevertheless, employing a standard search engine (Google) and terminology, I was able to locate one U.S.-based training program offering a one-year critical care medicine fellowship program recognized by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education for candidates with a background in anesthesiology, surgery, or internal medicine.

What would the status be for a hospitalist who could train for one year to become a critical care intensivist to address the shortage of intensivists? I’m one of the hospitalists who love critical care but cannot do two more years out for critical care training.

—Amadeo Rivera, MD

Has there been any progress in the 2012 SCCM/SHM proposal to train hospitalists as intensivists?

—Stephen M. Pastores, MD, Memorial

Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, New York, N.Y.

Dr. Hospitalist responds:

As you may recall, SHM and the Society of Critical Care Medicine (SCCM) published a joint position paper in the Journal of Hospital Medicine in June 2012 in which they proposed a one-year critical care fellowship for hospitalists with at least three years of experience.

Since only one year of clinical rotations is required for critical care board eligibility, and there already exists a one-year track for other medical subspecialists (e.g. nephrology, infectious disease), most of us in hospital medicine thought the recommendation would have been much better received. Well, you guessed it. The following month, the leadership of the American College of Chest Physicians and the American Association of Critical-Care Nurses wrote in an editorial that a one-year fellowship was inadequate for hospitalists to gain competence in critical care medicine. Since then, there has not been much progress, at least not publicly, toward a standardized, streamlined, and accredited process for hospitalists to achieve critical care certification in one year.

Nevertheless, employing a standard search engine (Google) and terminology, I was able to locate one U.S.-based training program offering a one-year critical care medicine fellowship program recognized by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education for candidates with a background in anesthesiology, surgery, or internal medicine.

Billing for Hospital Admission, Discharge in Same 24-Hour Period

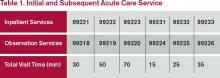

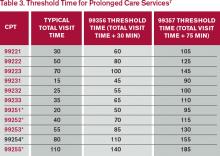

Should the admitting physician or the discharge physician bill the CPT code (99234-99236) for a patient who is admitted and discharged in the same 24-hour period?

—Charlette

Dr. Hospitalist responds:

Assuming both physicians are part of the same group and specialty, they are considered one physician. Since it appears that both face-to-face encounters are separated by eight hours, you’re correct, only one physician can bill the bundled care code 99234-99236. The group must decide which physician gets the RVU credit for the bundled code. Our group gives the credit to the admitting physician.

Should the admitting physician or the discharge physician bill the CPT code (99234-99236) for a patient who is admitted and discharged in the same 24-hour period?

—Charlette

Dr. Hospitalist responds:

Assuming both physicians are part of the same group and specialty, they are considered one physician. Since it appears that both face-to-face encounters are separated by eight hours, you’re correct, only one physician can bill the bundled care code 99234-99236. The group must decide which physician gets the RVU credit for the bundled code. Our group gives the credit to the admitting physician.

Should the admitting physician or the discharge physician bill the CPT code (99234-99236) for a patient who is admitted and discharged in the same 24-hour period?

—Charlette

Dr. Hospitalist responds:

Assuming both physicians are part of the same group and specialty, they are considered one physician. Since it appears that both face-to-face encounters are separated by eight hours, you’re correct, only one physician can bill the bundled care code 99234-99236. The group must decide which physician gets the RVU credit for the bundled code. Our group gives the credit to the admitting physician.

Hospital Violence Hits Home

Hospitalists could hardly be faulted for wondering: Am I safe? After all, the inpatient setting can be a tense place, and it’s where hospitalists work day in and day out.

David Pressel, MD, PhD, FHM, a pediatric hospitalist and medical director of inpatient services at Nemours Children’s Health System, which has locations in Delaware, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Florida, says it’s no wonder violence can erupt in the hospital setting.

“Violence is an issue in hospitals that is a reflection of our society, unfortunately,” says Dr. Pressel, a member of Team Hospitalist. “And it happens because these are very stressful places where people’s behavior can get outside the norm given the stress of the problems.”

Dr. Pressel, in collaboration with many others, has developed a workplace violence prevention program at Nemours aimed at de-escalating situations to avoid physical violence. The program teaches providers how to respond when something violent does happen. It’s a tiered training regimen that involves more training for those most involved in handling violent situations.

Dr. Pressel is no stranger to violence himself. Although he is a pediatric hospitalist and his patients are younger, some adolescent patients can have the physical presence of adults and pose just as serious a threat. He said that before the training program was put into place about a year ago, an episode of violence every month or two would require a patient to be placed in restraints.

“Staff has been hurt,” he explains. “I’ve been bitten twice by a patient. I have a scar on my arm that will be with me for life from one episode.”

A Slow, Disheartening, Upward Trend

Whether violence in hospitals and medical facilities is really a growing problem—or whether awareness of the issue is simply greater given these recent, high profile incidents—is not entirely known.

But according to the latest figures available from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), provided by the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), violent incidents in hospitals did appear to be on the rise through 2013. The number of hospital assaults rose from 5,030 in 2011 to 5,500 in 2012 to 5,660 in 2013.

The number of assaults rose across all private sector industries over that span, but the percentage of those assaults that occurred in hospitals grew greater during that time—an indication that hospitals might be getting more violent at a faster pace than other workplaces. In 2011, according to BLS data, 21.4% of all assaults in private sector industries occurred in hospitals. That number rose to 21.8% in 2012 and to 22.1% in 2013.

According to the 2014 Healthcare Crime Survey, published by the International Association for Healthcare Security and Safety (IAHSS)—an organization of hospital security officials and administrators—violent crime at U.S. facilities rose from two incidents per 100 beds in 2012 to 2.5 incidents per 100 beds in 2013. That category includes murder, rape, aggravated assault, and robbery.

Assaults rose from 10.7 incidents per 100 beds in 2012 to 11.1 incidents per 100 beds in 2013.

BLS data also show that more injuries in hospitals are due to assaults compared with the private sector overall. In 2011, 2.6% of all private sector injuries were due to assault; in 2012, the number rose to 2.8%; and, in 2013, it was 2.8%. In hospitals in 2011, 8.6% of all injuries resulted from assaults. That percentage rose to 9.5% in 2012 and to 9.8% in 2013.

“BLS data show that nonfatal injuries due to violence are greater in the healthcare/social assistance setting than in other workplaces,” an OSHA spokesperson says. “Assaults represent a serious safety and health hazard within healthcare, and data indicate that hospitals comprise a large percentage of workplace assaults.”

Incident Prevention

Programs aimed at preventing violence can reduce these incidents.

“How well prepared hospital workers are in dealing with violent situations depends on the workplace violence prevention program implemented at a facility,” the OSHA spokesperson says. “Some states have passed legislation that specifically requires workplace violence prevention programs in the healthcare setting.”

These programs should address management commitment and employee participation, worksite analysis, hazard prevention and control, safety and health training, and recordkeeping and program evaluation. These elements should be assessed regularly, with changes made to respond to changing conditions, OSHA says.

A large number of OSHA inspections in the healthcare setting occur because of complaints regarding lack of protections against workplace violence. In 2014, the agency did 35 inspections in response to such complaints; 25 of those were in a healthcare setting, with 12 specifically at hospitals. As a result, five citations were issued, all of which were in healthcare, including two at hospitals.

Last year, Brookdale University Hospital and Medical Center in Brooklyn, N.Y., was fined $78,000 after an OSHA inspection found 40 incidents of workplace violence between Feb. 7 and April 12. They included employees who were threatened or verbally or physically assaulted by patients and visitors or while breaking up fights between patients. In the worst attack, a nurse sustained severe brain injuries.

The bulk of the hospital’s fines came as a result of a willful violation—an intentional or voluntary disregard for laws meant to protect workers against hospital violence.

While data from IAHSS and the BLS show an increase in hospital violence, those national figures aren’t as important as what is happening at your own facility, says David LaRose, MS, CHPA, CPP, the president of IAHSS and director of safety, security, and emergency management at Lakeland Regional Medical Center in Florida.

“You have to do a vulnerability assessment, and you specifically have to look at your demographic,” he says. “You specifically have to look at what is the history and the culture of the facility” to determine a hospital’s specific risk factors.

Although it’s crucial that a hospital track its own statistics on violence, that’s not to say that incidents elsewhere are irrelevant.

“You also want to look at what’s happening in the real world,” he says. “Somebody else’s unfortunate (occurrence) is a learning experience for my system, so we can try to be proactively preventing that.”

Educate, Recognize, React

At Nemours, Dr. Pressel didn’t develop the training in response to a perceived rise in incidents there. It was apparent, he says, that deficiencies in readiness needed to be addressed.

In the Nemours program, every staff member with some level of patient care responsibility gets basic training in aggressive child emergencies: identifying these situations, responding appropriately, and keeping safe. This group includes doctors, nurses, and nurse’s aids. The training involves actually playing out scenarios of violence, with staff members attempting to subdue a would-be attacker.

Depending on the job, each worker receives extra training that is specific to the role he or she would play in handling violent scenarios.

The training is designed to help individuals respond to such situations with “the same alacrity and acuity as they would respond to a Code Blue,” Dr. Pressel says. “Drop what you’re doing and run. These events are dangerous. That’s what they teach people. They’re dangerous and they’re scary and they’re chaotic, just like a Code Blue. That’s how people need to treat it.”

The goal is to de-escalate a situation, verbally or physically, without more aggressive means. But if that doesn’t work, physical restraints, medication, or both are used.

Throughout the medical field, training in this area is scarce, Dr. Pressel says. In nursing school and medical school, “for the most part, it’s zero,” he says.

“If you’re in a psychiatric facility, these events happen,” he adds. “And then you get a lot of enhanced training.” But, he notes, “I had no formal training until I became tasked with dealing with this.”

Since the program was implemented at Nemours, it seems to have worked.

“We have had many of these episodes that have been resolved by verbal de-escalation, as opposed to physical restraints or medication,” he says.

His hospital has also made other changes. The facility used to have multiple entrances and exits that were unsecured, and anybody could walk into any unit “with no challenge whatsoever.” Now, everyone entering has to pass hospital personnel. And, to get into a patient unit, visitors have to check in and be issued a photo ID. Also, in response to an incident in 2013, the hospital now has “constables” who are trained and licensed to carry firearms, Dr. Pressel says.

Above all, he notes, is personal safety. If you yourself are hurt, you won’t be able to help anyone else.

“That’s absolutely the first thing that people hear, the last thing that people hear, and it’s repeated over and over again,” he says.

Both Dr. Pressel and LaRose say that even with the drumbeat of high profile incidents, they haven’t heard from colleagues that health professionals are concerned about people losing interest in entering the field or are feeling burned out because of safety concerns. Being prepared is the key, and the level of preparedness varies by facility, LaRose says. The IAHSS provides security and healthcare safety guidelines at iahss.org.

“We recognize that we are in an occupation that tends to be on the receiving end of more aggression and more violence than the average worker,” LaRose says. “Therefore, how proactively does the organization or the institution take that knowledge and provide the tools and the training to the staff?

“What can we do as a team to increase our sense of security and safety and make this a great place to continue your career?”

Tom Collins is a freelance writer in South Florida.

Hospitalists could hardly be faulted for wondering: Am I safe? After all, the inpatient setting can be a tense place, and it’s where hospitalists work day in and day out.

David Pressel, MD, PhD, FHM, a pediatric hospitalist and medical director of inpatient services at Nemours Children’s Health System, which has locations in Delaware, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Florida, says it’s no wonder violence can erupt in the hospital setting.

“Violence is an issue in hospitals that is a reflection of our society, unfortunately,” says Dr. Pressel, a member of Team Hospitalist. “And it happens because these are very stressful places where people’s behavior can get outside the norm given the stress of the problems.”

Dr. Pressel, in collaboration with many others, has developed a workplace violence prevention program at Nemours aimed at de-escalating situations to avoid physical violence. The program teaches providers how to respond when something violent does happen. It’s a tiered training regimen that involves more training for those most involved in handling violent situations.

Dr. Pressel is no stranger to violence himself. Although he is a pediatric hospitalist and his patients are younger, some adolescent patients can have the physical presence of adults and pose just as serious a threat. He said that before the training program was put into place about a year ago, an episode of violence every month or two would require a patient to be placed in restraints.

“Staff has been hurt,” he explains. “I’ve been bitten twice by a patient. I have a scar on my arm that will be with me for life from one episode.”

A Slow, Disheartening, Upward Trend

Whether violence in hospitals and medical facilities is really a growing problem—or whether awareness of the issue is simply greater given these recent, high profile incidents—is not entirely known.

But according to the latest figures available from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), provided by the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), violent incidents in hospitals did appear to be on the rise through 2013. The number of hospital assaults rose from 5,030 in 2011 to 5,500 in 2012 to 5,660 in 2013.

The number of assaults rose across all private sector industries over that span, but the percentage of those assaults that occurred in hospitals grew greater during that time—an indication that hospitals might be getting more violent at a faster pace than other workplaces. In 2011, according to BLS data, 21.4% of all assaults in private sector industries occurred in hospitals. That number rose to 21.8% in 2012 and to 22.1% in 2013.

According to the 2014 Healthcare Crime Survey, published by the International Association for Healthcare Security and Safety (IAHSS)—an organization of hospital security officials and administrators—violent crime at U.S. facilities rose from two incidents per 100 beds in 2012 to 2.5 incidents per 100 beds in 2013. That category includes murder, rape, aggravated assault, and robbery.

Assaults rose from 10.7 incidents per 100 beds in 2012 to 11.1 incidents per 100 beds in 2013.

BLS data also show that more injuries in hospitals are due to assaults compared with the private sector overall. In 2011, 2.6% of all private sector injuries were due to assault; in 2012, the number rose to 2.8%; and, in 2013, it was 2.8%. In hospitals in 2011, 8.6% of all injuries resulted from assaults. That percentage rose to 9.5% in 2012 and to 9.8% in 2013.

“BLS data show that nonfatal injuries due to violence are greater in the healthcare/social assistance setting than in other workplaces,” an OSHA spokesperson says. “Assaults represent a serious safety and health hazard within healthcare, and data indicate that hospitals comprise a large percentage of workplace assaults.”

Incident Prevention

Programs aimed at preventing violence can reduce these incidents.

“How well prepared hospital workers are in dealing with violent situations depends on the workplace violence prevention program implemented at a facility,” the OSHA spokesperson says. “Some states have passed legislation that specifically requires workplace violence prevention programs in the healthcare setting.”

These programs should address management commitment and employee participation, worksite analysis, hazard prevention and control, safety and health training, and recordkeeping and program evaluation. These elements should be assessed regularly, with changes made to respond to changing conditions, OSHA says.

A large number of OSHA inspections in the healthcare setting occur because of complaints regarding lack of protections against workplace violence. In 2014, the agency did 35 inspections in response to such complaints; 25 of those were in a healthcare setting, with 12 specifically at hospitals. As a result, five citations were issued, all of which were in healthcare, including two at hospitals.

Last year, Brookdale University Hospital and Medical Center in Brooklyn, N.Y., was fined $78,000 after an OSHA inspection found 40 incidents of workplace violence between Feb. 7 and April 12. They included employees who were threatened or verbally or physically assaulted by patients and visitors or while breaking up fights between patients. In the worst attack, a nurse sustained severe brain injuries.

The bulk of the hospital’s fines came as a result of a willful violation—an intentional or voluntary disregard for laws meant to protect workers against hospital violence.

While data from IAHSS and the BLS show an increase in hospital violence, those national figures aren’t as important as what is happening at your own facility, says David LaRose, MS, CHPA, CPP, the president of IAHSS and director of safety, security, and emergency management at Lakeland Regional Medical Center in Florida.

“You have to do a vulnerability assessment, and you specifically have to look at your demographic,” he says. “You specifically have to look at what is the history and the culture of the facility” to determine a hospital’s specific risk factors.

Although it’s crucial that a hospital track its own statistics on violence, that’s not to say that incidents elsewhere are irrelevant.

“You also want to look at what’s happening in the real world,” he says. “Somebody else’s unfortunate (occurrence) is a learning experience for my system, so we can try to be proactively preventing that.”

Educate, Recognize, React

At Nemours, Dr. Pressel didn’t develop the training in response to a perceived rise in incidents there. It was apparent, he says, that deficiencies in readiness needed to be addressed.

In the Nemours program, every staff member with some level of patient care responsibility gets basic training in aggressive child emergencies: identifying these situations, responding appropriately, and keeping safe. This group includes doctors, nurses, and nurse’s aids. The training involves actually playing out scenarios of violence, with staff members attempting to subdue a would-be attacker.

Depending on the job, each worker receives extra training that is specific to the role he or she would play in handling violent scenarios.

The training is designed to help individuals respond to such situations with “the same alacrity and acuity as they would respond to a Code Blue,” Dr. Pressel says. “Drop what you’re doing and run. These events are dangerous. That’s what they teach people. They’re dangerous and they’re scary and they’re chaotic, just like a Code Blue. That’s how people need to treat it.”

The goal is to de-escalate a situation, verbally or physically, without more aggressive means. But if that doesn’t work, physical restraints, medication, or both are used.

Throughout the medical field, training in this area is scarce, Dr. Pressel says. In nursing school and medical school, “for the most part, it’s zero,” he says.

“If you’re in a psychiatric facility, these events happen,” he adds. “And then you get a lot of enhanced training.” But, he notes, “I had no formal training until I became tasked with dealing with this.”

Since the program was implemented at Nemours, it seems to have worked.

“We have had many of these episodes that have been resolved by verbal de-escalation, as opposed to physical restraints or medication,” he says.

His hospital has also made other changes. The facility used to have multiple entrances and exits that were unsecured, and anybody could walk into any unit “with no challenge whatsoever.” Now, everyone entering has to pass hospital personnel. And, to get into a patient unit, visitors have to check in and be issued a photo ID. Also, in response to an incident in 2013, the hospital now has “constables” who are trained and licensed to carry firearms, Dr. Pressel says.

Above all, he notes, is personal safety. If you yourself are hurt, you won’t be able to help anyone else.

“That’s absolutely the first thing that people hear, the last thing that people hear, and it’s repeated over and over again,” he says.

Both Dr. Pressel and LaRose say that even with the drumbeat of high profile incidents, they haven’t heard from colleagues that health professionals are concerned about people losing interest in entering the field or are feeling burned out because of safety concerns. Being prepared is the key, and the level of preparedness varies by facility, LaRose says. The IAHSS provides security and healthcare safety guidelines at iahss.org.

“We recognize that we are in an occupation that tends to be on the receiving end of more aggression and more violence than the average worker,” LaRose says. “Therefore, how proactively does the organization or the institution take that knowledge and provide the tools and the training to the staff?

“What can we do as a team to increase our sense of security and safety and make this a great place to continue your career?”

Tom Collins is a freelance writer in South Florida.

Hospitalists could hardly be faulted for wondering: Am I safe? After all, the inpatient setting can be a tense place, and it’s where hospitalists work day in and day out.

David Pressel, MD, PhD, FHM, a pediatric hospitalist and medical director of inpatient services at Nemours Children’s Health System, which has locations in Delaware, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Florida, says it’s no wonder violence can erupt in the hospital setting.

“Violence is an issue in hospitals that is a reflection of our society, unfortunately,” says Dr. Pressel, a member of Team Hospitalist. “And it happens because these are very stressful places where people’s behavior can get outside the norm given the stress of the problems.”

Dr. Pressel, in collaboration with many others, has developed a workplace violence prevention program at Nemours aimed at de-escalating situations to avoid physical violence. The program teaches providers how to respond when something violent does happen. It’s a tiered training regimen that involves more training for those most involved in handling violent situations.

Dr. Pressel is no stranger to violence himself. Although he is a pediatric hospitalist and his patients are younger, some adolescent patients can have the physical presence of adults and pose just as serious a threat. He said that before the training program was put into place about a year ago, an episode of violence every month or two would require a patient to be placed in restraints.

“Staff has been hurt,” he explains. “I’ve been bitten twice by a patient. I have a scar on my arm that will be with me for life from one episode.”

A Slow, Disheartening, Upward Trend

Whether violence in hospitals and medical facilities is really a growing problem—or whether awareness of the issue is simply greater given these recent, high profile incidents—is not entirely known.

But according to the latest figures available from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), provided by the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), violent incidents in hospitals did appear to be on the rise through 2013. The number of hospital assaults rose from 5,030 in 2011 to 5,500 in 2012 to 5,660 in 2013.

The number of assaults rose across all private sector industries over that span, but the percentage of those assaults that occurred in hospitals grew greater during that time—an indication that hospitals might be getting more violent at a faster pace than other workplaces. In 2011, according to BLS data, 21.4% of all assaults in private sector industries occurred in hospitals. That number rose to 21.8% in 2012 and to 22.1% in 2013.

According to the 2014 Healthcare Crime Survey, published by the International Association for Healthcare Security and Safety (IAHSS)—an organization of hospital security officials and administrators—violent crime at U.S. facilities rose from two incidents per 100 beds in 2012 to 2.5 incidents per 100 beds in 2013. That category includes murder, rape, aggravated assault, and robbery.

Assaults rose from 10.7 incidents per 100 beds in 2012 to 11.1 incidents per 100 beds in 2013.

BLS data also show that more injuries in hospitals are due to assaults compared with the private sector overall. In 2011, 2.6% of all private sector injuries were due to assault; in 2012, the number rose to 2.8%; and, in 2013, it was 2.8%. In hospitals in 2011, 8.6% of all injuries resulted from assaults. That percentage rose to 9.5% in 2012 and to 9.8% in 2013.

“BLS data show that nonfatal injuries due to violence are greater in the healthcare/social assistance setting than in other workplaces,” an OSHA spokesperson says. “Assaults represent a serious safety and health hazard within healthcare, and data indicate that hospitals comprise a large percentage of workplace assaults.”

Incident Prevention

Programs aimed at preventing violence can reduce these incidents.

“How well prepared hospital workers are in dealing with violent situations depends on the workplace violence prevention program implemented at a facility,” the OSHA spokesperson says. “Some states have passed legislation that specifically requires workplace violence prevention programs in the healthcare setting.”

These programs should address management commitment and employee participation, worksite analysis, hazard prevention and control, safety and health training, and recordkeeping and program evaluation. These elements should be assessed regularly, with changes made to respond to changing conditions, OSHA says.

A large number of OSHA inspections in the healthcare setting occur because of complaints regarding lack of protections against workplace violence. In 2014, the agency did 35 inspections in response to such complaints; 25 of those were in a healthcare setting, with 12 specifically at hospitals. As a result, five citations were issued, all of which were in healthcare, including two at hospitals.

Last year, Brookdale University Hospital and Medical Center in Brooklyn, N.Y., was fined $78,000 after an OSHA inspection found 40 incidents of workplace violence between Feb. 7 and April 12. They included employees who were threatened or verbally or physically assaulted by patients and visitors or while breaking up fights between patients. In the worst attack, a nurse sustained severe brain injuries.

The bulk of the hospital’s fines came as a result of a willful violation—an intentional or voluntary disregard for laws meant to protect workers against hospital violence.

While data from IAHSS and the BLS show an increase in hospital violence, those national figures aren’t as important as what is happening at your own facility, says David LaRose, MS, CHPA, CPP, the president of IAHSS and director of safety, security, and emergency management at Lakeland Regional Medical Center in Florida.

“You have to do a vulnerability assessment, and you specifically have to look at your demographic,” he says. “You specifically have to look at what is the history and the culture of the facility” to determine a hospital’s specific risk factors.

Although it’s crucial that a hospital track its own statistics on violence, that’s not to say that incidents elsewhere are irrelevant.

“You also want to look at what’s happening in the real world,” he says. “Somebody else’s unfortunate (occurrence) is a learning experience for my system, so we can try to be proactively preventing that.”

Educate, Recognize, React

At Nemours, Dr. Pressel didn’t develop the training in response to a perceived rise in incidents there. It was apparent, he says, that deficiencies in readiness needed to be addressed.

In the Nemours program, every staff member with some level of patient care responsibility gets basic training in aggressive child emergencies: identifying these situations, responding appropriately, and keeping safe. This group includes doctors, nurses, and nurse’s aids. The training involves actually playing out scenarios of violence, with staff members attempting to subdue a would-be attacker.

Depending on the job, each worker receives extra training that is specific to the role he or she would play in handling violent scenarios.

The training is designed to help individuals respond to such situations with “the same alacrity and acuity as they would respond to a Code Blue,” Dr. Pressel says. “Drop what you’re doing and run. These events are dangerous. That’s what they teach people. They’re dangerous and they’re scary and they’re chaotic, just like a Code Blue. That’s how people need to treat it.”

The goal is to de-escalate a situation, verbally or physically, without more aggressive means. But if that doesn’t work, physical restraints, medication, or both are used.

Throughout the medical field, training in this area is scarce, Dr. Pressel says. In nursing school and medical school, “for the most part, it’s zero,” he says.

“If you’re in a psychiatric facility, these events happen,” he adds. “And then you get a lot of enhanced training.” But, he notes, “I had no formal training until I became tasked with dealing with this.”

Since the program was implemented at Nemours, it seems to have worked.

“We have had many of these episodes that have been resolved by verbal de-escalation, as opposed to physical restraints or medication,” he says.

His hospital has also made other changes. The facility used to have multiple entrances and exits that were unsecured, and anybody could walk into any unit “with no challenge whatsoever.” Now, everyone entering has to pass hospital personnel. And, to get into a patient unit, visitors have to check in and be issued a photo ID. Also, in response to an incident in 2013, the hospital now has “constables” who are trained and licensed to carry firearms, Dr. Pressel says.

Above all, he notes, is personal safety. If you yourself are hurt, you won’t be able to help anyone else.

“That’s absolutely the first thing that people hear, the last thing that people hear, and it’s repeated over and over again,” he says.

Both Dr. Pressel and LaRose say that even with the drumbeat of high profile incidents, they haven’t heard from colleagues that health professionals are concerned about people losing interest in entering the field or are feeling burned out because of safety concerns. Being prepared is the key, and the level of preparedness varies by facility, LaRose says. The IAHSS provides security and healthcare safety guidelines at iahss.org.

“We recognize that we are in an occupation that tends to be on the receiving end of more aggression and more violence than the average worker,” LaRose says. “Therefore, how proactively does the organization or the institution take that knowledge and provide the tools and the training to the staff?

“What can we do as a team to increase our sense of security and safety and make this a great place to continue your career?”

Tom Collins is a freelance writer in South Florida.

Hospitalists Try To Reclaim Lead Role in Bedside Procedures

On his way to a recent conference, David Lichtman, PA, stopped to talk with medical residents at a nearby medical center about their experiences performing bedside procedures. “How many times have you guys done something that you knew you weren’t fully trained for but you didn’t want to say anything?” asked Lichtman, a hospitalist and director of the Johns Hopkins Central Procedure Service in Baltimore, Md. “At least once?”

Everyone raised a hand.

When Lichtman asked how many of the residents had ever spoken up and admitted being uncomfortable about doing a procedure, however, only about 20% raised their hands.

It’s one thing to struggle with a procedure like drawing blood. But a less-than-confident or unskilled provider who attempts more invasive procedures, such as a central line insertion or thoracentesis, can do major harm. And observers say confidence and competence levels, particularly among internal medicine residents, are heading in the wrong direction.

Two years ago, in fact, three hospitalists penned an article in The Hospitalist lamenting the “sharp decline” of HM proficiency in bedside procedures.1 Co-author Joshua Lenchus, DO, RPh, FACP, SFHM, associate director of the University of Miami-Jackson Memorial Hospital Center for Patient Safety and medical director of the hospital’s Procedure Service, says the trend is continuing for several reasons.

“One is internal medicine’s willingness to surrender these bedside procedures to others,” Dr. Lenchus says, perhaps due to time constraints, a lack of confidence, or a perception that it’s not cost effective for HM providers to take on the role. Several medical organizations have loosened their competency standards, and the default in many cases has been for interventional radiologists to perform the procedures instead.

Another reason may be more practical: Perhaps there just isn’t a need for all hospitalists to perform them. Many new hospitalist positions advertised through employment agencies, Dr. Lenchus says, do not require competency in bedside procedures.

“The question is, did that happen first and then we reacted to it as hospitalists, or did we stop doing them and employment agencies then modified their process to reflect that?” he says.

For hospitalists, perhaps the bigger question is this: Is there a need to address the decline?

For Lichtman, Dr. Lenchus, and many other leaders, the answer is an emphatic yes—an opportunity to carve out a niche of skilled and patient-focused bedside care and to demonstrate real value to hospitals.

“I think it makes perfect sense from a financial and throughput and healthcare system perspective,” he says. The talent, knowledge, and experience of interventional radiologists, Dr. Lenchus says, is far better spent on procedures that cannot be conducted at a patient’s bedside.

It’s also a matter of professional pride for hospitalists like Michelle Mourad, MD, associate professor of clinical medicine and director of quality improvement and patient safety for the division of hospital medicine at the University of California San Francisco.

“I derive a tremendous amount of enjoyment from working with my hands, from being able to provide my patients this service, from often giving them relief from excessive fluid buildup, and from being able to do these procedures at the bedside,” she says.

Reversing the recent slide of hospitalist involvement in procedures, however, may require more cohesive expectations, an emphasis on minimizing complications, identification of willing and able procedure champions, and comprehensive technology-aided training.

Confounding Expectations

Paracentesis, thoracentesis, arthrocentesis, lumbar puncture, and central line placement generally are considered “core” bedside procedures. Experts like Lichtman, however, say little agreement exists on the main procedures for which hospitalists should demonstrate competency.

“We don’t have any semblance of that,” he says. “The reality is that different groups have different beliefs, and different hospitals have different protocols that they follow.”

Pinning down a consistent list can be difficult, because HM providers can play different roles depending on the setting, says hospitalist Sally Wang, MD, FHM, director of procedure education at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and a clinical instructor at Harvard Medical School in Boston.

“You could be in an academic center. You could be in a community hospital. You could be in a rural setting where there’s no other access to anyone else doing these procedures, or you can have a robust interventional radiology service that will do all the procedures for you,” she says.

In 2007, the American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM) revised its procedure-related requirements for board certification. Physicians still had to understand indications and contraindications, recognize the risks and benefits and manage complications, and interpret procedure results. But they no longer had to perform a minimum number to demonstrate competency. To assure “adequate knowledge and understanding” of each procedure, however, ABIM recommended that residents be active participants five or more times. The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) followed suit in its program requirements for internal medicine.

Furman McDonald, MD, ABIM’s vice president of graduate medical education, says the board isn’t suggesting that procedure training should be limited to “book learning.” Rather, he says, the revision reflects the broad range of practice among internists and the recognition that not all of them will be conducting bedside procedures as part of their daily responsibilities. In that context, then, perhaps more rigorous training should be linked to the honing of a subspecialty practice that demands competency in specific procedures.

“It really is one of those areas where I don’t think one size fits all when it comes to training needs,” Dr. McDonald says, “and it’s also an area where practices vary so much depending on the size of the institution and availability of the people who can do the procedures.”

Nevertheless, observers say the retreat from an absolute numerical threshold—itself a debatable standard—set the tone for many hospitalist groups and has contributed to a lack of consistency in expectations.

“If someone is never going to be doing these procedures in their career, we can argue whether they should be trained,” says Jeffrey Barsuk, MD, MS, associate professor of medicine at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine in Chicago. But evidence suggests that internal medicine residents are still performing many bedside procedures in academic hospitals, he says. A recent study of his, in fact, found that internal medicine and family medicine-trained clinicians frequently perform paracentesis procedures on complex inpatients.2 If they’re expected to be able to do these procedures safely on the first day of residency, he says, the lack of a requirement for hands-on competency is “ridiculous.”

Whatever the reasons, observers say, fewer well-trained hospitalists are performing bedside procedures on a routine basis.

“I think we’re seeing a trend away from an expectation that all residents are going to be comfortable and qualified to perform these procedures,” says Melissa Tukey, MD, MSc, a pulmonology critical care physician at Lahey Clinic in Burlington, Mass., who has studied procedural training and outcomes. “That is reflected in the literature showing that a lot of graduating residents, even before these changes were made, felt uncomfortable performing these procedures unsupervised, even later into their residency.”

By changing their requirements, however, she says the ABIM and ACGME have effectively accelerated the de-emphasis on procedures among internal medicine generalists and put the onus on individual hospitals to ensure that they have qualified and capable staff to perform them. As a result, some medical institutions are opting to train a smaller subset of internal medicine physicians, while others are shifting the workload to other subspecialists.

Lichtman says he’s frustrated that many medical boards and programs continue to link competency in bedside procedures to arbitrary numbers that seem to come out of “thin air.” While studies suggest that practitioners aren’t experienced until they’ve performed 50 central line insertions, for example, many guidelines suggest that they can perform the procedure on their own after only five supervised insertions. “My thought is, you need as many as it takes for you, as an individual, to become good,” Lichtman says. “That may be five. It may be 10. It may be 100.”

Virtually all of us started doing this because we were asked to do cases that couldn’t be done by others because we had imaging—usually ultrasound guidance—and that yielded superior results. —Robert L. Vogelzang, MD, FSIR, professor of radiology, Northwestern University Medical School, Chicago, and past president, Society for Interventional Radiology

Complicating Factors

Central venous line placement has been a lightning rod in the debate over training, standardization, and staffing roles for bedside procedures, Lichtman says, due in large part to the seriousness of a central line-associated bloodstream infection, or CLABSI. In 2008, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services deemed the preventable and life-threatening infection a “never” event and stopped reimbursing hospitals for any CLABSI-related treatment costs.

“If I’m trying to stick a needle in your knee to drain fluid out, there’s a really low risk of something catastrophically bad happening,” he says. But patients can die from faulty central line insertion and management. Stick the needle in the wrong place, and you could cause unnecessary bleeding, a stroke, or complications ranging from a fistula to a hemopneumothorax.

If discomfort and concern over potential complications are contributing to a decline in hospitalist-led bedside procedures, many experts agree that the role may not always make economic or practical sense either. “It doesn’t make sense to train all hospitalists to do all of these procedures,” Dr. Lenchus says. “If you’re at a small community hospital where the procedures are done in the ICU and you have no ICU coverage, then, frankly, that skill’s going to be lost on you, because you’re never going to do it in the real world in the course of your normal, everyday activities.”

Even at bigger institutions, he says, it makes sense to identify and train a core group of providers who have both the skill and the desire to perform procedures on a consistent basis. “It’s a technical skill. Not all of us could be concert pianists, even if we were trained,” Dr. Lenchus says.

Dr. Wang says it will be particularly important for hospitalist groups to identify a subset of “procedure champions” who enjoy doing the procedures, are good at it, have been properly trained, and can maintain their competency with regular practice.

Familiar Territory

At first glance, the significant time commitment and lackluster reimbursement of many bedside procedures would seem to do little to up the incentive for busy hospitalists. “If they have to stop and take two hours to do a procedure that 1) they don’t feel comfortable with and 2) they get very little reimbursement for, why not just put an order in and have interventional radiologists whisk them off and do these procedures?” Dr. Wang says.

Robert L. Vogelzang, MD, FSIR, professor of radiology at Northwestern University Medical School in Chicago and a past president of the Society of Interventional Radiology, says radiologists are regularly called upon to perform bedside procedures because of their imaging expertise.

“Virtually all of us started doing this because we were asked to do cases that couldn’t be done by others because we had imaging—usually ultrasound guidance—and that yielded superior results,” he says.

Dr. Vogelzang says he’s “specialty-agnostic” about who should perform the procedures, as long as they’re done by well-trained providers who use imaging guidance and do them on a regular basis. Hospitalists could defer to radiologists if they’re uncomfortable with any procedure, he says, while teams of physician assistants and nurse practitioners might offer another cost-effective solution. Ultimately, the question over who performs minor bedside procedures “is going to reach a solution that involves dedicated teams in some fashion, because as a patient, you don’t want someone who does five a year,” he says. “Patient care is improved by trained people who do enough of them to do it consistently.”

So why not train designated hospitalists as proceduralists? Dr. Lenchus and other experts say naysayers who believe hospitalists should give up the role aren’t fully considering the impact of a well-trained individual or team. “It’s not just the money that you bring in—it’s the money that you don’t spend,” he says. An initial hospitalist consultation, for example, may determine that a procedure isn’t needed at all for some patients. Perhaps more importantly, a well-trained provider can reduce or eliminate costly complications, such as CLABSIs.

Dr. Wang agrees, stressing that the profession still has the opportunity to build a niche in providing care that decreases overall hospital costs. Instead of regularly sending patients to the interventional radiology department, she says, hospitalist-performed bedside procedures can allow radiologists to focus on more complex cases.

A hospitalist, she says, can generate additional value by eliminating the need to put in a separate order, provide patient transportation, or spend more time fitting the patient into another specialist’s schedule—potentially extending that patient’s length of stay. The economic case for hospitalist-led procedures could improve even more under a bundled payment structure, Dr. Wang says.

“I see a future here if the accountable care organizations are infiltrated through the United States,” she says.

Future involvement of hospitalists in bedside procedures also could depend on the ability of programs to deliver top-notch teaching and training options. At Harvard Medical School, Dr. Wang regularly trains internal medicine residents, fellows, and even some attending physicians with a “robust” curriculum that includes hands-on practice with ultrasound in a simulation center and one-on-one testing on patients. Since instituting the training program a few years ago, she says, procedure-related infection rates have dropped to zero. Within the hospital’s ICUs, Dr. Wang says, complication rates have dropped as well.

Among the comments she now regularly hears: “Oh my gosh. I can’t believe we used to do this without a training program.”

Bryn Nelson is a freelance medical writer in Seattle and frequent contributor to The Hospitalist.

References

- Chang W, Lenchus J, Barsuk J. A lost art? The Hospitalist. 2012;16(6):1,28,30,32.

- Barsuk JH, Feinglass J, Kozmic SE, Hohmann SF, Ganger D, Wayne DB. Specialties performing paracentesis procedures at university hospitals: implications for training and certification. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(3):162-168.

- Mourad M, Auerbach AD, Maselli J, Sliwka D. Patient satisfaction with a hospitalist procedure service: Is bedside procedure teaching reassuring to patients? J Hosp Med. 2011;6(4):219-224.

- Tukey MH, Wiener RS. The impact of a medical procedure service on patient safety, procedure quality and resident training opportunities. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;29(3):485-490.

- Barsuk JH, McGaghie WC, Cohen ER, O’Leary KJ, Wayne DB. Simulation-based mastery learning reduces complications during central venous catheter insertion in a medical intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2009;37(10):2697-2701.

On his way to a recent conference, David Lichtman, PA, stopped to talk with medical residents at a nearby medical center about their experiences performing bedside procedures. “How many times have you guys done something that you knew you weren’t fully trained for but you didn’t want to say anything?” asked Lichtman, a hospitalist and director of the Johns Hopkins Central Procedure Service in Baltimore, Md. “At least once?”

Everyone raised a hand.

When Lichtman asked how many of the residents had ever spoken up and admitted being uncomfortable about doing a procedure, however, only about 20% raised their hands.

It’s one thing to struggle with a procedure like drawing blood. But a less-than-confident or unskilled provider who attempts more invasive procedures, such as a central line insertion or thoracentesis, can do major harm. And observers say confidence and competence levels, particularly among internal medicine residents, are heading in the wrong direction.

Two years ago, in fact, three hospitalists penned an article in The Hospitalist lamenting the “sharp decline” of HM proficiency in bedside procedures.1 Co-author Joshua Lenchus, DO, RPh, FACP, SFHM, associate director of the University of Miami-Jackson Memorial Hospital Center for Patient Safety and medical director of the hospital’s Procedure Service, says the trend is continuing for several reasons.

“One is internal medicine’s willingness to surrender these bedside procedures to others,” Dr. Lenchus says, perhaps due to time constraints, a lack of confidence, or a perception that it’s not cost effective for HM providers to take on the role. Several medical organizations have loosened their competency standards, and the default in many cases has been for interventional radiologists to perform the procedures instead.

Another reason may be more practical: Perhaps there just isn’t a need for all hospitalists to perform them. Many new hospitalist positions advertised through employment agencies, Dr. Lenchus says, do not require competency in bedside procedures.

“The question is, did that happen first and then we reacted to it as hospitalists, or did we stop doing them and employment agencies then modified their process to reflect that?” he says.

For hospitalists, perhaps the bigger question is this: Is there a need to address the decline?

For Lichtman, Dr. Lenchus, and many other leaders, the answer is an emphatic yes—an opportunity to carve out a niche of skilled and patient-focused bedside care and to demonstrate real value to hospitals.

“I think it makes perfect sense from a financial and throughput and healthcare system perspective,” he says. The talent, knowledge, and experience of interventional radiologists, Dr. Lenchus says, is far better spent on procedures that cannot be conducted at a patient’s bedside.

It’s also a matter of professional pride for hospitalists like Michelle Mourad, MD, associate professor of clinical medicine and director of quality improvement and patient safety for the division of hospital medicine at the University of California San Francisco.

“I derive a tremendous amount of enjoyment from working with my hands, from being able to provide my patients this service, from often giving them relief from excessive fluid buildup, and from being able to do these procedures at the bedside,” she says.

Reversing the recent slide of hospitalist involvement in procedures, however, may require more cohesive expectations, an emphasis on minimizing complications, identification of willing and able procedure champions, and comprehensive technology-aided training.

Confounding Expectations

Paracentesis, thoracentesis, arthrocentesis, lumbar puncture, and central line placement generally are considered “core” bedside procedures. Experts like Lichtman, however, say little agreement exists on the main procedures for which hospitalists should demonstrate competency.

“We don’t have any semblance of that,” he says. “The reality is that different groups have different beliefs, and different hospitals have different protocols that they follow.”

Pinning down a consistent list can be difficult, because HM providers can play different roles depending on the setting, says hospitalist Sally Wang, MD, FHM, director of procedure education at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and a clinical instructor at Harvard Medical School in Boston.

“You could be in an academic center. You could be in a community hospital. You could be in a rural setting where there’s no other access to anyone else doing these procedures, or you can have a robust interventional radiology service that will do all the procedures for you,” she says.