User login

Neonatal and Infantile Acne Vulgaris: An Update

Acne vulgaris typically is associated with adolescence and young adulthood; however, it also can affect neonates, infants, and small children.1 Acne neonatorum occurs in up to 20% of newborns. The clinical importance of neonatal acne lies in its differentiation from infectious diseases, the exclusion of virilization as its underlying cause, and the possible implication of severe acne in adolescence.2 Neonatal acne also must be distinguished from acne that is induced by application of topical oils and ointments (acne venenata) and from acneform eruptions induced by acnegenic maternal medications such as hydantoin (fetal hydantoin syndrome) and lithium.3

Neonatal Acne (Acne Neonatorum)

Clinical Presentation

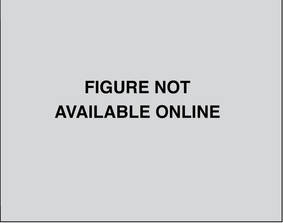

Neonatal acne (acne neonatorum) typically presents as small closed comedones on the forehead, nose, and cheeks (Figure 1).4 Accompanying sebaceous hyperplasia often is noted.5 Less frequently, open comedones, inflammatory papules, and pustules may develop.6 Neonatal acne may be evident at birth or appear during the first 4 weeks of life7 and is more commonly seen in boys.8

Etiology

Several factors may be pivotal in the etiology of neonatal acne, including increased sebum excretion, stimulation of the sebaceous glands by maternal or neonatal androgens,4 and colonization of sebaceous glands by Malassezia species.2 Increased sebum excretion occurs during the neonatal period due to enlarged sebaceous glands,2 which may result from the substantial production of β-hydroxysteroids from the relatively large adrenal glands.9,10 After 6 months of age, the size of the sebaceous glands and the sebum excretion rate decrease.9,10

Both maternal and neonatal androgens have been implicated in the stimulation of sebaceous glands in neonatal acne.2 The neonatal adrenal gland produces high levels of dehydroepiandrosterone,2 which stimulate sebaceous glands until around 1 year of age when dehydroepiandrosterone levels drop off as a consequence of involution of the neonatal adrenal gland.11 Testicular androgens provide additional stimulation to the sebaceous glands, which may explain why neonatal acne is more common in boys.1 Neonatal acne may be an inflammatory response to Malassezia species; however, Malassezia was not isolated in a series of patients,12 suggesting that neonatal acne is an early presentation of comedonal acne and not a response to Malassezia.2,12

Differential Diagnosis

There are a number of acneform eruptions that should be considered in the differential diagnosis,3 including bacterial folliculitis, secondary syphilis,13 herpes simplex virus and varicella zoster virus,14 and skin colonization by fungi of Malassezia species.15 Other neonatal eruptions such as erythema toxicum neonatorum,16 transient neonatal pustular melanosis, and milia and pustular miliaria, as well as a drug eruption associated with hydantoin, lithium, or halogens should be considered.17 The relationship between neonatal acne and neonatal cephalic pustulosis, which is characterized by papules and pustules without comedones, is controversial; some consider them to be 2 different entities,14 while others do not.18

Treatment

Guardians should be reassured that neonatal acne is mild, self-limited, and generally resolves spontaneously without scarring in approximately 1 to 3 months.1,2 In most cases, no treatment is needed.19 If necessary, comedones may be treated with azelaic acid cream 20% or tretinoin cream 0.025% to 0.05%.1,2 For inflammatory lesions, erythromycin solution 2% and benzoyl peroxide gel 2.5% may be used.1,20 Severe or recalcitrant disease warrants a workup for congenital adrenal hyperplasia, a virilizing tumor, or underlying endocrinopathy.19

Infantile Acne Vulgaris

Clinical Presentation

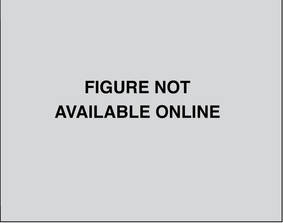

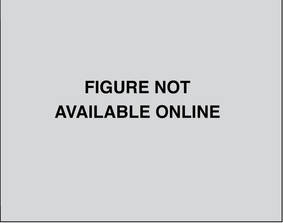

Infantile acne vulgaris shares similarities with neonatal acne21,22 in that they both affect the face, predominantly the cheeks, and have a male predominance (Figure 2).1,10 However, by definition, onset of infantile acne typically occurs later than acne neonatorum, usually at 3 to 6 months of age.1,4 Lesions are more pleomorphic and inflammatory than in neonatal acne. In addition to closed and open comedones, infantile acne may be first evident with papules, pustules, severe nodules, and cysts with scarring potential (Figure 3).1,2,5 Accordingly, treatment may be required. Most cases of infantile acne resolve by 4 or 5 years of age, but some remain active into puberty.1 Patients with a history of infantile acne have an increased incidence of acne vulgaris during adolescence compared to their peers, with greater severity and enhanced risk for scarring.4,23

Etiology

The etiology of infantile acne remains unclear.2 Similar to neonatal acne, infantile acne may be a result of elevated androgens produced by the fetal adrenal glands as well as by the testes in males.11 For example, a child with infantile acne had elevated luteinizing hormone, follicle-stimulating hormone, and testosterone levels.24 Therefore, hyperandrogenism should be considered as an etiology. Other causes also have been suggested. Rarely, an adrenocortical tumor may be associated with persistent infantile acne with signs of virilization and rapid development.25Malassezia was implicated in infantile acne in a 6-month-old infant who was successfully treated with ketoconazole cream 2%.26

Differential Diagnosis

Infantile acne often is misdiagnosed because it is rarely considered in the differential diagnosis. When closed comedones predominate, acne venenata induced by topical creams, lotions, or oils may be etiologic. Chloracne also should be considered.14

Treatment

Guardians should be educated about the likely chronicity of infantile acne, which may require long-term treatment, as well as the possibility that acne may recur in severe form during puberty.1 The treatment strategy for infantile acne is similar to treatment of acne at any age, with topical agents including retinoids (eg, tretinoin, benzoyl peroxide) and topical antibacterials (eg, erythromycin). Twice-daily erythromycin 125 to 250 mg is the treatment of choice when oral antibiotics are indicated. Tetracyclines are contraindicated in treatment of neonatal and infantile acne. Intralesional injections with low-concentration triamcinolone acetonide, cryotherapy, or topical corticosteroids for a short period of time can be used to treat deep nodules and cysts.2 Acne that is refractory to treatment with oral antibiotics alone or combined with topical treatments poses a dilemma, given the potential cosmetic sequelae of scarring and quality-of-life concerns. Because reducing or eliminating dairy intake appears beneficial for adolescents with moderate to severe acne,27 this approach may represent a good option for infantile acne.

Conclusion

Neonatal and infantile acne vulgaris may be overlooked or misdiagnosed. It is important to consider and treat. Early childhood acne may represent a virilization syndrome.

- Jansen T, Burgdorf WH, Plewig G. Pathogenesis and treatment of acne in childhood. Pediatr Dermatol. 1997;14:17-21.

- Antoniou C, Dessinioti C, Stratigos AJ, et al. Clinical and therapeutic approach to childhood acne: an update. Pediatr Dermatol. 2009;26:373-380.

- Kuflik JH, Schwartz RA. Acneiform eruptions. Cutis. 2000;66:97-100.

- Barbareschi M, Benardon S, Guanziroli E, et al. Classification and grading. In: Schwartz RA, Micali G, eds. Acne. Gurgaon, India: Nature Publishing Group; 2013:67-75.

- Mengesha YM, Bennett ML. Pustular skin disorders: diagnosis and treatment. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2002;3:389-400.

- O’Connor NR, McLaughlin MR, Ham P. Newborn skin: part I. common rashes. Am Fam Physician. 2008;77:47-52.

- Nanda S, Reddy BS, Ramji S, et al. Analytical study of pustular eruptions in neonates. Pediatr Dermatol. 2002;19:210-215.

- Yonkosky DM, Pochi PE. Acne vulgaris in childhood. pathogenesis and management. Dermatol Clin. 1986;4:127-136.

- Agache P, Blanc D, Barrand C, et al. Sebum levels during the first year of life. Br J Dermatol. 1980;103:643-649.

- Herane MI, Ando I. Acne in infancy and acne genetics. Dermatology. 2003;206:24-28.

- Lucky AW. A review of infantile and pediatric acne. Dermatology (Basel, Switzerland). 1998;103:643-649.

- Bernier V, Weill FX, Hirigoyen V, et al. Skin colonization by Malassezia species in neonates: a prospective study and relationship with neonatal cephalic pustulosis. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:215-218.

- Lambert WC, Bagley MP, Khan Y, et al. Pustular acneiform secondary syphilis. Cutis. 1986;37:69-70.

- Antoniou C, Dessinioti C, Stratigos AJ, et al. Clinical and therapeutic approach to childhood acne: an update. Pediatr Dermatol. 2009;26:373-380.

- Borton LK, Schwartz RA. Pityrosporum folliculitis: a common acneiform condition of middle age. Ariz Med. 1981;38:598-601.

- Morgan AJ, Steen CJ, Schwartz RA, et al. Erythema toxicum neonatorum revisited. Cutis. 2009;83:13-16.

- Brodkin RH, Schwartz RA. Cutaneous signs of dioxin exposure. Am Fam Physician. 1984;30:189-194.

- Mancini AJ, Baldwin HE, Eichenfield LF, et al. Acne life cycle: the spectrum of pediatric disease. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2011;30(suppl 3):S2-S5.

- Katsambas AD, Katoulis AC, Stavropoulos P. Acne neonatorum: a study of 22 cases. Int J Dermatol. 1999;38:128-130.

- Van Praag MC, Van Rooij RW, Folkers E, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of pustular disorders in the neonate. Pediatr Dermatol. 1997;14:131-143.

- Barnes CJ, Eichenfield LF, Lee J, et al. A practical approach for the use of oral isotretinoin for infantile acne. Pediatr Dermatol. 2005;22:166-169.

- Janniger CK. Neonatal and infantile acne vulgaris. Cutis. 1993;52:16.

- Chew EW, Bingham A, Burrows D. Incidence of acne vulgaris in patients with infantile acne. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1990;15:376-377.

- Duke EM. Infantile acne associated with transient increases in plasma concentrations of luteinising hormone, follicle-stimulating hormone, and testosterone. Br Med J (Clinical Res Ed). 1981;282:1275-1276.

- Mann MW, Ellis SS, Mallory SB. Infantile acne as the initial sign of an adrenocortical tumor [published online ahead of print September 14, 2006]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56(suppl 2):S15-S18.

- Kang SK, Jee MS, Choi JH, et al. A case of infantile acne due to Pityrosporum. Pediatr Dermatol. 2003;20:68-70.

- Di Landro A, Cazzaniga S, Parazzini F, et al. Family history, body mass index, selected dietary factors, menstrual history, and risk of moderate to severe acne in adolescents and young adults [published online ahead of print March 3, 2012]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:1129-1135.

Acne vulgaris typically is associated with adolescence and young adulthood; however, it also can affect neonates, infants, and small children.1 Acne neonatorum occurs in up to 20% of newborns. The clinical importance of neonatal acne lies in its differentiation from infectious diseases, the exclusion of virilization as its underlying cause, and the possible implication of severe acne in adolescence.2 Neonatal acne also must be distinguished from acne that is induced by application of topical oils and ointments (acne venenata) and from acneform eruptions induced by acnegenic maternal medications such as hydantoin (fetal hydantoin syndrome) and lithium.3

Neonatal Acne (Acne Neonatorum)

Clinical Presentation

Neonatal acne (acne neonatorum) typically presents as small closed comedones on the forehead, nose, and cheeks (Figure 1).4 Accompanying sebaceous hyperplasia often is noted.5 Less frequently, open comedones, inflammatory papules, and pustules may develop.6 Neonatal acne may be evident at birth or appear during the first 4 weeks of life7 and is more commonly seen in boys.8

Etiology

Several factors may be pivotal in the etiology of neonatal acne, including increased sebum excretion, stimulation of the sebaceous glands by maternal or neonatal androgens,4 and colonization of sebaceous glands by Malassezia species.2 Increased sebum excretion occurs during the neonatal period due to enlarged sebaceous glands,2 which may result from the substantial production of β-hydroxysteroids from the relatively large adrenal glands.9,10 After 6 months of age, the size of the sebaceous glands and the sebum excretion rate decrease.9,10

Both maternal and neonatal androgens have been implicated in the stimulation of sebaceous glands in neonatal acne.2 The neonatal adrenal gland produces high levels of dehydroepiandrosterone,2 which stimulate sebaceous glands until around 1 year of age when dehydroepiandrosterone levels drop off as a consequence of involution of the neonatal adrenal gland.11 Testicular androgens provide additional stimulation to the sebaceous glands, which may explain why neonatal acne is more common in boys.1 Neonatal acne may be an inflammatory response to Malassezia species; however, Malassezia was not isolated in a series of patients,12 suggesting that neonatal acne is an early presentation of comedonal acne and not a response to Malassezia.2,12

Differential Diagnosis

There are a number of acneform eruptions that should be considered in the differential diagnosis,3 including bacterial folliculitis, secondary syphilis,13 herpes simplex virus and varicella zoster virus,14 and skin colonization by fungi of Malassezia species.15 Other neonatal eruptions such as erythema toxicum neonatorum,16 transient neonatal pustular melanosis, and milia and pustular miliaria, as well as a drug eruption associated with hydantoin, lithium, or halogens should be considered.17 The relationship between neonatal acne and neonatal cephalic pustulosis, which is characterized by papules and pustules without comedones, is controversial; some consider them to be 2 different entities,14 while others do not.18

Treatment

Guardians should be reassured that neonatal acne is mild, self-limited, and generally resolves spontaneously without scarring in approximately 1 to 3 months.1,2 In most cases, no treatment is needed.19 If necessary, comedones may be treated with azelaic acid cream 20% or tretinoin cream 0.025% to 0.05%.1,2 For inflammatory lesions, erythromycin solution 2% and benzoyl peroxide gel 2.5% may be used.1,20 Severe or recalcitrant disease warrants a workup for congenital adrenal hyperplasia, a virilizing tumor, or underlying endocrinopathy.19

Infantile Acne Vulgaris

Clinical Presentation

Infantile acne vulgaris shares similarities with neonatal acne21,22 in that they both affect the face, predominantly the cheeks, and have a male predominance (Figure 2).1,10 However, by definition, onset of infantile acne typically occurs later than acne neonatorum, usually at 3 to 6 months of age.1,4 Lesions are more pleomorphic and inflammatory than in neonatal acne. In addition to closed and open comedones, infantile acne may be first evident with papules, pustules, severe nodules, and cysts with scarring potential (Figure 3).1,2,5 Accordingly, treatment may be required. Most cases of infantile acne resolve by 4 or 5 years of age, but some remain active into puberty.1 Patients with a history of infantile acne have an increased incidence of acne vulgaris during adolescence compared to their peers, with greater severity and enhanced risk for scarring.4,23

Etiology

The etiology of infantile acne remains unclear.2 Similar to neonatal acne, infantile acne may be a result of elevated androgens produced by the fetal adrenal glands as well as by the testes in males.11 For example, a child with infantile acne had elevated luteinizing hormone, follicle-stimulating hormone, and testosterone levels.24 Therefore, hyperandrogenism should be considered as an etiology. Other causes also have been suggested. Rarely, an adrenocortical tumor may be associated with persistent infantile acne with signs of virilization and rapid development.25Malassezia was implicated in infantile acne in a 6-month-old infant who was successfully treated with ketoconazole cream 2%.26

Differential Diagnosis

Infantile acne often is misdiagnosed because it is rarely considered in the differential diagnosis. When closed comedones predominate, acne venenata induced by topical creams, lotions, or oils may be etiologic. Chloracne also should be considered.14

Treatment

Guardians should be educated about the likely chronicity of infantile acne, which may require long-term treatment, as well as the possibility that acne may recur in severe form during puberty.1 The treatment strategy for infantile acne is similar to treatment of acne at any age, with topical agents including retinoids (eg, tretinoin, benzoyl peroxide) and topical antibacterials (eg, erythromycin). Twice-daily erythromycin 125 to 250 mg is the treatment of choice when oral antibiotics are indicated. Tetracyclines are contraindicated in treatment of neonatal and infantile acne. Intralesional injections with low-concentration triamcinolone acetonide, cryotherapy, or topical corticosteroids for a short period of time can be used to treat deep nodules and cysts.2 Acne that is refractory to treatment with oral antibiotics alone or combined with topical treatments poses a dilemma, given the potential cosmetic sequelae of scarring and quality-of-life concerns. Because reducing or eliminating dairy intake appears beneficial for adolescents with moderate to severe acne,27 this approach may represent a good option for infantile acne.

Conclusion

Neonatal and infantile acne vulgaris may be overlooked or misdiagnosed. It is important to consider and treat. Early childhood acne may represent a virilization syndrome.

Acne vulgaris typically is associated with adolescence and young adulthood; however, it also can affect neonates, infants, and small children.1 Acne neonatorum occurs in up to 20% of newborns. The clinical importance of neonatal acne lies in its differentiation from infectious diseases, the exclusion of virilization as its underlying cause, and the possible implication of severe acne in adolescence.2 Neonatal acne also must be distinguished from acne that is induced by application of topical oils and ointments (acne venenata) and from acneform eruptions induced by acnegenic maternal medications such as hydantoin (fetal hydantoin syndrome) and lithium.3

Neonatal Acne (Acne Neonatorum)

Clinical Presentation

Neonatal acne (acne neonatorum) typically presents as small closed comedones on the forehead, nose, and cheeks (Figure 1).4 Accompanying sebaceous hyperplasia often is noted.5 Less frequently, open comedones, inflammatory papules, and pustules may develop.6 Neonatal acne may be evident at birth or appear during the first 4 weeks of life7 and is more commonly seen in boys.8

Etiology

Several factors may be pivotal in the etiology of neonatal acne, including increased sebum excretion, stimulation of the sebaceous glands by maternal or neonatal androgens,4 and colonization of sebaceous glands by Malassezia species.2 Increased sebum excretion occurs during the neonatal period due to enlarged sebaceous glands,2 which may result from the substantial production of β-hydroxysteroids from the relatively large adrenal glands.9,10 After 6 months of age, the size of the sebaceous glands and the sebum excretion rate decrease.9,10

Both maternal and neonatal androgens have been implicated in the stimulation of sebaceous glands in neonatal acne.2 The neonatal adrenal gland produces high levels of dehydroepiandrosterone,2 which stimulate sebaceous glands until around 1 year of age when dehydroepiandrosterone levels drop off as a consequence of involution of the neonatal adrenal gland.11 Testicular androgens provide additional stimulation to the sebaceous glands, which may explain why neonatal acne is more common in boys.1 Neonatal acne may be an inflammatory response to Malassezia species; however, Malassezia was not isolated in a series of patients,12 suggesting that neonatal acne is an early presentation of comedonal acne and not a response to Malassezia.2,12

Differential Diagnosis

There are a number of acneform eruptions that should be considered in the differential diagnosis,3 including bacterial folliculitis, secondary syphilis,13 herpes simplex virus and varicella zoster virus,14 and skin colonization by fungi of Malassezia species.15 Other neonatal eruptions such as erythema toxicum neonatorum,16 transient neonatal pustular melanosis, and milia and pustular miliaria, as well as a drug eruption associated with hydantoin, lithium, or halogens should be considered.17 The relationship between neonatal acne and neonatal cephalic pustulosis, which is characterized by papules and pustules without comedones, is controversial; some consider them to be 2 different entities,14 while others do not.18

Treatment

Guardians should be reassured that neonatal acne is mild, self-limited, and generally resolves spontaneously without scarring in approximately 1 to 3 months.1,2 In most cases, no treatment is needed.19 If necessary, comedones may be treated with azelaic acid cream 20% or tretinoin cream 0.025% to 0.05%.1,2 For inflammatory lesions, erythromycin solution 2% and benzoyl peroxide gel 2.5% may be used.1,20 Severe or recalcitrant disease warrants a workup for congenital adrenal hyperplasia, a virilizing tumor, or underlying endocrinopathy.19

Infantile Acne Vulgaris

Clinical Presentation

Infantile acne vulgaris shares similarities with neonatal acne21,22 in that they both affect the face, predominantly the cheeks, and have a male predominance (Figure 2).1,10 However, by definition, onset of infantile acne typically occurs later than acne neonatorum, usually at 3 to 6 months of age.1,4 Lesions are more pleomorphic and inflammatory than in neonatal acne. In addition to closed and open comedones, infantile acne may be first evident with papules, pustules, severe nodules, and cysts with scarring potential (Figure 3).1,2,5 Accordingly, treatment may be required. Most cases of infantile acne resolve by 4 or 5 years of age, but some remain active into puberty.1 Patients with a history of infantile acne have an increased incidence of acne vulgaris during adolescence compared to their peers, with greater severity and enhanced risk for scarring.4,23

Etiology

The etiology of infantile acne remains unclear.2 Similar to neonatal acne, infantile acne may be a result of elevated androgens produced by the fetal adrenal glands as well as by the testes in males.11 For example, a child with infantile acne had elevated luteinizing hormone, follicle-stimulating hormone, and testosterone levels.24 Therefore, hyperandrogenism should be considered as an etiology. Other causes also have been suggested. Rarely, an adrenocortical tumor may be associated with persistent infantile acne with signs of virilization and rapid development.25Malassezia was implicated in infantile acne in a 6-month-old infant who was successfully treated with ketoconazole cream 2%.26

Differential Diagnosis

Infantile acne often is misdiagnosed because it is rarely considered in the differential diagnosis. When closed comedones predominate, acne venenata induced by topical creams, lotions, or oils may be etiologic. Chloracne also should be considered.14

Treatment

Guardians should be educated about the likely chronicity of infantile acne, which may require long-term treatment, as well as the possibility that acne may recur in severe form during puberty.1 The treatment strategy for infantile acne is similar to treatment of acne at any age, with topical agents including retinoids (eg, tretinoin, benzoyl peroxide) and topical antibacterials (eg, erythromycin). Twice-daily erythromycin 125 to 250 mg is the treatment of choice when oral antibiotics are indicated. Tetracyclines are contraindicated in treatment of neonatal and infantile acne. Intralesional injections with low-concentration triamcinolone acetonide, cryotherapy, or topical corticosteroids for a short period of time can be used to treat deep nodules and cysts.2 Acne that is refractory to treatment with oral antibiotics alone or combined with topical treatments poses a dilemma, given the potential cosmetic sequelae of scarring and quality-of-life concerns. Because reducing or eliminating dairy intake appears beneficial for adolescents with moderate to severe acne,27 this approach may represent a good option for infantile acne.

Conclusion

Neonatal and infantile acne vulgaris may be overlooked or misdiagnosed. It is important to consider and treat. Early childhood acne may represent a virilization syndrome.

- Jansen T, Burgdorf WH, Plewig G. Pathogenesis and treatment of acne in childhood. Pediatr Dermatol. 1997;14:17-21.

- Antoniou C, Dessinioti C, Stratigos AJ, et al. Clinical and therapeutic approach to childhood acne: an update. Pediatr Dermatol. 2009;26:373-380.

- Kuflik JH, Schwartz RA. Acneiform eruptions. Cutis. 2000;66:97-100.

- Barbareschi M, Benardon S, Guanziroli E, et al. Classification and grading. In: Schwartz RA, Micali G, eds. Acne. Gurgaon, India: Nature Publishing Group; 2013:67-75.

- Mengesha YM, Bennett ML. Pustular skin disorders: diagnosis and treatment. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2002;3:389-400.

- O’Connor NR, McLaughlin MR, Ham P. Newborn skin: part I. common rashes. Am Fam Physician. 2008;77:47-52.

- Nanda S, Reddy BS, Ramji S, et al. Analytical study of pustular eruptions in neonates. Pediatr Dermatol. 2002;19:210-215.

- Yonkosky DM, Pochi PE. Acne vulgaris in childhood. pathogenesis and management. Dermatol Clin. 1986;4:127-136.

- Agache P, Blanc D, Barrand C, et al. Sebum levels during the first year of life. Br J Dermatol. 1980;103:643-649.

- Herane MI, Ando I. Acne in infancy and acne genetics. Dermatology. 2003;206:24-28.

- Lucky AW. A review of infantile and pediatric acne. Dermatology (Basel, Switzerland). 1998;103:643-649.

- Bernier V, Weill FX, Hirigoyen V, et al. Skin colonization by Malassezia species in neonates: a prospective study and relationship with neonatal cephalic pustulosis. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:215-218.

- Lambert WC, Bagley MP, Khan Y, et al. Pustular acneiform secondary syphilis. Cutis. 1986;37:69-70.

- Antoniou C, Dessinioti C, Stratigos AJ, et al. Clinical and therapeutic approach to childhood acne: an update. Pediatr Dermatol. 2009;26:373-380.

- Borton LK, Schwartz RA. Pityrosporum folliculitis: a common acneiform condition of middle age. Ariz Med. 1981;38:598-601.

- Morgan AJ, Steen CJ, Schwartz RA, et al. Erythema toxicum neonatorum revisited. Cutis. 2009;83:13-16.

- Brodkin RH, Schwartz RA. Cutaneous signs of dioxin exposure. Am Fam Physician. 1984;30:189-194.

- Mancini AJ, Baldwin HE, Eichenfield LF, et al. Acne life cycle: the spectrum of pediatric disease. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2011;30(suppl 3):S2-S5.

- Katsambas AD, Katoulis AC, Stavropoulos P. Acne neonatorum: a study of 22 cases. Int J Dermatol. 1999;38:128-130.

- Van Praag MC, Van Rooij RW, Folkers E, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of pustular disorders in the neonate. Pediatr Dermatol. 1997;14:131-143.

- Barnes CJ, Eichenfield LF, Lee J, et al. A practical approach for the use of oral isotretinoin for infantile acne. Pediatr Dermatol. 2005;22:166-169.

- Janniger CK. Neonatal and infantile acne vulgaris. Cutis. 1993;52:16.

- Chew EW, Bingham A, Burrows D. Incidence of acne vulgaris in patients with infantile acne. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1990;15:376-377.

- Duke EM. Infantile acne associated with transient increases in plasma concentrations of luteinising hormone, follicle-stimulating hormone, and testosterone. Br Med J (Clinical Res Ed). 1981;282:1275-1276.

- Mann MW, Ellis SS, Mallory SB. Infantile acne as the initial sign of an adrenocortical tumor [published online ahead of print September 14, 2006]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56(suppl 2):S15-S18.

- Kang SK, Jee MS, Choi JH, et al. A case of infantile acne due to Pityrosporum. Pediatr Dermatol. 2003;20:68-70.

- Di Landro A, Cazzaniga S, Parazzini F, et al. Family history, body mass index, selected dietary factors, menstrual history, and risk of moderate to severe acne in adolescents and young adults [published online ahead of print March 3, 2012]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:1129-1135.

- Jansen T, Burgdorf WH, Plewig G. Pathogenesis and treatment of acne in childhood. Pediatr Dermatol. 1997;14:17-21.

- Antoniou C, Dessinioti C, Stratigos AJ, et al. Clinical and therapeutic approach to childhood acne: an update. Pediatr Dermatol. 2009;26:373-380.

- Kuflik JH, Schwartz RA. Acneiform eruptions. Cutis. 2000;66:97-100.

- Barbareschi M, Benardon S, Guanziroli E, et al. Classification and grading. In: Schwartz RA, Micali G, eds. Acne. Gurgaon, India: Nature Publishing Group; 2013:67-75.

- Mengesha YM, Bennett ML. Pustular skin disorders: diagnosis and treatment. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2002;3:389-400.

- O’Connor NR, McLaughlin MR, Ham P. Newborn skin: part I. common rashes. Am Fam Physician. 2008;77:47-52.

- Nanda S, Reddy BS, Ramji S, et al. Analytical study of pustular eruptions in neonates. Pediatr Dermatol. 2002;19:210-215.

- Yonkosky DM, Pochi PE. Acne vulgaris in childhood. pathogenesis and management. Dermatol Clin. 1986;4:127-136.

- Agache P, Blanc D, Barrand C, et al. Sebum levels during the first year of life. Br J Dermatol. 1980;103:643-649.

- Herane MI, Ando I. Acne in infancy and acne genetics. Dermatology. 2003;206:24-28.

- Lucky AW. A review of infantile and pediatric acne. Dermatology (Basel, Switzerland). 1998;103:643-649.

- Bernier V, Weill FX, Hirigoyen V, et al. Skin colonization by Malassezia species in neonates: a prospective study and relationship with neonatal cephalic pustulosis. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:215-218.

- Lambert WC, Bagley MP, Khan Y, et al. Pustular acneiform secondary syphilis. Cutis. 1986;37:69-70.

- Antoniou C, Dessinioti C, Stratigos AJ, et al. Clinical and therapeutic approach to childhood acne: an update. Pediatr Dermatol. 2009;26:373-380.

- Borton LK, Schwartz RA. Pityrosporum folliculitis: a common acneiform condition of middle age. Ariz Med. 1981;38:598-601.

- Morgan AJ, Steen CJ, Schwartz RA, et al. Erythema toxicum neonatorum revisited. Cutis. 2009;83:13-16.

- Brodkin RH, Schwartz RA. Cutaneous signs of dioxin exposure. Am Fam Physician. 1984;30:189-194.

- Mancini AJ, Baldwin HE, Eichenfield LF, et al. Acne life cycle: the spectrum of pediatric disease. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2011;30(suppl 3):S2-S5.

- Katsambas AD, Katoulis AC, Stavropoulos P. Acne neonatorum: a study of 22 cases. Int J Dermatol. 1999;38:128-130.

- Van Praag MC, Van Rooij RW, Folkers E, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of pustular disorders in the neonate. Pediatr Dermatol. 1997;14:131-143.

- Barnes CJ, Eichenfield LF, Lee J, et al. A practical approach for the use of oral isotretinoin for infantile acne. Pediatr Dermatol. 2005;22:166-169.

- Janniger CK. Neonatal and infantile acne vulgaris. Cutis. 1993;52:16.

- Chew EW, Bingham A, Burrows D. Incidence of acne vulgaris in patients with infantile acne. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1990;15:376-377.

- Duke EM. Infantile acne associated with transient increases in plasma concentrations of luteinising hormone, follicle-stimulating hormone, and testosterone. Br Med J (Clinical Res Ed). 1981;282:1275-1276.

- Mann MW, Ellis SS, Mallory SB. Infantile acne as the initial sign of an adrenocortical tumor [published online ahead of print September 14, 2006]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56(suppl 2):S15-S18.

- Kang SK, Jee MS, Choi JH, et al. A case of infantile acne due to Pityrosporum. Pediatr Dermatol. 2003;20:68-70.

- Di Landro A, Cazzaniga S, Parazzini F, et al. Family history, body mass index, selected dietary factors, menstrual history, and risk of moderate to severe acne in adolescents and young adults [published online ahead of print March 3, 2012]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:1129-1135.

Practice Points

- Infantile acne needs to be recognized and treated.

- Acne in early childhood may represent virilization.

Etanercept-Induced Cystic Acne

Case Report

A 35-year-old man with chronic plaque-type psoriasis presented for treatment of a flare-up caused by a combination of hot tub use and 3 missed etanercept injections. The patient had been prescribed subcutaneous etanercept (50 mg once weekly) approximately 2 years prior to presentation for treatment of psoriasis and had used it consistently with 2 brief periods of discontinuation due to upper respiratory infections; treatment was discontinued for 2 weeks until the infections resolved and was restarted at the same dose. Recent hot tub use induced localized folliculitis of the leg and caused koebnerization of his psoriasis. Treatment with etanercept (50 mg twice weekly) was reinitiated, but after 1 month of therapy, the patient developed a nodulocystic eruption on the face. The patient discontinued use of etanercept and subsequently was started on oral minocycline (50 mgonce daily) by his primary care physician. After 6 weeks of minocycline therapy, the patient reported gradual improvement of his cystic acne. At follow-up, physical examination revealed approximately 15 erythematous cystic papules and nodules on the bilateral cheeks. The dose of oral minocycline was increased to 100 mg twice daily and his face subsequently cleared after 12 weeks of treatment.

On rechallenge with etanercept (50 mg weekly) after a separate flare-up of his psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis, the patient again developed nodulocystic acne within 3 weeks of restarting the medication, which confirmed the association between etanercept and the eruption. Etanercept was subsequently discontinued and the patient was started on ustekinumab for treatment of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis as well as minocycline (100 mg twice daily) for treatment of nodulocystic acne. His acne subsequently cleared after 12 weeks of therapy. The patient’s psoriasis currently is well controlled on a regimen of methotrexate 20 mg weekly, as continued use of ustekinumab was not covered by his health insurance policy.

Comment

Etanercept, along with infliximab and adalimumab, is a tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) antagonist. Tumor necrosis factor α is a major cytokine of the immune system that is deregulated in autoimmune disorders, causing inflammation and a variety of systemic effects. Inhibition of TNF-α results in a decrease in inflammatory markers such as IL-1 and IL-6, leading to a reduction in endothelial permeability and leukocyte migration.1 Etanercept is unique in that it is a fully humanized soluble fusion protein consisting of a TNF-α receptor linked to the Fc region of IgG1, whereas infliximab and adalimumab are monoclonal antibodies that target TNF-α. Etanercept works by acting as a decoy receptor for TNF-α, thereby preventing it from binding cell surface receptors and subsequently decreasing inflammation. It is an approved treatment of rheumatoid arthritis, polyarticular juvenile rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, and plaque psoriasis.2

Many drugs have been implicated in acneform eruptions mimicking acne vulgaris, such as corticosteroids, cyclosporine, antipsychotics, anticonvulsants, epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors, antidepressants, danazol, antituberculosis drugs, quinidine, azathioprine, testosterone, and TNF-α antagonists.1 The TNF-α antagonists that have been associated with acne are infliximab and adalimumab, especially when used to treat Crohn disease or rheumatoid arthritis, though there also are reports of acneform eruptions when using these drugs to treat psoriasis.1,3 There have been reports of the use of etanercept in treating severe acne and acne conglobata4,5; our case documents etanercept-induced acne associated with psoriasis treatment. Theoretically, anti–TNF-α agents should suppress acne rather than induce it due to their inhibition of the inflammatory markers TNF-α, IL-1a, and IFN-γ, which are thought to play a role in hypercornification of the infundibulum.6 Thus the mechanism of TNF-α antagonists and associated acneform eruptions remains unknown. This observation should prompt further research to investigate the correlation between the use of TNF-α inhibitors, specifically etanercept, and cystic acne.

- Momin SB, Peterson A, Del Rosso JQ. A status report on drug-associated acne and acneiform eruptions. J Drugs Dermatol. 2010;9:627-636.

- Zhou H. Clinical pharmacokinetics of etanercept: a fully humanized soluble recombinant tumor necrosis factor receptor fusion protein. J Clin Pharmacol. 2005;45:490-497.

- Sun G, Wasko CA, Hsu S. Acneiform eruption following anti-TNF-alpha treatment: a report of three cases. J Drugs Dermatol. 2008;7:69-71.

- Campione E, Mazzotta AM, Bianchi L, et al. Severe acne successfully treated with etanercept. Acta Derm Venereol. 2006;86:256-257.

- Vega J, Sánchez-Velicia L, Pozo T. Efficacy of etanercept in the treatment of acne conglobata [in Spanish]. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2010;101:553-554.

- Bassi E, Poli F, Charachon A, et al. Infliximab-induced acne: report of two cases. Br J Dermatol. 2007;156:402-403.

Case Report

A 35-year-old man with chronic plaque-type psoriasis presented for treatment of a flare-up caused by a combination of hot tub use and 3 missed etanercept injections. The patient had been prescribed subcutaneous etanercept (50 mg once weekly) approximately 2 years prior to presentation for treatment of psoriasis and had used it consistently with 2 brief periods of discontinuation due to upper respiratory infections; treatment was discontinued for 2 weeks until the infections resolved and was restarted at the same dose. Recent hot tub use induced localized folliculitis of the leg and caused koebnerization of his psoriasis. Treatment with etanercept (50 mg twice weekly) was reinitiated, but after 1 month of therapy, the patient developed a nodulocystic eruption on the face. The patient discontinued use of etanercept and subsequently was started on oral minocycline (50 mgonce daily) by his primary care physician. After 6 weeks of minocycline therapy, the patient reported gradual improvement of his cystic acne. At follow-up, physical examination revealed approximately 15 erythematous cystic papules and nodules on the bilateral cheeks. The dose of oral minocycline was increased to 100 mg twice daily and his face subsequently cleared after 12 weeks of treatment.

On rechallenge with etanercept (50 mg weekly) after a separate flare-up of his psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis, the patient again developed nodulocystic acne within 3 weeks of restarting the medication, which confirmed the association between etanercept and the eruption. Etanercept was subsequently discontinued and the patient was started on ustekinumab for treatment of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis as well as minocycline (100 mg twice daily) for treatment of nodulocystic acne. His acne subsequently cleared after 12 weeks of therapy. The patient’s psoriasis currently is well controlled on a regimen of methotrexate 20 mg weekly, as continued use of ustekinumab was not covered by his health insurance policy.

Comment

Etanercept, along with infliximab and adalimumab, is a tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) antagonist. Tumor necrosis factor α is a major cytokine of the immune system that is deregulated in autoimmune disorders, causing inflammation and a variety of systemic effects. Inhibition of TNF-α results in a decrease in inflammatory markers such as IL-1 and IL-6, leading to a reduction in endothelial permeability and leukocyte migration.1 Etanercept is unique in that it is a fully humanized soluble fusion protein consisting of a TNF-α receptor linked to the Fc region of IgG1, whereas infliximab and adalimumab are monoclonal antibodies that target TNF-α. Etanercept works by acting as a decoy receptor for TNF-α, thereby preventing it from binding cell surface receptors and subsequently decreasing inflammation. It is an approved treatment of rheumatoid arthritis, polyarticular juvenile rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, and plaque psoriasis.2

Many drugs have been implicated in acneform eruptions mimicking acne vulgaris, such as corticosteroids, cyclosporine, antipsychotics, anticonvulsants, epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors, antidepressants, danazol, antituberculosis drugs, quinidine, azathioprine, testosterone, and TNF-α antagonists.1 The TNF-α antagonists that have been associated with acne are infliximab and adalimumab, especially when used to treat Crohn disease or rheumatoid arthritis, though there also are reports of acneform eruptions when using these drugs to treat psoriasis.1,3 There have been reports of the use of etanercept in treating severe acne and acne conglobata4,5; our case documents etanercept-induced acne associated with psoriasis treatment. Theoretically, anti–TNF-α agents should suppress acne rather than induce it due to their inhibition of the inflammatory markers TNF-α, IL-1a, and IFN-γ, which are thought to play a role in hypercornification of the infundibulum.6 Thus the mechanism of TNF-α antagonists and associated acneform eruptions remains unknown. This observation should prompt further research to investigate the correlation between the use of TNF-α inhibitors, specifically etanercept, and cystic acne.

Case Report

A 35-year-old man with chronic plaque-type psoriasis presented for treatment of a flare-up caused by a combination of hot tub use and 3 missed etanercept injections. The patient had been prescribed subcutaneous etanercept (50 mg once weekly) approximately 2 years prior to presentation for treatment of psoriasis and had used it consistently with 2 brief periods of discontinuation due to upper respiratory infections; treatment was discontinued for 2 weeks until the infections resolved and was restarted at the same dose. Recent hot tub use induced localized folliculitis of the leg and caused koebnerization of his psoriasis. Treatment with etanercept (50 mg twice weekly) was reinitiated, but after 1 month of therapy, the patient developed a nodulocystic eruption on the face. The patient discontinued use of etanercept and subsequently was started on oral minocycline (50 mgonce daily) by his primary care physician. After 6 weeks of minocycline therapy, the patient reported gradual improvement of his cystic acne. At follow-up, physical examination revealed approximately 15 erythematous cystic papules and nodules on the bilateral cheeks. The dose of oral minocycline was increased to 100 mg twice daily and his face subsequently cleared after 12 weeks of treatment.

On rechallenge with etanercept (50 mg weekly) after a separate flare-up of his psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis, the patient again developed nodulocystic acne within 3 weeks of restarting the medication, which confirmed the association between etanercept and the eruption. Etanercept was subsequently discontinued and the patient was started on ustekinumab for treatment of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis as well as minocycline (100 mg twice daily) for treatment of nodulocystic acne. His acne subsequently cleared after 12 weeks of therapy. The patient’s psoriasis currently is well controlled on a regimen of methotrexate 20 mg weekly, as continued use of ustekinumab was not covered by his health insurance policy.

Comment

Etanercept, along with infliximab and adalimumab, is a tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) antagonist. Tumor necrosis factor α is a major cytokine of the immune system that is deregulated in autoimmune disorders, causing inflammation and a variety of systemic effects. Inhibition of TNF-α results in a decrease in inflammatory markers such as IL-1 and IL-6, leading to a reduction in endothelial permeability and leukocyte migration.1 Etanercept is unique in that it is a fully humanized soluble fusion protein consisting of a TNF-α receptor linked to the Fc region of IgG1, whereas infliximab and adalimumab are monoclonal antibodies that target TNF-α. Etanercept works by acting as a decoy receptor for TNF-α, thereby preventing it from binding cell surface receptors and subsequently decreasing inflammation. It is an approved treatment of rheumatoid arthritis, polyarticular juvenile rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, and plaque psoriasis.2

Many drugs have been implicated in acneform eruptions mimicking acne vulgaris, such as corticosteroids, cyclosporine, antipsychotics, anticonvulsants, epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors, antidepressants, danazol, antituberculosis drugs, quinidine, azathioprine, testosterone, and TNF-α antagonists.1 The TNF-α antagonists that have been associated with acne are infliximab and adalimumab, especially when used to treat Crohn disease or rheumatoid arthritis, though there also are reports of acneform eruptions when using these drugs to treat psoriasis.1,3 There have been reports of the use of etanercept in treating severe acne and acne conglobata4,5; our case documents etanercept-induced acne associated with psoriasis treatment. Theoretically, anti–TNF-α agents should suppress acne rather than induce it due to their inhibition of the inflammatory markers TNF-α, IL-1a, and IFN-γ, which are thought to play a role in hypercornification of the infundibulum.6 Thus the mechanism of TNF-α antagonists and associated acneform eruptions remains unknown. This observation should prompt further research to investigate the correlation between the use of TNF-α inhibitors, specifically etanercept, and cystic acne.

- Momin SB, Peterson A, Del Rosso JQ. A status report on drug-associated acne and acneiform eruptions. J Drugs Dermatol. 2010;9:627-636.

- Zhou H. Clinical pharmacokinetics of etanercept: a fully humanized soluble recombinant tumor necrosis factor receptor fusion protein. J Clin Pharmacol. 2005;45:490-497.

- Sun G, Wasko CA, Hsu S. Acneiform eruption following anti-TNF-alpha treatment: a report of three cases. J Drugs Dermatol. 2008;7:69-71.

- Campione E, Mazzotta AM, Bianchi L, et al. Severe acne successfully treated with etanercept. Acta Derm Venereol. 2006;86:256-257.

- Vega J, Sánchez-Velicia L, Pozo T. Efficacy of etanercept in the treatment of acne conglobata [in Spanish]. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2010;101:553-554.

- Bassi E, Poli F, Charachon A, et al. Infliximab-induced acne: report of two cases. Br J Dermatol. 2007;156:402-403.

- Momin SB, Peterson A, Del Rosso JQ. A status report on drug-associated acne and acneiform eruptions. J Drugs Dermatol. 2010;9:627-636.

- Zhou H. Clinical pharmacokinetics of etanercept: a fully humanized soluble recombinant tumor necrosis factor receptor fusion protein. J Clin Pharmacol. 2005;45:490-497.

- Sun G, Wasko CA, Hsu S. Acneiform eruption following anti-TNF-alpha treatment: a report of three cases. J Drugs Dermatol. 2008;7:69-71.

- Campione E, Mazzotta AM, Bianchi L, et al. Severe acne successfully treated with etanercept. Acta Derm Venereol. 2006;86:256-257.

- Vega J, Sánchez-Velicia L, Pozo T. Efficacy of etanercept in the treatment of acne conglobata [in Spanish]. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2010;101:553-554.

- Bassi E, Poli F, Charachon A, et al. Infliximab-induced acne: report of two cases. Br J Dermatol. 2007;156:402-403.

- Tumor necrosis factor α antagonists have been implicated in causing acneform eruptions.

- Discontinuation of the agent along with initiation of oral antibiotics or isotretinoin can treat medication-induced nodulocystic acne.

- Ustekinumab is an alternative non–tumor necrosis factor α antagonist that can be used to treat psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis that has not been associated with acneform eruptions.

OTC topical acne meds can cause severe reactions

The Food and Drug Administration says that some over-the-counter acne products can cause severe hypersensitivity or allergic reactions and is warning consumers to discontinue use immediately and seek emergency medical attention if they experience such symptoms.

The reactions seem to be on the upswing, according to the agency’s review of reports from 1969 to early 2013.

The agency said in safety announcement that it has not determined whether the reactions are being triggered by the active ingredients in the products – benzoyl peroxide or salicylic acid – or by the inactive ingredients or a combination of the inactive and active ingredients.

The products include Proactiv, Neutrogena, MaxClarity, Oxy, Ambi, Aveeno, Clean & Clear, and private label store brands, and are sold as gels, lotions, face washes, solutions, cleansing pads, toners, and face scrubs, among other products, according to the agency.

The FDA has received reports stating that – within minutes to a day or longer of use – consumers have had hypersensitivity reactions that include throat tightness, difficulty breathing, or swelling of the eyes, face, lips, or tongue. Hives and itching are also indications of an allergic reaction.

From 1969 to January 2013, the agency identified 131 cases of hypersensitivity reactions, with the majority reported in 2012-2013. A total of 86% (113) of the cases were in women, and the reactions were reported in people aged 11-78 years.

There were no deaths, but 58 of the consumers were hospitalized. A total of 38 of the 131 cases (29%) were categorized as anaphylactic reactions, and the remainder were categorized as nonanaphylactic hypersensitivity. Almost half of the consumers said they had discontinued use after the reaction, the majority of whom reported some degree of recovery after discontinuing product use, with final outcomes unavailable for the rest. Four of the patients who used the product again reported a recurrence of the reaction.

The agency is encouraging manufacturers to add directions on testing for hypersensitivity to the labels of all OTC topical acne products. Some labels already include those instructions, which direct users to apply a small amount to one or two small affected areas of the skin for 3 days. If there is no reaction – topical or otherwise – then the product can be used according to the directions.

Consumers are also being urged to avoid using a product if they have previously experienced a hypersensitivity reaction with its use.

The FDA says that physicians should be aware that some topical prescription acne drug products also contain warnings about allergic reactions, including anaphylaxis.

Physicians can report adverse events involving OTC topical acne products to the FDA MedWatch program.

On Twitter @aliciaault

The Food and Drug Administration says that some over-the-counter acne products can cause severe hypersensitivity or allergic reactions and is warning consumers to discontinue use immediately and seek emergency medical attention if they experience such symptoms.

The reactions seem to be on the upswing, according to the agency’s review of reports from 1969 to early 2013.

The agency said in safety announcement that it has not determined whether the reactions are being triggered by the active ingredients in the products – benzoyl peroxide or salicylic acid – or by the inactive ingredients or a combination of the inactive and active ingredients.

The products include Proactiv, Neutrogena, MaxClarity, Oxy, Ambi, Aveeno, Clean & Clear, and private label store brands, and are sold as gels, lotions, face washes, solutions, cleansing pads, toners, and face scrubs, among other products, according to the agency.

The FDA has received reports stating that – within minutes to a day or longer of use – consumers have had hypersensitivity reactions that include throat tightness, difficulty breathing, or swelling of the eyes, face, lips, or tongue. Hives and itching are also indications of an allergic reaction.

From 1969 to January 2013, the agency identified 131 cases of hypersensitivity reactions, with the majority reported in 2012-2013. A total of 86% (113) of the cases were in women, and the reactions were reported in people aged 11-78 years.

There were no deaths, but 58 of the consumers were hospitalized. A total of 38 of the 131 cases (29%) were categorized as anaphylactic reactions, and the remainder were categorized as nonanaphylactic hypersensitivity. Almost half of the consumers said they had discontinued use after the reaction, the majority of whom reported some degree of recovery after discontinuing product use, with final outcomes unavailable for the rest. Four of the patients who used the product again reported a recurrence of the reaction.

The agency is encouraging manufacturers to add directions on testing for hypersensitivity to the labels of all OTC topical acne products. Some labels already include those instructions, which direct users to apply a small amount to one or two small affected areas of the skin for 3 days. If there is no reaction – topical or otherwise – then the product can be used according to the directions.

Consumers are also being urged to avoid using a product if they have previously experienced a hypersensitivity reaction with its use.

The FDA says that physicians should be aware that some topical prescription acne drug products also contain warnings about allergic reactions, including anaphylaxis.

Physicians can report adverse events involving OTC topical acne products to the FDA MedWatch program.

On Twitter @aliciaault

The Food and Drug Administration says that some over-the-counter acne products can cause severe hypersensitivity or allergic reactions and is warning consumers to discontinue use immediately and seek emergency medical attention if they experience such symptoms.

The reactions seem to be on the upswing, according to the agency’s review of reports from 1969 to early 2013.

The agency said in safety announcement that it has not determined whether the reactions are being triggered by the active ingredients in the products – benzoyl peroxide or salicylic acid – or by the inactive ingredients or a combination of the inactive and active ingredients.

The products include Proactiv, Neutrogena, MaxClarity, Oxy, Ambi, Aveeno, Clean & Clear, and private label store brands, and are sold as gels, lotions, face washes, solutions, cleansing pads, toners, and face scrubs, among other products, according to the agency.

The FDA has received reports stating that – within minutes to a day or longer of use – consumers have had hypersensitivity reactions that include throat tightness, difficulty breathing, or swelling of the eyes, face, lips, or tongue. Hives and itching are also indications of an allergic reaction.

From 1969 to January 2013, the agency identified 131 cases of hypersensitivity reactions, with the majority reported in 2012-2013. A total of 86% (113) of the cases were in women, and the reactions were reported in people aged 11-78 years.

There were no deaths, but 58 of the consumers were hospitalized. A total of 38 of the 131 cases (29%) were categorized as anaphylactic reactions, and the remainder were categorized as nonanaphylactic hypersensitivity. Almost half of the consumers said they had discontinued use after the reaction, the majority of whom reported some degree of recovery after discontinuing product use, with final outcomes unavailable for the rest. Four of the patients who used the product again reported a recurrence of the reaction.

The agency is encouraging manufacturers to add directions on testing for hypersensitivity to the labels of all OTC topical acne products. Some labels already include those instructions, which direct users to apply a small amount to one or two small affected areas of the skin for 3 days. If there is no reaction – topical or otherwise – then the product can be used according to the directions.

Consumers are also being urged to avoid using a product if they have previously experienced a hypersensitivity reaction with its use.

The FDA says that physicians should be aware that some topical prescription acne drug products also contain warnings about allergic reactions, including anaphylaxis.

Physicians can report adverse events involving OTC topical acne products to the FDA MedWatch program.

On Twitter @aliciaault

Adapalene/benzoyl peroxide gel halves acne lesion counts in 1 month

WAIKOLOA, HAWAII – The fixed-dose combination of adapalene/benzoyl peroxide gel 0.1%/2.5% typically results in reductions of 40%-50% in inflammatory and 30%-40% in noninflammatory acne lesion counts during the first 4 weeks of therapy.

In a pooled analysis of 14 studies totaling 2,358 acne patients aged 9-61 years, the proportion with an Investigator’s Global Assessment (IGA) of moderate or severe acne dropped from 92% at baseline to 51% at 4 weeks, according to Dr. Linda Stein Gold.

The pooled analysis was carried out to provide physicians and patients with information as to what to realistically expect in the first 4 weeks of therapy. The analysis is particularly timely in light of the Food and Drug Administration’s recent expansion of the indication for adapalene/benzoyl peroxide gel 0.1%/2.5% (Epiduo) to include acne patients as young as 9 years of age, noted Dr. Stein Gold, director of clinical research in the department of dermatology at Henry Ford Hospital, Detroit.

Mild skin irritation was common, especially in the first 2 weeks of use.

"It’s a fiction that retinoids are too harsh for younger patients to use," Dr. Stein Gold said. "I tell all my acne patients, especially the younger ones, no matter what topical retinoid they’re using, to use it every other night for the first 2 weeks, make sure their skin is completely dry, and use a gentle cleanser and a good moisturizer," she said at the Hawaii Dermatology Seminar sponsored by Global Academy for Medical Education/Skin Disease Education Foundation. "If they get through those first 2 weeks, they’ll see that the tolerability really improves."

Dr. Stein Gold said she likes the fixed combination of adapalene/benzoyl peroxide gel 0.1%/2.5% because it combines several key elements of cutting-edge acne treatment. Topical retinoids are not mere comedone busters, as formerly thought, but are also effective agents for papules and pustular lesions. While they do not kill Propionibacterium acnes, they down-regulate Toll-like receptor 2, which is produced by the bacterium and induces proinflammatory cytokines. Topical retinoids are a key part of maintenance-of-remission strategies. And adapalene is unique among topical retinoids in that it is inherently stable with benzoyl peroxide (BPO) and is stable in daylight.

BPO is unique in that it has potent antibacterial activity, but never causes P. acnes resistance, even after many years of treatment. BPO is quite effective for inflammatory lesions and moderately effective for comedonal acne lesions, Dr. Stein Gold noted. Also, it is well established that BPO at a concentration of 2.5% is as efficacious as 5% or 10%, and much better tolerated than at the higher concentrations. The molecule size and the use of a vehicle with good penetration into the hair follicle are much more important factors in treatment effectiveness than is the BPO concentration, she added.

In one study of acne patients with antibiotic-resistant P. acnes, including clindamycin-, doxycycline-, erythromycin-, and minocycline-resistant microorganisms, 88% of the antibiotic-resistant P. acnes bacteria were killed after 2 weeks of treatment with adapalene/BPO gel 0.1%/2.5%. After 4 weeks of treatment, 97% of the antibiotic-resistant organisms were dead. That’s testimony to the P. acnes–killing power of BPO, said Dr. Stein Gold.

"There’s a sense among many that with all the newer medications we have for acne, benzoyl peroxide is really your grandfather’s treatment, with no place in today’s modern world. This is totally false. I really feel that benzoyl peroxide should play a central role in all of our acne patients’ treatment regimens, unless of course they’re allergic to it, which occurs in only a small percentage of our patients," she said.

The pooled analysis was funded by Galderma. Dr. Stein Gold is a consultant to Galderma, Stiefel, Medicis, and Warner Chilcott.

SDEF and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

WAIKOLOA, HAWAII – The fixed-dose combination of adapalene/benzoyl peroxide gel 0.1%/2.5% typically results in reductions of 40%-50% in inflammatory and 30%-40% in noninflammatory acne lesion counts during the first 4 weeks of therapy.

In a pooled analysis of 14 studies totaling 2,358 acne patients aged 9-61 years, the proportion with an Investigator’s Global Assessment (IGA) of moderate or severe acne dropped from 92% at baseline to 51% at 4 weeks, according to Dr. Linda Stein Gold.

The pooled analysis was carried out to provide physicians and patients with information as to what to realistically expect in the first 4 weeks of therapy. The analysis is particularly timely in light of the Food and Drug Administration’s recent expansion of the indication for adapalene/benzoyl peroxide gel 0.1%/2.5% (Epiduo) to include acne patients as young as 9 years of age, noted Dr. Stein Gold, director of clinical research in the department of dermatology at Henry Ford Hospital, Detroit.

Mild skin irritation was common, especially in the first 2 weeks of use.

"It’s a fiction that retinoids are too harsh for younger patients to use," Dr. Stein Gold said. "I tell all my acne patients, especially the younger ones, no matter what topical retinoid they’re using, to use it every other night for the first 2 weeks, make sure their skin is completely dry, and use a gentle cleanser and a good moisturizer," she said at the Hawaii Dermatology Seminar sponsored by Global Academy for Medical Education/Skin Disease Education Foundation. "If they get through those first 2 weeks, they’ll see that the tolerability really improves."

Dr. Stein Gold said she likes the fixed combination of adapalene/benzoyl peroxide gel 0.1%/2.5% because it combines several key elements of cutting-edge acne treatment. Topical retinoids are not mere comedone busters, as formerly thought, but are also effective agents for papules and pustular lesions. While they do not kill Propionibacterium acnes, they down-regulate Toll-like receptor 2, which is produced by the bacterium and induces proinflammatory cytokines. Topical retinoids are a key part of maintenance-of-remission strategies. And adapalene is unique among topical retinoids in that it is inherently stable with benzoyl peroxide (BPO) and is stable in daylight.

BPO is unique in that it has potent antibacterial activity, but never causes P. acnes resistance, even after many years of treatment. BPO is quite effective for inflammatory lesions and moderately effective for comedonal acne lesions, Dr. Stein Gold noted. Also, it is well established that BPO at a concentration of 2.5% is as efficacious as 5% or 10%, and much better tolerated than at the higher concentrations. The molecule size and the use of a vehicle with good penetration into the hair follicle are much more important factors in treatment effectiveness than is the BPO concentration, she added.

In one study of acne patients with antibiotic-resistant P. acnes, including clindamycin-, doxycycline-, erythromycin-, and minocycline-resistant microorganisms, 88% of the antibiotic-resistant P. acnes bacteria were killed after 2 weeks of treatment with adapalene/BPO gel 0.1%/2.5%. After 4 weeks of treatment, 97% of the antibiotic-resistant organisms were dead. That’s testimony to the P. acnes–killing power of BPO, said Dr. Stein Gold.

"There’s a sense among many that with all the newer medications we have for acne, benzoyl peroxide is really your grandfather’s treatment, with no place in today’s modern world. This is totally false. I really feel that benzoyl peroxide should play a central role in all of our acne patients’ treatment regimens, unless of course they’re allergic to it, which occurs in only a small percentage of our patients," she said.

The pooled analysis was funded by Galderma. Dr. Stein Gold is a consultant to Galderma, Stiefel, Medicis, and Warner Chilcott.

SDEF and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

WAIKOLOA, HAWAII – The fixed-dose combination of adapalene/benzoyl peroxide gel 0.1%/2.5% typically results in reductions of 40%-50% in inflammatory and 30%-40% in noninflammatory acne lesion counts during the first 4 weeks of therapy.

In a pooled analysis of 14 studies totaling 2,358 acne patients aged 9-61 years, the proportion with an Investigator’s Global Assessment (IGA) of moderate or severe acne dropped from 92% at baseline to 51% at 4 weeks, according to Dr. Linda Stein Gold.

The pooled analysis was carried out to provide physicians and patients with information as to what to realistically expect in the first 4 weeks of therapy. The analysis is particularly timely in light of the Food and Drug Administration’s recent expansion of the indication for adapalene/benzoyl peroxide gel 0.1%/2.5% (Epiduo) to include acne patients as young as 9 years of age, noted Dr. Stein Gold, director of clinical research in the department of dermatology at Henry Ford Hospital, Detroit.

Mild skin irritation was common, especially in the first 2 weeks of use.

"It’s a fiction that retinoids are too harsh for younger patients to use," Dr. Stein Gold said. "I tell all my acne patients, especially the younger ones, no matter what topical retinoid they’re using, to use it every other night for the first 2 weeks, make sure their skin is completely dry, and use a gentle cleanser and a good moisturizer," she said at the Hawaii Dermatology Seminar sponsored by Global Academy for Medical Education/Skin Disease Education Foundation. "If they get through those first 2 weeks, they’ll see that the tolerability really improves."

Dr. Stein Gold said she likes the fixed combination of adapalene/benzoyl peroxide gel 0.1%/2.5% because it combines several key elements of cutting-edge acne treatment. Topical retinoids are not mere comedone busters, as formerly thought, but are also effective agents for papules and pustular lesions. While they do not kill Propionibacterium acnes, they down-regulate Toll-like receptor 2, which is produced by the bacterium and induces proinflammatory cytokines. Topical retinoids are a key part of maintenance-of-remission strategies. And adapalene is unique among topical retinoids in that it is inherently stable with benzoyl peroxide (BPO) and is stable in daylight.

BPO is unique in that it has potent antibacterial activity, but never causes P. acnes resistance, even after many years of treatment. BPO is quite effective for inflammatory lesions and moderately effective for comedonal acne lesions, Dr. Stein Gold noted. Also, it is well established that BPO at a concentration of 2.5% is as efficacious as 5% or 10%, and much better tolerated than at the higher concentrations. The molecule size and the use of a vehicle with good penetration into the hair follicle are much more important factors in treatment effectiveness than is the BPO concentration, she added.

In one study of acne patients with antibiotic-resistant P. acnes, including clindamycin-, doxycycline-, erythromycin-, and minocycline-resistant microorganisms, 88% of the antibiotic-resistant P. acnes bacteria were killed after 2 weeks of treatment with adapalene/BPO gel 0.1%/2.5%. After 4 weeks of treatment, 97% of the antibiotic-resistant organisms were dead. That’s testimony to the P. acnes–killing power of BPO, said Dr. Stein Gold.

"There’s a sense among many that with all the newer medications we have for acne, benzoyl peroxide is really your grandfather’s treatment, with no place in today’s modern world. This is totally false. I really feel that benzoyl peroxide should play a central role in all of our acne patients’ treatment regimens, unless of course they’re allergic to it, which occurs in only a small percentage of our patients," she said.

The pooled analysis was funded by Galderma. Dr. Stein Gold is a consultant to Galderma, Stiefel, Medicis, and Warner Chilcott.

SDEF and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM SDEF HAWAII DERMATOLOGY SEMINAR

Gold-coated microparticles aid acne treatment

PHOENIX – Application of gold-coated microparticles to the skin may enhance laser photothermolysis of sebaceous glands to treat acne, according to three small, preliminary studies.

Inadequate contrast in sebaceous glands has limited the effectiveness of selective photothermolysis to treat acne. Specially engineered 0.150-mcm microparticles of inert gold coating a silica core were designed for surface plasmon resonance at near-infrared wavelengths to optimize contrast and high absorption of light in the sebaceous glands during laser treatment.

In a randomized, controlled crossover study, 48 patients with acne vulgaris received either immediate or delayed treatment for 12 weeks, after which the delayed-treatment group also began receiving the treatment. Immediate treatment included three treatments at 2-week intervals. The treatment consisted of a microparticle suspension gently massaged into facial skin for about 8 minutes, superficial skin cleansing, and pulsed irradiation with two passes of an 800-nm laser. Patients in the delayed-treatment group used an over-the-counter face wash (2% salicylic acid) twice daily.

The mean number of inflammatory lesions decreased by 34% at 12 weeks after treatment started, compared with a 16% reduction in the control group, a statistically significant difference, Dilip Paithankar, Ph.D., reported at the annual meeting of the American Society for Laser Medicine and Surgery.

At 28 weeks after the crossover to treatment for all subjects (40 weeks after the start of the study), the mean number of inflammatory lesions decreased by 61%, reported Dr. Paithankar, chief technology officer at Sebacia, Duluth, Ga., which is developing the gold-coated microparticles treatment.

In another randomized, sham-controlled study, 49 patients with acne vulgaris underwent three laser photothermolysis treatments at weekly intervals using either the gold-coated microparticles or a control vehicle without the particles. Mean inflammatory lesion counts decreased significantly more in the treatment group than in the control group at 8, 12, and 16 weeks of follow-up. In the treatment group, mean inflammatory lesion counts were 44% lower at 8 weeks, 49% lower at 12 weeks, and 53% lower at 16 weeks, compared with baseline. In the control group, mean inflammatory lesion counts were 14% lower, 22% lower, and 31% lower at those time points, respectively, compared with baseline.

Inflammatory lesions were clear or almost clear by the end of the study in 24% in the treatment group and in none of the control patients.

Data from a separate histologic study suggest that using ultrasound to assist delivery of the gold-coated microparticles may improve selective destruction from laser treatment, Dr. Girish Munavalli reported at the meeting. Ultrasound has been used in other settings to enhance delivery of small molecules through the stratum corneum.

The study used an ultrasound horn vibrating in a microparticle suspension placed in an enclosure above preauricular skin in 37 subjects, followed by 800-nm laser treatment. Biopsies taken within 15 minutes showed localized thermal injury to infundibuli and sebaceous glands with no collateral damage to surrounding tissue or to the epidermis, reported Dr. Munavalli, a dermatologist in group practice in Charlotte, N.C. The extent of thermal damage correlated with the duration of the ultrasound.

The level of damage could be expected to improve acne, but that needs confirmation in clinical trials, he said.

In each of the studies, the treatments were well tolerated, with minimal side effects including mild to moderate pain (using no anesthetic) and short-lived erythema and edema.

Dr. Paithankar works for Sebacia. Dr. Munavalli reported having no disclosures; some of his coinvestigators work for Sebacia.

On Twitter @sherryboschert

PHOENIX – Application of gold-coated microparticles to the skin may enhance laser photothermolysis of sebaceous glands to treat acne, according to three small, preliminary studies.

Inadequate contrast in sebaceous glands has limited the effectiveness of selective photothermolysis to treat acne. Specially engineered 0.150-mcm microparticles of inert gold coating a silica core were designed for surface plasmon resonance at near-infrared wavelengths to optimize contrast and high absorption of light in the sebaceous glands during laser treatment.

In a randomized, controlled crossover study, 48 patients with acne vulgaris received either immediate or delayed treatment for 12 weeks, after which the delayed-treatment group also began receiving the treatment. Immediate treatment included three treatments at 2-week intervals. The treatment consisted of a microparticle suspension gently massaged into facial skin for about 8 minutes, superficial skin cleansing, and pulsed irradiation with two passes of an 800-nm laser. Patients in the delayed-treatment group used an over-the-counter face wash (2% salicylic acid) twice daily.

The mean number of inflammatory lesions decreased by 34% at 12 weeks after treatment started, compared with a 16% reduction in the control group, a statistically significant difference, Dilip Paithankar, Ph.D., reported at the annual meeting of the American Society for Laser Medicine and Surgery.

At 28 weeks after the crossover to treatment for all subjects (40 weeks after the start of the study), the mean number of inflammatory lesions decreased by 61%, reported Dr. Paithankar, chief technology officer at Sebacia, Duluth, Ga., which is developing the gold-coated microparticles treatment.

In another randomized, sham-controlled study, 49 patients with acne vulgaris underwent three laser photothermolysis treatments at weekly intervals using either the gold-coated microparticles or a control vehicle without the particles. Mean inflammatory lesion counts decreased significantly more in the treatment group than in the control group at 8, 12, and 16 weeks of follow-up. In the treatment group, mean inflammatory lesion counts were 44% lower at 8 weeks, 49% lower at 12 weeks, and 53% lower at 16 weeks, compared with baseline. In the control group, mean inflammatory lesion counts were 14% lower, 22% lower, and 31% lower at those time points, respectively, compared with baseline.

Inflammatory lesions were clear or almost clear by the end of the study in 24% in the treatment group and in none of the control patients.

Data from a separate histologic study suggest that using ultrasound to assist delivery of the gold-coated microparticles may improve selective destruction from laser treatment, Dr. Girish Munavalli reported at the meeting. Ultrasound has been used in other settings to enhance delivery of small molecules through the stratum corneum.

The study used an ultrasound horn vibrating in a microparticle suspension placed in an enclosure above preauricular skin in 37 subjects, followed by 800-nm laser treatment. Biopsies taken within 15 minutes showed localized thermal injury to infundibuli and sebaceous glands with no collateral damage to surrounding tissue or to the epidermis, reported Dr. Munavalli, a dermatologist in group practice in Charlotte, N.C. The extent of thermal damage correlated with the duration of the ultrasound.

The level of damage could be expected to improve acne, but that needs confirmation in clinical trials, he said.

In each of the studies, the treatments were well tolerated, with minimal side effects including mild to moderate pain (using no anesthetic) and short-lived erythema and edema.

Dr. Paithankar works for Sebacia. Dr. Munavalli reported having no disclosures; some of his coinvestigators work for Sebacia.

On Twitter @sherryboschert

PHOENIX – Application of gold-coated microparticles to the skin may enhance laser photothermolysis of sebaceous glands to treat acne, according to three small, preliminary studies.

Inadequate contrast in sebaceous glands has limited the effectiveness of selective photothermolysis to treat acne. Specially engineered 0.150-mcm microparticles of inert gold coating a silica core were designed for surface plasmon resonance at near-infrared wavelengths to optimize contrast and high absorption of light in the sebaceous glands during laser treatment.

In a randomized, controlled crossover study, 48 patients with acne vulgaris received either immediate or delayed treatment for 12 weeks, after which the delayed-treatment group also began receiving the treatment. Immediate treatment included three treatments at 2-week intervals. The treatment consisted of a microparticle suspension gently massaged into facial skin for about 8 minutes, superficial skin cleansing, and pulsed irradiation with two passes of an 800-nm laser. Patients in the delayed-treatment group used an over-the-counter face wash (2% salicylic acid) twice daily.

The mean number of inflammatory lesions decreased by 34% at 12 weeks after treatment started, compared with a 16% reduction in the control group, a statistically significant difference, Dilip Paithankar, Ph.D., reported at the annual meeting of the American Society for Laser Medicine and Surgery.

At 28 weeks after the crossover to treatment for all subjects (40 weeks after the start of the study), the mean number of inflammatory lesions decreased by 61%, reported Dr. Paithankar, chief technology officer at Sebacia, Duluth, Ga., which is developing the gold-coated microparticles treatment.

In another randomized, sham-controlled study, 49 patients with acne vulgaris underwent three laser photothermolysis treatments at weekly intervals using either the gold-coated microparticles or a control vehicle without the particles. Mean inflammatory lesion counts decreased significantly more in the treatment group than in the control group at 8, 12, and 16 weeks of follow-up. In the treatment group, mean inflammatory lesion counts were 44% lower at 8 weeks, 49% lower at 12 weeks, and 53% lower at 16 weeks, compared with baseline. In the control group, mean inflammatory lesion counts were 14% lower, 22% lower, and 31% lower at those time points, respectively, compared with baseline.

Inflammatory lesions were clear or almost clear by the end of the study in 24% in the treatment group and in none of the control patients.