User login

Glomus Tumor of Uncertain Malignant Potential on the Forehead

Glomus tumors (GTs) are uncommon benign tumors originating in the neuromyoarterial elements of the glomus body, an arteriovenous shunt specialized in thermoregulation.1 Glomus tumors usually occur in the distal extremities of young adults2 and rarely are seen in the deep soft tissue or viscera. Malignant GTs are rare and highly aggressive tumors that have been associated with both local recurrence and distant metastasis.1-11 Glomus tumors have been subdivided into 3 groups with different prognoses2: (1) malignant GT with metastatic potential (subfascial or visceral location, >2 cm in size, atypical mitotic figures, >5 mitoses per 50 high-power fields [HPFs], marked nuclear atypia); (2) symplastic GT (benign tumor with nuclear pleomorphism without mitotic activity); and (3) GT of uncertain malignant potential (GTUMP)(absence of metastatic disease, favorable prognosis, at least 1 feature of malignant GTs other than marked nuclear atypia [eg, high mitotic activity, >2 cm in size, deep location]).1,2

We report a case of GTUMP with unusual clinicopathologic features in a 74-year-old man that was treated via wide surgical excision. No local recurrence or distant metastasis was noted at 3-year follow-up.

Case Report

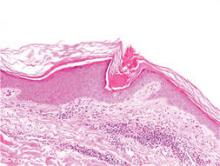

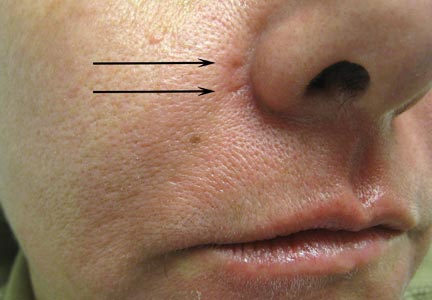

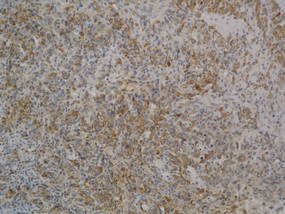

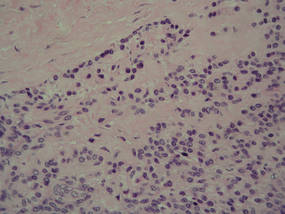

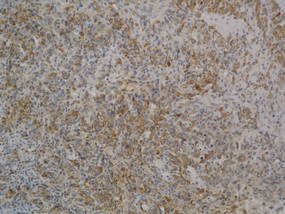

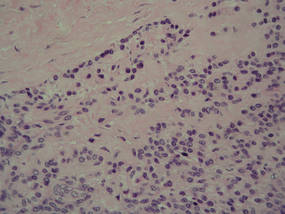

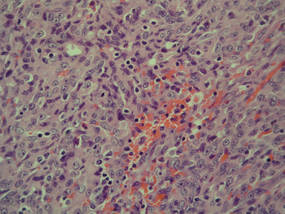

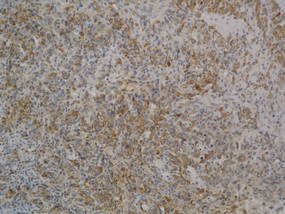

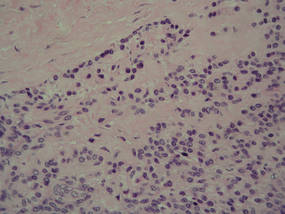

A 74-year-old man presented to the Unit of Surgery with a slowly progressing, painful, ulcerated, 2.5-cm, red-blue nodule on the forehead (Figure 1). An excisional biopsy of the nodule was performed. Histologically, the dermis and superficial subcutis were filled with a proliferation of atypical epithelioid cells to slightly spindled cells. Both cells displayed a weakly eosinophilic cytoplasm with indistinct membranes and larger ovoid nuclei, some with prominent nucleoli. Neoplastic cells showed a disordered arrangement or were organized in short fascicles separated by slitlike spaces, vascular lumens of various sizes, or hemorrhagic stroma resembling angiosarcoma or Kaposi sarcoma (Figure 2). No areas of necrosis were noted. Pleomorphic nuclei and some mitotic figures also were identified, but they were not atypical and showed fewer than 5 mitoses per 50 HPFs. Immunohistochemically, the neoplastic cells stained positive for vimentin, caldesmon (Figure 3), and a–smooth muscle actin, and they stained negative for cytokeratins, desmin, CD34, factor VIII–related antigen, S-100 protein, and the latent nuclear antigen of Kaposi sarcoma–associated herpesvirus. The Ki-67 labeling index revealed less than 20% positive cells.

|

| Figure 1. A painful, red-blue, ulcerated nodule on the forehead of a 74-year-old man. |

|

| Figure 2. The tumor was composed of atypical epithelioid cells to slightly spindled cells with indistinct membranes and larger ovoid nuclei, some with prominent nucleoli in a disordered arrangement or rather in short fascicles separated in a hemorrhagic background (H&E, original magnification ×40). |

|

| Figure 3. The neoplastic cells stained positive for caldesmon (original magnification ×20). |

|

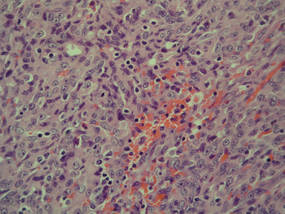

| Figure 4. A focus of round to polygonal tumor cells reminiscent of a preexisting benign-appearing glomus tumor was found on biopsy following reexcision (H&E, original magnification ×20). |

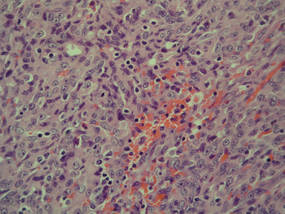

Because the tumor involved margins of excision, the patient successfully underwent wide reexcision with adequate margins. Histological examination of the reexcised specimen showed a focus of bland, round to polygonal tumor cells with the features of glomus cells (Figure 4). On the basis of the histologic features of both specimens, the lesion was classified as a GT. The biggest problem in our case was the classification of the lesion according to established pathologic criteria. We considered this case to be borderline because the lesion was greater than 2 cm but the location was superficial; marked atypia with sarcomatoid features also were present, but there was an absence of necrosis and fewer than 5 mitoses per 50 HPFs. For these reasons, we diagnosed this problematic lesion as a GTUMP. Following reexcision, the patient underwent strict follow-up. Wound healing was uncomplicated and the patient showed no local recurrence or distant metastasis at 3-year follow-up.

Comment

Clinically metastatic and histologically malignant GTs are exceptional.3-11 The classification system for GTs based on histologic criteria subdivided these tumors into 3 groups with different prognoses.2 Malignant GTs are highly aggressive tumors with metastatic potential, symplastic GTs are considered to be a degenerative phenomenon, and GTUMPs have a favorable clinical outcome and absence of metastatic disease.12

Diagnosis of malignant GTs and symplastic GTs is relatively easy in the presence of typical uniform, small, round epithelioid cells (glomus cells) located around blood vessels. Immunohistochemistry may be useful, as GTs express smooth muscle actin and caldesmon. Over the years the existence and diagnosis of malignant GT has been questioned because a residual component of benign GT in the surgical biopsy is useful in diagnosis but is not always present1-3 and because an unusual pattern may be present in malignant tumors with prevalent spindle cells resembling fibrosarcoma, leiomyosarcoma, spindle cell angiosarcoma, and spindle cell melanoma.1 In the absence of a preexisting GT, the differential diagnosis may be difficult; in such cases, a panel of immunohistochemical markers including smooth muscle actin, caldesmon, desmin, S-100, human melanoma black-45 (HMB-45), CD34, and CD31 is always necessary. The GTUMP category was introduced for GTs that demonstrate marked nuclear atypia but do not fulfill histologic criteria for malignancy. Along with other tumors of uncertain malignant potential, borderline cases should be considered GTUMPs to guarantee wide excision of the tumor with negative margins and an adequate follow-up due to the possibility of local recurrence or distant metastasis. In our patient, a diagnosis of GTUMP was made. Additionally, our case demonstrates some previously unreported features of GTUMPs, such as spindled cells in short fascicles separated by slitlike spaces, small vessels, and hemorrhagic stroma resembling Kaposi sarcoma. Along with these unusual sarcomatous features, the superficial location of the lesion, absence of necrosis, and a mitotic count of less than 5 per 50 HPFs were suggestive of an uncertain malignant potential for this tumor.

Distinction between malignant GTs and GTUMPs in the presence of unusual histologic features may be difficult.12 Glomus tumors that do not fulfill criteria for malignancy but have at least 1 atypical feature other than nuclear pleomorphism should be named GTUMPs. According to classification criteria, a true malignant GT is a highly aggressive tumor with metastatic potential. In a case series reported by Folpe et al,2 38% (20/52) of malignant GTs showed metastases, while metastatic disease was not observed in the tumors classified as GTUMPs. Wide surgical excision or Mohs micrographic surgery13 are the treatments of choice for malignant GTs and GTUMPs. Complete excision of the lesion with negative margins is always necessary in cases of GTUMPs. After the diagnosis of GTUMP, adequate follow-up should berecommended due to the possibility of local recurrence or distant metastasis.

Conclusion

Malignant GTs and GTUMPs are rare, and the nomenclature and classification of these tumors is controversial. These findings and the difficulty of differential diagnosis in a continuum between benignity and malignancy prompted our report.

1. Weiss SW, Goldblum JR. Perivascular tumors. In: Enzinger FM, Weiss SW, eds. Enzinger and Weiss’s Soft Tissue Tumors. 5th ed. St Louis, MO: Mosby; 2008:751-768.

2. Folpe AL, Fanburg-Smith JC, Miettinen M, et al. Atypical and malignant glomus tumors: analysis of 52 cases, with a proposal for the reclassification of glomus tumors. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25:1-12.

3. Aiba M, Hirayama A, Kuramochi S. Glomangiosarcoma in a glomus tumor. an immunohistochemical and ultrastructural study. Cancer. 1988;61:1467-1471.

4. Gould EW, Manivel JC, Albores-Saavedra J, et al. Locally infiltrative glomus tumors and glomangiosarcomas. a clinical, ultrastructural, and immunohistochemical study. Cancer. 1990;65:310-318.

5. Noer H, Krogdahl A. Glomangiosarcoma of the lower extremity. Histopathology. 1991;18:365-366.

6. Hiruta N, Kameda N, Tokudome T, et al. Malignant glomus tumor: a case report and review of the literature. Am J Surg Pathol. 1997;21:1096-1103.

7. Watanabe K, Sugino T, Saito A, et al. Glomangiosarcoma of the hip: report of a highly aggressive tumour with widespread distant metastases. Br J Dermatol. 1998;139:1097-1101.

8. Park JH, Oh SH, Yang MH, et al. Glomangiosarcoma of the hand: a case report and review of the literature. J Dermatol. 2003;30:827-833.

9. Kayal JD, Hampton RW, Sheehan DJ, et al. Malignant glomus tumor: a case report and review of the literature. Dermatol Surg. 2001;27:837-840.

10. Pérez de la Fuente T, Vega C, Gutierrez Palacios A, et al. Glomangiosarcoma of the hypothenar eminence: a case report. Chir Main. 2005;24:199-202.

11. Terada T, Fujimoto J, Shirakashi Y, et al. Malignant glomus tumor of the palm: a case report. J Cutan Pathol. 2011;38:381-384.

12. Gill J, Van Vliet C. Infiltrating glomus tumor of uncertain malignant potential arising in the kidney. Hum Pathol. 2010;41:145-149.

13. Cecchi R, Pavesi M, Apicella P. Malignant glomus tumor of the trunk treated with Mohs micrographic surgery [in English, German]. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2011;9:391-392.

Glomus tumors (GTs) are uncommon benign tumors originating in the neuromyoarterial elements of the glomus body, an arteriovenous shunt specialized in thermoregulation.1 Glomus tumors usually occur in the distal extremities of young adults2 and rarely are seen in the deep soft tissue or viscera. Malignant GTs are rare and highly aggressive tumors that have been associated with both local recurrence and distant metastasis.1-11 Glomus tumors have been subdivided into 3 groups with different prognoses2: (1) malignant GT with metastatic potential (subfascial or visceral location, >2 cm in size, atypical mitotic figures, >5 mitoses per 50 high-power fields [HPFs], marked nuclear atypia); (2) symplastic GT (benign tumor with nuclear pleomorphism without mitotic activity); and (3) GT of uncertain malignant potential (GTUMP)(absence of metastatic disease, favorable prognosis, at least 1 feature of malignant GTs other than marked nuclear atypia [eg, high mitotic activity, >2 cm in size, deep location]).1,2

We report a case of GTUMP with unusual clinicopathologic features in a 74-year-old man that was treated via wide surgical excision. No local recurrence or distant metastasis was noted at 3-year follow-up.

Case Report

A 74-year-old man presented to the Unit of Surgery with a slowly progressing, painful, ulcerated, 2.5-cm, red-blue nodule on the forehead (Figure 1). An excisional biopsy of the nodule was performed. Histologically, the dermis and superficial subcutis were filled with a proliferation of atypical epithelioid cells to slightly spindled cells. Both cells displayed a weakly eosinophilic cytoplasm with indistinct membranes and larger ovoid nuclei, some with prominent nucleoli. Neoplastic cells showed a disordered arrangement or were organized in short fascicles separated by slitlike spaces, vascular lumens of various sizes, or hemorrhagic stroma resembling angiosarcoma or Kaposi sarcoma (Figure 2). No areas of necrosis were noted. Pleomorphic nuclei and some mitotic figures also were identified, but they were not atypical and showed fewer than 5 mitoses per 50 HPFs. Immunohistochemically, the neoplastic cells stained positive for vimentin, caldesmon (Figure 3), and a–smooth muscle actin, and they stained negative for cytokeratins, desmin, CD34, factor VIII–related antigen, S-100 protein, and the latent nuclear antigen of Kaposi sarcoma–associated herpesvirus. The Ki-67 labeling index revealed less than 20% positive cells.

|

| Figure 1. A painful, red-blue, ulcerated nodule on the forehead of a 74-year-old man. |

|

| Figure 2. The tumor was composed of atypical epithelioid cells to slightly spindled cells with indistinct membranes and larger ovoid nuclei, some with prominent nucleoli in a disordered arrangement or rather in short fascicles separated in a hemorrhagic background (H&E, original magnification ×40). |

|

| Figure 3. The neoplastic cells stained positive for caldesmon (original magnification ×20). |

|

| Figure 4. A focus of round to polygonal tumor cells reminiscent of a preexisting benign-appearing glomus tumor was found on biopsy following reexcision (H&E, original magnification ×20). |

Because the tumor involved margins of excision, the patient successfully underwent wide reexcision with adequate margins. Histological examination of the reexcised specimen showed a focus of bland, round to polygonal tumor cells with the features of glomus cells (Figure 4). On the basis of the histologic features of both specimens, the lesion was classified as a GT. The biggest problem in our case was the classification of the lesion according to established pathologic criteria. We considered this case to be borderline because the lesion was greater than 2 cm but the location was superficial; marked atypia with sarcomatoid features also were present, but there was an absence of necrosis and fewer than 5 mitoses per 50 HPFs. For these reasons, we diagnosed this problematic lesion as a GTUMP. Following reexcision, the patient underwent strict follow-up. Wound healing was uncomplicated and the patient showed no local recurrence or distant metastasis at 3-year follow-up.

Comment

Clinically metastatic and histologically malignant GTs are exceptional.3-11 The classification system for GTs based on histologic criteria subdivided these tumors into 3 groups with different prognoses.2 Malignant GTs are highly aggressive tumors with metastatic potential, symplastic GTs are considered to be a degenerative phenomenon, and GTUMPs have a favorable clinical outcome and absence of metastatic disease.12

Diagnosis of malignant GTs and symplastic GTs is relatively easy in the presence of typical uniform, small, round epithelioid cells (glomus cells) located around blood vessels. Immunohistochemistry may be useful, as GTs express smooth muscle actin and caldesmon. Over the years the existence and diagnosis of malignant GT has been questioned because a residual component of benign GT in the surgical biopsy is useful in diagnosis but is not always present1-3 and because an unusual pattern may be present in malignant tumors with prevalent spindle cells resembling fibrosarcoma, leiomyosarcoma, spindle cell angiosarcoma, and spindle cell melanoma.1 In the absence of a preexisting GT, the differential diagnosis may be difficult; in such cases, a panel of immunohistochemical markers including smooth muscle actin, caldesmon, desmin, S-100, human melanoma black-45 (HMB-45), CD34, and CD31 is always necessary. The GTUMP category was introduced for GTs that demonstrate marked nuclear atypia but do not fulfill histologic criteria for malignancy. Along with other tumors of uncertain malignant potential, borderline cases should be considered GTUMPs to guarantee wide excision of the tumor with negative margins and an adequate follow-up due to the possibility of local recurrence or distant metastasis. In our patient, a diagnosis of GTUMP was made. Additionally, our case demonstrates some previously unreported features of GTUMPs, such as spindled cells in short fascicles separated by slitlike spaces, small vessels, and hemorrhagic stroma resembling Kaposi sarcoma. Along with these unusual sarcomatous features, the superficial location of the lesion, absence of necrosis, and a mitotic count of less than 5 per 50 HPFs were suggestive of an uncertain malignant potential for this tumor.

Distinction between malignant GTs and GTUMPs in the presence of unusual histologic features may be difficult.12 Glomus tumors that do not fulfill criteria for malignancy but have at least 1 atypical feature other than nuclear pleomorphism should be named GTUMPs. According to classification criteria, a true malignant GT is a highly aggressive tumor with metastatic potential. In a case series reported by Folpe et al,2 38% (20/52) of malignant GTs showed metastases, while metastatic disease was not observed in the tumors classified as GTUMPs. Wide surgical excision or Mohs micrographic surgery13 are the treatments of choice for malignant GTs and GTUMPs. Complete excision of the lesion with negative margins is always necessary in cases of GTUMPs. After the diagnosis of GTUMP, adequate follow-up should berecommended due to the possibility of local recurrence or distant metastasis.

Conclusion

Malignant GTs and GTUMPs are rare, and the nomenclature and classification of these tumors is controversial. These findings and the difficulty of differential diagnosis in a continuum between benignity and malignancy prompted our report.

Glomus tumors (GTs) are uncommon benign tumors originating in the neuromyoarterial elements of the glomus body, an arteriovenous shunt specialized in thermoregulation.1 Glomus tumors usually occur in the distal extremities of young adults2 and rarely are seen in the deep soft tissue or viscera. Malignant GTs are rare and highly aggressive tumors that have been associated with both local recurrence and distant metastasis.1-11 Glomus tumors have been subdivided into 3 groups with different prognoses2: (1) malignant GT with metastatic potential (subfascial or visceral location, >2 cm in size, atypical mitotic figures, >5 mitoses per 50 high-power fields [HPFs], marked nuclear atypia); (2) symplastic GT (benign tumor with nuclear pleomorphism without mitotic activity); and (3) GT of uncertain malignant potential (GTUMP)(absence of metastatic disease, favorable prognosis, at least 1 feature of malignant GTs other than marked nuclear atypia [eg, high mitotic activity, >2 cm in size, deep location]).1,2

We report a case of GTUMP with unusual clinicopathologic features in a 74-year-old man that was treated via wide surgical excision. No local recurrence or distant metastasis was noted at 3-year follow-up.

Case Report

A 74-year-old man presented to the Unit of Surgery with a slowly progressing, painful, ulcerated, 2.5-cm, red-blue nodule on the forehead (Figure 1). An excisional biopsy of the nodule was performed. Histologically, the dermis and superficial subcutis were filled with a proliferation of atypical epithelioid cells to slightly spindled cells. Both cells displayed a weakly eosinophilic cytoplasm with indistinct membranes and larger ovoid nuclei, some with prominent nucleoli. Neoplastic cells showed a disordered arrangement or were organized in short fascicles separated by slitlike spaces, vascular lumens of various sizes, or hemorrhagic stroma resembling angiosarcoma or Kaposi sarcoma (Figure 2). No areas of necrosis were noted. Pleomorphic nuclei and some mitotic figures also were identified, but they were not atypical and showed fewer than 5 mitoses per 50 HPFs. Immunohistochemically, the neoplastic cells stained positive for vimentin, caldesmon (Figure 3), and a–smooth muscle actin, and they stained negative for cytokeratins, desmin, CD34, factor VIII–related antigen, S-100 protein, and the latent nuclear antigen of Kaposi sarcoma–associated herpesvirus. The Ki-67 labeling index revealed less than 20% positive cells.

|

| Figure 1. A painful, red-blue, ulcerated nodule on the forehead of a 74-year-old man. |

|

| Figure 2. The tumor was composed of atypical epithelioid cells to slightly spindled cells with indistinct membranes and larger ovoid nuclei, some with prominent nucleoli in a disordered arrangement or rather in short fascicles separated in a hemorrhagic background (H&E, original magnification ×40). |

|

| Figure 3. The neoplastic cells stained positive for caldesmon (original magnification ×20). |

|

| Figure 4. A focus of round to polygonal tumor cells reminiscent of a preexisting benign-appearing glomus tumor was found on biopsy following reexcision (H&E, original magnification ×20). |

Because the tumor involved margins of excision, the patient successfully underwent wide reexcision with adequate margins. Histological examination of the reexcised specimen showed a focus of bland, round to polygonal tumor cells with the features of glomus cells (Figure 4). On the basis of the histologic features of both specimens, the lesion was classified as a GT. The biggest problem in our case was the classification of the lesion according to established pathologic criteria. We considered this case to be borderline because the lesion was greater than 2 cm but the location was superficial; marked atypia with sarcomatoid features also were present, but there was an absence of necrosis and fewer than 5 mitoses per 50 HPFs. For these reasons, we diagnosed this problematic lesion as a GTUMP. Following reexcision, the patient underwent strict follow-up. Wound healing was uncomplicated and the patient showed no local recurrence or distant metastasis at 3-year follow-up.

Comment

Clinically metastatic and histologically malignant GTs are exceptional.3-11 The classification system for GTs based on histologic criteria subdivided these tumors into 3 groups with different prognoses.2 Malignant GTs are highly aggressive tumors with metastatic potential, symplastic GTs are considered to be a degenerative phenomenon, and GTUMPs have a favorable clinical outcome and absence of metastatic disease.12

Diagnosis of malignant GTs and symplastic GTs is relatively easy in the presence of typical uniform, small, round epithelioid cells (glomus cells) located around blood vessels. Immunohistochemistry may be useful, as GTs express smooth muscle actin and caldesmon. Over the years the existence and diagnosis of malignant GT has been questioned because a residual component of benign GT in the surgical biopsy is useful in diagnosis but is not always present1-3 and because an unusual pattern may be present in malignant tumors with prevalent spindle cells resembling fibrosarcoma, leiomyosarcoma, spindle cell angiosarcoma, and spindle cell melanoma.1 In the absence of a preexisting GT, the differential diagnosis may be difficult; in such cases, a panel of immunohistochemical markers including smooth muscle actin, caldesmon, desmin, S-100, human melanoma black-45 (HMB-45), CD34, and CD31 is always necessary. The GTUMP category was introduced for GTs that demonstrate marked nuclear atypia but do not fulfill histologic criteria for malignancy. Along with other tumors of uncertain malignant potential, borderline cases should be considered GTUMPs to guarantee wide excision of the tumor with negative margins and an adequate follow-up due to the possibility of local recurrence or distant metastasis. In our patient, a diagnosis of GTUMP was made. Additionally, our case demonstrates some previously unreported features of GTUMPs, such as spindled cells in short fascicles separated by slitlike spaces, small vessels, and hemorrhagic stroma resembling Kaposi sarcoma. Along with these unusual sarcomatous features, the superficial location of the lesion, absence of necrosis, and a mitotic count of less than 5 per 50 HPFs were suggestive of an uncertain malignant potential for this tumor.

Distinction between malignant GTs and GTUMPs in the presence of unusual histologic features may be difficult.12 Glomus tumors that do not fulfill criteria for malignancy but have at least 1 atypical feature other than nuclear pleomorphism should be named GTUMPs. According to classification criteria, a true malignant GT is a highly aggressive tumor with metastatic potential. In a case series reported by Folpe et al,2 38% (20/52) of malignant GTs showed metastases, while metastatic disease was not observed in the tumors classified as GTUMPs. Wide surgical excision or Mohs micrographic surgery13 are the treatments of choice for malignant GTs and GTUMPs. Complete excision of the lesion with negative margins is always necessary in cases of GTUMPs. After the diagnosis of GTUMP, adequate follow-up should berecommended due to the possibility of local recurrence or distant metastasis.

Conclusion

Malignant GTs and GTUMPs are rare, and the nomenclature and classification of these tumors is controversial. These findings and the difficulty of differential diagnosis in a continuum between benignity and malignancy prompted our report.

1. Weiss SW, Goldblum JR. Perivascular tumors. In: Enzinger FM, Weiss SW, eds. Enzinger and Weiss’s Soft Tissue Tumors. 5th ed. St Louis, MO: Mosby; 2008:751-768.

2. Folpe AL, Fanburg-Smith JC, Miettinen M, et al. Atypical and malignant glomus tumors: analysis of 52 cases, with a proposal for the reclassification of glomus tumors. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25:1-12.

3. Aiba M, Hirayama A, Kuramochi S. Glomangiosarcoma in a glomus tumor. an immunohistochemical and ultrastructural study. Cancer. 1988;61:1467-1471.

4. Gould EW, Manivel JC, Albores-Saavedra J, et al. Locally infiltrative glomus tumors and glomangiosarcomas. a clinical, ultrastructural, and immunohistochemical study. Cancer. 1990;65:310-318.

5. Noer H, Krogdahl A. Glomangiosarcoma of the lower extremity. Histopathology. 1991;18:365-366.

6. Hiruta N, Kameda N, Tokudome T, et al. Malignant glomus tumor: a case report and review of the literature. Am J Surg Pathol. 1997;21:1096-1103.

7. Watanabe K, Sugino T, Saito A, et al. Glomangiosarcoma of the hip: report of a highly aggressive tumour with widespread distant metastases. Br J Dermatol. 1998;139:1097-1101.

8. Park JH, Oh SH, Yang MH, et al. Glomangiosarcoma of the hand: a case report and review of the literature. J Dermatol. 2003;30:827-833.

9. Kayal JD, Hampton RW, Sheehan DJ, et al. Malignant glomus tumor: a case report and review of the literature. Dermatol Surg. 2001;27:837-840.

10. Pérez de la Fuente T, Vega C, Gutierrez Palacios A, et al. Glomangiosarcoma of the hypothenar eminence: a case report. Chir Main. 2005;24:199-202.

11. Terada T, Fujimoto J, Shirakashi Y, et al. Malignant glomus tumor of the palm: a case report. J Cutan Pathol. 2011;38:381-384.

12. Gill J, Van Vliet C. Infiltrating glomus tumor of uncertain malignant potential arising in the kidney. Hum Pathol. 2010;41:145-149.

13. Cecchi R, Pavesi M, Apicella P. Malignant glomus tumor of the trunk treated with Mohs micrographic surgery [in English, German]. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2011;9:391-392.

1. Weiss SW, Goldblum JR. Perivascular tumors. In: Enzinger FM, Weiss SW, eds. Enzinger and Weiss’s Soft Tissue Tumors. 5th ed. St Louis, MO: Mosby; 2008:751-768.

2. Folpe AL, Fanburg-Smith JC, Miettinen M, et al. Atypical and malignant glomus tumors: analysis of 52 cases, with a proposal for the reclassification of glomus tumors. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25:1-12.

3. Aiba M, Hirayama A, Kuramochi S. Glomangiosarcoma in a glomus tumor. an immunohistochemical and ultrastructural study. Cancer. 1988;61:1467-1471.

4. Gould EW, Manivel JC, Albores-Saavedra J, et al. Locally infiltrative glomus tumors and glomangiosarcomas. a clinical, ultrastructural, and immunohistochemical study. Cancer. 1990;65:310-318.

5. Noer H, Krogdahl A. Glomangiosarcoma of the lower extremity. Histopathology. 1991;18:365-366.

6. Hiruta N, Kameda N, Tokudome T, et al. Malignant glomus tumor: a case report and review of the literature. Am J Surg Pathol. 1997;21:1096-1103.

7. Watanabe K, Sugino T, Saito A, et al. Glomangiosarcoma of the hip: report of a highly aggressive tumour with widespread distant metastases. Br J Dermatol. 1998;139:1097-1101.

8. Park JH, Oh SH, Yang MH, et al. Glomangiosarcoma of the hand: a case report and review of the literature. J Dermatol. 2003;30:827-833.

9. Kayal JD, Hampton RW, Sheehan DJ, et al. Malignant glomus tumor: a case report and review of the literature. Dermatol Surg. 2001;27:837-840.

10. Pérez de la Fuente T, Vega C, Gutierrez Palacios A, et al. Glomangiosarcoma of the hypothenar eminence: a case report. Chir Main. 2005;24:199-202.

11. Terada T, Fujimoto J, Shirakashi Y, et al. Malignant glomus tumor of the palm: a case report. J Cutan Pathol. 2011;38:381-384.

12. Gill J, Van Vliet C. Infiltrating glomus tumor of uncertain malignant potential arising in the kidney. Hum Pathol. 2010;41:145-149.

13. Cecchi R, Pavesi M, Apicella P. Malignant glomus tumor of the trunk treated with Mohs micrographic surgery [in English, German]. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2011;9:391-392.

Practice Points

- Glomus tumors have been subdivided into 3 groups with different prognoses.

- The term glomus tumor of uncertain malignant potential (GTUMP) was introduced to describe glomus tumors that demonstrate marked nuclear atypia but do not fulfill histologic criteria for malignancy.

- Complete excision with negative margins is always necessary in cases of GTUMPs.

Papular Eruption Following Excessive Tanning Bed Use

The Diagnosis: Disseminated Superficial Actinic Porokeratosis

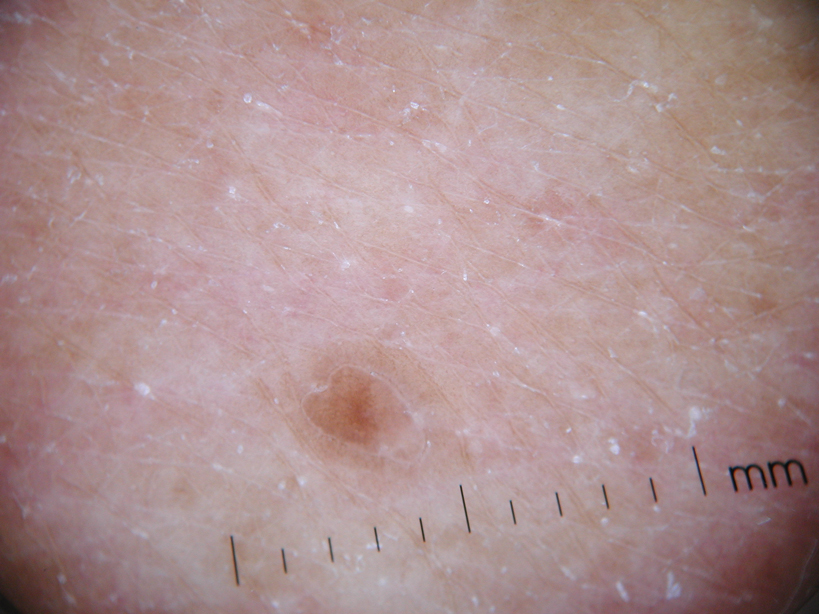

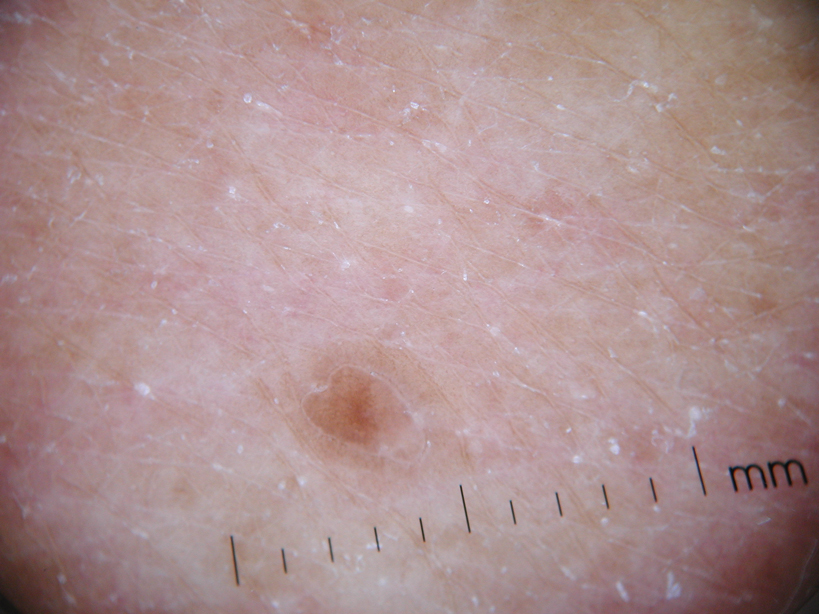

Physical examination after 7 years of tanning salon use showed a tanned white man with multiple 4- to 5-mm, discrete, round to oval, reddish brown papules on the chest, back, abdomen, arms, and legs that were rough to palpate (Figure 1), with a peripheral rim of scale seen more prominently on dermoscopy. There were no lesions on the palms or soles. A subsequent 4-mm punch biopsy was done on the right abdomen and right thigh, which showed focal thinning of the epidermis, loss of the granular layer, a discrete column of parakeratosis and a characteristic feature of a coronoid lamella in the epidermis (Figure 2). The patient received 14 narrowband UVB (NB-UVB) treatments; however, he could not continue due to transportation issues. He visited the clinic sporadically for 6 months thereafter and reportedly went to tanning salons daily. The patient was subsequently lost to follow-up.

|

|

| Figure 1. Multiple 4- to 5-mm, discrete, round to oval, reddish brown papules on the abdomen (A) and leg (B) that were rough to palpate. |

Disseminated porokeratosis, or disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis (DSAP), was first described in 1967 by Chernosky and Freeman.1 It is the most common variant of porokeratosis. Other variants include Mibelli type, porokeratosis palmaris et plantaris disseminata, punctuate porokeratosis, and linear porokeratosis.2-4 Porokeratosis is inherited in an autosomal-dominant fashion, presenting in the third or fourth decades of life; however, most cases are sporadic.5 Pruritus is a common symptom and can be debilitating.5

Disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis can be precipitated by excessive sun exposure, with a reported increase in lesions during summer months and resolution during the winter months.6 The lesions of DSAP can be experimentally induced by exposure to daily use of artificial UV sunlamps.7 Patients with psoriasis undergoing psoralen plus UVA and NB-UVB treatments also have been reported to trigger DSAP.8 A study by Neumann et al6 suggested that a combination of both UVB and UVA wavelengths may be most effective in inducing DSAP. Exposure to UVA and UVB light may explain an increased number of DSAP lesions in patients who excessively visit tanning salons, as the bulbs emit a combination of wavelengths with UVA in much greater amounts than UVB.

Our patient developed DSAP secondary to artificial UV light exposure from excessive tanning salon use. Medications (allopurinol and lisinopril) were initially thought to be etiologic agents for the eruption and also corroborated with histologic findings of a drug eruption on the initial biopsy. However, new lesions continued to develop even after cessation of medications and NB-UVB treatments. A subsequent biopsy and further history of daily tanning salon use confirmed the diagnosis of DSAP.

Therapies for this condition are limited with variable degrees of success. Cryotherapy, 5-fluorouracil cream, imiquimod cream 5%, Q-switched ruby laser, diclofenac gel 3%, and acitretin for more widespread or refractory lesions have been used with partial to complete resolution of DSAP.9

We present this case to highlight the occurrence of DSAP secondary to UV light exposure from excessive tanning salon use.

1. Chernosky ME, Freeman RG. Disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis (DSAP). Arch Dermatol. 1967;96:611-624.

2. Guss SB, Osbourn RA, Lutzner MA. Porokeratosis plantaris, palmaris et disseminata: a third type of porokeratosis. Arch Dermatol. 1971;104:366-373.

3. Brown FC. Punctate keratoderma. Arch Dermatol. 1971;104:682-683.

4. Eyre WG, Carson WE. Linear porokeratosis of Mibelli. Arch Dermatol. 1972;105:426-429.

5. Anderson DE, Chernosky ME. Disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis. Arch Dermatol. 1969;99:408-412.

6. Neumann RA, Knobler RM, Jurecka W, et al. Disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis: experimental induction and exacerbation of skin lesions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;21:1182-1188.

7. Chernosky ME, Anderson DE. Disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis: clinical studies and experimental production of lesions. Arch Dermatol. 1969;99:401-407.

8. Allen LA, Glaser DA. Disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis associated with topical PUVA. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43:720-722.

9. Arun B, Pearson J, Chalmers R. Disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis treated effectively with topical imiquimod 5% cream. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2011;36:509-511.

The Diagnosis: Disseminated Superficial Actinic Porokeratosis

Physical examination after 7 years of tanning salon use showed a tanned white man with multiple 4- to 5-mm, discrete, round to oval, reddish brown papules on the chest, back, abdomen, arms, and legs that were rough to palpate (Figure 1), with a peripheral rim of scale seen more prominently on dermoscopy. There were no lesions on the palms or soles. A subsequent 4-mm punch biopsy was done on the right abdomen and right thigh, which showed focal thinning of the epidermis, loss of the granular layer, a discrete column of parakeratosis and a characteristic feature of a coronoid lamella in the epidermis (Figure 2). The patient received 14 narrowband UVB (NB-UVB) treatments; however, he could not continue due to transportation issues. He visited the clinic sporadically for 6 months thereafter and reportedly went to tanning salons daily. The patient was subsequently lost to follow-up.

|

|

| Figure 1. Multiple 4- to 5-mm, discrete, round to oval, reddish brown papules on the abdomen (A) and leg (B) that were rough to palpate. |

Disseminated porokeratosis, or disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis (DSAP), was first described in 1967 by Chernosky and Freeman.1 It is the most common variant of porokeratosis. Other variants include Mibelli type, porokeratosis palmaris et plantaris disseminata, punctuate porokeratosis, and linear porokeratosis.2-4 Porokeratosis is inherited in an autosomal-dominant fashion, presenting in the third or fourth decades of life; however, most cases are sporadic.5 Pruritus is a common symptom and can be debilitating.5

Disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis can be precipitated by excessive sun exposure, with a reported increase in lesions during summer months and resolution during the winter months.6 The lesions of DSAP can be experimentally induced by exposure to daily use of artificial UV sunlamps.7 Patients with psoriasis undergoing psoralen plus UVA and NB-UVB treatments also have been reported to trigger DSAP.8 A study by Neumann et al6 suggested that a combination of both UVB and UVA wavelengths may be most effective in inducing DSAP. Exposure to UVA and UVB light may explain an increased number of DSAP lesions in patients who excessively visit tanning salons, as the bulbs emit a combination of wavelengths with UVA in much greater amounts than UVB.

Our patient developed DSAP secondary to artificial UV light exposure from excessive tanning salon use. Medications (allopurinol and lisinopril) were initially thought to be etiologic agents for the eruption and also corroborated with histologic findings of a drug eruption on the initial biopsy. However, new lesions continued to develop even after cessation of medications and NB-UVB treatments. A subsequent biopsy and further history of daily tanning salon use confirmed the diagnosis of DSAP.

Therapies for this condition are limited with variable degrees of success. Cryotherapy, 5-fluorouracil cream, imiquimod cream 5%, Q-switched ruby laser, diclofenac gel 3%, and acitretin for more widespread or refractory lesions have been used with partial to complete resolution of DSAP.9

We present this case to highlight the occurrence of DSAP secondary to UV light exposure from excessive tanning salon use.

The Diagnosis: Disseminated Superficial Actinic Porokeratosis

Physical examination after 7 years of tanning salon use showed a tanned white man with multiple 4- to 5-mm, discrete, round to oval, reddish brown papules on the chest, back, abdomen, arms, and legs that were rough to palpate (Figure 1), with a peripheral rim of scale seen more prominently on dermoscopy. There were no lesions on the palms or soles. A subsequent 4-mm punch biopsy was done on the right abdomen and right thigh, which showed focal thinning of the epidermis, loss of the granular layer, a discrete column of parakeratosis and a characteristic feature of a coronoid lamella in the epidermis (Figure 2). The patient received 14 narrowband UVB (NB-UVB) treatments; however, he could not continue due to transportation issues. He visited the clinic sporadically for 6 months thereafter and reportedly went to tanning salons daily. The patient was subsequently lost to follow-up.

|

|

| Figure 1. Multiple 4- to 5-mm, discrete, round to oval, reddish brown papules on the abdomen (A) and leg (B) that were rough to palpate. |

Disseminated porokeratosis, or disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis (DSAP), was first described in 1967 by Chernosky and Freeman.1 It is the most common variant of porokeratosis. Other variants include Mibelli type, porokeratosis palmaris et plantaris disseminata, punctuate porokeratosis, and linear porokeratosis.2-4 Porokeratosis is inherited in an autosomal-dominant fashion, presenting in the third or fourth decades of life; however, most cases are sporadic.5 Pruritus is a common symptom and can be debilitating.5

Disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis can be precipitated by excessive sun exposure, with a reported increase in lesions during summer months and resolution during the winter months.6 The lesions of DSAP can be experimentally induced by exposure to daily use of artificial UV sunlamps.7 Patients with psoriasis undergoing psoralen plus UVA and NB-UVB treatments also have been reported to trigger DSAP.8 A study by Neumann et al6 suggested that a combination of both UVB and UVA wavelengths may be most effective in inducing DSAP. Exposure to UVA and UVB light may explain an increased number of DSAP lesions in patients who excessively visit tanning salons, as the bulbs emit a combination of wavelengths with UVA in much greater amounts than UVB.

Our patient developed DSAP secondary to artificial UV light exposure from excessive tanning salon use. Medications (allopurinol and lisinopril) were initially thought to be etiologic agents for the eruption and also corroborated with histologic findings of a drug eruption on the initial biopsy. However, new lesions continued to develop even after cessation of medications and NB-UVB treatments. A subsequent biopsy and further history of daily tanning salon use confirmed the diagnosis of DSAP.

Therapies for this condition are limited with variable degrees of success. Cryotherapy, 5-fluorouracil cream, imiquimod cream 5%, Q-switched ruby laser, diclofenac gel 3%, and acitretin for more widespread or refractory lesions have been used with partial to complete resolution of DSAP.9

We present this case to highlight the occurrence of DSAP secondary to UV light exposure from excessive tanning salon use.

1. Chernosky ME, Freeman RG. Disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis (DSAP). Arch Dermatol. 1967;96:611-624.

2. Guss SB, Osbourn RA, Lutzner MA. Porokeratosis plantaris, palmaris et disseminata: a third type of porokeratosis. Arch Dermatol. 1971;104:366-373.

3. Brown FC. Punctate keratoderma. Arch Dermatol. 1971;104:682-683.

4. Eyre WG, Carson WE. Linear porokeratosis of Mibelli. Arch Dermatol. 1972;105:426-429.

5. Anderson DE, Chernosky ME. Disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis. Arch Dermatol. 1969;99:408-412.

6. Neumann RA, Knobler RM, Jurecka W, et al. Disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis: experimental induction and exacerbation of skin lesions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;21:1182-1188.

7. Chernosky ME, Anderson DE. Disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis: clinical studies and experimental production of lesions. Arch Dermatol. 1969;99:401-407.

8. Allen LA, Glaser DA. Disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis associated with topical PUVA. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43:720-722.

9. Arun B, Pearson J, Chalmers R. Disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis treated effectively with topical imiquimod 5% cream. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2011;36:509-511.

1. Chernosky ME, Freeman RG. Disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis (DSAP). Arch Dermatol. 1967;96:611-624.

2. Guss SB, Osbourn RA, Lutzner MA. Porokeratosis plantaris, palmaris et disseminata: a third type of porokeratosis. Arch Dermatol. 1971;104:366-373.

3. Brown FC. Punctate keratoderma. Arch Dermatol. 1971;104:682-683.

4. Eyre WG, Carson WE. Linear porokeratosis of Mibelli. Arch Dermatol. 1972;105:426-429.

5. Anderson DE, Chernosky ME. Disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis. Arch Dermatol. 1969;99:408-412.

6. Neumann RA, Knobler RM, Jurecka W, et al. Disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis: experimental induction and exacerbation of skin lesions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;21:1182-1188.

7. Chernosky ME, Anderson DE. Disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis: clinical studies and experimental production of lesions. Arch Dermatol. 1969;99:401-407.

8. Allen LA, Glaser DA. Disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis associated with topical PUVA. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43:720-722.

9. Arun B, Pearson J, Chalmers R. Disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis treated effectively with topical imiquimod 5% cream. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2011;36:509-511.

A 78-year-old man with Fitzpatrick skin type III presented to the dermatology department for evaluation of a pruritic, erythematous, papular eruption on the chest, back, abdomen, arms, and legs of 5 years’ duration. His medications include clonazepam, lisinopril, allopurinol, omeprazole, tramadol, and mirtazapine. The lesions did not respond to topical corticosteroids; however, the pruritus improved with narrowband UVB (NB-UVB) treatments. Review of systems did not reveal any abnormalities. The patient’s medical history included gout, hypertension, anxiety, esophageal stricture, and emphysema. He reported a history of tanning salon use at least 3 times weekly for 7 years. After initial consultation, the patient was treated with clobetasol propionate cream 0.05% twice daily and hydroxyzine 10 mg 3 times daily. Following 1 month of treatment, the eruption did not improve. A 4-mm punch biopsy of the left upper arm revealed a dense infiltrate in the upper dermis with prominent parakeratosis, lymphocytes, and numerous eosinophils, suggestive of a drug eruption. As a result, allopurinol was discontinued as a causative agent; however, the eruption presented prior to taking allopurinol. Because the patient experienced intense pruritus, he was started on NB-UVB treatments. After 14 treatments of NB-UVB 3 times weekly, the patient noticed some improvement with respect to pruritus, but the lesions did not resolve. A complete blood cell count indicated 7.6% eosinophils (reference range, 0%–5%). Liver function tests, complete metabolic profile, and renal function were within reference range. Lisinopril was then discontinued as a likely culprit for persistent drug eruption; however, new lesions continued to develop.

Best Practices in Pulsed Dye Laser Treatment

For more information, access Dr. Ezra's article from the August 2014 issue, "Linear Scarring Following Treatment With a 595-nm Pulsed Dye Laser."

For more information, access Dr. Ezra's article from the August 2014 issue, "Linear Scarring Following Treatment With a 595-nm Pulsed Dye Laser."

For more information, access Dr. Ezra's article from the August 2014 issue, "Linear Scarring Following Treatment With a 595-nm Pulsed Dye Laser."

Mastering the Masseter Muscle: Tailored Treatment of Masseter Hypertrophy

In the article “Classification of Masseter Hypertrophy for Tailored Botulinum Toxin Type A Treatment” (Plast Reconstr Surg. 2014;134:209e-218e), Xie et al systemically classified and compared degrees of masseter hypertrophy and then prospectively used this system to tailor treatment with botulinum toxin type A. The authors identified 5 different bulging types of a contracted masseter: minimal, mono, double, triple, and excessive. Ultrasound studies and cadaver dissections were used to identify the bulging type and showed that the masseter consists of 3 different muscle layers that exhibit different directions of muscle contraction. These muscle layers are innervated by separate nerve branches that originate from the nervus massetericus, the most prominent part of the masseter bulge corresponding to the distribution region of the nervus massetericus in the central lower one-third region. The authors concluded that an injection close to the nerve endings at this site of insertion would allow for a reduced injection dosage and limited dispersion. Therefore, they chose the most prominent point of the bulging masseter while clenching as the ideal initial injection point.

What’s the issue?

The off-label use of botulinum toxin type A for the treatment of masseter hypertrophy is becoming more popular. It has been used for aesthetic volume reduction of the masseter and lower-face recontouring. Masseter hypertrophy can cause a prominent mandibular angle resulting in a wide counter of the lower face, which can be a cause of aesthetic concern in women and men as well as individuals of many ethnicities, such as those of Asian descent. The reported doses of neurotoxin as well as injection points and techniques vary, making it difficult to translate into clinical practice. Xie et al have suggested a tailored approach to the treatment of masseter hypertrophy rather than injecting in a prototypical approach. The authors had the patient clench and palpated the masseter to classify it into 1 of 5 types. Then the main injection point was into the belly of the most prominent bulge. Further injection points (range, 1–3) were used depending on the type of masseter hypertrophy. The minimal dose of botulinum toxin type A used was 20 U with the highest amount being 40 U. The greatest effect in reduction of masseter hypertrophy occurred at 3 months. Adverse effects encountered were on par with prior reports and included unnatural smile, concavity below the zygomatic arch, and even paradoxical bulging. The overall complication rate was 9.1% (20/220), but it was 60% among patients who received higher doses. With this classification system and injection pattern described, the authors noted a reduction in injection dose and therefore complication rates as well as significantly reduced masseter volume and improved lower face contour (P<.01). When it comes to masseter injections and lower-face shaping, what is your method?

In the article “Classification of Masseter Hypertrophy for Tailored Botulinum Toxin Type A Treatment” (Plast Reconstr Surg. 2014;134:209e-218e), Xie et al systemically classified and compared degrees of masseter hypertrophy and then prospectively used this system to tailor treatment with botulinum toxin type A. The authors identified 5 different bulging types of a contracted masseter: minimal, mono, double, triple, and excessive. Ultrasound studies and cadaver dissections were used to identify the bulging type and showed that the masseter consists of 3 different muscle layers that exhibit different directions of muscle contraction. These muscle layers are innervated by separate nerve branches that originate from the nervus massetericus, the most prominent part of the masseter bulge corresponding to the distribution region of the nervus massetericus in the central lower one-third region. The authors concluded that an injection close to the nerve endings at this site of insertion would allow for a reduced injection dosage and limited dispersion. Therefore, they chose the most prominent point of the bulging masseter while clenching as the ideal initial injection point.

What’s the issue?

The off-label use of botulinum toxin type A for the treatment of masseter hypertrophy is becoming more popular. It has been used for aesthetic volume reduction of the masseter and lower-face recontouring. Masseter hypertrophy can cause a prominent mandibular angle resulting in a wide counter of the lower face, which can be a cause of aesthetic concern in women and men as well as individuals of many ethnicities, such as those of Asian descent. The reported doses of neurotoxin as well as injection points and techniques vary, making it difficult to translate into clinical practice. Xie et al have suggested a tailored approach to the treatment of masseter hypertrophy rather than injecting in a prototypical approach. The authors had the patient clench and palpated the masseter to classify it into 1 of 5 types. Then the main injection point was into the belly of the most prominent bulge. Further injection points (range, 1–3) were used depending on the type of masseter hypertrophy. The minimal dose of botulinum toxin type A used was 20 U with the highest amount being 40 U. The greatest effect in reduction of masseter hypertrophy occurred at 3 months. Adverse effects encountered were on par with prior reports and included unnatural smile, concavity below the zygomatic arch, and even paradoxical bulging. The overall complication rate was 9.1% (20/220), but it was 60% among patients who received higher doses. With this classification system and injection pattern described, the authors noted a reduction in injection dose and therefore complication rates as well as significantly reduced masseter volume and improved lower face contour (P<.01). When it comes to masseter injections and lower-face shaping, what is your method?

In the article “Classification of Masseter Hypertrophy for Tailored Botulinum Toxin Type A Treatment” (Plast Reconstr Surg. 2014;134:209e-218e), Xie et al systemically classified and compared degrees of masseter hypertrophy and then prospectively used this system to tailor treatment with botulinum toxin type A. The authors identified 5 different bulging types of a contracted masseter: minimal, mono, double, triple, and excessive. Ultrasound studies and cadaver dissections were used to identify the bulging type and showed that the masseter consists of 3 different muscle layers that exhibit different directions of muscle contraction. These muscle layers are innervated by separate nerve branches that originate from the nervus massetericus, the most prominent part of the masseter bulge corresponding to the distribution region of the nervus massetericus in the central lower one-third region. The authors concluded that an injection close to the nerve endings at this site of insertion would allow for a reduced injection dosage and limited dispersion. Therefore, they chose the most prominent point of the bulging masseter while clenching as the ideal initial injection point.

What’s the issue?

The off-label use of botulinum toxin type A for the treatment of masseter hypertrophy is becoming more popular. It has been used for aesthetic volume reduction of the masseter and lower-face recontouring. Masseter hypertrophy can cause a prominent mandibular angle resulting in a wide counter of the lower face, which can be a cause of aesthetic concern in women and men as well as individuals of many ethnicities, such as those of Asian descent. The reported doses of neurotoxin as well as injection points and techniques vary, making it difficult to translate into clinical practice. Xie et al have suggested a tailored approach to the treatment of masseter hypertrophy rather than injecting in a prototypical approach. The authors had the patient clench and palpated the masseter to classify it into 1 of 5 types. Then the main injection point was into the belly of the most prominent bulge. Further injection points (range, 1–3) were used depending on the type of masseter hypertrophy. The minimal dose of botulinum toxin type A used was 20 U with the highest amount being 40 U. The greatest effect in reduction of masseter hypertrophy occurred at 3 months. Adverse effects encountered were on par with prior reports and included unnatural smile, concavity below the zygomatic arch, and even paradoxical bulging. The overall complication rate was 9.1% (20/220), but it was 60% among patients who received higher doses. With this classification system and injection pattern described, the authors noted a reduction in injection dose and therefore complication rates as well as significantly reduced masseter volume and improved lower face contour (P<.01). When it comes to masseter injections and lower-face shaping, what is your method?

Cosmetic Corner: Dermatologists Weigh in on Toners

To improve patient care and outcomes, leading dermatologists offered their recommendations on the top toners. Consideration must be given to:

- Calendula Herbal Extract Alcohol-Free Toner

Kiehl’s

“There is no alcohol base in this toner, which makes it far less drying than most, but it still is suitable for patients with more sebaceous/oily skin.”—Anthony M. Rossi, MD, New York, New York

- Copper Firming Mist

Innovative Skincare

“Copper Firming Mist is a unique toner that contains copper to promote collagen production in the skin. Also, Copper Firming Mist assists to hydrate tissue while regulating sebaceous gland activity. This product is especially good to use after laser treatments, as it assists in healing and hydrating after a procedure.”—Wm. Philip Werschler, MD, Seattle, Washington

- Effaclar Toner

La Roche-Posay Laboratoire Dermatologique

“This toner has lipohydroxy acid, which helps with mild acne and enlarged pores.”—Gary Goldenberg, MD, New York, New York

- Teoxane RHA Prime Solution

Alphaeon Corporation

“[The product] doesn’t just cleanse and normalize pH but delivers resilient hyaluronic acid, vitamin B6, zinc, and copper, as well as peptides and antioxidants.”—Mary P. Lupo, MD, New Orleans, Louisiana

Cutis invites readers to send us their recommendations. Over-the-counter antioxidants and facial scrubs will be featured in upcoming editions of Cosmetic Corner. Please e-mail your recommendation(s) to cutis@frontlinemedcom.com.

Disclaimer: Opinions expressed herein do not necessarily reflect those of Cutis or Frontline Medical Communications Inc. and shall not be used for product endorsement purposes. Any reference made to a specific commercial product does not indicate or imply that Cutis or Frontline Medical Communications Inc. endorses, recommends, or favors the product mentioned. No guarantee is given to the effects of recommended products.

To improve patient care and outcomes, leading dermatologists offered their recommendations on the top toners. Consideration must be given to:

- Calendula Herbal Extract Alcohol-Free Toner

Kiehl’s

“There is no alcohol base in this toner, which makes it far less drying than most, but it still is suitable for patients with more sebaceous/oily skin.”—Anthony M. Rossi, MD, New York, New York

- Copper Firming Mist

Innovative Skincare

“Copper Firming Mist is a unique toner that contains copper to promote collagen production in the skin. Also, Copper Firming Mist assists to hydrate tissue while regulating sebaceous gland activity. This product is especially good to use after laser treatments, as it assists in healing and hydrating after a procedure.”—Wm. Philip Werschler, MD, Seattle, Washington

- Effaclar Toner

La Roche-Posay Laboratoire Dermatologique

“This toner has lipohydroxy acid, which helps with mild acne and enlarged pores.”—Gary Goldenberg, MD, New York, New York

- Teoxane RHA Prime Solution

Alphaeon Corporation

“[The product] doesn’t just cleanse and normalize pH but delivers resilient hyaluronic acid, vitamin B6, zinc, and copper, as well as peptides and antioxidants.”—Mary P. Lupo, MD, New Orleans, Louisiana

Cutis invites readers to send us their recommendations. Over-the-counter antioxidants and facial scrubs will be featured in upcoming editions of Cosmetic Corner. Please e-mail your recommendation(s) to cutis@frontlinemedcom.com.

Disclaimer: Opinions expressed herein do not necessarily reflect those of Cutis or Frontline Medical Communications Inc. and shall not be used for product endorsement purposes. Any reference made to a specific commercial product does not indicate or imply that Cutis or Frontline Medical Communications Inc. endorses, recommends, or favors the product mentioned. No guarantee is given to the effects of recommended products.

To improve patient care and outcomes, leading dermatologists offered their recommendations on the top toners. Consideration must be given to:

- Calendula Herbal Extract Alcohol-Free Toner

Kiehl’s

“There is no alcohol base in this toner, which makes it far less drying than most, but it still is suitable for patients with more sebaceous/oily skin.”—Anthony M. Rossi, MD, New York, New York

- Copper Firming Mist

Innovative Skincare

“Copper Firming Mist is a unique toner that contains copper to promote collagen production in the skin. Also, Copper Firming Mist assists to hydrate tissue while regulating sebaceous gland activity. This product is especially good to use after laser treatments, as it assists in healing and hydrating after a procedure.”—Wm. Philip Werschler, MD, Seattle, Washington

- Effaclar Toner

La Roche-Posay Laboratoire Dermatologique

“This toner has lipohydroxy acid, which helps with mild acne and enlarged pores.”—Gary Goldenberg, MD, New York, New York

- Teoxane RHA Prime Solution

Alphaeon Corporation

“[The product] doesn’t just cleanse and normalize pH but delivers resilient hyaluronic acid, vitamin B6, zinc, and copper, as well as peptides and antioxidants.”—Mary P. Lupo, MD, New Orleans, Louisiana

Cutis invites readers to send us their recommendations. Over-the-counter antioxidants and facial scrubs will be featured in upcoming editions of Cosmetic Corner. Please e-mail your recommendation(s) to cutis@frontlinemedcom.com.

Disclaimer: Opinions expressed herein do not necessarily reflect those of Cutis or Frontline Medical Communications Inc. and shall not be used for product endorsement purposes. Any reference made to a specific commercial product does not indicate or imply that Cutis or Frontline Medical Communications Inc. endorses, recommends, or favors the product mentioned. No guarantee is given to the effects of recommended products.

Effective treatments abound for children with heavy sweating in the hands and feet

COEUR D’ALENE, IDAHO – By the time patients seek a physician’s help for palmar/plantar focal hyperhidrosis, they may be well beyond the point at which even potent topical antiperspirants will help.

"Most people think there is nothing that can be done at all [for these patients]. But there are effective options. Even if you’re not going to offer them, get your patients to someone who will. We can make a profound difference for children and adolescents," Dr. Jane S. Bellet said at the annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology.

In fact, more potent therapies are available, ranging from iontophoresis to oral medications, botulinum toxin A injections, and surgical thoracic sympathetectomy.

Oral medications: "I’ve really changed my practice in the last 5 years. I didn’t use systemic medications very much. I use them much more frequently now. I think you can get a very nice response," said Dr. Bellet, a pediatric dermatologist at Duke University in Durham, N.C.

She typically turns to the anticholinergic agents glycopyrrolate and oxybutynin. Glycopyrrolate, marketed as Cuvposa in a cherry-flavored solution at 1 mg/5 mL, does not have an indication from the Food and Drug Administration for treatment of pediatric hyperhidrosis, she noted. However, it is FDA-approved in 3- to 16-year-olds for severe chronic drooling caused by neurologic disorders.

"Although we don’t have an indication for hyperhidrosis, we do have a pediatric indication, and I think many times that puts our parents at ease," she observed.

Glycopyrrolate is cost effective and painless, although approximately 30% of children treated for hyperhidrosis will develop dry mouth and/or dry eyes.

"I would definitely add glycopyrrolate to your armamentarium. I think the biggest concern most of us have is the side effects. Speak about them with the family ahead of time, guide them as to what to expect, and stop if it becomes intolerable," Dr. Bellet said.

A recent randomized, prospective, controlled clinical trial in 45 children aged 7-14 years with palmar hyperhidrosis showed excellent outcomes with oxybutynin (Ditropan), with more than 85% experiencing at least moderate improvement in sweating and 80% gaining improved quality of life (Pediatr. Dermatol. 2014;31:48-53).

Iontophoresis: "This is a wonderful treatment for palms and soles," said Dr. Bellet.

The treatment entails placing the hands or feet in a water bath tray filled with tap water through which direct electric current is running. The proposed mechanism of benefit is that hydrolysis of the bath water results in accumulation of hydrogen ions, which then induce sweat gland destruction.

The chief disadvantage of iontophoresis is that it is labor intensive. Unless the family rents or buys a home unit, the patient typically must visit the physician’s office on a daily basis initially, placing the hands or feet in the bath for 10 minutes, followed by a second 10-minute round after the polarity is switched. Eventually, many patients can step down to two or three 20- to 30-minute sessions per week, then perhaps once-weekly maintenance therapy, she said.

Adding glycopyrrolate to the water bath has been shown to result in longer improvement in a study in both children and adults (Australas. J. Dermatol. 2004;45:208-12); however, this poses a greater risk of systemic absorption in children.

"Interestingly enough, some insurance companies will cover iontophoresis if you add glycopyrrolate to the water, but they won’t cover regular iontophoresis," Dr. Bellet said.

In response to audience inquiries, she indicated she uses the Fischer MD-1a galvanic unit. It’s simple to operate, costs about $700 including accessories, and can be rented with the payments applied to a later purchase.

Botulinum toxin A: First using this product for hyperhidrosis is off-label therapy, Dr. Bellet emphasized. Second, the doses required to treat palmar/plantar hyperhidrosis – 75-100 units per palm or sole – are much higher than in treating the axillae. Also, injecting botulinum toxin A into the palms and soles is extraordinarily painful. Children typically require general anesthesia, because the alternative methods employed with mixed results in adults, including EMLA cream, ice packs, and ethyl chloride spray, don’t cut it in younger patients, Dr. Bellet noted.

That being said, botulinum toxin A therapy works quite well in children and adolescents. However, it’s important to explain to patients and parents up front that the injections can cause transient weakness of the hand muscles because of the diffusion of the toxin from dermis to muscles; for a budding pianist or baseball pitcher, that can be a deal-breaker, she said. Also, Dr. Bellet added, repeated injections can result in atrophy of the thenar and hypothenar eminences, with resultant irreversible weakness.

Thoracic sympathectomy: Not many American thoracic surgeons do sympathectomy to treat hyperhidrosis on a frequent basis, but those with extensive experience obtain outstanding results, Dr. Bellet said. To treat palmar hyperhidrosis, the nerve is clipped at the top of the third or fourth rib; for the soles, it’s at the fourth and fifth rib. The youngest reported treated patients have been 8 years old.

Dr. Bellet recommended the International Hyperhidrosis Society (www.sweathelp.org) as an excellent source of further information.

Dr. Bellet reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding her presentation.

How do you treat palmar/plantar hyperhidrosis in children? Take our Quick Poll on the Skin & Allergy News homepage.

COEUR D’ALENE, IDAHO – By the time patients seek a physician’s help for palmar/plantar focal hyperhidrosis, they may be well beyond the point at which even potent topical antiperspirants will help.

"Most people think there is nothing that can be done at all [for these patients]. But there are effective options. Even if you’re not going to offer them, get your patients to someone who will. We can make a profound difference for children and adolescents," Dr. Jane S. Bellet said at the annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology.

In fact, more potent therapies are available, ranging from iontophoresis to oral medications, botulinum toxin A injections, and surgical thoracic sympathetectomy.

Oral medications: "I’ve really changed my practice in the last 5 years. I didn’t use systemic medications very much. I use them much more frequently now. I think you can get a very nice response," said Dr. Bellet, a pediatric dermatologist at Duke University in Durham, N.C.

She typically turns to the anticholinergic agents glycopyrrolate and oxybutynin. Glycopyrrolate, marketed as Cuvposa in a cherry-flavored solution at 1 mg/5 mL, does not have an indication from the Food and Drug Administration for treatment of pediatric hyperhidrosis, she noted. However, it is FDA-approved in 3- to 16-year-olds for severe chronic drooling caused by neurologic disorders.

"Although we don’t have an indication for hyperhidrosis, we do have a pediatric indication, and I think many times that puts our parents at ease," she observed.

Glycopyrrolate is cost effective and painless, although approximately 30% of children treated for hyperhidrosis will develop dry mouth and/or dry eyes.

"I would definitely add glycopyrrolate to your armamentarium. I think the biggest concern most of us have is the side effects. Speak about them with the family ahead of time, guide them as to what to expect, and stop if it becomes intolerable," Dr. Bellet said.

A recent randomized, prospective, controlled clinical trial in 45 children aged 7-14 years with palmar hyperhidrosis showed excellent outcomes with oxybutynin (Ditropan), with more than 85% experiencing at least moderate improvement in sweating and 80% gaining improved quality of life (Pediatr. Dermatol. 2014;31:48-53).

Iontophoresis: "This is a wonderful treatment for palms and soles," said Dr. Bellet.

The treatment entails placing the hands or feet in a water bath tray filled with tap water through which direct electric current is running. The proposed mechanism of benefit is that hydrolysis of the bath water results in accumulation of hydrogen ions, which then induce sweat gland destruction.

The chief disadvantage of iontophoresis is that it is labor intensive. Unless the family rents or buys a home unit, the patient typically must visit the physician’s office on a daily basis initially, placing the hands or feet in the bath for 10 minutes, followed by a second 10-minute round after the polarity is switched. Eventually, many patients can step down to two or three 20- to 30-minute sessions per week, then perhaps once-weekly maintenance therapy, she said.

Adding glycopyrrolate to the water bath has been shown to result in longer improvement in a study in both children and adults (Australas. J. Dermatol. 2004;45:208-12); however, this poses a greater risk of systemic absorption in children.

"Interestingly enough, some insurance companies will cover iontophoresis if you add glycopyrrolate to the water, but they won’t cover regular iontophoresis," Dr. Bellet said.

In response to audience inquiries, she indicated she uses the Fischer MD-1a galvanic unit. It’s simple to operate, costs about $700 including accessories, and can be rented with the payments applied to a later purchase.

Botulinum toxin A: First using this product for hyperhidrosis is off-label therapy, Dr. Bellet emphasized. Second, the doses required to treat palmar/plantar hyperhidrosis – 75-100 units per palm or sole – are much higher than in treating the axillae. Also, injecting botulinum toxin A into the palms and soles is extraordinarily painful. Children typically require general anesthesia, because the alternative methods employed with mixed results in adults, including EMLA cream, ice packs, and ethyl chloride spray, don’t cut it in younger patients, Dr. Bellet noted.

That being said, botulinum toxin A therapy works quite well in children and adolescents. However, it’s important to explain to patients and parents up front that the injections can cause transient weakness of the hand muscles because of the diffusion of the toxin from dermis to muscles; for a budding pianist or baseball pitcher, that can be a deal-breaker, she said. Also, Dr. Bellet added, repeated injections can result in atrophy of the thenar and hypothenar eminences, with resultant irreversible weakness.

Thoracic sympathectomy: Not many American thoracic surgeons do sympathectomy to treat hyperhidrosis on a frequent basis, but those with extensive experience obtain outstanding results, Dr. Bellet said. To treat palmar hyperhidrosis, the nerve is clipped at the top of the third or fourth rib; for the soles, it’s at the fourth and fifth rib. The youngest reported treated patients have been 8 years old.

Dr. Bellet recommended the International Hyperhidrosis Society (www.sweathelp.org) as an excellent source of further information.

Dr. Bellet reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding her presentation.

How do you treat palmar/plantar hyperhidrosis in children? Take our Quick Poll on the Skin & Allergy News homepage.

COEUR D’ALENE, IDAHO – By the time patients seek a physician’s help for palmar/plantar focal hyperhidrosis, they may be well beyond the point at which even potent topical antiperspirants will help.

"Most people think there is nothing that can be done at all [for these patients]. But there are effective options. Even if you’re not going to offer them, get your patients to someone who will. We can make a profound difference for children and adolescents," Dr. Jane S. Bellet said at the annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology.

In fact, more potent therapies are available, ranging from iontophoresis to oral medications, botulinum toxin A injections, and surgical thoracic sympathetectomy.

Oral medications: "I’ve really changed my practice in the last 5 years. I didn’t use systemic medications very much. I use them much more frequently now. I think you can get a very nice response," said Dr. Bellet, a pediatric dermatologist at Duke University in Durham, N.C.

She typically turns to the anticholinergic agents glycopyrrolate and oxybutynin. Glycopyrrolate, marketed as Cuvposa in a cherry-flavored solution at 1 mg/5 mL, does not have an indication from the Food and Drug Administration for treatment of pediatric hyperhidrosis, she noted. However, it is FDA-approved in 3- to 16-year-olds for severe chronic drooling caused by neurologic disorders.

"Although we don’t have an indication for hyperhidrosis, we do have a pediatric indication, and I think many times that puts our parents at ease," she observed.

Glycopyrrolate is cost effective and painless, although approximately 30% of children treated for hyperhidrosis will develop dry mouth and/or dry eyes.

"I would definitely add glycopyrrolate to your armamentarium. I think the biggest concern most of us have is the side effects. Speak about them with the family ahead of time, guide them as to what to expect, and stop if it becomes intolerable," Dr. Bellet said.

A recent randomized, prospective, controlled clinical trial in 45 children aged 7-14 years with palmar hyperhidrosis showed excellent outcomes with oxybutynin (Ditropan), with more than 85% experiencing at least moderate improvement in sweating and 80% gaining improved quality of life (Pediatr. Dermatol. 2014;31:48-53).

Iontophoresis: "This is a wonderful treatment for palms and soles," said Dr. Bellet.

The treatment entails placing the hands or feet in a water bath tray filled with tap water through which direct electric current is running. The proposed mechanism of benefit is that hydrolysis of the bath water results in accumulation of hydrogen ions, which then induce sweat gland destruction.

The chief disadvantage of iontophoresis is that it is labor intensive. Unless the family rents or buys a home unit, the patient typically must visit the physician’s office on a daily basis initially, placing the hands or feet in the bath for 10 minutes, followed by a second 10-minute round after the polarity is switched. Eventually, many patients can step down to two or three 20- to 30-minute sessions per week, then perhaps once-weekly maintenance therapy, she said.

Adding glycopyrrolate to the water bath has been shown to result in longer improvement in a study in both children and adults (Australas. J. Dermatol. 2004;45:208-12); however, this poses a greater risk of systemic absorption in children.

"Interestingly enough, some insurance companies will cover iontophoresis if you add glycopyrrolate to the water, but they won’t cover regular iontophoresis," Dr. Bellet said.

In response to audience inquiries, she indicated she uses the Fischer MD-1a galvanic unit. It’s simple to operate, costs about $700 including accessories, and can be rented with the payments applied to a later purchase.

Botulinum toxin A: First using this product for hyperhidrosis is off-label therapy, Dr. Bellet emphasized. Second, the doses required to treat palmar/plantar hyperhidrosis – 75-100 units per palm or sole – are much higher than in treating the axillae. Also, injecting botulinum toxin A into the palms and soles is extraordinarily painful. Children typically require general anesthesia, because the alternative methods employed with mixed results in adults, including EMLA cream, ice packs, and ethyl chloride spray, don’t cut it in younger patients, Dr. Bellet noted.

That being said, botulinum toxin A therapy works quite well in children and adolescents. However, it’s important to explain to patients and parents up front that the injections can cause transient weakness of the hand muscles because of the diffusion of the toxin from dermis to muscles; for a budding pianist or baseball pitcher, that can be a deal-breaker, she said. Also, Dr. Bellet added, repeated injections can result in atrophy of the thenar and hypothenar eminences, with resultant irreversible weakness.

Thoracic sympathectomy: Not many American thoracic surgeons do sympathectomy to treat hyperhidrosis on a frequent basis, but those with extensive experience obtain outstanding results, Dr. Bellet said. To treat palmar hyperhidrosis, the nerve is clipped at the top of the third or fourth rib; for the soles, it’s at the fourth and fifth rib. The youngest reported treated patients have been 8 years old.

Dr. Bellet recommended the International Hyperhidrosis Society (www.sweathelp.org) as an excellent source of further information.

Dr. Bellet reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding her presentation.

How do you treat palmar/plantar hyperhidrosis in children? Take our Quick Poll on the Skin & Allergy News homepage.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE SPD ANNUAL MEETING

Botulinum toxin for men

Men make up an increasing number of dermatology patients seeking cosmetic procedures. According to data from the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery and the American Society of Plastic Surgery, 9%-10% of all cosmetic procedures performed in the United States in 2013 were on men, a 104% increase since 2000. Botulinum toxin is currently the most common minimally invasive cosmetic procedure performed in men. While the overall percentage of men undergoing treatment, compared with women, is relatively small, more than 385,000 botulinum toxin treatments were performed on men last year in the United States, an increase of 310% since 2000.

Studies have shown that men often require more units of onabotulinumtoxinA than women when treating the glabella. In a 2005 study by Alstair and Jean Carruthers, 80 men were randomized to receive 20, 40, 60, or 80 units of onabotulinumtoxinA (Botox or Vistabel). The 40-, 60-, and 80-U doses were consistently more effective than the 20-U dose was in reducing glabellar lines (duration, peak response rate, and improvement from baseline). I find this to be true in my practice. Men may often require 20-60 U in the superficial corrugator and procerus muscles, compared with 20-30 units of onabotulinumtoxinA in the same muscles in women. For the frontalis muscles, I may use 5-20 U in men, compared with 5-10 U of onabotulinumtoxinA in women, but I take care not to inject too inferiorly to avoid a heavy brow or brow ptosis. The orbicularis oculi muscles often require the similar doses of between 6-15 U (most often 12 U/side) depending on degree of muscle contraction and severity of rhytids.