User login

The Arthroscopic Superior Capsular Reconstruction

Rotator cuff tears are very common, and 250,000 to 500,000 rotator cuff repairs are performed in the United States each year.1,2 In most cases, a complete repair of even large or massive tears can be achieved. However, a subset of patients exist in whom the glenohumeral joint has minimal degenerative changes and the rotator cuff tendon is either irreparable or very poor quality and unlikely to heal (ie, failed previous cuff repair). Some authors have advocated for reverse shoulder arthroplasty (RSA) in these patients despite the lack of glenohumeral arthritis. However, due to the permanent destruction of the glenohumeral articular surfaces, complication rates, and concerns about implant longevity with RSA, we believe the superior capsular reconstruction (SCR) is a viable alternative in patients in whom joint preservation is appropriate based on age limitations and/or activity requirements.3

The SCR was first described by Mihata and colleagues4 as a means to reconstruct the superior capsule in shoulders with large, irreparable posterosuperior rotator cuff tears. Originally described using a fascia lata autograft, our technique has been adapted to incorporate a dermal allograft, which limits donor site morbidity and operative time. In most cases, the dermal allograft is fixed to the normal anatomic attachments of the superior glenoid just medial to the superior labrum, laterally to the greater tuberosity, and posteriorly with side-to-side sutures to the remaining rotator cuff. If there is a robust band of “comma” tissue anteriorly, we fix the anterior margin of the dermal graft to this with side-to-side sutures. The comma tissue represents the medial sling of the biceps tendon and connects the upper subscapularis tendon to the anterior supraspinatus. In most cases, this tissue is intact after repair of the subscapularis tendon.

Technique

The patient is positioned in either the lateral decubitus or beach chair position. The arm is positioned in 20° to 30° of abduction and 20° to 30° of forward flexion. A diagnostic arthroscopy is performed through a posterior glenohumeral viewing portal. The subscapularis is visualized and repaired if torn. A biceps tenodesis is performed in most cases, as there is often a tear of the subscapularis, tear or instability of the biceps tendon, and/or a compromised attachment of the biceps root.

Attention is turned to the subacromial space. Posterior viewing and lateral working portals are established. A 10-mm flexible cannula (PassPort; Arthrex) is placed in the lateral portal to aid with suture management and graft passage. A limited subacromial decompression is performed that preserves the coracoacromial arch. The rotator cuff is carefully dissected and freed from the internal deltoid fascia. The scapular spine is identified to visualize the raphé between the supraspinatus and infraspinatus. The infraspinatus is mobilized and repaired as much as possible.

If we think that the tear might be reparable by gaining added excursion from a posterior interval slide, or if it is clearly not reparable but the remaining rim of rotator cuff obscures clear visualization of the superior glenoid, we perform a posterior interval slide. If the additional excursion that is achieved by the posterior slide is adequate for a complete repair, we proceed with the repair. However, if the tear is not reparable even after the posterior interval slide, we have found that the exposure and preparation of the superior glenoid is greatly improved after the posterior slide. After fixation of the dermal graft, we typically perform a partial side-to-side repair of the supraspinatus to the infraspinatus over the top of the graft.

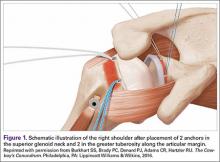

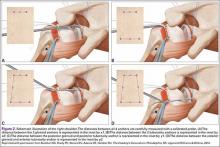

The bone beds of the greater tuberosity and just medial to the superior glenoid labrum are prepared with a shaver and motorized burr. Two anchors (3.0-mm BioComposite SutureTak; Arthrex) are placed in the superior glenoid neck at about the 10 o’clock and 2 o’clock positions approximately 5 mm medial to the superior labrum. Note: the placement medial to the labrum is chosen because this is the normal origin of the superior capsule and because of the angle of approach, these percutaneous portals are often more medial than typical portals for placing anchors during SLAP (superior labral anterior to posterior) repair. Next, 2 threaded anchors (4.75-mm BioComposite SwiveLock; Arthrex) preloaded with suture tape are placed in the greater tuberosity along the articular margin (Figure 1). However, if a biceps tenodesis with an interference screw is placed at the top of the bicipital groove, this anchor preloaded with suture tape can also serve as the anteromedial anchor in the greater tuberosity footprint. The distances between all 4 anchors are carefully measured with a calibrated probe (Figures 2A-2D).

We use a 3.0-mm acellular dermal allograft (ArthroFlex; Arthrex) to reconstruct the superior capsule. The positions of the 4 anchors are carefully marked on the dermal allograft. We routinely add an additional 5 mm of tissue to the medial, anterior, and posterior margins to decrease the risk of suture cut out. An additional 10 mm of tissue is added laterally to cover the greater tuberosity. The final contoured graft is typically trapezoidal in shape.

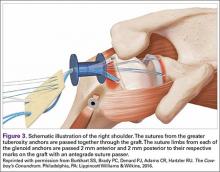

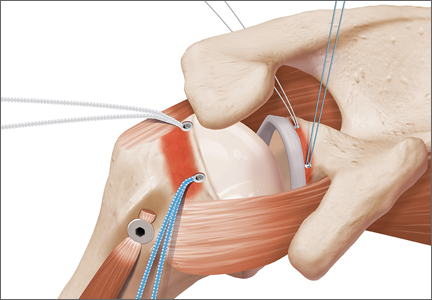

The sutures from the 4 anchors are then sequentially retrieved through the lateral cannula. The sutures from the greater tuberosity anchors are passed through their respective holes in the graft. However, the suture limbs from each of the glenoid anchors are individually passed 2 mm anterior and 2 mm posterior to their respective marks on the graft with an antegrade suture passer (Figure 3). It is important to have an assistant apply tension to each of the sutures after they are passed through the graft to decrease the chance of crossing and tangling the sutures.

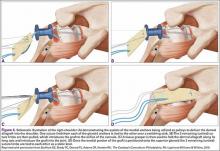

The eyelets of the medial anchors are utilized as pulleys to deliver the dermal allograft into the shoulder. One suture limb from each of the glenoid anchors is tied to the other over a switching stick (Figure 4A). The 2 remaining (untied) suture limbs are then pulled, which introduces the graft to the orifice of the cannula (Figure 4B). A tissue grasper is then used to fold the dermal allograft along its long axis and introduce the graft into the joint (Figure 4C). Once the medial portion of the graft is positioned onto the superior glenoid the 2 remaining (untied) suture limbs are tied to each other as a static knot in the subacromial space (Figure 4D).

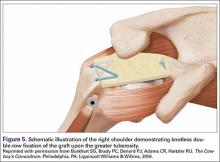

The redundancy in the suture tapes can be removed by sequentially sliding a retriever down each suture and tensioning the suture as the nose of the instrument pushes the dermal graft down to the tuberosity bone bed. The suture tapes are crisscrossed and secured laterally with 2 additional knotless threaded anchors (Figure 5). One may also place cinch stitches at the anterolateral and posterolateral corners of the graft that are incorporated into the lateral anchors. These sutures can be useful for pulling the graft back out of the subacromial space in the event of any suture tangles, and can be used for controlling the lateral aspect of the graft during lateral anchor placement.

At this point in the procedure, additional glenoid anchors can be placed both anterior and posterior to the superior glenoid anchors if additional glenoid fixation is desired. Finally, 2 to 3 side-to-side sutures are placed posteriorly attaching the anterior aspect of the infraspinatus to the posterior aspect of the dermal allograft (Figures 6A-6C). If rotator interval tissue (comma tissue) is present, anterior side-to-side sutures may be placed. However, we do not recommend placing anterior side-to-side sutures directly from the dermal allograft to the subscapularis as this may deform the graft, over- constrain the shoulder, and restrict motion.

Discussion

Reconstruction of the superior capsule has been shown to restore the normal restraint to superior translation of the humeral head and reestablish a stable fulcrum at the glenohumeral joint.5 It should be mentioned that we do not perform the SCR in patients with advanced glenohumeral arthritis. The short-term results of this novel procedure have been encouraging, including our own series of patients, in which most patients have had a significant reduction in pain, improvement in function, and very few complications (P. J. Denard, MD, S. S. Burkhart, MD, P. C. Brady, MD, J. Tokish, MD, C. R. Adams, MD, unpublished data, May 2016).

The early success of this procedure suggests that a robust superior capsule is necessary, in addition to functional muscle-tendon units, to restore the stable fulcrum and force couples that are necessary for normal shoulder function. Perhaps we have not paid enough attention to the integrity of the superior capsule in the past. In cases of revision cuff repair, we pay special attention to the quality of the capsular layer deep to the cuff tendon. If the capsule is poor quality, we sometimes reconstruct the capsule with a dermal allograft (SCR) and then do a rotator cuff repair (partial or complete) over the top of the SCR to maintain the normal anatomic deep to superficial layering of the capsule and rotator cuff.

We are very conservative with our postoperative rehabilitation program after a SCR. We know that the rate of stiffness with a conservative program after an arthroscopic rotator cuff repair, even in the revision setting, is very low.6 Furthermore, both basic science on healing of soft tissue to bone and radiographic analysis of healing after postoperative rotator cuff repairs support a slow rehabilitation program.7,8 A canine model specifically evaluating acellular dermal allografts in the shoulder suggests that these grafts undergo significant remodeling and become weaker before they get stronger.9 We would rather err on the side of healing of the SCR with potentially a slight increase in the rate of shoulder stiffness than to regain early motion at the expense of graft failure. Therefore, we have the patient wear a sling with no shoulder motion for 6 weeks. Passive motion is started at 6 weeks postoperative and strengthening is delayed until 12 to 16 weeks postoperative.

1. Orr SB, Chainani A, Hippensteel KJ, et al. Aligned multilayered electrospun scaffolds for rotator cuff tendon tissue engineering. Acta Biomater. 2015;24:117-126.

2. Austin L, Black EM, Lombardi NJ, Pepe MD, Lazarus M. Arthroscopic transosseous rotator cuff repair. A prospective study on cost savings, surgical time, and outcomes. Ortho J Sports Med. 2015;3(2 Suppl). doi:10.1177/2325967115S00156.

3. Denard PJ, Lädermann A, Jiwani AZ, Burkhart SS. Functional outcome after arthroscopic repair of massive rotator cuff tears in individuals with pseudoparalysis. Arthroscopy. 2012;28(9):1214-1219.

4. Mihata T, Lee TQ, Watanabe C, et al. Clinical results of arthroscopic superior capsule reconstruction for irreparable rotator cuff tears. Arthroscopy. 2013;29(3):459-470.

5. Mihata T, McGarry MH, Pirolo JM, Kinoshita M, Lee TQ. Superior capsule reconstruction to restore superior stability in irreparable rotator cuff tears: a biomechanical cadaveric study. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(10):2248-2255.

6. Huberty DP, Schoolfield JD, Brady PC, Vadala AP, Arrigoni P, Burkhart SS. Incidence and treatment of postoperative stiffness following arthroscopic rotator cuff repair. Arthroscopy. 2009;25(8):880-890.

7. Sonnabend DH, Howlett CR, Young AA. Histological evaluation of repair of the rotator cuff in a primate model. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2010;92(4):586-594.

8. Lee BG, Cho NS, Rhee YG. Effect of two rehabilitation protocols on range of motion and healing rates after arthroscopic rotator cuff repair: aggressive versus limited early passive exercises. Arthroscopy. 2012;28(1):34-42.

9. Adams JE, Zobitz ME, Reach JS Jr, An KN, Steinmann SP. Rotator cuff repair using an acellular dermal matrix graft: an in vivo study in a canine model. Arthroscopy. 2006;22(7):700-709.

Rotator cuff tears are very common, and 250,000 to 500,000 rotator cuff repairs are performed in the United States each year.1,2 In most cases, a complete repair of even large or massive tears can be achieved. However, a subset of patients exist in whom the glenohumeral joint has minimal degenerative changes and the rotator cuff tendon is either irreparable or very poor quality and unlikely to heal (ie, failed previous cuff repair). Some authors have advocated for reverse shoulder arthroplasty (RSA) in these patients despite the lack of glenohumeral arthritis. However, due to the permanent destruction of the glenohumeral articular surfaces, complication rates, and concerns about implant longevity with RSA, we believe the superior capsular reconstruction (SCR) is a viable alternative in patients in whom joint preservation is appropriate based on age limitations and/or activity requirements.3

The SCR was first described by Mihata and colleagues4 as a means to reconstruct the superior capsule in shoulders with large, irreparable posterosuperior rotator cuff tears. Originally described using a fascia lata autograft, our technique has been adapted to incorporate a dermal allograft, which limits donor site morbidity and operative time. In most cases, the dermal allograft is fixed to the normal anatomic attachments of the superior glenoid just medial to the superior labrum, laterally to the greater tuberosity, and posteriorly with side-to-side sutures to the remaining rotator cuff. If there is a robust band of “comma” tissue anteriorly, we fix the anterior margin of the dermal graft to this with side-to-side sutures. The comma tissue represents the medial sling of the biceps tendon and connects the upper subscapularis tendon to the anterior supraspinatus. In most cases, this tissue is intact after repair of the subscapularis tendon.

Technique

The patient is positioned in either the lateral decubitus or beach chair position. The arm is positioned in 20° to 30° of abduction and 20° to 30° of forward flexion. A diagnostic arthroscopy is performed through a posterior glenohumeral viewing portal. The subscapularis is visualized and repaired if torn. A biceps tenodesis is performed in most cases, as there is often a tear of the subscapularis, tear or instability of the biceps tendon, and/or a compromised attachment of the biceps root.

Attention is turned to the subacromial space. Posterior viewing and lateral working portals are established. A 10-mm flexible cannula (PassPort; Arthrex) is placed in the lateral portal to aid with suture management and graft passage. A limited subacromial decompression is performed that preserves the coracoacromial arch. The rotator cuff is carefully dissected and freed from the internal deltoid fascia. The scapular spine is identified to visualize the raphé between the supraspinatus and infraspinatus. The infraspinatus is mobilized and repaired as much as possible.

If we think that the tear might be reparable by gaining added excursion from a posterior interval slide, or if it is clearly not reparable but the remaining rim of rotator cuff obscures clear visualization of the superior glenoid, we perform a posterior interval slide. If the additional excursion that is achieved by the posterior slide is adequate for a complete repair, we proceed with the repair. However, if the tear is not reparable even after the posterior interval slide, we have found that the exposure and preparation of the superior glenoid is greatly improved after the posterior slide. After fixation of the dermal graft, we typically perform a partial side-to-side repair of the supraspinatus to the infraspinatus over the top of the graft.

The bone beds of the greater tuberosity and just medial to the superior glenoid labrum are prepared with a shaver and motorized burr. Two anchors (3.0-mm BioComposite SutureTak; Arthrex) are placed in the superior glenoid neck at about the 10 o’clock and 2 o’clock positions approximately 5 mm medial to the superior labrum. Note: the placement medial to the labrum is chosen because this is the normal origin of the superior capsule and because of the angle of approach, these percutaneous portals are often more medial than typical portals for placing anchors during SLAP (superior labral anterior to posterior) repair. Next, 2 threaded anchors (4.75-mm BioComposite SwiveLock; Arthrex) preloaded with suture tape are placed in the greater tuberosity along the articular margin (Figure 1). However, if a biceps tenodesis with an interference screw is placed at the top of the bicipital groove, this anchor preloaded with suture tape can also serve as the anteromedial anchor in the greater tuberosity footprint. The distances between all 4 anchors are carefully measured with a calibrated probe (Figures 2A-2D).

We use a 3.0-mm acellular dermal allograft (ArthroFlex; Arthrex) to reconstruct the superior capsule. The positions of the 4 anchors are carefully marked on the dermal allograft. We routinely add an additional 5 mm of tissue to the medial, anterior, and posterior margins to decrease the risk of suture cut out. An additional 10 mm of tissue is added laterally to cover the greater tuberosity. The final contoured graft is typically trapezoidal in shape.

The sutures from the 4 anchors are then sequentially retrieved through the lateral cannula. The sutures from the greater tuberosity anchors are passed through their respective holes in the graft. However, the suture limbs from each of the glenoid anchors are individually passed 2 mm anterior and 2 mm posterior to their respective marks on the graft with an antegrade suture passer (Figure 3). It is important to have an assistant apply tension to each of the sutures after they are passed through the graft to decrease the chance of crossing and tangling the sutures.

The eyelets of the medial anchors are utilized as pulleys to deliver the dermal allograft into the shoulder. One suture limb from each of the glenoid anchors is tied to the other over a switching stick (Figure 4A). The 2 remaining (untied) suture limbs are then pulled, which introduces the graft to the orifice of the cannula (Figure 4B). A tissue grasper is then used to fold the dermal allograft along its long axis and introduce the graft into the joint (Figure 4C). Once the medial portion of the graft is positioned onto the superior glenoid the 2 remaining (untied) suture limbs are tied to each other as a static knot in the subacromial space (Figure 4D).

The redundancy in the suture tapes can be removed by sequentially sliding a retriever down each suture and tensioning the suture as the nose of the instrument pushes the dermal graft down to the tuberosity bone bed. The suture tapes are crisscrossed and secured laterally with 2 additional knotless threaded anchors (Figure 5). One may also place cinch stitches at the anterolateral and posterolateral corners of the graft that are incorporated into the lateral anchors. These sutures can be useful for pulling the graft back out of the subacromial space in the event of any suture tangles, and can be used for controlling the lateral aspect of the graft during lateral anchor placement.

At this point in the procedure, additional glenoid anchors can be placed both anterior and posterior to the superior glenoid anchors if additional glenoid fixation is desired. Finally, 2 to 3 side-to-side sutures are placed posteriorly attaching the anterior aspect of the infraspinatus to the posterior aspect of the dermal allograft (Figures 6A-6C). If rotator interval tissue (comma tissue) is present, anterior side-to-side sutures may be placed. However, we do not recommend placing anterior side-to-side sutures directly from the dermal allograft to the subscapularis as this may deform the graft, over- constrain the shoulder, and restrict motion.

Discussion

Reconstruction of the superior capsule has been shown to restore the normal restraint to superior translation of the humeral head and reestablish a stable fulcrum at the glenohumeral joint.5 It should be mentioned that we do not perform the SCR in patients with advanced glenohumeral arthritis. The short-term results of this novel procedure have been encouraging, including our own series of patients, in which most patients have had a significant reduction in pain, improvement in function, and very few complications (P. J. Denard, MD, S. S. Burkhart, MD, P. C. Brady, MD, J. Tokish, MD, C. R. Adams, MD, unpublished data, May 2016).

The early success of this procedure suggests that a robust superior capsule is necessary, in addition to functional muscle-tendon units, to restore the stable fulcrum and force couples that are necessary for normal shoulder function. Perhaps we have not paid enough attention to the integrity of the superior capsule in the past. In cases of revision cuff repair, we pay special attention to the quality of the capsular layer deep to the cuff tendon. If the capsule is poor quality, we sometimes reconstruct the capsule with a dermal allograft (SCR) and then do a rotator cuff repair (partial or complete) over the top of the SCR to maintain the normal anatomic deep to superficial layering of the capsule and rotator cuff.

We are very conservative with our postoperative rehabilitation program after a SCR. We know that the rate of stiffness with a conservative program after an arthroscopic rotator cuff repair, even in the revision setting, is very low.6 Furthermore, both basic science on healing of soft tissue to bone and radiographic analysis of healing after postoperative rotator cuff repairs support a slow rehabilitation program.7,8 A canine model specifically evaluating acellular dermal allografts in the shoulder suggests that these grafts undergo significant remodeling and become weaker before they get stronger.9 We would rather err on the side of healing of the SCR with potentially a slight increase in the rate of shoulder stiffness than to regain early motion at the expense of graft failure. Therefore, we have the patient wear a sling with no shoulder motion for 6 weeks. Passive motion is started at 6 weeks postoperative and strengthening is delayed until 12 to 16 weeks postoperative.

Rotator cuff tears are very common, and 250,000 to 500,000 rotator cuff repairs are performed in the United States each year.1,2 In most cases, a complete repair of even large or massive tears can be achieved. However, a subset of patients exist in whom the glenohumeral joint has minimal degenerative changes and the rotator cuff tendon is either irreparable or very poor quality and unlikely to heal (ie, failed previous cuff repair). Some authors have advocated for reverse shoulder arthroplasty (RSA) in these patients despite the lack of glenohumeral arthritis. However, due to the permanent destruction of the glenohumeral articular surfaces, complication rates, and concerns about implant longevity with RSA, we believe the superior capsular reconstruction (SCR) is a viable alternative in patients in whom joint preservation is appropriate based on age limitations and/or activity requirements.3

The SCR was first described by Mihata and colleagues4 as a means to reconstruct the superior capsule in shoulders with large, irreparable posterosuperior rotator cuff tears. Originally described using a fascia lata autograft, our technique has been adapted to incorporate a dermal allograft, which limits donor site morbidity and operative time. In most cases, the dermal allograft is fixed to the normal anatomic attachments of the superior glenoid just medial to the superior labrum, laterally to the greater tuberosity, and posteriorly with side-to-side sutures to the remaining rotator cuff. If there is a robust band of “comma” tissue anteriorly, we fix the anterior margin of the dermal graft to this with side-to-side sutures. The comma tissue represents the medial sling of the biceps tendon and connects the upper subscapularis tendon to the anterior supraspinatus. In most cases, this tissue is intact after repair of the subscapularis tendon.

Technique

The patient is positioned in either the lateral decubitus or beach chair position. The arm is positioned in 20° to 30° of abduction and 20° to 30° of forward flexion. A diagnostic arthroscopy is performed through a posterior glenohumeral viewing portal. The subscapularis is visualized and repaired if torn. A biceps tenodesis is performed in most cases, as there is often a tear of the subscapularis, tear or instability of the biceps tendon, and/or a compromised attachment of the biceps root.

Attention is turned to the subacromial space. Posterior viewing and lateral working portals are established. A 10-mm flexible cannula (PassPort; Arthrex) is placed in the lateral portal to aid with suture management and graft passage. A limited subacromial decompression is performed that preserves the coracoacromial arch. The rotator cuff is carefully dissected and freed from the internal deltoid fascia. The scapular spine is identified to visualize the raphé between the supraspinatus and infraspinatus. The infraspinatus is mobilized and repaired as much as possible.

If we think that the tear might be reparable by gaining added excursion from a posterior interval slide, or if it is clearly not reparable but the remaining rim of rotator cuff obscures clear visualization of the superior glenoid, we perform a posterior interval slide. If the additional excursion that is achieved by the posterior slide is adequate for a complete repair, we proceed with the repair. However, if the tear is not reparable even after the posterior interval slide, we have found that the exposure and preparation of the superior glenoid is greatly improved after the posterior slide. After fixation of the dermal graft, we typically perform a partial side-to-side repair of the supraspinatus to the infraspinatus over the top of the graft.

The bone beds of the greater tuberosity and just medial to the superior glenoid labrum are prepared with a shaver and motorized burr. Two anchors (3.0-mm BioComposite SutureTak; Arthrex) are placed in the superior glenoid neck at about the 10 o’clock and 2 o’clock positions approximately 5 mm medial to the superior labrum. Note: the placement medial to the labrum is chosen because this is the normal origin of the superior capsule and because of the angle of approach, these percutaneous portals are often more medial than typical portals for placing anchors during SLAP (superior labral anterior to posterior) repair. Next, 2 threaded anchors (4.75-mm BioComposite SwiveLock; Arthrex) preloaded with suture tape are placed in the greater tuberosity along the articular margin (Figure 1). However, if a biceps tenodesis with an interference screw is placed at the top of the bicipital groove, this anchor preloaded with suture tape can also serve as the anteromedial anchor in the greater tuberosity footprint. The distances between all 4 anchors are carefully measured with a calibrated probe (Figures 2A-2D).

We use a 3.0-mm acellular dermal allograft (ArthroFlex; Arthrex) to reconstruct the superior capsule. The positions of the 4 anchors are carefully marked on the dermal allograft. We routinely add an additional 5 mm of tissue to the medial, anterior, and posterior margins to decrease the risk of suture cut out. An additional 10 mm of tissue is added laterally to cover the greater tuberosity. The final contoured graft is typically trapezoidal in shape.

The sutures from the 4 anchors are then sequentially retrieved through the lateral cannula. The sutures from the greater tuberosity anchors are passed through their respective holes in the graft. However, the suture limbs from each of the glenoid anchors are individually passed 2 mm anterior and 2 mm posterior to their respective marks on the graft with an antegrade suture passer (Figure 3). It is important to have an assistant apply tension to each of the sutures after they are passed through the graft to decrease the chance of crossing and tangling the sutures.

The eyelets of the medial anchors are utilized as pulleys to deliver the dermal allograft into the shoulder. One suture limb from each of the glenoid anchors is tied to the other over a switching stick (Figure 4A). The 2 remaining (untied) suture limbs are then pulled, which introduces the graft to the orifice of the cannula (Figure 4B). A tissue grasper is then used to fold the dermal allograft along its long axis and introduce the graft into the joint (Figure 4C). Once the medial portion of the graft is positioned onto the superior glenoid the 2 remaining (untied) suture limbs are tied to each other as a static knot in the subacromial space (Figure 4D).

The redundancy in the suture tapes can be removed by sequentially sliding a retriever down each suture and tensioning the suture as the nose of the instrument pushes the dermal graft down to the tuberosity bone bed. The suture tapes are crisscrossed and secured laterally with 2 additional knotless threaded anchors (Figure 5). One may also place cinch stitches at the anterolateral and posterolateral corners of the graft that are incorporated into the lateral anchors. These sutures can be useful for pulling the graft back out of the subacromial space in the event of any suture tangles, and can be used for controlling the lateral aspect of the graft during lateral anchor placement.

At this point in the procedure, additional glenoid anchors can be placed both anterior and posterior to the superior glenoid anchors if additional glenoid fixation is desired. Finally, 2 to 3 side-to-side sutures are placed posteriorly attaching the anterior aspect of the infraspinatus to the posterior aspect of the dermal allograft (Figures 6A-6C). If rotator interval tissue (comma tissue) is present, anterior side-to-side sutures may be placed. However, we do not recommend placing anterior side-to-side sutures directly from the dermal allograft to the subscapularis as this may deform the graft, over- constrain the shoulder, and restrict motion.

Discussion

Reconstruction of the superior capsule has been shown to restore the normal restraint to superior translation of the humeral head and reestablish a stable fulcrum at the glenohumeral joint.5 It should be mentioned that we do not perform the SCR in patients with advanced glenohumeral arthritis. The short-term results of this novel procedure have been encouraging, including our own series of patients, in which most patients have had a significant reduction in pain, improvement in function, and very few complications (P. J. Denard, MD, S. S. Burkhart, MD, P. C. Brady, MD, J. Tokish, MD, C. R. Adams, MD, unpublished data, May 2016).

The early success of this procedure suggests that a robust superior capsule is necessary, in addition to functional muscle-tendon units, to restore the stable fulcrum and force couples that are necessary for normal shoulder function. Perhaps we have not paid enough attention to the integrity of the superior capsule in the past. In cases of revision cuff repair, we pay special attention to the quality of the capsular layer deep to the cuff tendon. If the capsule is poor quality, we sometimes reconstruct the capsule with a dermal allograft (SCR) and then do a rotator cuff repair (partial or complete) over the top of the SCR to maintain the normal anatomic deep to superficial layering of the capsule and rotator cuff.

We are very conservative with our postoperative rehabilitation program after a SCR. We know that the rate of stiffness with a conservative program after an arthroscopic rotator cuff repair, even in the revision setting, is very low.6 Furthermore, both basic science on healing of soft tissue to bone and radiographic analysis of healing after postoperative rotator cuff repairs support a slow rehabilitation program.7,8 A canine model specifically evaluating acellular dermal allografts in the shoulder suggests that these grafts undergo significant remodeling and become weaker before they get stronger.9 We would rather err on the side of healing of the SCR with potentially a slight increase in the rate of shoulder stiffness than to regain early motion at the expense of graft failure. Therefore, we have the patient wear a sling with no shoulder motion for 6 weeks. Passive motion is started at 6 weeks postoperative and strengthening is delayed until 12 to 16 weeks postoperative.

1. Orr SB, Chainani A, Hippensteel KJ, et al. Aligned multilayered electrospun scaffolds for rotator cuff tendon tissue engineering. Acta Biomater. 2015;24:117-126.

2. Austin L, Black EM, Lombardi NJ, Pepe MD, Lazarus M. Arthroscopic transosseous rotator cuff repair. A prospective study on cost savings, surgical time, and outcomes. Ortho J Sports Med. 2015;3(2 Suppl). doi:10.1177/2325967115S00156.

3. Denard PJ, Lädermann A, Jiwani AZ, Burkhart SS. Functional outcome after arthroscopic repair of massive rotator cuff tears in individuals with pseudoparalysis. Arthroscopy. 2012;28(9):1214-1219.

4. Mihata T, Lee TQ, Watanabe C, et al. Clinical results of arthroscopic superior capsule reconstruction for irreparable rotator cuff tears. Arthroscopy. 2013;29(3):459-470.

5. Mihata T, McGarry MH, Pirolo JM, Kinoshita M, Lee TQ. Superior capsule reconstruction to restore superior stability in irreparable rotator cuff tears: a biomechanical cadaveric study. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(10):2248-2255.

6. Huberty DP, Schoolfield JD, Brady PC, Vadala AP, Arrigoni P, Burkhart SS. Incidence and treatment of postoperative stiffness following arthroscopic rotator cuff repair. Arthroscopy. 2009;25(8):880-890.

7. Sonnabend DH, Howlett CR, Young AA. Histological evaluation of repair of the rotator cuff in a primate model. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2010;92(4):586-594.

8. Lee BG, Cho NS, Rhee YG. Effect of two rehabilitation protocols on range of motion and healing rates after arthroscopic rotator cuff repair: aggressive versus limited early passive exercises. Arthroscopy. 2012;28(1):34-42.

9. Adams JE, Zobitz ME, Reach JS Jr, An KN, Steinmann SP. Rotator cuff repair using an acellular dermal matrix graft: an in vivo study in a canine model. Arthroscopy. 2006;22(7):700-709.

1. Orr SB, Chainani A, Hippensteel KJ, et al. Aligned multilayered electrospun scaffolds for rotator cuff tendon tissue engineering. Acta Biomater. 2015;24:117-126.

2. Austin L, Black EM, Lombardi NJ, Pepe MD, Lazarus M. Arthroscopic transosseous rotator cuff repair. A prospective study on cost savings, surgical time, and outcomes. Ortho J Sports Med. 2015;3(2 Suppl). doi:10.1177/2325967115S00156.

3. Denard PJ, Lädermann A, Jiwani AZ, Burkhart SS. Functional outcome after arthroscopic repair of massive rotator cuff tears in individuals with pseudoparalysis. Arthroscopy. 2012;28(9):1214-1219.

4. Mihata T, Lee TQ, Watanabe C, et al. Clinical results of arthroscopic superior capsule reconstruction for irreparable rotator cuff tears. Arthroscopy. 2013;29(3):459-470.

5. Mihata T, McGarry MH, Pirolo JM, Kinoshita M, Lee TQ. Superior capsule reconstruction to restore superior stability in irreparable rotator cuff tears: a biomechanical cadaveric study. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(10):2248-2255.

6. Huberty DP, Schoolfield JD, Brady PC, Vadala AP, Arrigoni P, Burkhart SS. Incidence and treatment of postoperative stiffness following arthroscopic rotator cuff repair. Arthroscopy. 2009;25(8):880-890.

7. Sonnabend DH, Howlett CR, Young AA. Histological evaluation of repair of the rotator cuff in a primate model. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2010;92(4):586-594.

8. Lee BG, Cho NS, Rhee YG. Effect of two rehabilitation protocols on range of motion and healing rates after arthroscopic rotator cuff repair: aggressive versus limited early passive exercises. Arthroscopy. 2012;28(1):34-42.

9. Adams JE, Zobitz ME, Reach JS Jr, An KN, Steinmann SP. Rotator cuff repair using an acellular dermal matrix graft: an in vivo study in a canine model. Arthroscopy. 2006;22(7):700-709.

Stem Cells in Orthopedics: A Comprehensive Guide for the General Orthopedist

Biologic use in orthopedics is a continuously evolving field that complements technical, anatomic, and biomechanical advancements in orthopedics. Biologic agents are receiving increasing attention for their use in augmenting healing of muscles, tendons, ligaments, and osseous structures. As biologic augmentation strategies become increasingly utilized in bony and soft-tissue injuries, research on stem cell use in orthopedics continues to increase. Stem cell-based therapies for the repair or regeneration of muscle and tendon represent a promising technology going forward for numerous diseases.1

Stem cells by definition are undifferentiated cells that have 4 main characteristics: (1) mobilization during angiogenesis, (2) differentiation into specialized cell types, (3) proliferation and regeneration, and (4) release of immune regulators and growth factors.2 Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) have garnered the most attention in the field of surgery due to their ability to differentiate into the tissues of interest for the surgeon.3 This includes both bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells (bm-MSCs) and adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells (a-MSCs). These multipotent stem cells in adults originate from mesenchymal tissues, including bone marrow, tendon, adipose, and muscle tissue.4 They are attractive for clinical use because of their multipotent potential and relative ease of growth in culture.5 They also exert a paracrine effect to modulate and control inflammation, stimulate endogenous cell repair and proliferation, inhibit apoptosis, and improve blood flow through secretion of chemokines, cytokines, and growth factors.6,7

Questions exist regarding the best way to administer stem cells, whether systematic administration is possible for these cells to localize to the tissue in need, or more likely if direct application to the pathologic area is necessary.8,9 A number of sources, purification process, and modes of delivery are available, but the most effective means of preparation and administration are still under investigation. The goal of this review is to illustrate the current state of knowledge surrounding stem cell therapy in orthopedics with a focus on osteoarthritis, tendinopathy, articular cartilage, and enhancement of surgical procedures.

Important Considerations

Common stem cell isolates include embryonic, induced pluripotent, and mesenchymal formulations (Table 1). MSCs can be obtained from multiple sites, including but not limited to the adult bone marrow, adipose, muscular, or tendinous tissues, and their use has been highlighted in the study of numerous orthopedic and nonorthopedic pathologies over the course of the last decade. Research on the use of embryonic stem cells in medical therapy with human implications has received substantial attention, with many ethical concerns by those opposed, and the existence of a potential risk of malignant alterations.8,10 Amniotic-derived stem cells can be isolated from amniotic fluid, umbilical cord blood, or the placenta and thus do not harbor the same social constraints as the aforementioned embryonic cells; however, they do not harbor the same magnitude of multi-differentiation potential, either.4

Adult MSCs are more locally available and easy to obtain for treatment when compared with embryonic and fetal stem cells, and the former has a lower immunogenicity, which allows allogeneic use.11 Safety has been preliminarily demonstrated in use thus far; Centeno and colleagues12 found no neoplastic tissue generation at the site of stem cell injection after 3 years postinjection for a cohort of patients who were treated with autologous bm-MSCs for various pathologies. Self-limited pain and swelling are the most commonly reported adverse events after use.13 However, long-term data are lacking in many instances to definitively suggest the absence of possible complications.

Basic Science

Stem cell research encompasses a wide range of rapidly developing treatment strategies that are applicable to virtually every field of medicine. In general, stem cells can be classified as embryonic stem cells (ESCs), induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells, or adult-derived MSCs. ESCs are embryonic cells derived typically from fetal tissue, whereas iPS cells are dedifferentiated from adult tissue, thus avoiding many of the ethical and legal challenges imposed by research with ESCs. However, oncogenic and lingering politico-legal concerns with introducing dedifferentiated ESCs or iPS cells into healthy tissue necessitate the development, isolation, and expansion of multi- but not pluripotent stem cell lines.14 To date, the most advantageous and widely utilized from any perspective are MSCs, which can further differentiate into cartilage, tendon, muscle, and bony tissue.7,15,16

MSCs are defined by their ability to demonstrate in vitro differentiation into osteoblasts, adipocytes, or chondroblasts, adhere to plastic, express CD105, CD73, and CD90, and not express CD43, CD23, CD14 or CD11b, CD79 or CD19, or HLA-DR.17 Porada and Almeida-Porada18 have outlined 6 reasons highlighting the advantages of MSCs: 1) ease of isolation, 2) high differentiation capabilities, 3) strong colony expansion without differentiation loss, 4) immunosuppression following transplantation, 5) powerful anti-inflammatory properties, and 6) their ability to localize to damaged tissue. The anti-inflammatory properties of MSCs are particularly important as they promote allo- and xenotransplantation from donor tissues.19,20 MSCs can be isolated from numerous sources, including but not limited to bone marrow, periosteum, adipocyte, and muscle.21-23 Interestingly, the source tissue used to isolate MSCs can affect differentiation capabilities, colony size, and growth rate (Table 2).24 Advantages of a-MSCs include high prevalence and ease of harvest; however, several animal studies have shown inferior results when compared to bm-MSCs.25-27 More research is needed to determine the ideal source material for MSCs, which will likely depend in part on the procedure for which they are employed.27

Following harvesting, isolation, and expansion, MSC delivery methods for treatments typically consist of either cell-based or tissue engineering approaches. Cell-based techniques involve the injection of MSCs into damaged tissues. Purely cell-based therapy has shown success in limited clinical trials involving knee osteoarthritis, cartilage repair, and meniscal repair.28-30 However, additional studies with longer follow-up are required to validate these preliminary findings. Tissue engineering approaches involve the construction of a 3-dimensional scaffold seeded with MSCs that is later surgically implanted. While promising in theory, limited and often conflicting data exist regarding the efficacy of tissue-engineered MSC implantation.31-32 Suboptimal scaffold vascularity is a major limitation to scaffold design, which may be alleviated in part with the advent of 3-dimensional printing and the ability to more precisely alter scaffold architecture.14,33 Additional limitations include ensuring MSC purity and differentiation potential following harvesting and expansion. At present, the use of tissue engineering with MSCs is promising but it remains a nascent technology with additional preclinical studies required to confirm implant efficacy and safety.

Clinical Entities

Osteoarthritis

MSC therapies have emerged as promising treatment strategies in the setting of early osteoarthritis (OA). In addition to their regenerative potential, MSCs demonstrate potent anti-inflammatory properties, increasing their attractiveness as biologic agents in the setting of OA.34 Over the past decade, multiple human trials have been published demonstrating the efficacy of MSC injections into patients with OA.35,36 In a study evaluating a-MSC injection into elderly patients (age >65 years) with knee OA, Koh and colleagues29 found that 88% demonstrated improved cartilage status at 2-year follow-up, while no patient underwent a total knee arthroplasty during this time period. In another study investigating patients with unicompartmental knee OA with varus alignment undergoing high tibial osteotomy and microfracture, Wong and colleagues37 reported improved clinical, patient-reported, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)-based outcomes in a group receiving a preoperative MSC injection compared to a control group. Further, in a recent randomized control trial of patients with knee osteoarthritis, Vega and colleagues38 reported improved cartilage and quality of life outcomes at 1 year following MSC injection compared to a control group receiving a hyaluronic acid injection. In addition to knee OA, studies have also reported improvement in ankle OA following MSC injection.39 While promising, many of the preliminary clinical studies evaluating the efficacy of MSC therapies in the treatment of OA are hindered by small patient populations and short-term follow-up. Additional large-scale, randomized studies are required and many are ongoing presently in hopes of validating these preliminary findings.36

Tendinopathy

The quality of repaired tissue in primary tendon-to-tendon and tendon-to-bone healing has long been a topic of great interest.40 The healing potential of tendons is inferior to that of other bony and connective tissues,41 with tendon healing typically resulting in a biomechanically and histologically inferior structure to the native tissue.42 As such, this has been a particularly salient opportunity for stem cell use with hopes of recapitulating a more normal tendon or tendon enthesis following injury. In addition to the acute injury, there is great interest in the application of stem cells to chronic states of injury such as tendinopathy.

In equine models, the effect of autologous bm-MSCs treatment on tendinopathy of the superficial digital flexor tendon has been studied. Godwin and colleagues43 evaluated 141 race horses with spontaneous superficial digital flexor tendinopathy treated in this manner, and reported a reinjury percentage in these treated horses of just 27.4%, which compared favorably to historical controls and alternative therapeutics. Machova Urdzikova and colleagues44 injected MSCs at Achilles tendinopathy locations to augment nonoperative healing in 40 rats, and identified more native histological organization and improved vascularization in comparison to control rat specimens. Oshita and colleagues45 reported histologic improvement of tendinopathy findings in 8 rats receiving a-MSCs at the location of induced Achilles tendinopathy that was significantly superior to a control cohort. Bm-MSCs were used by Yuksel and colleagues46 in comparison with platelet-rich plasma (PRP) for treatment of Achilles tendon ruptures created surgically in rat models. They demonstrated successful effects with its use in terms of recovery for the tendon’s histopathologic, immunohistochemical, and biomechanical properties, related to significantly greater levels of anti-inflammatory cytokines. However, these aforementioned findings have not been uniform across the literature—other authors have reported findings that MSC transplantation alone did not repair Achilles tendon injury with such high levels of success.47

Human treatment of tendinopathies with stem cells has been scarcely studied to date. Pascual-Garrido and colleagues48 evaluated 8 patients with refractory patellar tendinopathy treated with injection of autologous bm-MSCs and reported successful results at 2- to 5-year follow-up, with significant improvements in patient-reported outcome measures for 100% of patients. Seven of 8 (87.5%) noted that they would undergo the procedure again.

Articular Cartilage Injury

Chondral injury is a particularly important subject given the limited potential of chondrocytes to replicate or migrate to the site of pathology.49 Stem cell use in this setting assists with programmed growth factor release and alteration of the anatomic microenvironment to facilitate regeneration and repair of the chondral surface. Autologous stem cell use through microfracture provides a perforation into the bone marrow and a subsequent fibrin clot formation containing platelets, growth factors, vascular elements, and MSCs.50 A similar concept to PRP is currently being explored with bm-MSCs. Isolated bm-MSCs are commonly referred to as bone marrow aspirate or bone marrow aspirate concentrate (BMAC). Commercially available systems are now available to aid in the harvesting and implementation of BMAC. One of the more promising avenues for BMAC implementation is in articular cartilage repair or regeneration due to chondrogenic potential of BMAC when used in isolation or when combined with microfracture, chondrocyte transfer, or collagen scaffolds.19,51 Synovial-derived stem cells as an additional source for stem cell use has demonstrated excellent chondrogenic potential in animal studies with full-thickness lesion healing and native-appearing cartilage histologically.52 Incorporation of a-MSCs into scaffolds for surgical implantation has demonstrated success in repairing full-thickness chondral defects with continuous joint surface and extracellular proteins, surface markers, and gene products similar to the native cartilage in animal models.53,54 In light of the promising basic science and animal studies, clinical studies have begun to emerge.55-57

Fortier and colleagues58 found MRI and histologic evidence of full-thickness chondral repair and increased integration with neighboring cartilage when BMAC was concurrently used at the time of microfracture in an equine model. Fortier and colleagues58 also demonstrated greater healing in equine models with acute full-thickness cartilage defects treated by microfracture with MSCs than without delivery of MSCs. Kim and colleagues59,60 similarly reported superiority in clinical outcomes for patients with osteochondral lesions of the talus treated with marrow stimulation and MSC injection than by the former in isolation.

In humans, stem cell use for chondral repair has additionally proven promising. A systematic review of the literature suggested good to excellent overall outcomes for the treatment of moderate focal chondral defects with BMAC with or without scaffolds and microfracture with inclusion of 8 total publications.61 This review included Gobbi and colleagues,62 who prospectively treated 15 patients with a mean focal chondral defect size of 9.2 cm2 about the knee. Use of BMAC covered with a collagen I/III matrix produced significant improvements in patient-reported outcome scores and MRI demonstrated complete hyaline-like cartilage coverage in 80%, with second-look arthroscopy demonstrating normal to nearly normal tissue. Gobbi and colleagues55 also found evidence for superiority of chondral defects treated with BMAC compared to matrix-induced autologous chondrocyte implantation (MACI) for patellofemoral lesions in 37 patients (MRI showed complete filling of defects in 81% of BMAC-treated patients vs 76% of MACI-treated patients).

Meniscal Repair

Clinical application of MSCs in the treatment of meniscal pathology is evolving as well. ASCs have been added to modify the biomechanical environment of avascular zone meniscal tears at the time of suture repair in a rabbit, and have demonstrated increased healing rates in small and larger lesions, although the effect lessens with delay in repair.63 Angele and colleagues64 treated meniscal defects in a rabbit model with scaffolds with bm-MSCs compared with empty scaffolds or control cohorts and found a higher proportion of menisci with healed meniscus-like fibrocartilage when MSCs were utilized.

In humans, Vangsness and colleagues30 treated knees with partial medial meniscectomy with allogeneic stem cells and reported an increase in meniscal volume and decrease in pain in those patients when compared to a cohort of knees treated with hyaluronic acid. Despite promising early results, additional clinical studies are necessary to determine the external validity and broad applicability of stem cell use in meniscal repair.

Rotator Cuff Repair

The number of local resident stem cells at the site of rotator cuff tear has been shown to decrease with tear size, chronicity, and degree of fatty infiltration, suggesting that those with the greatest need for a good reparative environment are those least equipped to heal.65 The need for improvement in this domain is related to the still relatively high re-tear rate after rotator cuff repair despite improvements in instrumentation and surgical technique.66 The native fibrocartilaginous transition zone between the humerus and the rotator cuff becomes a fibrovascular scar tissue after rupture and repair with poorer material properties than the native tissue.67 Thus, a-MSCs have been evaluated in this setting to determine if the biomechanical and histological properties of the repair may improve.68

In rat models, Valencia Mora and colleagues68 reported on the application of a-MSCs in a rat rotator cuff repair model compared to an untreated group. They found no differences between those treated rats and those without a-MSCs use in terms of biomechanical properties of the tendon-to-bone healing, but those with stem cell use had less inflammation shown histologically (diminished presence of edema and neutrophils) at 2- and 4-week time points, which the authors suggested may lead to a more elastic repair and less scar at the bone-tendon healing site. Oh and colleagues1 evaluated the use of a-MSCs in a rabbit subscapularis tear model, and reported significantly reduced fatty infiltration at the site of chronic rotator cuff tear after repair with its application at the repair site; while the load-to-failure was higher in those rabbits with ASCs administration, it was short of reaching statistical significance. Yokoya and colleagues69 demonstrated regeneration of rotator cuff tendon-to-bone insertional site anatomy and in the belly of the cuff tendon in a rabbit model with MSCs applied at the operative site. However, Gulotta and colleagues70 did not see the same improvement in their similar study in the rat model; these authors failed to see improvement in structure, strength, or composition of the tendinous attachment site despite addition of MSCs.

Clinical studies on augmented rotator cuff repair have also found mixed results. MSCs for this purpose have been cultivated from arthroscopic bone marrow aspiration of the proximal humerus71 and subacromial bursa72 with successful and reproducibly high concentrations of stem cells. Hernigou and colleagues73 found a significant improvement in rate of healing (87% intact cuffs vs 44% in the control group) and repair surface tendon integrity (via ultrasound and MRI) for patients at a minimum of 10 years after rotator cuff repair with MSC injection at the time of surgery. The authors found a direct correlation in these outcomes with the number of MSCs injected at the time of repair. Ellera Gomes and colleagues74 injected bm-MSCs obtained from the iliac crest into the tendinous repair site in 14 consecutive patients with full-thickness rotator cuff tears treated by transosseous sutures via a mini-open approach. MRI demonstrated integrity of the repair site in all patients at more than 1-year follow-up.

Achilles Tendon Repair

The goal with stem cell use in Achilles repair is to accelerate the healing and rehabilitation. Several animal studies have demonstrated improved mechanical properties and collagen composition of tendon repairs augmented with stem cells, including Achilles tendon repair in a rat model. Adams and colleagues75 compared suture alone (36 tendons) to suture plus stem cell concentrate injection (36 tendons) and stem cell loaded suture (36 tendons) in Achilles tendon repair with rat models. The suture-alone cohort had lower ultimate failure loads at 14 days after surgery, indicating biomechanical superiority with stem cell augmentation means. Transplantation of hypoxic MSCs at the time of Achilles tendon repair may be a promising option for superior biomechanical failure loads and histologic findings as per recent rat model findings by Huang and colleagues.76 Yao and colleagues77 demonstrated increased strength of suture repair for Achilles repair in rat models at early time points when using MSC-coated suture in comparison to standard suture, and suggested that the addition of stem cells may improve early mechanical properties during the tendon repair process. A-MSC addition to PRP has provided significantly increased tensile strength to rabbit models with Achilles tendon repair as well.78

In evaluation of stem cell use for this purpose with humans, Stein and colleagues79 reviewed 28 sports-related Achilles tendon ruptures in 27 patients treated with open repair and BMAC injection. At a mean follow-up of 29.7 months, the authors reported no re-ruptures, with 92% return to sport at 5.9 months, and excellent clinical outcomes. This small cohort study found no adverse outcomes related to the BMAC addition, and thus proposed further study of the efficacy of stem cell treatment for Achilles tendon repair.

Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction

Bm-MSCs genetically modified with bone morphogenetic protein 2 (BMP2) and basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) have shown great promise in improvement of the formation of mechanically sound tendon-bone interface in anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) reconstruction.80 Similar to the other surgical procedures mentioned in this review, animal studies have successfully evaluated the augmentation of osteointegration of tendon to bone in the setting of ACL reconstruction. Jang and colleagues3 investigated the use of nonautologous transplantation of human umbilical cord blood-derived MSCs in a rabbit ACL reconstruction model. The authors demonstrated a lack of immune rejection, and enhanced tendon-bone healing with broad fibrocartilage formation at the transition zone (similar to the native ACL) and decreased femoral and tibial tunnel widening as compared to a control cohort at 12-weeks after surgery. In a rat model, Kanaya and colleagues81 reported improved histological scores and slight improvements in biomechanical integrity of partially transected rat ACLs treated with intra-articular MSC injection. Stem cell use in the form of suture-supporting scaffolds seeded with MSCs has been evaluated in a total ACL transection rabbit model; the authors of this report demonstrated total ACL regeneration in one-third of samples treated with this augmentation option, in comparison to complete failure in all suture and scaffold alone groups.82

The use of autologous MSCs in ACL healing remains limited to preclinical research and small case series of patients. One human trial by Silva and colleagues83 evaluated the graft-to-bone site of healing in ACL reconstruction for 20 patients who received an intraoperative infiltration of their graft with adult bm-MSCs. MRI and histologic analysis showed no difference in comparison to control groups, but the authors’ conclusion proposed that the number of stem cells injected might have been too minimal to show a clinical effect.

Other Applications

Although outside the scope of this article, stem cells have demonstrated efficacy in the treatment of a number of osseous clinical entities. This includes the treatment of fracture nonunion, augmentation of spinal fusion, and assistance in the treatment of osteonecrosis.84

Summary

As a scientific community, our understanding of the use of stem cells, their nuances, and their indications has expanded dramatically over the last several years. Stem cell treatment has particularly infiltrated the world of operative and nonoperative sports medicine, given in part the active patient population seeking greater levels of improvement.85 Stem cell therapy offers a potentially effective therapy for a multitude of pathologies because of these cells’ anti-inflammatory, immunoregulatory, angiogenic, and paracrine effects.86 It thus remains a very dynamic option in the study of musculoskeletal tissue regeneration. While the potential exists for stem cell use in daily surgery practices, it is still premature to predict whether this can be expected.

The ideal stem cell sources (including allogeneic or autologous), preparation, cell number, timing, and means of application continue to be evaluated, as well as those advantageous pathologies that can benefit from the technology. In order to better answer these pertinent questions, we need to make sure we have a safe, economic, and ethically acceptable means for stem cell translational research efforts. More high-level studies with standardized protocols need to be performed. It is necessary to improve national and international collaboration in research, as well as collaboration with governing bodies, to attempt to further scientific advancement in this field of research.49 Further study on embryonic stem cell use may be valuable as well, pending governmental approval. Finally, more dedicated research efforts must be placed on the utility of adjuncts with stem cell use, including PRP and scaffolds, which may increase protection, nutritional support, and mechanical stimulation of the administered stem cells.

1. Oh JH, Chung SW, Kim SH, Chung JY, Kim JY. 2013 Neer Award: Effect of the adipose-derived stem cell for the improvement of fatty degeneration and rotator cuff healing in rabbit model. J Shoulder Elb Surg. 2014;23(4):445-455.

2. Caplan AI, Correa D. PDGF in bone formation and regeneration: new insights into a novel mechanism involving MSCs. J Orthop Res. 2011;29(12):1795-1803.

3. Jang KM, Lim HC, Jung WY, Moon SW, Wang JH. Efficacy and safety of human umbilical cord blood-derived mesenchymal stem cells in anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction of a rabbit model: new strategy to enhance tendon graft healing. Arthroscopy. 2015;31(8):1530-1539.

4. Muttini A, Salini V, Valbonetti L, Abate M. Stem cell therapy of tendinopathies: suggestions from veterinary medicine. Muscles Ligaments Tendons J. 2012;2(3):187-192.

5. Xia P, Wang X, Lin Q, Li X. Efficacy of mesenchymal stem cells injection for the management of knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int Orthop. 2015;39(12):2363-2372.

6. Veronesi F, Giavaresi G, Tschon M, Borsari V, Nicoli Aldini N, Fini M. Clinical use of bone marrow, bone marrow concentrate, and expanded bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells in cartilage disease. Stem Cells Dev. 2013;22(2):181-192.

7. Caplan AI. Review: mesenchymal stem cells: cell-based reconstructive therapy in orthopedics. Tissue Eng. 2005;11(7-8):1198-1211.

8. Hirzinger C, Tauber M, Korntner S, et al. ACL injuries and stem cell therapy. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2014;134(11):1573-1578.

9. Becerra P, Valdés Vázquez MA, Dudhia J, et al. Distribution of injected technetium(99m)-labeled mesenchymal stem cells in horses with naturally occurring tendinopathy. J Orthop Res. 2013;31(7):1096-1102.

10. Lodi D, Iannitti T, Palmieri B. Stem cells in clinical practice: applications and warnings. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2011;30:9.

11. García-Gómez I, Elvira G, Zapata AG, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells: biological properties and clinical applications. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2010;10(10):1453-1468.

12. Centeno CJ, Schultz JR, Cheever M, et al. Safety and complications reporting update on the re-implantation of culture-expanded mesenchymal stem cells using autologous platelet lysate technique. Curr Stem Cell Res Ther. 2011;6(4):368-378.

13. Centeno CJ, Al-Sayegh H, Freeman MD, Smith J, Murrell WD, Bubnov R. A multi-center analysis of adverse events among two thousand, three hundred and seventy two adult patients undergoing adult autologous stem cell therapy for orthopaedic conditions. Int Orthop. 2016 Mar 30. [Epub ahead of print]

14. Schmitt A, van Griensven M, Imhoff AB, Buchmann S. Application of stem cells in orthopedics. Stem Cells Int. 2012;2012:394962.

15. Tuan RS, Boland G, Tuli R. Adult mesenchymal stem cells and cell-based tissue engineering. Arthritis Res Ther. 2003;5(1):32-45.

16. Anz AW, Hackel JG, Nilssen EC, Andrews JR. Application of biologics in the treatment of the rotator cuff, meniscus, cartilage, and osteoarthritis. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2014;22(2):68-79.

17. Dominici M, Le Blanc K, Mueller I, et al. Minimal criteria for defining multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells. The International Society for Cellular Therapy position statement. Cytotherapy. 2006;8(4):315-317.

18. Porada CD, Almeida-Porada G. Mesenchymal stem cells as therapeutics and vehicles for gene and drug delivery. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2010;62(12):1156-1566.

19. Filardo G, Madry H, Jelic M, Roffi A, Cucchiarini M, Kon E. Mesenchymal stem cells for the treatment of cartilage lesions: from preclinical findings to clinical application in orthopaedics. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2013;21(8):1717-1729.

20. Liechty KW, MacKenzie TC, Shaaban AF, et al. Human mesenchymal stem cells engraft and demonstrate site-specific differentiation after in utero transplantation in sheep. Nat Med. 2000;6(11):1282-1286.

21. Hung SC, Chen NJ, Hsieh SL, Li H, Ma HL, Lo WH. Isolation and characterization of size-sieved stem cells from human bone marrow. Stem Cells. 2002;20(3):249-258.

22. De Bari C, Dell’Accio F, Vanlauwe J, et al. Mesenchymal multipotency of adult human periosteal cells demonstrated by single-cell lineage analysis. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54(4):1209-1221.

23. Zuk PA, Zhu M, Ashjian P, et al. Human adipose tissue is a source of multipotent stem cells. Mol Biol Cell. 2002;13(12):4279-4295.

24. Mafi R, Hindocha S, Mafi P, Griffin M, Khan WS. Sources of adult mesenchymal stem cells applicable for musculoskeletal applications - a systematic review of the literature. Open Orthop J. 2011;5 Suppl 2:242-248.

25. Frisbie DD, Kisiday JD, Kawcak CE, Werpy NM, McIlwraith CW. Evaluation of adipose-derived stromal vascular fraction or bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells for treatment of osteoarthritis. J Orthop Res. 2009;27(12):1675-1680.

26. Vidal MA, Robinson SO, Lopez MJ, et al. Comparison of chondrogenic potential in equine mesenchymal stromal cells derived from adipose tissue and bone marrow. Vet Surg. 2008;37(8):713-724.

27. Yoshimura H, Muneta T, Nimura A, Yokoyama A, Koga H, Sekiya I. Comparison of rat mesenchymal stem cells derived from bone marrow, synovium, periosteum, adipose tissue, and muscle. Cell Tissue Res. 2007;327(3):449-462.

28. Hogan MV, Walker GN, Cui LR, Fu FH, Huard J. The role of stem cells and tissue engineering in orthopaedic sports medicine: current evidence and future directions. Arthroscopy. 2015;31(5):1017-1021.

29. Koh YG, Choi YJ, Kwon SK, Kim YS, Yeo JE. Clinical results and second-look arthroscopic findings after treatment with adipose-derived stem cells for knee osteoarthritis. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2015;23(5):1308-1316.

30. Vangsness CT Jr, Farr J 2nd, Boyd J, Dellaero DT, Mills CR, LeRoux-Williams M. Adult human mesenchymal stem cells delivered via intra-articular injection to the knee following partial medial meniscectomy: a randomized, double-blind, controlled study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96(2):90-98.

31. Goodrich LR, Chen AC, Werpy NM, et al. Addition of mesenchymal stem cells to autologous platelet-enhanced fibrin scaffolds in chondral defects: does it enhance repair? J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2016;98(1):23-34.

32. Kim YS, Choi YJ, Suh DS, et al. Mesenchymal stem cell implantation in osteoarthritic knees: is fibrin glue effective as a scaffold? Am J Sports Med. 2015;43(1):176-185.

33. Steinert AF, Rackwitz L, Gilbert F, Nöth U, Tuan RS. Concise review: the clinical application of mesenchymal stem cells for musculoskeletal regeneration: current status and perspectives. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2012;1(3):237-247.

34. Pers YM, Ruiz M, Noël D, Jorgensen C. Mesenchymal stem cells for the management of inflammation in osteoarthritis: state of the art and perspectives. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2015;23(11):2027-2035.

35. Mamidi MK, Das AK, Zakaria Z, Bhonde R. Mesenchymal stromal cells for cartilage repair in osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2016 Mar 10. [Epub ahead of print]

36. Wyles CC, Houdek MT, Behfar A, Sierra RJ. Mesenchymal stem cell therapy for osteoarthritis: current perspectives. Stem Cells Cloning. 2015;8:117-124.

37. Wong KL, Lee KB, Tai BC, Law P, Lee EH, Hui JH. Injectable cultured bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells in varus knees with cartilage defects undergoing high tibial osteotomy: a prospective, randomized controlled clinical trial with 2 years’ follow-up. Arthroscopy. 2013;29(12):2020-2028.

38. Vega A, Martín-Ferrero MA, Del Canto F, et al. Treatment of knee osteoarthritis with allogeneic bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells: a randomized controlled trial. Transplantation. 2015;99(8):1681-1690.

39. Kim YS, Lee M, Koh YG. Additional mesenchymal stem cell injection improves the outcomes of marrow stimulation combined with supramalleolar osteotomy in varus ankle osteoarthritis: short-term clinical results with second-look arthroscopic evaluation. J Exp Orthop. 2016;3(1):12.

40. Kraus TM, Imhoff FB, Reinert J, et al. Stem cells and bFGF in tendon healing: Effects of lentiviral gene transfer and long-term follow-up in a rat Achilles tendon defect model. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2016;17(1):148.

41. Thomopoulos S, Parks WC, Rifkin DB, Derwin KA. Mechanisms of tendon injury and repair. J Orthop Res. 2015;33(6):832-839.

42. Müller SA, Todorov A, Heisterbach PE, Martin I, Majewski M. Tendon healing: an overview of physiology, biology, and pathology of tendon healing and systematic review of state of the art in tendon bioengineering. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2015;23(7):2097-3105.

43. Godwin EE, Young NJ, Dudhia J, Beamish IC, Smith RK. Implantation of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells demonstrates improved outcome in horses with overstrain injury of the superficial digital flexor tendon. Equine Vet J. 2012;44(1):25-32.

44. Machova Urdzikova L, Sedlacek R, Suchy T, et al. Human multipotent mesenchymal stem cells improve healing after collagenase tendon injury in the rat. Biomed Eng Online. 2014;13:42.

45. Oshita T, Tobita M, Tajima S, Mizuno H. Adipose-derived stem cells improve collagenase-induced tendinopathy in a rat model. Am J Sports Med. 2016 Apr 11. [Epub ahead of print]

46. Yuksel S, Guleç MA, Gultekin MZ, et al. Comparison of the early-period effects of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells and platelet-rich plasma on achilles tendon ruptures in rats. Connect Tissue Res. 2016 May 18. [Epub ahead of print]

47. Chen L, Liu JP, Tang KL, et al. Tendon derived stem cells promote platelet-rich plasma healing in collagenase-induced rat achilles tendinopathy. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2014;34(6):2153-2168.

48. Pascual-Garrido C, Rolón A, Makino A. Treatment of chronic patellar tendinopathy with autologous bone marrow stem cells: a 5-year-followup. Stem Cells Int. 2012;2012:953510.

49. Zlotnicki JP, Geeslin AG, Murray IR, et al. Biologic treatments for sports injuries ii think tank-current concepts, future research, and barriers to advancement, part 3: articular cartilage. Orthop J Sports Med. 2016;4(4):2325967116642433.

50. McCormack RA, Shreve M, Strauss EJ. Biologic augmentation in rotator cuff repair--should we do it, who should get it, and has it worked? Bull Hosp Jt Dis (2013). 2014;72(1):89-96.

51. Mosna F, Sensebé L, Krampera M. Human bone marrow and adipose tissue mesenchymal stem cells: a user’s guide. Stem Cells Dev. 2010;19(10):1449-1470.

52. Nakamura T, Sekiya I, Muneta T, et al. Arthroscopic, histological and MRI analyses of cartilage repair after a minimally invasive method of transplantation of allogeneic synovial mesenchymal stromal cells into cartilage defects in pigs. Cytotherapy. 2012;14(3):327-338.

53. Dragoo JL, Carlson G, McCormick F, et al. Healing full-thickness cartilage defects using adipose-derived stem cells. Tissue Eng. 2007;13(7):1615-1621.

54. Masuoka K, Asazuma T, Hattori H, et al. Tissue engineering of articular cartilage with autologous cultured adipose tissue-derived stromal cells using atelocollagen honeycomb-shaped scaffold with a membrane sealing in rabbits. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater. 2006 79(1):25-34.

55. Gobbi A, Karnatzikos G, Sankineani SR. One-step surgery with multipotent stem cells for the treatment of large full-thickness chondral defects of the knee. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42(3):648-657.

56. Kim JD, Lee GW, Jung GH, et al. Clinical outcome of autologous bone marrow aspirates concentrate (BMAC) injection in degenerative arthritis of the knee. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol. 2014;24(8):1505-1511.

57. Krych AJ, Nawabi DH, Farshad-Amacker NA, et al. Bone marrow concentrate improves early cartilage phase maturation of a scaffold plug in the knee: a comparative magnetic resonance imaging analysis to platelet-rich plasma and control. Am J Sports Med. 2016;44(1):91-98.

58. Fortier LA, Potter HG, Rickey EJ, et al. Concentrated bone marrow aspirate improves full-thickness cartilage repair compared with microfracture in the equine model. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92(10):1927-1937.

59. Kim YS, Park EH, Kim YC, Koh YG. Clinical outcomes of mesenchymal stem cell injection with arthroscopic treatment in older patients with osteochondral lesions of the talus. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41(5):1090-1099.

60. Kim YS, Lee HJ, Choi YJ, Kim YI, Koh YG. Does an injection of a stromal vascular fraction containing adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells influence the outcomes of marrow stimulation in osteochondral lesions of the talus? A clinical and magnetic resonance imaging study. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42(10):2424-2434.

61. Chahla J, Dean CS, Moatshe G, Pascual-Garrido C, Serra Cruz R, LaPrade RF. Concentrated bone marrow aspirate for the treatment of chondral injuries and osteoarthritis of the knee: a systematic review of outcomes. Orthop J Sports Med. 2016;4(1):2325967115625481.

62. Gobbi A, Karnatzikos G, Scotti C, Mahajan V, Mazzucco L, Grigolo B. One-step cartilage repair with bone marrow aspirate concentrated cells and collagen matrix in full-thickness knee cartilage lesions: results at 2-year follow-up. Cartilage. 2011;2(3):286-299.

63. Ruiz-Ibán MÁ, Díaz-Heredia J, García-Gómez I, Gonzalez-Lizán F, Elías-Martín E, Abraira V. The effect of the addition of adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells to a meniscal repair in the avascular zone: an experimental study in rabbits. Arthroscopy. 2011;27(12):1688-1696.

64. Angele P, Johnstone B, Kujat R, et al. Stem cell based tissue engineering for meniscus repair. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2008;85(2):445-455.

65. Hernigou P, Merouse G, Duffiet P, Chevalier N, Rouard H. Reduced levels of mesenchymal stem cells at the tendon-bone interface tuberosity in patients with symptomatic rotator cuff tear. Int Orthop. 2015;39(6):1219-1225.

66. Goutallier D, Postel JM, Gleyze P, Leguilloux P, Van Driessche S. Influence of cuff muscle fatty degeneration on anatomic and functional outcomes after simple suture of full-thickness tears. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2003;12(6):550-554.

67. Kovacevic D, Rodeo SA. Biological augmentation of rotator cuff tendon repair. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2008;466(3):622-633.

68. Valencia Mora M, Antuña Antuña S, García Arranz M, Carrascal MT, Barco R. Application of adipose tissue-derived stem cells in a rat rotator cuff repair model. Injury. 2014;45 Suppl 4:S22-S27.

69. Yokoya S, Mochizuki Y, Natsu K, Omae H, Nagata Y, Ochi M. Rotator cuff regeneration using a bioabsorbable material with bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells in a rabbit model. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(6):1259-1268.

70. Gulotta LV, Kovacevic D, Ehteshami JR, Dagher E, Packer JD, Rodeo SA. Application of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells in a rotator cuff repair model. Am J Sports Med. 2009;37(11):2126-2133.

71. Beitzel K, McCarthy MB, Cote MP, et al. Comparison of mesenchymal stem cells (osteoprogenitors) harvested from proximal humerus and distal femur during arthroscopic surgery. Arthroscopy. 2013;29(2):301-308.

72. Utsunomiya H, Uchida S, Sekiya I, Sakai A, Moridera K, Nakamura T. Isolation and characterization of human mesenchymal stem cells derived from shoulder tissues involved in rotator cuff tears. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41(3):657-668.

73. Hernigou P, Flouzat Lachaniette CH, Delambre J, et al. Biologic augmentation of rotator cuff repair with mesenchymal stem cells during arthroscopy improves healing and prevents further tears: a case-controlled study. Int Orthop. 2014;38(9):1811-1818.

74. Ellera Gomes JL, da Silva RC, Silla LM, Abreu MR, Pellanda R. Conventional rotator cuff repair complemented by the aid of mononuclear autologous stem cells. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2012;20(2):373-377.

75. Adams SB Jr, Thorpe MA, Parks BG, Aghazarian G, Allen E, Schon LC. Stem cell-bearing suture improves Achilles tendon healing in a rat model. Foot Ankle Int. 2014;35(3):293-299.

76. Huang TF, Yew TL, Chiang ER, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells from a hypoxic culture improve and engraft Achilles tendon repair. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41(5):1117-1125.

77. Yao J, Woon CY, Behn A, et al. The effect of suture coated with mesenchymal stem cells and bioactive substrate on tendon repair strength in a rat model. J Hand Surg Am. 2012;37(8):1639-1645.

78. Uysal CA, Tobita M, Hyakusoku H, Mizuno H. Adipose-derived stem cells enhance primary tendon repair: biomechanical and immunohistochemical evaluation. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2012;65(12):1712-1719.

79. Stein BE, Stroh DA, Schon LC. Outcomes of acute Achilles tendon rupture repair with bone marrow aspirate concentrate augmentation. Int Orthop. 2015;39(5):901-905.

80. Chen B, Li B, Qi YJ, et al. Enhancement of tendon-to-bone healing after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction using bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells genetically modified with bFGF/BMP2. Sci Rep. 2016;6:25940.

81. Kanaya A, Deie M, Adachi N, Nishimori M, Yanada S, Ochi M. Intra-articular injection of mesenchymal stromal cells in partially torn anterior cruciate ligaments in a rat model. Arthroscopy. 2007;23(6):610-617.

82. Figueroa D, Espinosa M, Calvo R, et al. Anterior cruciate ligament regeneration using mesenchymal stem cells and collagen type I scaffold in a rabbit model. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2014;22(5):1196-1202.

83. Silva A, Sampaio R, Fernandes R, Pinto E. Is there a role for adult non-cultivated bone marrow stem cells in ACL reconstruction? Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2014;22(1):66-71.

84. Pepke W, Kasten P, Beckmann NA, Janicki P, Egermann M. Core decompression and autologous bone marrow concentrate for treatment of femoral head osteonecrosis: a randomized prospective study. Orthop Rev (Pavia). 2016;8(1):6162.