User login

Lower BP and better tumor control with drug combo?

It’s not ready for the clinic, but new research suggests that angiotensin receptor II blockers (ARBs) widely used to treat hypertension may improve responses to cancer immunotherapy agents targeted against the programmed death-1/ligand-1 (PD-1/PD-L1) pathway.

That conclusion comes from an observational study of 597 patients with more than 3 dozen different cancer types treated in clinical trials at the US National Institutes of Health. Investigators found that both objective response rates and 3-year overall survival (OS) rates were significantly higher for patients treated with a PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor who were on ARBs, compared with patients who weren’t taking the antihypertensive agents.

An association was also seen between higher ORR and OS rates for patients taking ACE inhibitors, but it was not statistically significant, reported Julius Strauss, MD, from the Center for Cancer Research at the National Cancer Institute in Bethesda, Md.

All study patients received PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors, and the ORR for patients treated with ARBs was 33.8%, compared with 19.5% for those treated with ACE inhibitors, and 17% for those who took neither drug. The respective complete response (CR) rates were 11.3%, 3.7%, and 3.1%.

Strauss discussed the data during an online briefing prior to his presentation of the findings during the 32nd EORTC-NCI-AACR Symposium on Molecular Targets and Cancer Therapeutics, which is taking place virtually.

Several early studies have suggested that angiotensin II, in addition to its effect on blood pressure, can also affect cancer growth by leading to downstream production of two proteins: vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and transforming growth factor–beta (TGF-beta), he explained.

“Both of these [proteins] have been linked to cancer growth and cancer resistance to immune system attack,” Strauss observed.

He also discussed the mechanics of possible effects. Angiotensin II increases VEGF and TGF-beta through binding to the AT1 receptor, but has the opposite effect when it binds to the AT2 receptor, resulting in a decrease in both of the growth factors, he added.

ACE inhibitors prevent the conversion of angiotensin I to angiotensin II, with the result being that the drugs indirectly block both the AT1 and AT2 receptors.

In contrast, ARBs block only the AT1 receptor and leave the AT2 counter-regulatory receptor alone, said Strauss.

More data, including on overall survival

Strauss and colleagues examined whether ACE inhibitors and/or ARBs could have an effect on the response to PD-1/PD-L1 immune checkpoint inhibitors delivered with or without other immunotherapies, such as anti-cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 (CTLA-4) checkpoint inhibitors, or targeted agents such as tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs).

They pooled data on 597 patients receiving PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors in clinical trials for various cancers, including 71 receiving concomitant ARBs, 82 receiving an ACE inhibitor, and 444 who were not receiving either class of antihypertensives.

The above-mentioned improvement in ORR with ARBs compared with patients not receiving the drug was statistically significant (P = .001), as was the improvement in CR rates (P = .002). In contrast, neither ORR nor CR were significantly better with patients on ACE inhibitors compared with patients not taking these drugs.

In multiple regression analysis controlling for age, gender, body mass index (BMI), tumor type, and additional therapies given, the superior ORR and CR rates with ARBs remained (P = .039 and .002, respectively), while there continued to be no significant additional benefit with ACE inhibitors.

The median overall survival was 35.2 months for patients on ARBs, 26.2 months for those on ACE inhibitors, and 18.8 months for patients on neither drug. The respective 3-year OS rates were 48.1%, 37.2%, and 31.5%, with the difference between the ARB and no-drug groups being significant (P = .0078).

In regression analysis controlling for the factors mentioned before, the OS advantage with ARBs but not ACE inhibitors remained significant (P = .006 for ARBs, and .078 for ACE inhibitors).

Strauss emphasized that further study is needed to determine if AT1 blockade can improve outcomes when combined anti-PD-1/PD-L1-based therapy.

It might be reasonable for patients who are taking ACE inhibitors to control blood pressure and are also receiving immunotherapy with a PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor to be switched to an ARB if it is deemed safe and if further research bears it out, said Strauss in response to a question from Medscape Medical News.

Hypothesis-generating study

Meeting cochair Emiliano Calvo, MD, PhD, from Hospital de Madrid Norte Sanchinarro in Madrid, who attended the media briefing but was not involved in the study, commented that hypothesis-generating research using drugs already on the market for other indications adds important value to cancer therapy.

James Gulley, MD, PhD, from the Center for Cancer Research at the NCI, also a meeting cochair, agreed with Calvo.

“Thinking about utilizing the data that already exists to really get hypothesis-generating questions, it also opens up the possibility for real-world data, real-world evidence from these big datasets from [electronic medical records] that we could really interrogate and understand what we might see and get these hypothesis-generating findings that we could then prospectively evaluate,” Gulley said.

The research was funded by the National Cancer Institute. Strauss and Gulley are National Cancer Institute employees. Calvo disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

It’s not ready for the clinic, but new research suggests that angiotensin receptor II blockers (ARBs) widely used to treat hypertension may improve responses to cancer immunotherapy agents targeted against the programmed death-1/ligand-1 (PD-1/PD-L1) pathway.

That conclusion comes from an observational study of 597 patients with more than 3 dozen different cancer types treated in clinical trials at the US National Institutes of Health. Investigators found that both objective response rates and 3-year overall survival (OS) rates were significantly higher for patients treated with a PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor who were on ARBs, compared with patients who weren’t taking the antihypertensive agents.

An association was also seen between higher ORR and OS rates for patients taking ACE inhibitors, but it was not statistically significant, reported Julius Strauss, MD, from the Center for Cancer Research at the National Cancer Institute in Bethesda, Md.

All study patients received PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors, and the ORR for patients treated with ARBs was 33.8%, compared with 19.5% for those treated with ACE inhibitors, and 17% for those who took neither drug. The respective complete response (CR) rates were 11.3%, 3.7%, and 3.1%.

Strauss discussed the data during an online briefing prior to his presentation of the findings during the 32nd EORTC-NCI-AACR Symposium on Molecular Targets and Cancer Therapeutics, which is taking place virtually.

Several early studies have suggested that angiotensin II, in addition to its effect on blood pressure, can also affect cancer growth by leading to downstream production of two proteins: vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and transforming growth factor–beta (TGF-beta), he explained.

“Both of these [proteins] have been linked to cancer growth and cancer resistance to immune system attack,” Strauss observed.

He also discussed the mechanics of possible effects. Angiotensin II increases VEGF and TGF-beta through binding to the AT1 receptor, but has the opposite effect when it binds to the AT2 receptor, resulting in a decrease in both of the growth factors, he added.

ACE inhibitors prevent the conversion of angiotensin I to angiotensin II, with the result being that the drugs indirectly block both the AT1 and AT2 receptors.

In contrast, ARBs block only the AT1 receptor and leave the AT2 counter-regulatory receptor alone, said Strauss.

More data, including on overall survival

Strauss and colleagues examined whether ACE inhibitors and/or ARBs could have an effect on the response to PD-1/PD-L1 immune checkpoint inhibitors delivered with or without other immunotherapies, such as anti-cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 (CTLA-4) checkpoint inhibitors, or targeted agents such as tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs).

They pooled data on 597 patients receiving PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors in clinical trials for various cancers, including 71 receiving concomitant ARBs, 82 receiving an ACE inhibitor, and 444 who were not receiving either class of antihypertensives.

The above-mentioned improvement in ORR with ARBs compared with patients not receiving the drug was statistically significant (P = .001), as was the improvement in CR rates (P = .002). In contrast, neither ORR nor CR were significantly better with patients on ACE inhibitors compared with patients not taking these drugs.

In multiple regression analysis controlling for age, gender, body mass index (BMI), tumor type, and additional therapies given, the superior ORR and CR rates with ARBs remained (P = .039 and .002, respectively), while there continued to be no significant additional benefit with ACE inhibitors.

The median overall survival was 35.2 months for patients on ARBs, 26.2 months for those on ACE inhibitors, and 18.8 months for patients on neither drug. The respective 3-year OS rates were 48.1%, 37.2%, and 31.5%, with the difference between the ARB and no-drug groups being significant (P = .0078).

In regression analysis controlling for the factors mentioned before, the OS advantage with ARBs but not ACE inhibitors remained significant (P = .006 for ARBs, and .078 for ACE inhibitors).

Strauss emphasized that further study is needed to determine if AT1 blockade can improve outcomes when combined anti-PD-1/PD-L1-based therapy.

It might be reasonable for patients who are taking ACE inhibitors to control blood pressure and are also receiving immunotherapy with a PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor to be switched to an ARB if it is deemed safe and if further research bears it out, said Strauss in response to a question from Medscape Medical News.

Hypothesis-generating study

Meeting cochair Emiliano Calvo, MD, PhD, from Hospital de Madrid Norte Sanchinarro in Madrid, who attended the media briefing but was not involved in the study, commented that hypothesis-generating research using drugs already on the market for other indications adds important value to cancer therapy.

James Gulley, MD, PhD, from the Center for Cancer Research at the NCI, also a meeting cochair, agreed with Calvo.

“Thinking about utilizing the data that already exists to really get hypothesis-generating questions, it also opens up the possibility for real-world data, real-world evidence from these big datasets from [electronic medical records] that we could really interrogate and understand what we might see and get these hypothesis-generating findings that we could then prospectively evaluate,” Gulley said.

The research was funded by the National Cancer Institute. Strauss and Gulley are National Cancer Institute employees. Calvo disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

It’s not ready for the clinic, but new research suggests that angiotensin receptor II blockers (ARBs) widely used to treat hypertension may improve responses to cancer immunotherapy agents targeted against the programmed death-1/ligand-1 (PD-1/PD-L1) pathway.

That conclusion comes from an observational study of 597 patients with more than 3 dozen different cancer types treated in clinical trials at the US National Institutes of Health. Investigators found that both objective response rates and 3-year overall survival (OS) rates were significantly higher for patients treated with a PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor who were on ARBs, compared with patients who weren’t taking the antihypertensive agents.

An association was also seen between higher ORR and OS rates for patients taking ACE inhibitors, but it was not statistically significant, reported Julius Strauss, MD, from the Center for Cancer Research at the National Cancer Institute in Bethesda, Md.

All study patients received PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors, and the ORR for patients treated with ARBs was 33.8%, compared with 19.5% for those treated with ACE inhibitors, and 17% for those who took neither drug. The respective complete response (CR) rates were 11.3%, 3.7%, and 3.1%.

Strauss discussed the data during an online briefing prior to his presentation of the findings during the 32nd EORTC-NCI-AACR Symposium on Molecular Targets and Cancer Therapeutics, which is taking place virtually.

Several early studies have suggested that angiotensin II, in addition to its effect on blood pressure, can also affect cancer growth by leading to downstream production of two proteins: vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and transforming growth factor–beta (TGF-beta), he explained.

“Both of these [proteins] have been linked to cancer growth and cancer resistance to immune system attack,” Strauss observed.

He also discussed the mechanics of possible effects. Angiotensin II increases VEGF and TGF-beta through binding to the AT1 receptor, but has the opposite effect when it binds to the AT2 receptor, resulting in a decrease in both of the growth factors, he added.

ACE inhibitors prevent the conversion of angiotensin I to angiotensin II, with the result being that the drugs indirectly block both the AT1 and AT2 receptors.

In contrast, ARBs block only the AT1 receptor and leave the AT2 counter-regulatory receptor alone, said Strauss.

More data, including on overall survival

Strauss and colleagues examined whether ACE inhibitors and/or ARBs could have an effect on the response to PD-1/PD-L1 immune checkpoint inhibitors delivered with or without other immunotherapies, such as anti-cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 (CTLA-4) checkpoint inhibitors, or targeted agents such as tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs).

They pooled data on 597 patients receiving PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors in clinical trials for various cancers, including 71 receiving concomitant ARBs, 82 receiving an ACE inhibitor, and 444 who were not receiving either class of antihypertensives.

The above-mentioned improvement in ORR with ARBs compared with patients not receiving the drug was statistically significant (P = .001), as was the improvement in CR rates (P = .002). In contrast, neither ORR nor CR were significantly better with patients on ACE inhibitors compared with patients not taking these drugs.

In multiple regression analysis controlling for age, gender, body mass index (BMI), tumor type, and additional therapies given, the superior ORR and CR rates with ARBs remained (P = .039 and .002, respectively), while there continued to be no significant additional benefit with ACE inhibitors.

The median overall survival was 35.2 months for patients on ARBs, 26.2 months for those on ACE inhibitors, and 18.8 months for patients on neither drug. The respective 3-year OS rates were 48.1%, 37.2%, and 31.5%, with the difference between the ARB and no-drug groups being significant (P = .0078).

In regression analysis controlling for the factors mentioned before, the OS advantage with ARBs but not ACE inhibitors remained significant (P = .006 for ARBs, and .078 for ACE inhibitors).

Strauss emphasized that further study is needed to determine if AT1 blockade can improve outcomes when combined anti-PD-1/PD-L1-based therapy.

It might be reasonable for patients who are taking ACE inhibitors to control blood pressure and are also receiving immunotherapy with a PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor to be switched to an ARB if it is deemed safe and if further research bears it out, said Strauss in response to a question from Medscape Medical News.

Hypothesis-generating study

Meeting cochair Emiliano Calvo, MD, PhD, from Hospital de Madrid Norte Sanchinarro in Madrid, who attended the media briefing but was not involved in the study, commented that hypothesis-generating research using drugs already on the market for other indications adds important value to cancer therapy.

James Gulley, MD, PhD, from the Center for Cancer Research at the NCI, also a meeting cochair, agreed with Calvo.

“Thinking about utilizing the data that already exists to really get hypothesis-generating questions, it also opens up the possibility for real-world data, real-world evidence from these big datasets from [electronic medical records] that we could really interrogate and understand what we might see and get these hypothesis-generating findings that we could then prospectively evaluate,” Gulley said.

The research was funded by the National Cancer Institute. Strauss and Gulley are National Cancer Institute employees. Calvo disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Thermography plus software shows efficacy for breast cancer screening

Sensitivity and area under the curve (AUC) analyses of thermography that is combined with diagnostic software demonstrate “the efficacy of the tool for breast cancer screening,” concludes an observational, comparative study from India published online Oct. 1 in JCO Global Oncology, a publication of the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

Siva Teja Kakileti of Niramai Health Analytix, Koramangala, Bangalore, India, and colleagues said that the product, Thermalytix, is potentially a good fit for low- and middle-income countries because it is portable and provides automated quantitative analysis of thermal images – and thus can be conducted by technicians with “minimal training.”

Conventional thermography involves manual interpretation of complex thermal images, which “often results in erroneous results owing to subjectivity,” said the study authors.

That manual interpretation of thermal images might involve looking at 200 color shades, which is “high cognitive overload for the thermographer,” explained Mr. Kakileti in an interview.

However, an American mammography expert who was approached for comment dismissed thermography – even with the new twist of software-aided diagnostic scoring by Thermalytix – as wholly inappropriate for the detection of early breast cancer, owing to inherent limitations.

“Thermal imaging of any type has no value in finding early breast cancer,” Daniel Kopans, MD, of Harvard University and Massachusetts General Hospital, both in Boston, said in an interview. He said that thermal imaging only detects heat on the skin and perhaps a few millimeters beneath the skin and thus misses deeper cancers, the heat from which is carried away by the vascular system.

The new study included 470 women who presented for breast screening at two centers in Bangalore, India. A total of 238 women had symptoms such as breast lump, nipple discharge, skin changes, or breast pain; the remaining 232 women were asymptomatic.

All participants underwent a Thermalytix test and one or more standard-of-care tests for breast cancer screening (such as mammography, ultrasonography, biopsy, fine-needle aspiration, or elastography). A total of 78 women, or 16.6% of the group overall, were diagnosed with a malignancy. For the overall group of 470 women, Thermalytix had a sensitivity of 91.02% (symptomatic, 89.85%; asymptomatic,100%) and a specificity of 82.39% (symptomatic, 69.04%; asymptomatic, 92.41%) in detection of breast malignancy. Thermalytix showed an overall AUC of 0.90, with an AUC of 0.82 for symptomatic and 0.98 for asymptomatic women.

The study authors characterized both the sensitivity and AUC as “high.”

The results from the study, which the authors characterized as preliminary, encouraged the study sponsor, Niramai, to start planning a large-scale, multicountry trial.

But Dr. Kopans, who serves as a consultant to DART, which produces digital breast tomosynthesis units in China, suggested that this research will be fruitless. “Thermal imaging seems to raise its head every few years since it is passive, but it does not work and is a waste of money,” Dr. Kopans reiterated.

“Its use can be dangerous by dissuading women from being screened with mammography, which has been proven to save lives,” he stressed.

Thermalytix compared with mammography

Investigators also compared screening results in the subset of 242 women who underwent both Thermalytix and mammography. Results showed that Thermalytix had a higher sensitivity than did mammography (91.23% vs. 85.96%), but mammography had a higher specificity than Thermalytix did (94.05% vs. 68.65%).

In the asymptomatic group who underwent both tests (n = 95), four cancers were detected, and Thermalytix demonstrated superior sensitivity than mammography (100% vs. 50%), Mr. Kakileti and colleagues state.

Thermalytix evaluates vascularity variations too

In the subset of 228 women who did not undergo mammography (owing to dense breasts, younger age, or other reasons), Thermalytix detected tumors in all but 3 of 21 patients who went on to be diagnosed with breast cancer. The authors state that, because their artificial intelligence–based analysis uses vascularity, as well as temperature variations on the skin, to complement hot-spot detection, it is able to detect small lesions.

In the current study, 24 malignant tumors were less than 2 cm in diameter, and Thermalytix was able to identify 17 of the tumors as positive, for a 71% sensitivity rate for T1 tumors. This compared with a 68% sensitivity rate for mammography for detecting the same T1 tumors. Thermalytix also showed promising results in women younger than 40 years, for whom screening mammography is not usually recommended. The automated test picked up all 11 tumors eventually diagnosed in this younger cohort.

“Thermalytix is a portable, noninvasive, radiation-free test that has shown promising results in this preliminary study,” the investigators wrote, “[and] it can be an affordable and scalable method of screening in remote areas,” they added.

“We believe that Thermalytix ... is poised to be a promising modality for breast cancer screening,” Mr. Kakileti and colleagues summarized.

The FDA warns about thermography in place of mammography

The US Food and Drug Administration fairly recently warned against the use of thermography as an alternative to mammography for breast cancer screening or diagnosis, noting that it has received reports that facilities where thermography is offered often provide false information about the technology that can mislead patients into believing that it is either an alternative to or a better option than mammography.

Dr. Kopans says that other groups have invested in thermography research. “The Israelis spent millions working on a similar approach that didn’t work,” he commented.

The new software from Thermalytix, which is derived from artificial intelligence, is a “gimmick,” says the Boston radiologist. “If the basic information is not there, a computer cannot find it,” he stated, referring to what he believes are deeper-tissue tumors that are inaccessible to heat-detecting technology.

Mr. Kakileti is an employee of Nirami Health Analytix and owns stock and has filed patents with the company. Other investigators are also employed by the same company or receive research and other funding or have patents filed by the company as well. Dr. Kopans serves as a consultant to DART, which produces digital breast tomosynthesis units in China.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Sensitivity and area under the curve (AUC) analyses of thermography that is combined with diagnostic software demonstrate “the efficacy of the tool for breast cancer screening,” concludes an observational, comparative study from India published online Oct. 1 in JCO Global Oncology, a publication of the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

Siva Teja Kakileti of Niramai Health Analytix, Koramangala, Bangalore, India, and colleagues said that the product, Thermalytix, is potentially a good fit for low- and middle-income countries because it is portable and provides automated quantitative analysis of thermal images – and thus can be conducted by technicians with “minimal training.”

Conventional thermography involves manual interpretation of complex thermal images, which “often results in erroneous results owing to subjectivity,” said the study authors.

That manual interpretation of thermal images might involve looking at 200 color shades, which is “high cognitive overload for the thermographer,” explained Mr. Kakileti in an interview.

However, an American mammography expert who was approached for comment dismissed thermography – even with the new twist of software-aided diagnostic scoring by Thermalytix – as wholly inappropriate for the detection of early breast cancer, owing to inherent limitations.

“Thermal imaging of any type has no value in finding early breast cancer,” Daniel Kopans, MD, of Harvard University and Massachusetts General Hospital, both in Boston, said in an interview. He said that thermal imaging only detects heat on the skin and perhaps a few millimeters beneath the skin and thus misses deeper cancers, the heat from which is carried away by the vascular system.

The new study included 470 women who presented for breast screening at two centers in Bangalore, India. A total of 238 women had symptoms such as breast lump, nipple discharge, skin changes, or breast pain; the remaining 232 women were asymptomatic.

All participants underwent a Thermalytix test and one or more standard-of-care tests for breast cancer screening (such as mammography, ultrasonography, biopsy, fine-needle aspiration, or elastography). A total of 78 women, or 16.6% of the group overall, were diagnosed with a malignancy. For the overall group of 470 women, Thermalytix had a sensitivity of 91.02% (symptomatic, 89.85%; asymptomatic,100%) and a specificity of 82.39% (symptomatic, 69.04%; asymptomatic, 92.41%) in detection of breast malignancy. Thermalytix showed an overall AUC of 0.90, with an AUC of 0.82 for symptomatic and 0.98 for asymptomatic women.

The study authors characterized both the sensitivity and AUC as “high.”

The results from the study, which the authors characterized as preliminary, encouraged the study sponsor, Niramai, to start planning a large-scale, multicountry trial.

But Dr. Kopans, who serves as a consultant to DART, which produces digital breast tomosynthesis units in China, suggested that this research will be fruitless. “Thermal imaging seems to raise its head every few years since it is passive, but it does not work and is a waste of money,” Dr. Kopans reiterated.

“Its use can be dangerous by dissuading women from being screened with mammography, which has been proven to save lives,” he stressed.

Thermalytix compared with mammography

Investigators also compared screening results in the subset of 242 women who underwent both Thermalytix and mammography. Results showed that Thermalytix had a higher sensitivity than did mammography (91.23% vs. 85.96%), but mammography had a higher specificity than Thermalytix did (94.05% vs. 68.65%).

In the asymptomatic group who underwent both tests (n = 95), four cancers were detected, and Thermalytix demonstrated superior sensitivity than mammography (100% vs. 50%), Mr. Kakileti and colleagues state.

Thermalytix evaluates vascularity variations too

In the subset of 228 women who did not undergo mammography (owing to dense breasts, younger age, or other reasons), Thermalytix detected tumors in all but 3 of 21 patients who went on to be diagnosed with breast cancer. The authors state that, because their artificial intelligence–based analysis uses vascularity, as well as temperature variations on the skin, to complement hot-spot detection, it is able to detect small lesions.

In the current study, 24 malignant tumors were less than 2 cm in diameter, and Thermalytix was able to identify 17 of the tumors as positive, for a 71% sensitivity rate for T1 tumors. This compared with a 68% sensitivity rate for mammography for detecting the same T1 tumors. Thermalytix also showed promising results in women younger than 40 years, for whom screening mammography is not usually recommended. The automated test picked up all 11 tumors eventually diagnosed in this younger cohort.

“Thermalytix is a portable, noninvasive, radiation-free test that has shown promising results in this preliminary study,” the investigators wrote, “[and] it can be an affordable and scalable method of screening in remote areas,” they added.

“We believe that Thermalytix ... is poised to be a promising modality for breast cancer screening,” Mr. Kakileti and colleagues summarized.

The FDA warns about thermography in place of mammography

The US Food and Drug Administration fairly recently warned against the use of thermography as an alternative to mammography for breast cancer screening or diagnosis, noting that it has received reports that facilities where thermography is offered often provide false information about the technology that can mislead patients into believing that it is either an alternative to or a better option than mammography.

Dr. Kopans says that other groups have invested in thermography research. “The Israelis spent millions working on a similar approach that didn’t work,” he commented.

The new software from Thermalytix, which is derived from artificial intelligence, is a “gimmick,” says the Boston radiologist. “If the basic information is not there, a computer cannot find it,” he stated, referring to what he believes are deeper-tissue tumors that are inaccessible to heat-detecting technology.

Mr. Kakileti is an employee of Nirami Health Analytix and owns stock and has filed patents with the company. Other investigators are also employed by the same company or receive research and other funding or have patents filed by the company as well. Dr. Kopans serves as a consultant to DART, which produces digital breast tomosynthesis units in China.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Sensitivity and area under the curve (AUC) analyses of thermography that is combined with diagnostic software demonstrate “the efficacy of the tool for breast cancer screening,” concludes an observational, comparative study from India published online Oct. 1 in JCO Global Oncology, a publication of the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

Siva Teja Kakileti of Niramai Health Analytix, Koramangala, Bangalore, India, and colleagues said that the product, Thermalytix, is potentially a good fit for low- and middle-income countries because it is portable and provides automated quantitative analysis of thermal images – and thus can be conducted by technicians with “minimal training.”

Conventional thermography involves manual interpretation of complex thermal images, which “often results in erroneous results owing to subjectivity,” said the study authors.

That manual interpretation of thermal images might involve looking at 200 color shades, which is “high cognitive overload for the thermographer,” explained Mr. Kakileti in an interview.

However, an American mammography expert who was approached for comment dismissed thermography – even with the new twist of software-aided diagnostic scoring by Thermalytix – as wholly inappropriate for the detection of early breast cancer, owing to inherent limitations.

“Thermal imaging of any type has no value in finding early breast cancer,” Daniel Kopans, MD, of Harvard University and Massachusetts General Hospital, both in Boston, said in an interview. He said that thermal imaging only detects heat on the skin and perhaps a few millimeters beneath the skin and thus misses deeper cancers, the heat from which is carried away by the vascular system.

The new study included 470 women who presented for breast screening at two centers in Bangalore, India. A total of 238 women had symptoms such as breast lump, nipple discharge, skin changes, or breast pain; the remaining 232 women were asymptomatic.

All participants underwent a Thermalytix test and one or more standard-of-care tests for breast cancer screening (such as mammography, ultrasonography, biopsy, fine-needle aspiration, or elastography). A total of 78 women, or 16.6% of the group overall, were diagnosed with a malignancy. For the overall group of 470 women, Thermalytix had a sensitivity of 91.02% (symptomatic, 89.85%; asymptomatic,100%) and a specificity of 82.39% (symptomatic, 69.04%; asymptomatic, 92.41%) in detection of breast malignancy. Thermalytix showed an overall AUC of 0.90, with an AUC of 0.82 for symptomatic and 0.98 for asymptomatic women.

The study authors characterized both the sensitivity and AUC as “high.”

The results from the study, which the authors characterized as preliminary, encouraged the study sponsor, Niramai, to start planning a large-scale, multicountry trial.

But Dr. Kopans, who serves as a consultant to DART, which produces digital breast tomosynthesis units in China, suggested that this research will be fruitless. “Thermal imaging seems to raise its head every few years since it is passive, but it does not work and is a waste of money,” Dr. Kopans reiterated.

“Its use can be dangerous by dissuading women from being screened with mammography, which has been proven to save lives,” he stressed.

Thermalytix compared with mammography

Investigators also compared screening results in the subset of 242 women who underwent both Thermalytix and mammography. Results showed that Thermalytix had a higher sensitivity than did mammography (91.23% vs. 85.96%), but mammography had a higher specificity than Thermalytix did (94.05% vs. 68.65%).

In the asymptomatic group who underwent both tests (n = 95), four cancers were detected, and Thermalytix demonstrated superior sensitivity than mammography (100% vs. 50%), Mr. Kakileti and colleagues state.

Thermalytix evaluates vascularity variations too

In the subset of 228 women who did not undergo mammography (owing to dense breasts, younger age, or other reasons), Thermalytix detected tumors in all but 3 of 21 patients who went on to be diagnosed with breast cancer. The authors state that, because their artificial intelligence–based analysis uses vascularity, as well as temperature variations on the skin, to complement hot-spot detection, it is able to detect small lesions.

In the current study, 24 malignant tumors were less than 2 cm in diameter, and Thermalytix was able to identify 17 of the tumors as positive, for a 71% sensitivity rate for T1 tumors. This compared with a 68% sensitivity rate for mammography for detecting the same T1 tumors. Thermalytix also showed promising results in women younger than 40 years, for whom screening mammography is not usually recommended. The automated test picked up all 11 tumors eventually diagnosed in this younger cohort.

“Thermalytix is a portable, noninvasive, radiation-free test that has shown promising results in this preliminary study,” the investigators wrote, “[and] it can be an affordable and scalable method of screening in remote areas,” they added.

“We believe that Thermalytix ... is poised to be a promising modality for breast cancer screening,” Mr. Kakileti and colleagues summarized.

The FDA warns about thermography in place of mammography

The US Food and Drug Administration fairly recently warned against the use of thermography as an alternative to mammography for breast cancer screening or diagnosis, noting that it has received reports that facilities where thermography is offered often provide false information about the technology that can mislead patients into believing that it is either an alternative to or a better option than mammography.

Dr. Kopans says that other groups have invested in thermography research. “The Israelis spent millions working on a similar approach that didn’t work,” he commented.

The new software from Thermalytix, which is derived from artificial intelligence, is a “gimmick,” says the Boston radiologist. “If the basic information is not there, a computer cannot find it,” he stated, referring to what he believes are deeper-tissue tumors that are inaccessible to heat-detecting technology.

Mr. Kakileti is an employee of Nirami Health Analytix and owns stock and has filed patents with the company. Other investigators are also employed by the same company or receive research and other funding or have patents filed by the company as well. Dr. Kopans serves as a consultant to DART, which produces digital breast tomosynthesis units in China.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Are oncologists ready to confront a second wave of COVID-19?

Canceled appointments, postponed surgeries, and delayed cancer diagnoses – all are a recipe for exhaustion for oncologists around the world, struggling to reach and treat their patients during the pandemic. Physicians and their teams felt the pain as COVID-19 took its initial march around the globe.

“We saw the distress of people with cancer who could no longer get to anyone on the phone. Their medical visit was usually canceled. Their radiotherapy session was postponed or modified, and chemotherapy postponed,” says Axel Kahn, MD, chairman of the board of directors of La Ligue Nationale Contre le Cancer (National League Against Cancer). “In the vast majority of cases, cancer treatment can be postponed or readjusted, without affecting the patient’s chances of survival, but there has been a lot of anxiety because the patients do not know that.”

The stay-at-home factor was one that played out across many months during the first wave.

“I believe that the ‘stay-home’ message that we transmitted was rigorously followed by patients who should have come to the emergency room much earlier and who, therefore, were admitted with a much more deteriorated general condition than in non-COVID-19 times,” says Benjamín Domingo Arrué, MD, from the department of medical oncology at Hospital Universitari i Politècnic La Fe in Valencia, Spain.

And in Brazil, some of the impact from the initial hit of COVID-19 on oncology is only now being felt, according to Laura Testa, MD, head of breast medical oncology, Instituto do Câncer do Estado de São Paulo.

“We are starting to see a lot of cancer cases that didn’t show up at the beginning of the pandemic, but now they are arriving to us already in advanced stages,” she said. “These patients need hospital care. If the situation worsens and goes back to what we saw at the peak of the curve, I fear the public system won’t be able to treat properly the oncology patients that need hospital care and the patients with cancer who also have COVID-19.”

But even as health care worker fatigue and concerns linger, oncologists say that what they have learned in the last 6 months has helped them prepare as COVID-19 cases increase and a second global wave kicks up.

Lessons from the first wave

In the United States, COVID-19 hit different regions at different times and to different degrees. One of the areas hit first was Seattle.

“We jumped on top of this, we were evidence based, we put things in place very, very quickly,” said Julie Gralow, MD, professor at the University of Washington and the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, both in Seattle.

“We did a really good job keeping COVID out of our cancer centers,” Dr. Gralow said. “We learned how to be super safe, and to keep symptomatic people out of the building, and to limit the extra people they could bring with them. It’s all about the number of contacts you have.”

The story was different, though, for oncologists in several other countries, and sometimes it varied immensely within each nation.

“We treated fewer patients with cancer during the first wave,” says Dirk Arnold, MD, medical director of the Asklepios Tumor Center Hamburg (Germany), in an interview. “In part, this was because staff were quarantined and because we had a completely different infrastructure in all of the hospitals. But also fewer patients with cancer came to the clinic at all. A lot of resources were directed toward COVID-19.”

In Spain, telemedicine helped keep up with visits, but other areas felt the effect of COVID-19 patient loads.

“At least in the oncology department of our center, we have practically maintained 100% of visits, mostly by telephone,” says Dr. Arrué, “but the reality is that our country has not yet been prepared for telemedicine.”

Laura Mezquita, MD, of the department of medical oncology at Hospital Clinic de Barcelona, describes a more dramatic situation: “We have seen how some of our patients, especially with metastatic disease, have been dismissed for intensive care and life-support treatments, as well as specific treatments against COVID-19 (tocilizumab, remdesivir, etc.) due to the general health collapse of the former wave,” she said. She adds that specific oncologic populations, such as those with thoracic tumors, have been more affected.

Distress among oncologists

Many oncologists are still feeling stressed and fatigued after the first wave, just as a second string of outbreaks is on its way.

A survey presented at last month’s ESMO 2020 Congress found that, in July-August, moral distress was reported by one-third of the oncologists who responded, and more than half reported a feeling of exhaustion.

“The tiredness and team exhaustion is noticeable,” said Dr. Arnold. “We recently had a task force discussion about what will happen when we have a second wave and how the department and our services will adapt. It was clear that those who were at the very front in the first wave had only a limited desire to do that again in the second wave.”

Another concern: COVID-19’s effect on staffing levels.

“We have a population of young caregivers who are affected by the COVID-19 disease with an absenteeism rate that is quite unprecedented,” said Sophie Beaupère, general delegate of Unicancer since January.

She said that, in general, the absenteeism rate in the cancer centers averages 5%-6%, depending on the year. But that rate is now skyrocketing.

Stop-start cycle for surgery

As caregivers quarantined around the world, more than 10% of patients with cancer had treatment canceled or delayed during the first wave of the pandemic, according to another survey from ESMO, involving 109 oncologists from 18 countries.

Difficulties were reported for surgeries by 34% of the centers, but also difficulties with delivering chemotherapy (22% of centers), radiotherapy (13.7%), and therapy with checkpoint inhibitors (9.1%), monoclonal antibodies (9%), and oral targeted therapy (3.7%).

Stopping surgery is a real concern in France, noted Dr. Kahn, the National League Against Cancer chair. He says that in regions that were badly hit by COVID-19, “it was not possible to have access to the operating room for people who absolutely needed surgery; for example, patients with lung cancer that was still operable. Most of the recovery rooms were mobilized for resuscitation.”

There may be some solutions, suggested Thierry Breton, director general of the National Institute of Cancer in France. “We are getting prepared, with the health ministry, for a possible increase in hospital tension, which would lead to a situation where we would have to reschedule operations. Nationally, regionally, and locally, we are seeing how we can resume and prioritize surgeries that have not been done.”

Delays in cancer diagnosis

While COVID-19 affected treatment, many oncologists say the major impact of the first wave was a delay in diagnosing cancer. Some of this was a result of the suspension of cancer screening programs, but there was also fear among the general public about visiting clinics and hospitals during a pandemic.

“We didn’t do so well with cancer during the first wave here in the U.K.,” said Karol Sikora, PhD, MBBChir, professor of cancer medicine and founding dean at the University of Buckingham Medical School, London. “Cancer diagnostic pathways virtually stalled partly because patients didn’t seek help, but getting scans and biopsies was also very difficult. Even patients referred urgently under the ‘2-weeks-wait’ rule were turned down.”

In France, “the delay in diagnosis is indisputable,” said Dr. Kahn. “About 50% of the cancer diagnoses one would expect during this period were missed.”

“I am worried that there remains a major traffic jam that has not been caught up with, and, in the meantime, the health crisis is worsening,” he added.

In Seattle, Dr. Gralow said the first COVID-19 wave had little impact on treatment for breast cancer, but it was in screening for breast cancer “where things really got messed up.”

“Even though we’ve been fully ramped up again,” she said, concerns remain. To ensure that screening mammography is maintained, “we have spaced out the visits to keep our waiting rooms less populated, with a longer time between using the machine so we can clean it. To do this, we have extended operating hours and are now opening on Saturday.

“So we’re actually at 100% of our capacity, but I’m really nervous, though, that a lot of people put off their screening mammogram and aren’t going to come in and get it.

“Not only did people get the message to stay home and not do nonessential things, but I think a lot of people lost their health insurance when they lost their jobs,” she said, and without health insurance, they are not covered for cancer screening.

Looking ahead, with a plan

Many oncologists agree that access to care can and must be improved – and there were some positive moves.

“Some regimens changed during the first months of the pandemic, and I don’t see them going back to the way they were anytime soon,” said Dr. Testa. “The changes/adaptations that were made to minimize the chance of SARS-CoV-2 infection are still in place and will go on for a while. In this context, telemedicine helped a lot. The pandemic forced the stakeholders to step up and put it in place in March. And now it’s here to stay.”

The experience gained in the last several months has driven preparation for the next wave.

“We are not going to see the disorganization that we saw during the first wave,” said Florence Joly, MD, PhD, head of medical oncology at the Centre François Baclesse in Caen, France. “The difference between now and earlier this year is that COVID diagnostic tests are available. That was one of the problems in the first wave. We had no way to diagnose.”

On the East Coast of the United States, medical oncologist Charu Aggarwal, MD, MPH, is also optimistic: “I think we’re at a place where we can manage.”

“I believe if there was going to be a new wave of COVID-19 cases we would be: better psychologically prepared and better organized,” said Dr. Aggarwal, assistant professor of medicine in the hematology-oncology division at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. “We already have experience with all of the tools, we have telemedicine available, we have screening protocols available, we have testing, we are already universally masking, everyone’s hand-washing, so I do think that means we would be okay.”

Dr. Arnold agreed that “we are much better prepared than for the first wave, but … we have immense tasks in the area of patient management, the digitization of patient care, the clear allocation of resources when there is a second or third wave. In many areas of preparation, I believe, unfortunately, we are not as well positioned as we had actually hoped.”

The first wave of COVID hit cancer services in the United Kingdom particularly hard: One modeling study suggested that delays in cancer referrals will lead to thousands of additional deaths and tens of thousands of life-years lost.

“Cancer services are working at near normal levels now, but they are still fragile and could be severely compromised again if the NHS [National Health Service] gets flooded by COVID patients,” said Dr. Sikora.

The second wave may be different. “Although the number of infections has increased, the hospitalizations have only risen a little. Let’s see what happens,” he said in an interview. Since then, however, infections have continued to rise, and there has been an increase in hospitalizations. New social distancing measures in the United Kingdom were put into place on Oct. 12, with the aim of protecting the NHS from overload.

Dr. Arrué describes it this way: “The reality is that the ‘second wave’ has left behind the initial grief and shock that both patients and health professionals experienced when faced with something that, until now, we had only seen in the movies.” The second wave has led to new restrictions – including a partial lockdown since the beginning of October.

Dr. Aggarwal says her department recently had a conference with Anthony Fauci, MD, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, about the impact of COVID-19 on oncology.

“I asked him what advice he’d give oncologists, and he said to go back to as much screening as you were doing previously as quickly as possible. That’s what must be relayed to our oncologists in the community – and also to primary care physicians – because they are often the ones who are ordering and championing the screening efforts.”

This article was originated by Aude Lecrubier, Medscape French edition, and developed by Zosia Chustecka, Medscape Oncology. With additional reporting by Kate Johnson, freelance medical journalist, Claudia Gottschling for Medscape Germany, Leoleli Schwartz for Medscape em português, Tim Locke for Medscape United Kingdom, and Carla Nieto Martínez, freelance medical journalist for Medscape Spanish edition.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Canceled appointments, postponed surgeries, and delayed cancer diagnoses – all are a recipe for exhaustion for oncologists around the world, struggling to reach and treat their patients during the pandemic. Physicians and their teams felt the pain as COVID-19 took its initial march around the globe.

“We saw the distress of people with cancer who could no longer get to anyone on the phone. Their medical visit was usually canceled. Their radiotherapy session was postponed or modified, and chemotherapy postponed,” says Axel Kahn, MD, chairman of the board of directors of La Ligue Nationale Contre le Cancer (National League Against Cancer). “In the vast majority of cases, cancer treatment can be postponed or readjusted, without affecting the patient’s chances of survival, but there has been a lot of anxiety because the patients do not know that.”

The stay-at-home factor was one that played out across many months during the first wave.

“I believe that the ‘stay-home’ message that we transmitted was rigorously followed by patients who should have come to the emergency room much earlier and who, therefore, were admitted with a much more deteriorated general condition than in non-COVID-19 times,” says Benjamín Domingo Arrué, MD, from the department of medical oncology at Hospital Universitari i Politècnic La Fe in Valencia, Spain.

And in Brazil, some of the impact from the initial hit of COVID-19 on oncology is only now being felt, according to Laura Testa, MD, head of breast medical oncology, Instituto do Câncer do Estado de São Paulo.

“We are starting to see a lot of cancer cases that didn’t show up at the beginning of the pandemic, but now they are arriving to us already in advanced stages,” she said. “These patients need hospital care. If the situation worsens and goes back to what we saw at the peak of the curve, I fear the public system won’t be able to treat properly the oncology patients that need hospital care and the patients with cancer who also have COVID-19.”

But even as health care worker fatigue and concerns linger, oncologists say that what they have learned in the last 6 months has helped them prepare as COVID-19 cases increase and a second global wave kicks up.

Lessons from the first wave

In the United States, COVID-19 hit different regions at different times and to different degrees. One of the areas hit first was Seattle.

“We jumped on top of this, we were evidence based, we put things in place very, very quickly,” said Julie Gralow, MD, professor at the University of Washington and the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, both in Seattle.

“We did a really good job keeping COVID out of our cancer centers,” Dr. Gralow said. “We learned how to be super safe, and to keep symptomatic people out of the building, and to limit the extra people they could bring with them. It’s all about the number of contacts you have.”

The story was different, though, for oncologists in several other countries, and sometimes it varied immensely within each nation.

“We treated fewer patients with cancer during the first wave,” says Dirk Arnold, MD, medical director of the Asklepios Tumor Center Hamburg (Germany), in an interview. “In part, this was because staff were quarantined and because we had a completely different infrastructure in all of the hospitals. But also fewer patients with cancer came to the clinic at all. A lot of resources were directed toward COVID-19.”

In Spain, telemedicine helped keep up with visits, but other areas felt the effect of COVID-19 patient loads.

“At least in the oncology department of our center, we have practically maintained 100% of visits, mostly by telephone,” says Dr. Arrué, “but the reality is that our country has not yet been prepared for telemedicine.”

Laura Mezquita, MD, of the department of medical oncology at Hospital Clinic de Barcelona, describes a more dramatic situation: “We have seen how some of our patients, especially with metastatic disease, have been dismissed for intensive care and life-support treatments, as well as specific treatments against COVID-19 (tocilizumab, remdesivir, etc.) due to the general health collapse of the former wave,” she said. She adds that specific oncologic populations, such as those with thoracic tumors, have been more affected.

Distress among oncologists

Many oncologists are still feeling stressed and fatigued after the first wave, just as a second string of outbreaks is on its way.

A survey presented at last month’s ESMO 2020 Congress found that, in July-August, moral distress was reported by one-third of the oncologists who responded, and more than half reported a feeling of exhaustion.

“The tiredness and team exhaustion is noticeable,” said Dr. Arnold. “We recently had a task force discussion about what will happen when we have a second wave and how the department and our services will adapt. It was clear that those who were at the very front in the first wave had only a limited desire to do that again in the second wave.”

Another concern: COVID-19’s effect on staffing levels.

“We have a population of young caregivers who are affected by the COVID-19 disease with an absenteeism rate that is quite unprecedented,” said Sophie Beaupère, general delegate of Unicancer since January.

She said that, in general, the absenteeism rate in the cancer centers averages 5%-6%, depending on the year. But that rate is now skyrocketing.

Stop-start cycle for surgery

As caregivers quarantined around the world, more than 10% of patients with cancer had treatment canceled or delayed during the first wave of the pandemic, according to another survey from ESMO, involving 109 oncologists from 18 countries.

Difficulties were reported for surgeries by 34% of the centers, but also difficulties with delivering chemotherapy (22% of centers), radiotherapy (13.7%), and therapy with checkpoint inhibitors (9.1%), monoclonal antibodies (9%), and oral targeted therapy (3.7%).

Stopping surgery is a real concern in France, noted Dr. Kahn, the National League Against Cancer chair. He says that in regions that were badly hit by COVID-19, “it was not possible to have access to the operating room for people who absolutely needed surgery; for example, patients with lung cancer that was still operable. Most of the recovery rooms were mobilized for resuscitation.”

There may be some solutions, suggested Thierry Breton, director general of the National Institute of Cancer in France. “We are getting prepared, with the health ministry, for a possible increase in hospital tension, which would lead to a situation where we would have to reschedule operations. Nationally, regionally, and locally, we are seeing how we can resume and prioritize surgeries that have not been done.”

Delays in cancer diagnosis

While COVID-19 affected treatment, many oncologists say the major impact of the first wave was a delay in diagnosing cancer. Some of this was a result of the suspension of cancer screening programs, but there was also fear among the general public about visiting clinics and hospitals during a pandemic.

“We didn’t do so well with cancer during the first wave here in the U.K.,” said Karol Sikora, PhD, MBBChir, professor of cancer medicine and founding dean at the University of Buckingham Medical School, London. “Cancer diagnostic pathways virtually stalled partly because patients didn’t seek help, but getting scans and biopsies was also very difficult. Even patients referred urgently under the ‘2-weeks-wait’ rule were turned down.”

In France, “the delay in diagnosis is indisputable,” said Dr. Kahn. “About 50% of the cancer diagnoses one would expect during this period were missed.”

“I am worried that there remains a major traffic jam that has not been caught up with, and, in the meantime, the health crisis is worsening,” he added.

In Seattle, Dr. Gralow said the first COVID-19 wave had little impact on treatment for breast cancer, but it was in screening for breast cancer “where things really got messed up.”

“Even though we’ve been fully ramped up again,” she said, concerns remain. To ensure that screening mammography is maintained, “we have spaced out the visits to keep our waiting rooms less populated, with a longer time between using the machine so we can clean it. To do this, we have extended operating hours and are now opening on Saturday.

“So we’re actually at 100% of our capacity, but I’m really nervous, though, that a lot of people put off their screening mammogram and aren’t going to come in and get it.

“Not only did people get the message to stay home and not do nonessential things, but I think a lot of people lost their health insurance when they lost their jobs,” she said, and without health insurance, they are not covered for cancer screening.

Looking ahead, with a plan

Many oncologists agree that access to care can and must be improved – and there were some positive moves.

“Some regimens changed during the first months of the pandemic, and I don’t see them going back to the way they were anytime soon,” said Dr. Testa. “The changes/adaptations that were made to minimize the chance of SARS-CoV-2 infection are still in place and will go on for a while. In this context, telemedicine helped a lot. The pandemic forced the stakeholders to step up and put it in place in March. And now it’s here to stay.”

The experience gained in the last several months has driven preparation for the next wave.

“We are not going to see the disorganization that we saw during the first wave,” said Florence Joly, MD, PhD, head of medical oncology at the Centre François Baclesse in Caen, France. “The difference between now and earlier this year is that COVID diagnostic tests are available. That was one of the problems in the first wave. We had no way to diagnose.”

On the East Coast of the United States, medical oncologist Charu Aggarwal, MD, MPH, is also optimistic: “I think we’re at a place where we can manage.”

“I believe if there was going to be a new wave of COVID-19 cases we would be: better psychologically prepared and better organized,” said Dr. Aggarwal, assistant professor of medicine in the hematology-oncology division at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. “We already have experience with all of the tools, we have telemedicine available, we have screening protocols available, we have testing, we are already universally masking, everyone’s hand-washing, so I do think that means we would be okay.”

Dr. Arnold agreed that “we are much better prepared than for the first wave, but … we have immense tasks in the area of patient management, the digitization of patient care, the clear allocation of resources when there is a second or third wave. In many areas of preparation, I believe, unfortunately, we are not as well positioned as we had actually hoped.”

The first wave of COVID hit cancer services in the United Kingdom particularly hard: One modeling study suggested that delays in cancer referrals will lead to thousands of additional deaths and tens of thousands of life-years lost.

“Cancer services are working at near normal levels now, but they are still fragile and could be severely compromised again if the NHS [National Health Service] gets flooded by COVID patients,” said Dr. Sikora.

The second wave may be different. “Although the number of infections has increased, the hospitalizations have only risen a little. Let’s see what happens,” he said in an interview. Since then, however, infections have continued to rise, and there has been an increase in hospitalizations. New social distancing measures in the United Kingdom were put into place on Oct. 12, with the aim of protecting the NHS from overload.

Dr. Arrué describes it this way: “The reality is that the ‘second wave’ has left behind the initial grief and shock that both patients and health professionals experienced when faced with something that, until now, we had only seen in the movies.” The second wave has led to new restrictions – including a partial lockdown since the beginning of October.

Dr. Aggarwal says her department recently had a conference with Anthony Fauci, MD, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, about the impact of COVID-19 on oncology.

“I asked him what advice he’d give oncologists, and he said to go back to as much screening as you were doing previously as quickly as possible. That’s what must be relayed to our oncologists in the community – and also to primary care physicians – because they are often the ones who are ordering and championing the screening efforts.”

This article was originated by Aude Lecrubier, Medscape French edition, and developed by Zosia Chustecka, Medscape Oncology. With additional reporting by Kate Johnson, freelance medical journalist, Claudia Gottschling for Medscape Germany, Leoleli Schwartz for Medscape em português, Tim Locke for Medscape United Kingdom, and Carla Nieto Martínez, freelance medical journalist for Medscape Spanish edition.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Canceled appointments, postponed surgeries, and delayed cancer diagnoses – all are a recipe for exhaustion for oncologists around the world, struggling to reach and treat their patients during the pandemic. Physicians and their teams felt the pain as COVID-19 took its initial march around the globe.

“We saw the distress of people with cancer who could no longer get to anyone on the phone. Their medical visit was usually canceled. Their radiotherapy session was postponed or modified, and chemotherapy postponed,” says Axel Kahn, MD, chairman of the board of directors of La Ligue Nationale Contre le Cancer (National League Against Cancer). “In the vast majority of cases, cancer treatment can be postponed or readjusted, without affecting the patient’s chances of survival, but there has been a lot of anxiety because the patients do not know that.”

The stay-at-home factor was one that played out across many months during the first wave.

“I believe that the ‘stay-home’ message that we transmitted was rigorously followed by patients who should have come to the emergency room much earlier and who, therefore, were admitted with a much more deteriorated general condition than in non-COVID-19 times,” says Benjamín Domingo Arrué, MD, from the department of medical oncology at Hospital Universitari i Politècnic La Fe in Valencia, Spain.

And in Brazil, some of the impact from the initial hit of COVID-19 on oncology is only now being felt, according to Laura Testa, MD, head of breast medical oncology, Instituto do Câncer do Estado de São Paulo.

“We are starting to see a lot of cancer cases that didn’t show up at the beginning of the pandemic, but now they are arriving to us already in advanced stages,” she said. “These patients need hospital care. If the situation worsens and goes back to what we saw at the peak of the curve, I fear the public system won’t be able to treat properly the oncology patients that need hospital care and the patients with cancer who also have COVID-19.”

But even as health care worker fatigue and concerns linger, oncologists say that what they have learned in the last 6 months has helped them prepare as COVID-19 cases increase and a second global wave kicks up.

Lessons from the first wave

In the United States, COVID-19 hit different regions at different times and to different degrees. One of the areas hit first was Seattle.

“We jumped on top of this, we were evidence based, we put things in place very, very quickly,” said Julie Gralow, MD, professor at the University of Washington and the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, both in Seattle.

“We did a really good job keeping COVID out of our cancer centers,” Dr. Gralow said. “We learned how to be super safe, and to keep symptomatic people out of the building, and to limit the extra people they could bring with them. It’s all about the number of contacts you have.”

The story was different, though, for oncologists in several other countries, and sometimes it varied immensely within each nation.

“We treated fewer patients with cancer during the first wave,” says Dirk Arnold, MD, medical director of the Asklepios Tumor Center Hamburg (Germany), in an interview. “In part, this was because staff were quarantined and because we had a completely different infrastructure in all of the hospitals. But also fewer patients with cancer came to the clinic at all. A lot of resources were directed toward COVID-19.”

In Spain, telemedicine helped keep up with visits, but other areas felt the effect of COVID-19 patient loads.

“At least in the oncology department of our center, we have practically maintained 100% of visits, mostly by telephone,” says Dr. Arrué, “but the reality is that our country has not yet been prepared for telemedicine.”

Laura Mezquita, MD, of the department of medical oncology at Hospital Clinic de Barcelona, describes a more dramatic situation: “We have seen how some of our patients, especially with metastatic disease, have been dismissed for intensive care and life-support treatments, as well as specific treatments against COVID-19 (tocilizumab, remdesivir, etc.) due to the general health collapse of the former wave,” she said. She adds that specific oncologic populations, such as those with thoracic tumors, have been more affected.

Distress among oncologists

Many oncologists are still feeling stressed and fatigued after the first wave, just as a second string of outbreaks is on its way.

A survey presented at last month’s ESMO 2020 Congress found that, in July-August, moral distress was reported by one-third of the oncologists who responded, and more than half reported a feeling of exhaustion.

“The tiredness and team exhaustion is noticeable,” said Dr. Arnold. “We recently had a task force discussion about what will happen when we have a second wave and how the department and our services will adapt. It was clear that those who were at the very front in the first wave had only a limited desire to do that again in the second wave.”

Another concern: COVID-19’s effect on staffing levels.

“We have a population of young caregivers who are affected by the COVID-19 disease with an absenteeism rate that is quite unprecedented,” said Sophie Beaupère, general delegate of Unicancer since January.

She said that, in general, the absenteeism rate in the cancer centers averages 5%-6%, depending on the year. But that rate is now skyrocketing.

Stop-start cycle for surgery

As caregivers quarantined around the world, more than 10% of patients with cancer had treatment canceled or delayed during the first wave of the pandemic, according to another survey from ESMO, involving 109 oncologists from 18 countries.

Difficulties were reported for surgeries by 34% of the centers, but also difficulties with delivering chemotherapy (22% of centers), radiotherapy (13.7%), and therapy with checkpoint inhibitors (9.1%), monoclonal antibodies (9%), and oral targeted therapy (3.7%).

Stopping surgery is a real concern in France, noted Dr. Kahn, the National League Against Cancer chair. He says that in regions that were badly hit by COVID-19, “it was not possible to have access to the operating room for people who absolutely needed surgery; for example, patients with lung cancer that was still operable. Most of the recovery rooms were mobilized for resuscitation.”

There may be some solutions, suggested Thierry Breton, director general of the National Institute of Cancer in France. “We are getting prepared, with the health ministry, for a possible increase in hospital tension, which would lead to a situation where we would have to reschedule operations. Nationally, regionally, and locally, we are seeing how we can resume and prioritize surgeries that have not been done.”

Delays in cancer diagnosis

While COVID-19 affected treatment, many oncologists say the major impact of the first wave was a delay in diagnosing cancer. Some of this was a result of the suspension of cancer screening programs, but there was also fear among the general public about visiting clinics and hospitals during a pandemic.

“We didn’t do so well with cancer during the first wave here in the U.K.,” said Karol Sikora, PhD, MBBChir, professor of cancer medicine and founding dean at the University of Buckingham Medical School, London. “Cancer diagnostic pathways virtually stalled partly because patients didn’t seek help, but getting scans and biopsies was also very difficult. Even patients referred urgently under the ‘2-weeks-wait’ rule were turned down.”

In France, “the delay in diagnosis is indisputable,” said Dr. Kahn. “About 50% of the cancer diagnoses one would expect during this period were missed.”

“I am worried that there remains a major traffic jam that has not been caught up with, and, in the meantime, the health crisis is worsening,” he added.

In Seattle, Dr. Gralow said the first COVID-19 wave had little impact on treatment for breast cancer, but it was in screening for breast cancer “where things really got messed up.”

“Even though we’ve been fully ramped up again,” she said, concerns remain. To ensure that screening mammography is maintained, “we have spaced out the visits to keep our waiting rooms less populated, with a longer time between using the machine so we can clean it. To do this, we have extended operating hours and are now opening on Saturday.

“So we’re actually at 100% of our capacity, but I’m really nervous, though, that a lot of people put off their screening mammogram and aren’t going to come in and get it.

“Not only did people get the message to stay home and not do nonessential things, but I think a lot of people lost their health insurance when they lost their jobs,” she said, and without health insurance, they are not covered for cancer screening.

Looking ahead, with a plan

Many oncologists agree that access to care can and must be improved – and there were some positive moves.

“Some regimens changed during the first months of the pandemic, and I don’t see them going back to the way they were anytime soon,” said Dr. Testa. “The changes/adaptations that were made to minimize the chance of SARS-CoV-2 infection are still in place and will go on for a while. In this context, telemedicine helped a lot. The pandemic forced the stakeholders to step up and put it in place in March. And now it’s here to stay.”

The experience gained in the last several months has driven preparation for the next wave.

“We are not going to see the disorganization that we saw during the first wave,” said Florence Joly, MD, PhD, head of medical oncology at the Centre François Baclesse in Caen, France. “The difference between now and earlier this year is that COVID diagnostic tests are available. That was one of the problems in the first wave. We had no way to diagnose.”

On the East Coast of the United States, medical oncologist Charu Aggarwal, MD, MPH, is also optimistic: “I think we’re at a place where we can manage.”

“I believe if there was going to be a new wave of COVID-19 cases we would be: better psychologically prepared and better organized,” said Dr. Aggarwal, assistant professor of medicine in the hematology-oncology division at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. “We already have experience with all of the tools, we have telemedicine available, we have screening protocols available, we have testing, we are already universally masking, everyone’s hand-washing, so I do think that means we would be okay.”

Dr. Arnold agreed that “we are much better prepared than for the first wave, but … we have immense tasks in the area of patient management, the digitization of patient care, the clear allocation of resources when there is a second or third wave. In many areas of preparation, I believe, unfortunately, we are not as well positioned as we had actually hoped.”

The first wave of COVID hit cancer services in the United Kingdom particularly hard: One modeling study suggested that delays in cancer referrals will lead to thousands of additional deaths and tens of thousands of life-years lost.

“Cancer services are working at near normal levels now, but they are still fragile and could be severely compromised again if the NHS [National Health Service] gets flooded by COVID patients,” said Dr. Sikora.

The second wave may be different. “Although the number of infections has increased, the hospitalizations have only risen a little. Let’s see what happens,” he said in an interview. Since then, however, infections have continued to rise, and there has been an increase in hospitalizations. New social distancing measures in the United Kingdom were put into place on Oct. 12, with the aim of protecting the NHS from overload.

Dr. Arrué describes it this way: “The reality is that the ‘second wave’ has left behind the initial grief and shock that both patients and health professionals experienced when faced with something that, until now, we had only seen in the movies.” The second wave has led to new restrictions – including a partial lockdown since the beginning of October.

Dr. Aggarwal says her department recently had a conference with Anthony Fauci, MD, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, about the impact of COVID-19 on oncology.

“I asked him what advice he’d give oncologists, and he said to go back to as much screening as you were doing previously as quickly as possible. That’s what must be relayed to our oncologists in the community – and also to primary care physicians – because they are often the ones who are ordering and championing the screening efforts.”

This article was originated by Aude Lecrubier, Medscape French edition, and developed by Zosia Chustecka, Medscape Oncology. With additional reporting by Kate Johnson, freelance medical journalist, Claudia Gottschling for Medscape Germany, Leoleli Schwartz for Medscape em português, Tim Locke for Medscape United Kingdom, and Carla Nieto Martínez, freelance medical journalist for Medscape Spanish edition.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

It’s not time to abandon routine screening mammography in average-risk women in their 40s

In the 1970s and early 1980s, population-based screening mammography was studied in numerous randomized control trials (RCTs), with the primary outcome of reduced breast cancer mortality. Although technology and the sensitivity of mammography in the 1980s was somewhat rudimentary compared with current screening, a meta-analysis of these RCTs demonstrated a clear mortality benefit for screening mammography.1 As a result, widespread population-based mammography was introduced in the mid-1980s in the United States and has become a standard for breast cancer screening.

Since that time, few RCTs of screening mammography versus observation have been conducted because of the ethical challenges of entering women into such studies as well as the difficulty and expense of long-term follow-up to measure the effect of screening on breast cancer mortality. Without ongoing RCTs of mammography, retrospective, observational, and computer simulation trials of the efficacy and harms of screening mammography have been conducted using proxy measures of mortality (such as stage at diagnosis), and some have questioned the overall benefit of screening mammography.2,3

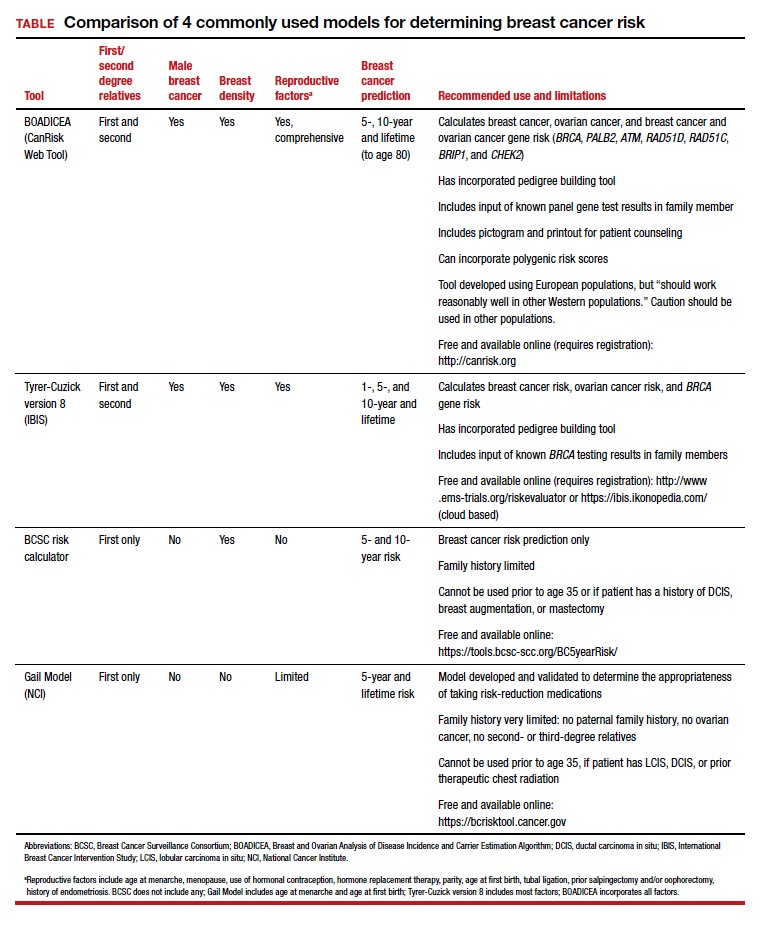

To further complicate this controversy, some national guidelines have recommended against routinely recommending screening mammography for women aged 40 to 49 based on concerns that the harms (callbacks, benign breast biopsies, overdiagnosis) exceed the potential benefits (earlier diagnosis, possible decrease in needed treatments, reduced breast cancer mortality).4 This has resulted in a confusing morass of national recommendations with uncertainty regarding the question of whether to routinely offer screening mammography for women in their 40s at average risk for breast cancer.4-6

Recently, to address this question Duffy and colleagues conducted a large RCT of women in their 40s to evaluate the long-term effect of mammography on breast cancer mortality.7 Here, I review the study in depth and offer some guidance to clinicians and women struggling with screening decisions.

Breast cancer mortality significantly lower in the screening group