User login

Drug-induced immune hemolytic anemia associated with albumin-bound paclitaxel

Click on the PDF icon at the top of this introduction to read the full article.

Click on the PDF icon at the top of this introduction to read the full article.

Click on the PDF icon at the top of this introduction to read the full article.

Evidence-based practices can cut breast cancer costs

HOUSTON – There are at least three evidence-based practices for reducing the costs of locoregional therapy for early breast cancer without compromising the quality of care, according to Dr. Rachel Adams Greenup of the department of surgery at Duke University Medical Center, in Durham, North Carolina.

Management of axilla per the ACOSOG Z0011 study, adherence to joint Society of Surgical Oncology/American Society of Radiation Oncology (SSO/ASTRO) margin guidelines, and alternative radiation regimens following lumpectomy can all cut costs without compromsing quality of care, she said at the annual Society of Surgical Oncology Symposium.

The results of ACOSOG Z0011, published in 2010, were universally acknowledged to be practice changing. They showed that for women undergoing lumpectomy and radiation therapy for T1-2 invasive breast cancer and positive sentinel lymph node biopsy, completion axiallary dissection did not improve either disease-free or overall survival (DFS/OS). There were low rates of locoregional recurrence regardless of whether patients received axillary node dissection.

The potential savings from eliminating the routine practice of axillary dissection were estimated to be a 64% reduction in inpatient days, and an 18% decrease in perioperative costs.

The SSO/ASTRO margin guidelines, published in 2014, were developed by a multidisciplinary panel based on a meta-analysis of 33 studies involving more than 28,000 patients. The guidelines note that positive surgical margins are associated with a 2-fold increase in ipsilateral breast tumor recurrence, with “no ink on tumor” sufficient for a negative margin. The guidelines say that further margin width resections do not decrease same-breast recurrences.

In a related analysis of the cost implications, Dr. Greenup and colleagues noted that there are wide variations in clinical practice, and that 20% of women with close but negative margins were re-excised needlessly. Eliminating 25,000 unnecessary re-excisions annually would save $31 million dollars. These savings do not include cost reductions from an estimated 8% to 12% reduction in conversions to mastectomy that would be avoided, the authors calculated.

The costs of radiation following lumpectomy correlate directly with the number of delivered radiation fractions or treatment sessions, and also with the technique. Alternatives to standard radiation schedules include the following:

Per-patient costs for each of these options in 2011 ranged from $0 for no radiation, as in CALGB 9343, to $5342 for APBI, $9122 for HF-WBI, and $13m358 for conventionally fractionated WBI.

Dr Greenup and colleagues looked at data on 43,247 women in the National Cancer Data Base with T1-T2, NO invasive breast cancers treated with lumpectomy, and compared the actual costs of treatment with the evidence-based alternative. They found that 26% of patients were treated with the least cost-effective radiation, while nearly all of the remaining patients received more expensive radiation than necessary. If every patient were treated with the most cost-effective approach, there would be an estimated 39% reduction in costs, translating into a saving of $164 million over a single year, they reported in an abstract presented at the 2014 San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium.

“We can’t make decisions based on cost alone, and value is certainly more important, but clinical trials, moving forward, should incorporate cost information. There is an opportunity to have small changes in clinical practice have the potential to make dramatic reductions in health care spending, and there are lots of opportunities in early stage breast cancer to practice evidence-based care while reducing health care spending,” Dr. Greenup concluded.

Dr. Greenup reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

HOUSTON – There are at least three evidence-based practices for reducing the costs of locoregional therapy for early breast cancer without compromising the quality of care, according to Dr. Rachel Adams Greenup of the department of surgery at Duke University Medical Center, in Durham, North Carolina.

Management of axilla per the ACOSOG Z0011 study, adherence to joint Society of Surgical Oncology/American Society of Radiation Oncology (SSO/ASTRO) margin guidelines, and alternative radiation regimens following lumpectomy can all cut costs without compromsing quality of care, she said at the annual Society of Surgical Oncology Symposium.

The results of ACOSOG Z0011, published in 2010, were universally acknowledged to be practice changing. They showed that for women undergoing lumpectomy and radiation therapy for T1-2 invasive breast cancer and positive sentinel lymph node biopsy, completion axiallary dissection did not improve either disease-free or overall survival (DFS/OS). There were low rates of locoregional recurrence regardless of whether patients received axillary node dissection.

The potential savings from eliminating the routine practice of axillary dissection were estimated to be a 64% reduction in inpatient days, and an 18% decrease in perioperative costs.

The SSO/ASTRO margin guidelines, published in 2014, were developed by a multidisciplinary panel based on a meta-analysis of 33 studies involving more than 28,000 patients. The guidelines note that positive surgical margins are associated with a 2-fold increase in ipsilateral breast tumor recurrence, with “no ink on tumor” sufficient for a negative margin. The guidelines say that further margin width resections do not decrease same-breast recurrences.

In a related analysis of the cost implications, Dr. Greenup and colleagues noted that there are wide variations in clinical practice, and that 20% of women with close but negative margins were re-excised needlessly. Eliminating 25,000 unnecessary re-excisions annually would save $31 million dollars. These savings do not include cost reductions from an estimated 8% to 12% reduction in conversions to mastectomy that would be avoided, the authors calculated.

The costs of radiation following lumpectomy correlate directly with the number of delivered radiation fractions or treatment sessions, and also with the technique. Alternatives to standard radiation schedules include the following:

Per-patient costs for each of these options in 2011 ranged from $0 for no radiation, as in CALGB 9343, to $5342 for APBI, $9122 for HF-WBI, and $13m358 for conventionally fractionated WBI.

Dr Greenup and colleagues looked at data on 43,247 women in the National Cancer Data Base with T1-T2, NO invasive breast cancers treated with lumpectomy, and compared the actual costs of treatment with the evidence-based alternative. They found that 26% of patients were treated with the least cost-effective radiation, while nearly all of the remaining patients received more expensive radiation than necessary. If every patient were treated with the most cost-effective approach, there would be an estimated 39% reduction in costs, translating into a saving of $164 million over a single year, they reported in an abstract presented at the 2014 San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium.

“We can’t make decisions based on cost alone, and value is certainly more important, but clinical trials, moving forward, should incorporate cost information. There is an opportunity to have small changes in clinical practice have the potential to make dramatic reductions in health care spending, and there are lots of opportunities in early stage breast cancer to practice evidence-based care while reducing health care spending,” Dr. Greenup concluded.

Dr. Greenup reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

HOUSTON – There are at least three evidence-based practices for reducing the costs of locoregional therapy for early breast cancer without compromising the quality of care, according to Dr. Rachel Adams Greenup of the department of surgery at Duke University Medical Center, in Durham, North Carolina.

Management of axilla per the ACOSOG Z0011 study, adherence to joint Society of Surgical Oncology/American Society of Radiation Oncology (SSO/ASTRO) margin guidelines, and alternative radiation regimens following lumpectomy can all cut costs without compromsing quality of care, she said at the annual Society of Surgical Oncology Symposium.

The results of ACOSOG Z0011, published in 2010, were universally acknowledged to be practice changing. They showed that for women undergoing lumpectomy and radiation therapy for T1-2 invasive breast cancer and positive sentinel lymph node biopsy, completion axiallary dissection did not improve either disease-free or overall survival (DFS/OS). There were low rates of locoregional recurrence regardless of whether patients received axillary node dissection.

The potential savings from eliminating the routine practice of axillary dissection were estimated to be a 64% reduction in inpatient days, and an 18% decrease in perioperative costs.

The SSO/ASTRO margin guidelines, published in 2014, were developed by a multidisciplinary panel based on a meta-analysis of 33 studies involving more than 28,000 patients. The guidelines note that positive surgical margins are associated with a 2-fold increase in ipsilateral breast tumor recurrence, with “no ink on tumor” sufficient for a negative margin. The guidelines say that further margin width resections do not decrease same-breast recurrences.

In a related analysis of the cost implications, Dr. Greenup and colleagues noted that there are wide variations in clinical practice, and that 20% of women with close but negative margins were re-excised needlessly. Eliminating 25,000 unnecessary re-excisions annually would save $31 million dollars. These savings do not include cost reductions from an estimated 8% to 12% reduction in conversions to mastectomy that would be avoided, the authors calculated.

The costs of radiation following lumpectomy correlate directly with the number of delivered radiation fractions or treatment sessions, and also with the technique. Alternatives to standard radiation schedules include the following:

Per-patient costs for each of these options in 2011 ranged from $0 for no radiation, as in CALGB 9343, to $5342 for APBI, $9122 for HF-WBI, and $13m358 for conventionally fractionated WBI.

Dr Greenup and colleagues looked at data on 43,247 women in the National Cancer Data Base with T1-T2, NO invasive breast cancers treated with lumpectomy, and compared the actual costs of treatment with the evidence-based alternative. They found that 26% of patients were treated with the least cost-effective radiation, while nearly all of the remaining patients received more expensive radiation than necessary. If every patient were treated with the most cost-effective approach, there would be an estimated 39% reduction in costs, translating into a saving of $164 million over a single year, they reported in an abstract presented at the 2014 San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium.

“We can’t make decisions based on cost alone, and value is certainly more important, but clinical trials, moving forward, should incorporate cost information. There is an opportunity to have small changes in clinical practice have the potential to make dramatic reductions in health care spending, and there are lots of opportunities in early stage breast cancer to practice evidence-based care while reducing health care spending,” Dr. Greenup concluded.

Dr. Greenup reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

EXPERT ANALYSIS AT SSO 2015

Stage 0 Breast Cancer May Not Be the Strongest Indicator of Patient Mortality

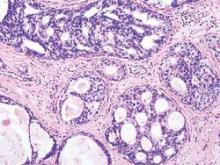

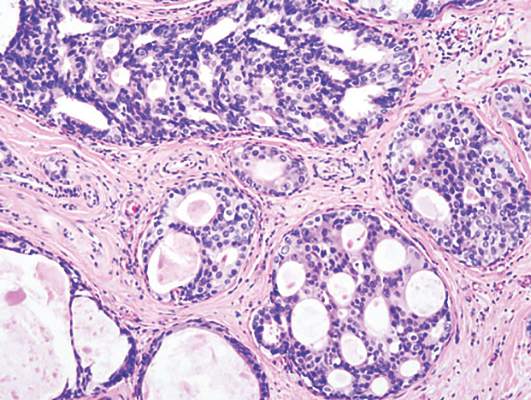

According to a study published today in JAMA Oncology, a diagnosis of ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS)—or stage 0 breast cancer—may not be reason enough for treatment.

Researchers conducted a multivariate analysis of 108,196 women, whose data were pulled from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) 18 registries database. The primary outcome of the study was 10- and 20-year cancer-specific mortality. The results showed that age at diagnosis and ethnicity were significant predictors of breast cancer mortality: Women diagnosed before age 35 had a higher risk of death from breast cancer at 20 years than did older women (7.8% vs 3.2%; hazard ratio [HR], 2.58; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.85-3.60; P < .001), and black women had a higher risk of death from DCIS than did white, non-Hispanic women (7.0% vs 3.0%; adjusted HR, 2.42, 95% CI, 2.05-2.87; P < .001).

Related: Dividing to Conquer Breast Cancer

In addition, the article notes that the finding of greatest clinical importance was that prevention of ipsilateral invasive recurrence did not prevent death from breast cancer. Women diagnosed with DCIS who developed an ipsilateral invasive in-breast recurrence were 18.1 times more likely to die of breast cancer than were women who did not; however, after adjustment for tumor size, grade, and other factors, the difference in survival for mastectomy vs lumpectomy was not significant (HR, 1.20; 95% CI, 0.96-1.50; P = .11).

Patients with breast cancer often undergo the Oncotype DX breast cancer assay to identify those who are at low risk for death from breast cancer and who might not benefit from chemotherapy. However, the researchers of the current study propose that the test be used instead to identify patients who are at high risk for invasive recurrence.

Related: Advances in Targeted Therapy for Breast Cancer

The 10-year mortality rate assessed in this study continues a downward trend established in previous studies, but “it is unlikely that the decline in mortality [for women who received a diagnosis of ductal carcinoma in situ between 1998 and 2011] is due to more effective treatments,” the authors note, “because we show here that mortality rates did not vary with specific treatment.”

View on the News: Reboot needed on DCIS treatment

Source

Narod SA, Iqbal J, Giannakeas V, Sopik V, Sun P. JAMA Oncol. [Published online ahead of print August 20, 2015.]

doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.2510.

According to a study published today in JAMA Oncology, a diagnosis of ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS)—or stage 0 breast cancer—may not be reason enough for treatment.

Researchers conducted a multivariate analysis of 108,196 women, whose data were pulled from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) 18 registries database. The primary outcome of the study was 10- and 20-year cancer-specific mortality. The results showed that age at diagnosis and ethnicity were significant predictors of breast cancer mortality: Women diagnosed before age 35 had a higher risk of death from breast cancer at 20 years than did older women (7.8% vs 3.2%; hazard ratio [HR], 2.58; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.85-3.60; P < .001), and black women had a higher risk of death from DCIS than did white, non-Hispanic women (7.0% vs 3.0%; adjusted HR, 2.42, 95% CI, 2.05-2.87; P < .001).

Related: Dividing to Conquer Breast Cancer

In addition, the article notes that the finding of greatest clinical importance was that prevention of ipsilateral invasive recurrence did not prevent death from breast cancer. Women diagnosed with DCIS who developed an ipsilateral invasive in-breast recurrence were 18.1 times more likely to die of breast cancer than were women who did not; however, after adjustment for tumor size, grade, and other factors, the difference in survival for mastectomy vs lumpectomy was not significant (HR, 1.20; 95% CI, 0.96-1.50; P = .11).

Patients with breast cancer often undergo the Oncotype DX breast cancer assay to identify those who are at low risk for death from breast cancer and who might not benefit from chemotherapy. However, the researchers of the current study propose that the test be used instead to identify patients who are at high risk for invasive recurrence.

Related: Advances in Targeted Therapy for Breast Cancer

The 10-year mortality rate assessed in this study continues a downward trend established in previous studies, but “it is unlikely that the decline in mortality [for women who received a diagnosis of ductal carcinoma in situ between 1998 and 2011] is due to more effective treatments,” the authors note, “because we show here that mortality rates did not vary with specific treatment.”

View on the News: Reboot needed on DCIS treatment

Source

Narod SA, Iqbal J, Giannakeas V, Sopik V, Sun P. JAMA Oncol. [Published online ahead of print August 20, 2015.]

doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.2510.

According to a study published today in JAMA Oncology, a diagnosis of ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS)—or stage 0 breast cancer—may not be reason enough for treatment.

Researchers conducted a multivariate analysis of 108,196 women, whose data were pulled from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) 18 registries database. The primary outcome of the study was 10- and 20-year cancer-specific mortality. The results showed that age at diagnosis and ethnicity were significant predictors of breast cancer mortality: Women diagnosed before age 35 had a higher risk of death from breast cancer at 20 years than did older women (7.8% vs 3.2%; hazard ratio [HR], 2.58; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.85-3.60; P < .001), and black women had a higher risk of death from DCIS than did white, non-Hispanic women (7.0% vs 3.0%; adjusted HR, 2.42, 95% CI, 2.05-2.87; P < .001).

Related: Dividing to Conquer Breast Cancer

In addition, the article notes that the finding of greatest clinical importance was that prevention of ipsilateral invasive recurrence did not prevent death from breast cancer. Women diagnosed with DCIS who developed an ipsilateral invasive in-breast recurrence were 18.1 times more likely to die of breast cancer than were women who did not; however, after adjustment for tumor size, grade, and other factors, the difference in survival for mastectomy vs lumpectomy was not significant (HR, 1.20; 95% CI, 0.96-1.50; P = .11).

Patients with breast cancer often undergo the Oncotype DX breast cancer assay to identify those who are at low risk for death from breast cancer and who might not benefit from chemotherapy. However, the researchers of the current study propose that the test be used instead to identify patients who are at high risk for invasive recurrence.

Related: Advances in Targeted Therapy for Breast Cancer

The 10-year mortality rate assessed in this study continues a downward trend established in previous studies, but “it is unlikely that the decline in mortality [for women who received a diagnosis of ductal carcinoma in situ between 1998 and 2011] is due to more effective treatments,” the authors note, “because we show here that mortality rates did not vary with specific treatment.”

View on the News: Reboot needed on DCIS treatment

Source

Narod SA, Iqbal J, Giannakeas V, Sopik V, Sun P. JAMA Oncol. [Published online ahead of print August 20, 2015.]

doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.2510.

Reduced invasive recurrence after DCIS does not reduce mortality

Radiotherapy after breast-conserving surgery for ductal carcinoma in situ reduces the risk of ipsilateral invasive recurrence but does not reduce breast cancer mortality, new research shows.

Analysis of data from 108,196 women diagnosed with ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS), who were included in the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) 18 registries database, showed radiotherapy significantly reduced the risk of ipsilateral invasive recurrence at 10 years (adjusted hazard, 0.47; 95% confidence interval, 0.42-0.53; P less than .001) but only achieved a nonsignificant reduction in breast cancer mortality (adjusted HR, 0.81; 95% CI, 0.63-1.04; P = .10).

“The finding of greatest clinical importance was that prevention of ipsilateral invasive recurrence did not prevent death from breast cancer,” wrote Dr. Steven A. Narod and his colleagues from the Women’s College Hospital and the University of Toronto.

Though it is often stated that DCIS is a preinvasive neoplastic lesion that is not lethal in itself, these results suggest that this interpretation should be revisited, they said in the report, published online August 20 in JAMA Oncology.

“Some cases of DCIS have an inherent potential for distant metastatic spread. It is therefore appropriate to consider these as de facto breast cancers and not as preinvasive markers predictive of a subsequent invasive cancer,” they said.

The mean age at diagnosis of DCIS for the women in the database was 53.8 (range, 15-69) years, and the mean duration of follow-up was 7.5 (range, 0-23.9) years. Overall, the 20-year breast cancer–specific mortality rate following a diagnosis of DCIS was 3.3% (95% CI, 3.0%-3.6%).

Just over 1% of the 42,250 women treated with lumpectomy and radiotherapy developed an ipsilateral invasive recurrence in the follow-up period and 163 women (0.4%) died of breast cancer. Of the 19,762 women who were treated with lumpectomy without radiotherapy, 595 women (3%) developed an ipsilateral invasive recurrence and 102 women (0.5%) died of breast cancer, Dr. Narod and his associates reported (JAMA Oncology. 2015 Aug. 20 doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.2510).

Among the 956 women who died of breast cancer in the follow-up period, over half (517) did not experience an in-breast invasive recurrence prior to death. Of the 163 women who were treated with lumpectomy and radiotherapy and then died of breast cancer, 57.7% (94) did not experience an in-breast invasive recurrence prior to death. Among the 102 women treated with lumpectomy without radiotherapy who died of breast cancer, 51 did not experience an in-breast invasive recurrence prior to death (50.0%). Among the 154 women treated with a mastectomy (unilateral or bilateral) who died of breast cancer, 112 did not experience an in-breast invasive recurrence prior to death (72.7%), the investigators reported.

They found that young age at diagnosis and black ethnicity were predictors of breast cancer mortality. Young women diagnosed with ductal carcinoma in situ before the age of 35 years had a more than twofold greater risk of dying from breast cancer than older women (7.8% vs. 3.2%; HR 2.58, 95% CI, 1.85-3.60; P less than .001). Black women also had a much greater risk of dying from breast cancer than non-Hispanic whites (7.0% vs. 3.0%; HR, 2.55, 95% CI, 2.17-3.01; P less than .001).

“If DCIS were truly a (noninvasive) precursor of breast cancer, then a woman with DCIS should not die of breast cancer without first experiencing an invasive breast cancer (ipsilateral or contralateral), and the prevention of an invasive recurrence should prevent her death from breast cancer. Surprisingly, the majority of women with DCIS in the cohort who died of breast cancer did not experience an invasive in-breast recurrence (ipsilateral or contralateral) prior to death (54.1%),” the investigators said.

“The outcome of breast cancer mortality for DCIS patients is of importance in itself and potential treatments that affect mortality are deserving of study,” they concluded.

No relevant conflicts of interest were declared.

The analysis by Dr. Narod and his associates fuels a growing concern that we should rethink our strategy for the detection and treatment of DCIS. Given the low breast cancer mortality risk, we should stop telling women that DCIS is an emergency and that they should schedule definitive surgery within 2 weeks of diagnosis. For the lowest-risk lesions, observation and prevention interventions alone should be tested. High-risk lesions (such as HER2 positive, those in patients aged less than 40 years, hormone-receptor negative, large size) should still be aggressively treated, but this analysis suggests that our current approach of surgical removal and radiation therapy may not suffice for the rare cases that lead to breast cancer mortality, so new approaches are needed.

We should continue to better understand the biological characteristics of the highest-risk DCIS and test targeted approaches to reduce death from breast cancer.

Dr. Laura Esserman and Christina Yau, Ph.D., are with the department of surgery at the University of California, San Francisco. These comments were taken from an accompanying editorial (JAMA Oncology. 2015 Aug. 20 doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.2607). No conflicts of interest were declared.

The analysis by Dr. Narod and his associates fuels a growing concern that we should rethink our strategy for the detection and treatment of DCIS. Given the low breast cancer mortality risk, we should stop telling women that DCIS is an emergency and that they should schedule definitive surgery within 2 weeks of diagnosis. For the lowest-risk lesions, observation and prevention interventions alone should be tested. High-risk lesions (such as HER2 positive, those in patients aged less than 40 years, hormone-receptor negative, large size) should still be aggressively treated, but this analysis suggests that our current approach of surgical removal and radiation therapy may not suffice for the rare cases that lead to breast cancer mortality, so new approaches are needed.

We should continue to better understand the biological characteristics of the highest-risk DCIS and test targeted approaches to reduce death from breast cancer.

Dr. Laura Esserman and Christina Yau, Ph.D., are with the department of surgery at the University of California, San Francisco. These comments were taken from an accompanying editorial (JAMA Oncology. 2015 Aug. 20 doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.2607). No conflicts of interest were declared.

The analysis by Dr. Narod and his associates fuels a growing concern that we should rethink our strategy for the detection and treatment of DCIS. Given the low breast cancer mortality risk, we should stop telling women that DCIS is an emergency and that they should schedule definitive surgery within 2 weeks of diagnosis. For the lowest-risk lesions, observation and prevention interventions alone should be tested. High-risk lesions (such as HER2 positive, those in patients aged less than 40 years, hormone-receptor negative, large size) should still be aggressively treated, but this analysis suggests that our current approach of surgical removal and radiation therapy may not suffice for the rare cases that lead to breast cancer mortality, so new approaches are needed.

We should continue to better understand the biological characteristics of the highest-risk DCIS and test targeted approaches to reduce death from breast cancer.

Dr. Laura Esserman and Christina Yau, Ph.D., are with the department of surgery at the University of California, San Francisco. These comments were taken from an accompanying editorial (JAMA Oncology. 2015 Aug. 20 doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.2607). No conflicts of interest were declared.

Radiotherapy after breast-conserving surgery for ductal carcinoma in situ reduces the risk of ipsilateral invasive recurrence but does not reduce breast cancer mortality, new research shows.

Analysis of data from 108,196 women diagnosed with ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS), who were included in the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) 18 registries database, showed radiotherapy significantly reduced the risk of ipsilateral invasive recurrence at 10 years (adjusted hazard, 0.47; 95% confidence interval, 0.42-0.53; P less than .001) but only achieved a nonsignificant reduction in breast cancer mortality (adjusted HR, 0.81; 95% CI, 0.63-1.04; P = .10).

“The finding of greatest clinical importance was that prevention of ipsilateral invasive recurrence did not prevent death from breast cancer,” wrote Dr. Steven A. Narod and his colleagues from the Women’s College Hospital and the University of Toronto.

Though it is often stated that DCIS is a preinvasive neoplastic lesion that is not lethal in itself, these results suggest that this interpretation should be revisited, they said in the report, published online August 20 in JAMA Oncology.

“Some cases of DCIS have an inherent potential for distant metastatic spread. It is therefore appropriate to consider these as de facto breast cancers and not as preinvasive markers predictive of a subsequent invasive cancer,” they said.

The mean age at diagnosis of DCIS for the women in the database was 53.8 (range, 15-69) years, and the mean duration of follow-up was 7.5 (range, 0-23.9) years. Overall, the 20-year breast cancer–specific mortality rate following a diagnosis of DCIS was 3.3% (95% CI, 3.0%-3.6%).

Just over 1% of the 42,250 women treated with lumpectomy and radiotherapy developed an ipsilateral invasive recurrence in the follow-up period and 163 women (0.4%) died of breast cancer. Of the 19,762 women who were treated with lumpectomy without radiotherapy, 595 women (3%) developed an ipsilateral invasive recurrence and 102 women (0.5%) died of breast cancer, Dr. Narod and his associates reported (JAMA Oncology. 2015 Aug. 20 doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.2510).

Among the 956 women who died of breast cancer in the follow-up period, over half (517) did not experience an in-breast invasive recurrence prior to death. Of the 163 women who were treated with lumpectomy and radiotherapy and then died of breast cancer, 57.7% (94) did not experience an in-breast invasive recurrence prior to death. Among the 102 women treated with lumpectomy without radiotherapy who died of breast cancer, 51 did not experience an in-breast invasive recurrence prior to death (50.0%). Among the 154 women treated with a mastectomy (unilateral or bilateral) who died of breast cancer, 112 did not experience an in-breast invasive recurrence prior to death (72.7%), the investigators reported.

They found that young age at diagnosis and black ethnicity were predictors of breast cancer mortality. Young women diagnosed with ductal carcinoma in situ before the age of 35 years had a more than twofold greater risk of dying from breast cancer than older women (7.8% vs. 3.2%; HR 2.58, 95% CI, 1.85-3.60; P less than .001). Black women also had a much greater risk of dying from breast cancer than non-Hispanic whites (7.0% vs. 3.0%; HR, 2.55, 95% CI, 2.17-3.01; P less than .001).

“If DCIS were truly a (noninvasive) precursor of breast cancer, then a woman with DCIS should not die of breast cancer without first experiencing an invasive breast cancer (ipsilateral or contralateral), and the prevention of an invasive recurrence should prevent her death from breast cancer. Surprisingly, the majority of women with DCIS in the cohort who died of breast cancer did not experience an invasive in-breast recurrence (ipsilateral or contralateral) prior to death (54.1%),” the investigators said.

“The outcome of breast cancer mortality for DCIS patients is of importance in itself and potential treatments that affect mortality are deserving of study,” they concluded.

No relevant conflicts of interest were declared.

Radiotherapy after breast-conserving surgery for ductal carcinoma in situ reduces the risk of ipsilateral invasive recurrence but does not reduce breast cancer mortality, new research shows.

Analysis of data from 108,196 women diagnosed with ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS), who were included in the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) 18 registries database, showed radiotherapy significantly reduced the risk of ipsilateral invasive recurrence at 10 years (adjusted hazard, 0.47; 95% confidence interval, 0.42-0.53; P less than .001) but only achieved a nonsignificant reduction in breast cancer mortality (adjusted HR, 0.81; 95% CI, 0.63-1.04; P = .10).

“The finding of greatest clinical importance was that prevention of ipsilateral invasive recurrence did not prevent death from breast cancer,” wrote Dr. Steven A. Narod and his colleagues from the Women’s College Hospital and the University of Toronto.

Though it is often stated that DCIS is a preinvasive neoplastic lesion that is not lethal in itself, these results suggest that this interpretation should be revisited, they said in the report, published online August 20 in JAMA Oncology.

“Some cases of DCIS have an inherent potential for distant metastatic spread. It is therefore appropriate to consider these as de facto breast cancers and not as preinvasive markers predictive of a subsequent invasive cancer,” they said.

The mean age at diagnosis of DCIS for the women in the database was 53.8 (range, 15-69) years, and the mean duration of follow-up was 7.5 (range, 0-23.9) years. Overall, the 20-year breast cancer–specific mortality rate following a diagnosis of DCIS was 3.3% (95% CI, 3.0%-3.6%).

Just over 1% of the 42,250 women treated with lumpectomy and radiotherapy developed an ipsilateral invasive recurrence in the follow-up period and 163 women (0.4%) died of breast cancer. Of the 19,762 women who were treated with lumpectomy without radiotherapy, 595 women (3%) developed an ipsilateral invasive recurrence and 102 women (0.5%) died of breast cancer, Dr. Narod and his associates reported (JAMA Oncology. 2015 Aug. 20 doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.2510).

Among the 956 women who died of breast cancer in the follow-up period, over half (517) did not experience an in-breast invasive recurrence prior to death. Of the 163 women who were treated with lumpectomy and radiotherapy and then died of breast cancer, 57.7% (94) did not experience an in-breast invasive recurrence prior to death. Among the 102 women treated with lumpectomy without radiotherapy who died of breast cancer, 51 did not experience an in-breast invasive recurrence prior to death (50.0%). Among the 154 women treated with a mastectomy (unilateral or bilateral) who died of breast cancer, 112 did not experience an in-breast invasive recurrence prior to death (72.7%), the investigators reported.

They found that young age at diagnosis and black ethnicity were predictors of breast cancer mortality. Young women diagnosed with ductal carcinoma in situ before the age of 35 years had a more than twofold greater risk of dying from breast cancer than older women (7.8% vs. 3.2%; HR 2.58, 95% CI, 1.85-3.60; P less than .001). Black women also had a much greater risk of dying from breast cancer than non-Hispanic whites (7.0% vs. 3.0%; HR, 2.55, 95% CI, 2.17-3.01; P less than .001).

“If DCIS were truly a (noninvasive) precursor of breast cancer, then a woman with DCIS should not die of breast cancer without first experiencing an invasive breast cancer (ipsilateral or contralateral), and the prevention of an invasive recurrence should prevent her death from breast cancer. Surprisingly, the majority of women with DCIS in the cohort who died of breast cancer did not experience an invasive in-breast recurrence (ipsilateral or contralateral) prior to death (54.1%),” the investigators said.

“The outcome of breast cancer mortality for DCIS patients is of importance in itself and potential treatments that affect mortality are deserving of study,” they concluded.

No relevant conflicts of interest were declared.

FROM JAMA ONCOLOGY

Key clinical point: Radiotherapy after ductal carcinoma in situ reduces the risk of ipsilateral invasive recurrence but does not reduce breast cancer mortality.

Major finding: Radiotherapy after DCIS halves the risk of recurrence but does not significantly impact the risk of death from breast cancer.

Data source: Observational study of data from 108,196 women diagnosed with ductal carcinoma in situ in the SEER18 registries.

Disclosures: No conflicts of interest were declared.

Weight program effective for breast cancer survivors

A group-based behavioral weight loss program supplemented with personal contact and support was effective in helping overweight or obese breast cancer survivors lose a clinically meaningful amount of weight, investigators reported online Aug. 17 in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

“Women who have been diagnosed and treated for breast cancer often have special issues and problems, such as treatment-related adverse effects, fatigue, and depression, that can complicate weight management efforts,” wrote Cheryl L. Rock, Ph.D., of the University of California, San Diego, Moores Cancer Center in La Jolla, and her colleagues.

The results from this trial demonstrate that weight loss, even though it was modest, and increased physical activity can be achieved in this population and suggest that these issues can be overcome, the authors noted.

The multicenter trial included 692 overweight or obese breast cancer survivors who were randomly assigned to either the intervention group – which included a cognitive-behavioral weight loss program with telephone counseling and tailored newsletters to support initial weight loss and subsequent maintenance – or a control group with a less intensive intervention (J Clin Oncol. 2015 Aug. 17 doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.61.1095).

At 6 months, the mean weight loss in the intervention group was 5.9%; at 12 months, the weight loss held steady and was maintained at 6%. In the control group, weight loss was 1.3% at 6 months and 1.5% at 12 months.

At 18 months, the women in the intervention group were 4.7% below their baseline weight, and at 24 months they weighed 3.7% less than at entry into the study. Those in the control group were 1.3% below baseline weight at 18 months and 1.1% below at 24 months.

The weight loss intervention was more effective among women older than 55 years than in younger women, who may need counseling and resources beyond that offered in this study, to achieve sufficient weight loss, Dr. Rock and her associates added.

The study was supported by the National Cancer Institute and by a grant from the National Center for Research Resources, a component of the NIH, and NIH Roadmap for Medical Research. Dr. Rock reported research funding from Jenny Craig and Nestle USA, and several of the coauthors reported financial relationships with various corporations.

A group-based behavioral weight loss program supplemented with personal contact and support was effective in helping overweight or obese breast cancer survivors lose a clinically meaningful amount of weight, investigators reported online Aug. 17 in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

“Women who have been diagnosed and treated for breast cancer often have special issues and problems, such as treatment-related adverse effects, fatigue, and depression, that can complicate weight management efforts,” wrote Cheryl L. Rock, Ph.D., of the University of California, San Diego, Moores Cancer Center in La Jolla, and her colleagues.

The results from this trial demonstrate that weight loss, even though it was modest, and increased physical activity can be achieved in this population and suggest that these issues can be overcome, the authors noted.

The multicenter trial included 692 overweight or obese breast cancer survivors who were randomly assigned to either the intervention group – which included a cognitive-behavioral weight loss program with telephone counseling and tailored newsletters to support initial weight loss and subsequent maintenance – or a control group with a less intensive intervention (J Clin Oncol. 2015 Aug. 17 doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.61.1095).

At 6 months, the mean weight loss in the intervention group was 5.9%; at 12 months, the weight loss held steady and was maintained at 6%. In the control group, weight loss was 1.3% at 6 months and 1.5% at 12 months.

At 18 months, the women in the intervention group were 4.7% below their baseline weight, and at 24 months they weighed 3.7% less than at entry into the study. Those in the control group were 1.3% below baseline weight at 18 months and 1.1% below at 24 months.

The weight loss intervention was more effective among women older than 55 years than in younger women, who may need counseling and resources beyond that offered in this study, to achieve sufficient weight loss, Dr. Rock and her associates added.

The study was supported by the National Cancer Institute and by a grant from the National Center for Research Resources, a component of the NIH, and NIH Roadmap for Medical Research. Dr. Rock reported research funding from Jenny Craig and Nestle USA, and several of the coauthors reported financial relationships with various corporations.

A group-based behavioral weight loss program supplemented with personal contact and support was effective in helping overweight or obese breast cancer survivors lose a clinically meaningful amount of weight, investigators reported online Aug. 17 in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

“Women who have been diagnosed and treated for breast cancer often have special issues and problems, such as treatment-related adverse effects, fatigue, and depression, that can complicate weight management efforts,” wrote Cheryl L. Rock, Ph.D., of the University of California, San Diego, Moores Cancer Center in La Jolla, and her colleagues.

The results from this trial demonstrate that weight loss, even though it was modest, and increased physical activity can be achieved in this population and suggest that these issues can be overcome, the authors noted.

The multicenter trial included 692 overweight or obese breast cancer survivors who were randomly assigned to either the intervention group – which included a cognitive-behavioral weight loss program with telephone counseling and tailored newsletters to support initial weight loss and subsequent maintenance – or a control group with a less intensive intervention (J Clin Oncol. 2015 Aug. 17 doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.61.1095).

At 6 months, the mean weight loss in the intervention group was 5.9%; at 12 months, the weight loss held steady and was maintained at 6%. In the control group, weight loss was 1.3% at 6 months and 1.5% at 12 months.

At 18 months, the women in the intervention group were 4.7% below their baseline weight, and at 24 months they weighed 3.7% less than at entry into the study. Those in the control group were 1.3% below baseline weight at 18 months and 1.1% below at 24 months.

The weight loss intervention was more effective among women older than 55 years than in younger women, who may need counseling and resources beyond that offered in this study, to achieve sufficient weight loss, Dr. Rock and her associates added.

The study was supported by the National Cancer Institute and by a grant from the National Center for Research Resources, a component of the NIH, and NIH Roadmap for Medical Research. Dr. Rock reported research funding from Jenny Craig and Nestle USA, and several of the coauthors reported financial relationships with various corporations.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF CLINICAL ONCOLOGY

Key clinical point: A group-based behavioral weight loss intervention can lead to clinically meaningful weight loss in overweight/obese breast cancer survivors

Major finding: At 24 months, mean weight loss was more than double in the intervention group, compared with controls (3.7% vs 1.3%).

Data source: Multicenter randomized trial involving 692 overweight/obese women who were about 2 years post treatment for early-stage breast cancer.

Disclosures: The study was supported by the National Cancer Institute and by a grant from the National Center for Research Resources, a component of the NIH, and NIH Roadmap for Medical Research. Dr. Rock reported research funding from Jenny Craig and Nestle USA, and several of the coauthors reported financial relationships with various corporations.

Younger breast cancer patients want tailored decision aids

WASHINGTON – An online decision aid can help premenopausal women with breast cancer make informed decisions about their treatment, investigators report.

“Web-based decision aids can be an important complement to clinical care, to help women and their families think about some of these very difficult decisions in a very short space of time,” said Dr. Claire Foster, a chartered health psychologist in the faculty of health sciences at the University of Southampton (England).

Decision aids can enhance understanding, reduce uncertainties, and support joint decision making by describing for patients and families the relative risks and benefits of treatment. Yet most such materials are aimed at older, often postmenopausal women, Dr. Foster noted at the joint congress of the International Psycho-Oncology Society and the American Psychosocial Oncology Society.

Approximately 20% of women with breast cancer are diagnosed before menopause. These women tend to have poorer prognosis and high-risk disease, with larger, higher-grade tumors at the time of diagnosis. In addition, they are more likely to have estrogen-receptor–negative disease and more lymph node involvement than older women. Even with successful treatment, younger women have a greater lifetime risk of local recurrence, contralateral recurrence, and distant metastases.

Young women also have special concerns about body image, disruptions of work and family life, and fears about loss of fertility and early menopause.

Dr. Foster and colleagues first interviewed 32 women with a mean age at diagnosis of breast cancer of 34. They conducted in-depth semistructured interviews and focus groups to determine how to convey information about treatments and their consequences that would help the patients in making decisions about their care.

The sample consisted of 30 white and 2 black women. In all, 22% were single, 59% had children, and 33% reported a family history of breast cancer. The majority of patients (63%) had undergone mastectomy (75% of this group also had reconstruction), and the remainder had breast-conserving surgery.

During the interviews and focus groups, the women identified specific factors as being important in their decision making, including breast cancer type (hormone receptor negative or positive, or triple-negative disease), surgical treatment (mastectomy, breast-conserving procedures, immediate or delayed reconstruction), nonsurgical therapies (radiation, chemotherapy, hormonal therapy), effects on fertility and fertility preservation options, and factors related to hospitalization, nutrition and exercise, and activities of daily living.

Participants especially expressed concerns about the effects of treatment on fertility and about having to make rapid decisions with little time to think about options.

Based on the discussions, the investigators have developed and are pilot-testing an online decision aid for young women diagnosed with early-stage breast cancer.

In a similar project, Dr. Foster and colleagues are developing a genetic testing decision aid for young women that focuses on the special concerns of those who may be carriers or high-risk mutations such as BRCA1 and BRCA2.

The work is supported by the UK National Institute for Health Research for Patient Benefit Programme and Breast Cancer Campaign. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

WASHINGTON – An online decision aid can help premenopausal women with breast cancer make informed decisions about their treatment, investigators report.

“Web-based decision aids can be an important complement to clinical care, to help women and their families think about some of these very difficult decisions in a very short space of time,” said Dr. Claire Foster, a chartered health psychologist in the faculty of health sciences at the University of Southampton (England).

Decision aids can enhance understanding, reduce uncertainties, and support joint decision making by describing for patients and families the relative risks and benefits of treatment. Yet most such materials are aimed at older, often postmenopausal women, Dr. Foster noted at the joint congress of the International Psycho-Oncology Society and the American Psychosocial Oncology Society.

Approximately 20% of women with breast cancer are diagnosed before menopause. These women tend to have poorer prognosis and high-risk disease, with larger, higher-grade tumors at the time of diagnosis. In addition, they are more likely to have estrogen-receptor–negative disease and more lymph node involvement than older women. Even with successful treatment, younger women have a greater lifetime risk of local recurrence, contralateral recurrence, and distant metastases.

Young women also have special concerns about body image, disruptions of work and family life, and fears about loss of fertility and early menopause.

Dr. Foster and colleagues first interviewed 32 women with a mean age at diagnosis of breast cancer of 34. They conducted in-depth semistructured interviews and focus groups to determine how to convey information about treatments and their consequences that would help the patients in making decisions about their care.

The sample consisted of 30 white and 2 black women. In all, 22% were single, 59% had children, and 33% reported a family history of breast cancer. The majority of patients (63%) had undergone mastectomy (75% of this group also had reconstruction), and the remainder had breast-conserving surgery.

During the interviews and focus groups, the women identified specific factors as being important in their decision making, including breast cancer type (hormone receptor negative or positive, or triple-negative disease), surgical treatment (mastectomy, breast-conserving procedures, immediate or delayed reconstruction), nonsurgical therapies (radiation, chemotherapy, hormonal therapy), effects on fertility and fertility preservation options, and factors related to hospitalization, nutrition and exercise, and activities of daily living.

Participants especially expressed concerns about the effects of treatment on fertility and about having to make rapid decisions with little time to think about options.

Based on the discussions, the investigators have developed and are pilot-testing an online decision aid for young women diagnosed with early-stage breast cancer.

In a similar project, Dr. Foster and colleagues are developing a genetic testing decision aid for young women that focuses on the special concerns of those who may be carriers or high-risk mutations such as BRCA1 and BRCA2.

The work is supported by the UK National Institute for Health Research for Patient Benefit Programme and Breast Cancer Campaign. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

WASHINGTON – An online decision aid can help premenopausal women with breast cancer make informed decisions about their treatment, investigators report.

“Web-based decision aids can be an important complement to clinical care, to help women and their families think about some of these very difficult decisions in a very short space of time,” said Dr. Claire Foster, a chartered health psychologist in the faculty of health sciences at the University of Southampton (England).

Decision aids can enhance understanding, reduce uncertainties, and support joint decision making by describing for patients and families the relative risks and benefits of treatment. Yet most such materials are aimed at older, often postmenopausal women, Dr. Foster noted at the joint congress of the International Psycho-Oncology Society and the American Psychosocial Oncology Society.

Approximately 20% of women with breast cancer are diagnosed before menopause. These women tend to have poorer prognosis and high-risk disease, with larger, higher-grade tumors at the time of diagnosis. In addition, they are more likely to have estrogen-receptor–negative disease and more lymph node involvement than older women. Even with successful treatment, younger women have a greater lifetime risk of local recurrence, contralateral recurrence, and distant metastases.

Young women also have special concerns about body image, disruptions of work and family life, and fears about loss of fertility and early menopause.

Dr. Foster and colleagues first interviewed 32 women with a mean age at diagnosis of breast cancer of 34. They conducted in-depth semistructured interviews and focus groups to determine how to convey information about treatments and their consequences that would help the patients in making decisions about their care.

The sample consisted of 30 white and 2 black women. In all, 22% were single, 59% had children, and 33% reported a family history of breast cancer. The majority of patients (63%) had undergone mastectomy (75% of this group also had reconstruction), and the remainder had breast-conserving surgery.

During the interviews and focus groups, the women identified specific factors as being important in their decision making, including breast cancer type (hormone receptor negative or positive, or triple-negative disease), surgical treatment (mastectomy, breast-conserving procedures, immediate or delayed reconstruction), nonsurgical therapies (radiation, chemotherapy, hormonal therapy), effects on fertility and fertility preservation options, and factors related to hospitalization, nutrition and exercise, and activities of daily living.

Participants especially expressed concerns about the effects of treatment on fertility and about having to make rapid decisions with little time to think about options.

Based on the discussions, the investigators have developed and are pilot-testing an online decision aid for young women diagnosed with early-stage breast cancer.

In a similar project, Dr. Foster and colleagues are developing a genetic testing decision aid for young women that focuses on the special concerns of those who may be carriers or high-risk mutations such as BRCA1 and BRCA2.

The work is supported by the UK National Institute for Health Research for Patient Benefit Programme and Breast Cancer Campaign. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

Key clinical point: Younger women with breast cancer diagnoses say they need information tailored to their needs.

Major finding: Women younger than 40 with early-stage breast cancer base treatment decisions on both clinical factors and concerns about fertility, body image, and the effects on work and family life.

Data source: Review of a pilot study with 32 women to develop a breast cancer treatment decision tool.

Disclosures: The work is supported by the UK National Institute for Health Research for Patient Benefit Programme and Breast Cancer Campaign. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

Why is breast density a weighty matter?

Case: Patient seeks clarification and next steps on her breast density classification

Your patient, a 51-year-old postmenopausal woman (G0P0) in good health, had an annual screening mammogram that showed no evidence of malignancy. She is white and has a mother with a history of breast cancer. She has never had a breast biopsy. Following the mammogram, she received a letter from the imaging center, stating:

She calls your office and asks, “What should I do next?”

Breasts are composed of fibrous, glandular, and adipose tissue. If the breasts contain a lot of fibrous and glandular tissue, and little adipose tissue, they are considered to be “dense.” Using mammography, the current standard is to report the density of breast tissue using 4 categories:

- almost entirely fatty

- scattered fibroglandular densities

- heterogeneously dense

- extremely dense.

Dense breast tissue is defined to include the 2 categories heterogeneously dense and extremely dense.

Observational studies have reported that dense breast tissue is associated with an increased risk of breast cancer, and dense breast tissue makes it more difficult to detect breast cancer on mammography. According to data from the Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium, among women aged 50 or older, the relative risk of breast cancer stratified by the 4 categories of breast density is 0.59, 1.00, 1.46, and 1.77, for almost entirely fatty, scattered fibroglandular densities, heterogeneously dense, and extremely dense, respectively.1 In one study, the sensitivity of mammography to detect breast cancer was 82% to 88% for women with nondense breasts and 62% to 69% in women with dense breasts.2 These data have catalyzed investigators to explore the use of supplemental imaging to enhance cancer detection in women with dense breasts.

The link between breast density and breast cancer risk and reduced sensitivity of mammography also has catalyzed activists and legislators to champion breast density notification laws, which have passed in more than 20 states. These laws require facilities that perform mammography to notify women with dense breasts that this finding is associated with an increased risk of breast cancer and that dense breasts reduce the ability of mammography to detect cancer. In some states, the law mandates that women with dense breasts be offered supplemental ultrasound imaging and that insurers must cover the cost of the ultrasound studies. Many of the laws recommend that the patient discuss the situation with the clinician who ordered the mammogram.

When I first saw the recommendation for patients to contact me about how to manage dense breasts, my initial response was, “Who? Me?” I felt ill equipped to provide any useful advice and suspected that many of my patients knew more than I about this issue.

Based on a review of the evidence, my current clinical recommendation is outlined in the 2 options below, including a low-resource utilization option and a high-resource utilization option. For patients, physicians, and health systems that are concerned that excessive breast cancer screening tests might cause more harm than benefit, the identification of dense breasts on mammogram is unlikely to be a trigger to perform any additional testing. In this situation, the pragmatic low-resource option is most relevant.

Alternatively, for patients and physicians who strongly believe in the value of screening mammography (see “Utilize tomosynthesis digital mammography technology for your patients” below), a reasonable strategy is to recommend that women with dense breasts and an increased risk for breast cancer be offered supplemental imaging.

In this editorial I elaborate these 2 approaches to breast cancer screening in women with dense breasts.

Utilize tomosynthesis digital mammography technology for your patients

Mammograms are the primary modality used for breast cancer screening because screening mammography has been shown to reduce breast cancer deaths by 15% to 30%.1,2 Annual or biennial mammograms are recommended for women aged 40 years or older by many professional organizations, including the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the American College of Radiology. However, mammography screening programs have been criticized because of false-positive tests resulting in unnecessary biopsies, limited sensitivity, and the theoretical risk of over-diagnosing clinically insignificant cancers.3,4

Mammography technology continues to evolve. Film-based mammography has been replaced by digital mammography. Tomosynthesis digital mammography, also known as 3-D mammography, is now replacing standard digital mammography.5

With tomosynthesis, digital mammography image acquisition is performed using an x-ray source that moves through an arc across the breast with the capture of a series of images from different angles and reconstruction of the data into thin slices approximately 1 mm in width. The presentation of breast images in thin slices permits superior detection of lesions. In addition, the collected images can be reconstructed to present a virtual 2-D image for analysis.

Tomosynthesis has been demonstrated to increase the sensitivity of mammography to detect cancer and reduce false-positive examinations. In a study of 454,850 mammography examinations, investigators found that the invasive cancer detection rate per 1,000 studies increased from 2.9 with standard digital mammography to 4.1 with tomosynthesis.6

Tomosynthesis also reduces the patient recall rate to perform additional views or subsequent ultrasound. In one large study, the recall rate was 12% for standard digital mammography and 8.4% for tomosynthesis.7

The limitations of tomosynthesis include higher costs and higher radiation doses.

If the technology is available, I recommend that women have their mammograms using the best technology, tomosynthesis digital mammography.8

References

1. Smith RA, Duffy SW, Gabe R, Tabar L, Yen AM, Chen TH. The randomized trials of breast cancer screening: what have we learned? Radiol Clin North Am. 2004;42(5):793–806.

2. Independent UK Panel on Breast Cancer Screening. The benefits and harms of breast cancer screening: an independent review. Lancet. 2012;380(9855):1778–1786.

3. US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for breast cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendations statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(10):716–726, W-236.

4. Welch HG, Passow HJ. Quantifying the benefits and harms of screening mammograms. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(3):448–454.

5. Destounis SV, Morgan R, Areino A. Screening for dense breasts: digital tomosynthesis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2015;204(2):261–264.

6. Friedewald SM, Rafferty EA, Rose SL, et al. Breast cancer screening using tomosynthesis in combination with digital mammography. JAMA. 2014;311(24):2499–2507.

7. Haas BM, Kalra V, Geisel J, Raghu M, Durand M, Philpotts LE. Comparison of tomosynthesis plus digital mammography and digital mammography alone for breast cancer screening. Radiology. 2013;269(3):694–700.

8. Pisano ED, Yaffe MJ. Breast cancer screening: should tomosynthesis replace digital mammography? JAMA. 2014;311(24):2488–2489.

A pragmatic, low-resource utilization screening approach for women with dense breasts

There are no published randomized clinical trials that provide high-quality evidence on what to do if dense breasts are identified on mammography.3 Authors of observational studies have evaluated the potential role of supplemental imaging, including ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), in the management of dense breast tissue (see “Supplemental breast cancer screening modalities” below). Supplemental imaging involves complex trade-offs, balancing the potential benefit of identifying occult early breast cancer lesions not identified by mammography with the risk of subjecting many women without cancer to additional testing and unnecessary biopsies.

A pragmatic, low-resource utilization plan for women with dense breasts involves emphasizing that mammography is the best available screening tool and that annual or biennial mammography is the foundation of all current approaches to breast cancer screening. Supplemental imaging is unnecessary with this approach because there is no evidence that it reduces breast cancer mortality. There is, however, substantial evidence that using supplemental imaging for all women with dense breasts will result in little benefit and great costs, including many unnecessary biopsies.1,4 Women with dense breasts also could consider annual clinical breast examination.

Supplemental breast cancer screening modalities

Ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are available as supplemental imaging, although ultrasound is the only supplemental imaging test that is specifically approved for women with dense breasts. Among the clinically available imaging modalities, MRI can detect the greatest number of cancers.

Ultrasound

In women with dense breasts, ultrasound can detect another 3 to 4 cancers that were not detected by mammography. However, ultrasound imaging generates many false positive results that lead to additional biopsies. According to one analysis, compared with mammography alone, mammography plus ultrasound would prevent 0.36 breast cancer deaths and cause 354 additional biopsies per 1,000 women with dense breasts screened biennially for 25 years.1

Ultrasound commonly is used to follow up an abnormal mammogram to further evaluate masses and differentiate cysts from solid tumors. Ultrasound is also a useful breast-imaging tool for women who are pregnant. In 2012, the US Food and Drug Administration approved an automated breast ultrasound device to be used for supplemental imaging of asymptomatic women with dense breasts and a mammogram negative for cancer. This device may facilitate the use of ultrasound for supplemental imaging of women with dense breasts on mammography.

Magnetic resonance imaging

MRI can detect the greatest number of cancers of any clinically available modality.

It is almost never covered by insurance for women whose only breast cancer risk factor is the identification of dense breasts on mammography. The cost of MRI testing is, however, typically covered for women at very high risk for breast cancer.

Women who are known to be at very high risk for breast cancer should begin annual clinical breast examinations at age 25 years and alternate between screening mammography and screening MRI every 6 months or annually. These women include:

- carriers of clinically significant BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations

- carriers of other high-risk genetic mutations such as Cowden syndrome (PTEN mutation), Lai-Fraumeni syndrome (TP53 mutation), and Peutz-Jeghers syndrome

- genetically untested women with a first-degree relative with a BRCA mutation.

Women who had thoracic radiation before age 30 also should be considered for this screening protocol beginning 8 to 10 years after the radiation exposure or at age 25 years.2

References

1. Sprague BL, Stout KN, Schechter MD, et al. Benefits, harms and cost-effectiveness of supplemental ultrasonography screening for women with dense breasts. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162(3):157–166.

2. CRICO Breast Care Management Algorithm. CRICO; Cambridge, Massachusetts; 2014. https://www.rmf.harvard.edu/~/media/Files/_Global/KC/PDFs/Guidelines/cricormfbca2014_locked.pdf. Accessed July 19, 2015.

A high-resource utilization screening approach

There are no randomized trials to help guide recommendations about how to respond to a finding of dense breasts on mammography. In addition to breast density, many factors influence breast cancer risk, including a patient’s:

- age

- family history

- history of previous breast biopsies

- many reproductive factors, including early age of menarche and late childbearing.

Women with both dense breasts and an increased risk of breast cancer may reap the greatest benefit from supplemental imaging, such as ultrasonography. Therefore, a two-step approach can help.

Step 1: Assess breast cancer risk. This can be accomplished using one of many calculators. Three that are commonly used are the:

- National Cancer Institute (NCI) Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium (BCSC) calculator5

- NCI Breast Cancer Risk Assessment Tool, Gail model (BRCAT)6

- IBIS Breast Cancer Risk Evaluation Tool (Tyrer-Cuzick model).7

The BCSC calculator uses age, race/ethnicity, first-degree relatives with breast cancer, a history of a breast biopsy, and breast density to calculate a 5-year risk of developing breast cancer.

The BCRAT tool uses current age, race/ethnicity, age at menarche, age at first live-birth of a child, number of first-degree relatives with breast cancer, a history of breast biopsies, and the identification of atypical hyperplasia to calculate a 5-year risk of breast cancer.

The IBIS model uses many more variables, including a detailed family history to calculate a 10-year and lifetime risk of breast cancer. If a patient has ductal carcinoma in situ, lobular carcinoma in situ, chest irradiation before age 30 years, or known BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations, she is instructed not to use the risk calculators because they are at very high risk for breast cancer, and they need an individualized intensive plan for monitoring and prevention (see MRI section in “Supplemental breast cancer screening modalities” above).

Step 2: Use breast density and breast cancer risk to develop a screening plan. The NIH Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium has published data estimating the risk that a woman with a mammogram negative for cancer will develop breast cancer within the next 12 months (based on her age, breast density, and breast cancer risk—calculated with the BCSC tool).8

It reported an increased risk of breast cancer diagnosed within 12 months following a mammogram that was negative for cancer in women with extremely dense breasts and a BCSC 5-year risk of breast cancer of 1.67% or greater and in women with heterogeneously dense breasts and a BCSC 5-year risk of breast cancer of 2.5% or greater.8

Using these cutoffs it is estimated that 24% of all women with heterogeneously or extremely dense breasts would be offered supplemental screening with a modality such as ultrasound, and 76% would be guided not to have supplemental screening because their risk of developing breast cancer in the 12 months following their negative mammogram is low.

If this guidance is followed, it would require 694 supplemental ultrasound studies and many biopsies to detect 1 additional breast cancer, significantly increasing overall health care costs.8 In many states insurers do not cover supplemental ultrasound imaging of the breasts. In most states insurers require preauthorization for supplemental MRI of the breasts. You need to know the insurance practices in the state to help guide decision making about supplemental imaging. The approach described above is consistent with the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommendation that women with dense breasts, who are asymptomaticand have no additional risk factors for breast cancer, do not need to be offered supplemental imaging.9

Case: Next steps

The BCSC calculator reveals that the 51-year-old woman with a family history of breast cancer and a mammogram showing extremely dense breasts has a 5-year risk of breast cancer of 2.68%. Given that this risk is elevated, this patient could be offered supplemental ultrasound screening and annual breast clinical examination. In addition, she could be further counseled about breast cancer chemoprevention options.10

Women with a strong family history of breast and/or ovarian cancer also could be referred for genetic counseling and BRCA testing.11 The risk of having a BRCA mutation can be calculated using the BRCAPRO tool.12

Most women with dense breast tissue on mammography will never develop breast cancer. Yet the presence of dense breast tissue both increases the risk of breast cancer and decreases the sensitivity of mammography to detect cancer. There are no high-quality data from randomized trials to help guide our recommendations concerning the management of dense breasts identified on mammography. Yet many states have laws that suggest patients ask you to provide advice about breast density.

Patients, clinicians, and health systems vary in their confidence in the clinical value of breast cancer screening programs. Consequently, there is no “right answer” to this vexing problem. The standard of care is to support a range of options tailored to the specific clinical characteristics and needs of each patient.

Many states mandate that patients receive letters from their mammography center that report on breast density. In many states the law requires that the letter contain a statement that dense breasts increase the risk of breast cancer and reduce the ability of mammography to detect breast cancer. Do you believe these letters:

b) are beneficial because they provide the patient important information

c) both a and b

To weigh in and send your Letter to the Editor, visit obgmanagement.com and look for the “Quick Poll” on the right side of the home page.

1. Sprague BL, Stout KN, Schechter MD, et al. Benefits, harms and cost-effectiveness of supplemental ultrasonography screening for women with dense breasts. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162(3):157–166.

2. Carney PA, Miglioretti DL, Yankaskas BC, et al. Individual and combined effects of age, breast density and hormone replacement therapy use on the accuracy of screening mammography. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138(3):168–175.

3. Gartlehner G, Thaler K, Chapman A, et al. Mammography in combination with breast ultrasonography versus mammography for breast cancer screening in women at average risk. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;4:CD009632.

4. Berg WA, Blume JD, Cormack JB, et al. Combined screening with ultrasound and mammography vs. mammography alone in women at elevated risk of breast cancer. JAMA. 2008;299(18):2151–2163.

5. Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium risk calculator. BCSC Web site. https://tools.bcsc-scc.org/BC5yearRisk/intro.htm. Updated February 13, 2015. Accessed July 17, 2015.

6. NCI Breast Cancer Risk Assessment Tool (Gail model). National Cancer Institute Web site. http://www.cancer.gov/BCRISKTOOL/. Accessed July 17, 2015.

7. IBIS Breast Cancer Risk Evaluation Tool. http://www.ems-trials.org/riskevaluator/. Updated January 9, 2015. Accessed July 17, 2015.

8. Kerlikowske K, Zhu W, Tosteson AN, et al; Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium. Identifying women with dense breasts at high risk for interval cancer. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162(10):673–681.

9. Committee on Gynecologic Practice. Committee Opinion No. 625: Management of women with dense breasts diagnosed by mammography. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125(3): 750–751.

10. Visvanathan K, Hurley P, Bantug E, et al. Use of pharmacologic interventions for breast cancer risk reduction: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(34):2942–2962.

11. Profato JL, Arun BK. Genetic risk assessment for breast and gynecological malignancies. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2015;27(1):1–5.

12. BRCAPRO. BayesMendel Lab. Harvard University Web site. http://bcb.dfci.harvard.edu/bayesmendel/brcapro.php. Accessed July 19, 2015.

Case: Patient seeks clarification and next steps on her breast density classification

Your patient, a 51-year-old postmenopausal woman (G0P0) in good health, had an annual screening mammogram that showed no evidence of malignancy. She is white and has a mother with a history of breast cancer. She has never had a breast biopsy. Following the mammogram, she received a letter from the imaging center, stating:

She calls your office and asks, “What should I do next?”

Breasts are composed of fibrous, glandular, and adipose tissue. If the breasts contain a lot of fibrous and glandular tissue, and little adipose tissue, they are considered to be “dense.” Using mammography, the current standard is to report the density of breast tissue using 4 categories:

- almost entirely fatty

- scattered fibroglandular densities

- heterogeneously dense

- extremely dense.

Dense breast tissue is defined to include the 2 categories heterogeneously dense and extremely dense.

Observational studies have reported that dense breast tissue is associated with an increased risk of breast cancer, and dense breast tissue makes it more difficult to detect breast cancer on mammography. According to data from the Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium, among women aged 50 or older, the relative risk of breast cancer stratified by the 4 categories of breast density is 0.59, 1.00, 1.46, and 1.77, for almost entirely fatty, scattered fibroglandular densities, heterogeneously dense, and extremely dense, respectively.1 In one study, the sensitivity of mammography to detect breast cancer was 82% to 88% for women with nondense breasts and 62% to 69% in women with dense breasts.2 These data have catalyzed investigators to explore the use of supplemental imaging to enhance cancer detection in women with dense breasts.

The link between breast density and breast cancer risk and reduced sensitivity of mammography also has catalyzed activists and legislators to champion breast density notification laws, which have passed in more than 20 states. These laws require facilities that perform mammography to notify women with dense breasts that this finding is associated with an increased risk of breast cancer and that dense breasts reduce the ability of mammography to detect cancer. In some states, the law mandates that women with dense breasts be offered supplemental ultrasound imaging and that insurers must cover the cost of the ultrasound studies. Many of the laws recommend that the patient discuss the situation with the clinician who ordered the mammogram.

When I first saw the recommendation for patients to contact me about how to manage dense breasts, my initial response was, “Who? Me?” I felt ill equipped to provide any useful advice and suspected that many of my patients knew more than I about this issue.

Based on a review of the evidence, my current clinical recommendation is outlined in the 2 options below, including a low-resource utilization option and a high-resource utilization option. For patients, physicians, and health systems that are concerned that excessive breast cancer screening tests might cause more harm than benefit, the identification of dense breasts on mammogram is unlikely to be a trigger to perform any additional testing. In this situation, the pragmatic low-resource option is most relevant.

Alternatively, for patients and physicians who strongly believe in the value of screening mammography (see “Utilize tomosynthesis digital mammography technology for your patients” below), a reasonable strategy is to recommend that women with dense breasts and an increased risk for breast cancer be offered supplemental imaging.

In this editorial I elaborate these 2 approaches to breast cancer screening in women with dense breasts.

Utilize tomosynthesis digital mammography technology for your patients

Mammograms are the primary modality used for breast cancer screening because screening mammography has been shown to reduce breast cancer deaths by 15% to 30%.1,2 Annual or biennial mammograms are recommended for women aged 40 years or older by many professional organizations, including the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the American College of Radiology. However, mammography screening programs have been criticized because of false-positive tests resulting in unnecessary biopsies, limited sensitivity, and the theoretical risk of over-diagnosing clinically insignificant cancers.3,4