User login

A Severe Presentation of Plasma Cell Cheilitis

Plasma cell cheilitis (PCC), also known as plasmocytosis circumorificialis and plasmocytosis mucosae,1 is a poorly understood, uncommon inflammatory condition characterized by dense infiltration of mature plasma cells in the mucosal dermis of the lip.2-5 The etiology of PCC is unknown but is thought to be a reactive immune process triggered by infection, mechanical friction, trauma, or solar damage.1,5,6

The most common presentation of PCC is a slowly evolving, red-brown patch or plaque on the lower lip in older individuals.2,3,5,7 Secondary changes with disease progression can include erosion, ulceration, fissures, edema, bleeding, or crusting.5 The diagnosis of PCC is challenging because it can mimic neoplastic, infectious, and inflammatory conditions.8,9

Treatment strategies for PCC described in the literature vary, as does therapeutic response. Resolution of PCC has been documented after systemic steroids, intralesional steroids, systemic griseofulvin, and topical calcineurin inhibitors, among other agents.6,7,10-16

We present the case of a patient with a lip lesion who ultimately was diagnosed with PCC after it progressed to an advanced necrotic stage.

Case Report

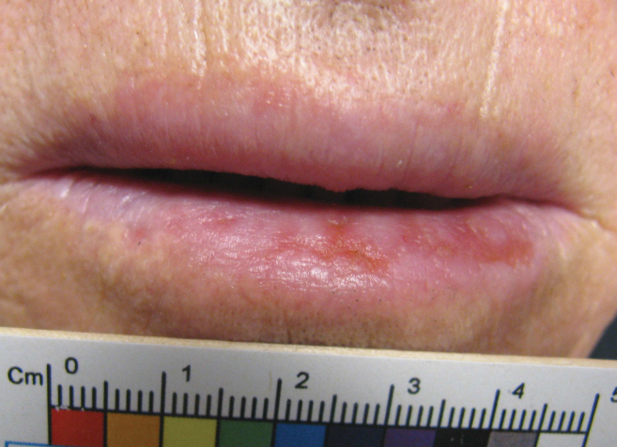

An 80-year-old male veteran of the Armed Services initially presented to our institution via teledermatology with redness and crusting of the lower lip (Figure 1). He had a history of myelodysplastic syndrome and anemia requiring iron transfusion. The process appeared to be consistent with actinic cheilitis vs squamous cell carcinoma. In-person dermatology consultation was recommended; however, the patient did not follow through with that appointment.

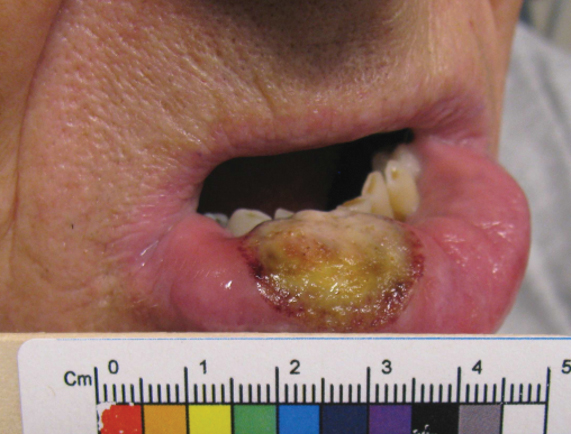

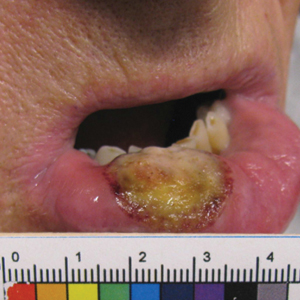

Five months later, additional photographs of the lesion were taken by the patient's primary care physician and sent through teledermatology, revealing progression to an erythematous, yellow-crusted erosion (Figure 2). The medical record indicated that a punch biopsy performed by the patient’s primary care physician showed hyperkeratosis and fungal organisms on periodic acid–Schiff staining. He subsequently applied ketoconazole and terbinafine cream to the lower lip without improvement. Prompt in-person evaluation by dermatology was again recommended.

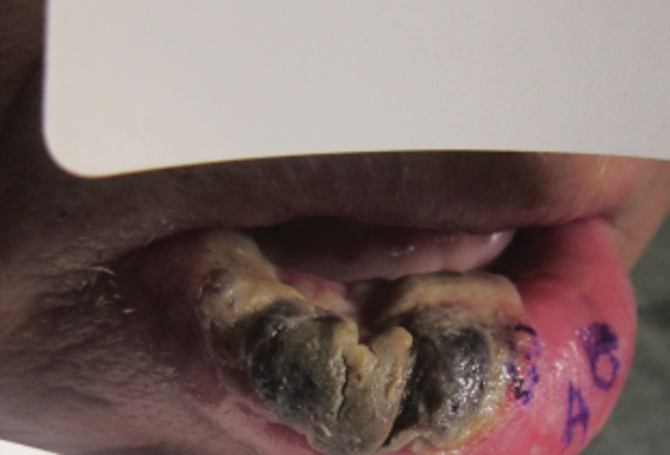

Ten days later, the patient was seen in our dermatology clinic, at which point his condition had rapidly progressed. The lower lip displayed a 3.0×2.5-cm, yellow and black, crusted, ulcerated plaque (Figure 3). He reported severe burning and pain of the lip as well as spontaneous bleeding. He had lost approximately 10 pounds over the last month due to poor oral intake. A second punch biopsy showed benign mucosa with extensive ulceration and formation of full-thickness granulation tissue. No fungi or bacteria were identified.

Consultation and Histologic Analysis

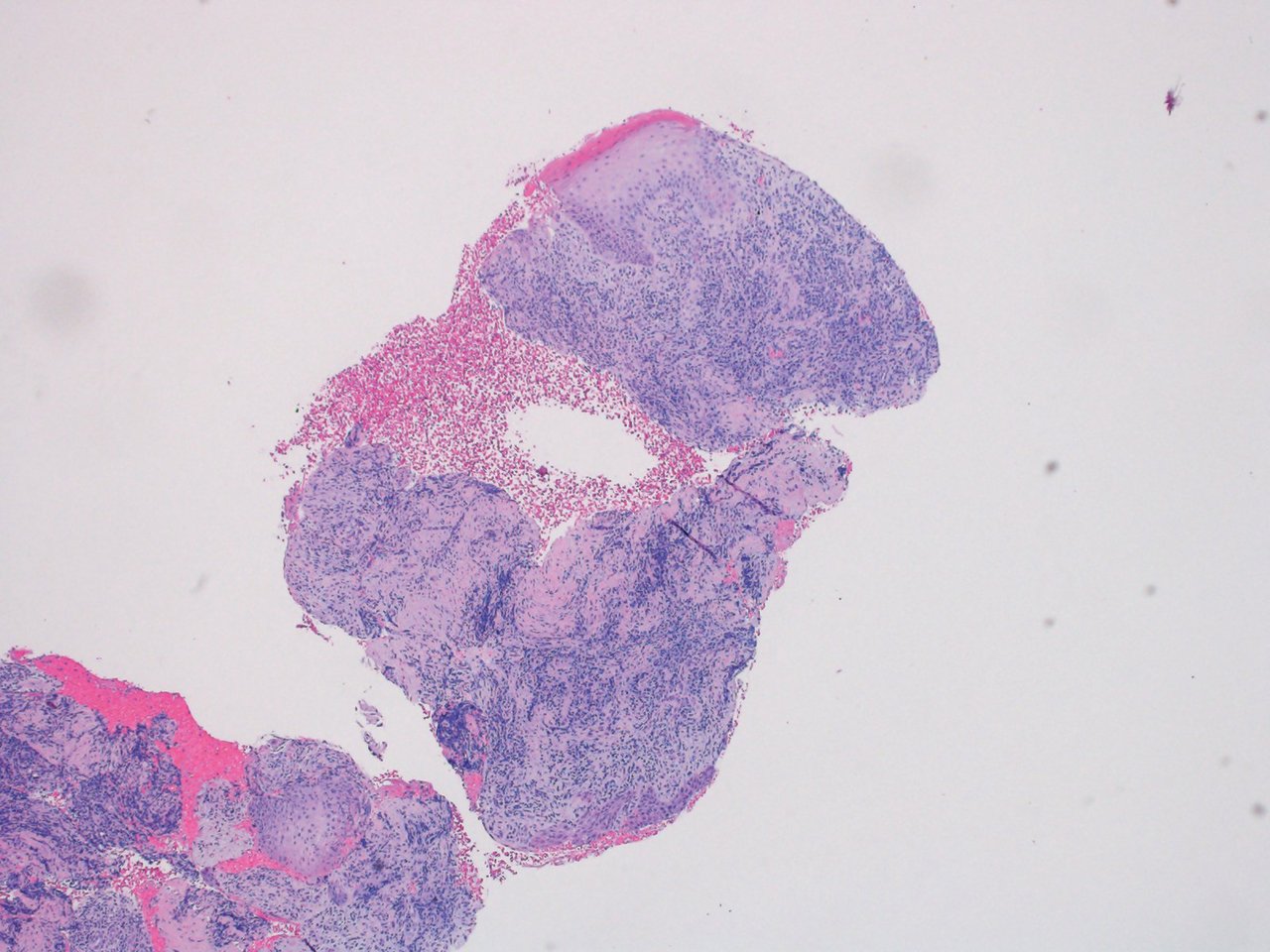

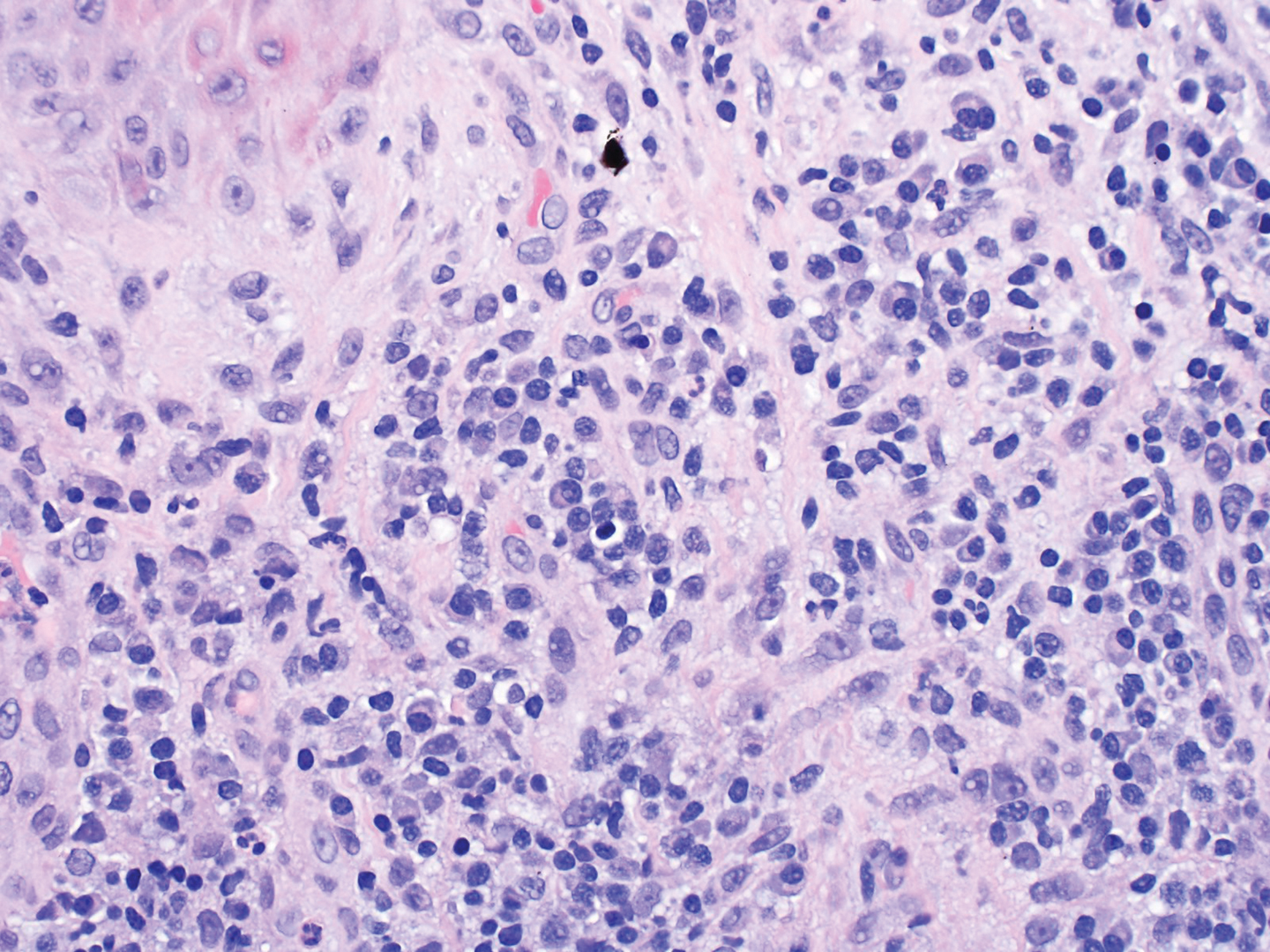

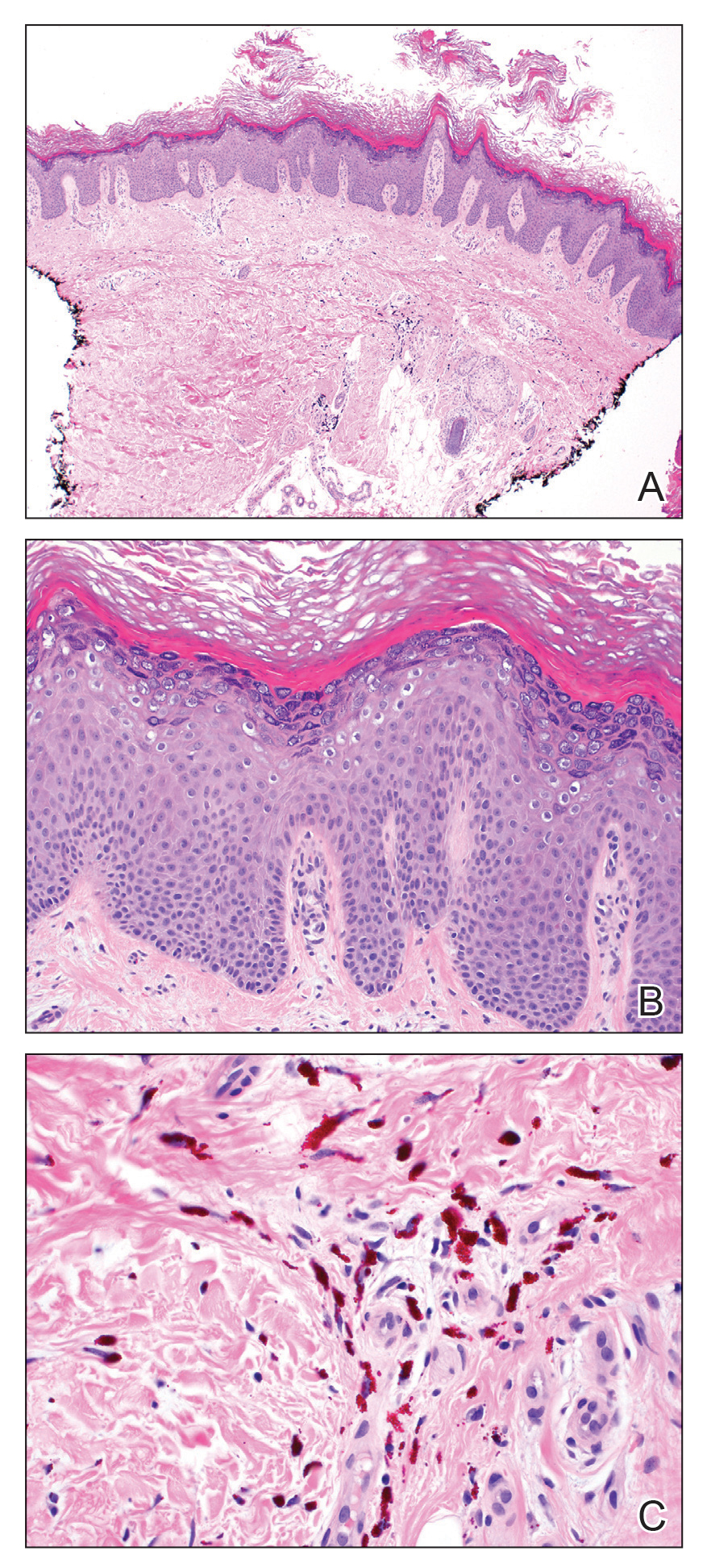

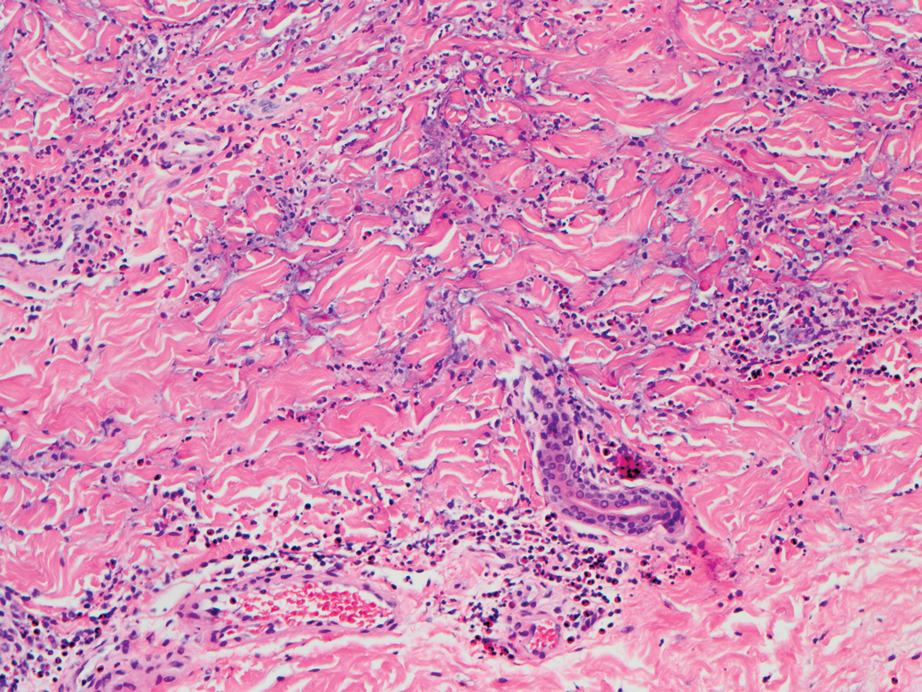

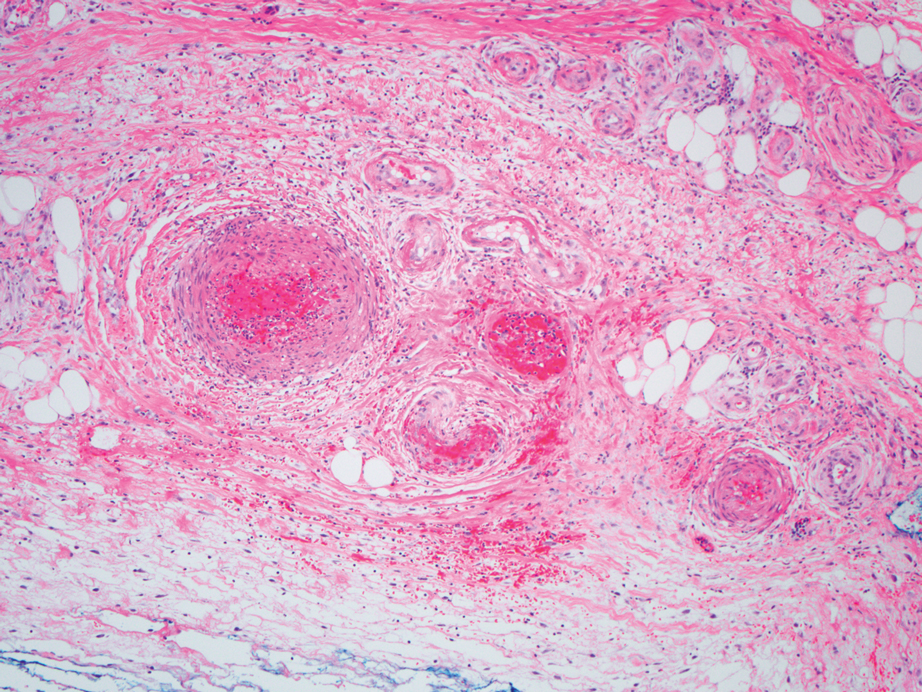

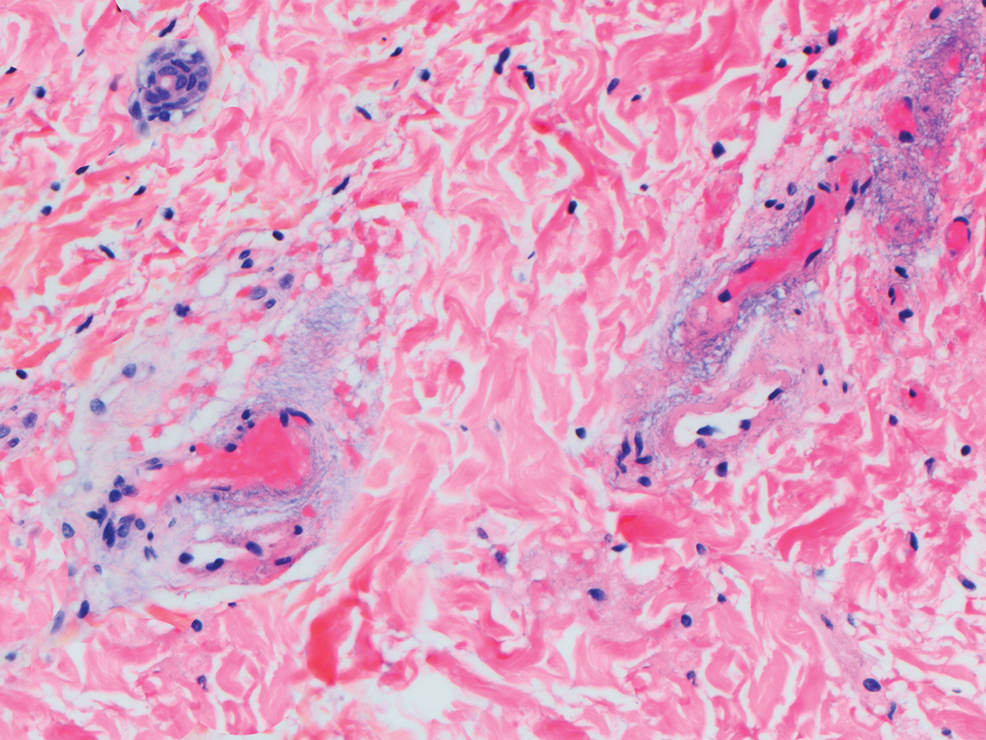

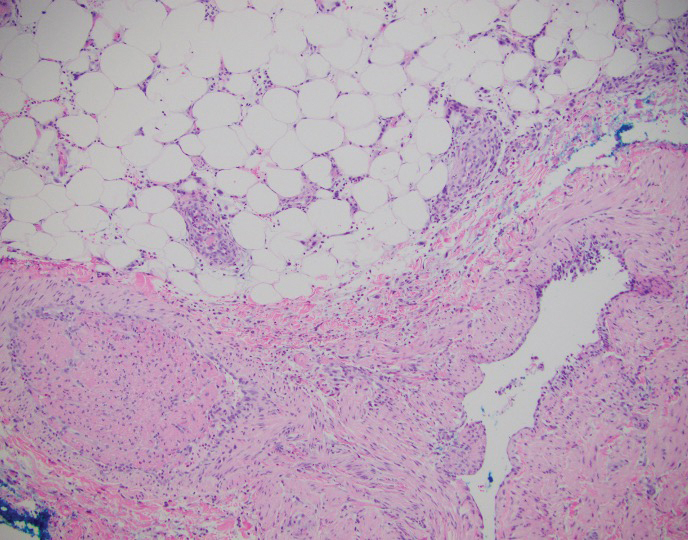

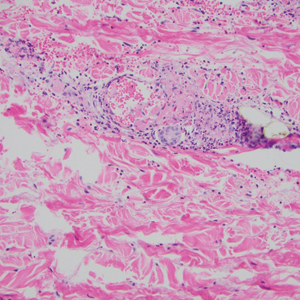

Dermatopathology was consulted and recommended a third punch biopsy for additional testing. A repeat biopsy demonstrated ulceration with lateral elements of retained epidermis and a dense submucosal chronic inflammatory infiltrate comprising plasma cells and lymphocytes (Figures 4 and 5). Immunohistochemical staining demonstrated a mixed inflammatory infiltrate with CD3+ T cells and CD20+ B cells. In situ hybridization studies demonstrated numerous lambda-positive and kappa-positive plasma cells without chain restriction. Periodic acid–Schiff with diastase and Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver staining demonstrated no fungi. Findings were interpreted to be most consistent with a diagnosis of PCC.

Treatment and Follow-up

The patient was treated with clobetasol ointment 0.05% twice daily for 6 weeks and topical lidocaine as needed for pain. At 6-week follow-up, he displayed substantial improvement, with normal-appearing lips and complete resolution of symptoms.

Comment

The diagnosis and management of PCC is difficult because the condition is uncommon (though its true incidence is unknown) and the presentation is nonspecific, invoking a wide differential diagnosis. In the literature, PCC presents as a slowly progressive, red-brown patch or plaque on the lower lip in older individuals.2,3,5,7 The lesion can progress to become eroded, ulcerated, fissured, or edematous.5

Differential Diagnosis

The clinical differential diagnosis of PCC is broad and includes inflammatory, infectious, and neoplastic causes, such as actinic cheilitis, allergic contact cheilitis, exfoliative cheilitis, granulomatous cheilitis, lichen planus, candidiasis, syphilis, and squamous cell carcinoma of the lip.7,9 The histologic differential diagnosis includes allergic contact cheilitis, secondary syphilis, actinic cheilitis, squamous cell carcinoma, cheilitis granulomatosa, and plasmacytoma.17-19

Histopathology

On biopsy, PCC usually is characterized by plasma cells in a bandlike pattern in the upper submucosa or even more diffusely throughout the submucosa.20 In earlier studies, polyclonality of plasma cells with kappa and lambda light chains has been demonstrated5; in this case, such polyclonality militated against a plasma cell dyscrasia. There have been reports of a various number of eosinophils in PCC,5,20 but eosinophils were not a prominent feature in our case.

Treatment

As reported in the literature, treatment of PCC has been attempted using a broad range of strategies; however, the optimal regimen has yet to be elucidated.15 Numerous therapies, including excision, radiation, electrocauterization, cryotherapy, steroids, systemic griseofulvin, topical fusidic acid, and topical calcineurin inhibitors, have yielded variable success.6,7,10-16

The success of topical corticosteroids, as demonstrated in our case, has been unpredictable; the reported response has ranged from complete resolution to failure.9 This variability is thought to be related to epithelial width and the degree of acanthosis, with ulcerative lesions demonstrating a superior response to topical corticosteroids.9

Conclusion

Our case highlights the challenges of diagnosing and managing PCC, especially through teledermatology. Initial photographs of the lesion (Figure 1) that were submitted demonstrated a nonspecific erosion, which was concerning for any of several infectious, inflammatory, and malignant causes. Prompt in-person evaluation was warranted; regrettably, the patient’s condition worsened rapidly in the 10 days it took for him to be seen in-person by dermatology.

Furthermore, this case necessitated 3 separate biopsies because the pathology on the first 2 biopsies initially was equivocal, demonstrating ulceration and granulation tissue. The diagnosis was finally made after a third biopsy was recommended by a dermatopathologist, who eventually identified a bandlike distribution of polyclonal plasma cells in the upper submucosa, consistent with a diagnosis of PCC. Our patient’s final disease presentation (Figure 3) was exuberant and may represent the end point of untreated PCC.

- Senol M, Ozcan A, Aydin NE, et al. Intertriginous plasmacytosis with plasmoacanthoma: report of a typical case and review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:265-268. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4632.2008.03385.x

- Rocha N, Mota F, Horta M, et al. Plasma cell cheilitis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2004;18:96-98. doi:10.1111/j.1468-3083.2004.00791.x

- Farrier JN, Perkins CS. Plasma cell cheilitis. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2008;46:679-680. doi:10.1016/j.bjoms.2008.03.009

- Baughman RD, Berger P, Pringle WM. Plasma cell cheilitis. Arch Dermatol. 1974;110:725-726.

- Lee JY, Kim KH, Hahm JE, et al. Plasma cell cheilitis: a clinicopathological and immunohistochemical study of 13 cases. Ann Dermatol. 2017;29:536-542. doi:10.5021/ad.2017.29.5.536

- da Cunha Filho RR, Tochetto LB, Tochetto BB, et al. “Angular” plasma cell cheilitis. Dermatol Online J. 2014;20:doj_21759.

- Yang JH, Lee UH, Jang SJ, et al. Plasma cell cheilitis treated with intralesional injection of corticosteroids. J Dermatol. 2005;32:987-990. doi:10.1111/j.1346-8138.2005.tb00887.x

- Solomon LW, Wein RO, Rosenwald I, et al. Plasma cell mucositis of the oral cavity: report of a case and review of the literature. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2008;106:853-860. doi:10.1016/j.tripleo.2008.08.016

- Dos Santos HT, Cunha JLS, Santana LAM, et al. Plasma cell cheilitis: the diagnosis of a disorder mimicking lip cancer. Autops Case Rep. 2019;9:e2018075. doi:10.4322/acr.2018.075

- Fujimura T, Furudate S, Ishibashi M, et al. Successful treatment of plasmacytosis circumorificialis with topical tacrolimus: two case reports and an immunohistochemical study. Case Rep Dermatol. 2013;5:79-83. doi:10.1159/000350184

- Tamaki K, Osada A, Tsukamoto K, et al. Treatment of plasma cell cheilitis with griseofulvin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;30:789-790. doi:10.1016/s0190-9622(08)81515-0

- Choi JW, Choi M, Cho KH. Successful treatment of plasma cell cheilitis with topical calcineurin inhibitors. J Dermatol. 2009;36:669-671. doi:10.1111/j.1346-8138.2009.00733.x

- Hanami Y, Motoki Y, Yamamoto T. Successful treatment of plasma cell cheilitis with topical tacrolimus: report of two cases. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17:6.

- Jin SP, Cho KH, Huh CH. Plasma cell cheilitis, successfully treated with topical 0.03% tacrolimus ointment. J Dermatolog Treat. 2010;21:130-132. doi:10.1080/09546630903200620

- Tseng JT-P, Cheng C-J, Lee W-R, et al. Plasma-cell cheilitis: successful treatment with intralesional injections of corticosteroids. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:174-177. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2230.2008.02765.x

- Yoshimura K, Nakano S, Tsuruta D, et al. Successful treatment with 308-nm monochromatic excimer light and subsequent tacrolimus 0.03% ointment in refractory plasma cell cheilitis. J Dermatol. 2013;40:471-474. doi:10.1111/1346-8138.12152

- Fujimura Y, Natsuga K, Abe R, et al. Plasma cell cheilitis extending beyond vermillion border. J Dermatol. 2015;42:935-936. doi:10.1111/1346-8138.12985

- White JW Jr, Olsen KD, Banks PM. Plasma cell orificial mucositis. report of a case and review of the literature. Arch Dermatol. 1986;122:1321-1324. doi:10.1001/archderm.122.11.1321

- Román CC, Yuste CM, Gonzalez MA, et al. Plasma cell gingivitis. Cutis. 2002;69:41-45.

- Choe HC, Park HJ, Oh ST, et al. Clinicopathologic study of 8 patients with plasma cell cheilitis. Korean J Dermatol. 2003;41:174-178.

Plasma cell cheilitis (PCC), also known as plasmocytosis circumorificialis and plasmocytosis mucosae,1 is a poorly understood, uncommon inflammatory condition characterized by dense infiltration of mature plasma cells in the mucosal dermis of the lip.2-5 The etiology of PCC is unknown but is thought to be a reactive immune process triggered by infection, mechanical friction, trauma, or solar damage.1,5,6

The most common presentation of PCC is a slowly evolving, red-brown patch or plaque on the lower lip in older individuals.2,3,5,7 Secondary changes with disease progression can include erosion, ulceration, fissures, edema, bleeding, or crusting.5 The diagnosis of PCC is challenging because it can mimic neoplastic, infectious, and inflammatory conditions.8,9

Treatment strategies for PCC described in the literature vary, as does therapeutic response. Resolution of PCC has been documented after systemic steroids, intralesional steroids, systemic griseofulvin, and topical calcineurin inhibitors, among other agents.6,7,10-16

We present the case of a patient with a lip lesion who ultimately was diagnosed with PCC after it progressed to an advanced necrotic stage.

Case Report

An 80-year-old male veteran of the Armed Services initially presented to our institution via teledermatology with redness and crusting of the lower lip (Figure 1). He had a history of myelodysplastic syndrome and anemia requiring iron transfusion. The process appeared to be consistent with actinic cheilitis vs squamous cell carcinoma. In-person dermatology consultation was recommended; however, the patient did not follow through with that appointment.

Five months later, additional photographs of the lesion were taken by the patient's primary care physician and sent through teledermatology, revealing progression to an erythematous, yellow-crusted erosion (Figure 2). The medical record indicated that a punch biopsy performed by the patient’s primary care physician showed hyperkeratosis and fungal organisms on periodic acid–Schiff staining. He subsequently applied ketoconazole and terbinafine cream to the lower lip without improvement. Prompt in-person evaluation by dermatology was again recommended.

Ten days later, the patient was seen in our dermatology clinic, at which point his condition had rapidly progressed. The lower lip displayed a 3.0×2.5-cm, yellow and black, crusted, ulcerated plaque (Figure 3). He reported severe burning and pain of the lip as well as spontaneous bleeding. He had lost approximately 10 pounds over the last month due to poor oral intake. A second punch biopsy showed benign mucosa with extensive ulceration and formation of full-thickness granulation tissue. No fungi or bacteria were identified.

Consultation and Histologic Analysis

Dermatopathology was consulted and recommended a third punch biopsy for additional testing. A repeat biopsy demonstrated ulceration with lateral elements of retained epidermis and a dense submucosal chronic inflammatory infiltrate comprising plasma cells and lymphocytes (Figures 4 and 5). Immunohistochemical staining demonstrated a mixed inflammatory infiltrate with CD3+ T cells and CD20+ B cells. In situ hybridization studies demonstrated numerous lambda-positive and kappa-positive plasma cells without chain restriction. Periodic acid–Schiff with diastase and Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver staining demonstrated no fungi. Findings were interpreted to be most consistent with a diagnosis of PCC.

Treatment and Follow-up

The patient was treated with clobetasol ointment 0.05% twice daily for 6 weeks and topical lidocaine as needed for pain. At 6-week follow-up, he displayed substantial improvement, with normal-appearing lips and complete resolution of symptoms.

Comment

The diagnosis and management of PCC is difficult because the condition is uncommon (though its true incidence is unknown) and the presentation is nonspecific, invoking a wide differential diagnosis. In the literature, PCC presents as a slowly progressive, red-brown patch or plaque on the lower lip in older individuals.2,3,5,7 The lesion can progress to become eroded, ulcerated, fissured, or edematous.5

Differential Diagnosis

The clinical differential diagnosis of PCC is broad and includes inflammatory, infectious, and neoplastic causes, such as actinic cheilitis, allergic contact cheilitis, exfoliative cheilitis, granulomatous cheilitis, lichen planus, candidiasis, syphilis, and squamous cell carcinoma of the lip.7,9 The histologic differential diagnosis includes allergic contact cheilitis, secondary syphilis, actinic cheilitis, squamous cell carcinoma, cheilitis granulomatosa, and plasmacytoma.17-19

Histopathology

On biopsy, PCC usually is characterized by plasma cells in a bandlike pattern in the upper submucosa or even more diffusely throughout the submucosa.20 In earlier studies, polyclonality of plasma cells with kappa and lambda light chains has been demonstrated5; in this case, such polyclonality militated against a plasma cell dyscrasia. There have been reports of a various number of eosinophils in PCC,5,20 but eosinophils were not a prominent feature in our case.

Treatment

As reported in the literature, treatment of PCC has been attempted using a broad range of strategies; however, the optimal regimen has yet to be elucidated.15 Numerous therapies, including excision, radiation, electrocauterization, cryotherapy, steroids, systemic griseofulvin, topical fusidic acid, and topical calcineurin inhibitors, have yielded variable success.6,7,10-16

The success of topical corticosteroids, as demonstrated in our case, has been unpredictable; the reported response has ranged from complete resolution to failure.9 This variability is thought to be related to epithelial width and the degree of acanthosis, with ulcerative lesions demonstrating a superior response to topical corticosteroids.9

Conclusion

Our case highlights the challenges of diagnosing and managing PCC, especially through teledermatology. Initial photographs of the lesion (Figure 1) that were submitted demonstrated a nonspecific erosion, which was concerning for any of several infectious, inflammatory, and malignant causes. Prompt in-person evaluation was warranted; regrettably, the patient’s condition worsened rapidly in the 10 days it took for him to be seen in-person by dermatology.

Furthermore, this case necessitated 3 separate biopsies because the pathology on the first 2 biopsies initially was equivocal, demonstrating ulceration and granulation tissue. The diagnosis was finally made after a third biopsy was recommended by a dermatopathologist, who eventually identified a bandlike distribution of polyclonal plasma cells in the upper submucosa, consistent with a diagnosis of PCC. Our patient’s final disease presentation (Figure 3) was exuberant and may represent the end point of untreated PCC.

Plasma cell cheilitis (PCC), also known as plasmocytosis circumorificialis and plasmocytosis mucosae,1 is a poorly understood, uncommon inflammatory condition characterized by dense infiltration of mature plasma cells in the mucosal dermis of the lip.2-5 The etiology of PCC is unknown but is thought to be a reactive immune process triggered by infection, mechanical friction, trauma, or solar damage.1,5,6

The most common presentation of PCC is a slowly evolving, red-brown patch or plaque on the lower lip in older individuals.2,3,5,7 Secondary changes with disease progression can include erosion, ulceration, fissures, edema, bleeding, or crusting.5 The diagnosis of PCC is challenging because it can mimic neoplastic, infectious, and inflammatory conditions.8,9

Treatment strategies for PCC described in the literature vary, as does therapeutic response. Resolution of PCC has been documented after systemic steroids, intralesional steroids, systemic griseofulvin, and topical calcineurin inhibitors, among other agents.6,7,10-16

We present the case of a patient with a lip lesion who ultimately was diagnosed with PCC after it progressed to an advanced necrotic stage.

Case Report

An 80-year-old male veteran of the Armed Services initially presented to our institution via teledermatology with redness and crusting of the lower lip (Figure 1). He had a history of myelodysplastic syndrome and anemia requiring iron transfusion. The process appeared to be consistent with actinic cheilitis vs squamous cell carcinoma. In-person dermatology consultation was recommended; however, the patient did not follow through with that appointment.

Five months later, additional photographs of the lesion were taken by the patient's primary care physician and sent through teledermatology, revealing progression to an erythematous, yellow-crusted erosion (Figure 2). The medical record indicated that a punch biopsy performed by the patient’s primary care physician showed hyperkeratosis and fungal organisms on periodic acid–Schiff staining. He subsequently applied ketoconazole and terbinafine cream to the lower lip without improvement. Prompt in-person evaluation by dermatology was again recommended.

Ten days later, the patient was seen in our dermatology clinic, at which point his condition had rapidly progressed. The lower lip displayed a 3.0×2.5-cm, yellow and black, crusted, ulcerated plaque (Figure 3). He reported severe burning and pain of the lip as well as spontaneous bleeding. He had lost approximately 10 pounds over the last month due to poor oral intake. A second punch biopsy showed benign mucosa with extensive ulceration and formation of full-thickness granulation tissue. No fungi or bacteria were identified.

Consultation and Histologic Analysis

Dermatopathology was consulted and recommended a third punch biopsy for additional testing. A repeat biopsy demonstrated ulceration with lateral elements of retained epidermis and a dense submucosal chronic inflammatory infiltrate comprising plasma cells and lymphocytes (Figures 4 and 5). Immunohistochemical staining demonstrated a mixed inflammatory infiltrate with CD3+ T cells and CD20+ B cells. In situ hybridization studies demonstrated numerous lambda-positive and kappa-positive plasma cells without chain restriction. Periodic acid–Schiff with diastase and Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver staining demonstrated no fungi. Findings were interpreted to be most consistent with a diagnosis of PCC.

Treatment and Follow-up

The patient was treated with clobetasol ointment 0.05% twice daily for 6 weeks and topical lidocaine as needed for pain. At 6-week follow-up, he displayed substantial improvement, with normal-appearing lips and complete resolution of symptoms.

Comment

The diagnosis and management of PCC is difficult because the condition is uncommon (though its true incidence is unknown) and the presentation is nonspecific, invoking a wide differential diagnosis. In the literature, PCC presents as a slowly progressive, red-brown patch or plaque on the lower lip in older individuals.2,3,5,7 The lesion can progress to become eroded, ulcerated, fissured, or edematous.5

Differential Diagnosis

The clinical differential diagnosis of PCC is broad and includes inflammatory, infectious, and neoplastic causes, such as actinic cheilitis, allergic contact cheilitis, exfoliative cheilitis, granulomatous cheilitis, lichen planus, candidiasis, syphilis, and squamous cell carcinoma of the lip.7,9 The histologic differential diagnosis includes allergic contact cheilitis, secondary syphilis, actinic cheilitis, squamous cell carcinoma, cheilitis granulomatosa, and plasmacytoma.17-19

Histopathology

On biopsy, PCC usually is characterized by plasma cells in a bandlike pattern in the upper submucosa or even more diffusely throughout the submucosa.20 In earlier studies, polyclonality of plasma cells with kappa and lambda light chains has been demonstrated5; in this case, such polyclonality militated against a plasma cell dyscrasia. There have been reports of a various number of eosinophils in PCC,5,20 but eosinophils were not a prominent feature in our case.

Treatment

As reported in the literature, treatment of PCC has been attempted using a broad range of strategies; however, the optimal regimen has yet to be elucidated.15 Numerous therapies, including excision, radiation, electrocauterization, cryotherapy, steroids, systemic griseofulvin, topical fusidic acid, and topical calcineurin inhibitors, have yielded variable success.6,7,10-16

The success of topical corticosteroids, as demonstrated in our case, has been unpredictable; the reported response has ranged from complete resolution to failure.9 This variability is thought to be related to epithelial width and the degree of acanthosis, with ulcerative lesions demonstrating a superior response to topical corticosteroids.9

Conclusion

Our case highlights the challenges of diagnosing and managing PCC, especially through teledermatology. Initial photographs of the lesion (Figure 1) that were submitted demonstrated a nonspecific erosion, which was concerning for any of several infectious, inflammatory, and malignant causes. Prompt in-person evaluation was warranted; regrettably, the patient’s condition worsened rapidly in the 10 days it took for him to be seen in-person by dermatology.

Furthermore, this case necessitated 3 separate biopsies because the pathology on the first 2 biopsies initially was equivocal, demonstrating ulceration and granulation tissue. The diagnosis was finally made after a third biopsy was recommended by a dermatopathologist, who eventually identified a bandlike distribution of polyclonal plasma cells in the upper submucosa, consistent with a diagnosis of PCC. Our patient’s final disease presentation (Figure 3) was exuberant and may represent the end point of untreated PCC.

- Senol M, Ozcan A, Aydin NE, et al. Intertriginous plasmacytosis with plasmoacanthoma: report of a typical case and review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:265-268. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4632.2008.03385.x

- Rocha N, Mota F, Horta M, et al. Plasma cell cheilitis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2004;18:96-98. doi:10.1111/j.1468-3083.2004.00791.x

- Farrier JN, Perkins CS. Plasma cell cheilitis. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2008;46:679-680. doi:10.1016/j.bjoms.2008.03.009

- Baughman RD, Berger P, Pringle WM. Plasma cell cheilitis. Arch Dermatol. 1974;110:725-726.

- Lee JY, Kim KH, Hahm JE, et al. Plasma cell cheilitis: a clinicopathological and immunohistochemical study of 13 cases. Ann Dermatol. 2017;29:536-542. doi:10.5021/ad.2017.29.5.536

- da Cunha Filho RR, Tochetto LB, Tochetto BB, et al. “Angular” plasma cell cheilitis. Dermatol Online J. 2014;20:doj_21759.

- Yang JH, Lee UH, Jang SJ, et al. Plasma cell cheilitis treated with intralesional injection of corticosteroids. J Dermatol. 2005;32:987-990. doi:10.1111/j.1346-8138.2005.tb00887.x

- Solomon LW, Wein RO, Rosenwald I, et al. Plasma cell mucositis of the oral cavity: report of a case and review of the literature. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2008;106:853-860. doi:10.1016/j.tripleo.2008.08.016

- Dos Santos HT, Cunha JLS, Santana LAM, et al. Plasma cell cheilitis: the diagnosis of a disorder mimicking lip cancer. Autops Case Rep. 2019;9:e2018075. doi:10.4322/acr.2018.075

- Fujimura T, Furudate S, Ishibashi M, et al. Successful treatment of plasmacytosis circumorificialis with topical tacrolimus: two case reports and an immunohistochemical study. Case Rep Dermatol. 2013;5:79-83. doi:10.1159/000350184

- Tamaki K, Osada A, Tsukamoto K, et al. Treatment of plasma cell cheilitis with griseofulvin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;30:789-790. doi:10.1016/s0190-9622(08)81515-0

- Choi JW, Choi M, Cho KH. Successful treatment of plasma cell cheilitis with topical calcineurin inhibitors. J Dermatol. 2009;36:669-671. doi:10.1111/j.1346-8138.2009.00733.x

- Hanami Y, Motoki Y, Yamamoto T. Successful treatment of plasma cell cheilitis with topical tacrolimus: report of two cases. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17:6.

- Jin SP, Cho KH, Huh CH. Plasma cell cheilitis, successfully treated with topical 0.03% tacrolimus ointment. J Dermatolog Treat. 2010;21:130-132. doi:10.1080/09546630903200620

- Tseng JT-P, Cheng C-J, Lee W-R, et al. Plasma-cell cheilitis: successful treatment with intralesional injections of corticosteroids. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:174-177. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2230.2008.02765.x

- Yoshimura K, Nakano S, Tsuruta D, et al. Successful treatment with 308-nm monochromatic excimer light and subsequent tacrolimus 0.03% ointment in refractory plasma cell cheilitis. J Dermatol. 2013;40:471-474. doi:10.1111/1346-8138.12152

- Fujimura Y, Natsuga K, Abe R, et al. Plasma cell cheilitis extending beyond vermillion border. J Dermatol. 2015;42:935-936. doi:10.1111/1346-8138.12985

- White JW Jr, Olsen KD, Banks PM. Plasma cell orificial mucositis. report of a case and review of the literature. Arch Dermatol. 1986;122:1321-1324. doi:10.1001/archderm.122.11.1321

- Román CC, Yuste CM, Gonzalez MA, et al. Plasma cell gingivitis. Cutis. 2002;69:41-45.

- Choe HC, Park HJ, Oh ST, et al. Clinicopathologic study of 8 patients with plasma cell cheilitis. Korean J Dermatol. 2003;41:174-178.

- Senol M, Ozcan A, Aydin NE, et al. Intertriginous plasmacytosis with plasmoacanthoma: report of a typical case and review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:265-268. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4632.2008.03385.x

- Rocha N, Mota F, Horta M, et al. Plasma cell cheilitis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2004;18:96-98. doi:10.1111/j.1468-3083.2004.00791.x

- Farrier JN, Perkins CS. Plasma cell cheilitis. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2008;46:679-680. doi:10.1016/j.bjoms.2008.03.009

- Baughman RD, Berger P, Pringle WM. Plasma cell cheilitis. Arch Dermatol. 1974;110:725-726.

- Lee JY, Kim KH, Hahm JE, et al. Plasma cell cheilitis: a clinicopathological and immunohistochemical study of 13 cases. Ann Dermatol. 2017;29:536-542. doi:10.5021/ad.2017.29.5.536

- da Cunha Filho RR, Tochetto LB, Tochetto BB, et al. “Angular” plasma cell cheilitis. Dermatol Online J. 2014;20:doj_21759.

- Yang JH, Lee UH, Jang SJ, et al. Plasma cell cheilitis treated with intralesional injection of corticosteroids. J Dermatol. 2005;32:987-990. doi:10.1111/j.1346-8138.2005.tb00887.x

- Solomon LW, Wein RO, Rosenwald I, et al. Plasma cell mucositis of the oral cavity: report of a case and review of the literature. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2008;106:853-860. doi:10.1016/j.tripleo.2008.08.016

- Dos Santos HT, Cunha JLS, Santana LAM, et al. Plasma cell cheilitis: the diagnosis of a disorder mimicking lip cancer. Autops Case Rep. 2019;9:e2018075. doi:10.4322/acr.2018.075

- Fujimura T, Furudate S, Ishibashi M, et al. Successful treatment of plasmacytosis circumorificialis with topical tacrolimus: two case reports and an immunohistochemical study. Case Rep Dermatol. 2013;5:79-83. doi:10.1159/000350184

- Tamaki K, Osada A, Tsukamoto K, et al. Treatment of plasma cell cheilitis with griseofulvin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;30:789-790. doi:10.1016/s0190-9622(08)81515-0

- Choi JW, Choi M, Cho KH. Successful treatment of plasma cell cheilitis with topical calcineurin inhibitors. J Dermatol. 2009;36:669-671. doi:10.1111/j.1346-8138.2009.00733.x

- Hanami Y, Motoki Y, Yamamoto T. Successful treatment of plasma cell cheilitis with topical tacrolimus: report of two cases. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17:6.

- Jin SP, Cho KH, Huh CH. Plasma cell cheilitis, successfully treated with topical 0.03% tacrolimus ointment. J Dermatolog Treat. 2010;21:130-132. doi:10.1080/09546630903200620

- Tseng JT-P, Cheng C-J, Lee W-R, et al. Plasma-cell cheilitis: successful treatment with intralesional injections of corticosteroids. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:174-177. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2230.2008.02765.x

- Yoshimura K, Nakano S, Tsuruta D, et al. Successful treatment with 308-nm monochromatic excimer light and subsequent tacrolimus 0.03% ointment in refractory plasma cell cheilitis. J Dermatol. 2013;40:471-474. doi:10.1111/1346-8138.12152

- Fujimura Y, Natsuga K, Abe R, et al. Plasma cell cheilitis extending beyond vermillion border. J Dermatol. 2015;42:935-936. doi:10.1111/1346-8138.12985

- White JW Jr, Olsen KD, Banks PM. Plasma cell orificial mucositis. report of a case and review of the literature. Arch Dermatol. 1986;122:1321-1324. doi:10.1001/archderm.122.11.1321

- Román CC, Yuste CM, Gonzalez MA, et al. Plasma cell gingivitis. Cutis. 2002;69:41-45.

- Choe HC, Park HJ, Oh ST, et al. Clinicopathologic study of 8 patients with plasma cell cheilitis. Korean J Dermatol. 2003;41:174-178.

PRACTICE POINTS

- Plasma cell cheilitis (PCC) is a benign condition that affects the lower lip in older individuals, presenting as a nonspecific, red-brown patch or plaque that can progress slowly to erosions and edema.

- Our patient with PCC experienced full resolution of symptoms with application of a class I topical corticosteroid.

Verruca Vulgaris Arising Within the Red Portion of a Multicolored Tattoo

To the Editor:

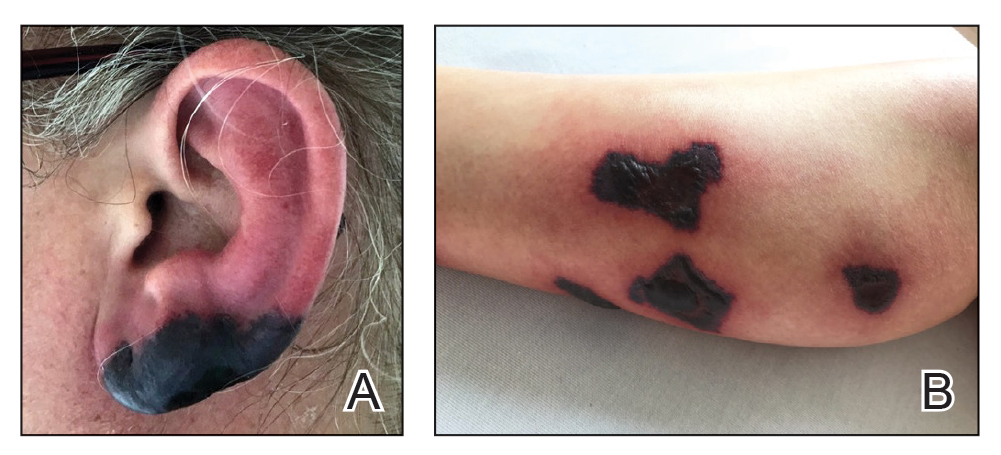

The art of tattooing continues to gain popularity in the 21st century, albeit with accompanying hazards.1 Reported adverse reactions to tattoos include infections, tumors, and hypersensitivity and granulomatous reactions.2 Various infectious agents may involve tattoos, including human papillomavirus (HPV), molluscum contagiosum, herpes simplex virus, hepatitis C virus, tuberculoid and nontuberculoid mycobacteria, and Staphylococcus aureus.2 Verruca vulgaris infrequently has been reported to develop in tattoos.3,4 Previously reported cases of verruca in tattoos suggest a predilection for blue or black pigment.1-5 We report a case of verruca vulgaris occurring within the red-inked areas of a tattoo that first appeared approximately 18 years after the initial tattoo placement.

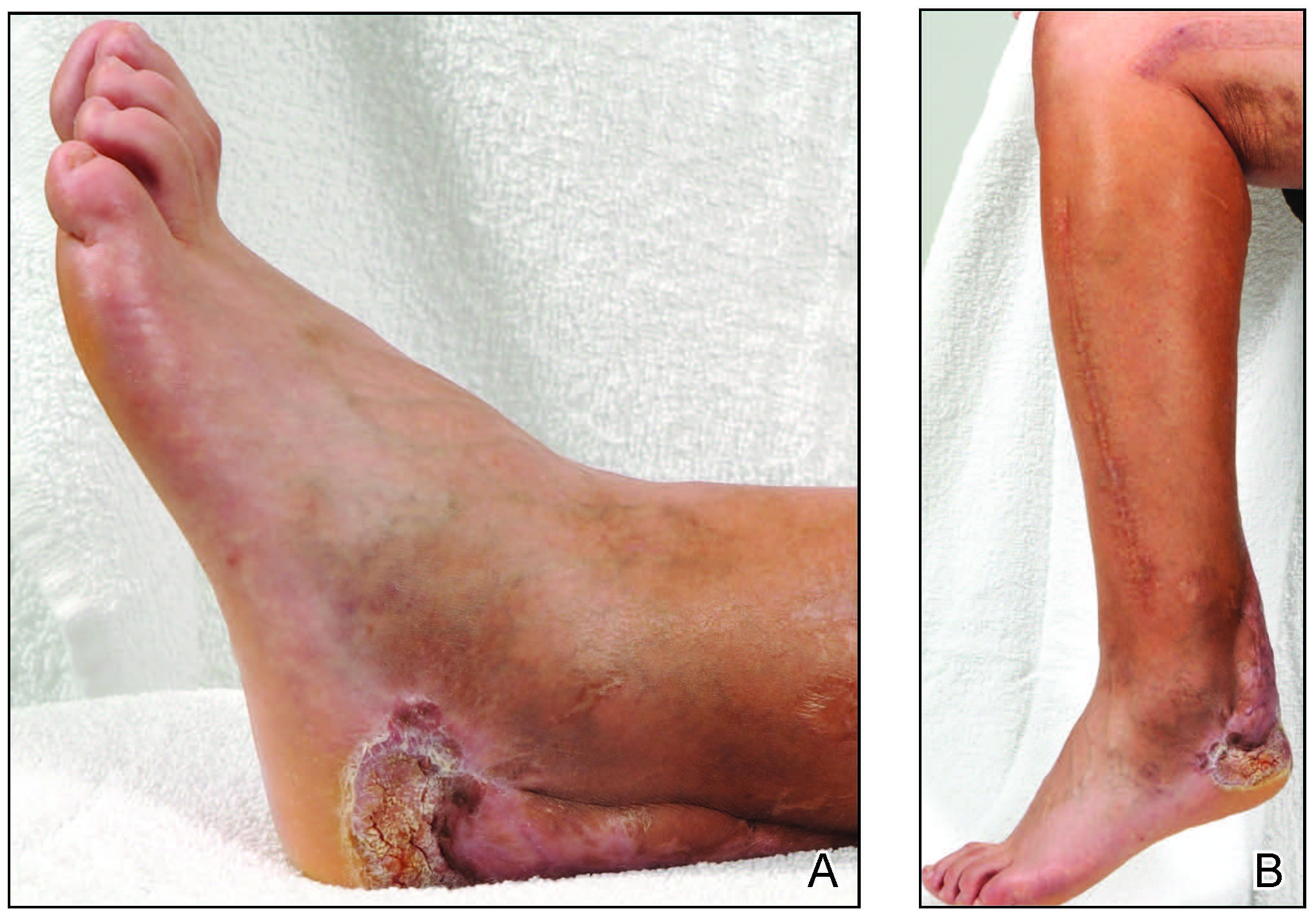

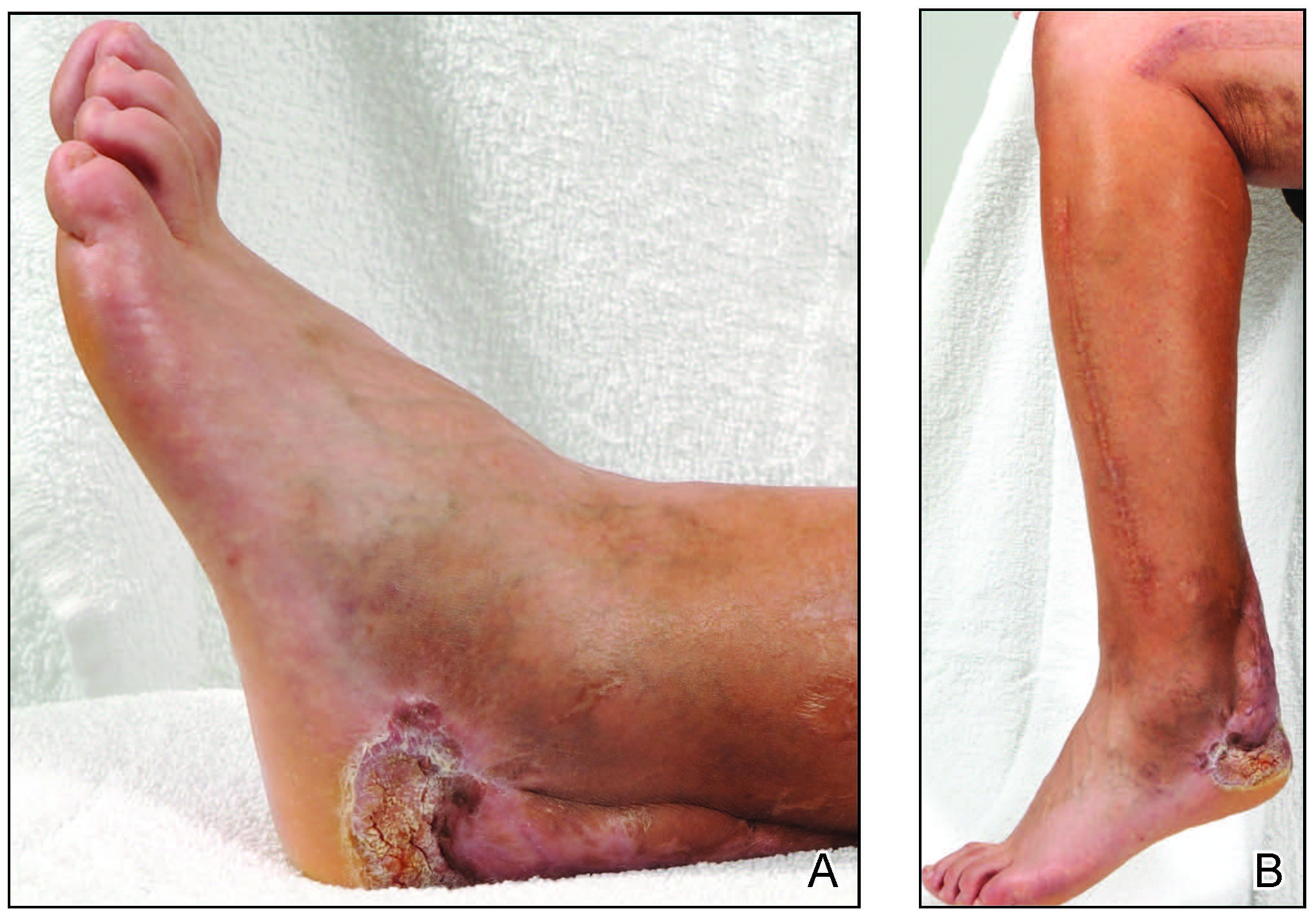

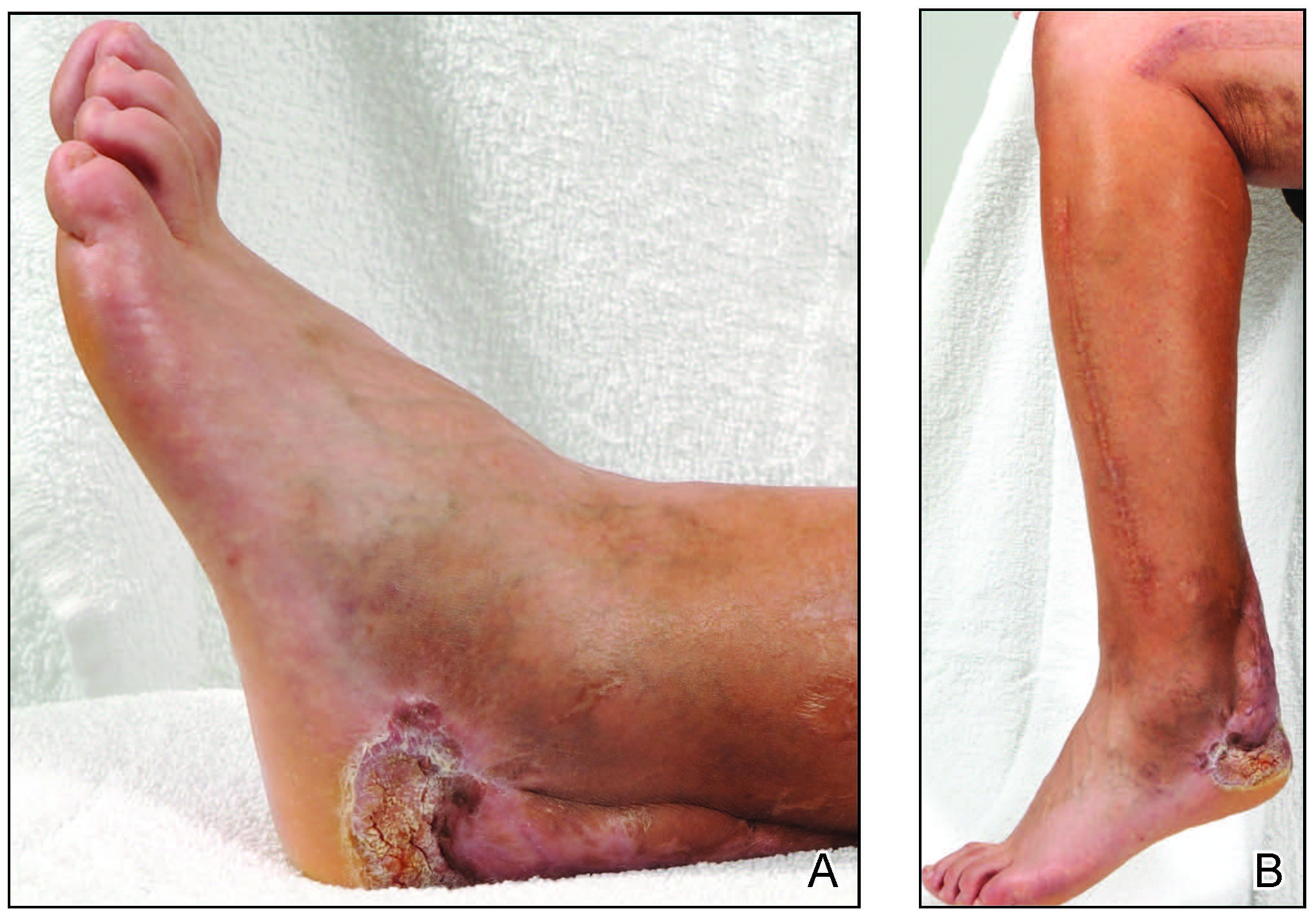

A 44-year-old woman presented with erythema, induration, and irritation of a tattoo on the left leg of 2 years’ duration. The tattoo initially was inscribed more than 20 years prior. The patient had a history of type 2 diabetes mellitus and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. She reported no prior trauma to the area, prior rash or irritation, or similar changes to her other tattoos, including those with red ink. The affected tattoo was inscribed at a separate time from the other tattoos. Physical examination of the irritated tattoo revealed hyperkeratotic papules with firm scaling in the zone of dermal red pigment (Figure 1). Notable nodularity or deep induration was not present. The clinical differential diagnosis included a hypersensitivity reaction to red tattoo ink, sarcoidosis, and an infectious process, such as an atypical mycobacterial infection. A punch biopsy demonstrated papillomatous epidermal hyperplasia with hyperkeratosis, focal parakeratosis, and frequent vacuolization of keratinocytes with enlarged keratohyalin granules, diagnostic of verruca vulgaris (Figure 2). Of note, the patient did not have clinically apparent viral warts elsewhere on physical examination. The patient was successfully managedwith a combination of 2 treatments of intralesional Candida antigen and 3 treatments of cryotherapy with resolution of most lesions over the course of 8 months. Over the following several months, the patient applied topical salicylic acid, which led to the resolution of the remaining lesions. The verrucae had not recurred 19 months after the initial presentation.

The development of verruca vulgaris within a tattoo may occur secondary to various mechanisms of HPV inoculation, including introduction of the virus through contaminated ink, the tattoo artist’s saliva, autoinoculation, or koebnerization of a pre-existing verruca vulgaris.4 Local immune system dysregulation secondary to tattoo ink also has been proposed as a mechanism for HPV infection in this setting.1,5 The contents of darker tattoo pigments may promote formation of reactive oxygen species inducing local immunocompromise.5

The pathogenic mechanism was elusive in our patient. Although the localization of verruca vulgaris to the zones of red pigment may be merely coincidental, this phenomenon raised suspicion for direct inoculation via contaminated red ink. The patient’s other red ink–containing tattoos that were inscribed separately were spared, compatible with contamination of the red ink used for the affected tattoo. However, the delayed onset of nearly 2 decades was exceptional, given the shorter previously reported latencies ranging from months to 10 years.4 Autoinoculation or koebnerization is plausible, though greater involvement of nonred pigments would be expected as well as a briefer latency. Finally, the possibility of local immune dysregulation seemed feasible, given the slow evolution of the lesions largely restricted to one pigment type.

We report a case of verruca vulgaris within the red area of a multicolored tattoo that occurred approximately 18 years after tattoo placement. This case highlights a rare presentation of an infectious agent that may complicate tattoos. Both predilection for red pigment rather than black or blue pigment and the long latency period raised interesting questions regarding pathogenesis. Confirmatory biopsy enables effective management of this tattoo complication.

- Huynh TN, Jackson JD, Brodell RT. Tattoo and vaccination sites: possible nest for opportunistic infections, tumors, and dysimmune reactions. Clin Dermatol. 2014;32:678-684.

- Wenzel SM, Rittmann I, Landthaler M, et al. Adverse reactions after tattooing: review of the literature and comparison to results of a survey. Dermatology. 2013;226:138-147.

- Trefzer U, Schmollack K, Stockfleth E, et al. Verrucae in a multicolored decorative tattoo. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:478-479.

- Wanat KA, Tyring S, Rady P, et al. Human papillomavirus type 27 associated with multiple verruca within a tattoo: report of a case and review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:882-884.

- Ramey K, Ibrahim J, Brodell RT. Verruca localization predominately in black tattoo ink: a retrospective case series. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30:E34-E36.

To the Editor:

The art of tattooing continues to gain popularity in the 21st century, albeit with accompanying hazards.1 Reported adverse reactions to tattoos include infections, tumors, and hypersensitivity and granulomatous reactions.2 Various infectious agents may involve tattoos, including human papillomavirus (HPV), molluscum contagiosum, herpes simplex virus, hepatitis C virus, tuberculoid and nontuberculoid mycobacteria, and Staphylococcus aureus.2 Verruca vulgaris infrequently has been reported to develop in tattoos.3,4 Previously reported cases of verruca in tattoos suggest a predilection for blue or black pigment.1-5 We report a case of verruca vulgaris occurring within the red-inked areas of a tattoo that first appeared approximately 18 years after the initial tattoo placement.

A 44-year-old woman presented with erythema, induration, and irritation of a tattoo on the left leg of 2 years’ duration. The tattoo initially was inscribed more than 20 years prior. The patient had a history of type 2 diabetes mellitus and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. She reported no prior trauma to the area, prior rash or irritation, or similar changes to her other tattoos, including those with red ink. The affected tattoo was inscribed at a separate time from the other tattoos. Physical examination of the irritated tattoo revealed hyperkeratotic papules with firm scaling in the zone of dermal red pigment (Figure 1). Notable nodularity or deep induration was not present. The clinical differential diagnosis included a hypersensitivity reaction to red tattoo ink, sarcoidosis, and an infectious process, such as an atypical mycobacterial infection. A punch biopsy demonstrated papillomatous epidermal hyperplasia with hyperkeratosis, focal parakeratosis, and frequent vacuolization of keratinocytes with enlarged keratohyalin granules, diagnostic of verruca vulgaris (Figure 2). Of note, the patient did not have clinically apparent viral warts elsewhere on physical examination. The patient was successfully managedwith a combination of 2 treatments of intralesional Candida antigen and 3 treatments of cryotherapy with resolution of most lesions over the course of 8 months. Over the following several months, the patient applied topical salicylic acid, which led to the resolution of the remaining lesions. The verrucae had not recurred 19 months after the initial presentation.

The development of verruca vulgaris within a tattoo may occur secondary to various mechanisms of HPV inoculation, including introduction of the virus through contaminated ink, the tattoo artist’s saliva, autoinoculation, or koebnerization of a pre-existing verruca vulgaris.4 Local immune system dysregulation secondary to tattoo ink also has been proposed as a mechanism for HPV infection in this setting.1,5 The contents of darker tattoo pigments may promote formation of reactive oxygen species inducing local immunocompromise.5

The pathogenic mechanism was elusive in our patient. Although the localization of verruca vulgaris to the zones of red pigment may be merely coincidental, this phenomenon raised suspicion for direct inoculation via contaminated red ink. The patient’s other red ink–containing tattoos that were inscribed separately were spared, compatible with contamination of the red ink used for the affected tattoo. However, the delayed onset of nearly 2 decades was exceptional, given the shorter previously reported latencies ranging from months to 10 years.4 Autoinoculation or koebnerization is plausible, though greater involvement of nonred pigments would be expected as well as a briefer latency. Finally, the possibility of local immune dysregulation seemed feasible, given the slow evolution of the lesions largely restricted to one pigment type.

We report a case of verruca vulgaris within the red area of a multicolored tattoo that occurred approximately 18 years after tattoo placement. This case highlights a rare presentation of an infectious agent that may complicate tattoos. Both predilection for red pigment rather than black or blue pigment and the long latency period raised interesting questions regarding pathogenesis. Confirmatory biopsy enables effective management of this tattoo complication.

To the Editor:

The art of tattooing continues to gain popularity in the 21st century, albeit with accompanying hazards.1 Reported adverse reactions to tattoos include infections, tumors, and hypersensitivity and granulomatous reactions.2 Various infectious agents may involve tattoos, including human papillomavirus (HPV), molluscum contagiosum, herpes simplex virus, hepatitis C virus, tuberculoid and nontuberculoid mycobacteria, and Staphylococcus aureus.2 Verruca vulgaris infrequently has been reported to develop in tattoos.3,4 Previously reported cases of verruca in tattoos suggest a predilection for blue or black pigment.1-5 We report a case of verruca vulgaris occurring within the red-inked areas of a tattoo that first appeared approximately 18 years after the initial tattoo placement.

A 44-year-old woman presented with erythema, induration, and irritation of a tattoo on the left leg of 2 years’ duration. The tattoo initially was inscribed more than 20 years prior. The patient had a history of type 2 diabetes mellitus and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. She reported no prior trauma to the area, prior rash or irritation, or similar changes to her other tattoos, including those with red ink. The affected tattoo was inscribed at a separate time from the other tattoos. Physical examination of the irritated tattoo revealed hyperkeratotic papules with firm scaling in the zone of dermal red pigment (Figure 1). Notable nodularity or deep induration was not present. The clinical differential diagnosis included a hypersensitivity reaction to red tattoo ink, sarcoidosis, and an infectious process, such as an atypical mycobacterial infection. A punch biopsy demonstrated papillomatous epidermal hyperplasia with hyperkeratosis, focal parakeratosis, and frequent vacuolization of keratinocytes with enlarged keratohyalin granules, diagnostic of verruca vulgaris (Figure 2). Of note, the patient did not have clinically apparent viral warts elsewhere on physical examination. The patient was successfully managedwith a combination of 2 treatments of intralesional Candida antigen and 3 treatments of cryotherapy with resolution of most lesions over the course of 8 months. Over the following several months, the patient applied topical salicylic acid, which led to the resolution of the remaining lesions. The verrucae had not recurred 19 months after the initial presentation.

The development of verruca vulgaris within a tattoo may occur secondary to various mechanisms of HPV inoculation, including introduction of the virus through contaminated ink, the tattoo artist’s saliva, autoinoculation, or koebnerization of a pre-existing verruca vulgaris.4 Local immune system dysregulation secondary to tattoo ink also has been proposed as a mechanism for HPV infection in this setting.1,5 The contents of darker tattoo pigments may promote formation of reactive oxygen species inducing local immunocompromise.5

The pathogenic mechanism was elusive in our patient. Although the localization of verruca vulgaris to the zones of red pigment may be merely coincidental, this phenomenon raised suspicion for direct inoculation via contaminated red ink. The patient’s other red ink–containing tattoos that were inscribed separately were spared, compatible with contamination of the red ink used for the affected tattoo. However, the delayed onset of nearly 2 decades was exceptional, given the shorter previously reported latencies ranging from months to 10 years.4 Autoinoculation or koebnerization is plausible, though greater involvement of nonred pigments would be expected as well as a briefer latency. Finally, the possibility of local immune dysregulation seemed feasible, given the slow evolution of the lesions largely restricted to one pigment type.

We report a case of verruca vulgaris within the red area of a multicolored tattoo that occurred approximately 18 years after tattoo placement. This case highlights a rare presentation of an infectious agent that may complicate tattoos. Both predilection for red pigment rather than black or blue pigment and the long latency period raised interesting questions regarding pathogenesis. Confirmatory biopsy enables effective management of this tattoo complication.

- Huynh TN, Jackson JD, Brodell RT. Tattoo and vaccination sites: possible nest for opportunistic infections, tumors, and dysimmune reactions. Clin Dermatol. 2014;32:678-684.

- Wenzel SM, Rittmann I, Landthaler M, et al. Adverse reactions after tattooing: review of the literature and comparison to results of a survey. Dermatology. 2013;226:138-147.

- Trefzer U, Schmollack K, Stockfleth E, et al. Verrucae in a multicolored decorative tattoo. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:478-479.

- Wanat KA, Tyring S, Rady P, et al. Human papillomavirus type 27 associated with multiple verruca within a tattoo: report of a case and review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:882-884.

- Ramey K, Ibrahim J, Brodell RT. Verruca localization predominately in black tattoo ink: a retrospective case series. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30:E34-E36.

- Huynh TN, Jackson JD, Brodell RT. Tattoo and vaccination sites: possible nest for opportunistic infections, tumors, and dysimmune reactions. Clin Dermatol. 2014;32:678-684.

- Wenzel SM, Rittmann I, Landthaler M, et al. Adverse reactions after tattooing: review of the literature and comparison to results of a survey. Dermatology. 2013;226:138-147.

- Trefzer U, Schmollack K, Stockfleth E, et al. Verrucae in a multicolored decorative tattoo. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:478-479.

- Wanat KA, Tyring S, Rady P, et al. Human papillomavirus type 27 associated with multiple verruca within a tattoo: report of a case and review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:882-884.

- Ramey K, Ibrahim J, Brodell RT. Verruca localization predominately in black tattoo ink: a retrospective case series. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30:E34-E36.

Practice Points

- Various adverse reactions and infectious agents may involve tattoos.

- Verruca vulgaris may affect tattoos in a color-restricted manner and demonstrate latency of many years after tattoo placement.

- Timely diagnosis of the tattoo-involving process, confirmed by biopsy, allows for appropriate management.

Verrucous Scalp Plaque and Widespread Eruption

The Diagnosis: Pemphigus Foliaceous

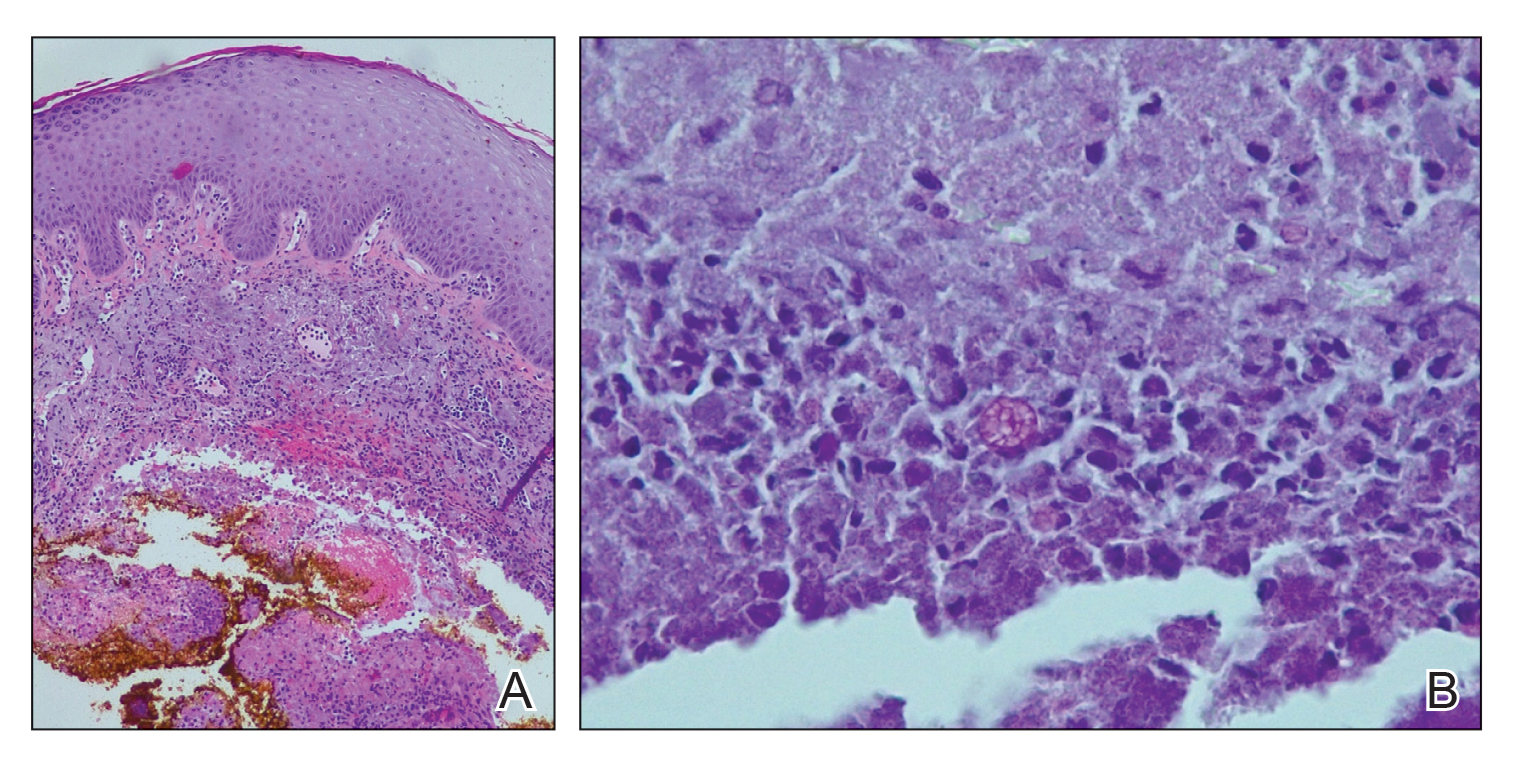

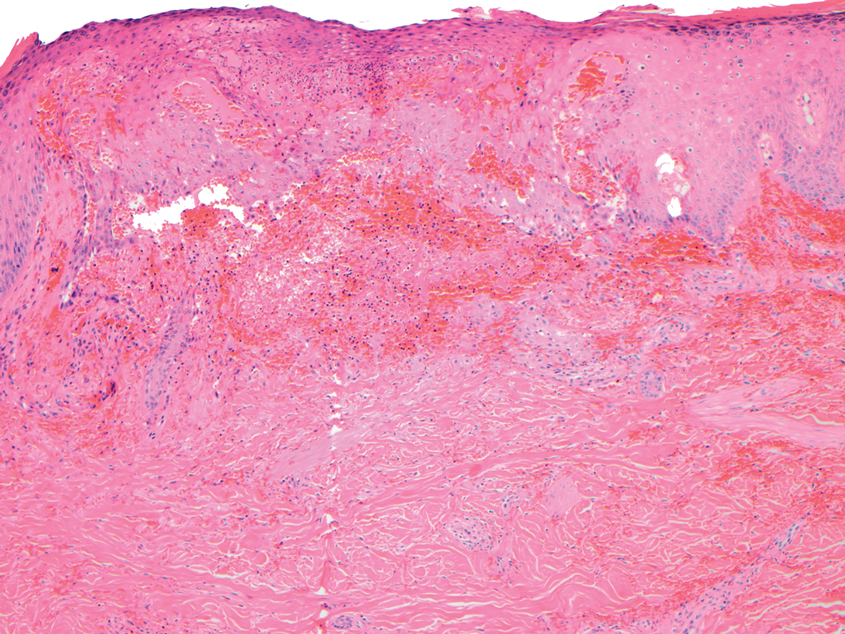

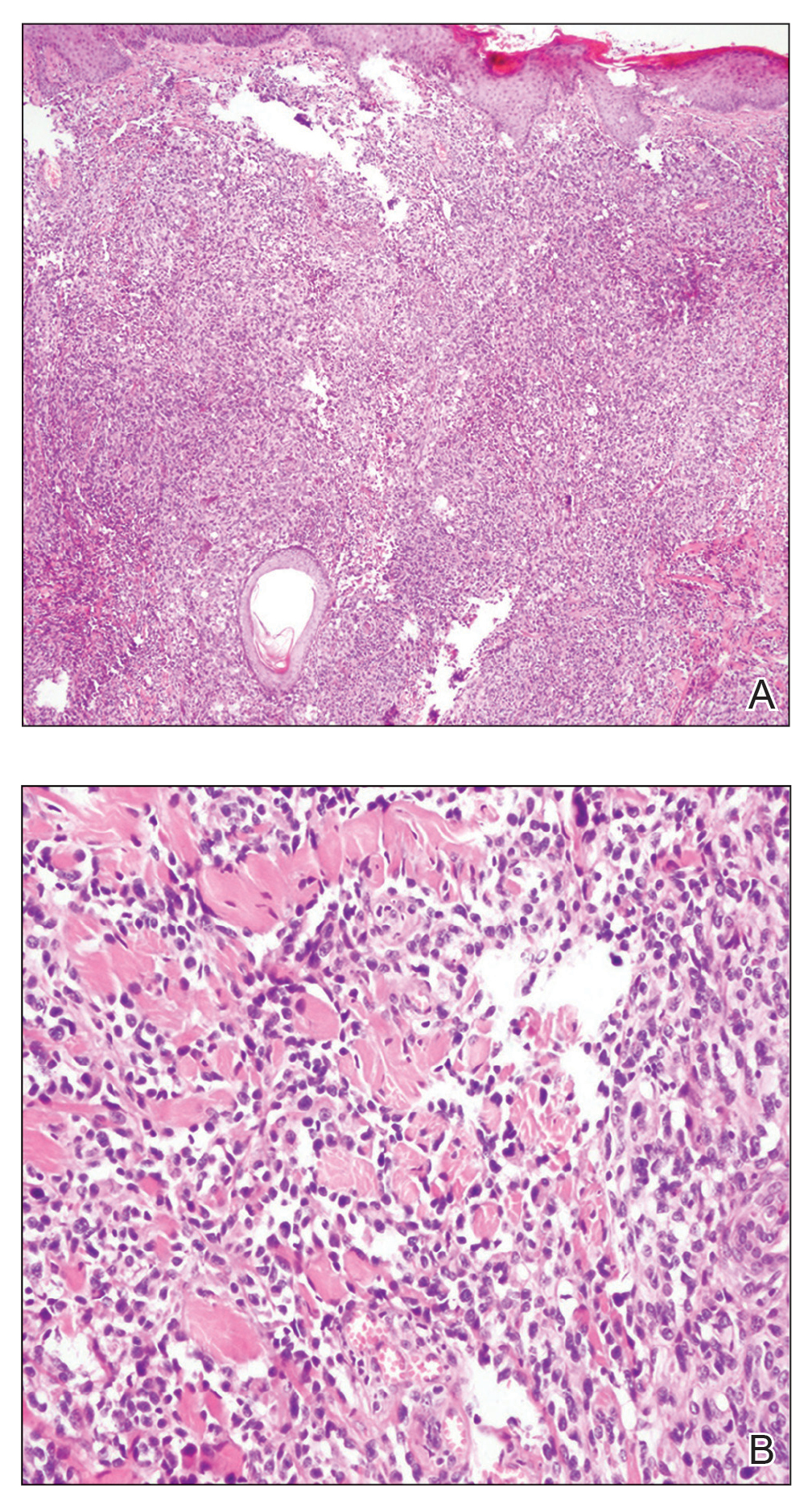

Laboratory workup including a complete blood cell count with differential, comprehensive metabolic panel, antinuclear antibodies, Sjögren syndrome A and B antibodies, hepatitis profile, rapid plasma reagin, HIV screen, aldolase, anti–Jo-1, T-Spot TB test (Quest Diagnostics), and tissue cultures was unremarkable. Two 4-mm punch biopsies were obtained from the left cheek and upper back, both of which demonstrated intragranular acantholysis suggestive of pemphigus foliaceous (Figure 1A). A subsequent punch biopsy from the right lower abdomen sent for direct immunofluorescence demonstrated netlike positivity of IgG and C3 in the upper epidermis (Figure 1B), and serum sent for indirect immunofluorescence demonstrated intercellular IgG antibodies to desmoglein (Dsg) 1 on monkey esophagus and positive Dsg-1 antibodies on enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, confirming the diagnosis.

The patient was started on a 60-mg prednisone taper as well as dapsone 50 mg daily; the dapsone was titrated up to 100 mg daily. After tapering down to 10 mg daily of prednisone over 2 months and continuing dapsone with minimal improvement, he was given 2 infusions of rituximab 1000 mg 2 weeks apart. The scalp plaque was dramatically improved at 3-month follow-up (Figure 2), with partial improvement of the cheek plaques (Figure 3). Dapsone was increased to 150 mg daily, and he was encouraged to use triamcinolone acetonide ointment 0.1% twice daily, which led to further improvement.

Pemphigus foliaceus is an autoimmune blistering disease that most commonly occurs in middle-aged adults. It generally is less common than pemphigus vulgaris, except in Finland, Tunisia, and Brazil, where there is an endemic condition with an identical clinical and histological presentation known as fogo selvagem.1

The pathogenesis of pemphigus foliaceous is characterized by IgG autoantibodies against Dsg-1, a transmembrane glycoprotein involved in the cellular adhesion of keratinocytes, which is preferentially expressed in the superficial epidermis.2-7 Dysfunction of Dsg-1 results in the separation of superficial epidermal cells, resulting in intraepidermal blisters.2,7 In contrast to pemphigus vulgaris, there typically is a lack of oral mucosal involvement due to compensation by Dsg-3 in the mucosa.4 Potential triggers for pemphigus foliaceous include exposure to UV radiation; radiotherapy; pregnancy; physiologic stress; and drugs, most commonly captopril, penicillamine, and thiols.8

Pemphigus foliaceous lesions clinically appear as eroded and crusted lesions on an erythematous base, commonly in a seborrheic distribution on the face, scalp, and trunk with sparing of the oral mucosa,2,6 but lesions can progress to a widespread and more severe exfoliative dermatitis.7 Lesions also can appear as psoriasiform plaques and often are initially misdiagnosed as psoriasis, particularly in patients with skin of color.9,10

Diagnosis of pemphigus foliaceous typically is made using a combination of histology as well as both direct and indirect immunofluorescence. Histologically, pemphigus foliaceus presents with subcorneal acantholysis, which is most prominent in the granular layer and occasionally the presence of neutrophils and eosinophils in the blister cavity.7 Direct immunofluorescence demonstrates netlike intercellular IgG and C3 in the upper portion of the epidermis.11 Indirect immunofluorescence can help detect circulating IgG antibodies to Dsg-1, with guinea pig esophagus being the ideal substrate.11,12

First-line treatment of pemphigus foliaceus consists of systemic glucocorticoid therapy, often administered with azathioprine, methotrexate, or mycophenolate mofetil.2,6,13 Although first-line treatment is effective in 60% to 80% of patients,2 relapsing cases can be treated with cyclophosphamide, intravenous immunoglobulin, immunoadsorption, plasmapheresis, or rituximab.2

Rituximab is a chimeric monoclonal antibody targeting CD20+ B cells, leading to decreased antibody production, which has been shown to be effective in treating severe and refractory cases of pemphigus foliaceus.6,13Rituximab with short-course prednisone has been found to be more effective in achieving complete remission at 24 months than prednisone alone.14 In patients with contraindications to systemic glucocorticoid therapy, rituximab has been shown as an effective first-line therapy.15 One-quarter of patients treated with rituximab relapsed within 2 years of treatment6 (average time to relapse, 6–26 months).16 High-dose rituximab regimens, along with a higher number of rituximab treatment cycles, have been shown to prolong time to relapse.6 Further, higher baseline levels of Dsg-1 antibody have been correlated to earlier relapse and can be used following rituximab therapy to monitor disease progression.6,16

The differential diagnosis for pemphigus foliaceous includes disseminated blastomycosis, hypertrophic lupus erythematosus, sebopsoriasis, and secondary syphilis. Disseminated blastomycosis presents with cutaneous manifestations such as nodules, papules, or pustules evolving over weeks to months into ulcers with subsequent scarring.17 Hypertrophic lupus erythematosus presents with papules and nodules with associated keratotic scaling on the face, palms, and extensor surfaces of the limbs.18 Sebopsoriasis is characterized by well-defined lesions with an overlying scale distributed on the scalp, face, and chest.19 Secondary syphilis presents as early hyperpigmented macules transitioning to acral papulosquamous lesions involving the palms and soles.20

- Hans-Filho G, Aoki V, Hans Bittner NR, et al. Fogo selvagem: endemic pemphigus foliaceus. An Bras Dermatol. 2018;93:638-650.

- Jenson KK, Burr DM, Edwards BC. Case report: reatment of refractory pemphigus foliaceus with rituximab. Practical Dermatology. February 2016:33-36. Accessed August 27, 2021. https://practicaldermatology.com/articles/2016-feb/case-report -treatment-of-refractory-pemphigus-foliaceus-with-rituximab -financial-matters-aad-asds-resources

- Amagai M, Hashimoto T, Green KJ, et al. Antigen-specific immunoadsorption of pathogenic autoantibodies in pemphigus foliaceus. J Invest Dermatol. 1995;104:895-901.

- Mahoney MG, Wang Z, Rothenberger K, et al. Explanations for the clinical and microscopic localization of lesions in pemphigus foliaceus and vulgaris. J Clin Invest. 1999;103:461-468.

- Oktarina DAM, Sokol E, Kramer D, et al. Endocytosis of IgG, desmoglein 1, and plakoglobin in pemphigus foliaceus patient skin. Front Immunol. 2019;10:1-12.

- Kraft M, Worm M. Pemphigus foliaceus-repeated treatment with rituximab 7 years after initial response: a case report. Front Med. 2018;5:315.

- Hale EK. Pemphigus foliaceous. Dermatol Online J. 2002;8:9.

- Tavakolpour S. Pemphigus trigger factors: special focus on pemphigus vulgaris and pemphigus foliaceus. Arch Dermatol Res. 2018;310:95-106.

- A boobaker J, Morar N, Ramdial PK, et al. Pemphigus in South Africa. Int J Dermatol. 2001;40:115-119.

- Austin E, Millsop JW, Ely H, et al. Psoriasiform pemphigus foliaceus in an African American female: an important clinical manifestation. J Drugs Dermatol. 2018;17:471.

- Arbache ST, Nogueira TG, Delgado L, et al. Immunofluorescence testing in the diagnosis of autoimmune blistering diseases: overview of 10-year experience. An Bras Dermatol. 2014;89:885-889.

- Sabolinski ML, Beutner EH, Krasny S, et al. Substrate specificity of antiepithelial antibodies of pemphigus vulgaris and pemphigus foliaceus sera in immunofluorescence tests on monkey and guinea pig esophagus sections. J Invest Dermatol. 1987;88:545-549.

- Palacios-Álvarez I, Riquelme-McLoughlin C, Curto-Barredo L, et al. Rituximab treatment of pemphigus foliaceus: a retrospective study of 12 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:484-486.

- Murrell DF, Sprecher E. Rituximab and short-course prednisone as the new gold standard for new-onset pemphigus vulgaris and pemphigus foliaceus. Br J Dermatol. 2017;177:1143-1144.

- Gregoriou S, Efthymiou O, Stefanaki C, et al. Management of pemphigus vulgaris: challenges and solutions. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2015;8:521-527.

- Saleh MA. A prospective study comparing patients with early and late relapsing pemphigus treated with rituximab. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:97-103.

- Castillo CG, Kauffman CA, Miceli MH. Blastomycosis. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2016;30:247-264.

- Herzum A, Gasparini G, Emanuele C, et al. Atypical and rare forms of cutaneous lupus erythematosus: the importance of the diagnosis for the best management of patients. Dermatology. 2013;1-10.

- Tull TJ, Noy M, Bunker CB, et al. Sebopsoriasis in patients with HIV: a case series of 20 patients. Br J Dermatol. 2016; 173:813-815.

- Balagula Y, Mattei P, Wisco OJ, et al. The great imitator revised: the spectrum of atypical cutaneous manifestations of secondary syphilis. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:1434-1441.

The Diagnosis: Pemphigus Foliaceous

Laboratory workup including a complete blood cell count with differential, comprehensive metabolic panel, antinuclear antibodies, Sjögren syndrome A and B antibodies, hepatitis profile, rapid plasma reagin, HIV screen, aldolase, anti–Jo-1, T-Spot TB test (Quest Diagnostics), and tissue cultures was unremarkable. Two 4-mm punch biopsies were obtained from the left cheek and upper back, both of which demonstrated intragranular acantholysis suggestive of pemphigus foliaceous (Figure 1A). A subsequent punch biopsy from the right lower abdomen sent for direct immunofluorescence demonstrated netlike positivity of IgG and C3 in the upper epidermis (Figure 1B), and serum sent for indirect immunofluorescence demonstrated intercellular IgG antibodies to desmoglein (Dsg) 1 on monkey esophagus and positive Dsg-1 antibodies on enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, confirming the diagnosis.

The patient was started on a 60-mg prednisone taper as well as dapsone 50 mg daily; the dapsone was titrated up to 100 mg daily. After tapering down to 10 mg daily of prednisone over 2 months and continuing dapsone with minimal improvement, he was given 2 infusions of rituximab 1000 mg 2 weeks apart. The scalp plaque was dramatically improved at 3-month follow-up (Figure 2), with partial improvement of the cheek plaques (Figure 3). Dapsone was increased to 150 mg daily, and he was encouraged to use triamcinolone acetonide ointment 0.1% twice daily, which led to further improvement.

Pemphigus foliaceus is an autoimmune blistering disease that most commonly occurs in middle-aged adults. It generally is less common than pemphigus vulgaris, except in Finland, Tunisia, and Brazil, where there is an endemic condition with an identical clinical and histological presentation known as fogo selvagem.1

The pathogenesis of pemphigus foliaceous is characterized by IgG autoantibodies against Dsg-1, a transmembrane glycoprotein involved in the cellular adhesion of keratinocytes, which is preferentially expressed in the superficial epidermis.2-7 Dysfunction of Dsg-1 results in the separation of superficial epidermal cells, resulting in intraepidermal blisters.2,7 In contrast to pemphigus vulgaris, there typically is a lack of oral mucosal involvement due to compensation by Dsg-3 in the mucosa.4 Potential triggers for pemphigus foliaceous include exposure to UV radiation; radiotherapy; pregnancy; physiologic stress; and drugs, most commonly captopril, penicillamine, and thiols.8

Pemphigus foliaceous lesions clinically appear as eroded and crusted lesions on an erythematous base, commonly in a seborrheic distribution on the face, scalp, and trunk with sparing of the oral mucosa,2,6 but lesions can progress to a widespread and more severe exfoliative dermatitis.7 Lesions also can appear as psoriasiform plaques and often are initially misdiagnosed as psoriasis, particularly in patients with skin of color.9,10

Diagnosis of pemphigus foliaceous typically is made using a combination of histology as well as both direct and indirect immunofluorescence. Histologically, pemphigus foliaceus presents with subcorneal acantholysis, which is most prominent in the granular layer and occasionally the presence of neutrophils and eosinophils in the blister cavity.7 Direct immunofluorescence demonstrates netlike intercellular IgG and C3 in the upper portion of the epidermis.11 Indirect immunofluorescence can help detect circulating IgG antibodies to Dsg-1, with guinea pig esophagus being the ideal substrate.11,12

First-line treatment of pemphigus foliaceus consists of systemic glucocorticoid therapy, often administered with azathioprine, methotrexate, or mycophenolate mofetil.2,6,13 Although first-line treatment is effective in 60% to 80% of patients,2 relapsing cases can be treated with cyclophosphamide, intravenous immunoglobulin, immunoadsorption, plasmapheresis, or rituximab.2

Rituximab is a chimeric monoclonal antibody targeting CD20+ B cells, leading to decreased antibody production, which has been shown to be effective in treating severe and refractory cases of pemphigus foliaceus.6,13Rituximab with short-course prednisone has been found to be more effective in achieving complete remission at 24 months than prednisone alone.14 In patients with contraindications to systemic glucocorticoid therapy, rituximab has been shown as an effective first-line therapy.15 One-quarter of patients treated with rituximab relapsed within 2 years of treatment6 (average time to relapse, 6–26 months).16 High-dose rituximab regimens, along with a higher number of rituximab treatment cycles, have been shown to prolong time to relapse.6 Further, higher baseline levels of Dsg-1 antibody have been correlated to earlier relapse and can be used following rituximab therapy to monitor disease progression.6,16

The differential diagnosis for pemphigus foliaceous includes disseminated blastomycosis, hypertrophic lupus erythematosus, sebopsoriasis, and secondary syphilis. Disseminated blastomycosis presents with cutaneous manifestations such as nodules, papules, or pustules evolving over weeks to months into ulcers with subsequent scarring.17 Hypertrophic lupus erythematosus presents with papules and nodules with associated keratotic scaling on the face, palms, and extensor surfaces of the limbs.18 Sebopsoriasis is characterized by well-defined lesions with an overlying scale distributed on the scalp, face, and chest.19 Secondary syphilis presents as early hyperpigmented macules transitioning to acral papulosquamous lesions involving the palms and soles.20

The Diagnosis: Pemphigus Foliaceous

Laboratory workup including a complete blood cell count with differential, comprehensive metabolic panel, antinuclear antibodies, Sjögren syndrome A and B antibodies, hepatitis profile, rapid plasma reagin, HIV screen, aldolase, anti–Jo-1, T-Spot TB test (Quest Diagnostics), and tissue cultures was unremarkable. Two 4-mm punch biopsies were obtained from the left cheek and upper back, both of which demonstrated intragranular acantholysis suggestive of pemphigus foliaceous (Figure 1A). A subsequent punch biopsy from the right lower abdomen sent for direct immunofluorescence demonstrated netlike positivity of IgG and C3 in the upper epidermis (Figure 1B), and serum sent for indirect immunofluorescence demonstrated intercellular IgG antibodies to desmoglein (Dsg) 1 on monkey esophagus and positive Dsg-1 antibodies on enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, confirming the diagnosis.

The patient was started on a 60-mg prednisone taper as well as dapsone 50 mg daily; the dapsone was titrated up to 100 mg daily. After tapering down to 10 mg daily of prednisone over 2 months and continuing dapsone with minimal improvement, he was given 2 infusions of rituximab 1000 mg 2 weeks apart. The scalp plaque was dramatically improved at 3-month follow-up (Figure 2), with partial improvement of the cheek plaques (Figure 3). Dapsone was increased to 150 mg daily, and he was encouraged to use triamcinolone acetonide ointment 0.1% twice daily, which led to further improvement.

Pemphigus foliaceus is an autoimmune blistering disease that most commonly occurs in middle-aged adults. It generally is less common than pemphigus vulgaris, except in Finland, Tunisia, and Brazil, where there is an endemic condition with an identical clinical and histological presentation known as fogo selvagem.1

The pathogenesis of pemphigus foliaceous is characterized by IgG autoantibodies against Dsg-1, a transmembrane glycoprotein involved in the cellular adhesion of keratinocytes, which is preferentially expressed in the superficial epidermis.2-7 Dysfunction of Dsg-1 results in the separation of superficial epidermal cells, resulting in intraepidermal blisters.2,7 In contrast to pemphigus vulgaris, there typically is a lack of oral mucosal involvement due to compensation by Dsg-3 in the mucosa.4 Potential triggers for pemphigus foliaceous include exposure to UV radiation; radiotherapy; pregnancy; physiologic stress; and drugs, most commonly captopril, penicillamine, and thiols.8

Pemphigus foliaceous lesions clinically appear as eroded and crusted lesions on an erythematous base, commonly in a seborrheic distribution on the face, scalp, and trunk with sparing of the oral mucosa,2,6 but lesions can progress to a widespread and more severe exfoliative dermatitis.7 Lesions also can appear as psoriasiform plaques and often are initially misdiagnosed as psoriasis, particularly in patients with skin of color.9,10

Diagnosis of pemphigus foliaceous typically is made using a combination of histology as well as both direct and indirect immunofluorescence. Histologically, pemphigus foliaceus presents with subcorneal acantholysis, which is most prominent in the granular layer and occasionally the presence of neutrophils and eosinophils in the blister cavity.7 Direct immunofluorescence demonstrates netlike intercellular IgG and C3 in the upper portion of the epidermis.11 Indirect immunofluorescence can help detect circulating IgG antibodies to Dsg-1, with guinea pig esophagus being the ideal substrate.11,12

First-line treatment of pemphigus foliaceus consists of systemic glucocorticoid therapy, often administered with azathioprine, methotrexate, or mycophenolate mofetil.2,6,13 Although first-line treatment is effective in 60% to 80% of patients,2 relapsing cases can be treated with cyclophosphamide, intravenous immunoglobulin, immunoadsorption, plasmapheresis, or rituximab.2

Rituximab is a chimeric monoclonal antibody targeting CD20+ B cells, leading to decreased antibody production, which has been shown to be effective in treating severe and refractory cases of pemphigus foliaceus.6,13Rituximab with short-course prednisone has been found to be more effective in achieving complete remission at 24 months than prednisone alone.14 In patients with contraindications to systemic glucocorticoid therapy, rituximab has been shown as an effective first-line therapy.15 One-quarter of patients treated with rituximab relapsed within 2 years of treatment6 (average time to relapse, 6–26 months).16 High-dose rituximab regimens, along with a higher number of rituximab treatment cycles, have been shown to prolong time to relapse.6 Further, higher baseline levels of Dsg-1 antibody have been correlated to earlier relapse and can be used following rituximab therapy to monitor disease progression.6,16

The differential diagnosis for pemphigus foliaceous includes disseminated blastomycosis, hypertrophic lupus erythematosus, sebopsoriasis, and secondary syphilis. Disseminated blastomycosis presents with cutaneous manifestations such as nodules, papules, or pustules evolving over weeks to months into ulcers with subsequent scarring.17 Hypertrophic lupus erythematosus presents with papules and nodules with associated keratotic scaling on the face, palms, and extensor surfaces of the limbs.18 Sebopsoriasis is characterized by well-defined lesions with an overlying scale distributed on the scalp, face, and chest.19 Secondary syphilis presents as early hyperpigmented macules transitioning to acral papulosquamous lesions involving the palms and soles.20

- Hans-Filho G, Aoki V, Hans Bittner NR, et al. Fogo selvagem: endemic pemphigus foliaceus. An Bras Dermatol. 2018;93:638-650.

- Jenson KK, Burr DM, Edwards BC. Case report: reatment of refractory pemphigus foliaceus with rituximab. Practical Dermatology. February 2016:33-36. Accessed August 27, 2021. https://practicaldermatology.com/articles/2016-feb/case-report -treatment-of-refractory-pemphigus-foliaceus-with-rituximab -financial-matters-aad-asds-resources

- Amagai M, Hashimoto T, Green KJ, et al. Antigen-specific immunoadsorption of pathogenic autoantibodies in pemphigus foliaceus. J Invest Dermatol. 1995;104:895-901.

- Mahoney MG, Wang Z, Rothenberger K, et al. Explanations for the clinical and microscopic localization of lesions in pemphigus foliaceus and vulgaris. J Clin Invest. 1999;103:461-468.

- Oktarina DAM, Sokol E, Kramer D, et al. Endocytosis of IgG, desmoglein 1, and plakoglobin in pemphigus foliaceus patient skin. Front Immunol. 2019;10:1-12.

- Kraft M, Worm M. Pemphigus foliaceus-repeated treatment with rituximab 7 years after initial response: a case report. Front Med. 2018;5:315.

- Hale EK. Pemphigus foliaceous. Dermatol Online J. 2002;8:9.

- Tavakolpour S. Pemphigus trigger factors: special focus on pemphigus vulgaris and pemphigus foliaceus. Arch Dermatol Res. 2018;310:95-106.

- A boobaker J, Morar N, Ramdial PK, et al. Pemphigus in South Africa. Int J Dermatol. 2001;40:115-119.

- Austin E, Millsop JW, Ely H, et al. Psoriasiform pemphigus foliaceus in an African American female: an important clinical manifestation. J Drugs Dermatol. 2018;17:471.

- Arbache ST, Nogueira TG, Delgado L, et al. Immunofluorescence testing in the diagnosis of autoimmune blistering diseases: overview of 10-year experience. An Bras Dermatol. 2014;89:885-889.

- Sabolinski ML, Beutner EH, Krasny S, et al. Substrate specificity of antiepithelial antibodies of pemphigus vulgaris and pemphigus foliaceus sera in immunofluorescence tests on monkey and guinea pig esophagus sections. J Invest Dermatol. 1987;88:545-549.

- Palacios-Álvarez I, Riquelme-McLoughlin C, Curto-Barredo L, et al. Rituximab treatment of pemphigus foliaceus: a retrospective study of 12 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:484-486.

- Murrell DF, Sprecher E. Rituximab and short-course prednisone as the new gold standard for new-onset pemphigus vulgaris and pemphigus foliaceus. Br J Dermatol. 2017;177:1143-1144.

- Gregoriou S, Efthymiou O, Stefanaki C, et al. Management of pemphigus vulgaris: challenges and solutions. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2015;8:521-527.

- Saleh MA. A prospective study comparing patients with early and late relapsing pemphigus treated with rituximab. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:97-103.

- Castillo CG, Kauffman CA, Miceli MH. Blastomycosis. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2016;30:247-264.

- Herzum A, Gasparini G, Emanuele C, et al. Atypical and rare forms of cutaneous lupus erythematosus: the importance of the diagnosis for the best management of patients. Dermatology. 2013;1-10.

- Tull TJ, Noy M, Bunker CB, et al. Sebopsoriasis in patients with HIV: a case series of 20 patients. Br J Dermatol. 2016; 173:813-815.

- Balagula Y, Mattei P, Wisco OJ, et al. The great imitator revised: the spectrum of atypical cutaneous manifestations of secondary syphilis. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:1434-1441.

- Hans-Filho G, Aoki V, Hans Bittner NR, et al. Fogo selvagem: endemic pemphigus foliaceus. An Bras Dermatol. 2018;93:638-650.

- Jenson KK, Burr DM, Edwards BC. Case report: reatment of refractory pemphigus foliaceus with rituximab. Practical Dermatology. February 2016:33-36. Accessed August 27, 2021. https://practicaldermatology.com/articles/2016-feb/case-report -treatment-of-refractory-pemphigus-foliaceus-with-rituximab -financial-matters-aad-asds-resources

- Amagai M, Hashimoto T, Green KJ, et al. Antigen-specific immunoadsorption of pathogenic autoantibodies in pemphigus foliaceus. J Invest Dermatol. 1995;104:895-901.

- Mahoney MG, Wang Z, Rothenberger K, et al. Explanations for the clinical and microscopic localization of lesions in pemphigus foliaceus and vulgaris. J Clin Invest. 1999;103:461-468.

- Oktarina DAM, Sokol E, Kramer D, et al. Endocytosis of IgG, desmoglein 1, and plakoglobin in pemphigus foliaceus patient skin. Front Immunol. 2019;10:1-12.

- Kraft M, Worm M. Pemphigus foliaceus-repeated treatment with rituximab 7 years after initial response: a case report. Front Med. 2018;5:315.

- Hale EK. Pemphigus foliaceous. Dermatol Online J. 2002;8:9.

- Tavakolpour S. Pemphigus trigger factors: special focus on pemphigus vulgaris and pemphigus foliaceus. Arch Dermatol Res. 2018;310:95-106.

- A boobaker J, Morar N, Ramdial PK, et al. Pemphigus in South Africa. Int J Dermatol. 2001;40:115-119.

- Austin E, Millsop JW, Ely H, et al. Psoriasiform pemphigus foliaceus in an African American female: an important clinical manifestation. J Drugs Dermatol. 2018;17:471.

- Arbache ST, Nogueira TG, Delgado L, et al. Immunofluorescence testing in the diagnosis of autoimmune blistering diseases: overview of 10-year experience. An Bras Dermatol. 2014;89:885-889.

- Sabolinski ML, Beutner EH, Krasny S, et al. Substrate specificity of antiepithelial antibodies of pemphigus vulgaris and pemphigus foliaceus sera in immunofluorescence tests on monkey and guinea pig esophagus sections. J Invest Dermatol. 1987;88:545-549.

- Palacios-Álvarez I, Riquelme-McLoughlin C, Curto-Barredo L, et al. Rituximab treatment of pemphigus foliaceus: a retrospective study of 12 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:484-486.

- Murrell DF, Sprecher E. Rituximab and short-course prednisone as the new gold standard for new-onset pemphigus vulgaris and pemphigus foliaceus. Br J Dermatol. 2017;177:1143-1144.

- Gregoriou S, Efthymiou O, Stefanaki C, et al. Management of pemphigus vulgaris: challenges and solutions. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2015;8:521-527.

- Saleh MA. A prospective study comparing patients with early and late relapsing pemphigus treated with rituximab. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:97-103.

- Castillo CG, Kauffman CA, Miceli MH. Blastomycosis. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2016;30:247-264.

- Herzum A, Gasparini G, Emanuele C, et al. Atypical and rare forms of cutaneous lupus erythematosus: the importance of the diagnosis for the best management of patients. Dermatology. 2013;1-10.

- Tull TJ, Noy M, Bunker CB, et al. Sebopsoriasis in patients with HIV: a case series of 20 patients. Br J Dermatol. 2016; 173:813-815.

- Balagula Y, Mattei P, Wisco OJ, et al. The great imitator revised: the spectrum of atypical cutaneous manifestations of secondary syphilis. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:1434-1441.

A 40-year-old Black man presented for evaluation of a thick plaque throughout the scalp (top), scaly plaques on the cheeks (bottom), and a spreading rash on the trunk that had progressed over the last few months. He had no relevant medical history, took no medications, and was in a monogamous relationship with a female partner. He previously saw an outside dermatologist who gave him triamcinolone cream, which was mildly helpful. Physical examination revealed a thick verrucous plaque throughout the scalp extending onto the forehead; thick plaques on the cheeks; and numerous, thinly eroded lesions on the trunk. Biopsies and a laboratory workup were performed.

Cutaneous Protothecosis

To the Editor:

Protothecosis infections are caused by an achlorophyllic algae of the species Prototheca. Prototheca organisms are found mostly in soil and water.1 Human infections are rare and involve 2 species, Prototheca wickerhamii and Prototheca zopfii. The former most commonly is responsible for human infections, though P zopfii results in more serious systemic infections with a poor prognosis. There are various types of Prototheca infection presentations, with a 2007 review of 117 cases reporting that cutaneous infections are most common (66%), followed by systemic infections (19%), and olecranon bursitis (15%).2 Skin lesions most commonly occur on the extremities and face, and they present as vesiculobullous and ulcerative lesions with purulent drainage. The skin lesions also may appear as erythematous plaques or nodules, subcutaneous papules, verrucous or herpetiformis lesions, or pyogenic granuloma–like lesions.3 Protothecosis typically affects immunocompromised individuals, especially those with a history of chronic corticosteroid use, malignancy, diabetes mellitus, AIDS, and/or organ transplant.1 We present a case of cutaneous protothecosis on the dorsal distal extremity of a 94-year-old woman. History of exposure to soil while gardening was elicited from the patient, and no immunosuppressive history was present aside from the patient’s age. This case may prompt workup for malignancy or immunosuppression in this patient subset.

A 94-year-old woman with a medical history of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) presented with a growing lesion on the dorsal surface of the left fourth digit of 2 months’ duration. The patient reported the lesion was painful, and she noted preceding trauma to the area that was suspected to have occurred while gardening. Physical examination revealed an ulcerated, hypertrophic, erythematous nodule on the dorsal surface of the left fourth metacarpophalangeal joint. The differential diagnosis included SCC, inflamed cyst, verruca vulgaris, and orf virus due to the clinical presentation. A shave biopsy was performed, and the lesion subsequently was treated with electrodesiccation and curettage.

Histopathologic evaluation revealed pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia with a mixed inflammatory infiltrate including lymphocytes and histiocytes. A morula within the dermis was characteristic of a protothecosis infection (Figure 1). On follow-up visit 6 weeks later, the lesion had grown back to its original size and morphology (Figure 2). At this time, the lesion was again treated with shave removal, followed by electrodesiccation and curettage, and the patient was placed on oral fluconazole 200 mg daily for 1 month. When the lesion did not resolve with fluconazole, she was referred to infectious disease as well as general surgery for surgical removal and debridement of the lesion. Unfortunately, the patient was lost to follow-up.

Protothecosis is an infectious disease comprised of achlorophyllic algae found in soil and water that rarely affects humans. When it does affect humans, cutaneous infections are most common. All human cases in which organisms were identified to species level have been caused by P wickerhamii or P zopfii species.2 Inoculation is suspected to occur through trauma to affected skin, especially when in the context of contaminated water. Our patient reported history of trauma to the hand, with soil from gardening as the potential aquagenic source of the infection.

The clinical presentation of protothecosis ranges from localized cutaneous to disseminated systemic infections, with most reported cases of systemic disease occurring in immunocompromised individuals. The cutaneous lesions of protothecosis vary greatly in clinical appearance including ulcerative nodules (as in our case), papules, plaques, pustules, and vesicles with erosion or crusting.4