User login

A starting point for precision medicine in type 1 diabetes

MADRID – With type 1 diabetes, there can be great differences in terms of epidemiology, genetics, and possible constituent causes, as well as in the course of the disease before and after diagnosis. This point was made evident in the Can We Perform Precision Medicine in T1D? conference.

At the 63rd Congress of the Spanish Society of Endocrinology (SEEN), María José Redondo, MD, PhD, director of research in the division of diabetes and endocrinology at Texas Children’s Hospital Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, noted that delving into this evidence is the “clue” to implementing precision medicine strategies.

“Physiopathologically, there are different forms of type 1 diabetes that must be considered in the therapeutic approach. The objective is to describe this heterogeneity to discover the etiopathogenesis underlying it, so that endotypes can be defined and thus apply precision medicine. This is the paradigm followed by the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD), the American Diabetes Association (ADA), and other organizations,” said Dr. Redondo.

She added that there have been significant advances in knowledge of factors that account for these epidemiologic and genetic variations. “For example, immunological processes appear to be different in children who develop type 1 diabetes at a young age, compared with those who present with the disease later in life.”

Metabolic factors are also involved in the development of type 1 diabetes in adolescents and adults, “and this metabolic heterogeneity is a very important aspect, since we currently use only glucose to diagnose diabetes and especially to classify it as type 1 when other factors should really be measured, such as C-peptide, since it has been seen that people with high levels of this peptide present a process that is closer to type 2 diabetes and have atypical characteristics for type 1 diabetes that are more like type 2 diabetes (obesity, older age, lack of typically genetic factors associated with type 1 diabetes),” noted Dr. Redondo.

Eluding classification

The specialist added that this evidence suggests a need to review the classification of the different types of diabetes. “The current general classification distinguishes type 1 diabetes, type 2 diabetes, gestational diabetes, monogenic (neonatal) diabetes, monogenic diabetes associated with cystic fibrosis, pancreatogenic, steroid-induced, and posttransplantation diabetes. However, in clinical practice, cases that are very difficult to diagnose and classify emerge, such as autoimmune diabetes, type 1 diabetes in people with insulin resistance, positive antibodies for type 2 diabetes, for example, in children with obesity (in which it is not known whether it is type 1 or type 2 diabetes), drug-induced diabetes in cases of insulin resistance, autoimmune type 1 diabetes with persistent C-peptide, or monogenic diabetes in people with obesity.

“Therefore, the current classification does not help to guide prevention or treatment, and the heterogeneity of the pathology is not as clear as we would like. Since, for example, insulin resistance affects both types of diabetes, inflammation exists in both cases, and the genes that give beta cell secretion defects exist in monogenic diabetes and probably in type 2 diabetes as well. It can be argued that type 2 diabetes is like a backdrop to a lot of diabetes that we know of so far and that it interacts with other factors that have happened to the particular person,” said Dr. Redondo.

“Furthermore, it has been shown that metformin can improve insulin resistance and cardiovascular events in patients with type 1 diabetes with obesity. On the other hand, most patients with type 2 diabetes do not need insulin after diagnosis, except for pediatric patients and those with positive antibodies who require insulin quickly. Added to this is the inability to differentiate between responders and nonresponders to immunomodulators in the prevention of type 1 diabetes, all of which highlights that there are pathogenic processes that can appear in different types of diabetes, which is why the current classification leaves out cases that do not clearly fit into a single disease type, while many people with the same diagnosis actually have very different diseases,” she pointed out.

Toward precision diagnostics

“Encapsulating” all these factors is the first step to applying precision medicine in type 1 diabetes, an area, Dr. Redondo explained, in which concrete actions are being carried out. “One of these actions is to determine BMI [body mass index], which has been incorporated into the diabetes prediction strategy that we use in clinical trials, since we know that people with a high BMI, along with other factors, clearly have a different risk. Likewise, we’ve seen that teplizumab could work better in the prevention of type 1 diabetes in individuals with anti-islet antibodies and that people who have the DR4 gene respond better than those who don’t have it and that those with the DR3 gene respond worse.”

Other recent advances along these lines involve the identification of treatments that can delay or even prevent the development of type 1 diabetes in people with positive antibodies, as well as the development of algorithms and models to predict who will develop the disease, thus placing preventive treatments within reach.

“The objective is to use all available information from each individual to understand the etiology and pathogenesis of the disease at a given moment, knowing that changes occur throughout life, and this also applies to other types of diabetes. The next step is to discover and test pathogenesis-focused therapeutic strategies with the most clinical impact in each patient at any given time,” said Dr. Redondo.

Technological tools

The specialist referred to recent advances in diabetes technology, especially semiclosed systems (such as a sensor/pump) that, in her opinion, have radically changed the control of the disease. “However, the main objective is to make type 1 diabetes preventable or reversible in people who have developed it,” she said.

Fernando Gómez-Peralta, MD, PhD, elected coordinator of the Diabetes Department at SEEN and head of the endocrinology and nutrition unit of General Hospital of Segovia, Spain, spoke about these technological advances in his presentation, “Technology and Diabetes: Clinical Experiences,” which was organized in collaboration with the Spanish Diabetes Society.

According to this expert, technological and digital tools are changing the daily lives of people with this disease. “Continuous glucose monitoring and new connected insulin pen and cap systems have increased the benefits for users of treatment with new insulins, for example,” said Dr. Gómez-Peralta.

He explained that most systems make it possible to access complete data regarding glycemic control and the treatment received and to share them with caregivers, professionals, and family members. “Some integrated insulin pump and sensor systems have self-adjusting insulin therapy algorithms that have been shown to greatly increase time-to-target glucose and reduce hypoglycemic events,” he said.

“Regarding glucose monitoring, there are devices with a longer duration (up to 2 weeks) and precision that are characterized by easier use for the patient, avoiding the need for calibration, with annoying capillary blood glucose levels.”

In the case of insulin administration, it is anticipated that in the future, some models will have very interesting features, Dr. Gómez-Peralta said. “Integrated closed-loop glucose sensor and insulin pump systems that have self-adjusting algorithms, regardless of the user, are highly effective and safe, and clearly improve glycemic control.

“For users of insulin injections, connected pens allow the integration of dynamic glucose information with doses, as well as the integration of user support tools for insulin adjustment,” Dr. Gómez-Peralta added.

The specialist stressed that a challenge for the future is to reduce the digital divide so as to increase the capacity and motivation to access these options. “In the coming years, health systems will have to face significant cost so that these systems are made available to all patients, and it is necessary to provide the systems with more material and human resources so that they can be integrated with our endocrinology and diabetes services and units.”

Dr. Redondo and Dr. Gómez-Peralta have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article was translated from the Medscape Spanish edition and a version appeared on Medscape.com.

MADRID – With type 1 diabetes, there can be great differences in terms of epidemiology, genetics, and possible constituent causes, as well as in the course of the disease before and after diagnosis. This point was made evident in the Can We Perform Precision Medicine in T1D? conference.

At the 63rd Congress of the Spanish Society of Endocrinology (SEEN), María José Redondo, MD, PhD, director of research in the division of diabetes and endocrinology at Texas Children’s Hospital Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, noted that delving into this evidence is the “clue” to implementing precision medicine strategies.

“Physiopathologically, there are different forms of type 1 diabetes that must be considered in the therapeutic approach. The objective is to describe this heterogeneity to discover the etiopathogenesis underlying it, so that endotypes can be defined and thus apply precision medicine. This is the paradigm followed by the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD), the American Diabetes Association (ADA), and other organizations,” said Dr. Redondo.

She added that there have been significant advances in knowledge of factors that account for these epidemiologic and genetic variations. “For example, immunological processes appear to be different in children who develop type 1 diabetes at a young age, compared with those who present with the disease later in life.”

Metabolic factors are also involved in the development of type 1 diabetes in adolescents and adults, “and this metabolic heterogeneity is a very important aspect, since we currently use only glucose to diagnose diabetes and especially to classify it as type 1 when other factors should really be measured, such as C-peptide, since it has been seen that people with high levels of this peptide present a process that is closer to type 2 diabetes and have atypical characteristics for type 1 diabetes that are more like type 2 diabetes (obesity, older age, lack of typically genetic factors associated with type 1 diabetes),” noted Dr. Redondo.

Eluding classification

The specialist added that this evidence suggests a need to review the classification of the different types of diabetes. “The current general classification distinguishes type 1 diabetes, type 2 diabetes, gestational diabetes, monogenic (neonatal) diabetes, monogenic diabetes associated with cystic fibrosis, pancreatogenic, steroid-induced, and posttransplantation diabetes. However, in clinical practice, cases that are very difficult to diagnose and classify emerge, such as autoimmune diabetes, type 1 diabetes in people with insulin resistance, positive antibodies for type 2 diabetes, for example, in children with obesity (in which it is not known whether it is type 1 or type 2 diabetes), drug-induced diabetes in cases of insulin resistance, autoimmune type 1 diabetes with persistent C-peptide, or monogenic diabetes in people with obesity.

“Therefore, the current classification does not help to guide prevention or treatment, and the heterogeneity of the pathology is not as clear as we would like. Since, for example, insulin resistance affects both types of diabetes, inflammation exists in both cases, and the genes that give beta cell secretion defects exist in monogenic diabetes and probably in type 2 diabetes as well. It can be argued that type 2 diabetes is like a backdrop to a lot of diabetes that we know of so far and that it interacts with other factors that have happened to the particular person,” said Dr. Redondo.

“Furthermore, it has been shown that metformin can improve insulin resistance and cardiovascular events in patients with type 1 diabetes with obesity. On the other hand, most patients with type 2 diabetes do not need insulin after diagnosis, except for pediatric patients and those with positive antibodies who require insulin quickly. Added to this is the inability to differentiate between responders and nonresponders to immunomodulators in the prevention of type 1 diabetes, all of which highlights that there are pathogenic processes that can appear in different types of diabetes, which is why the current classification leaves out cases that do not clearly fit into a single disease type, while many people with the same diagnosis actually have very different diseases,” she pointed out.

Toward precision diagnostics

“Encapsulating” all these factors is the first step to applying precision medicine in type 1 diabetes, an area, Dr. Redondo explained, in which concrete actions are being carried out. “One of these actions is to determine BMI [body mass index], which has been incorporated into the diabetes prediction strategy that we use in clinical trials, since we know that people with a high BMI, along with other factors, clearly have a different risk. Likewise, we’ve seen that teplizumab could work better in the prevention of type 1 diabetes in individuals with anti-islet antibodies and that people who have the DR4 gene respond better than those who don’t have it and that those with the DR3 gene respond worse.”

Other recent advances along these lines involve the identification of treatments that can delay or even prevent the development of type 1 diabetes in people with positive antibodies, as well as the development of algorithms and models to predict who will develop the disease, thus placing preventive treatments within reach.

“The objective is to use all available information from each individual to understand the etiology and pathogenesis of the disease at a given moment, knowing that changes occur throughout life, and this also applies to other types of diabetes. The next step is to discover and test pathogenesis-focused therapeutic strategies with the most clinical impact in each patient at any given time,” said Dr. Redondo.

Technological tools

The specialist referred to recent advances in diabetes technology, especially semiclosed systems (such as a sensor/pump) that, in her opinion, have radically changed the control of the disease. “However, the main objective is to make type 1 diabetes preventable or reversible in people who have developed it,” she said.

Fernando Gómez-Peralta, MD, PhD, elected coordinator of the Diabetes Department at SEEN and head of the endocrinology and nutrition unit of General Hospital of Segovia, Spain, spoke about these technological advances in his presentation, “Technology and Diabetes: Clinical Experiences,” which was organized in collaboration with the Spanish Diabetes Society.

According to this expert, technological and digital tools are changing the daily lives of people with this disease. “Continuous glucose monitoring and new connected insulin pen and cap systems have increased the benefits for users of treatment with new insulins, for example,” said Dr. Gómez-Peralta.

He explained that most systems make it possible to access complete data regarding glycemic control and the treatment received and to share them with caregivers, professionals, and family members. “Some integrated insulin pump and sensor systems have self-adjusting insulin therapy algorithms that have been shown to greatly increase time-to-target glucose and reduce hypoglycemic events,” he said.

“Regarding glucose monitoring, there are devices with a longer duration (up to 2 weeks) and precision that are characterized by easier use for the patient, avoiding the need for calibration, with annoying capillary blood glucose levels.”

In the case of insulin administration, it is anticipated that in the future, some models will have very interesting features, Dr. Gómez-Peralta said. “Integrated closed-loop glucose sensor and insulin pump systems that have self-adjusting algorithms, regardless of the user, are highly effective and safe, and clearly improve glycemic control.

“For users of insulin injections, connected pens allow the integration of dynamic glucose information with doses, as well as the integration of user support tools for insulin adjustment,” Dr. Gómez-Peralta added.

The specialist stressed that a challenge for the future is to reduce the digital divide so as to increase the capacity and motivation to access these options. “In the coming years, health systems will have to face significant cost so that these systems are made available to all patients, and it is necessary to provide the systems with more material and human resources so that they can be integrated with our endocrinology and diabetes services and units.”

Dr. Redondo and Dr. Gómez-Peralta have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article was translated from the Medscape Spanish edition and a version appeared on Medscape.com.

MADRID – With type 1 diabetes, there can be great differences in terms of epidemiology, genetics, and possible constituent causes, as well as in the course of the disease before and after diagnosis. This point was made evident in the Can We Perform Precision Medicine in T1D? conference.

At the 63rd Congress of the Spanish Society of Endocrinology (SEEN), María José Redondo, MD, PhD, director of research in the division of diabetes and endocrinology at Texas Children’s Hospital Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, noted that delving into this evidence is the “clue” to implementing precision medicine strategies.

“Physiopathologically, there are different forms of type 1 diabetes that must be considered in the therapeutic approach. The objective is to describe this heterogeneity to discover the etiopathogenesis underlying it, so that endotypes can be defined and thus apply precision medicine. This is the paradigm followed by the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD), the American Diabetes Association (ADA), and other organizations,” said Dr. Redondo.

She added that there have been significant advances in knowledge of factors that account for these epidemiologic and genetic variations. “For example, immunological processes appear to be different in children who develop type 1 diabetes at a young age, compared with those who present with the disease later in life.”

Metabolic factors are also involved in the development of type 1 diabetes in adolescents and adults, “and this metabolic heterogeneity is a very important aspect, since we currently use only glucose to diagnose diabetes and especially to classify it as type 1 when other factors should really be measured, such as C-peptide, since it has been seen that people with high levels of this peptide present a process that is closer to type 2 diabetes and have atypical characteristics for type 1 diabetes that are more like type 2 diabetes (obesity, older age, lack of typically genetic factors associated with type 1 diabetes),” noted Dr. Redondo.

Eluding classification

The specialist added that this evidence suggests a need to review the classification of the different types of diabetes. “The current general classification distinguishes type 1 diabetes, type 2 diabetes, gestational diabetes, monogenic (neonatal) diabetes, monogenic diabetes associated with cystic fibrosis, pancreatogenic, steroid-induced, and posttransplantation diabetes. However, in clinical practice, cases that are very difficult to diagnose and classify emerge, such as autoimmune diabetes, type 1 diabetes in people with insulin resistance, positive antibodies for type 2 diabetes, for example, in children with obesity (in which it is not known whether it is type 1 or type 2 diabetes), drug-induced diabetes in cases of insulin resistance, autoimmune type 1 diabetes with persistent C-peptide, or monogenic diabetes in people with obesity.

“Therefore, the current classification does not help to guide prevention or treatment, and the heterogeneity of the pathology is not as clear as we would like. Since, for example, insulin resistance affects both types of diabetes, inflammation exists in both cases, and the genes that give beta cell secretion defects exist in monogenic diabetes and probably in type 2 diabetes as well. It can be argued that type 2 diabetes is like a backdrop to a lot of diabetes that we know of so far and that it interacts with other factors that have happened to the particular person,” said Dr. Redondo.

“Furthermore, it has been shown that metformin can improve insulin resistance and cardiovascular events in patients with type 1 diabetes with obesity. On the other hand, most patients with type 2 diabetes do not need insulin after diagnosis, except for pediatric patients and those with positive antibodies who require insulin quickly. Added to this is the inability to differentiate between responders and nonresponders to immunomodulators in the prevention of type 1 diabetes, all of which highlights that there are pathogenic processes that can appear in different types of diabetes, which is why the current classification leaves out cases that do not clearly fit into a single disease type, while many people with the same diagnosis actually have very different diseases,” she pointed out.

Toward precision diagnostics

“Encapsulating” all these factors is the first step to applying precision medicine in type 1 diabetes, an area, Dr. Redondo explained, in which concrete actions are being carried out. “One of these actions is to determine BMI [body mass index], which has been incorporated into the diabetes prediction strategy that we use in clinical trials, since we know that people with a high BMI, along with other factors, clearly have a different risk. Likewise, we’ve seen that teplizumab could work better in the prevention of type 1 diabetes in individuals with anti-islet antibodies and that people who have the DR4 gene respond better than those who don’t have it and that those with the DR3 gene respond worse.”

Other recent advances along these lines involve the identification of treatments that can delay or even prevent the development of type 1 diabetes in people with positive antibodies, as well as the development of algorithms and models to predict who will develop the disease, thus placing preventive treatments within reach.

“The objective is to use all available information from each individual to understand the etiology and pathogenesis of the disease at a given moment, knowing that changes occur throughout life, and this also applies to other types of diabetes. The next step is to discover and test pathogenesis-focused therapeutic strategies with the most clinical impact in each patient at any given time,” said Dr. Redondo.

Technological tools

The specialist referred to recent advances in diabetes technology, especially semiclosed systems (such as a sensor/pump) that, in her opinion, have radically changed the control of the disease. “However, the main objective is to make type 1 diabetes preventable or reversible in people who have developed it,” she said.

Fernando Gómez-Peralta, MD, PhD, elected coordinator of the Diabetes Department at SEEN and head of the endocrinology and nutrition unit of General Hospital of Segovia, Spain, spoke about these technological advances in his presentation, “Technology and Diabetes: Clinical Experiences,” which was organized in collaboration with the Spanish Diabetes Society.

According to this expert, technological and digital tools are changing the daily lives of people with this disease. “Continuous glucose monitoring and new connected insulin pen and cap systems have increased the benefits for users of treatment with new insulins, for example,” said Dr. Gómez-Peralta.

He explained that most systems make it possible to access complete data regarding glycemic control and the treatment received and to share them with caregivers, professionals, and family members. “Some integrated insulin pump and sensor systems have self-adjusting insulin therapy algorithms that have been shown to greatly increase time-to-target glucose and reduce hypoglycemic events,” he said.

“Regarding glucose monitoring, there are devices with a longer duration (up to 2 weeks) and precision that are characterized by easier use for the patient, avoiding the need for calibration, with annoying capillary blood glucose levels.”

In the case of insulin administration, it is anticipated that in the future, some models will have very interesting features, Dr. Gómez-Peralta said. “Integrated closed-loop glucose sensor and insulin pump systems that have self-adjusting algorithms, regardless of the user, are highly effective and safe, and clearly improve glycemic control.

“For users of insulin injections, connected pens allow the integration of dynamic glucose information with doses, as well as the integration of user support tools for insulin adjustment,” Dr. Gómez-Peralta added.

The specialist stressed that a challenge for the future is to reduce the digital divide so as to increase the capacity and motivation to access these options. “In the coming years, health systems will have to face significant cost so that these systems are made available to all patients, and it is necessary to provide the systems with more material and human resources so that they can be integrated with our endocrinology and diabetes services and units.”

Dr. Redondo and Dr. Gómez-Peralta have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article was translated from the Medscape Spanish edition and a version appeared on Medscape.com.

Dubious diagnosis: Is there a better way to define ‘prediabetes’?

and subsequent complications, and therefore merit more intensive intervention.

“Prediabetes” is the term coined to refer to either “impaired fasting glucose (IFG)” or “impaired glucose tolerance (IGT),” both denoting levels of elevated glycemia that don’t meet the thresholds for diabetes. It’s a heterogeneous group overall, and despite its name, not everyone with prediabetes will progress to develop type 2 diabetes.

There have been major increases in prediabetes in the United States and globally over the past 2 decades, epidemiologist Elizabeth Selvin, PhD, said at the recent IDF World Diabetes Congress 2022.

She noted that the concept of “prediabetes” has been controversial, previously dubbed a “dubious diagnosis” and a “boon for Pharma” in a 2019 Science article.

Others have said it’s “not a medical condition” and that it’s “an artificial category with virtually zero clinical relevance” in a press statement issued for a 2014 BMJ article.

“I don’t agree with these statements entirely but I think they speak to the confusion and tremendous controversy around the concept of prediabetes ... I think instead of calling prediabetes a ‘dubious diagnosis’ we should think of it as an opportunity,” said Dr. Selvin, of Johns Hopkins University Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore.

She proposes trying to home in on those with highest risk of developing type 2 diabetes, which she suggests could be achieved by using a combination of elevated fasting glucose and an elevated A1c, although she stresses that this isn’t in any official guidance.

With the appropriate definition, people who are truly at risk for progression to type 2 diabetes can be identified so that lifestyle factors and cardiovascular risk can be addressed, and weight loss efforts implemented.

“Prevention of weight gain is ... important. That message often gets lost. Even if we can’t get people to lose weight, preventing [further] weight gain is important,” she noted.

Asked to comment, Sue Kirkman, MD, told this news organization, “The term prediabetes – or IFG or IGT or any of the ‘intermediate’ terms – is pragmatic in a way. It helps clinicians and patients understand that they are in a higher-risk category and might need intervention and likely need ongoing monitoring. But like many other risk factors [such as] blood pressure, [high] BMI, etc., the risk is not dichotomous but a continuum.

“People at the low end of the ‘intermediate’ range are not going to have much more risk compared to people who are ‘normal,’ while those at the high end of the range have very high risk,” said Dr. Kirkman, of the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, and a coauthor of the American Diabetes Association’s diabetes and prediabetes classifications.

“So we lose information if we just lump everyone into a single category. For individual patients, we definitely need better ways to estimate and communicate their potential risk.”

Currently five definitions for prediabetes: Home in on risk

The problem, Dr. Selvin explained, is that currently there are five official definitions for “prediabetes” using cutoffs for hemoglobin A1c, fasting glucose, or an oral glucose tolerance test.

Each one identifies different numbers of people with differing risk levels, ranging from a prevalence of 4.3% of the middle-aged adult population with the International Expert Committee’s definition of A1c 6.0%-6.4% to 43.5% with the American Diabetes Association’s 100-125 mg/dL fasting glucose.

“That’s an enormous difference. No wonder people are confused about who has prediabetes and what we should do about it,” Dr. Selvin said, adding that the concern about overdiagnosing “prediabetes” is even greater for older populations, in whom “it’s incredibly common to have mildly elevated glucose.”

Hence her proposal of what she sees as an evidence-based, “really easy solution” that clinicians can use now to better identify which patients with “intermediate hyperglycemia” to be most concerned about: Use a combination of fasting glucose above 100 mg/dL and an A1c greater than 5.7%.

“If you have both fasting glucose and hemoglobin A1c, you can use them together ... This is not codified in any guidelines. You won’t see this mentioned anywhere. The guidelines are silent on what to do when some people have an elevated fasting glucose but not an elevated A1c ... but I think a simple message is that if people have both an elevated fasting glucose and an elevated A1c, that’s a very high-risk group,” she said.

On the other hand, Dr. Kirkman pointed out, “most discrepancies are near the margins, as in one test is slightly elevated and one isn’t, so those people probably are at low risk.

“It may be that both being elevated means higher risk because they have more hyperglycemia ... so it seems reasonable, but only if it changes what you tell people.”

For example, Dr. Kirkman said, “I’d tell someone with A1c of 5.8% and fasting glucose of 99 mg/dL the same thing I’d tell someone with that A1c and a glucose of 104 mg/dL – that their risk is still pretty low – and I’d recommend healthy lifestyle and weight loss if overweight either way.”

However, she also said, “Certainly people with higher glucose or A1c are at much higher risk, and same for those with both.”

Tie “prediabetes” definition to risk, as cardiology scores do?

Dr. Selvin also believes that risk-based definitions of prediabetes are needed. Ideally, these would incorporate demographics and clinical factors such as age and body mass index. Other biomarkers could potentially be developed and validated for inclusion in the definition, such as C-reactive protein (CRP), lipids, or even genetic/proteomic information.

Moreover, she thinks that the definition should be tied to clinical decision-making, as is the pooled cohort equation in cardiology.

“I think we could do something very similar in prediabetes,” she suggested, adding that even simply incorporating age and BMI into the definition could help further stratify the risk level until other predictors are validated.

Dr. Kirkman said, “The concept of risk scores a la cardiology is interesting, although we’d have to make them simple and also validate them against some outcome.”

Regarding the age issue, Dr. Kirkman noted that although age wasn’t a predictor of progression to type 2 diabetes in the placebo arm of the landmark Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP) trial, “I do agree that it’s a problem that many older folks have the label of prediabetes because of a mildly elevated A1c and we know that most will never get diabetes.”

And, she noted, in the DPP people with prediabetes who had a BMI over 35 kg/m2 did have significantly higher progression rates than those with lower BMI, while women with a history of gestational diabetes mellitus are also known to be at particularly high risk.

Whom should we throw the kitchen sink at?

Some of this discussion, Dr. Kirkman said, “is really a philosophical one, especially when you consider that lifestyle intervention has benefits for almost everyone on many short- and long-term outcomes.”

“The question is probably whom we should ‘throw the kitchen sink at,’ who should get more scalable advice that might apply to everyone regardless of glycemic levels, and whether there’s some more intermediate group that needs more of a [National Diabetes Prevention Program] approach.”

Dr. Selvin’s group is now working on gathering data to inform development of a risk-based prediabetes definition. “We have a whole research effort in this area. I hope that with some really strong data on risk in prediabetes, that can help to solve the heterogeneity issue. I’m focused on bringing evidence to bear to change the guidelines.”

In the meantime, she told this news organization, “I think there are things we can do now to provide more guidance. I get a lot of feedback from people saying things like ‘my physician told me I have prediabetes but now I don’t’ or ‘I saw in my labs that my blood sugar is elevated but my doctor never said anything.’ That’s a communications issue where we can do a better job.”

The meeting was sponsored by the International Diabetes Federation.

Dr. Selvin is deputy editor of Diabetes Care and on the editorial board of Diabetologia. She receives funding from the NIH and the Foundation for the NIH, and royalties from UpToDate for sections related to screening, diagnosis, and laboratory testing for diabetes. Dr. Kirkman reports no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

and subsequent complications, and therefore merit more intensive intervention.

“Prediabetes” is the term coined to refer to either “impaired fasting glucose (IFG)” or “impaired glucose tolerance (IGT),” both denoting levels of elevated glycemia that don’t meet the thresholds for diabetes. It’s a heterogeneous group overall, and despite its name, not everyone with prediabetes will progress to develop type 2 diabetes.

There have been major increases in prediabetes in the United States and globally over the past 2 decades, epidemiologist Elizabeth Selvin, PhD, said at the recent IDF World Diabetes Congress 2022.

She noted that the concept of “prediabetes” has been controversial, previously dubbed a “dubious diagnosis” and a “boon for Pharma” in a 2019 Science article.

Others have said it’s “not a medical condition” and that it’s “an artificial category with virtually zero clinical relevance” in a press statement issued for a 2014 BMJ article.

“I don’t agree with these statements entirely but I think they speak to the confusion and tremendous controversy around the concept of prediabetes ... I think instead of calling prediabetes a ‘dubious diagnosis’ we should think of it as an opportunity,” said Dr. Selvin, of Johns Hopkins University Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore.

She proposes trying to home in on those with highest risk of developing type 2 diabetes, which she suggests could be achieved by using a combination of elevated fasting glucose and an elevated A1c, although she stresses that this isn’t in any official guidance.

With the appropriate definition, people who are truly at risk for progression to type 2 diabetes can be identified so that lifestyle factors and cardiovascular risk can be addressed, and weight loss efforts implemented.

“Prevention of weight gain is ... important. That message often gets lost. Even if we can’t get people to lose weight, preventing [further] weight gain is important,” she noted.

Asked to comment, Sue Kirkman, MD, told this news organization, “The term prediabetes – or IFG or IGT or any of the ‘intermediate’ terms – is pragmatic in a way. It helps clinicians and patients understand that they are in a higher-risk category and might need intervention and likely need ongoing monitoring. But like many other risk factors [such as] blood pressure, [high] BMI, etc., the risk is not dichotomous but a continuum.

“People at the low end of the ‘intermediate’ range are not going to have much more risk compared to people who are ‘normal,’ while those at the high end of the range have very high risk,” said Dr. Kirkman, of the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, and a coauthor of the American Diabetes Association’s diabetes and prediabetes classifications.

“So we lose information if we just lump everyone into a single category. For individual patients, we definitely need better ways to estimate and communicate their potential risk.”

Currently five definitions for prediabetes: Home in on risk

The problem, Dr. Selvin explained, is that currently there are five official definitions for “prediabetes” using cutoffs for hemoglobin A1c, fasting glucose, or an oral glucose tolerance test.

Each one identifies different numbers of people with differing risk levels, ranging from a prevalence of 4.3% of the middle-aged adult population with the International Expert Committee’s definition of A1c 6.0%-6.4% to 43.5% with the American Diabetes Association’s 100-125 mg/dL fasting glucose.

“That’s an enormous difference. No wonder people are confused about who has prediabetes and what we should do about it,” Dr. Selvin said, adding that the concern about overdiagnosing “prediabetes” is even greater for older populations, in whom “it’s incredibly common to have mildly elevated glucose.”

Hence her proposal of what she sees as an evidence-based, “really easy solution” that clinicians can use now to better identify which patients with “intermediate hyperglycemia” to be most concerned about: Use a combination of fasting glucose above 100 mg/dL and an A1c greater than 5.7%.

“If you have both fasting glucose and hemoglobin A1c, you can use them together ... This is not codified in any guidelines. You won’t see this mentioned anywhere. The guidelines are silent on what to do when some people have an elevated fasting glucose but not an elevated A1c ... but I think a simple message is that if people have both an elevated fasting glucose and an elevated A1c, that’s a very high-risk group,” she said.

On the other hand, Dr. Kirkman pointed out, “most discrepancies are near the margins, as in one test is slightly elevated and one isn’t, so those people probably are at low risk.

“It may be that both being elevated means higher risk because they have more hyperglycemia ... so it seems reasonable, but only if it changes what you tell people.”

For example, Dr. Kirkman said, “I’d tell someone with A1c of 5.8% and fasting glucose of 99 mg/dL the same thing I’d tell someone with that A1c and a glucose of 104 mg/dL – that their risk is still pretty low – and I’d recommend healthy lifestyle and weight loss if overweight either way.”

However, she also said, “Certainly people with higher glucose or A1c are at much higher risk, and same for those with both.”

Tie “prediabetes” definition to risk, as cardiology scores do?

Dr. Selvin also believes that risk-based definitions of prediabetes are needed. Ideally, these would incorporate demographics and clinical factors such as age and body mass index. Other biomarkers could potentially be developed and validated for inclusion in the definition, such as C-reactive protein (CRP), lipids, or even genetic/proteomic information.

Moreover, she thinks that the definition should be tied to clinical decision-making, as is the pooled cohort equation in cardiology.

“I think we could do something very similar in prediabetes,” she suggested, adding that even simply incorporating age and BMI into the definition could help further stratify the risk level until other predictors are validated.

Dr. Kirkman said, “The concept of risk scores a la cardiology is interesting, although we’d have to make them simple and also validate them against some outcome.”

Regarding the age issue, Dr. Kirkman noted that although age wasn’t a predictor of progression to type 2 diabetes in the placebo arm of the landmark Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP) trial, “I do agree that it’s a problem that many older folks have the label of prediabetes because of a mildly elevated A1c and we know that most will never get diabetes.”

And, she noted, in the DPP people with prediabetes who had a BMI over 35 kg/m2 did have significantly higher progression rates than those with lower BMI, while women with a history of gestational diabetes mellitus are also known to be at particularly high risk.

Whom should we throw the kitchen sink at?

Some of this discussion, Dr. Kirkman said, “is really a philosophical one, especially when you consider that lifestyle intervention has benefits for almost everyone on many short- and long-term outcomes.”

“The question is probably whom we should ‘throw the kitchen sink at,’ who should get more scalable advice that might apply to everyone regardless of glycemic levels, and whether there’s some more intermediate group that needs more of a [National Diabetes Prevention Program] approach.”

Dr. Selvin’s group is now working on gathering data to inform development of a risk-based prediabetes definition. “We have a whole research effort in this area. I hope that with some really strong data on risk in prediabetes, that can help to solve the heterogeneity issue. I’m focused on bringing evidence to bear to change the guidelines.”

In the meantime, she told this news organization, “I think there are things we can do now to provide more guidance. I get a lot of feedback from people saying things like ‘my physician told me I have prediabetes but now I don’t’ or ‘I saw in my labs that my blood sugar is elevated but my doctor never said anything.’ That’s a communications issue where we can do a better job.”

The meeting was sponsored by the International Diabetes Federation.

Dr. Selvin is deputy editor of Diabetes Care and on the editorial board of Diabetologia. She receives funding from the NIH and the Foundation for the NIH, and royalties from UpToDate for sections related to screening, diagnosis, and laboratory testing for diabetes. Dr. Kirkman reports no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

and subsequent complications, and therefore merit more intensive intervention.

“Prediabetes” is the term coined to refer to either “impaired fasting glucose (IFG)” or “impaired glucose tolerance (IGT),” both denoting levels of elevated glycemia that don’t meet the thresholds for diabetes. It’s a heterogeneous group overall, and despite its name, not everyone with prediabetes will progress to develop type 2 diabetes.

There have been major increases in prediabetes in the United States and globally over the past 2 decades, epidemiologist Elizabeth Selvin, PhD, said at the recent IDF World Diabetes Congress 2022.

She noted that the concept of “prediabetes” has been controversial, previously dubbed a “dubious diagnosis” and a “boon for Pharma” in a 2019 Science article.

Others have said it’s “not a medical condition” and that it’s “an artificial category with virtually zero clinical relevance” in a press statement issued for a 2014 BMJ article.

“I don’t agree with these statements entirely but I think they speak to the confusion and tremendous controversy around the concept of prediabetes ... I think instead of calling prediabetes a ‘dubious diagnosis’ we should think of it as an opportunity,” said Dr. Selvin, of Johns Hopkins University Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore.

She proposes trying to home in on those with highest risk of developing type 2 diabetes, which she suggests could be achieved by using a combination of elevated fasting glucose and an elevated A1c, although she stresses that this isn’t in any official guidance.

With the appropriate definition, people who are truly at risk for progression to type 2 diabetes can be identified so that lifestyle factors and cardiovascular risk can be addressed, and weight loss efforts implemented.

“Prevention of weight gain is ... important. That message often gets lost. Even if we can’t get people to lose weight, preventing [further] weight gain is important,” she noted.

Asked to comment, Sue Kirkman, MD, told this news organization, “The term prediabetes – or IFG or IGT or any of the ‘intermediate’ terms – is pragmatic in a way. It helps clinicians and patients understand that they are in a higher-risk category and might need intervention and likely need ongoing monitoring. But like many other risk factors [such as] blood pressure, [high] BMI, etc., the risk is not dichotomous but a continuum.

“People at the low end of the ‘intermediate’ range are not going to have much more risk compared to people who are ‘normal,’ while those at the high end of the range have very high risk,” said Dr. Kirkman, of the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, and a coauthor of the American Diabetes Association’s diabetes and prediabetes classifications.

“So we lose information if we just lump everyone into a single category. For individual patients, we definitely need better ways to estimate and communicate their potential risk.”

Currently five definitions for prediabetes: Home in on risk

The problem, Dr. Selvin explained, is that currently there are five official definitions for “prediabetes” using cutoffs for hemoglobin A1c, fasting glucose, or an oral glucose tolerance test.

Each one identifies different numbers of people with differing risk levels, ranging from a prevalence of 4.3% of the middle-aged adult population with the International Expert Committee’s definition of A1c 6.0%-6.4% to 43.5% with the American Diabetes Association’s 100-125 mg/dL fasting glucose.

“That’s an enormous difference. No wonder people are confused about who has prediabetes and what we should do about it,” Dr. Selvin said, adding that the concern about overdiagnosing “prediabetes” is even greater for older populations, in whom “it’s incredibly common to have mildly elevated glucose.”

Hence her proposal of what she sees as an evidence-based, “really easy solution” that clinicians can use now to better identify which patients with “intermediate hyperglycemia” to be most concerned about: Use a combination of fasting glucose above 100 mg/dL and an A1c greater than 5.7%.

“If you have both fasting glucose and hemoglobin A1c, you can use them together ... This is not codified in any guidelines. You won’t see this mentioned anywhere. The guidelines are silent on what to do when some people have an elevated fasting glucose but not an elevated A1c ... but I think a simple message is that if people have both an elevated fasting glucose and an elevated A1c, that’s a very high-risk group,” she said.

On the other hand, Dr. Kirkman pointed out, “most discrepancies are near the margins, as in one test is slightly elevated and one isn’t, so those people probably are at low risk.

“It may be that both being elevated means higher risk because they have more hyperglycemia ... so it seems reasonable, but only if it changes what you tell people.”

For example, Dr. Kirkman said, “I’d tell someone with A1c of 5.8% and fasting glucose of 99 mg/dL the same thing I’d tell someone with that A1c and a glucose of 104 mg/dL – that their risk is still pretty low – and I’d recommend healthy lifestyle and weight loss if overweight either way.”

However, she also said, “Certainly people with higher glucose or A1c are at much higher risk, and same for those with both.”

Tie “prediabetes” definition to risk, as cardiology scores do?

Dr. Selvin also believes that risk-based definitions of prediabetes are needed. Ideally, these would incorporate demographics and clinical factors such as age and body mass index. Other biomarkers could potentially be developed and validated for inclusion in the definition, such as C-reactive protein (CRP), lipids, or even genetic/proteomic information.

Moreover, she thinks that the definition should be tied to clinical decision-making, as is the pooled cohort equation in cardiology.

“I think we could do something very similar in prediabetes,” she suggested, adding that even simply incorporating age and BMI into the definition could help further stratify the risk level until other predictors are validated.

Dr. Kirkman said, “The concept of risk scores a la cardiology is interesting, although we’d have to make them simple and also validate them against some outcome.”

Regarding the age issue, Dr. Kirkman noted that although age wasn’t a predictor of progression to type 2 diabetes in the placebo arm of the landmark Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP) trial, “I do agree that it’s a problem that many older folks have the label of prediabetes because of a mildly elevated A1c and we know that most will never get diabetes.”

And, she noted, in the DPP people with prediabetes who had a BMI over 35 kg/m2 did have significantly higher progression rates than those with lower BMI, while women with a history of gestational diabetes mellitus are also known to be at particularly high risk.

Whom should we throw the kitchen sink at?

Some of this discussion, Dr. Kirkman said, “is really a philosophical one, especially when you consider that lifestyle intervention has benefits for almost everyone on many short- and long-term outcomes.”

“The question is probably whom we should ‘throw the kitchen sink at,’ who should get more scalable advice that might apply to everyone regardless of glycemic levels, and whether there’s some more intermediate group that needs more of a [National Diabetes Prevention Program] approach.”

Dr. Selvin’s group is now working on gathering data to inform development of a risk-based prediabetes definition. “We have a whole research effort in this area. I hope that with some really strong data on risk in prediabetes, that can help to solve the heterogeneity issue. I’m focused on bringing evidence to bear to change the guidelines.”

In the meantime, she told this news organization, “I think there are things we can do now to provide more guidance. I get a lot of feedback from people saying things like ‘my physician told me I have prediabetes but now I don’t’ or ‘I saw in my labs that my blood sugar is elevated but my doctor never said anything.’ That’s a communications issue where we can do a better job.”

The meeting was sponsored by the International Diabetes Federation.

Dr. Selvin is deputy editor of Diabetes Care and on the editorial board of Diabetologia. She receives funding from the NIH and the Foundation for the NIH, and royalties from UpToDate for sections related to screening, diagnosis, and laboratory testing for diabetes. Dr. Kirkman reports no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

AT IDF WORLD DIABETES CONGRESS 2022

Principles and Process for Reducing the Need for Insulin in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes

For people living with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2D), exogenous insulin, whether given early or later in T2D diagnosis, can provide many pharmacologically desirable effects. But it has always been clear, and is now more widely recognized, that insulin treatments are not completely risk-free for the patient. There are now newer, non-insulin therapy options that could be used, along with certain patient lifestyle changes in diet and activity levels, that have been shown to achieve desired glucose control—without the associated risks that insulin can bring.

But is it possible to markedly reduce the need for insulin in some 90% of T2D patients and to reduce the doses in the others? Yes—if patients have sufficient beta-cell function and are willing to change their lifestyle. This mode of treatment has been slowly gaining momentum as of late in the medical community because of the benefits it ultimately provides for the patient. In my practice, I personally have done this by using an evidence-based approach that includes thinking inside a larger box. It is a 2-way street, and each should drive the other: the right drugs (in the right doses), and in the right patients.

Why avoid early insulin therapy?

Is the requirement of early insulin therapy in many or most patients a myth?

Yes. It resulted from “old logic,” which was to use insulin early to reduce glucotoxicity and lipotoxicity. The American Diabetes Association guidelines recommend that glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) should not exceed 8.0% and consider a fasting blood glucose level >250 mg/dL as high, with a need to start insulin treatment right away; other guidelines recommend initiating insulin immediately in patients with HbA1c >9% and postprandial glucose 300 mg/dL. But this was at a time when oral agents were not as effective and took time to titrate or engender good control. We now have agents that are more effective and start working right away.

However, the main problem in early insulin treatment is the significant risk of over-insulinization—a vicious cycle of insulin-caused increased appetite, hypoglycemia-resultant increased weight gain, insulin resistance (poorer control), increased circulating insulin, etc. Moreover, weight gain and individual hypoglycemic events can cause an increase in the risk of cardiovascular (CV) events.

I believe clinicians must start as early as possible in the natural history of T2D to prevent progressive beta-cell failure. Do not believe in “first-, second-, or third-line”; in other words, do not prioritize, so there is no competition between classes. The goal I have for my patients is to provide therapies that aim for the lowest HbA1c possible without hypoglycemia, provide the greatest CV benefit, and assist in weight reduction.

My protocol, “the egregious eleven,” involves using the least number of agents in combinations that treat the greatest number of mechanisms of hyperglycemia—without the use of sulfonylureas (which cause beta-cell apoptosis, hypoglycemia, and weight gain). Fortunately, newer agents, such as glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonist (GLP-1 RA) and sodium-glucose cotransporter 1 (SGLT-2) inhibitors, work right away, cause weight reduction, and have side benefits of CV risk reduction—as well as preserve beta-cell function. Metformin remains a valuable agent and has its own potential side benefits, and bromocriptine-QR and pioglitazone have CV side benefits. So, there is really no need for early insulin in true T2D patients (ie, those that are non-ketosis prone and have sufficient beta-cell reserve).

Why reduce insulin in patients who are already on insulin?

Prior protocols resulted in 40%-50% of T2D patients being placed on insulin unnecessarily. As discussed, the side effects of insulin are many; they include weight gain, insulin resistance, hypoglycemia, and CV complications—all of which have been associated with a decline in quality of life.

What is your approach to reduce or eliminate insulin in those already on it (unnecessarily)?

First, I pick the right patient. Physicians should use sound clinical judgment to identify patients with likely residual beta-cell function. It is not just the “insulin-resistant patient," as 30%-50% of type 1 diabetes mellitus patients also have insulin resistance.

It needs to be a definite T2D patient: not ketosis prone, a family history T2D, no islet cell antibodies (if one has any concerns, check for them). They were often started on insulin in the emergency department with no ketosis and never received non-insulin therapy.

Patients need to be willing to commit to my strict, no-concentrated-sweets diet, to perform careful glucose monitoring, and to check their ketones. Patients should be willing to contact me if their sugar level is >250 mg/dL for 2 measurements in a row, while testing 4 times a day or using a continuous glucose-monitoring (CGM) device.

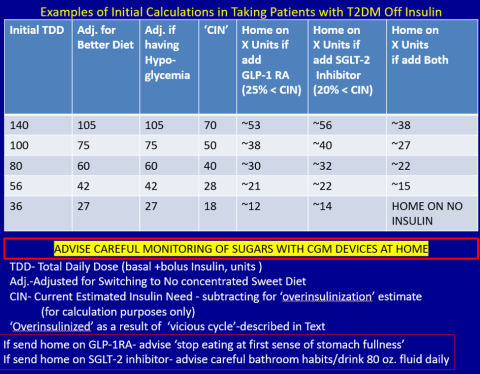

First, estimate a patient’s “current insulin need” (CIN), or the dose they might be on if they had not been subject to over-insulinization (ie, if they had not been subject to the “vicious cycle” discussed above). I do this by taking their total basal and bolus insulin dose, then reducing it by ~25% as the patient changes to a no-concentrated-sweets diet with an additional up-to-25% dose reduction if the patient has been experiencing symptomatic or asymptomatic hypoglycemia.

Next, I reduce this CIN number by ~25% upon starting a rapid-acting subcutaneous GLP-1 RA (liraglutide or oral semaglutide) and reduce the CIN another 20% as they start the SGLT-2 inhibitor. If patients come into my office on <40 U/d, I stop insulin as I start a GLP-1 RA and an SGLT-2 inhibitor and have them monitor home glucose levels to assure reasonable results as they go off the insulin and on their new therapy.

If patients come into my office on >40 U/d, they go home on a GLP-1 RA and an SGLT-2 inhibitor and ~30% of their presenting dose, apportioned between basal/bolus dosing based on when they are currently getting hypoglycemic.

The rapid initial reduction in their insulin doses, with initial adjustments in estimated insulin doses as needed based on home glucose monitoring, and rapid stabilization of glycemic levels by the effectiveness of these 2 agents give patients great motivation to keep up with the diet/program.

Then, as patients lose weight, they are told to report any glucose measurements <80 mg/dL, so that further reduction in insulin doses can be made. When patients achieve a new steady state of glycemia, weight, and GLP-1 RA and SGLT-2 inhibitor doses, you can add bromocriptine-QR, pioglitazone, and/or metformin as needed to allow for a further reduction of insulin. And, as you see the delayed effects of subsequently adding these new agents (eg, glucose <80 mg/dL), you can ultimately stop insulin when they get to <10-12 U/d. The process works very well, even in those starting on up to 300 units of insulin daily. Patients love the outcome and will greatly appreciate your care.

Feel free to contact Dr. Schwartz at stschwar@gmail.com with any questions about his protocol or diet.

For people living with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2D), exogenous insulin, whether given early or later in T2D diagnosis, can provide many pharmacologically desirable effects. But it has always been clear, and is now more widely recognized, that insulin treatments are not completely risk-free for the patient. There are now newer, non-insulin therapy options that could be used, along with certain patient lifestyle changes in diet and activity levels, that have been shown to achieve desired glucose control—without the associated risks that insulin can bring.

But is it possible to markedly reduce the need for insulin in some 90% of T2D patients and to reduce the doses in the others? Yes—if patients have sufficient beta-cell function and are willing to change their lifestyle. This mode of treatment has been slowly gaining momentum as of late in the medical community because of the benefits it ultimately provides for the patient. In my practice, I personally have done this by using an evidence-based approach that includes thinking inside a larger box. It is a 2-way street, and each should drive the other: the right drugs (in the right doses), and in the right patients.

Why avoid early insulin therapy?

Is the requirement of early insulin therapy in many or most patients a myth?

Yes. It resulted from “old logic,” which was to use insulin early to reduce glucotoxicity and lipotoxicity. The American Diabetes Association guidelines recommend that glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) should not exceed 8.0% and consider a fasting blood glucose level >250 mg/dL as high, with a need to start insulin treatment right away; other guidelines recommend initiating insulin immediately in patients with HbA1c >9% and postprandial glucose 300 mg/dL. But this was at a time when oral agents were not as effective and took time to titrate or engender good control. We now have agents that are more effective and start working right away.

However, the main problem in early insulin treatment is the significant risk of over-insulinization—a vicious cycle of insulin-caused increased appetite, hypoglycemia-resultant increased weight gain, insulin resistance (poorer control), increased circulating insulin, etc. Moreover, weight gain and individual hypoglycemic events can cause an increase in the risk of cardiovascular (CV) events.

I believe clinicians must start as early as possible in the natural history of T2D to prevent progressive beta-cell failure. Do not believe in “first-, second-, or third-line”; in other words, do not prioritize, so there is no competition between classes. The goal I have for my patients is to provide therapies that aim for the lowest HbA1c possible without hypoglycemia, provide the greatest CV benefit, and assist in weight reduction.

My protocol, “the egregious eleven,” involves using the least number of agents in combinations that treat the greatest number of mechanisms of hyperglycemia—without the use of sulfonylureas (which cause beta-cell apoptosis, hypoglycemia, and weight gain). Fortunately, newer agents, such as glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonist (GLP-1 RA) and sodium-glucose cotransporter 1 (SGLT-2) inhibitors, work right away, cause weight reduction, and have side benefits of CV risk reduction—as well as preserve beta-cell function. Metformin remains a valuable agent and has its own potential side benefits, and bromocriptine-QR and pioglitazone have CV side benefits. So, there is really no need for early insulin in true T2D patients (ie, those that are non-ketosis prone and have sufficient beta-cell reserve).

Why reduce insulin in patients who are already on insulin?

Prior protocols resulted in 40%-50% of T2D patients being placed on insulin unnecessarily. As discussed, the side effects of insulin are many; they include weight gain, insulin resistance, hypoglycemia, and CV complications—all of which have been associated with a decline in quality of life.

What is your approach to reduce or eliminate insulin in those already on it (unnecessarily)?

First, I pick the right patient. Physicians should use sound clinical judgment to identify patients with likely residual beta-cell function. It is not just the “insulin-resistant patient," as 30%-50% of type 1 diabetes mellitus patients also have insulin resistance.

It needs to be a definite T2D patient: not ketosis prone, a family history T2D, no islet cell antibodies (if one has any concerns, check for them). They were often started on insulin in the emergency department with no ketosis and never received non-insulin therapy.

Patients need to be willing to commit to my strict, no-concentrated-sweets diet, to perform careful glucose monitoring, and to check their ketones. Patients should be willing to contact me if their sugar level is >250 mg/dL for 2 measurements in a row, while testing 4 times a day or using a continuous glucose-monitoring (CGM) device.

First, estimate a patient’s “current insulin need” (CIN), or the dose they might be on if they had not been subject to over-insulinization (ie, if they had not been subject to the “vicious cycle” discussed above). I do this by taking their total basal and bolus insulin dose, then reducing it by ~25% as the patient changes to a no-concentrated-sweets diet with an additional up-to-25% dose reduction if the patient has been experiencing symptomatic or asymptomatic hypoglycemia.

Next, I reduce this CIN number by ~25% upon starting a rapid-acting subcutaneous GLP-1 RA (liraglutide or oral semaglutide) and reduce the CIN another 20% as they start the SGLT-2 inhibitor. If patients come into my office on <40 U/d, I stop insulin as I start a GLP-1 RA and an SGLT-2 inhibitor and have them monitor home glucose levels to assure reasonable results as they go off the insulin and on their new therapy.

If patients come into my office on >40 U/d, they go home on a GLP-1 RA and an SGLT-2 inhibitor and ~30% of their presenting dose, apportioned between basal/bolus dosing based on when they are currently getting hypoglycemic.

The rapid initial reduction in their insulin doses, with initial adjustments in estimated insulin doses as needed based on home glucose monitoring, and rapid stabilization of glycemic levels by the effectiveness of these 2 agents give patients great motivation to keep up with the diet/program.

Then, as patients lose weight, they are told to report any glucose measurements <80 mg/dL, so that further reduction in insulin doses can be made. When patients achieve a new steady state of glycemia, weight, and GLP-1 RA and SGLT-2 inhibitor doses, you can add bromocriptine-QR, pioglitazone, and/or metformin as needed to allow for a further reduction of insulin. And, as you see the delayed effects of subsequently adding these new agents (eg, glucose <80 mg/dL), you can ultimately stop insulin when they get to <10-12 U/d. The process works very well, even in those starting on up to 300 units of insulin daily. Patients love the outcome and will greatly appreciate your care.

Feel free to contact Dr. Schwartz at stschwar@gmail.com with any questions about his protocol or diet.

For people living with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2D), exogenous insulin, whether given early or later in T2D diagnosis, can provide many pharmacologically desirable effects. But it has always been clear, and is now more widely recognized, that insulin treatments are not completely risk-free for the patient. There are now newer, non-insulin therapy options that could be used, along with certain patient lifestyle changes in diet and activity levels, that have been shown to achieve desired glucose control—without the associated risks that insulin can bring.

But is it possible to markedly reduce the need for insulin in some 90% of T2D patients and to reduce the doses in the others? Yes—if patients have sufficient beta-cell function and are willing to change their lifestyle. This mode of treatment has been slowly gaining momentum as of late in the medical community because of the benefits it ultimately provides for the patient. In my practice, I personally have done this by using an evidence-based approach that includes thinking inside a larger box. It is a 2-way street, and each should drive the other: the right drugs (in the right doses), and in the right patients.

Why avoid early insulin therapy?

Is the requirement of early insulin therapy in many or most patients a myth?

Yes. It resulted from “old logic,” which was to use insulin early to reduce glucotoxicity and lipotoxicity. The American Diabetes Association guidelines recommend that glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) should not exceed 8.0% and consider a fasting blood glucose level >250 mg/dL as high, with a need to start insulin treatment right away; other guidelines recommend initiating insulin immediately in patients with HbA1c >9% and postprandial glucose 300 mg/dL. But this was at a time when oral agents were not as effective and took time to titrate or engender good control. We now have agents that are more effective and start working right away.

However, the main problem in early insulin treatment is the significant risk of over-insulinization—a vicious cycle of insulin-caused increased appetite, hypoglycemia-resultant increased weight gain, insulin resistance (poorer control), increased circulating insulin, etc. Moreover, weight gain and individual hypoglycemic events can cause an increase in the risk of cardiovascular (CV) events.

I believe clinicians must start as early as possible in the natural history of T2D to prevent progressive beta-cell failure. Do not believe in “first-, second-, or third-line”; in other words, do not prioritize, so there is no competition between classes. The goal I have for my patients is to provide therapies that aim for the lowest HbA1c possible without hypoglycemia, provide the greatest CV benefit, and assist in weight reduction.

My protocol, “the egregious eleven,” involves using the least number of agents in combinations that treat the greatest number of mechanisms of hyperglycemia—without the use of sulfonylureas (which cause beta-cell apoptosis, hypoglycemia, and weight gain). Fortunately, newer agents, such as glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonist (GLP-1 RA) and sodium-glucose cotransporter 1 (SGLT-2) inhibitors, work right away, cause weight reduction, and have side benefits of CV risk reduction—as well as preserve beta-cell function. Metformin remains a valuable agent and has its own potential side benefits, and bromocriptine-QR and pioglitazone have CV side benefits. So, there is really no need for early insulin in true T2D patients (ie, those that are non-ketosis prone and have sufficient beta-cell reserve).

Why reduce insulin in patients who are already on insulin?

Prior protocols resulted in 40%-50% of T2D patients being placed on insulin unnecessarily. As discussed, the side effects of insulin are many; they include weight gain, insulin resistance, hypoglycemia, and CV complications—all of which have been associated with a decline in quality of life.

What is your approach to reduce or eliminate insulin in those already on it (unnecessarily)?

First, I pick the right patient. Physicians should use sound clinical judgment to identify patients with likely residual beta-cell function. It is not just the “insulin-resistant patient," as 30%-50% of type 1 diabetes mellitus patients also have insulin resistance.

It needs to be a definite T2D patient: not ketosis prone, a family history T2D, no islet cell antibodies (if one has any concerns, check for them). They were often started on insulin in the emergency department with no ketosis and never received non-insulin therapy.

Patients need to be willing to commit to my strict, no-concentrated-sweets diet, to perform careful glucose monitoring, and to check their ketones. Patients should be willing to contact me if their sugar level is >250 mg/dL for 2 measurements in a row, while testing 4 times a day or using a continuous glucose-monitoring (CGM) device.

First, estimate a patient’s “current insulin need” (CIN), or the dose they might be on if they had not been subject to over-insulinization (ie, if they had not been subject to the “vicious cycle” discussed above). I do this by taking their total basal and bolus insulin dose, then reducing it by ~25% as the patient changes to a no-concentrated-sweets diet with an additional up-to-25% dose reduction if the patient has been experiencing symptomatic or asymptomatic hypoglycemia.

Next, I reduce this CIN number by ~25% upon starting a rapid-acting subcutaneous GLP-1 RA (liraglutide or oral semaglutide) and reduce the CIN another 20% as they start the SGLT-2 inhibitor. If patients come into my office on <40 U/d, I stop insulin as I start a GLP-1 RA and an SGLT-2 inhibitor and have them monitor home glucose levels to assure reasonable results as they go off the insulin and on their new therapy.

If patients come into my office on >40 U/d, they go home on a GLP-1 RA and an SGLT-2 inhibitor and ~30% of their presenting dose, apportioned between basal/bolus dosing based on when they are currently getting hypoglycemic.

The rapid initial reduction in their insulin doses, with initial adjustments in estimated insulin doses as needed based on home glucose monitoring, and rapid stabilization of glycemic levels by the effectiveness of these 2 agents give patients great motivation to keep up with the diet/program.

Then, as patients lose weight, they are told to report any glucose measurements <80 mg/dL, so that further reduction in insulin doses can be made. When patients achieve a new steady state of glycemia, weight, and GLP-1 RA and SGLT-2 inhibitor doses, you can add bromocriptine-QR, pioglitazone, and/or metformin as needed to allow for a further reduction of insulin. And, as you see the delayed effects of subsequently adding these new agents (eg, glucose <80 mg/dL), you can ultimately stop insulin when they get to <10-12 U/d. The process works very well, even in those starting on up to 300 units of insulin daily. Patients love the outcome and will greatly appreciate your care.

Feel free to contact Dr. Schwartz at stschwar@gmail.com with any questions about his protocol or diet.

Fitbit figures: More steps per day cut type 2 diabetes risk

The protective effect of daily step count on type 2 diabetes risk remained after adjusting for smoking and sedentary time.

Taking more steps per day was also associated with less risk of developing type 2 diabetes in different subgroups of physical activity intensity.

“Our data shows the importance of moving your body every day to lower your risk of [type 2] diabetes,” said the lead author of the research, Andrew S. Perry, MD. The findings were published online in the Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism.

Despite low baseline risk, benefit from increased physical activity

The study was conducted in more than 5,000 participants in the National Institutes of Health’s All of Us research program who had a median age of 51 and were generally overweight (median BMI 27.8 kg/m2). Three quarters were women and 89% were White.

It used an innovative approach in a real-world population, said Dr. Perry, of Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville, Tenn.

The individuals in this cohort had relatively few risk factors, so it was not surprising that the incidence of type 2 diabetes overall was low (2%), the researchers note. “Yet, despite being low risk, we still detected a signal of benefit from increased” physical activity, Dr. Perry and colleagues write.

The individuals had a median of 16 very active minutes/day, which corresponds to 112 very active minutes/week (ie, less than the guideline-recommended 150 minutes of physical activity/week).

“These results indicate that amounts of physical activity are correlated with lower risk of [type 2] diabetes, regardless of the intensity level, and even at amounts less than current guidelines recommend,” the researchers summarize.

Physical activity tracked over close to 4 years

Prior studies of the relationship between physical activity and type 2 diabetes risk relied primarily on questionnaires that asked people about physical activity at one point in time.

The researchers aimed to examine this association over time, in a contemporary cohort of Fitbit users who participated in the All of Us program.

From 12,781 participants with Fitbit data between 2010 and 2021, they identified 5,677 individuals who were at least 18 years old and had linked electronic health record data, no diabetes at baseline, at least 15 days of Fitbit data in the initial monitoring period, and at least 180 days of follow-up.

The Fitbit counts steps, and it also uses an algorithm to quantify physical activity intensity as lightly active (1.5-3 metabolic equivalent task (METs), fairly active (3-6 METs), and very active (> 6 METs).

During a median 3.8-year follow-up, participants made a median of 7,924 steps/day and were “fairly active” for a median of 16 minutes/day.

They found 97 new cases of type 2 diabetes over a follow-up of 4 years in the dataset.

The predicted cumulative incidence of type 2 diabetes at 5 years was 0.8% for individuals who walked 13,245 steps/day (90th percentile) vs. 2.3% for those who walked 4,301 steps/day (10th percentile).

“We hope to study more diverse populations in future studies to confirm the generalizability of these findings,” Dr. Perry said.

This study received funding from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Dr. Perry reports no relevant financial relationships. Disclosures for the other authors are listed with the original article.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The protective effect of daily step count on type 2 diabetes risk remained after adjusting for smoking and sedentary time.

Taking more steps per day was also associated with less risk of developing type 2 diabetes in different subgroups of physical activity intensity.

“Our data shows the importance of moving your body every day to lower your risk of [type 2] diabetes,” said the lead author of the research, Andrew S. Perry, MD. The findings were published online in the Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism.

Despite low baseline risk, benefit from increased physical activity

The study was conducted in more than 5,000 participants in the National Institutes of Health’s All of Us research program who had a median age of 51 and were generally overweight (median BMI 27.8 kg/m2). Three quarters were women and 89% were White.

It used an innovative approach in a real-world population, said Dr. Perry, of Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville, Tenn.

The individuals in this cohort had relatively few risk factors, so it was not surprising that the incidence of type 2 diabetes overall was low (2%), the researchers note. “Yet, despite being low risk, we still detected a signal of benefit from increased” physical activity, Dr. Perry and colleagues write.

The individuals had a median of 16 very active minutes/day, which corresponds to 112 very active minutes/week (ie, less than the guideline-recommended 150 minutes of physical activity/week).

“These results indicate that amounts of physical activity are correlated with lower risk of [type 2] diabetes, regardless of the intensity level, and even at amounts less than current guidelines recommend,” the researchers summarize.

Physical activity tracked over close to 4 years

Prior studies of the relationship between physical activity and type 2 diabetes risk relied primarily on questionnaires that asked people about physical activity at one point in time.