User login

Fast Track to Abdominal Pain

ANSWER

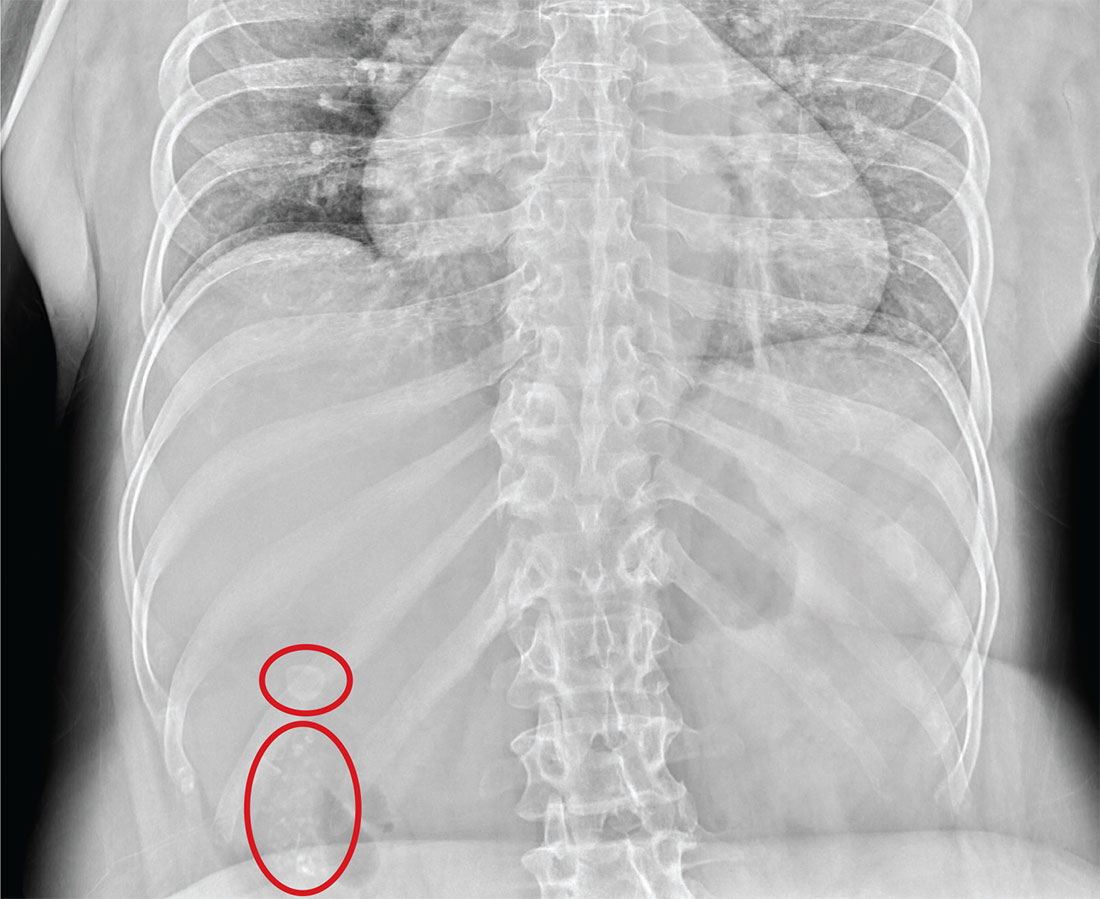

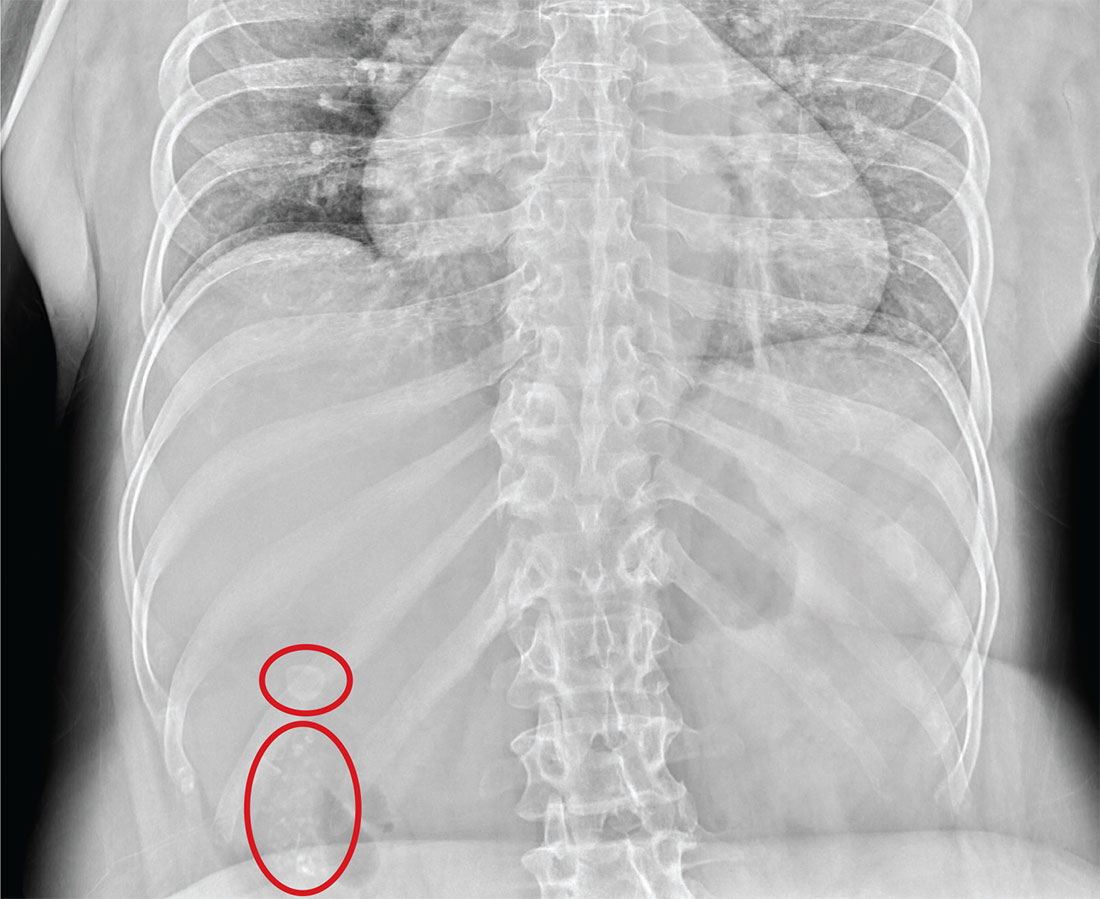

The radiograph illustrates a large calcification within the right upper quadrant—most likely a gallstone. Several smaller calcifications are clustered together in the same area, making the diagnosis cholelithiasis. The patient was referred to the general surgery clinic for further

evaluation.

For recent findings on gallstone disease and heart risk, see here.

ANSWER

The radiograph illustrates a large calcification within the right upper quadrant—most likely a gallstone. Several smaller calcifications are clustered together in the same area, making the diagnosis cholelithiasis. The patient was referred to the general surgery clinic for further

evaluation.

For recent findings on gallstone disease and heart risk, see here.

ANSWER

The radiograph illustrates a large calcification within the right upper quadrant—most likely a gallstone. Several smaller calcifications are clustered together in the same area, making the diagnosis cholelithiasis. The patient was referred to the general surgery clinic for further

evaluation.

For recent findings on gallstone disease and heart risk, see here.

An NP student you are precepting in the emergency department fast track area presents her patient to you: a 60-year-old woman with abdominal pain. The pain is chronic but has worsened slightly, prompting the patient, who does not have a primary care provider, to present today. She experiences occasional nausea but no fever, and she denies any bowel or bladder complaints other than constipation. Her medical history is significant for mild hypertension.

On exam, your student notes an obese female who is in no obvious distress. The patient’s vital signs are all within normal limits. The abdominal exam is unimpressive, revealing a soft abdomen with good bowel sounds. Although she does have mild diffuse tenderness, she has no rebound or guarding.

Although your student suspects the patient is just constipated, she orders blood work and urinalysis. An abdominal survey is obtained as well. What is your impression?

Woman, 36, With Fever and Malaise

IN THIS ARTICLE

- Clinical presentation and evaluation

- Terminology table

- Outcome for the case patient

A 36-year-old Bengali woman with a history of well-controlled diabetes presents to the emergency department with complaints of feeling “unwell” for about two weeks. She does not speak English, and a hospital-provided phone translator is used to obtain history and explain hospital course. The patient is vague regarding symptomatology, describing general malaise and tiredness. She says she became “much worse” two days ago and has shaking chills, sore throat, headache, and nonproductive cough, but she denies shortness of breath or chest pain. She also developed nausea and vomiting, stating, “I can’t keep anything down.”

She has not recently traveled out of the country and has no known sick contacts. Influenza activity is high in the area, and the patient has not received immunization. She had a “normal” menstrual period two weeks ago and firmly states, “There is no way I can be pregnant.” She admits to vaginal “spotting” off and on for the past two weeks without abdominal pain. She is married with six children and has no history of miscarriage, ectopic pregnancy, or induced abortion; she is not taking any form of birth control.

On exam, the patient is tachycardic, with a heart rate of 127 beats/min, and has a fever of 103.3°F. Blood pressure, respiratory rate, and pulse oximetry are normal. She appears unwell and dehydrated. Her mucous membranes are dry, but no skin rash is noted. There is no tonsillar swelling or exudate and no meningismus; the lung exam is clear, with no adventitious sounds. Abdominal exam demonstrates mild, generalized tenderness in the lower abdomen without peritoneal signs. No costovertebral angle tenderness is noted. Initial diagnostic considerations include sources of fever (eg, influenza, pneumonia, urinary tract infection, viral illness), or abdominal sources, such as appendicitis.

An upright anteroposterior chest x-ray shows no infiltrate, pleural effusion, or cardiomegaly. Laboratory results include a high white blood cell (WBC) count (16.9 k/mm3) with bandemia and normal electrolytes without anion gap. Rapid influenza A and B testing is negative. A urine pregnancy test is positive, and the urinalysis shows no infection but +2 ketones. Rh factor is positive. A serum quantitative β-hCG is 130,581 mIU/mL. Blood cultures are obtained, but results are not available.

Due to cultural differences, the patient is very reluctant to consent to a pelvic exam. After extensive counseling, she agrees to a bimanual exam only. The uterus is boggy and enlarged to about 12 weeks. There is exquisite uterine tenderness and purulent discharge on the gloved finger. The cervical os is closed, and there is scant bleeding.

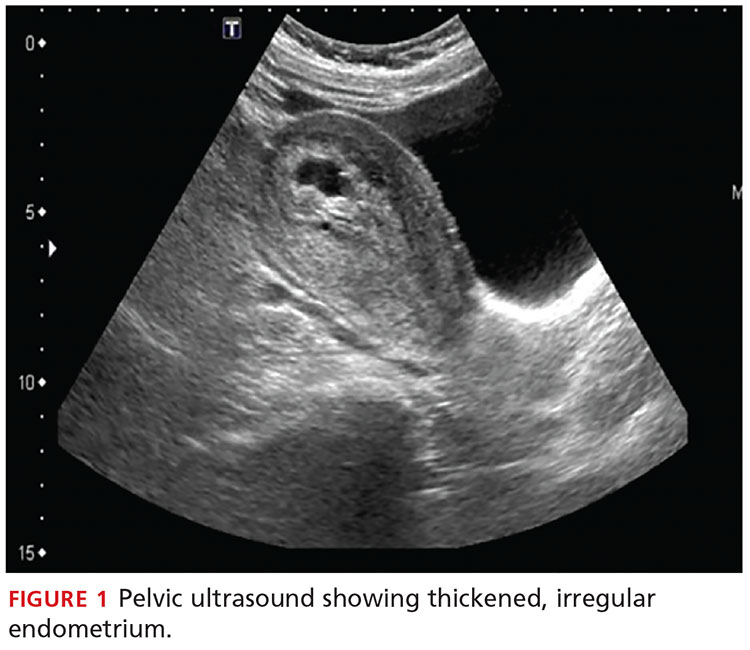

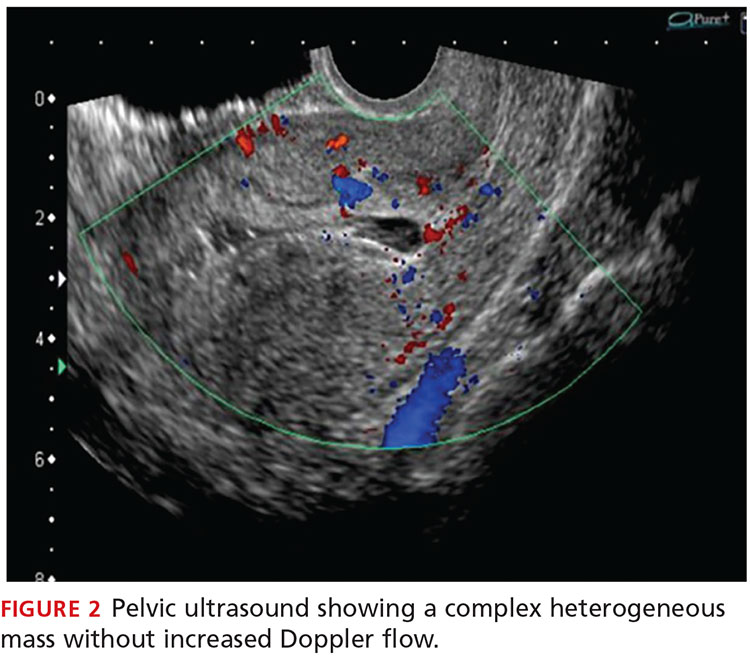

A transvaginal ultrasound is obtained; it reveals a thickened endometrium with echogenicity, without increased vascularity, and no identifiable intrauterine pregnancy. The adnexa have no masses, and there is no free fluid in the endometrium (see Figures 1 and 2).

The patient is given broad-spectrum antibiotics and urgently transported to the operating room by Ob-Gyn for uterine evacuation. She is found to have a septic abortion due to retained products of conception (RPOC) from an incomplete miscarriage.

Continue for discussion >>

DISCUSSIONIt is not uncommon for a woman to miscarry a very early pregnancy and not realize she had been pregnant.1 Many attribute it to a “heavy” or unusual period. In one study, 11% of patients who denied the possibility of pregnancy were, in fact, pregnant.2

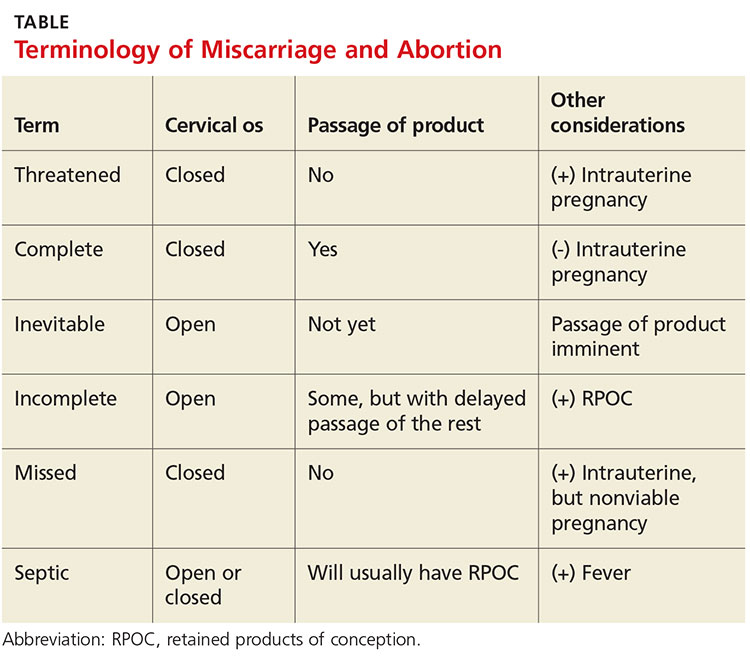

Miscarriage is a frequent outcome of early pregnancy; it is estimated that 11% to 20% of early pregnancies result in a spontaneous miscarriage.3-5 Most resolve without complications, but risk increases with gestational age. When they do occur, complications include RPOC, heavy prolonged bleeding, and endometritis. RPOC refers to placental or fetal tissue that remains in the uterus after a miscarriage, surgical abortion, or preterm/term delivery (see Table for additional terminology related to miscarriage and abortion). Because of increased morbidity, it is important to suspect RPOC after a known miscarriage or an induced abortion, or in a pregnant patient with bleeding.

Incidence and pathophysiologySeptic abortion is a relatively rare complication of miscarriage. It can refer to a spontaneous miscarriage complicated by a subsequent intrauterine infection, often caused by RPOC. Septic abortion is much more common after an induced abortion, in which there is instrumentation of the uterus.

The infection after a spontaneous miscarriage usually begins as endometritis. It involves the necrotic RPOC, which are prone to infection by the cervical and vaginal flora. It may spread further into the parametrium/myometrium and the peritoneal cavity. The infection may then progress to bacteremia and sepsis. Typical causative organisms include Escherichia coli, Enterobacter aerogenes, Proteus vulgaris, hemolytic streptococci, staphylococci, and some anaerobic organisms, including Clostridium perfringens.3

Death, although rare in developed countries, is usually secondary to the sequela of sepsis, including septic shock, renal failure, adult respiratory distress syndrome, and disseminated intravascular coagulation.3,6,7 Pelvic adhesions and hysterectomy are also possible outcomes of a septic abortion.

Continue for clinical presentation and evaluation >>

Clinical presentation and evaluationMany findings suggestive of septic abortion are nonspecific, such as bleeding, pain, uterine tenderness, and fever. A combination of historical risk, physical exam, and laboratory and ultrasound findings will often be needed to confirm the diagnosis.

Fever is never to be expected in an uncomplicated miscarriage. Vaginal bleeding and some cramping are common after miscarriage; women will bleed, on average, between eight and 11 days afterward.5 Women who fall outside the normal range and experience prolonged bleeding, heavy bleeding, or severe abdominal pain should be evaluated.

A workup for patients with a possible septic abortion should include a complete blood count, blood culture with additional laboratory investigation if there is concern for bacteremia/sepsis, and type and screen for Rh factor and for possible blood transfusion, if needed.

All patients with postabortion complications should be screened for Rh factor; Rho(D) immune globulin (RhoGAM) should be administered if results indicate that the patient is Rh-negative and unsensitized. A quantitative β-hCG level can be obtained to confirm pregnancy. A single measurement will not be helpful; β-hCG can remain positive for weeks after an uncomplicated miscarriage. On the other hand, a low level does not exclude RPOC—the RPOC, if necrotic, may remain in the uterus without secreting hormone. The trend of β-hCG over time can be helpful if the diagnosis is unclear.

A careful physical exam, including a pelvic exam, should be performed. Assess for uterine tenderness, peritoneal signs, and purulent discharge from the cervix. An open cervical os is suggestive of RPOC, as the cervix closes quickly after a complete miscarriage, but a closed cervical os does not exclude the possibility of RPOC or septic abortion. The amount of bleeding should be noted, along with any tissue or clots within the vaginal vault or cervix.

A pelvic ultrasound should be obtained in all patients concerning for a septic incomplete miscarriage. Ultrasound findings can be nonspecific, because small amounts of retained tissue can look like blood (a common finding after miscarriage). Ultrasound findings of heterogeneous, echogenic material within the uterus or a thick, irregular endometrium support a diagnosis of RPOC in patients considered at risk.8,9 Increased color Doppler flow is often seen with RPOC, but there may be decreased flow in the case of necrotic RPOC. Ultrasound findings consistent with RPOC in a febrile, ill patient suggest a septic abortion.

Continue for treatment and prognosis >>

Treatment and prognosisPatients with a septic abortion require immediate evacuation of the uterus to prevent deadly complications; antibiotics may not be able to perfuse to the necrotic source of infection.10 Suction curettage is less likely than sharp curettage to cause perforation.

Broad-spectrum antibiotics should be administered. The bacteria associated with a septic incomplete miscarriage are usually polymicrobial and represent the normal flora of the vagina and cervix. The choice of agents recommended is usually the same as for pelvic inflammatory disease.11

The treatment regimen typically includes clindamycin (900 mg IV q8h), plus gentamicin (5 mg/kg IV once a day), with or without ampicillin (2 g IV q4h).11,12 Alternatively, a combination of ampicillin, gentamicin, and metronidazole (500 mg IV q8h) can be used.

Further surgery, including laparotomy and possible hysterectomy, is indicated in patients who do not respond to uterine evacuation and parenteral antibiotics. Other possible complications requiring surgery include pelvic abscess, necrotizing Clostridium infections in the myometrium, and uterine perforation.

OUTCOME FOR THE CASE PATIENTThe patient was started on IV ampicillin, gentamicin, and clindamycin and taken promptly for a suction dilation and curettage. Pathology later showed a gestational sac with severe acute necrotizing chorioamnionitis and extensive bacterial growth. This confirmed the diagnosis of a septic, incomplete miscarriage.

Blood cultures remained without any growth, and the patient was afebrile on the second postop day. The WBC count and β-hCG level trended downward.

The patient was discharged on a 14-day course of oral doxycycline and metronidazole. She was then lost to further follow-up.

CONCLUSIONThe differential diagnosis in this ill, febrile patient was initially very broad. The importance of suspecting pregnancy in all women of childbearing age, especially those not using contraception, cannot be underestimated. The accuracy of patient history and recall of last menstrual period in determining the possibility of pregnancy is not sufficiently reliable.

1. Promislow JH, Baird DD, Wilcox AJ, et al. Bleeding following pregnancy loss prior to six weeks gestation. Hum Reprod. 2007;22(3):853-857.

2. Ramoska EA, Sacchetti AD, Nepp M. Reliability of patient history in determining the possibility of pregnancy. Ann Emerg Med. 1989;18(1):48-50.

3. Osazuwa H, Aziken M. Septic abortion: a review of social and demographic characteristics. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2007;275(2):117-119.

4. Hure AJ, Powers JR, Mishra GD, et al. Miscarriage, preterm delivery, and stillbirth: large variations in rates within a cohort of Australian women. PLoS One. 2012;7(5):e37109.

5. Nielsen S, Hahlin M. Expectant management of first-trimester spontaneous abortion. Lancet. 1995;345(8942):84-86.

6. Eschenbach DA. Treating spontaneous and induced septic abortions. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125(5):1042-1048.

7. Rana A, Pradhan N, Gurung G, Singh M. Induced septic abortion: a major factor in maternal mortality and morbidity. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2004;30(1):3-8.

8. Abbasi S, Jamal A, Eslamian L, Marsousi V. Role of clinical and ultrasound findings in the diagnosis of retained products of conception. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2008;32(5):704-707.

9. Esmaeillou H, Jamal A, Eslamian L, et al. Accurate detection of retained products of conception after first- and second-trimester abortion by color doppler sonography. J Med Ultrasound. 2015;23(7):34-38.

10. Finkielman JD, De Feo FD, Heller PG, Afessa B. The clinical course of patients with septic abortion admitted to an intensive care unit. Intensive Care Med. 2004;30(6):1097-1102.

11. CDC. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010;59(RR-12):1-110.

12. Mackeen AD, Packard RE, Ota E, Speer L. Antibiotic regimens for postpartum endometritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;2:CD001067.

IN THIS ARTICLE

- Clinical presentation and evaluation

- Terminology table

- Outcome for the case patient

A 36-year-old Bengali woman with a history of well-controlled diabetes presents to the emergency department with complaints of feeling “unwell” for about two weeks. She does not speak English, and a hospital-provided phone translator is used to obtain history and explain hospital course. The patient is vague regarding symptomatology, describing general malaise and tiredness. She says she became “much worse” two days ago and has shaking chills, sore throat, headache, and nonproductive cough, but she denies shortness of breath or chest pain. She also developed nausea and vomiting, stating, “I can’t keep anything down.”

She has not recently traveled out of the country and has no known sick contacts. Influenza activity is high in the area, and the patient has not received immunization. She had a “normal” menstrual period two weeks ago and firmly states, “There is no way I can be pregnant.” She admits to vaginal “spotting” off and on for the past two weeks without abdominal pain. She is married with six children and has no history of miscarriage, ectopic pregnancy, or induced abortion; she is not taking any form of birth control.

On exam, the patient is tachycardic, with a heart rate of 127 beats/min, and has a fever of 103.3°F. Blood pressure, respiratory rate, and pulse oximetry are normal. She appears unwell and dehydrated. Her mucous membranes are dry, but no skin rash is noted. There is no tonsillar swelling or exudate and no meningismus; the lung exam is clear, with no adventitious sounds. Abdominal exam demonstrates mild, generalized tenderness in the lower abdomen without peritoneal signs. No costovertebral angle tenderness is noted. Initial diagnostic considerations include sources of fever (eg, influenza, pneumonia, urinary tract infection, viral illness), or abdominal sources, such as appendicitis.

An upright anteroposterior chest x-ray shows no infiltrate, pleural effusion, or cardiomegaly. Laboratory results include a high white blood cell (WBC) count (16.9 k/mm3) with bandemia and normal electrolytes without anion gap. Rapid influenza A and B testing is negative. A urine pregnancy test is positive, and the urinalysis shows no infection but +2 ketones. Rh factor is positive. A serum quantitative β-hCG is 130,581 mIU/mL. Blood cultures are obtained, but results are not available.

Due to cultural differences, the patient is very reluctant to consent to a pelvic exam. After extensive counseling, she agrees to a bimanual exam only. The uterus is boggy and enlarged to about 12 weeks. There is exquisite uterine tenderness and purulent discharge on the gloved finger. The cervical os is closed, and there is scant bleeding.

A transvaginal ultrasound is obtained; it reveals a thickened endometrium with echogenicity, without increased vascularity, and no identifiable intrauterine pregnancy. The adnexa have no masses, and there is no free fluid in the endometrium (see Figures 1 and 2).

The patient is given broad-spectrum antibiotics and urgently transported to the operating room by Ob-Gyn for uterine evacuation. She is found to have a septic abortion due to retained products of conception (RPOC) from an incomplete miscarriage.

Continue for discussion >>

DISCUSSIONIt is not uncommon for a woman to miscarry a very early pregnancy and not realize she had been pregnant.1 Many attribute it to a “heavy” or unusual period. In one study, 11% of patients who denied the possibility of pregnancy were, in fact, pregnant.2

Miscarriage is a frequent outcome of early pregnancy; it is estimated that 11% to 20% of early pregnancies result in a spontaneous miscarriage.3-5 Most resolve without complications, but risk increases with gestational age. When they do occur, complications include RPOC, heavy prolonged bleeding, and endometritis. RPOC refers to placental or fetal tissue that remains in the uterus after a miscarriage, surgical abortion, or preterm/term delivery (see Table for additional terminology related to miscarriage and abortion). Because of increased morbidity, it is important to suspect RPOC after a known miscarriage or an induced abortion, or in a pregnant patient with bleeding.

Incidence and pathophysiologySeptic abortion is a relatively rare complication of miscarriage. It can refer to a spontaneous miscarriage complicated by a subsequent intrauterine infection, often caused by RPOC. Septic abortion is much more common after an induced abortion, in which there is instrumentation of the uterus.

The infection after a spontaneous miscarriage usually begins as endometritis. It involves the necrotic RPOC, which are prone to infection by the cervical and vaginal flora. It may spread further into the parametrium/myometrium and the peritoneal cavity. The infection may then progress to bacteremia and sepsis. Typical causative organisms include Escherichia coli, Enterobacter aerogenes, Proteus vulgaris, hemolytic streptococci, staphylococci, and some anaerobic organisms, including Clostridium perfringens.3

Death, although rare in developed countries, is usually secondary to the sequela of sepsis, including septic shock, renal failure, adult respiratory distress syndrome, and disseminated intravascular coagulation.3,6,7 Pelvic adhesions and hysterectomy are also possible outcomes of a septic abortion.

Continue for clinical presentation and evaluation >>

Clinical presentation and evaluationMany findings suggestive of septic abortion are nonspecific, such as bleeding, pain, uterine tenderness, and fever. A combination of historical risk, physical exam, and laboratory and ultrasound findings will often be needed to confirm the diagnosis.

Fever is never to be expected in an uncomplicated miscarriage. Vaginal bleeding and some cramping are common after miscarriage; women will bleed, on average, between eight and 11 days afterward.5 Women who fall outside the normal range and experience prolonged bleeding, heavy bleeding, or severe abdominal pain should be evaluated.

A workup for patients with a possible septic abortion should include a complete blood count, blood culture with additional laboratory investigation if there is concern for bacteremia/sepsis, and type and screen for Rh factor and for possible blood transfusion, if needed.

All patients with postabortion complications should be screened for Rh factor; Rho(D) immune globulin (RhoGAM) should be administered if results indicate that the patient is Rh-negative and unsensitized. A quantitative β-hCG level can be obtained to confirm pregnancy. A single measurement will not be helpful; β-hCG can remain positive for weeks after an uncomplicated miscarriage. On the other hand, a low level does not exclude RPOC—the RPOC, if necrotic, may remain in the uterus without secreting hormone. The trend of β-hCG over time can be helpful if the diagnosis is unclear.

A careful physical exam, including a pelvic exam, should be performed. Assess for uterine tenderness, peritoneal signs, and purulent discharge from the cervix. An open cervical os is suggestive of RPOC, as the cervix closes quickly after a complete miscarriage, but a closed cervical os does not exclude the possibility of RPOC or septic abortion. The amount of bleeding should be noted, along with any tissue or clots within the vaginal vault or cervix.

A pelvic ultrasound should be obtained in all patients concerning for a septic incomplete miscarriage. Ultrasound findings can be nonspecific, because small amounts of retained tissue can look like blood (a common finding after miscarriage). Ultrasound findings of heterogeneous, echogenic material within the uterus or a thick, irregular endometrium support a diagnosis of RPOC in patients considered at risk.8,9 Increased color Doppler flow is often seen with RPOC, but there may be decreased flow in the case of necrotic RPOC. Ultrasound findings consistent with RPOC in a febrile, ill patient suggest a septic abortion.

Continue for treatment and prognosis >>

Treatment and prognosisPatients with a septic abortion require immediate evacuation of the uterus to prevent deadly complications; antibiotics may not be able to perfuse to the necrotic source of infection.10 Suction curettage is less likely than sharp curettage to cause perforation.

Broad-spectrum antibiotics should be administered. The bacteria associated with a septic incomplete miscarriage are usually polymicrobial and represent the normal flora of the vagina and cervix. The choice of agents recommended is usually the same as for pelvic inflammatory disease.11

The treatment regimen typically includes clindamycin (900 mg IV q8h), plus gentamicin (5 mg/kg IV once a day), with or without ampicillin (2 g IV q4h).11,12 Alternatively, a combination of ampicillin, gentamicin, and metronidazole (500 mg IV q8h) can be used.

Further surgery, including laparotomy and possible hysterectomy, is indicated in patients who do not respond to uterine evacuation and parenteral antibiotics. Other possible complications requiring surgery include pelvic abscess, necrotizing Clostridium infections in the myometrium, and uterine perforation.

OUTCOME FOR THE CASE PATIENTThe patient was started on IV ampicillin, gentamicin, and clindamycin and taken promptly for a suction dilation and curettage. Pathology later showed a gestational sac with severe acute necrotizing chorioamnionitis and extensive bacterial growth. This confirmed the diagnosis of a septic, incomplete miscarriage.

Blood cultures remained without any growth, and the patient was afebrile on the second postop day. The WBC count and β-hCG level trended downward.

The patient was discharged on a 14-day course of oral doxycycline and metronidazole. She was then lost to further follow-up.

CONCLUSIONThe differential diagnosis in this ill, febrile patient was initially very broad. The importance of suspecting pregnancy in all women of childbearing age, especially those not using contraception, cannot be underestimated. The accuracy of patient history and recall of last menstrual period in determining the possibility of pregnancy is not sufficiently reliable.

IN THIS ARTICLE

- Clinical presentation and evaluation

- Terminology table

- Outcome for the case patient

A 36-year-old Bengali woman with a history of well-controlled diabetes presents to the emergency department with complaints of feeling “unwell” for about two weeks. She does not speak English, and a hospital-provided phone translator is used to obtain history and explain hospital course. The patient is vague regarding symptomatology, describing general malaise and tiredness. She says she became “much worse” two days ago and has shaking chills, sore throat, headache, and nonproductive cough, but she denies shortness of breath or chest pain. She also developed nausea and vomiting, stating, “I can’t keep anything down.”

She has not recently traveled out of the country and has no known sick contacts. Influenza activity is high in the area, and the patient has not received immunization. She had a “normal” menstrual period two weeks ago and firmly states, “There is no way I can be pregnant.” She admits to vaginal “spotting” off and on for the past two weeks without abdominal pain. She is married with six children and has no history of miscarriage, ectopic pregnancy, or induced abortion; she is not taking any form of birth control.

On exam, the patient is tachycardic, with a heart rate of 127 beats/min, and has a fever of 103.3°F. Blood pressure, respiratory rate, and pulse oximetry are normal. She appears unwell and dehydrated. Her mucous membranes are dry, but no skin rash is noted. There is no tonsillar swelling or exudate and no meningismus; the lung exam is clear, with no adventitious sounds. Abdominal exam demonstrates mild, generalized tenderness in the lower abdomen without peritoneal signs. No costovertebral angle tenderness is noted. Initial diagnostic considerations include sources of fever (eg, influenza, pneumonia, urinary tract infection, viral illness), or abdominal sources, such as appendicitis.

An upright anteroposterior chest x-ray shows no infiltrate, pleural effusion, or cardiomegaly. Laboratory results include a high white blood cell (WBC) count (16.9 k/mm3) with bandemia and normal electrolytes without anion gap. Rapid influenza A and B testing is negative. A urine pregnancy test is positive, and the urinalysis shows no infection but +2 ketones. Rh factor is positive. A serum quantitative β-hCG is 130,581 mIU/mL. Blood cultures are obtained, but results are not available.

Due to cultural differences, the patient is very reluctant to consent to a pelvic exam. After extensive counseling, she agrees to a bimanual exam only. The uterus is boggy and enlarged to about 12 weeks. There is exquisite uterine tenderness and purulent discharge on the gloved finger. The cervical os is closed, and there is scant bleeding.

A transvaginal ultrasound is obtained; it reveals a thickened endometrium with echogenicity, without increased vascularity, and no identifiable intrauterine pregnancy. The adnexa have no masses, and there is no free fluid in the endometrium (see Figures 1 and 2).

The patient is given broad-spectrum antibiotics and urgently transported to the operating room by Ob-Gyn for uterine evacuation. She is found to have a septic abortion due to retained products of conception (RPOC) from an incomplete miscarriage.

Continue for discussion >>

DISCUSSIONIt is not uncommon for a woman to miscarry a very early pregnancy and not realize she had been pregnant.1 Many attribute it to a “heavy” or unusual period. In one study, 11% of patients who denied the possibility of pregnancy were, in fact, pregnant.2

Miscarriage is a frequent outcome of early pregnancy; it is estimated that 11% to 20% of early pregnancies result in a spontaneous miscarriage.3-5 Most resolve without complications, but risk increases with gestational age. When they do occur, complications include RPOC, heavy prolonged bleeding, and endometritis. RPOC refers to placental or fetal tissue that remains in the uterus after a miscarriage, surgical abortion, or preterm/term delivery (see Table for additional terminology related to miscarriage and abortion). Because of increased morbidity, it is important to suspect RPOC after a known miscarriage or an induced abortion, or in a pregnant patient with bleeding.

Incidence and pathophysiologySeptic abortion is a relatively rare complication of miscarriage. It can refer to a spontaneous miscarriage complicated by a subsequent intrauterine infection, often caused by RPOC. Septic abortion is much more common after an induced abortion, in which there is instrumentation of the uterus.

The infection after a spontaneous miscarriage usually begins as endometritis. It involves the necrotic RPOC, which are prone to infection by the cervical and vaginal flora. It may spread further into the parametrium/myometrium and the peritoneal cavity. The infection may then progress to bacteremia and sepsis. Typical causative organisms include Escherichia coli, Enterobacter aerogenes, Proteus vulgaris, hemolytic streptococci, staphylococci, and some anaerobic organisms, including Clostridium perfringens.3

Death, although rare in developed countries, is usually secondary to the sequela of sepsis, including septic shock, renal failure, adult respiratory distress syndrome, and disseminated intravascular coagulation.3,6,7 Pelvic adhesions and hysterectomy are also possible outcomes of a septic abortion.

Continue for clinical presentation and evaluation >>

Clinical presentation and evaluationMany findings suggestive of septic abortion are nonspecific, such as bleeding, pain, uterine tenderness, and fever. A combination of historical risk, physical exam, and laboratory and ultrasound findings will often be needed to confirm the diagnosis.

Fever is never to be expected in an uncomplicated miscarriage. Vaginal bleeding and some cramping are common after miscarriage; women will bleed, on average, between eight and 11 days afterward.5 Women who fall outside the normal range and experience prolonged bleeding, heavy bleeding, or severe abdominal pain should be evaluated.

A workup for patients with a possible septic abortion should include a complete blood count, blood culture with additional laboratory investigation if there is concern for bacteremia/sepsis, and type and screen for Rh factor and for possible blood transfusion, if needed.

All patients with postabortion complications should be screened for Rh factor; Rho(D) immune globulin (RhoGAM) should be administered if results indicate that the patient is Rh-negative and unsensitized. A quantitative β-hCG level can be obtained to confirm pregnancy. A single measurement will not be helpful; β-hCG can remain positive for weeks after an uncomplicated miscarriage. On the other hand, a low level does not exclude RPOC—the RPOC, if necrotic, may remain in the uterus without secreting hormone. The trend of β-hCG over time can be helpful if the diagnosis is unclear.

A careful physical exam, including a pelvic exam, should be performed. Assess for uterine tenderness, peritoneal signs, and purulent discharge from the cervix. An open cervical os is suggestive of RPOC, as the cervix closes quickly after a complete miscarriage, but a closed cervical os does not exclude the possibility of RPOC or septic abortion. The amount of bleeding should be noted, along with any tissue or clots within the vaginal vault or cervix.

A pelvic ultrasound should be obtained in all patients concerning for a septic incomplete miscarriage. Ultrasound findings can be nonspecific, because small amounts of retained tissue can look like blood (a common finding after miscarriage). Ultrasound findings of heterogeneous, echogenic material within the uterus or a thick, irregular endometrium support a diagnosis of RPOC in patients considered at risk.8,9 Increased color Doppler flow is often seen with RPOC, but there may be decreased flow in the case of necrotic RPOC. Ultrasound findings consistent with RPOC in a febrile, ill patient suggest a septic abortion.

Continue for treatment and prognosis >>

Treatment and prognosisPatients with a septic abortion require immediate evacuation of the uterus to prevent deadly complications; antibiotics may not be able to perfuse to the necrotic source of infection.10 Suction curettage is less likely than sharp curettage to cause perforation.

Broad-spectrum antibiotics should be administered. The bacteria associated with a septic incomplete miscarriage are usually polymicrobial and represent the normal flora of the vagina and cervix. The choice of agents recommended is usually the same as for pelvic inflammatory disease.11

The treatment regimen typically includes clindamycin (900 mg IV q8h), plus gentamicin (5 mg/kg IV once a day), with or without ampicillin (2 g IV q4h).11,12 Alternatively, a combination of ampicillin, gentamicin, and metronidazole (500 mg IV q8h) can be used.

Further surgery, including laparotomy and possible hysterectomy, is indicated in patients who do not respond to uterine evacuation and parenteral antibiotics. Other possible complications requiring surgery include pelvic abscess, necrotizing Clostridium infections in the myometrium, and uterine perforation.

OUTCOME FOR THE CASE PATIENTThe patient was started on IV ampicillin, gentamicin, and clindamycin and taken promptly for a suction dilation and curettage. Pathology later showed a gestational sac with severe acute necrotizing chorioamnionitis and extensive bacterial growth. This confirmed the diagnosis of a septic, incomplete miscarriage.

Blood cultures remained without any growth, and the patient was afebrile on the second postop day. The WBC count and β-hCG level trended downward.

The patient was discharged on a 14-day course of oral doxycycline and metronidazole. She was then lost to further follow-up.

CONCLUSIONThe differential diagnosis in this ill, febrile patient was initially very broad. The importance of suspecting pregnancy in all women of childbearing age, especially those not using contraception, cannot be underestimated. The accuracy of patient history and recall of last menstrual period in determining the possibility of pregnancy is not sufficiently reliable.

1. Promislow JH, Baird DD, Wilcox AJ, et al. Bleeding following pregnancy loss prior to six weeks gestation. Hum Reprod. 2007;22(3):853-857.

2. Ramoska EA, Sacchetti AD, Nepp M. Reliability of patient history in determining the possibility of pregnancy. Ann Emerg Med. 1989;18(1):48-50.

3. Osazuwa H, Aziken M. Septic abortion: a review of social and demographic characteristics. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2007;275(2):117-119.

4. Hure AJ, Powers JR, Mishra GD, et al. Miscarriage, preterm delivery, and stillbirth: large variations in rates within a cohort of Australian women. PLoS One. 2012;7(5):e37109.

5. Nielsen S, Hahlin M. Expectant management of first-trimester spontaneous abortion. Lancet. 1995;345(8942):84-86.

6. Eschenbach DA. Treating spontaneous and induced septic abortions. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125(5):1042-1048.

7. Rana A, Pradhan N, Gurung G, Singh M. Induced septic abortion: a major factor in maternal mortality and morbidity. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2004;30(1):3-8.

8. Abbasi S, Jamal A, Eslamian L, Marsousi V. Role of clinical and ultrasound findings in the diagnosis of retained products of conception. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2008;32(5):704-707.

9. Esmaeillou H, Jamal A, Eslamian L, et al. Accurate detection of retained products of conception after first- and second-trimester abortion by color doppler sonography. J Med Ultrasound. 2015;23(7):34-38.

10. Finkielman JD, De Feo FD, Heller PG, Afessa B. The clinical course of patients with septic abortion admitted to an intensive care unit. Intensive Care Med. 2004;30(6):1097-1102.

11. CDC. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010;59(RR-12):1-110.

12. Mackeen AD, Packard RE, Ota E, Speer L. Antibiotic regimens for postpartum endometritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;2:CD001067.

1. Promislow JH, Baird DD, Wilcox AJ, et al. Bleeding following pregnancy loss prior to six weeks gestation. Hum Reprod. 2007;22(3):853-857.

2. Ramoska EA, Sacchetti AD, Nepp M. Reliability of patient history in determining the possibility of pregnancy. Ann Emerg Med. 1989;18(1):48-50.

3. Osazuwa H, Aziken M. Septic abortion: a review of social and demographic characteristics. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2007;275(2):117-119.

4. Hure AJ, Powers JR, Mishra GD, et al. Miscarriage, preterm delivery, and stillbirth: large variations in rates within a cohort of Australian women. PLoS One. 2012;7(5):e37109.

5. Nielsen S, Hahlin M. Expectant management of first-trimester spontaneous abortion. Lancet. 1995;345(8942):84-86.

6. Eschenbach DA. Treating spontaneous and induced septic abortions. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125(5):1042-1048.

7. Rana A, Pradhan N, Gurung G, Singh M. Induced septic abortion: a major factor in maternal mortality and morbidity. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2004;30(1):3-8.

8. Abbasi S, Jamal A, Eslamian L, Marsousi V. Role of clinical and ultrasound findings in the diagnosis of retained products of conception. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2008;32(5):704-707.

9. Esmaeillou H, Jamal A, Eslamian L, et al. Accurate detection of retained products of conception after first- and second-trimester abortion by color doppler sonography. J Med Ultrasound. 2015;23(7):34-38.

10. Finkielman JD, De Feo FD, Heller PG, Afessa B. The clinical course of patients with septic abortion admitted to an intensive care unit. Intensive Care Med. 2004;30(6):1097-1102.

11. CDC. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010;59(RR-12):1-110.

12. Mackeen AD, Packard RE, Ota E, Speer L. Antibiotic regimens for postpartum endometritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;2:CD001067.

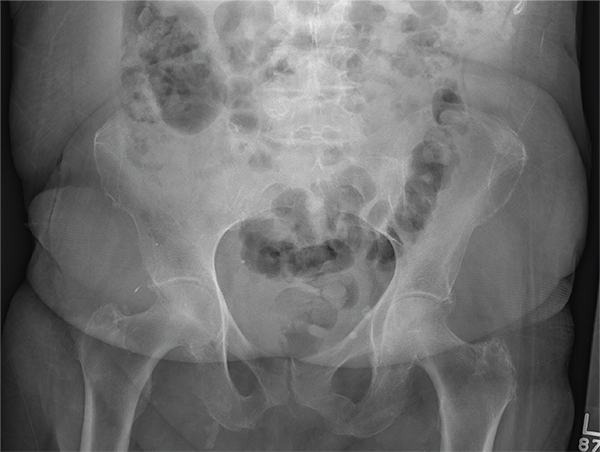

When Man’s Legs “Give Out,” His Buttocks Takes the Brunt

ANSWER

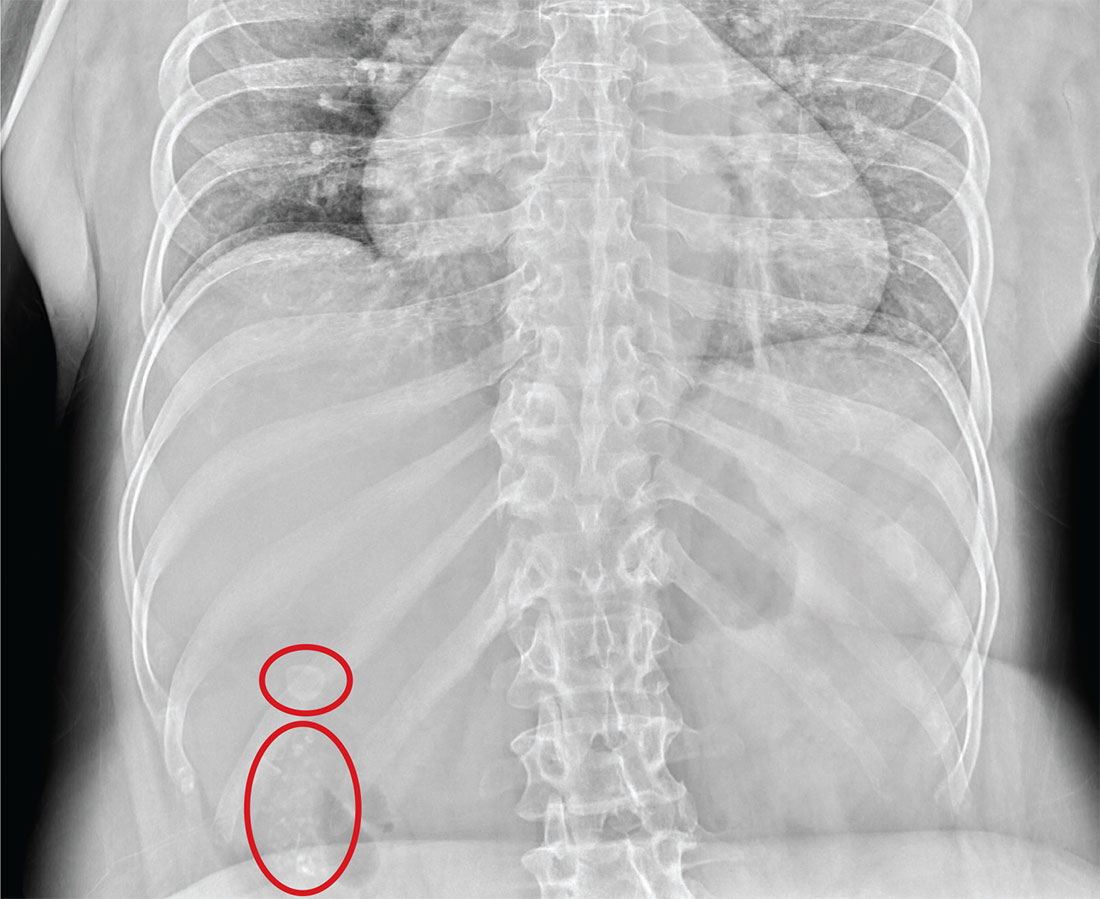

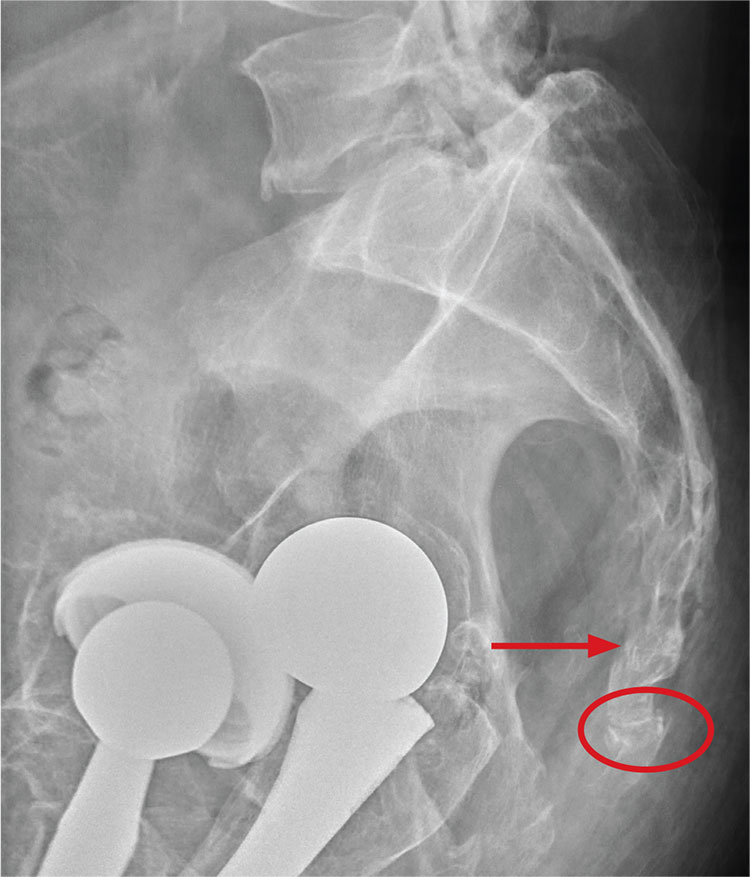

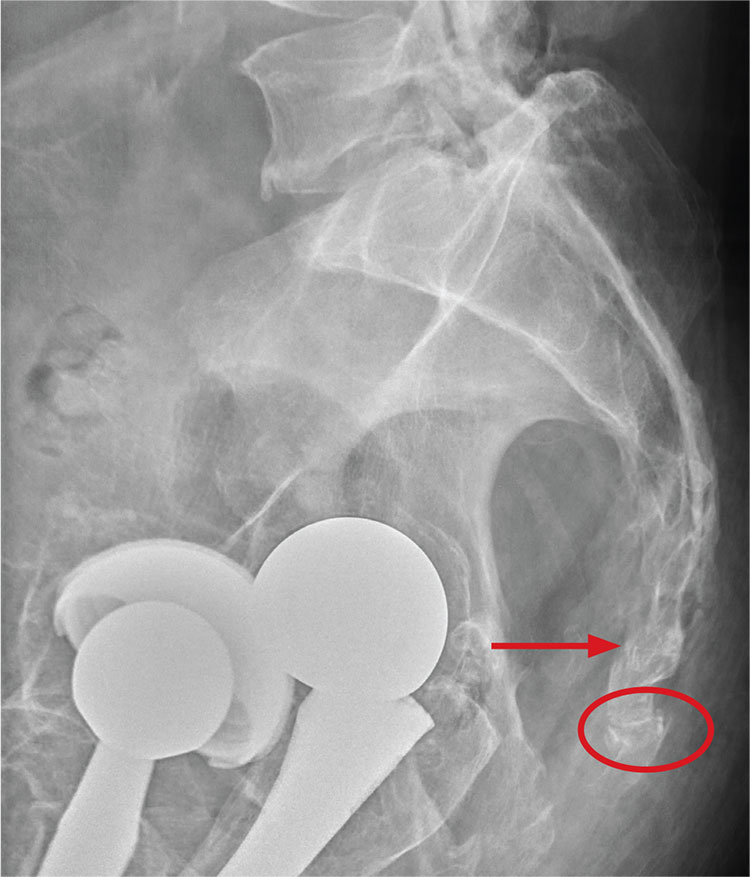

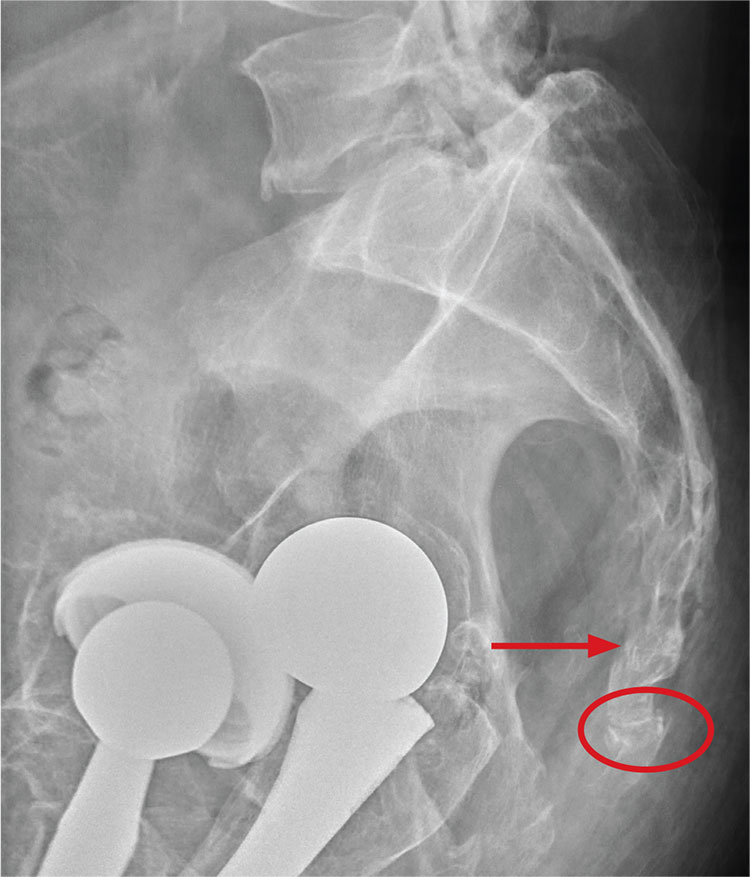

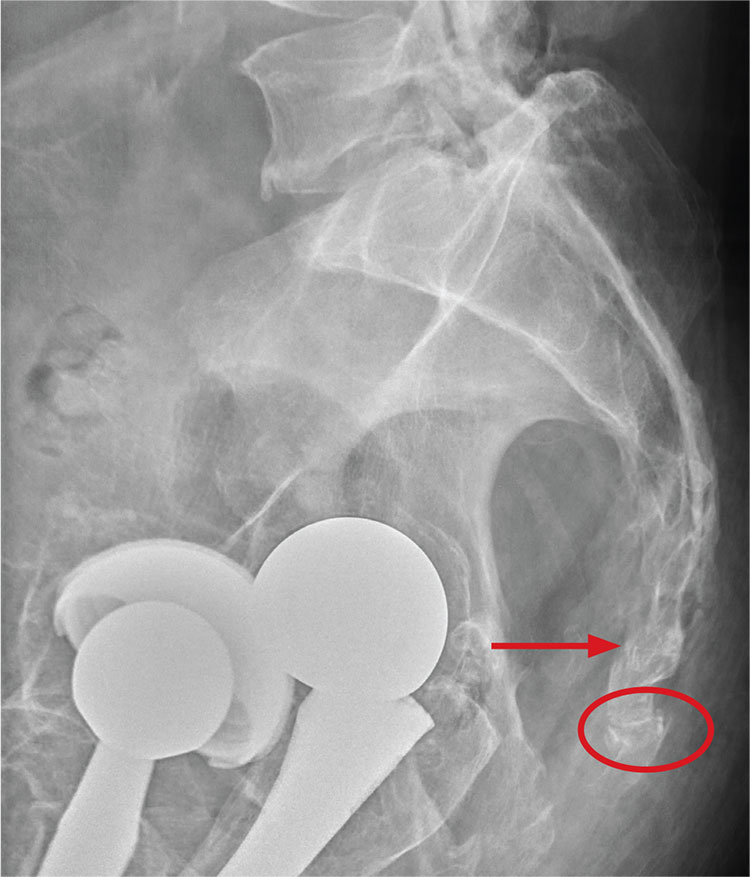

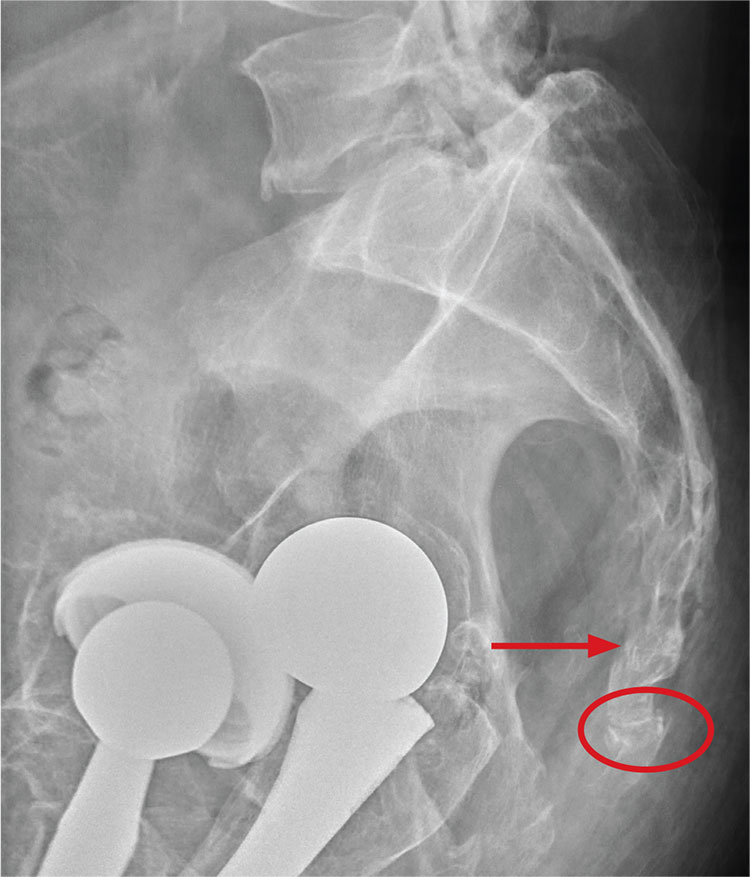

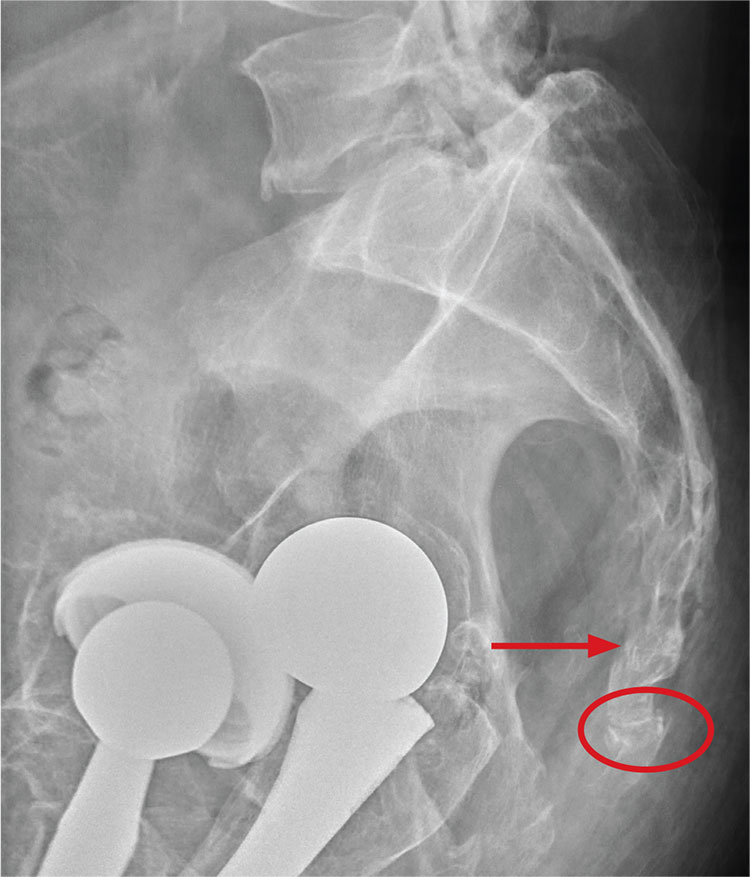

There are degenerative changes present. Bilateral hip prostheses are noted. Within the coccyx, there is bone remodeling and angulation that are likely chronic and related to remote trauma or injury (arrow). Below this, some cortical lucency (circled) is noted, most likely consistent with an acute fracture. The patient was prescribed a nonsteroidal medication and a mild narcotic pain medication.

ANSWER

There are degenerative changes present. Bilateral hip prostheses are noted. Within the coccyx, there is bone remodeling and angulation that are likely chronic and related to remote trauma or injury (arrow). Below this, some cortical lucency (circled) is noted, most likely consistent with an acute fracture. The patient was prescribed a nonsteroidal medication and a mild narcotic pain medication.

ANSWER

There are degenerative changes present. Bilateral hip prostheses are noted. Within the coccyx, there is bone remodeling and angulation that are likely chronic and related to remote trauma or injury (arrow). Below this, some cortical lucency (circled) is noted, most likely consistent with an acute fracture. The patient was prescribed a nonsteroidal medication and a mild narcotic pain medication.

A 75-year-old man presents to the urgent care center for evaluation of pain in his buttocks after a fall. He states he was walking when his “legs gave out” and he hit the ground. He landed squarely on his buttocks, causing immediate pain. He was eventually able to get up with some assistance. He denies current weakness or any bowel or bladder complaints.

His medical/surgical history is significant for coronary artery disease, hypertension, and bilateral hip replacements. Physical exam reveals an elderly male who is uncomfortable but in no obvious distress. His vital signs are stable. He has moderate point tenderness over his sacrum but is able to move all his extremities well, with normal strength.

Radiograph of his sacrum/coccyx is shown. What is your impression?

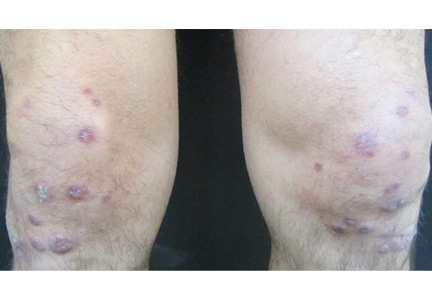

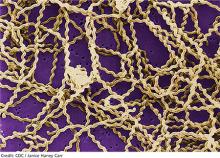

A man with HIV and papules and nodules on the knees

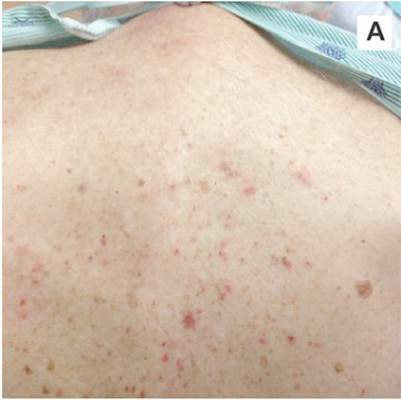

A 39-year-old man with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection and a CD4 cell count of 528 × 106/L without treatment was referred for evaluation of periarticular, indurated, erythematous papules and nodules on the knees and elbows and purpuric lesions on the ankles (Figure 1). He has had recurrent fever, arthralgia, and mild constitutional symptoms during the past month. He also reported a diagnosis of polyclonal immunoglobulin A gammopathy.

Punch biopsy of the purpuric lesions was performed, and histologic study showed leukocytoclastic vasculitis with eosinophilic necrosis of the epithelium.

Treatment with a systemic corticosteroid was started. The purpuric lesions disappeared after 3 weeks of therapy, but the nodules over the extensor surface of both knees showed no improvement (Figure 2). Subsequent biopsy of late-stage lesions (3 months after the start of therapy) demonstrated perivascular fibrosis with small, persistent foci of vasculitis, and confirmed the diagnosis of HIV-associated nodular erythema elevatum diutinum (EED). Antiretroviral therapy was started in addition to intralesional corticosteroids and topical dapsone 5% gel, with resolution of the lesions 1 month later.

ERYTHEMA ELEVATUM DIUTINUM

EED is an uncommon chronic dermatosis, classified as a fibrosing form of leukocytoclastic vasculitis and characterized clinically by violaceous papules, plaques, and nodules, usually distributed acrally and symmetrically over extensor surfaces. The histopathologic picture depends on the stage of the lesion. Features of leukocytoclastic vasculitis are found in early-stage lesions, while a fibrotic replacement of the dermis with small persistent foci of vasculitis is typical of late-stage lesions.

EED has clinical and histopathologic similarities to Sweet syndrome, but EED is distinguished from neutrophilic dermatosis by vasculitis.

In HIV-infected patients, it is important to include pruritic papular eruption in the differential diagnosis. It is characterized by chronic bilaterally symmetric pruritic papules on the trunk and extremities and is the most common cutaneous noninfectious manifestation of HIV.

The clinical presentation of EED may also be easily confused with Kaposi sarcoma and bacillary angiomatosis.2

AN EMERGING HIV-RELATED DERMATOSIS

EED is emerging as a specific HIV-associated dermatosis, with 20 cases reported in the medical literature as of this writing.3

The cause of EED is not known, but it is often associated with streptococcal infection, monoclonal IgA gammopathy, hematologic malignancy, cryoglobulinemia, rheumatoid arthritis, and autoimmune disease.3 The stimulus could be immune-complex deposition in blood vessels triggered by HIV infection, or by another infection acting as an antigenic stimulus.4 The nodular variant of EED is even rarer, but it evolves most often in HIV-positive individuals.5,6

Oral dapsone is the treatment of choice but is less effective in late-stage fibrotic lesions.7 Treatment courses tend to be long and recurrence is common.8 Intralesional, topical, and oral corticosteroids, topical dapsone 5% gel,9 tetracycline and nicotinamide, sulfonamides, colchicine, chloroquine, and surgical excision are other options.

Our patient’s presentation reminds us to consider EED in HIV-infected patients and illustrates the importance of histologic diagnosis to differentiate EED from assumed Kaposi sarcoma in patients with HIV. EED can also be the first clinical sign of HIV infection. It is important to rule out underlying disorders such as HIV infection, because directed therapy is often the best management.

- Yiannias JA, el-Azhary RA, Gibson LE. Erythema elevatum diutinum: a clinical and histopathologic study of 13 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol 1992; 26:38–44.

- Requena L, Sánchez Yus E, Martín L, Barat A, Arias D. Erythema elevatum diutinum in a patient with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Another clinical simulator of Kaposi’s sarcoma. Arch Dermatol 1991; 127:1819–1822.

- Momen SE, Jorizzo J, Al-Niaimi F. Erythema elevatum diutinum: a review of presentation and treatment. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2014; 28:1594–1602.

- Muratori S, Carrera C, Gorani A, Alessi E. Erythema elevatum diutinum and HIV infection: a report of five cases. Br J Dermatol 1999; 141:335–338.

- LeBoit PE, Cockerell CJ. Nodular lesions of erythema elevatum diutinum in patients infected with the human immunodeficiency virus. J Am Acad Dermatol 1993; 28:919–922.

- Rover PA, Bittencourt C, Discacciati MP, Zaniboni MC, Arruda LH, Cintra ML. Erythema elevatum diutinum as a first clinical manifestation for diagnosing HIV infection: case history. Sao Paulo Med J 2005; 123:201–203.

- Fakheri A, Gupta SM, White SM, Don PC, Weinberg JM. Erythema elevatum diutinum in a patient with human immunodeficiency virus. Cutis 2001; 68:41–42.

- Katz SI, Gallin JL, Hertz KC, Fauci AS, Lawley TJ. Erythema elevatum diutinum: skin and systemic manifestations, immunologic studies, and successful treatment with dapsone. Medicine (Baltimore) 1977; 56:443–455.

- Frieling GW, Williams NL, Lim SJ, Rosenthal SI. Novel use of topical dapsone 5% gel for erythema elevatum diutinum: safer and effective. J Drugs Dermatol 2013; 12:481–484.

A 39-year-old man with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection and a CD4 cell count of 528 × 106/L without treatment was referred for evaluation of periarticular, indurated, erythematous papules and nodules on the knees and elbows and purpuric lesions on the ankles (Figure 1). He has had recurrent fever, arthralgia, and mild constitutional symptoms during the past month. He also reported a diagnosis of polyclonal immunoglobulin A gammopathy.

Punch biopsy of the purpuric lesions was performed, and histologic study showed leukocytoclastic vasculitis with eosinophilic necrosis of the epithelium.

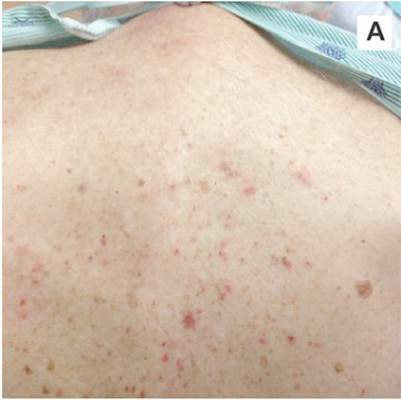

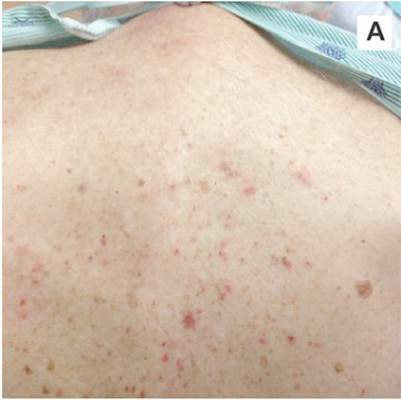

Treatment with a systemic corticosteroid was started. The purpuric lesions disappeared after 3 weeks of therapy, but the nodules over the extensor surface of both knees showed no improvement (Figure 2). Subsequent biopsy of late-stage lesions (3 months after the start of therapy) demonstrated perivascular fibrosis with small, persistent foci of vasculitis, and confirmed the diagnosis of HIV-associated nodular erythema elevatum diutinum (EED). Antiretroviral therapy was started in addition to intralesional corticosteroids and topical dapsone 5% gel, with resolution of the lesions 1 month later.

ERYTHEMA ELEVATUM DIUTINUM

EED is an uncommon chronic dermatosis, classified as a fibrosing form of leukocytoclastic vasculitis and characterized clinically by violaceous papules, plaques, and nodules, usually distributed acrally and symmetrically over extensor surfaces. The histopathologic picture depends on the stage of the lesion. Features of leukocytoclastic vasculitis are found in early-stage lesions, while a fibrotic replacement of the dermis with small persistent foci of vasculitis is typical of late-stage lesions.

EED has clinical and histopathologic similarities to Sweet syndrome, but EED is distinguished from neutrophilic dermatosis by vasculitis.

In HIV-infected patients, it is important to include pruritic papular eruption in the differential diagnosis. It is characterized by chronic bilaterally symmetric pruritic papules on the trunk and extremities and is the most common cutaneous noninfectious manifestation of HIV.

The clinical presentation of EED may also be easily confused with Kaposi sarcoma and bacillary angiomatosis.2

AN EMERGING HIV-RELATED DERMATOSIS

EED is emerging as a specific HIV-associated dermatosis, with 20 cases reported in the medical literature as of this writing.3

The cause of EED is not known, but it is often associated with streptococcal infection, monoclonal IgA gammopathy, hematologic malignancy, cryoglobulinemia, rheumatoid arthritis, and autoimmune disease.3 The stimulus could be immune-complex deposition in blood vessels triggered by HIV infection, or by another infection acting as an antigenic stimulus.4 The nodular variant of EED is even rarer, but it evolves most often in HIV-positive individuals.5,6

Oral dapsone is the treatment of choice but is less effective in late-stage fibrotic lesions.7 Treatment courses tend to be long and recurrence is common.8 Intralesional, topical, and oral corticosteroids, topical dapsone 5% gel,9 tetracycline and nicotinamide, sulfonamides, colchicine, chloroquine, and surgical excision are other options.

Our patient’s presentation reminds us to consider EED in HIV-infected patients and illustrates the importance of histologic diagnosis to differentiate EED from assumed Kaposi sarcoma in patients with HIV. EED can also be the first clinical sign of HIV infection. It is important to rule out underlying disorders such as HIV infection, because directed therapy is often the best management.

A 39-year-old man with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection and a CD4 cell count of 528 × 106/L without treatment was referred for evaluation of periarticular, indurated, erythematous papules and nodules on the knees and elbows and purpuric lesions on the ankles (Figure 1). He has had recurrent fever, arthralgia, and mild constitutional symptoms during the past month. He also reported a diagnosis of polyclonal immunoglobulin A gammopathy.

Punch biopsy of the purpuric lesions was performed, and histologic study showed leukocytoclastic vasculitis with eosinophilic necrosis of the epithelium.

Treatment with a systemic corticosteroid was started. The purpuric lesions disappeared after 3 weeks of therapy, but the nodules over the extensor surface of both knees showed no improvement (Figure 2). Subsequent biopsy of late-stage lesions (3 months after the start of therapy) demonstrated perivascular fibrosis with small, persistent foci of vasculitis, and confirmed the diagnosis of HIV-associated nodular erythema elevatum diutinum (EED). Antiretroviral therapy was started in addition to intralesional corticosteroids and topical dapsone 5% gel, with resolution of the lesions 1 month later.

ERYTHEMA ELEVATUM DIUTINUM

EED is an uncommon chronic dermatosis, classified as a fibrosing form of leukocytoclastic vasculitis and characterized clinically by violaceous papules, plaques, and nodules, usually distributed acrally and symmetrically over extensor surfaces. The histopathologic picture depends on the stage of the lesion. Features of leukocytoclastic vasculitis are found in early-stage lesions, while a fibrotic replacement of the dermis with small persistent foci of vasculitis is typical of late-stage lesions.

EED has clinical and histopathologic similarities to Sweet syndrome, but EED is distinguished from neutrophilic dermatosis by vasculitis.

In HIV-infected patients, it is important to include pruritic papular eruption in the differential diagnosis. It is characterized by chronic bilaterally symmetric pruritic papules on the trunk and extremities and is the most common cutaneous noninfectious manifestation of HIV.

The clinical presentation of EED may also be easily confused with Kaposi sarcoma and bacillary angiomatosis.2

AN EMERGING HIV-RELATED DERMATOSIS

EED is emerging as a specific HIV-associated dermatosis, with 20 cases reported in the medical literature as of this writing.3

The cause of EED is not known, but it is often associated with streptococcal infection, monoclonal IgA gammopathy, hematologic malignancy, cryoglobulinemia, rheumatoid arthritis, and autoimmune disease.3 The stimulus could be immune-complex deposition in blood vessels triggered by HIV infection, or by another infection acting as an antigenic stimulus.4 The nodular variant of EED is even rarer, but it evolves most often in HIV-positive individuals.5,6

Oral dapsone is the treatment of choice but is less effective in late-stage fibrotic lesions.7 Treatment courses tend to be long and recurrence is common.8 Intralesional, topical, and oral corticosteroids, topical dapsone 5% gel,9 tetracycline and nicotinamide, sulfonamides, colchicine, chloroquine, and surgical excision are other options.

Our patient’s presentation reminds us to consider EED in HIV-infected patients and illustrates the importance of histologic diagnosis to differentiate EED from assumed Kaposi sarcoma in patients with HIV. EED can also be the first clinical sign of HIV infection. It is important to rule out underlying disorders such as HIV infection, because directed therapy is often the best management.

- Yiannias JA, el-Azhary RA, Gibson LE. Erythema elevatum diutinum: a clinical and histopathologic study of 13 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol 1992; 26:38–44.

- Requena L, Sánchez Yus E, Martín L, Barat A, Arias D. Erythema elevatum diutinum in a patient with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Another clinical simulator of Kaposi’s sarcoma. Arch Dermatol 1991; 127:1819–1822.

- Momen SE, Jorizzo J, Al-Niaimi F. Erythema elevatum diutinum: a review of presentation and treatment. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2014; 28:1594–1602.

- Muratori S, Carrera C, Gorani A, Alessi E. Erythema elevatum diutinum and HIV infection: a report of five cases. Br J Dermatol 1999; 141:335–338.

- LeBoit PE, Cockerell CJ. Nodular lesions of erythema elevatum diutinum in patients infected with the human immunodeficiency virus. J Am Acad Dermatol 1993; 28:919–922.

- Rover PA, Bittencourt C, Discacciati MP, Zaniboni MC, Arruda LH, Cintra ML. Erythema elevatum diutinum as a first clinical manifestation for diagnosing HIV infection: case history. Sao Paulo Med J 2005; 123:201–203.

- Fakheri A, Gupta SM, White SM, Don PC, Weinberg JM. Erythema elevatum diutinum in a patient with human immunodeficiency virus. Cutis 2001; 68:41–42.

- Katz SI, Gallin JL, Hertz KC, Fauci AS, Lawley TJ. Erythema elevatum diutinum: skin and systemic manifestations, immunologic studies, and successful treatment with dapsone. Medicine (Baltimore) 1977; 56:443–455.

- Frieling GW, Williams NL, Lim SJ, Rosenthal SI. Novel use of topical dapsone 5% gel for erythema elevatum diutinum: safer and effective. J Drugs Dermatol 2013; 12:481–484.

- Yiannias JA, el-Azhary RA, Gibson LE. Erythema elevatum diutinum: a clinical and histopathologic study of 13 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol 1992; 26:38–44.

- Requena L, Sánchez Yus E, Martín L, Barat A, Arias D. Erythema elevatum diutinum in a patient with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Another clinical simulator of Kaposi’s sarcoma. Arch Dermatol 1991; 127:1819–1822.

- Momen SE, Jorizzo J, Al-Niaimi F. Erythema elevatum diutinum: a review of presentation and treatment. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2014; 28:1594–1602.

- Muratori S, Carrera C, Gorani A, Alessi E. Erythema elevatum diutinum and HIV infection: a report of five cases. Br J Dermatol 1999; 141:335–338.

- LeBoit PE, Cockerell CJ. Nodular lesions of erythema elevatum diutinum in patients infected with the human immunodeficiency virus. J Am Acad Dermatol 1993; 28:919–922.

- Rover PA, Bittencourt C, Discacciati MP, Zaniboni MC, Arruda LH, Cintra ML. Erythema elevatum diutinum as a first clinical manifestation for diagnosing HIV infection: case history. Sao Paulo Med J 2005; 123:201–203.

- Fakheri A, Gupta SM, White SM, Don PC, Weinberg JM. Erythema elevatum diutinum in a patient with human immunodeficiency virus. Cutis 2001; 68:41–42.

- Katz SI, Gallin JL, Hertz KC, Fauci AS, Lawley TJ. Erythema elevatum diutinum: skin and systemic manifestations, immunologic studies, and successful treatment with dapsone. Medicine (Baltimore) 1977; 56:443–455.

- Frieling GW, Williams NL, Lim SJ, Rosenthal SI. Novel use of topical dapsone 5% gel for erythema elevatum diutinum: safer and effective. J Drugs Dermatol 2013; 12:481–484.

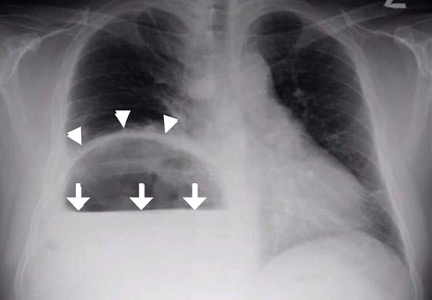

‘Air-raising’: An air-fluid level in the right subphrenic region

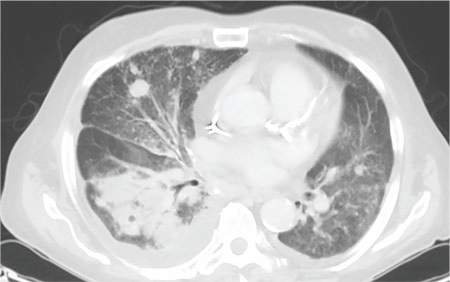

A 39-year-old Filipino man presented with nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain of 2 weeks’ duration. He did not report trauma, and he had no history of medical illness or surgery.

On arrival, his blood pressure was 123/83 mm Hg, pulse 122 beats per minute, respiratory rate 18 breaths per minute, and temperature 100.7°F (38.1°C). On physical examination, he exhibited marked tenderness of the right upper quadrant on palpation. The abdomen was otherwise soft with no guarding or rebound tenderness.

Results of initial laboratory testing were as follows:

- Leukocyte count 17.0 × 109/L (reference range 4.5–11.0)

- Serum glucose 558 mg/dL without ketoacidosis

- Aspartate aminotransferase 109 U/L (2–40)

- Alanine aminotranferase 28 U/L (2–50)

- Total serum bilirubin 4.0 mg/dL (0.0–1.5).

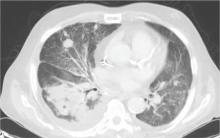

Plain chest radiography showed dramatic elevation of the right hemidiaphragm with a large subphrenic air-fluid level (Figure 1). Abdominal computed tomography (CT) demonstrated a multiloculated hepatic abscess 18 × 13.5 cm subjacent to the diaphragm (Figure 2). Cultures of blood and the abscess yielded Klebsiella pneumoniae. The patient recovered after percutaneous drainage and a course of ceftriaxone.

PRIMARY KLEBSIELLA LIVER ABSCESS

K pneumoniae, a gram-negative aerobic encapsulated bacillus of the normal human intestinal flora, is closely related to Escherichia coli, historically the most frequent bacterial cause of pyogenic liver abscess.1 Over the last 30 years, K pneumoniae has eclipsed E coli as the most common causative agent, with the epicenter of this trend being located in Taiwan and South Korea, perhaps because rates of fecal Klebsiella carriage in that region are particularly high.1,2

Concurrently, there has been increasing recognition—initially across Asia, but lately in Europe and the Western Hemisphere—of the so-called invasive Klebsiella liver abscess (KLA) syndrome, virtually unique to the hypervirulent K1 and K2 capsular serotypes of K pneumoniae prevalent in Asia.3–6 This community-acquired syndrome is characterized by hematogenous deposition of the organism at distant sites, such as the lung, soft tissues, central nervous system, and eyes. Impairment of phagocytic function, as occurs in diabetes mellitus, and the resistance to phagocytosis conferred by the K1 and K2 serotypes have been identified as predisposing factors for dissemination.7,8 The mucoid phenotype of K pneumoniae, very common in Asian isolates of the K1 and K2 serotypes, is also associated with hypervirulence and extrahepatic spread, presumably through evasion of phagocytosis and complement-mediated opsonization.2,9

Our patient’s risk factors for KLA were his Asian origin and uncontrolled diabetes. No evidence of remote infection was detected during his hospitalization.

HEMIDIAPHRAGM ELEVATION

Acquired hemidiaphragm elevation is most commonly unilateral and typically represents an incidental radiologic finding attributable to paralysis of the corresponding diaphragm after phrenic nerve injury caused by trauma, surgery, or infection. Unilateral diaphragmatic paralysis is classically confirmed by performing a fluoroscopic sniff test, which is positive if the affected hemidiaphragm is observed in real time to paradoxically move upward during forced inhalation.10 This condition is usually asymptomatic at rest but could cause exertional dyspnea and contribute to ventilatory failure when pulmonary disease coexists.11

Occasionally, as in our patient, hemidiaphragm elevation is part of the presentation of active abdominal pathology that displaces the corresponding hemidiaphragm cephalad by mass effect. Examples of such space-occupying abdominal lesions include infections, malignancy, hepatosplenomegaly, and pneumoperitoneum from a ruptured viscus. Pneumoperitoneum is suggested by the presence of an air crescent immediately subjacent to the affected hemidiaphragm on an upright radiograph accompanied by peritoneal signs.

Although there was subphrenic air on this patient’s initial chest radiograph, it was actually part of an air-fluid level without associated peritoneal signs. An air-fluid level is characterized by a sharp horizontal demarcation between the lighter gas component floating at the top and the heavier fluid component settling on the bottom (Figure 1). The subsequent CT excluded free intra-abdominal air while identifying a large hepatic abscess as the cause of hemidiaphragm elevation. In trauma victims, CT is also helpful in ruling out diaphragmatic rupture, which can have a similar radiographic appearance.12

Our patient’s presentation was a reminder that an elevated hemidiaphragm may reflect abdominal pathology and that subphrenic air in this context need not be either “free” or a surgical emergency. Drainage of the abscess restored the normal position of our patient’s right hemidiaphragm (Figure 3).

- Huang CJ, Pitt HA, Lipsett PA, et al. Pyogenic hepatic abscess: changing trends over 42 years. Ann Surg 1996; 223:600–607.

- Lin YT, Siu LK, Lin JC, et al. Seroepidemiology of Klebsiella pneumoniae colonizing the intestinal tract of healthy Chinese and overseas Chinese adults in Asian countries. BMC Microbiol 2012; 12:13.

- Wang JH, Liu YC, Lee SS, et al. Primary liver abscess due to Klebsiella pneumoniae in Taiwan. Clin Infect Dis 1998; 26:1434–1438.

- Pastagia M, Arumugam V. Klebsiella pneumoniae liver abscesses in a public hospital in Queens, New York. Travel Med Infect Dis 2008; 6:228–233.

- Rahimian J, Wilson T, Oram V, Holzman RS. Pyogenic liver abscess: recent trends in etiology and mortality. Clin Infect Dis 2004; 39:1654–1659.

- Moore R, O’Shea D, Geoghegan T, Mallon PW, Sheehan G. Community-acquired Klebsiella pneumoniae liver abscess: an emerging infection in Ireland and Europe. Infection 2013; 41:681–686.

- Lecube A, Pachón G, Petriz J, Hernández C, Simó R. Phagocytic activity is impaired in type 2 diabetes mellitus and increases after metabolic improvement. PLoS One 2011; 6:e23366.

- Lin JC, Siu LK, Fung CP, et al. Impaired phagocytosis of capsular serotypes K1 or K2 Klebsiella pneumoniae in type 2 diabetes mellitus patients with poor glycemic control. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2006; 91:3084–3087.

- Siu LK, Yeh KM, Lin JC, Fung CP, Chang FY. Klebsiella pneumoniae liver abscess: a new invasive syndrome. Lancet Infect Dis 2012; 12:881–887.

- Gierada DS, Slone RM, Fleishman MJ. Imaging evaluation of the diaphragm. Chest Surg Clin North Am 1998; 8:237–280.

- Qureshi A. Diaphragm paralysis. Semin Respir Crit Care Med 2009; 30:315–320.

- Havens JM, Kelly E, Patel V. A 78-year-old man with an elevated hemidiaphragm following trauma. Chest 2008; 134:1336–1339.

A 39-year-old Filipino man presented with nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain of 2 weeks’ duration. He did not report trauma, and he had no history of medical illness or surgery.

On arrival, his blood pressure was 123/83 mm Hg, pulse 122 beats per minute, respiratory rate 18 breaths per minute, and temperature 100.7°F (38.1°C). On physical examination, he exhibited marked tenderness of the right upper quadrant on palpation. The abdomen was otherwise soft with no guarding or rebound tenderness.

Results of initial laboratory testing were as follows:

- Leukocyte count 17.0 × 109/L (reference range 4.5–11.0)

- Serum glucose 558 mg/dL without ketoacidosis

- Aspartate aminotransferase 109 U/L (2–40)

- Alanine aminotranferase 28 U/L (2–50)

- Total serum bilirubin 4.0 mg/dL (0.0–1.5).

Plain chest radiography showed dramatic elevation of the right hemidiaphragm with a large subphrenic air-fluid level (Figure 1). Abdominal computed tomography (CT) demonstrated a multiloculated hepatic abscess 18 × 13.5 cm subjacent to the diaphragm (Figure 2). Cultures of blood and the abscess yielded Klebsiella pneumoniae. The patient recovered after percutaneous drainage and a course of ceftriaxone.

PRIMARY KLEBSIELLA LIVER ABSCESS

K pneumoniae, a gram-negative aerobic encapsulated bacillus of the normal human intestinal flora, is closely related to Escherichia coli, historically the most frequent bacterial cause of pyogenic liver abscess.1 Over the last 30 years, K pneumoniae has eclipsed E coli as the most common causative agent, with the epicenter of this trend being located in Taiwan and South Korea, perhaps because rates of fecal Klebsiella carriage in that region are particularly high.1,2

Concurrently, there has been increasing recognition—initially across Asia, but lately in Europe and the Western Hemisphere—of the so-called invasive Klebsiella liver abscess (KLA) syndrome, virtually unique to the hypervirulent K1 and K2 capsular serotypes of K pneumoniae prevalent in Asia.3–6 This community-acquired syndrome is characterized by hematogenous deposition of the organism at distant sites, such as the lung, soft tissues, central nervous system, and eyes. Impairment of phagocytic function, as occurs in diabetes mellitus, and the resistance to phagocytosis conferred by the K1 and K2 serotypes have been identified as predisposing factors for dissemination.7,8 The mucoid phenotype of K pneumoniae, very common in Asian isolates of the K1 and K2 serotypes, is also associated with hypervirulence and extrahepatic spread, presumably through evasion of phagocytosis and complement-mediated opsonization.2,9

Our patient’s risk factors for KLA were his Asian origin and uncontrolled diabetes. No evidence of remote infection was detected during his hospitalization.

HEMIDIAPHRAGM ELEVATION

Acquired hemidiaphragm elevation is most commonly unilateral and typically represents an incidental radiologic finding attributable to paralysis of the corresponding diaphragm after phrenic nerve injury caused by trauma, surgery, or infection. Unilateral diaphragmatic paralysis is classically confirmed by performing a fluoroscopic sniff test, which is positive if the affected hemidiaphragm is observed in real time to paradoxically move upward during forced inhalation.10 This condition is usually asymptomatic at rest but could cause exertional dyspnea and contribute to ventilatory failure when pulmonary disease coexists.11

Occasionally, as in our patient, hemidiaphragm elevation is part of the presentation of active abdominal pathology that displaces the corresponding hemidiaphragm cephalad by mass effect. Examples of such space-occupying abdominal lesions include infections, malignancy, hepatosplenomegaly, and pneumoperitoneum from a ruptured viscus. Pneumoperitoneum is suggested by the presence of an air crescent immediately subjacent to the affected hemidiaphragm on an upright radiograph accompanied by peritoneal signs.

Although there was subphrenic air on this patient’s initial chest radiograph, it was actually part of an air-fluid level without associated peritoneal signs. An air-fluid level is characterized by a sharp horizontal demarcation between the lighter gas component floating at the top and the heavier fluid component settling on the bottom (Figure 1). The subsequent CT excluded free intra-abdominal air while identifying a large hepatic abscess as the cause of hemidiaphragm elevation. In trauma victims, CT is also helpful in ruling out diaphragmatic rupture, which can have a similar radiographic appearance.12

Our patient’s presentation was a reminder that an elevated hemidiaphragm may reflect abdominal pathology and that subphrenic air in this context need not be either “free” or a surgical emergency. Drainage of the abscess restored the normal position of our patient’s right hemidiaphragm (Figure 3).

A 39-year-old Filipino man presented with nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain of 2 weeks’ duration. He did not report trauma, and he had no history of medical illness or surgery.

On arrival, his blood pressure was 123/83 mm Hg, pulse 122 beats per minute, respiratory rate 18 breaths per minute, and temperature 100.7°F (38.1°C). On physical examination, he exhibited marked tenderness of the right upper quadrant on palpation. The abdomen was otherwise soft with no guarding or rebound tenderness.

Results of initial laboratory testing were as follows:

- Leukocyte count 17.0 × 109/L (reference range 4.5–11.0)

- Serum glucose 558 mg/dL without ketoacidosis

- Aspartate aminotransferase 109 U/L (2–40)

- Alanine aminotranferase 28 U/L (2–50)

- Total serum bilirubin 4.0 mg/dL (0.0–1.5).

Plain chest radiography showed dramatic elevation of the right hemidiaphragm with a large subphrenic air-fluid level (Figure 1). Abdominal computed tomography (CT) demonstrated a multiloculated hepatic abscess 18 × 13.5 cm subjacent to the diaphragm (Figure 2). Cultures of blood and the abscess yielded Klebsiella pneumoniae. The patient recovered after percutaneous drainage and a course of ceftriaxone.

PRIMARY KLEBSIELLA LIVER ABSCESS

K pneumoniae, a gram-negative aerobic encapsulated bacillus of the normal human intestinal flora, is closely related to Escherichia coli, historically the most frequent bacterial cause of pyogenic liver abscess.1 Over the last 30 years, K pneumoniae has eclipsed E coli as the most common causative agent, with the epicenter of this trend being located in Taiwan and South Korea, perhaps because rates of fecal Klebsiella carriage in that region are particularly high.1,2

Concurrently, there has been increasing recognition—initially across Asia, but lately in Europe and the Western Hemisphere—of the so-called invasive Klebsiella liver abscess (KLA) syndrome, virtually unique to the hypervirulent K1 and K2 capsular serotypes of K pneumoniae prevalent in Asia.3–6 This community-acquired syndrome is characterized by hematogenous deposition of the organism at distant sites, such as the lung, soft tissues, central nervous system, and eyes. Impairment of phagocytic function, as occurs in diabetes mellitus, and the resistance to phagocytosis conferred by the K1 and K2 serotypes have been identified as predisposing factors for dissemination.7,8 The mucoid phenotype of K pneumoniae, very common in Asian isolates of the K1 and K2 serotypes, is also associated with hypervirulence and extrahepatic spread, presumably through evasion of phagocytosis and complement-mediated opsonization.2,9

Our patient’s risk factors for KLA were his Asian origin and uncontrolled diabetes. No evidence of remote infection was detected during his hospitalization.

HEMIDIAPHRAGM ELEVATION

Acquired hemidiaphragm elevation is most commonly unilateral and typically represents an incidental radiologic finding attributable to paralysis of the corresponding diaphragm after phrenic nerve injury caused by trauma, surgery, or infection. Unilateral diaphragmatic paralysis is classically confirmed by performing a fluoroscopic sniff test, which is positive if the affected hemidiaphragm is observed in real time to paradoxically move upward during forced inhalation.10 This condition is usually asymptomatic at rest but could cause exertional dyspnea and contribute to ventilatory failure when pulmonary disease coexists.11

Occasionally, as in our patient, hemidiaphragm elevation is part of the presentation of active abdominal pathology that displaces the corresponding hemidiaphragm cephalad by mass effect. Examples of such space-occupying abdominal lesions include infections, malignancy, hepatosplenomegaly, and pneumoperitoneum from a ruptured viscus. Pneumoperitoneum is suggested by the presence of an air crescent immediately subjacent to the affected hemidiaphragm on an upright radiograph accompanied by peritoneal signs.

Although there was subphrenic air on this patient’s initial chest radiograph, it was actually part of an air-fluid level without associated peritoneal signs. An air-fluid level is characterized by a sharp horizontal demarcation between the lighter gas component floating at the top and the heavier fluid component settling on the bottom (Figure 1). The subsequent CT excluded free intra-abdominal air while identifying a large hepatic abscess as the cause of hemidiaphragm elevation. In trauma victims, CT is also helpful in ruling out diaphragmatic rupture, which can have a similar radiographic appearance.12

Our patient’s presentation was a reminder that an elevated hemidiaphragm may reflect abdominal pathology and that subphrenic air in this context need not be either “free” or a surgical emergency. Drainage of the abscess restored the normal position of our patient’s right hemidiaphragm (Figure 3).

- Huang CJ, Pitt HA, Lipsett PA, et al. Pyogenic hepatic abscess: changing trends over 42 years. Ann Surg 1996; 223:600–607.

- Lin YT, Siu LK, Lin JC, et al. Seroepidemiology of Klebsiella pneumoniae colonizing the intestinal tract of healthy Chinese and overseas Chinese adults in Asian countries. BMC Microbiol 2012; 12:13.

- Wang JH, Liu YC, Lee SS, et al. Primary liver abscess due to Klebsiella pneumoniae in Taiwan. Clin Infect Dis 1998; 26:1434–1438.

- Pastagia M, Arumugam V. Klebsiella pneumoniae liver abscesses in a public hospital in Queens, New York. Travel Med Infect Dis 2008; 6:228–233.

- Rahimian J, Wilson T, Oram V, Holzman RS. Pyogenic liver abscess: recent trends in etiology and mortality. Clin Infect Dis 2004; 39:1654–1659.

- Moore R, O’Shea D, Geoghegan T, Mallon PW, Sheehan G. Community-acquired Klebsiella pneumoniae liver abscess: an emerging infection in Ireland and Europe. Infection 2013; 41:681–686.

- Lecube A, Pachón G, Petriz J, Hernández C, Simó R. Phagocytic activity is impaired in type 2 diabetes mellitus and increases after metabolic improvement. PLoS One 2011; 6:e23366.

- Lin JC, Siu LK, Fung CP, et al. Impaired phagocytosis of capsular serotypes K1 or K2 Klebsiella pneumoniae in type 2 diabetes mellitus patients with poor glycemic control. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2006; 91:3084–3087.

- Siu LK, Yeh KM, Lin JC, Fung CP, Chang FY. Klebsiella pneumoniae liver abscess: a new invasive syndrome. Lancet Infect Dis 2012; 12:881–887.

- Gierada DS, Slone RM, Fleishman MJ. Imaging evaluation of the diaphragm. Chest Surg Clin North Am 1998; 8:237–280.

- Qureshi A. Diaphragm paralysis. Semin Respir Crit Care Med 2009; 30:315–320.

- Havens JM, Kelly E, Patel V. A 78-year-old man with an elevated hemidiaphragm following trauma. Chest 2008; 134:1336–1339.

- Huang CJ, Pitt HA, Lipsett PA, et al. Pyogenic hepatic abscess: changing trends over 42 years. Ann Surg 1996; 223:600–607.

- Lin YT, Siu LK, Lin JC, et al. Seroepidemiology of Klebsiella pneumoniae colonizing the intestinal tract of healthy Chinese and overseas Chinese adults in Asian countries. BMC Microbiol 2012; 12:13.

- Wang JH, Liu YC, Lee SS, et al. Primary liver abscess due to Klebsiella pneumoniae in Taiwan. Clin Infect Dis 1998; 26:1434–1438.

- Pastagia M, Arumugam V. Klebsiella pneumoniae liver abscesses in a public hospital in Queens, New York. Travel Med Infect Dis 2008; 6:228–233.

- Rahimian J, Wilson T, Oram V, Holzman RS. Pyogenic liver abscess: recent trends in etiology and mortality. Clin Infect Dis 2004; 39:1654–1659.

- Moore R, O’Shea D, Geoghegan T, Mallon PW, Sheehan G. Community-acquired Klebsiella pneumoniae liver abscess: an emerging infection in Ireland and Europe. Infection 2013; 41:681–686.

- Lecube A, Pachón G, Petriz J, Hernández C, Simó R. Phagocytic activity is impaired in type 2 diabetes mellitus and increases after metabolic improvement. PLoS One 2011; 6:e23366.

- Lin JC, Siu LK, Fung CP, et al. Impaired phagocytosis of capsular serotypes K1 or K2 Klebsiella pneumoniae in type 2 diabetes mellitus patients with poor glycemic control. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2006; 91:3084–3087.

- Siu LK, Yeh KM, Lin JC, Fung CP, Chang FY. Klebsiella pneumoniae liver abscess: a new invasive syndrome. Lancet Infect Dis 2012; 12:881–887.

- Gierada DS, Slone RM, Fleishman MJ. Imaging evaluation of the diaphragm. Chest Surg Clin North Am 1998; 8:237–280.

- Qureshi A. Diaphragm paralysis. Semin Respir Crit Care Med 2009; 30:315–320.

- Havens JM, Kelly E, Patel V. A 78-year-old man with an elevated hemidiaphragm following trauma. Chest 2008; 134:1336–1339.

An Alarming Slip of the Hip

After a fall, an 80-year-old woman is brought to the emergency department for evaluation of hip pain. She was getting out of bed when she slipped, fell, and landed on her right hip; bearing weight now is painful. She denies hitting her head. The patient’s vital signs are normal. Her medical history is significant for hypertension and diabetes. Inspection of the hip reveals no obvious deformity or shortening. The right lateral aspect of the hip exhibits mild swelling and decreased range of motion secondary to the pain. You order a pelvic radiograph, which is shown. What is your impression?

Extreme Athlete, 18, With Worsening Cough

IN THIS ARTICLE

- Adverse effects of ciprofloxacin

- Symptoms of common tick-borne diseases

- Symptoms of phase 1 and late-phase disease

- Additional resources

Jane, an 18-year-old college student, presents in early November with a three-week history of worsening cough and sinus congestion. Recently, the cough has been interrupting her sleep and yellow-green nasal drainage and sinus pressure have increased. Ordinarily very fit and athletic, she reports that since she arrived at college two months ago, her body has become “more fragile.”

Further questioning reveals that, over the past two months, the patient’s symptoms have included extreme fatigue, severe unremitting headache, blurred vision, shortness of breath, and a racing heart rate on exertion. Her symptoms make it impossible for her to maintain her demanding exercise routine, a development that compounds her frustration and sadness. She has also been forced to limit her participation in school activities, with significant academic decline as a result.

Aside from depression (well controlled with bupropion HCl extended release, 300 mg/d), Jane’s medical history is unremarkable. She reports having “excellent health” until she arrived at her mid-Atlantic urban college.

A complicated history

Born and raised in Connecticut, Jane is an avid runner who competes in extreme sports. This past summer, she trained for and participated in two “mud run” events (ie, endurance races of several miles with numerous challenges and obstacles) in Connecticut and New York. Training included endurance runs and sprints, as well as crawling through mud-laden fields and woods.