User login

Adenomyosis: While a last resort, surgery remains an option

Adenomyosis causing severe dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, and heavy menstrual bleeding has been thought to affect primarily multiparous women in their mid- to late 40s. Often women who experience pain and heavy bleeding will tolerate their symptoms until they are done with childbearing, at which point they often go on to have a hysterectomy to relieve them of these symptoms. Tissue histology obtained at the time of hysterectomy confirms the diagnosis of adenomyosis.

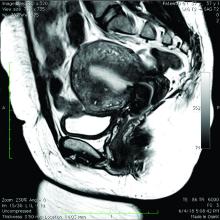

Because the diagnosis is made at the time of hysterectomy, the published incidence and prevalence of adenomyosis is more a reflection of a risk for hysterectomy and not for the disease itself. MRI has been used to evaluate the junctional zone in patients with symptoms of endometriosis. This screen tool is an expensive one, however, and has not been used extensively to evaluate women with symptoms of adenomyosis who are not candidates for a hysterectomy.

Ultrasound studies

Over the past 5-7 years, numerous studies have been performed that demonstrate ultrasound changes consistent with adenomyosis within the uterus. These changes include asymmetry and heterogeneity of the anterior and posterior myometrium, cystic lesions in the myometrium, ultrasound striations, and streaking and irregular junctional zone thickening seen on 3-D scans.

Our newfound ability to demonstrate changes consistent with adenomyosis by ultrasound – a tool that is much less expensive than MRI and more available to patients – means that we can and should consider adenomyosis in patients suffering from dysmenorrhea, heavy menstrual bleeding, back pain, dyspareunia, and infertility – regardless of the patient’s age.

In the last 5 years, adenomyosis has been increasingly recognized as a disorder affecting women of all reproductive ages, including teenagers whose dysmenorrhea disrupts their education and young women undergoing infertility evaluations. In one study, 12% of adolescent girls and young women aged 14–20 years lost days of school or work each month because of dysmenorrhea.1 This disruption is not “normal.”

Several meta-analyses have also demonstrated that ultrasound and MRI changes consistent with adenomyosis can affect embryo implantation rates in women undergoing in vitro fertilization. The implantation rates can be as low as one half the expected rate without adenomyosis. Additionally, adenomyosis has been shown to increase the risk of miscarriage and preterm delivery.2,3

The clinicians who order and carefully look at the ultrasound themselves, rather than rely on the radiologist to make the diagnosis, will be able to see the changes consistent with adenomyosis. Over time – I anticipate the next several years – a standardized radiologic definition for adenomyosis will evolve, and radiologists will become more familiar with these changes. In the meantime, our patients should not have missed diagnoses.

Considerations for surgery

For the majority of younger patients who are not trying to conceive but want to maintain their fertility, medical treatment with oral contraceptives, progestins, or the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device (Mirena) will relieve symptoms. The Mirena IUD has been found in studies of 6-36 months’ treatment duration to decrease the size of the uterus by 25%4 and improve dysmenorrhea and menorrhagia with a low profile of adverse effects in most women.

The Mirena IUD should be considered as a first-line therapy for all women with heavy menstrual bleeding and dyspareunia who want to preserve their fertility.

Patients who do not respond to or cannot tolerate medical therapy, and do not want to preserve their fertility, may consider hysterectomy, long regarded as the preferred method of treatment. Endometrial ablation can also be considered in those who no longer desire to preserve fertility and are experiencing heavy menstrual bleeding. Those with extensive adenomyosis, however, often experience poor results with endometrial ablation and may ultimately require hysterectomy. Endometrial ablation has a history of a high failure rate in women younger than 45 years old.

Patients with adenomyosis who wish to preserve their fertility and cannot tolerate or are unresponsive to hormonal therapy, or those with infertility thought to be caused by adenomyosis, should consider these three management options:

- Do nothing. The embryo implantation rate is not zero with adenomyosis, and we have no data on the number of patients who conceive with adenomyotic changes detected by MRI or ultrasound.

- Pretreat with a GnRH agonist for 2-3 months prior to a frozen embryo transfer (FET). Suppressing the disease prior to an FET seems to increase the implantation rate to what is expected for that patient given her age and other fertility factors.3 While this approach is often successful, an estimated 15%-20% of patients are unable to tolerate GnRH agonist treatment because of its side effects.

- Seek surgical resection of adenomyosis. Unlike uterine fibroids, adenomyosis has no pseudocapsule. When resecting the disease via laparotomy, laparoscopy, or hysteroscopy, the process is more of a debulking procedure. Surgical resection should be reserved for those who cannot tolerate hormonal suppression or have failed the other two options.

Surgical approaches

Surgical excision can be challenging because adenomyosis burrows its way through the muscle, is often diffuse, and cannot necessarily be resected with clean margins as can a fibroid. Yet, as demonstrated in a systematic review of 27 observational studies of conservative surgery for adenomyosis – 10 prospective and 17 retrospective studies with a total of almost 1,400 patients and all with adenomyosis confirmed histopathologically – surgery can improve pain, menorrhagia, and adenomyosis-related infertility in a significant number of cases.5

Disease may be resected through laparotomy, laparoscopy, or as we are currently doing with focal disease that is close to the endometrium, hysteroscopy. The type of surgery will depend on the location and characteristics of the disease, and on the surgeon’s skills. The principles are the same with all three approaches: to remove as much diseased tissue – and preserve as much healthy myometrial tissue – as possible and to reconstruct the uterine wall so that it maintains its integrity and can sustain a pregnancy.

The open approach known as the Osada procedure, after Hisao Osada, MD, PhD, in Tokyo, is well described in the literature, with a relatively large number of cases reported in prospective studies. Dr. Osada performs a radical adenomyosis excision with a triple flap method of uterine wall reconstruction. The uterus is bisected in the mid-sagittal plane all the way down through the adenomyosis until the uterine cavity is reached. Excision of the adenomyotic tissue is guided by palpation with the index finger, and a myometrial thickness of 1 cm from the serosa and the endometrium is preserved.

The endometrium is closed, and the myometrial defect is closed with a triple flap method that avoids overlapping suture lines. On one side of the uterus, the myometrium and serosa are sutured in the antero-posterior plane. The seromuscular layer of the opposite side of the uterine wall is then brought over the first seromuscular suture line.6

Others, such as Grigoris H. Grimbizis, MD, PhD, in Greece, have used a laparoscopic approach and closed the myometrium in layers similar to those of a myomectomy.7 There are no comparative trials that demonstrate one technique is superior to the other.

While there are no textbook techniques published for resecting adenomyotic tissue laparoscopically or hysteroscopically from the normal myometrium, there are some general principals the surgeon should keep in mind. Adenomyosis is defined as the presence of endometrial glands and stroma within myometrium, but biopsy studies have demonstrated that there are relatively few glands and stroma within the diseased tissue. Mostly, the adenomyotic tissue we encounter comprises smooth muscle hyperplasia and fibrosis.

Since there is no pseudocapsule surrounding adenomyotic tissue, the visual cue for the cytoreductive procedure is the presence of normal-appearing myometrium. The normal myometrium can be delineated by palpation with laparoscopic instruments or hysteroscopic loops as it clearly feels less fibrotic and firm than the adenomyotic tissue. For this reason, the adenomyotic tissue is removed in a piecemeal fashion until normal tissue is encountered. (This same philosophy can be applied to removing fibrotic, glandular, or cystic tissue hysteroscopically.)

If the disease involves the inner myometrium, it should resected as this may be very important to restoring normal uterine contractions needed for embryo implantation and development, even if it means entering the cavity laparoscopically.

Hysteroscopically, there is no ability to suture a myometrial defect. This limitation is concerning because the adenomyosis is thought to invade the myometrium and not displace it as seen with monoclonal uterine fibroids. There are no case reports of uterine rupture after hysteroscopic resection of adenomyosis, but the number of cases reported with this type of resection in general is very small.

Laparoscopically, the myometrial defect should be repaired similarly to a myomectomy defect. Chromic or polydioxanone (PDS) suture is appropriate. We have used 2-0 PDS V-loc and a 2-3 layer closure in our laparoscopic cases.

Diffuse adenomyosis can involve the entire anterior or posterior wall of the uterus or both. The surgeon should not attempt to remove all of the disease in this situation and must leave enough tissue, even diseased, to allow for structural integrity during pregnancy. Uterine rupture has not been reported in all published case series and studies, but overall, it is a concern with surgical excision of adenomyosis. An analysis of over 2,000 cases of adenomyomectomies reported worldwide since 1990 shows a uterine rupture rate in the 6% rate, with a pregnancy rate ranging from 7%-72%.8

When the disease is focal and close to the endometrium, as opposed to diffuse and affecting the entire back wall of the uterus, hysteroscopic excision may be an appropriate, less invasive approach.

One of the patients for whom we’ve taken this approach was a 37-year-old patient who presented with a history of six miscarriages, a negative work-up for recurrent pregnancy loss, an enlarged uterus, 8 years of heavy menstrual bleeding, and only mild dysmenorrhea. She had undergone in vitro fertilization with failed embryo transfers but normal genetic screens of the embryos. She was referred with a suspicion of fibroids. An MRI and ultrasound showed heterogeneous myometrium adjacent to the endometrium. This tissue was resected using a bipolar loop electrode until normal myometrium was encountered.

Hysteroscopic resections are currently described in the literature through case reports rather than larger prospective or retrospective studies, and much more research is needed to demonstrate the efficacy and safety of this approach.

At this point in time, while surgery to excise adenomyosis is a last resort and best methods are deliberated, it is still important to appreciate that surgery is an option. Continued infertility is not the only choice, nor is hysterectomy.

References

1. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol 2014;27:258-65.

2. Minerva Ginecol. 2018 Jun;70(3):295-302.

3. Fertil Steril. 2017;108(3):483-490.e3.

4. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;198(4):373.e1-7.

5. J. Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2018 Feb;25:265-76.

6. Reproductive BioMed Online. 2011 Jan;22(1):94-9.

7. Fertil Steril. 2014 Feb;101(2):472-87.

8. Fertil Steril. 2018 Mar;109(3):406-17.

Adenomyosis causing severe dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, and heavy menstrual bleeding has been thought to affect primarily multiparous women in their mid- to late 40s. Often women who experience pain and heavy bleeding will tolerate their symptoms until they are done with childbearing, at which point they often go on to have a hysterectomy to relieve them of these symptoms. Tissue histology obtained at the time of hysterectomy confirms the diagnosis of adenomyosis.

Because the diagnosis is made at the time of hysterectomy, the published incidence and prevalence of adenomyosis is more a reflection of a risk for hysterectomy and not for the disease itself. MRI has been used to evaluate the junctional zone in patients with symptoms of endometriosis. This screen tool is an expensive one, however, and has not been used extensively to evaluate women with symptoms of adenomyosis who are not candidates for a hysterectomy.

Ultrasound studies

Over the past 5-7 years, numerous studies have been performed that demonstrate ultrasound changes consistent with adenomyosis within the uterus. These changes include asymmetry and heterogeneity of the anterior and posterior myometrium, cystic lesions in the myometrium, ultrasound striations, and streaking and irregular junctional zone thickening seen on 3-D scans.

Our newfound ability to demonstrate changes consistent with adenomyosis by ultrasound – a tool that is much less expensive than MRI and more available to patients – means that we can and should consider adenomyosis in patients suffering from dysmenorrhea, heavy menstrual bleeding, back pain, dyspareunia, and infertility – regardless of the patient’s age.

In the last 5 years, adenomyosis has been increasingly recognized as a disorder affecting women of all reproductive ages, including teenagers whose dysmenorrhea disrupts their education and young women undergoing infertility evaluations. In one study, 12% of adolescent girls and young women aged 14–20 years lost days of school or work each month because of dysmenorrhea.1 This disruption is not “normal.”

Several meta-analyses have also demonstrated that ultrasound and MRI changes consistent with adenomyosis can affect embryo implantation rates in women undergoing in vitro fertilization. The implantation rates can be as low as one half the expected rate without adenomyosis. Additionally, adenomyosis has been shown to increase the risk of miscarriage and preterm delivery.2,3

The clinicians who order and carefully look at the ultrasound themselves, rather than rely on the radiologist to make the diagnosis, will be able to see the changes consistent with adenomyosis. Over time – I anticipate the next several years – a standardized radiologic definition for adenomyosis will evolve, and radiologists will become more familiar with these changes. In the meantime, our patients should not have missed diagnoses.

Considerations for surgery

For the majority of younger patients who are not trying to conceive but want to maintain their fertility, medical treatment with oral contraceptives, progestins, or the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device (Mirena) will relieve symptoms. The Mirena IUD has been found in studies of 6-36 months’ treatment duration to decrease the size of the uterus by 25%4 and improve dysmenorrhea and menorrhagia with a low profile of adverse effects in most women.

The Mirena IUD should be considered as a first-line therapy for all women with heavy menstrual bleeding and dyspareunia who want to preserve their fertility.

Patients who do not respond to or cannot tolerate medical therapy, and do not want to preserve their fertility, may consider hysterectomy, long regarded as the preferred method of treatment. Endometrial ablation can also be considered in those who no longer desire to preserve fertility and are experiencing heavy menstrual bleeding. Those with extensive adenomyosis, however, often experience poor results with endometrial ablation and may ultimately require hysterectomy. Endometrial ablation has a history of a high failure rate in women younger than 45 years old.

Patients with adenomyosis who wish to preserve their fertility and cannot tolerate or are unresponsive to hormonal therapy, or those with infertility thought to be caused by adenomyosis, should consider these three management options:

- Do nothing. The embryo implantation rate is not zero with adenomyosis, and we have no data on the number of patients who conceive with adenomyotic changes detected by MRI or ultrasound.

- Pretreat with a GnRH agonist for 2-3 months prior to a frozen embryo transfer (FET). Suppressing the disease prior to an FET seems to increase the implantation rate to what is expected for that patient given her age and other fertility factors.3 While this approach is often successful, an estimated 15%-20% of patients are unable to tolerate GnRH agonist treatment because of its side effects.

- Seek surgical resection of adenomyosis. Unlike uterine fibroids, adenomyosis has no pseudocapsule. When resecting the disease via laparotomy, laparoscopy, or hysteroscopy, the process is more of a debulking procedure. Surgical resection should be reserved for those who cannot tolerate hormonal suppression or have failed the other two options.

Surgical approaches

Surgical excision can be challenging because adenomyosis burrows its way through the muscle, is often diffuse, and cannot necessarily be resected with clean margins as can a fibroid. Yet, as demonstrated in a systematic review of 27 observational studies of conservative surgery for adenomyosis – 10 prospective and 17 retrospective studies with a total of almost 1,400 patients and all with adenomyosis confirmed histopathologically – surgery can improve pain, menorrhagia, and adenomyosis-related infertility in a significant number of cases.5

Disease may be resected through laparotomy, laparoscopy, or as we are currently doing with focal disease that is close to the endometrium, hysteroscopy. The type of surgery will depend on the location and characteristics of the disease, and on the surgeon’s skills. The principles are the same with all three approaches: to remove as much diseased tissue – and preserve as much healthy myometrial tissue – as possible and to reconstruct the uterine wall so that it maintains its integrity and can sustain a pregnancy.

The open approach known as the Osada procedure, after Hisao Osada, MD, PhD, in Tokyo, is well described in the literature, with a relatively large number of cases reported in prospective studies. Dr. Osada performs a radical adenomyosis excision with a triple flap method of uterine wall reconstruction. The uterus is bisected in the mid-sagittal plane all the way down through the adenomyosis until the uterine cavity is reached. Excision of the adenomyotic tissue is guided by palpation with the index finger, and a myometrial thickness of 1 cm from the serosa and the endometrium is preserved.

The endometrium is closed, and the myometrial defect is closed with a triple flap method that avoids overlapping suture lines. On one side of the uterus, the myometrium and serosa are sutured in the antero-posterior plane. The seromuscular layer of the opposite side of the uterine wall is then brought over the first seromuscular suture line.6

Others, such as Grigoris H. Grimbizis, MD, PhD, in Greece, have used a laparoscopic approach and closed the myometrium in layers similar to those of a myomectomy.7 There are no comparative trials that demonstrate one technique is superior to the other.

While there are no textbook techniques published for resecting adenomyotic tissue laparoscopically or hysteroscopically from the normal myometrium, there are some general principals the surgeon should keep in mind. Adenomyosis is defined as the presence of endometrial glands and stroma within myometrium, but biopsy studies have demonstrated that there are relatively few glands and stroma within the diseased tissue. Mostly, the adenomyotic tissue we encounter comprises smooth muscle hyperplasia and fibrosis.

Since there is no pseudocapsule surrounding adenomyotic tissue, the visual cue for the cytoreductive procedure is the presence of normal-appearing myometrium. The normal myometrium can be delineated by palpation with laparoscopic instruments or hysteroscopic loops as it clearly feels less fibrotic and firm than the adenomyotic tissue. For this reason, the adenomyotic tissue is removed in a piecemeal fashion until normal tissue is encountered. (This same philosophy can be applied to removing fibrotic, glandular, or cystic tissue hysteroscopically.)

If the disease involves the inner myometrium, it should resected as this may be very important to restoring normal uterine contractions needed for embryo implantation and development, even if it means entering the cavity laparoscopically.

Hysteroscopically, there is no ability to suture a myometrial defect. This limitation is concerning because the adenomyosis is thought to invade the myometrium and not displace it as seen with monoclonal uterine fibroids. There are no case reports of uterine rupture after hysteroscopic resection of adenomyosis, but the number of cases reported with this type of resection in general is very small.

Laparoscopically, the myometrial defect should be repaired similarly to a myomectomy defect. Chromic or polydioxanone (PDS) suture is appropriate. We have used 2-0 PDS V-loc and a 2-3 layer closure in our laparoscopic cases.

Diffuse adenomyosis can involve the entire anterior or posterior wall of the uterus or both. The surgeon should not attempt to remove all of the disease in this situation and must leave enough tissue, even diseased, to allow for structural integrity during pregnancy. Uterine rupture has not been reported in all published case series and studies, but overall, it is a concern with surgical excision of adenomyosis. An analysis of over 2,000 cases of adenomyomectomies reported worldwide since 1990 shows a uterine rupture rate in the 6% rate, with a pregnancy rate ranging from 7%-72%.8

When the disease is focal and close to the endometrium, as opposed to diffuse and affecting the entire back wall of the uterus, hysteroscopic excision may be an appropriate, less invasive approach.

One of the patients for whom we’ve taken this approach was a 37-year-old patient who presented with a history of six miscarriages, a negative work-up for recurrent pregnancy loss, an enlarged uterus, 8 years of heavy menstrual bleeding, and only mild dysmenorrhea. She had undergone in vitro fertilization with failed embryo transfers but normal genetic screens of the embryos. She was referred with a suspicion of fibroids. An MRI and ultrasound showed heterogeneous myometrium adjacent to the endometrium. This tissue was resected using a bipolar loop electrode until normal myometrium was encountered.

Hysteroscopic resections are currently described in the literature through case reports rather than larger prospective or retrospective studies, and much more research is needed to demonstrate the efficacy and safety of this approach.

At this point in time, while surgery to excise adenomyosis is a last resort and best methods are deliberated, it is still important to appreciate that surgery is an option. Continued infertility is not the only choice, nor is hysterectomy.

References

1. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol 2014;27:258-65.

2. Minerva Ginecol. 2018 Jun;70(3):295-302.

3. Fertil Steril. 2017;108(3):483-490.e3.

4. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;198(4):373.e1-7.

5. J. Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2018 Feb;25:265-76.

6. Reproductive BioMed Online. 2011 Jan;22(1):94-9.

7. Fertil Steril. 2014 Feb;101(2):472-87.

8. Fertil Steril. 2018 Mar;109(3):406-17.

Adenomyosis causing severe dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, and heavy menstrual bleeding has been thought to affect primarily multiparous women in their mid- to late 40s. Often women who experience pain and heavy bleeding will tolerate their symptoms until they are done with childbearing, at which point they often go on to have a hysterectomy to relieve them of these symptoms. Tissue histology obtained at the time of hysterectomy confirms the diagnosis of adenomyosis.

Because the diagnosis is made at the time of hysterectomy, the published incidence and prevalence of adenomyosis is more a reflection of a risk for hysterectomy and not for the disease itself. MRI has been used to evaluate the junctional zone in patients with symptoms of endometriosis. This screen tool is an expensive one, however, and has not been used extensively to evaluate women with symptoms of adenomyosis who are not candidates for a hysterectomy.

Ultrasound studies

Over the past 5-7 years, numerous studies have been performed that demonstrate ultrasound changes consistent with adenomyosis within the uterus. These changes include asymmetry and heterogeneity of the anterior and posterior myometrium, cystic lesions in the myometrium, ultrasound striations, and streaking and irregular junctional zone thickening seen on 3-D scans.

Our newfound ability to demonstrate changes consistent with adenomyosis by ultrasound – a tool that is much less expensive than MRI and more available to patients – means that we can and should consider adenomyosis in patients suffering from dysmenorrhea, heavy menstrual bleeding, back pain, dyspareunia, and infertility – regardless of the patient’s age.

In the last 5 years, adenomyosis has been increasingly recognized as a disorder affecting women of all reproductive ages, including teenagers whose dysmenorrhea disrupts their education and young women undergoing infertility evaluations. In one study, 12% of adolescent girls and young women aged 14–20 years lost days of school or work each month because of dysmenorrhea.1 This disruption is not “normal.”

Several meta-analyses have also demonstrated that ultrasound and MRI changes consistent with adenomyosis can affect embryo implantation rates in women undergoing in vitro fertilization. The implantation rates can be as low as one half the expected rate without adenomyosis. Additionally, adenomyosis has been shown to increase the risk of miscarriage and preterm delivery.2,3

The clinicians who order and carefully look at the ultrasound themselves, rather than rely on the radiologist to make the diagnosis, will be able to see the changes consistent with adenomyosis. Over time – I anticipate the next several years – a standardized radiologic definition for adenomyosis will evolve, and radiologists will become more familiar with these changes. In the meantime, our patients should not have missed diagnoses.

Considerations for surgery

For the majority of younger patients who are not trying to conceive but want to maintain their fertility, medical treatment with oral contraceptives, progestins, or the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device (Mirena) will relieve symptoms. The Mirena IUD has been found in studies of 6-36 months’ treatment duration to decrease the size of the uterus by 25%4 and improve dysmenorrhea and menorrhagia with a low profile of adverse effects in most women.

The Mirena IUD should be considered as a first-line therapy for all women with heavy menstrual bleeding and dyspareunia who want to preserve their fertility.

Patients who do not respond to or cannot tolerate medical therapy, and do not want to preserve their fertility, may consider hysterectomy, long regarded as the preferred method of treatment. Endometrial ablation can also be considered in those who no longer desire to preserve fertility and are experiencing heavy menstrual bleeding. Those with extensive adenomyosis, however, often experience poor results with endometrial ablation and may ultimately require hysterectomy. Endometrial ablation has a history of a high failure rate in women younger than 45 years old.

Patients with adenomyosis who wish to preserve their fertility and cannot tolerate or are unresponsive to hormonal therapy, or those with infertility thought to be caused by adenomyosis, should consider these three management options:

- Do nothing. The embryo implantation rate is not zero with adenomyosis, and we have no data on the number of patients who conceive with adenomyotic changes detected by MRI or ultrasound.

- Pretreat with a GnRH agonist for 2-3 months prior to a frozen embryo transfer (FET). Suppressing the disease prior to an FET seems to increase the implantation rate to what is expected for that patient given her age and other fertility factors.3 While this approach is often successful, an estimated 15%-20% of patients are unable to tolerate GnRH agonist treatment because of its side effects.

- Seek surgical resection of adenomyosis. Unlike uterine fibroids, adenomyosis has no pseudocapsule. When resecting the disease via laparotomy, laparoscopy, or hysteroscopy, the process is more of a debulking procedure. Surgical resection should be reserved for those who cannot tolerate hormonal suppression or have failed the other two options.

Surgical approaches

Surgical excision can be challenging because adenomyosis burrows its way through the muscle, is often diffuse, and cannot necessarily be resected with clean margins as can a fibroid. Yet, as demonstrated in a systematic review of 27 observational studies of conservative surgery for adenomyosis – 10 prospective and 17 retrospective studies with a total of almost 1,400 patients and all with adenomyosis confirmed histopathologically – surgery can improve pain, menorrhagia, and adenomyosis-related infertility in a significant number of cases.5

Disease may be resected through laparotomy, laparoscopy, or as we are currently doing with focal disease that is close to the endometrium, hysteroscopy. The type of surgery will depend on the location and characteristics of the disease, and on the surgeon’s skills. The principles are the same with all three approaches: to remove as much diseased tissue – and preserve as much healthy myometrial tissue – as possible and to reconstruct the uterine wall so that it maintains its integrity and can sustain a pregnancy.

The open approach known as the Osada procedure, after Hisao Osada, MD, PhD, in Tokyo, is well described in the literature, with a relatively large number of cases reported in prospective studies. Dr. Osada performs a radical adenomyosis excision with a triple flap method of uterine wall reconstruction. The uterus is bisected in the mid-sagittal plane all the way down through the adenomyosis until the uterine cavity is reached. Excision of the adenomyotic tissue is guided by palpation with the index finger, and a myometrial thickness of 1 cm from the serosa and the endometrium is preserved.

The endometrium is closed, and the myometrial defect is closed with a triple flap method that avoids overlapping suture lines. On one side of the uterus, the myometrium and serosa are sutured in the antero-posterior plane. The seromuscular layer of the opposite side of the uterine wall is then brought over the first seromuscular suture line.6

Others, such as Grigoris H. Grimbizis, MD, PhD, in Greece, have used a laparoscopic approach and closed the myometrium in layers similar to those of a myomectomy.7 There are no comparative trials that demonstrate one technique is superior to the other.

While there are no textbook techniques published for resecting adenomyotic tissue laparoscopically or hysteroscopically from the normal myometrium, there are some general principals the surgeon should keep in mind. Adenomyosis is defined as the presence of endometrial glands and stroma within myometrium, but biopsy studies have demonstrated that there are relatively few glands and stroma within the diseased tissue. Mostly, the adenomyotic tissue we encounter comprises smooth muscle hyperplasia and fibrosis.

Since there is no pseudocapsule surrounding adenomyotic tissue, the visual cue for the cytoreductive procedure is the presence of normal-appearing myometrium. The normal myometrium can be delineated by palpation with laparoscopic instruments or hysteroscopic loops as it clearly feels less fibrotic and firm than the adenomyotic tissue. For this reason, the adenomyotic tissue is removed in a piecemeal fashion until normal tissue is encountered. (This same philosophy can be applied to removing fibrotic, glandular, or cystic tissue hysteroscopically.)

If the disease involves the inner myometrium, it should resected as this may be very important to restoring normal uterine contractions needed for embryo implantation and development, even if it means entering the cavity laparoscopically.

Hysteroscopically, there is no ability to suture a myometrial defect. This limitation is concerning because the adenomyosis is thought to invade the myometrium and not displace it as seen with monoclonal uterine fibroids. There are no case reports of uterine rupture after hysteroscopic resection of adenomyosis, but the number of cases reported with this type of resection in general is very small.

Laparoscopically, the myometrial defect should be repaired similarly to a myomectomy defect. Chromic or polydioxanone (PDS) suture is appropriate. We have used 2-0 PDS V-loc and a 2-3 layer closure in our laparoscopic cases.

Diffuse adenomyosis can involve the entire anterior or posterior wall of the uterus or both. The surgeon should not attempt to remove all of the disease in this situation and must leave enough tissue, even diseased, to allow for structural integrity during pregnancy. Uterine rupture has not been reported in all published case series and studies, but overall, it is a concern with surgical excision of adenomyosis. An analysis of over 2,000 cases of adenomyomectomies reported worldwide since 1990 shows a uterine rupture rate in the 6% rate, with a pregnancy rate ranging from 7%-72%.8

When the disease is focal and close to the endometrium, as opposed to diffuse and affecting the entire back wall of the uterus, hysteroscopic excision may be an appropriate, less invasive approach.

One of the patients for whom we’ve taken this approach was a 37-year-old patient who presented with a history of six miscarriages, a negative work-up for recurrent pregnancy loss, an enlarged uterus, 8 years of heavy menstrual bleeding, and only mild dysmenorrhea. She had undergone in vitro fertilization with failed embryo transfers but normal genetic screens of the embryos. She was referred with a suspicion of fibroids. An MRI and ultrasound showed heterogeneous myometrium adjacent to the endometrium. This tissue was resected using a bipolar loop electrode until normal myometrium was encountered.

Hysteroscopic resections are currently described in the literature through case reports rather than larger prospective or retrospective studies, and much more research is needed to demonstrate the efficacy and safety of this approach.

At this point in time, while surgery to excise adenomyosis is a last resort and best methods are deliberated, it is still important to appreciate that surgery is an option. Continued infertility is not the only choice, nor is hysterectomy.

References

1. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol 2014;27:258-65.

2. Minerva Ginecol. 2018 Jun;70(3):295-302.

3. Fertil Steril. 2017;108(3):483-490.e3.

4. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;198(4):373.e1-7.

5. J. Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2018 Feb;25:265-76.

6. Reproductive BioMed Online. 2011 Jan;22(1):94-9.

7. Fertil Steril. 2014 Feb;101(2):472-87.

8. Fertil Steril. 2018 Mar;109(3):406-17.

Menstrual irregularity appears to be predictor of early death

than women with regular or short cycles, reported Yi-Xin Wang, PhD, of Harvard TH Chan School of Public Health, Boston, and associates. This is particularly true in the presence of cardiovascular disease and a history of smoking.

In a peer-reviewed observational study of 79,505 premenopausal women enrolled in the Nurses’ Health Study II, the researchers sought to determine whether a life-long history of irregular or long menstrual cycles was associated with premature death. Patients averaged a mean age of 37.7 years and had no history of cardiovascular disease, cancer, or diabetes at enrollment.

Although irregular and long menstrual cycles are common and frequently linked with an increased risk of major chronic diseases – such as ovarian cancer, coronary heart disease, type 2 diabetes, and mental health problems – in women of reproductive age, actual evidence linking irregular or long menstrual cycles with mortality is scant, the researchers noted in the BMJ.

During the study, participants checked in at ages 14-17 years, 18-22 years, and 29-46 years to report the usual length and regularity of their menstrual cycles. Over 24 years of follow-up, a total of 1,975 premature deaths were noted, including 894 from cancer and 172 from cardiovascular disease.

Irregular cycles appear to bring risks

After considering other possible factors of influence, including age, weight, lifestyle, and family medical history, Dr. Wang and associates noted higher rates of mortality among those consistently reporting irregular cycles than women in the same age ranges with very regular cycles. Specifically, women aged 18-22 years and 29-46 years with cycles of 40 days or more were at greater risk of dying prematurely than were those in the same age ranges with cycles of 26-31 days.

Cardiovascular disease was a stronger predictor of death than cancer or other causes. Also included in the higher-risk group were those who currently smoked.

Among women reporting very regular cycles and women reporting always irregular cycles, mortality rates per 1,000 person-years were 1.05 and 1.23 at ages 14-17 years, 1.00 and 1.37 at ages 18-22 years, and 1.00 and 1.68 at ages 29-46 years, respectively.

The study also found that women reporting irregular cycles or no periods had a higher body mass indexes (28.2 vs. 25.0 kg/m2); were more likely to have conditions including hypertension (13.2% vs. 6.2%), high blood cholesterol levels (23.9% vs. 14.9%), hirsutism (8.4%

vs. 1.8%), or endometriosis (5.9% vs. 4.5%); and uterine fibroids (10.0% vs. 7.8%); and a higher prevalence of family history of diabetes (19.4% vs. 15.8%).

Dr. Wang and associates also observed – using multivariable Cox models – a greater risk of premature death across all categories and all age ranges in women with decreasing menstrual cycle regularity. In models that were fully adjusted, cycle lengths that were 40 days or more or too irregular to estimate from ages 18-22 and 29-46 expressed hazard ratios for premature death at the time of follow-up of 1.34 and 1.40, compared with women in the same age ranges reporting cycle lengths of 26-31 days.

Of note, Dr. Wang and colleagues unexpectedly discovered an increased risk of premature death in women who had used contraceptives between 14-17 years. They suggested that a greater number of women self-reporting contraceptive use in adolescence may have been using contraceptives to manage symptoms of polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) and other conditions such as endometriosis.

Relying on the potential inaccuracy inherent in patient recall of their menstrual cycle characteristics, and the likelihood for other unmeasured factors, may have affected study results. Study strengths included the significant number of participants who had a high follow-up rate over many years, and the availability of menstrual cycle data at three different points across the reproductive lifespan.

Because the mechanisms underlying these associations are likely related to the disrupted hormonal environment, the study results “emphasize the need for primary care providers to include menstrual cycle characteristics throughout the reproductive life span as additional vital signs in assessing women’s general health status,” Dr. Wang and colleagues cautioned.

Expert suggests a probable underlying link

“Irregular menstrual cycles in women have long been known to be associated with significant morbidities, including the leading causes of mortality worldwide such as cardiovascular disease and cancer,” Reshef Tal, MD, PhD, assistant professor of obstetrics, gynecology & reproductive sciences at Yale University, New Haven, Conn., said in an interview. “The findings of this large study that irregular menstrual cycles are associated with premature death, most strongly from cardiovascular causes, are therefore not surprising.”

Dr. Tal acknowledged that one probable underlying link is PCOS, which is recognized as the most common hormonal disorder affecting women of reproductive age. The irregular periods that characterize PCOS are tied to a number of metabolic risk factors, including obesity, insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, and hypertension, which increase the long-term risk of cardiovascular disease and cancer of the uterus.

“The study did not have information on patients’ pelvic ultrasound findings and male hormone levels, which would have helped to establish PCOS diagnosis. However, women in this study who had irregular cycles tended to have more hirsutism, high cholesterol, hypertension as well as higher BMI, suggesting that PCOS is at least partly responsible for the observed association with cardiovascular disease. Interestingly, the association between irregular cycles and early mortality was independent of BMI, indicating that mechanisms other than metabolic factors may also play a role,” observed Dr. Tal, who was asked to comment on the study.

“Irregular periods are a symptom and not a disease, so it is important to identify underlying metabolic risk factors. Furthermore, physicians are advised to counsel patients experiencing menstrual irregularity, [to advise them to] maintain a healthy lifestyle and be alert to health changes,” Dr. Tal suggested.

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health. The investigators had no relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Tal said he had no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Chavarro J et al. BMJ. 2020. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m3464.

than women with regular or short cycles, reported Yi-Xin Wang, PhD, of Harvard TH Chan School of Public Health, Boston, and associates. This is particularly true in the presence of cardiovascular disease and a history of smoking.

In a peer-reviewed observational study of 79,505 premenopausal women enrolled in the Nurses’ Health Study II, the researchers sought to determine whether a life-long history of irregular or long menstrual cycles was associated with premature death. Patients averaged a mean age of 37.7 years and had no history of cardiovascular disease, cancer, or diabetes at enrollment.

Although irregular and long menstrual cycles are common and frequently linked with an increased risk of major chronic diseases – such as ovarian cancer, coronary heart disease, type 2 diabetes, and mental health problems – in women of reproductive age, actual evidence linking irregular or long menstrual cycles with mortality is scant, the researchers noted in the BMJ.

During the study, participants checked in at ages 14-17 years, 18-22 years, and 29-46 years to report the usual length and regularity of their menstrual cycles. Over 24 years of follow-up, a total of 1,975 premature deaths were noted, including 894 from cancer and 172 from cardiovascular disease.

Irregular cycles appear to bring risks

After considering other possible factors of influence, including age, weight, lifestyle, and family medical history, Dr. Wang and associates noted higher rates of mortality among those consistently reporting irregular cycles than women in the same age ranges with very regular cycles. Specifically, women aged 18-22 years and 29-46 years with cycles of 40 days or more were at greater risk of dying prematurely than were those in the same age ranges with cycles of 26-31 days.

Cardiovascular disease was a stronger predictor of death than cancer or other causes. Also included in the higher-risk group were those who currently smoked.

Among women reporting very regular cycles and women reporting always irregular cycles, mortality rates per 1,000 person-years were 1.05 and 1.23 at ages 14-17 years, 1.00 and 1.37 at ages 18-22 years, and 1.00 and 1.68 at ages 29-46 years, respectively.

The study also found that women reporting irregular cycles or no periods had a higher body mass indexes (28.2 vs. 25.0 kg/m2); were more likely to have conditions including hypertension (13.2% vs. 6.2%), high blood cholesterol levels (23.9% vs. 14.9%), hirsutism (8.4%

vs. 1.8%), or endometriosis (5.9% vs. 4.5%); and uterine fibroids (10.0% vs. 7.8%); and a higher prevalence of family history of diabetes (19.4% vs. 15.8%).

Dr. Wang and associates also observed – using multivariable Cox models – a greater risk of premature death across all categories and all age ranges in women with decreasing menstrual cycle regularity. In models that were fully adjusted, cycle lengths that were 40 days or more or too irregular to estimate from ages 18-22 and 29-46 expressed hazard ratios for premature death at the time of follow-up of 1.34 and 1.40, compared with women in the same age ranges reporting cycle lengths of 26-31 days.

Of note, Dr. Wang and colleagues unexpectedly discovered an increased risk of premature death in women who had used contraceptives between 14-17 years. They suggested that a greater number of women self-reporting contraceptive use in adolescence may have been using contraceptives to manage symptoms of polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) and other conditions such as endometriosis.

Relying on the potential inaccuracy inherent in patient recall of their menstrual cycle characteristics, and the likelihood for other unmeasured factors, may have affected study results. Study strengths included the significant number of participants who had a high follow-up rate over many years, and the availability of menstrual cycle data at three different points across the reproductive lifespan.

Because the mechanisms underlying these associations are likely related to the disrupted hormonal environment, the study results “emphasize the need for primary care providers to include menstrual cycle characteristics throughout the reproductive life span as additional vital signs in assessing women’s general health status,” Dr. Wang and colleagues cautioned.

Expert suggests a probable underlying link

“Irregular menstrual cycles in women have long been known to be associated with significant morbidities, including the leading causes of mortality worldwide such as cardiovascular disease and cancer,” Reshef Tal, MD, PhD, assistant professor of obstetrics, gynecology & reproductive sciences at Yale University, New Haven, Conn., said in an interview. “The findings of this large study that irregular menstrual cycles are associated with premature death, most strongly from cardiovascular causes, are therefore not surprising.”

Dr. Tal acknowledged that one probable underlying link is PCOS, which is recognized as the most common hormonal disorder affecting women of reproductive age. The irregular periods that characterize PCOS are tied to a number of metabolic risk factors, including obesity, insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, and hypertension, which increase the long-term risk of cardiovascular disease and cancer of the uterus.

“The study did not have information on patients’ pelvic ultrasound findings and male hormone levels, which would have helped to establish PCOS diagnosis. However, women in this study who had irregular cycles tended to have more hirsutism, high cholesterol, hypertension as well as higher BMI, suggesting that PCOS is at least partly responsible for the observed association with cardiovascular disease. Interestingly, the association between irregular cycles and early mortality was independent of BMI, indicating that mechanisms other than metabolic factors may also play a role,” observed Dr. Tal, who was asked to comment on the study.

“Irregular periods are a symptom and not a disease, so it is important to identify underlying metabolic risk factors. Furthermore, physicians are advised to counsel patients experiencing menstrual irregularity, [to advise them to] maintain a healthy lifestyle and be alert to health changes,” Dr. Tal suggested.

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health. The investigators had no relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Tal said he had no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Chavarro J et al. BMJ. 2020. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m3464.

than women with regular or short cycles, reported Yi-Xin Wang, PhD, of Harvard TH Chan School of Public Health, Boston, and associates. This is particularly true in the presence of cardiovascular disease and a history of smoking.

In a peer-reviewed observational study of 79,505 premenopausal women enrolled in the Nurses’ Health Study II, the researchers sought to determine whether a life-long history of irregular or long menstrual cycles was associated with premature death. Patients averaged a mean age of 37.7 years and had no history of cardiovascular disease, cancer, or diabetes at enrollment.

Although irregular and long menstrual cycles are common and frequently linked with an increased risk of major chronic diseases – such as ovarian cancer, coronary heart disease, type 2 diabetes, and mental health problems – in women of reproductive age, actual evidence linking irregular or long menstrual cycles with mortality is scant, the researchers noted in the BMJ.

During the study, participants checked in at ages 14-17 years, 18-22 years, and 29-46 years to report the usual length and regularity of their menstrual cycles. Over 24 years of follow-up, a total of 1,975 premature deaths were noted, including 894 from cancer and 172 from cardiovascular disease.

Irregular cycles appear to bring risks

After considering other possible factors of influence, including age, weight, lifestyle, and family medical history, Dr. Wang and associates noted higher rates of mortality among those consistently reporting irregular cycles than women in the same age ranges with very regular cycles. Specifically, women aged 18-22 years and 29-46 years with cycles of 40 days or more were at greater risk of dying prematurely than were those in the same age ranges with cycles of 26-31 days.

Cardiovascular disease was a stronger predictor of death than cancer or other causes. Also included in the higher-risk group were those who currently smoked.

Among women reporting very regular cycles and women reporting always irregular cycles, mortality rates per 1,000 person-years were 1.05 and 1.23 at ages 14-17 years, 1.00 and 1.37 at ages 18-22 years, and 1.00 and 1.68 at ages 29-46 years, respectively.

The study also found that women reporting irregular cycles or no periods had a higher body mass indexes (28.2 vs. 25.0 kg/m2); were more likely to have conditions including hypertension (13.2% vs. 6.2%), high blood cholesterol levels (23.9% vs. 14.9%), hirsutism (8.4%

vs. 1.8%), or endometriosis (5.9% vs. 4.5%); and uterine fibroids (10.0% vs. 7.8%); and a higher prevalence of family history of diabetes (19.4% vs. 15.8%).

Dr. Wang and associates also observed – using multivariable Cox models – a greater risk of premature death across all categories and all age ranges in women with decreasing menstrual cycle regularity. In models that were fully adjusted, cycle lengths that were 40 days or more or too irregular to estimate from ages 18-22 and 29-46 expressed hazard ratios for premature death at the time of follow-up of 1.34 and 1.40, compared with women in the same age ranges reporting cycle lengths of 26-31 days.

Of note, Dr. Wang and colleagues unexpectedly discovered an increased risk of premature death in women who had used contraceptives between 14-17 years. They suggested that a greater number of women self-reporting contraceptive use in adolescence may have been using contraceptives to manage symptoms of polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) and other conditions such as endometriosis.

Relying on the potential inaccuracy inherent in patient recall of their menstrual cycle characteristics, and the likelihood for other unmeasured factors, may have affected study results. Study strengths included the significant number of participants who had a high follow-up rate over many years, and the availability of menstrual cycle data at three different points across the reproductive lifespan.

Because the mechanisms underlying these associations are likely related to the disrupted hormonal environment, the study results “emphasize the need for primary care providers to include menstrual cycle characteristics throughout the reproductive life span as additional vital signs in assessing women’s general health status,” Dr. Wang and colleagues cautioned.

Expert suggests a probable underlying link

“Irregular menstrual cycles in women have long been known to be associated with significant morbidities, including the leading causes of mortality worldwide such as cardiovascular disease and cancer,” Reshef Tal, MD, PhD, assistant professor of obstetrics, gynecology & reproductive sciences at Yale University, New Haven, Conn., said in an interview. “The findings of this large study that irregular menstrual cycles are associated with premature death, most strongly from cardiovascular causes, are therefore not surprising.”

Dr. Tal acknowledged that one probable underlying link is PCOS, which is recognized as the most common hormonal disorder affecting women of reproductive age. The irregular periods that characterize PCOS are tied to a number of metabolic risk factors, including obesity, insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, and hypertension, which increase the long-term risk of cardiovascular disease and cancer of the uterus.

“The study did not have information on patients’ pelvic ultrasound findings and male hormone levels, which would have helped to establish PCOS diagnosis. However, women in this study who had irregular cycles tended to have more hirsutism, high cholesterol, hypertension as well as higher BMI, suggesting that PCOS is at least partly responsible for the observed association with cardiovascular disease. Interestingly, the association between irregular cycles and early mortality was independent of BMI, indicating that mechanisms other than metabolic factors may also play a role,” observed Dr. Tal, who was asked to comment on the study.

“Irregular periods are a symptom and not a disease, so it is important to identify underlying metabolic risk factors. Furthermore, physicians are advised to counsel patients experiencing menstrual irregularity, [to advise them to] maintain a healthy lifestyle and be alert to health changes,” Dr. Tal suggested.

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health. The investigators had no relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Tal said he had no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Chavarro J et al. BMJ. 2020. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m3464.

FROM THE BMJ

POP surgeries not tied to decreased sexual functioning

Danielle D. Antosh, MD, of the Houston Methodist Hospital and colleagues reported in a systematic review of prospective comparative studies on pelvic organ prolapse surgery, which was published in Obstetrics & Gynecology.

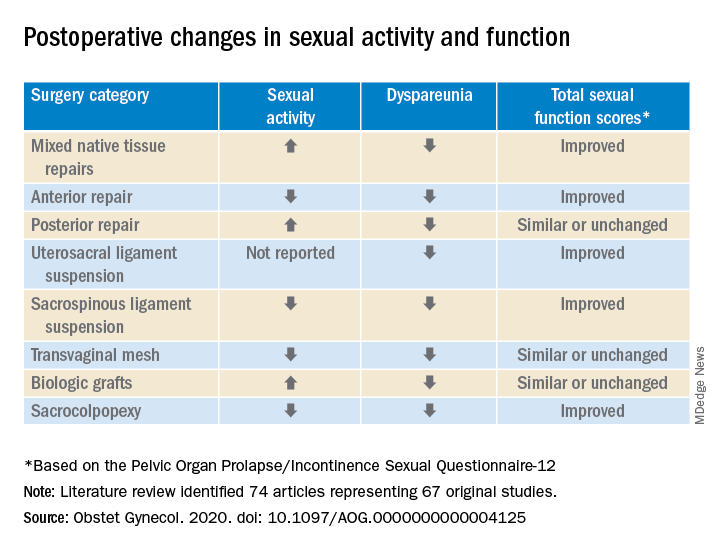

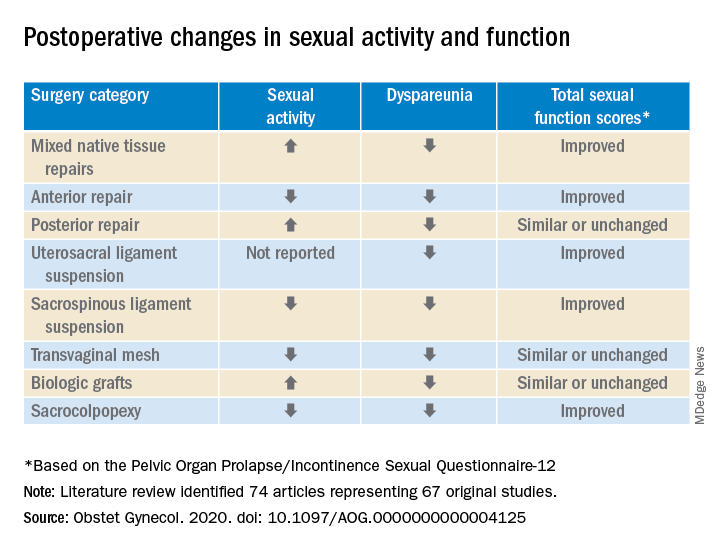

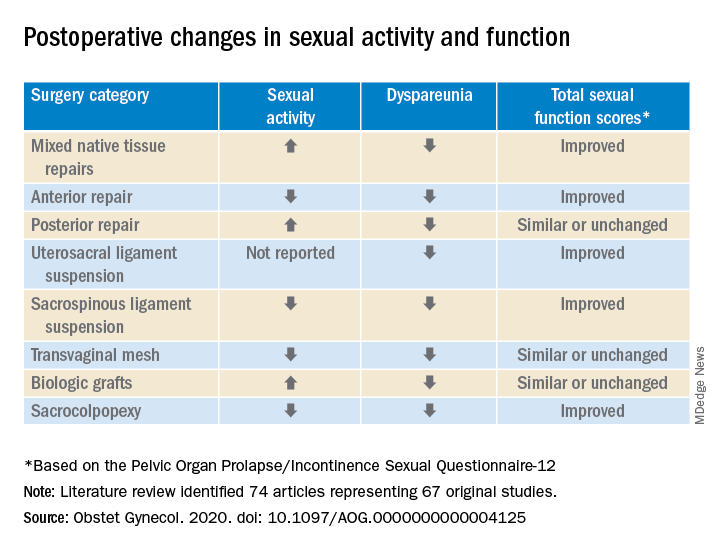

In a preliminary search of 3,124 citations, Dr. Antosh and her colleagues, who are members of the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons Systematic Review Group responsible for the study, identified and accepted 74 articles representing 67 original studies. Ten of these were ancillary studies with different reported outcomes or follow-up times, and 44 were randomized control trials. They compared the pre- and postoperative effects of pelvic organ prolapse (POP) surgery on sexual function for changes in sexual activity and function across eight different prolapse surgery categories: mixed native tissue repairs, anterior repair, posterior repair, uterosacral ligament suspension, sacrospinous ligament suspension, transvaginal mesh, biologic grafts, and sacrocolpopexy. In only three categories – posterior repair, transvaginal mesh, and biological grafts – postoperative changes in sexual function scores were similar or remained unchanged. In all other categories, total sexual function scores improved. Dyspareunia was lower after surgery for all prolapse surgery types.

“Although sexual function improves in the majority of women, it is important to note that a small proportion of women can develop de novo (new onset) dyspareunia after surgery. The rate of this ranges from 0%-9% for prolapse surgeries. However, there is limited data on posterior repairs,” Dr. Antosh said in a later interview.*

POP surgeries positively impact sexual function, dyspareunia outcomes

The researchers determined that there is “moderate to high quality data” supporting the influence of POP on sexual activity and function. They also observed a lower prevalence of dyspareunia postoperatively across all surgery types, compared with baseline. Additionally, no decrease in sexual function was reported across surgical categories; in fact, sexual activity and function improved or stayed the same after POP surgery in this review.

Across most POP surgery groups, Dr. Antosh and colleagues found that with the exception of the sacrospinous ligament suspension, transvaginal mesh, and sacrocolpopexy groups, the rate of postoperative sexual activity was modestly higher. Several studies attributed this finding to a lack of partner or partner-related issues. Another 16 studies (7.7%) cited pain as the primary factor for postoperative sexual inactivity.

Few studies included in the review “reported both preoperative and postoperative rates of sexual activity and dyspareunia, and no study reported patient-level changes in sexual activity or dyspareunia (except occasionally, for de novo activity or dyspareunia),” Dr. Antosh and associates clarified. As a result, they concluded that their findings are based primarily on qualitative comparisons of events reported pre- and postoperatively from different but overlapping sets of studies.

The finding that the prevalence of dyspareunia decreased following all types of POP surgery is consistent with previous reviews. Because the studies did not account for minimally important differences in sexual function scores, it is important to consider this when interpreting results of the review. Dr. Antosh and colleagues also noted that some studies did not define dyspareunia, and those that did frequently used measures that were not validated. They also were unable to identify the persistence of dyspareunia following surgery as this was not recorded in the literature.

Menopausal status and other considerations

Also worth noting, the mean age of women in the studies were postmenopausal, yet the “studies did not stratify sexual function outcomes based on premenopause compared with postmenopause status.”

The researchers advised that future studies using validated definitions of sexual activity, function, and dyspareunia, as well as reporting both their preoperative and postoperative measures would do much to improve the quality of research reported.

It is widely recognized that women with pelvic floor disorders experience a high rate of sexual dysfunction, so the need to achieve optimum outcomes that at least maintain if not improve sexual function postoperatively should be of key concern when planning POP surgery for patients, they cautioned. Previous studies have observed that women experiencing POP rated the need for improved sexual function second only to resolved bulge symptoms and improvement in overall function. The women also classified sexual dysfunction in the same category of adversity as having chronic pain or having to be admitted to an intensive care unit.

Study provides preoperative counseling help

David M. Jaspan, DO, chairman of the department of obstetrics and gynecology and Natasha Abdullah, MD, obstetrics and gynecology resident, both of Einstein Medical Center, Philadelphia, collaboratively commented on the study findings: “This review provides physicians with data to add to the preoperative counseling for patients undergoing pelvic organ prolapse surgery.”

In particular, they noted that, while the article “is a review of previous literature, Table 1 provides an opportunity for physicians to share with their patients the important answers to their concerns surrounding postoperative sexual activity, dyspareunia, and total changes in sexual function scores based on the Pelvic Organ Prolapse/Incontinence Sexual Questionnaire 12 (PISQ-12).”

Noting the clinical usefulness of the questionnaire, they added: “The PISQ-12 is a validated and reliable short form that evaluates sexual function in women with urinary incontinence and/or pelvic organ prolapse and predicts PISQ-31 scores. It was developed from the data of 99 of 182 women surveyed to create the long form (PISQ-31); 46 patients were recruited for further validation. Test-retest reliability was checked with a subset of 20 patients. All subsets regression analysis with R greater than 0.92 identified 12 items that predicted PISQ-31 scores. The PISQ-12 covers three domains of function: Behavioral/Emotive, Physical, and Partner-Related.”

Because ob.gyns. are trained to recognize the “multifactorial reasons (age, partner relationship, other health conditions etc.) that surround sexual activity,” Dr. Jaspan and Dr. Abdullah cautioned against prematurely concluding that the lower sexual activity score is directly related to POP surgery.

“Because sexual function is such an important postsurgical outcome for patients, this article provides significant preoperative counseling data for patients on all POP repair options,” they observed. “No surgical option worsens sexual function. The article concludes that individually validated definitions of sexual activity, function, and dyspareunia in a measuring instrument would improve the quality of data for future studies.”

The study authors reported no relevant financial disclosures. Although no direct funding was provided by the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons, they did provide meeting space, oversight, stipends for expert and statistical support, and aid in disseminating findings. Dr. Abdullah and Dr. Jaspan had no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Antosh DD et al. Obstet Gynecol. 2020. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000004125.

*This article was updated on 10/28.

Danielle D. Antosh, MD, of the Houston Methodist Hospital and colleagues reported in a systematic review of prospective comparative studies on pelvic organ prolapse surgery, which was published in Obstetrics & Gynecology.

In a preliminary search of 3,124 citations, Dr. Antosh and her colleagues, who are members of the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons Systematic Review Group responsible for the study, identified and accepted 74 articles representing 67 original studies. Ten of these were ancillary studies with different reported outcomes or follow-up times, and 44 were randomized control trials. They compared the pre- and postoperative effects of pelvic organ prolapse (POP) surgery on sexual function for changes in sexual activity and function across eight different prolapse surgery categories: mixed native tissue repairs, anterior repair, posterior repair, uterosacral ligament suspension, sacrospinous ligament suspension, transvaginal mesh, biologic grafts, and sacrocolpopexy. In only three categories – posterior repair, transvaginal mesh, and biological grafts – postoperative changes in sexual function scores were similar or remained unchanged. In all other categories, total sexual function scores improved. Dyspareunia was lower after surgery for all prolapse surgery types.

“Although sexual function improves in the majority of women, it is important to note that a small proportion of women can develop de novo (new onset) dyspareunia after surgery. The rate of this ranges from 0%-9% for prolapse surgeries. However, there is limited data on posterior repairs,” Dr. Antosh said in a later interview.*

POP surgeries positively impact sexual function, dyspareunia outcomes

The researchers determined that there is “moderate to high quality data” supporting the influence of POP on sexual activity and function. They also observed a lower prevalence of dyspareunia postoperatively across all surgery types, compared with baseline. Additionally, no decrease in sexual function was reported across surgical categories; in fact, sexual activity and function improved or stayed the same after POP surgery in this review.

Across most POP surgery groups, Dr. Antosh and colleagues found that with the exception of the sacrospinous ligament suspension, transvaginal mesh, and sacrocolpopexy groups, the rate of postoperative sexual activity was modestly higher. Several studies attributed this finding to a lack of partner or partner-related issues. Another 16 studies (7.7%) cited pain as the primary factor for postoperative sexual inactivity.

Few studies included in the review “reported both preoperative and postoperative rates of sexual activity and dyspareunia, and no study reported patient-level changes in sexual activity or dyspareunia (except occasionally, for de novo activity or dyspareunia),” Dr. Antosh and associates clarified. As a result, they concluded that their findings are based primarily on qualitative comparisons of events reported pre- and postoperatively from different but overlapping sets of studies.

The finding that the prevalence of dyspareunia decreased following all types of POP surgery is consistent with previous reviews. Because the studies did not account for minimally important differences in sexual function scores, it is important to consider this when interpreting results of the review. Dr. Antosh and colleagues also noted that some studies did not define dyspareunia, and those that did frequently used measures that were not validated. They also were unable to identify the persistence of dyspareunia following surgery as this was not recorded in the literature.

Menopausal status and other considerations

Also worth noting, the mean age of women in the studies were postmenopausal, yet the “studies did not stratify sexual function outcomes based on premenopause compared with postmenopause status.”

The researchers advised that future studies using validated definitions of sexual activity, function, and dyspareunia, as well as reporting both their preoperative and postoperative measures would do much to improve the quality of research reported.

It is widely recognized that women with pelvic floor disorders experience a high rate of sexual dysfunction, so the need to achieve optimum outcomes that at least maintain if not improve sexual function postoperatively should be of key concern when planning POP surgery for patients, they cautioned. Previous studies have observed that women experiencing POP rated the need for improved sexual function second only to resolved bulge symptoms and improvement in overall function. The women also classified sexual dysfunction in the same category of adversity as having chronic pain or having to be admitted to an intensive care unit.

Study provides preoperative counseling help

David M. Jaspan, DO, chairman of the department of obstetrics and gynecology and Natasha Abdullah, MD, obstetrics and gynecology resident, both of Einstein Medical Center, Philadelphia, collaboratively commented on the study findings: “This review provides physicians with data to add to the preoperative counseling for patients undergoing pelvic organ prolapse surgery.”

In particular, they noted that, while the article “is a review of previous literature, Table 1 provides an opportunity for physicians to share with their patients the important answers to their concerns surrounding postoperative sexual activity, dyspareunia, and total changes in sexual function scores based on the Pelvic Organ Prolapse/Incontinence Sexual Questionnaire 12 (PISQ-12).”

Noting the clinical usefulness of the questionnaire, they added: “The PISQ-12 is a validated and reliable short form that evaluates sexual function in women with urinary incontinence and/or pelvic organ prolapse and predicts PISQ-31 scores. It was developed from the data of 99 of 182 women surveyed to create the long form (PISQ-31); 46 patients were recruited for further validation. Test-retest reliability was checked with a subset of 20 patients. All subsets regression analysis with R greater than 0.92 identified 12 items that predicted PISQ-31 scores. The PISQ-12 covers three domains of function: Behavioral/Emotive, Physical, and Partner-Related.”

Because ob.gyns. are trained to recognize the “multifactorial reasons (age, partner relationship, other health conditions etc.) that surround sexual activity,” Dr. Jaspan and Dr. Abdullah cautioned against prematurely concluding that the lower sexual activity score is directly related to POP surgery.

“Because sexual function is such an important postsurgical outcome for patients, this article provides significant preoperative counseling data for patients on all POP repair options,” they observed. “No surgical option worsens sexual function. The article concludes that individually validated definitions of sexual activity, function, and dyspareunia in a measuring instrument would improve the quality of data for future studies.”

The study authors reported no relevant financial disclosures. Although no direct funding was provided by the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons, they did provide meeting space, oversight, stipends for expert and statistical support, and aid in disseminating findings. Dr. Abdullah and Dr. Jaspan had no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Antosh DD et al. Obstet Gynecol. 2020. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000004125.

*This article was updated on 10/28.

Danielle D. Antosh, MD, of the Houston Methodist Hospital and colleagues reported in a systematic review of prospective comparative studies on pelvic organ prolapse surgery, which was published in Obstetrics & Gynecology.

In a preliminary search of 3,124 citations, Dr. Antosh and her colleagues, who are members of the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons Systematic Review Group responsible for the study, identified and accepted 74 articles representing 67 original studies. Ten of these were ancillary studies with different reported outcomes or follow-up times, and 44 were randomized control trials. They compared the pre- and postoperative effects of pelvic organ prolapse (POP) surgery on sexual function for changes in sexual activity and function across eight different prolapse surgery categories: mixed native tissue repairs, anterior repair, posterior repair, uterosacral ligament suspension, sacrospinous ligament suspension, transvaginal mesh, biologic grafts, and sacrocolpopexy. In only three categories – posterior repair, transvaginal mesh, and biological grafts – postoperative changes in sexual function scores were similar or remained unchanged. In all other categories, total sexual function scores improved. Dyspareunia was lower after surgery for all prolapse surgery types.

“Although sexual function improves in the majority of women, it is important to note that a small proportion of women can develop de novo (new onset) dyspareunia after surgery. The rate of this ranges from 0%-9% for prolapse surgeries. However, there is limited data on posterior repairs,” Dr. Antosh said in a later interview.*

POP surgeries positively impact sexual function, dyspareunia outcomes

The researchers determined that there is “moderate to high quality data” supporting the influence of POP on sexual activity and function. They also observed a lower prevalence of dyspareunia postoperatively across all surgery types, compared with baseline. Additionally, no decrease in sexual function was reported across surgical categories; in fact, sexual activity and function improved or stayed the same after POP surgery in this review.

Across most POP surgery groups, Dr. Antosh and colleagues found that with the exception of the sacrospinous ligament suspension, transvaginal mesh, and sacrocolpopexy groups, the rate of postoperative sexual activity was modestly higher. Several studies attributed this finding to a lack of partner or partner-related issues. Another 16 studies (7.7%) cited pain as the primary factor for postoperative sexual inactivity.

Few studies included in the review “reported both preoperative and postoperative rates of sexual activity and dyspareunia, and no study reported patient-level changes in sexual activity or dyspareunia (except occasionally, for de novo activity or dyspareunia),” Dr. Antosh and associates clarified. As a result, they concluded that their findings are based primarily on qualitative comparisons of events reported pre- and postoperatively from different but overlapping sets of studies.

The finding that the prevalence of dyspareunia decreased following all types of POP surgery is consistent with previous reviews. Because the studies did not account for minimally important differences in sexual function scores, it is important to consider this when interpreting results of the review. Dr. Antosh and colleagues also noted that some studies did not define dyspareunia, and those that did frequently used measures that were not validated. They also were unable to identify the persistence of dyspareunia following surgery as this was not recorded in the literature.

Menopausal status and other considerations

Also worth noting, the mean age of women in the studies were postmenopausal, yet the “studies did not stratify sexual function outcomes based on premenopause compared with postmenopause status.”

The researchers advised that future studies using validated definitions of sexual activity, function, and dyspareunia, as well as reporting both their preoperative and postoperative measures would do much to improve the quality of research reported.

It is widely recognized that women with pelvic floor disorders experience a high rate of sexual dysfunction, so the need to achieve optimum outcomes that at least maintain if not improve sexual function postoperatively should be of key concern when planning POP surgery for patients, they cautioned. Previous studies have observed that women experiencing POP rated the need for improved sexual function second only to resolved bulge symptoms and improvement in overall function. The women also classified sexual dysfunction in the same category of adversity as having chronic pain or having to be admitted to an intensive care unit.

Study provides preoperative counseling help

David M. Jaspan, DO, chairman of the department of obstetrics and gynecology and Natasha Abdullah, MD, obstetrics and gynecology resident, both of Einstein Medical Center, Philadelphia, collaboratively commented on the study findings: “This review provides physicians with data to add to the preoperative counseling for patients undergoing pelvic organ prolapse surgery.”

In particular, they noted that, while the article “is a review of previous literature, Table 1 provides an opportunity for physicians to share with their patients the important answers to their concerns surrounding postoperative sexual activity, dyspareunia, and total changes in sexual function scores based on the Pelvic Organ Prolapse/Incontinence Sexual Questionnaire 12 (PISQ-12).”

Noting the clinical usefulness of the questionnaire, they added: “The PISQ-12 is a validated and reliable short form that evaluates sexual function in women with urinary incontinence and/or pelvic organ prolapse and predicts PISQ-31 scores. It was developed from the data of 99 of 182 women surveyed to create the long form (PISQ-31); 46 patients were recruited for further validation. Test-retest reliability was checked with a subset of 20 patients. All subsets regression analysis with R greater than 0.92 identified 12 items that predicted PISQ-31 scores. The PISQ-12 covers three domains of function: Behavioral/Emotive, Physical, and Partner-Related.”

Because ob.gyns. are trained to recognize the “multifactorial reasons (age, partner relationship, other health conditions etc.) that surround sexual activity,” Dr. Jaspan and Dr. Abdullah cautioned against prematurely concluding that the lower sexual activity score is directly related to POP surgery.

“Because sexual function is such an important postsurgical outcome for patients, this article provides significant preoperative counseling data for patients on all POP repair options,” they observed. “No surgical option worsens sexual function. The article concludes that individually validated definitions of sexual activity, function, and dyspareunia in a measuring instrument would improve the quality of data for future studies.”

The study authors reported no relevant financial disclosures. Although no direct funding was provided by the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons, they did provide meeting space, oversight, stipends for expert and statistical support, and aid in disseminating findings. Dr. Abdullah and Dr. Jaspan had no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Antosh DD et al. Obstet Gynecol. 2020. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000004125.

*This article was updated on 10/28.

FROM OBSTETRICS & GYNECOLOGY

PCOS tied to risk for cardiovascular disease after menopause

Women with polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS) before menopause appear to have a greater risk of stroke, heart attack, and other cardiovascular events after menopause, according to findings presented at the virtual American Society for Reproductive Medicine (ASRM) 2020 Scientific Congress.

“We found a PCOS diagnosis prior to menopause was associated with a 64% increased risk of cardiovascular disease after menopause independent of age at enrollment, race, body mass index, and smoking status,” presenter Jacob Christ, MD, a resident at the University of Washington in Seattle, told attendees. “Taken together, our results suggest that women with PCOS have more risk factors for future cardiovascular disease at baseline, and a present PCOS diagnosis prior to menopause is associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular disease after menopause.”

The results are important to consider in women seeking care related to fertility, according to Amanda N. Kallen, MD, assistant professor of reproductive endocrinology and infertility at Yale Medicine in New Haven, Conn.

“As fertility specialists, we often see women with PCOS visit us when they are having trouble conceiving, but often [they] do not return to our care once they’ve built their family,” said Dr. Kallen, who was not involved in the research.