User login

In the management of cesarean scar defects, is there a superior surgical method for treatment?

He Y, Zhong J, Zhou W, et al. Four surgical strategies for the treatment of cesarean scar defect: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2020;27:593-602.

EXPERT COMMENTARY

With the increase in cesarean deliveries performed over the decades, the sequelae of the surgery are now arising. Cesarean scar defects (CSDs) are a complication seen when the endometrium and muscular layers from a prior uterine scar are damaged. This damage in the uterine scar can lead to abnormal uterine bleeding and the implantation of an ectopic pregnancy, which can be life-threatening. Ultrasonography can be used to diagnose this defect, which can appear as a hypoechoic space filled with postmenstrual blood, representing a myometrial tear at the wound site.1 There are several risk factors for CSD, including multiple cesarean deliveries, cesarean delivery during advanced stages of labor, and uterine incisions near the cervix. Elevated body mass index as well as gestational diabetes also have been found to be associated with inadequate healing of the prior cesarean incision.2 Studies have shown that both single- and double-layer closure of the hysterotomy during a cesarean delivery have similar incidences of CSDs.3,4 There are multiple ways to correct a CSD; however, there is no gold standard that has been identified in the literature.

Details about the study

The study by He and colleagues is a meta-analysis aimed at comparing the treatment of CSDs via laparoscopy, hysteroscopy, combined hysteroscopy and laparoscopy, and vaginal repair. The primary outcome measures were reduction in abnormal uterine bleeding and scar defect depth. A total of 10 studies (n = 858) were reviewed: 4 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and 6 observational studies. The studies analyzed varied in terms of which techniques were compared.

Patients who underwent uterine scar resection by combined laparoscopy and hysteroscopy had a shorter duration of abnormal uterine bleeding when compared with hysteroscopy alone (standardized mean difference [SMD] = 1.36; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.37−2.36; P = .007) and vaginal repair (SMD = 1.58; 95% CI, 0.97−2.19; P<.0001). Combined laparoscopic and hysteroscopic technique also was found to reduce the diverticulum depth more than in vaginal repair (SMD = 1.57; 95% CI, 0.54−2.61; P = .003).

Continue to: Study strengths and weaknesses...

Study strengths and weaknesses

This is the first meta-analysis to compare the different surgical techniques to correct a CSD. The authors were able to compare many of the characteristics regarding the routes of repair, including hysteroscopy, laparoscopy, and vaginal. The authors were able to analyze the combined laparoscopic and hysteroscopic approach, which facilitates evaluation of the location and satisfaction of defect repair during the procedure.

Some weaknesses of this study include the limited amount of RCTs available for review. All studies were also from China, where the rate of CSDs is higher. Therefore, the results may not be generalizable to all populations. Given that the included studies were done at different sites, it is difficult to determine surgical expertise and surgical technique. Additionally, the studies analyzed varied by which techniques were compared; therefore, indirect analyses were conducted to compare certain techniques. There was limited follow-up for these patients (anywhere from 3 to 6 months), so long-term data and future pregnancy data are needed to determine the efficacy of these procedures.

CSDs are a rising concern due to the increasing cesarean delivery rate. It is critical to be able to identify as well as correct these defects. This is the first systematic review to compare 4 techniques of managing CSDs. Based on this article, there may be some additional benefit from combined hysteroscopic and laparoscopic repair of these defects in terms of decreasing bleeding and decreasing the scar defect depth. However, how these results translate into long-term outcomes for patients and their future pregnancies is still unknown, and further research must be done.

STEPHANIE DELGADO, MD, AND XIAOMING GUAN, MD, PHD

- Woźniak A, Pyra K, Tinto HR, et al. Ultrasonographic criteria of cesarean scar defect evaluation. J Ultrason. 2018;18: 162-165.

- Antila-Långsjö RM, Mäenpää JU, Huhtala HS, et al. Cesarean scar defect: a prospective study on risk factors. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018:219:458e1-e8.

- Di Spiezio Sardo A, Saccone G, McCurdy R, et al. Risk of cesarean scar defect following single- vs double-layer uterine closure: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2017;50:578-583.

- Roberge S, Demers S, Berghella V, et al. Impact of single- vs double-layer closure on adverse outcomes and uterine scar defect: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;211:453-460.

He Y, Zhong J, Zhou W, et al. Four surgical strategies for the treatment of cesarean scar defect: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2020;27:593-602.

EXPERT COMMENTARY

With the increase in cesarean deliveries performed over the decades, the sequelae of the surgery are now arising. Cesarean scar defects (CSDs) are a complication seen when the endometrium and muscular layers from a prior uterine scar are damaged. This damage in the uterine scar can lead to abnormal uterine bleeding and the implantation of an ectopic pregnancy, which can be life-threatening. Ultrasonography can be used to diagnose this defect, which can appear as a hypoechoic space filled with postmenstrual blood, representing a myometrial tear at the wound site.1 There are several risk factors for CSD, including multiple cesarean deliveries, cesarean delivery during advanced stages of labor, and uterine incisions near the cervix. Elevated body mass index as well as gestational diabetes also have been found to be associated with inadequate healing of the prior cesarean incision.2 Studies have shown that both single- and double-layer closure of the hysterotomy during a cesarean delivery have similar incidences of CSDs.3,4 There are multiple ways to correct a CSD; however, there is no gold standard that has been identified in the literature.

Details about the study

The study by He and colleagues is a meta-analysis aimed at comparing the treatment of CSDs via laparoscopy, hysteroscopy, combined hysteroscopy and laparoscopy, and vaginal repair. The primary outcome measures were reduction in abnormal uterine bleeding and scar defect depth. A total of 10 studies (n = 858) were reviewed: 4 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and 6 observational studies. The studies analyzed varied in terms of which techniques were compared.

Patients who underwent uterine scar resection by combined laparoscopy and hysteroscopy had a shorter duration of abnormal uterine bleeding when compared with hysteroscopy alone (standardized mean difference [SMD] = 1.36; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.37−2.36; P = .007) and vaginal repair (SMD = 1.58; 95% CI, 0.97−2.19; P<.0001). Combined laparoscopic and hysteroscopic technique also was found to reduce the diverticulum depth more than in vaginal repair (SMD = 1.57; 95% CI, 0.54−2.61; P = .003).

Continue to: Study strengths and weaknesses...

Study strengths and weaknesses

This is the first meta-analysis to compare the different surgical techniques to correct a CSD. The authors were able to compare many of the characteristics regarding the routes of repair, including hysteroscopy, laparoscopy, and vaginal. The authors were able to analyze the combined laparoscopic and hysteroscopic approach, which facilitates evaluation of the location and satisfaction of defect repair during the procedure.

Some weaknesses of this study include the limited amount of RCTs available for review. All studies were also from China, where the rate of CSDs is higher. Therefore, the results may not be generalizable to all populations. Given that the included studies were done at different sites, it is difficult to determine surgical expertise and surgical technique. Additionally, the studies analyzed varied by which techniques were compared; therefore, indirect analyses were conducted to compare certain techniques. There was limited follow-up for these patients (anywhere from 3 to 6 months), so long-term data and future pregnancy data are needed to determine the efficacy of these procedures.

CSDs are a rising concern due to the increasing cesarean delivery rate. It is critical to be able to identify as well as correct these defects. This is the first systematic review to compare 4 techniques of managing CSDs. Based on this article, there may be some additional benefit from combined hysteroscopic and laparoscopic repair of these defects in terms of decreasing bleeding and decreasing the scar defect depth. However, how these results translate into long-term outcomes for patients and their future pregnancies is still unknown, and further research must be done.

STEPHANIE DELGADO, MD, AND XIAOMING GUAN, MD, PHD

He Y, Zhong J, Zhou W, et al. Four surgical strategies for the treatment of cesarean scar defect: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2020;27:593-602.

EXPERT COMMENTARY

With the increase in cesarean deliveries performed over the decades, the sequelae of the surgery are now arising. Cesarean scar defects (CSDs) are a complication seen when the endometrium and muscular layers from a prior uterine scar are damaged. This damage in the uterine scar can lead to abnormal uterine bleeding and the implantation of an ectopic pregnancy, which can be life-threatening. Ultrasonography can be used to diagnose this defect, which can appear as a hypoechoic space filled with postmenstrual blood, representing a myometrial tear at the wound site.1 There are several risk factors for CSD, including multiple cesarean deliveries, cesarean delivery during advanced stages of labor, and uterine incisions near the cervix. Elevated body mass index as well as gestational diabetes also have been found to be associated with inadequate healing of the prior cesarean incision.2 Studies have shown that both single- and double-layer closure of the hysterotomy during a cesarean delivery have similar incidences of CSDs.3,4 There are multiple ways to correct a CSD; however, there is no gold standard that has been identified in the literature.

Details about the study

The study by He and colleagues is a meta-analysis aimed at comparing the treatment of CSDs via laparoscopy, hysteroscopy, combined hysteroscopy and laparoscopy, and vaginal repair. The primary outcome measures were reduction in abnormal uterine bleeding and scar defect depth. A total of 10 studies (n = 858) were reviewed: 4 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and 6 observational studies. The studies analyzed varied in terms of which techniques were compared.

Patients who underwent uterine scar resection by combined laparoscopy and hysteroscopy had a shorter duration of abnormal uterine bleeding when compared with hysteroscopy alone (standardized mean difference [SMD] = 1.36; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.37−2.36; P = .007) and vaginal repair (SMD = 1.58; 95% CI, 0.97−2.19; P<.0001). Combined laparoscopic and hysteroscopic technique also was found to reduce the diverticulum depth more than in vaginal repair (SMD = 1.57; 95% CI, 0.54−2.61; P = .003).

Continue to: Study strengths and weaknesses...

Study strengths and weaknesses

This is the first meta-analysis to compare the different surgical techniques to correct a CSD. The authors were able to compare many of the characteristics regarding the routes of repair, including hysteroscopy, laparoscopy, and vaginal. The authors were able to analyze the combined laparoscopic and hysteroscopic approach, which facilitates evaluation of the location and satisfaction of defect repair during the procedure.

Some weaknesses of this study include the limited amount of RCTs available for review. All studies were also from China, where the rate of CSDs is higher. Therefore, the results may not be generalizable to all populations. Given that the included studies were done at different sites, it is difficult to determine surgical expertise and surgical technique. Additionally, the studies analyzed varied by which techniques were compared; therefore, indirect analyses were conducted to compare certain techniques. There was limited follow-up for these patients (anywhere from 3 to 6 months), so long-term data and future pregnancy data are needed to determine the efficacy of these procedures.

CSDs are a rising concern due to the increasing cesarean delivery rate. It is critical to be able to identify as well as correct these defects. This is the first systematic review to compare 4 techniques of managing CSDs. Based on this article, there may be some additional benefit from combined hysteroscopic and laparoscopic repair of these defects in terms of decreasing bleeding and decreasing the scar defect depth. However, how these results translate into long-term outcomes for patients and their future pregnancies is still unknown, and further research must be done.

STEPHANIE DELGADO, MD, AND XIAOMING GUAN, MD, PHD

- Woźniak A, Pyra K, Tinto HR, et al. Ultrasonographic criteria of cesarean scar defect evaluation. J Ultrason. 2018;18: 162-165.

- Antila-Långsjö RM, Mäenpää JU, Huhtala HS, et al. Cesarean scar defect: a prospective study on risk factors. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018:219:458e1-e8.

- Di Spiezio Sardo A, Saccone G, McCurdy R, et al. Risk of cesarean scar defect following single- vs double-layer uterine closure: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2017;50:578-583.

- Roberge S, Demers S, Berghella V, et al. Impact of single- vs double-layer closure on adverse outcomes and uterine scar defect: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;211:453-460.

- Woźniak A, Pyra K, Tinto HR, et al. Ultrasonographic criteria of cesarean scar defect evaluation. J Ultrason. 2018;18: 162-165.

- Antila-Långsjö RM, Mäenpää JU, Huhtala HS, et al. Cesarean scar defect: a prospective study on risk factors. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018:219:458e1-e8.

- Di Spiezio Sardo A, Saccone G, McCurdy R, et al. Risk of cesarean scar defect following single- vs double-layer uterine closure: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2017;50:578-583.

- Roberge S, Demers S, Berghella V, et al. Impact of single- vs double-layer closure on adverse outcomes and uterine scar defect: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;211:453-460.

High BMI does not complicate postpartum tubal ligation

GRAPEVINE, TEXAS – Higher body mass index is not associated with increased morbidity in women undergoing postpartum tubal ligation, according to a study of more than 1,000 patients.

John J. Byrne, MD, said at the Pregnancy Meeting. Dr. Byrne is affiliated with the department of obstetrics and gynecology at University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas.

Physicians may recommend contraception within 6 weeks of delivery, but many patients do not attend postpartum visits. “One option for women who have completed childbearing is bilateral midsegment salpingectomy via minilaparotomy,” Dr. Byrne said at the Pregnancy Meeting, sponsored by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine. “Offering this procedure immediately after delivery makes it available to women who face obstacles to follow-up care.”

The procedure entails the risk of anesthetic complications, bowel injury, and vascular injury. Subsequent pregnancy or ectopic pregnancy also may occur. Some centers will not perform the procedure if a patient’s size affects the surgeon’s ability to feel the relevant anatomy, Dr. Byrne said. “Although operative complications are presumed to be higher among obese women,” prior studies have not examined whether BMI affects rates of procedure completion, complication, or subsequent pregnancy, the researchers said.

To study this question, Dr. Byrne and colleagues examined data from women who requested postpartum sterilization following vaginal delivery at their center in 2018. The center uses the Parkland tubal ligation technique. The researchers assessed complication rates using a composite measure that included surgical complications (that is, blood transfusion, aborted procedure, or extension of incision), anesthetic complications, readmission, superficial or deep wound infection, venous thromboembolism, ileus or small bowel obstruction, incomplete transection, and subsequent pregnancy. The investigators used statistical tests to assess the relationship between BMI and morbidity.

In all, 1,014 patients underwent a postpartum tubal ligation; 17% had undergone prior abdominal surgery. The researchers classified patients’ BMI as normal (7% of the population), overweight (28%), class I obesity (38%), class II obesity (18%), or class III obesity (9%). A composite morbidity event occurred in 2%, and the proportion of patients with a complication did not significantly differ across BMI categories. No morbid events occurred in patients with normal BMI, which indicates “minimal risk” in this population, Dr. Byrne said. One incomplete transection occurred in a patient with class I obesity, and one subsequent pregnancy occurred in a patient with class II obesity. Estimated blood loss ranged from 9 mL in patients with normal BMI to 13 mL in patients with class III obesity, and length of surgery ranged from 32 minutes to 40 minutes. Neither difference is clinically significant, Dr. Byrne said.

“For the woman who desires permanent contraception, BMI should not impede her access to the procedure,” he noted.

The researchers had no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Byrne JJ et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020 Jan;222(1):S290, Abstract 442.

GRAPEVINE, TEXAS – Higher body mass index is not associated with increased morbidity in women undergoing postpartum tubal ligation, according to a study of more than 1,000 patients.

John J. Byrne, MD, said at the Pregnancy Meeting. Dr. Byrne is affiliated with the department of obstetrics and gynecology at University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas.

Physicians may recommend contraception within 6 weeks of delivery, but many patients do not attend postpartum visits. “One option for women who have completed childbearing is bilateral midsegment salpingectomy via minilaparotomy,” Dr. Byrne said at the Pregnancy Meeting, sponsored by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine. “Offering this procedure immediately after delivery makes it available to women who face obstacles to follow-up care.”

The procedure entails the risk of anesthetic complications, bowel injury, and vascular injury. Subsequent pregnancy or ectopic pregnancy also may occur. Some centers will not perform the procedure if a patient’s size affects the surgeon’s ability to feel the relevant anatomy, Dr. Byrne said. “Although operative complications are presumed to be higher among obese women,” prior studies have not examined whether BMI affects rates of procedure completion, complication, or subsequent pregnancy, the researchers said.

To study this question, Dr. Byrne and colleagues examined data from women who requested postpartum sterilization following vaginal delivery at their center in 2018. The center uses the Parkland tubal ligation technique. The researchers assessed complication rates using a composite measure that included surgical complications (that is, blood transfusion, aborted procedure, or extension of incision), anesthetic complications, readmission, superficial or deep wound infection, venous thromboembolism, ileus or small bowel obstruction, incomplete transection, and subsequent pregnancy. The investigators used statistical tests to assess the relationship between BMI and morbidity.

In all, 1,014 patients underwent a postpartum tubal ligation; 17% had undergone prior abdominal surgery. The researchers classified patients’ BMI as normal (7% of the population), overweight (28%), class I obesity (38%), class II obesity (18%), or class III obesity (9%). A composite morbidity event occurred in 2%, and the proportion of patients with a complication did not significantly differ across BMI categories. No morbid events occurred in patients with normal BMI, which indicates “minimal risk” in this population, Dr. Byrne said. One incomplete transection occurred in a patient with class I obesity, and one subsequent pregnancy occurred in a patient with class II obesity. Estimated blood loss ranged from 9 mL in patients with normal BMI to 13 mL in patients with class III obesity, and length of surgery ranged from 32 minutes to 40 minutes. Neither difference is clinically significant, Dr. Byrne said.

“For the woman who desires permanent contraception, BMI should not impede her access to the procedure,” he noted.

The researchers had no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Byrne JJ et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020 Jan;222(1):S290, Abstract 442.

GRAPEVINE, TEXAS – Higher body mass index is not associated with increased morbidity in women undergoing postpartum tubal ligation, according to a study of more than 1,000 patients.

John J. Byrne, MD, said at the Pregnancy Meeting. Dr. Byrne is affiliated with the department of obstetrics and gynecology at University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas.

Physicians may recommend contraception within 6 weeks of delivery, but many patients do not attend postpartum visits. “One option for women who have completed childbearing is bilateral midsegment salpingectomy via minilaparotomy,” Dr. Byrne said at the Pregnancy Meeting, sponsored by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine. “Offering this procedure immediately after delivery makes it available to women who face obstacles to follow-up care.”

The procedure entails the risk of anesthetic complications, bowel injury, and vascular injury. Subsequent pregnancy or ectopic pregnancy also may occur. Some centers will not perform the procedure if a patient’s size affects the surgeon’s ability to feel the relevant anatomy, Dr. Byrne said. “Although operative complications are presumed to be higher among obese women,” prior studies have not examined whether BMI affects rates of procedure completion, complication, or subsequent pregnancy, the researchers said.

To study this question, Dr. Byrne and colleagues examined data from women who requested postpartum sterilization following vaginal delivery at their center in 2018. The center uses the Parkland tubal ligation technique. The researchers assessed complication rates using a composite measure that included surgical complications (that is, blood transfusion, aborted procedure, or extension of incision), anesthetic complications, readmission, superficial or deep wound infection, venous thromboembolism, ileus or small bowel obstruction, incomplete transection, and subsequent pregnancy. The investigators used statistical tests to assess the relationship between BMI and morbidity.

In all, 1,014 patients underwent a postpartum tubal ligation; 17% had undergone prior abdominal surgery. The researchers classified patients’ BMI as normal (7% of the population), overweight (28%), class I obesity (38%), class II obesity (18%), or class III obesity (9%). A composite morbidity event occurred in 2%, and the proportion of patients with a complication did not significantly differ across BMI categories. No morbid events occurred in patients with normal BMI, which indicates “minimal risk” in this population, Dr. Byrne said. One incomplete transection occurred in a patient with class I obesity, and one subsequent pregnancy occurred in a patient with class II obesity. Estimated blood loss ranged from 9 mL in patients with normal BMI to 13 mL in patients with class III obesity, and length of surgery ranged from 32 minutes to 40 minutes. Neither difference is clinically significant, Dr. Byrne said.

“For the woman who desires permanent contraception, BMI should not impede her access to the procedure,” he noted.

The researchers had no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Byrne JJ et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020 Jan;222(1):S290, Abstract 442.

REPORTING FROM THE PREGNANCY MEETING

What is the role of the ObGyn in preventing and treating obesity?

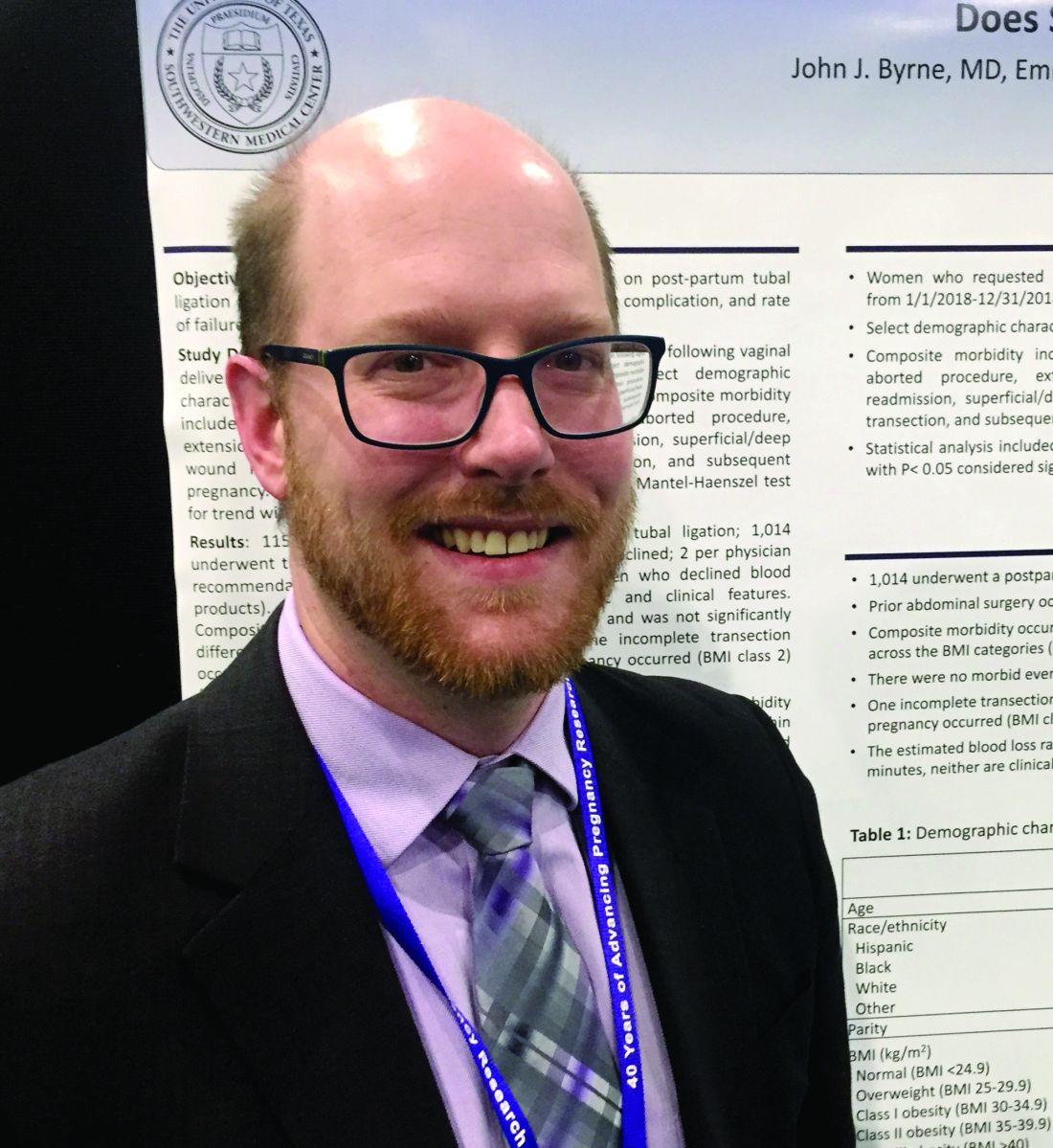

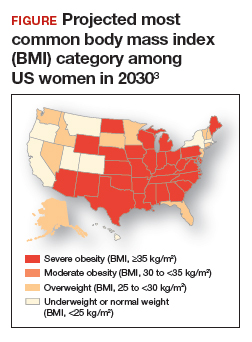

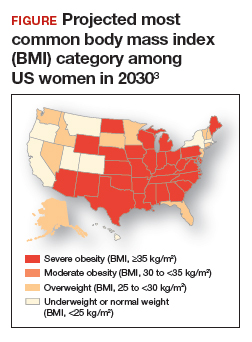

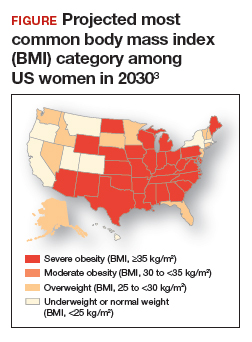

Obesity is a disease causing a public health crisis. In the United States, tobacco use and obesity are the two most important causes of preventable premature death. They result in an estimated 480,0001 and 300,0002 premature deaths per year, respectively. Obesity is a major contributor to diabetes mellitus, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and coronary heart disease. Obesity is also associated with increased rates of colon, breast, and endometrial cancer. Experts predict that in 2030, 50% of adults in the United States will have a body mass index (BMI) ≥ 30 kg/m2, and 25% will have a BMI ≥ 35 kg/m2.3 More women than men are predicted to be severely obese (FIGURE).3

As clinicians we need to increase our efforts to reduce the epidemic of obesity. ObGyns can play an important role in preventing and managing obesity, by recommending primary-care weight management practices, prescribing medications that influence central metabolism, and referring appropriate patients to bariatric surgery centers of excellence.

Primary-care weight management

Measuring BMI and recommending interventions to prevent and treat obesity are important components of a health maintenance encounter. For women who are overweight or obese, dietary changes and exercise are important recommendations. The American Heart Association recommends the following lifestyle interventions4:

- Eat a high-quality diet that includes vegetables, fruit, whole grains, beans, legumes, nuts, plant-based protein, lean animal protein, and fish.

- Limit intake of sugary drinks and foods, fatty or processed meats, full-fat dairy products, eggs, highly processed foods, and tropical oils.

- Exercise at least 150 minutes weekly at a moderate activity level, including muscle-strengthening activity.

- Reduce prolonged intervals of sitting.

- Consider using an activity tracker to monitor activity level.

Clinicians should consider referring overweight and obese patients to a nutritionist for a consultation to plan how to consume a high-quality, low-calorie diet. A nutritionist can spend time with patients explaining options for implementing a calorie-restricted diet. In addition, some health insurers will require patients to participate in a supervised calorie-restricted diet plan for at least 6 months before authorizing coverage of expensive weight loss medications or bariatric surgery. In addition to recommending diet and exercise, ObGyns may consider prescribing metformin for their obese patients.

Continue to: Metformin...

Metformin

Metformin is approved for the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Unlike insulin therapy, which is associated with weight gain, metformin is associated with modest weight loss. The Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP) randomly assigned 3,234 nondiabetic participants with a fasting glucose level between 95 and 125 mg/dL and impaired glucose tolerance (140 to 199 mg/dL) after a 75-g oral glucose load to intensive lifestyle changes (calorie-restricted diet to achieve 7% weight loss plus 150 minutes of exercise weekly), metformin (850 mg twice daily), or placebo.5,6 The mean age of the participants was 51 years, with a mean BMI of 34 kg/m2. Most (68%) of the participants were women.

After 12 months of follow-up, mean weight loss in the intensive lifestyle change, metformin, and placebo groups was 6.5%, 2.7%, and 0.4%, respectively. After 2 years of treatment, weight loss among those who reliably took their metformin pills was approximately 4%, while participants in the placebo group had a 1% weight gain. Among those who continued to reliably take their metformin pills, the weight loss persisted through 9 years of follow up.

The mechanisms by which metformin causes weight loss are not clear. Metformin stimulates phosphorylation of adenosine monophosphate (AMP)-activated protein kinase, which regulates mitochondrial function, hepatic and muscle fatty acid oxidation, glucose transport, insulin secretion, and lipogenesis.7

Many ObGyns have experience in using metformin for the treatment of polycystic ovary syndrome or gestational diabetes. Hence, the dosing and adverse effects of metformin are familiar to many obstetricians-gynecologists. Metformin is contraindicated in individuals with creatinine clearance less than 30 mL/min. Rarely, metformin can cause lactic acidosis. According to Lexicomp,8 the most common adverse effects of metformin extended release (metformin ER) are diarrhea (17%), nausea and vomiting (7%), and decreased vitamin B12 concentration (7%) due to malabsorption in the terminal ileum. Of note, in the DPP study, hemoglobin concentration was slightly lower over time in the metformin compared with the placebo group (13.6 mg/dL vs 13.8 mg/dL, respectively; P<.001).6 Some experts recommend annual vitamin B12 measurement in individuals taking metformin.

In my practice, I only prescribe metformin ER. I usually start metformin treatment with one 750 mg ER tablet with dinner. If the patient tolerates that dose, I increase the dose to two 750 mg ER tablets with dinner. Metformin-induced adverse effects include diarrhea (17%) and nausea and vomiting (7%). Metformin ER is inexpensive. A one-month supply of metformin (sixty 750 mg tablets) costs between $4 and $21 at major pharmacies.9 Health insurance companies generally do not require preauthorization to cover metformin prescriptions.

Weight loss medications

US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved weight loss medications include: liraglutide (Victoza), orlistat (Xenical, Alli), combination phentermine-extended release topiramate (Qsymia), and combination extended release naltrexone-bupropion (Contrave). All FDA-approved weight loss medications result in mean weight loss in the range of 6% to 10%. Many of these medications are very expensive (more than $200 per month).10 Insurance preauthorization is commonly required for these medications. For ObGyns, it may be best to refer patients who would like to use a weight loss medication to a specialist or specialty center with expertise in using these medications.

Sustainable weight loss is very difficult to achieve through dieting alone. A multitude of dietary interventions have been presented as “revolutionary approaches” to the challenging problem of sustainable weight loss, including the Paleo diet, the Vegan diet, the low-carb diet, the Dukan diet, the ultra-lowfat diet, the Atkins diet, the HCG diet, the Zone diet, the South Beach diet, the plant-based diet, the Mediterranean diet, the Asian diet, and intermittent fasting. Recently, intermittent fasting has been presented as the latest and greatest approach to dieting, with the dual goals of achieving weight loss and improved health.1 In some animal models, intermittent dieting has been shown to increase life-span, a finding that has attracted great interest. A major goal of intermittent fasting is to promote “metabolic switching” with increased reliance on ketones to fuel cellular energy needs.

Two approaches to “prescribing” an intermittent fasting diet are to limit food intake to a period of 6 to 10 hours each day or to markedly reduce caloric intake one or two days per week, for example to 750 calories in a 24-hour period. There are no long-term studies of the health outcomes associated with intermittent fasting. In head-to-head clinical trials of intermittent fasting and daily calorie restriction (classic dieting), both diets result in similar weight loss. For example, in one clinical trial 100 obese participants, with a mean body mass index (BMI) of 34 kg/m2 , including 86 women, were randomly assigned to2:

1. intermittent fasting (25% of energy needs every other day)

2. daily calorie restriction (75% of energy needs every day), or

3. no intervention.

After 12 months of follow up, the participants in the no intervention group had gained 0.5% of their starting weight. The intermittent fasting and the daily calorie restriction groups had similar amounts of weight loss, approximately 5% of their starting weight. More individuals dropped out of the study from the intermittent fasting group than the daily calorie restriction group (38% vs 29%, respectively).

In another clinical trial, 107 overweight or obese premenopausal women, average age 40 years and mean BMI 31 kg/m2 , were randomly assigned to intermittent fasting (25% of energy needs 2 days per week) or daily calorie restriction (75% of energy needs daily) for 6 months. The mean weight of the participants at baseline was 83 kg. Weight loss was similar in the intermittent fasting and daily calorie restriction groups, 6.4 kg (-7.7%) and 5.6 kg (-6.7%), respectively (P=.4).3

The investigators concluded that intermittent fasting and daily calorie restriction could both be offered as effective approaches to weight loss. My conclusion is that intermittent fasting is not a miracle dietary intervention, but it is another important option in the armamentarium of weight loss interventions.

References

1. de Cabo R, Mattson MP. Effects of intermittent fasting on health, aging and disease. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:2541-2551.

2. Trepanowski JF, Kroeger CM, Barnosky A, et al. Effect of alternate-day fasting on weight loss, weight maintenance, and cardioprotection among metabolically healthy obese adults: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177:930-938.

3. Harvie MN, Pegington M, Mattson MP, et al. The effects of intermittent or continuous energy restriction on weight loss and metabolic disc disease risk markers: a randomized trial in young overweight women. Int J Obes (Lond). 2011;35:714-727.

Sleeve gastrectomy

Two children are playing in a school yard. One child proudly states, “My mother is an endocrinologist. She treats diabetes.” Not to be outdone, the other child replies, “My mother is a bariatric surgeon. She cures diabetes.”

The dialogue reflects the reality that bariatric surgery results in more reliable and significant weight loss than diet, exercise, or weight loss medications. Diet, exercise, and weight loss medications often result in a 5% to 10% decrease in weight, but bariatric surgery typically results in a 25% decrease in weight. Until recently, 3 bariatric surgical procedures were commonly performed: Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB), sleeve gastrectomy (SG), and adjustable gastric banding (AGB). AGB is now seldom performed because it is less effective than RYGB and SG. Two recently published randomized trials compared the long-term outcomes associated with RYGB and SG. The studies found that SG and RYGB result in a similar degree of weight loss. RYGB resulted in slightly more weight loss than SG, but SG was associated with a lower rate of major complications, such as internal hernias. SG takes much less time to perform than RYGB. SG has become the most commonly performed bariatric surgery in premenopausal women considering pregnancy because of the low risk of internal hernias.

In the Swiss Multicenter Bypass or Sleeve Study (SM-BOSS), 217 participants with a mean BMI of 44 kg/m2 and mean age of 45.5 years were randomly assigned to RYGB or SG and followed for 5 years.11 The majority (72%) of the participants were women. At 5 years of follow-up, in the RYGB and SG groups, mean weight loss was 37 kg and 33 kg, respectively (P=.19). In both groups, weight loss nadir was reached 12 to 24 months after surgery. Expressed as a percentage of original weight, weight loss in the RYGB and SG groups was -29% and -25%, respectively (P=.02). Gastric reflux worsened in both the RYGB and SG groups (6% vs 32%, respectively). The number of reoperations in the RYGB and SG groups was 22% and 16%. Of note, among individuals with prevalent diabetes, RYGB and SG resulted in remission of the diabetes in 68% and 62% of participants, respectively.

In the Sleeve vs Bypass study (SLEEVEPASS), 240 participants, with mean BMI of 46 kg/m2 and mean age of 48 years, were randomly assigned to RYGB or SG and followed for 5 years.12 Most (70%) of the participants were women. Following bariatric surgery, BMI decreased significantly in both groups. In the RYGB group, BMI decreased from 48 kg/m2 preoperatively to 35.4 kg/m2 at 5 years of follow up. In the SG group, BMI decreased from 47 kg/m2 preoperatively to 36.5 kg/m2 at 5 years of follow up. Late major complications (defined as complications occurring from 30 days to 5 years postoperatively) occurred more frequently in the RYGB group (15%) versus the SG group (8%). All the late major complications required reoperation. In the SG group, 7 of 10 reoperations were for severe gastric reflux disease. In the RYGB group 17 of 18 reoperations were for suspected internal hernia, requiring closure of a mesenteric defect at reoperation. There was no treatment-related mortality during the 5-year follow up.

Guidelines for bariatric surgery are BMI ≥ 40 kg/m2 without a comorbid illness or BMI ≥ 35 kg/m2 with at least one serious comorbid disease, such as diabetes.13 ObGyns can build a synergistic relationship with bariatric surgeons by referring eligible patients for surgical consultation and, in return, accepting referrals. A paradox and challenge is that many health insurers require patients to complete a supervised medical weight loss management program prior to being approved for bariatric surgery. However, the medical weight loss program might result in the patient no longer being eligible for insurance coverage of their surgery. For example, a patient who had a BMI of 42 kg/m2 prior to a medical weight loss management program who then lost enough weight to achieve a BMI of 38 kg/m2 might no longer be eligible for insurance coverage of a bariatric operation.14

Continue to: ObGyns need to prioritize treatment for obesity...

ObGyns need to prioritize treatment for obesity

Between 1959 and 2014, US life expectancy increased from 69.9 years to 79.1 years. However, in 2015 and 2016 life expectancy in the United States decreased slightly to 78.9 years, while continuing to improve in other countries.15 What could cause such an unexpected trend? Some experts believe that excess overweight and obesity in the US population, resulting in increased rates of diabetes, hypertension, and heart disease, accounts for a significant proportion of the life expectancy gap between US citizens and those who reside in Australia, Finland, Japan, and Sweden.16,17 All frontline clinicians play an important role in reversing the decades-long trend of increasing rates of overweight and obesity. Interventions that ObGyns could prioritize in their practices for treating overweight and obese patients include: a calorie-restricted diet, exercise, metformin, and SG.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The Health Consequences of Smoking—50 Years of Progress. A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 2014.

- Allison DB, Fontaine KR, Manson JE, et al. Annual deaths attributable to obesity in the United States. JAMA. 1999;282:1530-1538.

- Ward ZJ, Bleich SN, Cradock AL, et al. Projected U.S. state-level prevalence of adult obesity and severe obesity. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:2440-2450.

- American Heart Association. My life check | Life’s simple 7. https://www.heart.org/en/healthyliving/healthy-lifestyle/my-life-check--lifessimple-7. Reviewed May 2, 2018. Accessed February 10, 2020.

- Knowler WC, Barrett-Connor E, Fowler SE, et al; Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group. Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:393-403.

- Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group. Long-term safety, tolerability and weight loss associated with metformin in the Diabetes Prevention Program Outcomes Study. Diabetes Care. 2012;35:731-737.

- Winder WW, Hardie DG. Inactivation of acetylCoA carboxylase and activation of AMP-activated protein kinase in muscle during exercise. Am J Physiol. 1996;270(2 pt 1):E299-E304.

- Lexicomp. https://online.lexi.com/lco/action/ home. Accessed February 13, 2020.

- Metformin ER (Glucophage XR). GoodRX website. https://www.goodrx.com/metformin-erglucophage-xr?dosage=750mg&form=tablet&la bel_override=metformin+ER+%28Glucophage+X R%29&quantity=60. Accessed February 13, 2020.

- GoodRX website. www.goodrx.com. Accessed February 10, 2020.

- Peterli R, Wolnerhanssen BK, Peters T, et al. Effect of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy vs laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass on weight loss in patients with morbid obesity: the SM-BOSS randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2018;319:255-265.

- Salminen P, Helmiö M, Ovaska J, et al. Effect of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy versus laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass on weight loss at 5 years among patients with morbid obesity: The SLEEVEPASS randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2018;319:241-254.

- Rubino F, Nathan DM, Eckel RH, et al; Delegates of the 2nd Diabetes Surgery Summit. Metabolic surgery in the treatment algorithm for type 2 diabetes: a joint statement by international diabetes organizations. Obes Surg. 2017;27:2-21.

- Gebran SG, Knighton B, Ngaage LM, et al. Insurance coverage criteria for bariatric surgery: a survey of policies. Obes Surg. 2020;30:707-713.

- Woolf SH, Schoomaker H. Life expectancy and mortality rates in the United States, 1959-2017. JAMA. 2019;322:1996-2016.

- Preston SH, Vierboom YC, Stokes A. The role of obesity in exceptionally slow US mortality improvement. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2019;115:957-961.

- Xu H, Cupples LA, Stokes A, et al. Association of obesity with mortality over 24 years of weight history: findings from the Framingham Heart Study. JAMA Network Open. 2018;1:e184587.

Obesity is a disease causing a public health crisis. In the United States, tobacco use and obesity are the two most important causes of preventable premature death. They result in an estimated 480,0001 and 300,0002 premature deaths per year, respectively. Obesity is a major contributor to diabetes mellitus, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and coronary heart disease. Obesity is also associated with increased rates of colon, breast, and endometrial cancer. Experts predict that in 2030, 50% of adults in the United States will have a body mass index (BMI) ≥ 30 kg/m2, and 25% will have a BMI ≥ 35 kg/m2.3 More women than men are predicted to be severely obese (FIGURE).3

As clinicians we need to increase our efforts to reduce the epidemic of obesity. ObGyns can play an important role in preventing and managing obesity, by recommending primary-care weight management practices, prescribing medications that influence central metabolism, and referring appropriate patients to bariatric surgery centers of excellence.

Primary-care weight management

Measuring BMI and recommending interventions to prevent and treat obesity are important components of a health maintenance encounter. For women who are overweight or obese, dietary changes and exercise are important recommendations. The American Heart Association recommends the following lifestyle interventions4:

- Eat a high-quality diet that includes vegetables, fruit, whole grains, beans, legumes, nuts, plant-based protein, lean animal protein, and fish.

- Limit intake of sugary drinks and foods, fatty or processed meats, full-fat dairy products, eggs, highly processed foods, and tropical oils.

- Exercise at least 150 minutes weekly at a moderate activity level, including muscle-strengthening activity.

- Reduce prolonged intervals of sitting.

- Consider using an activity tracker to monitor activity level.

Clinicians should consider referring overweight and obese patients to a nutritionist for a consultation to plan how to consume a high-quality, low-calorie diet. A nutritionist can spend time with patients explaining options for implementing a calorie-restricted diet. In addition, some health insurers will require patients to participate in a supervised calorie-restricted diet plan for at least 6 months before authorizing coverage of expensive weight loss medications or bariatric surgery. In addition to recommending diet and exercise, ObGyns may consider prescribing metformin for their obese patients.

Continue to: Metformin...

Metformin

Metformin is approved for the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Unlike insulin therapy, which is associated with weight gain, metformin is associated with modest weight loss. The Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP) randomly assigned 3,234 nondiabetic participants with a fasting glucose level between 95 and 125 mg/dL and impaired glucose tolerance (140 to 199 mg/dL) after a 75-g oral glucose load to intensive lifestyle changes (calorie-restricted diet to achieve 7% weight loss plus 150 minutes of exercise weekly), metformin (850 mg twice daily), or placebo.5,6 The mean age of the participants was 51 years, with a mean BMI of 34 kg/m2. Most (68%) of the participants were women.

After 12 months of follow-up, mean weight loss in the intensive lifestyle change, metformin, and placebo groups was 6.5%, 2.7%, and 0.4%, respectively. After 2 years of treatment, weight loss among those who reliably took their metformin pills was approximately 4%, while participants in the placebo group had a 1% weight gain. Among those who continued to reliably take their metformin pills, the weight loss persisted through 9 years of follow up.

The mechanisms by which metformin causes weight loss are not clear. Metformin stimulates phosphorylation of adenosine monophosphate (AMP)-activated protein kinase, which regulates mitochondrial function, hepatic and muscle fatty acid oxidation, glucose transport, insulin secretion, and lipogenesis.7

Many ObGyns have experience in using metformin for the treatment of polycystic ovary syndrome or gestational diabetes. Hence, the dosing and adverse effects of metformin are familiar to many obstetricians-gynecologists. Metformin is contraindicated in individuals with creatinine clearance less than 30 mL/min. Rarely, metformin can cause lactic acidosis. According to Lexicomp,8 the most common adverse effects of metformin extended release (metformin ER) are diarrhea (17%), nausea and vomiting (7%), and decreased vitamin B12 concentration (7%) due to malabsorption in the terminal ileum. Of note, in the DPP study, hemoglobin concentration was slightly lower over time in the metformin compared with the placebo group (13.6 mg/dL vs 13.8 mg/dL, respectively; P<.001).6 Some experts recommend annual vitamin B12 measurement in individuals taking metformin.

In my practice, I only prescribe metformin ER. I usually start metformin treatment with one 750 mg ER tablet with dinner. If the patient tolerates that dose, I increase the dose to two 750 mg ER tablets with dinner. Metformin-induced adverse effects include diarrhea (17%) and nausea and vomiting (7%). Metformin ER is inexpensive. A one-month supply of metformin (sixty 750 mg tablets) costs between $4 and $21 at major pharmacies.9 Health insurance companies generally do not require preauthorization to cover metformin prescriptions.

Weight loss medications

US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved weight loss medications include: liraglutide (Victoza), orlistat (Xenical, Alli), combination phentermine-extended release topiramate (Qsymia), and combination extended release naltrexone-bupropion (Contrave). All FDA-approved weight loss medications result in mean weight loss in the range of 6% to 10%. Many of these medications are very expensive (more than $200 per month).10 Insurance preauthorization is commonly required for these medications. For ObGyns, it may be best to refer patients who would like to use a weight loss medication to a specialist or specialty center with expertise in using these medications.

Sustainable weight loss is very difficult to achieve through dieting alone. A multitude of dietary interventions have been presented as “revolutionary approaches” to the challenging problem of sustainable weight loss, including the Paleo diet, the Vegan diet, the low-carb diet, the Dukan diet, the ultra-lowfat diet, the Atkins diet, the HCG diet, the Zone diet, the South Beach diet, the plant-based diet, the Mediterranean diet, the Asian diet, and intermittent fasting. Recently, intermittent fasting has been presented as the latest and greatest approach to dieting, with the dual goals of achieving weight loss and improved health.1 In some animal models, intermittent dieting has been shown to increase life-span, a finding that has attracted great interest. A major goal of intermittent fasting is to promote “metabolic switching” with increased reliance on ketones to fuel cellular energy needs.

Two approaches to “prescribing” an intermittent fasting diet are to limit food intake to a period of 6 to 10 hours each day or to markedly reduce caloric intake one or two days per week, for example to 750 calories in a 24-hour period. There are no long-term studies of the health outcomes associated with intermittent fasting. In head-to-head clinical trials of intermittent fasting and daily calorie restriction (classic dieting), both diets result in similar weight loss. For example, in one clinical trial 100 obese participants, with a mean body mass index (BMI) of 34 kg/m2 , including 86 women, were randomly assigned to2:

1. intermittent fasting (25% of energy needs every other day)

2. daily calorie restriction (75% of energy needs every day), or

3. no intervention.

After 12 months of follow up, the participants in the no intervention group had gained 0.5% of their starting weight. The intermittent fasting and the daily calorie restriction groups had similar amounts of weight loss, approximately 5% of their starting weight. More individuals dropped out of the study from the intermittent fasting group than the daily calorie restriction group (38% vs 29%, respectively).

In another clinical trial, 107 overweight or obese premenopausal women, average age 40 years and mean BMI 31 kg/m2 , were randomly assigned to intermittent fasting (25% of energy needs 2 days per week) or daily calorie restriction (75% of energy needs daily) for 6 months. The mean weight of the participants at baseline was 83 kg. Weight loss was similar in the intermittent fasting and daily calorie restriction groups, 6.4 kg (-7.7%) and 5.6 kg (-6.7%), respectively (P=.4).3

The investigators concluded that intermittent fasting and daily calorie restriction could both be offered as effective approaches to weight loss. My conclusion is that intermittent fasting is not a miracle dietary intervention, but it is another important option in the armamentarium of weight loss interventions.

References

1. de Cabo R, Mattson MP. Effects of intermittent fasting on health, aging and disease. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:2541-2551.

2. Trepanowski JF, Kroeger CM, Barnosky A, et al. Effect of alternate-day fasting on weight loss, weight maintenance, and cardioprotection among metabolically healthy obese adults: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177:930-938.

3. Harvie MN, Pegington M, Mattson MP, et al. The effects of intermittent or continuous energy restriction on weight loss and metabolic disc disease risk markers: a randomized trial in young overweight women. Int J Obes (Lond). 2011;35:714-727.

Sleeve gastrectomy

Two children are playing in a school yard. One child proudly states, “My mother is an endocrinologist. She treats diabetes.” Not to be outdone, the other child replies, “My mother is a bariatric surgeon. She cures diabetes.”

The dialogue reflects the reality that bariatric surgery results in more reliable and significant weight loss than diet, exercise, or weight loss medications. Diet, exercise, and weight loss medications often result in a 5% to 10% decrease in weight, but bariatric surgery typically results in a 25% decrease in weight. Until recently, 3 bariatric surgical procedures were commonly performed: Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB), sleeve gastrectomy (SG), and adjustable gastric banding (AGB). AGB is now seldom performed because it is less effective than RYGB and SG. Two recently published randomized trials compared the long-term outcomes associated with RYGB and SG. The studies found that SG and RYGB result in a similar degree of weight loss. RYGB resulted in slightly more weight loss than SG, but SG was associated with a lower rate of major complications, such as internal hernias. SG takes much less time to perform than RYGB. SG has become the most commonly performed bariatric surgery in premenopausal women considering pregnancy because of the low risk of internal hernias.

In the Swiss Multicenter Bypass or Sleeve Study (SM-BOSS), 217 participants with a mean BMI of 44 kg/m2 and mean age of 45.5 years were randomly assigned to RYGB or SG and followed for 5 years.11 The majority (72%) of the participants were women. At 5 years of follow-up, in the RYGB and SG groups, mean weight loss was 37 kg and 33 kg, respectively (P=.19). In both groups, weight loss nadir was reached 12 to 24 months after surgery. Expressed as a percentage of original weight, weight loss in the RYGB and SG groups was -29% and -25%, respectively (P=.02). Gastric reflux worsened in both the RYGB and SG groups (6% vs 32%, respectively). The number of reoperations in the RYGB and SG groups was 22% and 16%. Of note, among individuals with prevalent diabetes, RYGB and SG resulted in remission of the diabetes in 68% and 62% of participants, respectively.

In the Sleeve vs Bypass study (SLEEVEPASS), 240 participants, with mean BMI of 46 kg/m2 and mean age of 48 years, were randomly assigned to RYGB or SG and followed for 5 years.12 Most (70%) of the participants were women. Following bariatric surgery, BMI decreased significantly in both groups. In the RYGB group, BMI decreased from 48 kg/m2 preoperatively to 35.4 kg/m2 at 5 years of follow up. In the SG group, BMI decreased from 47 kg/m2 preoperatively to 36.5 kg/m2 at 5 years of follow up. Late major complications (defined as complications occurring from 30 days to 5 years postoperatively) occurred more frequently in the RYGB group (15%) versus the SG group (8%). All the late major complications required reoperation. In the SG group, 7 of 10 reoperations were for severe gastric reflux disease. In the RYGB group 17 of 18 reoperations were for suspected internal hernia, requiring closure of a mesenteric defect at reoperation. There was no treatment-related mortality during the 5-year follow up.

Guidelines for bariatric surgery are BMI ≥ 40 kg/m2 without a comorbid illness or BMI ≥ 35 kg/m2 with at least one serious comorbid disease, such as diabetes.13 ObGyns can build a synergistic relationship with bariatric surgeons by referring eligible patients for surgical consultation and, in return, accepting referrals. A paradox and challenge is that many health insurers require patients to complete a supervised medical weight loss management program prior to being approved for bariatric surgery. However, the medical weight loss program might result in the patient no longer being eligible for insurance coverage of their surgery. For example, a patient who had a BMI of 42 kg/m2 prior to a medical weight loss management program who then lost enough weight to achieve a BMI of 38 kg/m2 might no longer be eligible for insurance coverage of a bariatric operation.14

Continue to: ObGyns need to prioritize treatment for obesity...

ObGyns need to prioritize treatment for obesity

Between 1959 and 2014, US life expectancy increased from 69.9 years to 79.1 years. However, in 2015 and 2016 life expectancy in the United States decreased slightly to 78.9 years, while continuing to improve in other countries.15 What could cause such an unexpected trend? Some experts believe that excess overweight and obesity in the US population, resulting in increased rates of diabetes, hypertension, and heart disease, accounts for a significant proportion of the life expectancy gap between US citizens and those who reside in Australia, Finland, Japan, and Sweden.16,17 All frontline clinicians play an important role in reversing the decades-long trend of increasing rates of overweight and obesity. Interventions that ObGyns could prioritize in their practices for treating overweight and obese patients include: a calorie-restricted diet, exercise, metformin, and SG.

Obesity is a disease causing a public health crisis. In the United States, tobacco use and obesity are the two most important causes of preventable premature death. They result in an estimated 480,0001 and 300,0002 premature deaths per year, respectively. Obesity is a major contributor to diabetes mellitus, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and coronary heart disease. Obesity is also associated with increased rates of colon, breast, and endometrial cancer. Experts predict that in 2030, 50% of adults in the United States will have a body mass index (BMI) ≥ 30 kg/m2, and 25% will have a BMI ≥ 35 kg/m2.3 More women than men are predicted to be severely obese (FIGURE).3

As clinicians we need to increase our efforts to reduce the epidemic of obesity. ObGyns can play an important role in preventing and managing obesity, by recommending primary-care weight management practices, prescribing medications that influence central metabolism, and referring appropriate patients to bariatric surgery centers of excellence.

Primary-care weight management

Measuring BMI and recommending interventions to prevent and treat obesity are important components of a health maintenance encounter. For women who are overweight or obese, dietary changes and exercise are important recommendations. The American Heart Association recommends the following lifestyle interventions4:

- Eat a high-quality diet that includes vegetables, fruit, whole grains, beans, legumes, nuts, plant-based protein, lean animal protein, and fish.

- Limit intake of sugary drinks and foods, fatty or processed meats, full-fat dairy products, eggs, highly processed foods, and tropical oils.

- Exercise at least 150 minutes weekly at a moderate activity level, including muscle-strengthening activity.

- Reduce prolonged intervals of sitting.

- Consider using an activity tracker to monitor activity level.

Clinicians should consider referring overweight and obese patients to a nutritionist for a consultation to plan how to consume a high-quality, low-calorie diet. A nutritionist can spend time with patients explaining options for implementing a calorie-restricted diet. In addition, some health insurers will require patients to participate in a supervised calorie-restricted diet plan for at least 6 months before authorizing coverage of expensive weight loss medications or bariatric surgery. In addition to recommending diet and exercise, ObGyns may consider prescribing metformin for their obese patients.

Continue to: Metformin...

Metformin

Metformin is approved for the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Unlike insulin therapy, which is associated with weight gain, metformin is associated with modest weight loss. The Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP) randomly assigned 3,234 nondiabetic participants with a fasting glucose level between 95 and 125 mg/dL and impaired glucose tolerance (140 to 199 mg/dL) after a 75-g oral glucose load to intensive lifestyle changes (calorie-restricted diet to achieve 7% weight loss plus 150 minutes of exercise weekly), metformin (850 mg twice daily), or placebo.5,6 The mean age of the participants was 51 years, with a mean BMI of 34 kg/m2. Most (68%) of the participants were women.

After 12 months of follow-up, mean weight loss in the intensive lifestyle change, metformin, and placebo groups was 6.5%, 2.7%, and 0.4%, respectively. After 2 years of treatment, weight loss among those who reliably took their metformin pills was approximately 4%, while participants in the placebo group had a 1% weight gain. Among those who continued to reliably take their metformin pills, the weight loss persisted through 9 years of follow up.

The mechanisms by which metformin causes weight loss are not clear. Metformin stimulates phosphorylation of adenosine monophosphate (AMP)-activated protein kinase, which regulates mitochondrial function, hepatic and muscle fatty acid oxidation, glucose transport, insulin secretion, and lipogenesis.7

Many ObGyns have experience in using metformin for the treatment of polycystic ovary syndrome or gestational diabetes. Hence, the dosing and adverse effects of metformin are familiar to many obstetricians-gynecologists. Metformin is contraindicated in individuals with creatinine clearance less than 30 mL/min. Rarely, metformin can cause lactic acidosis. According to Lexicomp,8 the most common adverse effects of metformin extended release (metformin ER) are diarrhea (17%), nausea and vomiting (7%), and decreased vitamin B12 concentration (7%) due to malabsorption in the terminal ileum. Of note, in the DPP study, hemoglobin concentration was slightly lower over time in the metformin compared with the placebo group (13.6 mg/dL vs 13.8 mg/dL, respectively; P<.001).6 Some experts recommend annual vitamin B12 measurement in individuals taking metformin.

In my practice, I only prescribe metformin ER. I usually start metformin treatment with one 750 mg ER tablet with dinner. If the patient tolerates that dose, I increase the dose to two 750 mg ER tablets with dinner. Metformin-induced adverse effects include diarrhea (17%) and nausea and vomiting (7%). Metformin ER is inexpensive. A one-month supply of metformin (sixty 750 mg tablets) costs between $4 and $21 at major pharmacies.9 Health insurance companies generally do not require preauthorization to cover metformin prescriptions.

Weight loss medications

US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved weight loss medications include: liraglutide (Victoza), orlistat (Xenical, Alli), combination phentermine-extended release topiramate (Qsymia), and combination extended release naltrexone-bupropion (Contrave). All FDA-approved weight loss medications result in mean weight loss in the range of 6% to 10%. Many of these medications are very expensive (more than $200 per month).10 Insurance preauthorization is commonly required for these medications. For ObGyns, it may be best to refer patients who would like to use a weight loss medication to a specialist or specialty center with expertise in using these medications.

Sustainable weight loss is very difficult to achieve through dieting alone. A multitude of dietary interventions have been presented as “revolutionary approaches” to the challenging problem of sustainable weight loss, including the Paleo diet, the Vegan diet, the low-carb diet, the Dukan diet, the ultra-lowfat diet, the Atkins diet, the HCG diet, the Zone diet, the South Beach diet, the plant-based diet, the Mediterranean diet, the Asian diet, and intermittent fasting. Recently, intermittent fasting has been presented as the latest and greatest approach to dieting, with the dual goals of achieving weight loss and improved health.1 In some animal models, intermittent dieting has been shown to increase life-span, a finding that has attracted great interest. A major goal of intermittent fasting is to promote “metabolic switching” with increased reliance on ketones to fuel cellular energy needs.

Two approaches to “prescribing” an intermittent fasting diet are to limit food intake to a period of 6 to 10 hours each day or to markedly reduce caloric intake one or two days per week, for example to 750 calories in a 24-hour period. There are no long-term studies of the health outcomes associated with intermittent fasting. In head-to-head clinical trials of intermittent fasting and daily calorie restriction (classic dieting), both diets result in similar weight loss. For example, in one clinical trial 100 obese participants, with a mean body mass index (BMI) of 34 kg/m2 , including 86 women, were randomly assigned to2:

1. intermittent fasting (25% of energy needs every other day)

2. daily calorie restriction (75% of energy needs every day), or

3. no intervention.

After 12 months of follow up, the participants in the no intervention group had gained 0.5% of their starting weight. The intermittent fasting and the daily calorie restriction groups had similar amounts of weight loss, approximately 5% of their starting weight. More individuals dropped out of the study from the intermittent fasting group than the daily calorie restriction group (38% vs 29%, respectively).

In another clinical trial, 107 overweight or obese premenopausal women, average age 40 years and mean BMI 31 kg/m2 , were randomly assigned to intermittent fasting (25% of energy needs 2 days per week) or daily calorie restriction (75% of energy needs daily) for 6 months. The mean weight of the participants at baseline was 83 kg. Weight loss was similar in the intermittent fasting and daily calorie restriction groups, 6.4 kg (-7.7%) and 5.6 kg (-6.7%), respectively (P=.4).3

The investigators concluded that intermittent fasting and daily calorie restriction could both be offered as effective approaches to weight loss. My conclusion is that intermittent fasting is not a miracle dietary intervention, but it is another important option in the armamentarium of weight loss interventions.

References

1. de Cabo R, Mattson MP. Effects of intermittent fasting on health, aging and disease. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:2541-2551.

2. Trepanowski JF, Kroeger CM, Barnosky A, et al. Effect of alternate-day fasting on weight loss, weight maintenance, and cardioprotection among metabolically healthy obese adults: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177:930-938.

3. Harvie MN, Pegington M, Mattson MP, et al. The effects of intermittent or continuous energy restriction on weight loss and metabolic disc disease risk markers: a randomized trial in young overweight women. Int J Obes (Lond). 2011;35:714-727.

Sleeve gastrectomy

Two children are playing in a school yard. One child proudly states, “My mother is an endocrinologist. She treats diabetes.” Not to be outdone, the other child replies, “My mother is a bariatric surgeon. She cures diabetes.”

The dialogue reflects the reality that bariatric surgery results in more reliable and significant weight loss than diet, exercise, or weight loss medications. Diet, exercise, and weight loss medications often result in a 5% to 10% decrease in weight, but bariatric surgery typically results in a 25% decrease in weight. Until recently, 3 bariatric surgical procedures were commonly performed: Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB), sleeve gastrectomy (SG), and adjustable gastric banding (AGB). AGB is now seldom performed because it is less effective than RYGB and SG. Two recently published randomized trials compared the long-term outcomes associated with RYGB and SG. The studies found that SG and RYGB result in a similar degree of weight loss. RYGB resulted in slightly more weight loss than SG, but SG was associated with a lower rate of major complications, such as internal hernias. SG takes much less time to perform than RYGB. SG has become the most commonly performed bariatric surgery in premenopausal women considering pregnancy because of the low risk of internal hernias.

In the Swiss Multicenter Bypass or Sleeve Study (SM-BOSS), 217 participants with a mean BMI of 44 kg/m2 and mean age of 45.5 years were randomly assigned to RYGB or SG and followed for 5 years.11 The majority (72%) of the participants were women. At 5 years of follow-up, in the RYGB and SG groups, mean weight loss was 37 kg and 33 kg, respectively (P=.19). In both groups, weight loss nadir was reached 12 to 24 months after surgery. Expressed as a percentage of original weight, weight loss in the RYGB and SG groups was -29% and -25%, respectively (P=.02). Gastric reflux worsened in both the RYGB and SG groups (6% vs 32%, respectively). The number of reoperations in the RYGB and SG groups was 22% and 16%. Of note, among individuals with prevalent diabetes, RYGB and SG resulted in remission of the diabetes in 68% and 62% of participants, respectively.

In the Sleeve vs Bypass study (SLEEVEPASS), 240 participants, with mean BMI of 46 kg/m2 and mean age of 48 years, were randomly assigned to RYGB or SG and followed for 5 years.12 Most (70%) of the participants were women. Following bariatric surgery, BMI decreased significantly in both groups. In the RYGB group, BMI decreased from 48 kg/m2 preoperatively to 35.4 kg/m2 at 5 years of follow up. In the SG group, BMI decreased from 47 kg/m2 preoperatively to 36.5 kg/m2 at 5 years of follow up. Late major complications (defined as complications occurring from 30 days to 5 years postoperatively) occurred more frequently in the RYGB group (15%) versus the SG group (8%). All the late major complications required reoperation. In the SG group, 7 of 10 reoperations were for severe gastric reflux disease. In the RYGB group 17 of 18 reoperations were for suspected internal hernia, requiring closure of a mesenteric defect at reoperation. There was no treatment-related mortality during the 5-year follow up.

Guidelines for bariatric surgery are BMI ≥ 40 kg/m2 without a comorbid illness or BMI ≥ 35 kg/m2 with at least one serious comorbid disease, such as diabetes.13 ObGyns can build a synergistic relationship with bariatric surgeons by referring eligible patients for surgical consultation and, in return, accepting referrals. A paradox and challenge is that many health insurers require patients to complete a supervised medical weight loss management program prior to being approved for bariatric surgery. However, the medical weight loss program might result in the patient no longer being eligible for insurance coverage of their surgery. For example, a patient who had a BMI of 42 kg/m2 prior to a medical weight loss management program who then lost enough weight to achieve a BMI of 38 kg/m2 might no longer be eligible for insurance coverage of a bariatric operation.14

Continue to: ObGyns need to prioritize treatment for obesity...

ObGyns need to prioritize treatment for obesity

Between 1959 and 2014, US life expectancy increased from 69.9 years to 79.1 years. However, in 2015 and 2016 life expectancy in the United States decreased slightly to 78.9 years, while continuing to improve in other countries.15 What could cause such an unexpected trend? Some experts believe that excess overweight and obesity in the US population, resulting in increased rates of diabetes, hypertension, and heart disease, accounts for a significant proportion of the life expectancy gap between US citizens and those who reside in Australia, Finland, Japan, and Sweden.16,17 All frontline clinicians play an important role in reversing the decades-long trend of increasing rates of overweight and obesity. Interventions that ObGyns could prioritize in their practices for treating overweight and obese patients include: a calorie-restricted diet, exercise, metformin, and SG.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The Health Consequences of Smoking—50 Years of Progress. A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 2014.

- Allison DB, Fontaine KR, Manson JE, et al. Annual deaths attributable to obesity in the United States. JAMA. 1999;282:1530-1538.

- Ward ZJ, Bleich SN, Cradock AL, et al. Projected U.S. state-level prevalence of adult obesity and severe obesity. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:2440-2450.

- American Heart Association. My life check | Life’s simple 7. https://www.heart.org/en/healthyliving/healthy-lifestyle/my-life-check--lifessimple-7. Reviewed May 2, 2018. Accessed February 10, 2020.

- Knowler WC, Barrett-Connor E, Fowler SE, et al; Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group. Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:393-403.

- Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group. Long-term safety, tolerability and weight loss associated with metformin in the Diabetes Prevention Program Outcomes Study. Diabetes Care. 2012;35:731-737.

- Winder WW, Hardie DG. Inactivation of acetylCoA carboxylase and activation of AMP-activated protein kinase in muscle during exercise. Am J Physiol. 1996;270(2 pt 1):E299-E304.

- Lexicomp. https://online.lexi.com/lco/action/ home. Accessed February 13, 2020.

- Metformin ER (Glucophage XR). GoodRX website. https://www.goodrx.com/metformin-erglucophage-xr?dosage=750mg&form=tablet&la bel_override=metformin+ER+%28Glucophage+X R%29&quantity=60. Accessed February 13, 2020.

- GoodRX website. www.goodrx.com. Accessed February 10, 2020.

- Peterli R, Wolnerhanssen BK, Peters T, et al. Effect of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy vs laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass on weight loss in patients with morbid obesity: the SM-BOSS randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2018;319:255-265.

- Salminen P, Helmiö M, Ovaska J, et al. Effect of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy versus laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass on weight loss at 5 years among patients with morbid obesity: The SLEEVEPASS randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2018;319:241-254.

- Rubino F, Nathan DM, Eckel RH, et al; Delegates of the 2nd Diabetes Surgery Summit. Metabolic surgery in the treatment algorithm for type 2 diabetes: a joint statement by international diabetes organizations. Obes Surg. 2017;27:2-21.

- Gebran SG, Knighton B, Ngaage LM, et al. Insurance coverage criteria for bariatric surgery: a survey of policies. Obes Surg. 2020;30:707-713.

- Woolf SH, Schoomaker H. Life expectancy and mortality rates in the United States, 1959-2017. JAMA. 2019;322:1996-2016.

- Preston SH, Vierboom YC, Stokes A. The role of obesity in exceptionally slow US mortality improvement. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2019;115:957-961.

- Xu H, Cupples LA, Stokes A, et al. Association of obesity with mortality over 24 years of weight history: findings from the Framingham Heart Study. JAMA Network Open. 2018;1:e184587.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The Health Consequences of Smoking—50 Years of Progress. A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 2014.

- Allison DB, Fontaine KR, Manson JE, et al. Annual deaths attributable to obesity in the United States. JAMA. 1999;282:1530-1538.

- Ward ZJ, Bleich SN, Cradock AL, et al. Projected U.S. state-level prevalence of adult obesity and severe obesity. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:2440-2450.

- American Heart Association. My life check | Life’s simple 7. https://www.heart.org/en/healthyliving/healthy-lifestyle/my-life-check--lifessimple-7. Reviewed May 2, 2018. Accessed February 10, 2020.

- Knowler WC, Barrett-Connor E, Fowler SE, et al; Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group. Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:393-403.

- Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group. Long-term safety, tolerability and weight loss associated with metformin in the Diabetes Prevention Program Outcomes Study. Diabetes Care. 2012;35:731-737.

- Winder WW, Hardie DG. Inactivation of acetylCoA carboxylase and activation of AMP-activated protein kinase in muscle during exercise. Am J Physiol. 1996;270(2 pt 1):E299-E304.

- Lexicomp. https://online.lexi.com/lco/action/ home. Accessed February 13, 2020.

- Metformin ER (Glucophage XR). GoodRX website. https://www.goodrx.com/metformin-erglucophage-xr?dosage=750mg&form=tablet&la bel_override=metformin+ER+%28Glucophage+X R%29&quantity=60. Accessed February 13, 2020.

- GoodRX website. www.goodrx.com. Accessed February 10, 2020.

- Peterli R, Wolnerhanssen BK, Peters T, et al. Effect of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy vs laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass on weight loss in patients with morbid obesity: the SM-BOSS randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2018;319:255-265.

- Salminen P, Helmiö M, Ovaska J, et al. Effect of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy versus laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass on weight loss at 5 years among patients with morbid obesity: The SLEEVEPASS randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2018;319:241-254.

- Rubino F, Nathan DM, Eckel RH, et al; Delegates of the 2nd Diabetes Surgery Summit. Metabolic surgery in the treatment algorithm for type 2 diabetes: a joint statement by international diabetes organizations. Obes Surg. 2017;27:2-21.

- Gebran SG, Knighton B, Ngaage LM, et al. Insurance coverage criteria for bariatric surgery: a survey of policies. Obes Surg. 2020;30:707-713.

- Woolf SH, Schoomaker H. Life expectancy and mortality rates in the United States, 1959-2017. JAMA. 2019;322:1996-2016.

- Preston SH, Vierboom YC, Stokes A. The role of obesity in exceptionally slow US mortality improvement. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2019;115:957-961.

- Xu H, Cupples LA, Stokes A, et al. Association of obesity with mortality over 24 years of weight history: findings from the Framingham Heart Study. JAMA Network Open. 2018;1:e184587.

Abbreviated MRI bests digital breast tomosynthesis in finding cancer in dense breasts

For women with dense breasts, abbreviated magnetic resonance imaging was more effective than was digital breast tomosynthesis for detecting invasive breast cancer in a cross-sectional study of 1,444 women who underwent both procedures.

Dense breasts are a common reason for failed early diagnosis of breast cancer, wrote Christopher E. Comstock, MD, of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, and colleagues. Digital breast tomosynthesis (DBT) and abbreviated breast magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are becoming more popular as safe and cost-effective breast cancer screening options, but their effectiveness in women with dense breasts and average breast cancer risk has not been compared.