User login

Uterine balloon tamponade found safe in postpartum hemorrhage

A new study summarizing and reanalyzing the .

Of 90 studies that reported efficacy data for uterine balloon tamponade (UBT), the procedure had overall success of 85.9% in treating postpartum hemorrhage (PPH). The pooled success rate was highest for women who were treated with a condom UBT, at 90.4%, compared with those treated with a Bakri balloon, at 83.2%, though the one randomized trial that compared the two devices head-to-head found no difference in success rates, wrote Sebastian Suarez, MD, and coauthors.

In all, the investigators looked at 91 studies involving 4,729 women who sustained PPH. The systematic review and meta-analysis included randomized controlled trials (RCTs), nonrandomized studies, and case series in which UBT was used to treat PPH.

Dr. Suarez, of Boston University Medical Center, and colleagues explained that postpartum hemorrhage (PPH) accounts for more maternal mortality and morbidity worldwide than any other complication of pregnancy, with the vast majority of PPH deaths occurring in low- and middle-income countries.

“While treatment of PPH varies depending on the cause, generally less invasive methods should be tried initially,” commented Angela Martin, MD, a maternal-fetal medicine specialist at the University of Kansas, Lawrence,in interview. Dr. Martin, who was not involved in the study, explained that “these options typically include administration of uterotonics or pharmacologic agents, and tamponade of the uterus with intrauterine balloons.” The hope in using less invasive options is that pelvic artery embolization, other surgical techniques, or even hysterectomy can be avoided in the face of the emergency of severe PPH.

One retrospective, nonrandomized study compared UBT plus standard of care with standard of care alone for uterine atony after vaginal delivery. The study found significantly less blood loss (759 mL vs. 1,582 mL) and a 0.22 relative risk of surgical interventions and 0.18 relative risk of blood transfusion for women receiving UBT. However, the authors assessed the evidence for UBT in this study to be of very low quality. Two other RCTs compared UBT and no UBT, and the authors’ meta-analysis of these two studies showed no significant differences between the two groups in risk of maternal death or surgical interventions. The evidence was considered very low quality in these studies as well.

UBT was also examined in uterine atony after Cesarean delivery; a subgroup analysis found overall less efficacy than that in cases of vaginal delivery. Other subgroup analyses found that UBT was more likely to be successful when uterine atony or placenta previa was the cause of PPH, compared with PPH from placenta accreta spectrum or retained products of conception. Also, the overall success of UBT was higher for PPH in vaginal delivery, compared with Cesarean delivery, at 87% versus 81%, regardless of the etiology of hemorrhage.

Looking at safety of UBT, Dr. Suarez and coinvestigators found 39 studies reporting various complications of UBT use for PPH, not all of which reported on all complications. The overall rate for fever or infection was 6.5% in studies reporting on this complication, and endometritis was recorded in 2.3% of participants in studies tracking that complication. Cervical tears, laceration of the lower segment of the vagina, uterine incision rupture or uterine perforation, and acute colonic pseudo-obstruction were all reported in 2% or less of the patients participating in studies that recorded these complications.

The authors excluded studies that included simultaneous use of surgical techniques and UBT and those that involved UBT for hemorrhage after pregnancy loss with a gestation less than 20 weeks’ duration. However, studies were included if UBT was used after surgical procedure failure.

To assess the primary outcome of UBT success rate, the authors used the raw ratio of cases of success divided by the total number of women treated with UBT. For the analysis, successful UBT use was considered to be arrest of PPH bleeding without maternal death or other surgical or radiological interventions after UBT placement, regardless of the definition of “UBT success” used in each study. Similarly, the authors considered “UBT failure” to have occurred in cases of maternal death or when additional surgical or radiological interventions happened after UBT placement.

The authors considered a composite primary outcome measure for the RCT and nonrandomized studies that was made up of maternal death and/or surgical or radiologic interventions.

Secondary outcome measures included UBT’s success rate for individual PPH causes, frequency of surgical and invasive procedures, and maternal outcomes such as death, blood loss, transfusion, ICU admission, and complication rates.

Overall, about half of the studies (n = 48; 53%) were conducted in low- and middle-income countries. Asian countries were the site of 46 studies, or 52% of the total. A quarter were conducted in Europe, and just five studies were conducted in the United States; the remainder were conducted in Africa or Latin America or were multinational studies.

Dr. Martin said that “[the review] findings provide reassurance that UBT can be implemented as a treatment option with a high success rate and low complication rate.” However, she noted, “There was a discrepancy between nonrandomized studies and RCTs on the efficacy and effectiveness of UBT.”

“Two randomized studies concluded there is no benefit to introduction of UBT in management of refractory PPH,” she continued. “The authors point out risk of bias and multiple methodological concerns that likely favored the control group in one effectiveness trial. Lack of benefit may have been due to suboptimal implementation strategies and lack of consistent UBT use.”

Dr. Martin concluded, “Overall, UBT success rates were consistently high across all study types. These findings are reassuring to the practicing clinician. There are many benefits to UBT including ease of use by a variety of health care providers, affordability, and its minimally invasive nature. Now there is evidence that UBT appears safe and has a high rate of success for management of PPH.”

The study’s senior author is a board member of the nonprofit organization Ujenzi Charitable Trust, which received Food and Drug Administration approval for the “Every Second Matters–Uterine Balloon Tamponade” device. Dr. Suarez reported that he had no financial conflicts of interest. The authors reported that there were no external sources of funding for the research. Dr. Martin serves on the editorial board of Ob.Gyn. News.

SOURCE: Suarez S et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020 Jan 6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2019.11.1287.

A new study summarizing and reanalyzing the .

Of 90 studies that reported efficacy data for uterine balloon tamponade (UBT), the procedure had overall success of 85.9% in treating postpartum hemorrhage (PPH). The pooled success rate was highest for women who were treated with a condom UBT, at 90.4%, compared with those treated with a Bakri balloon, at 83.2%, though the one randomized trial that compared the two devices head-to-head found no difference in success rates, wrote Sebastian Suarez, MD, and coauthors.

In all, the investigators looked at 91 studies involving 4,729 women who sustained PPH. The systematic review and meta-analysis included randomized controlled trials (RCTs), nonrandomized studies, and case series in which UBT was used to treat PPH.

Dr. Suarez, of Boston University Medical Center, and colleagues explained that postpartum hemorrhage (PPH) accounts for more maternal mortality and morbidity worldwide than any other complication of pregnancy, with the vast majority of PPH deaths occurring in low- and middle-income countries.

“While treatment of PPH varies depending on the cause, generally less invasive methods should be tried initially,” commented Angela Martin, MD, a maternal-fetal medicine specialist at the University of Kansas, Lawrence,in interview. Dr. Martin, who was not involved in the study, explained that “these options typically include administration of uterotonics or pharmacologic agents, and tamponade of the uterus with intrauterine balloons.” The hope in using less invasive options is that pelvic artery embolization, other surgical techniques, or even hysterectomy can be avoided in the face of the emergency of severe PPH.

One retrospective, nonrandomized study compared UBT plus standard of care with standard of care alone for uterine atony after vaginal delivery. The study found significantly less blood loss (759 mL vs. 1,582 mL) and a 0.22 relative risk of surgical interventions and 0.18 relative risk of blood transfusion for women receiving UBT. However, the authors assessed the evidence for UBT in this study to be of very low quality. Two other RCTs compared UBT and no UBT, and the authors’ meta-analysis of these two studies showed no significant differences between the two groups in risk of maternal death or surgical interventions. The evidence was considered very low quality in these studies as well.

UBT was also examined in uterine atony after Cesarean delivery; a subgroup analysis found overall less efficacy than that in cases of vaginal delivery. Other subgroup analyses found that UBT was more likely to be successful when uterine atony or placenta previa was the cause of PPH, compared with PPH from placenta accreta spectrum or retained products of conception. Also, the overall success of UBT was higher for PPH in vaginal delivery, compared with Cesarean delivery, at 87% versus 81%, regardless of the etiology of hemorrhage.

Looking at safety of UBT, Dr. Suarez and coinvestigators found 39 studies reporting various complications of UBT use for PPH, not all of which reported on all complications. The overall rate for fever or infection was 6.5% in studies reporting on this complication, and endometritis was recorded in 2.3% of participants in studies tracking that complication. Cervical tears, laceration of the lower segment of the vagina, uterine incision rupture or uterine perforation, and acute colonic pseudo-obstruction were all reported in 2% or less of the patients participating in studies that recorded these complications.

The authors excluded studies that included simultaneous use of surgical techniques and UBT and those that involved UBT for hemorrhage after pregnancy loss with a gestation less than 20 weeks’ duration. However, studies were included if UBT was used after surgical procedure failure.

To assess the primary outcome of UBT success rate, the authors used the raw ratio of cases of success divided by the total number of women treated with UBT. For the analysis, successful UBT use was considered to be arrest of PPH bleeding without maternal death or other surgical or radiological interventions after UBT placement, regardless of the definition of “UBT success” used in each study. Similarly, the authors considered “UBT failure” to have occurred in cases of maternal death or when additional surgical or radiological interventions happened after UBT placement.

The authors considered a composite primary outcome measure for the RCT and nonrandomized studies that was made up of maternal death and/or surgical or radiologic interventions.

Secondary outcome measures included UBT’s success rate for individual PPH causes, frequency of surgical and invasive procedures, and maternal outcomes such as death, blood loss, transfusion, ICU admission, and complication rates.

Overall, about half of the studies (n = 48; 53%) were conducted in low- and middle-income countries. Asian countries were the site of 46 studies, or 52% of the total. A quarter were conducted in Europe, and just five studies were conducted in the United States; the remainder were conducted in Africa or Latin America or were multinational studies.

Dr. Martin said that “[the review] findings provide reassurance that UBT can be implemented as a treatment option with a high success rate and low complication rate.” However, she noted, “There was a discrepancy between nonrandomized studies and RCTs on the efficacy and effectiveness of UBT.”

“Two randomized studies concluded there is no benefit to introduction of UBT in management of refractory PPH,” she continued. “The authors point out risk of bias and multiple methodological concerns that likely favored the control group in one effectiveness trial. Lack of benefit may have been due to suboptimal implementation strategies and lack of consistent UBT use.”

Dr. Martin concluded, “Overall, UBT success rates were consistently high across all study types. These findings are reassuring to the practicing clinician. There are many benefits to UBT including ease of use by a variety of health care providers, affordability, and its minimally invasive nature. Now there is evidence that UBT appears safe and has a high rate of success for management of PPH.”

The study’s senior author is a board member of the nonprofit organization Ujenzi Charitable Trust, which received Food and Drug Administration approval for the “Every Second Matters–Uterine Balloon Tamponade” device. Dr. Suarez reported that he had no financial conflicts of interest. The authors reported that there were no external sources of funding for the research. Dr. Martin serves on the editorial board of Ob.Gyn. News.

SOURCE: Suarez S et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020 Jan 6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2019.11.1287.

A new study summarizing and reanalyzing the .

Of 90 studies that reported efficacy data for uterine balloon tamponade (UBT), the procedure had overall success of 85.9% in treating postpartum hemorrhage (PPH). The pooled success rate was highest for women who were treated with a condom UBT, at 90.4%, compared with those treated with a Bakri balloon, at 83.2%, though the one randomized trial that compared the two devices head-to-head found no difference in success rates, wrote Sebastian Suarez, MD, and coauthors.

In all, the investigators looked at 91 studies involving 4,729 women who sustained PPH. The systematic review and meta-analysis included randomized controlled trials (RCTs), nonrandomized studies, and case series in which UBT was used to treat PPH.

Dr. Suarez, of Boston University Medical Center, and colleagues explained that postpartum hemorrhage (PPH) accounts for more maternal mortality and morbidity worldwide than any other complication of pregnancy, with the vast majority of PPH deaths occurring in low- and middle-income countries.

“While treatment of PPH varies depending on the cause, generally less invasive methods should be tried initially,” commented Angela Martin, MD, a maternal-fetal medicine specialist at the University of Kansas, Lawrence,in interview. Dr. Martin, who was not involved in the study, explained that “these options typically include administration of uterotonics or pharmacologic agents, and tamponade of the uterus with intrauterine balloons.” The hope in using less invasive options is that pelvic artery embolization, other surgical techniques, or even hysterectomy can be avoided in the face of the emergency of severe PPH.

One retrospective, nonrandomized study compared UBT plus standard of care with standard of care alone for uterine atony after vaginal delivery. The study found significantly less blood loss (759 mL vs. 1,582 mL) and a 0.22 relative risk of surgical interventions and 0.18 relative risk of blood transfusion for women receiving UBT. However, the authors assessed the evidence for UBT in this study to be of very low quality. Two other RCTs compared UBT and no UBT, and the authors’ meta-analysis of these two studies showed no significant differences between the two groups in risk of maternal death or surgical interventions. The evidence was considered very low quality in these studies as well.

UBT was also examined in uterine atony after Cesarean delivery; a subgroup analysis found overall less efficacy than that in cases of vaginal delivery. Other subgroup analyses found that UBT was more likely to be successful when uterine atony or placenta previa was the cause of PPH, compared with PPH from placenta accreta spectrum or retained products of conception. Also, the overall success of UBT was higher for PPH in vaginal delivery, compared with Cesarean delivery, at 87% versus 81%, regardless of the etiology of hemorrhage.

Looking at safety of UBT, Dr. Suarez and coinvestigators found 39 studies reporting various complications of UBT use for PPH, not all of which reported on all complications. The overall rate for fever or infection was 6.5% in studies reporting on this complication, and endometritis was recorded in 2.3% of participants in studies tracking that complication. Cervical tears, laceration of the lower segment of the vagina, uterine incision rupture or uterine perforation, and acute colonic pseudo-obstruction were all reported in 2% or less of the patients participating in studies that recorded these complications.

The authors excluded studies that included simultaneous use of surgical techniques and UBT and those that involved UBT for hemorrhage after pregnancy loss with a gestation less than 20 weeks’ duration. However, studies were included if UBT was used after surgical procedure failure.

To assess the primary outcome of UBT success rate, the authors used the raw ratio of cases of success divided by the total number of women treated with UBT. For the analysis, successful UBT use was considered to be arrest of PPH bleeding without maternal death or other surgical or radiological interventions after UBT placement, regardless of the definition of “UBT success” used in each study. Similarly, the authors considered “UBT failure” to have occurred in cases of maternal death or when additional surgical or radiological interventions happened after UBT placement.

The authors considered a composite primary outcome measure for the RCT and nonrandomized studies that was made up of maternal death and/or surgical or radiologic interventions.

Secondary outcome measures included UBT’s success rate for individual PPH causes, frequency of surgical and invasive procedures, and maternal outcomes such as death, blood loss, transfusion, ICU admission, and complication rates.

Overall, about half of the studies (n = 48; 53%) were conducted in low- and middle-income countries. Asian countries were the site of 46 studies, or 52% of the total. A quarter were conducted in Europe, and just five studies were conducted in the United States; the remainder were conducted in Africa or Latin America or were multinational studies.

Dr. Martin said that “[the review] findings provide reassurance that UBT can be implemented as a treatment option with a high success rate and low complication rate.” However, she noted, “There was a discrepancy between nonrandomized studies and RCTs on the efficacy and effectiveness of UBT.”

“Two randomized studies concluded there is no benefit to introduction of UBT in management of refractory PPH,” she continued. “The authors point out risk of bias and multiple methodological concerns that likely favored the control group in one effectiveness trial. Lack of benefit may have been due to suboptimal implementation strategies and lack of consistent UBT use.”

Dr. Martin concluded, “Overall, UBT success rates were consistently high across all study types. These findings are reassuring to the practicing clinician. There are many benefits to UBT including ease of use by a variety of health care providers, affordability, and its minimally invasive nature. Now there is evidence that UBT appears safe and has a high rate of success for management of PPH.”

The study’s senior author is a board member of the nonprofit organization Ujenzi Charitable Trust, which received Food and Drug Administration approval for the “Every Second Matters–Uterine Balloon Tamponade” device. Dr. Suarez reported that he had no financial conflicts of interest. The authors reported that there were no external sources of funding for the research. Dr. Martin serves on the editorial board of Ob.Gyn. News.

SOURCE: Suarez S et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020 Jan 6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2019.11.1287.

FROM AMERICAN JOURNAL OF OBSTETRICS AND GYNECOLOGY

Product update: Neuromodulation device, cystoscopy simplified, hysteroscopy seal, next immunization frontier

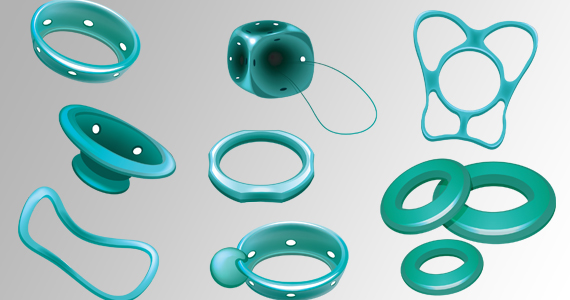

NEW SACRAL NEUROMODULATION DEVICE

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT: https://www.axonics.com/

CERVICAL SEAL FOR HYSTEROSCOPIC DEVICES

For more information, visit: https://gynsurgicalsolutions.com/product/omni-lok/

UNIVERSAL CYSTOSCOPY SIMPLIFIED

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT: https://cystosure.com/

NEXT FRONTIER IN VACCINE IMMUNIZATION

Globally, there are 410,000 cases of GBS every year. GBS is most common in newborns; women who are carriers of the GBS bacteria may pass it on to their newborns during labor and birth. An estimated 10% to 30% of pregnant women carry the GBS bacteria. The disease can manifest as sepsis, pneumonia, and meningitis, with potentially fatal outcomes for some. A maternal vaccine may prevent 231,000 infant and maternal GBS cases, says Pfizer.

According to Pfizer, RSV causes more hospitalizations each year than influenza among young children, with an estimated 33 million cases globally each year in children less than age 5 years.

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT: https://www.pfizer.com/

NEW SACRAL NEUROMODULATION DEVICE

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT: https://www.axonics.com/

CERVICAL SEAL FOR HYSTEROSCOPIC DEVICES

For more information, visit: https://gynsurgicalsolutions.com/product/omni-lok/

UNIVERSAL CYSTOSCOPY SIMPLIFIED

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT: https://cystosure.com/

NEXT FRONTIER IN VACCINE IMMUNIZATION

Globally, there are 410,000 cases of GBS every year. GBS is most common in newborns; women who are carriers of the GBS bacteria may pass it on to their newborns during labor and birth. An estimated 10% to 30% of pregnant women carry the GBS bacteria. The disease can manifest as sepsis, pneumonia, and meningitis, with potentially fatal outcomes for some. A maternal vaccine may prevent 231,000 infant and maternal GBS cases, says Pfizer.

According to Pfizer, RSV causes more hospitalizations each year than influenza among young children, with an estimated 33 million cases globally each year in children less than age 5 years.

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT: https://www.pfizer.com/

NEW SACRAL NEUROMODULATION DEVICE

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT: https://www.axonics.com/

CERVICAL SEAL FOR HYSTEROSCOPIC DEVICES

For more information, visit: https://gynsurgicalsolutions.com/product/omni-lok/

UNIVERSAL CYSTOSCOPY SIMPLIFIED

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT: https://cystosure.com/

NEXT FRONTIER IN VACCINE IMMUNIZATION

Globally, there are 410,000 cases of GBS every year. GBS is most common in newborns; women who are carriers of the GBS bacteria may pass it on to their newborns during labor and birth. An estimated 10% to 30% of pregnant women carry the GBS bacteria. The disease can manifest as sepsis, pneumonia, and meningitis, with potentially fatal outcomes for some. A maternal vaccine may prevent 231,000 infant and maternal GBS cases, says Pfizer.

According to Pfizer, RSV causes more hospitalizations each year than influenza among young children, with an estimated 33 million cases globally each year in children less than age 5 years.

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT: https://www.pfizer.com/

Should secondary cytoreduction be performed for platinum-sensitive recurrent ovarian cancer?

Coleman RL, Spirtos NM, Enserro D, et al. Secondary surgical cytoreduction for recurrent ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:1929-1939.

EXPERT COMMENTARY

Ovarian cancer represents the most lethal gynecologic cancer, with an estimated 14,000 deaths in 2019.1 While the incidence of this disease is low in comparison to uterine cancer, the advanced stage at diagnosis portends poor prognosis. While stage is an independent risk factor for death, it is also a risk for recurrence, with more than 80% of women developing recurrent disease.2-4 Secondary cytoreduction remains an option for patients in which disease recurs; up until now this management option was driven by retrospective data.5

Details of the study

Coleman and colleagues conducted the Gynecologic Oncology Group (GOG) 0213 trial—a phase 3, multicenter, randomized clinical trial that included 485 women with recurrent ovarian cancer. The surgical objective of the trial was to determine whether secondary cytoreduction in operable, platinum-sensitive (PS) patients improved overall survival (OS).

Patients were eligible to participate in the surgical portion of the trial if they had PS measurable disease and had the intention to achieve complete gross resection. Women with ascites, evidence of extraabdominal disease, and “diffuse carcinomatosis” were excluded. The primary and secondary end points were OS and progression-free survival (PFS), respectively.

Results. There were no statistical differences between the surgery and no surgery groups with regard to median OS (50.6 months vs 64.7 months, respectively; hazard ratio [HR], 1.29; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.97–1.72) or median PFS (18.9 months vs 16.2 months; HR, 0.82; 95% CI, 0.66 to 1.01). When comparing patients in which complete gross resection was achieved (150 patients vs 245 who did not receive surgery), there was only a statistical difference in PFS in favor of the surgical group (22.4 months vs 16.2 months; HR, 0.62; 95% CI, 0.48–0.80).

Of note, 67% of the patients who received surgery (63% intention-to-treat) were debulked to complete gross resection. There were 33% more patients with extraabdominal disease (10% vs 7% of total patients in each group) and 15% more patients with upper abdominal disease (40% vs 33% of total patients in each group) included in the surgical group. Finally, the median time to chemotherapy was 40 days in the surgery group versus 7 days in the no surgery group.

Continue to: Study strengths and weaknesses...

Study strengths and weaknesses

The authors deserve to be commended for this well-designed and laborious trial, which is the first of its kind. The strength of the study is its randomized design producing level I data.

Study weaknesses include lack of reporting of BRCA status and the impact of receiving targeted therapies after the trial was over. It is well established that BRCA-mutated patients have an independent survival advantage, even when taking into account platinum sensitivity.6-8BRCA status of the study population is not specifically addressed in this paper. The authors noted in the first GOG 0213 trial publication, which assessed bevacizumab in the recurrent setting, that BRCA status has an impact on patient outcomes. Subsequently, they state that they do not report BRCA status because “…its independent effect on response to an anti-angiogenesis agent was unknown,” but it clearly would affect survival analysis if unbalanced between groups.9

Similarly, in the introduction to their study, Coleman and colleagues list availability of maintenance therapy, for instance poly ADP (adenosine diphosphate–ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitors, as rationale for conducting their trial. They subsequently cite this as a possible reason that the median overall survival was 3 times longer than expected. However, they provide no data on which patients received maintenance therapy, which again could have drastically affected survival outcomes.10 They do report in the supplementary information that, when stratifying those receiving bevacizumab adjuvantly during the trial, the median OS was comparable between the surgical and nonsurgical groups (58.5 months vs 61.7 months).

The authors discuss the presence of patient selection bias as a weakness in the study. Selection bias is evident in this trial (as in many surgical trials) because patients with a limited volume of disease were selected to participate over those with large-volume disease. It is reasonable to conclude that this study is likely selecting patients with less aggressive tumor biology, not only evident by low-volume disease at recurrence but also by the 20.4-month median platinum-free interval in the surgical group, which certainly affects the trial’s validity. Despite being considered PS, the disease biology in a patient with a platinum-free interval of 20.4 months is surely different from the disease biology in a patient with a 6.4-month platinum-free interval; therefore, it is difficult to generalize these data to all PS recurrent ovarian cancer patients. Similarly, other research has suggested strict selection criteria, which was not apparent in this study’s methodology.11 While the number of metastatic sites were relatively equal between the surgery and no surgery groups, there were more patients in the surgical group with extraabdominal disease, which the authors used as an exclusion criterion.

Lastly, the time to treatment commencement in each arm, which was 40 days for the surgical arm and 7 days in the nonsurgical arm, could represent a flaw in this trial. While we expect a difference in duration to account for recovery time, many centers start chemotherapy as soon as 21 days after surgery, which is almost half of the median interval in the surgical group in this trial. While the authors address this by stating that they completed a landmark analysis, no data or information about what time points they used for the analysis are provided. They simply report an interquartile range of 28 to 51 days. It is hard to know what effect this may have had on the outcome.

This is the first randomized clinical trial conducted to assess whether secondary surgical cytoreduction is beneficial in PS recurrent ovarian cancer patients. It provides compelling evidence to critically evaluate whether surgical cytoreduction is appropriate in a similar patient population. However, we would recommend using caution applying these data to patients who have different platinum-free intervals or low-volume disease limited to the pelvis.

The trial is not without flaws, as the authors point out in their discussion, but currently, it is the best evidence afforded to gynecologic oncologists. There are multiple trials currently ongoing, including DESTOP-III, which had similar PFS results as GOG 0213. If consensus is reached with these 2 trials, we believe that secondary cytoreduction will be utilized far less often in patients with recurrent ovarian cancer and a long platinum-free interval, thereby changing the current treatment paradigm for these patients.

MICHAEL D. TOBONI, MD, MPH, AND DAVID G. MUTCH, MD

- Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin. 2019;69:7-34.

- Parmar MK, Ledermann JA, Colombo N, et al. Paclitaxel plus platinum-based chemotherapy versus conventional platinum-based chemotherapy in women with relapsed ovarian cancer: the ICON4/AGO-OVAR-2.2 trial. Lancet. 2003;361:2099-2106.

- International Collaborative Ovarian Neoplasm Group. Paclitaxel plus carboplatin versus standard chemotherapy with either single-agent carboplatin or cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, and cisplatin in women with ovarian cancer: the ICON3 randomised trial. Lancet. 2002;360:505-515.

- Mullen MM, Kuroki LM, Thaker PH. Novel treatment options in platinum-sensitive recurrent ovarian cancer: a review. Gynecol Oncol. 2019;152:416-425.

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: ovarian cancer. November 26, 2019. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/ovarian.pdf. Accessed December 18, 2019.

- Cass I, Baldwin RL, Varkey T, et al. Improved survival in women with BRCA-associated ovarian carcinoma. Cancer. 2003;97:2187-2195.

- Gallagher DJ, Konner JA, Bell-McGuinn KM, et al. Survival in epithelial ovarian cancer: a multivariate analysis incorporating BRCA mutation status and platinum sensitivity. Ann Oncol. 2011;22:1127-1132.

- Sun C, Li N, Ding D, et al. The role of BRCA status on the prognosis of patients with epithelial ovarian cancer: a systematic review of the literature with a meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2014;9:e95285.

- Coleman RL, Brady MF, Herzog TJ, et al. Bevacizumab and paclitaxel-carboplatin chemotherapy and secondary cytoreduction in recurrent, platinum-sensitive ovarian cancer (NRG Oncology/Gynecologic Oncology Group study GOG-0213): a multicentre, open-label, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18:779-791.

- Coleman RL, Spirtos NM, Enserro D, et al. Secondary surgical cytoreduction for recurrent ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:1929-1939.

- Chi DS, McCaughty K, Diaz JP, et al. Guidelines and selection criteria for secondary cytoreductive surgery in patients with recurrent, platinum-sensitive epithelial ovarian carcinoma. Cancer. 2006;106:1933-1939.

Coleman RL, Spirtos NM, Enserro D, et al. Secondary surgical cytoreduction for recurrent ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:1929-1939.

EXPERT COMMENTARY

Ovarian cancer represents the most lethal gynecologic cancer, with an estimated 14,000 deaths in 2019.1 While the incidence of this disease is low in comparison to uterine cancer, the advanced stage at diagnosis portends poor prognosis. While stage is an independent risk factor for death, it is also a risk for recurrence, with more than 80% of women developing recurrent disease.2-4 Secondary cytoreduction remains an option for patients in which disease recurs; up until now this management option was driven by retrospective data.5

Details of the study

Coleman and colleagues conducted the Gynecologic Oncology Group (GOG) 0213 trial—a phase 3, multicenter, randomized clinical trial that included 485 women with recurrent ovarian cancer. The surgical objective of the trial was to determine whether secondary cytoreduction in operable, platinum-sensitive (PS) patients improved overall survival (OS).

Patients were eligible to participate in the surgical portion of the trial if they had PS measurable disease and had the intention to achieve complete gross resection. Women with ascites, evidence of extraabdominal disease, and “diffuse carcinomatosis” were excluded. The primary and secondary end points were OS and progression-free survival (PFS), respectively.

Results. There were no statistical differences between the surgery and no surgery groups with regard to median OS (50.6 months vs 64.7 months, respectively; hazard ratio [HR], 1.29; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.97–1.72) or median PFS (18.9 months vs 16.2 months; HR, 0.82; 95% CI, 0.66 to 1.01). When comparing patients in which complete gross resection was achieved (150 patients vs 245 who did not receive surgery), there was only a statistical difference in PFS in favor of the surgical group (22.4 months vs 16.2 months; HR, 0.62; 95% CI, 0.48–0.80).

Of note, 67% of the patients who received surgery (63% intention-to-treat) were debulked to complete gross resection. There were 33% more patients with extraabdominal disease (10% vs 7% of total patients in each group) and 15% more patients with upper abdominal disease (40% vs 33% of total patients in each group) included in the surgical group. Finally, the median time to chemotherapy was 40 days in the surgery group versus 7 days in the no surgery group.

Continue to: Study strengths and weaknesses...

Study strengths and weaknesses

The authors deserve to be commended for this well-designed and laborious trial, which is the first of its kind. The strength of the study is its randomized design producing level I data.

Study weaknesses include lack of reporting of BRCA status and the impact of receiving targeted therapies after the trial was over. It is well established that BRCA-mutated patients have an independent survival advantage, even when taking into account platinum sensitivity.6-8BRCA status of the study population is not specifically addressed in this paper. The authors noted in the first GOG 0213 trial publication, which assessed bevacizumab in the recurrent setting, that BRCA status has an impact on patient outcomes. Subsequently, they state that they do not report BRCA status because “…its independent effect on response to an anti-angiogenesis agent was unknown,” but it clearly would affect survival analysis if unbalanced between groups.9

Similarly, in the introduction to their study, Coleman and colleagues list availability of maintenance therapy, for instance poly ADP (adenosine diphosphate–ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitors, as rationale for conducting their trial. They subsequently cite this as a possible reason that the median overall survival was 3 times longer than expected. However, they provide no data on which patients received maintenance therapy, which again could have drastically affected survival outcomes.10 They do report in the supplementary information that, when stratifying those receiving bevacizumab adjuvantly during the trial, the median OS was comparable between the surgical and nonsurgical groups (58.5 months vs 61.7 months).

The authors discuss the presence of patient selection bias as a weakness in the study. Selection bias is evident in this trial (as in many surgical trials) because patients with a limited volume of disease were selected to participate over those with large-volume disease. It is reasonable to conclude that this study is likely selecting patients with less aggressive tumor biology, not only evident by low-volume disease at recurrence but also by the 20.4-month median platinum-free interval in the surgical group, which certainly affects the trial’s validity. Despite being considered PS, the disease biology in a patient with a platinum-free interval of 20.4 months is surely different from the disease biology in a patient with a 6.4-month platinum-free interval; therefore, it is difficult to generalize these data to all PS recurrent ovarian cancer patients. Similarly, other research has suggested strict selection criteria, which was not apparent in this study’s methodology.11 While the number of metastatic sites were relatively equal between the surgery and no surgery groups, there were more patients in the surgical group with extraabdominal disease, which the authors used as an exclusion criterion.

Lastly, the time to treatment commencement in each arm, which was 40 days for the surgical arm and 7 days in the nonsurgical arm, could represent a flaw in this trial. While we expect a difference in duration to account for recovery time, many centers start chemotherapy as soon as 21 days after surgery, which is almost half of the median interval in the surgical group in this trial. While the authors address this by stating that they completed a landmark analysis, no data or information about what time points they used for the analysis are provided. They simply report an interquartile range of 28 to 51 days. It is hard to know what effect this may have had on the outcome.

This is the first randomized clinical trial conducted to assess whether secondary surgical cytoreduction is beneficial in PS recurrent ovarian cancer patients. It provides compelling evidence to critically evaluate whether surgical cytoreduction is appropriate in a similar patient population. However, we would recommend using caution applying these data to patients who have different platinum-free intervals or low-volume disease limited to the pelvis.

The trial is not without flaws, as the authors point out in their discussion, but currently, it is the best evidence afforded to gynecologic oncologists. There are multiple trials currently ongoing, including DESTOP-III, which had similar PFS results as GOG 0213. If consensus is reached with these 2 trials, we believe that secondary cytoreduction will be utilized far less often in patients with recurrent ovarian cancer and a long platinum-free interval, thereby changing the current treatment paradigm for these patients.

MICHAEL D. TOBONI, MD, MPH, AND DAVID G. MUTCH, MD

Coleman RL, Spirtos NM, Enserro D, et al. Secondary surgical cytoreduction for recurrent ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:1929-1939.

EXPERT COMMENTARY

Ovarian cancer represents the most lethal gynecologic cancer, with an estimated 14,000 deaths in 2019.1 While the incidence of this disease is low in comparison to uterine cancer, the advanced stage at diagnosis portends poor prognosis. While stage is an independent risk factor for death, it is also a risk for recurrence, with more than 80% of women developing recurrent disease.2-4 Secondary cytoreduction remains an option for patients in which disease recurs; up until now this management option was driven by retrospective data.5

Details of the study

Coleman and colleagues conducted the Gynecologic Oncology Group (GOG) 0213 trial—a phase 3, multicenter, randomized clinical trial that included 485 women with recurrent ovarian cancer. The surgical objective of the trial was to determine whether secondary cytoreduction in operable, platinum-sensitive (PS) patients improved overall survival (OS).

Patients were eligible to participate in the surgical portion of the trial if they had PS measurable disease and had the intention to achieve complete gross resection. Women with ascites, evidence of extraabdominal disease, and “diffuse carcinomatosis” were excluded. The primary and secondary end points were OS and progression-free survival (PFS), respectively.

Results. There were no statistical differences between the surgery and no surgery groups with regard to median OS (50.6 months vs 64.7 months, respectively; hazard ratio [HR], 1.29; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.97–1.72) or median PFS (18.9 months vs 16.2 months; HR, 0.82; 95% CI, 0.66 to 1.01). When comparing patients in which complete gross resection was achieved (150 patients vs 245 who did not receive surgery), there was only a statistical difference in PFS in favor of the surgical group (22.4 months vs 16.2 months; HR, 0.62; 95% CI, 0.48–0.80).

Of note, 67% of the patients who received surgery (63% intention-to-treat) were debulked to complete gross resection. There were 33% more patients with extraabdominal disease (10% vs 7% of total patients in each group) and 15% more patients with upper abdominal disease (40% vs 33% of total patients in each group) included in the surgical group. Finally, the median time to chemotherapy was 40 days in the surgery group versus 7 days in the no surgery group.

Continue to: Study strengths and weaknesses...

Study strengths and weaknesses

The authors deserve to be commended for this well-designed and laborious trial, which is the first of its kind. The strength of the study is its randomized design producing level I data.

Study weaknesses include lack of reporting of BRCA status and the impact of receiving targeted therapies after the trial was over. It is well established that BRCA-mutated patients have an independent survival advantage, even when taking into account platinum sensitivity.6-8BRCA status of the study population is not specifically addressed in this paper. The authors noted in the first GOG 0213 trial publication, which assessed bevacizumab in the recurrent setting, that BRCA status has an impact on patient outcomes. Subsequently, they state that they do not report BRCA status because “…its independent effect on response to an anti-angiogenesis agent was unknown,” but it clearly would affect survival analysis if unbalanced between groups.9

Similarly, in the introduction to their study, Coleman and colleagues list availability of maintenance therapy, for instance poly ADP (adenosine diphosphate–ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitors, as rationale for conducting their trial. They subsequently cite this as a possible reason that the median overall survival was 3 times longer than expected. However, they provide no data on which patients received maintenance therapy, which again could have drastically affected survival outcomes.10 They do report in the supplementary information that, when stratifying those receiving bevacizumab adjuvantly during the trial, the median OS was comparable between the surgical and nonsurgical groups (58.5 months vs 61.7 months).

The authors discuss the presence of patient selection bias as a weakness in the study. Selection bias is evident in this trial (as in many surgical trials) because patients with a limited volume of disease were selected to participate over those with large-volume disease. It is reasonable to conclude that this study is likely selecting patients with less aggressive tumor biology, not only evident by low-volume disease at recurrence but also by the 20.4-month median platinum-free interval in the surgical group, which certainly affects the trial’s validity. Despite being considered PS, the disease biology in a patient with a platinum-free interval of 20.4 months is surely different from the disease biology in a patient with a 6.4-month platinum-free interval; therefore, it is difficult to generalize these data to all PS recurrent ovarian cancer patients. Similarly, other research has suggested strict selection criteria, which was not apparent in this study’s methodology.11 While the number of metastatic sites were relatively equal between the surgery and no surgery groups, there were more patients in the surgical group with extraabdominal disease, which the authors used as an exclusion criterion.

Lastly, the time to treatment commencement in each arm, which was 40 days for the surgical arm and 7 days in the nonsurgical arm, could represent a flaw in this trial. While we expect a difference in duration to account for recovery time, many centers start chemotherapy as soon as 21 days after surgery, which is almost half of the median interval in the surgical group in this trial. While the authors address this by stating that they completed a landmark analysis, no data or information about what time points they used for the analysis are provided. They simply report an interquartile range of 28 to 51 days. It is hard to know what effect this may have had on the outcome.

This is the first randomized clinical trial conducted to assess whether secondary surgical cytoreduction is beneficial in PS recurrent ovarian cancer patients. It provides compelling evidence to critically evaluate whether surgical cytoreduction is appropriate in a similar patient population. However, we would recommend using caution applying these data to patients who have different platinum-free intervals or low-volume disease limited to the pelvis.

The trial is not without flaws, as the authors point out in their discussion, but currently, it is the best evidence afforded to gynecologic oncologists. There are multiple trials currently ongoing, including DESTOP-III, which had similar PFS results as GOG 0213. If consensus is reached with these 2 trials, we believe that secondary cytoreduction will be utilized far less often in patients with recurrent ovarian cancer and a long platinum-free interval, thereby changing the current treatment paradigm for these patients.

MICHAEL D. TOBONI, MD, MPH, AND DAVID G. MUTCH, MD

- Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin. 2019;69:7-34.

- Parmar MK, Ledermann JA, Colombo N, et al. Paclitaxel plus platinum-based chemotherapy versus conventional platinum-based chemotherapy in women with relapsed ovarian cancer: the ICON4/AGO-OVAR-2.2 trial. Lancet. 2003;361:2099-2106.

- International Collaborative Ovarian Neoplasm Group. Paclitaxel plus carboplatin versus standard chemotherapy with either single-agent carboplatin or cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, and cisplatin in women with ovarian cancer: the ICON3 randomised trial. Lancet. 2002;360:505-515.

- Mullen MM, Kuroki LM, Thaker PH. Novel treatment options in platinum-sensitive recurrent ovarian cancer: a review. Gynecol Oncol. 2019;152:416-425.

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: ovarian cancer. November 26, 2019. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/ovarian.pdf. Accessed December 18, 2019.

- Cass I, Baldwin RL, Varkey T, et al. Improved survival in women with BRCA-associated ovarian carcinoma. Cancer. 2003;97:2187-2195.

- Gallagher DJ, Konner JA, Bell-McGuinn KM, et al. Survival in epithelial ovarian cancer: a multivariate analysis incorporating BRCA mutation status and platinum sensitivity. Ann Oncol. 2011;22:1127-1132.

- Sun C, Li N, Ding D, et al. The role of BRCA status on the prognosis of patients with epithelial ovarian cancer: a systematic review of the literature with a meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2014;9:e95285.

- Coleman RL, Brady MF, Herzog TJ, et al. Bevacizumab and paclitaxel-carboplatin chemotherapy and secondary cytoreduction in recurrent, platinum-sensitive ovarian cancer (NRG Oncology/Gynecologic Oncology Group study GOG-0213): a multicentre, open-label, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18:779-791.

- Coleman RL, Spirtos NM, Enserro D, et al. Secondary surgical cytoreduction for recurrent ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:1929-1939.

- Chi DS, McCaughty K, Diaz JP, et al. Guidelines and selection criteria for secondary cytoreductive surgery in patients with recurrent, platinum-sensitive epithelial ovarian carcinoma. Cancer. 2006;106:1933-1939.

- Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin. 2019;69:7-34.

- Parmar MK, Ledermann JA, Colombo N, et al. Paclitaxel plus platinum-based chemotherapy versus conventional platinum-based chemotherapy in women with relapsed ovarian cancer: the ICON4/AGO-OVAR-2.2 trial. Lancet. 2003;361:2099-2106.

- International Collaborative Ovarian Neoplasm Group. Paclitaxel plus carboplatin versus standard chemotherapy with either single-agent carboplatin or cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, and cisplatin in women with ovarian cancer: the ICON3 randomised trial. Lancet. 2002;360:505-515.

- Mullen MM, Kuroki LM, Thaker PH. Novel treatment options in platinum-sensitive recurrent ovarian cancer: a review. Gynecol Oncol. 2019;152:416-425.

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: ovarian cancer. November 26, 2019. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/ovarian.pdf. Accessed December 18, 2019.

- Cass I, Baldwin RL, Varkey T, et al. Improved survival in women with BRCA-associated ovarian carcinoma. Cancer. 2003;97:2187-2195.

- Gallagher DJ, Konner JA, Bell-McGuinn KM, et al. Survival in epithelial ovarian cancer: a multivariate analysis incorporating BRCA mutation status and platinum sensitivity. Ann Oncol. 2011;22:1127-1132.

- Sun C, Li N, Ding D, et al. The role of BRCA status on the prognosis of patients with epithelial ovarian cancer: a systematic review of the literature with a meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2014;9:e95285.

- Coleman RL, Brady MF, Herzog TJ, et al. Bevacizumab and paclitaxel-carboplatin chemotherapy and secondary cytoreduction in recurrent, platinum-sensitive ovarian cancer (NRG Oncology/Gynecologic Oncology Group study GOG-0213): a multicentre, open-label, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18:779-791.

- Coleman RL, Spirtos NM, Enserro D, et al. Secondary surgical cytoreduction for recurrent ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:1929-1939.

- Chi DS, McCaughty K, Diaz JP, et al. Guidelines and selection criteria for secondary cytoreductive surgery in patients with recurrent, platinum-sensitive epithelial ovarian carcinoma. Cancer. 2006;106:1933-1939.

What is optimal hormonal treatment for women with polycystic ovary syndrome?

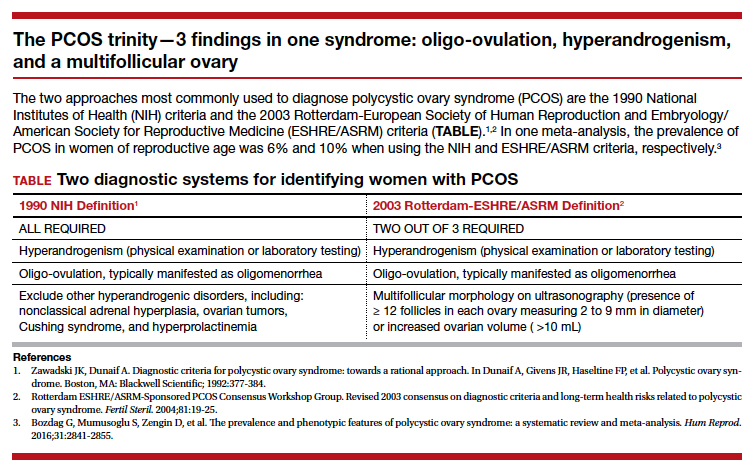

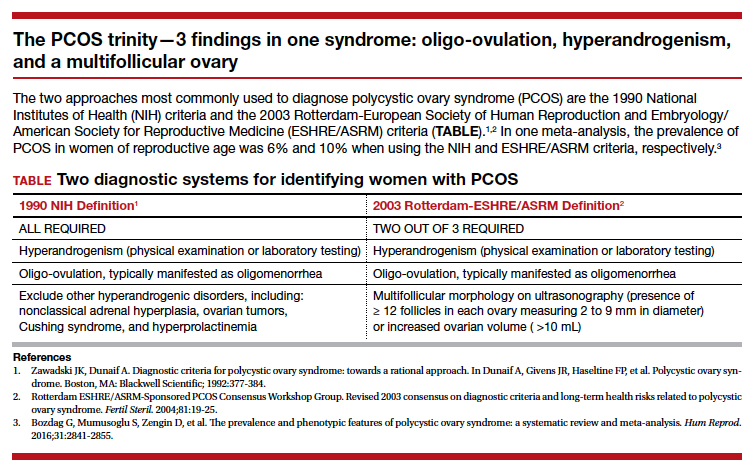

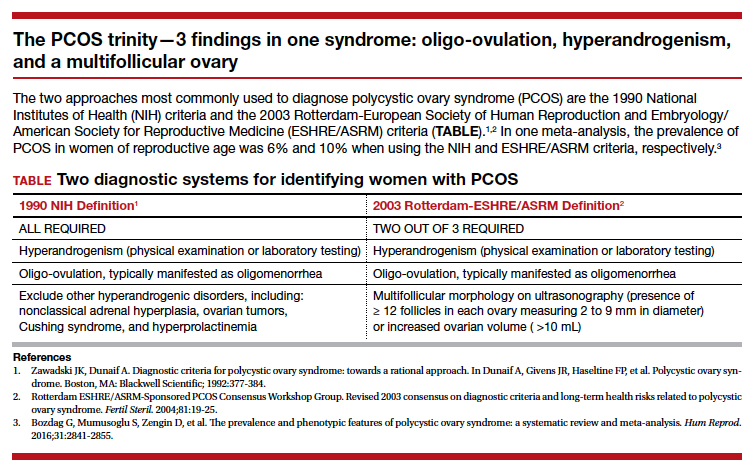

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is the triad of oligo-ovulation resulting in oligomenorrhea, hyperandrogenism and, often, an excess number of small antral follicles on high-resolution pelvic ultrasound. One meta-analysis reported that, in women of reproductive age, the prevalence of PCOS was 10% using the Rotterdam-European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology/American Society for Reproductive Medicine (ESHRE/ASRM) criteria1 and 6% using the National Institutes of Health 1990 diagnostic criteria.2 (See “The PCOS trinity—3 findings in one syndrome: oligo-ovulation, hyperandrogenism, and a multifollicular ovary.”3)

PCOS is caused by abnormalities in 3 systems: reproductive, metabolic, and dermatologic. Reproductive abnormalities commonly observed in women with PCOS include4:

- an increase in pituitary secretion of luteinizing hormone (LH), resulting from both an increase in LH pulse amplitude and LH pulse frequency, suggesting a primary hypothalamic disorder

- an increase in ovarian secretion of androstenedione and testosterone due to stimulation by LH and possibly insulin

- oligo-ovulation with chronically low levels of progesterone that can result in endometrial hyperplasia

- ovulatory infertility.

Metabolic abnormalities commonly observed in women with PCOS include5,6:

- insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia

- excess adipose tissue in the liver

- excess visceral fat

- elevated adipokines

- obesity

- an increased prevalence of glucose intolerance and frank diabetes.

Dermatologic abnormalities commonly observed in women with PCOS include7:

- facial hirsutism

- acne

- androgenetic alopecia.

Given that PCOS is caused by abnormalities in the reproductive, metabolic, and dermatologic systems, it is appropriate to consider multimodal hormonal therapy that addresses all 3 problems. In my practice, I believe that the best approach to the long-term hormonal treatment of PCOS for many women is to prescribe a combination of 3 medicines: a combination estrogen-progestin oral contraceptive (COC), an insulin sensitizer, and an antiandrogen.

The COC reduces pituitary secretion of LH, decreases ovarian androgen production, and prevents the development of endometrial hyperplasia. When taken cyclically, the COC treatment also restores regular withdrawal uterine bleeding.

An insulin sensitizer, such as metformin or pioglitazone, helps to reduce insulin resistance, glucose intolerance, and hepatic adipose content, rebalancing central metabolism. It is important to include diet and exercise in the long-term treatment of PCOS, and I always encourage these lifestyle changes. However, my patients usually report that they have tried multiple times to restrict dietary caloric intake and increase exercise and have been unable to rebalance their metabolism with these interventions alone. Of note, in the women with PCOS and a body mass index >35 kg/m2, bariatric surgery, such as a sleeve gastrectomy, often results in marked improvement of their PCOS.8

The antiandrogen spironolactone provides effective treatment for the dermatologic problems of facial hirsutism and acne. Some COCs containing the progestins drospirenone, norgestimate, and norethindrone acetate are approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of acne. A common approach I use in practice is to prescribe a COC, plus spironolactone 100 mg daily plus metformin extended-release 750 mg to 1,500 mg daily.

Continue to: Which COCs have low androgenicity?...

Which COCs have low androgenicity?

I believe that every COC is an effective treatment for PCOS, regardless of the androgenicity of the progestin in the contraceptive. However, some dermatologists believe that combination contraceptives containing progestins with low androgenicity, such as drospirenone, norgestimate, and desogestrel, are more likely to improve acne than contraceptives with an androgenic progestin such as levonorgestrel. In one study in which 2,147 women with acne were treated by one dermatologic practice, the percentage of women reporting that a birth control pill helped to improve their acne was 66% for pills containing drospirenone, 53% for pills containing norgestimate, 44% for pills containing desogestrel, 30% for pills containing norethindrone, and 25% for pills containing levonorgestrel. In the same study, the percent of women reporting that a birth control pill made their acne worse was 3% for pills containing drospirenone, 6% for pills containing norgestimate, 2% for pills containing desogestrel, 8% for pills containing norethindrone, and 10% for pills containing levonorgestrel.9 Given these findings, when treating a woman with PCOS, I generally prescribe a contraceptive that does not contain levonorgestrel.

Why is a spironolactone dose of 100 mg a good choice for PCOS treatment?

Spironolactone, an antiandrogen and inhibitor of 5-alpha-reductase, is commonly prescribed for the treatment of hirsutism and acne at doses ranging from 50 mg to 200 mg daily.10,11 In my clinical experience, spironolactone at a dose of 200 mg daily commonly causes irregular and bothersome uterine bleeding while spironolactone at a dose of 100 mg daily is seldom associated with irregular bleeding. I believe that spironolactone at a dose of 100 mg daily results in superior clinical efficacy than a 50-mg daily dose, although studies report that both doses are effective in the treatment of acne and hirsutism. Spironolactone should not be prescribed to women with renal failure because it can result in severe hyperkalemia. In a study of spironolactone safety in the treatment of acne, no adverse effects on the kidney, liver, or adrenal glands were reported over 8 years of use.12

What insulin sensitizers are useful in rebalancing the metabolic abnormalities observed with PCOS?

Diet and exercise are superb approaches to rebalancing metabolic abnormalities, but for many of my patients they are insufficient and treatment with an insulin sensitizer is warranted. The most commonly utilized insulin sensitizer for the treatment of PCOS is metformin because it is very inexpensive and has a low risk of serious adverse effects such as lactic acidosis. Metformin increases peripheral glucose uptake and reduces gastrointestinal glucose absorption. Insulin sensitizers also decrease visceral fat, a major source of adipokines. One major disadvantage of metformin is that at doses in the range of 1,500 mg to 2,250 mg it often causes gastrointestinal adverse effects such as borborygmi, nausea, abdominal discomfort, and loose stools.

Thiazolidinediones, including pioglitazone, have been reported to be effective in rebalancing central metabolism in women with PCOS. Pioglitazone carries a black box warning of an increased risk of congestive heart failure and nonfatal myocardial infarction. Pioglitazone is also associated with a risk of hepatotoxicity. However, at the pioglitazone dose commonly used in the treatment of PCOS (7.5 mg daily), these serious adverse effects are rare. In practice, I initiate metformin at a dose of 750 mg daily using the extended-release formulation. I increase the metformin dose to 1,500 mg daily if the patient has no bothersome gastrointestinal symptoms on the lower dose. If the patient cannot tolerate metformin treatment because of adverse effects, I will use pioglitazone 7.5 mg daily.

Continue to: Treatment of PCOS in women who are carriers of the Factor V Leiden mutation...

Treatment of PCOS in women who are carriers of the Factor V Leiden mutation

The Factor V Leiden allele is associated with an increased risk of venous thromboembolism. Estrogen-progestin contraception is contraindicated in women with the Factor V Leiden mutation. The prevalence of this mutation varies by race and ethnicity. It is present in about 5% of white, 2% of Hispanic, 1% of black, 1% of Native American, and 0.5% of Asian women. In women with PCOS who are known to be carriers of the mutation, dual therapy with metformin and spironolactone is highly effective.13-15 For these women I also offer a levonorgestrel IUD to provide contraception and reduce the risk of endometrial hyperplasia.

Combination triple medication treatment of PCOS

Optimal treatment of the reproductive, metabolic, and dermatologic problems associated with PCOS requires multimodal medications including an estrogen-progestin contraceptive, an antiandrogen, and an insulin sensitizer. In my practice, I initiate treatment of PCOS by offering patients 3 medications: a COC, spironolactone 100 mg daily, and metformin extended-release formulation 750 mg daily. Some patients elect dual medication therapy (COC plus spironolactone or COC plus metformin), but many patients select treatment with all 3 medications. Although triple medication treatment of PCOS has not been tested in large randomized clinical trials, small trials report that triple medication treatment produces optimal improvement in the reproductive, metabolic, and dermatologic problems associated with PCOS.16-18

- Rotterdam ESHRE/ASRM-Sponsored PCOS Consensus Workshop Group. Revised 2003 consensus on diagnostic criteria and long-term health risks related to polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertil Steril. 2004;81:19-25.

- Zawadski JK, Dunaif A. Diagnostic criteria for polycystic ovary syndrome: towards a rational approach. In Dunaif A, Givens JR, Haseltine FP, et al. Polycystic ovary syndrome. Boston, MA: Blackwell Scientific; 1992:377-384.

- Bozdag G, Mumusoglu S, Zengin D, et al. The prevalence and phenotypic features of polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Reprod. 2016;31:2841-2855.

- Baskind NE, Balen AH. Hypothalamic-pituitary, ovarian and adrenal contributions to polycystic ovary syndrome. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2016;37:80-97.

- Gilbert EW, Tay CT, Hiam DS, et al. Comorbidities and complications of polycystic ovary syndrome: an overview of systematic reviews. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2018;89:683-699.

- Harsha Varma S, Tirupati S, Pradeep TV, et al. Insulin resistance and hyperandrogenemia independently predict nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2019;13:1065-1069.

- Housman E, Reynolds RV. Polycystic ovary syndrome: a review for dermatologists: Part I. Diagnosis and manifestations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:847.e1-e10.

- Dilday J, Derickson M, Kuckelman J, et al. Sleeve gastrectomy for obesity in polycystic ovarian syndrome: a pilot study evaluating weight loss and fertility outcomes. Obes Surg. 2019;29:93-98.

- Lortscher D, Admani S, Satur N, et al. Hormonal contraceptives and acne: a retrospective analysis of 2147 patients. J Drugs Dermatol. 2016;15:670-674.

- Brown J, Farquhar C, Lee O, et al. Spironolactone versus placebo or in combination with steroids for hirsutism and/or acne. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;CD000194.

- Shaw JC. Low-dose adjunctive spironolactone in the treatment of acne in women: a retrospective analysis of 85 consecutively treated patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43:498-502.

- Shaw JC, White LE. Long-term safety of spironolactone in acne: results of an 8-year follow-up study. J Cutan Med Surg. 2002;6:541-545.

- Ganie MA, Khurana ML, Nisar S, et al. Improved efficacy of low-dose spironolactone and metformin combination than either drug alone in the management of women with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS): a six-month, open-label randomized study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98:3599-3607.

- Mazza A, Fruci B, Guzzi P, et al. In PCOS patients the addition of low-dose spironolactone induces a more marked reduction of clinical and biochemical hyperandrogenism than metformin alone. Nutr Metab Cardiovascular Dis. 2014;24:132-139.

- Ganie MA, Khurana ML, Eunice M, et al. Comparison of efficacy of spironolactone with metformin in the management of polycystic ovary syndrome: an open-labeled study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:2756-2762.

- Ibanez L, de Zegher F. Low-dose combination flutamide, metformin and an oral contraceptive for non-obese, young women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Hum Reprod. 2003;18:57-60.

- Ibanez L, de Zegher F. Flutamide-metformin plus an oral contraceptive (OC) for young women with polycystic ovary syndrome: switch from third- to fourth-generation OC reduces body adiposity. Hum Reprod. 2004;19:1725-1727.

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is the triad of oligo-ovulation resulting in oligomenorrhea, hyperandrogenism and, often, an excess number of small antral follicles on high-resolution pelvic ultrasound. One meta-analysis reported that, in women of reproductive age, the prevalence of PCOS was 10% using the Rotterdam-European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology/American Society for Reproductive Medicine (ESHRE/ASRM) criteria1 and 6% using the National Institutes of Health 1990 diagnostic criteria.2 (See “The PCOS trinity—3 findings in one syndrome: oligo-ovulation, hyperandrogenism, and a multifollicular ovary.”3)

PCOS is caused by abnormalities in 3 systems: reproductive, metabolic, and dermatologic. Reproductive abnormalities commonly observed in women with PCOS include4:

- an increase in pituitary secretion of luteinizing hormone (LH), resulting from both an increase in LH pulse amplitude and LH pulse frequency, suggesting a primary hypothalamic disorder

- an increase in ovarian secretion of androstenedione and testosterone due to stimulation by LH and possibly insulin

- oligo-ovulation with chronically low levels of progesterone that can result in endometrial hyperplasia

- ovulatory infertility.

Metabolic abnormalities commonly observed in women with PCOS include5,6:

- insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia

- excess adipose tissue in the liver

- excess visceral fat

- elevated adipokines

- obesity

- an increased prevalence of glucose intolerance and frank diabetes.

Dermatologic abnormalities commonly observed in women with PCOS include7:

- facial hirsutism

- acne

- androgenetic alopecia.

Given that PCOS is caused by abnormalities in the reproductive, metabolic, and dermatologic systems, it is appropriate to consider multimodal hormonal therapy that addresses all 3 problems. In my practice, I believe that the best approach to the long-term hormonal treatment of PCOS for many women is to prescribe a combination of 3 medicines: a combination estrogen-progestin oral contraceptive (COC), an insulin sensitizer, and an antiandrogen.

The COC reduces pituitary secretion of LH, decreases ovarian androgen production, and prevents the development of endometrial hyperplasia. When taken cyclically, the COC treatment also restores regular withdrawal uterine bleeding.

An insulin sensitizer, such as metformin or pioglitazone, helps to reduce insulin resistance, glucose intolerance, and hepatic adipose content, rebalancing central metabolism. It is important to include diet and exercise in the long-term treatment of PCOS, and I always encourage these lifestyle changes. However, my patients usually report that they have tried multiple times to restrict dietary caloric intake and increase exercise and have been unable to rebalance their metabolism with these interventions alone. Of note, in the women with PCOS and a body mass index >35 kg/m2, bariatric surgery, such as a sleeve gastrectomy, often results in marked improvement of their PCOS.8

The antiandrogen spironolactone provides effective treatment for the dermatologic problems of facial hirsutism and acne. Some COCs containing the progestins drospirenone, norgestimate, and norethindrone acetate are approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of acne. A common approach I use in practice is to prescribe a COC, plus spironolactone 100 mg daily plus metformin extended-release 750 mg to 1,500 mg daily.

Continue to: Which COCs have low androgenicity?...

Which COCs have low androgenicity?

I believe that every COC is an effective treatment for PCOS, regardless of the androgenicity of the progestin in the contraceptive. However, some dermatologists believe that combination contraceptives containing progestins with low androgenicity, such as drospirenone, norgestimate, and desogestrel, are more likely to improve acne than contraceptives with an androgenic progestin such as levonorgestrel. In one study in which 2,147 women with acne were treated by one dermatologic practice, the percentage of women reporting that a birth control pill helped to improve their acne was 66% for pills containing drospirenone, 53% for pills containing norgestimate, 44% for pills containing desogestrel, 30% for pills containing norethindrone, and 25% for pills containing levonorgestrel. In the same study, the percent of women reporting that a birth control pill made their acne worse was 3% for pills containing drospirenone, 6% for pills containing norgestimate, 2% for pills containing desogestrel, 8% for pills containing norethindrone, and 10% for pills containing levonorgestrel.9 Given these findings, when treating a woman with PCOS, I generally prescribe a contraceptive that does not contain levonorgestrel.

Why is a spironolactone dose of 100 mg a good choice for PCOS treatment?

Spironolactone, an antiandrogen and inhibitor of 5-alpha-reductase, is commonly prescribed for the treatment of hirsutism and acne at doses ranging from 50 mg to 200 mg daily.10,11 In my clinical experience, spironolactone at a dose of 200 mg daily commonly causes irregular and bothersome uterine bleeding while spironolactone at a dose of 100 mg daily is seldom associated with irregular bleeding. I believe that spironolactone at a dose of 100 mg daily results in superior clinical efficacy than a 50-mg daily dose, although studies report that both doses are effective in the treatment of acne and hirsutism. Spironolactone should not be prescribed to women with renal failure because it can result in severe hyperkalemia. In a study of spironolactone safety in the treatment of acne, no adverse effects on the kidney, liver, or adrenal glands were reported over 8 years of use.12

What insulin sensitizers are useful in rebalancing the metabolic abnormalities observed with PCOS?

Diet and exercise are superb approaches to rebalancing metabolic abnormalities, but for many of my patients they are insufficient and treatment with an insulin sensitizer is warranted. The most commonly utilized insulin sensitizer for the treatment of PCOS is metformin because it is very inexpensive and has a low risk of serious adverse effects such as lactic acidosis. Metformin increases peripheral glucose uptake and reduces gastrointestinal glucose absorption. Insulin sensitizers also decrease visceral fat, a major source of adipokines. One major disadvantage of metformin is that at doses in the range of 1,500 mg to 2,250 mg it often causes gastrointestinal adverse effects such as borborygmi, nausea, abdominal discomfort, and loose stools.

Thiazolidinediones, including pioglitazone, have been reported to be effective in rebalancing central metabolism in women with PCOS. Pioglitazone carries a black box warning of an increased risk of congestive heart failure and nonfatal myocardial infarction. Pioglitazone is also associated with a risk of hepatotoxicity. However, at the pioglitazone dose commonly used in the treatment of PCOS (7.5 mg daily), these serious adverse effects are rare. In practice, I initiate metformin at a dose of 750 mg daily using the extended-release formulation. I increase the metformin dose to 1,500 mg daily if the patient has no bothersome gastrointestinal symptoms on the lower dose. If the patient cannot tolerate metformin treatment because of adverse effects, I will use pioglitazone 7.5 mg daily.

Continue to: Treatment of PCOS in women who are carriers of the Factor V Leiden mutation...

Treatment of PCOS in women who are carriers of the Factor V Leiden mutation

The Factor V Leiden allele is associated with an increased risk of venous thromboembolism. Estrogen-progestin contraception is contraindicated in women with the Factor V Leiden mutation. The prevalence of this mutation varies by race and ethnicity. It is present in about 5% of white, 2% of Hispanic, 1% of black, 1% of Native American, and 0.5% of Asian women. In women with PCOS who are known to be carriers of the mutation, dual therapy with metformin and spironolactone is highly effective.13-15 For these women I also offer a levonorgestrel IUD to provide contraception and reduce the risk of endometrial hyperplasia.

Combination triple medication treatment of PCOS

Optimal treatment of the reproductive, metabolic, and dermatologic problems associated with PCOS requires multimodal medications including an estrogen-progestin contraceptive, an antiandrogen, and an insulin sensitizer. In my practice, I initiate treatment of PCOS by offering patients 3 medications: a COC, spironolactone 100 mg daily, and metformin extended-release formulation 750 mg daily. Some patients elect dual medication therapy (COC plus spironolactone or COC plus metformin), but many patients select treatment with all 3 medications. Although triple medication treatment of PCOS has not been tested in large randomized clinical trials, small trials report that triple medication treatment produces optimal improvement in the reproductive, metabolic, and dermatologic problems associated with PCOS.16-18

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is the triad of oligo-ovulation resulting in oligomenorrhea, hyperandrogenism and, often, an excess number of small antral follicles on high-resolution pelvic ultrasound. One meta-analysis reported that, in women of reproductive age, the prevalence of PCOS was 10% using the Rotterdam-European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology/American Society for Reproductive Medicine (ESHRE/ASRM) criteria1 and 6% using the National Institutes of Health 1990 diagnostic criteria.2 (See “The PCOS trinity—3 findings in one syndrome: oligo-ovulation, hyperandrogenism, and a multifollicular ovary.”3)

PCOS is caused by abnormalities in 3 systems: reproductive, metabolic, and dermatologic. Reproductive abnormalities commonly observed in women with PCOS include4:

- an increase in pituitary secretion of luteinizing hormone (LH), resulting from both an increase in LH pulse amplitude and LH pulse frequency, suggesting a primary hypothalamic disorder

- an increase in ovarian secretion of androstenedione and testosterone due to stimulation by LH and possibly insulin

- oligo-ovulation with chronically low levels of progesterone that can result in endometrial hyperplasia

- ovulatory infertility.

Metabolic abnormalities commonly observed in women with PCOS include5,6:

- insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia

- excess adipose tissue in the liver

- excess visceral fat

- elevated adipokines

- obesity

- an increased prevalence of glucose intolerance and frank diabetes.

Dermatologic abnormalities commonly observed in women with PCOS include7:

- facial hirsutism

- acne

- androgenetic alopecia.

Given that PCOS is caused by abnormalities in the reproductive, metabolic, and dermatologic systems, it is appropriate to consider multimodal hormonal therapy that addresses all 3 problems. In my practice, I believe that the best approach to the long-term hormonal treatment of PCOS for many women is to prescribe a combination of 3 medicines: a combination estrogen-progestin oral contraceptive (COC), an insulin sensitizer, and an antiandrogen.

The COC reduces pituitary secretion of LH, decreases ovarian androgen production, and prevents the development of endometrial hyperplasia. When taken cyclically, the COC treatment also restores regular withdrawal uterine bleeding.

An insulin sensitizer, such as metformin or pioglitazone, helps to reduce insulin resistance, glucose intolerance, and hepatic adipose content, rebalancing central metabolism. It is important to include diet and exercise in the long-term treatment of PCOS, and I always encourage these lifestyle changes. However, my patients usually report that they have tried multiple times to restrict dietary caloric intake and increase exercise and have been unable to rebalance their metabolism with these interventions alone. Of note, in the women with PCOS and a body mass index >35 kg/m2, bariatric surgery, such as a sleeve gastrectomy, often results in marked improvement of their PCOS.8

The antiandrogen spironolactone provides effective treatment for the dermatologic problems of facial hirsutism and acne. Some COCs containing the progestins drospirenone, norgestimate, and norethindrone acetate are approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of acne. A common approach I use in practice is to prescribe a COC, plus spironolactone 100 mg daily plus metformin extended-release 750 mg to 1,500 mg daily.

Continue to: Which COCs have low androgenicity?...

Which COCs have low androgenicity?

I believe that every COC is an effective treatment for PCOS, regardless of the androgenicity of the progestin in the contraceptive. However, some dermatologists believe that combination contraceptives containing progestins with low androgenicity, such as drospirenone, norgestimate, and desogestrel, are more likely to improve acne than contraceptives with an androgenic progestin such as levonorgestrel. In one study in which 2,147 women with acne were treated by one dermatologic practice, the percentage of women reporting that a birth control pill helped to improve their acne was 66% for pills containing drospirenone, 53% for pills containing norgestimate, 44% for pills containing desogestrel, 30% for pills containing norethindrone, and 25% for pills containing levonorgestrel. In the same study, the percent of women reporting that a birth control pill made their acne worse was 3% for pills containing drospirenone, 6% for pills containing norgestimate, 2% for pills containing desogestrel, 8% for pills containing norethindrone, and 10% for pills containing levonorgestrel.9 Given these findings, when treating a woman with PCOS, I generally prescribe a contraceptive that does not contain levonorgestrel.

Why is a spironolactone dose of 100 mg a good choice for PCOS treatment?